Title: The Irish Penny Journal, Vol. 1 No. 11, September 12, 1840

Author: Various

Release date: February 12, 2017 [eBook #54155]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by JSTOR www.jstor.org)

| Number 11. | SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 12, 1840. | Volume I. |

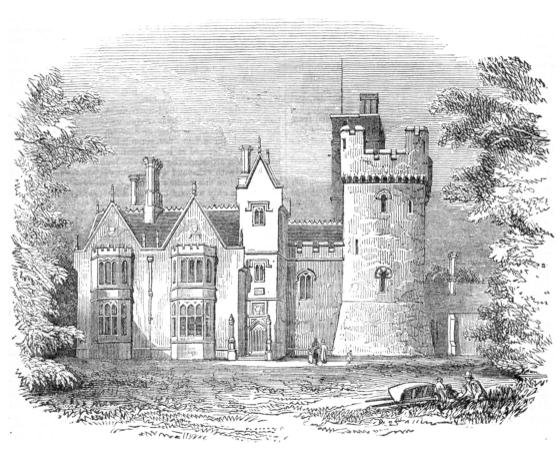

There are few things that afford us a higher pleasure than to observe our metropolis and our provincial cities and towns, despite of adverse circumstances, increasing in the number and splendour of their public buildings, for they are sure evidences of the advance of civilization, with its attendant train of arts, amongst us, and that we are progressing to the rank and dignity of a great nation. Yet we confess we enjoy a still higher gratification when we see springing up around us great architectural works of another class—those erected by individuals of the aristocracy as residences for themselves and those who are to come after them. Such architectural works are not merely interesting from the gratifications they afford to the feeling of taste, and the epic dignity and beauty which they contribute to landscape scenery, but have a higher interest as pledges to the nation that those who have erected them have a filial attachment to the soil which gave them birth, and which supplies them, whether for good or evil, with the means of greatness; and that they are not disposed to play the part of unwise and ungrateful children. To us it little matters what the creed or party of such individuals may be; however they may err in opinions, their feelings are at heart as they should be. The aristocrat of large means, who is resident not from necessity but from choice, and who spends a portion of his wealth in the adornment of his home, is rarely, if ever, a bad landlord. Desiring to see art and nature combine to produce the sentiment of beauty in the objects immediately about him, he cannot willingly allow it to be associated with the unsightly and discordant emblems of penury and sorrow. To be indifferent about the presence of such accompaniments would be an anomaly in human character, and only an exception proving the general rule. It is this class of men that we want—men who seek happiness in their legitimate homes, and the diffusion of blessings among those to whom it is their duty to be protectors—lovers of the arts of refined society, not the gross and generally illiterate pursuers of field sports, which, by hardening the heart towards the lower animals of creation, prepares it for reckless indifference to the wants and sufferings of our fellow men. Had we more of such patriots—more of such domestic architectural buildings starting into existence, evidencing as well their refined tastes and habits as the sincerity of the love they bear their native land, we should soon see the face of our country changed, and peace and happiness smiling around us. We do not, however, indulge in any feelings of despondence for the future. Very many beautiful creations of the architectural art have recently been erected in Ireland, and we have little apprehension that they[Pg 82] will not increase in number till our island shall rival any other portion of the empire in the possession of such characteristic features of civilization and beauty. Cheered by such pleasing anticipations, we shall endeavour to the best of our ability to make our readers familiar with the architectural styles of the chief residences of our nobility and gentry, as well as with the general features of the scenery in which they are situated; and, as a commencement, we have selected the seat of the Vernons—the recently re-erected Castle of Clontarf.

The name of this locality, which is situated on the northern shore of the Bay of Dublin, and about two miles from the city, must at least be familiar to most of our readers, being memorable in history as the scene of the most national and best contested battle ever fought in Ireland, when in 1014 the monarch Brian Boru obtained a decisive victory over the united forces of the Danish and Norwegian invaders of the British islands, assisted by the Irish troops of a recreant King of Leinster. This name signifies in English the lawn or recess of the bull, being formed from two Celtic words, cluain, a lawn or pastoral plain, and tarbh, a bull; the latter appellation expressing its contiguity to one of the two great sand-banks of the bay, now called the North and South Bulls, from the similitude of the sounds produced by the breaking of the sea upon their shores, to the roar of animals of that denomination.

As it is stated that a church or monastery was founded here as early as the year 550, it is probable that this name is of ecclesiastical origin, and that the site of that ancient church is still marked by the present parish one from which it was derived. But, however this may be, immediately after the settlement of the Anglo-Normans, the lands of Clontarf and Santry, constituting one knight’s fee, were granted by Hugh de Lacy, Lord of Meath, to one of his followers, named Adam de Feipo, or as the name is now written, Phepoe, by whom, as is generally supposed, the Castle of Clontarf was erected, and its lands created a manor. This manor, as well as its castle, appears, however, to have passed very soon after into the possession of the Knights Templars, by whom a commandery of the Order, dependent upon their splendid establishment at Kilmainham, was placed here. Upon the suppression of the Templars, their manor of Clontarf was granted, in 1311, to Richard de Burgo, Earl of Ulster, the religious edifices upon it remaining in the king’s hands as a royal house; and in 1326, Roger le Ken had a grant of the premises in Clontarf, which he had heretofore occupied at will, to hold henceforth to him and the heirs of his body. Towards the close of the same century, however, in obedience to the Pope’s decree in reference to the lands of the Templars, the manor passed into the possession of the Knights Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem, on which Clontarf became a preceptory of that Order, and a chief seat of the Grand Prior of Kilmainham. It seems somewhat probable, however, that the descendants of Roger le Ken still continued to hold the manor as lessees of the Hospitallers till the dissolution of the Order, as, immediately previous to that event, on an inquisition taken, the Prior of Kilmainham was found seised of the manor, rectory, tithes, and altarages of Clontarf, subject, however, to a lease made in the year 1538 to Matthew King (a corrupted form perhaps of the name Ken) of all the town and lordship, with the appurtenances, and also the pool of Clontarf, and the island lying to the west side thereof, and all the said rectory, tithes, &c. to endure for nine years. In this demise it was provided that the lessee should repair the manor-house and maintain a sufficient person to administer all sacraments to the parishioners at their proper charges. On the suppression of the monastic order in the thirty-second year of Henry the Eighth, Sir John Rawson, the Prior of Kilmainham—a very distinguished man, who had at various periods held the office of Treasurer of Ireland—having, with the consent of his Chapter under their common seal, surrendered the hospital with its dependencies into the King’s hands, he was created Viscount of Clontarf in 1541, on a representation made to his majesty by the Lord Deputy, with a pension of five hundred marks, in right of which dignity he sat in the parliament of that year.

In the year 1600, the manor, territory, tithes, town, and lordships of Clontarf, as enjoyed by the Priors of Kilmainham, were granted by Queen Elizabeth to Sir Geoffry Fenton, who had filled the office of Secretary of State for Ireland; and on his death in 1608 these premises were further assured to his son Sir William, who had a confirmation of this manor in 1637, under the commission for the remedy of defective titles. Yet it appears that very shortly afterwards, the manor, however acquired, was again in the possession of a member of the King family; for, on the breaking out of the rebellion of 1641, the town, manor-house, &c. of Clontarf, then the property of Mr George King, were burnt by Sir Charles Coote as a punishment for the supposed participation of that gentleman in a plunder made of a cargo from a vessel which lay there, by Luke Netterville and his adherents. King was shortly afterwards attainted, a reward of £400 offered for his head; and his estates, comprising this manor, Hollybrook, and the island of Clontarf, containing, as stated, 961 acres statute measure, were bestowed by Cromwell on Captain John Bakewell, who afterwards sold the estate to John Vernon, a scion of the noble Norman family of the De Vernons, and from whose brother the present proprietor descends.

In 1660, Colonel Edward Vernon, the son of John Vernon, passed patent for this manor in fee, together with all anchorages, fisheries, creeks, sands and sea-shores, wrecks of the sea, &c.; which right was saved in subsequent acts of parliament, and still remains to his successors. And in 1675, the king further enlarged the jurisdictions, tenures, and courts of this manor, with a grant of royalties (royal mines excepted), power to empark three hundred acres, with free warren, privilege of holding two fairs, one on the 10th of April and the other on the 16th of October, with customs, &c. These fairs have, however, been long discontinued.

We have thus briefly traced the origin, and succession of proprietors of this castle and manor, as immediately connected with the subject of our prefixed illustration; but our limits will not allow us to touch on the general history of the locality on the present occasion.

Of the original castle erected here in the twelfth century, a square tower, connected with additions of the sixteenth and subsequent centuries, was preserved as a residence for the proprietors of the manor till the year 1835, when the present noble structure was commenced from the designs and under the superintendence of the late William Morrison, Esq., the most eminent and accomplished architect whom Ireland has possessed within the present century. With the good feeling as well as refined taste for which this admirable artist was so distinguished, his first desire in the re-edification of this castle was to preserve as far as possible the original buildings; and while he increased their extent in the necessary additions to them, to preserve and restore them as much as possible to what might be supposed to have been their original state. But it was found impracticable to do so. The foundations were found to have sunk, and a nearly total re-erection was therefore necessary; yet, in the new edifice, attending to the historical associations connected with a spot so interesting, he so designed it as to exhibit with historical accuracy what might be supposed to have been the forms and features of the ancient buildings, and thus make it a consistent commentary on and illustration of the past history of its locality.

With these remarks, which were necessary to insure a just appreciation of the intention of the architect in the diversified character which he has given to this architectural composition, we may describe it generally as a structure in its character partly military, partly domestic, and to a certain extent ecclesiastical. Its grand feature is a tower in the Norman style of the twelfth century, which ascends to the height of seventy feet, or with a smaller tower which is placed behind it, eighty feet: it has turrets at its angles, and its windows as well as its interior are enriched with decorations in harmony with its architectural style. Connected with this tower, and placed on its west side, is the principal portion of the domestic buildings, which present the purest specimen, perhaps, of Tudor architecture to be found in Ireland. The entrance to this range is placed beneath a small but lofty tower, beneath which a vestibule leads into a spacious and lofty hall, fifty-one feet by twenty, which presents much the appearance of a Gothic church, the walls being panelled, and painted to imitate dark oak. This hall is floored with Irish oak polished, and its roof is supported by principals springing from richly ornamented corbels, or pendants—its beauty being much increased by gilded bosses with which it is studded, and which, sparkling among the dark tracery, have a singularly rich effect. The cornice is also richly ornamented, and presents at intervals similar gilded bosses. But the imposing feature of this great chamber is a magnificent staircase of oak, placed at its eastern end, which leads, by two return flights, to a gallery crossing the hall, and communicating with the principal bed-chambers, and which would serve for an orchestra on occasions[Pg 83] of festivity. At the other end of the hall are doors leading into the drawing-room, dancing-room, and library; and in the centre of this end is placed a beautiful chimney-piece of black marble, surrounded by a canopy of carved oak, the enrichments of which are in that peculiar style which characterises the ornaments of Tudor architecture, containing the single and double rose, stars, and other badges of that period. The hall is lighted by five stained glass windows of an ecclesiastical character, and level with the gallery; and on these windows are blazoned the arms of the families with whom the Vernons have intermarried, comprising some of the highest of the English and Irish nobility. Of the external architecture of this portion of the building some correct notion may be formed from our illustration, which exhibits the style of the gables and oriel or bay windows which are placed both on its southern and western sides; and we may justly apply to the whole of this range the description given by Chaucer in his imaginary palace of “pleasaunt regarde:”

Branching from the northern and eastern sides of the great tower, extensive ranges of building contain the servants’ apartments, and an extensive suite of inferior bed-rooms, and the tower itself contains a study, and above it a nursery, over which, again, a leaded platform with parapets commands most extensive and diversified prospects of the surrounding country.

The preceding description will, we fear, convey but an imperfect idea of the plan of this interesting structure, nor will our illustration, which only gives a representation of its southern front, give more than a general idea of the architectural character of a building, the great merit of which, next to the beauty and chronological accuracy of its details, consists in the number of picturesque points of view which it affords, from the irregularity of its plan and the variety of its outlines.

We shall only add a few words in respect to its locality.

The Castle of Clontarf is situated in a district rich in pastoral beauty, and at the head or northern extremity of the village of the same name, which consists of a single but wide street composed of houses of a respectable class, and extending from it in a right line to the sea. It is surrounded by forest trees of great age and grandeur, through which by vistas are obtained views of the bay and the mountain scenery of the southern shore.

Upon the whole, we may truly say of this structure that its beauty is no less striking than its moderate size and pretension are in happy proportion to the rank and means of its owner; nor is it a lesser merit, that—unlike too many of the lordly residences in Ireland—the close propinquity of its situation to the village of which he is lord, is characteristically expressive of the confidence and kindly familiarity which should ever exist between the proprietor and the community holding under him. Nor is it again a lesser merit, that—unlike most of the mansion-houses to which we have alluded—it is not enclosed by churlish and prison-like walls of stone, excluding it from the public eye, and indicating but too truly the cold and heartless selfishness of their owners, which would not allow to the many even the passing enjoyment of a glimpse of the grandeur and beauty which they claim as their own.

P.

A Wooden Glass Goblet.—The first night of the “Stratford Jubilee” in Dublin, Robert Mahon had to sing the song of the “Mulberry Tree,” the music composed by C. Dibdin senior, the words of which begin with

He walked on, and began the song, holding out in his hand a fine cut-glass rummer. The other performers, who were also on, looked at him and his fair glass goblet “carved from a tree” with wonder. The audience took the absurdity, and much mirth and loud hissing followed. The play over, Mahon had the folly to insist upon it he was right: “’Tis true,” he said, “the property-man did stand at the wing with a wooden cup in his hand, which he wanted to thrust into mine; but could I appear before the audience with such a rascally vulgar wooden mether?—no; I insisted he should that instant go and fetch me an elegant glass rummer, and here it is!”—O’Keefe’s Recollections.

One of the most difficult things a person has to do, who is getting ahead of the friends of his earlier and less prosperous years in the race of fortune, is to rid himself of these friends—to get quit of persons whose want of success in the world renders them no longer fit associates. The thing is not easily done, for you have to maintain appearances. You have to repel them gradually and gently, and in such a manner as to be able to defy them to lay any particular act of rudeness, any positive act of repulsion, to your charge. To manage the thing adroitly, therefore, requires some genius and a good deal of tact.

The difficulty of accomplishing this great manœuvre in a prosperous career, is much increased by the circumstance that as you advance your ancient cronies throng the thicker and closer around you. They in fact cling and cluster about you like so many bees, and with impertinent looks of glee seek to express their satisfaction with your prosperity.

Now, it is a most desirable thing to get quit of these gentry—to have them brushed off. But it would be rude to do this with the fly-flap and the strong hand. You must get rid of them by more tact and management. And after you have got rid of them, that is, driven them from personal contact as it were, you have to continue to keep them at a proper distance. No easy matter this, for somehow or other the obtuse creatures, your poor former acquaintance, will not see, what you see very distinctly, that you are now quite a superior sort of person to them, and that they are no longer fit to be ranked amongst your friends. This the perverse, dull-witted fellows will not see. And, more provoking still, no degree of advancement in the world on your part, no acquisition of wealth, will induce one of them, whatever you yourself may think to the contrary, to contemplate you with a whit more respect than they did when you were one of themselves. They insist on considering you merely as having been more fortunate than themselves—not a bit better or a bit cleverer.

Let us remark here, that the successful in the world are stout deniers of the doctrine of chances. They maintain that there is no such a thing as luck; while the unsuccessful, again, are firm believers in the doctrine, and insist on it that not only is there such a thing as luck, but that luck is every thing. The successful man’s vanity prompts him to attribute his prosperity solely to his talents and merit—the unsuccessful man’s self-love to deny that the want of these qualities has been his hindrance. Hence the conflicting opinions of the two on this curious subject. Then, where lies the truth? We suspect between.

From a good deal of experience in the science of “cutting” under the circumstances alluded to in this paper—we shall not say whether as cutters or cuttees—we have flattered ourselves that we could throw out a few hints that might be found useful to gentlemen who are getting on in the world, and who are desirous of ridding themselves of their earlier and poorer friends. Under this supposition we offer the few following remarks:—

For some time after you have started on the prosperous career on which you have luckily fallen, continue to smile and bow towards your old friends as formerly; and when you meet them accidentally (let this be, however, as seldom as you possibly can), shake hands with them as cordially as ever. You may even venture to remark, accompanying such remark with an expression of regret, that they are prodigious strangers now. But this is not quite safe ground, and we by no means advise its general adoption. Conducting yourself in this way, your old friends will never suspect that there is already a change working at your heart—a secret operation as yet known only to yourself.

By and bye, throw the least, the very least thing of distance into your greeting: let your smile be apparently as cordial as formerly, but let there now be a slight expression of the slightest degree possible of coolness, of an indefinable something or other in your general manner of a repulsive character: take care, however, that it be indefinable—that it be of a description that cannot be named.

This new feature in your bearing will probably startle the more shrewd and observant of your former friends: but never mind that—it is precisely the impression you desire to make. It is even possible that some of them may express by their manner towards you a feeling of irritation at your new mode of treating them. Meet it by an expression of surprise at their conduct, and by increased coolness. There is now good[Pg 84] ground for a quarrel—not open hostility, of course, but the warfare of distant looks and haughty salutations. Improve it to the utmost, and wonder what the fellows mean.

Observe that the whole of this nice process of dissolving former associations is carried on without one angry or offensive word being said on either side—without the slightest approach to an overt act of hostility; you, particularly, being as bland as ever. The whole is effected by look and manner alone.

To the gentleman who is rising in the world there are few things more offensive than the familiarity of old acquaintanceship when presented in the shape of notes and letters. Your old friends, still obstinately overlooking your advancement in the world, will in all probability continue to write to you when they have occasion to do so, in the free-and-easy way of former days. They will even sometimes so far forget themselves and you as to address you in a jocular strain. This must be instantly put down. Do it by brief and grave replies; take no notice of their jokes, and never attempt an approach to one in return. This in time will cure them: if not, you must have recourse to stronger measures. You must either not answer at all, or administer some decided dampers.

Should any of your former friends seek your patronage—a very probable case—take an early opportunity, while doing him some trifling service, of letting him feel sensibly your relative positions, all the while, however, exhibiting towards him the most friendly dispositions. But let him ever and anon feel the bit gently—let him feel that he has got somebody on his back. Begin as soon as possible to lecture him in a gentle way—all for his own good of course. Your character of patron gives you a right to do this; and under this guise you can say the most cutting things to him without affording him the slightest ground for complaint. Under this guise you can address the most insulting language to him, and defy him to take it amiss. If he should, however, you can without any difficulty prove him to be one of the most ungrateful monsters that ever lived. You were doing all you could for him, and when you ventured to advise him—having nothing but his own good at heart—he chose to take offence at you, and to resent the friendly advice you gave him. Such an ungrateful dog!

As few men can stand such treatment as that above alluded to long, we can venture to promise you that by a steady course of proceeding in the way we have pointed out, you will soon clear your hands of your old friends.

C.

“Ah! what a fatal gift from Heaven is a too sensitive heart!”—Rousseau.

M.

[1] The incidents of this narrative are founded on fact.

[2] Cloaks.

[3] The popular notion that the Mohammedans deny immortality to the souls of women is altogether a mistake, as will be apparent to any one who takes the trouble of looking through the Koran.

Were we to believe the chronicles of our grandmothers, Ireland at one period was held in fee-simple by witches, warlocks, white ladies, fairies, and leprahauns; the earth, the air, and the sky, were peopled by them; every crumbling and desolate cabin on the sterile moor or common was tenanted by a witch; while the margins of our beautiful loughs, the bosoms of our silent and sequestered glens, the recesses of our romantic mountain valleys, the echoing walls of every mouldering edifice, and the mystic circle of each rude hill-fort, were the chosen habitations of unearthly beings.

Nor was this belief held by the uneducated alone; many who moved in respectable situations in society were infected by it; and otherwise sensible and well-informed people on this head were deaf to the voice of reason and the dictates of common sense, and would as soon doubt the truth of Holy Writ as the existence of supernatural agency; and so interwoven was the superstition in the social system, that no event could happen poor mortality from the cradle to the grave, in which the good people were not implicated for good or evil. Did the head or a member of a leading family die, the wail of the banshee was sure to be heard in the twilight. Was a favourite child smitten with disease, the beautiful, the beloved one was believed to be changed for a squalling, ravenous, and decrepid starveling. Did your cattle pine, or was your dairy not productive, your cows were either elf-shot or bewitched. Was the wife of your bosom snatched away in her bloom, in the most interesting though dangerous moment of her existence, the fairies were whispered to be the authors of your misfortune—to have spirited her off, and to have left in her stead a wooden substitute.

Well do I remember the thrill of fear, mingled with a degree of pleasurable awe, with which I listened some forty years since to the narratives of a venerable aunt, who was lingering out the evening of her existence at my father’s fireside—her only occupation being, rocking the cradle and keeping the youngsters from mottling their shins. She was an experienced dame, and withal pious, but would as soon doubt her own identity as that of witches and fairies, and her memory was well stored with instances of their interference. These I then believed most implicitly, particularly as in many of them “the family” was concerned. She could relate how her grandfather one morning detected a hare in the act of milking one of his cows, which he fired at and wounded, and on tracking the blood, discovered it to flow from the thigh of an old crone who inhabited a neighbouring hovel. She also could tell how an elder brother had surprised a leprahaun in the act of making shoes for the gentle people—could describe his dress minutely, and how he had escaped captivity by making a feint with his awl at my uncle’s eye, and causing him to wink when in the very act of seizing him, and thereby marred his fortune. She also knew a child which was taken from its mother’s arms at night, but luckily was missed before he could be conveyed through the key-hole, and on the outcry of the bereaved parent, was dropped “with a whack” on the floor uninjured. It never occurred to her that probably the child had rolled out of the bed accidentally. There was another tale often related by her, which it would be worse than heresy to doubt, as she knew the parties intimately.

An honest man named John M’Kinstrey, who resided near Maheraveely, in the county Monaghan, was once compelled to leave his warm bed in “the witching time of night,” on a certain pressing occasion, and ride post-haste for a worthy dame whose assistance was indispensable. While returning with the “howdy” safely stowed on an ample pillion behind, he heard the strokes of an axe reverberating through a neighbouring wood, and voices in conversation. Curiosity prompted him to draw up and listen, when he distinctly heard the question asked, “What are you doing to-night?” and to his dismay the answer was responded, “I’m making a wife for Jack M’Kinstrey.” “Faith,” said Jack, “you’ll make no wife for me, my man—I’ll do very well with the one I have;” and giving his good beast the spur, regardless of the neck, bones, or outcry of his freight, he never drew rein until he had his better half clasped in his arms, where he held her in a death’s-grip until the crisis was over, and thus baulked the fairies.

Thus was the whole system of society pervaded by the idea of supernatural influence; and the consequence was an undefinable dread and fear, hanging like the sword of Damocles over the heads of all, and embittering existence. ’Tis true the evil was only imaginary, but not on that account the less hurtful; for, being a mental malady, it was the more difficult to be counteracted or eradicated, and often led to real anxiety and distress, as in the care of M’Kinstrey, whose ideas being full of witchcraft and fairy freaks, never reflected that the noise and voices he had heard might be a practical joke of some of his neighbours, and in consequence suffered all the suspense and trouble incident to real danger.

But the diffusion of useful knowledge and the dissemination of sound education among all classes, has latterly effected a mighty change in the intellectual powers of the people. Such reveries as those referred to, though sometimes used to “adorn a tale,” are now unheeded; and there are few indeed who would harbour for a moment in sincerity the absurd idea of evil agency. There may be, ’tis true, some exceptions—a few old women may be still haunted by the sprites of other days, and in some remote districts a belief in witchcraft certainly prevails, ingrafted by early prejudices, and fostered and kept alive by the practices of knaves, who profess to avert the effects by counter-charms, and live, like many others, on the credulity of the public; but, generally speaking, the thing is defunct—gone to the moles and the bats.

But there is an exception. In several districts in Ireland, in Connaught especially, an idea is very prevalent that it is in the power of evil-disposed persons to deprive their neighbours of their milk or butter. This is said to be done in various ways, the most usual being the use of a corpse hand, which is kept shrivelled and dried to stir the milk and gather the butter. Another plan is to follow the cows on a May morning, and gather the soil which drops from between their cloots. Another, by collecting the froth which forms on a stream running through their pasture, and milking your own cow on it. Indeed, the means used are represented to be so simple, that the very absurdity of the matter is its own refutation.

Yet it is believed in, and that firmly; and in order to prove that such is the case, and also expose the trickery and legerdemain by which some knaves succeed in throwing dust in the eyes of the natives, I will relate an occurrence in which I was concerned; and to open the matter fully in all its ramifications, windings, and train of circumstantials, I trust I will be pardoned if I enter into a rather minute detail, the rather as I confess I was for a short time myself almost inclined to credit its existence—in short, believed myself the dupe of a fairy man.

Some time since I resided in the neighbourhood of the “plains of Boyle,” a celebrated pasture country, and was the possessor of a cow whose milk and butter were plentiful in quantity and excellent in quality, and materially contributed to the comforts of my family. She was a beautiful and a gentle creature; and I flattered myself that in her I possessed the foundress of a numerous herd, and the germ of a profitable and extensive dairy.

As before observed, the idea was very prevalent there that it was in the power of evil-disposed persons to deprive you of your milk and butter, and I heard many complaints of the kind; the general voice fastened the imputation on a woman who lived in the vicinity, who was locally termed “the Hawk,” and certainly the fire of her eye and the sharpness of her beak justified the appellation: she was a comely middle-aged person, in rather easy circumstances, her husband being a small farmer; but he lay under the suspicion of being concerned in a murder some time before. She was a reputed witch, and the entire family were disliked and avoided.

One morning in the month of January, I was informed that a woman had come into my kitchen, who occupied herself in watching the motions of the family, without stating her business. On going down, I found her well dressed and well looking, but with a very sinister cast of countenance. On asking if she wanted me, she said she had heard I was in want of some geese, and that she had a few to dispose of. “How[Pg 86] many?” said I. “A goose and a gander,” she replied. “How much do you want for them?” “Seven-and-sixpence.” “Seven-and-sixpence!” I exclaimed in surprise, as the usual price then was from one shilling to one-and-sixpence each. “Why, how many have you?” as I really thought I had made a mistake in the number. “A goose and a gander,” said she. “And do you suppose me to be a goose to give such a price as that?” said I. “Oh!” said she, “they are good geese, and only I wish to serve you, I would not offer them at all.” “Indeed! I am much obliged by your good wishes,” said I; “but as I think you want to impose upon me, you must take your geese to another market, for I will not have them at any price, and the sooner you take yourself off the better.” She got highly offended, muttered something about my being sorry for refusing them, and went away in high dudgeon; and after she was gone, I found it was “the Hawk” who had favoured me with the visit.

On the same morning, a gang of strollers, consisting of tinkers, chimney-sweeps, a brace or two of beggars, and a piper, had pitched their tent on the road side, a short distance from my residence; the members of the party had distributed themselves over the surrounding district in pursuit of their various avocations; it also happened to be churning-day, and my wife having set her vessels in order, was proceeding with her lacteal operations favourably—the milk had cracked, the butter was expected—when the sound of music was heard; the piper attached to the party had come to give us a specimen of his skill; he favoured us with a few Connaught planxties, was duly rewarded, and departed. Shortly after he was gone, two buxom baggages, brown and bare-legged, with cans in their hands, kerchiefs on their heads, and huge massive rings on their fingers, came and demanded an alms. They were told there was nothing then ready, on which one of them asked a drink. “I have nothing to offer you but water,” said my wife, “until the churning’s done.” “Well, water itself,” said she; on getting which, she took a sup or two, put the remainder in her can, and went off; and, strange as it may seem, my butter went too. And from that day in January until May eve following, not a morsel had we from our beautiful Brownie.

As I did not put any faith in witchcraft, I was willing to attribute this to some natural cause affecting the cow, though the milk showed no perceptible change in either quantity or quality; neither did she exhibit any symptoms of ailment or disorder, except that she began to cast her hair. She was well supplied with good fodder, comfortably lodged, and well attended, and every possible care taken of the milk, but all to no purpose; the butter was not forthcoming; and for my incredulity I was laughed at by my neighbours. “Your cow is bewitched,” cried they; “and you may as well throw chaff against the wind, as think you will get your butter back, till you get the charm.” Some said “the Hawk” had it, some that the gipsy took it away in her can, and others that it followed the piper. Be that as it may, I had to eat my bread butterless, and brood over my loss, without even the comfort of common condolence.

Various were the counter-charms recommended for my adoption. “Send for Fraser the Scotchman from beyond the Lough,” said one; “he fears neither man nor fiend, and he will surely get it.” “Send for ‘the Hawk,’ and clip a bit off her ear,” said another. “Let them keep their mouths full of water, and never speak while they are churning,” said a third. In short, I found there were as many ways of getting it back, as there were of losing it—all equally simple, and probably as efficacious.

Thus matters continued until the early part of the month of April, when one morning a man called, who desired to see me. I found him a light, active, cute-looking fellow, low in stature and spare in habit, but sinewy, well set and well knit, and regularly smoke-dried. He was pretty well clad in frieze, cord breeches, and yarn stockings and pumps; his caubeen on one side, a cutty in his mouth, and a certain jauntiness in his air, and crafty audacity in his look, which seemed to say, “I’d have you to know I’m a clever fellow.”

“So,” said he at once without preamble, “so you’ve lost your butter.”

“Yes,” said I, “’tis certainly gone.”

“Well, if you like, I’ll get it for you. My name is Orohoo (O’Hara); I live at Sliev Bawn—the people call me the Fairy man—I can find things that’s stole—and I keep the garvally.”

“Indeed!” said I: “why, you must be a clever fellow: but can you get my butter?”

“Not a doubt of it,” said he, “if it is in the country.”

I had heard of the garvally before, which was described as “a crooked thing like the handle of an umbrella, covered with green baize.” It was formerly in much repute for swearing on; “and a terrible thing it was, for if you swore falsely and it round your neck, your mouth would turn to the back of your head, or you’d get such a throttling as you’d never get the better of.” It had latterly, however, lost much of its virtue, or rather of its fame, by an unbelieving vagabond yoking it on and swearing to a manifest falsehood, without suffering any visible inconvenience. But to return to Orohoo.

He made no stipulation; but requiring a deep plate, some water and salt, with a little of the cow’s milk, he commenced by desiring my wife and me to stand forward. He then asked our names, if I was the owner of the cow, how long I had had her, if that woman was my wife, when we had lost our butter, and if we suspected any person for taking it. To these queries I answered as was necessary; but to the last I replied, I did not believe in witchcraft.

“Don’t you believe in fairies?” he asked.

“Scarcely,” said I.

“No matter,” said he; “maybe before I’m done you will believe in them.”

He then in a very solemn manner poured some water into the plate at three several times, thus—“In the name of the Father,” a drop; “in the name of the Son,” ditto; “in the name of the Holy Ghost,” ditto. He added the milk in the same manner, and then sprinkled in the salt, using the same formula. He now stirred round the mixture three times with his finger, repeating the words as before, and desired us to do the same. To this I demurred, for I did not wish to evince any faith in the proceeding, by taking an active part; but he combated my scruples by asking “was it not done in a good name?” Certainly for so far I saw nothing very objectionable, and my wife feeling no scruple on the subject, at their joint persuasion I did as directed.

He next made the sign of the cross over the plate with his hands, and, waving them over his head, cut several curious figures in the air, at the same time muttering an unintelligible jargon I could not understand, but which, as I could catch a sound or syllable, bore a close affinity to what is called bog Latin. Gradually he became much excited; he raved like a demon, stamped with his feet, and threatened with his fists: now his tones were those of supplication or entreaty, anon of abjuration or command; while his eye seemed fixed upon and to follow the motions of some to us invisible being, with which he appeared to hold converse. Suddenly he gave an unearthly scream, as if in an agony of terror and perturbation, and, holding up his hands as in the act of warding off a threatened danger, he retreated backwards round the room, pursued, as it seemed, by an implacable enemy. Gradually he regained the spot he had left, turned himself to the four cardinal points, making the sign of the cross at each turn, dipped his fingers in the mixture, devoutly blessed himself, anointing his forehead, shoulders, and breast, regained his self-possession, raised his hands and eyes in an attitude of fervent thankfulness to heaven, wiped the perspiration which profusely streamed from his brow with the cuff of his coat, gradually recovered his breath, and from a state of the greatest possible excitement became calm and collected.

Now, this was all acting, to be sure, but it was inimitably done, and I confess, even armed as I was with unbelief, it made a very powerful impression on me. I acknowledge I did not feel at all comfortable. I did not like the idea of being in the same room with the evil one, who to all appearance was chasing my friend the conjuror round and round it. I felt an indescribable sensation of dread creeping over me, and, if I mistake not, there were a few drops of perspiration on my brow; and my hair, of which I have not a superabundance, to my apprehension began to get stiff and wiry. My wife, too, clung closely to my side for protection, and the agitation of her mind was evident by the audible action of her heart, which in that case beat only responsive to my own.

Having taken breath, he asked for a ribbon, which he passed over his forehead and round his head, and, bringing the ends in front, knotted it over his nose; then twining it round his fingers in the manner children call a cat’s cradle, he knelt down and peered through it attentively into the mixture, which I imagined at the moment fermented and sent up a blue vapour. After gazing a few seconds in this manner,

“Aha!” said he, “she is not far off that has your butter; bring me a lighted candle,” which on being brought he placed in the plate. “Now,” said he, “both of you kneel down; do[Pg 87] as I do, and say as I say, and we’ll have her here directly.”

“No,” said I decidedly, “we will not.”

I thought we had gone far enough, and was convinced that if what we were engaged in was not an unholy act, it was at least a piece of gross deception, and I would not countenance it by any further participation.

“Why,” exclaimed he, “don’t you want to get your butter?”

“Yes,” said I, “I would like to have my butter, but I don’t choose to resort to a charm to obtain it.”

“No doubt this is a charm,” said he, “but it is done in a good name; and I have done it before for as good as ever you were.”

“So much the worse,” I replied; “that holy name should never be profaned in such a manner, and I am sorry any person would be so wicked or so foolish as to encourage you in your tricks. I neither like you nor your proceedings, and the sooner you go about your business the better.”

He started to his feet in a passion, blew out the candle, seized the plate, and attempted to throw the contents into the fireplace; but my wife, who did not wish her hearth to be wet, took it from him and laid it past. He fumed and stormed, said I let him take a great deal of trouble on my account, and insisted on proceeding; but I was determined, and, being considerably chafed and annoyed by the transaction, I again ordered him off, and left him.

In a few moments I heard the noise of a violent altercation and scuffle, and I was loudly called on. I hastened to the scene of contention, and found my wife holding Orohoo by the neck, and preventing his departure. “What’s all this?” I exclaimed. “This fellow,” said she, “when he was going, took a live coal out of the grate, and told me to take care of my children.” This he stiffly denied, until confronted by the servant, and I threatened to give him up to the police as an impostor, when he quailed, and acknowledged that he had said so, but that he meant no harm by it. “And sure,” said he, “there’s no harm in bidding you mind them; for if your cow was hurt, so may your children. You’re not treating me well,” he continued; “I came at the bidding of a friend to do you a good turn, and asked nothing for it, and now you’re putting me out; you’ll be glad to see me yet, though. But take my advice: never throw out your Sunday’s ashes until Tuesday morning, and always sweep your floor in from the door to the hearth.” And away he went.

My heart now beat easy, for I thought we had fairly got rid of the fairy man; but I was to be still further mystified and bewildered. On examining the plate over which he had performed his incantations, we found the contents to be thick, yellow, and slimy, with a red sediment like globules of blood at the bottom. This seemed extraordinary, as I certainly watched him closely, and did not see him put any thing into the plate but milk, water, and salt.

The month now drew near a close, and our bread was still butterless. This often caused the morsel to stick in the throat of my poor dear partner, who felt none of the scruples of conscience with which I was affected, and firmly believed, her cow was bewitched. “Here we are day after day losing, our substance, and might have it only for your squeamishness in not letting the fairy man finish his job.” Thus she would argue, and hesitated not to call me a fool, nay, a downright ass; and indeed my neighbours were much of the same opinion: one of them, a respectable farmer’s wife, was particularly pertinacious. “My Robin,” said she one evening, as they were harping on the old string, “my Robin was down in Sligo, and he heard that if you got the coulter of a plough, and made it red-hot in the fire, while you were churning the butter would come back; or if you chose to churn on Sunday morning before the lark sings, you will surely get it.” “Tempt me no more with your spells or Sabbath-breaking; I will have none of them,” said I, impatiently; “I will never barter my peace of mind for a pound of butter, if I should never eat a morsel.”

But, in truth, my peace of mind was gone, for the continual urging and yammering I was subjected to made me heartily sick, and I inwardly resolved to sell the cow the first opportunity, and so end the matter.

On May eve, in the afternoon, I had occasion to leave home for a short time, and on my return was rather surprised to find all the windows closed and the door locked against me. I knocked and called for admittance, but received no answer; and hearing the noise of churning going on within, “fast and furious,” the truth flashed across my mind; and lamenting my wife’s credulity, I retired to the garden to await the result. In a short time she came running out like one demented, clapping her hands and screaming, “Oh! we’ve got the butter, we’ve got the butter!” and on going in I found a coulter phizzing and sparkling at a white heat in the fire, an ass’s shoe (which had been found a few days previously) under the churn, my worthy neighbour aforesaid standing over it, panting and blowing from the exertions she had made on my behoof, and wiping the dew-drops from her really comely countenance, and in the churn, floating like lumps of gold in a sea of silver, as fine a churning of butter as ever we were blessed with.

Well, I own I was staggered, and being triumphantly asked, “Now, is there no witchcraft or virtue in a red-hot coulter?” I could scarcely muster up courage to utter “No.” In vain I protested the butter came back because “Brownie” got back to her pasture, in consequence of the change in her feeding, from dry fodder to the mellow and genial produce of spring, as the loss at first was owing to the transition from grass to hay. ’Twas to no purpose to argue thus: all else were positive it was otherwise; but whether the virtue was in Orohoo’s incantations, the efficacy of the red-hot coulter, the influence of the ass’s shoe, or the tremendous pommelling the milk was subjected to on the occasion, no one could exactly say.

A few days after, I conversed on the subject with an intelligent person, a herd in charge of an extensive stock farm. After hearing my story to an end, he indulged in a hearty laugh at my expense. “Faith,” said he, “I took you for a sensible man, and did not suppose you would credit such folly.” “I’d as soon believe my mother was a bishop,” said I, “as put any faith in it some time ago. But how can I get over the chain of circumstantial evidence?—not a link of it wanting. First, ‘the Hawk’ coming with her seven-and-sixpenny geese, then the gipsies and the piper, and losing my butter just then.” “’Tis very easy,” said he, “to account for it. In the first place, you took your cow from grass and fed her on hay.” “Yes, but she had plenty of winter cabbage, and we gave her boiled potatoes.” “Just the thing; cabbage is good for plenty of milk, but not for butter. I’ll engage you gave her the potatoes warm.” “Yes.” “And she got a scour?” “Indeed she did, and her hair fell off.” “So I thought. And afterwards she got in good condition?” “Yes.” “Oh! ay, she put her butter on her ribs. Did you kill a pig at Christmas?” “I did.” “Where did you put your bacon in press?” “Why, under the shelf in the dairy.” “Now the murder is out! Never as long as you live put meat, either fresh or salt, near your milk-vessels; if you do, you will surely spoil your milk and lose your butter.” “This may account for my loss, but what have you to say to its coming back?” “Why, what’s to hinder it, when your bacon is in the chimney and your cow at grass?” “But the red blobs in the plate, and Orohoo fighting the devil for me, what do you say to that?” Here he gave way to such a violent fit of laughter that I really thought he would burst the waistband of his doe-skins. “Orohoo! ha! ha!—Orohoo! ha! ha! ha!—the greatest villain that ever breathed. He came to me one time that I had a cow sick, and said she was fairy-smitten, and that he would cure her. He began with his tricks with the milk and water, just the same as he did with you; but I watched him closer; and when I saw the smoke rising out of the plate, I got him by the neck, shook a little bottle of vitriol out of the cuff of his coat, and took a paper of red earthy powder out of his waistcoat pocket.” I looked aghast and confounded. Was I, then, the dupe of the fairy man? The thought was humiliating, and I even wished that I had remained in ignorance, but on reflection had reason to congratulate myself that it was only a temporary lapse, and that I was right in my original opinion, that, except the witchery of a pair of blue languishers, or the fairy spell of a silver-tongued syren, there is now no evil of the kind to be apprehended.

A.

Fashion is a poor Vocation.—Its creed, that idleness is a privilege, and work a disgrace, is among the deadliest errors. Without depth of thought, or earnestness of feeling, or strength of purpose, living an unreal life, sacrificing substance to show, substituting the fictitious for the natural, mistaking a crowd for society, finding its chief pleasure in ridicule, and exhausting its ingenuity in expedients for killing time, fashion is among the last influences under which a human being who respects himself, or who comprehends the great end of life, would desire to be placed.

The unwearied spirit of scientific research which so peculiarly marks the times in which we live, has ascertained the positions of the northern and southern magnetic poles to a degree of almost mathematical precision. This discovery will be hailed with pleasure by every person at all acquainted with the benefits derived to society by the labours of those gifted individuals who have devoted their thoughts more particularly to the study of this most abstruse and mysterious branch of physical knowledge. The position of the northern magnetic pole was determined by Sir John Ross, in his second northern expedition, fitted out at the sole expense of a British merchant, to be in 70 degrees 5 minutes 17 seconds north latitude, and 96 degrees 46 minutes 45 seconds west longitude, near the western coast of the newly discovered tract named, after the individual through whose munificence the boundaries of science have been thus enlarged, Boothia Felix. Its place is now marked on the globes and maps of the world published since the navigator’s announcement of the solution of this long-sought-for problem. The day of the discovery was the 1st of June 1831.

The position of the southern magnetic pole has not yet been ascertained to so great a degree of precision. Excited by a noble spirit of emulation caused by the success of the expedition fitted out by Mr Booth and led by Sir John Ross, three expeditions have been fitted out to complete the solution of the problem—to fix the position of the southern magnetic pole, as that of the northern had been already fixed. The parties in this noble rivalry are Great Britain, France, and the United States. The British magnetic expedition, under Captain James Ross, sailed on the 5th of May for Van Diemen’s Land. The only notices as yet received of its progress are, that soundings were obtained at the depth of 3600 fathoms in the South Atlantic, about 900 miles S.S.W. of St Helena; and again at the depth of 2680 fathoms, at 450 miles west of the Cape of Good Hope. A dispatch from Captain Dumont d’Urville, commandant of the French expedition, to the Minister of the Marine, details all the leading particulars of his voyage, by which it appears that he has nearly though not altogether succeeded in solving this part of the problem. On the 1st of January the expedition sailed from Hobart Town in a southern direction for 1350 miles, and in the latitude of 60 degrees south met with the first island of ice, and shortly afterwards discovered land ranging nearly along the south polar circle, and, as far as the navigator’s observations went, between 136 degrees and 142 degrees east longitude. The appearance was that of an ice-bound, barren coast, wholly unfit for the habitation of man. The snow and ice which covered it gave its surface an almost level appearance. Farther inward nothing was to be perceived but ravines, inlets, and projections, without a trace of vegetation. Whales, large porpoises, fur-seals, albatrosses, and petrels and penguins of different species, were seen near the shore. The commander gave this newly discovered coast the name of Terre Adelie. “This name,” he says in his dispatch, “was intended to perpetuate the remembrance of my profound gratitude for the devoted companion who has three times consented to a long and painful separation, to enable me to achieve my projects of foreign exploration.” On the 1st of February, in 65 degrees 20 minutes south latitude, and 131 degrees east longitude, the expedition crossed the meridian of no variation; and the magnetic observations afforded the means of determining that the position of the magnetic pole must be in the neighbouring land of Adelie itself, or on the compact ice which adjoined it. Having so far succeeded in attaining the main object of his mission, Captain Dumont bade a final adieu to these dreary regions, and steered for Hobart Town, where he arrived on the 17th of February, after an absence of forty-six days, having lost sight of the ice altogether in the parallel of 57 degrees south latitude.

The American expedition, under Captain Wilkes, has been equally successful in discovering the south polar island or continent, for its geographical character has not yet been ascertained. The land was first seen in 64 degrees 50 minutes south latitude, and 154 degrees 18 minutes east longitude, by a singular coincidence precisely on the same day, 19th January, that it had been observed by the French navigator; and Wilkes was enabled to run along the shore, for about 1700 miles, as far as 97 degrees 45 minutes east longitude, so near the land as often to find soundings with a few fathoms of line, and to be able to carry away several valuable geological specimens of the rocks and soil. His description of the appearance of the coast corresponds with that already given.

Whether any immediate beneficial results, practically applicable to the improvement of commerce and colonization, will accrue from these discoveries, may be doubtful, but the experience of the era in which we live forbids us to reject the prospect of ultimate benefits to society from any discovery tending to enlarge the bounds of science, though the means by which they are to be sought for are still out of sight. The discovery of the extensive line of coast ranging nearly along the south polar circle, serves in some degree to realize the conjectures of former geographers, who, observing that by much the greater mass of known land was in the northern hemisphere, laid down the position that there must lie a countervailing quantity of land somewhere in the southern hemisphere; so fully convinced were they of the existence of this fancied continent, that in the maps constructed by Herman Moll and other scientific artists of his time, the coast is laid down in a line nearly corresponding in latitude with that of Terre Adelie, and continued round the globe, so as to represent the whole of the south frigid zone as a continent, on which they inscribe the name of Terra Australia Incognita—the unknown southern region. With those who originated the supposition, this unknown region was a mere creature of the imagination. They were in possession of no facts to prove its reality; yet it is singular that in this, as well as in many other fictions, the ideal creature of the fancy has been discovered to have some foundation in the realities of existence.

Paying down upon the Nail.—The origin of this phrase is thus stated in the Recollections of O’Keefe the dramatist:—“During the Limerick assizes I saw a stuffed glove, about four feet long, hanging out from the top of the Exchange, nearly across the main street; this was the accustomed token that for a week or a fortnight, whilst the courts were sitting, no debtor could be arrested. Debtor or creditor, this was a good thing for the theatres, as during that time the city was thronged. An ample piazza under the Exchange was a thoroughfare: in the centre stood a pillar about four feet high, and upon it a circular plate of copper about three feet in diameter; this was called the nail, and on it was paid the earnest for any commercial bargains made, which was the origin of the saying, ‘Paid down upon the nail.’” Perhaps, however, the custom was common to other ancient towns.

General Use of Tea in China.—In China an ardent spirit is made from rice, and called sam-shu, of which punch is made in a coffee-pot, and it is drunk out of China cups; but the natives are not much addicted to its use, a simple infusion of tea being the general beverage of all classes. At all hours of the day the artisan, as he sits at work, has his little tea-pot and miniature cup beside him, out of which he quaffs a little at pleasure, or presents a cup to his visitor. The more refined class make the infusion in cups, in the manner already described. After this process, as nothing is allowed to go to waste in China, the tea-leaves are collected, dried, and rolled up again, and sold to the English and Americans, under the denomination of hyson mun-dun-go; that is, tea having neither taste nor smell. None of this tea is sold in England under its proper name, being for the most part mixed with other kinds, and thus brought into the market. I never saw green tea used in the houses of the natives, or of the Fanqui merchants, where of course the best kinds were to be had. The fact is, the consumption of green tea is for the most part confined to the lower orders and the opium smokers, who require its stimulating effects to settle the disturbed state of their nervous system; and with us it is found to correct the effects of an over-dose of opium—Dr Fulton’s Travelling Sketches.

Progression.—He that is good may hope to become better—he that is bad may fear that he will become worse; for vice, virtue, and time, never stand still.—Colton.

“A great lie,” says the poet Crabbe, “is like a great fish on dry land; it may fret and fling, and make a frightful bother, but it cannot hurt you. You have only to keep still, and it will die of itself.”

Printed and Published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; J. Drake, Birmingham; M. Bingham, Broad Street, Bristol; Fraser and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.