Title: The Mythology of the British Islands

Author: Charles Squire

Release date: April 27, 2017 [eBook #54616]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MWS and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet

Archive/American Libraries.)

This book is what its author believes to be the only attempt yet made to put the English reader into possession, in clear, compact, and what it is hoped may prove agreeable, form, of the mythical, legendary, and poetic traditions of the earliest inhabitants of our islands who have left us written records—the Gaelic and the British Celts. It is true that admirable translations and paraphrases of much of Gaelic mythical saga have been recently published, and that Lady Charlotte Guest’s translation of the Mabinogion has been placed within the reach of the least wealthy reader. But these books not merely each cover a portion only of the whole ground, but, in addition, contain little elucidatory matter. Their characters stand isolated and unexplained; and the details that would explain them must be sought for with considerable trouble in the lectures and essays of scholars to learned societies. The reader to whom this literature is entirely new is introduced, as it were, to numerous people of whose antecedents he knows nothing; and the effect is often disconcerting enough to make him lay down the volume in despair.

But here he will at last make the formal acquaintance of all the chief characters of Celtic myth: of the Gaelic gods and the giants against whom they struggled; of the “Champions of the Red Branch” of Ulster, heroes of a martial epopee almost worthy to be placed beside “the tale of Troy divine”; and of Finn and his Fenians. He will meet also with the divine and heroic personages of vithe ancient Britons: with their earliest gods, kin to the members of the Gaelic Pantheon; as well as with Arthur and his Knights, whom he will recognize as no mortal champions, but belonging to the same mythic company. Of all these mighty figures the histories will be briefly recorded, from the time of their unquestioned godhood, through their various transformations, to the last doubtful, dying recognition of them in the present day, as “fairies”. Thus the volume will form a kind of handbook to a subject of growing importance—the so-called “Celtic Renaissance”, which is, after all, no more—and, indeed, no less—than an endeavour to refresh the vitality of English poetry at its most ancient native fount.

The book does not, of course, profess to be for Celtic scholars, to whom, indeed, its author himself owes all that is within it. It aims only at interesting the reader familiar with the mythologies of Greece, Rome, and Scandinavia in another, and a nearer, source of poetry. Its author’s wish is to offer those who have fallen, or will fall, under the attraction of Celtic legend and romance, just such a volume as he himself would once have welcomed, and for which he sought in vain. It is his hope that, in choosing from the considerable, though scattered, translations and commentaries of students of Old Gaelic and Old Welsh, he has chosen wisely, and that his readers will be able, should they wish, to use his book as a stepping-stone to the authorities themselves. To that end it is wholly directed; and its marginal notes and short bibliographical appendix follow the same plan. They do not aspire to anything like completeness, but only to point out the chief sources from which he himself has drawn.

To acknowledge, as far as possible, such debts is now the author’s pleasing duty. First and foremost, he has relied upon the volumes of M. H. d’Arbois de Jubainville’s Cours de Littérature celtique, and the Hibbert Lectures for 1886 of John Rhys, Professor of Celtic in the University viiof Oxford, with their sequel entitled Studies in the Arthurian Legend. From the writings of Mr. Alfred Nutt he has also obtained much help. With regard to direct translations, it seems almost superfluous to refer to Lady Charlotte Guest’s Mabinogion and Mr. W. F. Skene’s Four Ancient Books of Wales, or to the work of such well-known Gaelic scholars as Mr. Eugene O’Curry, Dr. Kuno Meyer, Dr. Whitley Stokes, Dr. Ernest Windisch, Mr. Standish Hayes O’Grady (to mention no others), as contained in such publications as the Revue Celtique, the Atlantis, and the Transactions of the Ossianic Society, in Mr. O’Grady’s Silva Gadelica, Mr. Nutt’s Voyage of Bran, Son of Febal, and Miss Hull’s Cuchullin Saga. But space is lacking to do justice to all. The reader is referred to the marginal notes and the Appendix for the works of these and other authors, who will no doubt pardon the use made of their researches to one whose sole object has been to gain a larger audience for the studies they have most at heart.

Finally, perhaps, a word should be said upon that vexed question, the transliteration of Gaelic. As yet there is no universal or consistent method of spelling. The author has therefore chosen the forms which seemed most familiar to himself, hoping in that way to best serve the uses of others.

| Chap. | Page | |

| I. | The Interest and Importance of Celtic Mythology | 1 |

| II. | The Sources of our Knowledge of the Celtic Mythology | 8 |

| III. | Who were the “Ancient Britons”? | 18 |

| IV. | The Religion of the Ancient Britons and Druidism | 31 |

| THE GAELIC GODS AND THEIR STORIES | ||

| V. | The Gods of the Gaels | 47 |

| VI. | The Gods Arrive | 65 |

| VII. | The Rise of the Sun-God | 78 |

| VIII. | The Gaelic Argonauts | 89 |

| IX. | The War with the Giants | 107 |

| X. | The Conquest of the Gods by Mortals | 119 |

| XI. | The Gods in Exile | 132 |

| XII. | The Irish Iliad | 153 |

| XIII. | Some Gaelic Love-Stories | 184 |

| XIV. | Finn and the Fenians | 201 |

| XV. | The Decline and Fall of the Gods | 227 |

| THE BRITISH GODS AND THEIR STORIES | ||

| XVI. | The Gods of the Britons | 251 |

| XVII. | The Adventures of the Gods of Hades | 278 |

| XVIII. | The Wooing of Branwen and the Beheading of Brân | 289 |

| xXIX. | The War of Enchantments | 298 |

| XX. | The Victories of Light over Darkness | 305 |

| XXI. | The Mythological “Coming of Arthur” | 312 |

| XXII. | The Treasures of Britain | 336 |

| XXIII. | The Gods as King Arthur’s Knights | 354 |

| XXIV. | The Decline and Fall of the Gods | 371 |

| SURVIVALS OF THE CELTIC PAGANISM | ||

| XXV. | Survivals of the Celtic Paganism into Modern Times | 399 |

| Appendix | 419 | |

| Index | 425 | |

It should hardly be necessary to remind the reader of what profound interest and value to every nation are its earliest legendary and poetical records. The beautiful myths of Greece form a sufficing example. In threefold manner, they have influenced the destiny of the people that created them, and of the country of which they were the imagined theatre. First, in the ages in which they were still fresh, belief and pride in them were powerful enough to bring scattered tribes into confederation. Secondly, they gave the inspiration to sculptor and poet of an art and literature unsurpassed, if not unequalled, by any other age or race. Lastly, when “the glory that was Greece” had faded, and her people had, by dint of successive invasions, perhaps even ceased to have any right to call themselves Hellenes, they have passed over into the literatures of the modern 2world, and so given to Greece herself a poetic interest that still makes a petty kingdom of greater account in the eyes of its compeers than many others far superior to it in extent and resources.

This permeating influence of the Greek poetical mythology, apparent in all civilized countries, has acted especially upon our own. From almost the very dawn of English literature, the Greek stories of gods and heroes have formed a large part of the stock-in-trade of English poets. The inhabitants of Olympus occupy, under their better-known Latin names, almost as great a space in English poetry as they did in that of the countries to which they were native. From Chaucer downwards, they have captivated the imagination alike of the poets and their hearers. The magic cauldron of classic myth fed, like the Celtic “Grail”, all who came to it for sustenance.

At last, however, its potency became somewhat exhausted. Alien and exotic to English soil, it degenerated slowly into a convention. In the shallow hands of the poetasters of the eighteenth century, its figures became mere puppets. With every wood a “grove”, and every rustic maid a “nymph”, one could only expect to find Venus armed with patch and powder-puff, Mars shouldering a musket, and Apollo inspiring the versifier’s own trivial strains. The affectation killed—and fortunately killed—a mode of expression which had become obsolete. Smothered by just ridicule, and abandoned to the commonplace vocabulary of the inferior hack-writer, classic myth became a subject 3which only the greatest poets could afford to handle.

But mythology is of such vital need to literature that, deprived of the store of legend native to southern Europe, imaginative writers looked for a fresh impulse. They turned their eyes to the North. Inspiration was sought, not from Olympus, but from Asgard. Moreover, it was believed that the fount of primeval poetry issuing from Scandinavian and Teutonic myth was truly our own, and that we were rightful heirs of it by reason of the Anglo-Saxon in our blood. And so, indeed, we are; but it is not our sole heritage. There must also run much Celtic—that is, truly British—blood in our veins.[1] And Matthew Arnold was probably right in asserting that, while we owe to the Anglo-Saxon the more practical qualities that have built up the British Empire, we have inherited from the Celtic side that poetic vision which has made English literature the most brilliant since the Greek.[2]

We have the right, therefore, to enter upon a new spiritual possession. And a splendid one it is! The Celtic mythology has little of the heavy crudeness that repels one in Teutonic and Scandinavian story. 4It is as beautiful and graceful as the Greek; and, unlike the Greek, which is the reflection of a clime and soil which few of us will ever see, it is our own. Divinities should, surely, seem the inevitable outgrowth of the land they move in! How strange Apollo would appear, naked among icebergs, or fur-clad Thor striding under groves of palms! But the Celtic gods and heroes are the natural inhabitants of a British landscape, not seeming foreign and out-of-place in a scene where there is no vine or olive, but “shading in with” our homely oak and bracken, gorse and heath.

Thus we gain an altogether fresh interest in the beautiful spots of our own islands, especially those of the wilder and more mountainous west, where the older inhabitants of the land lingered longest. Saxon conquest obliterated much in Eastern Britain, and changed more; but in the West of England, in Wales, in Scotland, and especially in legend-haunted Ireland, the hills and dales still keep memories of the ancient gods of the ancient race. Here and there in South Wales and the West of England are regions—once mysterious and still romantic—which the British Celts held to be the homes of gods or outposts of the Other World. In Ireland, not only is there scarcely a place that is not connected in some way with the traditionary exploits of the “Red Branch Champions”, or of Finn and his mighty men, but the old deities are still remembered, dwarfed into fairies, but keeping the same attributes and the same names as of yore. Wordsworth’s complaint[3] 5that, while Pelion and Ossa, Olympus and Parnassus are “in immortal books enrolled”, not one English mountain, “though round our sea-girt shore they rise in crowds”, had been “by the Celestial Muses glorified” doubtless seemed true to his own generation. Thanks to the scholars who have unveiled the ancient Gaelic and British mythologies, it need not be so for ours. On Ludgate Hill, as well as on many less famous eminences, once stood the temple of the British Zeus. A mountain not far from Bettws-y-Coed was the British Olympus, the court and palace of our ancient gods.

It may well be doubted, however, whether Wordsworth’s contemporaries would have welcomed the mythology which was their own by right of birth as a substitute for that of Greece and Rome. The inspiration of classic culture, which Wordsworth was one of the first to break with, was still powerful. How some of its professors would have held their sides and roared at the very notion of a British mythology! Yet, all the time, it had long been secretly leavening English ideas and ideals, none the less potently because disguised under forms which could be readily appreciated. Popular fancy had rehabilitated the old gods, long banned by the priests’ bell, book, and candle, under various disguises. They still lived on in legend as kings of ancient Britain reigning in a fabulous past anterior to Julius Caesar—such were King Lud, founder of London; King Lear, whose legend was immortalized by Shakespeare; King Brennius, who conquered Rome; as well as many others who will be found 6filling parts in old drama. They still lived on as long-dead saints of the early churches of Ireland and Britain, whose wonderful attributes and adventures are, in many cases, only those of their original namesakes, the old gods, told afresh. And they still lived on in another, and a yet more potent, way. Myths of Arthur and his cycle of gods passed into the hands of the Norman story-tellers, to reappear as romances of King Arthur and his Knights of the Table Round. Thus spread over civilized Europe, their influence was immense. Their primal poetic impulse is still resonant in our literature; we need only instance Tennyson and Swinburne as minds that have come under its sway.

This diverse influence of Celtic mythology upon English poetry and romance has been eloquently set forth by Mr. Elton in his Origins of English History. “The religion of the British tribes”, he writes, “has exercised an important influence upon literature. The mediæval romances and the legends which stood for history are full of the ‘fair humanities’ and figures of its bright mythology. The elemental powers of earth and fire, and the spirits which haunted the waves and streams appear again as kings in the Irish Annals, or as saints and hermits in Wales. The Knights of the Round Table, Sir Kay and Tristrem and the bold Sir Bedivere, betray their mighty origin by the attributes they retained as heroes of romance. It was a goddess, ‘Dea quaedam phantastica’, who bore the wounded Arthur to the peaceful valley. ‘There was little sunlight on its woods and streams, and the nights were dark 7and gloomy for want of the moon and stars.’ This is the country of Oberon and of Sir Huon of Bordeaux. It is the dreamy forest of Arden. In an older mythology, it was the realm of a King of Shadows, the country of Gwyn ap Nudd, who rode as Sir Guyon in the ‘Fairie Queene’—

To trace Welsh and Irish kings and saints and hermits back to “the elemental powers of earth and fire, and the spirits that haunted the woods and streams” of Celtic imagination, and to disclose primitive pagan deities under the mediæval and Christian trappings of “King Arthur’s Knights” will necessarily fall within the scope of this volume. But meanwhile the reader will probably be asking what evidence there is that apocryphal British kings like Lear and Lud, and questionable Irish saints like Bridget are really disguised Celtic divinities, or that the Morte D’Arthur, with its love of Launcelot and the queen, and its quest of the Holy Grail, was ever anything more than an invention of the Norman romance-writers. He will demand to know what facts we really possess about this supposed Celtic mythology alleged to have furnished their prototypes, and of what real antiquity and value are our authorities upon it.

The answer to his question will be found in the next chapter.

We may begin by asserting with confidence that Mr. Elton has touched upon a part only of the material on which we may draw, to reconstruct the ancient British mythology. Luckily, we are not wholly dependent upon the difficult tasks of resolving the fabled deeds of apocryphal Irish and British kings who reigned earlier than St. Patrick or before Julius Caesar into their original form of Celtic myths, of sifting the attributes and miracles of doubtfully historical saints, or of separating the primitive pagan elements in the legends of Arthur and his Knights from the embellishments added by the romance-writers. We have, in addition to these—which we may for the present put upon one side as secondary—sources, a mass of genuine early writings which, though post-Christian in the form in which they now exist, none the less descend from the preceding pagan age. These are contained in vellum and parchment manuscripts long preserved from destruction in mansions and monasteries in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, and only during the last century brought to light, copied, and translated by the patient labours of scholars who have grappled with 9the long-obsolete dialects in which they were transcribed.

Many of these volumes are curious miscellanies. Usually the one book of a great house or monastic community, everything was copied into it that the scholar of the family or brotherhood thought to be best worth preserving. Hence they contain matter of the most diverse kind. There are translations of portions of the Bible and of the classics, and of such then popular books as Geoffrey of Monmouth’s and Nennius’ Histories of Britain; lives of famous saints, together with works attributed to them; poems and romances of which, under a thin disguise, the old Gaelic and British gods are the heroes; together with treatises on all the subjects then studied—grammar, prosody, law, history, geography, chronology, and the genealogies of important chiefs.

The majority of these documents were put together during a period which, roughly speaking, lasted from the beginning of the twelfth century to the end of the sixteenth. In Ireland, in Wales, and, apparently, also in Scotland, it was a time of literary revival after the turmoils of the previous epoch. In Ireland, the Norsemen, after long ravaging, had settled peacefully down, while in Wales, the Norman Conquest had rendered the country for the first time comparatively quiet. The scattered remains of history, lay and ecclesiastical, of science, and of legend were gathered together.

Of the Irish manuscripts, the earliest, and, for our purposes, the most important, on account of the great store of ancient Gaelic mythology which, in 10spite of its dilapidated condition, it still contains, is in the possession of the Royal Irish Academy. Unluckily, it is reduced to a fragment of one hundred and thirty-eight pages, but this remnant preserves a large number of romances relating to the old gods and heroes of Ireland. Among other things, it contains a complete account of the epical saga called the Táin Bó Chuailgné, the “Raiding of the Cattle of Cooley”, in which the hero, Cuchulainn, performed his greatest feats. This manuscript is called the Book of the Dun Cow, from the tradition that it was copied from an earlier book written upon the skin of a favourite animal belonging to Saint Ciaran, who lived in the seventh century. An entry upon one of its pages reveals the name of its scribe, one Maelmuiri, whom we know to have been killed by robbers in the church of Clonmacnois in the year 1106.

Far more voluminous, and but little less ancient, is the Book of Leinster, said to have been compiled in the early part of the twelfth century by Finn mac Gorman, Bishop of Kildare. This also contains an account of Cuchulainn’s mighty deeds which supplements the older version in the Book of the Dun Cow. Of somewhat less importance from the point of view of the student of Gaelic mythology come the Book of Ballymote and the Yellow Book of Lecan, belonging to the end of the fourteenth century, and the Books of Lecan and of Lismore, both attributed to the fifteenth. Besides these six great collections, there survive many other manuscripts which also contain ancient mythical lore. In one of these, dating from the fifteenth century, is to be found the 11story of the Battle of Moytura, fought between the gods of Ireland and their enemies, the Fomors, or demons of the deep sea.

The Scottish manuscripts, preserved in the Advocates’ Library at Edinburgh, date back in some cases as far as the fourteenth century, though the majority of them belong to the fifteenth and sixteenth. They corroborate the Irish documents, add to the Cuchulainn saga, and make a more special subject of the other heroic cycle, that which relates the not less wonderful deeds of Finn, Ossian, and the Fenians. They also contain stories of other characters, who, more ancient than either Finn or Cuchulainn, are the Tuatha Dé Danann, the god-tribe of the ancient Gaels.

The Welsh documents cover about the same period as the Irish and the Scottish. Four of these stand out from the rest, as most important. The oldest is the Black Book of Caermarthen, which dates from the third quarter of the twelfth century; the Book of Aneurin, which was written late in the thirteenth; the Book of Taliesin, assigned to the fourteenth; and the Red Book of Hergest, compiled by various persons during that century and the one following it. The first three of these “Four Ancient Books of Wales” are small in size, and contain poems attributed to the great traditional bards of the sixth century, Myrddin, Taliesin, and Aneurin. The last—the Red Book of Hergest—is far larger. In it are to be found Welsh translations of the British Chronicles; the oft-mentioned Triads, verses celebrating famous traditionary persons or things; 12ancient poems attributed to Llywarch Hên; and, of priceless value to any study of our subject, the so-called Mabinogion, stories in which large portions of the old British mythology are worked up into romantic form.

The whole bulk, therefore, of the native literature bearing upon the mythology of the British Islands may be attributed to a period which lasted from the beginning of the twelfth century to the end of the sixteenth. But even the commencement of this era will no doubt seem far too late a day to allow authenticity to matter which ought to have vastly preceded it. The date, however, merely marks the final redaction of the contents of the manuscripts into the form in which they now exist, without bearing at all upon the time of their authorship. Avowedly copies of ancient poems and tales from much older manuscripts, the present books no more fix the period of the original composition of their contents than the presence of a portion of the Canterbury Tales in a modern anthology of English poetry would assign Chaucer to the present year of grace.

This may be proved both directly and inferentially.[5] In some instances—as in that of an elegy upon Saint Columba in the Book of the Dun Cow—the dates of authorship are actually given. In others, we may depend upon evidence which, if not quite so absolute, is nearly as convincing. Even where the writer does not state that he is copying from older manuscripts, 13it is obvious that this must have been the case, from the glosses in his version. The scribes of the earlier Gaelic manuscripts very often found, in the documents from which they themselves were copying, words so archaic as to be unintelligible to the readers of their own period. To render them comprehensible, they were obliged to insert marginal notes which explained these obsolete words by reference to other manuscripts more ancient still. Often the mediæval copyists have ignorantly moved these notes from the margin into the text, where they remain, like philological fossils, to give evidence of previous forms of life. The documents from which they were taken have perished, leaving the mediæval copies as their sole record. In the Welsh Mabinogion the same process is apparent. Peculiarities in the existing manuscripts show plainly enough that they must have been copied from some more archaic text. Besides this, they are, as they at present stand, obviously made up of earlier tales pieced together. Almost as clearly as the Gaelic manuscripts, the Welsh point us back to older and more primitive forms.

The ancient legends of the Gael and the Briton are thus shown to have been no mere inventions of scholarly monks in the Middle Ages. We have now to trace, if possible, the date, not necessarily of their first appearance on men’s lips, but of their first redaction into writing in approximately the form in which we have them now.

Circumstantial evidence can be adduced to prove that the most important portions both of Gaelic 14and British early literature can be safely relegated to a period of several centuries prior to their now-existing record. Our earliest version of the episode of the Táin Bó Chuailgné, which is the nucleus and centre of the ancient Gaelic heroic cycle of which Cuchulainn, fortissimus heros Scotorum, is the principal figure, is found in the twelfth-century Book of the Dun Cow. But legend tells us that at the beginning of the seventh century the Saga had not only been composed, but had actually become so obsolete as to have been forgotten by the bards. Their leader, one Senchan Torpeist, a historical character, and chief bard of Ireland at that time, obtained permission from the Saints to call Fergus, Cuchulainn’s contemporary, and a chief actor in the “Raid”, from the dead, and received from the resurrected hero a true and full version. This tradition, dealing with a real personage, surely shows that the story of the Táin was known before the time of Senchan, and probably preserves the fact, either that his version of Cuchulainn’s famous deeds became the accepted one, or that he was the first to reduce it to writing. An equally suggestive consideration approximately fixes for us the earliest redaction of the Welsh mythological prose tales called the “Mabinogion”, or, more correctly speaking, the “Four Branches of the Mabinogi”.[6] In none of these is there the slightest mention, or apparently the least knowledge, of Arthur, around whom and whose supposed contemporaries centres the mass of British legend as it was transmitted by 15the Welsh to the Normans. These mysterious mythological records must in all probability, therefore, antedate the Arthurian cycle of myth, which was already being put into form in the sixth century. On the other hand, the characters of the “Four Branches” are mentioned without comment—as though they were personages with whom no one could fail to be familiar—in the supposed sixth-century poems contained in those “Four Ancient Books of Wales” in which are found the first meagre references to the British hero.

Such considerations as these throw back, with reasonable certainty, the existence of the Irish and Welsh poems and prose tales, in something like their present shape, to a period antedating the seventh century.

But this, again, means only that the myths, traditions, and legends were current at that to us early, but to them, in their actual substance, late date, in literary form. A mythology must always be far older than the oldest verses and stories that celebrate it. Elaborate poems and sagas are not made in a day, or in a year. The legends of the Gaelic and British gods and heroes could not have sprung, like Athena from the head of Zeus, full-born out of some poet’s brain. The bard who first put them into artistic shape was setting down the primitive traditions of his race. We may therefore venture to describe them as not of the twelfth century or of the seventh, but as of a prehistoric and immemorial antiquity.

Internal evidence bears this out. An examination 16of both the Gaelic and British legendary romances shows, under embellishing details added by later hands, an inner core of primeval thought which brings them into line with the similar ideas of other races in the earliest stage of culture. Their “local colour” may be that of their last “editor”, but their “plots” are pre-mediæval, pre-Christian, pre-historic. The characters of early Gaelic legend belong to the same stamp of imagination that created Olympian and Titan, Æsir and Jötun. We must go far to the back of civilized thought to find parallels to such a story as that in which the British sun-god, struck by a rival in love with a poisoned spear, is turned into an eagle, from whose wound great pieces of carrion are continually failing.[7]

This aspect of the Celtic literary records was clearly seen, and eloquently expressed, by Matthew Arnold in his Study of Celtic Literature.[8] He was referring to the Welsh side, but his image holds good equally for the Gaelic. “The first thing that strikes one”, he says, “in reading the Mabinogion is how evidently the mediæval story-teller is pillaging an antiquity of which he does not fully possess the secret: he is like a peasant building his hut on the site of Halicarnassus or Ephesus; he builds, but what he builds is full of materials of which he knows not the history, or knows by a glimmering tradition merely: stones ‘not of this building’, but of an older architecture, greater, cunninger, more majestical.” His heroes “are no mediæval personages: they belong to an older, pagan, mythological world”. So, 17too, with the figures, however euhemerized, of the three great Gaelic cycles: that of the Tuatha Dé Danann, of the Heroes of Ulster, of Finn and the Fenians. Their divinity outshines their humanity; through their masks may be seen the faces of gods.

Yet, gods as they are, they had taken on the semblance of mortality by the time their histories were fixed in the form in which we have them now. Their earliest records, if those could be restored to us, would doubtless show them eternal and undying, changing their shapes at will, but not passing away. But the post-Christian copyists, whether Irish or Welsh, would not countenance this. Hence we have the singular paradox of the deaths of Immortals. There is hardly one of the figures of either the Gaelic or the British Pantheon whose demise is not somewhere recorded. Usually they fell in the unceasing battles between the divinities of darkness and of light. Their deaths in earlier cycles of myth, however, do not preclude their appearance in later ones. Only, indeed, with the closing of the lips of the last mortal who preserved his tradition can the life of a god be truly said to end.

But, before proceeding to recount the myths of the “Ancient Britons”, it will be well to decide what people, exactly, we mean by that loose but convenient phrase. We have, all of us, vague ideas of Ancient Britons, recollected, doubtless, from our school-books. There we saw their pictures as, painted with woad, they paddled coracles, or drove scythed chariots through legions of astonished Romans. Their Druids, white-bearded and wearing long, white robes, cut the mistletoe with a golden sickle at the time of the full moon, or, less innocently employed, made bonfires of human beings shut up in gigantic figures of wicker-work.

Such picturesque details were little short of the sum-total, not only of our own knowledge of the subject, but also of that of our teachers. Practically all their information concerning the ancient inhabitants of Britain was taken from the Commentaries of Julius Caesar. So far as it went, it was no doubt correct; but it did not go far. Caesar’s interest in our British ancestors was that of a general who was his own war-correspondent rather than that of an exhaustive and painstaking scientist. It has been reserved for modern archæologists, philologists, and 19ethnologists to give us a fuller account of the Ancient Britons.

The inhabitants of our islands previous to the Roman invasion are generally described as “Celts”. But they must have been largely a mixed race; and the people with whom they mingled must have modified to some—and perhaps to a large—extent their physique, their customs, and their language.

Speculation has run somewhat wild over the question of the composition of the Early Britons. But out of the clash of rival theories there emerges one—and one only—which may be considered as scientifically established. We have certain proof of two distinct human stocks in the British Islands at the time of the Roman Conquest; and so great an authority as Professor Huxley has given his opinion that there is no evidence of any others.[9]

The earliest of these two races would seem to have inhabited our islands from the most ancient times, and may, for our purpose, be described as aboriginal. It was the people that built the “long barrows”; and which is variously called by ethnologists the Iberian, Mediterranean, Berber, Basque, Silurian, or Euskarian race. In physique it was short, swarthy, dark-haired, dark-eyed, and long-skulled; its language belonged to the class called “Hamitic”, the surviving types of which are found among the Gallas, Abyssinians, Berbers, and other North African tribes; and it seems to have come originally from some part either of Eastern, Northern, or Central Africa. Spreading thence, it was 20probably the first people to inhabit the Valley of the Nile, and it sent offshoots into Syria and Asia Minor. The earliest Hellenes found it in Greece under the name of “Pelasgoi”; the earliest Latins in Italy, as the “Etruscans”; and the Hebrews in Palestine, as the “Hittites”. It spread northward through Europe as far as the Baltic, and westward, along the Atlas chain, to Spain, France, and our own islands.[10] In many countries it reached a comparatively high level of civilization, but in Britain its development must have been early checked. We can discern it as an agricultural rather than a pastoral people, still in the Stone Age, dwelling in totemistic tribes on hills whose summits it fortified elaborately, and whose slopes it cultivated on what is called the “terrace system”, and having a primitive culture which ethnologists think to have much resembled that of the present hill-tribes of Southern India.[11] It held our islands till the coming of the Celts, who fought with the aborigines, dispossessed them of the more fertile parts, subjugated them, even amalgamated with them, but certainly never extirpated them. In the time of the Romans they were still practically independent in South Wales. In Ireland they were long unconquered, and are found as allies rather than serfs of the Gaels, ruling their own provinces, and preserving their own customs and religion. Nor, in spite of all the successive invasions of Great Britain and Ireland, 21are they yet extinct, or so merged as to have lost their type, which is still the predominant one in many parts of the west both of Britain and Ireland, and is believed by some ethnologists to be generally upon the increase all over England.

The second of the two races was the exact opposite to the first. It was the tall, fair, light-haired, blue- or gray-eyed, broad-headed people called, popularly, the “Celts”, who belonged in speech to the “Aryan” family, their language finding its affinities in Latin, Greek, Teutonic, Slavic, the Zend of Ancient Persia, and the Sanscrit of Ancient India. Its original home was probably somewhere in Central Europe, along the course of the upper Danube, or in the region of the Alps. The “round barrows” in which it buried its dead, or deposited their burnt ashes, differ in shape from the “long barrows” of the earlier race. It was in a higher stage of culture than the “Iberians”, and introduced into Britain bronze and silver, and, perhaps, some of the more lately domesticated animals.

Both Iberians and Celts were divided into numerous tribes, but there is nothing to show that there was any great diversity among the former. It is otherwise with the Celts, who were separated into two main branches which came over at different times. The earliest were the Goidels, or Gaels; the second, the Brythons, or Britons. Between these two branches there was not only a dialectical, but probably, also, a considerable physical difference. Some anthropologists even postulate a different shape of skull. Without necessarily admitting this, 22there is reason to suppose a difference of build and of colour of hair. With regard to this, we have the evidence of Latin writers—of Tacitus,[12] who tells us that the “Caledonians” of the North differed from the Southern Britons in being larger-limbed and redder-haired, and of Strabo,[13] who described the tribes in the interior of Britain as taller than the Gaulish colonists on the coast, with hair less yellow and limbs more loosely knit. Equally do the classic authorities agree in recognizing the “Silures” of South Wales as an entirely different race from any other in Britain. The dark complexions and curly hair of these Iberians seemed to Tacitus to prove them immigrants from Spain.[14]

Professor Rhys also puts forward evidence to show that the Goidels and the Brythons had already separated before they first left Gaul for our islands.[15] He finds them as two distinct peoples there. We do not expect so much nowadays from “the merest school-boy” as we did in Macaulay’s time, but even the modern descendant of that paragon could probably tell us that all Gaul was divided into three parts, one of which was inhabited by the Belgae, another by the Aquitani, and the third by those who called themselves Celtae, but were termed Galli by the Romans; and that they all differed from one another in language, customs, and laws.[16] Of these, Professor Rhys identifies the Belgae with the Brythons, and the Celtae with the Goidels, the 23third people, the Aquitani, being non-Celtic and non-Aryan, part of the great Hamitic-speaking Iberian stock.[17] The Celtae, with their Goidelic dialect of Celtic, which survives to-day in the Gaelic languages of Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man, were the first to come over to Britain, pushed forward, probably, by the Belgae, who, Caesar tells us, were the bravest of the Gauls.[18] Here they conquered the native Iberians, driving them out of the fertile parts into the rugged districts of the north and west. Later came the Belgae themselves, compelled by press of population; and they, bringing better weapons and a higher civilization, treated the Goidels as those had treated the Iberians. Thus harried, the Goidels probably combined with the Iberians against what was now the common foe, and became to a large degree amalgamated with them. The result was that during the Roman domination the British Islands were roughly divided with regard to race as follows: The Brythons, or second Celtic race, held all Britain south of the Tweed, with the exception of the extreme west, while the first Celtic race, the Goidelic, had most of Ireland, as well as the Isle of Man, Cumberland, the West Highlands, Cornwall, Devon, and North Wales. North of the Grampians lived the Picts, who were probably more or less Goidelicized Iberians, the aboriginal race also holding out, unmixed, in South Wales and parts of Ireland.

It is now time to decide what, for the purposes of this book, it will be best to call the two different 24branches of the Celts, and their languages. With such familiar terms as “Gael” and “Briton”, “Gaelic” and “British”, ready to our hands, it seems pedantic to insist upon the more technical “Goidel” and “Brython”, “Goidelic” and “Brythonic”. The difficulty is that the words “Gael” and “Gaelic” have been so long popularly used to designate only the modern “Goidels” of Scotland and their language, that they may create confusion when also applied to the people and languages of Ireland and the Isle of Man. Similarly, the words “Briton” and “British” have come to mean, at the present day, the people of the whole of the British Islands, though they at first only signified the inhabitants of England, Central Wales, the Lowlands of Scotland, and the Brythonic colony in Brittany. However, the words “Goidel” and “Brython”, with their derivatives, are so clumsy that it will probably prove best to use the neater terms. In this volume, therefore, the “Goidels” of Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man are our “Gaels” and the “Brythons” of England and Wales are our “Britons”.

We get the earliest accounts of the life of the inhabitants of the British Islands from two sources. The first is a foreign one, that of the Latin writers. But the Romans only really knew the Southern Britons, whom they describe as similar in physique and customs to the Continental Gauls, with whom, indeed, they considered them to be identical.[19] At the time they wrote, colonies of Belgae were still 25settling upon the coasts of Britain opposite to Gaul.[20] Roman information grew scantier as it approached the Wall, and of the Northern tribes they seem to have had only such knowledge as they gathered through occasional warfare with them. They describe them as entirely barbarous, naked and tattooed, living by the chase alone, without towns, houses, or fields, without government or family life, and regarding iron as an ornament of value, as other, more civilized peoples regarded gold.[21] As for Ireland, it never came under their direct observation, and we are entirely dependent upon its native writers for information as to the manners and customs of the Gaels. It may be considered convincing proof of the authenticity of the descriptions of life contained in the ancient Gaelic manuscripts that they corroborate so completely the observations of the Latin writers upon the Britons and Gauls. Reading the two side by side, we may largely reconstruct the common civilization of the Celts.

Roughly speaking, one may compare it with the civilization of the Greeks, as described by Homer.[22] Both peoples were in the tribal and pastoral stage of culture, in which the chiefs are the great cattle-owners round whom their less wealthy fellows gather. Both wear much the same attire, use the same kind of weapons, and fight in the same manner—from the war-chariot, a vehicle already obsolete even in Ireland by the first century of the Christian era. 26Battles are fought single-handed between chiefs, the ill-armed common people contributing little to their result, and less to their history. Such chiefs are said to be divinely descended—sons, even, of the immortal gods. Their tremendous feats are sung by the bards, who, like the Homeric poets, were privileged persons, inferior only to the war-lord. Ancient Greek and Ancient Celt had very much the same conceptions of life, both as regards this world and the next.

We may gather much detailed information of the early inhabitants of the British Islands from our various authorities.[23] Their clothes, which consisted, according to the Latin writers, of a blouse with sleeves, trousers fitting closely round the ankles, and a shawl or cloak, fastened at the shoulder with a brooch, were made either of thick felt or of woven cloth dyed with various brilliant colours. The writer Diodorus tells us that they were crossed with little squares and lines, “as though they had been sprinkled with flowers”. They were, in fact, like “tartans”, and we may believe Varro, who tells us that they “made a gaudy show”. The men alone seem to have worn hats, which were of soft felt, the women’s hair being uncovered, and tied in a knot behind. In time of battle, the men also dispensed with any head-covering, brushing their abundant hair forward into a thick mass, and dyeing it red with a soap made of goat’s fat and beech ashes, until they looked (says Cicero’s tutor Posidonius, who visited Britain about 27110 B.C.) less like human beings than wild men of the woods. Both sexes were fond of ornaments, which took the form of gold bracelets, rings, pins, and brooches, and of beads of amber, glass, and jet. Their knives, daggers, spear-heads, axes, and swords were made of bronze or iron; their shields were the same round target used by the Highlanders at the battle of Culloden; and they seem also to have had a kind of lasso to which a hammer-shaped ball was attached, and which they used as the Gauchos of South America use their bola. Their war-chariots were made of wicker, the wooden wheels being armed with sickles of bronze. These were drawn either by two or four horses, and were large enough to hold several persons in each. Standing in these, they rushed along the enemy’s lines, hurling darts, and driving the scythes against all who came within reach. The Romans were much impressed by the skill of the drivers, who “could check their horses at full speed on a steep incline, and turn them in an instant, and could run along the pole, and stand on the yoke, and then get back into their chariots again without a moment’s delay”.[24]

With these accounts of the Roman writers we may compare the picture of the Gaelic hero, Cuchulainn, as the ancient Irish writers describe him dressed and armed for battle. Glorified by the bard, he yet wears essentially the same costume and equipment which the classic historians and geographers described more soberly. “His gorgeous raiment that he wore in great conventions” 28consisted of “a fair crimson tunic of five plies and fringed, with a long pin of white silver, gold-enchased and patterned, shining as if it had been a luminous torch which for its blazing property and brilliance men might not endure to see. Next his skin, a body-vest of silk, bordered and fringed all round with gold, with silver, and with white bronze, which vest came as far as the upper edge of his russet-coloured kilt.... About his neck were a hundred linklets of red gold that flashed again, with pendants hanging from them. His head-gear was adorned with a hundred mixed carbuncle jewels, strung.” He carried “a trusty special shield, in hue dark crimson, and in its circumference armed with a pure white silver rim. At his left side a long and golden-hilted sword. Beside him, in the chariot, a lengthy spear; together with a keen, aggression-boding javelin, fitted with hurling thong, with rivets of white bronze.”[25] Another passage of Gaelic saga describes his chariot. It was made of fine wood, with wicker-work, moving on wheels of white bronze. It had a high rounded frame of creaking copper, a strong curved yoke of gold, and a pole of white silver, with mountings of white bronze. The yellow reins were plaited, and the shafts were as hard and straight as sword-blades.[26]

In like manner the ancient Irish writers have made glorious the halls and fortresses of their mythical kings. Like the palaces of Priam, of Menelaus, and of Odysseus, they gleam with gold 29and gems. Conchobar,[27] the legendary King of Ulster in its golden age, had three such “houses” at Emain Macha. Of the one called the “Red Branch”, we are told that it contained nine compartments of red yew, partitioned by walls of bronze, all grouped around the king’s private chamber, which had a ceiling of silver, and bronze pillars adorned with gold and carbuncles.[28] But the far less magnificent accounts of the Latin writers have, no doubt, more truth in them than such lavish pictures. They described the Britons they knew as living in villages of bee-hive huts, roofed with fern or thatch, from which, at the approach of an enemy, they retired to the local dún. This, so far from being elaborate, merely consisted of a round or oval space fenced in with palisades and earthworks, and situated either upon the top of a hill or in the midst of a not easily traversable morass.[29] We may see the remains of such strongholds in many parts of England—notable ones are the “castles” of Amesbury, Avebury, and Old Sarum in Wiltshire, Saint Catherine’s Hill, near Winchester, and Saint George’s Hill, in Surrey—and it is probable that, in spite of the Celtic praisers of past days, the “palaces” of Emain Macha and of Tara were very like them.

The Celtic customs were, like the Homeric, those of the primitive world. All land (though it may have theoretically belonged to the chief) was cultivated in common. This community of possessions 30is stated by Caesar[30] to have extended to their wives; but the imputation cannot be said to have been proved. On the contrary, in the stories of both branches of the Celtic race, women seem to have taken a higher place in men’s estimation, and to have enjoyed far more personal liberty, than among the Homeric Greeks. The idea may have arisen from a misunderstanding of some of the curious Celtic customs. Descent seems to have been traced through the maternal rather than through the paternal line, a very un-Aryan procedure which some believe to have been borrowed from another race. The parental relation was still further lessened by the custom of sending children to be brought up outside the family in which they were born, so that they had foster-parents to whom they were as much, or even more, attached than to their natural ones.

Their political state, mirroring their family life, was not less primitive. There was no central tribunal. Disputes were settled within the families in which they occurred, while, in the case of graver injuries, the injured party or his nearest relation could kill the culprit or exact a fine from him. As families increased in number, they became petty tribes, often at war with one another. A defeated tribe had to recognize the sovereignty of the head man of the conquering tribe, and a succession of such victories exalted him into the position of a chief of his district. But even then, though his decision was the whole of the law, he was little more than the mouthpiece of public opinion.

The ancient inhabitants of Britain—the Gaelic and British Celts—have been already described as forming a branch of what are roughly called the “Aryans”. This name has, however, little reference to race, and really signifies the speakers of a group of languages which can be all shown to be connected, and to descend remotely from a single source—a hypothetical mother-tongue spoken by a hypothetical people which we term “Aryan”, or, more correctly, “Indo-European”. This primeval speech, evolved, probably, upon some part of the great plain which stretches from the mountains of Central Europe to the mountains of Central Asia, has spread, superseding, or amalgamating with the tongues of other races, until branches of it are spoken over almost the whole of Europe and a great portion of Asia. All the various Latin, Greek, Slavic, Teutonic, and Celtic languages are “Aryan”, as well as Persian and other Asiatic dialects derived from the ancient “Zend”, and the numerous Indian languages which trace their origin to Sanscrit.

Not very long ago, it was supposed that this 32common descent of language involved a common descent of blood. A real brotherhood was enthusiastically claimed for all the principal European nations, who were also invited to recognize Hindus and Persians as their long-lost cousins. Since then, it has been conceded that, while the Aryan speech survived, though greatly modified, the Aryan blood might well have disappeared, diluted beyond recognition by crossing with the other races whom the Aryans conquered, or among whom they more or less peacefully settled. As a matter of fact, there are no European nations—perhaps no people at all except a few remote savage tribes—which are not made up of the most diverse elements. Aryan and non-Aryan long ago blended inextricably, to form by their fusion new peoples.

But, just as the Aryan speech influenced the new languages, and the Aryan customs the new civilizations, so we can still discern in the religions of the Aryan-speaking nations similar ideas and expressions pointing to an original source of mythological conceptions. Hence, whether we investigate the mythology of the Hindus, the Greeks, the Teutons, or the Celts, we find the same mythological groundwork. In each, we see the powers of nature personified, and endowed with human form and attributes, though bearing, with few exceptions, different names. Like the Vedic brahmans, the Greek and Latin poets, and the Norse scalds, the Celtic bards—whether Gaels or Britons—imagined the sky, the sun, the moon, the earth, the sea, and the dark underworld, as well as the mountains, the streams 33and the woods, to be ruled by beings like their own chiefs, but infinitely more powerful; every passion, as War and Love, and every art, as Poetry and Smithcraft, had its divine founder, teacher, and exponent; and of all these deities and their imagined children, they wove the poetical and allegorical romances which form the subject of the present volume.

Like other nations, too, whether Aryan or non-Aryan, the Celts had, besides their mythology, a religion. It is not enough to tell tales of shadowy gods; they must be made visible by sculpture, housed in groves or temples, served with ritual, and propitiated with sacrifices, if one is to hope for their favours. Every cult must have its priests living by the altar.

The priests of the Celts are well-known to us by name as the “Druids”—a word derived from a root DR which signifies a tree, and especially the oak, in several Aryan languages.[31] This is generally—though not by all scholars—taken as proving that they paid an especial veneration to the king of trees. It is true that the mistletoe—that strange parasite upon the oak—was prominent among their “herbs of power”, and played a part in their ritual;[32] but this is equally true of other Aryan nations. By the Norse it was held sacred to the god Balder, while the Romans believed it to be the “golden bough” that gave access to Hades.[33]

34The accounts both of the Latin and Gaelic writers give us a fairly complete idea of the nature of the Druids, and especially of the high estimation in which they were held. They were at once the priests, the physicians, the wizards, the diviners, the theologians, the scientists, and the historians of their tribes. All spiritual power and all human knowledge were vested in them, and they ranked second only to the kings and chiefs. They were freed from all contribution to the State, whether by tribute or service in war, so that they might the better apply themselves to their divine offices. Their decisions were absolutely final, and those who disobeyed them were laid under a terrible excommunication or “boycott”.[34] Classic writers tell us how they lorded it in Gaul, where, no doubt, they borrowed splendour by imitating their more civilized neighbours. Men of the highest rank were proud to cast aside the insignia of mere mortal honour to join the company of those who claimed to be the direct mediators with the sky-god and the thunder-god, and who must have resembled the ecclesiastics of mediæval Europe in the days of their greatest power, combining, like them, spiritual and temporal dignities, and possessing the highest culture of their age. Yet it was not among these Druids of Gaul, with their splendid temples and vestments and their elaborate rituals, that the metropolis of Druidism was to be sought. We learn from Caesar that the Gallic Druids believed 35their religion to have come to them, originally, from Britain, and that it was their practice to send their “theological students” across the Channel to learn its doctrines at their purest source.[35] To trace a cult backwards is often to take a retrograde course in culture, and it was no doubt in Britain—which Pliny the Elder tells us “might have taught magic to Persia”[36]—that the sufficiently primitive and savage rites of the Druids of Gaul were preserved in their still more savage and primitive forms. It is curious corroboration of this alleged British origin of Druidism that the ancient Irish also believed their Druidism to have come from the sister island. Their heroes and seers are described as only gaining the highest knowledge by travelling to Alba.[37] However this may be, we may take it as certain that this Druidism was the accepted religion of the Celtic race.

Certain scholars look deeper for its origin, holding its dark superstitions and savage rites to bear the stamp of lower minds than those of the poetic and manly Celts. Professor Rhys inclines to see three forms of religion in the British Islands at the time of the Roman invasion: the “Druidism” of the Iberian aborigines; the pure polytheism of the Brythons, who, having come later into the country, had mixed but little with the natives; and the mingled Aryan and non-Aryan cults of the Goidels, who were already largely amalgamated with them.[38] 36But many authorities dissent from this view, and, indeed, we are not obliged to postulate borrowing from tribes in a lower state of culture, to explain primitive and savage features underlying a higher religion. The “Aryan” nations must have passed, equally with all others, through a state of pure savagery; and we know that the religion of the Greeks, in many respects so lofty, sheltered features and legends as barbarous as any that can be attributed to the Celts.[39]

Of the famous teaching of the Druids we know little, owing to their habit of never allowing their doctrines to be put into writing. Caesar, however, roughly records its scope. “As one of their leading dogmas”, he says, “they inculcate this: that souls are not annihilated, but pass after death from one body to another, and they hold that by this teaching men are much encouraged to valour, through disregarding the fear of death. They also discuss and impart to the young many things concerning the heavenly bodies and their movements, the size of the world and of our earth, natural science, and of the influence and power of the immortal gods.”[40] The Romans seem to have held their wisdom in some awe, though it is not unlikely that the Druids themselves borrowed whatever knowledge they may have had of science and philosophy from the classical culture. That their creed of transmigration was not, however, merely taken over from the Greeks seems certain from its appearance in the 37ancient Gaelic myths. Not only the “shape-shifting” common to the magic stories of all nations, but actual reincarnation was in the power of privileged beings. The hero Cuchulainn was urged by the men of Ulster to marry, because they knew “that his rebirth would be of himself”,[41] and they did not wish so great a warrior to be lost to their tribe. Another legend tells how the famous Finn mac Coul was reborn, after two hundred years, as an Ulster king called Mongan.[42]

Such ideas, however, belonged to the metaphysical side of Druidism. Far more important to the practical primitive mind are ritual and sacrifice, by the due performance of which the gods are persuaded or compelled to grant earth’s increase and length of days to men. Among the Druids, this humouring of the divinities took the shape of human sacrifice, and that upon a scale which would seem to have been unsurpassed in horror even by the most savage tribes of West Africa or Polynesia. “The whole Gaulish nation”, says Caesar, “is to a great degree devoted to superstitious rites; and on this account those who are afflicted with severe diseases, or who are engaged in battles and dangers, either sacrifice human beings for victims, or vow that they will immolate themselves, and these employ the Druids as ministers for such sacrifices, because they think that, unless the life of man be repaid for the life of man, the will of the immortal gods cannot be 38appeased. They also ordain national offerings of the same kind. Others make wicker-work images of vast size, the limbs of which they fill with living men and set on fire.”[43]

We find evidence of similarly awful customs in pagan Ireland. Among the oldest Gaelic records are tracts called Dinnsenchus, in which famous places are enumerated, together with the legends relating to them. Such topographies are found in several of the great Irish mediæval manuscripts, and therefore, of course, received their final transcription at the hands of Christian monks. But these ecclesiastics rarely tampered with compositions in elaborate verse. Nor can it be imagined that any monastic scribe could have invented such a legend as this one which describes the practice of human sacrifice among the ancient Irish. The poem (which is found in the Books of Leinster, of Ballymote, of Lecan, and in a document called the Rennes MS.)[44] records the reason why a spot near the present village of Ballymagauran, in County Cavan, received the name of Mag Slecht, the “Plain of Adoration”.

Such, we gather from a tradition which we may deem authentic, was human sacrifice in early Ireland. According to the quoted verse, one third of the healthy children were slaughtered, presumably every year, to wrest from the powers of nature the grain and grass upon which the tribes and their cattle subsisted. In a prose dinnsenchus preserved in the Rennes MS.,[46] there is a slight variant. “’Tis there”, (at Mag Slecht), it runs, “was the king idol of Erin, namely the Crom Croich, and around him were twelve idols made of stones, but he was of gold. Until Patrick’s advent he was the god of every folk that colonized Ireland. To him they used to offer the firstlings of every issue and the chief scions of every clan.” The same authority also tells us that these sacrifices were made at “Hallowe’en”, which took the place, in the Christian calendar, of the heathen Samhain—“Summer’s End”—when the sun’s power waned, and the strength of the gods of darkness, winter, and the underworld grew great.

41Who, then, was this bloodthirsty deity? His name, Cromm Cruaich, means the “Bowed One of the Mound”, and was evidently applied to him only after his fall from godhead. It relates to the tradition that, at the approach of the all-conquering Saint Patrick, the “demon” fled from his golden image, which thereupon sank forward in the earth in homage to the power that had come to supersede it.[47] But from another source we glean that the word cromm was a kind of pun upon cenn, and that the real title of the “king idol of Erin” was Cenn Cruaich, “Head” or “Lord” of the Mound. Professor Rhys, in his Celtic Heathendom,[48] suggests that he was probably the Gaelic heaven-god, worshipped, like the Hellenic Zeus, upon “high places”, natural or artificial. At any rate, we may see in him the god most revered by the Gaels, surrounded by the other twelve chief members of their Pantheon.

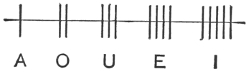

It would appear probable that the Celtic State worship was what is called “solar”. All its chief festivals related to points in the sun’s progress, the equinoxes having been considered more important than the solstices. It was at the spring equinox (called by the Celts “Beltaine”[49]) in every nineteenth year that, we learn from Diodorus the Sicilian, a writer contemporary with Julius Caesar, Apollo himself appeared to his worshippers, and was seen harping and dancing in the sky until the rising of the Pleiades.[50] The other corresponding festival was 42“Samhain”[51], the autumn equinox. As Beltaine marked the beginning of summer, so Samhain recorded its end. The summer solstice was also a great Celtic feast. It was held at the beginning of August in honour of the god called Lugus by the Gauls, Lugh by the Gaels, and Lleu by the Britons—the pan-Celtic Apollo, and, probably, when the cult of the war-god had fallen from its early prominence, the chief figure of the common Pantheon.

It was doubtless at Stonehenge that the British Apollo was thus seen harping and dancing. That marvellous structure well corresponds to Diodorus’s description of a “magnificent temple of Apollo” which he locates “in the centre of Britain”. “It is a circular enclosure,” he says, “adorned with votive offerings and tablets with Greek inscriptions suspended by travellers upon the walls. The rulers of the temple and city are called ‘Boreadæ’[52], and they take up the government from each other according to the order of their tribes. The citizens are given up to music, harping and chanting in honour of the sun.”[53] Stonehenge, therefore, was a sacred religious centre, equally revered by and equally belonging to all the British tribes—a Rome or Jerusalem of our ancient paganism.

The same great gods were, no doubt, adored by all the Celts, not only of Great Britain and Ireland, but of Continental Gaul as well. Sometimes they can be traced by name right across the ancient 43Celtic world. In other cases, what is obviously the same personified power of nature is found in various places with the same attributes, but with a different title. Besides these, there must have been a multitude of lesser gods, worshipped by certain tribes alone, to whom they stood as ancestors and guardians. “I swear by the gods of my people”, was the ordinary oath of a hero in the ancient Gaelic sagas. The aboriginal tribes must also have had their gods, whether it be true or not that their religion influenced the Celtic Druidism. Professor Rhys inclines to see in the genii locorum, the almost nameless spirits of well and river, mountain and wood—shadowy remnants of whose cults survive to-day,—members of a swarming Pantheon of the older Iberians.[54] These local beings would in no way conflict with the great Celtic nature-gods, and the two worships could exist side by side, both even claiming the same votary. It needs the stern faith of monotheism to deny the existence of the gods of others. Polytheistic nations have seldom or never risen to such a height. In their dealings with a conquered people, the conquerors naturally held their own gods to be the stronger. Still, it could not be denied that the gods of the conquered were upon their own ground; they knew, so to speak, the country, and might have unguessed powers of doing evil! What if, to avenge their worshippers and themselves, they were to make the land barren and useless to the conquerors? So that conquering pagan nations have usually been quite ready to stretch out the hand of 44welcome to the deities of their new subjects, to propitiate them by sacrifice, and even to admit them within the pale of their own Pantheon.

This raises the question of the exact nationality of the gods whose stories we are about to tell. Were they all Aryan, or did any of the greater aboriginal deities climb up to take their place among the Gaelic tribe of the goddess Danu, or the British children of the goddess Dôn? Some of the Celtic gods have seemed to scholars to bear signs of a non-Aryan origin.[55] The point, however, is at present very obscure. Neither does it much concern us. Just as the diverse deities of the Greeks—some Aryan and Hellenic, some pre-Aryan and Pelasgian, some imported and Semitic—were all gathered into one great divine family, so we may consider as members of one national Olympus all these gods whose legends make up “The Mythology of the British Islands”.

Of the two Celtic races that settled in our islands, it is the earlier, the Gaels, that has best preserved its old mythology. It is true that we have in few cases such detailed account of the Gaelic gods as we gain of the Hellenic deities from the Greek poets, of the Indian Devas from the Rig Veda, or of the Norse Æsir from the Eddas. Yet none the less may we draw from the ancient Irish manuscripts quite enough information to enable us to set forth their figures with some clearness. We find them, as might have been anticipated, very much like the divine hierarchies of other Aryan peoples.

We also find them separated into two opposing camps, a division common to all the Aryan religions. Just as the Olympians struggled with the Giants, the Æsir fought the Jötuns, and the Devas the Asuras, so there is warfare in the Gaelic spiritual world between two superhuman hosts. On one side are ranged the gods of day, light, life, fertility, wisdom, and good; on the other, the demons of night, darkness, death, barrenness, and evil. The first were the great spirits symbolizing the beneficial aspects of nature and the arts and intelligence of man; the second were the hostile powers thought to be behind such baneful manifestations as storm and 48fog, drought and disease. The first are ranged as a divine family round a goddess called Danu, from whom they took their well-known name of Tuatha Dé Danann,[56] “Tribe” or “Folk of the Goddess Danu”. The second owned allegiance to a female divinity called Domnu; their king, Indech, is described as her son, and they are all called “Domnu’s gods”. The word “Domnu” appears to have signified the abyss or the deep sea,[57] and the same idea is also expressed in their better-known name of “Fomors”, derived from two Gaelic words meaning “under sea”.[58] The waste of water seems to have always impressed the Celts with the sense of primeval ancientness; it was connected in their minds with vastness, darkness, and monstrous births—the very antithesis of all that was symbolized by the earth, the sky, and the sun.

Therefore the Fomors were held to be more ancient than the gods, before whom they were, however, destined to fall in the end. Offspring of “Chaos and Old Night”, they were, for the most part, huge and deformed. Some had but one arm and one leg apiece, while others had the heads of goats, horses, or bulls.[59] The most famous, and perhaps the most terrible of them all was Balor, whose father is said to have been one Buarainech, that is, the “cow-faced”,[60] and who combined in himself the two classical rôles of the Cyclops and the Medusa. Though he had two eyes, one was always 49kept shut, for it was so venomous that it slew anyone on whom its look fell. This malignant quality of Balor’s eye was not natural to him, but was the result of an accident. Urged by curiosity, he once looked in at the window of a house where his father’s sorcerers were preparing a magic potion, and the poisonous smoke from the cauldron reached his eye, infecting it with so much of its own deadly nature as to make it disastrous to others. Neither god nor giant seems to have been exempt from its dangers; so that Balor was only allowed to live on condition that he kept his terrible eye shut. On days of battle he was placed opposite to the enemy, the lid of the destroying eye was lifted up with a hook, and its gaze withered all who stood before it. The memory of Balor and his eye still lingers in Ireland: the “eye of Balor” is the name for what the peasantry of other countries call the “evil eye”; stories are still told of Balar Beimann, or “Balor of the Mighty Blows”; and “Balor’s Castle” is the name of a curious cliff on Tory Island. This island, off the coast of Donegal, was the Fomorian outpost upon earth, their real abode being in the cold depths of the sea.

This rule, however, as to the hideousness of the Fomors had its exceptions. Elathan, one of their chiefs, is described in an old manuscript as of magnificent presence—a Miltonic prince of darkness. “A man of fairest form,” it says, “with golden hair down to his shoulders. He wore a mantle of gold braid over a shirt interwoven with threads of gold. Five golden necklaces were round 50his neck, and a brooch of gold with a shining precious stone thereon was on his breast. He carried two silver spears with rivets of bronze, and his sword was golden-hilted and golden-studded.”[61] Nor was his son less handsome. His name was Bress, which means “beautiful”, and we are told that every beautiful thing in Ireland, “whether plain, or fortress, or ale, or torch, or woman, or man”, was compared with him, so that men said of them, “that is a Bress”.[62]

Balor, Bress, and Elathan are the three Fomorian personages whose figures, seen through the mists of antiquity, show clearest to us. But they are only a few out of many, nor are they the oldest. We can learn, however, nothing but a few names of any ancestors of the Gaelic giants. This is equally true of the Gaelic gods. Those we know are evidently not without parentage, but the names of their fathers are no more than shadows following into oblivion the figures they designated. The most ancient divinity of whom we have any knowledge is Danu herself, the goddess from whom the whole hierarchy of gods received its name of Tuatha Dé Danann. She was also called Anu or Ana, and her name still clings to two well-known mountains near Killarney, which, though now called simply “The Paps”, were known formerly as the “Paps of Ana”.[63] She was the 51universal mother; “well she used to cherish the gods”, says the commentator of a ninth-century Irish glossary.[64] Her husband is never mentioned by name, but one may assume him, from British analogies, to have been Bilé, known to Gaelic tradition as a god of Hades, a kind of Celtic Dis Pater from whom sprang the first men. Danu herself probably represented the earth and its fruitfulness, and one might compare her with the Greek Demeter. All the other gods are, at least by title, her children. The greatest of these would seem to have been Nuada, called Argetlám, or “He of the Silver Hand”. He was at once the Gaelic Zeus, or Jupiter, and their war-god; for among primitive nations, to whom success in war is all-important, the god of battles is the supreme god.[65] Among the Gauls, Camulus, whose name meant “Heaven”,[66] was identified by the Romans with Mars; and other such instances come readily to the mind. He was possessed of an invincible sword, one of the four chief treasures of the Tuatha Dé Danann, over whom he was twice king; and there is little doubt that he was one of the most important gods of both the Gaels and the Britons, for his name is spread over the whole of the British Isles, which we may surmise the Celts conquered under his auspices. We may picture him as a more savage Mars, delighting in battle and slaughter, and worshipped, like his Gaulish affinities, Teutates and Hesus, of whom the 52Latin poet Lucan tells us, with human sacrifices, shared in by his female consorts, who, we may imagine, were not more merciful than himself, or than that Gaulish Taranis whose cult was “no gentler than that of the Scythian Diana”, and who completes Lucan’s triad as a fit companion to the “pitiless Teutates” and the “horrible Hesus”.[67] Of these warlike goddesses there were five—Fea, the “Hateful”, Nemon, the “Venomous”, Badb, the “Fury”, Macha, a personification of “battle”, and, over all of them, the Morrígú, or “Great Queen”. This supreme war-goddess of the Gaels, who resembles a fiercer Herê, perhaps symbolized the moon, deemed by early races to have preceded the sun, and worshipped with magical and cruel rites. She is represented as going fully armed, and carrying two spears in her hand. As with Arês[68] and Poseidon[69] in the “Iliad”, her battle-cry was as loud as that of ten thousand men. Wherever there was war, either among gods or men, she, the great queen, was present, either in her own shape or in her favourite disguise, that of a “hoodie” or carrion crow. An old poem shows her inciting a warrior:

With her, Fea and Nemon, Badb and Macha also 53hovered over the fighters, inspiring them with the madness of battle. All of these were sometimes called by the name of “Badb”[71]. An account of the Battle of Clontarf, fought by Brian Boru, in 1014, against the Norsemen, gives a gruesome picture of what the Gaels believed to happen in the spiritual world when battle lowered and men’s blood was aflame. “There arose a wild, impetuous, precipitate, mad, inexorable, furious, dark, lacerating, merciless, combative, contentious badb, which was shrieking and fluttering over their heads. And there arose also the satyrs, and sprites, and the maniacs of the valleys, and the witches and goblins and owls, and destroying demons of the air and firmament, and the demoniac phantom host; and they were inciting and sustaining valour and battle with them.” When the fight was over, they revelled among the bodies of the slain; the heads cut off as barbaric trophies were called “Macha’s acorn crop”. These grim creations of the savage mind had immense vitality. While Nuada, the supreme war-god, vanished early out of the Pantheon—killed by the Fomors in the great battle fought between them and the gods—Badb and the Morrígú lived on as late as any of the Gaelic deities. Indeed, they may be said to still survive in the superstitious dislike and suspicion shown in all Celtic-speaking countries for their avatar, the hoodie-crow.[72]

After Nuada, the greatest of the gods was the 54Dagda, whose name seems to have meant the “Good God”.[73] The old Irish tract called “The Choice of Names” tells us that he was a god of the earth; he had a cauldron called “The Undry”, in which everyone found food in proportion to his merits, and from which none went away unsatisfied. He also had a living harp; as he played upon it, the seasons came in their order—spring following winter, and summer succeeding spring, autumn coming after summer, and, in its turn, giving place to winter. He is represented as of venerable aspect and of simple mind and tastes, very fond of porridge, and a valiant consumer of it. In an ancient tale we have a description of his dress. He wore a brown, low-necked tunic which only reached down to his hips, and, over this, a hooded cape which barely covered his shoulders. On his feet and legs were horse-hide boots, the hairy side outwards. He carried, or, rather, drew after him on a wheel, an eight-pronged war-club, so huge that eight men would have been needed to carry it; and the wheel, as he towed the whole weapon along, made a track like a territorial boundary.[74] Ancient and gray-headed as he was, and sturdy porridge-eater, it will be seen from this that he was a formidable fighter. He did great deeds in the battle between the gods and the Fomors, and, on one occasion, is even said to have captured single-handed a hundred-legged and four-headed monster called Mata, dragged him to the “Stone of Benn”, near the Boyne, and killed him there.