Title: Yorktown and the Siege of 1781

Author: Jr. Charles E. Hatch

Release date: January 31, 2017 [eBook #54080]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, MFR and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Stewart L. Udall, Secretary

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Conrad L. Wirth, Director

HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER FOURTEEN

This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System, administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents

by Charles E. Hatch, Jr.

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 14

Washington, D. C., 1954 (Revised 1957)

The National Park System, of which Colonial National Historical Park is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and inspiration of its people.

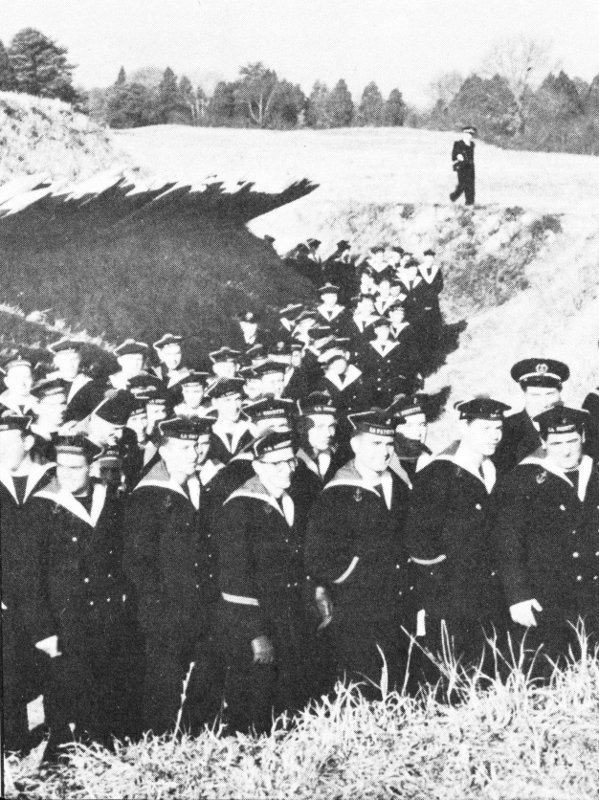

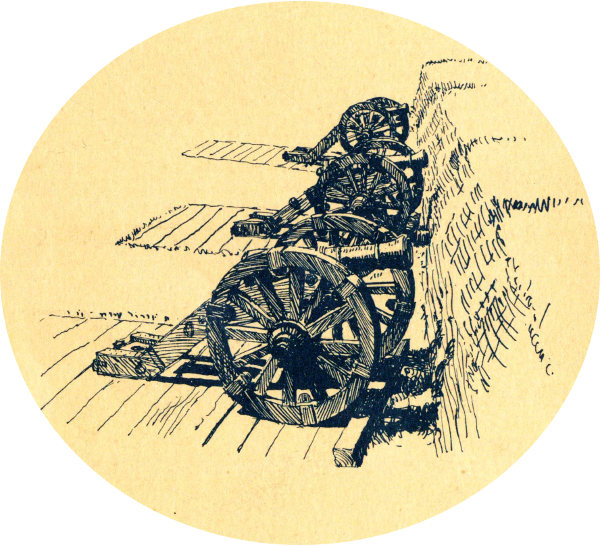

The reconstructed Grand French Battery—a strong link in the First Allied Siege Line.

On the level fields outside the small colonial village of Yorktown occurred one of the great decisive battles of world history and one of the most momentous events in American history. Here, on October 19, 1781, after a prolonged siege, Lord Cornwallis surrendered his British Army to an allied French and American Army force under George Washington, virtually ending the American Revolution and assuring American independence. While hostilities did not formally end until 2 years later—on September 3, 1783, when the treaty was signed—in reality the dramatic victory at Yorktown had ended forever the subservience of the American colonies to England. Because of this victory the United States became truly a free and independent nation.

At Yorktown, in the early autumn of 1781, Gen. George Washington, ably assisted by the Count de Rochambeau of the French Army and supported by the Count de Grasse of the French Navy, forced the capitulation of Lieutenant General Earl Cornwallis. On October 19, the allied French and American forces accepted the surrender of the British troops in what was the climax of the last major British field operation of the American Revolution—the Virginia Campaign.

The early campaigns, except the decisive repulse of British arms in the Carolinas in 1776, were fought mostly in the New England and Middle Atlantic colonies. After 1778, most activity was to the south. In 1780 and early 1781, Lord Cornwallis led his victorious British Army out of Charleston and through the Carolinas; not, however, without feeling the effective use of American arms at Kings Mountain (October 7, 1780) and at Cowpens (January 17, 1781). On March 15, 1781, he was at Guilford Courthouse in north-central North Carolina and there Gen. Nathanael Greene accepted his challenge to battle.

The battle of Guilford Courthouse was a British victory which left the victor weakened to the extent that he was unable to capitalize on his success. Cornwallis’ loss in officers and men was so heavy that his army was “crippled beyond measure.” In April, he decided to move to Wilmington, N. C., on the coast, for the avowed purpose of recruiting and refitting his exhausted force. Thus the stage was set for the final campaign of the war.

Cornwallis’ next move changed the strategy of the Southern Campaign. He did not believe himself strong enough for field action out of Wilmington and declined to return to Charleston and South Carolina. According to his own statement, “I was most firmly persuaded, that, until Virginia was reduced, we could not hold the more southern provinces, and that after its reduction, they would fall without much difficulty.” He made this decision alone, and Commanding General Sir Henry Clinton in New York never approved. On April 25, he marched from Wilmington, reaching Petersburg, Va., on May 20, where he formed a junction with Gen. William Phillips who commanded the British forces already in the State.

By this time there was already a considerable concentration of troops in Virginia. Gen. Alexander Leslie had been sent there with a detachment of troops in October 1780, but he had gone on to join Cornwallis in South Carolina. Shortly thereafter, another British force under Benedict Arnold was sent to operate in the area. To contain Arnold’s force, or at least to watch it, Washington had dispatched the Marquis de Lafayette to Virginia to work in conjunction with the Baron von Steuben, and later with Greene. Clinton then countered by sending Phillips with a large detachment to join Arnold. As a result of these and other moves, but by no prearranged plan, the stage was set in May 1781, for Virginia to be the battleground. From the British point of view the subjugation of the province was the tempting prize. For the Americans, the goal was to prevent this, and prevent it they did. The strategy of Yorktown was in the making, but had not yet taken form.

Cornwallis, leading a reasonably well-supplied and able field force of more than 5,300 troops, was opposed by Lafayette, commanding a small force not strong enough to risk battle. Lafayette had been ordered by Greene to remain in Virginia, take command of the troops there, and defend the State. Even though Lafayette expected reinforcements from the Pennsylvania Line under Gen. Anthony Wayne, it would not give him battle strength or even enable him to resist seriously the progress of the enemy. Consequently, the young general’s first move was to apply in every direction for more men and supplies.

In the meantime, Cornwallis prepared to force the issue. He selected his field force and dispatched the remaining units to the British base at Portsmouth. After assuring the commander there that he would reinforce him further should a French fleet appear in Chesapeake Bay, he put his army in motion toward that of Lafayette. On May 24, he reached 3 a point on the James River opposite Westover, about 24 miles below Richmond, and began to cross the river. At this point General Leslie arrived with reinforcements, further augmenting British strength. With these men, Cornwallis planned first to dislodge Lafayette from Richmond and then to employ his light troops in the destruction of magazines and stores destined for use by American forces in Virginia and farther south.

The Marquis de Lafayette (Gilbert du Mortier) commanded a division of Continental troops at Yorktown.

Lafayette, with his small army of about 3,250 men, did not attempt a stand at Richmond, but withdrew northward. The role of this youthful commander was “that of a terrier baiting a bull.” He had a heavy responsibility and was faced by an experienced commander in the person of Cornwallis. In the weeks that followed, Lafayette distinguished himself. He continually repeated a series of harassing, threatening, feinting, and retiring tactics. He retreated, usually northward, always maintaining a position higher up the river and nearer the Potomac, thus insuring that Cornwallis would not get between him and Philadelphia.

While encamped in Hanover County, Cornwallis learned that Wayne was only a few days away from a junction with Lafayette. Consequently, he hesitated to move further from his base at Portsmouth, but decided on a quick dash westward before withdrawing. With this in mind he dispatched Banastre Tarleton to Charlottesville to break up the Virginia Legislature then in session—a move that disrupted the assembly and might have led to the capture of Governor Jefferson but for the ride of Capt. “Jack” (John) Jouett to warn him—a ride which is reminiscent 4 of the better-known ride of Paul Revere. At the same time, Cornwallis sent Simcoe to harass Von Steuben who was then at Point-of-Fork on the James River. Von Steuben withdrew, but Simcoe was able to destroy a quantity of arms, powder, and supplies, which had been assembled there, before he rejoined Cornwallis.

About June 15, with the season hot, his troops tired, and Lafayette still evading him, Cornwallis decided that it was time to return to the coast. He had accomplished as much as possible in the destruction of supplies, he had found no great body of Loyalists to join him, and his opponent was gaining strength daily. He moved east through Richmond and proceeded down the Peninsula toward Williamsburg. Lafayette followed, venturing closer to him all the while.

On June 10, Wayne joined the American force with 1,000 men, and 2 days later Col. William Campbell—one of the famous American leaders at Kings Mountain—provided an additional 600 “mountain men.” On the 19th, Von Steuben appeared with his detachment. These reinforcements made Lafayette’s corps strong enough for more aggressive action. His strength was now about 4,500, but heavily weighted with untrained militia and short of arms, artillery, and cavalry.

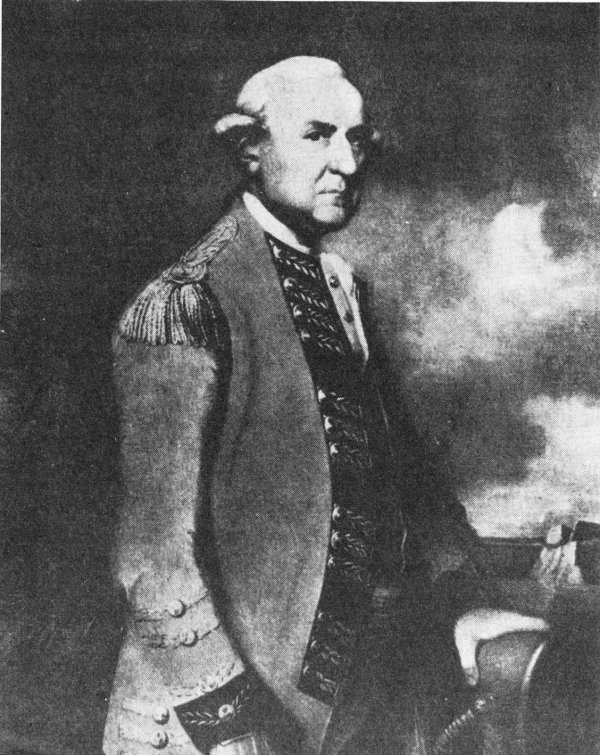

Lieutenant General Earl Cornwallis, Commander of the British forces which surrendered at Yorktown.

On June 26, there was “a smart action” at “Hot Water Plantation” (Spencer’s Ordinary), 7 miles northeast of Williamsburg, where Col. Richard Butler with a detachment of the Pennsylvania Line engaged Simcoe’s Queen’s Rangers. Following this, the British Army came to a halt at Williamsburg, sending out patrols to various points on the York and James Rivers, including Yorktown.

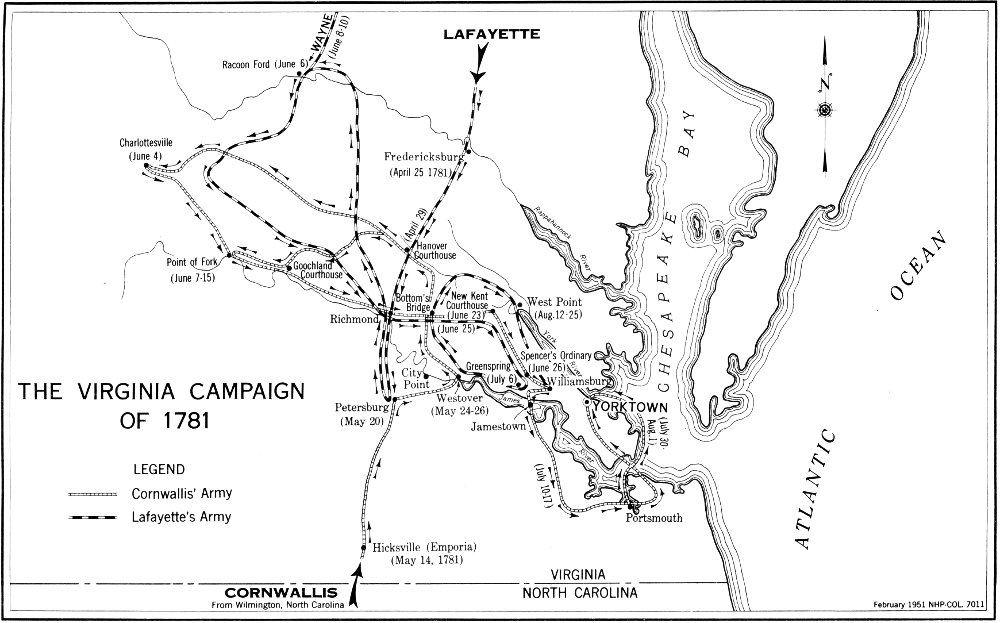

THE VIRGINIA CAMPAIGN OF 1781

By this time, the controversy, or misunderstanding, between Cornwallis, in Virginia, and Clinton, his superior, in New York, which involved matters of strategy, the theater of operations, and troop deployment, began to shape the direction of affairs in Virginia. Cornwallis received instructions to take a defensive station at Williamsburg, or Yorktown, reserve the troops needed for his protection, and send the remainder of his army by transport to New York to help Clinton in the siege that he expected there. In the execution of these orders Cornwallis readied his army for a move across the James (a move for which Clinton severely criticized him) and a march towards Portsmouth, where he could direct the dispatch of troops to New York.

On July 4, Cornwallis broke camp at Williamsburg and moved toward Jamestown Island, the most convenient point for crossing the James. He sent some troops immediately across the river, but ordered the bulk of the army to encamp on the “Main” a little beyond Glasshouse Point, within sight of Jamestown, as a precaution in the event Lafayette should attempt to hinder the crossing.

Cornwallis was right—Lafayette did intend to strike the British at this unfavorable moment. On July 6, Wayne, commanding the American advance unit, made his way slowly toward the British encampment. Lafayette, cautious and not wanting to be deceived about the enemy strength, went with him to make personal observations. The young general quickly decided that Cornwallis was laying a trap, as indeed he was, but before he could call in his scouts and advance units, action had been joined. Wayne, with only about 800 men and 3 field pieces, came face to face with the major part of the British Army. To halt the advancing enemy, Wayne called for a charge against a seemingly overwhelming force—a brave and daring action by a leader already marked as a man of courage. Both American and British troops fought well, but the charge stopped the British advance momentarily. At this point Wayne called for a retreat, which was effected with reasonable success. Marshy terrain and the approach of darkness prevented effective pursuit by Cornwallis’ units. The British losses, killed and wounded, apparently numbered about 70 rank and file and 5 officers. American losses approached 140 killed, wounded, and missing.

The engagement at Green Spring, sometimes called the “Affair Near James Island,” was a direct prelude to the struggle at Yorktown. The same forces later faced each other over the parapets on the York. Actual military victory, as at Guilford Courthouse, rested with the British. The most significant result of the encounter, however, may have been the stimulating effect on the Americans of the bravery and courage displayed by soldiers and officers alike. It was another good test of training and 7 discipline—a detachment of American troops had confronted Cornwallis’ main force and again they had fought well.

Following the action at Green Spring, Cornwallis continued his move across the James River, and, on July 17, he was able to report by letter to Clinton that the troops which the latter had requested were about ready to sail from Portsmouth. Three days later, Cornwallis learned that all plans had been drastically changed. Clinton now instructed him to hold all of his troops and await further orders. More detailed instructions reached Cornwallis on July 21, including strong words about the necessity for holding a position on the peninsula—the area between the York and James Rivers. Clinton, it seems, now thought that Yorktown was a good location for a naval station, offering protection for large and small ships—a vital necessity.

In compliance with his new orders, Cornwallis ordered a careful survey of Old Point Comfort and Hampton Roads to find the best location for such a naval station. This was done by Lt. Alexander Sutherland, of the Royal Engineers, who recommended against Old Point Comfort, which had been mentioned at length in the more recent correspondence between the British commanders in Virginia and New York as a possible location for a base to replace Portsmouth. Cornwallis wrote to Clinton: “This being the case, I shall, in obedience to the spirit of your Excellency’s orders, take measures with as much dispatch as possible, to seize and fortify York and Gloucester, being the only harbour in which we can hope to be able to give effectual protection to line of battle ships. I shall, likewise, use all the expedition in my power to evacuate Portsmouth and the posts belonging to it....”

Having stated his intentions, Cornwallis began to take action. On July 30, the British transports, loaded with about 4,500 men, left Portsmouth and set sail for Yorktown, where they arrived on the night of August 1. On August 2, landings were made at both Yorktown and Gloucester. Banastre Tarleton, with his men and horses, crossed Hampton Roads in small boats and proceeded to Yorktown by road, arriving on August 7. By the 22d, the detachment which remained at Portsmouth to level the works completed its assignment and joined the main army. The construction of defenses was begun immediately at Yorktown and Gloucester, a job that Cornwallis estimated would require 6 weeks. On August 31, one of the British soldiers wrote from “Camp Yorktown” that “Nothing but hard labour goes on here at present in constructing & making Batteries towards the River, & Redoubts toward the Land.” Actually, the siege of Yorktown began before this task was completed.

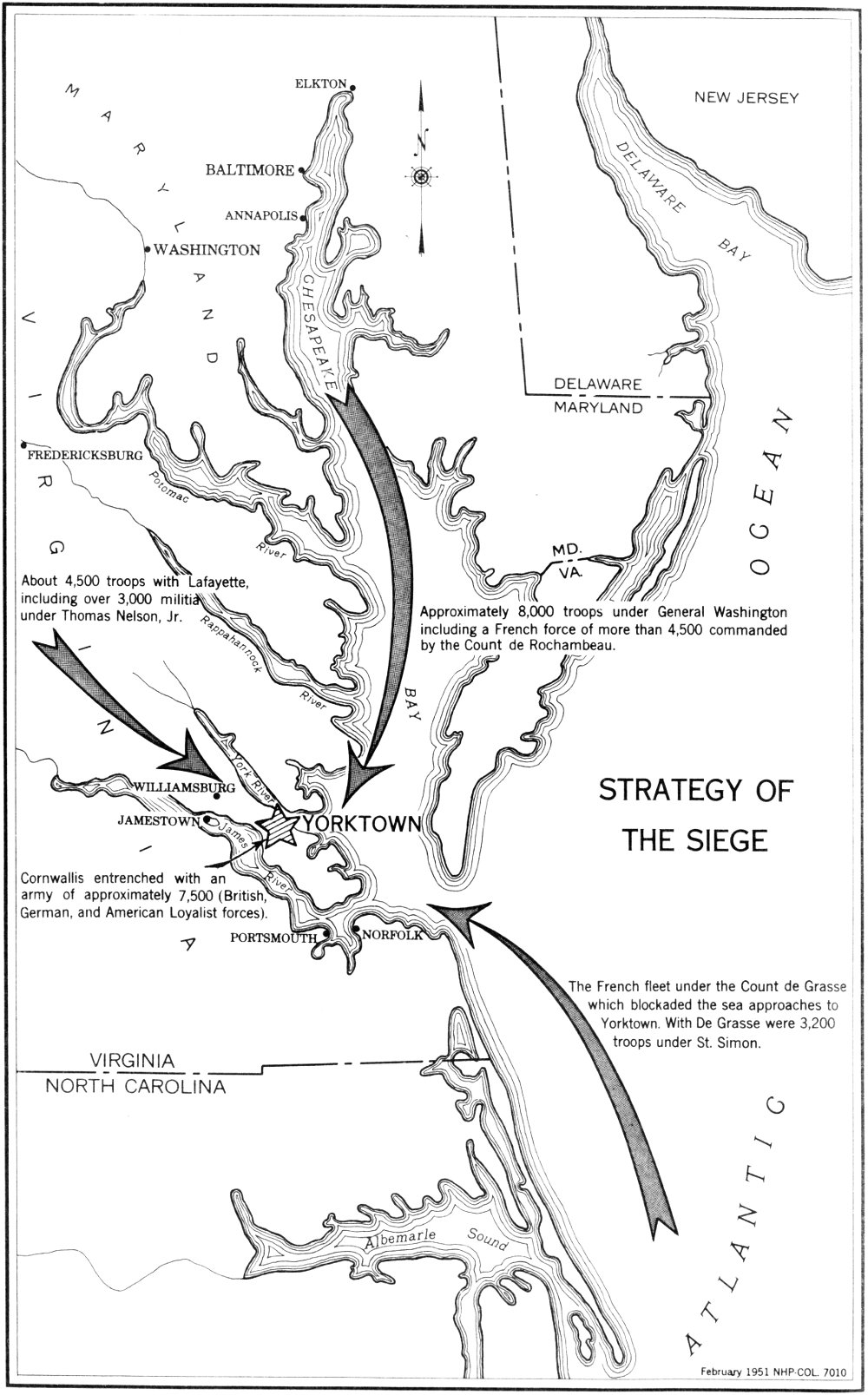

STRATEGY OF THE SIEGE

Meanwhile, the Americans were still keeping watch on the British. When the British Army moved south toward Portsmouth after the engagement at Green Spring, Lafayette dispatched Wayne to the south side of the James to follow Cornwallis and to attempt to check Tarleton’s raiding parties in this area. The Marquis himself took position at Malvern Hill. When Cornwallis left Portsmouth, Lafayette supposed that his destination was Baltimore. Acting quickly, he broke camp at Malvern Hill, and, with his Light Infantry, moved toward Fredericksburg. When he learned that the British were actually “digging in” at Yorktown and Gloucester, he took position on the Pamunkey River near West Point, Va., about 30 miles northwest of Cornwallis’ position. Wayne, with the Pennsylvania Line, remained south of the James. From this point Wayne was to have begun his march toward Greene in the Carolinas. On August 25, however, Lafayette learned that the Count de Grasse, with a sizeable fleet, was expected in Virginia, and he immediately cancelled Wayne’s orders for leaving the State, requesting instead that he remain where he was pending further instructions.

As the year 1781 opened, Clinton continued to hold New York with a strong force of about 10,000. Washington’s force opposing him numbered some 3,500. American leaders saw that recruiting was poor and supplies were low. The whole civilian system on which the army depended had proved loose and difficult, and apathy had come with a long period of inactivity. As the year progressed, change was in the air. There was thought of action and a plan. The commander in chief continued to be troubled, however, by the lack of assistance to the South and the now long-standing inability to achieve anything decisive in the North.

New hope came when the French Government approved additional assistance for the struggling colonies. Already a sizeable naval force was being organized for operations in American waters. The excellent French army corps under the Count de Rochambeau was then at Newport, R. I., to cooperate with Washington. From February 10 to August 14, Washington was engaged with the French in working out a plan of operations. His initial thought, perhaps, was to invest New York should Clinton’s position be deemed vulnerable and the expected French fleet move inside Sandy Hook for action. An alternate plan was to attempt the capture of the British force in Virginia or to project an operation elsewhere in the South.

On May 22, 1781, a planning conference was held at Wethersfield, Conn., between Washington and Rochambeau and members of their staffs. A general outline of movement was laid down; but not knowing that Cornwallis was in Virginia or when or where to expect the French fleet under the Count de Grasse, it was necessarily fluid. The plan called for a union of French and American armies for a demonstration against New York—something that might induce Clinton to call troops from the South, thereby relieving, to some extent, the pressure there. This move, executed in July, actually did cause Clinton to ask for troops then 10 in Virginia and resulted in the removal of Cornwallis to Portsmouth, already described.

It was early in June that Washington learned of Cornwallis’ move into Virginia. Shortly afterwards, there was more definite word of the plans of De Grasse, although the point at which he would support military operations was not fixed. It was during the first week in July that Rochambeau and his army joined Washington on the Hudson, and some opening moves were made against Clinton in New York. On July 20 Washington entered in his diary that the uncertainties of the situation “rendered it impracticable for me to do more than to prepare, first, for the enterprize against New York as agreed to at Weathersfield and secondly for the relief of the Southern States if after all my efforts, and earnest application to these States it should be found at the arrivl. of Count de Grasse that I had neither Men, nor means adequate to the first object....”

At last, on August 14, Washington received dispatches telling him that the Count de Grasse was to sail from the West Indies with a substantial fleet and 3,200 troops. These troops had been requested by Rochambeau in previous dispatches to Admiral de Grasse. His destination was the Chesapeake; he could be in the area only a short time; and he hoped everything would be in readiness upon his arrival. Washington saw immediately that a combined land and naval operation in Virginia was the only possible plan, and he moved quickly to effect this insofar as he could.

In preliminary maneuvers every attempt was made to deceive Clinton as to the real destination of the units that were now scheduled for operations at Yorktown. These troops included the French Army and units from the American Army, totaling some 8,000 men. The remainder of Washington’s force, less than 4,000, under Maj. Gen. William Heath, was left before New York to guard West Point, N. Y., and the Highlands.

The movement toward Virginia began on August 19, 4 days after receipt of definite news from De Grasse. The troops used three distinct and separate routes as far as Princeton, N. J. This was partly to confuse Clinton, who did not fully understand what was happening, until Washington was well under way. Few in the French and Americans camps actually knew the objective. Jonathan Trumbull, Washington’s secretary, wrote: “By these maneuvers and the correspondent march of the Troops, our own army no less than the Enemy are completely deceived. No movement perhaps was ever attended with more conjectures, or such as were more curious than this ... not one I believe penetrated the real design.”

From Princeton, the march continued to Trenton where they found there were not enough ships available to transport the men and stores. The decision was to continue on foot to the head of Chesapeake Bay. The passage of the French and American troops through Philadelphia early in September became almost a festive occasion. With the American 11 units leading the way, the trek continued through Chester, Pa., and Wilmington, Del., to Head-of-Elk. It was at Chester, on September 5, that Washington learned that the Count de Grasse had arrived in the Chesapeake Bay with 28 ships of the line, a number of frigates and sloops, and 3,200 troops. At that time these troops, under the Marquis de St. Simon, had already debarked at Jamestown for union with Lafayette’s growing force.

On September 8, Washington, Rochambeau, and the Chevalier de Chastellux left to subordinates the task of preparing the allied armies for transport down the bay by ship. They, themselves, proceeded overland to Williamsburg, stopping en route for several days at Mount Vernon. This was Washington’s first visit to his home in 6 years. The party reached Williamsburg on September 14, and there was “great joy among troops and people” as Washington assumed active command of the growing American and French forces.

The Count de Grasse left Cape Français, on the northern coast of Haiti in the West Indies, for the Atlantic coast and Chesapeake Bay on August 5. He had reached the West Indies in April, after a 38 days’ crossing of the Atlantic from Brest, France. There had been some contact with the sizeable British fleet under Rear Adm. Sir Samuel Hood who, with his superior in this theater, Sir George Rodney, did not seem willing to bring on a general action at this time. De Grasse had moved on against Tobago, proceeded to Santo Domingo, and reached Cape Français on July 16.

At Santo Domingo, negotiations for land forces for use in Virginia were completed with M. de Lillancourt, the new commander there, who agreed to supply from the West Indies garrison a detachment from the Gatinois, Agenois, and Touraine regiments, as well as some artillery, dragoons, and field and siege ordnance. It was further agreed that the troops could be maintained on the continent only until October 15, as they might be needed in the West Indies after that time. In Havana, De Grasse, as had been requested of him, concluded arrangements for financial aid—a virtual necessity at this point.

De Grasse approached the Virginia Capes on August 30, encountering the British frigate Guadaloupe and the corvette Loyalist which had been posted as lookouts. Both were pursued, the corvette being taken and the frigate forced into the York River. The next day, the French fleet moved into Chesapeake Bay for anchorage, individual ships having been delegated to block the mouths of the York and the James. On September 2, the land forces under the Marquis de St. Simon were sent up the James in long boats for landing at Jamestown.

Dispatches telling of the arrival of De Grasse were sent to Washington and Rochambeau, contact having already been established with Lafayette. De Grasse felt that there was urgent need for action, but Lafayette, even with the reinforcements of St. Simon, thought that it would 12 not be wise to attack before Washington and the army under his command reached the area. He wrote “... having so sure a game to play, it would be madness, by the risk of attack, to give any thing to chance.” Perhaps De Grasse was wondering how he had been able to reach Virginia and establish a blockade of Cornwallis’ position without interference from the British fleet. Such good fortune might not continue.

The undisturbed voyage had indeed been a stroke of luck. In July, word had been received by Rear Adm. Thomas Graves, in command of the British naval units at New York, that a convoy, with valuable aid for the American cause, had sailed for America and that it was important that it be intercepted. This led him to put to sea, believing that Rodney, in the West Indies, would take steps to cover any movement of the French fleet of De Grasse which was known to be in that area. As a precautionary measure, however, he sent some light craft on reconnaissance south along the Atlantic coast.

Count de Grasse, Admiral of the French fleet in the Battle of the Virginia Capes and in the blockade of Yorktown in September-October 1781. (From a painting in the U. S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, Md.)

Graves left Sandy Hook, off New York harbor, on July 6. He was still at sea when a sloop reached New York with dispatches from Rodney telling of De Grasse’s fleet and the fact that at least a part of it was destined for North America. Rodney further reported that if the situation should require him to send a squadron to contact the French that he would order it to “make the Capes of Virginia,” proceed along the Capes of the Delaware, and move on to Sandy Hook. Not finding Graves, the commander of the sloop put to sea to locate him, but was attacked by a privateer and forced ashore. Thus, Graves did not get word 13 of De Grasse from Rodney until he himself returned to New York on August 18.

Needing repairs, Graves did not want to sail again until his fleet was in readiness. Another matter that was troubling him was the French squadron of eight ships under Admiral De Barras at Newport; and it was tentatively agreed that when he was at full strength joint operations would be undertaken against that station. Then, on August 28, Rear Adm. Samuel Hood anchored off Sandy Hook with the greater part of the West Indies fleet. Rodney, suffering from poor health, had turned over his command to Hood and sailed for home, but one of his last acts had been to dispatch Hood northward along the Atlantic coast with comprehensive instructions to act against, or to head off, De Grasse. Hood, on August 25, had entered the Chesapeake and found no enemy, since he had sailed in advance of De Grasse. From Virginia he had continued on to New York. Thus Hood had missed De Grasse, and the latter was now in the Chesapeake.

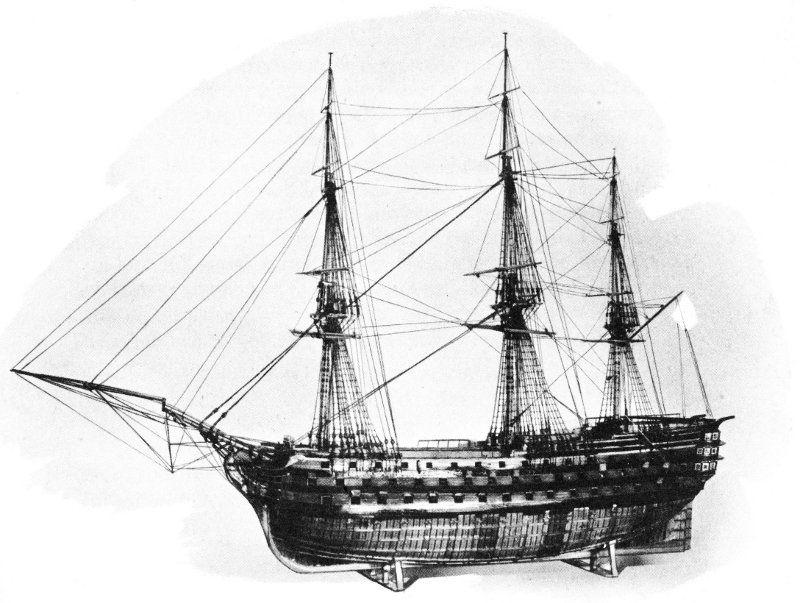

The VILLE DE PARIS.

A model of the flagship of the Count de Grasse during his operations

in Virginia waters in the autumn of 1781.

An intelligence report was received about this time by the British that De Barras had sailed from Newport with his entire squadron and that he, too, was headed for Virginia. Immediate action was imperative. Graves assumed command of the entire British fleet, now made up of 14 Hood’s ships and all of his own that were ready for duty. On August 31, he sailed south, hoping to intercept either De Barras or De Grasse, or of engaging them both.

On the morning of September 5, Graves approached the capes of the Chesapeake. The French fleet was sighted and a signal was made to form a line of battle. By noon, his ships were getting to their stations. The fleet was divided into three divisions, with Graves directing operations from his flagship, the London, of 98 guns. Division commanders were Rear Adm. Samuel Hood and Rear Adm. Francis Samuel Drake.

Meanwhile, in the French fleet, De Grasse ordered all hands to prepare for action. The tide was right by noon, and, even though 90 officers and 1,800 men were not aboard, his ships got under way and moved out into the Atlantic to allow more room for maneuver. De Grasse commanded from his flagship, the Ville de Paris, a 110-gun ship, and deployed his fleet in three sections, commanded respectively by Le Sieur de Bougainville, De Latouche-Treville, and Le Sieur de Monteil. Action began about 4 o’clock in the afternoon and continued for 2½ hours, when darkness necessitated a cease-fire order. A French account of the battle related that:

At four o’clock the van, commanded by M. de Bougainville, began the action with a very brisk fire and successively the ships of the line of battle took part. Only the eight leading ships of the English line took any great part in the fight. The combat was violent here. For the most part the center of their fleet and their rear held themselves at half a cannon shot without inclining to engage. The wind failed the nine last vessels of our line entirely.... At five o’clock the winds having continued to vary up to four points placed again the French van too much to windward. Count de Grasse desired ardently that the action be general, and in order to have the enemy at command there he ordered his van to bear down a second time. That of Admiral Graves was very abused, and that admiral profited by the advantage of the wind which rendered him master of distance, in order to avoid being attacked by the French rear-division which was making every effort to reach him and his center. Sunset ended this battle.... The first fifteen ships in the French line were the only ones to participate in the battle....

It was later learned that the “ship London commanded by Admiral Graves had been so well raked by the Ville de Paris that they [the English] had been obliged to change all its masts.”

In the action, 24 French ships of the line, carrying approximately 1,700 guns and 19,000 seamen, were opposed by 19 British ships of the line, having about 1,400 guns and 13,000 seamen. Casualties for the British were 90 killed and 246 wounded. The French counted about 200 15 in killed and wounded. Several English ships were damaged, and one, the Terrible, had to be sunk several days after the engagement.

During the night of September 5-6, the two fleets remained close together. At a conference on the London, on the 6th, Graves decided that with a number of his ships disabled it would be too hazardous to renew the action. He also declined Hood’s suggestion to try to slip into the Chesapeake. De Grasse, having stopped the British and having inflicted considerable damage, likewise hesitated to renew the engagement. On the 7th and 8th, the two fleets remained from 2 to 5 leagues apart. Meanwhile, a northeast wind was carrying them south. On the 9th, they were below Albemarle Sound, and by the next day the British fleet was off Cape Hatteras. It was on the 9th that De Grasse lost sight of the British and, fearing that a change of wind might prevent it, sailed toward the Chesapeake Bay, which he reached on the 11th. On the 10th, De Barras reached Virginia with his squadron from Newport, R. I., and entered the bay, later to join De Grasse. Admiral Graves followed De Grasse northward, realizing that the situation was now out of hand. On September 14, he sailed from the Virginia coast for New York, where he intended to “... use every possible means for putting the Squadron into the best state for service....” His departure had momentous consequences for Cornwallis.

The Battle of the Virginia Capes, as the action of September 5 has come to be called, was a most important phase of the siege of Yorktown. At a critical point the French had seized control of the sea and had sealed in the British at Yorktown. This prevented the evacuation of Cornwallis and ended his hopes of reinforcement and supply. The next phase of the combined operation against Cornwallis was encirclement by land. Already this was being accomplished.

On September 7, Lafayette moved his force from the Pamunkey River to Williamsburg where he could at least temporarily block any movement that Cornwallis might make up the peninsula. His army was substantially enlarged the next day by the more than 3,000 troops under St. Simon, who had arrived with De Grasse and landed at Jamestown. On September 14, Washington arrived at Lafayette’s headquarters in Williamsburg for a “joyful reunion” with the young French general and to assume direct command of the operations in the Virginia theater.

The combined French and American forces, which Washington had left at the head of the Chesapeake early in September, found a shortage of shipping also at Head-of-Elk. It was necessary to use most of the vessels available for the transport of ordnance and stores, with the result that the bulk of the troops had to march on to Baltimore and Annapolis to embark. On September 15, Washington wrote to De Grasse about the transport of his army. The French admiral had anticipated this need, and had already dispatched the transports brought to the area from Newport 16 by De Barras plus some frigates which had been seized—enough to accommodate about 4,000 troops.

Count de Rochambeau, Commander of the French wing of the allied armies which besieged Yorktown.

On September 17, Washington, with Rochambeau, Chastellux, Henry Knox, and the Chevalier Duportail, visited De Grasse aboard the Ville de Paris to pay their respects and to confer on the joint operation now in progress against Cornwallis. In the discussion, Washington was able to prevail on De Grasse to extend his stay in Virginia waters past the October 15 deadline which he had originally set. He agreed to remain at least through the month of October. He did not, however, approve plans to move ships into the York River.

By September 22, when Washington returned to Williamsburg, parts of the allied armies from the North had arrived, having landed along College Creek and at other points on the James. Included among the troops, too, was a force under M. de Choisy which had come down from Newport with De Barras. Late in the same day other parts of the convoy, which De Grasse had sent up the bay, began to arrive, and De Grasse was able to write: “Everything is entering the river today, even your artillery.” Landing operations continued for several days with much of the artillery being put ashore at Trebell’s Landing below College Creek.

About this time the allied commanders learned that the English fleet in New York had been augmented by the arrival of a squadron under Adm. Robert Digby. This led to apprehension on the part of De Grasse and increased the need for haste in operations against Yorktown. De Grasse debated the need of putting to sea—a turn of events that caused Washington moments of “painful anxiety.” In the end, however, De Grasse was persuaded against this move, and he remained in the bay. 17 Nevertheless, the need for immediate land action had become imperative.

By September 27, the organization of the allied French and American armies assembled at Williamsburg had been completed. There were three parts—American Continentals (approximately 5,200), French auxiliaries (about 7,500), and American militia (over 3,000). The Continentals were grouped in three divisions, commanded respectively by Major General Lafayette, Major General von Steuben, and Major General Lincoln. In addition to his divisional duties, Lincoln also commanded the American wing. Detachments of artillery, with siege and field pieces, several companies of sappers and miners, and other units, were under the command of Brig. Gen. Henry Knox of Massachusetts. There was a cavalry grouping too, under Col. Stephen Moylan of Pennsylvania.

The French wing of the allied armies made up approximately one-half of the total land forces which opposed the British. Commanded by the Count de Rochambeau, it included 7 infantry regiments grouped in 3 brigades. The cavalry was under the Duke de Lauzun and the artillery under Colonel d’Aboville. The French engineers were headed by Colonel Desandrouins and Lieutenant Colonel Querenet, both of whom were instrumental in the preparation of an excellent set of siege plans.

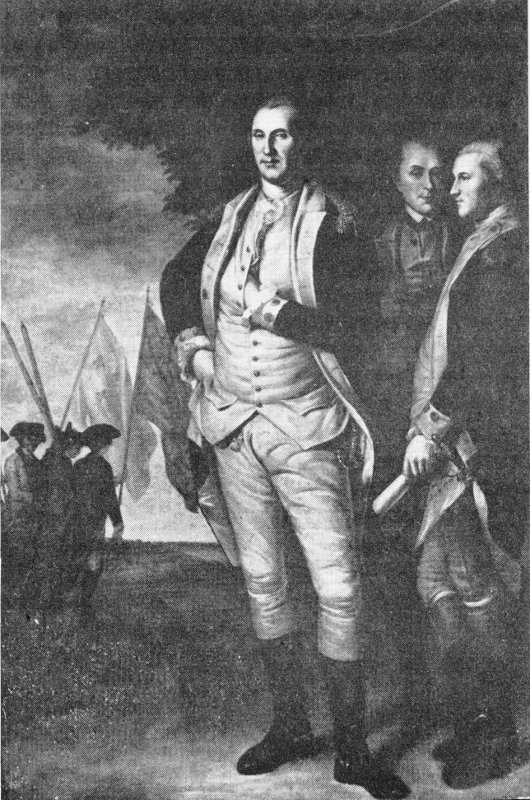

Gen. George Washington, Commander in Chief of the allied French and American forces at Yorktown. (From the Peale portrait in the State House, Annapolis, Md.)

The third component of the allied armies was the militia, chiefly from Virginia, commanded by Gen. Thomas Nelson, Jr., a native of Yorktown, who was supported by Brig. Gen. George Weedon, Brig. Gen. Robert Lawson, and Brig. Gen. Edward Stevens.

On September 27 all was in readiness for the movement of the allied armies against the British position at Yorktown and an “Order of Battle” was drawn up. At 5 o’clock in the morning of September 28 the French and American units, on instruction from Washington, their commander in chief, began to move toward Yorktown. The Continentals, followed by the French troops, formed the left column and the militia, the right. The route lay over the principal highways down the peninsula. At the “Halfway House,” midway between Williamsburg and Yorktown, the American regulars moved off to the right, while the French continued on the more direct route.

About noon both sections approached Yorktown, and contact was made with British pickets who fell back. Lt. Col. Robert Abercrombie’s Light Infantry, covering the British right, first gave the alarm, and some shots were exchanged with Tarleton’s Legion, which covered the British left, as the American and French troops reached the approaches to Yorktown. By nightfall, the allied units reached temporary positions along Beaverdam Creek within a mile of the main enemy posts. At this point, orders were issued that “The whole army, officers and soldiers, will lay on their arms this night.”

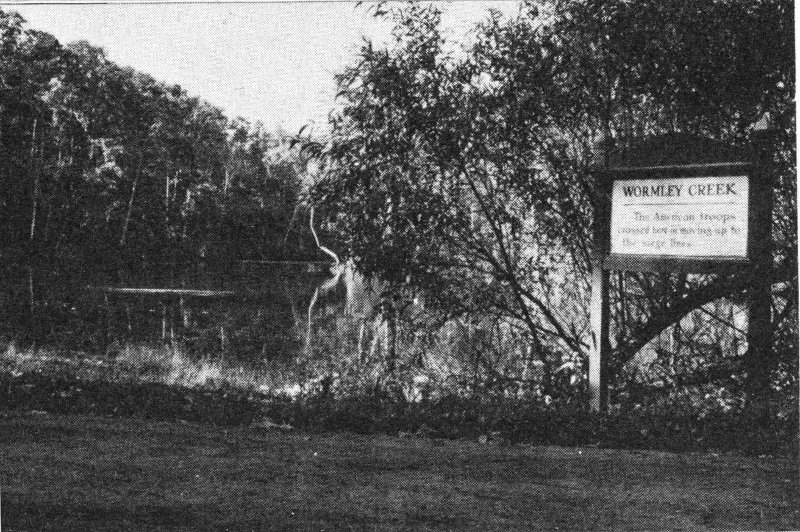

The investment of Yorktown, which began so auspiciously on the 28th, was more securely established during the 2 days that followed. On the 29th, the American wing moved more to the east (right) and nearer to the enemy, while both French and American units spread out to their designated campsites, forming a semicircle around Yorktown from the York River on the northwest to Wormley Creek, a tributary of the York, on the south and east. Reconnoitering was extended within cannon range of the enemy’s works, and several skirmishes developed with British patrols. There was also some minor action at Moore’s Dam over Wormley Creek, where the British had thrown up temporary positions.

When the British entered Yorktown in August 1781, the town, one of the most important in the lower Chesapeake region, was described by one of the soldiers as:

This Yorktown, or Little-York, is a small city of approximately 300 houses; it has, moreover, considerable circumference. It is located on the bank of the York River, somewhat high on a sandy but level ground. It has 3 churches, 2 reformed English and 1 German Lutheran, but without steeples, and 2 Quaker meeting houses, and a beautiful court or meeting house, which building, like the majority of the houses, is built of bricks. Here stood many houses which were destroyed and abandoned by 19 their occupants. There was a garrison of 300 militia men here, but upon our arrival they marched away without firing a shot back to Williamsburg, which is 16 English miles from here.

We found few inhabitants here, as they had mostly gone with bag and baggage into the country beyond.

The task confronting Cornwallis was the fortification of this town and Gloucester Point, just across the York, as a base. In early August, he had little reason to expect that 2 months later he would be besieged. Nevertheless, on arrival in Yorktown he turned to the task at hand with vigor. As the days passed, Cornwallis began to realize that enemy forces were assembling around him.

In planning his defense, he established a line of fortifications, close in about the town, supported by small enclosed earthworks, or redoubts, and batteries. Just in advance of the main line he constructed two positions, Redoubts Nos. 9 and 10, to command the high ground in that sector. Along the York-Hampton Road he strengthened the main line by extending it outward on the highway in the form of a point, or wedge, that was called the “Horn-Work.” In the inner and principal line, he had 10 redoubts and 14 batteries in which were mounted some 65 guns, the largest being 18-pounders. Some of this ordnance came from the British ships anchored offshore in the York.

The British outer line utilized the protective features of ravines and creeks. Close on the west of Yorktown was Yorktown Creek. On the east, but at a greater distance, ran Wormley Creek. These creeks, with their marshes and irregular terrain, constituted rather formidable barriers to the rapid advance of troops. The area between the headwaters of these two creeks, however, was a weak link. This high ground, less than half a mile wide, carried the road from Yorktown to Hampton. To control this, British engineers laid out four redoubts and some gun emplacements. On the west side of Yorktown Creek, near the point where a road to Williamsburg crossed, a large star-shaped work was built. This, manned by a part of the Royal Welch Fusiliers (23d) Regiment, was known as the Fusiliers Redoubt. These positions, some works at Moore’s Mill Dam, and the two creeks constituted the British outer line at Yorktown.

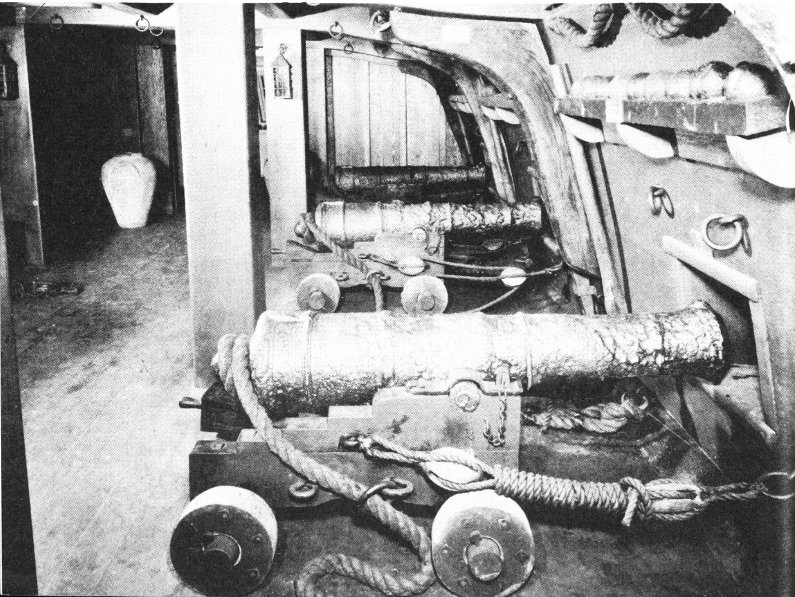

The village at Gloucester Point, across the river, was fortified with a single line of entrenchments with 4 redoubts and 3 batteries. In the York River, between Yorktown and Gloucester, there were British transports, supply boats, and some armed vessels, notably the Charon and Guadaloupe.

Behind his lines, Cornwallis had a force of some 7,500 troops, most of them seasoned veterans. To aid his gunners, all buildings, trees, and other obstructions in front of his main line were removed for a distance of 1,000 yards. All roads were blocked, and the completion of fixed positions was pushed.

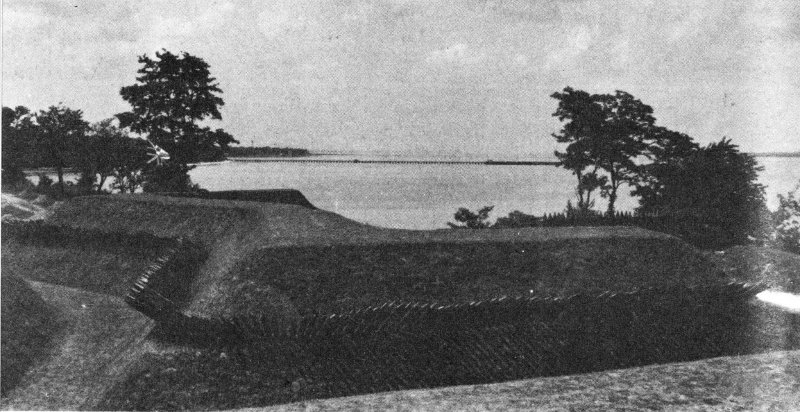

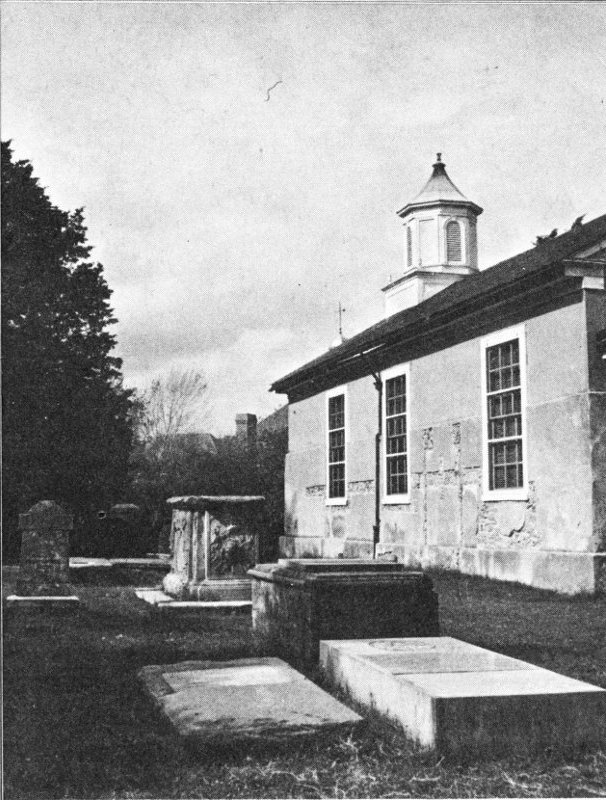

The Fusiliers Redoubt (reconstructed), a position which supported the right side of the British main line.

Cornwallis had begun to feel the pinch of the French fleet blockade even before the allied armies reached Yorktown. On September 11, one of his soldiers wrote: “We get terrible provisions now, putrid ship’s meat and wormy biscuits that have spoiled on the ships. Many of the men have taken sick here with dysentery or the bloody flux and with diarrhea. Also the foul fever is spreading, partly on account of the many hardships from which we have had little rest day or night, and partly on account of the awful food; but mostly, the nitrebearing water is to blame for it.” Sickness and also a lack of officers were to remain a severe handicap for the British.

Cornwallis continued to keep in touch by letter with Clinton in New York. On September 16, he had received word that Clinton was planning to move south with a sizeable force to aid him. When he received this word, Cornwallis decided against any offensive action and so wrote to Clinton. On September 29, a dispatch from New York, written on the 24th, told of ship repairs and a strengthened British fleet, as well as the preparation of reinforcements for Cornwallis’ Virginia garrison. Clinton continued: “There is every reason to hope we start from hence the 5th October.”

About 10 o’clock on the night of September 29, Cornwallis made an important decision which he described in a letter to Clinton: “I have this evening received your letter of the 24th, which has given me the greatest satisfaction. I shall retire this night within the works, and have no doubt, if relief arrives in any reasonable time, York and Gloucester will be both in possession of his Majesty’s troops.” This decision to abandon his outer line without a fight definitely shortened the siege of Yorktown. It was a move for which Cornwallis has been criticized and an advantage which the allied armies quickly seized.

Washington wrote of the morning of September 30: “... we discovered, that the Enemy had evacuated all their Exterior Line of Works, and withdrawn themselves to those near the body of the Town. By this Means we are in possession of very advantageous Grounds, which command, in a very near Advance, almost the whole remaining line of their Defence.” Even before Washington had written, American and French units had moved into these works. Within the day, the construction of an additional redoubt and a battery was begun in this sector.

On the morning of the 30th, while these moves were being made on the south side of Yorktown, on the extreme west a French unit from St. Simon’s command drove in the British pickets in the vicinity of the Fusiliers Redoubt. A sharp skirmish resulted, with several casualties—an action that enabled the allies to take a more advantageous position in this quarter.

One event only marred the successful moves of the 30th. Col. Alexander Scammell, of New Hampshire, a well-known soldier with much service, was wounded during the early morning while reconnoitering with a small party south of Yorktown. He died from his wound a week later in the base hospital in Williamsburg.

American Battery No. 2.

In the first days of October, the allies completed their surveying and planning and pushed the construction and collection of siege material which consisted of gabions (wickerwork-like baskets to be filled with earth to support embankments); fascines (long bundles of sticks of wood 22 bound together for use in filling ditches, strengthening ramparts, etc.); fraises (pointed stakes to be driven into embankments in an upright or inclined position); and saucissons (large fascines). There was some delay while the heavy guns were being transported from the landing points on the James. Perhaps James Thacher penned an accurate short description when he wrote on October 1-2: “Heavy cannon and mortars are continually arriving, and the greatest preparations are made to prosecute the siege in the most effectual manner.” By October 6, however, the work of reconnoitering the abandoned British positions south of Yorktown and constructing supporting works there was complete. All was in readiness for the next move—construction of the First Allied Siege Line.

Throughout this interval the British had maintained a steady and effective artillery fire which tended to slow the work of the allies. The journals of the siege are full of accounts, such as that written by Lt. William Feltman on October 2: “A continual cannonading this whole day at our fatigue parties. One Maryland soldier’s hand shot off and one militia man killed.” Behind the British lines feverish activity continued, and there was fear of a general “alarm.” Ships were sunk in the river immediately in front of the town to block any allied landing attempt from that quarter. Cornwallis’ positions were not complete, nor were his magazines. Every available man was on the line to help in the construction, particularly the large force of Negro labor which the British general had acquired. To complicate the picture for Cornwallis, smallpox was taking its toll.

View of Gloucester Point, across the York River from Yorktown, before construction of the Coleman Memorial Bridge.

Even though Washington was directing his principal force against Yorktown where the main British force was located, it was necessary that he take measures to contain the enemy post at Gloucester 23 Point on the north side of the river. This would close a possible means of escape for Cornwallis and halt the heavy foraging parties that were sweeping the Gloucester countryside. The first allied force here was 1,500 militia under Brig. Gen. George Weedon. By September 28, Weedon had been reinforced by the Duke de Lauzun’s Legion of 600, half of them mounted. Several days later, 800 marines were landed from the French fleet and Brigadier General Choisy was assigned to command the whole. By early October, the British garrison on the Gloucester side had grown and included both Simcoe’s and Tarleton’s cavalry, as well as ground units.

On October 3, as Choisy moved down toward Gloucester Point to tighten his lines and to force the enemy into their fixed positions on the point, a brief but spirited encounter occurred at “the Hook,” near present Hayes Store, in which the daring cavalry leaders, Lauzun and Tarleton, had major roles. Casualties numbered about 16 for the allies and perhaps 50 for the British. The allies succeeded in holding the ground. The British withdrew behind their works where they remained until the end of the siege.

By the evening of October 6 all was in readiness for the opening of the First Allied Siege Line—a series of positions which, together with terrain advantages, completely encircled the British works and brought men and artillery within firing range of the enemy. The first line was based on the York River southeast of Yorktown and extended westward just above the headwaters of Wormley Creek, across the York-Hampton Road, to Yorktown Creek, which in a real sense functioned as a continuation of the line. The first line was about 2,000 yards long and was supported by four redoubts and five batteries. Its average distance from the main British works was about 800 yards, although, on the right, this was somewhat greater because of two detached British Redoubts, Nos. 9 and 10. About half of this line, the right or York River end, was assigned to American units; the left was built and manned by the French.

At dusk on October 6, more than 4,000 allied troops paraded and marched to their assigned stations. The entrenching party, 1,500 strong, carrying knapsacks, guns, and bayonets, as well as shovels, found a line of split pine strips already on the ground. They had been placed by the engineers to mark the line where the digging was to begin. Twenty-eight hundred soldiers lay under arms close at hand to repel attack should it come. Evidently the British were caught unawares, for their guns were not particularly active. The night was dark and cloudy, with a gentle rain falling—a factor which may have aided the troops who were being directed by General Lincoln and the Baron de Viomenil. By morning, the work was well advanced, enough to give those in the trenches protection from British gunners.

During the next few days, with precision and dispatch, unit followed 24 unit on fatigue duty as the trenches, redoubts, and batteries were brought to perfection. Major General von Steuben, one of the few veterans of siege warfare in the American wing, had a leading role in planning and constructing the siege works. Brigadier General Knox, with the American artillery, played a significant part, too, since effective gunnery was a prime prerequisite to success in the operation.

While the main line was taking form south of Yorktown, the French constructed a trench and battery between the York River and one of the branches of Yorktown Creek west of town. This closed a possible point of break-through for the enemy, partly encircled the Fusiliers Redoubt, and permitted the installation of ordnance at a point where it could, and did, sweep the British ships anchored in the river. This French battery on the left, with its four 12-pounders and six mortars and howitzers, was the first to go into action, firing about 3 o’clock on October 9. Two hours later, an American battery southeast of Yorktown added its six 18- and 24-pounders, four mortars, and two howitzers to the bombardment. Washington, seemingly, fired the first round from this battery with telling accuracy. On October 10, other batteries, including the Grand French athwart the York-Hampton Road, were completed and began firing. For the next 2 days there was no let-up in the concentrated and methodical bombardment of Yorktown, with Gen. Thomas Nelson, reportedly, even directing fire against his own home.

The effect was terrible as charge after charge was sent pounding into the British works or went ricocheting or skipping along the ground. Enemy batteries were knocked out or were slowly silenced. Cornwallis’ headquarters were all but demolished and he himself narrowly escaped with his life at one point. All the while, the tempo of the cannonade mounted. Johann Conrad Doehla, a soldier in the British Army, wrote:

Tonight [October 9] about tattoo the enemy began to salute our left wing and shortly afterward our entire line with bombs, cannons, and howitzers.... Early this morning [October 10] we had to change our camp and pitch our tents in the earthworks, on account of the heavy fire of the enemy.... One could ... not avoid the horribly many cannon balls either inside or outside the city ... many were badly injured and mortally wounded by the fragments of bombs which exploded partly in the air and partly on the ground, their arms and legs severed or themselves struck dead.... [October 11] One saw men lying nearly everywhere who were mortally wounded.... I saw bombs fall into the water and lie there for 5, 6-8 and more minutes and then still explode ... fragments and pieces of these bombs flew back again and fell on the houses and buildings of the city and in our camp, where they still did much damage and robbed many a brave soldier of his life or struck off his arm and leg.

Such was the bombardment of Yorktown as described by one participant and testified to by others who witnessed it. The fire had been devastating. Its effect was reported first-hand to the allied leaders by Secretary Thomas Nelson, who, “under a flag of truce,” was permitted by the British to leave Yorktown and seek the allied lines.

The bombardment was directed, too, against the British ships in the harbor with equal effect. Here “red hot shot” were used to ignite the heavily tarred rigging and ship timbers. On the night of October 10, artillery “set fire to two transport vessels and to the ship of war Charon ... [44 guns], which burned completely. The other ships anchored under York set sail in the night and went over to anchor at Gloucester, to put themselves under shelter and out of range of our fire.” Other boats, large and small, including the Guadaloupe (28 guns), were hit and burned. On the night of the 11th, a British “fire ship,” designed for setting fires to enemy vessels, was struck and burned with a brilliant blaze. Against such heavy artillery fire, Cornwallis found it difficult to keep his own batteries in operation, and even the sailors and marines from the English vessels added little strength.

The destruction caused by the superior French and American artillery, firing at ranges from 800 to 1,200 yards, was so great and the enemy batteries were so completely overpowered that Washington was soon ready to open the Second Allied Siege Line, which would bring his troops within storming distance of the enemy works. An “over the top” charge by the infantry would be the final stage of the siege should Cornwallis continue to hold out.

Work on the second line began on the night of October 11-12, about midway between the first siege line and the left front of the British works. By morning, the troops had wielded their shovels, spades, and “grubbing hoes” so effectively that the work was well advanced and casualties were few. For the next 3 days the construction continued and artillery was moved from the first line into the new positions where it could be even more deadly. The British gunners did all they could with “musketry, cannon, cannister, grapeshot, and especially, a multitude of large and small bombs and shells” to delay the work, but, although they exacted some casualties, they were not particularly successful.

At this time, however, only half of the second siege line could be undertaken. British Redoubt No. 10 near the river, a square position manned by about 70 soldiers, and Redoubt No. 9, a 5-sided strong point held by approximately 125 troops, near the road from Yorktown to the Moore House, blocked the extension of the second line on the allied right. Before work could proceed, these would have to be reduced.

Prior to the attacks on these redoubts, Washington had ordered a feint on the extreme left against the Fusiliers Redoubt and also a demonstration at Gloucester Point to 26 distract the enemy. For several days before the assault, allied gunners directed fire to weaken the positions, a fire that actually was not very harmful. The attacks were made at 8 o’clock, after dark, on October 14, in one of the most dramatic and heroic moves of the siege of Yorktown, and it proved to be a definite turning point in the operations.

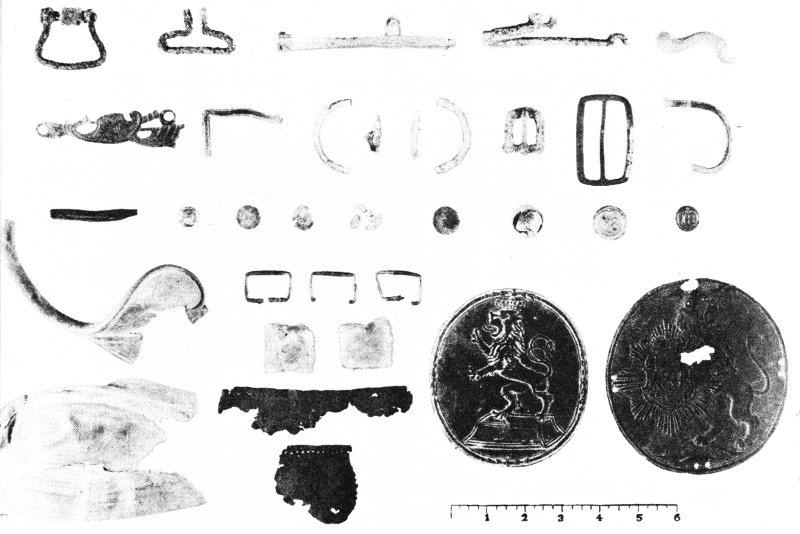

Representative objects recovered at the site of British Redoubt No. 9 during the archeological exploration that preceded its reconstruction.

Redoubt No. 10 was attacked by 400 Americans drawn from Lafayette’s Light Infantry Division and commanded by Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton, who, being officer of the day, had claimed this honor, when the assignment was first given to another. He was assisted by Lt. Col. Jean-Joseph Sourbader de Gimat, Lt. Col. John Laurens, and Maj. Nicholas Fish. The detachment moved out at the prearranged signal—the burst of six shells. The American soldiers carried unloaded muskets, as they advanced in darkness, since the assignment at hand was to be done with bayonets. On reaching their objective, they charged without waiting for the removal of the abatis (an entanglement of pointed tree tops and branches which ringed the redoubt), and thereby saved a few minutes—an interval that could have been costly. Within 10 minutes the position was in American hands with a loss of 9 killed and 31 wounded, according to Hamilton’s own report.

As the Americans were moving out for their attack from the right end of the First Allied Siege Line, a party of 400 French soldiers led by Col. William Deux Ponts, with the Baron de l’Estrade second in command, 27 launched an assault on Redoubt No. 9 from the temporary end of the second siege line. French casualties mounted when the detachment halted until the abatis was cleared. Then the cry was “on to the redoubt.” A British charge was met by musket fire and a countercharge which took the French over the top, and the redoubt was theirs. Losses, however, totaled almost 25 percent, including 15 killed. The entire operation lasted less than half an hour.

Immediately following the capture of the two key redoubts, troops moved up to resume work on the second siege line. Before morning, this line was extended all the way to the York River and incorporated the formerly held British Redoubts No. 9 and No. 10. Communicating trenches were opened to the First Allied Siege Line and, adjacent to Redoubt No. 9, a large American Battery was begun. On October 15, Ebenezer Wild recorded: “The works were carried on last night with such spirit that at daylight we found the parallel [line] extended quite to the river on our right and nearly completed. Batteries are erecting with great expedition.”

With this turn of events, Cornwallis knew that he must act and act quickly or all would be lost. The web had tightened; and the destruction of his positions, plus sickness and casualties among his troops, made his situation critical, even perilous. Against the fully operating allied second line, he would be unable to hold out for 24 hours.

On the night of October 15-16, Cornwallis ordered an attack against the second line. This was launched, 350 strong, under Lt. Col. Robert Abercrombie at a point near the center of the line. It was a gallant sortie, yet it accomplished little, for, within a few hours, the guns which had been spiked by the British were again firing upon Yorktown.

On the night of October 16-17, Cornwallis ordered all of his effectives moved across the river to Gloucester Point. This, he thought, might enable him to make a breakthrough, which could be followed by a quick march north toward New York. The effort was futile. He was handicapped by a shortage of small boats, and a storm about midnight further interfered with the operation.

Early on the morning of the 17th he recalled those who had crossed the river. Later that morning he held a council with his officers, and at 10 o’clock a drummer in red, accompanied by an officer, was sent to a point on the parapet on the south side of Yorktown to beat a “parley.”

Cornwallis’ situation was hopeless. Casualties (killed, wounded, and missing) during the siege, it seems, numbered about 552 for the British, 275 for the French, and 260 for the Americans. Of these totals, more than one-fourth were killed in action. Yorktown was surrounded at close range, relief had not yet come, and the enemy was superior in men and firepower. In short, his position was untenable. Surrender was now the only alternative. Cornwallis himself reported: “We at that time could not fire a single gun.... I therefore proposed to capitulate.”

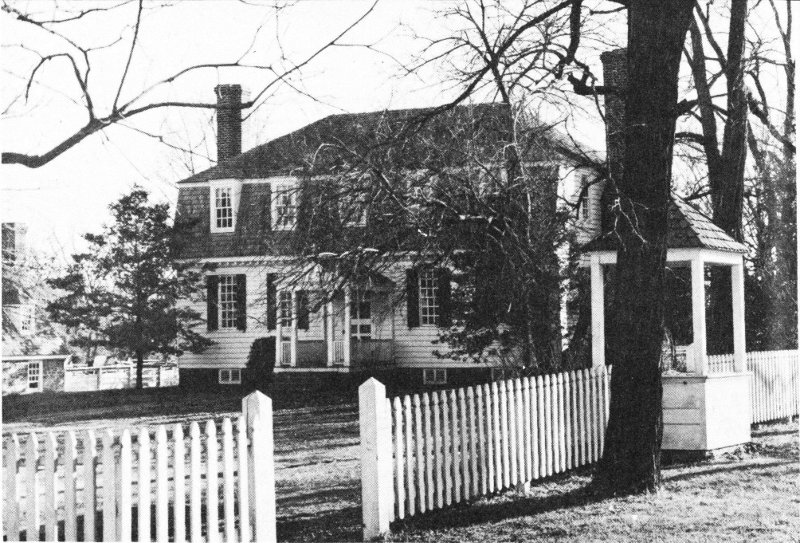

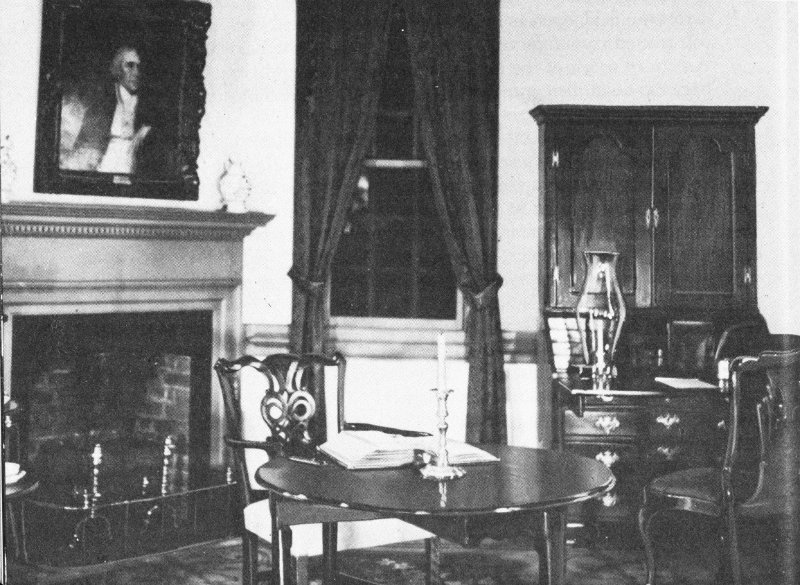

The restored Moore House where the Articles of Capitulation for the British Army were drafted.

When the British flag of truce was seen by the allied officers on the morning of the 17th, the incessant and devastating artillery fire ceased. It had been continuous since October 9, except for short intervals when batteries were being shifted or a flag of truce was passing between the lines. Cornwallis’ letter, which was transmitted immediately to Washington, read: “I propose a cessation of hostilities for twenty four hours, and that two officers may be appointed by each side, to meet at Mr. Moore’s house, to settle terms for the surrender of the posts of York and Gloucester.”

Washington replied that he would grant the British general 2 hours in which to submit definite terms. At about 4:30 p. m., Cornwallis replied. Washington found his proposals satisfactory in part, and in his reply stated that the British could expect that: “The same Honors will be granted to the Surrendering Army as were granted [by the British] to the [American] Garrison of Charles Town [in 1780].”

Arrangements were concluded for the differences of opinion to be ironed out during a meeting of commissioners at the home of Augustine Moore in the rear of the first siege line. The commissioners (Lt. Col. Thomas Dundas and Maj. Alexander Ross, representing the British; the Viscount de Noailles, the French; and Lt. Col. John Laurens, the Americans) met there on October 18 and, after a heated and prolonged session, drafted the Articles of Capitulation. On the morning of the 19th, Washington reviewed the draft and, after some modification, had the articles transcribed. The document was then sent to Cornwallis for his signature, with a deadline of 11 a. m. Cornwallis duly signed, as did Capt. Thomas 31 Symonds, representing the British naval units in the York. The allied commanders, Washington and Rochambeau, appear to have signed the document in captured British Redoubt No. 10. The Count de Barras, designated to act in place of the Count de Grasse for the French fleet, also signed for the allies.

The articles provided that the troops, seamen, and marines should surrender as prisoners of war. Officers were to retain their sidearms and private papers and property. The soldiers were to be kept in prison camps in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Cornwallis and certain of the officers were to be allowed freedom on parole and the sloop Bonetta was to be made available for the British commander to carry dispatches to Sir Henry Clinton, after which she was to be surrendered.

At noon on October 19, two redoubts southeast of Yorktown were occupied by allied troops—one by an American unit and the other by a French detachment. At 2 p. m., the British Army, clad in a new issue of uniforms and led by Brigadier General O’Hara (Cornwallis was ill), marched out from Yorktown along the York-Hampton Road to the tune of an old British march titled “The World Turned Upside Down.”

In the vicinity of the present national cemetery, O’Hara reached the head of the allied column. It appears that he sought first the Count de Rochambeau, but was referred to Washington. Washington, in turn, sent him to Major General Lincoln, who accepted his sword—the token of defeat and surrender—and then returned it. Following this, the British Army marched down Surrender Road between columns of allied troops, Americans on the British left (east) and French on the British right (west), to Surrender Field where the formal surrender was effected. “... we came directly onto a level field or large meadow, where ... we ... marched one regiment after another, stacked muskets and lay down all arms ...”, wrote one of the British soldiers. Thus, the siege of Yorktown ended, the climax of the Revolution had passed, and America could look forward toward a free and independent status. A new nation had been born!

After the surrender, the British units returned to Yorktown. After 2 days’ rest, the rank and file and junior officers were marched off to prison camps in western Virginia and Maryland. Both Washington and Rochambeau invited their distinguished prisoners to their tables, and for several days camp dinners were the fashion, the English attending as guests. The American units of the Allied armies took up the return march to the Hudson about November 1. The French, for the most part, remained on the peninsula until spring and then left for Rhode Island, having wintered in Yorktown, Williamsburg, Hampton, and other nearby points. De Grasse sailed for the West Indies shortly after the siege was over. The British expedition, which was to relieve Cornwallis, reached Virginia waters late in October, too late to be of any use.

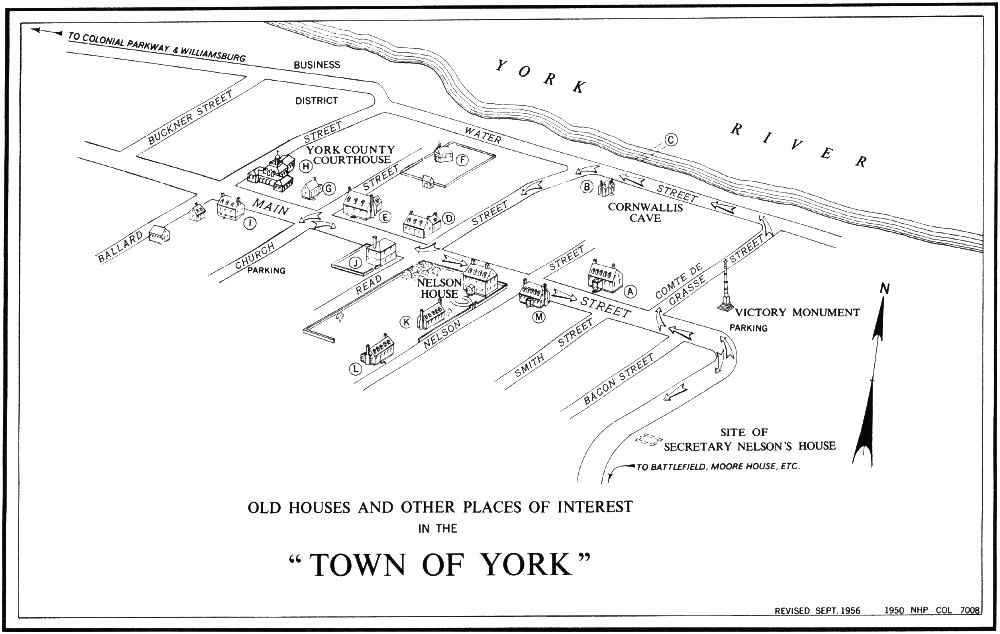

Yorktown had its origin in the Virginia Port Act of 1691—one of the legislative measures by which British colonial authorities and Virginia leaders sought to force urban development in the colony. It specified that 50 acres should be procured for a port to serve York County and that it would be upon “Mr. Benjamin Reads land.” This was a part of the Capt. Nicholas Martiau property (originally patented about 1635) which, by 1691, had descended through Martiau’s daughter, Elizabeth, and George Read to their son, Benjamin Read. The 50 acres were situated at the point where the York River narrows to about half a mile. There had been a ferry here for many years. Maj. Lawrence Smith was engaged to make the survey, and a plat made by him is still preserved in the official records of York County.

Although Yorktown (variously called Port of York, Borough of York, York, Town of York, and Yorktown) was not established until 1691, the area around Yorktown had been well known to the English for generations. The river itself had been explored, and frequently visited, by Capt. John Smith and his fellow settlers at Jamestown. They came most frequently by water, but it was not until the 1630-32 period that early Virginians began to push overland from the James River and to establish homes on the banks of the York. Among the men who braved the Indians, the forests, and natural enemies to establish homes on the creeks and tidewaters above and below Yorktown were Capt. John West (who became Governor in 1635), Capt. John Utie, Capt. Robert Felgate, and, a little later, Henry Lee. The Indians before them had seen, and recognized, the strategic value and beauty of this location. Chief Powhatan was residing on the north side of the river, above Gloucester Point, when Smith first saw him in 1607, and the Chiskiack Indians lived on the south side near present-day Yorktown until pressure from the white man caused them to move.

Nicolas Martiau, a French Huguenot, first received a grant of land in the Yorktown area. It was a part of this tract, which originally lay between the holdings of Gov. Sir John Harvey and the estate of Richard Townsend, that in 1691 was acquired and laid out into the original 85 lots of Yorktown. Through the marriages of his descendants, Martiau became the earliest-known American ancestor of George Washington. A granite marker in his honor now stands on Ballard Street.

The earliest settlers on the York pointed the way for others who came in increasing numbers in the years that followed. The population grew to such an extent that in 1634 a county was laid out to embrace the settlements which had been made on the York (those around later Yorktown and those on the Back and Poquoson Rivers some miles to the southeast). Designated Charles River Shire, it was one of Virginia’s eight original shires (counties). At that time, the York River was known as the Charles, this having replaced the Indian name of Pamunkey. 33 About 1643, the name of the river was changed to York, from which both town and county take their name.

About 2 miles southeast of Yorktown is a tidal inlet, Wormley Creek, named for Christopher Wormley, a local property owner and a member of the council of colonial Virginia. On the west side of this inlet, a little town (perhaps best described as a small settlement) took form. It seemingly grew up around “Yorke Fort,” built on the point formed by Wormley Creek and York River. In 1633, “Yorke” was selected as a receiving point, and stores were ordered built to serve this settlement and that of Chiskiack just up the river. “Yorke” was separate and distinct from present Yorktown, but actually a direct antecedent. Early courts convened here, and there were a church and a courthouse with its customary instruments of justice (stocks, a pillory, and a ducking stool). The tomb of Maj. William Gooch here is one of the oldest existing dated tombs in the United States.

In establishing his survey of Yorktown in 1691, Lawrence Smith proceeded to the high bluffs above the river and laid out 85 half-acre lots arranged along a principal street (Main Street) running parallel with the river and seven streets which intersected Main. Many of the original street names still remain, as do original lot lines. In proceeding to the high ground to make the survey, a strip of land, described in 1691 as “a Common Shore of no value,” was left between the town and the river. This area actually proved of considerable value. Here, Water Street took form as the second Yorktown street running parallel with the river. Along it developed wharves, loading places, ships, stores, lodging accommodations, and considerable miscellaneous development. It was officially made a part of the town in 1738, but designated a commons until surveyed into lots in 1788.

Yorktown’s history has been continuous since 1691, although its prosperous era of growth was not destined to extend beyond the colonial period. Soon after its establishment lots were taken up, homes began to appear, and a number of vigorous families settled in the town. Public activities for the county were soon concentrated here. In 1697, the meeting place for York County Court was moved to a building on Lot 24, and this lot still functions for county purposes. About the same time, too, the York Parish Church was erected on Lot 35.

The excellent harbor in the York River, plus restrictive legislation on trade, stimulated the growth of the town as the framers of the Port Act had hoped. It became a tobacco port of first importance as it drew on the crops grown on the plantations round about. None was better known, perhaps, than the famous “E. D.” brand grown on the Digges estate (later Bellfield) just above Yorktown. Ships came singly and in fleets to get hogsheads of tobacco which had been duly examined by the inspectors provided through the Colonial Government. Warehouses and wharves were busy with tobacco shipments, and later in the century, with other crops. Incoming freight for the town residents, plantation 34 owners, and others included clothing of latest fashion, wines and liquor, furniture, jewelry and silver plate, riding gear and coaches, swords and firearms, books, and slaves for the fields and kitchens. This was the trade that made Yorktown a thriving business center in the 18th century—a port that led in Chesapeake Bay commerce until it was later outstripped by its rivals.

Yorktown stood overlooking the York River, with the better homes, inns, and public buildings on the bluffs in the town proper. Below the bluffs on the waterfront wharves, warehouses, small stores, and drinking places predominated. Along the water’s edge, too, were establishments such as that of Charles Chiswell, who was given a patent for land there on which to build accommodations “for his greater Conveniency in Victualing His Majesties Ships of War according to his Contract.”

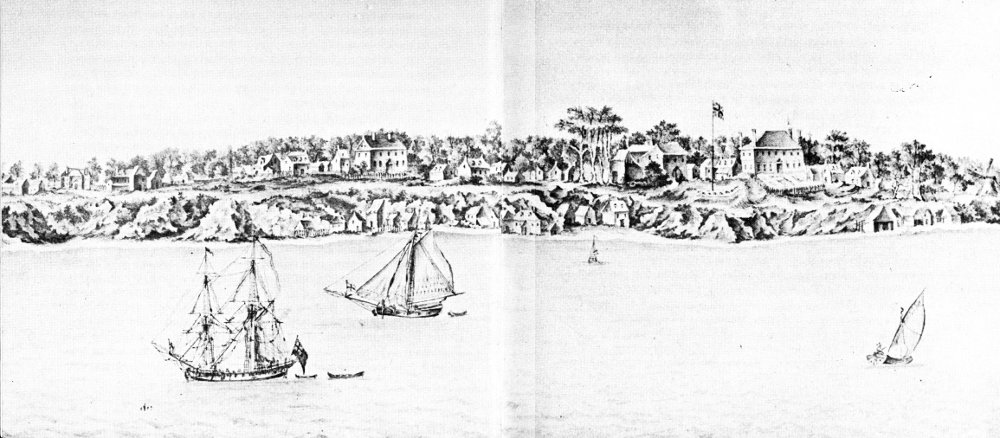

Yorktown in 1754. From a sketch (now in the Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, Va.) drawn by a British Naval Officer.

When fully extended and at peak prosperity, colonial Yorktown must have been a rather pleasant little town. At best, its population very likely never exceeded 3,000—a small number by present standards, yet sizeable 35 for that period. An English visitor who stopped here in 1736 wrote of it:

You perceive a great Air of Opulence amongst the Inhabitants, who have some of them built themselves Houses, equal in Magnificence to many of our superb ones at St. James’s.... Almost every considerable Man keeps an Equipage.... The Taverns are many here, and much frequented.... The Court-House is the only considerable publick Building, and is no unhandsome Structure.... The most considerable Houses are of Brick; some handsome ones of Wood, all built in the modern Taste; and the lesser Sort, of Plaister. There are some very pretty Garden Spots in the Town; and the Avenues leading to Williamsburg, Norfolk, &c., are prodigiously agreeable.

Between 1691 and 1781, fortunes were made at Yorktown in the tobacco trade. But not everyone was a wealthy merchant or prosperous planter. There were men of all types and classes on the streets, in the 36 taverns, and on the wharves—merchants, planters, planter-merchants, propertied yeomen, unsuccessful merchants, shopkeepers and innkeepers in large number, indentured servants, and slaves. Apprentices rose to become partners, as in the case of Augustine Moore in the Nelson firm. In 1781, he was the owner of the Moore House, where the Articles of Capitulation were drafted.

The more prominent families were united by marriage with all the noted Tidewater families. The most famous son of Yorktown was Thomas Nelson, Jr., signer of the Declaration of Independence, Governor of Virginia, and commander of the militia at the siege of 1781. His remains rest in the churchyard of Grace Church in Yorktown.

From the point of view of growth and prosperity, Yorktown was at its peak about 1750. The shops continued busy and the wharves full, perhaps for another quarter of a century; yet, even before the Revolution, evidences of decline were discernible. Whatever commercial good fortune may have been expected for the town was rendered difficult by the destruction and waste that came with the siege of 1781. Other forces of decline, however, were also at work. Rival points of trade, because of location, took much of the produce that might have come to Yorktown. The soil of the surrounding country was worn thin, and the center of tobacco culture moved southwest. All in all, it meant that Yorktown would not continue to grow.

The events of September and October 1781 gave Yorktown its position of first rank in the story of the American Revolution, yet its earlier and less publicized history in that war is both interesting and significant. The leaders of opinion in Yorktown were merchants who stood to suffer much as supporters of the patriotic cause. Their losses were heavy in many cases, but they stood behind the Revolution practically to a man.

As early as July 18, 1774, York County had called a meeting “to consider what was to be done in the present distressed and alarming situation of affairs throughout the British Colonies in America.” Five months later there was a miniature “tea party” in the Yorktown harbor. In 1775, Thomas Nelson, Jr., and Dudley Digges were named as delegates to the Virginia Convention of that year. In 1776, Nelson went on to the Continental Congress, became a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and in 1781 was elected Governor of Virginia. Other Yorktown personalities prominent on the political scene during the Revolution include David Jameson, Lieutenant Governor of Virginia in 1781; Thomas Everard, a commissioner of accounts from 1776 to 1781; Dudley Digges, councilor and leader; Jaquelin Ambler, a councilor and then, in 1781, State Treasurer; and Thomas Nelson, Sr., made Secretary of the Commonwealth in 1776.

In the spring of 1775, Governor Dunmore of Virginia became fearful of the vulnerability of the powder stores in Williamsburg and, during the night of April 20-21, he had them moved secretly to the man-of-war, Fowey, anchored off Yorktown. This was the spark that set off the Revolution 37 in Virginia. Then came Patrick Henry’s march on Williamsburg and more alarm. At this point Dunmore became greatly disturbed. He sent his family aboard the Fowey, still at Yorktown, and he himself set up headquarters on this warship in the harbor on June 6. The assembly refused to meet in Yorktown, as Dunmore suggested, and proceeded to do business without the governor. It was mid-July before Dunmore finally left Yorktown harbor, thus ending royal government in Virginia.

The enlistment of troops soon got under way in York County. The first move was for two companies of minutemen. The one with Yorktown men was to be captained by William Goosley. The council ordered Yorktown to be garrisoned in June 1776, since the strategic location and value of the port were recognized from the very beginning. These troops were soon sent elsewhere, however, and the barracks at Yorktown were often woefully empty. The garrison apparently continued active until the British occupied the town in 1781. The battery built here and manned, first in 1776, to protect the town and “to command the River,” particularly the means of “trade and commerce,” suffered varying fortunes, but mostly, it seems, from “too little and too late.” In 1777, a troop hospital was set up in the town in time to render service in the smallpox epidemic of that year.

From 1776 to mid-1781, Yorktown residents heard the drums roll, became familiar with the tread of marching columns, and witnessed periodic scares of attack and invasion. They contributed supplies, work, money, men, and life. They saw trade decline, “hard times” set in, property wantonly destroyed by thoughtless troops, and received the varying news of war with rejoicing, or with sorrow.

In the winter of 1779-80, French war vessels used the York River and may have found some comfort in the guns of the Yorktown fort. In March 1781, Lafayette stepped ashore here, after his trip down the bay at the beginning of his operations in Virginia. The raid on Yorktown by Lieutenant Colonel Simcoe and his Queen’s Rangers in April of the same year was a foretaste of what was soon to come, as was Cornwallis’ preliminary inspection of the post on June 28. There was little active campaigning, however, and the full meaning of conquest and occupation by the enemy was not understood until the advance units of Cornwallis’ army entered the town in August 1781.