EDITED BY SIR JAMES YOXALL, M.P.

Each Volume Illustrated. Price 3s 6d net

Title: Collecting Old Glass, English and Irish

Author: Sir J. H. Yoxall

Release date: March 18, 2017 [eBook #54381]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Chris Jordan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

THE COLLECTORS’ POCKET SERIES

EDITED BY SIR JAMES YOXALL, M.P.

COLLECTING

OLD GLASS

COLLECTING

OLD GLASS

ENGLISH AND IRISH

BY J. H. YOXALL

Author of “The Wander Years” “The A B C

about Collecting” “More about Collecting”

The glass of fashion and the mould of form: Hamlet, iii. 1

LONDON

WILLIAM HEINEMANN, LTD

First published January 1916

New Impression March 1925

Printed in Great Britain

I hope the reader may find that this book, though smaller than others on the same subject, is more helpful and even more comprehensive than they are; that it deals with the glass articles which they mention and with others which they omit; that it simplifies and classifies the study and practice of glass-collecting more than has been done in print heretofore; and that it can do these things because it is written out of personal knowledge, gained from much experience, and not from hearsay or from other books.

Diffuseness has been avoided, but this, I hope, has enabled me to make the book the more lucid, as well as the more succinct. At any rate, it affords hints, general rules, and warnings more numerous and more practical than any published until now; I have also tried to give to it a quality which reviewers have found present in my other books on Collecting—that is, a simplicity and clearness of explanation, done at the most difficult and necessary points, and in an interesting way. Moreover, this book has had the great advantage of revision (before printing) by Mr. G. F. Collins, of 53 the Lanes, Brighton, a pupil of Mr.[vi] Hartshorne’s, and well known to all principal collectors of old glass. Most of the illustrations represent typical pieces in my own collection, but for some of the finest I have to thank the kindness of Mrs. Devitt, of Herontye, East Grinstead, a collector indeed. The illustrations do not represent relative sizes to the same scale.

J. H. YOXALL

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | OLD ENGLISH GLASSWARE | 1 |

| II. | SEVEN GENERAL GUIDES AND TESTS | 14 |

| III. | BLOWN WARE | 26 |

| IV. | CUT, MOULDED, AND ENGRAVED WARE | 29 |

| V. | OLD COLOURED GLASS | 35 |

| VI. | OLD DRINKING GLASSES | 40 |

| VII. | THE VARIOUS TYPES OF STEM | 46 |

| VIII. | THE VARIOUS SHAPES OF BOWL | 56 |

| IX. | OTHER STEMMED DRINKING GLASSES | 60 |

| X. | JACOBITE, WILLIAMITE, AND HANOVERIAN GLASSES | 66 |

| XI. | TUMBLERS, TANKARDS, “JOEYS,” AND “BOOT” GLASSES | 73 |

| XII. | BOTTLES, DECANTERS, AND JUGS | 76 |

| XIII. | BOWLS, LIFTERS, SUGAR-CRUSHERS, SPOONS, ETC. | 79 |

| XIV. | CANDLESTICKS, LUSTRES, AND LAMPS | 81 |

| XV. | COMPORTS, SWEETMEAT, JELLY AND CUSTARD GLASSES | 84 |

| XVI. | SALT CELLARS, PEPPER BOXES, SUGAR BASINS, ETC. | 88 |

| XVII. | MIRRORS, GLASS PICTURES, GLASS KNOBS | 90 |

| XVIII. | OLD PASTE, GLASS BEADS, AND TAWS | 92 |

| XIX. | GENERAL HINTS AND WARNINGS | 95 |

| INDEX | 107 |

The glassware made in England and Ireland during the eighteenth and part of the nineteenth century was the best of the kind ever made. In quality, tint, feel, and ring the plain blown glass was a beautiful product, and when it was cut or engraved the decoration was done by fine craftsmen and often with excellent taste. Old glass has its own peculiar charm; the dark beauty of the crystal metal, the variety of form, the bell-like ring when flipped, the satiny feeling of the surface, the sparkle of the cut facets, and the combination of gracefulness and usefulness attract a collector: in cabinets it shines, gleams, glows, and sparkles in a reticent, well-bred way.

Then there is attraction in the historical and social traditions which have gathered around the ware; romance lingers on in the Jacobite glasses, the Williamite glasses, the Georgian glasses, the rummers and groggers engraved and drunk from to celebrate the victories of Nelson or famous elections; and humour resides in many of the relics of the punch-bowl and six-bottle days. To honour particular occasions one’s fine old glasses may come out of the cabinet and be used at table again; I know a collector of “captain glasses” who brings them out for champagne. For decoration or in use old glass has a refined, artistic, aristocratic air.

The sound of the past seems to throb in the ring of this frail and dainty ware; at your touch the cry of the bygone seems heard again. Because of fragility, enough of eighteenth-century glass has not lasted on to make it common, and yet so much of it is still extant that a collector’s hunt for it is by no means a hopeless quest. It may still be acquired at reasonable prices from dealers in antiques, and a hunter for it in odd corners, who buys in shillings, not in pounds, may reasonably hope to pick up many fine specimens for next to nothing even yet. Four years ago I bought a fine drawn cordial glass for 2d. Within the past three years I have myself bought a perfect captain glass for 3s. 6d.; within the last year I have bought six punch-lifters for 17s. 6d. in all, uncommon as these bibulous old siphons are. A large Bristol coloured-glass paper-weight may cost you £3 in a dealer’s shop, because[3] three years ago they began to be a “rage,” but within the past two years I have bought a Bristol glass article, equally beautiful in colour and glass-flowers, and much rarer, for 2s. Footless coaching glasses and thistle-shaped fuddling glasses are seldom seen, even on a dealer’s shelves, but I have found one of each, in odd corners, for 6d.

Now, if ever, is the time to collect old glass rather cheaply, for already the prices of it are mounting in a remarkable way. Thirty years ago old wine glasses engraved with roses, rosebuds, and butterflies—rose glasses, as they are called—could be bought for half-a-crown apiece or less—dozens of them; this price has multiplied nearly twentyfold. Waterford cut-glass grows more and more dear to buy, from dealers who know it when they possess it—they will soon be selling it as if it were antique silver, at so much per ounce—but only last year I bought in a provincial town a captain[4] glass of this ware for 15s., though £8 was the price asked for one just like it in the West End. Now, if ever, is the time for a beginner to take up this line of collecting; old English and Irish glass will never again be so easy to find at reasonable prices as it is now.

Collecting is a form of education, but it is not difficult to become a knowledgeable collector of old glass. Counterfeits are sent out by the thousand, forgeries lie in wait, totally new glassware, imitative of the old, is on sale in hundreds of curio dealers’ shops, some of them otherwise honest and respectable; but only ignorance or carelessness need be taken in. A little study, a little observation, a little care, and the beginner will soon be able to avoid mistakes. Connoisseurship in old glass is less difficult than it is in old china, for example; porcelain or earthenware collecting is more various, more detailed, has reference to longer periods of manufacture, and involves much more specific knowledge than glass-collecting does. Yet I have known two or three collectors of porcelain who declined to begin collecting old glass because, they said, they would “never dare”—as if an almost miraculous skill were needed to become a connoisseur in old glass! In point of fact, this is the easiest hobby to study and know; glass-collecting requires an eye for the different shades and tints of the metal, a finger-tip for the feel of it, an ear for the ring of it, and not much money as yet, and practically that is all. There are no trade-marks to[5] puzzle or deceive you; there is no such distinction, difficult to understand and master, as between “soft” china and “hard.” At present old glass is easy to know, and not difficult to find.

I propose in this book to give general hints, “tips,” and instructions applicable to every variety of old glass; to explain the seven principal tests of genuine age and antique make; to prepare the beginner to go out collecting glass with the infallible rules and principles for it fixed in his mind. Equipped with these, anyone may examine, test, and if satisfactory buy any vessel of glass which he or she may find in any odd corner. I am not writing the book for the rich, but for people with more taste and cultivation than money, and though I deprecate “collecting” for the sake of selling again at a profit, I may well point out that old English and Irish glass, bought cheaply now, may become an investment de père de famille; the collector may have the joy of finding it, the continual pleasure of owning it, and yet know that it will turn out to be “good business” for his heirs, when the sale comes, at the end.

The collecting of old glass is not yet systematized; there are no dealers’ catalogues of it or prices current. For the next few years this advantage will continue in connexion with old glass. Every dealer knows the high price which square-marked Worcester china can command; every second-hand bookseller knows the price current of first editions, or copies of rare books;[6] but such is not the case with old glass as yet. Systematization has hardly begun; there has been little research into the history of makes and the names of makers. Here is another advantage for a collector: he may discover things of that kind at present unknown, and thus attach his name to the history of old glass which will some day be written. A local collector may at no great cost make a donation of his treasures to the local museum. There is no public collection of Newcastle-made glass at Newcastle, for instance, or of Sunderland-made glass at Sunderland, and no local antiquary has studied the history of the fine glass products made on the Tyne and the Wear. Nobody knows which kinds of glass were made at Norwich or Lynn. A history of Stourbridge glass-making and glassware has yet to be written. So that research, that additional delight of collecting, is more open in connexion with glass than with any other well-known “line.”

The number and diversity of old glass articles may be indicated by the following incomplete list: wine glasses, beer glasses, cider glasses, rummers, cordial glasses, liqueur glasses, tumblers, firing glasses, coaching glasses, fuddling glasses, beakers, mugs, tankards, champagne glasses, grog glasses, Masonic glasses, goblets, Joey glasses, “boot” glasses, “yards of ale,” toy glasses; flasks, decanters, trays and waiters; punch or salad bowls, trifle bowls; wine bottles, spirit bottles; jugs, punch-lifters, decanter stands; jelly glasses, custard glasses, flip glasses, syllabub glasses; fruit[7] baskets, centre-pieces, sweetmeat glasses, captain glasses, comports or sweetmeat glass stands, epergnes, tazzas; salt cellars, sugar castors, pepper boxes; caddy sugar bowls; lamps, lanterns, chandeliers, candlesticks, nightlight glasses, taper holders; finger bowls, wine coolers; oil bottles, vinegar bottles, mustard bottles; jars, pickle jars; tea trays, preserve pots; vases, covered vases; rolling-pins, knife rests, knife and fork handles, spoons, sugar crushers; butter pots, celery glasses; weather glasses, chemical glasses, eye baths, witch-balls, porringers, posset vessels, holy-water vessels; door-stops, paper-weights; mirrors, knobs, glass pictures, bellows-shaped flasks, lustres, paste jewels, beads, taws, toy birds, animals, tobacco pipes, bellows on stands, walking-sticks, rapiers, and other elaborate baubles and oddities made for ornament or as tours de force. There seems to have been a Glass-makers’ Festival held at Newcastle some hundred years ago, and it was for exhibition then[8] that most of the freak glass toys and ornaments were made.

Much old English and Irish glass was contemporaneously sent to the American market, and the following articles were advertised as on sale at New York in the year 1773: “Very Rich Cut Glass Candlesticks, Cut Glass Sugar Boxes and Cream Potts, Wine, Wine-and-Water Glasses, and Beer Glasses, with Cut Shanks, Jelly and Syllabub Glasses, Glass Salvers, also Cyder Glasses, Orange and Top Glasses, Glass Cans, Glass Cream Buckets and Crewets, Royal Arch Mason Glasses, Globe and Barrel Lamps, etc.” The “etc.” would be capacious; it would include most of the articles mentioned in the paragraph just preceding this, and such things as crystal globes to be filled with water through which a candle might throw and condense its rays, for sewing or lace-making purposes, at night.

A collector ignores window-glass, unless he can come upon stained glass, purchasing, for £5 perhaps, a leaded square or oval of sixteenth-century Swiss or German painted glass, to hang in one of his windows. A collector ignores plate-glass, except in the form of mirrors,[9] perhaps. A collector ignores carboys, and also ordinary bottles, but he acquires when he can one of the thick, stumpy, almost black glass bottles in which Georgian people bottled their own claret or port, imported in the cask. It adds interest to an antique bookcase, corner cupboard, or cabinet if the panes, or some of them, show the slight curvature characteristic before perfectly flat sheet-glass could be cast; and there are some old panes in which the oxides have turned to a violet colour—a silversmith’s shop nearly opposite the top end of the Haymarket still displays some—which are of interest to-day. There used to be glass objects which, I suppose, we shall never come upon now: the “mortar” or nightlight-glass, of the kind which stood beside the last sleep of Charles I, and the “singing-glasses” which Pepys heard in 1668, when he “had one or two singing-glasses made, which make an echo to the voice, the first I ever saw; but so thin, that the very breath broke one or two of them.” These, and many other beautiful pieces of old glass, are for ever gone out of reach.

But the hunter may come upon pieces which came into existence before Queen Anne died: Jacobean glass, of the reign of Charles II at latest, is occasionally found. For a guinea I obtained a fine sacramental vessel in purfled and wreathed glass bearing the symbol of the Trinity (see next page); for 5s. a pistol-shaped scent bottle; and for 12s. 6d. a hand lamp, all three of Jacobean date.

In fact, the limits in glass-collecting are not yet fixable; you never know what quaint or rare thing you may not come upon in old glass. Other lines of collecting are already systematized, and part of the systematization is a limiting of what you may expect to find and a raising of what you may have to pay. With glass there are no such boundaries, at present; anything out of the ordinary in shape, purpose, or date, may be acquired, and should be—the uncommon pieces are the best—though often because a piece is quite unusual, it will be offered you at a very low price. The smaller dealers know that from half a guinea to a couple of guineas is what they may charge for an old wine glass, according to the knobs or the spiral in its stem, but they do not know any fixed price for less common specimens, and they will sell at a hundred per cent. profit on the very small charges they themselves have paid.

Armed with knowledge of the general tests which I give in the next chapter, a collector may enter a dealer’s shop near Bond Street or a marine stores in the Old Kent Road, a broker’s at Hackney or a cabinet-maker’s warehouse in a country town, a second-hand furniture shop at Hammersmith or the Caledonian market on a Friday; he may look into a butler’s pantry, peer into a cupboard in a kitchen corner, search amidst the dust of a lumber-room, or reach to the deep interior of a farmhouse dresser or sideboard; and almost always he will come upon a collectable bit of old glass. He may hope to come upon an old crystal gazing-ball, used by fashionable fortune-tellers a century ago; or even one of the old glass eggs which eighteenth-century ladies held in their hands to keep their palms cool for a lover’s kiss.

The beginner should recognize from the first that the range of the collector of old glass is not yet defined; that the practical hints and rules given in this book may be applied to any piece of glass, and should be, no matter how unusual its form or inexplicable now its use in its time. During the next few years things which now seem oddities, because they are so unusual, may become particularly sought after, and valued because they are rare. I therefore advise the beginner to be a general and diffusing collector, leaving no genuine old piece unsnapped-up which comes within his reach and means. At present cut Waterford glass and spiral-stemmed blown wine glasses are the things most sought after by glass collectors, but they may not be so a few years[12] hence. I do not mean that they will ever drop in selling value now, but I anticipate that the selling value of other glass articles, rather neglected now, may appreciate; that is why I recommend the practice of general and diffusive collecting and a wide range. But if a collector prefers to specialize, he may set out to collect wine glasses only, or inscribed glasses only, or what-not in that way; he may go in for cut-glass only, or blown glass only, or coloured glass only, or toys and eccentricities only; he may choose geographically, collecting Irish glass only, or English glass only, or Bristol glass only, and so forth. In any case his range will be limited by certain dates; he will very seldom come upon a piece so old as the reign of Charles II, and he will not care to collect glassware made so late as the year in which Victoria came to the throne. With Venice-made glass this book has nothing to do. Much old Dutch-made glass exists in England, but the student of this book will be enabled to detect it, and not unintentionally to acquire it believing it to be English[13] made. Bohemian-made glass, cut and coloured, is seldom taken up by collectors here. The range in these islands is for English and Irish glass, for it is the ware most readily collectable, most likely to increase in value, and to be most readily sold when a collection comes to be dispersed; I mention this latter consideration because any collector not wealthy must, in justice to his heirs and dependents, in this matter[14] “look to the end.”

Setting forth to collect old glassware, therefore, what general guides may the beginner use, and what reliable tests can he apply?

There are seven: (1) the tint of the glass; (2) the sound of the glass; (3) the quality of the glass metal (or material); (4) the weight; (5) the signs of use and wear; (6) the pontil-mark; and (7) the workmanship.

These seven suffice to equip the beginner. But as he collects and gains experience, many details and developments of them will come to his knowledge, which I shall refer to in their place.

It should be remembered that there are no maker’s marks to go by in glass, as there are in porcelain, earthenware, Sheffield plate, or pewter; and no signatures, as there are in paintings, drawings, and etchings.

Old glass is darkly brilliant. It is not whitely crystal as modern glass is; the eye can only see what it looks for, ever, and to uninstructed eyes all glass is merely glass-colour, but the experienced collector sees that there are many different tints and tinges in the crystal of glass. These tints and tinges are the chief guide, test, and principle by which one judges whether a piece of glass[15] is one of the nineteenth century, eighteenth century, or seventeenth century, as the case may be.

To judge the tint, place the piece of glass upon a white tablecloth, near to a tumbler or decanter known to be modern because of recent purchase from an ordinary vendor of household glass. The eye, looking for it, will then notice in the two pieces of glass a striking difference of tint, if one of them is old, that is; the old piece is not only darker than the white of the tablecloth, but darker than the piece of modern glass. And the darker (or sootier) its tint the older the glass, as a rule. Tint or tinge is a constant feature in old glass, and an obvious feature directly the eye knows what to look for. Varieties of dark tint may be detected, and by these varieties the bit of glass may be dated, its period determined, and its age assigned.

If you place near each other, upon a white damask cloth, a glass of Charles II date, a William and Mary glass, a George III glass, and a Victorian glass, you will notice a darkening and then a whitening in tint (though not a brightening) as your eye travels from the oldest glass to[16] the most modern. By “tint” or “tinge” I do not mean “colour,” in the sense of red or green or blue; I will deal with coloured glass later on. By “tint” or “tinge” I mean the shade of leaden, darkish hue in the metal from which the glass article was blown or moulded. This tint or tinge was inherent in the molten glass, before shaping and cooling began. The metal or raw material was mixed according to recipe—each glassworks had its own recipe—and one of the materials was lead. The older the Georgian glass, the more impure the metal—that is, the fuller of lead oxides—and therefore the darker; what are called improvements in glass-mixing have gradually eliminated the oxides, and therefore the leaden tint or tinge also; it is astonishing how many different shades and tinges of darkness (in that sense) a cabinet of old glass can show. In a few glasses the bowl is pale sapphire or aquamarine colour, the stem being the tint of plain glass.

The glass collector exercises his sight and applies the[17] test; it enables him to detect a counterfeit, though in shape and general appearance it imitates the genuine antique; it is too whitely crystal, too tintless to be old. Curio-shop windows at Brighton, for instance, are full of frauds in glass, chiefly cut-glass, or glass moulded to resemble cut-glass; but the chalky-white tint betrays and condemns them, and the instructed collector will not be taken in. Also he will recognize genuine Waterford glass by its own tinge of colour, and genuine Cork glass in a similar way; he will see that old Dutch-made glass, when thick, has a smeary, milk-and-watery tint, and when thin has a flashy, meretricious absence of deep tinting: he will learn that old Stourbridge glass was whiter than antique Bristol or Newcastle glass, and sometimes was milky-white; in course of time and practice he will come to be able to “date” and “place” a piece of old glass at sight, as well as instantly to reject a fraud.

The tints of Irish-made glass. Glass made at Waterford, late in the eighteenth century and early in the nineteenth, was a fine product, often exquisitely cut: it is distinguishable in more than one way, but has a characteristic tinge which, once seen, is unmistakable. I cannot find exact words for it, it is not a blue nor a green nor a blackish tint, but is something of all three, and was due to excessive presence of oxide of lead. Nobody has done any research as to Irish-made glass, and people suppose that Cork-made glass resembled the Waterford glass, but that is very unlikely, because each factory mixed according to its own recipe, and also used a different variety of each of the raw materials common to all glass. In point of fact, Cork glass is[18] “duller” than Waterford, and it has quite a different, a pale, almost dun or yellowish, tinge, particularly visible in the thicker parts; a good many lustre-ornaments seem to have been made at Cork. Belfast glass was yellowish, too, if we may judge by the tint of Williamite glasses.

Perhaps because more lead was used in the “metal” or raw material, but at any rate for some distinctive reason, old English and Irish-made glass has a more musical sound than any made abroad. Flick or flip with your finger-nail, or pinch near your ear, a piece of this old ware, and a vibrant, resonant, and lingering ring is audible. The thinner the part of the glass you flick the more the sound, of course; but something of a ring should come from almost any part of the article. Another way of producing this characteristic sound is to keep on rubbing a wetted finger around the edge of the bowl of a wine glass or finger bowl, till rhythmic vibration is set up, and the sound steals forth. And it is a bell-like, musical note, almost the F sharp or G sharp, or A or B of the 4th octave in a pianoforte keyboard: darkish glass with this resonance is almost sure to be old English or Irish[19] made. Much eighteenth-century Dutch glass is still extant here, and is often mistaken for English; but it need not be: thin or thick, Dutch glass sends out no lingering resonance, long, clear, musical, and true. Dutch glass tinkles when you flip it, but the sound is dead a few seconds after being born. The sound test for old English or Irish glass is, Does it ring with a musical note that throbs, sings, and lingers in a way to delight the ear? The sound of old Dutch, French, Italian, or German glass is cracked, so to speak, though the vessel itself is not; but

are lines which Tennyson might have written to describe the music of old English and Irish glass; too much stress cannot be laid upon this test—the lasting note is the criterion.

So that now, with both tint and sound to guide us, we need not be taken in by modern copies or old Dutch glass.

Italians and Frenchmen came to England in the sixteenth century to teach the art and mystery of glass-making to our islanders; yet neither old Italian nor French glass metal has the quality of old English and Irish glass metal. The glassware made here between the reigns of Queen Anne and Queen Victoria had the best quality of any glass ever made in the world. But what is quality in this connexion? It means material,[20] but it also means the manipulation of material and the effect produced. The glass made during the reigns of the four Georges was called “flint glass” and “lead glass”—misnomers, perhaps, but I need not take up space here in discussing that; the important point is that the quality of the metal and the skill of the manipulation resulted in thinness, rigidity, shapeliness, a velvety surface, dark sheen, brilliancy, radiancy of facets when cut, and the vibrant, musical ring of the eighteenth-century glass. Glass made under Charles II was not so dark, and Victorian glass was whiter; Victorian and modern English glass is of excellent quality, but is uniform to almost a painful degree. It lacks character and diversity; the Georgian glass was individual and original, so to speak. There were faults in it—little air-blobs, or vesicles, that feel like pimples on the surface, or show as bubbles within it; striations, like lines of fibre, also; and deviations from the strict mathematic line or curve, which were due to hand-work. But if you examine contemporary Dutch-made, French-made, or Italian-made glass, you notice that the same defects exist, and more numerously, while there is a flimsiness, or a lumpiness, or a smeary[21] look and harsh feel which are absent from old English and Irish glass.

A specked, pimply surface, and a dull thickness and clumsy lumpiness or flashy thin lightness, are found in old Dutch-made glass; and this, taken in conjunction with the absence of true ring, enables a collector to reject the old ware sent over from Holland. The quality of the English and Irish glass metal comes out in the surface, too, a little; the fingers feel the surface of an old blown wine glass to be cool, smooth, hard, and yet velvety; while the surface of Waterford cut-glass has a silky feel.

In his privately circulated book on “English Baluster Stemmed Glasses of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries” Mr. Francis Buckley aptly says that “English-made glasses of the first period were all light in weight and cloudy in appearance. Some time between the Restoration and the end of the seventeenth century, but when precisely it is difficult to say, the English glass-makers began to try experiments with a view to removing from their glasses this dull and cloudy appearance. Their object was to produce a substance like crystal; and this object they eventually achieved by introducing into their metal a large quantity of lead.” This gave the characteristic weight.

The old Dutch glass seems light in weight, even when it is thick; old English and Irish glass seems relatively heavy even when it is thin. Waterford glass is especially heavy. These differences in weight are probably due to differences in the materials used for mixing the metal; but[22] whatever the cause, they aid the collector to know the real from the counterfeit, and the old English from the Dutch. Even the thick, clumsy glasses made here in the reign of William and Mary seem more weighty than those otherwise exactly similar which were then brought over from Holland.

Many fantastic pieces of old glass were made as curiosities or ornaments, but most old glass was made for use. Glass is easily scratched; as the wine glasses and decanters were set down upon the hard, polished mahogany of dinner-tables, after the cloth was drawn, and were moved, the feet of the wine glasses and the bases of the decanters become scratched thereby. Lustre-ornaments, glass candlesticks, or glass vases which stood upon marble or hard wood mantelpieces, being moved when maidservants were dusting, became scratched at the base. The collector will therefore carefully examine those parts of a piece of glass which, if it is old, may be expected to show the signs of use and wear caused by contact and movement upon hard surfaces; it is well to do this by the aid of a pocket-lens—which ought to be a glass collector’s constant companion.

In a genuine old piece the scratches are numerous, do not all run the same way, and are dust-coloured, more or less. Most counterfeits show no scratches at all, but the more elaborate forgeries show artificial scratches; these usually run all one way, however, or seem all to have been made together at the same time, and sometimes these artificial scratchings appear in parts of the glass which would not be[23] exposed to marking of the kind when in use, as, for instance, inside the bowls.

Yet it is not wise to condemn and refuse as a fraud a piece of glass which shows the other four or five general evidences of genuineness simply because only slight scratching is evident; for the glass may have been standing in a cupboard unused for many years, its nose put out of joint by some change of fashion in table-ware soon after it had been bought, and have passed into a collector’s cabinet before coming into your hands for examination. Nor is it safe to suppose that the more the scratches the older the piece; it may have had more than the common amount of usage. If the glass has a “folded foot” or a “ring-base” to stand on, the scratches will be at the very edge of the foot, or on the ring, just where it touched the table or mantelpiece, and there only.

I mention this last because it does not apply to all old glass; it does not apply to glass that was cast or moulded, but it applies to all old blown glass, and is a very important test and guide indeed.

The pontil-mark is either a depression in the glass, shallow, about the size of the third finger-end, or a lump about that size, standing up from the level of the glass around it. The pontil-mark indicates first that the piece of glass was originally blown, and second that before removing the blow-pipe the workman, as usual, attached the blown glass to a pontil. The pontil or punt is an iron rod, joined to the vessel by a little melted glass while[24] the vessel is still hot. When the time comes for taking away the pontil, it is done by contact with cold water, which causes the glass to contract around the pontil-end and the pontil to become detached. Glass vessels which were blown, only, show the depression or the lump accordingly: blown-glass vessels which were afterwards “cut” show it in part only, or not at all, if the glass-cutter removed it: vessels neither blown nor cut, but cast in a mould, do not show it because they never had it. In the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth, glass moulding seldom took place; so that the presence of the pontil-mark, whether it be a hollow or a lump, usually indicates age in the vessel which shows it.

In the oldest glass the pontil-hole is flaked with something which rather resembles mica. In the oldest wine glasses the pontil-lump stands out knobbily. In every case there are signs of the local fracture. As a rule, the older the glass the bigger and rougher the pontil-mark.

The sensible, practical adaptation to purpose and the workmanlike make of English and Irish old glass afford another test; compared with our native product, French glass of the same period seems meagre, and Dutch flimsy or clumsy; Italian is fantastic and tawdry. The French and the Italian ware was often gilded, the Dutch painted: these are features seldom seen on English and Irish glass. In place of gilding or other added external decoration the island ware presented a substance neither too thin nor too thick, bowls perfectly rounded, stems strong and stout but not bulky, too tall, or too short; feet that hold on to the table well, and are not warped and uneven. In the freak and toy pieces, too, the excellence of the workmanship is obvious.

The blow-pipe is not so old an implement as the potter’s wheel, but it seems to have been used 5000 years ago, in Egypt. Pliny first gave the fanciful account of Phœnician mariners accidentally fusing carbonate of soda with sea-sand; Dr. Johnson commented on that as follows: “Who, when he saw the first sand or ashes by a casual intenseness of heat melted into a metallic form, rugged with excrescences, and clouded with impurities, would have imagined that in this shapeless lump lay concealed so many conveniences of life as would in time constitute a great part of the happiness of the world? Yet by some such fortuitous liquefaction was mankind taught to procure a body at once in a high degree solid and transparent; which might admit the light of the sun and exclude the violence of the wind; which might extend the view of the philosopher to new ranges of existence, supply the decays of nature, and succour old age with subsidiary sight.”

Perhaps the first glassware was cast, or moulded, and there is no record of when or where the blow-pipe was first used. Ancient glass beads were probably made by moulding: probably the first glass ever made in England (the windows at Wearmouth Church, in A.D. 675) was cast. Not until the sixteenth century,[27] apparently, was any blown glass made in England, and none of it remains both extant and intact; collectors are fortunate who come upon a piece of date so early as the first half of the seventeenth century, even; but from the last few years of the seventeenth century to the first few years of the nineteenth century inclusive, English and Irish blown glass was the best in the world. Therefore it is the blown pieces which are the most characteristic, whether blown only or blown and afterwards engraved or cut. And the blown pieces, being intended for use, are the more numerous, and the more readily collected; the cut and engraved pieces, being for ornament, were more costly, and therefore fewer—though perhaps they have been more carefully preserved.

Drinking glasses are the most favoured aim of collectors and at present are the old glass objects most[28] frequently offered, but as glass-collecting becomes more popular other glass objects are brought out of cupboards and places where they have been lying neglected; and my counsel is that a collector should acquire any piece of old blown-glass ware which he can.

A collector nervous about frauds should take note that counterfeits of old cut-glass are much more numerous than counterfeits of old blown glass; the latter is forged, in the shape of wine glasses with spiral stems, but not at all successfully. In cut-glass there is also the confusion with moulded glass to beware of, but the finger feels the edges of cut-glass to be slightly rough—rather like woodwork edges not sand-papered off—and the eye can detect a difference between what was cut and what was moulded. In fine old cut-glass the surface feels silky, and the touch slips upon it where the cutting is shallow; moulded glass has a wavy, rounded feel. Cut-ware glass seems to be the more popular “line” of collecting in glass, so it is well to consider the kinds of cutting here; remembering all the while the tests of tint, etc., as between the old and the new.

English-and Irish-made glass, being heavier and better quality than any other, lent itself to cutting especially well; but probably the chief cause of the development of cut-glass here was the excise duty, which was levied on the plain manufactured article, so to speak—the glassware as the blower or moulder turned it out. The[30] excise on that having been paid, all additional value given to the ware afterwards was non-taxable; therefore cutting came into vogue, and the glass cut in these islands became the best in the world. Of all cut-glass “Waterford” was the most beautiful; its specific gravity was the greatest, and deep cutting could take place without the ware being clumsily heavy to begin with.

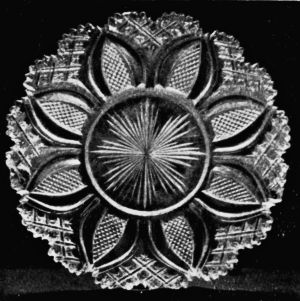

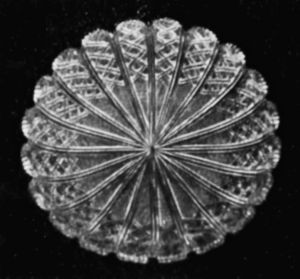

Cork, Dublin, and Belfast cut-glass resembles Waterford cut-glass in everything but tint and weight, and perhaps it was the Celtic strain in the Irish glass-cutters’ blood which gave a more than English freedom and fantasy to their art. At any rate, the style of their cutting may be described as “curved” and “arabesque”; it was also shallow, generally; flowing lines and slight hollows, flattish rounded curves, and interlacings are evident; stems and candlesticks are “whittled” rather than cut deeply; rims are often surrounded by little semicircles, the edge of each semicircle being cut into angles with sharp points; sometimes these resemble half-open fans. The less the amount of cut ornament, the earlier the piece, as a rule. There is English style diamond-shaped cutting in Irish glass, and some “hob-nail” cutting—shaped flat ends standing out as hob-nails do from boot soles: there is some “strawberry” cutting; but as a rule, a fluent, curving, arabesquing style of cutting, with parallel horizontal lines, hollow prisms, upright fluting, and parallel vertical lines in panels, the latter sometimes resembling basket-plaiting, characterize Waterford cut-glass.

The Stourbridge glass-cutters, on the other hand, rather over-did and abused the deep, regular, machine-like repetition of the “diamond” and the “hob-nail” and the “pomegranate.” Sometimes, however, the cutting was flat and flowing, and a festoon-like, hung-tapestry-like form may be seen.

Bristol glass-cutters went in for depth, but also for fantasy: a leaflike arrangement may be seen: the flowing lines in “Bristol” cutting are not so fine and curved as they are in Waterford glass.

Perhaps the “thistle” glasses, so popular in Scotland, were made and cut at Newcastle, the nearest glass-making centre: but “thistle cutting” does not mean cut like a thistle; it means minute diamond-shape cuts[32] upon a vessel conventionally resembling a thistle-head in shape.

In old cut-glass a star is often found, cut in the base of the vessel, under it; usually the old glass-cutters extended this star to the very edges of the base. In more modern cutting the rays of the star do not extend so far.

About 1850 moulded imitations of cut-glass begun to oust the more expensive originals, and moulded glass of that date and since then is not worth a collector’s attention. But old moulded glass, with the right tint in it, is worth acquiring; in the shape of candlesticks, for instance.

Cutting could be done, and was done, either upon glassware originally blown, or upon glass originally moulded—that is, cast in a mould. Sometimes the stem or shank and foot were left untouched while the[33] upper part of the vessel was cut. Moulded glass uncut shows no acuteness of edge nor sharpness in the depressions. Modern moulded glass is often very elaborate, however, and the beginner may readily be deceived.

Some part of the engraving on some glasses was really cutting: in roses which form part of the decoration of finely engraved glasses, the finger feels plane after plane of depression, where the engraver deeply cut away the metal to imitate the petals of the rose. When the engraving goes as deep as this, or deeper than usual, the effect is to give a dust colour to the engraved work, which helps one to be sure that the object before one is not an old plain glass recently “engraved up” with a Jacobite or other design to make it sell for more money.

But as a rule engraving is a surface operation, done with a diamond or on the wheel, or by sandblast, or by use of acids. Where the engraving is flat, not cut in, the original greyish-white effect may long remain; a collector need not suppose that the engraving is recent because the tint of it is not brownish, a colour due to[34] years and accumulations of dust. Indeed, the rougher and coarser the recent engraving the more likely dust to settle in it, as well as upon it, and to give it a dusty tint. Really fine old engraving can remain almost as fresh in appearance and tint as it ever was, even till to-day. And the natural tint of glass engraving resembles the tint of ground glass. Of course, when the polishing-wheel was applied, either to parts or to the whole of the engraving, this greyish-white tint was polished away.

The polishing-wheel was also used to remove the pontil-mark (when it was a lump or knob) from the feet of wine and other glasses.

Dutch or German engraved old glass shows more smeary in the engraved part than English or Irish glassware does.

At Bristol, Nailsea, Wrockwardine, and perhaps at Norwich, glassware of various colours was made. There are collectors who care for nothing else but coloured glass; there are collectors who only care for coloured glass paper-weights; there are collectors who will not buy coloured glass at all.

Bristol coloured glass is the most sought for. There are several varieties. The rarest is the opaque, whitish glass which rather resembles porcelain or Battersea enamel in general tint, and is painted upon as if it were porcelain or enamel: held to a good light this ware is seen to be rather opalescent, and might be dubbed opal glass. Edkins, a painter of Bristol delft, used delft-like colours and designs on this opal glass; wreaths of flowers (the rose and the fuchsia in particular) and flourishes in the Louis XV style are characteristic. Cups and saucers, teapots, tumblers, bowls and jugs, cruet vessels, and candlesticks of this ware exist, though few; the last-named imitated Battersea enamel candlesticks in shape and decoration. A characteristic of this glass is ridges or waves on the surface, detected by the finger. The earliest examples have domed and folded feet.

Less rare, but rare, are the wine glasses with red and white or blue and white spirals in the stems which were made at Bristol; if the white is not cotton-white but greyish, however, such a glass is probably old Dutch.

Fine tableware of transparent blue, blue-green, red, and purple was made at Bristol; the blue is a peculiar, unique blue, imitated but never well reproduced; where the glass is thick, it, held to the light, shows a Royal purple, and where thin it is almost a sea-blue. Egg-cups of this ware are handsome. Bristol red glass is of a ruby hue, with not so much vermilion in it as in Bohemian glass: there is also “cherry-red” glass. Bristol blue and red glass was sometimes touched with gilt, in lettering and lines; this did not wear well except when embossed.

Bristol produced the finest glass paper-weights—of a size and shape to fill the palm of one’s hand if only the wrist and finger-tips are touching the paper—and at the base of these you see flowers of coloured glass, bright and various in hue, and rendered with wonderful skill; of the same kind of mosaic or tessellated glass is a small[37] pepper pot in my possession, a very rare example. Other Bristol paper-weights, larger, and door-stops, still larger and heavier, were tall ovals, two or three or four times the size of a goose’s egg and rather resembling one in shape; the colour is a verdant or a sage green, and the inner decoration is flower-petals and leaves, pearled over as if by dew, and blown with extraordinary skill.

Collectors should beware of forgeries of parti-coloured paper-weights. They may be known by the coarseness of the flowers inside the glass, the lack of fine workmanship, and the tawdriness of the colours.

Nailsea is a small place near Bristol, and nobody can now be sure from which of the two came any particular bauble—coloured glass-flask, pestle, bell, witch-ball, tobacco pipe, trumpet, jug, rolling-pin, bellows-shaped[38] article, walking-stick or rapier, or the (excessively rare) long glass cylinders containing coloured glass counters for games. But it is thought that the Bristol wares of this kind were brighter in colour than the Nailsea product, which, because less skilful and daring, perhaps, was cooler in tint, less striking in mixture of colours, and therefore more refined. Probably Bristol produced the glass which is ornamented by alternate broad stripes of red and opal-white. Perhaps Nailsea was responsible for glass of a “greenery-yallery” hue containing whitish spots or splashes: there are many forgeries of jugs and rolling-pins, in this style, about.

At Wrockwardine, in Salop, the glass works turned out coloured walking-sticks, ewers, scent-bottles, flasks, twin bottles for oil and vinegar, and toys; the characteristic being that the glass is striped, in white and one or more colours.

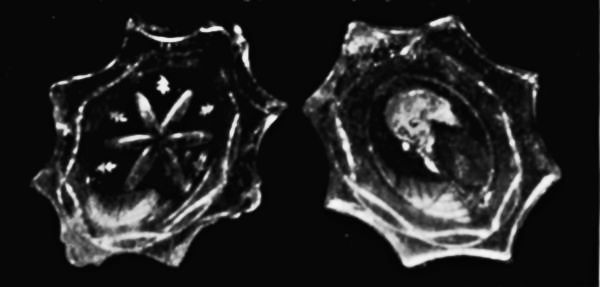

The Sunderland glassworks are supposed to have made rolling-pins, and almost certainly produced the curious polygonal salt cellars (which some people have thought to be insulators for piano-feet), that reflect colour and gilding or coloured heads of men or women, from their bases, talc keeping the ornament there in place.

Witch-balls seem to have been made at Bristol, for I own one of the Bristol red and opal-white; at Nailsea[39] (in inferior, watery blue); and at Wrockwardine (greenish-blue striped with pale white). These balls, it is said, were hung at each door and window, “to keep the witches out” (see illustration, page 8).

Glass articles splashed with colour outside, on the exterior of the article, exist, but in great rarity; the splashed-on colours are glass-oxides, but look like oil-paint; the greenish clear glass beneath the splashing resembles the Nailsea product.

Fine wine glasses, for hock or other white wines, were made in olive-green, grass-green, purple, and orange; these are collected by some people for use at table, by some for the collector’s cabinet. The older ones show the characteristics of dimensions and shape which will be described later in this book.

These are the favourite quarry of the hunter for old glass. I prefer the more uncommon and out-of-the-way pieces myself, but the old wine glasses, goblets, cordial glasses, rummers, ale glasses, cider glasses, and so forth are so interesting, often so beautiful, and sometimes so quaint, that I do not wonder at the eager collecting of them.

Seeking as I do right through this book to state general rules and tests which the beginner may apply to all glass he comes across, I now mention the general features of old drinking glasses.

In days when men did not rise from the dinner-table quite so easily as they fell under it, the stem of a drinking glass must be thick, lest it snap in the convulsive hand, and was more safely held when it was also lumpy or bulbous—“knopped” and “baluster”-like are other terms for it: the fingers clung to the knobs.

Even when the bulbous or lumpy stem ceased to be the rule, a thick stem—three or four times the thickness of modern wine-glass stems—was the rule, for the reason just given.

Similarly, old drinking glasses were always made with very broad “feet” or bases; usually the foot had a larger circumference than the bowl. A semi-drunken hand, setting the vessel down on the table, might leave it rocking for two or three seconds, but the foot was so broad that it could hardly rock over.

Because of the pontil-mark being often a knob, or protuberance, the foot of the glass must not wholly rest upon the table, but touch it near the circumference of the foot only, lest the knob at the end of the stem should prevent the glass standing level, or should scratch the mahogany.

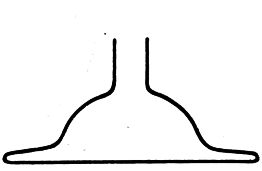

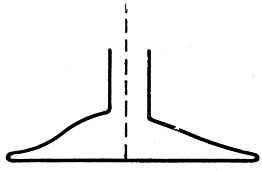

Some of the oldest glasses, in which the pontil-mark is quite a large protuberance, stand upon feet which, flat upon the table at and near the edge, rise domelike in the centre. These dome feet are seldom symmetrical; made by hand, the flat part is usually wider on one side of the dome than on the other.

As the pontil-mark became smaller and not so rough, the dome foot gave place to one which is mainly flat at the base but slightly conical, rising like a low round hillock, to join the stem: seen in profile, these somewhat resemble a leg and a foot with a high instep. No seventeenth-or eighteenth-century stemmed drinking[43] glass except a “firing” glass has a foot with an uniformly flat section.

Many old wine glasses are chipped at the edge of the foot; this was due to carelessness in the scullery sometimes, but often to careless use by convivial guests. Therefore glass-makers learned the advantage of folding the edge of the foot under, like a hem in needlework; a rounded edge, less likely to be chipped, was thus obtained. This “hem” is nearly always irregular, being turned in more at one part of the base than another. As a rule, the presence of a folded foot indicates that the glass was made before 1760.

Nobody knows what kind of glasses were made at Norwich or Lynn, but there is a supposition that horizontal lines, in the bowl or in the foot, mean “Norwich-made”: the foot is slightly terraced, so to speak.

There is, I believe, in certain Lodges, a semi-ritual practice of hammering on the table with the feet of glasses, rhythmically, after a toast, somewhat in the style of applause called “Kentish fire.” This seems never to have been done with wine glasses, but old cordial or spirit glasses exist in considerable numbers which were expressly made for the purpose, and furnished with flat[44] feet an eighth of an inch thick or more, so that they should not crack by concussion; in these old “firing-glasses,” too, the foot is bigger in circumference than the bowl.

These considerations apply to stemmed glasses for ale, beer, cider, and cordials also; and to rummers and grog glasses upon stems that are short but stout. Therefore a genuine English or Irish drinking glass of seventeenth-, eighteenth-, or early nineteenth-century make has, in addition to the tint, ring, quality, pontil-mark, workmanship, and signs of use, a stout stem and an extensive, raised foot.

About 1830, the six-bottle men being all dead, and even the three-bottle men becoming rare, the thickness of the stem and the extensiveness of the foot could safely be reduced; the pontil-mark, too, was smaller, and the foot of a glass could be made with a lower instep, so to speak. Therefore a thin stem and a foot not bigger, or smaller, than the top of the bowl, with no pontil-mark, or hardly any, signify that the glass was made during Victoria’s reign or just before it began.

“Thumb” glasses are those in which the external surface of the bowl is pitted with depressions the size of a finger-end, so that the shaking hand of the bibulous might be the less likely to let the glass drop. They are usually tall of bowl and short of stem, but rather big of foot.

Old glasses with thick square bases appear to belong to the end of the eighteenth century, when the “Empire” style was influencing manufacture: often the base is of inferior workmanship to the bowl.

Even the bases of tumblers were made thick, though they were smaller in circumference than the top of the tumbler.

Wine glasses and other drinking vessels of glass may best be classified according to the shape or decoration of the stem.

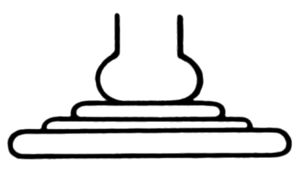

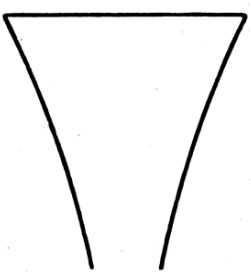

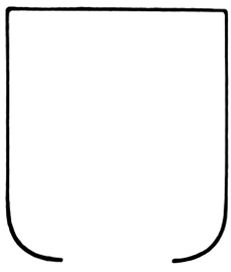

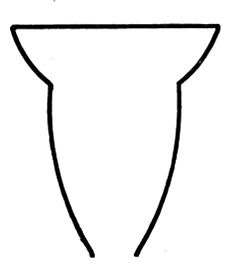

The oldest English drinking glasses are those which have lumpy, knobby, bulbous stems, of wavy outlines imitating the stems of Tudor and Stuart silver goblets, and rather resembling the shape of balusters in stair or terrace balustrades, or the uprights in some old gate-leg tables; perhaps among the baluster stems we should class those which rather resemble an inverted obelisk, the broad part just under the bowl and the point within the foot (see illustration, page 84); this long remained the favourite shape (and is almost the characteristic shape) for what are called sweetmeat glasses on stems, and for comports or glass stands for sweetmeat glasses; it gives a kind of shoulder to the stem. Sometimes the lower part of such a stem as this is square in section.

Often the stem does not directly join the bottom of the bowl, but has a “neck,” with an outstanding ring of glass or “collar” around the neck; sometimes the[47] collar is double or triple; the neck and collar were often used later, in other than baluster stems. Sometimes the collar is near the foot; sometimes there are two collars. Around some stems a fillet is found; these are very rare.

The stouter and lumpier the older the baluster stem, as a rule; after the accession of William and Mary, the baluster stems grew more and more refined and less heavy as the years went on. But baluster-stem glasses are prized by most collectors according to their bigness and lumpiness of outline; the older the better, from this point of view. The massive stems are very handsome; where they touch the bowl the bowl is very thick, and because the stem and pontil-mark were big, the foot is often domed; so that the curves of the bowl, the undulations of the stem, and the domelike or high-instep-like curve of the foot make a matched and pleasant outline for the whole. Almost invariably baluster-stem glasses have folded feet.

Two things may be looked for inside these stems—coins and “tears.” Sometimes one of the swelling-out parts of the baluster stem was large enough to enclose[48] a small silver coin; a coin glass is exceedingly rare and correspondingly valuable, but the date of the coin does not necessarily indicate the date of the glass.

Many baluster stems enclose a separate blob or bubble of glass, called a “tear.” It has been thought that this was an accidental feature, due to imperfect mixing of the metal and the presence of air in the molten glass. Obviously, that is an unlikely cause, and in the Diary of Mr. Pepys I have discovered a passage which seems to show how these “tears” in the stem would begin. Writing little more than twenty years before 1689, Pepys refers to the “chymical glasses which break all to dust by breaking off a little end; which is a great mystery to me.” These were called lacrymæ Batavicæ, or “Dutch tears,” and were made by letting drops of molten glass fall into water; hissing, the glass became tearlike in shape, a blob with a long slender tail, and hollow. Probably such as these were the “tears” which appear as ornaments within the old drinking-glass stems, distinctly visible and separate from the rest of the glass in the stem, though of the same tinge and quality of material.[49] The name “tear” is to this extent a misnomer, that nearly always the “tear” is bigger at the top than the bottom; whereas a tear proper swells out more the lower it slips on the cheek. But I own a baluster-stem glass in which the lower part of the “tear” is the bigger, and in some such glasses the “tear” swells out or in to match the shape of the stem. Sometimes three or five or more very small “tears” appear in one of the bulbs.

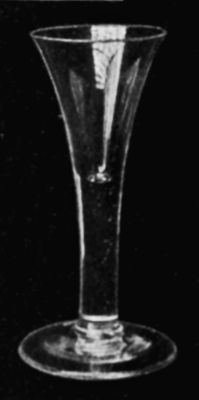

“Drawn glasses” were made at twice—the bowl and the stem in one, the foot added later. To understand better this meaning of the word “drawn,” imagine a soap-bubble with the extra suds adhering to one part of it, and suppose that the extra suds could be drawn out to make a stem; that was the method used in glass. The plain, round stem resembles a solid cylinder, but it is part of the bowl, in fact it is a continuation of the bowl. The end of the cylinder, around which the foot was welded, made a pontil-lump, and therefore the plain stem glass has either a high instep or a dome foot.

The plain round stems were made stout because of insobriety, though that had begun to lessen when this second type of stem came into vogue. “Tears” are often seen in the plain round stems.

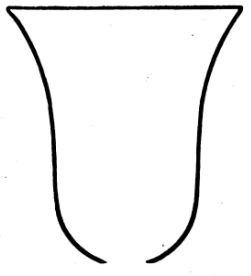

Stems which are ornamented by outside spirals, or series of small ridges and grooves alternating, are usually old Dutch; but some of them are English, though of inferior quality and ring. The quality is so poor and the make so unsatisfactory that probably they were a “cheap and nasty” contemporary imitation and substitute for glasses adorned with the air spiral, the type which succeed the plain round stem. It is hardly likely that the corrugated stem preceded the air-spiral stem; or, if at all, for more than a few years. With these corrugated stems one expects to find, almost without exception, that the bowl of the glass is shaped like an inverted, incurving, waisted bell.

At any rate, out of the “tears” in the baluster and plain round stems was developed the idea of ornamenting stems by internal spirals or twists, and whether these[51] should be number four or number three in the chronological order is not very important. By twisting while drawing out the stem from the surplus metal of the bowl (which contained several small “tears”) the graceful and beautiful effect of the air spiral inside the stem was produced. Sometimes the spiral starts within the bowl; sometimes it winds round the base of the bowl; but always the ornamentation becomes a trellis-work or network when it fills up the whole stem; when it does not fill up the whole stem, it meanders down it medially, in one substantial spiral, like a corkscrew or a rope, or in two that interlace: and in the finest examples the finger can feel no ridging of the surface at all, though a slight ridging is palpable in many glasses. Now all this meant splendid workmanship—English aptitude at handicraft, the best of its kind in the world.

Sometimes the spiral is so very brilliant that it seems as if it were made of quicksilver, and collectors call it “silver spiral” or “brilliant air-twist”; but this is probably an effect of light. In all cases the air spiral is glass colour, the tint of the rest of the glass; red, cotton-white, and blue spirals belong to the type of stem to be mentioned next. Sometimes, it is true, a white thread is seen running down the centre of the stem, within the[52] network of air spirals; but oftener when this central thread occurs, it is “air-colour” itself.

Air spirals are often seen in stems of knobby or baluster form; sometimes air-spiral stems have “necks.” This probably means that long rods of glass containing air spirals were made, with the baluster shape recurring at regular intervals of suitable length, so that the rod could be cut up into lengths and each length welded on to the bowl and the foot of a glass. These are the air-spiral glasses most sought after. Sometimes the stem of a drawn glass was welded to a foot of which a bulb was the upper part, this bulb sometimes containing beadlike “tears,” but these are very rare: sometimes the upper part of the stem is plain, and the lower part, beginning with a knob, is air spiral, or vice versa. Sometimes old air-spiral glasses with small feet are found; this was due to a practice of grinding away the edge, when the feet had become chipped by much use, and re-polishing the feet of these much-valued glasses; the folded foot for these glasses was not the rule.

Tall, slender-bowled air-spiral glasses for champagne are sometimes found, in shape resembling the glasses called flûtes; I own one of this sort not less than 9½ inches high. Rarer still are spiral-stemmed glasses for ale; I own one 11 inches high (see illustration, page 60). The former I gave 7s. 6d. for, the latter 10s., a tithe of their West-End prices. But these are very exceptional glasses.

Air-spiral stems are found in cordial and spirit glasses, firing glasses, and goblets with short stems.

During the latter half of the eighteenth century the air-spiral glasses continued to be made, but the opaque or cotton-white spiral stems came into fashion and general use. These were not “drawn” stems; they could not be, because the white glass was not inherent in the metal. The stem was made by lining a long cylindrical mould with wirelike “canes” of cotton-white and other glass alternately. Then melted plain glass was poured into the cylinder. The canes adhered to the warm metal, and when the whole was reheated, it could be twisted into spiral designs. Then the parti-coloured rod thus made was cut into stem-lengths. By this means a great variety of designs in the spirals could be produced, and indeed, the countless differences in English-made cotton-white spirals, hardly any two alike, are one of the features of a collection. Sometimes the design spreads like the air-twist; sometimes it circles around a central, wavy tube; sometimes the cotton-white is tapelike, in a “Greek key” pattern;[54] sometimes an outer spiral runs around the inner corkscrew; but always the effect is pleasing, and rather striking, though perhaps not quite in the reticent good taste of the air-spiral stems.

Dome feet or folded feet are hardly ever found under cotton-white or other coloured spiral stems; any example of that should at once be acquired; but the pontil-mark is always found—if the glass be old. The white in English-made glasses is generally a pure, vivid, cotton-white; in Dutch glasses it is usually a dull greyish hue. (This is why I use the term “cotton-white” as descriptive of these English stems.)

The next step, to coloured or “mixed” spirals, was obvious, but not very often taken at English glassworks: most of the red and white spiral stems now seen came from Holland or Liège. However, at Bristol red and white, and blue and white, spiral stems were made; they are known by the ruby red and the peculiar Bristol blue. Yellow and white, purple and white, and green and white spirals are known; rare indeed is a three-colour spiral. Coloured twist stems were only made in England about the end of the eighteenth century. An almost constant feature of tri-coloured stems made in[55] Holland or at Liège is a wavy central tube of white, with coloured spirals around it, swelling or contracting to suit the usually bulbous shape of the stem.

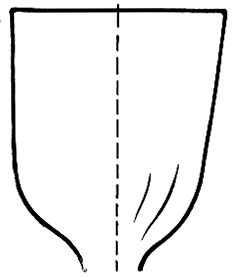

These seem to have been in fashion during the period 1775–1825. Usually the stems are hexagonal, and the cutting had, of course, to be continued, in a shallow way, on the lower part of the bowl. “Thistle” glasses are those in which the cutting of the stem and bowl to some extent suggests the thistle in shape and appearance. The stems were often knopped—this is a feature of Waterford glass cut stems—but towards the end of the period mentioned above the stems became cylindrical except for the cutting, and the cutting did not so much produce facets as long grooves.

The dates just given would suggest that the dome foot and the folded foot are not to be looked for under cut stems, but they are met with, the dome foot having been kept in use for ornament’s sake, probably. Nor is the pontil-mark present, if the cutter removed it; except that sometimes he left just the faintest trace of it, which the finger can detect.

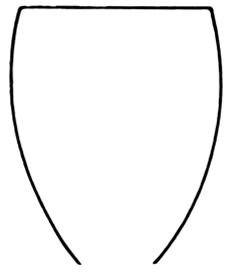

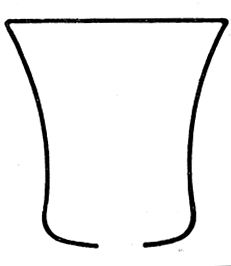

Stemmed drinking vessels, whether for wine or ale, for rum or cordials, cider or drams, can be classified according to shape of bowl; this is important for descriptive purposes, and to some extent for dating. The following names of shapes do not apply to tumblers, mugs, or tankards, of course.

There are ten general shapes of bowl:

1. Drawn, found with the plain round stem and the air-spiral stem.

2. Bell, found with the baluster stem, the necked and collared stem, the air-spiral stem, the cotton-white spiral stem, with coin glasses, and with rose glasses.

3. Waisted bell, found with the corrugated stem and the plain stem.

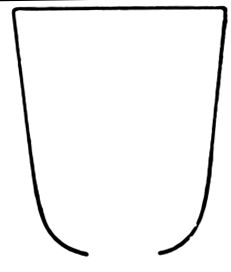

4. Straight-sided, found with each class of stem.

5. Rectangular, a variety of the straight-sided, found with the plain round stem and the air-spiral stem.

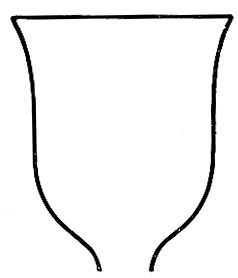

6. Egg-cup-shaped, or ovoid, found with the cotton-white spiral stem, the air-spiral stem, and the cut stem.

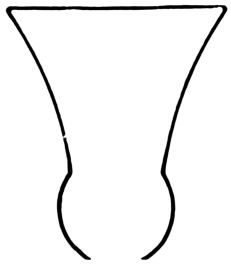

7. Ogee (named after a term in architecture, signifying a curve, somewhat like the letter S), found mostly with[58] the cotton-white spiral stem and the coloured spiral stem. These are believed to be of Bristol make as a rule, as many of them have the Bristol characteristic of perpendicular or spiral flutings in the lower half of the bowl, produced by pressure (a kind of moulding). The ogee bowl is also found with the cut stem, the plain round stem, and moulded stems.

8. Lipped ogee, found with the coloured spiral stem, the cotton-white stem, and moulded stems mainly.

9. Double ogee, found with the air-spiral stem, and the cotton-white stem; some of the oldest have knops and the folded foot.

10. Waisted, found with the air-spiral stem and the mixed spiral stem.

In many of the older wine glasses the finger can feel, inside the bowl, just above the top of the stem, a small conical projection, like that of half a bead. But this is not invariable, or an essential proof of genuineness.

Wine glasses do not by any means exhaust the list of collectable glasses on stems; there are many desirable stemmed glasses once used for ale, cider, perry, or spirits, to be acquired.

Many glasses, drawn, bell, or waisted-bell shape in bowl and baluster, plain round, air spiral, cotton-white spiral, or cut in stem, exist, which appear to have been used for the very strong ale then brewed; often these are engraved with representations of hops and barley.

Large vessels, perhaps used for “small beer,” exist, from 9 to 16 inches tall, and proportionately capacious: the biggest of the kind I ever saw was engraved with[61] Jacobite emblems. The smaller examples of this class may have been used daily; the larger may have been kept for occasional use as loving-cups, or were never used at all, perhaps, being merely tours de force of the glass-maker, and kept as ornaments to a sideboard. The very large ones are drawn glasses, with plain round stems, as a rule; the nine-or ten-inch tall glasses of this kind are baluster or plain round in stem. I bought one of these (see page 48) for £2 5s. not long ago; its West-End price now might be £10, for it is “Waterford.”

No doubt some of the glasses mentioned just above were used at times for strong cider; perhaps large goblets were used for draught perry or cider at times. But special cider glasses exist, engraved with representations of apples and apple-tree leaves, or apple-trees, and these, from 6 to 7 inches tall, have ogee or rectangular bowls as a rule, and usually cotton-white spiral stems.

There are two types of old champagne or mum glasses, each rare: one type has a wide-lipped bell or double-ogee bowl, upon a baluster stem, and much resembles some of the bigger sweetmeat glasses; the other type is 7 to 9 inches high, ogee bowl, and cotton-white stem.

There were three shapes of rummers used, one goblet shape, one on a tall stem, and one on a stem which is also[62] a base: sometimes the base of an old rummer is square. The first of these three shapes has a baluster stem, the second a plain round, spiral, or cut stem.

Fine mugs, with handles, imitating contemporary old silverware, are found; the mugs show something of a stem (see illustration, page 7). Often they are engraved with the initials of their first owner, and sometimes are dated also. Fine double-handled mugs, like loving-cups, exist.

These are small in bowl and short in stem, the bowl is often straight-sided, and the stem is usually drawn, and often cut. But there are many with drawn bowls and plain stems. A “thistle” glass of this kind is specially valued. Often the bowl is engraved. Cordial glasses may have long stems.

These are glasses which have no feet: they were used at one draught of the liquor in them. I bought a Bristol opal glass of the kind for 6d., but these are excessively rare. Almost as rare are the plain glasses, with cut stems, used in coaching days. When the stage coach paused at an inn, a waiter came out with a tray of footless glasses, each resting on its bowl; the traveller took one up, inverted it into the proper position, held it out to the bottle or decanter in the waiter’s hand, drank, and set the glass down upon its bowl again. A fuddling glass was a variety of coaching glass used indoors, for a rapid dram; a “thistle” glass of this kind was favoured in Scotland.

These are less capacious dram glasses than they seem; the lower part of the bowl was deceptively made very thick, so that the toastmaster at a banquet need not[64] drink so much as would otherwise have been necessary, when announcing and sharing in every one of the score or two of the toasts and “sentiments” which were honoured at every convivial board. A relic of the “sentiment” habit was preserved by Dickens in the language of Mr. Dick Swiveller: “May the wing of friendship never moult a feather” was a “sentiment” in its day.

Certain short, short-stemmed, or almost stemless glasses, with “Norwich” feet often, and with drawn or waisted-bell bowls wide at the mouth, are known as “Hogarth” glasses, because they were often shown in Hogarth’s pictures of contemporary social life.

Old glasses are often found which in shape and purpose correspond with those described in this chapter and chapters vi, vii, and viii, but were obviously inferior in finish of make when new. These may be taken to be glasses made cheaply for tavern and kitchen use; though not so attractive as the better qualities, they should not be neglected by the collector.

Evelyn tells in his diary that in 1683 the health of James II was drunk at Bromley “in a flint glass of a yard long.” Imitations of these are made, but the real old ones are excessively rare. In shape they rather resemble a coaching-horn, the mouthpiece being the foot, or the[65] mouthpiece being replaced by a bulb. They were used at merry-makings, as proof of bibulous skill in emptying a glass a yard long. There are also half-yard glasses.

These have a very small straight-sided or ogee bowl, upon a plain round, or spiral stem and big foot. They are very rare.

These are the aristocracy among the wine glasses, goblets, and spirit glasses. They are rare, difficult to find, and costly to buy, but not impossible to come upon by lucky hazard.

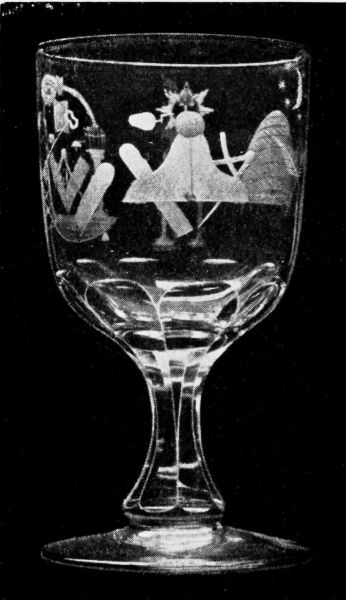

The dearest aim of every collector of old wine glasses is to come upon a Jacobite glass. The more sanguine and less strict kind of collector declares himself the owner of a Jacobite example if he possesses a glass engraved with a six-petalled heraldic Stuart rose (one petal for each King or Queen of Stuart blood who actually reigned in England, he says), a large bud (representing the Old Pretender, he explains), a smaller bud (for the Young Pretender), and a bird or (see illustration, page 20) butterfly (crossing the narrow seas, he explains, to bring the Stuarts back).

A stricter, less easily satisfied collector points out that[67] those were “the ordinary rose glasses,” used at all fashionable dinner-tables in the eighteenth century (see illustration, page 59). The reply to that is that the six-petalled rose and one of the buds, at least, are heraldic, not naturally represented; that the heraldic, six-petalled white rose was the Stuart rose; and that, at any rate, the “ordinary rose glasses” were sometimes used by Jacobites, particularly in general assemblies, because of their covert meaning, when it would have been unsafe to use the treasonable Jacobite glasses proper. A slight addition to the rose glass makes it truly Jacobite; thus I own a fine goblet which is made Jacobite by a monk’s-hood flower being added—a reference to General Monk. An “ordinary rose glass”—not so ordinary after all, and difficult to procure now, as well as dear to buy—which has a Stuart emblem engraved under the foot of it is allowed to pass[68] muster by the stricter collector, but what he aims at or boasts of if he possesses one is a “Jacobite glass proper.”

Now a “Jacobite glass proper” is engraved with a portrait of the Old Pretender, or of his son “Bonnie Prince Charlie”; or with the rose, two buds, a butterfly or a bird, and also a Jacobite motto or emblem, or both; or with the cypher of the Old Pretender and the words of a loyalist song. Upon a firing glass (the rarest of the Jacobite variety) may be seen the touching emblem of a thunder-smitten tree putting forth new branches, and the motto Revirescit (It becomes green again). Upon a wine glass may be seen the word “Fiat” with a star (perhaps standing for fiat lux, “Let there be light,” or perhaps for “Let it be done”—the second Restoration of the Stuarts). Or the motto may be Redeat (let him return), or, very rare, Redi; or Radiat (perhaps a misspelling of Redeat, or possibly meant for “let him shine”). If an oak-leaf (as well as the other features) appear on the glass, it was probably used in England; if a thistle, probably in Scotland.

There still are a few Jacobite glasses lying unrecognised no doubt; two were found in a London broker’s shop a few years ago, and bought for 5s.; in 1914 a Bristol schoolmaster learned accidentally that two glasses which had stood on a shelf on a sideboard in the family for forty years were Fiat glasses, and a valuer going to a house in Sussex for other purposes, discovered a Prince Charlie portrait glass (worth a hundred guineas now) still passing incognito—there had been “the pair of it,” but that had been “smashed to bits,” the servants said.

The rarest form of Jacobite glasses is the short toasting or firing glass, for strong waters, of “Hogarth” shape. I possess one of these; it has a “Norwich” foot; the thickness of the base of the bowl, and the “tear” in that and the short bulbous stem, seem to date it at about 1725, so that it will be an “Old Pretender” glass. It is very beautifully engraved with the six-petalled rose, the two buds, the word “Fiat,” the rising star and the (Boscobel) oak-leaf. It had been kept in an armoury, belonging to a collector who did not collect old glass.

No wonder people hunt for Jacobite glasses. They were the romantic, loyal, treasonable vessels which were emptied to the toast of “his Majesty over the water,” in clandestine and dangerous gatherings of fair women and conspiring men. Then the great punch-bowl was filled with water, to represent the narrow seas, and the red wine sparkled in the glasses held out above it; as often at loyal Georgian assemblies a Jacobite would be seen to hold his wine glass above a tumbler of water, if called on to drink to “the King”:

Flip these old glasses with the finger-nail, and they ring like a tuning-fork; draw thumb and finger upwards to the edge of the bowl, and you hear a clear faint resonance, sad as the wailings after Culloden, when final defeat had come.

I bought two fine, perfect, baluster-stemmed Williamite glasses for a guinea once; they show William of Orange on horseback, and are inscribed with “The Glorious Memory of King William, No Surrender, Boyne, 1st. Iuly 1690”; and the initials “T.C” and “S.C”; on some such glasses two of the initials are “S.T.” (see illustration, page 47). The glass is a yellowish-white where it is thick, and if not made at Belfast, may have been made in Cork; but the engraving would be done in Ulster. Some such glasses are rather recent; no doubt the making of Williamite glasses continued longer than the making of Jacobite glasses did, because of the continued existence of Orange Lodges. Some of these glasses are inscribed “The Immortal Memory” only, or “To the glorious memory of King William” only. Williamite firing glasses, of “Hogarth” shape, are also found.

When the House of Hanover came to the throne of the United Kingdom, loyal drinking glasses were made accordingly. “God save King George” and “Liberty” are the usual inscriptions on them; sometimes[72] the heraldic white horse of Hanover was engraved on the bowl, or the three crosses of the Union Jack inside a garter and the rays of the sun. Hanoverian glasses are rarer than Jacobite or Williamite, but Jacobite glasses are the most valued and costly.

I class these together because they are stemless. Pewter and silver tankards were imitated in glass, and these differ from mugs in being straight-sided and quite stemless; often they were engraved with initials and dates.

Old tumblers are not found so numerously as old wine glasses are; they are usually large, are often cut, and are sometimes engraved. Some tumblers are barrel-shaped, like some rummers, but most tumblers are “straight-sided” or “rectangular.” Some tumblers are engraved with portraits (as of Admiral Keppel) or with inscriptions (as of “Wellington for ever”). I own two which celebrate the “Independence of Durham and Richd. Wharton its defender,” probably made at Sunderland in 1802, to commemorate a Parliamentary Election in which the freedom of the citizens of Durham from rule by the bishop’s bailiff was involved. Masonic tumblers are rare; so are Bristol opal-glass tumblers, yet I own one which cost me 1s.

“Joeys” are dram glasses, shaped like tumblers, or like fuddling glasses with no foot or stem (see illustration, page 62). Mr. Joseph Hume, M.P., had caused[74] fourpenny bits to be coined; fourpenny bits were accordingly called “joeys”; even to-day people call for a “joey” of brandy. When a tax was put on gin, less of the liquor could then be sold for fourpence; so that the glass was made thicker, and the contents accordingly less. For a similar reason to-day there are in public-houses glasses called “Lloyd Georges,” I am told. The two “joeys” I own are of grass-green hue; one is inscribed with “4d.”