Title: A Broken Journey

Author: Mary Gaunt

Release date: March 21, 2017 [eBook #54402]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I—THE LURE OF THE UNKNOWN

CHAPTER II—TRUCULENT T'AI YUAN FU

CHAPTER III—THE FIRST SIGN OF UNREST

CHAPTER IV—A CITY UNDER THE HILLS

CHAPTER VI—BY MOUNTAIN AND RIVER

CHAPTER VIII—LAST DAYS IN CHINA

CHAPTER IX—KHARBIN AND VLADIVOSTOK

CHAPTER X—ONE OF THE WORLD'S GREAT RIVERS

CHAPTER XI—THE ENDS OF THE EARTH

CHAPTER XIII—THE UPPER REACHES OF THE AMUR

CHAPTER XIV—MOBILISING IN EASTERN SIBERIA

CHAPTER XV—ON A RUSSIAN MILITARY TRAIN

CHAPTER XVI—THE WAYS OF THE FINNS

CHAPTER XVII—CAPTURED BY GERMANS

I have to thank my friend Mrs Lang for the drastic criticism which once more has materially helped me to write this book. Other people also have I to thank, but so great was the kindness I received everywhere I can only hope each one will see in this book some token of my sincere gratitude.

Mary Gaunt.

Mary Haven, New Eltham, Kent.

Each time I begin a book of travel I search for the reasons that sent me awandering. Foolishness, for I ought to know by this time the wander fever was born in my blood; it is in the blood of my sister and brothers. We were brought up in an inland town in Victoria, Australia, and the years have seen us roaming all over the world. I do not think any of us has been nearer the North Pole than Petropaulovski, or to the South Pole than Cape Horn—children of a sub-tropical clime, we do not like the cold—but in many countries in between have we wandered. The sailors by virtue of their profession have had the greater opportunities, but the other five have made a very good second best of it, and always there has been among us a very understanding sympathy 'with the desire that is planted in each and all to visit the remote corners of the earth.

Anybody can go on the beaten track. It only requires money to take a railway or steamer ticket, and though we by no means despise comfort—indeed, because we know something of the difficulties that beset the traveller beyond the bounds of civilisation, we appreciate it the more highly—still there is something else beyond comfort in life. Wherein lies the call of the Unknown? To have done something that no one else has done—or only accomplished with difficulty? Where lies the charm? I cannot put it into words—only it is there, the “something calling—beyond the mountains,” the “Come and find me” of Kipling. That voice every one of the Gaunts hears, and we all sympathise when another one goes.

And that voice I heard loudly in China.

“Come and find me! Come and find me!”

The livelong day I heard it, and again and again and yet again I tried to stifle it, for you who have read my Woman in China will know that travelling there leaves much to be desired. To say it is uncomfortable is to put it in the mildest terms. Everything that I particularly dislike in life have I met travelling in China; everything that repells me; and yet, having unwisely invested $10 (about £1) in an atlas of China, the voice began to ring in my ears day and night.

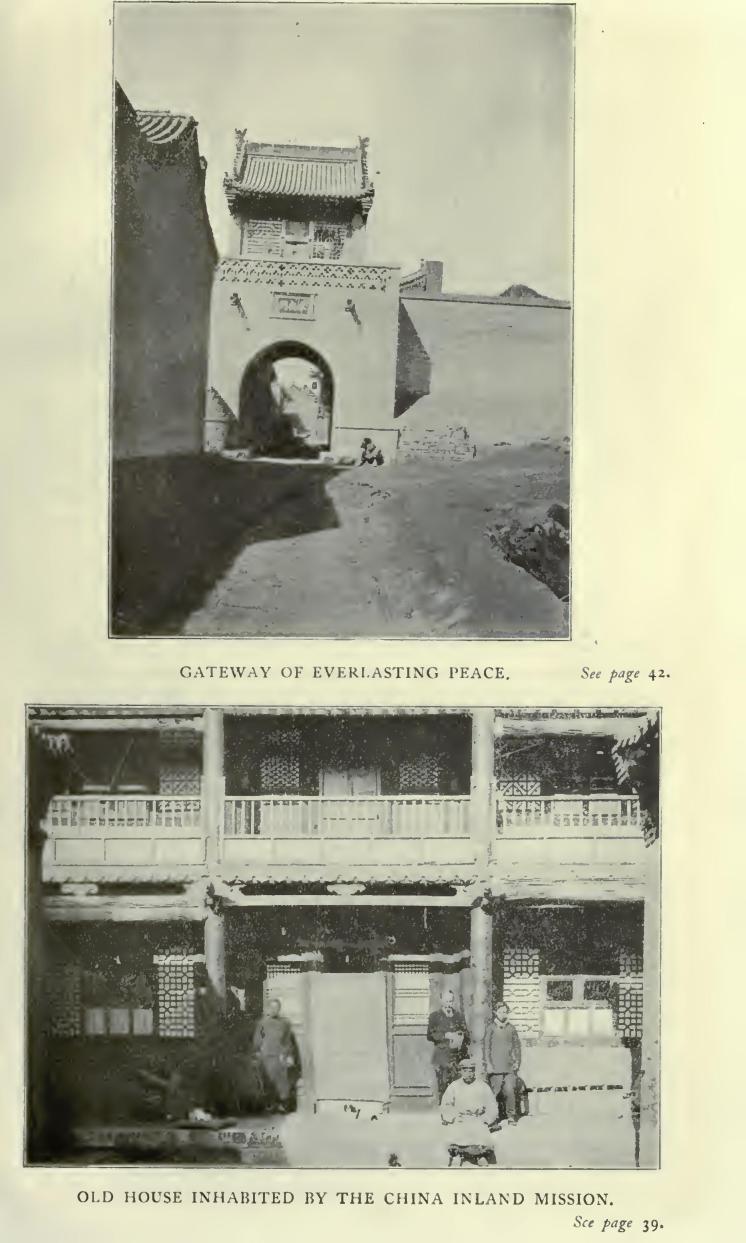

I was living in an American Presbyterian mission station in the western suburb of the walled town of Pao Ting Fu, just beyond European influence, the influence of the Treaty Ports and the Legation quarter of Peking. I wanted to see something of the real China, to get material for a novel—not a novel concerning the Chinese; for I have observed that no successful novel in English deals with anybody but the British or the Americans; the other peoples come in as subordinates—and the local colour was best got on the spot. There was plenty in Pao Ting Fu, goodness knows. It had suffered severely in the Boxer trouble. In the northern suburb, just about a mile from where we lived, was a tomb, or monument rather, that had been raised to the missionaries massacred then. They have made a garden plot where those burning houses stood, they have planted trees and flowers, and set up memorial tablets in the Chinese style, and the mission has moved to the western suburb, just under the frowning walls of the town, and—is doubly strong. A God-given fervour, say the missionaries, sends them forth.'Who am I to judge? But I see that same desire to go forth in myself, that same disregard of danger, when it is not immediate—I know I should be horribly scared if it materialised—and I cannot claim for myself it is God-given, save perhaps that all our desires are God-given.

So there in the comfortable mission station I studied the local colour, corrected my last book of China, and instead of planning the novel, looked daily at the atlas of China, till there grew up in me a desire to cross Asia, not by train to the north as I had already done, as thousands of people used to do every year, but by the caravan route, across Shensi and Kansu and Sinkiang to Andijan in Asiatic Russia, the terminus of the Caspian Railway. Thousands and thousands of people go slowly along that way too, but the majority do not go all the way, and they do not belong to the class or nation whose comings and goings are recorded. In fact, you may count on the fingers of one hand the people who know anything of that road. The missionaries, particularly the womenkind, did not take very cheerful view's about it.

“If I wanted to die,” said one woman, meeting me as I was going round the compound one day in the early spring of 1914, “I would choose some easier way.”

But the doctor there was keenly interested. He would have liked to have gone himself, but his duty kept him alongside his patients and his hospital in Pao Ting Fu, and though he pulled himself up every now and then, remembering I was only a woman and probably couldn't do it, he could not but take as great an interest in that map and ways and means as I did myself. Then there was Mr Long, a professor at the big Chinese college in the northern suburb—he was young and enthusiastic and as interested as Dr Lewis.

He too knew something about travel in unknown China, for he had been one of the band of white men who had made their way over the mountains of Shansi and Shensi in the depths of winter to go to the rescue of the missionaries in Sui Te Chou and all the little towns down to Hsi An Fu at the time of the Revolution. Yes, he knew something of the difficulties of Chinese travel, and he thought I could do it.

“The only danger would be robbers, and—well, you know, there mightn't be robbers.”

But Peking—the Peking of the Legations—that, I knew, held different view's. I wrote to an influential man who had been in China over ten years, who spoke the language well, and he was against it.

“I was very much interested” (wrote he) “to read of your intention to do that trek across country. You ask my opinion about it, but I can only give you the same advice that Punch gave many years ago, and that is, don't. You must realise that the travelling will be absolutely awful and the cost is very great indeed. You have not yet forgotten your trip to Jehol, I hope, and the roughness of the road. The trip you contemplate will make the little journey to Jehol look like a Sunday morning walk in Hyde Park, particularly as regards travelling comfort, to say nothing about the danger of the journey as regards hostile tribes on the southern and western borders of Tibet. You will be passing near the Lolo country, and I can assure you that the Lolos are not a set of gentlemen within the meaning of the Act. They are distinctly hostile to foreigners, and many murders have taken place in their country that have not been published because of the inability of the Chinese troops to stand up against these people. What the peoples are like farther north I do not know, but I understand the Tibetans are not particularly trustworthy, and it will follow that the people living on their borders will inherit a good many of their vices and few of their virtues.

“If you have really made up your mind to go, however, just let me know, and I will endeavour to hunt up all the information that it is possible to collect as to the best route to take, etc., though I repeat I would not advise the journey, and the Geographical Society can go to the deuce.”

This not because he despised the Geographical Society by any means, but because I had advanced as one reason for going across Asia the desire to win my spurs so and be an acceptable member.

“My dear,” wrote a woman, “think of that poor young Brooke. The Tibetans cut his throat with a sharp stone, which is a pleasant little way they have.”

Now the man's opinion was worth having, but the woman's is a specimen of the loose way people are apt to reason—I do it myself—when they deal with the unknown. The “poor young Brooke” never went near Tibet, and was murdered about a thousand miles distant from the route I intended to take. It was something as if a traveller bound to the Hebrides was warned against dangers to be met upon the Rhone.

One man who had travelled extensively in Mongolia was strongly against the journey, but declared that “Purdom knew a great deal more about travelling in China” than he did, and if “Purdom” said I might got—well then, I might. Mr Purdom and Mr Reginald Farrer were going west to the borders of Tibet botanising, and one night I dined with them, and Mr Purdom was optimistic and declared if I was prepared for discomfort and perhaps hardship he thought I might go.

So it was decided, and thereupon those who knew took me in hand and gave me all advice about travelling in China, how to minimise discomfort, what to take and what to leave behind. One thing they were all agreed upon. The Chinese, as a rule, are the most peaceable people upon earth, the only thing I had to fear was a chance band of robbers, and if I fell into their hands—well, it would probably be finish.

“The Chinese are fiendishly cruel,” said my friend of Mongolian travel; “keep your last cartridge for yourself.”

I intimated that a pistol was quite beyond me, that that way of going out did not appeal to me, and anyhow I'd be sure to bungle it.

“Then have something made up at the chemist's and keep it always on your person. You do not know how desperately you may need it.”

I may say here that these remarks made no impression upon me whatever. I suppose in most of us the feeling is strong that nothing bad could possibly happen. It happens to other people, we know, but to us—impossible! I have often wondered how near I could get to danger without feeling that it really threatened—pretty close, I suspect. It is probably a matter of experience. I cannot cross a London road with equanimity—but then twice have I been knocked down and rather badly hurt—but I gaily essayed to cross Asia by way of China, and would quite certainly as gaily try again did I get the chance. Only next time I propose to take a good cook.

To some, of course, the unknown is always full of danger.

The folks who walked about Peking without a qualm warned me I would die of indigestion, I would be unable to drink the water, the filth would be unspeakable, hydrophobia raged, and “when you are bitten, promptly cut deep into the place and insert a chloride of mercury tabloid.”

That last warning made me laugh. It reminded me of the time when as a little girl, living in a country where deadly snakes swarmed—my eldest brother killed sixty in a week, I remember, in our garden—I used to think it would be extremely dangerous to go to Europe because there were there mad dogs, things we never had in Australia! I think it was the reference to hydrophobia and the chloride of mercury tabloid helped me to put things in their proper prospective and made me realise that I was setting out on a difficult journey with a possible danger of robbers; but a possible danger is the thing we risk every day we travel in a railway train or on an electric tramcar. I am always ready for possible risks, it is when they become probable I bar them, so I set about my preparations with a quiet mind.

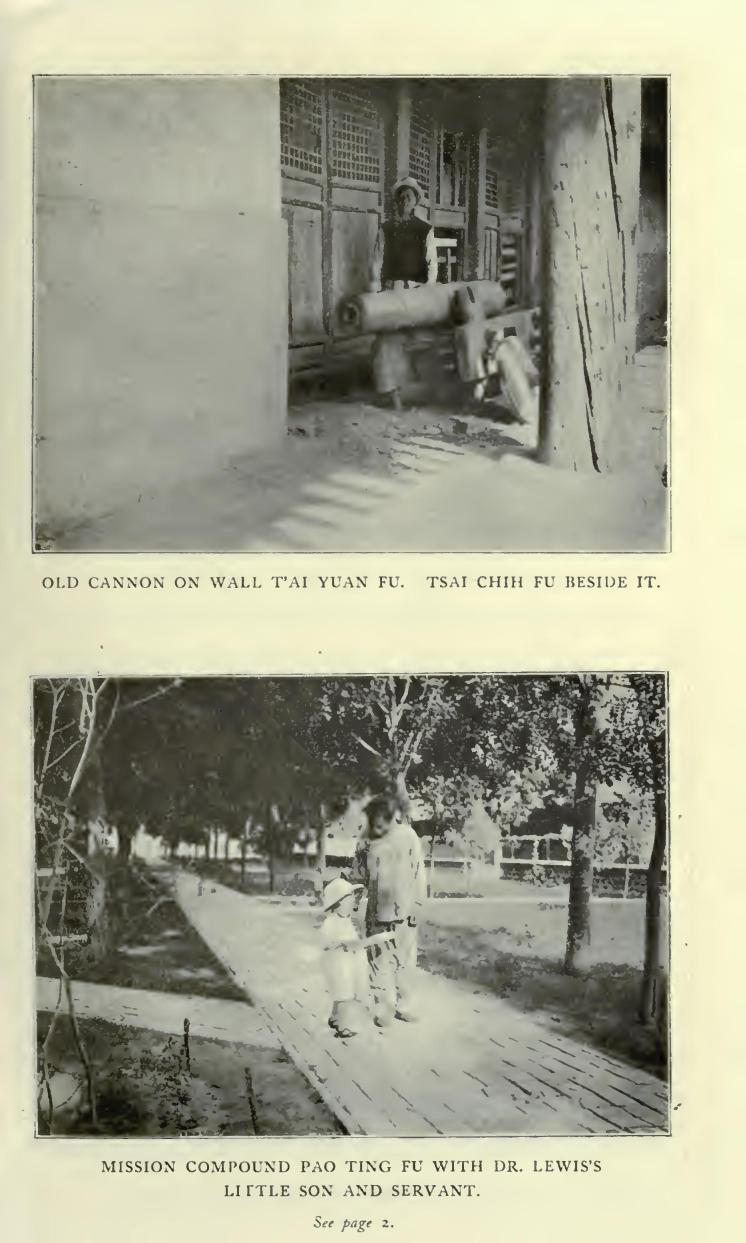

A servant. I decided I must have a tall servant and strong, because so often in China I found I had to be lifted, and I had suffered from having too small a man on my former journeys. The missionaries provided me with a new convert of theirs, a tall strapping Northern Chinaman, who was a mason by trade. Tsai Chih Fu, we called him—that is to say, he came of the Tsai family; and the Chih Fu—I'm by no means sure that I spell it right—meant a “master workman.” He belonged to a large firm of masons, but as he had never made a dollar a day at his trade, my offer of that sum put him at my service, ready to go out into the unknown. He was a fine-looking man, dignified and courteous, and I had and have the greatest respect for him. He could not read or write, of course. Now a man who cannot read or write here in the West we look upon with contempt, but it would be impossible to look upon Tsai Chih Fu with contempt. He was a responsible person, a man who would count in any company. He belonged to another era and another civilisation, but he was a man of weight. A master of transport in Babylon probably closely resembled my servant Tsai Chih Fu.

My interpreter, Wang Hsien—that is, Mr Wang—was of quite a different order. He was little and slight, with long artistic hands, of the incapable artistic order, and he was a fool in any language; but good interpreters are exceedingly difficult to get. He used to come and see me every day for a fortnight before we started, and I must say my heart sank when the simplest remark, probably a greeting, or a statement as to the weather, was met with a “Repeat, please.” I found this was the invariable formula and it was not conducive to brisk conversation. On my way through the country things were apt to vanish before I had made Mr Wang understand that I was asking, and was really in search of, information. He had his black hair cut short in the progressive foreign fashion (it looked as if he had had a basin put on his head—a good large one—and the hair snipped off round), and he wore a long blue cotton gown buttoned to his feet. Always he spoke with a silly giggle. Could I have chosen, which I could not, he would have been about the very last man I should have taken on a strenuous journey as guide, philosopher and friend.

And there was another member of the party, a most important member, without whom I should not have dreamt of stirring—my little black and white k'ang dog, James Buehanan, who loved me as no one in the world has ever loved me, thought everything I did was perfect, and declared he was willing to go with me to the ends of the earth.

So I began my preparations. One thing only was clear, everyone was agreed upon it, all my goods must be packed in canvas bags, because it is impossible to travel by mule, or cart, or litter with one's clothes in ordinary boxes. And I had, through the kindness of Messrs Forbes & Company, to make arrangements with Chinese bankers, who have probably been making the same arrangements since before the dawn of history, to get money along the proposed route. These things I managed satisfactorily; it was over the stores that, as usual, I made mistakes. The fact of the matter is that the experience gained in one country is not always useful for the next. When first I travelled in Africa I took many “chop” boxes that were weighty and expensive of transport, and contained much tinned meat that in a warm, moist climate I did not want. I found I could live quite happily on biscuits and fruit and eggs, with such relishes as anchovy paste or a few Bologna sausages for a change. My expensive tinned foods I bestowed upon my servants and carriers, greatly to my own regret. I went travelling in China, in Northern Chihli and Inner Mongolia, I dwelt apart from all foreigners in a temple in the western hills, and I found with a good cook I lived very comfortably off the country, with just the addition of a few biscuits, tea, condensed milk, coffee and raisins, therefore I persuaded myself I could go west with few stores and do exactly the same. Thus I added considerably to my own discomfort. The excellent master of transport was a bad cook, and a simple diet of hard-boiled eggs, puffed rice and tea, with raisins for dessert, however good in itself, is apt to pall when it is served up three times a day for weeks with unfailing regularity.

However, I didn't know that at the time.

And at last all was ready. I had written to all the mission stations as far west as Tihwa, in Sinkiang, announcing my coming. I had provided myself with a folding table and chair—they both, I found, were given to fold at inconvenient moments—some enamel plates, a couple of glasses, a knife and fork, rudimentary kitchen utensils, bedding, cushions, rugs, etc., and all was ready. I was to start the next week, ten days after Mr Purdom and Mr Farrer had set out, for Honan, when there came a telegram from Hsi An Fu:

“Delay journey” (it read).

“White wolf in Shensi. Shorrocks.”

Was there ever such country? News that a robber was holding up the road could be sent by telegram!

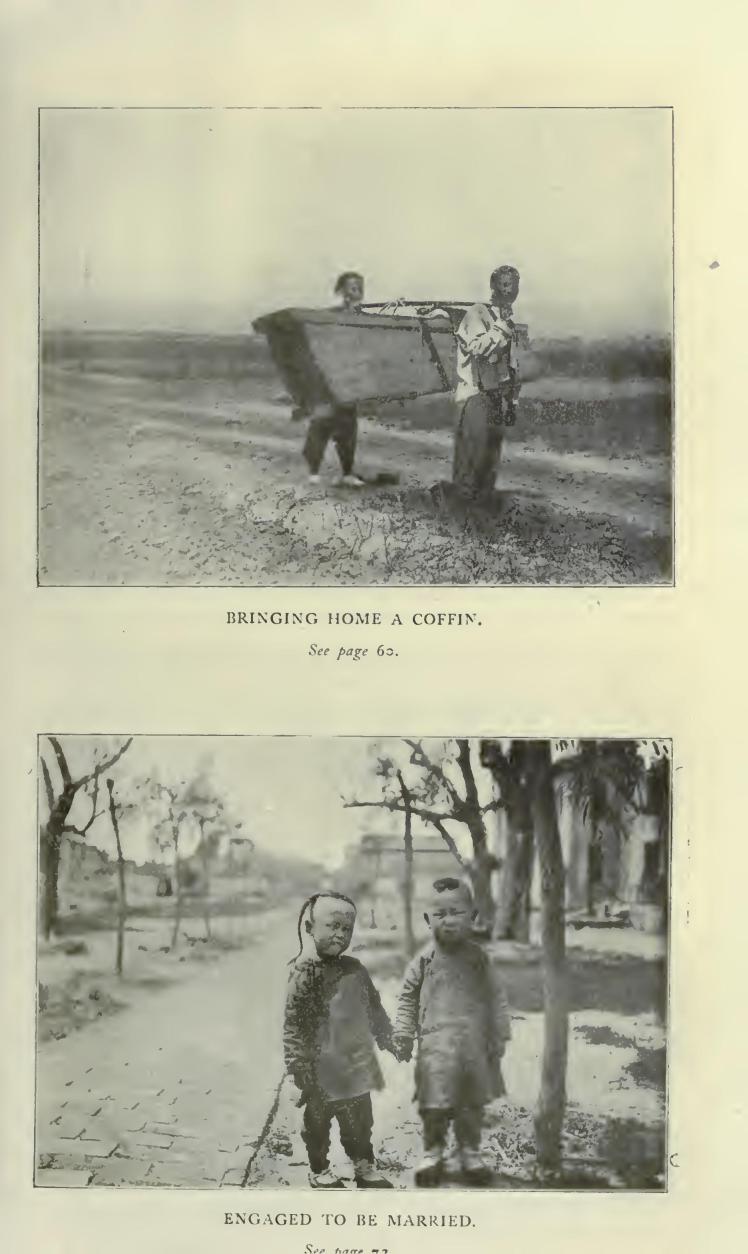

China rather specialises in robbers, but White Wolf was considerably worse than the average gentleman of the road. He defied the Government in 1914, but the last time we of the mission station had heard of him he was making things pleasant for the peaceful inhabitants of Anhwei, to the east, and the troops were said to have him “well in hand.” But in China you never know exactly where you are, and now he was in Shensi!

I read that telegram in the pleasant March sunshine. I looked up at the boughs of the “water chestnuts,” where the buds were beginning to swell, and I wondered what on earth I should do. The roads now were as good as they were ever likely to be, hard after the long winter and not yet broken up by the summer rains. We discussed the matter from all points that day at the midday dinner. The missionaries had a splendid cook, a Chinese who had had his kitchen education finished in a French family, and with a few good American recipes thrown in the combination makes a craftsman fit for the Savoy, and all for ten Mexican dollars a month! Never again do I expect to meet such salads, sweet and savoury! And here was I doing my best to leave the flesh-pots of Egypt. It seemed foolish.

I contented my soul with what patience I might for a week, and then I telegraphed to Honan Fu, at which place I expected to be well away from the railway. Honan Fu answered promptly:

“The case is hopeless. Hsi An Fu threatened. Advise you go by T'ai Yuan Fu.”

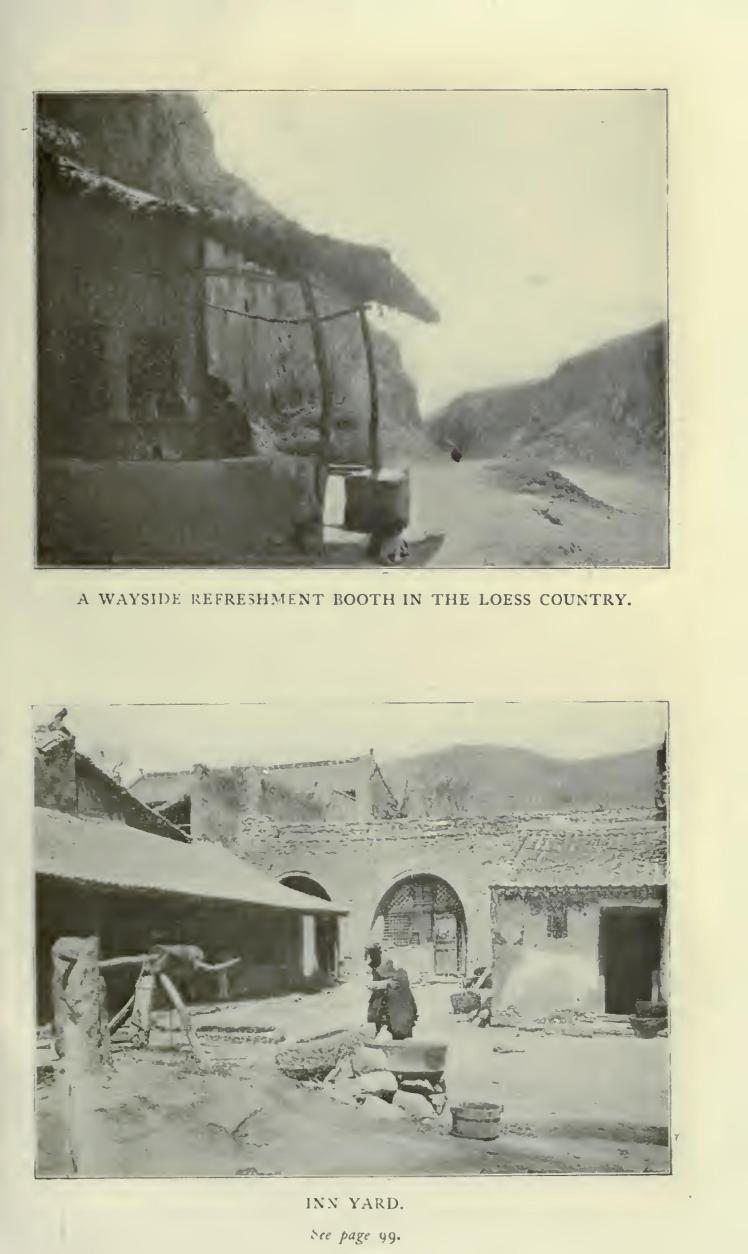

Now the road from Honan Fu to Hsi An Fu is always dangerous. It is through the loess, sunken many feet below the level of the surrounding country, and at the best of times is infested with stray robbers who, from the cliffs above, roll down missiles on the carts beneath, kill the mules and hold the travellers at their mercy. The carters go in large bodies and are always careful to find themselves safe in the inn-yards before the dusk has fallen.

These were the everyday dangers of the way such as men have faced for thousands of years; if you add to them an organised robber band and a large body of soldiers in pursuit, clearly that road is no place for a solitary foreign woman, with only a couple of attendants, a little dog, and for all arms a small pistol and exactly thirteen cartridges—all I could get, for it is difficult to buy ammunition in China. Then to clinch matters came another telegram from Hsi An Fu, in cipher this time:

“Do not come” (it said).

“The country is very much disturbed.”

From Anhwei to Shensi the brigands had operated. They had burned and looted and outraged by order of Pai Lang (White Wolf), leaving behind them ruined homes and desolated hearths, and when the soldiers came after them, so said Rumour of the many tongues, White Wolf, who was rich by then, left money on the roads and so bribed the avenging army to come over to him.

But to the ordinary peaceful inhabitant—and curiously enough the ordinary Chinese is extremely peaceful—it is not a matter of much moment whether it be Pai Lang or the soldier who is hunting him who falls upon the country. The inhabitants are sure to suffer. Both bandit and soldier must have food, so both loot and outrage impartially, for the unpaid soldiery—I hope I shall not be sued for libel, but most of the soldiery when I was in China appeared to be unpaid—loot just as readily as do the professional bandits. A robber band alone is a heavy load for a community to carry, and a robber band pursued by soldiers more than doubles the burden.

Still the soldiers held Tungkwan, the gate into Shensi, the mountains on either side blocked the way, and Hsi An Fu breathed for a moment till it was discovered that Pai Lang in strategy was equal to anyone who had been sent against him. He had taken the old and difficult route through the mountains and had come out west of the narrow pass of Tungkwan and, when I became interested in him, was within a day's march of Hsi An Fu, the town that is the capital of the province of Shensi and was the capital of China many hundreds of years ago. It is a walled city, but the people feared and so did the members of the English Baptist Mission sheltering behind those walls. And, naturally, they feared, for the Society of the Elder Brethren had joined Pai Lang, and the Society of Elder Brethren always has been and is markedly anti-foreign. This was the situation, growing daily a little worse, and we foreigners looked on; and the Government organs in Peking told one day how a certain Tao Tai had been punished and degraded because he had been slack in putting down White Wolf and possibly the next day declared the power of White Wolf was broken and he was in full retreat. I don't know how many times I read the power of White Wolf had been broken and yet in the end I was regretfully obliged to acknowledge that he was stronger than ever. Certainly Pai Lang turned my face north sooner than I intended, for the idea of being a target for rocks and stones and billets of wood at the bottom of a deep ditch from which there could be no escape did not commend itself to me. True, in loess country, as I afterwards found, there are no stones, no rocks and no wood. I can't speak for the road through Tungkwan, for I didn't dare it. But, even if there were no stones, loose earth—and there is an unlimited quantity of that commodity in Northern China—flung down from a height would be exceedingly unpleasant.

Of course it all might have been rumour—it wasn't, I found out afterwards; but unfortunately the only way to find out at the time was by going to see for myself, and if it had been true—well, in all probability I shouldn't have come back. That missionary evidently realised how keen I was when he suggested that I should go by T'ai Yuan Fu, the capital of Shansi, and I determined to take his advice. There was a way, a little-known way, across the mountains, across Shansi, by Sui Te Chou in Shensi, and thence into Kansu, which would eventually land me in Lan Chou Fu if I cared to risk it.

This time I asked Mr Long's advice. He and the little band of nine rescuers who had ridden hot haste to the aid of the Shensi missionaries during the revolution had taken this road, and they had gone in the depths of winter when the country was frozen hard and the thermometer was more often below zero, very far below zero, than not. If they had accomplished it when pressed for time in the great cold, I thought' in all probability I might manage it now at the best time of the year and at my leisure. Mr Long, who would have liked to have gone himself, thought so too, and eventually I set off.

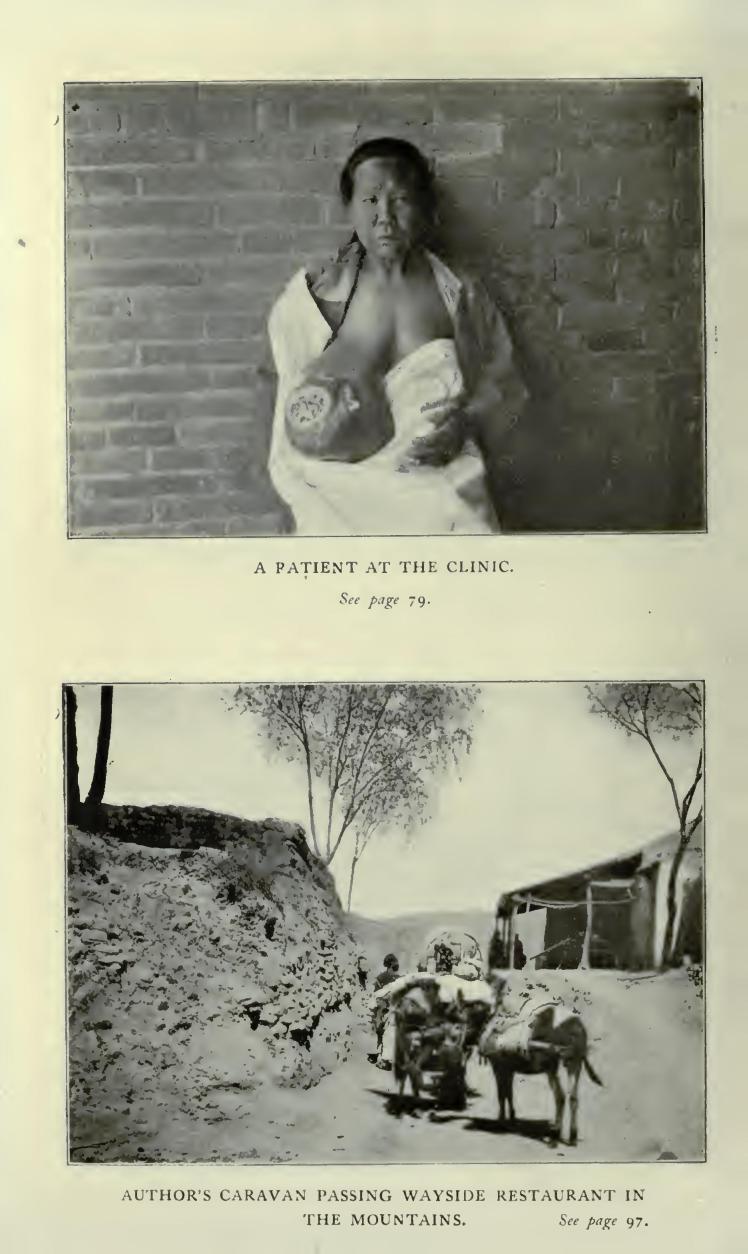

The missionaries were goodness itself to me. Dr Mackay, in charge of the Women's Hospital, set me up with all sorts of simple drugs that I might require and that I could manage, and one day in the springtime, when the buds on the trees in the compound were just about to burst, and full of the promise of the life that was coming, I, with most of the missionaries to wish me “Godspeed,” and with James Buchanan under my arm, my giggling interpreter and my master of transport following with my gear, took train to T'ai Yuan Fu, a walled city that is set in the heart of a fertile plateau surrounded by mountains.

The great adventure had begun.

But you mayn't go to T'ai Yuan Fu in one day. The southern train puts you down at Shih Chia Chuang—the village of the Stone Family—and there you must stay till 7.40 a.m. next morning, when the French railway built through the mountains that divide Shansi from Shensi takes you on to its terminus at T'ai Yuan Fu. There is a little Chinese inn at Shih Chia Chuang that by this time has become accustomed to catering for the foreigner, but those who are wise beg the hospitality of the British American Tobacco Company.

I craved that hospitality, and two kindly young men came to the station through a dust-storm to meet me and took me off to their house that, whether it was intended to or not, with great cool stone balconies, looked like a fort. But they lived on perfectly friendly terms with people. Why not? To a great number of the missionaries the B.A.T. is anathema maranatha, though many of the members rival in pluck and endurance the missionaries themselves. And why is it a crime for a man or a woman to smoke? Many of the new teachers make it so and thus lay an added burden on shoulders already heavily weighted. Personally I should encourage smoking, because it is the one thing people who are far apart as the Poles might have in common.

And goodness knows they have so few things. Even with the animals the “East is East and West is West” feeling is most marked. Here at the B.A.T. they had a small pekinese as a pet. She made a friend of James Buchanan in a high and haughty manner, but she declined to accompany him outside the premises. Once she had been stolen and had spent over three months in a Chinese house. Then one day her master saw her and, making good his claim, took her home with him. Since that time nothing would induce her to go beyond the front door. She said in effect that she got all the exercise she needed in the courtyard, and if it did spoil her figure, she preferred a little weight to risking the tender mercies of a Chinese household, and I'm sure she told Buchanan, who, having the sacred V-shaped mark on his forehead, was reckoned very beautiful and was much admired by the Chinese, that he had better take care and not fall into alien hands. Buchanan as a puppy of two months old had been bought in the streets of Peking, and when we started on our journey must have been nearly ten months old, but he had entirely forgotten his origin and regarded all Chinese with suspicion. He tolerated the master of transport as a follower of whom we had need.

“Small dog,” Mr Wang called him, and looked upon him doubtfully, but really not as doubtfully as Buchanan looked at him. He was a peaceful, friendly little dog, but I always thought he did not bite Mr Wang simply because he despised him so.

Those two young men were more than good to me. They gave me refreshment, plenty of hot water to wash away the ravages of the dust-storm, and good company, and as we sat and talked—of White Wolf, of course—there came to us the tragedy of a life, a woman who had not the instincts of Buchanan.

Foreign women are scarce at Shih Chia Chuang; one a month is something to remark upon, one a week is a crowd, so that when, as we sat in the big sitting-room talking, the door opened and a foreign woman stood there, everyone rose to his feet in astonishment. Mr Long, who had been up the line, stood beside her, and behind her was a Chinaman with a half-caste baby in his arms. She was young and tall and rather pretty.

“I bring you a lady in distress,” said Mr Long rather hastily, explaining matters. “I met Mrs Chang on the train. She has miscalculated her resources and has not left herself enough money to get to Peking.”

The woman began to explain; but it is an awkward thing to explain to strangers that you have no money and are without any credentials. I hesitated. Eventually I hope I should have helped her, but my charity and kindliness were by no means as ready and spontaneous as those of my gallant young host. He never hesitated a moment. You would have thought that women and babies without any money were his everyday business.

“Why, sure,” said he in his pleasant American voice, “if I can be of any assistance. But you can't go to-day, Mrs Chang; of course you will stay with us—oh yes, yes; indeed we should be very much hurt if you didn't; and you will let me lend you some money.”

And so she was established among us, this woman who had committed the unpardonable sin of the East, the sin against her race, the sin for which there is no atoning. It is extraordinary after all these years, after all that has been said and written, that Englishwomen, women of good class and standing, will so outrage all the laws of decency and good taste. This woman talked. She did not like the Chinese, she would not associate with them; her husband, of course, was different. He was good to her; but it was hard to get work in these troubled times, harder still to get paid for it, and he had gone away in search of it, so she was going for a holiday to Peking and—here she tumed|to the young men and talked about the society and the dances and the amusement she expected to have among the foreigners in the capital, she who for so long had been cut off from such joys in the heart of China among an alien people.

We listened. What could we say?

“People in England don't really understand,” said she, “what being in exile means. They don't understand the craving to go home and speak to one's own people; but being in Peking will be something like being in England.”

We other five never even looked at each other, because we knew, and we could hardly believe, that she had not yet realised that in marrying a Chinese, even one who had been brought up in England, she had exiled herself effectually. The Chinese look down upon her, they will have none of her, and among the foreigners she is outcast. These young men who had come to her rescue with such right good will—“I could not see a foreign woman in distress among Chinese”—will pass her in the street with a bow, will not see her if they can help themselves, will certainly object that anyone they care about should see them talking to her, and their attitude but reflects that of the majority of the foreigners in China. Her little child may not go to the same sehool as the foreign children, even as it may not go to the same school as the Chinese. She has committed the one error that outclasses her, and she is going to pay for it in bitterness all the days of her life. And everyone in that room, while we pitied her, held, and held strongly, that the attitude of the community, foreign and Chinese, was one to be upheld.

“East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet,” and yet here and there one still comes across a foolish woman who wrecks her life because she never seems to have heard of this dictum. She talked and talked, and told us how good was her husband to her, and we listeners said afterwards she “doth protest too much,” she was convincing herself, not us, and that, of course, seeing he was a Chinaman, he was disappointed that the baby was a girl, and that his going off alone was the beginning of the end, and we were thankful that she was “the only girl her mother had got,” and so she could go back to her when the inevitable happened.

The pity of it! When will the stay-at-home English learn that the very worst thing one of their women can do with her life is to wed an Oriental? But when I think of that misguided woman in that remote Chinese village I shall always think too of those gallant young gentlemen, perfect in courteous kindliness, who ran the B.A.T. in Shih Chia Chuang.

The next day Buchanan and I and our following boarded the luxurious little mountain railway and went to T'ai Yuan Fu.

This railway, to me, who know nothing of such things, is a very marvel of engineering skill. There are great rugged mountains, steep and rocky, and the train winds its way through them, clinging along the sides of precipices, running through dark tunnels and cuttings that tower high overhead and going round such curves that the engine and the guard's van of a long train are going in exactly opposite directions. A wonderful railway, and doubly was I interested in it because before ever I came to China I had heard about it.

When there are disturbances in China it is always well for the foreign element to flee while there is yet time, for the sanctity of human life is not yet thoroughly grasped there, and there is always the chance that the foreigner may be killed first and his harmlessness, or even his value, discovered later. So in the revolution in the winter of 1910-1911, though all train traffic had stopped, the missionaries from T'ai Yuan Fu and those from the country beyond fled down this railway. A friend of mine, an artist, happened to be staying at a mission station in the mountains and made one of the party. It was the depth of a Shansi winter, a Continental winter, with the thermometer generally below -15° at the warmest part of the day, and the little band of fugitives came fleeing down this line on trollies worked by the men of the party. They stayed the nights at the deserted railway stations, whence all the officials had fled, and the country people in their faded blue cotton wadded coats came and looked at them and, pointing their fingers at them exactly as I have seen the folks in the streets of London do at a Chinaman or an Arab in an outlandish dress, remarked that these people were going to their death.

“Death! Death!” sounded on all sides. They, the country people, were peaceful souls; they would not have killed them themselves; they merely looked upon them as an interesting exhibit because they were foreign and they were going to die. That the audience were wrong the people on show were not quite as sure as they would have liked to be, and a single-line railway through mountainous country is by no means easy to negotiate on a trolly. They came to places where the line was carried upon trestles; they could see a river winding its way at the bottom of a rocky ravine far below them, and the question would be how to get across. It required more nerve than most of them had to walk across the skeleton bridge. The procedure seems to have been to give each trolly a good hard push, to spring upon it and to trust to Providence to get safely across to the firm earth upon the other side. The tunnels too, and the sharp curves, were hair-raising, for they knew nothing of what was happening at the other end of the line, and for all they could say they might have come full butt upon a train rushing up in the other direction.

Eventually they did get through, but with considerable hardship, and I should hesitate to say how many days that little company went without taking off their clothes. I thought of them whenever our train went into a tunnel, and I thought too of the gay girl who told me the story and who had dwelt not upon the discomfort and danger, but upon the excitement and exhilaration that comes with danger.

“I lived,” said she, “I lived,” and my heart went out to her. It is that spirit in this “nation of shopkeepers” that is helping us to beat the Germans.

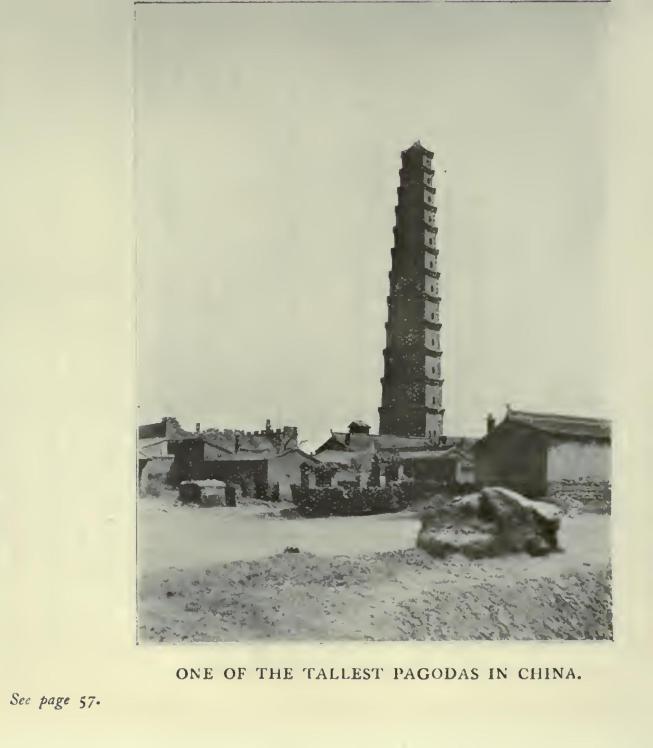

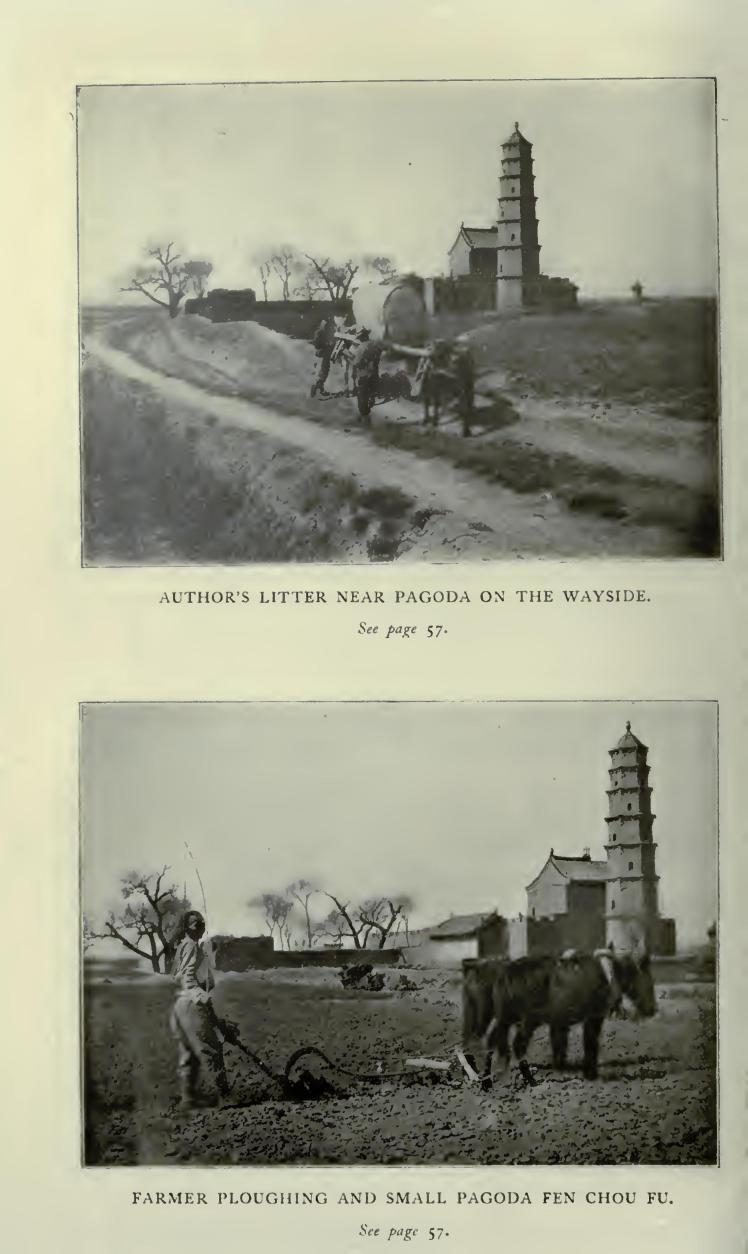

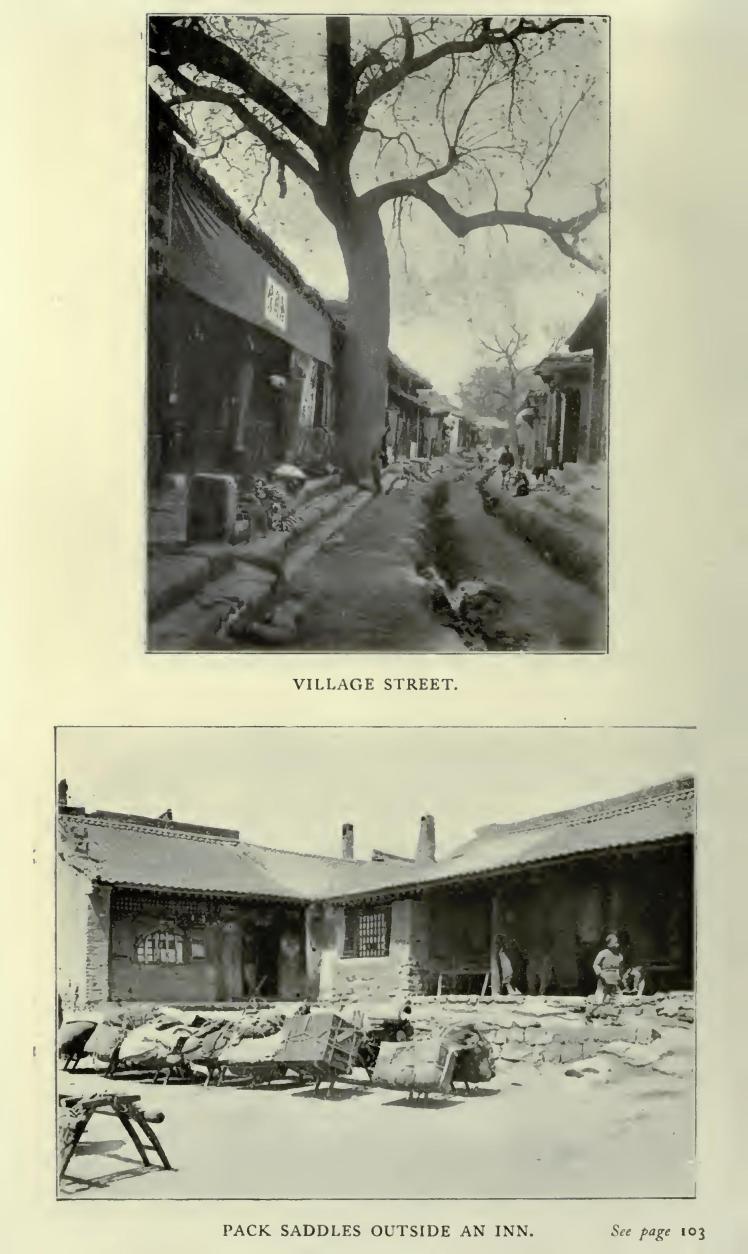

The scenery through which we went is beautiful—it would be beautiful in any land—and this in China, where I expected not so much beauty as industry. There were evidences of industry in plenty on every side. These people were brethren of the bandits who turned me north and they are surely the most industrious in the world. Wherever among these stony hills there was a patch of ground fit for cultivation, though it was tiny as a pocket handkerchief, it was cultivated. Everywhere I saw people at work in the fields, digging, weeding, ploughing with a dry cow or a dry cow and a donkey hitched to the primitive plough, or guiding trains of donkeys or mules carrying merchandise along the steep and narrow paths, and more than once I saw strings of camels, old-world camels that took me back before the days of written history. They kept to the valleys and evidently made their way along the river beds.

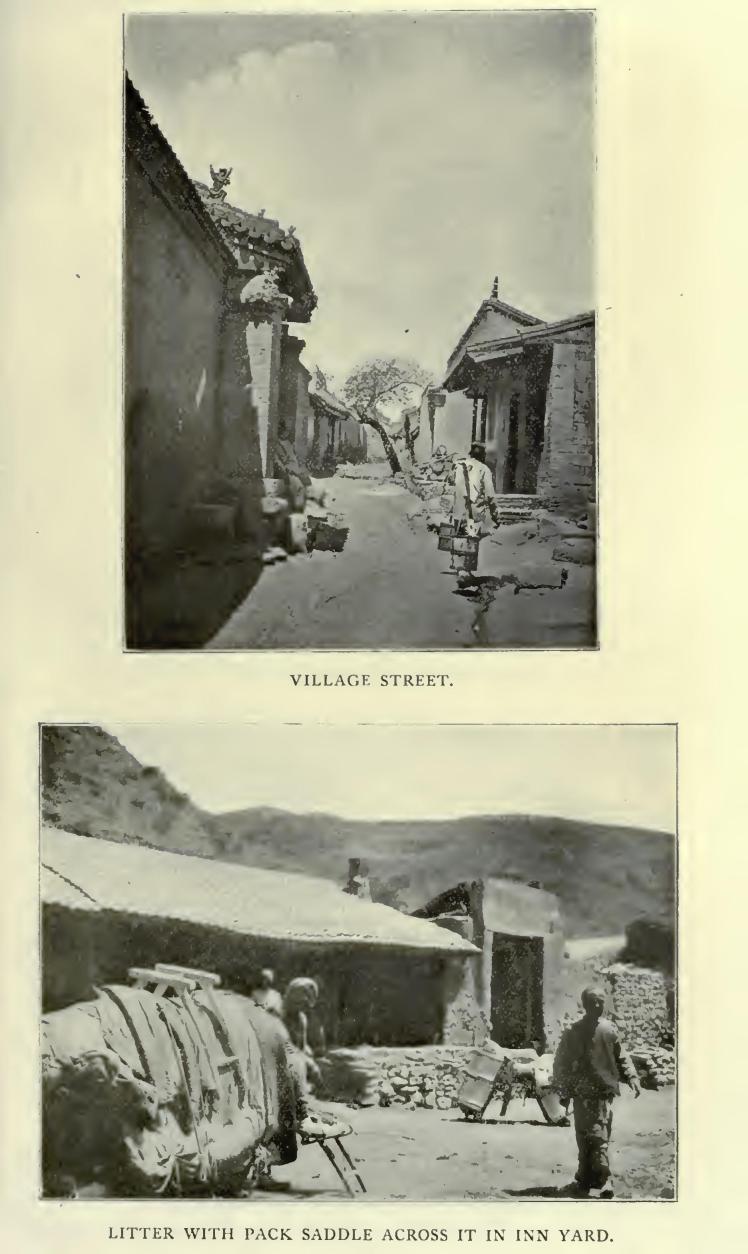

Through mountain sidings and tunnels we came at length to the curious loess country, where the friable land is cut into huge terraces that make the high hills look like pyramids carved in great clay-coloured steps, and now in April the green crops were already springing; another month and they would be banks of waving green. The people are poor, their faces were browned by the sun and the wind, their garments were scanty and ragged, and the original blue was faded till the men and the clothes were all the same monotonous clay colour of the surrounding country. The women I saw here were few, and only afterwards I found the reason. The miserably poor peasant of Shansi binds the feet of his women so effectually that to the majority movement is a physical impossibility.

We climbed up and up through the mountains into the loess country, and at last we were on the plateau, about four thousand feet above the sea-level, whereon is T'ai Yuan Fu, the capital of the province. There are other towns here too, little walled eities, and the train drew up at the stations outside the grey brick walls, the most ancient and the most modern, Babylon and Crewe meeting. Oh, I understand the need of those walled eities now I have heard so much about Pai Lang. There is a certain degree of safety behind those grey walls, so long as the robber bands are small and the great iron-bound gates ean keep them out, but dire is the fate of the city into which the enemy has penetrated, has fastened the gates and holds the people in a trap behind their own walls.

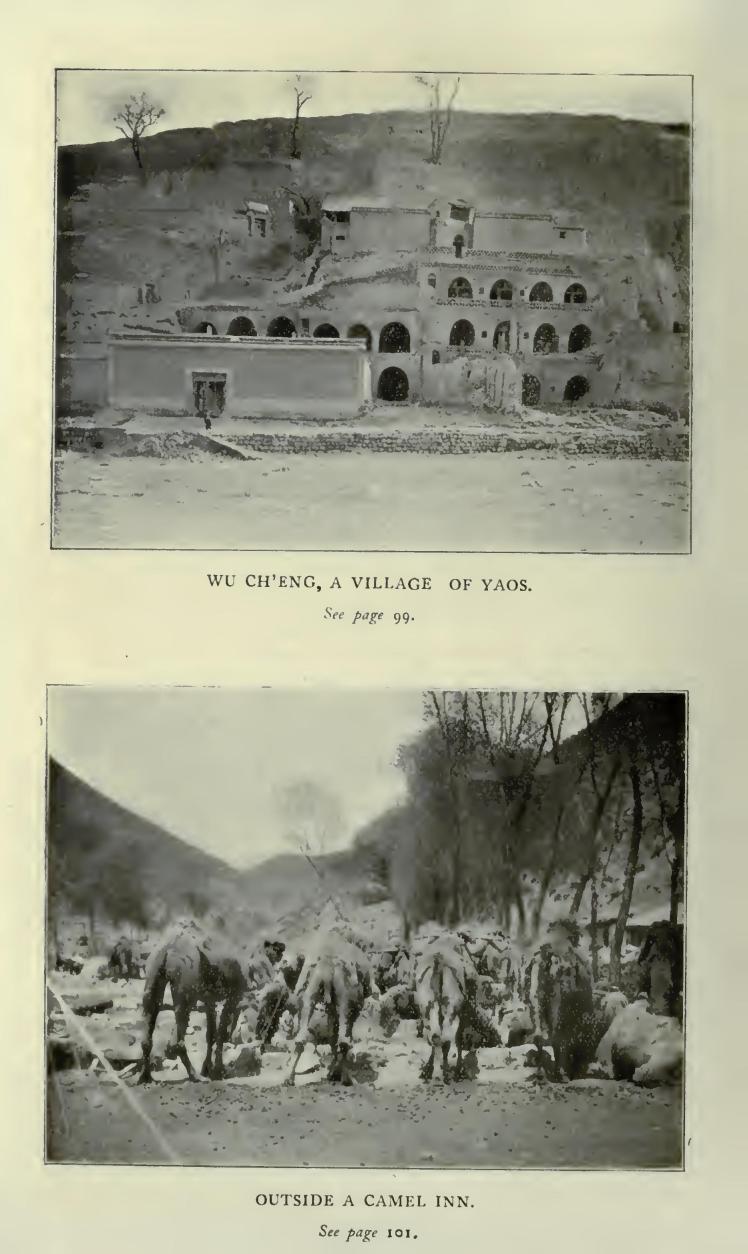

But these people were at peace; they were thinking of no robbers. Pai Lang was about five hundred miles away and the station platforms were crowded with would-be travellers with their belongings in bundles, and over the fence that shut off the platform hung a vociferating crowd waving white banners on which were inscribed in black characters the signs of the various inns, while each banner-bearer at the top of his voice advocated the charms of his own employer's establishment. The queue was forbidden for the moment, but many of these ragged touts and many of the other peasants still wore their heads shaven in front, for the average Chinaman, especially he of the poorer classes, is loath to give up the fashions of his forefathers.

Every railway platform was pandemonium, for every person on that platform yelled and shrieked at the top of his voice. On the main line every station was guarded by untidy, unkempt-looking soldiers armed with rifles, but there on this little mountain railway the only guards were policemen, equally unkempt, clad in very dusty black and white and armed with stout-looking bludgeons. They stood along the line at regular intervals, good-natured-looking men, and I wondered whether they would really be any good in an emergency, or whether they would not take the line of least resistance and join the attacking force.

All across the cultivated plain we went, where not an inch of ground is wasted, and at half-past five in the evening we arrived at T'ai Yuan Fu—arrived, that is, at the station outside the little South Gate.

T'ai Yuan Fu is a great walled city eight miles round, with five gates in the walls, gates that contrast strangely with the modern-looking macadamised road which goes up from the station. I don't know why I should feel that way, for they certainly had paved roads even in the days before history. Outside the walls are neat, perhaps forty feet high and of grey brick, and inside you see how these city walls are made, for they are the unfinished clay banks that have been faced in front, and when I was there in the springtime the grass upon them was showing everywhere and the shrubs were bursting into leaf. But those banks gave me a curious feeling of being behind the scenes.

I was met at the station by some of the ladies of the English Baptist Mission who had come to welcome me and to offer me, a total stranger to them, kindly hospitality, and we walked through the gate to the mission inside the walls. It was only a short walk, short and dusty, but it was thronged. All the roadway was crowded with rickshaws and carts waiting in a long line their turn to go underneath the gateway over which frowned a typical many-roofed Chinese watch tower, and as cart or rickshaw came up the men along with it were stopped by the dusty soldiery in black and grey and interrogated as to their business.

When I got out on to the platform I had looked up at the ancient walls clear-cut against the bright blue sky, and the women meeting me looked askance at Tsai Chih Fu, who, a lordly presence, stood behind me, with James Buchanan in his arms, a little black satin cap on his head and his pigtail hanging down his back.

“There is some little commotion in the town,” said Miss Franklin. “They are cutting off queues.”

The master of transport smiled tolerantly when they told him, and, taking off his cap, he wound his tightly round his head.

“I know,” he said in the attitude of a man of the world, “some people do not wear them now. But I have always worn one, and I like it,” and his manner said he would like to see the person who would dare dictate to him in what manner he should wear his hair. He could certainly have put up a good fight.

It was not needed. He passed through unchallenged; he was a quietly dressed man who did not court notice and his strapping inches were in his favour. He might well be passed over when there were so many slighter men more easily tackled. One man riding along in a rickshaw I saw put up a splendid fight. At last he was hauled out of his carriage and his little round cap tossed off his head, and then it was patent his queue could not be cut, for he was bald as a billiard ball! The Chinese do understand a joke, even a mob. They yelled and howled with laughter, and we heard it echoing and re-echoing as we passed under the frowning archway, tramping across many a dusty coil of coarse black hair roughly shorn from the heads of the luckless adherents to the old fashion. The missionaries said that Tsai Chih Fu must be the only man in T'ai Yuan Fu with a pigtail and that it would be very useful to us as we went farther west, where they had not yet realised the revolution. They doubted if he would be able to keep it on so strict was the rule, but he did—a tribute, I take it, to the force of my “master of transport.”

The ladies lived in a Chinese house close under the walls. There is a great charm about these houses built round courtyards in the Chinese style; there is always plenty of air and sunshine, though, as most of the rooms open into the courtyard only, I admit in rough weather they must sometimes be awkward, and when—as is always the case in Shansi in winter-time—the courtyard is covered with ice and snow, and the thermometer is far below zero for weeks at a time, it is impossible to go from bedroom to sitting-room without being well wrapped up. And yet, because China is not a damp country, it could never be as awkward as it would be in England, and for weeks at a time it is a charming arrangement. Staying there in April, I found it delightful. Buchanan and I had a room under a great tree just showing the first faint tinge of green, and I shall always be grateful for the kindly hospitality those young ladies gave me.

From there we went out and saw T'ai Yuan Fu, and another kindly missionary engaged muleteers for me and made all arrangements for my journey across Shansi and Shensi and Kansu to Lan Chou Fu.

But T'ai Yuan Fu is not a nice town to stay in.

“The town,” said the missionaries, “is progressive and anti-foreign.” It is. You feel somehow the difference in the attitude of the people the moment you set foot inside the walls. It seems to me that if trouble really came it would be an easy matter to seize the railway and cut off the foreign missionaries from all help, for it is at least a fortnight away in the mountains.

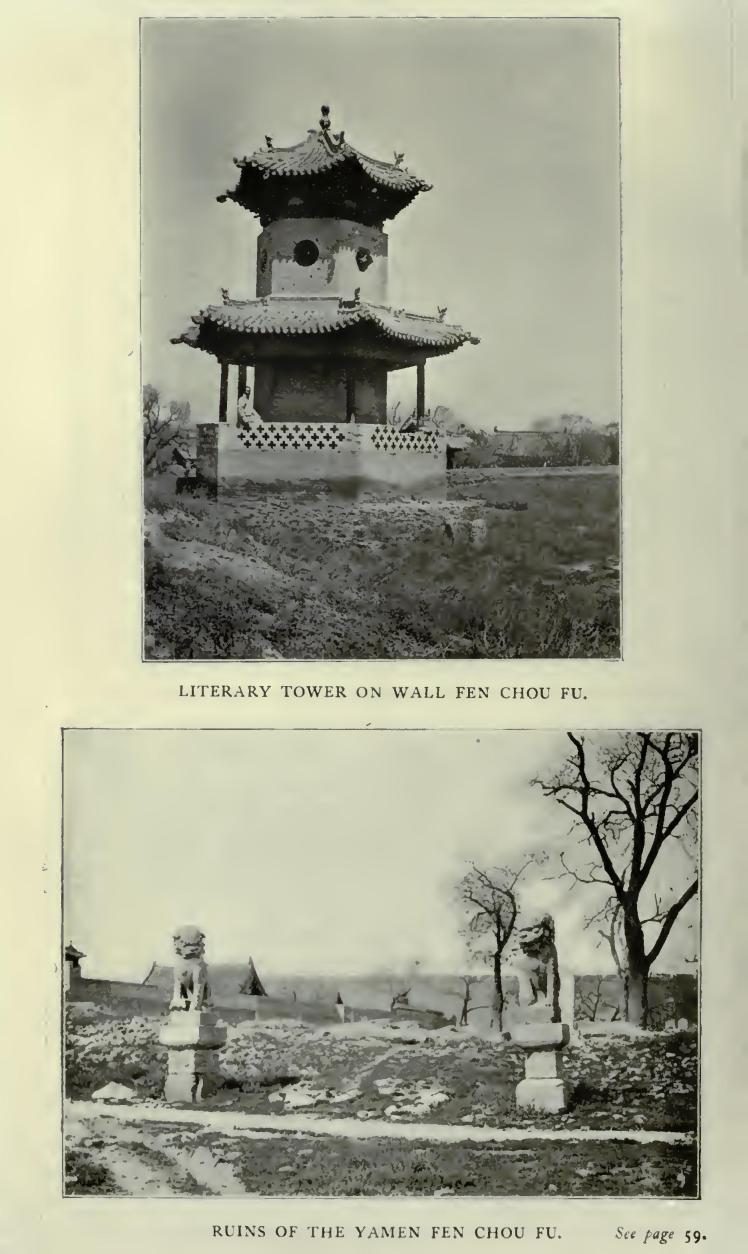

They suffered cruelly at the Boxer time: forty men, women and little helpless children were butchered in cold blood in the yamen, and the archway leading to the hospital where Miss Coombs the schoolmistress was deliberately burned to death while trying to guard and shelter her helpless pupils still stands. In the yamen, with a refinement of torture, they cut to pieces the little children first, and then the women, the nuns of the Catholic Church the fierce soldiery dishonoured, and finally they slew all the men. Against the walls in the street stand two miserable stones that the Government were forced to put up to the memory of the foreigners thus ruthlessly done to death, but a deeper memorial is engraven on the hearts of the people. Some few years later the tree underneath which they were slain was blasted by lightning and half destroyed, and on that very spot, during the recent revolution, the Tao Tai of the province was killed.

“A judgment!” said the superstitious people. “A judgment!” say even the educated.

And during the late revolution the white people shared with the inhabitants a terribly anxious time. Shut up in the hospital with a raging mob outside, they waited for the place to be set on fire. The newest shops in the principal streets were being looted, the Manchu city—a little walled city within the great city—was destroyed, and though they opened the gates and told the Manchus they might escape, the mob hunted down the men as they fled and slew them, though, more merciful than Hsi An Fu, they let the women and children escape. Men's blood was up, the lust of killing was upon them, and the men and women behind the hospital walls trembled.

“We made up our minds,” said a young missionary lady to me, “that if they fired the place we would rush out and mingle in the mob waiting to kill us. They looked awful. I can't tell you how they looked, but it would have been better than being burned like rats in a trap.”

A Chinese crowd, to my Western eyes, unkempt, unwashed, always looks awful; what it must be like when they are out to kill I cannot imagine.

And then she went on: “Do you know, I was not really as much afraid as I should have thought I would have been. There was too mueh to think about.” Oh, merciful God! I pray that always in such moments there may be “too much to think about.”

The mob looted the city. They ruined the university. They destroyed the Manehus. But they spared the foreigners; and still there flourishes in the town a mission of the English Baptists and another of the Catholics, but when I was there the town had not yet settled down. There was unrest, and the missionaries kept their eyes anxiously on the south, on the movements of Pai Lang. We thought about him at Pao Ting Fu, but here the danger was just a little nearer, help just a little farther away. Besides, the people were different. They were not quite so subservient, not quite so friendly to the foreigner, it would take less to light the tinder.

For myself, I was glad of the instinct that had impelled me to engage as servant a man of inches. I dared never walk in the streets alone as I had been accustomed to in Pao Ting Fu. It marks in my mind the jumping-off place. Here I left altogether the civilisation of the West and tasted the age-old civilisation of the East, the civilisation that was in full swing when my ancestors were naked savages hunting the deer and the bear and the wolf in the swamps and marshes of Northern Europe. I had thought I had reached that civilisation when I lived in Peking, when I dwelt alone in a temple in the mountains, when I went to Pao Ting Fu, but here in T'ai Yuan Fu the feeling deepened. Only the mission stations stood between me and this strange thing. The people in the streets looked at me askance, over the compound wall came the curious sounds of an ancient people at work, the shrieking of the greased wheel-barrows, the beating of gongs, the whir of the rattle of the embroidery silk seller, the tinkling of the bells that were hung round the necks of the donkeys and the mules, the shouting of the hucksters selling scones and meat balls, all the sounds of an industrious city, and I was an outsider, the alien who was something of a curiosity, but who anyhow was of no account. Frankly, I don't like being of no account. As a matter of fact, I shocked all Chinese ideas of correct deportment. When a well-bred Chinese gentleman arrives at a strange place, he does not look around him, he shows no curiosity whatever in his surroundings, he retires to his room, his meal is brought to him and he remains quietly in his resting-place till it is time for him to take his departure, and what applies to a man, applies, of course, in an exaggerated degree, to a woman. Now I had come to see China, and I made every effort in my power to see all I could. I tremble to think what the inhabitants of Shansi must have thought of me! Possibly, since I outraged all their canons of decency, I was lucky in that they only found me of no account.

All the while I was in T'ai Yuan Fu I was exceedingly anxious about the measure of safety for a foreign woman outside the walls, and opinions differed as to the wisdom of my venture, but, on the whole, those I consulted thought I would be all right. They rather envied me, in fact, the power to go wandering, but on one point they were very sure: it was a pity Dr Edwards, the veteran missionary doctor, was not there, because he knew more about China and travelling there than all the rest of them put together. But he had gone out on his own account and was on the way to Hsi An Fu, the town I had given up as hopeless. He did not propose to approach it through the Tungkwan, but from the north, and they did not expect him to have any difficulty.

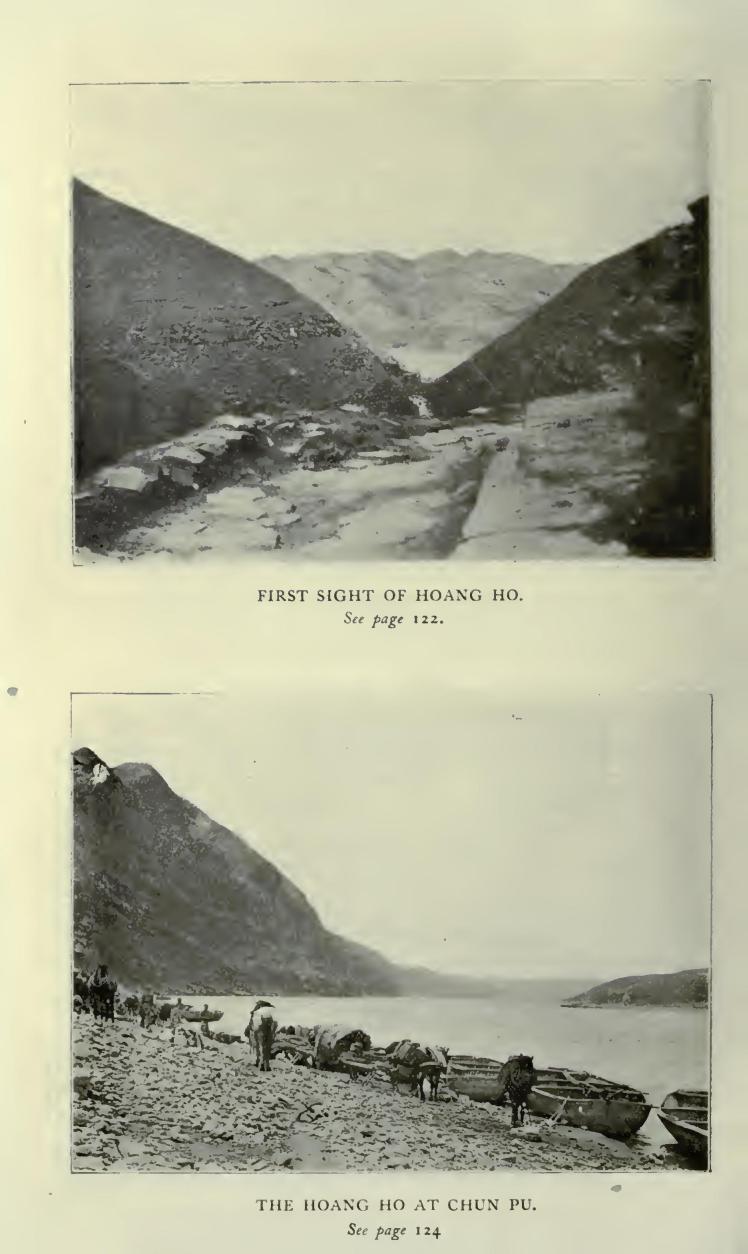

Then I found I had not brought enough money with me and the missionaries lent me more, and they engaged muleteers with four mules and a donkey that were to take me across the thousand miles that lay between the capital of Shansi and that of Kansu. Two men were in charge, and the cost of getting there, everything included—the men to feed themselves and their animals and I only to be responsible for the feeding and lodging of my own servants—was exactly eighteen pounds. It has always seemed to me ridiculously cheap. Money must go a long way in China for it to be possible for two men to take four mules and a donkey laden a thousand miles, and then come back unladen and keep themselves by the way, for so small a sum.

So I sent off my servants the day before, then Buchanan and I bade good-bye to the missionaries and went the first day's journey back along the line to Yu Tze, where the road started for the Yellow River, and as I left the train and was taken by Tsai Chih Fu and Mr Wang to the enclosure of the inn where they had spent the night I felt that I had indeed left the West behind, and the only companion and friend I had was James Buchanan. It was lucky he was a host in himself.

I was to ride a pack-mule. Now riding a pack-mule at any time is an unpleasant way of getting along the road. I know no more uncomfortable method. It is not quite as comfortable as sitting upon a table with one's legs dangling, for the table is still, the mule is moving, and one's legs dangle on either side of his neck. There are neither reins nor stirrups, and the mule goes at his own sweet will, and in a very short time your back begins to ache, after a few hours that aching is intolerable. To get over this difficulty the missionary had cut the legs off a chair and suggested that, mounted on the pack, I might sit in it comfortably. I don't know whether I could, for the mule objected.

It was a sunny morning with a bright blue sky above, and all seemed auspicious except my mule, who expressed in no measured language his dislike to that chair. Tsai Chih Fu had no sooner hoisted me into it than up he went on his hind legs and, using them as a pivot, stood on end pawing the air. Everybody in the inn-yard shrieked and yelled except, I hope, myself, and then Tsai Chih Fu, how I know not, rescued me from my unpleasant position, and thankfully I found myself upon the firm ground again. He was a true Chinese mule and objected to all innovations. He stood meekly enough once the chair was removed.

I wanted to cross Asia and here I was faced with disaster at the very outset! Finally I was put upon the pack minus the chair, Buchanan was handed up to me and nestled down beside me, and the procession started. My heart sank. I don't mind acknowledging it now. I had at least a thousand miles to go, and within half-an-hour of the start I had thoroughly grasped the faet that of all modes of progression a pack-mule is the most abominable. There are no words at my command to express its discomforts.

Very little did I see of the landscape of Shansi that day. I was engaged in hanging on to my pack and wondering how I could stick it out. We passed along the usual hopeless cart-track of China. I had eschewed Peking carts as being the very acme of misery, but I was beginning to reflect that anyhow a cart was comparatively passive misery while the back of a pack-mule was decidedly active. Buchanan was a good little dog, but he mentioned several times in the course of that day that he was uncomfortable and he thought I was doing a fool thing. I was much of his opinion.

The day was never ending. All across a plain we went, with rough fields just showing green on either hand, through walled villages, through little towns, and I cared for nothing, I was too intent on holding on, on wishing the day would end, and at last, as the dusk was falling, the muleteer pointed out, clear-cut against the evening sky, the long wralls of a large town—Taiku. At last! At last!

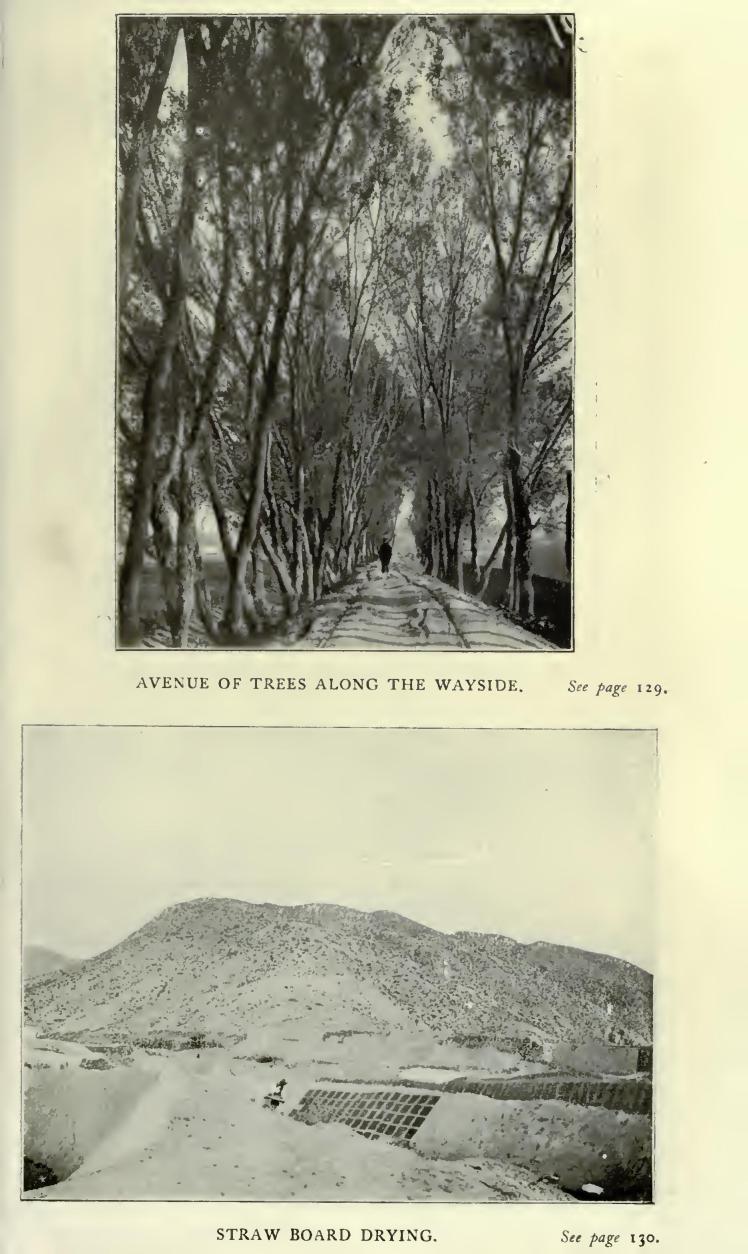

I was to stay the night at a large mission school kept by a Mr and Mrs Wolf, and I only longed for the comfort of a bed, any sort of a bed so long as it was flat and warm and kept still. We went on and on, we got into the suburbs of the town, and we appeared to go round and round, through an unending length of dark, narrow streets, full of ruts and holes, with the dim loom of houses on either side, and an occasional gleam of light from a dingy kerosene lamp or Chinese paper lantern showing through the paper windows.

Again and again we stopped and spoke to men who were merely muffled shapeless figures in the darkness, and again we went on. I think now that in all probability neither Tsai Chih Fu nor Mr Wang understood enough of the dialect to make the muleteers or the people of whom we inquired understand where we wanted to go, but at last, more probably by good luck than good management, somebody, seeing I was a foreigner, sent us to the foreigners they knew, those who kept a school for a hundred and twenty-five boys in the lovely Flower Garden. It certainly was lovely, an old-world Chinese house, with little courtyards and ponds and terraces and flowers and trees—and that comfortable bed I had been desiring so long. As we entered the courtyard in the darkness and Tsai Chili Fu lifted me down, the bed was the only thing I could think of.

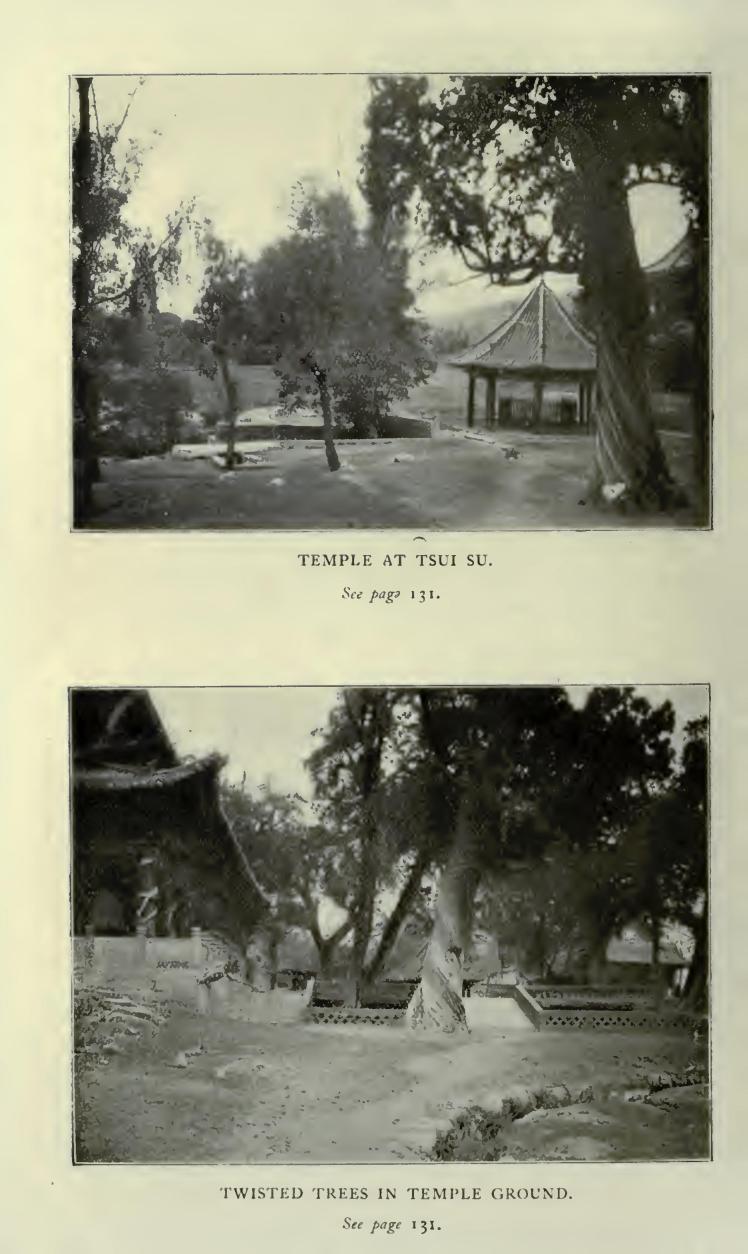

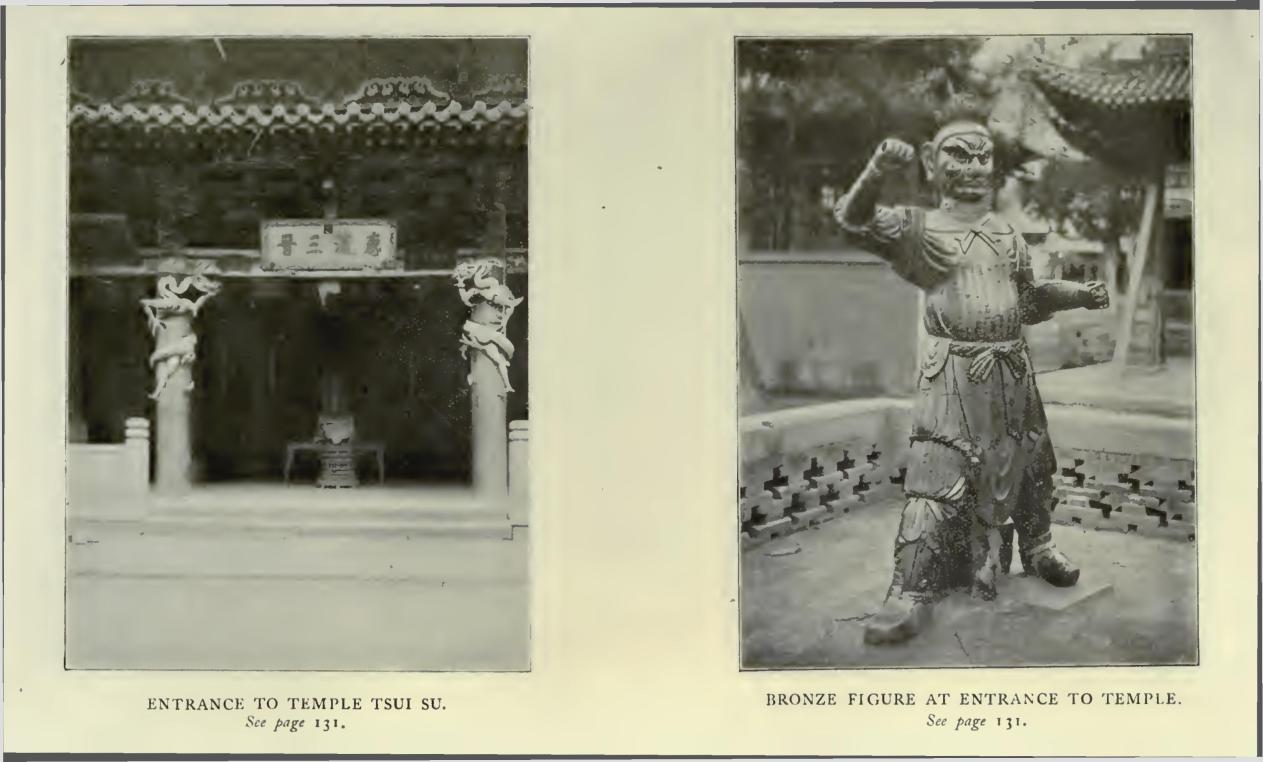

And yet next day I started again—I wonder now I dared—and we skirted the walls of Taiku. We had gone round two sides and then, as I always do when I am dead-tired, I had a bad attack of breathlessness. Stay on that pack I knew I could not, so I made my master of transport lift me down, and I sat on a bank for the edification of all the small boys in the district who, even if they had known how ill I felt, probably would not have cared, and I deeided there and then that pack-mule riding was simply impossible and something would have to be done. Therefore, with great difficulty, I made my way baek to the mission school and asked Mr Wolf what he would recommend.

Again were missionaries kindness itself to me. They sympathised with my trouble, they took me in and made me their guest, refusing to take any money for it, though they added to their kindness by allowing me to pay for the keep of my servants, and they strongly recommended that I should have a litter. A litter then I decided I would have.

It is, I should think, the very earliest form of human conveyance. It consists of two long poles laid about as far apart as the shafts of an ordinary cart, in the middle is hung a coarse-meshed rope net, and over that a tilt of matting—the sort of stuff we see tea-chests covered with in this country. Into the net is tumbled all one's small impedimenta—clothes-bags, kettles, anything that will not conveniently go on mule-back; the bedding is put on top, rugs and cushions arranged to the future inmate's satisfaction, then you get inside and the available people about are commandeered to hoist the concern on to the backs of the couple of mules, who object very strongly. The head of the one behind is in the shafts, and the ends rest in his pack-saddle, and the hind quarters of the one in front are in the shafts, just as in an ordinary buggy. Of course there are no reins, and at first I felt very much at the mercy of the mules, though I am bound to say the big white mule who conducted my affairs seemed to thoroughly understand his business. Still it is uncomfortable, to say the least of it, to find yourself going, apparently quite unattended, down steep and rocky paths, or right into a rushing river. But on the whole a litter is a very comfortable way of travelling; after a pack-mule it was simply heaven, and I had no doubts whatever that I could comfortably do the thousand miles, lessened now, I think, by about thirty, that lay before me. If I reached Lan Chou Fu there would be time enough to think how I would go on farther. And here my muleteers had me. When I arranged for a litter, I paid them, of course, extra, and I said another mule was to be got to carry some of the loads. They accepted the money and agreed. But I may say that that other mule never materialised. I accepted the excuse when we left Taiku that there was no other mule to be hired, and by the time that excuse had worn thin I had so much else to think about that I bore up, though not even a donkey was added to our equipment.

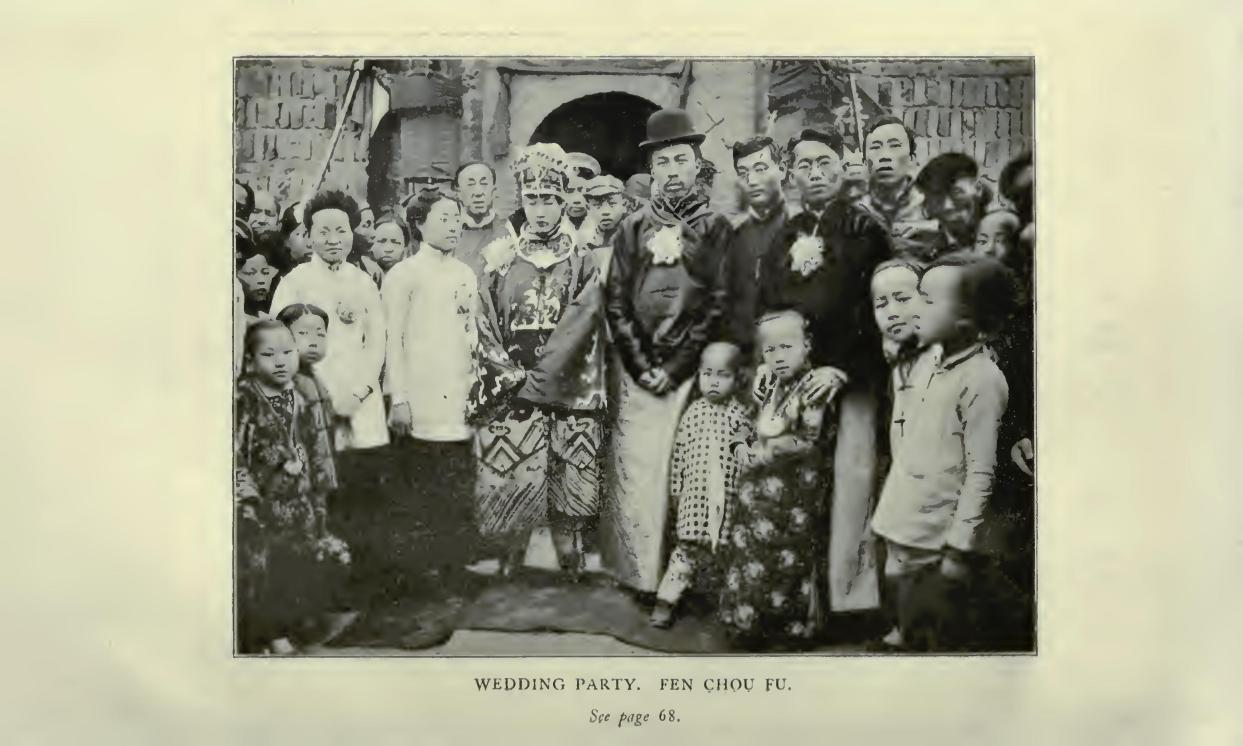

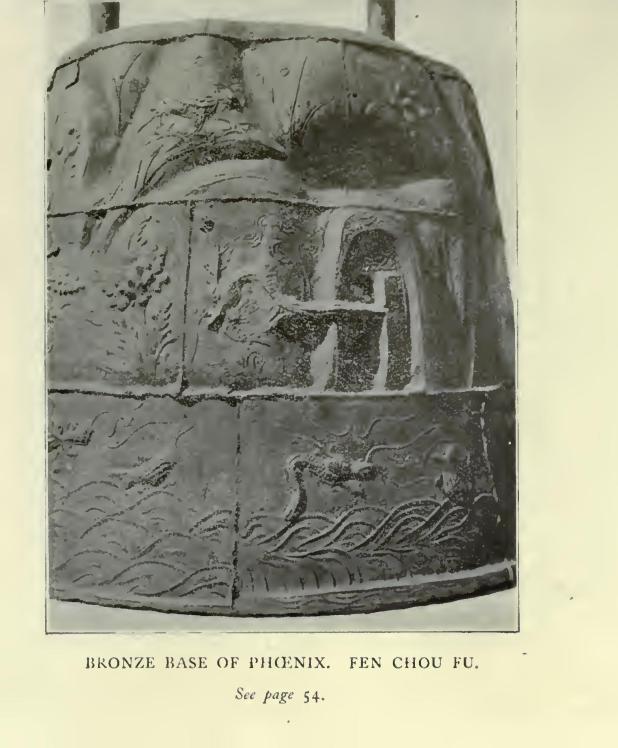

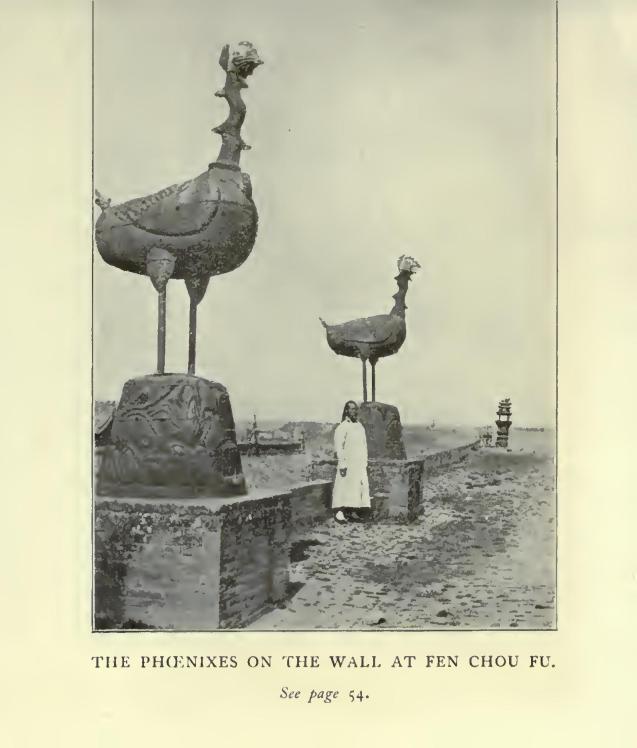

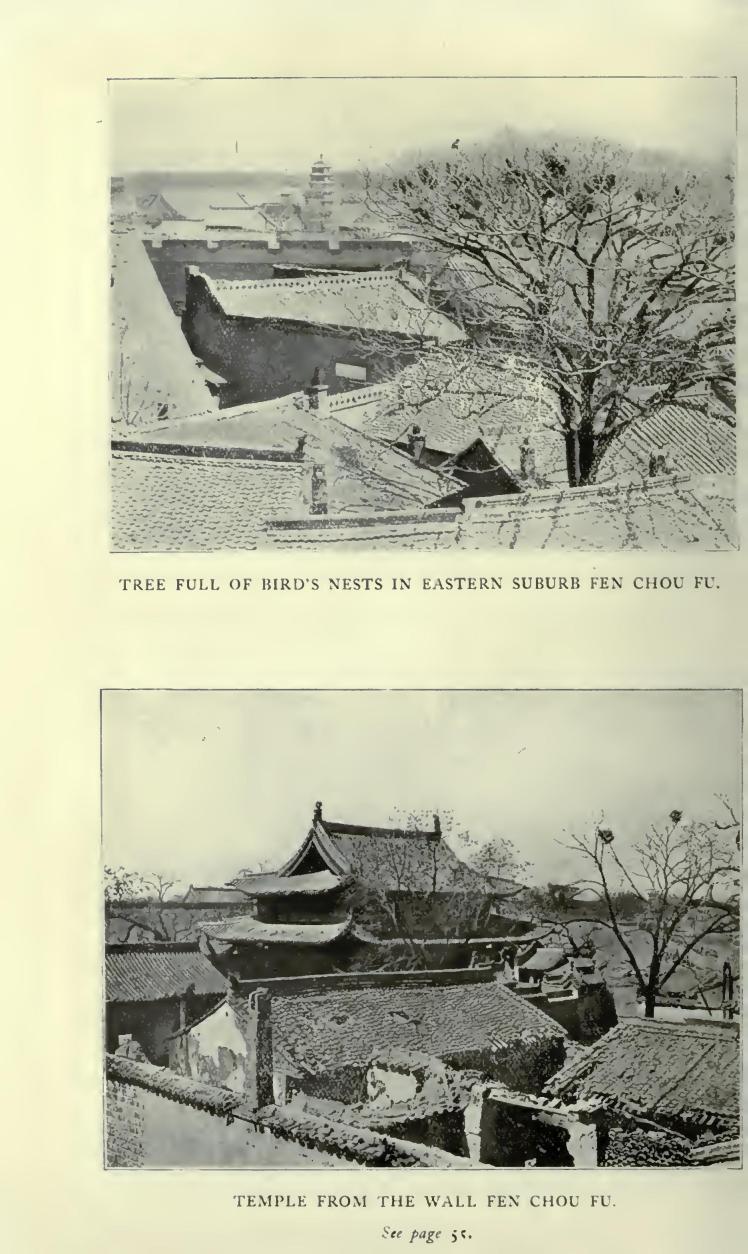

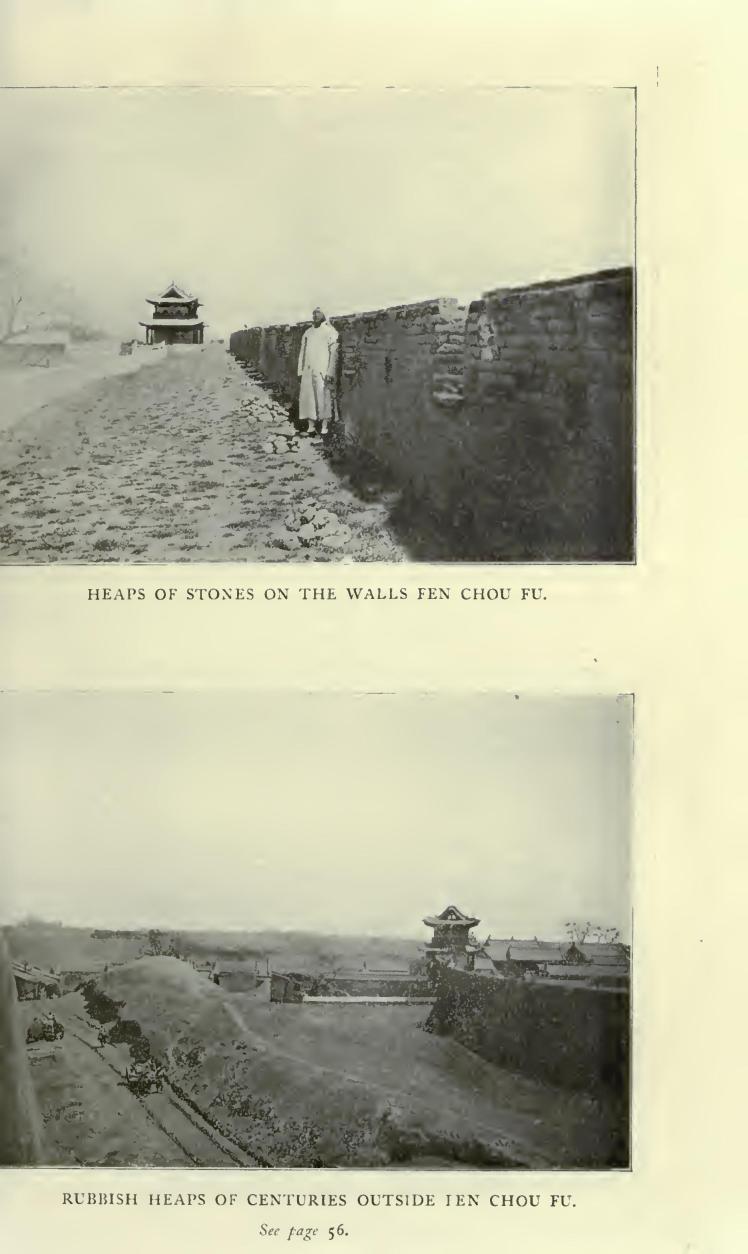

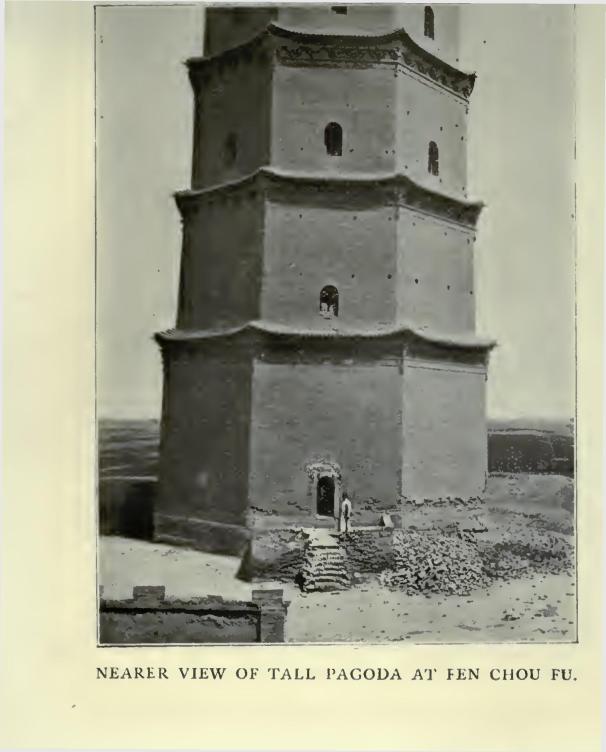

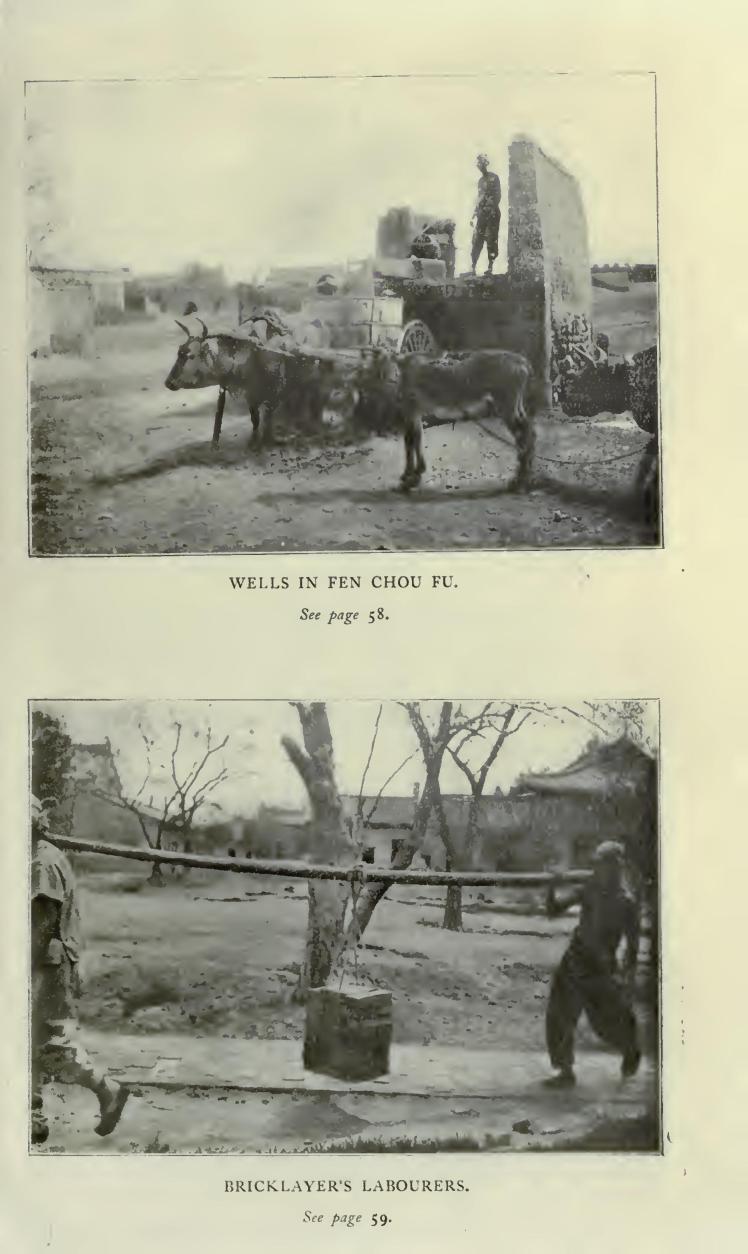

Money I took with me in lumps of silver, sycee—shoes, they called them—and a very unsatisfactory way it is of carrying cash. It is very heavy and there is no hiding the fact that you have got it. We changed little bits for our daily needs as we went along, just as little as we could, because the change in cash was an intolerable burden. On one occasion in Fen Chou Fu I gave Tsai Chih Fu a very small piece of silver to change and intimated that I would like to see the result. That piece of silver I reckon was worth about five shillings, but presently my master of transport and one of the muleteers came staggering in and laid before me rows and rows of cash strung on strings! I never felt so wealthy in my life. After that I never asked for my change. I was content to keep a sort of general eye on the expenditure, and I expect the only leakage was the accepted percentage which every servant levies on his master. 'When they might easily have cheated me, I found my servants showed always a most praiseworthy desire for my welfare. And yet Mr Wang did surprise me occasionally. While I was in Pao Ting Fu I had found it useful to learn to count in Chinese, so that roughly I knew what people at the food-stalls were charging me. On one occasion I saw some little cakes powdered with sesame seed that I thought I should like and I instructed Mr Wang to buy me one. I heard him ask the price and the man say three cash, and my interpreter turned to me and said that it was four! I was so surprised I said nothing. It may have been the regulation percentage, and twenty-five per cent is good anywhere, but at the moment it seemed to me extraordinary that a man who considered himself as belonging to the upper classes should find it worth his while to do me out of one cash, which was worth—no, I give it up. I don't know what it was worth. 10.53 dollars went to the pound when I was in Shansi and about thirteen hundred cash to the dollar, so I leave it to some better mathematician than I am to say what I was done out of on that occasion.

There was another person who was very pleased with the litter and that was James Buchanan. Poor little man, just before we left the Flower Garden he was badly bitten by a dog, so badly he could no longer walk, and I had to carry him on a cushion alongside me in the litter. I never knew before how dearly one could love a dog, for I was terrified lest he should die and I should be alone in the world. He lay still and refused to eat, and every movement seemed to pain him, and whenever I struck a missionary—they were the only people, of course, with whom I could converse—they always suggested his back was broken.

I remember at Ki Hsien, where I was entertained most hospitably, and where the missionary's wife was most sympathetic, he was so ill that I sat up all night with him and thought he would surely die. And yet in the morning he was still alive. He moaned when we lifted him into the litter and whined pitifully when I got out, as I had to several times to take photographs.

“Don't leave me, don't leave me to the mercy of the Chinese,” he said, and greeted me with howls of joy when I returned. It was a great day for both of us when he got a little better and could put his pretty little black and white head round the tilt and keep his eye upon me while I worked. But really he was an ideal patient, such a good, patient little dog, so grateful for any attention that was paid him, and from that time he began to mend and by the time I reached Fen Chou Fu was almost his old gay happy little self again.

Taiku is a dying town over two thousand years old, and I have before seen dead towns in China. Fewer and fewer grow the inhabitants, the grass grows in the streets, the bricks fall away from the walls, the houses fall down, until but a few shepherds or peasant farmers dwell where once were the busy haunts of merchants and tradesmen.

From Taiku I went on across the rich Shansi plain. Now in the springtime in the golden sunshine the wheat was just above the ground, turning the land into one vivid green, the sky was a cloudless blue, and all was bathed in the golden sunshine of Northern China. The air was clear and invigorating as champagne. “Every prospect pleases,” as the hymn says, “and only man is vile.” He wasn't vile; really I think he was a very good fellow in his own way, which was in a dimension into which I have never and am never likely to enter, but he was certainly unclean, ignorant, a serf, poverty-stricken with a poverty we hardly conceive of in the West, and the farther away I found myself from T'ai Yuan Fu the more friendly did I find him. This country was not like England, where until the last four years has been in the memory of our fathers and our fathers' fathers only peace. Even now, now as I write, when the World War is on, an air raid is the worst that has befallen the home-staying citizens of Britain. But Shansi has been raided again and again. Still the land was tilled, well tilled; on every hand were men working hard, working from dawn to dark, and working, to a stranger's eyes, for the good of the community, for the fields are not divided by hedge or fence; there is an occasional poplar or elm, and there are graves everywhere, but there is nothing to show where Wang's land ends and Lui's begins. All through the cultivated land wanders, apparently without object, the zigzag track of sand and ruts and stones known as the Great South Road, impossible for anything with wheels but a Chinese cart, and often impossible for that. There are no wayside cottages, nothing save those few trees to break the monotony, only here and there is a village sheltering behind high walls, sometimes of mud, but generally of brick, and stout, substantial brick at that; and if, as is not infrequent, there is a farmhouse alone, it, too, is behind high brick walls, built like a baronial castle of mediaeval times, with a look-out tower and room behind the walls not only for the owner's family even unto the third and fourth generation, but for all his hinds and his dependents as well. The whole is built evidently with a view to defence, and built apparently to last for hundreds of years. For Shansi is worth raiding. There is oil and there is wheat in abundance. There is money too, much of which comes from Mongolia and Manchuria. The bankers (the Shansi men are called the Jews of China) wander across and trade far into Russian territory while still their home is in agricultural Shansi, and certain it is that any disturbances in these countries, even in Russia, affect the prosperity of Shansi. I wonder if the Russian Revolution has been felt there. Very probably.

Shansi is rich in other things too not as yet appreciated by the Chinaman. She has iron and copper and coal that has barely been touched, for the popular feeling is against mining. They say that no part of the globe contains such stores of coal. I hesitate about quoting a German, but they told me that Baron Reichthoffen has said that this province has enough coal to supply the world for two thousand years at the present rate of consumption. I haven't the faintest notion whether the Baron's opinion is worth anything, but if it is, it is no wonder that Germany, with her eye for ever on the main chance, has felt deeply being thrust out of China.

With ample coal, and with iron alongside it, what might not Shansi be worth to exploit!

Ki Hsien is a little walled town five li round. Roughly three li make a mile, but it is a little doubtful. For instance, from Taiku to Ki Hsien is fifty li, and that fifty li is sixteen miles, from Ki Hsien to Ping Yao is also fifty li, but that is only fourteen English miles. The land, say the Chinese, explaining this discrepancy, was measured in time of famine when it wasn't of any value! A very Chinese explanation.

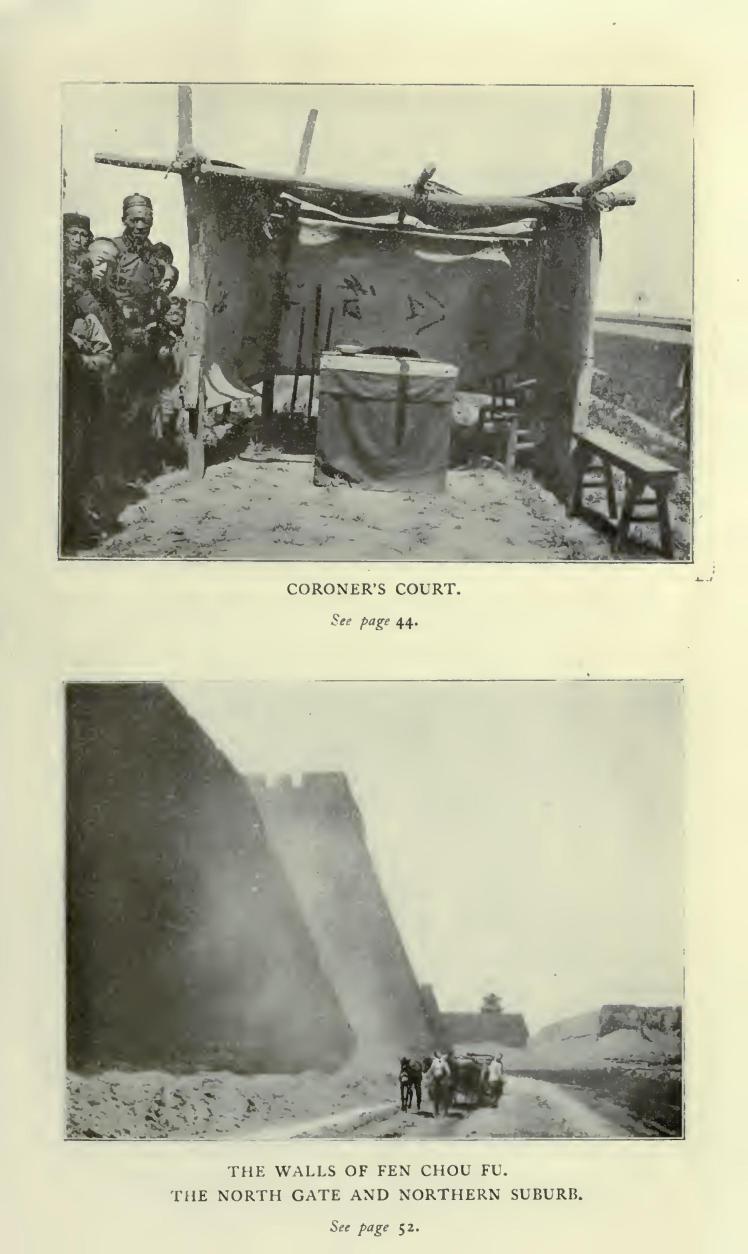

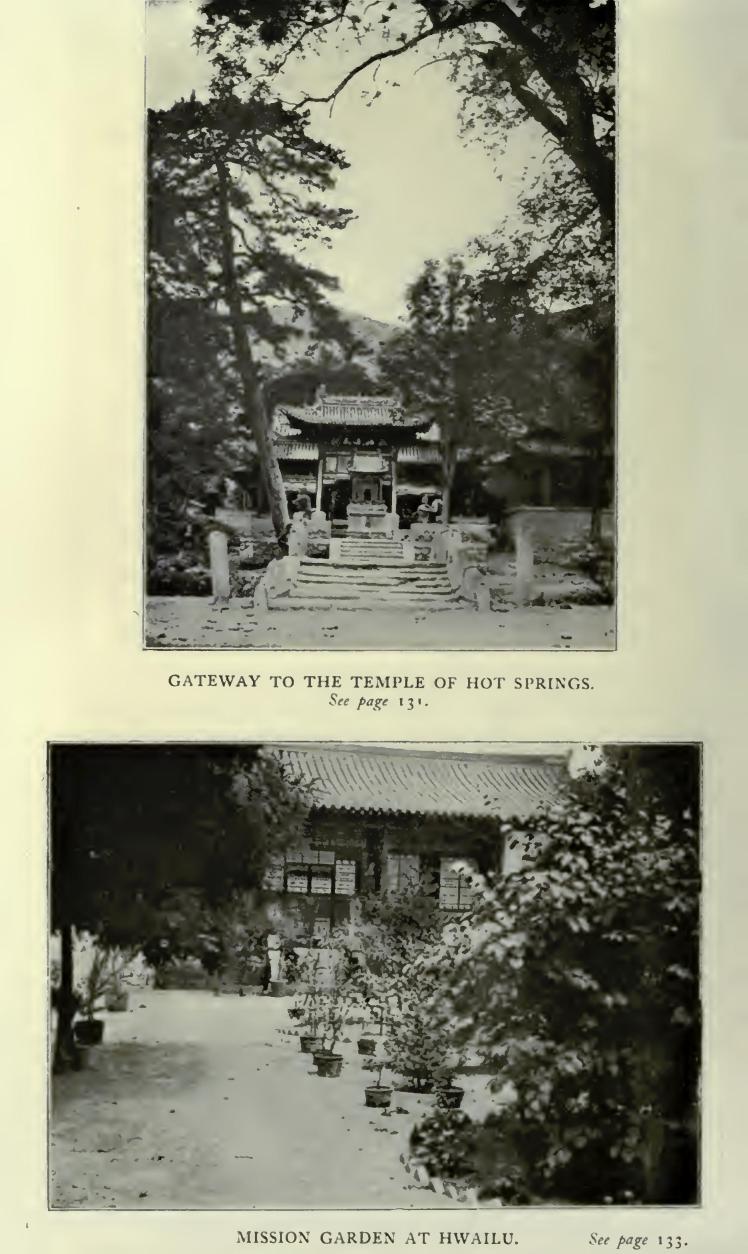

The city of Ki Hsien is very, very crowded; there were hundreds of tiny courtyards and flat roofs. In the picture of the missionary's house I have not been able to get the roof in because the courtyard—and it was a fairly large courtyard as courtyards in the city go—was not big enough. I stood as far away as I possibly could. Mr and Mrs Falls belonged to the Chinese Inland Mission and the house they lived in was over three hundred years old. Like many of the houses in Shansi, it was two storeys high and, strangely enough, a thing I have never seen anywhere else, the floors upstairs were of brick.

I do not know how I would like to live in such a crowded community, but it has its advantages on occasion. At the time of the revolution, when those missionaries who had come through the Boxer times were all troubled and anxious about their future, the Falls decided to stay on at their station, and a rich native doctor, a heathen, but a friend, who lived next door, commended that decision.

“Why go away?” said he. “Your courtyard adjoins mine. If there is trouble we put up a ladder and you come over to us.”

And there was hint of trouble then. As we sat at supper there came in the Chinese postman in his shabby uniform of dirty blue and white, with his large military cap pushed on the back of his head, and he brought to the Falls a letter from Dr Edwards, the missionary doctor all foreign T'ai Yuan Fu thought I ought to meet.

When I was within reach of the Peking foreign daily papers they mentioned Pai Lang as one might mention a burglar in London, sandwiching him in between the last racing fixtures or the latest Cinema attraction, but from a little walled town within a day's march of Hsi An Fu the veteran missionary wrote very differently, and we in this other little walled town read breathlessly.

White Wolf had surrounded Hsi An Fu, he said; it was impossible to get there and he was returning.

The darkness had fallen, the lamp in the middle of the table threw a light on the letter and on the faces of the middle-aged missionary and his wife who pored over it. It might mean so much to them. It undoubtedly meant much to their friends in Hsi An Fu, and it meant much to me, the outsider who had but an hour ago walked into their lives. For I began to fear lest this robber might affect me after all, lest in coming north I was not going to outflank him. According to Dr Edwards, he had already taken a little walled city a hundred li—about a day's journey—north-west of Hsi An Fu, and when 'White Wolf took a town it meant murder and rapine. And sitting there in the old Chinese room these two people who knew China told me in no measured terms what might happen to a woman travelling alone in disturbed country.

Missionaries, they said, never left their stations when the country was disturbed, they were safer at home, surrounded by their friends. Once the country is raided by a robber band—and remember this is no uncommon thing in China—all the bad characters in the country come to the fore, and robber bands that have nothing to do with the original one spring into existence, the cities shut their gates to all strangers, and passports are so much waste paper. Between ourselves, I have a feeling they always are in China. I could hardly tell the difference between mine and my agreement with my muleteers, and I have an uneasy feeling that occasionally the agreement was presented when it should have been the passport.

Now no one could be certain whether Pai Lang intended to take Lan Chou Fu, but it looked as if that were his objective. If he took the city it would not be much good my getting there, because the bankers would certainly not be able to supply me with money; even if he only raided the country round, it would be so disturbed that my muleteers would be bound to take alarm. If they left me, and they certainly would leave me if they thought there was a chance of their mules being taken, I should be done. It would spell finish not only to the expedition but to my life. A foreigner, especially a woman without money and without friends, would be helpless in China. Why should the people help her? It takes them all they know to keep their own heads above water. And Kansu was always turbulent; it only wanted a match to set the fire alight. Air and Mrs Falls—bless them for their kindness and interest!—thought I should be mad to venture.

So there in the sitting-room which had been planned for a merchant prince and had come into the possession of these two who desired to bring the religion of the West to China I sat and discussed this new obstacle. After coming so far, laying out so much money, could I turn back when danger did not directly press? I felt I could not. And yet my hosts pointed out to me that if danger did directly threaten I would not be able to get away. If Pai Lang did take Lan Chou Fu, or even if he did not, it might well be worth his while to turn east and raid fertile Shansi. In a little town like Ki Hsien there was loot well worth having. In the revolution a banker there was held to ransom, and paid, as the people put it, thirty times ten thousand taels (a tael is roughly three shillings, according to the price of silver), and they said it was but a trifle to him—a flea-bite, I believe, was the exact term—and I ean well believe, in the multitude of worse parasites that afflict the average Chinaman, a flea-bite means much less than it does in England.

However, I didn't feel like giving up just yet, so I decided to go on to Fen Chou Fu, where was a big American mission, and see what they had to say about the matter. If then I had to flee, the missionaries would very likely be fleeing too, and I should have company.

And the very next day I had what I took for a warning.

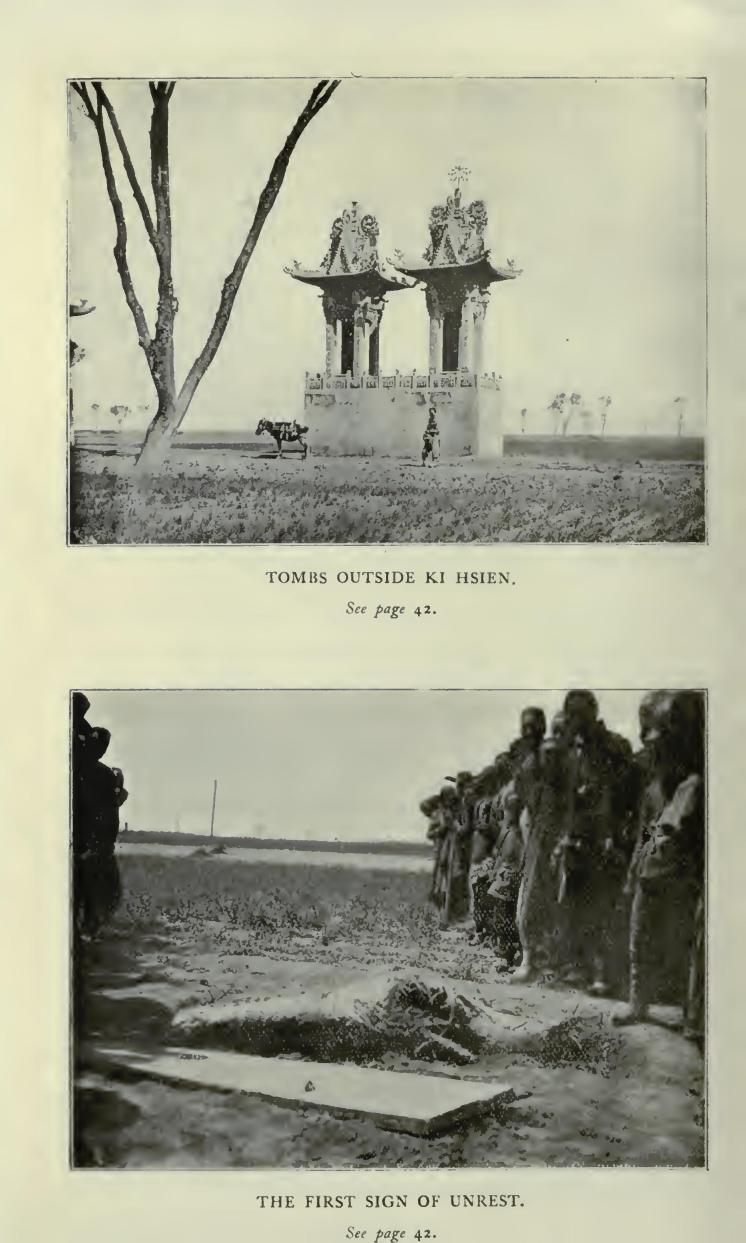

It was a gorgeous day, a cloudless blue sky and brilliant sunshine, and I passed too many things of interest worth photographing. There were some extraordinary tombs, there was a quaint village gateway—the Gate of Everlasting Peace they call it—but I was glad to get back into my litter and hoped to stay there for a little, for getting out of a litter presents some difficulties unless you are very active indeed. It is a good long drop across the shafts on to the ground; the only other alternative is to drop down behind the mule's hind quarters and slip out under those shafts, but I never had sufficient confidence in my mule to do that, so that I generally ealled upon Tsài Chih Fu to lift me down. I had set out full of tremors, but taking photographs of the peaceful scenes soothed my ruffled nerves. I persuaded myself my fears had been born of the night and the dread of loneliness which sometimes overtakes me when I am in company and thinking of setting out alone, leaving kindly faces behind.

And then I came upon it, the first sign of unrest.

The winding road rose a little and I could see right ahead of us a great crowd of people evidently much agitated, and I called to Mr Wang to know what was the matter.

“Repeat, please,” said he as usual, and then rode forward and came baek saying, “I do not know the word.”

“What word?”

“What is a lot of people and a dead man?”

“Ah!” said I, jumping to conclusions unwarrantably, “that is a funeral.”

“A funeral!” said he triumphantly. “I have learned a new word.”

Mr Wang was always learning a new word and rejoicing over it, but, as I had hired him as a finished product, I hardly think it was unreasonable of me to be aggrieved, and to feel that I was paying him a salary for the pleasure of teaching him English. However, on this occasion his triumph was short-lived. .

“Would you like to see the funeral?” he said.

I intimated that I would. My stalwart master of transport lifted me down and the crowded people made a lane for me to pass through, and half of them turned their attention to me, for though there were missionaries in the big towns, a foreigner was a sight to these country people, and, Mr Wang going first, we arrived at a man with his head cut off! Mercifully he was mixed up with a good deal of matting and planks, but still there was no mistaking the poor dead feet in their worn Chinese shoes turned up to the sky.

Considering we are mortal, it is extraordinary how seldom the ordinary person looks upon death. Always it comes with a shock. At least it did. I suppose this war has accustomed some of us to the sight, so that we take the result of the meeting of mortal man with his last friend on earth more as a matter of eourse, as indeed it should be taken. Of course I know this is one of the results of the war.

My sister's son, staying with me after six months in hospital, consequent upon a wound at Gallipoli, came home from a stroll one day and reported that he had seen nothing, and then at dinner that night mentioned in a casual manner that he had seen two dead men being carried out of a large building and put in a motor ear.

I said in astonishment:

“They couldn't have been dead!”

“Of course they were. Do you think I don't know dead men when I see them? I've seen plenty.”

So many that the sight of a couple in the streets of a quiet little country town seemed not even an occasion for remark.

But I was not even accustomed to thinking of dead men and I turned upon Mr Wang angrily:

“But that isn't a funeral. That's a corpse,” and once more to my irritation he rejoiced over a new word.

“Who killed him?” I asked.

“They think an enemy has done this thing,” said he sententiously and unnecessarily, as, ignorant as I am of tilings Chinese, I should hardly think even they could have called it a friendly action. The body had been found the day before, and the people were much troubled about it. An official from Ping Yow—a coroner, I suppose we should call him—was coming out to inquire about it, and because the sun was already hot the people had raised a little screen of matting with a table and chairs where he could sit to hold inquiry.

And here was the thing the missionaries had warned me against. Trouble, said they, always begins by the finding of dead bodies that cannot be accounted for, and this body was on the Great South Road. It might be only a case of common murder such as one might perchance meet in Piccadilly, possibly it was due to the bands of soldiers that were pouring into the country—to defend the crossings of the Yellow River, some people said—but it was to me an emphatic reminder that the warnings of Mr and Mrs Falls had not been given lightly, and I meditated upon it all the way to Ping Yow.

All day long the soldiers had been pouring through Ki Hsien, all night long they poured through the suburbs of Ping Yow. Not through the town itself—the townspeople were not going to allow that if they could help themselves; and as it was evidently a forced march and the regiments were travelling by night, they could help themselves, for every city gate is shut at sundown. The China Inland Mission had a station at an old camel inn in the eastern suburb, and there the missionary's young wife was alone with five young children, babies all of them, and there I found her. I think she was very glad to see me, anyhow I was someone to discuss things with, and we two women talked and talked over our evening meal. She was a tall, pretty young woman—not even the ugly Chinese dress and her hair drawn back, not a hair out of place, Chinese fashion, could disguise her pathetic beauty. And she was a countrywoman of mine, born and brought up in the same state, Victoria, and her native town was Ararat, green and fresh among the hills. And how she talked Australia! What a beautiful land it was! And the people! The free, independent people! The women who walked easily and feared no man! To thoroughly appreciate a democratic country you should dwell in effete China. But she feared too, this woman, feared for herself and her five tiny children. It would be no easy job to get away. I told her of the dead man I had seen—how should I not tell her?—and she trembled.

“Very likely it is the soldiers,” she said. “I am afraid of the Chinese soldiers.” And so am I in bulk, though taken singly they seem sueh harmless little chaps.

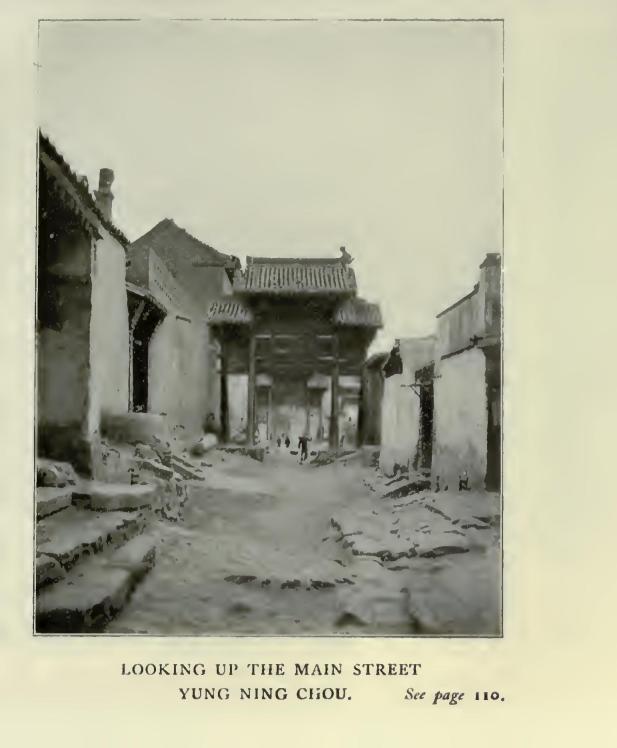

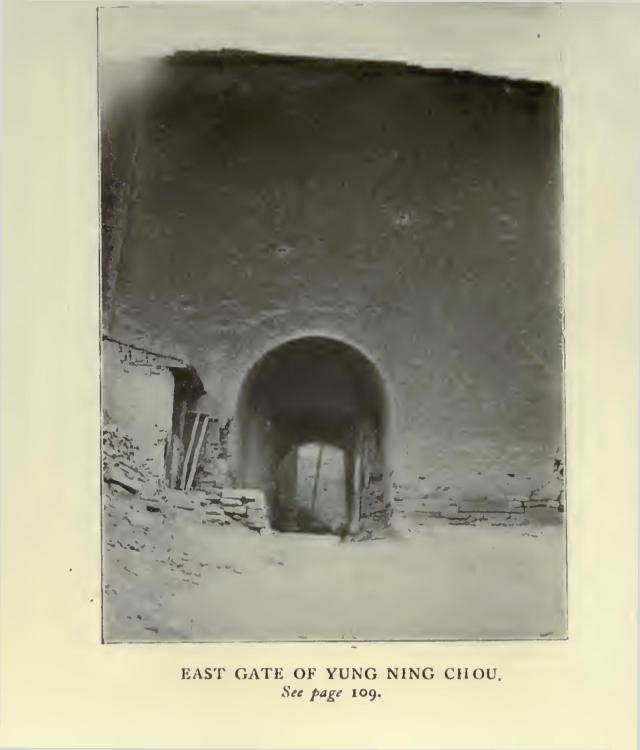

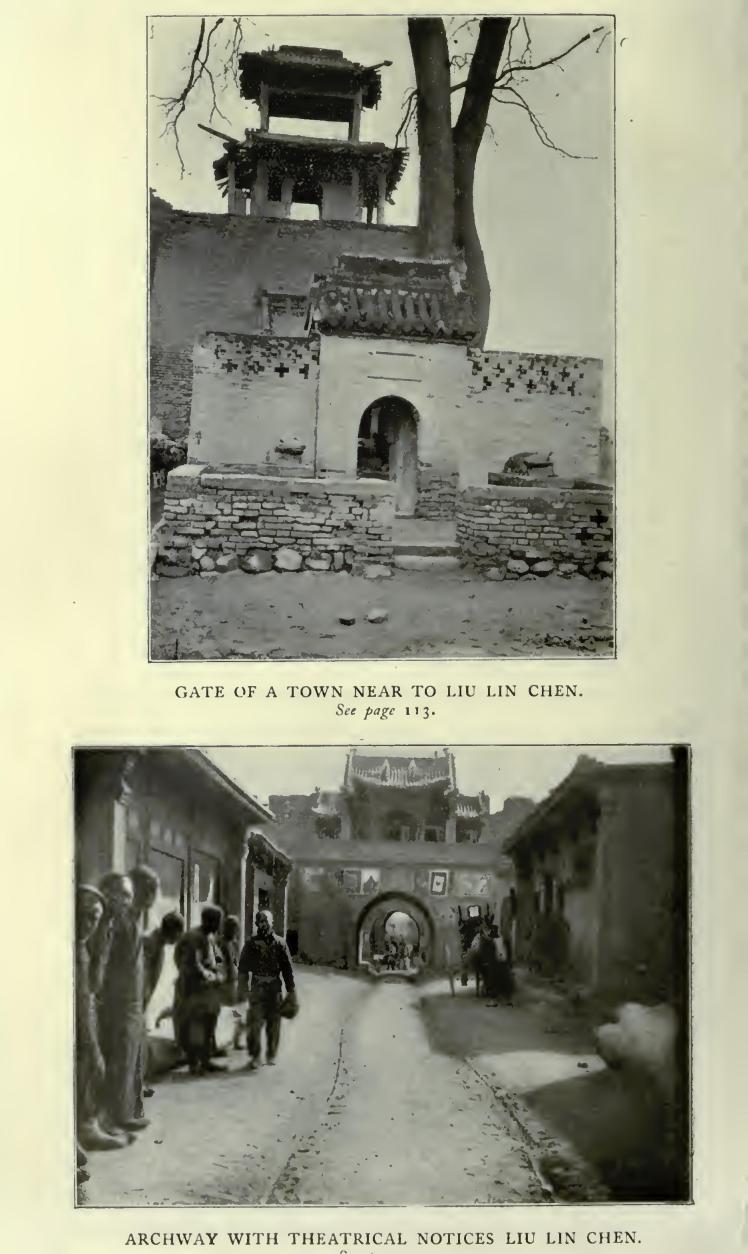

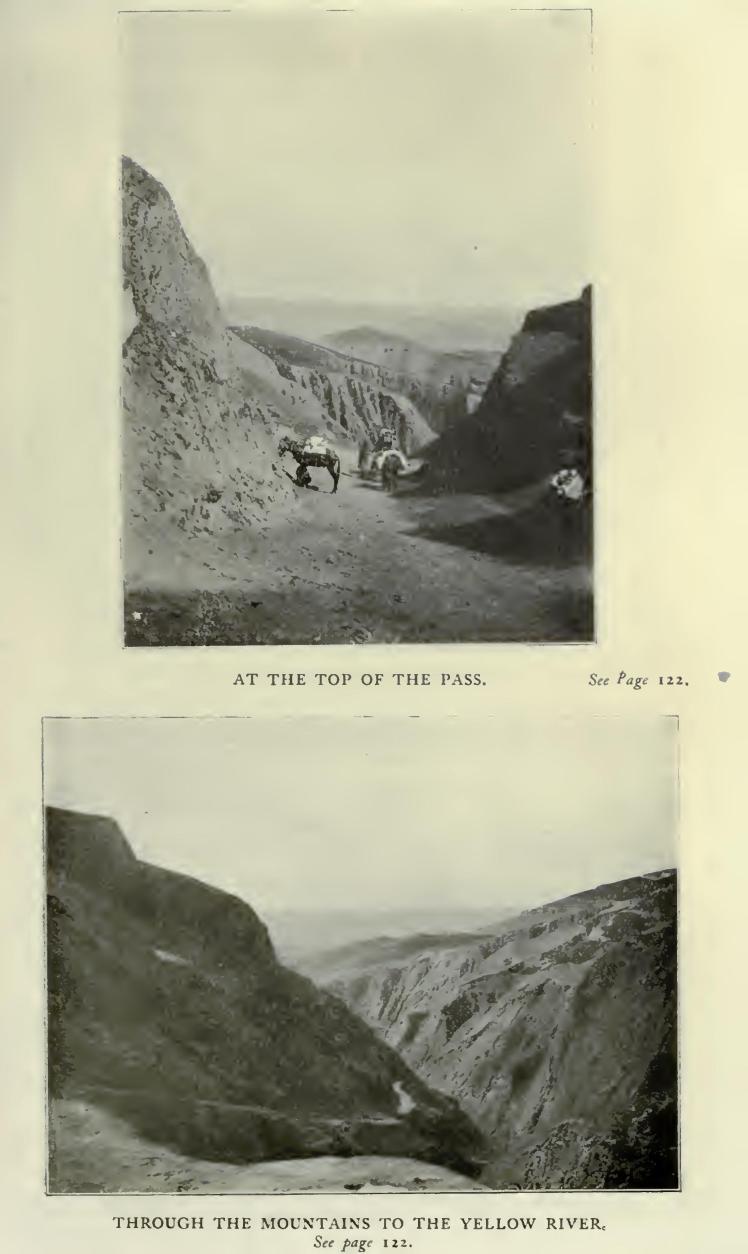

“When the willow is green and the apricot yellow in the fifth moon,” said a metrical inscription on a stone dug up at Nankin in that year—the fatal year 1914—“terrible things will happen in the land of Han.” Terrible things, it seems to me, always happen in the land of Han; but if it spoke for the great world beyond, truly the stone spoke truth, though we did not know it then.