Title: Wanderings in Spain

Author: Théophile Gautier

Translator: Thomas Robert McQuoid

Release date: August 9, 2016 [eBook #52763]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Josep Cols Canals, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

BY

THÉOPHILE GAUTIER.

With numerous Engravings.

LONDON:

INGRAM, COOKE, AND CO.

MDCCCLIII.

WANDERINGS IN SPAIN.

BY

THÉOPHILE GAUTIER.

With numerous Engravings.

LONDON:

INGRAM, COOKE, AND CO.

MDCCCLIII.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| FROM PARIS TO BORDEAUX. | |

| PAGE | |

| Departure from Paris—Subterranean Dwellings—Château Regnault—Tours—Châtellerault— Angoulême—The Landes—Cubzac—Bordeaux—The Theatre—The Cathedral— St. Michael's Tower—Mummified Corpses—The Museum | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| FROM BORDEAUX TO VERGARA. | |

| The Landes—Arrival at Bayonne—Information for Travellers—Urrugne— Saint Jean de Luz—Human Smuggling—Bridge over the Bidassoa—Irun—Travelling with Mules— Primitive Carts—Beggar Children—Spanish Bridges—Oyarzun—Astigarraga— A Spanish Supper—Puchero—Arrival at Vergara | 11 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| FROM VERGARA TO BURGOS. | |

| Vergara—Vittoria: the Baile Nacional and the French Hercules—The Passage of Pancorbo— The Asses and the Greyhounds—Burgos—A Spanish Fonda—Galley Slaves in Cloaks— The Cathedral—The Coffer of the Cid | 20 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| BURGOS—continued. | |

| The Cloisters; Paintings and Sculptures—The Cid's House; the Casa del Cordon; the Puerta de Santa Maria—The Theatre and the Actors—La Cartuja de Miraflores—General Thibaut and the Cid's bones | 34 |

| CHAPTER V.[iv] | |

| FROM BURGOS TO MADRID. | |

| El Correo Real; the Galeras—Valladolid—San Pablo—A Representation of Hernani— Santa Maria—Madrid | 47 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| MADRID. | |

| Bull-fights—The Arena—Calesins—Espadas, Chulos, Banderilleros, and Picadores— Sevilla the Picador—La Estocada a Vuela Pies | 59 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| MADRID—continued. | |

| The Prado—The Mantilla and Fan—The Spanish Type—Water-Merchants; Coffee-houses of Madrid—Newspapers—The Politicians of the Puerta del Sol—Post-Office—The Houses of Madrid—Tertullias; Spanish Society—The Teatro del Principe—The Queen's Palace; the Palace of the Cortes, and the Monument of the Dos de Mayo—The Armeria and El Buen Retiro | 73 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| VISIT TO THE ESCURIAL. | |

| Aridity and Desolation of the Country—First View of the Escurial—Sombre appearance of the building—The Church—The blind Cicerone—The Pantheon Pictures—Anecdote of Spanish Robbers | 103 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| EXCURSION TO TOLEDO. | |

| Illescas—The Puerta del Sol—Toledo—The Alcazar—The Cathedral—The Gregorian and Mozarabic Ritual—Our Lady of Toledo—San Juan de los Reyes—The Synagogue— Galiana, Karl, and Bradamant—The Bath of Florinda—The Grotto of Hercules—The Cardinal's Hospital—Toledo Blades | 113 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| MADRID TO GRANADA. | |

| Procession of the Corpus Christi at Madrid—Aranjuez—A Patio Ocaña and its Environs— Tembleque and its Garters—A Night at Manzanares— [v] Santa Cruz Knives—The Puerto de los Perros—Colony of Carolina—Baylen—Jaen, its Cathedral and its Majos—Granada—The Alameda—The Alhambra—The Generalife— The Albaycin—Life at Granada—The Gitanos—The Carthusian Convent—Santo Domingo— Ascent of the Mulhacen | 144 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| FROM GRANADA TO MALAGA. | |

| The Robbers and Cosarios of Andalusia—Alhama—Malaga—Travelling Students— A Bull-Fight—Montes—The Theatre | 208 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| FROM MALAGA TO SEVILLE. | |

| Four-wheeled galera—Caratraca—The "Mayoral"—Ecija—The "Calle de los Caballeros"—La Carlotta—Cordova—The Archangel Raphael—The Mosque— Caliph Abderama—The Guadalquiver—Road to Seville | 236 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| SEVILLE. | |

| Seville—The Cristina—The Torre del Oro—Italica—The Cathedral—The Giralda— The Alcazar—The Caridad and Don Juan de Marana | 258 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| FROM CADIZ TO BARCELONA AND HOME. | |

| Cadiz—Visit to the brig "Le Voltigeur"—The Rateros—Jeres—Bull-fights—The Steamer—Gibraltar—Carthagena—Valencia—The Lonja de Seda—The Convent de la Merced—The Valencians—Barcelona—The Return to France | 274 |

| THE GATE OF VIVARAMBLA | Frontispiece. |

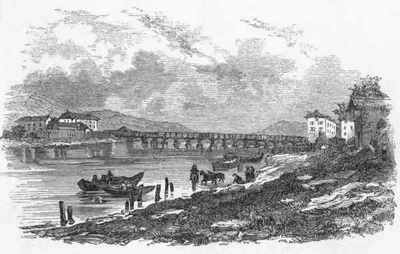

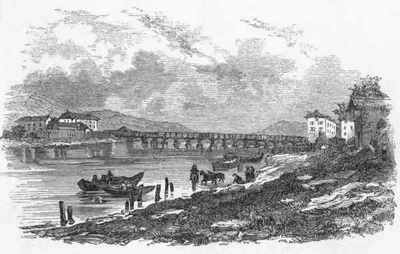

| THE BRIDGE OF IRUN | Vignette in Title. |

| BORDEAUX | p. 6 |

| PASS OF PANCORBO | 25 |

| CLOISTERS, BURGOS CATHEDRAL | 30 |

| PUERTA DE SANTA MARIA | 41 |

| SEVILLA THE PICADOR | 66 |

| LADIES ON THE PRADO | 75 |

| FOUNTAIN AT MADRID | 80 |

| MADRID | 95 |

| THE ESCURIAL | 105 |

| STREET IN TOLEDO | 118 |

| VEGA DE GRANADA | 163 |

| WELL DE LAS ALGIVES, ALHAMBRA | 180 |

| EXTERIOR OF THE ALHAMBRA | 182 |

| PAVILION OF THE COURT OF LIONS, ALHAMBRA | 185 |

| FOUNTAIN, COURT OF LIONS, ALHAMBRA | 187 |

| MALAGA FROM THE ALAMEDA | 219 |

| MOSQUE, CORDOVA | 251 |

| CHAPEL IN MOSQUE, CORDOVA | 253 |

| MOORISH MILLS, CORDOVA | 255 |

| TORRE DEL ORO | 262 |

| HALL OF DON PEDRO, THE ALCAZAR, SEVILLE | 270 |

| CITY GATE, VALENCIA | 297 |

WANDERINGS IN SPAIN,

ETC. ETC.

A few weeks ago (April, 1840), I happened, in an off-hand manner, to give utterance to the following phrase:—"I should like to go to Spain." Five or six days afterwards, my friends had suppressed the prudent "I should like," with which I had qualified my wish, and had told every one who chose to listen that I was about to undertake a trip to Spain. This positive formula was soon followed by the interrogation, "When do you set out?" while I, without thinking of the obligation under which I was placing myself, replied, "In a week." At the end of the week people began to manifest some astonishment at seeing me still in Paris. "I thought you were at Madrid," said one. "What! come back?" asked another. I saw at once that I owed my friends an absence of several months, and that I must pay the debt with the least possible delay, unless I wished to be mercilessly pursued, without a moment's respite, by my obliging creditors. The lobbies of the theatres, the various asphaltic and bituminous pavements of the Boulevards, were to me forbidden luxuries for the time being. All I could obtain was the grace of three or four days, and[2] on the 5th of May I commenced relieving my native land of my importunate presence, by scrambling into the Bordeaux diligence.

I shall pass very rapidly over the first few posts, which possess nothing worthy of observation. Right and left stretch all kinds of crops, streaked like tiger or zebra skins, and bearing a most satisfactory resemblance to a tailor's book, in which are pasted his various specimens of trowsers and waistcoat patterns. Although these kinds of views are productive of great delight to farmers, landlords, and other worthies of a similar stamp, they afford but meagre entertainment to the enthusiastic and graphic traveller, who, spy-glass in hand, sets out to note the peculiarities of the universe in the same manner as a police agent does those of an individual. Having left Paris in the evening, my first impressions, after passing Versailles, are but so many feeble sketches stumped in by the hand of Night. I regret that I passed through Chartres without being able to see its cathedral.

Between Vendôme and Château-Regnault, which is pronounced Chtrnô in the language of the postilions, so well imitated by Henri Monnier in his sketch of the "Diligence," there rise a number of well-wooded hills, where the inhabitants dig their houses out of the living rock, and live under ground, after the fashion of the ancient Troglodytes. The stone obtained from these excavations they sell, so that each house thus scooped out produces another en relief, like a plaster figure taken out of a mould, or a tower dragged out of a well. The chimney, which is a long passage hammered through the rock, ends at the surface, so that the smoke ascends from the ground itself in bluish spirals, and without any visible cause, exactly as if it proceeded from a sulphur mine, or from some volcano. A facetious traveller would not experience the slightest difficulty in throwing stones into the omelets of this cryptic population, and the rabbits, if they are ever absent or short-sighted, must certainly fall, very often, all alive, into the saucepans. By constructing houses on this principle, the trouble of going down into the cellar to fetch your wine is entirely avoided.

Château-Regnault is a small town built upon a number of serpentine and rapid declivities, bordered by ill-pitched and tottering houses, which appear to lean against one another to keep themselves upright. A large round tower, situated upon the talus of some old fortifications, enveloped here and there in green patches of ivy, redeems, to a certain extent, the appearance of the town. From Château-Regnault to Tours there is nothing remarkable. Earth in the middle, and trees on each side, forming those long yellow bands, which lose themselves in the distance, and which, in the language of the wagoners, are termed rubans de queue, are all that is to be seen:[3] then, on a sudden, the road dives down a couple of pretty steep hills, and in a few minutes you perceive the town of Tours, rendered famous by its prunes, Rabelais, and de Balzac.

The Bridge of Tours is very celebrated, and possesses in itself nothing exceedingly remarkable; but the appearance of the town is lovely. On my arrival, the sky, with a few flakes of snow floating negligently over its surface, was tinged with the sweetest blue; a white line, similar to that traced by a diamond upon glass, cut the limpid surface of the Loire, and was formed by a tiny cascade proceeding from one of the sand-banks so frequent in the bed of this river. In the clear air, Saint Gatien reared its brown profile and Gothic spires, ornamented with balls and roundings similar to those of the steeples of the Kremlin, giving to the city a most romantically Muscovite air; a few other towers and spires, belonging to churches the names of which I do not know, completed the picture; while numerous vessels, with their white sails, floated, like so many sleeping swans, upon the azure bosom of the stream. I should have liked to have paid a visit to the house of Tristan l'Ermite, the terrible gossip of Louis XI., which is still in a marvellous state of preservation, with its horribly significant ornaments, composed of coils of rope, entwined with other instruments of torture; but I had not time; I was obliged to content myself with the Grande Rue, which must be the pride of the inhabitants of Tours, and which aspires to the rank of another Rue de Rivoli.

Châtellerault, which enjoys a high reputation for the article of cutlery, possesses nothing particular except a bridge, ornamented at each extremity with old towers, which present a most charmingly feudal and romantic appearance. As for its manufactory of arms, it is a large white mass, with a multitude of windows. Of Poitiers, having passed through it in a beating rain, and a night as dark as pitch, I can say nothing, except that it is paved in the most execrable manner possible.

At break of day, the coach was traversing a country wooded with trees of an apple green planted in a soil of the brightest red, and producing a very singular effect. The houses were covered with tiles ridged after the Italian fashion; these tiles, too, were staring red, a colour which appears very strange to eyes accustomed to the brown and sooty roofs of the houses of Paris. From a piece of eccentricity, of which I forget the motive, the builders of those parts commence at the roofs of the houses; the walls and foundations follow. They place the framework upon four strong beams, and the tilers perform their portion of the work before the masons.

It is about this spot that the long orgy of stone commences,[4] which ends only at Bordeaux. The smallest hut, without doors or windows, is of stone; the walls of the gardens are formed of large blocks placed one above the other without mortar; along the road, by the side of the doors, you perceive enormous heaps of superb stone, with which it would be easy, at a trifling expense, to build new Chenonceaux and Alhambras. The inhabitants, however, are contented with piling them in squares, and surmounting the whole with a cover of red or yellow tiles, the different forms of which compose a festoon of a tolerably graceful effect.

The town of Angoulême, queerly perched on an extremely steep hill, at the foot of which the Charente turns two or three babbling mills, is built in the same manner. It has a kind of second-hand Italian look, which is increased still more by the thick masses of trees which crown its rugged eminences, and a tall parasol-shaped pine, like those of the Roman villas. An old tower, which, if my memory does not deceive me, is surmounted by a telegraph (many old towers have been saved by a telegraph), imparts a tone of severity to the general aspect of the town, and renders it a tolerably imposing object on the edge of the horizon. While toiling up the ascent, I remarked a house daubed externally with rude frescoes representing something like Bacchus, Neptune, or perhaps Napoleon. As the artist forgot to paint the name underneath, every supposition is admissible and capable of being defended.

As yet, I confess that an excursion to Romainville or Pantin would have been quite as picturesque. Nothing can be more flat, more inane, more insipid, than these interminable strips of ground, similar to the little bands with which lithographers enclose all the Boulevards of Paris in one sheet of paper. Hedges of hawthorn and consumptive-looking elms, consumptive-looking elms and hedges of hawthorn, with, a little further on, a row of poplars, resembling a number of green feathers stuck in a flat soil, or perhaps a solitary willow, with its deformed trunk and powdered wig, compose the landscape; while, for figures, you have that of some pionnier, or cantonnier, as sunburnt as a Moor, leaning upon the handle of his long hammer as he looks at you pass by, or else some poor soldier rejoining his regiment, and sweating and staggering under his harness. Beyond Angoulême, however, the physiognomy of the soil changes, and you begin to feel that you are at a certain distance from the suburbs of the Capital.

It is on leaving the Department of the Charente that the traveller meets with the first of the Landes, those monster patches of grey, violet, and bluish land, diversified with undulations of various depths. A kind of short and scanty moss, red-tinged heather, and some dwarf broom compose all the vegetation. The desolation is[5] that of the Egyptian Thebaid, and every minute you expect to see a file of dromedaries and camels; it seems as if the spot had never been pressed by the foot of man.

After traversing the Landes, you enter a tolerably picturesque region. Here and there along the road are groups of houses, concealed like birds' nests in the thickets. These houses remind one of the pictures of Hobbema, with their large roofs, their walls over-run with wild vine, their well-grown wondering-eyed oxen and their poultry foraging on the dung-hills. All the houses, by the way, as well as the garden walls, are built of stone. On every side are to be seen the beginning of buildings afterwards abandoned out of pure caprice, and recommenced a few paces further on. The inhabitants almost resemble children when they get a birthday present of a "box of bricks," with which, by the aid of a certain number of square-cut pieces of wood, all sorts of edifices may be constructed. They unroof their houses, remove the stones, and with the very same ones build another edifice of a totally different character. On the road-side are blooming gardens, surrounded by fine trees with beautifully fresh foliage, and variegated with peas in blossom, daisies, and roses; the eye at the same time roaming over meadows, where the cows are almost hidden by the grass which reaches to their breasts. A cross path all redolent of hawthorn and eglantine, a group of trees, beneath which is seen an empty wagon, a country-girl or two, with their spreading caps like the turban of the Turkish Ulemas, and with their narrow yellow skirts, offer a thousand little unexpected details which charm the eye and diversify the route. By slightly glazing the scarlet tint of the roofs with a little bitumen, you might think yourself in Normandy. Flers and Cabat would here find pictures ready made to their hand. It is about this latitude that the "berets" begin to show themselves. They are all blue, and the elegance of their form is greatly superior to that of the hat.

Hereabouts, too, the first vehicles drawn by oxen are to be met with. These wagons have rather a Homeric and primitive appearance. The oxen are harnessed by the head to a common yoke covered with a small head-piece of sheepskin. They have a mild, grave, and resigned look, which is pre-eminently sculptural, and worthy of the Elginetic bas-reliefs.

Most of them wear a covering of white cloth, which serves as a protection against the flies and other insects. Nothing is more singular than to see these oxen, dressed en chemises, raise towards you their humid and lustrous muzzles and their large deep blue eyes, which the Greeks, who were certainly judges of beauty, thought sufficiently remarkable to furnish the sacramental epithet of Juno—Boopis Ere.

A marriage, which happened to be in course of celebration at an inn, afforded me an opportunity of seeing some of the natives of these parts assembled together; for in a distance of more than a hundred leagues I had not perceived ten persons. These said natives are excessively ugly, especially the women: there is no difference between the old and the young ones; a countrywoman of five and twenty is as haggard and wrinkled as one of sixty. The little girls wear caps quite as developed as those of their grandmothers, which makes them look like the Turkish boys in Decamp's sketches, with their enormous heads and slender bodies. In the stable of the inn I saw a huge black he-goat, with immense twisted horns and glaring yellow eyes. He had a hyper-diabolic appearance, and would, in the middle ages, have made a most worthy president at a witches' sabbath.

Evening was beginning to set in when we arrived at Cubzac. Formerly the Dordogne used to be traversed in a ferry-boat, but the breadth and rapidity of the stream rendered the passage dangerous, and the boat is, at present, replaced by a suspension bridge of the most daring construction. It is well known that I am no very great admirer of modern innovations, but this bridge is really a work worthy of Egypt or of Rome for its colossal dimensions and the grandeur of its appearance. Piers formed by a succession of arches, which gradually increase in height, lead to the suspended platform, beneath which vessels can pass in full sail, as they did between the legs of the Colossus of Rhodes. Tower-shaped buildings of cast iron, with openings to render them lighter, serve as supports to the iron chains, which are crossed with a most skilfully calculated symmetry of resistance, and which stand out against the background of the sky with the fineness and delicacy of a spider's web, thereby adding still more to the wonderful effect of the whole. Two obelisks of cast iron are placed at each end, as if before the peristyle of some Theban monument, and form a kind of ornament not at all out of place; for the gigantic architectural genius of the Pharaohs would not be ashamed to own the Bridge of Cubzac. It requires thirteen minutes, watch in hand, to cross it.

Two or three hours afterwards, the lamps of the Bridge of Bordeaux, another, although less striking wonder, were gleaming at a distance which my appetite could have wished considerably shorter, for speed in travelling is always bought at the expense of the stomach. After having exhausted all our sticks of chocolate, biscuits, and the other ordinary provisions for a journey, we began to entertain slightly cannibal ideas. My companions looked on me with famishing eyes, and if we had had another stage, we should have renewed the horrors of the raft of the Medusa, and eaten our braces,[7] the soles of our boots, and our Gibus hats, besides all the other articles in request among shipwrecked individuals, who digest this kind of food in the most satisfactory fashion.

On leaving the diligence, you are assailed by a crowd of porters, who take possession of your luggage at the rate of twenty to each pair of boots. This is usual enough, but the most ridiculous part of the business is the kind of gaolers stationed by the hotel proprietors, as vedettes, to seize upon the traveller as he goes along. All these wretches cry themselves hoarse and create a confusion equal to that of the Tower of Babel, by their long litanies of praise and abuse. One catches hold of your arm, another of your leg, a third of the tail of your coat, a fourth of the button of your paletôt. "Come to the Hotel of Nantes, sir; you will find everything very comfortable there." "Don't go there, sir; its real name is the Hotel of Bugs," immediately replies the representative of a rival establishment. "Hôtel de France," "Hôtel de Rouen," holla the crew, pursuing you with their vociferations. "They never clean their saucepans, sir; they cook all their dishes with lard. The rain comes through into their rooms; you will be robbed, plundered, assassinated." Each one endeavours to disgust you with every place but his own, and the band never leaves you until you enter, definitively, one particular hotel. They then quarrel among themselves, exchange blows, call each other thieves, robbers, and other epithets of the like description, and finish by hastening away in pursuit of fresh prey.

Bordeaux resembles very closely Versailles in the style of its buildings. The same idea of surpassing Paris in magnificence is very manifest. The streets are broader, the houses larger, the[8] rooms higher. The dimensions of the theatre are enormous. It looks like the Odéon melted down into the Bourse. But it is in vain that the inhabitants endeavour to fill their city. They exert themselves to the utmost to appear numerous, but all their meridional turbulence is not sufficient to people their disproportioned structures. The lofty windows have rarely any curtains, and the melancholy grass grows in the immense court-yards. The grisettes and the women of the lower orders, who are really very pretty, lend animation to the place. Almost all have a Grecian nose, flat cheek bones, and large black eyes placed in a pale oval face of the most pleasing kind. Their head-dress is very original, being composed of a bright coloured silk handkerchief, worn after the Creole fashion, very far back, and confining their hair, which falls rather low down upon their neck. The remainder of their costume consists of a large straight shawl descending to their heels, and a print gown with long folds. These women are quick and lively in their movements, and possess a supple, well-formed, and naturally delicate figure. They carry upon their heads their baskets, parcels, and water-jugs, which, I may mention by way of parenthesis, are of the most elegant form. With their amphora on their head, and the long folds of their dress, they might be taken for Greek girls, or the princess Nausicaa going to the fountain.

The Cathedral, built by the English, is rather fine; the portal contains statues of bishops as large as life, executed in a much more natural and careful style than the ordinary Gothic statues, which are handled like arabesques, and completely sacrificed to the exigencies of the architect. On visiting the church, I saw, placed against the wall, the magnificent copy of Christ Scourged, by Riesener, after Titian: it is waiting for a frame.

From the Cathedral, my companion and myself proceeded to the Tower of St. Michael, where there is a vault which possesses the power of mummifying the bodies placed there. The lowest story of the tower is inhabited by the keeper and his family, who cook their victuals at the entrance of the cavern, and live on a footing of the most intimate familiarity with their frightful neighbours. The man took a lantern, and we descended by the worn steps of a winding staircase into the funeral vault. The corpses, about forty in number, are placed around the vault, with their backs against the wall. This upright position, so different from the general horizontal posture of the dead, gives them a horribly phantom-like appearance of life, especially in the yellow and flickering light of the lantern, which oscillates in the hand of the guide, and causes the shadows to change their place every instant. The imagination of poets and[9] painters has never produced a more horrible nightmare; the most monstrous caprices of Goya, the raving productions of Louis Boulanger, the diabolical creations of Callot and of Teniers, are nothing in comparison, and all the most fantastic writers of ballads are here surpassed. Never did more abominable spectres rise from out the night of a German mind. They are worthy of figuring at the midnight orgies of the Brocken with the witches of Faust. Their faces are distorted and grinning; their skulls have half the flesh peeled off; their sides gape open, exposing, through the grating of their ribs, their lungs, dried and shrivelled up like sponge. In one instance the flesh has crumbled into dust, and the bones protrude; in another, the parchment skin, no longer sustained by the fibres of the cellular tissue, floats round the corpse like a second windingsheet. Not one of the heads possesses that impassible calmness which death imparts, as a last seal, to those whom it touches. Their mouths gape frightfully, as if drawn asunder by the immeasurable weariness of eternity, or grin with the sardonic grin of Nothingness which laughs life to scorn. Their jaws are dislocated, and the muscles of the neck swollen. Their fists are furiously clenched, and their spines writhe in the contortions of despair. They appear enraged at being moved from their tombs, and troubled in their sleep by the curiosity of the profane.

The keeper pointed out to us a general killed in a duel; the wound, like a large blue lipped mouth laughing in his side, is distinctly visible;—a porter who expired suddenly while lifting an enormous burden;—a negress, who is not much blacker than her white sisters near her;—a woman with all her teeth, and with her tongue almost fresh;—a family poisoned with mushrooms;—and, as a crowning horror, a little boy who, to all appearance, must have been interred alive. This figure is sublime with pain and despair; never was the expression of human suffering carried to a greater extent. The nails are buried in the palms of the hands; the nerves are stretched like the strings of a violin over the bridge; the knees form convulsive angles; and the head is violently thrown back. The poor child, by an extraordinary effort, must have turned round in his coffin.

The place where these corpses are assembled is a low-roofed vault. The soil, which is of suspicious elasticity, is composed of human detritus, fifteen feet deep. In the middle is raised a pyramid of remains in a tolerable state of preservation. These mummies emit a faint and earthy smell, more disagreeable than the acrid perfumes of bitumen and Egyptian natron. Some of the bodies have been in their present abode two or three hundred years, while others have[10] been placed there sixty years only: the cloth of their shrouds or winding-sheets is yet in a tolerably perfect condition.

On leaving the cavern, we proceeded to view the belfry, composed of two towers, united at the summit by a balcony of a most original and picturesque design. We afterwards went to the Church of Sainte-Croix, next to the Hospice des Vieillards.

The portal is enriched with a multitude of groups, which rather boldly carry out the command: Crescite et multiplicamini. Fortunately the flowery and tufted arabesques soften whatever degree of eccentricity this method of rendering the text of Holy Writ might otherwise possess.

The Museum, which is situated in the magnificent Mansion-house, contains a fine collection of plaster casts and a great number of remarkable pictures; among others, two small canvasses of Bega, which are two pearls of inestimable value: they unite the warmth and freedom of Adrien Brauwer with the delicacy and the peculiarity of Teniers. There are also some extremely delicate specimens of Ostade, some of the most quaint and fantastic creations of Tiepolo, some Jordaens, some Van Dycks, and a Gothic painting, which must be by Ghirlandajo or Fiesole. The Museum at Paris possesses nothing in the way of Middle Age art which is worth it; it is impossible, however, for the pictures to be hung with less taste and discrimination; the best places are occupied by enormous daubs of the modern school, contemporary with Guérin and Lethiers.

The port is crowded with vessels of all nations and every burden. In the haze of twilight, they might be taken for a multitude of floating cathedrals—for nothing more resembles a church than a ship, with its spire-like masts, and the tangled tracery of its rigging. To finish the day, we went to the Grand Théâtre. Our conscience obliges us to say that it was full, although they were playing La Dame Blanche, which is anything but a novelty. The interior is nearly as large as that of the Grand Opera at Paris, but with much less ornament about it. The actors sang as much out of tune as at the real Opéra Comique.

At Bordeaux, the influence of Spanish customs begins to be felt. Almost all the sign-boards are in the two languages, and the book-sellers have quite as many Spanish as French publications. A great number of persons can hablar in the idiom of Don Quixote and Guzman of Alfarache. This influence increases as you approach the frontier; and, in fact, the Spanish portion, in this half-tint of demarcation, carries off the victory from the French—the patois spoken by the inhabitants having much more resemblance to Spanish than to the language of the mother country.

On leaving Bordeaux, the Landes recommence, if possible more sad, more desolate, and more gloomy than before. Heather, broom, and pinadas (pine forests), with here and there a shepherd squatted down, tending his flocks of black sheep, or a miserable hut in the style of the Indian wigwams, offer a very lugubrious and by no means diverting spectacle. No tree is seen but the pine, with the gash in it from which the resin trickles down. This large salmon-coloured wound forming a strong contrast with the grey tones of the bark, gives the most miserable look in the world to these sickly trees, deprived of the greatest portion of their sap. They have the appearance of a forest unjustly assassinated, raising its arms to Heaven for justice.

We passed through Dax at midnight, and traversed the Adour during the most wretched weather, with a beating rain and a wind strong enough to blow the horns off an ox. The nearer we approached a warmer climate, the sharper and more penetrating became the cold; and had not our cloaks been at hand, we should have had our noses and feet frost-bitten, like the soldiers of the Grande Armée in the Russian campaign.

When day broke we were still in the Landes, but the pines were mingled with cork-trees, which I had hitherto pictured to my mind only under the form of corks, but which are really enormous trees,[12] partaking simultaneously of the nature of the oak and of the carob-tree in the eccentricity of their shape and the deformity and ruggedness of their branches. A number of blackish pools of a leaden colour, stretched on each side of the road; gusts of saltish air greeted our nostrils, and a sort of vague rumbling noise resounded on the horizon. A bluish outline next stood out upon the pale background of the heavens. It was the chain of the Pyrenees. A few instants afterwards an almost invisible line of azure, the sign of the ocean, told us that we had arrived. It was not long ere Bayonne rose up before us, in the form of a mass of tiles crushed by an awkward and squat-looking spire; but I will not abuse Bayonne, since any town viewed under the disadvantage of rainy weather is always wretched. The port was not very full. A few decked boats floated in a negligent and admirably idle manner alongside the quays. The trees which form the public promenade are very fine, and somewhat soften the austerity of the numerous right lines produced by the fortifications and parapets. As to the church, it is plastered over with yellow, varied with a dirty fawn; it possesses nothing remarkable save a kind of baldaquin of red damask, and a few paintings of Lépicié and others, in the style of Vanloo.

The town of Bayonne is almost Spanish in its language and customs; the hotel where we put up was called the Fonda San Estaban. As it was known that we were about making a long trip in the Peninsula, we were pursued with all sorts of recommendations. "Buy some red belts to sustain your body; arm yourselves with blunderbusses, combs, and bottles of water to kill the insects; take some biscuits and other provisions; the Spaniards breakfast on a spoonful of chocolate, dine on a piece of garlic washed down with a little water, and sup on a paper cigar; you ought also to take a mattress and a saucepan to serve as your bed and make your soup." The French and Spanish Dialogues, too, for the use of travellers, were not very encouraging. Under the head of "A Traveller at an Inn," we read the following frightful conversation—"I should like to take something." "Take a chair," replies the landlord. "With pleasure; but I should prefer something more nutritious." "What have you brought?" replies the master of the posada. "Nothing," says the traveller, sadly. "Then how can you suppose I can give you anything to eat? The butcher lives yonder, the baker a little further on. Go and get some meat and bread, and my wife, who is something of a cook, will prepare your provisions." The traveller, in a fury, begins creating a most frightful disturbance, and the host calmly puts into his bill—"Disturbance, 6 reals."

The Madrid coach sets out from Bayonne. The conductor is a mayoral, with a peaked hat adorned with velvet and silk tufts, a brown waistcoat embroidered with coloured ornaments, leather gaiters, and a red sash; these impart a nice little amount of local colouring. Beyond Bayonne, the country is exceedingly picturesque; the chain of the Pyrenees becomes more distinct, and beautifully undulating lines of mountains vary the aspect of the horizon, while the sea appears frequently to the right of the road. At each turn, between two mountains, its sombre mild and deep blue suddenly starts into sight, traversed, here and there, by volutes of foam whiter than snow, which no painter has, as yet, succeeded in re-producing. I here beg to apologise to the sea, never having seen it before but at Ostend, where it is nothing more than the Scheldt, transformed into a canal, as my dear friend Fritz used so wittily to express it.

We passed through the church of Urrugne, the dial of which has the following mournful inscription, in black letters, on it—"Vulnerant omnes, ultima necat." Yes, melancholy dial, you are right. Each hour wounds us with the sharp point of your hands, and each turn of your wheel hurries us towards the Unknown!

The houses of Urrugne, and of Saint Jean de Luz, which is not far distant, possess a sanguinary and barbarous physiognomy, owing to the strange custom of painting red or blood-colour the doors and the beams which sustain the compartments of the masonry. Beyond Saint Jean de Luz is Behobie, the last French village. On the frontier, the inhabitants practise two kinds of trade to which the war has given rise—first, that of the balls found in the fields, and, secondly, that of human smuggling. A Carlist is passed just like a bale of goods. There is a certain tariff, so much for a colonel, so much for an inferior officer. As soon as the bargain is struck, the contrabandist makes his appearance, carries off his man, passes him over the frontier, and smuggles him to his destination, as he would a dozen handkerchiefs or a hundred cigars. On the other side of the Bidassoa, Irun, the first Spanish village, is visible: one-half of the bridge belongs to France, the other to Spain. Close to this bridge is the famous Isle of Pheasants, where the marriage of Louis XIV. was celebrated by deputy. It would be difficult to celebrate anything there at present, for it is not larger than a moderately-sized fried sole.

A few more revolutions of the wheel, and I shall perhaps lose one of my illusions, and behold the Spain of my dreams, the Spain of the Romancero, of the ballads of Victor Hugo, of the tales of Merimée, and the stories of Alfred de Musset, fade before me. On passing the line of demarcation, I remembered what the good and[14] witty Henri Heine once said to me at Liszt's concert, with his German accent, full of humour and sarcasm, "How will you manage to speak of Spain when you have been there?"

One half of the bridge over the Bidassoa belongs to France, and the other half to Spain, so that you may have, at the same time, a foot in each kingdom, which is a great achievement. On one side you perceive the gendarme, grave, respectable, and serious; the gendarme red as a peony at having been restored to his social position by Edward Ourliac, in Curmer's "Français Peints par Eux-Memes;"[1] while, on the other, is beheld the Spanish soldier, clad in green, and enjoying on the sward the voluptuous pleasure of repose with happy nonchalance. At the extremity of the bridge, you enter at once into Spanish life, with all its local colouring. Irun does not possess a single feature in common with a French town. The roofs of the houses jut out beyond the walls, while the tiles, alternately round and hollow, give the houses a most strange and Moorish battlemented appearance. The ironwork of the balconies, which project over the street, is of the most elaborate description, very surprising in an out-of-the-way village like Irun, and indicating a great degree of opulence now passed away. The women spend their lives upon these balconies, which are shaded with an awning with coloured stripes, and which are like so many aërian chambers attached to the body of the edifice. The two sides remain open, and allow a passage to fresh breezes and burning glances; but you must not look, however, for those dull and culotté[2] tints (I beg pardon for the expression), those shades of bistre and old pipes that a painter might hope to see; everything is whitewashed, according to the Arabian fashion, but the contrast of this chalky tone against the deep brown of the beams, roofs, and balconies, is not without a fine effect.

The horses left us at Irun; and ten mules, shaved as far as the middle of their body—half skin, half hair—like those costumes of the middle-ages, which look as if they were two-halves of different suits sown together by chance, were then harnessed to the vehicle. These animals thus shaved present a strange sight, and appear most horribly thin; for this denudation enables you to see their whole anatomy, bones, muscles, and even the smallest veins. With their peeled tails and their pointed ears, they resemble so many enormous mice. Besides the ten mules, our band was increased by a zagal and two escopeteros, furnished with their trabuco (blunderbuss). [15]The zagal is a kind of under-mayoral, who puts the drag on whenever there is a dangerous descent, looks after the harness and the springs, hurries the relays, and plays about the coach the part of the fly in the fable, only with a great deal more effect. The costume of the zagal is charming, being most elegant and light. He wears a peaked hat, ornamented with silk tufts; a chestnut-coloured or brown jacket, surmounted by a collar composed of different coloured pieces, generally blue, white, and red; a large arabesque, which blossoms out upon the middle of his back, knee-breeches studded with filigree buttons, and for shoes, alpargatas, or sandals tied with thin cord. Add to all this a red sash and a variegated neck-tie, and you will have a most characteristic costume. The escopeteros are guards, or miquelets, whose office it is to escort the coach and frighten the rateros, as the petty robbers are termed, who would not resist the temptation of plundering a solitary traveller, but whom the edifying sight of the trabuco is sufficient to awe, and who pass on their way with the sacramental salutation of—Vaya Usted con Dios: "Pursue your road with God." The dress of the escopeteros is nearly the same as that of the zagal, but less coquettish and ornamented. They take up their position on the seat at the back of the coach, and thus command the country around. In this description of our caravan, I have forgotten to mention a little postilion, mounted on horseback at the head of the convoy, who leads off the whole line.

Before leaving, we had to get our passports, already pretty well covered with signatures, viséd. While this important operation was in course of performance, we had leisure to cast a glance at the population of Irun, which offers nothing very particular, unless it be that the women wear their hair, which is remarkably long, united in one plait hanging down to the middle of their back; shoes are a rarity, and stockings a still greater one.

A strange, inexplicable, hoarse, frightful, and laughable noise had astonished my ears for some time; it sounded like that of a number of jays being plucked alive, of children being whipped, of cats making love, of saws scraping their teeth against a hard stone, of tin-kettles scraped by some harsh instrument, or of the rusty hinges of a prison door turning round and obliged to release its prisoner; I imagined that it was, at the least, some princess being assassinated by a savage necromancer. It was nothing but a cart, drawn by oxen, ascending the street of Irun, and the wheels creaking and groaning piteously for want of being greased, the driver preferring, doubtless, to put the grease in his soup. This cart was, certainly, exceedingly primitive. The wheels were of one piece, and turned with the axle,[16] as is the case with those wagons which children manufacture out of the rind of a pumpkin. The noise can be heard at the distance of half a league, and is not displeasing to the aborigines of these parts. In this fashion they hear a musical instrument which costs nothing, and plays of its own accord as long as the wheel lasts. The noise is to them as harmonious as the feats of a violinist upon the fourth string are to us. A peasant would not give a "thank you" for a cart which did not play. This kind of vehicle must date from the deluge.

On an old palace, now transformed into an official residence, we beheld for the first time the placard of white plaster which disgraces many other old buildings, with the inscription—Plaza de la Constitucion. It must certainly be a fact, that whatever is concealed in anything comes out somehow or other; a better symbol of the actual state of the country could not have been selected. A constitution forced upon Spain is a handful of plaster upon granite.

As the ascent was toilsome, I walked as far as the gates of the town, and, turning round, cast a last look of farewell upon France. It was truly a magnificent sight. The chain of the Pyrenees sloped away in harmonious undulations towards the blue surface of the sea, crossed here and there by bars of silver; while, thanks to the excessive clearness of the air, in the far, far distance was seen a faint line of pale salmon-colour, which advanced in the immeasurable azure, and formed an immense indentation in the side of the coast. Bayonne and its advanced guard, Biarritz, occupied the extremity of this point, and the Bay of Biscay was mapped out as sharply as on a geographical chart. After this, we shall see the sea no more until we are in Andalusia. Good night, honest Ocean!

The coach ascended and descended at full gallop the most rapid declivities: a kind of exercise, without a balancing-pole, upon the tight rope, which can only owe its success to the prodigious dexterity of the drivers, and the extraordinary sure-footedness of the mules. Despite this velocity, however, there would, from time to time, fall in our laps a branch of laurel, a little nosegay of wild flowers, or a wreath of mountain strawberries—ruddy pearls strung upon a blade of grass. These nosegays were flung in by little beggars, boys and girls, who kept running after the coach with their bare feet upon the sharp stones. This manner of asking alms, by first making a present themselves, has something noble and poetic about it.

The landscape, though rather Swiss perhaps, was charming, and exceedingly varied. Mountain ridges, the interstices of which permitted the eye to dwell upon others more elevated still, rose up on each side of the road; their sides goffered with different crops and[17] wooded with green oaks, stood out vigorously against the distant and vapoury peaks. Villages, with their roofs of red tiles, bloomed amid thickets at the mountains' feet, and every moment I expected to see Ketly or Getly walk out of these new châlets. Fortunately, Spain does not push its Opéra Comique so far.

Torrents, as capricious as a woman, come and go, form little cascades, divide, meet each other again, after traversing rocks and flint stones, in the most amusing fashion, and serve as an excuse for a number of the most picturesque bridges in the world. These bridges, thus indefinitely multiplied, have a singular characteristic: the arches are hollowed out almost up to the very railing, so that the road over which the coach passes does not appear to be more than six inches thick. A kind of triangular pile, shaped like a bastion, generally occupies the middle. The business of a Spanish bridge is not a very fatiguing one; there was never a more perfect sinecure; three quarters of the year you can walk under it. There it stands, with an imperturbable calmness and patience worthy of a better lot, waiting for a river, a rill of water, or even a little moisture, for it feels that its arches are merely arcades, and that their title of "bridge" is pure flattery. The torrents I have just mentioned have at most but four or five inches of water in them, but they are sufficient to make a great deal of noise, and serve to give life to the solitudes which they traverse. At long intervals they turn some mill or other machinery, by means of sluices, built in a manner that would enchant a landscape-painter. The houses, which are scattered over the country in little groups, are of a strange colour. They are neither black, nor white, nor yellow, but of the colour of a roasted turkey. This definition is of the most striking truth, although it is trivial and culinary. Tufts of trees, and patches of green oaks, impart a happy effect to the large outlines and the misty and severe tints of the mountains. I dwell particularly upon these trees, because nothing is more rare in all Spain, and henceforth I shall hardly have occasion to describe any.

We changed mules at Oyarzun, and at nightfall reached Astigarraga, where we were to sleep. We had not yet had a taste of a Spanish inn. The picaresque and "lively" descriptions of Don Quixote and Lazarille de Tormes occurred to our memory, and our whole bodies shuddered at the very thought. We made up our minds to omelettes adorned with Merovingian hairs and mixed up with feathers and birds' feet, to gammons of rancid bacon with all the bristles, equally adapted for making soup or brushing boots, to wine in goat-skins, like those which the good knight de la Mancha cut so furiously into, and we even made up our minds to nothing at all,[18] which is much worse, and trembled lest all we should get would be the fresh evening breeze, supposing we were not obliged to sup, like the valorous Don Sancho, off the dry air of a mandoline.

Taking advantage of the little daylight that remained, we went to look at the church, which, to speak truth, was more like a fortress than a temple; the smallness of the windows, formed like loopholes, together with the solidity of the buttresses, gave it a robust and massive appearance, more warlike than pensive. This form occurs in every church in Spain. All around stretched a sort of open cloister, in which was hung a bell of immense size, which is rung by moving the clapper with a rope, instead of putting in motion the vast metal capsule itself.

On being shown to our rooms, we were dazzled with the whiteness of the beds and windows, the Dutch cleanliness of the floors, and the scrupulous care shown in every particular. Fine handsome, strapping girls, exceedingly well dressed, and with their magnificent tresses falling upon their shoulders, not bearing the slightest resemblance to the Maritornes we had been led to expect, bustled about with an activity that augured well for the supper, which did not keep us long waiting: it was excellent, and very well dished up. I will run the risk of appearing too minute, and describe it; for the difference between one people and another consists in the thousand little details which travellers neglect for those profound poetical and political considerations which anyone may very well write without ever having been in the country itself. First of all comes a meat soup, which differs from ours from the fact of its having a reddish tinge, due to the saffron with which it is flavoured. Red soup! I hope this is a pretty good commencement of local colouring. The bread is very white, of exceedingly close texture, with a smooth crust, slightly glazed over with yolk of egg; it is salted in a manner very apparent to Parisian palates. The handles of the forks are turned the wrong way, and the points are flat and shaped like the teeth of a comb. The spoons, too, have a spatula-kind of appearance not possessed by our plate. The table linen is a sort of coarse damask. As for the wine, I must confess that it was of the most beautiful violet, and thick enough to be cut with a knife, and the decanters which held it did not tend to increase its transparency.

After the soup, we had the puchero, an eminently Spanish dish, or rather the only Spanish dish—for they eat it every day from Irun to Cadiz, and reciprocally. A comfortable puchero is compounded of a quarter of veal, a piece of mutton, a fowl, some pieces of a sausage stuffed full of pepper, and called chorizo, with allspice and other spices, slices of bacon and ham, and, to crown all, a violent[19] tomato and saffron sauce. So much for the animal portion. The vegetable part, called verdura, varies with the season; but cabbages and garbanzos always play a principal part. The garbanzo is not much known at Paris, and I cannot define it better than "as a pea which aspires to be considered as a haricot-bean, and succeeds but too well." All this is served up in different dishes, and the ingredients then mixed up on your plate, so as to produce a Mayonnaise of a complicated description and excellent flavour. This mixture will appear rather barbarous to those connoisseurs who read Carême, Brillat-Savarin, Grimat de la Reynière, and Mons. de Cussy; it has, however, its charm, and cannot fail to please the Eclectics and Pantheists. Next come fowls cooked in oil, for butter is an article unknown in Spain; trout or salt cod, roasted lamb, asparagus, and salad; and, for dessert, little macaroons, almonds browned in a frying-pan, and of a most delicious taste, with goats'-milk cheese, queso de Burgos, which enjoys a high reputation, that it sometimes deserves. As a finish, they bring you a set of bottles with Malaga, sherry, brandy, aguardiente, resembling French aniseed, and a little cup (fuego) filled with live cinders to light the cigarettes. Such, with a few trifling variations, is the invariable meal in all Spain.

We left Astigarraga in the middle of the night. As there was no moon, there is naturally a gap in our account. We passed through the small town of Ernani, the name of which conjures up the most romantic recollections; but we did not perceive aught save a heap of huts and rubbish vaguely sketched on the obscurity. We traversed Tolosa without stopping. We saw some houses decorated with frescoes, and gigantic blazons sculptured in stone. It was market-day, and the market-place was covered with asses, mules, picturesquely harnessed, and peasants of singular and wild appearance.

By dint of ascending and descending, of passing over torrents on bridges of uncemented stone, we at last reached Vergara, where we were to dine. We experienced a decided degree of satisfaction on our arrival, for we had almost forgotten the jicara de chocolate, which we had gulped down, half asleep, in the inn at Astigarraga.

At Vergara, which is the place where the treaty between Espartero and Maroto was concluded, I saw, for the first time, a Spanish priest. His appearance struck me as rather grotesque, although, thank heaven, I entertain no Voltairean ideas with regard to the clergy; but the caricature of Beaumarchais' Basile involuntarily suggested itself to my recollection. Just fancy a black cassock, with a cloak of the same colour, and to crown the whole, an immense, prodigious, phenomenal, hyperbolical, and Titanic hat, of which no epithet, however inflated and gigantic, can give any idea at all approaching the reality. This hat is, at least, three feet long; the brim is turned up, and forms, before and behind the hat, a kind of horizontal roof. It would be difficult to invent a more uncouth and fantastic shape; this, however, did not prevent the worthy priest from presenting a very respectable appearance, and walking about with the air of a man whose conscience is perfectly tranquil about the form of his head-dress; instead of bands, he wore a little collar (alzacuello), blue and white, like the priests in Belgium.

Beyond Mondragon, which is the last small market-town, the last pueblo of the province of Guipuzcoa, we entered the province of Alava, and were not long before we found ourselves at the foot of the hill of Salinas. The Montagnes Russes[3] are nothing compared to this, and, at first sight, the idea of a carriage passing over it appears as preposterous as that of your walking head downwards on the ceiling like a fly. This prodigy was however effected, thanks to six oxen which were harnessed on before the mules. Never in my whole life [21]did I hear so horrible a disturbance; the mayoral, the zagal, the escopeteros, the postilion, and the oxen-drivers, tried which could excel each other in hooting, swearing, using their whips, and exercising their goads; they thrust forward the wheels, held up the body of the coach behind, and pulled on the mules by their halters and the oxen by their horns, with a most incredible amount of fury and vehemence. The coach thus placed at the end of this long string of animals and men, produced a most astonishing effect. There were, at least, fifty paces between the first and last beast in the team. I must not forget to mention, en passant, the steeple of Salinas, which has a very pleasing Saracenic form. From the top of the hill the traveller beholds on looking back, the Pyrenees rising one above the other until lost in the distance; they resemble immense pieces of rich velvet drapery, thrown together by chance and rumpled by the whim of a Titan. At Royane, which is a little further on, I observed a magical effect in optics. A snowy mountain-top (Sierra Nevada), that the proximity of the other mountains had till then veiled from our sight, suddenly appeared standing out from the sky, which was of a blue so dark as to be almost black. Soon afterwards, at all the edges of the table-land we were traversing, more mountains raised, in a most curious manner, their summits loaded with snow and bathed in clouds. This snow was not compact, but divided into thin veins like sides of gauze worked with silver; it appeared still whiter from the contrast it formed with the azure and lilac tints of the precipices. The cold was tolerably severe, and became more intense in proportion as we advanced. The wind had not warmed itself by caressing the pale cheeks of these beautiful and chilly virgins, and came to us as icy as if it had arrived direct from the North or South Pole. We wrapped ourselves up as hermetically as we could in our cloaks, for it is extremely scandalous to have your nose frost-bitten in a torrid clime; I should not have cared had we been merely fried.

The sun was setting when we entered Vittoria; after threading all sorts of streets, of but middling architectural style and very bad taste, the coach stopped at the parador vejo, where our luggage was scrupulously examined. Our Daguerreotype especially alarmed the worthy custom-house officers a good deal; they approached it with the greatest precautions, like people who are afraid of being blown up; I think they imagined it to be an electrifying machine, and I took care not to undeceive them.

As soon as our things had been searched and our passports stamped, we had the right to scatter ourselves over the pavement of the town. We immediately took advantage of this, and, crossing a[22] fine square surrounded by arcades, proceeded straightway to the church. The shades of night already filled the nave, and lowered with a mysterious and threatening look in obscure corners, where phantom-like forms might now and then be seen. A few small lamps, yellow and smoky, trembled ominously like stars in a fog. A sort of sepulchral chill came over me, and it was not without a slight feeling of dread that I heard a mournful voice murmur, just at my elbow, the stereotyped formula "Caballero, una limosina por l'amor de Dios." It was a poor wretch of a soldier who had been wounded, and who was asking an alms of us. In this country the soldiers beg; this is excusable on account of their miserable state of destitution, for they are paid very irregularly. In the church at Vittoria I became acquainted with those frightful sculptures in coloured wood, the use of which the Spaniards carry to such excess.

After a supper (cena) which caused us to regret that at Antigarraga, we suddenly thought of going to the play. We had been allured, as we passed along, by a pompous poster announcing the extraordinary performances of two French Herculeses, which were to terminate with a certain baile nacional (national dance), which we pictured to ourselves big with cachuchas, boleros, fandangos, and other diabolical dances.

The theatres in Spain have generally no façade, and are only distinguished from the houses around by two or three smoky lamps stuck before the door. We took two orchestra-stalls, surnamed places de lunette (asientos de luneta), and bravely precipitated ourselves into a corridor, where the floor was neither planked nor paved, but was nothing more or less than the bare earth. The frequenters of the place are not very particular about the uses to which they turn the walls of the corridor, but, by hermetically sealing our noses, we reached our places not more than half suffocated. When I add that smoking is perpetually practised between the acts, the reader will not have a very fragrant idea of a Spanish theatre.

The interior of the house is, however, more comfortable than the approaches to it promise; the boxes are tolerably arranged, and although the decorations are simple, they are fresh and clean. The asientos de luneta are armchairs placed in rows and numbered; there is no checktaker at the door to take your tickets, but a little boy comes round for them before the end of the performance; at the outer door you are merely asked for the card that admits you within the theatre.

We had hoped to find the true type of the Spanish woman, of which we had as yet seen but few specimens; but the ladies who filled the boxes and galleries had nothing Spanish about them save the[23] mantilla and the fan: this was a good deal, it is true, but not sufficient. The audience was mostly composed of the military, which is the case in all garrison towns. In the pit, the spectators stand as in the most primitive theatres. There was, in truth, but a row of candles and a candle-snuffer wanting to give the place the appearance of the Hôtel de Bourgogne; the lamps, however, were enclosed by thin plates of glass, disposed in the shape of a melon, and united at the top by a circle of tin: this was certainly no great sign of an advanced state of the industrial arts. The orchestra, which consisted of one row of musicians, almost all of whom played brass instruments, blew most valiantly on their cornets-à-piston an air which was always the same, and recalled to one's recollection the flourishes of the band at Franconi's.

Our Herculean compatriots raised immense weights, and bent a considerable number of iron bars, to the great delight of the assembly; while the lighter of the two made an ascent upon the tight rope, and performed a variety of other feats, rather stale in Paris, but new, probably, to the population of Vittoria. During this time we were dying with impatience in our stalls, and I was cleaning the glass of my lorgnette with a furious degree of activity, in order not to lose anything of the baile nacional. At last, the supports of the tight-rope were loosened, and the stage-carpenters, dressed as Turks, cleared away the weights and all the other paraphernalia of the Herculeses. Think, dear reader, of the frightful anxiety of two enthusiastic and romantic young Frenchmen about to behold, for the first time, a Spanish dance ... in Spain!

At last the curtain rose upon a scene which seemed to entertain a feeble desire, which was certainly not gratified, of being enchanting and fairy-like. The cornets-à-piston played, with more fury than ever, the strain already described, and the baile nacional advanced in the form of a danseur and danseuse, armed with a pair of castagnettes each. Never have I seen anything more sad and lamentable than these two miserable ruins qui ne se consolaient pas entre eux: a penny theatre never bore upon its worm-eaten boards a couple more used-up, more worn-out, more toothless, more blear-eyed, more bald, and more dilapidated. The wretched woman, who had besmeared herself with bad Spanish white, had a sky-blue complexion, which recalled to your mind the Anacreontic pictures of a person who had died of cholera, or been drowned some time; the two dabs of rouge that she had placed upon her prominent cheek-bones, to add a little brilliancy to her fishy eyes that seemed as if they had been boiled, contrasted strangely with the aforesaid blue. With her veiny and emaciated hands she shook a pair of cracked[24] castagnettes, which chattered like the teeth of a man who has got a fever, or like the wires of a skeleton in motion. From time to time, she stretched, with a desperate effort, the relaxed fibres of her calves, and managed to raise her poor old baluster-looking leg, so as to produce a nervous little capriole, like a dead frog submitted to the operation of the voltaic battery, and, for a second, to cause the copper spangles of the doubtful rags which served her for a robe, to sparkle and glisten. As for the man, he kept fluttering about most horribly in his own corner; he rose and fell flatly, like a bat crawling along upon its stumps; he looked like a grave-digger burying himself. His forehead, wrinkled like a boot, and his goat-like cheeks, gave him a most fantastic air: if, instead of castagnettes, he had only had a Gothic rebec in his hands, he might have set up to lead the Dance of Death at Basle.

During all the time the dance lasted, they did not once raise their eyes on one another; it struck you that they were frightened of their reciprocal ugliness, and feared lest they should burst into tears at seeing themselves so old, so decrepit, and so mournful. The man, especially, avoided his companion as if she had been a spider, and appeared to shiver in his old parchment skin every time the figure of the dance forced him to approach her. This lively bolero lasted five or six minutes, after which the fall of the curtain put an end to the torture of these two wretched beings, ... and to ours.

Such was the specimen of the bolero which greeted our poor eyes, so enamoured of "local colouring." Spanish dancers exist only at Paris, like the shells which are only found at the curiosity-shops, and never on the sea shore. O Fanny Elssler, who art now in America, among the savages! even before going to Spain, we always had an idea that it was thou who inventedst the cachucha!

We went to bed rather disappointed. In the middle of the night we were woke up to resume our journey. The cold was still intense, to a Siberian extent; this is accounted for by the height of the table-land we were crossing, and the snow by which we were surrounded. At Miranda, our trunks were once more examined, and then we entered Old Castile (Castilla la Vieja), the kingdom of Castile and Leon, symbolically represented by a lion holding a shield studded with castles. These lions, which are repeated until you are sick of them, are generally of a greyish granite, and have rather an imposing heraldic appearance.

Between Ameyugo and Cubo, small insignificant towns, where we changed mules, the landscape is extremely picturesque; the mountains contract and draw near one another, while immense perpendicular rocks, as steep as cliffs, rise up at the road-side. On the left,[25] a torrent, crossed by a bridge with a truncated ogive arch, whirls round and round at the bottom of a ravine, turns a mill, and covers with spray the stones that stop its course. That nothing may be wanting to complete the effect, a gothic church, falling to ruin, with its roof staved in, and its walls covered with parasite plants, rises in the midst of the rocks; in the background is seen the vague and bluish outline of the Sierra. The view is certainly very fine, but the passage of Pancorbo carries off the palm for singularity and grandeur. There the rocks leave only just room enough for the road, and there is one point where two immense granite masses, leaning towards one another, give you the idea of a gigantic bridge, which has been cut in the middle, to stop the march of an army of Titans. A second, but smaller, arch, pierced through the thickness of the rock, adds still more to the illusion. Never did a scene-painter imagine a more picturesque and more admirably-contrived scene. When you are accustomed to the flat views of plains, the astonishing[26] effects met with at every step, in the mountains, appear impossible and fabulous.

The posada where we stopped to dine had a stable for a vestibule. This architectural arrangement is invariably repeated in all Spanish posadas, and to reach your room you are obliged to pass behind the cruppers of the mules. The wine, which was blacker than usual, had a certain taste of goat-skin sufficiently local. The maidservants of the inn wore their hair hanging down to the middle of their backs, but, with this exception, their dress was the same as that of French women of the lower classes. The national costumes are, in general, seldom preserved, save in Andalusia, and, at present, there are very few ancient costumes in Castile. The men wore the pointed hat, edged with velvet and silk tufts, or a wolf-skin cap of rather ferocious shape, and the inevitable tobacco or dirty-coloured mantle. Their faces, however, had nothing characteristic about them.

Between Pancorbo and Burgos we fell in with three or four little villages, such as Briviesca, Castil de Peones, and Quintanapalla, half in ruins, as dry as pumice-stone, and of the colour of a toast. I doubt whether Decamps ever found in the heart of Asia Minor, any walls more roasted, more reddened, more tawny, more seedy, more crusty, and more scratched over, than these. Along these said walls wandered carelessly certain asses, who are decidedly well worth the Turkish ones, and which I would advise him to go and study. The Turkish ass is a fatalist, and, as is evident from his humble air, resigned to the blows which Fate has in store for him, and which he endures without a murmur. The Castilian ass has a more philosophical and deliberate look; he is aware that people cannot do without him; he makes one of the family; he has read Don Quixote, and he flatters himself that he is descended in a straight line from the celebrated donkey of Sancho Panza. Side by side with these asses were also dogs of the purest blood and most superb breed, with splendid claws, broad backs, and beautiful ears, and among the rest some large greyhounds, in the style of Paul Veronese and Velasquez, of most magnificent size and beauty, not to speak of some dozen muchachos, or boys, whose eyes glistened in the midst of their rags, like so many black diamonds.

Old Castile is, doubtless, so called, on account of the great number of old women you meet there; and what old women! The witches in "Macbeth" crossing the heath of Dunsinane, to prepare their diabolical cookery, are charming young girls in comparison: the abominable hags in the capricious productions of Goya, which I had till then looked upon as monstrous nightmares and chimeras, are but[27] portraits frightfully like; most of these old women have a beard like mouldy cheese, and moustaches like French grenadiers; and then, their dress! You might take a piece of cloth, and work hard ten years to dirty, to rub, to tear, to patch, and to make it lose all traces of its original colour, and you would not even then attain the same sublimity of raggedness! These charms are increased by a haggard and savage look, very different from the humble and piteous mien of the poor wretches in France.

A little before reaching Burgos, a large edifice, situated upon a hill, was, in the distance, pointed out to us. It was the Cartuja de Miraflores (Carthusian convent), of which I shall have occasion, later, to speak more at length. Soon afterwards the spires of the Cathedral displayed their embrasures more and more distinctly against the sky, and in another half-hour we were entering the ancient capital of Old Castile.

The public place of Burgos, in the midst of which stands a very middling bronze statue of Charles III., is large, and not without some character. Red houses, supported by pillars of bluish granite, inclose it on all sides. Under the arcades and on the place, are stationed all sorts of petty dealers, besides an infinite number of asses, mules, and picturesque peasants who promenade up and down. The rags of Castile are seen there in all their splendour. The poorest beggar is nobly draped in his cloak, like a Roman emperor in his purple. I know nothing better with which to compare these cloaks, for colour and substance, than large pieces of tinder jagged at the edges. Don Cæsar de Bazan's cloak, in the drama of "Ruy Blas," does not come near these proud and haughty rags. They are all so threadbare, so dry, and so inflammable, that it strikes you the wearers are very imprudent to smoke or strike a light. The little children, also, six or eight years old, have their cloaks, which they wear with the most ineffable gravity. I cannot help laughing at the recollection of a poor little wretch, who had nothing left but a collar which hardly covered his shoulder, and who draped himself in the absent folds with an air so comically piteous, that he would have unwrinkled the countenance of the Spleen in person. The men condemned to the presidio (convicts) sweep the town and clear away the filth, without quitting the rags in which they are swathed. These convicts in cloaks are the most astonishing blackguards it is possible to behold. After each stroke of their broom, they go and sit down, or else recline upon the door-steps. Nothing would be easier for them than to escape; and on my hinting this, I was informed that they did not do so on account of the natural goodness of their disposition.

The fonda where we alighted was a true Spanish fonda, where no one spoke a word of French; we were fairly obliged to exert our Castilian, and to tear our throats with uttering the abominable jota—a guttural and Arabian sound which does not exist in our language. I must confess that, thanks to the extreme intelligence which distinguishes the people, we made ourselves understood pretty well. They sometimes, it is true, brought us candles when we asked for water, or chocolate when we desired ink; but, with the exception of these little mistakes, which were very pardonable, everything went on beautifully. We were waited on by a population of masculine and dishevelled females, with the finest names in the world; as, for instance, Casilda, Matilda, and Balbina. Spanish names are always charming. Lola, Bibiana, Pepa, Hilaria, Carmen, Cipriana, serve to designate some of the most unpoetical beings it is possible to imagine. One of the creatures who waited on us had hair of the most fiery red. Light haired, and especially red haired persons abound in Spain, contrary to the generally-received idea.

We did not find any holy box-wood in the rooms, but branches of trees, in the shape of palms, plaited, woven, and twisted with great elegance and care. The beds possess no bolsters, but have two flat pillows placed one on the other. They are generally extremely hard, although the wool of which they are composed is good; but the Spanish are not accustomed to card their mattresses, merely turning the wool with the aid of two sticks. Opposite our windows hung a strange kind of sign-board. It belonged to a surgical practitioner, who had caused himself to be represented in the act of sawing off the arm of a poor devil seated in a chair; we also perceived the shop of a barber, who, I can assure my readers, did not bear the least resemblance to Figaro. Through the panes of his shop-front we could see a large and rather highly-polished brazen shaving-dish, which Don Quixote, had he still been of this world, might easily have mistaken for Mambrino's helmet. It is true that the Spanish barbers have lost their ancient costume, but they still retain their former skill, and shave with great dexterity.

Although Burgos was long the first city of Castile, there is nothing peculiarly Gothic in its general appearance. With the exception of one street, in which there are a few windows and door-ways of the time of the Renaissance, and ornamented with coats of arms and their supporters, the houses do not date further back than the commencement of the seventeenth century, and merely strike the observer by their very commonplace look; they are old, but they are not ancient. Burgos, however, can boast of its Cathedral, which is one of the finest in the world; but, unfortunately, like all[29] Gothic cathedrals, it is hemmed in by a number of ignoble structures, which prevent the eye from appreciating the general disposition of the building and seizing the whole mass at one glance. The principal entrance looks out upon a large square, in the middle of which is a handsome fountain, surmounted by a delicious statue of Our Saviour in white marble. This fountain serves as a target to all the idle vagabonds of the town who can find no more amusing occupation than to throw stones at it. The entrance, which I have just mentioned is magnificent, being worked and covered with a thousand different patterns like a piece of lace. Unfortunately it has been rubbed and scraped down to the outer frieze by some Italian prelates or other, who were great admirers of architectural simplicity, of plain walls and ornaments in "good taste," and wished to arrange the cathedral in the Roman style, pitying very much the poor, barbarous architects, for not employing the Corinthian order, and not appearing to have been alive to Attic beauty and the charm of triangular frontons.

There are still many people of this way of thinking in Spain, where the so-called Messidor style flourishes in all its purity. These persons prefer to the richest and most profusely carved specimens of Gothic architecture, all sorts of abominable edifices riddled with windows, and ornamented with Pæstumian columns, exactly as was the case in France before the disciples of the Romantic School had caused the public to appreciate once more the style of the Middle Ages, and understand the meaning and the beauty of their cathedrals. Two pointed spires, carved in zigzag, and pierced as if with a punch, festooned, embroidered, and sculptured with most delicate minuteness, like the bezel of a ring, spring upwards towards Heaven with all the ardour and impetuosity of unshakable conviction. It is very certain that the campaniles of our incredulous times would never dare to rise thus into the air with nothing to support them, save so much stone lacework and nerves as thin as a spider's web. Another tower, which is also adorned with an unheard-of profusion of sculpture, but which is not so high, marks the spot where the arms of the cross join, and completes the magnificence of the outline. A countless number of statues, representing saints, archangels, kings, and monks, ornament the whole; and this population of stone is so numerous, so crowded, so multitudinous, that it must most certainly exceed the population in flesh and blood that inhabit the town.

Thanks to the charming politeness of the political chief, Don Enrico de Vedia, we were enabled to visit the cathedral most minutely. An octavo volume of description, a folio of two thousand plates, and twenty rooms filled with plaster casts would not be[30] sufficient to convey a complete idea of this prodigious production of Gothic art with its immense mass of sculptures, more thick and more complicated than a virgin forest in Brazil. Such being the case, we shall, perhaps, be pardoned for some few slight omissions and instances of seeming negligence, having been obliged to scribble these lines hastily and from recollection, on the table of a posada.