Title: The Story of the American Merchant Marine

Author: John Randolph Spears

Release date: September 22, 2016 [eBook #53122]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Story of the American Merchant Marine, by John Randolph Spears

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/cu31924030112977 |

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

THE STORY

OF THE

AMERICAN MERCHANT MARINE

BY

JOHN R. SPEARS

AUTHOR OF "STORY OF THE NEW ENGLAND

WHALERS," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1910

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1910,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published March, 1910.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | In the Beginning | 1 |

| II. | Early Growth | 22 |

| III. | Evolution of the Smuggler and the Pirate | 40 |

| IV. | Before the War of the Revolution | 59 |

| V. | Merchantmen in Battle Array | 85 |

| VI. | Early Enterprise of the United States Merchant Marine | 100 |

| VII. | French and Other Spoliations | 119 |

| VIII. | The British Aggressions | 132 |

| IX. | The Beginnings of Steam Navigation | 150 |

| X. | Privateers, Pirates, and Slavers of the Nineteenth Century | 177 |

| XI. | The Harvest of the Sea before the Civil War | 197 |

| XII. | The Packet Lines and the Clippers | 214 |

| XIII. | Deep-water Steamships—Part I | 240 |

| XIV. | Deep-water Steamships—Part II | 258 |

| XV. | The Critical Period | 277 |

| XVI. | During a Half Century of Depression | 298 |

| South Street, New York; from Maiden Lane, 1834 | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

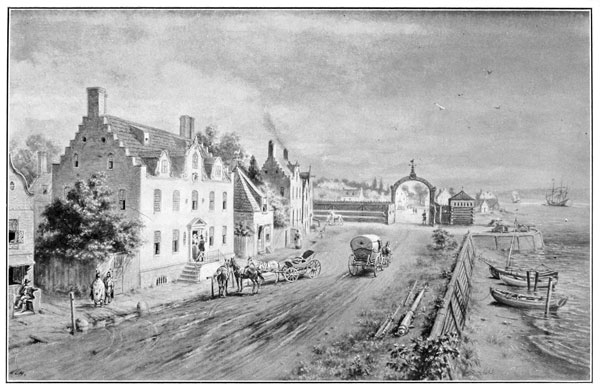

| An Early View of Charleston Harbor | 38 |

| Captain Kidd's House at Pearl and Hanover Streets, New York, 1691 | 70 |

| Custom House, Salem | 100 |

| Elias Hasket Derby | 108 |

| An Early Type of Clipper Ship: Maria, of New Bedford, built 1782 | 122 |

| A Virginia Pilot-boat, with a Distant View of Cape Henry, at the Entrance of the Chesapeake | 148 |

| Engines of the Clermont | 158 |

| Clipper Ship Syren | 220 |

| Captain Samuel Samuels | 222 |

| Clipper Ship Witch of the Wave | 232 |

| Sailing of Britannia, February 3, 1844 | 254 |

| Four-master Dirigo, First Steel Ship built in the United States | 298 |

| Seven-masted Schooner Thomas Lawson | 312 |

| A Modern Clipper Ship and a Modern Brig | 318 |

| Cunard S. S. Lusitania | 334 |

THE STORY OF THE MERCHANT MARINE

[1]THE first vessel built within the limits of the United States for commercial uses was a sea-going pinnace of thirty tons named the Virginia. Her keel was laid at the mouth of the Kennebec River, in Maine, on an unnamed day in the fall of 1607. The story of this vessel, though brief, is of great interest because, in part, of certain peculiarities of rig and hull which, in connection with a sea-going vessel, now seem astounding, but chiefly because it portrays something of the character of the men who, a little later, laid the foundations of the American Republic.

The adventure which led to the building of the Virginia grew out of that wonderful harvest of the sea, the cod fishery on the banks of Newfoundland. For more than a hundred years before she was built many fishermen of Europe had been sailing to the Banks in early spring and returning home each fall. Throughout the sixteenth century there were from 100 to 300 fishing vessels there [2] every year, excepting only those years when wars raged the hardest. In 1577, for instance, as the records show, 350 vessels sailed for the Banks, gathered their harvest, went ashore in the bay where St. John, Newfoundland, now stands, cured the catch on flakes built on the beach, and then sailed for home well satisfied.

Though dimly seen now, those fishermen, as they flocked across the sea in the spring, form one of the most striking pictures in history. For no one had ever charted the western limits of that waste of waters. The Banks lay beyond a belt of the sea famous, or infamous, as the "roaring forties." And yet in ships so rude that the hulls were sometimes bound with hawsers to hold them together these men anchored where black fogs shut them in, where sleet-laden gales were a part of their common life, where bergs and fields of ice assaulted them, and where irresistible hurricanes from the unknown wilds beyond came to overwhelm them. To these real dangers they added others that, though born of the imagination, were still more terrifying. They saw evil spirits in the storm clouds, and demons came shrieking in the gales to carry their souls to eternal torment.

Even in pleasant weather life was hard. Masters ruled their crews by torture. To punish an obstinate sailor they wrapped a stout cord around his forehead and then set it taut until his eyes were popped from the sockets. The food brought from home spoiled. In the best vessels the crew slept in leaking, unwarmed forecastles, while [3] in some of the vessels—those that were but partly decked over—they slept unsheltered. The brine of the sea covered them with sores called sea boils, and their hands dripped blood as they hauled in their cod lines.

Consider further that these fishermen came from four nations that were always at war with each other, either openly or in an underhanded way. And yet the English, the French, the Spanish, and the Portuguese anchored side by side on the Banks, built their flakes side by side on the Newfoundland beach, and when a ship opened her seams as she wallowed in the gale, the crews of the others within reach eagerly lowered their boats to rescue the drowning.

In courage, fortitude, sea skill, and resourcefulness those Banks fishermen had never been surpassed.

This is by no means to say that the fishermen never fought each other. Good fair fighting was a part of the comfort of life as they saw it. But the conditions that eliminated the weaklings naturally created in their minds a standard of justice under which all who survived could work.

Let it be noted now that with all their hardships they were not without compensating rewards. Good digestion waited on appetite. The life ashore while curing the catch—a life where venison and wild fowl replaced their salted meats, and the red people of the region came to visit them—was a time for jollification. But more important than all else they had leisure as well as hard work. For having a share in the catch instead of wages, they obtained enough money, on reaching home, to enable them to pass [4] the winter beside the hearthstone, where they told tales of adventures that stirred the blood. So the love of the sea was cultivated and the race was perpetuated.

Into the midst of these fishermen, as they worked among their flakes upon the Newfoundland beach, came Sir Humphrey Gilbert, on August 5, 1583, who was the forerunner of the New England colonists. He told them he had come to take possession of the country and establish an English colony there. The fishermen saw that such a settlement would interfere with their business, but no resistance was made while he erected a monument and did such other things as the customs of the day required of those taking possession of a new land. One may fancy they saw in Sir Humphrey a man of their own sort. For he had crossed the sea in the ten-ton Squirrel, and although she was, as they said, "too small a bark to pass through the ocean sea at that season of the year," he sailed in her when bound for home; he would not ask his men to take a risk which he would not share. And when the storm that overwhelmed him came, he sat down at the stern of the little bark with a book in his hand, and shouted in a cheerful voice to the crew of the Hind, which was close alongside:—

"We are as near to heaven by sea as by land."

The sailors of Gilbert's expedition have been called "no better than pirates" (Bancroft), but at worst they were able to cherish the abiding faith of their master as expressed in those words. The seamen who sailed (1530) [5] with William Hawkins in that "tall and goodlie ship of his own," the Paul, to the coasts of Africa and Brazil, and with Drake in the Pelican in that famous voyage around the world, and with Raleigh's expedition to the coast of North Carolina, were recruited from among these fishermen, to whom adventure was as the breath of life. And the men who did the actual work of building the Virginia were of the same class.

As the reader remembers, the first charter of Virginia as a colony provided for two colony-planting companies. One, the London Company, settled its colonists in what is now the State of Virginia, while the other, the West-of-England or Plymouth Company, was to people the northern coast. In May, 1607, the Plymouth Company sent two vessels to establish a fishing colony on what is now the coast of Maine. One of the vessels was a "fly-boat" called the Gift of God. A fly-boat was a flat-bottomed, shoal-draft vessel handy for exploring inland waters. The other was "a good ship" named the Mary and John. These ships shaped their course to an island off the coast then well known to the fishermen, and now called Monhegan, "a round high Ile," where they arrived on August 9. On the 18th they located their settlement on a peninsula, on the west side of the mouth of the Kennebec, which was "almost an island." There they erected dwellings, a storehouse, and a church, with a fort enclosing all. Then "the carpenters framed a pretty pinnace of about 30 tons, which they called the Virginia, the chief [6] shipwright being one Digby of London." A plan of the fort as "taken by John Hunt, the VIII day of October in the yeere of our Lorde 1607," is reproduced in Brown's Genesis of the United States. This chart is important because it shows under the guns of the fort a small vessel which was, no doubt, the "pretty pinnace" Virginia.

While the dimensions of the Virginia were not recorded, we can get a fair idea of her size from Charnock's History of Marine Architecture (II, 431), where a smack named the Escape Royal, in 1660, was of 34 tons burden and 30 feet 6 inches long by 14 feet 3 inches wide, and 7 feet 9 inches deep. The 30-ton Virginia was not far from these dimensions. She carried a spritsail and a jib. As the sail spread was insufficient for driving the vessel in light airs and confined waters, oars were provided. The hull was partly decked, enough to protect the cargo.

The crew had to be content with an awning when the wind was light. When the wind was heavy, they had to face the gale, as was the custom on the Banks. And yet the Virginia was built by men who intended to use her not only in the fishery and the coasting trade with the Indians, but for oversea trade as well. It is a matter of record, too, that she made at least one voyage from England to the Chesapeake, and it is believed that some of the Kennebec colonists sailed in her upon that voyage.

Curiously enough, however, the Kennebec colony failed somewhat ingloriously. The winter was long and severe. A fire destroyed the storehouse and the provisions that [7] had been brought from England. The unexplored wilderness oppressed them. In fact, while they would face a hurricane at sea in an open boat, the terrors of the wilderness, though chiefly of their own imagining, drove them away, and they were hard pressed at home to find excuses for what they had done.

In the meantime a settlement was made at Jamestown, Virginia. Of the 105 colonists at Jamestown, 48 were described as gentlemen, 12 as laborers, 4 as carpenters, and the others as servants and soldiers. The servants were white slaves, who were not, however, held for life. The ships with this oddly assorted colony arrived in the Chesapeake on April 20, 1607. Of the things done at Jamestown two only need be considered here. They began creating a merchant marine in 1611 by building a shallop of twelve or thirteen tons' burden. A Spaniard who visited the colony at that time noted that the iron used in the boat had been taken from a wreck at Bermuda—a fact that shows the colonists had not had enough interest in ship-building to bring iron for that purpose from home.

The truth is the Virginia colonists never had much interest in shipping, save only as they built many vessels of small size for use in local transportation on their inland waters. The reason for this condition of affairs is pointed out in Bruce's Economic History of Virginia. The money crop was, as it is now, in many parts of the State, tobacco. Tobacco had been introduced into England in [8] 1586. The settlers found the Indians cultivating it on the James River, but they gave little heed to it until 1612, when John Rolfe, the first American "squaw man," began producing it partly for his own use and partly because he was trying to find some product that could be exported to England with profit. Thus Rolfe's garden was the first American agricultural experiment station. Under cultivation the leaf produced was of better quality than that obtained from the Indians, and when a trial shipment was sent to England the success of the venture was great. Thereupon the colonists became so eager to produce it that the authorities felt obliged to prohibit the crop unless at least two acres of grain were grown at the same time by each planter.

The demand for Virginia tobacco increased until the merchants sent their agents to the colony to buy and pay for the crop long before it was harvested; they even sent ships to lie there for months before the harvest in order to have first chance to secure it. Why should the Virginians build or buy ships under such circumstances?

Now consider some of the conditions surrounding the first New England settlers. Many fishermen had visited the New England coast before a settlement was made there. These adventurers found full fares and they looked upon the coast at a season when it was not "stern."

It was to this coast that the Pilgrims came.

Of the well-known story of the Pilgrims it seems necessary to recall here, first of all, the fact that they were Englishmen [9] who had lived for several years among the Dutch, a people who described themselves upon their coinage as a nation whose "way is on the sea." More than a thousand ships were built every year in Holland where the Pilgrims were sojourning, and everybody lived in a seafaring atmosphere. Though a distinct people, the Pilgrims necessarily absorbed, as one may say, something of the Dutch aptitude for trade and sea life. Thus, when ready to migrate to America, they were able to secure the capital they needed for the venture from merchants who were acquainted with the success that had attended the fishing voyages to the coast.

It is worth noting, too, that Captain Thomas Jones, of the Mayflower, had fished in Greenland waters, and that Mate Robert Coppin was carried as the pilot of the ship because he had been on the parts of the coast to which the expedition was bound. The Pilgrims intended to settle somewhere near the Hudson River, but on November 11, 1620, the Mayflower was found at anchor under Cape Cod. While lying there a number of the company came to think that a settlement there would serve their purpose well, and the reasons given in support of this proposition are of interest because they show what business ideas animated these Pilgrims. The location, they said, "afforded a good harbor for boats." It was "a place of profitable fishing." "The master and his mate and others experienced in fishing" preferred it to the Greenland fishery where whaling made large profits. Moreover, the situation [10] was "healthy, secure and defensible." While the desire for "freedom to worship God" was perhaps uppermost in their talk, as it was in their writings, the Pilgrims were "intensely practical in applying their theories of Providence and Divine control to the immediate business in hand," as Weeden says, in his Economic History of New England.

After settling at Plymouth, as the reader remembers, life was hard during the first years. But the poetic rhapsodies about the "stern and rock-bound coast" do not convey an accurate idea of the agricultural possibilities of the region. Some of the farm lands of eastern Massachusetts are among the most prolific and profitable in the nation. The average yield of Indian corn per acre in Massachusetts in 1907 (see Year Book, Department of Agriculture) was exceeded only by that of Maine (another part of the "stern and rock-bound coast") and that of the irrigated lands of Arizona. Arizona averaged 37.5 bushels per acre, Maine 37, and Massachusetts 36. Consider, too, that it was in April, "while the birds sang in the woods most pleasantly," that Squanto and Hobomoc, red neighbors, taught these Englishmen how to fertilize the fields with fish, and to plant corn in fields that the Indians had cleared. And corn, produced on these fields, formed the first cargo of the first American sea-trader of which we have a definite record.

Through various causes not necessary to enumerate the Pilgrims got on so poorly that it was not until 1624 [11] that they began ship-building. The prosperity that came to them in that year was due to success in fishing. They took enough cod to freight a ship for England. The profit on the cod was so much beyond the immediate need of the people that they launched "two very good and strong shallops (which after did them greate service)."

As it happened, in the year following the building of these shallops the Pilgrims produced such an abundant crop of corn that they had some to sell. Accordingly they loaded a shallop with it, and sent it, under Winslow, to the Kennebec, where he traded it for 700 pounds of beaver skins.

A year later a more important, or at any rate a more profitable, voyage was made. Some English merchants who had maintained a trading-post on Monhegan Island sent word down the beach that they were going to abandon it and would sell the remainder of their goods at a bargain. Although in the years that had passed the Pilgrims had, at times, come so near to starvation that men had been seen to stagger in the street because they were faint with hunger, they had persisted. They had caught and sold fish. They had produced forest products and corn for sale. They had traded with the Indians for furs. They had traded with the fishermen who came over from England, and they had made a profit on every deal—they had not lived in Holland for nothing. When a bargain in trade goods on Monhegan Island was offered, they had capital to make a purchase, and going there with a shallop they [12] secured stuff worth £400. Then, on finding at the mouth of the Kennebec some other goods that had been taken from a French ship wrecked on that coast, they bought an additional £100 worth, which was all their boat would hold, as one may suppose. For as soon as they reached Plymouth Bay they cut their shallop in two and lengthened her, so that when another opportunity was offered to buy goods at a bargain she would have a larger capacity.

Recall, now, a number of events occurring in America before, and at about the time of, the first voyages of the Pilgrim shallops. Henry Hudson had sailed in the Half Moon up the river that bears his name (September, 1609), and the Dutch, after building a few fur-buying posts in that country, had begun a permanent settlement on the lower end of Manhattan Island (1623). Adrien Block, a Dutch explorer, had built a "yacht" on Manhattan Island (during the winter of 1614-1615), that was used later in the coasting trade. At New Amsterdam the Dutch built many small boats for gathering furs on the Hudson, and they repaired ships coming to the port when there was need. But as late as October 10, 1658, J. Aldrichs wrote a letter from that town saying, in connection with a "galliot" that was needed for local use (N. Y. C. docs. II, 51):—

"We are not yet in condition to build such a craft here."

At a still earlier date the French had made a permanent settlement in Canada. In the long story of the French in America it is of interest to note first that the Bretons and [13] Basques had been among the pioneers on the Newfoundland fishing banks. It is not difficult to believe that the Basques were there before Cabot's time.

Of the French explorers we need to recall but one, Samuel de Champlain, "young, ardent, yet ripe in experience, a skilled seaman and a practiced soldier," who had been leading a strenuous life in the West Indies. In 1603 he made a voyage to the St. Lawrence River. In 1604 he helped to make a settlement on the St. Croix River, where he remained until the next year. When a badly needed relief ship came in 1605, he explored the New England coast down around Cape Cod.

In 1608 Champlain built a trading-post where Quebec now stands, and in 1616 there were two real home-builders there, a farmer named Louis Hebert and Champlain himself. In 1626 the population numbered 105, all told. It is not unlikely that the French ship, from which the Pilgrims obtained enough cheap goods to fill their shallop, in their second voyage to the Maine coast, had been wrecked while on a voyage to Quebec. The seafaring merchants of New England inevitably took much interest in the development of this colony from a rival nation.

Still more interesting, though in a different way, were the settlements of the West Indies. The Spaniards had introduced the sugar-cane and negro slavery, an economic combination of the greatest importance to the commerce of the world; for while the Spaniards maintained, as far as possible, a monopoly of their own trade, both slavery [14] and sugar-planting spread all over the islands. Moreover, Spanish exclusiveness was to lead to adventures on the part of some New Englanders.

In 1605 the crew of an English ship took possession of Barbados. On February 17, 1625, an English ship "landed forty English and seven or eight negroes" on the island, and thus began building a colony that was of the utmost importance to New England traders in later years. In 1676 the export of sugar "was capable of employing 400 sail of vessels, averaging 150 tons."

In the meantime (1619), a Dutch privateer had come to Jamestown, Virginia, where "twenty Africans were disembarked," and sold to planters who were to use negro slaves, for many years thereafter, with profit, in the production of tobacco. And slaves, sugar, and tobacco were among the first articles of merchandise to bring profit to the New England ship-owners.

Most interesting of all, however, were the centres of population established upon the New England coast. The English fishermen who came to the coast after the arrival of the Pilgrims, occasionally landed men to remain through the winter in order to trade for furs and procure a supply of provisions—venison, wild fowl, etc.—for the use of the crews of the ships that were to return in the spring.

Of this character was a settlement made at Cape Ann in 1623. The Rev. John White, of Dorchester, England, having become interested in the fishermen, persuaded some merchants to send out people to form a colony. The [15] whole business was badly managed; in 1626 the merchants abandoned the colony, and most of the people returned to England. But one Roger Conant and "a few of the most honest and industrious resolved to stay." They removed, however, to a point on the coast known as Naumkeag, where they made a settlement which they named Salem.

In the meantime White had been working faithfully in England to promote the interests of these men, and in 1628 sixty or seventy emigrants were sent over to join them. In 1629 White and other English Puritans procured a charter for "a colony under the title of The Governor and Company of Massachusetts Bay." The settlers who came to America and lived under this charter were the "Puritans" of American history, a fact that seems worth especial mention because a modern mark of intelligence in New England is found in the ability to distinguish between the "Pilgrims" who formed the colony on Plymouth Bay, or the "Old Colony," and the "Puritans" who made the settlements at the head of Massachusetts Bay.

The colonists who came over in 1628 explored the head of the bay, and some of them located where Charlestown now stands. With its dancing waters, its green islands, and its views of the distant blue hills from which the Indians had already called it Massachusetts, the region was enchanting, and the Puritan explorers described it in such glowing colors that 200 more settlers were brought over [16] the next year. The Puritans were the original "boomers" of America.

Among the 200 who arrived in 1629 there were wheelwrights, carpenters, and ship-builders. The ship-builders went up the Mystic River to the place where Medford now stands, and established a shipyard. A considerable number of the emigrants of 1630 joined them. This was the first American shipyard, properly so called.

It is also to be noted that some of these emigrants, under the lead of John Winthrop, located on the peninsula opposite Charlestown, which was distinguished by a three-pointed hill and a "Backbay," where they built a town named Boston.

The French, having a water-road to the far-away regions of the Great Lakes, became wholly absorbed in the fur trade. The Dutch on the Hudson, though less favorably situated, had a western outlet through the Iroquois Indian country, and did a large business in furs. The English on Barbados, having a favorable climate, a fertile soil, and slaves, were preparing to supply all Englishmen with sugar, while the English on the Chesapeake, having facilities similar to those at Barbados, were already astonishing the commercial world with their product of tobacco.

The New Englanders had no considerable back country from which they could draw furs; they had no water route to the interior, and at that time they were unable to produce any crop from the soil for which a good market [17] could be found in Europe. But what they lacked in these respects they made up by hard work in the development of such resources as their country afforded. The histories of New England are full of tales of privation and suffering endured during the first years of their existence, and the stories are all true. But as soon as those settlers had learned how to supplement their prayers for daily bread by well-directed efforts to secure it, hunger fled. They then saw that the waters laving their feet were inviting them to go afloat to seek fortune in the uttermost parts of the earth, and they accepted the invitation.

On July 4, 1631 (the fact that it was on July 4 has attracted the attention of more than one New Englander as a "beautiful coincidence"), the ship-builders on the Mystic launched their first sea-going vessel. "The bark, being of thirty tons," was named the Blessing of the Bay. Her owner, Governor John Winthrop, recorded his reason for building her:—

"The general fear of want of foreign commodities, now that our money was gone, set us on work to provide shipping of our own."

That statement was characteristic of the people as well as of Winthrop. A "want"—any want—"set them on work" to provide for themselves.

The Blessing of the Bay was not a "bark" according to modern nomenclature. She was a vessel of one mast, and much like the vessel built by the less persistent people in the earlier settlement at the mouth of the Kennebec. [18] On August 31 she "went on a voyage to eastward," to trade with the Indians, beyond a doubt, and to pick up such business as might be offered by the few settlers and the fishermen to be found along shore. The fishing and trading station which "fishmongers in London" had built on the Piscataqua, at which no planting was done, was probably the most important point visited.

Another incident of this year, 1631, is of almost as much interest as the launch of the Blessing of the Bay. One John Winter established a shipyard on Richmond Island, off Cape Elizabeth (near the site of the modern Portland), Maine. Some time in December Winter began to build there a ship for merchants in Plymouth, England. As already noted, other ships had been built in America by Europeans for European use, but Winter's work may be called the beginning of the American business of building ships for export.

Three facts about Winter's shipyard may be correlated. In 1638 sixty men were at work in it. During the year a 300-ton ship brought a cargo of wines and liquors to the island. "It was a sporadic" settlement, and it "dwindled away."

Winthrop's Blessing of the Bay appears to have been the first New England vessel to open trade with the Dutch on Manhattan Island. She went there in 1633, perhaps sooner. In 1627 the Dutch had invited "friendly commercial relations" with the Pilgrims by sending the governor of the colony "a rundlet of sugar and two Holland [19] Cheeses," with a letter in which they offered to "accommodate"—to give credit. But the Pilgrims were shy because the Dutch had been trading with the Connecticut Indians, a region claimed by the English; the Dutch had come even to the head of Buzzard's Bay, where the Pilgrims were maintaining a post for the fur trade. However, in September, 1627, the Dutch sent Isaac de Rasieres with a small trial cargo in the "barque Nassau" to see what he could do, and he proved a worthy forerunner of the great race of American commercial travellers. For he carried soldiers and trumpeters along, not to fight, but to do honor to the occasion by means of salutes and blaring music; and he chose these men from among the residents of New Amsterdam who had known some of the Pilgrims in Holland. Indeed, some of them were related to the Pilgrims. Naturally, after "the joyful meeting of kindred as well as friends," and after much fine talk and the display of goods,—especially of "wampum,"—De Rasieres made what he called "the beginning of a profitable trade."

Wampum (bits of sea-shell) was the coin of the red men. The chief mint of the continent was on Long Island. All red men, at that time, were much more anxious to get wampum than the silver coin of the white man. The Pilgrims were glad to buy the wampum because the Indians of New England had but little, and were eager to get it.

It was no doubt to secure a supply of wampum and [20] such West India products as sugar and salt, in which the Dutch traded, that Winthrop sent his Blessing of the Bay to Manhattan Island.

Certain details of the earlier voyages should now prove interesting. For instance, Winthrop's vessel was at first engaged in trading on her owner's account. She was not a freighter, looking for cargo to carry at a price per ton, but a floating store, so to say, carrying merchandise for sale or exchange. The distinction between the freighter and the ship trading on owners' account is to be kept in mind.

After the New Englanders had spread to Connecticut there is a record of the employment of the Blessing of the Bay as a freighter. She carried goods from Massachusetts Bay to Connecticut at 30s. per ton.

In 1629 the freight rate between England and Massachusetts Bay was £3 per ton. Passengers were carried at £5 each, and horses at £10 each. The goods rate increased after a time.

That the oversea rates were remunerative is manifest from the increase in the number of ships finding employment in the trade. In 1635 the Secretary to the Admiralty learned that forty ships were regularly employed in the trade, of which "six sail of ships, at least" belonged to the Americans.

The profits in the trade on owners' account were also recorded. In 1636 Thomas Mayhew and John Winthrop, Jr., as partners, sent a vessel to the Bermudas, then called the Summer Islands, where she sold corn and pork and bought oranges, lemons, and potatoes. Perhaps that [21] was the first importation of Bermuda potatoes. The profit on the venture was "twenty od pounds."

The Richmond, a 30-ton vessel, built by Winter at Richmond Island, Maine, carried 6000 pipe-staves from the island to England, where they were sold at a profit of a little over £25 per thousand.

An idea of the profits on some of the voyages "eastward" to trade with the Indians can be had from the records of the Pilgrims, who, with their shallops, became experts in that line. Between 1631 and 1636, inclusive, the Pilgrims bought and shipped 12,150 pounds of beaver skins and 1156 of otter. "Ye parcells of beaver came to little less than 10,000 li. [pounds]. And ye otter skins would pay all ye charges," as Governor Bradford wrote. As otter skins sold for from 14 to 15s. a pound, "ye charges" in a business that gave a profit of "little less than £10,000" did not exceed £867. And this profit was made, although the Pilgrims had to buy some of their trade goods on credit and pay 40 per cent interest per annum on the sum thus borrowed.

It was at this period of the history of the American merchant marine that Captain Thomas Wiggin, an observing shipmaster from Bristol, England, wrote a letter about the New Englanders, in which he said:—

"The English, numbering about two thousand, and generally most industrious, have done more in three years than others in seven times that space, and at a tenth of the expense." [22]

ALTHOUGH geographical conditions were in most respects against them, it is manifest from any study of the New Englanders that their chief mercantile interests, during the earliest years, were concentrated in the fur trade. The Pilgrims devoted their first surplus crop to that trade, and the first voyage of Winthrop's Blessing of the Bay was to "eastward." According to the contracts, they had come to make fishing stations; yet the large profits made on such furs as they were able to secure kept their minds fixed on the Indian trade. But, happily, at an opportune moment a man came to Salem who was able to see that enduring prosperity could be found by the colonists only in the fisheries; and by example as well as precept he speedily led them to accept his view. Curiously enough, as it must seem in our modern view of the profession, this man was a clergyman, the Rev. Hugh Peter (written also Peters).

Few more stirring stories are to be found in the history of New England than the biography of Hugh Peter. He was born in England, of wealthy parents, in 1599, graduated [23] at Cambridge in 1622, and immediately took holy orders. Very soon, however, he had (or made) such trouble with the church authorities that he had to flee from the country. Then he served an English congregation in Rotterdam until 1634, when he came to New England and was made pastor of the Puritans at Salem.

In 1641 Peter was sent as ambassador to treat with the Dutch of New Amsterdam for a settlement of the disputes over the territory of Connecticut, and the records of his work, especially the proposals which he submitted (N. Y. C. docs. I, 567), show that he was a master of diplomacy. His work with the Dutch led the colonists to send him as their ambassador to England, when the civil war began there. Being a Puritan, he naturally joined the hosts of Cromwell and with such energy and zeal as were characteristic of the man.

In June, 1645, he was made "Chaplain of the Train," and a little later private secretary to Cromwell. He was with his chief at the storming of the castle at Winchester and when the dour hosts swept over the works at Basing. As a special honor, and because of his eloquence, Cromwell sent him on each occasion to tell Parliament how the battles were won; and the reader who would like to learn what a preacher had to say about such fighting as was done in those battles can find one of the addresses in Carlyle's Cromwell. Having been sent on a mission to Holland, he delivered a sermon which stirred the audience until "crowds of women" stripped the wedding rings from [24] their fingers to aid in providing funds for the work of the great Commoner.

For his zeal he was arrested soon after the Restoration. "His trial was a scene of flagrant injustice," and he was condemned, hanged, and quartered. But he faced his accusers and death as he had faced all else in life. He was placed on the gallows while one of his friends was yet hanging there, and was compelled to look on while the corpse was lowered and cut to pieces. When this had been done, one of the executioners turned, and rubbing his bloody hands together, said to Peter:—

"How like you this?"

But Peter, in a voice of unconcern, replied—

"I thank God I am not terrified at it; you may do your worst."

When Hugh Peter came to Salem, he found the people of the colony, with few exceptions, living in log houses that had thatched roofs and dirt floors. They were frontiersmen, a thin line of population stretched along the beach. Although there were masters and servants, there was less division of labor than that fact would now seem to imply. Owners and servants worked together. They cut timber in the forest for lumber and fuel; they built houses of all needed kinds; they cultivated the soil and they cared for their cattle. The New World was almost without form and void, but the divine power of labor was moving upon the wastes. A natural-born leader was needed, however, and Hugh Peter was the man for the [25] hour. He saw that the fur trade was slipping away and that some other resource must be provided. Better yet, he saw that the fisheries would provide a permanent prosperity, and he began to preach the gospel of good fish markets in far countries. No record of his arguments remains, but we may easily learn what he said by reading the contemporary writings of John Smith, who used the facts vigorously, as Peter did beyond a doubt.

In 1619 "there went" to America, said Smith, a ship "of 200 tuns ... which with eight and thirty men and boys had her freight, which she sold for £2100 ... so that every poor sailor that had but a single share had his charges and sixteen pounds ten shillings for his seven months work." In 1620 three different ships "made so good a voyage that every sailor that had a single share had twenty pounds for his seven months work, which is more than in twenty months he should have gotten had he gone for wages anywhere."

If a statement of the gains of a foremast hand would serve as an effective argument in England, it would be much more effective in New England, where many men low in the social scale were finding opportunities to rise—where, indeed, men who had come over as indentured servants had already become capitalists able to join in a venture afloat. The profits of the merchants were also known and printed, however, even though not considered a matter of first importance by Smith. Thus there was a statement that "the charge of setting forth a ship of 100 [26] tuns with 40 persons to make a fishing voyage" was £420 11s. The average take of fish on the American coast would sell for £2100, of which £700 would be the share of the merchant supplying the outfit costing £420 11s. His profit on the voyage would therefore be near 100 per cent, even though the prevailing rate of interest on borrowed money were 40 per cent. The ship-owner took a third of the income from the voyage, and made a still larger profit, for a hundred-ton ship could be built in New England, as Randolph noted, for £4 per ton.

With these facts in hand Hugh Peter went among his people preaching the gospel of enterprise with as much enthusiasm no doubt as he felt and displayed later in preaching religious doctrines before Cromwell's men. As a result of his work he "procured a good sum of money to be raised to set on foot the fishing business, and wrote into England to raise as much more." Further than that, the General Court, as the governing body of the colony was called, appointed six men to fish "for general account."

The Salem people made money from the first. The business spread to near-by Marblehead, and the people there became so much interested that when a minister in the pulpit told them that they ought to seek the "kingdom of heaven to the exclusion of all earthly blessings," one of the congregation interrupted him by saying, "You think you are preaching to the people at the Bay. Our main end is to catch fish."

By 1640 the Salem people had made such progress and [27] profits in their fishery that they were able to launch a ship of 300 tons, a monster of a vessel for the day and place. Moreover, Boston people were so wrought up by Peter's enterprise in this matter that they also built a ship at the same time, the Trial, of 160 (or 200) tons.

Unhappily for Salem, her people had no leader after Peter sailed for England, and Boston soon gained the ascendancy in commerce as in politics. But for many years Salem was a port of vast importance in the story of our merchant marine.

In the meantime (1636), the Desire, a ship of 120 tons, was built at Marblehead for the fishing business. It is likely that Peter inspired the people there to build her. She was engaged in fishing for two years and then made a voyage in the slave trade, and thus acquired enduring notoriety.

Of much more importance than these large vessels in promoting the shipping interests of the colonists were the small vessels, smacks, and shallops, which men of limited means built and used. A seven-ton shallop could be built for £25, and in the hands of her owners she was well able to go fishing. Friends and neighbors united their labor as well as their accumulations of capital in sending the small boats to sea. Even the dugout canoe which a man could make for himself was used in the bay fisheries, and the whole world was within the reach and grasp of a man who had the courage and enterprise to launch forth in a dugout canoe of his own making. It [28] was in and through such men that the American colonists were gaining the sea habit.

The cod was the fish of chief importance, though other varieties were sent abroad, and used at home in enormous quantities. Mackerel, though some were eaten and some exported, were used chiefly for bait. Sturgeon eggs were made into caviare then, as now, while the flesh of the sturgeon was smoked and sold—perhaps as the flesh of some more delicate fish. Hake, halibut, and haddock were of some importance, but the one fish that ranked next after the cod was the alewife.

It is said that alewives were so called because their well-rounded abdomens reminded the fishermen of such of their wives as were too fond of malt drinks! Millions of alewives came to the coast and swarmed up the streams until the channels seemed to be filled solid with the struggling bodies. Seines, scoop-nets, and even the naked hands were used in taking them, but the weir was in common use from the first. Indeed, the Indians used weirs before the white men came.

The people naturally looked upon these swarming fish as common property, and when weirs were built by private enterprise and the owners were thus able to "control the market" to a certain extent, laws were promptly enacted to regulate these primitive "trusts." One John Clark was allowed to build a weir at Cambridge on condition that he sell to no one not an inhabitant of the town "except for bait." The interests of the commonwealth were placed [29] ahead of those of the small community when there was a need of "bait." The price of alewives was fixed at "IIIs 6d per thousand." Another monopolist was to "fetch home the alewives from the weir; and he is to have XVId a thousand and load them himself for carriage; and to have the power to take any man to help him, he paying of him for his work."

The importance of alewives to the people is thus shown clearly. The notable uses of alewives were as food, as fertilizers, and as bait, but a few were smoked for export.

The early laws governing the fisheries may well have still further consideration here. After Hugh Peter began arousing an interest in the fisheries, the General Court exempted fishing vessels from all charges for a period of seven years, beginning in 1639. Fishermen and ship carpenters were excused from serving the public on training days. When alewives were taken at the weirs, the fishermen were to be served at statute-made prices before any were to be offered to the public. This was provided for, of course, after the farmers had learned their art well enough to prevent the fear of starvation. Land was set aside for fish-curing stages, and pasture was provided for the cattle which fishermen owned but could not attend to while at sea.

Until 1648 the fishermen, on coming ashore to "make" their catch, were allowed to land, cut timber, and erect their stages for the work regardless of the ownership of the ground where they landed. After that date they were [30] still allowed to do the same things, but they were then required to pay the owner of the land for the use of land and timber. In 1652, to preserve the reputation of the colony product of fish, the law provided for "fish viewers" at "every fishing place," whose duty it was to separate cured fish into grades according to quality.

Some details of the early methods of taking fish on the Banks were recorded. Neither the dory nor the trawl had then been developed. Hand-lines thrown from the deck of the fishing ship were used exclusively. The hooks and lines were imported from England, and Smith records the price: "12 dozen of fishing lines, £6; 24 dozen of fishing hooks, £2." The Indians made fairly good hooks of bones and shells. They spun lines from the fibres of Indian hemp, which they saturated with grease and the wax of the bayberry bush, but the white men would not use any such gear.

Cod lines for use on the Grand Banks were from 50 to 75 fathoms long; the lines now used on the Georges Bank are often as much as 150 fathoms long. Sinkers (conical plummets of lead), were from 3 to 8 pounds in weight according to the strength of the tidal current where the fishing vessel anchored. The enthusiastic John Smith said: "Is it not pretty sport to pull up two pence, six pence and twelve pence as fast as you can haul and veer a line?" But the fishermen who stood at the rail, in freezing weather, hauling a wet line that was 75 fathoms or more in length, and weighted with 8 pounds [31] of lead and a 100-pound codfish, did not find it exactly "pretty sport." Moreover, hauling and veering did not end their work, for when the school of fish was lost, the catch had to be cleaned and salted, even though the men had been at the rail day and night for 48 hours. But the work afforded better opportunities for "getting on," and so they found in it the "pleasing content" of which Smith also speaks.

As the reader knows, stoves were not invented until many years later, but the fishermen made shift by carrying a half hogshead nearly filled with sand. In the centre of the sand they scooped a hole in which the fire was built. By means of such a fire, built on deck, they cooked their food, warmed themselves, and dried their wet clothing. The scene where a fleet of fishermen anchored together on the banks by night, and all together cooked their suppers by the flaring fires, was memorable. One sees how easy it was for the imaginative sailor to name such a tub of fire a "galley," the name applied to the modern ship's kitchen.

In food supplies the New Englanders naturally fared better than their old-country competitors. Being nearer home, they had fresh vegetables for a greater proportion of the time afloat. Food was cheaper, too, and the circumstances or conditions under which the food was produced made them more lavish in using it. They raised their own peas and had barrels of them at home; why should they stint themselves on the Banks? To this [32] day American ships are noted for superior food and hard work. Of course they ate plenty of fish, as all fishermen did, and they caught many sea-birds, of which they made savory dishes.

John Smith emphasizes the fact that in the English ships the catch was divided into three parts, of which the crew received only a third, the two-thirds going to the owner and the merchant who fitted out the expedition. Where one man owned and outfitted the ship, he took the two-thirds, of course. But as Weeden, in his Economic History of New England (quoting Bourne's Wells and Kennebunk), shows, in 1682-1685, if not earlier, "the capitalist fitting out the expedition with boat, provisions, seines, &c., took one-half the value of the catch, and the other part went to the crew." In the eighteenth century the share of the capitalist was reduced to one-fifth.

The whale fishery of the first half of the seventeenth century was of small importance in comparison with that of later years, but it is still worth mention. The chief source of oil and bone seems to have been found in the whales that died from natural causes and drifted to the beach. But men did go afloat in chase when the spouting spray and vapor were seen from the shore, and laws were provided at an early day to regulate the catch. The General Court, under these laws, took a share of all drift whales—from two barrels to a third of the whole product. In the chase the first harpoon that held its place claimed the whale. It was provided "5ly, that no whael shall be [33] needlessly or fouellishly lansed behind ye vitall." The most important fact here is that at first the men who killed a whale shared equally. Later, when the men of superior skill claimed shares in proportion to the work they did, the "lay" system was evolved. The captain of a ship received from 1 barrel in 17 to 1 in 25; in recent years still more. Mates had from 1 in 30 to 1 in 50. The men who threw the harpoon had 1 in 75, say, while foremast men had still less, even down to 1 in 200 for a green hand. No better system for encouraging men to do as well as they could has ever been devised.

Of similar importance was the custom then prevailing of allowing the crews of merchant ships to carry a "private venture." When Skipper Cornell's Ewoutsen, in a Dutch cruiser, captured four New England ketches "in the neighborhood of Blocx Island," Captain Richard Hollingworth, commanding of one of the four, declared that he was "freighted on account of Wharton and Company, merchants of Boston, with 47 tubs of tobacco; Item, 6 tubs of tobacco for Mathew Cartwright and 13 tubs for himself and crew ... in all 66 tubs, with eight hides." The crew owned nearly a fifth of the cargo. (N. Y. C. docs. II, 662.) Seamen before the mast as well as officers took from port, in stated quantities, any commodities which they supposed they could sell to advantage in any of the ports to which the ship was bound. Here or there these goods were exchanged for others, which were again traded at other ports, or carried home to be sold. Wages [34] were not so very low for common sailors, even by modern standards. They received on an average £2 10s. per month. Mates had, say, £3 10s., and captains £4 10s., and, rarely, £6 a month. On top of this the private venture was carried free, and the shrewd sailormen often made much more on the private venture than from wages. It is a matter of much importance.

The sailor, having a direct interest in the voyage, made haste to shorten sail when a squall threatened to carry away the masts; he worked with all his might whenever any danger threatened, because she carried his merchandise. More important still is the fact that the custom made merchants of the men, and that is to say, it made them self-respecting and ambitious. There were instances where the crew received no wages whatever; the owner, master, and men were all adventurers together.

There is no more instructive comparison in the history of the nation than that between these early-day merchants of the forecastle and the driven brutes before the mast in the clippers of a later day.

Consider now the influence of the poverty of the builder upon the character of the ship. Capital was so scarce that a man worth £4000 was called wealthy. Ships were built where scarcely a shilling in currency changed hands. The workmen were paid with goods. Where neighbors united to build a vessel, they traded produce of fishery field, or forest to the merchant for such iron, sails, and cordage as they needed, or they gave him a share in the [35] vessel. The merchant traded the produce of the fisheries or forest in Europe for the outfit he gave to the builders. By hard labor and severe economy only were these vessels sent afloat. It was the European fashion of the day to build ships with enormous cabins piled high at the stern end, and to ornament the superstructures with carvings and paints. The New Englanders, having no capital to spare, had to forego the pleasure of ornamenting their ships with decorated superstructures; they were obliged to consider efficiency only. They did not know it at the time, but the fact was that this enforced economy led to an advance in the art of ship-building. On navigating the ships without superstructures, it was seen that the tall cabins had made the ships top-heavy, and had served to strain instead of strengthen the hulls. Moreover, the huge pile of timber had held the ship back in any winds but the fairest. Ships without superstructures were stronger, of greater capacity, swifter and handier.

Then there were the geographical influences which affected the model and rigs of ships. Whether in fishing or coasting voyages, the American ship must be prepared to meet winds from any point of the compass on every day she was out of port. The prevailing winds were westerly, but there was neither trade wind nor monsoon. The ship must therefore be rigged to force her way ahead against adverse winds. For such winds the spritsails, lugs, and others, where the cloth was stretched fore and aft, rather than to yards hung square across the masts, [36] were more convenient. The schooner was a natural evolution of the coasting conditions.

The waters of the harbors were shallow. In England deep-water ports had favored deep hulls, but the American designer who wished to increase the capacity of a hull had to make it wider instead of deeper. Wide beam gave greater stability; a wide ship could carry wide sails and yet "stand up like a church" in a heavy wind. Of course stout masts were needed for wide sails, but the forests were full of enormous pines that could be had, at first, for the cutting. Wide hulls of shoal draft, with wide sails spread upon stout spars, made speedy ships, a fact that even now is not as well understood as it should be. The speedy ships invited their masters to "carry on"—to keep their sails spread full breadth while the gale increased to a weight that would "take the sticks out of" vessels of inferior design. The swift ship, well driven, soon brought fame as well as additional profit to crew and owners, and the pride in the ship which was thus developed led all who were in any way connected with her to look for still further improvements.

The short distances between harbors also had some influence upon the forms of ships. For one thing, short passages favored small vessels with small crews. The greater the number of vessels, the greater the number of captains accustomed to responsibility, a matter of no small importance in its effect upon the formation of the sea habit among a people. Then the short passage naturally led [37] the crew into taking chances; they would risk a growing gale in a short run. Once out of port in "dirty weather," the manifest dangers set all hands thinking of improved ways of shortening sail in an emergency, and of improved shapes of hull and cut of canvas to help a vessel to "claw off" a lee shore. The men who worked in the shipyard building for themselves, and then went afloat, were particularly observant at such times. One of the most common statements to be found in the stories of perils at sea, as related by American shipmasters of other days, is this: "Every dollar I owned in the world was in that ship, and" for that reason every hardship was endured and every effort made to bring her to port.

In 1624 the Pilgrims exported their first cargo of fish. Boston sent its first cargo away in 1633. The owners of these fish had to pay three or four pounds a ton freight; and an agent in England, who charged a good commission for doing so, found a customer to buy them. The New Englanders saw that the vessel carrying the cargo made a profit for her owner. They saw, too, that an agent in a foreign country across the water would never have quite the interest in selling to advantage that they themselves would have if they were there to sell. In short, if the fish business were to be handled in the most profitable way possible, they must carry the cargo in their own ship direct to the consumer. Hugh Peter preached this doctrine with emphasis, beyond doubt, for it was he who led in building the 300-ton ship at Salem. From catching fish [38] to carrying them to the oversea market was a short passage quickly made. With this in mind, consider the brief story of the voyage of the good ship Trial, Captain Thomas Coytemore, made after the fishing business was well in hand.

The Trial, as noted, was the ship built in Boston when the people there were stirred to emulation by the work of Hugh Peter in Salem. Loaded with fish and pipe-staves, she sailed away to Fayal (1642). Fayal was chosen because the people there had religious views leading them to eat fish instead of flesh on many days of the year, and they were wine-makers who used many casks every year. The Trial found the market at Fayal "extraordinary good," and Captain Coytemore exchanged the fish and staves for wine, sugar, etc., which he carried to St. Christopher's, in the West Indies. There he traded wine for cotton, tobacco, and some iron which the people had taken from a ship that had been wrecked on the coast, and was then visible, though so far under water that the wreckers had abandoned all work upon it. As the New Englanders were exceedingly anxious to get all kinds of iron things used about a ship, Captain Coytemore must needs have a look at the wreck, and after due examination, he determined to try to recover more of the wreckage. Slinging a "diving tub" (doubtless a good stout cask, well weighted, and with the open end down), above the hulk, he got into it, and having been lowered to the sunken deck, made shift to hook good stout grapnels to the valuable things lying within reach.

[39] Comparisons, though sometimes odious, may be excused when instructive. The conditions of life in Canada led the French to devote themselves to furs only. The Dutch at Manhattan Island were absorbed in furs and the trade of the West India Company. The Virginians and the English West Indians devoted themselves almost exclusively to producing tobacco and sugar by means of slave labor.

Under the conditions of life in New England, the people became perforce farmers, growing their own food; loggers, cutting timber in the near-by forest for use in building houses, fishing smacks, and ships; fishermen, going afloat in the smacks and then curing the catch on the beach; seamen, who, blow high or blow low, carried the catch in their own ships direct to the consumer; traders, meeting the competition of the keenest merchants in the world; inventors, who, when unable to do their work by methods already in use, promptly improvised something new that would serve the purpose. [40]

AMONG the first acts of the English Parliament for the regulation of the commerce of the American colonies, notable here, was that passed in 1646, by which it was provided that no colonial produce should be carried away to foreign ports except in vessels under the British flag.

Since the days of Raleigh, who had done his utmost to create the sea habit among his countrymen, the English people had been growing jealous of the enterprising Dutch, who then were carrying the commerce of the world. This act was a measure to restrain the freedom of the Dutch carrying trade and to give it to English (including colonial) ships. In 1650, although England was yet torn by civil war, Parliament prohibited all foreign ships from trading with the colonies without first obtaining a license. A year later came the culminating act of the Protector's Parliament, "the famous Act of Navigation," as McCulloch calls it (London edition, 1839, p. 817). It provided that no goods produced or manufactured in Asia, Africa, or America should be imported into any part of the English domain [41] except in ships belonging to English subjects whereof the master and more than half the crew were Englishmen. The importation of European goods was prohibited except in English ships, or ships belonging to the country where the goods were produced, or those of the country from which they could only be or were most usually exported. As is well known, this act was intended as a final blow at the Dutch carrying trade.

Consider, now, that "shipping" means one thing, "commerce" or "trade" another. While modern American "commerce" is increasing in a way that seems marvellous, American shipping has been almost entirely driven from the foreign "carrying trade." The English enactments relating to the colonies, from the settlement of Virginia down to and including the "famous Act of Navigation," were all designed to favor all colonial commerce as well as shipping.

After the Restoration, Parliament passed what is known as the Navigation Act of 1660, which was followed by another in 1663, which was still more stringent. The object of these laws, as expressly stated in the later act itself, was in part "the maintaining the greater correspondence and kindness between subjects at home and those in the plantations; keeping the colonies in a firmer dependence upon the mother country; making them yet more beneficial to it; ... it being the usage of other nations to keep their plantation trade exclusively to themselves."

[42] To this end it was first "enacted" (to quote McCulloch), "that certain specified articles, the produce of the colonies, and since well known in commerce by the name of enumerated articles, should not be exported directly from the colonies to any foreign countries, but that they should first be sent to Britain, and there unladen (the words of the act are, laid upon the shore), before they could be forwarded to their final destination. Sugar, molasses, ginger, fustic, tobacco, cotton and indigo were originally enumerated; and the list was subsequently enlarged by the addition of coffee, hides and skins, iron, corn [i.e. grain], lumber, &c."

That is to say, the colonists were compelled to take the enumerated products to England and there lay them "upon the shore." The restriction was laid upon the "commerce" of the colonists; there was no restriction upon the use of colonial ships.

The writer begs the indulgence of intelligent readers while he treats this matter as if for a kindergarten. From the days of McCulloch to the present time no one has sufficiently emphasized the difference between commerce and shipping, a distinction that must be made entirely plain before one can see clearly just how these navigation acts affected the American merchant marine.

Having compelled the colonies to send all their enumerated products to England (it was not necessary to sell them there; they could be reëxported under certain regulations), Parliament went still further in its effort to [43] maintain a "greater correspondence and kindness" between the colonists and the home subjects, by enacting, in 1663, that "no commodity of the growth, production or manufacture of Europe, shall be imported into the British plantations but such as are laden and put on board in England, Wales, or Berwick-upon-Tweed," and in English-built shipping with an English crew.

The export trade of the colonies was to be restricted for the benefit of the merchants of England; so also was this import trade. Whether so intended or not, the restrictions resulted in a lowering of the prices of the colonial enumerated products when sent to England, because the market was glutted. At the same time the prices of the European products, which the colonist wished to buy, were, with few exceptions, greatly enhanced. The colonial producer was robbed by the artificial reduction of the selling price of his products, and the artificial increase of the price he paid for his European goods—robbed twice by arbitrary laws.

In 1672 Parliament passed another act still further to increase the "correspondence and kindness" existing between the colonials and the subjects living in the mother-country. A heavy tax was laid upon the commerce between the colonies.

"By these successive regulations," says Robertson, "the plan of securing to England a monopoly of its colonies ... was perfected."

It should now be interesting to note the actual influence [44] of all this legislation upon the colonial merchant marine. On July 4, 1631, Massachusetts had launched her first ship, a vessel of 30 tons. In 1676 Randolph reported that her people owned 30 ships of from 100 to 250 tons' burden, 200 of from 50 to 100 tons, 200 of from 30 to 50 tons, and 300 of from 6 to 10 tons, the latter being chiefly fishing smacks, though some were engaged in the coasting trade. The colony owned 430 vessels as large or larger than the Blessing of the Bay. Many ships were also owned in the other New England colonies. In 1678 New York owned "5 smale ships and a Ketch" that were in the coasting trade.

Sir Josiah Child, a notable Englishman engaged in the trade with America, said, in a book which he wrote on commercial matters:—

"Of all the American plantations his Majesty has none so apt for building of shipping as New England, nor any comparably so qualified for the breeding of seamen, not only by reason of the natural industry of that people, but principally by reason of their cod and mackerel fisheries." And to this he adds a statement which for the first time gave expression to what has since been known as the "American Peril." He said, "And, in my poor opinion, there is nothing more prejudicial and in prospect more dangerous to any mother kingdom than the increase of shipping in her colonies."

All this is to say that while Parliament had passed three acts that were confessedly intended to prohibit a [45] part, and hamper all of the colonial trade, except that with the mother-country; and while these acts had proved injurious and vexatious to the colonial producers and merchants, the colonial shipping, the merchant marine, had had such a vigorous growth that it was alarming the ship-owners who lived in England.

This condition of affairs becomes all the more interesting when it is remembered that a restriction of colonial trade was likely to affect colonial shipping indirectly, at any rate; that is, through a reduction in the amount of cargo to be carried. This injury was sure to appear in any reduction of trade between the colonies, and it was certain to affect the ships trading on owner's account first of all.

One easily finds a variety of reasons why colonial shipping had grown so rapidly in spite of legislation adverse to trade. For one thing, good ships were built in New England for £4 per ton burden—carrying capacity; the cost in England was higher. Charnock says it was a little less than £6 there, while Sir Josiah Child says it was from £7 to £8. Whatever the difference, it is a memorable fact that the mechanics in New England received higher wages than those in the old country.

Naturally many merchants of England bought colony-built ships, and this proved beneficial indirectly to all colonial shipping. The New England shipyards were full of orders the year round. The percentage of the inhabitants engaged in building ships and in supplying the [46] ships' builders with forest and farm products was therefore very large. These forest and farm owners, as well as the shipyard hands and the crews of colonial vessels, helped to cultivate the sea habit among all the people. Then the farms were all within driving distance of navigable water; all farm surplus exported, either abroad or to other colonies, went in ships, and the farmer from the most remote plantation was not unlikely to see his produce loaded upon a ship of some kind. In fact, many a man behind the plough could "hand, reef and steer."

Reference has already been made to the resourcefulness of the American seaman of the period, but it may be said again that the manner of life of the people—the fact that "even at the end of the colonial period the average American led a life of struggling and privation"—made American crews the most efficient in the world. Captain John Gallop, in a sloop of twenty tons, manned by two men and two boys, was, in 1636, not only able to take care of his vessel in a gale of wind but to retake another sloop that had been captured by the Indians. Many vessels traded to the West Indies with but five men and a boy on board. Raleigh had mourned because Dutch ships, in his day, needed no more than half as many sailors as English ships, but in 1676 the New England ships needed less than the Dutch or any other ships. It was when contemplating a New England ship manned by a New England crew that Sir Josiah Child discovered the "American Peril." He saw that a colonial ship manned [47] by a colonial crew was more efficient than the same ship manned by any other crew, and that is a most important fact in this story.

A most interesting cause of the growth of the colonial merchant marine is found in the bounties which the navigation laws offered to, and the facilities they provided for, those who would engage in clandestine trade. It was unlawful to carry tobacco from the colonies direct to a foreign port, but the export of fish and staves was permitted. Importations of salt were permitted, but Spanish iron must be purchased in England at a time when Spanish iron was the best in the world for ship-builder's use. The restriction on tobacco lowered the price in the colonies; that on the iron raised the price there. If tobacco were clandestinely exported direct to Spain and iron brought directly home, the ship made far greater profits than in the days before the hated laws. Moreover, the smuggled cargo paid no tariff-for-revenue dues or port charges. And it was easy to smuggle in any kind of a cargo.

In connection with this provision of a bounty on smuggling, consider the influence of the fact that the laws were intentionally unfair to the colonists. The colonists resented the injustice, and all the more because their trade previous to the enactment of the laws had been free. Then the conditions under which the laws were enforced were inquisitorial and otherwise vexatious. A time came when forts were built and revenue cutters were provided for the enforcing of the laws, and the officials of forts [48] and cutters were insolent and overanxious to confiscate accused ships.

Recall, now, the mental attitude of the colonists toward all authority. Some had emigrated from England to escape religious tyranny. Many had come over as indentured servants, looking forward to a time when they should be free, and become men of influence. Then all the conditions of colonial life, and especially its dangers, cultivated a feeling of manly independence of all authority. Finally, the colonists had from the first made at least their local laws according to their own standards of right.

"It is not unknown to you that they look upon themselves as a free State ... there being many against owning the King, or having any dependence on Engld." (Letter dated March 11, 1660.)

In short, the colonists had been rapidly developing the American habit of doing what they happened to believe to be right, regardless of the law in the case, and they called, or were to call, this habit an appeal to the "higher law."

Inspired by honest indignation and an opportunity to increase their profits, the colonial ship-owners and crews, with much unanimity, appealed to the "higher law."

Smuggling began as soon as attempts were made to enforce the law. It was estimated that the losses to the British revenue through the direct sale of tobacco to the Dutch at Manhattan Island previous to the year 1664 amounted to £10,000 a year. When, in 1665, the king took [49] notice of colonial dereliction, by issuing instructions for a strict enforcement of the laws, the General Court of Massachusetts replied that they were not conscious of having "greatly violated" them. In 1776 Edward Randolph was sent over especially "Impowered" to prevent "Irregular Trade," and the letters he wrote to the "Lords Commissioners of the Council of Trade and Plantations"[1] are full of references to the ways of the smugglers. Other letters of the period, especially those of Governor Bellomont, are similarly interesting.

At first the evasions were quite open. It is related that Skipper Clæs Bret loaded the ship De Sterre in the Chesapeake "in the name of an English skipper," and sent her to the Island of Jersey. Virginia officials must have aided this transaction. Weeden quotes from the Massachusetts archives the story of another Dutch skipper whose ship was seized because he "broake his word to the Governor in not clearing his ship to belong to the English." Governor Andros, who tried to enforce the laws, complained because there were "noe Custom houses," and because the "Governor of Massachusetts gives clearings, certificates and passes for every particular thing from thence to New York" without inquiring whether these things had been lawfully imported into Massachusetts.

The king's instructions to Governor Dongan tell him [50] how "to prevent the acceptance of forged Cockets (which hath been practiced to our great prejudice)." A cocket is a document given by a customs officer to a merchant as a certificate that the goods have been entered according to law. Randolph reported (April, 1698) that he had asked the Governor of Pennsylvania "to appoint an Attorney Generall to prosecute" certain men who had aided in an evasion of the laws, "but he did nothing in it." In the same year Randolph was arrested in New York by aggrieved merchants because he had, as he alleges, seized a smuggler in Virginia, and although his case seems now to have been according to law, Governor Bellomont had much difficulty in getting him out of jail. No one sympathized with a revenue official.

Before Bellomont's time no official except Governor Andros had tried to enforce the navigation acts. When Bellomont took office, he found all New York opposing him in his efforts to enforce them. When the ship Fortune, Captain Thomas Moston, came to port, bringing cargo worth £20,000 direct from Madagascar (where it had been purchased of a gang of pirates), and Bellomont asked Collector of Customs Chidley Brooks to seize her, he replied that "it was none of his business, but belonged to a Man of Warr; that he had no boat; and other excuses; and when I gave him positive commands to do it, which he could not avoid, yet his delay of four days" gave the smugglers time to unload and conceal all of the cargo except a part estimated to be worth £1000. Thus runs one of Bellomont's [51] letters. He also acknowledged that several cargoes had already been smuggled in without his learning the fact until it was too late to intercept them.

In Boston, as Bellomont learned, there were various ways of smuggling. "When ships come in the masters swear to their manifests; that is, they swear to the number of parcels they bring, but the contents unknown; then the merchant comes and produces an invoice, and whether true or false is left to his ingenuity."

"If the merchants of Boston be minded to run their goods," he continues, "there's nothing to hinder them. Mr. Brenton, the Collector is absent and has been these two years; his deputy is a merchant; the two waiters keep public houses, and besides that, that coast is naturall shap'd and cut out to favour unlawful trade." It was a "common thing to unload their ships at Cape Ann and bring their goods to Boston in wood boats." If that were thought too expensive the goods could be "run" within the city, where there were "63 wharfs," or in Charlestown, where there were fourteen more, all unguarded. French and Spanish ships were bringing many goods to Newfoundland and the ports of Canada, where they met New England ships ready to "swap" cargoes. There was lively trade carried directly to the ports of Canada and to the French and Spanish ports of the West Indies.

After returning to New York from Boston, Bellomont wrote that "Nassaw alias Long Island" was notorious for [52] smugglers and pirates. "There are four towns that make it their daily practice to receive ships and sloops with all sorts of merchandise, tho' they be not allowed ports." They were "so lawless and desperate a people" that the governor could "get no honest man" to go among them to collect the revenue. From Long Island the goods were brought to New York by wagons and small boats. "There is a town called Stamford in Connecticut colony" where "one Major Selleck lives who has a warehouse close to the Sound.... That man does us great mischief with his warehouse for he receives abundance of goods, and the merchants afterwards take their opportunity of running them into this town." During Bellomont's time Selleck's warehouse was the favorite resort of the merchants doing business with the Madagascar pirates. Selleck had £10,000 worth of the goods which Captain Kidd brought from the East.

Turning now to the stories of the pirates, we read that when one Captain Cromwell, a pirate with three ships, manned by eighty men, came to Plymouth in 1646, and remained five or six weeks with the Pilgrims, Governor Bradley referred to the visit in these words:—

"They spente and scattered a great deal of money among ye people, and yet more, sine, than money."

The statement that the Pilgrims (of all others!) entertained the pirates so well as to detain them for weeks in the harbor is somewhat shocking to one not fully acquainted with the conditions of commerce in that period. [53] The facts regarding the pirates seem worth, therefore, some consideration.