Title: The Dreadnought Boys in Home Waters

Author: John Henry Goldfrap

Illustrator: Charles L. Wrenn

Release date: April 7, 2017 [eBook #54496]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Demian Katz and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy

of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

BY

CAPTAIN WILBUR LAWTON

AUTHOR OF "THE BOY AVIATORS' SERIES," "THE DREADNOUGHT BOYS

ON BATTLE PRACTICE," "THE DREADNOUGHT BOYS ABOARD A

DESTROYER," "THE DREADNOUGHT BOYS ON A SUBMARINE,"

"THE DREADNOUGHT BOYS ON AERO

SERVICE," "THE DREADNOUGHT BOYS'

WORLD CRUISE," ETC., ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

CHARLES L. WRENN

NEW YORK

HURST & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1914,

BY

HURST & COMPANY

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | On Special Duty | 5 |

| II. | Red vs. Blue | 14 |

| III. | "Are We Awake?" | 24 |

| IV. | Herc "Mixes In" | 31 |

| V. | Off to Their First Command | 39 |

| VI. | Welcome to the "Seneca" | 48 |

| VII. | Midshipman Kenworth | 58 |

| VIII. | Aground! | 67 |

| IX. | "Your Duty Is to Obey!" | 76 |

| X. | "The Eyes of the Red Fleet" | 84 |

| XI. | The Eavesdropper | 91 |

| XII. | Saki—Steward | 97 |

| XIII. | Another Watcher | 104 |

| XIV. | Ned at a Disadvantage | 113 |

| XV. | A Prisoner on "the Neck" | 121 |

| XVI. | The Friendly Sun | 128 |

| XVII. | Surprises | 136 |

| [Pg 4]XVIII. | Off for a Cruise | 144 |

| XIX. | The Storm | 151 |

| XX. | Confession | 158 |

| XXI. | Orders are Orders | 165 |

| XXII. | On the "Twin Sisters" | 173 |

| XXIII. | The Trail | 185 |

| XXIV. | The Japanese Store | 192 |

| XXV. | A Box of Matches | 200 |

| XXVI. | Mysteries | 207 |

| XXVII. | Through the Crack in the Wall | 214 |

| XXVIII. | Herc's Subterfuge | 222 |

| XXIX. | Tables Turned—Twice! | 228 |

| XXX. | In Fresh Terror | 237 |

| XXXI. | Ned's Escape | 246 |

| XXXII. | In the Enemy's Camp | 254 |

| XXXIII. | Waiting for the End | 261 |

| XXXIV. | A New Assignment | 272 |

| XXXV. | The Outcome | 282 |

ON SPECIAL DUTY.

There was a sudden stir in the forward section of the stuffy, crowded railway coach.

The interruption to the stolid apathy that had crept over the passengers, for the dust and heat had made them drowsy, came in the form of voices raised in anger and indignant protest.

The racket proceeded from a cross-seat occupied by two young fellows. One of them was a youth of about eighteen with hair of a violent ruddy hue. His seat-mate was, perhaps, a trifle older, heavy set, rather sallow, with close-cropped black hair. Both were sunburned and bore, somehow, the unmistakable look of those who follow the sea.

"See here, you, what have you got your hand in my pocket for, hey?"

Thus the red-haired lad, before whom reposed a leather suit-case bearing the name,—neatly stenciled on one end,—"H. Taylor, U.S.N."

"I've lost my wallet," came the rejoinder in angry, high-pitched tones. "It had most of my pay in it, too."

"Well, what's the matter with looking in your own pocket?" sputtered Herc Taylor indignantly.

"I did, but I can't find it."

"So you assume that I'm the thief, do you?"

This was certainly a conversation to attract attention. Both speakers appeared to be in highly belligerent moods. Several of the passengers seated in the vicinity of the excitement began to rise in their seats and crane their necks, the better to behold the "scrap" that appeared imminent.

But those nearest to the pair saw that Herc[Pg 7] Taylor's large, freckled fist had closed on the wrist of the other's investigating hand, so that, for the present at any rate, the latter was not able to attempt retaliation except verbally.

Herc was neatly but quietly dressed in a gray-mixture suit. His seat-mate, the one who had made the ugly accusation, wore clothes that appeared to have been rather neglected recently. They were crumpled and stained and the whole air of the fellow, despite his healthy-looking tan, was slouchy and shiftless.

Herc glared straight into the other's eyes for possibly the space of a minute or so. Before his direct glance the slouchy-looking youth's eyes fell.

"Aw, leggo my hand, will yer?" he muttered.

"Sure, it's no pleasure to me to hold it," rejoined Herc, relaxing his grip. Where he had held the other, a white bracelet of skin appeared, showing that Herc possessed a mighty set of muscles.

"I'd advise you to keep your hand where it belongs in the future," added Herc.

A third young fellow, who had been seated behind the quarreling pair, leaned forward. He had been reading a naval-service periodical. But now his attention was distracted, and he tapped the red-headed youth on the shoulder.

"What appears to be the trouble, Herc?"

"Oh, it's all right, Ned," rejoined the younger of the Dreadnought Boys, turning to his cousin, Ned Strong. "This fellow just suffered from a severe case of wandering hand, that's all."

A smile came over Ned Strong's clean-cut, bronzed features. His blue eyes twinkled as he directed a glance to the floor of the section in front of him.

"What's that lying on the floor right there by your feet, my friend?" he asked of Herc's seat-mate.

"Gosh! if it isn't my wallet!" exclaimed the stranger.

He stooped and picked it up, looking rather sheepish and foolish as he encountered Ned's smile.

"You see, it isn't a good plan to go up in the air before you make quite sure you won't have to come down again with a hard bump," said the Dreadnought Boy quietly, but with a good-natured intonation.

"Aw, stow that," growled the other. "I didn't do no harm."

"No, but if I hadn't been a young person of marked coolness and restraint, I might have done you some," grinned Herc.

Here the incident appeared to be terminated for the time being. Soon after, the disgruntled neighbor of Herc Taylor arose and sought a seat in another part of the car. The smiling looks of the passengers in the vicinity of the little ruction had proved too much for his sensibilities.

As he rose from his seat, he carried with him[Pg 10] his suit-case. After he was beyond ear-shot, Ned turned to Herc.

"That fellow may be one of our shipmates," he said in low tones.

"How do you make that out?"

"I saw the name 'Dilworth Rankin' and the letters 'U.S.N.' after it," was Ned's rejoinder.

"Can't say that I'm much impressed with what I've seen of young Mr. Rankin," retorted Herc, carelessly. "At any rate we are under special commissions now, so that if he gets gay or anything like that, I'll have him put in the brig in short order. I always said, after I had that little session of mine in the brig, that if I ever got a chance I'd see how it felt to slap somebody else in there; and if he gets fresh it might just as well be Rankin as anyone else."

"You'll do no such thing," retorted Ned seriously. "Just because we're holding little temporary commissions as junior officers, you can't show off your authority like that."

"Huh! what's the use of being officers, then?"

"To teach us something. To get some new ideas and experiences into that red head of yours."

"See here, now that I'm an officer, I'll thank you to refer to my locks as auburn," muttered Herc. "I'll feel like using my new sword on anybody who calls attention to the color of my sky-piece hereafter."

"All right," laughed Ned, "I'll call it any color you like. But, hullo! there's blue water. We must be getting near to Miller's Haven. I wonder if the Seneca has arrived yet?"

"Hope so," rejoined Herc. "I want to be boss just as quickly and just as long as possible. I wish some of the old boys on the Manhattan could see us when we start out to sea. Have you opened your orders yet?"

"Not yet. As you know, they are sealed and not to be opened till we have coaled and proceeded to sea. The first thing we must do when[Pg 12] we reach Miller's Haven is to report to Ensign Summerville, at present in command of the Seneca, and hand him his orders."

"His walking papers," interpolated Herc. "I wonder if we'll get orders to join the Red fleet right off?"

"That's impossible to say," replied Ned. "As I understand it, we are to do duty as a scout cruiser, depending largely on our wireless for keeping in touch with the Red fleet and informing them of every move of the Blues."

"Then we may not be with the fleet at all?"

"Not necessarily. But I guess our work as scouts will keep us so busy that we won't notice the lack of company."

"I'd rather be back with the fleet," muttered Herc.

"I wouldn't," rejoined Ned, his eyes flashing and his cheeks flushing under the tan. "Why, Herc, boy, we've got the biggest chance of our lives! To my mind this detail to which we have[Pg 13] been assigned will prove the most interesting work we have ever tackled."

"Miller's Haven!"

The voices of the trainmen rang raucously through the car. The boys arose and made their way to the forward door. As Ned had surmised, they were indeed on the threshold of some of the most interesting experiences they had ever encountered.

RED VS. BLUE.

Within the last week the Dreadnought Boys had taken their first big step upward. They entered Miller's Haven with their commissions on new, crackly parchment, tucked over a pair of as proud and happy hearts as there were in the navy.

Great had been their surprise, when, some four days before we encountered them on the train for Miller's Haven, their commander, Captain Dunham, of the Dreadnought Manhattan, had sent for them. Both lads, as readers of other volumes of this series know, had already gained high non-commissioned ratings.

Captain Dunham's unexpected summons had come on the eve of the long-looked-for "siege" of New York harbor. The Red fleet to which the[Pg 15] Manhattan had been commissioned as flagship, was to have the task of attacking the harbor at the gates of Long Island Sound. The Blue squadron was to have the defense of the port. Final arrangements for the biggest naval war game of its kind ever attempted had been made, with an attention to detail and probable actual conditions of a sea attack on the harbor which was little short of marvelous.

With wireless, big guns, Argand signals, torpedoes and submarines every effort was to be made to duplicate as perfectly as possible conditions of a real attack. The newspapers had been carrying columns of copy concerning the big war game, and public interest was wrought to its highest pitch.

But it was in the navy itself that enthusiasm ran the highest. Strategists from all over the world were to be present, and elaborate precautions had been taken to insure Uncle Sam's carefully guarded naval secrets from leaking out.[Pg 16] In this connection, what practically amounted to a Secret Service had been established, both on board the great sea-fighters of the two squadrons and also at the twin forts, Totten and Schuyler, which guard the Sound entrance to the East River and the port of New York.

Such, as has been said, was the interesting eve of "hostilities" which prevailed, when to Ned and Herc came the orders to report aft in the commander's quarters at once.

The Manhattan lay in the Brooklyn navy yard being groomed, like a thoroughbred on the eve of a great race, for the important part she was to play as the flagship of the Red fleet. Jackies, every one of them with an alert and keen pride in his work, were dismantling and fitting the big craft till everything about her grim, slate-colored hull was attuned to the condition in which she would be placed were she actually answering a summons to defend the Empire City from the invasion of a foreign foe.

Captain Dunham sat in his cabin in the midst of a great pile of documents of all kinds. The pictures and other objects usually to be found adorning the commander's comfortable quarters were missing. The cabin had been stripped and everything breakable packed away, just as would have been the case had the Manhattan been going to steam out and engage an actual foe. This had been done so that the earthquake-like shock and tremble of the mighty broadsides,—the grim fangs of this sea bulldog,—might not work havoc with breakable things.

The two young non-commissioned officers were passed by the orderly and then stood smartly at attention, trim heels together, bright eyes looking straight in front of them till the commander looked up from some departmental papers he was perusing.

During this interval they had time to notice that a tall, slender, alertly-built man, with threads of gray in his dark hair, was seated near the[Pg 18] commander. He eyed the boys interestedly with the critical air of a man who is in the habit of making swift appraisal of those with whom he comes in contact.

His keen gray eyes swept the two well-built, clean-cut and reliable-looking young sailors with a look that appeared to spell approval. As a matter of fact, the assistant secretary of the navy, for such was the office of Commander Dunham's companion, was deeply interested in his inspection of the two lads of whom he had heard much.

It will be recalled that not long after they entered the service of Uncle Sam and deeded their lives to the flag, Ned and Herc had had an opportunity to distinguish themselves.

How they foiled a desperate plot against the navy, then assembled in Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, at the naval base established there, and also their conspicuous bravery in the panic that followed a disastrous "flare-back" in a thirteen-inch[Pg 19] turret, were told, with many other of their adventures, in the first volume of this series, "The Dreadnought Boys on Battle Practice."

In the next book, devoted to describing the lives of the spruce young jack-tars of to-day on board the big, drab sea-fighters, we followed the lads through a long siege of mystery and intrigue, intermingled with plenty of stern fighting. This book was called "The Dreadnought Boys Aboard a Destroyer."

Grim as the name of "destroyer" that she bore was the Beale; and when she was despatched to South America with the duty of straightening out a peculiar international tangle confronting her commander, the boys were detailed to duty on board her. In the midst of a revolution, involving the lives and property of American citizens, they played their parts right well, and by a display of clever strategy turned a defeat, which had seemed imminent to the interests amicable to the Americans, into a brilliant victory.[Pg 20] Readers of that volume will not soon forget the defense of the hill, with the battery of machine guns breathing flame and destruction from their iron throats.

"The Dreadnought Boys on a Submarine" showed an intimate picture of naval life on a diving torpedo boat. In realistic detail all that befell the lads on the surface and in the depths of old ocean was related, and their many adventures were faithfully set forth. As in previous chapters of their lives, the boys were not found wanting when perils and dangers called for quick, decisive action and cool, alert minds. In the submarine service they added new laurels to their already growing fame, and moved up more steps on the long ladder of promotion.

When the navy department began its experiments with aeroplanes as important auxiliaries to modern battleships, Ned and Herc were among the first in the fleet to volunteer, although such service involved the signing of a grim paper[Pg 21] which absolved the government of all responsibility for the naval aviator's life. As might be expected, the lads found things by no means tame in the aero squad. Ned's great feat of landing on a battleship,—a common enough maneuver now,—was long talked of in the fleet after the boy had successfully made the first attempt in the history of the world to accomplish such a thing.

Naturally, too, the boys who had worked so ambitiously for name and fame had made enemies among small-minded and envious men. These foes made things exciting for the lads for a time; but in the end both Ned and Herc righted themselves and were vindicated from a severe charge which had resulted from the machinations of those who disliked them. This book, which was called "The Dreadnought Boys on Aero Service," teemed with incident and shifting scenes. Much attention was paid to the manipulation and flying of modern aeroplanes, and the[Pg 22] book was instructive as well as interesting.

The famous "Round the World Cruise of the American Navy," a voyage that will go down in history as one of the most effective demonstrations of sea power ever made, formed the theme of the succeeding volume, which was "The Dreadnought Boys' World Cruise." As petty officers of the first rank, Ned and Herc found many opportunities to distinguish themselves. Jack ashore is sometimes a difficult proposition to handle, and Ned, as a non-commissioned officer, had much responsibility to shoulder. In carrying out his duties he incurred the enmity of some of those he had been obliged to discipline, and a thrilling adventure in the pyramids of Egypt was the result.

Then, too, Ned and Herc met with many other experiences in the various countries the fleet visited, including a laughable predicament on the Rock of Gibraltar, when, through the stupidity of an over-officious British army sergeant,[Pg 23] they were compelled to spend some hours in a dungeon excavated in the rock. Herc solved the problem of escape and unlocked the dungeon doors by means of wig-wagged signals to the fleet, lying at anchor below the rock.

And now you are better acquainted with Ned Strong and Herc Taylor, and can understand, by perusal of the preceding long but necessary digression, just why it was that they were admired and loved by their shipmates and respected by their officers; and why, too, Captain Dunham should have singled them out for the duty to which he was about to assign them.

"ARE WE AWAKE?"

The commander of the Manhattan, an imposing, bronzed figure of a man, and a thorough sailor, swung around in his chair and faced the two young Jackies he had summoned.

"These are the lads I was speaking to you about, Mr. Secretary," he said, addressing his companion.

The lads drew themselves up and saluted, not without a quickened action of their hearts. They guessed at once from the manner in which he had been addressed, that the stranger was one of the "big-wigs" of the naval department. Herc turned as red as his thatch, and the freckles stood out on his round and jolly countenance like the famous spots on the sun.

Ned retained his self-possession better, but in[Pg 25] reality he was quite as excited as was his shipmate and chum. Eagerly he waited for words which might offer a key to the meaning of this unusual summons.

They were not long in coming. The Secretary nodded his head and looked approvingly at the boys.

"They quite measure up, sir, to all that I have heard of them," he said. "And now," with a kindly smile at the two embarrassed lads, "I don't think we need keep them in suspense any longer."

"I quite agree with you," rejoined the captain. "Lads, I have sent for you to confer upon you, at the request of the Secretary of the Navy, a most unusual honor. I know you will appreciate it as it merits."

The boys did not utter, in words, a reply. It would not have been proper for them to have made any comments or to have spoken, except in answer to direct orders or to questions. The commander continued:

"Your careers in the navy have been marked by more than ordinary devotion to duty and by frequent exhibitions of ability that have made you both appear to be worthy of still higher promotion than you have yet achieved. I think that you both possess executive ability, and the Secretary and myself have decided to assign you to roles in the coming war game that will give you ample opportunity to show of what sort of stuff you are made."

The boys, with burning faces, drew themselves up and saluted. But within their breasts was a wild tumult despite their calm exteriors. What could be coming?

"And now for what you are to do. You are to proceed to Miller's Haven on the Connecticut shore and there join the gunboat Seneca. You will convoy two submarines for use in scout work against the Blue fleet, which, of course, you know, is opposed to us and is defending the harbor of New York. You understand?"

"Y-y-yes, sir," rejoined Ned; while Herc, so taken by surprise that he was deprived of articulate speech, merely mumbled something.

"To whom are we to report, sir?" ventured Ned.

Commander Dunham smiled and exchanged glances with the departmental visitor.

"You will report to yourselves. That is, you will be in command of the Seneca."

Even Ned's sense of discipline deserted him at this announcement.

"In—in command? I—I'm afraid, sir, I——"

"I said in command. Practically every commissioned officer in the service will be on other and more important duties. We have, therefore, secured for you temporary commissions, enduring, of course, only during your period of attachment to the Seneca. She is a small boat of not very modern design, but I shall expect to see you perform some important work with her. She is equipped with wireless, of course, and the fact[Pg 28] that both of you understand wireless and the naval code has been another inducement to give you this big chance. You will each get a copy of the special code to be used in the war game when you join the ship."

"Then we—we are officers?" stuttered Herc, unable to keep silent any longer. As for Ned, outwardly cool and collected, his glowing eyes showed what he thought.

"Officers temporarily," was the reply. "Here are your commissions."

From his desk Commander Dunham took the two documents which to the Dreadnought Boys appeared the most wonderful things they had ever set eyes on.

Handing one to Ned, the commander then spoke some words that sent the boy soaring up into the seventh heaven of delight.

"This confers on you, Strong, the rank, pay and authority of a lieutenant, junior grade, in the United States Navy. Taylor, your commission[Pg 29] confers upon you the special rank of ensign.

"That is all. Your uniforms will be secured from the yard tailor. Your instructions are in this sealed package. You are not to open them till you have cleared. From time to time you will get other instructions by wireless, couched in the terms of the secret code adopted by the Red fleet. Your duty, in a nutshell, will be to be the eyes of the Red squadron. Carry on!"

With this crisp expression of dismissal, the commander turned to his table again. The lads saluted, and marched out of the cabin.

They appeared to be traversing fleecy clouds of wonderful brightness as they made their way forward.

"Hello, Red-head," hailed a gunner's mate as Herc strutted with all the pride of a peacock to the forward part of the ship, "what's biting you?"

"Don't talk to me like that, Jenks," returned Herc with some hauteur. "I'm an officer."

"A what?" roared Jenks. "Say, turn over. You're on your back. You haven't been working hard enough lately, Brick-top, and you're talking in your sleep."

"Wonderful as it all seems, though, Jenks, it's true," said Ned, with dancing eyes. "But I can't realize yet that I'm not asleep and dreaming the greatest dream a fellow could ever have."

Jenks stared for a minute and then clasped Ned's hand.

"I'm mighty glad, shipmate," said he. "You had it coming to you."

"But it isn't going to last," said Herc plaintively. "It will only hold out as long as the war game, and then we'll be back in the ranks—that is, if we don't fall out of bed first."

Ned said nothing, but he gazed with absent eyes over the busy scene,—the swarming river and the great yard with its life and movement and busy note of preparation. He was indulging in the most delicious reverie he had ever experienced.

HERC "MIXES IN."

Miller's Haven was a small place on the Sound shore, several miles up. It boasted a bay full of shoals and tricky channels and a group of islands lying in a cluster near the mouth of this bay.

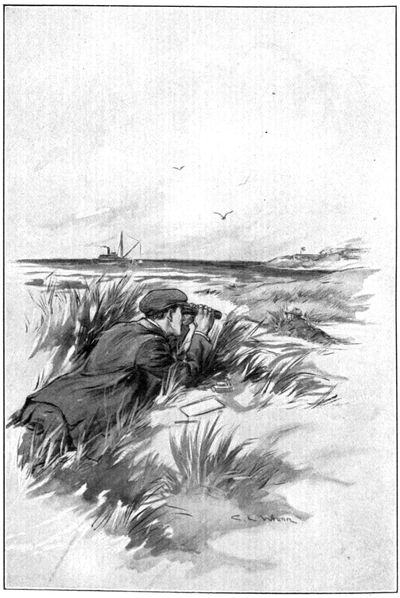

Ned knew from his previous instructions that the Seneca would be lying in the shelter of one of these islands, as securely moored to avoid observation from the scouts of the Blue squadron as was possible. Miller's Haven was a sleepy spot,—little more than a fishing village, in truth,—and nobody in the place was likely to pay much attention to the fact that a small gunboat, looking more like a yacht than a vessel of the navy, lay, with every appearance of secrecy, off their hamlet.

In fact, the Seneca had been used in several capacities. Her latest work, before being told off as a scout and despatch craft, was with the Revenue Service.

In this capacity the Seneca had been deemed worthy of refitting so far as boilers and engines were concerned, so that, although she was not large, she was swift and powerful and just the craft for the work in which she was to be employed during the maneuvers. Her speed had been shown in several chases after motor-boat smugglers, in most cases she having easily overhauled even the fastest of these wasp-like violators of Uncle Sam's customs regulations.

"We'll go to the hotel first," decided Ned as they stood on the wind-swept platform at Miller's Haven.

Out on the Sound the blue water was flecked with white and a brisk wind, salt-laden and delightful to the boys' sea-going nostrils, had left the sky clear and cloudless.

"You're going to meet Ensign Summerville there?" asked Herc.

"Yes, he'll come ashore with a boat and take us out and introduce us to our first command."

"Huh! it may be our last, too," grunted Herc. "Say, this thing of being a real, full-fledged officer scares me just a little. Suppose we fall down?"

"We can only attend to our duty the best we know how," rejoined Ned. "If we can carry out the work cut out for us in good shape, it will mean that we'll go a few more rungs up the ladder."

"Yes, if nobody pulls the ladder down," mumbled Herc pessimistically.

The two trim, trig lads, in their quiet, unassuming clothes, attracted little or no attention on the single street that Miller's Haven boasted. True, one or two passers-by looked rather curiously at the yellow leather sword cases that they carried, but that was all.

The hotel soon came in sight, a dingy-looking structure sadly in need of paint. A dejected-looking citizen with a drooping mustache, a drooping manner, drooping gray garments and a drooping way of draping himself in his chair, occupied the porch.

"Doesn't look like much of a place," commented Ned, "but we can get a room here that will be good enough to change in, I dare say."

"A room!" demanded Herc. "What do you want a room for? I thought we were going to eat."

"No, we will change into our uniforms first. It would not be the correct thing to board our new command in ordinary clothes. I should think you'd know that."

"Have we got to wear our swords?" inquired Herc with a rebellious look.

"Don't you know enough of navy usages yet to be aware that officers must wear their swords under certain conditions, such as taking command[Pg 35] of a new craft and other ceremonial occasions?"

"Umph! Well, all I hope is I don't tumble over that cheese toaster of mine."

"If you do anything like that, I'll disown you for a brother officer of mine," laughed Ned. "But, seriously, Herc, I want you to be on your best behavior and not make any bad breaks."

"Huh! Just as if you were any more used to carrying a sticker,—I mean a sword,—than I am! I'll be all right. Don't you worry about me, Mister Lieutenant. I bet I will be just as good an officer as there is in the navy."

"We'll wait and see——" began Ned good-naturedly, when Herc cut him short with an exclamation.

"Look who's here! Right behind us!"

"Well, what is it?" asked Ned, for he was half-way up the steps by this time and the drooping eyes of the landlord, as Ned had rightly conjectured[Pg 36] that the dejected man was, were regarding him with languid interest.

"It's that Rankin fellow! He's looking at us disrespectfully. I've a good mind to tell him that we are officers!"

"You'll do no such thing. If he has been detailed to the Seneca, which I think probable, he'll find out our rank for himself soon enough."

"Just the same, I'd like to make him salute me," grumbled Herc.

Rankin ascended the steps behind the two Dreadnought Boys. He was close on their heels, when suddenly Herc's feet flew up and out behind him. In his new dignity he had been holding his head so high that he did not notice a bit of banana peel lying on the untidy steps of the Eagle Hotel.

Crash! The newly created officer performed an almost complete back somersault with great effect. Plump! came down his not over-light form right on top of the ascending Rankin. Together[Pg 37] they rolled down the steps and into the dusty road, while Ned looked on in dismay.

"You done that a-purpose! I'll fix you for it!" bellowed Rankin furiously.

"What are you talking about, you numbskull?" retaliated Herc, as the two rolled on the dusty street. "Don't be a fool! Let me up."

But Rankin clung tightly to Herc, for whom he had conceived an intense dislike ever since the episode on the train.

"You try to make a fool out of me, will you?" he growled; and as they clinched and tumbled about at the foot of the steps, Rankin aimed a vicious blow at Herc, who returned it with right good will.

"Gracious! Here's a fine kettle of fish!" exclaimed Ned in consternation.

He started back down the steps at top speed, determined to stop such a scene at all costs. It was really too bad that their arrival in Miller's[Pg 38] Haven should be marked by such a disgraceful mix-up.

Ned glanced anxiously down the street and was glad to see that no one was in sight. He would not, for the world, have had anyone witness the mêlée who was in any way connected with the navy.

"Get up at once, Herc!" he cried, thoroughly angry. "Stop it instantly. Do you hear?"

But despite Ned's admonitions, the pair on the ground continued their struggle, the noise of their thumps and pantings rising above Ned's voice. Flushed with vexation and indignation at Herc, Ned determined to take decisive action.

He cleared the last two steps of the flight leading to the street in one jump. The next instant his hands shot out.

"Stop this and stop it quick!" he ejaculated. "What sort of a way do you consider this to behave?"

OFF TO THEIR FIRST COMMAND.

Herc felt a strong hand on his collar. The next second he was yanked to his feet "all standing." Flushed, dust-covered and indignant he began a fusillade of irritated speech.

But Ned cut short the flow with a peremptory gesture.

"That's quite enough. Come inside at once."

"But I——"

"At once, I said; march!"

Herc knew it was no use to disobey, and with a backward look at Rankin, he sulkily climbed up the steps. Rankin picked himself up out of the dust. He appeared to be about to say something, but before he could find words, the two Dreadnought Boys were through the door of the hotel and inside the small office.

The drooping man, who had watched the battle without a shadow of interest or excitement, betrayed no great change in manner as he came forward.

"'Kin I do fer yer?" he inquired.

"We want to get a room here. Not for very long; just for sufficient time in which to change into our uniforms," explained Ned. "We are expecting a Mr. Summerville of the United States Navy to meet us here."

"Be you in the navy?" inquired the drooping man, allowing himself to betray momentarily a slight, very slight accession of interest.

"We are. We can get a room, I suppose?"

"You kin, an' if you'll pardon my saying so, yer pardner sure needs a change."

Herc colored hotly. The hotel man must have noticed this, for he went on.

"You don't know that feller Rankin, then?"

"We do not," replied Ned shortly.

"'Cause if you did, you'd know he's always[Pg 41] picking quarrels. He's an 'sistant 'gineer on the Senecy, which I reckon is the boat yer goin' ter jine."

"Yes, I believe she is anchored off here. But will you show us to our room right away, please? We don't wish to keep Mr. Summerville waiting."

The drooping and dejected landlord looked more dismal than ever as he showed the boys to a small room. It did not take them long to don the natty uniforms of junior officers in the United States Navy. While they changed their attire, Herc was roundly lectured by Ned for taking part in the scene in front of the hotel.

"I'm sorry it happened," declared Ned; "Rankin being a petty officer of the Seneca, too, doesn't make it any the easier."

"I ought to have lambasted him with my new sword," muttered Herc truculently.

"And made a bad matter worse."

"I don't see how it would. That fellow needs a good lesson."

"You'll never teach him one in that way. Besides, naval officers don't behave in such a fashion. You must have dignity and self-control."

"Huh! If I'd had foot control instead of self-control, I wouldn't have tumbled down those steps, and then nothing would have happened," grumbled Herc, tenderly patting a bump on the top of his head.

"You look like an officer, Ned," he went on a few moments later, as, pausing in his own preparations, he gazed at the trim, natty figure of Ned Strong.

Herc was right. The slender, yet strongly built lad did indeed look every inch fitted for the quarter-deck of a naval vessel when, having finished his other sartorial duties, he buckled on his sword and adjusted his cap.

"Well, so do you, don't you?" laughed Ned, watching Herc as, with a face fiery red with his[Pg 43] exertions, his comrade buckled himself into his tightly fitting uniform.

"Don't know," responded Herc briefly, "I feel rather more like a tailor's dummy. How do I look?"

"All right. But cool your face off in that water. It looks as if you'd been taking a turn in the fire room."

"Well, so long as I don't do a flop over my sword, I don't care," rejoined Herc, as he carefully removed the scabbard of that weapon from between his knees where it threatened at any moment to cause disaster.

Not many minutes later they descended from the room, just in time to be greeted by a stalwart coxswain.

"Lieutenant Strong, sir?" asked the man, coming to attention just as Ned and Herc had done so often.

It certainly felt strange to acknowledge the salute in an official way, not to mention being[Pg 44] addressed as Lieutenant. Herc was, in fact, compelled to hide a grin behind his pocket handkerchief. Luckily, Ned did not see this, or Herc might have had another lecture.

"Yes," rejoined Ned, returning the man's salute. "You are from the Seneca?"

"Aye, aye, sir. The gig is waiting to take you aboard, sir. Ensign Summerville sent his regrets, sir, and he is too busy attending to matters wirelessed from the flagship to come ashore himself."

"Very well, we may as well get aboard, then," said Ned.

At this moment Rankin emerged from the hotel. He had evidently been busy removing traces of battle from his face, for his sallow countenance shone with soap. To say that he looked surprised when he saw Ned and Herc transformed into naval officers of rank much above his own, would be to put it mildly. That[Pg 45] expressive word "flabbergasted" better describes the look on Rankin's well-soaped visage.

He was far too well trained in naval usage to put his astonishment into words, however. Returning from a furlough, he knew nothing, of course, of the change in the commanding officers of the Seneca; but he recognized that Ned, as his uniform showed, outranked Ensign Summerville, and from this fact deduced that he must have come to take command of the little gunboat.

He drew himself up and saluted with naval conciseness. The boys returned the salute with perfect gravity. To judge by the countenances of all three, no bystander would ever have guessed how it had been with them not so very long before.

Herc, however, noted, perhaps not without a certain malicious satisfaction, that over Rankin's right eye was a plum-colored discoloration which appeared to be swelling. Once, too, when on the[Pg 46] way to the boat he happened to glance in Rankin's direction, he surprised a glowering look on the assistant engineer's face which was instantly wiped off when Rankin saw that he was being observed.

"Huh, that was a quick change, like sponging something off a slate," thought Herc to himself. "However, Mr. Rankin, I've no idea that you love your second in command any better than you ought to. I guess I'll keep my weather eye on you, for at times you certainly do look most uncommonly like a rattlesnake."

The coxswain had taken charge of the boys' suit and sword cases. Rankin carried his own valise. It did not take them long to reach the little wharf, alongside which lay the Seneca's gig, the four men of her crew smoking and lolling at their ease at her oarlocks.

Like a flash all inertia vanished as Ned and Herc hove in sight. The coxswain saluted once more. The men saluted. Ned and Herc saluted.

As the two lads sank into the stern thwart seat, Herc found opportunity to whisper to Ned, "Give me a teeny jab with that sword if you can."

"Why on earth do you want me to do that?" demanded Ned, in astonishment at Herc's seemingly perfectly serious request.

With his hand over his mouth Herc gave a veiled rejoinder.

"Because if it doesn't hurt, I'll know I'm tucked in my little hammock and dreaming!"

"All ready, sir," suggested the coxswain, taking his seat.

"Give way," ordered Ned calmly, and the four oars struck the water like one.

The boys were fairly off on their way to their first command.

WELCOME TO THE "SENECA."

Swiftly, steadily urged on, like some great beetle moving across the surface of a sheet of burnished glass, the gig was impelled over the smooth expanse of the sheltered waters; for, although outside in the Sound itself the whitecaps were prancing under the lee of the islands, here it was almost a flat calm.

The men rowed in perfect unison, like some accurately timed piece of mechanism. Before long they could make out, lying in under the shoulder of a distant island, the outlines of a slate-colored craft.

"The Seneca?" asked Ned of the coxswain.

"Yes, sir; that's the Seneca."

"She looks a trim little hooker."

"Aye, aye, sir; she's all of that, sir."

Ned and Herc gazed with burning eyes and dancing pulses at the little craft. She was certainly not very large or imposing, but to them just then the finest Dreadnought ever launched could not have brought such emotions.

Not more than two hundred and fifty feet long, the Seneca appeared at first glance more like the ideal of a smart yacht than a craft of war. She had a sharp, overhanging bow and a beautifully modeled stern. Her rigging was of the schooner type, with the spider-web outlines of her wireless aerials slung between them.

In respect, doubtless, of her yachty lines, the Seneca had been used by a former President as a sort of official craft to convoy him to maneuvers and reviews.

Ned felt his enthusiasm rising, too, as lying against the Seneca's side, like the young of some sea monster, he made out the porpoise-like backs of the two submarines of which she was the parent ship. The sight of them brought back to[Pg 50] him the stirring days when he and Herc had aided the inventor of that type of diving boat, both in his pioneer voyages and in his romance.

He had only time to drink in this and other details with greedy eyes, when the gig swept around to the starboard gangway, reserved by immemorial custom for officers' embarkation.

From the marine sentry stationed at the head of the gangway came a sharp hail.

"Boat ahoy! What boat is that?"

"Aye! aye!" came from the coxswain.

This showed that there were commissioned officers on board. Had they been non-commissioned passengers, the reply to the hail would have been: "No! no!" For the captain and for other higher naval ranks there were other rejoinders, which have been enumerated in preceding volumes.

The gig was made fast. With a springy step and glowing features, Ned stepped out first. He was followed closely by Herc. A rattling sound[Pg 51] and an exclamation behind him, made Ned pause as he set foot on the gangway platform.

For an instant there was every sign that poor Herc was going to get into hot water for the second time that day. That unlucky sword had become entangled in his long legs, and for a time he hovered on the brink of disaster. But the watchful coxswain caught his arm and saved him the humiliation of tumbling into the water, new uniform and all.

It was all over in a moment and both boys hastened up to the head of the gangway. A corporal and four other marines besides the sentry now stood there. There was a sharp command and the sea-soldiers presented arms smartly.

"Goodness, I'll wear out my new cap with much more of this," thought Herc, as he acknowledged the salute simultaneously with Ned.

Just then a smart looking young naval officer behind the marines saluted. This, of course,[Pg 52] called for another answer. "Lieutenant Strong, I presume?" inquired this personage.

"Yes. And this is Ensign Taylor."

They shook hands and then the young officer, who was Ensign Summerville, suggested that the new arrivals be shown to their quarters.

"You may as well make yourselves at home as soon as possible," he said with a smile.

"Thanks; you are very kind," rejoined Ned, speaking for himself and Herc, for the latter was in a sort of happy daze.

"Then if you will come this way, please."

At a word from the corporal of marines, the boys' baggage was picked up by two of his men who preceded the party along the deck and turned into an alleyway, from which in turn they descended a companionway into the wardroom from which the cabins opened.

Up till the actual moment that he beheld his cabin, Ned still entertained fears that it might all be a vision which was likely to fade out at[Pg 53] any moment. But the sight of the snug cabin with its big double ports and broad berth, bookcase, desk and chairs made him realize that it was no figment of his imagination.

Knowing men-of-war of all types as well as he did, the boy appreciated with a throb of delight that this was no ordinary junior officer's cabin into which he had been ushered. Its size and the elaborateness of its fittings precluded that idea.

"Why—why, this is a magnificent stateroom," he found himself saying.

"It is the room that the commander of this vessel has always occupied," was the smiling rejoinder.

Lieutenant Ned Strong gave one of his winning laughs in return.

"Upon my word, Mr. Summerville," said he, "I can hardly wake up to the fact that I am to command this fine little craft."

"Well, you certainly are, for the purposes of[Pg 54] this war game, anyhow. They've got a notion that I'm rather a dab at strategic navigation, so they've passed me on to the Washington cruiser. Let me congratulate you on the command of a fine little craft."

"Thank you, you are very good," replied Ned; "but I hate to dispossess you."

"Pray don't mention it. You see I have often heard of you and your shipmate, and I am as glad as anyone of your deserved promotion. I only hope that it may be permanent."

An inspection of Herc's cabin next door followed. It was smaller and very much plainer than Ned's and contained no desk and only two chairs. But had it been Aladdin's palace, it could not have gratified Herc's delighted eyes any more than it did.

"But I'm forgetting something," said the Ensign suddenly. "Let us go back to your cabin, Mr. Strong. Your orders are on your desk. You will also find a secret code book, to which[Pg 55] you, only, will possess the key with one of your junior officers, and signed copies of your commissions."

As Ned already knew that the orders under which he sailed were sealed, he did not glance over them just then. Instead, he let his eyes feast on the engrossed copies of their commissions and a document which stated that Lieutenant Edward Strong was to take charge of the gunboat Seneca till "further orders from this department," and that Ensign Hercules Taylor was to be his second in command and assume such duties as were assigned to him on board.

"And now, sir," suggested Ensign Summerville, "the Seneca is under steam. She is ready for your orders."

Ned thrilled at the sound of the words. This trim little craft was absolutely at his command!

"First, however, you will no doubt wish to see your other officers. There is Mr. Drayton, chief[Pg 56] engineer; Mr. Rankin, his assistant, but you have already met him——"

"We have," rejoined Ned with a certain grim note in his voice.

"We most certainly have," added Herc, in a way which made the ensign give him a quick look of understanding. He made no audible comment, but those who knew Ensign Summerville would have guessed from a peculiar expression that came over his face that he recognized and sympathized with the antipathy the boys had formed for the assistant engineer.

"Our only other commissioned officer besides yourselves is Mr. Kenworth, not long out of Annapolis. Ah! there he is now. Kenworth, come here a moment, will you?"

He addressed a tall, slender, very erect young man in a midshipman's uniform who was just passing through the wardroom.

"This is Lieutenant Strong, of whom I have already told you. He assumes my command.[Pg 57] This is Mr. Taylor, the newly commissioned second in command.

"Hullo, you fellows have met before?" he demanded the next instant, for Kenworth had drawn back slightly, a supercilious smile on his thin, dark face.

"Yes, I have met Lieutenant Strong as a boatswain's mate," said Kenworth, with a disagreeable intonation; "Mr. Taylor, too, I have seen before the mast."

It was all true enough; both the Dreadnought Boys had good cause to recollect Mr. Kenworth. For a moment the air in the wardroom appeared charged with electricity.

Ensign Summerville looked from one to the other in surprise. He saw hauteur and dislike on Kenworth's face, a look that might have meant anything on Ned's countenance and undisguised disgust on Herc's freckled features.

MIDSHIPMAN KENWORTH.

It had all happened back early in the naval careers of young Strong and his chum Taylor. Kenworth, a sprig just out of Annapolis, had come to the Manhattan with an idea not uncommon among young gentlemen just out of the Academy, that next to the captain he was probably the most important person on the ship.

To strengthen him in this belief, he had influential relatives who had promised to smooth out his path in life for him. Despite this fact, though, Kenworth was still a midshipman. Why was this, when many of his own class had passed him?

Possibly the incident which Ned and Herc had such good cause to recollect will throw a sidelight on Mr. Kenworth's character that may serve to explain this condition.

It was one night when the wind was blowing "great guns." Ned and Herc, the former then a coxswain, were part of a crew sent to bring some young officers off to the ship from Guantanamo harbor. As it happened, the young officers were all middies and, by right of length of service, Kenworth outranked them.

He was quarrelsome and inclined to be obstreperous when he came on board. He began by abusing Ned, who had incurred Kenworth's ill-will by his sturdy independence and the steady command of his temper, even under the fledgling officer's insults and slurs.

The boat put off with a sea running that threatened momentarily to swamp her. It required the whole strength of Ned's arm to keep the craft, which was deeply loaded, headed into the seas in such a way as to insure safety.

"Let her off a point there, you," ordered Kenworth, when they had proceeded a short distance.

"It will hardly be safe, sir," rejoined Ned.

"Hang your impudence," cried young Kenworth; "do what I tell you, do you hear?"

"Very well, sir," and sorely against his will Ned did let the boat's head swing a trifle.

The instant result was what he had anticipated. The crest of a sea broke on them, drenching Kenworth to the skin. He flew into a frenzy of rage.

"You clumsy, incompetent nincompoop," he sputtered, "I'll have you up at the mast for that."

"I obeyed your orders, sir," rejoined Ned simply, knowing there was nothing to be gained by getting into an argument with an officer.

"Don't answer me, sir!" howled Kenworth. "Confound your impudence!"

"Oh, look here, Kenworth," remonstrated another midshipman. "It wasn't his fault. He told you it wouldn't do and you insisted."

"And got jolly well wet for your pains," came from one of the men at the oars in a low voice intended only for his mate's ears.

But Kenworth heard him, heard, too, the smothered laugh from the men, none of whom bore him any liking, his ways having made him the most unpopular officer on the ship.

"How dare you make such a remark to me, sir?" he demanded of Ned, choosing in his anger to make a victim of the man he disliked most.

"I said nothing, sir," rejoined Ned.

"That's right; he didn't utter a word," came from another midshipman.

"He'll sing a different tune at the mast to-morrow, insolent waterfront scum," gritted out Kenworth.

He said no more, but the next day the word was passed forward by the sergeant-at-arms for Ned to appear "at the mast," the man-o'-war tribunal where the captain deals out justice. Luckily Ned had no difficulty in clearing himself, thanks to friendly witnesses, and Kenworth was privately reprimanded by the captain for bringing a trumped-up charge against an enlisted man.

From that day on, Kenworth had nourished such a hatred of Ned as only a mean nature like his could cherish. He never, while he remained on the Manhattan, lost a chance to "work him up," as it is called. On one occasion, he went so far as to order Ned to count the sails of every ship in the harbor of Hong Kong and report their number to him.

Ned stood at the rail with a grave face for an hour enjoying the scenery, and then, stepping up to Kenworth, who was swelling with importance as officer of the deck, he saluted with a quiet smile.

"Well, did you do what I told you?" blustered Kenworth.

"Yes, sir; there are just three thousand nine hundred and ninety-five," replied Ned with great gravity.

Kenworth looked sharply at him.

"How do you know?" he asked.

"I counted them, sir," was the reply. "You[Pg 63] can check up my count if you like, sir; you'll find it correct."

As Ned saluted and turned away, he heard a burst of laughter at Kenworth's expense from some Jackies who had heard the little dialogue, and who discreetly vanished before the arrogant middie's wrath could descend on them. Soon after this Kenworth had left the Manhattan and Ned lost all track of him; not, indeed, that he felt any great interest in the matter.

And now, by a strange quip of circumstance, they had come face to face once more in the wardroom of the little gunboat. But now their positions were reversed. Ned was in command, Herc was his second in authority, with Kenworth, although he shaved daily and boasted a blue chin, still a midshipman.

"I'm very glad to meet Mr. Kenworth again," he said, when he had recovered his self-possession; "I recollect him on the Manhattan very well indeed."

Kenworth mumbled something about duty aft and hurried off. Ensign Summerville saw that there was an embarrassing situation in the air and hastened to suggest that they go on deck, where he would have the crew mustered and formally turn over the command of the Seneca to Ned.

The crew was piped to quarters and the ensign handed Ned a complete roster of the men. The shrill sounds of the bos'un's whistles filled the air, reminding Ned and Herc of the days when a response was part of their duty.

The inspection did not last long. It was actually more a ceremony of introduction. When it was over, the ensign tarried to help Ned in working out his course into the Sound.

"I would suggest that Mr. Kenworth take the ship out to deep water, as he knows the channels hereabouts thoroughly," said the ensign, as he bade good-by to the new commander of the Seneca.

"Mr. Kenworth, you will take the bridge, then," said Ned.

Kenworth saluted and hurried off to take his post. But as he did so, he grinned to himself.

"Good luck!" he exclaimed. "I think I see a chance to take the wind out of your sails before very long, you beggar on horseback, you forecastle Jack on the quarter deck! If I don't fix you and your ambitions and double spike 'em before this cruise is over, my name isn't Raymond Kenworth."

Swords were removed and sent below as soon as Ensign Summerville was over the side.

While waiting for the gig to return, Ned and Herc lingered over the charts and gave a few necessary orders.

"Well, Ned," confided Herc in a lull, "this is actually real after all."

"No doubt of that, old boy. I'm crazy to get under way and look at my orders. Who knows what they may contain and what lies before us?"

What, indeed, did the future hold for these two ambitious young officers of Uncle Sam's? They were destined to learn ere long. Over the horizon of that day of life lay new experiences to be met, new problems and dangers to be faced like officers and gentlemen and true Americans.

AGROUND!

The anchor was hauled up immediately on the return of the gig. The crews of the submarines, already on board the diving craft, took their stations. "Captain" Ned gave the word and the Seneca began to move slowly through the water.

Having superintended the work of getting under way, Ned and Herc ascended to the bridge. They found Midshipman Kenworth there, standing by the side of the quartermaster, who had the wheel.

Behind the wheel, which was a small, light affair controlling the steam steering gear, was a small house in which the machinery that operated the rudder control was situated.

Ned caught Herc by the sleeve just as the red-headed lad was stepping impulsively forward,[Pg 68] and drew him into the doorway of the structure. There was a small port in the place looking out over the bridge. It was open, and through it they could readily see.

"What's the idea of this?" demanded Herc. "I don't like this spying business. I've no use for Kenworth, but——"

"That's all right," responded Ned. "I don't wish to spy on the young man; I merely want to find out what sort of a pilot he is."

They skirted the little cape that formed the end of the island, in the lee of which the Seneca had been anchored. Beyond this island, the boys, somewhat to their surprise, saw that there was still quite an expanse of shoal water threaded by narrow channels between the outer island and the blue of the Sound itself.

"Ticklish work through here," commented Ned in a low tone, as he observed how the darker color of the channels that threaded the numerous shallow places alternated with broad expanses of[Pg 69] yellow water that showed the presence of dangerous sand banks.

"You're dead right," responded Herc; "about as bad a place as I ever clapped eyes on."

The rattle and roar of the steering machinery as the wheel was spun right and left drowned the sound of their voices. Kenworth was looking straight ahead. From time to time they could see him turn slightly and give some order to the helmsman; but what the orders were they could not catch.

The Seneca appeared to be following the channel perfectly, however, winding among the mazes of deeper waterways like a dancer.

"Kenworth is no slouch at this work," said Ned in a low voice as they watched.

"Shucks!" grunted Herc, "I guess the Seneca has been in and out of here a hundred times. Anyhow, a blind man could see those channels."

Ned turned on his companion with a stern look.

"See here, Herc Taylor, we want peace and harmony on this craft; do you understand?"

"Even if we have to scrap to get it," muttered Herc. "All right; from now on, I'm the greatest little peace delegate ever you saw."

A minute later, while they were still watching, they saw something that gave them a momentary shock of surprise. Rankin appeared on the bridge. There was nothing extraordinary in his so doing, of course. He probably had something to report to the watch officer.

But somehow Ned, with a quick flash of intuition that he could not explain, felt that more than that lay in this sudden conjunction of their two enemies; for that Rankin disliked them, Ned had no doubt.

He laid a hand on Herc's arm to keep him quiet, for the impulsive red-headed youth was about, apparently, to break forth into some emphatic exclamation at what he had just seen.

Rankin approached Kenworth with an air of[Pg 71] familiarity that showed there existed some friendship between them. Kenworth greeted him with an easy nod, and then, after giving some directions to the man at the wheel, he placed his hand on Rankin's shoulder and drew him back toward the steering-gear house.

"Come back here while we talk," the boys heard him say, "I don't want that quartermaster to overhear us."

For a moment it appeared that they were coming into the steering house, but they merely stood close back against its metal wall. They had taken up positions right under the porthole through which Ned had been making his observations.

But they had not seen their superior officers. Ned had been too quick for that. As the two approached the steering-gear structure, he grabbed Herc and drew him down. Now they crouched quietly under the porthole, through[Pg 72] which they could catch perfectly everything that was said.

"Well, here's a fine how-de-do," they heard Rankin complain in a grumbling tone; "a couple of snips that aren't dry behind the ears been set over us. I thought you were to get the command when Summerville left."

"So did I; but it seems these two interlopers succeeded in getting it for themselves."

"Didn't you tell me that they started in the navy just as enlisted men?"

"Yes, the gutter-snipes never saw even the outside of Annapolis. I'd like to know what the service is coming to when good men are passed over for useless propositions like this!"

"So would I. By the way, I had a row with them on the train coming down. They've no use for me, I fancy. I wish I could hit upon some plan to take them down a peg or two."

"I have," was Kenworth's rejoinder, in a tone which was acid with malignant hatred.

"Have what?"

"Formed such a plan. I've got a scheme to discredit them with the department right from the jump."

"Shoal ahead, sir!"

The voice of the man at the wheel cut in raspingly like a file. Kenworth sprang up. Ned also ventured to steal a look through the port. He saw the shoal the helmsman had drawn attention to, a long daub of yellow stretching on their port bow.

He saw in a flash that there was only one way to save the ship from going aground.

"Stay here," he ordered Herc, and then bounded out of the steering-gear house, colliding with Rankin as he did so.

"What, you here, sir?" exclaimed Rankin with a sickly smile as Ned shoved past him. The Dreadnought Boy, with a sinking sense of dread, guessed somehow that already the conspiracy[Pg 74] against him was under way, and that, with the flukes of the anchor not yet dry at the cat-head!

Rankin reeled and staggered as Ned brushed by with scant regard for gentleness. He turned and gazed after the figure of the young officer as he made for the steersman. Kenworth already stood at the man's side.

"Hard a'port!" Ned heard Kenworth roar.

It was precisely the command that, under the circumstances, would bring the bow of the Seneca grating and rasping on the shoal.

"Hard over! Hard over! For your life, man!" shouted Ned.

"Aye, aye, sir!" cried the man, recognizing the superior authority of the temporary commander.

But it was too late. The next instant it happened, even as Ned's hand jerked the engine-room telegraph over to "Full speed astern." With a grating, jarring succession of bumps, the Seneca, Ned's first command, slipped upon the[Pg 75] shoal, even while her reversed engines were frantically biting the water astern.

Before the lad's eyes arose a sickening vision of failure and disgrace, even at the very outset of his important commission.

"YOUR DUTY IS TO OBEY!"

It was no time then to try to fix the blame. Turning to Kenworth, who was standing with chalky-white face by his side, Ned curtly ordered him to go below and summon the engineer and the ship's armorers to the bridge.

When they came, he gave swift, incisive orders to have the ship examined from stem to stern, and any damage she might have sustained reported to him immediately. Herc, who by this time of course was by his young leader's side, was ordered to take charge of this work.

The next half hour was the most anxious Ned had ever passed; but he knew that yet more suspense was bound to follow when it came to testing how hard and fast the Seneca was piled on the shoal.

There was a possibility that she might get off under her own steam. But of course this could not be foretold till an actual trial could be made. For the present, with engines that had ceased revolving, the Seneca lay helpless and motionless on the shoal.

Ned's naval training stood him in good stead then. Without a quiver of a lip or a flicker of an eyelid to betray the ordeal through which he was passing, he stood erect on the bridge awaiting the report of the investigators. Only the pallor under his tanned cheeks showed what he was enduring.

If naval tugs had to be sent for to extricate the Seneca from her predicament, Ned knew that his brief career as a naval commander was over before it had well begun. Then, too, with this thought mingled another.

Had Kenworth deliberately given the order that had resulted in the grounding of the ship, or had he lost his head and "piled her up"?[Pg 78] Judging from the conversation he had overheard, Kenworth was determined to stop at nothing to discredit and disgrace Herc and himself with the Navy Department.

But it was inconceivable, almost, that he should have formed his plan and executed it so quickly. Ned was more inclined to put the entire affair down to stupidity. But he knew that as commander of the Seneca, he, and not Kenworth, would assuredly be held responsible for any damage done.

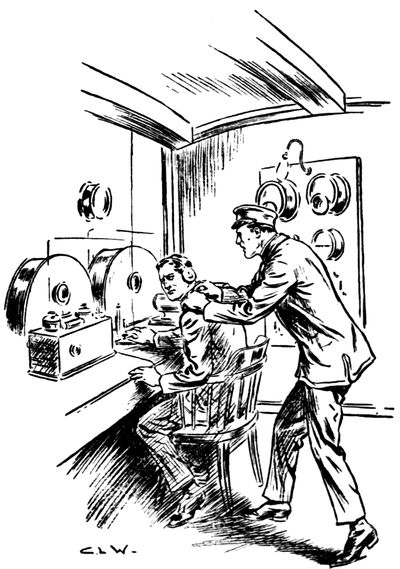

It was at this moment that he was aroused by the clicking and whining of the wireless spark in its little metal house just abaft of the funnel. The stinging, whip-like crack and the crepitant sputter of the spark as it leaped back and forth across its gap like a caged animal was borne with clean-cut distinctness to his ears.

"Somebody working the wireless," decided Ned, for the arrival of a message is not attended by any sound audible outside the ear receivers.[Pg 79] "Who can it be? Trevor, the regular wireless man, is off duty. He was one of the emergency gang I sent below with all the other hands I could spare."

There followed a moment of indecision, and then a flame of anger swept Ned's face.

Whoever was sending out those thundering detonations of electricity that were splitting space like a scimitar was no novice. Moreover, he was trying to raise the Manhattan, the flagship of the Red Squadron, and using the secret code to do it.

"I'll find out what this means in two shakes," exclaimed Ned to himself. "I miss my guess if it isn't somebody trying, absolutely without orders, to flash news of this accident to the flagship and put me in bad."

He hastened from the bridge to the upper deck and through an alleyway to where a short flight of steel steps led to the wireless room, perched like a miniature pilot house astern of the funnel.

As he gained the door of the place and looked in, he stopped as abruptly as if he had been struck a blow in the face.

For an instant he stood there rigid, taking in the picture that had suddenly presented itself to his indignant gaze.

Bending over the key and sending out impatient waves of sound into the atmosphere was Kenworth. His pale face was alight with poisonous glee, as again and again he sent out the secret call for the flagship of the Reds.

Ned was into the room in a bound. In another instant he had Kenworth by the collar. The astonished and startled midshipman was as helpless as a puppy in Ned's powerful grasp.

"I—how—what's the matter?" he sputtered.

"What are you doing here, Mr. Kenworth?" demanded Ned sternly. He was in no mood to be trifled with. He fancied now that he saw the whole contemptible plot, swiftly as the storm had broken.

"Well, you see, sir—I—that is, when——"

"Answer me at once, please. What are you doing here?"

"I—I thought I'd practice up a bit."

"What!"

Ned's eyes blazed and a dangerous flicker of white came around his nostrils. He despised a liar more than he held contempt for a coward, and if he was not much mistaken, Kenworth was both.

"You see," stuttered Kenworth, absolutely shaken and flaccid, "I'm wireless officer, with Trevor as assistant. I'm not very good yet, and I——"

"On the contrary, it strikes me that you are remarkably efficient, Mr. Kenworth," snapped Ned; "and as for practicing, you assuredly choose an extraordinary time for it when the ship, for anything you know, is in danger."

"Danger?" exclaimed Kenworth, and Ned[Pg 82] thought that he caught an evil glint in the midshipman's eyes.

"That remains to be seen," rejoined Ned coldly. "Tell me if you can, why, without orders and without informing anyone, you were in here trying to raise the Manhattan. You are silent. Then I will tell you myself. You wanted to send out word of the accident."

Kenworth shuffled from foot to foot uneasily.

"My duty——" he began.

Then Ned boiled over.

"Your duty, Mr. Kenworth, is to obey my orders. You will now oblige me by going to your cabin, unless you wish me to adopt harsher measures."

With a half-hearted salute, Kenworth turned and without a word left the wireless room. But as he descended the companionway stairs he muttered to himself:

"I guess I've got you badly worried already, Mr. Monkey-on-a-Stick, and this is only the beginning.[Pg 83] I said I'd fix you and I will, too. If only I could have raised the Manhattan and got that message through with my version of the accident, Master Ned Strong's career would have ended with a hard bump."

"THE EYES OF THE RED FLEET."

While Kenworth, in his cabin, was consoling himself for his smart "dressing down" from Ned with the reflection that in the event of the Seneca being badly damaged the lad he so disliked would lose his berth, Ned, on deck, had forgotten in the business of the moment the incident of the intercepted wireless.

Herc reported that no serious strain had been found, and that so far as could be seen the Seneca was resting on the edge of a sand bank. The tide, it had been ascertained, was rising, in itself a fortunate circumstance, and within a short time things would be propitious for an attempt to back the craft off under her own steam.

"I hope to goodness we succeed, old fellow," said Ned fervently, "although I can't tell you[Pg 85] what an unspeakable relief to me it has been to know that we are not damaged."

"You can rest assured of that. Every plate and rivet from fore-peak to shaft tunnel has been gone over. Not a drop of water anywhere."

"In that case, provided we can get afloat again without summoning assistance, we may get by without a reprimand or, even worse, a recall," declared Ned.

"Oh, that would be terrible!" exclaimed Herc. "But say, Ned, have you done any thinking about this accident?"

"What a question to ask! Thinking! I've been doing nothing else since we struck."

"But you know what I mean?"

"Putting two and two together?" asked Ned significantly, with a glance at the steering-wheel house that had been their place of concealment.

"That's it exactly. Have you been doing that?"

"Hum, yes, but they don't make four—yet."

"But you've come to the conclusion that the[Pg 86] accident may not have been quite so accidental as it appeared?"

"I didn't say so. What I do say, though, is this, that there is one person on board who was quite willing to take advantage of it, accident or no accident, to discredit us."

"And that was——?"

"Mr. Midshipman Kenworth. The rascal! caught him in the wireless room trying to send a message to the Manhattan."

Ned went on to relate all that had occurred at that momentous encounter, being frequently interrupted by Herc's exclamations of indignation.

"You ought to have Kenworth put in the brig, or at least keep him in his cabin for the rest of the cruise," blustered Herc.

"How can I do that? I have no proof against the fellow. Suspicion is one thing, proof quite another."

"Anyone who knows the fellow——"

"That's quite aside from the question. Kenworth has powerful influences behind him. We don't want to make any more enemies than we have to."

"Oh, pshaw! If I had your powers——"

"If I had the proof, I'd act quick enough, you may be sure. I wouldn't care if his father was Secretary of the Navy—yes, or President. All the more reason for getting rid of such a scalawag. But as it is——"

"All ready, sir!"

The chief bos'un's mate made the announcement.

"Very well, Bowles. You may pass the word."

"Now for the tug-of-war," said Ned grimly, as, warning the man at the wheel to keep his helm hard over, he sent the signal below for the engines to be started at reverse "slow."

Once more the vibration of her machinery thrilled the hull of the Seneca; but—she did not move.

Undisturbed, so far as anyone could see, Ned shoved the telegraph over till little by little the pointer stopped at "Full speed astern." He rang up on the bridge telephone.

"Give her every ounce you've got," he ordered.

The water churned whitely; the pipes of the safety valves roared with the pressure of the escaping steam from the high-pressure boilers. The Seneca shook and trembled like a live thing. Then came a sudden impulse. Ned's eyes began to dance, but he dared not speak.

The next instant he knew that he had not been mistaken. The Seneca was moving.

A cheer burst from the men, who knew that Ned had risen from the foredeck, and liked and admired him on that account. Nobody attempted to check it. Below, in his cabin, Kenworth heard the cheer and felt the slight movement.

"Confound him! So he has managed to get her afloat, after all," he muttered. "I didn't pile[Pg 89] her up quick enough. Well, I'll get another chance, and this time I won't fall down."

Little by little the bulk of the gunboat began to slide backward off the shoal.

From the leadsmen posted on the bow, bridge and stern, came every moment cries announcing deeper and deeper water. Herc silently wrung Ned's hand. Ned said nothing, but his face showed what he felt.

At last there came a sudden backward lurch and the gunboat was freed from her sandy prison and floated in deep water once more.

"We'll have no pilot this time," declared Ned, as he himself took the guidance of the ship, scanning the waters ahead with keen eyes and directing the helmsman on his course. They reached open water without accident. And then Ned was at leisure to forward his report of the accident to the Manhattan.

To his relief no comment was made upon it, which he attributed to the fact that there had[Pg 90] been no serious results. But through the air came an order that caused Ned to thrill with delight. He was commanded to peruse his sealed orders and follow them out without delay.

The Manhattan was then some miles north of Block Island, well out to sea with the Red Squadron. Of the Blues, nothing had been heard.

It was for Ned's ship, as the "Eyes of the Red Fleet" to spy out and report the whereabouts of the "enemy."

THE EAVESDROPPER.

Ned, after the receipt of the message authorizing him to open his orders, lost no time in hastening below.

Herc, as his junior officer, went with him. Kenworth was ordered out of his cabin and told off to assume charge of the after-watch, an assignment on which Ned was sure the evilly disposed midshipman could not do any harm.

In the meantime, the ship was steaming slowly down the Sound in charge of one of the junior warrant officers.

"Now for the big secret," exclaimed Ned, as he opened his desk and took out the slender package. "We'll step into the wardroom to look it over, Herc."

"Look out, somebody may have put a bomb[Pg 92] in it while we were gone," warned Herc, leaning over Ned's shoulder, a look of intense interest on his freckled countenance.

"Hardly any danger of that, I think," laughed Ned.

He ripped open the envelope, glanced hastily at the first sheet of the numerous typewritten pages it contained, and gave vent to a low whistle.

"Well, what do you think of that?" gasped Herc. "I thought we were to——"

"Obey orders," said Ned quietly; "although I must admit this is a bit of a surprise. I suppose a change in plans came late so that we were not forewarned."

"Well, let's hear what it is all about," prompted Herc impatiently.

"Simple enough, apparently. The army folks are protecting the mouth of the harbor. There are important fortifications there, because in time of war the protecting fleet, or part of it, might gather there.

"The army folks have planted mines there. While watching for the Blue fleet to arrive, we are to test those mines."

"Phew!" gasped Herc. "There's only one way to test how much kick there is to a mine."

"And what's that?" asked Ned.

"To blow it up and—yourself with it," declared Herc sententiously. "Well, for a nice little holiday job, we have sure picked a dandy."

"Hold on a minute, will you?" interrupted Ned. "Let me finish this. The mines are wired up by a new system. What we have to find out is if we can sneak into the harbor mouth in our submarines and disconnect the firing wires of the mines without blowing ourselves up. If we can do this, the system is a failure."

"Humph! and so are we."

"So are we what?"

"Failures! If one of these mines blew up, what else would we be——"

Ned exploded in a loud laugh.

"Why, you chump," he exclaimed, "they are not loaded mines!"

"Then how can they tell if they've been exploded or not when we go submarining around them?"

"It's up to us to see if we can dodge the wires or contrive some way to disconnect them."

"That disconnecting idea doesn't appear very feasible."

"No, it does not," agreed Ned; "but I think I can find a way to evade them, for all that."

"Hum! So long as they're not loaded, I don't care even if we run bumpety-bang into one," declared Herc; "but a loaded mine—no, thank you!"

"Our orders after that are general. We are to use our own discretion entirely, acting as the eyes and ears of the Red fleet, and forwarding to the flagship, via wireless, every scrap of information we think might be valuable to the attacking party."

"That's one thing I don't like about this command," muttered Herc.

"What is that?"

"Why, we're supposed to be enemies to the flag."

"But only supposed to be, Herc, for the purposes of perfecting the strength of Uncle Sam's defenses, and playing a useful part in exposing any weakness in our nation's fortifications."

"Huh; well, that's all the kind of enemy I ever want to be—a supposed one."

"I'm going into my cabin to lay out our course," said Ned, after a few more words. "I want you on deck, Herc, to see how things are going on. It won't take me long and—— What on earth is the matter? Got a stroke?"

There was a large glass skylight over the wardroom and, owing to the warmth of the weather, the flaps of this had been raised. With the expression of one who has been suddenly hypnotized, Herc was staring with open eyes and mouth straight up at the wardroom roof.

"What do you see?" demanded Ned, springing[Pg 96] to his feet. "Shall I get you a glass of water? Shall I——"

"Umph! You might get me a gun," snorted Herc.

"A gun! What on earth do you want with a gun?"

"I want it to shoot a skunk!"

"A skunk! Do you think you're back on the farm?"

"No, but just the same I'd like to go gunning with grandpap's old scatter gun."

"I wish we had a doctor on board, Herc. Any fellow who can go around seeing skunks——"

"Ought to shoot 'em on sight," muttered Herc belligerently. "Well, Ned, this was a skunk I saw, all right, all right! And what do you think his name was?"

Without waiting for a reply, Herc rushed on, "Kenworth! He'd been listening to every word we were saying!"

SAKI—STEWARD.

For the time being there was no opportunity to investigate the case of the eavesdropper. It was important that they should get under way at once. Herc hastened on deck after a few hurried words with Ned.

Just at that moment two bells—one o'clock—sounded in the slow, deep, mellow tones of the ship's bell. Simultaneously there appeared, through a doorway at one end of the wardroom, the figure of a dapper Japanese, dressed in white garments.

"Hullo! Who are you?" demanded Ned, looking up from a reverie into which he had fallen, following Herc's departure.

"Me Saki. Officer steward. Me getee lunch for honorable capitan," rejoined the Jap with a low bow.

"Mr. Summerville made no mention to me of you," said Ned, looking the Jap over.

"No doubt, sir, no doubt," was the reply; "me only joinee ship in New York."

Ned said no more, but, telling the steward to summon him when the meal was ready, he resumed his meditations. Truly the young skipper of the Seneca was in need of time to think and ponder.