Title: Waterfowl Identification Guide

Author: Central Flyway Council

Release date: April 5, 2017 [eBook #54487]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, MFR and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Published by

The Central Flyway Council

The Central Flyway Council wishes to thank the Atlantic Flyway Council for making available the illustrations and most of the text of this booklet.

The Council also wishes to thank the many persons who assisted in preparation of this publication, particularly the Vermont Fish and Game Commission and Alan R. Munro, the artist.

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

BY THE LANE PRESS. INC. · BURLINGTON, VERMONT

The North American continent, at the time of its discovery and early settlement, had a waterfowl population which was one of its many wonders. So far as the evidence shows, no equal area of the earth’s surface ever supported such vast numbers of so many different ducks and geese, and this situation persisted to a time within the memory of living men. Long after the end of early settlement on this continent, hunting was free and harvest unlimited. But as the advancing tide of settlement reached into the north-central prairie states and provinces in the final years of the Nineteenth Century, radical changes began. From that time on North American waterfowl habitat began to deteriorate. Literally millions of acres of former nesting ground in the north have now been drained and put to the plow. South of the breeding range, not only agriculture, but industrialization and urbanization also have steadily reduced available resting and wintering grounds.

The progressive decline in waterfowl numbers which followed these changes in land use led eventually to the scientific management of waterfowl. Spring shooting and market hunting were abolished in the second decade of this century. Ten years later the federal government undertook detailed regulation of migratory waterfowl so the annual harvest could be made proportional to the annual production. This was accomplished through collective effort by State, Provincial and Federal agencies of Canada, Mexico and the United States to obtain scientific information. In keeping with biological principles, most of the restrictions on bag limit and means of taking have been used with some flexibility.

Throughout the decline of all waterfowl populations some species have been underharvested. These species have declined in about the same proportion as those species on which the bulk of the harvest occurred. The Central Flyway Council feels that a refinement in waterfowl management is possible by directing hunting pressure on these previously underharvested species. This goal can only be accomplished through a knowledge of species identification by the waterfowl hunter. This booklet is a start in that direction.

In recent years most waterfowl populations have made encouraging recoveries from the low point of the early 1930’s, when disastrous drouths, drainage and changing land use patterns took their toll. Still drainage continues, and industrialization is further reducing the habitat. Hunting continues as a major sport, however, 6 maximum utilization of all species must be accomplished if hunting is to be fostered at a reasonable level of freedom and enjoyment.

The very future of duck hunting depends upon a more effective partnership between regulatory agencies and the many thousands of gunners whom they serve. The federal agency is charged by treaty and law with husbandry of the waterfowl resource. The State agencies assist in the responsibility. However, they need the help of all sportsmen, and particularly they need the understanding help of waterfowlers who know their birds and who keep abreast of current plans for management. To foster this essential cooperation between agencies and gunners is a primary purpose of this booklet.

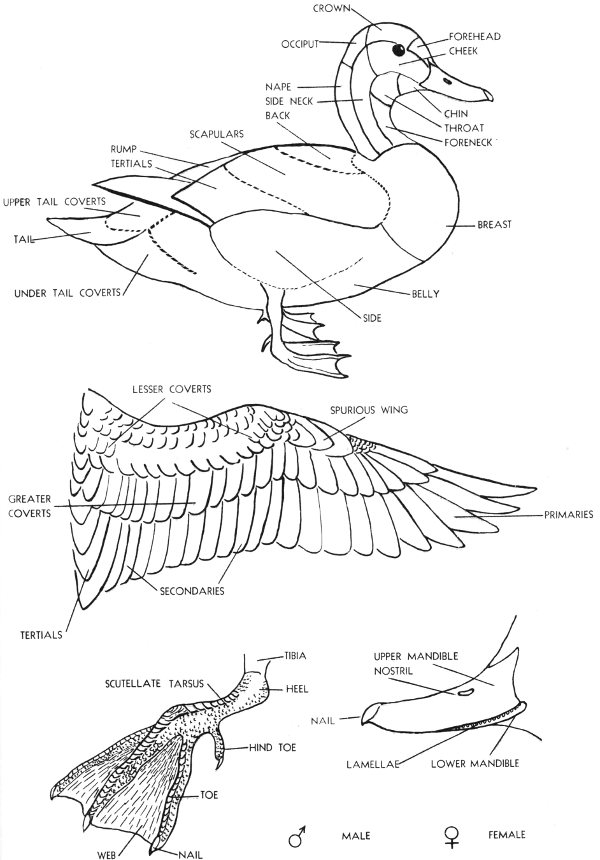

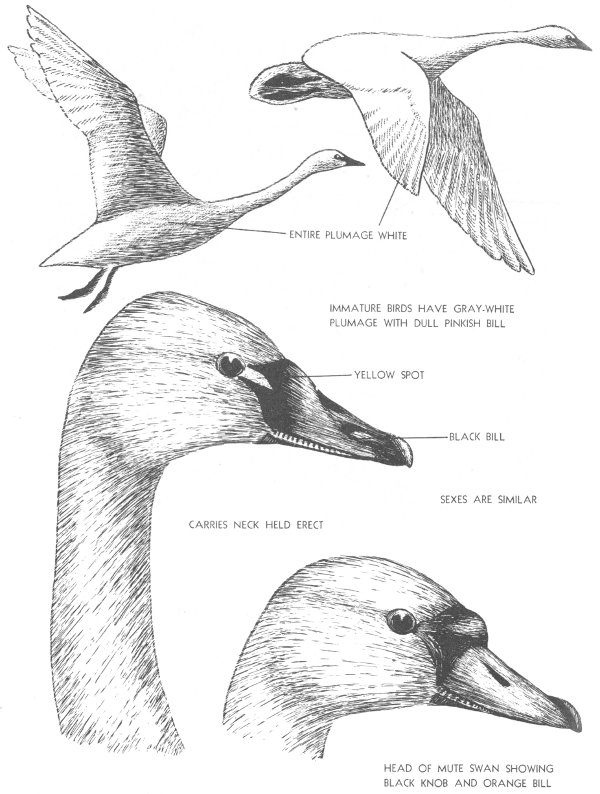

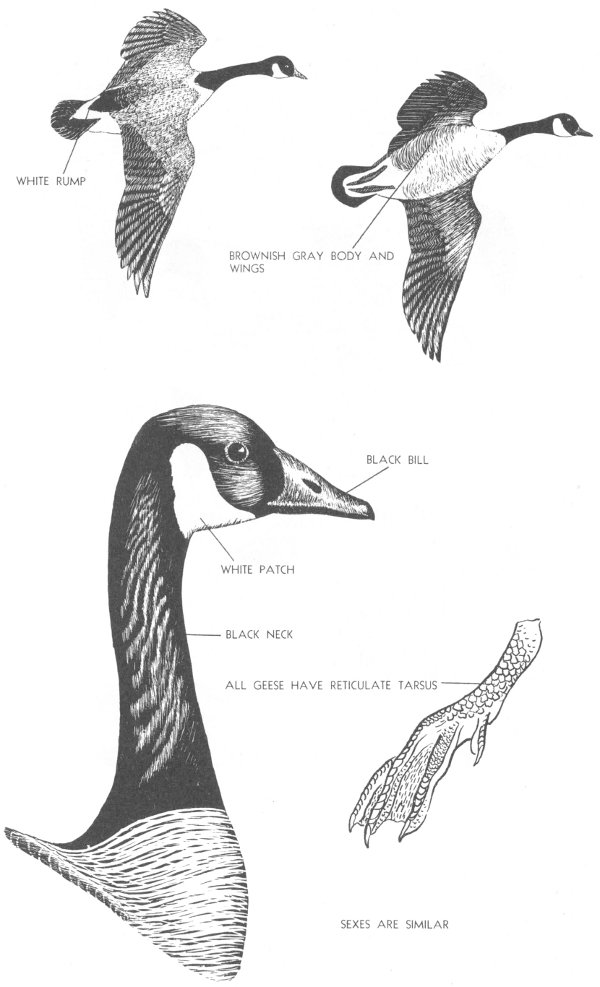

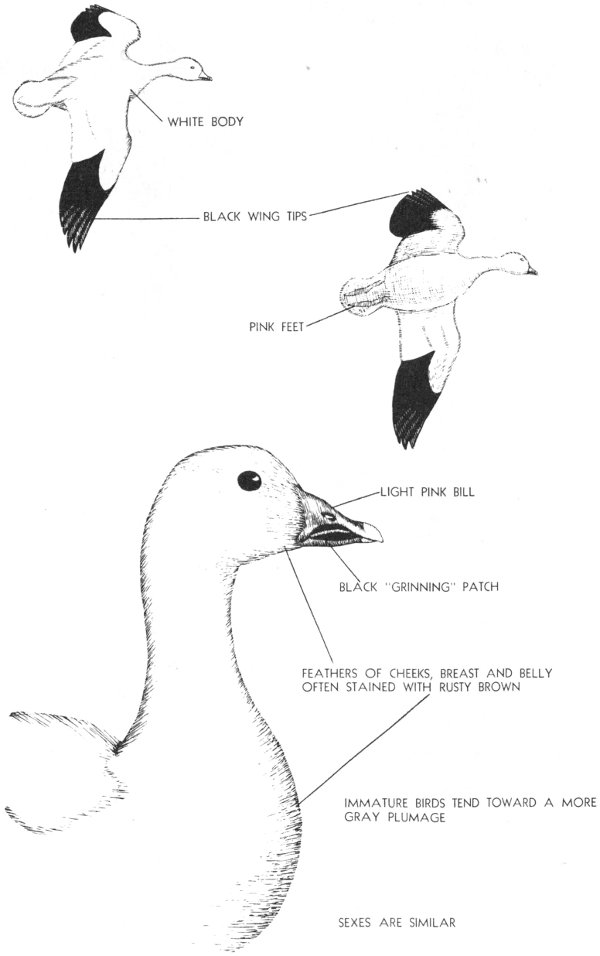

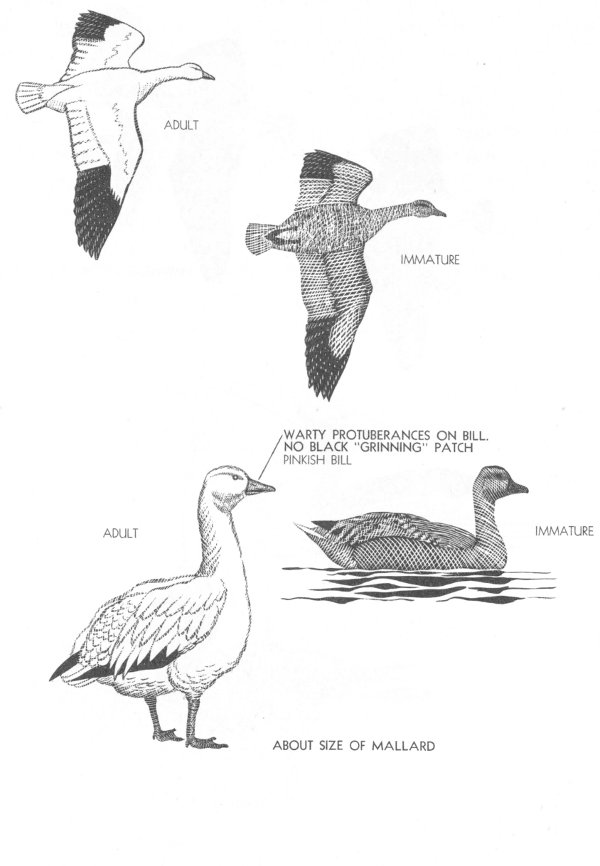

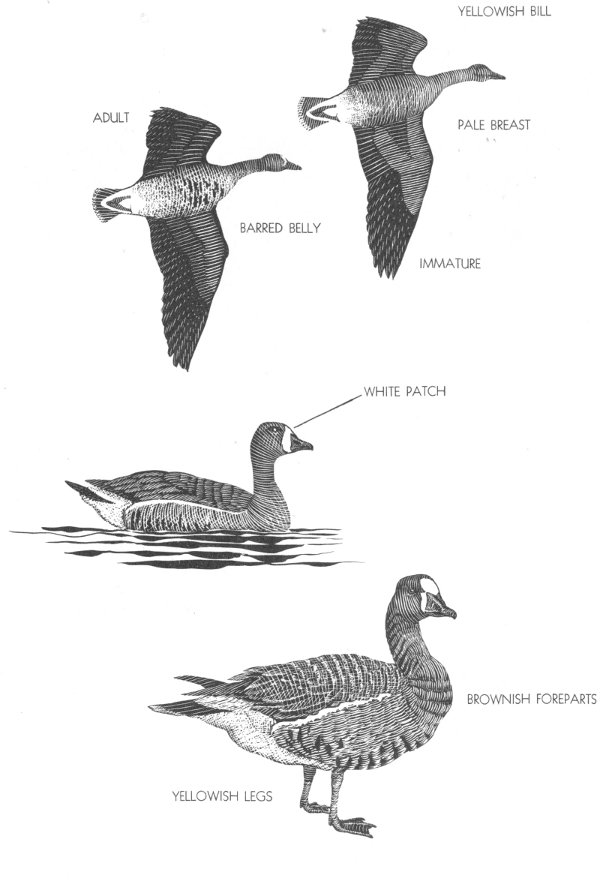

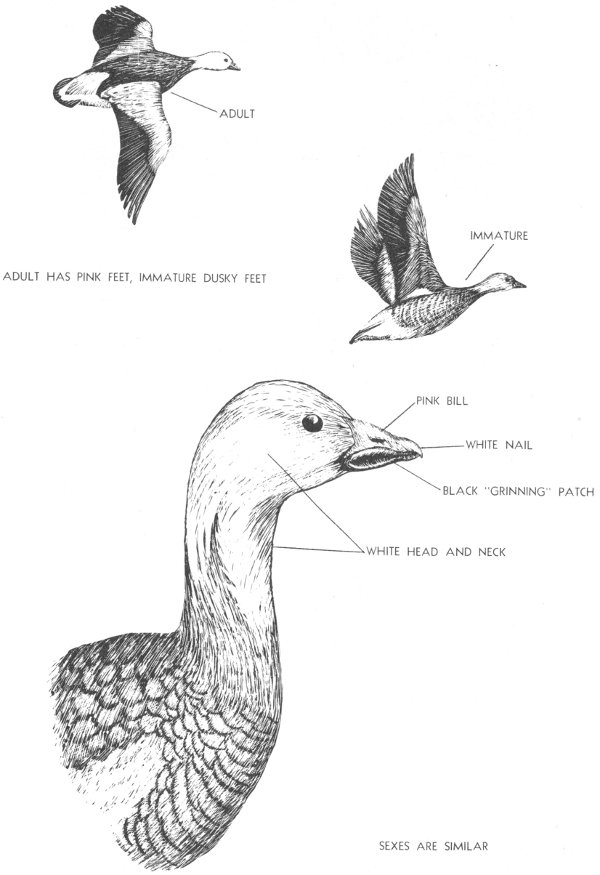

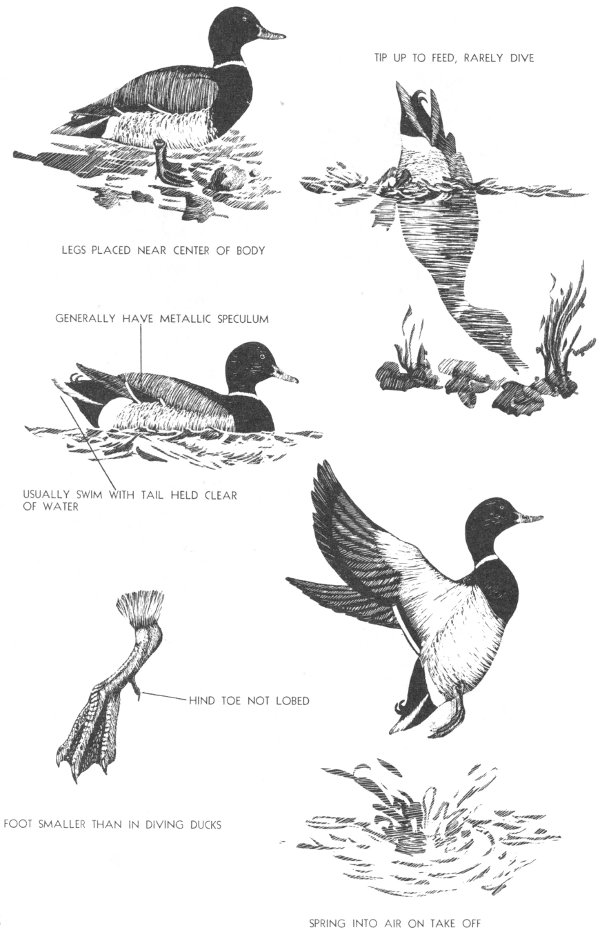

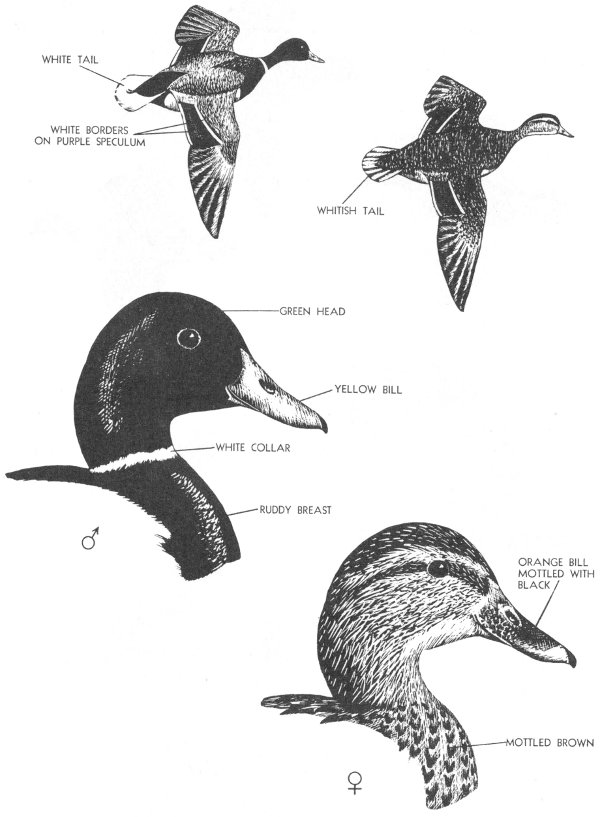

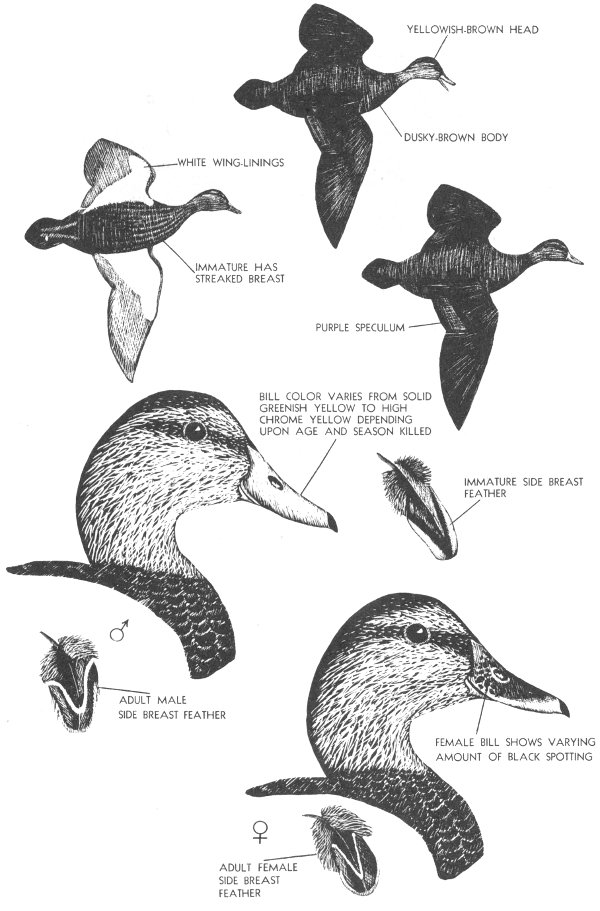

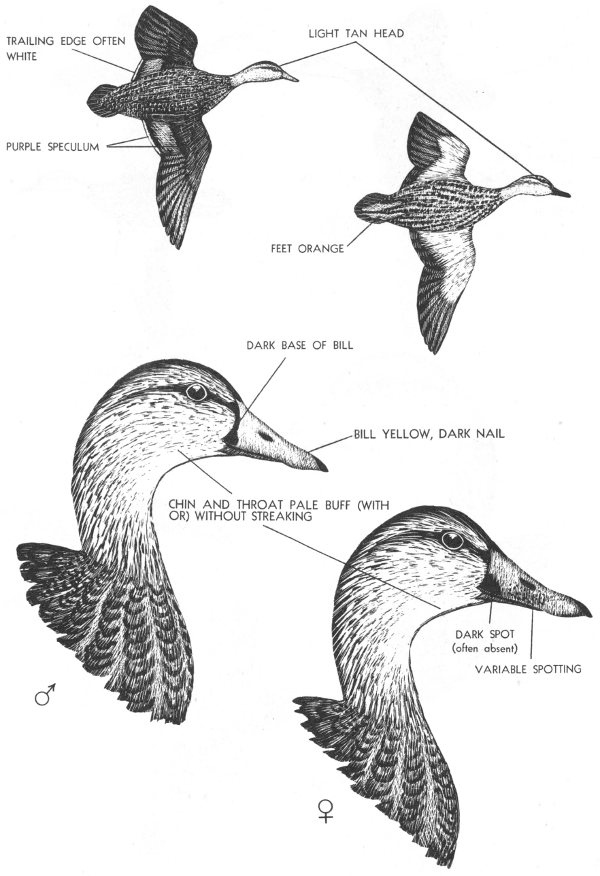

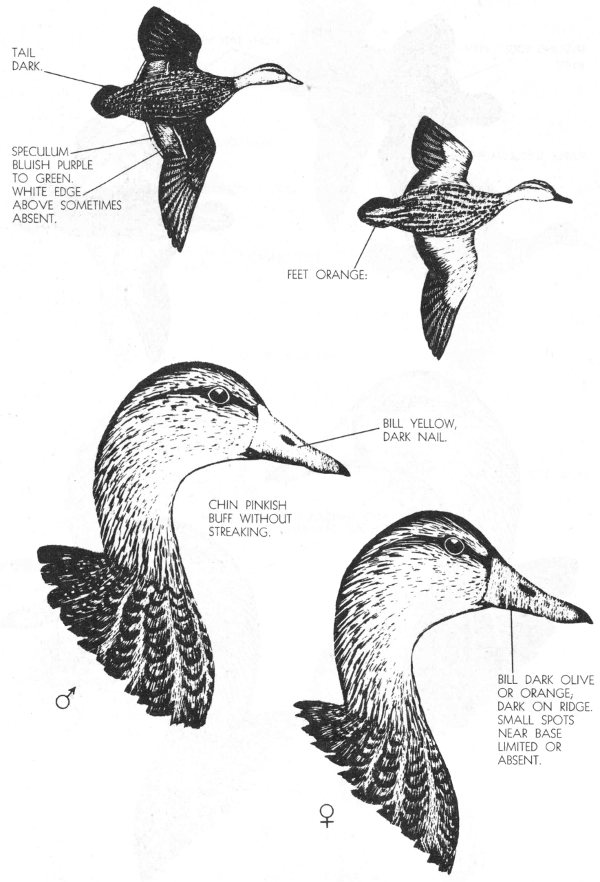

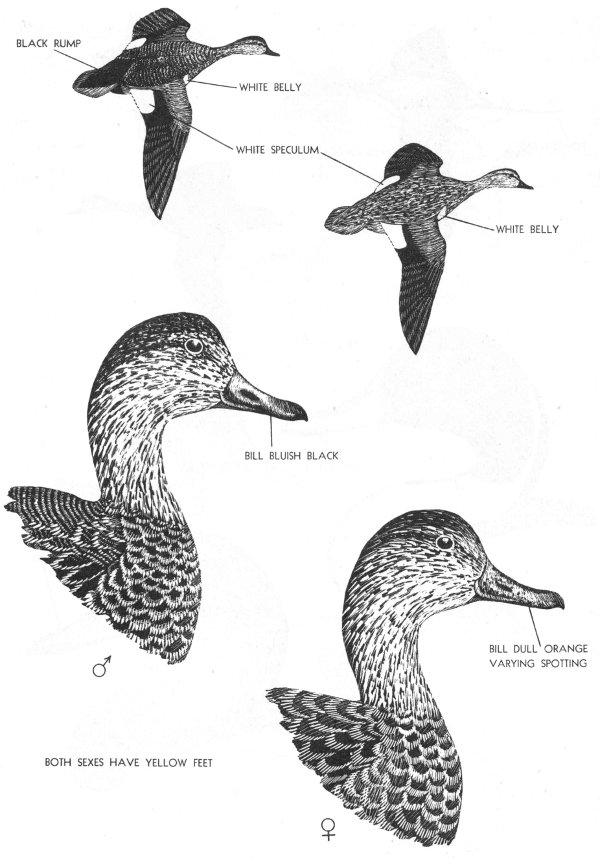

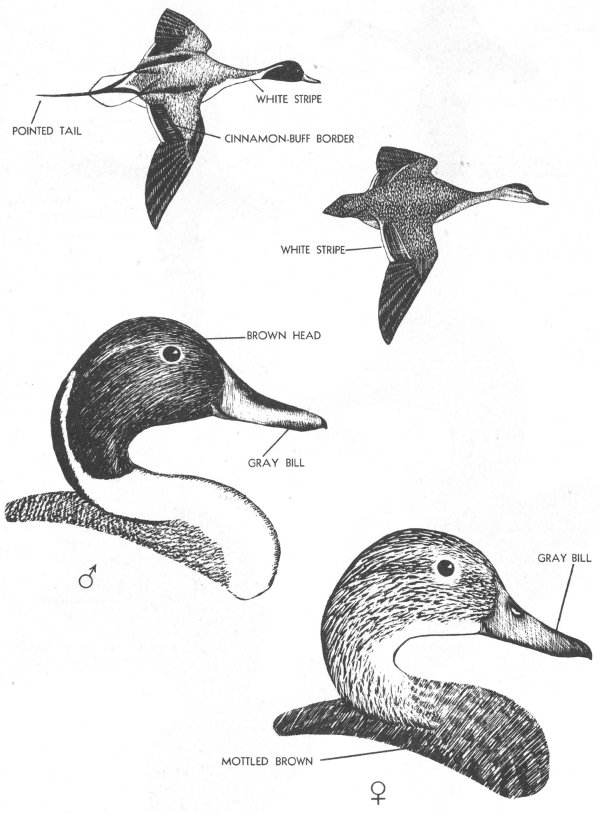

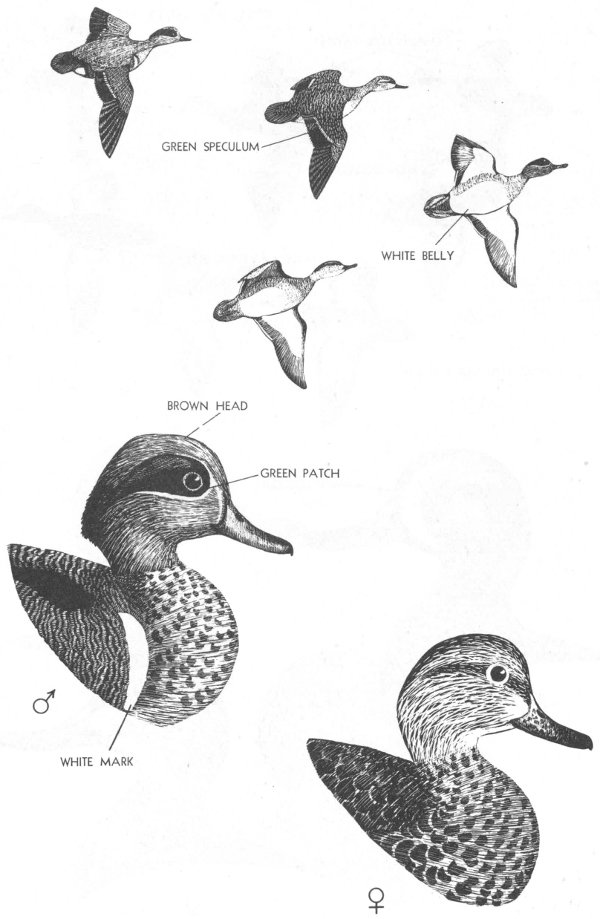

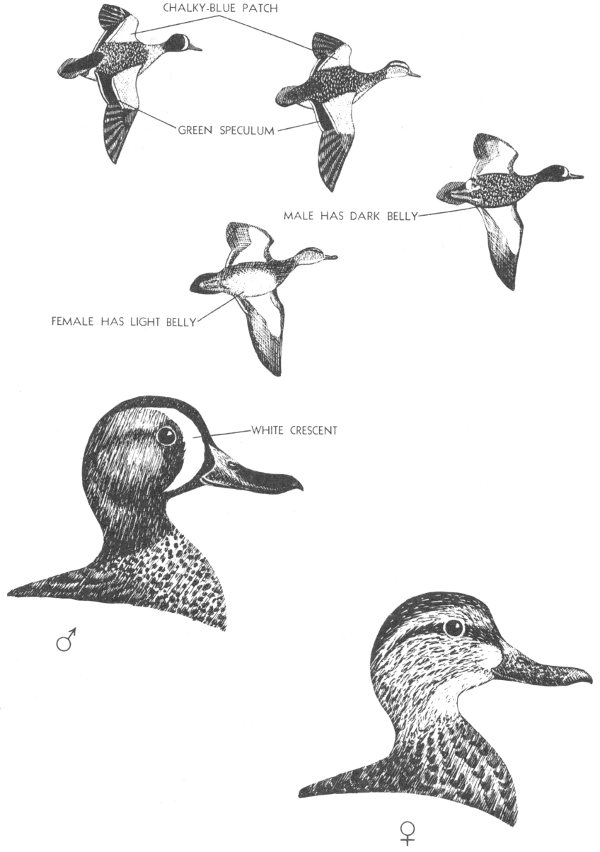

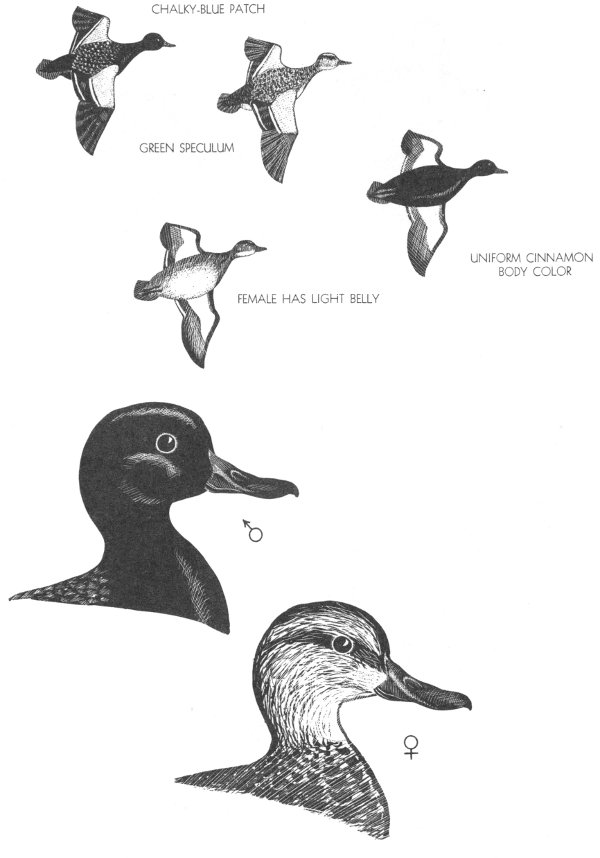

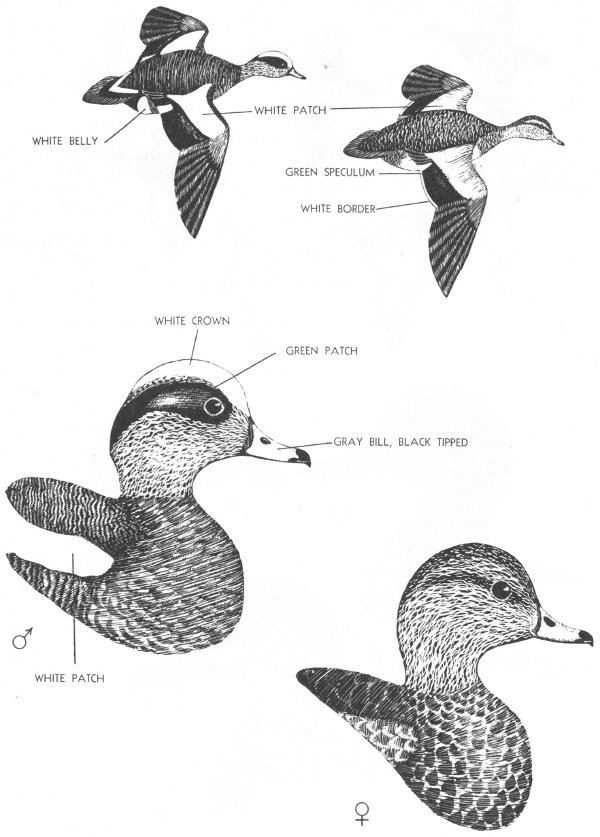

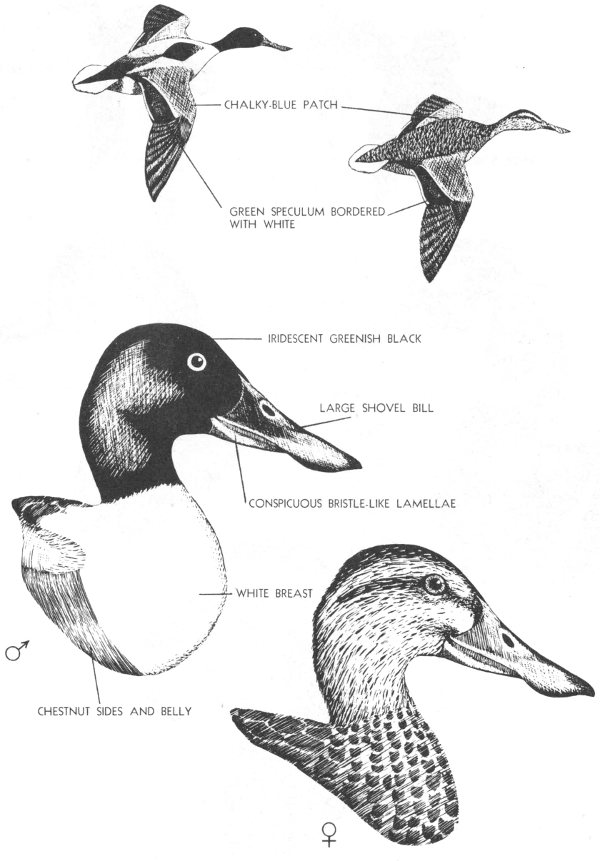

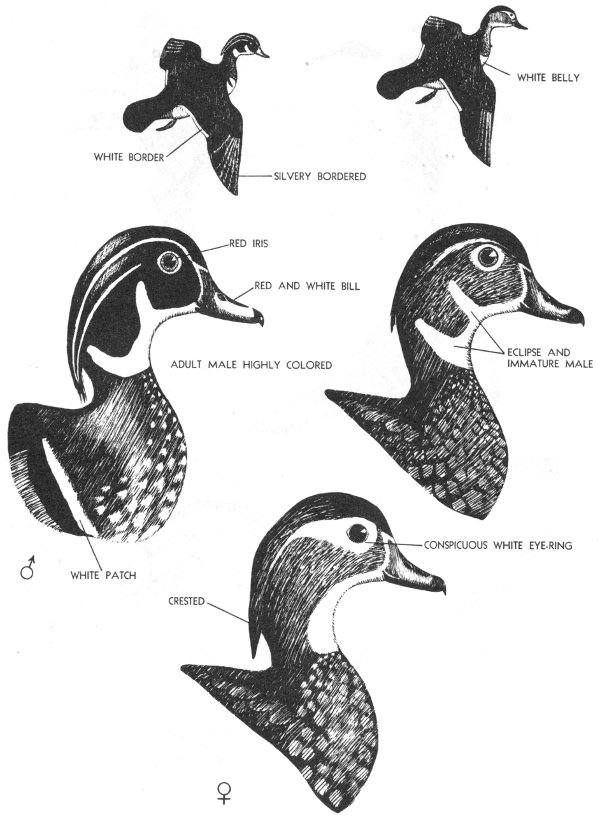

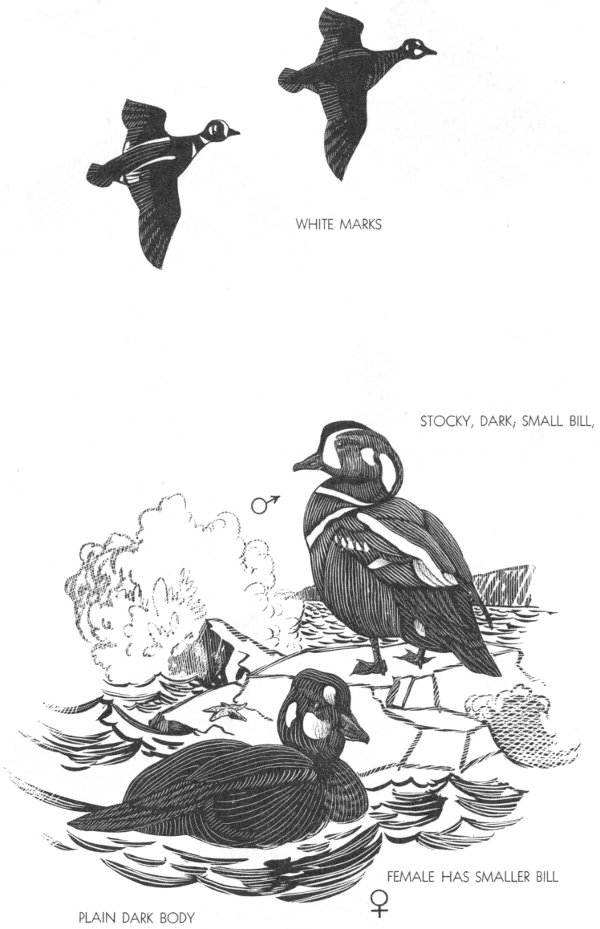

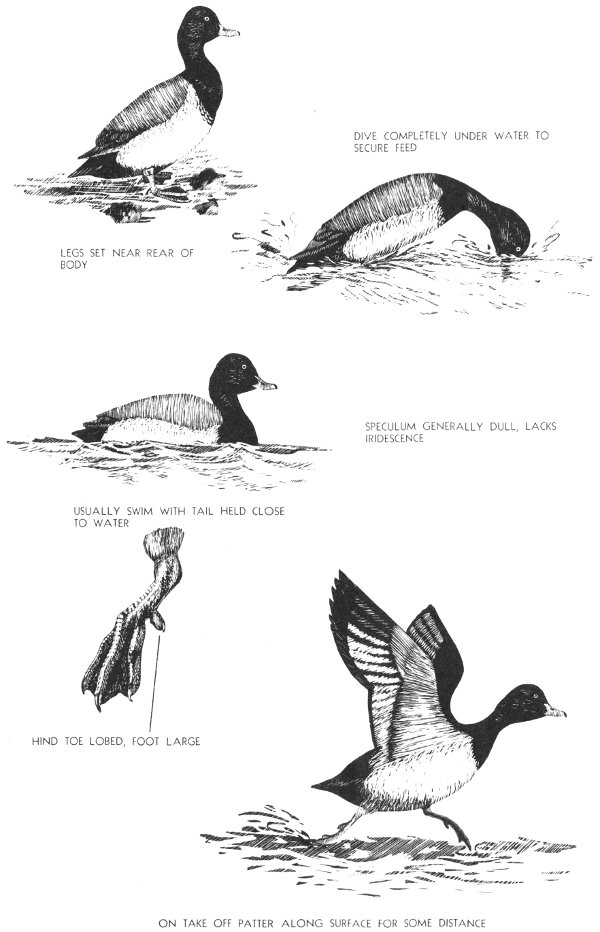

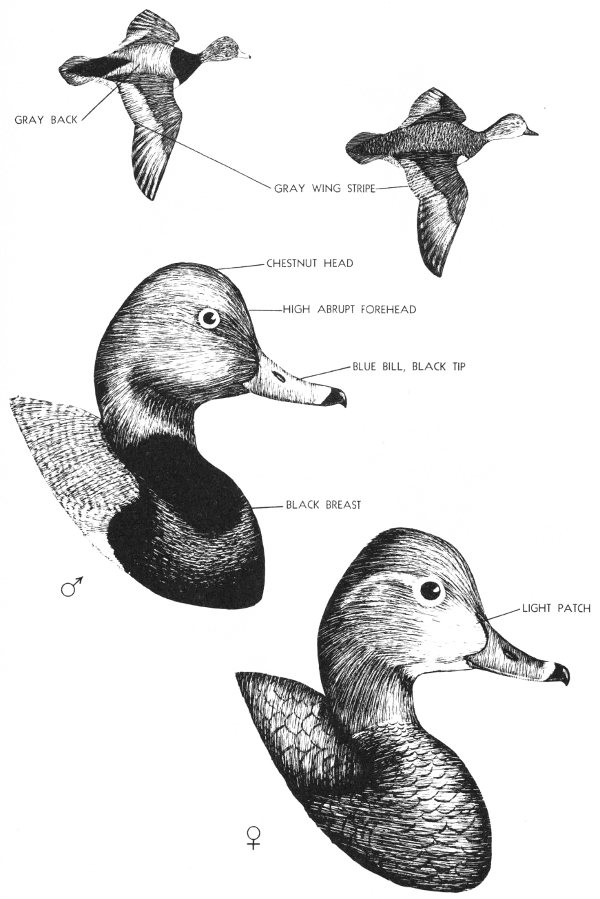

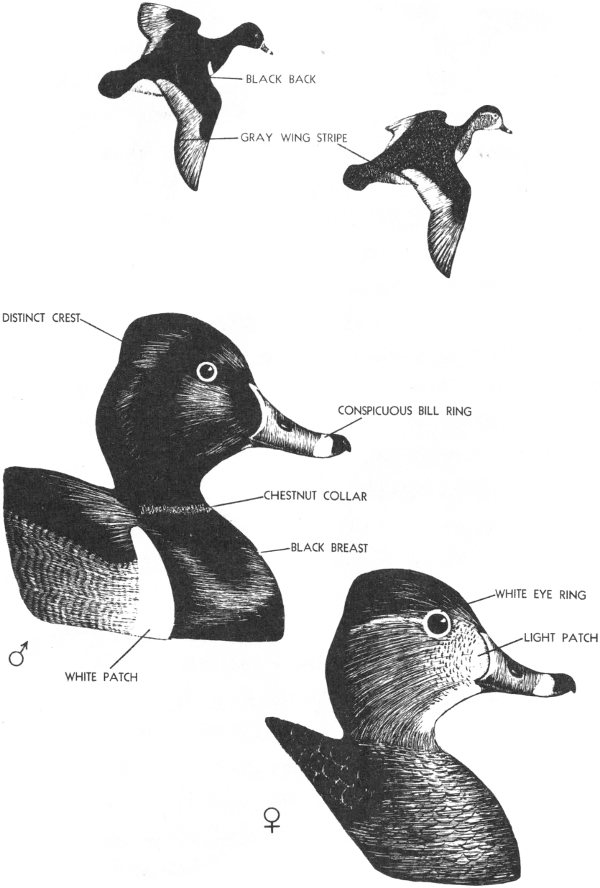

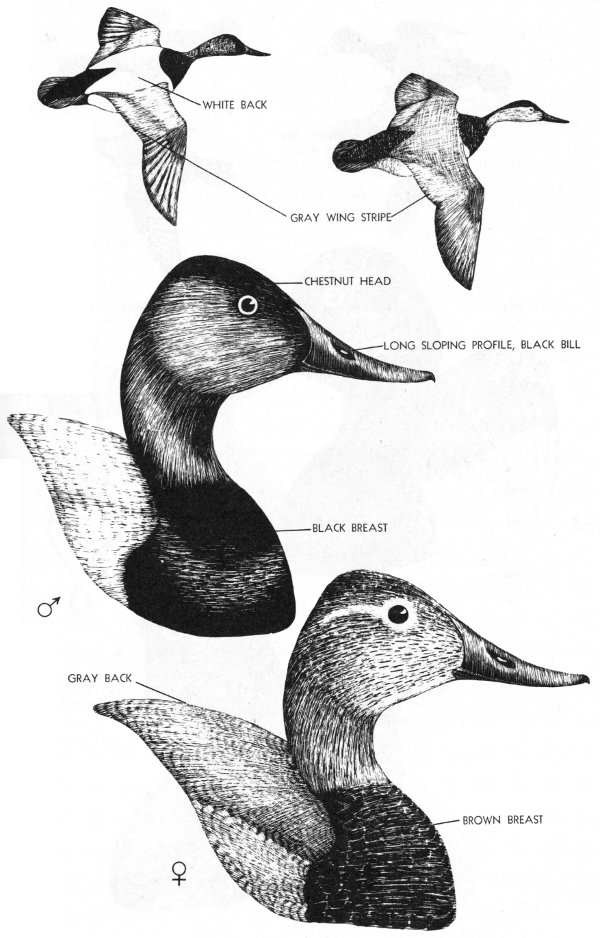

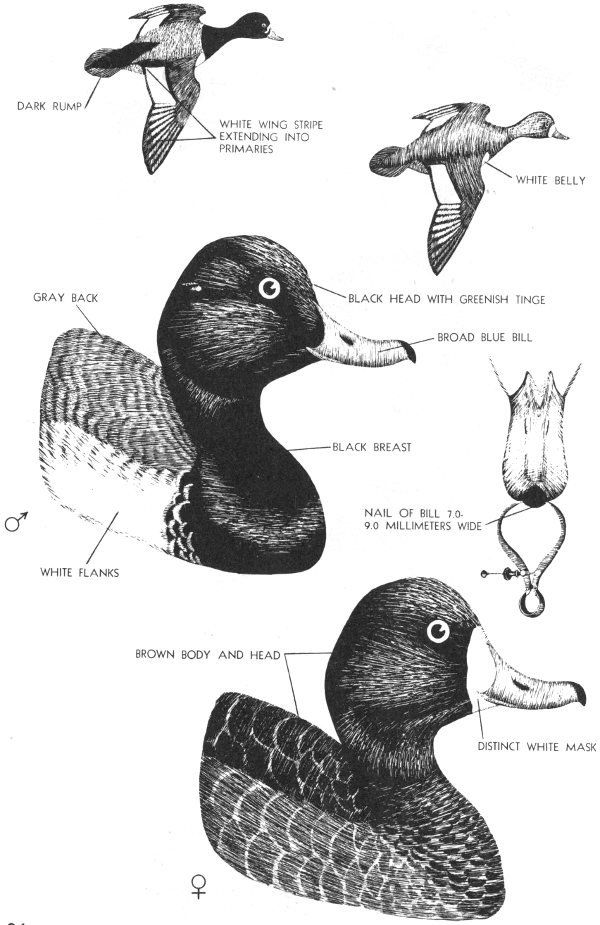

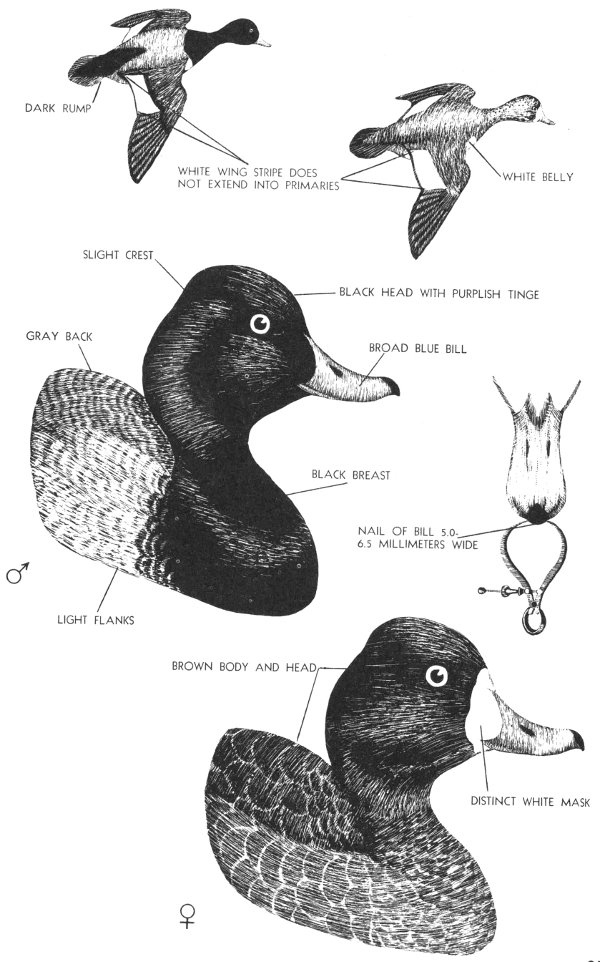

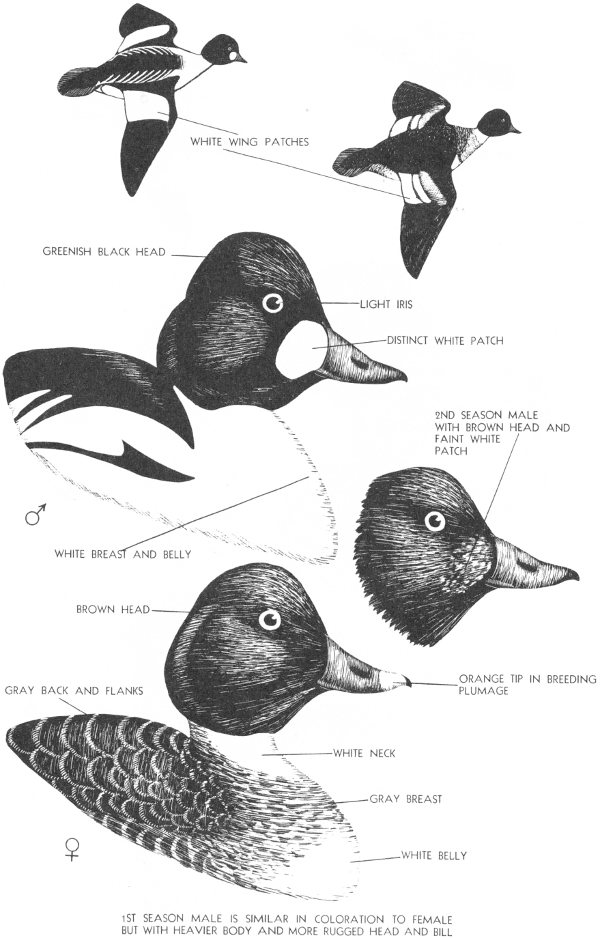

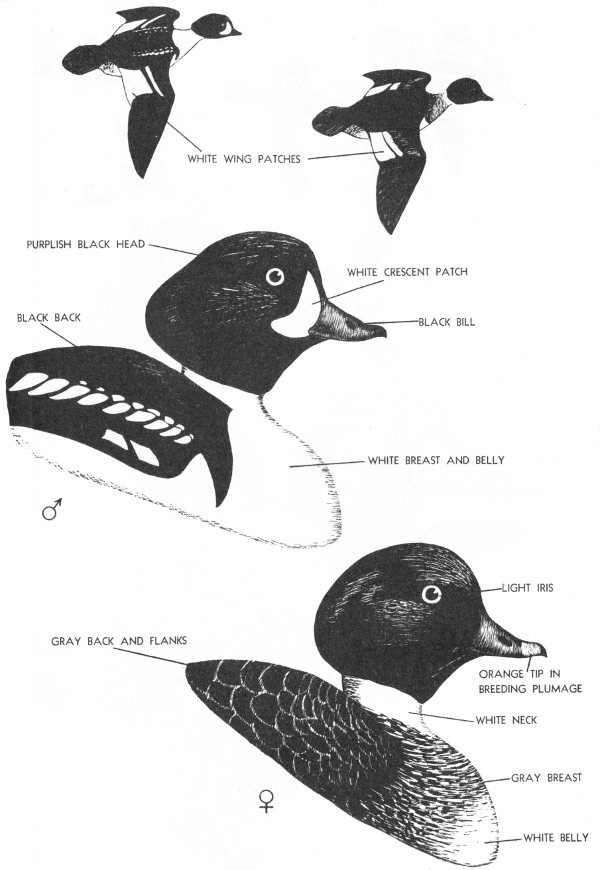

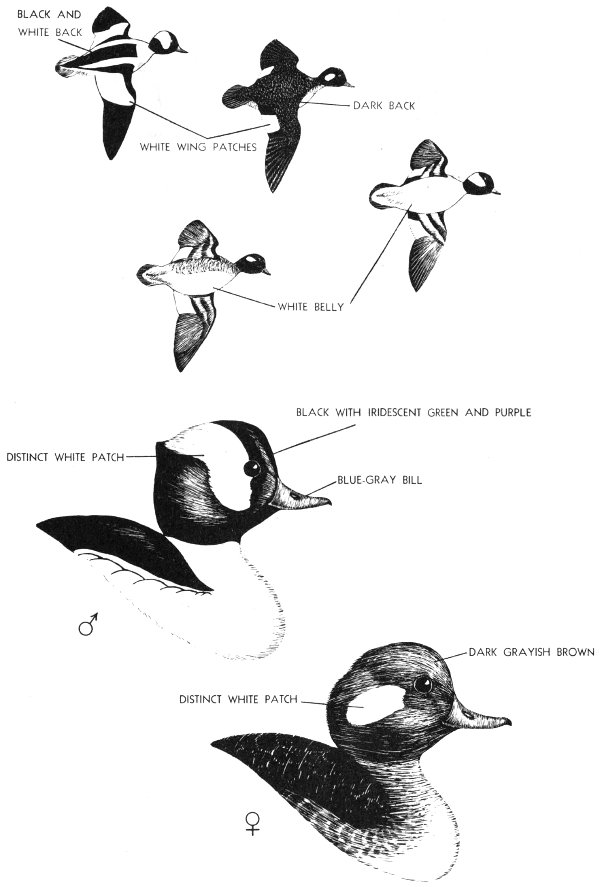

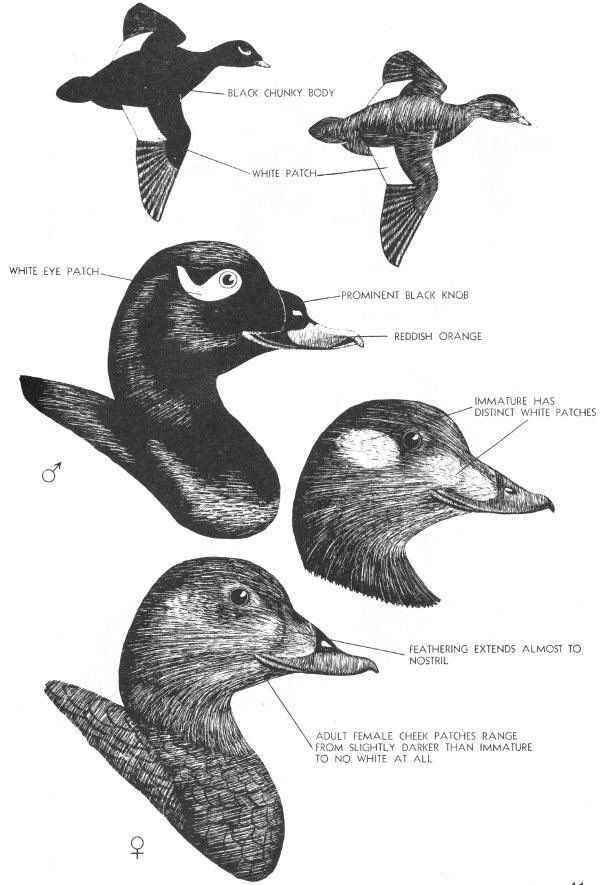

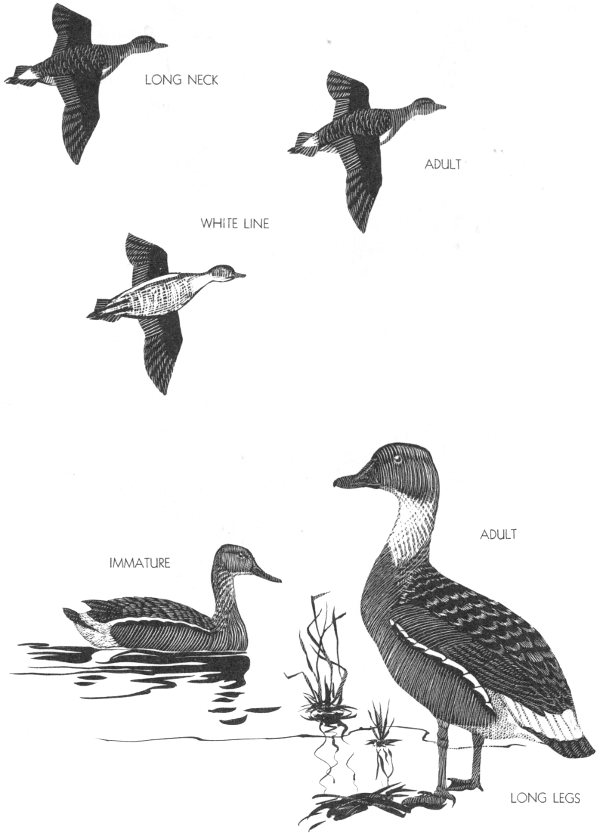

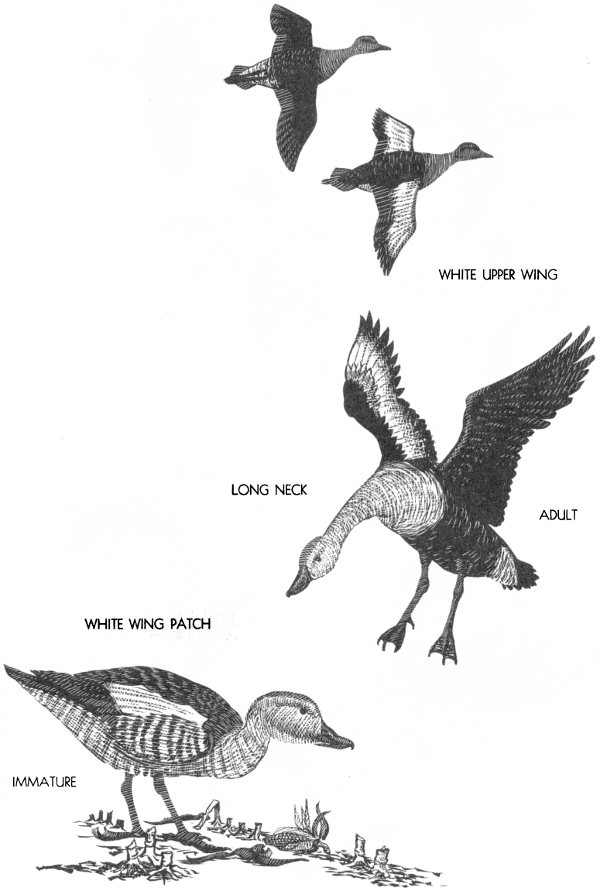

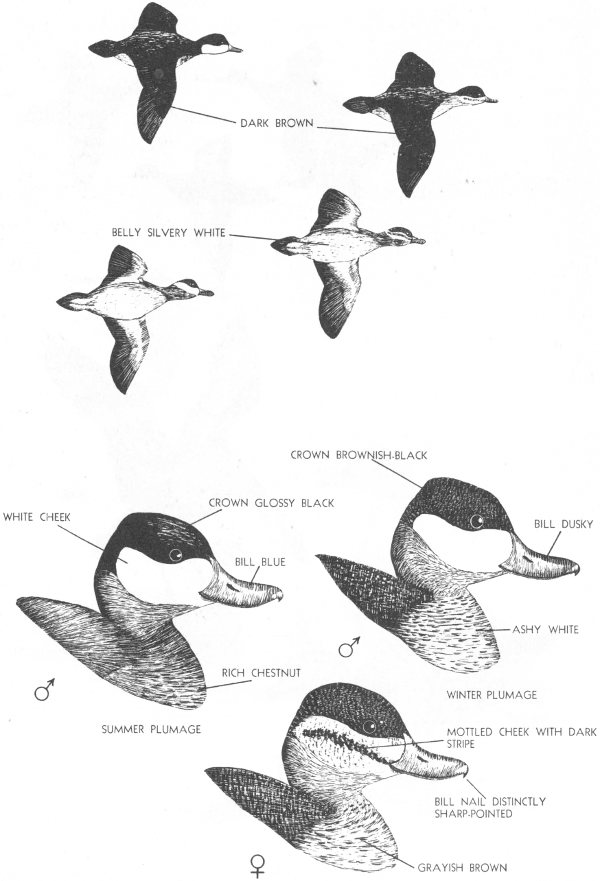

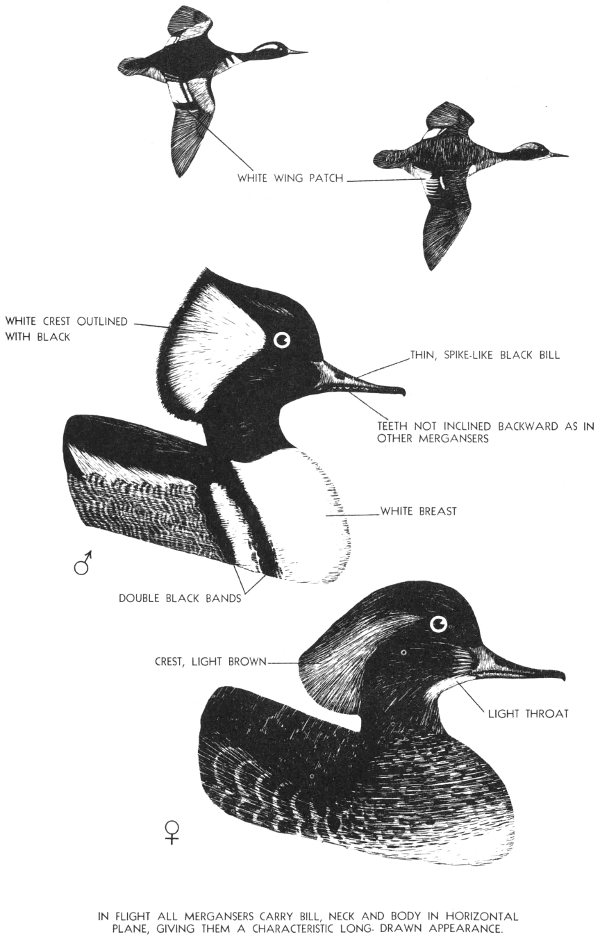

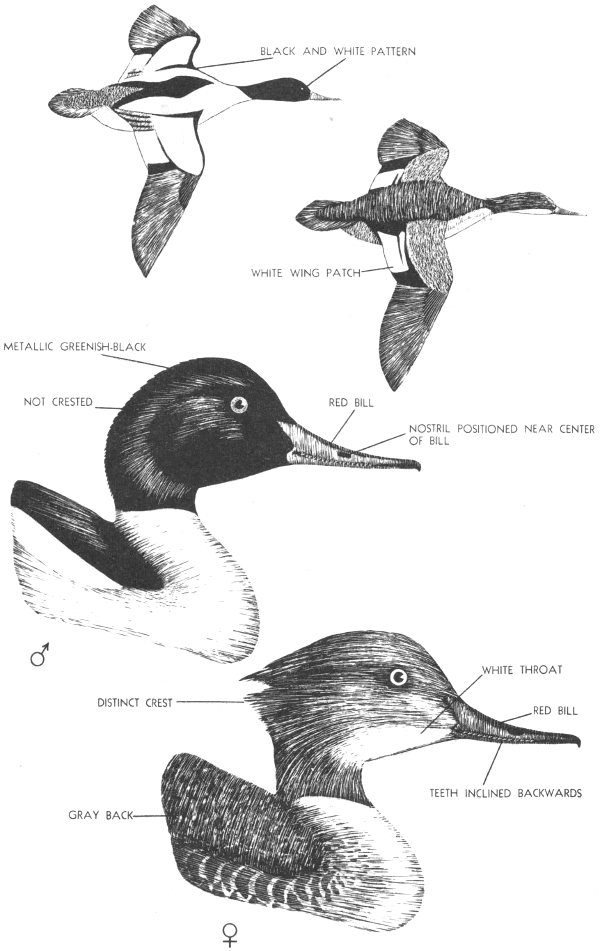

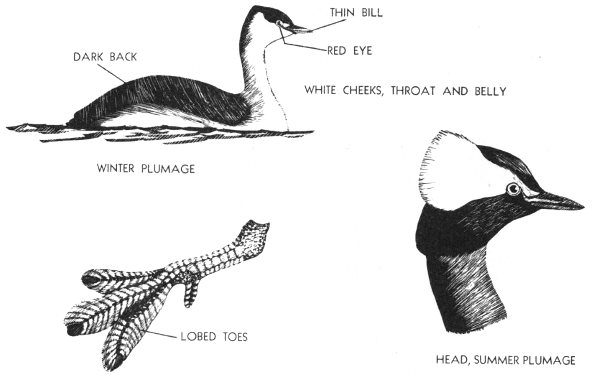

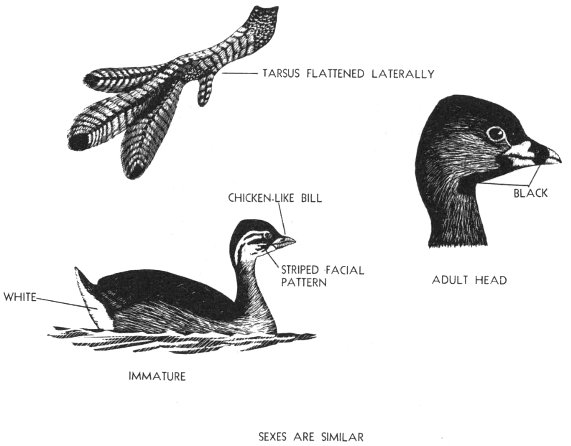

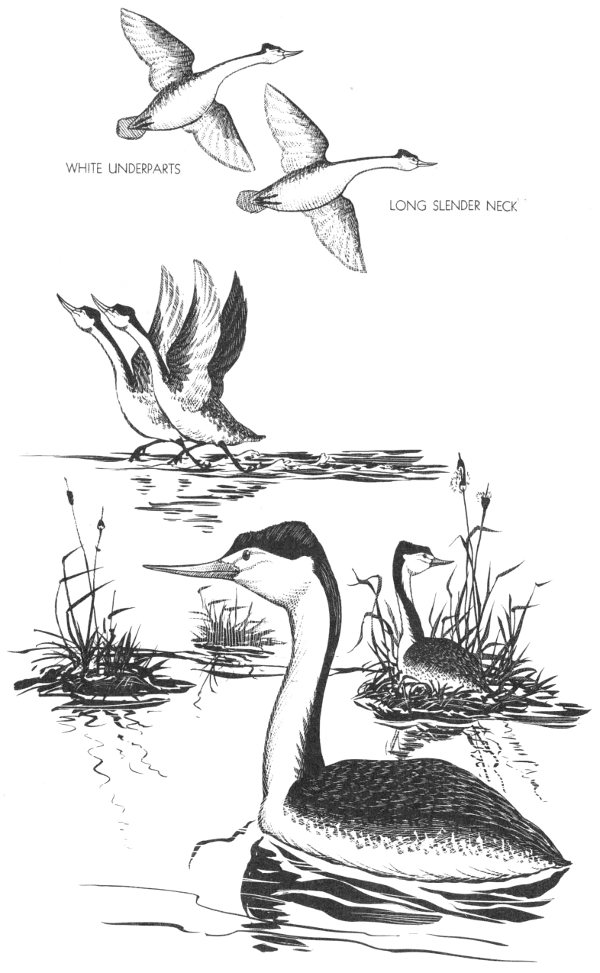

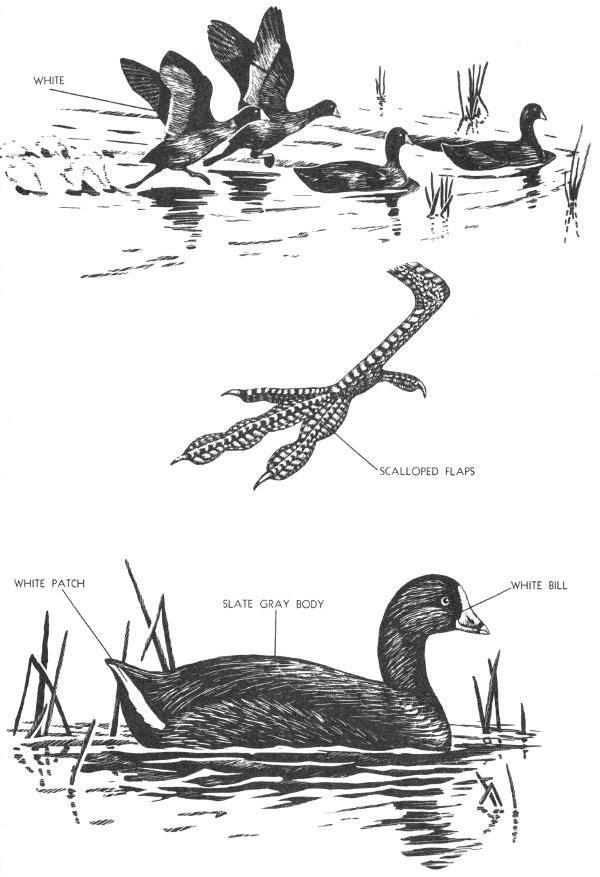

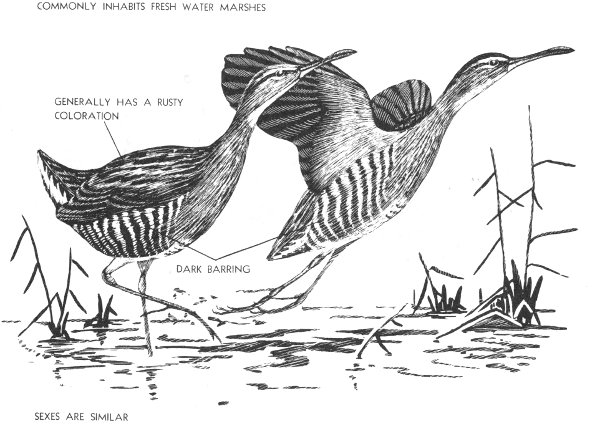

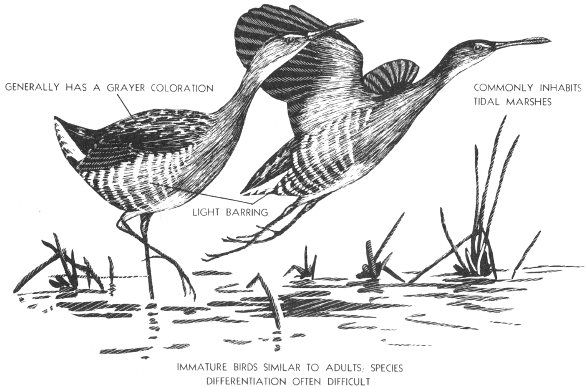

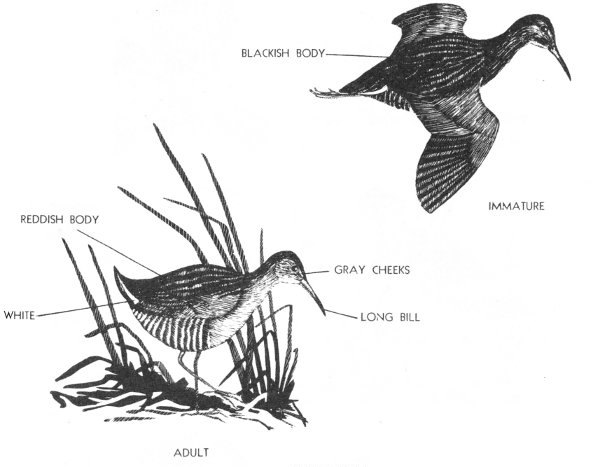

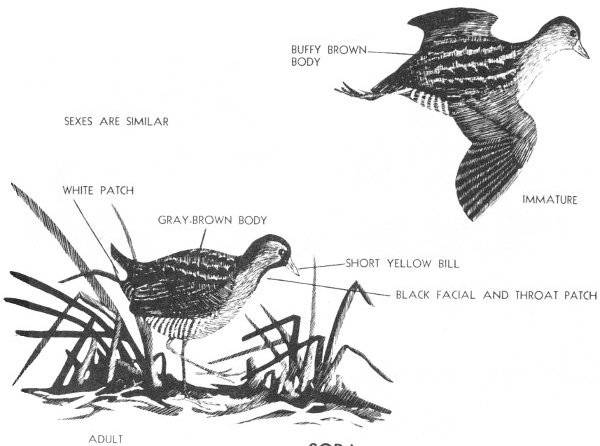

Identification of birds in the field, and particularly on the wing, as ducks and geese are usually seen over decoys, is easier than appears at first try. The trick is to note, in addition to shape and approximate size, the general arrangement of light and dark areas in the plumage, for nearly every species has its own distinctive pattern. With practice, the eye can be trained to pick out this pattern at a glance, and within a short time recognition becomes automatic. The illustrations which follow, one for each important species of Central Flyway waterfowl, make use of this practice of “pattern recognition” in the two or more flying birds at the top of the page. Actually in many cases recognition by flight pattern and flight characteristics will soon become evident.

In each drawing of ducks the flying female leads, with the drake following, for this is the usual order in a mated pair during winter, and spring. On the lower part of each page are shown enlarged heads, adult male on the left, female on the right, with an immature head added when the difference is substantial, or with certain details which further aid identification when the bird is in hand. All ducks, both flying pairs and heads, are drawn in direct proportion to each other, but geese, because of their larger size, are reduced one third from the duck proportion.

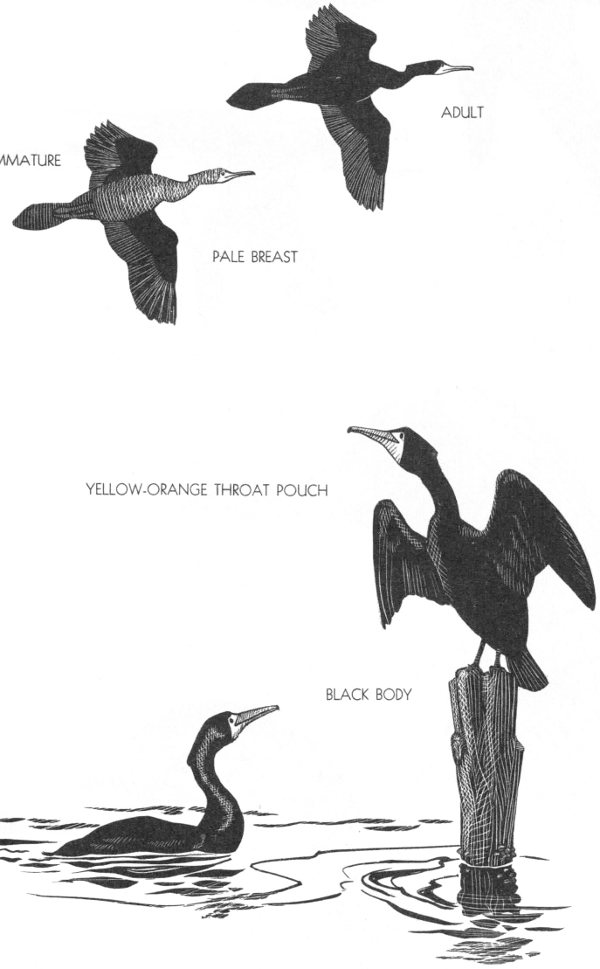

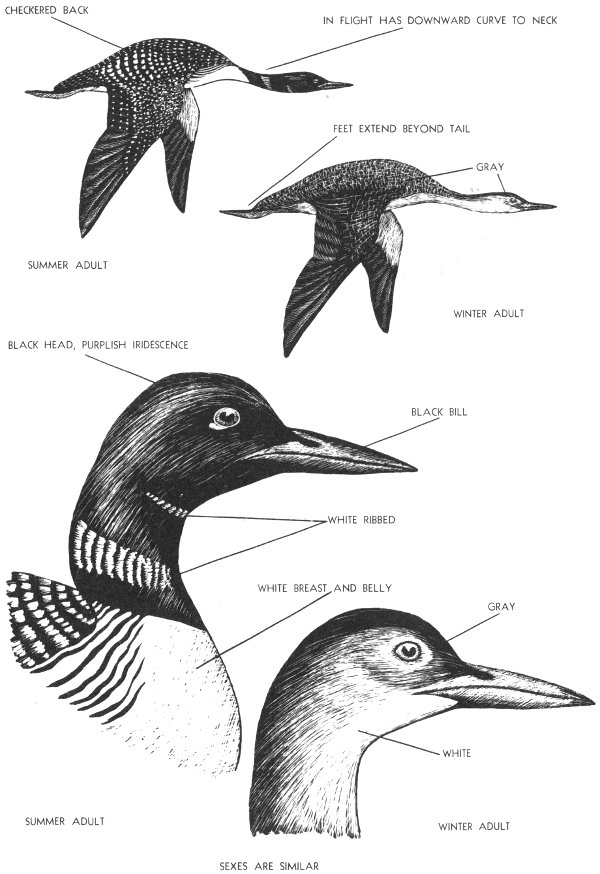

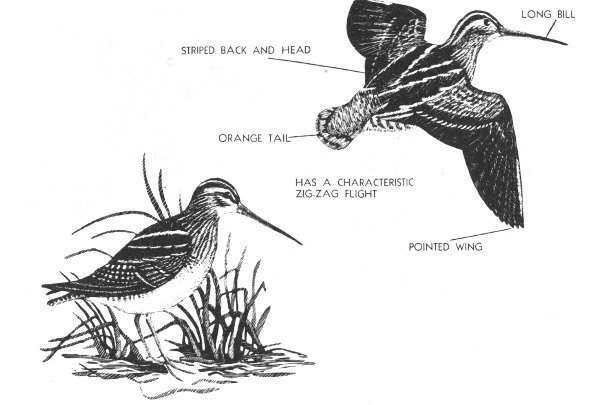

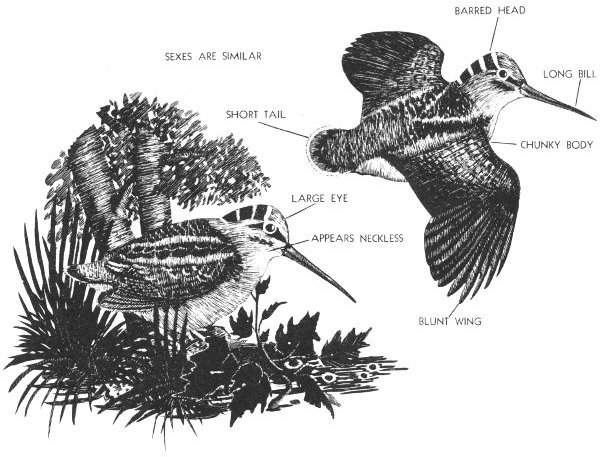

Drawings of geese show only a single enlarged head on each plate because male and female geese are alike in color pattern. Finally, some birds which are not “waterfowl” in the strict sense of the word, but are nevertheless often seen, are shown in the last few illustrations. Some of them (loon, grebe, and cormorant), although protected at all times, are included because they are 7 often mistakenly shot for waterfowl. Others (rails, coot, and snipes) are included because they occupy wet-land habitat along with ducks.

Although “pattern recognition” simplifies the problem of identification for the waterfowler, there are still several complications to be considered. Of these, the most troublesome by far is the matter of moults. The adult drakes of most species of ducks, very soon after the hens begin to incubate eggs, moult the bright body-feathers of their breeding dress and assume an “eclipse” plumage which resembles the year-round coloration of the female. This dull plumage, serving as a protective factor during the wing-moult which follows, is retained until the new flight feathers are fully developed. By September a second body-moult is under way by which these old drakes assume the bright courting plumage of late fall and winter. During the same period, the young males of the year, whose juvenile plumage likewise resembles the female dress, are also assuming the adult plumage. Following December 1 most difficulties of identification by reason of the moult are resolved, but in early fall the hunter may be puzzled by some of the transition plumages noted on birds in his bag. Identification during this period may appear extremely difficult, but it is well to remember that wing patterns remain virtually unchanged regardless of stage of the moult.

The remaining problems of identification require only brief mention for they appear but rarely. In the first place, this booklet includes all species of ducks and geese which occur in numbers in any part of the Central Flyway, but omits others which may be occasional visitors. Second, hybrids are rather frequent among waterfowl, and some are extremely puzzling. In such special cases as these your local wildlife manager or biologist may be able to help.

The following publications contain further information for the hunter interested in additional facts of natural history, distribution and description:

For the nonhunter—and many avid outdoorsmen prefer to watch rather than shoot—this guide to waterfowl can provide enjoyment beyond the simple pleasure of seeing ducks and geese. Most of us remember seeing some “oldtimer” identify flights or singles or rafts of birds at what seemed impossible distances. The ability to do this does not really stem from some mystic communion with the birds. Rather, through such a booklet as this the waterfowling layman can develop the same powers in himself. For the cost of a little concentrated effort he can gain great personal satisfaction and the increased understanding that comes from resolving “ducks” into the wide variety of individual species they really are.

Further, some knowledge of waterfowl distribution, annual abundance and the approximate source and destination of the ducks and geese he hunts, will often help the waterfowler understand the overall picture of waterfowl management. For both administrative and biological purposes of waterfowl management, the United States is divided into four flyways—the Atlantic, the Mississippi, the Pacific, and the one for which this booklet is written, the Central. Each flyway has its own segment of the waterfowl population, subject to different conditions and pressures than the populations of other flyways, and therefore is administered as a separate unit. In general this is a sound premise, but it must not be considered too rigid. Since the flyway principle is in part an administrative device, it is important principally in fall and winter when most North American waterfowl are within the United States. As the wintering populations begin to move northward in the spring, many species disperse throughout the nesting grounds of the northern states and Canada. Much overlapping of the populations from various flyways in which the birds wintered occurs.

Methods developed over the years and applied systematically supply information which is necessary to intelligent management. Breeding pair and brood surveys indicate the distribution of nesting populations, and their success from year to year in hatching and raising their broods of young. The banding of waterfowl, carefully aged, sexed, and released, gives specific information on the 9 travels of individual birds, on mortality, and on some phases of hunting pressure. Periodic air-counts in late summer and fall serve to measure, in a rough way, the distribution of different species during southward migration, and the rate of movement. Hunter-bag checks, carried out in the field during the shooting season, complement fall counts with regard to distribution at given points. A post-season sampling of hunter success, by mail, supplies data on additional aspects of hunting pressure, and gives an index of total kill. Finally, the annual winter count indicates the distribution and relative size of populations remaining after the shooting season ends. In combination, these methods are steadily increasing our knowledge of North American waterfowl, and in particular are providing the sort of “running inventory” which is the first requirement for intelligent management of this resource.

The Central Flyway Council is the clearing house for coordinated planning in this Flyway. It is a delegate organization, including in its membership administrative and technical representatives from the fish and game departments of all states and provinces in the flyway. A Flyway Representative has been assigned from the Fish and Wildlife Service. This group is concerned with all phases of waterfowl research and management in the flyway. The Central Flyway Council provides for an effective interchange of information between member agencies and assists in the coordination and integration of flyway management programs. These purposes have been furthered by regular meetings for the open discussion of flyway problems.

In early 1953, the Council and the Fish and Wildlife Service, acting jointly, adopted a flyway program which has been expanded and improved as factual information and experience dictate. This program outlines objectives and suggests methods and priorities for accomplishment. State game departments now pattern their activities around the flyway program.

Extending the cooperative idea, the Council has joined with corresponding organizations from the other flyways to form the National Waterfowl Council, which annually participates in the official discussion of continental and flyway management problems and regulations. From their inception, the flyway councils 10 have been successful in promoting understanding and teamwork so necessary for the perpetuation of the waterfowl resource.

As an individual reader of this booklet, you have a part to play in the essential partnership between agencies and waterfowlers. Your part may be small and may take various forms, depending on the circumstances, but certainly it is there. Perhaps, having sent in one or two waterfowl bands in the past and having experienced the initial novelty of hearing where your birds came from, you now forget to report them. The next time you have this choice between reporting or forgetting a band, remember that its prompt recovery, with full data, might be the clue to some missing fact to improve your future gunning.

Hunter bag checks indicate crippling losses in the Central Flyway run to an average of about one quarter of the total kill. In certain marshes, early in the season, crippling can greatly exceed the one quarter loss. Shooting at birds on the fringe of effective killing range is a crippling practice and, moreover, as you probably know from observation is contagious. The usual effect of one “sky shooter” in a marsh is to force other gunners nearby to attempt impossible shots which increase crippling losses and soon ruin shooting for everybody. Controlling such practices lies solely in the hands of individual gunners. With large-gauge guns of modified bore, the shot-pattern that will produce kills should be consistent up to forty yards, a distance well within capabilities of the average gunner to hold and compute necessary lead. Successful duck shooting is a matter of good judgment. To avoid errors in judgment drive stakes in front of your blind at distances of thirty and forty yards to indicate safe killing range. Hold your fire until the feet of an incoming duck can be seen distinctly, for only then will the bird be in range. Good sportsmanship in duck blinds and marshes is equally as important as remaining friendly with your home neighbors. Train a good retrieving dog, and add to your day’s pleasure by watching him at work on downed birds.

Above all, remember that the future of waterfowling is partly in your hands—that your good sportsmanship and cooperation are as necessary to the work of the Central Flyway Council and its member agencies as their activities are to you.

Buy a State License, and if You Are 16 Years of Age or Older Obtain Federal Duck Stamp. It is illegal to hunt waterfowl without these licenses, and the dollars you spend for them help to maintain your sport.

Know Your State, Provincial and Federal Migratory Bird Laws. When in doubt consult your local game protector or U.S. Game Management Agent.

Treat the Landowner with Respect and Courtesy. Ownership of game is vested in the State and Province, but landowners have the right to prevent trespass on their land.

Learn to Identify Before You Shoot. A mistake may prove both embarrassing and costly, a correct identification adds to your day’s enjoyment.

Cooperate with Your Federal, State and Provincial Agencies. Solving the many problems of waterfowl production, harvest and research is possible only through continued cooperation of the duck hunter and conservationist.

Use a Retriever if Possible, or at Least Pick Up Every Bird You Shoot. A good dog will pick up cripples you would otherwise have to leave. A good sportsman will never kill game needlessly. The use of retrieving dogs is a sound conservation practice in reducing crippling losses in addition to providing the pleasure of watching a good dog in action.

Good Sportsmanship in the Duck Blind and on the Marshes Is Equally Important as Remaining Friendly with Your Neighbors.

DISTRIBUTED BY:

TEXAS GAME and FISH COMMISSION