Title: A system of practical medicine. By American authors. Vol. 3

Diseases of the respiratory, circulatory, and hæmatopoietic systems

Editor: William Pepper

Louis Starr

Release date: October 17, 2016 [eBook #53305]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ron Swanson

|

LARYNGOSCOPY AND RHINOSCOPY. By CARL SEILER, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE NASAL PASSAGES. By HARRISON ALLEN, M.D.

NEUROSES OF THE LARYNX. By HOSMER A. JOHNSON, M.D., LL.D.

ACUTE CATARRHAL LARYNGITIS (FALSE OR SPASMODIC CROUP). By ABRAHAM JACOBI, M.D.

PSEUDO-MEMBRANOUS LARYNGITIS. By ABRAHAM JACOBI, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE LARYNX. By LOUIS ELSBERG, A.M., M.D.

DISEASES OF THE TRACHEA. By LOUIS ELSBERG, A.M., M.D.

TRACHEOTOMY. By GEORGE M. LEFFERTS, A.M., M.D.

DISEASES OF THE BRONCHI. By N. S. DAVIS, M.D., LL.D.

BRONCHIAL ASTHMA. By W. H. GEDDINGS, M.D.

HAY ASTHMA. By W. H. GEDDINGS, M.D.

DILATATION OF THE BRONCHIAL TUBES, CIRCUMSCRIBED AND DIFFUSED. By SAMUEL C. CHEW, M.D.

EMPHYSEMA. By SAMUEL C. CHEW, M.D.

COLLAPSE OF THE LUNG (ATELECTASIS). By SAMUEL C. CHEW, M.D.

CONGESTION AND OEDEMA OF THE LUNGS (HYPOSTATIC PNEUMONIA). By SAMUEL C. CHEW, M.D.

HÆMOPTYSIS. By WILLIAM CARSON, M.D.

PULMONARY APOPLEXY. By WILLIAM CARSON, M.D.

ABSCESS OF THE LUNG. By WILLIAM CARSON, M.D.

GANGRENE OF THE LUNG. By WILLIAM CARSON, M.D.

CROUPOUS PNEUMONIA. By ALFRED L. LOOMIS, M.D., LL.D.

CATARRHAL PNEUMONIA. By WILLIAM PEPPER, M.D., LL.D.

PULMONARY EMBOLISM. By BEVERLEY ROBINSON, M.D.

PULMONARY PHTHISIS (FIBROID PHTHISIS OR CHRONIC INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA). By AUSTIN FLINT, M.D.

SYPHILITIC DISEASE OF THE LUNG. By EDWARD T. BRUEN, M.D.

PNEUMONOKONIOSIS. By EDWARD T. BRUEN, M.D.

CANCER OF THE LUNGS. By EDWARD T. BRUEN, M.D.

PULMONARY HYDATIDS. By EDWARD T. BRUEN, M.D.

ACUTE MILIARY TUBERCULOSIS. By JOHN S. LYNCH, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE PLEURA. By FRANK DONALDSON, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE SUBSTANCE OF THE HEART. By WILLIAM OSLER, M.D.

ENDOCARDITIS AND CARDIAC VALVULAR DISEASES. By ALFRED L. LOOMIS, M.D., LL.D.

CYANOSIS AND CONGENITAL ANOMALIES OF THE HEART AND GREAT VESSELS. By MORRIS LONGSTRETH, M.D.

CARDIAC THROMBOSIS. By BEVERLEY ROBINSON, M.D.

NEUROSES OF THE HEART. By AUSTIN FLINT, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE PERICARDIUM. By J. M. DACOSTA, M.D., LL.D.

THE OPERATIVE TREATMENT OF PERICARDIAL EFFUSIONS. By JOHN B. ROBERTS, A.M., M.D.

DISEASES OF THE AORTA. By G. M. GARLAND, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE CORONARY, PULMONARY, SUPERIOR MESENTERIC, INFERIOR MESENTERIC, AND HEPATIC ARTERIES, AND OF THE COELIAC AXIS. By ELBRIDGE G. CUTLER, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE VEINS. By ANDREW HEERMANCE SMITH, M.D.

THE CAISSON DISEASE. By ANDREW HEERMANCE SMITH, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE MEDIASTINUM. By EDWARD T. BRUEN, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE BLOOD AND BLOOD-GLANDULAR SYSTEM. By WILLIAM OSLER, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE SPLEEN. By I. EDMONDSON ATKINSON, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE THYROID GLAND. By D. HAYES AGNEW, M.D., LL.D.

SIMPLE LYMPHANGITIS. By SAMUEL C. BUSEY, M.D.

AGNEW, D. HAYES, M.D., LL.D.,

Professor of Principles and Practice of Surgery in the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

ALLEN, HARRISON, M.D.,

Emeritus Professor of Physiology in the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

ATKINSON, I. EDMONDSON, M.D.,

Professor of Pathology and Clinical Medicine and Clinical Professor of Dermatology in the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

BRUEN, EDWARD T., M.D.,

Assistant Professor of Physical Diagnosis in the University of Pennsylvania; Physician to Philadelphia (Blockley) Hospital; Lecturer on Pathology in the Woman's Medical College, Philadelphia.

BUSEY, SAMUEL C., M.D.,

Attending Physician and Chairman of the Board of Hospital Administration of the Children's Hospital, Washington, D.C.

CARSON, WILLIAM, M.D.,

Physician to and Clinical Lecturer at the Cincinnati Hospital, Cincinnati.

CHEW, SAMUEL C., M.D.,

Professor of Materia Medica, Therapeutics, and Clinical Medicine in the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

CUTLER, ELBRIDGE G., M.D.,

Clinical Instructor in Auscultation in the Harvard Medical School; Physician to Out-Patients, Massachusetts General Hospital.

DACOSTA, J. M., M.D., LL.D.,

Professor of Theory and Practice of Medicine in the Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia.

DAVIS, N. S., M.D., LL.D.,

Professor of Principles and Practice of Medicine in the Chicago Medical College, Chicago.

DONALDSON, FRANK, M.D.,

Clinical Professor of Diseases of the Throat and Chest in the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

ELSBERG, LOUIS, A.M., M.D.,

Late Professor of Laryngology and Rhinology in the New York Polyclinic and in Dartmouth Medical College; Physician to Charity Hospital, Blackwell's Island (Throat Wards), New York.

FLINT, AUSTIN, M.D.,

Professor of the Principles and Practice of Medicine and Clinical Medicine in the Bellevue Hospital Medical College, New York.

GARLAND, G. M., M.D.,

Formerly Professor of Thoracic Diseases in the University of Vermont, and Assistant in Clinical Medicine in Harvard Medical School.

GEDDINGS, W. H., M.D.,

Aiken, South Carolina, and Bethlehem, N.H.

JACOBI, ABRAHAM, M.D.,

Clinical Professor of Diseases of Children in the College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, etc.

JOHNSON, HOSMER A., M.D., LL.D.,

Emeritus Professor of Practical Medicine in the Chicago Medical College, Chicago.

LEFFERTS, GEORGE M., A.M., M.D.,

Professor of Laryngoscopy and Diseases of the Throat in the College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York; Consulting Laryngoscopic Surgeon to St. Luke's Hospital, etc.

LONGSTRETH, MORRIS, M.D.,

Physician to the Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia.

LOOMIS, ALFRED L., M.D., LL.D.,

Professor of Pathology and Practice of Medicine in the University of the City of New York.

LYNCH, JOHN S., M.D.,

Professor of Principles and Practice of Medicine in the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Baltimore.

OSLER, WILLIAM, M.D.,

Professor of Clinical Medicine in the University of Pennsylvania; formerly Professor of the Institutes of Medicine in McGill University, Montreal.

PEPPER, WILLIAM, M.D., LL.D.,

Professor of the Theory and Practice of Medicine and of Clinical Medicine in the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

ROBERTS, JOHN B., A.M., M.D.,

Professor of Applied Anatomy and Operative Surgery in the Philadelphia Polyclinic and College for Graduates in Medicine.

ROBINSON, BEVERLEY, M.D.,

Clinical Professor of Medicine in the Bellevue Hospital Medical College, New York.

SEILER, CARL, M.D.,

Instructor in Laryngoscopy in the University of Pennsylvania; Professor of Acoustics and Vocal Physiology at the National School of Oratory, Philadelphia.

SMITH, ANDREW HEERMANCE, M.D.,

Professor of Therapeutics and Clinical Medicine in the New York Post-Graduate Medical School; Physician to the Presbyterian Hospital, New York.

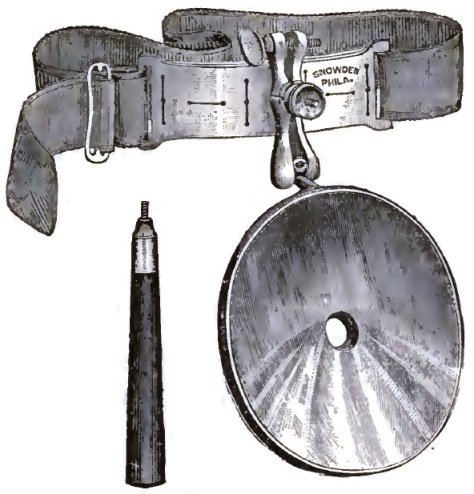

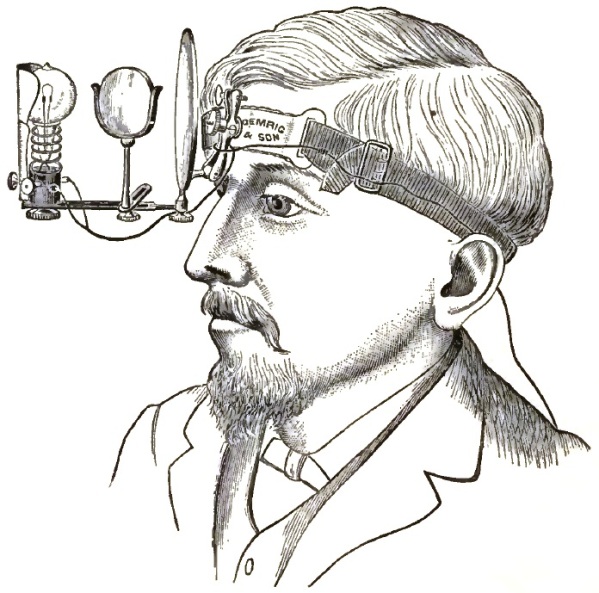

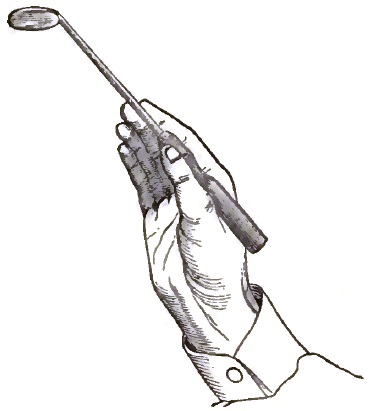

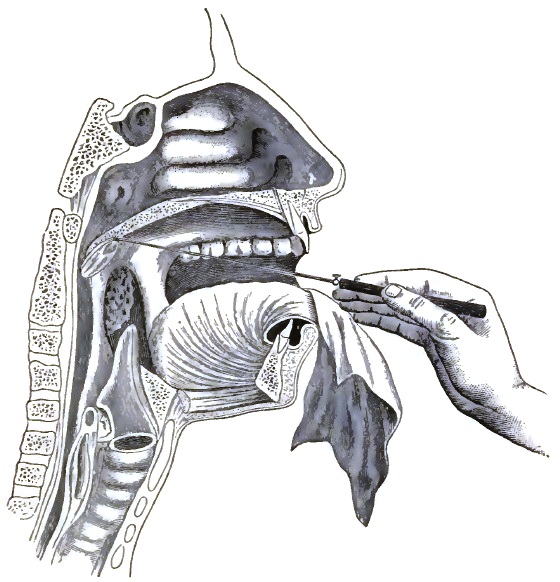

| FIGURE | |

| 1. | LARYNGEAL MIRROR |

| 2. | HEAD REFLECTOR |

| 3. | SEILER'S ELECTRIC ILLUMINATOR FOR THE LARYNGOSCOPE |

| 4. | POSITION OF HAND IN HOLDING THE LARYNGEAL MIRROR |

| 5. | SECTION OF THE HEAD, SHOWING THE POSITION OF LARYNGEAL MIRROR IN THE PHARYNX |

| 6. | ELSBERG'S SPONGE-HOLDER AND EPIGLOTTIS FORCEPS |

| 7. | LARYNGEAL IMAGE DURING RESPIRATION |

| 8. | LARYNGEAL IMAGE DURING PHONATION |

| 9. | LARYNGOSCOPIC DIAGRAM, SHOWING VOCAL CORDS WIDELY DRAWN APART, AND THE POSITION OF THE VARIOUS PARTS DURING QUIET BREATHING |

| 10. | THE SAME, SHOWING APPROXIMATION OF VOCAL CORDS AND POSITION OF THE VARIOUS PARTS DURING VOCALIZATION |

| 11. | VERTICAL SECTION OF THE HEAD |

| 12. | NASAL SPECULUM |

| 13. | BOSWORTH'S NASAL DILATOR |

| 14. | SEPTOMETER FOR MEASURING THICKNESS OF NASAL SEPTUM |

| 15. | FOLDING TONGUE DEPRESSOR |

| 16. | COHEN'S TONGUE DEPRESSOR |

| 17. | JARVIS'S RHINOSCOPIC MIRROR AND TONGUE DEPRESSOR |

| 18. | RHINOSCOPIC IMAGE |

| 19. | SHOWING ANTERO-POSTERIOR SECTION OF BONES OF THE FACE IN POSITION |

| 20. | BELLOCQ'S CANULA |

| 21. | ALLEN'S NASAL FORCEPS |

| 22. | THE GALVANO-CAUTERY SNARE |

| 23. | DOUBLE BATTERY AND FLEMING ELECTRODE FOR USE IN NASAL DISEASES |

| 24. | TWO ELECTRODES OF PECULIAR SHAPE, FOR USE IN NASAL DISEASES |

| 25. | ACUTE TRACHEITIS: ANTERIOR WALL |

| 26. | SAME CASE AS FIG. 25: POSTERIOR WALL |

| 27. | TUBERCULOUS ULCERATION OF THE TRACHEA, AS SEEN DURING LIFE |

| 28. | SAME CASE AS FIG. 27: POST-MORTEM APPEARANCE |

| 29. | SYPHILITIC ULCERATION OF TRACHEA, AS SEEN DURING LIFE |

| 30. | SAME CASE AS FIG. 29: POST-MORTEM APPEARANCE |

| 31. | PAPILLOMA OF TRACHEA |

| 32. | INVOLUTION OF TRACHEA, DUE TO ANEURISM |

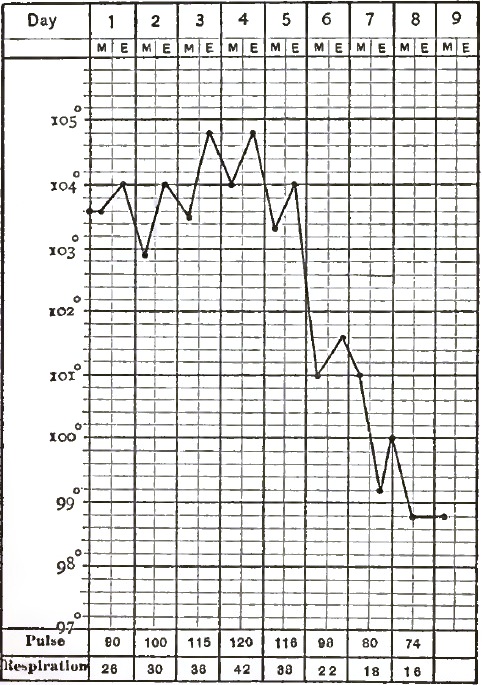

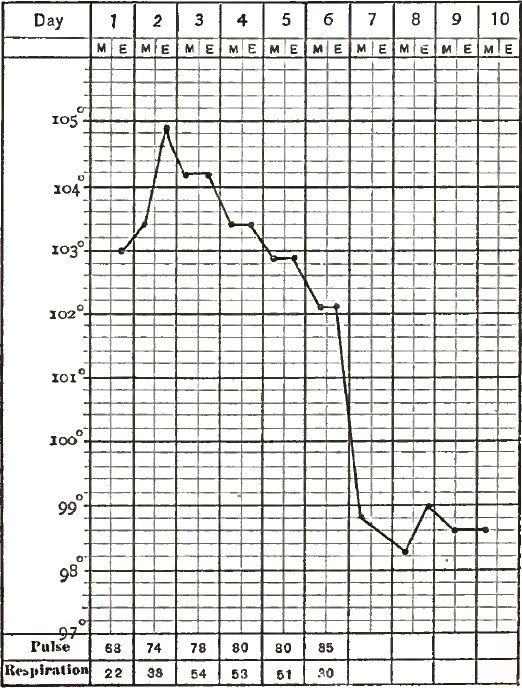

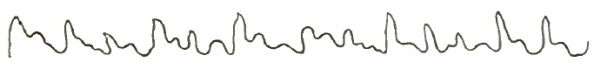

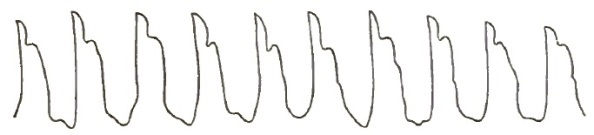

| 33. | A TYPICAL CASE OF LOBAR PNEUMONIA IN THE ADULT: RECOVERY |

| 34. | LOBAR PNEUMONIA, WITH CRISIS MARKED BY EVENING EXACERBATIONS REACHING NEARLY THE HIGHEST PYREXIA OF THE SECOND STAGE |

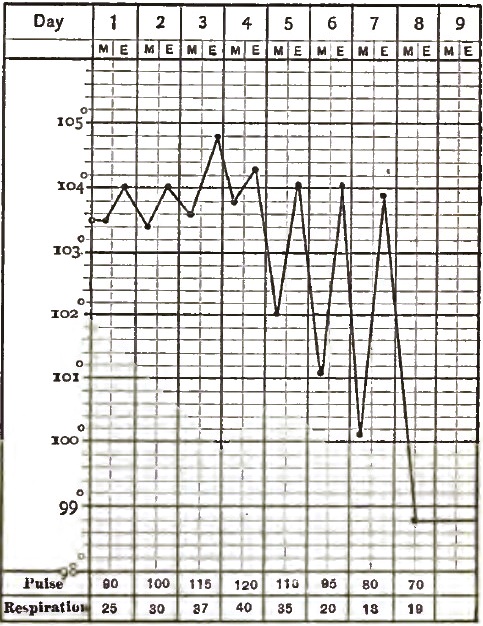

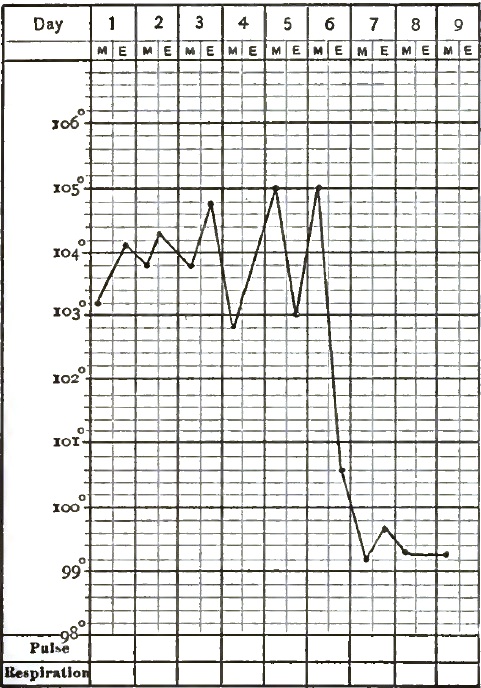

| 35. | A TYPICAL CASE OF LOBAR PNEUMONIA IN A CHILD: RECOVERY |

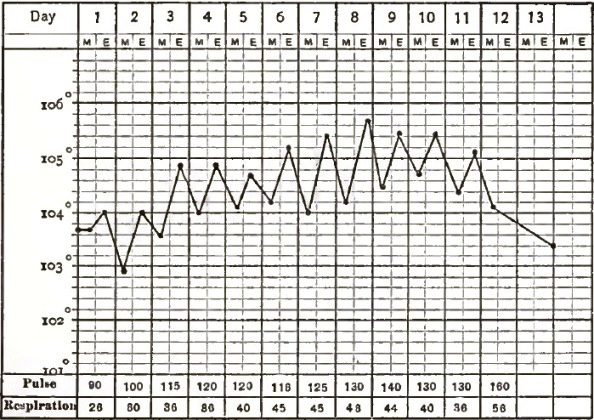

| 36. | A CASE OF LOBAR PNEUMONIA IN A BOY TEN YEARS OLD, IN WHICH TEMPERATURE WAS TAKEN EVERY FOUR HOURS |

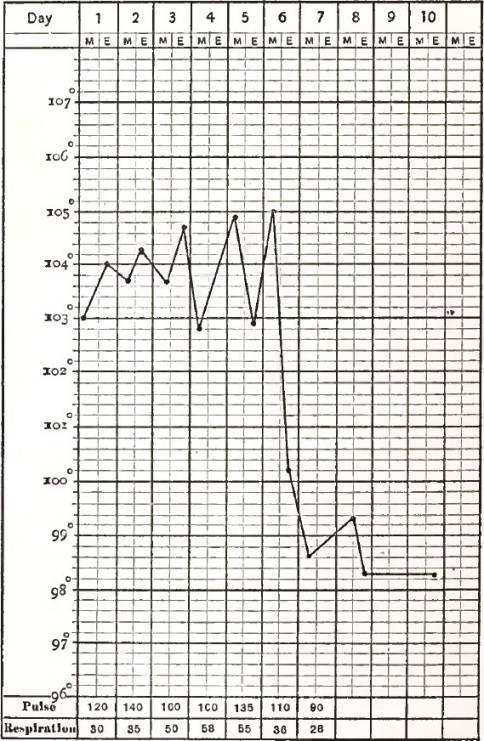

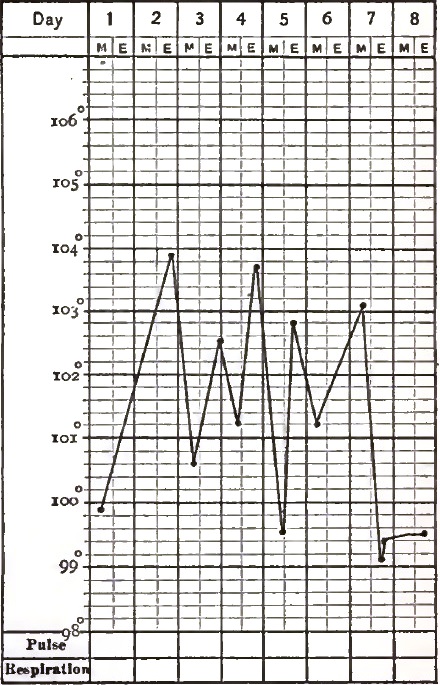

| 37. | A TYPICAL CASE OF SENILE LOBAR PNEUMONIA |

| 38. | CROUPOUS PNEUMONIA IN THE ADULT, TERMINATION OF, IN PURULENT INFILTRATION |

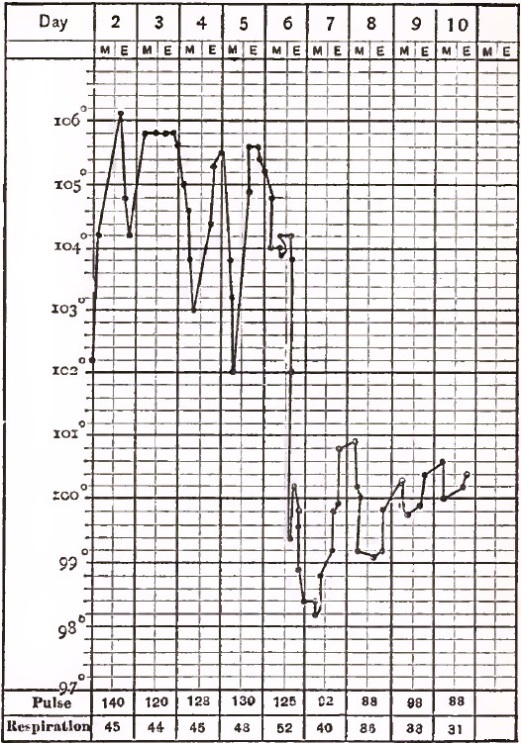

| 39. | ACUTE LOBAR (CROUPOUS) PNEUMONIA IN A CHILD: RECOVERY |

| 40. | ACUTE LOBULAR (CATARRHAL) PNEUMONIA IN A CHILD: RECOVERY |

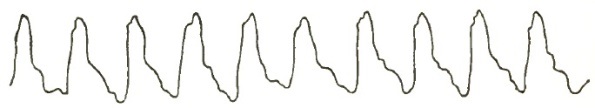

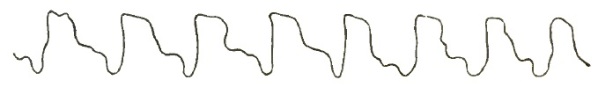

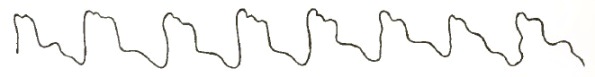

| 41. | SPHYGMOGRAPHIC TRACING OF AORTIC OBSTRUCTION (AFTER FOSTER) |

| 42. | SPHYGMOGRAPHIC TRACING OF AORTIC REGURGITATION |

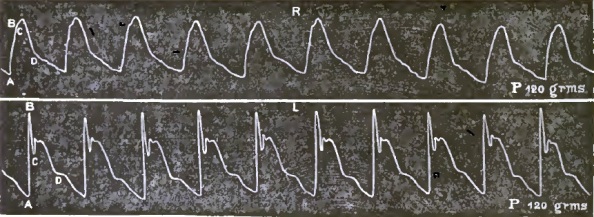

| 43. | SPHYGMOGRAPHIC TRACING OF AORTIC OBSTRUCTION AND REGURGITATION |

| 44. | SPHYGMOGRAPHIC TRACING OF MITRAL OBSTRUCTION |

| 45. | SPHYGMOGRAPHIC TRACING OF MITRAL AND AORTIC OBSTRUCTION AND REGURGITATION |

| 46. | SPHYGMOGRAPHIC TRACING OF MITRAL REGURGITATION |

| 47. | SPHYGMOGRAPHIC TRACING OF MITRAL AND AORTIC REGURGITATION |

| 48. | SPHYGMOGRAPHIC TRACING OF TRICUSPID REGURGITATION |

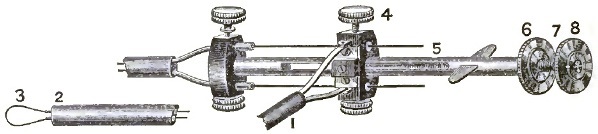

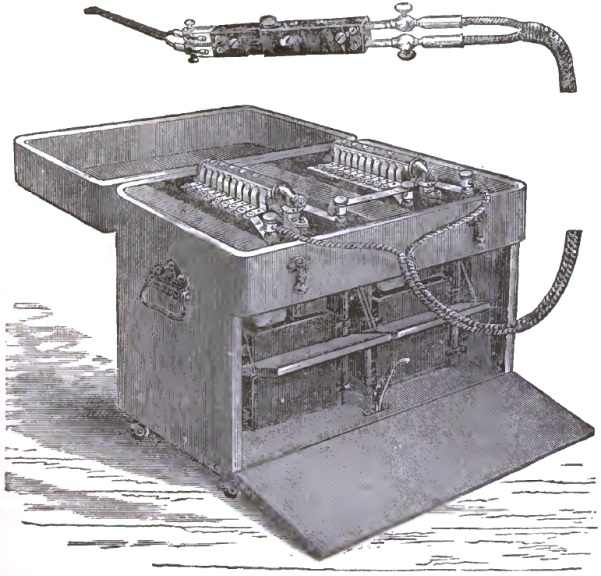

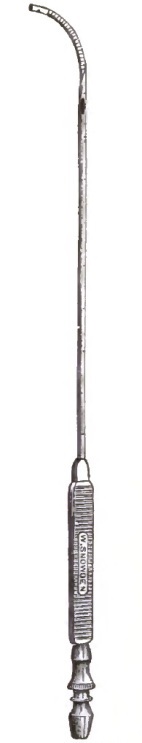

| 49. | ROBERTS'S PERICARDIAL ASPIRATING TROCAR |

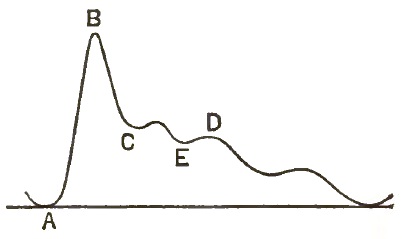

| 50. | SPHYGMOGRAPHIC TRACING OF NORMAL PULSE |

| 51. | SPHYGMOGRAPHIC TRACING OF RIGHT AND LEFT RADIAL PULSE IN ANEURISM OF THE AORTA |

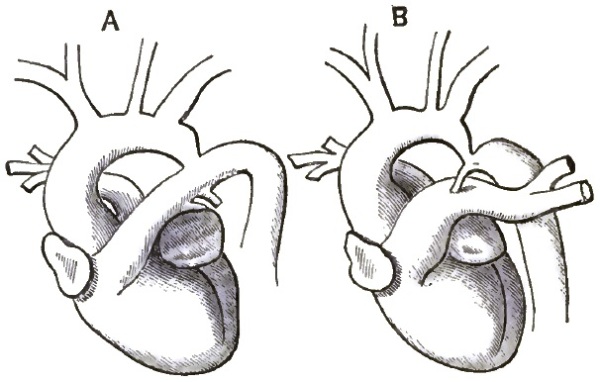

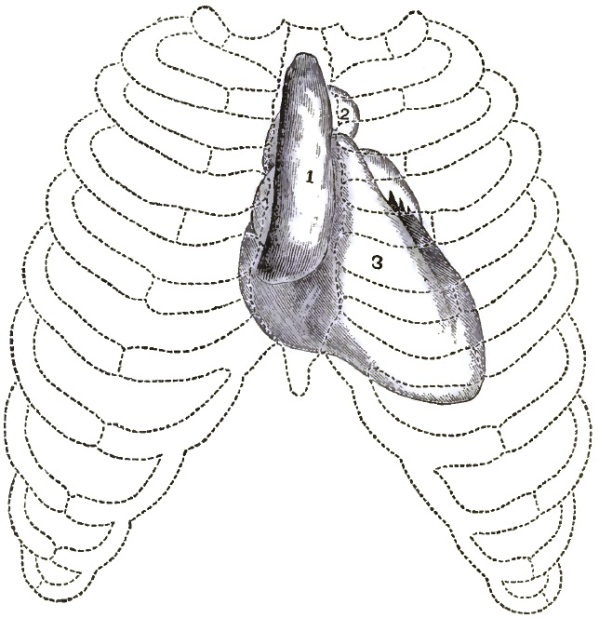

| 52. | ARCH OF AORTA DURING EARLY FOETAL LIFE |

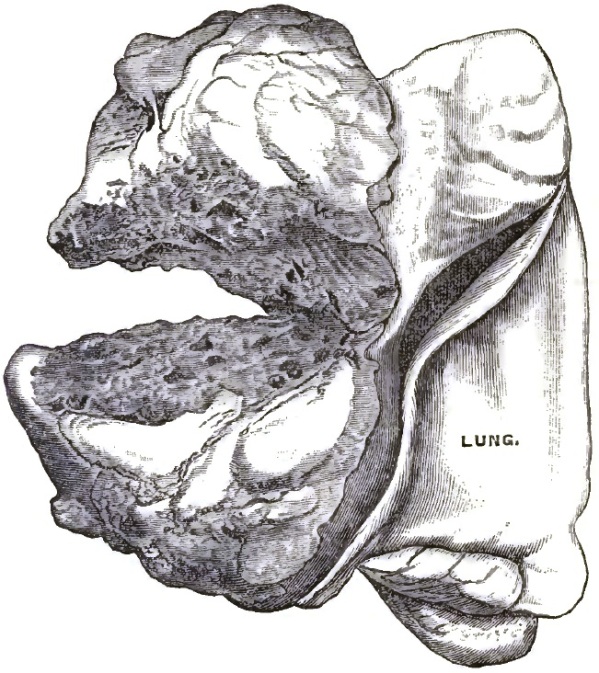

| 53. | SARCOMATOUS TUMOR OF ANTERIOR MEDIASTINUM |

| 54. | SECONDARY MYELOID SARCOMA OF MEDIASTINUM |

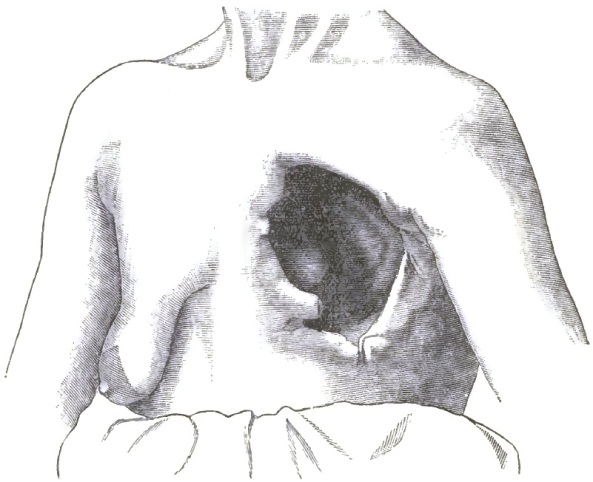

| 55. | RESECTION OF STERNUM FOR REMOVAL OF ENCHONDROMA |

The laryngoscope is a combination of instruments designed for the examination of the interior of the larynx and upper part of the trachea, while the rhinoscope is a similar combination of instruments designed to explore the posterior nasal cavity; and both are comparatively recent inventions.

HISTORY OF THE LARYNGOSCOPE.—In medical literature before the middle of the eighteenth century no mention is made of an instrument or apparatus resembling the laryngoscope, but recent excavations at Pompeii have brought to light small polished metal mirrors attached to slender handles which are supposed to have been used to inspect the cavities of the human body. The first authenticated attempt at laryngoscopy and rhinoscopy was made by the distinguished French accoucheur M. Levret in the year 1743, who invented, among other surgical instruments, an apparatus by means of which polypoid growths in the cavities of the nose, throat, ear, etc. could be seen, and a ligature be passed around them for their removal.1 This apparatus consisted mainly of a polished metal mirror which "reflected the luminous rays in the direction of the tumor," and on whose surface the image of the growth was seen to be reflected. The great value of this apparatus for the diagnosis and treatment of nasal and laryngeal diseases was, however, not recognized, and it shared the fate of many other valuable discoveries which were made before the world was ready to receive them: it was forgotten.

1 Mercure de France, 1743, p. 2434.

In 1807 a certain Dr. Bozzini, living in Frankfort-on-the-Main, published a work describing an apparatus which he had invented for the illumination and examination of the cavities of the human body.2 This apparatus consisted of a peculiarly-shaped lamp and of a number of metal tubes, polished on their inner surface, of various shapes and sizes adapted for the different cavities of the body. The one intended for the examination of the larynx was bent near its end at a right angle, and had a mirror placed at the bend, which served to throw the light downward toward the opening of the larynx when the tube was inserted into the mouth. When reflected light was to be used, the interior of the tube or speculum was divided into two portions by a longitudinal septum, and two mirrors were inserted at the bend—one for the reflection of the light downward, and the other for receiving the reflected image. This invention of Bozzini was treated, however, with derision by the medical profession, probably on account of the extravagant descriptions given of it in the papers, which were not verified by its performances.

2 "Der Lichtleiter," Philipp Bozzini, Med. und Chir. Dr., Weimar, 1807.

In 1825, Cagniard de Latour, an investigator of the physiology of the voice, made some unsuccessful attempts to examine the living larynx.3

3 Physiologie de la Voix, par Ed. Tournié, Paris, 1865.

[p. 20] Senn of Geneva in 1827 endeavored to examine the larynx of a little girl suffering from an affection of the throat by means of a small mirror which he had made and which he inserted into the pharynx, but he failed to see the glottis, because, as he says, the mirror was too small, and because he used neither direct nor reflected light to illuminate the cavity below the mirror.4

4 Journal de Progrès des Sciences, etc., 1829.

In the year 1829, Benjamin Guy Babington published5 an account of what he called the glottiscope, an apparatus which consisted mainly of two mirrors. One of these was small and attached to a slender stem, and was used to receive the image, while the other, an ordinary hand-glass, was used to reflect the rays of the sun or ordinary daylight upon the smaller mirror in the fauces. This combination was essentially the same as is used at the present day in the laryngoscope, with the difference that we now use artificial light in most instances, and a concave mirror instead of a plane one for reflecting the light.

5 Lond. Med. Gazette, 1829, vol. iii.

While Babington was still engaged in perfecting his instruments, a mechanic named Selligue, who suffered from an affection of the throat, in 1832 invented a speculum for his physician, Bennati of Paris, with which the latter was able, as he asserted,6 to see the vocal cords. This instrument was similar to the one invented by Bozzini, and consisted of a double speculum bent at right angles and carrying two mirrors—one for illuminating the cavity, and the other for reflecting the image. Selligue was rewarded for his efforts by a complete cure of his affection.

6 Recherches sur le Mécanisme de la Voix humane.

A number of others worked in the same direction, and endeavored to see the interior of the larynx in the living subject by employing different apparatus and methods of illumination. Thus, in 1838, Baumès of Lyons described a mirror the size of a two-franc piece (11/8 inches in diameter) as useful in examining the larynx and posterior nares.7 Then Liston in 1840 used a dentist's mirror,8 and Warden of Edinburgh employed a prism of flint glass attached to a long stem as a laryngeal mirror.9 In the latter part of the same year Avery of London employed a speculum with a mirror in its end for examining the larynx, using as an illuminator a concave reflector with a central opening, which was supported by a frame to be worn on the head of the operator.10

7 Compte Rendu des Travaux de la Société de Médecine de Lyons, 1836–38.

8 Practical Surgery, 1840.

9 Lond. Med. Gazette, vol. xxiv. p. 256.

10 Med. Circ., June, 1862.

Up to this time all efforts at laryngoscopy had been made with a view to diagnose diseases of the larynx, with the exception of those made by Latour. In the year 1854, however, Signor Manuel Garcia of London, without any knowledge of previous efforts, conceived the idea of studying the changes in the larynx during phonation in his own throat. For this purpose he placed a small dentist's mirror against the uvula and reflected the rays of the sun into his mouth and upon the small mirror by means of a hand-glass held in the other hand. By arranging his position in relation to the sun in such a manner that he could see the reflected image of the small mirror in his throat in the hand-glass, and in it the illuminated image of his larynx, after a few ineffectual attempts his efforts at auto-laryngoscopy were crowned with such success that he was enabled to study the movements of the vocal cords during phonation, and accurately describe the registers of the voice in a paper read before the Royal Society of London in 1855.11 Although Garcia was the first who practised laryngoscopy successfully, his communication to the Royal Society attracted little attention, and would have been forgotten if it had not been that, in 1857, Tuerk of Vienna, having heard of Garcia's paper, began to use the laryngeal mirror on the patients in the K. K. Algem. Krankenhaus for [p. 21] diagnostic purposes.12 At first he was not very successful in his attempts, and began to experiment with laryngeal mirrors of different sizes and shapes. While thus engaged Czermak borrowed Tuerk's mirrors, and modified them until he succeeded in the greater number of cases in seeing the vocal cords,13 using artificial light for illuminating the larynx. Meanwhile, Tuerk continued his experiments, and also succeeded in almost all cases of throat disease which came to his department of the hospital in seeing the interior of the larynx and in treating the lesions. Both Tuerk and Czermak improved their apparatus, and especially the latter, who by substituting artificial light for sunlight, and by inventing a number of different illuminating apparatuses, has given us the laryngoscope in the form in which it is used at the present day. It is but natural that Tuerk should have claimed priority in the successful use of this instrument, and in consequence of this claim a controversy was carried on for a number of years in the medical press between him and Czermak, which at times became quite spirited, but which left Czermak master of the field. In the winter of 1858–59, Madam E. Seiler, having heard of Czermak's experiments, had a laryngeal mirror constructed from his description, practised laryngoscopy successfully on herself and others, among them the writer, with a view to study the physiology of the voice. Her efforts being crowned with success, she was able not only to verify Garcia's observations in regard to the registers, but also discovered the so-called head register of the female voice, as well as two small cartilages in the vocal cords.14

11 Proc. Royal Society of London, vol. vii. No. 13, 1855.

12 Zeitschrift der Ges. der Aerzte zu Wien, April, 1858.

13 Wien. Medicin. Wochenschrift, March, 1858.

14 Altes und Neues, Leipzig, 1861.

HISTORY OF THE RHINOSCOPE.—Rhinoscopy, or the art of viewing the naso-pharyngeal space by placing a small mirror behind the velum palati, naturally suggested itself almost as soon as any attempts at laryngoscopy were made, but in the literature we find that Bozzini was the first to clearly express the idea.15

15 Loc. cit.

A number of years later Wilde endeavored to see the opening of the Eustachian tubes by means of a small mirror: an account of these experiments he published in his famous work on the diseases of the ear.

In 1836, Baumès used the rhinoscope, and claimed to have seen ulcerations in the naso-pharyngeal cavity.16 It remained, however, for modern times to develop this field of research, and it is again Czermak whom we have to thank for the perfection of this valuable means of diagnosis.

16 Loc. cit.

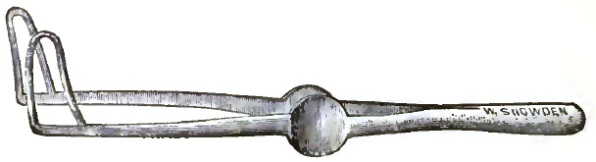

THE LARYNGOSCOPE.—The laryngoscope as it is used at the present day, both by the specialist and the general practitioner of medicine, consists of a so-called laryngeal mirror and of an illuminating apparatus more or less complicated. The laryngeal mirror is a small circular glass mirror mounted in a metal frame varying in size from ¾ inch to 1½ inches in diameter, and attached to a wire stem at an angle of 120°. This stem, about 4 inches in length and about 1/10 inch in thickness, should be soldered to the back of the mirror in such a manner that the rim of the frame forms the angle with the stem, and should not be below it, as this would increase the diameter of the instrument without increasing its reflecting surface. The stem is made to slide into a hollow handle of wood, ivory, or ebonite, and is clamped at any desired length by a set-screw. This arrangement is preferable to having the stem permanently fixed in the handle, inasmuch as the stem can be pushed entirely into it, thus economizing space and rendering the instrument more portable, and also allowing an adjustment of the length of the stem when in use. The handle should be 4 inches in length, and of the thickness of an ordinary lead-pencil (Fig. 1).

| FIG. 1. |

|

| Laryngeal Mirror. |

Mirrors of various shapes have been used, but it has been found that the circular form is the one most easily borne by the patient, and can be used in [p. 22]a greater number of cases than any other shape, at the same time giving the largest reflecting surface for its size. However, in cases where an hypertrophy of the tonsils is present an oval mirror can be introduced between the protruding glands more easily than a round one.

This laryngeal mirror, however, would be of little or no value as an instrument of diagnosis if used by itself, for in order to see the cavity of the larynx it must be illuminated, lying as it does far below the level of the back of the tongue; and this cannot be done satisfactorily by merely allowing ordinary daylight to fall into the oral cavity. It becomes, therefore, necessary to use a stronger light to illuminate the larynx, and for this purpose either direct or reflected artificial or sunlight may be used.

Direct illumination, by allowing a strong artificial light or sunlight to fall into the patient's mouth, although it is used by several of the eminent laryngologists of Europe, is both inconvenient and unsatisfactory, because the observer must either place his head in the path of the light in order to be able to see the surface of the laryngeal mirror, as in the case when sunlight is used, or he must place the lamp, candle, or other source of light between himself and the patient, which materially interferes with the freedom of his motions. For these reasons reflected light is now almost universally employed in laryngoscopy.

Reflected light may be obtained by throwing the light of a lamp, candle, gas-jet, or light from any other source into the mouth of the patient by means of a round concave reflector. This concave mirror—which, when made of glass, should be silvered and not backed with amalgam—is from 3 to 4 inches in diameter, and should have a focus of from 12 to 14 inches. The metal frame in which it is mounted is attached by means of a ball-and-socket joint to some contrivance by which it can be supported on the observer's head or be attached to the source of illumination if a stationary artificial light, such as a gas-lamp, is used at the physician's office.

A variety of devices for fastening the reflector on the head of the observer is in use, among which the head band, introduced by Cramer, will be found the most serviceable. It consists of a broad strap of some strong material which passes around the head and is fastened at the back by a buckle. To the part of the band or strap resting on the forehead is attached a padded plate, to which the reflector is fastened with its ball-and-socket joint (Fig. 2). The reflector usually either has a small hole in the centre or a small space in the centre is left unsilvered. This opening is intended to be brought before the pupil of one or the other eye of the observer in such a manner that the line of vision and that of light have exactly the same direction. Using the reflector in this way like the reflector of the ophthalmoscope, it is easier to obtain the image of the larynx well illuminated, but with the great disadvantage of [p. 23]monocular vision, which makes all objects appear on the same plane and prevents a correct interpretation of distances—a very important point in laryngoscopy. It will therefore be found more advantageous to place the reflector on the forehead, and from thence reflect the light into the patient's larynx. Both eyes may thus be employed in viewing the laryngeal image, and a correct idea of the relations of parts in regard to distance may be formed.

| FIG. 2. |

|

| Head Reflector. |

The line of vision and the path of the beam of light in order to obtain the best results should be in the same plane as though the light emanated from the pupil of the observer; but practically the position of the reflector upon the forehead is nearly as good as when the hole in it is brought before the eye, because a line drawn from the pupil of the eye to the laryngeal mirror, and a line from the reflector upon the forehead to the mirror, do not form an angle sufficient to make any very great difference in the reflection of the light downward, and very little difficulty will be experienced in obtaining the desired image.

The head reflector should be concave when artificial light or ordinary daylight is used, but be plane when direct sunlight is employed, for the concentration of the sun's rays by a concave reflector produces so much heat as to become painful to the patient.

THE SOURCE OF LIGHT.—As an artificial source of light a candle, coal oil lamp, gas-flame, or incandescent electric lamp suffices for ordinary purposes. But frequently it is desirable to have a much stronger light than can be obtained without concentration, and several forms of apparatus for concentrating artificial light have been constructed and are in use. Among these, Tobold's lamp and Mackenzie's light concentrator are the most convenient and most universally used.

Tobold's lamp consists of a brass tube containing several lenses, which are placed, one before the other, at such distances as to give the greatest possible amount of concentration of light. The back part of the tube is closed, while near the end two large holes are cut in its sides opposite to each other, through which the chimney of the lamp projects. The whole is fastened by means of clamps to a stand, to which is also attached a jointed arm bearing the reflector. This apparatus is used either in connection with a student's lamp or with an argand gas-lamp, and it will be found very convenient to have it mounted upon a gas-bracket which can be raised and lowered and swung from side to side.

Mackenzie's light concentrator consists of a cylinder of sheet iron about 6 inches long by 2½ in diameter. Near one end a hole is cut in the side of the cylinder, and a short piece of tube holding a condensing lens is attached to the edge of the hole. This lens, which is plano-convex with a spherical curve, and of 2½ inches diameter, is placed with the plane side toward the light. [p. 24]This concentrator is intended to be slipped over the chimney of an argand burner, and should be so adjusted that the centre of the flame corresponds with the centre of the lens. It may, however, be used in connection with a student's lamp, incandescent electric lamp, or even a candle, giving in all cases a very satisfactory light, which, however, must be reflected from the head mirror into the patient's mouth.

The best light, however, when the examinations are conducted in the office of the physician, is the electric incandescent light, which presents numerous advantages over the gas or oil lamp. It is more brilliant and whiter than any other suitable artificial light, giving off neither gases nor heat, nor does it consume the oxygen in the room; and since the introduction and perfection of storage batteries it has become available and convenient for use in private houses. Numerous experiments which the author has carried on for some time have resulted in the application of this form of light for laryngoscopy in two ways which are both very satisfactory. The incandescent lamp is mounted upon the universal gas-bracket in place of the argand burner, and either the Tobold lamp or Mackenzie's light concentrator is slipped over it, so that it comes opposite the centre of the lens. In fact, the electric lamp is substituted for the gas-burner, and the whole apparatus is used as described above. The arc light may also be used in the same manner, but does not give as satisfactory results on account of its unsteadiness.

| FIG. 3. |

|

| The Author's Electric Illuminator for the Laryngoscope. |

The second method is to mount the electric lamp on the head mirror in such a way that it projects a little from the surface and is a little to one side of the centre of the reflector (Fig. 3). The light is then thrown forward in a cone, and can be directed with great ease into the mouth of the patient. Since thus the source of the light moves with the mirror, the observer can follow the motions of the patient more easily; and if, in the first place, an easy position of the head has been assumed when adjusting the light, much less [p. 25]fatigue is experienced by the examiner with this apparatus than when the light is reflected from a stationary source. Still another mode of using the incandescent lamp, which was suggested by Trouvé, is to mount the lamp within a tube one end of which is closed by a plano-convex lense, while the other end is covered by a metal cap carrying in its centre a ball-and-socket joint, by means of which it is fastened to the frontal plate of the head band. In this way the light with its condensing apparatus is carried on the forehead like the head mirror.

Sunlight is certainly the best source of light for the illumination of the interior of the larynx and nasal cavities, but, unfortunately, it is not available at all times and in all localities. When it can be obtained, however, the student should not neglect the opportunity, and should not be deterred from using it for examination by the little extra apparatus and trouble necessary.

The most convenient plan is to place a small plane mirror mounted upon a stand in such a manner that it can be turned in any direction, such as a small toilet-glass, in the direct rays of the sun coming through a southern window. Then turn the mirror until the reflection falls upon a second plane mirror supported by a jointed arm and placed in a distant corner of the room, and in front of the chair upon which the patient is seated, with his back to the first mirror. The light from the second mirror is then thrown into the patient's mouth in the same manner as when a light concentrator is used. The second mirror may also be mounted on the head band and used as a head reflector, but this latter plan is not as satisfactory, because the reflected light from the first mirror is apt to strike the observer's eye and temporarily blind him.

Sunlight, as well as the light from the oxyhydrogen and electric-arc lamps, is white, and therefore shows us the parts in their natural coloring, which is claimed as a great advantage over all other sources of light. It is true that the yellow rays which are predominant in all other artificial lights make the mucous membrane appear redder than it really is, and the observer may be led to believe that a congestion exists if the patient be examined by white light first, and then by yellow light on different occasions. But as all our knowledge and appreciation of shades of color depend upon a comparison with a standard, it makes no difference whether this standard, as in the case before us, is a little redder when viewed by yellow light or not so red when seen by white light. This advantage of the white light is, therefore, not of much practical value, and the expense and difficulties connected with the use of the oxyhydrogen or electric arc-light for laryngoscopy fully outweigh any advantage which can be claimed for it.

THE ART OF LARYNGOSCOPY.—Before entering upon a description of the details of the art it will be necessary to clearly understand the optical principle upon which the use of the laryngoscope is based, and, further, to remember that the object to be viewed is situated below the straight path of light and vision. The optical law referred to is, that "The angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection," and consequently, in order to illuminate the cavity of the larynx and to see its details, the laryngeal mirror must be placed in such a position in the fauces that the light is reflected downward. The light rays forming the laryngeal image will then be reflected from the surface of the laryngeal mirror into the eye of the observer. It should always be borne in mind that the image seen in the mirror is a reflected one, like the image of one's self seen in a looking-glass, so that what appears to be right is left, and vice versâ. On account of the difference in height of the parts forming the image, and because the mirror must be placed above and slightly behind the opening of the larynx, the picture appears reversed in an antero-posterior direction. The same holds good when viewing a drawing of a laryngeal image.

[p. 26]POSITION OF PATIENT AND OBSERVER.—The relative positions of the patient, observer, and the source of light are of very great importance, especially to the beginner, and a want of proper adjustment will often make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to obtain the desired view of the larynx. The patient having been seated upon a chair, or better still upon a piano-stool, the source of light is placed upon a table at his right, at such a height that the centre of the flame is on a level with his eyes and a few inches behind. The observer then takes a seat directly in front of the patient, and, separating his knees, places his feet on either side of those of the patient, thus being able to grasp the patient's knees with his own should occasion require him to do so. This position is preferable to the one in which the knees of the observer are either on one side or the other of the patient's knees, because then the observer, in order to throw the light from the head mirror into the mouth of the patient, has to assume a constrained position which very soon becomes fatiguing. Under no circumstances should the patient be allowed to grasp the observer's knees, for then the latter is powerless to restrain the struggles of his patient, and cannot quickly leave his seat should vomiting occur. When the examination is made at the physician's office or wherever it is practicable, it is of advantage to have a head-rest, such as photographers use, for the patient's head.

The positions having been taken, the observer places the head reflector upon his forehead a little above the left eye, and by rotating it upon its ball-and-socket joint reflects the light from the lamp- or gas-flame upon the patient's face so that the circle of light is bounded above by the tip of the nose and below by the tip of the chin. It is of great importance that the adjustment of the reflector should be made by means of its joint, and not by rotating or inclining the head, for it is necessary that the head should have an easy position which can quickly be resumed should it become necessary to move the head. It requires considerable practice to quickly reflect the light from the head mirror in any desired direction, and it is therefore well for the beginner to practise this by throwing the light upon a spot on the wall before he attempts to examine a patient, as he will thus save himself, as well as the patient, unnecessary annoyance. If a light concentrator be used which supports the reflector on the jointed arm, this of course is not necessary, but the practice with the head mirror will even then be found advantageous, because when a patient is to be examined in the sick room a light concentrator cannot usually be employed, and the physician has to fall back upon the head mirror for illuminating the laryngeal cavity.

When the reflector has thus been properly adjusted the patient is required to incline his head backward and open his mouth as wide as possible, when it will be found that the centre of the circle of light falls upon the root of the uvula. A careful examination of the oral cavity, the anterior and posterior pillars, the tonsils, and the wall of the pharynx should be made before the laryngeal mirror is introduced, not only because the condition of these parts often imparts valuable information, but also in order to be sure that no infectious sores be present which might contaminate the instruments to be introduced. The laryngologist cannot be too careful to prevent the carrying of infectious material from one patient to another; and if he should by this preliminary examination discover a specific sore, he should use only such instruments as are reserved for this class of cases, and which are kept in a separate box or drawer of the instrument-case.

Everything being in readiness, the laryngeal mirror is held over the lamp, with the glass side down, for a few seconds until it is warm, so as to prevent the condensation of moisture on its reflecting surface, and is then introduced in the following manner: The handle is held between the thumb and fore finger of the right hand like a pen-holder (Fig. 4); the hand is bent [p. 27]backward upon the wrist and held below the chin of the patient. Meanwhile, the protruded tongue is grasped between the folds of a napkin or towel held in the left hand, and gently but firmly pulled out of the mouth. Great care should be exercised to prevent the frænum of the tongue from coming in contact with the sharp edge of the front teeth, for this soon becomes very painful and may prevent a successful examination. Many laryngologists are in the habit of letting the patient hold his tongue, which becomes necessary when operations or applications are to be made to the larynx; but for the purpose of examining only it is better for the observer to hold the tongue, as he thus gains more control over the movements of the head of the patient.

| FIG. 4. |

|

| Position of Hand in holding the Laryngeal Mirror. |

The mirror is now rapidly introduced into the mouth of the patient, without touching the tongue or the palate, and carried backward until its rim touches the wall of the pharynx, when it is lifted upward, carrying on its back the uvula, and the stem is brought into the angle of the mouth, so as to be out of the line of vision (Fig. 5). In this position the light of the reflector will fall upon the reflecting surface of the laryngeal mirror, and will be reflected downward so as to illuminate the laryngeal cavity and reflect the laryngeal image into the eye of the observer.

| FIG. 5. |

|

| Diagram of Section of Head, showing the Position of Laryngeal Mirror in the Pharynx. |

[p. 28]There are, however, numerous obstacles and difficulties which must be overcome to successfully practise laryngoscopy—obstacles which are partly due to the want of skill on the part of the operator, and partly to over-sensitiveness and want of control of the patient, or, finally, to abnormal positions of the parts. Taking them up one by one, in the order named above, the reader will soon learn to overcome these obstacles by practice and careful attention to details.

As has already been pointed out, a satisfactory view of the laryngeal image cannot be obtained if the position of the light, of the patient's head, and of the observer is not properly arranged; further, if the laryngeal mirror is either too cold or too hot. In the former case the moisture of the breath will condense on its reflecting surface and render it non-reflecting, and in the latter case the patient will feel the heat and will object to the presence of the mirror in the fauces. The examiner should therefore carefully test the temperature of the mirror on the back of his hand before introducing it. Many laryngologists are in the habit of testing the temperature by placing the mirror against the cheek, but this is a dangerous practice, for a slight scratch or abrasion of the skin from shaving may be inoculated with infectious material from a specific sore, and the writer knows of more than one instance in which such infection has occurred; while a scratch on the hand is not so likely to be overlooked, and therefore the danger is much less. Pulling too hard upon the tongue, so that the frænum becomes injured by the edge of the teeth, is another obstacle, for the patient will not bear the pain thus occasioned. Touching the tongue or palate in the act of introducing the mirror, besides coating the reflecting surface with the secretions of the mouth, causes in most patients gagging, and should therefore be avoided. When the mirror has been introduced it should be held very still, and if it becomes necessary to rotate it, this should be done slowly and steadily, because the slightest trembling motion of the rim of the mirror resting against the wall of the pharynx produces gagging and cuts the examination short at once. It is therefore advisable to steady the hand holding the mirror by placing the third finger against the cheek of the patient, or, better still, against the thumb of the hand holding the tongue.

Undue irritability of the fauces is of very rare occurrence, and is almost invariably produced by one or the other of the above-mentioned mistakes of the examiner. When it does exist independently, it can in a measure be overcome by letting the patient drink a large draught of ice-water immediately before introducing the mirror, and by holding the mirror so that it does not touch either the pharyngeal wall or the palate. In this manner but a very unsatisfactory view of the larynx can be obtained, and it is better to overcome the irritability by practice on the part of the patient—i.e. by introducing the mirror frequently and removing it before gagging sets in, and by directing the patient to introduce a teaspoon into the fauces before a looking-glass several times a day. Even the most obstinate cases can thus be educated to allow of a lengthy examination. No matter how tolerant a patient may be, however, the mirror should never be left in the fauces after the first symptoms of gagging show themselves, but should at once be removed. It is better in all cases to leave the mirror in the mouth but a short time and to introduce it frequently, thus studying the different parts of the image one after the other, than to attempt to see everything at once. In laryngoscopy, as in many other arts, not only the hand, but also the eye, must be educated to appreciate all the details and the variations from the normal.

Among the malformations of the parts which present obstacles to laryngoscopy are, in the first place, hypertrophied tonsils, which by narrowing the space in the fauces make it impossible to introduce the ordinary-sized mirror. A smaller mirror or one of oval shape can, however, usually be slipped past the [p. 29]enlarged glands and the desired image obtained. An elongated uvula does not exactly prevent a view of the larynx, but it materially interferes with a good image, because its end by hanging below the rim of the mirror is seen in the reflecting surface and obscures part of the image. Removal of the uvula by surgical means is of course the best remedy.

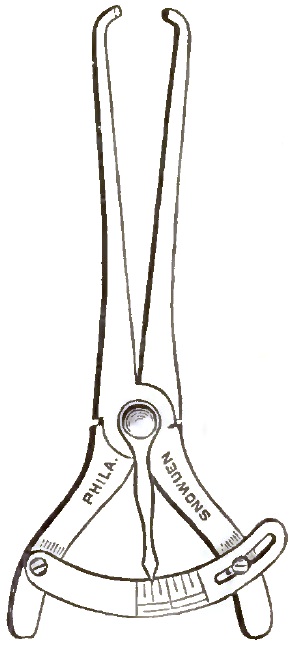

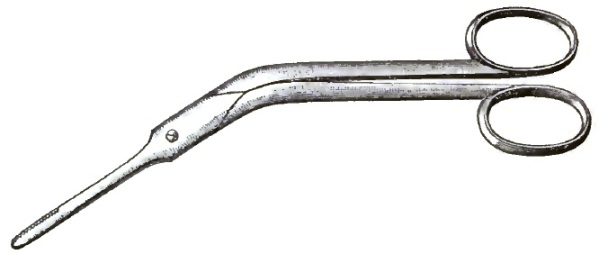

The third and most serious obstacle presented by malformation or malposition of parts is a pendent epiglottis—i.e. an epiglottis which by being bent too far over covers the laryngeal opening and prevents a view. This obstacle exists to a certain extent in most cases that come under observation, but is easily overcome by letting the patient sound the vowel sound of eh, which causes a rising of the epiglottis and opens the laryngeal cavity to view. There are some cases, however, in which this expedient does not sufficiently raise the epiglottis to obtain a glimpse of the vocal cords, and only the arytenoid cartilages are seen, from the motion and color of which we can often obtain valuable information in regard to pathological processes. In these cases, when it becomes absolutely necessary to see the whole extent of the vocal cords, we may succeed by causing the patient to laugh in a high key, but when this fails the only resource left is to lift the epiglottis by grasping its upper margin with a pair of curved forceps especially designed for this purpose and called epiglottis forceps (Fig. 6). If this instrument is not at hand, the same object may be attained by clasping the edge of the epiglottis with a bull-nose forceps, to which is fastened a string weighted at the other end by a small weight, such as a rifle-bullet. The string with its weight hanging out of the mouth of the patient makes traction upon the forceps, and thus the epiglottis is raised. In cases of operation within the laryngeal cavity this method of raising the epiglottis is even preferable to the epiglottis forceps, because it leaves the hands of the operator free to use the mirror and the instrument to be used in operating.

| FIG. 6. |

|

| Elsberg's Sponge-holder and Epiglottis Forceps. |

AUTO-LARYNGOSCOPY.—There is perhaps no better method for the beginner to overcome the difficulties besetting laryngoscopy than to practise the art on himself, for then only will he be able to appreciate to its full extent the necessity of observing all the minute details described above, as the pain and inconvenience which he inflicts upon himself by his false movements will teach him better, and enable him to attain proficiency in the use of his instruments quicker than any other method of practice. Nothing need, for auto-laryngoscopy, be added to the stock of instruments necessary for the examination of others, except a stand to which the reflector is fastened and a small toilet-mirror. The observer seats himself beside a table upon which, at his left, is placed the lamp a little behind his head and the centre of the flame on a level with his eyes. The stand, an ordinary retort-stand, is placed in front of him, and to it is fastened at the proper height the reflector. On the same stand, and immediately above the reflector, is attached the plane mirror in such a manner that it can be inclined at an angle. Inclining the head slightly backward, the observer then by watching his face in the plane mirror directs the light upon his mouth by moving the reflector upon its ball-and-socket joint until the circle falls upon his mouth. He then opens his mouth as wide as possible, grasps his protruded tongue between the folds of a towel or [p. 30]napkin held between the thumb and fore finger of the left hand, and introduces the laryngeal mirror with the right hand in the manner described above. The laryngeal image as it appears on the surface of the laryngeal mirror is reflected by the toilet-glass above the reflector, and can be seen in all its details by the person practising auto-laryngoscopy. By substituting a perforated mirror for the toilet-glass the student can demonstrate the image to others in his own person if the observers look through the perforation in the mirror.

Before giving a description of the laryngeal image it will be well, for the sake of completeness, to mention the fact that of late photography has been employed to reproduce this image, both in this country by T. R. French of Brooklyn17 and by Lennox Browne of London, England, with very gratifying results. The writer himself several years ago made experiments in this direction, which, however, were not very satisfactory in their results. The method employed by French is a very simple one, and it will be best to give his own description of the process:

"The camera consists of a box 4½ inches long, 17/8 inches wide, and ¾ of an inch in thickness. The back opens upon hinges, and admits of the introduction of either the ground glass or the plate-holder. On the anterior face a tube 11/8 inches long is attached, in the outer end of which the lens is placed. This lens has a focus of 1¼ inches. At the side of the tube a part of the handle of a throat mirror is fixed, and into that the shank of the throat mirror is passed and fastened by a thumb-screw. The shank of the mirror is somewhat curved, and is attached to the side of the frame holding the mirror. The object of this is to allow the lens being held opposite any part of the opening of the mouth, and also to prevent the possibility of a shadow being cast upon the mirror. In the front part of the box is a shutter made of lead and perforated with a hole just the size of the lens. The shutter is held in position by a lever acting as a key on the anterior face of the camera.

"The apparatus is used in the following manner: A reflector, either plane or concave, attached to a head band, is arranged over the left eye so that the pencil of sunlight from the solar condenser is received upon it and thrown into the mouth. The patient, with the head inclined slightly backward, now protrudes the tongue and holds it well out between the fore finger and thumb of the right hand. The throat mirror with the camera attached, held in the right hand of the observer, is placed in position in the fauces, and the light adjusted so that the larynx can be seen with the observer's left eye to be well illuminated. If, now, the tongue does not mount above the level of the lower edge of the lens and the lower edge of the mirror, it may be taken for granted that when the plate is exposed the picture received upon it will be nearly the same as that seen with the left eye in the throat mirror. The photograph is taken by pressing upon the key with the index finger; this releases the shutter, which in falling makes an instantaneous exposure amounting to perhaps one-seventh of a second.

"In using condensed sunlight with a small camera it is important to throw the circle of light from the inner side of the reflector, that nearest the nose; for in this way a part of the larynx exposed to the lens of the camera may be illuminated which cannot be seen with the eye. To ensure this it is best to cover the outer half of the reflector with black silk. On account of the parallax or displacement of the image due to the difference in point of view between the eye and the camera, some skill is necessary in managing the illumination so that the part which it is desired to bring out will be exposed to the lens if not to the eye."

17 Archives of Laryngology, vol. iv. No. 4.

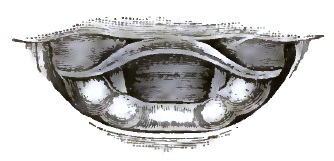

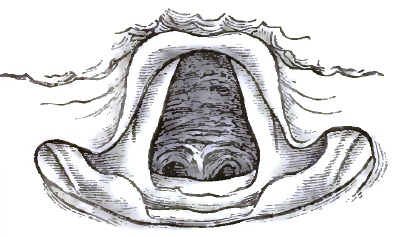

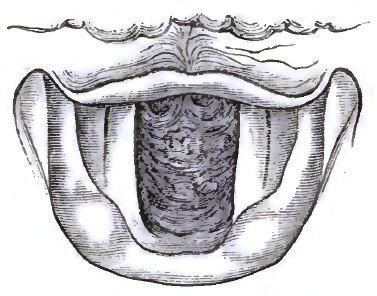

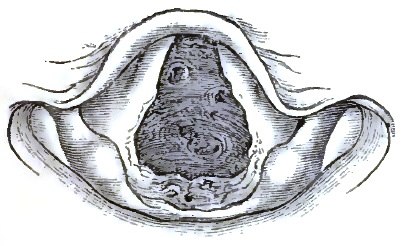

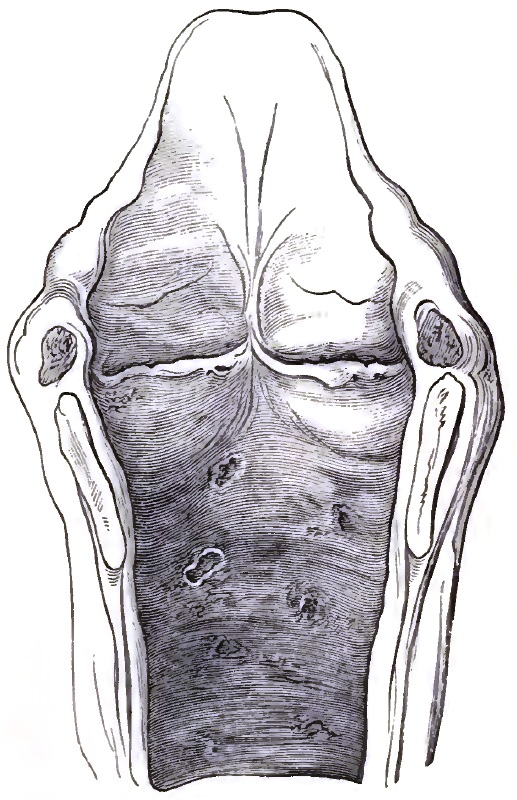

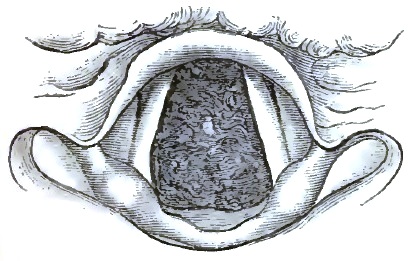

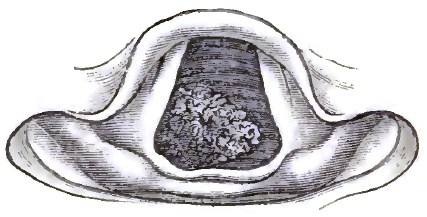

THE LARYNGEAL IMAGE.—When the mirror is introduced and is held in the proper place, and the light is reflected downward, the laryngeal image [p. 31] will appear on the surface of the mirror. As it is, however, so different from what might be expected after having examined a larynx removed from the body, it requires a detailed description, and the student will do well to refer to the diagrams frequently while examining patients, to make himself familiar with the details he sees, and to recognize them when they are altered by disease or when they are slightly different in shape in different individuals. Figs. 7 and 8 represent the image of the larynx in the act of respiration and of phonation as it appears on the surface of the mirror, while Figs. 9 and 10 are diagrammatic, and are intended to represent the same.

| FIG. 7. |

|

| Laryngeal Image during Respiration. |

| FIG. 8. |

|

| Laryngeal Image during Phonation. |

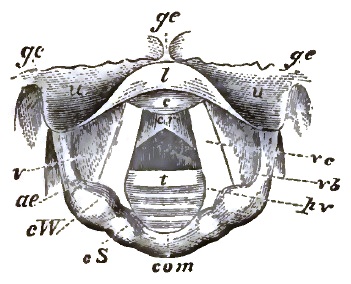

| FIG. 9. |

|

| Laryngoscopic Diagram showing the vocal cords widely drawn apart, and the position of the various parts above and below the glottis during quiet breathing. g. e. Glosso-epiglottic fold. s. u. Upper surface of epiglottis. l. Lip or arch of epiglottis. c. Protuberance of epiglottis. v. Ventricle of the larynx. a. e. Ary-epiglottic fold. c. W. Cartilage of Wrisberg. c. S. Cartilage of Santorini. com. Arytenoid commissure. v. c. Vocal cord. v. b. Ventricular band. p. v. Processus vocalis. c. r. Cricoid cartilage. t. Rings of trachea. (From Mackenzie.) |

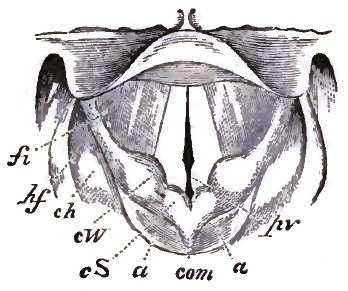

| FIG. 10. |

|

| Laryngoscopic Diagram showing the approximation of the vocal cords and arytenoid cartilages, and the position of the various parts during vocalization. f. i. Fossa innominata. h. f. Hyoid fossa. c. h. Cornu of hyoid bone. c. W. Cartilage of Wrisberg. c. S. Cartilage of Santorini. a. Arytenoid cartilages. com. Arytenoid commissure. p. v. Processus vocalis and cartilages of Seiler. (From Mackenzie.) |

The first detail to attract the eye is the epiglottis, which appears as a yellowish-red arch reaching from side to side across the image. It is thicker in the middle than at either end, and a protuberance is usually seen in the centre pointing forward. This arch is the upper margin of the epiglottis, and the protuberance is the tubercle, situated near the insertion of the epiglottis into the thyroid cartilage. The shape as well as the color of the epiglottis is very variable in different individuals, being sometimes rounded as in the drawings, sometimes rolled up like a dried leaf, sometimes notched in the centre, and sometimes presenting a point at this place. However, all these variations in shape have nothing to do with any pathological process, and may therefore be termed normal. The color of the organ also varies from a bluish-yellow to a pink-red, and these variations are also normal, being due to a greater or less thickness of the tissue covering the cartilage, which by shining through imparts its bluish color to the tissue. The superficial blood-vessels also are more prominent in some individuals than in others, and may not be noticeable in some cases.

[p. 32] Immediately behind the epiglottis we see two pit-like depressions, separated from each other in the middle by a fold of mucous membrane and bounded on either side by similar folds less prominent. These folds are the glosso-epiglottic ligaments, and serve to connect the tongue with the epiglottis, while the depressions are the glosso-epiglottic grooves, in which we usually find the foreign bodies which have accidentally been swallowed.

The ends of the epiglottic arch are lost in folds of mucous membrane, which run forward and inward to meet in the median line some distance in front of the epiglottis. Along their course several nodules of different size are noticed, which are symmetrically situated on either side. The one nearest to the epiglottis is the cartilage of Wrisberg, a small cartilaginous nodule imbedded in the tissue. The larger one, situated at the end of the fold of mucous membrane, is the arytenoid cartilage, and a third small nodule is noticed close to the arytenoid cartilage between it and the cartilage of Wrisberg, which is called the capitulum Santorini. The folds of mucous membrane are termed the aryteno-epiglottidean or ary-epiglottic folds. Their color is normally of a pinkish-red, and does not vary much in different individuals.

The arytenoid cartilages forming the ends of the ary-epiglottic folds are movable, approaching and separating alternately during the act of respiration, while during phonation they are pressed against each other, thus obliterating the space between them which is seen when they are separated. This space is the inter-arytenoid space or commissure, and is formed by the lateral walls of the arytenoid cartilages and the upper margin of the posterior portion of the cricoid cartilage. The mucous membrane in this commissure is very loosely attached to the deeper structures, and is thrown into folds by the approximation of the arytenoid cartilages. Its color is much lighter than that of the ary-epiglottic folds, due to the shining through of the cricoid cartilage. Outside of the ary-epiglottic folds and the inter-arytenoid commissure is the tissue forming the posterior and lateral walls of the oesophagus (not shown in the diagrams), and near the epiglottis a space called the pyriform sinus is noticed between the ary-epiglottic folds and the wall of the oesophagus.

Running from the epiglottis to the ary-epiglottic folds are two broad bands, one on either side, covered with mucous membrane and of a pinkish-red color, which are lost on either side in the tissue forming the walls of the laryngeal cavity, while toward the middle of the image they present concave and tolerably sharp edges. These are the ventricular bands, which were formerly termed the false vocal cords, and which form the lip to the opening of the ventricle of the larynx. Between the ventricular bands filling up the central portion of the image are seen the vocal cords, two bands of a pearl-white color which are attached to a cartilaginous process of the arytenoid cartilages, and run from these parallel with each other to the angle of the thyroid cartilage immediately below the tubercle of the epiglottis. These present sharp edges toward each other, and follow the motions of the arytenoid cartilages to which they are attached, so that when in inspiration the cartilages are separated the edges of the vocal cords are also some distance apart, forming, together with the inter-arytenoid commissure, a triangular opening called the glottis. That portion of the opening which is bounded on either side by the edges of the vocal cords alone is called the membranous portion, while the base of the triangle is termed the cartilaginous portion, being bounded on either side by the vocal processes of the arytenoid cartilages. This portion is readily distinguished from the membranous portion by its slightly yellow color, and by the fact that a very obtuse angle is formed at the junction of the two portions when the glottis is wide open during respiration. Through the open glottis the lower edge of the cricoid cartilage and several of the rings of the trachea can usually be seen, and there are a few cases in which even the bifurcation of the trachea can be dimly illuminated, showing in the [p. 33] laryngeal image the openings of the bronchi. The distance is, however, too great for bright illumination, and nothing can be seen distinctly, so that it is of little value in a diagnostic point of view. During phonation the glottis is narrowed to a slit by the approximation of the arytenoid cartilages and inner edges of the vocal cords, and, as has already been stated, the inter-arytenoid space becomes obliterated. In the higher notes of the female voice, the so-called head tones, the cartilaginous portion of the glottis remains closed entirely, while the membranous portion appears as an elliptical opening which is diminished in its longitudinal diameter with each rise in pitch. This becomes possible because of the presence in the vocal cords of a slender rod-like cartilage attached to the end of the vocal process, which can readily be seen in the female larynx, but which is only rudimentary in the male.

This description, intentionally, has been made without reference to the anatomical relation of the parts, but to give a clear idea of what is seen in the laryngeal mirror. The reader should therefore always bear in mind that the laryngeal image, being a reflected one, is reversed, and that, on account of giving a bird's-eye view of the larynx from a point above and behind the organ, distances are materially diminished; and the image is also reversed in an antero-posterior direction, so that the epiglottis appears to be posterior when in reality it is anterior.

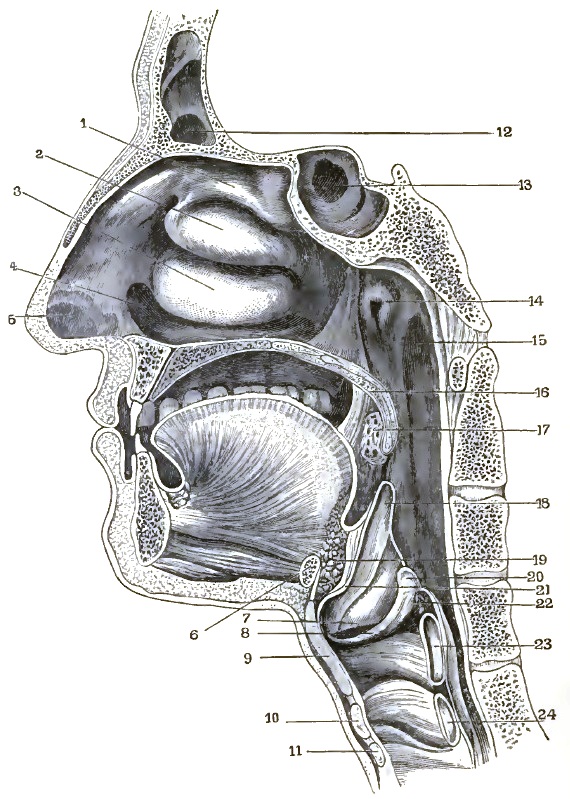

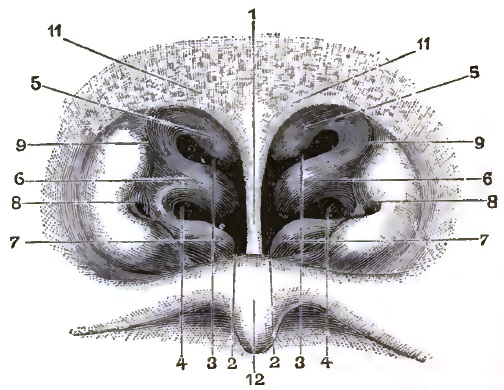

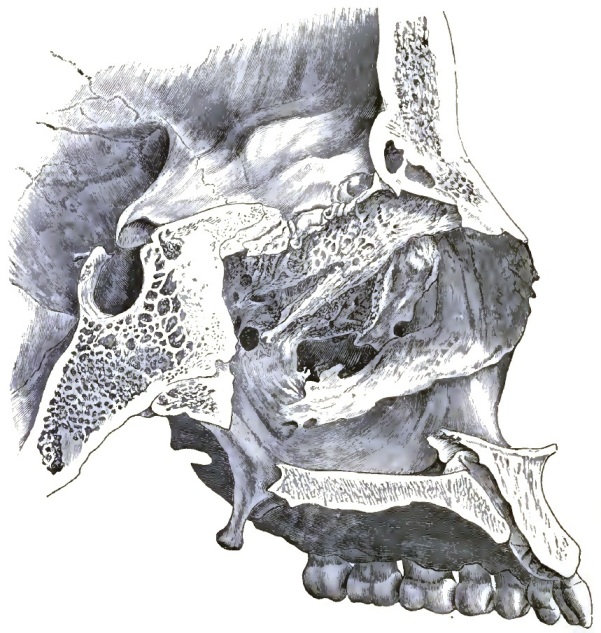

RHINOSCOPY.—Rhinoscopy, or the art of inspecting the nasal cavities and the naso-pharyngeal space, is divided into two portions—viz. anterior and posterior rhinoscopy; and it will be convenient to observe this division in the following description of the methods employed. But before proceeding with the description it will be well to briefly review the topographic anatomy of the parts, because in most works on general anatomy the nasal and naso-pharyngeal cavities are discussed in a few sentences, and they are rarely if ever examined in the dissecting-room, so that the student has but a very imperfect knowledge of the relation of the parts belonging to these cavities. (See Fig. 11.) The nasal cavities, which are wedge-shaped, with a narrow arched roof, extend from the nostrils to the upper portion of the vault of the pharynx. Their outer walls are formed by the nasal process of the superior maxillary and lachrymal bones in front; in the middle, by the ethmoid and inner surface of the superior maxillary bones; behind, by the vertical plate of the palate bone and the internal pterygoid process of the sphenoid and the turbinated bones. These latter run before backward, three on each side, and are designated as the inferior, middle, and superior, the latter being the smallest of the three. The sinuses or spaces between these turbinated bones are called meatuses; so that the space between the floor of the nose and the lower turbinated bone is called the inferior meatus, the one between the lower and middle turbinated bones is the middle meatus, and the one between the middle and superior turbinated bones is the superior meatus.

| FIG. 11. |

|

| VERTICAL SECTION OF HEAD, SLIGHTLY DIAGRAMMATIC. |

| 1. Superior turbinated bone. 2. Middle turbinated bone. 3. Lower turbinated bone. 4. Floor of nasal cavity. 5. Vestibule. 6. Section of hyoid bone. 7. Ventricular band. 8. Vocal cord. 9 and 23. Section of thyroid cartilage. 10 and 24. Section of cricoid cartilage. 11. Section of first tracheal ring. 12. Frontal sinus. 13. Sphenoidal cells. 14. Pharyngeal opening of Eustachian tube. 15. Rosenmüller's groove. 16. Velum palati. 17. Tonsil. 18. Epiglottis. 19. Adipose tissue behind tongue. 20. Arytenoid cartilage. 21. Tubercle of epiglottis. 22. Section of arytenoid muscle. |

The nasal cavities are separated from each other by a septum or division wall composed of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone and the vomer posteriorly and the cartilaginous septum anteriorly, thus presenting a smooth surface as the inner wall of each cavity. The floor is formed by the palatine process of the superior maxillary bone and by the palate bone, and runs in a slanting, downward direction from before backward. The roof is formed by the nasal bones and nasal spine of the frontal in front, in the middle by the cribriform plate of the ethmoid, and posteriorly by the under surface of the body of the sphenoid bone. Directly communicating with the nasal cavities are other cavities situated in the bones of the skull, the lining mucous membrane of which no doubt is largely affected by the pathological processes in nasal diseases: these are the antra of Highmore, large triangular cavities situated in the body of the superior maxillary bone and communicating with the nasal cavities by an irregularly-shaped opening in the middle meatus; [p. 34] then the frontal sinuses, two irregular cavities situated between the two tables of the frontal bone. The communication between them and the nasal cavities is established by the infundibulum, a round opening in the middle meatus, and finally the sphenoidal cells or sinuses, found in the body of the sphenoid bone, communicating with the nasal cavities by small openings in the superior meatus. That portion of the nasal cavities which projects beyond the end of the nasal bone is surrounded by cartilages forming the alæ of the nose.

In the cartilaginous septum of the lower animals we find a small cavity lined with mucous membrane, called after its discoverer Jacobson's organ, the minute anatomy of which has lately been described by Klein.18 This [p. 35] organ in man is, however, only rudimentary. The nasal cavities are lined with mucous membrane, which varies greatly in thickness in different localities, and which materially decreases the size of the cavities in the living subject from that seen in the denuded skull. This mucous membrane is covered by ciliated epithelium in man, with the exception of that portion which lines the vestibule—i.e. that portion of the cavity of the nose surrounded by cartilage only—which is covered by pavement epithelium.

18 Quarterly Journal of Mic. Science, January, 1881.

In the lower animals we find that in the olfactory region the ciliated epithelium is either absent, or that ciliated and non-ciliated epithelium alternates in patches.19 The author has not been able to find a statement in the literature on the subject as to the kind of epithelium found in the accessory cavities in man, but it is very probable that the mucous membrane of the frontal sinuses and the antra of Highmore is covered with ciliated epithelium; otherwise it would be difficult, if not impossible, for the secretions of that mucous membrane to pass through the narrow channels into the nasal cavities. The color of the normal nasal mucous membrane is of a light pink shade in what is termed the respiratory portion, while it is of a yellowish hue in the olfactory region, that portion of the mucous membrane which covers the roof and the outer walls of the nasal cavities down to the upper margin of the middle turbinated bone and the septum down to about the same level. It is in this region that the nerve-ends of the olfactory nerve are distributed. Immediately beneath the mucous membrane, and between it and the periosteum of the bony walls and the perichondrium of the cartilaginous portion of the septum, we find a tissue which bears a striking resemblance to the erectile tissue of the genital organs.20 It is composed of a network of fibrous tissue, the trabeculæ of which contain a few organic muscular fibres. Its meshes of various sizes and shapes are occupied by venous sinuses lined with endothelium. These are supplied with blood by small arterioles and capillaries, which are quite numerous in the fibrous tissue and can readily be demonstrated under the microscope. In this arrangement of elements of the nasal mucous membrane we find a ready explanation of the fact that liquids of greater or less density than the serum of the blood when introduced into the nasal cavities produce pain, for we have here the most favorable conditions for osmosis, which will cause either a contraction or a distension of the sinuses. In the larger masses of fibrous tissue between the sinuses or caverns we find imbedded the glands, with their ducts opening out between the epithelial cells of the mucous membrane. There are two kinds of glands in this region, which have been described by Klein21—viz. serous and mucous glands.

19 Haenle, Anatomy des Menschen, vol. ii.

20 Haenle, loc. cit.

21 Loc. cit.

This cavernous erectile tissue is most abundant at the lower portion of the septum and of the lower turbinated bones; and, although it has been recognized and described as true erectile tissue by Haenle, Virchow, and others, yet to Bigelow of Boston belongs the honor of having first called attention to the part which this tissue plays in nasal diseases. He gave to it the name turbinated corpora cavernosa.22 The expansion of the nasal cavities formed by the alæ of the nose is termed the vestibule, which is lined with pavement epithelium and forms the entrance to the cavities proper. The naso-pharyngeal cavity extends from the posterior ends of the turbinated bones and the edge of the vomer to the line where the velum palati touches the pharyngeal wall during the act of deglutition or phonation. In this cavity we find the openings of the Eustachian tubes, two crater-like elevations, with a pit-like depression of variable size and shape, one on either side; and a collection of glands with a central duct-like opening disposed on the roof and posterior wall of the cavity. This gland was named by Luschka23 the pharyngeal [p. 36]tonsil. The openings between the edge of the vomer and the lateral walls of the naso-pharyngeal cavity are termed the posterior nares.

22 Boston Med. and Surg. Journal, April, 1875.

23 Der Schlundkopf des Menschen.

ANTERIOR RHINOSCOPY.—Anterior rhinoscopy is a very easy and simple procedure, and is practised as follows: The patient is placed in position as for laryngoscopy, and the light directed upon his face so that the centre of the circle of reflection from the head mirror falls upon the tip of the nose. The examiner then elevates the tip of the nose with his left hand, resting the fingers on the forehead of the patient, and lifts the ala away from the septum with a slightly bent probe, when he will be enabled to see a considerable distance into the nasal cavity. It is, however, better to employ a speculum instead of the bent probe, because the parts then are seen in their usual relation to each other, and are not distorted by the forcible traction necessary when the probe or a dilator is employed. The nasal speculum (Fig. 12) is best made of hard rubber and shaped like the ordinary ear speculum, except that the narrow end is oval instead of round. This instrument is to be introduced by a sort of rotatory motion until the end has passed the edge of the vestibule, when it will remain in position, displaying the interior of the nose. Great care should be exercised, when introducing the speculum, not to scratch the mucous membrane of the septum, for this will give rise to pain and start hemorrhage, both of which are to be avoided as much as possible. When applications are to be made to the mucous membrane of the septum or turbinated bones, or when operations are to be performed within the cavity, it is best to employ an instrument called a nasal dilator, of which there are a large number of different forms, the most satisfactory of which is shown in Fig. 13. The dilator is introduced by compressing the blades between the thumb and fore finger, and pushing them into the nostril until their ends have passed the edge of the vestibule. The pressure is then removed, and the spring separating the blades holds the nostril open; the handle or stem of the instrument, hanging down, need not be held or supported, as the blades press sufficiently upon the tissues to retain the instrument in position. If the pressure is too great, however, it will soon produce pain, and the patient will object to the use of the instrument.

| FIG. 12. |

|

| Nasal Speculum. |

| FIG. 13. |

|

| Bosworth's Nasal Dilator. |

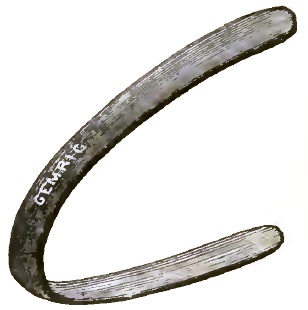

The view obtained both by the speculum and the dilator is rather limited, and usually comprises only the anterior portions of the lower and middle turbinated bones, together with the cartilaginous portion of the septum. In order to get a good view of the lower and middle meatus and of the floor of the nose the patient's head should be inclined forward or backward as occasion requires. The student should, however, not be satisfied by simply inspecting the parts, but should aid the eye by the sense of touch, for pathological changes are of common occurrence, and their nature, whether soft and fleshy or hard and bony, erosions of the mucous membrane, or deep ulcerations, can often only be determined by the aid of the probe. In the same manner can the permeability of the meatuses be determined better than by inspection [p. 37] only. In cases where it becomes necessary to determine whether the anterior portion of the septum is of normal thickness, or whether a projection seen through the speculum is due to localized deflection, an instrument called the septometer is of great assistance (Fig. 14). This instrument is similar to the one used by mechanics to determine the diameter of a piece of wood or iron being turned on the lathe. In using it the long straight shanks are introduced one in each nostril, and, being closed upon the septum, the rounded points are gently moved up and down and backward and forward over the bulging portion of the septum. The motion of the index attached to the curved shanks of the instrument accurately indicates the relative thickness of tissue grasped between the points in the nose. By means of this instrument we can thus ascertain whether we have to deal with a deviation or a localized thickening of the septum; for if it is a deviation the index will move but slightly, while it will travel a considerable distance when the points pass over a thickened portion.

| FIG. 14. |

|

|

Septometer for Measuring Thickness of Nasal Septum. |

Although simple in its details, anterior rhinoscopy is often made difficult or altogether prevented by obstacles which are mostly due to malformation of the parts, such as deviation of the cartilaginous portion of the septum, exostoses from the superior maxillary bones reaching into the nasal cavity, adhesion between the anterior portion of the lower turbinated bone and the septum, nasal polypi, anterior hypertrophies of the mucous membrane, and so forth; or they may be due to faulty instruments, as too much pressure in the spring of the dilator; or, finally, they may be caused by want of care in the handling of the instruments, as when the septum is scratched by the edge of the speculum and hemorrhage ensues.

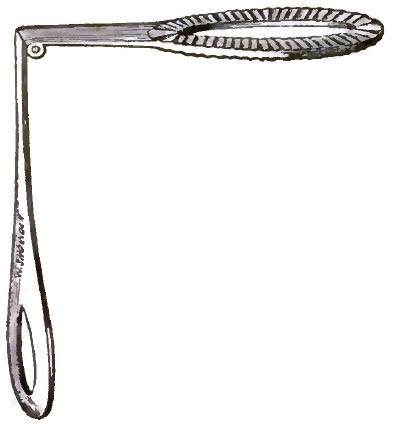

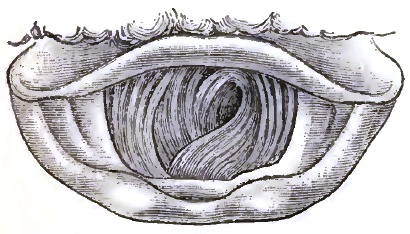

POSTERIOR RHINOSCOPY.—Posterior rhinoscopy is much more difficult than laryngoscopy or anterior rhinoscopy, and requires more patience and dexterity on the part of the examiner than either of the former, because but very few persons have control over the movements of the velum palati, and in most of these the upper portion of the pharyngeal wall is so sensitive that the slightest touch with an instrument gives rise to reflex cough and to gagging. In many cases, however, with patience and skill the naso-pharyngeal cavity and the posterior portion of the nasal cavities can be illuminated and inspected. To do this the patient is placed in the same position as for laryngoscopy, except that the head is not inclined backward, and after the mouth is opened as wide as possible the light from the reflector is thrown into the oral cavity. The tongue is then depressed with a tongue depressor. This instrument in its simplest form in which it is daily used by the practitioner for examining the fauces is the handle of a spoon. For laryngoscopic or rhinoscopic purposes, however, the spoon is not to be recommended, because the hand holding it must be on a level with the mouth, thus obstructing the view and light. An instrument has therefore been constructed which obviates this difficulty. It consists of a leaf-shaped blade of silver or German silver bent at right angles and inserted into a flat wooden handle. The lower surface of the blade is slightly concave, and ribbed so as to take a better hold of the slippery back of the tongue, and from the bend is about 3 inches in length. It is introduced into the mouth as far back as possible, and pressed upon the back of the tongue while the hand of the examiner is below the chin of the patient. For the sake of convenience in carrying the instrument the blade has been so hinged to the handle that it will fold up against the latter and will [p. 38]open at a right angle with it (Fig. 15). A more elegant and lighter instrument of the same description has lately been introduced in which the handle is also made of metal, and, like the blade, is heavily nickel-plated, and which when folded can be carried in a pocket-case. Soon, however, the metal tongue depressor becomes tarnished by the secretions of the mouth or by the substances used for applications to the throat, and then presents an appearance disgusting to many patients, who will not on that account submit to its use. For the sake of greater cleanliness, J. Solis Cohen devised a tongue depressor made of hard rubber, which is known as Cohen's tongue depressor (Fig. 16). It consists of a piece of ebonite bent upon itself, either end being a little over 3 inches long. The bend being more than at right angles, the hand holding the instrument rests underneath the chin of the patient; but if a different curve be desired for any particular case it can easily be obtained by placing the instrument for a little while in hot water. When soft it can be bent into any shape, which it will retain when cooled by immersion in cold water. Great care should be exercised not to carry the blade of the instrument too far back, as then gagging will at once set in. In cases where the tongue resists the pressure of the tongue depressor, it is better to exert but a gentle pressure upon the back of the organ, under which it will slowly recede, than to try to subdue it by force, for in the latter case it will unavoidably slip from under the blade of the instrument, and the desired space in the fauces is not obtained. With children the writer has found the fore finger of the left hand to be the best means of depressing the tongue, for the little patients as a rule have a horror of the formidable-looking instrument.

| FIG. 15. |

|

| Folding Tongue Depressor. |

| FIG. 16. |

|

| Cohen's Tongue Depressor. |