Title: The Irish Penny Journal, Vol. 1 No. 22, November 28, 1840

Author: Various

Release date: March 23, 2017 [eBook #54416]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by JSTOR www.jstor.org)

| Number 22. | SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 28, 1840. | Volume I. |

English and other visitors to our metropolis who dare the perils of the deep, and various other perils now equally imaginary, to see something of our Emerald Isle, are generally directed as a matter of course to our far-famed county of Wicklow as the only picturesque lion within a few hours’ journey; and certainly in this romantic region they will find much to gratify the taste, and which will remain indelibly fixed on the memory. But, delightful as such excursion undoubtedly is, it will only convey to a stranger’s mind a partial and imperfect impression of Irish scenery; and he will be apt to conclude that however rich we may be in the possession of lakes and mountains—the grand but solitary domains of nature—we are wholly wanting in scenery of a different class, that of the richly wooded pastoral valley, blooming with artificial as well as natural beauty, the anciently chosen abodes of luxury and rank, and, as such, rich in memorials of the past, with their attendant historical associations. Scenery such as this, the proud Briton will most probably think the exclusive boast of his own favoured isle. He will not imagine that it is also to be found in equal perfection in Ireland, and even within a short distance of the metropolis. It is not in the Guide or Tour Book, and is but little known even to the well informed of the citizens of Dublin themselves, more of whom have seen and enjoyed the scenery of the Thames than that of the Boyne, which is within four hours’ journey. Yet the scenery of the Boyne, following its course upwards from Drogheda to Navan, a distance of eleven miles, and the scenery of the Blackwater, a river tributary to the Boyne, ascending from Navan to Kells, a distance of eight miles more, is, in its way, of a character as beautiful and luxuriant as could be found anywhere, or even be imagined. Scenery of this class of equal richness may be often found in England; but we do not know of any river’s course of the same length in which natural beauty so happily combines with the artificial, or in which so many interesting memorials of past ages could be found. Scattered in rich profusion along the banks of this beautiful river we find the noblest monuments of the various races of men who have held sway in Ireland: the great earthen fortresses, stone circles and dome-roofed sepulchres of the Tuatha de Dananns and the Fir-Bolgs—the raths of the Milesians—the churches and round towers of the earliest Christian times—the proud castles of the Anglo-Norman chiefs and their equally imposing[Pg 170] architectural structures dedicated to the services of religion. In the variety, if not the number of such monuments here found, the Boyne is without a rival in any Irish river, nor do we think it could be paralleled by any river in the empire; and we might truly add, that it is on its luxuriant banks, amid so many instructive memorials of past ages, that the history of our country, as traced in its monuments would be best studied.

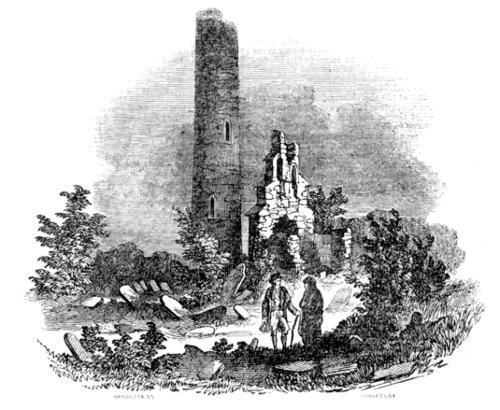

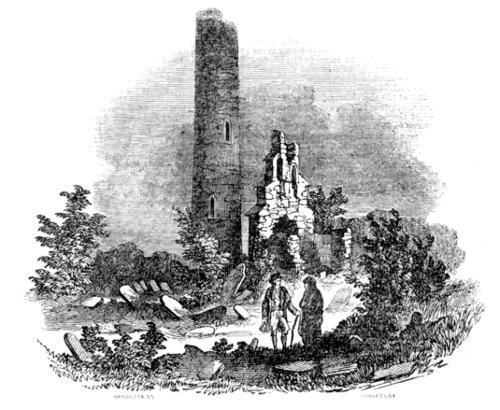

It is from amongst these interesting remains that we have selected the subject of our prefixed illustration—the Church and Round Tower of Donaghmore, situated a little more than a mile from Navan, on the road to Slane.

This religious establishment, which was anciently called Dumnach-mor muighe Echnach, owes its origin to St Patrick, as will appear from the following passage translated from the life of the Irish apostle, attributed to St Evin:—

“While the man of God was baptising the people called Luaiguii, at a place where the church of Domnach-mor in the plain of Echnach stands at this day, he called to him his disciple Cassanus, and committed to him the care of the church recently erected there, preadmonishing him, and with prophetic mouth predicting that he might expect that to be the place of his resurrection; and that the church committed to his care would always remain diminutive in size and structure, but great and celebrated in honour and veneration. The event has proved this prophecy to be a true one, for St Cassanus’s relics are there to be seen in the highest veneration among the people, remarkable for great miracles, so that scarcely any of the visitors go away without recovering health, or receiving other gifts of grace sought for.”—Tr. Th. p. 130.

But though the existing ruins of the Church of Donaghmore sufficiently indicate it to have been a structure “diminutive in size,” its architectural features clearly prove that it is not the original church of St Patrick’s erection, but a re-edification of the thirteenth century, in the usual style of the parish churches erected by the Anglo-Norman settlers within the Pale. Neither can the Round Tower, though unquestionably a structure of much higher antiquity than the present church, be referred to the time of the Irish apostle, or perhaps to an earlier age than the ninth or tenth century. At all events, its erection cannot be ascribed to an earlier date than that of the Tower of the Church of Kells—a religious establishment founded by St Columbkille in the sixth century—as these towers so perfectly agree in architectural style and masonwork, that they appear to have been constructed by the same architects or builders.

This very beautiful tower is built entirely of limestone undressed, except around the doorway and other apertures, and is of admirable masonry. It has two projecting ledges or steps at its base, and six rests for stories, with intermediate projecting stones or brackets in its interior. These stories are each, as usual, lighted by a single aperture, with the exception of the upper one, which has two openings, one facing the east, and the other the west; and the apertures present all the architectural varieties of form observable in our most ancient churches. The circumference of this tower, near its base, is 66 feet 6 inches, and its height, to the slant of the roof, which is wanting, is about 100 feet. The wall is 3 feet 9 inches in thickness, and the doorway is 12 feet from the ground. This doorway—which is of very beautiful execution, and, as usual, faces the west end of the church—is 5 feet 2 inches in height, and has inclined sides, and a semicircularly arched top. It is 2 feet 3 inches wide at bottom, and 2 feet beneath the spring of the arch at top. Over the door there is a figure of the Saviour sculptured in relief, partly on the keystone and partly on the stone over it; and on each side of the architrave there is a human head also in relief, as on the doorway of the church of Kells.

Some antiquaries, in their zeal to support the theory of the Pagan origin and the antiquity of the Round Towers, have asserted that this doorway is not the original one, but an “after work.” But there is not the slightest ground for such a supposition, and this sculpture, as a profoundly skilled architectural antiquary, the late Sir Richard Colt Hoare, well observed, furnishes “a decided proof that these buildings were not (as some writers have conjectured) built by the Pagans.”

A similar argument against the application of the Round Towers to the purposes of a belfry, has been grounded on the circumstance of the western front of the church having three apertures for bells above its gable. But it should not be forgotten that this structure has no claim to an earlier date than the thirteenth century, when a variety of bells, and a different mode of hanging them, were brought into use by the Anglo-Norman settlers.

The Church of Donaghmore has been confounded by Archdall and subsequent writers with the ancient church of Domnach-Tortain, also founded by St Patrick, but which was situated near Ardbraccan.

P.

In one of those admirable tales which Mrs Hall is now publishing with the praiseworthy object of the melioration of the Irish character, the ordinary effects of a too faint resistance to the fascinations of strong drink are faithfully detailed. The moral which our generous countrywoman intended to convey is undoubtedly of universal application, but I am afraid that the circumstances I am about to relate will convey no moral. It is the simple and true record of an appalling calamity which befell the subjects of my story, with all the melancholy unaccountableness and fatality of lunacy. No one would warn his fellow-creatures against the danger of madness—against any unforeseen dispensation of God’s wrath: it is in this sense, then, that I am afraid I have no moral to convey in narrating an event of which I was all but a spectator.

It must have struck every observer of human character that there are two classes of drunkards in this country. One class is composed of those persons, who, at first being well enough disposed to be temperate in all things, are insensibly led on by the charm of good fellowship to create for themselves an artificial want, which in the end leaves them the helpless victims of a miserable disease: they begin with a little—they continue the draught under the self-deceiving sophism “it’s only a drop”—they fall into excess—they lose all sense of decorum and proper spirit—they become mean and unbashful in their craving after spirituous liquor, which condition unfits them for an upright and honourable course of thought and action in any of the details of daily existence—a mental dissipation accompanies the bodily languor: while the hand trembles, the brain wanders, and the last scene of the tragedy is delirium tremens.

But there is another class of drunkards—God forbid that I should attribute any thing to the decrees of Providence inconsistent with mercy and justice—but I am almost tempted to designate this class the drunkards by necessity. However worldly condition, education, or other causes, may modify the result in individual cases, it is not the less certain that there are persons—very many of them—who appear to have come into the world predisposed to an inordinate desire for intoxicating liquors. These wretched people do not begin with thimblesful, and end with gills—the stroke seizes them like a thief in the night—sometimes in the prime of manhood—sometimes in the flush of youth—sometimes (it is a fearful truth) in the thoughtlessness of boyhood. It is a passion with them—a madness. You may know one of these unhappy beings, especially if he be a very young man, by the sullen and dogged air with which, early in the morning, he enters the public house, and sits down in solitude and silence to his double-shotted measure of undiluted whisky—whisky is the only drink for one of this calibre—alas! the worst and fiercest stuff that can be made is the most acceptable to him—his palate is too long palled to distinguish between tastes and flavours—it is the liquid fire he wants; you may know him at other times by the pitiable imbecility which prompts him in his awful craving to reach his tumbler to his lips with both his hands, till he finishes the draught with all the apparent eagerness of intense thirst; you may know such a one by his frightful sleeps, begun, continued, and closed in terrific dreams! The wife and family of the progressive or occasional drunkard are wretched enough as every body knows; but, oh! who can possibly estimate the amount of misery which the wife and children of a madman like this are destined to endure.

I have not overdrawn the picture in the abstract—take an individual instance:—

In the spring of 18— I was living, on a visit with a friend, in the neighbourhood of a small country town in one of the most fertile and prosperous districts of the island. The population was almost entirely free from that abject and squalid poverty which is the lot of the Irish peasantry beyond that of all other descriptions of civilized people. I remarked particularly of this neighbourhood that it had a larger proportion of respectable farmers and of that species of country gentlemen[Pg 171] called squireens, than any other part of the country I had ever lived in. To this latter class belonged the heads of two branches of the same family, both of whom resided in the immediate vicinity of my friend’s house. Their names were Peter and James Kavanagh. Peter was by many years the elder of the two; his family consisted of three grown-up sons and one daughter. Peter had married in early life, and his wife died in giving birth to a fifth child, which did not long survive its mother. James had a large family of young children. Peter’s only daughter, Alice, had been brought up in her uncle’s house in order that she might receive the education and care which a girl of her tender age, without a mother, might expect from the kindness of her nearest female relative.

The family of Peter Kavanagh, then, consisted of himself, his three sons, and a single in-door servant as housekeeper, who was already an old woman and of indolent habits. The household of a widower in the middle and humbler ranks of life is rarely ordered with regularity and decorum, and Peter’s was no exception to the general case. Every room had an aspect of untidiness and discomfort. Seldom were the boards of the floors or staircase washed or swept—seldom were the window panes cleansed, or the hearth-flag whitened, or the tables rubbed, or the chairs dusted. Things soiled were never cleaned—things broken were never mended—things lost were never replaced. Each of the family felt in turn the inconvenience of this state of things, but one threw the blame upon the other, and nothing was done to remedy the evil. Every one thought it strange that such a good practical farmer and shrewd man-of-the-world as Peter Kavanagh should care so little about the comforts or conveniences of every-day existence—but so it was.

Peter, however, had or thought he had one especial household virtue to be proud of. Very early in life he had narrowly escaped disgrace and ruin by severing himself from a parcel of dissipated associates, who had led him step by step into all the labyrinths of premature debauchery. He receded before it was quite too late, and the recollection of what he suffered (for he did suffer) was sufficient to make him resolve that his sons should never be tempted in a similar manner. The eldest of these, Richard, was now one-and-twenty, the second, Matthew, nineteen, and the youngest, Gerald, fifteen years of age, at the time I lived near P——, and they had never yet partaken of any spirituous liquor at their father’s table. That father, however, was by no means so abstemious as he had compelled his boys to be. Every day since they had first learned the taste of whisky toddy had they been tantalised with the sight of the “materials” for their father’s favourite beverage. Peter Kavanagh was indeed a temperate man, but he was not a generous man. He was not one of those kind parents who cannot bear to gratify their appetite with any delicacy, whether much or little, dear or cheap, while their children are looking on with wistful eyes and watering mouths in vain expectancy. He had his reward. One day the two eldest lads, Dick and Matt, were carried home from a neighbouring fair, stupidly drunk. It was the first time they had ever been so, and the quantity they had taken was perhaps trifling; but the father was thenceforward more watchful than ever to prevent them from repeating the excess. In his usual manner to his sons Peter Kavanagh was not particularly harsh, but the least evasion of his strict commands in respect of drink was sure to be visited with great severity. How wretchedly inconsistent was this man’s practice! Other misdemeanours of infinitely a greater degree of moral crime were winked at, nay encouraged, by him. The young men were not naturally vicious; but when they found that they could with impunity curse and swear in their father’s hearing—when they found that even some of the graver offences against society could be committed without their father’s reprehension, was it any wonder that they should soon grow ripe in wickedness? Matt and Dick, in their personal appearance, showed every token of the accomplished village scamp—battered hats jauntily carried on one side of the head—rusty shooting coats of bottle green, with an amazing plurality of pockets—knee-breeches of once-white corduroy insufficiently buttoned over coarse worsted stockings, and heavy brogues with nails like the rivets of a steam-boiler. These were the hardiest betters of the ball-alley, the keenest lads at the roulette-table—the deadest shots at a mark over all the country side. Plenty of money had they, and who dared to ask them how they came by it? Their father had lots of cash lying by, and selfish as he was, and knowing as he was, many a heavy handful of hard silver was he relieved of by his dutiful sons. Hence the dashing “bit of blood” which carried Dick and Matt alternately over the stubbles—hence the couple of spaniels and the leash of greyhounds, which had the reputation of being the best noses or the fleetest feet in the county—hence the double-barrelled “Rigby” belonging to Dick, which was the admiration and envy of his acquaintances. As they grew up, and cared less for the anger of their father, vicious habits became more settled-looking and systematic with them. They drank to frightful excess whenever they had the slightest opportunity. No one ever saw them for twenty minutes at a time without having full proof that they were slaves to as odious and disgusting a tyranny as ever the depraved tastes of human creatures created for mankind—I mean, no one ever saw them for so long a time without a tobacco pipe between their teeth, and surrounded by every one of the usual nastinesses which accompany the practice when carried to a hateful extent; and yet, even as they were, the county could not boast of two manlier looking fellows than Richard and Matt Kavanagh when dressed for Sunday mass, which they still attended with a punctuality which would be more praiseworthy if it sprang from anything but a motive of vanity and pride. Under different culture they might have become excellent members of society. They had still some faint pretensions to generosity and spirit, and many a pretty girl of the neighbourhood would have trusted to her sole powers of persuasion for their reclamation.

Gerald Kavanagh, the youth of fifteen, was a lad of different stamp. He was open-featured and open-hearted both. He was never seen with a pipe in his mouth, or a tattered “racing calendar” sticking out of his pocket; and while his brothers were out upon their sporting expeditions, or amusing themselves in a less innocent way, it was poor Gerald’s pleasure to scamper across the fields to his uncle James’s garden, and walk, or talk, or read, or play with his pretty little sister Alley, or romp with his pretty little cousins Bill and Bess, and Peter and Dick, after school hours—the time he knew he would find most company looking out for him. Alley and he were as fond as they could be of each other, and not the less so because they did not live entirely together. “Absence makes the heart grow fonder,” is as true a line as ever was penned, whether we apply it to the lover and his mistress, or the brother and his distant sister. Many of us, with sighs and tears, can testify this. It was a lovely sight to see that affectionate boy and his fond sister sauntering along the borheens in the wild-strawberry season, with their arms around each other’s necks in the intervals of their fruit-finding, until they bade each other good-bye for another day, and returned, “with lingering steps and slow,” to homes, alas, how different!

Such were these three youths when Peter Kavanagh, after a short illness, died, and left his property, such as it was, to be equally divided between his children.

I may venture to say that Richard and Matt were not sorry for their father’s loss. On the night of the grand “wake” they collected all the idle and profligate young men of their acquaintance together at the house, and dreadful was the depth of drunkenness to which they sank, as might be expected. Every more prudent person present saw how it was—saw that the previous restraint was about to be amply atoned for, and many a shake of the head was intended to be prophetic of coming calamity.

On that same night—early in the night too—little Alley perceived that all was not right with her brother Gerald. She had seen Richard plying him with liquor, which he at first refused, but afterwards accepted—stealthily, however, and with an abashed and crimsoning face as he met the first reproachful glance of Alice. Gradually the temptation worked, and again and again the draught was repeated with less hesitation at the request of his brothers, who seemed happy in the idea of making their innocent companion as guilty as themselves. The devil surely has those in his clutches who find comfort and consolation in the visible abandonment of the fair and innocent to the miserable pleasures for which they have sold their own souls. At length she was frightened to perceive that Gerald had grown hardy and boastful of his feat—he had asked for more whisky, and had been given it by Dick, who, half drunk himself already, was determined to make Gerald drunk for once in his life. The boy was now in the condition wished for by his brother; he had slunk behind Matt’s chair; Alice could see his head hanging upon one shoulder, while his eyes were closing in the stupor of intoxication—he[Pg 172] was about to fall to the ground. Quietly she stole to his side, and leaning her head upon his shoulder she whispered,

“Gerald, darling, I didn’t think you would drink so much—why did you do it?”

“Don’t tell uncle James, Alley, if he hasn’t seen me this way, and I’ll never drink so much again.”

“Hold up your head for another bucket, you dog,” said Matt, with sundry drunken hiccupings, as he heard the boy speaking behind his chair, and proffering at the same time a fresh bumper. “Come, Gerald, my boy, it will do you no harm—sorrow’s dry, they say, and Lord knows but you’ve blubbered enough all day for a little fellow.”

“Matt, dear Matt, don’t ask him,” said Alice.

Matt, however, was not to be thwarted: with a brutal cuff he struck his little sister to the ground, and tried to force the liquor upon Gerald’s acceptance. In the attempt the glass fell from his hand, and Alice rose and drew her brother softly from the room.

The funeral took place, and there was another carouse more disgraceful than the first, and another, and another, and another! until the week was out. When Gerald’s uncle saw how completely besotted his nephews had become, he took Gerald to live with him, but not until it had become too painfully evident that the boy had acquired a liking for the liquor which had turned his two brothers into human beasts. Poor little Alice wept over the change. There was no more reading, or playing, or wandering through the country together. He sat sulky and silent in the house all day, more like a poor relation on charitable allowance than the joint-heir of the largest farm in the parish. But this was to have an end!

A month had passed away since the death of Peter Kavanagh, and the zeal of the eldest heirs had by this time drunk up his entire stock of “mountain dew,” when in some out-of-the-way nook or other they discovered five gallons of malt whisky, which perhaps had lain there forgotten for twenty years. It was on a Saturday morning this was found, and one of the Kavanaghs was heard to swear that he would never quit it till the last drop was drained. It was to be the last bout before they set off for Australia, whither they intended to emigrate that very spring, having, with their uncle’s consent on behalf of the two younger orphans, converted their land into money for the purpose. One or two choice spirits had been invited to join them, but these begged to be excused—even these were appalled at the dreadful excesses of their boon companions. Towards evening Gerald had been missing from his uncle’s house. James Kavanagh guessed how it was, and with little Alice in his hand repaired to the brothers’ dwelling. The door was locked on the inside, and on asking for Gerald he was told that he was all safe there, with the saucy addition that “there wasn’t any admission for any d—— teetotaller.” Shocked and grieved, James Kavanagh went away with his dejected niece.

The next day was Easter Sunday. The festival had occurred that year unusually late in the spring, and there was already a foretaste of summer in the air. A lovely noon it was when James Kavanagh, his wife, Alice, and the children, walked out in Sunday trim to the parish chapel. The sky was fretted with light silver clouds—the fields were already green with the new growth of the grass—the hawthorn bushes were almost visibly bursting their buds—the whin braes were in a blaze of golden beauty—the birds, especially the red-breast, were chirping away with intense glee, being, in the glorious language of the poet Shelley,

They continued to walk on, and now the bells of the neighbouring church struck out their Easter jubilee with such exquisite sweetness as we might fancy arrested the sceptical purpose of the despairing Faust in Goëthe’s surpassing drama, when the heart-touched metaphysician exclaimed,

Yes! indeed, those bells almost distinctly said to the heart as they swung in the soft air of that delicious noon, “Christ our passover is sacrificed for us; therefore let us keep the feast!” They passed the church—groups of joyous children were playing in the graveyard—five or six immense chestnuts towered, coeval and almost coequal with the ancient steeple, and in these there was a rookery, now in full din—the voices of the children and the cawing of the rooks, disturbed by the sudden peal of the bells, mingled with the chime without discord to the ear. Alice’s eyes glistened for a moment when she recognised her youthful playmates; but she suddenly felt she could not laugh with them—her heart was heavy. At length they stood before the door of the brothers’ house. No signs of wakefulness had it yet exhibited.

“Let us go in, uncle, and tell them to get up,” said the little Alice.

“Let them sleep it out, the scoundrels!” was the indignant reply of James Kavanagh.

They passed on to the place of worship.

In about an hour and a half from this time the same group were on their way homewards, with hearts elevated by the imposing service which they had just been witnessing. A gloom was, notwithstanding, perceptible upon the face of James Kavanagh and of his little niece, as they walked along in company with their happy and smiling neighbours. None of the three sons of Peter Kavanagh had ever before been known to have absented himself from Sunday mass, and their absence on that most holy day was of course a subject of much wonder.

“I could not have thought it possible,” said James Kavanagh gravely, “that they could become so wicked all at once—God forgive them! God help them!”

“Oh, uncle!” cried Alice, as they came in view of the house of guilt once more, “they are not up yet! See, the shutters are still closed!”

They were now in front of the house. “Dear uncle,” said Alice entreatingly, “go into them—do, dear uncle, bring out poor Gerald to eat his Easter dinner with us.”

A thought struck James—he knocked loudly at the door. There was no answer. Another loud knock, and a long pause; and still no sound within the house.

Alice’s little heart echoed the last unsuccessful knock—it almost said. “Wake, Gerald, with the knocking.”

She could endure the suspense no longer, and, running to the gripe at the road-side, she took up a heavy stone, with which she battered the panels of the hall-door as long as her strength permitted her. When she was obliged to desist, her screams might be heard afar off, and still there was no sound in the house.

James Kavanagh had dispatched one of his little boys to a neighbouring cottage for a crow-bar. The boy quickly returned with one, and James, assisted by the crowd who gathered near, was not long in forcing the door.

“Good people,” said he to the anxious company outside, “don’t come in till I tell you—there’s no use in further exposing the shame of my brother’s house.”

He and Alice, with one or two particular friends, entered the hall with faltering steps, and they closed the door behind them.

The first object which met their eyes was Peggy, the old housekeeper, lying on the mat at the foot of the staircase, in a trance of intoxication: she had evidently fallen down stairs in her attempt to reach the door, and had been for hours perhaps insensible. Alice jumped over her, and darted up stairs with the speed of lightning. James and his companions, after a vain attempt at arousing the housekeeper, slowly followed her.

They entered the room which fronted them on the landing. The thick stench of tobacco-smoke, mingled with the fumes of ale and whisky, almost overpowered them. The room would have been quite dark had it not been for the flickering remnants of two candles, which still glared in the heated sockets of a large old-fashioned branch candlestick. James went to the window, opened the shutters, and let down the sash. The glorious sunshine streamed into the reeking apartment, with the blessed air of the Sabbath. How strange—how painful was the paling glimmer of those expiring candles in that holy light! The three young men were lying on the floor at some distance from each other, around the legs of a crazy table in the centre of the room. On the table were huddled together the fragments of salt herrings, the parings of cheese, broken glasses, half-emptied decanters, and the other usual paraphernalia of a low debauch. The whole meaning of the scene was taken in at a glance by James Kavanagh, as soon as he had opened the window. He stooped over one of the[Pg 173] prostrate forms—it was that of Richard. He turned up the face—great God! it was the face of a livid corpse! A smothered groan burst from James: he rushed towards the next—Matt Kavanagh was dead also, quite dead and stiff! James and his friends looked at each other solemnly, and without speaking a word. They turned their glance simultaneously to the place where Gerald was lying. They moved or rather tottered to the spot. There he lay, with Alice in a swoon beside him, his eyes glazed, the skin of his face tightened over his nose and cheek-bones, his lips covered with viscid froth, and his beautiful brown hair tossed backwards from his damp forehead, glistening in a streak of sunshine which came full upon it from the window. “He is alive still!” they all three exclaimed: “he may yet be saved!”

One of them ran to the window and made a sign to the neighbours to come in. The room was soon full of horrified spectators.

They parted Alice from her dying brother, and both were brought out into the open air as quickly as possible.

Amidst the cries and lamentations of the bystanders Alice recovered. She sat for a while on the grass, trying to recall her scattered senses. The sight of Gerald lying near her, as the crowd opened to admit the air to his face with a freer freshness, brought the whole terrible truth to her mind. She rose with difficulty, but, gathering strength with recollection, she succeeded in breaking from the woman who had her in charge, and in a moment the head of Gerald was pillowed upon her bosom.

The soft cooling breeze had restored the unfortunate boy to a momentary consciousness. He was barely able to turn his head towards Alice in recognition of their presence. A faint pleasure was expressed in his glassy eyes as he did so.

“Won’t you speak to me, Gerald? Won’t you speak to your own Alley?”

The boy shook with a convulsive shudder, but could not utter a syllable.

“Don’t die, dear Gerald; don’t leave poor Alley all alone in the world! Och, och, och!” said the little girl in the very agony of childish despair, “he’ll never be the same again—he’ll never speak to me again!”

The boy made an effort to bring Alice’s ear to his clammy lips; she strove to hear the almost inarticulate whisper which hovered upon them.

“Is—uncle James—here?” gasped the dying lad; “tell him—I—couldn’t—help it! Oh! Alley! oh!”

Gradually the groan, extorted by the last pang of dissolution, died away, and with it the spirit of poor Gerald Kavanagh.

Alice perceived what had happened as soon as any of the bystanders, but high and shrill her scream mounted over the wailing which arose from the others, ere she once more sank down in the swoon which the excess of her anguish had so mercifully caused.

On the following day a coroner’s inquest was held upon the bodies of the three sons of Peter Kavanagh, in a public-house not far distant from the scene of this fatal debauch. A surmise had been afloat that poison had somehow or other been the cause of their death, and an examination of one of the bodies was considered needful. I will not shock my readers with a description of the fearful chamber where this most loathsome operation was performed. The result was a verdict to the effect that the three Kavanaghs had died “from the excessive use of ardent spirits.”

I commenced by saying I feared that this narrative might fail in pointing a moral. It has a moral—a moral to selfish and ill-judging parents, and equally ill-judging societies, who lay the flattering unction to their souls that coercion will have a better effect than a fair and consistent example. Verily, the Spartan nobles, who exhibited the drunken slave before their children, and then placed the wine-cup within their reach, had a better knowledge of human nature than the Irish father who would exorcise the demon of alcohol out of his children by pledges of abstinence, or threats of punishment, while, in the security of his own experience, he feels he can temperately enjoy the luxury of spirituous drink.[1]

R. M.

[1] From the Londonderry Standard.

Fine connexions are apt to plunge you into a sea of extravagance, and then not to throw you a rope to save you from drowning.

We endeavoured in our last article to describe the principal circumstances of interest with respect to the ascending or unelaborated sap. We have found that it is derived from the aliment which consists of water and carbonic acid; that it is composed of a solution of sugar and gum in water; that it ascends in the ordinary trees of this country through the wood, which is situated between the bark and pith; that the causes which elevate it are partly a vital attraction or suction exercised by the buds, and partly an endosmose, by which, in consequence of its superior density, it draws in its aliment through the spongy extremities of the roots; that its use is not only to furnish materials for the descending or elaborated sap, but by developing the fleshy part of plants to cause the growth of stems in length and roots in thickness. We shall now proceed to show the origin, the course, the composition, and the uses of the descending or elaborated sap.

The elaborated sap is formed out of the ascending sap. The place where this change takes place is in the leaves and green parts of vegetables; it is generally in the spring season that the ascending sap pushes out the buds into branches, and developes the little scales which had surrounded these organs into leaves; but when these leaves are formed, the sap continues to ascend into them, and there undergoes those alterations from whence the elaborated sap results. Now, these alterations consist in the getting rid of all superfluous water and carbonic acid, which, originally absorbed as aliment, had not undergone the conversion into gum and sugar during the ascent of the sap; secondly, in the acquisition of additional nutriment from the atmosphere; and, thirdly, in the conversion of these substances into a variety of new compounds.

Let us examine each of those changes to which the ascending sap is subjected, in succession; and, first, with respect to the disengagement of superfluous water and carbonic acid, every one must have observed drops of water collected on the leaves of cabbages and other vegetables, when examined early in the morning. These are commonly supposed to be dew-drops, but are truly in great part the result of a kind of perspiration which is always taking place from the surface of plants. That this is the case, can be proved by covering a cabbage-plant with a bell-glass, and placing it in a room sufficiently heated to prevent the deposition of dew, when drops of water will be found equally to collect upon its leaves. These drops are not observed during the day, because the temperature is then commonly so high as to evaporate them as fast as they are transuded; but the fact is, that plants actually give off much more water during the day than night. The escape of carbonic acid is not so easily detected as that of water; it can, however, be proved, through the resources of chemistry. Unlike water, which is liberated both night and day, and indeed in greatest quantity during the latter period of time, carbonic acid is found to be disengaged during the night only. As long as plants are exposed to the light of the sun, their green parts liberate none of this gas.

We have mentioned that when the ascending sap arrives into the leaves, it not only throws off superfluous water and carbonic acid, but likewise derives an additional quantity of nutriment from the atmosphere. The presence of light is necessary for this latter circumstance to take place. The nutriment which, under the influence of sunlight, it acquires from this source, is a substance named “carbon;” this substance is a constituent of carbonic acid, which is indeed composed of carbon and oxygen; carbonic acid is contained in the atmosphere in the proportion of one part in a thousand; the green parts of plants absorb it, and under the influence of light decompose it; the carbon is retained, but the oxygen is again liberated. We now may perceive the reason of the fact mentioned in the preceding paragraph: plants give out no carbonic acid during the day, because the superfluous carbonic acid of the ascending sap becomes decomposed under the influence of light, in the same way as that which has been absorbed from the atmosphere.

A great many compound products are obtained from the vegetable kingdom. We need merely recall to the reader’s recollection starch, resin, camphor, bland and aromatic oils, bitter principles, colouring matters, the acids of the grape, the lemon, and the apple, &c. to assure him of this truth. All these different substances form themselves out of the sugar and gum of the ascending sap, together with the carbon absorbed under the influence of light.

When the ascending sap has parted with its superfluous water and carbonic acid, when under the influence of light it has absorbed carbon from the atmosphere, and when its constituents arrange themselves anew, so as to produce some or all of the substances above enumerated, its name as well as its functions cease: it has now become the descending or elaborated sap.

Let us now inquire the course which the descending sap pursues. We have stated in our last article, that if a ligature be twisted tightly round a branch of one of our common trees, the portion immediately above the ligature will become swollen, while that beneath it will retain its former thickness. If instead of a ligature we remove a circular ring of bark, the same phenomenon will take place: the part above this annular incision will swell out on every side. From this experiment we derive several important inductions. We learn from hence that this kind of sap descends, and moreover that the channel which conveys it is the bark.

Having ascertained the course which the elaborated sap pursues, let us now turn our attention to its composition. This is found to vary in different plants: thus in some, bitter principles are the chief constituents; in others, aromatic substances; in others it is principally resinous; but whatever may be the principal components, they may always be divided into two groups—namely, those which are subservient to the growth of the vegetable, and those which, becoming deposited in the different organs, confer on them those properties which entitle them to be employed as articles of medicine or aliment for animals, and by means of which different plants are in this respect distinguished from each other. The portion of the descending sap which serves for the growth of the vegetable, exudes in ordinary trees between the bark and the wood, forming a glutinous layer which separates these organs, and is the cause of the facility with which in autumn the bark can be detached from the stem: this portion is called cambium. In palms, and other trees of warm climates, there is no bark, and in such vegetables the nutritive part of the descending sap passes down through the centre of the stem.

The portion of elaborated sap which becomes deposited in the organs, and which varies more or less in every plant, is called the proper juice: proper vessels is the name given to the reservoirs which contain the proper juices; and according to the nature of their contents, the proper vessels are called milk-vessels, turpentine-vessels, vesicles of essential oil, &c.

In the foregoing paragraphs we have somewhat anticipated the uses of the descending sap: we have found that one portion of it is destined for the nutrition of the vegetable. Now, the same means which revealed to us the uses of the ascending sap, will also tell us how far the elaborated sap is concerned in vegetable nutrition. In the dark no sap is elaborated, and no vegetable fibre is developed. Are we not therefore justified in supposing that vegetable fibre is formed out of this elaborated sap? Again, let our readers call to their remembrance the experiment of tying a ligature around a branch: in that experiment not only does a considerable swelling take place above the ligature, but from this swollen portion cereal roots frequently protrude. These facts afford us a clue to the uses of the descending sap, for by developing vegetable fibre, it increases the thickness of the stem and the length of the roots, just as the ascending sap, by developing vegetable flesh, lengthens the stem, and enlarges the root in diameter.

T. A.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE IRISH PENNY JOURNAL.

Sir—In the 12th number of your Journal you have given insertion to a paper tending to involve our ancient and honourable race in considerable disrepute—I allude to an article entitled “A Chapter on Curs, by a Man.” Every story will on investigation be found to have two sides: you have given publication to the one, and surely you will not, in justice, refuse to give your readers an opportunity of judging of the other.

I remain, Sir, your faithful servant,

An Aged Cur.

By what means I have acquired the facility of expressing my thoughts upon paper, it is not my intention to divulge. It is true that I have made an important discovery—that I have gained possession of a secret which mankind would give worlds to possess; but I owe too little gratitude to any member of the human race to be induced to part with it. I am old: nearly fifteen winters have passed over my head since I first drew breath, and in the course of nature death cannot be far distant. My discovery shall shortly perish with me; and the same ditch or dunghill shall witness the dissolution of both.

Of my parentage I can record but little, as I remember nothing whatever of my father, and my unfortunate mother was hanged shortly after having given me birth. Alas! my recollections of her are tinged with any but pleasurable emotions, for to her I owe much of the misery with which my career has been chequered. Had she conducted herself with prudence, and been satisfied to have selected a mate from amongst the many dogs of her own degree who solicited her paw, my existence might have been passed in happy, because unnoticed obscurity. But no: stern destiny decreed that it should be otherwise, and had marked me for misfortune ere even I was born. Let not the reader start to hear me mention destiny: if he object to my opinions on this subject, he has a wide field open to him for reply in the pages of the daily press, which, CUR though I be, I am, by virtue of the discovery already alluded to, in the habit of reading; and he may rely upon it I am prepared to defend every position I advance. Why should I not mention destiny? I am a rigid fatalist, and well for me that I am. What else would enable me to bear up against the scoff and scorn of man? What else would steel my feelings against the blows of stones, thrown by the hands of such cowardly insensible men as he who published the philippic against our race, which has called forth this reply? What else would console me, when the staff of the churlish boor comes across my back, or when the urchin-rout attach the terrible kettle to my trembling tail? What supports me under such heart-rending circumstances, save the feeling that all is fixed—that such is my sad destiny, against which my barking or my struggling would avail me nought? But I digress—it is facts and not feelings that it is my province to record.

My ambitious parent, infatuated with the admiration and assiduity of her numerous suitors, despised them all, and falling a victim to her vanity, suffered herself to be seduced from the paths of propriety by a designing young pointer, who threw himself in her way, and employed every artifice, until at length he induced her to elope with him from her master’s comfortable farm-yard. For a while the guilty pair contrived to escape detection. My unhappy mother took up her abode under a hay-stack in the neighbourhood, and for a week or two was well and kindly treated by her gay and youthful lover, who regularly saved a portion of his daily meals for her use. After a little, however, meeting with a new and more beautiful object on whom to bestow his worthless affections, he abandoned my mother to her own resources, and from that period she saw him no more. Dreading to return to the home she had left, and being pressed with hunger, she was compelled to steal for her subsistence, and the poultry in the neighbouring homesteads visibly diminished in number; while, to crown all, my parent was brought to the straw, and became the mother of five little ones, including myself. The additional drag which the suckling of so large a family produced, increased my progenitor’s rapacity four-fold, and the indulgence of it caused her destruction. One day as she lay beside us, half famished, and ready almost to devour her own offspring, a little pig chanced to pass by. My mother belonged to a fierce breed, that called the bull-terrier, and, accordingly, stimulated by the gnawings of hunger, she sprang upon the little pig, and[Pg 175] had well nigh silenced it for ever, when its loud squeals brought one of the farm-servants to the spot. We were discovered, the unlucky pig rescued, my mother hanged to a post in the barn, and we—thrown into the horsepond. My brothers and sisters all perished; but I, who was rather stronger than the rest, contrived to struggle to the bank, and was found there some short time afterwards by a young man belonging to the establishment, who carried me home with the intention of rearing me.

Oh, how grateful I felt to that young man, and how I blessed him for his kindness! But, alas! I knew little of the cruel race whose servants we are, or I should have preferred being left to die on the brink of the old pond. As soon as he got me home to his father’s, the lad put me into a bag, and having bound me securely with many cords, took a large pair of blunt and rusty scissors, and proceeded to deprive me of my ears. Why should I weary your patience with a description of the excruciating torments I suffered! Indeed, no description could convey an adequate idea of one-tenth part of the pain I endured while my ears, and then nearly the whole of my tail, were slowly and mercilessly hacked away. As to the manner in which my tail was removed, it betrayed sufficient of the savage and bloodthirsty disposition of man, to give me a foretaste of what I might expect at his hands—my tail was actually gnawed asunder by his teeth!

When about nine months old, my master came home one day in a great hurry, and summoning me to attend him, left the house as abruptly as he had entered it. He bent his steps to a neighbour’s, where we found a crowd of men and dogs assembled, apparently intent upon some exhilarating sport, for on their countenances much glee was depicted. In a corner of the room a long narrow box was placed, with a sliding door at one end. Wondering what it could contain, I stepped up to a young bull-dog, with whom I was acquainted, and inquired of him. “Lord! how green!” exclaimed he; “why, a badger to be sure; and you’ll see the fun we’ll have drawing him, presently;” and my friend Boxer licked his lips with the anticipation of a fight. I had not long to wait, when Boxer was called by his owner, who held him opposite to the box by the neck, while another person raised the sliding door. Boxer was then let loose; when, darting with excessive speed into the interior, a growling and struggling was heard, and in about a minute my friend reappeared, dragging forth to view a wild beast called a badger—an animal that I until now had conceived to be a very gentle, harmless creature; for I at once recognised in this badger one which I had frequently met in a neighbouring hedgerow when out by myself, and with which I had begun to form a slight acquaintance. What was the cause of this creature and Boxer being thus induced to tear each other, I could not divine. But guess my consternation, when, Boxer having been separated from his antagonist, and the latter restored to his cage, I was dragged forward, and held in front of it, while my master patted and encouraged me, saying, “Hiss, hurroo!—good dog, shake him!—hurroo!” The door was raised, and I was thrown forward towards it. As, however, I had no cause of quarrel with its friendly inmate, I did not, as my acquaintance Boxer had done, rush into the box; but, determining to investigate the cause of the recent conflict, I entered it slowly, whimpering as I put in my head, to let my acquaintance of the hedgerow know that I came as a friend. He had, however, been so enraged by the previous encounter, that he would not listen to my remonstrances, but growled forth, “Get out, you cur!” “Don’t be in a passion,” whimpered I; “I come as a friend.” “That’s a lie,” replied he; “you can’t be the friend of that tyrant and be mine. You are but seeking to put me off my guard;” and with this snarling answer he flew at me and seized me by the nose. This was treatment too gross to be endured, so I accordingly returned the compliment; and conceiving that I should have more room to fight on the outside, I exerted all my strength, and dragged the irascible inhabitant of the box forth to light. To my utter astonishment, however, no sooner had I reappeared, pulling old Grey along with me, than I was seized, and my throat compressed so rudely as to give me considerable pain, and indeed almost to strangle me. For this inconvenience, however, I was amply repaid by the caresses of my master, and the plaudits of the company, both men and dogs. Among others, Boxer walked up to me, and growled in his usual cynical tone. “You may come to some good yet, if you’ll only be quicker at your work.” I did not at this time understand the human language, and I accordingly detail my impressions as they struck me then, not as they appear to me now. After two or three more dogs had had a pull at the badger, many others refusing to face him, or running away when they felt his sharp teeth, on which occasions they were well kicked by their owners, I observed an unusual bustle, and was amazed at hearing my name and Boxer’s uttered in a very loud tone. The latter at the same time approached me and said, “Tell you what, young ’un, they’re talking of a fight ’twixt you and me; and if so be they’re in earnest, take care of yourself—that’s all.” “But, dear Boxer,” inquired I, wagging my tail in a conciliatory manner, “why should we fight?—surely we have no cause of quarrel?” “No business of mine,” answered he; “pleases my master; likes to see us bite and tear each other; great fun to him; must please him; gr-r-r.” So indeed it was, and I, though scarcely more than a puppy, was pitted against the redoubted Boxer. I was very unwilling to fight; for, besides that I had no quarrel with him, I did not think I was his match, and was sure of being beaten. When he seized me, however, my spirit stirred within me, and I put forth all my strength and determination. For nearly an hour we contested. Boxer at first got the better of me, and threw me down; but after a little I discovered that his tender point was his legs: so at them I directed my attack, and, getting hold of one of them, obtained an advantage which I retained to the last; when, neither being likely to prove victorious, and neither disposed to give up, we were separated. I was dreadfully cut, and my wounds smarted me amazingly; but how terrible was my torture when my master, taking me by the neck, proceeded to wash them with a liquid of a fiery burning nature, since known to me as spirit of turpentine. This was I believe designed to stop the bleeding! Such was my initiation into what men call sport. I now found that I must live without a friend, for every strange dog my master compelled me to attack. My course was marked out. My rage was to be directed against every other animal, dog, cat, rat, badger, cow, pig, &c. except such as were the property of my owner. My occupation was henceforth to be slaughter and bloodshed, and my existence was hereafter to be devoted exclusively to violence.

In scenes such as I have described passed the first three or four years of my life. My wounds were ever open, ever painful; for no sooner had one set of cuts closed, than I was forced into a new conflict, in which they were re-opened, and I received others into the bargain. At length premature old age, the result of the hardships I had endured, came upon me, and I was no longer deemed serviceable for fighting. I now suffered less from wounds and cruelties; but being regarded as a useless member of the household, I was treated with unfeeling neglect, and receiving hardly any food at the hands of my master, was driven to seek a scanty subsistence among the bones cast out upon the dunghill; and these, with an occasional crust thrown me by a good-natured stranger, were my sole support.

My master had an aged father, who lived in the house with him, and whom the neighbours conceived to have laid by a considerable sum of money. I usually slept across the hearth in the kitchen, and was one night awakened by a cry for help in the half-choking, gurgling accents of a man under the effects of strangulation. The sounds proceeded from the old man’s room. The door was open, and I darted in. The old farmer was lying half naked upon the floor: in his hand was clutched a bag, and numbers of those round yellow pieces of metal so much coveted by the human race, and called guineas, were scattered near him. A man was leaning over him, his knee upon his breast, one hand upon his throat, and the other endeavouring to drag from him the precious bag. I saw not the face of the spoiler, but perceiving only the danger of my master’s old father, whom, harsh as he too had been to me, I instinctively loved, and felt it my duty to defend, I sprang upon the robber, for such I judged him, and pulled him to the ground. The old man fainted away. A gleam of moonlight at this crisis entered the casement, and disclosed to my horrified gaze, in the countenance of the robber whom I was throttling, the features of MY MASTER! In the suddenness of my surprise and consternation I relaxed my gripe; and the villain who had striven to rob his father, and had raised his hand against the person of his aged parent, sprang to his feet and fled. I had by this time learned to understand a little of the human language; and as the ruffian darted through the door, the word “damnation!” struck upon my ear.

The old man, as I have stated, had fainted. Happy for him that he had not recognised his assailant before my interference, for further opportunity of recognition he had none.[Pg 176] From that fit of insensibility he awoke in another and I hope a better world.

I was now an outcast—a wanderer over the face of the earth. I went forth, wretched and desponding, moralising upon the dreadful lengths to which their love of gold will lead our masters, mankind. “Oh!” thought I, “if we but take a bone from a larder-shelf to satisfy our hunger, how we are abused, sworn at, and flogged! Yet the same man who will punish us for a trifling theft, will not hesitate to wrong or murder his neighbour for a few worthless, perishable pieces of yellow metal. Oh, destiny, how I thank thee, despite my sufferings, that I was not born a man! What sordid, selfish wretches these men are! Their thoughts from morning until night are occupied with speculations intended to promote their own comfort, their own aggrandizement. The dog alone loves his master better than himself, and will lay down his life in his defence. Man is a base, selfish wretch. The dog alone honours and practises generosity uninfluenced by hope of recompense.”

I soon afterwards met with another master. For a time he treated me well enough, and but for an untoward accident I might still have remained in his service. While sitting one day peaceably beholding the industry of my new master, who was a turf cutter, I heard at a distance a prodigious clamour as if of a number of dogs engaged in conflict. Being old and peaceably inclined, it occurred to me that I could not do better than hurry to the spot and exert myself to effect a reconciliation. Off therefore I set as fast as my old legs would carry me. Before, however, I arrived at the scene of riot, silence had ensued, and I was about to return, when I perceived a stout-looking man engaged in pelting with huge stones two or three wretched, half-starved looking little dogs, that were endeavouring, howling with pain, to make their escape from his cruel attack. I raised a loud barking, encouraging the dogs in our own language to get out of his way, hoping also that the noise might frighten their assailant, and induce him to desist from his barbarous amusement. I thought that I had succeeded in my design, for the ruffian ran away as fast as he could; but determined to give him a lesson, I resolved to terrify him to the utmost, and so gave chase. Of the result of this encounter I need not inform you, as you are already acquainted with it from the account of the “Man” himself, as published in the 12th number of your Journal. I have, however, in justice to my own character, to state, that it was not cowardice which prevented my biting him, and which induced me to put up with his ducking, &c., without resistance. It was not cowardice—it was the singular resemblance which he bore to my wicked master. That alone saved him from a hearty shaking. But he shall not long escape. No; I am in the daily habit of walking up and down Sackville Street, in hopes of meeting with him, when, old as I am, I shall manage to make my teeth, or rather their stumps, acquainted with his calves.

I could not, on my return to the turf bog, find my master; and as I was on the road to look for him, I met with an old beggarman, who coaxed me over to him, regaled me with a crust, and in short exhibited so kindly a disposition, that, not feeling myself bound to my late owner by similar ties which had linked my destiny with that of him who had rescued me from the horsepond, I resolved I would seek after him no further, but join company with the good-hearted old beggarman—the same, doubtless, so irreverently spoken of by the “Man” in his ill-natured paper—(oh! that I had him by the leg this moment!) I did not, however, remain long with him, for he was taken up by an overfed bloated-looking variety of his species and lodged in prison, for no fault but that involuntary one of being poor; and as I would not be permitted to share his confinement, I wandered forth, and soon met with another master.

Thus going from one to another—now feasting, now enduring the most agonizing hunger, now received with kindness, now with blows—passed away the next five or six years of my superannuated being. I longed to know what had become of my master, ruffian as he was, and my wanderings had for their object the discovery of his abode. For several years I roamed unsuccessfully: no traces of him could I perceive; his ancient haunts had all been abandoned; his former companions unvisited. At length, coming one morning into a country town, I observed an unusual bustle in the streets; great multitudes of people hurrying along; and, what surprised me most, all in one direction. Determined to see what this meant, I followed the stream, and presently came to an open place, crowded with people of all sorts and sizes. Making my way onward amongst their feet, though not without many a bitter curse and hearty kick, I arrived at a singular wooden erection, like a signpost, with a rope hanging from it, and underneath a cart with three men in it. I uttered a yelp of joy, for in one of the three I recognised my long-lost master! To join him was of course my immediate impulse, and I accordingly sprang into the cart, but was rudely hurled out of it by one of the other men; and ere I could repeat my attempt, the vehicle moved away, the wheel passing over my body, and breaking three of my ribs. I looked again. I saw a human figure swinging in the wind—a single convulsive struggle of the legs, and all was over. It was my master—he died the same death that had been inflicted upon my mother. “Well,” thought I, “I shall never again express my wonder that men should be so fond of hanging us, for I now perceive that they likewise hang one another.” I was in too great pain from my broken ribs to make my way to the body of my poor master; I strove to crawl as near the post from which it was suspended as I could, and as I lay there I heard an old man say, “Ah, I knew it would be thus: he began with dog-fighting and badger-baiting—’twas but the first step to lead him to the gallows!”

After a while the body of my master was taken down, but I was not suffered to approach it. It was concealed from my sight in a long narrow box, with a black cloth over it, somewhat similar to the one from which in life he used to make me pull the badger. A hole was dug in the ground beneath the post, the box thrown into it, and the earth being shovelled in, falling heavily upon it, recalled me to a sense of my situation, and I went forth once more, a houseless wanderer and an ill-starred cur.

H. D. R.

Horrors of the Slave Trade.—Commander Castle, R.N., while on service with the preventive squadron in 1828, in command of H.M.S. Medina, captured the Spanish brig El Juan, with 407 slaves on board. It appeared that, owing to a press of sail during the chase, the El Juan had heeled so much as to alarm the negroes, who made a rush to the grating. The crew thought they were attempting to rise, and getting out their arms, they fired upon the wretched slaves through the grating, till all was quiet in the hold. When Captain Castle went on board, the negroes were brought up, one living and one dead shackled together; it was an awful scene of carnage and blood; one mass of human gore. Captain Castle said he never saw anything so horrible in his life. In the year 1831, the Black Joke and Fair Rosamond fell in with the Rapido and Regulo, two slave vessels, off the Bonny river. On perceiving the cruisers they attempted to make their escape up the river; but finding it impracticable, they ran into a creek, and commenced pitching the negroes overboard. The Fair Rosamond came up in time to save 212 slaves out of the Regulo, but before she could secure the other, she had discharged her whole human cargo into the sea. Captain Huntley, who was then in command of the Rosamond, in a letter, remarks—“The scene occasioned by the horrid conduct of the Rapido I am unable to describe; but the dreadful extent to which the human mind is capable of falling was never shown in a more painfully humiliating manner than on this occasion, when, for the mere chance of averting condemnation of property amounting to perhaps 3000l., not less than 250 human beings were hurled into eternity with utter remorselessness.”

Hypocrisy.—Hypocrisy is, of all vices, the most hateful to man; because it combines the malice of guilt with the meanness of deception. Of all vices it is the most dangerous; because its whole machinery is constructed on treachery, through the means of confidence, on compounding virtue with vice, on making the noblest qualities of our nature minister to the most profligate purposes of our ruin. It erects a false light where it declares a beacon, and destroys by the very instrument blazoned as a security.

Cant resembles a young wife married to an ancient husband: she weds religion, looking forward to live by his death.

Printed and published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; J. Drake, Birmingham; Slocombe & Simms, Leeds; Frazer and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.