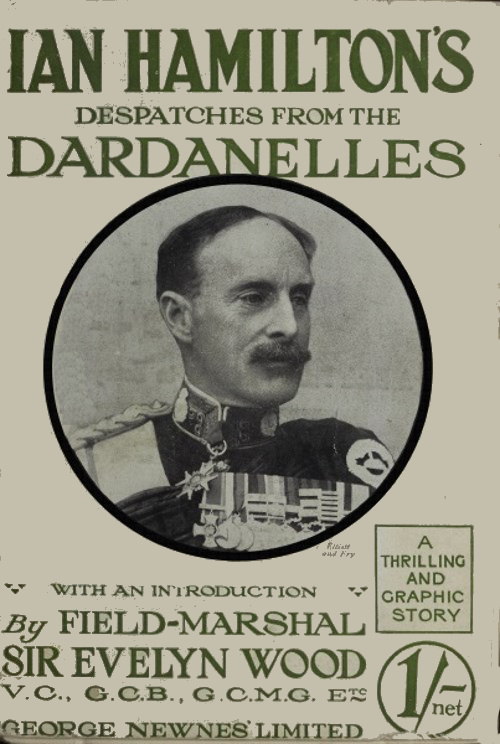

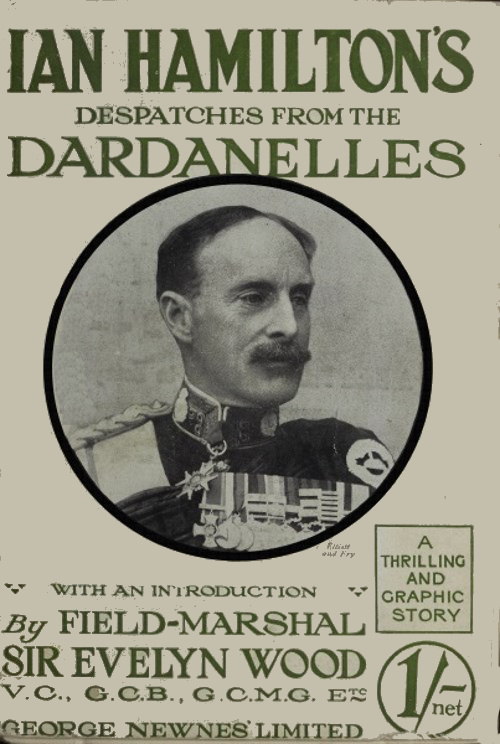

Title: Sir Ian Hamilton's Despatches from the Dardanelles, etc.

Author: Ian Hamilton

Author of introduction, etc.: Evelyn Wood

Release date: January 13, 2017 [eBook #53959]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MWS, Alan and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

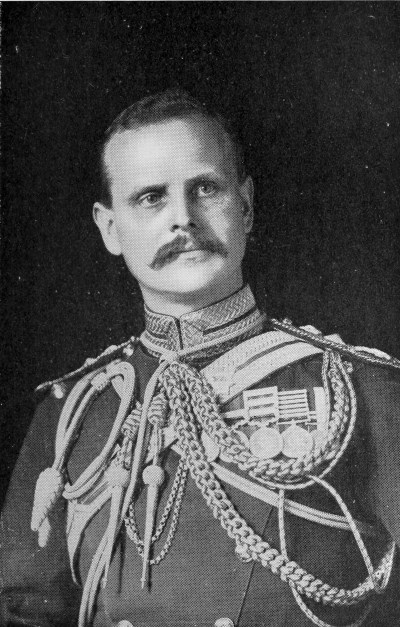

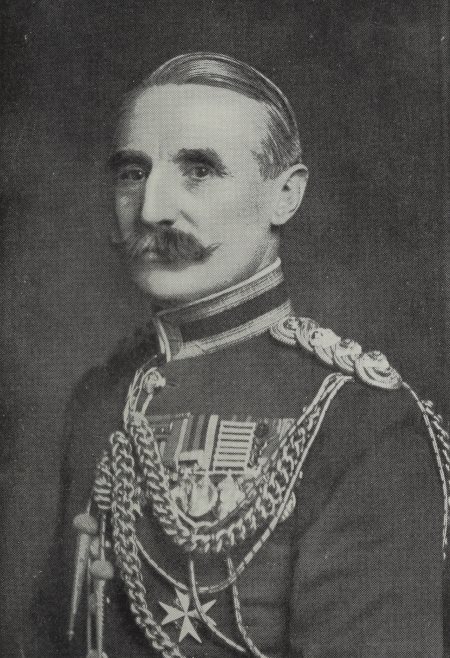

General Sir Ian Hamilton.

| PAGE | |

| The First Despatch | 1 |

| The Second Despatch | 43 |

| Press Bureau Statements | 84 |

| Vice-Admiral de Robeck's Despatch | 89 |

| General Sir Ian Hamilton | Frontispiece | |

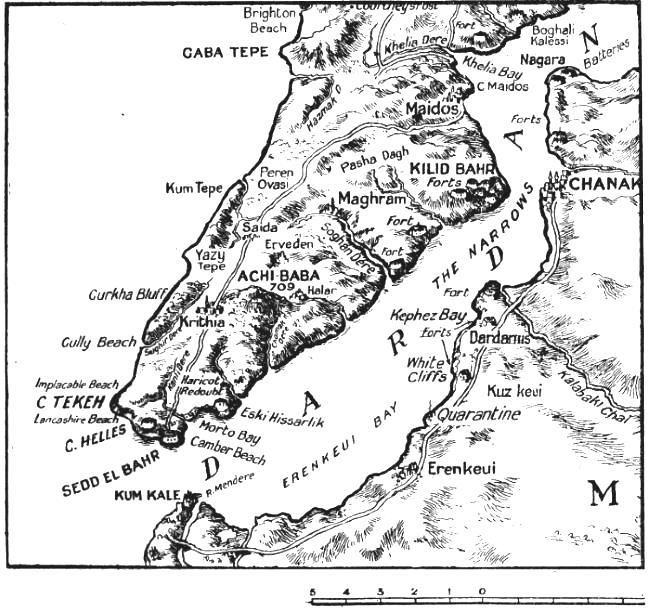

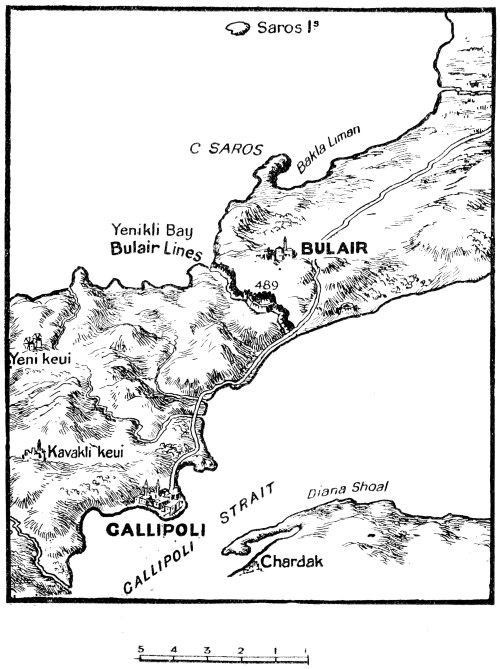

| Map 1 | facing | p. 16 |

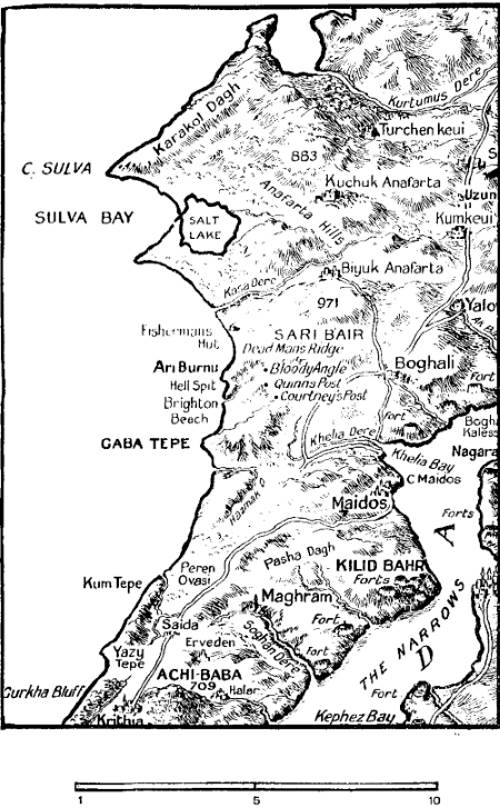

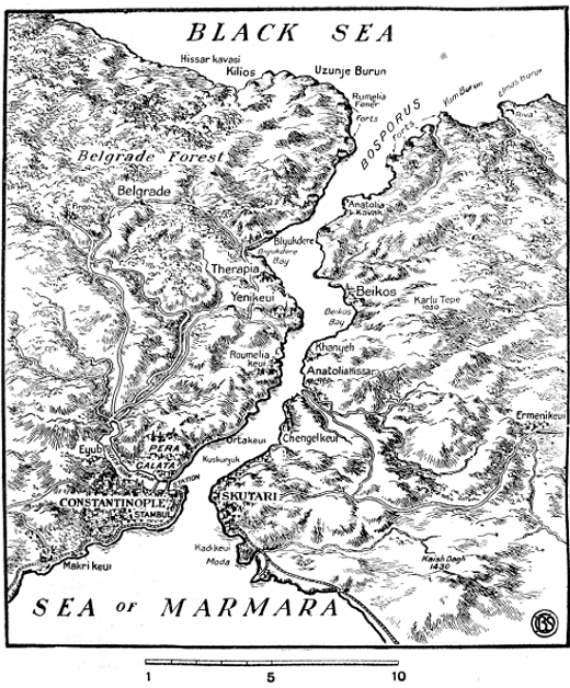

| Map 2 | " | 32 |

| Lieut.-General Sir W. R. Birdwood, | ||

| K.C.S.I. | " | 40 |

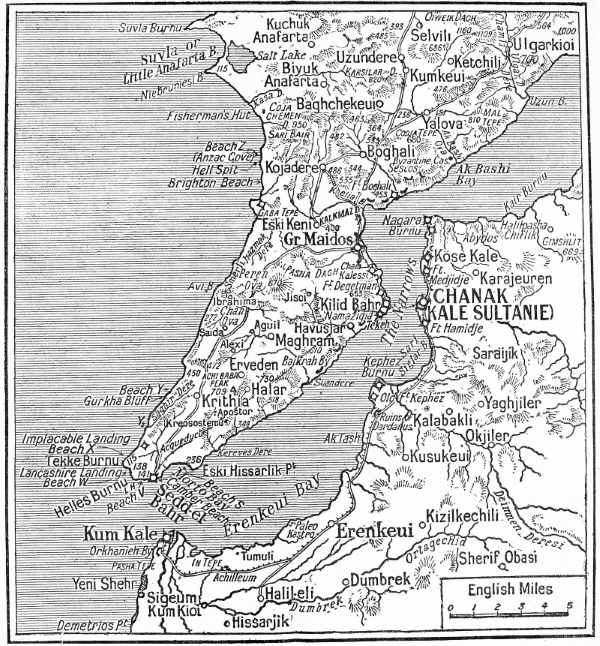

| Map 3 | " | 64 |

| Brigadier-General R. W. M. | ||

| Jackson, C.B. | " | 78 |

| Lieut.-General A. G. Hunter-Weston, | ||

| C.B. | " | 82 |

| Map 4 | " | 96 |

| Map 5 | " | 116 |

I was serving in the Royal Navy when Lieutenant Lucas, H.M.S. Hecla, earned the first Victoria Cross that was gazetted, for having thrown overboard a live shell. I was in the 21-gun battery before Sevastopol sixty-one years ago when Captain Sir William Peel, R.N., picked up from amongst a number of powder cases, and carried resting on his chest, a 42-pounder live Russian shell, which burst as he threw it over the parapet; and having seen many extraordinarily gallant deeds performed by men of all ranks in both Services, I think that I am a fair judge of fighting values.

Just sixty-one years ago an Ordinary Seaman, H.M.S. Queen, was one of a detachment of a Petty Officer and six Bluejackets who had left our advanced trenches carrying a heavy scaling ladder, 18 feet long, to enable the soldiers to cross the ditch of the Great Redan at Sevastopol. When the only surviving ladder-party was close up to the abatis, three of the men under the Rear[Pg viii] part of the ladder were shot down, and a young midshipman then put his shoulder under it. The boy was young, had already been wounded, and was moreover weak, being officially on the sick list, so doubtless was an inefficient carrier. The Bluejacket in front was unaffected by the storm of missiles of all sorts through which he had passed in crossing the 500 yards between our trenches and the Redan, although in his company of sixty men, nineteen sailors had been killed and twenty-nine wounded within twenty minutes.

The fire was vividly described by Field-Marshal Lord Raglan, who was looking on. He, with the experience of the Peninsular War, and having witnessed the assaults of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajos, thus portrayed it: "I never before witnessed such a continuous and heavy fire of grape and musketry"; and again: "I had no conception of such a shower of grape." The Bluejacket had remained apparently unconcerned by the carnage, but he realised that the now one-surviving carrier at the Rear end of the ladder was not doing much to help, and thinking that he was addressing a messmate, exclaimed encouragingly, as he half turned his head: "Come on, Bill, let's get our ladder up first," being shot dead as he finished the sentence.

I was often asked in the early days of[Pg ix] the War whether I thought that the men in the ranks were of the same fighting value as those of two generations ago, and invariably answered confidently as follows: "Yes, just the same at heart, but with better furnished heads." The contents of this Booklet clearly attest the accuracy of that opinion.

Education has done much to improve the "Fighting Services," but the most potent magnet for bringing out the best of the Anglo-Saxon Nation is the fuller appreciation of Democracy. The officers, not content with leading their men gallantly, which they have always done, now feel for them and with them as staunch comrades. All ranks are now nearer, geographically, mentally and morally, than they have ever been before to the heart of England.

Sixty years ago a brave officer could think of no better prize for the reward of gallantry than money, and a General about to assault Sevastopol on September 8, 1855, offered £5 for the first man inside the Great Redan.

When, in the winter 1854-5, the institution of the Victoria Cross was suggested, the Royal Warrant for which was not issued until 1856, nearly all the senior officers disliked the innovation, and our Government,[Pg x] realising this feeling, hesitated to entrust them with the selection of the recipients of the distinction. In one battalion the men were instructed to nominate a private soldier. They, as in all good regiments, reflected the views of their officers, as regards the innovation, and unanimously elected a comrade who, being trusted for his sobriety and honesty, used to carry down the grog-can at dinner-time to the trenches, and so, not only enjoyed a "soft billet," but was never under fire except for one hour in twenty-four.

A perusal of the despatches and of the London Gazette announcing the bestowal of decorations is like reading of the mortal combats described in Virgil's Twelfth Book of the "Æneid," and fills the mind with admiration.

It is perhaps only soldiers who can fully appreciate the enduring courage of the Munster Fusiliers, who, after losing half their numbers by drowning, and by fire of shrapnel and bullets, with their Brigadier-General, his Brigade-Major, and most of their Regimental officers down, could reform into remnants of Companies, and after a night without food, follow a Staff Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Doughty Wylie, from the beach up to the Old Castle, and assault successfully Hill No. 141. These men are, indeed, worthy descendants[Pg xi] of their predecessors who carried the walls of Delhi in 1857.

No soldiers can read the story of the heroism shown by the 1st Lancashire Fusiliers commanded by Major Bishop; how they jumped ashore under a hurricane of lead which was rained on Beach W, and how they broke through the wire, and had by 10 a.m. carried three lines of hostile trenches, without feeling proud of the people of the "Clothing Towns." The men are worthy of their forefathers, who at Minden in 1759 advanced in line with "Colours flying and Drums beating" against a mass of hostile cavalry, which they defeated.

I hope that the young soldiers of the King's Own Scottish Borderers may be taught to recall, not only the deeds of their predecessors at Namur, 1695, and the glorious victory of the infantry over a mass of hostile cavalry, which they shared with the Lancashire Fusiliers; but also what their battalion did on Y Beach of the Dardanelles on April 26 last, when after many hours of fighting, causing the battalion a loss of 50 per centum, the survivors held with determination a trench which had been constructed for four times their number of effectives; and then, when orders were given to abandon the position, how the courage of a small Rear-guard[Pg xii] enabled all the wounded, ammunition, and stores to be safely re-embarked.

The burning courage of the Australian and New Zealand Division must make any soldier proud of his Colonial brothers. They were disembarked at night, and the units became unavoidably mixed up, for some of them had in their ardour followed up the Turks, whom they had repulsed, further than had been intended. It seems from a perusal of the despatch, that in spite of their short military training, the self-reliance naturally acquired by men who lead a less artificial life than those brought up in cities and towns in England, enabled our Colonials, inspired by their personal courage, to resist successfully for hours the attacks of a vastly superior number of Turks.

In a number of glorious deeds recorded in the London Gazette it is somewhat difficult to select any deed standing out beyond the rest, but it seems probable that the personal prowess of Lance-Corporal Albert Jacka, 14th Battalion Australian Imperial Forces, can scarcely ever be surpassed. During the night of May 19-20 he, with four other Australians, was holding a trench which was heavily attacked. The five men accounted for many Turks, but when Jacka's four comrades had been killed or wounded, the trench was[Pg xiii] rushed, and occupied by seven Moslems. Lance-Corporal Jacka attacked and killed all seven, five by successive shots from his rifle, and two with his bayonet.

Commander Unwin's exploits were remarkable. He had fitted admirably for the work in view the River Clyde steamship, and successfully beached her; and although hit by three bullets, he worked for hours in the water to save wounded men, and continued his self-sacrificing efforts until he became inanimate from cold and exhaustion.

One of Commander Unwin's subordinates, George Samson, who vied with him in tasks of enduring gallantry, belongs to the Royal Naval Reserve, and is mentioned for having worked on a lighter all day attending to the stricken until he was dangerously wounded. Yet at the annual dinner last week of the National Sailors' and Firemen's Union, when Samson, apparently now a Petty Officer, as modest as he is brave, was presented with a gold watch and chain, in returning thanks, said: "I would sooner land again in the Dardanelles than have to make a speech."

Commander Robinson is a remarkable instance not only of calculating courage, but also of the thorough training which Naval officers receive. "He refused to allow anyone to accompany him on his dangerous[Pg xiv] mission, as his men's white clothing made them very conspicuous. After having penetrated alone into a two-gun battery of the enemy, on the 26th February, he destroyed a gun and then returning for another demolition charge, wrecked the remaining piece."

The Commander-in-Chief at Gallipoli, affectionately termed by his friends in the Service "Johnnie," being a very brave man, appreciates the courage of those under his command. He showed great determination in the unhappy war in South Africa in 1881, when he was severely wounded, and in the battle of Eland's Laaghte in October, 1899, led so determinedly in front that he would have been recommended for the Victoria Cross but for his senior rank.

The Services in the Dardanelles are fortunate in having a scholarly General to narrate their stirring deeds, for many of our commanders, from Marlborough to Clyde, have felt more difficulty in writing a description of a victory than they had experienced in winning it.

In the last half century the power of appreciating noble deeds and the merits of capable officers has increased. The days are fortunately passed since our senior generals said: "We find all our officers are much of a[Pg xv] muchness."

There is now a more generous acknowledgment of the fact that the life of a labouring man is as much to him as is that of a peer to a duke's son; there has grown up amongst our soldiers a deeper sense of appreciating valour apart from natural or acquired advantages.

As Admiral Holmes and his Squadron in the St. Laurence enabled General Wolfe to capture Quebec in 1759, so Admiral John de Robeck has enabled General Sir Ian Hamilton to land his troops and hold the western coast of the Gallipoli Peninsula, and Hamilton, happier than Wolfe, lives to acknowledge his debt to the Senior Service, describing it affectionately as "The father and mother of the Army."

October 1. 1915 Evelyn Wood

From the General Commanding the Mediterranean

Expeditionary Force to the Secretary of State for

War, War Office, London, S.W.

My Lord,

I have the honour to submit my report on the operations in the Gallipoli Peninsula up to and including May 5.

In accordance with your Lordship's instructions I left London on March 13 with my General Staff by special train to Marseilles, and thence in H.M.S. Phæton to the scene of the naval operations in the Eastern Mediterranean, reaching Tenedos on March 17 shortly after noon.

Immediately on arrival I conferred with Vice-Admiral de Robeck, Commanding the Eastern Mediterranean Fleet; Général d'Amade, Commanding the French Corps Expéditionnaire; and Contre-Amiral Guepratte, in command of the French Squadron. At this conference past difficulties were explained to me, and the intention to make a fresh attack on the morrow was announced. The amphibious battle between warships and land fortresses[Pg 2] took place next day, March 18. I witnessed these stupendous events, and thereupon cabled your Lordship my reluctant deduction that the co-operation of the whole of the force under my command would be required to enable the Fleet effectively to force the Dardanelles.

By that time I had already carried out a preliminary reconnaissance of the north-western shore of the Gallipoli Peninsula, from its isthmus, where it is spanned by the Bulair fortified lines, to Cape Helles, at its extremest point. From Bulair this singular feature runs in a south-westerly direction for 52 miles, attaining near its centre a breadth of 12 miles. The northern coast of the northern half of the promontory slopes downwards steeply to the Gulf of Xeros, in a chain of hills, which extend as far as Cape Sulva. The precipitous fall of these hills precludes landing, except at a few narrow gullies, far too restricted for any serious military movements. The southern half of the peninsula is shaped like a badly-worn boot. The ankle lies between Gaba Tepe and Kalkmaz Dagh; beneath the heel lie the cluster of forts at Kilid Bahr; whilst the toe is that promontory, five miles in width, stretching from Tekke Burnu to Sedd-el-Bahr.

The three dominating features in this southern section seemed to me to be:

(1) Sari Bair Mountain, running up in a succession of almost perpendicular escarpments to 970 feet. The whole mountain seemed to be a network of ravines and covered with thick jungle.

(2) Kilid Bahr plateau, which rises, a natural fortification artificially fortified, to a height of 700 feet to cover the forts of the Narrows from an attack from the Aegean.

(3) Achi Babi, a hill 600 feet in height, dominating at long field-gun range what I have described as being the toe of the peninsula.

A peculiarity to be noted as regards this last southern sector is that from Achi Babi to Cape Helles the ground is hollowed out like a spoon, presenting only its outer edges to direct fire from the sea. The inside of the spoon appears to be open and undulating, but actually it is full of spurs, nullahs, and confused under-features.

Generally speaking the coast is precipitous, and good landing-places are few. Just south of Tekke Burnu is a small sandy bay (W), and half a mile north of it is another small break in the cliffs (X). Two miles farther up the coast the mouth of a stream indents these same cliffs (Y 2), and yet another mile and a half up a scrub-covered gully looked as if active infantry might be able to scramble up it on to heights not altogether dissimilar to those of Abraham by Quebec (Y). Inside Sedd-el-Bahr is a sandy beach (V), about 300[Pg 4] yards across, facing a semicircle of steeply-rising ground, as the flat bottom of a half-saucer faces the rim, a rim flanked on one side by an old castle, on the other by a modern fort. By Eski Hissarlik, on the east of Morto Bay (S), was another small beach, which was, however, dominated by the big guns from Asia. Turning northwards again, there are two good landing-places on either side of Gaba Tepe. Farther to the north of that promontory the beach was supposed to be dangerous and difficult. In most of these landing-places the trenches and lines of wire entanglements were plainly visible from on board ship. What seemed to be gun emplacements and infantry redoubts could also be made out through a telescope, but of the full extent of these defences and of the forces available to man them there was no possibility of judging except by practical test.

Altogether the result of this and subsequent reconnaissances was to convince me that nothing but a thorough and systematic scheme for flinging the whole of the troops under my command very rapidly ashore could be expected to meet with success; whereas, on the other hand, a tentative or piecemeal programme was bound to lead to disaster. The landing of an army upon the theatre of operations I have described—a theatre strongly garrisoned throughout, and prepared for any such attempt—involved difficulties for which no precedent was forthcoming in military history except possibly in the sinister legends of Xerxes. The beaches were either so well defended by works and guns or else[Pg 5] so restricted by nature that it did not seem possible, even by two or three simultaneous landings, to pass the troops ashore quickly enough to enable them to maintain themselves against the rapid concentration and counter-attack which the enemy was bound in such case to attempt. It became necessary, therefore, not only to land simultaneously at as many points as possible, but to threaten to land at other points as well. The first of these necessities involved another unavoidable if awkward contingency, the separation by considerable intervals of the force.

The weather was also bound to play a vital part in my landing. Had it been British weather there would have been no alternative but instantly to give up the adventure. To land two or three thousand men, and then to have to break off and leave them exposed for a week to the attacks of 34,000 regular troops, with a hundred guns at their back, was not an eventuality to be lightly envisaged. Whatever happened the weather must always remain an incalculable factor, but at least by delay till the end of April we had a fair chance of several days of consecutive calm.

Before doing anything else I had to redistribute the troops on the transports to suit the order of their disembarkation. The bulk of the forces at my disposal had, perforce, been embarked without its having been possible to pay due attention to[Pg 6] the operation upon which I now proposed that they should be launched.

Owing to lack of facilities at Mudros redistribution in that harbour was out of the question. With your Lordship's approval, therefore, I ordered all the transports, except those of the Australian Infantry Brigade and the details encamped at Lemnos Island, to the Egyptian ports. On March 24 I myself, together with the General Staff, proceeded to Alexandria, where I remained until April 7, working out the allocation of troops to transports in minutest detail as a prelude to the forthcoming disembarkation. General d'Amade did likewise.

On April 1 the remainder of the General Headquarters, which had not been mobilized when I left England, arrived at Alexandria.

Apart from the rearrangements of the troops, my visit to Egypt was not without profit, since it afforded me opportunities of conferring with the G.O.C. Egypt and of making myself acquainted with the troops, drawn from all parts of the French Republic and of the British Empire, which it was to be my privilege to command.

By April 7 my preparations were sufficiently advanced to enable me to return with my General Staff to Lemnos, so as to put the finishing touches to my plan in close co-ordination with the Vice-Admiral Commanding the Eastern Mediterranean Fleet.

The covering force of the 29th Division left Mudros Harbour on the evening of April 23 for the five beaches, S, V, W, X, and Y. Of these, V, W,[Pg 7] and X were to be main landings, the landings at S and Y being made mainly to protect the flanks, to disseminate the forces of the enemy, and to interrupt the arrival of his reinforcements. The landings at S and Y were to take place at dawn, whilst it was planned that the first troops for V, W, and X beaches should reach the shore simultaneously at 5.30 a.m. after half an hour's bombardment from the Fleet.

The transports conveying the covering force arrived off Tenedos on the morning of the 24th, and during the afternoon the troops were transferred to the warships and fleet-sweepers in which they were to approach the shore. About midnight these ships, each towing a number of cutters and other small boats, silently slipped their cables and, escorted by the 3rd Squadron of the Fleet, steamed slowly towards their final rendezvous at Cape Helles. The rendezvous was reached just before dawn on the 25th. The morning was absolutely still; there was no sign of life on the shore; a thin veil of mist hung motionless over the promontory; the surface of the sea was as smooth as glass. The four battleships and four cruisers which formed the 3rd Squadron at once took up the positions that had been allotted to them, and at 5 a.m., it being then light enough to fire, a violent bombardment of the enemy's defences was begun.[Pg 8] Meanwhile the troops were being rapidly transferred to the small boats in which they were to be towed ashore. Not a move on the part of the enemy; except for shells thrown from the Asiatic side of the Straits the guns of the Fleet remained unanswered.

The detachment detailed for S beach (Eski Hissarlik Point) consisted of the 2nd South Wales Borderers (less one company) under Lieut.-Colonel Casson. Their landing was delayed by the current, but by 7.30 a.m. it had been successfully effected at the cost of some fifty casualties, and Lieut.-Colonel Casson was able to establish his small force on the high ground near De Totts Battery. Here he maintained himself until the general advance on the 27th brought him into touch with the main body.

The landing on Y beach was entrusted to the King's Own Scottish Borderers and the Plymouth (Marine) Battalion, Royal Naval Division, specially attached to the 29th Division for this task, the whole under the command of Lieut.-Colonel Koe. The beach at this point consisted merely of a narrow strip of sand at the foot of a crumbling scrub-covered cliff some 200 feet high immediately to the west of Krithia.

A number of small gullies running down the face of the cliff facilitated the climb to the summit,[Pg 9] and so impracticable had these precipices appeared to the Turks that no steps had been taken to defend them. Very different would it have been had we, as was at one time intended, taken Y 2 for this landing. There a large force of infantry, entrenched up to their necks, and supported by machine and Hotchkiss guns, were awaiting an attempt which could hardly have made good its footing. But at Y both battalions were able in the first instance to establish themselves on the heights, reserves of food, water, and ammunition were hauled up to the top of the cliff, and, in accordance with the plan of operations, an endeavour was immediately made to gain touch with the troops landing at X beach. Unfortunately, the enemy's strong detachment from Y 2 interposed, our troops landing at X were fully occupied in attacking the Turks immediately to their front, and the attempt to join hands was not persevered with.

Later in the day a large force of Turks were seen to be advancing upon the cliffs above Y beach from the direction of Krithia, and Colonel Koe was obliged to entrench. From this time onward his small force was subjected to strong and repeated attacks, supported by field artillery, and owing to the configuration of the ground, which here drops inland from the edge of the cliff, the guns of the supporting ships could render him little assistance. Throughout the afternoon and all through the night the Turks made assault after assault upon the British line. They threw bombs into the trenches, and, favoured by darkness, actually[Pg 10] led a pony with a machine gun on its back over the defences, and were proceeding to come into action in the middle of our position when they were bayoneted.

The British repeatedly counter-charged with the bayonet, and always drove off the enemy for the moment, but the Turks were in a vast superiority and fresh troops took the place of those who temporarily fell back. Colonel Koe (since died of wounds) had become a casualty early in the day, and the number of officers and men killed and wounded during the incessant fighting was very heavy. By 7 a.m. on the 26th only about half of the King's Own Scottish Borderers remained to man the entrenchment made for four times their number. These brave fellows were absolutely worn out with continuous fighting; it was doubtful if reinforcements could reach them in time, and orders were issued for them to be re-embarked. Thanks to H.M.S. Goliath, Dublin, Amethyst, and Sapphire, thanks also to the devotion of a small rearguard of the King's Own Scottish Borderers, which kept off the enemy from lining the cliff, the re-embarkation of the whole of the troops, together with the wounded, stores, and ammunition, was safely accomplished, and both battalions were brought round the southern end of the peninsula. Deplorable as the heavy losses had been, and unfortunate as was the tactical failure to make good so much ground at the outset, yet, taking the operation as it stood, there can be no doubt it has contributed greatly to the success of the main attack,[Pg 11] seeing that the plucky stand made at Y beach had detained heavy columns of the enemy from arriving at the southern end of the peninsula during what it will be seen was a very touch-and-go struggle.

The landing-place known as X beach consists of a strip of sand some 200 yards long by 8 yards wide at the foot of a low cliff. The troops to be landed here were the 1st Royal Fusiliers, who were to be towed ashore from H.M.S. Implacable in two parties, half a battalion at a time, together with a beach working party found by the Anson Battalion, Royal Naval Division. About 6 a.m. H.M.S. Implacable, with a boldness much admired by the Army, stood quite close in to the beach, firing very rapidly with every gun she could bring to bear. Thus seconded, the Royal Fusiliers made good their landing with but little loss. The battalion then advanced to attack the Turkish trenches on the Hill 114, situated between V and W beaches, but were heavily counter-attacked and forced to give ground. Two more battalions of the 87th Brigade soon followed them, and by evening the troops had established themselves in an entrenched position extending from half a mile round the landing-place and as far south as Hill 114. Here they were in touch with the Lancashire Fusiliers, who had landed on W beach. Brigadier-General Marshall, commanding the 87th Brigade, had been[Pg 12] wounded during the day's fighting, but continued in command of the brigade.

The landing on V beach was planned to take place on the following lines:

As soon as the enemy's defences had been heavily bombarded by the Fleet, three companies of the Dublin Fusiliers were to be towed ashore. They were to be closely followed by the collier River Clyde (Commander Unwin, R.N.), carrying between decks the balance of the Dublin Fusiliers, the Munster Fusiliers, half a battalion of the Hampshire Regiment, the West Riding Field Company, and other details.

The River Clyde had been specially prepared for the rapid disembarkation of her complement, and large openings for the exit of the troops had been cut in her sides, giving on to a wide gangplank by which the men could pass rapidly into lighters which she had in tow. As soon as the first tows had reached land the River Clyde was to be run straight ashore. Her lighters were to be placed in position to form a gangway between the ship and the beach, and by this means it was hoped that 2,000 men could be thrown ashore with the utmost rapidity. Further, to assist in covering the landing, a battery of machine guns, protected by sandbags, had been mounted in her bows.

The remainder of the covering force detailed for this beach was then to follow in tows from the attendant battleships.

V beach is situated immediately to the west of Sedd-el-Bahr. Between the bluff on which stands Sedd-el-Bahr village and that which is crowned by No. 1 Fort the ground forms a very regular amphitheatre of three or four hundred yards radius. The slopes down to the beach are slightly concave, so that the whole area contained within the limits of this natural amphitheatre, whose grassy terraces rise gently to a height of a hundred feet above the shore, can be swept by the fire of a defender. The beach itself is a sandy strip some 10 yards wide and 350 yards long, backed along almost the whole of its extent by a low sandy escarpment about 4 feet high, where the ground falls nearly sheer down to the beach. The slight shelter afforded by this escarpment played no small part in the operations of the succeeding thirty-two hours.

At the south-eastern extremity of the beach, between the shore and the village, stands the old fort of Sedd-el-Bahr, a battered ruin with wide breaches in its walls and mounds of fallen masonry within and around it. On the ridge to the north, overlooking the amphitheatre, stands a ruined barrack. Both of these buildings, as[Pg 14] well as No. 1 Fort, had been long bombarded by the Fleet, and the guns of the forts had been put out of action; but their crumbled walls and the ruined outskirts of the village afforded cover for riflemen, while from the terraced slopes already described the defenders were able to command the open beach, as a stage is overlooked from the balconies of a theatre. On the very margin of the beach a strong barbed-wire entanglement, made of heavier metal and longer barbs than I have ever seen elsewhere, ran right across from the old fort of Sedd-el-Bahr to the foot of the north-western headland. Two-thirds of the way up the ridge a second and even stronger entanglement crossed the amphitheatre, passing in front of the old barrack and ending in the outskirts of the village. A third transverse entanglement, joining these two, ran up the hill near the eastern end of the beach, and almost at right angles to it. Above the upper entanglement the ground was scored with the enemy's trenches, in one of which four pom-poms were emplaced; in others were dummy pom-poms to draw fire, while the debris of the shattered buildings on either flank afforded cover and concealment for a number of machine guns, which brought a cross-fire to bear on the ground already swept by rifle fire from the ridge.

Needless to say, the difficulties in the way of previous reconnaissance had rendered it impossible to obtain detailed information with regard either to the locality or to the enemy's preparations.

As often happens in war, the actual course of[Pg 15] events did not quite correspond with the intentions of the Commander. The River Clyde came into position off Sedd-el-Bahr in advance of the tows, and, just as the latter reached the shore, Commander Unwin beached his ship also. Whilst the boats and the collier were approaching the landing-place the Turks made no sign. Up to the very last moment it appeared as if the landing was to be unopposed. But the moment the first boat touched bottom the storm broke. A tornado of fire swept over the beach, the incoming boats, and the collier. The Dublin Fusiliers and the naval boats' crews suffered exceedingly heavy losses while still in the boats. Those who succeeded in landing and in crossing the strip of sand managed to gain some cover when they reached the low escarpment on the further side. None of the boats, however, was able to get off again, and they and their crews were destroyed upon the beach.

Now came the moment for the River Clyde to pour forth her living freight; but grievous delay was caused here by the difficulty of placing the lighters in position between the ship and the shore. A strong current hindered the work and the enemy's fire was so intense that almost every man engaged upon it was immediately shot. Owing, however, to the splendid gallantry of the naval working party, the lighters were eventually placed in position, and then the disembarkation began.

A company of the Munster Fusiliers led the way; but, short as was the distance, few of the[Pg 16] men ever reached the farther side of the beach through the hail of bullets which poured down upon them from both flanks and the front. As the second company followed, the extemporized pier of lighters gave way in the current. The end nearest to the shore drifted into deep water, and many men who had escaped being shot were drowned by the weight of their equipment in trying to swim from the lighter to the beach. Undaunted workers were still forthcoming, the lighters were again brought into position, and the third company of the Munster Fusiliers rushed ashore, suffering heaviest loss this time from shrapnel as well as from rifle, pom-pom, and machine-gun fire.

(To face page 16.)

Map 1.

For a space the attempt to land was discontinued. When it was resumed the lighters again drifted into deep water, with Brigadier-General Napier, Captain Costeker, his Brigade-Major, and a number of men of the Hampshire Regiment on board. There was nothing for them all but to lie down on the lighters, and it was here that General Napier and Captain Costeker were killed. At this time, between 10 and 11 a.m., about one thousand men had left the collier, and of these nearly half had been killed or wounded before they could reach the little cover afforded by the steep, sandy bank at the top of the beach. Furt[Pg 17]her attempts to disembark were now given up. Had the troops all been in open boats but few of them would have lived to tell the tale. But, most fortunately, the collier was so constructed as to afford fairly efficient protection to the men who were still on board, and, so long as they made no attempt to land, they suffered comparatively little loss.

Throughout the remainder of the day there was practically no change in the position of affairs. The situation was probably saved by the machine-guns on the River Clyde, which did valuable service in keeping down the enemy's fire and in preventing any attempt on their part to launch a counter-attack. One half-company of the Dublin Fusiliers, which had been landed at a camber just east of Sedd-el-Bahr village, was unable to work its way across to V beach, and by midday had only twenty-five men left. It was proposed to divert to Y beach that part of the main body which had been intended to land on V beach; but this would have involved considerable delay owing to the distance, and the main body was diverted to W beach, where the Lancashire Fusiliers had already effected a landing.

Late in the afternoon part of the Worcestershire Regiment and the Lancashire Fusiliers worked across the high ground from W beach, and seemed likely to relieve the situation by taking the defenders of V beach in flank. The pressure on their own front, however, and the numerous barbed-wire entanglements which intervened, checked this advance, and at nightfall the Turkish garrison still[Pg 18] held their ground. Just before dark some small parties of our men made their way along the shore to the outer walls of the Old Fort, and when night had fallen the remainder of the infantry from the collier were landed. A good force was now available for attack, but our troops were at such a cruel disadvantage as to position, and the fire of the enemy was still so accurate in the bright moonlight, that all attempts to clear the fort and the outskirts of the village during the night failed one after the other. The wounded who were able to do so without support returned to the collier under cover of darkness; but otherwise the situation at daybreak on the 26th was the same as it had been on the previous day, except that the troops first landed were becoming very exhausted.

Twenty-four hours after the disembarkation began there were ashore on V beach the survivors of the Dublin and Munster Fusiliers and of two companies of the Hampshire Regiment. The Brigadier and his Brigade-Major had been killed; Lieutenant-Colonel Carrington Smith, commanding the Hampshire Regiment, had been killed and the Adjutant had been wounded. The Adjutant of the Munster Fusiliers was wounded, and the great majority of the senior officers were either wounded or killed. The remnant of the landing-party still crouched on the beach beneath the shelter of the sandy escarpment which had saved so many lives. With them were two officers of my General Staff—Lieutenant-Colonel Doughty-Wylie and[Pg 19] Lieutenant-Colonel Williams. These two officers, who had landed from the River Clyde, had been striving, with conspicuous contempt for danger, to keep all their comrades in good heart during this day and night of ceaseless imminent peril.

Now that it was daylight once more, Lieutenant-Colonels Doughty-Wylie and Williams set to work to organize an attack on the hill above the beach. Any soldier who has endeavoured to pull scattered units together after they have been dominated for many consecutive hours by close and continuous fire will be able to take the measure of their difficulties. Fortunately General Hunter-Weston had arranged with Rear-Admiral Wemyss about this same time for a heavy bombardment to be opened by the ships upon the Old Fort, Sedd-el-Bahr Village, the Old Castle north of the village, and on the ground leading up from the beach. Under cover of this bombardment, and led by Lieutenant-Colonel Doughty-Wylie, and Captain Walford, Brigade-Major R.A., the troops gained a footing in the village by 10 a.m. They encountered a most stubborn opposition and suffered heavy losses from the fire of well concealed riflemen and machine guns. Undeterred by the resistance, and supported by the naval gunfire, they pushed forward, and soon after midday they penetrated to the northern edge of the village,[Pg 20] whence they were in a position to attack the Old Castle and Hill 141. During this advance Captain Walford was killed. Lieutenant-Colonel Doughty-Wylie had most gallantly led the attack all the way up from the beach through the west side of the village, under a galling fire. And now, when, owing so largely to his own inspiring example and intrepid courage, the position had almost been gained, he was killed while leading the last assault. But the attack was pushed forward without wavering, and, fighting their way across the open with great dash, the troops gained the summit and occupied the Old Castle and Hill 141 before 2 p.m.

W beach consists of a strip of deep, powdery sand some 350 yards long and from 15 to 40 yards wide, situated immediately south of Tekke Burnu, where a small gully running down to the sea opens out a break in the cliffs. On either flank of the beach the ground rises precipitously, but, in the centre, a number of sand dunes afford a more gradual access to the ridge overlooking the sea. Much time and ingenuity had been employed by the Turks in turning this landing-place into a death trap. Close to the water's edge a broad wire entanglement extended the whole length of the shore, and a supplementary barbed network lay concealed under the surface of the sea in the shallows. Land mines and sea mines had been[Pg 21] laid. The high ground overlooking the beach was strongly fortified with trenches to which the gully afforded a natural covered approach. A number of machine guns also were cunningly tucked away into holes in the cliff so as to be immune from a naval bombardment whilst they were converging their fire on the wire entanglements. The crest of the hill overlooking the beach was in its turn commanded by high ground to the north-west and south-east, and especially by two strong infantry redoubts near point 138. Both these redoubts were protected by wire entanglements about 20 feet broad, and could be approached only by a bare glacis-like slope leading up from the high ground above W beach or from the Cape Helles lighthouse. In addition, another separate entanglement ran down from these two redoubts to the edge of the cliff near the lighthouse, making intercommunication between V and W beaches impossible until these redoubts had been captured.

So strong, in fact, were the defences of W beach that the Turks may well have considered them impregnable, and it is my firm conviction that no finer feat of arms has ever been achieved by the British soldier—or any other soldier—than the storming of these trenches from open boats on the morning of April 25.

The landing at W had been entrusted to the 1st Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers (Major Bishop),[Pg 22] and it was to the complete lack of the sense of danger or of fear of this daring battalion that we owed our astonishing success. As in the case of the landing at X, the disembarkation had been delayed for half an hour, but at 6 a.m. the whole battalion approached the shore together, towed by eight picket boats in line abreast, each picket boat pulling four ship's cutters. As soon as shallow water was reached, the tows were cast off and the boats were at once rowed to the shore. Three companies headed for the beach and a company on the left of the line made for a small ledge of rock immediately under the cliff at Tekke Burnu. Brigadier-General Hare, commanding the 88th Brigade, accompanied this latter party, which escaped the cross fire brought to bear upon the beach, and was also in a better position than the rest of the battalion to turn the wire entanglements.

While the troops were approaching the shore no shot had been fired from the enemy's trenches, but as soon as the first boat touched the ground a hurricane of lead swept over the battalion. Gallantly led by their officers, the Fusiliers literally hurled themselves ashore, and, fired at from right, left, and centre, commenced hacking their way through the wire. A long line of men was at once mown down as by a scythe, but the remainder were not to be denied. Covered by the fire of the warships, which had now closed right in to the shore, and helped by the flanking fire of the company on the extreme left, they broke through the entanglements and collected under the cliffs[Pg 23] on either side of the beach. Here the companies were rapidly re-formed, and set forth to storm the enemy's entrenchments wherever they could find them.

In making these attacks the bulk of the battalion moved up towards Hill 114 whilst a small party worked down towards the trenches on the Cape Helles side of the landing-place.

Several land mines were exploded by the Turks during the advance, but the determination of the troops was in no way affected. By 10 a.m. three lines of hostile trenches were in our hands, and our hold on the beach was assured.

About 9.30 a.m. more infantry had begun to disembark, and two hours later a junction was effected on Hill 114 with the troops which had landed on X beach.

On the right, owing to the strength of the redoubt on Hill 138, little progress could be made. The small party of Lancashire Fusiliers which had advanced in this direction succeeded in reaching the edge of the wire entanglements, but were not strong enough to do more, and it was here that Major Frankland, Brigade-Major of the 86th Infantry Brigade, who had gone forward to make a personal reconnaissance, was unfortunately killed. Brigadier-General Hare had been wounded earlier in the day, and Colonel Wolley-Dod, General Staff 29th Division, was now sent ashore to take command at W beach and organize a further advance.

At 2 p.m., after the ground near Hill 138 had been subjected to a heavy bombardment, the[Pg 24] Worcester Regiment advanced to the assault. Several men of this battalion rushed forward with great spirit to cut passages through the entanglement; some were killed, others persevered, and by 4 p.m. the hill and redoubt were captured.

An attempt was now made to join hands with the troops on V beach, who could make no headway at all against the dominating defences of the enemy. To help them out the 86th Brigade pushed forward in an easterly direction along the cliff. There is a limit, however, to the storming of barbed-wire entanglements. More of these barred the way. Again the heroic wire-cutters came out. Through glasses they could be seen quietly snipping away under a hellish fire as if they were pruning a vineyard. Again some of them fell. The fire pouring out of No. 1 fort grew hotter and hotter, until the troops, now thoroughly exhausted by a sleepless night and by the long day's fighting under a hot sun, had to rest on their laurels for a while.

When night fell, the British position in front of W beach extended from just east of Cape Helles lighthouse, through Hill 138, to Hill 114. Practically every man had to be thrown into the trenches to hold this line, and the only available reserves on this part of our front were the 2nd London Field Company R.E. and a platoon of the Anson Battalion, which had been landed as a beach working party.

During the night several strong and determined counter-attacks were made, all successfully repulsed[Pg 25] without loss of ground. Meanwhile the disembarkation of the remainder of the division was proceeding on W and X beaches.

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps sailed out of Mudros Bay on the afternoon of April 24, escorted by the 2nd Squadron of the Fleet under Rear-Admiral Thursby. The rendezvous was reached just after half-past one in the morning of the 25th, and there the 1,500 men who had been placed on board H.M. ships before leaving Mudros were transferred to their boats. This operation was carried out with remarkable expedition, and in absolute silence. Simultaneously the remaining 2,500 men of the covering force were transferred from their transports to six destroyers. At 2.30 a.m. H.M. ships, together with the tows and the destroyers, proceeded to within some four miles of the coast, H.M.S. Queen (flying Rear-Admiral Thursby's flag) directing on a point about a mile north of Kaba Tepe. At 3.30 a.m. orders to go ahead and land were given to the tows, and at 4.10 a.m. the destroyers were ordered to follow.

All these arrangements worked without a hitch, and were carried out in complete orderliness and silence. No breath of wind ruffled the surface of the sea, and every condition was favourable save for the moon, which, sinking behind the ships, may have silhouetted them against its orb, betraying them thus to watchers on the shore.

A rugged and difficult part of the coast had been selected for the landing, so difficult and rugged that I considered the Turks were not at all likely to anticipate such a descent. Indeed, owing to the tows having failed to maintain their exact direction the actual point of disembarkation was rather more than a mile north of that which I had selected, and was more closely overhung by steeper cliffs. Although this accident increased the initial difficulty of driving the enemy off the heights inland, it has since proved itself to have been a blessing in disguise, inasmuch as the actual base of the force of occupation has been much better defiladed from shell fire.

The beach on which the landing was actually effected is a very narrow strip of sand, about 1,000 yards in length, bounded on the north and the south by two small promontories. At its southern extremity a deep ravine, with exceedingly steep, scrub-clad sides, runs inland in a north-easterly direction. Near the northern end of the beach a small but steep gully runs up into the hills at right angles to the shore. Between the ravine and the gully the whole of the beach is backed by the seaward face of the spur which forms the north-western side of the ravine. From the top of the spur the ground falls almost sheer except near the southern limit of the beach, where gentler slopes give access[Pg 27] to the mouth of the ravine behind. Further inland lie in a tangled knot the under-features of Sari Bair, separated by deep ravines, which take a most confusing diversity of direction. Sharp spurs, covered with dense scrub, and falling away in many places in precipitous sandy cliffs, radiate from the principal mass of the mountain, from which they run north-west, west, south-west, and south to the coast.

The boats approached the land in the silence and the darkness, and they were close to the shore before the enemy stirred. Then about one battalion of Turks was seen running along the beach to intercept the lines of boats. At this so critical a moment the conduct of all ranks was most praiseworthy. Not a word was spoken—every one remained perfectly orderly and quiet awaiting the enemy's fire, which sure enough opened, causing many casualties. The moment the boats touched land the Australians' turn had come. Like lightning they leapt ashore, and each man as he did so went straight as his bayonet at the enemy. So vigorous was the onslaught that the Turks made no attempt to withstand it and fled from ridge to ridge pursued by the Australian infantry.

This attack was carried out by the 3rd Australian Brigade, under Major (temporary Colonel) Sinclair Maclagan, D.S.O. The 1st and 2nd Brigades followed promptly, and were all disembarked by[Pg 28] 2 p.m., by which time 12,000 men and two batteries of Indian Mountain Artillery had been landed. The disembarkation of further artillery was delayed owing to the fact that the enemy's heavy guns opened on the anchorage and forced the transports, which had been subjected to continuous shelling from his field guns, to stand farther out to sea.

The broken ground, the thick scrub, the necessity for sending any formed detachments post-haste as they landed to the critical point of the moment, the headlong valour of scattered groups of the men who had pressed far further into the peninsula than had been intended—all these led to confusion and mixing up of units. Eventually the mixed crowd of fighting men, some advancing from the beach, others falling back before the oncoming Turkish supports, solidified into a semicircular position with its right about a mile north of Gaba Tepe and its left on the high ground over Fisherman's Hut. During this period parties of the 9th and 10th Battalions charged and put out of action three of the enemy's Krupp guns. During this period also the disembarkation of the Australian Division was being followed by that of the New Zealand and Australian Division (two brigades only).

From 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. the enemy, now reinforced to a strength of 20,000 men, attacked the whole line, making a specially strong effort against the 3rd Brigade and the left of the 2nd Brigade. This counter-attack was, however, handsomely repulsed with the help of the guns of H.M. ships. Between 5 and 6.30 p.m. a third most determined[Pg 29] counter-attack was made against the 3rd Brigade, who held their ground with more than equivalent stubbornness. During the night again the Turks made constant attacks, and the 8th Battalion repelled a bayonet charge; but in spite of all the line held firm. The troops had had practically no rest on the night of the 24th to 25th; they had been fighting hard all day over most difficult country, and they had been subjected to heavy shrapnel fire in the open. Their casualties had been deplorably heavy. But, despite their losses and in spite of their fatigue, the morning of the 26th found them still in good heart and as full of fight as ever.

It is a consolation to know that the Turks suffered still more seriously. Several times our machine guns got on to them in close formation, and the whole surrounding country is still strewn with their dead.

The reorganization of units and formations was impossible during the 26th and 27th owing to persistent attacks. An advance was impossible until a reorganization could be effected, and it only remained to entrench the position gained and to perfect the arrangements for bringing up ammunition, water, and supplies to the ridges—in itself a most difficult undertaking. Four battalions of the Royal Naval Division were sent up to reinforce the Army Corps on April 28 and 29.

On the night of May 2 a bold effort was made to seize a commanding knoll in front of the centre of the line. The enemy's enfilading machine guns were too scientifically posted, and 800 men were lost without advantage beyond the infliction of a corresponding loss to the enemy. On May 4 an attempt to seize Kaba Tepe was also unsuccessful, the barbed wire here being something beyond belief. But a number of minor operations have been carried out, such as the taking of a Turkish observing station; the strengthening of entrenchments; the reorganization of units, and the perfecting of communication with the landing-place. Also a constant strain has been placed upon some of the best troops of the enemy, who, to the number of 24,000, are constantly kept fighting and being killed and wounded freely, as the Turkish sniper is no match for the Kangaroo shooter, even at his own game.

The assistance of the Royal Navy, here as elsewhere, has been invaluable. The whole of the arrangements have been in Admiral Thursby's hands, and I trust I may be permitted to say what a trusty and powerful friend he has proved himself to be to the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps.

Concurrently with the British landings a regiment of the French Corps was successfully dis[Pg 31]embarked at Kum Kale under the guns of the French Fleet, and remained ashore till the morning of the 26th, when they re-embarked. Five hundred prisoners were captured by the French on this day.

This operation drew the fire of the Asiatic guns from Morto Bay and V beach on to Kum Kale, and contributed largely to the success of the British landings.

On the evening of the 26th the main disembarkation of the French Corps was begun, V beach being allotted to our Allies for this purpose, and it was arranged that the French should hold the portion of the front between the telegraph wire and the sea.

The following day I ordered a general advance to a line stretching from Hill 236 near Eski Hissarlik Point to the mouth of the stream two miles north of Tekke Burnu. This advance, which was commenced at midday, was completed without opposition, and the troops at once consolidated their new line. The forward movement relieved the growing congestion of the beaches, and by giving us possession of several new wells afforded a temporary solution to the water problem, which had hitherto been causing me much anxiety.

By the evening of the 27th the Allied forces had established themselves on a line some three miles long, which stretched from the mouth of the nullah, 3,200 yards north-east of Tekke Burnu, to Eski Hissarlik Point, the three brigades of the 29th Division less two battalions on the left and in the[Pg 32] centre, with four French battalions on the right, and beyond them again the South Wales Borderers on the extreme right.

Owing to casualties this line was somewhat thinly held. Still, it was so vital to make what headway we could before the enemy recovered himself and received fresh reinforcements that it was decided to push on as quickly as possible. Orders were therefore issued for a general advance to commence at 8 a.m. next day.

The 29th Division were to march on Krithia, with their left brigade leading, the French were directed to extend their left in conformity with the British movements and to retain their right on the coast-line south of the Kereves Dere.

The advance commenced at 8 a.m. on the 28th, and was carried out with commendable vigour, despite the fact that from the moment of landing the troops had been unable to obtain any proper rest.

(To face page 32.)

Map 2.

The 87th Brigade, with which had been incorporated the Drake Battalion, Royal Naval Division, in the place of the King's Own Scottish Borderers and South Wales Borderers, pushed on rapidly, and by 10 a.m. had advanced some two miles. Here the further progress of the Border Regiment was barred by a strong work on the left flank. They halted to concentrate and make dispositions[Pg 33] to attack it, and at that moment had to withstand a determined counter-attack by the Turks. Aided by heavy gun-fire from H.M.S. Queen Elizabeth, they succeeded in beating off the attack, but they made no further progress that day, and when night fell entrenched themselves on the ground they had gained in the morning.

The Inniskilling Fusiliers, who advanced with their right on the Krithia ravine, reached a point about three-quarters of a mile south-west of Krithia. This was, however, the farthest limit attained, and later on in the day they fell back into line with other corps.

The 88th Brigade on the right of the 87th progressed steadily until about 11.30 a.m., when the stubbornness of the opposition, coupled with a dearth of ammunition, brought their advance to a standstill. The 86th Brigade, under Lieutenant-Colonel Casson, which had been held in reserve, were thereupon ordered to push forward through the 88th Brigade in the direction of Krithia.

The movement commenced at about 1 p.m., but though small reconnoitring parties got to within a few hundred yards of Krithia, the main body of the brigade did not get beyond the line held by the 88th Brigade. Meanwhile, the French had also pushed on in the face of strong opposition along the spurs on the western bank of the Kereves Dere, and had got to within a mile of Krithia with their right thrown back and their left in touch with the 88th Brigade. Here they were unable to make further progress; gradually the strength of the[Pg 34] resistance made itself felt, and our Allies were forced during the afternoon to give ground.

By 2 p.m. the whole of the troops with the exception of the Drake Battalion had been absorbed into the firing line. The men were exhausted, and the few guns landed at the time were unable to afford them adequate artillery support. The small amount of transport available did not suffice to maintain the supply of munitions, and cartridges were running short despite all efforts to push them up from the landing-places.

Hopes of getting a footing on Achi Babi had now perforce to be abandoned—at least for this occasion. The best that could be expected was that we should be able to maintain what we had won, and when at 3 p.m. the Turks made a determined counter-attack with the bayonet against the centre and right of our line, even this seemed exceedingly doubtful. Actually a partial retirement did take place. The French were also forced back, and at 6 p.m. orders were issued for our troops to entrench themselves as best they could in the positions they then held, with their right flank thrown back so as to maintain connection with our Allies. In this retirement the right flank of the 88th Brigade was temporarily uncovered, and the Worcester Regiment suffered severely.

Had it been possible to push in reinforcements in men, artillery, and munitions during the day, Krithia should have fallen, and much subsequent fighting for its capture would have been avoided.

Two days later this would have been feasible, but I had to reckon with the certainty that the enemy would, in that same time, have received proportionately greater support. I was faced by the usual choice of evils, and although the result was not what I had hoped, I have no reason to believe that hesitation and delay would better have answered my purpose.

For, after all, we had pushed forward quite appreciably on the whole. The line eventually held by our troops on the night of the 28th ran from a point on the coast three miles north-west of Tekke Burnu to a point one mile north of Eski Hissarlik, whence it was continued by the French south-east to the coast.

Much inevitable mixing of units of the 86th and 88th Brigades had occurred during the day's fighting, and there was a dangerous re-entrant in the line at the junction of the 87th and 88th Brigades near the Krithia nullah. The French had lost heavily, especially in officers, and required time to reorganize.

April 29 was consequently spent in straightening the line, and in consolidating and strengthening the[Pg 36] positions gained. There was a certain amount of artillery and musketry fire, but nothing serious.

Similarly, on the 30th, no advance was made, nor was any attack delivered by the enemy. The landing of the bulk of the artillery was completed, and a readjustment of the line took place, the portion held by the French being somewhat increased.

Two more battalions of the Royal Naval Division had been disembarked, and these, together with three battalions of the 88th Brigade withdrawn from the line, were formed into a reserve.

This reserve was increased on May 1 by the addition of the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade, which released the three battalions of the 88th Brigade to return to the trenches. The Corps Expéditionnaire d'Orient had disembarked the whole of their infantry, and all but two of their batteries by the same evening.

At 10 p.m. the Turks opened a hot shell fire upon our position, and half an hour later, just before the rise of the moon, they delivered a series of desperate attacks. Their formation was in three solid lines, the men in the front rank being deprived of ammunition to make them rely only upon the bayonet. The officers were served out with coloured Bengal lights to fire from their pistols, red indicating to the Turkish guns that they were[Pg 37] to lengthen their range; white that our front trenches had been stormed; green that our main position had been carried. The Turkish attack was to crawl on hands and knees until the time came for the final rush to be made. An eloquent hortative was signed Von Zowenstern and addressed to the Turkish rank and file who were called upon, by one mighty effort, to fling us all back into the sea.

"Attack the enemy with the bayonet and utterly destroy him!

"We shall not retire one step; for, if we do, our religion, our country, and our nation will perish!

"Soldiers! The world is looking at you! Your only hope of salvation is to bring this battle to a successful issue or gloriously to give up your life in the attempt!"

The first momentum of this ponderous onslaught fell upon the right of the 86th Brigade, an unlucky spot, seeing all the officers thereabouts had already been killed or wounded. So when the Turks came right on without firing and charged into the trenches with the bayonet they made an ugly gap in the line. This gap was instantly filled by the 5th Royal Scots (Territorials), who faced to their flank and executed a brilliant bayonet charge against the[Pg 38] enemy, and by the Essex Regiment detached for the purpose by the Officer Commanding 88th Brigade. The rest of the British line held its own with comparative ease, and it was not found necessary to employ any portion of the reserve. The storm next broke in fullest violence against the French left, which was held by the Senegalese. Behind them were two British Field Artillery Brigades and a Howitzer Battery. After several charges and counter-charges the Senegalese began to give ground, and a company of the Worcester Regiment and some gunners were sent forward to hold the gap. Later, a second company of the Worcester Regiment was also sent up, and the position was then maintained for the remainder of the night, although about 2 a.m. it was found necessary to dispatch one battalion Royal Naval Division to strengthen the extreme right of the French.

About 5 a.m. a counter-offensive was ordered, and the whole line began to advance. By 7.30 a.m. the British left had gained some 500 yards, and the centre had pushed the enemy back and inflicted heavy losses. The right also had gained some ground in conjunction with the French left, but the remainder of the French line was unable to progress. As the British centre and left were now subjected to heavy cross fire from concealed machine guns, it was found impossible to maintain[Pg 39] the ground gained, and therefore, about 11 a.m., the whole line withdrew to its former trenches.

The net result of the operations was the repulse of the Turks and the infliction upon them of very heavy losses. At first we had them fairly on the run, and had it not been for those inventions of the devil—machine guns and barbed wire—which suit the Turkish character and tactics to perfection, we should not have stopped short of the crest of Achi Babi. As it was, all brigades reported great numbers of dead Turks in front of their lines, and 350 prisoners were left in our hands.

On the 2nd, during the day, the enemy remained quiet, burying his dead under a red crescent flag, a work with which we did not interfere. Shortly after 9 p.m., however, they made another attack against the whole Allied line, their chief effort being made against the French front, where the ground favoured their approach. The attack was repulsed with loss.

During the night 3rd/4th the French front was again subjected to a heavy attack, which they were able to repulse without assistance from my general reserve.

The day of the 4th was spent in reorganization, and a portion of the line held by the French, who had lost heavily during the previous night's fighting, was taken over by the 2nd Naval Brigade. The night passed quietly.

During the 5th the Lancashire Fusilier Brigade of the East Lancashire Division was disembarked and placed in reserve behind the British left.

Orders were issued for an advance to be carried out next day, and these and the three days' battle which ensued will be dealt with in my next despatch.

The losses, exclusive of the French, during the period covered by this despatch, were, I regret to say, very severe, numbering:

177 Officers and 1,990 other ranks killed.

412 Officers and 7,807 other ranks wounded.

13 Officers and 3,580 other ranks missing.

From a technical point of view it is interesting to note that my Administrative Staff had not reached Mudros by the time when the landings were finally arranged. All the highly elaborate work involved by these landings was put through by my General Staff working in collaboration with Commodore Roger Kayes, C.B., M.V.O., and the Naval Transport Officers allotted for the purpose by Vice-Admiral de Robeck. Navy and Army carried out these combined duties with that perfect harmony which was indeed absolutely essential to success.

(To face page 40.)

Lieut.-General Sir W. R. Birdwood K.C.S.I.

Throughout the events I have chronicled the Royal Navy has been father and mother to the Army. Not one of us but realises how much[Pg 41] he owes to Vice-Admiral de Robeck; to the warships, French and British; to the destroyers, mine sweepers, picket boats, and to all their dauntless crews, who took no thought of themselves, but risked everything to give their soldier comrades a fair run in at the enemy.

Throughout these preparations and operations Monsieur le Général d'Amade has given me the benefit of his wide experiences of war, and has afforded me, always, the most loyal and energetic support. The landing of Kum Kale planned by me as a mere diversion to distract the attention of the enemy was transformed by the Commander of the Corps Expéditionnaire de l'Orient into a brilliant operation, which secured some substantial results. During the fighting which followed the landing of the French Division at Sedd-el-Bahr no troops could have acquitted themselves more creditably under very trying circumstances, and under very heavy losses, than those working under the orders of Monsieur le Général d'Amade.

Lieutenant-General Sir W. R. Birdwood, K.C.S.I., C.B., C.I.E., D.S.O., was in command of the detached landing of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps above Kapa Tepe, as well as during the subsequent fighting. The fact of his having been responsible for the execution of these difficult and hazardous operations—operations which were crowned with a very remarkable success—speaks, I think, for itself.

Major-General A. G. Hunter-Weston, C.B., D.S.O., was tried very highly, not only during[Pg 42] the landings, but more especially in the day and night attacks and counter-attacks which ensued. Untiring, resourceful, and ever more cheerful as the outlook (on occasion) grew darker, he possesses, in my opinion, very special qualifications as a Commander of troops in the field.

Major-General W. P. Braithwaite, C.B., is the best Chief of the General Staff it has ever been my fortune to encounter in war. I will not pile epithets upon him. I can say no more than what I have said, and I can certainly say no less.

I have many other names to bring to notice for the period under review, and these will form the subject of a separate report at an early date.

General Headquarters,

Mediterranean Expeditionary Force,

August 26, 1915.

My Lord,

At the close of the ten days and ten nights described in my first despatch our troops had forced their way forward for some 5,000 yards from the landing-places at the point of the peninsula. Opposite them lay the Turks, who since their last repulse had fallen back about half a mile upon previously prepared redoubts and entrenchments. Both sides had drawn heavily upon their stock of energy and munitions, but it seemed clear that whichever could first summon up spirit to make another push must secure at least several hundreds of yards of the debatable ground between the two fronts. And several hundred yards, whatever it might mean to the enemy, was a matter of life or death to a force crowded together under gun fire on so narrow a tongue of land. Such was the situation on May 5, the date last mentioned in my despatch of the 20th of that month.

On that day I determined to continue my advance, feeling certain that even if my tired troops could not carry the formidable opposing lines they would at least secure the use of the intervening ground. Orders were forthwith issued for an attack.

The many urgent calls for reinforcements made during the previous critical fighting had forced me to disorganize and mix together several of the formations in the southern group, to the extent even of the French on our right having a British battalion holding their own extremest right. For the purposes of the impending fight it became therefore necessary to create temporarily a Composite Division, consisting of the 2nd Australian and New Zealand Infantry Brigades (withdrawn for the purpose from the northern section), together with a Naval Brigade formed of the Plymouth and Drake Battalions. The 29th Division was reconstituted into four brigades, i.e. the 88th and 87th Brigades, the Lancashire Fusilier Brigade (T.F.), and the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade. The French Corps Expéditionnaire was reinforced by the 2nd Naval Brigade, and the new Composite Division formed my General Reserve.

The 29th Division, whose left rested on the coast about three miles north-east of Cape Tekke, was ordered to direct, its right moving on the south-east edge of Krithia, while the Corps Expéditionnaire with the 2nd Naval Brigade had assigned to them for their first point of attack the commanding ridge running from north to south above the Kereves Dere. A foothold upon this ridge was essential, as its capture would ensure a safe pivot on which the 29th Division could swing in making any further advance. Communi[Pg 45]cation between these two sections of the attack was to be maintained by the Plymouth and Drake Battalions.

During the three days (May 6-8) our troops were destined to be very severely tried. They were about to attack a series of positions scientifically selected in advance which, although not yet joined up into one line of entrenchment, were already strengthened by works on their more important tactical features.

The 29th Division led off at 11 a.m., the French corps followed suit at 11.30 a.m.; every yard was stubbornly contested; some Brigades were able to advance, others could do no more than maintain themselves. Positions were carried and held, other positions were carried and lost; but, broadly, our gunners kept lengthening the fuses of their shrapnel, and by 1.30 p.m. the line had been pushed forward two to three hundred yards. Here and there this advance included a Turkish trench, but generally speaking the main enemy position still lay some distance ahead of our leading companies.

By 4.30 p.m. it became clear that we should make no more progress that day. The French Corps were held up by a strong field work. They had made good a point upon the crest line of the lower slope of the Kereves Dere ridge, but there they had come under a fire so galling that they[Pg 46] were unable, as it turned out, to entrench until nightfall. The 88th Brigade could not carry a clump of fir trees to their front; company after company made the perilous essay, but the wood, swept by hidden machine-guns, proved a veritable deathtrap. The Lancashire Fusiliers Brigade also were only just barely holding on and were suffering heavy losses from these same concealed machine-guns. The troops were ordered to entrench themselves in line and link up their flanks on either side.

At night, save for rifle fire, there was quiet along the whole British line. On the right a determined bayonet charge was made upon the French, who gave ground for the moment, but recovered it again at dawn.

Next morning (May 7) we opened with shrapnel upon the enemy's trenches opposite our extreme left, and at 10 a.m. the Lancashire Fusiliers Brigade began the attack. But our artillery had not been able to locate the cleverly sited German machine-gun batteries, whose fire rendered it physically impossible to cross that smooth glacis. Next to the right the 88th Brigade swept forward, and the 1/5th Royal Scots, well supported by artillery fire, carried the fir trees with a rush. This time it was discovered that not only the enfilading machine-guns had made the wood so difficult to hold.[Pg 47] Amongst the branches of the trees Turkish snipers were perched, sometimes upon small wooden platforms. When these were brought down the surroundings became much healthier. The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, of the 87th Brigade, were pushed up to support the left of the 88th, and all seemed well, when, at 1.20 p.m., a strong Turkish counter-attack drove us back out of the fir clump. As an off-set to this check the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers captured three Turkish trenches, and a second battalion of the 87th Brigade, the King's Own Scottish Borderers, was sent forward on the left to make these good.

At 3 p.m. the Lancashire Fusiliers Brigade again reported they were definitely held up by the accurate cross-fire of batteries of machine-guns concealed in the scrub on the ridge between the ravine and the sea, batteries which also enfiladed the left flank of the 88th Brigade as it endeavoured to advance in the centre. Unless we were to acquiesce in a stalemate the moment for our effort had arrived, and a general attack was ordered for 4.45 p.m., the whole of the 87th Brigade to reinforce the 88th Brigade, and the New Zealand Brigade to support it.

Despite their exhaustion and their losses the men responded with a will. The whole force, French and British, rose simultaneously and made[Pg 48] a rush forward. All along the front we made good a certain amount of ground, excepting only on our extreme left. For the third time British bayonets carried the fir clump in our centre, and when darkness fell the whole line (excepting always the left) had gained from 200 to 300 yards, and had occupied or passed over the first line of Turkish trenches.

The troops were now worn out; the new lines needed consolidating, and it was certain that fresh reinforcements were reaching the Turks. Balancing the actual state of my own troops against the probable condition of the Turks I decided to call upon the men to make one more push before the new enemy forces could get into touch with their surroundings.

Orders were therefore issued to dig in at sundown on the line gained; to maintain that line against counter-attack, and to prepare to advance again next morning. The Lancashire Fusiliers Brigade was withdrawn into reserve, and its place on the left was taken by the Brigade of New Zealanders.

General Headquarters were shifted to an entrenchment on a hill in rear of the left of our line. Under my plan for the fresh attack the New Zealand Brigade was to advance through the line held during the night by the 88th Brigade and press on towards Krithia. Simultaneously, the 87th Brigade was to threaten the works on the west of the ravine, whilst endeavouring, by means of parties of scouts and volunteers, to steal patches of ground from the areas dominated by the German machine-guns.

At 10.15 a.m. heavy fire from ships and batteries was opened on the whole front, and at 10.30 a.m. the New Zealand Brigade began to move, meeting with strenuous opposition from the enemy, who had received his reinforcements. Supported by the fire of the batteries and the machine-guns of the 88th Brigade, they pushed forward on the right and advanced their centre beyond the fir trees, but could make little further progress. By 1.30 p.m. about 200 yards had been gained beyond the previously most advanced trenches of the 88th Brigade.

At this hour the French Corps reported they could not advance up the crest of the spur west of Kereves Dere till further progress was made by the British.

At 4 p.m. I gave orders that the whole line, reinforced by the 2nd Australian Brigade, would fix bayonets, slope arms, and move on Krithia precisely at 5.30 p.m.

At 5.15 p.m. the ships' guns and our heavy artillery bombarded the enemy's position for a quarter of an hour, and at 5.30 p.m. the field guns opened a hot shrapnel fire to cover the infantry advance.

The co-operation of artillery and infantry in this attack was perfect, the timing of the movement being carried out with great precision. Some of the companies of the New Zealand regiments[Pg 50] did not get their orders in time, but acting on their own initiative they pushed on as soon as the heavy howitzers ceased firing, thus making the whole advance simultaneous.

The steady advance of the British could be followed by the sparkle of their bayonets until the long lines entered the smoke clouds. The French at first made no move, then, their drums beating and bugles sounding the charge, they suddenly darted forward in a swarm of skirmishers which seemed in one moment to cover the whole southern face of the ridge of the Kereves Dere. Against these the Turkish gunners now turned their heaviest pieces, and as the leading groups stormed the first Turkish redoubt the ink-black bursts of high-explosive shells blotted out both assailants and assailed. The trial was too severe for the Senegalese tirailleurs. They recoiled. They were rallied. Another rush forward, another repulse, and then a small supporting column of French soldiers was seen silhouetted against the sky as they charged upwards along the crest of the ridge of the Kereves Dere, whilst elsewhere it grew so dark that the whole of the battlefield became a blank.