Title: The Life Story of an Otter

Author: J. C. Tregarthen

Release date: June 9, 2017 [eBook #54872]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed

Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net from

page images generously made available by the Internet

Archive (https://archive.org)

THE LIFE STORY OF AN OTTER

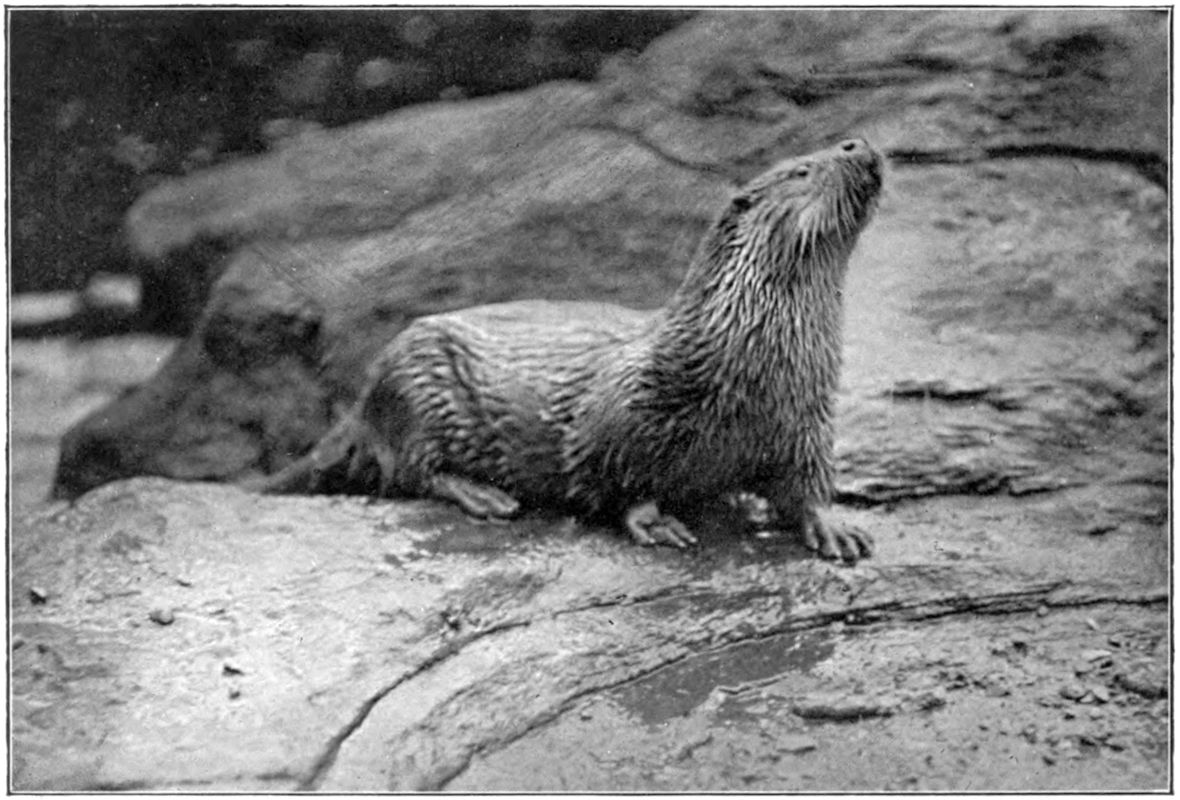

OTTER CUBS.

Reproduced by kind permission of Her Grace the Duchess of Bedford.

Frontispiece.

THE LIFE STORY OF

AN OTTER

BY J. C. TREGARTHEN

AUTHOR OF ‘WILD LIFE AT THE LAND’S END’ AND

‘THE LIFE STORY OF A FOX’

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1909

TO

MY WIFE

The otter has long seemed to me worthy of serious attention, if only for the successful struggle it has waged against those exterminating agencies under which the badger, the wildcat, the polecat and the marten have all but succumbed.

Its survival throughout Great Britain is due, partly to its endurance and resources when hunted, partly to qualities and habits which differentiate it from the other creatures of the wild. Its scent, for instance, unlike that of fox or badger, to which every tike and lurcher will stoop, is noticed by few dogs save hounds that have been trained to own it; and the outlawed beast thus gains a certain immunity from destruction.

Then the otter is a great wanderer, who not only traverses long stretches of coast and follows streams and rivers to their source, but crosses hills and even mountains to reach its fishing-grounds. It has been known to travel fifteen miles in a night, and not infrequently the holts where it lies up during the day are ten or twelve miles apart.

On the way to its quarters it will linger to fish or hunt, and the remains of eel, salmon, pike, rabbit, moorhen or wild-duck mark the scene of the midnight feast. But no matter how much it may leave uneaten the otter never returns to a kill, and so escapes the traps with which gamekeeper or water-bailiff is sure to ring the ground about it. Unlike its congener the polecat, the otter does not hoard food; unless the caches of frogs occasionally found in marshes are its work, and not that of the heron as is generally supposed.

However that may be it is certain that it does not hibernate, but is abroad night after night the whole year round. Indeed, as often as not, the female produces her young in the depth of winter, and indefatigable forager though she is, must often be sore pressed to provide food for her litter. At times the conditions are too severe, and a tragedy ensues. At Mullyon, in Mount’s Bay, one bitterly cold December, when the Poldhu stream was frozen and the sea too rough and discoloured for the otter to fish, the poor creature in her extremity crept into a bungalow in the course of erection, and was there found curled up dead.

It seems to me a matter for regret that such an interesting beast is not better known; and the present narrative is an attempt to portray it amidst the wild surroundings that are so congenial to its shy nature.

The critical reader will perhaps wonder at the daring that essays to interpret the workings of the most subtle of animal brains, but I submit that the inferences are, for the most part, of a very safe character; and modest as they are, they would not have been adventured on, had it not been for my long familiarity with the ways and habits of a creature that is by general consent the most mysterious and inscrutable of our fauna, for the incidents described embody the gleanings of a lifetime of observation and inquiry. It will be noted that I agree with those who hold that in pursuit of fish the otter is guided wholly by sight, though it may well be that the extraordinary powers of scent which enable the creature to detect the presence of fish in a stream or pond by sniffing the surface are called into play during immersion.

The story of the otter is, I believe, now told at any length for the first time; and my hope is to bring about a wider and deeper interest in the animal, and be the means of removing some of the prejudice which unjustly attaches to it.

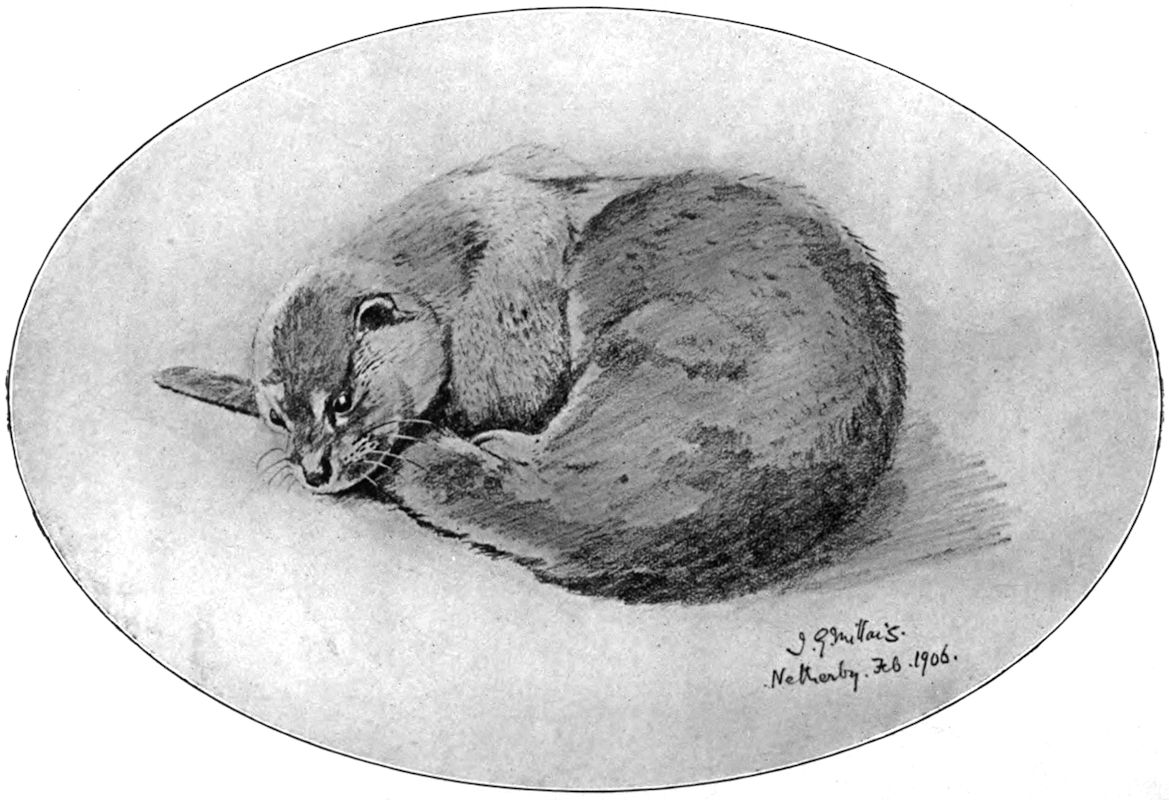

I take this opportunity of thanking the Duchess of Bedford and Mr. J. G. Millais for their courtesy in allowing me the use of most valuable illustrations.

Tregonebris,

Sancreed,

West Cornwall.

March 10, 1909.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||||

| I. | IN THE NURSERY | 1 | |||

| II. | EARLY TRAINING | 10 | |||

| III. | THE FIRST TREK | 21 | |||

| IV. | AT THE CREEK | 39 | |||

| V. | SEA AND MARSH | 53 | |||

| VI. | THE FAMILY BROKEN UP | 69 | |||

| VII. | THE OTTER AT THE TARN | 83 | |||

| VIII. | THE OTTER AND HIS MATE | 104 | |||

| IX. | FROST AND FAMINE | 120 | |||

| X. | TRACKED | 131 | |||

| XI. | BACK IN THE OLD HAUNTS | 145 | |||

| XII. | THE LONG TRAIL | 166 | |||

| INDEX | 187 | ||||

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

| OTTER CUBS | frontispiece | ||||

| HURRYING HOME | to face page | 8 | |||

| THE RIVER BELOW THE MILL | " | 18 | |||

| THE WILD COAST-LINE | " | 62 | |||

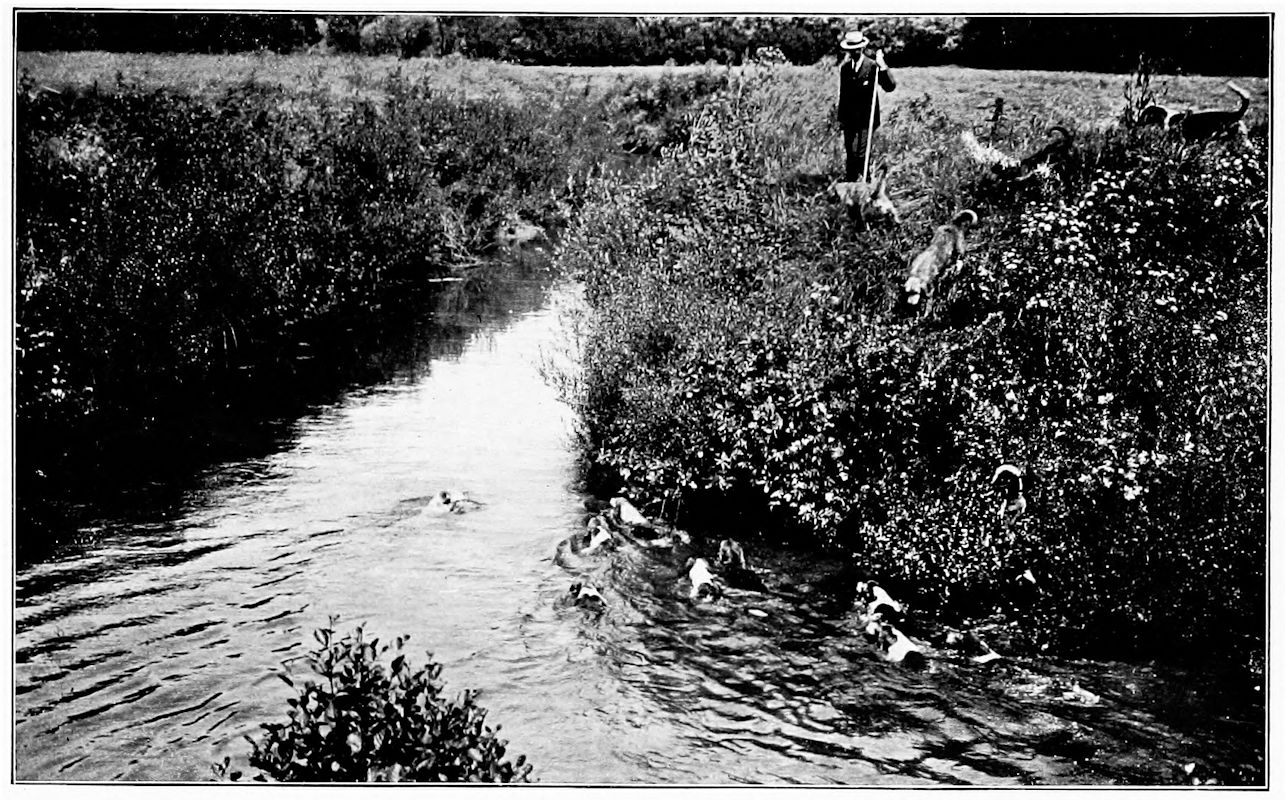

| HOUNDS SWIMMING AN OTTER | " | 78 | |||

| THE OTTER | " | 83 | |||

| ON HIS WAY UP THE CREEK | " | 107 | |||

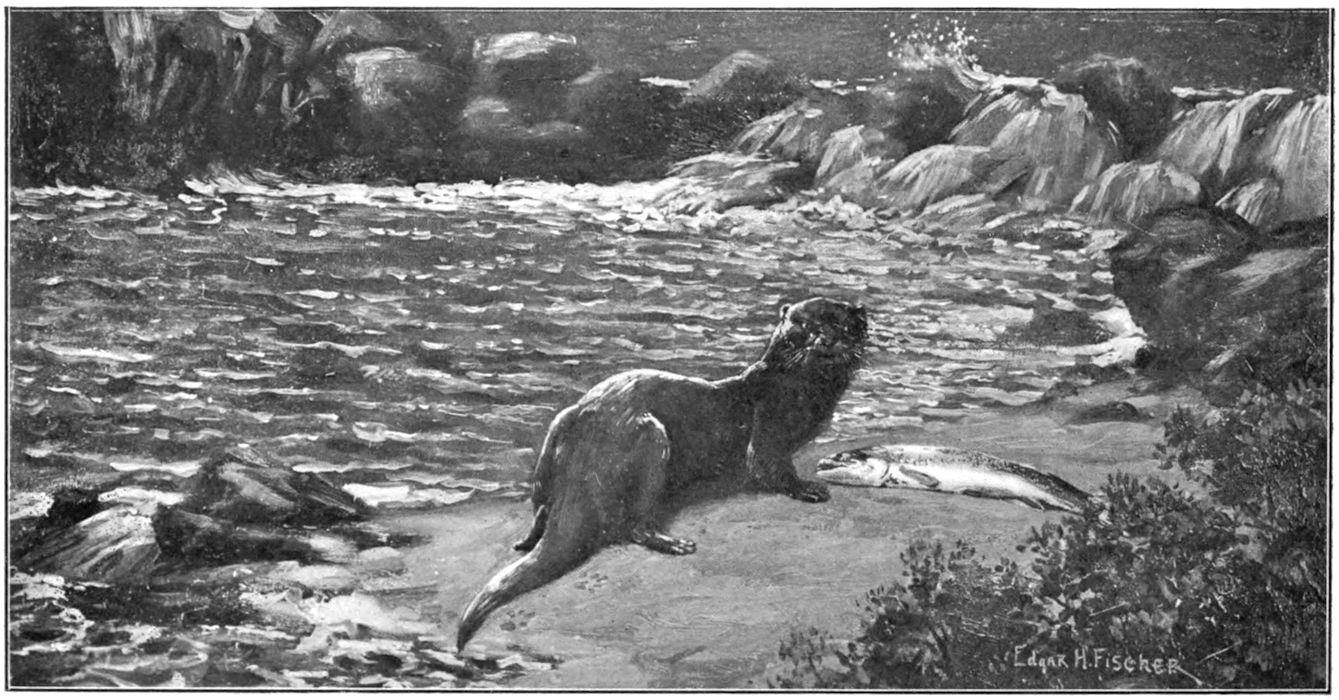

| HIS LAST SALMON | " | 173 |

THE LIFE STORY OF AN OTTER

IN THE NURSERY

It was in a morass in a hollow of the foothills that he was littered. His mother chose this inaccessible spot for the security it promised to her helpless young. In the heart of the quagmire they would be safe, she thought, from floods and—what was still more important to her—from man. She could not find a hover quite to her liking, but in lack of a better, she chose a ledge where, in an angle of the stream that drained the bog, the bank furnished a screen from the biting wind which blew up the valley and soughed over the uplands. After enlarging the ledge into a shelf, she shaped the excavation for the nest, which she fashioned out of dead rushes and withered grasses, and which she lined with the softest products that Nature offered her—tattered reed-plumes and seed-down of the bulrush. Night after night she ransacked the waste in quest of these rare spoils, lest the rude structure should be wanting in cosiness for the cubs which, even before it was quite finished, were deposited in it.

There were only two to share her affection—the intense affection of the hunted creature for its offspring. The dread of being reft of them haunted her from their birth, but happily the mites themselves knew no fear, knew nothing but the warm, furry mother who fondled and suckled them. Whelps and dam were as one, for she seldom left them save to get food; and this she sought and devoured with feverish energy, that she might the sooner return to them. She foraged sometimes, it is true, in the morass itself; but usually she had to go to the river at the foot of the long, undulating slope, and though the inconvenience of having the fishing-ground so far away was often borne in upon her, she put up with it, and never for a moment thought of moving the cubs from the safe keeping of the bog.

Under the grey skies, the rain and the sleet of January, few more cheerless scenes could be found than the moorland and the morass within it; yet there in the hollowed bank the otter and the wee, blind, downy-coated creatures she had entrusted to the chill mercies of midwinter, lay nestled in the snuggest of hovers. And the grim season would relent at times, breaking into bright days when the sun bestowed its warmth on the cold, sodden earth. Then the morass and all the hills about it were bathed in the glow, and the swollen stream, visible over the edge of the nest, glistened like silver. Quick to accept Nature’s bounty for the winterlings, the otter, when satisfied that no eye observed her, took them between her lips, carried them from the gloomy hover, and laid them on a tussock which screened her where she crouched, ready to protect them. There the cubs stretched themselves and basked with quiet content in the health-giving rays. But when the sun passed behind the clouds, they would complain at the withdrawal of the warmth, and raise their blinking eyes to the sky as if protesting to a second mother against such unfeeling treatment.

For before this they had opened their eyes—black, restless eyes, like those which kept constant watch and ward over their safety. The otter, of course, managed to get a little sleep, but it was of the lightest. At the startled note of a bird, or even the sudden rustling of the reeds when a gust shook them, her head would pop up from the grasses concealing her; and she generally made a keen inspection of the sky-line and of the ground within her ken before she lay down again and snatched another forty winks. But as morning after morning passed without intrusion of aught to warrant her suspicions, her vigilance gradually relaxed; and one noon, when she was very weary from the night’s foraging, she curled up and fell sound asleep at her post.

Whilst she slept, a buzzard, mewing as he quartered the ground beneath, espied the cubs, and thinking they were at his mercy, stooped to seize the easy prey. He was about to lay hold of the smaller cub when the otter, awakened by the strange cry, rose from her hiding-place and confronted him. At sight of her the bird, taken aback, thought only of escape, but the mother was bent on avenging the attempted wrong. Quick as lightning she sprang at him, and, had not the hummock given way beneath her, she must have gripped him despite the frantic down-strokes of the big wings which lifted him well beyond her second leap. Her fierce eyes and bristling hair made her terrible to behold as she stood watching the marauder’s retreat, and hissing the while like a fury. Then, as if fearful that the fray had attracted attention, she took her eyes off the bird and scrutinized the approaches to the morass before removing the cubs to the nest, where she stilled their complaints by fondling them until they fell asleep and forgot their sunny couch on the grass. The incident troubled the otter so greatly that, resisting all their importunities, she never again exposed them to the risk of capture.

To break the monotony of the hover, the cubs, as their limbs grew stronger, would, in the intervals of sleep, clamber to the wide parapet of the nest and take note of the things that moved within their narrow field: of trembling grasses, of the bramble spray that moved to and fro in the current, of the reeds that nodded in the wind, and, above all, of the creatures that visited the stream to feed or quench their thirst. They watched every step taken by the snipe, every thrust of his long bill; they regarded with wonder the gay kingfisher that perched on their ledge and fished in their pool; they were moved to the keenest curiosity by the old dog-fox, who stole from the reeds to drink and set their young nostrils working with his strong scent. When sure of their footing, with pads outstretched and every webbed toe expanded they advanced to the very edge of the nest, pushed their dusky grey heads through the grassy curtain, and looked down at the eddy gurgling below, contemplating the element in which their lives would be spent and whose every change they were to know.

They resembled kittens more than any other young creatures, the difference lying in their tiny ears and shy, wild eyes. But, suggestive of fear as was their look, they were not as yet conscious of the danger besetting them, even when able to scramble up the bank and sprawl about the bog. Thither the otter led them in all weathers, and it was for this duty that she hurried back to them the instant she had done foraging. Now and again the scarcity of prey or the difficulty of securing it would detain her far into the night and sorely tax the patience of the cubs, eager for her return. In the intervals of listening they would pace round the now dishevelled nest, increasing their speed as the hours passed without sign of her. At length the shrill whistle, heard even above the storm or downpour, would reach them, and set them dancing with delight. Two furry heads and little red tongues greeted the panting mother as soon as her feet rested on the ledge, and the next instant the capering creatures followed her as she led to the gambolling-ground beyond the great reed-bed. There they frolicked to their heart’s content through the hours of darkness, and even after sun-up when thick fog shrouded the morass. On reaching the nest the otter suckled them to sleep, and, lying between them and the mouth of the holt, as was her invariable custom, shielded them from cold and danger.

These were happy days for the dam, but owing to the wilfulness of the male cub they did not last long. He had taken it into his head that he was big enough to go out alone, and one night out he ventured. He was more than half-way to the reed-bed when his mother found him. This first demonstration of independence caused her little concern, but she was almost beside herself with anxiety when, two days later, he made an attempt to sally out in broad daylight, and all but succeeded in getting away. He was nearly over the bank when she pulled him back by the tail and gave him a sharp nip by way of punishment. The very next day the incorrigible fellow got even farther away; but she discovered his absence before he had got beyond the tussocks, fetched him back, and bit him severely as she laid him down in the nest. Thus disobedience brought unhappiness into the hover, and the cub, shrinking from the mother he deemed cruel, shuffled to the inmost corner, where fibrous roots protruded from the low roof, and there licked his bruises in morose isolation.

Photo C. Reid, Wishaw, N.B. To face p. 8.

HURRYING HOME.

Aware now of his rashness, the otter dared not leave the nest by day as she had occasionally done before. One noon, however, impelled by her own hunger and the cubs’ piteous entreaties for food, she put aside her apprehensions and stole out, leaving them to their own devices. As quickly as her pads could carry her, she made her way down the hill along the rents that fissured the peaty ground, dived across the swollen pool in the hollow below, dashed over the sward beyond some alders, and gained the wood and the river unobserved. The river was bank-high and much discoloured, but after a long quest she came on an eel abroad in the flood. Landing under some bushes on the far side, she devoured half the fish, and then, without a moment’s delay, slipped into the river and floated down with the current. At a rapid pace she rounded bend after bend, came ashore at a backwater, leapt some felled trees, and regained the bog by the same hidden ways. To her dismay she found, as she had feared, the nest deserted and cold. In great distress she set out to fetch the truants home. She followed their trail to the reed-bed, through which she dashed like a thing demented, and came upon her two cubs playing in the open as fearlessly as only tame creatures may play. On sighting their mother, the runaways, instead of slinking off guilt-stricken, rushed at the full speed of their ungainly limbs to meet her, and tried by winning antics to induce her to join in their midday romp. Gladly as she would have complied, her response was to drag them into cover, take the smaller cub in her mouth, carry it to the nest, and return for the ringleader, who squealed with rage until soundly ducked in the pool below the hover. The dark-pelted creature was a conspicuous object as she splashed across the exposed spaces; but, as good fortune would have it, both she and the cubs escaped the observation of the keeper who was occasionally to be seen on the hills overlooking the morass. Still, the poor outlaw had been taught a sharp lesson, and resolved never again on any pretext to leave the cubs by day. So greatly was she perturbed by their escapade that she even longed for the moment when fear should awaken in them and whisper its monitions.

Meanwhile, she looked forward with impatience to the night when they would be able to follow her afield and learn the many lessons she was anxious to teach them; and in order to hasten the time, she devoted every hour she could spare to sharing their frolics, so that they might develop rapidly.

EARLY TRAINING

When the cubs were a little over eight weeks old, their mother resolved to take them to the pool and teach them to swim; so one starry night at setting-out time she led the young creatures—overjoyed, as their excited antics showed, at this new departure—to the brow of the rising ground, till then the boundary of their narrow world. There, whilst the otter stood and reconnoitred, the eyes of the cubs wandered wonderingly from slope and rushy hollow to the woods across the ravine, where a vixen was squalling. As no danger threatened, dam and whelps made for the faintly silvered pool lying so still and silent in contrast with the river that ran brawling along its boulder-strewn channel. On reaching it the mother swam slowly out, turning her head the while as if to invite the cubs to follow her, landed on the islet and, in order to work on their feelings and draw them across the water, hid herself amongst the withered sedge. This was not without its effect, as the cries of the cubs showed; yet, distressed though they were at the separation, they were afraid to commit themselves to the pool and try to join her. Thereupon the otter swam back to within a few feet of the foreland where the shrinking creatures stood and, wheeling slowly, returned again to the islet, calling as she went.

This she did many times, employing every wile she knew to coax them after her; but all in vain. For three nights, despite all her pains, she failed to tempt them beyond the shallows. At last, just when she was about to put them out of their depth, the smaller cub overcame its hesitation, waded till it lost foothold, then swam bravely across, landed with a little wriggling jump, and sent the spray flying from every silky hair along the fourteen inches of its length, as it shook itself before rolling on the sedge to dry its coat more thoroughly. The male cub, who had watched her every movement, was now beside himself at being left alone, and after running for some time up and down the bank, uttering the most piteous plaints, followed the others across and dried his fur as his sister had done. Presently they all swam back to the foreland. Before returning to the hover, they crossed and recrossed four times more; and once even, in the absence of the otter, who was away foraging, the cubs crossed alone.

From this night their fear of the water abated, and soon, with scarce a ripple to mark their smooth progress, they were able to accompany their proud mother in her circlings round and round the pool. When the smaller cub tired, the otter slackened her pace, sank very low, took it on her back, and carried it to the shallows; but the male cub always had to take care of himself. The subsequent improvement was very rapid, and at the end of a week so fond did they become of the water that when released from the hover they scurried to the pool in advance of their mother, stumbling and falling as they ran in their eagerness to reach it.

Being full of the young creature’s love of ‘hide-and-seek,’ they often concealed themselves before she came up. On hearing her approach, they drew their heads beneath the surface until only their nostrils showed and, though thrilling with excitement, kept as motionless as the alder snags about them until discovered. Then mother and cubs joined in play, disporting themselves at times on the surface, but more often in the depths. Presently they would rise, locked together as if in deadly struggle, and roll over and over like a water-logged ball in a current. All at once, and frequently whilst immersed, they would break up, land, and make the circuit of the banks, passing one another as though they were utter strangers, and then suddenly, as if by signal, take to the water again and resume their mimic warfare. Once whilst they were thus engaged the whistle of an otter reached them from the river. In a twinkling they stayed their gambols, and, floating side by side, listened until the call grew faint as the traveller passed up the valley; then they fell again to their romps.

Wonderful ease and grace marked their movements in the pool, and still more in the streams and eddies of the river, to which the otter lost no time in taking them. They spent hours shooting the rapids below the salmon pool, landing at the end of the long run where the rush of water loses its force, and regaining the head of the current by climbing the rocky bank. So attractive did this diversion prove that but for their mother’s restraint the eager creatures would have left the nest for the river long before it was safe to be abroad. Once, indeed, overborne by their importunities, she so far yielded as to lead them out before the afterglow had paled; but this concession only made them more exacting. On the morrow they would have her release them the moment the sun dipped below the crest and the shadow of the upland fell on the morass. But she turned a deaf ear to their entreaties and, when they became insubordinate and attempted to force a way past her, punished them with many sharp nips and kept them back.

She was also much troubled at this time by their refusal to eat the fish with which she had been doing her best to tempt them. It mattered not whether she offered them samlet, trout, or eel, they turned from all alike, and it seemed as if they would never be brought to touch any. Nevertheless she persisted, till one night, on the bank of the deep pool below the rapids, the male cub took a trout from her mouth, and the next night, just before dawn, his sister did the same. Their aversion to solid food once overcome, they would chatter over the new diet as if to testify to the pleasure they found in the exercise of their newly acquired taste, or even hiss angrily when their savage passions were stirred by the wriggling or quivering of the fish in their grip. They held the prey between the fore-paws, slicing off delicate morsels with their pearly teeth, and champing them fine before swallowing. Most remarkable was the way they set about eating two of the fish their mother provided for them. With the trout they began at the head, but in the case of the eel they attacked the part below the vent, leaving the upper portion untouched.

This fish diet produced a most significant change: the cubs became fierce, and at the same time fearful. No longer was any restraint needed to keep them to the nest or to the holts in the river-banks, where they occasionally lay; no longer had the mother any difficulty in getting them to obey the dawn-cry and follow whither she led. Henceforth the sense of dread lay on their lives like a shadow and deepened with their development. It was seen in their readiness to crouch or make for the water at any strange sound, in their suspicion of any strange object. A bottle left on the bank by the water-bailiff caused them to take a wide détour, and the snapping of a stick under the foot of a lumbering badger nearly frightened these noiseless movers out of their wits. Once a thunderstorm terrified them with its vivid flashes, and one day even a brilliant rainbow was a source of alarm, until their mother awoke and showed no concern.

These trifling scares were followed towards the close of March by an incident they never forgot—an incident which caused the otter even greater consternation than it caused the cubs. It happened late one afternoon. The male cub had awakened from his second sleep and, with head resting on his mother’s flank, sat looking at the light fade over the wind-swept morass. During a lull an unaccountable rustling in the reeds caught his ears and brought him to his feet. The startled movement aroused his mother and sister, and in a trice all three otters were watching from behind the grass screen for a sight of the noisy intruder. The next instant they saw a fox, bedraggled almost beyond recognition, stagger from the reeds, drop from the bank to the stream, lap, raise his head and listen, lap again, then toil with bog-stained body and sodden brush up the opposite bank and pass from view. He could not have got far beyond the river, for which he seemed to be heading, before a hound came in sight, then two more, followed almost immediately by the body of the pack, which poured over the brow of the upland and streamed down a gully towards the morass. Soon they had disappeared, but whine after whine reached the otters’ ears, mingled with the crashing of the brake as the pack approached the stream and swept by full in their view. Some minutes later two yapping, bog-stained terriers crossed, and then the morass resumed its wonted calm. All this the otters had watched, hissing through their bared teeth, eyes starting from their sockets, and hair bristling erect on their thick necks: even when all was quiet again a great dread still possessed them. Their feral nature had been stirred to the depths, and they listened and listened, though no sound reached them save a faint toot of the horn. Setting-out time came and went, but the otters did not stir, till at length, taking heart from the owls, who filled the wood with their wild hooting, they stole down to the river.

The otter fished, but not a moment was given to gambolling, and long ere the woodman’s bantam heralded the day the scared creatures sought harbourage in the branches of a fallen pine whose top lay half immersed in the river. Hidden amidst the flotsam caught by the boughs, with the deep pool just below them, they felt safe, and at length slept as soundly as they had done in the morass.

They repaired to the same hover the next day and the day following. In their waking hours they would watch the eddying water and rising trout, and at times cast a glance at the belt of timber beyond, as if attracted by the crimson blossom of the elms. Not only did the flowering of forest tree tell of the passing of winter, but green shoots of flag and reed shyly whispered the same story, and wild daffodils in glade and dell proclaimed it. A gold-crest in the tall fir had begun laying her tiny freckled eggs; a throstle on the lone poplar by the pool sang to his mate guarding her turquoise treasures by the river’s bank, while the ravens up the face of the cliff were already busy feeding their young. Day by day, as the sun grew stronger and the west wind blew, the sycamores unfolded their fresh green leaves, and soon, the woodland over, all the buds, responsive to the quickened underworld, opened to greet the spring.

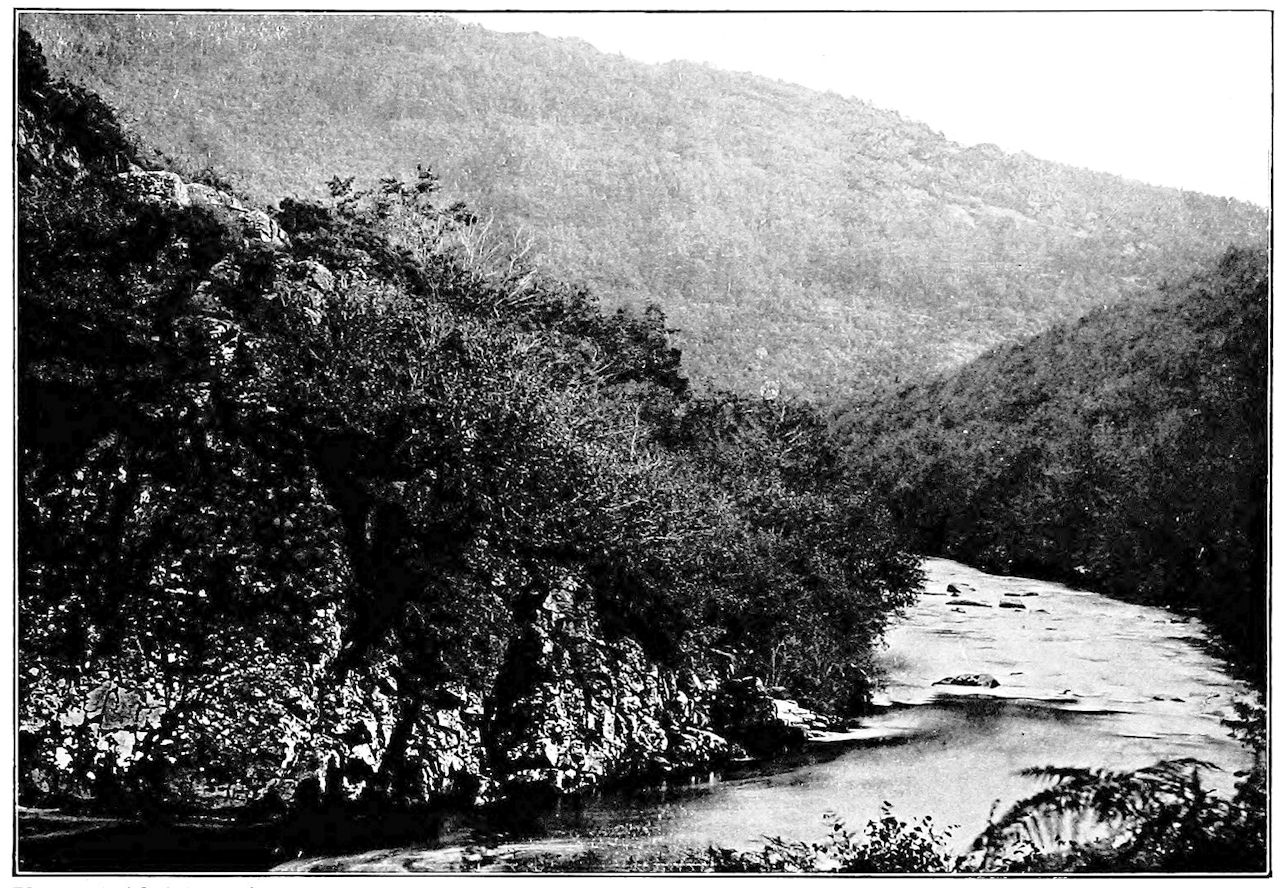

Photo F. Frith & Co., Reigate. To face p. 18.

THE RIVER BELOW THE MILL.

At the close of a hot day, when every furry wildling had felt its coat a burden, and longed for sundown and the drinking-place, the otter, who had been gradually extending her nocturnal rambles, took the cubs three miles down the river to a point where a part of the water is diverted into a tranquil mill-stream. Along its bank she brought them to the gate leading to the mill-yard, where all three stood and listened momentarily to the croaking of the frogs in the meadow beyond. Then they slipped under the low bar, crossed the yard, skirted the house, and hurried towards the ditch from which the noise proceeded. The croaking ceased on their approach, and before the otter entered the water every frog had sought a hiding-place at the bottom. The otter had scarcely dived before she was out again with two frogs in her mouth. These she skinned and gave to the cubs. Finding the morsel toothsome, and learning that if they wanted more they must fish for themselves, they joined in the easy pursuit, and for the first time in their lives satisfied their hunger with prey of their own taking.

Finally, they quarrelled like little tigers over a frog, of which each claimed possession, and so loud a chattering did they make that the miller got out of bed and opened his window to learn the cause of the disturbance. The creak of the sash silenced and alarmed them, and the next instant they and their mother were heading for the river at their best speed. An hour later the raiders started to return home by a route that took them wide of the mill where the danger lurked, thus reaching the morass without mishap; and the otter soon fell asleep, but the cubs lay awake thinking of an incident of the night. It was not the frogs that occupied their thoughts, not the bare yard or the fearsome trail across it, but the night-capped monster whom they still pictured as he appeared at the window.

THE FIRST TREK

Not a single night was given up to frogging after the cubs had learnt to skin their prey. Forthwith the little mother, anxious to make the best of their time, led them to the moorland waters of one of the tributary streams to teach them to fish. There she had taken her first litter for their earliest lessons, and now, as then, she made for the pool above the old two-arched bridge, which she still thought most suited for a starting-point. To reach the fishing-ground betimes, she left the morass with the first shades of night and, crossing the river near the fallen pine, struck across country towards her destination. Her path led through the woodland to a waste of furze, and this to the high moorland which the stream serves to drain. Once on the heathery tableland, otter and cubs advanced at a rapid pace, and presently hit the track to the bridge, which they followed, leaving their footprints here and there on the margin of the shrunken puddles. When nearly abreast of the Giant’s Quoits, first the otter and then the cubs caught the voice of the stream. The low murmur was almost lost in the sigh of the night wind, but grew louder and louder, till soon chattering run and plashing cascade appeared in the dip below.

On reaching the pool, the otter entered the water with the cubs at her side, dived, and drove the trout to the shelter of the banks. Thereupon the cubs, who saw where the fish had fled, fell to drawing the hovers, thrusting their flat heads into hole and crevice as far as they could reach. But the trout had found secure recesses, and though a few felt the lips of the otters, they could not be seized, and all but one escaped. In the pool at the bend, however, where the bank, hollowed though it is, affords poor shelter, three were taken. Then the captors, two on the gravel, the other on a mid-stream boulder, lay at full length and ate their prey, munching ravenously. The otter seemed to have set aside her fears since reaching the moor, for never once did she trouble to listen or even to scan the sable waste around her. All her thoughts were for the cubs, whom she led from pool to pool, aiding them until they began to fish for themselves; then she stood aside and watched them. Trout after trout they caught and devoured along the winding reaches leading to the long, sullen pool in the midst of the moor, where the mother, elated by their success, joined merrily in their gambols, which were kept up until past the usual hovering-time.

Day was on them when they landed and sought the most inviting couches the bank offered. First the cubs wormed themselves out of sight, then the otter; and so effectually were all three concealed amongst the rocks and heather that a kestrel, hovering over the spot, failed to get a glimpse of their brown forms, and flew on without a suspicion of their presence. Nevertheless, the open bank, though it had a marshy tract on one side and a deep pool on the other, was an insecure lodging, so that it was only because the moorland afforded no better that they returned thither on the morrow. After that the otter, jealous for the cubs’ safety, made some five miles downstream, where the holts amongst the roots of withy and alder were strong and sheltered from the rain that had rendered the upland hovers so uncomfortable on the second day. It is true the trout were scarce, but this mattered little to the otters, for eels, their favourite prey, were abundant. Amongst them was a very large one which, on being gripped by the male cub, coiled itself round his neck and threatened to strangle him. In this predicament the otter, after a short struggle, made for the bank and rolled amongst the fern and bramble to free himself of his antagonist. Finding this of no avail, he shifted his grip to a point nearer the head and, using the terrible force of his jaws, broke the back of the eel, and so got rid of it. This fish had been captured in the shallows, but for the most part the eels were only to be had by turning over the big stones under which they darted at sight of their pursuers. The young otters eagerly joined their mother in dislodging their prey and catching them when they bolted. The swiftness of the animals in this pursuit was amazing, and no less so the quick turning movements in which rudder and fore-paw were both brought into play. Indeed the long, lissom, tapering creatures resembled huge eels, and might have been mistaken for eels but for the bubbles which rose to the surface and marked their course.

The otters kept to this part of the stream for nearly a week—that is, until the freshet which had caused the run of eels subsided, and rendered a change of quarters necessary. They then betook themselves to the main tributary on the opposite bank, three miles above the morass; but finding that some other otters had disturbed the water in front, they pressed on, and at length came up with them where the stream winds sluggishly through a swampy bottom. Two were fishing in the stream, the rest in the marsh; but presently the whole party came into view, and as they trotted along the bank were seen to be four well-grown cubs with their dam, old and slightly grizzled. They all went on in company, but as day approached drew only the best pools, and gave up fishing altogether after striking the trail of the moorman who had forded the stream at sundown. Indeed on finding the dreaded taint of man there was quite a stir amongst them, especially amongst the cubs, who kept close alongside their mothers, and wondered where harbourage was to be found on the seemingly bare upland to which they were being led. At length the scared creatures sighted the weedy lakelet where the stream rises and, just as the rim of the sun showed gained the shelter of the reeds that fringed it.

The day proved intensely hot and still, with not a breath to ripple the surface or freshen the stifling air of the brake where the otters lay panting until dusk fell and allowed them to quench their tormenting thirst without fear of detection. Then, leaving their quarters, the two families travelled together till, after crossing two naked hills, they came to a rushy flat, lined with sour watercourses, where the trail forked, and there they parted company.

The otter was bound for the head-waters of the tributary nearest the source of the river, and soon after midnight reached the boggy gathering ground with its network of runnels and chain of pools in which she and the cubs fished until the stars began to pale. Then the hunters in single file made along the slender stream for the basin below the fall, sporting together till the sun rose over the distant sea and flooded the upland with its beams. The otter, usually observant of the first signs of dawn, seemed not to heed the golden light, even when the cubs began to grow uneasy and to shoot reproachful glances at her for keeping them abroad at so late an hour. But she needed not to be reminded of her duty. She knew they ran no risk in that untrodden spot; indeed on leaving the pool she stood on the bank to gaze across the dew-spangled waste and then at the gilded crags of Lone Tarn, before at length withdrawing to a clitter some half-mile down the stream.

There the dark recesses of the pile of rocks proved a welcome retreat to the cubs, and with the music of the waters for a lullaby they soon fell asleep. They hovered there again on the morrow; after which they continued on their journey laying up under the bank of the wide pool where the stream joins the river.

At setting-out time the otter seemed half-minded to follow the river to its source, for she kept looking towards the lone hill where it rises; but presently—the lowness of the water probably weighing with her—she decided to go downstream, summoned her cubs and trotted across the bend to the head of the long rapids, where they entered the water and drifted with the current. At dawn they sought a rabbit-burrow on the river-bank so near the woods that the cubs, who lay by the mouth of one of the holes, could hear the pigeons cooing. The retreat was safe and very dry, and would have left little to desire if the rabbits had taken no notice. But the timid creatures, thoroughly alarmed at the presence of the otters, stamped almost without intermission and prevented their uninvited guests from sleeping. At noon the otter, annoyed beyond endurance, rose and chased the rabbits along the tunnels; but this only made them worse. After that the drumming was kept up in every level, and made the visitors long for night. So at early dusk, after another raid on the persecutors, the otters slid down the bank into the water and let the stream take them along reach after reach until they were far into the wood. All the way they never ceased to scan the banks; they seemed to suspect an enemy behind every tree, but surely without sufficient cause. At one spot the green eyes of a fox watched them as they passed, otherwise they floated along unnoticed save by the bats flitting up and down the dark spaces beneath the overhanging boughs. On reaching the fallen pine they began to fish, and so continued all the way to the salmon pool, where they sported till dawn drove them again to the morass.

During the weeks that followed they kept to the neighbourhood of the old nursery, lying up for the most part under rocks and tree-roots at the water’s edge, but occasionally in the morass itself. It was whilst couching there that the otter, alarmed by the continued fall of the river and the exposure of the mouths of the strongest hovers, suddenly resolved to make for the tidal waters, whose holts are unaffected by droughts, and where she could teach the cubs many new lessons. She first thought of going down the river to the estuary, but changed her plans almost at the last moment and determined to make for a creek where she had had good fishing with her mate, the father of the cubs. The destination was two good marches distant, but she knew a stronghold by the way where they could lodge, and from which they could easily reach the creek on the following night.

In her anxiety to gain this refuge before dawn, she left her couch in the reed-bed at early dusk and, full of her purpose, made for the old hover where the cubs always slept when in the morass. Hearing the faint rustle of the herbage as she approached, the quick-eared creatures left the nest, and when she came up, fell into their place at her side. Leading past the pool to the river, she crossed it and headed towards the woodman’s cottage. The rapid pace at which the animals travelled soon brought them within sight of the low, thatched building beneath its sheltering oak, but as nothing stirred they passed close to the garden fence and into the gloom of the pines beyond.

A happier little band of nomads could not be found than the otter and her cubs, quite unsuspicious of danger, though they were running straight into its jaws. At a sudden turn of the mossy track where rocks contract the way they came face to face with Venom, the woodman’s terrier. Venom was returning from a badgers’ sett which he visited whenever he could slip away unobserved, and his begrimed and bloodstained condition told how severe had been the fray between him and one of the badgers. He looked a woebegone mongrel as he limped along on three legs; but the instant he found himself face to face with the strangers he forgot his fatigue and flew at the otter’s throat with a fury that threatened to make short work of her. He soon discovered, however, that he had caught a Tartar. The shaking he gave her had little other result than further to exhaust himself, while the otter began punishing him about the face and shoulders, making her teeth meet at every bite. Besides inflicting severe wounds, she was actually pushing the dog back, and after a prolonged tussle was clear of the rocks and close to a fallen tree from which the terrified cubs were watching the fray. Another scrimmage here took place, even longer and fiercer than the first: then the dog hesitated to renew the fight and stood on the defensive. Thereupon the otter, whose one thought was escape, joined the cubs and made off. The sight of their retreat was, however, more than Venom could stand, and they had scarcely disappeared before he was in pursuit. On overtaking them, he laid hold of the male cub, probably mistaking him for his mother. With a viciousness that belied his cubhood, the young dog-otter closed with his first assailant, and would have made a brave fight had he been allowed to conduct it alone. But he was not. Like a tiger the mother fell on the terrier, and it looked as if the dog would be cut to pieces. His one thought, however, was to destroy the vermin, and instead of drawing off as he might have done at the foot of the steep slope, down which they fell rather than rolled, he actually closed again, fought to the edge of the pool there, even held on to the otter when she dived, and kept his hold until his lungs were exhausted. Then he let go, but on coming to the surface he did not make for the bank. He swam round and round, looking for his enemy, and only when he had lost hope of viewing her again did he land at last. On being freed from his grip, the otter had made her way close along the bottom to the upper end of the pool, where the cubs were waiting for her among some rushes. From their shelter mother and cubs now watched the movements of their puzzled foe, who began examining the banks of the pool. When he came near, they sank almost out of sight, their nostrils alone showing, and so remained until he had time to pass; then the otter raised her head to reconnoitre. Once as she did so she found the terrier standing within a few yards, but looking so intently in another direction that he failed to sight her; whereupon she sank again as noiselessly as she had risen, not leaving even her nostrils exposed. A score of times, at least, did the dog make the circuit of the pool; and had he been able to scent the otter—a thing which but few dogs can do—he must at least have driven them from their shelter, and possibly from the pool, for it was very small. Yet, insensible though he was to the scent, he was so convinced the animals were there that, after departing, he actually came back and looked again before taking himself off for good and leaving the otters free to resume their interrupted march.

For three hours they had been detained, and now, hurry as they might, it was impossible to reach the cairn before daybreak. Indeed, they were yet two miles away when the ridges above them were touched by the risen sun. To add to their troubles a magpie espied them, and though they were strange to him as to the terrier, he knew they were nightlings with no right to be abroad after sunrise, and mobbed them as he would have mobbed a leash of foxes. Under the brambles and osmunda ferns they were hidden from the pest, but in the open he had them at his mercy and, now fluttering just beyond their reach, now hopping from branch to branch of rowan or alder or wild-cherry, he annoyed them with impunity. At last they came to the foot of the slope at the head of the ravine threaded the furze as fast as their pads could carry them, reached the pile of rocks, and one by one disappeared through the narrow crevice near its base. The magpie, however, instead of flying off, perched on the pinnacle of the cairn and, with his head knowingly cocked on one side, watched for their reappearance. Long, long he waited, but as the creatures made no sign, he tired, took wing, flew down the ravine past the precipice where the ravens had their nest, and regained the wood of which he was so vigilant a sentinel.

The persecuted beasts soon forgot the magpie, but the terrier had left a deeper memory, and all three were long in falling asleep. The otter, indeed, was still awake at noon, when a weasel threaded the way to the heart of the cairn, and, poking his snake-like head round the angle of rock, saw the curled-up forms of the animals whose scent had drawn him thither. But a single peep satisfied his curiosity, and he went out into the blazing sunlight, fragrant with the perfume of the furze. Then the mother otter slept like the cubs.

The ravine was weird with the shades of night, raven and magpie were asleep, when the nomads left the cairn and took to the trail. Like three shadows they stole over the crest above and entered the covert. In the silence of that still, sultry night they might have been heard forcing a way where the furze was densest, and presently they emerged from the lower edge, and, traversing a strip of open ground where a rabbit was feeding, came to a stream. This they crossed by springing from rock to rock, the otter first and the male cub last. In the same order they threaded the oak coppice that clad the opposite steep, and made their way over the craggy summit that crowned it. And so they passed stream after stream, surmounted ridge after ridge of the wild watershed, and gained the outlying spur where the cultivated lowland lay before them. It looked like a sombre, blurred plain unrelieved by water, until the moon rode clear of the clouds and revealed the winding reaches of the tidal creek for which they were bound. Their destination was yet a good way off, but as the going was now very easy the tireless creatures covered the fields at a swinging pace. The pastures seemed strange to the cubs; stranger still the sheep and cattle, asleep at such an hour without a bush to hide them; but leaving them lying there, the otters kept straight on. A homestead rose almost across their trail; the trail, however, had been traced ages before the buildings were raised or even the land was broken, and though disturbed by spade and plough a thousand times, it was still the otters’ way, so mother and cubs kept to it faithfully, past the snow-white hawthorns and into the rickyard, where they stayed to roll and dry their coats, wet from the mowing-grass. The stamping of a horse’s feet sent them off before they had finished; but what alarmed them much more was a scarecrow in a top-hat standing amongst the growing corn. The suspicious creatures gave a wide berth to this horror, and kept looking back to see whether it was following, until presently they caught the scent of water; then they never gave it another thought.

In their eagerness to reach the fishing-ground they increased their pace across the three enclosures that separated them from it; but at the sight of the smooth, broad creek the cubs stood and gazed, till a call from their mother reminded them there was no time to be lost. So they made down the bank and over the beach to join her on the rocky foreland, round which the current was eddying. Together they dived and scoured the sandy bed in search of prey. In her anxiety to secure supper, the otter soon got separated from the cubs, who, through inexperience, wasted their efforts in vain pursuit of the bass instead of questing for the flat-fish that were to be had for the finding. In the end they tired without having obtained a meal. The last time they landed they were near the wooded island where the herons build, a long way from the point where they took to the tide, and it was whilst lapping the water of a runnel there that they heard their mother’s call from far down the creek. At once they hurried along the strand, answering as they ran, and even after they had taken to the flood they repeated their shrill whistlings until they reached her side. To their delight, a big flat-fish lay at her feet, its white underside uppermost. The smell of the prey, strange though it was, so pleased them that their nostrils twitched with anticipation. Indeed, the flounder was an appetizing morsel for creatures sated with eels and trout, and soon all three were busy devouring it. They were not long over the feast, but they had scarcely finished when the grey light stealing across the creek drove them to a cave in the overgrown bank.

This was not a hover suddenly chanced on, but a much-frequented place of call that the otter intended making for when she left the cairn. The dank vault had been occupied the day before, as was evident from the dry place on the slab, but it was untenanted then, save by a few bats hanging from the low roof, and it afforded the new-comers the accommodation they required. The mother chose the ledge close to the landing-place, whilst the cubs scrambled to a shelf above, along the rude way worn in the slaty wall by generations of their tribe. Before curling up for the day, the otters, as was their wont, teased with their claws every bit of under-fur, and removed the thorns and furze-spines about which it had matted. Then, liking the taste of the salt water, they licked themselves until their glossy coats were as smooth as satin. As soon as their toilet was finished they settled down to sleep, and so soft was their breathing, so thoroughly did their dark pelt harmonize with its surroundings, that there was nothing to betray their presence except eyes which glowed in the sombre light until the lids closed and hid their amber fires.

AT THE CREEK

The otter was awakened about noon by the patter and drip of the rain that had silenced the birds in the woods outside, but the cubs slept through it all. The downpour, which lasted off and on for hours, ceased towards sundown, and at star-peep the sky had cleared of clouds, save where a black pall hung over the uplands. The otters then stole from the cave, coming singly through the mouth and, keeping within the shadow of the rocky wall, landed on the beach beyond.

After shaking their coats, they made down the creek over the rain-pitted sand until nearly abreast of a rock showing above the surface, and there took to the water. For awhile it looked as if they meant to cross to the opposite shore, but on reaching mid-stream they dived, and the next minute were busy detaching mussels from the bed of the channel. The bubbles which kept rising showed the position of the animals, which presently came up with their mouths full of shell-fish and swam swiftly to land. There the otter dropped the mussels she carried, seized one between her paws, bit off the end of the shell and devoured the fish. Scarcely had she swallowed it before the cubs were busy breaking the brittle shells and feasting on the succulent contents; and the crackling noise that broke the silence would have puzzled any chance visitor to the wood, but was no unfamiliar sound to the birds that roosted in the overhanging oaks. The otters made several journeys to and from the mussel-bed, till they had eaten their fill; then fell to gambolling on the edge of the tideway, to the annoyance of a heron, which soon took wing for a station higher up the creek. Two or three hours they there spent in play, varied by excursions into the wood, where they startled a hare and put the brooding pheasants in a fever. Once they penetrated to the craggy summit, climbed the rocks, lapped the water in the highest of the basins, and, before jumping down, gazed across the intervening country to where the estuary glimmered between its dusky shores.

The beach was almost covered by the advancing tide when the otters took to the water and drifted up with the flood. Their outstretched limbs being flush with the surface, they looked like floating skins as the current bore them along; but soon after passing the heron, spectral in the uncertain light, they began swimming, and so entered the cave, where they shook their coats and lay down in the places they had occupied the day before. The lapping of the tide was their slumber-song, and the happy creatures were sound asleep before the last of the bats came flitting in to roost.

That day a fiery sun beat down upon the country-side and exhausted toiler and sportsman abroad in the sweltering heat. The mower sweated and panted behind the scythe, the otter-hunters crossing the moor longed for the cool woods they had left, and the boy on the smack at the end of the creek gobbled up his pasty to spend the dinner-hour in the pool beneath the bridge. Not only man and boy suffered from the heat; beast and bird too sought the shade, abandoning their haunts to the insect hosts that revelled in the scorching rays. The flower-gay selvage margining the far shore of the creek and the tangle of honeysuckle and wild-rose that curtained the portals of the otters’ lair, hummed with the noise of countless wings. Honey-bees were there, green-bodied flies and blue, and, preying on them, dragon-flies that darted to and fro, casting sharp shadows on yellow sand-bank and sapphire pool. But, glaring and dazzling as was the light, no ray penetrated the gloom that shrouded the otters, who never moved until near their usual stirring-time. Then they rose, but only to stretch themselves, for they lay down again, listened to the fading voices of the mowers, and watched the afterglow pale upon the face of the water.

At length, when all was still and the light sombre, they slipped noiselessly into the current, raising scarce a ripple as they passed from pool to pool on their way down the creek. They landed at the turn below the mussel-bed to quench their thirst, then took to the water again, and were soon busy disporting themselves in Deadman’s Pool. On leaving it, they moved forward, climbing every rock, and resting there as if they enjoyed the warmth till, two miles beyond the pool, they came to where the creek broadens between marshy flats given over to wild-fowl. As it was in this reach that the otter intended to hunt when the coming tide had brought up the fish that came there to feed, she and the cubs landed and played about on the bank to while away the time of waiting. Presently they entered the fen, where they disturbed some wild-duck and set the moorhens calling in notes of alarm which were taken up by the fowl on the other side of the creek, but subsided the instant the intruders’ gambols showed they had no murderous intentions.

Close on midnight, when the tide was about half flood, the otter, with the cubs at her side, re-entered the creek in search of flat-fish. Her quest was no easy one, for she had crossed the sandy bottom but once before the fish, becoming aware of the presence of their dreaded enemies, gave up feeding, and buried themselves in the sand. A pair of eyes dotted here and there about the wide bed was all that showed, and it was for this sign of the fish’s presence that the otter searched, jerking her head this way and that to scan the ground on each side of her course. At the fourth dive she suddenly sighted prey, as suddenly ceased propelling herself, and stopped within a foot of the spot where the restless eyes were watching her, while the cubs, who had shot past, turned, full of wonder, and rejoined their mother. Then the otter stretched out a fore-leg, touched the plaice through the thin layer of sand and put it to flight. The cubs, taken aback by the unexpected appearance of the fish, did not move till it had got some yards away, but once in pursuit the male cub soon recovered the lost ground, seized the prey, rose to the surface, and swam ashore. Two more plaice were captured within the hour, one by the cubs without assistance, and from that moment their mother let them quarter the sand alone. They propelled themselves by their hind-legs as their mother did, the fore-legs being pressed against the side, except when used for sudden turning movements; but on rising to the surface all four limbs came into play, while the massive tail alone did the steering. When their hunger was appeased they made up the creek, ducking their heads as they went, until a stone fell from the crumbling cliff above Deadman’s Pool and scared them; they then gave over their bobbing, but redoubled their speed, passing the flotsam at a rapid pace, and all the way to the cave they scanned the banks as if they dreaded an ambush, though they had never once been waylaid.

That day, whilst awaiting the dusk, the otter resolved to make a journey up the creek after the school bass. The tide did not serve before midnight; then the rain, which had threatened, began to fall and, as the animals drifted by the herons’ island, was coming down in torrents, but under it the current bore them rapidly along the reaches without sign of man’s neighbourhood, save a disused limekiln, until the last bend brought them within sight of a bridge and of the hamlet that straggles down the hillside to a wharf on the water’s edge. When they were abreast of it the bass began to rise, and drew them in pursuit. Shooting up from below, the hunters seized the unsuspecting fish, and soon were busy eating their take, the cubs on buoys, the otter on a projecting stone of one of the buttresses of the bridge. Once all three landed under the farthest arch and dropped their prey in affright at the unexpected presence of the parish constable, who was sheltering there and was almost as much scared himself.

Soon the crowing of the village cocks warned the otter that she ought to withdraw; but it was not until the smoke began to rise from the galley of the smack by the wharf that she at last gave up fishing and made for the drain hard by, where she had twice laid up before. Against a strong head of water they forced their way up the tunnel till they came to the rude ledges of masonry in it, and there curled up as best they could for the day. The cubs had never hovered in such scant quarters before, but their discomfort was as nothing in comparison with the terror which the rumbling of a van over their heads occasioned them. In the course of the morning, towards noon, things were still worse. A sheep-dog with a nose for otters winded them, and came and sniffed at the grating within a couple of yards of where they lay. In his excitement he kept pawing the iron bars and whimpering until the cry of ‘Shep, boy!’ recalled him to the flock, the patter of whose feet had set the otters on the alert before the dog darkened the twilight of their hiding-place. These were the great alarms of the day—indeed, the only alarms, for the otters took little notice of the bell which rang each time a customer entered the grocer’s shop, and scarcely more of the voices of the children abroad when the rain ceased.

The street was deserted and the windows aglow when the otters made their way down the drain and, after listening at the mouth, stole out into the moonlight. They ran some danger of being seen as they approached the smack, and again after passing it, but fortune favoured them; they escaped observation, and got clear away.

They kept to the margin of the creek till near the limekiln. Then the otter struck inland, with stealthy motion threading the tufts that covered the rising ground. Half-way up the slope she suddenly turned and looked at the cubs as if a careless step had annoyed her, but at once resumed her stalk. Presently her nostrils twitched; she had scented a rabbit that was feeding just over the brow. Coming within sight of the unsuspecting creature she gathered herself for a spring, and a fox could scarcely have launched itself more swiftly than did the otter. A timely movement, however, saved the rabbit, which, with others feeding there, gained the shelter of the bank. Balked of her prey, the otter stood for a moment where the unavailing leap had taken her, but as soon as the cubs came up she made for the biggest of the holes, and through it all three disappeared. Rabbits popping out here and there along the bank showed how quickly the otters traversed the set, and presently the male cub, looking with its arched back like a big ferret, issued from the hole out of which a rabbit had come and, following the scent with great eagerness, entered another hole into which it had darted. The mother otter, meanwhile, had been more successful, for a squeal underground heralded her appearance with a dead rabbit in her mouth, closely followed by the cubs. When she had bitten off the head and the pads, she removed the skin as if it had been a glove, and broke up the carcass. Except for a few moorhen, it was the first warm prey the cubs had eaten, and they devoured it greedily, as they did their share of another rabbit surprised in the furze beyond the burrow. This ended the night’s hunting, and leaving the out-turned skins on the turf, the otters went back to the creek across the dewy grass which they marked with a clearly visible track.

On gaining the shore they burst into a gallop from sheer high spirits, spurning the sand as they hurried along the lone reach in a silence unbroken save by the sob of the restless tide that was mounting along their path. Within a mile of the heronry they crossed the flood and sported in the great eddy there; at times they landed on the cone-shaped rock that rose amidst the swirl and cast its inky shadow on the silvery surface. The playful creatures seemed to have set aside their fears and lingered till sunrise, when the shout of a farm-boy to a neighbour caused them to dive and make for the cave. Time after time they rose to breathe, always in the slack water, and at last, when the brimming tide was all ablush and every songster pouring out its greetings to the sun, they gained their sanctuary beyond the reach of danger.

Thus day followed day and week succeeded week, until they had got to know the creek as they knew the morass. By the beginning of August there was not an inlet left unexplored nor a stream unvisited. The biggest of the streams they followed to its source among the hills, within easy reach of the sea, and laid up there, but partly retraced their steps the next night, and curled up at dawn beneath the roots of a sycamore that overhung a mill-pool. That day very heavy rain fell, and continued till a late hour, soaking the country-side and causing even the cave to drip, to the discomfort of the otters, who repaired there on the morrow. This decided the otter to make without further delay for the sea, and that night, after a big feast on the mussels, she led the cubs along the widening reaches to the estuary and couched on an island at the meeting of the waters. A barge drifted by at sunrise; later a peel leaped within a few feet of them; but the otters heeded neither the one nor the other, nor, indeed, did they raise their heads until a boy, blowing a penny may-horn, came to fetch the geese from the moor opposite, and startled them not a little. But by this time the sun was dipping below the pines near the homestead; it was almost time to be afoot, and as soon as the stars were bright, the otters took to the water and began the descent of the estuary.

The river, in spate after the rains, bore them swiftly along, now between long spits of sand, now close to the shadowed banks, dotted here and there with glow-worms. The surroundings were as peaceful as the drifting was easy; yet safe as the way seemed there was danger ahead, and a mile or so down they came on one of the worst enemies of their kind. They saw him the instant they rounded the bend; and little wonder, for the burly figure was clearly outlined against the latticed window of the keeper’s cottage. Had he moved, they would merely have sunk out of sight; had he coughed or sneezed, they would have dived, to reappear a furlong below. But to scare them was the last thing he wished, and, excited though he was, he never moved a muscle. He had set a trap for the otters, which he knew would follow the peel; and since dusk he had been all ears for the rattle of the chain that would tell of a capture. As soon as they were gone by, he rose and tiptoed along the bank, wondering, as he picked his way, what made them go down when the peel were running. By the trunk of a dead ash he stopped to listen.

The otters, on coming to the loop where the estuary wellnigh returns upon itself, landed, as the keeper knew they would, and passed through a belt of young larch to a glade in which the still air was heavy with the scent of flower and fern, and a night-jar was busy among the moths. When nearly across it, the otter swerved from the trail to avoid the coppice where her mate had been trapped. It was not likely she could mistake the spot, for she had stood by him till at dawn the footfall of the keeper had driven her away. She had even returned the two following nights, and called and called and called before going off alone to prepare a nest for her unborn cubs. And now another trouble beset her: the male cub persisted in following the trail, and, owing to his great strength, succeeded, despite all her efforts, in getting amongst the bushes where the trap was set. He was on the point of putting his pad on the plate, when, in desperation, she bit him and made him turn. As he did so she closed with him, for she would rather kill him than suffer him to fall a victim to man; but when, at the sound of the struggle, the keeper came crashing through the undergrowth, the otter made off, and the cub followed her.

They struck the estuary near a jetty piled with bundles of oak-bark, floundered through the mud, and reached the river. The tedious bend, of which the otters had crossed the neck, now lay behind, and in front stretched the long reach marked by broad sand-banks that the tide was beginning to crawl over. So otter and cubs, after passing two branch creeks, musical with the whistlings of night-feeding birds, came to the deeper water, where hulks rode at their last anchorage, and, farther on, to the landlocked haven in which tall-masted vessels swung to their moorings, and the lights of a little seaport and fishing village winked at one another across the salt waters. On viewing the uncanny lights and hearing the shouts of a drunken sailor the male cub sidled up to his mother; and great was his relief when she rounded the rocky promontory that projects into the harbour, and entered the tranquil creek, whose waters reflected only the friendly moon.

SEA AND MARSH

The otters landed opposite a white buoy, and, to pass the time till the fish came in, played about on the rocks that strewed the shore. When the tide had covered most of them, the otter set out to reconnoitre, and had not been gone long before she summoned the cubs to join her. At the signal they took to the water, and soon reached the spot where she awaited them. On seeing her excitement they became excited too, dived the instant she did, and the three, swimming in line abreast, soon viewed the prey. It was but the merest glimpse they got of half a score tails, for the fish, finding there were three otters, wheeled round in affright and fled before their advance. At this timid manœuvre, so favourable to their purpose, the otters, eager though they were to seize the prey, rose to vent, and on resuming the chase came on the alarmed mullet in a fathom of water. Further retreat meant certain capture, and the mullet—craftiest of all the finny tribe—knew it. So the little school of fish made a dash for the deeper water, and, as the otters flashed up from beneath to seize them, scattered, leaping wildly to avoid the fatal grip. The confusion of that moment taxes description, but one detail stands out clear—the effort of the otter to reach the leader in its leap for life. She did indeed lip it, but no more; and the fish, which in its fall splashed the water into ripples of silver, got right away and resumed the lead of the retreating shoal. A few scales only remained to mark the scene of the fray, and the chagrin of the otters was complete when, on drawing the rest of the water blank, they realized that every mullet had escaped.

The disappointed hunters landed through the maggoty seaweed which had attracted the fish, and making their way along the stream that flows into the creek, reached the mill where the otter intended to hover. To her dismay she found the holt behind the wheel in possession of another otter with cubs, and quite young ones, as she could tell by their squeals. It was a difficult situation, for day was near; but she was equal to it. Without losing an instant, she hastened back along her trail towards the only other lodging she knew within easy reach—a hole in the wall of the quay. They might be detected whilst making for it, so the mother scanned the sleeping port from the end of the promontory before committing herself to the open; but as nobody stirred, the three made across the estuary straight towards it. When they were about mid-passage, where the tide ran strongest, a big fish leaped clear of the water and fell with a resounding splash. It was a salmon. The cubs turned their questioning eyes on their mother, but she gave no heed. She was filled with anxiety lest the hole in the quay should prove to be beyond their reach. High above the water though it was, she herself entered it easily, for she could throw herself out of the water almost like a seal; but, as she had feared, the cubs fell back again and again. The whistling of the distressed creatures must have been audible to anyone on the quay. An old man was, indeed, there, putting out the green light which had frightened the cubs as they crossed, but he was as deaf as his ladder, and before he approached the edge to see how high the tide had risen, they had made their greatest effort and gained the shelter of the masonry.

That day they hardly slept a wink. They were within earshot of the busiest spot in the port, and every one of the varied sounds that reached them was a cause for fresh anxiety. To the ceaseless pacing to and fro of hobbler and pilot there was soon added the shout of the fish-hawker, the bell of the town-crier, and other sounds of trade, varied towards noon by the squeakings of Punch and Judy, the yelping of Toby, and the roars of laughter that punctuated their performance—a strange hullabaloo indeed for the shy wildlings that had been reared in the quiet of the desolate moorland, where only the calls of bird and beast reached them; and many a time through the trying hours they longed to be back in the morass, under the cairn, or in the cave now so far back on the trail. Welcome at last to their eyes were the dying rays that fired the windows of the cottages across the harbour; doubly welcome the departure of the last fisherman from the quay-head. His footsteps had scarcely died away when the otters slid down the face of the wall into the water and, threading the moorings of the boats above them, rose to the surface in the fairway. Three dark spots that to the man leaning over the side of the brigantine might well have seemed three corks, showed where the otters swam noiselessly towards the harbour-mouth.

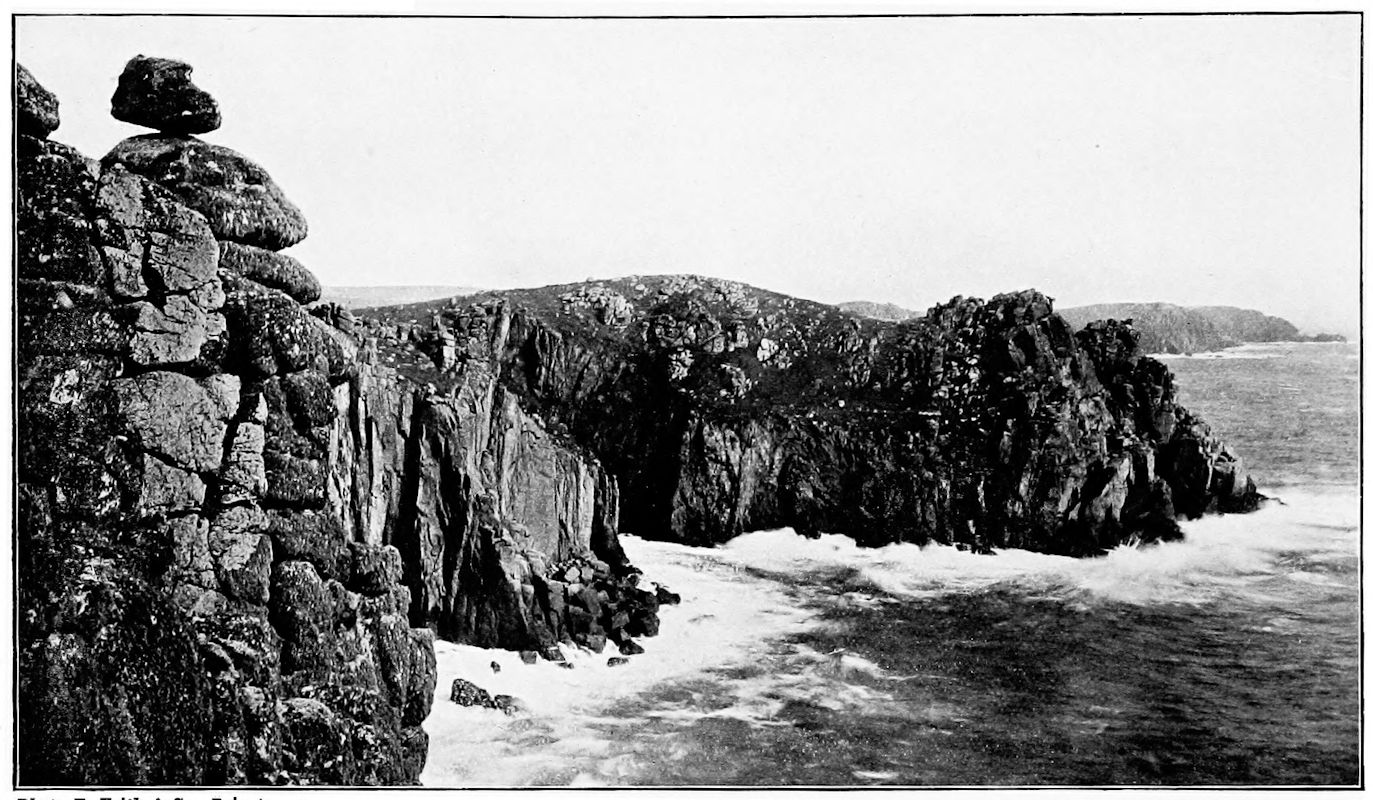

After they had passed the last buoy and, indeed, covered most of the mile that separated them from the lighthouse, they learnt that they were not the only creatures abroad that fine summer night. Barely a furlong could have separated them from the castles that once guarded the narrow entrance when they caught sight of some monsters whose noisy breathing, growing louder and louder as they drew near, might well have proved most terrifying to the easily scared cubs, had not their mother’s indifference convinced them they had nothing to fear; and presently mother and cubs were among the shoal of porpoises, the great backs of which gleamed as they showed above the waves. The mother knew the errand of these corsairs, and understood that they were raiding the salmon that the flooded river had attracted from the offing. Awakened memories of great chases in the pools and of feasts on the banks flashed across her brain as she swam, and before she set foot on the point opposite the lighthouse she resolved to complete the round with as little delay as possible and regain the upper reaches of the river, where she could teach the cubs how to weary out the fresh-run fish and bring them to the bank.

But the lesson she had come to give the cubs in the sea itself was not a whit less important, she thought, as she watched their wonderment on beholding the vast liquid plain that stretched out to no shore their piercing gaze could discern. Streamlet, pool, river, creek, estuary—all in turn had been cause for astonishment, but on the ocean they looked with awe. And it was theirs to fish in. In the recognition of this spacious hunting-ground the timid creatures quite forgot the terrors of the quay, which had but momentarily passed from their minds in the presence of the porpoises, and the next minute they were following in the wake of their mother as she swam towards the Gull Rock in the midst of the cliff-skirted bay. Bravely the cubs faced the waves, and bravely they battled with the surf through which they landed; then they looked to their mother to direct them how to fish in the deep water by which they were surrounded.

They had not long to wait. After a glance at the birds on the ledges above her head, she dived; both cubs instantly dived, too, and putting forth all the strength of their hind-legs, they succeeded in keeping her in sight along the spiral course by which she made her way down and down to the bottom, full six fathoms below. To their surprise, they found the bed of the sea alive with tiny shell-fish, which they spurned here and there as they quested. On their left rose a wall of rock, in turning the point of which they came face to face with a turbot, that the otter seized and bore writhing to the surface. The cubs, who rose with her, kept gripping the fish as they swam, and by the time they reached the landing-place it had ceased to struggle. Then all three settled down to the feast. Nothing but the tail and backbone remained when they again took to the water. This time they made the circuit of the rock, and the male cub, rising from beneath, seized a pollack, carried it in triumph to a reef just a-wash with the tide, and there consumed it. Before he had quite finished, the other cub, and later, the otter, were busy devouring wrasse they had taken. When they had eaten their fill, the young otters amused themselves in capturing fish which they no longer needed but left uneaten; and it was over these abandoned spoils that the gulls clamoured at dawn, whilst the otters lay in a cave they had entered by a submerged mouth at the foot of the cliffs. Curled up in pits on the sand above the line of flotsam, with the roar of the sea to lull them, the cubs soon dropped asleep; but the mother, her thoughts on the big silvery salmon, lay awake making her plans, till at length she, too, yielded to her fatigue and slept like the cubs.

Night had fallen when the otters stole through the outlet, left half uncovered by the ebb, and swam with rapid strokes for the head of the bay. They were off to a new fishing-ground. They landed where a stream crosses the beach and, striking into the valley down which it flows, followed its course without a halt, until they reached the junction of the two rivulets that form it. There, however, the otter stood irresolute. Each water led towards a delectable destination—the one to the salmon pools, the other to her native marsh, with its abundant food-supply and secure hovers among the reed-beds—and which to make for she could not decide, until it struck her that the cubs might never find the outlying water without her. Then she set aside her hesitation, and held along the western branch at a pace quicker than before, as if to recover the time lost in making up her mind.

Leaving the valley about a mile above the confluence, she cut straight across the middle of the hilly field to the upper corner, where a flock of lambs stood awestruck to watch the strange intruders climb the bank into the next pasture, from which the otters could hear the startled creatures stamping with excitement, until first the otter, then the cubs one after the other, got over the wall and dropped into a neglected road. This led to a stately gateway with big iron gates, and beneath them the animals crept to the moss-grown drive, flecked by the moonlight which filtered through the arching crowns of the oaks. They passed a mole-heap or two and numerous little pits scratched by rabbits, but the way was innocent of rut or hoof-mark or any evidence of man’s proximity. Yet they had not long been following its windings before they all at once found themselves face to face with a scene that filled them with consternation. At a spot where the road makes a sharp bend about an angle of the cliff lay a heap of ruddy embers, and near them a dog. The animal was not asleep, but stretched to his full length and, as his restless ears showed, alert to the slightest sound. His every movement was visible against the dying fire, the glow of which fell on the curtained window of a caravan and dimly revealed the gnarled branches above it. The otters, thoroughly alive to the danger of attack, stood ready to defend themselves; but, seeing that the enemy gave no sign, they sidled towards the overgrown riding-path just beyond the firelight, and gained it without attracting the dog’s attention. The moment, however, the herbage rustled with their movements his head was raised and pointed towards the very spot where they stood concealed. Still as death, they regarded the lurcher through the fronds, nor did they advance a single step till the drooping of the pricked ears and the resettling of the long head on the fore-legs showed that suspicion was lulled. Then, with a stealth that cheated the prating ferns, they left their shelter, stole noiselessly as shadows past the gipsy’s bivouac and the side road by which the human nomads had come, and escaped into the safe darkness beyond, where the murmur of the sea far below reached their ears.

Photo F. Frith & Co., Reigate. To face p. 62.

THE WILD COAST-LINE.