Title: Abraham Lincoln and the Abolition of Slavery in the United States

Author: Charles Godfrey Leland

Release date: June 25, 2016 [eBook #52412]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

A. Lincoln 1

2

COPYRIGHT BY

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS.

1879

3

In issuing this second edition of Mr. Leland’s biography, the publishers have taken occasion to correct a few errors in dates and proper names, and in citations from documents, that had crept into the first edition.

The book was prepared during the author’s residence abroad, where he did not have at hand for reference all the authorities needed, and as it was stereotyped in London the above oversights were not at once detected. 4 5

I make no apology for adding another “Life of Abraham Lincoln” to the many already written, as I believe it impossible to make such an example of successful perseverance allied to honesty, as the great President gave, too well known to the world. And as I know of no other man whose life shows so perfectly what may be effected by resolute self-culture, and adherence to good principles in spite of obstacles, I infer that such an example cannot be too extensively set before all young men who are ambitious to do well in the truest sense. There are also other reasons why it should be studied. The life of Abraham Lincoln during his Presidency is simply that of his country—since he was so intimately concerned with every public event of his time, that as sometimes happens with photographs, so with the biography of Lincoln and the history of his time, we 6 cannot decide whether the great picture was enlarged from the smaller one, or the smaller reduced from a greater. His career also fully proves that extremes meet, since in no despotism is there an example of any one who ever governed so great a country so thoroughly in detail as did this Republican of Republicans, whose one thought was simply to obey the people.

It is of course impossible to give within the limits of a small book all the details of a busy life, and also the history of the American Emancipation and its causes; but I trust that I have omitted little of much importance. The books to which I have been chiefly indebted, and from which I have borrowed most freely, are the lives of Lincoln by W. H. Lamon, and by my personal friends H. J. Raymond and Dr. Holland; and also the works referring to the war by I. N. Arnold, F. B. Carpenter, L. P. Brockett, A. Boyd, G. W. Bacon, J. Barrett, Adam Badeau, and F. Moore.

June, 1879. 7

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE |

|---|---|

Birth of Abraham Lincoln—The Lincoln Family—Abraham’s first Schooling—Death of Mrs. Lincoln, and the new “Mother”—Lincoln’s Boyhood and Youth—Self-Education—Great Physical Strength—First Literary Efforts—Journey to New Orleans—Encouraging Incident, |

9 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

Lincoln’s Appearance—His First Public Speech—Again at New Orleans—Mechanical Genius—Clerk in a Country Store—Elected Captain—The Black Hawk War—Is a successful Candidate for the Legislature—Becomes a Storekeeper, Land Surveyor, and Postmaster—His First Love—The “Long Nine”—First Step towards Emancipation, |

30 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

Lincoln settles at Springfield as a Lawyer—Candidate for the office of Presidential Elector—A Love Affair—Marries Miss Todd—Religious Views—Exerts himself for Henry Clay—Elected to Congress in 1846—Speeches in Congress—Out of Political Employment until 1854—Anecdotes of Lincoln as a Lawyer, |

53 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

Rise of the Southern Party—Formation of the Abolition and the Free Soil Parties—Judge Douglas and the Kansas-Nebraska Bill—Douglas defeated by Lincoln—Lincoln resigns as Candidate for Congress—Lincoln’s Letter on Slavery—The Bloomington Speech—The Fremont Campaign—Election of Buchanan—The Dred-Scott Decision, |

64 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

Causes of Lincoln’s Nomination to the Presidency—His Lectures in New York, &c.—The First Nomination and the Fence Rails—The Nomination at Chicago—Elected President—Office-seekers and Appointments—Lincoln’s Impartiality—The South determined to Secede—Fears for Lincoln’s Life, |

78 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

A Suspected Conspiracy—Lincoln’s Departure for Washington—His Speeches at Springfield and on the road to the National Capital—Breaking out of the Rebellion—Treachery of President Buchanan—Treason in the Cabinet—Jefferson Davis’s Message—Threats of Massacre and Ruin to the North—Southern Sympathisers—Lincoln’s Inaugural Address—The Cabinet—The Days of Doubt and of Darkness, |

888 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

Mr. Seward refuses to meet the Rebel Commissioners—Lincoln’s Forbearance—Fort Sumter—Call for 75,000 Troops—Troubles in Maryland—Administrative Prudence—Judge Douglas—Increase of the Army—Winthrop and Ellsworth—Bull Run—General M‘Clellan, |

102 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

Relations with Europe—Foreign Views of the War—The Slaves—Proclamation of Emancipation—Arrest of Rebel Commissioners—Black Troops, |

117 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

Eighteen Hundred and Sixty-two—The Plan of the War, and Strength of the Armies—General M‘Clellan—The General Movement, January 27th, 1862—The brilliant Western Campaign—Removal of M‘Clellan—The Monitor—Battle of Fredericksburg—Vallandigham and Seymour—The Alabama—President Lincoln declines all Foreign Mediation, |

154 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

Eighteen Hundred and Sixty-three—A Popular Prophecy—General Burnside relieved and General Hooker appointed—Battle of Chancellorsville—The Rebels invade Pennsylvania—Battle of Gettysburg—Lincoln’s Speech at Gettysburg—Grant takes Vicksburg—Port Hudson—Battle of Chattanooga—New York Riots—The French in Mexico—Troubles in Missouri, |

147 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

Proclamation of Amnesty—Lincoln’s Benevolence—His Self-reliance—Progress of the Campaign—The Summer of 1864—Lincoln’s Speech at Philadelphia—Suffering in the South—Raids—Sherman’s March—Grant’s Position—Battle of the Wilderness—Siege of Petersburg—Chambersburg—Naval Victories—Confederate Intrigues—Presidential Election—Lincoln Re-elected—Atrocious Attempts of the Confederates, |

172 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

The President’s Reception of Negroes—The South opens Negotiations for Peace—Proposals—Lincoln’s Second Inauguration—The Last Battle—Davis Captured—End of the War—Death of Lincoln—Public Mourning, |

203 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

President Lincoln’s Characteristics—His Love of Humour—His Stories—Pithy Sayings—Repartees—His Dignity, |

233 |

| APPENDIX, | 245 |

| FOOTNOTES, | 249 |

| INDEX, | 249 |

9

Life of Abraham Lincoln.

Birth of Abraham Lincoln—The Lincoln Family—Abraham’s first Schooling—Death of Mrs. Lincoln, and the new “Mother”—Lincoln’s Boyhood and Youth—Self-Education—Great Physical Strength—First Literary Efforts—Journey to New Orleans—Encouraging Incident.

Abraham Lincoln was born in Kentucky, on the 12th day of February, 1809. The log-cabin which was his birth-place was built on the south branch of Nolin’s Creek, three miles from the village of Hodgensville, on land which was then in the county of Hardin, but is now included in that of La Rue. His father, Thomas Lincoln, was born in 1778; his mother’s maiden name was Nancy Hanks. The Lincoln family, which appears to have been of unmixed English descent, came to Kentucky from Berks County, Pennsylvania, to which place tradition or conjecture asserts they had emigrated from Massachusetts. But they did not remain long in Pennsylvania, since they seem to have gone before 1752 to Rockingham, County Virginia, which state was then 10 one with that of Kentucky. There is, however, so much doubt as to these details of their early history, that it is not certain whether they were at first emigrants directly from England to Virginia, an offshoot of the historic Lincoln family in Massachusetts, or of the highly respectable Lincolns of Pennsylvania.1 This obscurity is plainly due to the great poverty and lowly station of the Virginian Lincolns. “My parents,” said President Lincoln, in a brief autobiographic sketch,2 “were both born of undistinguished families—second families, perhaps, I should say.” To this he adds that his paternal grandfather was Abraham Lincoln, who migrated from Rockingham, County Virginia, to Kentucky, “about 1781 or 2,” although his cousins and other relatives all declare this grandsire’s name to have been Mordecai—a striking proof of the ignorance and indifference of the family respecting matters seldom neglected.

This grandfather, Abraham or Mordecai, having removed to Kentucky, “the dark and bloody ground,” settled in Mercer County. Their house was a rough log-cabin, their farm a little clearing in the midst of the forest. One morning, not long after their settlement, the father took Thomas, his youngest son, and went to build a fence a short distance from the house, 11 while the other brothers, Mordecai and Josiah, were sent to a field not far away. They were all intent upon their work, when a shot from a party of Indians in ambush was heard. The father fell dead. Josiah ran to a stockade, or settlement, two or three miles off; Mordecai, the eldest boy, made his way to the house, and, looking out from a loop-hole, saw an Indian in the act of raising his little brother from the ground. He took deliberate aim at a silver ornament on the breast of the Indian, and brought him down. Thomas sprang towards the cabin, and was admitted by his mother, while Mordecai renewed his fire at several other Indians who rose from the covert of the fence, or thicket. It was not long before Josiah returned from the stockade with a party of settlers; but the Indians had fled, and none were found but the dead one, and another who was wounded, and had crept into the top of a fallen tree. Mordecai, it is said, hated the Indians ever after with an intensity which was unusual even in those times. As Allan Macaulay, in “Waverley,” is said to have hunted down the Children of the Mist, or as the Quaker Nathan, in Bird’s romance of “Nick of the Woods,” is described as hunting the Shawnese, so we are told this other avenger of blood pursued his foes with unrelenting, unscrupulous hatred. For days together he would follow peaceable Indians as they passed 12 through the settlements, in order to get secret shots at them.3

Mordecai, the Indian-killer, and his brother, Josiah, remained in Virginia, and grew up to be respectable, prosperous men. The younger brother, Thomas, was always “idle, thriftless, poor, a hunter, and a rover.” He exercised occasionally in a rough way the calling of a carpenter, and, wandering from place to place, began at different times to cultivate the wilderness, but with little success, owing to his laziness. Yet he was a man of great strength and vigour, and once “thrashed the monstrous bully of Breckinridge County in three minutes, and came off without a scratch.” He was an inveterate talker, or popular teller of stories and anecdotes, and a Jackson Democrat in politics, which signified that he belonged to the more radical of the two political parties which then prevailed in America. In religion, he was, says Lamon, who derived his information from Mr. W. H. Herndon, “nothing at times, and a member of various denominations by turns.” In 1806, he lived at Elizabethtown, in Hardin County, Kentucky, where, in the same year and place, he married Nancy Hanks: the exact date of the marriage is unknown. It is said of this young woman that she was a tall and beautiful brunette, 13 with an understanding which, by her family at least, was considered wonderful. She could read and write—as rare accomplishments in those days in Kentucky backwoods as they still are among the poor whites of the South or their Western descendants.4 In later life she was sadly worn by hard labour, both in the house and fields, and her features were marked with a melancholy which was probably constitutional, and which her son inherited.

It is to be regretted that President Abraham Lincoln never spoke, except with great reluctance, of his early life, or of his parents. As it is, the researches of W. H. Herndon and others have indicated the hereditary sources of his chief characteristics. We know that the grandfather was a vigorous backwoodsman, who died a violent death; that his uncle was a grim and determined manslayer, carrying out for years the blood-feud provoked by the murder of his parent; that his mother was habitually depressed, and that his father was a favourite of both men and women, though a mere savage when irritated, fond of fun, an endless storyteller, physically powerful, and hating hard work. Out of all these preceding traits, it is not difficult 14 to imagine how the giant Abraham came to be inflexible of purpose and strong of will, though indolent—why he was good-natured to excess in his excess of strength—and why he was a great humourist, and at the same time a melancholy man.

It should be remembered by the reader that the state of society in which Abraham Lincoln was born and grew up resembled nothing now existing in Europe, and that it is very imperfectly understood even by many town-dwelling Americans. The people around him were all poor and ignorant, yet they bore their poverty lightly, were hardly aware of their want of culture, and were utterly unconscious of owing the least respect or deference to any human being. Some among them were, of course, aware of the advantages to be derived from wealth and political power; but the majority knew not how to spend the one, and were indifferent to the other. Even to this day, there are in the South and South-West scores of thousands of men who, owning vast tracts of fertile land, and gifted with brains and muscle, will not take the pains to build themselves homes better than ordinary cabins, or cultivate more soil than will supply life with plain and unvaried sustenance. The only advantage they have is the inestimable one, if properly treated, of being free from all trammels save those of ignorance. To rightly appreciate the good or evil qualities of men 15 moulded in such society, requires great generosity, and great freedom from all that is conventional.

Within the first few years of her married life, Nancy Hanks Lincoln bore her husband three children. The first was a daughter, named Sarah, who married at fifteen, and died soon after; the second was Abraham; and the third Thomas, who died in infancy.5 The family were always wretchedly poor, even below the level of their neighbours in want; and as the father was indolent, the wife was obliged to labour and suffer. But it is probable that Mrs. Lincoln, who could read, and Thomas, who attributed his failure in life to ignorance, wished their children to be educated. Schools were, of course, scarce in a country where the houses are often many miles apart. Zachariah Riney, a Catholic priest, was Abraham’s first teacher; his next was Caleb Hazel. The young pupil learned to read and write in a few weeks; but in all his life, reckoning his instruction by days, he had only one year’s schooling.

When Thomas Lincoln was first married (1806), he took his wife to live in Elizabethtown, in a wretched shed, which has since been used as a slaughter-house and stable. About a year after, he removed to Nolin’s Creek. Four years after the 16 birth of Abraham (1809), he again migrated to a more picturesque and fertile place, a few miles distant on Knob Creek. Here he remained four years, and though he was the occupant of over 200 acres of good land, never cultivated more than a little patch, “being satisfied with milk and meal for food.” When his children went to school they walked eight miles, going and returning, having only maize bread for dinner. In 1816, the father, after having sold his interest in the farm for ten barrels of whiskey and twenty dollars, built himself a crazy flat-boat, and set sail alone on the Ohio, seeking for a new home. By accident, the boat foundered, and much of the cargo was lost; but Thomas Lincoln pushed on, and found a fitting place to settle in Indiana, near the spot on which the village of Gentryville now stands. It was in the untrodden wilderness, and here he soon after brought his family, to live for the first year in what is called a half-faced camp, or a rough hut of poles, of which only three sides were enclosed, the fourth being open to the air. In 1817, Betsy Sparrow, an aunt of Mrs. Lincoln, and her husband, Thomas, with a nephew named Dennis Hanks, joined the Lincolns, who removed to a better house, if that could be called a house which was built of rough logs, and had neither floor, door, nor window. For two years they continued to live in this manner. Lincoln, a carpenter, 17 was too lazy to make himself the simplest furniture. They had a few three-legged stools; the only bed was made in a singular manner. Its head and one side were formed by a corner of the cabin, the bed-post was a single crotch cut from the forest. Laid upon this crotch were the ends of two hickory poles, whose other extremities were placed in two holes made in the logs of the wall. On these sticks rested “slats,” or boards rudely split from trees with an axe, and on these slats was laid a bag filled with dried leaves. This was the bed of Thomas and Nancy Lincoln, and into it—when the skins hung at the cabin entrance did not keep out the cold—little Abraham and his sister crept for warmth.6 Very little is recorded of the childhood of the future President. He was once nearly drowned in a stream, and when eight years of age shot a wild turkey, which, he declared in after life, was the largest game he had ever killed—a remarkable statement for a man who had grown up in a deer country, where buck-skin formed the common material for clothing, and venison hams passed for 18 money. One thing is at least certain—that, till he was ten years old, the poor boy was ill-clad, dirty, and ill-used by his father. He had, however, learned to write.

In 1818, a terrible but common epidemic, known in Western America as the milk-fever, broke out in Indiana, and within a few days Thomas and Betsy Sparrow and Mrs. Lincoln all died. They had no medical attendance, and it was nine months before a clergyman, named David Elkin, invited by the first letter which Abraham ever wrote, came one hundred miles to hold the funeral service and preach over the graves. Strange as it may seem, the event which is universally regarded as the saddest of every life, in the case of Abraham Lincoln led directly to greater happiness, and to a change which conduced to the development of all his better qualities. Thirteen months after the death of Nancy Lincoln, Thomas married a widow, Mrs. Johnston, whom he had wooed ineffectually in Kentucky when she was Miss Sally Bush. She was a woman of sense, industrious, frugal, and gifted with a pride which inspired her to lead a far more civilised life than that which satisfied poor Tom Lincoln. He had greatly exaggerated to her the advantages of his home in Indiana, and she was bitterly disappointed when they reached it. Fortunately, she owned a stock of good furniture, which greatly 19 astonished little Abraham and Sarah and their cousin Dennis. “She set about mending matters with great energy, and made her husband put down a floor, and hang windows and doors.” It was in the depth of winter, and the children, as they nestled in the warm beds she had provided, enjoying the strange luxury of security from the cold winds of December, must have thanked her from the depths of their hearts. She had brought a son and two daughters of her own, but Abraham and his sister had an equal place in her affections. They were half naked, and she clad them; they were dirty, and she washed them; they had been ill-used, and she treated them with motherly tenderness. In her own language, she “made them look a little more human.”7

This excellent woman loved Abraham tenderly, and her love was warmly returned. After his death she declared to Mr. Herndon—“I can say what not one mother in ten thousand can of a boy—Abe never gave me a cross look, and never refused, in fact or appearance, to do anything I requested him; nor 20 did I ever give him a cross word in all my life. His mind and mine—what little I had—seemed to run together. He was dutiful to me always. Abe was the best boy I ever saw, or ever expect to see.” “When in after years Mr. Lincoln spoke of his ‘saintly mother’ and of his ‘angel of a mother,’ he referred to this noble woman, who first made him feel ‘like a human being’—whose goodness first touched his childish heart, and taught him that blows and taunts and degradation were not to be his only portion in the world.” And if it be recorded of George Washington that he never told a lie, it should also be remembered of Abraham Lincoln, who carried his country safely through a greater crisis than that of the Revolutionary War,8 that he always obeyed his mother.

Abraham had gone to school only a few weeks in Kentucky, and Mrs. Lincoln soon sent him again to receive instruction. His first teacher in Indiana was Hazel Dorsey; his next, Andrew Crawford. The latter, in addition to the ordinary branches of education, also taught “manners.” One scholar would be introduced by another, while walking round 21 the log schoolroom, to all the boys and girls, taught to bow properly, and otherwise acquire the ordinary courtesies of life. Abraham distinguished himself in spelling, which has always been a favourite subject for competition in rural America, and he soon began to write short original articles, though composition formed no part of the studies. It was characteristic of the boy that his first essays were against cruelty to animals. His mates were in the habit of catching the box-turtles, or land-terrapins, or tortoises, and putting live coals on their backs to make them walk, which greatly annoyed Abraham. All who knew him, in boyhood or in later life, bear witness that this tenderness was equal to his calm courage and tremendous physical strength. The last school which he attended for a short time, and to reach which he walked every day nine miles, was kept by a Mr. Swaney. This was in 1826.

Abraham was now sixteen years of age, and had grown so rapidly that he had almost attained the height which he afterwards reached of six feet four inches. He was very dark, his skin was shrivelled even in boyhood by constant exposure, and he habitually wore low shoes, a linsey-woolsey shirt, a cap made from the skin of a raccoon or opossum, and buckskin breeches, which were invariably about twelve inches too short for him. When not working for his father, he was hired out as a farm-labourer 22 to the neighbours. His cousin, John Hanks, says—“We worked barefoot, grubbed it, ploughed, mowed, and cradled together.”

All who knew him at this time testify that Abraham hated hard-work, though he did it well—that he was physically indolent, though intellectually very active—that he loved to laugh, tell stories, and joke while labouring—and that he passed his leisure moments in hard study or in reading, which he made hard by writing out summaries of all he read, and getting them by heart. He would study arithmetic at night by the light of the fire, and cipher or copy with a pencil or coal on the wooden shovel or on a board. When this was full, he would shave it off with his father’s drawing-knife, and begin again. When he had paper, he used it instead; but in the frequent intervals when he had none, the boards were kept until paper was obtained. Among the first books which he read and thoroughly mastered were “Æsop’s Fables,” “Robinson Crusoe,” Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress,” a “History of the United States,” Weem’s “Life of Washington,” and “The Revised Statutes of Indiana.” From another work, “The Kentucky Preceptor,” a collection of literary extracts, he is said by a Mrs. Crawford, who knew him well, to have “learned his school orations, speeches, and pieces to write.” The field-work, which Abraham Lincoln disliked, did not, however, exhaust his body, 23 and his mind found relief after toil in mastering anything in print.9 It is not unusual to see poor and ignorant youths who are determined to “get learning,” apply themselves to the hardest and dryest intellectual labour with very little discrimination of any difference between that and more attractive literature, and it is evident that young Lincoln worked in this spirit. There is no proof that his memory was by nature extraordinary—it would rather seem that the contrary was the case, from the pains which he took to improve it. During his boyhood, any book had to him all the charm of rarity; perhaps it was the more charming because most of his friends believed that mental culture was incompatible with industry. “Lincoln,” said his cousin, Dennis Hanks, “was lazy—a very lazy man. He was always reading, scribbling, writing, ciphering, writing poetry, and the like.” It is evident that his custom of continually exercising his memory on all subjects grew with his growth and strengthened with his strength. By the time he was twenty-five, he had, without instruction, made himself a good lawyer—not a mere “case-practitioner,” but one who argued from a sound knowledge of principles. It is said that when he began to read Blackstone, he thoroughly learned the first forty pages at one 24 sitting. There is also sufficient proof that he had perfectly mastered not only “Euclid’s Geometry,” but a number of elementary scientific works, among others one on astronomy. And many anecdotes of his later life prove that he learned nothing without thinking it over deeply, especially in all its relations to his other acquisitions and its practical use. If education consists of mental discipline and the acquisition of knowledge, it is idle to say that Abraham Lincoln was uneducated, since few college graduates actually excelled him in either respect. These facts deserve dwelling on, since, in the golden book of self-made men, there is not one who presents a more encouraging example to youth, and especially to the poor and ambitious, than Abraham Lincoln. He developed his memory by resolutely training it—he brought out his reasoning powers as a lawyer by using his memory—he became a fluent speaker and a ready reasoner by availing himself of every opportunity to speak or debate. From the facts which have been gathered by his biographers, or which are current in conversation among those who knew him, it is most evident that there seldom lived a man who owed so little to innate genius or talents, in comparison to what he achieved by sheer determination and perseverance.

When Abraham was fifteen or sixteen, he began to exercise his memory in a new direction, by 25 frequenting not only religious but political meetings, and by mounting the stump of a tree the day after and repeating with great accuracy all he had heard. It is said that he mimicked with great skill not only the tones of preachers and orators, but also their gestures and facial expressions. Anything like cruelty to man or beast would always inspire him to an original address, in which he would preach vigorously against inflicting pain. Wherever he spoke an audience was sure to assemble, and as this frequently happened in the harvest-field, the youthful orator or actor was often dragged down by his angry father and driven to his work. His wit and humour, his inexhaustible fund of stories, and, above all, his kind heart, made him everywhere a favourite. Women, says Mr. Lamon, were especially pleased, for he was always ready to do any kind of work for them, such as chopping wood, making a fire, or nursing a baby. Any family was glad when he was hired to work with them, since he did his work well, and made them all merry while he was about it. In 1825, he was employed by James Taylor as a ferry-man, to manage a boat which crossed the Ohio and Anderson’s Creek. In addition to this he worked on the farm, acted as hostler, ground corn, built the fires, put the water early on the fire, and prepared for the mistress’s cooking. Though he was obliged to rise so early, he always studied till 26 nearly midnight. He was in great demand when hogs were slaughtered. For this rough work he was paid 31 cents (about 16d.) a-day. Meanwhile, he became incredibly strong. He could carry six hundred pounds with ease; he once picked up some huge posts which four men were about to lift, and bore them away with little effort. Men yet alive have seen him lift a full barrel of liquor and drink from the bung-hole. “He could sink an axe,” said an old friend, “deeper into wood than any man I ever saw.” He was especially skilled in wrestling, and from the year 1828 there was no man, far or near, who would compete with him in it.10 From his boyhood, he was extremely temperate. Those who have spoken most freely of his faults admit that, in a country where a whiskey-jug was kept in every house, Lincoln never touched spirits except to avoid giving offence. His stepmother thought he was temperate to a fault.

Meanwhile, as the youth grew apace, the neighbouring village of Gentryville had grown with him. Books and cultivated society became more accessible. The great man of the place was a Mr. Jones, the storekeeper, whose shop supplied all kinds of goods required by farmers. Mr. Jones took a liking to young Lincoln, employed him sometimes, taught 27 him politics, giving him deep impressions in favour of Andrew Jackson, the representative of the Democratic party, and finally awoke Abraham’s ambition by admiring him, and predicting that he would some day be a great man. Another friend was John Baldwin, the village blacksmith, who was, even for a Western American wag, wonderfully clever at a jest, and possessed of an inexhaustible fund of stories. It was from John Baldwin that Lincoln derived a great number of the quaint anecdotes with which he was accustomed in after years to illustrate his arguments. His memory contained thousands of these drolleries; so that, eventually, there was no topic of conversation which did not “put him in mind of a little story.” In some other respects, his acquisitions were less useful. Though he knew a vast number of ballads, he could not sing one; and though a reader of Burns, certain of his own satires and songs, levelled at some neighbours who had slighted him, were mere doggerel, wanting every merit, and very bitter. But, about 1827, he contributed an article on temperance and another on American politics to two newspapers, published in Ohio. From the praise awarded by a lawyer, named Pritchard, to the political article, it would appear to have been very well written. Even in this first essay in politics, Lincoln urged the principle by which he became famous, and for which he died—adherence 28 to the constitution and the integrity of the American Union.

In March, 1828, Abraham Lincoln was hired by Mr. Gentry, the proprietor of Gentryville, as “bow-hand,” and “to work the front oars,” on a boat going with a cargo of bacon to New Orleans. This was a trip of 1800 miles, and then, as now, the life of an Ohio and Mississippi boatman was full of wild adventure. One incident which befel the future President was sufficiently strange. Having arrived at a sugar-plantation six miles below Baton Rouge, the boat was pulled in, and Lincoln, with his companion, a son of Mr. Gentry, went to sleep. Hearing footsteps in the night, they sprang up, and saw that a gang of seven negroes were coming on board to rob or murder. Seizing a hand-spike, Lincoln rushed towards them, and as the leader jumped on the boat, knocked him into the water. The second, third, and fourth, as they leaped aboard, were served in the same way, and the others fled, but were pursued by Lincoln and Gentry, who inflicted on them a severe beating. In this encounter, Abraham received a wound the scar of which he bore through life. It is very probable that among these negroes who would have taken the life of the future champion of emancipation, there were some who lived to share its benefits and weep for his death.11 29

It was during this voyage, or about this time, that two strangers paid Abraham half a silver dollar each for rowing them ashore in a boat. Relating this to Mr. Seward, Secretary of State, he said—“You may think it was a very little thing, but it was a most important incident in my life. I could scarcely believe that I, a poor boy, had earned a dollar in less than a day. I was a more hopeful and confident being from that time.” 30

Lincoln’s Appearance—His First Public Speech—Again at New Orleans—Mechanical Genius—Clerk in a Country Store—Elected Captain—The Black Hawk War—Is a successful Candidate for the Legislature—Becomes a Storekeeper, Land-Surveyor, and Postmaster—His First Love—The “Long Nine”—First Step towards Emancipation.

In 1830, Thomas Lincoln had again tired of his home, and resolved to move Westward. This time he did not change without good reason: an epidemic had appeared in his Indiana neighbourhood, which was besides generally unhealthy. Therefore, in the spring, he and Abraham, with Dennis Hanks and Levi Hall, who had married one of Mrs. Lincoln’s daughters by her first husband, with their families, thirteen in all, having packed their furniture on a waggon, drawn by four oxen, took the road for Illinois. After journeying 200 miles in fifteen days, Thomas Lincoln settled in Moron County, on the Sangamon River, about ten miles west of Decatur. Here they built a cabin of hewn timber, with a smoke-house for drying meat, and a stable, and broke up and fenced fifteen acres of land.

Abraham Lincoln was now twenty-one, and his father had been a hard master, taking all his wages. He therefore, after doing his best to settle the 31 family in their new home, went forth to work for himself among the farmers. One George Cluse, who worked with Abraham during the first year in Illinois, says that at that time he was “the roughest-looking person he ever saw: he was tall, angular, and ungainly, and wore trousers of flax and tow, cut tight at the ankle and out at the knees. He was very poor, and made a bargain with Mrs. Nancy Miller to split 400 rails for every yard of brown jean, dyed with walnut bark, that would be required to make him a pair of trousers.”

Thomas Lincoln found, in less than a year, that his new home was the most unhealthy of all he had tried. So he went Westward again, moving to three new places until he settled at Goose Nest Prairie, in Coles County, where he died at the age of seventy-three, “as usual, in debt.” From the time of his death, and as he advanced in prosperity, Abraham aided his stepmother in many ways besides sending her money. It was at Decatur that he made his first public speech, standing on a keg. It was on the navigation of the Sangamon River, and was delivered extemporaneously in reply to one by a candidate for the Legislature, named Posey.

During the winter of 1831, a trader, named Denton Offutt, proposed to John Hanks, Abraham Lincoln, and John D. Johnston, his stepmother’s son, to take a flat-boat to New Orleans. The wages offered were 32 very high—fifty cents a day to each man, and sixty dollars to be divided among them at the end of the trip. After some delay, the boat, loaded with corn, pigs, and pork, sailed, but just below New Salem, on the Sangamon, it stuck on a dam, but was saved by the great ingenuity of Lincoln, who invented a novel apparatus for getting it over. This seems to have turned his mind to the subject of overcoming such difficulties of navigation, and in 1849 he obtained a patent for “an improved method of lifting vessels over shoals.” The design is a bellows attached to each side of the hull, below the water-line, to be pumped full of air when it is desired to lift the craft over a shoal. The model, which is eighteen or twenty inches long, and which is now in the Patent Office at Washington, appears to have been cut with a knife from a shingle and a cigar-box.12 John Hanks, apparently a most trustworthy and excellent man, declared that it was during this trip, while at New Orleans, Lincoln first saw negroes chained, maltreated, and whipped. It made a deep impression on his humane mind, and, years after, he often declared that witnessing this cruelty first induced him to think slavery wrong. At New Orleans the flat-boat discharged its cargo, and was sold for its timber. Lincoln returned on a steamboat 33 to St. Louis, and thence walked home. He had hardly returned, before he received a challenge from a famous wrestler, named Daniel Needham. There was a great assembly at Wabash Point, to witness the match, where Needham was thrown with so much ease that his pride was more hurt than his body.

In July, 1831, Abraham again engaged himself to Mr. Offutt, to take charge of a country store at New Salem. While awaiting his employer, an election was held, and a clerk was wanted at the polls. The stranger, Abraham, being asked whether he was competent to fill the post, said, “I will try,” and performed the duties well. This was the first public official act of his life; and as soon as Offutt’s goods arrived, Lincoln, from a day-labourer, became a clerk, or rather salesman, in which capacity he remained for one year, or until the spring of 1832, when his employer failed. Many incidents are narrated of Lincoln’s honesty towards customers during this clerkship—of his strict integrity in trifles—his bravery when women were annoyed by bullies—and of his prowess against a gang of ruffians who infested and ruled the town. He is said to have more than once walked several miles after business hours to return six cents, or some equally trifling sum, when he had been overpaid. It is very evident that he managed all matters with so much tact as 34 to make fast friends of everybody, and was specially a favourite of the men with whom he fought. It was now that he began to cultivate popularity, quietly, but with the same determination which he had shown in acquiring knowledge. To his credit be it said, that he effected this neither by flattery nor servility, but by making the most of his good qualities, and by inducing respect for his honesty, intelligence, and bravery. It is certain that, during a year, Mr. Offutt was continually stimulating his ambition, and insisting that he knew more than any man in the United States, and would some day be President. Lincoln himself knew very well by this time of what stuff many of the men were made who rose in politics, and that, with a little luck and perseverance, he could hold his own with them. When out of the “store,” he was always busy, as of old, in the pursuit of knowledge. He mastered the English grammar, remarking that, “if that was what they called a science, he thought he could subdue another.” A Mr. Green, who became his fellow-clerk, declares that his talk now showed that he was beginning to think of “a great life and a great destiny.” He busied himself very much with debating clubs, walking many miles to attend them, and for years continued to take the “Louisville Journal,” famous for the lively wit of its editor, George D. Prentice, and for this newspaper he paid regularly when he 35 had not the means to buy decent clothing. From this time his life rapidly increases in interest. It is certain that, from early youth, he had quietly determined to become great, and that he thoroughly tested his own talents and acquirements before entering upon politics as a career. His chief and indeed his almost only talent was resolute perseverance, and by means of it he passed in the race of life thousands who were his superiors in genius. Among all the biographies of the great and wise and good among mankind, there is not one so full of encouragement to poor young men as that of Abraham Lincoln, since there is not one which so illustrates not only how mere personal success may be attained, but how, by strong will and self-culture, the tremendous task of guiding a vast country through the trials of a civil war may be successfully achieved.

In the spring of 1832, Mr. Offutt failed, and Lincoln had nothing to do. For some time past, an Indian rebellion, led by the famous Black Hawk, Chief of the Sac tribe, had caused the greatest alarm in the Western States. About the beginning of this century (1804-5), the Sacs had been removed west of the Mississippi; but Black Hawk, believing that his people had been unjustly exiled, organised a conspiracy which for a while embraced nine of the most powerful tribes of the North-West, and announced his intention of returning and settling in 36 the old hunting-grounds of his people on the Rock River. He was a man of great courage and shrewdness, skilled as an orator, and dreaded as one gifted with supernatural power, combining in his person the war-chief and prophet. But the returning Indians, by committing great barbarities on the way, caused such irritation and alarm among the white settlers, that when Governor Reynolds of Illinois, issued a call for volunteers, several regiments of hardy frontiersmen were at once formed. Black Hawk’s allies, with the exception of the tribe of the Foxes, at once fell away, but their desperate leader kept on in his course. Among the companies which volunteered was one from Menard County, embracing many men from New Salem. The captain was chosen by vote, and the choice fell on Lincoln. He was accustomed to say, when President, that nothing in his life had ever gratified him so much as this promotion; and this may well have been, since, to a very ambitious man, the first practical proofs of popularity are like the first instalment of a great fortune paid to one who is poor.

Though he was never in an actual engagement during this campaign, Lincoln underwent much hunger and hardship while it lasted, and at times had great trouble with his men, who were not only mere raw militia, but also unusually rough and rebellious. One incident of the war, however, 37 as narrated by Lamon, not only indicates that Abraham Lincoln was sometimes in danger, but was well qualified to grapple with it.

“One day, during these many marches and countermarches, an old Indian, weary, hungry, and helpless, found his way into the camp. He professed to be a friend of the whites; and, although it was an exceedingly perilous experiment for one of his colour, he ventured to throw himself upon the mercy of the soldiers. But the men first murmured, and then broke out into fierce cries for his blood. “We have come out to fight Indians,” they said, “and we intend to do it.” The poor Indian, now in the extremity of his distress and peril, did what he should have done before—he threw down before his assailants a soiled and crumpled paper, which he implored them to read before taking his life. It was a letter of character and safe conduct from General Cass, pronouncing him a faithful man, who had done good service in the cause for which this army was enlisted. But it was too late; the men refused to read it, or thought it a forgery, and were rushing with fury upon the defenceless old savage, when Captain Lincoln bounded between them and their appointed victim. “Men,” said he, and his voice for a moment stilled the agitation around him, “this must not be done—he must not be shot and killed by us.” “But,” said some of them, “the Indian is a spy.” Lincoln 38 knew that his own life was now in only less danger than that of the poor creature that crouched behind him. During this scene, the towering form and the passion and resolution in Lincoln’s face produced an effect upon the furious mob. They paused, listened, fell back, and then sullenly obeyed what seemed to be the voice of reason as well as authority. But there were still some murmurs of disappointed rage, and half-suppressed exclamations which looked towards vengeance of some kind. At length one of the men, a little bolder than the rest, but evidently feeling that he spoke for the whole, cried out—“This is cowardly on your part, Lincoln!” “If any man think I am a coward, let him test it,” was the reply. “Lincoln,” responded a new voice, “you are larger and heavier than we are.” “This you can guard against; choose your weapons,” returned the Captain. Whatever may be said of Mr. Lincoln’s choice of means for the preservation of military discipline, it was certainly very effectual in this case. There was no more disaffection in his camp, and the word “coward” was never coupled with his name again. Mr. Lincoln understood his men better than those who would be disposed to criticise his conduct. He has often declared himself that “his life and character were both at stake, and would probably have been lost, had he not at that supremely critical moment forgotten the officer and asserted 39 the man.” The soldiers, in fact, could not have been arrested, tried, or punished; they were merely wild backwoodsmen, “acting entirely by their own will, and any effort to court-martial them would simply have failed in its object, and made their Captain seem afraid of them.”

During this campaign, Lincoln made the acquaintance of a lawyer—then captain—the Hon. T. Stuart, who had subsequently a great influence on his career. When the company was mustered out in May, Lincoln at once re-enlisted as a private in a volunteer spy company, where he remained for a month, until the Battle of Bad Axe, which resulted in the capture of Black Hawk, put an end to hostilities. This war was not a remarkable affair, says J. G. Holland, but it was remarkable that the two simplest, homeliest, and truest men engaged in it afterwards became Presidents of the United States—namely, General, then Colonel, Zachary Taylor and Abraham Lincoln.

It has always been usual in the United States to urge to the utmost the slightest military services rendered by candidates for office. The absurd degree to which this was carried often awoke the satire of Lincoln, even when it was at his own expense. Many years after, he referred thus humorously to his military services13:— 40

“By the way, Mr. Speaker, did you know I was a military hero? Yes, sir, in the days of the Black Hawk war I fought, bled, and came away. Speaking of General Cass’s career reminds me of my own. I was not at Sullivan’s defeat, but I was about as near to it as Cass was to Hull’s surrender, and, like him, I saw the place soon after. It is quite certain that I did not break my sword, for I had none to break;14 but I bent my musket pretty badly on one occasion. If Cass broke his sword, the idea is he broke it in desperation. I bent the musket by accident. If General Cass went in advance of me in picking whortleberries, I guess I surpassed him in charges upon the wild onions. If he saw any live fighting Indians, it was more than I did; but I had a great many bloody struggles with the mosquitoes, and, although I never fainted from loss of blood, I certainly can say I was often very hungry.”

The soldiers from Sangamon County arrived home just ten days before the State election, and Lincoln was immediately applied to for permission to place 41 his name among the candidates for the Legislature.15 He canvassed the district, but was defeated, though he received the almost unanimous vote of his own precinct. The young man had, however, made a great advance even by defeat, since he became known by it as one whose sterling honesty had deserved a better reward. Lincoln’s integrity was, in this election, strikingly evinced by his adherence to his political principles; had he been less scrupulous, he would not have lost the election. At this time there were two great political parties—the Democratic, headed by Andrew Jackson, elected President in 1832, and that which had been the Federalist, but which was rapidly being called Whig. The Democratic party warred against a national bank, paper money, “monopolies” or privileged and chartered institutions, a protective tariff, and internal improvements, and was, in short, jealous of all public expenditure which could tend to greatly enrich individuals. Its leader, Jackson, was a man of inflexible determination and unquestionable bravery, which he had shown not only in battle, but by subduing the incipient rebellion in South Carolina, when that state had threatened to nullify or secede from the Union. Lincoln’s heart was with Jackson; he had unbounded admiration for the man, but he 42 knew that the country needed internal improvements, and in matters of political economy inclined to the Whigs.

After returning from the army, he went to live in the house of W. H. Herndon, a most estimable man, to whose researches the world owes nearly all that is known of Lincoln’s early life and family, and who was subsequently his law-partner. At this time the late Captain thought of becoming a blacksmith, but as an opportunity occurred of buying a store in New Salem on credit, he became, in company with a man named Berry, a country merchant, or trader.

He showed little wisdom in associating himself with Berry, who proved a drunkard, and ruined the business, after a year of anxiety, leaving Lincoln in debt, which he struggled to pay off through many years of trouble. It was not until 1849 that the last note was discharged. His creditors were, however, considerate and kind. While living with Mr. Herndon, Lincoln began to study law seriously. He had previously read Blackstone, and by one who has really mastered this grand compendium of English law the profession is already half-acquired. He was still very poor, and appears to have lived by helping a Mr. Ellis in his shop, and to have received much willing aid from friends, especially John T. Stuart, who always cheerfully supplied his wants, and lent him law-books. 43

About this time, Lincoln attracted the attention of a noted Democrat, John Calhoun, the surveyor of Sangamon County, who afterwards became famous as President of the Lecompton Council in Kansas, during the disturbances between the friends and opponents of slavery prior to the admission of the state. He liked Lincoln, and, wanting a really honest assistant, recommended him to learn surveying, lending him a book for the purpose. In six weeks he had qualified himself, and soon acquired a small private business.

On the 7th May, 1833, Lincoln was appointed postmaster at New Salem. As the mail arrived but once a-week, neither the duties nor emoluments of the office were such as to greatly disturb or delight him. He is said, indeed, to have kept the letters in his hat, being at once, in his own person, both office and officer. The advantages which he gained were opportunities to read the newspapers, which he did aloud to the assembled inhabitants, and to decipher letters for all who could not read. All of this was conducive, in a creditable way, to notoriety and popularity, and he improved it as such. In the autumn of 1834, a great trouble occurred. His scanty property, consisting of the horse, saddle, bridle, and surveyor’s instruments by which he lived, were seized under a judgment on one of the notes which he had given for “the store.” But two good 44 friends, named Short and Bowlin Greene, bought them in for 245 dollars, which Lincoln faithfully repaid in due time. It is said that he was an accurate surveyor, and remarkable for his truthfulness. He never speculated in lands, nor availed himself of endless opportunities to profit, by aiding the speculations of others.

Miserably poor and badly clad, Lincoln, though very fond of the society of women, was sensitive and shy when they were strangers. Mr. Ellis, the storekeeper for whom he often worked, states that, when he lived with him at the tavern, there came a lady from Virginia with three stylish daughters, who remained a few weeks. “During their stay, I do not remember Mr. Lincoln ever eating at the same table where they did. I thought it was on account of his awkward appearance and wearing apparel.” There are many anecdotes recorded of this kind, showing at this period his poverty, his popularity, and his kindness of heart. He was referee, umpire, and unquestioned judge in all disputes, horse-races, or wagers. One who knew him in this capacity said of him—“He is the fairest man I ever had to deal with.”

In 1834, Lincoln again became a successful candidate for the Legislature of Illinois, receiving a larger majority than any other candidate on the ticket. A friend, Colonel Smoot, lent him 200 45 dollars to make a decent appearance, and he went to the seat of government properly dressed, for, perhaps, the first time in his life. During the session, he said very little, but worked hard and learned much. He was on the Committee for Public Accounts and Expenditures, and when the session was at an end, quietly walked back to his work.

Lamon relates, at full length, that at this time Lincoln was in love with a young lady, who died of a broken heart in 1835, not, however, for Lincoln, but for another young man who had been engaged to, and abandoned her. At her death, Lincoln seemed for some weeks nearly insane, and was never the same man again. From this time he lost his youth, and became subject to frequent attacks of intense mental depression, resulting in that settled melancholy which never left him.

In 1836, he was again elected to the Legislature. Political excitement at this time ran high. The country was being settled rapidly, and people’s minds were wild with speculation in lands and public works, from which every man hoped for wealth, and which were to be developed by the legislators. Lincoln’s colleagues were in an unusual degree able men, and the session was a busy one. It was during the canvass of 1836 that he made his first really great speech. He had by this time fairly joined the new 46 Whig party, and it was in reply to a Democrat, Dr. Early, that he spoke. From that day he was recognised as one of the most powerful orators in the state.

The principal object of this session, in accordance with the popular mania, was internal improvements, and to this subject Lincoln had been devoted for years. The representatives from Sangamon County consisted of nine men of great influence, every one at least six feet in height, whence they were known as the Long Nine. The friends of the adoption of a general system of internal improvements wished to secure the aid of the Long Nine, but the latter refused to aid them unless the removal of the capital of the state from Vandalia to Springfield should be made a part of the measure. The result was that both the Bill for removal and that for internal improvements, involving the indebtedness of the state for many millions of dollars, passed the same day. Lincoln was the leader in these improvements, and “was a most laborious member, instant in season and out of season for the great measures of the Whig party.”16 At the present day, though grave doubts 47 may exist as to the expediency of such reckless and radical legislation, there can be none as to the integrity or good faith of Abraham Lincoln. He did not enrich himself by it, though it is not impossible that, in legislation as in land-surveying, others swindled on his honesty.

It was during this session that Lincoln first beheld Stephen Douglas, who was destined to become, for twenty years, his most formidable opponent. Douglas, from his diminutive stature and great mind, was afterwards popularly known as the Little Giant. Lincoln merely recorded his first impressions of Douglas by saying he was the least man he ever saw. This legislation of 1836-37 was indeed of a nature to attract speculators, whether in finance or politics. Within a few days, it passed two loans amounting to 12,000,000 dollars, and chartered 1,300 miles of railway, with canals, bridges, and river improvements in full proportion. The capital stock of two banks was increased by nearly 5,000,000 dollars, which the State took, leaving it to the banks to manage the railroad and canal funds. Everything was undertaken on a colossal and daring scale by the legislators, who were principally managed by the Long Nine, who were in their turn chiefly directed by Lincoln. The previous session had been to him only as the green-room in which to prepare himself for the stage. When he made this his first appearance in 48 the political ballet, it was certainly with such a leap as had never before been witnessed in any beginner. The internal improvement scheme involved not only great boldness and promptness in its execution, but also a vast amount of that practical business talent in which most “Western men” and Yankees are instinctively proficient. With all this, there was incessant hard work and great excitement. Through the turmoil, Lincoln passed like one in his true element. He had at last got into the life to which he had aspired for years, and was probably as happy as his constitutional infirmity of melancholy would permit. He was, it is true, no man of business in the ordinary sense, but he understood the general principles of business, and was skilled in availing himself in others of talents which he did not possess.

During this session, he put on record his first anti-slavery protest. It was, in the words of Lamon, “a very mild beginning,” but it required uncommon courage, and is interesting as indicating the principle upon which his theory of Emancipation was afterwards carried out. At this time the whole country, North as well as South, was becoming excited concerning the doctrines and practices of the small but very rapidly-growing body of Abolitionists, who were attacking slavery with fiery zeal, and provoking in return the most deadly hatred. The Abolitionist, carrying the Republican theory to its logical extreme, 49 insisted that all men, white or black, were entitled to the same political and social rights; the slave-owners honestly believed that society should consist of strata, the lowest of which should be bondmen. The Abolitionist did not recognise that slavery in America, like serfdom in Russia, had developed into culture a country which would, without it, have remained a wilderness; nor did the slave theorists recognise that a time must infallibly come when both systems of enforced labour must yield to new forms of industrial development. The Abolitionists, taking their impressions from the early English and Quaker philanthropists, thought principally of the personal wrong inflicted on the negro; while the majority of Americans declared, with equal conviction, that the black’s sufferings were not of so much account that white men should be made to suffer much more for them, and the whole country be possibly overwhelmed in civil war. Even at this early period of the dispute, there were, however, in the old Whig party, a few men who thought that the growing strife was not to be stopped simply by crushing the Abolitionists. But while they would gladly have seen the latter abate their furious zeal, they also thought that slavery might, with propriety, be at least checked in its progress, since they had observed, with grave misgiving, that wherever it was planted, only an aristocracy flourished, while the poor white men 50 became utterly degraded. Such were the views of Abraham Lincoln—views which, in after years, led, during the sharp and bitter need of the war, to the formation of the theory of Emancipation for the sake of the Country, as opposed to mere Abolition for the sake of the Negro, which had had its turn and fulfilled its mission.

The feeling against the Abolitionists was very bitter in Illinois. Many other states had passed severe resolutions, recommending that anti-slavery agitation be made an indictable offence, or a misdemeanour; and in May, 1836, Congress declared that all future “abolition petitions” should be laid on the table without discussion. But when the Legislature of Illinois took its turn in the fashion, and passed resolutions of the same kind, Abraham Lincoln presented to the House a protest which he could get but one man, Dan Stone, to sign. Perhaps he did not want any more signatures, for he was one of those who foresaw to what this cloud, no larger than a man’s hand, would in future years extend, and was willing to be alone as a prophet. The protest was as follows:—

The following protest was presented to the House, which was read and ordered to be spread on the journals, to wit:—

Resolutions upon the subject of domestic slavery having 51 passed both branches of the General Assembly at its present session, the undersigned hereby protest against the passage of the same.

They believe that the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy; but that the promulgation of Abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than abate its evils.

They believe that the Congress of the United States has no power under the Constitution to interfere with the institution of slavery in the different states.

They believe that the Congress of the United States has the power, under the Constitution, to abolish slavery in the district of Columbia; but that the power ought not to be exercised, unless at the request of the people of the district.

The difference between these opinions and those contained in the said resolutions is their reason for entering this protest.

This was indeed a very mild protest, but it was the beginning of that which, in after years, grew to be the real Emancipation of the negro. Never in history was so fine an end of the wedge succeeded by such a wide cleaving bulk. Much as Lincoln afterwards accomplished for the abolition of slavery, he never, says Holland, became more extreme in his views than the words of this protest intimate. It was during this session also that he first put 52 himself in direct opposition to Douglas by another protest. The Democrats, in order to enable the aliens—virtually the Irishmen—in their state to vote on six months’ residence, passed a Bill known as the Douglas Bill, remodelling the judiciary in such a way as to secure judges who would aid them. Against this, Lincoln, E. D. Baker, and others protested vigorously, but without avail. Both of these protests, though failures at the time, were in reality the beginnings of the two great principles which led to Lincoln’s great success, and the realisation of his utmost ambition. During his life, defeat was always a step to victory. 53

Lincoln settles at Springfield as a Lawyer—Candidate for the Office of Presidential Elector—A Love Affair—Marries Miss Todd—Religious Views—Exerts himself for Henry Clay—Elected to Congress in 1846—Speeches in Congress—Out of Political Employment until 1854—Anecdotes of Lincoln as a Lawyer.

Abraham Lincoln’s career was now clear. He was to follow the law for a living, as a step to political eminence. And as the seat of State Government was henceforth to be at Springfield, he determined to live where both law and politics might be followed to the greatest advantage, since it was in Springfield that, in addition to the State Courts, the Circuit and District Courts of the United States sat. He obtained his license as an attorney in 1837, and commenced his practice in the March of that year. He entered into partnership with his friend, J. T. Stewart, and lived with the Hon. W. Butler, who was of great assistance to him in the simple matter of living, for he was at this time as poor as ever. During 1837, he delivered several addresses in which there was a strong basis of common sense, though they were fervid and figurative to extravagance, as suited the tastes of his hearers. In these speeches he predicted the great struggle on which 54 the country was about to enter, and that it would never be settled by passion but by reason—“cold, calculating, unimpassioned reasoning, which must furnish all the materials for our future defence and support.” He also distinguished himself in debate and retort, so that ere long he became unrivalled, in his sphere, in ready eloquence. From this time, for twenty years, he followed his great political rival, Douglas, seeking every opportunity to contend with him. From 1837 he concerned himself little with the politics of his state, but entered with zeal into the higher interests of the Federal Union.

In 1840, Lincoln was a candidate for the office of Presidential elector on the Harrison ticket, and made speeches through a great part of Illinois. Soon after, he again became involved in a love affair, which, through its perplexities and the revival of the memory of his early disappointment, had a terrible effect upon his mind. He had become intimate with a Mr. Speed, who remained through life his best friend. For a year he was almost a lunatic, and was taken to Kentucky by Mr. Speed, and kept there until he recovered. It was for this reason that he did not attend the Legislature of 1841-42. It is very characteristic of Lincoln that, from boyhood, he never wanted true friends to aid him in all his troubles.

Soon after his recovery, Lincoln became engaged 55 to Miss Mary Todd. This lady was supposed to be gifted as a witty and satirical writer, though it must be admitted that the specimens of her literary capacity, exhibited in certain anonymous contributions to the newspapers, show little talent beyond the art of irritation. Several of these were levelled at a politician named James Shields, an Irishman, who, being told that Lincoln had written them, sent him a challenge. The challenge was accepted, but the duel was prevented by mutual friends. Lincoln married Miss Todd on the 4th November, 1842. This marriage, which had not been preceded by the most favourable omens, was followed by a singular misfortune. In 1843, Lincoln was a Whig candidate for Congress, but was defeated. “He had a hard time of it, and was compelled to meet accusations of a strange character. Among other things, he was charged with being an aristocrat, and with having deserted his old friends, the people, by marrying a proud woman on account of her blood and family. This hurt him keenly,” says Lamon, “and he took great pains to disprove it.” Other accusations, equally frivolous, relative to his supposed religion or irreligion, also contributed to his defeat.

On this much-vexed subject of Lincoln’s religious faith, or his want of it, something may here be said. In his boyhood, when religious associations are most valuable in disciplining the mind, he had never even 56 seen a church, and, as he grew older, his sense of humour and his rude companions prevented him from being seriously impressed by the fervid but often eccentric oratory of the few itinerant preachers who found their way into the backwoods. At New Salem, he had read “Volney’s Ruins” and the works of Thomas Paine, and was for some time a would-be unbeliever. It is easy to trace in his youthful irreligion the influence of irresistible causes. As he grew older, his intensely melancholy and emotional temperament inclined him towards reliance in an unseen Providence and belief in a future state; and it is certain that, after the unpopularity of freethinkers had forced itself upon his mind, the most fervidly passionate expressions of piety began to abound in his speeches. In this he was not, however, hypocritical. From his childhood, Abraham Lincoln was possessed even to unreason with the idea that whatever was absolutely popular, was founded on reason and right. He was a Republican of Republicans, faithfully believing that whatever average common sense accepted must be followed.17 His own personal popularity was at all times very great. 57 One who knew him testifies that, when the lawyers travelling the judicial circuit of Illinois arrived at the villages where trials were to be held, crowds of men and women always assembled to welcome Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln himself had a great admiration for Henry Clay. In 1844, he went through Illinois delivering speeches and debating and speaking, or, as it is called in America, “stumping” for him, and he even extended his labours into Indiana. It was all in vain, and Clay’s defeat was a great blow to Lincoln.18 At this time, though he withdrew from politics in favour of law, he began to think seriously of getting a seat in Congress. His management of this affair indicates forcibly his entire faith in party-right, and his principle of never advancing beyond his party. Of all the men of action known to history as illustrating great epochs, there never was a more thorough man of action than Lincoln, but the brain which inspired his action was always that of the people.

Through all his poverty, Lincoln was always just and generous. In 1843, while living with his wife for four dollars a-week, at a country tavern, he gave up a promissory-note for a large fee to an impoverished client who, after the trial, had lost a hand. 58 He paid all his own debts, and generously aided his stepmother and other friends.

In 1846, Lincoln accepted the nomination for Congress. His Democratic opponent was Peter Cartwright, a celebrated pioneer Methodist preacher. It is a great proof of Lincoln’s popularity that he was elected by an unprecedented majority, though he was the only Whig Congressman from Illinois. At this session, his almost life-long adversary, Douglas, took a place in the Senate. Both houses shone with an array of great and brilliant names, and Lincoln, as the only representative of his party from his state, was in a critical and responsible situation. But he was no novice in legislation, and he acquitted himself bravely. He became a member of the Committee on Post Offices and Post Roads, and in that capacity made his first speech. He found it as easy a matter to address his new colleagues as his old clients. “I was about as badly scared,” he wrote to W. J. Herndon, “and no worse, as when I speak in court.” During this session, the United States were at war with Mexico, and Lincoln was, with his party, in a painful dilemma. They were opposed to the principle of the war, since they detested forcible acquisition of territory, and it was evident that Mexico was wanted by the South to extend the area of slavery. Yet they could not, in humanity, withhold supplies from the army in Mexico while fighting bravely. 59 So Lincoln denounced the war, and yet voted the supplies—an inconsistency creditable to his heart, but which involved him in trouble with his constituents. But he struck the Administration a severe blow in what was really his first speech before the whole House. President Polk having declared, in a Message, that “the Mexicans had invaded our territory, and shed the blood of our citizens on our own soil,” Lincoln introduced what were called the famous “spot resolutions,” in which the President was invited in a series of satirical yet serious questions to indicate the spot where this outrage had been committed.

Lincoln was very busy this year. The Whig National Convention was to nominate a candidate for President on the 1st June, and he was to be one of its members. On July 27th, he delivered, in Congress, a speech as remarkable in some respects for solid sense and shrewdness as it was in others for eccentric drollery and scathing Western retorts. The second session, 1848-49, was quieter. At one time he proposed, as a substitute for a resolution that slavery be at once abolished by law in the district of Columbia, another, providing that the owners be paid for their slaves. If he did little in this session to attract attention, he made for himself a name, and was known as a powerful speaker and a rising man; but, after returning to Springfield, 60 though a Whig President had been elected, and his own reputation greatly increased, he was thrown out of political employment until the year 1854. He made great efforts to secure the office of Commissioner of the General Land Office, but failed. President Fillmore, it is true, offered him the Governorship of Oregon, but Mrs. Lincoln induced him to decline it.

In 1850, his friends wished to nominate him for Congress, but he positively refused the honour. It is thought that he wished to establish himself in his profession for the sake of a support for his family, or that he had entered into a secret understanding with other candidates for Congress, who were to nominally oppose each other, but in reality secure election in turn by excluding rivals.19 But it is most probable that he clearly foresaw at this time the tremendous struggle which was approaching between North and South, and wished to prepare himself for some great part in it. To engage in minor political battles and be defeated, as would probably be the case in his district, where his war-vote in Congress was still remembered to his disadvantage, would have 61 seriously injured his future prospects of every kind. He said, in 1850, to his friend Stuart—“The time will come when we must all be Democrats or Abolitionists. When that time comes, my mind is made up. The slavery question can’t be compromised.”

Many interesting anecdotes of Lincoln’s legal experiences at this time have been preserved. In his first case, at Springfield, he simply admitted that all laws and precedents were in favour of his opponent, and, having stated them in detail, left the decision to the Court. He would never take an unjust, or mean, or a purely litigious case. When retained with a colleague, named Swett, to defend a man accused of murder, Lincoln became convinced of his client’s guilt, and said to his associate—“You must defend him—I cannot.” Mr. Swett obtained an acquittal, but Lincoln would take no part of the large fee which was paid. On one occasion, however, when one of his own friends of boyhood, John Armstrong, was indicted for a very atrocious murder, Lincoln, moved by the tears and entreaties of the aged mother of the prisoner, consented to plead his cause. It having been testified that, when the man was murdered, the full moon was shining high in the heavens, Lincoln, producing an almanac, proved that, on the night in question, there was in fact no moon at all. Those who were associated with him for 62 years declare that they never knew a lawyer who was so moderate in his charges. Though he attained great reputation in his profession, the highest fee he ever received was 5,000 dollars. His strength lay entirely in shrewd common sense, in quickly mastering all the details of a case, and in ready eloquence or debate, for he had very little law-learning, and was averse to making researches. But his rare genius for promptly penetrating all the difficulties of a legal or political problem, which aided him so much as President, enabled him to deal with juries in a masterly manner. On one occasion, when thirty-four witnesses swore to a fact on one side, and exactly as many on the other, Mr. Lincoln proposed a very practical test to the jury—“If you were going to bet on this case,” he said, “on which side would you lay a picayune?”20

Any poor person in distress for want of legal aid could always find a zealous friend in Lincoln. On one occasion, a poor old negro woman came to him and Mr. Herndon, complaining that her son had been imprisoned at New Orleans for simply going, in his ignorance, ashore, thereby breaking a disgraceful law which then existed, forbidding free men of colour from other states to enter Louisiana. Having been condemned to pay a fine, and being without 63 money, the poor man was about to be sold for a slave. Messrs. Lincoln and Herndon, finding law of no avail, ransomed the prisoner out of their own pockets. In those days, a free-born native of a Northern state could, if of African descent, be seized and sold simply for setting foot on Southern soil. 64

Rise of the Southern Party—Formation of the Abolition and the Free Soil Parties—Judge Douglas and the Kansas-Nebraska Bill—Douglas defeated by Lincoln—Lincoln resigns as Candidate for Congress—Lincoln’s Letter on Slavery—The Bloomington Speech—The Fremont Campaign—Election of Buchanan—The Dred-Scott Decision.

The great storm of civil war which now threatened the American Ship of State had been long brewing. Year by year the party of slave-owners—small in number but strong in union, and unanimously devoted to the acquisition of political power—had progressed, until they saw before them the possibility of ruling the entire continent. To please them, the nation, after purchasing, had admitted as slave territory the immense regions of Louisiana and Florida, and in their interests a war had been waged with Mexico. But, so early as 1820, the North, alarmed at the incredible progress of slave-power, and observing that wherever it was established white labour was paralysed, and that society resolved itself at once into a small aristocracy, with a large number of blacks and poor whites who were systematically degraded,21 attempted to check its territorial 65 extension. There was a contest, which was finally settled by what was known as the Missouri Compromise, by which it was agreed that Missouri should be admitted as a slave state, but that in future all territory North and West of Missouri, above latitude 36° 30´, should be for ever free.22

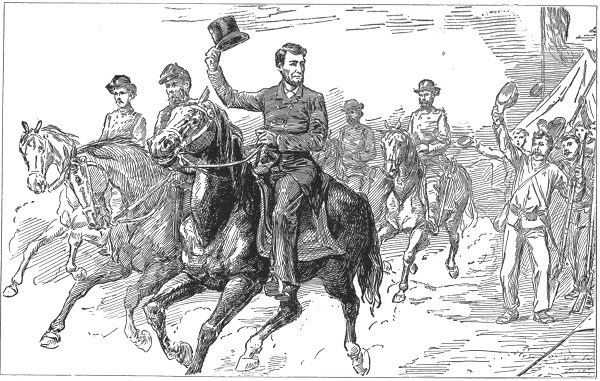

Abraham Lincoln.

While the inhabitants of the Eastern and Western States applied themselves to every development of industrial pursuits, art, and letters, the Southerners lived by agricultural slave-labour, and were entirely devoted to acquiring political power. The contest was unequal, and the result was that, before the Rebellion, the slave-holders—who, with their slaves, only constituted one-third of the population of the United States—had secured two-thirds of all the offices—civil, military, or naval—and had elected two-thirds of the Presidents. Law after law was passed, giving the slave-holders every advantage, until Governor Henry A. Wise, of Virginia, declared in Congress that slavery should pour itself abroad, and have no limit but the Southern Ocean. He also asserted that the best way to meet or answer Abolition arguments was with death. His house was afterwards, during the war, used for a negro school, under care of a New England Abolitionist. Large pecuniary rewards were offered by Governors of slave states for the persons—i.e., the lives—of eminent Northern anti-slavery men. Direct 66 efforts were made to re-establish the slave-trade between Africa and the Southern States.