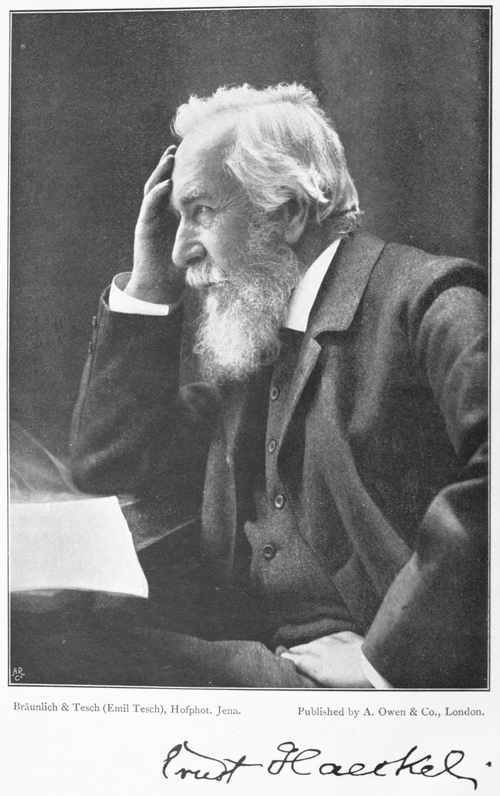

Ernst Haeckel.

Title: Last Words on Evolution: A Popular Retrospect and Summary

Author: Ernst Haeckel

Translator: Joseph McCabe

Release date: November 30, 2016 [eBook #53639]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by MWS, Adrian Mastronardi, John Campbell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Last Words on Evolution , by Ernst Haeckel, Translated by Joseph McCabe

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/lastwordsonevolu00haeciala |

Last Words on Evolution

A Popular Retrospect and Summary

BY

ERNST HAECKEL

Professor at Jena University

TRANSLATED FROM THE SECOND EDITION

BY

JOSEPH McCABE

With Portrait and Three Plates

LONDON

A. OWEN & CO.

28 REGENT STREET, S.W.

1906

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION | 7 |

| PREFACE | 11 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Controversy about Creation | |

| Evolution and Dogma | 15 |

| Plate I.—Genealogical Tree of the Vertebrates | 17 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Struggle over our Genealogical Tree | |

| Our Ape-Relatives and the Vertebrate-Stem | 49 |

| Plate II.—Skeletons of Five Anthropoid Apes | 51 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Controversy over the Soul | |

| The Ideas of Immortality and God | 83 |

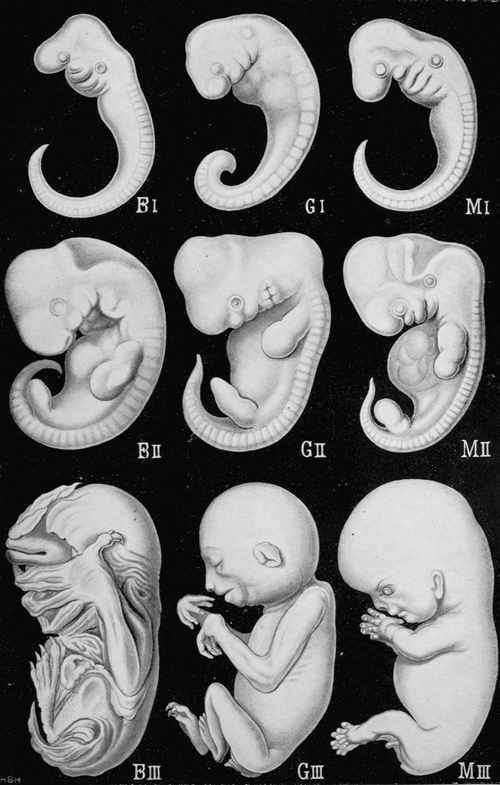

| Plate III.—Embryos of Three Mammals | 85 |

| APPENDIX | |

| Evolutionary Tables | |

| Geological Ages and Periods | 115 |

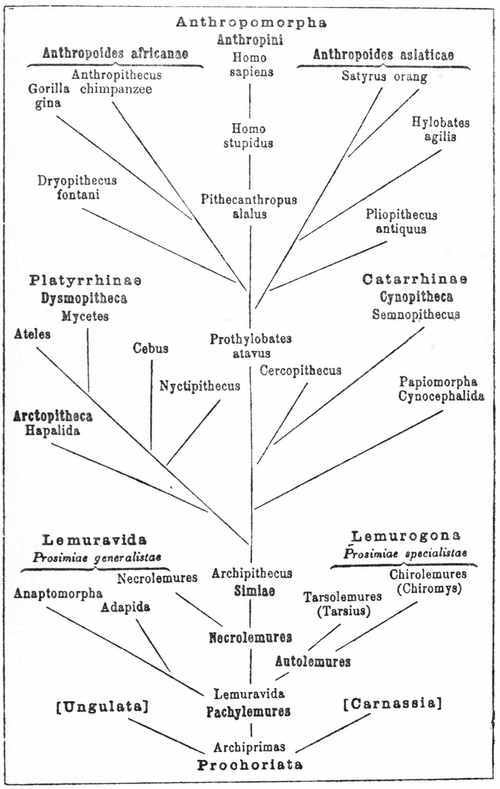

| Man's Genealogical Tree—First Half | 116 |

| Man's Genealogical Tree—Second Half | 117 |

| Classification of the Primates | 118 |

| Genealogical Tree of the Primates | 119 |

| Explanation of Genealogical Table 1. | 120 |

| Postscript | |

| Evolution and Jesuitism | 121 |

A few months ago the sensational announcement was made that Professor Haeckel had abandoned Darwinism and given public support to the teaching of a Jesuit writer. There was something piquant in the suggestion that the "Darwin of Germany" had recanted the conclusions of fifty years of laborious study. Nor could people forget that only two years before Haeckel had written with some feeling about the partial recantation of some of his colleagues. Many of our journals boldly declined to insert the romantic news, which came through one of the chief international press agencies. Others drew the attention of their readers, in jubilant editorial notes, to the lively prospect it opened out. To the many inquiries addressed to me as the "apostle of Professor Haeckel," as Sir Oliver Lodge dubs me in a genial letter, I timidly represented that even a German reporter sometimes drank. But the correction quickly came that the telegram had exactly reversed the position taken up by the great biologist. It is only just to the honourable calling of the reporter to add that, according to the theory current in Germany, the message was tampered with by subtle and ubiquitous Jesuistry. Did they not penetrate even into the culinary service at Hatfield?

I have pleasure in now introducing the three famous[8] lectures delivered by Professor Haeckel at Berlin, and the reader will see the grotesqueness of the original announcement. They are the last public deliverance that the aged professor will ever make. His enfeebled health forbids us to hope that his decision may yet be undone. He is now condemned, he tells me, to remain a passive spectator of the tense drama in which he has played so prominent a part for half a century. For him the red rays fall level on the scene and the people about him. It may be that they light up too luridly, too falsely, the situation in Germany; but the reader will understand how a Liberal of Haeckel's temper must feel his country to be between Scylla and Charybdis—between an increasingly clear alternative of Catholicism or Socialism—with a helmsman at the wheel whose vagaries inspire no confidence.

The English reader will care to be instructed on the antithesis of Virchow and Haeckel which gives point to these lectures, and which is often misrepresented in this country. Virchow, the greatest pathologist and one of the leading anthropologists of Germany, had much to do with the inspiring of Haeckel's Monistic views in the fifties. Like several other prominent German thinkers, Virchow subsequently abandoned the positive Monistic position for one of agnosticism and scepticism, and a long and bitter conflict ensued. It is hardly too much to say that Virchow's ultra-timid reserve in regard to the evolution of man and other questions has died with him. Apart from one or two less prominent anthropologists, and the curious distinction drawn by Dr. A. R.[9] Wallace, science has accepted the fact of evolution, and has, indeed, accepted the main lines of Haeckel's ancestral tree of the human race.

In any case, Haeckel had the splendid revenge of surviving his old teacher and almost lifelong opponent. Berlin had for years been dominated by the sceptical temper of Virchow and Du Bois-Reymond. The ardent evolutionist and opponent of Catholicism was impatient of a reserve that he felt to be an anachronism in science and an effective support of reactionary ideas. It was, therefore, with a peculiar satisfaction that he received the invitation, after Virchow's death, to address the Berlin public. Among the many and distinguished honours that have been heaped upon him in the last ten years this was felt by him to hold a high place. He could at last submit freely, in the capital of his country, the massive foundations and the imposing structure of a doctrine which he holds to be no less established in science than valuable in the general cause of progress.

The lectures are reproduced here not solely because of the interest aroused in them by the "Jesuit" telegram. They contain a very valuable summary of his conclusions, and include the latest scientific confirmation. Rarely has the great biologist written in such clear and untechnical phrases, so that the general reader will easily learn the outlines of his much-discussed Monism. To closer students, who are at times impatient of the Lamarckian phraseology of Haeckel—to all, in fact, who would like to see how the same evolutionary truths are expressed without reliance on the inheritance of acquired characters—I[10] may take the opportunity to say that I have translated, for the same publishers, Professor Guenther's "Darwinism and the Problems of Life," which will shortly be in their hands.

JOSEPH McCABE.

November, 1905.

In the beginning of April, 1905, I received from Berlin a very unexpected invitation to deliver a popular scientific lecture at the Academy of Music in that city. I at first declined this flattering invitation, with thanks, sending them a copy of a printed declaration, dated 17th July, 1901, which I had made frequent use of, to the effect that "I could not deliver any more public lectures, on account of the state of my health, my advanced age, and the many labours that were still incumbent on me."

I was persuaded to make one departure from this fixed resolution, firstly, by the pressing entreaties of many intimate friends at Berlin. They represented to me how important it was to give an account myself to the educated Berlin public of the chief evolutionary conclusions I had advocated for forty years. They pointed out emphatically that the increasing reaction in higher circles, the growing audacity of intolerant orthodoxy, the preponderance of Ultramontanism, and the dangers that this involved for freedom of thought in Germany, for the university and the school, made it imperative to take vigorous action. It happened that I had just been following the interesting efforts that the Church has lately made to enter into a peaceful compromise with its deadly enemy, Monistic science. It has decided to accept to a certain extent, and to accommodate to its[12] creed (in a distorted and mutilated form) the doctrine of evolution, which it has vehemently opposed for thirty years. This remarkable change of front on the part of the Church militant seemed to me so interesting and important, and at the same time so misleading and mischievous, that I chose it as the subject of a popular lecture, and accepted the invitation to Berlin.

After a few days, when I had written my discourse, I was advised from Berlin that the applications for admission were so numerous that the lecture must either be repeated or divided into two. I chose the latter course, as the material was very abundant. In compliance with an urgent request, I repeated the two lectures (17th and 18th April); and as demands for fresh lectures continued to reach me, I was persuaded to add a "farewell lecture" (on 19th April), in which I dealt with a number of important questions that had not been adequately treated.

The noble gift of effective oratory has been denied me by Nature. Though I have taught for eighty-eight terms at the little University of Jena, I have never been able to overcome a certain nervousness about appearing in public, and have never acquired the art of expressing my thoughts in burning language and with appropriate gesture. For these and other reasons, I have rarely consented to take part in scientific and other congresses; the few speeches that I have delivered on such occasions, and are issued in collected form, were drawn from me by my deep interest in the great struggle for the triumph of truth. However, in the three Berlin lectures—my[13] last public addresses—I had no design of winning my hearers to my opinions by means of oratory. It was rather my intention to put before them, in connected form, the great groups of biological facts, by which they could, on impartial consideration, convince themselves of the truth and importance of the theory of evolution.

Readers who are interested in the evolution-controversy, as I here describe it, will find in my earlier works (The History of Creation, The Evolution of Man, The Riddle of the Universe, and The Wonders of Life) a thorough treatment of the views I have summarily presented. I do not belong to the amiable group of "men of compromise," but am in the habit of giving candid and straightforward expression to the convictions which a half-century of serious and laborious study has led me to form. If I seem to be a tactless and inconsiderate "fighter," I pray you to remember that "conflict is the father of all things," and that the victory of pure reason over current superstition will not be achieved without a tremendous struggle. But I regard ideas only in my struggles: to the persons of my opponents I am indifferent, bitterly as they have attacked and slandered my own person.

Although I have lived in Berlin for many years as student and teacher, and have always been in communication with scientific circles there, I have only once before delivered a public lecture in that city. That was on "The Division of Labour in Nature and Human Life" (17th December, 1868). I was, therefore, somewhat gratified to be able to speak there again (and for[14] the last time), after thirty-six years, especially as it was in the very spot, the hall of the Academy of Music, in which I had heard the leaders of the Berlin University speak fifty years ago.

It is with great pleasure that I express my cordial thanks to those who invited me to deliver these lectures, and who did so much to make my stay in the capital pleasant; and also to my many hearers for their amiable and sympathetic attention.

ERNST HAECKEL.

Jena, 9th May, 1905.

THE CONTROVERSY ABOUT CREATION

EVOLUTION AND DOGMA

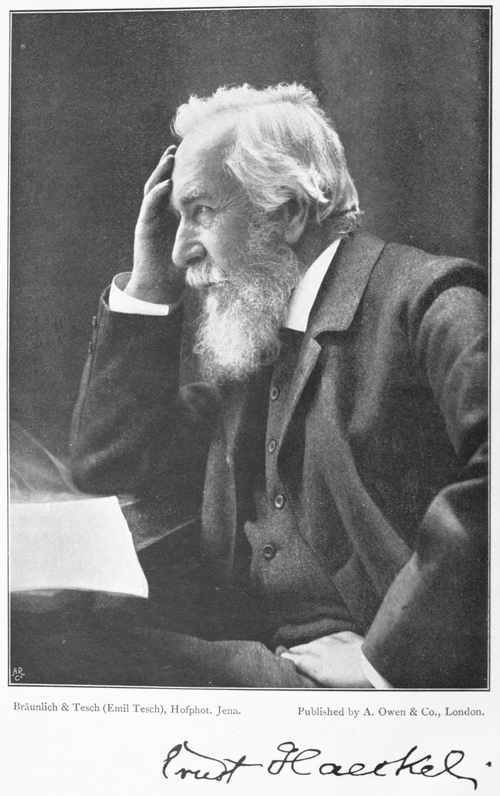

EXPLANATION OF PLATE I

GENEALOGICAL TREE OF THE VERTEBRATES

The genetic relationship of all vertebrates, from the earliest acrania and fishes up to the apes and man, is proved in its main lines by the concordant testimony of paleontology, comparative anatomy, and embryology. All competent and impartial zoologists now agree that the vertebrates are all descended from a single stem, and that the root of this is to be sought in extinct pre-Silurian Acrania (1), somewhat similar to the living lancelet. The Cyclostoma (2) represent the transition from the latter to the Fishes (3); and the Dipneusts (4) the transition from these to the Amphibia (5). From the latter have been developed the Reptiles (6) on the one hand, and the Mammals (7) on the other. The most important branch of this most advanced class is the Primates (8); from the half-apes, or lemurs, a direct line leads, through the baboons, to the anthropoid apes, and through these on to man. (Cf. the tables on pp. 115-120). Further information will be found in chapters xxiv.-xxvii. of the History of Creation, and chapters xxi.-xxiii. of the Evolution of Man.

Plate I.

LAST WORDS ON EVOLUTION

CHAPTER I

THE CONTROVERSY ABOUT CREATION

EVOLUTION AND DOGMA

The controversy over the idea of evolution is a prominent feature in the mental life of the nineteenth century. It is true that a few great thinkers had spoken of a natural evolution of all things several thousand years ago. They had, indeed, partly investigated the laws that control the birth and death of the world, and the rise of the earth and its inhabitants; even the creation-stories and the myths of the older religions betray a partial influence of these evolutionary ideas. But it was not until the nineteenth century that the idea of evolution took definite shape and was scientifically grounded on various classes of evidence; and it was not until the last third of the century that it won general recognition. The intimate connection that was proved to exist between all branches of knowledge, once the continuity of historical development was realised, and the union of them all through the Monistic philosophy, are achievements of the last few decades.

The great majority of the older ideas that thoughtful men had formed on the origin and nature of the world and their own frame were far removed from the notion of "self-development." They culminated in more or less obscure creation-myths, which generally put in the foreground the idea of a personal Creator. Just as man has used intelligence and design in the making of his weapons and tools, his houses and his boats, so it was thought that the Creator had fashioned the world with art and intelligence, according to a definite plan. Among the many legends of this kind the ancient Semitic story of creation, familiar to us as the Mosaic narrative, but drawn for the most part from Babylonian sources, has obtained a very great influence on European culture owing to the general acceptance of the Bible. The belief in miracles, that is involved in these religious legends, was bound to come in conflict, at an early date, with the evolutionary ideas of independent philosophical research. On the one hand, in the prevalent religious teaching, we had the supernatural world, the miraculous, teleology: on the other hand, in the nascent science of evolution, only natural law, pure reason, mechanical causality. Every step that was made by this science brought into greater relief its inconsistency with the predominant religion.[1]

If we glance for a moment at the various fields in which the idea of evolution is scientifically applied we find that, firstly, the whole universe is conceived as a unity; secondly, our earth; thirdly, organic life on the earth; fourthly, man, as its highest product; and fifthly, the soul, as a special immaterial entity. Thus we have, in historical succession, the evolutionary research of cosmology, geology, biology, anthropology, and psychology.

The first comprehensive idea of cosmological evolution was put forth by the famous critical philosopher Immanuel Kant, in 1755, in the great work of his earlier years, General Natural History of the Heavens, or an Attempt to Conceive and to Explain the Origin of the Universe mechanically, according to the Newtonian Laws. This remarkable work appeared anonymously, and was dedicated to Frederick the Great, who, however, never saw it. It was little noticed, and was soon entirely forgotten, until it was exhumed ninety years afterwards by Alexander von Humboldt. Note particularly that on the title-page stress is laid on the mechanical origin of the world and its explanation on Newtonian principles; in this way the strictly Monistic character of the whole cosmogony and the absolutely[20] universal rule of natural law are clearly expressed. It is true that Kant speaks much in it of God and his wisdom and omnipotence; but this is limited to the affirmation that God created once for all the unchangeable laws of nature, and was henceforward bound by them and only able to work through them. The Dualism which became so pronounced subsequently in the philosopher of Koenigsberg counts for very little here.

The idea of a natural development of the world occurs in a clearer and more consistent form, and is provided with a firm mathematical basis, forty years afterwards, in the remarkable Mécanique Céleste of Pierre Laplace. His popular Exposition du Système du Monde (1796) destroyed at its roots the legend of creation that had hitherto prevailed, or the Mosaic narrative in the Bible. Laplace, who had become Minister of the Interior, Count, and Chancellor of the Senate, under Napoleon, was merely honourable and consistent when he replied to the emperor's question, "What room there was for God in his system?": "Sire, I had no need for that unfounded hypothesis." What strange ministers there are sometimes![2] The shrewdness of the [21]Church soon recognised that the personal Creator was dethroned, and the creation-myth destroyed, by this Monistic and now generally received theory of cosmic development. Nevertheless it maintained towards it the attitude which it had taken up 250 years earlier in regard to the closely related and irrefutable system of Copernicus. It endeavoured to conceal the truth as long as possible, or to oppose it with Jesuitical methods, and finally it yielded. If the Churches now silently admit the Copernican system and the cosmogony of Laplace and have ceased to oppose them, we must attribute the fact, partly to a feeling of their spiritual impotence, partly to an astute calculation that the ignorant masses do not reflect on these great problems.

In order to obtain a clear idea and a firm conviction of this cosmic evolution by natural law, the eternal birth and death of millions of suns and stars, one needs some mathematical training and a lively imagination, as well as a certain competence in astronomy and physics. The evolutionary process is much simpler, and more readily grasped in geology. Every shower of rain or wave of the sea, every volcanic eruption and every pebble, gives us a direct proof of the changes that are constantly taking place[22] on the surface of our planet. However, the historical significance of these changes was not properly appreciated until 1822, by Karl von Hoff of Gotha, and modern geology was only founded in 1830 by Charles Lyell, who explained the whole origin and composition of the solid crust of the earth, the formation of the mountains, and the periods of the earth's development, in a connected system by natural laws. From the immense thickness of the stratified rocks, which contain the fossilised remains of extinct organisms, we discovered the enormous length—running into millions of years—of the periods during which these sedimentary rocks were deposited in water. Even the duration of the organic history of the earth—that is to say, the period during which the plant and animal population of our planet was developing—must itself be put at more than a hundred million years. These results of geology and paleontology destroyed the current legend of the six days' work of a personal Creator. Many attempts were made, it is true, and are still being made, to reconcile the Mosaic supernatural story of creation with modern geology.[3] All these efforts of believers are in vain. We may say, in fact, that it is precisely the study of geology, the reflection it entails on the enormous periods of evolution, and[23] the habit of seeking the simple mechanical causes of their constant changes, that contribute very considerably to the advance of enlightenment. Yet in spite of this (or, possibly, because of this), geological instruction is either greatly neglected or entirely suppressed in most schools. It is certainly eminently calculated (in connection with geography) to enlarge the mind, and acquaint the child with the idea of evolution. An educated person who knows the elements of geology will never experience ennui. He will find everywhere in surrounding nature, in the rocks and in the water, in the desert and on the mountains, the most instructive stimuli to reflection.

The evolutionary process in organic nature is much more difficult to grasp. Here we must distinguish two different series of biological development, which have only been brought into proper causal connection by means of our biogenetic law (1866); one series is found in embryology (or ontogeny), the other in phylogeny (or race-development). In Germany "evolution" always meant embryology, or a part of the whole, until forty years ago. It stood for a microscopic examination of the wonderful processes by means of which the elaborate structure of the plant or animal body is formed from the simple seed of the plant or the egg of the bird. Until the beginning of the nineteenth century the erroneous view was generally received that this marvellously complicated structure existed, completely formed, in the simple ovum, and that the various organs had merely to grow and to[24] shape themselves independently by a process of "evolution" (or unfolding), before they entered into activity. An able German scientist, Caspar Friedrich Wolff (son of a Berlin tailor), had already shown the error of this "pre-formation theory" in 1759. He had proved, in his dissertation for the doctorate, that no trace of the later body, of its bones, muscles, nerves, and feathers, can be found in the hen's egg (the commonest and most convenient object for study), but merely a small round disk, consisting of two thin superimposed layers. He had further showed that the various organs are only built up gradually out of these simple elements, and that we can trace, step by step, a series of real new growths. However, these momentous discoveries, and the sound "theory of epigenesis" that he based on them, were wholly ignored for fifty years, and even rejected by the leading authorities. It was not until Oken had re-discovered these important facts at Jena (1806), Pander had more carefully distinguished the germinal layers (1817), and finally Carl Ernst von Baer had happily combined observation and reflection in his classical Animal Embryology (1828), that embryology attained the rank of an independent science with a sound empirical base.

A little later it secured a well-merited recognition in botany also, especially owing to the efforts of Matthias Schleiden of Jena, the distinguished student who provided biology with a new foundation in the "cell theory" (1838). But it was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that people generally recognised[25] that the ovum of the plant or animal is itself only a simple cell, and that the later tissues and organs gradually develop from this "elementary organism" by a repeated cleavage of, and division of labour in, the cells. The most important step was then made of recognising that our human organism also develops from an ovum (first discovered by Baer in 1827), in virtue of the same laws, and that its embryonic development resembles that of the other mammals, especially that of the ape. Each of us was, at the beginning of his existence, a simple globule of protoplasm, surrounded by a membrane, about 1 120 of an inch in diameter, with a firmer nucleus inside it. These important embryological discoveries confirmed the rational conception of the human organism that had been attained much earlier by comparative anatomy: the conviction that the human frame is built in the same way, and develops similarly from a simple ovum, as the body of all other mammals. Even Linné had already (1735) given man a place in the mammal class in his famous System of Nature.

Differently from these embryological facts, which can be directly observed, the phenomena of phylogeny (the development of species), which are needed to set the former in their true light, are usually outside the range of immediate observation. What was the origin of the countless species of animals and plants? How can we explain the remarkable relationships which unite similar species into genera and these into classes? Linné answers the question very simply with the belief[26] in creation, relying on the generally accepted Mosaic narrative: "There are as many different species of animals and plants as there were different forms created by God in the beginning." The first scientific answer was given in 1809 by the great French scientist, Lamarck. He taught, in his suggestive Philosophie Zoologique, that the resemblances in form and structure of groups of species are due to real affinity, and that all organisms descend from a few very simple primitive forms (or, possibly, from a single one). These primitive forms were developed out of lifeless matter by spontaneous generation. The resemblances of related groups of species are explained by inheritance from common stem-forms; their dissimilarities are due to adaptation to different environments, and to variety in the action of the modifiable organs. The human race has arisen in the same way, by transformation of a series of mammal ancestors, the nearest of which are ape-like primates.

These great ideas of Lamarck, which threw light on the whole field of organic life, and were closely approached by Goethe in his own speculations, gave rise to the theory that we now know as transformism, or the theory of evolution or descent. But the far-seeing Lamarck was—as Caspar Friedrich Wolff had been fifty years before—half a century before his time. His theory obtained no recognition, and was soon wholly forgotten.

It was brought into the light once more in 1859 by the genius of Charles Darwin, who had been born in the very year that the Philosophie Zoologique was[27] published. The substance and the success of his system, which has gone by the name of Darwinism (in the wider sense) for forty-six years, are so generally known that I need not dwell on them. I will only point out that the great success of Darwin's epoch-making works is due to two causes: firstly, to the fact that the English scientist most ingeniously worked up the empirical material that had accumulated during fifty years into a systematic proof of the theory of descent; and secondly, to the fact that he gave it the support of a second theory of his own, the theory of natural selection. This theory, which gives a causal explanation of the transformation of species, is what we ought to call "Darwinism" in the strict sense. We cannot go here into the question how far this theory is justified, or how far it is corrected by more recent theories, such as Weismann's theory of germ-plasm (1844), or De Vries's theory of mutations (1900). Our concern is rather with the unparalleled influence that Darwinism, and its application to man, have had during the last forty years on the whole province of science; and at the same time, with its irreconcilable opposition to the dogmas of the Churches.

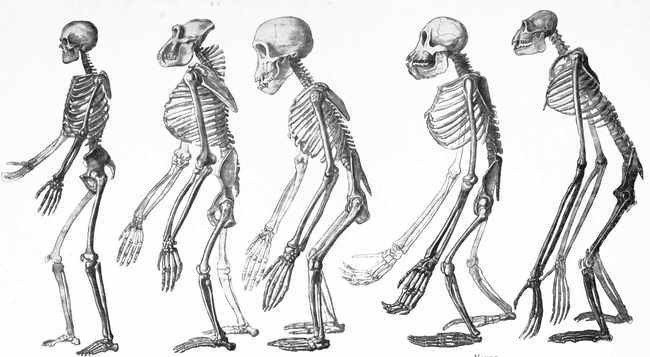

The extension of the theory of evolution to man was, naturally, one of the most interesting and momentous applications of it. If all other organisms arose, not by a miraculous creation, but by a natural modification of earlier forms of life, the presumption is that the human race also was developed by the transformation of the most man-like mammals, the primates of Linné—the apes and lemurs. This natural inference, which Lamarck[28] had drawn in his simple way, but Darwin had at first explicitly avoided, was first thoroughly established by the gifted zoologist, Thomas Huxley, in his three lectures on Man's Place in Nature (1863). He showed that this "question of questions" is unequivocally answered by three chief witnesses—the natural history of the anthropoid apes, the anatomic and embryological relations of man to the animals immediately below him, and the recently discovered fossil human remains. Darwin entirely accepted these conclusions of his friend eight years afterwards, and, in his two-volume work, The Descent of Man and Sexual Selection (1871), furnished a number of new proofs in support of the dreaded "descent of man from the ape." I myself then (1874) completed the task I had begun in 1866, of determining approximately the whole series of the extinct animal ancestors of the human race, on the ground of comparative anatomy, embryology, and paleontology. This attempt was improved, as our knowledge advanced, in the five editions of my Evolution of Man. In the last twenty years a vast literature on the subject has accumulated. I must assume that you are acquainted with the contents of one or other of these works, and will turn to the question, that especially engages our attention at present, how the inevitable struggle between these momentous achievements of modern science and the dogmas of the Churches has run in recent years.

It was obvious that both the general theory of evolution and its extension to man in particular must[29] meet from the first with the most determined resistance on the part of the Churches. Both were in flagrant contradiction to the Mosaic story of creation, and other Biblical dogmas that were involved in it, and are still taught in our elementary schools. It is creditable to the shrewdness of the theologians and their associates, the metaphysicians, that they at once rejected Darwinism, and made a particularly energetic resistance in their writings to its chief consequence, the descent of man from the ape. This resistance seemed the more justified and hopeful as, for seven or eight years after Darwin's appearance, few biologists accepted his theory, and the general attitude amongst them was one of cold scepticism. I can well testify to this from my own experience. When I first openly advocated Darwin's theory at a scientific congress at Stettin in 1863, I was almost alone, and was blamed by the great majority for taking up seriously so fantastic a theory, "the dream of an after-dinner nap," as the Göttinger zoologist, Keferstein, called it.

The general attitude towards Nature fifty years ago was so different from that we find everywhere to-day, that it is difficult to convey a clear idea of it to a young scientist or philosopher. The great question of creation, the problem how the various species of plants and animals came into the world, and how man came into being, did not exist yet in exact science. There was, in fact, no question of it.

Seventy-seven years ago Alexander von Humboldt delivered, in this very spot, the lectures which afterwards[30] made up his famous work, Cosmos, the Elements of a Physical Description of the World. As he touched, in passing, the obscure problem of the origin of the organic population of our planet, he could only say resignedly: "The mysterious and unsolved problem of how things came to be does not belong to the empirical province of objective research, the description of what is." It is instructive to find Johannes Müller, the greatest of German biologists in the nineteenth century, speaking thus in 1852, in his famous essay, "On the Generation of Snails in Holothurians": "The entrance of various species of animals into creation is certain—it is a fact of paleontology; but it is supernatural as long as this entrance cannot be perceived in the act and become an element of observation." I myself had a number of remarkable conversations with Müller, whom I put at the head of all my distinguished teachers, in the summer of 1854. His lectures on comparative anatomy and physiology—the most illuminating and stimulating I ever heard—had captivated me to such an extent that I asked and obtained his permission to make a closer study of the skeletons and other preparations in his splendid museum of comparative anatomy (then in the right wing of the buildings of the Berlin University), and to draw them. Müller (then in his fifty-fourth year) used to spend the Sunday afternoon alone in the museum. He would walk to and fro for hours in the spacious rooms, his hands behind his back, buried in thought about the mysterious affinities of the vertebrates, the "holy enigma" of which was so forcibly impressed[31] by the row of skeletons. Now and again my great master would turn to a small table at the side, at which I (a student of twenty years) was sitting in the angle of a window, making conscientious drawings of the skulls of mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and fishes.

I would then beg him to explain particularly difficult points in anatomy, and once I ventured to put the question: "Must not all these vertebrates, with their identity in internal skeleton, in spite of all their external differences, have come originally from a common form?" The great master nodded his head thoughtfully, and said: "Ah, if we only knew that! If ever you solve that riddle, you will have accomplished a supreme work." Two months afterwards, in September, 1854, I had to accompany Müller to Heligoland, and learned under his direction the beautiful and wonderful inhabitants of the sea. As we fished together in the sea, and caught the lovely medusæ, I asked him how it was possible to explain their remarkable alternation of generations; if the medusæ, from the ova of which polyps develop to-day, must not have come originally from the more simply organised polyps? To this precocious question, I received the same resigned answer: "Ah, that is a very obscure problem! We know nothing whatever about the origin of species."

Johannes Müller was certainly one of the greatest scientists of the nineteenth century. He takes rank with Cuvier, Baer, Lamarck, and Darwin. His insight was profound and penetrating, his philosophic judgment[32] comprehensive, and his mastery of the vast province of biology was enormous. Emil du Bois-Reymond happily compared him, in his fine commemorative address, to Alexander the Great, whose kingdom was divided into several independent realms at his death. In his lectures and works Müller treated no less than four different subjects, for which four separate chairs were founded after his death in 1858—human anatomy, physiology, pathological anatomy, and comparative anatomy. In fact, we ought really to add two more subjects—zoology and embryology. Of these, also, we learned more from Müller's classic lectures than from the official lectures of the professors of those subjects. The great master died in 1858, a few months before Charles Darwin and Alfred R. Wallace made their first communications on their new theory of selection in the Journal of the Linnæan Society. I do not doubt in the least that this surprising answer of the riddle of creation would have profoundly moved Müller, and have been fully admitted by him on mature reflection.

To these leading masters in biology, and to all other anatomists, physiologists, zoologists, and botanists up to 1858, the question of organic creation was an unsolved problem; the great majority regarded it as insoluble. The theologians and their allies, the metaphysicians, built triumphantly on this fact. It afforded a clear proof of the limitations of reason and science. A miracle only could account for the origin of these ingenious and carefully designed organisms; nothing[33] less than the Divine wisdom and omnipotence could have brought man into being. But this general resignation of reason, and the dominance of supernatural ideas which it encouraged, were somewhat paradoxical in the thirty years between Lyell and Darwin, between 1830 and 1859, since the natural evolution of the earth, as conceived by the great geologist, had come to be universally recognised. Since the earlier of these dates the iron necessity of natural law had ruled in inorganic nature, in the formation of the mountains and the movement of the heavenly bodies. In organic nature, on the contrary, in the creation and the life of animals and plants, people saw only the wisdom and power of an intelligent Creator and Controller; in other words, everything was ruled by mechanical causality in the inorganic world, but by teleological finality in the realm of biology.

Philosophy, strictly so called, paid little or no attention to this dilemma. Absorbed almost exclusively in metaphysical and dialectical speculations, it looked with supreme contempt or indifference on the enormous progress that the empirical sciences were making. It affected, in its character of "purely mental science," to build up the world out of its own head, and to have no need of the splendid material that was being laboriously gathered by observation and experiment. This is especially true of Germany, where Hegel's system of "absolute idealism" had secured the highest regard, particularly since it had been made obligatory as "the royal State-philosophy[34] of Prussia"—mainly because, according to Hegel, "in the State the Divine will itself and the monarchical constitution alone represent the development of reason; all other forms of constitution are lower stages of the development of reason." Hegel's abstruse metaphysics has also been greatly appreciated because it has made so thorough and consistent a use of the idea of evolution. But this pretended "evolution of reason" floated far above real nature in the pure ether of the absolute spirit, and was devoid of all the material ballast that the empirical science of the evolution of the world, the earth, and its living population, had meantime accumulated. Moreover, it is well known how Hegel himself declared, with humorous resignation, that only one of his many pupils had understood him, and this one had misunderstood him.

From the higher standpoint of general culture the difficult question forces itself on us: What is the real value of the idea of evolution in the whole realm of science? We are bound to answer that it varies considerably. The facts of the evolution of the individual, or of ontogeny, were easy to observe and grasp: the evolution of the crust of the earth and of the mountains in geology seemed to have an equally sound empirical foundation; the physical evolution of the universe seemed to be established by mathematical speculation. There was no longer any serious question of creation, in the literal sense, of the deliberate action of a personal Creator, in these great[35] provinces. But this made people cling to the idea more than ever in regard to the origin of the countless species of animals and plants, and especially the creation of man. This transcendental problem seemed to be entirely beyond the range of natural development; and the same was thought of the question of the nature and origin of the soul, the mystic entity that was appropriated by metaphysical speculation as its subject. Charles Darwin suddenly brought a clear light into this dark chaos of contradictory notions in 1859. His epoch-making work, The Origin of Species, proved convincingly that this historical process is not a supernatural mystery, but a physiological phenomenon; and that the preservation of improved races in the struggle for life had produced, by a natural evolution, the whole wondrous world of organic life.

To-day, when evolution is almost universally recognised in biology, when thousands of anatomic and physiological works are based on it every year, the new generation can hardly form an idea of the violent resistance that was offered to Darwin's theory and the impassioned struggles it provoked. In the first place, the Churches at once raised a vigorous protest; they rightly regarded their new antagonist as the deadly enemy of the legend of creation, and saw the very foundations of their creed threatened. The Churches found a powerful ally in the dualistic metaphysics that still claims to represent the real "idealist philosophy" at most universities. But most[36] dangerous of all to the young theory was the violent resistance it met almost everywhere in its own province of empirical science. The prevailing belief in the fixity and the independent creation of the various species was much more seriously menaced by Darwin's theory than it had been by Lamarck's transformism. Lamarck had said substantially the same thing fifty years before, but had failed to convince through the lack of effective evidence. Many scientists, some of great distinction, opposed Darwin because either they had not an adequate acquaintance with the whole field of biology, or it seemed to them that his bold speculation advanced too far from the secure base of experience.

When Darwin's work appeared in 1859, and fell like a flash of lightning on the dark world of official biology, I was engaged in a scientific expedition to Sicily and taken up with a thorough study of the graceful radiolarians, those wonderful microscopic marine animals that surpass all other organisms in the beauty and variety of their forms. The special study of this remarkable class of animals, of which I afterwards described more than 4,000 species, after more than ten years of research, provided me with one of the solid foundation-stones of my Darwinian ideas. But when I returned from Messina to Berlin in the spring of 1860, I knew nothing as yet of Darwin's achievement. I merely heard from my friends at Berlin that a remarkable work by a crazy Englishman had attracted great attention, and that it turned upside down all previous ideas as to the origin of species.

I soon perceived that almost all the experts at Berlin—chief amongst them were the famous microscopist, Ehrenberg; the anatomist, Reichert; the zoologist, Peters; and the geologist, Beyrich—were unanimous in their condemnation of Darwin. The brilliant orator of the Berlin Academy, Emil du Bois-Reymond, hesitated. He recognised that the theory of evolution was the only natural solution of the problem of creation; but he laughed at the application of it as a poor romance, and declared that the phylogenetic inquiries into the relationship of the various species had about as much value as the research of philologists into the genealogical tree of the Homeric heroes. The distinguished botanist, Alexander Braun, stood quite alone in his full and warm assent to the theory of evolution. I found comfort and encouragement with this dear and respected teacher, when I was deeply moved by the first reading of Darwin's book, and soon completely converted to his views. In Darwin's great and harmonious conception of Nature, and his convincing establishment of evolution, I had an answer to all the doubts that had beset me since the beginning of my biological studies.

My famous teacher, Rudolf Virchow, whom I had met at Würtzburg in 1852, and was soon associated with in the most friendly relations as special pupil and admiring assistant, played a very curious part in this great controversy. I am, I think, one of those elderly men who have followed Virchow's development, as man and[38] thinker, with the greatest interest during the last fifty years. I distinguish three periods in his psychological metamorphoses. In the first decade of his academic life, from 1847 to 1858, mainly at Würtzburg, he effected the great reform of medicine that culminated brilliantly in his cellular pathology. In the following twenty years (1858-1877) he was chiefly occupied with politics and anthropology. He was at first favourable to Darwinism, then sceptical, and finally rejected it. His powerful and determined opposition to it dates from 1877, when, in is famous speech on "The Freedom of Science in the Modern State," he struck a heavy blow at that freedom, denounced the theory of evolution as dangerous to the State, and demanded its exclusion from the schools. This remarkable metamorphosis is so important, and has had so much influence, yet has been so erroneously described, that I will deal with it somewhat fully in the next chapter, especially as I have then to treat one chief problem, the descent of man from the ape. For the moment, I will merely recall the fact that in Berlin, the "metropolis of intelligence," as it has been called, the theory of evolution, now generally accepted, met with a more stubborn resistance than in most of our other leading educational centres, and that this opposition was due above all to the powerful authority of Virchow.

We can only glance briefly here at the victorious struggle that the idea of evolution has conducted in the last three decades of the nineteenth century. The violent resistance that Darwinism encountered nearly everywhere in its early years was paralysed towards the[39] end of the first decade. In the years 1866-1874 many works were published in which not only were the foundations of the theory scientifically strengthened, but its general recognition was secured by popular treatment of the subject. I made the first attempt in 1866, in my General Morphology, to present connectedly the whole subject of evolution and make it the foundation of a consistent Monistic philosophy; and I then gave a popular summary of my chief conclusions in the ten editions of my History of Creation. In my Evolution of Man I made the first attempt to apply the principles of evolution thoroughly and consistently to man, and to draw up a hypothetical list of his animal ancestors. The three volumes of my Systematic Phylogeny (1894-1896) contain a fuller outline of a natural classification of organisms on the basis of their stem-history. There have been important contributions to the science of evolution in all its branches in the Darwinian periodical, Cosmos, since 1877; and a number of admirable popular works helped to spread the system.

However, the most important and most welcome advance was made by science when, in the last thirty years, the idea of evolution penetrated into every branch of biology, and was recognised as fundamental and indispensable. Thousands of new discoveries and observations in all sections of botany, zoology, protistology, and anthropology, were brought forward as empirical evidence of evolution. This is especially true of the remarkable progress of paleontology, comparative anatomy, and embryology, but it applies also[40] to physiology, chorology (the science of the distribution of living things), and œcology (the description of the habits of animals). How much our horizon was extended by these, and how much the unity of our Monistic system gained, can be seen in any modern manual of biology. If we compare them with those that gave us extracts of natural history forty or fifty years ago, we see at once what an enormous advance has taken place. Even the more remote branches of anthropological science, ethnography, sociology, ethics, and jurisprudence, are entering into closer relations with the theory of evolution, and can no longer escape its influence. In view of all this, it is ridiculous for theological and metaphysical journals to talk, as they do, of the failure of evolution and "the death-bed of Darwinism."

Our science of evolution won its greatest triumph when, at the beginning of the twentieth century, its most powerful opponents, the Churches, became reconciled to it, and endeavoured to bring their dogmas into line with it. A number of timid attempts to do so had been made in the preceding ten years by different free-thinking theologians and philosophers, but without much success. The distinction of accomplishing this in a comprehensive and well-informed manner was reserved for a Jesuit, Father Erich Wasmann of Luxemburg. This able and learned entomologist had already earned some recognition in zoology by a series of admirable observations on the life of ants, and the captives that they always keep in their homes, certain very small[41] insects which have themselves been curiously modified by adaptation to their peculiar environment. He showed that these striking modifications can only be rationally explained by descent from other free-living species of insects. The various papers in which Wasmann gave a thoroughly Darwinian explanation of the biological phenomena first appeared (1901-1903) in the Catholic periodical, Stimmen aus Maria-Laach, and are now collected in a special work entitled, Modern Biology and the Theory of Evolution.

This remarkable book of Wasmann's is a masterpiece of Jesuitical sophistry. It really consists of three entirely different sections. The first third gives, in the introduction, what is, for Catholics, a clear and instructive account of modern biology, especially the cell-theory, and the theory of evolution (chapters i.-viii.). The second third, the ninth chapter, is the most valuable part of the work. It has the title: "The Theory of Fixity or the theory of Evolution?" Here the learned entomologist gives an interesting account of the results of his prolonged studies of the morphology and the œcology of the ants and their captives, the myrmecophilæ. He shows impartially and convincingly that these complicated and remarkable phenomena can only be explained by evolution, and that the older doctrine of the fixity and independent creation of the various species is quite untenable. With a few changes this ninth chapter could figure as a useful part of a work by Darwin or Weismann or some other evolutionist. The succeeding chapter (the last third) is flagrantly[42] inconsistent with the ninth. It deals most absurdly with the application of the theory of evolution to man. The reader has to ask himself whether Wasmann really believes these confused and ridiculous notions, or whether he merely aims at befogging his readers, and so preparing the way for the acceptance of the conventional creed.

Wasmann's book has been well criticised by a number of competent students, especially by Escherich and Francé. While fully recognising his great services, they insist very strongly on the great mischief wrought by this smuggling of the Jesuitical spirit into biology. Escherich points out at length the glaring inconsistencies and the obvious untruths of this "ecclesiastical evolution." He summarises his criticism in the words: "If the theory of evolution can really be reconciled with the dogmas of the Church only in the way we find here, Wasmann has clearly proved that any such reconciliation is impossible. Because what Wasmann gives here as the theory of evolution is a thing mutilated beyond recognition and incapable of any vitality." He tries, like a good Jesuit, to prove that it does not tend to undermine, but to give a firm foundation to, the story of supernatural creation, and that it was really not Lamarck and Darwin, but St. Augustin and St. Thomas of Aquin, who founded the science of evolution. "God does not interfere directly in the order of Nature when he can act by means of natural causes." Man alone constitutes a remarkable exception; because "the human soul, being a spiritual entity, cannot be derived[43] from matter even by the Divine omnipotence, like the vital forms of the plants and animals" (p. 299).

In an instructive article on "Jesuitical Science" (in the Frankfort Freie Wort, No. 22, 1904), R. H. Francé gives an interesting list of the prominent Jesuits who are now at work in the various branches of science. As he rightly says, the danger consists "in a systematic introduction of the Jesuitical spirit into science, a persistent perversion of all its problems and solutions, and an astute undermining of its foundations; to speak more precisely, the danger is that people are not sufficiently conscious of it, and that they, and even science itself, fall into the cleverly prepared pit of believing that there is such a thing as Jesuitical science, the results of which may be taken seriously."[4]

While fully recognising these dangers, I nevertheless feel that the Jesuit Father Wasmann, and his colleagues, have—unwittingly—done a very great service to the[44] progress of pure science. The Catholic Church, the most powerful and widespread of the Christian sects, sees itself compelled to capitulate to the idea of evolution. It embraces the most important application of the idea, Lamarck and Darwin's theory of descent, which it had vigorously combated until twenty years ago. It does, indeed, mutilate the great tree, cutting off its roots and its highest branch; it rejects spontaneous generation or archigony at the bottom, and the descent of man from animal ancestors above. But these exceptions will not last. Impartial biology will take no notice of them, and the religious creed will at length determine that the more complex species have been evolved from a series of simpler forms according to Darwinian principles. The belief in a supernatural creation is restricted to the production of the earliest and simplest stem-forms, from which the "natural species" have taken their origin; Wasmann gives that name to all species that are demonstrably descended from a common stem-form; in other words, to what other classifiers call "stems" or "phyla." The 4,000 species of ants in his system, which he believes to be genetically related, are comprised by him in one "natural species." On the other hand, man forms one isolated "natural species" for himself, without any connection with the other mammals.

The Jesuitical sophistry that Wasmann betrays in this ingenious distinction between "systematic and natural species" is also found in his philosophic "Thoughts on Evolution" (chap. viii.), his distinction between philosophic and scientific evolution, or between[45] evolution in one stem and in several stems. His remarks (in chap. vii.) on "the cell and spontaneous generation" are similarly marred by sophistry. The question of spontaneous generation or archigony—that is to say, of the first appearance of organic life on the earth, is one of the most difficult problems in biology, one of those in which the most distinguished students betray a striking weakness of judgment. Dr. Heinrich Schmidt, of Jena, has lately written an able and popular little work on that subject. In his Spontaneous Generation and Professor Reinke (1903), he has shown to what absurd consequences the ecclesiastical ideas lead on this very question. The botanist Reinke, of Kiel, is now regarded amongst religious people as the chief opponent of Darwinism; for many conservatives this is because he is a member of the Prussian Herrenhaus (a very intelligent body, of course!). Although he is a strong evangelical, many of his mystic deductions agree surprisingly with the Catholic speculations of Father Wasmann. This is especially the case with regard to spontaneous generation. They both declare that the first appearance of life must be traced to a miracle, to the work of a personal deity, whom Reinke calls the "cosmic intelligence." I have shown the unscientific character of these notions in my last two works, The Riddle of the Universe, and The Wonders of Life. I have drawn attention especially to the widely distributed monera of the chromacea class—organisms of the simplest type conceivable, whose whole body is merely an unnucleated, green, structureless globule of plasm[46] (Chroococcus); their whole vital activity consists of growth (by forming plasm) and multiplication (by dividing into two). There is little theoretical difficulty in conceiving the origin of these new simple monera from inorganic compounds of albumen, or their later transformation into the simplest nucleated cells. All this, and a good deal more that will not fit in his Jesuitical frame, is shrewdly ignored by Wasmann.

In view of the great influence that Catholicism still has on public life in Germany, through the Centre party, this change of front should be a great gain to education. Virchow demanded as late as 1877 that the dangerous doctrine of evolution should be excluded from the schools. The Ministers of Instruction of the two chief German States gratefully adopted this warning from the leader of the progressive party, forbade the teaching of Darwinian ideas, and made every effort to check the spread of biological knowledge. Now, twenty-five years afterwards, the Jesuits come forward, and demand the opposite. They recognise openly that the hated theory of evolution is established, and try to reconcile it with the creed! What an irony of history! And we find much the same story when we read the struggles for freedom of thought and for the recognition of evolution in the other educated countries of Europe.

In Italy, its cradle and home, educated people generally look upon the papacy with the most profound disdain. I have spent many years in Italy, and have never met an educated Italian of such[47] bigoted and narrow views as we usually find amongst educated German Catholics—represented with success in the Reichstag by the Centre party. It is proof enough of the reactionary character of German Catholics that the Pope himself describes them as his most vigorous soldiers, and points them out as models to the faithful of other nations. As the whole history of the Roman Church shows, the charlatan of the Vatican is the deadly enemy of free science and free teaching. The present German Emperor ought to regard it as his most sacred duty to maintain the tradition of the Reformation, and to promote the formation of the German people in the sense of Frederick the Great. Instead of this we have to look on with heavy hearts while the Emperor, badly advised and misled by those in influence about him, suffers himself to be caught closer and closer in the net of the Catholic clergy, and sacrifices to it the intelligence of the rising generation. In September, 1904, the Catholic journals announced triumphantly that the adoption of Catholicism by the Emperor and his Chancellor was close at hand.[5]

The firmness of the belief in conventional dogmas,[48] which hampers the progress of rational enlightenment in orthodox Protestant circles as well as Catholic, is often admired as an expression of the deep emotion of the German people. But its real source is their confusion of thought and their credulity, the power of conservative tradition, and the reactionary state of political education. While our schools are bent under the yoke of the creeds, those of our neighbours are free. France, the pious daughter of the Church, gives anxious moments to her ambitious mother. She is breaking the chains of the Concordat, and taking up the work of the Reformation. In Germany, the birthplace of the Reformation, the Reichstag and the Government vie with each other in smoothing the paths for the Jesuits, and fostering, instead of suppressing, the intolerant spirit of the sectarian school. Let us hope that the latest episode in the history of evolution, its recognition by Jesuitical science, will bring about the reverse of what they intend—the substitution of rational science for blind faith.

THE STRUGGLE OVER OUR GENEALOGICAL TREE

OUR APE-RELATIVES AND THE VERTEBRATE-STEM

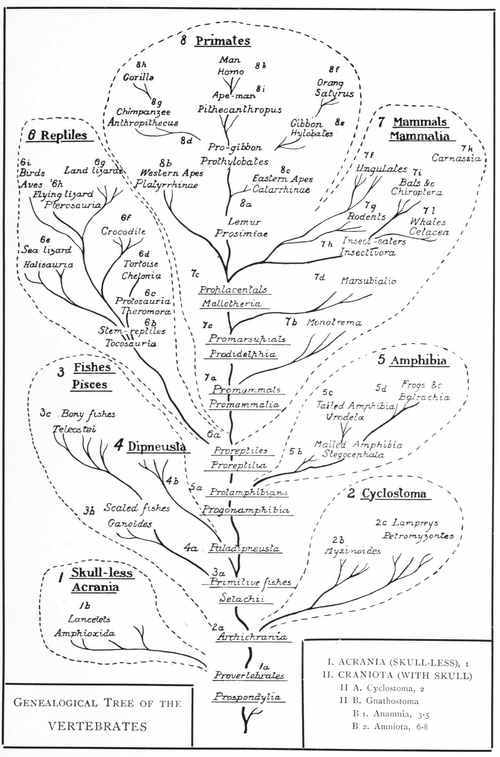

EXPLANATION OF PLATE II

SKELETONS OF FIVE ANTHROPOID APES

These skeletons of the five living genera of anthropomorpha are reduced to a common size, in order to show better the relative proportions of the various parts. The human skeleton is 1 20 th natural size, the gorilla 1 18 th, the chimpanzee 1 7 th, the orang 1 7 th, the gibbon 1 9 th. Young specimens of the chimpanzee and orang have been selected, because they approach nearer to man than the adult. No one of the living anthropoid apes is nearest to man in all respects; this cannot be said of either of the African (gorilla and chimpanzee) or the Asiatic (orang and gibbon). This anatomic fact is explained phylogenetically on the ground that none of them are direct ancestors of man; they represent divergent branches of the stem, of which man is the crown. However, the small gibbon is nearest related to the hypothetical common ancestor of all the anthropomorpha to which we give the name of Prothylobates. Further information will be found in my Last Link and Evolution of Man (chap. xxiii.).

Plate II.

SKELETONS OF FIVE ANTHROPOID APES.

YoungYoung

1/20

1/18

1/7

1/7

1/9

MAN

GORILLA

CHIMPANZEE

ORANG

GIBBON

(Homo)

(Anthropithecus)

(Satyrus)

(Hylobates)

CHAPTER II

THE STRUGGLE OVER OUR GENEALOGICAL TREE

OUR APE-RELATIVES AND THE VERTEBRATE-STEM

In the previous chapter I tried to give you a general idea of the present state of the controversy in regard to evolution. Comparing the various branches of thought we found that the older mythological ideas of the creation of the world were driven long ago out of the province of inorganic science, but that they did not yield to the rational conception of natural development until a much later date in the field of organic nature. Here the idea of evolution did not prove completely victorious until the beginning of the twentieth century, when its most zealous and dangerous opponent, the Church, was forced to admit it. Hence the open acknowledgment of the Jesuit, Father Wasmann, deserves careful attention, and we may look forward to a further development. If his force of conviction and his moral courage are strong enough, he will go on to draw the normal conclusions from his high scientific attainments and leave the Catholic Church, as the prominent Jesuits, Count Hoensbroech and the able geologist, Professor Renard of Ghent, one of the workers on the deep-sea deposits in the Challenger expedition,[52] have lately done. But even if this does not happen, his recognition of Darwinism, in the name of Christian belief, will remain a landmark in the history of evolution. His ingenious and very Jesuitical attempt to bring together the opposite poles will have no very mischievous effect; it will rather tend to hasten the victory of the scientific conception of evolution over the mystic beliefs of the Churches.

You will see this more clearly if we go on to consider the important special problem of the "descent of man from the ape," and its irreconcilability with the conventional belief that God made man according to His own image. That this ape or pithecoid theory is an irresistible deduction from the general principle of evolution was clearly recognised forty-five years ago, when Darwin's work appeared, by the shrewd and vigilant theologians; it was precisely in this fact that they found their strongest motive for vigorous resistance. It is quite clear. Either man was brought into existence, like the other animals, by a special creative act, as Moses and Linné taught (an "embodied idea of the Creator," as the famous Agassiz put it so late as 1858); or he has been developed naturally from a series of mammal ancestors, as is claimed by the systems of Lamarck and Darwin.

In view of the very great importance of this pithecoid theory, we will first cast a brief glance at its founders and then summarise the proofs in support of it. The famous French biologist, Jean Lamarck, was the first scientist definitely to affirm the descent of man from[53] the ape and seek to give scientific proof of it. In his splendid work, fifty years in advance of his time, the Philosophie Zoologique (1809), he clearly traced the modifications and advances that must have taken place in the transformation of the man-like apes (the primate forms similar to the orang and the chimpanzee); the adaptation to walking upright, the consequent modification of the hands and feet, and later, the formation of speech and the attainment of a higher degree of intelligence. Lamarck's remarkable theory, and this important consequence of it, soon fell into oblivion. When Darwin brought evolution to the front again fifty years afterwards, he paid no attention to the special conclusion. He was content to make the following brief prophetic observation in his work: "Light will be thrown on the origin and the history of man." Even this innocent remark seemed so momentous to the first German translator of the work, Bronn, that he suppressed it. When Darwin was asked by Wallace whether he would not go more fully into it, he replied: "I think of avoiding the whole subject, as it is so much involved in prejudice; though I quite admit that it is the highest and most interesting problem for the thinker."

The first thorough works of importance on the subject appeared in 1863. Thomas Huxley in England, and Carl Vogt in Germany, endeavoured to show that the descent of man from the ape was a necessary consequence of Darwinism, and to provide an empirical base for the theory by every available argument. Huxley's[54] work on Man's Place in Nature was particularly valuable. He first gave convincingly, in three lectures, the empirical evidence on the subject—the natural history of the anthropoid apes, the anatomical and embryological relations of man to the next lowest animals, and the recently discovered fossil human remains. I then (1866) made the first attempt to establish the theory of evolution comprehensively by research in anatomy and embryology, and to determine the chief stages in the natural classification of the vertebrates that must have been passed through by our earlier vertebrate ancestors. Anthropology thus becomes a part of zoology. In my History of Creation I further developed these early evolutionary sketches, and improvements were made in the successive editions.

In the meantime, the great master, Darwin, had decided to deal with this chief evolutionary problem in a special work. The two volumes of his Descent of Man appeared in 1871. They contained an able discussion of sexual selection, or the selective influence of sexual love and high psychic activities connected therewith, and their significance in regard to the origin of man. As this part of Darwin's work was afterwards attacked with particular virulence, I will say that, in my opinion, it is of the greatest importance, not only for the general theory of evolution, but also for psychology, anthropology, and æsthetics.

My own feeble early efforts (1866), not only to establish the descent of man from the nearest related apes, but also to determine more precisely[55] the long series of our earlier and lower vertebrate ancestors, had not at all satisfied me. In particular, I had had to leave unanswered in my General Morphology the very interesting question: from which invertebrate animals the vertebrate stem originally came. A clear and unexpected light was thrown on it some time afterwards by the astounding discoveries of Kowalevsky, which revealed an essential agreement in embryonic development between the lowest vertebrate (Amphioxus) and a lowly tunicate (Ascidia). In the succeeding years, the numerous discoveries in connection with the formation of the germinal layers in different animals so much enlarged our embryological outlook that I was able to prove the complete homology of the two-layered gastrula (a cup-shaped embryonic form) in all the tissue-forming animals (metazoa) in my Monograph on the Sponges. From this I inferred, in virtue of the biogenetic law, the common descent of all the metazoa from one and the same gastrula-shaped stem-form, the gastræa. This hypothetical stem-form, to which man's earliest multicellular ancestors also belong, was afterwards proved by Monticelli's observations to be still in existence. The evolution of these very simple tissue-forming animals from still simpler unicellular forms (protozoa) is shown by the corresponding processes that we witness in what is called the segmentation of the ovum or gastrulation, in the development of the two-layered germ from the single cell of the ovum.

Encouraged by these great advances of modern[56] phylogeny, and with the support of many new discoveries in comparative anatomy and embryology, in which a number of distinguished observers were at work, I was able in 1874 to venture on the first attempt to trace continuously the whole story of man's evolution. In doing so, I took my stand on the firm ground of the biogenetic law, seeking to give a phylogenetic cause for each fact of embryology. My Evolution of Man, which made the first attempt to accomplish this difficult task, was materially improved and enlarged as new and important discoveries were made. The latest edition (1903 [1904 in English]) contains thirty chapters distributed in two volumes, the first of which deals with embryology (or ontogeny), and the second with the development of species (or phylogeny).

Though I was quite conscious that there were bound to be gaps and weak points in these first attempts to frame a natural anthropogeny, I had hoped they would have some influence on modern anthropology, and especially that the first sketches of a genealogical tree of the animal world would prove a stimulus to fresh research and improvement. In this I was much mistaken. The dominant school of anthropology, especially in Germany, declined to suffer the introduction of the theory of evolution, declaring it to be an unfounded hypothesis, and described our carefully prepared ancestral trees as mere figments. This was due, in the first place, to the great authority of the founder and president (for[57] many years) of the German Anthropological Society, Rudolf Virchow, as I briefly pointed out in the previous chapter. In view of the great regard that is felt for this distinguished scientist, and the extent to which his powerful opposition prevented the spread of the theory, it is necessary to deal more fully with his position on the subject. I am still further constrained to do this because of the erroneous views of it that are circulating, and my own fifty years' acquaintance with my eminent teacher enables me to put them right.

Not one of Virchow's numerous pupils and friends can appreciate more than I do his real services to medical science. His Cellular Pathology (1858), his thorough application of the cell-theory to the science of disease, is, in my opinion, one of the greatest advances made by modern medicine. I had the good fortune to begin my medical studies at Würzburg in 1852, and to spend six valuable terms under the personal guidance of four biologists of the first rank—Albert Kölliker, Rudolf Virchow, Franz Leydig and Carl Gegenbaur. The great stimulus that I received from these distinguished masters in every branch of comparative and microscopic biology was the starting-point of my whole training in that science, and enabled me subsequently to follow with ease the higher intellectual flight of Johannes Müller. From Virchow especially I learned, not only the analytic art of careful observation and judicious appreciation of the detailed facts of anatomy, but also the synthetic conception of the whole human frame, the[58] profound conviction of the unity of our nature, the inseparable connection of body and mind, to which Virchow gave a fine expression in his classic essay on "The Efforts to bring about Unity in Scientific Medicine" (1849). The leading articles which he wrote at that time for the Journal of Pathological Anatomy and Physiology, which he had founded, contain much new insight into the wonders of life, and a number of excellent general reflections on their significance—pregnant ideas that we can make direct use of for Monistic purposes. In the controversy that broke out between empirical rationalism and materialism and the older vitalism and mysticism, he took the side of the former, and fought together with Jacob Moleschott, Carl Vogt, and Ludwig Büchner. I owe the firm conviction of the unity of organic and inorganic nature, of the mechanical character of all vital and psychic activity, which I have always held to be the foundation of my Monistic system, in a great measure to Virchow's teaching and the exhaustive conversations I had with him when I was his assistant. The profound views of the nature of the cell and the independent individuality of these elementary organisms, which he advanced in his great work Cellular Pathology, remained guiding principles for me in the prolonged studies that I made thirty years afterwards of the organisation of the radiolaria and other unicellular protists; and also in regard to the theory of the cell-soul, which followed naturally from the psychological study of it.

His life at Würtzburg was the most brilliant period[59] of Virchow's indefatigable scientific labours. A change took place when he removed to Berlin in 1856. He then occupied himself chiefly with political and social and civic interests. In the last respect he has done so much for Berlin and the welfare of the German people that I need not enlarge on it. Nor will I go into his self-sacrificing and often thankless political work as leader of the progressive party; there are differences of opinion as to its value. But we must carefully examine his peculiar attitude towards evolution, and especially its chief application, the ape-theory. He was at first favourable to it, then sceptical, and finally decidedly hostile.

When the Lamarckian theory was brought to light again by Darwin in 1859, many thought that it was Virchow's vocation to take the lead in defending it. He had made a thorough study of the problem of heredity; he had realised the power of adaptation through his study of pathological changes; and he had been directed to the great question of the origin of man by his anthropological studies. He was at that time regarded as a determined opponent of all dogmas; he combated transcendentalism either in the form of ecclesiastical creeds or anthropomorphism. After 1862 he declared that "the possibility of a transition from species to species was a necessity of science." When I opened the first public discussion of Darwinism at the Stettin scientific congress in 1863, Virchow and Alexander Braun were among the few scientists who would admit the subject to be important and deserving[60] of the most careful study. When I sent to him in 1865 two lectures that I had delivered at Jena on the origin and genealogical tree of the human race, he willingly received them amongst his Collection of Popular Scientific Lectures. In the course of many long conversations I had with him on the matter, he agreed with me in the main, though with the prudent reserve and cool scepticism that characterised him. He adopts the same moderate attitude in the lecture that he delivered to the Artisans' Union at Berlin in 1869 on "Human and Ape Skulls."

His position definitely changed in regard to Darwinism from 1877 onward. At the Scientific Congress that was then held at Munich I had, at the pressing request of my Munich friends, undertaken the first address (on 18th September) on "Modern Evolution in Relation to the whole of Science." In this address I had substantially advanced the same general views that I afterwards enlarged in my Monism, Riddle of the Universe, and Wonders of Life. In the ultramontane capital of Bavaria, in sight of a great university which emphatically describes itself as Catholic, it was somewhat bold to make such a confession of faith. The deep impression that it had made was indicated by the lively manifestations of assent on the one hand, and displeasure on the other, that were at once made in the Congress itself and in the Press. On the following day I departed for Italy (according to an arrangement made long before). Virchow did not come to Munich until two days afterwards, when he[61] delivered (on 22nd September, in response to entreaties from people of position and influence) his famous antagonistic speech on "The Freedom of Science in the Modern State." The gist of the speech was that this freedom ought to be restricted; that evolution is an unproved hypothesis, and ought not to be taught in the school because it is dangerous to the State: "We must not teach," he said, "that man descends from the ape or any other animal." In 1849, the young Monist, Virchow, had emphatically declared this conviction, "that he would never be induced to deny the thesis of the unity of human nature and its consequences"; now, twenty-eight years afterwards, the prudent Dualistic politician entirely denied it. He had formerly taught that all the bodily and mental processes in the human organism depend on the mechanism of the cell-life; now he declared the soul to be a special immaterial entity. But the crowning feature of this reactionary speech was his compromise with the Church, which he had fought so vigorously twenty years before.

The character of Virchow's speech at Munich is best seen in the delight with which it was at once received by the reactionary and clerical papers, and the profound concern of all Liberal journals, either in the political or the religious sense. When Darwin read the English translation of the speech he—generally so gentle in his judgments—wrote: "Virchow's conduct is shameful, and I hope he will some day feel the shame." In 1878, I made a full reply to it in my Free Science and Free[62] Teaching, in which I collected the most important press opinions on the matter.[6]

From this very decided turn at Munich until his death, twenty-five years afterwards, Virchow was an indefatigable and very influential opponent of evolution. In his annual appearances at congresses he has always contested it, and has obstinately clung to his statement that "it is quite certain that man does not descend from the ape or any other animal." To the question: "Whence does he come, then?" he had no answer, and retired to the resigned position of the Agnostic, which was common before Darwin's time: "We do not know how life arose, and how the various species came into the world." His son-in-law, Professor Rabl, has tried to draw attention once more to his earlier conception, and has declared that even in later years Virchow often recognised the truth of evolution in private conversation. This only makes it the more regrettable that he always said the contrary in public. The fact remains that ever since the opponents of evolution, especially the reactionaries and clericals, have appealed to the authority of Virchow.