Title: Woodbarrow Farm: Play in Three Acts

Author: Jerome K. Jerome

Release date: May 10, 2017 [eBook #54698]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

Piffin.........

Allen Rollitt.......

Luke Cranbourne.....

Mike Stratton.......

Mr. Purtwee.........

Hon. Tom Gussett....

Baron Von Schnorr...

Richard Hanningford

Ichabod.............

Peters.............

Colonel Jack Dexter.

Clara Dexter........

Mrs. Rollitt........

Rachael.............

Deborah Deacon......

CONTENTS

Act I

Woodbarrow Farm, Exmoor

Act II

13a, St. James’ Mansions

Act III

Scene 1—Same as Act II., or Library at 13a, St. James’ Mansion

Scene 2—Woodbarrow Farm

Time: The Present

SCENE: Kitchen at Woodbarrow Farm. An ideal old farmhouse kitchen. From the smoke-blackened ceiling beams hang huge sides of bacon, strings of onions, and herbs, and poultry. Over the great fireplace are the guns, and in profusion everywhere are the homely furnishings of a prosperous farmhouse kitchen. A huge fire burns r. in old-fashioned fireplace, with settle on each side. Door l.c. at back opening on corner of farmyard. Latticed window looking out on yard to r. of door. Table r.c. piled with linen waiting to be folded. Linen press l. Door l. below press. Settle in front of press. Mrs. Rollitt at table r.c. discovered ironing. She folds up clothes as she finishes with them, and crosses and places them one by one in press l.

MRS. R. Rachael! Rachael!! (Crossing l. then crosses to r. at back of table r.c.) Ah, drat the girls—alius philandering about with the boys when they’re wanted. Rachael!

(Enter Rachael, she comes slowly forward to l.c.)

RACH. Did you call, ma’am?

MRS. R. (At table.) Did I call? Why thee be getting deaf in thee old age sure, Rachael.

RACH. I was in the dairy, ma’am.

MRS. R. In the dairy! Well, and the dairy bean’t a mile off, be it? I expect there wur Joe’s thick head ’twixt you and the sound of my voice, warn’t there?

RACH. No, ma’am.

MRS. R. Whose wur it, then?

RACH. Ichabod’s, ma’am. I—I mean Mr. Ichabod was helping me, ma’am.

MRS. R. What at? (Pause.) How often am I to tell ’ee I won’t have that hulking scamp hanging about here after his work’s done. Do ’ee understand?

RACH. Yes, ma’am.

MRS. R. Here’s getting on for 8 o’clock, and thee master may be home any minute as hungry as a hunter, poor lad, and noothing ready for his supper. Get down the ham (Rachael goes to fireplace r.), and bring me in the frying-pan and I’ll do it myself.

RACH. (Turning to go.) Yes, ma’am.

MRS. R. And don’t be half-an-hour about it. Is Ichabod gone?

RACH. Oh yes, ma’am.

(Mrs. R. turns to her work, Ichabod appears at door at hack, with a trout in his hand. Rachael catching sight of him stops, and motions him to go away.)

MRS. R. Ah, a good thing for un as he has, if I catch un here again to-night, I’ll—(Rachael makes sign to Ichabod who is up c. Mrs. R. looks at Rachael)—Lord help the lass, be she struck foolish? Bean’t ’ee agoing?

RACH. Yes, ma’am.

MRS. R. Well then, do ut. Thee keeps on saying, “yes, ma’am,” “yes, ma’am,” and there ’ee sticks. (Drops eyes. Rachael makes sign to Ichabod. Mrs. Rollitt catches her.)

(Ichabod does not understand Rachel, and tries to explain to her in pantomime about the trout, which he holds up and points to. Mrs. Rollitt follows Rachael’s eyes, and sees Ichabod. Rachael is struck dumb, and Ichabod grins and pulls his hair.)

MRS. R. If thee don’t take theeself off pretty, soon, my boy, I’ll do that for un. (He makes no answer but continues pulling his hair and grinning, making a few steps forward and still holding out the trout. Mrs. Rollitt advances to him slowly.)

MRS. R. (Comes c.) How often am I to tell ’ee I won’t have ’ee loafing about here after thee work’s done, and thee mother waiting for thee at home, thee good-for-nothing young—(eyeing the trout)—aye, but he be a bonny un that.

ICH. Thowt maybe he’d do for the measter’s supper, ma’am. He wur a-having his own not half-an-hour agone, ma’am.

MRS. R. (l. with fish in hand.) Her be a three pound un, Ichabod.

ICH. As full as an egg, her be, just. Thee feel her, ma’am.

MRS. R. Ah, well, I won’t say but what thee art a thoughtful lad, Ichabod, and it will be main good for thee measter’s supper. See there’s a clear fire. (Crosses r.Enter Deborah from staircase L.) Rachael, and bring me the stew pan and we’ll boil un.

DEB. No, don’t boil it, aunt. (Takes fish from Mrs. R.) Let me fry it. Allen alius likes ‘em best that way. (Goes r. c. up stage.)

MRS. R. So un does, lass, so un does. Ah, thee knaw what the lad loikes, thee shall fry it. (Hands trout to Deb.) And I’ll finish the linen while I’ve got my hand on it. (At back of table r.c.)

DEB. Allen will like that, I know. Where did you get it?

ICH. (Confused and grinning.) What, me, Miss?

DEB. Not poached, I hope, Ichabod?

ICH. (Offended.) Poached, Miss? No, Miss, I wur trying to teach a fly of mine to swim, that wur all, Miss, and when I took un from the water there wur this thing hanging on to the end of un, and I couldn’t get ‘un off.

MRS. R. (At table r. c.) Thee’d best stop awhile now, Ichabod, and the girls will gie un a bit sup. Thee mother will be main glad to be rid o’ ye a bit, I take it.

ICH. Thank ye, ma’am. Mother’s alius glad to be rid of me at supper toime. (To Deborah.) Gie me un, Miss, I’ll clean un for ye. (Takes fish from Deborah, goes down l. at back of settle.)

RACH. Shall I cook un, Miss?

MRS. R. Na, na, thee bring the pan in here, Rachael, I woan’t trust the master’s supper to ‘ee, while there’s a pair of breeches about the room.

RACH. (Crosses l. with a toss of her head.) I’m sure I don’t want ‘em there at all. (Picks up buckets near door l. down stage.)

MRS. R. Ah, thee wouldn’t ha’ the lad theer wi’out ‘em! Go and do as I tell ‘ee.

[Rachael hits Ichabod with bucket. Exeunt Rachael and Ichabod l. door down stage.]

MRS. R.MRS. R. The lad will enjoy it all the more if thee cook it for un. Ah. and he do enjoy his food too. It do me good to see un eat.

DEB. He does you a lot of good that way, doesn’t he, aunt?

MRS. R. (Laughing.‘) Ah, yes, he be like his father wur before him, a rare trencher man. Ah, but they’re better than those as doesn’t eat much, but sits a-turning and a-smelling, and a-grumbling at everything that’s set before them, for all the world like an overfed turkey cock trying to eat potato peelings. Thee wean’t ha’ much trouble looking arter un when I’m gone.

DEB. (Goes to fireplace R.) Oh, aunt, how naughty you are, always talking of being “gone,” just as if you were an old woman.

MRS. R. No, no, lass, I bean’t talking of being gone now. I’ve many a year before me yet, please God. But it must come sometime, thee knaws, and I like to think that when it do there’ll be someone to gie the lad his bit of food, and look arter un loike—and, Lord, a man do want a power of looking arter to be sure.

DEB. (At fire R. making it up.) I think that’s why we love ‘em, aunt, because they’re so helpless.

MRS. R. (Cross to l.) Ah, maybe it is. There must be summut to account for it.

DEB. And I suppose they be like the poultry. They get fond of us because we feed them. He does say I’ve got a good hand for cooking, aunt.

MRS. R. (Cross to r.) Ah, yes, lass. It be a light hand for the kitchen and a cool hand for the dairy. It will make a good hand for a farmer’s wife. (Takes Deborah’s hand at table R.)

DEB. I don’t think Allen will want a farmer’s wife, aunt.

MRS. R. Lord, whose wife should a farmer want, then?

DEB. (Pokes fire r.) I don’t think Allen wants to be a farmer at all. He says he wants to be a somebody, not a nobody.

MRS. R. Well, bean’t a farmer somebody?

DEB. Somebody, aunt, but not a somebody. Allen wants to be in the world, you know, aunt.

MRS. R. Well, and he be in the world sure, ain’t he? Sure I think I ought to know. (Cross to l.)

DEB. No, not in the world he means, aunt. Not in the great world as they call it.

MRS. R. Ah! he be in God’s world, that ought to be big enough for un. (Cross to r.)

DEB. (A little spitefully.) Yes, aunt, but it’s not select enough. There’s all sorts of common people in God’s world. Allen wants to be in the big world of lords and ladies and big folk up in London. He says it’s being buried alive down here; that he wants to be among the stir and bustle.

MRS. R. (Cross to h., putting clothes in press.) Ah! that be only his talk. The young uns be all alike. They run arter shadows like the chickens do arter chaff. (Cross l.) Why, I mind when I wur a lass, I used to look in the glass and think I’d be a duchess. But the dook didn’t come, so I just married thee uncle. The young ducks all fancies as they’ll paddle off to the sea, But they live and dies in the old pond arter all. (Crosses to R.)

DEB. (Laughing.) And you think that your duck will live and die in the Woodbarrow pond, aunt? (Helps Mrs. Rollitt to fold.)

MRS. R. Ah, bless un, yes, the lads they fancy that any place is better than the old home; but arter they’ve had a good look round, they know that the old home’s better than any place else. He’ll flutter about a bit maybe (looks at Deborah), but he’ll settle down in the nest ‘fore long, and the children will be running about the house (Deborah turns away a little) and making it untidy—Bless ‘em—afore I close my eyes.

DEB. (Demurely.) I wonder who he’ll marry.

MRS. R. Ah, I wonder now. (Crosses to put linen in chest of drawers.)

DEB. (r. folding linen.) There’s Polly Steddles. He walked home from church with her last Sunday. I think he’s a little sweet on Polly Steddles, don’t you, aunt?

(Mrs. R. comes l. of table r.)

MRS. R. Ah, it bean’t much good being a little sweet on a girl that size. It would take a power of sweetness to go round her. (Crosses L. with linen.).

DEB. She’s big, but then men like big women, don’t they, aunt?

MRS. R. (l.) Ah, some on ’em goes in for quantity, and some on ’em goes in for quality. The little ones, they go in for size cause they bean’t much of it themselves; and the big ones goes in for sense, cause that be what they be most in need of. (Goes R.) And Allen, he be’s medium, so he can just please himself.

DEB. And there’s Miss Dexter, that he drives over to Minehead so often. (Mrs. Rollitt goes l.) He thinks a lot of her, I know.

MRS. R. (l.) What, Colonel Dexter’s darter, oop at Lucott’s Hill? Oh, yes, her’d be a fine un to make the butter and cure the hams, her would. Her be loike them umbrellas they be a selling at Peter’s for 1s. 11d.—only meant to be walked out wi’. (Near press l.)

DEB. Ah, but she’s so beautiful, aunt, and she’s a lady! (Sighs.)

MRS. R. Ah! (goes to table r. c.) there be a good many sorts o’ them.

DEB. She is a lady, isn’t she, aunt?

MRS. R. Her’s got the clothes all right. (Sits l. of table r. A pause—goes up and pats Deborah’s cheek.)

As if thee didn’t know the lad were in love with theeself.

DEB. (Tossing her head.) Sure an’ I don’t see how I should—he never says anything.

MRS. R. Ah, the men bain’t much to say for their-selves, poor things. Thee must go by what they does. Why, thee uncle kept company wi’ me for three years, an’ un never said a word. The first year un only sot and stared, and the second year un put un’s arm round my waist, and the third year un kissed me, and then mother said it were time to put up the banns, and her done it.

DEB. (Laughs.) Ah, the man that wants to marry me will have to ask me ever and ever so many times and plead, oh, as if his life depended on it (tossing her head—at fire.)

MRS. R. Ah, the lad be shy, that be all. He be frightened ’o thee.

DEB. (Smiling.) Of me, aunt?

MRS. R. Ah, sure!—(Laughs.)—I expect un be worrying hisself finely for fear thee doan’t care for un, a fancying thee prefers Jim Harkabuck, maybe.

DEB. (Demurely—goes up r. and gets l. of Mrs. Rollitt.) Jim Harkabuck is a very nice fellow, and he does stare. (Smiling, and going to her aunt.) Do you think Allen really—really does—Aunt? (Kneels to Mrs. Rollitt, who turns her head away r. a little.)

MRS. R. (Laughing, and shaking her off playfully. Pauses.) Does he! Why beant he alius quarreling wi’ thee, and doan’t he eat twice as much o’ anything if he knows thee cooked it—and besides—(Pauses and becomes absorbed in stockings.)

DEB. Besides what, aunt?

MRS. R. Why didn’t I find un only the evening afore last when un didn’t know I wur there. (Laughing.)

(Enter Rachael l. door with fish in frying-pan.—Deborah rises.)

RACH. (Crossing r. and giving it to Deborah.) Shall I put it on, Miss?

DEB. (c. goes R. to fireplace.) No, I’ll see to it; Rachael, thank you.

RACH. I have put some butter in the pan, Miss.

(Exit Rachael l. down stage.)

DEB. Yes, aunt. (r. of table and seeing to fish with back to Mrs. Rollitt.) You—you were saying how you came upon Allen the other evening, aunt, when he didn’t know you were there, and he was doing something.

MRS. R. Ah, yes, it wur Toosday, and he—not in love wi’ ’ee—(laughing)—why—(taking up stocking and looking at hole.) Ah, look at that now, blest if I can make out where the holes come from, just.

DEB. What was he doing, aunt?

MRS. R. Why there un wur wi’ your—

(Enter Purtwee c.—who coughs.)

MRS. R. (Turning, and seeing him as he stands in doorway.) What, Mr. Purtwee! (Deborah in despair goes to fire and cooks fish.) Well, ’ee do surprise me! ’Ee be quite a stranger. Come in. Thee be just in time for a bit of sup.

MR. P. (Coming down l. c., puts hat on staircase rail.) I couldn’t pass the place without looking in, I’ve just left the trap outside. (Shakes hands.) And how are we?

MRS. R. Oh, I be middlin’ well, thank ’ee, and how’s yerself?

MR. P. Oh, nicely enough, and—(To Deborah crossing r.)—how’s Miss Deborah Deacon?

DEB. Very well, thank you, Mr. Purtwee.

MR. P. That’s all right—you look it, my dear (Taking her hands.) Why I declare she’s getting quite a woman!

MRS. R. Ah! she’s been that for some time. Her be thinking more about getting a man now. (Purtwee crosses to l. c. laughing.)

DEB. Oh, aunt!

MRS. R. Did ’ee see the lad up town?

MR. P. What, Allen?

MRS. R. Ah, that be the only lad in the world I know. Did ’ee see un? (Goes up l.)

MR. P. Yes, I met him, and I wanted to have a chat with him. (Mrs. Rollitt is up l. near linen press.) But, Lord! There he was off to Lucott’s Hill, and there was no holding him. (Taking off his coat.)

DEB. (Who has been engaged in her cooking, at this suddenly stops, and looks up.) What was he going up there for?

MR. P. (Stopping and facing round.) What for?

DEB. (Excitedly, but quietly.) Who was he going to see up there?

MR. P. (Laughing and folding coat.) Ah! who is it he always goes to see up there?

(Deborah turns a little sick at this confirmation of her fears. Purtwee, who is a sharp old fellow, notices the expression of her face and the whole truth flashes across him. He pauses suddenly, looks hard at her, then assuming an ordinary laughing tone, continues—Mrs. Rollitt (up l.) is engaged with the linen, and does not notice this.)

MR. P. Why, the Walleys, of course. He and Jim seem to be inseparable of late.

DEB. Oh, yes, I know. I asked him to try and see if the Walleys would part with one of their short-horns.

MR. P. Ah! that was it, then—yes, I remember that was it. (Turns away and looks back at Deborah, who has resumed her cooking—aside.) Poor child! There’s trouble for her I fear. (Throws coat over chair l.)

MRS. R. (Comes c.) Well, what be going on up at Minehead?

MR. P. The same that is going on everywhere, Mrs. Rollitt—people lying and slandering and evil-speaking; everybody thieving and cheating and quarreling. (Sits on table l.)

MRS. R. Well, I guess I could have told thee that. Haven’t thee any real news to gie us. Tell us what one person’s be a-doing. Never mind “everybody,” I don’t know him.

MR. P. Well, you see, Susan, a lawyer mustn’t gossip. (Shakes finger.)

(Deborah crosses to linen press L., sets tablecloth and lays table r. c. for meal.)

MRS. R. (c.) Oh, hoity, toity! What be the use of being a lawyer and knowing things if ’ee never tells a body a bit o’ news? And now I come to think of it, I’ve got a bone to pick wi’ thee about that very thing. Thee never told me old Hanningford wur agoing to die without leaving my boy so much as a brass farthing. Do you think as how I’d ’a’ gone on sending the old skinflint the best turkey in the yard every Christmas, and the best goose come every Michaelmas, if I’d known as how he’d hadn’t given us so much as the price as a suit o’ black, and Allen his own cousin’s child. (Crossing R.)

A cousin is a cousin, even if it be a distant one. (Sits l. of table r.)

MR. P. Now, my dear Mrs. Rollitt, how could I tell he was going to die?

MRS. R. Thee knowed he wur going to die sometime, and thee knowed he hadn’t left the boy anything, and thee might a’ dropped me a hint. “Mrs. Rollitt,” thee might ha’ said, “thee’s only wasting good poultry on a worthless man. The old sinner’s a going to die as hard-fisted and ungrateful as he’s lived.” It would ’a’ been a neighbourly act o’ thee!

MR. P. (Laughing.) But I didn’t know he wasn’t going to leave you anything. You see he died intestate.

MRS. R. In——— what?

MR. P. (Rises.) Intestate. (Deborah laughs a little.) Without leaving a will; he left nobody anything.

MRS. R. (Rising.) Well, then, where does the old fool’s money go to?

MR. P. Why, to his son, of course! (Cross to r. near chair, fireplace down stage.)

MRS. R. Ah, where be his son?

MR. P. (Folding his knee in his hand and looking at her quietly.) On the road from Texas to Devon. (Sits r.)

MRS. R. What! Thee don’t mean to say thee’ve found un! (Deborah gets dish off dresser r. and puts it down in front of firm Mrs. R. in front of table r., Mrs. R. and Deborah draw near interested.)

MR. P. That’s just exactly what I do mean. We traced him at last—found him at Port Chadbourne black as a nigger and dressed as a red Indian.

MRS. R. What was he doing there—play-acting?

MR. P. No, cow-boy. (Mrs. R. sits l. of table r.)

MRS. R. Lord love us all! and do un know?

MR. P. Yes, my agent saw him—went down to meet him as he came through with a drove of cattle, gave him my letters and told him everything.

MRS. R. Has he written to you?

MR. P. No, didn’t know how to write—a sort of half savage he seems to be, he and all his companions. He said he was going to give the boys a three days’ drink, or as he expressed it, “paint the town red,” and then start straight for home.

MRS. R. When do you expect him?

MR. P. Any day now; it was six weeks ago my agent saw him. He might walk into my office to-morrow morning.

MRS. R. Lor! to think o’ it all. Him running away—driven away, as a body might say, by ’is own father, when scarce more than a baby, and now coming back to all this money. When do ’ee expect un?

MR. P. To-morrow—in six months time—never!

MRS. R. Never! (Purtwee rises, crosses to l.)

MR. P. Perhaps never.

MRS. R. Why I thought thee said he’d started.

MR. P. Started, yes; but there’s a long road between that and arriving. He may be dead and buried—drowned—murdered—for all we can tell. They’re a rough lot where he’s coming from. (Takes coat off settle L. Feels for snuff box in pockets; rises; goes c.)

MRS. R. Well, thee’s picturing a nice fate for the lad. An’ who would the money all go to if he were gone?

MR. P. Why the next o’ kin of course! He isn’t married.

MRS. R. And who be the next of kin?

MR. P. (Dryly.) Oh! there’s no need to worry about that now.

Mrs R. Well, I’d just like to know, that’s all. Would it be any of the Leeds folk?

MR. P. Oh, I really can’t say! (Gets snuff box, puts coat on settle l.) I—I can’t say at all who it would be. (Angrily, rather.) Why there’s about a hundred different relations scattered all over the country, and goodness knows who it might turn out to be. It isn’t a matter to be considered yet at all.

MRS. R. Lord bless us all, don’t put theeself out, man. I didn’t know as a body’s relations wur any secret—(pauses)—provided they be coom by honestly. Doan’t tell us if ’ee doan’t want to. (Turns away r. a little.)

MR. P. No—no, Mrs. Rollitt! I’m not put out, only you see it’s always a most complicated question a next of kin, especially in a case of this kind where the man shunned all his relations. It might be someone in Hong Kong; it might be someone here in Devonshire—(Enter Allen c. door.)—it might be,—(he is l., taking handkerchief from his overcoat pocket, and turning sees Allen in doorway and stops. Deborah puts on the fish.)

ALLEN. (Coming down r. c.) Well mother! (Kisses her.)

MRS. R. Why, my boy, wherever ha’ ye been to—I wur getting quite anxious about ’ee!

ALLEN. (Taking off his hat and coat and throwing them down at back.) Ah, I be a rare anxiety to ’ee, baint I, mother? (To Mr. Purtwee.) Mother alius fancies as I’ve been run off with by gypsies if I be out more than an hour. (Crossing and shaking hands with Mr. Purtwee.) And how be Mr. Purtwee for the second time to-day?

MR. P. (Laughing and shaking hands.) Ah! your mother’s a regular old hen with one chick I expect. (Sits l.)

ALLEN. Never thee mind, mother, thee be quite right to be careful o’ me! There baint another son like me in the whole country, be there?

DEB. (At fire.) To the credit of old Devon be it said.

ALLEN. Halloa! (Goes r. to Deborah.)

MRS. R. Ah! now that just serves thee right for laughing at thee old mother. (Crosses l. and sits knitting next to Purtwee.)

ALLEN. Ah! that be the worst of letting the children stop oop arter their proper toime, they allus gets so saucy. What have thee there? Lurd bust me, I have got a vacuum inside o’ me. Poached eggs?

DEB. No; poached trout.

MR. P. Eh! what’s that?

ALLEN. Hulloa! Thee’ve done it now. Why, Mr. Purtwee be Lord Netherby’s lawyer, and he’ll ha’ thee hanged in chains on Dunkery Beacon, sure as fate.

DEB. Ah, well, you see I didn’t poach him, I’m only frying him. There’s no law against frying fish, is there?

ALLEN. (r.c.) Aye, well, us’ll forgive thee this time, if ee’ll promise to do it again soon. Come and give us a kiss.

DEB. Thee’ll kiss the frying-pan if you come any o’ your nonsense round here.

ALLEN. What! won’t thee, when I tell ’ee I’ve bought Jim Whalley’s tan and cream shorthorn for ’ee?

DEB. (Pleased.) No! Have you?

ALLEN. I bought her this afternoon, and I got her for—(l.c., turning to his mother) I say, mother, our Deb’s bin and smoshed young Whalley.

MRS. R. Done what to un.

ALLEN. Smoshed him.

DEB. Why, I never touched him.

ALLEN. Yes thee have, thee’ve smoshed un—that be the new Lunnun word; made un in love wi’ thee.

MRS. R. It’s a funny way o’ doing it.

ALLEN. I doan’t know how her done it, but her done it. Why he wanted £25 for the cow at first, and when I told un her wur for Deb he looked as stupid as an old cow unself and said I could have her for £20, and then he asked me if she would like a calf. (Goes R.)

DEB. We could do with one. What did you say?

ALLEN. (Laughing.) I told un her’d better let the calf come down and ask for unself. (Laughs boisterously.) He never saw what I meant. (All laugh.)

DEB. Oh, I expect he saw it all right. Jim Whalley is a very sharp fellow; there was no need to insult him just because he’d done a kind action. (Warmly—turns away r. a little.)

ALLEN. Oh, I wouldn’t ha’ said it if I’d known. I didn’t know thee was in love wi’ him.

DEB. (Half laughing and half indignant.) Oh, don’t be silly, Allen, as if I cared for Jim Whalley.

ALLEN. I might ha’ guessed it too. Why, I expect that’s why thee wanted the cow so as to have something about the place to remind thee o’ un.

DEB. Oh, you great stupid!

ALLEN. Why, look how you’re blushing. Look, look at her face, mother. (Goes to back of settle r. takes up looking-glass which is hanging on settle r., brings it down and holds it before her.) Look at yourself! (she catches him a sound box on the ear. He puts his hand to his face, and crossing puts back glass.) I didn’t know thee was so strong. That all comes of those squab pies o’ yourn, mother, I told thee thee wur putting too much meat in ‘em.

MRS. R. (Laughing.) Ah, it’s thy sauce lad, not my meat, that’s done it. (Rises.) Thee’d better try and make thy peace, while me and Mr. Purtwee has a look round the out-buildings. (To Mr. Purtwee) I’ve been wanting to get hold of thee for a long time. Thee’s never given us so much as a bit o’ paint for the last ten years, and the stable roof won’t bear an owl on it. (Goes up c. with Purtwee.)

ALLEN. (r. near settle.) Thee might show Mr. Purtwee the barn floor while thee’s about it, mother. It be more like an earthquake than a floor.

MRS. R. Oh, I be a going to show him more than he wants to see, don’t thee worrit. (Aside to Mr. Purtwee at door c.) Ah, they’d make a pretty couple, wouldn’t they?

MR. P. (Looking at them.) No, no, we must make ’em one.

(Exit Mrs. Rollitt and Mr. Purtwee c. door.)

ALLEN. (After a pause, r.c.) Well I’ve got thee the cow, anyhow, and it’s a beauty.

DEB. (At tire in a tone of severe and offended dignity.) Thank you, Mr. Rollitt, it is very kind of you.

ALLEN. (After a pause, with exaggerated politeness.) Don’t mention it, Miss Deacon—quite a pleasure!

(Allen crosses to l., whistles—a pause—pretends to take off leggings. Puts foot on settle.)

DEB. Thee may bring me over the butter.

ALLEN. (Looking up.) Hulloa! come back again! Butter, certainly! (Takes it from chair off l. on staircase, crosses with it, and holds it for Deborah while she takes some.) Jolly good butter this week; who made it? Thee?

DEB. (Other side of plate.) Of course I did! I make all the butter now, and the cream.

ALLEN. What, wi’ them little hands. They don’t look big enough to do anything but be kissed.

DEB. (Looking up and smiling.) They can do something else, can’t they?

ALLEN. Ah! They be like the parson’s, not as soft as they looks. (Puts down butter on the table—pause—during which Deborah proceeds with her cooking, and Allen stands watching her.) What a jolly little farmer’s wife thee’d make.

DEB. Yes; I only want the jolly little farmer.

ALLEN. Ah, thee won’t find many of that sort about. Farming don’t pay enough for a man to get jolly on, now-a-days.

DEB. Oh, we have enough to eat and drink, and a little to spend on foolishness. You want so much.

ALLEN. (Goes l.) Not more than what a many has. Not more than a little bit of what this young Hanning-ford is coming back to—enough to let a man see what the world’s like a bit, instead of being cooped oop all one’s life, like an old cow, in one corner of it.

DEB. But you can’t live all over it, and one corner must be much as good as another.

ALLEN. (Crosses r.) Ah, thee don’t understand it, lass. Thee women folk can stand day arter day the same, but we lads are restless wi’ it. We feel as there’s summat big and stirring going on somewhere, and we long to be among it—to be in the great world. It seems to call to me—(puts foot on settle L.)—to come to it, sometimes. I hear it of a night when I’m watching the sheep on the hill fields. Maybe it’s only the sea breaking on the rocks down by Glenthorn—or the wind among the old oaks, but it sounds like a distant far-off voice—(gets l. of table R. with back to Deborah)—calling to me, and it rings and echoes in my ears, till I feel at times that I must start up then and there and follow it. (Deborah r. of table r. Allen l. of table r.)

DEB. (Very gravely, laying her hand on his arm.) Allen, lad, don’t you remember reading one evening to us of the sirens, who in the old days used to haunt the sea caves, and sing so sweetly that the sailors who once paused to listen, were lured on and on till they were wrecked among the cruel rocks? May not the voices that you hear be like the singing of those sirens?

ALLEN. Maybe, lass; but the sailors couldn’t help but follow when they did hear it. (Sits in chair l. of table R.)

DEB. (After a pause.) What be the matter, Allen? Thee used to be contented enough. Now thee’s always talking about riches, and wanting to go away from the dear old farm. Somethin’s come over thee, lad. (Puts hand on Allen’s shoulder.)

ALLEN. No, I wur allus like an old crow—(Deborah takes her hand away)—sitting on a fence, and looking at summat too far off to see. But thee be right partly, lass. Summat has come over me, and made me want what I can’t get more than ever now.

DEB. (Very kindly, r.) What be it? (With elbows leaning on table, R.)

ALLEN. (Rises, goes l. c.) Well, I be in love, lass. (Still looking away from her.)

DEB. (After a pause, during which she has smiled to herself with a happy little sigh, and clasped her hands together in a sort of little joyful ecstacy, unnoticed by Allen.) In love!

ALLEN. I fancy it must be that. I think of her all day and I dream of her all night, and I’m jolly miserable. (At settle, R.)

DEB. (Demurely.) Have you any reason to suppose that she returns your affection?

ALLEN. I don’t know, her’s never said anything.

DEB. Have you?

ALLEN. Me! No, I haven’t said anything.

DEB. Most extraordinary that she doesn’t propose. Have you given her any encouragement? (Leans against settle R.)

ALLEN. Noa—I can’t say as I have, much. (Goes r.c.) I’ve looked at her, you know—soft like—and sighed. (Does so.) But her’s mostly been looking t’other way and an’t seen it, and as for saying anything to her—well, I can talk to her all right about other things and joke and laugh wi’ her, but the moment I goes to say I love her—it—it seems as if I’d got a hot potato stuck in my throat. (Speaking as if she had, turns away to l. corner of r.table, back to Deborah. His manner throughout this scene carries out the idea that it is Deborah he is in love with.)

DEB. (After a pause, with a coquettish smile to herself.)

I—I can’t do anything to help thee, I suppose? (Goes and leans against settle R.)

ALLEN. Do thee think as her could care for a mere common farmer, Deborah?

DEB. (Turning and looking at him earnestly—comes to front of table R.) Well—I think if he were a good farmer, and pleaded very hard, I—

ALLEN. (Delighted.) No, lass! Do ’ee really think a girl could? (Advancing to her.)

DEB. (Putting her hand to stop him with dignity.) A girl might—though, of course, a superior sort of girl, such as she appears to be, might think it presumption for—(turns away r.puts hand on corner of table R.)

ALLEN. (Depressed.) Yes—I’m afraid her would. (Turns away l.)

DEB. (Eagerly turning around again.) Then, of course, she mightn’t. You never can tell till you try. (Goes to fireplace r. Fish is changed.)

ALLEN. (Scratching his head.) Blest if I know how to go about it! I say, Deb, you’ve been proposed to, how do they begin?

DEB. (Bending over fire.) Don’t thee think thee’d better tell me who it is and let me ask her for thee? (Looking slyly round, pauses.) Who be her, Allen?

ALLEN. (Going up to window R.c.) Ah, I expect thee knows who her be!

DEB. (Beginning softly to creep toward him.) How should I when thee’s never told me? What be her name? (Close to him, his back is still towards her and he doesn’t see her.) Eh?

ALLEN. (Without turning, looking out of the back window up R.c.) Clara. (Music cue.)

(Bus. Deb. stands still—for the first moment she hardly comprehends. Then she understands, and stands staring straight before her with a wild scared look—shivers, crosses back to fireplace on tip-toe and bends down over it attending to the fish—after Deb. sobs Allen comes down c.—music dies away.)

ALLEN. (Half turning round.) Colonel Dexter’s daughter, you know. Thee’ve seen her. Her wur at the Barnstaple ball and I danced wi’ her and thee said how beautiful her wur and that her dress was all made o’ some’at or other, and you—(he has gradually come close over to her r.) What be the matter, Deb?

DEB. (In a changed, hard tone, bending more intently than ever over her cooking.) Nothing—Nothing.

ALLEN. (Taking her hand.) Why, thee be quite cold, lass; be thee ill?

DEB. (Snatching her hand away.) No, no, there’s nothing the matter with me. Don’t be so foolish, don’t don’t.

ALLEN. (Surprised.) I say, Deb, have I said anything I oughtn’t to? I know I’m allus a-doing it. (A pause—Allen stands looking at her, troubled and bewildered—Deb. bends closer over the fire—then takes the pan off the fire and with it in her hand turns to Allen smiling.)

DEB. (Gives dish to Allen.) Yes, thee have—talking to a cook at the very moment the trout is on the turn. (Puts trout on dish.) Serve thee right if I’d spoilt it.

ALLEN. Lor’, thee quite frightened me! (Pauses.) Yes—I went up there this afternoon. (Deb. takes dish from Allen, puts it down in front of fireplace.)

DEB. (Arranging fish.) Did you see her?

ALLEN. Yes, I saw her.

DEB. It doesn’t seem to have made thee any more cheerful. Did thee quarrel.

ALLEN. Us never got a chance. There wur a cousin or summat of the kind hanging about all the time—just come over with some chap from America. Can’t say as I like un much.

DEB. Thee’d best summon up thy courage and speak quick or thee may lose thy turn. (Allen turns away L.) Go and tell aunt supper’s ready—be quick, it’s all spoiling.

ALLEN. (Moving quickly towards door l. down stage.) Where shall I find her?

DEB. (Sharply.) How should I know?

ALLEN. (Looks around surprised—sotto voce.) How the fire do draw out a woman’s temper, to be sure.

(Exit Allen l., down stage.)

DEB. (Left alone stands r.a moment without speaking.) What right has she to come down here and take him away? She doesn’t love him. Couldn’t she have found enough fine gentlemen in London to amuse her? I don’t believe she’s a good woman, and I hate her. (Stamps her foot.) She shan’t have him—she—(bursts into quiet tears and, slipping down on ground, buries her face in chair by fire—pause—after a few seconds Luke Cranbourne appears in door c. front r., Mike Stratton behind him. Luke pauses on threshold and coughs. Deb. hastily rises, trying to hide her tears and stands r. Luke comes forward slowly, followed by Mike at some distance.)

LUKE. (After pause, coming forward r.c.) I—beg pardon—there was nobody about. Are Mrs. Rollitt and Mr. Rollitt at home?

DEB. Yes, they are at home. I will go and find them. (Crosses to l.) Who shall I say it is?

LUKE. (r.c.) Ah, thank you very much, my dear. Would you say Mr. Cranbourne—Mr. Luke Cranbourne and Mr. Richard Hanningford?

DEB. (Amazed.) Dick Hanningford!

LUKE. (Smiling.) You know the name?

DEB. Old Mr. Hanningford’s son? Why, we were only speaking of him just this instant, and wondering when he’d come back. (To Luke hesitatingly.) Are—are you—

LUKE. No—this is Mr. Hanningford. (Turns to Mike, who stands awkward and shy l.c. looking at the ground.) Did you know him? (Laughs.)

DEB. Oh, I’m Miss Deacon—Miss Deborah Deacon. We were school-fellows, you know. (Timidly approaching Mike with outstretched hand.) I am very glad to see you Mr.—Mr. Hanningford.

MIKE. Thank you, Miss—I’m very pleased to see you.

LUKE. (Sitting r.) I suppose you hardly recognize our friend? (Watches her intently without her noticing it. Mike has turned away again, and looks down, flicking leg with cane.)

DEB. (Hesitating.) Um! (Laughs.) Well, he’s certainly altered since we used to go to school together. But yes—(examining his face)—there’s something of the old face left, I think.

LUKE. We only arrived from America last night, traveling hard all the time. Pretty nearly worked me to death. Dick has—(with a yawn)—but there, I suppose I should have hurried up pretty smart myself if I’d been coming home to a fortune.

DEB. You are staying in the village then, I suppose?

LUKE. Yes, we’ve put up at Colonel Dexter’s—my uncle’s—slow place. (Laughing.) But better than the inn apparently.

DEB. Oh. then you are the—Miss Dexter’s cousin that Allen—(pauses hesitating)—was—was speaking of?

LUKE. Oh, the young fellow that was there this afternoon—was that Allen? (With a would-be playful laugh.) And who’s Allen, eh?

DEB. (A little stiffly.) Allen is Mr. Rollitt.

LUKE. Oh, I wish I’d known that this afternoon. Dick’s been dying to see him and his mother all day. I wanted him to wait till the morning, but he would come down to-night.

DEB. Oh, I’m sure Allen and Aunt will both be delighted. (Approaching Mike, who still stands aside and looks down.) Won’t you be seated, Mr. Hanningford? (He makes no sign—hesitatingly.) Dick. (Mike still takes no notice. Luke has risen and crossed with assumed carelessness, towards him and nozu from opposite side of him to Deborah gives him a sharp kick. Mike starts and looks up.),

LUKE. (Turning away carelessly.) Lost in reveries of old scenes, Dick, eh? Miss Deacon is asking you if you won’t sit down.

MIKE. (Sitting L.c.) Oh, I beg your pardon, Miss, I’m sure. Oh, thank you, I will.

DEB. (Going.) I shan’t be a minute. They are only somewhere about the yard.

(Exit Deborah c. door l. down stage. Luke goes to door, looks off, closes door, then goes up to door c., looks off, then closes it. Comes r. of Mike, who is l.c.)

LUKE. (After waiting an instant, and making sure that no one is about.) Try and keep some of your wits about you, Mike—if you don’t mind.

MIKE. (Sulkily.) I don’t see the darned good of this part of the trick, so I tell you.

LUKE. I’m afraid we shall have a rough time if your memory doesn’t improve. I’ve explained to you at least half-a-dozen times that it was as a sort of trial canter that I wanted to come here. If anyone in Devon can tell who is Dick Hanningford and who isn’t it will be these Rollitts. If you pass here you pass anywhere.

MIKE. Well, it’s the very place I should have avoided, and for the same reason. The old woman knew Dick Hanningford as well as she knows her own son, and I’d rather avoid her.

Luke, (r.) You’re bound to meet her sooner or later. Better get it over and know the worst—or the best. (Turns away r. a little.) Sixteen years make it a little difficult to tell a man, especially between the age of nine and twenty-five, and you’re like him enough, and always were.

MIKE. And suppose she gets asking questions—do I remember this, do I remember that—you know what old women are.

LUKE. Well, you can’t be expected to remember all the details of your pinafore days after all this time, and knocking about as you have been. You know all that is necessary for you to know. You knew the old man, and you were in the house, and you knew young Hanningford. Besides, you needn’t recollect anything yourself. You recollect what other people recollect, that’s all you’re wanted to do.

MIKE. (Rising.) I hope we don’t make a mess of it! (Turns L.)

LUKE. (Crossing and laying his hand on Mike’s shoulder, turns him to c.) We shan’t make a mess of it—don’t you. You know what it’s for—£100,000 apiece. I’ve done my share of the job—you do yours. (Turns r.a little.)

MIKE. (Turning round and facing him.) Are you sure you did your share?

LUKE. (l.) What do you mean? (Turns c.)

MIKE. (r.) Are you sure he was dead?

LUKE. (After pausing, during which they have looked steadily at each other, turning away l.) Well, the bullet went in above his ear, because I examined the wound: and his body went over a two hundred-foot precipice—that I could also take an affidavit to—only I’d rather not. (Turning round and facing Mike again.) What makes you doubt it?

MIKE. I don’t know—nothing. The idea occurred to me, that’s all. (Turns l. a little.)

LUKE. Don’t you drink so much and you won’t have so many ideas. (After a pause, during which he seems troubled, shaking it oft with an effort.) Have you got the letters with you? It will look well to take them out casually while talking. (Crosses R.; sits on table.)

MIKE. (Who has crossed to L., taking them out of his breast pocket and holding them in his hand.) Yes, here they are all right. Bah! (With a shudder.) I always see his face when I look on the darned things—I—Mrs. R. (Without, loudly.) Dick Hanningford—Dick Hanningford, my boy! (Mike drops suddenly in sitting posture on sofa L. with a cry “Ah.” Luke works round at back and drops down l.)

(Enter Mrs. R., excitedly, followed at little distance by Allen and Deborah from c. Allen and Deborah remain up. Rachel from door down l.)

MRS. R. (Coming down towards Mike.) What, Dick, my boy, where be thee? (Sees Mike on sofa; making towards him.) Ah, there thee be—I thought I’d know thee again though thee wur only in knickerbockers when I last saw ’ee. Tain’t thy fault thy father wur a bit stingy. Come and gie us a hug, lad. Lord love us—(she is just in font of him, begins to speak in a bewildered, hesitating manner, in tones gradually dying away to an awed whisper, as she slowly step by step backs from him.) How—how you’ve grown—Dick—Dick Hanningford—what—(stands staring at him; a strange awed silence prevails).

DEB. (Advancing in a terrified voice.) Aunt.

MRS. R. (Motioning her back with her arm, but not turning and speaking in a quick, excited, loud tone.) Keep back, child, don’t come near. (Luke is near Mike down c.)

ALLEN. (Springing forward.) Mother! What’s the matter?

MRS. R. (As before.) The man’s dead.

LUKE. (r. stepping forward.) Dead!

MR. P. (Who has entered c. followed by Ichabod and Rachel l. He goes quietly up to Mike and lays his hand on his heart, and bends over him earnestly, and it is a few seconds before he speaks.) Heart disease, I suppose. (At back of settee l. Gets r.c. of settle.) My letter in his hand. (Gets to back of settle.) It’s an ill wind that blows nobody any good. (Turns and feels Mike’s heart once again, then quietly turns away to Allen. Comes c.) He stood between you and £200,000. You are now old Hanningford’s heir!

ALLEN. I!

MRS. R. Allen!

LUKE. (To corpse of Mike—aside as he crosses to back.) Curse you!

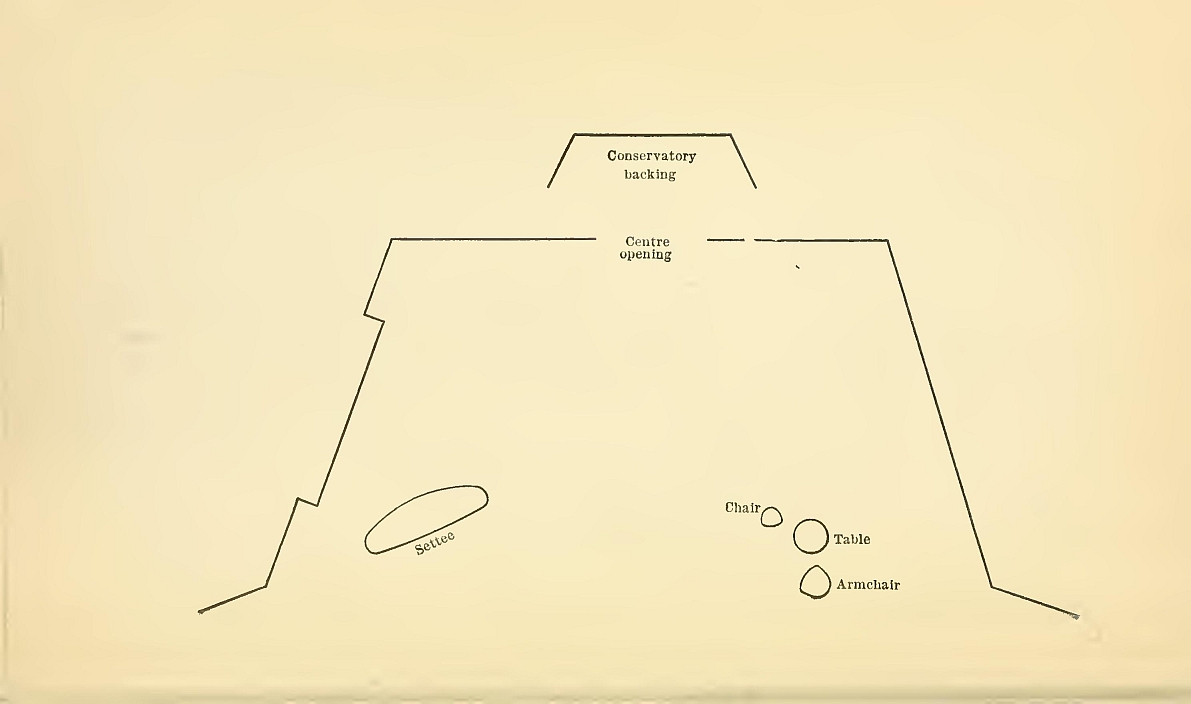

Scene: Morning room in a handsome flat—a showily furnished room—rather ostentatious and loud in its decoration and appointments. Large table in bay window r.upper corner. Fire-place r.Doors at back l.c. and two in l. wing. Small tables r.and L.. Easy chairs l. and R.

Breakfast is laid on large table—it is a gorgeously laid meal—silver and plate in profusion, and a great number of dishes—tea urn and coffee urn—a boiling kettle—flowers and ferns in vases and stands. One, a large wavy one, is at left edge of table close to Allen. The table in short is crowded and showy to the last degree. A magnificent footman in gorgeous livery is standing behind; and Mr. Piffin in solemn black waits close to Allen’s chair, a dish in his hand. Allen is discovered sitting l. of table, and eating his breakfast in a most melancholy fashion. He looks intensely miserable and awed. The terrible solemnity of the whole affair has depressed his spirits to their lowest ebb. He glances nervously now and then as the meal proceeds, from the footman to the valet, and vice versa, as they silently and with much ceremony walk about and wait on him. The fern by his side keeps getting in his way, tickling and irritating him, but he dare not move it. He eats in silence, and when he does speak, does so in a humble, deprecating, nervous manner. He is dressed in a loose morning costume. Music to open Act.

PIFF. (Standing by Allen’s l. elbow c. Peters r. of table R.) May I get you a little pâté de foie gras, sir?

ALLEN. (Looking round, and speaking in a hushed voice.) I beg pardon?

PIFF. A little pâté de foie gras, sir.

ALLEN. Patty who?

PIFF. Goose’s liver, sir. I think you will like it.

ALLEN. No, thanks; I never eats liver. It don’t agree with me. I will have a bit o’ the bacon though.

PIFF. No, sir; it is not dressed that way, sir. I would get used to it if I were you, sir. You will so often come across it. Peters, just pass your master the pâté de foie gras.

(Peters goes to do so. Allen who has turned again towards his breakfast is about to take up some gravy from his plate with his knife).

PIFF. (Checks him.) I wouldn’t lap up the gravy with my knife, sir. I don’t think. It’s never done now in good society, sir.

ALLEN. It—it’s the best part of it, you know, I alius thinks—the gravy

PIFF. Yes, it’s very tasty, sir. It’s unfortunate it’s so sloppy; and you see, sir, eating it in that way does not show off the figure to advantage. Peters, remove your master’s plate.

(Peters does so, placing it a few feet beyond Allen’s left hand. Allen watches it with jealous eyes. Peters then holds the pâté de foie gras to Allen. He slowly runs his eye up Peters with awe, and then looks at the pâté de foie gras, then using one hand attempts to take it. Peters, not moving a muscle, holds it tight. Allen seems surprised, and partly rising, attempts to take it with both hands.)

PIFF. (Coming to his rescue, cutting a piece, and putting it on his plate.) Allow me, sir. Peters, the brown bread and butter.

PET. (Looking for it.) It is not on the table, sir.

PIFF. No brown bread and butter; dear me, how remiss!

(Crosses l. and rings bell. Peters also crosses l.c. door, Allen looks cautiously round and sees they are not watching him, and stealthily reaches over and secures a knifeful of gravy. He is about having a second and has the knife close to his mouth, when he becomes aware that Piff has returned and is watching him. He tries to hide the knife out of sight. Peters has returned with bread and butter.)

PIFF. (Severely.) Peters, remove your master’s knife. Don’t you see that it is in his way?

(Peters does so, and then holds the bread and butter to Allen, who takes a thin slice, folds it up, and holds it in his left hand while taking the pâté on a fork in his right. He puts first the pâté and then the bread and butter into his mouth and swallows them.)

PIFF. I must apologize for serving you your breakfast in here, sir. Of course, you will not have it in the drawing-room as a rule.

ALLEN. No, a’ coorse not. No; us alius used to have it in the kitchen at home.

PIFF. Yes, sir. Must have been very convenient. But I think I’ll get you to put up with the breakfast parlour in future, sir—when the room’s ready. Have you quite finished, sir?

ALLEN. (Humbly suggesting.) I think I’d like a little more o’ that pie. (Looking longingly at pie the other side of table.) You see, I alius wur a hearty eater. (Said as apology).

PIFF. Yes, sir, I’m delighted to hear it, sir; but I wouldn’t eat any more breakfast, sir. You will find it is considered correct among bons vivants to eat a very sparse dejeuner. My late lamented master, the Count de Fizziani, never partook of anything but a cup of weak tea and a little dry toast, and he was one of the oldest families in Europe.

(Allen rises, Peters bows as he does so, and Allen returns the bow and comes dozen R.)

ALLEN. Ah, I shouldn’t ’a’ thought as anyone could ‘a’ lived long on that. (He bows).

PIFF. No necessity to bow, sir.

ALLEN. He did it. (Indicating Peters).

PIFF. He’s paid for it.

ALLEN. I allus seem to want a good feed myself in the morning. (Takes out an old clay pipe and prepares to fill it. Goes down r. and sits in chair. Peters is clearing away the breakfast things).

PIFF. Are you thinking of smoking, sir?

ALLEN. Yes; I allus has a whiff or two arter breakfast.

PIFF. It’s very soothing, sir. My late lamented master, the Count de Fizziani, used to follow precisely the same course. But I wouldn’t smoke a pipe, sir. Pipes are going out in good society. (Takes cigarette case from pocket and offers it to Allen. Takes pipe from Allen and puts it on corner of table R.c.) I have some cigarettes here, sir, which I think you will like, sir. These are much more comme il faut, sir. This case is a present from my late lamented master, the Count.

(Allen looks at them and gingerly takes one.)

ALLEN. Which end?

PIFF. (Lighting match.) Either end, sir. Allow me. (Showing matchbox.) Another little souvenir from my late master. He was always acknowledging, if I may say so, my value to him. That sort of thing is always done in good society now. (Lights cigarette.) It is a full flavored one, sir. (Piffin takes Allen’s pipe from table r.c., crossing with it to window r.)

ALLEN. (Watching him, anxiously.) Don’t hurt him.

PIFF. (Turning round.) I was just going to put it outside on the window-sill, sir.

ALLEN. No, don’t put him there. We used to sit up together of a night watching the sheep. I don’t like the thought of putting him outside the window, now I’m a gentleman. Drop him in the pocket of that old shooting coat o’ mine that thee won’t let me wear. They know each other. (Sits r.and smokes his cigarette. Piff. puts the pipe on table and returns r.c.)

PIFF. (Noticing that Allen is looking at his cigarette.) All right, sir? (r.)

ALLEN. Yes—yes, thank you, Mr. Puffin—

PIFF. Piffin, sir.

ALLEN. I wur looking to see if it wur alight, that’s all.

PIFF. You will soon get to like them, sir. And whenever you are ready to dress, sir—

ALLEN. (Surprised.) Dress? Why, I be dressed, bain’t I?

PIFF. Oh, only for breakfast, you see, sir. I understood you were going out walking, sir.

ALLEN. Why can’t I walk in these?

PIFF. Oh, no, sir—all London would laugh at you.

ALLEN. Lord! I should never a’ thought as they’d take so much notice. (Rising. Piff. crosses to l. near down stage door.) Ah, well, I’ll dress. (Crossing l.) I don’t want to upset London if I can help it. I’ll dress. (Exit l. Bows to Piffin as Piffin does so to him).

PIFF. No necessity to bow, sir. (Aside.) Ah, I’ve got a big job on here!

(Exit Piffin, following Allen l. Piffin immediately returns, having forgotten the pipe, which he takes. He is recrossing l. as enter Dexter and Clara, c., preceded by Peters, who takes tray from table R.c. and exits up L.)

And I’ve got to live in the house with this.

(Dexter goes c., Clara r. at back.)

DEX. (Coming down.) Good-morning, Piffin, goodmorning. Having a quiet whiff?

PIFF. Thank you, sir. My stomach does not permit my indulging in the luxury of a cutty pipe.

DEX. Is Mr. Rollitt about?

PIFF. He has just this minute gone upstairs to dress, sir. I will let him know you are here, sir.

DEX. No hurry—no hurry at all, Piffin. We are before our time. You are not looking well, Piffin.

PIFF. Anxiety, sir. May be anxiety. You see Mr. Rollitt’s unacquaintance with the manners of the beaux esprits throws much responsibility on myself.

DEX. But you must be careful, Piffin. What would he do without you?

PIFF. (Smiling.) Well, I’m afraid he would be a little up a tree, sir, if I may be permitted a vulgarism. (Moving to door l.) I will go and acquaint him with your arrival, sir. (Takes plate from table l., puts pipe on it.) I’ll send him to you directly, sir. (Smells pipe.) Shag! (Exit l.l.)

DEX. Thank you, Mr. Piffin, thank you. (Turning round.) Always be affable with your inferiors—never know when you may want ‘em.

CLARA. (By window, looking out.) Do you come across many of that sort? (Comes down r. of table R.)

DEX. Ah, you beast—you vixen. I wonder you don’t cut yourself with that tongue of yours.

CLARA. (Turning round with a hard laugh. At fireplace R.) It must be pretty sharp if it goes through your skin.

DEX. Ah, you damned—

(Enter Allen l. He has on slippers and a smoking coat).

ALLEN. (Crossing.) Don’t ’ee look at us too closely. I bean’t properly dressed yet.

CLARA. (r.c. turns head away.) I don’t think we had better look at you at all under those circumstances, Mr. Rollitt. (Laughs.)

ALLEN. (Laughs.) Oh, I be covered up all right everywhere. I merely meant as I wasn’t up to fashion plate standard. (Crossing c.) And how be Colonel Dexter? (Shaking hands.)

DEX. (l.) Jolly, my boy—and how’s yourself?

ALLEN. (c.) Oh, I be spry enough. (Crossing before him and shaking hands with Clara, and keeping her hand.) I think us’ll have a pleasant day.

CLARA. (r. looking tenderly at him.) I’m sure we shall. (Crosses to sofa, stands at head of it.)

DEX. Well, you young folks will, I know, and the old folks will be happy looking on. (Sitting, and taking Clara’s hand in his and fondling it. Allen crosses r.) To see his little girl happy, that’s always happiness enough for old Jack Dexter.

CLARA. (Leaning over and kissing the top of his hand.) Silly old dad.

DEX. (Taking out his handkerchief and pretending to weep.) Ah, like her mother—like her mother.

ALLEN. (r. c., laughs nervously.) Her—her mother must ha’ been rare beautiful, mustn’t her?

DEX. (c. rising and taking Allen by the hand.) Thank you,—ah, Mr. Rollitt, you have never known the blessing of a wife—(Clara looks at him)—you do not understand the feelings of a widower. (Weeping.)

ALLEN. No—but—(laughing)—but—I hopes to one day; no—no—I don’t mean that—I—(confused)—Have thee had breakfast? (Clara sits on the soft L.)

DEX. Yes, thank you, Allen, my boy.

ALLEN. (Cheerfully.) Have another.

DEX. No thanks, not to-day.

ALLEN. What’s the matter? Off thee feed?

DEX. No, my lad, but we old folks ain’t like you young country ones—nothing at present thank you—(pauses)—to eat.

ALLEN. Have summat to drink. (Clara crosses l. Both men laugh, each in his own distinctive way. Dex. turns l. and catches Clara’s face.) There be some rare old whiskey in the library. Thee’ll find it on the sideboard—(Dex. goes up c.)—and it be more comfortable like in there than here. I’ll just go and finish making myself beautiful. (Crosses to l.)

CLARA. Don’t be too long. (Crossing and sitting L.c.)

ALLEN. (Laughing.) No, it oughtn’t to take me long to—(Dex. has his back to them, wine business at table r.c.)—do that, ought it? (Goes to l. door down stage. Laughs, and then low to Clara as he is going.) I am not likely to stop upstairs long when I know thee’s downstairs.

CLARA. Go away, go away.

(Exit Allen down stage l. Bus. She kisses her hand.)

DEX. And I suppose you will go and throw this chance away, like you have every other.

CLARA. Well, what if I do? (Rises, crosses it.)

DEX. What if you do? What are we to live on? (Goes to Clara l.)

CLARA. Gulls, I suppose—as we always have done.

DEX. Yes, and is it pleasant living? Is it pleasant to have to slave and trick for every dinner? Is it pleasant to be kicked—sooner or later—out of every society one goes into? (Coming close and speaking low.) Was it pleasant to be buried for two years in that God-forsaken hole by Exmoor, not daring to show our heads above ground for a moment? You’ve got a fine chance of being respectable now.

CLARA. Too late, I’m afraid, though.

DEX. (r. c.) Too late?

CLARA. Yes—you see, papa, dear, you haven’t exactly brought me up in that way, and I’m afraid I’m too old to learn now. I don’t think I should be quite at home as the wife of a piously brought up young man from the country. (Leans back—laughs.)

DEX. And so you’re going to let six thousand a year slip through your fingers. It’s wicked—it’s wicked.

CLARA. (Laughs—rises.) Well, it hasn’t slipped through my fingers just at present, it is sticking to them pretty freely. (Crosses to R.—Dex is c.—toys with ring.)

DEX. (Goes to table r.c.) And how long do you think he will stand you playing with him?

CLARA. Oh, a good long while yet. (Goes up.)

DEX. (Puts hat on table r.c.) That’s just where you’re making a mistake then. He’s not a fool. He’ll want an answer, “Yes,” or “No,” soon, and what are you going to say then?

CLARA. (Looking out of window.) No. (Looking into fireplace r.)

DEX. (After a pause—violently.) Luke Cranbourne’s at the bottom of this. What devil’s game is it that’s going on between you and him? (Loudly.)

CLARA. I do wish you wouldn’t drink when you’re coming out anywhere, it always makes you so noisy. (At glass.)

DEX. (Violently.) Take care, Clara—you seem to forget I’m your father.

CLARA. (Coldly.) The relationship was none of my seeking. Whatever responsibility attaches to the unfortunate—(moves near Dex.)—occurrence is not mine.

DEX. (l. making movement as if to strike her.) Clara.

CLARA. (Facing him with quiet contempt—a pause.) Put down your hands, father. That period of my life is over. (Crosses. Dex. steps back, then throws himself into chair, leans his head on his arms, and bursts into tears r.c.)

DEX. (Crying.) My own child hates me.

CLARA. (Crossing and laying a hand on his shoulder gently.) I don’t mean to be hard, father, but you can’t expect much love and duty from me. Curses and blows were all you ever gave me as a child, and ever since I became a woman you have merely hawked me about as your decoy.

DEX. ( Whimpering.) I only want you to do what’s for your own good.

CLARA. (Turns away L.) Yes, but you must allow me to be the judge of that—and come—you haven’t had much cause to grumble up to now. You’ve been able to be drunk every night for the last three months.

DEX. (Rises c.) I ain’t been drunk. (Takes hat off table r. c.)

CLARA. Not for you perhaps—(goes l. a little)—drunk in the ordinary sense of the word—and I will get you something to-day if I can.

DEX. (Drying his eyes.) God bless you, Clara, you’re a good girl. Do you think you’ll be able to get a twenty?

CLARA. You must leave it to me. I’ll get you as much as I can.

ALLEN. (Off l.) Thank you, Mr. Puffin.

PIFF. (Off l.) Piffin, Piffin, sir.

CLARA. (Moving away towards door—upper l.) Come into the next room now. Here’s Allen coming back.

DEX. (As he follows her out.) Say you want to help a poor woman who’s very ill, and has been ordered nourishing food and—(gags.)

(Exeunt Clara and Dex. upper l.)

(Enter Allen and Piff. l. Allen is completely dressed in the height of walking costume, and is evidently very uncomfortable. Enter Peters c. Pet. puts photo case on table r. c. Exits down c. Allen has on hat and coat, and Piff. is carrying his umbrella and gloves. Allen should be got up in a slightly exaggerated masher style. He is smoking a cigarette.)

ALLEN. I carn’t breathe, Mr. Puffin.

PIFF. Oh, you will soon get used to that, sir. And would you please to remember my name is Piffin, sir? (Taking his hand.) Why, surely these are nines, sir, I think we could get them down to eight and a half, and if I were you, sir, I would show a little more cuff, sir, it’s always done in good society, sir; besides, it makes the hand look smaller; a little cuff, sir, goes a long way in good society.

ALLEN. Thank you, Mr. Piffin. (Shakes his hand.)

PIFF. Thank you, sir, but I don’t think you ought to shake hands with me, sir. And when you do shake hands with your friends, sir—allow me (takes Allen’s hand) shake high, sir. (Shakes his hand high.) You’ll see it’s always done in good society, sir. Lord Carmichael’s man told me he met you yesterday, sir.

ALLEN. I—I don’t know him, do I?

PIFF. Oh, no, sir, but he knows you, sir, and he was rather complaining of your walk, sir?

ALLEN. Why, what’s it got to do with him?

PIFF. Well, sir, knowing as I’m your coach, sir, he meant it as a friendly hint. You have rather a countrified walk, if you will forgive me for saying so—a more négligé style is adopted by the savoir vivre now, sir, and a more insouciant manner of carrying the umbrella. You walk too much in this way, sir. (Taking up umbrella, gags, and imitates.)

ALLEN. Lord love us, do I walk like that?

PIFF. Just like that, sir. You see yourself, sir, what a very undestingué appearance it presents. The present fashionable style is more like this, sir. (Performing an exaggerated Piccadilly dawdle.) See, sir—body a little forward—knees stiff—and a slight wobble, sir—very slight. (Handing Allen the umbrella.) Perhaps, sir, you would take the umbrella and try it, sir.

(Allen attempts the business.)

PIFF. (Criticising Allen’s practice. Allen crosses to R.) A little more bend, sir—a little wobble, sir—umbrella held lightly between the first and second fingers, sir, (Allen goes l.) and if you could manage—allow me, sir—. (takes umbrella, shows him, and returns it) to swing it right round now and then, sir, it adds great aplomb.

ALLEN. Great what?

PIFF. French, sir.

ALLEN. (Swings umbrella round awkwardly.) Like that?

PIFF. Not quite like that, sir. A little more airily, sir.

ALLEN. (Swinging it.) Does it ever put anybody’s eye out behind?

PIFF. I don’t think that point is considered of much importance in good society, sir—that is much better, sir. (Goes r.Allen l.) If you would practice like that a little every day, sir, you would soon pick it up, sir. A little more bend, sir, and—er—don’t forget the wobble.

(Exit l. down stage.)

(Allen goes on practicing to himself, making as much fun as possible, consistent with comedy, out of the bus. As he is in the middle of it, enter Mrs. R.and Deb. door c., the door being opened for them by Peters. They stand c. staring aghast at Allen, who continues, unconscious of their presence.)

ALLEN. (Gags.) Soon pick it up! Strikes me someone’ll have to pick me up. It puts me in mind of one of our old turkey cocks.

(Mrs. R. and Deb. come down stage a little.)

ALLEN. (Bus. in r. corner of stage. Peters withdraws, grinning.)

DEB. (After a long pause, clapping her hands.) I know what it is, aunt. It’s our Allen.

ALLEN. (Seeing them.) Mother! (Comes down r.c. Deb. l. c.)

MRS. R. My boy! (They rush into each other’s arms c. and Mrs. R. gives him a huge hug—gets r.of Allen, Deb. l. Then he and Deb. have an embrace, and then he and Mrs. R. for the second time.)

ALLEN. (In the middle of Mrs. R. second hug.) Hold hard!

MRS. R. (Alarmed.) What’s the matter, lad?

ALLEN. Summat’s gone.

MRS. R. What?

ALLEN. I don’t know; summat behind. (Drawing back r. and looking down at himself.) Mother, you’ve spoilt me.

MRS. R. Ah, they used to tell me I allus did that, lad. (Laughs.)

DEB. (After gazing in silent admiration at Allen.) Oh, aunt, isn’t it lovely? Look at its hat!

MRS. R. (Critically examining his clothes.) Ah—and there’s some good stuff there, too. (Moving away.)

DEB. (Going near and sniffing.) Oh, oh! Doesn’t it smell nice—and—oh, look at its collar! (Allen pleased—begins to plume himself—Deb. begins to laugh.)

ALLEN. What’s the matter with the collar—what are you laughing at? (Trying to look at his own collar. Debt’s laugh only grows, and Allen’s indignation begins to rise.)

ALLEN. What’s the matter—what are you laughing at? (Deb. laughing more and more, goes to walk round him. Turning round, so as to face her—his collar prevents him turning his head, and he has to walk round.) What are you up to?

DEB. I want to see it all round.

ALLEN. (Very indignantly.) Well then, you can’t do it. I ain’t a show. What are you laughing at? There’s nothing to laugh at. (Mrs. R. laughs first time.) It’s your ignorance, because you don’t understand things. What are you laughing at?

(Mrs. R., who has hitherto sat R. looking on, now also begins to laugh, and she and Deb. go on laughing more and more, Allen growing more and more indignant.)

ALLEN. I am surprised at you, mother. Deb. allus was a—(the two women only laugh louder, and Allen in spite of himself begins to laugh too; afterwards he joins in heartily and all three laugh, after which they have another hug. Bus.)

MRS. R. (Exhausted.) Well, lad, and how dost thee like being a gentleman? (Sits r., Deb. sits l.)

ALLEN. (c. doubtfully.) Well, it’s got its drawbacks, mother. There’s more work about it than you’d think for, you know,—but I think I shall be all right, I’ve got a good man learning me. He wur teaching me to walk this morning. That wus the Park stroll I wur practicing when you come in; see, mother? (Imitates stroll.)

MRS. R. Ah, well, us made a good man of ’ee down in Devon. I hopes they don’t spoil ’ee, lad, in turning thee into a gentleman.

ALLEN. Ah, no, mother. It’s only a polishing up the outside. I’m old Exmoor oak—(puts his hat and umbrella on table r. c.)—I hope, right through, and they can’t hurt that. When did ’ee come up? (Sits r. c.)

MRS. R. Only yesterday, and us went to Mrs. Clouter’s and slept, and then us come on here this morning.

ALLEN. And how long can you stop?

MRS. R. Well, us must start off to-morrow, some time.

ALLEN. To-morrow! Oh, nonsense, mother.

MRS. R. Nonsense! Why, bless the lad, thee wouldn’t have me away on Saturday. Why, who’d pay the wages, and see to everything?

ALLEN. Why, there’s Rogers there, ain’t there?

MRS. R. Ah, why thee might just as well leave the key of the stable in charge o’ the old bay mare, as trust him to look arter anything, except his own inside.

ALLEN. (After a pause.) Mother! (Rises, goes to Mrs. R. r.) What do ye want to go back at all for, and work and worry yourself to death? Let me take a little house up here in London for thee and Deb, and then we can all be together.

MRS. R. (Aghast.) And leave the farm?

DEB. (Turning round.) Oh, Allen!

ALLEN. Why not? You’ve worked hard enough, mother—give the farm up and enjoy yourself.

MRS. R. Enjoy myself! Away from Woodbarrow

Farm! Why, lad, thy father wur born there and brought me home there—and he died there, and thee wur born there—and there be the pigs and the poultry! (Begins to cry.)

ALLEN. (Tenderly patting her.) All right, mother, all right. Us’ll keep it on.

MRS. R. (Wiping her eyes.) And thee might want to come back to it theeself some day, lad.

ALLEN. (Laughing.) Why, thee don’t think I’m going to run through two hundred thousand, do ye, mother? We Devonshire lads win fortunes, not lose ‘em. (Crossing c.)

MRS. R. Ah, no, lad. But thee knows the saying “Roses blossom for a day, But stout old ivy’s green al-way.” Thee ain’t likely to lose the money, if thee can help it, lad, but us all be in God’s hands, and I’ll be easier in my mind if the farm’s there for thee to come home to. If anything happens, thee knows the way across the Moor, and thee knows how the latch goes, and me and the lass will be inside to welcome thee.

ALLEN. (Goes l. takes Deb.‘s hand.) Ah, I know you will, mother, both of you.

MRS. R. (Music—piano.) Leastways I shall—and the lass until her gets married, I suppose. (Deb. goes up a little; gets r.)

ALLEN. (Surprised.) Until her gets married? (Deb. goes to Mrs. R. r.; tries to stop her speaking.)

MRS. R. (Sharply.) Ah, the lads ain’t all fools.

ALLEN. (Evidently troubled.) I never seemed to think o’ Deb’s getting married, somehow.

MRS. R. Well, other folks have.

ALLEN. I can’t fancy the old farm wi’out Deb. Lord, how lonesome it would be.

DEB. (Who has been trying to stop Mrs. R., has come down and stands by her aunt, l.) Oh, it’s only aunt’s fun. (Goes to Allen, l. c.) I’m not going to get married. Sure the pigs and cows are worrit enough wi’ their foolish ways. I don’t want any husband.

ALLEN. Ah, thee will some day, o’ course, and when thee does we must make thee comfortable, lass. (Taking her hand.) Thee shalt ha’ the best farm in all the country, and the best dairy, and the best stock.

DEB. (Little c.) Thank thee, Allen dear. (Turns up stage.)

MRS. R. (Rising; music dies away.) Well, lass, I suppose us had better have a clean down and summat to eat, and then see about our bit o’ shopping.

ALLEN. Lord help us! (Starting.) If I ain’t forgot all about ‘em.

MRS. R. All about whom?

ALLEN. Why, Clara—Miss Dexter and her father—they be in the library waiting for me.

DEB. Oh, don’t let us keep you from them. (A little spitefully.)

ALLEN. Oh, I shan’t go out this morning, now. (Gets hat and umbrella from table r.c.) I shall get them to stop here instead, and us can have a nice quiet day all together. (Going towards door, lower l.) Come on, mother. (Crosses to c.) I’ve got a room fitted up a’purpose for thee and Deb, with a roost just outside the window with a cock and three hens in it, and he crows all night.

(Exeunt Allen, Deb., and Mrs. R. down stage.)

(Enter Baron von Schorr (1) and the Hon. Tom. Gus-sett (2), ushered in by Peters c. (3). Enter Luke c., and Dexter u. l. (4), afterwards Clara (5.) Baron goes down l., Gussett r., Luke r. c., Dexter l. c.)

DEX. (l.) Rollitt’s going out. You can’t see him. It’s no good your coming here to try and fleece him this morning. I tell you he’s going out.

LUKE. (Coming down r.c.) Ah, we’ll wait and say good-bye to him, Jack.

BARON. (l. c.) Ah, greedy Jack,—greedy Jack—you want de bird all to yourself. Nein—nein, zhare and zhare alike. Herr Cranbourne have a ving, Tom Gussett, he have de oder ving. You and your fair daughter have de legs, and I vill have de breast.

CLARA. No, you shall have the bones after we’ve done with them. Make ’em into a stew—keep a German baron for a week. (Others laugh.)

BARON. Ah, Trickey, you here. (Motioning towards Clara and her father.) Ah, de early birds—de early birds.

CLARA. Yes, we have to be. (Rises, and goes r.imitating him.) De worms get up so early nowadays. (Enter Allen lower l. Baron goes to meet him. Guss. puts him away and he turns up c. Speaks to Dex.)

ALLEN. Hullo! Unexpected pleasure!

(Luke comes forward and greets Allen c.)

GUSS. (r.) Haven’t seen you for an age, dear boy.

ALLEN. No. (Goes to Luke r.) I’ve been keeping pretty respectable of late—I—I mean, you know, I haven’t been going out much.

LUKE. (l.) Tom and I are going over to Paris for the Vincennes meeting, and we’ve come to see if you will join.

GUSS. (l. of Allen r.) Yes, do come; then we can show you about Paris a bit, you know.

LUKE. Ah, yes, and we shall be able to get you into one or two things in the betting line if you are with us. We can introduce you to some friends of ours.

ALLEN. Ah, it be very kind of thee, I’m sure.

(They go on talking r.)

BARON. (Aside to the Dexters, back of Clara.) I say, Jack, my boy, how long have you been Colonel? I did not know you vas a militaire.

CLARA. Papa joined the Salvation Army about the same time that you were raised to the German Peerage. Don’t talk so loud, my dear Baron.

BARON. Gut, gut.

(Luke sits down stage r. with back to audience, looking at betting book.)

GUSS. (To Allen r.) Of course we shall take care of your interests as if it was for ourselves.

BARON. (Comes and puts arm in Allen’s.) Of course they vill take care ob your interests for themselves. Come here. (Goes l.) You know I have been tinking about you so much ob late. Ja!

ALLEN. Ah, very kind of thee, I’m sure.

BARON. (l.) Ja, I say to myself, my fren Rollitt—I always call you my fren—my fren Rollitt, I say, he is a gut fellow—he has money—all he vants is family. (Guss. goes to Dex. l. c.) He must marry family. (Dex. goes c. and tries to hear conversation—Baron notices it and crosses to r.with Allen.) Now, Miss Dexter, she is a nice girl—ach, such a nice girl—but she has no family.

ALLEN. No—not yet. (Luke gets near fireplace R.)

BARON. (r. Seeing it after a while.) Ah, nein, nein—I do not mean vat you mean—I mean family de oder vay—backvards—dead uns.

ALLEN. Oh!

BARON. Ja. Now, dere is my niece, look at her family! Look at her ancestors—all barons—German barons! And she is such a nice girl—so beaudiful—so plump—ach, I will indroduce her to you. She vill mash you—so much. She—

(Enter Mrs. R., Deb. behind her, lower l. door. Seeing the room full she stands by door hesitatingly.)

GUSS. (Coming down and interrupting, with a sneering laugh.) Your nurse, Rollitt, I think. (Comes c. Luke goes to fireplace R.)

ALLEN. (Turns and sees them, and then goes towards them.) Yes, Mr. Gussett—the best nurse a man can have—my mother.

(Guss. confused, but soon recovers himself and laughs it off. Col. D., Luke, and Clara come forward to greet Mrs. R. and Deb. l. c., and the customary ceremony, etc., is gone through—all speaking together.)

CLARA. (Smiling pleasantly, shakes hands with Mrs. R.) Good-morning, Mrs. Rollitt. You are looking so well and jolly. How are you, my dear? (To Deb. Between these two the greeting is really strained and awkward, although outwardly pleasant enough. Clara kisses Deb., but Deb. seems to shrink—she turns away. Clara notices this, and follows Deb. as she turns away up c., with a meaning look. While it has been going on the greeting between Mrs. R. and Luke has taken place—Mrs. R. down l.)

ALLEN. (Finishing his introduction of Mrs. R. and Baron.) The Baron von Schnorr—Mrs. Rollitt, my mother.

BARON. Your mudder—Oh, impossible. (Goes l. c.)

MRS. R. (Huffy.) I beg your pardon, Mr. Snort.

BARON. Ach, ja, you are laughing at me—not your mudder.

(Clara walks round at back, drops down r. near Luke.)

MRS. R. (Very indignant.) Yes—his mother. Don’t you cast any of your nasty foreign insinuations upon me. I’m his lawful married mother, and his father was his father, and a better man never lived, as anyone in Exmoor—

ALLEN. (Soothing her.) It’s all right, mother, the Baron only means it complimentary. Thee’st supposed to look too young to be anybody’s mother. He has to take (Clara sits r.) thee for my sister. (Laughing—goes up l. c. with Dex.)

BARON. Ja—I take you for his sister. Ach, you English ladies, you never seem to get more old—you only get more round, more—more jolly.

MRS. R. (Still indignant.) Ah—foolishness. (Ruffling her dress and sitting very stiff l. on sofa.)

BARON. (Sitting on sofa beside her.) It must be de climate keep you so moist. (Drawing closer.) I knew a man, he lives in your Manchester, and—(goes on talking to Mrs. R. but is not heard.)

(Allen goes up and joins Col. Dex. up l. c. and Clara. After a little while Col. Dex. appropriates him, leaving Clara a little to r.of them unnoticed. Guss. continues talking to Deb. Deb. evidently bored and anxious to get away. Guss. trying to be very agreeable. At this point when all the others are occupied, Luke r. beckons Clara to him and she crosses. Their conversation is in eager undertone and they watch to see that no one is noticing them.)

LUKE. Have you got him to join yet?

CLARA. No—he kicks against it.

LUKE. If his name isn’t down in the list of directors before Monday I shall be arrested.

CLARA. Can’t you get away?

LUKE. No, I’m watched night and day. If he joins, the company will float and it will be all right.

CLARA. I shall be seeing him alone this morning. I will try again.

LUKE. And keep to plain gold and diamonds for presents. Those fallal things (touching her bracelet) are no good. Don’t fetch ten per cent, of their value.

DEB. (Part of the conversation between herself and Guss. Abstractedly, her attention being fixed on Luke and Clara.) Ha, ha! that was very funny.

(Guss. r. with Deb. looks at her in amazement.)

LUKE. (Down r.) There’s that milkmaid watching us—don’t look around, answer as though I had been proposing to you—that will account for our talking together. (In a louder but still undertone.) Is there no hope for me?

CLARA. (Down r.—smiling.) None, Luke—please don’t refer to the subject again. I like you—respect you—will be a sister to you—but love—

LUKE. (Grinning.) Yes, it’s that Rollitt that you love. (Deb., followed by Guss., has moved away to window.)

CLARA. Mr. Cranbourne, you have no right—

LUKE. (Who has been watching Deb.) Chuck it up, it’s all right, she’s gone to the window.

CLARA. I don’t suppose we’ve deceived her very much, she’s a sharp little minx. Get these men away.

(Clara takes up book, and standing, toys with it up r. front of r.c. table.)

BARON. (Finishing.) She never leave her bed for eighteen years—she take dree dozes—den she get up and go for a dree mile walk.

MRS. R. (Rising.) Lor! It must have been quite a change for her.

BARON. (Rising.) Ja. It vas a miragle. (Turning and seeing Luke beside him.) Ha, my dear boy, ready?

LUKE. (Crosses to Baron.) Ready and off.

ALLEN. (Coming down c. followed by Dex.) Oh, are you three going?

(Baron goes c.)

LUKE. Yes, I know you’ll be glad to be rid of us. (Laughing.)

ALLEN. Well, I have (looking at watch) one or two little things to do this morning.

(Baron goes up c.)

DEX. Well, look here, Allen, I’m just going to have a quiet weed in the smoking room till you’re ready. See?

ALLEN. Oh, it be a billiard room now, thee know.

LUKE. Oh. have you had a table put up?

CLARA. (Who has just crossed over and joined the group l. to Mrs. R. who is just about quitting the room by door l. lower.) Do you allow your little boy to play billiards, Mrs. Rollitt? I don’t think I should if I had charge of him. (Playfully.)

MRS. R. Oh, the more he’s up to every sort o’ game that’s played the better for him, to my thinking.

(Exit Mrs. R. l.)

ALLEN. (Laughing.) Oh, it keeps me at home out of mischief, like. (Moves to upper door L.) Come and have a look at it. (Goes up c.)

BARON. (As they go.) Ach, billiards iz a beaudiful game. (Aside to Luke.) But you cannot vin much at id, id take so dam long.

(Exeunt all but Guss. and Deb. [l.]—all talking as they go. Guss. and Deb. near fireplace.)

DEB. (r.) Well, I’m afraid, Mr. Gussett, I must really go now. (Goes down stage. Guss. goes l. c. and stops her.)

GUSS. (Getting between her and the door l. to which she is backing.) Oh, no, don’t go. Do you know, I shall really think you are trying to avoid me.

DEB. (Retreating behind table—Guss. takes a step.) Oh, not at all.

GUSS. (c. gets l. of r. c. table.) Ah, so pleasant to hear you say so. You know, Miss Deacon, I so want you to like me.