TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

The 'Apothecary System' of measurement was used in the original text.

The etext uses the following Unicode symbols:

℞ Prescription symbol

ʒ Dram

℥ Ounce

ℳScruple

Roman numerals, and 'ss.' for 'half', are retained, so for example

'℥iss.' indicates 'one and a half ounces'.

The 'Apothecary System' of measurement was used in the original text.

The etext uses the following glyphs taken from the text images:

Prescription symbol

Prescription symbol

Dram

Dram

Ounce

Ounce

Scruple

Scruple

Roman numerals, and 'ss.' for 'half', are retained, so for example

' iss.' indicates 'one and a half ounces'.

iss.' indicates 'one and a half ounces'.

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been

corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within

the text and consultation of external sources.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

[Pg 113]

THE

LONDON MEDICAL GAZETTE,

BEING A

WEEKLY JOURNAL

OF

Medicine and the Collateral Sciences.

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 27, 1828.

PATHOLOGICAL ESSAYS

ON SOME

DISEASES OF THE HEART;

Being the Substance of Lectures delivered before

the College of Physicians,

By P. Mere Latham, M.D.

Physician to St. Bartholomew's Hospital.

[Continued from p. 7.]

ESSAY II.

Morbid Anatomy of the Internal Lining

Membrane of the Heart.

The membrane which lines the cavities

of the heart is very liable to disease,

but not equally so in every part. Where

it is thin and transparent, and admits

the colour and character of the muscular

structure upon which it is spread

to be seen through it, it is seldom found

diseased; but where it is of a denser

texture, either in itself or from an admixture

of other structures, whether

cellular or fibrous, with its own, it is

frequently, and often exclusively diseased.

This latter character of a denser

texture belongs to it where it forms

the tough white circles which surround

the apertures of communication between

the auricles and ventricles; also

where it is reflected upon itself, and

forms the loose duplicatures of membrane,

which are given off, as it were,

from the internal surface of the heart,

either at the fibrous circles intermediate

between the auricles and ventricles,

constituting the tricuspid and the mitral

valves, or at the commencement of the

pulmonary artery and aorta, constituting

the semilunar valves.

It is remarkable how curiously disease

is apt to limit itself to the spaces

just pointed out. Of the fibrous circle

between the auricle and ventricle, of

the valves which originate from it, and

of the tendinous cords which connect

the valves with the carneæ columnæ,

there will not be the smallest space free

from disease; but the disease will

abruptly stop where the tendinous

cords cease and the carneæ columnæ

begin[1].

The membrane, however, where it

covers the fleshy columns of the heart,

is not exempt from the possibility of

disease: but when disease actually

affects it, it has seldom originated there,

but has generally spread from other

parts of the same membrane, although

(as we have just remarked) it is apt to

stop short before it reaches this.

Of the two sides of the heart, the

membrane which lines the left is unquestionably

the more liable to disease.

But my own observation would never

have led me to conclude that the membrane

of the right side was so far exempt

as it is commonly thought to be.

Speaking from the best recollection I

have of the specimens which have fallen

under my examination, I should say

that, in one-third of the cases where

disease has been found on the left side,

it has existed on the right side also,

and been essentially of the same character.

But there has been a remarkable

difference in the extent to which it

has proceeded on each side respectively:

while on the left it has gone so far as to

be the undoubted cause of death, on

the right, although essentially of the

same character, it has been only just

beginning.

[114]

It very seldom happens that disease

appertains to the lining of the right cavities

of the heart exclusively; and,

where it affects both, the disease in the

right cavities is very seldom found in

advance of that in the left.

It should seem, indeed, according to

the ordinary course of things, that disease

does not begin in the lining of the

right cavities of the heart, until it has

already advanced to an extreme degree

in the left.

The internal lining of the heart, as well

as of the arteries, is often found to have

become of a red colour. This redness,

so well known to all who are accustomed

to examine dead bodies, used to be

regarded as a mere stain imparted to it

by the colouring matter of the blood

after death. Yet a due consideration of

various circumstances connected with

it will hardly warrant this conclusion.

It has been found whether the heart

or artery be full or empty of blood;

and if blood be present it has been

found, whether it is liquid or clotted;

and if it be clotted, whether it does or

does not retain its colouring matter.

External temperature, and length of

time between the death of the patient

and the dissection of his body, have not

made any difference in the frequency

with which this peculiar appearance occurs.

Lastly, no artificial methods,

such as washing of any kind, can get

rid of it; nor will inclosing blood within

an artery for any period produce it[2].

This simple redness is sometimes seen

universally in both sides of the heart

and throughout the whole arterial system,

and sometimes in patches only, of

greater or less extent, whether in the

arteries or in the heart.

Now, when all these circumstances

are considered, although in some instances

it may be a mere stain imparted

by the colouring matter of the blood

after death, it is plainly impossible that

it should be of that nature in any large

proportion of the numerous instances

in which it is found.

But if the appearance in question implies

(as I believe it generally does) a

morbid condition, of what kind is that

condition? There are the same objections

to considering mere redness as

equivalent to inflammation here as in

the pericardium, or in any other part of

the body: here, as elsewhere, in one

case it may be the condition out of

which inflammation is to spring;

while in another it may not be destined

to give origin to any change in the

structure of the part beyond itself, and

may itself constitute the whole disease.

It appears to me, that this mere redness

of the internal lining of the heart

and arteries has become a matter of

undue perplexity to pathologists, because

they have laboured to infer from

it more than the simple fact itself will

authorize. All I wish to establish concerning

it is, first, that it is not always

(probably very seldom) a mere stain

imparted by the colouring matter of the

blood after death; secondly, that it

alone does not constitute inflammation.

It may not be improper to mention

the circumstances under which it has

occurred to myself to find it. I have

met with it most frequently, and to

the largest extent, in subjects whose

previous disease has produced a constant

and habitual impediment to the transmission

of blood through the heart and

through the lungs, and that impediment

has gone on increasing to the hour of

their death; also in those, whatever

might have been the nature of their disease,

whose dissolution (I mean the actual

process of dying) has been tardy and

agonizing, and marked by great labour

of respiration; in the apoplectic, for

example, in whom, after sense and

consciousness were extinct, life had

been protracted, with stertorous breathing,

for many days.

In such subjects the countenance,

the lips, and the whole skin, give

evidence during life of blood pushed

beyond the natural sphere of the circulation,

and detained in the extreme

blood-vessels. Hence it is obvious

that the causes which have loaded and

distended the capillaries in every part

of the body have had a like influence

upon the vasa vasorum.

I do not mean to say that I never met

with this peculiar condition of the heart

and arteries under other circumstances,

or that other causes may not produce it;

but that I am not acquainted with it

under any other with which, from frequent

coincidence, it has seemed to have

a natural connexion, or which have

afforded a reasonable explanation of the

phenomenon.

This condition of the heart and arteries,

considered as inflammation, has

been assigned by some as the cause of

[115]

fevers of the more malignant kind.

The frequency with which it has been

found in some particular epidemic,

must have led to the conclusion. But,

however this may be, from my own observation,

not restricting myself to the

fever of any particular season, but taking

into account all complaints called

febrile, and belonging to all seasons,

also from the result of inquiry among

medical men who have had large acquaintance

with morbid dissections,

and from the experience of those who

have made this particular point a subject

of investigation (Laënnec and Andral)

I venture to conclude that it has

no essential connexion with fevers of

any kind, either as cause or as effect.

On some occasions the internal membrane

of the heart and arteries, wherever

it exhibits the appearance described,

will allow itself to be peeled off from

the subjacent structure with the least

possible force; this facility of separation

ceasing entirely beyond the boundary

of the red tinge.

Here unquestionably is further evidence

of a diseased condition: but of

what nature? Most pathologists would

consider this to be of the nature of inflammation—and

I believe justly.

There is indeed much difficulty in pronouncing

upon the nature of minuter

changes of structure detected in the internal

parts of the body after death. We

are obliged to arrive at conclusions by

help of analogies drawn from morbid

processes, which we have watched in

their progress during life, upon the external

surfaces; for during life we have

the functions and sensibilities of the part

to aid us in forming a right judgment

concerning its disease. When, during

life, one tissue is separated from another,

as the periosteum from the bone,

or the cuticle from the skin, or the mutual

cohesion between different tissues

is sensibly weakened, we find it to be

owing to the intervention of serous fluid

which does not belong to their healthy

state; and this, together with increased

vascularity, or redness and heat, and

pain, is enough to bespeak the presence

of inflammation. All these conditions

cannot remain after death. Hence, if

we desire to form positive opinions concerning

much which is unfolded by dissection,

we must supply the defect by

analogy. Thus, whenever, in any part

of the heart or arteries, the cohesion between

the internal membrane and the

subjacent structure is manifestly lessened,

and the membrane is unusually red

at that part, we may regard these appearances

as the vestiges of inflammation,

without thinking that we go too far

in so regarding them.

The internal lining of the heart and

arteries is often found red solely in the

neighbourhood of ulcerated spaces,

when there can be no doubt concerning

the existence of inflammatory action.

But the internal lining of the heart

and arteries gives the most unequivocal

evidence of its inflammation when it is

found of a deep red colour, with coagulable

lymph adhering to its surface.

This condition is represented, as it was

found in the aorta, in one of the beautiful

plates, illustrative of the diseases of

arteries, by Mr. Hodgson[3]. And the

same condition, in the heart, I

have seen in a preparation of Dr.

Farre's, where lymph is deposited,

upon the circular zone, which forms the

aperture of communication between the

left auricle and ventricle. These appearances

denote the most acute inflammation:

they are, I suspect, very rarely

met with. In the few instances in which

I have heard of them, they have been

found where death has taken place

after short and severe suffering, and with

symptoms which characterize inflammation.

But the specimens of disease most

frequently met with in the internal lining

of the heart, consist in an entire

change of its natural structure, and in

the formation of new products upon it

or within it. Many of these, from the

analogy of morbid actions in other parts

of the body, must be considered to result

from chronic inflammation.

In any of those situations which have

been stated as especially liable to disease,

the membrane will become thick,

tough, inelastic, puckered and shrivelled;

and cartilage or gristle, and bone, will

enter into its structure; excrescences

will sprout out from it, resembling warts

and fungus; and it will become ruptured

and ulcerated.

Cartilaginous depositions are often

found beneath the membrane where it is

single; or between its folds where it is

double, in the situation of the valves;

and thus they seem rather to belong to

some structure contiguous to the membrane

than to the membrane itself.

[116]

Such depositions will proceed to a considerable

extent, while the membrane

still remains free from disease. From

a valve, which has been thick, opaque,

and cartilaginous, I have seen the membrane

separated on both sides, and

transparent; the opaque and cartilaginous

matter being left behind. Where, in

cartilaginous depositions, the lining of the

heart has become puckered and uneven

on its surface, and the valves shortened

and altered in their shape, the membrane

itself participates in the disease,

and is generally incapable of being separated

from the subjacent structure.

But great thickening may take place in

the situation of the valves, from deposition

of cartilage, without any unevenness

of their surface or alteration of their

shape; and under these circumstances

the membrane itself you may expect to

find hitherto exempt from disease[4].

Osseous depositions are always, I

believe, originally formed beneath, or

exterior to, the membrane, both in the

heart and in the arteries. There are two

circumstances especially worthy of remark

in this process of ossification:

sometimes it is a pure and unmixed process:

bone is formed, and nothing else.

It is deposited in minute granules, or

little brittle scales, or in plates of a

larger size; and the intermediate spaces,

whether in the heart or arteries, preserve

their natural and healthy appearance.

At first, these granules or scales,

or plates of pure bone, are covered by a

delicate pellicle, which is in fact the internal

membrane of the heart or artery,

separating them from the immediate

contact of the circulating blood. But

in process of time, as they increase in

size, and become rough and unequal on

their surface, they cause a rupture of the

internal membrane, and have now nothing

to separate them from the immediate

contact of the blood[5].

Sometimes ossification is a mixed

process, or rather, I suspect, the result

of another morbid process preceding it.

With the cartilaginous depositions already

described there is an admixture of

bone. The quantity of bone generally

bears a very small proportion to the cartilage

when they both occur together, as

if the bone proceeded from the cartilage,

and not the cartilage from the bone. It

is sometimes seen growing from the surface

of the cartilage, and is sometimes

deposited in its substance, and only detected

by the knife.

Simple ossification, as it occurs

in the heart and arteries, has been

classed among the natural changes

which the parts in question are liable to

undergo after a certain period of life.

Of persons above the age of sixty years

the proportion is that of seven in ten

according to Bichât, in which ossification

is discovered in some part of the

arterial system. It very rarely happens

that simple ossification is found before

the period of old age: still it is difficult

not to regard it as a morbid process.

But ossification, when it is a mixed

process, is unquestionably the result of

disease. It is met with at all periods of

life; and probably constitutes one of

the terminations of inflammation. The

kind of morbid structures with which

the bone is united leads to this belief.

Fungous, and wart-like excrescences,

are found in all those parts of the internal

lining of the heart, which have been

already mentioned as most subject

to disease. They seem to be the result

of a new morbid action set up in parts

already disorganized; for I have not

met with them where the membrane has

been otherwise healthy, but only where

it has been thickened or cartilaginous,

or ossified, ruptured, or ulcerated.

They grow either from the surface of the

membrane, or from its ruptured or ulcerated

edges, and are always in immediate

contact with the circulating

blood[6].

According to my observation, when a

fungous or warty excrescence has

grown from the ruptured edges of the

membrane, it has been from them exclusively,

[117]

and from no other part of the

lining of the same heart. And as rupture

of the membrane seldom occurs in

more than one situation at a time, the

heart of the same individual seldom presents

more than one excrescence of this

kind: and as the aortic valves are the

parts most liable to rupture, it is there

that this single excrescence is most frequently

found; not that rupture may

not take place elsewhere. I once saw a

single chorda tendinea ruptured; and a

single fungous excrescence of considerable

size hanging from it into the cavity

of the left ventricle.

Now, this morbid growth is evidently

connected with the lacerated state of the

membrane in the conditions of its production,

whereby it is limited to a small

space.

It is probable that the membrane is

first ruptured; that its lacerated edges

inflame, and then throw out unhealthy

lymph, or unhealthy granulations, in the

shape of these fungous or wart-like excrescences.

When they have sprung

from a ruptured membrane, they

have, in the specimens which I have

examined, been larger than when

they have arisen under other conditions.

But when such excrescences grow

from the surface of the membrane which

is thickened and cartilaginous only, but

not lacerated, they are more apt to

occur in many parts of it at the same

time. I have seen the valvular apparatus

between the auricles and ventricles

on both sides, as well as the aortic

valves of the same heart, studded with

them. They were all about the size of

hemp seeds: they adhered to the membrane

with different degrees of tenacity,

and wherever they were capable of

being detached, they left a rough surface.

The lining of the arteries has

been known to give origin to morbid

growths of the same kind, which have

obstructed the passage of blood, and

given occasion to the formation of a

coagulum, which has obliterated the

pulse.

The internal lining of the heart is

liable to ulceration, not as a common

consequence of simple inflammation,

but as an occasional consequence of

some of those diseased conditions which

have been described.

It is most commonly found around

scales and spiculæ of bone, and under

such circumstances as to leave no doubt

that the bone itself has furnished the

source of irritation from which it springs.

The ulceration commences from the

very border of the bony scale, as if it

was a process of nature for detaching it,

and to a considerable distance around

the ulceration the membrane is reddened,

and easily detached from the subjacent

structure. Where there are several

distinct scales of bone, it is not uncommon

to find a circle of ulceration

around each of them.

Ulceration is also met with where

there is a thickened and cartilaginous

state of the membrane without ossification.

Under these circumstances, as

far as I know, it affects no definite form.

It is often a very destructive process of

disease, obliterating large portions of

the valvular structure, and penetrating

deep into the muscular substance of the

heart.

Rupture of the internal lining of the

heart is not easily distinguished from

ulceration. In collections of morbid

anatomy, many unquestionable specimens

of ulceration are described as specimens

of rupture. Rupture must

always be looked for in the valvular

apparatus of the heart, i. e. in the

valves themselves, or in the chordæ

tendineæ which are their appendages.

It is probably incapable of taking place

elsewhere, except as a part of a rupture,

which involves the whole organ.

That solution of continuity which is

evidently without loss of substance;

that of which the separated edges when

they are brought together are completely

adapted to each other; also that

which is unaccompanied by any thickening

or other morbid condition of the

valve; the solution of continuity which

is found under these circumstances, may

safely be considered to proceed from

rupture, and not from ulceration[7].

But it is probable that these characteristic

conditions do not long remain

after the occurrence of the rupture.

Complete specimens of them are very

rare; but specimens are numerous

where the solution of continuity, by its

form and direction, bespeaks rupture,

while its rounded edges and the general

thickening of the valve denote ulceration.

These, it may be fairly conjectured,

do in fact exhibit a compound of

both. The membrane was originally

ruptured, but disease has subsequently

arisen and obscured the character of

the mechanical injury.

The greater number of those concretions,

[118]

which were regarded by the

older anatomists as polypi of the heart,

were unquestionably portions of mere

blood, which had undergone coagulation

after death. The blood remaining

in the heart after death discharges itself

of its colouring matter as it coagulates,

and, giving off processes between

the muscular fasciculi, assumes a shape

which has suggested the name of

polypus[8].

I have often found (I presume, therefore,

that it is not an uncommon occurrence)

coagula of an irregularly

laminated texture having their colouring

matter not entirely discharged,

but unequally distributed through

them, which have been most intimately

adherent to some part of the lining

of the heart. Of these some have admitted

of separation, while the surface

of the membrane and the surface of the

clot were left rough at the place of contact,

and others were incapable of being

detached without the membrane being

detached along with them. The appendix

of the left auricle is a situation in

which they are apt to occur, and they

are generally accompanied by an extensively

diseased condition of the lining

membrane. These coagula, from their

laminated texture, and from the intimacy

of their union with the internal

lining, seem to be essentially different

from polypi of the heart. They appear

to be connected with a process

of disease in the membrane, and to

have obtained their union with it long

before the death of the patient.

I once saw two separate tumors, entirely

resembling what are called polypi, between

the carneæ columnæ of the left

ventricle, and firmly adherent to the

heart; and in the centre of each a distinct

formation of pus. The heart was

otherwise healthy[9].

There are three preparations in the

museum of the College of Surgeons,

put up by Mr. Hunter himself, and

noted by him as exhibiting "Tumors

on the inner surface of the right

ventricle, seemingly composed of layers

of coagulable lymph one upon another,

the central part having the appearance

of glary mucus." This last appearance

(the mucus) no longer remains

in any of the three, but in its stead

there is a cavity. The tumors

which I have mentioned as originally

containing in their centre a distinct

formation of pus, also now present

in its stead a cavity. The preparation

preserved at St. Bartholomew's,

and those at the College of Surgeons,

are probably specimens of the same

disease.

Here what in the recent parts seemed

to be pus or glary mucus, and the cavities

still remaining in the preparations,

must suggest the suspicion, that these

tumors, whether they grew from the

surface or were deposited from the

blood, had become organized, and afterwards

inflamed; and that the inflammation

had terminated in the formation of

an abscess.

ESSAY III.

Morbid Anatomy of the Muscular Substance

of the Heart.

Dr. Baillie, speaking of inflammation

of the substance of the heart,

says, "When the pericardium covering

its surface is inflamed, the inflammation

sometimes passes a little way into

the substance of the heart:" and then

he gives these as the characteristic

marks of such inflammation—that "it

(the substance of the heart) becomes

much more crowded with small vessels

than in its natural state, and there are

sometimes to be seen a few spots of

extravasated blood." Now, this undue

vascularity, and these few extravasated

spots, where inflammation unquestionably

belongs to a contiguous structure,

may be deemed sufficient evidence of

the muscular substance of the heart

participating, or beginning to participate,

in the same disease; but, absolutely

and exclusively, it may be doubted

whether more is not required to give

a certain assurance of its inflammation.

Here, as elsewhere, we must look for

some of the proper products of inflammation;

or for some of the permanent

changes of texture which naturally result

from it, according to its several

modes of disorganizing.

It is a very rare event to find pus

among the products of inflammation

of the substance of the heart: yet this

event has occurred twice to my observation.

In one instance the whole

heart was deeply tinged with dark-coloured

[119]

blood, and its substance

softened; and here and there, upon the

section of both ventricles, innumerable

small points of pus oozed from among

the muscular fibres. This was the result

of a most rapid and acute inflammation,

in which death took place after

an illness of only two days. In another

instance, after death, which terminated

an illness of long duration and

characterized by symptoms referable to

the heart, a distinct abscess was found

in the substance of the left ventricle,

closed externally by a portion of adherent

pericardium, and connected internally

with an ossified portion of the

lining membrane.

This diffusion of pus, or rather its

formation in innumerable separate

points, throughout the muscular structure

of the heart, by a rapid and acute

inflammation, is a singular occurrence.

No such case has ever fallen within the

knowledge of the most experienced in

morbid anatomy, of whom I have made

inquiry; neither has any such (as far

as I can learn) been recorded in books[10].

A single collection of pus[11], constituting

an ulcer or abscess of the heart,

and resulting from chronic inflammation,

is also a rare occurrence, yet not

so rare but that a specimen of it may

be found in most collections of morbid

anatomy[12].

But independent of the formation of

pus, softening and attenuation, as well

as induration and thickening of the

muscular substance of the heart, do,

in different cases, according to the circumstances

under which they are found,

both bespeak inflammation.

Together with the unequivocal evidence

of inflammation in other parts of

the heart, the muscular fibres have at

the same time been found very soft and

loose, and easily torn; and with this

looseness of texture the heart has sometimes

presented a dark and almost black

appearance, and sometimes it has been

almost blanched and colourless. The

deep dark tinge shews that the muscular

substance is unnaturally loaded with

blood; whereas the absence of colour

shews that it is destitute of its natural

quantity. These different appearances

do, in fact, belong to different stages of

the same disease. The first indicates

inflammation of the muscular substance

in its present state of activity; the

second, an irreparable disorganization

of the muscular substance left by inflammation,

when it has been unarrested

in its earliest stages. The first is

found when death takes place in a

few days after the accession of the disease;

the second, when the patient survives

the first attack, and dies at a remoter

period.

The inflammation, which produces

softening and attenuation of the muscular

structure, is, I believe, always of

an acute kind.

But induration and thickening of

the muscular substance of the heart is

also the result of inflammation. This

must be distinguished from hypertrophy,

or mere augmentation of bulk, of

which we shall speak hereafter. In this

induration, which proceeds from inflammation,

there is, besides increase

of bulk and firmness, a manifest alteration

of texture. A substance[13] is produced

offering a peculiar resistance to

the knife. This condition unquestionably

must result from an interstitial deposition

of new matter among the muscular

fibres. From concomitant circumstances,

as well as from its own

character, I presume that it proceeds

from chronic, not from acute inflammation.

I confess that I never saw a

specimen of what I now allude to. It

is described with some minuteness by

Corvisart; but it may be presumed to

be very rare, since Laënnec admits that

it never fell under his observation.

These opposite states of softening

and attenuation in one case, and induration

and thickening in another, are

known to those conversant with morbid

dissection as the evidences of inflammation

in other parts of the body besides

the muscular substance of the heart.

But there are changes of structure

incident to the muscular substance of

the heart which are independent upon

inflammation, or, perhaps, upon

any process which can properly be

called morbid. They consist of simple

augmentation and simple diminution of

bulk and consistence. This simple

augmentation of bulk and consistence is

owing exclusively to a more ample development

of natural structure. The

muscular substance is more red than

[120]

natural, its carneæ columnæ are increased

in thickness, and its proper fibrous

texture is every where more strikingly

manifest; but there is no interstitial

deposition of matter new in its

kind. It has been called hypertrophia

of the heart, and the name conveys a

tolerably just idea of its actual condition.

The simple diminution of bulk and

consistence is a condition the exact opposite

of the former. The muscular

substance is less red than natural; its

proper fibrous texture less distinguishable;

but there is still the appearance

of muscle shrunk and withered, as if

from an insufficient supply of nourishment.

It may be called atrophia of

the heart.

Conjoined with augmentation, as well

as with diminution of strength and bulk

in the walls of the heart, there is almost

always an increase in the capacity of its

cavities; and in whichsoever part of

the heart the walls are thus augmented

or diminished, it is the cavity appertaining

to the same part which undergoes

the increase of capacity. Hence

it appears either that one of these conditions

is the immediate and necessary

consequence of the other, or that both

are the simultaneous effects of the

same causes.

Dilatation of any cavity of the heart,

with thickening of its walls, is called

active dilatation; and dilatation of any

cavity, with attenuation, is called passive[14].

Active dilatation may appertain to

every cavity of the heart simultaneously;

and so may passive dilatation. But

such occurrences are very rare: for

one cavity being naturally more liable

to this species of dilatation, and another

to that, it most frequently happens that

specimens of both conditions are found

in the different cavities of the same

heart.

The left ventricle is much more

liable to active dilatation than the

right; and the right ventricle more so

than either of the auricles; and of the

auricles unquestionably the left. Upon

the whole, perhaps, the fact may be

truly stated thus—that the left ventricle

commonly gains an increase of bulk

and strength, with an increase of capacity;

and that all the other cavities, at

the time that they expand, are rather

apt to become attenuated.

It sometimes (though rarely) happens,

that, with an increase of strength

and bulk in its muscular structure, the

left ventricle suffers a diminution of

capacity in its cavity. In a case reported

by Laënnec, the left ventricle

was an inch and a half thick at its

broadest, and an inch thick at its

thinnest part; and yet its cavity was

only capable of containing an unblanched

almond. I have seen the same condition

in a less degree.—(Laënnec,

vol. ii. 698.)

The circumstances under which these

opposite conditions, this hypertrophy

and atrophy of the heart, with the enlargement

or diminution of its cavities,

arise, must be explained hereafter.

At present I would only remark that

they are often found conjoined with

actual disease in other structures of the

heart, such as osseous or cartilaginous

thickening of internal lining, adhesion

of the pericardium, and ossification

of the coronary arteries, to which they

owe their origin; and, moreover, that

they are often found where the heart is

otherwise perfectly sound in texture,

and where their cause must be sought

in other parts of the body.

The heart is liable to undergo a simple

dilatation of its cavities without either

thickening or attenuation of its muscular

substance. This simple dilatation

is sometimes of the whole organ, sometimes

of one side, and sometimes only

of one auricle or ventricle. When it is

of one cavity only, it may be complicated

with active or passive dilatation of

another, or of all the rest.

There is reason to believe that the

heart sometimes undergoes a temporary

dilatation, and again returns to its natural

capacity; but that the dilatation

can only subsist for a short time without

becoming permanent.

The power of thus enlarging its cavities,

and restoring them to their natural

condition, belongs more especially to

the right side of the heart.

A large accumulation of fat is sometimes

met with about the heart.

The healthy heart is always more or

[121]

less marked upon its external surface

with streaks of white, and this appearance

results from the deposition of fat in

the cellular texture, which unites the

serous covering with the subjacent muscular

structure. It is found principally

where the venæ cavæ unite to form the

right auricle; also at the base of the

ventricles, and along the line which

marks the boundary between the two,

and around the origin of the great blood-vessels

as they emerge from the heart.

But when fat is deposited in more than

these situations, and in more than the

natural quantity, it is not so much

added to the healthy substance of the

heart, as existing at its expense and detriment,

and the muscular structure is

that which especially suffers. The fibre

of the fat heart is pale and wasted,

like that of a paralytic limb.—Mus. of

the Coll. of Surg. 327.

A rupture of the heart is sometimes

met with; but all the cases of reputed

rupture are not such in reality. An

aperture in the walls of the heart,

through which blood escapes into the

cavity of the pericardium, may result

from ulceration as well as from rupture,

or from a mixed process of one and

the other; but whatever be the precise

nature of the process by which this

perforation of the heart is effected, it is

undoubtedly of rare occurrence.

Where it has been found, there has

generally been at the same time some

peculiar condition of the organ, which

might be presumed favourable to its

production. Its muscular substance

has been so soft and loose of texture,

that it could be pierced through by the

weight of a probe[15]; or it has been converted

into, or greatly intermixed with

fat[16]; or its muscular fibres have been

absolutely defective, leaving a certain

transparent space, where the internal

lining and the pericardium have been

in contact, and served to maintain the

completeness of the cavity, until the

rupture has taken place[17].

Not that a rupture has not been

found where the texture of the parts has

seemed to offer no natural facilities to

its occurrence—as in the case related

by Harvey himself, who found a lacerated

aperture in the left ventricle, capable

of admitting his finger, through

which blood had escaped into the pericardium,

the walls of the ventricle being

increased in thickness and strength,

while an obstacle existed at the entrance

of the aorta[18]. Here the heart must

have torn itself asunder by the simple

violence of its contraction, in contending

against the impediment to the egress

of blood from its cavity. This is an

effect which would hardly be thought

capable of being thus produced; but

I can well believe it possible after having

seen one of the recti muscles of the

abdomen literally torn in twain, in a

man who died of tetanus[19].

[To be continued.]

DILATED ŒSOPHAGUS.

To the Editor of the London Medical

Gazette.

Sir,

Permit me to send the following case

to you for insertion in the Gazette.

Mary Blores, æt. 33, was admitted

into the Middlesex Hospital on the 16th

of November. She was in a state of

extreme feebleness and emaciation.

Those who brought her said that during

the preceding month she had appeared

to swallow nothing: what she took

as food seemed to her to stop in the

gullet, and after a few minutes returned.

I found, however, that a

large œsophagus-bougie passed readily

into the stomach, meeting with no obstruction

beyond a spasmodic resistance

in the pharynx. A draught of

milk and water was given her—she

swallowed it without much effort, but

it quickly returned. In the course of the

[122]

afternoon a pint of beef tea was injected

through an elastic tube into the stomach—it

was thrown up directly.

I now learnt from her that she could

swallow liquids much more readily than

solid food; that when she took a small

quantity, it seemed to her not to reach

the stomach, and in three or four

minutes was invariably thrown up; that

on taking a large draught she had an

impression that it reached the stomach—in

this case vomiting did not follow so

soon, and some part of the draught was

permanently retained; that she craved

food and drink, and was literally dying

of hunger and thirst; that the vomiting

which took place was not preceded by

nausea, although in its progress it had

all the appearance of ordinary retching;

that the matter vomited was not

thrown up at once, but by successive

efforts; it consisted of the food she had

last taken, mixed with colourless

mucus. The belly was so shrunk that

the umbilicus was not more than an

inch distant from the spine, upon

which the pulsations of the aorta were

readily felt: there was no enlargement

or hardness about the stomach,

no particular tenderness on pressing

the epigastrium, no sensation of pain or

heat now or formerly.

The complaint had began ten years

ago, during pregnancy, since when she

had never been free from it, although

at times her sufferings had been less,

and she had been able to retain some

portion of her meals. She had borne

in this period three children; the vomiting

had lasted during the whole

period of her pregnancies, and during

her confinement. The principal remedies

which had been used for her relief

were a succession of blisters on the pit

of the stomach—but they had produced

no benefit. Latterly her symptoms had

been greatly aggravated.

This patient was attended by Dr.

Watson and myself. But the means

which we tried to enable her to retain

her food, and to support her expiring

strength, had scarcely a temporary

effect. She died on the 2d Dec. sixteen

days after her admission. The body

was carefully examined, at the expressed

wish of her relatives.

The unusual appearances found in the

abdomen were—1. the smallness of

the first part of the duodenum, which

was but half the ordinary size of

the ileum; 2. the capaciousness and

fulness of the gall bladder,—from

which, however, on compressing it,

the bile flowed readily into the intestine;

3. a contraction of the middle of the

stomach of the length of two inches,

for which extent the peritoneal coat

was thickened and opaque, and the inner

membranes folded in deep longitudinal

rugæ, the mucous surface of which was

partially suffused with circular spots of

red. The breadth of the contracted

part of the stomach, as it lay collapsed,

was an inch and a half.

But it was in the chest that the most

remarkable circumstance presented itself.

The œsophagus gradually enlarged

from the pharynx, which was

perhaps rather narrower than usual,

to an extraordinary degree of dilatation;

the greatest breadth which it

attained was situated about four inches

above the cardia: the tube then contracted

more abruptly, so as to render

the termination of the œsophagus, like

its commencement, of nearly the usual

dimensions. The structure likewise of

the cardiac extremity for about an

inch, and of the pharyngeal end for

about half an inch, was healthy. The

intermediate part presented, when inverted,

the following curious appearance:—The

inner membrane was thickened

and opaque, and had the appearance

of having partially yielded from dilatation;

at the upper part the furrows or

thinner parts of the membrane followed

in some degree a longitudinal direction;

at the lower part the surface was pitted

with shallow depressions of various

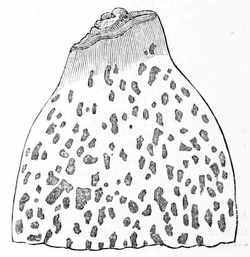

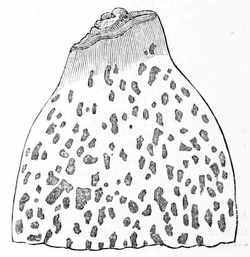

figures. I have represented in the adjoined

sketches these appearances, which on

the middle of the œsophagus passed

from one into the other; at the furrows

[123]

or depressions the membrane seemed of

the natural thickness and colour; the

intermediate raised and thickened part

was opaque and whitish. The muscular

fibres of the œsophagus were of the

natural colour and thickness.

I remain, Mr. Editor,

Your obedient servant,

Herbert Mayo.

19, George-street, Hanover-square,

Dec. 6, 1828.

HYDROPHOBIA.

To the Editor of the London Medical Gazette.

Sir,

As the following case may throw some

additional light on the pathology of

hydrophobia, I have sent it you for

publication.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

F. Godrich.

Grove House, Little Chelsea,

Nov. 29, 1828.

On Thursday morning, the 25th ult.

I was called up about seven o'clock to

see a man who I understood was exceedingly

ill, and waiting in the surgery

very impatiently for my arrival. I

found my patient (Mr. Barham), a fine

looking old man, about 60, labouring

at intervals of about five minutes under

strong spasmodic paroxysms, affecting

the muscles concerned in breathing

and deglutition. There was a wildness

and an impatience depicted in his

countenance, totally different from any

thing I had ever observed in other spasmodic

affections. His bowels were open,

tongue clean, skin moist, pulse full and

a little accelerated. I took away twenty

ounces of blood, and prescribed a mixture

containing

ʒss. ss.

of laudanum for a

dose every hour until I should see him

again. He walked home half a mile

from my house (Gloucester Road, Old

Brompton), and left me ruminating on

the possible cause of so much mischief

occurring suddenly in a fine healthy

subject. At ten a message was sent,

saying that he was much worse, and

requesting me to call as soon as possible.

He received me tranquilly, and

said he was very glad that I had come

to see him, for he was very ill. His

symptoms were now more distressing

than when I first saw him: he looked

wildly and suspiciously at every one entering

his apartment, and his breathing

was accompanied by a short convulsive

sobbing. On looking at his medicine

I perceived he had taken none, and expressing

my surprise, he assured me it

was impossible for him to swallow a

single drop, as the attempt had been

followed by violent spasms, and produced

so much distress, that he had desisted.

At this period no one had the

slightest idea of the origin of his

malady. I poured out some medicine

into a tea-cup, the very act of which

produced much excitement and alarm.

My first impression as to the true nature

of his disease arose at this period, from

the circumstance of his requiring a tea-spoon,

with which he endeavoured to

take some of the medicine. The attempt

produced much excitement and

alarm, and after two or three painful

efforts at deglutition, with one desperate

effort he swallowed a tea-spoonful, threw

away the spoon, and begged, unless I

wished to destroy him, that he might

have nothing more to swallow. I now

left his room, and inquired of a bystander

whether any thing particular

had occurred to him within the last

few weeks. On recollection she said,

"About a month since, late at night, a

strange dog came into the premises and

fought with his own dog; he got out of

bed to separate them, and the strange

dog bit him in two places, on the left

arm and hand; and bit a puppy, which

died about a fortnight after in a strange

[124]

way, which was thought to be some

kind of a fit." To ascertain if this occurrence

had produced any effect on his

mind, while again bleeding him I said,

"You have been in the wars, Sir, and

had your hand and arm torn; how did

it occur?"—"Oh!" said he, carelessly,

"that was done by a dog a long time

ago, but it healed." The circumstance

was never again mentioned to him, and

he died in total ignorance of the cause

of his malady. The wounds were perfectly

cicatrised, and there was not the

least action going on indicative of recent

absorption. He bore the bleeding

pretty quietly:

40℥.40

ss.

of laudanum for a

dose every hour until I should see him

again. He walked home half a mile

from my house (Gloucester Road, Old

Brompton), and left me ruminating on

the possible cause of so much mischief

occurring suddenly in a fine healthy

subject. At ten a message was sent,

saying that he was much worse, and

requesting me to call as soon as possible.

He received me tranquilly, and

said he was very glad that I had come

to see him, for he was very ill. His

symptoms were now more distressing

than when I first saw him: he looked

wildly and suspiciously at every one entering

his apartment, and his breathing

was accompanied by a short convulsive

sobbing. On looking at his medicine

I perceived he had taken none, and expressing

my surprise, he assured me it

was impossible for him to swallow a

single drop, as the attempt had been

followed by violent spasms, and produced

so much distress, that he had desisted.

At this period no one had the

slightest idea of the origin of his

malady. I poured out some medicine

into a tea-cup, the very act of which

produced much excitement and alarm.

My first impression as to the true nature

of his disease arose at this period, from

the circumstance of his requiring a tea-spoon,

with which he endeavoured to

take some of the medicine. The attempt

produced much excitement and

alarm, and after two or three painful

efforts at deglutition, with one desperate

effort he swallowed a tea-spoonful, threw

away the spoon, and begged, unless I

wished to destroy him, that he might

have nothing more to swallow. I now

left his room, and inquired of a bystander

whether any thing particular

had occurred to him within the last

few weeks. On recollection she said,

"About a month since, late at night, a

strange dog came into the premises and

fought with his own dog; he got out of

bed to separate them, and the strange

dog bit him in two places, on the left

arm and hand; and bit a puppy, which

died about a fortnight after in a strange

[124]

way, which was thought to be some

kind of a fit." To ascertain if this occurrence

had produced any effect on his

mind, while again bleeding him I said,

"You have been in the wars, Sir, and

had your hand and arm torn; how did

it occur?"—"Oh!" said he, carelessly,

"that was done by a dog a long time

ago, but it healed." The circumstance

was never again mentioned to him, and

he died in total ignorance of the cause

of his malady. The wounds were perfectly

cicatrised, and there was not the

least action going on indicative of recent

absorption. He bore the bleeding

pretty quietly:

40℥.40 .

were removed,

which on cooling presented strong

marks of inflammation.

.

were removed,

which on cooling presented strong

marks of inflammation.

Ordered

ℳiv. iv.

Acid. Hydrocyan. omni horâ, in a little water.

iv.

Acid. Hydrocyan. omni horâ, in a little water.

Twelve o'clock.—With much difficulty

he has taken two doses of the

acid; pulse full and hard, 110.

30℥.30 .

more blood were removed.

.

more blood were removed.

Three o'clock.—Has taken two more

doses; complains of a dreadful sense

of suffocation, and implores that nothing

more may be given him. Pulse full, and

beating at 120 to 130. Continue the

acid.

Eight o'clock.—Pulse full and hard.

Has taken in all

24ℳ.24 .

of the acid, but

so painfully distressing has the deglutition

now become, that all attempts at

repeating his medicine are discontinued.

.

of the acid, but

so painfully distressing has the deglutition

now become, that all attempts at

repeating his medicine are discontinued.

V. S. ad

℥xxx. xxx.

xxx.

During the bleeding he looked wildly

at the basin, and begged that no more

might be spilt (a drop or two had fallen),

repeating frequently, in great

agitation, as the blood was running,

"Take care! take care!"

Between two and three o'clock next

morning my assistant (Mr. Davies) visited

him. He found him tolerably

passive, but observing every movement

with intense anxiety. Pulse full and

hard, face flushed, eyes denoting cerebral

irritation. He had been at times

outrageous. On its being intimated

that bleeding was again necessary, a

paroxysm came on more intense than

any preceding,—and with great effort he

submitted. As the blood flowed he became

more and more alarmed, till at

length he got quite unmanageable; he

raged violently at his nephew, who was

holding the basin, and ordered it peremptorily

to be removed. 30 or

40℥.40 .

were taken away. It was found necessary

to put on the straight waistcoat.

About four o'clock Mr. Davies wished

him to take some more of his medicine.

He said, "I can take no more," and on

reaching the bottle to put out a few drops,

he became violently agitated, threw himself

from side to side, and, as well as

the incessant spasmodic sobbings would

allow, he begged that not one more drop

of any thing might be offered him, and

that the bottle might be taken from his

sight. He did not become tranquillized

until its removal. He lingered on till

ten A.M. in the same state, a few minutes

before which he insisted on getting

up, and walked a short way down

his garden, returned, laid down on his

bed, and died.

.

were taken away. It was found necessary

to put on the straight waistcoat.

About four o'clock Mr. Davies wished

him to take some more of his medicine.

He said, "I can take no more," and on

reaching the bottle to put out a few drops,

he became violently agitated, threw himself

from side to side, and, as well as

the incessant spasmodic sobbings would

allow, he begged that not one more drop

of any thing might be offered him, and

that the bottle might be taken from his

sight. He did not become tranquillized

until its removal. He lingered on till

ten A.M. in the same state, a few minutes

before which he insisted on getting

up, and walked a short way down

his garden, returned, laid down on his

bed, and died.

Mr. Frederick Salmon, of Old Broad

Street, and Mr. Wilson, of Chelsea,

were kind enough to assist me in conducting

the post mortem examination.

On opening the chest, the heart was free

from disease, with rather more water in

the pericardium than natural; the lungs

were completely gorged with grumous

blood, and the pleura adherent on the

right side. On removing the cranium,

which was remarkably thin, and cutting

the substance of the brain, numerous

red spots presented themselves in the

medullary portion; about a table-spoonful

of water in each ventricle; the

plexus choroides was turgid; the corpora,

striata, thalami, and basis of the

brain every where preternaturally injected;

the cerebellum, crura cerebri,

and cerebelli, in a high state of inflammation.

On removing the spinous process

of the vertebra, the whole cord

was considerably inflamed; and opposite

the two last cervical and dorsal

vertebræ the cellular substance was

studded with dark patches of coagulated

blood, the theca vertebralis thickened,

and the cord in an active state of inflammation.

The larynx and pharynx

bore not the slightest vestige of disease.

The preparation of the cord is deposited

in the museum of the London

University.

The post mortem examination of this

case tends to prove the correctness of

Professor Thompson's theory of the

proximate cause and seat of this afflicting

malady; and the plate accompanying

a case recorded by him, in the

13th volume of the Med. Chir. Society,

gives a faithful delineation of the state

in which the spinal cord was found in

this case.

[125]

CASE OF LONG PROTRACTED CONSTIPATION.

To the Editors of the London Medical

Gazette.

Gentlemen,

Perhaps the following case may interest

some of your readers, and if you

think so, its insertion in your Journal

will oblige

Your obedient and

humble servant,

S. D. Broughton.

12, Great Marlborough Street,

Dec. 3, 1828.

On Tuesday, Nov. 25, I was called

upon at the St. George's and St. James's

Dispensary to advise for an infant at

the breast, of five months and fourteen

days of age, that had not passed

any fæces during six weeks up to the

day before I saw it. After its birth it

had no passage till the fifth day, and

this had apparently been effected by the

introduction of a bougie, and which

was subsequently continued at intervals

for a short time. The infant was otherwise

healthy and strong at its birth, and remained

so until it had gone about three

weeks without any evacuation, when it

was observed to be weak in the lower

extremities; and at the period of my

seeing it the legs were much fallen

away in flesh, hanging flaccid and inert.

Many aperient enemas and medicines

had been given, and, as a last resource,

one drop of the croton oil had been

prescribed the preceding evening. The

infant appeared to suffer from distention,

and to be disposed to coma, and

the croton oil had distressed it much

some hours after it was given. The

fæces could be felt blocking up the intestine,

but the irritation of the finger

produced no attempt at evacuation;

very small pieces only having been

brought away. Hot baths also had

frequently been used some time ago.

Considering the case as one of paralysis

in the parts naturally employed to

relieve the bowels, I recommended

the suspension of all purgative remedies

by the mouth, and a table-spoonful

of the following injection to be substituted,

and to be thrown up with three

table-spoonfuls of thin gruel occasionally

during the day, by means of a

syringe.

℞ Spir. Terebenth. ʒiij.

Træ Zinzib. ʒj.

Aquæ, ℥iss. M.

Spir. Terebenth.

Spir. Terebenth.

iij.

iij.

Træ Zinzib.  j.

j.

Aquæ,  iss. M.

iss. M.

The following liniment was also directed

to be rubbed in frequently along

the course of the spine.

℞ Linimenti Saponis, ℥iss.

Liquor. Ammon. Comp. ℥ss. M.

Linimenti Saponis,

Linimenti Saponis,

iss.

iss.

Liquor. Ammon. Comp.  ss. M.

ss. M.

The result justified my expectations;

for, during the night after this prescription,

two injections having been

given, some large and hard ash-coloured

lumps came away, and these were

shortly followed by a forcible spouting

out of a continued stream of feculent

dark liquid; a brisk diarrhœa having

been kept up till the Saturday following.

The infant's appetite is become

voracious, its appearance lively and

healthy, and its legs as firm and strong

as is usual at such an age. Cold water

is recommended to be dashed upon the

loins, the liniment to be continued

occasionally, moderate doses of magnesia

and rhubarb to be given when

required, and the turpentine injection

to be used if any return of the complaint

should be threatened.

DISLOCATION OF THE PATELLA.

To the Editor of the London Medical

Gazette.

Sir,

Having seen a case of dislocation of the

patella, reported by Mr. Mayo, in your

Journal a few weeks since, in which

there was experienced some difficulty in

the reduction of the bone, I beg leave

to send you the following, in case you

may think it worth insertion.

On Saturday last, I was called to a

young woman who had dislocated the

patella of the left knee joint outwards;

the inner edge rested upon the outer

surface of the external condyle, and was

immoveably fixed, and caused great pain

when touched. She says it was occasioned

by her foot slipping backwards

from one stair to another, and she immediately

fell down.

I commenced the reduction, as stated

by Mr. Mayo, but I could only produce

semiflexion, and that gave her great

pain; insomuch that I was obliged to

desist, and the patella remained in statu

quo. But when the knee was thus semiflexed,

I desired my assistant to extend

the leg suddenly; and having my fingers

on the patella at the time, and pressing

[126]

it inwards, it immediately returned to

its natural position.

I must confess, sir, that I should

have been afraid to have continued the

flexion as described in Mr. Mayo's case,

"by bending the knee to the utmost,"

fearing that the remedy might be worse

than the disease, and the result proved

that in this case it was not necessary.

I remain, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

P. M. Hoskings.

168, Fleet-Street,

Dec. 3d, 1828.

VACCINATION.

To the Editor of the London Medical

Gazette.

Sir,

The mistake of the printer in substituting

the word "every" for "even,"

in the paper on Vaccination (p. 40), so

materially affects the sense of the passage,

that I must request the favour of

the following insertion:—

"3d. That while the vaccine cicatrix

retains even one distinct fovea or depression,

the individual continues unsusceptible

both of small pox and of re-vaccination;

but that," &c.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

Thos. H. Burder.

2, Brunswick Square, Dec. 15, 1828.

SINGULAR BICEPS MUSCLE.

To the Editor of the London Medical

Gazette.

Sir,

The valuable paper communicated to

your Journal, by Mr. Stanley, last

week, has brought to my recollection a

singular appearance of the parts in front

of the shoulder-joint which I dissected

about two years ago. It is a fact

worth recording; and perhaps you will

be kind enough to insert it in your next

number.

The circumstance was this—that in

the right arm, instead of there being

a biceps muscle having two origins, the

one the shorter from the corocoid process,

the other the longer from the

upper part of the glenoid cavity of the

scapula, there was simply a one-headed

muscle arising from the corocoid process.

I could find no tendon passing

through the joint answering to the long

head of the biceps, neither was there

any appearance of a biceptical groove;

the capsular ligament was, perhaps,

thicker than it is found in ordinary

cases.

I knew nothing of this man during

life, and am therefore unable to give

any account of the use which he made

of this arm.

I am, your obedient servant,

C. M. Burnett.

House Surgeon's Apartments,

St. Bartholomew's Hospital, Dec. 8th.

STETHOSCOPE.

To the Editors of the London Medical

Gazette.

Gentlemen,

As you did me the honour, on a former

occasion, to publish some remarks in

defence of auscultation, against its

enemies and detractors, I trust you will

permit me to say a few words in reference

to a communication in a late

number, from a gentleman who appears

to be a friend of that method of diagnosis,

but whose ignorance of the subject

is likely to be more injurious to the

cause than either open enmity or secret

detraction. The case in question (page

780, vol. ii.) appears, from the dissection,

to have been clearly emphysema of the

lungs, as there stated; but I appeal to

every one practically acquainted with

the physical signs of diseases of the

lungs, whether the results of the exploration

with the stethoscope, as narrated

in the case, were those pathognomonic

of that disease? I say they were

not only not pathognomonic of this

affection, but they were actually incompatible

with its existence. The same

ignorance of the subject is shewn in relation

to the disease of the heart, which,

I boldly maintain, no one was justified

in pronouncing to be hypertrophy of the

left ventricle from the stethoscopic indications

stated in the case.

It is just possible that the writer of

the case may have made further explorations

on which his diagnosis was founded;

but if he had such in his case-book,

it is equally unfortunate for the credit

of the stethoscope and his own, that he

suppressed them in his printed case.

I have the honour to be,

Gentlemen,

Your obedient servant,

A Stethoscoper.

Nov. 25, 1828.

[127]

MECHANISM OF VOMITING.

To the Editor of the London Medical

Gazette.

Glasgow University, Nov. 26, 1828.

Sir,

Having lately perused, in the 35th

Number of the Medical Gazette, some

observations "on the mechanism of

the act of vomiting," by Dr. Marshall

Hall, in which, after controverting the

different opinions which have been entertained

by physiologists on this

question, he endeavours to prove that

vomiting is an effort, not of inspiration,

but of expiration, and advances this

opinion as having originated in himself,

I beg, through the medium of your

Journal, to refer that gentleman to

Richerand's Physiology, where, on the

subject of vomiting, page 70, he says,

"Sometimes the action of the muscular

fibres of the stomach is quite inverted;

they contract from the pylorus towards

the cardia; and this antiperistaltic motion,

in which the contractions act

with more force and rapidity, and in a

manner decidedly convulsive, produces

vomiting. The action of the abdominal

muscles then connects itself with that

of the stomach; the viscera are propelled

upwards and backwards, by the

contraction of the large muscles of the

abdomen; the diaphragm ascends towards

the chest; if it descended, in contracting,

the œsophagus that passes between

its two crura would be compressed,

and the expulsion of food

through the cardia could not be effected.

It is also observed, that during expiration

only, any thing can pass from the

stomach into the œsophagus." Again, on

respiration, page 147—"In every effort

of expiration, as coughing and vomiting,"

&c. Here, then, we see that Dr.

Hall's views, as far as regards vomiting

being an effort of expiration, have

long since been advanced by Richerand.

The profession are certainly much

indebted to Dr. Hall for his corroboration

of these views; at the same time

he should not have taken to himself the

merit of having first suggested them.

Sir,

Your most obedient servant,

A Subscriber.

CHARACTER OF THE LANCET.

To the Editor of the London Medical

Gazette.

Dec. 19, 1828.

Sir,

The events disclosed during the late

trial in the Court of King's Bench, must

fill every well-disposed mind with astonishment

and horror. The moral aspect

of the case is marked by every feature

capable of exciting a sense of shame

for our profession, and of sorrow for

our kind. Can it be that a publication

conducted in the spirit of the extracts

produced at the late trial of Cooper

against Wakley should be fostered and

encouraged by a large proportion of the

medical public? Is it indeed true that

no feeling of loathing and disgust

should have induced the purchasers of

the Lancet to protest against its glaring

injustice, its undisguised ferocity and

malignity?

I am not a reader of that work myself,

and but for the disclosures recently

made in our courts of justice, together

with what I have learned from your

own pages, I should know little about

it. Some of its early numbers convinced

me that it was a production not

deserving of support, whatever ability

there might be connected with it; subsequent

events have amply justified this

decision, and I now address these few

hasty lines to you, to express my humble

hope that all the respectable medical

men throughout the kingdom will arise,

and with one voice oppose this moral

pestilence, which at once corrupts and

degrades their profession.

The odium medicum, bitter and vindictive

as it unfortunately has been,

never, I believe, appeared in a form so

repulsive. Are we living in the nineteenth

century? Have arts and sciences,

which are asserted of old to soften the

manners and temper the violence of our

nature, produced no such fruits amongst

us? Is serious, and perhaps irremediable

injury, to be inflicted on reputation;

and is the sufferer thereafter to be

dared to mortal combat, and this too by

the wrong-doer? Is it thus that professional

justice is to be awarded? Is

it thus that knowledge is to be advanced,

the dignity of our profession

to be maintained, its benefits enlarged,

and its usefulness transmitted? Is it

thus that the young men are to be

taught how to acquire an unworthy and

discreditable notoriety; to disregard all

[128]

the decencies, charities, and higher

virtues of life; and to bring into the

exercise of our art the insidious cunning

of the knave, the vulgar dishonesty of

the pilferer, and the audacious bearing

of the bravo?

I know not how others may feel on

the present occasion: I am entirely unacquainted

with the parties who have

been at issue in the late suit—I have no

bias of any kind, but what must arise in

the mind of every man who has any regard

for the profession to which he

belongs, or who loves truth and fair

dealing—I am sure that it is not less for

the interests of society at large than for

the advancement of medical science,

that just principles should regulate all

our dealings, both with the public and

with each other. It is manifest that of

late we have signally and woefully departed

from them; and it is most distressing

to know that this departure has

been sanctioned by so many members of

the profession. I now entertain a confident

hope that all who reflect on the

character of the late libel will feel that

their own character is at stake if they

do not mark their disapprobation of it

in every possible way. Sure I am that,

if the principles which guide the Lancet

become generally acceptable, it will

mark an æra of moral degradation

which no surgical dexterity, no medical

acquirements, however eminent, could

possibly redeem.

Veritas.

DURATION OF HUMAN LIFE IN RUSSIA.

Cases of longevity are not only

much more common, but also more extraordinary

in respect to a greater duration,

in Russia than in any other part of

Europe; thus, from the report of the

holy synod, published in 1827, it appears

that there were living in 1825,

among those who professed the Greco-Russian

religion throughout the empire,

not fewer than 848 males who

were 100 and more years old; among

whom, 32 had passed the age of 120, 4

were between 125 and 130, and 4 others

between 130 and 135 years of age. Out

of 606,881 males who died in 1826,

2785 had passed the age of 90 years;

1432 that of 95; and 818 that of 100.

Among the latter, 38 were more than

115 years of age; 24 more than 120;

7 more than 125; and one was 160

years old at his death.

MEDICAL GAZETTE.

Saturday, December 27, 1828.

"Licet omnibus, licet etiam mihi, dignitatem Artis

Medicæ tueri; potestas modo veniendi in publicum

sit, dicendi periculum non recuso."—Cicero.

ANALYSIS OF WAKLEY'S DEFENCE ON THE LATE TRIAL.

We last week presented our readers

with a full[20] and, we trust, accurate

account of the trial for libel, which

has recently excited so much interest;

and we offered some remarks of a general

nature upon its result and tendency.

We had purposed at the same time to

subject Mr. Wakley's mode of conducting

his cause to a critical investigation,

but this we were prevented from doing

by want of time and space. We thought

it likely, too, that the Editor of the

Lancet would have fairly met the question

in his next publication, and himself

put the facts of the case, at least,

on record: instead of this, however,

he has devoted his pages to compliments

to himself, and scurrilous and

absurd abuse of Sir James Scarlett, in

which he informs us that in his opinion

that gentleman is "prodigiously overrated

even as a lawyer," and says many

other things, which serve only to shew

how dreadfully Wakley himself had

smarted under his lash.

We find the general opinion to correspond

with that which we expressed

last week—that the defendant had managed

his cause in a very bungling

manner; and the estimation in which

he and his witnesses were held by Judge