Title: Half-hours with the Highwaymen - Vol 1

Author: Charles G. Harper

Illustrator: Paul Hardy

Release date: October 10, 2016 [eBook #53111]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by deaurider, Christian Boissonnas and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

This book was published in two volumes, of which this is the first. The second volume was released as Project Gutenberg ebook #53112, available at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/53112

HALF-HOURS WITH THE HIGHWAYMEN

WORKS BY CHARLES G. HARPER

The Portsmouth Road, and its Tributaries: To-day and in Days of Old.

The Dover Road: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike.

The Bath Road: History, Fashion, and Frivolity on an Old Highway.

The Exeter Road: The Story of the West of England Highway.

The Great North Road: The Old Mail Road to Scotland. Two Vols.

The Norwich Road: An East Anglian Highway.

The Holyhead Road: The Mail-Coach Road to Dublin. Two Vols.

The Cambridge, Ely, and King's Lynn Road: The Great Fenland Highway.

The Newmarket, Bury, Thetford, and Cromer Road: Sport and History on an East Anglian Turnpike.

The Oxford, Gloucester, and Milford Haven Road: The Ready Way to South Wales. Two Vols.

The Brighton Road: Speed, Sport, and History on the Classic Highway.

The Hastings Road and the "Happy Springs of Tunbridge."

Cycle Rides Round London.

A Practical Handbook of Drawing for Modern Methods of Reproduction.

Stage Coach and Mail in Days of Yore. Two Vols.

The Ingoldsby Country: Literary Landmarks of "The Ingoldsby Legends."

The Hardy Country: Literary Landmarks of the Wessex Novels.

The Dorset Coast.

The South Devon Coast.

The North Devon Coast.

The Old Inns of Old England. Two Vols.

Love in the Harbour: a Longshore Comedy.

Rural Nooks Round London (Middlesex and Surrey).

The Manchester and Glasgow Road; This way to Gretna Green. Two Vols.

Haunted Houses; Tales of the Supernatural.

The Somerset Coast. [In the Press.]

PICTURESQUE BIOGRAPHIES AND TRADITIONS OF THE "KNIGHTS OF THE ROAD"

By CHARLES G. HARPER

VOL. I

Illustrated by Paul Hardy and by the Author, and from Old Prints

London

CHAPMAN & HALL, Limited

1908

All rights reserved

PRINTED AND BOUND BY

HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY.

Preface

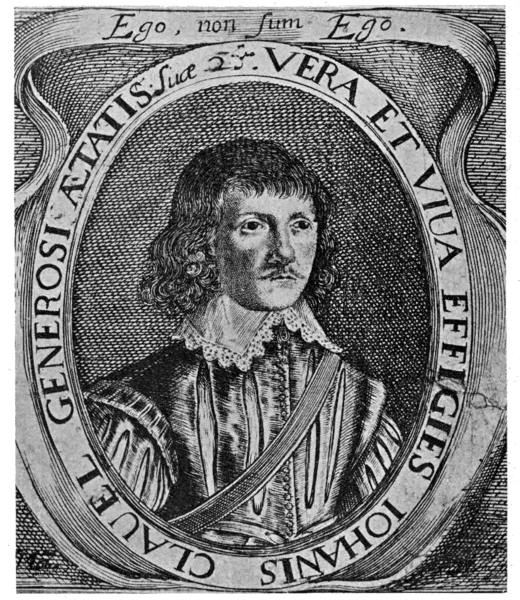

In a series of books designed to tell the story of the roads, and not only of the roads, but of all subjects connected with road-travel in all ages, a book on the Highwaymen was sooner or later inevitable. We have had in this series the story of the rise and progress towards perfection of coaching, and of the decay of stage-coach and mail when the era of steam came in; and we have had two volumes on the Old Inns of Old England, to which the travellers of a bygone age came, wearied, when the day's tedious travel was done. The story of the highwaymen, who robbed those travellers, is now told, for the first time since Captain Alexander Smith in 1719-20, in three small octavo volumes, and Captain Charles Johnson in 1742, in one folio volume, collated the numerous chapbooks and "last dying speeches and confessions" of that and earlier ages. Captain Johnson, who stole extensively [Pg viii] from Smith, who himself was prone to include the most extravagant myths in his pages, calls his folio A General and True History of the Lives and Actions of the Most Famous Highwaymen. Both of them include pirates and murderers. Of the "truth" of much in Smith and Johnson, the less said the better.

No one has ever reprinted those authors in their original extravagance, or their grossness. It would be impossible; and, if possible, it would not be entertaining. Nor has any one ever edited them, or even written an independent history of the highwaymen. When we consider how astonishingly popular those romances have ever been which have had Claude Du Vall, and Turpin, and their like for heroes, this is not a little surprising.

Perhaps the task has been abandoned because of the difficulty—the almost insuperable difficulty—of sifting fact from fiction, and because of a chilling sense that it would be a thankless task to present the highwayman as he really was: a fellow rarely heroic, generally foul-mouthed and cruel, and often cowardly. No novelist would be likely to thank the frank historian for this disservice; and I do not think the historian who came to the subject in this cold scientific spirit of a demonstrator in surgery would be widely read. [Pg ix] Most of us like to keep a few of the illusions we believed in when schoolboys. Scientific historians have degraded many of our ancient heroes and exalted the villains, for whom of old no mud was too thick and slab. Beliefs are being assailed on every side. To abolish the traditional courtesy of Claude Du Vall or the considerate conduct of Captain Hind would, therefore, be strokes of the unkindest, and I have here attempted no such iconoclasm. Even where I cannot believe, I have told the tale—whenever it has been worth the telling—as it is found in criminal trials, or in Smith or Johnson, and other old sources, decorously stripped of much vile language. For really, where much that seems incredible may be fully proved, and where the believable turns out not rarely to be false, 'tis your only way.

To continue the story of the highwaymen from Smith and Johnson down to the approaching end of all such things in the beginning of the nineteenth century, is like taking up and concluding a half-told tale. But it was worth the doing. Only in respect of the great figure Turpin has always made, has it been found really necessary to seriously consider and re-state the career of that much-overrated scoundrel, and to put him in his proper place: a very much lower one than he usually occupies.

Hero-worshippers of the highwaymen we cannot be; as thorough disbelievers of their picturesque exploits we dare not pose: for the rest, the proper spirit in which to treat the subject is that of ironic tolerance.

CHARLES G. HARPER.

Petersham,

Surrey,

October 1908.

SEPARATE PLATES

ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

HALF-HOURS

WITH THE

HIGHWAYMEN

INTRODUCTORY

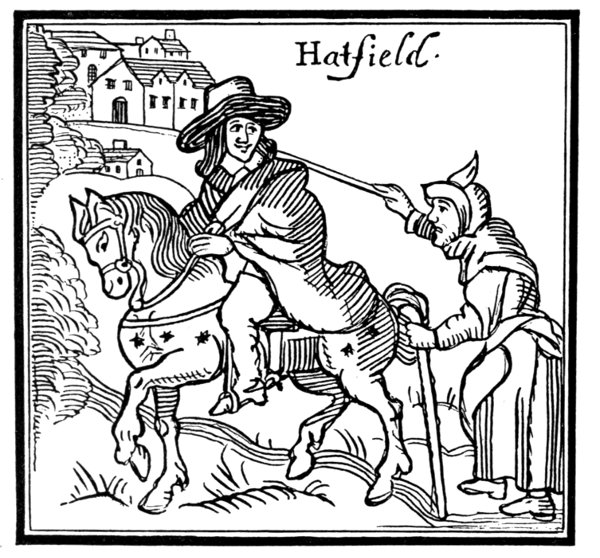

THE GENERAL DECLENSION FROM OUTLAW TO HIGHWAYMAN, AND THENCE TO FOOTPAD, THIEF, AND BURGLAR—GAMALIEL RATSEY—THOMAS DUN, OF DUNSTABLE

Half-hours! In the days when the highwaymen flourished, and made travel perilous for law-abiding persons, a five-minutes' interview with one of these "Knights of the Road," who were but rarely knightly in their manners, would have been more than sufficient. Travellers, who had been [Pg 2] violently abused, threatened, and robbed, did not observe that atmosphere of romance about the highwaymen, with which, not only modern times, but their own age, enwrapped them. The highwaymen have ever been accounted romantic, as we shall see in these ensuing pages; from the more or less mythical Robin Hood, down to the Carolean age of Captain Hind, Swiftnicks, and Du Vall, whose exploits were followed with interest and sympathy by their contemporaries. From a lengthy study of these things, one fact rises prominently above all others: it is the fact that the highwayman's only ceased to be a romantic figure when he stopped and robbed one's self, under the usual circumstances of coarse vituperation and personal indignity. On all other occasions, although he commonly practised after nightfall, he paradoxically moved in a rosy atmosphere, in company with the knightly figures of ancient chivalry (who themselves, if the truth of it were told, would probably be disclosed as a rather sordid crew).

The thrilling romance—or the side-splitting humorous circumstances, as the case might be—of one's acquaintance or next-door neighbour being plundered, threatened with death at the pistol-muzzle, and then, with his very coat stripped off his back, being bidden make haste away, is obvious enough, and the highwayman who did all the threatening and the plundering is easily seen to be at once a hero and a humorist; but when he met yourself in the darkling lane, [Pg 3] and had your purse, your coat, and your gold watch, and d——d you because you did not carry more wealth, and so make it better worth the while of a gentleman like himself to be out upon the roads at such unconscionable hours—why, then he was a rogue of the most debased description, and the occasion was not so much humorous as tragical; while, as for Romance: what sickly cant is this? Where are the patrol? What are the peace-officers doing, to earn their pay? Is this a civilised country?

We shall see in these pages the fine flower and the gradual declension of the highwaymen: shall trace the mythical and the almost wholly imaginary figures to the time when, under Charles the First and the Commonwealth, it was difficult to tell where the Cavalier ended and the highwayman began; and shall thence come, by way of the disbanded troopers, who turned highway robbers in William the Third's reign, to that curious age when there was an even chance that the armed and mounted man who bade you "Stand and deliver!" was a baronet, or a footman out of place, turned gentleman of the road to support the vices he had learned of his masters.

From the middle of the eighteenth century, to its close—the era of Maclaine and Sixteen String Jack, the art of highway robbery becomes less idealised. There is more police-court about it, and less hazy glamour. Beau Brocade is a fine figure, well-dressed and splendidly mounted, on the heath, but in the dock at Bow Street, and [Pg 4] later at the Old Bailey, he never showed to advantage, Sixteen String Jack excepted, with his pea-green coat and his bouquet, as big as a cabbage. And as the eighteenth century closed and gave place to the nineteenth, the mounted highwayman gradually disappeared, and the footpad, a miserable, muddy, cowardly figure, for whom no one ever had a good word, is seen in his dark lurk, in the wayside ditch, not often courageous enough to work alone, and generally found in couples, ready perhaps with the suffocating pitch-plasters that so terrified the wayfarers of that time.

The footpad never had the slightest inkling of romance, and was always brutal, whether he clapped that pitch-plaster over your mouth, or terrified you, or finished off his examination of your pockets by knocking you down and jumping on your body. A far cry, indeed, from the generous days of Captain Hind, or Claude Du Vall.

No one would ever contemplate a work on "Half-Hours with the Footpads." It would be to introduce the reader into the very worst of society, and the least entertaining; and so we come by degrees to the present era of the housebreakers and the newspaper records, where you may seek romance if you will.

The history of the highwaymen is a lengthy emergence from ancient fables and marvellous rustic folklore, to more settled records. It is not peculiar in that gradual development. Such is [Pg 5] the evolution of all history. But that of the highwaymen begins with the giants and the heroes, continued down through the legendary period of Robin Hood, to the times of the Civil War in England, between King Charles and his Parliament, when highway robbers cloaked their villainies with Royalist partisanship, to the less romantic eighteenth century, and finally ended, early in the nineteenth century, with all the glamour and tinselled things of the past, in squalid, commonplace circumstances. The highwaymen begin in the dimness of antiquity, continue very largely as heroic myths throughout the middle ages, become philanthropic and chivalric figures in succeeding eras, and later are seen to be mere masquerading footmen, brave only in their masters' fine clothes, seeking money wherewith to gamble and to live dissolute lives. They end, sordid, mud-splashed figures, from which romance shrinks; in no detail distinguishable from such vermin as the footpads, who on dark nights robbed women and children, and defenceless old men, for coppers in solitary lanes, and fled in terror from the robust.

When the profession of highwayman became extinct, those of pickpocket, card-sharper, and burglar were greatly reinforced. Some severe censors of modern times declare that the Joint Stock and Limited Liability Acts were passed in the interest of the classes in whose veins the highwayman blood flowed, and whose instincts could not, in the altered conditions of life, find [Pg 6] expression on the road. As company promoters of the Whitaker Wright and Jabez Balfour type, it has been said, these providential enactments enabled them to satisfy their natural leanings. And so the old world journeys down the ringing grooves of change, even as Tennyson desired it should do, though perhaps not on the exact lines of his thoughts.

There are no heroes in these days; or, at the most of it, the hero of to-day, beslavered with overmuch praise, is discovered to-morrow to be a greatly overrated person, not so heroic as ourselves, if the truth were known and every one had his due.

The very last hero in the records of these allied criminal enterprises was Charles Peace, the burglar, who was hanged February 25th, 1879, for the murder (not in the way of his business), of Mr. Dyson, at Banner Cross, near Sheffield, on November 29th, 1876.

There can be no doubt that "Charley," as the police themselves almost affectionately called him, would in a more favourable era have been a highwayman. He had the instincts for the career, and was undoubtedly courageous enough, resourceful enough, and sufficiently equipped with what passed for wit and humour to have shone with no dim light, even in such days as those of Hind and Du Vall. He was not a hero, and the age insisted that he should ply a less respected craft than that of the highwayman, but he could have risen to such an occasion on the road, and perhaps because the public dimly saw as much, he figures [Pg 9] in the imagination less as the armed midnight burglar he was, ready in cold blood to shoot down any one who stood in his way, than as a wonderfully daring and skilful adventurer, whose known exploits and whose legendary doings—for legends have accumulated around his well-known and ascertained career—can stir the pulse and heat the imagination. He was well-equipped even in the accident of his name. The heathen gods themselves might have laughed in their heavens—for humour was appreciated among the Olympians—at the sardonic jest of one named Peace prowling at dead of night, armed with a six-chambered revolver, ready and willing to slay those who should bar his path. And then how fine his gauge of the average intelligence, which even nowadays does not often range beyond that primitive conception of the typical burglar, in which he is pictured in the ankle-jacks, the breeches, the velveteen coat, and the moleskin cap of Bill Sikes. He saw that was the mental picture the British public cherished of gentlemen of his trade, and he took his cue therefrom, posing as an independent gentleman. It mattered little that his physiognomy actually reproduced the Bill Sikes head and face, with remarkable closeness; he dressed well, talked well, lived in nicely furnished houses in respectable neighbourhoods, and—last and clinching sign of respectability—he kept a horse and trap.

Until his arrest on the night of November 17th, 1878, in the act of committing a burglary at St. John's Park, Blackheath, he was a respected [Pg 10] villa resident, who had a liking for art, a great fondness for music, and, in general, cultivated tastes. There was no reason, except such reason or such elements of chance, as may be found in the busy conduct of his trade, why he should ever have been caught. He burgled as cleverly as he lived; and had too much sense to work in company. Keeping his own counsel, and working alone, he was quite sure no pal would betray him.

His impudent assurance is well displayed in the authentic and well-known anecdote of his offering a choice cigar from among some he had looted, to a tradesman well acquainted with him. He entered the Peckham chemist's shop, made a purchase, passed the time o' day, and offered him his cigar-case. The shopkeeper took one, and later smoked it with great satisfaction.

When next Peace entered the shop, the shopkeeper said: "That was a fine cigar, sir, you gave me the other day."

"Yes," replied Peace, "they are good. I can't afford to buy, so I steal them."

"Do you?" rejoined the man, with a laugh at the absurdity of such a statement from a customer so apparently respectable as Peace; "I wish, then, you would steal me some more."

"I will!" said Peace; and he did. He had the effrontery to again burgle the place whence his original supply had come.

"Here," he said in a day or two, giving the shopkeeper a box full, "are the cigars I promised [Pg 11] to steal for you." The delighted recipient thought how exquisitely his customer's kindness and humour blended.

There is nothing neater in all the history of highwaymen than this anecdote, twinkling brightly amid the matter-of-fact records of a degenerate day.

There is plentiful evidence that when Captain Alexander Smith in 1719-20 wrote and published his work upon the highwaymen and other evil-doers, he based his book upon the many chapbooks and broadsides then in existence. Many of them may even now be found by those who do not mind searching for them, but whether they will repay the trouble is quite another matter. He includes in his gallery even Robin Hood and Sir John Falstaff; and, not concerned to point out their legendary or merely literary character, gives an exact (though necessarily not a truthful) biography of each.

Several editions of Smith exist; some in three, others in two volumes. The title-pages vary largely, but all are extremely lengthy, and so curious that it is well worth while to reproduce one as on the next page.

A Compleat

HISTORY

of the

LIVES AND ROBBERIES

of the most Notorious

Highway-Men, Foot-Pads, Shop-Lifts,

and Cheats of both Sexes, in and about

London and Westminster, and all Parts of

Great Britain, for above an Hundred Years

past, continu'd to the present Time.

Wherein their most Secret and Barbarous Murders,

Unparalell'd Robberies, Notorious Thefts,

and Unheard of Cheats, are set in a true Light,

and Expos'd to publick View, for the common

Benefit of Mankind.

To which is prefix'd,

The Thieves New Canting-Dictionary,

Explaining the most mysterious Words,

New Terms, Significant Phrases, and Proper

Idioms, used at this present Time by

our Modern Thieves.

By Capt. ALEX. SMITH.

The Fifth Edition (adorn'd with Cuts) with the Addition of near Two Hundred Robberies lately committed.

In Two Volumes.

London. Printed for Sam. Briscoe, and sold by A. Dodd at the Peacock without Temple-Bar, 1719.

Captain Alexander Smith took an immense delight in his villains. You cannot fail to perceive, if you read his book, that his only contempt was for a bungler in the art. Royalist to the heart's core of him, he expends his most loving labours upon the freebooters who displayed his own political bias, and there can be little doubt [Pg 13] that, while they did the robbing, it is the eloquence of Smith himself that supplies the embittered harangues, which the victims of Captain Hind, of Stafford, and of many another in his pages are supposed to endure. Nay, Smith enriches the career of many a Royalist highwayman with incidents those gallant fellows were entire strangers to; and himself robs (in the mere narration of pen, ink, and the printed page) prominent Puritans, who in actual life were assuredly never "held up" on the road.

The convention of disapproval of his heroes' villainies sits very lightly upon Alexander Smith. He pays that merest homage to virtue, but then starts rollicking through the biographies of the highwaymen with an unmistakable gusto. His table of comparative sinfulness is an oddity in itself. He says, ".... we have given them Precedency according as they excelled one another in Villainy. In their general Character the Reader will find the most unaccountable Relations of irregular Actions as ever were heard; penn'd all from their own Mouths, not borrow'd from the Account given of Malefactors by any of the Ordinaries of Newgate...."

He then continues, not very convincingly: "If we have here and there brought in some of these wicked Offenders venting a prophane Oath or curse, which is dash'd" (much is left to the imagination in a ——) "it is to paint them in their proper Colours; whose Words are always so odious, detestable, and foul, that some (as [Pg 14] little acquainted with a God as they) would be apt to conclude that Nature spoil'd them in the Making, by setting their Mouths at the wrong end of their Bodies."

Sir John Falstaff strangely comes first in this Valhalla. Who ever, loving the Shakespearian Falstaff, would have expected him to be exalted on this particularly bad eminence, over the heads of the several atrocious murderers Smith does not scruple to include in his pages?

Johnson, Smith's copyist of twenty years later, like his precursor, boggles at no marvellous tale. They knew the temper of their times and worked in accord with it. Why be a critic in an uncritical age?

There were poets before Homer, but by all accounts they were a sorry lot; and there were biographers of highwaymen before Alexander Smith, but for the most part their works are deadly dull. They had excellent materials, but did not know how to handle them. Shakespeare alone, in the scenes on Gad's Hill with Falstaff and Prince Hal and the men in buckram, knew the way, and all London laughed with him at those merry adventures; but such tiresome productions as the Life and Death of Gamaliel Ratsey, published in 1605, continued to appear.

That little work is typical. Gamaliel Ratsey—whether a real or imaginary person I dare not say—appears by this publication to have been "a famous thiefe in England, executed at Bedford the 26 of March last past, 1605." Probably there [Pg 15] was a Gamaliel Ratsey, highwayman, hanged then and there; but the adventures related of him are almost certainly inventions: well invented, but told without the slightest scintilla of literary merit. Yet this ragbag stuff has figured in reprints of "old English literature." So much the worse, then, for Old English literature, if this be representative; or, more likely so much the worse for the critical ability of those who considered it worth disinterring on those grounds. It is not "literature," and not representative of what old England could then produce in literature; but it is valuable as one of the origins of the highwaymen legends.

Gamaliel Ratsey, according to this publication, was born at Market Deeping, in Lincolnshire, the son of a respected local gentleman, one Richard Ratsey, who held a position in the service of a greater gentleman: an esquire, probably, in the train of a nobleman. His only son, Gamaliel, received a good education, but was of a roving disposition and went over to Ireland and joined the army of occupation there, under the Earl of Essex. He so distinguished himself, early in those operations, that he was made sergeant. Soon after the death of Queen Elizabeth, he returned to England with the Earl of Devonshire, and went home to Market Deeping. At the not far distant town of Spalding he began his filching career, by making use of the good terms he enjoyed with the landlady of an inn to steal a bag containing £40 in gold, which had been [Pg 16] entrusted to her keeping by a farmer attending the market. To convince Ratsey how trusted a person she was, she foolishly showed where she had placed the bag; and as soon as her back was turned he had taken it from the cupboard where it lay, and made off.

When the farmer returned and wanted his money, there was the very deuce to pay. He and the landlady went off to the nearest justice and swore an information against Gamaliel, who was arrested and thrown into prison, but not before he had found time to return home and bury the bag in the garden. In confidence he told his mother where it was hid, his mother told his sister, his sister told her husband, her husband told his friends, and so at last the confession reached the ears of the justices. Gamaliel would undoubtedly have been hanged on that occasion, only he broke prison and escaped, clad only in his shirt.

His further adventures with Snell and Shorthose, two companions of like inclination, are in themselves amusing when reduced to less stilted language than that of the Life. Curiously enough, one of these incidents is concerned with the robbing of an actor, whom Ratsey bids deliver his money first, and a scene from Hamlet afterwards. So it was not from any want of acquaintance with the best models that the unnamed author of Ratsey's life failed to put life into his narrative. The incident is treated in as dead and wooden a manner as the rest.

A Cambridge scholar, robbed in similar manner, [Pg 17] was bidden deliver a learned thesis. We find almost exactly parallel stories in Smith and Johnson. In those pages it is Sir Josselin (? Joscelin) Denville and his numerous band of robbers, who, meeting a Benedictine monk in a wood, make him preach a sermon in praise of thieving. Captain Dudley, a hundred years or so later, is represented demanding a sermon from a clergyman.

More shadowy even than Robin Hood, is "Thomas Dun." We may be in some reasonable doubt as to the validity of many incidents and biographies in the pages of Smith and Johnson, but there is no possible doubt whatever that the "Life of Thomas Dun" is what one of our own eighteenth-century highwaymen and cutpurses would have called a "flam." There was never a Thomas Dun, highwayman, bandit, and murderer, as depicted in those classic pages; but the fact that he was a myth does not prevent those painstaking authors from presenting us with a very exact narrative of his deeds.

The curious "moral reflection" prefaced to Thomas Dun's entirely apocryphal adventures is itself worth reproducing. It says: "A man who is not forced from necessity or a desire of pleasure to become dishonest, but follows his natural dispositions in robbing and maltreating others, will generally be found to be destitute of every humane and generous principle. So will it be found with this character—a person of mean extraction—who was born in Bedfordshire, [Pg 18] and who, even in childhood, was noted for his pilfering propensity and the cruelty of his disposition."

He lived, it seems, in the time of Henry the First, "and so many were his atrocities," writes Johnson, "that we can only find limits for the recital of a few." The limits were perhaps more accurately determined by Johnson's own powers of invention.

Johnson did not, of course, invent Thomas Dun. He is the child of the ages. Equally with Robin Hood, every generation, until the decay of folklore, added some new touch to him, and Johnson did but reduce him to print, add a little more, and shape him out of the somewhat formless but threatening figure he presented.

There is this much basis for him: that, on the site of the town of Dunstable, and for some distance along the Holyhead Road in that direction, there extended, from Saxon times until the reign of Henry the First, a dense thicket of scrub woods, overgrowing the ancient ruins of the Roman station of Durocobrivæ. From the time of the Norman conquest the neighbourhood had been infested with robbers, and it was to drive them out and establish some sort of order that the king had clearings made in the woods that afforded such safe harbourage for outlaws. Under Royal encouragement a new town was founded, and in 1131 given, with the rights of market, to a priory that had been founded in the meanwhile. The King himself had a residence at "Dunstaplia," [Pg 19] as the town was named, i.e. the "hill-staple" or market, and his successors were often there. The wool market was the most important at Dunstable; the monks long maintaining great flocks of sheep on the adjacent downs.

The robbers became only a memory, but a memory that never faded. It merely took on another form, and in the course of time the name of the town itself was twisted into an allusion to them and to their leader. It needed the collusion of gross ignorance and wild legend to effect so much, but the thing was done; and for centuries Dunstable was, and perhaps even now is, locally said to owe its name to "Dun's Stable," a hollow in the chalk downs, pointed out as having been the place where "Dun," the entirely imaginary leader of the outlaws, stabled his horse. If you doubt this there is the town seal to convince the sceptical, showing as it does what is said to be a horseshoe (a shoe of Dun's horse!), but is really intended for a staple or hasp.

The legendary Dun was a kind of bogey to the children of the neighbourhood, and in Johnson's pages is a most blood-thirsty creature. There we read that his first exploit was on the highway to Bedford, where he met a waggon full of corn, going to market, drawn by a fine team of horses. He accosted the waggoner, and in the midst of conversation stabbed him to the heart with a dagger. He buried the body, and drove the waggon off to the town, where he sold the corn and the waggon as well, and then disappeared!

Dun had a great animosity to lawyers (or, rather, the authors of the legends worked into them their own dislike of the legal profession, and it is curious to note how this runs, like a thread, throughout all the fabric of highwaymen stories), and, hearing that some were to dine at a certain inn at Bedford, went hurriedly into the house about an hour before the appointed time, and desired the landlord to hasten with the dinner, and to provide for ten or twelve. The company soon arrived, and while the lawyers thought Dun a servant of the inn, the innkeeper thought him an attendant of the lawyers. He bustled about, and on the bill being called for, collected the amount, and walked off with it. The company, tired of waiting for him to return with their change, rang the bell for it, and then discovered him to be an impostor. And the hats and cloaks and the silver spoons had gone too.

Dun became such a terror, that the sheriff of Bedford assembled a considerable force to attack him and his band. But Dun, finding his own men to equal, if not actually to outnumber, those sent against him, assumed the offensive, and, furiously attacking the sheriff's expedition, routed it and took eleven prisoners, whom he hanged upon trees in the woods, by way of a hint how rash a thing it was to interfere with him. Removing the prisoners' clothing, they dressed themselves in it, and forming a plan to rob the castle of a neighbouring nobleman, appeared before it in the uniform of the sheriff's men and [Pg 21] demanded admission, "to search for Dun." Failing to find him, they requested all the keys of the place, to make a narrower search, and so looted many costly articles. Upon a complaint being lodged with the sheriff, the ruse was belatedly discovered.

It would be wearisome to follow all the fables that tell of Dun's twenty years' bloodstained progress to the scaffold. There is this much to be said in commendation of the popular legends of bandits: that when they are shown to be really bad, without redeeming traits, the legends duly see to it that justice is satisfied. And so with Dun, who is made to end disastrously at Bedford, even without the advantage of a formal trial. "When two executioners approached him he warned them of their danger if they should lay hands on him," and when they insisted upon doing so he struggled with them so successfully that he flung them nine times upon the scaffold, before his strength gave way. The crowds who gloated horribly over executions at Tyburn and elsewhere never had so great a treat as pictured in this fictitious scene: but this was merely the appetiser, the anchovies, so to speak, before the more solid course. Better was to follow.

The original executioners having been put out of action by Dun's violence, reinforcements were brought to bear, and did their business very effectually. "His hands were first chopped off at the wrist; then his arms at the elbows; next, about an inch from the shoulders; his feet below [Pg 22] the ankles; his legs at the knees; and his thighs about five inches from the trunk. The horrible scene was then concluded by severing his head from the body, and consuming it to ashes. The other portions were set up in the principal places of Bedfordshire."

This by no means pretty ending, when told to children, terrified them more than all the terrific deeds attributed to Dun himself, and often woke them at night, screaming.

ROBIN HOOD AND HIS MERRY MEN

The mythical Thomas Dun's redeeming qualities, supposing him, indeed, to have possessed any, are not set forth in those legends of him. He is a blackguard shape; while the equally legendary Robin Hood is one of the brightest figures of romance.

Robin Hood is a poor man's hero, and has been, for over seven centuries, to the peasantry of England something of what King Arthur was to the nobles and the aristocracy. While Arthur was, and is some day again to be, the national hero in the larger issues of war and conquest, Robin remains the lion-hearted outlaw; warring from his boskage in the greenwood of Sherwood Forest, or Barnsdale, against the rich oppressors of the people, whether they be the nobles or the fat ecclesiastics of mediæval satire.

Many industrious writers have sought to reduce the Robin Hood myths to a connected whole, and to trace their origin, but the task has [Pg 24] proved hopeless. He is as pervasive as the winds, and came whence no one knows, but may be traced back to the reign of Edward the Second, when he was already fully established as a ballad hero. Ritson, who collected and edited the ancient literature referring to him, is of opinion that he was a real person, Robert Fitzooth, and was born at Locksley, in Nottinghamshire, in 1160. But no evidence settles that point, and it is abundantly possible that he was really evolved from dim memories of Hereward the Wake, the Saxon hero, who long withstood William the Norman in the fens of Ely. In course of time his championship of a conquered nation was lost sight of, and merged into the endearing character of an English yeoman, outlawed for debt, taking refuge with others of his kin in the forest, whence they levied toll upon the oppressor, and, as they themselves were outlawed, respected no law, save that of the greenwood, where the best man was he who could draw the stoutest bow and shoot the straightest; who could make the best play with that truly English weapon, the quarter-staff, or deal the mightiest blow with the fist.

The whole cycle of Robin Hood legend is delightfully and most characteristically English, instinct with the purest and most passionate love of the countryside, and nerved with the championship of manhood's rights and with the fiercest hatred of the law and of the ruling classes in days when laws were the repressive measures instituted by the wealthy for the purpose of denying simple [Pg 25] justice to the poor. The hatred of authority and the armed resistance to it, that are the leading features of Robin Hood legend, are no mere criminal traits, but violent protests (the only kind of protest then possible) against the bloody forest laws of the Norman and Plantagenet times, and the system by which the peasantry were serfs, with no more social rights than the negroes enjoyed before their emancipation in 1833.

Robin Hood legend was for centuries the expression of what might now be styled Liberal, or even Radical, or Socialist opinion, but it has an innate poetry and chivalry which those modern schools of thought conspicuously lack; and indeed, as personal liberty broadened, so did the legends of this splendid figure of romance become blunted and vulgarised in the countryside, until he is made interchangeable with the highwaymen who had only their own pockets to fill and no cause to represent.

How popular and how astonishingly widespread was the story of Robin Hood, we may readily guess from the many places or natural objects named after him. "Robin Hood's Butts" on the racecourse near Onibury, a mile and a half from Ludlow, are still pointed out. They are in the nature of sepulchral barrows. From there, says legend, Robin Hood shot an arrow that sped the mile and a half to Ludlow church, and fixed itself on the apex of the gable of the north transept! An arrow is certainly there, but Robin never shot it. It is, in fact, an iron likeness of an arrow, [Pg 26] and is the sign of the guild of Fletchers, or arrow-makers, who built the transept.

There are other "Robin Hood's Butts" in the country: his "Cairns" on the Blackdown Hills in Somerset; "Robin Hood's Bay," on the Yorkshire Coast; his "Barrows," near Whitby; "Robin Hood's Tor," near Matlock; boundary-stones in Lincolnshire, known as "Robin Hood's Crosses"; a large logan-stone in Yorkshire, styled his "Penny Stone"; a fountain near Nottingham that figures as his; "Robin Hood's Well," between Doncaster and Wetherby; "Robin Hood's Stable," a cave in Nottinghamshire; a natural rock in Hopedale, Derbyshire, known as his "Chair"; his "Leap," a chasm at Chatsworth. A number of ancient oaks are "Robin Hood's," and legends of his exploits still cling to Skelbrooke Park, Plumpton Park, Cumberland, Feckenham Forest, Worcestershire, and the forests of Sherwood, Barnsdale, Needwood, and Inglewood.

The forest of Inglewood, in Cumberland, is indeed associated with other outlaws as legendary as Robin himself or as that Irish figure of wild romance, "Rory o' the Hills." Andrew Bel, William of Cloudisdale, and Clym o' th' Clough are the great woodland triumvirate of the north.

It would be a thankless office to dwell greatly upon the probability that Robin Hood, as an individual person, never existed, and that he was perhaps not even typical of the woodland outlaws of old, whose ideas and practices doubtless fell far short of the ballad Robin's ideals. It is much [Pg 29] more pleasant to consider the romantic spirit that evolved him and gave him his exquisite setting of mossy glades and giant oaks, where the sun comes in golden-green shafts through the embowering foliage, and you hear the winding of the hunters' horns in chase of the deer. There is a springtime gladness in the old verses, of which this is typical:

It is the springtime of the year and of the English nation that you glimpse in these lines; a picture of that larger rural England of possible adventure, and uncontaminated skies that is now a thing of the past.

Nature is portrayed in these ballads with a vividness and certainty that more ambitious poets cannot match:

It is versification of the simplest and the most sincere kind.

Robin Hood, real or imaginary character, has himself no criminal taint, but he is one of the [Pg 30] original founts whence the stream of highwayman legend is fed. It does not, or should not, sully his fame, that the stream becomes polluted with much vileness as it flows down the channel of time. A gradual vulgarising of the beautiful old story of the manly outlaws in Lincoln green, who went on foot and chased and shot the deer, and redressed wrongs in the leafy coverts, is sadly to be noted; and by the middle of the eighteenth century it became so obscured that it was possible for one of the booksellers of the time to foist upon an undiscriminating public an absurd production, in which Robin and the seventeenth-century Captain Hind figure as contemporaries. The poor threadbare rags of chivalry are thrown over the recreant shoulders of the highwaymen, but they suit them ill; and the fine clothes the highwaymen sometimes wore and the excellent horses they rode, do not hide from us their essential coarseness.

When Langland's Vision of Piers Plowman was written, about 1362, Robin Hood long had been a popular figure; and in that wonderful descriptive poem we find, among those lifelike figures, Sloth, the priest, who confesses himself ignorant of hymns of the Saviour and the Virgin, and unable even to repeat his paternoster; "but," he says, "I can ryme of Robin Hode."

That confession would scarce have pleased the real Robin, who was an exceedingly religious man. In the oldest ballad surviving of him, he is found lamenting that he has not been to mass for a fortnight, and he thereupon, at great risk, [Pg 31] goes to Nottingham town, to repair the omission. He especially venerated the Virgin, and is in one ballad found to be so extremely devoted to his religious duties as to have three masses daily, before dinner.

At the same time, although he is found declaring to his band that no damage is to be done to any husbandman "that tylleth with his plough," nor to any good yeoman, nor to any knight or squire "that wolde be a good felowe," he delights in persecuting ecclesiastical dignitaries. A fat abbot, or a steward of a monastery, unlucky enough to fall in with him, has a weary time of it. The higher these personages, the worse the treatment meted out to them. "Ye shall then beat and bind," we find Robin directing his merry men; and as these ballads were but the essence of the public feeling of the age, it is quite evident that when at last Henry the Eighth made away with the monasteries, he must have had a very considerable and long-established force of popular sentiment entirely in accord with him.

One of the chief exploits of Robin with the dignified clergy was the traditional meeting with the Bishop of Hereford, in Skelbrooke Park, where he was said to have made the Bishop dance round an oak, and then, after plundering him, to have left him bound securely to the tree. Variations of the story are met with in plenty in legends of other outlaws and highwaymen.

That the Robin Hood legends impelled other [Pg 32] romantic souls to take to the woodlands and be also Robin Hoods, in admiring imitation, seems sufficiently evident from old records, of which the Derbyshire petition to Parliament in 1439 is typical. The petitioners solicited help to procure the arrest of a certain Piers Venables and others who, it is stated, "wente into the wodes like as it hadde be Robyn-hode and his meyne."

Nottingham was ever a town inimical to our Robin; probably because it was nearest to his haunts in Sherwood Forest. In the earliest ballad extant of his exploits, we learn how, going piously into the town for the feast of Pentecost, he met an old monk whom he had once robbed of £100. The monk "betrays" him, and to prevent his escape the town gates are closed. Robin, seeking to leave, is captured, after a desperate resistance, and thrown into prison; and the false-hearted monk sets out for London, to convey the welcome news to the King, who will be delighted to learn that the bold outlaw is at last laid by the heels.

But Little John and Much waylay the monk, and kill him and his little page, and themselves, with the despatches, seek audience of the King, who sends a command by them to the Sheriff of Nottingham, ordering him to bring Robin Hood before him.

Arriving at Nottingham, these bearers of the King's commands are received with due honours and elaborately entertained. Finally, after much feasting and drinking, and when the sheriff and his men are sunk in a drunken sleep, Little John [Pg 33] and Much steal their keys, kill the gaoler, and release Robin Hood. Then they return happily to the forest. The ballad ends by the pardon of Little John, in consideration of his fidelity to his chief.

Another ballad tells of the adventure of Robin and the potter. Meeting an itinerant seller of earthenware pots, Robin challenges him to the usual test of who is best man, a fight with quarter-staff. On this occasion he meets his match and is badly beaten. But there was never such a hungry man for a fight as our hero, and he then suggested a combat with swords, in which he was also vanquished. Then he changes clothes with the man of pots, buys his stock, and goes to Nottingham, where he sells them at less than cost price and so makes a speedy clearance of all but five. These he gives to the sheriff's wife, who then invites him to dinner. At the dinner-table he hears of a trial of skill at archery to be decided that afternoon, and attends and surpasses all competitors. The sheriff asks him of whom he learned such marvellous archery. "Of Robin Hood," he answered; and then the sheriff expresses a wish to see the outlaw. The pretended potter then conducts him into the depths of the forest and there blows a single blast upon his horn.

Immediately they are surrounded by Robin's own merry men, who compel the sheriff to leave his horse and other gear; glad enough to get away on any terms. Robin, however, courteously [Pg 34] sends the sheriff's wife a white palfrey that "ambles like the wind."

Indeed, Robin was very much of a lady's man, and no outlaw worthy the name of forester was ever else. They were all squires of dames, and in this at least were equal, in theory at any rate, to the best "perfit gentil knight" that ever wore a lady's kerchief.

Courtesy to beauty in distress was ever one of the chiefest salves with which bandits salved their self-respect. No sentence of outlawry could make them rue, if to that principle they held them true. Even an outlaw had his ideals: to play special providence, to succour the distressed, to punish the oppressor, and "never to lay hands on a woman, save in the way of kindness." There were, of course, many lapses from these altitudes of conduct, but the ideal long remained, and only seems to have greatly decayed in the eighteenth century.

We have the historical instance of that adventure of the fugitive Queen of Henry the Sixth, lost in 1459 in the wilds of Staffordshire, after the disastrous battle of Blore Heath. Plying from that stricken field, on horseback, with her son, the youthful Prince Edward and one only retainer, the little party were surprised in the mountainous district of Axe Edge by a band of robbers, who seized their money, jewels, and every article of value. These savage men knew nothing of their rank, save that they were obviously people of quality. Then the rogues fell to [Pg 37] quarrelling among themselves, as to the division of the spoil. Menaces were growled out, and swords drawn. Margaret of Anjou, the high-spirited Queen, seeing the bandits so engaged with each other, took her son by the arm and hurried with him into an adjacent wood.

We hear no more of the solitary retainer. He seems to have left early.

The Queen and her son had not gone far when they encountered another outlaw. With the simple frankness of a great despair, she threw herself and the young Prince upon his mercy. "Friend," said she, "I entrust to your loyalty the son of your King."

What a generous-hearted bandit could do, he did. Taking them under his protection, he conducted them by secret and intricate ways into the comparative safety of the Lancastrian headquarters.

But to resume our Robin. The fate of Guy of Gisborne shows how rash it was to attack our friend in Lincoln green, who was by no means so green as he looked. Guy had sworn to apprehend the outlaw, and roamed the forest in search of him, in a "capull hyde," which is said to mean a horse's skin. Guy found him at last, with disastrous results to himself, for Robin slew him and mangled his body with what is particularly described as an "Irish knife." He then clothed himself in the "capull hyde" and took his deceased enemy's horn, and went off to Barnsdale, where his men, unknown to himself, had been in combat with the [Pg 38] sheriff's force, with the result that several were killed and wounded on both sides. Robin's men had, however, the worst of the fight, and Little John had been taken prisoner and bound fast to a tree.

Robin, drawing near his men's haunts, blew a blast upon the horn he had taken, and the sheriff, recognising the note, and thinking it was Guy of Gisborne, come back victorious, went to meet him, with the result that he and his force were taken, and Robin's men released.

The many scattered ballads of Robin Hood that had long passed from mouth to mouth were collected, edited, and printed about 1500 by Wynkyn de Worde, under the title of A Lytell Geste of Robyn Hode and his meyne, and of the proude Sheryfe of Notyngham.

According to this, the home of Robin Hood was in Barnsdale, the woodland tract between Doncaster and Pontefract. There Little John and two companions waylay Sir Richard at the Lea, a knight passing through the forest: a melancholy man, as sad as he of the Rueful Countenance. He is not afraid to accompany the rovers to their master, for he has little to lose. But Robin, far from ill-using, entertains him to a sumptuous dinner, served (by what marvellous means we are not told) in the merry greenwood. Such mediæval delicacies as swans, with, of course, pheasants, smoke at the outlaw's spread. The feast being concluded, the knight prepares to depart; but "Pay you, ere you wend!" says [Pg 39] Robin; "it was never the custom of a yeoman to pay for a knight."

The knight, deeply humiliated, confessed he had but ten shillings.

"Go search," commands Robin to Little John. "If, sir, you have no more," he says to the knight, "I will not have a penny."

The search confirmed the knight's words; and it then appeared that this was a sorely stricken knight indeed.

"For a hundred winters," he explains, his ancestors had been knights, and until within the last two or three years he had possessed an income of four hundred pounds a year, as his neighbours well knew.

But his son was unlucky enough to kill a Lancashire knight, and a squire as well, in a joust; and, to help pay the penalty of his son's mishap, the father's goods had been "sette and solde," and his lands pledged to the Abbot of St. Mary's, for four hundred pounds. The day for repayment of this loan was close at hand, and the knight, unprovided with money, already foresees his estate pass from him.

Robin Hood then asks him, who would be the knight's surety, if he advanced the sum.

Alas! replies the knight, he is as badly in want of friends as of money. He can offer no surety, save Our Lady, who had never failed him before.

In Robin Hood's way of thinking, no better surety could be found, even if England were [Pg 40] sought through and through; and the knight is immediately provided, not only with money, but with clothes, a horse, and a trusty squire, in the person of Little John. The whole band enter deeply into their leader's feelings, and weep salt tears over the knight's misfortunes, and themselves contribute liberally to supply his needs.

The second "fytte," or act, is placed at St. Mary's Abbey, on the day of reckoning, and the abbot is introduced, chuckling at the absence of the knight, and the probability of his lands being forfeited. The prior entreats his superior to show a little pity, but his call for moderation is scornfully rejected by the abbot, and by the cellarer, a fatheaded monk of the type made familiar in modern German paintings of tonsured voluptuaries eyeing tables full of food and stroking their paunches.

In midst of these proceedings, the knight enters, and humbly begs for an extension of time; but the abbot insists on his bond, and will have, and at once, either the money or the land. Then the high justice is introduced, as moderator:

The debt thus paid, the knight takes leave of the disappointed abbot, and "went hym forthe full merye syngynge, as men have told the tale."

Living at home in retirement, he soon saves sufficient to get together the sum that Robin had advanced; and then equips himself with a splendid present of bows and arrows for the outlaw, and rides, with a merry song and a light heart, to Barnsdale.

The third fytte tells the adventures of Little John, who, straying into Nottingham, attracts the attention of the sheriff by his skill in archery, and enters into his service for one year, in the name of Reynold Greenleaf. But in a little while, in the sheriff's absence, Little John raises a quarrel in the house and runs away with the cook. Together they go off to the greenwood, with the family plate, and ready money, "three hundred pounds and three." Robin Hood receives them, but they have not long returned when Little John plans to capture the sheriff himself, on his way home. The seizure is easily made, and the sheriff is taken to the foresters' camp, where supper is served to him on his own plate. He is then stripped to his [Pg 42] shirt and breeches, and released the next morning, after being obliged to take an oath never to lie in wait for Robin Hood, "by water, ne by londe," and if any of the band fall into his custody, to help them to the best of his power.

The fourth fytte opens with the cellarer of St. Mary's, travelling with a large sum of money. He falls in with Robin and his men, but declares he has only twenty marks. Little John, however, on searching him, discovers eight hundred pounds; whereupon Robin Hood exclaims that the money must be sent by Our Lady, who, with her accustomed goodness, had doubled the sum he lent the knight.

The monk is then bidden go his way, after refusing a parting glass; vowing, with much truth, that he might have dined cheaper at Blyth or Doncaster. The knight, at this moment, arrives with the money to repay his loan. Robin accepts his presents, but will not take the money, as Our Lady has just now paid it back, together with another four hundred pounds, which he begs the knight to accept.

The fifth fytte opens with the Sheriff of Nottingham proclaiming a shooting match. Robin attends, and bears off the prize, but as he leaves the town, the cry of "Robin Hood" is raised. "Great horns 'gan they to blow"; the townsmen assemble, and a fight begins, in which Little John is wounded in the knee, so that he can neither walk nor ride. In this desperate pass, he entreats his captain to smite off his head with his sword, [Pg 43] so that he may not fall alive into the hands of the enemy, but Robin indignantly refuses. Little Much takes him on his back, and carries him off, halting from time to time to speed arrows into the ranks of the pursuing sheriff's men. They then all escape to the castle of their knightly friend, who, in the sixth fytte, is waylaid, and carried off by the sheriff.

The knight's lady then appeals to Robin Hood, who calls his men, and, proceeding to Nottingham, slays the "proud Sheriff" and releases the knight.

In the seventh fytte we have the arrival of "our comely King," Edward the Third, at Nottingham, come to inquire into a complaint the sheriff had made against the knight for harbouring outlaws. The King, for a whole year, endeavours to capture Robin or the knight, but has no sort of success until a forester offers, if the King will assume the costume of an abbot, to conduct him to the outlaws' retreat, "a mile under the lynde"; i.e. in the midst of the lime-trees, or lindens.

This offer is accepted, and Robin receives the pretended abbot with unusual courtesy, taking but one-half of the forty pounds he offers for ransom of himself. The "abbot" then produces a summons under the Royal seal, inviting Robin to Nottingham "both to meat and meal."

Robin goes down on bended knee before this august message, and entertains the "abbot" in the best style, with venison and

After dinner he entertains his guest at a shooting-match; [Pg 44] the chief condition being that whoever misses a rose-garland suspended between two poles shall forfeit bow, arrows, and quiver, and submit to receive a buffet on the head.

Robin misses by three fingers and more, and the King is entitled to inflict the penalty. He hesitates. "Smite boldly!" says Robin; "I give thee large leave."

Thus encouraged, the king, with one blow of his stalwart arm, makes the outlaw reel. Such an exhibition of vigour was more convincing than moral suasion, and Robin, perceiving that this is no abbot, but the King himself, submits at once, with his men. The sovereign graciously pardons them and invites them to London.

The eighth fytte concludes the story. Robin and his men follow the King to the Court; but within a year the love of the free and unconventional forest had lured away all but Robin and two companions, and Robin himself was sick to be gone. The finishing touch was the sight of a gathering of young archers.

says the sometime outlaw, longing to be a forester again.

So he forswears the Court, and retires again to the forest.

And there, the legends say, he lived as of [Pg 45] old for twenty-two years; until falling sick, he resorted to the priory of Kirklees, where a kinswoman of his was prioress. After the medical fashion of the time, the remedy was to be slightly bled; but the treacherous prioress, and one Sir Roger of Doncaster, opened a vein by which he bled to death: dying "from the perfidy of a woman," as had been prophesied.

From the chamber in the gatehouse of the priory where he lay, he shot his final arrow, his faithful Little John whom he had summoned by three blasts of his horn, supporting him. The spot where the arrow fell was to be his grave, and there Little John was to lay him, with his bow bent by his side, a turf under his head, and another at his feet. The old ballad of his affecting end piously concludes:

The railed-in spot where he, by tradition, lies buried had once, we are told, a stone inscribed

But this appears to have been the invention of Martin Parker, author of the "True Tale" [Pg 46] of the hero, c. 1632. It still, however, imposes upon the credulous and supports the somewhat sweeping saying current in Camden's time: "Tales of Robin Hood are good for fools."

Wykyn de Worde's collection of Robin Hood romances is itself a proof of the wide popularity the hero had always enjoyed, and did still enjoy; but it does not stand alone as proof. In 1444 we hear a grumbling voice speaking of Robin, Little John, Friar Tuck, and the others of that immortal band, "of whom the foolish vulgar, in comedies and tragedies, make entertainments, and are delighted to hear the jesters and minstrels sing them, above all other ballads."

A century later, none other than Latimer, Bishop of Worcester, preaching before Edward the Sixth, bore unwilling testimony to Robin's popularity with the masses: "I came once myself," he said, "to a place, riding on a journey homeward from London, and I sent word overnight into the town that I would preach there in the morning, because it was a holyday.... I thought I should have found a great company in the church, but when I came there, the church door was fast locked. I tarried there half an hour and more, and at last the key was found; and one of the parish comes to me, and says, 'Sir, this is a busy day with us, we cannot hear you; it is Robin Hood's Day. The parishes are gone abroad to gather for Robin Hood.'

"I thought my rochet should have been regarded, though I were not," added Latimer, [Pg 47] plaintively; "but it would not serve; it, too, was fain to give place to Robin Hood's men."

Apparently at this point the congregation laughed, for we find him, resuming, rather heatedly: "It is no laughing matter, my friends, but rather a weeping matter, a heavy matter, under the pretence of gathering for Robin Hood, a traitor, and a thief, to put out a preacher, to have his office less esteemed, to prefer Robin Hood before the preaching of God's Word."

In 1601, when England was living under a recently reformed religion, it became again necessary to reconstruct Robin Hood legend for popular acceptance, and in a play, written by Anthony Munday and Henry Chettle, he appears as the outlawed Earl of Huntingdon; a figure for which there is not the slightest historical warranty. Thus the fabricated "epitaph" at Kirklees must itself have been, as it were, a by-product of this play. Maid Marian and several other characters who appear in it originated only a century earlier, and have no part in the earliest ballads. The play then gradually merged into May Day festivities and the once familiar "Jack-in-the-Green," extinct only within the last forty years, but greatly vulgarised towards the end, when chimney-sweeps acted "Jacks-in-the-Green," and the Maids Marian were too often fat and fiery-faced sluts. The entertainment was found all too often outside public-houses.

Robin Hood has, of course, equally with other heroes, suffered greatly from being continually [Pg 48] edited and restated, from age to age. How should he escape the fate that King Arthur experienced, of being made into a distinctly Victorian gentleman? Tennyson has redressed old Robin, with new clothes and a new conscience, in The Foresters; Robin Hood and Maid Marian, and there you cannot but entertain the horrible suspicion that he has become a typically respectable mid-Victorian, and that if any one offered to exchange his greenwood tree for a "parlour" with perhaps a suite of walnut furniture upholstered in green repp, and a marble clock with a couple of glass lustres on the dining-room mantel-piece, he would gladly accept, forswear his woodland glades, and live cleanly thereafter.

But the two most striking evidences of the old-time popularity of Robin Hood, not so long dead, are found in the many inns named after him, and in that great friendly society, the "Ancient Order of Foresters," whose title is directly inspired by the legendary story of Robin and his fellow outlaws. No one who has ever seen the Foresters in their regalia at their annual day at the Crystal Palace can have any doubt of that inspiration.

THE "HAND OF GLORY"—LIABILITY OF COUNTRY DISTRICTS FOR ROBBERIES—EXEMPTION IN RESPECT OF SUNDAY TRAVELLING

Those far-distant, unpleasant days when "highway lawyers," and entirely unromantic bands of robbers, murderers, and footpads swarmed over the country, and robbed and slew with comparatively little fear of the law, were also extremely superstitious days. Good men and bad were alike steeped in a degrading belief in white and black magic, portents, and omens. Magical aids in the prosecution of both innocent and guilty enterprises were employed; and among them none more fearful than the charm known generally as the "Hand of Glory": the "open sesame" of thieves and assassins, among whom, it is to be feared, we must include not a few of our "romantic" highwaymen; although probably the larger number of them would actually have felt themselves insulted at being styled thieves, and certainly only a minority slew wilfully. Most desired nothing so little as to shed blood, in spite of the terrible alternative they threatened—"Your money, or your life!"

But among the thieves and the murderous the superstition of the "Hand of Glory" was widely prevalent. It appears to have originally derived from mediæval Germany, that storehouse of terrible imaginings. What the "Hand of Glory" was, and the effect it produced, may be seen better by the following quotation from the Ingoldsby Legends, which is one of the most genuinely thrilling passages in literature. It is full of the most dreadful description, but exquisitely done:

The dried hand, thus obtained, was fitted with wicks, one to each finger and the thumb, made from the five locks of hair dipped in grease from the murderer's own body and the fat of a black tom cat, and generally consecrated with the saying of the Lord's Prayer, backwards. When all these wicks were lighted, and the blazing Hand of Glory carried into a house, a spell was supposed [Pg 53] to be cast on place and inmates, in which the malefactor could work his will:

Traditions not so long since surviving in the North Riding of Yorkshire tell a horrid story of the use of an enchanted hand of this kind. One wild and bitter night—the sort of night when homeless wayfarers were more than usually to be pitied—a man clad in ragged clothes knocked at the door of a lone inn on a solitary moor, and asked for a lodging. There was no accommodation to spare, but as the night was so inclement and the way was long to the next house, he was told that if he liked, he might lie in the front of the kitchen fire. He accepted this offer with every appearance of thankfulness, and soon after, when the family had gone to bed, he was left there. But although the innkeeper and his family had retired and left the stranger alone, the servant was still engaged for a few minutes in another room which chanced to command a view of the kitchen. Happening to glance in that direction, she was at first astonished, and then horrified, to find that the stranger had risen up from the floor and had seated himself at the table where she saw him take a shrivelled, mummified hand from his pocket, set it up, and then, one by one, light the [Pg 54] fingers. The girl rushed upstairs to warn her master of these extraordinary doings, but she found him and his family all already in a charmed sleep. It was impossible to arouse them; and here she found herself alone in the house with the evil-intentioned stranger and his uncanny movements. She quietly went downstairs again and saw the beggarman exploring the house and collecting articles that appeared to him worth taking. Still on the kitchen table burnt the four fingers of the Hand of Glory, in blue, sickly flames; but the thumb was not burning. To that fact was due the circumstance that one person in the house remained unaffected by the spell.

Stealing on noiseless feet into the kitchen, she blew upon the Hand, but could not blow it out. She poured beer over it, but the Hand only seemed to burn better. She tried water, but that appeared to have no effect, one way or the other. Then she emptied the milk-jug over it. Immediately the place was in darkness, except for the glow of the kitchen-fire. The spell was instantly removed, the sleepers awakened, and the robber seized and afterwards tried and hanged.

Harrison Ainsworth, revelling as always in the horrible, gives us his version of the Hand of Glory in Rookwood. In this variant you recognise the nastiness of it, rather than the horror:

The ancient condition of Merry England was a despotic rule tempered by rebellion and highway robbery, in which the Barons revolted from time to time against kingly encroachments, and the peasantry were generally at odds with both those estates. The woodland tracts that then overspread the greater part of the country were filled with outlaws, of whom Robin Hood, as we have already [Pg 58] seen, was a sublimated idealisation, and in those tangled thickets a man, or a body of men, might lurk and exist for years, subsisting upon the deer whom it was then, under the old forest laws, mutilation and death to slay. But with the law already arrayed against them, the outlaws who had been deprived of the very few rights a man of the peasant class might then own, cared little for the fearful penalties that awaited those who took a fat buck and converted it into venison, and valued not at all the punishments that awaited the highway robber. A man proscribed for some offence, who had then taken to the woods of necessity, might even, for sheer love of the life, elect to remain in them for sport; for the sporting instinct has ever been deeply implanted in the character of the English race, without respect of class. It is largely the sporting instinct, and not so much the actual worth of the quarry, that makes the modern poacher brave the keepers of the squire's preserves.

It was but a step from specialising in unlawful chase of the deer to robbing travellers. The deer-stealers were already Ishmaels, before they had dared so greatly, and they were doubly outlawed after so boldly usurping the hunting prerogatives of kings and nobles. What mattered, then, the taking of a purse; nay, even of a life?

The Legislature early attempted to put pressure upon local authorities, to secure the arrest of robbers, and, as usual, the pressure was exercised [Pg 59] through that most vulnerable part, the pocket, the "Achilles' heel" of civilisation. The country (often in later years we find it "the county") was supposed to be responsible for good governance, and if the country was unfortunate enough to be infested with robbers, it was expected to arrest them; or failing that, to be financially answerable for their robberies. We find this specifically provided for by Act of Parliament in 1285, and again in 1354.

But it was impossible in those times, in the sparsely populated country, to suppress robbers, and the rural districts suffered severely in pocket as a result of bold pillaging in the day-time.

In 1509 Margaret Paston, writing from Norfolk, is found nervous of sending gold to London, and telling her husband, then staying in town, that a sum of twenty marks had been paid for a ward, but that the person who paid it "dare not aventure her money to be brought up to London for feere of robbyng; for it is seide heere that there goothe many thefys be twyx this and London." He was therefore to have the money at his coming home.

The county division known as "the hundred" was the area responsible and liable to reimburse losses occasioned in this manner. Thus, inter alia, we find the Hundred of Benhurst, in Berkshire, continually assessed to make good the losses sustained by travellers, along what is now the Bath Road, through Maidenhead Thicket, a place whose ill repute was second only to that of Hounslow [Pg 60] Heath. By an Act of Parliament of 1585 (27 Elizabeth c. 13, s. 2) the sum recoverable from the hundreds was limited to half the travellers' loss. The reasons given for this limitation were the distress and impoverishment of the inhabitants by reason of these frequent and severe levies upon their purses. It is evidence of the extraordinary increase of highway robbery at that period. Five years after this enactment, the Hundred of Benhurst paid £255 compensation for robberies committed in the Thicket.

Even so, the liability of the country, the county, or the hundred, had always been limited to robberies committed in daylight. "Between sun and sun," i.e. between the setting of the sun and the next morning's sunrise, the highwaymen might work double tides and plunder as they would, and no action for damages would lie against the inhabitants.

Nor could travellers who were robbed on Sunday have any redress. It was particularly enacted by the statute of 1676, known as the Sunday Trading Act, that any one travelling on the Lord's Day did so entirely at his own risk, and was barred from bringing an action. "But nevertheless," the section continues, "the inhabitants of the counties and hundreds (after notice of such robbery to them, or some of them, given, or after hue-and-cry for the same to be brought) shall make or cause to be made fresh suit and pursuit after the offenders, with horsemen and footmen, according to the statute made in the twenty-seventh [Pg 61] year of Queen Elizabeth, upon pain of forfeiting to the King's Majesty, his heirs and successors, as much money as might have been recovered against the hundred by the party robbed, if this had not been made."

THE YOUNGER SONS—JUDGE POPHAM—SHAKESPEAREAN HIGHWAYMEN—THE "CAVALIER" BRIGANDS—A SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY RELIGIOUS TRACT

No doubt many of the "highwaymen's" escapades in the times of Henry the Eighth and Queen Elizabeth were the coltish pranks of high-spirited young men of family, or the freaks of university students. To assume a disguise, to buckle on a sword, and then take to the highway, singly or in bands, would be just the kind of adventure to tickle the fancy of such youths, and the danger that lay behind it all was really rather an appetising spice than a discouragement. The tradition of Henry the Fifth, when yet Prince of Wales, robbing on Gad's Hill for pastime, was still current, and Shakespeare had just revived it, and invested the doings of the Prince and Falstaff and their merry men with the glamour of the stage, which even then set the fashion.

Such a young man, according to Aubrey, was John Popham, afterwards Sir John, and Chief Justice of the King's Bench. "In his youthful days," says Aubrey, "he was a stout and skilful [Pg 63] man at sword and buckler as any in that age, and wild enough in his recreations, consorting with profligate companions, and even at times wont to take a purse with them."

This wild fellow became, as a member of Parliament and a judge, an extremely severe personage in dealing with the class of people with whom we thus learn him to have associated. Partly his work was the Act of 1589, which prescribed banishment (or, as later times phrased it, "transportation") "into such parts beyond the seas as shall be at any time hereafter for that purpose assigned."

Shakespeare's highwaymen are, as a rule, gentlemen. Such were the outlaws who in the Two Gentlemen of Verona waylaid Valentine and Speed in the forest. They had been banished from Verona and Mantua merely for such trivial and essentially gentlemanly peccadilloes as an attempt to abduct an heiress, and stabbing another gentleman to the heart. Too bad!

They found Valentine so presentable a young man that, finding he had no property to lose, they immediately proposed to make him their captain. They were prepared to do him homage, and be ruled by him. "But if thou scorn our courtesy, thou diest."

Making the best of circumstances—being rather prepared to captain a band of desperadoes than lose his life, Valentine consented, with one proviso:

To which the outlaws indignantly reply that they "detest such vile, base practices."

The doings of Falstaff and Prince Hal in their highway robbery exploits on Gad's Hill are classic farce, with elements of probability, although Sir John Fastolf, the original Falstaff, was introduced by Shakespeare without the slightest warranty: the real Sir John having been no dissolute, cowardly old man, but a brave and stern soldier, who had warred nobly for King and country for forty years.

The point of view from which the gentlemen highwaymen regarded themselves is admirably set forth in the play of Sir John Oldcastle, produced in 1600. The stage is generally regarded as the mirror of life, and thus, when "Sir John à Wrotham" is made to introduce himself to the audience, by frankly acknowledging he was, "in plain terms, a thief; yet, let me tell you, too, an honest thief," we doubtless have the real mental attitude of the "collectors"—as they were pleased to fancifully style themselves—set forth. He goes on to declare himself, in the good old Robin Hood vein, to be "one that will take it where it may be spared, and spend it freely in good fellowship." A modern company-promoter, of the Whitaker Wright type, might say as much, but even if true, it would not be held an excuse.

The same outlook upon life is observed in The Cashiered Soldier, a tract published in 1643. It represents that warrior out of work exclaiming:

Again, Bishop Earle, in his Microcosmography, shows us how the highwaymen were recruited. Speaking of the sorrows of younger sons, and narrating the shifts to which they were often reduced, he says: "Others take a more crooked path, through the King's highway, where at length the vizard is plucked off, and they strike fair for Tyburne."

The biographies of highwaymen given later in these pages, fully illustrate the position of affairs in the succeeding age, and show that the country swarmed with highway robbers after the conclusion of the Civil War between King and Parliament. Many of them were impoverished cavaliers, but the most prominent were only pretended gentlemen, who used any Royalist sympathies they may have had in giving a specious excuse for their misdeeds. Captain Hind is typical of these plundering fellows in the era of the Commonwealth. So many were they, and so formidable, travelling, as they often did, in bands, that it became the business of the troops, at the conclusion of the war, to hunt out all such associated brigands.

On September 17th, 1649, General Fairfax issued a proclamation addressed to the commanders [Pg 66] of "every respective regiment of horse," urging them to activity in the apprehension of all robbers, and promising high rewards for everyone captured. To this a Royalist print, the Man in the Moon, sarcastically rejoined that the "House of Robbers"—by which the House of Commons was meant—had voted for the next six months a reward of £10 for the taking of every burglar or highway-robber, "the State's officers exempted."

The proclamation, however, had its due effect, for on December 24th, no fewer than twenty-eight malefactors, principally of the classes specified, were all gibbeted together at Tyburn. Among them was "one Captain Reynolds, who was of the King's party in Cornwall, at the disbanding of the Lord Hopton's army at Truro.... His carriage was very bold, and, as he was going to be turned off, he cried: 'God bless King Charles: Vive le Roi.'"

But they were generally defiant at the last, whether Royalists or mere purse-takers; whether of the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. Conscience, which makes cowards of all, did not awake and begin to unnerve these candidates for Jack Ketch until the very opening of the nineteenth century.

Thus, in the olden times we find the condemned highwaymen nearly always nursing the grievance of their doom, and speaking of Justice and her emissaries as their "enemies"; as witness Thomas Hill, executed July 19th, 1694. Was he penitent at Tyburn? Not at all. His last words were, [Pg 67] "God bless all my friends, and let all my enemies be hanged as I am"; and, adds his biographer "other reflecting and abusive Expressions."

Although it might well seem, after an extensive course of reading in the thoughts and deeds of those times, that the country was entirely populated by two classes: the scoundrels who were always trying to evade Justice, and the officers of the law, continually occupied in tracing them, an unobtrusive residuum of well-intentioned and well-conducted people existed. We do not, it is true, hear much of them, which is only to be expected; but they existed, nevertheless, and were often as anxious to save sinners as any modern tract-distributor.