Abagha Plain, ii. 401

Abaran (Kasagh) river, i. 136, 242, 316

Abas, king of the Bagratid dynasty, i. 352, 390, 407

Abastuman, Russian watering place, i. 48, 53–55,

432

Abazbek, posting station, i. 84

Abbas, Shah of Persia, transports a colony of Armenians

to Ispahan and carries off slabs from Edgmiatsin, i. 262, 264 note

5.

Comes into possession of Van, ii. 78.

Reputed to have taken Kars, i. 396

Abdul Miseh, grave of a supposed king of this name, ii.

133

Abdurrahman Gazi, valley and pass into Tekman from

Erzerum, ii. 202

Abgar, king of Edessa, who is said to have corresponded

with Christ, i. 278,

is claimed by the Armenians as one of their own royal line,

ibid.

Receives St. Thaddeus and with his people embraces the Christian faith,

ibid. and 277 note 2.

Under his successors his people lapse into polytheism, 278.

The authenticity of the story of Abgar is examined by Professor

Carrière, who shows that Moses of Khorene used an Armenian

version of this legend which began to form about A.D. 250, ibid. note 2

Abich, Hermann, i. 78, 79, 166, 177, 182, 187, 188,

191, 192, 193, 195, 199, 388, 394, 437, 445. ii. 376, 383, 386; i. 93,

174, 340, 374, 375, 381, 383, 385, 386, 416, 434, 435, 442, ii. 43, 46,

47, 76, 229, 363, 385, 401, notes

Abkhasia, i. 42;

its Bagratid king, i. 356

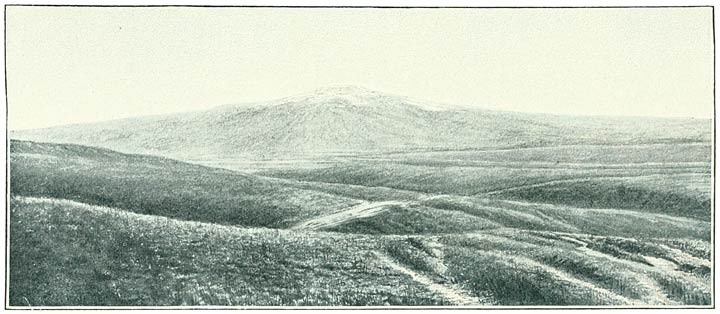

Abul, Mt., i. 92–95, 104, 105, 119, 441

Abul, village of, i. 92, 93

Abul-Samsar volcanic system, i. 95, 441

Abulsevar (Chawir, Aplesphares), chief of the

Beni-Cheddad family, q.v.; styled by Byzantine annalists and

Armenian writers prince of Dvin, i. 365; 362, 363, 365 note 1

Abulsevar, prince of Ani, i. 365

Abu-Said, Mongol king of Persia, his edict at Ani, i.

377

Achote, Monseigneur, Superior of the Monastery of Mugni,

i. 141

Adamanli, a division of the Hasananli Kurds, ii. 21,

26

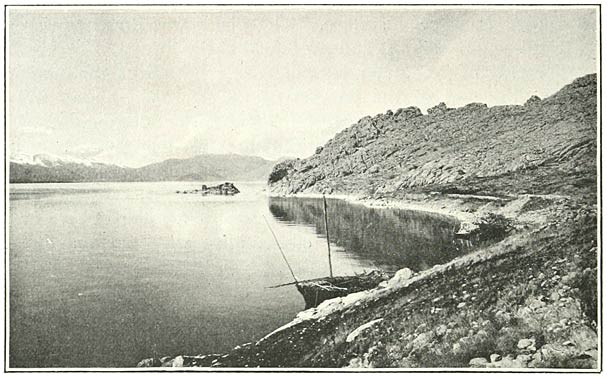

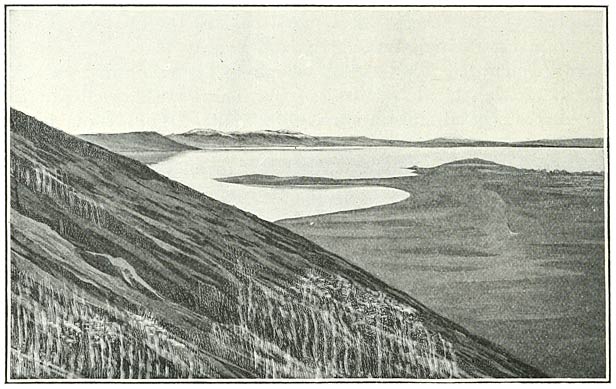

Adeljivas (Lake Van), town of, ii. 326–330,

403.

Mileage to Akhlat, ii. 325 note.

Earthquake there, 47 note 1; 341.

Rise in the level of Lake Van there, 52.

Cuneiform inscriptions there, 75

Adrianople treaty of, i. 36, 125; 397. ii. 204.

Exodus of Armenian population from Erzerum province as a result of, ii.

206

Afrikean, M. Karapet, improvement in wine accomplished

by, i. 226

Afshin, Arab Governor of Azerbaijan, i. 341–343,

352

Agathangelus Treatise, our earliest authority for the

reign of Tiridates and the events connected with the conversion of the

Armenians as a nation to Christianity, i. 291 note.

Von Gutschmid has succeeded in discriminating between the various

sources from which the treatise has been built up, ibid., 295

note 1

Aghdznik, ancient Armenian province, ii. 429; i. 309

note 1

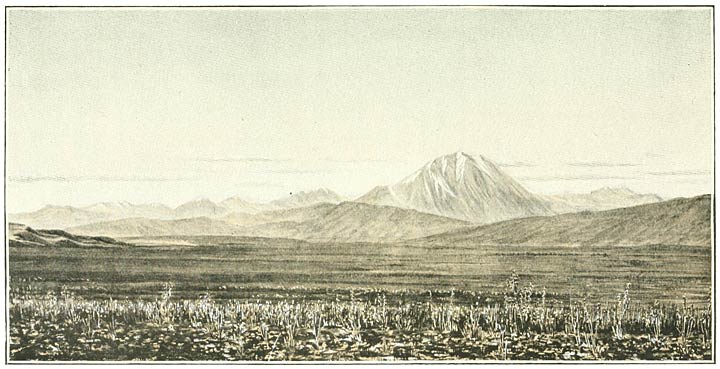

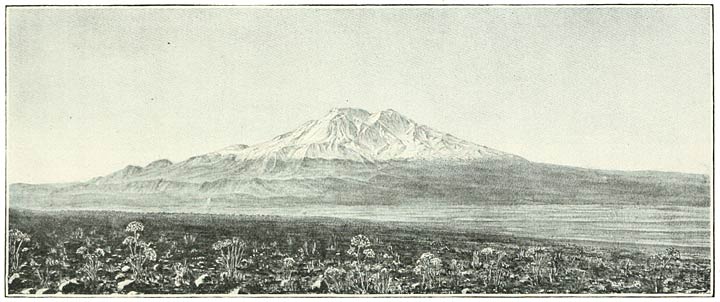

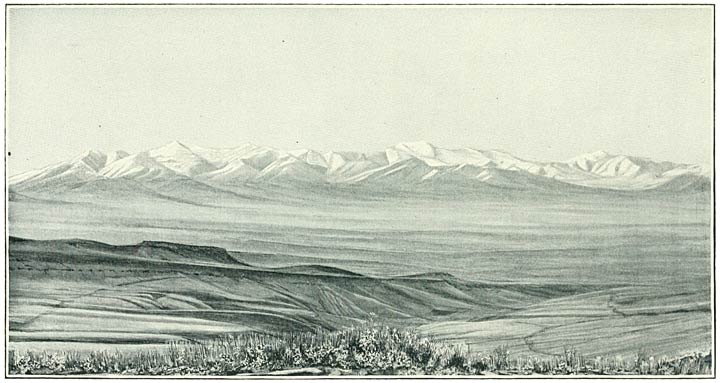

Aghri Dagh, name given by the Mussulman peoples to

Ararat as well as to the Ararat system, i. 148, 197, 409, 414 (Fig.

101), 415, 419 (Fig. 106), 420 (Fig. 107), 423, 435, 436. ii. 10

(Fig. 112), 384 seq.

Frontier between the Russian and Turkish empires, i. 435. ii. 384.

And see Shatin Dagh

Aghzi Achik, pass over the heights south of Erzerum, ii.

202

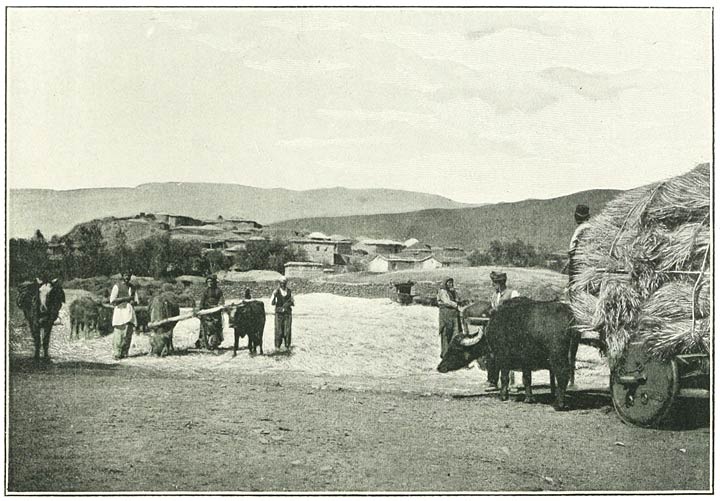

Agriculture finds in Armenia extremely favourable

conditions, due to the climate and the nature of the soil—a

mixture of lavas and lacustrine deposits, i. 87, 105, 442. ii. 255,

345, 404, 405–406.

Character of and seasons in various districts, i. 56, 57, 73, 75, 94,

105, 106;

among the Dukhobortsy, 107; 118, 121, 123;

on the plain of Alexandropol, 131; 133;

in the valley of the Araxes, 142, 202, 203, 229, 316, 318, 444; 321,

326, 410, 411; 443;

in Alashkert and basin of Upper Murad, ii. 3, 15, 19, 277;

in basin of Lake Van, 82, 315;

in plain of Mush, 167, 172, 318;

in plain of Khinis, 188, 256, 258;

in Bulanik, 344–345;

among the Circassians, 331, 353; 359;

in plain of Kharput, 391.

Backwardness in Russian Armenia, i. 56, 139,

and causes, i. 225, 461;

in Turkish Armenia, ii. 21, 164, 218, 219, 259,

and causes, ch. xxiv. passim.

Estimate of the levels at which cereals will flourish in Armenia, i.

107 note

Agrikar Dagh, peak of the Gori Mokri in Northern

Armenia, i. 87, 434

Ahmed, Arab Emir, cherishes pretensions to the district

of Taron (Mush), i. 343,

and defeats Sembat I., ibid.

Aiana, Greek Monastery of, ii. 238

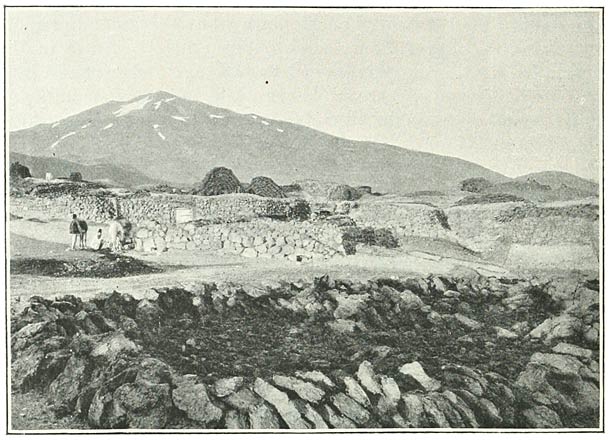

Aiger Göl, on the southern slopes of Sipan, ii.

339

Ainalu Dagh, Kars district, i. 394

Ainsworth, Mr. W. F., ii. 162, 176 note

Aintab, Mesopotamia, massacre there, ii. 427

Ajara, Mts. and district of, i. 41, 42, 62, 437, 442

Ajars, The, i. 42, 432

Akantz, town on N.E. coast of Lake Van, ii. 26.

Pop., ibid.

Mileage from Karakilisa, 12

Akhalkalaki, town in Northern Armenia (Govt. of Tiflis),

visited and described, i. 86 seq., 66 note, 72, 85, 438,

455.

Pop., 86.

Brave defence of by the Turks against the Russians in 1828, 89;

schools in, see under Education

Akhalkalaki, plain of, i. 87 and note.

Character of the soil, 442

Akhalkalaki (Toporovan) river, i. 76, 78, 87, 88, 92

Akhaltsykh, town in Northern Armenia, visited and

described, i. 58–61 and 64–71.

History, i. 66–67;

was captured and partly razed by the Russians in 1828, 67;

the Mussulman pop. emigrated into Turkey and the town received large

bodies of Armenian immigrants, ibid.;

reasons given by inhabitants for the decline in prosperity, 68;

pop. [498]in 1833, 67;

in 1886 and 1891, 65 and note 2;

description of the modern town, 68;

of the old town, 69;

of the Jewish quarter, 70;

schools in, see under Education.

Mileage to Akhalkalaki, 72

Akhaltsykh river, i. 57, 73

Akhaltsykh-Imeritian Mts., i. 430, 431, 433, 434, 438,

441

Akhashen, valley of, i. 74

Akhashen, village of, i. 75

Akhavank (Iskele), residence on the mainland of the

Katholikos of Akhtamar, ii. 126

Akhbaba Dagh, peak of the northern border heights of

Erzerum, ii. 203, 227

Akhbaba Dagh, Lake Chaldir, i. 438

Akh Bulakh Dagh, peak of Aghri Dagh, i. 420

Akh Dagh (Tekman Dagh, Kozli Dagh), name applied to the

northern border heights of the plain of Khinis, ii. 189.

View of from the south, 186 (Fig. 159);

from the Palandöken Pass, 249;

from village of Demian, 277;

from summit of Khamur, 351;

from Bingöl Dagh, 372.

Appearance of from Tekman, 249,

from the plain of Khinis, 256–258,

from the Kartevin Dagh, 269.

Structure and composition of, 389, 402

Akh Dagh, Akhmangan region, i. 445

Akh Deve (White Camel Hill), Kars-Kagyzman district, i.

412

Akher Göl Su (plain of Khinis), source of the, ii.

257

Akhja Kala, Tartar village on southern slopes of

Alagöz, i. 320

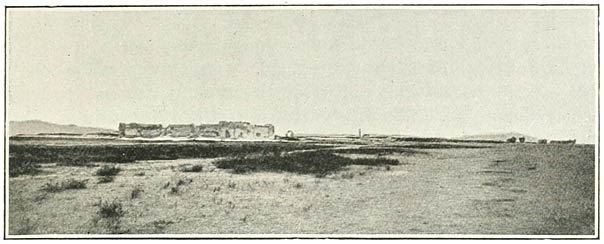

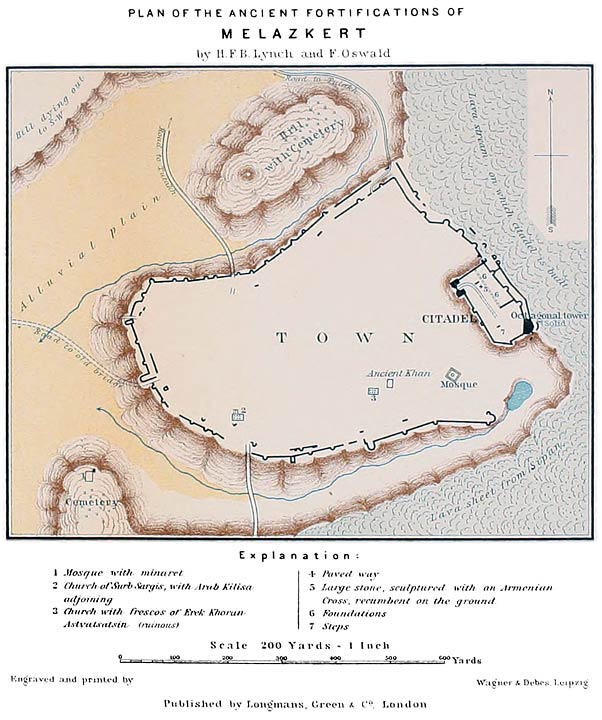

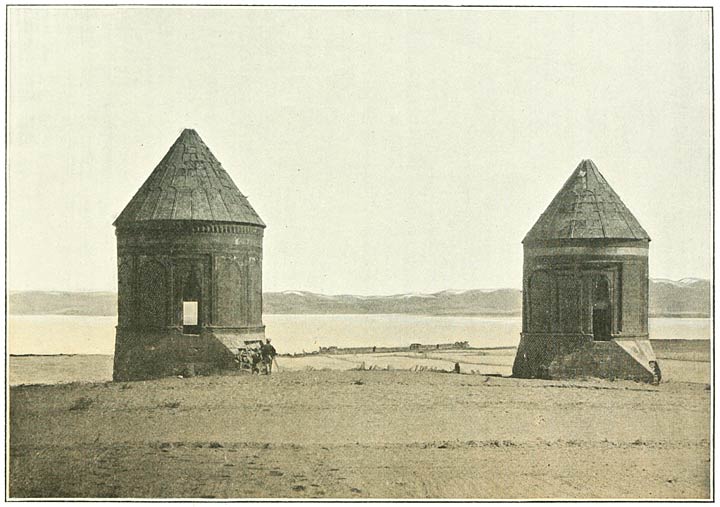

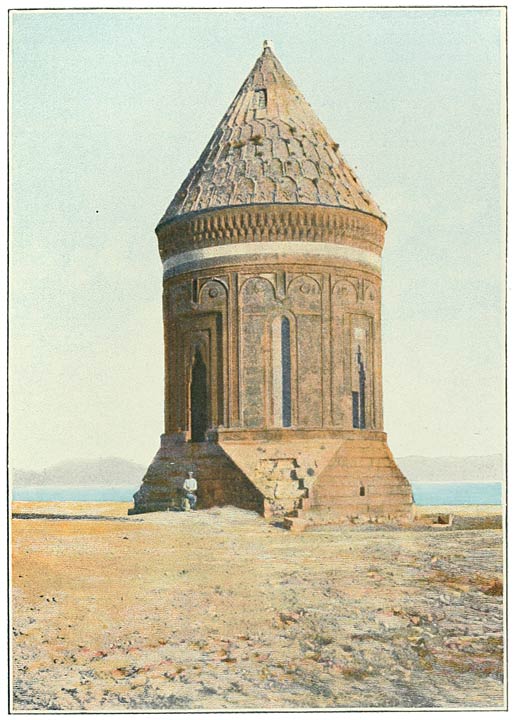

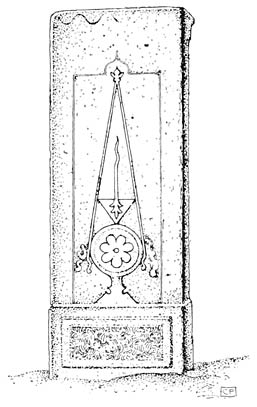

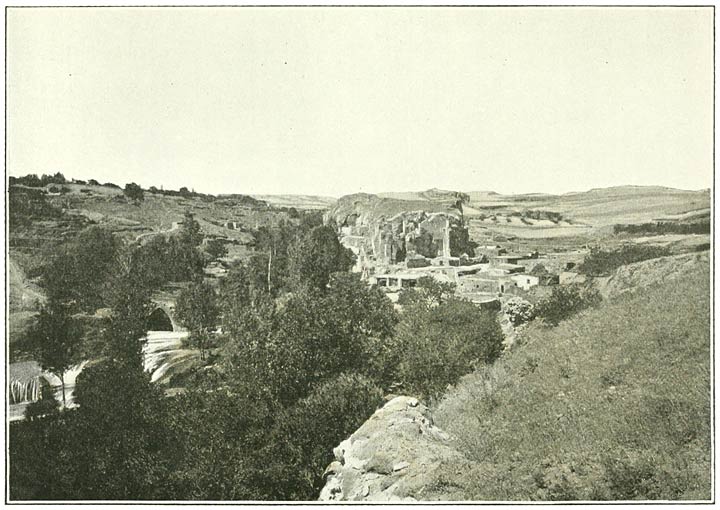

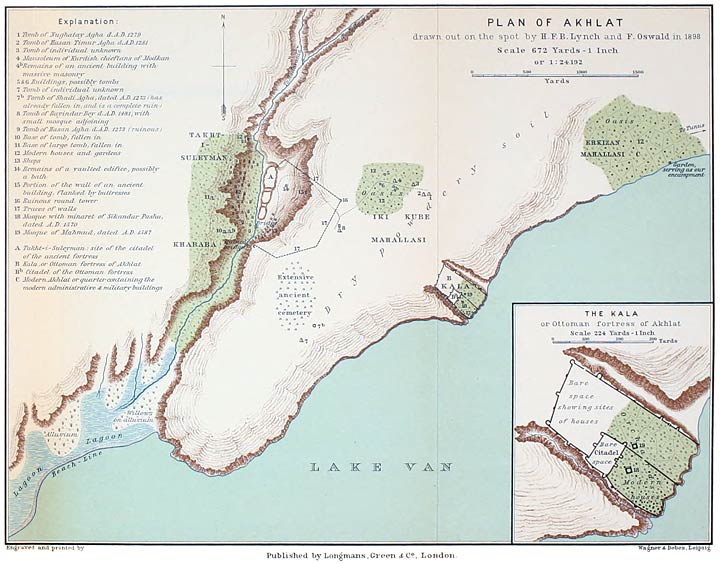

Akhlat, is the name of a district on the north-western

shore of Lake Van, which includes:

1st, the ancient city of Akhlat, now known as Kharaba or

Takht-i-Suleyman, situated in a ravine some distance from the shore;

2nd, the Ottoman fortress of Akhlat (Kala) on the shore; 3rd, the

modern township in the quarter of Erkizan, ii. 284.

Pop. of entire district, ibid.

Characteristics of the site, ibid.

Erkizan described, 285;

the Kala described, 287–289;

the ancient city described, 291–292.

The mausolea or kumbets described and their dates ascertained,

285–293.

The ancient cemetery, 290.

History of Akhlat, 294–297; i. 355, 360, 366.

Mileage to Adeljivas, ii. 325 note.

Plan, ii. 296

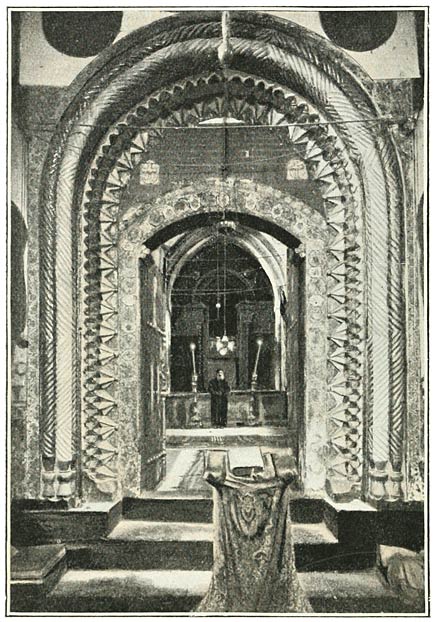

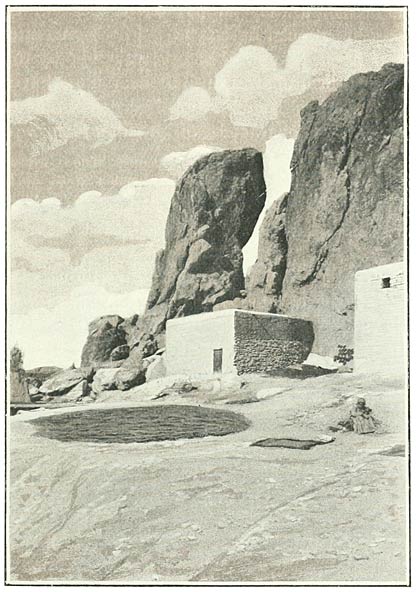

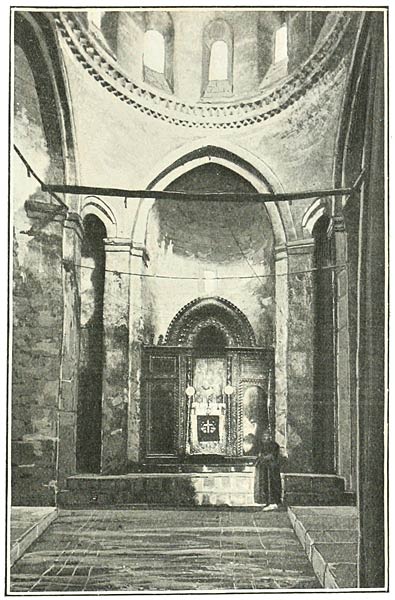

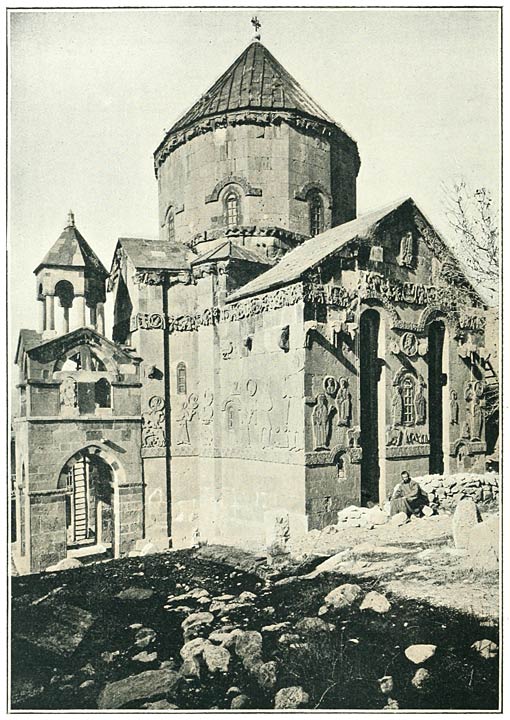

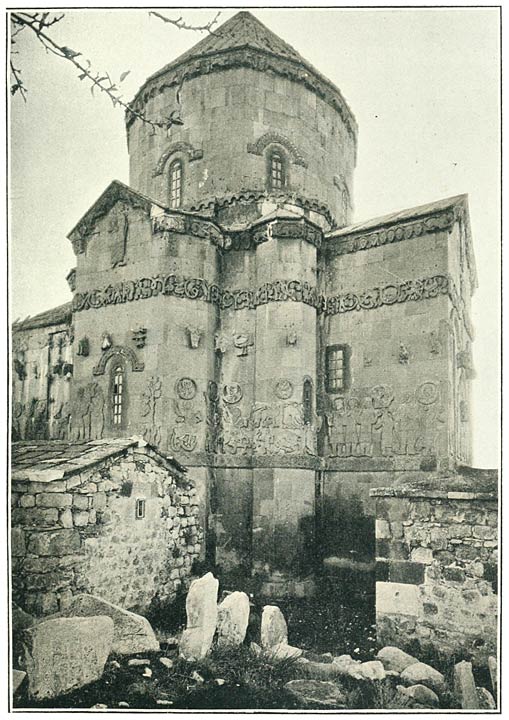

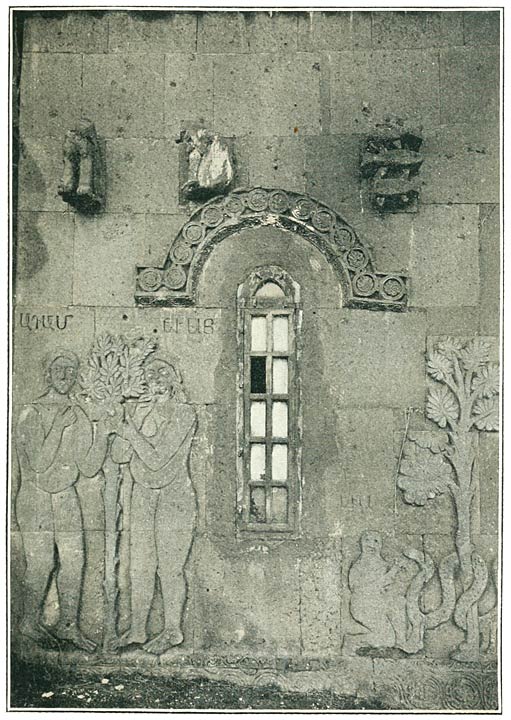

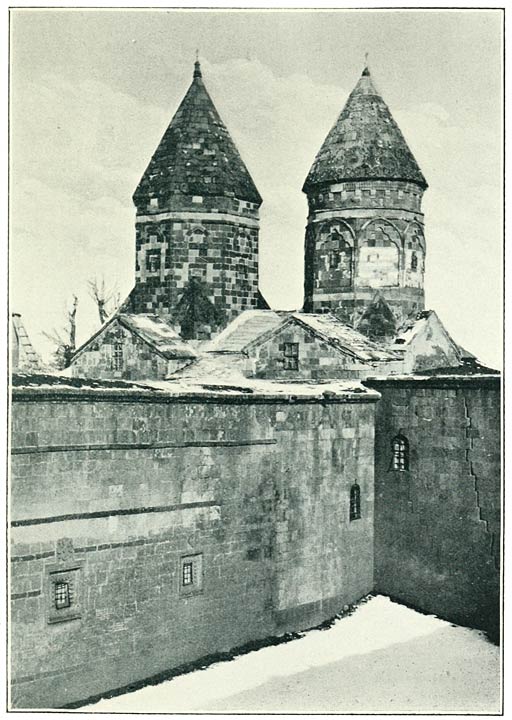

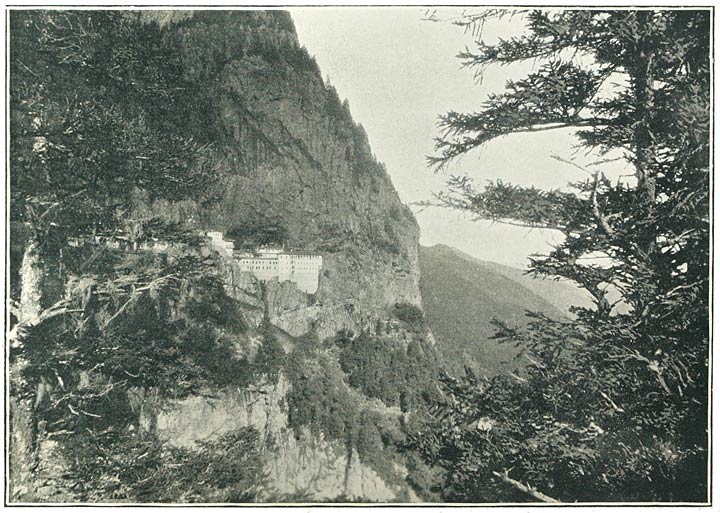

Akhtamar, Lake Van, island and monastery of, described,

ii. 129–135;

architecture of the church, 132, and date, 131

Akhtamar, Katholikos of, his jurisdiction and status,

ii. 135, and cp. i. 276;

visited at Akhavank, ii. 127–129, 135–136

Akhurean river, see Arpa Chai

Akhury (Arguri, Acorhi, Akuri, Agguri, Arkuri), ancient

Armenian settlement on Ararat, destroyed by the catastrophe of 1840, i.

183 seq.;

is said by the Armenians to have been built on the site of Noah’s

vineyard, 183;

their attempt to connect it with the Armenian for “he has planted

the vine” has probably led to a corruption of the name,

ibid. note 4.

May it not be the Adduri of the Assyrian inscription of Shalmaneser

II.? ibid.

A willow tree there was said to have sprung from a plank of the Ark,

183,

and the church to have been built on the site of Noah’s altar,

erected on his departure from the Ark, ibid.

The date of the church, 184.

Pop. according to Dubois and Wagner, 183, 184 note 1.

There was also at A. a square fortress built of clay, 184;

and a summer palace for the Persian Sirdars of Erivan, ibid.

Account of the catastrophe of 1840, 185–187;

investigations undertaken by the Russian Govt., 187.

Divergent conclusions of Wagner and Abich as to character of

convulsion, 188.

What remains of the ancient settlement at the present time, 192,

193.

The old cemetery with the graves of seven brothers said to have been

killed by a single snake, 193

Akhury, chasm of, Ararat. Entrance to the chasm, i.

184;

Kurdish village at the mouth of the chasm, 192;

excursion up the ravine, 193;

the peculiar formation of a side valley, ibid.;

which probably owes its distinctive features to the action of ice,

194;

arrival at St. Jacob’s Well and the sacred rose bush,

ibid.,

elevation of the site, 195.

The boulders covering the bottom of the ravine are worn by the action

of ice and water, 195.

According to Abich the long ridges which appear in his illustration

were composed of dirty glacier ice, covered with stone and

débris, 195;

but we did not see any ice in the trough of the chasm, 196,

though we admired a lake of glacier water, ibid.

Akhury, New, settlement of Tartars on Ararat, i.

193;

pop., ibid.

Akhviran Pass into the Khinis Plain, ii. 249, 252,

373

Akhviran, village of, ii. 278

Ak Köpri, crag of near Van, ii. 111, 112 note 1

Ak Köpri, river, ii. 112

Ak-kul (Gubudgokh) Mt., west of Akhtamar, ii. 137

Akrag, Armenian village on the Murad near Shakhberat,

ii. 351

Akstafa river, tributary to the Kur, ii. 39, 40, 437

Akstafa station, i. 39, 226

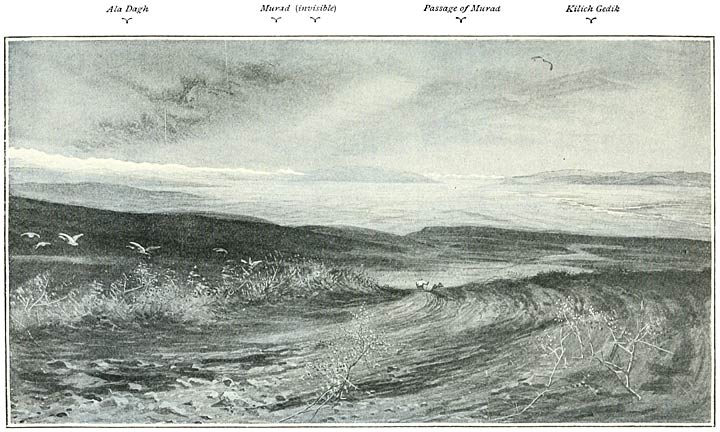

Ala Dagh Mts. (Nepat, Niphates), ii. 10, 12, 22,

401.

Seen from Lake Van, 31, 121;

from Kartevin Dagh, 269.

Strabo says that the Tigris rises in these mountains, ii. 41.

Viewed from Tutakh, 265.

A seat of the Thonraki (Thonraketzi), i. 285

Ala Dagh, Chaldiran district, i. 413 note

Ala Göl, i. 434

Alagöz, extinct volcano and natural barrier between

Northern Armenia and the valley of the Araxes about Erivan, i. 119,

124, 147, 438, 444; 135, 148, 149, 152, 205, 228, 325, 326, 330, 331,

367, 419, 442.

Seen from summit of Abul, i. 95;

from plain of Alexandropol, 122 (Fig. 23), 127, 134;

from the east, 136 (Fig. 28);

from Erivan, 208 (Fig. 41);

from Ararat, 138;

from the plains on the west, 327 (Fig. 68).

Journey along the southern slopes, i. 316 seq.

Alagöz, hamlet of near Gumgum, ii. 358

Alaja (Tsaghkotz) river at Ani, i. 368, 369

Alaja Dagh, i. 330, 368, 399

Ala-Kilisa, village of Armenian-speaking Greeks, i.

122

Alander, Col., Governor of Akhaltsykh, i. 60, 61, 64,

65, 66

Alarodians, name by which the inhabitants of Urardhu

were known to Herodotus, ii. 67 and note 4;

were joined with the Matienians, etc., in 18th satrapy of the Persian

empire, 68

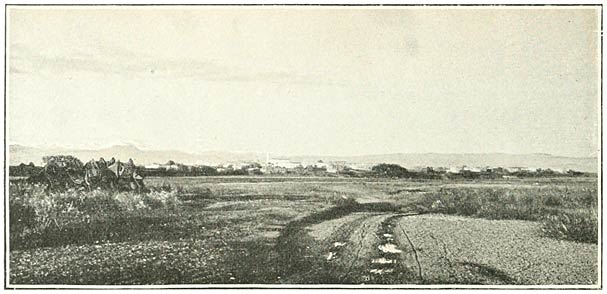

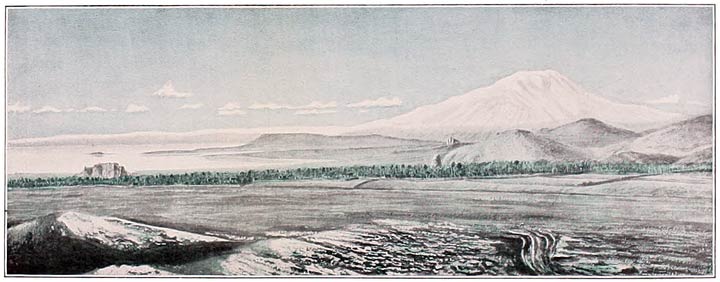

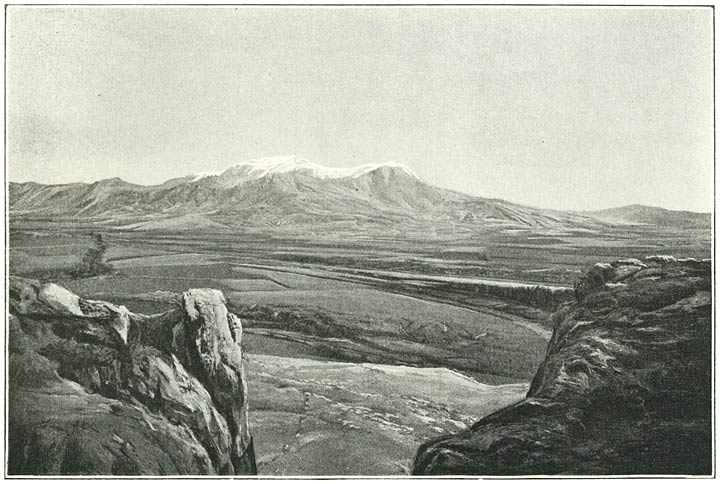

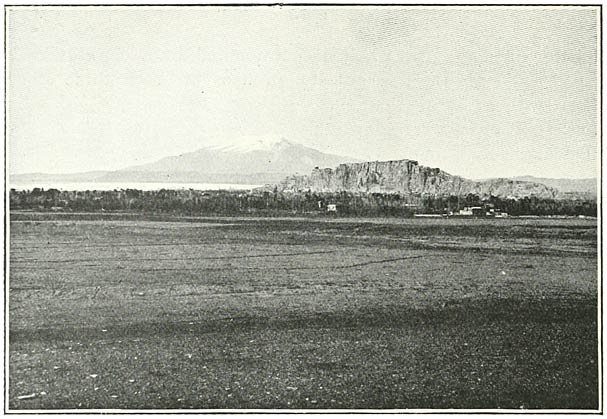

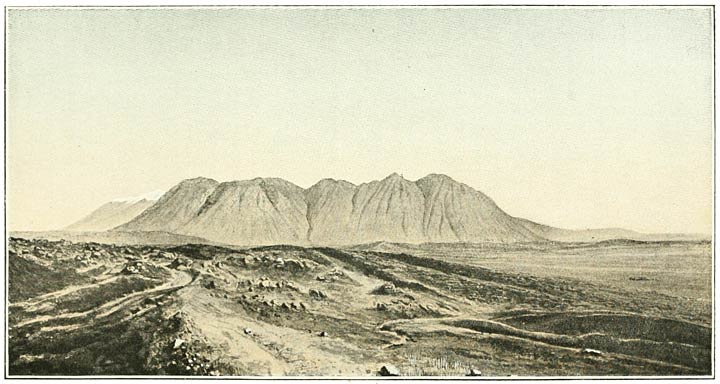

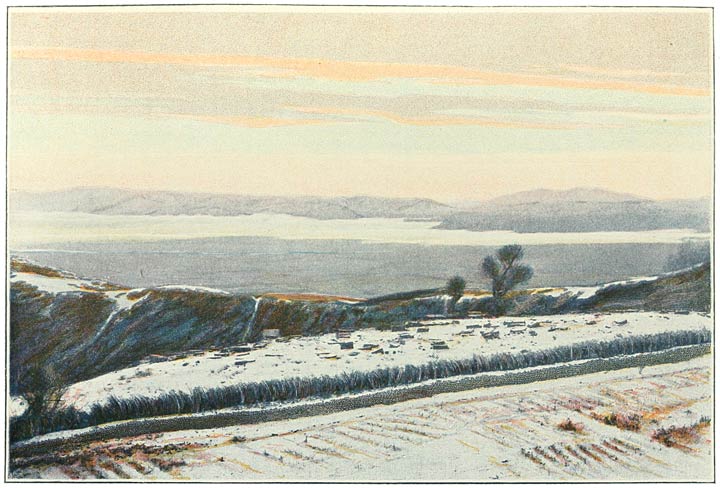

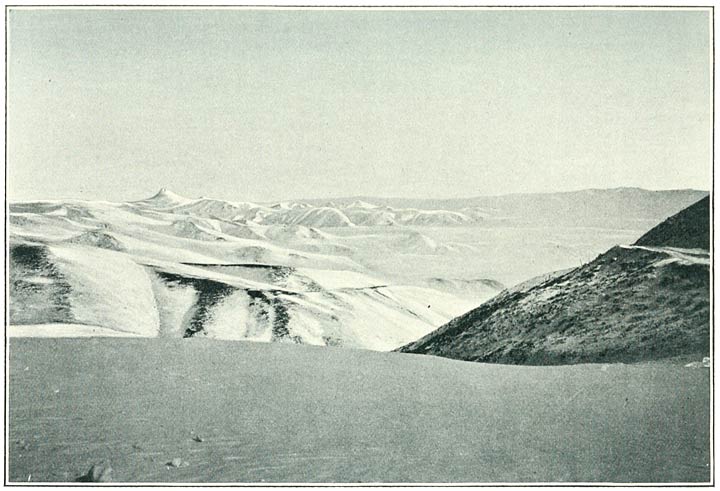

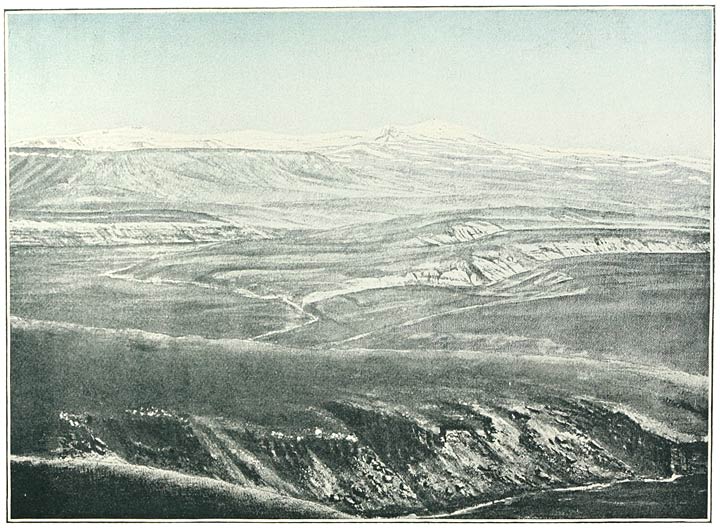

Alashkert, plain of, i. 148, ii. 2 seq. and

Fig. 108, 384, 389, 400, 401, 404.

Elevation of, ii. 3

Alexander I., Emperor of Russia, extends great

privileges to the Protestant emigrants from Würtemberg on their

arrival in Georgia, i. 97.

Encourages Protestant missionary enterprise, 99.

His humane and liberal policy towards the Dukhobortsy, 103

Alexander Severus, Roman Emperor, i. 287

Alexandropol (Gümri), Russian fortress town on the

Arpa Chai visited and described, i. 124–132, 330, 443, 445, 453,

455, 462, 467. ii. 46 note.

Visited by Emperor Nicholas I. in 1836, i. 125.

History and description of city, 124–125, 127–129;

pop., 124 and note 1;

is almost exclusively inhabited by Armenians, 124;

who have inherited the love of building of their forefathers, 127;

but their churches and other buildings are pretentious and commonplace,

128.

Greek chapel of St. George with Byzantine picture of St. George and the

Dragon, 129.

Schools in, see under Education

Alexandropol, plain of, i. 122, 131, 133, 134, 442. ii.

404

Ali Bey, chief of Karapapakhs at Karakilisa (Alashkert),

ii. 6, 255

Ali Bey, chief of Sipkanli Kurds, ii. 267, 268

Ali Gedik, village near Charbahur on the Murad, ii.

352

Ali-Kuchak, village on Alagöz, i. 137 [499]

Ali Mur, hamlet of Kizilbash Kurds, district of Shushar,

ii. 252

Alkhes, village of the district of Elmali Dere, ii. 262,

263, 399

Allah Akbar Dagh, Soghanlu range, i. 441

Allen, Mr., American missionary at Van, ii. 92

Allen, T. G., and Sachtleben, W. L. Their ascent of

Ararat, i. 199

Alp Arslan, Seljuk sultan, captures Tiflis, i. 337,

and Ani, 353, 363,

and Melazkert, ii. 275

Altai Mts., their connection with the structural system

of Asia, i. 424, 425

Altun, plain of, Upper Araxes, ii. 379, 398

Alur, village, Van district, ii. 122

Amasia, Turkish settlement on the Arpa Chai, i. 122

Amat, Armenian village, district of Alashkert, ii. 2

American Missions, see Missions

Amisus, ruins of (near Samsun), i. 4

Anak, Parthian of the blood royal, murderer of the

Parthian King of Armenia, Chosroes, and father of St. Gregory, i.

288.

View of Von Gutschmid, ibid. note 2

Anania of Shirak, i. 312, note 1

Anastasius, Roman Emperor, ii. 222

Anguil Su (Enghil Su) or Khoshab, river flowing into

Lake Van, ii. 122

Anguil, village, ii. 123

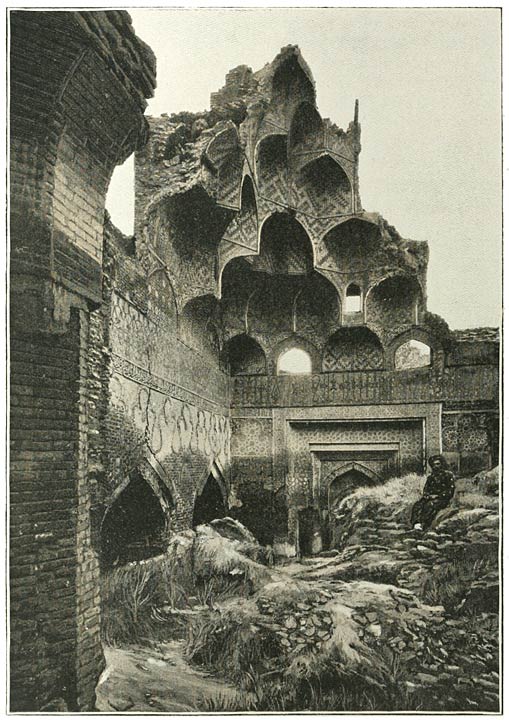

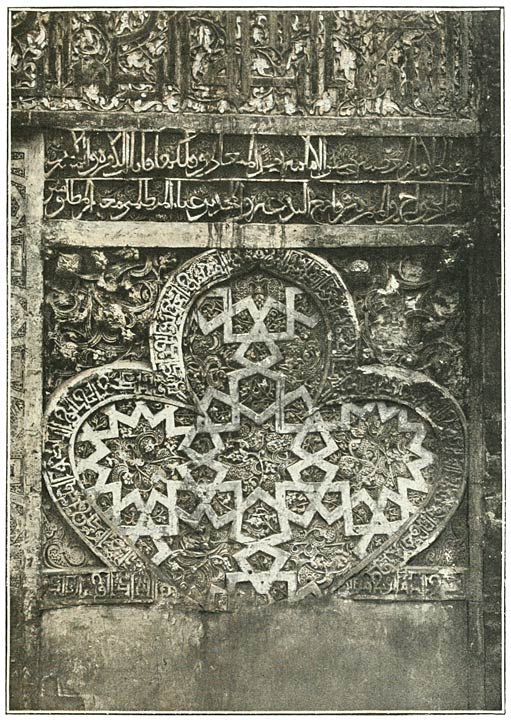

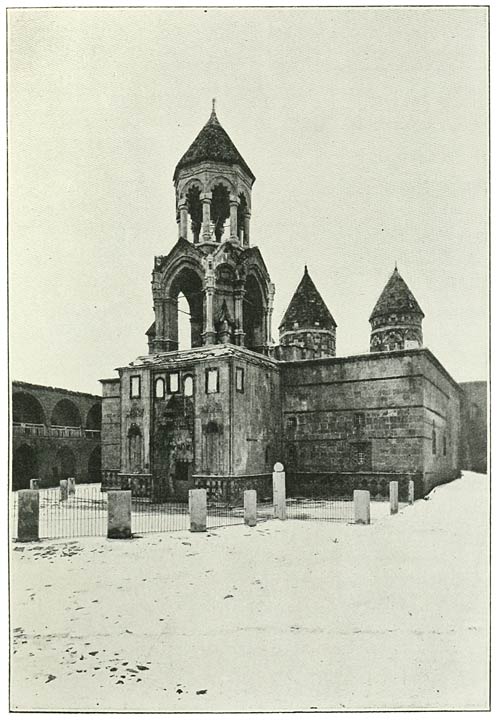

Ani, Armenian mediæval town and fortress on the

Arpa Chai (Akhurean), now in ruins and uninhabited, visited and

described, i. 329, 334, 354–392, 268, 269;

history of, 354–366; 345, 350.

Description of the various buildings and fortifications,

369–390;

distinctive features of the architecture of the Ani buildings, 390;

appeal to the Russian Government for their preservation, 391;

date of the Cathedral, 354, 355.

Mr. Marr’s excavations at Ani, 377–378.

Plan, 309

Ani, the modern Kemakh, ancient Armenian fortress on the

W. Euphrates, i. 294;

fane of Aramazd at this place destroyed by St. Gregory and King

Tiridates, ibid.

Anti-Taurus Mts., their connection with the structural

system of Asia, i. 424;

probable representatives of the A-T. elevation in Armenia, ii. 386

Aplesphares, see Abulsevar

Aplgharib, Pahlavuni family at Ani, i. 382, 383

Apughamir, Pahlavuni family, son of Vahram, i. 382, 383

note 3, 385

Arabion Castellum on the Gt. Zab, i. 277 note 2, 279

Arabkir, massacre at, ii. 412

Arakelotz Vank, plain of Mush, ii. 166

Arakh Su, Mush plain, ii. 166

Aralykh, Russian military post at the foot of Ararat, i.

154–155;

climate of, 202

Aramzalu, village of, district of Erivan, i. 154

Ararat, Mt. (Masis of the Armenians, Aghri Dagh of the

Tartars), first view of from the southern slopes of Alagöz, i.

137.

It does not appear that there was an independent local tradition of the

Flood, 197;

but the identification of Ararat with the mountain upon which the Ark

rested may have been made by Jewish prisoners of war, ibid.

The Ararat of Scripture is the Assyrian Urardhu, ibid. and ii.

57—a geographical designation which appears to have travelled

north during the course of time; the historical Urardhu or Ararat is

the province around Mt. Ararat, well known as Ararat to Agathangelus

and other early Armenian writers, i. 197.

Supposed vestiges of the Flood, 157.

The district has been covered within comparatively recent geological

times by a lake, 317, ii. 404

The fabric of Ararat is built up by Great and Little Ararat, i.

197;

though due to eruptive volcanic action, no eruption is known to have

occurred during historical period, 197, 188.

View of from the plains about Erivan, 149, 198.

Orography, 148–153, 156, 197.

Vegetation abundant on parts of the mountain, 160;

also partridges, ibid.;

but the fabric is entirely devoid of trees, the only wood being a

covert of low birch, 161.

Ascent of, 167–178;

start made from the encampment at Sardar Bulakh, 167.

Three structural divisions to be distinguished in that part of the

mountain between Aralykh and the summit, 170.

The great snowfield has a minimum depth of 2000 feet, 171.

The south-eastern summit attained, 176.

Temperature of the air a few feet below the summit, 177 note.

Descent to encampment of Sardar Bulakh, 179.

Best season and starting point for the ascent, 37, 199.

List of successful ascents, ibid.

View of Ararat from the summit of Sipan, ii. 336, 337

Ararat, Chasm of Akhury, see under Akhury

Ararat, Monastery of St. Jacob, i. 184

Ararat, Little, i. 149, 150, 160–168 and Fig. 33,

197, 199, 436

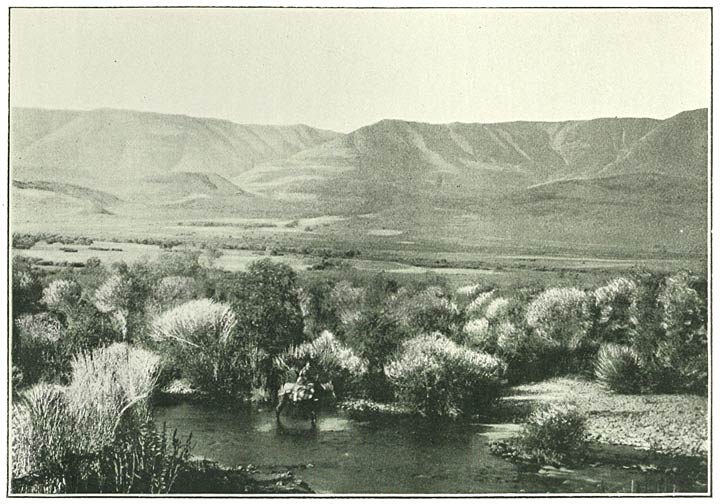

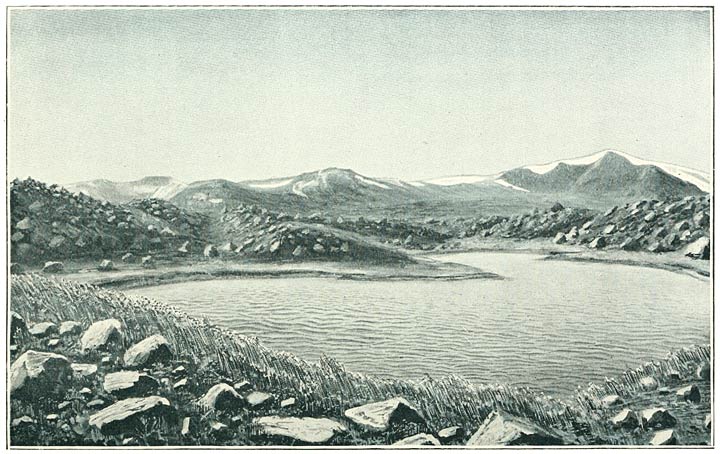

Araxes river (Aras, Egri Chai), sources of on the

Bingöl Dagh, ii. 374 and Fig. 194;

its course through Armenia, ii. 379, 251, 190, 192 seq., i. 138,

146, 154, 201, 317 seq., 416, 436, 444, ii. 406, and see

Bingöl Su

Araxes, plain of the (district of Ararat), i. 130, 137,

138, 146, 154, 201, 206, 317 seq. 444.

Elevation, 146.

Tradition that it was the seat of Paradise, 318

Archelaus, Bishop of Karkhar, author of a disputation

with Mani, was probably bishop of a see not far from Van, i. 279 and

note 3.

Adoptionist theory, 281

Ardabil, town in Persia, i. 366, 387, 435 note

Ardahan, town and district in Northern Armenia, i. 443;

66 note 1, 430, 431, 432, 437, 438, 439

Ardahan river, see Kur

Ardasa, town of, ii. 243

Ardashir, first Sasanian King of Persia, i. 286;

the supporter of the fire-worshippers, 287;

is harassed by Chosroes, Arsakid King of Armenia, 288,

whose death he encompasses, ibid.

Ardavan, Arsakid King of Persia, i. 286

Ardos, Mt., Lake Van, ii. 123, 126, 135, 137, 279

Arenjik, Kurdish village on the slope of Kolibaba, ii.

348

Arghana, town in Mesopotamia, ii. 388, 396

Argistis I., Vannic King, ii. 61, 73

Argistis II., Vannic King, ii. 75.

Inscription of, at Hargin, ii. 29

Arjish, ruins of (Lake Van) some miles south-west of

Akantz, ii. 26 seq.

The site to be distinguished from an earlier Arjish, 27 seq. and

71.

Deserted by its inhabitants owing to rise in level of the lake, 30.

Was known to Marco Polo as one of the greatest cities of Armenia,

29

Armavir, ruins of, i. 318, 319, ii. 61, 71, 73–74,

76

Armenak, son or grandson of Hayk, progenitor of the

Armenians, i. 318

Armenia, natural boundaries of, i. 428–35, ii. 231

note 1, 235–236, 244, 386–390, 394.

Its connection with the system of the great Asiatic tablelands, i.

421–428.

Geology of, i. 428, ii. 402–404, and passim in the

narrative of the journeys.

Characteristics of, i. 52, 86, 428, 429, 436–439, 449, ii.

235–236, 244, 382, 400, 405–407.

It is naturally divided into two parts by the Ararat system—a

north-easterly and a south-westerly, i. 409, 435–436, ii.

384.

Limits and characteristics of north-easterly or Russian Armenia, i.

436–445;

area, 445;

Pop. 451.

Do. of south-westerly or Turkish or Tauric Armenia, ii. 386–394,

397–406;

area, 407;

pop.,

412–414.

Communications with Armenia, i. 7, 39, 431, 432, 433 note, 437, ii. 89,

148, 203, 205, 225, 239, 240 note, 382, 388, 390, 396.

Routes and communications in Armenia passim in the narrative of

the journeys and i. 146, ii. 393

Armenia, history of, seems to fall naturally into four

periods,

(I.) the pre-Armenian period, with an obscure interval preceding the

rise of the Arsakid dynasty, i. 285–286, ii. 70 and

53–76;

(II.) the Arsakid period, with an interval preceding the evolution of

the petty Armenian dynasties of the Middle Ages, i. 286–312;

(III.) the Armenian Kingdom of the Middle Ages, i. 335–364, 391,

and

(IV.) a long sleep, dating from the overthrow of [500]that

kingdom by hordes of Seljuk Turks towards the close of the 11th century

to the advent of the modern epoch, i. 364–367.

Impressive part played in the history of these countries by the Roman

Empire of the East, i. 34.

Scanty knowledge of Armenia displayed by Greek and Roman writers, ii.

40

Local Mussulman dynasties have flourished in most of the great Armenian

centres, notably Akhlat, q.v. and i. 366.

Mussulman art is well represented by the ruins of the Ulu Jami at Van,

ii. 106, and by the mausolea at Akhlat, q.v.

Modern history of, i. 446, 458; 66, 67, 89, 96 seq., 124, 125,

210, 232 seq., 393, 396–399; ii. 78, 148, 149, 204, 205,

223, and see Armenian Movement

Armenian alphabet, i. 312 note

Armenian Church, history of, i. 276–314, and

cp. 264.

Ripsimian legend, 256–261.

Differences with the Greek and with the Roman Churches, 313–314

and note 1, 352, 363.

Contemporary importance of the A.C., 231

Hierarchy and Government of the Church:

The katholikos at Edgmiatsin the supreme head, i. 231, 276 (and see

298–300).

Elective character of his office, 231, 233 note 2.

The synod at Edgmiatsin, its antiquity and functions, 234, 235, 218,

220;

revived by the Russian Govt. and provided with a Russian procurator,

234.

The Tsar appoints its members, 235.

Fetters placed upon the katholikos by the Russian Govt., 235.

The Regulating Statute or Polojenye, 233–236.

The twelve bishops at Edgmiatsin, 253.

The bishops, monks (vardapets) and parish priests, 274, 275, and

233 note 2.

The A.C. represents a compromise between opposite principles in the

organisation of Christianity, 276 and 307.

Power of the laity, 276; ii. 213.

The patriarch of Constantinople, ii. Appendix I.;

his relations to the katholikos, i. 276.

Regulation of the Armenian Church in Turkey, ii. Appendix I.

Need of reforms in the A.C., i. 469, ii. 93.

Reforming spirit of the present régime at Edgmiatsin, i. 274

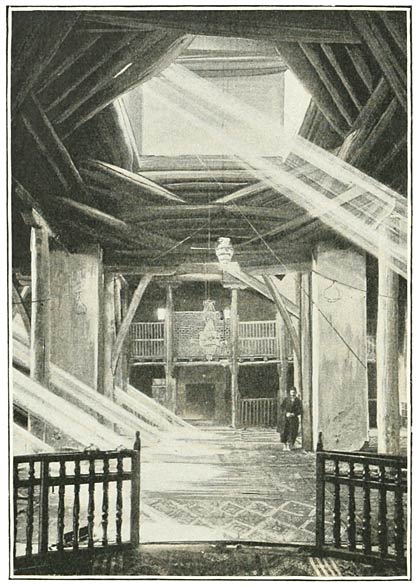

Armenian architecture, i. 63, 131, 262–272, 323,

369–390, 407, ii. 34, 101–102 (the log churches of Van),

106, 107, 114, 115, 131–133, 155, 179, 188, 233, 271.

Love of building among the Armenians at all periods, i. 127, 265,

344.

Their architecture exhibits capacities of the first order, i. 391.

Characteristics of the style, i. 390.

The conical dome, i. 63.

Function of the niche, i. 269.

Possible traces of Assyrian influences, ii. 65, 132.

Their churches exhibit the coupled pier, wand-like pillar and pointed

arch at least as early as the commencement of the 11th century, i.

372.

Influence upon them of Mussulman art, i. 391;

their influence upon Mussulman art, ii. 294.

Instance of conveying stone from a great distance, ii. 131 note 2

Armenian language, its harshness to the ear, i. 450, ii.

33, 236

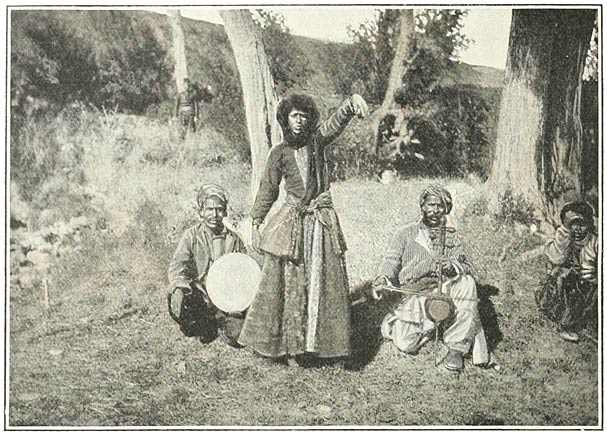

Armenian music, i. 250, 254, 255

Armenian Movement, i. 239–242; ii. 83–87,

157–159, 408, 420–423, 428–429, 432.

The talk about a modern Armenian Kingdom examined, i. 468, ii. 435

Armenian Constitution (in Turkey), ii. 436, and Appendix

I.

Armenian law, i. 367

Armenians, The, their capacities and character, i. 255,

314, 391, 465–468.

Fidelity of Armenian women under trying circumstances, ii. 92.

The assistance the A.’s have rendered to the Russian advance, i.

233.

Their disillusionment, ibid.

Will they ultimately enter the Russian Orthodox Church? i. 463.

Their position in Turkey, see under Armenian Movement references

to vol. ii.

Ethnology of the Armenians, ii. 67, 390.

They have probably received at various epochs an admixture of Semitic

blood, ii. 70, i. 237, 299, 305, ii. 77, 99

Armutli, village near the Araxes, i. 440, 443

Aron-Magistros, General of the Empress Zoe, i. 373

Arpa Chai (Akhurean), i. 119, 121, 442; 122, 131, 327,

328, 363, 367, 368, 376, 377, 381, 386, 389, 453;

confluence with the Araxes, 319

Arpa Göl, i. 439

Arshak, King of the Arsakid dynasty, i. 304, 305, 307,

309

Arshakavan, a city of refuge founded by Arshak, i.

308

Arsissa, Areesa, name by which Lake Van was known to

Ptolemy, ii. 27, 42.

See also Van, Lake

Artaxata, ancient Armenian city in the district of

Ararat, i. 201; 258, 259, 271, 287 note 3, 288, 293, 294, 304, 305

Artemid (Atramit, Artamit), a village on Lake Van, ii.

119–121; 36, 42, 135.

Researches at made by Schulz, ii. 120 note 1

Arter, Islet of, Lake Van, ii. 135

Artsruni, The, ancient Armenian family of princely rank

claiming descent from a king of Assyria, i. 336, ii. 429.

Their vast possessions in Vaspurakan (Van) during the decline of the

caliphate, i. 336.

Their territory overrun and their prince captured by the Arab armies,

338.

Their attitude towards the Bagratuni family, raised to royal rank under

Ashot, i. 342, 343, 345, 346.

Their prince, Gagik, obtains a royal crown from the Arab governor of

Azerbaijan, 345, and allies himself with the Mussulmans against the

Bagratids, 346.

But the alliance is broken, 348, and better relations with the

Bagratids ensue, 349.

Gagik is crowned by order of the caliph, ibid.

Divergence of policy towards him on the part of the governor of

Azerbaijan and of the caliph, 349.

His territories overrun by the former, 350.

Visited by John Katholikos, ibid.

The Artsruni furnish one of the three kinglets of Armenia under Ashot

III., 354.

Their country experiences the first shocks of the Seljuk invasions,

356, 357, 359, and their king, Senekerim, bargains away his kingdom to

the Byzantine emperor, Basil II., in return for a retreat in the Greek

Empire, 357.

Extent of the ceded dominions, ibid.

Significance of the event, 359, ii. 77–78

Artsruni, Thomas, historian, i. 340 note 1; ii. 131 note

2

Artsruni, ——, his ascent of Little

Ararat, i. 199

Artvin, town and valley of, i. 430, 443

Artze (Artsn, Arzen, Erzen), unfortified town in the

vicinity of Erzerum, ii. 223;

may have been called Artze of Rum to distinguish it from an Artze in

Southern Kurdistan, ibid. note 6.

Sacked by the Seljuks in 1049, i. 358

Arzanene (Arrhene), a country comprised in the present

vilayet of Diarbekr, ii. 41

Arzasku, site unknown, capital of Arame, king of

Urardhu, ii. 59

Arzen, see Artze

Arzian Dagh, Northern Armenia, i. 441

Asbeleff, M., i. 54

Ashakh Dagh, Ararat system, ii. 384

Ashkala, Mohammedan village on the banks of the

Euphrates, ii. 226, 228

Ashkala Plain, special features of, ii.

228–229

Ashkhen, queen of Armenia, i. 261

Ashot I., king of the Bagratid dynasty, i. 339

seq.

Ashot II., king of the Bagratid dynasty, i. 347

seq.

Ashot III., king of the Bagratid dynasty, i. 353

seq.;

his tomb at Khosha Vank, 389, 390

Ashot IV., king of the Bagratid dynasty, i. 355

seq.

Ashtarak, a township near Erivan, i. 139, 140, 141,

142

Asia, structural features of, i. ch. xxi. and map

Asoghik, Armenian historian, i. 382, 390

Aspinja, Mohammedan village on the Upper Kur, i. 74,

75;

discontent of the inhabitants, ibid.; 66 note 1

Astishat (District of Mush), place famous for its

temples in pagan times, i. 295.

The temples destroyed by St. Gregory, ibid., who erects the

[501]first Christian church in Armenia upon the site,

296.

Site of Astishat identified with that of the present cloister of Surb

Karapet, 296 note 2

Astrakhan, diocese of the Armenian Church, i. 233 note

2;

emigration of Armenians to, 367

Astvatsadur, katholikos, i. 262, 264 note 5, 268

Atabegs, governors of Upper Georgia, i. 62;

they became independent kings of Georgia, and were suppressed at a late

date by the Ottoman Turks, ibid.

Atanon village, near Lake Van, ii. 123

Aternerseh, Bagratid prince of Georgia, i. 341, 343,

344, 345

Athenogenes, Christian Saint, whose bones were obtained

as holy relics by St. Gregory, i. 295 and note 3

Athenogenes, son of Yusik and father of Nerses the

Great, i. 303, 306

Aurelian, Roman Emperor, i. 281, 289 note 2

Avdi, village between Karakilisa and Tutakh, ii. 13

Avrin Dagh, Persian frontier, ii. 386

Ayubids, dynasty of Kurdish extraction in Mesopotamia,

descendants of Saladin, ii. 211, 295

Azat, village in district of Kars, i. 409

Azerbaijan, frontier province of Persia on the side of

Armenia.

Nature of the frontier, i. 428, 440.

Geology of, ii. 389.

Governed by semi-independent Arab governors during the decline of the

caliphate, whose relations with the kinglets of Armenia occupy a

prominent place in Armenian mediæval history, i. 341

seq.

See Afshin, Yusuf.

Exodus of the Armenian inhabitants upon its evacuation by the Russian

armies in 1828, ii. 206.

Its Armenian pop. at the present day, ii. 428.

A diocese of the Armenian Church, i. 233 note 2

Baba, Cape, Black Sea, i. 2

Bafra, port on the Black Sea, i. 4

Bagaran, in the province of Ararat, i. 296, 324;

the capital of Ashot I., 340, 350

Bagdad, village, Kutais district, i. 48, 49

Baghdasareantz, Sembat, member of the Society of

Evangelical preachers in Shusha, i. 98, 102, 104

Baghmesheh, Bay of, Lake Van, ii. 138

Bagrat-Magistros, governor-general of the eastern

provinces, i. 373

Bagratuni or Bagratids, ancient Armenian family of

princely rank giving kings to Armenia as well as to Georgia during the

Middle Ages, i. 337.

See Armenia, History of, III.

Their Jewish origin, 337.

Their hereditary seats, ibid.

Baiburt, town in the valley of the Chorokh, i. 432, ii.

233, 244, 382

Baiburt, plain of, ii. 402

Baïndir, Karapapakh settlement on the Murad near

Tutakh, ii. 267

Baker, G. P., his ascent of Ararat, i. 199

Baku, on the Caspian, i. 226, 449;

Govt. of, i. 447, 449

Balakhor Valley, ii. 234

Baliki or Beleke, tribe in Kurdistan, ii. 430

Balük, Lake, district of Ararat, ii. 7, 384, 385,

386

Baralet, village, district of Shubaret, i. 86

Bartholomew, Saint, i. 277, 279

Bash Abaran, Armenian village, Alagöz district, i.

137

Bashit Dagh, Taurus range, ii. 388

Basil II., Byzantine emperor, intervenes in Armenian

affairs, i. 360 and makes an armed peregrination of the country,

ibid.

Again marches into the territories of the Armenian kinglets,

ibid. and 361.

Inherits the principality of Akhaltsykh, 360, and is named heir to the

dominions of the king of Armenia, 361.

Takes over the dominions of the Artsruni family, 357.

His forward policy in Armenia, 361.

Dies before its completion, ibid.

Basil, Saint, of Cæsarea, i. 307, 310; 275

Bashkala, Jews at, ii. 80 note

Bashkent, village of, ii. 185

Bashkent, plain of, ii. 185 and note

Baskan, village, Bingöl district, ii. 182, 360

Basle, Evangelical Mission, see Missions

Bastok, Kurdish village, Bingöl district, ii.

379

Batum, i. 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 226, 236, 430, 432,

455

Bayaz Tuzla, village, Bingöl district, ii. 260

Bayazid, town near Ararat, i. 37, 160, 321, 435;

Kurds and Karapapakhs in the district, ii. 11, 14 note, 416.

Pop. of the sanjak, 413

Bayindar Bey, tomb at Akhlat, ii. 293, 294;

probably a chieftain of the Turkoman horde of the White Sheep, 296

Behagel, von, companion of Parrot, i. 184, 185, 321,

notes

Bejano (Kestano), village on plain of Akhalkalaki, i. 87

note 1

Bejeshkean, Father Minas, i. 32 note 1, 33, 367 note

1

Beka, atabeg, i. 63

Bekant, village of, i. 437

Belck, Dr., i. 197–272, ii. 28, 44, 51, 56

seq.; i. 183, ii. 47, 121, 122, notes

Bendimahi Chai, Lake Van, ii. 38, 44, 50

Beni-Cheddad, Mussulman family belonging to the Kurdish

clan of Rewadi, establish a dynasty in Karabagh during the decline of

the caliphate, i. 362, 364, 365 note 1, 382.

Become possessed of the Armenian capital, Ani, in A.D. 1072, i. 365.

Lords of Ani until towards the close of the 12th century, ibid.,

and 366, 371 note 1.

See Abulsevar, Fathlun, Manuchar

Berkri, town near Lake Van, i. 358, ii. 29 note 4

Berlin, Congress and Treaty of, i. 238, 241, ii. 205,

409 note, 410–411

Besh Parmak Mts., Lake Van, ii. 23

Bessarabia, a diocese of the Armenian Church, i. 233

note 2

Bessarion, Cardinal, his account of Trebizond, i. 19

Beth Lapat, Synod of, at which the old Christian church

of Persia adopted the Nestorian confession, i. 313

Biaina, territory of which Dhuspas (Van) was the

capital, ii. 57

Bilejan Dagh, ii. 257, 258, 269, 309, 311, 333, 343,

347, 351, 372, 397, 401

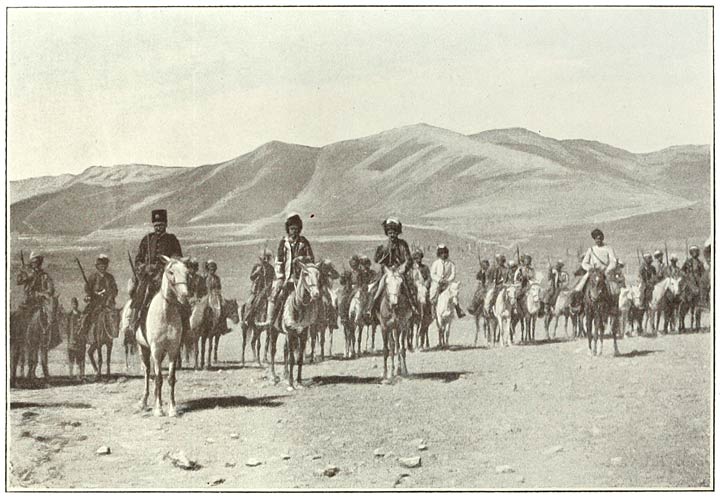

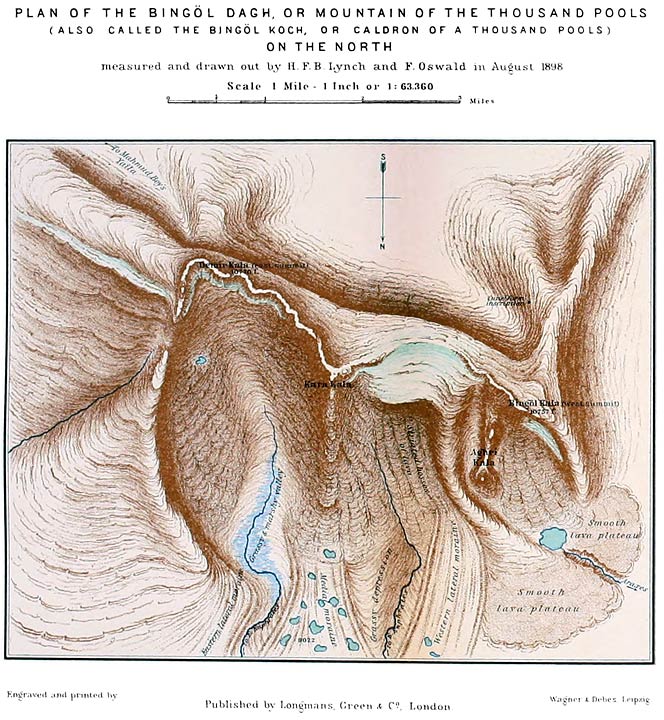

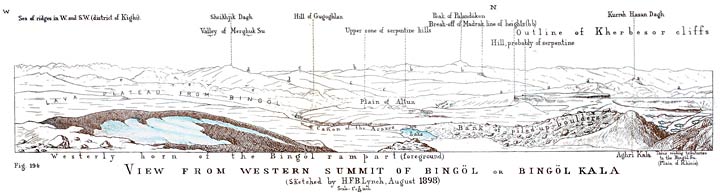

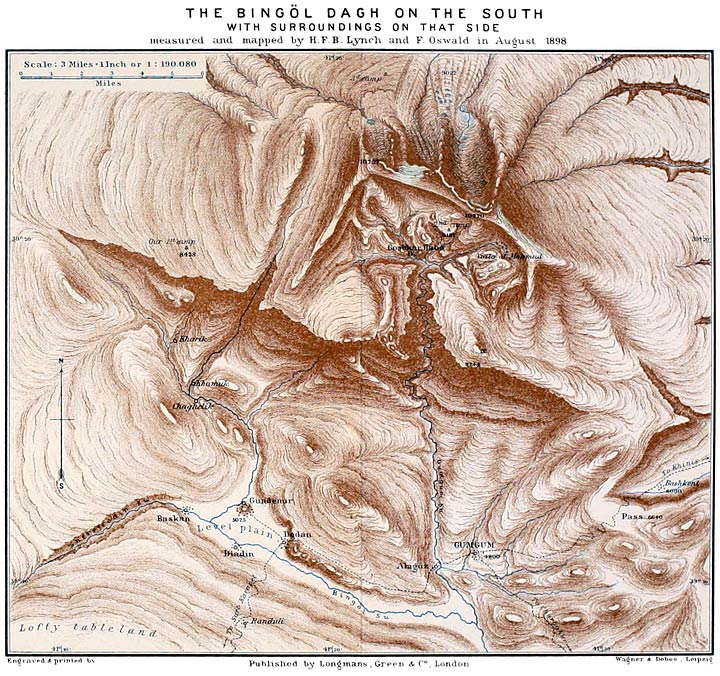

Bingöl Dagh (mountain of the thousand tarns) or

Bingöl Koch (caldron of the thousand tarns), parent mountain of

the Araxes and of the principal tributaries of the Euphrates, ii.

182;

seen from the highlands above the village of Kulli, 190;

from the Palandöken Pass, 247;

from Tekman, 247, 251, 252, 253;

from Khinis, 254, 255, 257;

from Kartevin Dagh, 269;

from Sipan, 333, 337;

from Nimrud, 311;

from Khamur, 351.

Description of the mountain, 363–377, 389.

Ascent of, 363;

altitude, 364, 366, 367;

names given to the three principal elevations, 364, 365, that of

Demir-Kala being slightly the highest, 182.

View from the summit, 372–374.

Traces of ice action on the Bingöl Dagh, 369, 370.

Flora, 361, 362, 369.

Our discovery of a cuneiform inscription, 373.

Inspiring surroundings, 361.

Plans, 366, 378

Bingöl Plateau, ii. 122, 182 185, 188, 189, 374,

398, 399.

The stupendous cliffs by which it breaks away on the south, ii. 182,

358, 359, 360 (Fig. 192), 361, 371

Bingöl Su, name given to several rivers in Central

Armenia, notably

1. the Upper Araxes, ii. 190, 191,

2. a considerable tributary of the Murad or Eastern Euphrates flowing

through the plain of Khinis and effecting the confluence in Bulanik,

ii. 253, 257;

the confluence visited, 346; 373, and

3. a second tributary to the Murad, coming in near Charbahur, ii. 182,

183, 354, 358, 360, 362

Birmalek, Tartar settlement, Alagöz district, i.

325, 326

Bitanu or Bitani in the Assyrian inscriptions may be

Biaina, ii. 57, and ibid. note 4

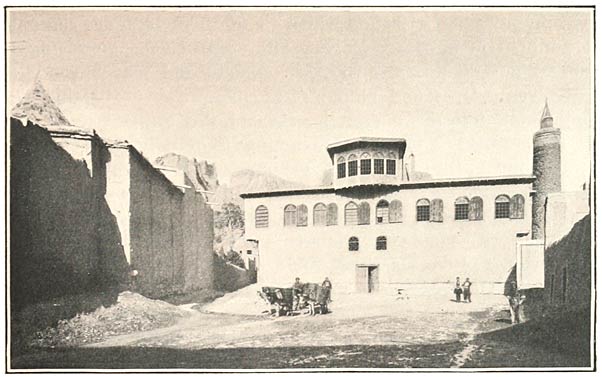

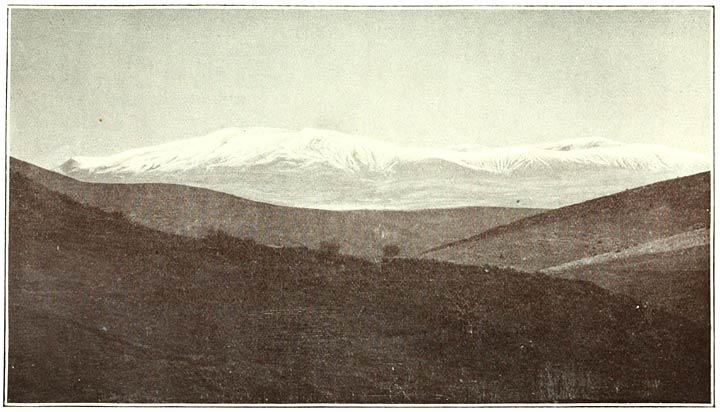

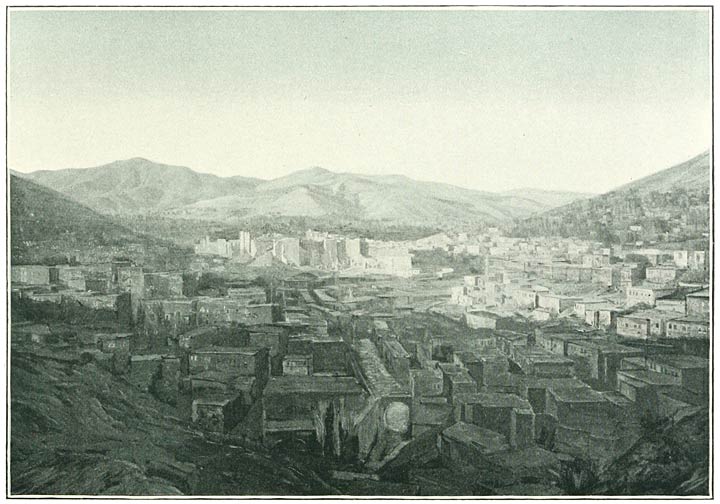

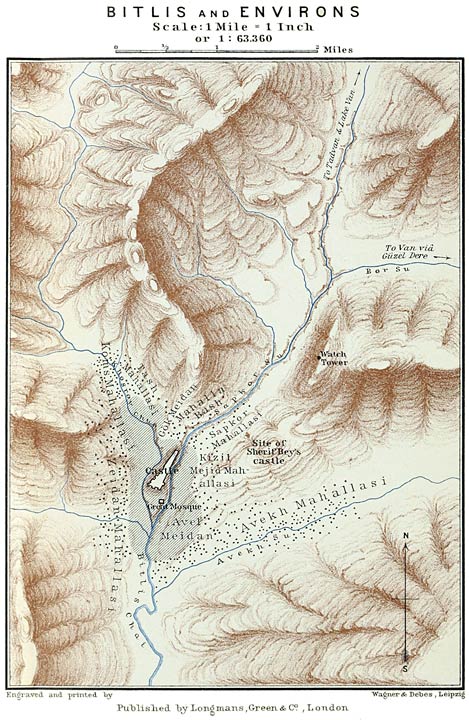

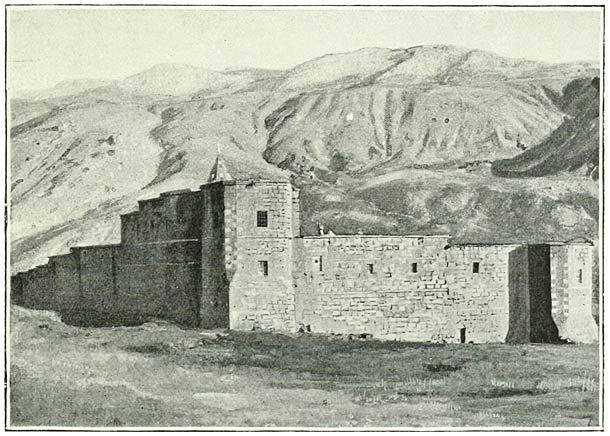

Bitlis, town on the borders of Armenia and Kurdistan,

visited and described, ii. 145–157; 51.

Elevation above sea level, 147.

Solidity of the [502]buildings, ibid.

Importance of the situation, 148.

History, 148–151.

Greek coins found in the vicinity, 150.

Pop., 151, 413.

Industries, 151.

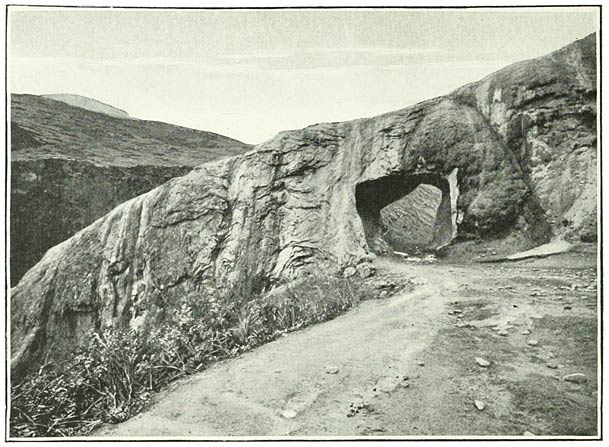

The tunnel of Semiramis in the neighbourhood, 156 and Fig. 148.

Political unrest at Bitlis, 85, 157–159, 318, 431.

Plan, 147.

View of, 145

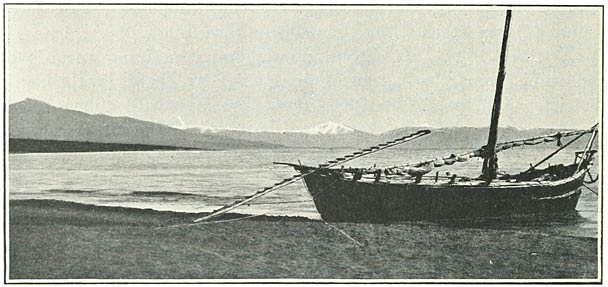

Black Sea (Pontus Euxinus, Euxine) and southern

seaboard, i. 1–36, 37, 38, 41–43, 432, ii. 225, 236,

237–240, 382.

Closed to European commerce by the Ottoman Turks in the 15th century,

i. 36.

Its free navigation secured by the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829,

ibid.

Commencement of steam navigation in 1836, ibid.

Blagodarnoe, Molokan village, district of Kars, i.

403.

Bogdanovka, a Russian settlement on the plain of

Akhalkalaki, i. 105; ii 86, 115, 118

Bohtan Su, tributary of the Tigris, ii. 395; 57 note

4

Bor, Armenian village near Bitlis, ii. 143

Bor, Pass of, ii. 143

Borchala, Valley of the, i. 40 note

Borchali, Ouezde, i. 430, 453

Boré, Eugène, i. 348, ii. 153; i. 281, 367

notes

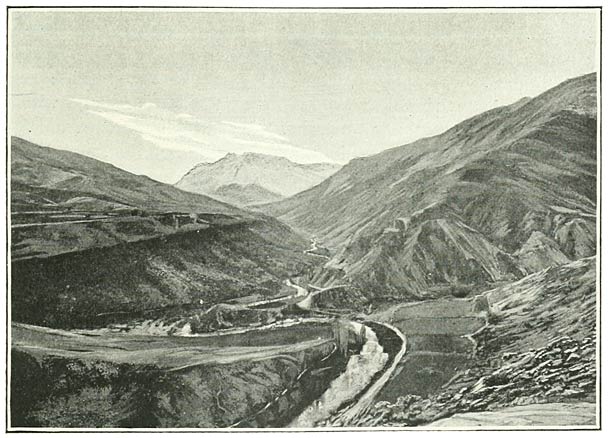

Borjom, Gorge of, i. 39, 430, 443

Boyajean, Armenian revolutionary, ii. 431

Boyajean, Consul, ii. 413

Boz Tepe (Mt. Mithros), i. 9, 12, 13, 32, ii. 238

Brant, Consul James, ii. 44, 79, 151, 173, 182, 206,

440; i. 406, ii. 121, 165, 187, 190, 195, 197, 283, 287, 313, 339,

notes

Brosset, M. F., i. 63, 64, 65, 71, 370–380,

382–385, 387–390, 407; 75, 78, 79, 80, 81, 84, 132, 183,

266, 270, 271, 272, 338, 354, 366, notes

Bryce, Rt. Hon. J., his ascent of Mt. Ararat, i. 166,

197, 199.

His description of the valley of the Araxes, 146

Buga Tepe (Kars district), i. 394

Bugutu, Crag of, Alagöz, i. 321, 325

Bulama, Lake, see Gop, Lake

Bulanik, district of, ii. 344, 394, 404, 345, 351, 401,

424, 425

Burnu Bulakh, Kurdish village near Köshk, ii.

18

Butyka, Dr., ii. 49

Buwayhids, Turkish dynasty, i. 353

Buyuk Chai (Erishat), Lake Van, ii. 24

Caffa, port on the Black Sea, i. 36

Canning, Stratford, British ambassador, his

correspondence with Consul Brant, ii. 440

Canterbury, Archbishop of, i. 102;

his Mission to the Assyrian Christians, ibid.

Carrière, Prof., i. 278 note

Caucasus Mts., connection of the range with the

structural system of Asia, i. 425.

Joined by the Meschic Mts. to the Armenian border chain, 425, 433; 40,

70.

Viewed from the Zikar Pass, 52;

from the summit of Abul, 95;

from Ararat, 198.

Height of the snow-line on, 198 note 2

Chabakchur, plain of, ii. 387, 392

Chaghelik, Kurdish hamlet, Bingöl district, ii.

360

Chakhar Dagh, i. 436

Chalcedon, Council of, i. 312, 313, 348

Chaldæans, name under which the Chaldians, or

remnant of the subjects of the old Vannic kings inhabiting the northern

peripheral mountains of Armenia, are sometimes alluded to by classical

authors, ii. 68, 69

Chaldæans, name sometimes given to the Assyrian

Christians inhabiting the recesses of Kurdistan, ii. 69, 70.

Their supposed origin, ibid.

Relations of the English Church with them, i. 102.

Their incidence in Armenia, 451. ii. 80 note

Chaldees, ii. 70 and note 1

Chaldia, see Khaldians

Chaldians, see Khaldians

Chaldir Mts. (Northern Armenia), i. 105, 119, 121, 123,

438, 441

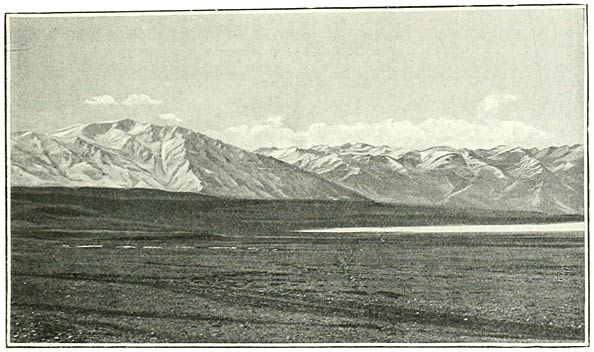

Chaldir, Lake of, i. 439, 443.

How formed, ii. 404

Chaldiran, district in central Armenia, i. 435, ii.

421

Chamar Dagh, i. 431

Chambers, Rev. W. N. and Mrs., American missionaries in

Erzerum, ii. 217, 256

Chamchean, Father M. (Chamich), i. 339 note

Changalli, name sometimes given to the cloister of Surb

Karapet (Mush district), q.v.

Changly, village, i. 416 note

Chantre, M. and Mme., i. 167, 195 note 1, 199, 434

note

Charbahur, Circassian village near the slopes of the

Khamur heights, ii. 353

Charbahur Tepe, Circassian village, ii. 354

Chardaklu Dagh, Tauric Armenia, ii. 386

Chardin, J., i. 209, 211, 256 note, 262, 267

Charshembeh, town in the delta of the Iris, i. 4

Chat, Kurdish village, Alashkert district, ii. 1

Chaurma village, Tekman district, ii. 249

Chavarchan (Ardaz), ancient canton, i. 277 note 2

Chawir, see Abulsevar

Chembek Dagh, Taurus Range, ii. 389

Cheremetieff, General, his reclamations in the valley of

the Araxes, i. 226

Chermaly, Armenian village and posting station

(Kars-Kagyzman), i. 412

Chernomorsk, Govt. of, i. 447

Chesney, F. R., expeditions of, ii. 440

Chevelik, village, ii. 392

Chevermeh, Armenian village, Khinis district, ii.

256

Chibukh-Naryn-Bashi Dagh, i. 441

Chonchal, lake, i. 105, 106

Chonchal, river, i. 105

Chorzene, name by which district of Kars was known to

Strabo, i. 395

Chorokh river, i. 41, 62, 337, 358, 430, 431, 436, 437,

442, 453, ii. 68 note 3, 203, 232, 386–387, 402, 406

Chorsa, see Kars

Chosroes, Arsakid king of Armenia, i. 286–288

Chosroes the Little, Arsakid king of Armenia, i. 301

note, 302

Chunak, pseudo-katholikos, i. 309, 310

Cilicia, mountainous district of Asia Minor. After the

Seljuk conquest of Armenia some Armenian emigrants founded a kingdom in

these mountains, i. 367,

which endured for almost 300 years, ibid.

These colonists resisted the spiritual guidance of the Roman popes,

ibid.;

but as friends of the Crusaders they were at length overwhelmed by the

Turks, ibid.

Their descendants still maintain themselves in the district,

ibid., and ii. 427.

Status of the katholikos of Sis, i. 276

Circassians, immigrants into Turkish Armenia, ii. 340,

341.

List of their villages, 340.

Characteristics, ii. 331, 332, 353, 354, 356, 357, 359

Clayton, Major, British Consul at Van, ii. 62, 313,

388

Cole, Mr. R. M., American missionary at Bitlis, ii.

154

Comneni, distinguished Greek family, perhaps of Italian

origin, i. 35;

called to the throne of the Byzantine Empire, ibid.;

their tragic overthrow, ibid.;

furnish a line of emperors of the Black Sea coasts, ibid.

See Grand-Comneni

Constantine the Great, Byzantine Emperor, i. 293 note 1,

300

Constantine V., Byzantine Emperor, ii. 222

Constantine VII., Porphyrogenitus, Byzantine Emperor, i.

336 note, 352, ii. 223

Constantine X., Monomachus, Byzantine Emperor, i. 353,

362, 363

Constantine XI., Dukas, Byzantine Emperor, i. 373

Constantinople, Council of, i. 312 note

Constantinople, Armenian Patriarchate of, ii. 450

seq.

Conybeare, Mr. F. C., i. 280, 281, 283, 407; 277, 279,

284, 285, 301, 312 notes

Cossacks, i. 158 seq., 401–403

Crimea, emigration of Armenians to, i. 367

Cuinet, Vital, ii. 25; 26, 79, 139, 152, notes

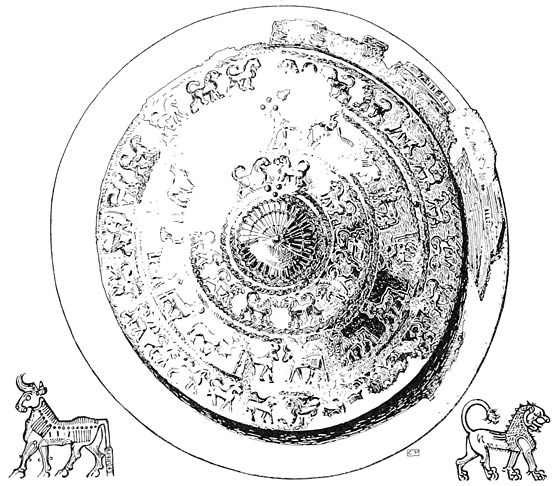

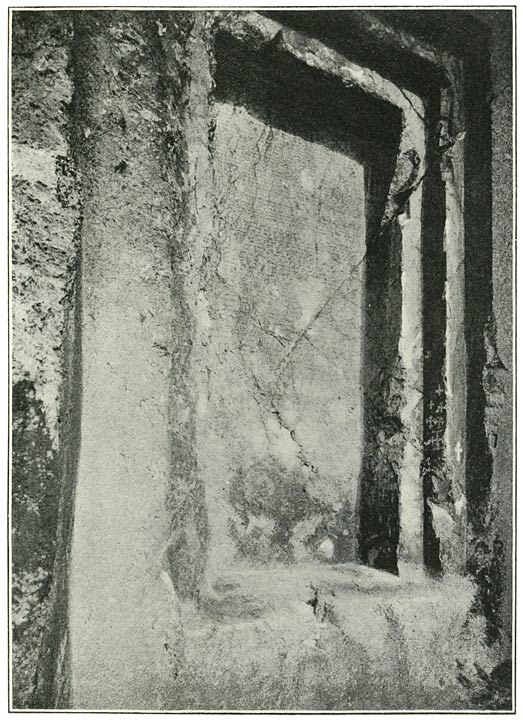

Cuneiform inscriptions, their widespread occurrence

[503]in Armenia, ii. 53, 56, 61.

Difficulties attending their decipherment, 54–56.

The ancient civilisation which they disclose, 56–76.

The inscriptions on the rock of Van, 108–110.

Inscription of Choban or Meher Kapusi near Van, 112 and Fig. 134.

Inscription at Akhtamar, 133;

do. at Melazkert, 275 note 2;

on the Bingöl Dagh, 373, 73;

at Palu, 392

Cyprus Convention, ii. 409

Dadian Dagh, ii. 386

Daghestan, i. 447

Dalmatian, Armenian equivalent for Latin, i. 300 note

2

Daly Dagh, peak of the Gori Mokri, i. 434

Damadean, notorious Armenian revolutionary, ii.

157–159; 172; 431

Daniel, Syrian philosopher, i. 312 note 1

Daniel the Syrian, katholikos, i. 299 note 1

Daniel, monk of Tigranocerta, i. 388

Daniel Vardapet, of Varag, ii. 113

Darachichak, summer resort near Erivan, i. 139, 143,

445

David II., king of Georgia, i. 365

David, Prince of Akhaltsykh country, i. 355, 360

David, Prince of Van, i. 356

Dedeveren, Kurd village, Khinis plain, ii. 256

Deir, town in valley of the Great Zab, i. 277 note 2

Deïrmen Dere, valley of the ancient Pyxitis river

in the Pontic region near Trebizond, ii. 238; i. 8, 9, 22

Delijan, posting station, Northern Armenia, i. 40

Demian, Pass of, ii. 277

Demian, village of Hasananli Kurds above the plain of

Melazkert, ii. 277, 342.

Mileage to Melazkert and Akhlat, 277 note

Demir Kala, see Bingöl Dagh

Dersim, The, country and administrative division

belonging to western Armenia, ii. 388, 389, 390, 393.

Pop.,

413, 416.

Its Kizilbash inhabitants, 418

Deveh Boyun, Camel’s Neck, volcanic ridge dividing

the plains of Pasin and Erzerum, ii. 194, 196, 227.

Strategical importance to Erzerum, 201, 245;

fortifications on the ridge, ibid.

Dhuspas, ancient name for city of Van, q.v.

Diadin, town on the Upper Murad, i. 272, 297 note. ii.

406

Diarbekr, city on the lowlands of Mesopotamia, i. 359

et passim;

device of double-headed eagle there, ii. 211 note 3;

communications with Kharput and Erzerum, 388, 396;

with Bitlis, 148

Dignuk, village on the Murad near Melazkert, ii. 276,

265

Dimitri, king of Georgia and lord of Ani, i. 365

Diocletian, Roman Emperor, i. 256, 293, 295 note 3,

300

Dittrich, Protestant missionary, i. 98, 99

Diyadin, Armenian village, Bingöl district, ii.

182

Dochus Punar, radial volcanic mountain system in

Northern Armenia, i. 73, 94, 438, 440, 441, 443

Dodan, Armenian village, Bingöl district, ii. 182,

358, 360; 180 note 2

Dodan Chai, see Bingöl Su

Dombat, village of Kizilbash Kurds on Upper Murad, ii.

10, 12

Dosp, see Van

Dubois de Montpéreux, i. 62, 64, 71, 75–84,

183, 185, 203, 216–218, 264, 267, 269, 318, 319, 327; 66, 67,

201, 230, 261, notes

Dukhobortsy or Dukhoborians, Russian sectaries settled

in Armenia, i. 96, 102–104.

Their settlements visited, i. 105–111.

Character of their religion, 103, 111–112.

Feud arises among their communities, 112–113.

A considerable party resolve to defy the Government, 113, 114.

Govt. retaliates with savage cruelty, 114–116.

Large numbers emigrate to British territory, first to Cyprus and then

to Canada, 116.

Reflections, 116, 117, 120.

See also 456, 457

Dümlü Dagh, source of the Western Euphrates,

i. 431, ii. 209 and note 2, 406

Duzyurt, Kurdish village, Tekman district, ii. 249,

381

Dvin (Tovin), ancient Armenian city in Ararat district,

i. 201 note 1;

the seat of the katholikos transferred to, i. 264 note 5, 265;

its importance in the Middle Ages, 338, 342, 346, 364, 365, 382

Dvin, Council of, i. 284, 301 note 1

“Eagle of Vaspurakan,” newspaper founded by

the Katholikos Mekertich Khrimean, i. 240

Ebeling, Herr, his ascent of Little Ararat, i. 199

Edessa (Urfa), town in Mesopotamia, i. 277 note 2, 279,

306

Edgmiatsin (Vagharshapat, q.v.), Armenian

monastery and town in the district of Ararat, visited and described, i.

228–276, 453.

Sometimes called by Armenian writers Nor-Kaghak; origin of this name,

287 note 3.

Known as Uch Kilisa in Mussulman times, 256.

Tradition that the cathedrals and chapels occupy a site of great

sanctity in pagan times, ibid. note 2.

Ripsimian legend attributes the origin of the cathedral to a direct

mandate of Jesus Christ, 256–261.

The legend examined, 311.

Academy, see under Education.

Plan, 244.

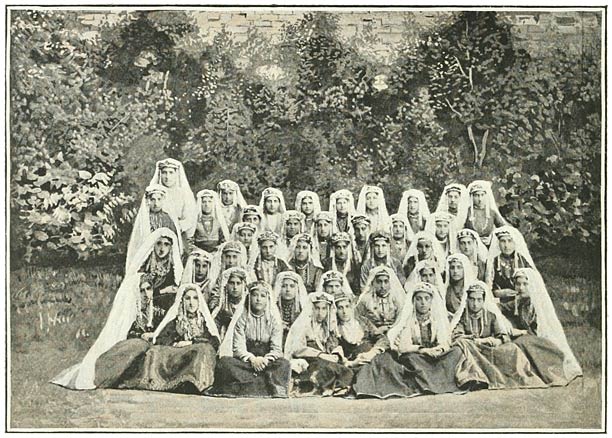

Education, (I.) Russian provinces. The Russian State

schools and the Armenian Church schools: their status and regulation,

i. 218–220, 273, ii. 97.

The two systems contrasted, i. 220–222.

The Armenian system culminates in the Academy at Edgmiatsin,

272–274.

Several Russian State schools visited and described: at

Akhaltsykh, i. 68;

at Akhalkalaki, i. 90;

at Alexandropol, i. 129;

at Erivan, i. 221–224;

at Kars, i. 408;

in villages, i. 203, 316, 332.

The Russian solution of the religious difficulty, 223–224.

Armenian schools: at Akhaltsykh, i. 68;

at Akhalkalaki, i. 90;

at Alexandropol, i. 129;

at Erivan, 221;

at Kars, i. 408;

in villages, i. 140, 203, 325.

The teachers are as a rule laymen.

(II.) Turkish provinces. The Turkish State schools and

the Armenian Church schools: their status and regulation, ii. 96, 97,

99, 100, 215.

Much greater latitude allowed in Turkey to the Armenian schools,

97;

but Russian methods are creeping in, ibid. and 100.

The two systems contrasted, 101.

The Armenian teachers are laymen and belong as a rule to a high class

in society, 97. Turkish State schools visited and described: at

Van, ii. 100–101;

at Bitlis, ii. 152 and note 1;

at Mush the school is in abeyance, ii. 170;

at Khinis, ii. 186;

at Erzerum, ii. 217. Armenian schools: at Van, ii.

96–99,

and private schools, ibid.;

at Bitlis, ii. 152;

at Mush the schools are closed;

at Erzerum, 216–217,

and Sanasarean School, 213–216, 97.

In villages they are for the most part closed, cp. ii. 165.

Rigorous Turkish censorship over foreign literature, ii. 95, 180.

American Mission schools, culminate in Armenia College at

Kharput, ii. 391.

Visited in various centres ii. 94–95, 154, 217, 256. Armenian

Catholic schools, ii. 153, 217

Efremovka, Russian settlement and posting-station in

northern Armenia, i. 118, 119

Egin, town on W. Euphrates, i. 449, ii. 386, 390

Eleazar, katholikos, i. 262, 263, 270

Elizabetpol (Gandzak), i. 364, 365

Elizabetpol, Govt. of, i. 447, 449; 97, 103 note, 113,

114, 115, 447, 449, 455

Elliot, Capt., British Consul at Van, ii. 304, 314

Elmali Dere or Vale of Apple Trees, district between

Khinis and Tutakh, ii. 263, 399

Elmali Dere, Lake Van, ii. 142

Emlekli Dagh, Gori Mokri, i. 434

Enghil Su, Lake Van, see Anguil Su

Enzakh, Armenian hamlet, Lake Van, ii. 137

Ephesus, Council of, i. 312 note, 314 note

Ephraim, katholikos, i. 264 note 5

Erazgavors, town in Shirak, residence of Sembat I., i.

341, 345

Erimenas, Vannic king, known only from an inscription on

a shield found at Toprak Kala, ii. 66, 75 [504]

Erishat River (Irshat), Lake Van, ii. 24, 44

Erivan, the town of gardens, visited and described, i.

142, 143–146, 153, 206–227, 229, 427, ii. 404.

Derivation of the name and history, i. 209–210, 446.

Industries, 226.

Material prosperity of the Armenian inhabitants, 225, 467;

yet there does not exist a single bookseller’s shop, 225.

Pop. of the town, 209;

of the province, 447, 451.

Schools, see under Education.

View of from the north, Fig. 42, p. 208

Erkizan, quarter of Akhlat, ii. 45, 284

Erovant, Armenian Arsakid king, 1st cent., i. 209

Ertev, village, Pasin district, ii. 193

Ervandakert, ancient Armenian fortress on the Arpa Chai,

i. 319, 324

Ervandashat, ancient Armenian city on the Arpa Chai, i.

319, 324

Erzen, see Artze

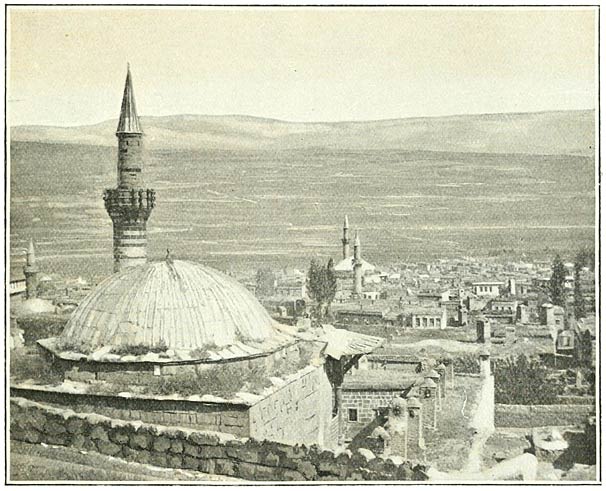

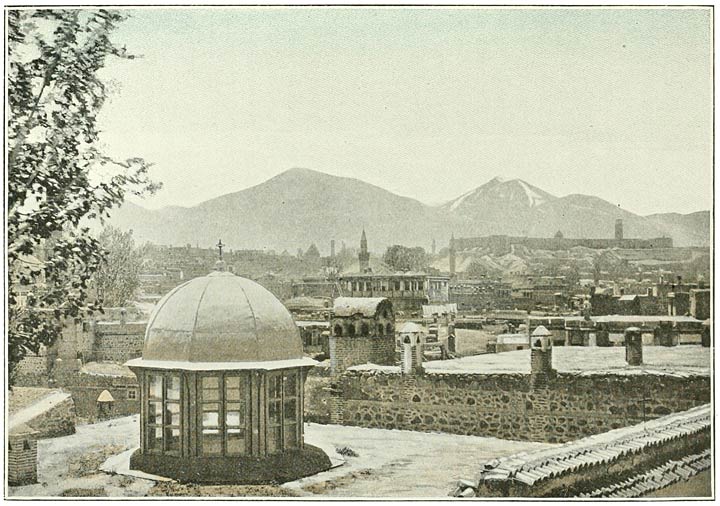

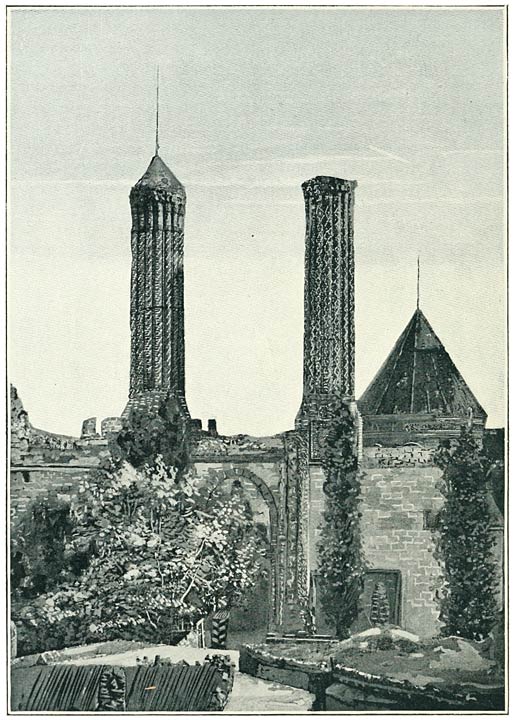

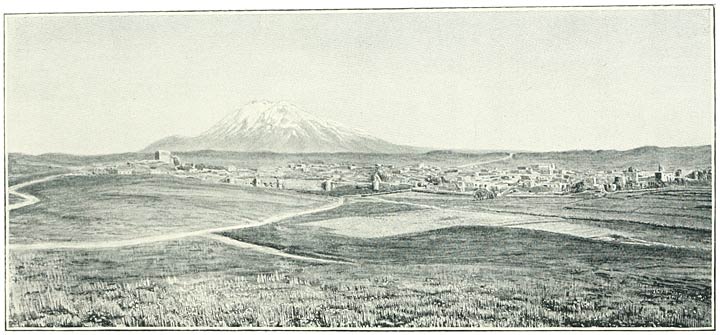

Erzerum (Karin, Karnoy Kaghak, Theodosiopolis), fortress

and capital in Turkish Armenia, visited and described, ii.

198–224, 244, 245.

Derivation of the name, 223.

History, 221–224, 204–205.

Climate, 208 and cp. i. 107 note, 427.

Trade, ii. 205–207, i. 32;

pop. of the town, ii. 206–207, and cp. i. 67, 128;

of the province, ii. 413.

Schools, see under Education.

View of from the south, Fig. 164, p. 207,

from the north, Fig. 165, p. 208.

Mileage to Khinis, 174 note;

to Trebizond, 225, 240.

Route to Rizeh, 382, i. 431,

and to Olti, ibid.

Suggestions for railway communication, ii. 206, 382

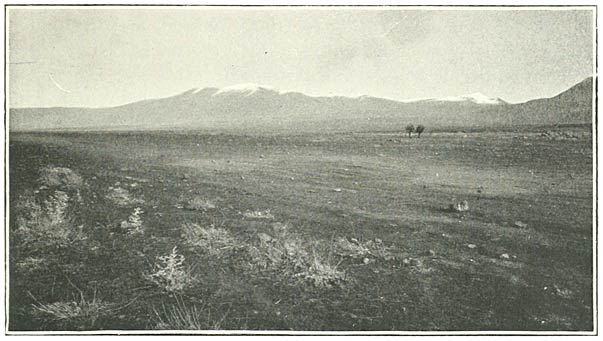

Erzerum, plain of, area and elevation, ii. 209.

Connection with other Armenian plains, i. 146, ii. 401

Erzinjan, ancient Armenian town and Turkish military

station on the Western Euphrates, i. 348 note, 431, 432, ii. 204, 227,

228, 234, 386, 390, 404, 413, 418.

Statue of the goddess Anahid at E. destroyed by St. Gregory, i. 294

Eugenius, Saint, of Trebizond, i. 36

Euphrates, Western (Kara Su, Frat), its sources in the

Dümlü Dagh, i. 431, ii. 209, 401;

fed by the Central Tableland, ii. 398;

its course through Armenia, i. 146, ii. 201, 203, 222, 227, 228 and

note, 230, 404, 406;

its valley apportioned to the Roman Empire, i. 306

Euphrates, Eastern (Murad), its sources and principal

affluents, ii. 406; 373, 398;

course through Armenia, i. 420, ii. 2, 9, 10, 12–15,

264–273, 277, 342, 343, 346–355; 183, 175, 177;

the ancient Arsanias, ii. 41.

Tiridates and his people baptized on the banks of, i. 296

Eusebius, Bishop of Nicomedia, i. 300

Eyerli Dagh, Erzerum, ii. 202, 245, 381, 398

Eyub Pasha, Kurd Hamidiyeh, ii. 5

Eznik, i. 301 note 1

Ezra, katholikos, i. 270

Fadéeff, General, Governor of Kars, i. 399, 400,

403, 417

Fallmerayer, J. P., historian of Trebizond, i. 33, 34,

19

Fars (Shiraz, Persepolis), i. 286, 287, 340 note 5

Fath Ali, Shah of Persia, i. 217

Fathlun I., Beni-Cheddad, i. 365

Fathlun II., i. 365

Faustus of Byzantium, i. 291 note 1, 303, 311

Feodoroff, companion of Parrot, i. 198 note 1

Fergusson, J., History of Architecture, i. 263, 368, 372

note

Fethulla Bey, chieftain of Hasananli Kurds, ii. 276

Finlay, G., History of Trebizond, i. 33, 34

Flora and fauna. The flora in Armenia is as a

rule composed of the species familiar to the traveller in Europe, ii.

246, 248; 208, 253, 256, 265, 268, 269, 303.

It is perhaps most remarkable on the sandy slopes of Ararat, i. 190,

191,

as also on the higher seams, i. 181.

The great mountain masses appear to have their distinctive flowers, ii.

362, and see Bingöl, Nimrud, Sipan.

Wealth and variety of the flora in the regions bordering Armenia on the

side of the Black Sea, i. 18, 51, 432, ii. 236, 239, 241, 242, 382

Of big game there is little, ii. 302, 304, 339;

but partridges are found in abundance on the mountains, i. 161,

181;

and the plain of Alashkert is a nursery of wild fowl, ii. 3, 9.

Wild geese are frequent on the rivers, ii. 346,

and pelicans on some of the lakes, 323, 344.

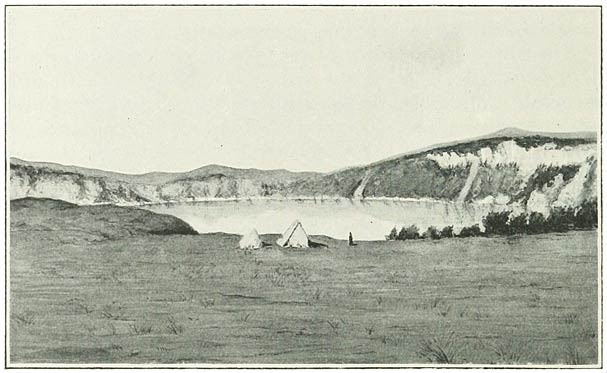

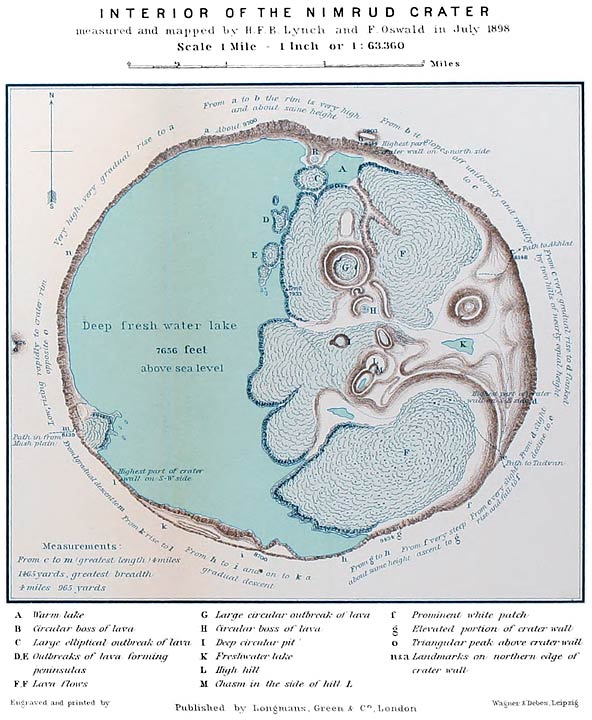

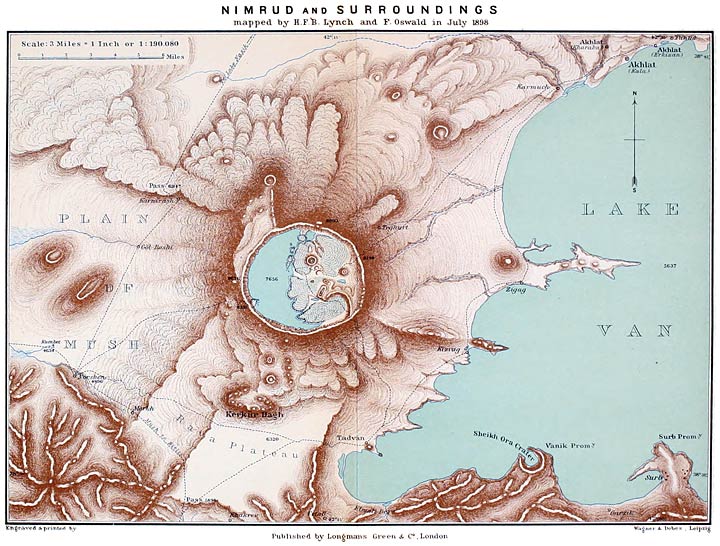

The Nimrud crater is a nursery for all kinds of butterflies, ii.

303.

Remarkable about Lake Van are the rollers (coracias garrulus),

ii. 280.

Lizards dart among the rocks, i. 74

Forests, scarcity of in Armenia and causes, ii. 405

Fraser, Miss, member of the American Mission in Van, ii.

92

Frat river, see Euphrates, Western

Frese, General, Governor of Erivan, i. 143, 226, 246,

248, 253

Freshfield, Mr. D. W., i. 198 note

Gagik, Kinglet of Van (Artsruni) and rival of King

Sembat I., Bagratid dynasty, i. 345, 346, 348, 349, 350.

Builds the church at Akhtamar, ii. 131 note 2

Gagik I., Shahanshah, King of the Bagratid dynasty, i.

354–355, 360, 373, 382, 383

Gagik II., King of the Bagratid dynasty, i. 362

Galerius, Roman Emperor, i. 300

Galicia, emigration of Armenians to, i. 367

Gandzak, see Elizabetpol

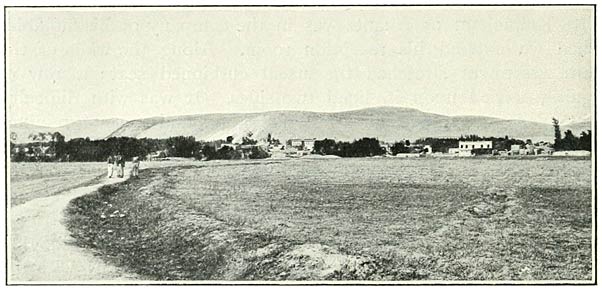

Ganibuk, village, Khamur district, ii. 348

Garchigan, district and caza, Lake Van, ii. 138, 139

Gargalik, village of Sipkanli Kurds on the Murad, ii.

267

Garni, ruined town, village and river, district of

Ararat, i. 201, 264

Garni Chai, Mush, ii. 166, 170, 175

Garuts, see Kars

Garzik village, Lake Van, ii. 141

Garzoni, Maurizio, Roman Catholic missionary in

Kurdistan in the 18th century, ii. 149

Gegham, Lake, see Sevan Lake

Gelarash Dagh, spur of the Ala Dagh, ii. 16

Gelat, Monastery of, district of Kutais, i. 45, 46,

47

Gelzer, Prof. H., i. 277, 292, 295, 299, 300, 309, 310,

notes

Genj, District of, ii. 392

George I. of Georgia, i. 360

George III. of Georgia, i. 365, 366

George IV., katholikos, i. 236, 254, 263, 267, 273

Georgia, i. 429, 432, 433; 37, 39–51; 448.

Glance at the Georgian kingdom during the Middle Ages, i. 337 seq.

passim.

It abdicates in favour of the Tsars, 446

Georgians, overlap into Armenia, i. 55–85, 86,

443.

Numbers in Armenia, 451, 455

(often classed as Turks, ibid. and ii. 417).

Their Church accepts the Council of Chalcedon, i. 313.

Unites with the Russian Orthodox Church, 463.

Their curious method of catching fish, i. 76.

Their language, ii. 68 note 3

German colonists, their origin in Transcaucasia, i.

96–99;

met with in Armenia, 410

Gez, village near Erzerum, ii. 227

Ghubanoff, Michael Vasilievich (Dukhobortsy), brother of

Lukeria Vasilievna, i. 108

Giaour Dagh, northern border of Armenia, i. 430, ii.

243

Ginal Dagh, i. 434

Girdim Dagh, Turkish Armenia, ii. 386, 392

Glak Vank (Changalli), ii. 180 note 1

Gobet, Mussulman village, Akhaltsykh district, i. 74

Godorebi, Mt. of the Abul-Samsar volcanic system, i.

95

Gökcheh Lake, see Sevan Lake

Göl Bashi, hamlet on Mush plain, ii. 319

Göl Bashi, Pool of, a source of the Kara Su, ii.

319

Göleh, district in northern Armenia, i. 430, 431,

437, 439, 443

Golgat, Armenian village, Alagöz district, i.

133

Göli, Armenian hamlet, Lake Van, ii. 138

Göljik, Lake, ii. 387;

indications of a rise in the level, 53 note [505]

Gop, Lake (Bulama, Lake of Shailu), near Bilejan Dagh,

ii. 337, 343, 344.

Analysis of its water, Appendix II.

Gop, large Armenian village, district of Bulanik, ii.

344, 345.

Mileage to Charbahur, 353 note

Gopal, Armenian village, Akh Dagh district, ii. 258,

259

Gopal Su, tributary of the Bingöl Su (Khinis), ii.

260

Gorelovka, see Dukhobortsy

Gori Mokri Mts., Northern Armenia, i. 87, 433

Goschen, Rt. Hon. G. J., ambassador to Turkey, ii,

410

Goshkar Baba (shoemaker to the Prophet), grave near

Bingöl Dagh, ii. 372

Gotimeria Dagh, Northern Armenia, i. 430, 431

Gotni, Kurdish village, Mush plain, ii. 163

Gotok, village of settled Kurds, vilayet of Bitlis, ii.

142

Gozme Gedik Pass, Mush plain, ii. 396

Grand-Comneni, line of Greek emperors at Trebizond, i.

35–36

Graves, Mr. R. W., British Consul at Erzerum, ii. 8,

199, 413 note 2

Greeks in Armenia, i. 122, 129, 331, 332, 451, 455;

in the northern peripheral region, i. 432, 456, ii. 236,

237–244

Greene, Mr. F. D., American missionary at Van, ii. 92,

95

Gregory, Saint (Lusavorich or The Illuminator), i.

259–261; 288–301; 200, 201, 204, 254, 262, 264 note 5, 265,

269, 271, 283, 284, 306, 311, 348, ii. 178 and note 2

Gregory Magistros, persecutes the Thonraki, i. 285

Grigor, grandson of St. Gregory, i. 267

Grigor (Pahlavid), father of Vahram, i. 381, 382, 383

note 3

Grigor, son of Vahram, i. 385

Gudubgokh (Surb Yakob), Chapel near Lake Van, ii.

137

Gugoghlan, Kurdish village, Shushar district, ii.

375

Gujaretis, Valley of the, i. 433

Gumbet Dagh, i. 430, 431

Gumgum, village and capital of the caza of Varto, ii.

183, 356, 371

Gumgum Su, affluent of the Bingöl Su (Charbahur),

ii. 358, 367, 368

Gümri, see Alexandropol

Gümüshkhaneh, town in vilayet of Trebizond and

capital of Greek diocese of Chaldia, ii. 69, 240, 243, 382;

famous for its silver mines, 243.

Communications, i. 432

Gundemir, ancient Armenian village, Bingöl

district, ii. 182, 358, 359

Gunduz, Armenian hamlet, plain of Khinis, ii. 257

Gunek Su, affluent of Eastern Euphrates, ii. 389, 392,

406

Günther, Mr. R. T., ii. 43 note, 48 and Appendix

II.

Gurgi Boghaz (Georgian Gates), Erzerum-Olti, ii. 203,

227, 245

Gurgur, name given to the passage of the Murad out of

Mush plain, ii. 177.

Ruins of a fortress there, ibid.

Guria, Province of, i. 42, 43

Gutschmid, Alfred von, i. 278, 287, 288, 289, 291, 292,

295, 300, 301, notes

Guyard, M. Stanislas, ii. 56

Güzel Dere, Beauteous Valley, Bitlis district, ii.

45, 143, 402

Güzul Dere, village on Alagöz, i. 135

Gypsies, in Garchigan, ii. 139 note.

At Gopal, 260.

Are they the remnant of a Hindu colony? 178

Hadrian, Roman Emperor, i. 12, ii. 40

Haidar Bey, village near Lake Van, ii. 28

Haini, town of, ii. 388, 396

Haji Khalil, village, Alagöz district, i. 135

Hakkiari, district of, ii. 88, 421 note, 424

Halys River, i. 4;

its delta is celebrated for tobacco, ibid.

Hamdun, Arab emir, i. 353

Hamidiyeh, irregular cavalry recruited by the Turkish

Govt. among the Kurds and Karapapakhs, ii. 5, 6, 13, 14, 17, 26, 88,

172, 184, 187, 195, 219, 255, 260, 266, 276, 283, 314, 344, 356, 357,

421, 422, 423

Hamilton W. J., i. 33; 32, 367 notes

Hamsi Keui, Upper and Lower, villages, Machka Dere, ii.

241, 236 note

Hargin, village on Lake Van, ii. 27, 29

Hasan Kala, ancient town in Pasin, ii. 61, 174, 193,

219

Hasan Keif, primeval village on the Tigris, ii. 395

Hasuna, village of Hasananli Kurds at the foot of

Kartevin Dagh, ii. 268, 275

Haxthausen, A. von, i. 235; 66, 90, 234, 273, notes

Hayk, city of, result of excavations at, ii. 71

Hayk, son of Togarmah, grandson of Japhet, reputed

progenitor of the Armenians, i. 318, ii. 70, 78, 274

Haykaberd, ruins of an Armenian fortress near the

passage of the Murad from Mush Plain, ii. 177

Hayotz-dzor, district of, Lake Van, ii. 71, 394

Hazo, town of, ii. 429, 431

Heraclius, Roman emperor, i. 314, ii. 222

Heraklea, Black Sea, i. 2

Hieron Oros, see Ieros

Hincks, Dr., ii. 56 note 1

Hindu refugees, their temples at Surb Karapet destroyed

by St. Gregory, ii. 178;

the gypsies in Armenia are said to be their descendants,

ibid.,

and their language is known as Sanskrit among the Armenians,

ibid.

Hindu Kush Mts., i. 423, 424, 425, 435

Hipsinek, Armenian village, Akantz district, ii. 23

Hittites, The, ii. 61

Hiznavuz (Kiznaus), Armenian village near Edgmiatsin, i.

316

Honentz, family of, i. 375

Hoseyn Ali Khan, Sirdar of Erivan, i. 214, 217

Hoseyn Pasha, chief of the Haideranli and ruler of

territory of Patnotz, ii. 17, 20, 21

Hrazdan or Zanga River, see Zanga

Huns, The, i. 287, 303

Iberians, The, i. 395, ii. 68 note 3

Ibn-Alathir, Arab historian, ii. 29 and note 2

Ibrahim Pasha, adjutant of Kurd Hamidiyeh, ii 344

Ibrahim Sheikh, unknown ruler at Vostan, Lake Van, ii.

125–126

Ieros (Hieron Oros), cape near Trebizond, i. 8, 13,

33

Igmal, village on Lake Van, ii. 27

Iki Kube, quarter of Akhlat, ii. 284–287

Ilantash or Karatash, plateau of, near Akantz, ii.

28

Ildigiz, Atabeg governor of Azerbaijan, i. 366

Ilija, village in Erzerum district, ii. 227

Imeritia, i. 42, 45, 47, 430

Ineboli, ancient town on the Black Sea, i. 3, 4, 6,

35

Innaknean Vank (Changalli), ii. 180 note 1

Inuspuas, Vannic king, ii. 72, 110 note

Iris, river flowing into Black Sea, i. 4;

its delta is celebrated for its Indian corn, ibid.

Isa, Arab governor, i. 340

Isaac the Great, katholikos, i. 312

Iskandar Pasha, ii. 289

Iskele, harbour of Van city and name of a gate, ii. 36,

49, 108 note

Ismail I., Shah, i. 210, ii. 78

Ispahan, i. 264 note 5, 440

Ispir, town on the Chorokh, i. 431, ii. 68 and note

3

Ispuinis, Vannic king, ii. 60 and note 3, 72.

Inscription of, 110 note, 112

Issaverdens, i. 277 note 2, ii. 222

Jacob, Saint, Bishop of Nisibis, his attempt to ascend

Ararat, i. 184, 185; 269

Jacob (James IV.), katholikos, i. 262, 268 note

Jagluya Mts., near Kagyzman, famous for their rich

pastures, i. 419 [506]

Jaila, Armenian hamlet, Alexandropol district, i.

119

Jala, Armenian village, Shuragel district, i. 330

Javresh Dagh, Kighi district, ii. 389

Jejen Dagh, ii. 203, 227, 230, 245, 382, 400, 403

Jejen Dagh, Pass of (Khoshabpunar), ii. 382 and 240

note

Jelal-ud-Din, Sultan of Kharizme, ii. 295, 296

Jellap, Armenian village and posting station,

Alexandropol district, i. 122

Jelu Dagh, Kurdistan, ii. 388, 395

Jenghiz Khan, Ani sacked by, i. 366, 377

Jerusalem, Armenian patriarchate of, ii. 453

Jesuits, see Missions

Jevizlik, town of Deïrmen Dere, ii. 238;

mileage to Trebizond and Baiburt, 225 note, 240 note

Jezireh, town in Kurdistan, ii. 433

Jezirok, village on Lake Nazik, ii. 323

Jil Göl, Lake of Rushes, Sipan district, ii.

331;

outlet of the waters, 341;

increase in the level, ibid., and 47 note 1

John Katholikos, Armenian historian, i. 335, 341, 344,

345, 346, 347, 348, 350, 352

John the Baptist, Saint (Surb Karapet), cult of in

Armenia, i. 283–284, 295

John the Philosopher, katholikos, i. 284

John Sembat, Bagratid dynasty, i. 355 seq., 373,

390

John Zimiskes, Byzantine emperor of Armenian descent, i.

353, 354

Jude, Saint, the apostle, i. 277 note 2

Julfa, village on the Araxes, i. 434, 435, 444

Julfa, New, i. 233 note 2, 264 note 5

Justinian, Roman Emperor, i. 27, ii. 222

Kabak-Tepe or Kizilkaya, Kars district, i. 394

Kagdarich, village on the Western Euphrates, ii. 228

Kagyzman, town near the Araxes, i. 148, 413–417,

419, 459.

Pop. of, 417;

account of town and castle by Evliya, 416 note

Kala-i-Zerin, see Zernak

Kalaji, Kurdish village, Shushar district, ii. 251

Kalajik, village of, Lake Van. ii. 38, 112

Kalajik, castled crag of, near the Vavuk Pass, ii.

243

Kala Su, Pasin district, ii. 193

Kamarlu, village of Armenians and Tartars, Ararat

district, i. 154, 201, 203

Kanjean, village in the Elmali Dere, ii. 399

Kanlija, near Alexandropol, cuneiform inscriptions found

at, ii. 61, 73

Kanly Dagh, Northern Armenia, i. 437

Kara Ali, Circassian village, plain of Melazkert, ii.

277

Karabagh, country forming an Armenia in miniature on the

side of the Caspian, i. 434; 254, 423, 445, 449, 453, 454.

Kurds in, 455 and cp. 364

Karachanta, Mussulman village, Alexandropol district, i.

122

Karachoban, Armenian village on Bingöl Su, ii.

257

Karadagh, northern Azerbaijan, i. 434, 435

Karaghun, Kurdish hamlet, Sipan district, ii. 342

Kara Hasan Su, affluent to the Western Euphrates, ii.

228

Karaja Dagh, Mesopotamia, ii. 388

Karakach Dagh (Gori Mokri, Northern Armenia), i. 87,

434, 438, 441

Karakala, ruins on the Araxes, i. 318, 319, 321

Karahisar, town of (Shabin Karahisar), i. 431, ii.

204

Kara Kala, see Bingöl Dagh

Karakaya Dagh, Tauric Armenia, ii. 386

Karakilisa, Alashkert, ii. 2–10, 266.

Kaimakam of, 7–8, 255

Karakilisa, village near Lake Van, ii. 23

Kara Mehemet, Armenian village on plain of Alexandropol,

i. 122

Karaogli, village on Murad, ii. 346, 347

Karapapakhs or Black Caps, ii. 6, 14, 266; i. 455,

456; ii. 5,

267

Karass, Scotch mission at i. 99

Kara Su, Ararat, i. 156, 183, 187, 201

Kara Su, Mush plain, ii. 162 note, 176, 317, 319

Kara Su, Western Euphrates, ii. 209, 228, 406

Karatash, see Ilantash

Kara Vank, Armenian village on Aghri Dagh, i. 418

Karchkhal Mts., Pontic region, i. 430

Karembe, Cape (Black Sea), i. 3

Kargabazar Heights (Pasin), ii. 193, 203, 227.

See also i. 431, 432

Karin, see Erzerum

Karkar Dagh (Lake Van), ii. 388

Karke, Mt. (in Taron), site of heathen temples, i. 295,

296.

Site identified, 296 note 2

Karlik Tepe, Trebizond, i. 34

Karmuch, Armenian village near Akhlat, ii. 45, 299

Karniarch, mountain and landmark near Alagöz, i.

138, 140, 317

Karnirash, hamlet of Kurds, foot of Nimrud, ii. 319

Karri Chai, tributary to the Kur, i. 443

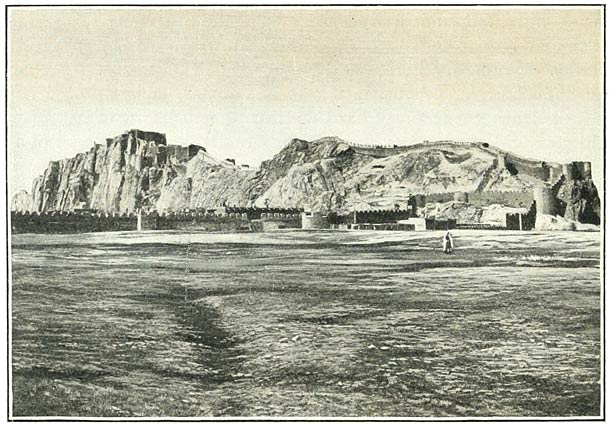

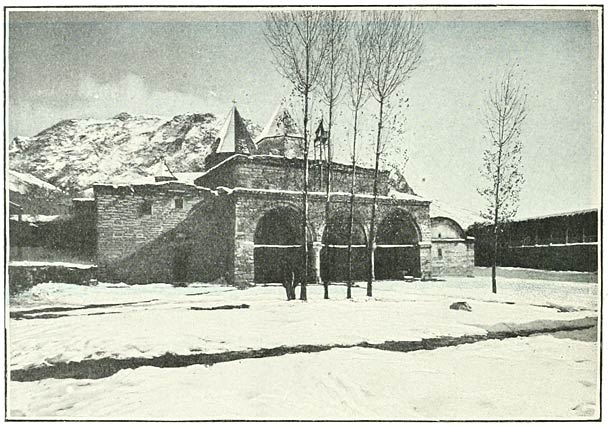

Kars (Karutz), ancient fortified city and modern

fortress in Northern Armenia, visited and described, i. 393–408;

39, 61, 330, 331, 332, 333, 442, 459.

History, 395–399, 352, 353, 354, 356, 358, 360, 364.

Elevation, 439.

Pop. of the town, 405, 406.

Do. of the province, 451.

View of, 406.

Plan, 395.

Railway from Tiflis recently completed, 40 note

Kars, river of, curiosities attending its course, i.

442, 394, 413

Kartevin Dagh, ii. 16, 263, 265, 268, 277, 333, 337,

397, 401

Kasagh River (Abaran Su), i. 242, 245, 316

Kastamuni, town in Asia Minor, i. 3, 6, 35

Katranideh, Queen of Armenia, wife of Gagik, i. 373

Kazikly Dagh, northern border, ii. 240, 382

Keban-Maden, Euphrates, ii. 390

Kegham, Lake, see Sevan Lake

Kekeli, Armenian village, Bilejan district, ii. 343

Kelkid-Chiftlik, town on the Lycus, ii. 234

Kelkid Su (Lycus), i. 431, ii. 406

Kemakh (Ani), the burial-place of Armenian Arsakid

kings, ii. 390.

Fane of Aramazd destroyed by St. Gregory, i. 294

Kemurly, Upper and Lower, Kagyzman district, i. 413,

414, 416

Kerasun, Black Sea, i. 6, 18, 431

Keremitlu Dagh, fortified hill near Erzerum, ii. 203

Kerim, notorious brigand in the Caucasus, i. 153

Kerkür Dagh, volcanic pile on the flank of Nimrud,

ii. 50, 160–161, 312, 316, 317

Ker Porter, Sir R., i. 201 note, 319, 323, 324, 367,

405

Kersik or Kersuk Su, Elmali Dere district, ii. 263;

confluence with the Murad, 265

Kerwanserai, Kurdish settlement, slopes of Alagöz,

i. 135

Keser Su, tributary of the Tigris, ii. 148

Keshish Göl, on the slopes of Mt. Varag, ii.

64;

stele near with inscription of Rusas I., ibid.

Kestano (Bejano), Plain of Akhalkalaki, i. 87 note

Ketivan, Mohammedan village near Hasan Kala, ii. 193

Kety Dagh, Karabagh border, i. 434

Keupek Dagh, Terjan district, ii. 386

Khach Dagh, Terjan district, ii. 386, 393

Khachkar Mts., i. 430

Khadrak station, valley of Balakhor, ii. 234

Khaldians, subjects of the old Vannic kings, their

history, language and art, ii. 56–65.

Character of their civilisation, 53, 65, 71, 76, 111, 116.

Was there any racial or cultural link between them and the Chaldees?

70.

Approximate date of their overthrow, 65, 66.

The remnant known to Greek writers as Chaldians and the mountainous

country to which they were driven as Chaldia—a name which

survives to the present day, 68, 69

Khaldis, supreme god of the old Vannic kings and their

people, ii. 57

Khalias Dagh or Mergemir, ii. 263, 269, 337, 389

Khama Dagh, ii. 384 [507]

Khamur Dagh, seen from Köshk, ii. 13,

from Tutakh, 14;

from Bashkent Ova, 185;

from the Palandöken Pass, 247;

from Khinis plain, 257;

from the village of Demian, 277.

Ascent of the principal ridge, 348–351.

Geological composition of, 257, 349, 371.

Monument on the summit, 350;

view of the surrounding country, 351.

Connection with Bingöl, 350, 371.

Photograph, 252, Fig. 177

Khancharli, village of, Northern Armenia, i. 119

Khanik, Circassian village, Sipan district, ii. 278

Khanikoff, N. V., his ascent of Ararat, i. 199

Khan Mahmud, Kurdish chieftain, ii. 78

Kharaba, ruins of village on the site of Ali Mur,

district of Khinis, ii. 252

Kharaba, quarter of Akhlat q.v., ii. 284

Kharput, ancient Armenian town on a hill near the banks

of the Murad, ii. 390;

pop. 391;

do. of the province, 413, 425.

Large number of villages in the vicinity, 391;

products of the neighbourhood, ibid.

The Americans have a flourishing Mission and a well-equipped College,

ibid.; 388, 396.

Plain of, 390

Kharshut River, ii. 234, 236, 242

Khashkeui, Armenian village on Plain of Mush, ii.

165

Khashlu, village, Bilejan district, ii. 345

Khedonun, village of Jibranli Kurds, ii. 250

Kherbesor, village, Shushar district, ii. 252, 373

Kherbesor cliffs, Bingöl plateau, ii. 373, 398

Khertvis, town at the junction of Kur and river of

Akhalkalaki, i. 76;

66 note, 74, 85.

Khindris Plain, ii. 389, 392

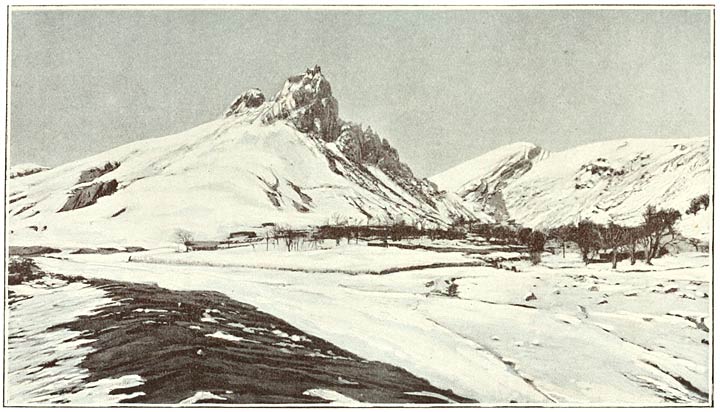

Khinis, town of, visited and described, ii.

186–188, 253, 254–255.

Pop. 187.

Emigration of Armenians from the district, 219.

Mileage to Mush and Erzerum, 174 note.

Do. to Tutakh, 255 note

Khinis, plain of, ii. 186, 188, 256–258, 351,

401.

A seat of the Thonraki, i. 285

Khinis, river of, a component of the Bingöl Su, ii.

186, 188, 253

Khizan, region south of Lake Van, ii. 397

Khodzko, J., his ascent of Ararat, i. 199

Khojabek, Armenian village, Akhalkalaki district, i.

105

Khorasan, village at the narrows of the Araxes, i. 146,

ii. 194

Khorasan, Province and Mts. of northern Persia, i. 423,

426

Khoren Stephaneh, monk at Edgmiatsin, i. 248

Khor Virap, Monastery near the Araxes, visited, i. 200,

203, 204.

Erected on the site of St. Gregory’s dungeon, ibid.

Khoshab River (Enghil Su) Lake Van, ii. 44, 50, 122,

394.

The waters of the Khoshab basin are taken to the suburbs of Van by the

Shamiram Su, 60

Khosha Vank (Kizil Kilisa), Armenian village on the Arpa

Chai, i. 328

Khosha Vank, Monastery of (Horomos), visited and

described, i. 387–390; 328

Khoshkhosh, Queen, her tomb at Varag, ii. 115

Khosrov Pasha, donor of a pulpit to the mosque at

Vostan, ii. 125

Khosrovidukht, sister of King Tiridates, i. 259, 261,

264

Khozapin, Lake, Northern Armenia, i. 87 note

Khram, Valley of the, i. 89

Khram Mts., i. 433

Khrimean, Katholikos Mekertich, i. 236, 242,

246–248, 249, 250, 251–256, ii. 86, 96, 103, 115, 408

Khvandzeh, wife of Shahanshah, i. 375

Kiaya, the head man of a Christian village, ii. 176 note

2

Kiepert, Prof. H., ii. 383 note, 408

Kighi Su or Peri Su, ii. 389, 392, 406

Kighi Kasaba, town of, ii. 390, 393

Kighi, district of, view of the from the hill of

Gugoghlan, ii. 376.

Eastern limits, 380.

Characteristics, 393, 405

Kilich Gedik Mts., ii. 2, 12, 13, 262, 263, 264, 266,

337

Kilisa Deresi, Armenian Church on the Plain of Khinis,

ii. 188, 253

Kimball, Dr. Grace, of the American Mission at Van, ii.

92

Kindirantz, capital of the caza of Garchigan, ii.

138–140

Kindirantz, plain of, natural phenomenon which is

repeated every year, ii. 139

Kinneir, Macdonald, ii. 151, 231 note

Kip Göl, crater lake on Ararat, i. 199

Kirakos, katholikos, i. 264 note 5

Kirk Bulakh River (Forty Springs), Erivan, i. 209

Kirk Deïrmen, pass near Erzerum, ii. 202

Kirklar, a quarter of Akhlat, ii. 284

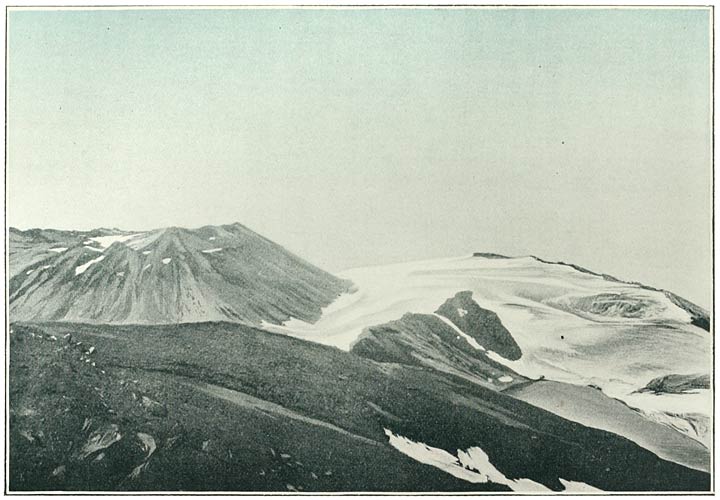

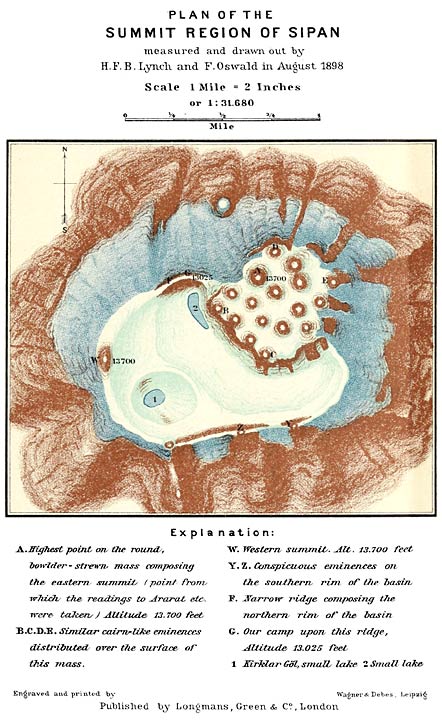

Kirklar Göl, pool on summit of Sipan, ii. 334

Kisir Dagh, Chaldir, i. 394, 438, 441

Kitowa Dagh Pass, ii. 240, 242, 382

Kizilbash, people usually classed as Kurds but

professing a distinctive form of religion, ii. 418, 419;

numbers in Armenia, 414, 416 note; 12, 185, 187, 252, 390

Kizil-Goch River, tributary to the Arpa Chai, i. 119

Kizilkaya, see Kabak Tepe

Kizilkilisa, village on the Arpa Chai, i. 328

Kiziltash, cuneiform slab near Artemid, ii. 120, 121

Kizvag, village on Lake Van, ii. 315;

menaced by increase in level of water, 52

Klupffell, M. de, i. 38

Knapp, Messrs. G. C. and George, American missionaries,

ii. 154

Koblian Chai, tributary of the Kur, i. 57

Kobulety, station, i. 42

Koch, K., i. 107, 436, 437, 443, ii. 176, 210, 211

Kohanam Dagh (Sepuh), i. 348 note

Kolchis, i. 7, 18, 42, 432, ii. 239;

glances at the history of, i. 62, 343, 344, 345, 349

Kolibaba Mt., Khamur, ii. 333, 348, 350, 372

Komitas, katholikos, i. 263, 264 note 5, 265, 270, 291

note