Title: The Autobiography of Goethe

Author: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Translator: A. J. W. Morrison

John Oxenford

Release date: July 26, 2016 [eBook #52654]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Laura Natal Rodriguez and Marc D'Hooghe (Images generously made available by the Internet Archive.)

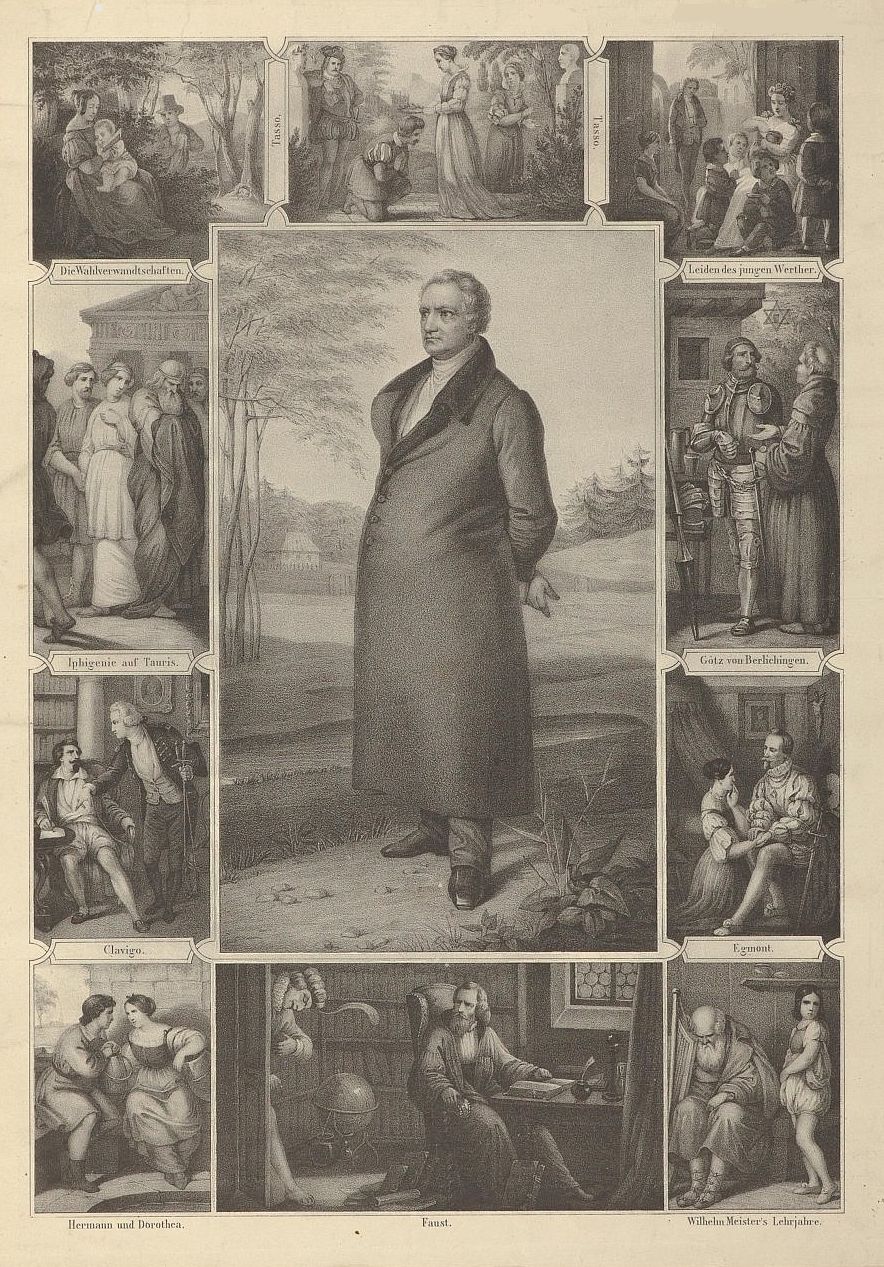

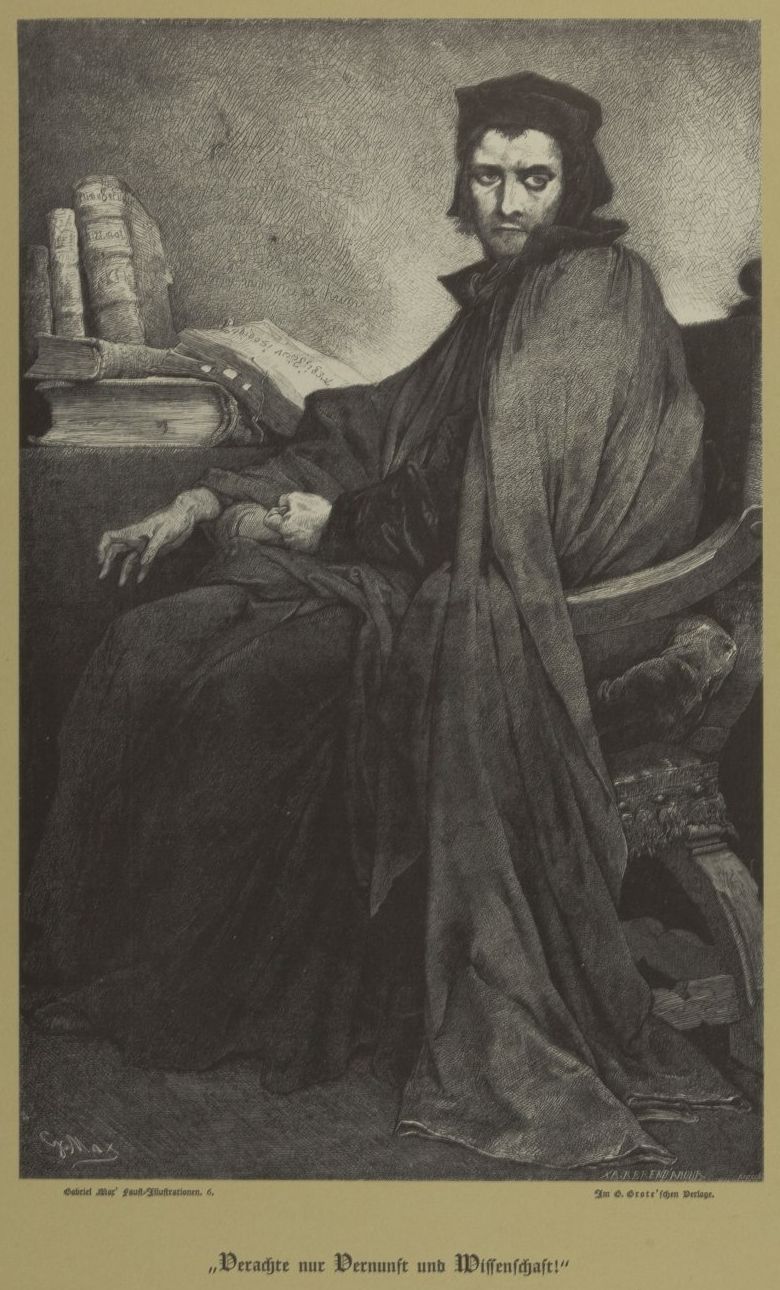

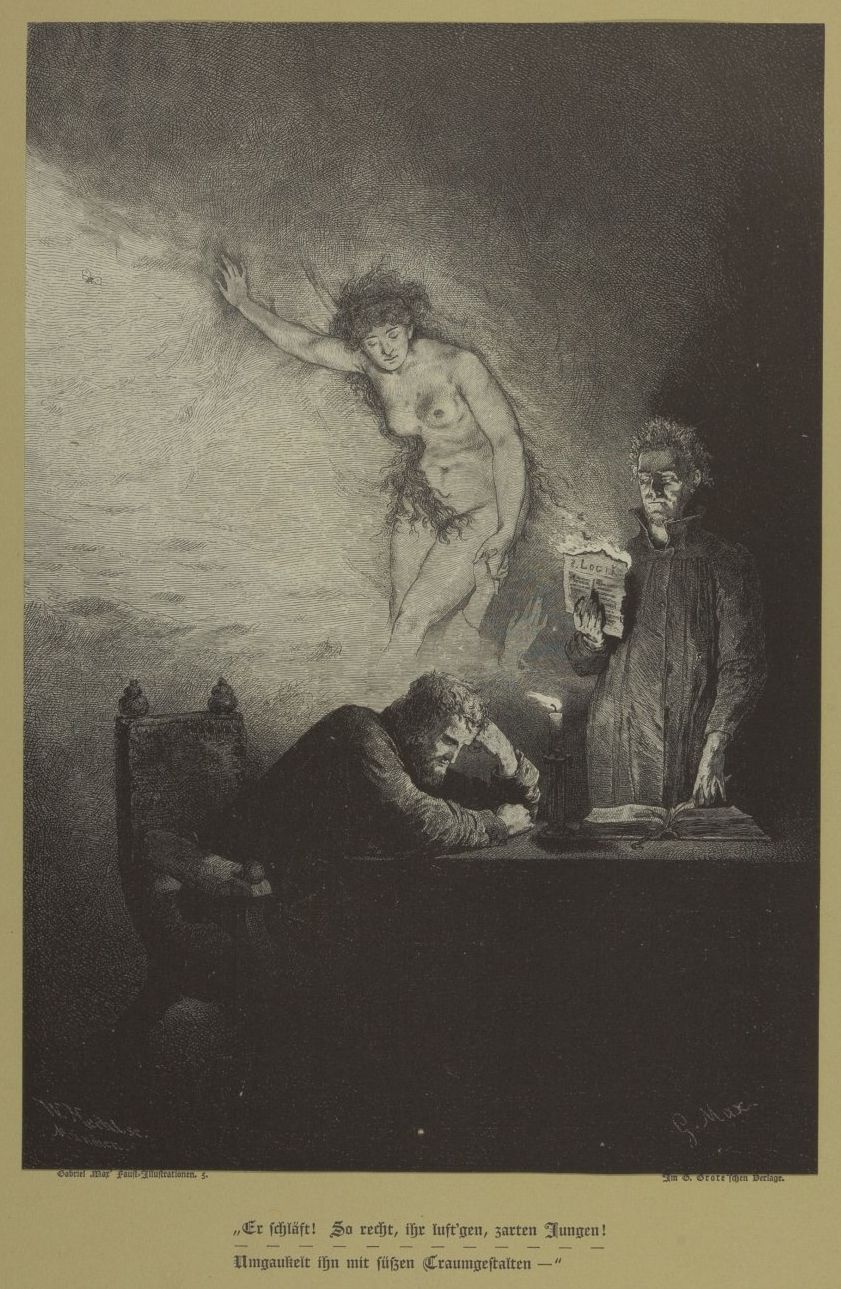

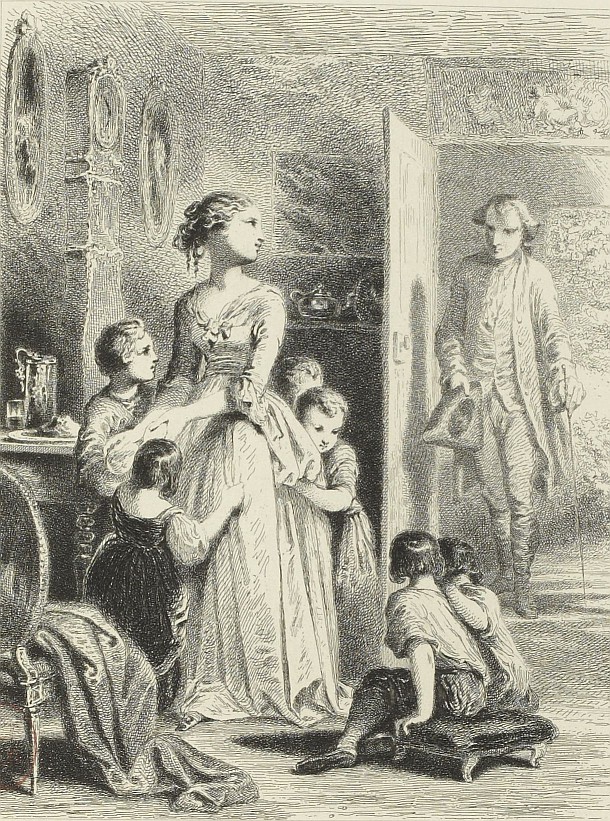

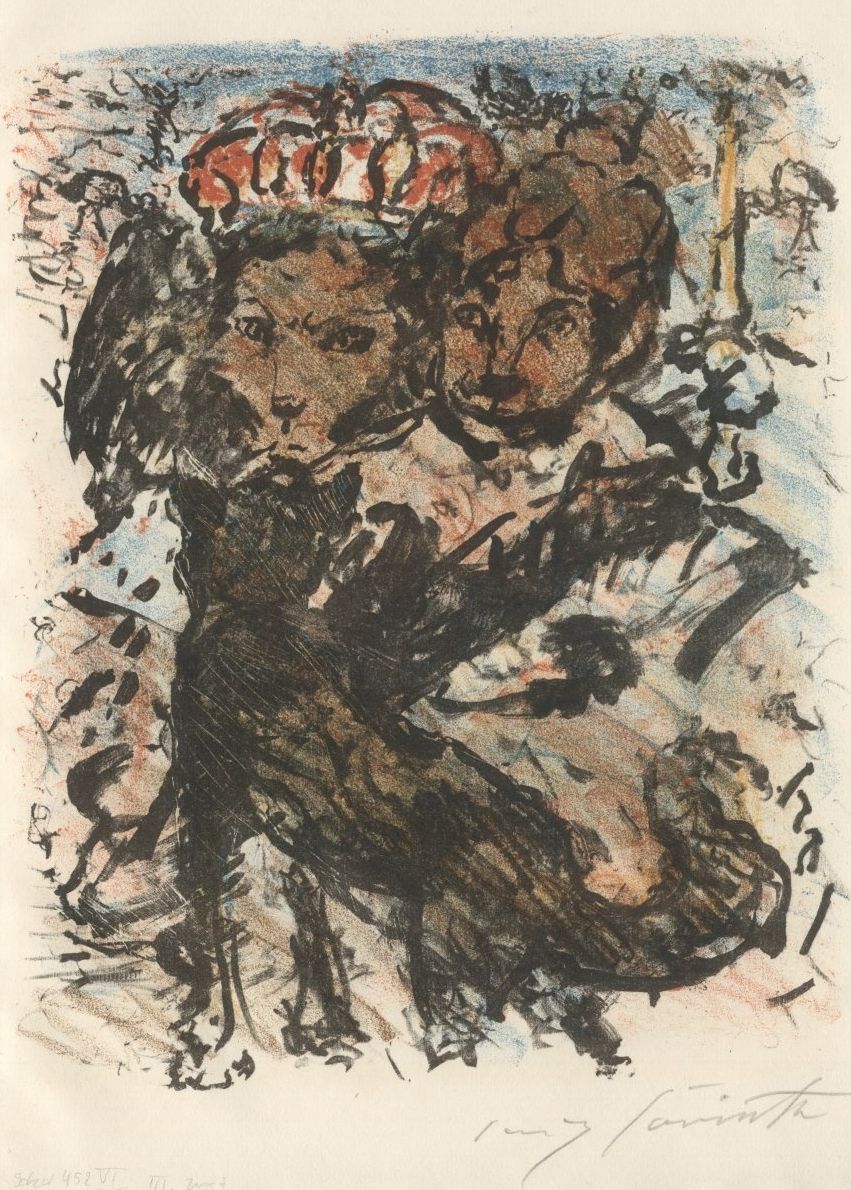

Goethe umgeben von Illustrationen seiner Dramen (Frankfurter Goethehaus, Freies Deutsches Hochstift)

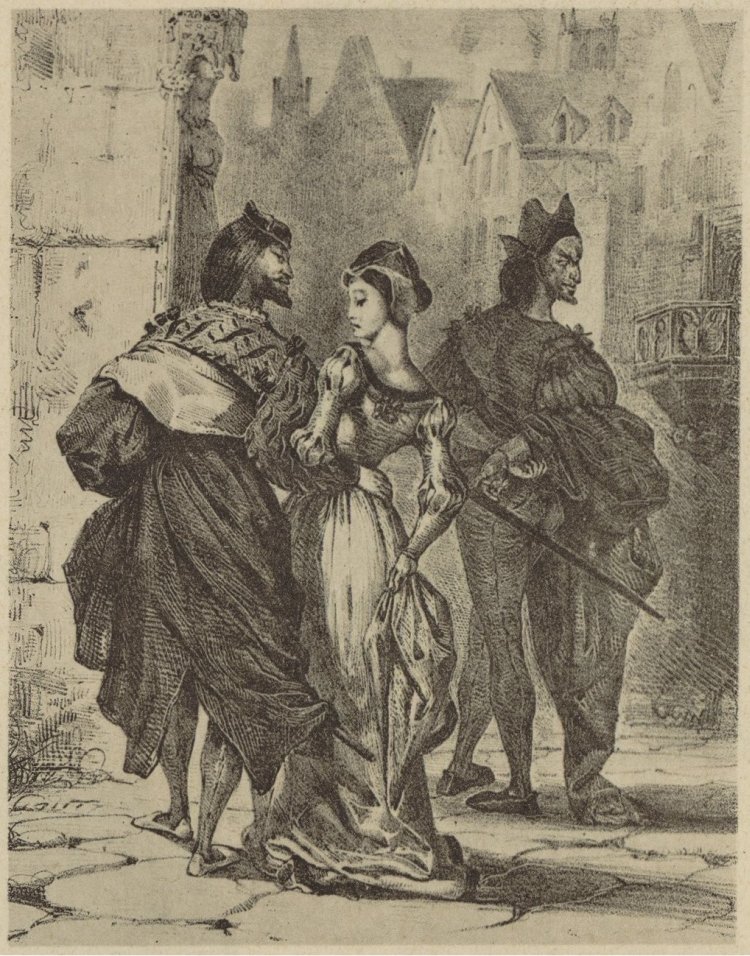

Frontispiece: Johan Wolfgang von Goethe par Eugène Delacroix (Source: Faust, tragédie de M. de Goethe, traduite en français par M. Albert Stapfer. C. Motte (Paris) 1828 - Gallica Bnf)

Before the following translation was commenced, the first Ten Books had already appeared in America. It was the intention of the Publisher to reprint these without alteration, but on comparing them with the original, it was perceived that the American version was not sufficiently faithful, and therefore the present was undertaken. The Translator, however, is bound to acknowledge, that he found many successful renderings in the work of his predecessor, and these he has engrafted without hesitation.

The title "Truth and Poetry" is adopted in common with the American translation, as the nearest rendering of Wahrheit und Dichtung. The "Prose and Poetry of my Life" would, perhaps, convey to the English reader the exact meaning of the Author, although not literally his words.

As a preface to the present work, which, perhaps, more than another requires one, I adduce the letter of a friend, by which so serious an undertaking was occasioned.

"We have now, my dear friend, collected the twelve parts of your poetical works, and on reading them through, find much that is known, much that is unknown; while much that had been forgotten is revived by this collection. These twelve volumes, standing before us, in uniform appearance, we cannot refrain from regarding as a whole; and one would like to sketch therefrom some image of the author and his talents. But it cannot be denied, considering the vigour with which he began his literary career, and the length of time which has since elapsed, that a dozen small volumes must appear incommensurate. Nor can one forget that, with respect to the detached pieces, they have mostly been called forth by special occasions, and reflect particular external objects, as well as distinct grades of inward culture; while it is equally clear, that temporary moral and æsthetic maxims and convictions prevail in them. As a whole, however, these productions remain without connexion; nay, it is often difficult to believe that they emanate from one and the same writer.

"Your friends, in the meantime, have not relinquished the inquiry, and try, as they become more closely acquainted with your mode of life and thought, to guess many a riddle, to solve many a problem; indeed, with the assistance of an old liking, and a connexion of many years? standing, they find a charm even in the difficulties which present themselves. Yet a little assistance here and there would not be unacceptable, and you cannot well refuse this to our friendly entreaties.

"The first thing, then, we require, is that your poetical works, arranged in the late edition according to some internal relations, may be presented by you in chronological[Pg vi] order, and that the states of life and feeling which afforded the examples that influenced you, and the theoretical principles by which you were governed, may be imparted in some kind of connexion. Bestow this labour for the gratification of a limited circle, and perhaps it may give rise to something that will be entertaining and useful to an extensive one. The author, to the most advanced period of his life, should not relinquish the advantage of communicating, even at a distance, with those whom affection binds to him; and if it is not granted to everyone to step forth anew, at a certain age, with surprising and powerful productions, yet just at that period of life when knowledge is most perfect, and consciousness most distinct, it must be a very agreeable and re-animating task to treat former creations as new matter, and work them up into a kind of Last Part, which may serve once more for the edification of those who have been previously edified with and by the artist."

This desire, so kindly expressed, immediately awakened within me an inclination to comply with it; for, if in the early years of life our passions lead us to follow our own course, and, in order not to swerve from it, we impatiently repel the demands of others, so, in bur later days, it becomes highly advantageous to us, should any sympathy excite and determine us, cordially, to new activity. I therefore instantly undertook the preparatory labour of separating the poems of my twelve volumes, both great and small, and of arranging them according to years. I strove to recall the times and circumstances under which each had been produced. But the task soon grew more difficult, as full explanatory notes and illustrations were necessary to fill up the chasms between those which had already been given to the world. For, in the first place, all on which I had originally exercised myself were wanting, many that had been begun and not finished were also wanting, and of many that were finished even the external form had completely disappeared, haring since been entirely reworked and cast into a different shape. Besides, I had also to call to mind how I had laboured in the sciences and other arts, and what, in such apparently foreign departments, both individually and in conjunction with friends, I had practised in silence, or had laid before the public.

All this I wished to introduce by degrees for the satisfaction of my well-wishers; but my efforts and reflections always led me further on; since while I was anxious to comply with that very considerate request, and laboured to set forth in succession my internal emotions, external influences, and the steps which, theoretically and practically, I had trod, I was carried out of my narrow private sphere into the wide world. The images of a hundred important men, who either directly or indirectly had influenced me, presented themselves to my view; and even the prodigious movements of the great political world, which had operated most extensively upon me, as well as upon the whole mass of my contemporaries, had to be particularly considered. For this seems to be the main object of Biography, to exhibit the man in relation to the features of his time; and to show to what extent they have opposed or favoured his progress; what view of mankind and the world he has formed from them, and how far he himself, if an artist, poet, or author, may externally reflect them. But for this is required what is scarcely attainable, namely, that the individual should know himself and his age: himself, so far as he has remained the same under all circumstances; his age, as that which carries along with it, determines and fashions, both the willing and the unwilling; so that one may venture to pronounce, that any person born ten years earlier or later would have been quite a different being, both as regards his own culture and his influence on others.

In this manner, from such reflections and endeavours, from such recollections and considerations,arose the present delineation; and from this point of view, as to its origin, will it be the best enjoyed and used, and most impartially estimated. For anything further it may be needful to say, particularly with respect to the half-poetical, half-historic mode of treatment, an opportunity will, no doubt, frequently occur in the course of the narrative.

Part the First.

First Book. 1

Childhood—the

City of Frankfort

Second Book. 32

The New Paris—Frankfort

Citizen

Third Book. 64

Occupation of Frankfort by

the French

Fourth Book. 92

Studies—The Bible—Frankfort

Characters

Fifth Book.135

Gretchen—Coronation Ceremonies

Part the Second.

Sixth Book.181

Illness and Recovery—Leipzig

Seventh Book.218

Leipzig (continued)—German

Literature

Eighth Book.264

Art—Dresden—Return from

Leipzig

Ninth Book.308

Strasbourg

Tenth Book.342

Strasbourg (continued)—Herder—Tour

in Alsace and Lorraine—Frederika

Part the Third.

Eleventh Book.388

Frederica (continued)—Return

from Strasbourg

Twelfth Book.437

Merck—Wetzlar; the Imperial

Chamber—Charlotte

Thirteenth Book.484

Goetz von Berlichingen and Werther

Fourteenth Book.521

Lenz—Lavater and Basedow—Cologne

Fifteenth Book.552

Moravians—"The Wandering Jew"—Zimmerman—"Clavigo"

Part the Fourth.

Sixteenth Book.582

Spinoza—Jung (Stilling)

Seventeenth Book.599

Lili—Betrothal—Ulrich von

Hutten

Eighteenth Book.624

Hans Sachs—The Stolbergs—Switzerland

Nineteenth Book.650

Switzerland—Lavater—"Egmont"

Twentieth Book.673

Kraus—Daemonic Influence—Heidelberg—Departure

for Weimar

Childhood—the City of Frankfort

On the 28th of August, 1749, at mid-day, as the clock struck twelve, I came into the world, at Frankfort-on-the-Maine. My horoscope was propitious: the sun stood in the sign of the Virgin, and had culminated for the day; Jupiter and Venus looked on him with a friendly eye, and Mercury not adversely; while Saturn and Mars kept themselves indifferent; the Moon alone, just full, exerted the power of her reflection all the more, as she had then reached her planetary hour. She opposed herself, therefore, to my birth, which could not be accomplished until this hour was passed.

These good aspects, which the astrologers managed subsequently to reckon very auspicious for me, may have been the causes of my preservation; for, through the unskilfulness of the midwife, I came into the world as dead, and only alter various efforts was I enabled to see the light. This event, which had put our household into sore straits, turned to the advantage of my fellow-citizens, inasmuch as my grandfather, the Schultheiss[1], John Wolfgang Textor, took occasion from it to have an accoucheur established, and to introduce or revive the tuition of midwives, which may have done some good to those who were born after me.

When we desire to recall what befel us in the earliest period of youth, it often happens that we confound what we have heard from others with that which we really possess from our own direct experience. Without, therefore, instituting a very close investigation into the point, which after all could[Pg 2] lead to nothing, I am conscious that we lived in an old house, which in fact consisted of two adjoining houses, that had been opened into each other. A spiral stair-case led to rooms on different levels, and the unevenness of the stories was remedied by steps. For us children, a younger sister and myself, the favourite resort was a spacious floor below, near the door of which was a large wooden lattice that allowed us direct communication with the street and open air. A bird-cage of this sort, with which many houses were provided, was called a Frame (Geräms). The women sat in it to sew and knit; the cook picked her salad there; female neighbours chatted with each other, and the streets consequently in the fine season wore a southern aspect. One felt at ease while in communication with the public. We children, too, by means of these frames, were brought into contact with our neighbours, of whom three brothers Von Ochsenstein, the surviving sons of the deceased Schultheiss, living on the other side of the way, won my love, and occupied and diverted themselves with me in many ways.

Our family liked to tell of all sorts of waggeries to which I was enticed by these otherwise grave and solitary men. Let one of these pranks suffice for all. A crockery fair had just been held, from which not only our kitchen had been supplied for a while with articles for a long time to come, but a great deal of small gear of the same ware had been purchased as playthings for us children. One fine afternoon, when every thing was quiet in the house, I whiled away the time with my pots and dishes in the Frame, and finding that nothing more was to be got out of them, hurled one of them into the street. The Von Ochsensteins, who saw me so delighted at the fine smash it made, that I clapped my hands for joy, cried out, "Another." I was not long in flinging out a pot, and as they made no end to their calls for more, by degrees the whole collection, platters, pipkins, mugs and all, were dashed upon the pavement. My neighbours continued to express their approbation, and I was highly delighted to give them pleasure. But my stock was exhausted, and still they shouted, "More." I ran, therefore, straight to the kitchen, and brought the earthenware, which produced a still livelier spectacle in breaking, and thus I kept running backwards and forwards, fetching one plate after another as I could reach it[Pg 3] from where they stood in rows on the shelf. But as that did not satisfy my audience, I devoted all the ware that I could drag out to similar destruction. It was not till afterwards that any one appeared to hinder and save. The mischief was done, and in place of so much broken crockery, there was at least a ludicrous story, in which the roguish authors took special delight to the end of their days.

My father's mother, in whose house we properly dwelt, lived in a large back-room directly on the ground floor, and we were accustomed to carry on our sports even up to her chair, and when she was ill, up to her bedside. I remember her, as it were, a spirit,—a handsome, thin woman, always neatly dressed in white. Mild, gentle, and kind, she has ever remained in my memory.

The Stag-Ditch.

The street in which our house was situated passed by the name of the Stag-Ditch; but as neither stags nor ditches were to be seen, we wished to have the expression explained. They told us that our house stood on a spot that was once outside the city, and that where the street now ran had formerly been a ditch, in which a number of stags were kept. These stags were preserved and fed here because the senate every year, according to an ancient custom, feasted publicly on a stag, which was therefore always at hand in the ditch for such a festival, in case princes or knights interfered with the city's right of chase outside, or the walls were encompassed or besieged by an enemy. This pleased us much, and we wished that such a lair for tame animals could have been seen in our times.

The back of the house, from the second story particularly, commanded a very pleasant prospect over an almost immeasurable extent of neighbouring gardens, stretching to the very walls of the city. But, alas! in transforming what were once public grounds into private gardens, our house and some others lying towards the corner of the street had been much stinted, since the houses towards the horse-market had appropriated spacious out-houses and large gardens to themselves, while a tolerably high wall shut us out from these adjacent paradises.

On the second floor was a room which was called the garden-room, because they had there endeavoured to supply the want of a garden by means of a few plants placed before the[Pg 4] window. As I grew older, it was there that I made my favourite, not melancholy but somewhat sentimental, retreat. Over these gardens, beyond the city's walls and ramparts, might be seen a beautiful and fertile plain; the same which stretches towards Höchst. In the summer season I commonly earned my lessons there, and watched the thunder-storms, but could never look my fill at the setting sun, which went down directly opposite my windows. And when, at the same time, I saw the neighbours wandering through their gardens taking care of their flowers, the children playing, parties of friends enjoying themselves, and could hear the bowls rolling and the nine pins dropping, it early excited within me a feeling of solitude, and a sense of vague longing resulting from it, which, conspiring with the seriousness and awe implanted in me by Nature, exerted its influence at an early age, and showed itself more distinctly in after years.

The old, many cornered, and gloomy arrangement of the house was moreover adapted to awaken dread and terror in childish minds. Unfortunately, too, the principle of discipline that young persons should be early deprived of all fear for the awful and invisible, and accustomed to the terrible, still prevailed. We children, therefore, were compelled to sleep alone, and when we found this impossible, and softly slipped from our beds to seek the society of the servants and maids, our father, with his dressing-gown turned inside out, which disguised him sufficiently for the purpose, placed himself in the way, and frightened us back to our resting-places. The evil effect of this any one may imagine. How is he who is encompassed with a double terror to be emancipated from fear? My mother, always cheerful and gay, and willing to render others so, discovered a much better pedagogical expedient. She managed to gain her end by rewards. It was the season for peaches, the plentiful enjoyment of which she promised us every morning if we overcame our fears during the night. In this way she succeeded, and both parties were satisfied.

In the interior of the house my eyes were chiefly attracted by a series of Roman Views, with which my father had ornamented an ante-room. They were engravings by some of the accomplished predecessors of Piranesi, who well understood perspective and architecture, and whose touches were clear[Pg 5] and excellent. There I saw every day, the Piazza del Popolo, the Colosseum, the Piazza of St. Peter's and St. Peter's Church, within and without, the castle of St. Angelo, and many other places. These images impressed themselves deeply upon me, and my otherwise very laconic father was often so kind as to furnish descriptions of the objects. His partiality for the Italian language, and for every thing pertaining to Italy, was very decided. A small collection of marbles and natural curiosities, which he had brought with him thence, he often showed to us; and he devoted a great part of his time to a description of his travels, written in Italian, the copying and correction of which he slowly and accurately completed, in several parcels, with his own hand. A lively old teacher of Italian, called Giovinazzi, was of service to him in this work. The old man moreover did not sing badly, and my mother every day must needs accompany him and herself upon the clavichord, and thus I speedily learned the Solitario bosco ombroso so as to know it by heart before I understood it.

My father was altogether of a didactic turn, and in his retirement from business liked to communicate to others what he knew or was able to do. Thus, dining the first years of their marriage, he had kept my mother busily engaged in writing, playing the clavichord, and singing, by which means she had been laid under the necessity of acquiring some knowledge and a slight readiness in the Italian tongue.

The Puppet-Show.

Generally we passed all our leisure hours with my grandmother, in whose spacious apartment we found plenty of room for our sports. She contrived to engage us with various trifles, and to regale us with all sorts of nice morsels. But one Christmas evening, she crowned all her kind deeds, by having a puppet-show exhibited before us, and thus unfolding a new world in the old house. This unexpected drama attracted our young minds with great force; upon the Boy particularly it made a very strong impression, which continued to vibrate with a great and lasting effect.

The little stage with its speechless personages, which at the outset had only been exhibited to us, but was afterwards given over for our own use and dramatic vivification, was prized more highly by us children, as it was the last bequest of our good grandmother, whom encroaching disease first withdrew from our sight, and death next tore away from our[Pg 6] hearts for ever. Her departure was of still more importance to our family, as it drew after it a complete change in our condition.

As long as my grandmother lived, my father had refrained from any attempt to change or renovate the house, even in the slightest particular, though it was known that he had pretty large plans of building, which were now immediately begun. In Frankfort, as in many other old towns, when anybody put up a wooden structure, he ventured, for the sake of space, to make not only the first, but each successive story project over the lower one, by which means narrow streets especially were rendered somewhat dark and confined. At last a law was passed, that every one putting up a new house from the ground, should confine his projections to the first upper story, and carry the others up perpendicularly. My father, that he might not lose the projecting space in the second story, caring little for outward architectural appearance, and anxious only for the good and convenient arrangement of the interior, resorted to the expedient which others had employed before him, of propping the upper part of the house, until one part after another had been removed from the bottom upwards and a new house, as it were, inserted in its place. Thus, while comparatively none of the old structure remained, the new one merely passed for a repair. Now as the tearing down and building up was done gradually, my father determined hot to quit the house, that he might better direct and give his orders—as he possessed a good knowledge of the technicalities of building. At the same time he would not suffer his family to leave him. This new epoch was very surprising and strange for the children. To see the rooms in which they had so often been confined and pestered with wearisome tasks and studies, the passages they had played in, the walls which had always been kept so carefully clean, all falling before the mason's hatchet and the carpenter's axe—and that from the bottom upwards; to float as it were in the air, propped up by beams, being, at the same time, constantly confined to a certain lesson, or definite task—all this produced a commotion in our young heads that was not easily settled. But the young people felt the inconvenience less, because they had somewhat more space for play than before, and had many opportunities of swinging on beams, and playing at see-saw with the boards.

At first my father obstinately persisted in carrying out his plan; but when at last even the roof was partly removed, and the rain reached our beds, in spite of the carpets that had been taken up, converted into tarpaulin, and stretched over as a defence, he determined, though reluctantly, that the children should be entrusted for a time to some kind friends, who had already offered their services, and sent to a public school.

This transition was rather unpleasant; for when the children who had all along been kept at home in a secluded, pure, refined, yet strict manner, were thrown among a rude mass of young creatures, they were compelled unexpectedly to suffer everything from the vulgar, bad, and even base, since they lacked both weapons and skill to protect themselves.

The Walk Round Frankfort.

It was properly about this period that I first became acquainted with my native city, which I strolled over with more and more freedom, in every direction, sometimes alone, and sometimes in the company of lively companions. To convey to others in any degree the impression made upon me by these grave and revered spots, I must here introduce a description of my birth-place, as in its different parts it was gradually unfolded to me. I loved more than anything else to promenade on the great bridge over the Maine. Its length, its firmness, and its fine appearance, rendered it a notable structure, and it was, besides, almost the only memorial left from ancient times of the precautions due from the civil government to its citizens. The beautiful stream above and below bridge, attracted my eye, and when the gilt weathercock on the bridge-cross glittered in the sunshine, I always had a pleasant feeling. Generally I extended my walk through Sachsenhausen, and for a Kreutzer was ferried comfortably across the river. I was now again on this side of the stream, stole along to the wine market, and admired the mechanism of the cranes when goods were unloaded. But it was particularly entertaining to watch the arrival of the market-boats, from which so many and such extraordinary figures were seen to disembark. On entering the city, the Saalhof, which at least stood on the spot where the Castle of Emperor Charlemagne and his successors was reported to have been, was greeted every time with profound reverence. One liked to lose oneself in the old trading town, particularly on market-days,[Pg 8] among the crowd collected about the church of St. Bartholomew. From the earliest times, throngs of buyers and sellers had gathered there, and the place being thus occupied, it was not easy in later days to bring about a more roomy and cheerful arrangement. The booths of the so-called Pfarreisen were very important places for us children, and we carried many a Batzen to them in order to purchase sheets of coloured paper stamped with gold animals. But seldom, however, could one make one's way through the narrow, crowded, and dirty market-place. I call to mind, also, that I always flew past the adjoining meat-stalls, narrow and disgusting as they were, in perfect horror. On the other hand, the Roman Hill (Römerberg) was a most delightful place for walking. The way to the New-Town, along by the new shops, was always cheering and pleasant; yet we regretted that a street did not lead into the Zeil by the Church of Our Lady, and that we always had to go a round-about way by the Hasengasse, or the Catherine Gate. But what chiefly attracted the child's attention, were the many little towns within the town, the fortresses within the fortress; viz., the walled monastic enclosures, and several other precincts, remaining from earlier times, and more or less like castles—as the Nuremberg Court, the Compostella, the Braunfels, the ancestral house of the family of Stallburg, and several strongholds, in later days transformed into dwellings and warehouses. No architecture of an elevating kind was then to be seen in Frankfort, and every thing pointed to a period long past and unquiet, both for town and district. Gates and towers, which defined the bounds of the old city,—then further on again, gates, towers, walls, bridges, ramparts, moats, with which the new city was encompassed,—all showed, but too plainly, that a necessity for guarding the common weal in disastrous times had induced these arrangements, that all the squares and streets, even the newest, broadest, and best laid out, owed their origin to chance and caprice and not to any regulating mind. A certain liking for the antique was thus implanted in the Boy, and was specially nourished and promoted by old chronicles and wood-cuts, as for instance, those of Grave relating to the siege of Frankfort. At the same time a different taste was developed in him for observing the conditions of mankind, in their manifold variety and naturalness, without[Pg 9] regard to their importance or beauty. It was, therefore, one of our favourite walks, which we endeavoured to take now and then in the course of a year, to follow the circuit of the path inside the city walls. Gardens, courts, and back buildings extend to the Zwinger; and we saw many thousand people amid their little domestic and secluded circumstances. From the ornamental and show gardens of the rich, to the orchards of the citizen, anxious about his necessities—from thence to the factories, bleaching-grounds, and similar establishments, even to the burying-grounds—for a little world lay within the limits of the city—we passed a varied, strange, spectacle, which changed at every step, and with the enjoyment of which our childish curiosity was never satisfied. In fact, the celebrated Devil-upon-two-sticks, when he lifted the roofs of Madrid at night, scarcely did more for his friend, than was here done for us in the bright sunshine and open air. The keys that were to be made use of in this journey, to gain us a passage through many a tower, stair and postern, were in the hands of the authorities, whose subordinates we never failed to coax into good-humour.

The Council-House.

But a more important, and in one sense more fruitful place for us, was the Council-House, named from the Romans. In its lower vault-like halls we liked but too well to lose ourselves. We obtained an entrance, too, into the large and very simple session-room of the Council. The walls as well as the arched ceiling were white, though wainscotted to a certain height, and the whole was without a trace of painting, or any kind of carved work; only, high up on the middle wall, might be read this brief inscription:

"One man's word is no man's word,

Justice

needs that both be heard."

After the most ancient fashion, benches were ranged around the wainscotting, and raised one step above the floor for the accommodation of the members of the assembly. This readily suggested to us why the order of rank in our senate was distributed by benches. To the left of the door, on the opposite corner, sat the Schöffen; in the corner itself the Schultheiss, who alone had a small table before him; those of the second bench sat in the space to his left as far as the wall to where the windows were; while along the windows ran the[Pg 10] third bench, occupied by the craftsmen. In the midst of the hall stood a table for the registrar (Protocolführer).

Once within the Römer, we even mingled with the crowd at the audiences of the burgomasters. But whatever related to the election and coronation of the Emperors possessed a greater charm. We managed to gain the favour of the keepers, so as to be allowed to mount the new gay imperial staircase, which was painted in fresco, and on other occasions closed with a grating. The election-chamber, with its purple hangings and admirably-fringed gold borders, filled us with awe. The representations of animals on which little children or genii, clothed in the imperial ornaments and laden with the insignia of the Empire, made a curious figure, were observed by us with great attention; and we even hoped that we might live to see, some time or other, a coronation with our own eyes. They had great difficulty to get us out of the great imperial hall, when we had been once fortunate enough to steal in; and we reckoned him our truest friend who, while we looked at the half-lengths of all the emperors painted around at a certain height, would tell us something of their deeds.

We listened to many a legend of Charlemagne. But that which was historically interesting for us began with Rudolph of Hapsburg, who by his courage put an end to such violent commotions. Charles the Fourth also attracted our notice We had already heard of the Golden Bull, and of the statutes for the administration of criminal justice. We knew, too, that he had not made the Frankforters suffer for their adhesion to his noble rival, Emperor Günther of Schwarzburg. We heard Maximilian praised both as a friend to mankind, and to the townsmen, his subjects, and were also told that it had been prophesied of him he would be the last Emperor of a German house; which unhappily came to pass, as after his death the choice wavered only between the King of Spain, (afterwards) Charles V., and the King of France, Francis I. With some anxiety it was added, that a similar prophecy, or rather intimation, was once more in circulation; for it was obvious that there was room left for the portrait of only one more emperor—a circumstance which, though seemingly accidental; filled the patriotic with concern.

Having once entered upon this circuit, we did not fail to[Pg 11] repair to the cathedral, and there visit the grave of that brave Günther, so much prized both by friend and foe. The famous stone which formerly covered it is set up in the choir. The door close by, leading into the conclave, remained long shut against us, until we at last managed through the higher authorities, to gain access to this celebrated place. But we should have done better had we continued as before to picture it merely in our imagination; for we found this room, which is so remarkable in German history, where the most powerful princes were accustomed to meet for an act so momentous, in no respect worthily adorned, and even disfigured with beams, poles, scaffolding, and similar lumber, which people had wanted to put out of the way. The imagination, for that very reason, was the more excited and the heart elevated, when we soon after received permission to be present in the Council-House, at the exhibition of the Golden Bull to some distinguished strangers.

Imperial Coronations.

The Boy then heard, with much curiosity, what his own family, as well as other older relations and acquaintances, liked to tell and repeat, viz., the histories of the two last coronations, which had followed close upon each other; for there was no Frankforter of a certain age who would not have regarded these two events, and their attendant circumstances, as the crowning glory of his whole life. Splendid as had been the coronation of Charles Seventh, during which particularly the French Ambassador had given magnificent feasts at great cost and with distinguished taste, the results were all the more afflicting to the good Emperor, who could not preserve his capital Munich, and was compelled in some degree to implore the hospitality of his imperial towns.

If the coronation of Francis First was not so strikingly splendid as the former one, it was dignified by the presence of the Empress Maria Theresa, whose beauty appears to have created as much impression on the men, as the earnest and noble form and the blue eyes of Charles Seventh on the women. At any rate, the sexes rivalled each other in giving to the attentive Boy a highly favourable opinion of both these personages. All these descriptions and narratives were given in a serene and quiet state of mind; for the peace of Aix-la-Chapelle had, for the moment, put an end to all feuds; and they spoke at their ease of past contests, as well as of their[Pg 12] former festivities—the battle of Dettingen, for instance, and other remarkable events of by-gone years; and all that was important or dangerous seemed, as generally happens when a peace has been concluded, to have occurred only to afford entertainment to prosperous and unconcerned people.

Half a year had scarcely passed away in this narrow patriotism before the fairs began, which always produced an incredible ferment in the heads of all children. The erection, in so short a time, of so many booths, creating a new town within the old one, the roll and crush, the unloading and unpacking of wares, excited from the very first dawn of consciousness an insatiable active curiosity and a boundless desire for childish property, which the Boy with increasing years endeavoured to gratify, in one way or another, as far as his little purse permitted. At the same time he obtained a notion of what the world produces, what it wants, and what the inhabitants of its different parts exchange with each other.

These great epochs, which came round regularly in spring and autumn, were announced by curious solemnities, which seemed the more dignified because they vividly brought before us the old time, and what had come down from it to ourselves. On Escort-day, the whole population were on their legs, thronging to the Fahrgasse, to the bridge, and beyond Sachsenhausen; all the windows were occupied, though nothing unusual took place on that day; the crowd seeming to be there only for the sake of jostling each other, and the spectators merely to look at one another; for the real occasion of their coming did not begin till nightfall, and was then rather taken upon trust than seen with the eyes.

The affair was thus: in those old, unquiet times, when every one did wrong according to his pleasure, or helped the right as his liking led him, traders on their way to the fairs were so wilfully beset and harassed by waylayers, both of noble and ignoble birth, that princes and other persons of power caused their people to be accompanied to Frankfort by an armed escort. Now the burghers of the imperial city would yield no rights pertaining to themselves or their district; they went out to meet the advancing party; and thus contests often arose as to how far the escort should advance, or whether it had a right to enter the city at all. But, as this took place, not only[Pg 13] in regard to matters of trade and fairs, but also when high personages came, in times of peace or war, and especially on the days of election; and as the affair often came to blows when a train which was not to be endured in the city strove to make its way in along with its lord, many negotiations had from time to time been resorted to, and many temporary arrangements concluded, though always with reservations of rights on both sides. The hope had not been relinquished of composing once for all a quarrel that had already lasted for centuries, inasmuch as the whole institution, on account of which it had been so long and often so hotly contested, might be looked upon as nearly useless, or at least as superfluous.

Meanwhile, on those days, the city cavalry in several divisions, each having a commander in front, rode forth from different gates and found on a certain spot some troopers or hussars of the persons entitled to an escort, who with their leaders were well received and entertained. They stayed till towards evening, and then rode back to the city, scarcely visible to the expectant crowd, many a city knight not being in a condition to manage his horse, or keep himself in the saddle. The most important bands returned by the bridge-gate, where the pressure was consequently the strongest. Last of all, just as night fell, the Nuremberg post-coach arrived, escorted in the same way, and always containing, as the people fancied, in pursuance of custom, an old woman. Its arrival, therefore, was a signal for all the urchins to break out into an ear-splitting shout, though it was utterly impossible to distinguish any one of the passengers within. The throng that pressed after the coach through the bridge-gate was quite incredible, and perfectly bewildering to the senses. The houses nearest the bridge were those, therefore, most in demand among spectators.

The Piper's Court.

Another more singular ceremony, by which the people were excited in broad daylight, was the Piper's-court (Pfeifer-gericht). It commemorated those early times when important larger trading-towns endeavoured, if not to abolish tolls altogether, at least to bring about a reduction of them, as they increased in proportion with trade and industry. They were allowed this privilege by the Emperor who needed their aid, when it was in his power to grant it, but commonly only for one year; so that it had to be annually renewed. This was[Pg 14] effected by means of symbolical gifts, which were presented before the opening of St. Bartholomew's Fair to the imperial magistrate (Schultheiss), who might have sometimes been the chief toll-gatherer; and, for the sake of a more imposing show, the gifts were offered when he was sitting in full court with the Schöffen. But when the chief magistrate afterwards came to be no longer appointed by the Emperor, and was elected by the city itself, he still retained these privileges; and thus both the immunities of the cities from toll, and the ceremonies by which the representatives from Worms, Nuremberg, and Old Bamberg once acknowledged the ancient favour, had come down to our times. The day before Lady-day, an open court was proclaimed. In an enclosed space in the great Imperial Hail, the Schöffen took their elevated seats; a step higher, sat the Schultheiss in the midst of them; while below on the right hand, were the procurators of both parties invested with plenipotentiary powers. The Actuarius begins to read aloud the weighty judgments reserved for this day; the lawyers demand copies, appeal, or do whatever else seems necessary. All at once a singular sort of music announces, if we may so speak, the advent of former centuries. It proceeds from three pipers, one of whom plays an old shawm, another a sack-but, and the third a pommer, or oboe. They wear blue mantles trimmed with gold, having the notes made fast to their sleeves, and their heads covered. Having thus left their inn at ten o'clock, followed by the deputies and their attendants, and stared at by all, natives and strangers, they enter the hall. The law proceedings are stayed—the pipers and their train halt before the railing—the deputy steps in and stations himself in front of the Schultheiss. The emblematic presents, which were required to be precisely the same as in the old precedents consisted commonly of the staple wares of the city offering them. Pepper passed, as it were, for everything else; and, even on this occasion, the deputy brought a handsomely turned wooden goblet filled with pepper. Upon it lay a pair of gloves, curiously slashed, stitched, and tasseled with silk—a token of a favour granted and received—such as the Emperor himself made use of in certain cases. Along with this was a white staff, which in former times was not easily dispensable in judicial proceedings. Some small pieces of silver money were added; and the city of Worms brought an[Pg 15] old felt hat, which was always redeemed again, so that the same one had been a witness of these ceremonies for many years.

After the deputy had made his address, handed over his present, and received from the Schultheiss assurance of continued favour, he quitted the enclosed circle, the pipers blew, the train departed as it had come, the court pursued its business, until the second and at last the third deputy had been introduced. For each came some time after the other; partly that the pleasure of the public might thus be prolonged, and partly because they were always the same antiquated virtuosi whom Nuremberg, for itself and its co-cities, had undertaken to maintain and produce annually at the appointed place.

Summer Amusements.

We children were particularly interested in this festival, because we were not a little flattered to see our grandfather in a place of so much honour; and because commonly, on the self-same day, we used to visit him, quite modestly, in order that we might, when my grandmother had emptied the pepper into her spice box, lay hold of a cup or small rod, a pair of gloves or an old Räder Albus.[2] These symbolical ceremonies, restoring antiquity as if by magic, could not be explained to us without leading us back into past times and informing us of the manners, customs, and feelings of those early ancestors who were so strangely made present to us, by pipers and deputies seemingly risen from the dead, and by tangible gifts, which might be possessed by ourselves.

These venerable solemnities were followed, in the fine season, by many festivals, delightful for us children, which took place in the open air, outside of the city. On the right shore of the Maine going down, about half an hour's walk from the gate, there rises a sulphur-spring, neatly enclosed and surrounded by aged lindens. Not far from it stands the Good-People's-Court, formerly a hospital erected for the sake of the waters. On the commons around, the herds of cattle from the neighbourhood were collected on a certain day of the year; and the herdsmen, together with their sweethearts, celebrated a rural festival, with dancing and singing, with all sorts of pleasure and clownishness. On the other side of the city lay[Pg 16] a similar but larger common, likewise graced with a spring and still finer lindens. Thither, at Whitsuntide, the flocks of sheep were driven; and, at the same time, the poor, pale orphan children were allowed to come out of their walls into the open air; for the thought had not yet occurred that these destitute creatures, who must some time or other help themselves through the world, ought soon to be brought in contact with it; that instead of being kept in dreary confinement, they should rather be accustomed to serve and to endure; and that there was every reason to strengthen them physically and morally from their infancy. The nurses and maids, always ready to hike a walk, never failed to carry or conduct us to such places, even in our first years; so that these rural festivals belong to the earliest impressions that I can recall.

Meanwhile, our house had been finished, and that too in tolerably short time, because everything had been judiciously planned and prepared, and the needful money provided. We now found ourselves all together again, and felt comfortable: for, when a well-considered plan is once carried out, we forget he various inconveniences of the means that were necessary to its accomplishment. The building, for a private residence, was roomy enough; light and cheerful throughout, with broad staircases, agreeable parlours, and a prospect of the gardens that could be enjoyed easily from several of the windows. The internal completion, and what pertained to mere ornament and finish, was gradually accomplished, and served at the same time for occupation and amusement.

The first thing brought into order was my father's collection of books, the best of which, in calf and half-calf binding, were to ornament the walls of his office and study. He possessed the beautiful Dutch editions of the Latin classics, which for the sake of outward uniformity he had endeavoured to procure all in quarto; and also many other works relating to Roman antiquities, and the more elegant jurisprudence. The most eminent Italian poets were not wanting, and for Tasso he showed a great predilection. There were also the best and most recent Travels; and he took great delight in correcting and completing Keyssler and Nemeiz from them. Nor had he omitted to surround himself with all needful assistants to learning, such as dictionaries of various languages, and encyclopedias of science and art, which with[Pg 17] much else adapted to profit and amusement, might be consulted at will.

The other half of this collection, in neat parchment bindings, with very beautifully written titles, was placed in a separate attic. The acquisition of new books, as well as their binding and arrangement, he pursued with great composure and love of order: and he was much influenced in his opinion by the critical notices that ascribed particular merit to any work. His collection of juridical treatises was annually increased by some volumes.

Next, the pictures, which in the old house had hung about promiscuously, were now collected and symmetrically hung on the walls of a cheerful room near the study, all in black frames, set off with gilt mouldings. My father had a principle, which he often and strongly expressed, that one ought to employ the living Masters, and to spend less upon the departed, in the estimation of whom prejudice greatly concurred. He had the notion that it was precisely the same with pictures as with Rhenish wines, which, though age may impart to them a higher value, can be produced in any coming year of just as excellent quality as in years past. After the lapse of some time, the new wine also becomes old, quite as valuable and perhaps more delicious. This opinion he chiefly confirmed by the observation that many old pictures seemed to derive their chief value for lovers of art from the fact that they had become darker and browner; and that the harmony of tone in such pictures was often vaunted. My father, on the other hand, protested that he had no fear that the new pictures would not also turn black in time, though whether they were likely to gain anything by this he was not so positive.

Frankfurt Artists.

In pursuance of these principles, he employed for many years the whole of the Frankfort artists:—the painter Hirt, who excelled in animating oak and beech woods, and other so-called rural scenes, with cattle; Trautmann, who had adopted Rembrandt as his model, and had attained great perfection in inclosed lights and reflections, as well as in effective conflagrations, so that he was once ordered to paint a companion-piece to a Rembrandt; Schütz, who diligently elaborated landscapes of the Rhine country, in the manner of Sachtlebens; and Junker, who executed with great purity flower and fruit pieces, still life, and figures quietly employed,[Pg 18] after the models of the Dutch. But now, by the new arrangement, by more convenient room, and still more by the acquaintance of a skilful artist, our love of art was again quickened and animated. This artist was Seekatz, a pupil of Brinkmann, court-painter at Darmstadt, whose talent and character will be more minutely unfolded in the sequel.

In this way, the remaining rooms were finished, according to their several purposes. Cleanliness and order prevailed throughout. Above all, the large panes of plate-glass contributed towards a perfect lightness, which had been wanting in the old house for many causes, but chiefly on account of the panes, which were for the most part round. My father was cheerful on account of the success of his undertaking, and if his good humour had not been often interrupted because the diligence and exactness of the mechanics did not come up to his wishes, a happier life than ours could not have been conceived, since much good partly arose in the family itself, and partly flowed from without.

But an extraordinary event deeply disturbed the Boy's peace of mind, for the first time. On the 1st of November, 1755, the earthquake at Lisbon took place, and spread a prodigious alarm over the world, long accustomed to peace and quiet. A great and magnificent capital, which was, at the same time, a trading and mercantile city, is smitten, without warning, by a most fearful calamity. The earth trembles and totters, the sea roars up, ships dash together, houses fall in, and over them churches and towers, the royal palace is in part swallowed by the waters, the bursting land seems to vomit flames, since smoke and fire are seen everywhere amid the ruins. Sixty thousand persons, a moment before in case and comfort, fall together, and he is to be deemed most fortunate who is no longer capable of a thought or feeling about the disaster. The flames rage on, and with them rage a troop of desperadoes, before concealed, or set at large by the event. The wretched survivors are exposed to pillage, massacre, and every outrage: and thus, on all sides, Nature asserts her boundless capriciousness.

Earthquake at Lisbon.

Intimations of this event had spread over wide regions more quickly than the authentic reports: slight shocks had been felt in many places: in many springs, particularly those of a mineral nature, an unusual receding of the waters had been[Pg 19] remarked; and so much, the greater was the effect of the accounts themselves, which were rapidly circulated, at first in general terms, but finally with dreadful particulars. Hereupon, the religious were neither wanting in reflections, nor the philosophic in grounds for consolation, nor the clergy in warnings. So complicated an event arrested the attention of the world for a long time; and, as additional and more detailed accounts of the extensive effects of this explosion came from every quarter, the minds already aroused by the misfortunes of strangers, began to be more and more anxious about themselves and their friends. Perhaps the demon of terror had never so speedily and powerfully diffused his terrors over the earth.

The Boy, who was compelled to put up with frequent repetitions of the whole matter, was not a little staggered. God, the Creator and Preserver of Heaven and Earth, whom the explanation of the first article of the Creed declared so wise and benignant, having given both the just and the unjust a prey to the same destruction, had not manifested Himself, by any means, in a fatherly character. In vain the young mind strove to resist these impressions. It was the more impossible, as the wise and scripture-learned could not themselves agree as to the light in which such a phenomenon should be regarded.

The next summer gave a closer opportunity of knowing directly that angry God, of whom the Old Testament records so much. A sudden hail-storm, accompanied by thunder and lightning, violently broke the new panes at the back of our house, which looked towards the west, damaged the new furniture, destroyed some valuable books and other things of worth, and was the more terrible to the children, as the whole household, quite beside themselves, dragged them into a dark passage, where, on their knees, with frightful groans and cries, they thought to conciliate the wrathful Deity. Meanwhile, my father, who was alone self-possessed, forced open and unhinged the window-frames, by which we saved much glass, but made a broader inlet for the rain that followed the hail, so that after we were finally quieted, we found ourselves in the rooms and on the stairs completely surrounded by floods and streams of water.

These events, startling as they were on the whole, did not greatly interrupt the course of instruction which my father[Pg 20] himself had undertaken to give us children. He had passed his youth in the Cobourg Gymnasium, which stood as one of the first among German educational institutions. He had there laid a good foundation in languages, and other matters reckoned part of a learned education, had subsequently applied himself to jurisprudence at Leipzig, and had at last taken his degree at Giessen. His dissertation, "Electa de aditione Hereditatis," which had been earnestly and carefully written, is yet cited by jurists with approval.

It is a pious wish of all fathers to see what they have themselves failed to attain, realized in their sons, as if in this way they could live their lives over again, and, at last, make a proper use of their early experience. Conscious of his acquirements, with the certainty of faithful perseverance, and distrusting the teachers of the day, my father undertook to instruct his own children, allowing them to take particular lesson from particular masters only so far as seemed absolutely necessary. A pedagogical dilettantism was already beginning to show itself everywhere. The pedantry and heaviness of the masters appointed in the public schools had probably given rise to this evil. Something better was sought for, but it was forgotten how defective all instruction must be, which is not given by persons who are teachers by profession.

My father had prospered in his own career tolerably according to his wishes: I was to follow the same course, only more easily, and much farther. He prized my natural endowments the more, because he was himself wanting in them; for he had acquired everything only by means of unspeakable diligence, pertinacity, and repetition. He often assured me, early and late, both in jest and earnest, that with my talents he would have deported himself very differently, and would not have turned them to such small account.

Juvenile Studies.

By means of a ready apprehension, practice, and a good, memory, I very soon outgrew the instructions which my father and the other teachers were able to give, without being thoroughly grounded in anything. Grammar displeased me, because I regarded it as a mere arbitrary law; the rules seemed ridiculous, inasmuch as they were invalidated by so many exceptions, which had all to be learned by themselves. And if the first Latin work had not been in rhyme, I should have got on but badly in that; but as it was, I hummed and[Pg 21] sang it to myself readily enough. In the same way we had a Geography in memory-verses, in which the most wretched doggerel best served to fix the recollection of that which was to be retained: e. g.:

Upper-Yssel has many a fen,

Which makes it hateful to all men.

The forms and inflections of language I caught with ease; and I also quickly unravelled what lay in the conception of a thing. In rhetoric, composition, and such matters, no one excelled me, although I was often put back for faults of grammar. Yet these were the attempts that gave my father particular pleasure, and for which he rewarded me with many presents of money, considerable for such a lad.

My father taught my sister Italian in the same room in which I had to commit Cellarius to memory. As I was soon ready with my task, and was yet obliged to sit quiet, I listened with my book before me, and very readily caught the Italian, which struck me as an agreeable softening of Latin.

Other precocities, with respect to memory and the power to combine, I possessed in common with those children who thus acquire an early reputation. For that reason my father could scarcely wait for me to go to college. He very soon declared, that I must study jurisprudence in Leipzig, for which he retained a strong predilection, and I was afterwards to visit some other university and take my degree. As for this second one he was indifferent which I might choose, except that he had for some reason or other a disinclination to Göttingen, to my disappointment, since it was precisely there that I had placed such confidence and high hopes.

He told me further, that I was to go to Wetzlar and Ratisbon as well as to Vienna, and thence towards Italy, although he repeatedly mentioned that Paris should first be seen, because after coming out of Italy nothing else could be pleasing.

These tales of my future youthful travels, often as they were repeated, I listened to eagerly, the more since they always led to accounts of Italy, and at last to a description of Naples. His otherwise serious and dry manner seemed on these occasions to relax and quicken, and thus a passionate wish awoke in us children to participate in the paradise he described.

Private lessons, which now gradually multiplied, were shared with the children of the neighbours. This learning in common did not advance me; the teachers followed their routine; and the rudeness, sometimes the ill-nature, of my companions, interrupted the brief hours of study with tumult, vexation, and disturbance. Chrestomathies, by which learn learning is made pleasant and varied, had not yet reached us. Cornelius Nepos, so dry to young people, the New Testament which was much too easy, and which by preaching and religious instructions had been rendered even common-place, Cellarius and Pasor could impart no kind of interest; on the other hand, a certain rage for rhyme and versification, a consequence of reading the prevalent German poets, took complete possession of us. Me it had seized much earlier, as I had found it agreeable to pass from the rhetorical to the poetical treatment of subjects.

We boys held a Sunday assembly where each of us was to produce original verses. And here I was struck by something strange, which long caused me uneasiness. My poems, whatever they might be, always seemed to me the best. But I soon remarked, that my competitors who brought forth very lame affairs, were in the same condition, and thought no less of themselves. Nay, what appeared yet more suspicious, a good lad (though in such matters altogether unskilful), whom I liked in other respects, but who had his rhymes made by his tutor, not only regarded these as the best, but was thoroughly persuaded they were his own, as he always maintained in our confidential intercourse. Now, as this illusion and error was obvious to me, the question one day forced itself upon me, whether I myself might not be in the same state, whether those poems were not really better than mine, and whether I might not justly appear to those boys as mad as they to me? This disturbed me much and long; for it was altogether impossible for me to find any external criterion of the truth; I even ceased from producing, until at length I was quieted by my own light temperament, and the feeling of my own powers, and lastly by a trial of skill—started on the spur of the moment by our teachers and parents, who had noted our sport—in which I came off well and won general praise.

No libraries for children had at that time been established. The old had themselves still childish notions, and found it[Pg 23] convenient to impart their own education to their successors. Except the Orbis Pictus of Amos Comenius, no book of the sort fell into our hands; but the large folio Bible, with copperplates by Merian, was diligently gone over leaf by leaf: Gottfried's Chronicles, with plates by the same master, taught us the most notable events of Universal History; the Acerra Philologica added thereto all sorts of fables, mythologies and wonders; and, as I soon became familiar with Ovid's Metamorphoses, the first books of which in particular I studied carefully, my young brain was rapidly furnished with a mass of images and events, of significant and wonderful shapes and occurrences, and I never felt time hang upon my hands, as I always occupied myself in working over, repeating, and reproducing these acquisitions.

Popular Works.

A more salutary moral effect than that of these rude and hazardous antiquities, was produced by Fénelon's Telemachus, with which I first became acquainted in Neukirch's translation, and which, imperfectly as it was executed, had a sweet and beneficent influence on my mind. That Robinson Crusoe was added in due time, follows in the nature of things; and it may be imagined that the Island of Falsenberg was not wanting. Lord Anson's Voyage round the Globe combined the dignity of truth with the rich fancies of fable, and while our thoughts accompanied this excellent seaman, we were conducted over all the world, and endeavoured to follow him with our fingers on the globe. But a still richer harvest was to spring up before me, when I lighted on a mass of writings, which, in their present state, it is true, cannot be called excellent, but the contents of which, in a harmless way, bring near to us many a meritorious action of former times.

The publication, or rather the manufacture, of those books which have at a later day become so well known and celebrated under the name Volkschriften, Volksbücher (popular works or books), was carried on in Frankfort. The enormous sales they met with, led to their being almost illegibly printed from stereotypes on horrible blotting-paper. We children were so fortunate as to find these precious remains of the Middle Ages every day on a little table at the door of a dealer in cheap books, and to obtain them at the cost of a couple of kreutzer. The Eulenspiegel, the Four Sons of Haimon, the Emperor Octavian, the Fair Melusina, the Beautiful[Pg 24] Magelone, Fortunatus, with the whole race down to the Wandering Jew, were all at our service, as often as we preferred the relish of these works to the taste of sweet things. The greatest benefit of this was, that when we had read through or damaged such a sheet, it could soon be reprocured and swallowed a second time.

As a family pic-nic in summer is vexatiously disturbed by a sudden storm, which transforms a pleasant state of things into the very reverse, so the diseases of childhood fall unexpectedly on the most beautiful season of early life. And thus it happened with me. I had just purchased Fortunatus with his Purse and Wishing-hat, when I was attacked by a restlessness and fever which announced the small-pox. Inoculation was still with us considered very problematical, and although it had already been intelligibly and urgently recommended by popular writers, the German physicians hesitated to perform an operation that seemed to forestall Nature. Speculative Englishmen, therefore, had come to the Continent and inoculated, for a considerable fee, the children of such persons as were opulent and free from prejudices. Still the majority were exposed to the old disease; the infection raged through families, killed and disfigured many children; and few parents dared to avail themselves of a method, the probable efficacy of which had been abundantly confirmed by the result. The evil now invaded our house and attacked me with unusual severity. My whole body was sown over with spots, and my race covered, and for several days I lay blind and in great pain. They tried the only possible alleviation, and promised me heaps of gold if I would keep quiet and not increase the mischief by rubbing and scratching. I controlled myself, while, according to the prevailing prejudice, they kept me as warm as possible, and thus only rendered my suffering more acute. At last, after a woful time, there fell as it were a mask from my face. The blotches had left no visible mark upon the skin, but the features were plainly altered. I myself was satisfied merely with seeing the light of day again, and gradually putting off my spotted skin; but others were pitiless enough to remind me often of my previous condition; especially a very lively aunt, who had formerly regarded me with idolatry, but in after years could seldom look at me without exclaiming—"The deuce, cousin! what a fright he's[Pg 25] grown!" Then she would tell me circumstantially how I had once been her delight, and what attention she had excited when she carried me about; and thus I early learned that people very often subject us to a severe atonement for the pleasure which we have afforded them.

Diseases of Childhood.

I neither escaped measles, nor chicken-pox, nor any other of the tormenting demons of childhood; and I was assured each time that it was a great piece of good luck that this malady was now past for ever. But, alas! another again threatened in the back-ground, and advanced. All these things increased my propensity to reflection; and as I had already practised myself in fortitude, in order to remove the torture of impatience, the virtues which I had heard praised in the Stoics appeared to me highly worthy of imitation, and the more so, as something similar was commended by the Christian doctrine of patience.

While on the subject of these family diseases, I will mention a brother about three years younger than myself, who was likewise attacked by that infection, and suffered not a little from it. He was of a tender nature, quiet and capricious, and we were never on the most friendly terms. Besides, he scarcely survived the years of childhood. Among several other children born afterwards, who like him did not live long, I only remember a very pretty and agreeable girl, who also soon passed away; so that, after the lapse of some years, my sister and I remained alone, and were therefore the more deeply and affectionately attached to each other.

These maladies and other unpleasant interruptions were in their consequences doubly grievous; for my father, who seemed to have laid down for himself a certain calendar of education and instruction, was resolved immediately to repair every delay, and imposed double lessons upon the young convalescent. These were not hard for me to accomplish, but were so far troublesome, that they hindered, and to a certain extent repressed, my inward development, which had taken a decided direction.

From these didactic and pedagogic oppressions, we commonly fled to my grandfather and grandmother. Their house stood in the Friedberg street, and appeared to have been formerly a fortress; for, on approaching it, nothing was seen but a large gate with battlements, which were joined on either side[Pg 26] to the two neighbouring houses. On entering through a narrow passage, we reached at last a tolerably broad court, surrounded by irregular buildings, which were now all united into one dwelling. We usually hastened at once into the garden, which extended to a considerable length and breadth behind the buildings, and was very well kept. The walks were mostly skirted by vine trellises; one part of the space was used for vegetables, and another devoted to flowers, which from spring till autumn adorned in rich succession the borders as well as the beds. The long wall erected towards the south was used for some well-trained espalier peach-trees, the forbidden fruit of which ripened temptingly before us through the summer. Yet we rather avoided this side, because we here could not satisfy our dainty appetites; and we turned to the side opposite, where an interminable row of currant and gooseberry bushes furnished our voracity with a succession of harvests till autumn. Not less important to us was an old, high, wide-spreading mulberry-tree, both on account of its fruits, and because we were told that the silk-worms fed upon its leaves. In this peaceful region my grandfather was found every evening, tending with genial care and with his own hand the finer growths of fruits and flowers; while a gardener managed the drudgery. He was never vexed by the various toils which were necessary to preserve and increase a fine show of pinks. The branches of the peach-trees were carefully tied to the espaliers with his own hands, in a fan-shape, in order to bring about a full and easy growth of the fruit. The sorting of the bulbs of tulips, hyacinths, and plants of a similar nature, as well as the care of their preservation, he entrusted to none; and I still with pleasure recall to my mind how diligently he occupied himself in inoculating the different varieties of roses. That he might protect himself from the thorns, he put on a pair of those ancient leather gloves, of which three pair were given him annually at the Piper's Court, so that there was no dearth of the article. He wore also a loose dressing-gown, and a folded black velvet cap upon his head, so that he might have passed for an intermediate person between Alcinoüs and Laërtes.

Goethe's Maternal Grandfather.

All this work in the garden he pursued as regularly and with as much precision as his official business; for, before he came down, he always arranged the list of causes for the next[Pg 27] day, and read the legal papers. In the morning he proceeded to the Council House, dined after his return, then nodded in his easy chair, and so went through the same routine every day. He conversed little, never exhibited any vehemence and I do not remember ever to have seen him angry. All that surrounded him was in the fashion of the olden time. I never perceived any alteration in his wainscotted room. His library contained, besides law works, only the earliest books of travels, sea voyages, and discoveries of countries. Altogether I can call to mind no situation more adapted than his to awaken the feeling of uninterrupted peace and eternal duration.

But the reverence which we entertained for this venerable old man was raised to the highest degree by a conviction that he possessed the gift of prophecy, especially in matters that pertained to himself and his destiny. It is true he revealed himself to no one, distinctly and minutely, except to my grandmother; yet we were all aware that he was informed of what was going to happen, by significant dreams. He assured his wife, for instance, at a time when he was still junior Councillor, that on the first vacancy he would obtain the place left open on the bench of the Schöffen; and soon afterwards when one of those officers actually died of apoplexy, my grandfather gave orders that his house should be quietly got ready prepared on the day of electing and balloting, to receive his guests and congratulators. Sure enough, the decisive gold ball was drawn in his favour. The simple dream by which he had learned this, he confided to his wife as follows: He had seen himself in the ordinary full assembly of Councilmen, where all went on just as usual. Suddenly, the late Schöff rose from his seat, descended the steps, pressed him in the most complimentary manner to take the vacant place, and then departed by the door.

Something like this occurred on the death of the Schultheiss. They make no delay in supplying this place, as they always have to fear that the Emperor will at some time resume his ancient right of nominating the officer. On this occasion, the messenger of the Court came at midnight to summon an extraordinary session for the next morning; and as the light in his lantern was about to expire, he asked for a candle's end to help him on his way. "Give him a whole one," said my grandfather to the ladies, "he takes the trouble[Pg 28] all on my account." This expression anticipated the result—he was made Schultheiss; and what rendered the circumstance particularly remarkable was, that although his representative was the third and last to draw at the ballot, the two silver balls first came out, leaving the golden ball at the bottom of the bag for him.

Perfectly prosaic, simple, and without a trace of the fantastic or miraculous, were the other dreams, of which we were informed. Moreover, I remember that once, as a boy, I was turning over his books and memoranda, and found among some other remarks which related to gardening, such sentences as these: "To-night N. N. came to me and said——" the name and revelation being written in cipher; or "This night I saw——" all the rest being again in cipher, except the conjunctions and similar words, from which nothing could be learned.

It is worthy of note also, that persons who showed no signs of prophetic insight at other times, acquired, for the moment, while in his presence, and that by means of some sensible evidence, presentiments of diseases or deaths which were then occurring in distant places. But no such gift has been transmitted to any of his children or grandchildren, who for the most part have been hearty people, enjoying life, and never going beyond the Actual.

While on this subject, I remember with gratitude many kindnesses I received from them in my youth. Thus, for example, we were employed and entertained in many ways when we visited the second daughter, married to the druggist Melbert, whose house and shop stood near the market, in the midst of the liveliest and most crowded part of the town. There we could look down from the windows pleasantly enough upon the hurly-burly in which we feared to lose ourselves; and though, at first, of all the goods in the shop, nothing had much interest for us but the liquorice, and the little brown stamped cakes made from it, we became in time better acquainted with the multitude of articles bought and sold in that business. This aunt was the most vivacious of all the family. When my mother, in her early years, took pleasure in being neatly dressed, working at some domestic occupation, or reading a book, the other, on the contrary, ran about the neighbourhood to pick up neglected children, take[Pg 29] care of them, comb them, and carry them round, as indeed she did me for a good while. At a time of public festivities, such as coronations, it was impossible to keep her at home. When a little child, she had already scrambled for the money scattered on such occasions; and it was related of her, that once when she had got a good many together, and was looking at them with great delight in the palm of her hand, it was struck by somebody, and all her well-earned booty vanished at a blow. There was another incident of which she was very proud. Once, while standing on a post as the Emperor Charles VII. was passing, at a moment when all the people were silent, she shouted a vigorous "Vivat!" into the coach, which made him take off his hat to her, and thank her quite graciously for her bold salutation.

Everything in her house was stirring, lively, and cheerful, and we children owed her many a gay hour.

Religious Instruction.

In a quieter situation, which was however suited to her character, was a second aunt, married to the Pastor Stark, incumbent of St. Catharine's Church. He lived much alone, in accordance with his temperament and vocation, and possessed a fine library. Here I first became acquainted with Homer, in a prose translation, which may be found in the seventh part of Herr Von Loen's new collection of the most remarkable travels, under the title, Homer's Description of the Conquest of the Kingdom of Troy, ornamented with copper-plates, in the theatrical French taste. These pictures perverted my imagination to such a degree, that for a long time I could conceive the Homeric heroes only under such forms. The incidents themselves gave me unspeakable delight; though I found great fault with the work for affording us no account of the capture of Troy, and breaking off so abruptly Math the death of Hector. My uncle, to whom I mentioned this defect, referred me to Virgil, who perfectly satisfied my demands.

It will be taken for granted, that we children had among our other lessons, a continued and progressive instruction in religion. But the Church-Protestantism imparted to us was, properly speaking, nothing but a kind of dry morality: ingenious exposition was not thought of; and the doctrine appealed neither to the understanding nor to the heart. For that reason, there were various secessions from the[Pg 30] Established Church. Separatists, Pietists, Herrnhuter (Moravians), Quiet-in-the-Lands, and others differently named and characterized sprang up, all of whom were animated by the same purpose of approaching the Deity, especially through Christ, more closely than seemed to them possible under the forms of the established religion.

The Boy heard these opinions and sentiments constantly spoken of; for the clergy as well as the laity divided themselves into pro and con. The minority were composed of those who dissented more or less broadly, but their modes of thinking attracted by originality, heartiness, perseverance, and independence. All sorts of stories were told of their virtues and of the way in which they were manifested. The reply of a pious master-tinman was especially noted, who, when one of his craft attempted to shame him by asking "who is really your confessor?" answered with great cheerfulness and confidence in the goodness of his cause,—"I have a famous one—no less than the confessor of King David."

Things of this sort naturally made an impression on the Boy, and led him into similar states of mind. In fact, he came to the thought that he might immediately approach the great God of Nature, the Creator and Preserver of Heaven and Earth, whose earlier manifestations of wrath had been long forgotten in the beauty of the world, and the manifold blessings in which we participate while upon it. The way he took to accomplish this was very curious.