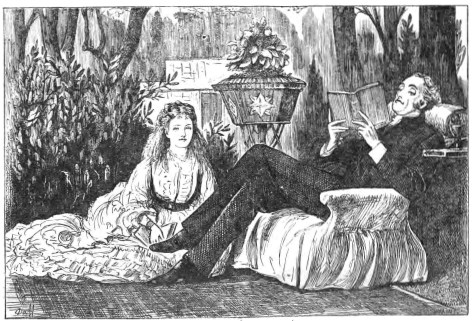

The Rose of my story was half-sitting, half-reclining at his feet.

Title: A Rose in June

Author: Mrs. Oliphant

Illustrator: George Du Maurier

Release date: June 10, 2017 [eBook #54882]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Google Books project.)

| Chapter I.,

II.,

III.,

IV.,

V.,

VI.,

VII.,

VIII.,

IX.,

X.,

XI.,

XII.,

XIII.,

XIV.,

XV.,

XVI.,

XVII.,

XVIII. List of Illustrations |

BY

MRS. OLIPHANT.

[From Advance Sheets.]

ILLUSTRATED BY GEORGE DU MAURIER.

BOSTON:

JAMES R. OSGOOD AND COMPANY.

Late Ticknor & Fields, and Fields, Osgood, & Co.

181 FRANKLIN STREET.

1874.

artha, Martha, thou art careful and troubled about many things. Let

the child alone—she will never be young again if she should live a

hundred years!”

artha, Martha, thou art careful and troubled about many things. Let

the child alone—she will never be young again if she should live a

hundred years!”

These words were spoken in the garden of Dinglefield Rectory on a very fine summer day a few years ago. The speaker was Mr. Damerel, the rector, a middle-aged man with very fine, somewhat worn features, a soft benignant smile, and, as everybody said who knew him, the most charming manners in the world. He was a man of very elegant mind as well as manners. He did not preach often, but when he did preach all the educated persons in his congregation felt that they had very choice fare indeed set before them. I am afraid the poor folk liked the curate best, but then the curate liked them best, and it mattered very little to any man or woman of refinement what sentiment existed between the cottagers and the curate. Mr. Damerel was perfectly kind and courteous to everybody, gentle and simple, who came in his way, but he was not fond of poor people in the abstract. He disliked everything that was unlovely, and alas! there are a great many unlovely things in poverty. The rectory garden at Dinglefield is a delightful place. The house is on the summit of a little hill, or rather table-land, for in the front, towards the green, all is level and soft as becomes an English village; but on the other side the descent begins towards the lower country, and from the drawing-room windows and the lawn, where Mr. Damerel now sat, the view extended over a great plain, lighted up{8} with links of the river, and fading into unspeakable hazes of distance, such as were the despair of every artist, and the delight of the fortunate people who lived there and were entertained day by day with the sight of all the sunsets, the midday splendors, the flying shadows, and soft, prolonged twilights. Mr. Damerel was fond of saying that no place he knew so lent itself to idleness as this. “Idleness! I speak as the foolish ones speak,” he would say, “for what occupation could be more ennobling than to watch those gleams and shadows—all nature spread out before you, and demanding attention, though so softly that only they who have ears hear? I allow, my gentle nature here does not shout at you, and compel your regard, like her who dwells among the Alps, for instance. My dear, you are always practical—but so long as you leave me my landscape I want little more.”

Thus the rector would discourse. It was very little he wanted—only to have his garden and lawn in perfect order, swept and trimmed every morning like a lady’s boudoir, and refreshed with every variety of flower: to have his table not heavily loaded with vulgar English joints, but daintily covered, and oh! so daintily served; the linen always fresh, the crystal always fine, the ladies dressed as ladies should be: to have his wine, of which he said he took very little, always fine, of choice vintage, and with a bouquet which rejoiced the heart: to have plenty of new books: to have quiet, undisturbed by the noise of the children, or any other troublesome noise such as broke the harmony of nature: and especially undisturbed by bills and cares, such as, he declared, at once shorten the life and take all pleasure out of it. This was all he required; and surely never man had tastes more moderate, more innocent, more virtuous and refined.

The little scene to which I have thus abruptly introduced the reader took place in the most delicious part of the garden. The deep stillness of noon, was over the sunshiny world; part of the lawn was brilliant in light; the very insects were subdued out of their buzz of activity by the spell of the sunshine; but here, under the lime-tree, there was grateful shade, where everything took breath. Mr. Damerel was seated in a chair which had been made expressly for him, and which combined the comfort of soft cushions with such a rustic appearance as became its habitation out of doors; under his feet was a soft Persian rug in colors blended with all the harmony which belongs to the Eastern loom; at his side a pretty carved table, with a raised rim, with books upon it, and a thin Venice glass containing a rose. Another Rose, the Rose of my story, was half-sitting, half-reclining on the grass at his feet—a pretty, light figure in a soft muslin dress, almost white, with bits of soft, rose-colored ribbon here and there. She was the eldest child of the house. Her features I do not think were at all remarkable, but she had a bloom so soft, so delicate, so sweet, that her father’s fond title for her, “a Rose in June,” was everywhere acknowledged as appropriate. A rose of the very season of roses was this Rose. Her very smile, which came and went like breath, never away for two minutes together, yet never lasting beyond the time you took to look at her, was flowery too, I can scarcely tell why. For my own part, she always reminded me not so much of a garden-rose in its glory, as of a branch of wild roses all blooming and smiling from the bough, here pink, here white, here with a dozen ineffable tints. Her hair was light-brown with the least little curl in the world just about her forehead, but shining like satin on her pretty head; her eyes too were brown, with a dancing gleam of light in each; the delicate eyebrows curved, the eyelashes curved, the lips curved, all wavy and rounded. Life and light shone out of the girl, and sweet, unconscious happiness. In all her life she had never had any occasion to ask herself was she happy. Of course she was happy! did not she live, and was not that enough? Rose Damerel was the last dainty ornament of his house in which her father delighted most. He had spoiled her lessons when she was younger because of his pleasure in her and her pretty looks, and he interfered now almost altogether with that usefulness in a house which is demanded by every principle of duty from the eldest daughter of a large family; for alas! there was a large family, a thing which was the cause of all trouble to the Damerels. Had there been only Rose, and perhaps{9} one brother, how much more pleasantly would everything have gone! In that case there might have been fewer lines in the brow of the third person whom Mr. Damerel spoke to, but whom the reader has not yet seen.

What Mrs. Damerel was like in her June of life, when she married her husband and was a Rose too, like her daughter, it is difficult to tell. Life, which often makes so little real change, brings out much that is latent both of good and evil. I have said she was a Rose, like her daughter—and so, indeed, she was still, so far as formal documents went; but, somehow or other, the name had gone from her. She had acquired from her husband, at first in joke and loving banter of her early cares of housekeeping, while they were still no more than married lovers, the name of Martha, and by degrees that name had so fastened to her that no one recognized her by any other. Nobody out of her own family knew that it was not her name, and of course the children, some of whom were indignant at the change, could not set it right. In her letters she signed herself “R. M. Damerel”—never Rose; and her correspondents took it for granted that the “M” stood for Martha. That she was careful and troubled about many things was the rector’s favorite joke. “My careful wife—my anxious wife,” he called her, and, poor soul, not without a cause. For it stands to reason that when a man must not be disturbed about bills, for example, his wife must be, and doubly; when a man cannot bear the noise of children, his wife must, and doubly; and even when a clergyman dislikes poverty, and unlovely cottages, and poor rooms, which are less sweet than the lawn and the roses, why, his wife must, and make up for his fastidiousness. She had eight children, and a husband of the most refined tastes of any clergyman in England, and an income—not so much as might have been desired. Alas! how few of us have so much as might be desired! Good rich people, you who have more money than you want, how good you ought to be to us, out of pure gratitude to Heaven for the fact that you can pay your bills when you like, and never need to draw lines on your forehead with thinking which is imperative and which will wait! Mrs. Damerel was well dressed—she could not help it—for that was one of the rector’s simple luxuries. Fortunately, in summer it is not so difficult to be well dressed at a small cost. She had on (if any one cares to know) a dress of that light brown linen which everybody has taken to wearing of late, over an old black silk petticoat, which, having been good once, looked good even when tottering on the brink of the grave. She was no more than forty, and but for her cares, would have looked younger; but June was long over for this Rose, and the lines in her forehead contradicted the softness of the natural curves in her features. Those lines were well ruled in, with rigid straightening, by an artist who is very indifferent to curves and prettiness, and had given a certain closeness, and almost sternness, to the firm-shutting of her mouth. I am afraid, though she had great command of herself, that Mr. Damerel’s delightful and unbroken serenity had an irritating effect on his wife, in addition to the effects produced by her burden of care; and irritation works with a finer and more delicate pencil than even anxiety. She had come out this morning to ask Rose’s help with the children, to whom, among her other fatigues, she had lately begun to give lessons, finding the daily governess from the village impracticable. She had been called away to other duties, and the children were alone in the school-room. She had just asked her daughter to go in and take charge of them, and I scarcely think—let alone the answer she had just received from her husband—that the sight of this cool, fresh, delightful leisure in direct contrast with the hot house, and the school-room, where all the children were more tiresome than usual by reason of the heat, had any agreeable effect upon Mrs. Damerel’s nerves. Such a contrast to one’s own frets and annoyances seldom is deeply consolatory.

“Martha, Martha, thou art careful and troubled about many things. Let the child alone!”

The rector smiled, yet his tone was one of playful reproof. His was the superior position. With the soft air fanning him, and the shade refreshing him, and the beautiful landscape displaying itself for him, and all the flowers{10} blooming, the leaves waving, the butterflies fluttering, the pretty daughter prattling, all for his pleasure, master of the creation as he was, he was in a position to reprove any harsh and hasty intruder who brought into this Paradise a discordant note.

“I do not want to burden her youth,” said Mrs. Damerel, with a resolute quiet in her voice, which her children knew the sound of, and which they all learned to recognize as the tone of suppressed irritation, “but I think it would do Rose no harm, Herbert, to make herself useful a little, and help me.”

“Useful!” he said, with a half-pitying smile; “the other roses are still less useful. What would you have the child do? Let her get the good of this beautiful morning. Besides, she is useful to me.”

“Ah,” said Mrs. Damerel, faltering slightly, “if she is doing anything for you, Herbert!”

“My dear,” said the rector, with a gentle elevation of his eyebrows, “don’t confound things which are different. Doing something is your sole idea of human use, I know. No, Rose is doing nothing—it helps me to have her there. She is part of the landscape; suppose you sit down yourself, instead of fretting, and enjoy it.”

“Enjoy it!” Mrs. Damerel echoed, with faint irony. She heard already the noise of the school-room growing louder and louder, and Mary, the housemaid, stood at the door, looking out anxiously, shading her eyes from the sun, for the mistress. Some one was waiting, she knew, in the hall, to see her; pray Heaven, not some one with a bill! “I am afraid I must go back to my work,” she said, “and I hope you will come to me, Rose, as soon as your papa can spare you. I have no more time now.”

Rose stirred uneasily, half-rising, and, with a prick of conscience, made a feeble attempt to detain her. “But, mamma”—she began, as her mother moved away, crossing the broad sunshine of the lawn with hasty steps. Mrs. Damerel did not or would not hear, but went swiftly into the house as they watched her, meeting Mary, who was coming with a message. Her light dress shone out for a moment in the fierce blaze of the sunshine, and then disappeared. When she was out of sight the rector said softly, changing his position with the leisureliness of extreme comfort, putting under-most the leg which had been upper-most, “What a pity that your mother does not see the beauty of repose more than she does! If I had not learnt long ago to take no notice, I don’t know what I might not have been worried into by now.”

“Mamma never worries any one,” said Rose, flushing at once with instantaneous opposition. The more she felt guilty towards her mother, the less she would hear a word to her discredit. She blazed up quite hot and fiery, with a loyalty which was a very good quality in its way, though not so good as helping in the school-room. The father put forth his fine ivory hand, and patted her pretty head.

“Quite right, dear, quite right,” he said; “always stand up for your mother. And it is true, she never worries anybody; but I wish she had more perception of the excellence of repose.”

“Perhaps if she had, we should not be able to enjoy it so much,” said the girl, still giving expression to a slight compunction.

“Very well said, Rose; and it is quite possible you are right again. We should not be so comfortable, and the house would not go on wheels as it does, if she thought more of her own ease. One star differeth from another star in glory,” said Mr. Damerel, who was fond of quoting Scripture, almost the only point in him which savored slightly of the church. “At the same time, my Rose in June, when you marry, yourself—as I suppose you will one day—remember that there is nothing that worries a man like being constantly reminded of the struggle and wear and tear that life demands. He has enough of that outside in the world,” said the rector, gazing out over the fair prospect before him, and again changing the position of his legs, “without having it thrust upon him in what ought to be the sanctity of his home.”

Rose looked at her father with a little dawning wonder mingled with the admiration she felt for him. As a picture, Mr. Damerel was perfect. He had a fine head, with beautiful and refined features, and that paleness which has always been found to be so much more interesting than brighter{11} coloring. He lay half-reclined in his easy-chair, with his eyes dreamily regarding the landscape, and the book he had been reading closed over his hand. That hand was in itself a patent of gentility, and his whole appearance confirmed the title. Somewhat fragile—a piece of delicate porcelain among the rough delf of this world—not able to endure much knocking about; fastidious, loving everything that was beautiful, and supporting with difficulty that which was not, the rector looked like a choice example of the very height of civilization and refinement. And everything around him was in harmony: the velvet lawn on which no fallen leaf was allowed to lie for an hour; the pretty house behind, perfection of English comfort and daintiness; the loose morning clothes, not more than half clerical, and perfectly unpretending, yet somehow more fine, better cut, and better fitting than other people’s clothes. Rose had for him that enthusiasm of admiration which a girl often entertains for a handsome and gentle-minded father, who takes the trouble to enter into her feelings, and make her his companion. I do not know any more exquisite sentiment in humanity. She loved him entirely, and he was to her a very model of everything that was most delightful, kind, tender, and beautiful.

But as she looked at this model of man, his words somehow struck and vibrated upon a new chord in the girl’s mind. “The struggle and wear and tear that life demands.” Did Mr. Damerel have much of that “outside,” as he said? He resumed his reading, but his daughter did not look again at the book of poetry which lay open on her knee. Somehow a reflection of the pucker on her mother’s brow had got into her heart—her mother, whom Rose loved, but who was not an idol and model of excellence, like the gentle and graceful being at her side. The contrast struck her for perhaps the first time in her life. What was the meaning of it? Was it because Mrs. Damerel did not understand the beauty of repose, or because a woman’s business in this world is more detailed and engrossing than a man’s? “Fancy mamma spending the whole morning out of doors reading poetry!” Rose said to herself, with an involuntary silent laugh over the absurdity of the notion. No doubt it was because of the difference between man and woman; one of those disabilities which people talked about; and perhaps (Rose went on philosophizing) women are wrong to absorb themselves in this way in the management of their houses, and ought to rule their domestic affairs with a lighter hand, not interfering with all the little minutiæ, and making slaves of themselves. She looked towards the house as she mused, and the vague compunction which had been in her mind sharpened into something like a prick of conscience. It was delightful being out here in the soft shade of the lime-trees, watching when she liked the flitting shadows over the plain below, and the gleam of the river here and there among the trees—reading when she liked “Balaustion’s Adventure,” which was the book on her knee. The significance of the old story embedded in that book did not for the moment strike her. I think she was, on the whole, rather annoyed with Mr. Browning for having brought down the story of a woman’s sacrifice, all for love, into the region of even poetic reason. To Rose, at that period of her development, it seemed the most ideal climax of life to die for the man she loved. What could be more beautiful, more satisfactory? Such an ending would reconcile one, she thought, to any suffering; it gave her heart a thrill of high sensation indescribable in words. How sweet the air was, how lovely all the lights! Rose was just enough of an artist to be able to talk about “the lights” with some faint understanding of what she meant. She was in a kind of soft Elysium, penetrated by the thousand sensations of the morning, the quiet, the flattering soft air that caressed her, the poetry, the society, the beauty all around. But then there came that sharp little prick of conscience. Perhaps she ought to go in and offer the help her mother wanted. Rose did not jump up to do this, as she would have done at once (she felt sure) had she been required to die, like Iphigenia, for her country, or, like Alcestis, for her husband. The smaller sacrifice somehow was less easy; but it disturbed her a little in the perfection of{12} her gentle enjoyment, and dictated a few restless movements which caught her father’s eye. He turned and looked at her, asking fretfully, with a look, what was the matter, for he did not like to be disturbed.

“Perhaps,” said Rose, inquiringly, and appealing to him with another look, “I ought to go in and see what is wanted. Perhaps I could be of some use to mamma.”

Mr. Damerel smiled. “Use?” he said. “Has your mother bitten you with her passion for use? You are not of the useful kind, take my word for it; and make yourself happy, like your namesakes, who toil not, neither do they spin.”

“But perhaps”—said Rose softly to herself—her father gave her a friendly little nod and returned to his book—and she had to solve her problem without his assistance. She tried to do it, sitting on the grass, and it was a long and rather troublesome process. It would have been much more easily and briefly settled, had she gone into the school-room; but then I am afraid Rose did not wish it to be solved that way.

Mrs. Damerel went back into the house with a countenance much less placid than that of her husband. I scarcely know why it is that the contrast of perfect repose and enjoyment with anxiety, work, and care should irritate the worker as it invariably does; but here indeed there was reason enough; for Mrs. Damerel felt that the two people luxuriating in total absence of care on this delightful morning ought to have taken a considerable share with her in her labors and lightened the burden she was now obliged to bear alone. This mingled a sharpness of feeling with her toils. People who interpret human nature coarsely—and they are, perhaps, the majority—would have said that Mrs. Damerel was jealous of her husband’s preference for Rose’s society, and this would have been a total and vulgar mistake; but she had in her mind a feeling which it is difficult to explain, which for the moment made her irritation with Rose more strong than her irritation with Rose’s father. He was, in the first place, a man—grand distinction, half contemptuous, half respectful, with which women of Mrs. Damerel’s age (I don’t say young women often do it, at least consciously—except in the case of their fathers and brothers) account for and make up their minds to so many things. I am not attempting to account for this sentiment, which is so similar to that with which men in their turn regard women; I only acknowledge its existence. He was a man, brought up as all men are (I still quote Mrs. Damerel’s thoughts, to which she seldom or never gave expression), to think of themselves first, and expect everything to give in to them. But Rose had none of these privileges. What her mother as a woman had to take upon her, Rose had an equal right to take too. Mrs. Damerel herself could not forget, though everybody else did, that she had been a Rose too, in her proper person; the time even since that miraculous period was not so far off to her as to the others; but before she was Rose’s age she had been married, and had already become, to some extent, Mr. Damerel’s shield and buckler against the world and its annoyances. And here was Rose growing up as if she, instead of being a woman as nature made her, was herself one of the privileged class, to whom women are the ministers. This annoyed Mrs. Damerel more, perhaps, than the facts justified; it gave her a sense of injured virtue as well as feeling. It would be the ruin of the girl—it was wrong to let her get into such ways. The mother was angry, which is always painful and aggravates everything. She was too proud to struggle with her daughter, or to exact help which was not freely given; for Rose was no longer a child to be sent hither and thither and directed what to do. And Mrs. Damerel was no more perfect than Rose was—she had her own difficulties of temper like other people. This was one of them—that she drew back within herself when she felt her appeal refused or even left without response. She went in with a little scorn, a little pride, a good deal of anger and more of mortification. “I must do everything myself, it appears,” she said, with a swelling of the heart which was very natural, I think. After the sun on the lawn, it was very warm in-doors and the school-room was very{13} noisy indeed by the time she had got rid of the applicants in the hall, one of whom (most respectful and indeed obsequious, and perfectly willing to accept her excuses, but yet a dun notwithstanding) had come to say that he had many heavy payments to make up, etc.—and if Mrs. Damerel could oblige him—Mrs. Damerel could not oblige him, but he was very civil and full of apologies for troubling her.

I do not, by any means, intend to say that the rector’s wife was tortured by perpetual struggling with her creditors. It was not so bad as that. The difficulty was rather to keep going, to be not too much in debt to any one, to pay soon enough to preserve her credit, and yet get as long a day as possible. Mrs. Damerel had come by long practice to have the finest intuition in such matters. She knew exactly how long a tailor or a wine merchant would wait for his money without acerbation of temper, and would seize that crowning moment to have him paid by hook or by crook. But by thus making a fine art of her bills, she added infinitely to her mental burdens—for a woman must never forget anything or neglect anything when she holds her tradespeople so very delicately in hand.

The school-room, as I have just said, was very noisy, not to say uproarious, when she got back to it, and it was hard not to remember that Rose ought to have been there. There were five children in it, of various ages and sizes. The two big boys were both at Eton. The eldest, Bertie, who was bright and clever, was “on the foundation,” and therefore did not cost his parents much; the second had his expenses paid by a relation—thus these two were off their mother’s hands. The eldest in the school-room was Agatha, aged fourteen, who taught the two little ones; but who, during her mother’s absence, ought to have been playing “her scales,” and had conscientiously tried to do so for ten minutes, at the end of which time she had been obliged to resign the music in order to rescue these same two little ones, her special charge, from the hands of Dick, aged ten, who was subjecting them to unknown tortures, which caused the babes to howl unmercifully. Patty, the next girl to Agatha, aided and abetted Dick; and what with the laughter of these two pickles, and the screams of the small ones, and poor Agatha’s remonstrances, the scene was Pandemonium itself, and almost as hot; for the room was on the sunny side of the house, and blazing, notwithstanding the drawn blinds. The children were all languid and irritable with the heat, hating their confinement in-doors; and, indeed, if Rose had come, she would have made a very poor exchange. Agatha’s music had tumbled down from the piano, the old red cover was half drawn off the table, and threatened at any moment a clean sweep of copybooks, inkbottles and slates. Dick stood among his books, all tumbled on the floor, his heels crushing the cover of one, while Patty sat upon the open dictionary, doubling down half the leaves with her weight. Such a scene for a bothered mother to come into! Mr. Damerel himself heard some faint rumor of the noise, and his fine brow had begun to draw itself into lines, and a resolution to “speak to their mother” formed itself within his mind. Poor mother! She could have cried when she went in out of all her other troubles; but that was a mere momentary weakness, and the rebels were soon reduced to order, Agatha sent back to her scales, and Dick and Patty to their copybooks. “You two little ones may go,” Mrs. Damerel said, and with a shriek of delight the babies toddled out and made their way to the hayfield behind the house, where they were perfectly happy, and liable to no more danger than that of being carried off in a load of fragrant hay. When Mr. Nolan, the curate, came in to talk about parish business, Agatha’s “scales,” not badly played, were trilling through the place, and Patty and Dick, very deep in ink, and leaning all their weight upon their respective pens, were busy with their writing; and calm—the calm of deep awe—prevailed.

“Shall I disturb you if I come in here?” asked the curate, with a mellow sound in his voice which was not brogue—or at least he thought it was not, and was ingenuously surprised when he was recognized as an Irish-man. (“It will be my name, to be sure,” he would say on such occasions, somewhat puzzled.) He was a bony man, loosely put together, in a long coat, with rather a wisp of a white{14} tie; for, indeed, it was very hot and dusty on the roads, and where the rector is an elegant man of very refined mind, the curate, like the wife, has generally a good deal to do.

“Indeed, the lessons have been so much disturbed as it is, that it does not much matter,” said Mrs. Damerel. “On Monday morning there are so many things to call me away.”

“How selfish of me!” said the curate. “Monday morning is just the time I’ve little or nothing to do, except when there’s sickness. What a brute I was not to offer meself,—and indeed, that’s just what I’ve come to speak about.”

“No, no, you are too kind, and do too much already,” said Mrs. Damerel, looking at him with a grateful smile, but shaking her head. “And, indeed,” she added, the cloud coming over her face again, “Rose ought to come and relieve me; but her father has to be attended to, and that takes up so much of her time.”

“To be sure,” said the curate cheerily, “and reason good. Besides, it would be wearing work for one like her—whereas the like o’ me is made for it. Look here, Dick, my boy, will you promise to learn your lessons like a brick to-morrow if I ask the mother for a holiday to-day?”

“Oh, hurrah!” cried Dick, delighted.

“Oh, mamma, like twenty bricks,” cried Patty, “though how a brick can learn lessons?—It’s so hot, and one keeps thinking of the hayfield.”

“Then be off wi’ you all,” cried the curate. “Don’t you see the mother smile? and Agatha too. I’m going to talk business. Sure, you don’t mind for one day?”

“Oh, mind!” said poor Mrs. Damerel, with a half-smile; then waiting till they were all out of hearing, an exit speedily accomplished, “if it were not for duty, how glad I should be to give it up altogether!—but they could not go on with Miss Hunt,” she added, with a quick glance at the curate to see whether by chance he understood her. Good curate, he could be very stolid on occasion, though I hope he was not fool enough to be taken in by Mrs. Damerel’s pretences: though it was true enough that Miss Hunt was impracticable. She could not afford a better; this was what she really meant.

“Out of the question,” said Mr. Nolan; “and I’m no scholar myself to speak of, notwithstanding what I’m going to have the presumption to say to you. It’s just this—I don’t do much visiting of mornings; they don’t like it. It takes them all in a mess as it were, before they’ve had time to get tidy, and these mornings hang heavy on my hands. I want you to let me have the three big ones. I might get them on a bit; and time, as I tell you, my dear lady, hangs heavy on my hands.”

“How can you tell me such a fib?” said Mrs. Damerel, half crying, half laughing. “Oh, you are too good, too good; but, Mr. Nolan, I can’t take anything more from you. Rose must help me, it is her duty; it is bad for her to be left so much to herself; why, I was married and had all the troubles of life on my head at her age.”

“And so she’ll have, before you know where you are,” said the good curate, which will show the reader at once that he entertained no absorbing passion for Miss Rose, though I am aware it is a curate’s duty so to do. “So she’ll have; she’ll be marrying some great grandee or other. She looks like a princess, and that’s what she’ll be.”

“She has no right to be a princess,” said the mother, overwrought and irritable, “and duty is better than ease surely. You, I know, think so.”

“For the like of me, yes,” said the curate; “for her, I don’t know.”

“I was once very much like her, though you would not think it,” said the mother, with the slightest tinge of bitterness, “but that is not the question—no, no, we must not trouble you.”

“When I tell you the mornings hang on my hands! I don’t know what to do with my mornings. There’s Tuesday I’m due at the schools, but the rest of the week I do nothing but idle. And idling’s a great temptation. A cigar comes natural when you’ve nothing to do. You don’t like a man smoking in the morning; I’ve heard you say so. So you see the young ones will save me from a—no, I won’t say cigar; worse than that; cigars are too dear for a curate, me dear lady—from a pipe.”

“Mr. Nolan, you are too good for this world,” said poor Mrs. Damerel,{15} affected to tears; “but I must first try what can be done at home,” she added after a pause; “no, no, you weigh me down under your kindness. What would the parish be but for you?”

“It would be just the same if I were dead and buried,” said the curate, shrugging his shoulders. “Ah, that’s the worst of it: try for a little bit of a corner of work like a child’s lessons, and you may be of service; but try to mend the world, even a bit of a parish, and you’re nowhere. They don’t think half as much of me as they do of the rector?” he added, with a curious smile, which the rector’s wife only half understood. Was it satirical? or could it be possible that the curate was surprised that the people thought more of the rector than of himself? Mrs. Damerel was aware, no one better, of her husband’s faults. Many a time she was ready to say in bitterness (to herself) that he was wearing her to death; but nevertheless she looked at long, loosely-built, snub-nosed Mr. Nolan, with mingled amusement and surprise. Was it possible that he could entertain any hopes of rivalling her husband? Of course a visit from the rector was an honor to any one, for Mr. Damerel was a man who, notwithstanding a little human weakness, was the very picture and model of a gentleman; and the idea of comparing him with good Mr. Nolan was too absurd.

“Yes, no doubt they are pleased to see him,” she said: “poor people are very quick to recognize high breeding; but I am sure, my dear Mr. Nolan, that they are all very fond of you.”

The curate made no immediate answer. I am not sure that he had not in his private heart something of the same feeling with which his present companion had been thinking of her daughter, a feeling less intense in so far as it was much more indifferent to him, yet in a way stronger because untempered by affection. The rector was of his own kind, the ornamental and useless specimen, while he was the worker whom nobody thought of; but these secret feelings neither of the two confided to the other. Mr. Nolan would have been horrified had he detected in Mrs. Damerel that slight bitterness about Rose, which indeed would have shocked herself as deeply had she paused to identity the sentiment, and she would have been, and was, to some slight extent—suspecting the existence of the feeling—contemptuous and indignant of Nolan’s “jealousy,” as I fear she would have called it. They returned, however, to the educational question, which did not involve anything painful, and after considerable discussion it was settled that he should give the elder children lessons in the morning “if their papa approved.” It is impossible to say what a relief this decision was to the mother, who had felt these lessons to be the last straw which proverbially breaks the camel’s back. She was glad of the chat with a sympathizing friend, who understood, without saying anything about, her troubles—and doubly glad of the holiday exacted from her by his means—and gladder still to get rid of him and return to her many other occupations; for it was Monday, as has already been mentioned, and there was the laundress to look after, and a thousand other things awaiting her. The curate went out by the garden door when he left her, out upon the lawn, where he paused to look at as charming a scene as could be found in England: a fair country spreading out for miles its trees and fields and soft undulations under a summer sky, which was pale with excess of light, and ran into faint lines of misty distance almost colorless in heat and haze. Here and there the sunshine caught in a bend of the river, and brought out a startling gleam as from a piece of silver. The world was still with noon and distance, no sound in the air but the rustle of the leaves, the hum of insects; the landscape was all the sweeter that there was no remarkable feature in it, nothing but breadth and space, and undulating lines, and light, everywhere light; and to make up for its broad, soft vagueness, how distinct, like a picture, was the little group in the foreground—the lime-trees in their silken green, the soft rippling shadows on the grass, the picturesque figure in the chair, and the beautiful girl!

The beauty of the sight charmed good Mr. Nolan. Had it been put to him at that moment, I believe he would have protested that his rector should never do anything in his life except recline with languid limbs out-stretched,{16} and his poetical head bent over his book, under the sweet shadow of the trees. And if this was true even in respect to Mr. Damerel, how much more true was it with Rose?

“Well, Nolan,” said Mr. Damerel, suavely, as the bony curate and his shadow came stalking across the sunshine; “well, worrying yourself to death as usual in this hot weather? My wife and you are congenial souls.”

“That is true, and it’s a great honor for me,” said Nolan. “She is worrying herself to death with the children, and one thing and another. As for me, in the mornings, as I tell her, I’ve next to nothing to do.”

Rose looked up hastily as he spoke. How angry she felt! If her mother chose to worry herself to death, who had anything to do with that? was it not her own pleasure? A hot flush came over the girl’s face. Mr. Nolan thought it was the quick, ingenuous shame which is so beautiful in youth; but it was a totally different sentiment.

“Mamma does nothing she does not choose to do,” she cried; then blushed more hotly, perceiving vaguely that there was something of self-defense in the heat with which she spoke.

Mr. Nolan was not graceful in his manners, like Mr. Damerel, but he had that good breeding which comes from the heart, and he changed the subject instantly, and began to talk to the rector of parish business, over which Mr. Damerel yawned with evident weariness. “Excuse me; the heat makes one languid,” he said. “You have my full sanction, Nolan. You know how entirely I trust to your discretion; indeed, I feel that you understand the people in some respects better than I do. Don’t trouble yourself to enter into details.”

Mr. Nolan withdrew from these refined precincts with an odd smile upon his face, which was not half so handsome as Mr. Damerel’s. He had the parish in his hands, and the rector did not care to be troubled with details; but the rector had all the advantages of the position, all the income, and even so much the moral superiority over his curate, that even they (by which pronoun Mr. Nolan indicated his poorer parishioners) felt much more deeply honored by a chance word from the rector than they did by his constant ministrations and kindness.

What an odd, unequal world this is! he was thinking of himself—not ruled by justice, or even a pretence at justice, but by circumstances alone and external appearances. This did not make him bitter, for he had a kind of placid philosophy in him, and was of the kind of man who takes things very easily, as people say; but the curious force of the contrast made him smile.

Rose Damerel’s life had, up to this time, been spent altogether in the sunshine. She had been too young when she went to school to ponder much over anything that went on at home, and had concluded during her holidays that home, which was so dainty, so pleasant, so sweet, was a kind of paradise on earth, infinitely more delightful than any of the other homes of which she heard from her school-fellows. None of them had a father so delightful, a mother so kind; and in these holiday times, as everybody indulged and petted her, the private shadows—I will not say skeletons—in the house were never divined by her. She had, as sometimes happens to the eldest of a large family, much more care taken of her education and training than her sisters were likely to meet with. The burden had not begun to be so heavily felt when the eldest girl grew into bright intelligence, to her parents’ pride. The others were still too young to demand or even to suggest the expense that would be involved in their education—and nothing was spared upon Rose. She had returned from school not much more than a year before the time of which I treat, and had gone on for some time in her delightful youthful confidence that everything around her was exactly as it ought to be. But shadows had begun to flit vaguely across the picture before that memorable day in the garden, which henceforward became a turning point in her thoughts. This was the first moment at which she fully identified the occasional clouds upon her mother’s face, and learned that Mrs. Damerel was not merely a little cross—that easy and rapid solution with which a child settles all problems concerning its parents{17}—but had a distinct cause for the little irritabilities which she tried so carefully to restrain. Perhaps it was in the very nature of things that Rose should be more attracted by the gentle indulgence and indolent perfection of her father than by her mother’s stronger character. Mr. Damerel, had he been very rich, and free of all occasion to think of his children’s future, would have been a model father to grown-up and well-behaved sons and daughters. He could not bear any roughness, coarseness, or disorderliness, therefore the school-boys were but little congenial to him, and he was never sorry when the holidays were over. And the little children were too troublesome and too noisy to please him; but Rose was the perfection of a child to such a man, and to her he was the perfection of a father. Everything in her pleased and gratified him. She was pretty, gentle, full of intelligence, eager to read with him if he would, still more eager to hear him talk, yet quick to perceive when he was disinclined to talk, and regarding all his moods with religious respect.

She would sit by him for hours together, like a charming piece of still-life, when he pleased, and was ready to converse or to listen, to walk, to sing, to follow his lead in everything, as only a woman-child, full of the beautiful enthusiasm of youthful admiration, can do. Nothing except perhaps the devotion of a young wife, when she really loves the man much older than herself, whom she has married, can equal the devotion of a girl to her father. She admired everything about him—his beautiful refined head, his fine voice, his grace and high breeding, his sermons, and what she called his genius. To find this faultless father to be anything less than a demi-god was terrible to Rose. I do not mean to say that she got within a hundred miles of this discovery all at once; nay, the first result of the vague and dreamy doubts that stole into her mind was rather an increase of enthusiasm for her father, an instinctive making-up to her own ideal for the sense of failure in him, of which she was vaguely conscious. Rose loved her mother after a totally different fashion, in an ordinary and matter-of-fact way, but she had no romance of feeling towards her; and when her whole little world, began, as it were, to sway upon its axis, to yield beneath her feet, as if it might swing round altogether in space, turning what she had supposed the brighter side into shadow, and elevating that which she had held lowly enough, she, poor girl, grew giddy with this strange and sickening sensation. She was at the age, too, when everything is apt to reel about the young experimentalist taking her first steps in life. She was vaguely conscious of being now a free agent, consulted as to her own movements, no longer told curtly to do this and that, but exercising personal choice as to what she should do. This change is of itself sufficiently bewildering. Nature makes, as it were, a pause at this first crisis of personal life. The child, wondering, half-delighted and half-troubled to have no longer its duties clearly and sharply indicated, falls into a partial trance, and neglects many things for sheer want of use and knowledge how to act for itself.

This was Rose’s position. Between the mother, who, a little mortified and hurt at her child’s want of sympathy with her, did not give her orders, but only suggested employment, and the father, who said, “Never mind, let her alone,” she stood, not knowing how to settle the question, but inclining naturally to the side on which she was most indulged and smiled upon, though with a secret uneasiness which she could not shake off, and moral sense of a false situation which grew upon her day by day.

Rose had lovers, too, in this new, miraculous life upon which she had entered: two lovers, not yet declared, but very evident to all knowing eyes; and in the village there were many keen observers. One of these suitors was the most wealthy proprietor, in the neighborhood—a man much above her own age, yet not old, and perfectly qualified to please a lady’s eye; and the other, a young naval lieutenant without a penny, the son of Mrs. Wodehouse, who lived on the Green, and had nothing in the world but her pension as an officer’s widow. Of course I do not need to say that it was the poor man whom Rose preferred. She was not in love with him—far from it; but she was so completely on the verge of universal awakening,{18} that a word or touch might be enough to arouse her whole being at any moment—might open her eyes to her own position and that of her parents, and show her the nature of her individual sentiments, as by a sudden gleam of light. Rose, however, was not the least in the world aware of this; and at the present moment she was no further advanced than was consistent with saying frankly that she liked Wodehouse very much—and feeling (but of this she said nothing) more glad when she saw him coming than about any other event in her simple days.

Dinglefield is a sociable place, and there is something in a soft summer evening after a very hot, blazing summer day which fosters a disposition to stroll about and interchange greetings with your neighbors. As it began to darken upon the evening of this particular day, various people in the houses about stepped out of their wide-open windows after dinner, and, tempted by the beauty of twilight, strayed along the road or over the Green to the rectory garden, which was by universal acknowledgment “the most perfect spot” in the village. Much has been said about the charms of twilight, but little, I think, of its peculiar English beauty, which is not so magical as the momentary interval between light and dark in the south, or the lingering, prolonged, silvery, and ineffable dimness of those northern twilights which last half the night; but has a dusky softness altogether peculiar to itself, like the shadowing of downy wings. The air was delicious, fresh after the hot day, yet so warm as to make wrappings quite unnecessary. The sky, still somewhat pale in its blue after the languor of the heat, looked down faint yet friendly, as if glad to see again a little movement and sense of life. A few subdued stars peeped out here and there, and the wide stretch of country lay dim underneath, revealing itself in long soft lines of gray, till it struck into a higher tone of blue on the horizon where earth and heaven met. All the Damerels who were out of bed were in the garden, and the neighbors, who had made this pleasant terrace the end of their walk, were scattered about in various groups. Mr. Incledon, who was Rose’s wealthy lover, came late and stood talking with Mrs. Damerel, watching with wistful eyes her appropriation by his rival, young Wodehouse—whose mother, hooded in the white Shetland shawl, which she had thrown over her cap to come out, sat on a garden-chair with her feet upon the rector’s Persian rug, listening to him while he talked, with the devout admiration which became a member of his flock. The rector was talking politics with General Peronnet, and Mrs. Wodehouse thought it was beautiful to see how thoroughly he understood a subject which was so much out of his way as the abolition of purchase in the army. “If he had been in parliament now!” she said to the general’s wife, who thought her husband was the object of the eulogy. There were two or three other members of this group listening to the rector’s brilliant talk, saying a few words, wise or foolish, as occasion served. Others were walking about upon the lawn, and one lady, with her dress lifted, was hastening off the grass which she had just discovered to be wet with dew. Upon none of them, however, did Mr. Incledon’s attention turn. He followed with his eyes a pair whose young figures grew less and less in the distance, half lost in the darkness. The persistence with which he watched them seemed a reproach to the mother, with whom he talked by fits and starts, and whose anxiety was not at all awakened by the fact that Rose was almost out of sight. “I am afraid Rose is not so careful as she ought to be about the dew on the grass,” she said, half apologetically, half smiling, in reply to his look.

“Shall I go and tell her you think so?” said Mr. Incledon, hastily. He was a man of about five-and-thirty, good looking, sensible, and well dispositioned; a personage thoroughly comme il faut. He was the sort of suitor whom proper parents love to see approaching a favorite child. He could give his wife everything a woman could desire—provide for her handsomely, surround her with luxury, fill her life with pleasures and prettinesses, and give her an excellent position. And the man himself was free of cranks and crotchets, full of good sense, well educated, good tempered. Where are girls’ eyes, that they do not perceive such advantages? Mrs. Damerel hesitated a moment between{19} sympathy with her child and sympathy with this admirable man. There was a struggle in her mind which was to have the predominance. At length some gleam of recollection or association struck her, and moved the balance in Rose’s favor, who she felt sure did not want Mr. Incledon just at that moment.

“Never mind,” she said tranquilly, “it will not hurt her;” and resumed a conversation about the music in the church, which was poor. Mr. Incledon was very musical, but he had no more heart for anthems at that moment than had he never sung a note.

Rose had strayed a little way down the slope with Edward Wodehouse. They were not talking much, and what they did say was about nothing in particular—the garden, the wild flowers among the grass on this less polished and less cultured lawn which sloped down the little hill. At the moment when the elder suitor’s glances had directed Mrs. Damerel’s attention towards them they were standing under a gnarled old hawthorn-tree, round which was a little platform of soft turf.

“We lose the view lower down,” said Rose; and there they stopped accordingly, neither of them caring to turn back. The soft plain stretched away in long lines before them into the haze and distance like the sea. And as they stood there, the young moon, which had been hidden behind a clump of high trees, suddenly glinted out upon them with that soft, dewy glimmer which makes the growing crescent so doubly sweet. They were both a little taken aback, as if they had been surprised by someone suddenly meeting and looking at them—though indeed there was not a syllable of their simple talk that all the world might not have heard. Both made a step on as if to return again after this surprise, and then they both laughed, with a little innocent embarrassment, and turned back to the view.

“What a lovely night!” said Rose, with a faint little sigh. She had already said these not remarkable words two or three times at least, and she had nothing in the world to sigh about, but was in fact happier than usual; though a little sad, she knew not why.

“Look at those lights down below there,” said young Wodehouse; “how they shine out among the trees!”

“Yes, that is from Ankermead,”, said Rose; “you know it?—the prettiest little house!”

“When we are away, we poor mariners,” he said, with a little laugh which was more affected than real, “that is, I think, the thing that goes to our hearts most.”

“What?”

“The lights in the windows—of course I don’t mean at sea,” said young Wodehouse; “but when we are cruising about a strange coast, for instance, just one of those twinkles shining out of the darkness—you can see lights a long way off—gives a fellow a stab, and makes him think of home.”

“But it is pleasant to think of home,” said Rose. “Oh, what am I saying? I beg your pardon, Mr. Wodehouse. To be sure, I know what you mean. When I was at school something used to come in my throat when I remembered—many a time I have stood at the window, and pretended I was looking out, and cried.”

“Ah!” said Wodehouse, half sympathetic, half smiling, “but then you know it would not do if I looked over the ship’s side and cried—though I have had a great mind to do it sometimes, in my midshipman days.”

“To cry is a comfort,” said Rose; “what do you men do, instead?”

“We smoke, Miss Damerel; and think. How often I shall think of this night and the lights yonder, and mix up this sweet evening with an interior, perhaps sweeter still!”

“I don’t think so,” said Rose, with a soft laugh, in which there was, however, a shade of embarrassment which somewhat surprised herself. “The room is rather stuffy, and the lamps not bright, if you were near enough; and two old people half dozing over the tea-table, one with the newspaper, one with her worsted-work. It is very humdrum, and not sweet at all inside.”

“Well, perhaps they are all the fonder of each other for being humdrum; and it must have been sweet when they were young.”

“They were never young,” said Rose, with a silvery peal of laughter, turning to go back to the lawn. “See what tricks imagination plays! You would not like to spend an evening there, though the lights are so pretty outside.”{20}

“Imagination will play many a trick with me before I forget it,” said young Wodehouse in subdued tones. Rose’s heart fluttered a little—a very little—with the softest preliminary sensations of mingled happiness and alarm. She did not understand the flutter, but somehow felt it right to fly from it, tripping back to the serenity of society on the lawn. As for the young man, he had a great longing to say something more, but a feeling which was mingled of reverence for her youth and dread of frightening her by a premature declaration kept him silent.

He followed her into the hum of friendly talk, and then across the lawn to the house, where the neighbors streamed in for tea. The bright lights in the rectory drawing-room dazzled them both—the windows were wide open; crowds of moths were flickering in and out, dashing themselves, poor suicides, against the circle of light; and all the charmed dimness grew more magical as the sky deepened into night, and the moon rose higher and began to throw long shadows across the lawn. “On such a night” lovers once prattled in Shakespeare’s sweetest vein. All that they said, and a great deal more, came into young Wodehouse’s charmed heart and stole it away. He heard himself saying the words, and wondered how it was that he himself was so entirely happy and sad, and thought how he might perhaps soon say them to himself as his ship rustled through the water, and the moonlight slept broad and level and uninterrupted by any poetry of shadows upon the sea. To think of that filled his heart with a soft, unspeakable pang; and yet the very pain had a sweetness in it, and sense of exaltation. “There are the lights still,” he said, standing over her where she had seated herself near the window. “I shall always remember them, though you will not allow of any romance”—

“Romance! oh no,” said Rose lightly; “only two old people. We have not any romance here.”

Mr. Incledon, who had been watching his opportunity so long, now came forward with a cup of tea. Poor Edward was too much abstracted in his thoughts and in her, and with the confusion of a little crisis of sentiment, to think of the usual attentions of society which he owed to her. He started and blushed when he saw how negligent he had been, and almost stumbled over her chair in his anxiety to retrieve his carelessness. “My dear Wodehouse, Miss Damerel cannot drink more than one cup of tea at a time,” said the elder suitor, with that air of indulgent pity for his vagaries which so irritates a young man; and he mounted guard over Rose for the rest of the evening. The good neighbors began to go home when they had taken their tea, and the rector and his daughter went with them to the gate, when there was a soft babble and commotion of good nights, and every two people repeated to each other, “What a lovely moon!” and “What a glorious night!” As for poor Wodehouse, in his climax of youth and love, his very heart was melted within him. Twice he turned back, murmuring to his mother some inarticulate explanation that he had forgotten something—that he wanted to speak to the rector—and twice went back to her solemnly saying it did not matter. “No, no,” he said to himself, “he must not be premature.”

Rose took another turn round the lawn with her father before they went in. Mrs. Damerel was visible inside, sending the tray away, putting stray books in their places, and stray bits of work in the work-basket, before the bell should ring for prayers. Mr. Damerel looked in as he passed with an indulgent smile.

“She calleth her maidens about her,” he said, “though it is not to spin, Rose, but to pray. Somehow it enhances the luxury of our stroll to see your mother there, putting everything in order with that careful and troubled face—eh, child, don’t you think with me?”

“But does it enhance her luxury to have us walking and talking while she has everything to lay by?” said Rose with an uncomfortable sense that her own work and several books which she had left about were among those which her mother was putting away.

“Ah, you have found out that there are two sides to a question,” said her father, patting her on the cheek, with his gentle habitual smile; but he gave no answer to her question; and then the maids became visible, trooping in, in their white caps and aprons, and the rector with a sigh and a last look at the midnight and the dim, dewy{21} landscape, went in to domesticity and duty, which he did not like so well.

Rose went to her room that night with a thrill of all her gentle being which she could not explain. She looked out from her window among the honeysuckles, and was so disappointed as almost to cry when she found the lights out, and the little cottage on Ankermead lost in the darkness. She could have cried, and yet but for that fanciful trouble, how happy the child was! Everything embraced her—the clinging tendrils of the honeysuckle, so laden with dew and sweetness; the shadows of the trees, which held out their arms to her; the soft, caressing moon which touched her face and surrounded it with a pale glory. Nothing but good and happiness was around, behind, before her, and a trembling of happiness to come, even sweeter than anything she had ever known, whispered over her in soft, indefinite murmurs, like the summer air in the petals of a flower. She opened her bosom to it, with a delicious half-consciousness fresh as any rose that lets its leaves be touched by the sweet south. This Rose in June expanded, grew richer, and of a more damask rosiness, but could not tell why.

Mrs. Damerel thought it her duty, a few nights after this, to speak to her husband of Rose’s suitors. “Mr. Incledon has spoken so plainly to me that I cannot mistake him,” she said; “and in case you should not have noticed it yourself, Herbert”—

“I notice it!” he said, with a smile; “what chance is there that I should notice it? So my Rose in June is woman enough to have lovers of her own!”

“I was married before I was Rose’s age,” said Mrs. Damerel.

“So you were, Martha. I had forgotten the progress of time, and that summer, once attained, is a long step towards autumn. Well, if it must be, it must be. Incledon is not a bad fellow, as men go.”

“But, I think—there is another, Herbert.”

“Another!” said the rector, leaning back in his chair with gentle laughter. “Why, this is too good; and who may he be—the No. 2?”

“It is young Wodehouse, the sailor”—

“The widow’s son on the Green! Come now, Martha, once for all this is absurd,” said Mr. Damerel, suddenly rousing himself up. “This is out of the question: I say nothing against Incledon; but if you have been so foolishly romantic as to encourage a beggar like young Wodehouse”—

“I have not encouraged him. I disapprove of it as much as you can do,” said Mrs. Damerel, with a flush on her cheek; “but whether Rose will agree with us I dare not say.”

“Oh, Rose!” said her husband, dropping into his easy tone; “Rose is a child; she will follow whatever lead is given to her. I am not afraid of Rose. You must speak to her, and show her which way you intend her mind to go; be very plain and unequivocal; an unawakened mind always should be treated in the plainest and most distinct way.”

“But, Herbert—you have more influence than I have ever had over her. Rose is more your companion than mine. I am not sure that it is the best thing for her, so far as practical life is concerned”—

“My dear,” said Mr. Damerel, benignly, “Rose has nothing to do with practical life. You women are always excessive, even in your virtues. I do not mean to throw any doubt upon your qualities as the most excellent of wives; but you have not the discrimination to perceive that duties that suit you admirably would be quite out of place in her. It is a matter of natural fitness. The practical is adapted to forty, but not to nineteen. Let the child alone, my love, to enjoy her youth.”

“I think you argue like a Jesuit, Herbert,” said Mrs. Damerel; “but whether you are right or wrong on this point does not affect what I ask—which is, that you would speak to her. She is much more likely to attend to you than to me.”

“Who—I?” said Mr. Damerel, with a fretful line in his fine forehead. “It is totally out of the question, Martha. I speak to Rose about her lovers! It would be quite indelicate, in the first place; and in the second, it would be most disagreeable to me.”{22}

“But still we have a duty to our child, even if it is disagreeable,” said his wife, not willing to give up her object without a struggle.

“My dear Martha, spare me! I knew you would say something about duty. You are very didactic, my love, by nature; but this, you must remember, is rather a reversal of positions between you and me. Let Rose see,” he continued, once more relaxing in tone, “that her path is quite clear before her. Incledon is a very good fellow; he will be of use to me in many ways. Nothing could be more desirable. There is a new box of books which I must look over, Martha; do not let me detain you. You will manage the matter admirably, I am sure, in your own sensible way.”

And the rector lighted his wife’s candle, and opened the door for her with a suavity and almost gallantry which would have brought tears to the eyes of the parish, had they been there to see. “How perfect Mr. Damerel’s behavior is to that rather common-place wife!” Such was the kind of thing people said. He went to look over his box of books from the London library after his talk, with much amusement in his mind as to Rose’s lovers. He thought his child perfect as a child; but the idea that a serious man like Incledon should think of her in the serious position of a wife, tickled the rector’s fancy. He thought over the matter as he glanced at the books which had been unpacked for him, leaving nothing for his delicate ivory hands to do but turn the volumes over. There was an agreeable and a disagreeable side to it. Incledon, for one thing, would be a capable referee in all money matters, and would help to arrange about the boys and get them on in the world, which was a great relief to think of; for ere now Mr. Damerel had felt the painful reflection thrust upon him, that some time or other he must do something about the boys. The other side of the question was, that he would lose the society of his Rose in June, his pretty companion, whose ornamental presence lent a new charm to his pretty house. He shrugged his shoulders a little over this, saying to himself that it must be sooner or later, and that, after all, he had done without Rose for many years, and had been much of a sufferer in consequence. It was the way of the world; and then he smiled again at the thought of Rose in the serious position of Mr. Incledon’s wife.

Mrs. Damerel had very different feelings on the subject as she went up-stairs with the candle he had so politely lighted for her, in her hand. I am afraid she was not so softened as she ought to have been by his charming politeness, which made her slightly angry, and she was deeply disturbed by the task he had thrown back upon her. Mrs. Damerel knew that girls were not so easily moulded as their fathers sometimes think. She felt by instinct that, according to all precedent, Wodehouse, who was young and gay and penniless, must be the favorite. She knew, too, that to endeavor to turn the current in favor of the other was almost enough to decide matters against him; and, beyond all this, Mrs. Damerel felt it hard that everything that was painful and disagreeable should be left on her shoulders. Rose was separated from her; she was her father’s companion; she was being trained to prefer refined but useless leisure with him to the aid and sympathy which her mother had a right to look for; yet, when it came to be needful to do any disagreeable duty for Rose, it was the mother who had to put herself in the breach. It was hard upon Mrs. Damerel. All the reproof, the unpleasant suggestions of duty, the disagreeable advice, the apparent exactions to come from her side; while nothing but indulgence, petting, and fondness, and unlimited compliance with every desire she had, should be apparent on the side of the father. I think Mrs. Damerel was right, and that hers was a very hard case indeed.

The Wodehouses came hastily to the rectory the very next day to intimate the sad news of Edward’s approaching departure. His mother fairly broke down, and cried bitterly. “I hoped to have had him with me so much longer,” she said; “and now he must go off about this slave-trade. Oh! why should we take it upon us to look after everybody, when they don’t want to be looked after? If those poor African wretches cared as much for it as we suppose, wouldn’t they take better care of themselves? What have we to do, always interfering? When I think of my boy, who is all I have in the world, going out to that{23} dreadful coast, to risk his life for the sake of some one he never saw or heard of”—

“My dear lady, we cannot be altogether guided by private motives,” said the rector; “we must take principle for something. Were we to permit the slave-trade, we should depart from all our traditions. England has always been the guardian of freedom.”

“Oh, Mr. Damerel!” said the poor lady, with tears in her eyes, “freedom is all very well to talk about, and I suppose it’s a great thing, to have; but what is freedom to these poor savages, that it should cost me and other women our boys?”

“It will not cost you your boy,” said Mrs. Damerel; “he will come back. Don’t take the gloomiest view of the question. He has been there before, and it did not hurt him; why should it now?”

“Ah! who can tell that?” said poor Mrs. Wodehouse, drying her eyes. She was a woman who liked the darker side of all human affairs, and she felt it almost an insult to her when any one prognosticated happiness. Her son was doing all he could to bear up under the depressing influence of her predictions and his regret at leaving her, and disappointment in having his holiday shortened—along with a deeper reason still which he said nothing about. He tried to be as cheerful as he could; but when he turned to Rose and met the one piteous look the girl gave him, and saw her lip quiver—though he did not know whether it was out of sympathy with his mother, or from any personal feeling of her own—he very nearly broke down. He had still ten days to make his preparations for leaving, and before that time he thought to himself he must surely find out whether Rose cared anything for him more than she did for the others whom she had known like him almost all her life. He looked anxiously into her face when he shook hands with her; but Rose, feeling, she could not tell why, more inclined to cry than she had ever been before, without any reason, as she said, would not meet his looks. “This is not my farewell visit,” he said, with an attempt at a laugh. “I don’t know why I should feel so dismal about it; I shall see you all again.”

“Oh, many times, I hope!” said Mrs. Damerel, who could not help feeling kindly towards the poor young fellow, notwithstanding her conspiracy against his interests. The rector did not commit himself in this foolish way, but took leave of the young sailor solemnly. “However that may be,” he said, “God bless you, Edward; I am sure you will do your duty, and be a credit to all that wish you well.”

This address chilled poor Wodehouse more and more. Was it his dismissal? He tried to bear up against that too, talking of the garden party he was coming to on Wednesday, and of the repeated visits he still hoped for; but, somehow, from the moment he received the rector’s blessing he believed in these farewell visits and the explanations they might give rise to, no more. When he went away with his mother, Rose ran up-stairs on some pretext, and her father and mother were left alone.

“Martha,” said the rector, “your usual careful solicitude failed you just now. You as good as asked him to come back; and what could possibly be so bad for Rose?”

“How could I help it?” she said. “Poor boy, he must come again, at least to say good-by.”

“I don’t see the necessity. It will only make mischief. Rose is quite cast down, whether from sympathy or from feeling. We should take care not to be at home when he calls again.”

Mr. Damerel said this in so even a voice that it was delightful to hear him speak, and he went out and took his seat under the lime-trees as a man should who has discharged all his duties and is at peace and in favor with both God and man. Rose did not venture to face her mother with eyes which she felt were heavy, and therefore stole out of doors direct and went to her father, who was always indulgent. How good and tender he was, never finding fault! If perhaps, as Rose was beginning to fear, it must be confessed that he was deficient in energy—a gentle accusation which the fondest partisan might allow—yet, to balance this, how good he was, how feeling, how tender! No one need be afraid to go to him. He was always ready to hear one’s story, to forgive one’s mistakes. Rose, who did not want to be catechised, stole across the lawn and sat down on the grass without{24} a word. She did not care to meet anybody’s look just at that moment. She had not cried; but the tears were so very near the surface, that any chance encounter of looks might have been more than she could bear.

Mr. Damerel did not speak all at once. He took time, the more cunningly to betray her; and then he entered upon one of his usual conversations, to which poor Rose gave but little heed. After a while her monosyllabic answers seemed to attract his curiosity all at once.

“You are not well,” he said; “or sorry, is it? Sorry for poor Mrs. Wodehouse, who is going to lose her son?”

“Oh yes, papa! Poor old lady—she will be so lonely when he is away.”

“She is not so very old,” he said, amused; “not so old as I am, and I don’t feel myself a Methuselah. It is very good of you to be so sympathizing, my dear.”

“Oh, papa, who could help it?” said Rose, almost feeling as if her father would approve the shedding of those tears which made her eyes so hot and heavy. She plucked a handful of grass and played with it, her head held down and the large drops gathering; and her heart, poor child, for the moment, in the fulness of this first trouble, felt more heavy than her eyes.

“Yes, it is a pity for Mrs. Wodehouse,” said Mr. Damerel, reflectively; “but, on the other hand, it would be very selfish to regret it for Edward. He has not a penny, poor fellow, and not much influence that I know of. He can only get his promotion by service, and in this point of view his friends ought to be glad he is going. Look across Ankermead, Rose; how soft the shadows are! the most delicate gray with silvery lights. If you were a little more ambitious as an artist, you might get your sketch-book and try that effect.”

Rose smiled a wan little smile in answer to this invitation, and looking down upon the landscape, as he told her to do, saw nothing but a bluish-green and yellow mist through the prismatic medium of the big tear, which next moment, to her terror and misery, came down, a huge, unconcealable wet blot, upon her light summer dress. She was herself so struck by consternation at the sight that, instead of making any attempt to conceal it, she looked up at him, her lips falling apart, her eyes growing larger and larger with fright and wonder, half appealing to him to know what it could mean, half defying observation. Mr. Damerel saw that it was necessary to abandon his usual rule of indulgence.

“You are too sympathetic, my dear,” he said. “If any one but me saw this they might say such feeling was too strong to be lavished on Mrs. Wodehouse. Don’t let us hear any more of it. Have you finished ‘Balaustion’? You have no book with you to-day.”

“No, papa—I came out—the other way”—

“What does that mean? Not through the drawing-room, where you left it, and where your mother was? I think you were right, Rose,” said Mr. Damerel, dropping back in his chair with his easy smile; “your mother has little patience with Mrs. Wodehouse’s despairs and miseries. You had better keep your sympathy to yourself in her presence. Look here; I want this read aloud. My eyes ache; I was up late last night.”

Rose took the book obediently, and read. She saw the white page and letters clear without any prismatic lights. Her tears were all driven away, forced back upon her heart as if by a strong wind. She read, as Milton’s daughters might have read his Latin, if they did not understand it, as some people say—not missing a word nor seeing any meaning in one; going on as in a dream, with a consciousness of herself, and the scene, and her father’s look, and not a notion what she was reading about. It was very good mental discipline, but so sharp that this poor soft child, utterly unused to it, not knowing why she should suddenly be subjected to such fierce repression, wretched and sick at heart, and sorry and ashamed, never forgot it all her life. She read thus for about an hour, till her father stopped her to make some notes upon the margin of the book; for he was one of those elegantly studious persons who weave themselves through the books they read, and leave volumes of notes on every possible subject behind them. He had been entering into every word, though Rose had not understood a syllable; and he smiled and discoursed to her about it, while she{25} kept silent, terrified lest he should ask some question, which would betray her inattention. Rose had been learning smilingly, with happy bewilderment, for some months back, to consider herself an independent individual. She felt and realized it without any difficulty to-day. She stood quite alone in all that bright scene; apart from the real world and the ideal both—neither the lawn, nor the book, nor the landscape, nor her father’s talk having power to move her; frightened at herself—still more frightened for him, and for the tone, half sarcastic, half reproving, which for the first time in her life she had heard in his voice; and without even the satisfaction of realizing the new sentiment which had come into her mind. She realized nothing except that sudden dismay had come over her, that it had been checked summarily; that her tears, driven back, were filling her head and her heart with confusing pain; that there was something wrong in the strange new emotion that was at work within her—and this without even the melancholy sweetness of knowing what it was.

Poor Rose in June! It was the first storm that had ever disturbed her perfect blossom. She began to get better after a while, as at her age it is easy to do, and gradually came out of her mist and was restored to partial consciousness. By the evening of that day she was nearly herself again, though much subdued, remembering that she had been very unhappy, as she might have remembered a very bad headache, with great content, yet wonder that it should be gone or almost gone. The cessation of the active pain gave her a kind of subdued happiness once more, as relief always does—which the heart never feels to be negative, but positive. What a thing ease is, after we are once conscious of having lost it even for an hour! This brought Rose’s color back and her smile. All mental pain, I suppose, is spasmodic; and the first fit, when not too well defined nor hopeless in character, is often as brief as it is violent.

Rose got better; her mind accustomed itself to the shadow which for one short interval had covered it with blackness. She began to perceive that it did not fill all earth and heaven, as she had at first supposed.