Title: Mammals of Mount Rainier National Park

Author: Merlin K. Potts

Russell K. Grater

Release date: June 21, 2016 [eBook #52390]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Dave Morgan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

MERLIN K. POTTS

Assistant Park Naturalist

and

RUSSELL K. GRATER

Park Naturalist

Copyright 1949 by

Mount Rainier

Natural History Association

Published by

THE MOUNT RAINIER

NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION

Longmire, Washington

1949

There are few places remaining in this country today where one may observe wild animals in a natural setting, free to move about, unrestricted by bars or enclosures, and exhibiting little of the instinctive fear of man instilled through many wildlife generations by the advance and expansion of settlement and civilization.

The national parks are among the greatest wildlife sanctuaries of the world. Most wild creatures are quick to recognize the protection afforded by such a refuge, and thus become less shy and elusive than they are elsewhere. As a result of protection, it is not difficult to attain an acquaintance with these wilderness folk.

To know Nature in her various forms is to increase appreciation of the natural scene. It is for this purpose that Mammals of Mount Rainier National Park has been written, the third of a series published by the Mount Rainier Natural History Association.

JOHN C. PRESTON

Superintendent

Mount Rainier National Park

United States Department of the Interior

The writers of Mammals of Mount Rainier National Park are indebted to the following individuals for their critical assistance and encouragement in the preparation of the manuscript:

Dr. A. Svihla, Zoology Department, University of Washington,

Mr. Herbert Evison, Chief of Information, National Park Service,

Mr. Victor H. Cahalane, Biologist, National Park Service,

Mr. E. Lowell Sumner, Regional Biologist, Region Four, National Park Service.

Through their constructive suggestions the finished publication has been materially strengthened.

Photographs were obtained through the courtesy of Mount Rainier, Yellowstone, Rocky Mountain, and Glacier National Parks; and Mr. Joseph M. Dixon, Mr. E. Lowell Sumner, and Mr. F. J. McGrail.

Merlin K. Potts Russell K. Grater

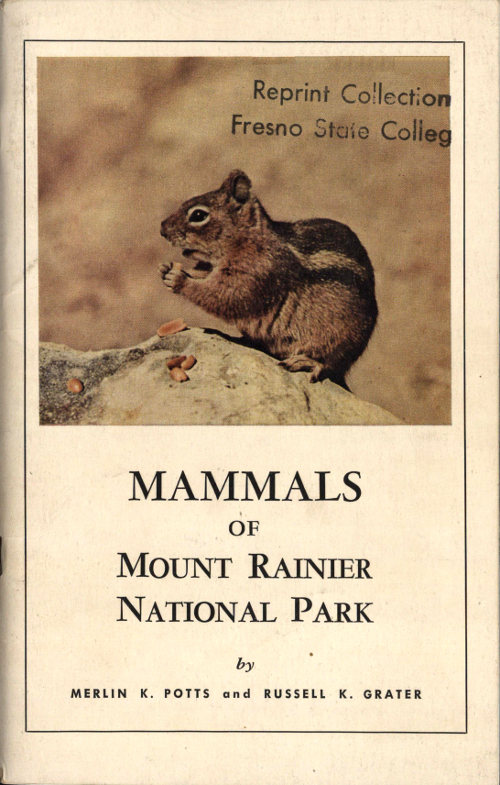

Bench Lake, Hudsonian life zone lakeshore-fireburn habitat. This type of cover is extensively utilized in summer by the coyote and black-tailed deer, and on the southern exposures by the Hollister chipmunk and mantled ground squirrel. The lake shore is favored by the water-loving shrews.

In looking back through the years during which mammal studies have been carried on at Mount Rainier, three periods stand out in which considerable field research was accomplished. The first of these was in July and August, 1897, when a party headed by Dr. C. Hart Merriam, Vernon Bailey, Dr. A. K. Fisher and Walter K. Fisher made the first field studies of the mammals of the park. Following this very important piece of work there was a lull in field activities until the summer of 1919 when a party working under the auspices of the National Park Service and the Bureau of Biological Survey conducted studies on the local bird and mammal populations. In this party were such well known scientists as Dr. Walter P. Taylor, in charge, George G. Cantwell, Stanley G. Jewett, Professor J. B. Flett, Professor William T. Shaw, Professor J. W. Hungate and Mr. and Mrs. William L. Finley. Upon the completion of this study there was again a long period in which little of a systematic nature was accomplished. The last period of note came during the years 1934-1936 when Mr. E. A. Kitchin, a member of the Wildlife Division of the National Park Service, supervised field studies in various portions of the park. Many of these studies were concerned with observational data rather than extensive collecting. For the next few years only brief observations from members of the park staff were added to the park records. Then, during the summer of 1947, special studies were begun by the Naturalist Staff on the status of the mountain goat and the problems arising from a foot disease that occurred in the deer population. It is planned that other special studies shall be carried on in future years, designed to clarify the status of other important mammalian species in the park.

Because of the extensive data that have slowly accumulated through the years since the 1919 survey, the need for a publication to bring all information up to date has become increasingly apparent. This booklet is designed to answer that need.

The sequence of species used brings many of the larger animals ahead of the smaller and more obscure kinds, and thus 2 does not in many cases follow in systematic order. However, it is felt that the order used best meets the needs in a publication of this type. Common names selected are those most generally accepted for the animals in question.

When the first wildlife survey was made in 1897 it is likely that the conditions of that year came nearest to representing the original status of the various species—a status that has changed drastically in many instances in the years that have followed. At that time the park was little known and the faunal relationships were relatively undisturbed. In the years since 1900, however, the region has experienced radical changes. Trappers have reduced the fur bearers in large numbers, logging activities in the valleys and on the mountain slopes near the park have entirely changed the ecology of the region. Many important predators, such as the wolf and wolverine, either became extinct or virtually so, while the changing forest scene due to fires and logging brought new species into prominence, such as the porcupine and coyote. Recently elk, released in the nearby valleys, have entered the park and are now firmly established, promising still new changes in the mammal picture as time goes on. In many respects Mount Rainier has become a biotic island in a region where the original conditions no longer exist except in the park. The smallness of this biotic island makes it impossible for even an undeveloped area of this type to represent really primitive conditions. Thus the park today cannot be considered as representing the original wilderness as seen by the first white men to enter the region. It is merely as near the original wilderness as it has been possible to keep it in the midst of all the changes brought about by man.

However, by the preservation of the natural environment, the National Park Service does much to conserve the wildlife as well. In many instances the national parks are among the last remaining refuges for rare and vanishing species of wildlife. The wolverine, the grizzly bear, and the wolf, now extinct over much of their range in North America, may still be found in these sanctuaries, and, along with other species, these creatures of the remote wilderness are fighting their battle of survival in the only areas left to them.

Extirpated species, those native forms which are known to have existed in some areas, but which have since disappeared, are being restored where possible. The muskrat, formerly present in Mount Rainier National Park, now not known to occur, is an example of an extirpated species which should be restored.

Since the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916, it has become increasingly obvious that the occupation of the national parks by man and wildlife must inevitably result in wildlife problems. The act creating the National Park Service is specific in its language; it says that the Service thus established shall promote and regulate the use of the areas by such means and measures necessary “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

The apparent inconsistency presents itself immediately. Natural features must be conserved and protected, they must not be impaired, yet provision must be made for their enjoyment by the millions of visitors who come to the national parks each year. The course that must be followed, then, is one of permitting modification of the natural scene only to the degree required to provide for perpetual enjoyment of “the scenery, the natural and historic objects and the wildlife.”

The relations between man and the wildlife of the national parks are complex. Both occupy the parks, with equal rights to that occupancy. It can scarcely be argued that man is not a part of the natural scene; certainly there is nothing essentially unnatural in the progress of our civilization from the dawn of history to the present. In the national parks, however, the unimpaired values to be preserved are those of the primitive natural scene. Man can strive to maintain these values, unimpaired, because he has the power of reason. Through that power he can recognize the effect of his conflict with nature, and so prevent the destruction of the primitive natural scene by a proper regulation of his acts.

Specifically, the wildlife problems now readily recognized in Mount Rainier National Park are those which have developed because of relations between man and mammals. The deer, bear, and raccoon are outstanding examples. In the developed areas of the park many of these animals have become so accustomed to the proximity of man that they no longer exhibit timidity in his presence. They are essentially “wild” animals, yet because of close association with man for several wildlife generations, they may be practically considered as “semi-domestic” animals.

This “semi-domesticity” is a problem in itself. First, it is not in keeping with the primitive natural scene. The true wildlife picture is not one of a deer eating from a visitor’s hand; that is scarcely more natural than seeing the animal within the fenced enclosure of a zoo. The artificial feeding of any form of wildlife is objectionable for several other reasons. Such feeding encourages an unnatural concentration of the animals in restricted localities, thus increasing the danger of the spread of any contagious disease or infection. In the case of deer, feeding affects, often disastrously, the normal habit of migration to lower elevations in winter. Deer encouraged by feeding to remain at Longmire, for example, encounter difficult times during the winter months. Natural forage is buried beneath the snow, migratory routes to the lowlands are blocked, and starvation is not unusual.

In every instance, experience has shown that when animals are hand-fed, petted, and tamed, the results have been detrimental to both the animals and to man. The “tamed” animals are often dangerous, or may become so. Even the harmless appearing deer may, and do, inflict severe injuries by striking with the fore feet or hooking with the antlers, and bears often strike or bite, once they have lost their instinctive fear of man. When any animal becomes dangerous, the only solutions are to eliminate the danger by killing the animal, or to live-trap and remove it to a more isolated section of the park. The latter is often a temporary expedient because the animal is likely to return almost at once to its original home.

“Semi-domestic” bears may become unruly. Such animals must be live-trapped and removed to isolated sections of the park. A wary bruin is often suspicious of the trap.

That many park visitors are entirely unaware of the concept of presenting wildlife in its natural setting is exemplified by the man who dashed excitedly into the Chief Ranger’s office and breathlessly exclaimed, “Hey, one of your bears is loose!” Park animals are not “zoo animals.” They have simply adapted themselves to man’s presence, and although their habits have been materially changed in many instances, they retain the wild instinct to fight when cornered, to strike back against a real or fancied danger, to quarrel with anything which seeks to rob them of food. It seems hardly necessary to emphasize the futility of attempting to argue the right to possession of a choice morsel with a three-hundred-pound bear.

Bears are often condemned as nuisances because they rob the camper’s food cache, even to the extent of forcing open locked cupboards or entering automobiles. Raccoons may make a shambles of food stores, if the larder is left unprotected. That these things are nuisances is true, but had the animals not been encouraged to expect food, it is unlikely that they would go to such lengths to obtain it. The original approach was undoubtedly made by man, not by the animal, and man has little reason 6 to condemn, under the circumstances. The sad sequence, however, is that it is all too often the unsuspecting innocent who suffers. One party entices a bear into camp today, feeds the animal, and moves on. Tomorrow another camper receives a rude shock when bruin moves in and appropriates his food supply.

It appears then, that these wildlife problems, which have developed through man’s influence upon the animals, have been brought about by man’s failure to employ his power of reason, his failure to recognize the effect he may have upon the natural scene. Indeed, it would seem, in many instances, that man is the problem, not the animals. They have adapted themselves to a condition at variance with their nature; man has failed to do so.

These problems, and others which are similar, are not impossible of solution. Of the many phases of wildlife management that are a part of the adjustments to be made in our relations with the animals of the parks, these of living together must be approached by our recognition of the need for such adjustment. The late George M. Wright has well expressed the goal to be attained:

“These problems are of such magnitude that some observers have concluded that only the childish idealist, pathetically blind to the practical obstacles, would attempt to accomplish the thing. There are others who believe the effort is warranted. Much of man’s genuine progress is dependent upon the degree to which he is capable of this sort of control. If we destroy nature blindly, it is a boomerang which will be our undoing.

“Consecration to the task of adjusting ourselves to natural environment so that we secure the best values from nature without destroying it is not useless idealism; it is good hygiene for civilization.

“In this lies the true portent of this national parks effort. Fifty years from now we shall still be wrestling with the problems of joint occupation of national parks by men and mammals, but it is reasonable to predict that we shall have mastered some of the simplest maladjustments. It is far better to pursue such a course though success be but partial than to relax in despair and allow the destructive forces to operate unchecked.”

Life zones, as defined in relation to plant and animal life, are areas inhabited by more or less definite groups of plants and animals. The classification of these zones which is accepted by many biologists was devised by Dr. C. Hart Merriam, who named six zones; the Arctic-alpine, Hudsonian, Canadian, Transition, Upper Sonoran and Lower Sonoran. If one travels from the Southwestern United States into the high country of the Rockies or the Pacific Northwest, he will pass through all six of these zones, beginning with the Lower Sonoran, or low desert zone, through the Upper Sonoran, or high desert, and so on through the others until the highest, or Arctic-alpine Zone is reached. The area immediately adjacent to Puget Sound, for example, falls within the Transition Zone. Moving inland toward Mount Rainier, one passes from the Transition into the Canadian Zone, usually a short distance inside the park boundaries, and the major portion of Mount Rainier National Park is within the upper three zones.

Temperature is the basis for the separation of these zones, and temperature, as we know, is affected by both altitude and latitude. In general a difference of 1,000 feet in altitude is equivalent to a difference of 300 miles in latitude. Variation in latitude explains the high elevation of tree line in the southern Sierra Nevada of California in relation to the comparatively low limit of tree growth in northern British Columbia or Alaska. Variation in temperature explains the tremendous difference in size and variety of tree species at 2,000 feet and at forest line, 6,500 feet, on Mount Rainier. On a very high mountain we might find all six of the life zones represented. The mountain presenting such a condition, however, would necessarily be located in a more southern latitude than Mount Rainier.

Four life zones are represented in Mount Rainier National Park: the Transition Zone, which occupies the lower elevations of the park up to 3,000 feet; the Canadian Zone, which, with the exception of the Transition area, extends from park boundaries to about 5,000 feet; the Hudsonian Zone, with an altitudinal range of from approximately 5,000 to 6,500 feet; and the Arctic-alpine Zone, from 6,500 feet to the summit of the Mountain.

As stated previously, the zones are inhabited by more or less definite groups of plants and animals, but there is no distinct line of demarcation between the various zones, and there is often considerable variation in the altitudinal distribution of plants. If temperature and moisture were uniform at a given altitude, the zones would probably be quite distinct. However, these conditions are obviously not uniform. On northern exposures, for example, there is less evaporation, consequently soil moisture is increased, and lack of sunshine results in lower temperatures. Plants which normally occur at 5,000 feet on a sunny southern exposure may be found at a lower elevation on northern slopes, and the reverse is true, of course, with a reversal of exposures.

Such variation is even more marked in the distribution of mammals and birds. Many species are characteristic of one or more life zones, depending upon the season of the year, the scarcity or abundance of food, and other factors.

For example, deer occupy the Transition or the extreme lower limits of the Canadian Zone in winter, but in summer range up to and occasionally beyond the limits of the Hudsonian Zone. Goats normally range within the upper limits of the Hudsonian and upward into the Arctic-alpine Zone in summer, but are most commonly found in the lower Hudsonian Zone in winter.

The general characteristics of the zones are as follows:

Transition Zone: This zone occupies that portion of the park which lies below 3,000 feet. For the most part it may be more adequately designated the Humid Transition Zone, although a limited area (roughly 4 to 6 square miles) on Stevens Creek and the Muddy Fork of Cowlitz River is characterized by a modified plant and animal population due to repeated fires in old Indian days. This burning favored the upward advance of low zone elements, the destruction of the original forest cover by fire opened the forest stand, accomplished a marked change in conditions of temperature and moisture, thus creating a drier, warmer site.

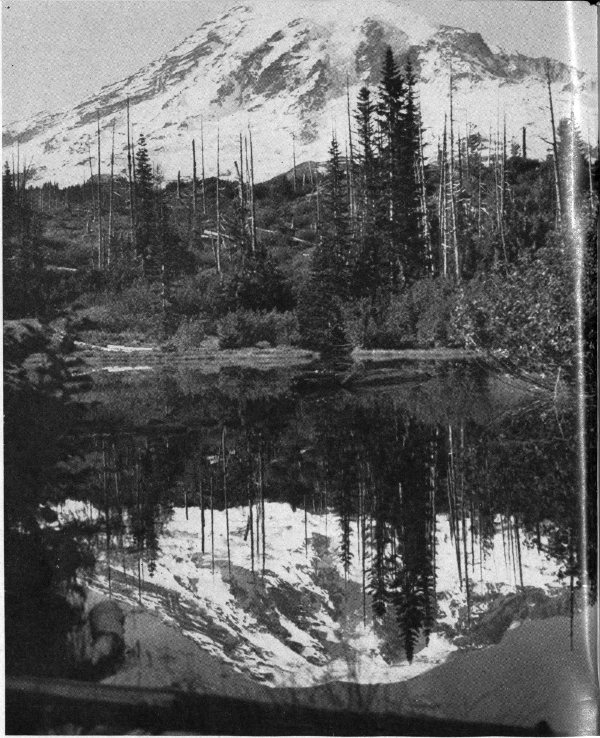

The Humid Transition Zone proper is one of dense, sombre forest; magnificent trees rising from a mass of shade-loving plants with a great number of fallen trees of huge size. Even on bright, mid-summer days the evergreen canopy of interlaced branches permits only a little sunlight to penetrate to the forest floor, and semi-twilight conditions exist in the peaceful solitude of this cathedral-like serenity.

The Humid Transition life zone is one of magnificent trees.

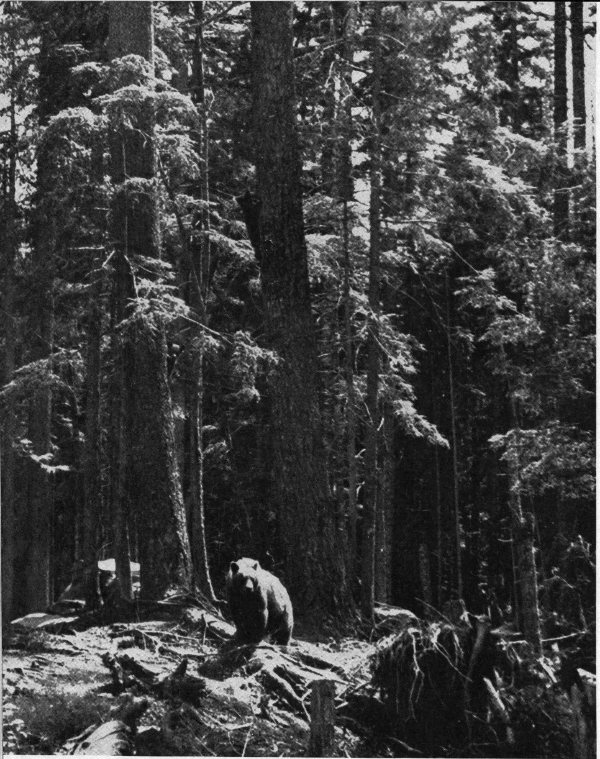

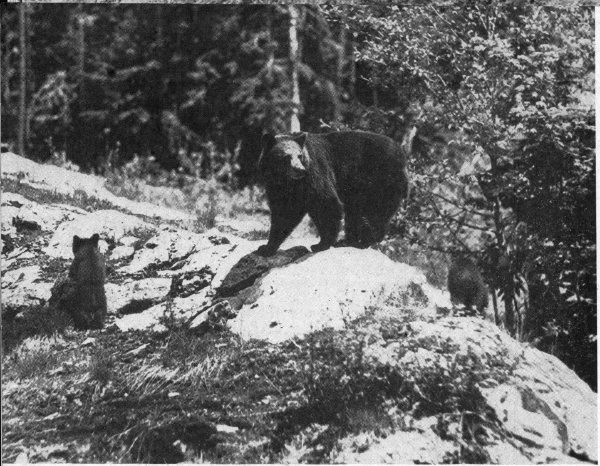

The forests of the Canadian life zone afford excellent cover for many mammals throughout the year. In summer such retreats are favored habitats for bear families.

Characteristic plants of this zone, though not confined to such association, include the Douglas fir, western red cedar, western hemlock, salal, Oregon grape, black cottonwood, bigleaf maple, and swordfern.

Here are found the raccoon, little spotted skunk, Oregon and Olympic meadow mice, and the mink. In this zone are seen in late spring the new-born fawns of the black-tailed deer.

Canadian Zone: This zone does not become well defined until above the 3,000-foot level. There is a considerable mixture of both Transition and Canadian elements at the approximate area of separation. While still heavily forested, the trees of the Canadian Zone are noticeably smaller than those at lower elevations and the forest is more open in character. Although common tree species include the Douglas fir and western hemlock of the Transition Zone, the most typical trees are the silver fir, Alaska yellow cedar, noble fir, and western white pine. Other typical plants are the Canadian dogwood, pipsissewa, and Cascades azalea.

There are no mammals which may be considered as characteristic exclusively of the Canadian Zone, since those occupying this zone also range into the Hudsonian.

Hudsonian Zone: At an elevation of from 4,500 to 5,000 feet the character of the forest cover begins to change. The trees are smaller, and the alpine fir and mountain hemlock become dominant tree species. Ascending to higher levels the forest becomes broken, with the number and extent of grassy parks and subalpine meadows increasing until finally all tree growth vanishes at an elevation of about 6,500 feet. This is the zone of beautiful summer wildflower gardens, a region of extensive panoramas and rugged mountain scenes. The avalanche lily, glacier lily, the heathers, paintbrushes, and the mountain phlox are common, as well as the white-barked pine.

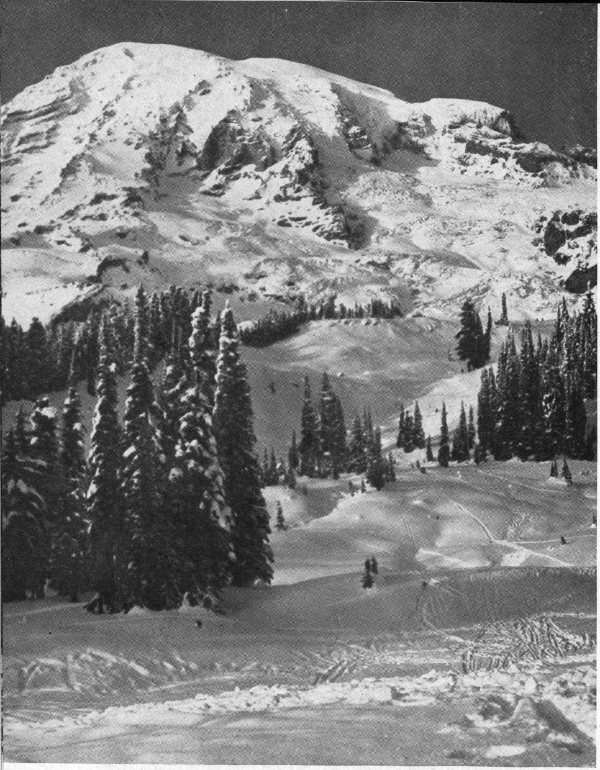

Snow blankets the Hudsonian life zone throughout most of the year. Paradise Valley lies within this zone, the towering bulk of the Mountain above 6,500 feet is in the Arctic-alpine zone.

Snow blankets these highlands throughout most of the year, and the larger mammals are usually at the lower elevations during the winter months. Many of the permanent wildlife inhabitants are those which hibernate or are active beneath the snow, as the Hollister chipmunk, marmot, pika, Rainier meadow mouse, and Rainier pocket gopher.

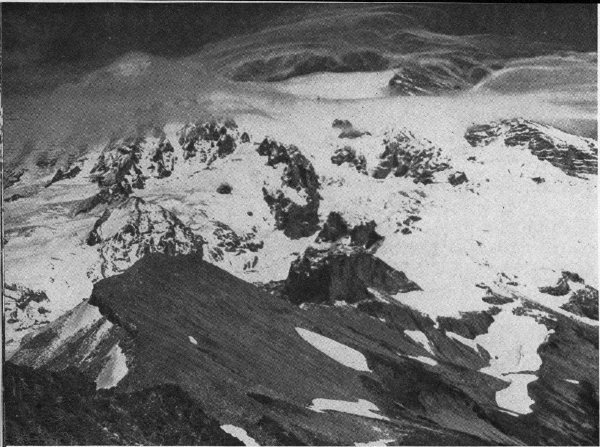

Arctic-alpine Zone: Above the forest line all plant life diminishes rapidly in extent. This is a region of barren, rocky soils; perpetual snow fields; and glacial ice; a bleak and forbidding expanse of awe-inspiring grandeur where the storm king yields supremacy for only a few brief weeks in mid-summer.

Characteristic plants, found in the lower portions of this zone, include the Lyall’s lupine, Tolmie’s saxifrage, mountain buckwheat, and golden aster.

Only one mammal, the mountain goat, may be considered as characteristic of this zone.

The Columbian black-tailed deer is a typical member of the deer family, about the size of its eastern relative, the white-tailed deer. The antlers of the males are forked, rather than having the tines rise from a single main beam as do those of the white-tail. The upper surface of the tail is conspicuously dark brown or black over its entire length. The color of the pelage varies with the season, but is the same in both sexes. In summer the back and flanks are reddish to reddish yellow; in winter gray, intermixed with black, with a dark line along the back, black on the top of the head, and conspicuous white on the chin and upper throat. The underparts are sooty, with white on the inner sides of the legs. The young, at birth, are a dark, rich brown, profusely spotted with creamy yellow. The dark coloration very shortly fades to a lighter brown, or reddish, similar to the summer coat of the adult, and the spots disappear in the early fall when the change to winter pelage begins.

Specimens in park collection: RNP-14 and RNP-113; Longmire Museum, Park Headquarters.

The range of the Columbian black-tailed deer is the Pacific Northwest from northern California to British Columbia and from the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Mountains to the Pacific Coast.

The bleak and awe-inspiring grandeur of the Arctic-alpine life zone is the summer habitat of the mountain goat.

It is the most common large animal in the park, distributed in summer throughout the forested areas and occasionally wandering above tree line, the males generally ranging higher than the females and young, preferring the sub-alpine parks and meadows. Deer in general exhibit a preference for burned-over brush lands and other less densely forested areas.

In winter they are found at lower elevations, usually below snow line, generally outside park boundaries, although common along the Nisqually River from Longmire Meadows downstream, along lower Tahoma Creek, and in the vicinity of the Ohanapecosh Hot Springs and lower Carbon River.

Nearly all visitors to Mount Rainier National Park soon become familiar with this graceful animal so commonly seen along the trails and roadsides. Indeed, it is a rare occasion when one or more deer are not seen in a short drive or hike in any section of the park. It is only with the arrival of the snows that they are less frequently observed, and even during the winter months they are quite abundant at the lower elevations.

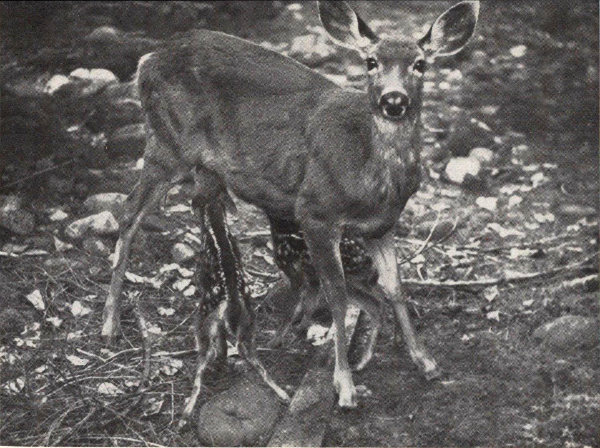

Columbian black-tailed deer and fawns. The young were less than an hour old when this photograph was made.

The seasonal migration is a noteworthy characteristic. With the coming of spring, deer move upward from the lowlands, closely following the retreating snow. The young are born in late May or June, usually after the does have reached their summer range, although they may move higher to find relief from flies. There is practically no banding together of the deer at this time. Each mother and her offspring, usually twins, sometimes one and rarely three, comprise a family group, and tend to keep to themselves. The fawns are hidden at birth, and remain in some secluded spot until they are several days old. The mother visits them at intervals during the day so that they may be fed, and stays near their place of concealment. Almost every season “abandoned” fawns are discovered and brought in to one or another of the park’s ranger stations by well-meaning but ill-informed park visitors. In exceptionally rare instances the mother may have been killed by some predator or a passing automobile, but under no known circumstances has a fawn ever been deliberately abandoned. Fawns, if found, should be left unmolested.

At the time of the spring migration to the uplands, the older bucks habitually move to higher levels than do the young bucks and does. They prefer the subalpine parks and meadows, and often range in pairs or in groups of from three to five or six individuals.

New-born fawns, if found, should be left unmolested.

The first heavy snow starts the deer on their annual trek to the lowlands, and the journey is ordinarily a consistent one, once begun it is completed over a period of from several hours to a day or two, depending upon the distance to be covered. Study has revealed that deer follow regularly established routes during migration, returning year after year to the same general winter and summer ranges. Well-worn game trails along prominent ridges and watercourses are testimony to this concentrated movement, the intersecting minor paths are but tributaries to the major current of travel.

It is prior to the fall migration that the deer herds assemble, the does, fawns, and yearling bucks banding together, the older bucks breaking away from their summer associations and joining the does for the mating season, which occurs in November and December.

Vicious battles are frequent at this season. Determined to assert supremacy, the bucks are merciless antagonists, and at times the struggle is fatal to the loser. In rare instances both may 17 perish, with antlers so tightly locked that escape for either is impossible, exhaustion and starvation the inevitable result. At the conclusion of the mating season the two sexes go their separate ways again, the bucks often assuming again the easy companionship of the summer months.

The abundance or lack of forage is an important factor, perhaps the most important, in determining local abundance of deer. Densely forested sections are not capable of supporting large deer populations because of the lack of sufficient brush, shrubbery, and succulent plants which make up the bulk of the deer’s diet. Primarily a browser, only in spring does this animal show a preference for grass, and then only for a short period.

Deer have many natural enemies. It is fortunate that nature has provided for an abundant reproduction in this species. Snow is perhaps most serious of all, since a heavy snowfall may cover the food supply, and certainly hampers the movement of the animals when they must escape predatory coyotes or cougars. Late spring snows, in particular, come at a critical time. At best forage diminishes steadily during the winter months, and when this period is followed by even a short space when food is unavailable, starvation and death strikes the weaker and aged animals.

Of the predatory animals, the coyote and cougar are most effective. The fox, wildcat, and bear undoubtedly take an occasional fawn, but cannot be considered dangerous to an adult deer. In view of the powers of rapid reproduction shown by deer, it is well that they have numerous natural enemies; otherwise wholesale destruction of brush lands and forest reproduction would occur as the animals reached a peak of overpopulation, followed by mass starvation. This frequently happens in many parts of the West where the natural enemies of the deer have been exterminated. Predators follow, in most instances, the line of least resistance. As a consequence, it is the weaker, the diseased, or the otherwise unfit animals that tend to be struck down first, and so the fittest survive.

A reasonable balance seems to have been attained in the numbers of deer in the park. For the past several years there has been no apparent change, an estimated 600 range within park boundaries during the summer months.

The mule deer is similar to the preceding subspecies in general character. Perhaps the most noticeable field difference is the tail, which in the mule deer is narrow and black-tipped, above and below, rather than wider and dark brown or black over the entire upper surface and entirely white below as in the black-tailed. The large ears, from which this species derives its common name, are distinctive, the black-tailed deer is the smaller and darker of the two subspecies.

Specimens in park collection: None.

The mule deer ranges over most of the Rocky Mountain region and the western United States, from the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma westward to eastern British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and California.

The range of this species in the park is at present restricted to the extreme northeastern section, where it is observed on rare occasions during the summer months.

The mule deer is very similar to the black-tailed deer in habits as well as in appearance. Seasonal migrations, food preferences, natural enemies, and other characteristics are much alike in both species, although the mule deer habitually favors a more sparsely timbered, less rugged terrain.

The typical habitat is an open forest, with many parks, meadows, and brush-covered hillsides. As a general rule the mule deer prefers the Ponderosa pine and sagebrush region, and avoids densely wooded areas. The occasional records of this species in the park are of those rare stragglers which drift in from east of the Cascade crest.

Taylor and Shaw (Mammals and Birds of Mount Rainier National Park, 1927) state that mule deer “May occur in small numbers in the White River region, on the east side of the park.” Although their parties did not observe mule deer while in the field in 1919, they believed that observations made by others familiar with the region were reliable.

A report submitted by the chief ranger of the park in 1932 states: “While mule deer are rarely seen they do range along the east side.” It was not until 1941, however, that this species was included in the park’s annual wildlife census, when it was listed as, “Uncommon, only a few have been seen. Tipsoo Lake, Deadwood Lake, and Yakima Park.”

The 1948 wildlife census estimates 10 to 20 mule deer observed occasionally on the east side during the summer months in previous years. While no reports were recorded in 1948, it is believed that the status of the species is unchanged.

The elk is the largest animal found in the park, and the largest member of the deer family found in North America, except the moose. The adult males have tremendous, wide-branching antlers, which are shed annually. The sexes are slightly different in coloration, with females lighter than the males. The head and neck are dark brown, flanks and back a tawny to brownish gray, large yellowish rump patch, legs dark brown. The young are light brown, spotted with white. An adult male in good condition will weigh from 800 to 1,000 pounds; females are somewhat smaller.

Specimens in park collection: None.

Elk are found in western North America, mostly in the Rocky Mountain area and the far west. They formerly ranged over most of the United States and southern Canada.

During summer elk occur in the park along the eastern boundary, north and west to the Deadwood Lakes and Goat Island Mountain, up the Cowlitz River and Stevens drainages to The Bench on the north side of the Tatoosh Range. They are reported very rarely from the northern and western slopes of the Mountain. In winter a few elk range along the Ohanapecosh drainage in the southeastern part of the park.

The early settlers of this country gave the name “elk” to this magnificent member of the deer family. This is an unfortunate designation, since the animal in no way resembles the Old 20 World elk, which is actually a moose. However, elk it has been since early American history, and elk it is likely to remain, although the Indian name “wapiti” seems preferable and more appropriate.

The history of the elk in Mount Rainier National Park is an interesting study. There can be little doubt that the Roosevelt or Olympic elk, Cervus canadensis roosevelti, formerly ranged over much of the Cascade Range in the State of Washington, and so must be considered the native species of Mount Rainier, although no longer found in this region.

An attempt was made to reestablish the Roosevelt elk in the park in June, 1934, when two young animals, obtained from the Washington State Department of Game, were liberated at Longmire Springs. Two more were released in October, 1934; all had been captured on the Olympic Peninsula, and the four were to form a nucleus for the park herd.

However, to the keen disappointment of park officials, the transplanted elk were unfavorably affected by their proximity to civilization, as is often the case with wild creatures. So unafraid did they become that soon they were regarded as a nuisance, a dangerous nuisance because of their size, pugnacity, and their total lack of timidity, and recapture and deportation to a nearby zoo was the final step in this attempted repatriation.

The elk now ranging into the park have been introduced on lands outside park boundaries by the Washington State Department of Game and the Pierce County Game Commission. These animals belong to the species called American elk, Cervus canadensis nelsoni, and were imported from the Yellowstone region. They do not differ greatly from the native species, though somewhat smaller and lighter in general coloration.

The seasonal migration of elk is well defined. Early in spring, with the retreat of the snow from the uplands, they move to higher pastures, where they remain until driven down by the approach of winter. During recent years a gradual increase in numbers and an extension of range within the park has been observed. The wildlife census for 1948 estimated the summer herd to number some 40 to 50 individuals, with several animals wintering 21 along the Ohanapecosh drainage in the southeastern section of the park.

Bull elk are the most polygamous of all deer. During the mating season, which occurs late in the fall, a single bull will gather together a “harem” of from three or four to as many as two dozen cows with the current year’s calves, and defiantly assert his mastery over the group, driving away younger bulls of lesser strength. Should another bull challenge his dominance, the ensuing battle is rarely fatal, although it may result in a new master. It is not unusual to see the loser, reduced to the status of a “bachelor bull,” ranging alone.

The “bugling” of the bulls, a shrill, high-pitched invitation to combat, is a thrilling call, an unusual record of the music of nature.

The young are born in late May or June, usually one to a mother, sometimes two, and rarely three. Like all deer, they are spotted, somewhat lighter in color than the fawns of the black-tailed deer. The spots are retained until replaced by the winter coat.

The goat is completely unlike any other park animal, and is easily identified by its resemblance to a large white or yellowish-white domestic goat. Both sexes have short, black, sharp-pointed horns, and are otherwise alike, except that the males are generally somewhat larger, and have a distinct beard.

Specimens in park collection: None.

The Cascade mountain goat is found in the Cascade Mountains of Washington. Records indicate that it probably ranged into the Oregon Cascades some decades ago, but there are no recent authentic reports from that area. Sub-species similar to the Cascades goat are found in the northern Rocky Mountains, northward through Canada and into Alaska, as well as on the Olympic Peninsula.

The mountain goat is an indomitable mountaineer.

In the park in summer this denizen of the rocky crags is rather frequently seen in the high country on all slopes of the Mountain. The principal bands may be found in the region of Van Trump Park, Cowlitz Rocks, Cowlitz Chimneys, Steamboat Prow, Burroughs Mountain, the Colonnade, the Puyallup Cleaver, and Emerald Ridge, where they normally range at elevations of from 6,000 to 10,000 feet.

In winter it is not uncommon to observe small bands on Cougar Rock, the southern slopes of Tum-Tum Peak, Mount Wow, lower Emerald Ridge, Mother Mountain, and the western slope of Chenuis Mountain.

Here we have another example of an animal that has been misnamed. Although it is called a mountain goat it is not a true goat, but is more of a rock antelope. Its nearest living relatives are the Alpine chamois of south central Europe and the Himalayan serow of Asia. At one time near relatives of our present goats were spread over much of the western part of North America and fossils have been found in caves in lower Grand Canyon and as far south as Nuevo Leon, Mexico. While it is not known what happened to cause their extinction over much of their original 23 range, it appears likely that early man had an important part in it. It is known that the Indians of the Mount Rainier country hunted the goats extensively at one time, and undoubtedly this awkward appearing dweller of the remote and inaccessible sections is an animal most park visitors hope to encounter.

Chief feeding grounds during the summer are on the heavily vegetated slopes near forest line. In the early morning hours the goats move out of their nighttime resting places and begin feeding as they climb to higher elevations. They travel in a very leisurely fashion, seldom running, and they select their course with considerable care. An old billy usually takes the lead, the other following along behind in single file. Young goats are “sandwiched” between the adults. In moving across any slope area where the footing is treacherous or where rocks might roll, it is customary for only one goat to cross at a time, the others staying back until it is safe to cross.

Without doubt the characteristic of the mountain goats that excites the most interest and admiration is their ability to travel across steep cliffs and narrow ledges with no apparent difficulty or hesitation. Nor does this trail lead only over perilous rock ridges. The goats may venture out upon the ice fields of some of the glaciers. Even glare ice does not present an impasse, it only serves to slow the progress of these indomitable mountaineers.

The female usually has one or two kids born in late spring. By September they are about half grown, and quite capable of keeping up with their parents in even the most difficult going. They remain with their mother through the first winter. Like most young animals, kids are quite playful.

Apparently the goat population of this area is fairly stable, perhaps increasing slightly under the complete sanctuary afforded by the park. As long ago as 1894, John Muir reckoned that there were over 200 goats on Mount Rainier. Ernest Thompson Seton, in his Lives of Game Animals states that “There are certainly 300 now (1929).” The wildlife census for the park lists from 250-300 goats in 1931, and census reports in recent years indicate from 350-400.

Bears are a feature attraction of the park.

There are two color forms of the black bear in the park—the black and the brown. The all black or mostly black is the phase most commonly observed, but brown individuals may often be seen. The black phase sometimes has a brown patch covering the muzzle and a white spot on the chest. The color ratio is usually about five black to one brown.

Specimens in park collection: None.

The black bear was formerly found over most of wooded North America, but has now become extinct over much of the original range. The Olympic black bear occurs in western Washington, western Oregon, and northwestern California.

In the park it is likely to be encountered anywhere in the timbered regions, with an occasional record coming from above forest line. One record of an unusual nature was obtained several years ago by Mr. Harry Meyers of the Mountaineers Club and 25 Major E. S. Ingraham of Seattle. They reported that while blizzard bound in the crater on the summit of Mount Rainier they saw a black bear walk up to the rocks on the rim of the crater and then disappear in the storm. They suggested that the bear possibly was lost in the storm while on a glacier and instinctively climbed higher and higher until it reached the top of the peak. In October, 1948, a record was obtained of a bear well up on the Paradise Glacier, 6,500 feet. This animal was climbing steadily higher, and disappeared over the crest west of Cowlitz Rocks.

There can be no doubt that the bear is one of the feature attractions of the park. The appearance of one of these animals is a signal for visitors of all ages to come running to get a look. Unfortunately the attention paid to the bear doesn’t always stop at this point, and someone is almost sure to pull out a piece of candy or some other tidbit to see if bruin will eat it. Thus a bear problem is soon in the making. Loving sweets, bacon and grease as he does, the bear cannot be blamed too much if he eats quantities of these items offered him and then makes a shambles of tents and food stores looking for more.

Contrary to popular belief the black bear is not a vicious animal, and in the normal wild state is timid and takes to his heels whenever anything of an unusual nature happens. Sudden loud noises will send him off in a wild stampede. This can certainly be attested to by one visitor whose car was invaded by a bear. Unwittingly the bear sat heavily upon the car’s horn—and simply took out glass, door and all in his mad scramble to get out!

The bear is an expert climber and handles himself with great skill. When frightened the cub will almost always shinny up the nearest tree before looking to see what caused the alarm. The mother bear will often send her youngsters up a tree when she is afraid they may be in danger or when she wants them to “stay put” for a time. Bear cubs in a tree are a fair warning to stay away because the mother is bound to be somewhere close by.

The baby bears are usually two in number and are born in January or February while the mother is in her winter quarters. They are small and helpless at birth, weighing only a few ounces. By the middle of June, when most folks see them, they are about 26 the size of raccoons, and by the time fall comes around they are large enough to take pretty good care of themselves, although they still remain with their mother. There is nothing more humorous and clown-like in the forests than a young bear cub. Filled with an endless desire to learn something new, he is forever getting into difficulties. The cub loves to wrestle and box, and a play session with a husky brother or sister is usually somewhat of a rough and tumble affair.

Falltime is the time of year to see bears, because the abundance of huckleberries on the many slopes and ridges above 5,000 feet brings them out in large numbers. It is nothing uncommon to see as many as six of these animals at one time in a berry patch, industriously stripping the bushes of the luscious fruit. The bear is also in his best physical condition at this time, as he prepares to go into hibernation and his coat is rich-toned and glossy. The hibernation period varies with the individual, some animals going into their winter sleep rather early while others may prowl around for some time after the first snows have fallen. Bears have been observed out of hibernation as early as February 26, near Longmire.

The kind of food available is really no great problem for a bear; his main worry is getting enough of it. He seems to like almost anything, with the list including such varied items as bumblebees, clover, skunk-cabbage roots and many other succulent plants, frogs, toads, field mice, ants, berries of all types and a wide assortment of meats.

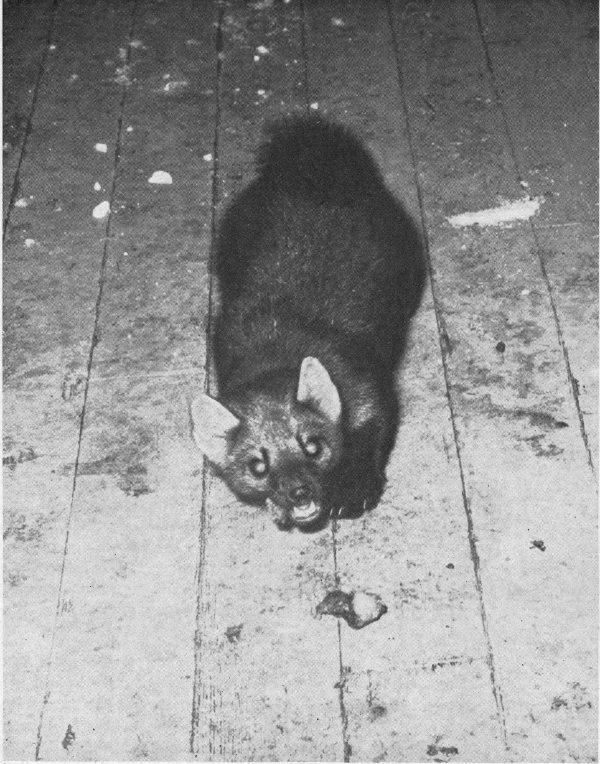

The raccoon has a stocky body about the size of a small dog, with relatively short legs and a sharp-pointed muzzle. The coloration is grizzled gray-brown with black-tipped hairs sometimes giving a dark appearance. The top of the head is blackish, and a broad, “mask-like” black band extends across the face and eyes, bordered above and below with white. The tail is brownish, encircled by six or seven blackish rings. The underparts are light brown, silvered here and there with whitish hairs. The soles of the feet are black.

Specimens in park collection: Mounted specimen, Longmire Museum, Park Headquarters.

Raccoons are widely distributed through the forested regions of North America. The Pacific raccoon is found from southern British Columbia south to northern California, in and west of the Cascade Mountains. In the park it normally ranges up to around 3,000 feet, although some individuals have taken up residence in the buildings around Paradise Valley, 5,500 feet.

Cunning, clever, and inquisitive, with a truly remarkable ability for adaptation to human influences, the raccoon has firmly established residence in a few locations of the park during recent years. Formerly uncommon, these animals are now abundant at Longmire, and are frequently seen in other developed areas as well.

A comparison of the habits of the ’coons thus subjected to close contact with man, and the traits of the true wilderness animals is amazing. The semi-domestic raccoons are no longer strictly nocturnal in their wanderings, but are often abroad at all times of the day. A whole family may parade leisurely across the lawn or parking plaza at mid-day, pausing to peer curiously through slitted eyes at an assemblage of camera-laden visitors. Competition for food is keen, and so avid in their pursuit of forage do the animals become that no time is wasted in “washing” any morsel, it is bolted immediately.

Quarrels, squabbles, and vicious battles are waged vociferously. The raccoon is a surly, short-tempered creature at best, and when two or more get together, especially members of different families, a “gang fight” may be expected to develop, with half a dozen clawing, biting, snarling ’coons entangled in one furry mass. For some reason the ringed tail appears to be a particularly vulnerable point of attack, as several “bob-tailed” animals at Longmire attest.

In some regions this animal is reported as hibernating during the winter months, but the local raccoons do not do so. They remain as active with three feet of snow on the ground as during the summer, although not seen in their normal abundance during periods of extremely inclement weather.

The marmot is abundant in rock slides above 5,000 feet.

The raccoon seems to eat practically anything, with meat of any type freely accepted. Under normal conditions the diet is largely made up of frogs, fish, small animals, birds, eggs, insects, and fruits.

The Cascade hoary marmot is one of the largest North American rodents, a close relative of the woodchuck of the East, with the head and body about twenty inches in length, tail about nine inches. The body is stout and clumsy in appearance; the legs are short and stout; the head is short and broad with a blunt nose, small, broad, rounded ears, and small eyes. Adults have a black face; the nape, shoulders, and upper back gray; the remaining portion of the back and rump is black grizzled with gray; the tail is brown. The young are darker in color than the adults. In midsummer the pelage is in poor condition, with the 29 darker portions more brown than black. The large size, gray shoulders, and shrill, whistling call are distinguishing characters which permit easy identification of this animal.

Specimens in park collection: RNP-40, RNP-41, RNP-112; Longmire Museum, Park Headquarters.

The woodchucks (genus Marmota) are found over most of the United States, well into Canada, and in the west north into Alaska. The Cascade hoary marmot occurs in the northern Cascade Mountains from Mount Rainier northward into southern British Columbia.

On Mount Rainier the whistler is abundant in the rock slides from about 5,000 feet to forest line and above. Occasionally the alpine parks and meadows are chosen habitats; the animals are common in the Paradise Valley and on the open slopes above Alta Vista.

A piercing, far-carrying whistle is often the park visitor’s introduction to the marmot or rockchuck of Mount Rainier. A careful scrutiny of the nearby terrain will often be rewarded by the sight of one or several of these animals, old and young, perched on a rock above the entrance to the burrow, or galloping clumsily but swiftly toward home and safety.

It is usually possible to continue the acquaintance at closer range, particularly if the observer approaches slowly and the animals are in areas where they have become accustomed to having human visitors in their neighborhood.

The whistler is almost strictly vegetarian in his food habits, feeding upon green succulent vegetation in the near vicinity of the burrow. It is common to find well-beaten paths from the animal’s “front door” to the forage areas. Moving about on a grassy slope the fat, lazy rodent seems anything but alert, as he crawls from one spot to another. But the observer soon becomes aware that the chuck’s pauses to survey the landscape are frequent; his head is raised, if no danger threatens his tail flips and feeding is resumed. If frightened, swift retreat is generally preceded by the shrill whistle, and the sluggish, crawling fat one becomes a scurrying bundle of fur following a well-worn and familiar route to the sanctuary of his den.

The marmot is a sun-worshiper. After an early morning feeding period, it is his custom to sprawl, rug-like, on a favorite rock slab, sometimes for hours, resting and obviously enjoying his sun-bath. Chucks are rarely abroad for any extended length of time on cloudy, drizzly days. They may appear if driven out by hunger, but seem to prefer the warmth and comfort of the den during inclement weather.

The hibernating period of the marmot begins in September and lasts well into spring, the time of emergence is usually late in April. There is no evidence that any food is stored, and for some time after coming out of hibernation the animals may travel a considerable distance over the snowfields in search of open ground and green vegetation.

The famous naturalist, Ernest Thompson Seton, has well expressed the marmot’s way of life:

“Convincing evidence there is that, during lethargy—the little death of the winter sleep—the vital functions are suspended—the sleeper neither grows, suffers, wastes, nor ages. He did not lay up stores of food; yet, in the spring, he comes out just as fat as he went in the fall before.

“If then, the Powers-that-Be have allotted to the Marmot five full years of life, and he elects to live that life in ten bright summer times, then must he spend the six dark months each year in deathlike sleep. And this he does, in calm, deliberate choice.

“Oh, happy Whistler of the Peaks! How many of us would do the very same, were we but given choice.”

Not many natural enemies threaten the marmot. Perhaps the most to be feared is the golden eagle, which may drop from the blue to seize him in the midst of his luxurious sun-bath. Because of his size the smaller predators are harmless to him, but the coyotes and foxes are relentless hunters and ever-present dangers.

Two kinds of chipmunks, the Cooper and Hollister, are known to occur within the park. Although their altitudinal ranges overlap, the two species may be quite readily distinguished by their variation in size and other characteristics. A brief discussion of each follows:

The Hollister chipmunk is a lively and audacious little animal.

The Cooper chipmunk, Tamias townsendii cooperi Baird, is the larger of the two species mentioned above. It is predominantly dark brown in color; the light colored stripes above and below the eye are indistinct; the black head stripes are not conspicuous; the nine alternating black and grayish white lengthwise stripes on the back are somewhat obscured by the dark color; the tail is black above, grizzled with white, silvery margined, reddish brown below. The total length of a typical specimen is ten inches; head and body, five and one-half inches, tail four and one-half inches.

This chipmunk is found in the higher eastern Cascade Mountains and Olympic Mountains of Washington. In Mount Rainier National Park it occurs from park boundaries to 6,000 feet, almost to forest line.

The Hollister chipmunk, Tamias amoenus ludibundus (Hollister), also called the little chipmunk or Alpine chipmunk, is about a third smaller in size than the Cooper chipmunk. It is predominantly gray brown in color. The light colored stripes above and below the eye are distinct; the black head stripes are more conspicuous than those of the Cooper, the back stripes are 32 sharply defined; the tail is brown mixed with black above, margined with yellowish brown, yellowish brown below. The total length is about eight and three-fourths inches; head and body four and three-fourths inches, tail four inches.

The Hollister chipmunk is found in the higher Cascade Mountains of Washington. In Mount Rainier National Park it occurs generally in the Hudsonian Zone between 4,500 and 6,500 feet, rarely lower or above forest line, but it is one of the few park animals recorded on the summit of Mount Rainier.

Specimens in park collection: Cooper chipmunk, RNP-7, RNP-8, RNP-9, RNP-16, RNP-18, RNP-74, RNP-110; Hollister chipmunk, RNP-28, RNP-29, RNP-30, RNP-95; Longmire Museum, Park Headquarters.

The lively, audacious, and beautifully marked chipmunks are the most popular of all the animals of the park. Locally abundant as they are in the neighborhood of the campgrounds and lodges, easily observed because of their diurnal habits and lack of fear, they are a source of entertainment and amusement to many park visitors.

Like the mantled ground squirrels, the chipmunks adapt themselves rapidly to man’s presence, forage about camps and lodges in search of various delicacies, invade camp stores without hesitation, but are such engaging company that it is difficult to regard them as anything other than friendly guests.

Many varieties of seeds and berries furnish the food supply of this animal, and quantities are stored in their burrows for use during the spring and early summer. Although the chipmunks hibernate during most of the winter, they sometimes venture out on warm, spring-like days, returning to their winter nests when the weather again becomes inclement.

Predaceous birds and mammals active during the daylight hours are all enemies of the chipmunks. These natural enemies work to keep the chipmunk populations free of contagious diseases such as relapsing fever, which is transmissible to human beings, by removing sick and sluggish chipmunks before they can infect their companions.

Mantled ground squirrels are popular with park visitors.

As the name implies, the mantled ground squirrels are ground dwellers. In general external appearance they resemble the eastern chipmunks, but are considerably larger, and much bigger than their environmental associates, the western chipmunks. They may be further distinguished from the latter species by the more robust body, the conspicuous white eye-ring, and the absence of stripes on the head. The Cascade species of mantled ground squirrel is about twelve inches in length overall, with a flattened, somewhat bushy, narrow tail some four inches long. The sexes are colored alike, the mantle over the head, sides of the neck, shoulders, and forearms is reddish-brown, mixed with black, which is in distinct contrast to the rest of the upper parts. The back is grizzled black, merging into grizzled red-brown over the rump, with a narrow yellowish-white stripe, edged with black, on each flank from shoulder to thigh. The underparts and the upper surfaces of the feet are yellowish-white. The tail is well-clothed with dark, yellow-tipped hair above, yellowish-brown below.

Specimens in park collection: RNP-33, RNP-34, RNP-36; Longmire Museum, Park Headquarters.

The mantled ground squirrels are found only in western North America, on the forested mountain slopes from California, Arizona, and New Mexico north into British Columbia.

The species common to Mount Rainier National Park is found in the Cascade Mountains of Washington, and on the Mountain it is confined principally to the Hudsonian zone, between 4,500 and 6,500 feet. It is most abundant on the east side, but is very common locally in the Paradise Valley vicinity.

This animal inhabits by preference the rather open, rocky hillsides, and is seldom seen in the heavily forested sections. Burned over brush lands are favored localities, particularly on those slopes exposed to the sun.

The big chipmunks are less graceful than their livelier, smaller cousins; they are unsuspicious and easily observed, and are very popular with park visitors because of their obvious lack of timidity. They are quick to adapt themselves to the proximity of humans, and sometimes become nuisances about campsites and dwellings because of their audacious thefts of various foodstuffs.

The capacious cheek pouches are used in collecting seeds, nuts, roots, berries, and the bulbs of various plants, which are stored in underground caches. Although these ground squirrels hibernate from early fall until late spring, forage is meager during the first few weeks after emergence from their long winter nap, and without provision for these lean times, the animals would surely starve. They often appear when the snow is still deep over their burrows, digging several feet upward through this white blanket to emerge on the surface.

The most dreaded enemy is the weasel, but the ground squirrels are preyed upon by coyotes, foxes, and hawks as well, since they are a staple item in the diet of most predators.

A dark grayish brown squirrel about twelve inches in length overall; with prominent ears; moderately slender in form; tail 35 almost as long as the body, somewhat flattened, well clothed with hair but not bushy, more gray than the body. The underparts vary from a pale yellow brown to reddish brown. The sexes are colored alike; the pelage is fairly long, soft, but not silky. The characteristic appearance is one of extreme alertness.

Common throughout forested sections, the Douglas pine squirrel is a vociferous bundle of energy.

Specimens in park collection: RNP-10, RNP-11, RNP-15, RNP-47, RNP-100, RNP-107; Longmire Museum, Park Headquarters.

The Douglas squirrel is classified as one of the red squirrels, or chickarees, which are distributed over most of forested North America.

In Mount Rainier National Park these squirrels are common, and are found throughout the area from the park boundaries to forest line, and occasionally even higher.

This vociferous, restless bundle of energy is seen and heard by almost every park visitor, bounding across the highway or trail, or scampering madly up a nearby tree, to peer around the trunk or perch upon limb just out of reach where it scolds and chatters vehemently at all intruders.

Unlike the flying squirrel, the chickaree is abroad throughout the daylight hours, busy, inquisitive, obviously and usually noisily, resentful of interference with what it considers its own affairs. Only in the spring is this squirrel somewhat subdued, probably because of the youngsters tucked away in a nearby nest in some tree hollow. The young do not venture into the world until more than half grown, when they take their places in the regular routine of family activities.

Because the Douglas squirrel does not hibernate, it gathers the cones of most of the coniferous trees, as well as the winged seeds of the vine maple and even mushrooms to furnish food over the lean winter months. The late summer and early fall is a busy time for this industrious fellow. The swish and thump of falling cones is a common sound through the woods when the harvest is in progress. A number of cones are neatly clipped from the tree tops, then the worker descends the tree to gather and store them in a hollow stump, beneath a log or the roots of a tree, or even in a hastily excavated hole in the forest floor. Interrupt this activity by secreting a few of the fallen cones, and the imprecations called down upon your head would scorch the printed page if they could be translated into human speech.

Although preyed upon by winged and four-footed predators alike, the chickaree holds its own very well, probably because this fellow is seldom caught napping, certainly not because of shy and retiring habits, since the “chatterer” is one of the most conspicuous and interesting of our woodland creatures.

A medium-sized, arboreal squirrel; dark-brown above, light brown on the under parts, light gray or sometimes light brown on the sides of the face, the sexes colored alike, the young darker than the adults. The eyes are large and dark, the pelage is soft and silky. The flat, furry tail and the fold of loose skin between the fore and hind legs on either side distinguish this animal from any other.

Specimens in park collection: None.

Flying squirrels inhabit a large part of forested North America. The Cascade sub-species is found from southern British Columbia 37 southward along the Cascade Range to the Siskiyou Mountains of Northern California.

Park visitors rarely see the beautiful little flying squirrel.

Although seldom seen because of its nocturnal habits, the flying squirrel is locally abundant in some sections of the park, particularly at Ohanapecosh Hot Springs.

The most interesting characteristic of this little tree-dweller is its unique habit of gliding from tree to tree through the air. In launching its “flight” the squirrel leaps into space from its perch on a dead snag or tree, extends the fore and hind legs, spreading the loose fold of skin along its sides, and with the flat tail fluttering behind, sails obliquely downward, alighting on the ground or the lower trunk of another tree. This aerial maneuver cannot truly be called flight, but has resulted in the name “flying squirrel.”

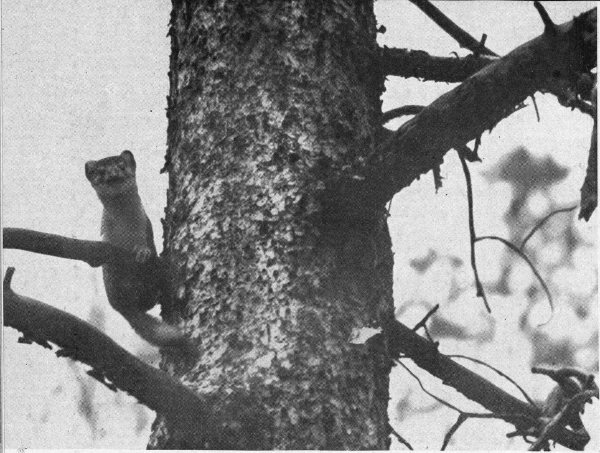

Little is known of the life history of this beautiful little animal, because of the difficulty of observation. Old woodpecker holes or natural cavities in trees are favorite nesting places, and the flying squirrel is almost never found away from the nest 38 except at night or when disturbed. It is a shy and retiring creature, preyed upon by owls, martens, weasels, and other small carnivorous animals on the rare occasions when it comes to the ground. Flying squirrels are omnivorous, nuts and other vegetable foods are apparently preferred, although meat is sometimes taken when available.

This small, rodent-like animal is robust, short-legged, with a tail so short that it is not noticeable in field observation. The sexes are colored alike; gray-brown above, whitish below, ears darker, feet light. The pelage is soft and quite dense. In general appearance the pikas closely resemble the rabbits, except for their small size, short legs, and short, rounded ears. The peculiar “bleating” call is unmistakable.

Specimens in park collection: RNP-12, RNP-13, and one mounted specimen; Headquarters Museum, Longmire.

The many sub-species of the pika are widely distributed at the higher elevations throughout the Rocky Mountains and the Coast Ranges. The typical habitat is the rock-slides and talus slopes near forest line.

In the park one may expect to find the pika on any rocky slope from 3,000 (rarely lower) to 8,000 feet. They are infrequently seen in winter, due to the depth of snow over most sites which they inhabit, but during clear, sunny days they occasionally venture out in exposed locations.

The common name “hay-maker” has often been applied to the pika, because it is one of those provident creatures which literally “makes hay” during the summer months, curing and drying a wide variety of grasses and other plants which are stored for winter food. The hay-barn of the pika is in a sheltered crevice or beneath an overhanging boulder in the masses of rock where it makes its home. These hay-piles are much in evidence where pikas are abundant.

The protective coloring of the animal makes it difficult to distinguish among the rocks, and it is commonly heard before it is seen. The sharp, short bleat, almost a chirp or squeak, often 39 repeated at rapid intervals when the pika is alarmed, is distinctive. If the observer remains motionless, and carefully searches nearby with his eyes, he is almost certain to see a tiny “rock-rabbit” scamper quickly and with silent, sure feet across the rocks, to disappear in a crevice or to perch on an exposed boulder. Should the watcher remain quiet, the pika will resume its interrupted activities until again disturbed.

The busy beaver is an industrious engineer.

The well-chosen shelter of the pika, deep down beneath the rocks, affords adequate protection from most predators. Only the weasels, and their relatives, the martens, are capable of following these elusive creatures through the talus. Undoubtedly the hawks and eagles may strike suddenly from the air and be successful in capturing a pika less alert than his fellows, but such occasions must be rare.

The beaver is the largest North American rodent, and the species found in Mount Rainier National Park is the largest of any of the recognized geographical range. An adult will weigh 40 thirty pounds or more, up to a maximum of sixty pounds. The form is robust; the tail is broad, flat, and scaly; the ears are short; the hind feet webbed. The pelage is composed of short, soft underfur, with long guard hairs. The sexes are alike in size and color, a dark, glossy, reddish brown above, lighter brown below. The beaver is aquatic in habit.

Specimens in park collection: Mounted specimen, Longmire Museum, Park Headquarters.

The geographical range of the beaver extends over most of North America from the Rio Grande northward.

Beaver are not now abundant in the park, and it is doubtful that they were ever numerous. Observations have been made in many sections, notably Fish Creek, Tahoma Creek, along the Nisqually River from the park entrance to the mouth of the Paradise River, Longmire Meadows, the Ohanapecosh River, and Reflection and Tipsoo Lakes. Records indicate that Fish Creek and Tahoma Creek are the sites most extensively used by beavers during recent years, although intermittent activities have been noted in the vicinity of Longmire Meadows. A colony on Kautz Creek was undoubtedly destroyed by the flood of October, 1947.

No other animal played as important a role in the early history and exploration of this country as did the beaver. This is particularly true of the Rocky Mountain west, and to a lesser extent of the Northwest. The fur trade made the beaver pelt a standard of exchange, and to get beaver the trappers moved westward, seeking out this valuable animal in the most inaccessible and remote regions. These early explorations, which had as their incentive fur rather than the expansion of territory, paved the way for later settlement by those seeking new lands and a better livelihood in the West. So great was the demand for fur that the beavers, in the beginning abundant, were reduced in numbers to a point where returns did not compensate trappers for the risk and hardship involved.

The first mention of beaver in the park is found in Mammals and Birds of Mount Rainier, Taylor and Shaw, which states:

“Dr. A. K. Fisher records that several beavers lived at Longmire Springs until 1896, when a trapper killed them all.”

By 1905, according to the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior, beaver had been exterminated within the boundaries of the park.

However, by 1919, beaver were again active on Fish Creek, along the eastern base of Mount Wow, and in December, Mr. Roger W. Toll, park superintendent, reported two dams, each 100 to 200 feet in length. Mr. Toll’s observations were set forth thus in a letter:

“The beavers are now living in these lakes, and fresh signs are abundant. There are numerous tracks in the snow leading from the lakes to the thickets of alder, elder, and willow which they are eating. There is no typical beaver house in the lakes, but the under-water entrance to their house can be seen leading under the roots of a fir tree about four feet in diameter that stands on the edge of the upper lake.”

It is in this immediate vicinity that fairly extensive beaver workings were observed in November, 1947, including newly repaired small dams and fresh cuttings.

The house or burrow in the stream bank studied by Mr. Toll appears typical of the beaver in this area. In other sections, notably Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado, where beavers are abundant, an extensive system of dams and canals is frequently developed on the smaller streams, with a large house completely surrounded by the impounded water a central feature of the colony. No such elaborate workings have been found here. Since the beavers habitually reside in burrows along the margins of streams they are referred to as “bank-beavers.” A plausible explanation for this habit is the constant and ample flow of water, which eliminates the necessity for large dams, and is adequate to cover at all times the underwater entrances to the burrows.

A small stream, bordered by cottonwood, alder, and willow, tracing its course through swampy places or meadow lands at intervals, is the preferred habitat of the beaver. The bulk of its food is made up of the bark of the tree species mentioned above, although coniferous trees are sometimes used, perhaps as an appetizer. The roots of aquatic plants are eaten also, as well as the smaller roots of tree species. In an active beaver colony, freshly peeled twigs and branches will be found lodged against 42 the upstream side of the dam, as well as along the stream and pond margins.

Much has been written concerning the sagacity, engineering ability, and industry of the beaver. Certainly “busy as a beaver” is an apt comparison for the industrious. The amount of tree-felling, food harvesting, and construction and repair which a colony of beavers will accomplish overnight is remarkable.

Other characteristics, while impressive, are not the unerring instincts that were often attributed to the animal by early writers. While the dams are in most instances sturdily constructed of brush, small stones, mud, and, at times, sizeable short lengths of trees, a sudden spring freshet may completely destroy a poorly located structure. That the beaver exhibits what might be considered good judgment in taking advantage of natural stream barriers in dam construction is commonly demonstrated, however. It is not unusual to find trees that have fallen across water courses, or boulders in or on the margins of streams, used to provide a portion of a dam, apparently by design rather than by accident.

The felling of trees is approached in a haphazard fashion, without regard to the direction of fall. It appears that the beaver, or beavers, set to work to gnaw the trunk through at a comfortable working height above the ground, a point they can reach from a sitting position. Where the tree falls is left entirely to chance. There may be a half circle of open space in one direction, yet it is quite possible that the tree will topple in the opposite direction and so lodge before it reaches the ground. Under such circumstances the beavers may cut another section or several sections from the butt of the tree, without eventually accomplishing their purpose.

Nevertheless, to give credit where credit is due, it must be admitted that the beaver is unique in the animal kingdom by virtue of its feats, even though these are largely the result of instinct.

Among the natural enemies of the beaver clan are listed most of the predators; fox, coyote, cougar, bear, wildcat, and where their habitats coincide, the otter. It seems that all of these exhibit a liking for the flesh of this largest of rodents, although 43 a painstaking stalk, consummated by a swift rush or leap is necessary for success, lest the beaver escape to his natural refuge, the water. The otter, of course, may enter the burrow or house and kill the young, but it is not likely that it has the strength required to deal with a full grown animal.

A stout-bodied rodent, about the size of a muskrat, with a tail so short that it is concealed in the fur. Sexes are alike in size and color; upper parts light brown with a darker overcast, under parts a dull brown, sometimes showing white patches. Eyes and ears small.

Specimens in park collection: RNP-80, RNP-104, and a mounted specimen, Longmire Museum, Park Headquarters.

The various subspecies of aplodontia are found only along the western coast of North America, from the mountain ranges westward to the Pacific. It is not known to occur elsewhere in the world.

The Mount Rainier mountain beaver is found only on and in the immediate vicinity of Mount Rainier, where it is abundant in some localities from park boundaries to 6,000 feet. It has been reported from the Paradise River (5,200 feet), Longmire, Reflection Lake, Ohanapecosh, Comet Falls, the Rampart Ridge Trail, the Nisqually Entrance, in the Nickel Creek burn, and on the Wonderland Trail on the north side of Stevens Canyon (3,000 feet).

The common name of this animal is not particularly appropriate, since it resembles the muskrat and pocket gophers in appearance and habits more closely than it does the beaver to which it is not closely related. It prefers a wet habitat, but is not aquatic. It occasionally gnaws through the small stems of willow, alder, and other shrubs, felling them to the ground, but it makes no attempt to construct dams or canals. Tiny rivulets are often diverted to flow through the mountain beaver’s burrows, perhaps by accident, possibly because the animal intended such diversion.

The food of the aplodontia includes almost every succulent plant found in the park, as well as many shrubs and the bark of 44 some trees. Bracken appears to be on the preferred list. During the summer months the presence of the animal in a locality is often indicated by bundles of plants cut and piled in exposed places to cure. The mountain beaver is more particular in this respect than the pika, the bundles are often rather neatly arranged on a log or stump, the base of the stems at one end of the pile, nicely evened up, and the entire bundle intact. After curing, the bundles are stored in the burrows, to serve as food and nesting material.

A rather extensive system of burrows from a few inches to a foot or two beneath the surface, and piles of freshly excavated earth are also evidence of the workings of this animal. The typical site chosen for development is ordinarily moist, probably not because the aplodontia is a lover of water, but because it is in such locations that suitable food plants abound. The burrows are constructed as exploratory routes in foraging, with what appears to be a main gallery intersected by a number of branches. These burrows emerge in thick cover or under logs, with the openings often connected by well-beaten runways where the overhanging plants and shrubs afford concealment.

Such extensive workings were found along the Wonderland Trail in Stevens Canyon in 1947 and 1948. The first indication of the activity of mountain beavers was the undermined condition of the trail in several places, where burrows crossed under the path and caved beneath the feet. Upon investigation many freshly cut stems of bracken were discovered, and several piles of recently excavated earth, in some instances sufficient to fill a bushel basket. This site was typical: excellent cover; several small streams; and deep, very moist soil with few rocks and an abundance of food plants.

Natural enemies of aplodontia undoubtedly include nearly all of the predatory animals, particularly the skunks and weasels, which can invade the dens without difficulty.

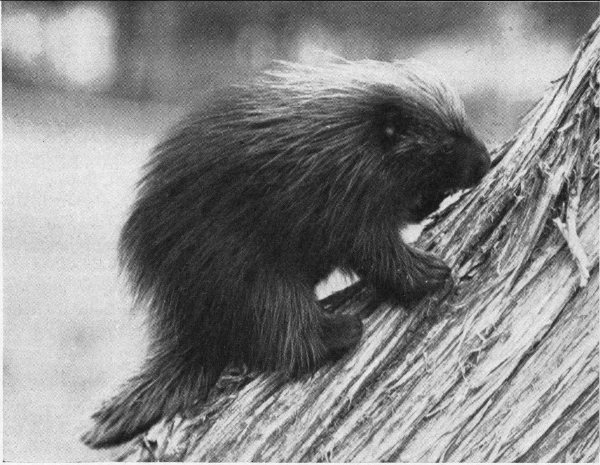

The porcupine is a large, short-legged rodent (total length about 30 inches), clumsy and awkward appearing, slow-moving, bearing long, sharp quills or spines over most of the body and 45 on the short, club-like tail. The pelage is composed of soft, brownish-black or black hair. Intermixed with the pelage, and extending beyond it are the quills and long, stiff, shiny, yellowish-tipped hairs, which give a yellow tinge to the underlying dark color. It is impossible to confuse this unique animal with any other found in the park.

The almost impregnable armor of the porcupine is adequate protection against most predators.