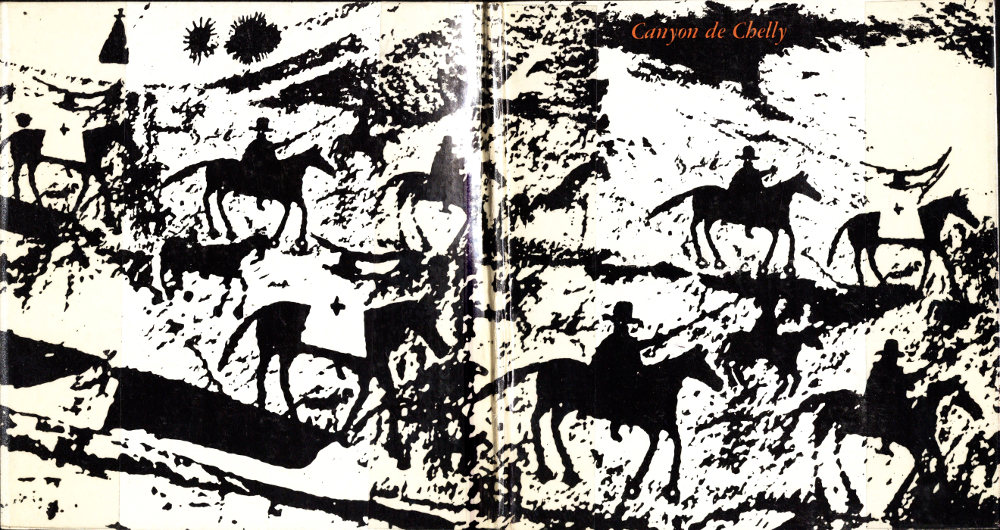

Title: Canyon de Chelly: The Story of Its Ruins and People

Author: Zorro A. Bradley

Release date: November 29, 2016 [eBook #53631]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, MFR and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The Story of its Ruins and People

by Zorro A. Bradley

Office of Publications

National Park Service

U.S. Department of the Interior

Washington, D.C.,

1973

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 73-600078

Far up above me, a thousand feet or so, set in a great cavern in the face of the cliff, I saw a little city of stone asleep. It was as still as sculpture—and something like that. It all hung together, seemed to have a kind of composition: pale little houses of stone nestling close to one another, perched on top of each other, with flat roofs, narrow windows, straight walls, and in the middle of the group, a round tower....

In sunlight it was the colour of winter oak leaves. A fringe of cedars grew along the edge of the cavern, like a garden. They were the only living things. Such silence and stillness and repose—immortal repose. That village sat looking down into the canyon with the calmness of eternity.... I had come upon the city of some extinct civilization, hidden away in this inaccessible mesa for centuries, preserved in the dry air and almost perpetual sunlight like a fly in amber, guarded by the cliffs and the river and the desert.

—Willa Cather

Quotation from The Professor’s House, 1925, by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

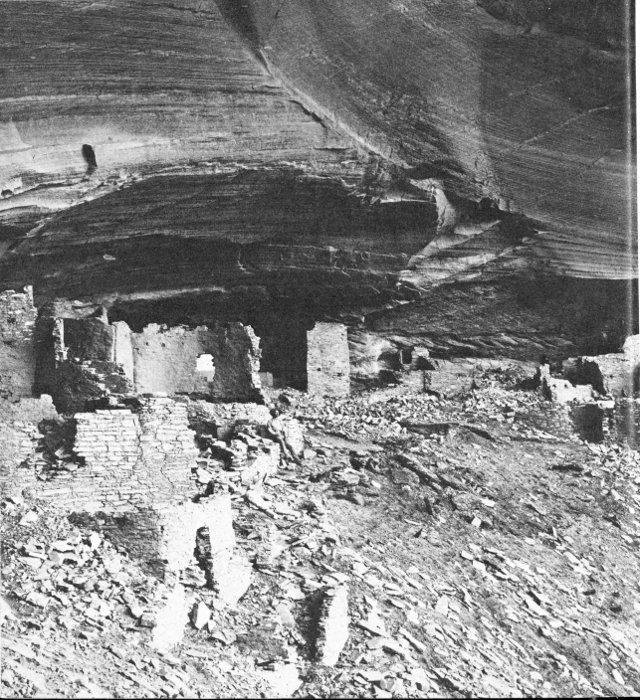

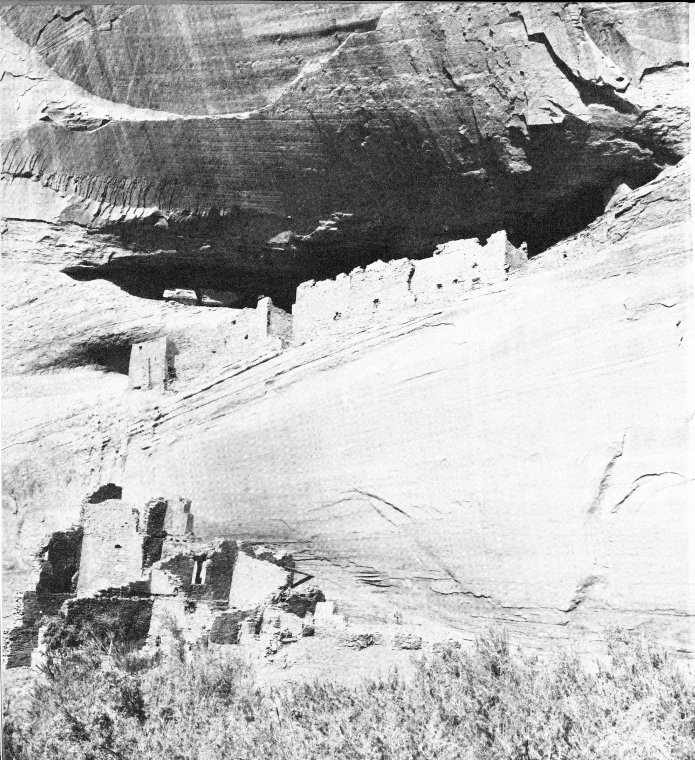

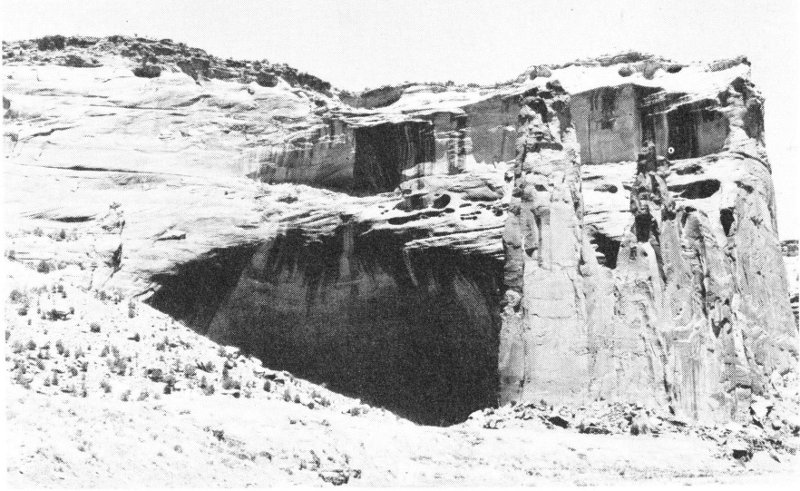

The righthand section of Mummy Cave Ruin as it was photographed by Ben Wittick in 1882 during the James Stevenson Survey for the Smithsonian Institution.

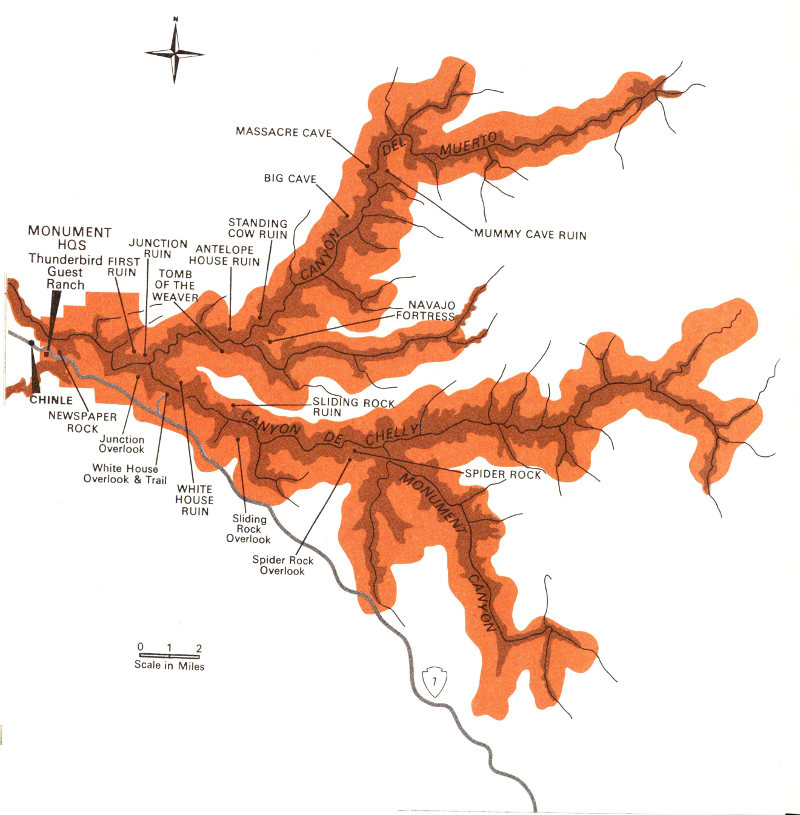

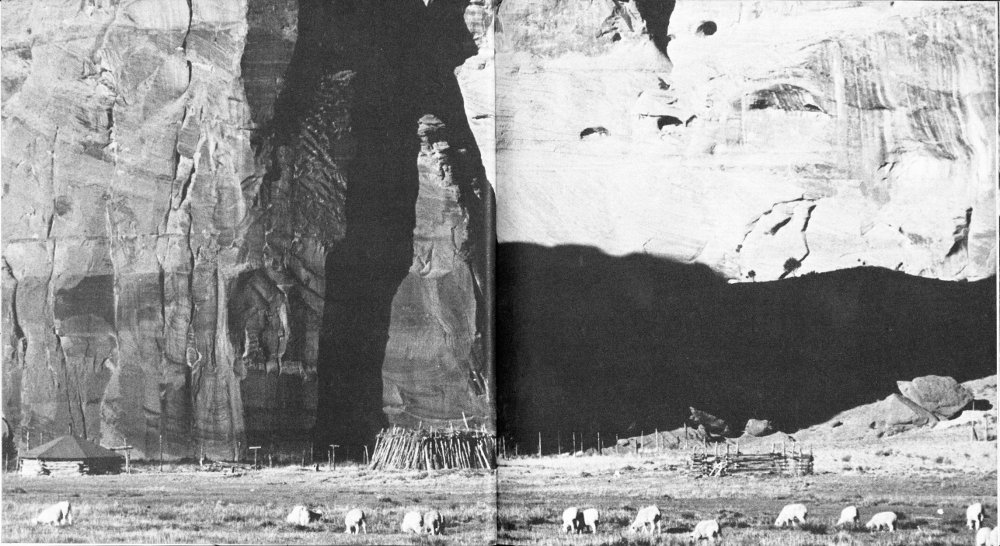

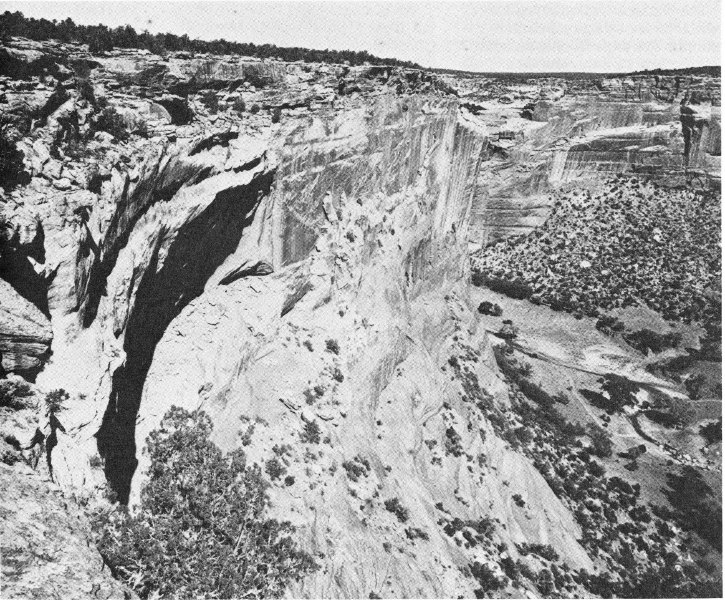

Canyon de Chelly National Monument is located in the red rock country of northeastern Arizona’s high plateau, near the center of the Navajo Indian Reservation. Included in its 131 square miles are three spectacular canyons—Canyon de Chelly, Canyon del Muerto, and Monument Canyon—and many ruins of long-deserted villages. Perched in alcoves and on high ledges along the sheer-walled canyons, these villages are evidence of man’s ability to adjust to a difficult environment, using bare hands, simple stone age tools, and his own ingenuity. They stand as enduring monuments to the culture of the ancestors of the present-day Pueblo Indians of the southwestern United States.

The ancestors of the Navajo Indians who now live in the shadows of these deep canyons came here long after the earlier peoples had left. Originally the Navajos did not live in the canyon, but only passed through it on their yearly migrations. Today some live here permanently, and their hogans are scattered along the sandy canyon floor, almost hidden by the thick growth of willows and cottonwoods and detectable only by a column of smoke slowly rising from a cook fire or by the barking of dogs. Occasionally one may catch a glimpse of a brightly dressed woman working around the hogan or of black-hatted men trotting their horses between the nearby trading post, cornfields, or peach orchards. A reserved and dignified people, they still live in the tradition of their fathers.

The main canyon’s name, de Chelly, stems from the Navajo word “Tsegi” (pronounced tsay-yih or tsay-yhi and meaning “Rock Canyon”), the name by which they know the canyon network. Two centuries of Spanish and English usage have corrupted both the form and pronunciation. Most people now pronounce it “dah-SHAY” or “d’SHAY.”

The first Europeans to see the extensive ruins in Canyon de Chelly are unknown. A Spanish map of 1776 indicates its location, and other documents reveal that Spanish military expeditions sometimes passed through the neighborhood. In 1805, Spanish troops entered the canyon while trying to suppress Navajo raids. During the period of Mexican rule (1821-46), a number of military expeditions against the Navajo invaded the Canyon de Chelly region. Though the ruins had not been described in writing, the area was fairly well known, and by 1846, when the “Army of the West” brought the 4 region under United States control, there were many tall tales and rumors about the wonderful cities built in the cliffs.

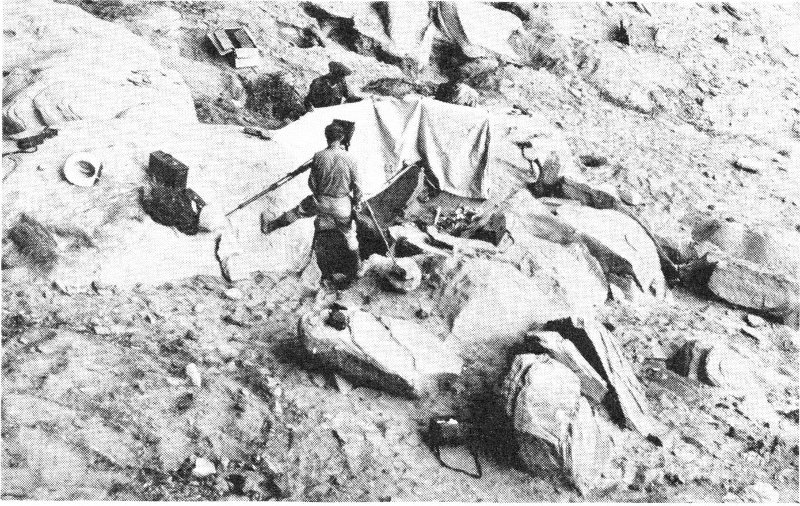

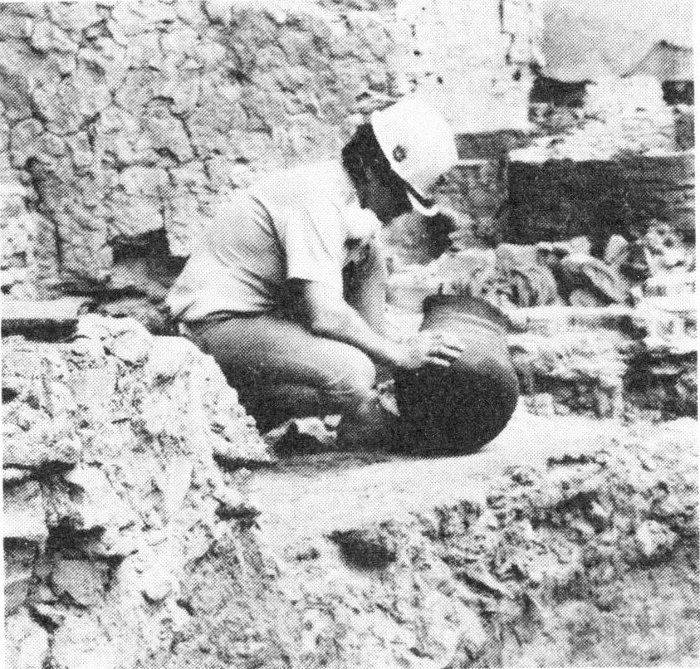

Archeological excavations in Canyon del Muerto, 1929.

In 1849, the New Mexico territorial government found it necessary to request that a U.S. Army expedition be sent to subdue the Navajos. Lt. J. H. Simpson of the Topographical Engineers accompanied the troops. His journal, published in 1850, contained the first detailed account of some of the Canyon de Chelly ruins.

After Simpson’s visit, other military expeditions and a few civilian parties probably entered the canyons. No archeological investigations were made, however, until 1882, when James Stevenson surveyed the area for the Smithsonian Institution, making sketches, photographs, and ground plans of 46 ruins in the two main canyons.

Stevenson found two mummies in a rock shelter ruin in the northern canyon. Because of this find the ruin is known as Mummy Cave, and Stevenson gave the canyon a Spanish name, Canyon de los Muertos, or canyon of the dead men. The name has since been shortened to del Muerto.

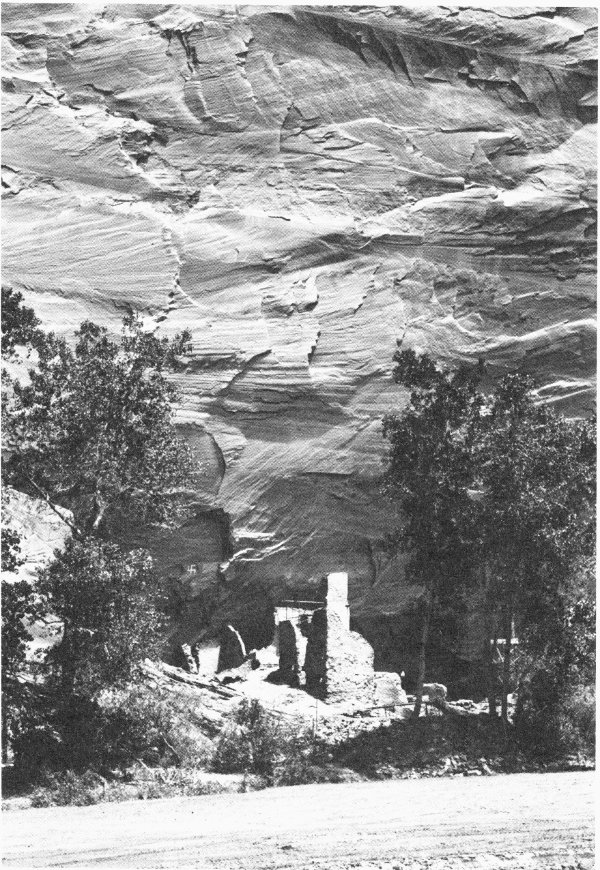

First Ruin in the lower part of Canyon de Chelly. It has 10 rooms and two kivas.

Later in 1882, Cosmos Mindeleff, also from the Smithsonian and a member of Stevenson’s party, mapped the canyons and showed the locations of some of the larger ruins. Mindeleff’s monumental architectural survey of the ruins of Canyon de Chelly was published in 1896, after two more visits.

Much of our knowledge about material objects used by the early Puebloan inhabitants of the canyons comes from the work of the late Earl H. Morris, who excavated a number of the important cave sites in the 1920’s. Since then a comprehensive survey of the monument has been carried out by David L. De Harport for the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, and additional excavations have been conducted by National Park Service archeologists.

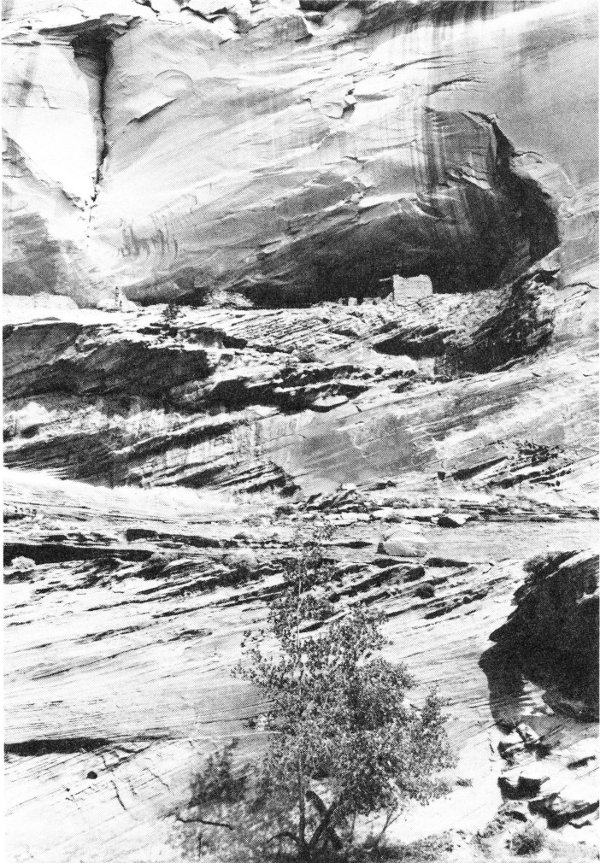

The upper and lower White House ruins were probably connected when the ancient Indians lived there.

Within the national monument are perhaps 800 prehistoric and historic Indian village sites, representing various stages of Pueblo and later Navajo cultural development and spanning a period of about 1,800 years. The most interesting and important ruins are described below.

Located up the main canyon, about 6 miles from Park Service headquarters, White House is one of the largest, best preserved, and most accessible ruins in the monument.

A kiva at the White House ruin, where religious and other ceremonies were held.

Lt. J. H. Simpson described this ruin after his 1849 visit, calling it Casa Blanca (White House). It is also known by its Navajo name, Kini-na-e-kai. Both names derive from a conspicuous white-plastered wall in the upper portion.

White House was constructed in two sections; one stands against the base of the cliff on the canyon floor, and the other is in a small cave immediately above. Mindeleff estimated that at one time the whole ruin contained as many as 80 rooms. Much of the lower building has probably been washed away by the stream nearby (a retaining wall now helps to prevent this), but evidence of about 60 rooms and 4 kivas (special ceremonial chambers) still survives.

Behind the back walls of the lower ruin the smooth cliff face rises 35 feet to the floor of the cave above. Marks on the face indicate that at one time the rooms of the lower building stood several stories high, and its roof came to within 4 feet of the cave floor above.

This map shows only the principal ruins in the canyons that are open to visitors. Only some of these are discussed in the text. The rock formations of these canyons eroded easily, thus producing the steep cliffs and cave formations that provided protection for the Anasazi.

The upper ruin contains 10 rooms and has a large room nearly in the center of the cave. The outside front wall of this room is 12 feet high and still has the coating of white gypsum clay plaster with a decorative band of yellow clay for which the ruin was named.

At the western edge of the lower ruin are the partial remains of two well-built kivas. One kiva used to have holes in the floor like those used to support looms in modern Pueblo kivas. The other kiva shows evidence of six layers of plaster. Modern Zuni Indians have a ceremony every 4 years in which they replaster the smoke-stained kiva interior, and this tradition may give some idea of how long this kiva was in use.

A study of the annual growth rings of its roof timbers indicates that most of the lower ruin was built after A.D. 1070.

Many large ruins are located in the narrow and twisting Canyon del Muerto. One of the biggest is Antelope House, some 5 miles above del Muerto’s junction with Canyon de Chelly. This 40- to 50-room village was built on the stream bank against the base of a cliff which towers nearly 600 feet above it.

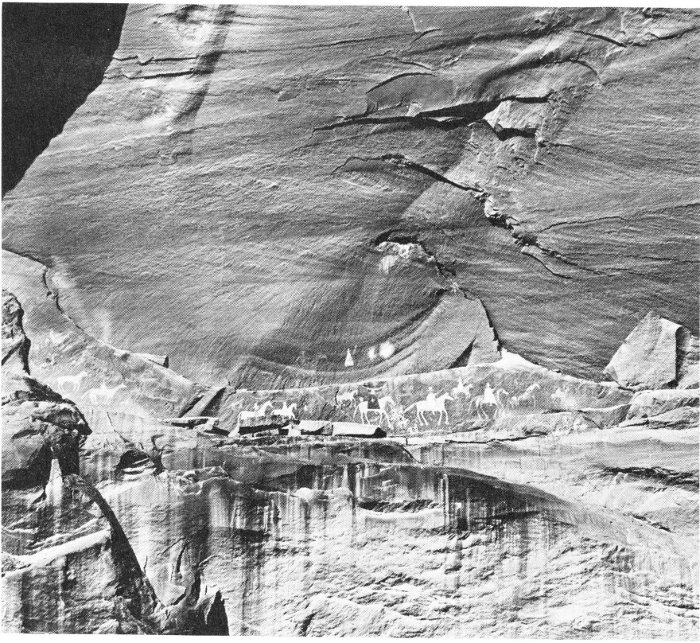

Antelope House received its name from four antelopes painted in tan and white, about half life size, high on the cliff nearby. Navajo families living in the canyon believe that these well-executed paintings were done by Dibe Yazhi (Little Sheep), a Navajo artist who lived here in the 1830’s. Other figures in white paint are probably the work of the prehistoric inhabitants of Antelope House.

Because it stands on the river bank, Antelope House has also eroded badly. Yet many of the house walls still rise two and three stories high, and the masonry outlines of dozens of unexcavated rubble-filled rooms and of two kivas can still be seen.

Antelope House in Canyon del Muerto is on the canyon floor under a towering, overhanging cliff.

An Anasazi pictograph.

The famous “Burial of the Weaver” was found in a small cliff alcove not far from Antelope House. The grave was against the cliff, and a curved masonry wall in front held back the earth. Inside was the tightly flexed body of an old man lying on his left side. His hair was streaked with gray and tied back in a bob; a billet of wood served as a pillow. The body’s outer wrapping was a feather blanket made from the breast down of golden eagles. Under the feather cloth was a white cotton blanket, excellently made and appearing as clean and new as if freshly woven; and under the white blanket was an old gray cotton blanket. Beneath that blanket, lying on the mummy’s breast, was a single ear of corn.

A reed mat covered the floor of the grave, and the amount and variety of objects laid away with the body suggest that the individual was highly respected in life. A long wooden digging stick, broken to fit into the grave, lay across the burial bundle. Beside this, and also broken, was a bow so thick that only a powerful arm could have pulled it. With the bow was a single reed arrow with a fire-hardened wooden point. Five pottery jars, one broken, together with four bowl-shaped baskets woven from yucca leaves, were also in the grave. These containers were filled with cornmeal, shelled corn, four ears of husked corn, pinyon nuts, beans, and salt. Tightly packed around the body and offerings were thick skeins of cotton yarn which measured more than 2 miles in length. A spindle whorl—a wooden disc on a reed stem which probably had been used to spin the cotton—lay on the yarn.

A National Park Service archeologist examines a storage jar found at Antelope House.

This cave in Canyon del Muerto was named for a large white and blue pictograph of a cow, drawn in the historic period and undoubtedly the work of a Navajo. Not much can be seen of this ancient ruin, for Navajos have lived on the site in recent times and still use the old bins for storing corn and the leveled areas for drying peaches.

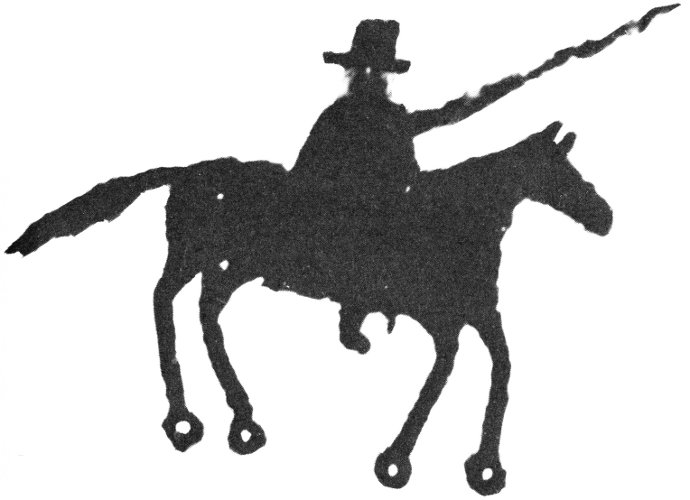

On the cliff near this ruin is an interesting old Navajo painting of Spanish cavalrymen.

This blue-headed cow, painted by an early Navajo artist on the shelter wall, gave Standing Cow Ruin its name.

This Navajo rock painting in Canyon del Muerto shows a procession of soldiers. It probably records a Spanish expedition in the 19th century.

One of the largest concentrations of very early material at Canyon de Chelly came from Big Cave (Tse-Ya-Tso) in Canyon del Muerto. Tree-ring dates ranging from A.D. 331 to 835 indicate an intensive occupation of the site in Basketmaker times.

Several burials of interest were found at Big Cave. One was of an old man who had broken both legs across the shin bones. The fractures were set so well that only the smallest of bumps were left.

The remains of 14 infants were found in a slab-lined cist used earlier as a storage bin. Below the infants were the bodies of four other children packed in an enormous basket. None showed any signs of violence, and it is thought that some disease must have swept through the cave, killing many children in a short time.

The unique “Burial of the Hands” was discovered in another part of Big Cave. This burial consisted of just a pair of arms and hands lying side by side on a bed of grass. The elbows touched the wall of the cave in a way that suggested that the rest of the body had not been removed at a later time. Three necklaces of abalone shell pendants were wrapped around the wrists, and two pairs of exceptionally fine, unworn sandals, patterned in black and red, were lying beside the hands, as was a small basket half full of white shell beads. Another basket nearly 2 feet in diameter covered the burial. No satisfactory explanation of this burial has ever been advanced.

Excavations at Big Cave in Canyon del Muerto yielded valuable artifacts of the Basketmaker period.

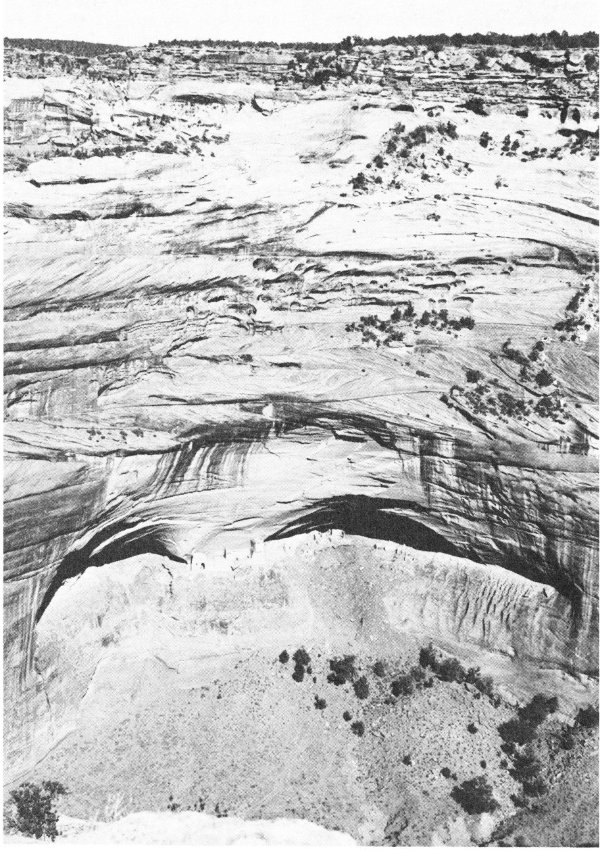

Mummy Cave, bathed in sun with its flanking ruins almost hidden in shadows.

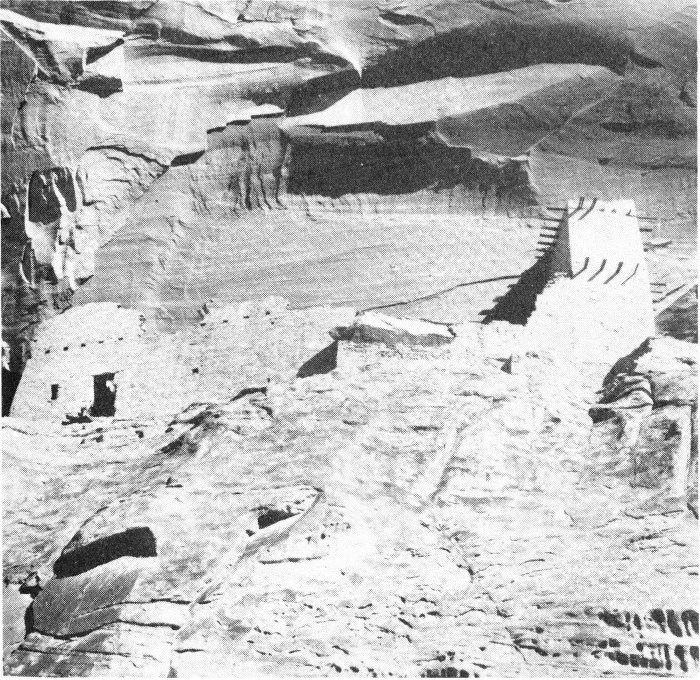

This fretwork design decorates a kiva in Mummy Cave.

The central tower structure at Mummy Cave shows strong Mesa Verde affiliations and was constructed in A.D. 1284.

One of the most beautifully situated ruins in the national monument is Mummy Cave in Canyon del Muerto 21 miles northeast of park headquarters. This dwelling, the largest in the canyons, was built in two adjacent caves about 300 feet up a talus slope from the streambed.

The largest part of the structure, about 55 rooms and 4 kivas, was built in the eastern cave. The western cave, with about 20 rooms, is now accessible only by a ledge from the east cave, although traces of an eroded hand-and-toe trail can be seen leading directly from the top of the talus to the ruin. Along the ledge connecting the two caves are 15 rooms, including a “tower” house; these are the best preserved of all the ruins here. Much original plaster in several colors remains on inner and outer walls throughout the village. Especially notable is the white clay plaster on the interior of the third story of the tower house and the red-painted fret design on white plaster in the large kiva of the east cave.

A Navajo family has settled below the ruins of the ancient ones in Canyon del Muerto.

Though the stunning sheer red cliffs of Canyon de Chelly are easily the national monument’s most spectacular feature, the area was set aside for its importance to the study of prehistoric peoples in the Southwest. The architecture, tools, clothing, ceramics, and other decorative or useful objects found here contain a comprehensive record of many hundreds of years of human activity.

Nothing was known about the ancient culture sheltered here until archeologists began piecing together the information gleaned from Canyon de Chelly’s many ruins and burials. Their story survived because these people lived in a physical environment that posed a minimal threat to normally fragile remains.

Wherever the remains of ancient man occur in the open, building ruins and some objects of stone, bone, and pottery survive, but those of wood and fiber disappear completely. Most of what we know about peoples from the dim past thus comes from materials that have been buried and protected. For the archeologist there are few better sources of information than formal burials, which often contain extensive offerings, and situations like those at Canyon de Chelly and Canyon del Muerto, where sites served as dwelling places for long periods of time and the steady accumulation of refuse buried layers of cultural debris.

The extremely arid conditions in the caves of these canyons offered additional protection. The climate here is so dry that human burials are perfectly preserved as natural mummies or desiccated bodies (there being no attempt at artificial preservation by these people), and such fragile buried objects as baskets more than a thousand years old are in good condition.

The people who lived at Canyon de Chelly in prehistoric times are today called the Anasazi, a Navajo word meaning “old people.” These people were the ancestors of modern Pueblo Indians, and they lived in the vicinity of northern Arizona and New Mexico, southwestern Colorado, and southeastern Utah from about the beginning of the Christian era to the end of the 13th century. Over most of that period they lived in these canyons. Before they learned to build in the cliffs they located and constructed their houses much differently. But the canyons always sheltered them, and their homes, their dead, and their debris tell us how it was with these people from the beginning to the end of their time here.

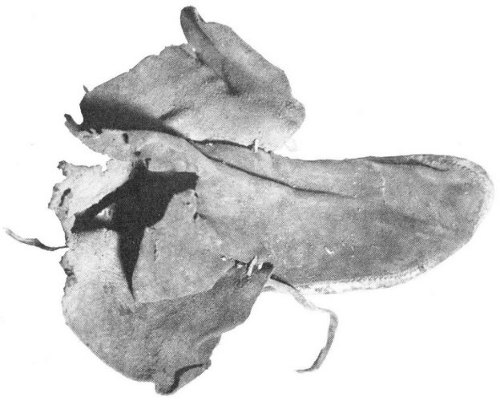

These bone tools were used to work leather and weave baskets.

Early man, a nomadic hunter of big-game animals, came to the Americas from Asia over the Bering Strait some time between 20,000 and 15,000 B.C. Thousands of years later, after the big animals had become extinct, larger bands of hunters and gatherers preyed on game animals of species still living today. Still later, groups began to settle in favorable areas and to grow maize (corn), which reached them from more complex cultures in what is now Mexico. From this time on, the spread and development of prehistoric Indian cultures in the northern Southwest can be traced in increasing detail.

No one knows exactly when the first people arrived in the Canyon de Chelly area. But a tree-ring date of A.D. 306 from the West Alcove at Mummy Cave and the accumulation of sweepings and ashes at this site suggest that people were living in Canyon del Muerto at about the beginning of the Christian era.

These early people were primarily farmers rather than nomadic hunters, although they still depended to some extent on game animals for food. They established their homes in the shelter of the many caves and alcoves in the canyon walls, and farmed the mesa tops and canyon bottoms. Dogs were their only domestic animal, and corn was their major crop and main source of food. Squashes (pumpkins) were grown in some quantity, and beans were introduced at an early time. Pinyon nuts and acorns, sunflower seeds, yucca and cactus fruit, and small seeds of other wild plants were gathered for food.

This burial at Sliding Rock Ruin shows pottery, baskets, corn, and the remains of a blanket used in the day-to-day life of the Anasazi.

Ring-baskets of split yucca leaves have been in common use from about A.D. 1100 to the present.

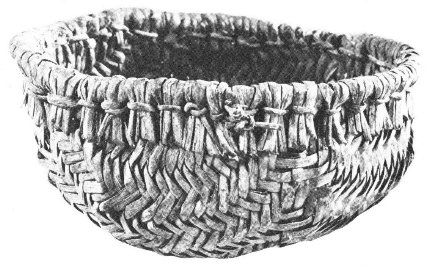

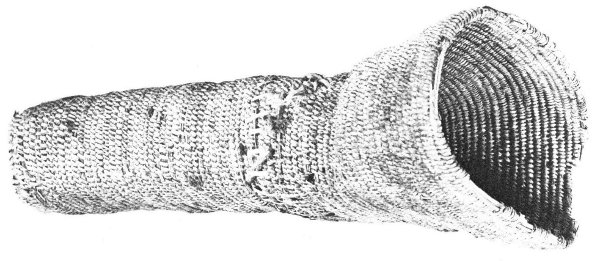

This coiled basket was used for carrying burdens.

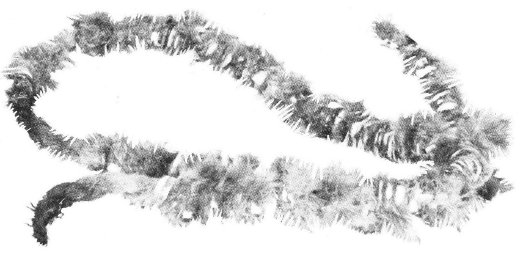

Indian women fastened rabbit fur to lengths of twine by twisting them to form a rope of fur such as this one. A number of these would then be entwined to form a blanket or a robe.

The early farmers were accomplished makers of baskets, and for this reason archeologists commonly call them Basketmakers. Instead of pottery they used baskets for many utilitarian purposes: carrying sacks, burden baskets, food containers, cooking pots, water carriers, storage containers, and even “coffins.” Sometimes plain, often decorated, they are the most impressive surviving artifact of the culture which produced them. More baskets made by these early people have been found in Canyon de Chelly caves than in any other locality.

The caves in Canyon de Chelly have produced no evidence of houses built by these early farmers. If these groups had shelters at all, they were little more than brush-and-pole windbreaks or lean-tos made of poles and skins propped against the sides of the rock shelters. The only architectural remains found so far are pits lined with stone slabs and located in deposits on the cave floors. These pits were used to store corn and wild plant foods.

Permanent dwellings apparently were not constructed until about A.D. 500. The first such houses of which we have knowledge were small and generally insubstantial circular or squarish pits, shallowly dug into the ground. They were walled and roofed with brush and dirt or mud-covered poles. Later the people often built their houses in deep excavations, and then the structures became essentially roofed pits.

The atlatl, or dart-thrower, and dart constituted the early implement for hunting and warfare. There is no definite evidence that the Anasazi used a bow and arrow until the 7th century, but one find in Canyon del Muerto suggests that they were attacked by a group that did use such weapons. The evidence was found in a cave across the canyon from Antelope House at a typical dwelling site of the early people. It appears that a massacre took place inside the cave and the remains of the dead were scattered about the floor until almost completely dried or skeletonized. The bones were then gathered up and dumped into one of the many storage pits that dotted the cave floor, where the archeologists found them. Among the artifacts discovered with the bones was a short, slender piece of wood, more like the shaft of an arrow than a dart, between the ribs and dried skin on the left side of an old woman.

Little clothing was worn in these early years. Men usually wore sandals and a loin cloth and women an apron like skirt. In cold weather the only additional body covering was a blanket woven from strips of fur.

Several exceptions to this mode of dress have been found. One mummy recovered from the slope in front of Mummy Cave (perhaps of a tribal leader) was elaborately dressed and had a great many possessions to take with him to the spirit world. He was wrapped in a woven robe of rabbit fur and 22 had a basket over his face and one under his head. His feet were covered with buckskin moccasins lined with soft juniper bark. Buckskin leggings were wrapped around his legs from ankle to knee. Another piece of buckskin was wound around his waist; one end fell like a breechclout to his thighs, and the other end was thrown over his shoulder like a toga.

The man’s moccasins are a surprising item, because the Anasazi of this time usually wore well-made sandals. These sandals were typically woven of plant fibers with intricate designs in several colors, and are outstanding among the textiles of any prehistoric people.

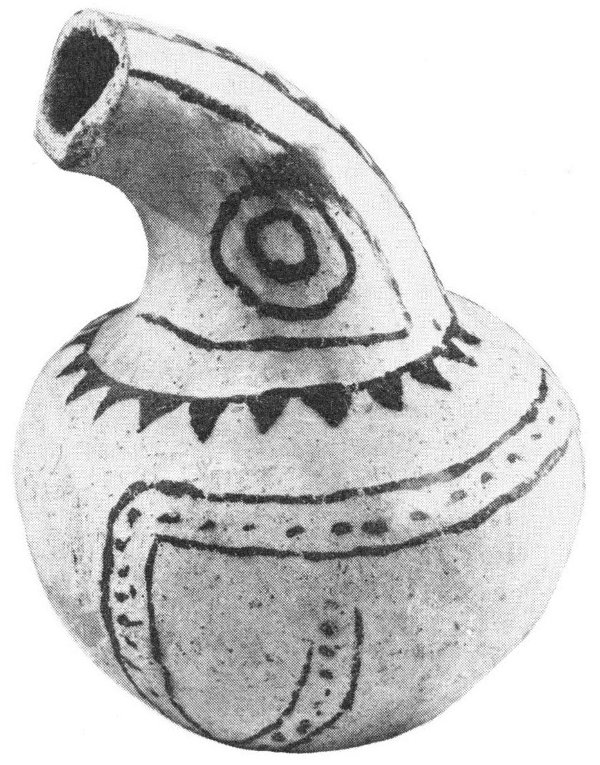

In the 5th century A.D., the Anasazi acquired from the south the technique of making fired pottery, and they adopted the craft rapidly. Ceramics was a significant addition to the equipment which these people needed to live in what was at best a difficult environment. It made the everyday business of cooking food and storing water much easier. During the next several centuries the Anasazi achieved a high degree of skill in the art of ceramics and produced handsome pots in a variety of shapes, decorated both by relief and painting. Various styles of design were developed by different groups.

The Anasazi used black-on-white pottery jars at home and also for trade with other groups.

Basketry, the ancient craft, survived the competition from ceramics but became less important. Sandals, coiled bowls, plaited yucca trays, and rush mattings were still made, but were not as well manufactured or designed as they once had been.

Other changes followed the introduction of pottery, and they profoundly altered the culture of the Anasazi. More substantial and permanent houses were developed, the bow and arrow replaced the dart-thrower and dart for hunting and fighting, and handles were placed on stone axes and hammers, greatly increasing the effectiveness of these tools. Turkeys were domesticated, and their feathers replaced some of the fur in the blankets which they used for clothing. New varieties of corn, squash, and beans became known, and, more importantly, the cultivation of cotton was introduced.

Gourd-shaped black-on-white Anasazi water jar from the period A.D. 500 to 700.

Sometime during these years of change the Anasazi adopted the practice of deforming the skulls of their children by the use of rigid cradleboards. The cradleboards of their direct ancestors were webbed and lined with soft rabbit fur, but a new conception of beauty led them to strap newborn infants onto flat, hard boards which flattened the back of the skull and broadened the forehead.

These characteristics of the Anasazi developed slowly and were well established only around A.D. 750. Sometime after that date they began to live above ground, building their homes of upright poles and mud plaster. Each family’s room adjoined one or more other rooms, making more and more compact village units. In the 900’s, these pole and mud structures gave way to masonry buildings, some of which eventually became two-and three-story terraced apartment houses.

The ancient pithouse was not forgotten. Its counterpart survived in almost all of the new villages in the form of a circular underground room that soon lost all resemblance to a house. Each of the larger villages had two or more of these underground rooms, which undoubtedly were ceremonial structures, serving as meeting places for men of the various clan societies and secret religious brotherhoods and for the performance of rituals. The rooms may have functioned very much like men’s clubhouses. Similar ceremonial rooms of present-day Pueblo Indians are called kivas.

Much of the ceremonial activity in the ancient kivas can be inferred from the religious practices of modern Pueblo Indians. A large part of their ceremonials takes place within the privacy of the kiva and includes praying, chanting, and dancing. Details of costumes, in which feathers are extensively used, and of dance steps are important, for the whole ceremony is a prayer. The rituals are performed as petitions for rain, to insure a good harvest, or for success in hunting.

In testimony to the traditions which endure in some human societies, a cache of bird feathers, undoubtedly saved to make a costume for such a ritual, was found in Big Cave in Canyon del Muerto. A carefully worked cylinder of wood was filled with packets of brightly colored feathers and bird skins. There were dozens of blue-green skins from mallard ducks, and even parrot feathers that must have come from Mexico. Skins of a red bird, still not identified, and bundles of hawk and eagle down were also found in the cylinder.

The Anasazi

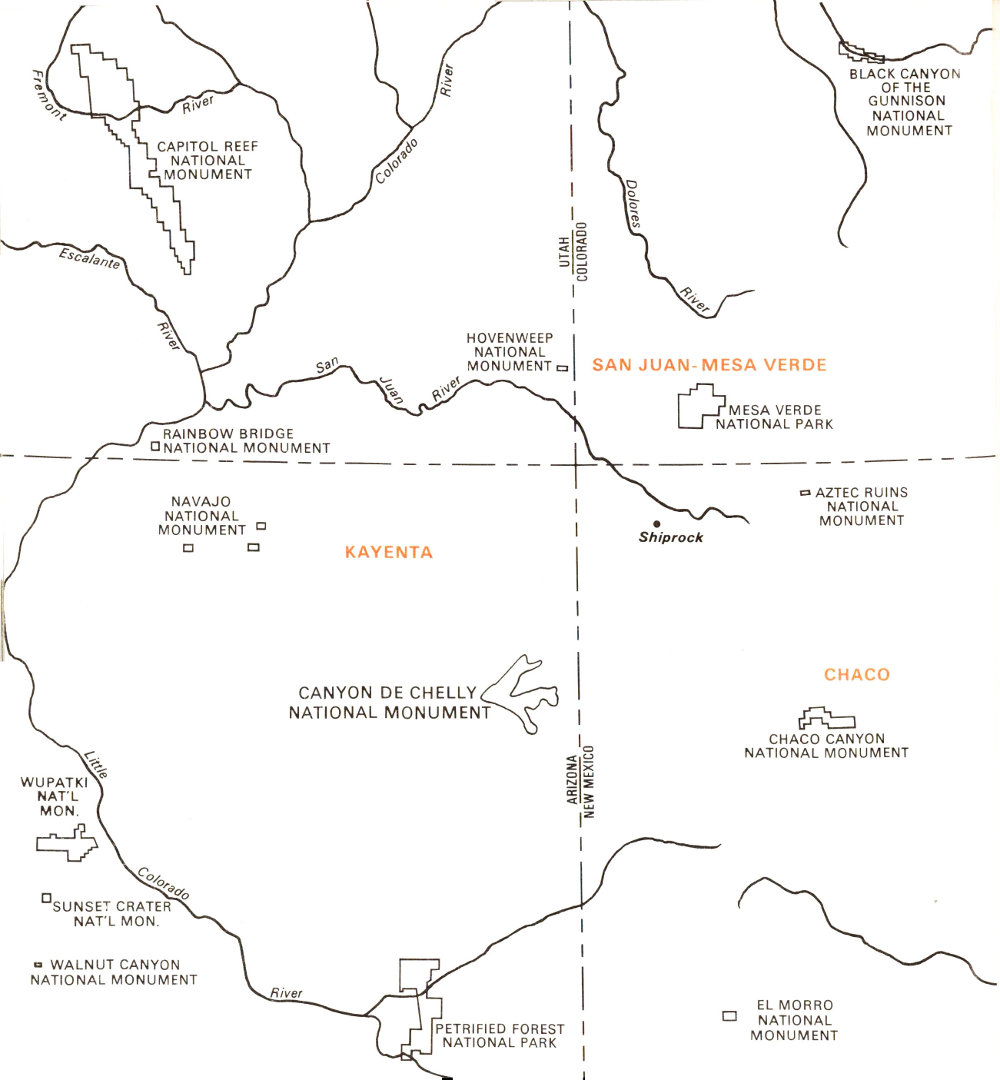

Few regions in North America have such spectacular archeological sites as the Four Corners area of the Southwest. This semiarid high plateau country, drained by the San Juan River, saw the development and later the disappearance of an Indian culture that archeologists call the Anasazi.

During the Great Pueblo period, the Anasazi developed three important regional centers: Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, and the Kayenta country. Their influence extended deep into the territories of neighboring Indian groups, who followed different agricultural traditions. By A.D. 1100, all three had become heavily populated, and the Anasazi were building their largest towns and fabled cliff dwellings.

The fertile Chaco valley attracted aboriginals early in the 10th century. They first built on such sites as Pueblo Bonito, which expanded to a village of over 800 rooms. Their pueblos on the valley floor near the cliffs tended to be D-shaped, with central courts closed by walls often as high as four stories.

A hundred miles to the north, on the steep-cliffed fingers of rock of southwest Colorado, the Mesa Verdians built pithouses, pueblos, and about 300 cliff dwellings, the largest of which is Cliff Palace.

The decline of the Anasazi culture from its Great Pueblo period coincided with a concentration of population at Chaco, Mesa Verde, and Kayenta that made the people particularly dependent on a year-round flow of water. Long years of drought from 1270 to 1300 dried up the rivers and caused an exodus from the San Juan River region.

First the Chaco residents dispersed southwestward to join their cousins in the Little Colorado River area. Then the Mesa Verdians moved to the northern Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico. Finally, the Kayenta people, the last holdouts, gave up and joined the population in what is now the Hopi country.

Between A.D. 1000 and 1050 the culture of the Anasazi reached its height and became stable for a few centuries, until about A.D. 1275-1300. Their homes were now substantial buildings of stone masonry, containing numerous adjoining rooms. Their kivas followed standard lines and were often incorporated in the house structures, though they were sometimes built as separate, semisubterranean chambers. No other abrupt changes or new forms distinguish this late period, which was essentially a continuation and fulfillment of earlier times. The large pueblos, most of which were begun about A.D. 1000, are the most outstanding development of this period.

In Canyon de Chelly, construction was started on White House and Antelope House during these years. Other important population centers were developing simultaneously at Mesa Verde (Mesa Verde National Park, Colo.), where the largest concentration of surviving cliff dwellings is located, and at Chaco Canyon (Chaco Canyon National Monument, N. Mex.), where spacious apartment houses, one with more than 26 800 rooms, were constructed on the floor of the canyon. Other villages were built in the Kayenta-Marsh Pass area (near Navajo National Monument, Ariz.).

As permanent homes gave them social stability and well-developed agriculture ensured adequate food, the Anasazi had leisure and sufficient security for greater activity in their arts, crafts, and ceremonials. As a consequence, trade with other peoples seems to have grown and flourished because it brought in the specialized and exotic materials needed for rituals and pleasure. Parrots were traded from Mexico for their plumage, and ornamental shells from the Gulf of California and the West Coast found their way to Anasazi settlements. Turquoise, jet, and salt also became important trade items.

The mode of dress changed little. Feather-string blankets were still commonly worn in winter. Cotton became almost the only fiber used for making cloth. Sandals, which were woven from whole yucca leaves, were crude, compared to those of earlier periods. But painted pottery reached its highest development in both variety and quality.

These great pueblo centers flourished for about two centuries. But this was a time of increasing dryness in the Southwest, and the end for these settlements came during a severe drought late in the 13th century. Tree-ring data indicate that there was not enough moisture to produce crops during most of the years between 1276 and 1299. The drought brought crop failures, and the ensuing erosion destroyed the fields. Hunger, decline, and migration followed. Family after family and group after group left their homes in the cliffs and canyons. Taking what few possessions they could carry on their backs, they drifted away in search of land with a dependable water supply suitable for farming.

The villages in Canyon de Chelly apparently lasted longer than most and may even have provided a temporary haven for refugees from other regions to the north. The four-story tower house at Mummy Cave might have been built for such refugees by skilled masons from the Mesa Verde area.

By 1300, however, all the great cliff dwellings were abandoned, and the people of the Canyon de Chelly area had moved on to new lands. Most of them probably joined the tribes that were gathering around Black Mesa to the west, near the location of the modern Hopi pueblos. Others may have turned south, settling finally near the middle of the present boundary between Arizona and New Mexico. Other Anasazi made their way to the upper Rio Grande Valley in north-central New Mexico. In these localities the Pueblo farmers renewed their way of life, and it was there that Spanish explorers found them on their first trip through the region in 1540-42.

At White House and a few other ruins there is evidence of structural 27 additions made long after the villages were abandoned. These and other indications of occupation well after 1300 probably represent the work of Hopi Indians who used the canyons seasonally for agriculture, taking the harvest back to their villages about 70 miles to the west. Peach trees, which the Spanish introduced to the Hopi in the 17th century, were evidently brought to Canyon de Chelly in either that century or the next, and the small orchards still scattered through the canyons were started. The use of the canyons by the Hopi probably dropped off rapidly after the Navajos appeared in the area in the 18th century.

This pictograph of a soldier on horseback is taken from the Navajo rock painting in Canyon del Muerto near Standing Cow Ruin.

The present Indian occupants of Canyon de Chelly are Navajos. They are not related to the Anasazi who built the masonry villages now in ruins.

No one is certain just when the Navajos came to this region nor do we know exactly where they came from. The best available evidence now suggests that these people and their close relatives, the Apaches, both of whom speak an Athapascan language, came south along the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains as a single group. They may have reached the Southwest between the 13th and the 16th centuries. The earliest mention of people who were probably Navajos is in the Oñate documents of 1598. This account places them in north-central New Mexico, an area they still call their homeland but no longer occupy.

The name “Navajo” has never been adequately translated. The first interpretation of the word came from Father Alonso de Benavides, a Spanish priest who started missionary work among the Navajos. In his “Memorial of New Mexico,” which was presented to the court of Spain in 1630, he stated:

But these Apache de Nabahu [Navajo] are very great farmers for this is what Navajo signifies ... great planted fields....

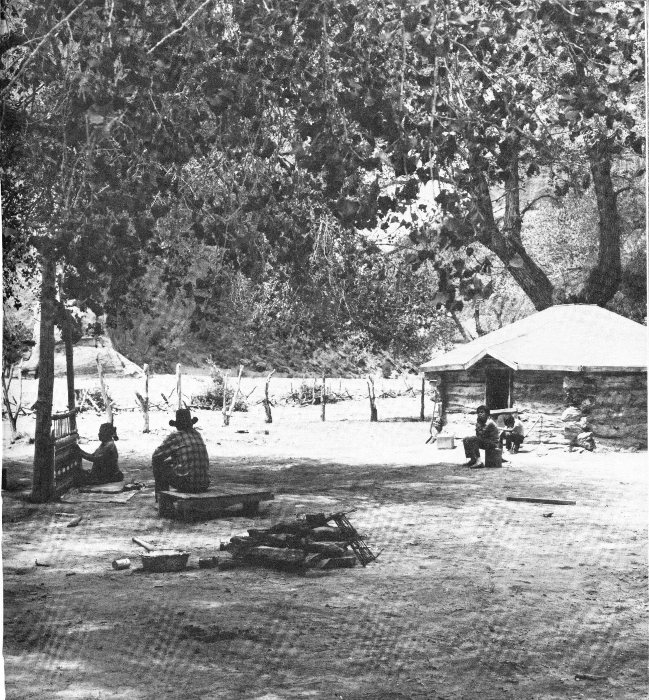

The pastoral scene shows two contemporary Navajo structures. To the left is a modern hogan, and to the right, a ramada.

By 1750, the Navajos had abandoned their homes west of the Chama River Valley because of pressure from the Utes to the north. Generally they moved westward, but a few split off to the south. We do not know when they first entered Canyon de Chelly, but there is evidence at the site of Tse-ta’a to suggest that it was after 1700.

Hunters, gatherers, and farmers, the Navajos changed their way of life sharply when they acquired horses and sheep from the Spanish after the Pueblo Rebellion of 1680. Horses made the Navajos highly mobile and increased their ability to raid the alluring towns along the Rio Grande and then vanish into mountain and canyon hideouts. Sheep gradually changed the basis of their economy, converting them from hunters and raiders to the pastoral herders they are today.

After the Spanish reconquered New Mexico in 1692, many Pueblo families from the Rio Grande sought sanctuary with the Navajos. Some of these refugees were absorbed into the tribe, and they brought with them not only weaving, but sheep raising, pottery and basketry techniques, architectural and agricultural ideas, the clan system, and much religious lore.

Navajo-Spanish relations were generally quiet after the Spanish returned because the tribe was preoccupied with fighting the Utes to the north and was interested in enlisting Spanish support or, at least, forbearance. This comparatively peaceful interlude came to an end in the 1770’s because of land disputes, and friction continued from that time until the 1860’s.

In 1805, during this period of strife, a Spanish punitive expedition entered Canyon de Chelly, bent on taking slaves, or servants as the whites called them.

According to the Navajo account of the episode, all the Navajo men had gone out on an expedition, leaving the old men, and women, and children hidden in a deep ledge high up the canyon wall. Their position was strengthened by a wall of loose stones placed along the rim of the ledge. As the Spanish troops, commanded by Lt. Antonio Narbona, passed below, an old woman who had been a Spanish slave could not resist scoffing at them and thus exposed the hiding place.

In a letter on January 25, 1805, to the Governor of New Mexico, Narbona described the action which followed:

On the 17th of the current month I managed to attack in Cañon de Chelli a great number of enemy Indians and though they entrenched themselves in an almost inaccessible spot, and fortified beforehand, we succeeded after having battled all day long with the greatest ardor and effort, in taking [it] the morning after and that our arms had the result of ninety dead warriors, twenty-five women and children, and as prisoners three warriors, eight women and twenty-two boys and girls....

Narbona reported his losses as 1 dead and 64 wounded. Massacre Cave in Canyon del Muerto was named for this event.

Massacre Cave sits high up on the west wall of Canyon del Muerto, a short way upstream from Mummy Cave.

The Navajos had been held in partial check by Spanish bribes and punitive expeditions, but after Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, the Navajos returned to raiding in behalf of all those enslaved by the Spanish. In 1823, 1833, 1836, and 1838 the Mexicans mounted large expeditions against the Navajos, sometimes sending as many as 1,500 men after them. It was during this period that Canyon de Chelly was most often referred to as the stronghold of the Navajos. Although Mexican reprisals often forced the Indians to take temporary refuge north of the San Juan River, they were too sporadic to effectively quell the raiders, who always came back with new attacks. Conditions were so bad that the Navajos boasted they let the Mexicans live on only because they made good shepherds for the tribe. The taunt hardly exaggerated their power at the time.

Navajo depredations had very nearly decimated the frontier settlements in the central Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico when the United States went to war with Mexico in 1846. Col. Stephen Watts Kearny had the task of seizing the northern Mexican provinces, an area that is now part of the American Southwest. In late June 1846 he left Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Marching over the Santa Fe Trail without opposition, Kearny and his American Dragoons arrived in Santa Fe on August 18, 1846, and proclaimed New Mexico a part of the United States.

When Kearny and the Army of the West marched off to Mexico, Col. Alexander W. Doniphan was left behind with orders to invade the Navajo country, release captives, reclaim stolen property, and either to awe or beat the Indians into submission. In August 1846 he led the first United States expedition against the Navajos. Maj. William Gilpin, with 200 men, entered the Navajo country on the north and swung south to meet Doniphan and several Navajo chiefs at Bear Springs near the town of Grants, New Mexico, later the site of Fort Wingate. The treaty signed there turned out to be little more than a scrap of paper. Five more unsuccessful military expeditions were sent against the Navajos between 1846 and 1849 in vain attempts to end the Indian raids.

In trying to contain the Navajos, the U.S. Government made the same mistake that the Mexican and Spanish Governments did before them. They all assumed that a single chief led the several Navajo bands. Actually, each local Navajo group had its own leader, and time and again treaties of “lasting peace with the Navajos” were signed by these local chiefs, who spoke only for their own small bands and had no influence with others.

The U.S. Army expedition of 1849 clearly illustrated this problem. Lt. Col. John W. Washington, military commander of New Mexico, led an expedition to Canyon de Chelly, then considered 33 to be the Navajo heartland. Washington met local Navajo chiefs on the crest of a small hill between the present Thunderbird Guest Ranch and the mouth of the canyon. Here on Treaty Hill a treaty of “lasting peace” was signed with the Indians. Washington had no sooner returned to Albuquerque, however, than he learned that another Navajo band had raided a small village near Santa Fe.

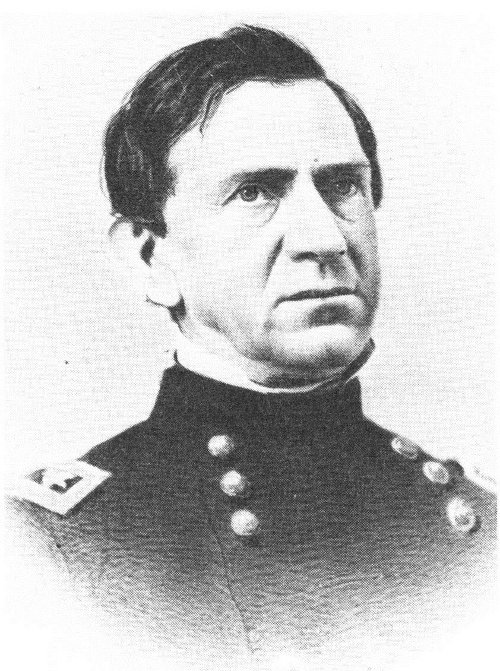

Col. E. R. S. Canby led the last campaign against the Navajos before the Civil War.

Regardless of treaties and punitive expeditions, Navajo depredations continued. Late in 1851, Col. E. V. Sumner marched into the Navajo country in still another effort to settle the problem. After a single encounter with the Navajo in Canyon de Chelly, Sumner returned to a spot southwest of the Chuska Mountains where he established Fort Defiance in the autumn of 1851. Fighting broke out again in 1858, when a Negro slave of the post commander at Fort Defiance was killed by a Navajo arrow. The Army retaliated with an attack on a party of peaceful Navajos, and the Indians retreated northward.

Up to this time, U.S. Army commanders had controlled Indian policies; the authority of the civil agents appointed by the Indian Department was negligible. But now the civilian agents brought political pressure to bear upon the unsuccessful Army. To soothe the politicians, the Army drew up still another treaty with the Navajos on December 25, 1858. This treaty was the second attempt to outline the boundaries of a proposed Navajo reservation. Like an earlier proposal, the Meriweather Treaty of 1855, it was never ratified.

The year 1859 was relatively peaceful, with few raids on either side. But the next year opened with a series of Navajo raids that culminated in a concentrated attack on Fort Defiance. Some of the old Navajos who participated later recalled that it was a carefully planned assault at dawn, with as many as 2,000 warriors taking part. After attacking for two hours, 34 the Indians were forced to withdraw.

In the winter of 1860-61, Col. E. R. S. Canby led the last military expedition against the Navajos before the Civil War, but his efforts failed to bring peace. Zarcillos Largos, a great Navajo leader who had worked for more peaceful relations with whites, was killed in an ambush during the campaign. The Indians soon resorted to their old tactic of dispersing, and the campaign ended with another treaty. When troops were withdrawn from Fort Defiance in March 1861 for Civil War duty, the last restraint was removed from both sides, and raiding began once more. For the Spanish-Americans, it was the high point of their warfare against the Navajos.

The job of subjugating the recalcitrant Navajos now fell to Brig. Gen. James H. Carleton, commander of the Department of New Mexico and a seasoned Indian fighter with 25 years of active service. His earlier experience in Indian affairs had convinced Carleton that establishing reservations where the Indians could be educated would be the only way to get them to settle down. Carleton said:

Soon they will acquire new habits, new ideas, new modes of life; the old Indians will die off, and carry with them the latent longings for murdering and robbing; the young ones will take their place without these longings; and thus, little by little, they will become a contented people....

Brig. Gen. James H. Carleton defeated the Navajos and built Fort Sumner at Bosque Redondo, the Navajo’s place of exile.

In 1863, Carleton drew up plans for a 40-square-mile reservation at Fort Sumner on the Pecos River in central New Mexico. He called the new reservation Bosque Redondo, which is Spanish for circular thicket.

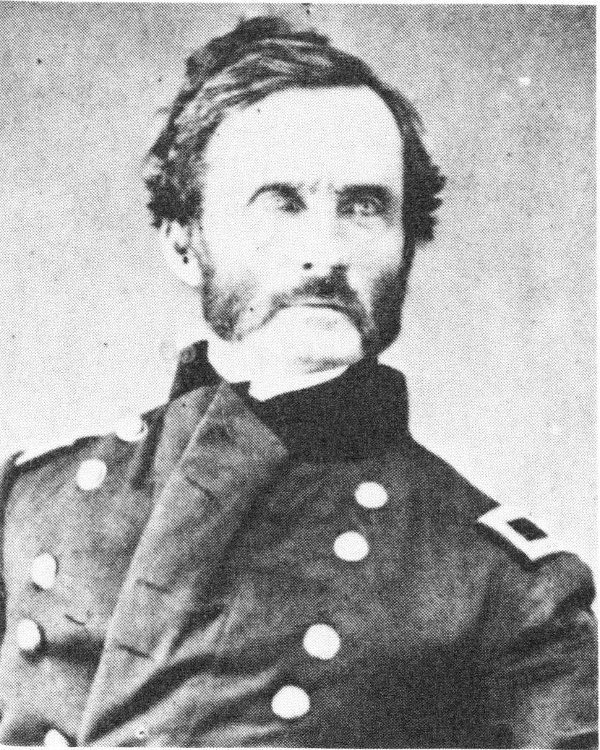

The valiant Manuelito fought against the whites, but without permanent success. In 1863 he was one of a number of prominent Navajo leaders.

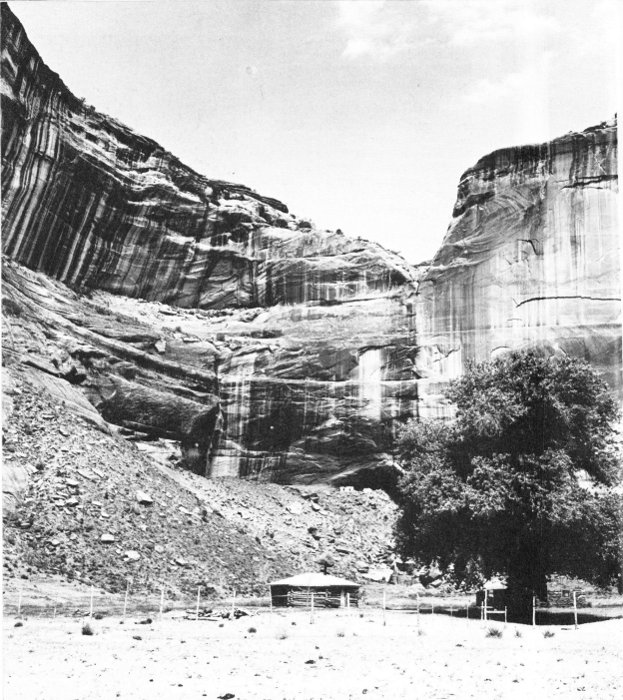

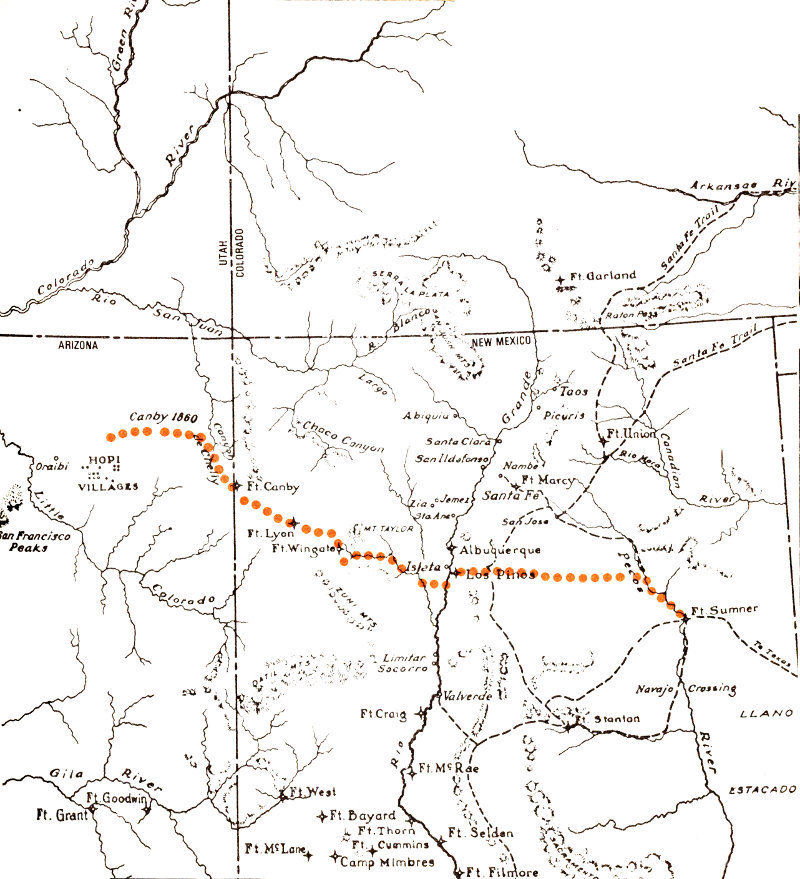

Capt. Albert Pfeiffer led his men down Canyon del Muerto between these cliffs, destroying hogans and crops.

When the reservation was ready, Carleton ordered Col. Christopher (Kit) Carson to take the field against the Navajos in June 1863. Carson’s force consisted of four companies of New Mexican Volunteers, two mounted and two unmounted, and 200 Ute Indians, who were guides and scouts, altogether a force of about 1,000 men. Their first operation was to reoccupy and repair the abandoned Fort Defiance, which they renamed Fort Canby in honor of General Canby.

The Navajos were led by Barboncito of Canyon de Chelly, a spokesman for the bands living west of the Chuska Mountains, and Manuelito, a leader of those who dwelt east of the mountains. Many subchiefs, as usual, led individual bands.

Carson had orders from General Carleton to destroy all cornfields and livestock. He sent word to the Navajos that they should surrender at Fort Canby, and then moved into the field to persuade them. The first skirmish took place in August near the fort. Under constant pressure from the military through the winter of 1863, their herds being killed and crops burned, the Navajos were soon destitute and began to surrender in small numbers.

The crowning blow to Navajo pride, however, was the Army’s ostentatious penetration of Canyon de Chelly, their most secure refuge. A detachment of men under Capt. Albert Pfeiffer carried the “Navaho Fortress” in January 1864. Entering through Canyon del Muerto, Pfeiffer guarded the junction while Capt. A. B. Carey led a detail through the main gorge of de Chelly, marching west to east. Captain Pfeiffer described his progress through del Muerto:

My travel through the cañon, for the first 12 miles, was accomplished on the ice of the bed of the stream which courses through it.... Lt. C. M. Hubbell, who was in charge of the rear, had a great deal of trouble in proceeding with the pack trains, as the mules frequently broke through the ice and tumbled down with their loads. All the Indian prisoners taken thus 38 far were half starved and naked. The cañon has no road except the bottom of the creek. We traveled mostly on the ice, our animals breaking through every few minutes, and one mule split completely open under the exhausting fatigue of the march. On the 12th instant traveled 8 miles; had several skirmishes with the enemy. Indians on both sides of the cañon whooping, yelling and cursing, firing shots and throwing rocks down upon my command. Killed two buck Indians in the encounter and one squaw, who obstinately persisted in hurling rocks and pieces of wood at the soldiers. Six prisoners were captured on this occasion. Lieutenant Hubbell followed up some Indians in a tributary cañon, but could not overtake them on account of the steepness of the hillsides, where nothing save an Indian or mountain goat could make their way....

This raid, which netted only about 100 prisoners, convinced the Navajos that even though Carson was not out to destroy them, he would go anywhere to ferret them out. They had no choice but to surrender at Fort Canby. Shortly after the Canyon de Chelly raid some 500 Navajos, with their flocks, straggled into the fort. By February 15, 1864, 1,500 Navajos were being fed and clothed there, and by the first of March about 2,400.

The much storied “Long Walk” and exile of the Navajos began on March 6, 1864, when these 2,400 people with 30 wagons, 400 horses, and 3,000 sheep and goats left Fort Canby for Bosque Redondo, 300 miles away in New Mexico Territory. Only the aged, the children, and the crippled rode in wagons—all others walked the entire distance. One old Navajo recalled the exodus in later years, saying:

It was a great sight, we stretched from Fort Defiance to the Window Rock ‘haystacks’ ... a distance of about 7 miles.

On March 14-15, a second group of about 3,000 Navajos began the foot journey. The last large escort of Navajos to Fort Sumner was on April 24, when 1,200 persons started their “Long Walk.”

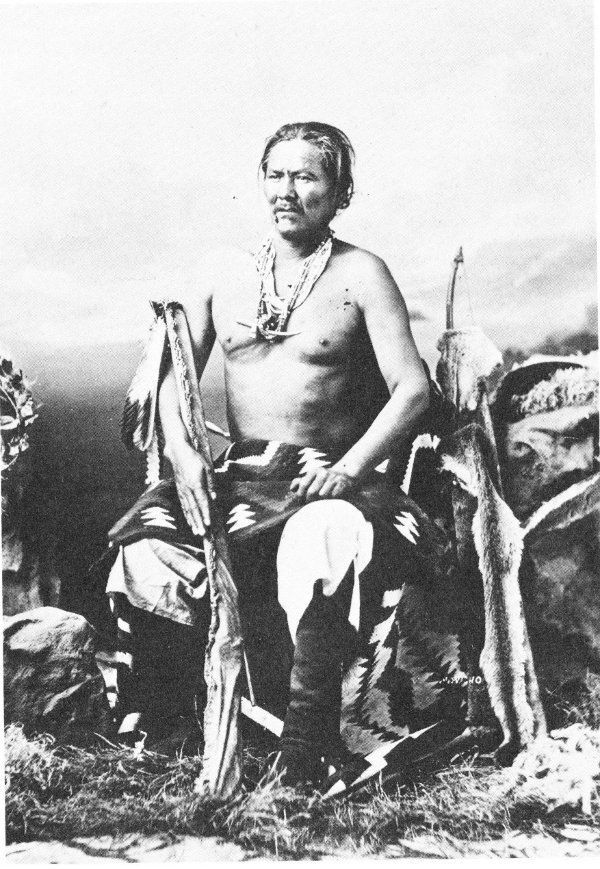

This old army map shows the military posts of the 1860’s. The red line traces the “Long Walk” of the defeated Navajos to Fort Sumner at Bosque Redondo.

Scenes of the Navajos in their place of exile at Fort Sumner on the Pecos River. The top view shows them lined up to receive their issue of food and clothing. National ArchivesMuseum of New MexicoNational Archives

Not all the Navajos surrendered. Many tribesmen remained free and continued to raid settlements. On April 9, 1864, the very day that the Governor of New Mexico had set aside to celebrate the end of the Navajo war, a band of Navajos stole 40 head of cattle from Laguna Pueblo, 140 miles southwest of Canyon de Chelly. Those who surrendered endured extreme hardship at Fort Sumner from disease, crop failure, famine, and their sense of exile from their homeland. After 4 years, the several thousand reservation Navajos were broken in body and spirit, while their still-free tribesmen continued their troublesome guerrilla activities. Carleton’s experiment was judged a complete failure.

The Government then decided that the Navajos should return to a part of their old homeland. A new treaty signed on June 1, 1868, stated that the tribe and the United States were at peace, and in it the Navajos pledged to stop their raiding. In return, the Government promised the tribe school facilities and a reservation that included Canyon de Chelly in its total area of 3,500,000 acres. The Navajos were to stay within this reservation.

Twenty-nine Navajo chiefs and council members signed the treaty, and the Navajos began leaving Fort Sumner almost immediately, slipping away family by family. Those without horses or who had old or sick persons in their family awaited Government transportation. On June 15, a wagon train with a military escort carried the last Navajos from Fort Sumner to Fort Wingate. There the tribe waited while final arrangements were worked out.

By November the new reservation boundaries had been surveyed and shown to the tribe’s head men, and a headquarters for the Indian agent had been prepared at Fort Defiance. At long last the Navajos were allowed to go home. They were now united into a single tribe with leaders, appointed by the Indian agents, to represent them in their dealings with the whites. But their troubles were not over.

Only a fraction of the Navajos’ sheep had survived Carson’s slaughter and the years of famine at Fort Sumner. The treaty had promised sheep and goats to replenish the herds, but more than a year passed before any were received. Meantime, hunger pursued the Navajos, and they had to exist 42 on army issue rations of beef, coffee, and flour.

The treaty also promised that during the first 10 years—called the Treaty Years—each family head who took up farming would receive $25 worth of agricultural tools and supplies every 2 years to help him in his new pursuit. It was 14 years before this promise was fulfilled, and the tribe was badly hampered in their efforts to fill out their slender larder through agriculture.

During these years the Navajos eked out a living through their traditional crafts of weaving and silver working. Blankets and wool were beginning to find a market in the expanding settlements of the Rio Grande Valley, at army posts, and in the Mormon settlements of Utah. In 1869, the first trading post was established on the reservation, and it provided the tribe with a source of supplies and an outlet for their wares. As Navajo blankets, wool, and silverwork became more important, other traders entered the Navajo country.

Still there was little substantial change in either the Navajo’s mode of life or their economy by the end of the Treaty Years in 1878. True, the tribe and their flocks had increased in numbers especially after 1872, when the U.S. Government distributed 10,000 sheep among them. The coming of the railroad in 1881-82, however, accelerated change and growth in the Navajos more than any other event. New techniques for making a living, learned from working with construction crews, and new possessions brought by the railroad, started the people toward the modern world.

One vexing problem that has confronted the Navajos since their days at Fort Sumner is the lack of adequate grazing land to support an expanding population. The reservation boundaries have been enlarged many times over the years, but now there is no space for further expansion. Today the tribe numbers over 120,000 members, and tribal lands cannot support that large a population nor the uncontrolled grazing that it causes.

The old way of life is gradually being replaced. In 1924, Congress granted citizenship rights to all Indians in recognition of their service during World War I when their men enlisted by the hundreds, even though exempt from the draft. After 1923 Navajo tribal business became less of a haphazard affair. A tribal council, 43 made up of elected delegates, began to handle contacts with the world beyond the reservation. Little or no work was done to remedy undesirable conditions on the reservation until the public works program of the 1930’s, when a good many schools and hospitals were built. During World War II, hundreds of young Navajo men enlisted in the armed forces and other thousands went into war work. These involvements in American society demonstrated that an education was essential if Indians were to compete successfully in the outer world, and so the tribal council passed a compulsory schooling law in 1947. Many schools and hospitals were built in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

A Navajo weaver, 1873. Their looms have changed little in the years since then.

Little by little the Navajos became acquainted with the world outside the reservation and learned its ways and advantages. Today their prospects for a better life are brighter. Oil, gas, coal, timber, and uranium deposits on their lands are being developed for the benefit of all the Navajos. Children are more eager to attend school, and many Navajos are now leaving the reservation to put their education to work at jobs in the larger community. The Navajo people are beginning to find a place within the Nation.

Despite these changes and prospects, many Navajo families are still seminomadic camp dwellers, following old traditions. Each family’s grazing land covers about 10 to 15 square miles. Within this area they have two or more hogans and corrals, built near suitable grass, water, and wood.

In winter the family moves to the foothills or mesa tops to be near a plentiful wood supply, for winters in the Navajo country are severe. The winter hogans, or houses, are constructed with considerable care by the men. Brush shelters are used for cooking and camping in summer.

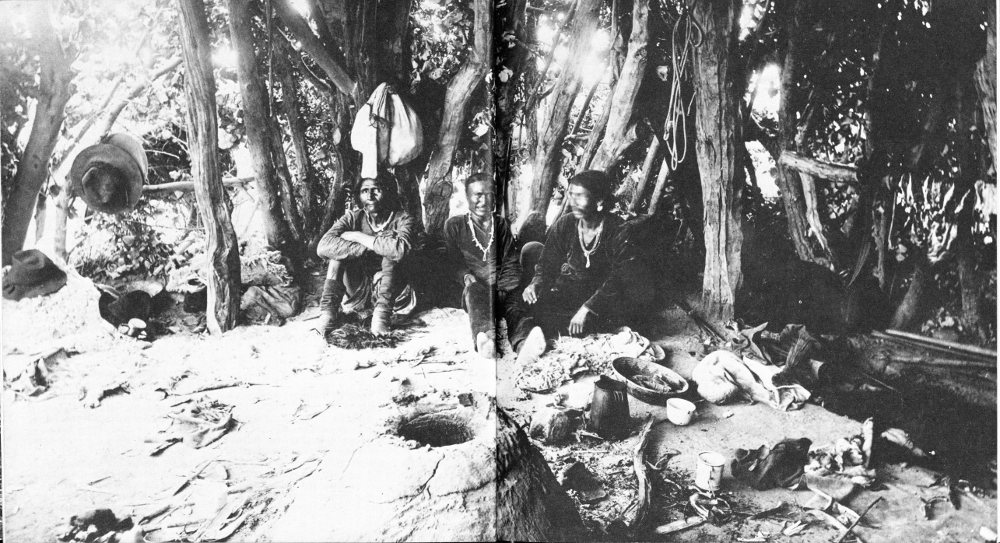

Navajo headmen inside a summer brush shelter, 1898.

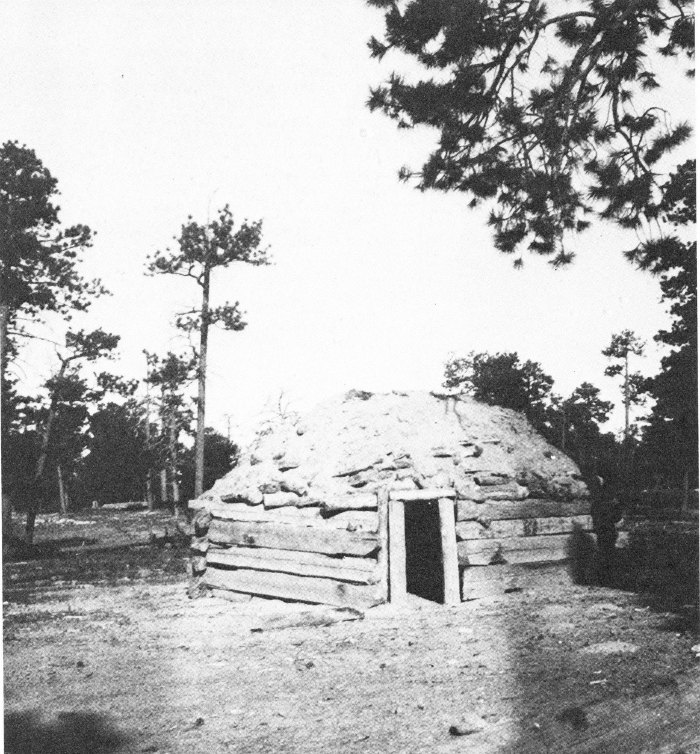

A Navajo cribbed (log-cabin) style hogan in the high pine forest in 1908.

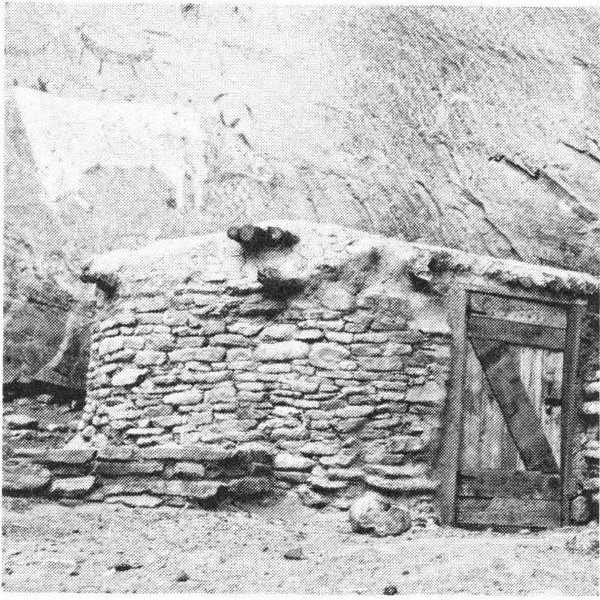

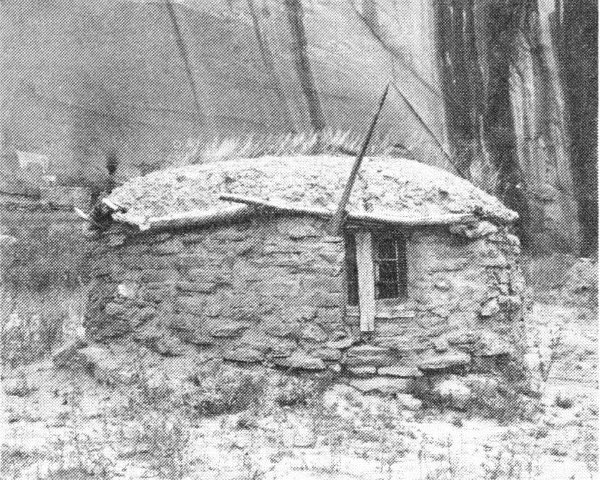

A modern hogan built of stone and mud-plaster with a pane glass window, at Standing Cow Ruin.

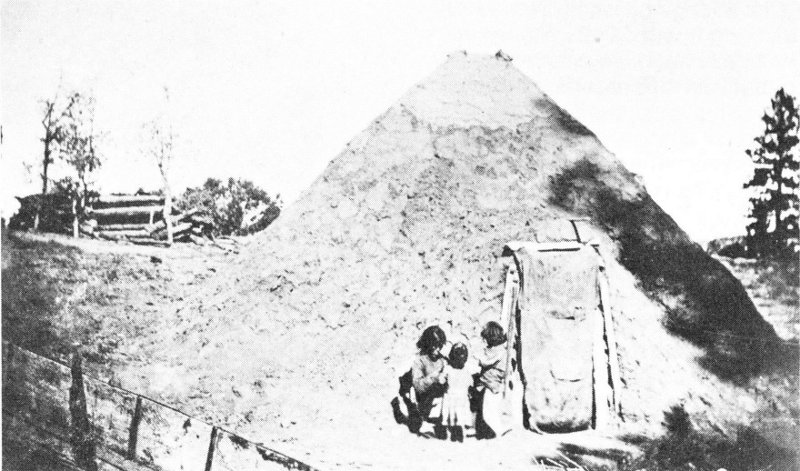

Several types of hogans can be seen on the reservation today. Some recent ones attempt to copy houses in off-reservation towns, but most follow traditional styles. The earliest type of hogan known is the so-called “forked-stick” hogan. This is a tipi-shaped structure made of three poles with forked ends that interlock at the top. Spaces between this framework are filled with smaller poles; the whole is plastered with mud. Another style of hogan is made of cribbed logs and usually has six or eight sides, a design made necessary by the shortness of the logs available. Circular hogans of stone, adapted from Pueblo Indian masonry construction, are sometimes built. The roofs on both types of hogans are constructed of cribbed logs and appear domed rather than flat. A feature common to every hogan is its door facing east, toward the sunrise.

A Navajo forked-pole hogan, traditionally the earliest form used by the tribe. Shaped like a tipi, it is built of heavy logs covered with soil. National Archives

Furnishings of hogans were simple and limited, but today tables, chairs, cabinets, and beds are commonly used. Food was once cooked in a firepit in the center of the floor, below a hole in the roof which allowed the smoke to escape, but today it is 48 prepared on stoves which increasingly are butane gas or electric models. In good weather, cooking is done outside. Iron and aluminum pots and pans have replaced homemade pottery and baskets as kitchen utensils.

Water is scarce over much of the reservation and must be hauled in wagons or pickup trucks from as far away as 10 miles. Water is used sparingly.

The Navajos are fond of goat meat and mutton, which have almost entirely replaced the wild game of the old diet. Canned goods from the traders’ shelves have supplanted the wild plants that used to be gathered and, in some homes, have eliminated garden plots of corn and squash. At Fort Sumner the Navajos learned to roast and brew coffee and to use wheat flour. Now coffee and wheat bread are important items in their diet.

In aboriginal times Navajo clothing was meager. Women wore an apron and men a breechclout of buckskin. Footwear probably consisted of yucca fiber sandals, although moccasins of animal skins were also common. During winter, blankets of animal skins or yucca were added for warmth.

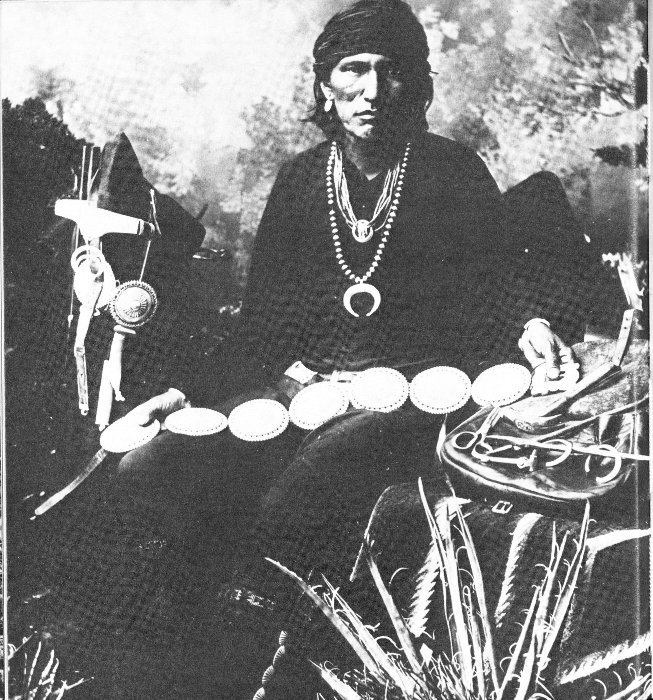

After the Spaniards arrived in the Rio Grande Valley, the Navajos copied Spanish costumes. This style, which prevailed until after the return from Bosque Redondo in 1868, consisted of tightly buttoned knee-length breeches of buckskin, worn with knitted blue stockings copied from those of Pueblo men. A V-neck shirt was made from a small blanket or piece of flannel and was worn outside the trousers. The shirt was held by a leather belt heavily ornamented with silver. Moccasins and leggings of dyed buckskin completed the men’s dress. When Navajo women began loom weaving, they copied the Pueblo woman’s woven cotton dress in wool and wore it with a woven belt. Dyed buckskin moccasins with wrap-around leggings were their footwear.

Navajo clothing of the 19th century, a pair of moccasins and a shirt.

After Bosque Redondo, cotton clothing in Anglo-American and Mexican styles became popular. 49 Today Navajo men wear typical western ranch and farm clothing: blue jeans, shirts, and broad-brimmed felt or straw hats. The women still prefer the bright calico skirts and velveteen blouses which they copied from the styles worn by American women in the mid-19th century. The skirt is ankle length and voluminous, containing from 12 to 15 yards of material. Moccasins of dyed buckskin are still popular with the women at home, but modish shoes and stockings have been adopted for town wear. In winter, both men and women use commercially made blankets draped over their shoulders for protection against the cold.

Today many Navajo men take off-reservation jobs with railroads, in lumber camps, or as migratory workers following crop harvests. Sheep still play a major role in the family economy, and annual income is supplemented by the sale of rugs and, sometimes, silverwork and jewelry.

The Navajos have worn silver ornaments for many years. A 1795 Spanish reference mentions that the Navajo captains were rarely seen without their silver ornaments, but there is no evidence that they made them at that time. They got most of their silver pieces by trading, and picked up others on raids against Ute and Commanche Indians, who in turn had obtained them from eastern Indians who were in contact with Anglo-American or French traders. A great many silver ornaments probably came from the Spaniards.

Present evidence indicates that the Navajos learned silversmithing sometime after 1850. Old silversmiths in the tribe have claimed that Mexicans taught them the craft during the Bosque Redondo captivity, citing their first smith, Atsidi Sani or “Old Smith,” who was taught by a Mexican blacksmith.

An early Navajo silversmith named Slim-Maker-of-Silver. Museum of New Mexico

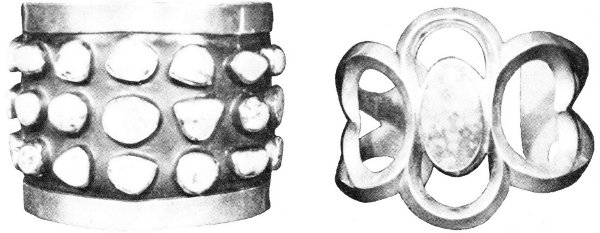

Navajo silver bracelets and ring from the period 1880-1900. Smithsonian Institution

Recent Navajo bracelets.

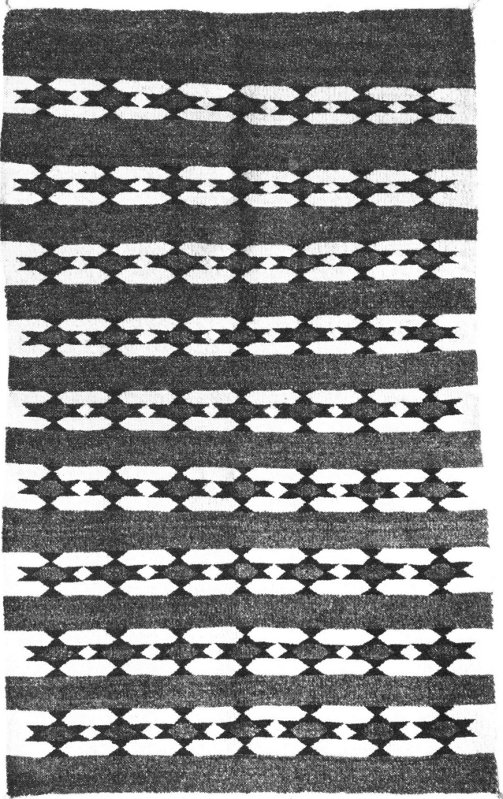

A Navajo vegetal-dye rug, hand woven from hand-spun, home-grown wool. It is representative of the Chinle style.

A Navajo wife weaving a rug in her front yard at their home near Standing Cow Ruin.

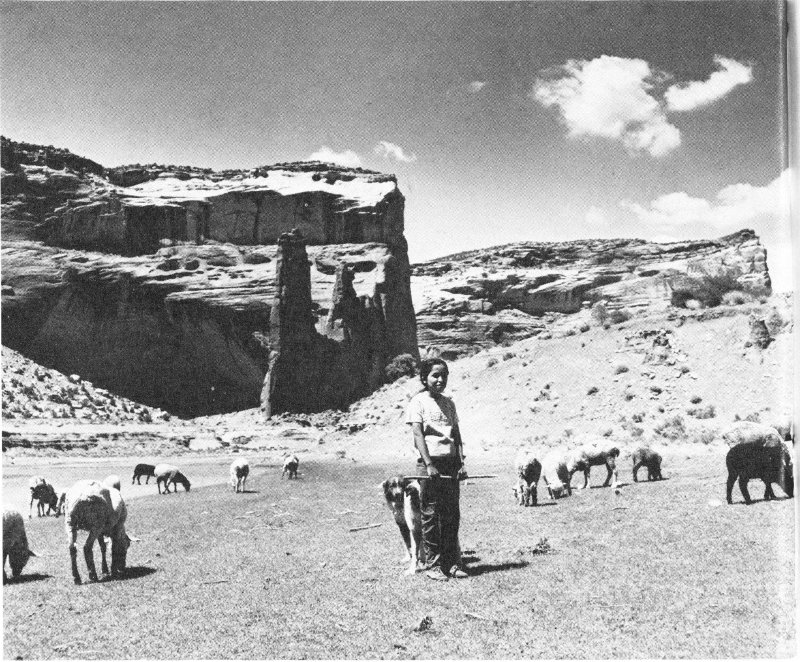

A Navajo girl and her dogs guard the family sheep near Big Cave.

By 1881 they had completely mastered the art, and began to use turquoise in their jewelry. Commercialization of their silver-work began in 1899, when the Fred Harvey Company first placed large orders for pieces to sell to tourists.

Perhaps more than anything else, the colorful rugs and silver and turquoise jewelry produced by these people have made the name “Navajo” a household word. The two crafts did not develop simultaneously, for weaving is almost two centuries older than silversmithing. The Navajo mastery of both skills is exceptional, however, and both lend themselves readily to Navajo designs.

The loom used in Navajo weaving is a native American device, similar to that of the ancient Pueblo people. It has changed little over the centuries. Men usually construct the loom and women do the weaving.

In spite of three centuries of work by Christian missionaries, the Navajos have clung to their native religion. Their religious leaders are medicine men, or healers, and their rites are intended primarily to secure and maintain good health.

The ceremonies, called chants, sometimes last as long as 9 days. They consist of songs, dances, the construction of sand paintings, and the administration of herbal medicines and sweat baths.

The Navajos, a unique people in many ways, are far from being “vanishing” Americans. Vigorous and growing in numbers, they have only recently begun to understand their potential. While they are making rapid strides to join the world around them, they are keenly aware of their own heritage and what it can contribute to the larger culture of America.

Kluckholm, Clyde, and Dorothea Leighton. The Navaho. Cambridge, Mass. 1946.

McGregor, John C. Southwestern Archeology. Second Ed. Urbana, Ill. 1965.

Morris, Ann A. Digging in the Southwest. N.Y. 1934.

Underhill, Ruth M. The Navajos. Norman, Okla. 1956.

Wormington, H. M. Prehistoric Indians of the Southwest. Third Ed. Denver, Colo. 1956.

As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has basic responsibilities for water, fish, wildlife, mineral, land, park, and recreational resources. Indian and Territorial affairs are other major concerns of America’s “Department of Natural Resources.” The Department works to assure the wisest choice in managing all our resources so each will make its full contribution to a better United States—now and in the future.

National Park Service

U.S. DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR

★ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1973 O—503-170

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402. Price 80 cents, domestic postpaid; 60 cents, GPO Bookstore

Stock Number 2405-00508