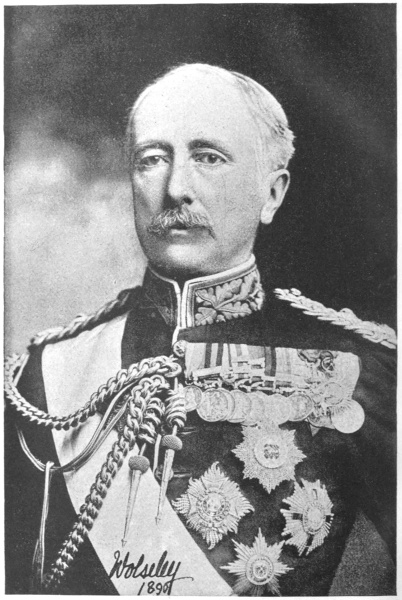

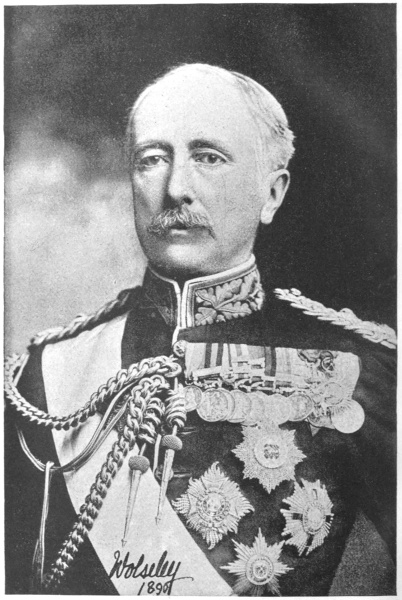

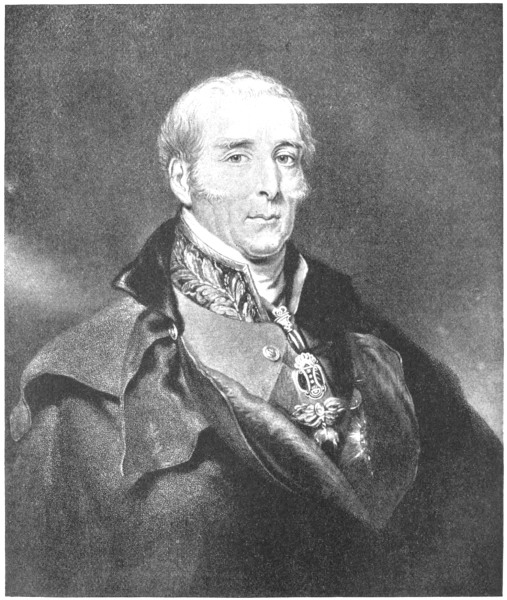

FIELD MARSHAL THE RIGHT HON. VISCOUNT WOLSELEY, K.P., G.C.B., G.C.M.G., &C., &C.

From a Photograph by Werner & Son, Dublin

Title: The Story of the British Army

Author: Charles Cooper King

Release date: August 5, 2016 [eBook #52723]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Map and Plan Drawing

History of Berkshire

George Washington

The British Army

ALSO EDITOR OF

Great Campaigns in Europe

FIELD MARSHAL THE RIGHT HON. VISCOUNT WOLSELEY, K.P., G.C.B., G.C.M.G., &C., &C.

From a Photograph by Werner & Son, Dublin

THE STORY

OF

THE BRITISH ARMY

BY

Lieut.-Colonel

C. COOPER KING, F.G.S.

WITH PLANS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET, W.C.

LONDON

1897

IN TOKEN OF A LENGTHENED FRIENDSHIP

I DEDICATE THIS STORY

OF

HER MAJESTY’S ARMY

TO

ITS COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF

F.-M. THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

VISCOUNT WOLSELEY, K.P., G.C.B., G.C.M.G.

I have endeavoured in the space at my disposal to show how the British Army has grown up. I have tried merely to tell a “story,” and therefore omitted much that might have been said regarding the noble work the Queen’s Army has done. As regards the opinions advanced, I have always, as far as possible, given the reasons for my views and the authorities which induced me to form them.

I have adhered to the principle of using the old regimental numbers, for the sake of continuity; though, after the date when these were altered, I have, in most cases, added their present territorial titles.

I wish to express my great appreciation of the courtesy of the Colonel and the Officers of the Lancashire Fusiliers (20th), South Wales Borderers (24th), and the Prince of Wales’s Own (West Yorkshire) Regiment (14th), in allowing me to sketch the uniforms of their men from the interesting histories of their respective regiments, and to E. C. Brett, Esq., for permitting me to copy the suits of armour that I have chosen as types from his father’s magnificent volume on Arms and Armour.

Kingsclear, Camberley,

March 1897.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Army of the People—to 1100 | 1 |

| II. | The Army of the Nobles—to 1500 | 14 |

| III. | The Puritan Host | 35 |

| IV. | The Army of the King—to 1701 | 55 |

| V. | Marlborough and his Men—to 1714 | 72 |

| VI. | The Embers of the Civil War—to 1755 | 87 |

| VII. | The Army in America—to 1793 | 107 |

| VIII. | The Army at Sea—to 1815 | 128 |

| IX. | The Peninsular Army: (a) Its Making—1793–1808 | 155 |

| X. | The Peninsular Army: (b) Its Training—1808–1811 | 173 |

| XI. | The Peninsular Army: (c) Its Reward—1811–1814 | 191 |

| XII. | The Army in the Netherlands—Waterloo, 1815 | 206 |

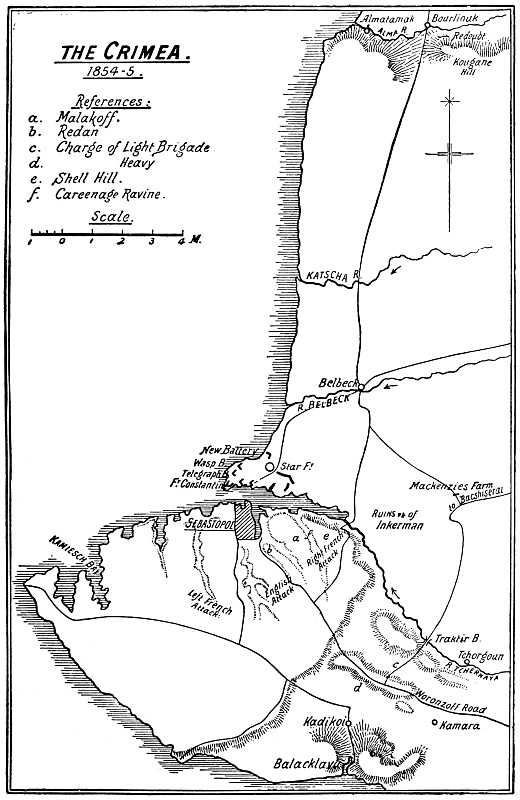

| XIII. | The Army after the Long Peace—The Crimea, 1854 | 236 |

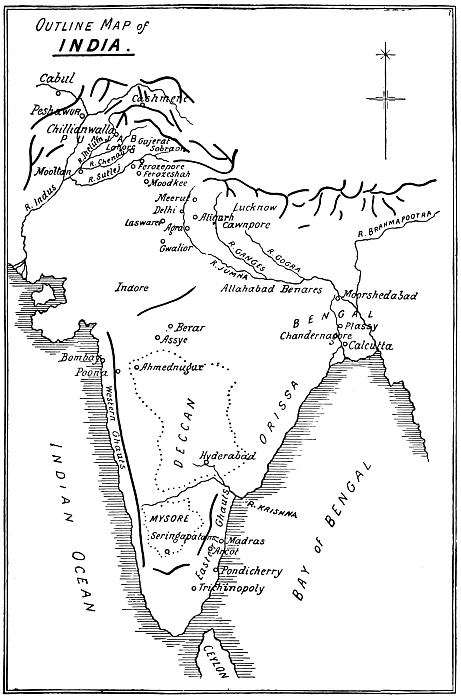

| XIV. | The Army in India: (a) The East India Company, Its Rise—1600–1825 | 264 |

| XV. | The Army in India: (b) The Fall of the Company and Afterwards—1825–1858 | 277 |

| XVI. | The Army in India: (c) The Army of the Queen-Empress—1858–1896 | 318 |

| XVII. | The Army in the Far East—1819–1875 | 336 |

| XVIII. | The Army in South and West Africa—1834–1836 | 351 |

| XIX. | The Army in North Africa—1867–1896 | 374 |

| XX. | The Army as it is | 396 |

| Appendix I.—The Principal Campaigns and Battles of the British Army since 1658 | 407 | |

| Appendix II.—The List of Regiments with their Present and Former Titles | 411 | |

| Appendix III.—List of Badges, Mottoes, and Nicknames of the Army | 416 | |

| Index | 424 |

| LEADERS | |

| PAGE | |

| Field-Marshal Viscount Wolseley, K.P., G.C.B., G.C.M.G., etc. | Frontispiece |

| The Duke of Marlborough (from an old print) | 73 |

| The Duke of Wellington | 209 |

| ARMOUR | |

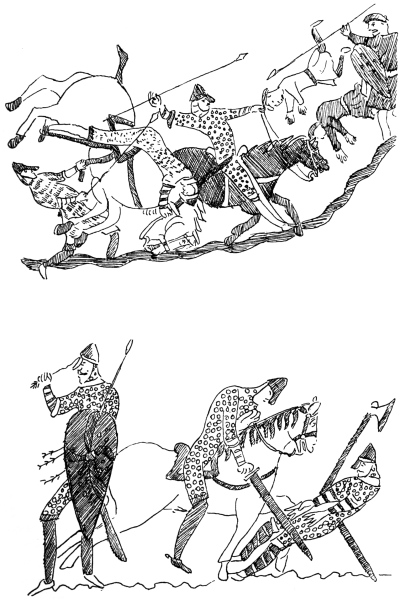

| Norman (from the Bayeux Tapestry) | 10 |

| Plate Armour, circa 1500 | 23 |

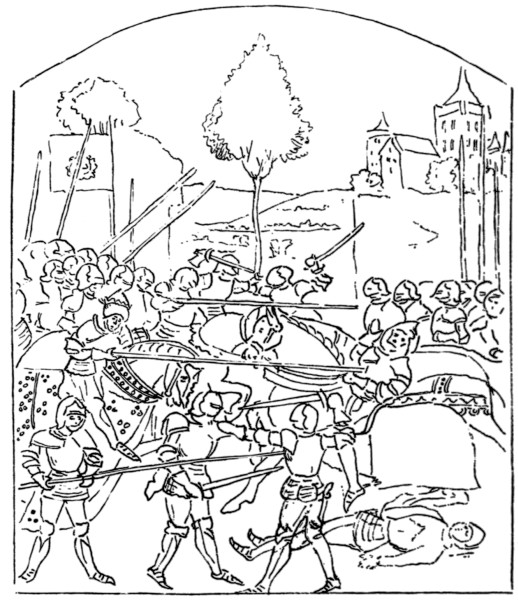

| Plate Armour at Barnet, 1471 | 29 |

| Half Armour, 1640 | 35 |

| UNIFORMS | |

| Private Soldier, 14th Regiment, 1712 | 72 |

| Private Soldier, 24th Regiment, 1751 | 104 |

| Private Soldier, 14th Regiment, 1792 | 126 |

| Private Soldier, 20th Regiment, 1812 | 200 |

| Private Soldier, 24th Regiment, 1840 | 239 |

| Officer, Light Company, 20th Regiment, 1853 | 260 |

| Private Soldier, 14th Regiment, 1864 | 322 |

| Private Soldier, 24th Regiment, 1879 | 370 |

| BATTLES | |

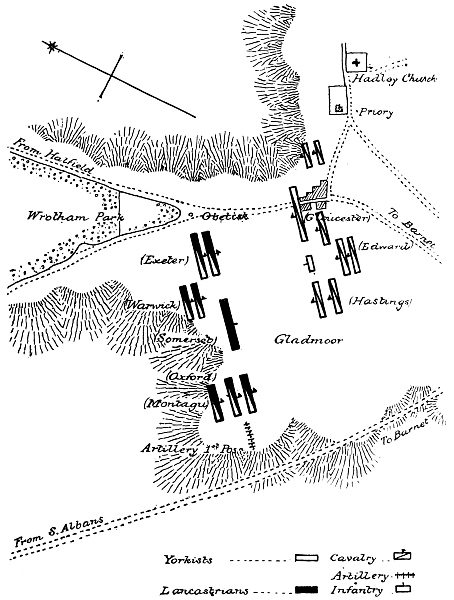

| The Lines of Battle at Barnet, 1471 | 32 |

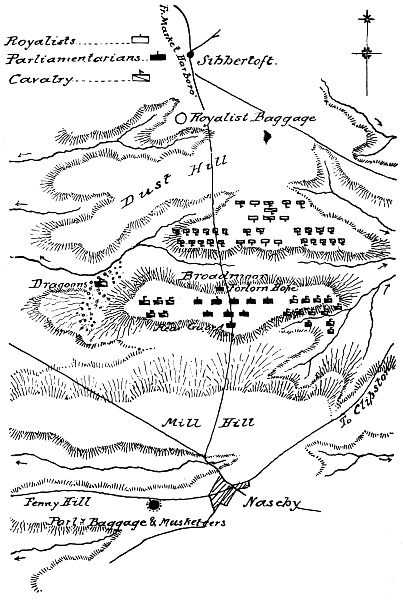

| The Lines of Battle at Naseby, 1645 | 43 |

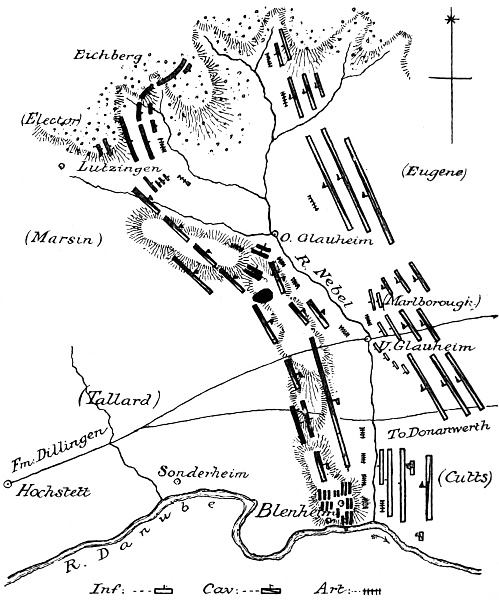

| The Lines of Battle at Blenheim, 1704 | 77 |

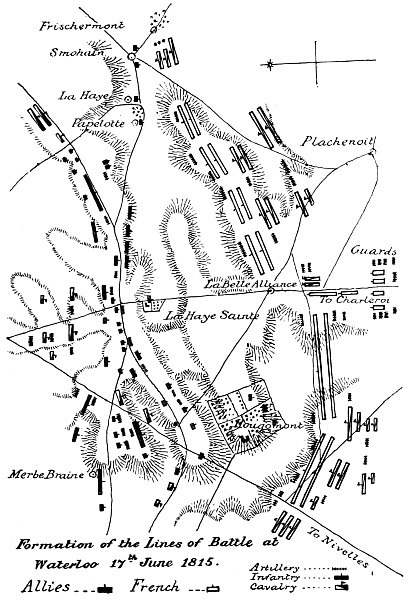

| The Lines of Battle at Waterloo, 1815 | 228 |

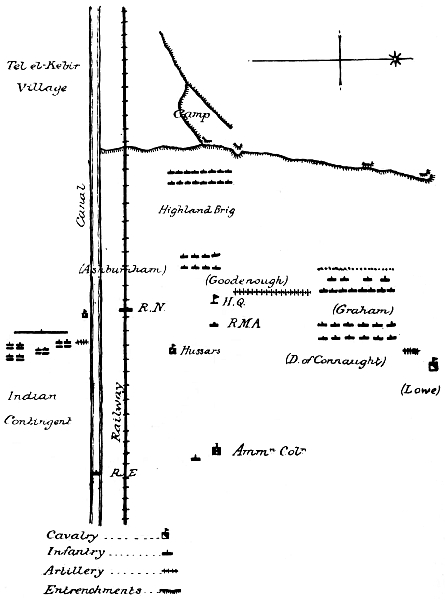

| The Lines of Battle at Tel el Kebir, 1882 | 383 |

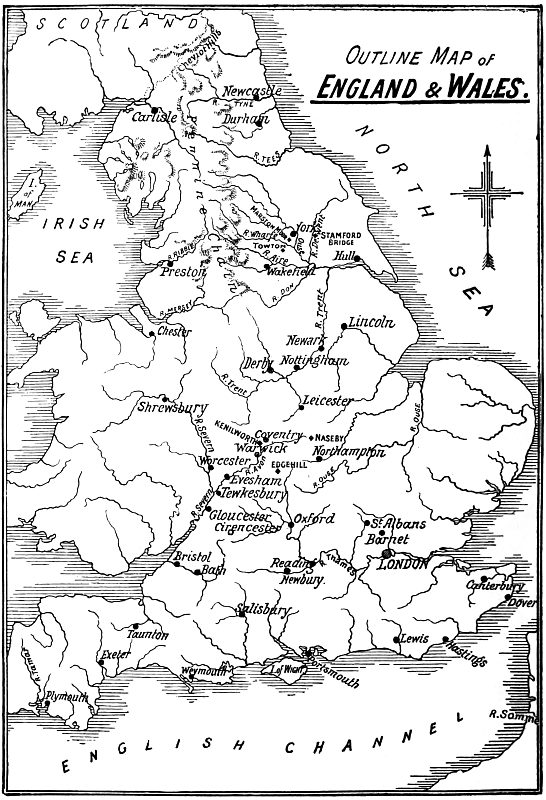

| GENERAL MAPSx | |

| England and Wales | 5 |

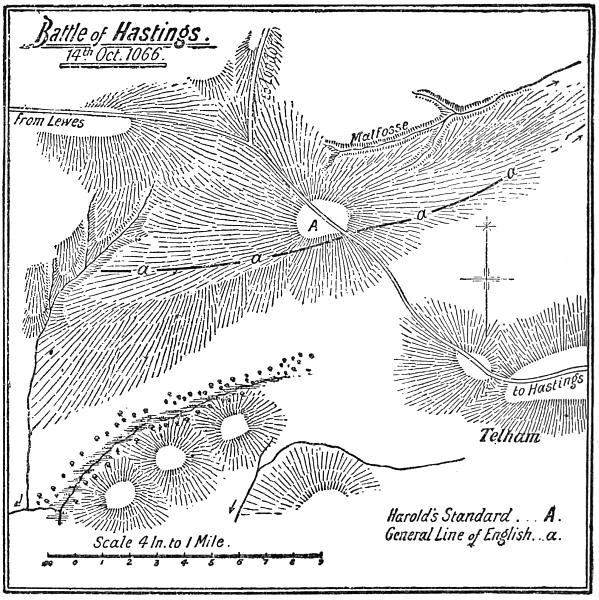

| Hastings | 7 |

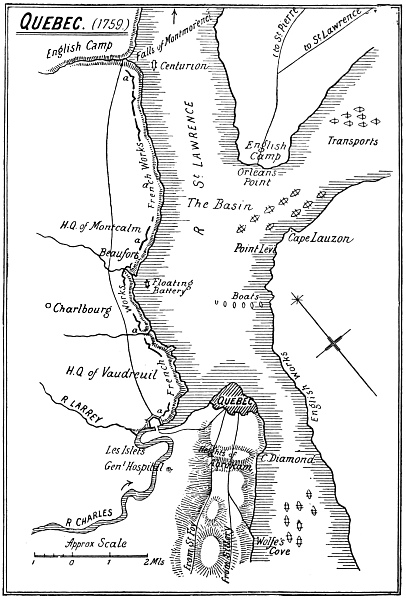

| Quebec | 111 |

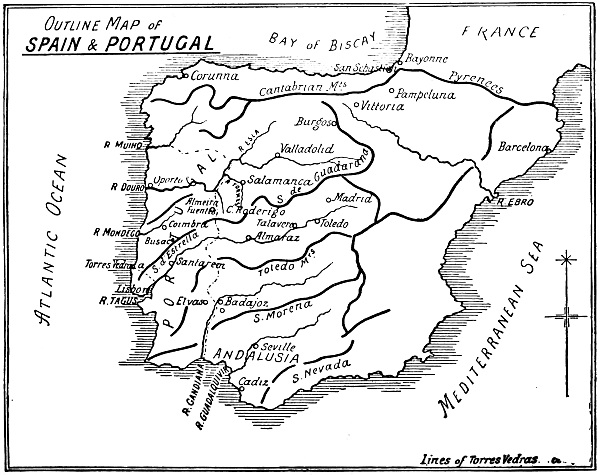

| Spanish Peninsula | 173 |

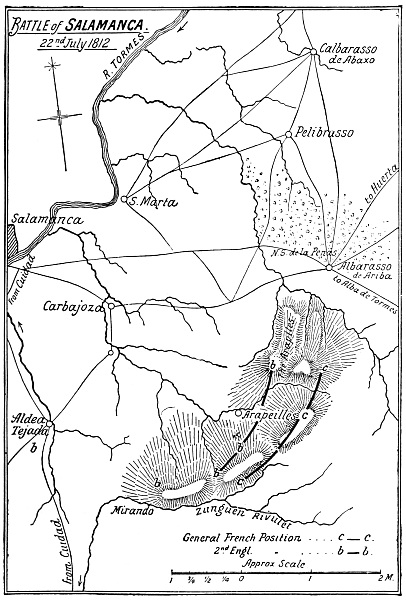

| Salamanca | 198 |

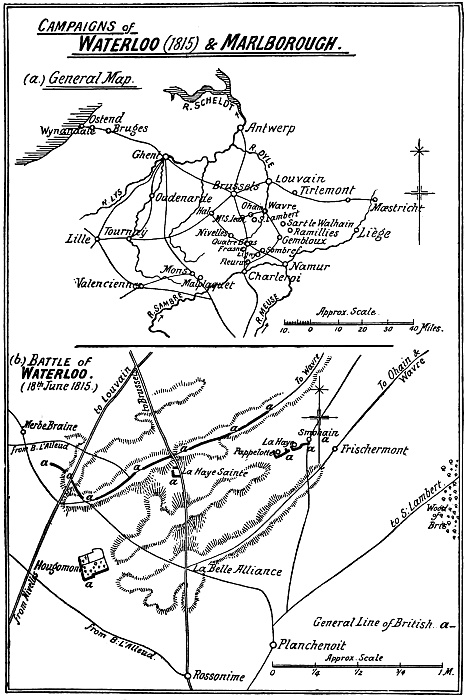

| Belgium and Waterloo | 208 |

| Crimea | 250 |

| India | 266 |

| ARMS | |

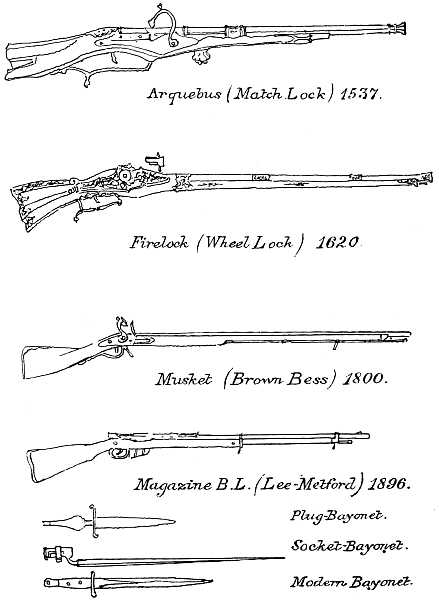

| Muskets, etc. | 125 |

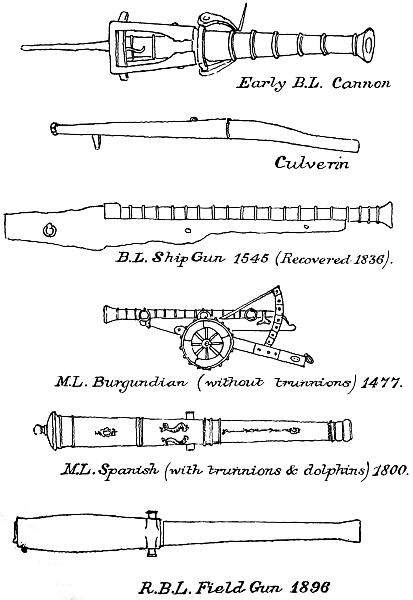

| Field Artillery | 38 |

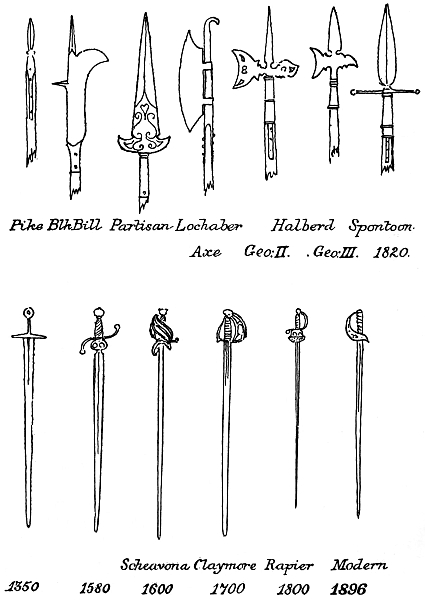

| Spears and Swords | 231 |

All nations have passed, more or less, through the same stages in the up-growth of that military system which is as essential to the political security of the mass as the formation of a police force is necessary for the protection of the individual in civil life. From the outset, the history of human existence has been one of combat.

First, in the earliest of primeval days, archaic man had to contend with mammoth, cave bear, and all the host of extinct mammals primarily for food, and then for safety when the need for clearing them away became more and more apparent as population increased. With this increase in numbers grew also the instinctive hostility between man and man. The desire for conquest is one of his strongest attributes. The stronger has always tried to make the weaker subservient; and as time went on, that desire was accentuated by the wish to possess the women or slaves—the terms were then synonymous—of the weaker family.

It was no mere poetic statement, therefore, that the head of a patriarchal household felt safe with a body of stalwart sons, and was not afraid “to speak with his enemy in the gate.” That old-world text tells volumes, behind which lie sinister pages and details of family feud and rapine.

2 But families segregated together and became tribes; these in their turn formed clans under a general head, and this led to the further development of inter-tribal and clannish contest, of which the greater wars of the present time are the natural outcome.

Still, throughout all this pre-historic or semi-historic time, there was no organisation of what is called an army. Every able-bodied male was bound to join in the defence of his poor village or district, or, on the other hand, to acquiesce in the general desire of a more courageous or dominant group, and share in the attack on, and despoiling of, some other group weaker or richer than itself. A king of men, a stronger soul, a man with more ambition or more boundless energy than his compeers, carried his fellows, by the divine right of leadership, to war. Except as a consequence of his greater bravery, he stood in no one place higher than those he led. The fighting was individual. There were no tactics; there was no systematic military organisation. All fought singly, with a view to the common end of success.

It was only when the character of arms themselves advanced, as civilisation and greater inter-dependence of peoples increased, as communication from point to point improved, rendering combined operations possible, that systematic war began. Even then, there was much of the personal element in the matter. The known chief planted his standard, and round it gathered, at first, a mass of subordinate units, led by their chosen sub-chiefs. But even this was the beginning of greater things. Organisation, on which the real art of war depends, had arisen. The chief now directed subordinate commanders, and command became subdivided. He no longer led only; he directed, in addition to infusing courage into his men by his personal bravery.

So it has been with the successive races that have fought in those early days on British soil. The first real military system worthy of the name was that which brought woad-clad Britons in collision with the military might of Rome. But wonderful as the Roman organisation was, it seems to3 have left but little permanent trace on the people it had governed and civilised for four hundred years, from the time of Cæsar’s first landing to that in which Honorius recalled the last legion from the deserted province of Britannia to assist the main trunk of the empire. There is little evidence that the Saxons met with any more valuable opposition than mere courage, an attribute of little real permanent importance against a foe that had at the least a sort of military organisation. For that the Saxons had such is clear. They had learned from the Romans indirectly if not directly; and there is a distinct trace of Roman influence in the way they arranged a battle. This applies still more to their fighting organisation after they had conquered and subdued the effete defenders of Roman Britain, before the Danes came. Though they, too, had succumbed to the enervating influence of peace, they had established a genuine system which had in it the elements of the army as it is, or at least some portion of it. For the army of Saxon England was, in all essential respects, a militia; that is to say, a body closely resembling the tribal array, but better organised. Against these came the Danes, whose methods were those of the early Saxons; that is to say, tribal leading under renowned chiefs. But the stronger and more correct principles that underlay the Saxon organisation triumphed in the end; and the raids of Danish hordes were beaten in detail, and became absorbed in the Saxon stock, to revivify and strengthen it. The Roman was an alien, and remained so; but both Saxon and Dane had the same racial origin, became, finally, part of the nation they had conquered, and were absorbed by it, to form the English, when the still stronger tone that Norman soldiers gave—coming also, be it remembered, from the same group of peoples—had borne fruit.

The story of the Saxon conquest and of the Danish invasion contains few points of military interest, though that period was the cradle in which the future army was to be reared. Still there is one battle of that time which should rank with the decisive battles of the English world,4 for it stemmed the tide of Danish success, and led to the amalgamation of the hostile sides against the next new comer. This turning-point is the battle of Æscesdune, or Ashdown, fought most probably on the Berkshire hills.

The Saxon had retained, somewhat, the Roman fighting formation, as they had utilised Roman villas in Britain, and altered them to suit Saxon tastes. A spearman—one of the hastati, say, of a Roman legion—required for the free use of his weapons a space of three clear yards round the spot on which he stood;1 and it is more than probable that the later Saxons had adopted some of the Roman methods. The arms varied little from those in use during the Roman invasion. The spear or javelin and arrow showed no change; the sword was broad and two-edged, with a heavy pommel; the favourite Saxon weapon, the axe, was either double or single, like the Gallic Francisca.2 The body armour and head armour was of leather, strengthened in some cases with iron, and the chief defence, the shield, was of wood with bosses or umbos of iron. Their skill with the latter, as tradition tells it, seems fabulous: it is even stated that Harold, surrounded by ten archers, was able, his back being protected by a tree, to intercept every shaft aimed at him. Until later, both antagonists fought mainly on foot.

Turn then again to the battle of Ashdown, and let the Saxon chronicler, Bishop Asher of Sherborne, tell the story of the last great Saxon fight, but one, on English soil. The next was to show the descendants of the combatants at Ashdown united against yet another invader—and the last. “The Pagans, dividing themselves into two bodies of equal strength, draw up their lines—for they had there two kings and several jarls—and they give the central part of the army to the two kings (Baegsaeg and Halfdene), and the rest to all the jarls (Fraena, Hareld, and the two Sidrochs). When the Christians perceive this, they, in the same manner, divide themselves into two bodies, and draw themselves up5 with equal diligence. But Alfred comes more speedily and readily with his men, as we have heard from trustworthy reporters who saw it, and arrives at the place of battle; for his brother, Ethelred the king, was still remaining in the tent in prayer, hearing the Mass, and declaring that he would not depart thence alive before the priest should end the Mass, nor would desert the divine service for the human. And he did as he had said, which faith of the Christian king availed greatly with the Lord, as in the sequel shall be fully shown. The Christians, therefore, had decreed that Ethelred the king with his own forces should fight against the two pagan kings; but Alfred his brother with his companies would know how to try the chance of war against all the leaders of the pagans. Thus strongly were they placed on either side when the king was lingering long in prayer, and the pagans were prepared and had hastened to the place of conflict. Alfred then being second in command, when he could no longer endure the ranks of the foe, except he either retreated from the fight, or dashed forward against the hostile forces before his brother’s arrival, at last boldly, after the manner of a wild boar, guided the Christian forces against the foe as had been determined, though still the king had not come. Thus relying on the guidance of God, and supported by His help, with the lines drawn up closely, he moves forward the standard with speed against the enemy. But to those who know not the place it must be explained that the site of the battle was unequal for the belligerents, for the pagans had occupied beforehand a higher position; but the Christians drew up their lines from a lower place. There was also, in the same place, a single thorn-tree of very small size, which we ourselves have seen with our own eyes. Around this, therefore, the hostile armies, all with a great shout, meet together in conflict, the one acting most wickedly, the other to fight for life and friends and country. And when they fought for some time, fiercely and very cruelly on both sides, the pagans, by the divine judgment, could endure the attack of the Christians no longer; and the chief part of their forces being slain, they6 took to flight disgracefully. And in this place one of the two pagan kings and five jarls were slain; and many thousands on the pagan side, both in that place and along the whole breadth of the plain of Æscesdune, where they had been everywhere scattered, were slain far and wide. For there fell their king Baegsaeg and Jarl Sidroc the elder and Jarl Sidroc the younger, and Jarl Obsbern, and Jarl Fraena, and Jarl Hareld; and the whole army of the pagans was put to flight till the night, and even to the following day, until those who escaped arrived at the citadel, for the Christians pursued them until night and overthrew them everywhere.” “Never before or since,” says a Saxon writer later on, “was ever such slaughter known, since the Saxons first gained England by their armies.” All the next day the rout was followed up, until the shattered remnants gained the shelter of their fort. Whether it was absolutely abandoned by the Danes after their defeat is doubtful; but it is recorded that fourteen days later Alfred and Ethelred suffered a reverse at Basing, which shows, at anyrate, that some portion of the enemy’s forces had retreated to the south.

To meet the last invasion of foreign blood, the Anglo-Saxons had, by that time, a military organisation which differed but little from the hosts that William of Normandy brought against Harold the king at Senlac. There had been much intercommunication between the British Isles and the mainland. Both armies were armed and equipped in much the same way. Their leaders wore the same kind of armour, and there was little to distinguish between them, save that the Norman’s chief strength was in his cavalry, that of Harold in his infantry. The Bayeux Tapestry shows both Harold and William clad in the same attire.

The Saxon fighting system at Hastings differed little from that of the mercenaries of the most varied character that followed the banner of the Conqueror, except that on Harold’s side there was union of men, then of the same nationality to a great degree, against a mere collection of adventurers. As to the political situation there is little to7 be said. The true history of the eleventh century is still, and ever will be, unwritten; the most reliable account is after all largely, if not entirely, traditional. It is poetical rather than actual. It is based on “hearsay” rather than fact. Yet, notwithstanding, before real recorded history was, tradition had to take its place, and this is what it and legend have to say of that great conflict which destroyed Saxondom in Britain, and which placed William the Norman on the English throne as king.

Battle of Hastings. 14th. Oct. 1066.

This, then, is what the fighting seems to have been. Curiously enough, Harold selected the defensive, as did Wellington, as a rule, seven hundred and fifty years after, and fought on foot while fortifying his front with palisades; while the Normans attacked in a series of lines, much as was done by British troops before the introduction of the breech-loader led to the abandonment of “linear” tactics. The last of the Saxon kings had chosen for his stand for crown and kingdom the hill where Battle is now built; but there was one vast difference between the opposing leaders. On the one side the Saxons feasted and made merry, though there is little evidence that Harold made any effort to rouse the enthusiasm of his men as his adversary did. In the Saxon camp there was wine and wassail, and in that of William penitence and prayer. William knew the guiding spirit of the art of war of the time, the infusing into his host that religious fervour which later on made Cromwell defeat Royalists as physically brave as his own Ironsides, and the instilling in their minds confidence in their own powers, which has been at the base of every English victory since then. The Saxons were “slow to find out they were beaten”;3 but the Norman enthusiasm was raised by the duke’s address on the morning of the fight, in which he recalled to their minds that the Normans “had won their land in Gaul with their own swords; how they had given lands to the kings of the Franks and conquered all their enemies everywhere; while the English had never been famed in war, the Danes having8 conquered them and taken their land whenever they would.”

All this may be fable, and probably is, but what we know of William tends to show it was likely. Even omens he turned to advantage. He fell on landing, but, rising with his hands full of English soil, he exclaimed, “What is the matter? I have thus taken seisin of this land, and so far as it reaches, by the splendour of God, it is yours and mine.” He put on his mailed shirt back in front, only to laughingly exclaim, as he reversed it, “A good sign and a lucky one: a duke shall this day be turned into a king.”

All this evidences genius for war such as Harold never had. His bravery is undoubted, but mere bravery counts little against bravery plus skill. So it was that, armed with sword and priest-blessed relics, protected by the “consecrated” banner of Pope Alexander, and bearing on his finger a ring set “with one of St. Peter’s hairs,” William went into battle with not merely an army of sixty thousand men, to whom success meant profit, but to whom death meant falling in a holy cause, and to whom the very battle itself was a crusade. Everything was in his favour, when, singing the battle hymn of Roland, he moved his three lines against the hill on which Harold’s royal standard was planted.

The details of the battle are of little interest. It was one of hand-to-hand fighting. “The English axe, in the hand of King Harold, or any other strong man, cut down the horse and his rider by a single blow.”

The personal element entered largely, as it did later, into the contest. The fall of the leader led to the fall of the army. Where Harold was, where his standard flew, there was the “tactical key” of the field of battle. True tactics do not depend on the death of the king, or the capture of so many yards of silk embroidery. But true tactics, rightly understood, were not in these days.

The duke formed his army in two wings and a centre, each of which seems to have advanced covered by archers, supported by heavy infantry, and strengthened by the main arm of battle, then the mailed cavalry. The left wing,9 composed of men from Ponthieu, Maine, and Brittany, was led by Alan; the right, adventurers from Picardy and France, was directed by Roger de Montgomery; and the centre, comprising the flower of the Norman host, was commanded by William himself.

The bowmen covered the advance by arrow fire, and seemed to have produced little effect; but towards the end of the day they, possibly and apparently from the flanks,4 poured in a vertical fire, and so covered, without interfering with, the attack of the main bodies, and it was from this, in a sense, long-ranged fire that Harold received the wound that disabled him, caused his death and the ruin of the Saxon cause.

Whether the statement that William, by a feigned retreat, drew the Saxons from their entrenchments in pursuit and then turned on them with success, is true or not, may be open to doubt. Harold’s tactics and his method of entrenchment all point rather to passive than active defence. His best armed and best equipped men were in the centre, round his royal standard, armed with javelin, axe, and sword, and covered close by the large Saxon shield; on his flanks were the less reliable and poorly armed “ceorls,” who could not be trusted to meet the main brunt of battle. It is quite possible, however, that these less disciplined troops may have been decoyed into a pursuit which was counter attacked by the cavalry, and thus the flank was turned, and with it the line of obstacles along the front, whatever they might have been.

Be that as it may, it is most likely that the traditional termination of the battle is in the main correct, and that William, by his “high angle” fire of arrows, was able to “search” the ground behind the stockade, and that the last Saxon king received his death-wound in the eye from one of these missiles. It would have been better strategy on his part to have fought a merely rearguard action at Hastings, and, falling back, have both weakened his adversary by the guards he must have left on the coast, and increased10 his own power of resistance by the aid of the reinforcements that were coming up. So night went down on the bloody field of Senlac, where Harold lay dead with fifteen thousand Normans and “threescore thousand Englishmen,” though the latter statement is, on the face of it, exaggeration. But the fight had broken the Saxon power, and the Conqueror—as William of Poictiers says—refused his royal brother burial, swearing “that he guarded the coast while he was alive, let him thus continue to guard it after death.” None the less, it is believed he was buried eventually at Waltham, and William the duke passed on to cross the Thames at Wallingford, seized London, and become William the king.

With Senlac perished the militia system of the Saxon rulers of England. The new-comers had brought with them the elements, though not the completion, of the feudal system that was to follow and be the outcome of the Norman Conquest. As a matter of fact, the invading army that William led was only after all a gathering of armed men under leaders of sorts. Its very origin prevented the full organisation which means a real or regular army. Mercenaries, men who had never before the war met the chiefs who were to lead them, in rare cases religious enthusiasts, who believed that the cause of the Pope and the Normans was the cause of God, mere soldiers of fortune, who thought from the fair English land they might obtain fortune even more than fame;—these were the men who were to break up the Saxon kingdom, still existent more or less, and were to weld into one homogeneous whole the English race. Never has the end better justified the means. Never have the means themselves in 1066 been more ignoble. The Norman host as men had scarcely a redeeming feature. To count descent from them, is to count often enough from the meanest social ancestry, though age has made it venerable and respected. Some of the noblest of English families trace, or rather claim, descent from men of the lowest origin, who rose from such a place as that of “Hugo the Dapifer,” to be the rulers of England and replace Saxon jarls whose descent was more distinct, and on whom the Norman parvenu11 looked down. It cannot be too definitely expressed that to “have come in with the Conquest” is only a confession that those who use the expression are ignoring the fact that many a Saxon thane could show a family title far deeper set in the history of England than any of the men who usurped and trampled on those whose pedigree went back to the days of Æscesdune, before the soldiers of fortune of the Duke of Normandy had emerged from their original obscurity.

None the less the new invaders were “men,” and had a “man” to govern them, while William, the king by right of everything that in those days made kingcraft, ruled.

“Stark was he,” says the English Chronicler, “to men that withstood him; none dared resist his will. Earls that did aught against his bidding he cast into bonds; bishops he stripped of their bishopricks and abbots of their abbacies. But stern as his rule was, it gave peace unto the land.”

This was William. “Out of the strong cometh forth sweetness,” out of the horrors that followed the Norman Conquest came the English people, and, as time went on, that army which has mostly conquered, often suffered, and generally met disaster with a bold front. And so the new, or rather the last successful invaders seized the fair isle of Britain, added their names to old place-names of Celtic or Saxon origin as an affix, converting, for example, the “town by the water” of Ashton into “Ashton Tyrrold,” and, holding the richest lands as their own appanage, raised the massive frowning towers of Norman castles at all important strategic points throughout the country, marking their conquest as by a sign-manual that they held the land, as they had gained it, by the sword.

Notwithstanding that the Norman had many friends in England, it was long before the whole country was subdued. There was fighting in the north of England and on the marches of Wales; there was prolonged resistance by Hereward in the Fenland and central forests, until, in 1071, the “Wake” surrendered, and became the “king’s man.” There was much still to settle, and William settled them in his own stern way. So much so that his own often parvenu barons12 revolted, and for many a century rebelled against the royal authority, which, backed by the clergy and English, won in the end. Ralf Guader was quieted in 1074, and Robert of Bellème, with Robert Mowbray and Prince Robert, were beaten in 1078. Similarly, when Rufus reigned, the same Robert Mowbray, with Odo of Bayeux and others, held their castles as rebels until they were stormed in 1095.

The Celts of both Wales and Scotland proved troublesome, so to hold the latter frowning Norman castles were erected at each end of the neck between North Britain and England at Carlisle and Newcastle, while the former were shut in by a chain of similar fortresses from Cheshire to the Severn valley, along which hostilities continued for many a year, to the territorial aggrandisement of the defenders of the “Marches.”

Henry I.’s marriage, uniting the old royal race with the new, much pacified matters, or at anyrate gave the king still more aid from the English people as distinct from the Norman barons. Again Robert of Bellème on the Welsh border revolted, but was driven into exile by the sovereign: in the claim of Robert to the throne, Englishmen sided with Henry, and for the first time served abroad to defeat the pretender at Tenchebrai. But Henry left no male successor, and Matilda his daughter was distasteful to the barons, who chose Stephen, grandson of the Conqueror, as king. This created two factions—that of Stephen and that of Matilda, the first of the great Civil Wars (for now the “English” counted for much more than heretofore), and the king, unlike his predecessors, unwisely allowing the barons to build castles on their own lands, paid for his over-confidence. For Matilda’s party, led first by the Earl of Gloucester, formed in the west of England, assisted by David King of Scots in the north. Stephen advanced against the latter, defeating the former at Northallerton, and after many vicissitudes on both sides, the war ceased by the retirement of Matilda to Normandy.

So in anarchy and suffering—suffering so great that it was said “that God and His saints were asleep,” so terrible were13 the wrongs done in the land—the Norman power as such ceased to be, and Plantagenet kings (no longer Norman but English) reigned over the realm for more than three hundred years.

Out of that time grew up the system of feudal levies, that is, of men who served as the personal retainers of some baron or overlord, and who fought therefore no longer as freemen, fighting freely in their country’s wars. Military service long remained personal rather than national.

With the rise of feudalism arose a further expansion of the principle of subdivision of command, though in its earliest days it degraded fighting to the mere personal prowess of the individual, and tactics as an art of war consequently made little, if any progress. Armies were built up much as before, and were still in many respects a species of militia. The knightly tenure was one of personal service for variable periods,—generally of about forty days,—during which the knight received no pay, and beyond which the king or overlord was supposed to defray the cost, and too frequently didn’t.

Sometimes he compounded for service by a money payment to the king, which enabled the latter to pay others to do his work; this indirectly leading to the mercenary soldier, or one who serves for pay. Throughout all the feudal times armies for foreign service therefore had to be paid, as campaigns could never be concluded within the period of free service. Hence they were composed partly of feudal retainers, partly of forced levies or mercenaries raised by some knight or gentleman, expert in war, to serve the king at a fixed rate of pay, which was often higher than that of a day labourer at home, with the prospect of adventure and booty. There seems to have been little difficulty in thus raising recruits. The money for this, which was paid in advance, was raised from the royal revenues, crown funds, fines, or parliamentary grants. These armies were disbanded, therefore, directly the war ceased.

It is calculated that this system produced a levy of about 60,000 knights and men-at-arms, and the country was15 divided into areas or “knights’ fees,” each of which provided one armed man.

The main “arm” in battle was the mailed cavalry, and infantry was long thought little of; but in England speedily grew up the steady and trustworthy bowmen, the foundation of that infantry which has carried the national flag to victory in every part of the world, and which had no counterpart in those days in foreign armies, such as France, where the footmen were, till much later, merely armed serfs or dependants, armed indifferently, and treated with contumely. In England it was otherwise. There were both greater freedom, and better, because more independent men. The trust that successive governments had in the people is best evidenced by the fact that all classes were armed. As far back as the reign of Henry II. it had been enacted that every man should possess at least a bow, and it is said that a good bowman could fire twelve shots a minute at two hundred and forty yards. Archery and archers were encouraged on the one side of the Channel, and on the other looked upon with contempt. Nowhere is the difference between the English and foreign footmen better shown than at Crecy and Poitiers; and the former is a type of the fighting of the period immediately before the active employment of gunpowder. The political events which brought about the battle need not be detailed here: it will be sufficient to bear in mind that the “Hundred Years’ War” with France commenced by the claim of Edward III. to the throne of France, and the corresponding effort on the part of Philip to possess Guienne, which the King of England held in fief as Duke of Aquitaine, one of the six “peers of France.” After sundry fruitless expeditions, Edward landed at St. Vaart on the 11th October, with an army composed of 4000 men-at-arms, 10,000 bowmen, 12,000 Welshmen, and 6000 Irishmen, and one of his first acts was to bestow on his gallant son, the Black Prince, the honour of knighthood.5

16 It is interesting to notice how even at this date footmen and infantry formed an important part of the British army, which, after advancing almost to the gates of Paris, was compelled to fall back to the coast for many reasons, among which want of supplies predominated, and finally, after a brilliant skirmish in crossing the Somme, took up a position at Crecy-en-Ponthieu—whence, even if defeated, it had a secure retreat through Flanders—there to give battle to the French. When day dawned on the 26th August 1346, the battle was formed on the slopes of the Vallé des Clercs, with the right flank resting on the village of Crecy, situated à cheval the river Maye, a shallow stream some ten feet broad. The left flank was protected somewhat by a belt of trees near Wadicourt, and the position—about a mile long—faced south-east, and was held in three bodies; the first, on the right, under the Prince of Wales, with Lords Warwick and Oxford, was composed of 800 men-at-arms, 1000 Welsh infantry, and 200 archers, with 2000 Welsh and Irish infantry in support;6 the second, on the left, commanded by the Earls of Arundel, Northampton, and Willoughby, with Lords Basset and Ross, contained 800 men of all arms; while in rear of the right wing was the reserve, 1700 men-at-arms and 2000 archers, commanded by the king in person.

The baggage was securely packed in a wood in rear of all. Each of the wings was arranged with archers “formed in the manner of a portcullis or barrow,” and the men-at-arms dismounted. The king utilised the steadiness of the dismounted men-at-arms to resist the charge of the enemy’s cavalry, while shaking and demoralising him in his advance by fire. It was not unlike the “Battaglia” of the civil war in principle, which were composed of “pikes” in the mass and “shot” at the angles. The longbow was no bad weapon as time went. It could range four hundred yards, was silent, and rapid to shoot, and, like modern smokeless powder, did not obscure the field of view. There is little doubt that the real formation was that of a line of men-at-arms, flanked by two wings of archers, thrown forward, and with a central body of17 archers forming a “herse” by the meeting of the inner wings.7 Cannon, in the shape of six small pieces slung to a beam, and called “brakes,” were used for the first time, and both entrenchments and abattis seem to have been made along the front.

Philip himself, with an army estimated at as much as 120,000 men, was meanwhile advancing from Abbeville with 15,000 Genoese crossbowmen, forming an advanced guard, led by Antonio Doria and Carlo Grimaldi, followed by 4000 men-at-arms and foot soldiers under the Dukes of Alençon and Flandres, behind which came the remainder of the army in four lines, under the command of the king. The march was disordered and confused. “There is no man,” writes Froissart, “unless he had been present, that can imagine or describe truly the confusion of the day.” It was a case again of “those behind cried Forward, and those in front cried Back”; and while the masses surged backward and forward, under contradictory orders and want of plan, a gathering thunderstorm burst with peals of heaven’s artillery, and the driving rain lasted long enough to wet the bowstrings of the crossbowmen and render them of little use. The superiority of the longbow was fully shown then, for the English were able to keep the bows cased and the strings dry until the moment for their use came. And come it did; for the sunshine again broke through the clouds, and now full in the faces of the French. Other omens too were there, which in days of superstition helped to raise the courage of one side and depress that of the other; for over the French early gathered great flocks of ravens, which “was deemed,” so writes De Mezeray, “a presage of their defeat.”

When, therefore, the Genoese were ordered to attack, they did little execution, and under a fire of clothyard shafts so heavy that “it seemed as if it snowed,” they fell back in panic and disorder. Whether Edward’s artillery had any real effect is doubtful, but the noise of the new weapon, probably firing stone shot, may have tended to add to the débâcle, even if the actual loss it caused was small. The18 Genoese were between two fires. In front were still the English line, cool on the defensive, as they have always been; behind was Alençon’s cavalry, who cared but little—in that chivalric age—for mere men on foot. “Kill me those scoundrels,” said Philip, “for they block up our road without any reason. “Truly,” also answered D’Alençon, “a man is well at ease to be charged with these kind of rascals who are faint, and fail us now when most at need;” so through the flying men rode the French knights, whilst over the disordered crowd still fell the heavy rain of English arrows. To add to the confusion, too, the Irish and Welsh infantry, though they were of little value apparently otherwise, joined in the mêlée, to slay with their long knives the dismounted knights, whether wounded or not, “nor was any quarter given that day by the victors.”

But when the French cavalry had cleared a way to the English line, they were a mere crowd, and the Black Prince advanced his line to counter attack. But there was no lack of bravery in his antagonists. They fought brilliantly and well, and so far succeeded as to place the prince’s command in some danger. And while the French knights assailed the flanks of the English right wing, a sharp attack was made by some German and Savoyard cavalry which broke through the bowmen, and even engaged the men-at-arms in rear. To his aid, therefore, pressed Arundel’s left wing, and soon the French second line also fell back routed, leaving its chief behind dead. It was too late to retrieve the disaster, and it is somewhat pitiful to read how at that moment the poor old blind King of Bohemia turned to those around him to say, “Sirs, ye are my men, my friends and companions, I require you to lead me so far forward that I may strike one stroke with my sword.” Verily there were men in those days, and two knights did not fear to humour him; so, tying their reins to his, they led him into the thick of the fight, where, seeking death, the king “struck a stroke with his sword, yea, and more than four, and fought valiantly, and so did all his company; but they adventured so far forward that they were all slain, and the next day were found in the place about the19 king, with their horses tied to each other.” His was a valiant death, and though his son, the King of the Romans, had fled, with him fell the flower of the French army, the King of Majorca, the Duke of Lorraine, the Count of Flanders, the Count of Blois, eight other counts, two archbishops, 1200 knights, and 30,000 men. The loss on the English side is not recorded, but was probably small, and the battle was won chiefly by the fire of infantry,—in this case, arrow-fire,—as modern battles are mainly decided by the bullet.

Among the spoil of eighty banners was captured the banner of the King of Bohemia, charged with three ostrich feathers, and the motto “Ich Dien,” though the statement that the Black Prince thereupon adopted them for his crest and motto is probably mythical, as many such stories are.

Philip seems to have been stunned by the disaster, and long refused to leave the field. When late that night he reached the castle of La Broyes, he had with him, of all his armed host, but Sir John Heynault and five barons. On the other hand, Edward had the joy of embracing his victorious son, with the words, “Persevere in your honourable career. You are indeed my son, for valiantly have you acquitted yourself this day, and shown yourself worthy of empire.”

When the sound of conflict ceased, even Edward did not then know the magnitude of the victory he had gained. And the night passed without festivity, while the king himself “made frequent thanksgiving to the Lord.”

The battle of Crecy is a marked stage in the history of our own army, for it shows clearly the value of the English infantry of the past, the importance of infantry fire, and the dawn of the employment of artillery. But by other nations and in other parts of the world, too, had the value of resolute infantry been recognised, except in France. The age of chivalry—so called—had increased, and fostered the use of body armour. Its very dead weight literally and metaphorically prevented the growth of tactics. There was no real organisation in the crusading hosts; they were but gatherings of armed men such as William led at Hastings, and battles were but a series of incidents of rivalry between leading or20 ambitious chiefs. The age of chivalry was an age of vanity, both of deeds and of iron clothes. Magnificent was the armour of the knight; magnificent, too, his inordinate desire to be noticed! These were not the days of personal interviews, daily papers, or self-advertisement; but Sir Galahad, going from tournament to tournament to show he was a stronger man, or with a Christian desire to hurt somebody, did his best in that line none the less! The Irishman who drags his coat along the ground at a fair—another sort of tournament—in the hope that somebody will tread on the tail of it, differs little from the challenger at Ashby de la Zouche. There was the same human nature at the bottom of both—each was spoiling for a fight! Still the spirit of the time sensibly increased the military spirit. To individual prowess was open the tournament where doughty deeds, or what were considered such, met with immediate reward and encouragement. No better school for mediæval war ever existed than that in which men learned to fight under the personal criticism of women. Vanity, pride, love were all brought to play in these contests, and poetry spread far and wide through the songs of the troubadour the deeds of the valiant, the defeats of the weaker—

War was for long the only career open to men who did not care to don the cowl of the monk. It, therefore, in the Middle Ages, was essentially the one pursuit of the gentle born. It tended in a brutal time to lessen some of the evils of war, which “is a barbarism which civilisation only intensifies.” “Væ victis” was softened by the feeling that the conquered opponent could be held to ransom and treated gently. The very training of the knights combined the religious, the romantic and combatant elements. The right of conferring it from time to time varied. Before 1102 abbots21 of the Church had the power to bestow the golden spurs. Hereward the Wake received his knighthood from the Abbot of Crowland. But later on, only bishops, princes, or knights themselves were permitted to bestow the honour, and, with them all, great care was exercised that the recipient should be worthy thereof. Considering the value of money in those days, the costs were heavy, the robes alone amounting to £33. The golden collar of SS. or Esses, part of the knightly decoration, must have been costly. Its origin is very doubtful. Whether from “Souveraine,” from “Sanctus Simo Simplicius” (an eminent Roman lawyer) or in compliment to the Countess of Salisbury, has not yet been determined.

The knightly duty was laid down with exactness, though probably few carried out all the wholesome rules in their entirety. “They must learn from the beginning to labour, run, carry weights, and bear the sun and dust; to use sparing and rustic food, sometimes to live in the open air and sometimes in tents; then to practise the use of arms.” The “true merit of a knight is correctly stated by the Troubadour Arnaud de Marveil.” It is “to fight well, to conduct a troop well, to do his exercise well, to be well armed, to ride his horse well, to present himself with a good grace at courts, and to render himself agreeable there. Seldom are these qualities in the same person. To unite martial habits and vigour with the courteous elegancies of polished life, could not be often accomplished in a half-civilised age.”

His oath declared his duty to be “To defend the Church, to attack the perfidious, to venerate the priesthood, to repel the injuries of the poor, to keep the country quiet, and to shed his blood, and if necessary to lose his life, for his brethren.” But if his duties were grave, his privileges were great. Knights were freed from all “gelds” and taxes and from all other services and burthens by Henry I., in order “that being so alleviated, they may instruct themselves in the use of horses and arms, and be apt and ready for my service and the defence of my kingdom.” Salisbury also mentions that knighthood “rejoices in many immunities and more eminent privileges, and has not to provide horses,22 carriages, and other sordid burthens.” Yet another advantage, of doubtful value perhaps, was that of being rated at a high value when taken prisoner in war. His ransom, always higher than a less titled personage, sometimes amounted to ten thousand crowns, but if of higher value than that, the captor was obliged to surrender him to the king. Those who were knighted for valour on the field of battle were empowered to use the square instead of the swallow-tailed pennon, as knights banneret, and had the privilege of a war-cry. From this came the mottoes of the modern “coats of arms.”

The history of knighthood is a part, and a very important part too, of the history of arms. To its institution can be traced many of the decorations and forms of the arms and armour of the Middle Ages. The honours it offered were so great and highly prized, that it increased martial enthusiasm and encouraged military exercises; and the part taken by women in rewarding the exertions of the knights both in the tournament and in battle, exercised an enormous influence over the warlike portion of mankind. Where the prizes were so great, attention to arms of offence and armour of defence became natural and right. The chivalric feeling engendered by knighthood and knightly exercises was not confined to joust and tournament in times of peace. It was a useful and valuable adjunct to personal bravery in war. “Oh that my lady could see me now!” said a knight as he successfully led his men to the storm of a well defended breach. The spirit thus aroused was due to the knightly customs of the times.

But this “chivalrous” and in a wide sense “cowardly” system was to receive two rude shocks. The first came from the Swiss mountaineers, who with the pike grievously routed the gorgeous knighthood of Charles of Burgundy, and the second from the results of the brain-thought of the peaceful chemist who rediscovered gunpowder.

That cavalry were useless against determined infantry was a new and lurid light to the iron-coated feudalist, and led to a considerable increase of foot-soldiers and the use of the23 half pike. As the firearms improved, so the unhappy knight tried to meet the bullet by thickening his armour of proof, until on foot he was helpless, and mounted not much better.

Armour, therefore, had much changed since the Conquest, and was still changing. The Norman knight was chiefly clad in mail, composed at first of rings sewn side by side on quilted cotton or leather, rings overlapping (jazerant), scales overlapping (lorica), or square plates overlapping (tegulated); to be followed by rings set edgewise (as single mail); and finally regular double mail extending over the head and entire body. Over the mail coif was worn a conical helmet with a “nasal” or nose-piece, followed by a cylindrical flat-topped helmet over the coif; and finally the latter was replaced by a round topped helmet from which depended a mail cape or camail. Similarly as iron replaced mail for the headpiece, so were knee-pieces, elbow-guards and neck-guards of plate added. The foot-soldier wore an iron headpiece, and now and then a back and breast plate, but he was generally badly provided with defensive armour, and relied on the leather “buff” coat or clothing of quilted cloth. But the armour from the end of the fourteenth century to the beginning of the sixteenth century became more and more massive. At first mixed armour,—mail and plate,—then plate armour chiefly. In the former period more and more pieces of iron plate were used to cover weak parts, such as knees, elbows and shoulders, cuirasses, leg-pieces, thigh-pieces, gorgets (for the neck), shoes (sollerettes), and gauntlets for the hands, appear successively, until the only mail armour was that hung from the waist in front, between the plate cuisses that protected the outer part of the thighs. The helmet or headpiece also became gradually closer, with a visor that could be opened or closed at will, until it completely covered the face, so that by the fifteenth century, the whole of the armour was practically plate. Underneath the armour was generally worn a leather suit, and over it the “tabard,” which not only bore the wearer’s coat of arms, but protected him from the sun. Arms remained much the same—sword, lance and dagger chiefly for the mounted man, with at times24 the axe and mill-pick; on foot the two-handed sword, with halberts and partisans of various types, such as the glaive or byl, together with sword or dagger. The missile weapons, the longbow and crossbow, were still common, though giving way slowly but surely to the firearm; and the former was long more formidable than the latter. It could be discharged much more quickly, it was less liable to get out of order, it did not require heavy stores of powder and shot. The arrow missiles were twofold in character. “Flight” arrows had both heads and feathers small, and were used for ranges up to two hundred and forty yards. “Sheaf” arrows were shorter in the shaft, were heavily feathered and pointed, and were intended for close range. Even when this ammunition was expended, there was no lack of similar missiles to be found, either in the bodies of the slain or sticking in the ground. Moreover, the flight of the clothyard projectile could be directed over the heads of the men fighting in first line, and reach therefore the reinforcements hurrying up in rear. Still the firearm slowly gained ground, and the extensive use of body armour practically lasted until the end of the sixteenth century, though by that time leg-armour was generally falling into disuse.

During this same period there was a corresponding growth, in addition to the increasing appreciation of infantry already referred to, of permanently organised armies. Their origin as “Free Companies” from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries was probably largely due to the constant state of war and political contests that characterised the time. A numerous soldiery, disbanded after the termination of a campaign, were only too eager for further employment, however hazardous. Their mode of life had destroyed their peaceful instincts, and so as paid soldiers they served under the banner of any of the unscrupulous leaders, often of noble birth, that such a condition of affairs was likely to force to the front. Thus arose the mercenary soldier, the forerunner of the paid soldier; and from the continuous training the former perforce received also came the permanently embodied armies of later days. The system insensibly influenced the feudal25 levies, for among them served many others besides knights who made a profession of arms. Finally, the practical value of a permanent force was recognised in France, when “Compagnies d’ordonnance” were raised by paid officers and composed of paid men. So things and matters went, until the first of the great civil wars brought into the field English armies that fairly typify the final development of the feudal system that had been growing up. It differed much from what obtained elsewhere still. There were but few mercenaries in England, at least of foreign origin. The native independence of character had produced a splendid infantry as times were. And with the Wars of the Roses terminated mediæval tactics and its warfare, as with them finally came in the dire foe to feudal knight and iron-clad noble, that “villainous saltpetre” which was to revolutionise war and abolish armour altogether.

So when, on the 13th October 1453, a prince, Edward, was born to the feeble Henry VI. of Lancaster, the hope Edward of York cherished of peacefully succeeding to the throne was rudely destroyed. Before him lay the chance of a long minority under an imperious queen, Margaret of Anjou, a prospect that pleased neither the duke nor the people. Many who would have otherwise lived and died peaceful, unwarlike, citizens sided, half in apprehension, half in sympathy, with the “White Rose,” a feeling which acquired political importance by the temporary appointment of the Duke of York as Protector during the king’s mental feebleness and his son’s minority. “This Richard of York was a personage to be reckoned with.” And political excitement was soon followed by a political badge, as in later days the primrose became a party emblem. In the gardens of the Temple—so tradition has it—the white and red roses were plucked and worn by the spectators, the latter by those who followed the reigning house of Lancaster; and from this small beginning, from this outward and visible sign of internal disagreement, sprang an internecine contest that lasted for thirty years, brought about on English soil twelve pitched battles, more than decimated both branches of the royal26 family, all the noble houses, and for savage rancour and hideous cruelty is unequalled in the world’s history. Yet it is not a war as modern military historians would class it: there was little method, no “plan of campaign,” worthy the name. Where “armies”—or rather, bodies of armed men—gathered together, there a similar body went to fight them like two pugnacious cocks in a farmyard.

Not that Richard of York began with any certain idea of kingship, though his son, afterwards to be Edward IV., was less scrupulous. After the first battle of St. Albans,8 matters went quite mildly to begin with. Henry VI. was made prisoner, but was treated with courtesy, and but for his determined queen, whose influence on his weak character was as that of Jezebel on Ahab, the end of his reign may yet have been peace. She was naturally despotic, and a conspiracy to seize the Yorkist leaders drove them again into open revolt, and gave them a victory at Blackheath in 1459, but much panic and some treachery led to the dispersion of the Yorkist soldiery at Ludlow the next month; to be followed in February 1460 by a complete victory at Northampton, in which Richard’s son Edward, Earl of March, with Warwick the Kingmaker, led the hosts of the White Rose, and Henry became a prisoner once more. This led to a second temporary compromise, whereby the Yorkists were promised the succession on the death of King Henry. But it availed little. The war-spirit and the blood feud were27 aroused. Wakefield Green witnessed the defeat and death of Richard of York, and the cruel murder of his twelve-years old son, Edmund of Rutland, by Lord Clifford. The cruelties of the Lancastrian party, the systematic pillaging which their soldiery—recruited often from the ruder North—so often indulged in, alienated the sympathy of the London men; while the more commercial spirit of Edward of York also tended to strengthen the party of the White Rose, to keep alive and embitter the strife, and postpone the long-looked-for peace. The country had practically subdivided itself into geographical as well as political factions. The North and Midlands sympathised with Henry, who had there the support of the landowners, the nobles, and their retainers; the south more or less with Edward, with whom the great towns, such as London, Bristol, and Norwich sided. Hence, after the latter had been proclaimed king, there was still a powerful army of some sixty thousand Lancastrians at York that had to be dealt with. And dealt with it was, by the new king and Warwick his Kingmaker, who at Towton won one of the most decisive and bloody battles during the struggle, and drove Margaret first to Scotland, and then to exile. Much as her character may be disliked,—and she was after all only a type of the imperious feudal “divinely-appointed” ruler,—her dauntless energy and courage cannot but meet with sympathy. So exile meant with her but reculer pour sauter le mieux, and in France such poor supplies as she could raise enabled her to make one despairing effort for her son’s sake, and she landed in Northumberland in 1462; but nothing came of it except dispersion again and despair. Unhappy queen! unhappy more by her own faults than aught else. The legal claim of her branch to the kingdom was never seriously contested. Her method of asserting that claim was contested, and with results fatal to her and her line, together with fateful results to her people. Commercial Edward was more likely to develop English handicraft and English trade than pious Henry. As later the divine right of Tudor, and still more of Stuart, had to give way to the rising spirit of freedom from autocratic28 control, whether of king or pope, so out of the Wars of the Roses began to sprout, from the soil of feudalism, broken by many a sword, manured by the best of English blood, the plant of English liberty. Yet one more great contest between rulers and ruled, and that plant was to spring into full and vigorous life, of which we now see the matured and widespreading tree. The nation hardened under the troubles of that stormy time; and, hardening, grew to stout manhood. In thinking this we see that Margaret unknowingly helped to make it. For “God fulfils Himself in many ways”; and by many means, often seemingly of the meanest, do great things come. Not that Edward was faultless, it was rather the other way. His private conduct was not beyond reproach; his marriage with Elizabeth Woodville, and the rise of that lady’s family, alienated many of the leading nobles, Warwick among the number. So the smouldering embers of civil war broke out again into flame, and now Margaret had to help her the mighty power of Warwick, with and by whose direction her next descent on England was to be made. But this, too, availed nothing. Though first so successful that Edward fled, later on, he too returned, but, unlike Margaret, to conquer. For at Barnet the great earl fell, and with him the last hope of Lancaster.

This remarkable battle is instructive as showing how slow was the change in tactics during feudal days. There was still the feeling of personal chieftaincy, so strongly held, that the result of the battle depended largely on the life of one of its leaders. With the death of Warwick the battle became a rout, and the feudal retainers fled when the head of their house fell. Again, to deal with the special political details which brought about the great fight would be foreign to the object of this book. The battle of Barnet must be taken as a type of the progress, such as it was, that had been made in the art of war since Crecy and Poitiers had been won. It began thus. Edward, after a five months’ exile, had landed at Ravenspur, and by the time he reached Nottingham he had raised an army of about ten thousand men, with, it is said, three hundred Flemings armed with handguns,29 and apparently some other artillery. On the other side, the Lancastrians, about equal in strength, had also some artillery, and had taken up a position on Gladmore, or Hadley Heath, north of Chipping Barnet, and awaited the approach of the Yorkists. The night preceding the battle was dark and gloomy, and the morning broke in heavy mists and rain; notwithstanding which the troops engaged between four and five o’clock on the morning of Easter Day, the 14th of April 1471.

Warwick had at first his artillery on his extreme right, and this fired through the gloom, but with no effect, as Edward’s right wing did not extend so far, and was overlapped by the Lancastrians. This army was commanded by the Earl of Oxford, who led the van, and by the Marquis of Montagu, who led the second line; the left wing was commanded by the Duke of Exeter—both wings being largely composed of cavalry. The extreme left was occupied by archers and pikemen entrenched or palisaded in a small wood. This probably extended at that time from Wrotham Park to the column now marking the site of the battle, and near which tradition says Warwick fell. The centre, consisting of bows and pikes, was commanded by the Duke of Somerset; and behind this there appears to have been a reserve under Lord St. John, Sir John Conyers, and, for a time at least, Warwick himself.

The order of march of the host was with the right wing leading and the left closing the column of march. On the other side, Edward from his initial dispositions similarly outflanked the left of his antagonist, opposite which was the Duke of Gloucester commanding that wing, and presumably the artillery, if any. The left wing was led by the Marquis of Hastings; and, as in the Lancastrian army, both wings were mainly composed of cavalry. In the centre were the Londoners, infantry armed with bows and bills, and in general reserve was a force commanded by Edward himself. Some writers speak as if the armies were formed in three parallel lines, but it would seem that the formation customary for long after Barnet was that of two wings and a centre.30 It is impossible otherwise to account for the curiously isolated and impulsive attacks on either side by Oxford and Gloucester. Still, it is practically certain that each of the three bodies into which the army was divided was more than one line deep. Thus from the outset these dispositions show a tendency to employ infantry in battle with cavalry and artillery on the flanks, but the feudal idea still preponderated, and paramount importance was still attached to the mounted arm, which on both sides, as in all cavalry actions, simultaneously took the offensive.

One point, however, is especially noteworthy, and that is, the appearance of London citizens in Edward’s fighting line. Though not strong in numbers, they none the less represented the beginning of a new era, which was to see a citizen soldiery formed of London trained bands even more important in the next civil war, and which was to find its climax in the later citizen soldiery, the Volunteer Army of modern England. The natural result of such a primary disposition of the troops on either side was that the right wings of both armies, practically equal in number, gained a temporary success. The battle began by Oxford’s attack on the wing opposite him, which actually routed it and dispersed it; but the value of a reserve in the hand of the general was never more clearly evidenced than when, during Oxford’s absence and ill-advised, because too prolonged pursuit, Edward launched his reserve against Warwick’s then exposed flank and the left centre. To the suddenness of the attack was added the demoralisation caused by imagined treachery. On that misty Easter morning it was difficult to distinguish between the badges and banners of one side and the other. The dress was not a different-coloured uniform, as later on; it had only the uniforms of iron and steel. A false war-cry was easily raised, the Oxford banner with a “star” not readily distinguishable from that of Edward with the “sun.” So that when Oxford returned to the fray, he fell on his own centre and produced the cry of “Treachery!” which was always likely to be raised in an army composed of selections from two factions deadly hostile to one another, and in31 which the Lancastrians especially looked with something more than doubt on their new friends, once the followers of hated York. So that confusion began and spread. Somerset did little, and soon the centre and right dissolved, and only on the left assembled round Warwick the relics of the beaten host, and defended the entrenched wood. Here it was essentially a foot encounter, with London archers and bills against Lancastrian bows and pikes, aided by dismounted cavalry and supported by mounted troops, threatening the flanks and rear. It is said even that Edward’s artillery was brought up close to aid in destroying the defences; but the defence only delayed the inevitable end. The battle was lost already, but it wanted yet one death to make it a type of the death of a system. When Warwick dismounted of his own will, and after slaying his favourite charger, so that no retreat should be possible, took up his position with his friends and personal retainers in the wood at Wrotham, and fell there, axe in hand, he did something more than destroy the last practical hope of Lancaster, for with him fell the feudalism of which he was so magnificent an exemplar. No such man or soldier was ever afterwards to hold from his own remarkable personality such a position as his. Cromwell’s resembles it only in his becoming a great and prominent leader in a civil war. Warwick, and nobles such as he, fought as much for their order as their king; all succeeding soldiers fought more for a cause than either.

Meanwhile, Margaret and her son had landed in the West at Plymouth, to be present at the fatal fight at Tewkesbury where defeat was followed by the death of her son, whom Edward struck before subservient attendant lords and stabbed to death, the imprisonment of the queen, and, later on, the death of Henry VI. in the Tower. Neither he nor all the house of Lancaster had been able to save his order from decay.

Edward, too, according to his views, had unconsciously aided its downfall. His death was illumined only by the lurid light of an ill-spent life. However enthusiastic in bygone years was the following of the Earl of March, he32 played the game so badly that with him the feudal spirit practically disappeared. No son of his succeeded. No kindly thought clung round the last of the Yorkist line. For he was practically the last, inasmuch as his son was king but in name, his brother Richard but a transient star. When on Bosworth field Richard III. died, with him finished the civil wars of mediæval England and the feudalism that had accompanied them. In Henry VII., a personality of no great merit, though he certainly instituted a nucleus of the future army in raising the “Yeomen of the Guard,” fifty archers strong, was united the two Roses; and then was born the nation that in the next civil troubles laid the foundation as far as England is concerned of modern life, modern armies, and modern war.

Never had a class suffered so severely as that of the nobles in this prolonged struggle. Many of the royal princes, half of the nobility and gentry of England, and quite a hundred thousand men had fallen in the great wars. At Barnet the loss was accentuated by Edward’s own orders. So many of the leaders of the great houses had been killed, murdered, or beheaded, that the very decimation of the aristocracy rendered the growth of the middle class more easy, its fusion with the higher class, as time went on and wealth increased, more possible. The knighthood of men of low degree was rare in feudal days; the Tudors were to extend it to the merchant princes who developed English commerce sword in hand, and taught foreign nations the prowess of the English race.

But there is also a marked distinction between the conduct of the battles of the houses of York and Lancaster, and those of the Stuarts and the Parliament of England in the next civil war. Up to Bosworth, armies raised at a convenient feudal centre advanced, when “mobilised,” against another army collected in a similar way at another place convenient for the faction to which it belonged. They met as soon as they were ready. They selected no “position for defence,” a primary tactical law for a weaker force, which by so doing enlisted on its side the elements afforded by such a selection.33 This was chiefly due to the fact that the bulk of each army was still cavalry, but the other “arms” were increasing in number and value, though still not fully appreciated by the mounted men.

The two battles of St. Albans and the fight at Barnet fully show this. In both of the former the combatants met en plein face. The one was making for London, the other stopped him. In the second battle the Lancastrians tried to check the opponent, and failed in preventing his advance, both armies in which mounted troops predominated. There was nothing but a mutual offensive, the system that was at the basis of feudal tactics, and which crystallised in the personal battle between knight and knight in the lists. Strategy in its best sense was not, neither were tactics, for tactics mean the development of a means of equalising the deficiency of one side in numbers, arms, or morale.

So long as a battle depended on personal prowess, the personal fighting power, or even the personal domestic influence of a leader, so long were battles often a mere matter of chance. When Warwick fell, Barnet was lost. The next civil war changed this: neither the death of Falkland nor that of Carnarvon at Newbury affected the fight seriously in one single degree. Finally, as a rule throughout all these days armies moved in order to subsist, and supply trains were rare. Thus true strategy was barely in existence yet, but shock tactics in battle were just beginning to give way to the fire tactics of bow and musket.

As regards supplies in the Wars of the Roses, it must be remembered that, as in later times, notoriously in the Peninsula, when the armies had at times to collect the enemy’s shot and bullets, the weapons of either side were interchangeable.

Doubtless at certain places—castles or fortresses—the actual munitions were stored. To these the armies must have either periodically gone to refit, or what answered to convoys, conveying absolutely necessary warlike stores, must have been formed for the specific purpose of replenishing the locally exhausted stores. All that was really required34 for the purposes of such wars must have been carried on the persons of the combatants, as seems generally to have been the case, or even on pack animals or country carts. The state of the roads and both their poverty and paucity must have rendered regular organised supply trains impracticable. Similarly as regards food supplies little could have been carried. Like the French about 1811 and 1812, necessity must have rendered the soldiers hardy and self-dependent, though of course at the cost of the civil population. Thus it is said of the French troops in 1811 that they “were trained to reap the standing corn, and grind it by portable mills into flour; if green, they mowed it down with equal dexterity for their horses; if reaped (and hidden away by the inhabitants), they forced it from the peasants’ place of concealment, by placing the bayonet to their throats.” And Wellington himself writes, that “the French armies in Spain have never had any secure communications beyond the ground which they occupy; and provided the enemy opposed to them is not too strong for them, they are indifferent in respect to the quarter from which their operations are directed, or upon which side they carry them on.”

And, later, the French “live by the authorised and regular plunder of the country if any should remain; they suffer labour, hardships, and privations every day; they go on without pay, provisions, money, or anything, but they lose in consequence half their army in every campaign.” This accounts for the enormous losses of the rank and file in the early days of the nineteenth century, while the losses in the fifteenth century, with little or no medical or surgical knowledge for the aid of sick and wounded, can only be surmised.

History, military history especially, always repeats itself in pointing out the necessary results of such unsystematically organised systems.

The early part of the seventeenth century saw a considerable alteration in the armament of the soldiery, and, notwithstanding the increasing use of gunpowder, body armour long continued to be worn. On it was lavished the highest skill of the artisan in its workmanship, and the highest taste of the artist in its decoration by engraving and inlaying. But the firearm, a matchlock, had, to all intents and purposes, everywhere superseded the bow, so that even in Elizabeth’s reign leg-armour was falling into disrepute, and, except in the corselet or cuirass, was steadily lessening in weight. Buff coats with sleeves, leather gauntlets, and leather boots were lighter than iron; just as useful against a sword-cut, and no worse against a shot. What little armour was left soon became too heavy to wear.

Even James I. thought that the heavy armour of his time was “an excellent invention, for it not only saved the life of the wearer, but prevented his hurting anybody else”;9 while “Dugald Dalgetty” found the metal thigh-pieces were powerless to stop the bullets of the firearms used by those who pursued him when he escaped from “that high and mighty prince,” the Duke of Argyle. To summarise the gradual disuse of arms from Tudor times to those of Anne, it may be stated that though body armour and the helmet were long used, the former had become but a cuirass to which a short skirt of metal was attached. The helmet became more open; still36 covering the head, the back of the neck and ears, but the face was only guarded by a “nasal” (like that of the time of the Conqueror somewhat), which could be moved up or down, or by a triple bar attached to the peak, which could be raised bodily like the visor was. This soon gave way to the mere iron “pot-helmet” without any face guards; and when this went, the cuirass soon followed. Last of all, the neck-piece or gorget was worn finally as a mere ornament. For mounted men the lance disappeared, and the sword, pistol, carbine, or “dragon” took its place. On foot, as the musket became general, the ammunition was long carried in a bandolier. But in addition to the firearms, or “shot,” there were pikemen carrying plain pikes eighteen to twenty-four inches long, and forming an important part of the infantry.

Naturally, therefore, by degrees the proportion of firearms in the battaglia (whence comes our modern “battalion”) increased, and the formation of definite fighting units, such as brigades, by Gustavus Adolphus, Maurice of Nassau, and others, began to make the force more capable of direction and control. De Rohan in France, too, devised regiments on what were then scientific principles. His were composed of 600 pikes, 600 musketeers, and 240 swordsmen, and, later, cavalry were placed between these massive battalions. Speaking generally, the artillery was little moved, and remained stationary during a battle. The cavalry charged sword in hand or with pistols, and the infantry received the charge with the pike or partially met it by fire. But with an improved artillery arose also the necessity for ammunition and other supply trains from fixed magazines, and hence more careful strategy based on care for these magazines or “bases of operations,” and regard for the roads “or lines of communication” leading from them to the army, influenced the conduct of campaigns; so also did the introduction of superior organisation.

For food supplies, armies on the move were still dependent on the good-will of the people, open markets, or plunder. It was long before the supply of troops formed part of the37 serious study of the art of war. There was yet but little change in the method of fighting. Artillery as an “arm” was not. Rupert thought still that cavalry was the principal arm and could do anything. Cromwell alone recognised what trained infantry could be made to do.

It is only here and there that strategical enterprise is apparent, while the old tactical methods too were changing, but very slowly. Mr. Ward in his Animadversions of War, dated 1639, shows the cavalry formed five ranks deep, and (as the battles show) an undue dependence was placed on this arm, though in the early battles it, seriously, effected little, and was rather a cause of disaster than of victory. They were armed with firearms of sorts and the sword, the lance of the Middle Ages having fallen into complete disuse. They were classed as cuirassiers, arquebusiers, carbineers, and dragoons; but all fought much the same way, and were, taken altogether, rather mounted infantry than true cavalry. Each battaglia, even as late as 1677, so says Lord Orrery in his Act of War, had still one-third of its number “pikes”; the remainder, as “shot,” were assembled in groups at the four angles of the mass of pikes, which were ten ranks deep; but at the beginning of the Civil War the proportion of pikes to shot was about one-half. No wonder that the weapon “which never missed fire,” and was sixteen feet long, for many a year was all-important, and that the heavy arquebus, a matchlock with a rest which trailed, was long looked on as an adjunct, not as the primary weapon of the foot-soldier. The weapon was fired by a slow match, and one common stratagem at night, in retreat, was to leave these matches attached to the branches of trees in a hedgerow, to make believe that it was still held after the defenders had actually fallen back.