PETERS, ENGRS., BOSTON

Title: Gallant Little Wales: Sketches of its people, places and customs

Adapter: Jeannette Augustus Marks

Release date: October 10, 2016 [eBook #53248]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MWS and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet

Archive/American Libraries.)

By Jeannette Marks

GALLANT LITTLE WALES. Sketches of its People, Places, and Customs. Illustrated.

THE END OF A SONG. Illustrated.

THROUGH WELSH DOORWAYS. Illustrated.

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston and New York

Gallant Little Wales

THE LADIES OF LLANGOLLEN

Gallant Little Wales

Sketches of its People, Places

and Customs

BY JEANNETTE MARKS

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1912

COPYRIGHT 1912, BY JEANNETTE MARKS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published October 1912

CALON WRTH GALON

As a guide-book this volume will be found to contain too few unpronounceable Welsh place-names to be adequate, but as an introduction to the North Welsh land, its customs, its village life, its little churches, its holiday possibilities, its history and associations, its folk-lore and romance, its music, its cottages and castles, Gallant Little Wales should be useful. It is my intention to follow this book with a companion volume on South Wales.

I wish to express my debt to Mr. Henry Blackwell, who has always been quick to lend me volumes from his priceless Welsh library and who went over some of my manuscript for me. I am under obligations also to Rev. Gwilym O. Griffith of Carnarvonshire, North Wales. Thanks, too, I owe to Miss Dorothy Foster for her work upon the map which appears as a separate page in this volume.

The English know where beauty and comfort, good care, and good Welsh mutton are to be had for a moderate tariff. But long before the Englishman went for his vacations to these British[viii] Alps and the American followed him, excursions were made into Wales. The Roman spent a summer holiday or so both in North and South Wales, and left there his villas and his fortresses and his roads. The Roman, having set or followed a good example—and who shall say which it was?—and having with Roman certainty got what he wanted, departed, leaving the country open to other invaders who pillaged and plundered. Nor, since that time, has the country ever been without an invader.

I, too, have gone my wonder-ways in Wales, plundering where I could. I, too, Celt and Celt again, have followed its beauty and felt a biting hunger for a land which, once loved, can never be forgotten. As did another Celt, William Morris, in his poems, so in prose this little book and I have wrought in an old garden, hoping to make “fresh flowers spring up from hoarded seed” and to bring back again—“back to folk weary”—some fragrance of old days and old deeds. Friendliness, solitude, memories, beauty for the eye and beauty for the ear,—he who would have one or all of these, let him go and go again to gallant little Wales.

Jeannette Marks.

Attic Peace, May 13, 1912.

| I. | Welsh Wales | 3 |

| II. | A Village in Eryri | 17 |

| III. | Hilltop Churches | 30 |

| IV. | Dr. Johnson’s Tour of North Wales | 59 |

| V. | Welsh Folk-Lore | 86 |

| VI. | The City of the Prince of Wales | 105 |

| VII. | The Eisteddfod | 117 |

| VIII. | Cambrian Cottages | 133 |

| IX. | Castle and Abbeys in North Wales | 155 |

| Appendix: Suggestions for Some Tours | 177 |

| The Ladies of Llangollen | Frontispiece |

| Conway Castle | 10 |

| From an old print. | |

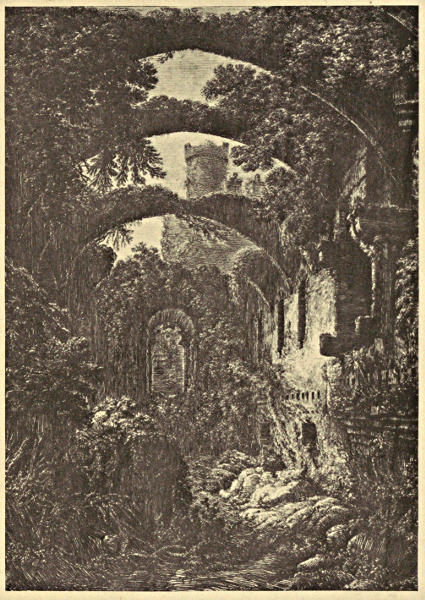

| The Queen’s Tower, Conway Castle | 24 |

| From an engraving by Cuitt, 1817. | |

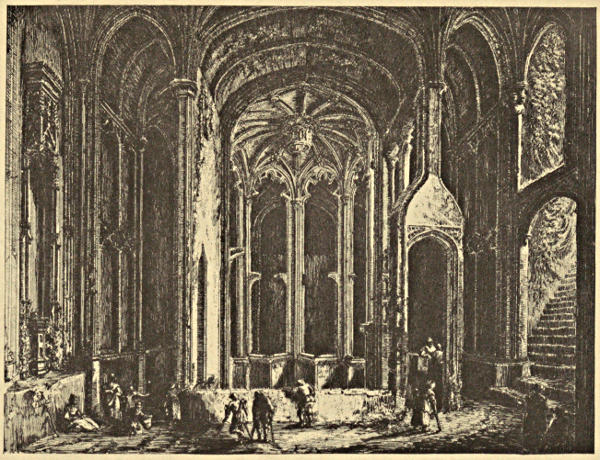

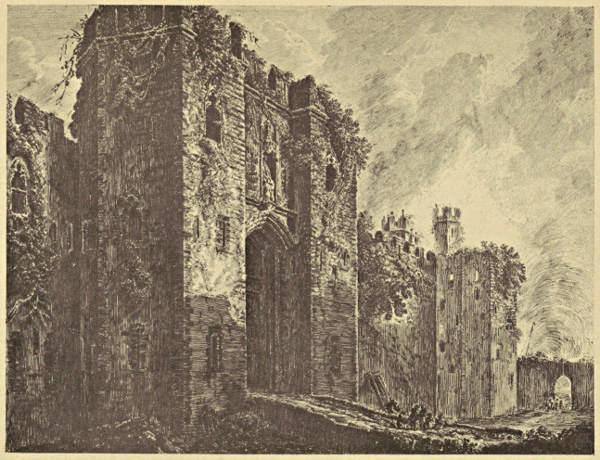

| The Great Hall at Conway Castle | 32 |

| From an engraving by Cuitt. | |

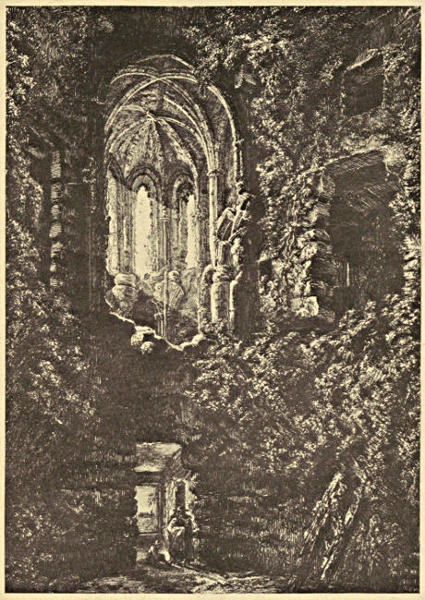

| St. Winifred’s Well, Holyhead | 40 |

| From an engraving by Cuitt, 1813. | |

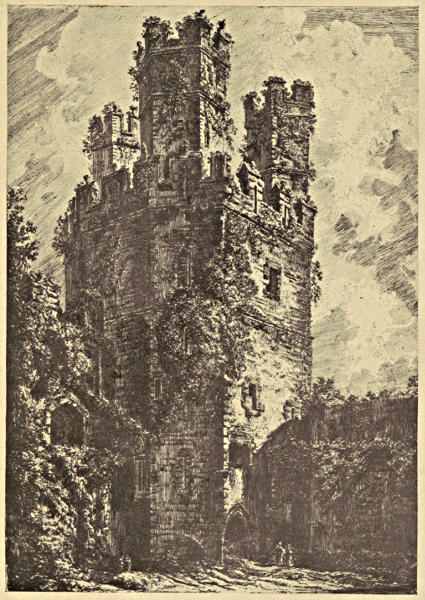

| The Eagle Tower of Carnarvon Castle | 52 |

| From an engraving by Cuitt. | |

| Gateway of Carnarvon Castle | 66 |

| From an engraving by Cuitt. | |

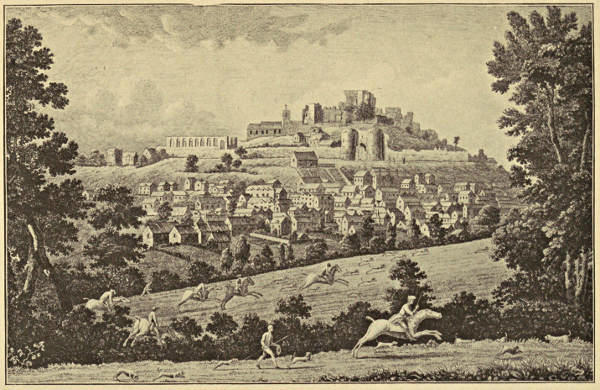

| A View of Denbigh Castle | 80 |

| From an engraving by Boydell, 1750. | |

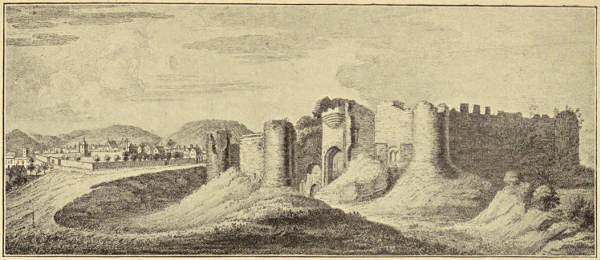

| Ruthin Castle | 92 |

| From an engraving by Buck, 1742. | |

| [xii]The Compleat Angler in Wales | 100 |

| The Tower of Dolbadarn on Llanberis Lake | 112 |

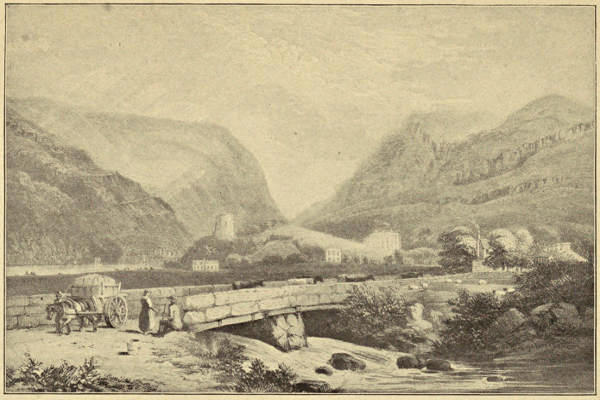

| Llanberis | 124 |

| From an old print. | |

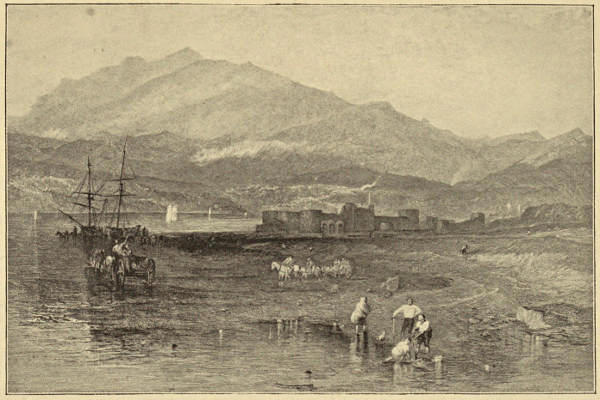

| Beaumaris | 140 |

| From a proof before letters by Turner. | |

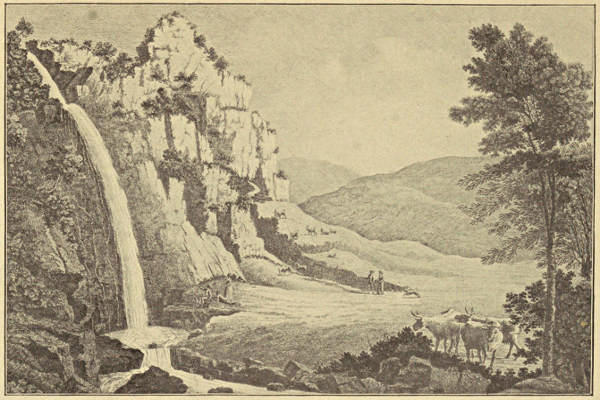

| A Welsh Waterfall near Penmaen-Mawr | 148 |

| From an engraving by Boydell, 1750. | |

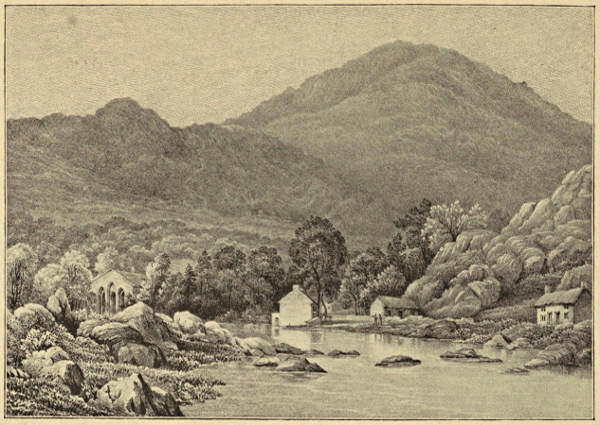

| Beddgelert | 160 |

| From an old print. | |

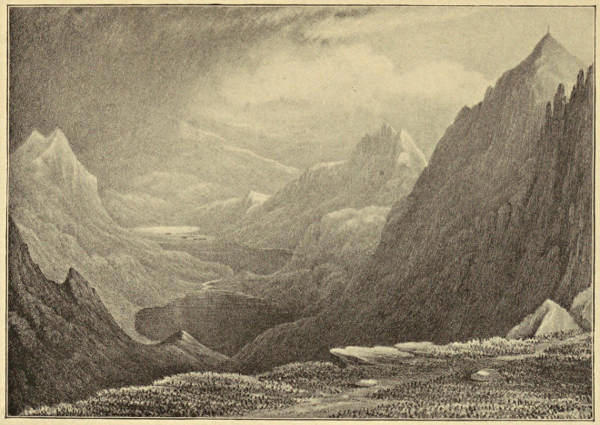

| The Summit of Snowdon | 172 |

| From an old print. | |

| Map | Inside front cover |

It is a vanished past that haunts the imagination in Wales, so that forever after in thoughts of that country one goes spellbound. It is the beautiful present, the cry of the sheep upon the mountain-sides, the church bells ringing from their little bell-cots and sounding sweetly in valleys and on highland meadows, the very flowers of the roadsides,—foxglove, bluebell, heather,—that keep one lingering in Wales or draw one back to that land again. There are little churches of twelfth-century foundation, gray or washed white,—their golden glowing saffron wash of long ago unrenewed by the Welsh of to-day. There are little cottages, white or yellow or pink, with their bright doorsills of copper, their clean, shining flagstones, their latticed windows, and all the homely and dignified tranquillity within. There, towering above, are bare rock-strewn summits upon which[4] the yew still stands, and, by its side, springing from the tuft of grass which the wind has not swept away, grows the white harebell; the yew monument to a thousand years, the harebell a fragile thing of yesterday. And above these church-crowned hills are mountain summits, gray and craggy, stripped of everything verdant, places where there are “shapes that haunt thought’s wilderness,” and suggestions of an endless, unending journey.

It was Bishop Baldwin, I think, accompanied on his famous twelfth-century journey through Cambria by Gerald of Wales, who said, getting his breath with difficulty as he surmounted a Welsh hill, “The nightingale followed wise counsel and never came into Wales.” Were this true, the reply might be that Wales has no need of nightingales, so many and so beautiful are the wind-played songs over the rocks, and so incomparably lovely are the voices of the Welsh people themselves. In any event, had the nightingales come into Wales, a plump one—as it seems Bishop Baldwin himself must have been—would never have remained long in the mountain fastnesses of northern Wales,—at least not in the neighbourhood of Snowdon[5] or Nant Francon or Twll Ddu,—the “black hole” of Wales. Neither, if Bishop Baldwin ever climbed to a Welsh mountain-top, would this princely prelate have liked the views there. A comfortable, fat living in some Welsh community like Valle Crucis Abbey, near the river Dee, by Llangollen, would probably have been far more to his liking. Even now these mountain inns are not of the accepted kind, but merely a cromlech over which the wind still plays its devil tunes, a cave or the ridgepole of a long sharp mountain crest, broken by crags down to the very edge of the sea.

Wales is a land of mountains, of little alpine heights ranged on the western coast of Great Britain. Set between plain and sea, full of hill fastnesses, its turbulent history is partly explained by the topography of Gwalia. Independence, lack of unity,—these words summarize most of the early history of Wales. To the different parts of Cambria, alpine Snowdonia, the pasture lands of Berwyn, the moorlands and vast coal-fields of the south, came two races: one short and dark, the Iberian; the other tall and fair, the Celtic. These are still the two peoples of Wales. And after them came Rome;[6] but Rome is gone, has vanished, except for her walls and foundations and roads, and these dark and fair races are still there, mingled, their racial traits still impregnable, still intact.

When you add to what might be called the natural and inherent difficulties of the necessary mountain climbing in Wales, those of the Welsh language, you have a combination that is beyond words to describe. Even the veriest tyro a-visiting Wales will tell you that the language defies all description and the most conscientious efforts to master it.

One warm day we were making a melancholy progress up a mountain-side when steps passed swiftly and a voice said in Welsh, “Stepping upwards?” The young man, an itinerant Welsh minister, was travelling in the same direction with us and it did not seem polite to say “Goodbye,” although I could think of no other Welsh words. Finally two inept ones came to me, “Da iawn” (very good), and I spoke them. But then, not content to let well enough alone, something more had to be said and I kept on repeating those words like a parrot. The Welshman looked around doubtfully, as if he wondered what the “Very good” was all about, and I[7] heard him murmuring to himself and saw him hasten upwards a little faster.

“Say something else,” my companion whispered.

“I am going to if you will just give me time,” I snapped back.

But I didn’t say anything else; I couldn’t, for not another thing would come. If any one feels disposed to criticize an alien because he is unable to speak Welsh, then let him go test its difficulties for himself, its long words, its savage consonants, its poor little vowels lost like some bleating lamb upon rocky mountain-sides. You just get it satisfactorily settled in your own mind that “Dad” means father,—very natural and proper,—when suddenly you discover that “Tad” and “Nhad” and “Thad” also mean father and are one and the same word. With mother or “Mam” you suffer a similar though not the same fate. To begin with, the Cymric alphabet differs from ours: it consists of thirty-one letters, some of which, “mh,” “ch,” “dd,” “ff,” “ng,” “ngh,” “ll,” “nh,” “ph,” “rh,” “th,” never occur in the English alphabet as letters per se. Your honest grammarian will tell you flatly that in the case of “ll” there is no sound[8] in any language corresponding to it. Most like it are the Spanish “ll” and the Italian “gl.” Then what to do? Do as you would have to do in rope skipping: watch the rope, run and jump in if you can. The “c” is hard in Welsh, never soft like “c” in “city”; “ch” is like the guttural German “ch”; the “dd” sometimes like “eth”; “f” like “v”; “ff” like “f”; “g” is never soft as in “giant,” but like “g” in “get”; “i,” both long and short, as “i” in “pin” and “ee” in “fleet”; “o” is short like “o” in “got” or long like “o” in “note”; “p” as in English; “s” is like “s” in “sin”; “u” is sometimes like “i” and sometimes not; the “w” is like “u”; “y” has two sounds, first like “u” in “fur,” second like the Welsh “u.” A few words will illustrate Welsh pronunciation. “Cymru” is pronounced, as nearly as one can suggest its pronunciation, as if spelled “Kumree”; “Gwalia” as if “Gooalia”; “Mawddwy” as if “Mauthooy”; “Wnion” as if “Oonion”; “Pwllheli” as if “Pooltheli”; “Dolgelley” as if “Dolgethley.”

I have had some experiences with my “small” Welsh which I would not exchange for those of “big” German in the past, or of any other[9] language in which I have been trained to read or speak. I remember one experience that happened when we were in search of a certain little church of ancient foundation, set upon a hilltop. In Wales there are many of these little churches on the hilltops, like Llanrychwyn and Llangelynin, and also little churches by the sea, like Llandanwg, almost at the foot of Harlech. Within their mediæval lychgates and high stone walls the dead are crowded close in their last sleep. Sweet places are those old churches, with the yew standing sentinel near them, and about them the shelter of the valley or the wide sweep of the hilltop view. This time it was a hilltop church for which we were searching. Again it was “Da iawn” which graced the conversation, but in how different a manner!

We were in need of tea, and at the cottage next to the church, the only cottage upon that summit, I rapped with my stick and said to the old woman who came, “Dyma le da i gael te” (this is a good place to have tea).

“Yiss,” was her reply, her face brightening; “Te?”

“Yes,” said I; “tea and bread-and-butter.”

“Jam?” asked she, remembering what I had forgotten.

“Yes,” I answered.

She spread the cover in the place on the turf to which we pointed and smiled brightly at me, as if she, too, appreciated the beauty of that place with its wide mountain and valley landscape, the trustful sheep browsing near me, and down at our feet the magnificent pile of Harlech Castle looking across the wide flat marsh at its feet and over the sea toward the palace of King Mark.

“Da iawn” (very good), said I emphatically.

And her answering smile told me that we understood each other, even if we could not speak each other’s language very well.

CONWAY CASTLE

From an old print

Changeling Welsh words are begot of elves and fairies. Even as those words are full of poetry, of romance, of a wild emotionalism,—the “Scream of the Celt” it has been called, but in Wales it is a subdued scream,—so, still, are the superstitions about fairies and elves living among these Welsh hills and valleys. Childish tales they may seem to you, if you are fortunate enough to be told anything about them at all by the Welsh peasants, who are both suspicious and shy of the “foreigner.” The tales one may hear even now in Wales are full of a haunting race life. The Welsh speak of the fairies as the “little folk” or the “fair folk” or “family”—“y Tylwyth Teg.” And well do these little creatures deserve the name, for they are friendly in Wales. Ghosts there are, too, and the death portents, the old hag of the mist and others that groan or moan or sing or stamp with their feet. And there are “Corpse Candles” and “Goblin Funerals.” Shakespeare knew a deal about Welsh folk-lore, but where he got it from no one has yet discovered. With Shakespeare “mab” meant a little thing, just as in any Welsh village to-day “mabcath” means a kitten.

No matter where I have been I have found the Welsh conscious of the beauty and significance of their land, its legendary lore, its history, its marvellous natural attraction. They have always been eager to give me information about some landmark, some incident about which I might be inquiring. Over their shop counters, across the doorsills of the humblest of Welsh cottages, by some kitchen fire where the brass tea-kettle sang and glowed in the subdued light of the ingle, they have poured forth titles of[12] books and data,—things for which I was searching, or needed to know. One old man, eighty-six years old and bedridden, held my hand in an eager, childish clasp, while he tried to tell me something about a church, the poor tired mind working like a rundown clock, the half-sightless eyes looking at me in petition to help him recall the days that had slipped so far away. He asked me about friends of his,—people who had died before I had thought of being born. He corrected my few words of Welsh, a ghost of a smile about the old mouth, but he could not recollect what I wanted to know. Without the information I was seeking, I went away saying “Nos da” to him, which was, indeed, good night.

When Dr. Samuel Johnson made his memorable tour of Wales, he wrote, “Wales is so little different from England that it offers nothing to the speculations of the traveller.” He seemed wholly oblivious to the strong racial difference between Welsh and English, which alters not only the visage of the people, but also the visage of the very country. He was so indifferent to the grandeur of Snowdon scenery that, going around the base of that mountain of[13] eagles in a chaise, he spent his time keeping account of the number of sheep for “Miss Thrale,”—his little favourite “Queenie.” I do not believe that Johnson’s disgust would have been the least appeased by knowing that in the years to come other great people were to go and go again to Wales, as to a beloved lap of rest: Wordsworth, Shelley, Kingsley, Froude, Newman, Huxley, Tyndall, Tennyson, Arnold, Tom Taylor, John Bright, Carmen Sylva, and many another. The good Doctor scorned Welsh rivers, called them brooks and offered to jump over them. He would have despised such a cottage kitchen as I have lingered in many a time impressed by its beautiful and dignified simplicity. Sweet places are these old kitchens, hospitable, warm, cheerful. Sunlight or firelight, one or the other, you may have always in them. Bright they are with fuchsias and little gleaming leaded window-panes, with polished oak and polished brass and copper, with the shining face of a grandfather clock, with pewter, with lustre pitchers and creamers, with gleaming pots and kettles, and the salt glistening on bacons and hams hanging from the blackened oak rafters. Gay are they, too, with the life and laughter[14] of children, with the good cheer of contented older people, with the purr of the house cat and the bubbling of the tea-kettle. More homelike, more motherly, more charming old kitchens, it has never been my good fortune to see.

There was only one thing in Wales which profoundly satisfied the great Doctor and that was its castles, Harlech and Conway, and Carnarvon Castle most of all. Almost every Welsh town has its historical traditions of importance, but Carnarvon, the city of the Prince of Wales, even more than others. There Elen, the Great Welsh road-maker, was sought and won by the Emperor Maximus. Of that little city, once the Roman city of Segontium, there is a description in the “Mabinogion,” the classic of Welsh literature and one of the classics of the world. The Roman Emperor saw in his dream but what we see now, a fair and mighty castle, rocks, precipices, mountains of great height. The Prince of Wales was born, according to legend, in Carnarvon Castle, and there investiture ceremonies are still held. But veracious history assures us that he was born in the town, outside the castle of which he himself had built the very tower where he was supposed to have been born.[15] Tumultuous, confused, legendary is Welsh history, full of the more or less mythical deeds of their great King Arthur, their brave Prince Llewelyn, the fate that overtook the hopes and ideals of this prince, their last fight for independence and their loss of it; their submission to the yoke of conquerors and the history of English princes who were put over them. It is a wild, sad, eventful history whose sorrows and tragedies seem only to have bitten all that is most Cymric in Welsh Wales deeper into Welsh lives and hearts, so that to-day, despite all that conqueror or civilization can do, their language, their lives, are still separate.

And the Welsh Eisteddfod, a festival of song and poetry, is a revelation of the unique national Welsh spirit. From every hamlet in Wales, even those reached only by Welsh ponies, visitors travel on foot or by train to this feast of song and to witness the Gorsedd, a druidical ceremony old as the Eye of Light itself. “Gallant little Wales” shows itself to the least and last participant in the Eisteddfod as Welsh Wales. Educationally this Eisteddfod ceremony is of great value to Wales, democratic, representative, instructive; and nowhere[16] could the fact that Welsh educational ideals are quite different from those of England—popular and progressive, with something of the so-called American spirit in them—reveal itself more completely than in this assembly of the people. Wales is essentially a democracy—a democracy of song, a democracy of poetry, a democracy of education and religion, and the Eisteddfod is the popular university of the people. To comprehend what is deepest and best in Welsh Wales one must go to the Eisteddfod and hear the Welsh, sensitive, capable of the “Hwyl,” imaginative, passionate, fervidly patriotic, sing,—

HEN WLAD FY NHADAU (OLD LAND OF MY FATHERS)

At the centre of a wide meadow with valleys running in towards the centre from east and south and west lies a little village of North Wales. All the cottages are gray, gray as the stones of St. John’s, but they are of the crisp, compact gray of slate, and not the crumbling, fretted stone of Oxford. Occasionally some cottage nestling to the craggy side of one of the valley roads is whitewashed with white or pink, or fitted so neatly into the jutting rocks of the mountain-side that only the humble façade, a screen of blooming roses, is visible. Whitewash, roses, gleam of copper doorsills, running water, flash gaily in the midst of the gray of Beddgelert. Above the houses is the blue roadway of sky walled in by craggy mountain-summits, the sides of the mountains carpeted with[18] myriad tufts of heather, lavender or purple or pink, and in autumn with the vivid yellow of the prickly gorse. Bees desert tiny gardens of well-hedged roses for this wide principality of bracken and heather, where around tufted blossoms they hum to the tossing of some stream casting itself down the hills. Up the rocks clamber ivy and sheep; about the moist edges of the pools and over the cushions of damp moss, black and brown watered-silk snails measure leisurely in well-fed content; and in little terraced glens of thick sod and along the roadways grow bluebells and columbine and foxglove and elfin white birches. But above these troops of upland bluebells and slender, swaying birches hang rocks, wild, rugged, whipped bare even of heather. And from the rough spine of Craig-y-Llan stretches away towards Snowdon and Pen-y-Pass, a wilderness of naked rocks, weird, jagged, shining gray and black in utter desolation.

At the meeting of the Colwyn and Gwynen rivers, with the hollow sound of rushing water in its village lanes and the tinkling of sheep bells scattering from the overhanging hills, the meadow strips lie beside the valley roads, deep[19] green with abundant grass or yellow with grain. Life, however, has been strenuous in this village of fourscore mountain huts, and many fathers and sons have had to labour to clear the grassy fields. For these honest, independent, thrifty Welshmen, slate and sheep are the chief means of support. The rivers yield, too, a fair quantity of salmon as pink as some of the mountain huts, salmon weighing from one to eighteen pounds. In a flood, although the torrent sometimes reduces the number of inhabitants, the catch of salmon is greater, and the villagers face the delicate task of balancing an all-wise but unscrupulous Providence.

The way to a Welshman’s heart, nevertheless, is not through his stomach; the Welsh think but little of what they eat. Before English tourists came to the village the inns of the place, Ty Ucha—now the Saracen’s Head—and Ty Isaf, provided a bill of fare consisting of oat and barley bread, ale, porter, and eggs. English and Americans, unlike the Welsh, do not go lightly on a holiday without consideration of what there will be to eat. And our lodging-table, set by as kindly and generous a hostess as three wanderers ever found, bore slender chickens whose proportions[20] suggested mountain climbing, mutton tender as the ivy the poor sheep had been nibbling, salmon trout fresh as the stream pouring by the corner of our cottage, Glan Afon, pound-cake filled with plums, and tawny mountain honey. And, too, there were vegetables for whose mere names we felt a careless indifference. Even the loaf of bread Baucis and Philemon set before their wanderers was no better, I am certain, than the bread of Beddgelert, light, sweet, with crackly golden-brown crust. Often have we done nothing but watch—and joy enough it was—the mammoth loaves coming home from the village bakery across the village bridge, little children staggering under them, small boys bearing them jauntily, mothers grasping them firmly under one arm, a baby tucked away under the other.

At the inns, of which the Royal Goat is most pretentious,—it has a piano,—there is much quiet holiday life led by quiet holiday people. The simple folk who come to stay are for the most part the Welsh people themselves, for whom Beddgelert is in the nature of a shrine, a place canonized by the brave deed of one of their own Welsh greyhounds, Prince Llewelyn’s[21] Gelert. The visitors who travel through the valley during the holiday month of August are English and Welsh tourists on the coaches driving over Llanberis Pass, said to be the highest coach drive in the world, and going to Carnarvon, the ancient Roman city of Segontium, fourteen miles distant from Beddgelert.

In the last hundred years the village has harboured many a distinguished man who, giving thanks for his undiscovered seclusion, has come and gone unknown. Wordsworth came there with his friend, Robert Jones; Shelley, living at Tan yr Allt, a few miles out of Beddgelert, must often have passed through its lanes, his ragged brown hair whipped by the valley wind, his great eyes blue as the roadway of sky overhead; Kingsley, with a quick smile for the jolly little urchins perched venturesomely on the sharp slate coping of the bridge, Frederic Temple, Derwent Coleridge, J. A. Froude, Professor F. W. Newman, Huxley, Tyndall, all found holiday rest in this quiet meadow sheltered by its rampart of mountains. Gladstone came there, too. A village cow with an eye for distinction endeavoured to hook the Prime Minister and had afterwards the satisfaction of being sold for[22] a large sum of money. There also in the valley was born “Golden Rule” Jones, of Toledo fame, a good man, and but one of many good men who have gone forth from this fastness of peace to dream ever afterwards of a return to its gray houses, its streams, its hills and heather and wilderness of crags.

Ty Isaf and Ty Ucha are the oldest inns of the village. Ty Isaf is at the entrance of the lane leading to the church, and it was there, not so many years ago, that the minister was still expected to drink a cup or two of ale before entering the pulpit or fail in due prelusive inspiration. At Ty Isaf was kept the Large Pint of Beddgelert (“Hen Beint Mawr Bedd Gelert”), a pewter mug which held two quarts of old beer. Any man who could drink this quantity at a breath might charge the amount to the lord of the manor; if he failed, he paid for it himself. But so often was the heroic deed accomplished by capacious Welshmen that it is recorded the tenants paid but half their rent in money. It would be interesting to know for how many goblins, fairies, “Lantern Jacks,” flickering “Candles of the Dead,” Hen Beint Mawr was responsible! Now over every little[23] inn is the sign “Temperance,” for Welsh revivals have played havoc with these noble drinking-feats. One signboard, I can never pass without a smile, has gone so far as rather to insist upon the temperance issue in the words, “Rooms and Temperance.” Incidentally, the rector of the Episcopal Church has given up his potation, and next door the Welsh Calvinistic Methodist minister, also unsupported by home-brewed beer, wrestles with his flock. Beddgelert Sabbath-keeping has all the force of an unbroken tradition. A gentleman riding a-hunting on Sunday was confronted by an old woman who shook her Welsh Bible at him and showered vindictive Welsh l’s on his worldly head. Nor was our own experience much happier. Our drinking-water was fetched from Ty Ucha, and we had good reason to believe it was responsible for wretched feelings. One Sunday morning I consulted our Welsh hostess, explained to her what we thought of the water, and asked whether we might have some brought from another spring. We were told that it could not be drawn on the Sabbath, but would be brought to us on Monday morning! In every cottage there is a mammoth Welsh Bible,[24] and groups of smaller Bibles both Welsh and English. We went into one deserted mountain hut to take pictures of the interior; inside, together with an old trunk, a rusty fluting-iron, kettles, pans, a portion of the woven couch strung over the wide fireplace, and old clothes, we found two Welsh Bibles, one English Bible, and a torn portion of “Pilgrim’s Progress.”

THE QUEEN’S TOWER, CONWAY CASTLE

From an engraving by Cuitt, 1817

Indeed, the religious spirit of the place is a tradition but infrequently broken in the past thousand years. Edward I had burned the priory (now St. Mary’s Church), which was erected as a hospitium in connexion with a small chapel and schoolhouse in the second half of the sixth century; Henry VIII endeavoured to crush its power, and then in 1830 the good villagers themselves entered upon the pious task of renovation. In order to make the renovation as thorough as possible, they tore down all the rare wood-carving, using it for kindling-wood, and in some instances making pieces of household furniture from it; they put in a false ceiling of clapboards hiding the fine Gothic arch of the roof; the ceiling, together with the walls, they whitewashed, and completed their pious task by boarding up several exquisitely shaped[25] lancet windows. Fortunately the renovation has been followed by a restoration, and now the priory may be seen in some of its ancient beauty, with the old yew tree spreading low over the gravestones and the Gwynen pouring by its northern walls, singing the same mountain song it sang when the canons regular of St. Augustine, barefooted, gray-habited, with crucifix and rosary, marched solemnly from chapel to hospitium.

The name Beddgelert, the Grave of Gelert (?), brings hundreds of Welsh people to see this town each year. It is not an uncommon spectacle to see a man, as he stands by the dog’s grave, brushing away tears, or a little child crying bitterly. The story is of Prince Llewelyn’s greyhound, who saved his master’s baby by killing a fierce wolf, and then was slain by his master’s sword, for the Prince, entering, saw the cradle overturned and the greyhound’s mouth covered with blood. The name of the place, however, has nothing to do with the myth of Gelert; the little hill on which the grave stands had for hundreds of years been called “Bryn-y-Bedd,” the “Hill of the Grave,” a mound where the Irish chief Celert, a far[26] earlier hero than the dog, may have been buried. There are parallels in other folk-lore for this tale, and one even in the Sanscrit has been discovered in which, in place of Northern wolf, a snake is the evil agent. There is an unmistakable twinkle in a Beddgelert eye whenever the story is told. Alas! that the greyhound buried there was not presented to Prince Llewelyn by his father-in-law, King John, in the year 1205, but, the petted possession of two Beddgelert spinsters, was presented by them at the beginning of the nineteenth century to the sagacious David Prichard, the first owner of the Royal Goat Hotel, and promptly interred by him in the famous mound.

Every one of the three valley roads of Beddgelert is filled with incidents of Welsh legend and folk-lore. Even in our materialistic age the credulous spirit abides here in this mountain-bred people, quick, lively, romantic. The village is filled with lovely legend and quaint lore; in the farmhouses among the hills heroic stories are still told about Arthur and songs sung to Welsh melodies. There are tales of ghosts, and of goblins, brown road goblins, and gray goblins of the mist; of water sprites in the[27] mountain torrents, now a beautiful, half-naked maiden, now a fleshless old man; of the “Candle of the Dead” with its clear white flame; of the little red-eyed, red-eared “Hounds of Hell” flocking like sheep down some mountain-path; of the pranks of “Lantern Jack” on dark winter nights; of the fairies living in the summer among the bracken, in winter among heather and gorse, coming out of their haunts to dive thievishly into the farmers’ pockets, or to steal butter and milk and cheese from the careful housewives. There are stories, too, of amiable, kindly fairies who carol and dance nightly.

Driving up from Tremadoc past Tan yr Allt, where Shelley lived for a year, one comes to the bridge at the mouth of the pass. This bridge is said to have been built by no less a person than the Devil, who for his trouble got nothing in toll but a poor little dog that was first to scamper over it. Down the Nant Gwynen Valley, a narrow river valley running east out of Beddgelert, is Dinas Emrys, the home of the magician Merlin and at many times the abiding place of King Arthur. Merlin’s well, on the very summit of Dinas Emrys, is still a discoverable well. There, too, surrounding the crown[28] of this singular hill, are traces and remains of the walls of an old Roman fortress; and the entrance over the narrow ridge to the crown of Dinas Emrys bears marks of stone hewn hundreds of years ago. Not more than three miles further in the same valley is a precipitous pass leading up towards Lliwedd by Snowdon, where some legends say Arthur fell and lies buried. Up this valley road over Pen y Pass, in a wilderness of boulders and crags tumbled hither and thither, is an interesting specimen of cromlech, and near by some gigantic rocks so fitted together that they form a hut in which an old woman is said to have lived many, many years. I hope life was pleasanter to her during all those years than it was for us during even the few minutes we were within the strange enclosure.

The third valley running out of Beddgelert is the valley of the Colwyn. This leads past Moel Hebog—in a cave on whose perpendicular side Owen Glendwr lay in hiding for months—towards Carnarvon, a city of a castle with casements:—

There lying before one over the summer sea is the rim of Anglesey, quiet in its mirage of white sand and the green land stretching away into gray distance. Still many portions of the old Roman road connecting Segontium and Heriri Mons may be seen in this valley, bridle-paths the Welsh call “Ffyrdd Elen,” “Elen’s Roads.” Towering above, Snowdon looks down, untroubled, from its splendid reach, upon these paths, from which, in sunshine and in mist, Druid and Roman, henchman of Edward and John, prince and poet and painter, have made the steep ascent and seen swimming before them, like the sea of time, a hundred hills; beyond, the wide glimmer of the ocean; and heard rising through the air the roar of torrent and stream. Halfway up Snowdon are the remains of a druidical temple. There, kneeling on some of the stones, I listened to the song of wind and sea, the Harp of Eryri, and tried to catch a little of the vast panorama, which was, somehow, strangely, mournfully human, holding in sky-line and sea-line dim shadow of the hearts which had knelt here before—the immemorial worshippers of untold beauty.

“Ah,” said Bishop Baldwin, recovering his breath, “the nightingale followed wise counsel and never came into Wales.” So, jocund as the most unordained, Baldwin’s holy company of the twelfth century moved on its way, gathering ever more and more to it cloaks signed with the crusading cross of red. To mind come other figures and to mind come other pictures—wild, powerful, beautiful, pathetic—of a past that is a thousand or two thousand years old. In some rock-strewn valley, bleak and barren as the uttermost parts of the earth or terrible as the valley of the shadow of death, rises the cry of human sacrifice. Hundreds of years later, down a roadway bordered then as now with foxglove and bluebells and heather, rides a gallant company, gentle-mannered, on pleasure bent. Or by the walls of Conway Castle, Edward I bears the body of his Eleanor to its far resting-place in Westminster Abbey, where the stones are still fresh from the chisels of the builders. Here is “the[31] unimaginable touch of Time,” a Past that as it slips away joins the mystery of a Future even at this instant in retreat.

But the traveller does not go on foot week after week many scores of miles, with these thoughts always present, like Christian with a pack upon his back, and meeting as did Christian many difficulties. True, a good heart faces the open road expecting many obstacles, and can find its wonder-ways even if it loses a night’s rest. Giraldus Cambrensis, on the forward march with the Bishop through Wales, could vouch for an island in which no one dies, for a wandering bell, for a whale with three golden teeth, for grasshoppers that sing better when their heads are cut off. He tells the story of a lad, Sisillus Long Leg by name, who suffered a violent persecution from toads that in the end consumed the young man to the very bones. And like most ecclesiastics, Giraldus allows himself the relaxation of a good fish story.

This credulity, charming as it is and panacea for the physical tedium of the open road, is the faculty of which the pedestrian of to-day must strip himself. No other pilgrimages of which I know have been made to these little churches,[32] except by Mr. Herbert North, of Wales,—who has studied the old churches of Arllechwyd simply, and to whose architectural insight I am greatly indebted,—and by myself. During many weeks my journey took me from hillside to hillside and mountain-top to mountain-top, studying these ancient foundations. My work was grounded upon incredulity; everything was recorded, nothing concluded. As a motto the remark of the only thoughtful sexton I have met out of literature might have been taken. Contemplating an old stone at St. Mary, Conway, inscribed “Y 1066,” he said, “Hit wants a wise ’ead to find hit out.” At Gyffin beyond Conway we pointed to one object after another in the church with the single question—an American question:—

“How old is it?”

“It’s very old, mum,” came the reply.

“How old?”

“Oh, very old, mum,” in an impressive voice.

THE GREAT HALL AT CONWAY CASTLE

From an engraving by Cuitt

Having tested barrel vault, paintings, chancel, windows, rood screen, roof, walls, doors, in this fashion, we had worked ourselves out of the church, so to speak, and I pointed up to a shiny tin rooster crowing upon the bell-cot.

“How old is it, the rooster?” I said.

“Oh, very old, mum,” came the solemn reply.

At another place we were told that the bell swinging in the cot, and sounding sweetly after the long journey uphill, dated from the fourth century. It was useless to inform the poor soul that there were none but hand-bells then in North Wales, and that she was in this case only a little matter of one thousand years out of the way. After a mount up to Llangelynin, taken hastily, and much investigation of objects genuinely ancient, the woman who had us in thrall said, pointing to a dark recess under a narrow, fixed pew, black as darkness, and not more than one foot from the pew in front of it, “There’s a very old tablet there, mum, my son says.” Perhaps she had calculated the discrepancy between the width of the pew and myself; however, I got through to the floor, wiped off the dust with a handkerchief, and out blinked, as sleepily as if it were the very Rip Van Winkle of stones, the young date 1874! Wild steeple chases there were in plenty, with minor fatalities to limb and courage. It is useless, when one mountain-top has been achieved, to find that after all there is nothing left except the inconsiderable[34] mountain itself,—it is useless then to discover upon an opposite summit, whose peak could be reached by a well-modulated voice, an extant church of indubitable antiquity, for to meet with that church would require an all-day’s walk. There was one steeple chase without even the comfort of another church in view.

Once reconciled to these surprises, for which no one can be held accountable, and to the ineffectiveness of the sextons whom no one must suppose responsible, there are no chances for disappointments except such as are self-created. The attendants in most cases are women, and wretched creatures some of them are. In one place a woman with a goitre, and one eye gone, kept the keys. She was admirably proud of her son because he did know something, but as the son spent all his days in a mine we were not in a way to inherit his wisdom. Another woman was deaf and dumb and foolish. A lad who took us through a church of considerable importance, if antiquity can make these deserted churches important, was so stupid he received a lecture upon his ignorance. His unanswerable sectarian reply was that he did not belong to that church anyway. We met with some smart young girls[35] who, with their twenty years of wisdom, were above knowledge concerning anything so rusty and tumble-down as the church by means of which they hoped to win sixpences for ribbons. There were two or three apple-cheeked old women clad in caps and bobbing their curtsies. To one, a sweet old soul, I was explaining that a certain door could not be very ancient and have the big nails it had in it. “Uch,” she replied, in distress. “Well, indeed, mum, perhaps they were put in later to hold it together.” It may be said, I think, that the keys are kept as far away as possible, why I cannot say. So is the vicar kept as far away as possible: even the curates get the habit and stay away when they can. As a rule, the churches are not set down in the midst of habitable villages, but most often upon remote hillsides or hilltops. There is another difficulty to be encountered also, in the person of the kindly individual who could show you what you wish, but wishes to show you something else. One old woman—the Ancient Mariner himself could not have been more irresistible—detained us endlessly while she searched for and displayed the Duchess of Westminster’s photograph.

These are some of the troubles in a progress otherwise enchanting; once realized, it is well to forget them, together with the feet that were sometimes too weary to travel five miles further and the shoulder that ached under the strap. With its ache of all the ages the dream of ancient beauty has no place in it for an hour’s weariness. As if the riddle of existence could be explained by a wall rain-washed and worn, upon which grow lichen, moss, rustling grass, and even trees, and by lintels tipping earthward, golden flowers blowing upon them! The eye travels thirstily from stone to stone, or to some peaceful bell-cot pointing the bare ridge of a bleak, sheep-covered hill, or to the far-away hills and gray sky and solemn, dreary places. Spiritually it is easy to understand why these churches are on the hills, and the controversy about their position seems a matter of no further moment. There are other pictures, too, of churches by the sea, in the main not as old as those upon the mountains, enclosures where even the tombstones are crowded together in their last sleep. Beyond these churchyards lies the encircling shore with ever the white lip of the sea at its edge; above, low-lying regiments of clouds[37] march Snowdon-wards. Upon one eminence is the church, upon another, nearer the water, a castle, and in the valley between these crumbling sanctities of power and spirit is the little town, busy still, its roofs making a joyous show of colour beneath the blue sky. Within these churches by the sea there is ever the tideless roar of the waters ringing upon the shores, and from these church doorways the eye dreams upon the castle wasting with the land at its feet, or the “llys” of King Mark, or upon the faint blue rim of some island, holy as the mother of good men. Along the road on one side is the sea; on the other, green hills rise into the blue of the sky, their slopes a mosaic of gray sheep walls. And here out of the village at the end of a grass-grown road, by the sea, lies a little church, around which the sands have blown through so many centuries that the windows show just the caps looking like sleepy eyes out of the huddled graves. One minute time rolls like a chariot wheel crushing all things, another moment and it is a mystic circle without beginning and without end. The graves upon the hillsides, young in their hundreds of years, look down upon the mounds of the British undisturbed in[38] a millennial repose, and upon a stone lying as hands two thousand years ago placed it. And past the ears rush the centuries of all eternity, as in the travelling of a mighty wind.

Seeing with the eye of visions it is not hard to re-create a vanished past, to construct again the primitive British church of wood and wattle, with its beauty of oaken rafter and carved wood which stone now encloses. There is still an ancient wooden church in Greenstead, Essex, in plan much like little churches of North Wales,—the walls six feet high made of half trees side by side, the roof a tie beam, with struts, less than six feet from the floor. This parallelogram follows out the double square of what was undoubtedly the plan of the ancient British church, something that was still geometrically the square sanctuary with its square altar typifying the heavenly Jerusalem. Bede, in his “Ecclesiastical History,” speaks of “a church fit for an Episcopal See; which, however, after the manner of the Scots, he [Finan] did not erect of stone, but of sawn timber, covering it with reeds.” It is worth remembering that the little churches being discussed are unique examples of a national type based, not[39] upon the Roman basilica, but upon the Temple, with its square Holy of Holies, and illustrating certain features; a square east end with east window, an altar concealed behind screens, and a south door instead of a western portal. The wood and wattle churches have disappeared, but upon the foundation lines have arisen the present stone churches of North Wales, dating back in general to the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Their walls of stone are daubed at the joints with mud, similar to the treatment the wattle buildings had received, and the whole whitewashed inside and out. The roof, later covered with oaken shingles and now with soft-coloured slates, was in the Middle Ages thatched deeply with reed or straw. At the east end was the small slit window, and at the south end a door so low that even a short person must stoop to enter it. Originally there were no bell turrets or porches, and at the eastern gable merely a wooden cross. Inside, a screen divided the building in half, the squints covered by veils, and several doors opening into the altar space. Probably the screen was decorated with painting as the barrel vaults came to be. Within and without, the sanctuary[40] gleamed pure white. The Saxons learned the use of whitewash from the British, and St. Wilfrid gloried in having washed the York Minster of his day “whiter than snow.”

ST. WINIFRED’S WELL, HOLYHEAD

From an engraving by Cuitt, 1813

As the cottages, coloured white or yellow or pink, are seen nestling against the hills of Wales, one regrets that the church no longer receives as in olden days the same treatment. With the wash worn from the churches and never renewed, the country has lost in picturesque beauty. How pretty these buildings must have looked, with their steep thatched roofs and white bell-cots gleaming in the midst of dark yews, or perhaps some golden-tinted church glowing like a crocus in the midst of pines. Not only have the colours faded, as if the land were some bright missal turning gray, but the odd circular huts with their conical thatched roofs, in which the natives once lived, have tumbled down. In those days was a beautiful hospitality, the host and hostess serving until all were served, and in these rude dwellings the ancient harp was played; and from the wooden book, its revolving square crossbars inscribed with letters or notes of music, were read the ancient song and poetry of Wales.[41] When the rectangular cottage came in it did not differ greatly from the circular hut. There were windows—“wind-eyes”—covered with a wooden lattice and shutter, the walls smoothly plastered, and the interior made less primitive by the use of three-legged tables and chairs. Still later, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the one space was divided off into kitchen, chamber, and loft, the kitchen open to the roof and airy, healthful, and clean. Hospitality was sacred then; any man might enter a dwelling, and delivering up his arms stay as long as he would.

The church was but another sanctuary in olden days where men could take refuge from sin or foe. The “llan,” which is the prefix to fully eight tenths of all the names of ancient churches in North Wales, means “enclosure.” Probably in these places were the earliest monastic settlements, at a time when the “llan,” as the Irish “rath,” enclosed habitation as well as sanctuary. But as the years brought about greater specification in the functions of church and state the term narrowed itself down and was applied solely to the church. The old churchyard walls are still more or less circular like British fort[42] walls. Llangelynin has an enclosure that undoubtedly follows the old lines. The walls of the churchyard near Holyhead are extremely ancient, seventeen feet high and six feet thick. This masonry, from the presence of certain round towers and the particular plastering used, is known to be Roman. Set away from the world that is “too much with us,” these enclosures are charming old spaces, habitable in a sweet sense. The grass looks peace into tired eyes, and to eyes eager with plans rest here is merely an emphasis upon the joy of living. And here, as the stiles into the close show, the children play and have played from generation to generation. Here they climbed upon the roof, and here against the north and west walls, where burials are never made, they played ball and scratched upon the stone their scoring-marks.

At Llangelynin there are no yew trees; that windy height is too bleak for even the sturdy yew. Only white harebells and hardy grass blow about on its bare rock-strewn summit. But in most of the enclosures the yew still stands as the one enduring monument of a past whose very rocks have been covered by the silt of over a thousand years. Many of these trees date from[43] a British period and remain emblematic to-day as they were then. Sometimes it is a single yew by the lychgate which one sees, or an alley of the deathless green, or perhaps yew branches completely veil a gable end of the little church. At Beddgelert, the oldest foundation in all Wales, the yew stands to-day as it stood some two thousand years ago; about its base have rushed the floods of wild mountain torrents, from its feet the graves of centuries have been washed away down to the all-embracing sea. Like children of yesterday are the mediæval lychgates through which one passes into the church enclosure and through which is often caught the first glimpse of the church bell-cot. At Caerhûn (the ancient Canovium), where the yew spreads over the gate is a double bell-cot, which, as it has the traditional straight ridge and gable in the middle, is amongst the oldest in Wales, of the fourteenth or fifteenth century, for the cots as well as the lychgates are “recent” in the life of these churches. The little crucifixes with their straight arms are also of this date. Before this time the local churches had nothing but hand-bells, which were held in great reverence. One of them may be seen in the stone coffin of Llewelyn the Great[44] at Llanrwst. It is about ten inches high and cast on an oblong plan. Gildas gave such a bell to St. David. Six hundred years later, in the twelfth century, Giraldus Cambrensis tells the story of a portable bell called “Bangu” which, when a certain woman carried it to a castle where her husband was wrongfully imprisoned, caused the destruction of the whole town except the church walls. The campanology of North Wales is a romance in itself, a collection of odd, interesting, pathetic tales of past miracles, past friendships, past enmities.

The original buildings not only did not have lychgates and bell-cots, they also did not have porches, and some to-day do not have them. But they are being added from time to time, and fearful are some of them to behold. At St. Mary’s, Llanfwrog Church, just across the bridge from quaint Ruthin, where the Duchess of Westminster has lived and is of vastly more interest to the people than gable ends and oaken rafters and other such stuff, fit only for the attics of men’s minds, is a bit of “restoration” suitable for display in the windows of a carriage-shop. The chancel railing is bright green, red, and black, the pews black and red,—a foretaste[45] possibly of the landscape into which some of their occupants will one day take a dip,—and the stained glass vies with a refracted solar ray in yellows and oranges and reds and blues and greens. From this “restored” edifice drops a long flight of steps past the windows and signboard of an ancient hostelry, “Ye Labour in Vain Inn.” One cannot help wishing that the white gentleman upon the signboard, who is scrubbing a black man in a tub of water, would take his scrubbing-brush up to the church. Often, after all else has been hopelessly restored and all vestiges of harmonious beauty have disappeared, the old doorway remains, witness of an instinctive reverence for a threshold. Many of the circular-headed doorways, now hooded with porches, date from the eleventh and twelfth centuries and even earlier, and through them one passes over a mere sill into the sacred enclosure.

A few points, simple and easy to remember as well as easy to discover, give an added intelligent pleasure in the study of these churches. The oldest churches are generally from twelve feet six inches to fourteen feet wide; the early walls from three feet to three feet six inches[46] thick. Sixteenth-century walls rarely exceed two feet and a half in thickness. The old wattle buildings were daubed with a mixture of clay and cow dung; these church walls are built with earth and rendered on the face with lime and mortar. Buttresses are sometimes found, but they do not belong to early local work. The roofs are easy to examine and often of an enchanting beauty. At Llangelynin is a roof which is probably the original twelfth-century covering. The roof at Llanrhychwyn is also of the close couple type; here the struts are straight, but carved, and there are two ties across the nave. In some of these roofs are intermediary rafters, added when the thatch was replaced by slate.

The earliest mention of a chancel of which I know is that in the poems of Cynddelw, who lived in the twelfth century, in his ode to Tysilio, when he speaks of a certain church as the “light or shining church” with a chancel for mass. We cannot assume that even in the twelfth century chancels were by any means common in North Wales. At Mallwyd Church there was, not so long ago, a communion table in the centre of the building, and there is no[47] question but that holy ceremonies were performed originally, instead of at a chancel end, in the midst of this rectangular Holy of Holies. At Bardsey, Pennant found an insulated stone altar rather nearer the east end than the centre. The rough, uneven slate paving in these churches is comparatively modern, and it might be added comparatively luxurious. The first paving was mud and sometimes flat stones. Formerly the windows were covered by wooden shutters or lattices; that was the usage in all conventual buildings. Now the windows are either well or illy filled with coloured glass. In many of the churches falling into great dilapidation the windows have been stuffed with stone and mortar, or rudely boarded over. Some of the stained glass is genuinely ugly and some of it genuinely and anciently lovely. That at Llanrhychwyn, coloured in brown line and yellow stain and representing the Virgin and Child and the Holy Trinity, is of the fifteenth century and still beautiful. Probably the use of glass was not introduced into Wales till the thirteenth century. West windows were unknown in local Welsh work. Where a window with such an exposure is found, the opening did not belong to the early[48] church. There are windows of great antiquity in these churches. Look at the lintelled window in the passageway into St. Beuno’s Chapel. Courage hesitates at assigning a date to this bit of work. There are windows far more elaborate of a comparatively early date, but they are the work of Latin monks and do not follow the straight lines of the native British architecture. An exquisite example of early Latin work is that of the Gilbertine monks upon the Beddgelert triplet.

The barrel vaults in these churches are curious concave coverings over the chancel end, ark-like in form and supposed type of the ancient church. These oaken canopies have been elaborately painted in the past; now they are to be seen in every stage of dilapidation, provoking the eye by their interrupted pictures or faint lines of red and blue. They are approximately of the same date, although not in the same condition, for their destruction is due to leaky roofs and not to age. The ground colour was the green-blue the Middle Ages loved so well, and the other colours red, yellow, and white. At Llandanwg, where the sea would flow into the western door were it not for a big embankment,[49] there is a barrel vault with faint traces of painting upon it. An old man whose father and mother were the last people to be married there told us he took an interest in it, it was the only church in Harlech Parish fifty years ago, and “the only service held there then was when the parson and the clerk used to go over and enjoy drinking their beer on the gravestones.” English came stiff to his tongue, but he described the fearful condition of the church, and the way the people took off the seats for firewood and the children made a playhouse of the abandoned structure. In one corner of the barrel vault was a picture of the Devil prodding people down into hell. The children threw things at these paintings, mud and other articles, till the pictures were completely destroyed. Whatever the subject, it is pleasant to recall the colouring of the barrel vaults, for, executed five or six hundred years ago, they must have been brightly beautiful like the margins of an illuminated book, radiant with something of the blue and gold of very heaven itself. Of the rood screens and lofts that veiled the chancel space, there are but few left intact; of the sacred rood itself, no vestige except the socket on the candlebeam into which[50] its pedestal slipped. Fanaticism has swept this feature away. In Beddgelert their rood-screen carving was converted into chairs for household use or fuel for warmth. Strangely enough, Queen Elizabeth was the last defender of the screen’s mystical beauty of carven wood and the silent admonishing figure stretched upon its façade. At Llanengan there is a screen of rare delicacy, stolen, together with some elbow stalls and silver bells, from Bardsey, that resting-place of saints which seems to have been to the ecclesiastical world what Fuseli said Blake was to the art world, “good to steal from.” Chests, worm-eaten and with rusty bolts, are often among the church treasures. St. Beuno’s chest at Clynnog is as old as the saint himself. And at Clynnog, too, are dog tongs, or lazy tongs as they were sometimes called, in each paddle four sharpened nails which must have seemed bitter to any doggie’s sides, lean or fat, as he was lifted ignominiously out of the sanctuary. And, oh, woe if it caught him by the tail or foot! There are different types of fonts in these churches: small square fonts like the earliest of Palestine, Asia Minor, Egypt; extremely small fonts of various shapes dating from the eleventh to the fourteenth[51] century; large fonts used for immersion, and belonging to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. At Llanderfel near Corwen is a wooden image, never, I imagine, satisfactorily accounted for. It is a horse, though curiously like a deer in appearance. This figure was the standard for the image that rested upon it and which went, several hundred years ago, to help in the burning of poor Friar Forest at Smithfield, to whom, while the fire crackled about his feet, Latimer preached a sermon. Now even the brass tablet on the standard has been sent to the British Museum, and the standard itself, till within the last few years, used for a pig-trough.

Apparently London thought a Welshman who denied the supremacy of the king worth burning, difficult to be rid of. Well might Englishmen consider such a man’s forebears in saintship. The Latins tried to rid the Western world of these anomalies in spiritual heritage—in vain! The Reformation burnt them. In vain, too, for the Welshman to-day, nonconformist and conformist alike, is as tenacious of the lists of his hagiology as ever he was a thousand years ago. To the ancient Celt there were three free dignitaries: church, land, and poet. To-day[52] these remain the revered dignitaries to the Welshman. In the past these offices had been closely united, for to a Welshman saintship came by birth, celebrity depended afterwards upon how he acted. There is an odd title to a Welsh catalogue of saints: “Bonedd Saint ynys Prydain,”—the Gentility of the Saints of the Isle of Britain. An old Irish song says of St. Patrick that he “was a gentleman and came of decent people,” a fact which to us does not seem prerequisite for saintdom. Not so to the Celt; and it is best to keep this essential difference in mind, or one might be puzzled by running across the annals, some day, of a saint in so cheery a state that he fell into his own holy well and escaped drowning only because of the good luck universally known to attend people in a similar condition. The object of the Celtic saint, till he became Latinized, was to serve his tribe by increasing its riches and enlarging its boundaries. It was not necessary for him, as it was for his brother Latin, to receive any papal sanction for his sainthood or to work any miracles. His carte to sanctity was membership in a certain family or monastery. The Latin Christian world, establishing its supremacy by[53] degrees, could not fail to scoff at the temporal emphasis of Welsh saintdom. Even Giraldus, a Welshman, comments mildly upon the vindictiveness of certain saints, of whom he often knew more than he cared to tell. Gradually, by ridicule chiefly, the lists of Celtic holy men were closed. Even Bardsey, the Insula Sanctorum of the Welsh, does not escape a laugh from many critics, one of whom observes that “It would be more facile to find graves in Bardsey for so many saints than saints for so many graves”; a remark grudging and ungracious, for the world has condescended to steal everything from Bardsey and might leave it at least the glory of claiming as many dead saints as it pleases.

THE EAGLE TOWER OF CARNARVON CASTLE

From an engraving by Cuitt

The tales, fabulous and odd, told of Welsh saints, Welsh relics, and holy wells, are particularly charming because they are not marred by over-didacticism. Tydecho was an illustrious saint who lived in the time of King Arthur. Retiring from the world, he led a life of mingled austerity in penance and of useful hours of ploughing. One day a youth seized his oxen, but the next day wild stags were drawing the plough, and a wolf harrowing after them. Furious,[54] the youth brought his dogs to chase away Tydecho’s wild friends. While enjoying this diversion he seated himself upon a stone; attempting to rise he found himself fixed to the rock. Truly a humiliating position for a proud-spirited youth who enjoys taunting an old man! Friendship between man and beast is woven into these tales like the bright colours threading the letters of an ancient bestiary. St. Monacella protected hares from Brochwel Yscythrog, who was hunting them. She hid the trembling little beasts under her robe and, praying devoutly, faced the dogs. The dogs ceased their running, and even when the horn was blown as a command to them to follow the hare, they stole away howling and the horn stuck to the huntsman’s lips. After Brochwel had listened to Monacella’s plea, the little creatures were released, and to this day no one in the parish will hunt one of Monacella’s lambs.

Many and attractively full of poetry are the superstitions that still live in the solitudes of northern Wales. “Bees were created in paradise,” say the “Leges Wallicæ,” “and no light save beeswax is to be used at mass.” When on the fall of man they left paradise, God Himself[55] is said to have blessed them. They produced, too, the nectarious “medd” of which the ancient Britons thought so much. One day we encountered a hillside woman in great distress, breathless and flapping her apron; her bees were running away and apparently the worldly creature had no intention of letting them run back to paradise. Bent pins are still to be found at the bottom of the sacred well within the church close, pins dropped in before bathing to cure warts. Woe to the bather who failed to drop in the propitiatory pin, for he promptly caught the warts of which others had got rid. And in these holy wells the clothes of sick children were washed, with happy auguries if the little garments floated, with fell portent if they sank. At Llangelynin, where the well is still in excellent condition, an old woman told me that to cure a sick child a stranger to the family must dip the child in after sundown. Spitting upon hearing the name of the Devil may not be polite, but it is a simple way of expressing contempt, and so, too, is smiting the breast in self-condemnatory woe at the name of Judas. Some of their superstitions and customs, despite the smack of folly, are wise in[56] their emphasis upon the power of the imagination.

There are, too, some wholesome customs of precedence. The parson always used to go out of chapel first,—in some places he does so still,—and the parishioner who disputed this order of rank might have his ears boxed for his trouble. After the baptism of a little child old women wash their failing eyes in the font with pathetic faith in the virtue of new, God-given life. There used to be some sweet customs, not entirely lost yet, connected with burial. As the coffin rested on the bier outside the door, the next of kin among the women gave to the poorest persons in the parish, over the body of the dead, a great dish filled with white bread. Then a cup of drink was handed across the bier to the same poor and all knelt to repeat the Lord’s Prayer. At every crossroad between the house and church they knelt again to pray, the sexton’s hand-bell quiet only when all knees were on the earth.

On the way from church to church many tablets arrest the eye, kneeling fathers and mothers with processions of kneeling children in a line behind them. The viva voce history of[57] these reliefs suggests the less quaint and more beautiful and enduring relievo of sepulchral urns. At Clynnog I counted thirteen children in happy procession after one father. At Conway I might have counted twenty-nine if I had wished to, but I had no such wish. At Corwen we found knee-holes in both footstones and headstones to make comfortable the knees of friends while they prayed,—or meditated, as I confess I did, upon the hideousness of most sepulchral carving and inscription. There was one part of these records which, with even the best traditions behind me, could not be undertaken—the epitaph or similar memento. Early in the journey this inscription was encountered:

Heare lyeth the body of

John, ap Robert, ap Porth, ap

David, ap Griffith, ap David

Vauchan, ap Blethyn, ap

Griffith, ap Meredith,

ap Jerworth, ap Llewelyn,

ap Jerorh, ap Heilin, ap

Cowryd, ap Cadvan, ap

Alawgwa, ap Cadell, the

King of Powys, who

[58]departed this life the

XX day of March, in the

Year of our Lord God

1642, and of

his age XCV.

Now it was plain that this was one of the results of the saints’ unsaintly emphasis upon a family-tree. Certainly a man has a right to as many ancestors as he can compass. But thereafter, when I saw the usual clusters of “aps” and “Griffyevanjoneses,” I experienced a reluctant and fluttering sensation within accompanied by external haste to get elsewhere. Just one other epitaph, by reason of its brevity, caught my pencil:—

Even the motion of driving in a post-chaise captivated the fancy of Dr. Johnson, for he said, “If I had no duties, and no reference to futurity, I would spend my life in driving briskly in a post-chaise with a pretty woman; but she should be one who could understand me, and would add something to the conversation.” Mrs. Piozzi, who, except for that of prettiness, fulfilled these requirements both as a brilliant conversationalist and owner of a post-chaise, asked her beloved Doctor why he doted on a coach. Johnson’s reply was, that in the first place the company was shut in with him “and could not escape as out of a room,” and that in the second place, he could hear all the conversation in a[60] carriage. Any lamentations while travelling thus he considered proof of an empty head or tongue that wished to talk and had nothing about which to talk. “A mill that goes without grist,” he exclaimed, “is as good a companion as such creatures.” As for himself, he felt no inconvenience upon the road and he expected others to feel none. He allowed nobody to complain of rain, sun, or dust. And so greatly did he love this act of going forward that Mrs. Thrale (Mrs. Piozzi) said she could not tell how far he might be taken before he would think of refreshments.

Yet the impression which Macaulay gave of Johnson’s attitude towards travelling is the one generally held: “Of foreign travel and of history he spoke with the fierce and boisterous contempt of ignorance. ‘What does a man learn by travelling? Is Beauclerk the better for travelling? What did Lord Claremount learn in his travels, except that there was a snake in one of the pyramids of Egypt?’” History has proved that Macaulay could be brilliantly inaccurate; certainly in this estimate of Johnson he was so. In still another passage Macaulay says that Dr. Johnson “took it for granted that everybody[61] who lived in the country was either stupid or miserable.” The first twenty-seven years of his life Johnson spent in small country towns and, although he was sometimes miserable, because he was wretchedly poor, he was never stupid.

It was the young traveller whom he censured, not the mature traveller or travelling in general. It was characteristic of him to say, “I never like young travellers; they go too raw to make any great remarks.” Indeed, so grave was his sense of the value of travel that he took it upon himself to rebuke Boswell, as Boswell records: “Dr. Johnson expressed a particular enthusiasm with respect to visiting the Wall of China. I catched it for the moment, and said I really believed I should go and see the Wall of China had I not children, of whom it was my duty to take care. ‘Sir,’ (said he), ‘by doing so you would do what would be of importance in raising your children to eminence. There would be a lustre reflected upon them from your spirit and curiosity. They would be at all times as the children of a man who had gone to view the Wall of China. I am serious, sir.’”

In his college days Johnson may not have had the same reasons as the young poet Keats[62] for going “wonder-ways,” but reasons he had. With the Doctor, perhaps even more truly than with Keats, curiosity was “the first passion and the last.” While an undergraduate he was heard to say, “I have a mind to see what is done in other places of learning. I’ll go and visit the universities abroad. I’ll go to France and Italy. I’ll go to Padua.” Twice he urged Boswell “to perambulate Spain,” and of their tour to the Hebrides everybody knows. There was talk of his going to Iceland, and for a time the great Doctor discussed travelling around the world with two friends.

Of the existence of the journal of Johnson’s tour in North Wales even Boswell did not know. This journey was begun by the Thrales and the Doctor leaving Streatham at eleven o’clock on Tuesday morning of July 15, 1774. On their way they stopped at Litchfield at the house of Dr. Darwin, psychologist, poet, and grandfather of Charles Darwin, of whose roses Mrs. Piozzi wrote, “I have no roses equal to those at Litchfield, where on one tree I recollect counting eighty-four within my own reach; it grew against the house of Dr. Darwin.”

After passing through several towns on their[63] route to North Wales they came, a party of four, Mr. and Mrs. Thrale, little Queenie and Johnson, to Chester on July twenty-seventh. Of Chester the Doctor made short work. He was more interested in a grammar school held in part of the Abbey refectory than in aught else, and wrote particularly, “The Master seemed glad to see me.” Of course the Master was glad, for was not Johnson the greatest man of his day? There is not one word for the quiet beauty of the Dee, no mention of Cheshire cheese, and nothing about Chester ale, which perhaps Johnson found as bad as did Sion Tudor. Of their sojourn in Chester we get a more lively picture from Mrs. Thrale’s comment on the entry in the Doctor’s journal than from the journal itself. Johnson wrote, “We walked round the walls, which are compleat.” Mrs. Piozzi observed, “Of those ill-fated walls Dr. Johnson might have learned the extent from any one. He has since put me fairly out of countenance by saying, ‘I have known my mistress fifteen years, and never saw her fairly out of humour but on Chester wall’; it was because he would keep Miss Thrale beyond her hour of going to bed to walk on the wall, where from the want of[64] light, I apprehended some accident to her,—perhaps to him.” Probably nine-year-old “Miss Thrale” did not mind being kept beyond her hour of going to bed by a stout gentleman who was her devoted slave!

The next day they entered Wales, dined at Mold and came to Llewenni. Mrs. Thrale’s cousin, Robert Cotton, was living at Llewenni Hall, which in 1817, after having been one thousand years in possession of the family, was torn down. At Whitchurch, a few miles away, is an alabaster altar monument to one of the Salusbury’s who owned this hall, Sir John, or Syr John y Bodiau (“Sir John of the Thumbs”). This ancestor of Mrs. Piozzi was not only distinguished by two thumbs on either hand, but also by a giant’s strength. With his bare fist he is supposed to have slain a white lioness in the Tower of London. Since then white lionesses have all disappeared. Sir John of the Thumbs also killed a mythical beast in a lair below a near-by castle, and overthrew a famous giant. Is it any wonder that Mrs. Thrale, with such a forefather, should sometimes have painted things plus beau que le vérité, and that, even as her ancestor was fond of pulling up trees by the roots when he[65] had nothing better to do, his descendant should once in a while give truth a little tug?

But if Mrs. Thrale had a distinguished progenitor, she had an even more distinguished ancestress, for there at Llewenni Hall lived “Mam Cymru,” the Mother of Wales. This Catherine de Berain’s first husband was a Salusbury, her second husband was Sir Richard Clough. The second daughter of the second marriage married Salusbury of Bachycraig, and from this marriage Mrs. Piozzi was descended. Later, Catherine de Berain became the third wife of Maurice Wynne, who was her third husband. It is said that on the way home from the funeral of her first husband, Wynne asked her to marry him. She had to refuse, however, as Sir Richard Clough had asked her on the way to the church. But she assured him that she was not superstitious about the number 3, and agreed to give Wynne the next opportunity. She kept her word.

When the Welsh used to speak of a rich person, they did not say “rich as Crœsus” but “rich as a Clough.” On July thirtieth, Johnson and the Thrales visited a remarkable house built by Sir Richard, the second husband of “Mam Cymru.” On the thirty-first day they[66] drove to the Cathedral of St. Asaph, once the even smaller church of Llanelwy, to which Giraldus Cambrensis in his tour in 1188 referred as “paupercula.” About that time this tiny cathedral was changed from wickerwork or wood to stone. On the same day they saw the Chapel of Llewenni, founded by one of the Salusburys, where Johnson was surprised because the service, read thrice on Sundays, was read only once in English.

GATEWAY OF CARNARVON CASTLE

From an engraving by Cuitt

He was dissatisfied not only with the order of Welsh services, but also with the behaviour of Welsh rivers. On this day he writes: “The rivers here are mere torrents which are suddenly swelled by the rain to great breadth and great violence, but have very little constant stream; such are the Clwyd and the Elwy.” About Welsh rivers Johnson makes a great many remarks. He is as scornful of them as an American is of the Thames. Mrs. Piozzi says that his “ideas of anything not positively large were ever mingled with contempt.” He asked of one of the sharp currents in North Wales, “Has this brook e’er a name?” “Why, dear Sir, this is the River Ustrad.” “Let us,” said Dr. Johnson, turning to his friend, “jump over it directly,[67] and show them how an Englishman should treat a Welsh river.” Johnson was always of opinion that when one had seen the ocean, cascades were but little things. He used to laugh at Shenstone most unmercifully for not caring whether there was anything good to eat in the streams he was so fond of. “As if,” says Johnson, “one could fill one’s belly with hearing soft murmurs, or looking at rough cascades!”

It would be difficult to make a summary of all the objects Johnson called “mean” in North Wales. Among them were towns, rivers, inns, dinners, churches, houses, choirs. It is safe to say that the great Doctor could not rid himself altogether of English prejudices against the Welsh and all things Welsh. George Borrow’s experience on the summit of Snowdon was not at all unusual, except that in this instance an Englishman in the presence of English people became the champion of the Welsh. Undoubtedly Johnson was influenced in his contempt not only by his English feeling, but also by the fact that he was a true son of the eighteenth century, with all that century’s emphasis on power, on size, on utility.