T. F. BELL

NATIONAL SCHOLAR IN DESIGN (1875-8) AND

THIRD GRADE CERTIFICATED ART MASTER,

SCIENCE AND ART DEPARTMENT, S. K.: MEDALLIST IN HONOURS AND

CERTIFICATED TEACHER IN ‘LINEN MANUFACTURING,’ AND IN

‘WEAVING AND PATTERN DESIGNING,’ CITY AND GUILDS OF LONDON INSTITUTE

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | | PAGE |

| I. | INTRODUCTION |

1 |

| II. | JACQUARD MACHINES |

27 |

| III. | FULL-HARNESS MOUNTINGS |

69 |

| IV. | DESIGNING AND DRAUGHTING |

110 |

| V. | CARD-CUTTING AND LACING |

139 |

| VI. | SPECIAL JACQUARDS AND HARNESSES |

155 |

| VII. | GAUZE |

196 |

| VIII. | DOUBLE CLOTH |

233 |

| IX. | TAPESTRY AND PILE WORK |

255 |

| X. | CARPETS |

264 |

| XI. | LAPPETS AND SWIVELS |

294 |

| | INDEX |

301 |

[1]

JACQUARD WEAVING AND DESIGNING

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Though the term ‘jacquard weaving’ is properly applied to work

done by the jacquard machine, it will here be taken to apply to all

harness weaving, or work that extends beyond the range of shafts, or

leaves of heddles.

The question arises, When is the limit to the number of shafts that

ought to be used reached? It apparently used to be when no more

could be got into the loom, as up to ninety-six shafts were used; and

this seems to be quite enough for any weaver to get the yarn through,

or for any loom to hold, but it must be remembered that at present the

appliances are much more suited to the work than they formerly were;

and now, except in woollen or worsted goods, where it is desirable to

use shafts on account of their firmness in comparison with that of a

harness, from twelve to sixteen shafts are as many as it is generally

thought desirable to have in a power loom. I have seen thirty-five

shafts, all in one tier or set, working diaper very conveniently in a

hand loom, and more than double that number of leaves working

worsted in a power loom; but whether the latter was desirable, or not, I

must leave to the judgment of the manufacturer who possessed it.

Many ingenious inventions have been made for the purpose of

simplifying the working of a large number of shafts, but as a description

of them would be out of place here, we may pass on to the draw

loom, which appears to be the first form of harness of which we have[2]

an accurate description. How the cloths of Babylon were woven, in

which

Men’s figured counterfeits so like have been

That if the party’s self had been in place,

Yet Art would vie with Nature for the grace—

is not known, though in Gilroy’s report of Arphaxad’s description of

his loom to Deioces, king of the Medes, it is stated to have been

accomplished by means of carved blocks of wood acting on needles,

which wrought the harness or heddles and thus formed the pattern;

but as Gilroy has admitted that the introduction to his work on weaving

is a pure invention of his own, for the purpose of making it appear

that the Ancients were acquainted with motions

similar to those on our modern looms, or as a ‘take-off

on those who angle hourly to surprise, and bait

their hooks with prejudice and lies,’ we need not

dwell further on the subject. In any case, figured

cloths must have attained considerable excellence

in very early ages. The curtains of the Tabernacle

were embroidered with figures, and the veil of the

Temple was, according to Josephus, embroidered with all sorts of

flowers, and interwoven with various ornamental figures, the door

curtain being embroidered with blue and purple and scarlet. The

ephod of the High Priest was similarly embroidered.

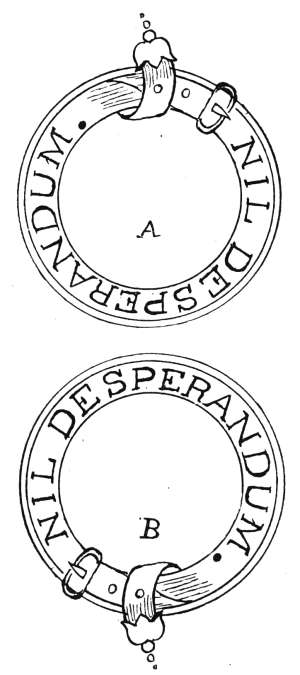

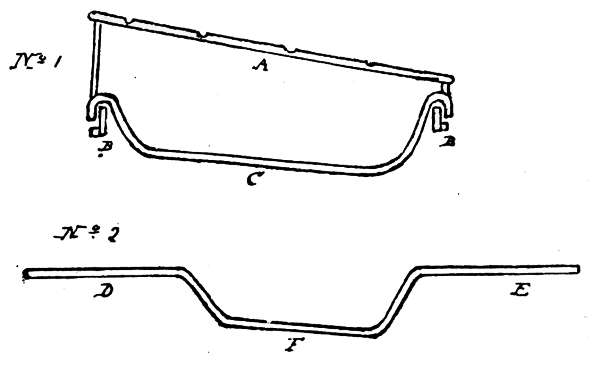

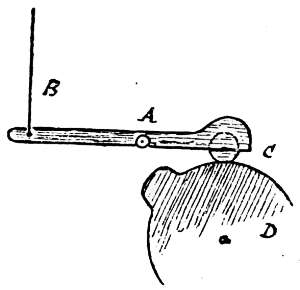

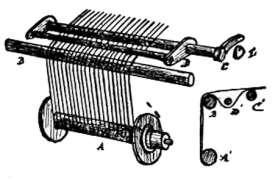

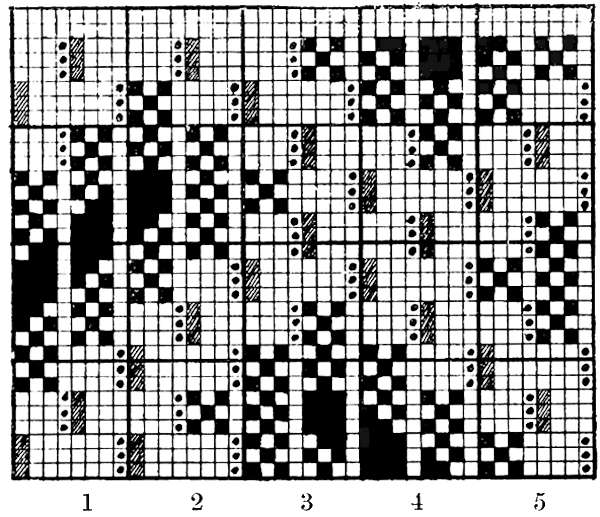

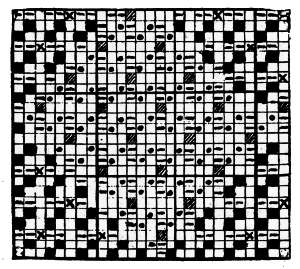

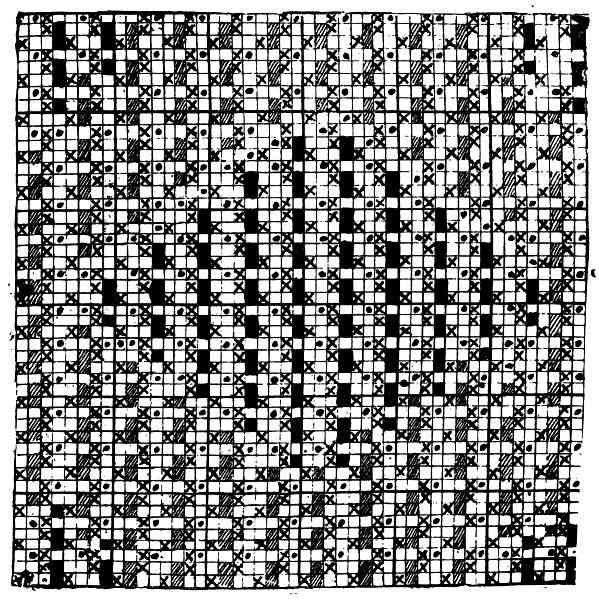

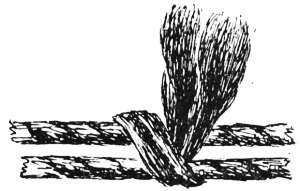

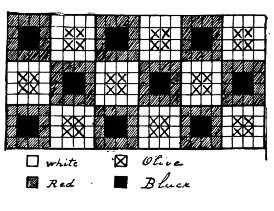

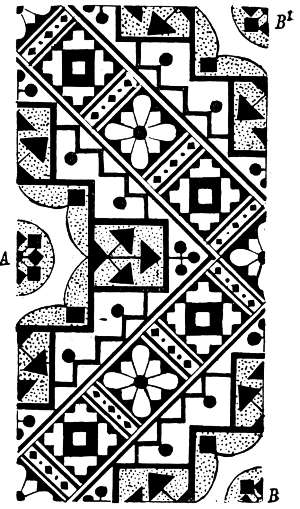

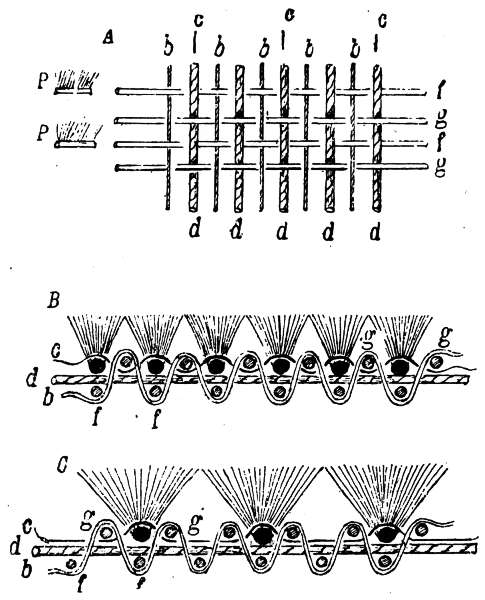

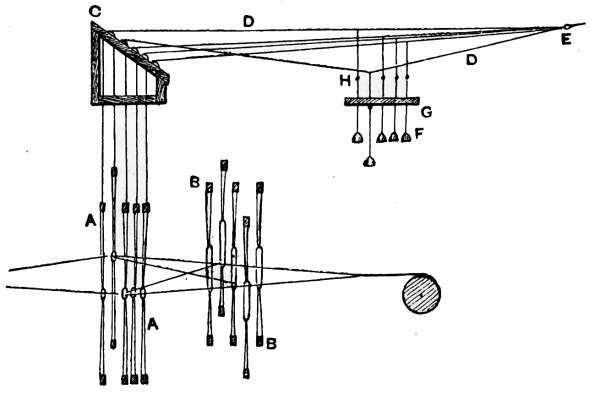

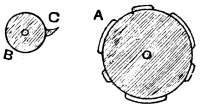

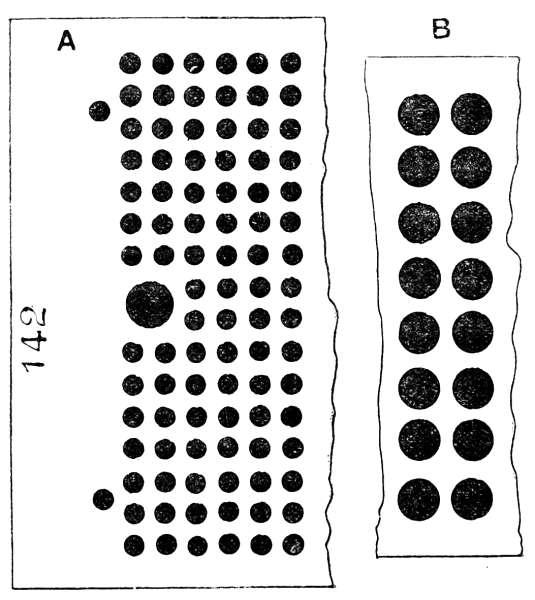

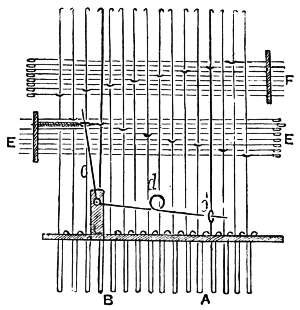

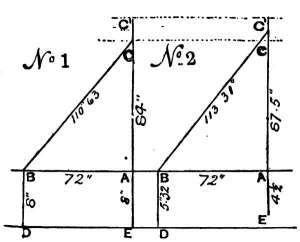

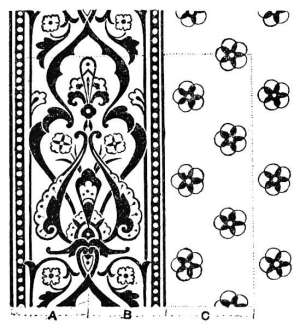

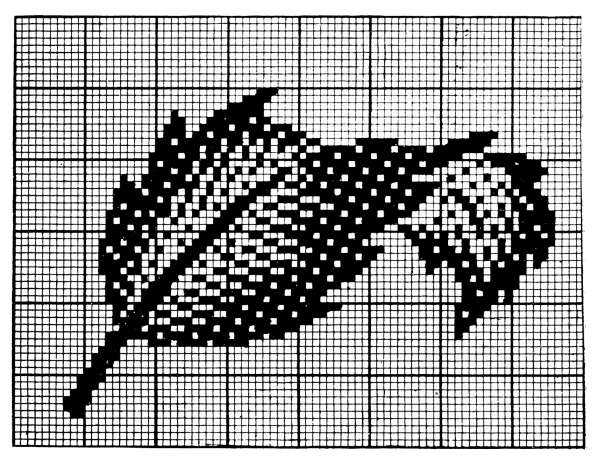

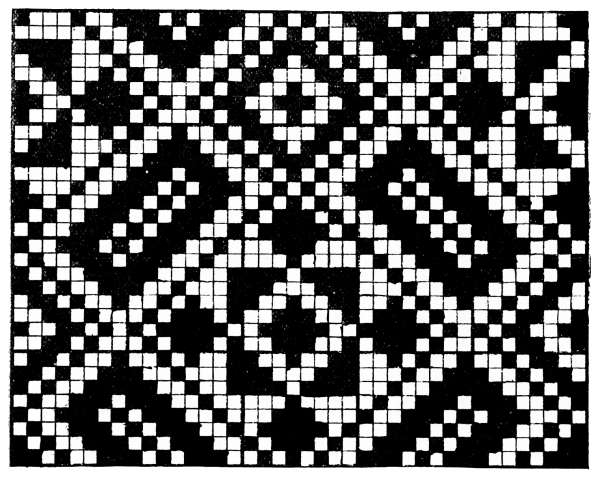

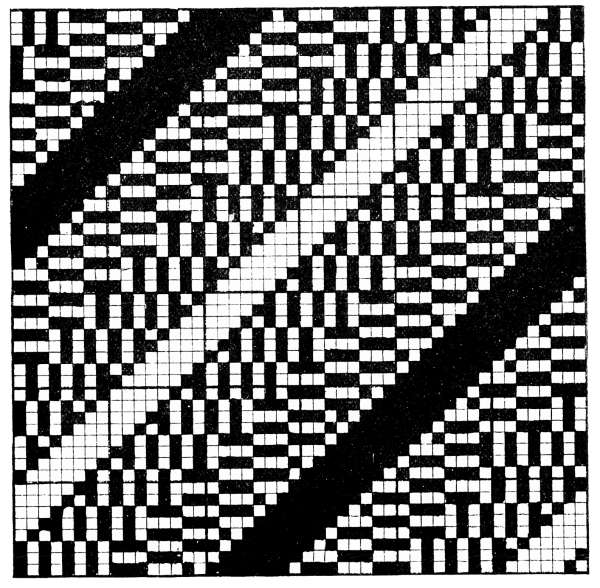

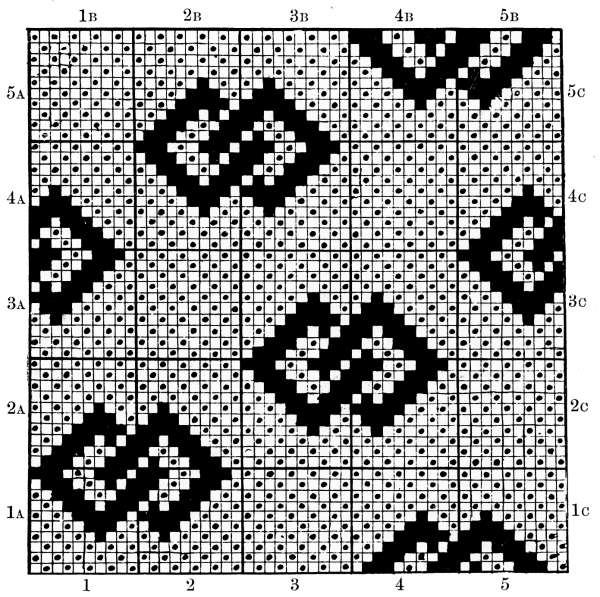

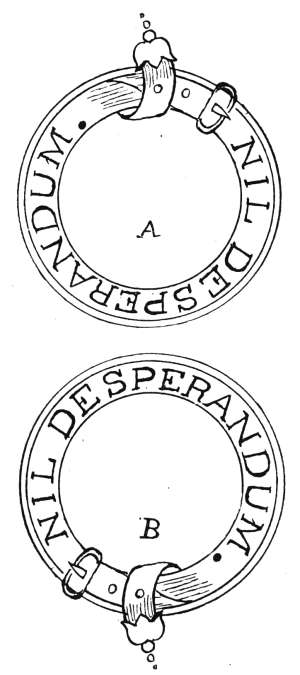

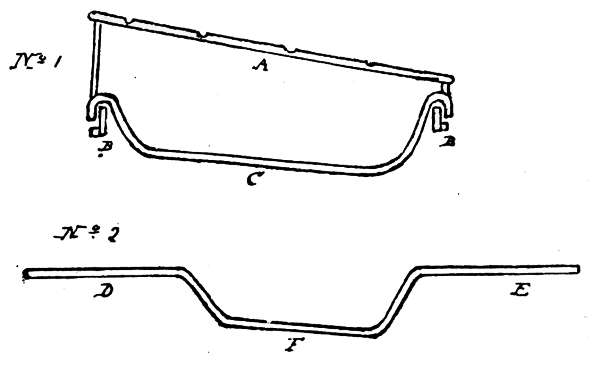

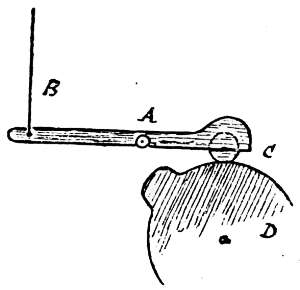

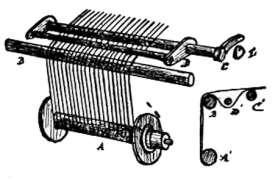

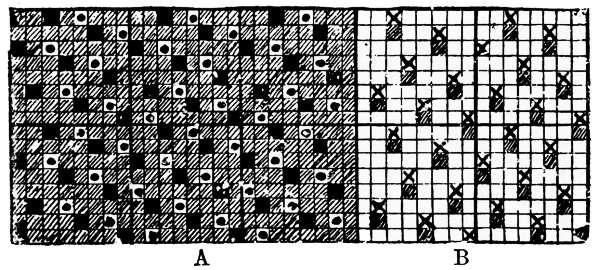

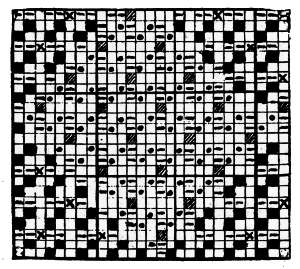

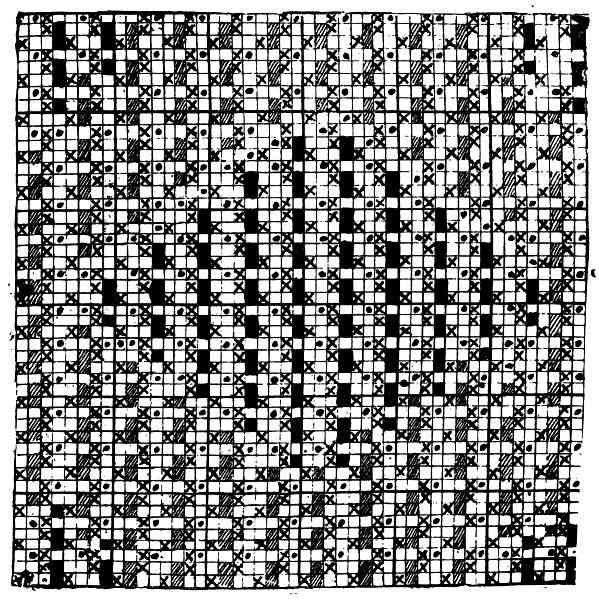

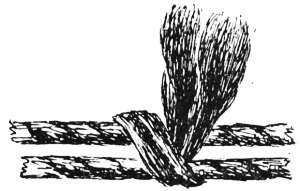

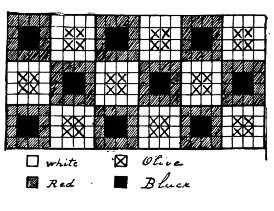

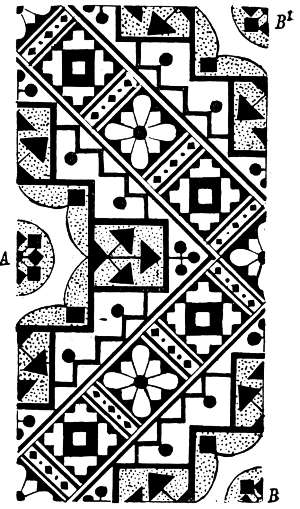

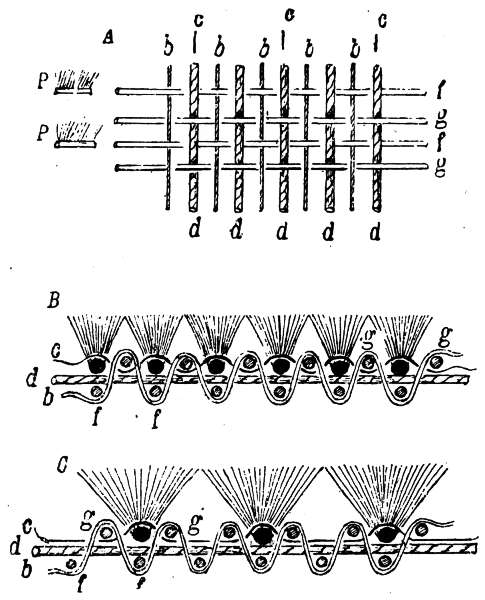

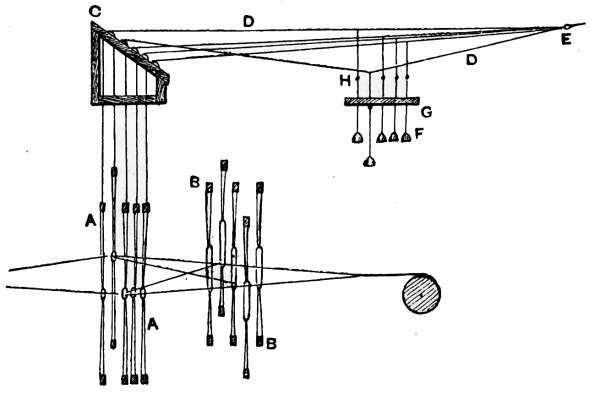

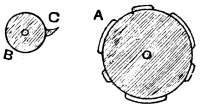

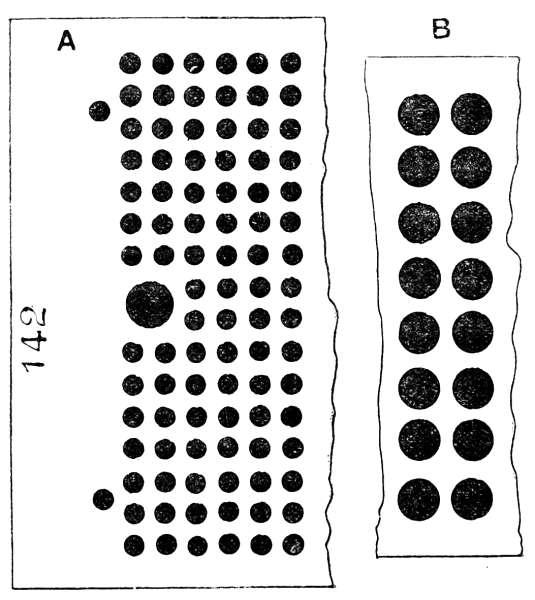

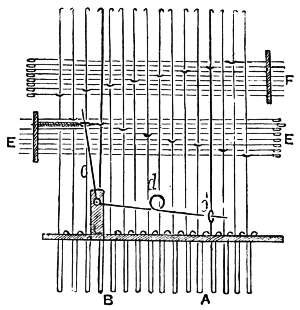

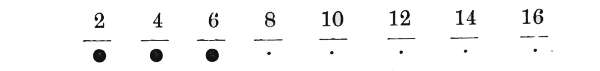

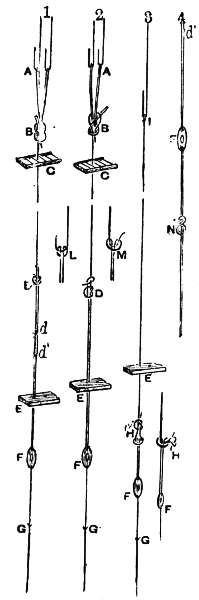

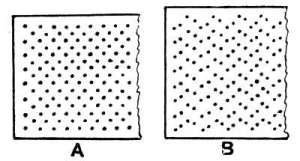

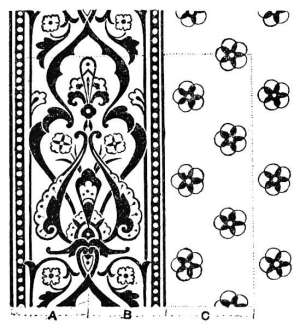

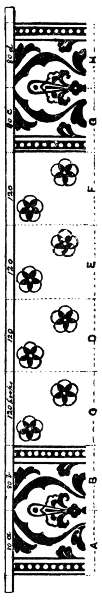

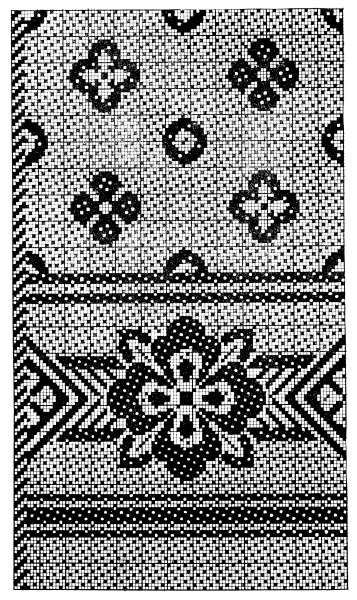

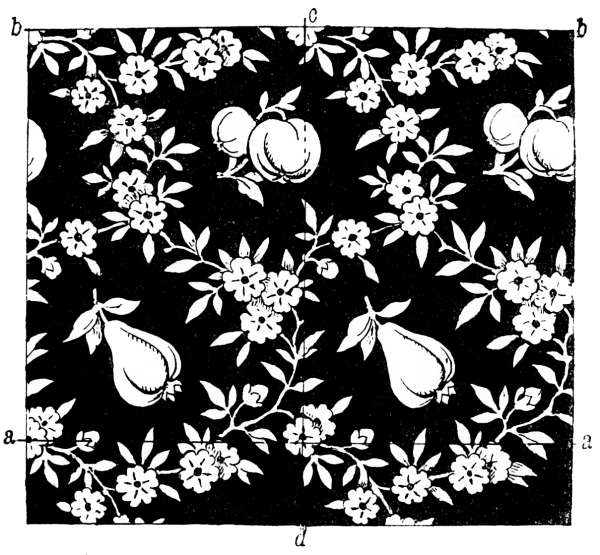

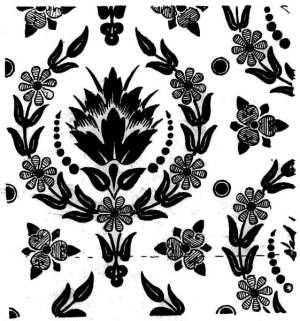

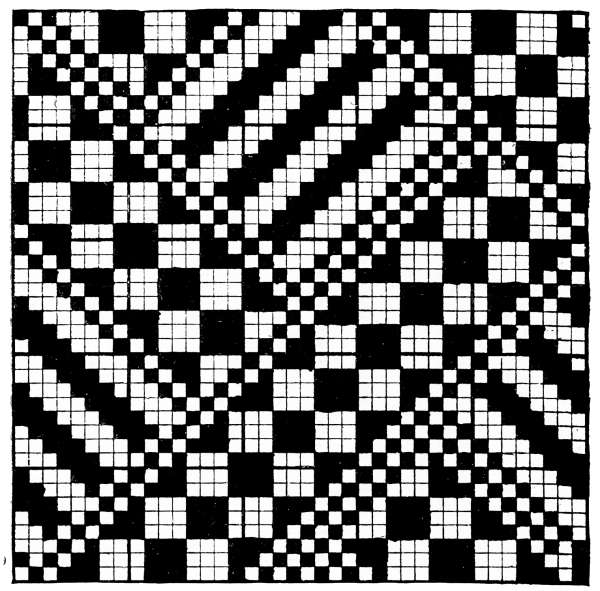

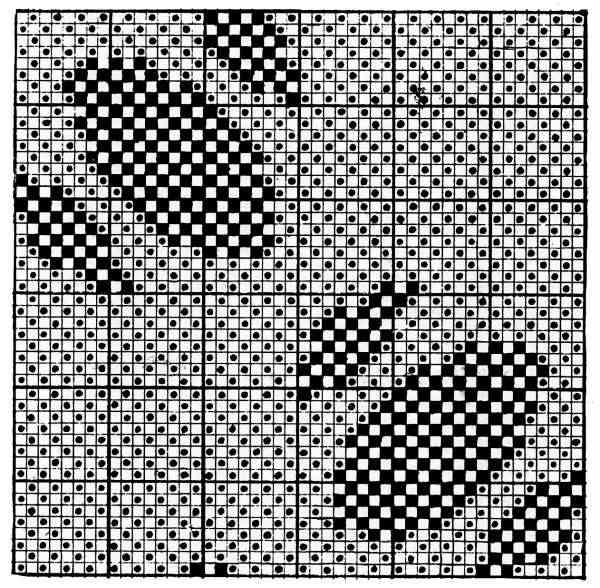

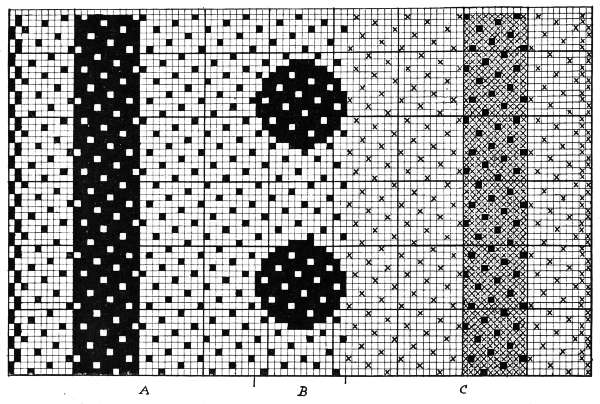

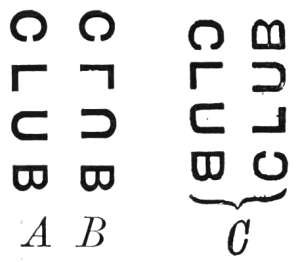

Fig. 1

The Egyptians worked coloured patterns in the loom so rich that

they vied with the Babylonian cloths, which were embroidered with

the needle. The method of working is unknown, but cloths taken from

the tombs in Egypt, which may be seen in South Kensington Museum

and in the Gobelins tapestry manufactory, Paris, appear to be made on

a principle similar to that of the Gobelins tapestry; the warp is of flax

and the weft of coloured wool: and the looms depicted on the catacombs

in Egypt are very similar in appearance to tapestry looms.

Embroidering was practised in Egypt prior to the Exodus of the

Israelites; and gold and silver threads or wires were used both for

embroidering and weaving, being known nearly 4,000 years.

The Babylonish garment taken by Achan, whose sin brought much[3]

woe upon the Israelites, is said, by Josephus, to have been a Royal

garment woven entirely of gold; but it might only have been embroidered

with gold, and was probably wrought in the plain of Shinar,

as it was not till long after that Babylon was celebrated for its manufactures.

Pliny says that weaving cloth with gold thread was invented by

Attalus, an Asiatic king, and that the Babylonians were most noted for

their skill in weaving coloured cloths. This was in Homer’s time,

about 900 B.C., when weaving and embroidering appear to have attained

great excellence, and to have been very gorgeous. At that time the

labour of the loom was considered an accomplishment, which ladies

and even princesses tried to excel in.

As before stated, the draw loom is the first form of machine for

figured weaving of which we have any record. It is not known where

it was invented, but it probably passed from China to Western Asia with

the silk manufacture. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans

do not appear to have known it. The Chinese have still in use a draw

loom in which the drawboy stands on the top and draws up the parcels

of twines which have been previously arranged for him. After

being established in Damascus (hence the name damask), the draw

loom passed on to Europe, where the Chinese method of working was

used till 1604, when M. Simblot, in France, connected to the neck a

separate series of cords, called the ‘Simple’ (perhaps a corruption of

his name), so that the drawboy could work when standing at the side

of the loom. It is said to have been introduced into England in 1567.

The next improvement was to dispense with the drawboy’s services,

and for this purpose a patent was taken out in 1687, by Joseph Mason,

for ‘a draw boy engine by which a weaver may performe the whole

worke of weaving such stuffe as the greatest weaving trade in Norwich

doth now depend upon without the help of a draught boy.’ In 1779

William Cheape patented a plan to dispense with the drawboy by

having the ‘simple’ above his head, and drawing it down with knots

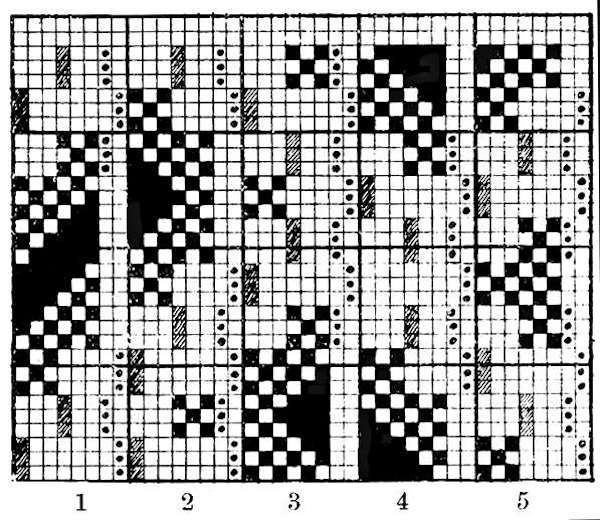

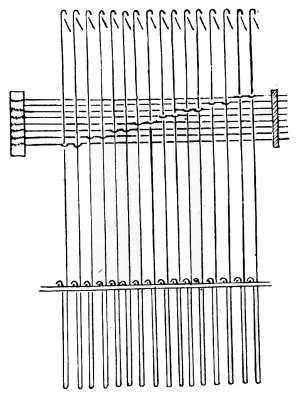

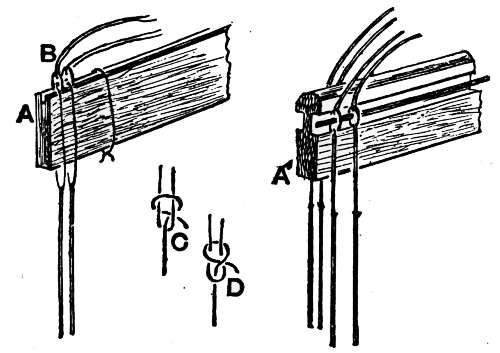

which were held in notches, as described in Fig. 2.

Before beginning to describe the draw loom it may be better first to

describe what it is required to do.

[4]

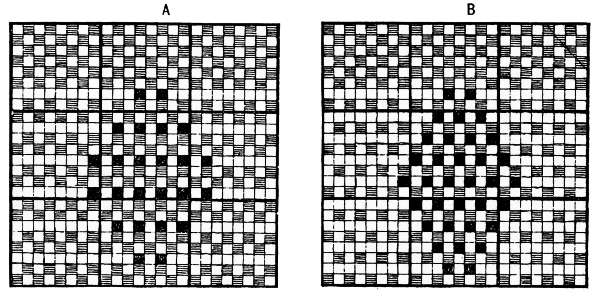

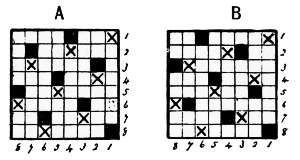

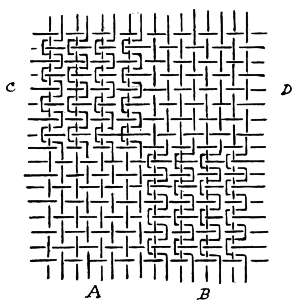

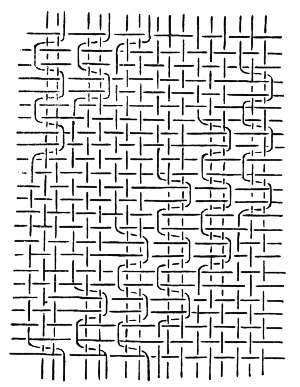

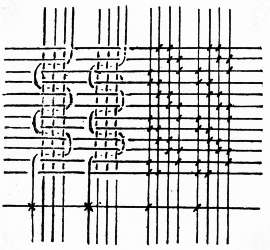

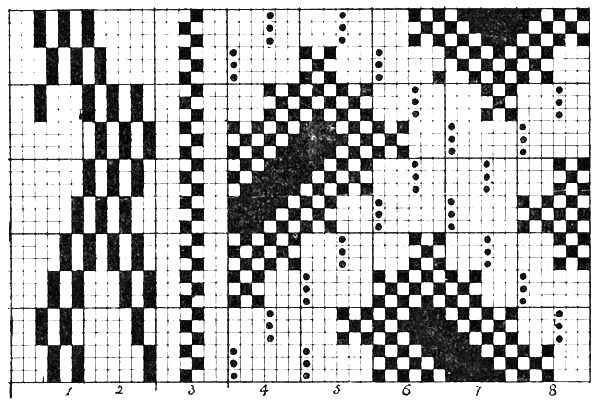

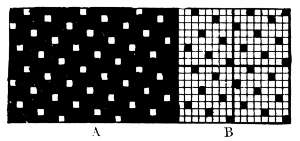

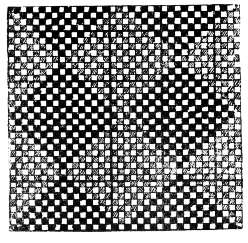

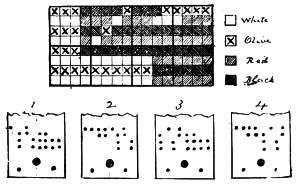

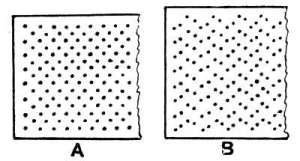

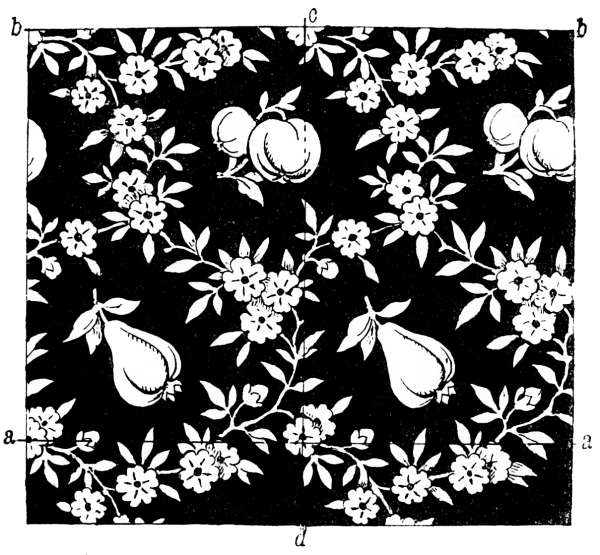

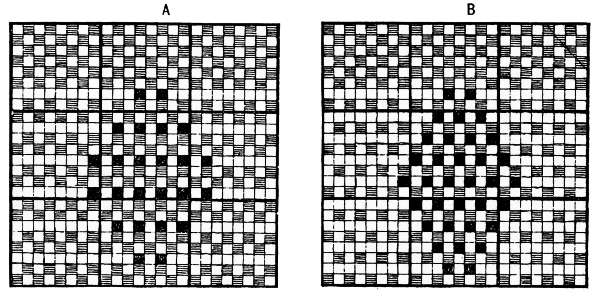

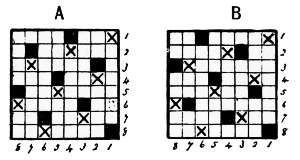

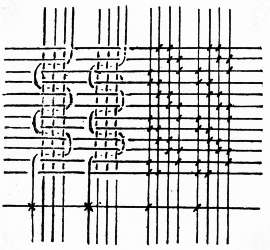

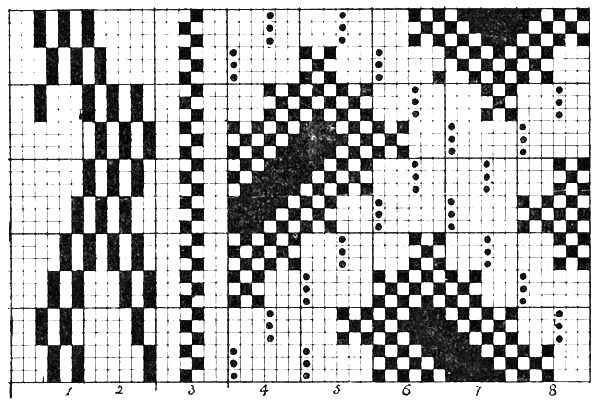

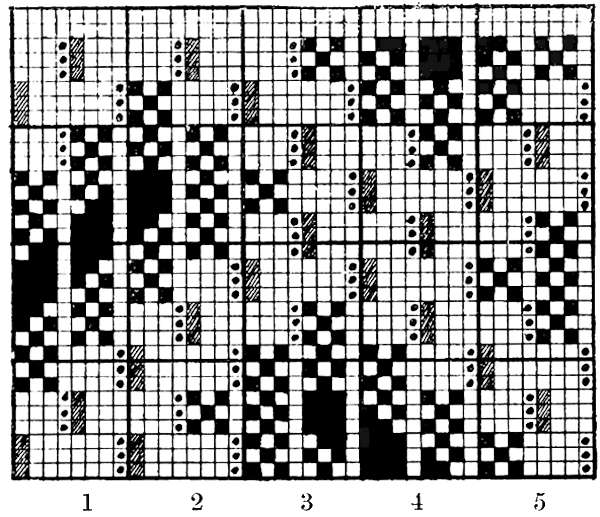

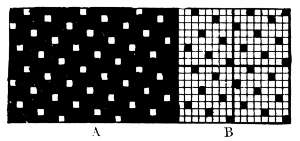

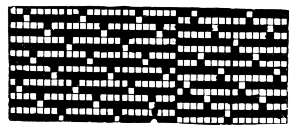

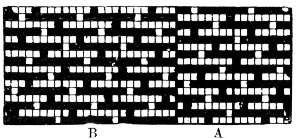

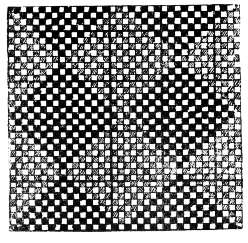

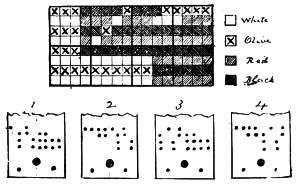

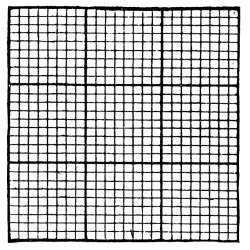

Its principal use appears to have been for the weaving of damask,

which is one of the simplest forms of figured weaving. Reduce a

damask texture to its elementary form, and it consists of twilling, or,

more correctly, turned or reversed twilling. If we take a common dice

pattern woven with shafts, it will easily be seen that one dice is formed

by a warp twill, and the next one by a weft twill, or that the dices are

formed by warp and weft twills alternately.

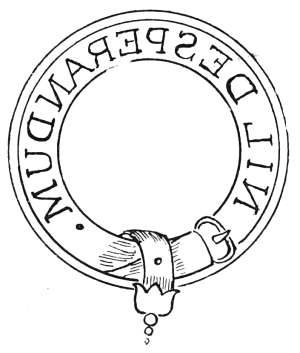

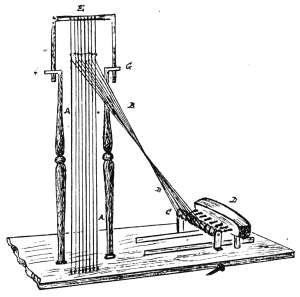

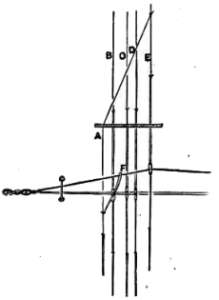

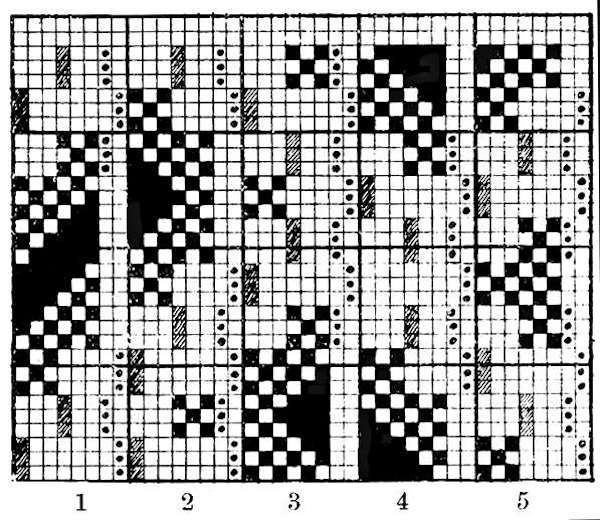

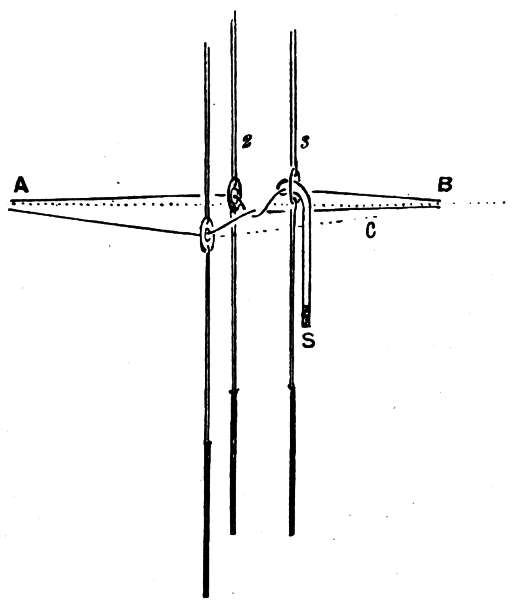

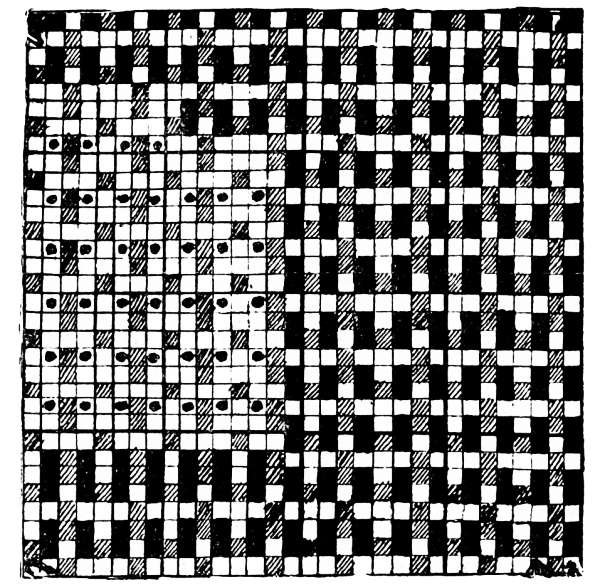

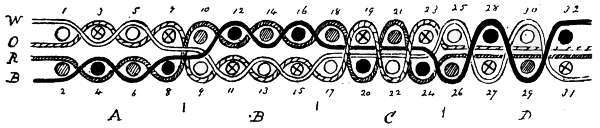

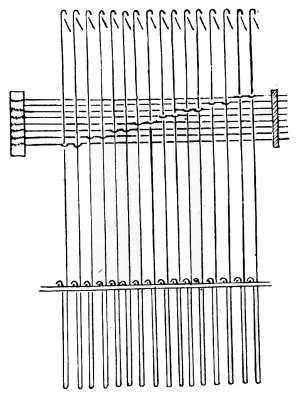

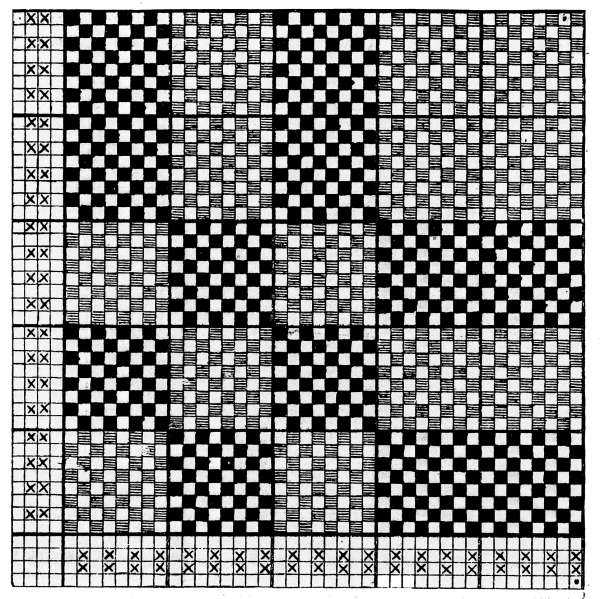

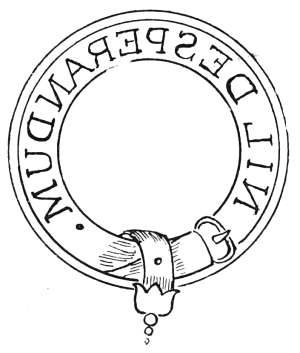

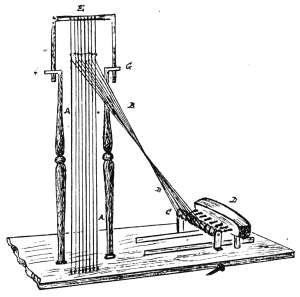

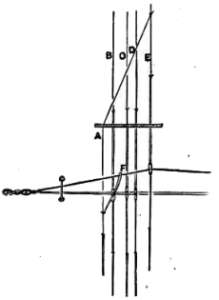

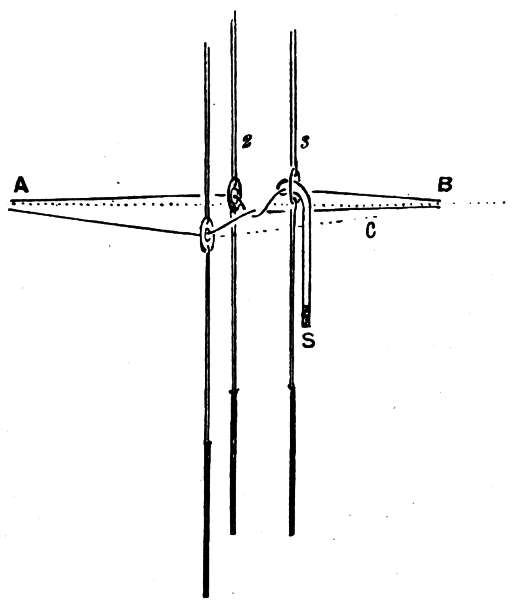

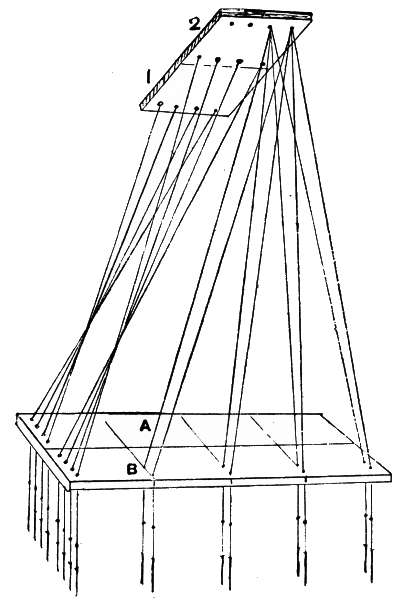

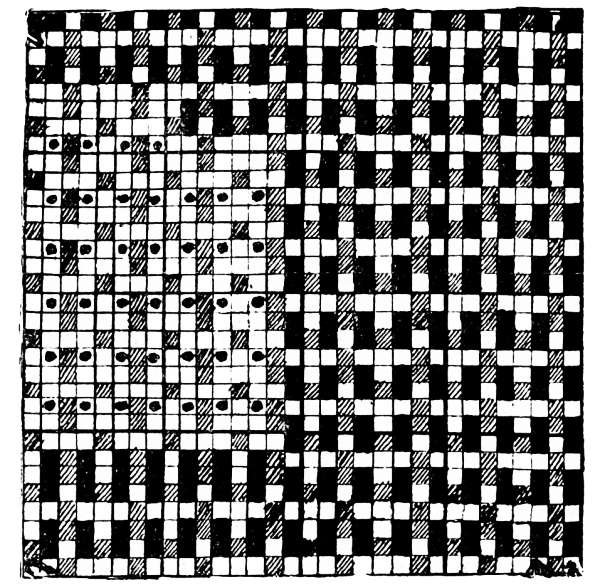

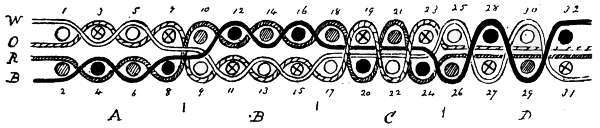

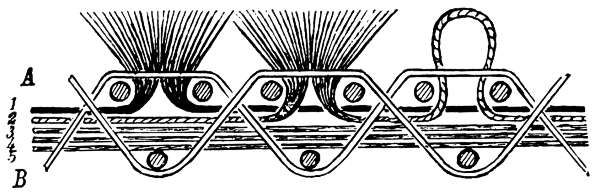

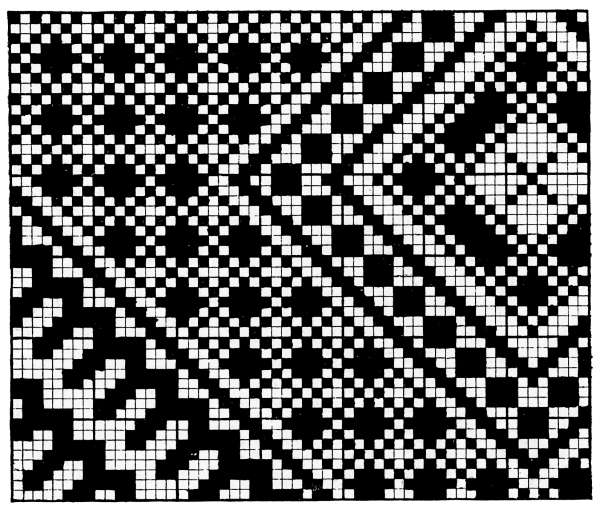

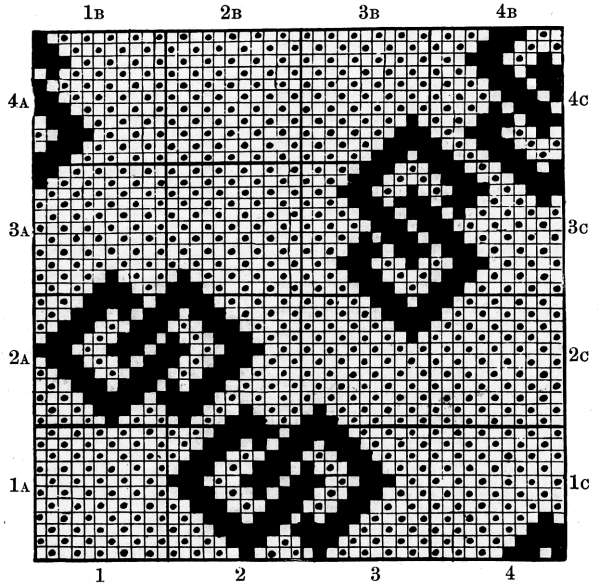

Fig. 2

Now, what forms the pattern? The yarn may be all of one colour,

the threads may be so closely set together as to make them individually

invisible, or to appear as a plain surface, and yet the dices come out

distinctly in two shades of colour. The play of light on the longitudinal

and latitudinal threads produces this effect. The dices formed

by the latitudinal or horizontal threads will always appear darker than

the yarn in the cloth when the latter is placed between the observer

and the light, whether these threads be warp or weft, as there is a

certain amount of shade on each of them, and of shadow cast by them,

whereas the longitudinal or vertical threads are illuminated, without

any shade or shadow, and appear lighter than the yarn did before being

woven; and this is the reason why a good side light is the best for

showing up the pattern on damask, it developing the above to the

utmost. In a good material the difference of shade between the

ground and figure is very considerable, but in some thin, coarse goods[5]

it is hardly visible, requiring them to be held in a favourable light to

show the distinction: the pattern will appear light on a darker ground,

or the reverse of this, according as the surface threads forming it run

across the light or in the direction of it.

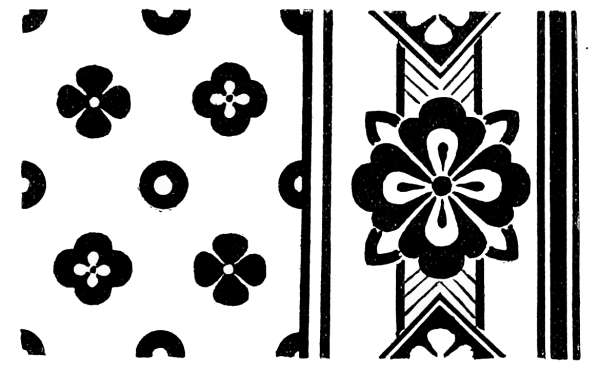

This is the reason of the pattern appearing on the cloth; then it

is the business of the designer to regulate what form it is to partake

of, by preparing a suitable design; and according to instructions

furnished to him by the design, it is the duty of the drawboy to raise

the warp by regulating the cording of his harness, and drawing it so

as to reverse the twill from a weft one to a warp one wherever the

figure is to be formed on the cloth, and to do so in such order as to

produce the pattern required.

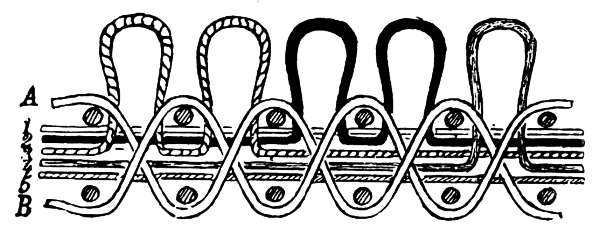

The draw-loom mounting consists of two parts—the drawboy

mounting, or the harness with its tail and simples, to be wrought by

the drawboy; and the shaft mounting, which is required to form the

texture of the cloth, or to interlace the warp and weft through both

ground and figures; the harness only interlaces them at the edges of

the pattern, or causes either warp or weft to be above, to form the figure

en bloc, but without interlacing them together.

It is therefore a ‘compound mounting,’ and is known as a ‘presser’

or ‘pressure’ harness. For simplicity’s sake let us suppose the

principle of the drawboy to be applied to shafts or healds, and take

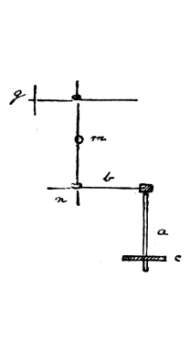

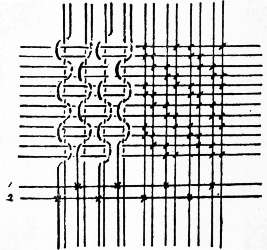

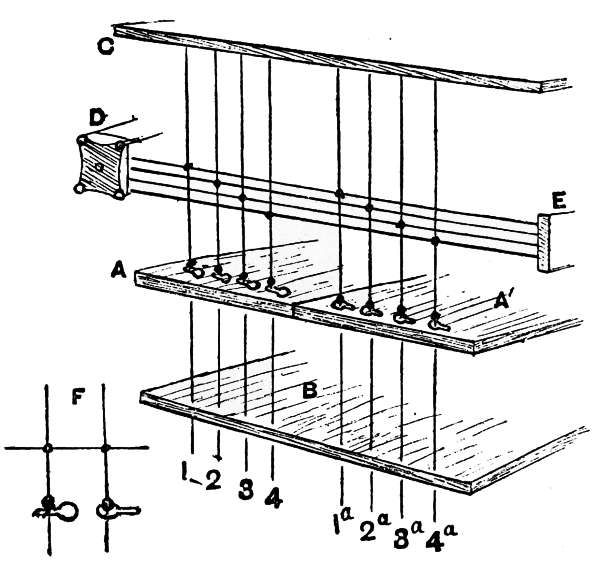

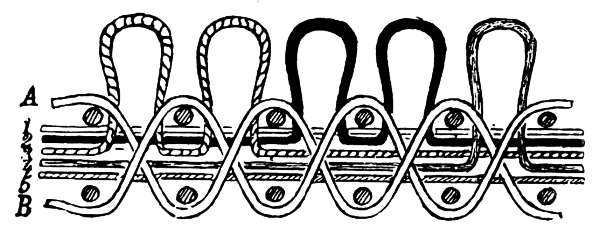

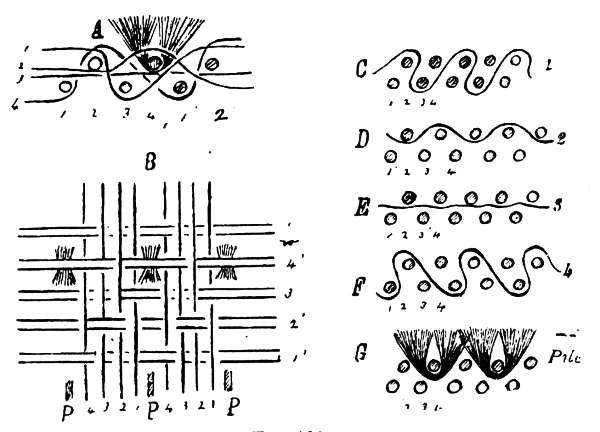

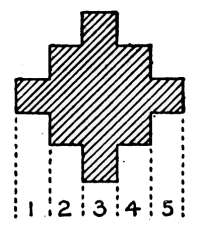

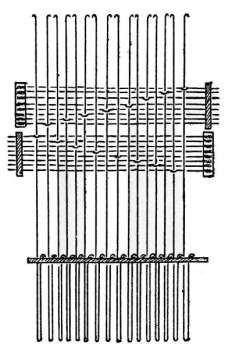

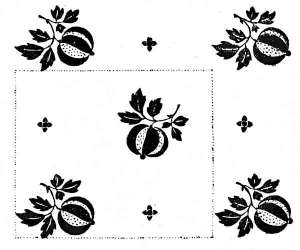

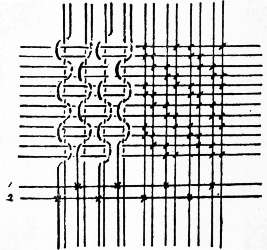

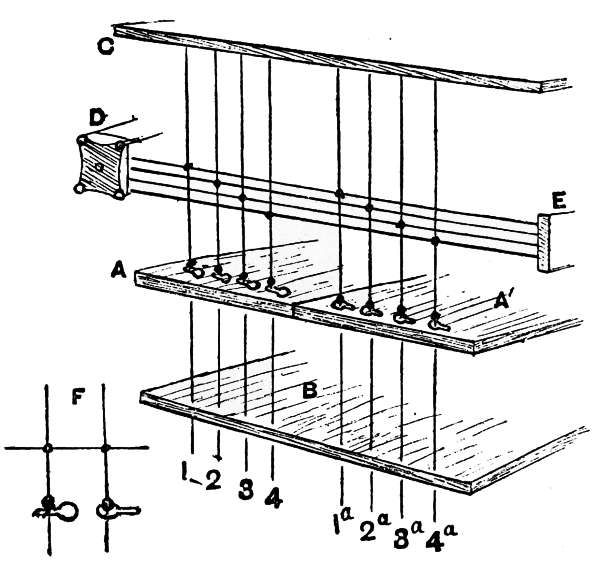

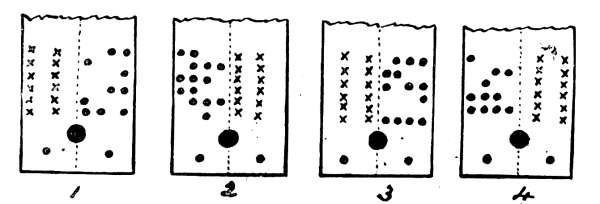

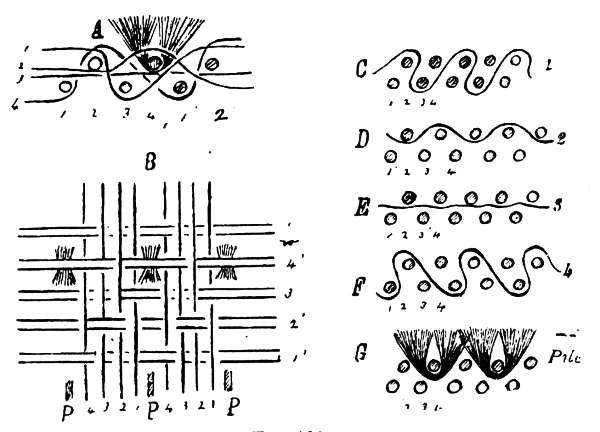

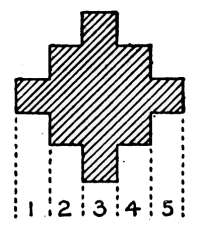

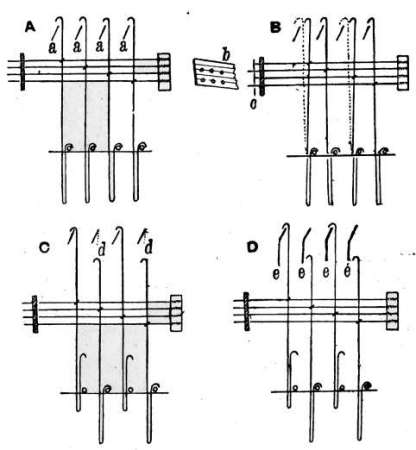

a simple figure, as Fig. 1.

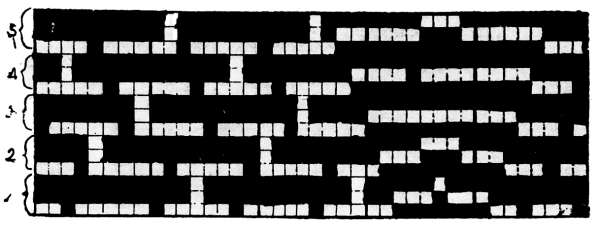

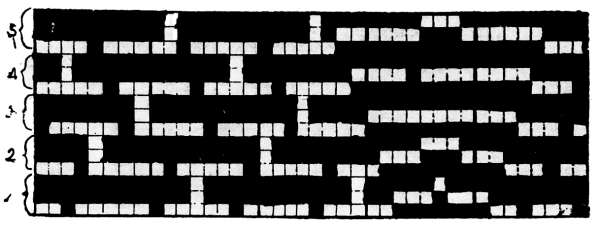

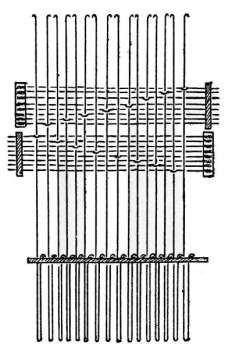

For it there are 5 parts, or it could be wrought with 5 leaves of

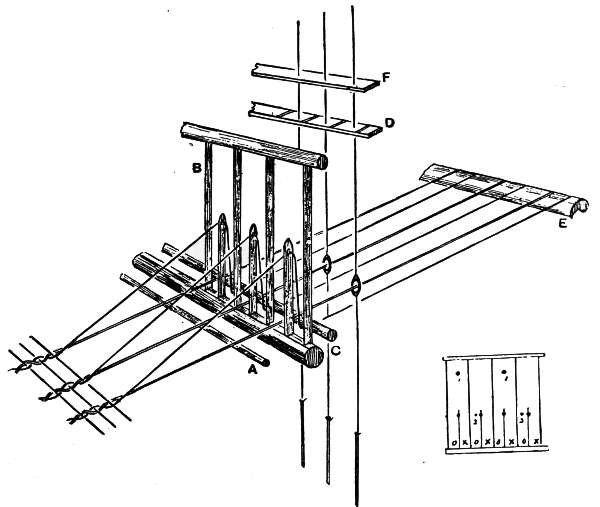

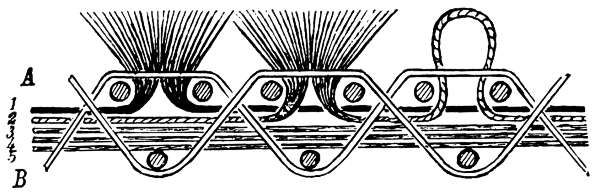

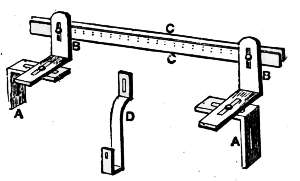

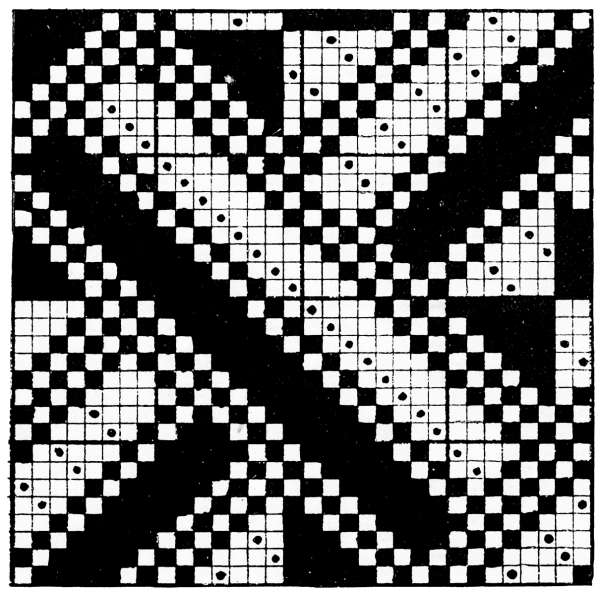

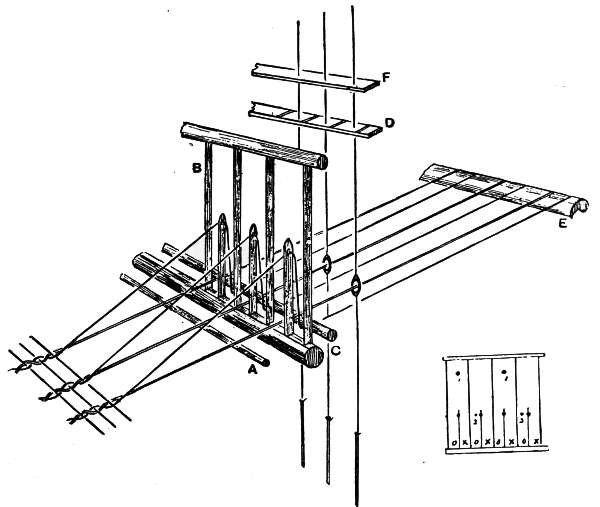

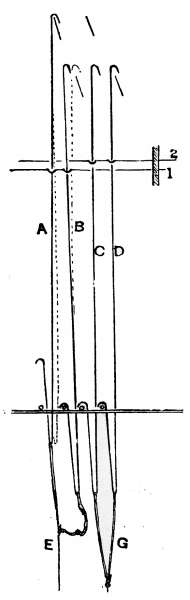

heddles with a straight draught. Fig. 2 shows the mounting; A A

is the back mounting, which in this case is a shaft mounting, but

would be a harness for a more extensive pattern. B, B are the pressure

heddles or front mounting. These are 5 in number, as the ground or

texture is taken as a 5-end satin or twill, C is the pulley box with the

tail cords, D, D, passing over the pulleys, and tied to the wall or to the

loom framing as at E. The knobs F hang over the weaver’s head,

and are attached by cords H, passing through a hole board G, to the

tail cords, D, D. There are heads on the cords H, and the holes in the

hole board are made thus  ; so that when the weaver pulls down

a knob the bead can pass through the round hole, and the shaft or[6]

shafts of the back mounting attached to it will be raised, and can be

kept in this position by drawing the cord into the notch or narrow

part of the hole, which the bead will not pass through. Any number

of shafts can be raised that are required to form the pattern, either by

pulling down the knob for each shaft, or by having the knots corded

to the shafts, so that each one will raise the proper number of shafts.

Thus, in the figure, each knob is only tied to one of the tail cords;

therefore a knob must be pulled down for each leaf of heddles to be

raised, but each knob might be attached to any number of the tail

cords according to the number of leaves of heddles it is required to

raise, so that pulling down each knob in succession will complete the

pattern. It might require too many knobs to do this, and then the

former method would have to be adopted. When the weaver begins

to work he draws the first figure shed with the back mounting by

pulling down one or more of the knobs as is required; he then works

over the ground treadles, b, b, till a change of pattern is required. Next

he releases the drawn shed by pulling the cord out of the notch in the

hole board; draws another shed, and works over the ground treadles as

before. This gives the principle of how the draw loom works, but

the principle of forming the texture with the back and front mountings

combined will be fully explained under ‘Pressure Harness.’

; so that when the weaver pulls down

a knob the bead can pass through the round hole, and the shaft or[6]

shafts of the back mounting attached to it will be raised, and can be

kept in this position by drawing the cord into the notch or narrow

part of the hole, which the bead will not pass through. Any number

of shafts can be raised that are required to form the pattern, either by

pulling down the knob for each shaft, or by having the knots corded

to the shafts, so that each one will raise the proper number of shafts.

Thus, in the figure, each knob is only tied to one of the tail cords;

therefore a knob must be pulled down for each leaf of heddles to be

raised, but each knob might be attached to any number of the tail

cords according to the number of leaves of heddles it is required to

raise, so that pulling down each knob in succession will complete the

pattern. It might require too many knobs to do this, and then the

former method would have to be adopted. When the weaver begins

to work he draws the first figure shed with the back mounting by

pulling down one or more of the knobs as is required; he then works

over the ground treadles, b, b, till a change of pattern is required. Next

he releases the drawn shed by pulling the cord out of the notch in the

hole board; draws another shed, and works over the ground treadles as

before. This gives the principle of how the draw loom works, but

the principle of forming the texture with the back and front mountings

combined will be fully explained under ‘Pressure Harness.’

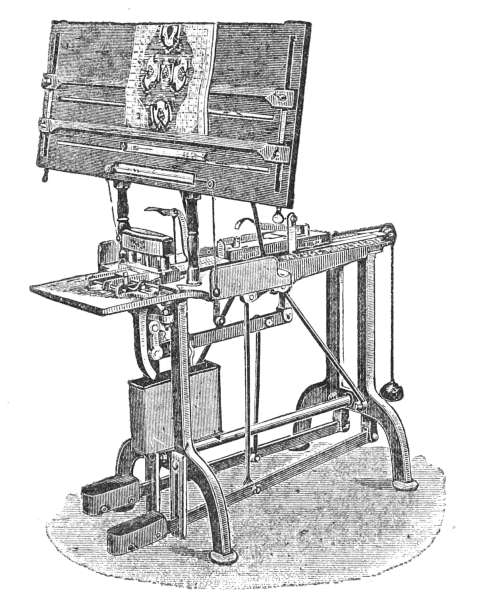

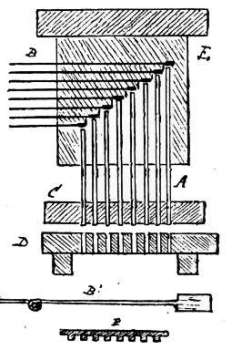

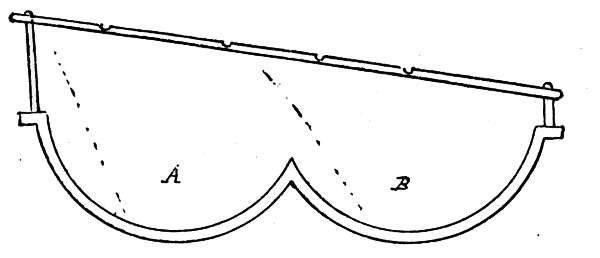

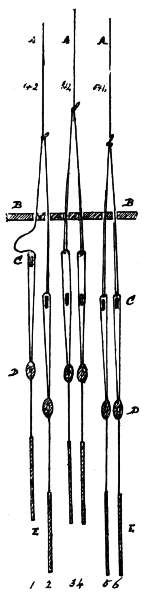

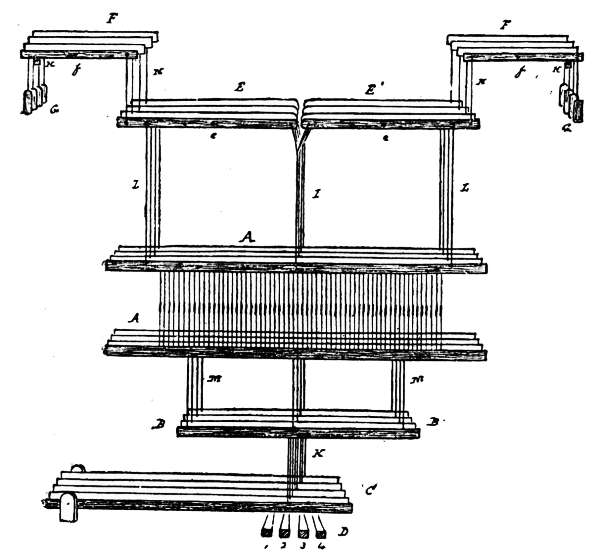

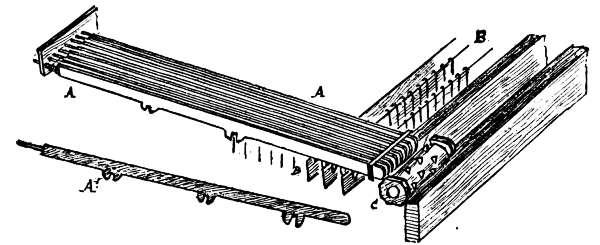

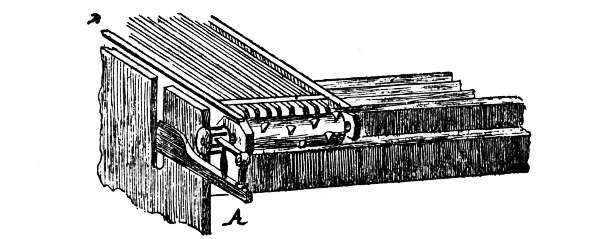

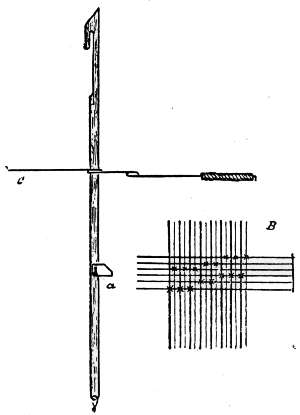

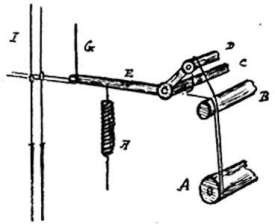

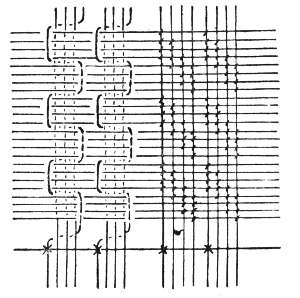

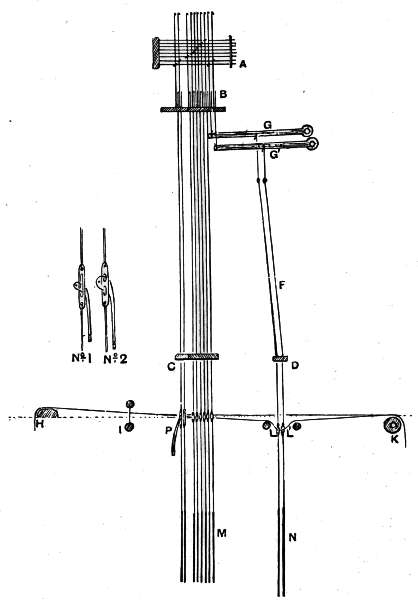

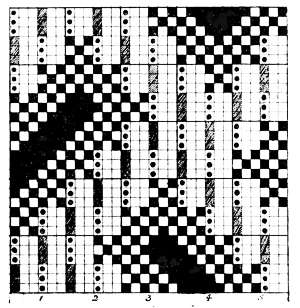

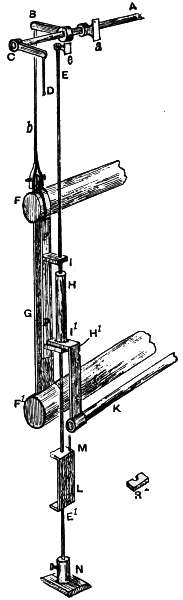

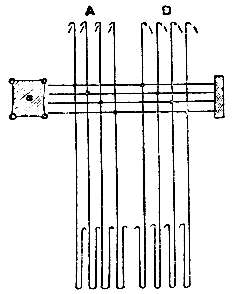

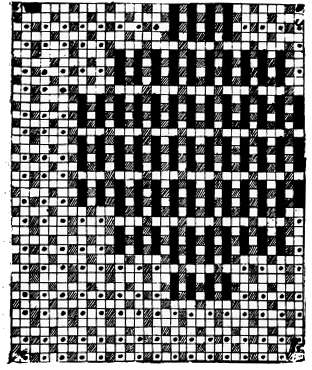

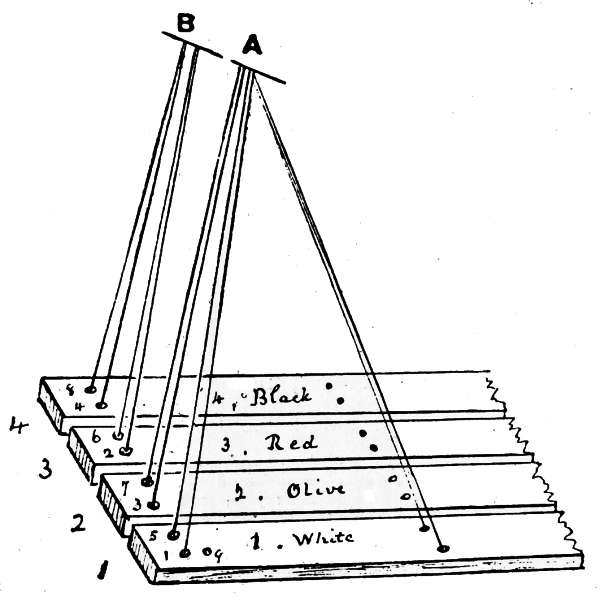

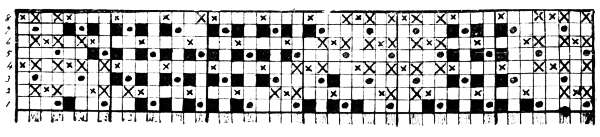

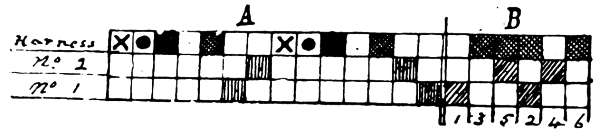

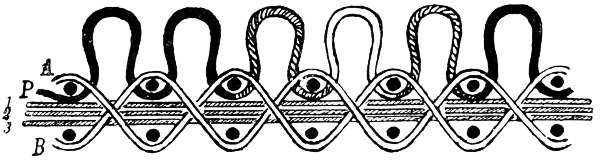

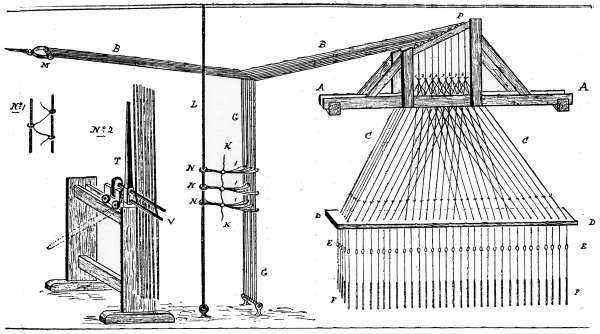

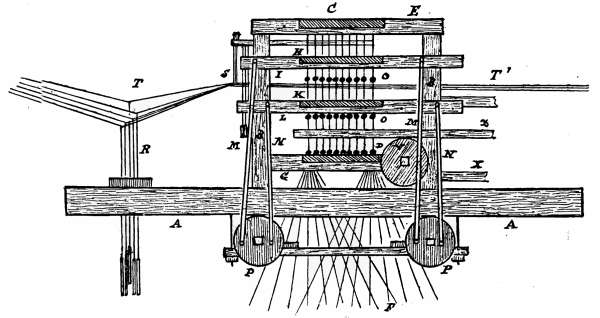

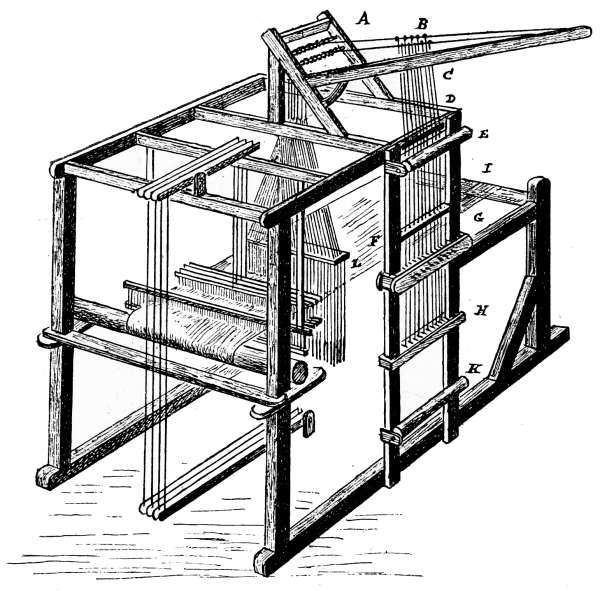

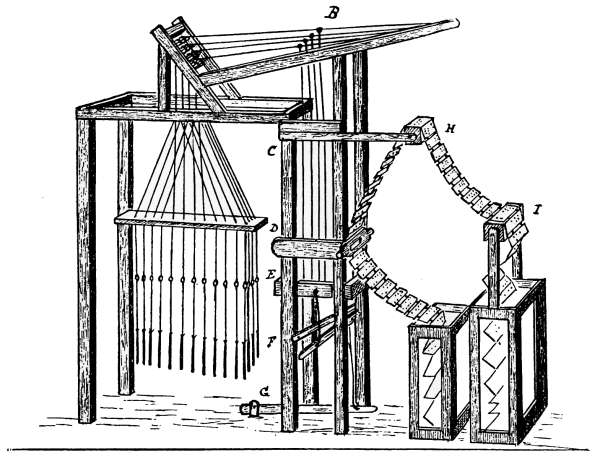

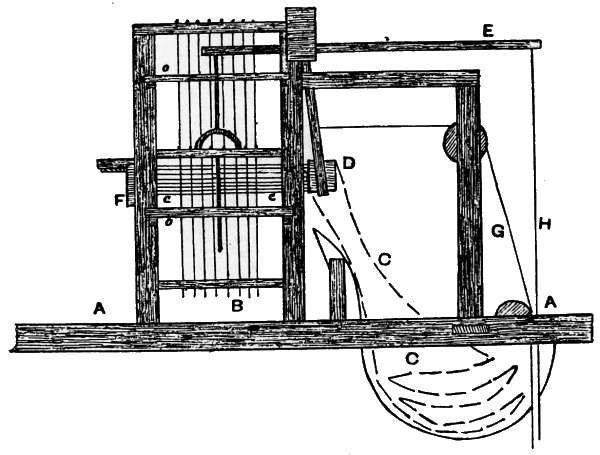

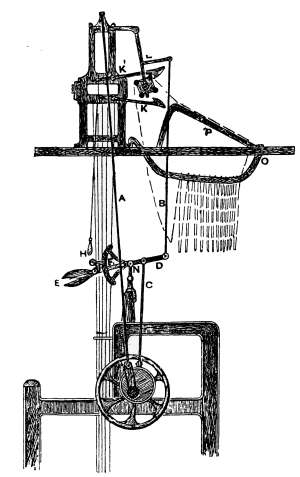

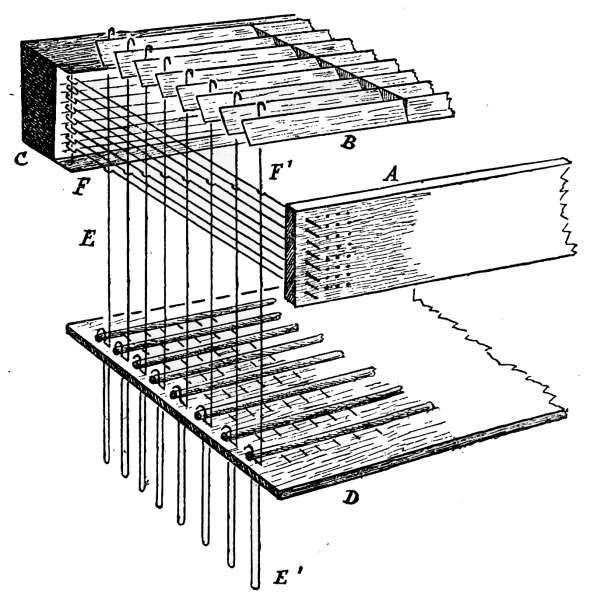

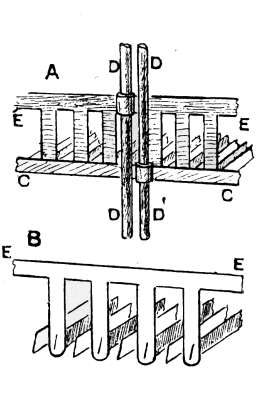

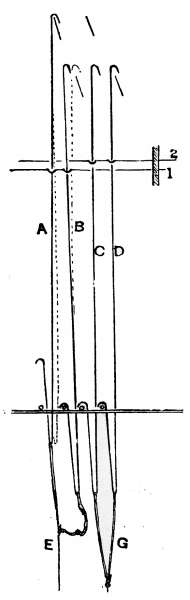

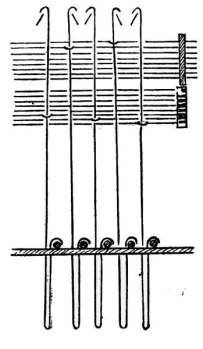

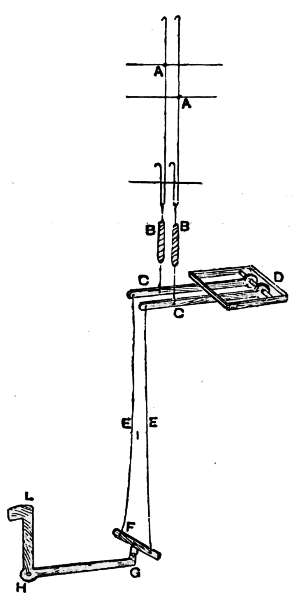

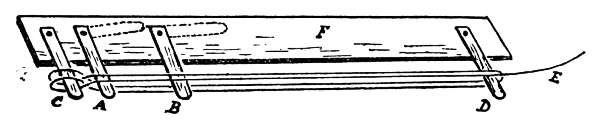

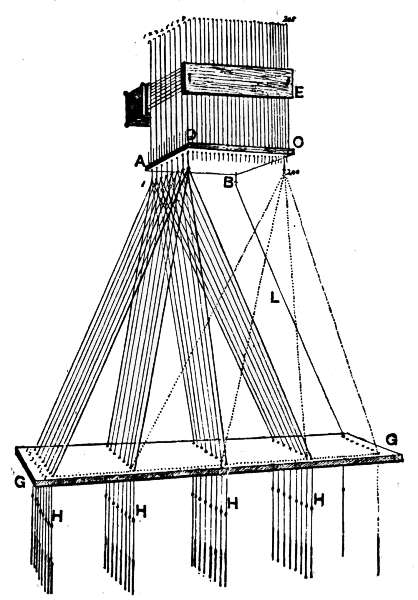

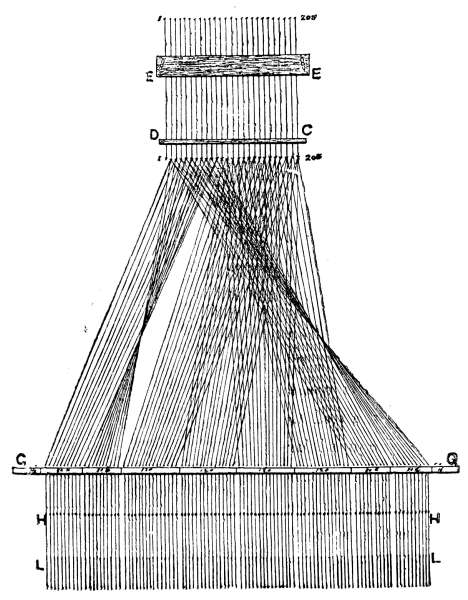

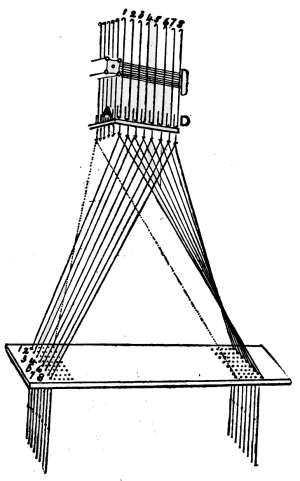

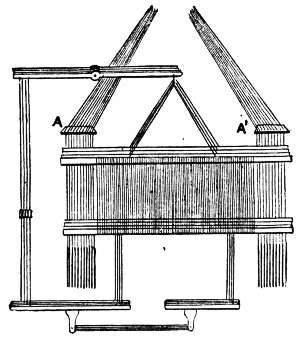

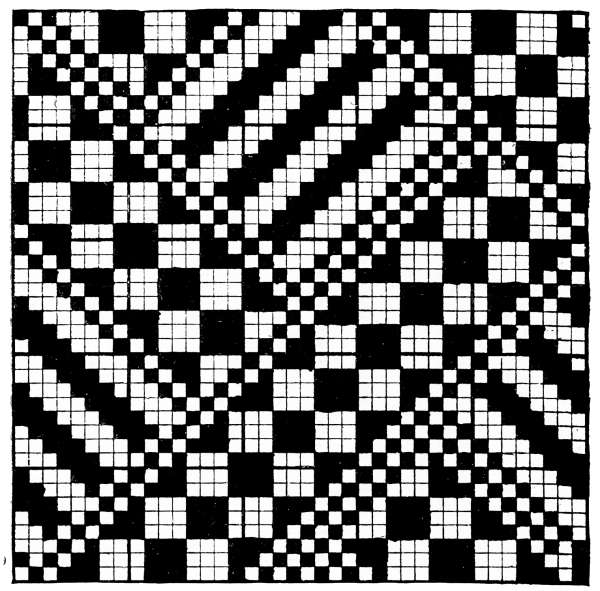

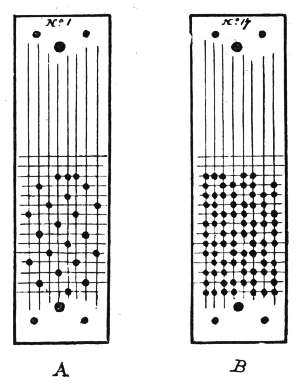

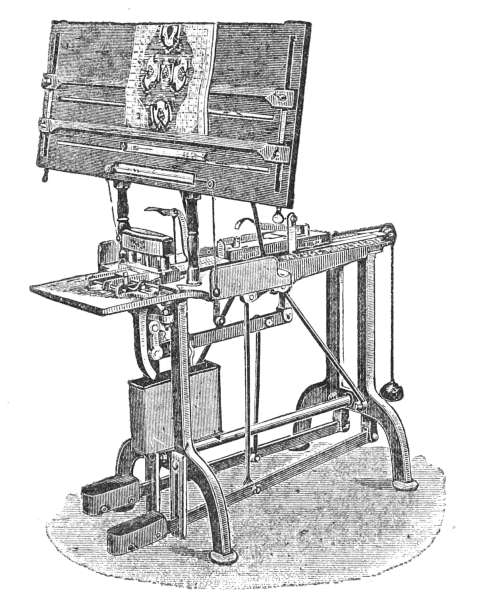

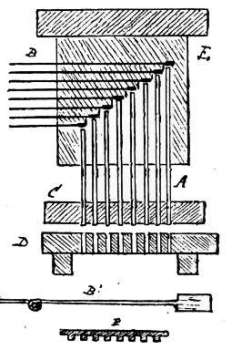

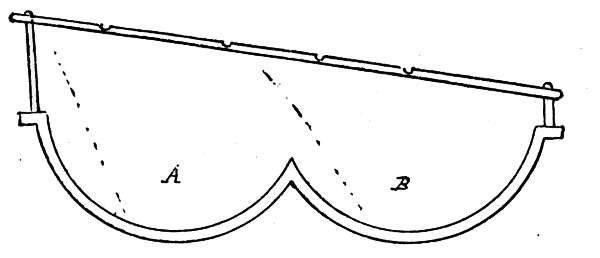

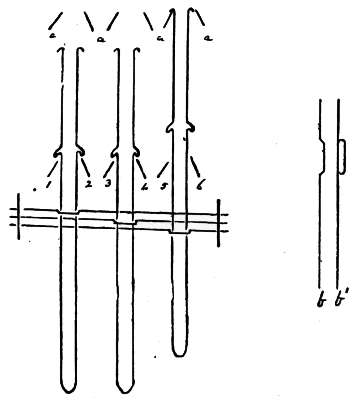

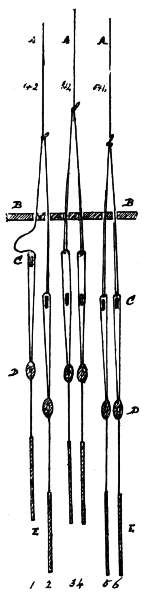

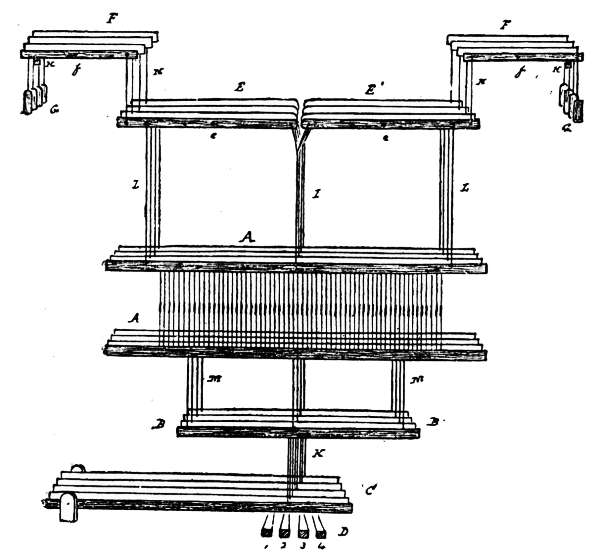

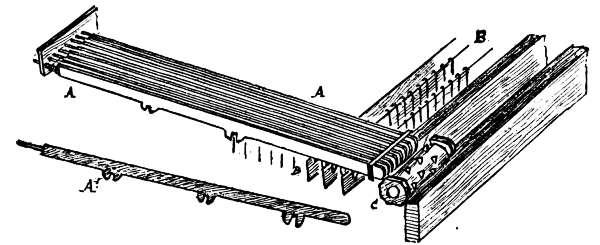

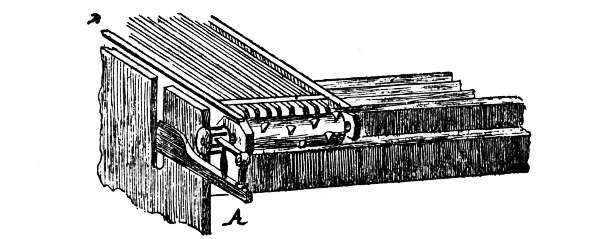

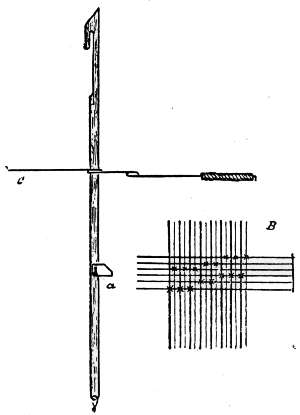

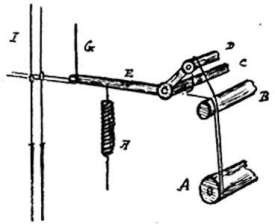

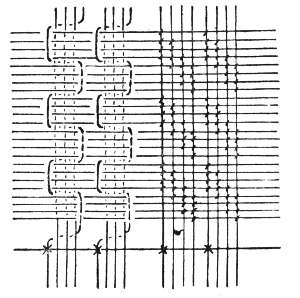

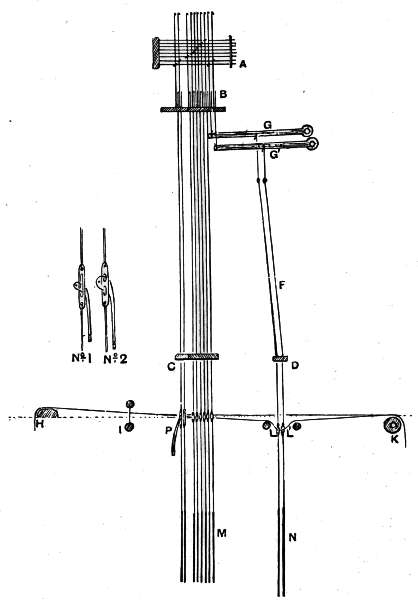

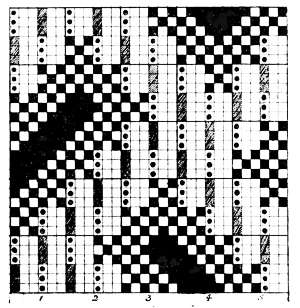

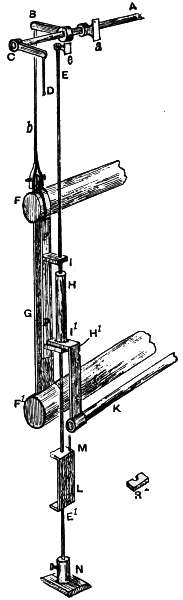

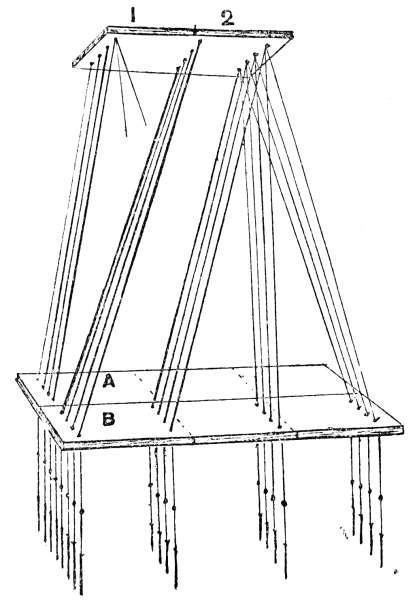

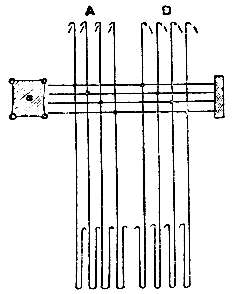

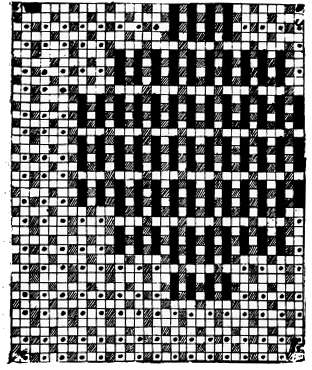

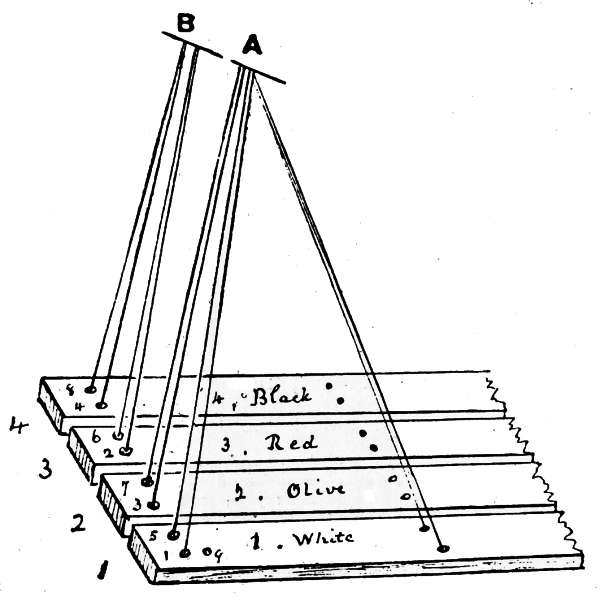

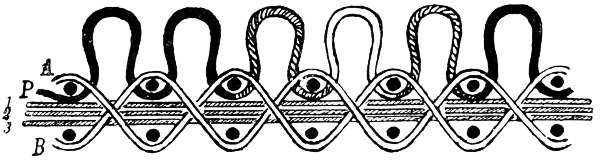

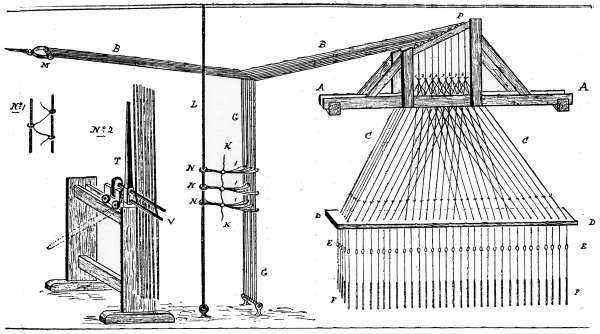

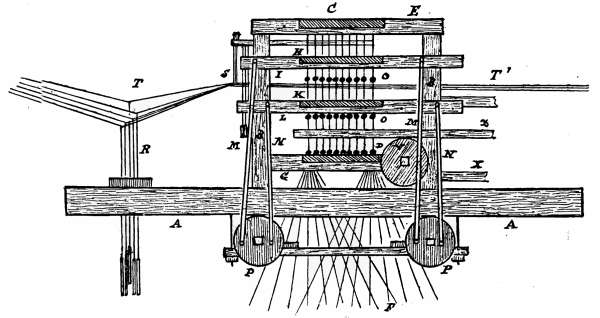

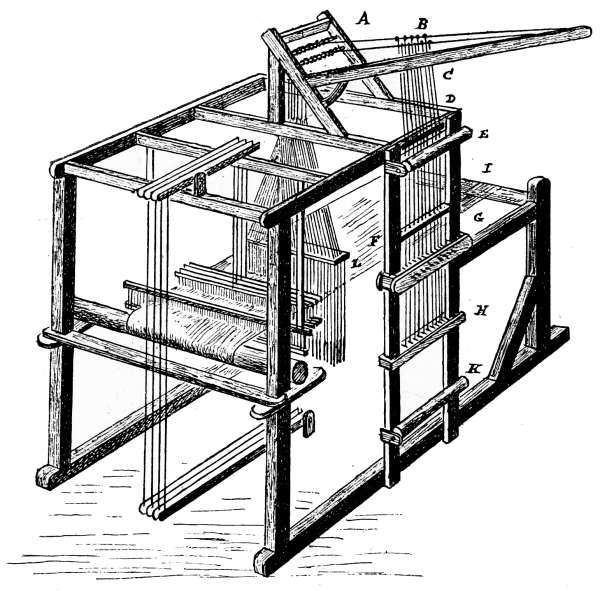

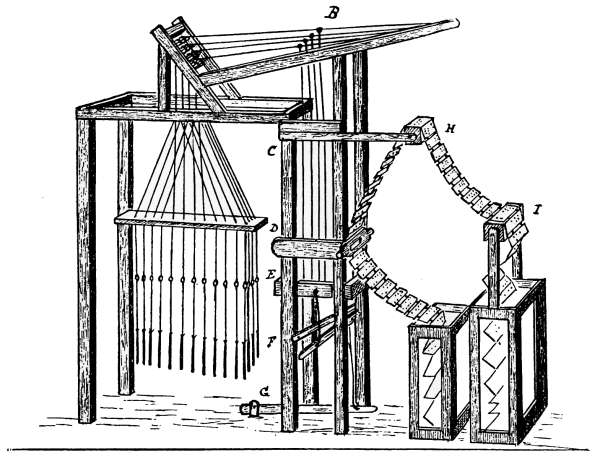

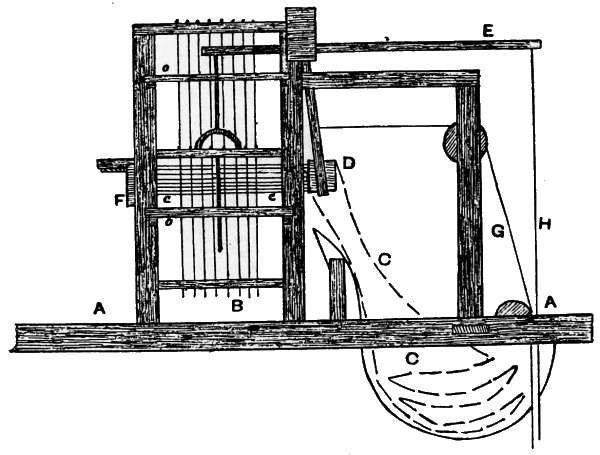

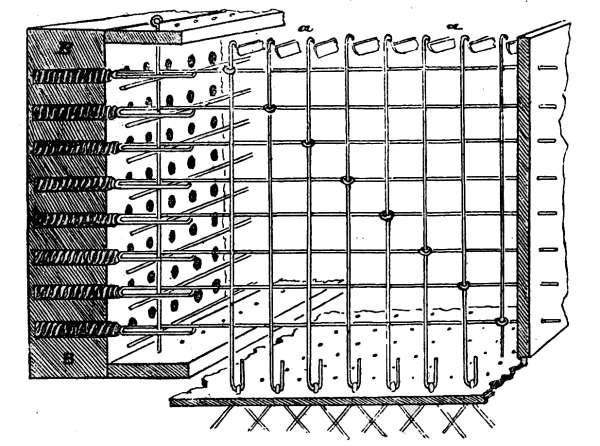

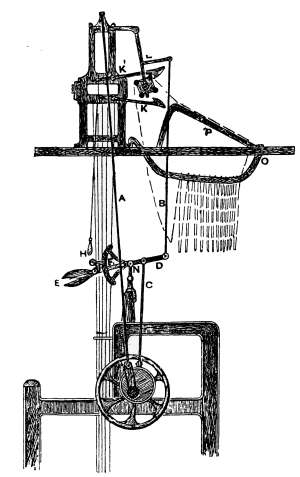

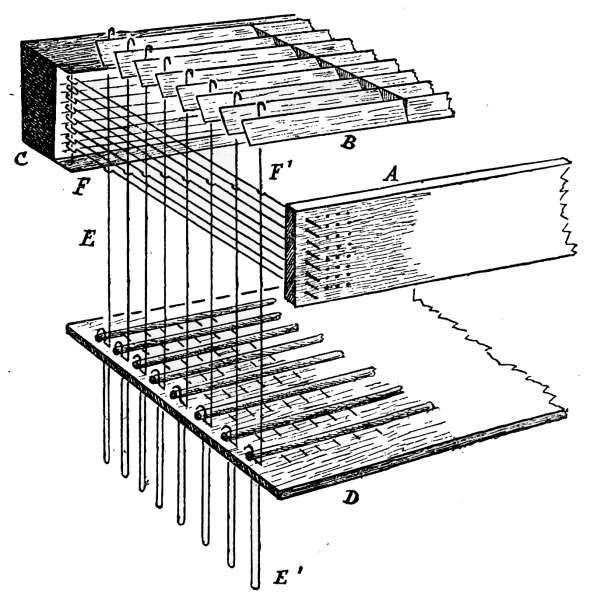

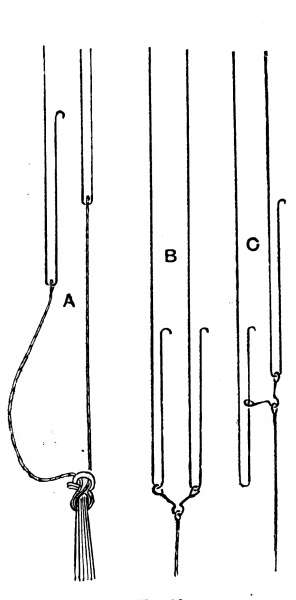

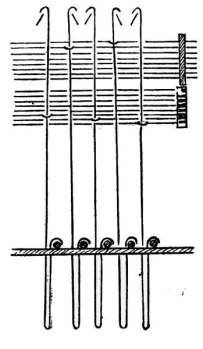

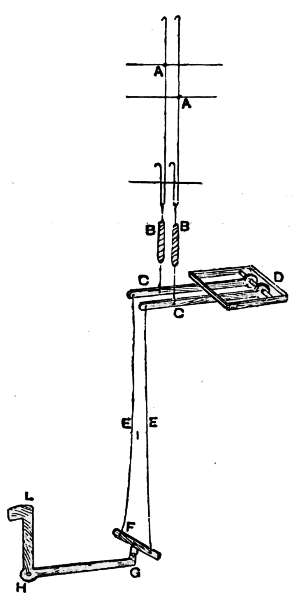

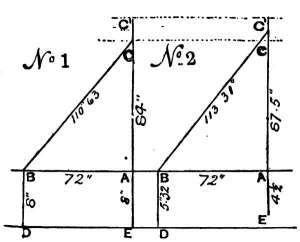

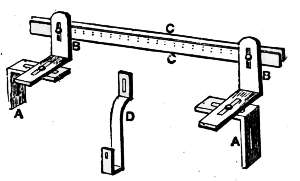

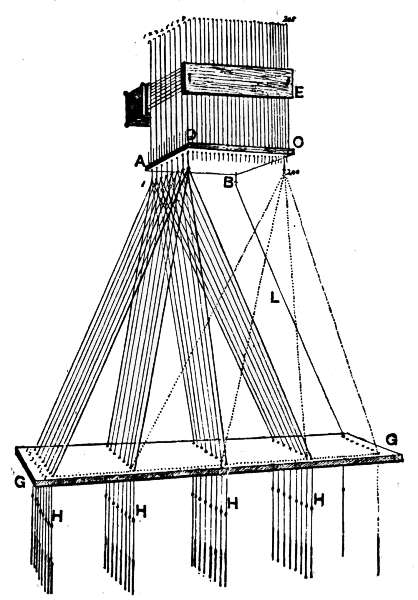

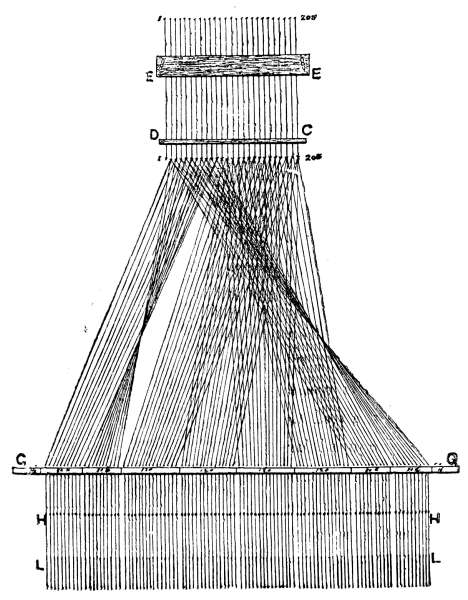

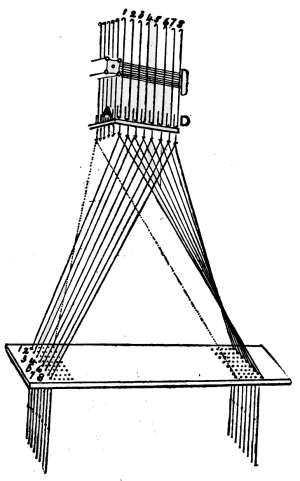

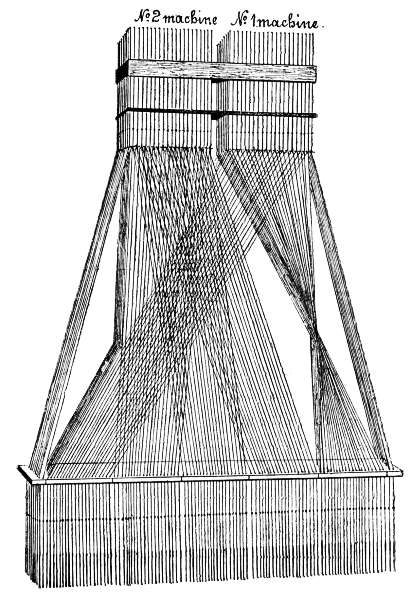

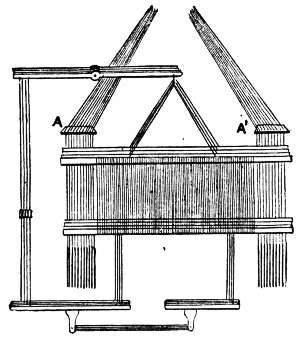

Fig. 3 gives the draw-loom harness; A, A is the carriage, or the

rails that support the harness, which rests on the capes or side rails

of the loom. Supported by the carriage is the pulley box P, which is

a frame fitted with small pulleys, and must be sloped at such an angle

as will allow the tail cords to sink when opening the sheds without

obstructing the pulleys underneath them. The neck twines extend

from the figures 1 to 8 to the knots above the hole board D D. The

cords which connect the neck twines to the mails E, E are called

sleepers, and those which connect the mails with the leads F, F are

called hangers. The hole board is made of hardwood perforated with

holes, which run from front to back in diagonal rows from right to

left; it should be a little finer than the set of the reed, to allow for

empty holes that are sometimes caused by the tie of the harness ending

with broken rows of hooks in some or all of the repeats. In Scotland,[8]

for this reason, when the reed is set on 37 in., the cumber board, or

hole board, is set on 36 in.

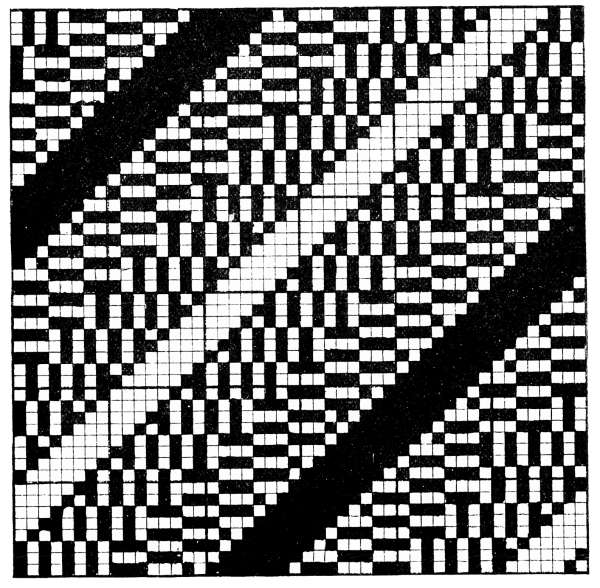

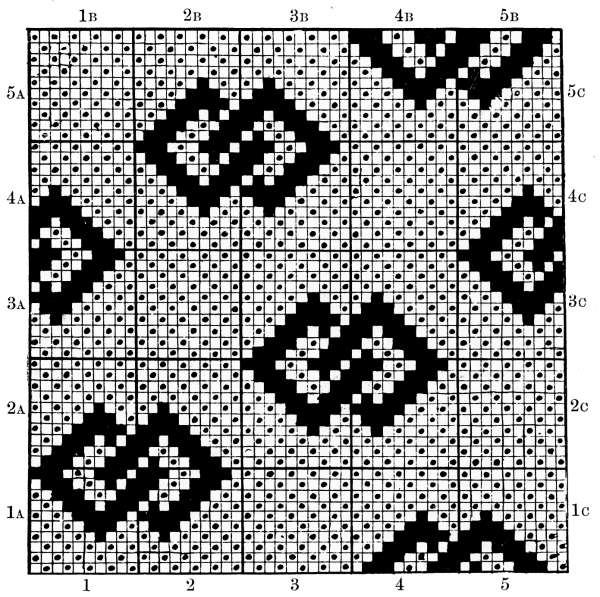

Fig. 3

B, B are the tail cords, attached to the neck of the harness at one

end, and at the other end all of them are fastened to the tail stick M,

by means of which they are secured to the roof of the house. There

must be a tail cord for each part of the harness; here only eight are

shown for the front row of the harness, and if there were eights rows

of harness in the hole board, 64 tail cords would be required, and the

complete harness would be made up of several repetitions of the 64

neck twines; four of these repetitions are here given for the first row

of the hole board. Of course there might be 400 to 600 tail cords in a

full mounting.

From each tail cord descends a vertical cord to the ground, as

shown at G, G. These are the simple cords, which, taken collectively, are

termed the ‘Simple.’ It is on these cords that the pattern is read, or,

rather, tied up. The simple cords are gathered together, according to

the pattern, by passing twines round them and forming the twines

into lashes or leashes, as shown at I, I. Heads of stronger cord, to

which the lashes are attached, are shown at N, N. The leashes or

lashes are made of cotton yarn No. 48, from six to eighteen plies of

which are moderately twisted together so that the twine will not curl;

the heavy twine is used for coarse work, where only a small number of

lashes is necessary. The length of the lashes is from 8 to 12 in.,

according to the breadth of the simple. The heads are about 4-1/2 in.

long, of good cord, as foot twine, which is used finer or coarser according

as more or less heads are required. The heads are made with a

noose on them that will run up or down on the gut cord L, which is a

strong cord, generally extending from the ground to the roof of the

house. K, K are the bridles connected with the lashes, and used to

draw them down in succession as they are wanted by the drawboy.

When there are a great number of lashes, two gut cords are used, as

shown at No. 1 (Fig. 3), and the lashes are looped alternately on each

and bridled accordingly. In coloured work, where three or four draws

are required for each weft line of the pattern—that is, one draw for

each colour—it is usual to have two gut cords with cross bridles from[9]

the one to the other which will slide up and down on them. On these,

cross bridles the heads of the lashes are fastened, about 1 in. apart, so

that the drawboy can take them in succession and draw the shed for

each colour.

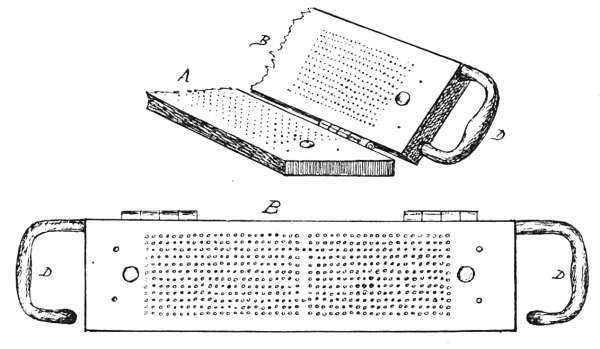

The method of preparing and mounting the draw-loom harness is

much the same as that now in use for jacquard harnesses, and, as it is

entirely out of use, it is unnecessary to describe it.

In order to make the neck twines draw evenly, rollers are placed

between each set of cords at the points 1, 2, 3, &c.; these rollers keep

the cords straight and make them all rise the same height at the mails,

which they would not do unless they all sloped to the hole board at

the same angle.

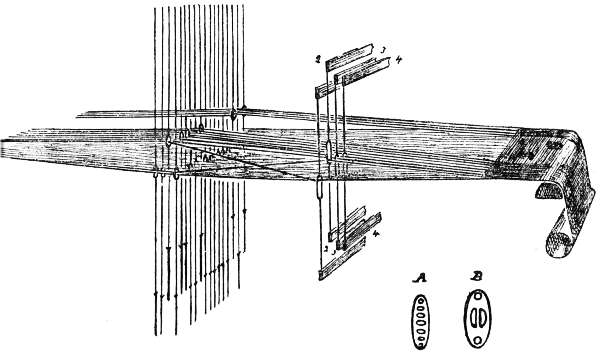

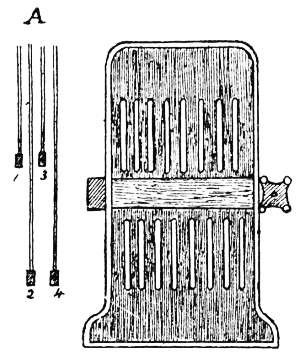

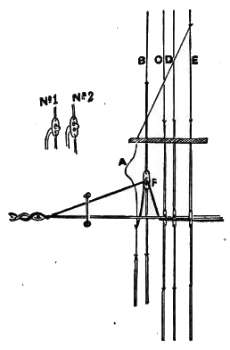

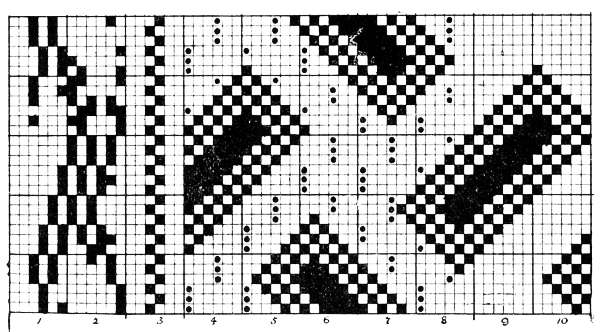

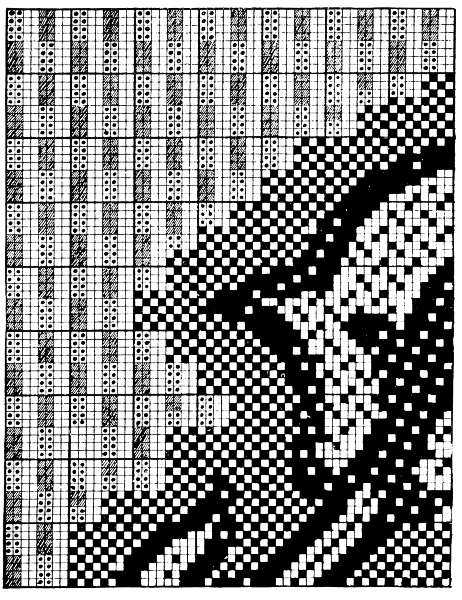

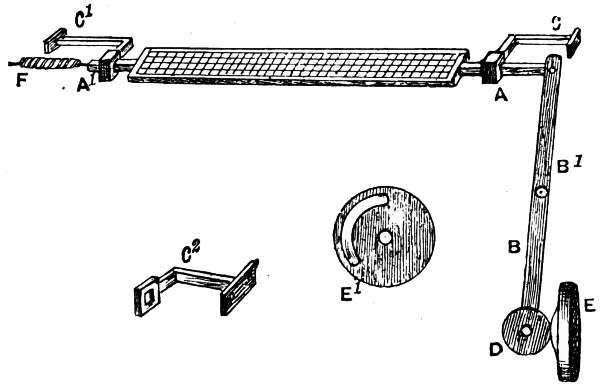

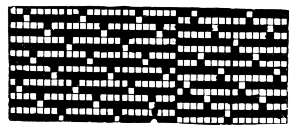

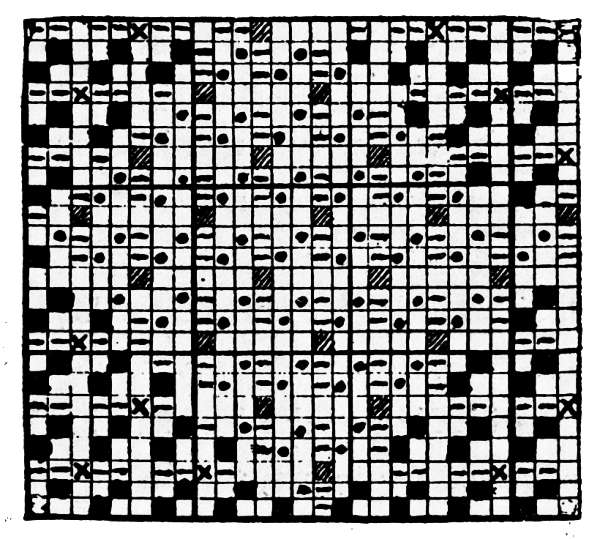

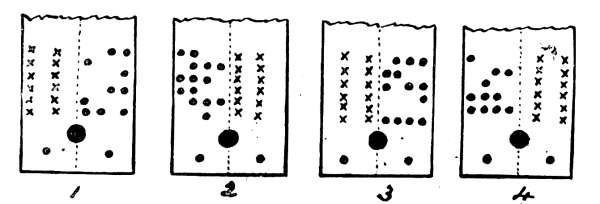

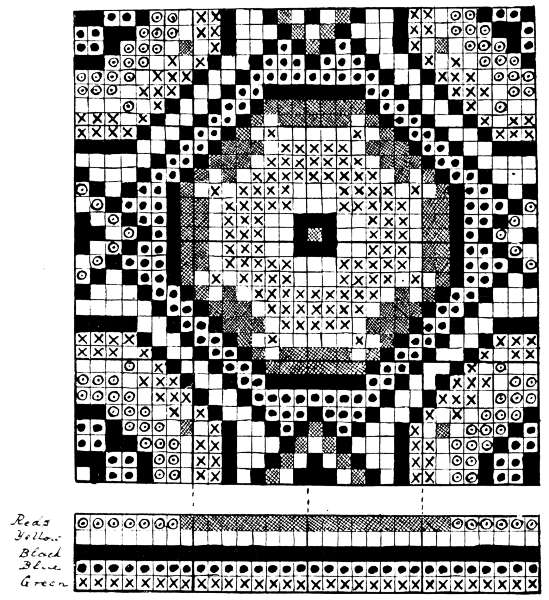

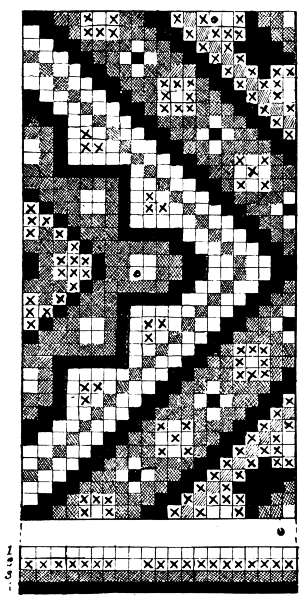

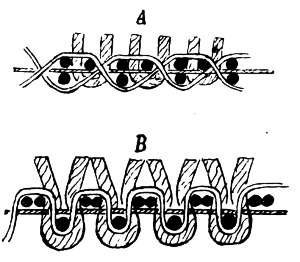

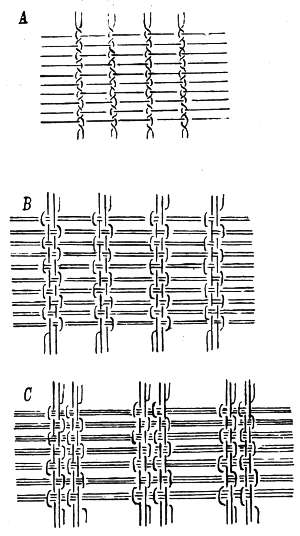

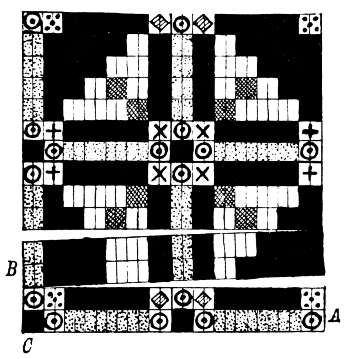

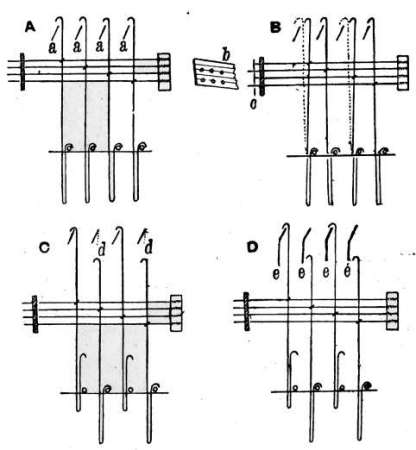

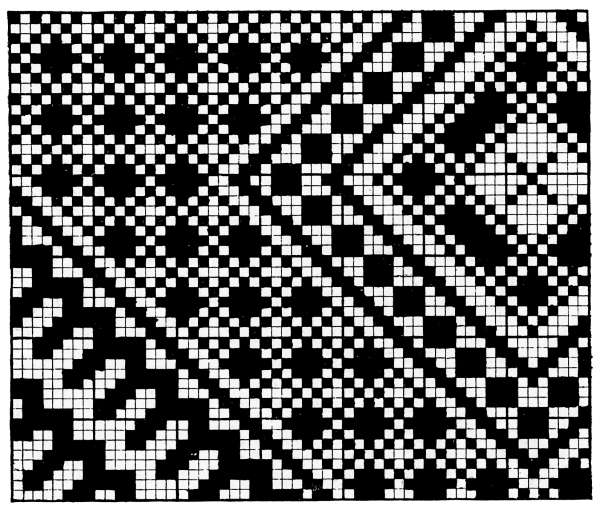

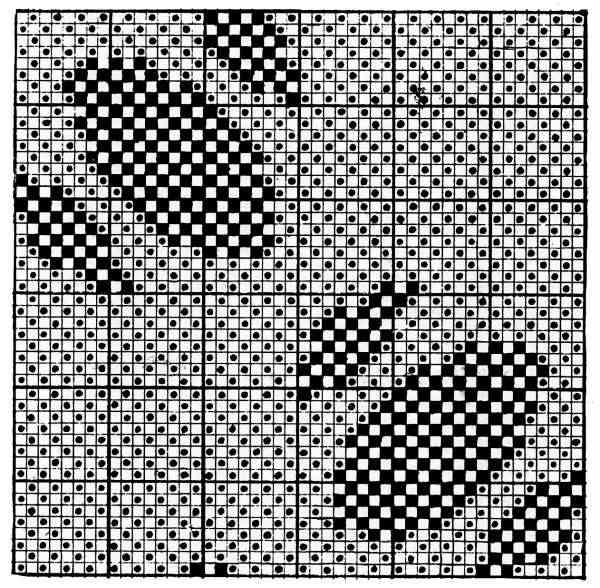

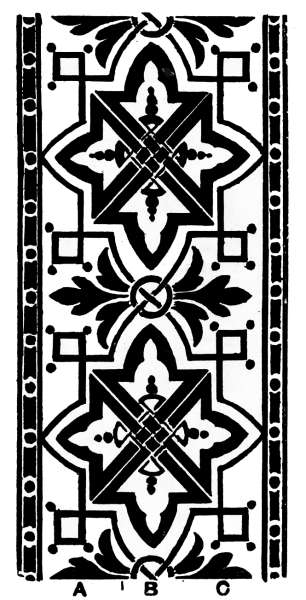

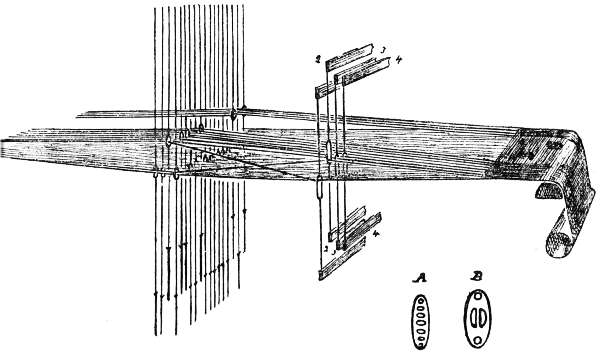

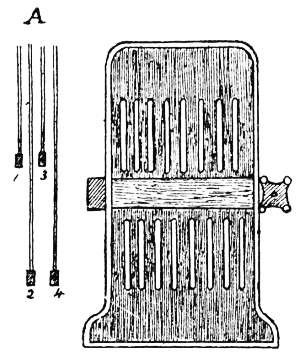

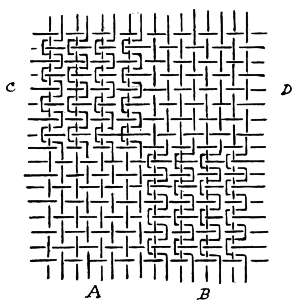

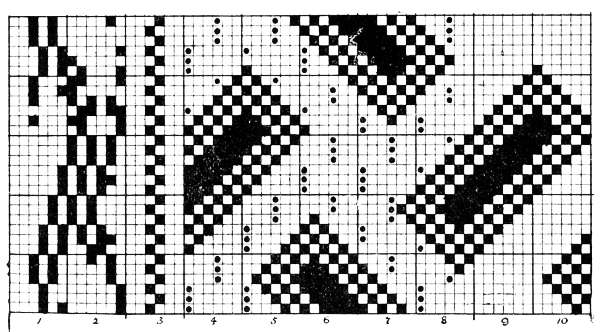

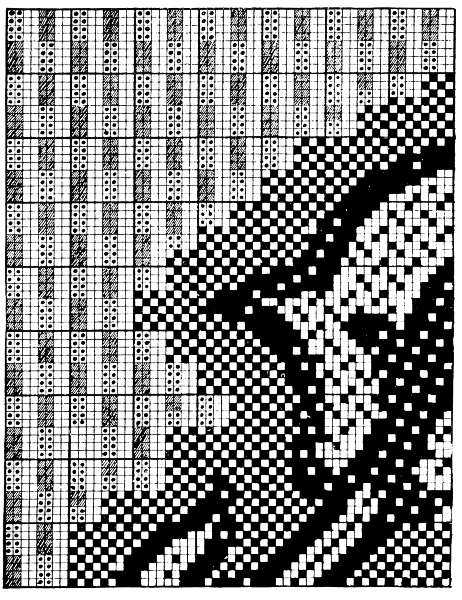

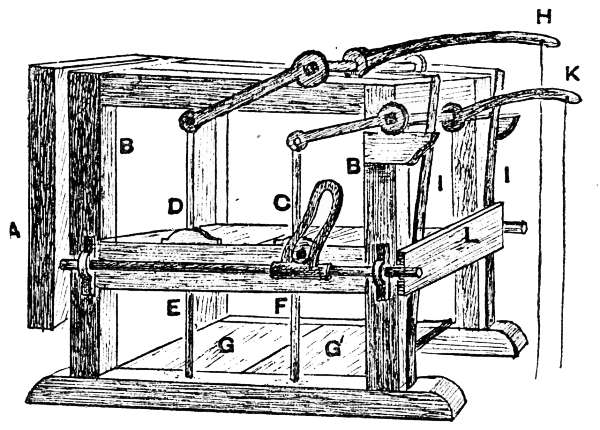

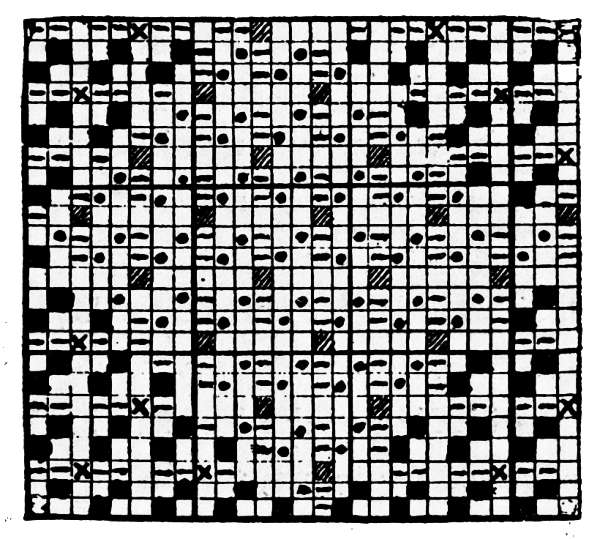

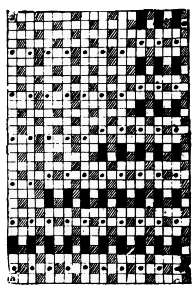

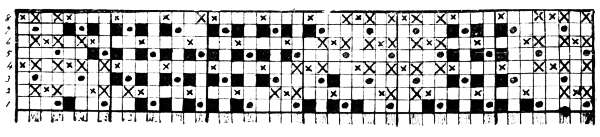

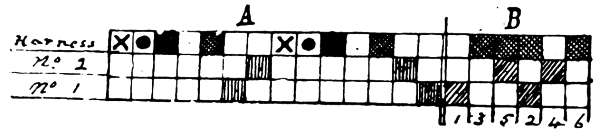

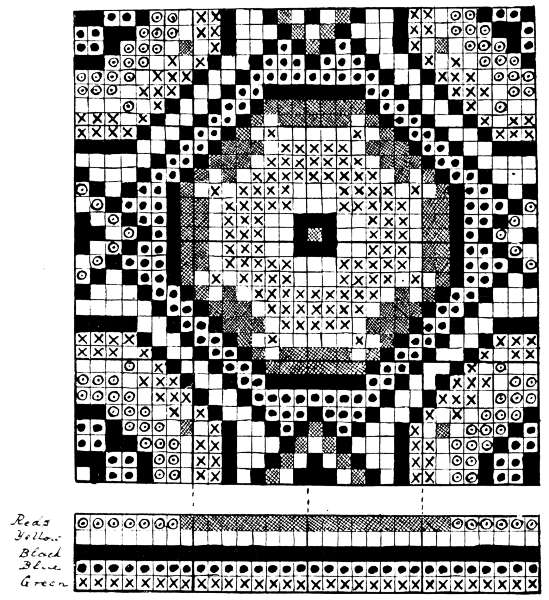

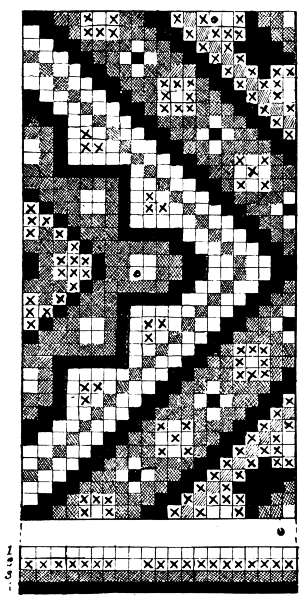

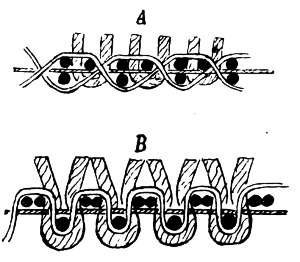

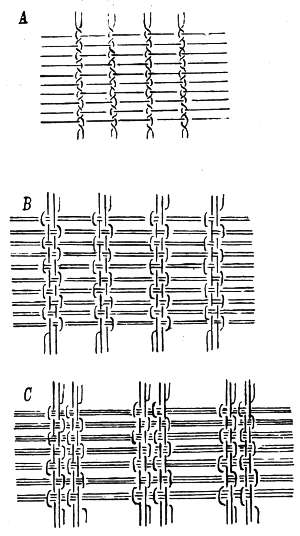

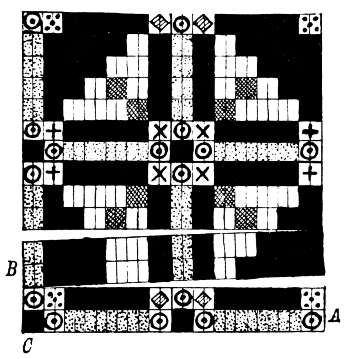

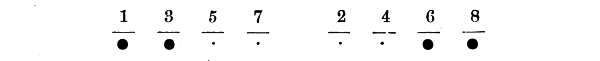

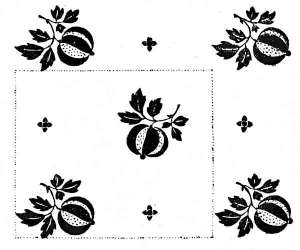

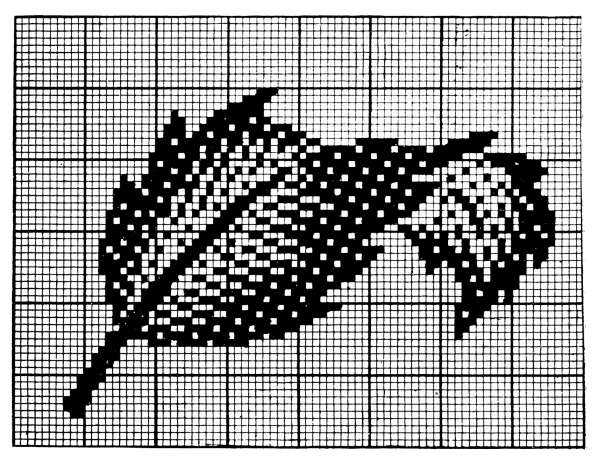

READING OR LASHING THE PATTERN

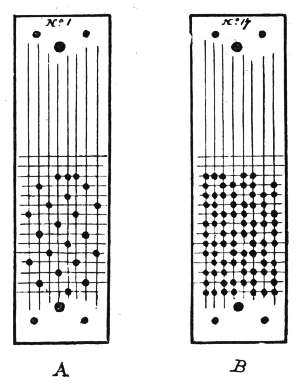

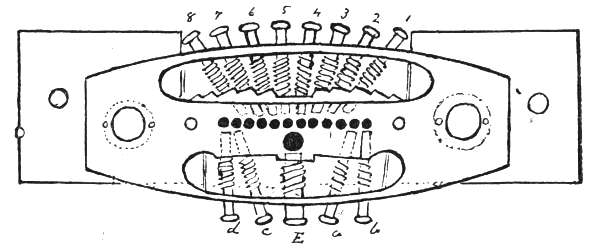

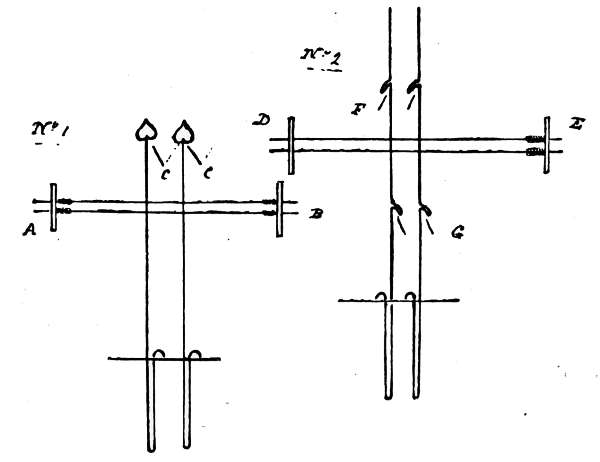

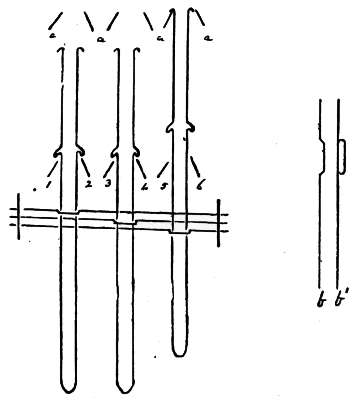

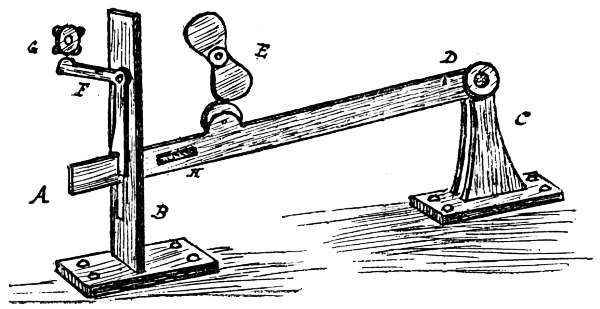

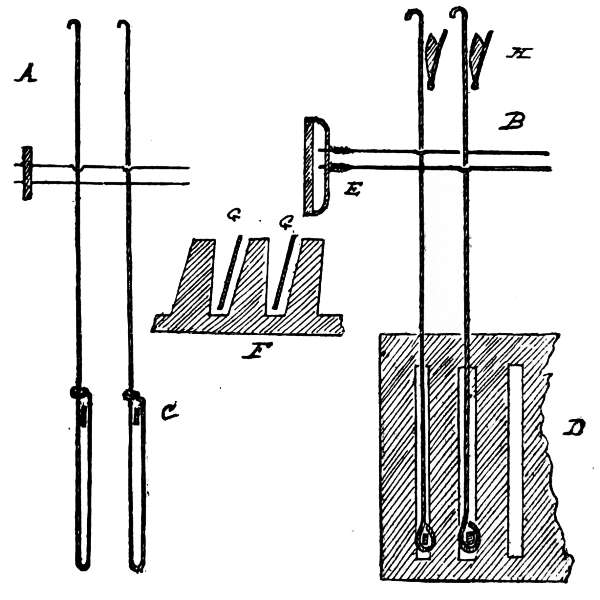

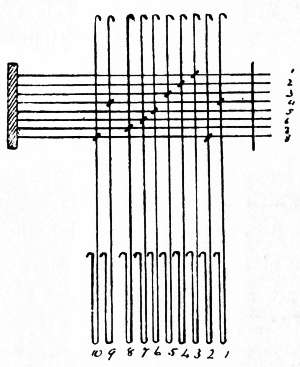

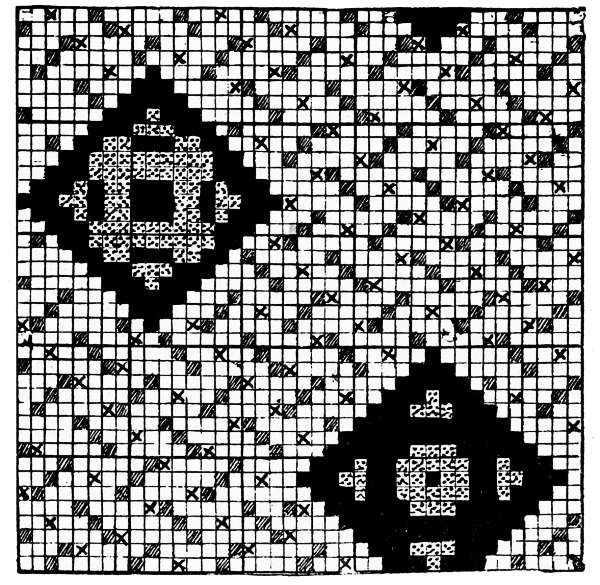

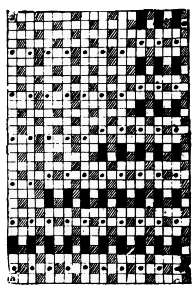

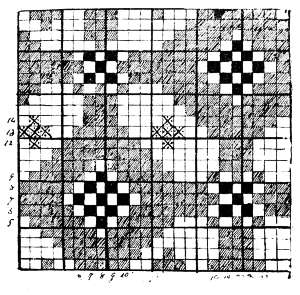

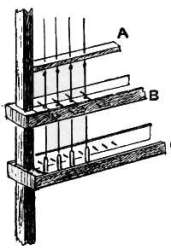

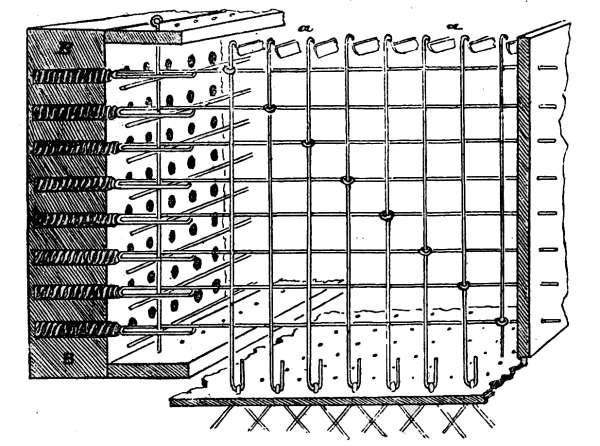

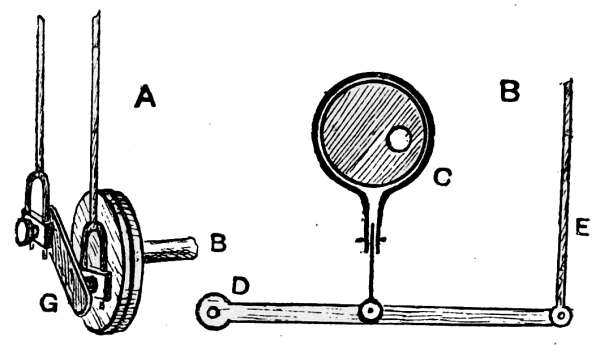

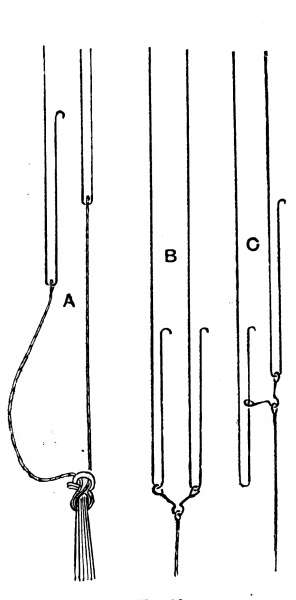

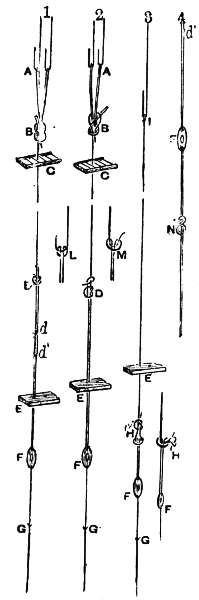

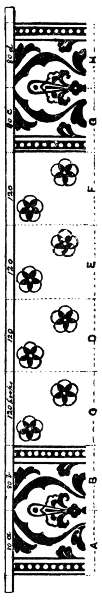

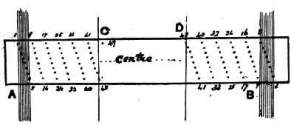

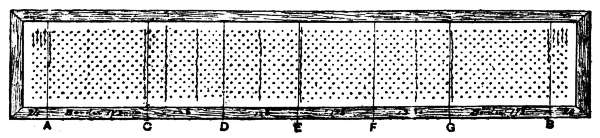

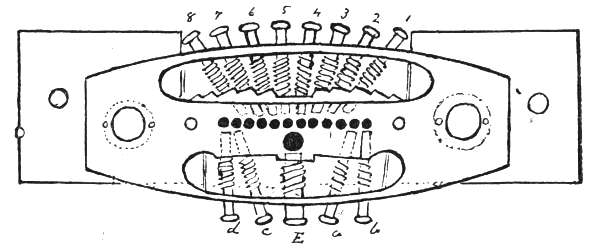

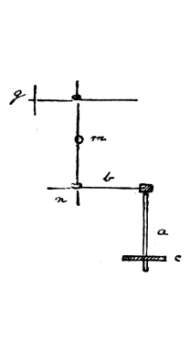

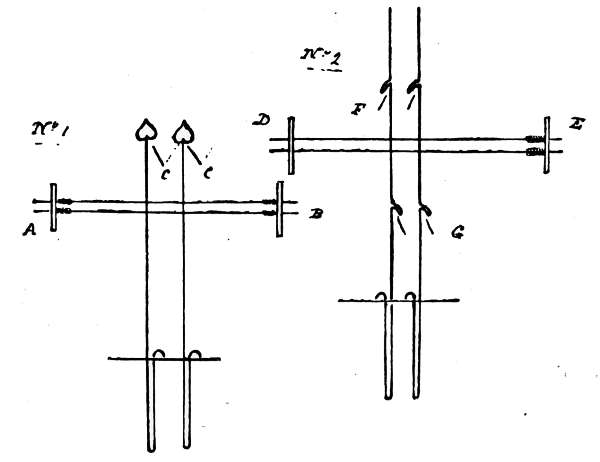

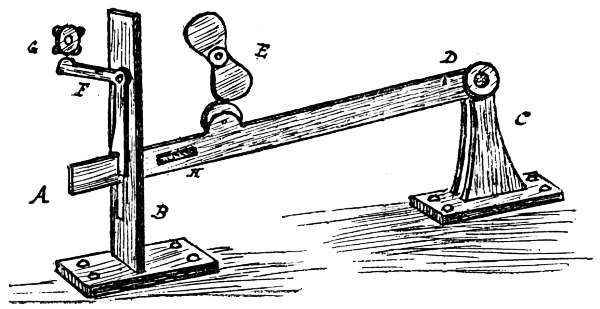

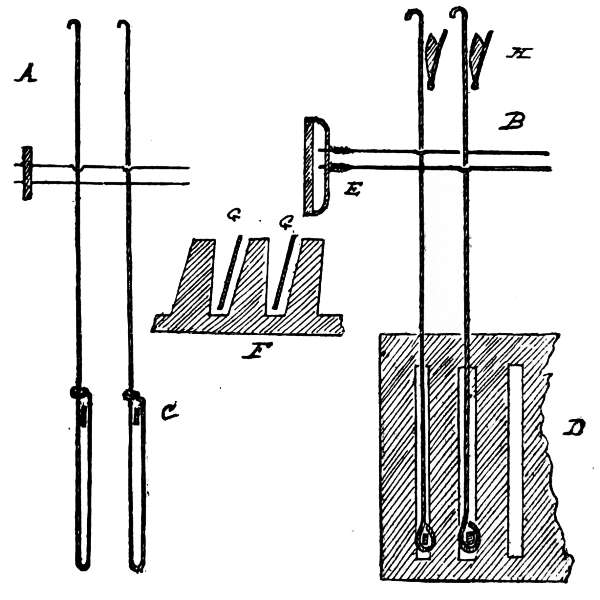

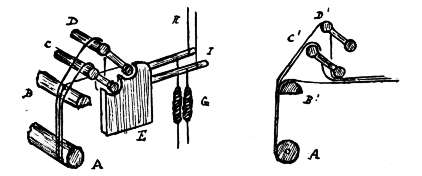

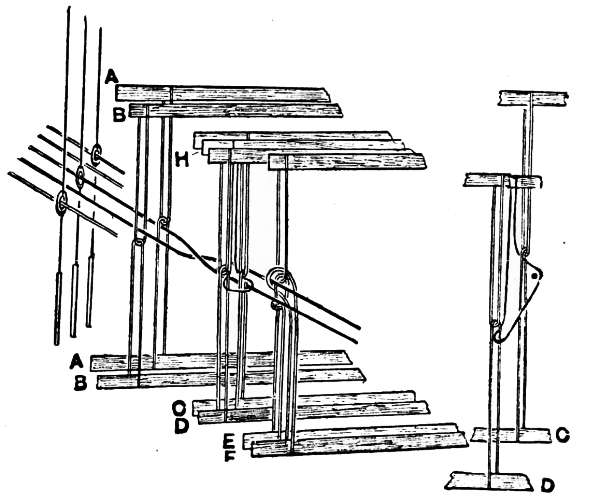

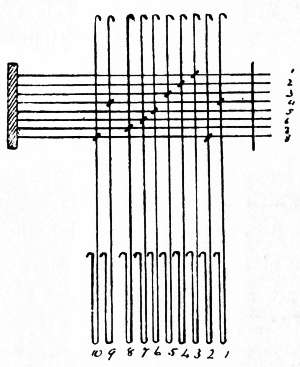

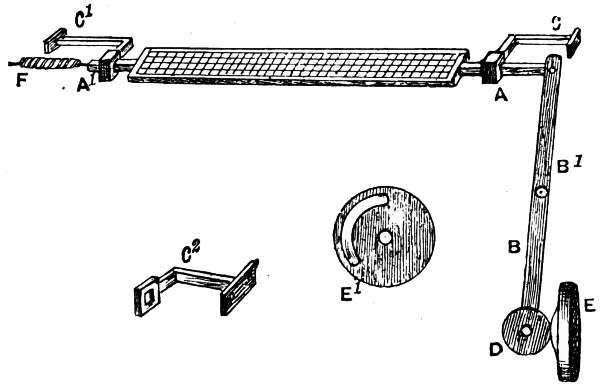

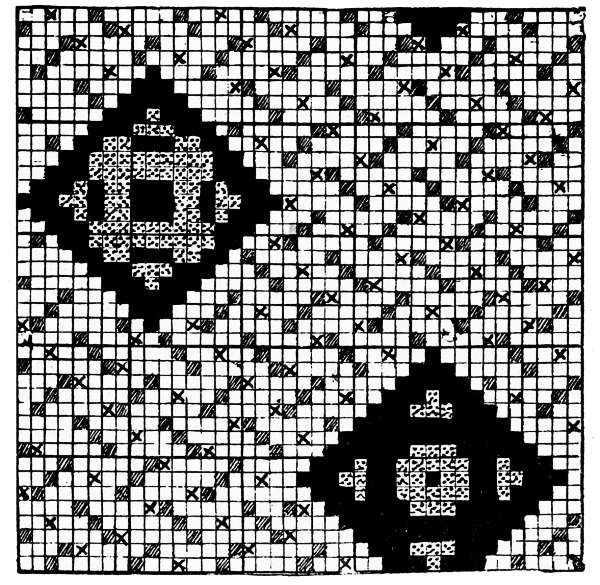

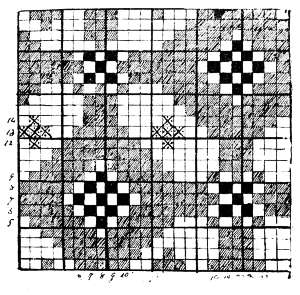

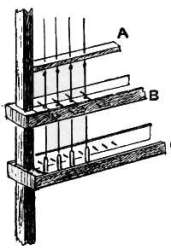

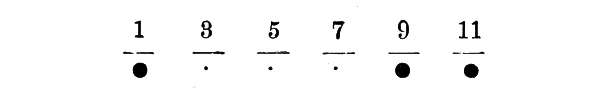

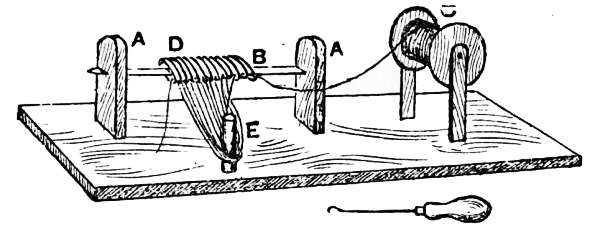

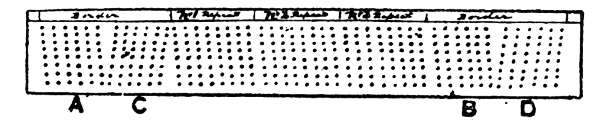

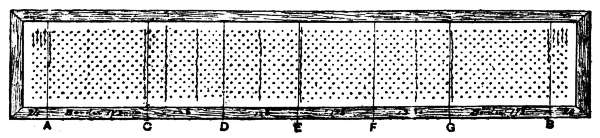

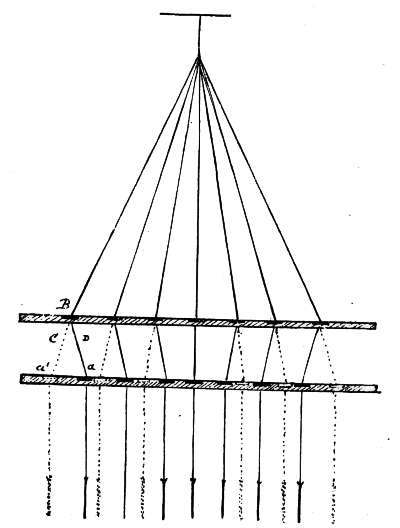

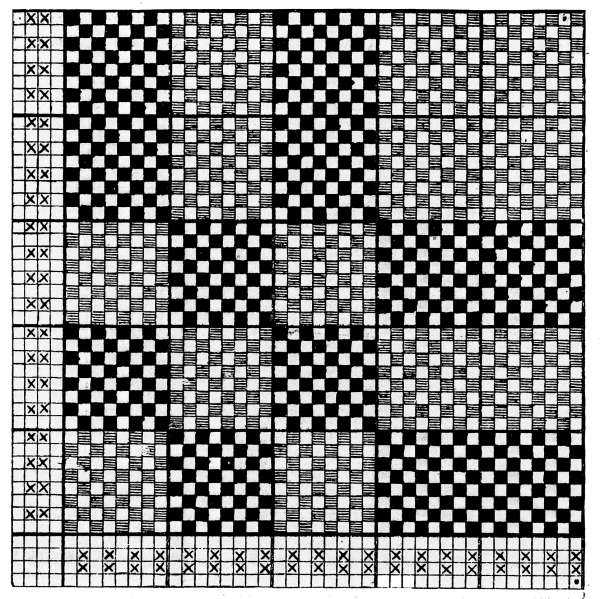

Fig. 4

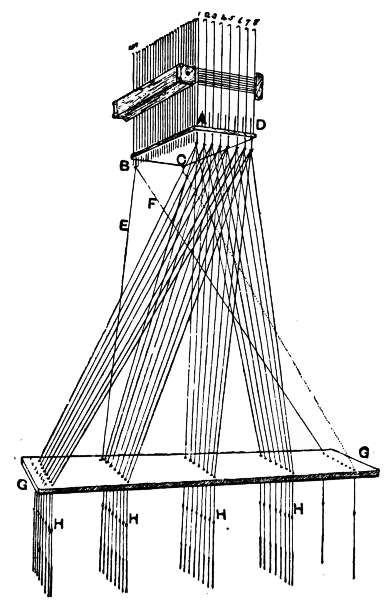

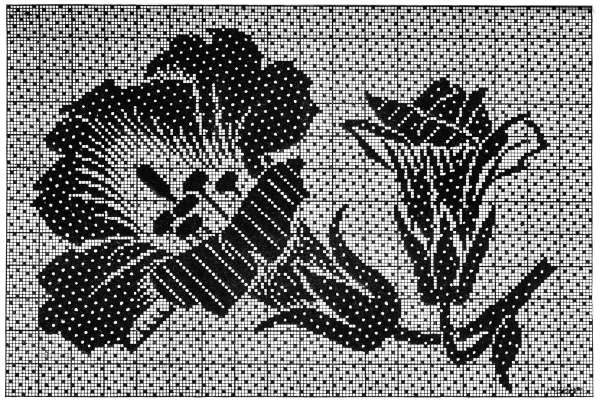

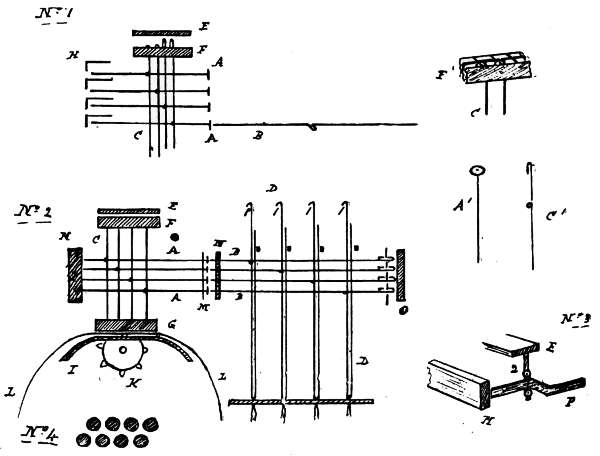

The pattern, painted on design paper, same as for pressure-harness

damask, is fixed upon a lashing frame, as shown in Fig. 4, and the

lower ends of the simples are passed over it and fastened to the crossbar

B. The simple cords are held in position over the design by the

comb C, C, which must be of such a fineness as to make each simple

cord stand directly opposite that space of the pattern to which it corresponds,

one simple cord being placed between each pair of teeth of

the comb. It will thus be seen that there must be a simple cord for

each vertical line on the pattern, or rather for each vertical space between

the black lines. In the same way, there must be a head of lashes

for each horizontal space, or line, as it is usually called, and which

would answer to a card for the jacquard or dobby. The straight-edge

E E is made so that it will slide up and down in the frame, to mark

the line on the design paper that is to be next read by the lasher. Now

refer to the line of the pattern above the straight-edge, and it will be

seen that the first square or check to the left is blank, and it is accordingly

passed over by the lasher; the second and third checks are

painted, and as the simple cords corresponding to them have to be

drawn to form the pattern, the lasher twists one end of his lash over

the pin G, and takes a turn of it round the second and third simples,[10]

again passing it round the pin G. The fourth check, being blank, is

passed over, and a turn or tack of the lash twine is taken round the

fifth, sixth, and seventh simples, as the checks on the design paper

opposite these are painted. The reading and lashing proceeds in this

way till the line is finished, as shown in the figure; then the two ends

of the lash twine are tied together round the pin G, which is then taken

out, and the loop made round it by the lash twine is twisted round

and formed into a snitch for the purpose of fastening it to the head.

The lash is now pushed down behind the board H, to make room

for another; the straight-edge is then shifted to the next line, and the

lashing proceeded with as before. If too many painted squares of the

design paper come together, all the simple cords corresponding to them

must not be looped or lashed together, but can be taken in two or more[11]

loops or tacks, never taking more than six or seven simple cords into

one tack of the lash twine.

It will be observed that the board H is rounded at the back;

this is for the purpose of having all the simples at an equal distance

from the pin G when they are tacked up by the lash twine, and consequently

a more regular shed will be produced when they are drawn in

the process of weaving.

The method of fastening the head to the lash is to loop the cord

for the head, which should be double, round the gut cord, then knot

the two ends of it together, and take this knot through the snitch formed

on the end of the lash, and when the snitch is drawn tight the knot

prevents the head from slipping out.

In weaving with the draw loom two persons are required—the

weaver, who works over the ground treadles, throws the shuttle, beats

up the weft, &c.; and the drawboy, who takes the lashes in succession

as he draws them down by the bridle, and by pulling out the simples

raises the harness and holds it in this position till the weaver has

worked as many shots as are required to be given to each draught.

When some thousands of twines were required for the harness, and

with a simple of three or four hundred cords, the weight and friction

made it very severe work for the drawboy. To assist him a fork, as

shown at V, No. 2, Fig. 3, was used. It was made to run to and fro

on a carriage, so that when the simples were drawn forward by the

lashes, one spike of the fork could be run in behind those drawn forward,

while the other spike was in front of them. When the fork was depressed,

till the handle T came to the position shown by the dotted

lines, it drew down the simple cords, and they could easily be held in

that position till a change of draught was required.

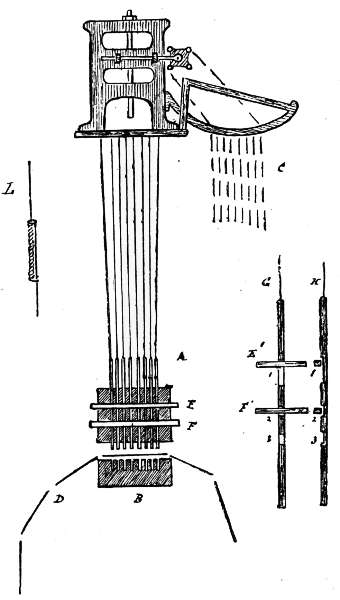

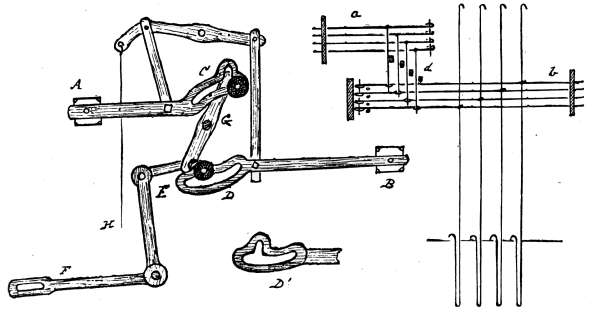

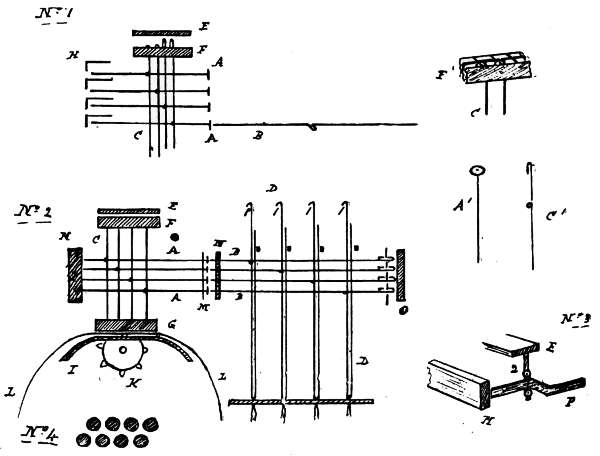

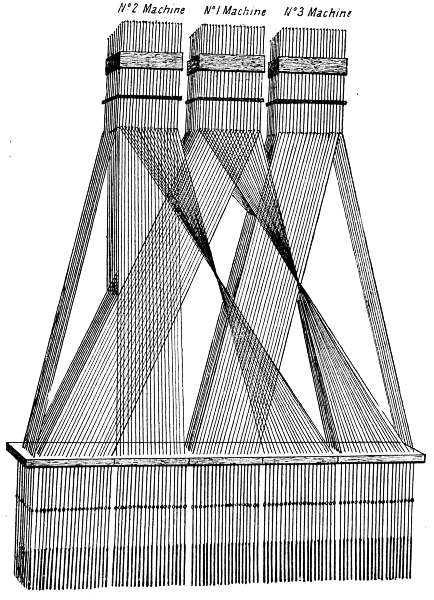

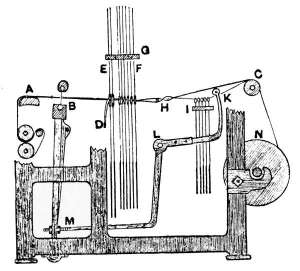

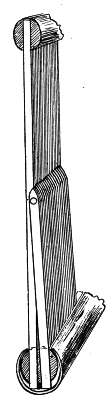

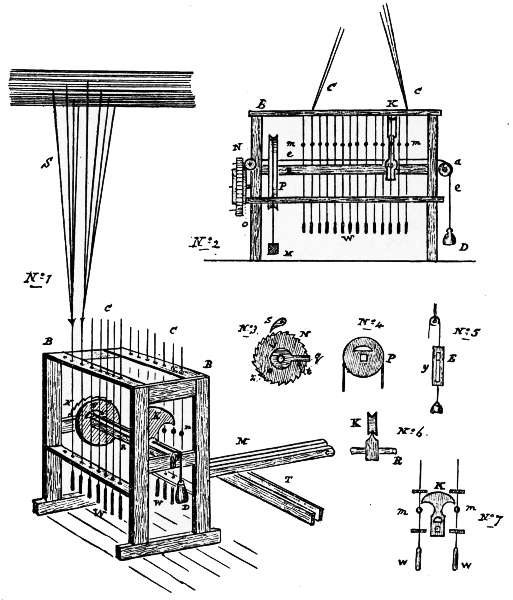

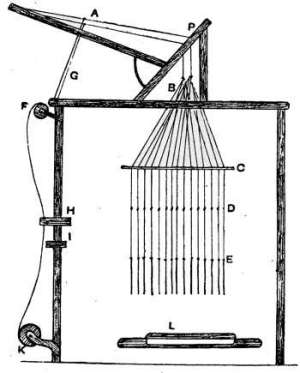

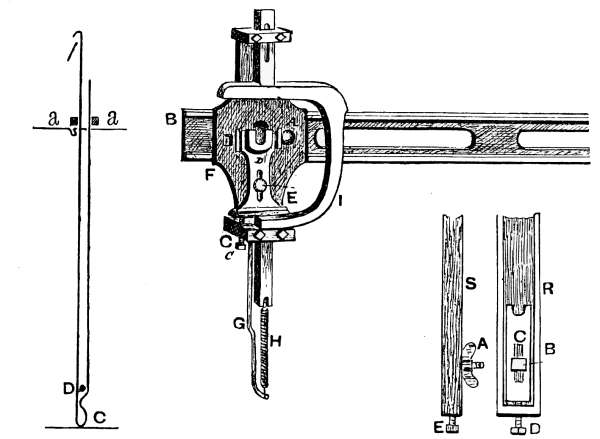

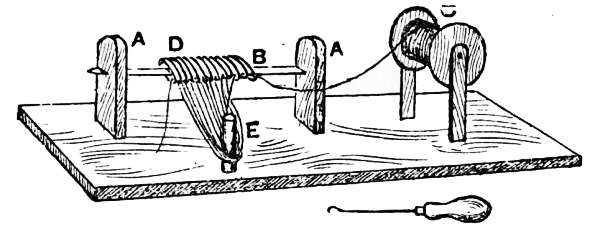

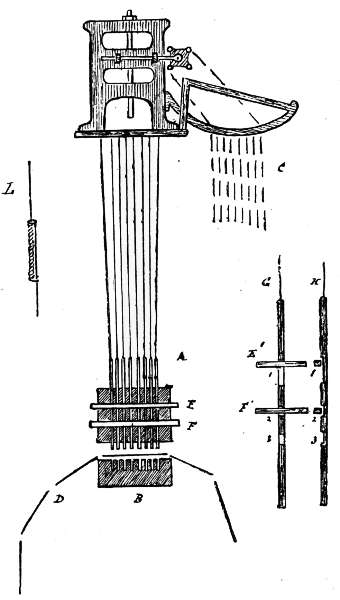

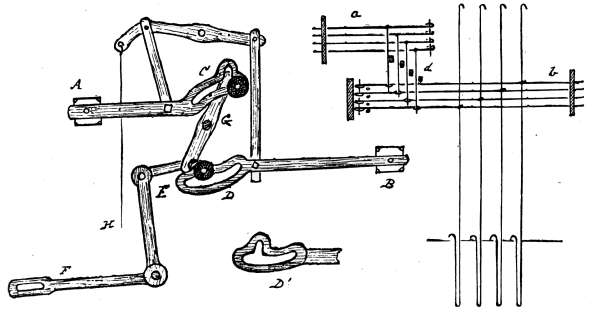

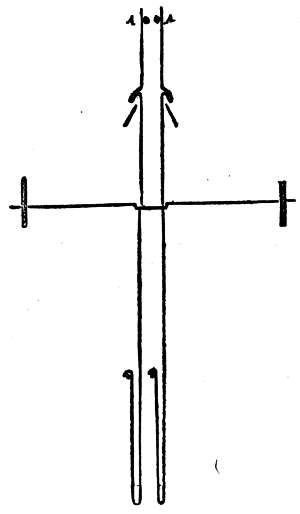

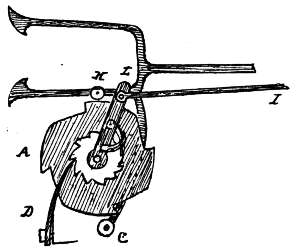

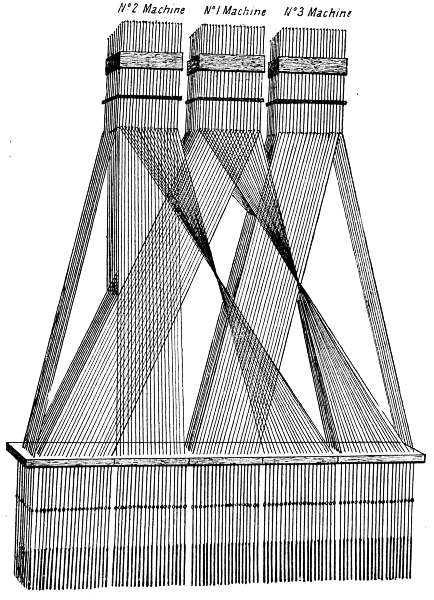

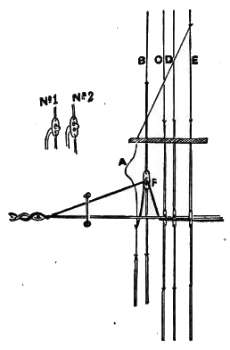

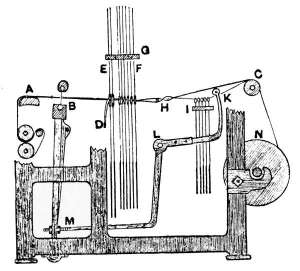

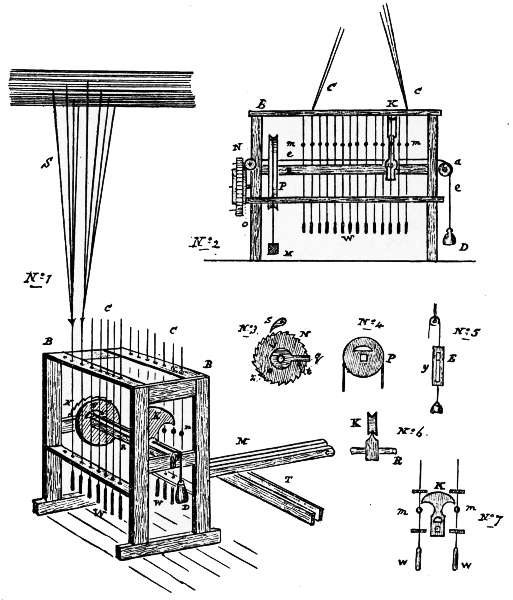

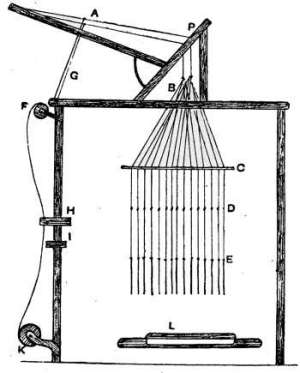

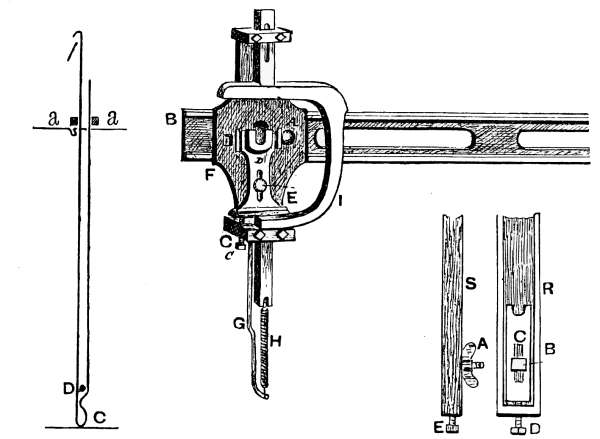

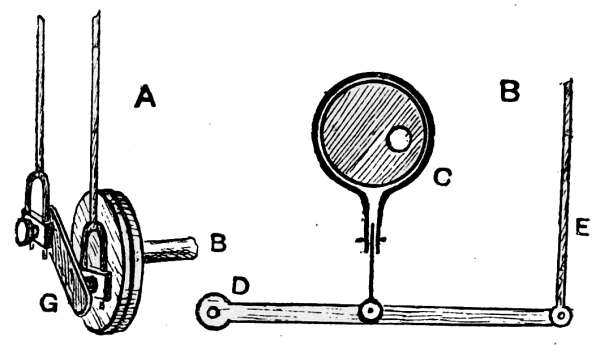

Fig. 5

When the mounting of the draw loom was very extensive, it was

necessary to employ from two to ten pulley-boxes and as many drawboys,

so that it is not surprising that many endeavours were made to

work without the aid of a drawboy. One of these machines, known

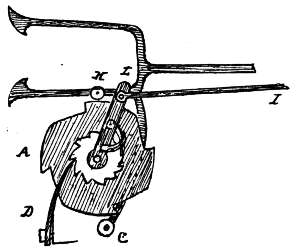

as the ‘Parrot’ or ‘Pecker,’ is shown in Fig. 5. It is wrought by the

treadles T, which are attached to the marches M, and these are connected

by the pulley P, on the rocking shaft R, by a cord which passes[12]

over and is fastened to it. When one of the treadles is pressed down

the pulley rocks and turns the shaft to one side, and when the other

treadle is pressed down the shaft will rock to the other side. The

parrot or pecker K is movable on the rocking shaft—that is, it can

slide along it—but it must rock from one side to the other with the

shaft. The cords C, C are passed through holes in the boards B, B, for

the purpose of keeping them in position, and they have knots or beads

on them at m, m, and weights, W, W, at their ends to keep them in[13]

tension. Fastened to the cords C, C is another set of cords, S, connected

with the tail cords of the draw-loom harness, and so corded or arranged

as to draw those tail cords required to be sunk to raise the harness to

form the pattern. As the shaft R is rocked from side to side by depressing

the treadles in succession, it carries with it the pecker K, and

the groove or notch at the point of the pecker, shown clearly in Nos. 2

and 6, coming into contact with the knots or beads on the cords,

draws them down alternately, first at one side of the machine and then

at the other, until the pecker, as it slides along the rocking shaft, has

passed over all the cords; it is then released and drawn back to its

original position by means of the weight D, attached to it by the cord e.

At the end of the rocking shaft is a ratchet wheel, N. The cord e passes

from the pecker through the segmental hole in the pulley P, as shown in

No. 4, and is fastened to a boss, O, on the inner side of the ratchet

wheel. This wheel receives its motion from a catch, as shown at E,

No. 5, which is simply a pin fixed in a slotted piece of wood. The pin

y forms the catch, and the slot acts as a guide, which passes over the

edge of the ratchet wheel, and keeps the catch in position. The catch

is attached to the marches and works vertically. It is raised by the

treadles, and when released is drawn down by the weight attached to

it, the wire y catching one of the teeth of the ratchet and moving it

round. There are two pins, z and t, in the ratchet, as shown in No. 3,

and it is according to their distance apart that the length of traverse

of the pecker is determined. The bar q, shown in No. 3 attached to

the pulley V, which is loose on the axle, is raised by the stud t, as the

ratchet wheel is advanced tooth by tooth, till it comes into contact

with the catch S, and raises it; this allows the ratchet wheel to be

reversed by the weight D on the end of the cord e till the stud z comes

round and draws away the bar, which allows the catch to fall into

position again and stops the pecker where the pattern is to begin.

Thus, the distance between the studs z and t must be arranged to suit

the number of cords the pecker has to pass, or to give the number of

threads in the pattern. The teeth of the ratchet wheel and traverse of

the catch must be of such a pitch that as each tooth is moved round

the pulley will be turned the exact distance required to move the[14]

pecker from one cord to the next one. No. 2, Fig. 5, is an elevation of

a ‘parrot’ arranged for a single row of cords, as these machines were

first made. There was only one treadle, as shown in section at M, No.

2, and the pecker only rocked to one side. Either this or the double

machine could be used for a shaft mounting where a large number of

treads are necessary. The cords C pass over pulleys, and are fastened

to long coupers or levers with their fulcrum at the side of the loom,

and to these the shafts are hung from jacks or otherwise. These

machines were made to work very exactly. In the double machine

the pecker would travel over three or four hundred cords in consecutive

order.

To avoid confusion the beads are not shown on the front cords in

No. 1.

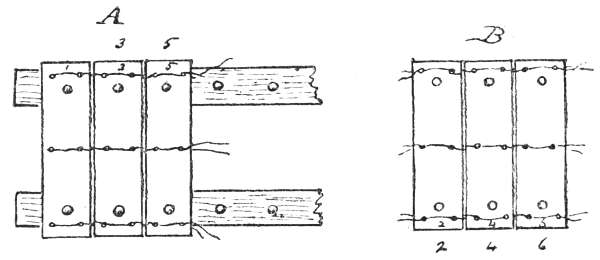

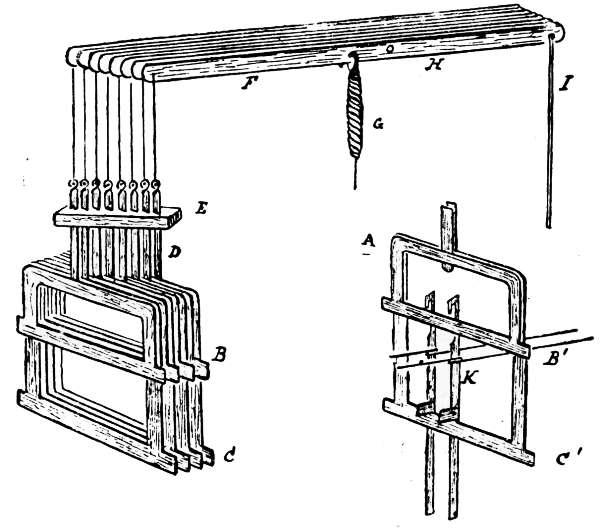

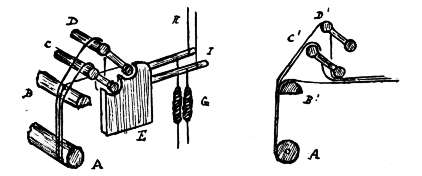

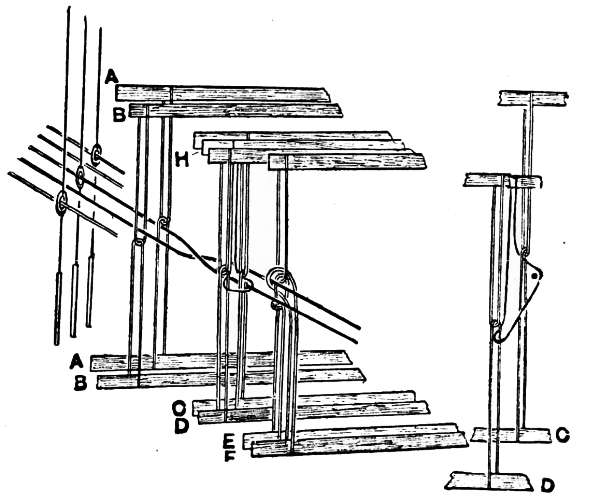

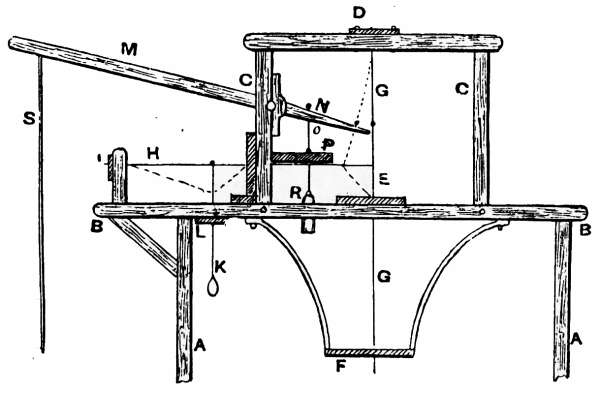

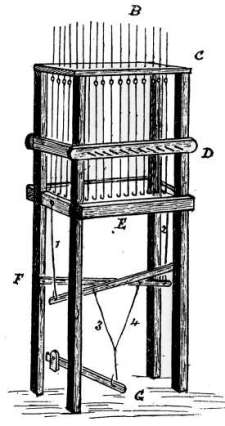

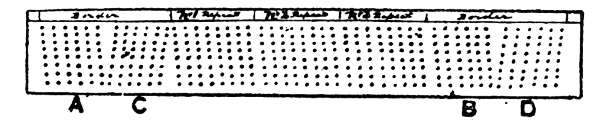

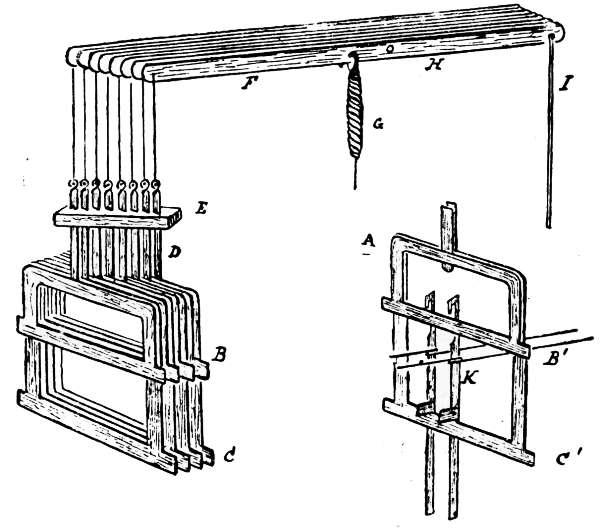

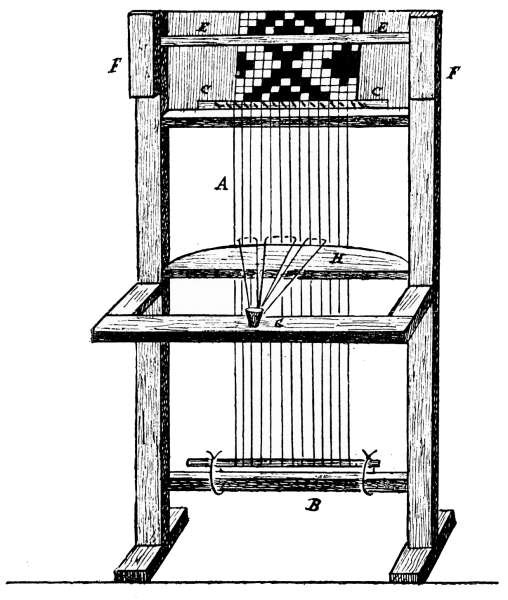

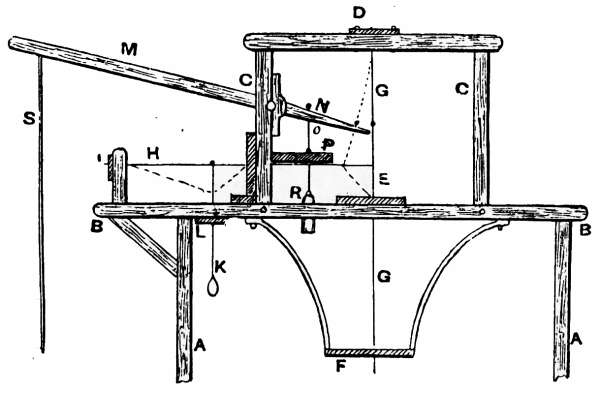

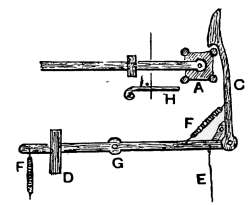

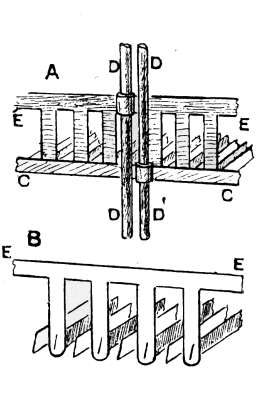

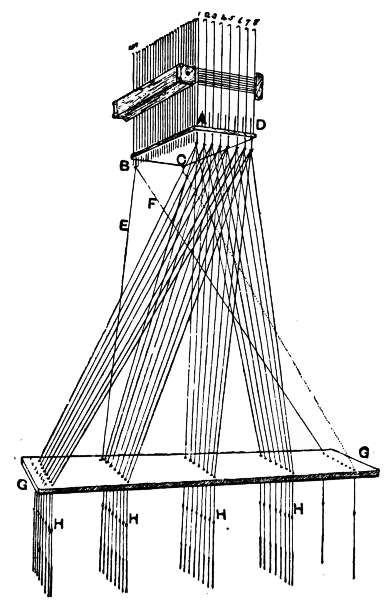

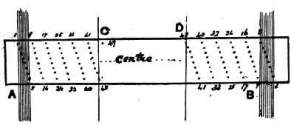

CROSS’S COUNTERPOISE HARNESS

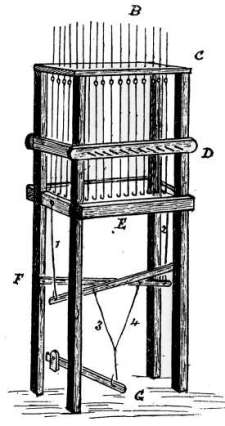

About the year 1816 Mr. James Cross, of Paisley, invented a

machine to do away with the drawboys.

Fig. 6

This machine is fully described by Murphy and Gilroy in their

works on weaving. Only the general principle of it will be given here,

as an introduction to the jacquard. The detail of drawing the lashes

and treading, though ingenious, is not of any practical importance

now, and it requires rather a lengthy description to explain it. The

harness F is the same as in the common draw loom till it reaches the

tail cords, where the counterpoise apparatus commences. The framing

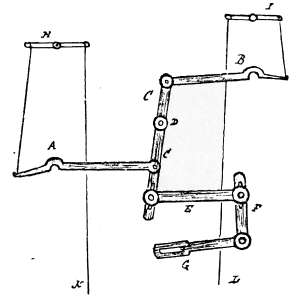

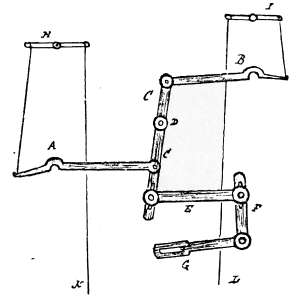

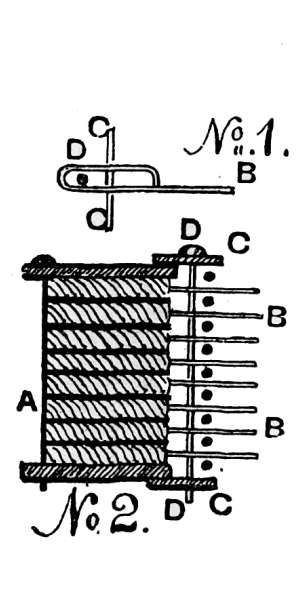

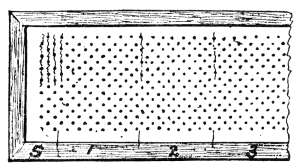

B B (Fig. 6) of this machine is supported by the carriage A A, which

rests on the capes or top rails of the loom. In this frame are two

boards, C and D, perforated with holes corresponding in number with

the tie of the harness or cords in the simple. The top board is called

the suspension board, and is mortised into the bar E. From this

board the harness hangs, the neck being taken up through the holes

in it, and fastened above them. The lower board, D, which is mortised

into the bar G, is called the neck board, or directing board, as it keeps

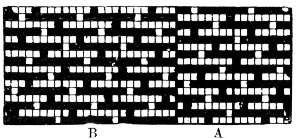

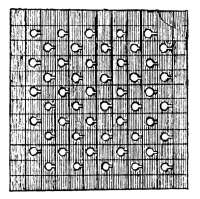

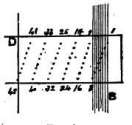

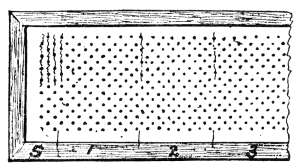

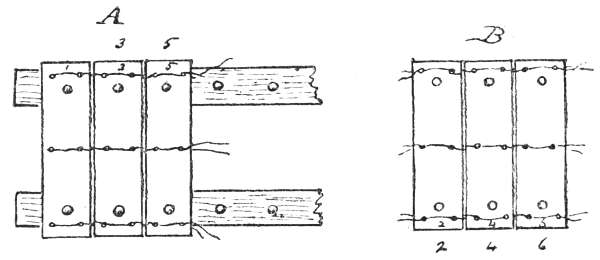

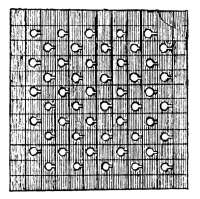

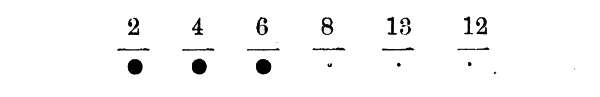

the harness in its proper place. H and K are two other boards, perforated

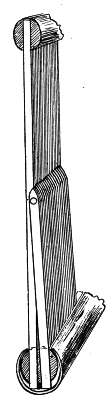

as shown in Fig. 7, mortised into the sliding bars I and L respectively;

these are called the trap boards, M, M and N, M are four[15]

bars, called pushers, which are fastened to the sliding bars I and L as

well as to the pulleys P, P, and when the pulleys are oscillated by

means of a treadle the sliding bars will be moved up and down. The

knot cords or tail cords O, O are fastened to the suspension board C,

and pass through the two trap boards, then through the neck board,

and are tied to the harness. Only two of these cords are shown tied

to the harness, to avoid confusion. These knot cords have knots or

beads on them as shown, and the round

holes in the trap boards H and K, as

shown in Fig. 7, must be sufficiently large

(about 1/4 in. in diameter) to allow the knots

or beads to pass freely through. There

are notches or saw-cuts at the sides of

the holes to admit the cords, but support

the knots. T, T1 is the simple, extending

horizontally through the knot cords. It is

fastened to the ceiling beyond T, and to

the frame of the machine beyond T1. S is a half-leaf of heddles for the

purpose of supporting the simple cords. Each simple cord is tied to a

knot cord, and beyond T1 the simple is lashed according to the pattern.

In working the machine the lashes are drawn by means of hooked[16]

levers, wrought by a treadle connected with the pulley V, and those

simple cords that are drawn down pull the knot cords into the notches or

saw-cuts in the trap boards, so that when the trap board is raised the

harness fastened to those knot cords that are drawn into the saw-cuts

will also be raised. R is a set of cords with weights on their ends for

the purpose of drawing the knot cords out of the saw-cuts as soon as

the simple is released by the lashes. The two trap boards rise and

fall alternately, and this is why the machine is called a counterpoise.

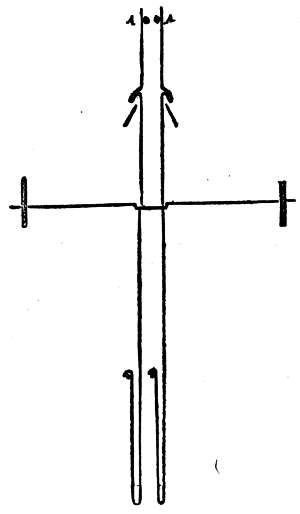

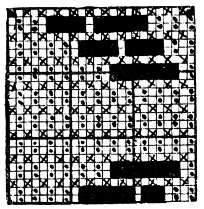

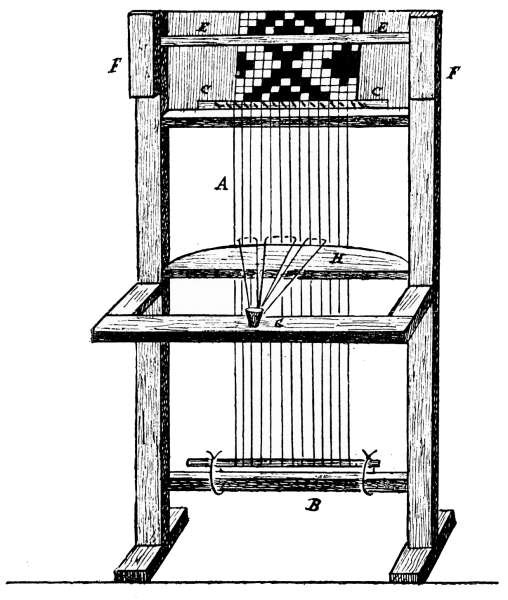

Fig. 7

Some time after an improvement was made upon this machine

which was known as

THE COMB DRAW LOOM

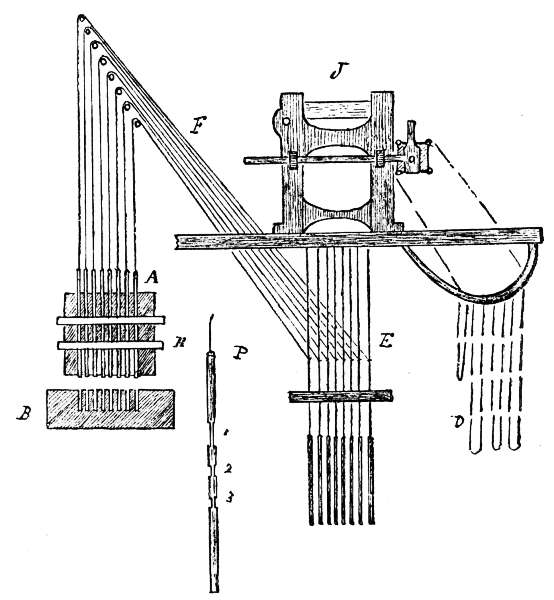

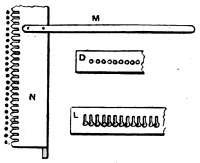

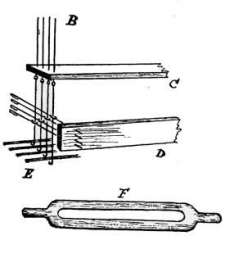

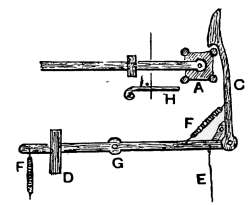

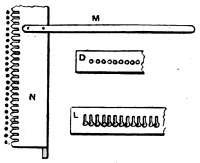

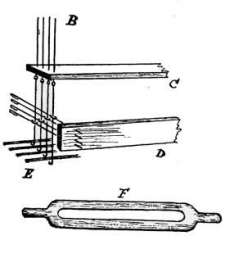

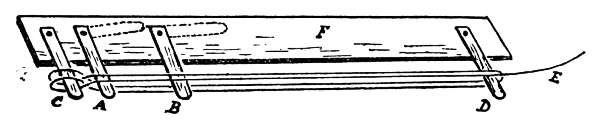

Fig. 8

This machine appears to have been invented in both Scotland and

Ireland, as Gilroy describes it as an invention of Dr. McLaughlin, of

Ballyshannon, County Donegal; and Murphy describes a similar machine

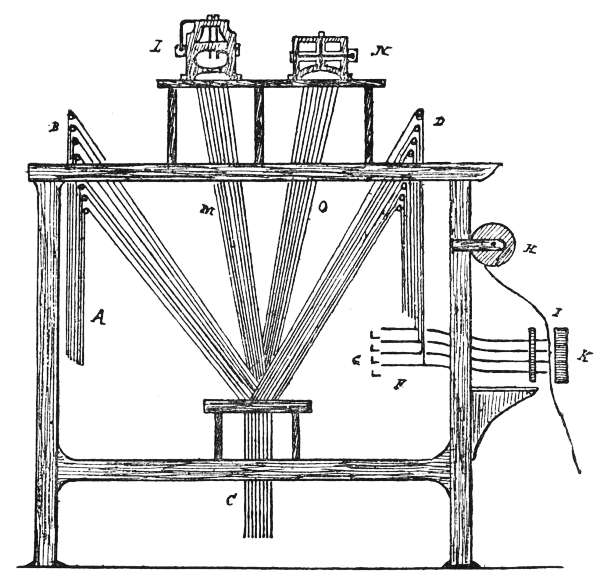

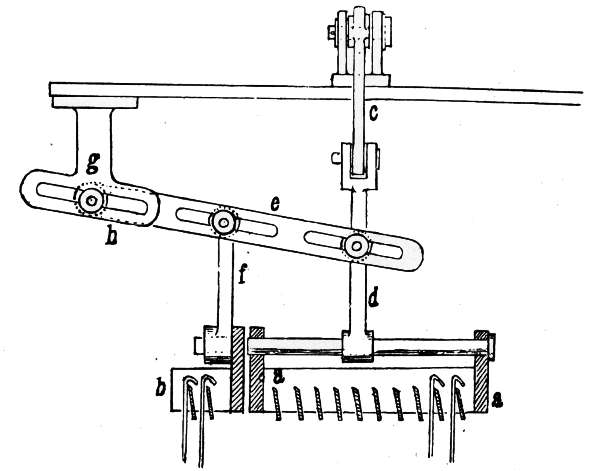

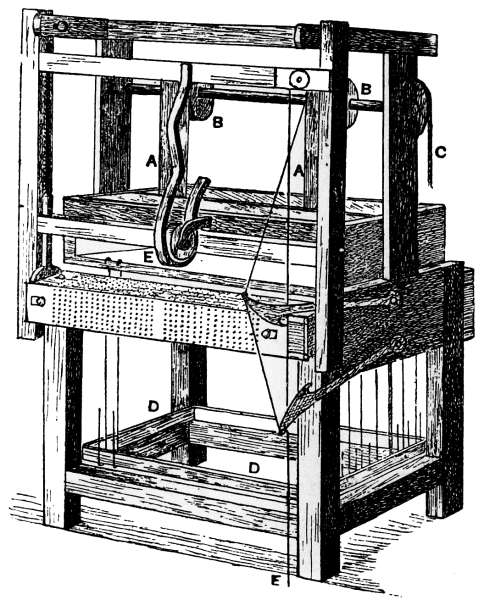

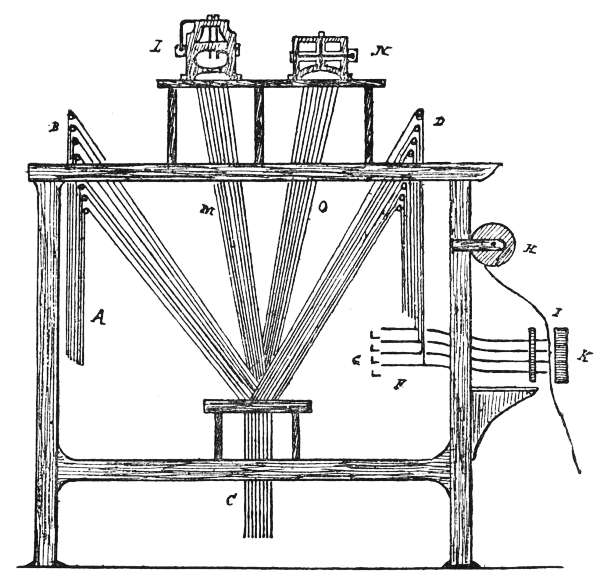

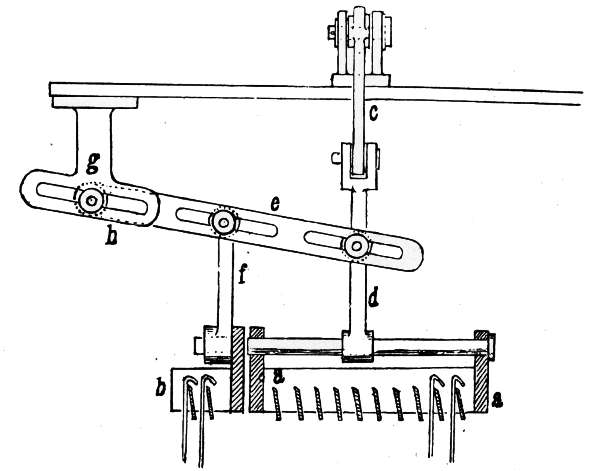

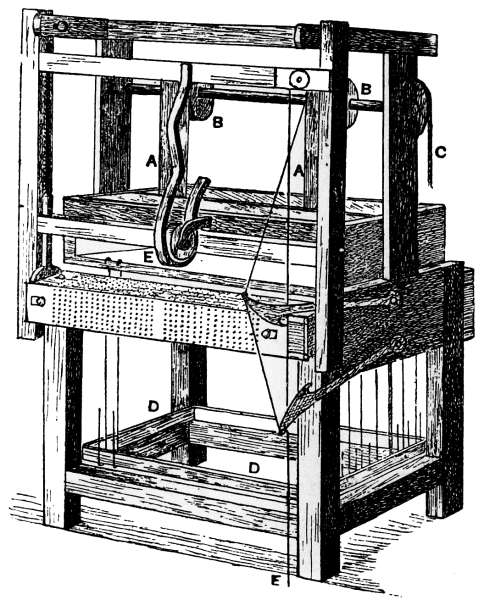

invented by Mr. Bonnar, of Dunfermline. The machine is shown in Fig.

8. A, A are the posts of the loom, and B B the top rail; C C is the

framing of the machine. The harness G, G is suspended from the

suspension board D, and passes through the guide board E and the

cumber board F. The upper portion of the harness is composed of tail

or knot cords, as in Cross’s machine. From each of the tail cords a

simple cord, H, extends horizontally over the weaver’s head, and is

fastened to the board I. The lashes K hang from the simples over the[17]

weaver’s head, and have a knob on the end of each, so that the weaver

can catch them and draw his own draught.

Fig. 9

The lash cords have a knot or bead on them, so that when drawn

they can be held in the cuts of the board L, also shown in plan at L

(Fig. 9). M, N (Fig. 8) is a side view of the comb and handle, or

lever, shown in plan at M, N (Fig. 9). S is a cord or chain attached to

the end of the lever M, and passing down to a treadle. When the

weaver draws one of the knobs, the tail cords connected with the

simples in this lash are drawn between the teeth of the comb, as

shown by the dotted lines in

Fig. 8. He then depresses the

treadle, which raises the comb,

and the harness along with it;

he holds the treadle down with

his left foot, and works over the

ground treadles with his right

one. The comb is recovered or

counterbalanced by the cord O,

which passes from the comb

through the board P, and has

a weight, R, suspended on it. D (Fig. 9) is a plan of the boards D, E,

F and I (Fig. 8).

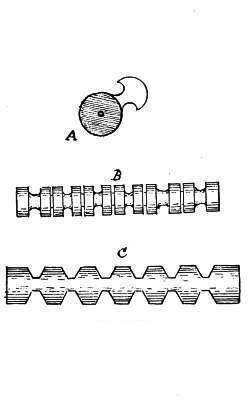

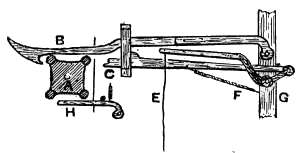

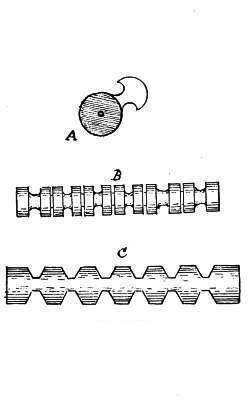

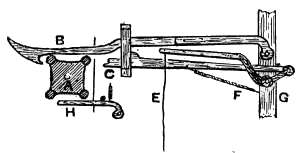

THE BARREL OR CYLINDER LOOM

This machine was introduced by Mr. Thomas Morton, of Kilmarnock.

The harness and tail or knot cords are arranged similarly to

those in the comb draw loom; but instead of the simple cords for

drawing out the tail cords, each tail cord in the barrel loom passes

through a slide, or horizontal wire. The points of these slides are

acted upon by the pattern cylinder or barrel, and those held back press

out their tail cords from the others, and the knots on these tail cords

are caught by the teeth on the comb or roller, and the harness

raised.

The pattern is arranged upon the barrel much in the same way as

a tune is arranged on the cylinder of a barrel organ or musical box.[18]

A section of the barrel is shown at A (Fig. 10), with wire staples driven

into it to form the pattern.

Fig. 10

Each of these staples represents so many lines of the design paper,

or so many lashes or draughts. The pattern is ruled out and painted

on the barrel, and staples are driven into it so as to cover the painted

squares of the pattern. The barrel is so

arranged on the loom that exactly the

space of one line of the design paper is

turned round for each draught, and the

slides are drawn back by cords attached

from their ends to a roller when the shift

of the barrel is being made. B is a section of the comb; it is a cylinder

with teeth, C, like a parrot’s beak fixed to it. The teeth are made of

this shape to hold the knot cords when they are caught by them, and

they rise or fall as the roller is rocked upwards or downwards by a

treadle.

Whilst these improvements on the draw loom were being made in

this country for the purpose of producing a convenient method of

harness weaving, the French were endeavouring to obtain the same

result, but on a different principle, and their method has proved successful.

In 1725 M. Bouchon employed a band of pierced paper, pressed by

hand against a row of horizontal needles, so as to push back those

which were opposite the blank spaces, and thus bring loops on the

extremities of vertical wires into connection with a comb-like rack

below, which, being depressed, drew down the wires, pushed on the pins

in it, and raised the harness.

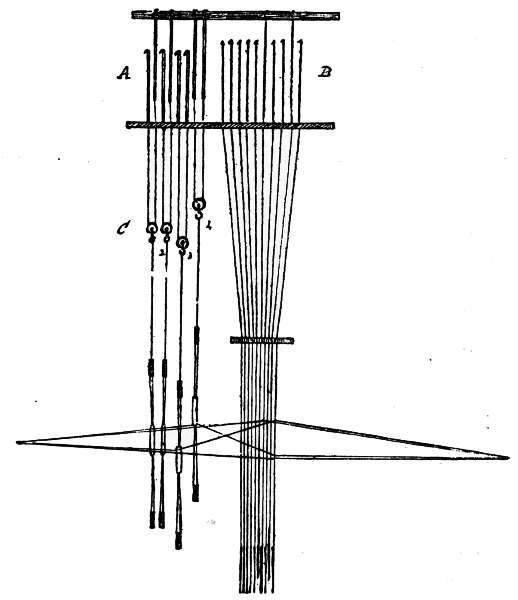

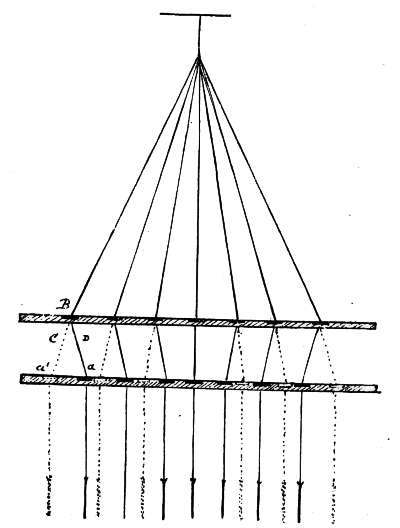

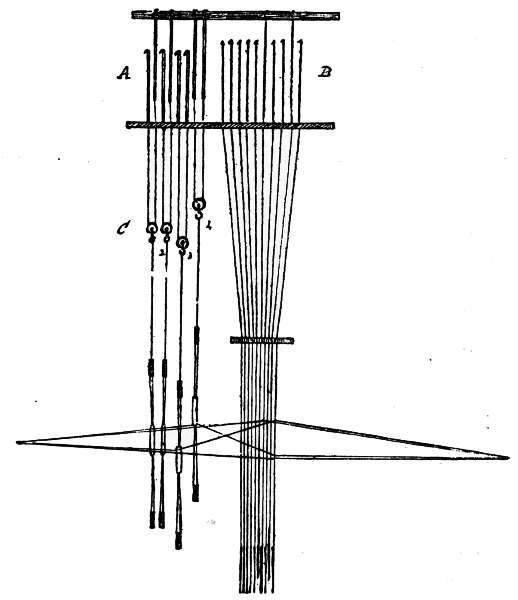

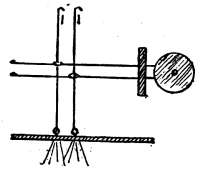

Fig. 11

Fig. 11 is a sketch of a model of this loom in the Conservatoire des

Arts, Paris. A is the pulley-box with two rows of pulleys in it; B the

tail cords; C the simples, tied to rings on their upper ends, which run

on the tail cords at B; the other ends of the simples pass over a small

roller at D to prevent them rubbing against the side of the loom, then

down through the hole board F, under which they are tied to wire

hooks or loops, as shown under A (Fig. 11a). Next these wires pass

through the needle box G, also shown at B, Fig. 11a, and down to the[19]

comb H (Fig. 11), and C (Fig. 11a). The perforated paper is rolled on

the roller E, and passing downwards, is pressed against the needles with

a hand bar, as shown at L, Fig. 11b. The roller K is for rolling up

the paper as it passes down from the upper roller.

Fig. 11b is a back view of the mounting. A shows where the

simples are connected with the tail cords P; B shows the connection

of the tail cords with the harness; C is the cumber board; D the mails

and E the leads. F and K are the two rollers for the paper, H the

needle box, and I the comb. This was the first attempt at forming the

pattern by means of perforated paper acting upon needles and wires.

In 1728 M. Falcon adopted a chain of perforated cards in lieu of

the perforated paper, and placed his horizontal wires or needles in

several rows or ranks, thereby admitting the use of a greater number[20]

of them in a moderate space. He also used a square prism or cylinder,

as it is called, for the cards to pass over.

Fig. 11a

Fig. 11b

Fig. 12 is a sketch from a model of his loom, also in the Conservatoire

des Arts. The principle of it is much the same as the preceding.

A is the pulley box for four rows of pulleys, B the connection of the

simple with the tail cords, C the hole board for the simple to pass

through and also the support for the cylinder H, D is the needle box,

E the comb or griffe, F the levers for drawing down the griffe, and G

the treadle. The cards are laced in a chain and pass over the cylinders

I and H, but they are pressed against the needles by a hand bar, similar

to that used by Bouchon. There are two racks or receptacles for

holding the cards, as shown. The cylinders H and I are simply used as

rollers to support the cards, and not for pressing them against the

needles, as in the jacquard.

Fig. 12

Figs. 12a and 12b give detailed views of the hooks, etc., for drawing

the harness: the letters in both refer to the same parts as are marked

with similar letters in Fig. 12. The simples B are tied to loops on the

hooks under the hole board C. In Fig. 12b it will be clearly seen how[21]

the needles in four rows act upon the hooks. The griffe consists of

four round iron rods or wires set in the frame E, Fig. 12a, which can

be drawn down by the treadle G, connected with the levers F by the

cords 3 and 4. One of the levers has its fulcrum at one side and the

other has it at the opposite side, and the points of the levers are tied

to the griffe frame by the cords 1 and 2. The griffe, when sunk, is

brought back to its place again by weights hanging on cords running

over pulleys. It may be seen that the hooks hang in front of the rods

or bars of the griffe; therefore, those hooks will be pushed on the griffe

whose needles come against the solid portions of the cards, thus acting

similarly to Bouchon’s machine. The hand bar for pressing the cards

against the needles is shown at F. The needles can pass through the

slot in it, and, when a card is pressed against the needles, the bar can

be fastened with hooks for the purpose, so that the operator is free to

depress the treadle. There are no springs on the needles, but a clap

board comes behind them, which is pressed in by means of a cord

passing over each end of it and fastened to a spiral spring. There are[22]

ten leaves of heddles in front of the harness. They are plain clasped

heddles, and apparently act as five, the front five being raised by the

top levers connected with the treadles, as shown in Fig. 11, and the

back five are held up by a set of levers at each side, with weights on

the ends of them, similarly to those now used for hand-loom damasks,

and tied to the treadles below, so that sinking a treadle would cause

one of the back leaves to sink and one of the front ones to rise. Only

the harness mechanism of Falcon’s loom is given in Fig. 12, the front

portion being similar to that of Bouchon, or to any hand loom.

Fig. 12a

Fig. 12b

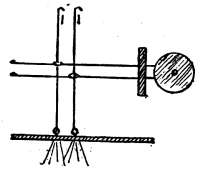

In 1746 the accomplished mechanician, Vaucanson, altogether dispensed

with the cumbrous tail cords and simple of the draw loom, and

made the draw-boy machine completely self-acting by placing the

hooks upright on the top of the loom, and hanging the harness from

them. This loom may be seen in the Conservatoire des Arts, as well[23]

as a model of it on the same scale as those already mentioned—viz.,

one-third the size. The machine for drawing the harness is exactly

like a small jacquard, with two rows of hooks and two rows of needles,

as shown in Fig. 13. Instead of a square cylinder and cards, the

pattern is punched on a band of paper, which passes over a round or

true cylinder. This cylinder is fitted with a rack wheel, so that a tooth

can be passed for each change of pattern, the cylinder moving out and

turning one tooth, then pressing in against the cards again. The diameter

of the cylinder is about twelve inches. The hooks are raised

with a griffe, similar to that in a jacquard, which is fastened to a lever

connected to a treadle below. This treadle, and four others for working

the heddles, is wrought by tappets, made of wood, on a shaft

running along the side of the loom and turned by a wince handle in

front. Altogether, the loom is a nice mechanical

contrivance, and a great step in advance of

its predecessors.

Fig. 13

Joseph Marie Jacquard, a working mechanic

of Lyons, having invented a fishing net loom,

turned his attention to improving the means

of drawing the harness in looms for figured

weaving, about 1790. A model of a machine

by him, dated 1790, to dispense with the drawing of the harness, is

in the Conservatoire des Arts. It is made with cords and rollers,

and has no resemblance to the machine bearing his name. He

was brought to Paris to repair Vaucanson’s loom about 1804, and

it appears to be then that he combined the best qualities of the

machines of his predecessors, and produced the jacquard, a model

of which, dated 1804, is in the Conservatoire des Arts. This is very

much like our present jacquard, but with four rows of hooks and

needles made similar to those of Vaucanson, Fig. 13. He dispensed

with Vaucanson’s cylinder and band of paper, and used instead a

square prism with a chain of cards passing over it. The cylinder (or

prism) he set in a frame or carriage, made to run on four wheels or

pulleys on the top of the frame of the loom. The carriage is drawn

out by depressing a treadle, and brought back again to press the[24]

cylinder against the needles, by means of weights tied to cords running

over pulleys. The griffe is raised by means of two levers, one at each

side; one end of each is connected with the griffe, and the others to a

crossbar at the bottom of the loom, and this crossbar is fastened from

its centre to a treadle. In all these looms the cards or paper hang at

the side of the loom, the mounting being on the principle known as

the London tie. Jacquard was born in 1752, and died in 1834.

Vaucanson died in 1782.

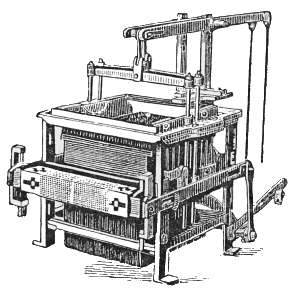

FRENCH DRAW LOOM

Shortly after the introduction of Cross’s counterpoise harness, a

machine was imported from France, which is shown in Fig. 14, and

described in Murphy’s ‘Art of Weaving’ as a French draw loom. This

machine far surpassed any attempts at the improvements at the draw

loom that had hitherto appeared, in simplicity of construction and

operation. From the neck upwards the harness is similar in construction

to Cross’s counterpoise, having the knot cords arranged in the

same manner, but with only one trap board. Instead of the cumbrous

tail, the knot cords are acted upon by wires or needles, on each of which

is a loop, through which one of the knot cords passes. D is the cylinder

or barrel, perforated with holes, as in the common jacquard cylinder,

and C, C shows the chain of cards for forming the pattern; E is the

lever for raising the trap board, to which it is connected by means of

pieces of iron at each side, with a bar across between them, to the centre

of which the lever is connected with a piece of wire. O O are crossbars

of wood, with holes in their centres, through which run pieces of strong

iron wire, which are fixed into the trap board at each end to keep it

steady while in operation. There is no spring box for the needles as is

now used in the jacquard, but into the crossbar or frame F is inserted

a flat piece of wood moving on springs, which yields to the pressure of

the needles that are forced back by the barrel, and recovers them again

when the barrel is withdrawn. The lever E is drawn down by the cord

H, attached to a treadle, when the trap board is to be raised, and the

barrel is drawn back by the cord G, which is attached to another treadle.

The barrel is pressed against the needles by springs, and when it is[25]

relieved by the treadle and is moving inwards, it is turned by one of

the catches shown in Fig. 14a. Either of these catches can be brought

into action, so as to turn the barrel either way, by raising or lowering

them with a cord. When at rest the knot cords stand in the notches

or saw cuts of the trap board, but when the cards are pressed against

the needles, except where there are holes in the cards, the needles are

pressed back and the cords are pushed out of the notches so that the

knots stand above the holes in the trap board, and pass through them

when the board is raised by depressing the treadle connected with the

lever E. The trap board is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 14

Fig. 14a

Whether this machine was Jacquard’s invention or not, I have not

been able to ascertain; but Gilroy states that Jacquard’s first machines

were made with cords and trap boards, like Cross’s counterpoise

machine. It is also recorded that William Jennings, of Bethnal Green,

invented a machine, similar to the above, about 1830, as an improvement

on the jacquard, on account of its simplicity, as the latter appears

to have given the weavers some trouble, and notice was taken of his

machine by the Society of Arts.

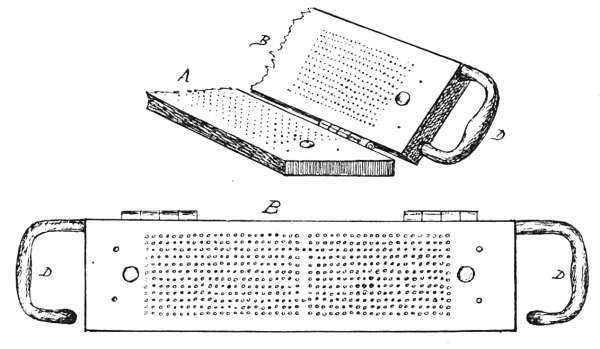

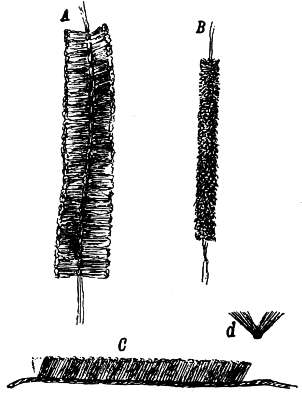

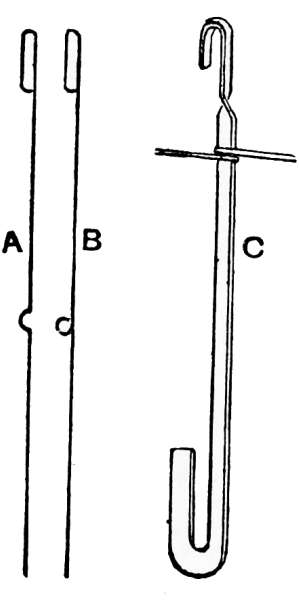

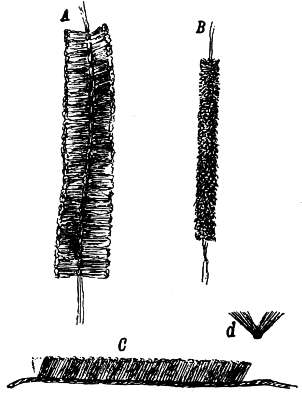

Fig. 15

Machines similar to the above are still in use for hand-loom work,

and answer very well. They have also been used for power looms, but[26]

the cords do not stand the friction long. As at present made about

Glasgow, the cylinders of these machines work on slide rods, and

receive their motion from the rising of the trap board, same as the

cylinders in jacquards are sometimes wrought by the rising of the griffe

with what is known as the ‘swan neck’ motion. The spring board

at the ends of the needles is held back by a spring and drawn in by the

cylinder frame as it moves outwards,

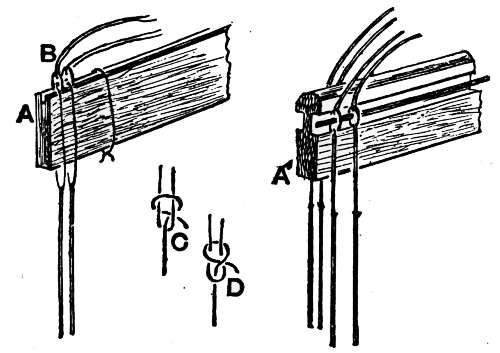

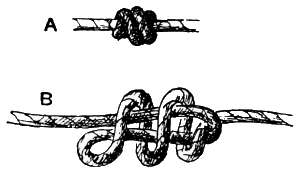

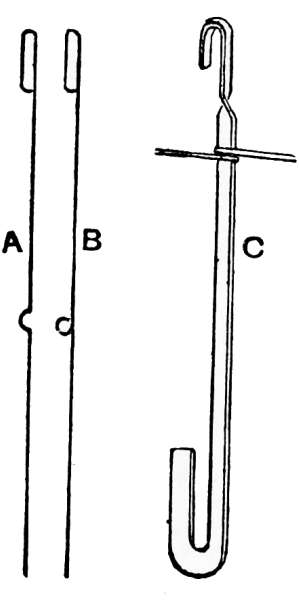

which brings all the needles forward,

and the cords into the saw cuts in the

trap board, or comb as it is frequently

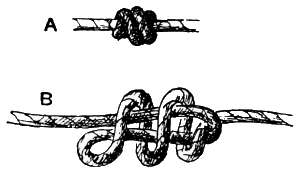

called. The knots on the cords for

these machines are made as at B,

Fig. 15, which, when drawn tight, are

as shown at A. The cord is a good twisted cord, such as whipcord, and

the holes in the trapboard are about 3/16 in. in diameter, which the

knots on the cords must pass freely through. The upper ends of the

cords pass through a perforated board on the top of the machine, and

another cord is drawn through loops on their ends, which prevents

them from being drawn through the holes.

[27]

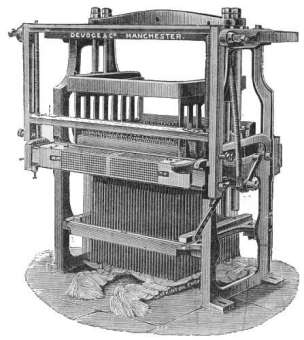

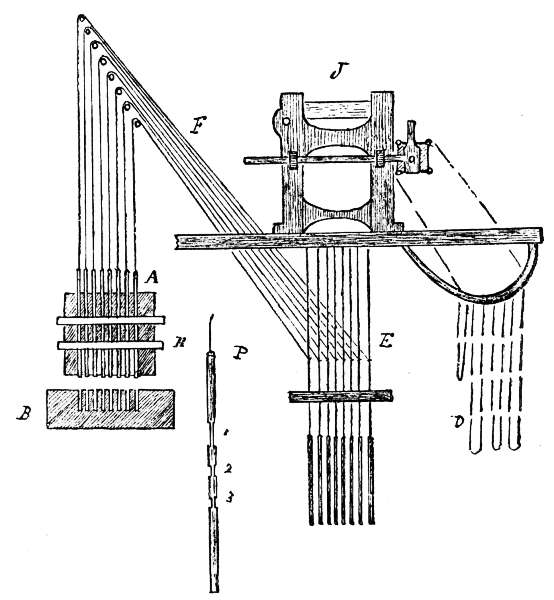

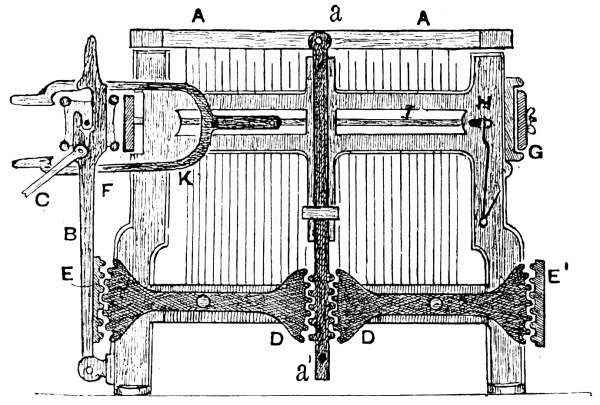

CHAPTER II

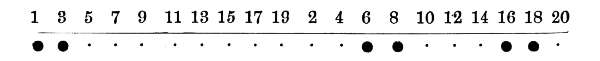

JACQUARD MACHINES

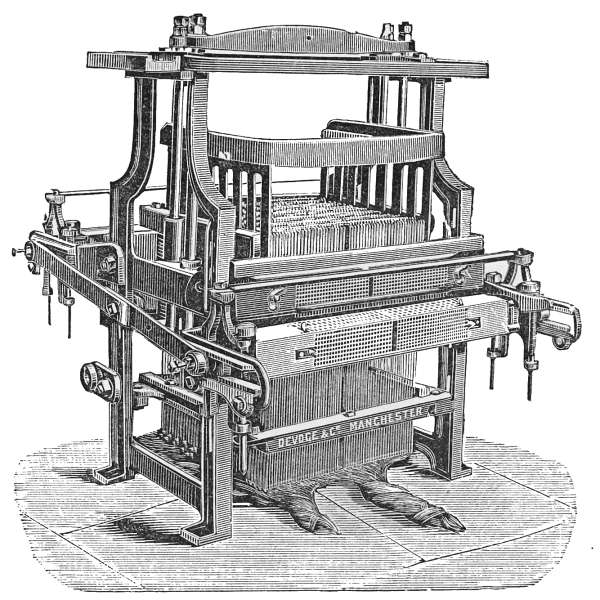

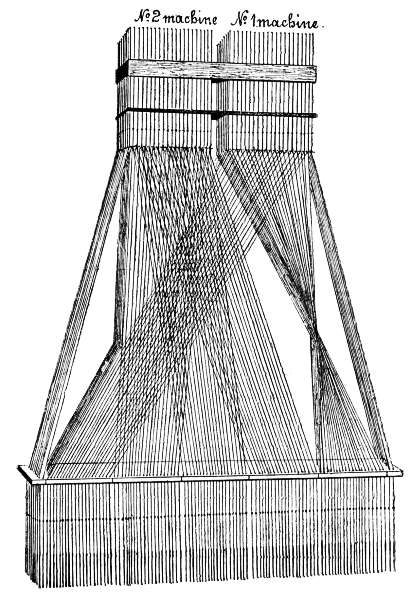

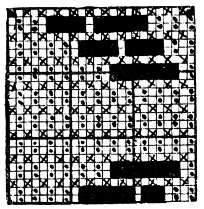

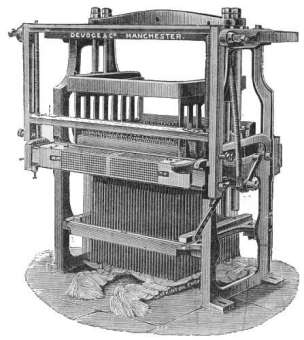

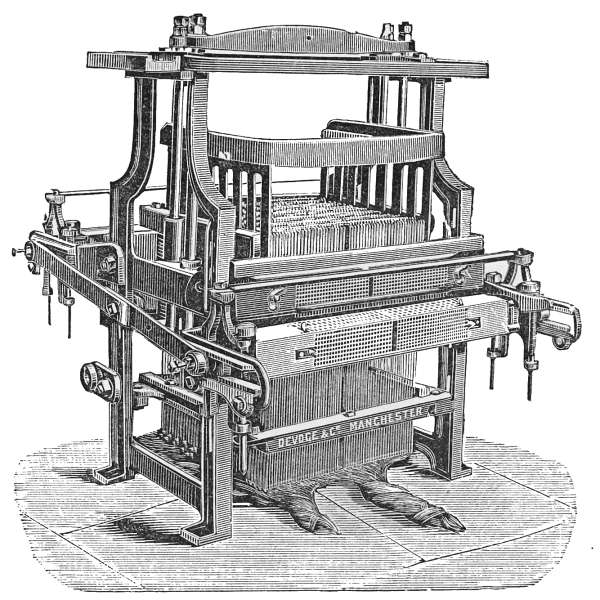

The jacquard machine was introduced into England about 1818 and

came into general use from 1824 to 1832. It was introduced into

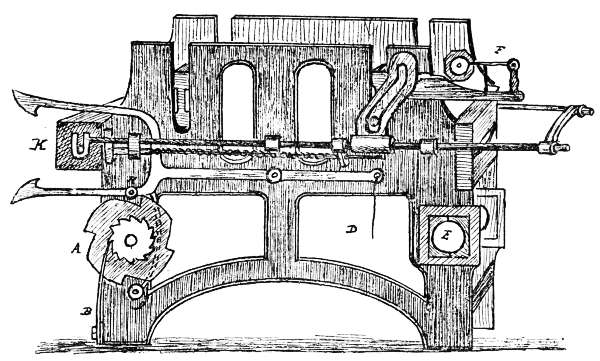

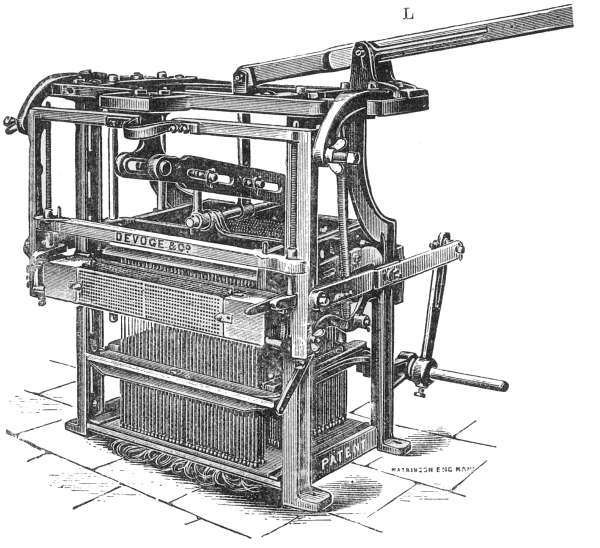

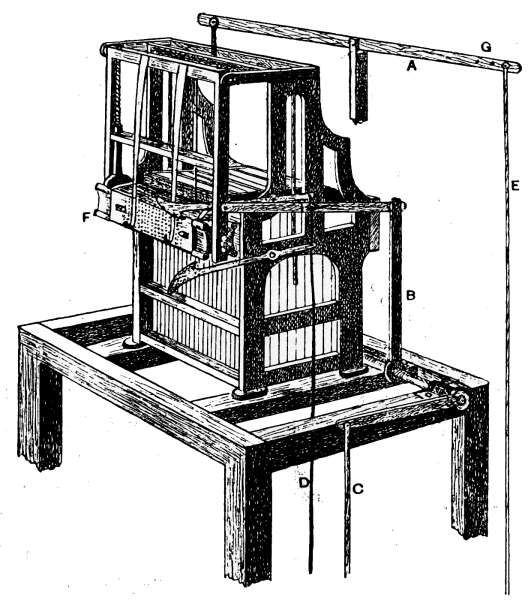

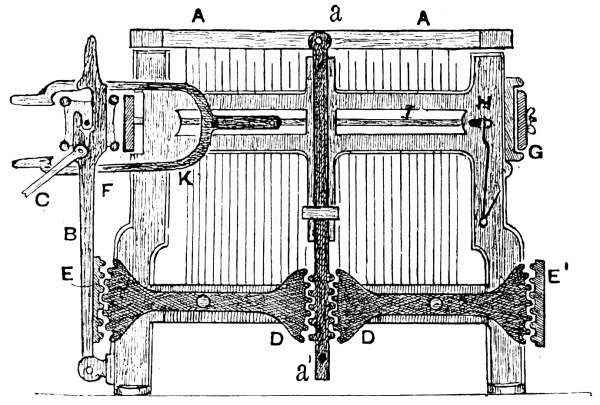

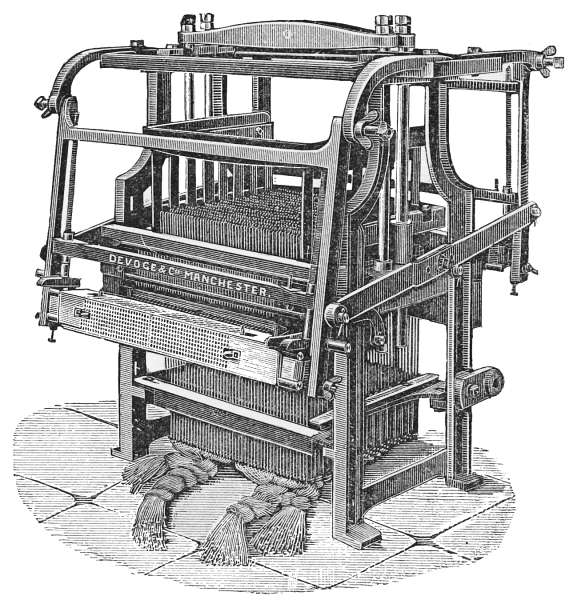

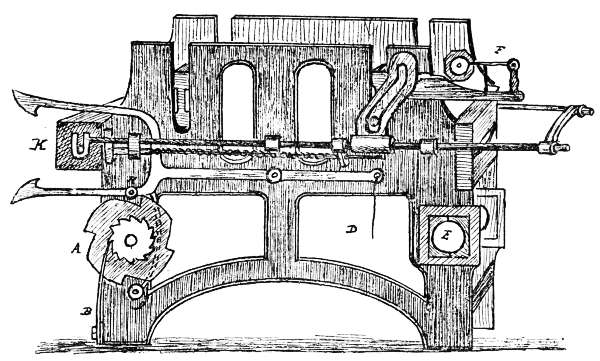

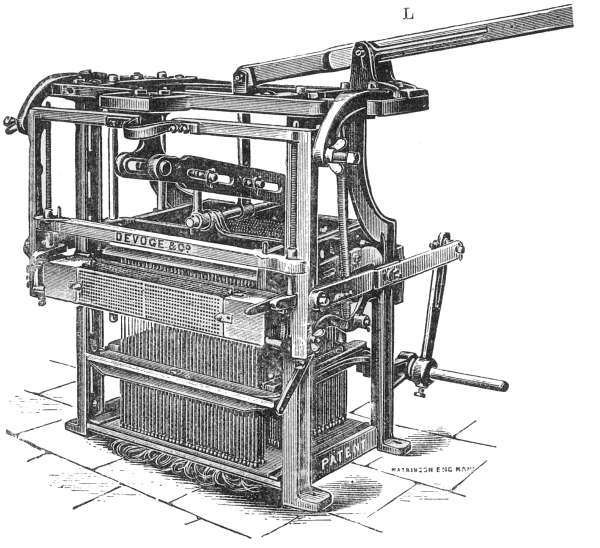

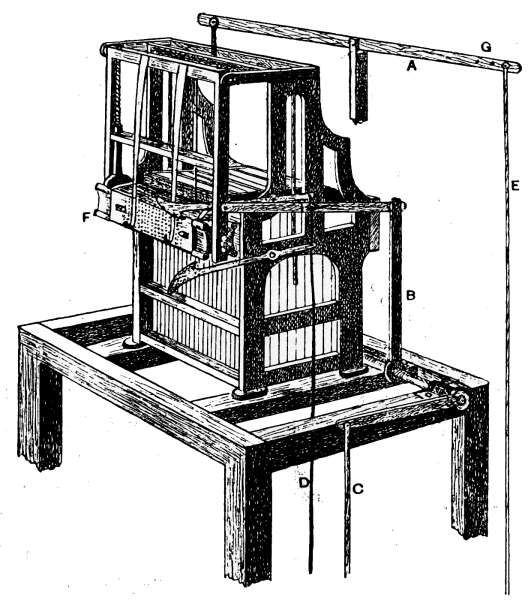

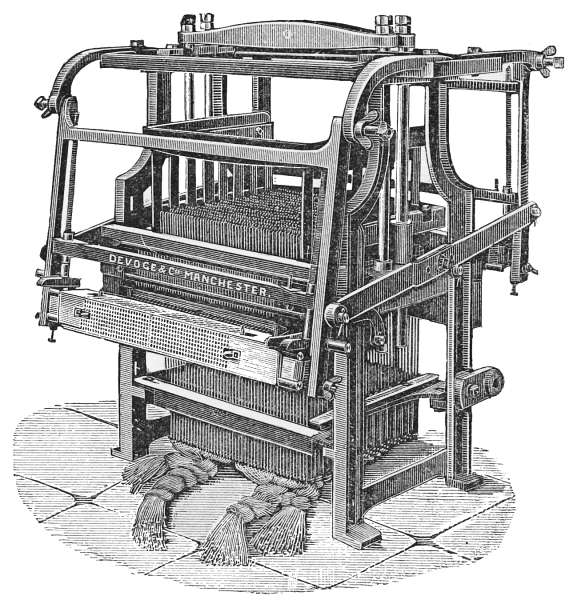

Scotland about 1824. Fig. 16 is a representation of the early form of

jacquard, and of course intended for hand-loom work. Although the

present machines for power-loom work are very different in make,

nearly all the working parts as here used are to be found in different

machines at present working, or still being made, though the best

machine makers have adopted newer and better principles for fast working

and withstanding wear and tear. Fig. 16a is a view of the interior

of the machine. The working of the machine will be explained further

on; only those parts that will not be given in the new machines will

now be noticed. The griffe or frame for raising the hooks is lifted by

the straps A, A, Fig. 16, which are attached to the pulleys B, B, and a

cord C over a pulley on the same shaft as B, B, is attached to a treadle

beneath the loom. As the weaver presses down this treadle the griffe

is raised, and when the treadle is released the griffe falls of its own

weight. The cylinder is moved out and in by the pulley E, fastened on

the bent iron bar, attached to the frame which carries the cylinder,

when the griffe rises and falls. D, D is a frame which lies in the

turned-up portion of the hooks; only a few hooks are shown, and the

outer bars of the frame. There should be a bar in the frame for each

row of hooks. This frame rises up and down with the hooks, the turn

on the ends of which must be of such length that when the frame is

raised by the hooks lifted by the griffe, it will not be raised out of the

turns on those that are left down. This frame is for the purpose of

preventing the hooks from turning round, so that the turns on the[28]

upper end of them, as shown at A, A, Fig. 16a, cannot get out of

position to be caught by the blades or crossbars of the griffe. The

lower ends of the hooks rest on a perforated board as shown in

Fig. 16a, and tail cords are looped on them and pass through the

perforated board as shown. To these cords is fastened the neck of the

harness. Machines with these perforated boards and frames to keep

the hooks in position are still (1890) being made in Yorkshire. In

Fig. 16a is shown a section through the spring box B. This box contains

a spiral spring for each of the horizontal needles, the ends of

which press against the springs, which allow them to yield or move

back as the cards press on their points; but recover them again

when the card is moved away by the cylinder. Similar spring-boxes

are now used.

Fig. 16

It might be interesting to describe the various changes and attempted

improvements that have been made on the original jacquard, but it

would take up too much space, and many of them are of more historical[29]

than practical importance; some of them will be mentioned that

may be interesting from a mechanical point of view, in connection with

the descriptions of the machines, even though they have only been

partially successful. Though a very different machine from what it

originally was, the principle of the jacquard remains the same, and is

not likely to be altered or superseded till a revolution takes place in the

process of weaving.

Fig. 16a

A jacquard machine is simply a shedding motion by which a great

variety of sheds can be formed; the larger the machine, or the greater

the number of hooks it contains, the greater is the variety of shedding

that can be produced by it.

If a jacquard is made small, with, say, from 16 to 48 hooks, it is

called a dobby or shedding motion, and is used for working shaft

mountings; but the ordinary jacquard machines have from 200 to 600

hooks, which have long cords, called the harness, connected to them,

no shafts being required, as each hook has only a few cords tied to it,

which can be raised independently of the others. The fewer the cords

that are tied to each hook, the greater is the variety of shedding that

can be made on the same number of warp threads, till, when there is

but one cord to the hook, any thread or any number of threads can be

raised independently of any of the others.

[30]

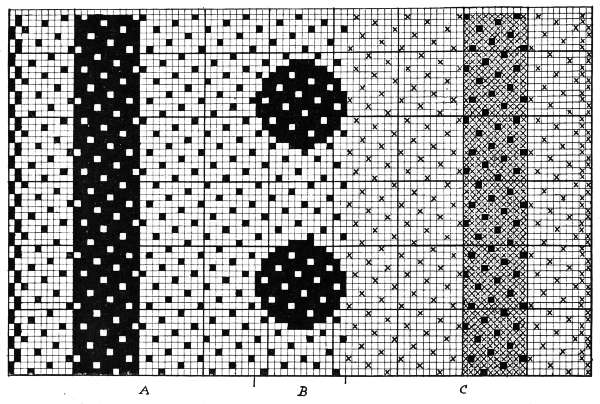

Jacquards may be divided into four classes—viz. single-acting,

double-acting lift, double acting with double cylinders, and twilling

jacquards; and besides these there are several other varieties made for

special purposes. The single-acting is the real jacquard, and much

the simplest machine. It has the disadvantage which all single-acting

shedding motions have—viz. that one shed must be closed before the

following one begins to open. This is on account of the same lifter

having to open each shed; it must bring down the set of hooks that

are raised, and then raise the next set.

This constitutes the true jacquard lift; and while it makes a clear

shed, and is desirable for some purposes, it is generally considered the

most imperfect form of shedding—that is, so far as the making of a

good cloth is concerned. It is not suitable for making a heavy, well-covered

cloth, nor for working at a high speed, 120 to 140 picks per

minute being a very good speed to drive it.

A single-acting jacquard is a very simple machine, and when

properly made should give very little trouble in working, particularly

if the motions are properly set in relation to each other, and if such

methods of working are adopted as will cause the least wear and tear

on it.

In whatever way jacquards are made, the principle of working is

much the same. There are a number of upright hooks set in a frame;

attached to each hook is a horizontal wire or needle, one end of which

is pressed upon by a spring, which keeps both it and the hook steady

and in position, while the other end, or point, passes through a perforated

plate, beyond which it projects about half an inch (see Fig. 16a).

To lift the hooks there is a set of bars or knives arranged in a frame,

just below the heads of the hooks; this frame is called the ‘griffe’ or

‘brander,’ and if raised would draw all the hooks up with it. What

hooks will be lifted for each shed is regulated by perforated cards being

pressed against the points of the needles. A perforation in the card

allows the point of a needle to pass through and the hook to be raised;

but where there is no perforation the card comes against the point of

the needle, pressing it back, and holding the head of the hook clear of

the blade of the griffe, so that the griffe will pass without raising the[31]

hook. It will thus be seen that any variety of shedding can be made

by punching the cards to suit it. Fig. 17 shows one of the best makes

of single-acting jacquards. One of the best methods of driving is shown

in this and the following figure. The griffe is raised by means of the

lever G, which is sometimes supported on a beam fastened to the roof

or pillars of the shed, or it may be supported by an upright fastened

on the frame of the loom. A portion of this upright is shown in Fig.

17, and as well as being fastened to the loom frame, it should be stayed

to the top of the machine. One end of the lever is fastened by a link

connection to the centre of the bar across the griffe frame, care being

taken that the connection is so made as to draw up the griffe vertically,

and not have any strain on the slide rods or spindles that are used for

keeping the griffe horizontal when rising.

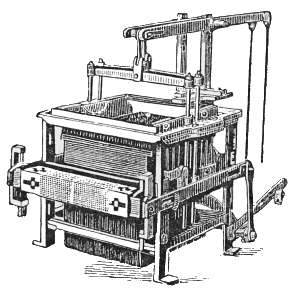

Fig. 17

The other end of the lever is connected to a crank on the crank-shaft[32]

of the loom by a rod, E (Fig. 17); also shown at A (Fig. 18), where

the crank is also given.

Fig. 18

In hand-loom machines the griffe is frequently pushed up from

below instead of being drawn up from the top as is shown in Fig. 17.

The method of doing this

is similar to that given

for lifting the griffes of

twilling jacquards.

F (Fig. 17) is called

the cylinder or barrel,

evidently taking its name

from the round cylinders

or barrels used in the old

machines, but is in reality

a square prism. It is

made of wood, and perforated

on each side with

a set of holes—a hole for

each needle in the machine;

its use is to draw

round the chain of cards

and press each one against

the needles, or horizontal

wires, in the machine. In

order to keep the cards

firmly on the cylinder,

flat steel springs are sometimes

used, as shown,

attached to the top rail of the frame which holds the cylinder; and

there are also steel wires which pass down in front of the cylinder over

the ends of the cards. These springs are useful when only a small

number of cards is used and the machine driven quickly; with a

large set of cards, where there is plenty of drag on them from their

own weight, they are not necessary, and but seldom used; but they

are in common use in the Yorkshire districts.

[33]

It will be seen from the illustrations (Figs. 17 and 18) that the

cylinder hangs in a frame suspended from the top of the machine; this

is called the swing or batten motion, to distinguish it from the horizontal

or sliding motion which is shown at Fig. 20 (No. 1) and in Fig.

27. The swing motion is the simpler of the two, and is cleaner,

requiring less oil; but the sliding motion is steadier, and does not

swing the cards so much, consequently is more suitable when the

cylinder has to travel quickly. The swing motion also requires the

machine to be higher; with a slide motion the frame is usually cut off

a little above the griffe.

The cylinder has to travel out and in when the machine is working,

so that it may be turned round and bring a fresh card against the

needles for each shot. There are many methods of accomplishing this,

which may be divided into two classes—viz. independent motions, or

those which are driven from the loom independently of the machine;

and self acting motions, or those which drive the cylinder out and in

through the rising and falling of the griffe. The latter are the simpler,

but the former are much better, causing less wear and tear on

both the cards and machine, as will be explained further on.

It will be seen in Fig. 18 that as the cylinder travels out it will be

caught by the hook K1, and turned round; the head or lantern of the

cylinder is made of iron, as shown, so that the hook, or shears, will

take a firm catch on it. To prevent the cylinder from turning more

than one card at once, and to keep it steady so that it will always come

in fair against the needles, it is held firm by a hammer pressed on it

by a spring. This pressure is applied in different ways, one of which

may be clearly seen in Fig. 17, and another in Fig. 27. When taking

out the cylinder, or wanting to run it round quickly to draw over a

number of cards, the hammers can be held up by a hook or sliding

catch, which should be fitted to the machine for the purpose.

One of the best independent motions for driving the cylinder is

shown in Fig. 17; and that shown in Fig. 18 is also a very good one for

small machines, perhaps the most convenient that is made; but the

former is much stronger. In Fig. 17 a connecting-arm from the frame

of the cylinder is attached to the lever B. The connecting-arm should[34]

have a slotted joint, so that it can be made shorter or longer, if required,

for the purpose of regulating the pressure of the cylinder on

the needles.

The lever B is on a horizontal shaft, bracketed to the frame of the

loom, or to the beams on which the machine rests; or some machines

have bearings attached to their framing for it. There is, of course, a

lever, as B, and a connecting-arm at each side of the machine. There

is another lever on the end of the shaft, at right angles to B, which is

connected with an eccentric on the crank-shaft of the loom by a rod, C,

in the same way as the rod C is connected with the eccentric in Fig. 18.

The eccentric can be set to bring the cylinder against the needles at

any required time, independent of the lifting motion of the machine,

which cannot be done when the self-acting motions are used. The

larger the eccentric, the greater dwell the cylinder will have against

needles. The method of working the cylinder in Fig. 18 is somewhat

similar, and can easily be seen; but it will be observed that a good deal

of pressure will be put upon the studs on which the cylinder frame, or

batten, hangs, particularly when the cylinder is being pressed in, as

this is effected by drawing down the lever L; however, in a light

machine this does not matter much.

Fig. 19

The principal feature in this motion is the escapement apparatus

for the purpose of disengaging the cylinder from its connection with

the driving eccentric when it is required to turn some of the cards back.

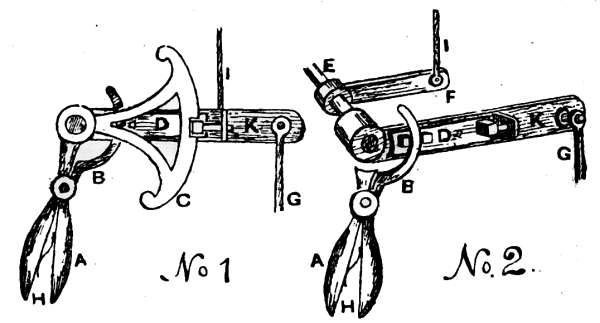

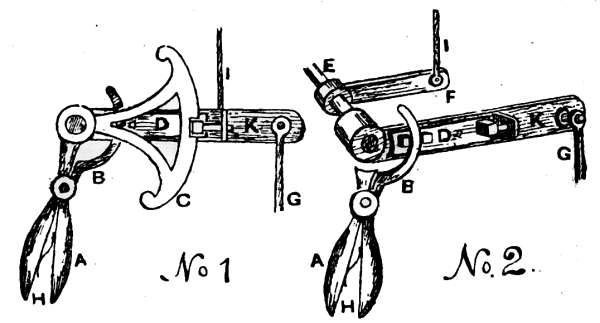

Fig. 19 (Nos. 1 and 2) shows this arrangement. The motion is not quite

the same as that given in Fig. 18, but is on the same principle, and

one may be easily understood from the other. In Fig. 18 the latch G[35]

comes out of the notch in the quadrant F, when the handle E is pressed

close; the handle is on the lever D, having its fulcrum on the shaft N,

and the quadrant F is connected to the eccentric rod C. The quadrant

is loose on the shaft, and the lever is fast on it. Fig. 19 is a more

convenient motion. The two halves of the handle A are held apart by

the spring H, and this, through the hook B on the inner end of the

handle, presses the latch or catch on the slide D into the notch on the

quadrant C. The quadrant and handle are one piece, and are fast on

the shaft E, and a lever F on this shaft is connected to the batten of

the machine, in the same manner as shown by D and B in Fig. 18.

When there are two or more machines, one of these levers would be

required for each. The lever K is loose on the shaft E, and the rod G

connects it with the eccentric, same as is shown by the rod C in Fig. 18.

In No. 2, Fig. 19, the quadrant is left out to show clearly how the hook

B acts on the slide D, and also to show the lever K on the shaft. The

two halves of the handle, being pressed out by the spring, keep D in

position, firmly pressed inwards; but when the handle is pressed the

hook B presses the slide D outwards, leaving the quadrant free to pass

up or down; and by pulling down the cord H (Fig. 18), which raises the

shears K and K1, the cards can easily be turned back by working the

handle up and down, as the under shears will catch the cylinder and

turn it the reverse way. The weaver must be careful not to jerk the

motion and throw the cards off the cylinder or damage them; but a

very little practice will enable anyone to turn them back quite easily

and quickly. This motion answers very well for one, or perhaps two,

small machines; for a 400 or 600 machine, or any smaller size working

spottings, &c., it is very convenient, but when large mountings are

required, as in 800 to 2400 machines, it is quite too weak for the

work; even if made strong enough it would not be satisfactory, as the

strength of spring that would be required to bear the strain and keep

the catch in the notch would make it a very difficult matter to use the

motion for reversing the cylinder. For heavy machinery the method

of working the cylinder shown in Fig. 17 is far preferable, and separate

motions for turning back the cards can be fixed on the machine.

These will be explained further on.

[36]

Instead of the eccentric and crank for driving the cylinder and

raising the griffe being as they are shown in Fig. 18, though a plan

frequently in use, it is neater, and perhaps better, to have the eccentric

at the back of the fly-wheel, and the fly-wheel either cast with one

half solid, or have a plate fastened across two or more of the spokes, to

which the connecting-rod can be attached with a bolt fastened in a slot.

The amount of lift can be increased or diminished, either by shifting

the top of the connecting-rod along the lever G (Fig. 17), or by increasing

or reducing the throw of the crank at the fly-wheel.

Fig. 19a

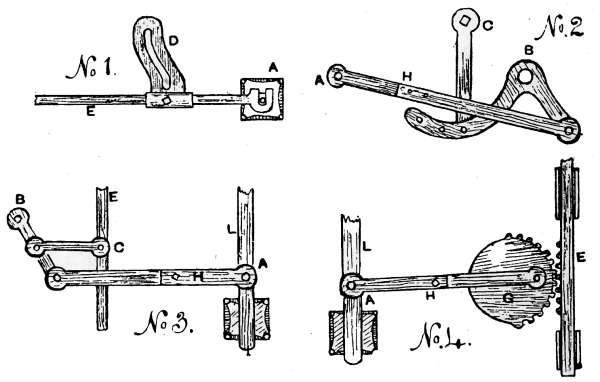

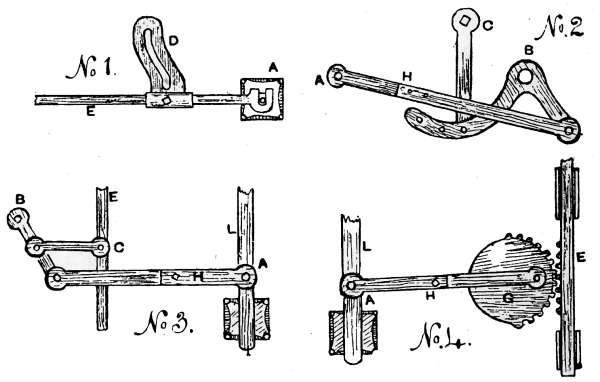

Self-acting motions actuate the cylinder through the rising and

falling of the griffe without requiring any special connection from the

loom. One of the most convenient of these is that frequently used

on hand-loom machines, and known as the S iron or swan-neck motion.

It is shown in Fig. 19a (No. 1), and another form of it on a swing

cylinder motion is shown in Fig 16. D is the swan-neck or S iron. In

the groove in it a roller stud on the griffe frame travels, sliding in and

out the cylinder A as the griffe falls and rises. E is the slide bar, which

may be flat or round; if round, there must be some means of keeping

it from turning in its bearings, which is generally accomplished by

having a crossbar bolted across the two slide bars behind the machine.

No. 2, Fig. 19a, is a motion for the same purpose, but consists of a[37]

series of levers; and No. 3 is an arrangement of a similar nature. B is

the fulcrum of the levers, or fast pin by which they are connected to

the machine. C shows the attachment of the levers to the slide rod of

the machine. A is the connection with the cylinder frame. As the

griffe rises or falls it will easily be seen that the cylinder will be driven

out or in.

The connecting-bar H is in two parts, slotted and bolted together at

H to admit of regulating the position of the cylinder.

No. 4 is a motion on a different principle; it is a French motion.

It will readily be seen that the cylinder is driven out and in by the

toothed wheel, which is wrought by a rack on the slide rod E. This

slide rod works outside the framing of the machine, as is common in

the French machines. One point must be observed about these

motions—viz. that they must have a certain amount of dwell at the

bottom of the stroke, or when the cylinder is in. The reason of this

dwell will be explained further on, but the method of obtaining it may

be given here. In the swan-neck motion (No. 1), any desired dwell

can easily be obtained at either top or bottom by the length of the slot

that is in a vertical direction, as when the stud is passing through this

portion of the slot no motion is given to the cylinder. In the lever

motions Nos. 2 and 3, as well as in No. 4, the dwell is got by the levers

or arms passing the centres; in Nos. 2 and 4 it is by the lever or arm

H passing the back centre, which may be considered as a crank; and in

No. 3 it is the short lever C passing the centre that gives the dwell.

Fig. 20

Fig. 21

Fig. 22

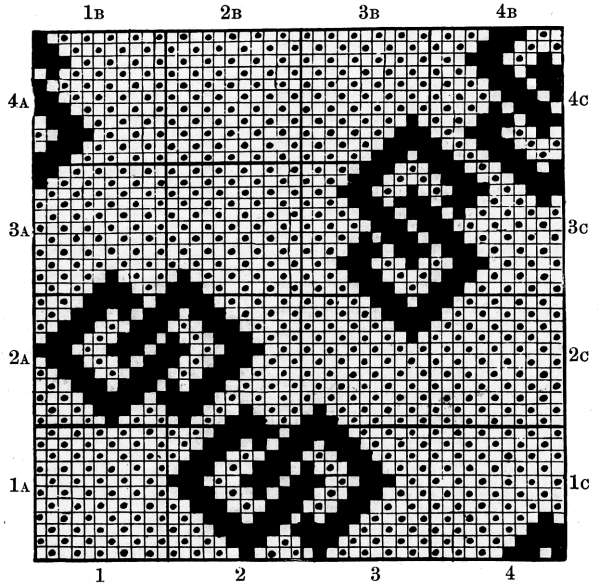

Fig. 20 is a view of the interior of a single-acting jacquard machine

with the framework removed; only one row of hooks and needles are

given, to avoid confusion. The blades or knives of the griffe, with a

support running across their centres, are shown at B. A is the face-plate

or needle board, sometimes made of iron, but better to be of hard

wood. C is the spring-box, the detail of which is given in Fig. 24.

E, E1 are the hooks, and F, F1 the needles. D is the grating through

which the hooks pass, and are supported by it. It will be seen that

the hooks and needles are arranged in rows of eight: a 400 machine

would have 50 or 51 of these rows in it; 500 machines are usually

arranged in rows of 10, and 600 machines in rows of 12. The hooks[38]

should be set perfectly upright or vertical, and should be close up

against the knives, but not pressing against them. There should be

a provision made for shifting both the grating and the knives, so as to

admit of both them and the hooks being properly set in relation to

each other; but if set correctly by the maker, which they should be, no

alteration is necessary. A (Fig. 21) is a side view of four hooks and

needles, with the ends of the knives of the griffe shown at a, a, a, a.

When the machine is working the needles are acted upon by perforated

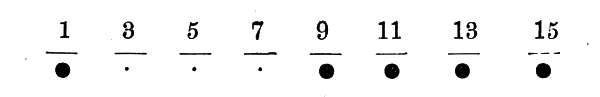

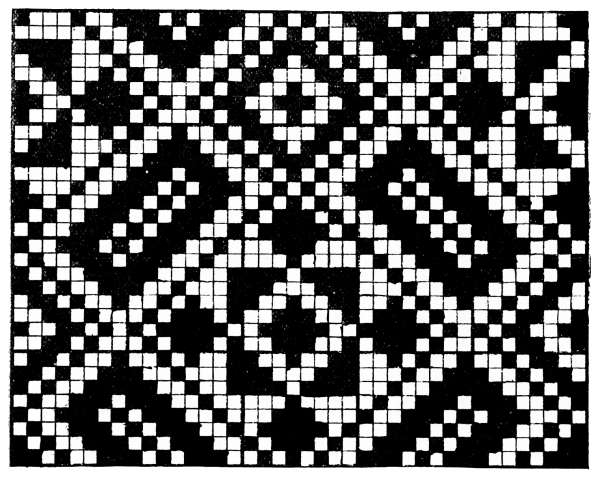

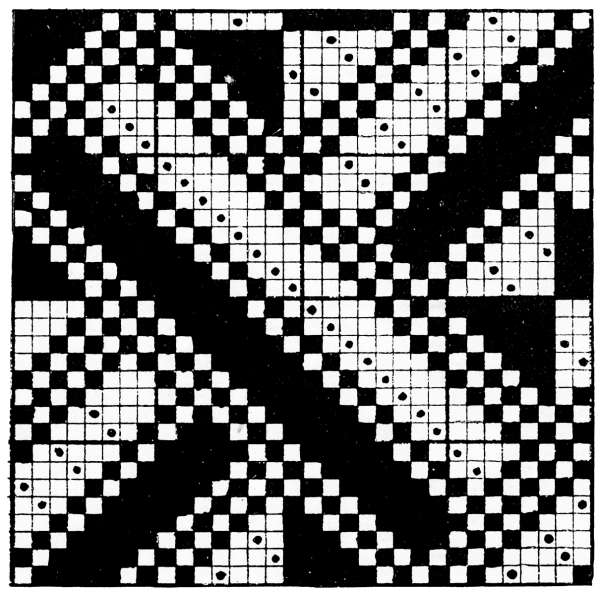

cards cut from the pattern. Suppose we take plain cloth—that is, a

pattern in which each half of the warp, or every alternate thread, is

raised and sunk alternately; then, if the first card acts on all the odd

numbers of the needles, and the second card on all the even numbers,

this repeated would make plain cloth. Whenever a hook of the

jacquard is to be raised a hole is cut in the card for the needle connected

with that hook, and a card with all the even numbers of holes[39]

cut in it will cause the griffe to raise all the even-numbered hooks.

Refer to b (Fig. 21), where the second and fourth holes are cut in the

card. If the card is pressed against the needles, as at c, the first and

third needles will be pressed back, and will push the first and third

hooks back from their position—shown by the dotted lines—to the

position in which they are shown in B (Fig. 21); but the second and

fourth hooks are not moved, as their needles pass through the holes in

the card. If the griffe is now raised, the blades or knives will pass the

first and third hooks, but will lift the second and fourth; and if the

odd numbers of holes are cut on the next card, the first and third

hooks will be lifted when it is pressed against the needles, as shown at

C (Fig. 21), thus making the cross-shed; and this explains the principle

of working any pattern by the jacquard without taking into consideration

the intricacies of mounting, &c. In C (Fig. 21), it will be seen

that if the knives d, d were upright instead of slanting, they would

come down on the heads of the hooks that are under them, but, being[40]

slanted, their lower edges pass the heads of the hooks, and press them

away as the griffe descends. Sometimes, even with slanting knives, if

there is much vibration in the hooks, or if the loom ‘bangs off,’ some

of the hooks are liable to get under the knives and be ‘crowned,’ or

bent down. To avoid this deep blades are often used, principally in

double-acting machines, so that the lower edges of the blades will not

pass the bottom hook, as shown at D (Fig. 21). This prevents any

danger of crowning, but it darkens the machine a little—that is, makes

it more difficult to see down into it if any of the wires require to be

examined; it also requires the heads of the hooks to be somewhat

higher above the heads of the needles than is necessary with the

narrow blades. Another principle has been tried—viz. that of making

the heads of the hooks as shown in Fig. 22, and using narrow blades.

This effects its object well, but there is too much friction of the knives

against the hooks, and the latter are liable to wear out too quickly. A

good machine with firmly set hooks should work very well without

these protections if it is steadily placed above the loom, and it is better

not to be resting on the loom framing, if convenient to have it so. It

will be seen from the foregoing explanation that the proper time, or,

rather, the necessary time, for the cylinder to press against the needles

is just after the griffe begins to rise. When the griffe is down the top

edges of the knives should be 3/16in. or 1/4in. lower than the turned points

of the hooks, and before this edge rises up to the hooks those that are

not to be lifted should be full back, or the cylinder should be close in,

having the front of the head of the hooks 3/16in. or 1/4in. behind the

blades. The cylinder should have a short dwell in this position; and

if it has a longer dwell it may assist to reduce the friction of the heads

of the hooks against the knives; but if it has too great a dwell it may

have to travel out and in too quickly to make up for the lost time, which

will probably not be compensated for by the advantage of the increase

in the dwell. Now, when the cylinder is driven with an independent

motion, as in Figs. 17 and 18, it is easy to set the eccentric so that it

can be brought in at any required time; but when a self-acting motion

is used, it is plain that if the cylinder must press against the needles

when the blades of the griffe are passing the heads of the hooks in rising,[41]

it must also press against them in the same position when the griffe

is falling, unless some special escapement motion could be devised

to avoid it, and this is where the dwell is required, and where the evil

effect of the motion takes place; and it is worse in a double-lift

machine with one cylinder, as the heads of the hooks in it are larger,

or have a longer turn on them. A little consideration will suffice to

show that when the brander or griffe is falling, say, with one-half of

the hooks hanging on its knives, and the cylinder is brought in against

the needles before the hooks are quite down, as it must be, it will

either cause the hooks to be shot off the knives, or will put a considerable

strain on them, as well as upon the needles and cards. It is for

this reason that these motions are objectionable, particularly in power-loom

work, where the speed is high and the hooks are strong. In

hand-loom work it is not so objectionable, as there is more spring in

the wires, and the heads of the hooks need not be too large, and,

besides, the speed is less and the wear and tear not so great; but, even

with this, if a hand-loom machine that has been in use for some time

be examined, it will be seen that the points of the hooks are considerably

worn, and that the edges of the knives are hollowed out like a

coarse saw by the friction of the hooks on them. This latter will partly

arise from the lifting of the hooks.

Fig. 23

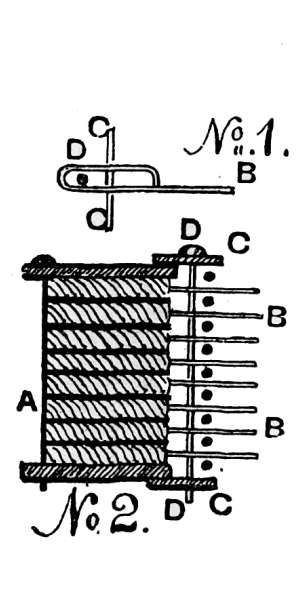

In the old Jacquard, given in Figs. 15 and 16, the hooks are shown

resting on a perforated board, and it was mentioned that in order to

prevent them from turning round a frame lay in the turned-up portion

of the hooks. The grating in Fig. 20, through which the turned-up

bottoms of the hooks pass, readily accomplishes this object. Sometimes

flattened hooks are used, as in C (Fig. 23), with the needles twisted

once or twice round the hooks; this makes a firm arrangement, but if

anything goes wrong with a hook it is not easy to get it clear of the

needle. When the needles were made with a full twist or loop on

them, as at B, the same was the case; they are now usually made as

at A, and if arranged in the machine as in Fig. 20, there is no danger

of the hooks sliding out of the recess in the needle, and if a hook gets

bent or broken, it can be taken out and replaced by a new one without

disturbing the needles.

[42]

Fig. 16 shows how the needles press against the springs in the

spring-box, which is much the same as that at present in use. Fig.

24 is the present arrangement. No. 1 gives a plan of the end of a

needle, B. C C is the horizontal wire which supports it as shown in

section at C C in No. 2. D (No. 1) is a section of the vertical wire

shown at D D (No. 2), which passes through the loops or eyes on the

ends of the needles, and keeps the springs from shooting them too far

forward. A (No. 2) is a wire which passes down at the outside of the

box over the ends of a row of springs, so that by drawing out this wire

any of the springs can be drawn out without taking off the spring-box,

as the springs pass through the box. The springs should be strong

enough to keep the hooks and needles steady, but if unnecessarily

strong they give the card and cylinder unnecessary work.

Fig. 24

In some machines there is no spring-box. The hooks are made

double, as shown in Fig. 25, and rods, as a, a, run along between the

rows of hooks; the spring of the double wire keeps the hooks steady.

There is a clap-board used, similar to that in the French draw loom,

(Fig. 13), which is pressed against the needles with springs; this board

is connected with the face-plate by a bar at each end, forming a frame.

The needles do not project much through the face-plate, but when the

cylinder is pressed against it, it slides back on the needles, and presses[43]

the clap-board back, which also allows those needles to go back which

the card presses against. The needles are not looped on the hooks,

but have a turned catch in front of them as shown. The bottom of the

hook rests on a hole board, C, through which the tail cords pass; and

through the hooks at D are wires fixed in a frame which rises and falls

when the hooks are raised, and keeps them from turning round, same

as explained in Fig. 15. Machines of this description are at present

being made in France, and work with a rising and falling shed, which

will be hereafter explained (see Fig. 30).

Fig. 25

Fig. 26 Fig. 27

In working, the card cylinder must be so set that it will come forward

fair on the needles—that is, that when it comes forward the

points of the needles will enter fair into the centres of the holes in it.