Title: The Whip Hand: A Tale of the Pine Country

Author: Samuel Merwin

Release date: February 3, 2017 [eBook #54102]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE—The Young Man at the Stern

CHAPTER III—George and His Troubles

CHAPTER IV—The End of the Beginning

CHAPTER III—Tightening the Blockade

CHAPTER IV—Mr. Babcock Breakfasts Late

CHAPTER V—A Venture in Matrimony

CHAPTER VII—Halloran Goes to Chicago

CHAPTER XI—High Life at the Le Ducs

CHAPTER I—A Little Talk with Captain Craig

CHAPTER II—Going to Headquarters

CHAPTER III—Mr. Babcock's Last Card

CHAPTER VII—Three Announcements

A THICK, wet night on the southwest coast of Lake Michigan a dozen years ago; a wind that sweeps over the pitching lake and on over the dim white beach with a rush that whirls the sand up and away. Trees are bending up there on the bluff. The sand and the rain are in the air—or do we feel the spray from yonder line of breakers, a hundred yards away?

And deep in a mudhole on the lonely road that skirts the bluff—the four horses, fetlock-deep in the sticky clay, straining forward like heroes, the members of the student crew in their oilskins throwing their weight on the wheels of the truck—is the Evanston surf-boat.

The driver has pulled his sou'wester hat down on his neck behind and swung the U. S. L. S. S. lantern on his arm; he stands beside the forward wheel, cracks his long whip and swears vigorously.

“Hold on a minute, boys,” he calls over his shoulder; and he must shout it twice before he is heard. “Whoa, there! Stand back! Now, boys, get your breath and try it together. When I call——— Now. All ready! Let her go!”

The men throw themselves on the spokes, the horses plunge forward under the lash of the whip. A moment of straining—an uncertain moment—then the wheels turn slowly forward, the horses' feet draw out with a sucking sound, and the boat rolls ahead. The driver unbuttons his oilskins at the waist and reaches beneath an under coat for his watch. They have been out two hours; distance covered, two miles. Before him is darkness, save where the lantern throws a yellow circle on the ground; behind him is darkness, save for the white boat, the little group of panting, grunting men, and, a long mile to the southward, the gleaming eye of the Grosse Pointe lighthouse, now red, now white. But somewhere in the darkness ahead, somewhere beyond the white of the breakers, a big steamer is pounding herself to pieces on the bar. So he buttons his coat and shifts the reins and swears at the horses. He seems to swear easily, this young fellow; but he is thinking of the poor devils on the big steamer, lashed to the mast perhaps, if the masts are still standing; and he is wondering how many of them will ever ship again.

A huge bonfire lighted up beach and breakers. Around it huddled a motley crowd, students in rain-coats or sweaters, sober citizens and residents of the north shore, fishermen, and all the village loafers. But the students were in the majority and were making most of the noise. It was they who had built the fire, raiding fences and wood-yards to send up a blaze that should tell the poor fellows out yonder of the warmth and comfort awaiting them on shore—if they should ever get in through the surf. They were cheering, too, giving the college yells and shouting out inspiriting messages—as if any noise below the sound of a gun or a steam fog-horn could hope to be heard over the roar of the lake! But this was a great occasion and must be made the most of.

Of course no such body of students could act in concert without a recognized leader; and the young man who claimed the honour could be distinguished at a glance. Now issuing orders to the foragers, now mounting the pile to adjust with a flourish the top barrel and to pour out the last can of kerosene, now heading the war-dance around the crackling fire or leading the yells with an improvised baton, always in evidence, as busy and breathless as though his labours had an aim—was a long-faced, long-legged student. He wore a cap that was too small to hide his curly chestnut hair. His face was good-natured, if flushed with the responsibilities of his position. His rain-coat thrown aside, he stood attired in a white sweater with a wide-rolling collar, and a pair of striped trousers that fitted close to his nimble legs.

“Hi, there! Here they come!”

A small boy was shouting. He had been stationed on the bluff; and now he was sliding down, using his trousers as a toboggan on the steep clay. “Here they come!”

The news spread. “Here they come!” was passed from mouth to mouth. Those who had gone out of the firelight, in order to get a glimpse of the hulk that stood out dimly against the horizon, now came running back and joined their voices to the cheer that was rising.

Yes, they had come. A Coston signal was burning up on the bluff; and half a hundred pair of legs were running up the beach to lend a hundred hands in getting a ton and more of surf-boat down the ravine road. The tall young man led the way, thanks to the nimble legs, and called over his shoulder as he ran:

“This way, boys! Everybody this way!”

The horses were taken out in a hurry and led off to the nearest barn. Long ropes were rigged to the back axle, “everybody” laid hold, and then, with the crew men still hanging to the spokes and the young driver leaning back on the tongue to guide the forward wheels, the surf-boat went bumping and lurching down the road. With a rush and a cheer she went, as if the fever of the waiting crowd had got into the wheels, as if the desperate hands of the half-drowned men out yonder were hauling them on—impatiently, madly, courageously hauling them on.

On down the beach, the broad wheels plowing through the sand; on toward the breakers that came running to meet them: into the water with a splash and a plunge, until ankles were wet and knees were wet—then a halt. The eight young men in oilskins bustled about the boat, their yellow coats and hats glistening in the firelight; and the crowd stood silent at the water's edge, looking first at them and then at the black-and-white sea out yonder—and an ugly sea it was. But in a moment the confusion resolved into harmony. The eight men fell into place around the boat, lashed on their cork jackets, laid hold of the gunwales, ran her out into the surf, tumbled aboard—and the fight was on.

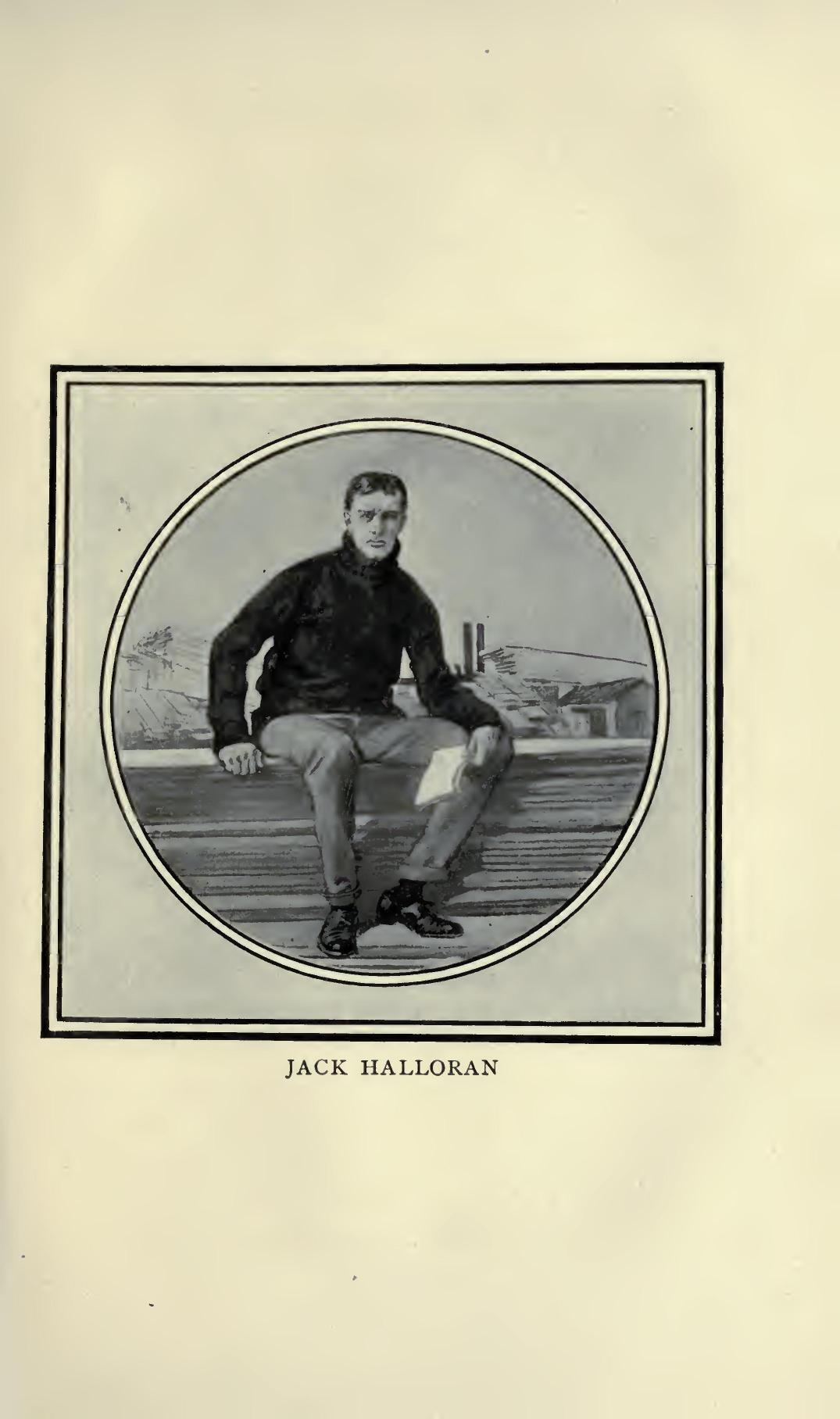

It was a fight that made those young fellows set their teeth hard as their backs bent over the oars. They did not know that this storm had strewn the coast with wrecks; they did not know that the veteran crew at Chicago had refused to venture out in their big English life-boat. And they did not care. Too young to be prudent, too strong to be afraid, these youngsters fought for the sake of the fighting; and they loved it. So they worked through the surf with never a thought of failure, with never a thought that the white waves might beat them back; and they shook the water out of their eyes and watched Number Two, who was pulling stroke to-night, and went in to win. And all the while the young man standing erect in the stern, swinging the twenty-foot steering-oar, was swearing, letting out a flow of language that would, as Number Two said afterward, have made a crab go forwards. It was plain that he was enjoying it, too.

The fire was sinking; the drizzle was cold and penetrating. The little groups down on the hard sand near the water were tired of straining their eyes into the blackness. The moment of enthusiasm was past. The surf-boat had slipped away like a dream—a moment of tossing against the sky, a glimpse of set faces, a shout or two over the pounding surf, then the lead-black lake with its white flecks, the lead-black sky, and the spot of deeper black where the steamer lay. A shivering fellow brought an armful of driftwood from a dry nook and threw it on the fire. The idea was good and the others took it up. Soon the flames were leaping up again.

And now what more natural than a song! The bleached-out bones of a forty-ton lumber schooner lay curving up from the sand; here mounted a student, he of the white sweater and long legs, and the others crowded around.

“All right, Apples; let her go!”

And they sang out merrily there, with the glare of the fire in their wet faces and the wildness of the lake in their throats:

“Oh, my name is Captain Hall, Captain Hall!”

A rush of wind carried the next words down the beach; but the last lines came out strong:

“Hope to———you go to Hell!

Hope to——— you're roasted well!

Damn your eyes!”

“Hi-yi!”—it is the small boy again. “There she is! There she is!”

“Where, boy?”

“Out there—off the breakwater! There—see!”

Again the straining eyes, again the lead-black of the sky and water. Is that the boat, that speck of white away out, or is it a whitecap? Now it is gone. Has the boat dropped into a hollow of the sea? Who knows! A white speck here, another there, white specks everywhere! “Boy, you're dreaming.”

“Sure he's dreaming. They haven't been gone twenty minutes. What's the matter with you!” Yes, it is only twenty minutes; and there is a weary, bitter hour yet for the poor devils before they may set foot on land. Another song is the cry; and more wood—heap her up! Again Apples mounts his grim perch—the head- and footstone of half a dozen forgotten sailors—and marches the “Grand Old Duke of York” up the hill, and marches him down again; and when he was up he was up, up, up; and when he was down he was down, down, down; and when he was only half way up he was neither up nor down; and the rain thickens; and the smoke and flames run along parallel to the sand, so fierce is the wind; and the poor devils out yonder call up what prayers they may have known in childhood—and lucky the sailor who remembers how those prayers used to go!

There is more singing and more watching; then, after a long while, the boat is sighted. She is coming in from the north, making full allowance for the set of the surf. As she works slowly nearer they can make out the figure of the steersman and the huddled lot of crew men and sailors. The fire is renewed again and a shout goes up. She hovers outside the line of surf, then lifts on a roller and comes swiftly in to the sand, so swiftly that the oars must be hauled in with a rush, and the crew must tumble out, waist-deep, and catch the gunwales and heave her forward before the wave glides back.

There is one man in the stem, rolling about between the feet of Number Two. Even in that uncertain light, and bedraggled as he is, it is plain that his dress is of a different quality from that of the sailors. Bareheaded he is, and one can see the white in his hair and the wrinkles on his smooth-shaven face. It seems, too, that he wants the physique of his companions, most of whom are able, for all the exposure, to spring out without assistance. The steersman, who has been watching him with some anxiety, leans over and helps him out, and then, swinging him on his shoulders, carries him pickaback up out of the water and toward the fire. Word goes around that this is the owner of the steamer.

“Here, Jack,” calls Apples, bobbing up close at hand, “you're to go up to the house on the bluff. They are making coffee for all the boys. Let me give you a hand.”

The steersman makes no reply, but, as his burden protests that he can walk, lets him down, and each young man takes an arm. In a few moments they are all, rescuers and rescued, in a hospitable kitchen drinking black coffee and crowding, with steaming clothes, about the range. The steersman drinks a second cup at a gulp and looks around for his men. He is not joining in the talk, for a heavy responsibility rests on him, but his eyes have the blaze of excitement in them and his square jaw is set hard. His white, drawn face shows that the work is telling.

“Come on, boys,” he says quietly. “Time for the next trip.”

Quiet falls on the room that was just now loud with talk. It continues while the crew men toss down their coffee, hastily retie their cork jackets, and file out into the night. The sailors have been exultant over their rescue; but now they are reminded of the comrades out yonder, and they fall into moody silence.

But after all, it is a great thing to be alive when one has been clinging to a rope in a desperate sea with ugly thoughts to face. At any rate, these men seemed to find it so; for, after a time, when doubtless the white surf-boat was bobbing far out, one of the hundred white flecks on the black lake; when doubtless the poor fellows who had to wait, old Captain Craig with them, were still cursing and praying—and one of them had wept foolish tears when they parted—they fell back into talk. The drama had reached but the second act, and no one could say if it was to be a tragedy, but the warm kitchen and the plentiful coffee, and the thoughtless talk of the half-dozen students who had followed them in, were not to be resisted. Within half an hour the banter and jokes were flying fast.

The elderly man, whose name was Higginson, was sitting close to the range, wrapped in a blanket. He found Apples at his elbow and spoke to him.

“What crew is this?”

“The Evanston crew.”

The man nodded and was silent, but after a few moments he spoke again.

“Who was that young man in the stem? Is he the Captain?”

“No, the Captain is sick. He is Number One.”

“What is his name?”

“Halloran—Jack Halloran.”

In a mahogany office high up in a very high building sat Mr. G. Hyde Bigelow. An elaborate building it was, with expensive statuary about the entrance, with unusually expensive mosaic floors on all of the fifteen or more stories. A dozen elevators were at Mr. Bigelow's service, and a dozen uniformed elevator boys to bow deferentially whenever he granted his brief presence in the necessary actions of going up to his office or coming down from his office—boys that were fond of remarking casually when the great man had stepped out, “That's G. Hyde Bigelow.” A very expensive building, in fact, such as best comported with his dignity.

For Mr. Bigelow was a rising man; and the simple inscription on the ground-glass door, “G. Hyde Bigelow & Company,” already stood in the eyes of a small quarter of the financial world of Chicago for unqualified success. If a syndicate was to be floated, if a mysterious new combine was to be organized, what so important to its success as the name of G. Hyde Bigelow somewhere behind the venture—what so necessary in the somewhat difficult task of making it plain that paper is gold, that water is a solid, as the indorsement of G. Hyde Bigelow & Company? If Bigelow invested largely in Kentucky coal lands, what more reasonable than an immediate boom in Kentucky coal—and that men should speak sagely on the street of the immense value of the new mines? If Bigelow went heavily into the new-style freighters that were to revolutionize the lake-carrying trade, what more natural than a rush in “new freighters,” and who could know if the Bigelows should unload rapidly on an inflated market? But the great man is speaking!

Before him, on the mahogany desk, were spread some papers—vastly important papers, or they could never have penetrated to the Presence to take up time of such inestimable value. “Time is money” is a phrase that had been heard to fall from the Bigelow lips. Perhaps some one else had coined this phrase years before; perhaps Mr. Bigelow himself might even vaguely remember hearing it: what matters it! Did not old phrases fall new-minted from his lips? Did not the minor earths and moons and satellites that revolved about the Bigelow sun recognize in each authoritative Bigelow utterance an addition to the language? And were there ever such jokes as the Bigelow jokes?

Before him were the papers; beside him, in a broad-armed, leather-backed mahogany chair, sat the junior partner, the “Company” of Bigelow & Company, Mr. William H. Babcock. A youngish man was Mr. Babcock; a very well dressed man with a shrewd, somewhat incredulous eye; a man who speaks cautiously, is even inclined to mumble in a low voice; and who finds his worth and caution recognized as a useful, if secondary, part of the importance of Bigelow & Company. Lacking in the audacious qualities of his senior, it would seem, but shrewd, very shrewd—not a man given to unnecessary promises or straight-out declarations. And if Mr. Babcock had a phrase, a creed, locked securely away in the depths behind that quiet face, it was “Business is Business.” Business was business to Mr. Babcock; and he had hopes, even a fair prospect, indeed, of himself rising to a point where Time should be Money, thanks to the aid of the Bigelow name. And in the part of those depths where the thinking was done, the thought lurked, that if the time should ever come when Business-is-Business and Time-is-Money should be combined in his career (and everything about him tended to combination), Chicago would be too small for William H. Babcock.

The papers were before Mr. Bigelow, and the great brain was grappling with them; it being Mr. Babcock's part to weed out details and trouble Mr. Bigelow only with the broader facts.

“And now, Mr. Babcock,” said the head of the firm, “how are we to arrive at this?”

Mr. Babcock leaned forward and mumbled a few sentences with the air of a man habitually afraid of being overheard and caught. Mr. Bigelow's brow drew together, in such a state of concentration was the massive brain. History has not recorded the subject of these documents; whether it was Kentucky Coal or New Freighters, or the booming town of Northwest Chicago, or suburban street-railways, or one of the dozen or more growing interests that absorbed at this time the attention and some of the money of G. Hyde Bigelow & Company (to say nothing of the money of the Bigelow followers), we may never know. For at the moment when the Bigelow brows were knitted the closest, when the questions raised by the papers were about to attain a masterly and decisive solution, an office-boy entered the room—a round-eyed boy so awed by the Presence that he was visibly impatient to deliver his message and efface himself—a boy who was habitually out of breath.

“Lady t' see y'u, sir.”

Mr. Bigelow turned with some annoyance. How often had his subordinates instructed this boy to demand the card of every visitor and to lay it silently on the mahogany desk. But, on the other hand, Mr. Bigelow made it a point to rise above petty annoyances.

“Well, boy, what is the name?”

“Sh' wouldn' give 't, sir.”

The great man's expression changed slightly; it was as if he had suddenly remembered something. He turned to the desk and fingered the papers for a moment.

“We will take up this matter after lunch, Mr. Babcock.”

He spoke a shade more pompously than was his wont in dealing with his junior.

Mr. Babcock bowed and went out. Then Mr. Bigelow turned to his stenographer, who was clicking away by the window.

“Miss Brown, I wish you would go out to the files and look up all the Pine Lands correspondence for me.”

The stenographer laid aside her work and went out.

And now Mr. Bigelow, once more bland and gracious, turned to the boy who was holding fast to the bronze door-knob.

“Here, boy, you may show the lady in.”

Having said this, he bent over a letter and was so busy that he seemed not to hear the woman enter. For some moments she stood there by the closed door. Once she coughed timidly; and even that failed to reach the attention of the much-absorbed man. But at last the letter was laid down and Mr. Bigelow turned.

“Sit down,” he said, motioning to the chair that Mr. Babcock had just now vacated.

But the woman, it seemed, preferred to stand. “Why have you come here?”

“I think you know why I have come.”

Mr. Bigelow took up the letter again and regarded it closely. A great many thoughts apparently were passing through his mind—thoughts not of Kentucky Coal and New Freighters, but of a stately suburban home of granite completed within the year; of a certain Mrs. Bigelow who was rising rapidly toward the social leadership of her suburb, and was carrying Mr. G. Hyde Bigelow into circles that he, with all his prestige of a sort, could hardly have penetrated alone; of a certain dignified, comfortable, downright conservative suburban church, where the Bigelow money and judgment, new as they were in such surroundings, were undoubtedly earning a place; and, lastly, of certain small Bigelows. Of all these things thought Mr. Bigelow.

“Well,” he said at length, without raising his eyes, “what is it now? What do you want?”

“If I had only myself to think of,” began the woman, speaking in a low voice and with noticeable effort, “I should never come near you. But I have others to think of, and I think you have, too. I have not come for money. If I could do it, I should like to bring every cent you have given me and throw it in your face.”

Rather unpleasant words these—unpleasant to Mr. Bigelow, at least. Indeed, they seemed quite to disturb him, to drive him even toward something that in a man of smaller reputation might have been called brutality.

“See here,” he burst out, wheeling around, “how long is this going to keep up? How many years more must I support you in idleness? There is a limit to this sort of thing.”

It may be that this was not so much brutality as sagacity. It may be that Mr. Bigelow had in mind certain steps that might relieve him from a situation which was growing more and more annoying and disagreeable, and that this was one of the steps. For such words as these—such a blaze of righteous anger—should be very hard to answer in a man's own office; hard at least for an unknown woman before the great G. Hyde Bigelow. Even if the woman had come with vague notions that she was acting within her rights, that the law which had severed her life from the life of this man so long ago would support her now—what was she, after all, but an unfortunate woman standing before a great man?

But there was a curious expression in her eyes: perhaps she was more resolute than he supposed; perhaps simply she had reached a point in wretchedness where such words fail of an impression.

“When I told you I should never come to your office, I did not know how you would take advantage of me. I should not have come even now if I could have helped it. I don't know if it will interest you to hear that I have not had enough to eat this week.”

She was mistaken; Mr. Bigelow was interested. Indeed, he was beginning to recover himself and to look down on the ill-dressed woman before him from the proper altitude of G. Hyde Bigelow. As he looked down he told himself that he was quite calm, that he was standing frankly and firmly, as became him, on his proper footing as a prominent citizen. And such a sight as this, an ill-dressed woman standing in this mahogany office and talking about starvation, was really shocking. He felt that he must dismiss her, must rid himself of her; but on the other hand he was really touched by her distress. Mr. Bigelow leaned back in his chair and half closed his eyes.

“How long has this been going on?” he asked, in a voice that showed signs of leading up to something further.

She gave him a puzzled, indignant flash of her eyes and replied in the same low voice:

“It is more than fourteen years.”

More than fourteen years—think of it! For fourteen years this woman had been suffering for an error of judgment, the mistake of two deluded years, the mistake of giving her life to the wrong man, and now had even faced starvation because of it. So mistakes are punished in this world. Mr. Bigelow, on his part, looking down from his great altitude, was running over these fourteen years and recalling the mistakes of his own that had brought this annoying visit upon him. He had been soft-hearted; he saw it plainly enough now. In his effort to do right, to comply voluntarily with certain nominal requirements which a less honourable man would have easily evaded; in his effort to be kind to a foolish young woman—and a very young woman indeed she had been at first—to humour her childish notions of the facts of this real world—his impulses had carried him too far, and she, of course, had taken advantage of him. He should have known better.

“Hum! More than fourteen years,” he repeated, still sitting in his chair and looking dreamily at a group picture of a certain Board of Directors that hung above his desk. “Has it ever occurred to you to stop and figure up how much you have cost me during these years—how many times I have sent you large sums without a word? If you will think of it now you will remember that I have asked no questions—that I have known nothing whatever about your life and your acquaintances. I have not known how real your needs were.”

He might have gone on to much plainer speaking, even to harshness (it being necessary sometimes in dealing with such people), had not his half-shut eyes strayed downward from the Board of Directors to her face. What he saw there seemed to weaken his self-possession. And, for another thing, it was certainly getting time for his stenographer to be returning with the Pine Lands correspondence. It was really a rather awkward moment for Mr. Bigelow.

“Well,” he said abruptly, opening his eyes again, “there is no use in prolonging this conversation. Tell me what you have come here for and be done with it.”

It was so abrupt that she had to wait a moment and compose herself before beginning in the same low tone:

“I told you I had not come for money, and I meant it. I am tired of begging for my living. But it would cost you very little to help me to some situation. If you will do this, I will try not to trouble you again.”

Mr. Bigelow pressed his lips and beat a tattoo with his fingers.

“What kind of work can you do?”

“I couldn't take skilled work, I suppose,” she replied a little wearily, “and I could hardly expect an office position—at my age. But I have thought of going into a department store. I really ought to be able to do something there.” Mr. Bigelow was fidgeting a little: he was thinking of the Pine Lands correspondence.

“Why, yes,” he said, “I don't know but what that could be arranged. I will speak to Murray of the New York store. He is employing hundreds of people all the time, and I know he has difficulty in getting good ones.”

He finished with a wave of dismissal and turned back to his letter. But the woman waited.

“You will see him to-day?” she asked.

“Why, yes”—rather impatiently—“I will try to see him this noon.”

“And shall I come back this afternoon?”

Mr. Bigelow leaned back again.

“No, I hardly think that will be necessary. Let me see———”

“I don't see how I am to know if I don't come back—unless you write to me.”

He hesitated at this and, thanks to his hesitation, received a keen stroke below his armour.

“If it is the writing,” she said, with quiet, bitter scorn, “you know I have letters enough now.” Yes, she had, and he knew it: there had been blue moments in his life when he would have given a great deal to get those letters back—letters relating to money matters, most of them; explanations why certain sums were still unpaid, perhaps; letters sent back into another life, a life which had gone under Mr. Bigelow's feet as he mounted to higher things. And she added: “You needn't sign your name, if you'd rather not.”

Yes, it was time to close this interview. He was not enjoying it at all—was even willing to concede a point in order to be rid of her. So he said shortly:

“Very well, I will see him at noon and let you know by the morning delivery if he has a place for you.” She turned to go but he detained her. “Here—wait! I will tell him that you are a cousin of mine. Do you understand?”

She made no reply to this, but simply went out as swiftly and silently as possible. She was evidently as glad as he to be through with it. And Mr. Bigelow, after glancing at the Pine Lands correspondence and after a look at his watch, put on his hat and coat and left the office. It was not yet his lunch time, but when bent upon a benevolent errand Mr. Bigelow would hear of no delay; and recalling that Mr. Murray was usually on the point of leaving the club when he entered, he was willing even to hasten his lunch in order to make sure of a chat with him.

And chat they did, those two powerful, public-spirited ones, over their cigars, of the questions of the day, handled as only masters of commerce could handle them; until at length—this from Mr. Bigelow, lighting a fresh cigar and speaking casually over his hollowed hands:

“By the way, Murray, I have a cousin who is in a bad way—husband dead, and some children, and that sort of thing. I want to do a little something for her if I can. Could you give her any work?”

“I'm afraid the best place I could offer would be behind the counter in my North Side store at three dollars a week or so.”

“She'd be grateful for anything. It's a matter of keeping alive.”

Mr. Murray was always glad of an opportunity to oblige Mr. Bigelow.

“Send her around, with a letter, and I will do the best I can for her.”

And thus did Mr. Bigelow free himself from an entangling alliance. He had now given the woman an opportunity to prove her worth; if after this she should stumble into dark ways, there would be only herself to blame. It had cost him considerable effort, to say nothing of his time; but had it not been worth while?

Dear Mr. Halloran: Won't you come down to the Settlement Friday evening? The young men's class and the girls' class are going to entertain themselves, and Mr. Appleton Le Duc has promised to help them. I want to have another talk with you about George. We have heard nothing from him for a week, and I am afraid he is in trouble. After such encouragement as he has given us I don't like to let go of him.

“Be sure to come if you can.

“Very sincerely yours,

“Margaret Davies.”

The above note accounts for the presence of Halloran and Le Duc (he of the nimble legs) in a suburban train, on that Friday evening, bound for Clybourn and the Settlement. A few seats behind them sat Miss Davies, escorted by Mr. Babcock, a young business man who seemed to be going in heartily for charity work at this time. Le Duc was talking earnestly with Halloran. Apparently a momentous question had arisen in his life, and the young man beside him, who had had plenty of experience in earning his own living, who could steer a life-boat in a boiling sea, whose generalship alone, it was conceded by one party in college, had won the Chicago game that fall, was, he felt sure, the best counselor to be found in the difficult task of guiding a life straight toward its destiny.

“I don't know another fellow I could come to with a question like this, Jack; but you understand these things; you know life. You've learned things already that the rest of us spend the most of our lives finding out. Now what would you say—how far do you think a man ought to go in sticking to the idea of an education?” Le Due's “education,” for several years now, had consisted of the study of elocution, with an occasional peck at English Literature or the French language, and a few, a very few, disastrous examinations. “I've got an offer to quit college right now to go in as second comedian with the Pooh Bah Company. They offer thirty dollars a week to begin with, with every prospect for a future. It is a rising company, you see—a sure thing. They are as safe as the First National Bank. If that were just the work I wanted, I couldn't do better.”

Halloran was sitting back with his hat down on his forehead, listening conscientiously, but losing a word now and then, thanks to the roar of the train.

“You see, old chap, I set my mind on Shakespeare when I first came to college. I decided then it would be Shakespeare or nothing with me. A man's got to have a goal, you know; he's got to aim high or he will never get anywhere; and my goal has been Shakespeare. But the question is just this: Ought I to give up this offer, when it may be my chance to get a good start on the stage? I might be able to work up into Shakespeare by keeping at this for awhile, and making a professional acquaintance, and saving up money. Men have done it, you know. What do you say?” He evidently really expected an answer, so Halloran gave it to him.

“I am afraid you'll have to decide that for yourself, Apples. If you care enough for first-class work to stick it out in college and then take your chances, you ought to do it: if you don't, take this. That's all I can say.”

With which casual conversation did an evening begin that later promised to influence considerably the lives of several members of the party.

They found a crowd of ragged boys and girls at the Settlement. Le Duc was to “read” for them; but he found himself fairly eclipsed by the performances of two of their own number, one a youthful dancer with a wizened face and remarkably thin legs, named Jimmie McGinnis, the other a dark-eyed girl, one Lizzie Bigelow, who sang some popular songs in a really good natural voice.

This girl made an immediate impression on Apples. At the close of her first song he stopped applauding long enough to say confidentially to Halloran, “Remarkable what a lot of talent you find among these people. That girl ought to be in the profession. Really a stunning girl—and clever, awfully clever. Splendid! Splendid!” he exclaimed again, turning toward her as she came into the hall, and applauding vigorously.

She laughed and shook her head, but made no reply. She evidently liked applause.

“You must have studied—to sing like that,” Le Duc went on.

She flushed with pleasure, but only shook her head again and sat down on the stairs to listen to the next recitation.

As Le Duc stepped out, bowing with his easy, good-natured smile, Miss Davies saw her opportunity to speak to Halloran. At the beginning of the evening she had talked a moment with Lizzie Bigelow, but with unsatisfactory results as her troubled expression showed. She now led the way to a sitting-room behind the stairs. For a short space they were silent—this young woman who, with the buoyancy of youth, with sanguineness hardly justified by the facts of the black city that was pulsing around her, had plunged into its darkness the feeble light of her hopes—and this young man who knew so well the difficulty of climbing up from sloth and incompetency and vicious ignorance that he was willing to help. He put his hands in his pockets and stood waiting for her to begin. He liked to look at her, she was so earnest and unconscious of herself; perhaps, too, because she was well worth looking at, with her clear, delicate skin now a little flushed and the masses of brown hair above her forehead.

“I wrote you,” she began, “that we have lost track of George. He was here as usual a week ago Wednesday, but then he disappeared. Lizzie, his sister, says they have no idea where he is; and I don't think she cares very much. She says he can look out for himself, and that is more than they can do for him at home. Now what are we to do?”

“Have you seen his mother?”

“No—not yet. She always rebuffs me. If she were more like our other women it would be easier. I wanted to talk with you first, and see if we couldn't think of some way to find him.”

“But we have no clue. She might be able to give us a hint. Even to learn something about his loafing places would be a start—something to work from.”

“I suppose—if she would tell. She is proud, you know. But we must do something. I can't leave that boy wandering around the city like this. The first thing we will hear of him in jail, and after that———” She ended with a shake of the head.

At a thought that entered his mind Halloran smiled slightly. “Have you talked with Jimmie?” he asked. .

“Jimmie McGinnis?” She had to smile, too.

“He might tell something. One always knows what the other is up to. I can't think of any other way.”

She looked earnestly at him as she asked:

“Will you try it—if I bring him here?”

He nodded, and soon she returned with him.

Jimmie looked from one to the other, his small eyes devoid of expression, his inscrutable thin face as innocent as that of a sleeping baby.

“Sit down, Jimmie,” said Halloran, “Miss Davies and I want to talk with you about George.”

Jimmie seated himself and waited respectfully, his thin legs dangling off the floor, his hands clasped meekly in his lap. He was always willing to be talked to—rather enjoyed it, in fact—was particularly fond of moral lectures; had a keen little mind somewhere behind his narrow forehead, and could bring himself to discuss moral questions with his lady teachers, showing all the symptoms of an eager water-lily striving upward from its dark bed toward the light of day. Miss Davies he understood perfectly and really liked, in a way. She was good—and why not? Who wouldn't be good with plenty to eat and wear, with fathers and mothers, and grand suburban homes with real trees about them (he had been taken out there once for some Fresh Air, on which occasion he had seen a cow for the first time in his life). But he was a little afraid of Halloran, and inclined to grow secretive in his presence. To sum him up, Jimmie was already launched upon a professional career—he sold score-cards at the baseball park—and he fully realized the importance of his place in life; even hoped some day to be a manager and walk out to the players' bench before the game in a checked suit, announce the battery of the day, and toss out the new ball from a capacious pocket, a new ball in a red box with a white seal around it.

“Now, Jimmie, do you know where he is?”

Jimmie shook his head.

“No, sir. I heard some one say he hadn't been around for a week.”

Halloran threw a quick glance at Miss Davies; but it was not too quick for Jimmie.

“He has run off, Jimmie, and we want to find him. It don't make any difference why he went. Anybody's likely to get into trouble now and then; and I'm not going to ask any questions. But if he has lost his job or got into trouble I think we could help him.”

“Yes, sir, I'm sure you could,” Jimmie replied gratefully; and what little expression there was in his face said plainly enough, “Don't I know how you have helped me?” And then he added in eagerness to assist, “I could stop at the box-factory, if you like, and see if he ain't working any more.”

“All right, I wish you would. Tell us about it Monday at class. That's all.”

At this Jimmie got soberly down from the chair and went out, leaving Miss Davies and Halloran to look at each other expressively.

“Well, what do you think?” said she.

“He is going straight to warn him. Something is the matter. We must try his mother now. And we ought to do it quickly—before Monday.” Miss Davies mused for a moment. “We could hardly get there to-night—we might go to-morrow afternoon, when she gets back from her work. I will arrange to have dinner here.”

Halloran nodded; and they returned to the hall. Jimmie was dancing again when they reached the parlour door, to music by one of the resident teachers who had volunteered to take the place of Miss Davies. Apples had disappeared and Lizzie Bigelow also. Miss Davies looked around for them; then, realizing after a moment that Jimmie's feet were not the only ones that were stepping in time to the music, she glanced up the stairway. A laugh from the upper hall and the fling of a skirt at the head of the stairs brought a puzzled expression to her face. But the explanation came in a moment. Just as Jimmie stopped dancing and was turning toward the hall, Apples came running down the stairs, a cane in his hand, and after him Lizzie Bigelow, laughing, nearly breathless, and with a heightened colour.

“Oh, Miss Davies,” Apples exclaimed with all his good-natured assurance on the surface, “Miss Bigelow and I are going to do a cake-walk, and we want you to play for us—a good, lively march, with a lot of jump in it.”

Miss Davies looked at him surprised, then at Lizzie; finally, in distress, she turned to Halloran. But he found nothing to say. Before Miss Davies could collect her wits and think of some excuse Apples was blundering on.

“Play the one you did for the boy—that'll do splendidly. We've been practising up-stairs, and it goes mighty well. We'd better do it now, before we get our steps mixed. Miss Bigelow says she'd rather do this than the song she is down to sing—didn't you?” he added, appealing to her.

She assented rather shamefacedly, and Miss Davies gave up. There was no rule against cakewalks, and she herself had invited Le Duc to entertain the boys and girls; so she concealed her dislike for this juvenile way of overstepping boundaries and went to the piano. Halloran was downright sorry for her, but he did not see what he could do..

Halloran foresaw that it might be late Saturday evening before Miss Davies and he could return to Evanston, so he arranged with another member of the crew to stand his watch from ten to midnight; and then, knowing nothing of what might be before them, these two young people set out on their search for George.

Picture a tenement far out on the North Side, one of thousands of smoke-coloured buildings, somewhere on an obscure street that was discouragingly like dozens of other streets. Without the tenement an electric light (for it was six o'clock and dark on this autumn day) threw its flare on an uneven cedar-block pavement, worn into ruts and holes that had given up, hopeless of repair, to mud and filth; on obscure little tailor shops and masquerade-costume shops, and dirty tobacco shops with windows hung full of questionable prints; on an itinerant popcorn-and-peanut man, who had stationed his glass-enclosed cart on the corner and was himself sitting on the curbstone, the picture of disgust with life; on a prosperous red-brick corner building, that shed light and comfort from half a dozen broad windows, announcing itself by its curtained inner door and its black-and-gilt signs to be Hoffman's sample room. So much for the neighbourhood. Within the tenement, up three flights of stairs, was an apartment of two rooms where lived Mrs. Craig with her daughter and her son, who bore the name of Bigelow.

Lizzie was sewing: her mother, back home for supper in the intermission between the work of afternoon and evening, was taking off her hat.

“Is the fire going, Lizzie?”

The girl shook her head without looking up. “How did I know you were coming home so early?”

“It is six o'clock.”

“Well, how do you suppose I'm ever going to get my work done if I have to make fires for you? Where's George, I'd like to know! That's his business, anyway.”

Mrs. Craig, herself wondering where George was, went to the next room and built the fire herself.

A few moments later Halloran knocked at the door, and Miss Davies and he were admitted. And while Miss Davies was opening the subject, trying with the utmost delicacy to obtain the confidence of this woman, trying to show by simple, honest words how sincerely she and Halloran were interested in George, another boy, a small, wizened-faced boy with thin legs, was hiding in a doorway across the street, watching with keen little eyes for their exit and pondering with a keen little mind on their probably next move.

Miss Davies was beginning to wonder if she had not overestimated the difficulty of talking with Mrs. Craig. Or was it the present topic that made it a little easier? For she had come now with no offers of food, or coal for the fires; but only to talk about George, to see if she and the young man with her might not, by giving their time and interest, make the search easier. And the main difficulty seemed now to be that the woman knew no more about it than they did.

“It was early last week,” she explained, speaking quietly, in a voice that had been brought to a dead level by habitual restraint. “He went off to work as usual, after dinner, and said he would be back to supper. I don't know where he can be. He has never been a bad boy.”

Lizzie, now that so much trouble was going on about George, began to feel unusually sorrowful herself—was even moved to tears, and had to go into the other room and bustle about getting supper ready before she could bring her feelings under control.

“Mr. Halloran thought the best thing would be to go out and search for him,” said Miss Davies. “And he thought you could help—:—” She turned to him and finished by saying, “Won't you explain to Mrs. Craig?”

“Can you tell us,” he responded, “of some place in the neighbourhood that George has been in the habit of going to—some place where he has friends?”

Mrs. Craig shook her head. “No; when he was not working he was almost always at home.”

“But he surely had acquaintances. You see, Mrs. Craig, we must have some place to start from.”

She thought for a moment. “No; so far as I know, there was only one man in the neighbourhood who took the least interest in him. And he wouldn't know anything about this. We have not lived here so very long———”

“Who is this man?”

“Mr. Hoffman, on the corner. He has been kind to George, once or twice.”

Halloran rose, saying aside to Miss Davies, “I will speak to him and come back here,” and went out.

He found a stout German behind the bar in the corner saloon who proved, upon inquiry, to be Hoffman himself. He was a substantial sort of man, speaking excellent English, and representing, if one could judge from the neat, well-stocked bar, the clean floor, the geraniums in the windows, and the general air of thrift and order, what he might have been pleased to call a decent saloon. Halloran began without preliminary by asking Hoffman if he knew George Bigelow.

The saloon-keeper rested both hands on the bar and looked across it, scrutinizing him closely before answering.

“Yes, there is a boy of that name around here.”

“He disappeared from home last week and his family are worried about him. I have been told that you might help me find him.”

Hoffman shook his head, still watching him closely. “No,” he said; “I know nothing about him.”

“Has he been about here at all lately?”

“No; it is two weeks since I saw him.”

The honest German face had the word suspicion plainly written on it, Halloran saw that he was not getting at the man at all, so he leaned on the bar and explained himself.

“I have come from the University Settlement. George has been at class there regularly until lately. His teachers believe in him and want to help him. They are afraid now that he has got into trouble and is afraid to come back. Do you know anything about it?”

For reply Hoffman asked:

“What is your name?”

“Halloran.”

“You come from the Settlement?”

“Yes.”

“Have you seen Mrs. Craig?”

“I have just come from there. Miss Davies, George's teacher, is with her now.”

The big man slowly turned it over in his mind. Finally he said:

“I will tell you all I know, but it is not very much. There is another little boy named McGinnis who is around with him most of the time. The McGinnis boy worked at the ball park until the season closed last week. For ten days now he has been coming here for a glass of beer pretty often, and he always carries away the lunch. You say you want to help George?”

Halloran nodded.

“Well, I will tell you what I think.” He used the word “think,” but his expression showed that he knew pretty nearly the facts. “McGinnis has an uncle, a boat-builder, who has a place under the Wells Street Bridge. You go down there and you will learn more than I can tell you.”

Halloran thanked him and returned to Miss Davies, Mrs. Craig, he found, was getting ready to go back to work. They were all waiting anxiously for him.

“I think we are started right,” he said cheerily, addressing the mother. “I will be back later in the evening and report progress.” To Miss Davies he said: “You would rather wait at the Settlement, I suppose. I shan't be back probably before eight or nine o'clock.”

“Why,” she said in a low voice as they were passing out the door, “don't you want me to go with you?”

“I am afraid not. I could hardly take you prowling around the wharves at night.” And he told her, as they went down the stairs behind Mrs. Craig, what directions the saloon-keeper had given him. They were still talking about it when they joined the woman on the sidewalk; and then the three of them walked together to the second corner, talking it over and over again. For Mrs. Craig was beginning to discover that the young people were downright interested in her and in her boy. There was no gracious down-reaching here, no lending a kind hand to the unfortunate; but just a young woman who believed she could help, and a young man who knew a little of what it all meant; in short, here were two real persons who said little and meant more. She was not afraid, as she looked at them, that they would pray for her, loudly and zealously, kneeling on the floor of her own tenement rooms. And she was inclined to wonder, looking out at them across her own sea of troubles, what life was to hold for them.

Something of this last thought got into her manner as she took their hands at parting; indeed, her reserve so nearly broke that she gave them—not singly, but the two of them together—a look that brought a faint blush to the young woman's cheek and to her mind other thoughts than George and his difficulties—-thoughts that disturbed her a little later when she and Halloran were walking toward the Settlement, so foolish and trivial were they beside the realities of the scene that had passed—thoughts that were resolutely put from her mind.

At the Settlement steps she lingered a moment.

“I wish I were going with you,” she said, hesitating. “There is pride in the family, and George has his share of it. If you—if he should think you blamed him or looked down on him, he would never come back with you. He has always been hard to reach, and I think it is because of a rough sort of sensitiveness.”

Was it unreasonable that she should wish to continue handling this case, just now when tact was so urgently needed? Or that she should give Halloran a hint of the best course to take with the boy?

“I don't blame him,” he replied. “The way to help him is to make him feel like somebody. If you once let him get to thinking that he is good for nothing he'll run down hill fast. Jimmie McGinnis, now, will take all the knocks you can give him, and go right on turning his pennies; he will be in the City Council yet.”

She nodded, for she saw that he understood. And he turned away to begin the search, walking over to the car-line. As he sat down in the first trailer a small boy ran alongside the rear car and swung himself aboard, hurriedly drawing in a pair of thin legs after him.

Through gloomy Kinzie Street walked Halloran, when he had reached the river district, and after him, half a block or more, came the thin legs. He got to the bridge by the Northwestern Station, crossed over, and looked around for a means of descent to the wharves. After a moment he saw in the shadow of a brick building—a building that was a South Water Street market in front, a factory in the upper half and a tug-office behind—what seemed to be a break in the railing. He crossed to it and found, sure enough, a narrow stairway, covered with mud and slime, leading down toward the oily surface of the river. It was curious—he had crossed the bridge a hundred times, but it had never occurred to him that there was any life below the street, that men came and went down there on the strip of wharf, so narrow that it seemed little more than a fender for the buildings that backed on the river. Picking his way carefully to avoid slipping, he walked down.

Not far away, in the basement of one of these buildings, was a sailors' grog-shop: hardly three rods from the bridge-walk, even in sight from it, yet so quietly tucked away below story on story of brick building, behind half a dozen smoking tugs, in a spot where no sober doorway, no saloon doorway even, had a right to be—so hidden, in fact, that not half a dozen of the tens of thousands of people on the bridge daily had ever observed it. It was a wonder how a drunken man could ever get out through the door without falling into the river—perhaps one did fall now and then. There was music in the saloon now—a squeaking fiddle and loud noises.

Beyond, the river was splashed with red and white and green from lanterns and side-lights; and a dozen masts, their spars and rigging apparently interlaced, were outlined against the western sky. At the moment a big freighter, bound out, was headed for the draw, forging slowly and almost silently down the sluggish stream, passing along like some dim modern Flying Dutchman. Above, on the bridge, cars were rumbling and footsteps were pattering—the feet of the late suburbanites hurrying to their trains. All Chicago was alive and bustling above him and around him; but here, at the end of a crooked passage, was a quiet spot—a shop filled with boats, completed and uncompleted; and sprawled on his stomach behind one of the boats, a cigarette in his mouth, an Old Sleuth story spread on the boards before him, a candle stuck in a beer bottle at his elbow, was a boy, who was trying to believe that he was, in spite of cold feet and sniffling nose, really tough and comfortable.

“Well, George,” said Halloran, “how's business?”

George started, turned pale, and hastily took the cigarette from his mouth; then remembering his independence, he as hastily put it back. Halloran sat down on the stem of a ship's boat and filled his pipe.

“Miss Davies and I heard you were in hard luck,” he went on, “and I thought I'd look you up and see what's the matter.”

George had not been able to speak until now. He sat up, pulled doggedly a moment at his cigarette, and said in a very sulky tone:

“Who told you I was here?”

Halloran would have been glad to answer him, but as it fell out no reply was necessary. For just as he was pausing to light his pipe a step was heard in the passage and a wizened-faced boy appeared in the outer circle of the candle-light.

It was Jimmie, eyeing Halloran with distrust, glancing apologetically at George, more disturbed, in fact, than Halloran had yet seen him. To him now George turned a reproachful face.

“I never done it, George,” said Jimmie. “I'd a-busted first. He went around to old Hoffman and he put him onto my uncle. I see him go in there and I followed him up.”

“That's right, George,” Halloran put in by way of seconding Jimmie. “We couldn't get a word out of him. It was your mother that sent me to Hoffman. But I've come down to talk with you, and I'm not sorry that Jimmie is here. Now, what's the trouble? Tell me about it; and then I will see what we can do for you.”

The two boys looked at each other. George had been told so often by certain Settlement workers never to smoke, never to read bad books, never to be seen in company with beer bottles, he had supposed that of course these things would be the first subjects under discussion; and the omission disconcerted him. Jimmie, meanwhile, being the shrewder of the two, was signaling him to go ahead and spit it out. So he began, in a blundering, sullen sort of a way; stumbled, blushed and stopped. Finally Jimmie had to take it up.

“You see, it's just this way. George's folks was getting down pretty close to the boards, and they was the rent coming, and George he had his week's pay, but it wasn't enough, so I just told him”—very patronizing here, was Jimmie, as became a young capitalist who had once clasped the hand of Captain Anson—“I told him to give it to me and I'd put it up on the Washington game, with a little wad of my own. It was an easy mark, 'cause the Washingtons were tail-enders, and I had hold of their mascot, and he was willing to put up even. It was like taking the money out of his pocket, but a man can't throw away a chance like that—and then I'll be damned if Billy Connors didn't up and throw the game.”

“He's a hell of a pitcher,” was George's comment, spoken with a sidelong glance at Halloran.

“Never you mind,” said Jimmie, “Watson 'll never sign him again, after a trick like that.”

Rather an interesting situation this—an odd confusing of good motives with bad—an amusing symptom of good feeling in speculator Jimmie, to be taking up the support of a young man who had been ruined through his advice. He would doubtless get over it as he grew older. If every man were to feel the same responsibility, what a wreck it would make of our institutions! What a scrambling there would be in Wall Street, in La Salle Street! Incipient socialism this—a bad thing, very bad!

Halloran nodded and smiled a little. “I know,” he said. “We're all of us likely to fall down now and then. I don't know as I should have done just that, though. A man can't afford to gamble unless he can afford to lose; and there aren't many such men. I'm not sure there are any.” He smiled again—he knew just how George felt, just about what he was thinking behind that clouded face. “But now the question is, how are we going to fix you up again? You can't stay here. How much did you lose?”

Again it was Jimmie that answered, “Three fifty.”

Halloran thought for a moment, doing some sums in his head; then he took a purse from his pocket and counted out the money.

“Now, George,” he said, “this is a loan. I know you're square, and I'm willing to take your word for it. There is no hurry; but some day, when you feel you can, you may pay it back. We needn't either of us say anything about it.” George's expression was changing every moment; but he took the money. “Suppose we go back to the house now, George. You will find your mother and sister mighty glad to see you. And Miss Davies is waiting at the Settlement to hear about you. She has worried a good deal. Then Monday we will see if we can't get the factory to give you another trial.”

George's armour was not proof against such an attack as this. He got up, put the story in his pocket, and lighted Halloran and Jimmie along the passage with his candle; then he snuffed it out and put it in his pocket, threw the bottle into the river and followed the two others up the stairway to the street.

Bending over a book sat Halloran, both elbows on the table, the fingers of both hands run through his hair. The book lay open, and spread out on the leaves was a note from Miss Davies; in part this ran as follows:

“. . . George is to have another trial at the box-factory. They seem willing to be kind to him, but Mr. ———— says emphatically that he will not be taken back a second time. But I have confidence in him, and particularly in your influence.. . .

“I will tell you all about it when you next come up to the house. I am more grateful than you know—indeed, we all are—for your. . .”

Halloran had made a discovery. Had he been given to self-scrutiny it would have come earlier; and it would then have been a little easier to face. But this way of thinking would not help him now; it had not come earlier, it was difficult, and the question lay before him: should he make that next visit to the house or not?

He glanced up at his nickel alarm-clock and saw that it was time to go on watch; so he put on his sweater and oilskins and sou'wester, blew out his lamp and walked across the Sheridan road to the station.

It was nearly four years since he had taken care of the Davies's furnace and slept in their barn. That had been in his days of “subbing” for a crew position, and he had not been a boy even then; he had entered college at twenty-two. Since then, thanks to his salary as a surfman in the pay of the Treasury Department, he had got along rather better; he was no longer the traditional poor student. He was not ashamed of his struggles, nor especially proud of them; he was inclined to think that struggling is not in itself particularly commendable; that it is success that counts. He knew that Mrs. Davies and her daughter had followed his work with interest, and he was grateful for it. “Grateful!”—there was the word that he stuck at. For, after all, had there not been from the start an element of patronage in their kindness to him? “Kindness” another word that hurt.

Number Six was “punching” the watchman's clock that always hung just within the station door.

“Hallo,” he said to Halloran.

“Hallo.”

“Wet night.”

“Yes, rather.”

“Better keep an eye on that light off the long pier. She's running in pretty close, I think.”

“All right; good-night.”

Number Six disappeared in the dark of the road, bound for bed; and Halloran pulled his sweater up around his neck and fell to pacing the veranda. The surf was booming on the beach below; the rain was cutting in toward the land. Out beyond the breakers were lights—a line of them along the horizon.

The time had come to look ahead. In another six months his college course would be completed; his playtime would be over; realities lay beyond—downright realities that surround a man, that show clear through him, that bear him down and under unless he be made of stronger stuff than they. Wits were needed, and judgment; the determination that goes against things, not with them. There would be no making up of cuts, out there in the world, no special examinations; a man must look higher than the faculty there. Mistakes would be hard to rectify, perhaps could never be rectified, where a man was already nearer thirty than twenty. He decided not to make that next call.

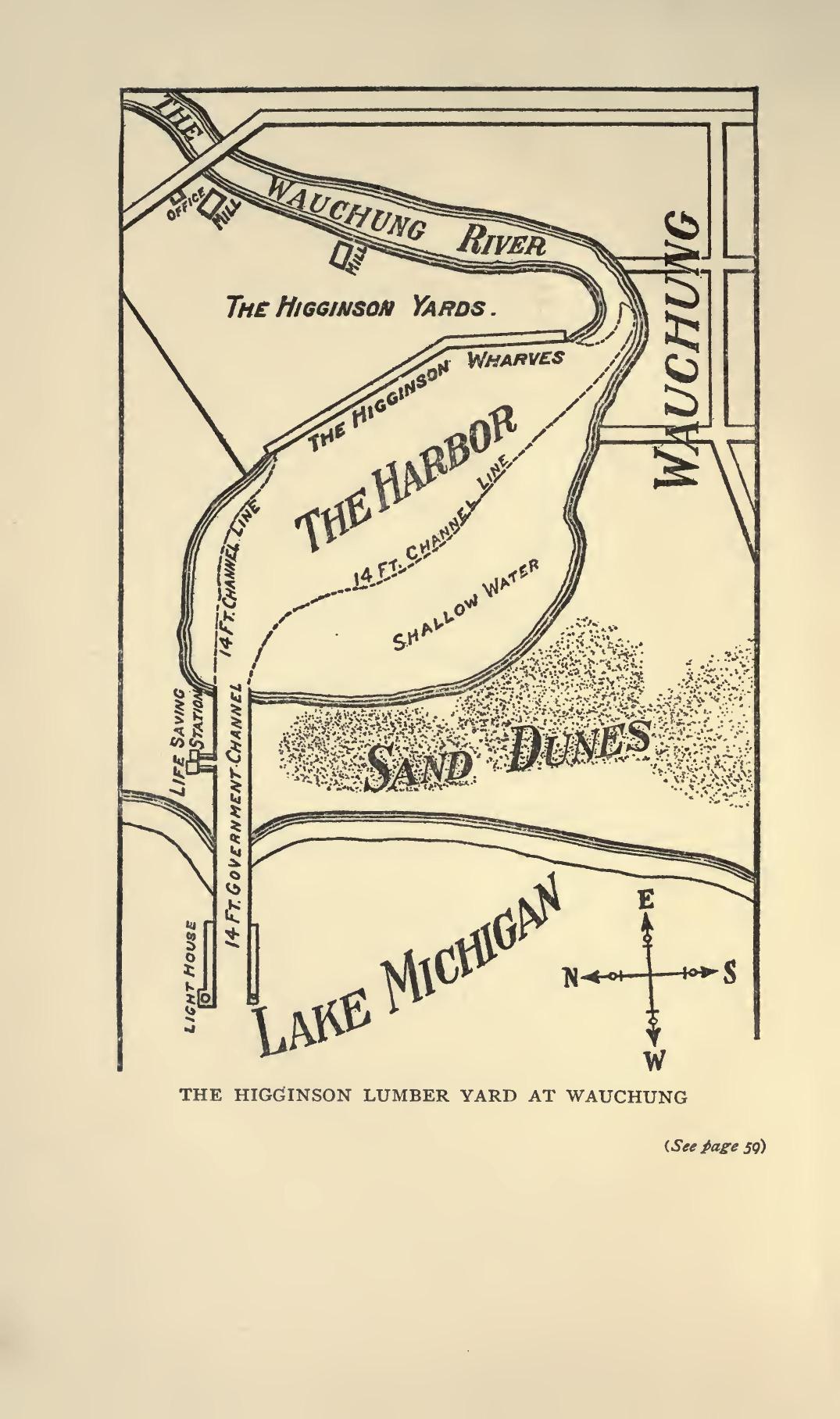

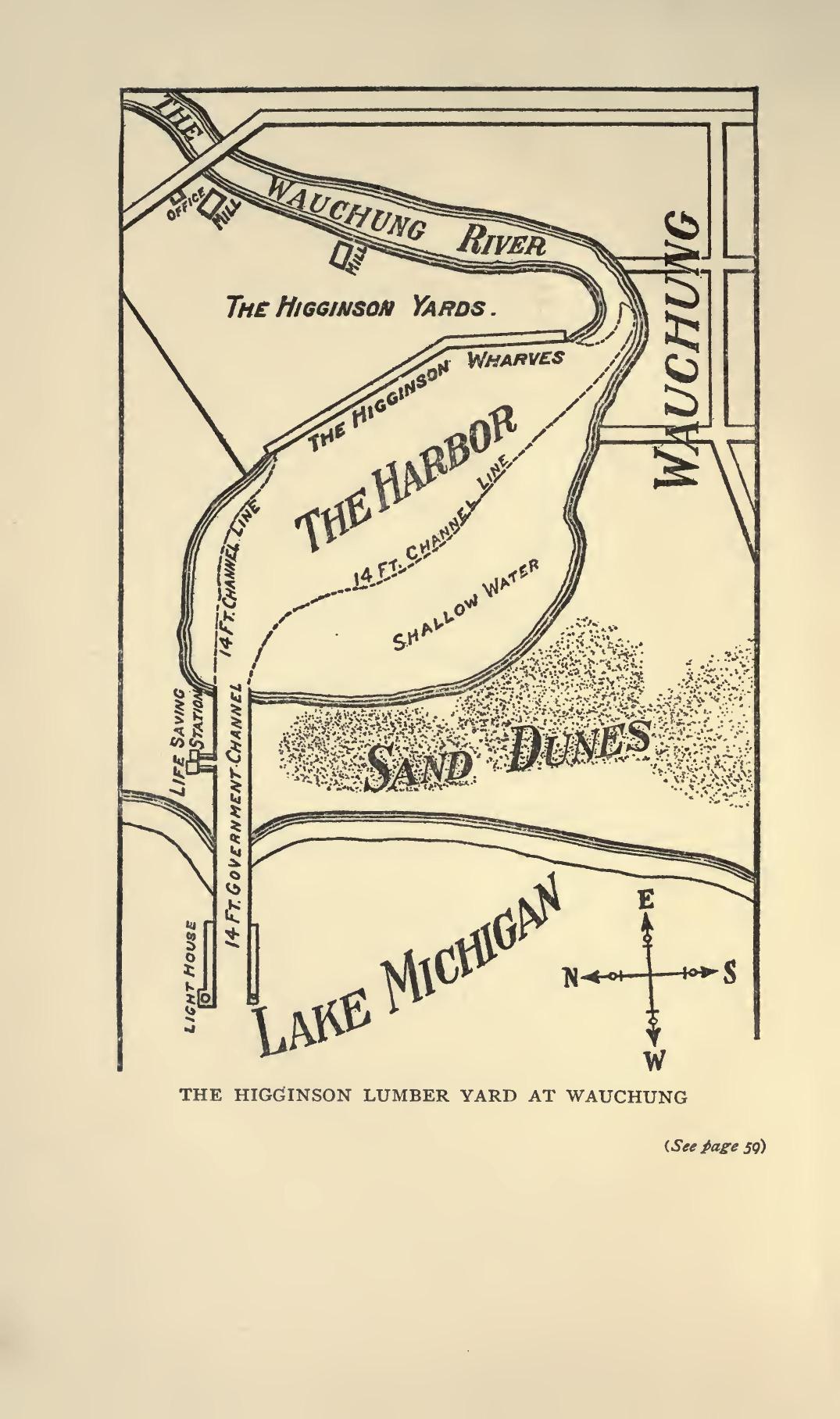

The little city of Wauchung straggled over and between and almost burrowed under a chain of sand-hills—shining yellow hills with tops entirely bald save for a spear of rank grass here and there or a dwarfed pine. Outside the mouth of the river was Lake Michigan; behind the little city were the pine forests of the Lower Peninsula. And the one interesting object of this whole region was a man—for houses and shops were commonplace, streets were ill-paved, the railroad was wanting in energy and capital, the inhabitants were mostly leveled down to the colourless monotony of the sand-hills—a man named Martin L. Higginson.

There was one imposing building of granite and red bricks on the business street—a glance showed the name of Higginson over the entrance. Two large mills stood by the river, surrounded by piles of lumber on the land, fronted by rafts of logs in the water, sending out their droning hum all day long (and frequently all night long); inside, men were bustling and pushing in the effort to keep up with the drive of work outside, the long runways were active with men and with moving lumber—and on each of the mills was the name Higginson. Two steamers lay at the Higginson wharves—lake carriers, both, of the Higginson line. A logging railroad ran back some twenty miles into the forest; it ran over Higginson land to Higginson land, to bring what logs the little river could not bring—for the Higginson property extended far to north, south and eastward. There was, in fact, one rich man in the little city—one man who had done what he could to keep the railroad busy, to keep the harbour dredged, to keep the streets in better condition, to make Wauchung a real city, awake, energetic, proud—one man who represented Wauchung to the outside world: Mr. Higginson.

An elderly gentleman he was, a man who had passed the fighting age, who would have stopped to rest any time these last six or eight years if the business had permitted it; but it had stood until recently that the one man in Wauchung who did not take his vacation every year was Mr. Higginson. As it often falls out, however, one of his severest misfortunes had brought its blessing. For five years and more he had looked for a man, for the man, whom he could trust to take up the burden that was beginning to weigh so heavily; and for five years he had failed. He liked young Crosman, the head clerk in the office; but Crosman, though welcome enough at the house as Mamie Higginson's regular caller, hardly showed administrative qualities—his limitations were marked. And so the search had gone on: he had tried them, young “men and middle-aged men”—and he had found that all of them wanted money, and none of them wanted work. And what he had to offer was work, little else—hard work, work for head and hands, much thinking of the business, little thinking of self: the spirit that would live for the business, that would take its pride in the quality of the Higginson work, that would strive, as he had striven, to make the name of Higginson a synonym for honest work, work done on time, work done a little better than the contract demanded. Where could he find a man like this?

And then, after five years, through a shipwreck of all occurrences, he had found him. He knew him at once, as he had thought he should. Looking down from the heights of character and accomplishments, on a world of little persons, foolish persons, earnest, weak persons, dishonest persons, pompous, empty persons—all the sorts that go to make up a man's world, and nearly all that he is likely to see, unfortunately, from the heights—looking out and down and all about, he had seen a young man's head and shoulders climbing up above the rabble. The young man had not yet climbed very high; but he was climbing, and that was enough. So Mr. Higginson had come to think more lightly of the rheumatism, the failing eyes, the many signs of age that had been brought sharply to his notice by that shock and exposure on the west coast.

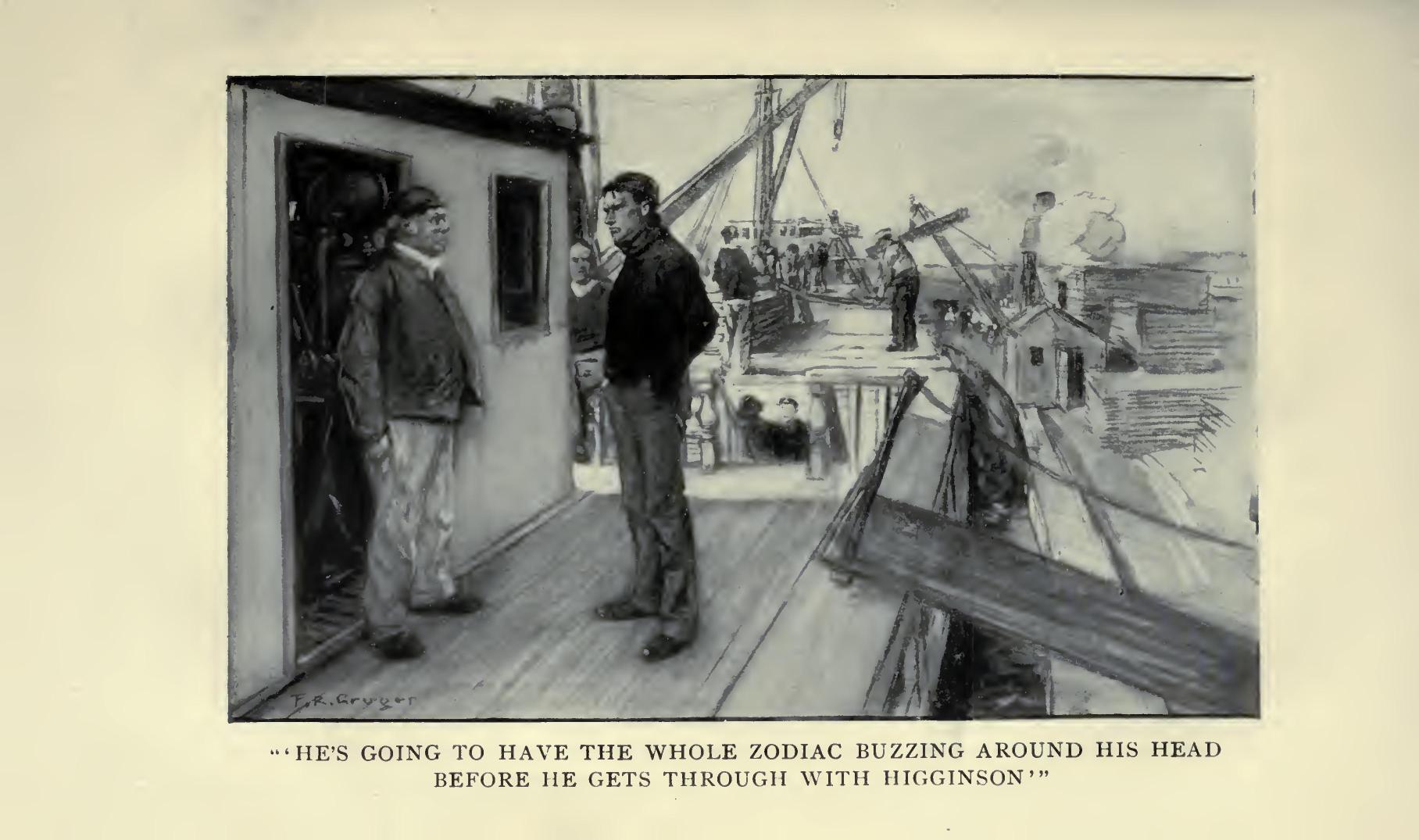

At the time of this chapter, Mr. Higginson and Halloran were seated in the office—Halloran before his desk, Mr. Higginson beside it—looking at a typewritten letter or statement. Twenty-four hours earlier Mr. William H. Babcock, of G. Hyde Bigelow & Company, had taken the train for Chicago, leaving this document behind him; and now the time had come to answer it.

This was the culmination of a long series of letters and interviews. The beginning had been when this same Mr. Babcock had endeavoured to buy the Wauchung mills in the interest of Mr. Bigelow. It seemed that Mr. Bigelow was about to enter the lumber business. His genius for combination, for exploitation, was to be given a new direction. Kentucky Coal, New Freighters, Northwest Chicago, all his various interests were prospering, thanks to the name of Bigelow, and now the lumber business was to be vitalized, to be vivified. Just how it was to be done, or what was to be done, was not known; that secret was kept close in the Bigelow office. Each newspaper published its own version, to be believed or disbelieved at the discretion of the reader. All Mr. Higginson knew was that the Bigelow firm could never buy him out, that he had not spent his years in building up a business for the benefit of Mr. Bigelow. The business was his life, and he meant to keep it for himself and his family and his legitimate successors. So the first refusal had been a simple matter—a plain, emphatic no had sufficed.

Then for a time there had been silence; until one day Halloran learned that the Pewaukoe Lumber Company, twenty-odd miles up the shore, had succumbed to the blandishments of the low-voiced Mr. Babcock, and had sold out mills, standing timber and all. It had not been a prosperous company, thanks to the shiftless management of the children of the original owner; but there was no reason why it should not do well in good hands. There was no question now that, whatever he meant to do next, Mr. Bigelow had a footing in the lumber trade, and Halloran had been watching him closely.

The document on the desk was a statement of the “understanding” or secret agreement that was henceforth to be law among the lumber producers of Lake Michigan. It had been presented and accompanied with much confidential talk from Mr. Babcock—all tending to show that the lumbermen, with the sole exception of Mr. Higginson, were already united to forward this agreement, that the business would be organized as never before, that great economies would be brought about in the carrying side of the trade, that the strain of competition' would be avoided, that prices would be maintained at a somewhat higher figure (a main point, this) under penalty of fines, that—much more low talk and friendly disinterested confidences. For their interests were identical, said Mr. Babcock; and there was room for them all. Efficiency was the keyword—efficiency, productiveness, economy, identity of interests, good prices. And lastly there had been friendly, almost deferential intimations that G. Hyde Bigelow & Company held the key to the situation, that the combination was already a fact, and that a firm which might decide to stay out must take the consequences.

Simplified, the whole matter came to this: Within the combination, prosperity in plenty, but always subject to the guiding judgment of G. Hyde Bigelow, hence a certain loss of identity and of control to self-respecting heads of companies; without the combination, a fight to a finish against the combined power and momentum of Bigelow & Company and the “Lumber Trust.” Just how great was this momentum no one exactly knew: but Bigelow was a magic name, no doubt of it.

“You have gone over it, have you, Mr. Halloran?” said Mr. Higginson.

His voice was disturbed and his expression showed worry and trouble. For a year Mr. Higginson had been changing, very slightly but none the less perceptibly to one as close to him, day after day, as Halloran was. Until he had assured himself that his assistant was able to take up the burden, he had kept up; but after that moment he had seemed, in a measure, to let go. On routine matters he was as strong as ever, but his mind refused to work automatically through new problems; there were sometimes gaps in his reasoning that he found it difficult to bridge over, and this worried him. So it had come about that a tacit agreement existed between the older man and the younger, that in questions where vigour was needed, of body or mind, the younger man should take the lead; and Mr. Higginson mildly deceived himself by giving more attention than formerly to routine matters and trivial details. It was Halloran, therefore, who had spent the better part of a night thinking out this question, whether to yield or fight. And it was Mr. Higginson, naturally enough, who had put the question:

“You have gone over it, have you, Mr. Halloran?”

“Yes. The Bigelow part of it is what I like least. I am not sure that he is just the man you would want to stand responsible for this business, and therefore he certainly is not the man to take charge of all the companies together—and that is pretty nearly what this paper means.”

“Why do you think that?”

“Well, he isn't solid. He's been lucky, and just now he's on the top of the wave. But his interests and investments are spread out so wide that a run of bad luck might upset him. I don't know that it would, but it might. And then I have seen a little of him.”

“You know him personally?”

“Yes. I cut his grass for two summers in Evanston, and did odd jobs for him.”

Mr. Higginson pondered, and Halloran went on: “On the other hand, his resources are large, and if we decide to stand out it may mean a long, hard fight. It might be harder than we think.”

Mr. Higginson was still thinking hard, forcing his mind to take up one phase of the question after another; and the worried expression, so frequently on his face nowadays, was more noticeable than ever. Finally he said:

“Then you are in favour of declining to join the combination?”

This was the direct question that Halloran had partly foreseen. He hesitated, marking at random with a pencil while his thoughts came fast. At this moment he saw more clearly than he had seen at any time during the night what a refusal would mean. Wealthy as Mr. Higginson was, his wealth lay in the lumber lands, the logging railroad, in the mills and the steamers, and in Wauchung property; to a certain extent the whole town of Wauchung had grown up around Mr. Higginson and was directly or indirectly dependent upon him; and all these interests, hanging as they did on the lumber business, must suffer when this business was attacked. But he caught himself—if he ran on into this way of thinking he was lost.

“Yes,” he replied; “I think we had better decline.”

Mr. Higginson arose.

“I will leave the letter to you,” he said; and then went out with a face that seemed to express downright-dread. Honest old gentleman, he had thought to take a rest; and instead he found himself facing the hardest fight of his career.

Halloran took up his pen and made the attitude of Higginson & Company plain in three lines.

In the parlour of the Higginson home, one evening shortly after the incident of the last chapter, sat Mrs. Higginson and her daughter, with expressions hardly significant of an intense joy in life. In the library, talking earnestly behind closed doors, were Mr. Higginson and Halloran.

“Well, Mr. Halloran, what is it?” had begun the head of the firm.

“The fight is on. I got the first word of it to-day.”

Mr. Higginson bowed slightly and waited.

“Bigelow has cut the price down below cost.”

It took a moment for the older man to grasp the meaning of this.

“Below cost?” he repeated.

“Yes; it's going to be a question of endurance.”

“But we have some large orders on hand. They will keep us busy for awhile. How does the Carroll & Condit lumber stand?”

“It's about half cut out.”

“You can go ahead with it, then, for this week. And after that the Michigan City contract will keep us busy for awhile.”

“The Carroll & Condit business is what brought me here to-night. Here is a letter from them.” Halloran laid it on the table. “They offer us a chance to meet the new price before they place their order elsewhere.”

Gradually the meaning of Halloran's words had been sinking into Mr. Higginson's mind; the relations of cause and effect had been clearing before him. He looked the letter over silently, twice, three times.

“I—I can hardly believe this———” He saw that this was useless talk and he stopped. It had been a verbal order from Carroll, a man whom he had reason to hold as the soul of honour; the price had been stated and agreed to, precisely as for twenty years back; everything had been satisfactory. Good Mr. Higginson had been the victim of a delusion. After half a century of struggle he had allowed himself to believe that the fight was about over, that his personal achievement meant something; that he could stand securely on the heights. He had forgotten that Business is Business, that Time is Money and Money Talks; he had forgotten that the glorious old world was spinning along, as heedless as ever, after the ever-receding glitter, and that there could be no stopping until the last great stop should be reached.

“From what I can gather,” said Halloran, “they mean to fight us all along the line. The Michigan City contract, I think, is good. We have it down in black and white, and we can make the delivery in our own steamers; but we should have to use the railroads for most of our other orders, and I'm afraid we can't do it.” He disliked this hammering one trouble after another into the old gentleman's aching head, but it had to be done. “I'm quite sure that Bigelow has influence with the railroads, and of course he will use it.”

Mr. Higginson was thinking—thinking.

“How much—” he was still thinking, desperately raking his facts together and facing what seemed like chaos—“how much is this going to cost us, Mr. Halloran?”

Halloran shook his head.

“It's too early to tell. He must show his hand before we can plan our game. He's beginning now, and before he gets through, by ———, we'll smash him. We'll make him feel like a whipped coach-dog every time he passes a lumber pile.” Halloran was getting so excited he had to get up and pace the carpet. “I know the man; I know his meanness and his vanity. I've worked for him, and I've seen him off his guard, and I know his insolence. Before we get through with him he'll wish he had gone into a bucket-shop, where he belongs, and stayed there, the damned old bloated frog of a tin-horn gambler. Let him wreck his Kentucky Coal and his New Freighters all he pleases, but he'll get a bellyful if he tries to wreck the lumber business.”

He stopped short, looked around at the dark, olive-tinted walls, at the stately row of books in their morocco and calf and yellow and red and gold; looked at the rich carpet and the restful chairs and at the soft light of the polished student-lamp; looked last at Mr. Higginson—and felt a cold sweat breaking out all over his body. What had he said?

Somewhere in Halloran's make-up, deep-hidden beneath the laborious years of work and study, lay a well, a spouting, roaring geyser of profanity. It had come into the world with him; it had been richly fed during his rough, knockabout boyhood; and now, in spite of the weights he had put on it, a year or two of Michigan lumbermen had been enough to prime it.

Mr. Higginson was still thinking—thinking. The facts were before him now; at last he had penetrated to them and brought them together. And he was facing them—meeting them squarely without flinching. Quietly he sat, one elbow on the green-topped table, his hand shading his eyes; and the lamplight fell gently on his head. He was facing the question of himself, of his ability to conduct his own business; and another question, granting that he was unable, whether he could, in his best judgment, place everything he had in the world—his business, his family, himself—in the hands of this man and bid him Godspeed in his work. So he sat thinking—thinking; and Halloran, a little abashed, but angry still, dropped into a chair and waited. At last the old gentleman spoke—in a low, changed voice. “Mr. Halloran, I have not been well lately; and I think it best—to tell you that—for the present the business is in your hands. I will stay here and advise with you, but—I do not wish you to feel hampered by my presence in carrying on this fight. I am laying a heavy responsibility on you—but I think—I trust you will be equal to it.”

Mr. Higginson's part of the fight was over; and he had won.