Title: Historical Record of the First, or the Royal Regiment of Dragoons

Author: Richard Cannon

Release date: June 11, 2017 [eBook #54891]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Some minor changes are noted at the end of the book.

HISTORICAL RECORDS

OF THE

BRITISH ARMY.

PREPARED FOR PUBLICATION UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE

ADJUTANT-GENERAL.

LONDON

Printed by William Clowes and Sons.

14, Charing Cross.

HORSE-GUARDS,

1st January, 1836.

His Majesty has been pleased to command, that, with a view of doing the fullest justice to Regiments, as well as to Individuals who have distinguished themselves by their Bravery in Action with the Enemy, an Account of the Services of every Regiment in the British Army shall be published under the superintendence and direction of the Adjutant-General; and that this Account shall contain the following particulars: viz.,

—— The Period and Circumstances of the Original Formation of the Regiment; The Stations at which it has been from time to time employed; The Battles, Sieges, and other Military Operations, in which it has been engaged, particularly specifying any Achievement it may have performed, and the Colours, Trophies, &c., it may have captured from the Enemy.

—— The Names of the Officers and the number of Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates, Killed or Wounded by the Enemy, specifying the Place and Date of the Action.

—— The Names of those Officers, who, in consideration of their Gallant Services and Meritorious Conduct in Engagements with the Enemy, have been distinguished with Titles, Medals, or other Marks of His Majesty's gracious favour.

—— The Names of all such Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates as may have specially signalized themselves in Action.

And,

—— The Badges and Devices which the Regiment may have been permitted to bear, and the Causes on account of which such Badges or Devices, or any other Marks of Distinction, have been granted.

By Command of the Right Honourable

GENERAL LORD HILL,

Commanding-in-Chief.

John Macdonald,

Adjutant-General.

The character and credit of the British Army must chiefly depend upon the zeal and ardour, by which all who enter into its service are animated, and consequently it is of the highest importance that any measure calculated to excite the spirit of emulation, by which alone great and gallant actions are achieved, should be adopted.

Nothing can more fully tend to the accomplishment of this desirable object, than a full display of the noble deeds with which the Military History of our country abounds. To hold forth these bright examples to the imitation of the youthful soldier, and thus to incite him to emulate the meritorious conduct of those who have preceded him in their honourable career, are among the motives that have given rise to the present publication.

The operations of the British Troops are, indeed, announced in the 'London Gazette,' from whence they are transferred into the public prints: the achievements of our armies are thus made known at the time of their occurrence, and receive the tribute of praise and admiration to which they are entitled. On extraordinary occasions, the Houses of Parliament have been in the habit of conferring on the Commanders, and the Officers and Troops acting under their orders, expressions of approbation and of thanks for their skill and bravery, and these testimonials, confirmed by the high honour of their Sovereign's Approbation, constitute the reward which the soldier most highly prizes.

It has not, however, until late years, been the practice (which appears to have long prevailed in some of the Continental armies) for British Regiments to keep regular records of their services and achievements. Hence some difficulty has been experienced in obtaining, particularly from the old Regiments, an authentic account of their origin and subsequent services.

This defect will now be remedied, in consequence of His Majesty having been pleased to command, that every Regiment shall in future keep a full and ample record of its services at home and abroad.

From the materials thus collected, the country will henceforth derive information as to the difficulties and privations which chequer the career of those who embrace the military profession. In Great Britain, where so large a number of persons are devoted to the active concerns of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce, and where these pursuits have, for so long a period, been undisturbed by the presence of war, which few other countries have escaped, comparatively little is known of the vicissitudes of active service, and of the casualties of climate, to which, even during peace, the British Troops are exposed in every part of the globe, with little or no interval of repose.

In their tranquil enjoyment of the blessings which the country derives from the industry and the enterprise of the agriculturist and the trader, its happy inhabitants may be supposed not often to reflect on the perilous duties of the soldier and the sailor,—on their sufferings,—and on the sacrifice of valuable life, by which so many national benefits are obtained and preserved.

The conduct of the British Troops, their valour, and endurance, have shone conspicuously under great and trying difficulties; and their character has been established in Continental warfare by the irresistible spirit with which they have effected debarkations in spite of the most formidable opposition, and by the gallantry and steadiness with which they have maintained their advantages against superior numbers.

In the official Reports made by the respective Commanders, ample justice has generally been done to the gallant exertions of the Corps employed; but the details of their services, and of acts of individual bravery, can only be fully given in the Annals of the various Regiments.

These Records are now preparing for publication, under His Majesty's special authority, by Mr. Richard Cannon, Principal Clerk of the Adjutant-General's Office; and while the perusal of them cannot fail to be useful and interesting to military men of every rank, it is considered that they will also afford entertainment and information to the general reader, particularly to those who may have served in the Army, or who have relatives in the Service.

There exists in the breasts of most of those who have served, or are serving, in the Army, an Esprit de Corps—an attachment to every thing belonging to their Regiment; to such persons a narrative of the services of their own Corps cannot fail to prove interesting. Authentic accounts of the actions of the great,—the valiant,—the loyal, have always been of paramount interest with a brave and civilised people. Great Britain has produced a race of heroes who, in moments of danger and terror, have stood, "firm as the rocks of their native shore;" and when half the World has been arrayed against them, they have fought the battles of their Country with unshaken fortitude. It is presumed that a record of achievements in war,—victories so complete and surprising, gained by our countrymen,—our brothers—our fellow-citizens in arms,—a record which revives the memory of the brave, and brings their gallant deeds before us, will certainly prove acceptable to the public.

Biographical memoirs of the Colonels and other distinguished Officers, will be introduced in the Records of their respective Regiments, and the Honorary Distinctions which have, from time to time, been conferred upon each Regiment, as testifying the value and importance of its services, will be faithfully set forth.

As a convenient mode of Publication, the Record of each Regiment will be printed in a distinct number, so that when the whole shall be completed, the Parts may be bound up in numerical succession.

The ancient Armies of England were composed of Horse and Foot; but the feudal troops established by William the Conqueror in 1086, consisted almost entirely of Horse. Under the feudal system, every holder of land amounting to what was termed a "knight's fee," was required to provide a charger, a coat of mail, a helmet, a shield, and a lance, and to serve the Crown a period of forty days in each year at his own expense; and the great landholders had to provide armed men in proportion to the extent of their estates; consequently the ranks of the feudal Cavalry were completed with men of property, and the vassals and tenants of the great barons, who led their dependents to the field in person.

In the succeeding reigns the Cavalry of the Army was composed of Knights (or men at arms) and Hobiliers (or horsemen of inferior degree); and the Infantry of spear and battle-axe men, cross-bowmen, and archers. The Knights wore armour on every part of the body, and their weapons were a lance, a sword, and a small dagger. The Hobiliers were accoutred and armed[ii] for the light and less important services of war, and were not considered qualified for a charge in line. Mounted Archers[1] were also introduced, and the English nation eventually became pre-eminent in the use of the bow.

About the time of Queen Mary the appellation of "Men at Arms" was changed to that of "Spears and Launces." The introduction of fire-arms ultimately occasioned the lance to fall into disuse, and the title of the Horsemen of the first degree was changed to "Cuirassiers." The Cuirassiers were armed cap-à-pié, and their weapons were a sword with a straight narrow blade and sharp point, and a pair of large pistols, called petrenels; and the Hobiliers carried carbines. The Infantry carried pikes, matchlocks, and swords. The introduction of fire-arms occasioned the formation of regiments armed and equipped as infantry, but mounted on small horses for the sake of expedition of movement, and these were styled "Dragoons;" a small portion of the military force of the kingdom, however, consisted of this description of troops.

The formation of the present Army commenced[iii] after the Restoration in 1660, with the establishment of regular corps of Horse and Foot; the Horsemen were cuirassiers, but only wore armour on the head and body; and the Foot were pikemen and musketeers. The arms which each description of force carried, are described in the following extract from the "Regulations of King Charles II.," dated 5th May, 1663:—

"Each Horseman to have for his defensive armes, back, breast, and pot; and for his offensive armes, a sword, and a case of pistolls, the barrels whereof are not to be undr. foorteen inches in length; and each Trooper of Our Guards to have a carbine, besides the aforesaid armes. And the Foote to have each souldier a sword, and each pikeman a pike of 16 foote long and not undr.; and each musqueteer a musquet, with a collar of bandaliers, the barrels of which musquet to be about foor foote long, and to conteine a bullet, foorteen of which shall weigh a pound weight[2]."

The ranks of the Troops of Horse were at this period composed of men of some property—generally the sons of substantial yeomen: the young men received as recruits provided their own horses,[iv] and they were placed on a rate of pay sufficient to give them a respectable station in society.

On the breaking out of the war with Holland, in the spring of 1672, a Regiment of Dragoons was raised[3]; the Dragoons were placed on a lower rate of pay than the Horse; and the Regiment was armed similar to the Infantry, excepting that a limited number of the men carried halberds instead of pikes, and the others muskets and bayonets; and a few men in each Troop had pistols; as appears by a warrant dated the 2nd of April, 1672, of which the following is an extract:—

"Charles R.

"Our will and pleasure is, that a Regiment of Dragoones which we have established and ordered to be raised, in twelve Troopes of fourscore in each beside officers, who are to be under the command of Our most deare and most intirely beloved Cousin Prince Rupert, shall be armed out of Our stoares remaining within Our office of the Ordinance, as followeth; that is to say, three corporalls, two serjeants, the gentlemen at armes, and twelve souldiers of each of the said twelve Troopes, are to have and carry each of them one halbard, and one case[v] of pistolls with holsters; and the rest of the souldiers of the several Troopes aforesaid, are to have and to carry each of them one matchlocke musquet, with a collar of bandaliers, and also to have and to carry one bayonet[4], or great knife. That each lieutenant have and carry one partizan; and that two drums be delivered out for each Troope of the said Regiment[5]."

Several regiments of Horse and Dragoons were raised in the first year of the reign of King James II.; and the horsemen carried a short carbine[6] in addition to the sword and pair of pistols; and in a Regulation dated the 21st of February, 1687, the arms of the Dragoons at that period are commanded to be as follow:—

"The Dragoons to have snaphanse musquets, strapt, with bright barrels of three foote eight inches long, cartouch-boxes, bayonetts, granado pouches, bucketts, and hammer-hatchetts."

After several years' experience, little advantage was found to accrue from having Cavalry Regiments formed almost exclusively for engaging the [vi]enemy on foot; and, the Horse having laid aside their armour, the arms and equipment of Horse and Dragoons were so nearly assimilated, that there remained little distinction besides the name and rate of pay. The introduction of improvements into the mounting, arming, and equipment of Dragoons rendered them competent to the performance of every description of service required of Cavalry; and, while the long musket and bayonet were retained, to enable them to act as Infantry, if necessary, they were found to be equally efficient, and of equal value to the nation, as Cavalry, with the Regiments of Horse.

In the several augmentations made to the regular Army after the early part of the reign of Queen Anne, no new Regiments of Horse were raised for permanent service; and in 1746 King George II. reduced three of the old Regiments of Horse to the quality and pay of Dragoons; at the same time, His Majesty gave them the title of First, Second, and Third Regiments of Dragoon Guards: and in 1788 the same alteration was made in the remaining four Regiments of Horse, which then became the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Regiments of Dragoon Guards.

At present there are only three Regiments which are styled Horse in the British Army,[vii] namely, the two Regiments of Life Guards, and the Royal Regiment of Horse Guards, to whom cuirasses have recently been restored. The other Cavalry Regiments consist of Dragoon Guards, Heavy and Light Dragoons, Hussars, and Lancers; and although the long musket and bayonet have been laid aside by the whole of the Cavalry, and the Regiments are armed and equipped on the principle of the old Horse (excepting the cuirass), they continue to be styled Dragoons.

The old Regiments of Horse formed a highly respectable and efficient portion of the Army, and it is found, on perusing the histories of the various campaigns in which they have been engaged, that they have, on all occasions, maintained a high character for steadiness and discipline, as well as for bravery in action. They were formerly mounted on horses of superior weight and physical power, and few troops could withstand a well-directed charge of the celebrated British Horse. The records of these corps embrace a period of 150 years—a period eventful in history, and abounding in instances of heroism displayed by the British troops when danger has threatened the nation,—a period in which these Regiments have numbered in their ranks men of loyalty, valour, and good conduct, worthy of imitation.

Since the Regiments of Horse were formed into Dragoon Guards, additional improvements have been introduced into the constitution of the several corps; and the superior description of horses now bred in the United Kingdom enables the commanding officers to remount their regiments with such excellent horses, that, whilst sufficient weight has been retained for a powerful charge in line, a lightness has been acquired which renders them available for every description of service incident to modern warfare.

The orderly conduct of these Regiments in quarters has gained the confidence and esteem of the respectable inhabitants of the various parts of the United Kingdom in which they have been stationed; their promptitude and alacrity in attending to the requisitions of the magistrates in periods of excitement, and the temper, patience, and forbearance which they have evinced when subjected to great provocation, insult, and violence from the misguided populace, prove the value of these troops to the Crown, and to the Government of the country, and justify the reliance which is reposed on them.

[1] In the 14th year of the reign of Edward IV. a small force was established in Ireland by Parliament, consisting of 120 Archers on horseback, 40 Horsemen, and 40 Pages.

[2] Military Papers, State Paper Office.

[3] This Regiment was disbanded after the Peace in 1674.

[4] This appears to be the first introduction of bayonets into the English Army.

[5] State Paper Office.

[6] The first issue of carbines to the regular Horse appears to have taken place in 1678; the Life Guards, however, carried carbines from their formation in 1660.—Vide the 'Historical Record of the Life Guards.'

HISTORICAL RECORD

OF

THE FIRST,

OR

THE ROYAL REGIMENT

OF

DRAGOONS;

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF ITS FORMATION

IN THE REIGN OF

KING CHARLES THE SECOND,

AND OF ITS SUBSEQUENT SERVICES TO 1839.

ILLUSTRATED WITH PLATES.

LONDON:

PUBLISHED BY LONGMAN, ORME, AND CO.,

PATERNOSTER-ROW;

AND BY MESSRS. CLOWES AND SONS,

14, Charing Cross;

AND TO BE HAD OF ALL BOOKSELLERS.

1840.

LONDON:

Printed by William Clowes and Sons,

Stamford-street.

THE FIRST

OR

THE ROYAL REGIMENT

OF

DRAGOONS

BEARS ON ITS GUIDONS,

AS A

REGIMENTAL BADGE,

AN

"EAGLE,"

WITH THE FOLLOWING HONORARY INSCRIPTIONS—

"PENINSULA"—"WATERLOO."

| Anno | Page | |

| 1661 | A troop of Horse raised for service at Tangier, and equipped as Cuirassiers | 1 |

| —— | Proceeds to Africa | 3 |

| 1663 | Skirmishes with the Moors | 4 |

| 1664 | Captures a splendid Moorish standard | — |

| 1664} | ||

| to } | Skirmishes with the Moors | 5 |

| 1679} | ||

| 1680 | Three additional troops of Horse raised and sent to Tangier | — |

| —— | A general engagement with the Moors | 7 |

| 1683 | The Tangier Horse constituted the Royal Regiment of Dragoons | 8 |

| 1684 | Establishment | 9 |

| —— | Returns to England, and equipped as dragoons | 11 |

| —— | Description of the standards—Names of officers | 12 |

| —— | Royal warrant respecting the rank of the regiment | 13 |

| 1685 | Battle of Sedgemoor | 15 |

| 1688 | The Revolution | 18 |

| 1689 | Proceeds to Scotland | 21 |

| —— | Embarks for Ireland | 22 |

| 1690 | Siege of Charlemont | 23 |

| —— | Battle of the Boyne | 24 |

| —— | Embarks for England—Returns to Ireland | — |

| —— | Skirmishes with the Rapparees | 25 |

| 1691 | Actions with the Irish | 26 |

| —— | Siege of Limerick | 27 |

| 1692 | Embarks for England | 29 |

| 1694 | Proceeds to the Netherlands | — |

| —— | Skirmishes near the Mehaine | 30 |

| 1695 | Covering the siege of Namur | 31 |

| 1697 | Returns to England | 32 |

| 1702 | Proceeds to Holland | 33 |

| —— | Covering the sieges of Venloo, Ruremonde, Stevenswaert, and Liege | 34 |

| [vi] 1703 | Covering the siege of Bonn | 34 |

| —— | Skirmish with a French piquet | — |

| —— | Covering the sieges of Huy and Limburg | 35 |

| —— | Proceeds from Holland to Portugal | — |

| 1704 | Services on the frontiers of Spain | 36 |

| 1705 | Capture of Valencia de Alcantara and Albuquerque | 37 |

| —— | ————– Barcelona | 38 |

| —— | Relief of St. Mattheo | 40 |

| 1706 | Services in Catalonia and Valencia | — |

| —— | ———– during the siege of Barcelona by the French | 43 |

| —— | Advances to Madrid | 44 |

| —— | Returns to Valencia | 45 |

| 1707 | Services after the battle of Almanza | 46 |

| 1709 | Capture of Balaguer and Ager | 47 |

| 1710 | Battle of Almanara | 48 |

| —— | Skirmish at Penalva | 49 |

| —— | Battle of Saragossa | — |

| —— | Advances to Madrid—Disaster at Brihuega | 51 |

| 1712 | Returns to England | 53 |

| 1715 | Rebellion of the Earl of Mar—Affair at Preston | 54 |

| 1719 | Proceeds to Scotland—Returns to England | 56 |

| —— | Detachment to Spain—Capture of Vigo, &c. | — |

| 1720 | Prices of commissions | 57 |

| 1735 | Proceeds to Scotland | 59 |

| 1737 | Returns to England | — |

| 1742 | Embarks for Flanders | 60 |

| 1743 | Battle of Dettingen | 61 |

| 1745 | ———– Fontenoy | 63 |

| —— | Embarks for England | 64 |

| 1751 | Description of the clothing and guidons | 65 |

| 1755 | A light troop added | 67 |

| 1758 | Expedition to St. Maloes and Cherbourg | 68 |

| 1760 | Embarks for Germany | — |

| —— | Battle of Warbourg | 69 |

| —— | ———– Campen | 70 |

| 1761 | ———– Kirch Denkern | 72 |

| —— | Skirmishes at Eimbeck and Foorwohle | — |

| 1762 | Battle of Groebenstien | 73 |

| 1763 | Returns to England | 74 |

| —— | The light troop disbanded | 75 |

| —— | Proceeds to Scotland | — |

| [vii] 1764 | Returns to England | 75 |

| 1766 | Drummers replaced by trumpeters | — |

| 1769 | Proceeds to Scotland | — |

| 1770 | Returns to England | — |

| 1773 | Proceeds to Scotland | 76 |

| 1775 | Returns to England | — |

| 1781 | Proceeds to Scotland | 77 |

| 1784 | Returns to England | — |

| 1790 | Proceeds to Scotland | — |

| 1791 | Returns to England | — |

| 1793 | Embarks for the Netherlands | — |

| —— | Action at the Camp de Cæsar | — |

| 1794 | ———— Prémont | 78 |

| —— | ———— Villers en Couché | — |

| —— | Battle of Cateau | — |

| —— | ———– Tournay | 79 |

| —— | Retreats to Germany | 80 |

| 1795 | Returns to England | 81 |

| 1806 | Proceeds to Scotland | 83 |

| 1807 | Embarks for Ireland | — |

| 1809 | ————— Portugal | 84 |

| 1810 | Skirmishes at Frexadas and Alverca | 86 |

| —— | Battle of Busaco | — |

| —— | Skirmishes at Pombal and Quinta de Torre | 87 |

| 1811 | —————– Pecoloo, Pombal, Redinha, Casal Nova, Foz d'Aronce, Sernadilla, and Alverca | 88 |

| —— | Battle of Sabugal | 90 |

| —— | Skirmish near Fort Conception | — |

| —— | Battle of Fuentes d'Onor | — |

| —— | Skirmish near Barba del Puerco | 91 |

| —— | ———– during the retreat to Nave d'Aver | 92 |

| —— | ———– at Aldea de Ponte | 93 |

| 1812 | Covering the sieges of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz | 94 |

| —— | Skirmishes at Llera, Maguilla, &c. | 95 |

| —— | Advances to Madrid—Retreats to Portugal | 97 |

| —— | Skirmish at Arguilla | — |

| 1813 | Battle of Vittoria | 98 |

| —— | Blockade of Pampeluna | 99 |

| 1814 | Battle of Toulouse | 100 |

| —— | Returns to England | — |

| 1815 | Embarks for Flanders | 101 |

| —— | Battle of Waterloo | 102 |

| [viii] 1815 | Advances to Madrid | 109 |

| 1816 | Returns to England | 110 |

| 1817 | Proceeds to Scotland | 111 |

| 1818 | Embarks for Ireland | — |

| 1820 | Returns to England | — |

| 1824 | Proceeds to Scotland | 112 |

| 1825 | Embarks for Ireland | 113 |

| 1829 | Returns to England | — |

| 1835 | Embarks for Ireland | 115 |

| 1839 | Returns to England | — |

| —— | The conclusion | — |

SUCCESSION OF COLONELS. | ||

| 1683 | John Lord Churchill | 117 |

| 1685 | Edward Viscount Cornbury | 122 |

| 1688 | Robert Clifford | — |

| —— | Edward Viscount Cornbury | — |

| 1689 | Anthony Hayford | 123 |

| 1690 | Edward Matthews | — |

| 1697 | Thomas Lord Raby | — |

| 1715 | Richard Lord Cobham | 124 |

| 1721 | Sir Charles Hotham, Bart. | 126 |

| 1723 | Humphrey Gore | — |

| 1739 | Charles Duke of Marlborough | 127 |

| 1740 | Henry Hawley | — |

| 1759 | Honourable Henry Seymour Conway | 128 |

| 1764 | Henry Earl of Pembroke | 129 |

| 1794 | Philip Goldsworthy | 130 |

| 1801 | Thomas Garth | — |

| 1829 | Lord Edward Somerset | 131 |

| 1836 | Sir Frederick C. Ponsonby | — |

| 1837 | Sir Hussey Vivian, Bart. | 133 |

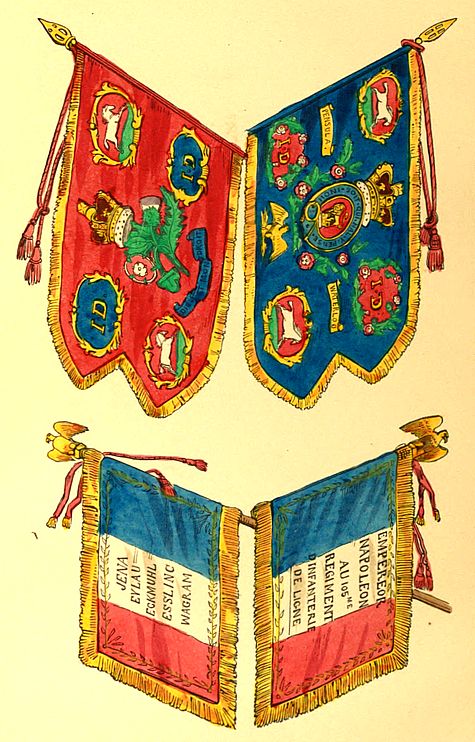

The regimental guidons;—with the Eagle and Colour of the 105th French Infantry Regiment, captured at Waterloo; to follow the title-page.

The capture of a Moorish Standard at Tangier in 1664, to face page 4.

The uniform of 1839 to face 116.

OF

THE FIRST,

OR

THE ROYAL REGIMENT

OF

DRAGOONS.

The anarchy, devastation, and bloodshed which had prevailed in Britain during the rebellion and tyrannical usurpation of Cromwell, having been succeeded by the restoration of monarchy,—the despotic sway of sectarians and republicans put down by the establishment of a regular government on constitutional principles,—and the army of the commonwealth disbanded, King Charles II. directed his attention to domestic concerns, and engaged in a matrimonial alliance with Donna Catherina, Infanta of Portugal; and this event gave rise to the formation of a troop of Cuirassiers, which was the nucleus of the corps now bearing the distinguished title of The Royal Regiment of Dragoons.

By the marriage treaty the ancient and once magnificent city of Tangier, in Africa, and the island of Bombay in the East Indies, were ceded by the king of Portugal to the British crown; and,[2] with a sum equal to three hundred thousand pounds, constituted the Infanta's dowry.

As the possession of the important fortress of Tangier, with its harbour and local advantages, appeared to open a new field for commercial pursuits, and was expected to be followed by the acquisition of extensive possessions in that part of the world, four regiments of foot and a troop of horse were appointed to garrison that fortress, and the Earl of Peterborough was constituted captain general, chief governor, and vice admiral of that part of his Majesty's dominions.

Three of the regiments of foot, commanded by Sir Robert Harley, and Colonels Fitzgerald and O'Farell, were withdrawn from the garrison of Dunkirk, and were composed of men who had fought in the royal cause during the civil war, and afterwards in the Netherlands. The other regiment of foot, (now the second, or Queen's royal,) and the troop of Horse (now Royal Dragoons) were raised in England by the Earl of Peterborough in the autumn of 1661, and were mustered, the former on Putney Heath, and the latter in St. George's Fields, Southwark, in October.[7]

The troop of Horse consisted of three officers, one quarter-master, four corporals, one trumpeter, and one hundred private men; the ranks were completed with veterans of the civil war, who were armed with cuirasses, iron head-pieces called potts, long swords, and a pair of large pistols, to which a short carbine was afterwards added: they[3] were mounted on long-tailed horses of superior weight and power, wore high boots reaching to the middle of the thigh, and scarlet vests: the officers wore hats decorated with a profusion of feathers; and both officers and men ornamented their horses' heads and tails with large bunches of ribands. The officers of this troop were,—

The Earl of Peterborough, Captain and Colonel.

Robert Leech, Captain-Lieutenant.

James Mordaunt, Cornet.

The appearance and equipment of the officers and men were commended in the ephemeral publications of that period. They embarked in the middle of December, and in a letter to the Earl of Peterborough, dated the 21st of December, the King observed: 'I desire you to lett those honest men knowe who are along with you, yt they shall allwayes be in my particular care and protection as persons yt venture themselves in my service. And so, wishing you a good voyage, I remain, &c., Charles R.'[8]

The troops arrived at Tangier in January, 1662, and a war commencing soon afterwards between the British occupants of this part of Africa and the Moors, frequent encounters occurred between detachments of the garrison of Tangier and the barbarians, in which the former had a decided superiority, and the English horsemen became celebrated for gallant achievements.[9]

The veteran Earl of Teviot, who was appointed governor of Tangier in 1663, in succession [4]to the Earl of Peterborough, occasionally penetrated into the adjacent country at the head of a detachment of horse, and many brilliant exploits were performed by the gallant English troopers, among the rocks, in the woods, and on the plains of this part of Africa, where they frequently surprised lurking parties of Moors, and captured cattle and other booty. The Africans were, however, expert horsemen, and fought with lance, sword, and short fusils.

In February, 1664, a Moorish army, commanded by Gaylan, usurper of Fez, appeared before Tangier to besiege the fortress. On the 1st of March the Earl of Teviot, observing a body of Moors, with a splendid scarlet standard, stationed on an eminence near the city, ordered the troop of Horse to sally and bring in the standard. The command was instantly obeyed; the brave troopers, led by Captain Witham, issued from the city, traversed the intervening space with signal intrepidity, routed the Moorish band, and captured the standard, with which they returned in triumph to the fortress, and erected it on the top of one of the towers, to the surprise and chagrin of the Moorish chiefs, who, being posted at a distance with the main body of their army, witnessed this brilliant exploit.

[To face page 4

On the 13th of March the English horsemen had a sharp encounter with some of the enemy's best cavalry; and on the 27th, the Earl of Teviot led them against a horde of Moorish lancers and foot who were concealed in ambush, and the barbarians were routed and pursued among the woods [5]and broken grounds with great slaughter. The English horsemen, however, suffered severely on the 4th of May in the same year, when the governor, having been deceived by a false report, advanced too far into the country, and was surprised by a numerous band of Moors in ambush. A fearful slaughter followed, and the Earl of Teviot was numbered among the slain.

Frequent encounters took place in the subsequent years between detached parties of British and Moors, and in this desultory warfare the English horsemen preserved their high character. Hostilities were occasionally terminated, and renewed after short intervals of peace; and during the period of seventeen years the garrison resisted, with firmness and success, every attempt of the Moors against the city.

In 1679 a numerous army of Moors appeared before Tangier, and destroyed two forts situate at a distance from the town. They afterwards withdrew, but re-appeared in the spring of 1680, with augmented numbers, and swarms of expert Moorish lancers, on light and swift horses, hovered round the fortress and confined the Christians within narrow limits. King Charles II. sent a battalion of foot guards and sixteen companies of Dumbarton's (now first royal) regiment, to reinforce the garrison, and issued commissions for raising a regiment of foot (now the fourth, or the King's own) and six troops of Horse in England: at the same time arrangements were made for procuring the service of three troops of Spanish cavalry.

The six troops of English horse were raised by Major-General the Earl of Ossory, Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Lanier,[10] Captains Robert Pulteney, John Coy,[11] Charles Nedby, and Thomas Langston:[12] the three last-named officers having been captains in the Duke of Monmouth's regiment of horse, which was disbanded only a few months before, their troops were speedily completed with disciplined men who had served in that regiment; and the demand for cavalry at Tangier being urgent, they were furnished with horses and equipment from the life guards,[13] and arrived at Tangier in the early part of September: at the same time the three troops of Spanish horse arrived from Gibraltar.

The cavalry at Tangier now consisted of seven efficient troops of cuirassiers, who were engaged in a sally on the 12th of September, when the Moorish horsemen were driven from under the walls, and several outworks were recovered from the barbarians. Another sally was made on the 21st of the same month, and on the following day the English cuirassiers had a sharp skirmish with the Moorish lancers, and had eight men killed and [7]twenty wounded. An attack was made on the enemy's lines on the 24th of September, when the governor, Sir Palmes Fairborne, was mortally wounded.

On the 27th of September, the garrison, amounting to about 4000 men, issued from the fortress and attacked the Moorish army of about 15,000 men in its intrenched camp with signal gallantry. So eager were the troopers to engage their adversaries that a dispute occurred between the English and Spanish horse, each claiming the honour of charging first: the subject was referred to the lieutenant-governor, Colonel Sackville, who gave the Spaniards the precedence on this occasion, because they fought as auxiliaries. The Moors, having a great superiority of numbers, stood their ground resolutely for some time; and the thunder of cannon, the roll of musketry, the clash of arms, the loud shouts of the British, the cries of the Africans, produced an awful scene of carnage and confusion. The English horse stood in column of troops until the first intrenchment was carried, and a space levelled for the cavalry to pass, when they filed through the aperture and rushed at speed upon the dark masses of barbarians, who were broken, trampled down, and pursued with a dreadful slaughter; while the musketeers, pikemen, and grenadiers followed, shouting as the dismayed Africans fell in succession beneath the sabres of the English and Spanish troopers. Many of the Moors faced about and confronted their pursuers; numerous single combats took place, and the vicinity of the camp was[8] covered with slain. Captain Nedby's troop of English horse particularly distinguished itself, and captured a splendid Moorish colour of curious workmanship. The Spaniards also captured a colour, Dumbarton's Scots another, and a fourth was taken by a battalion of marines and seamen from the fleet.[14]

The Moorish legions, having been driven from before the town with severe loss, this victory was followed by a treaty of peace, and the troops of horse raised by the Earl of Ossory, Sir John Lanier, and Robert Pulteney, not having left England, were disbanded.

The improved military system introduced among the Moors by European renegades, having rendered it necessary to employ a much stronger garrison at Tangier than formerly, the subject was brought before parliament; but the question of a popish successor to the throne was agitating the people, and no grant was voted. The king, being unwilling to bear the expense of the fortifications and troops without pecuniary aid from parliament, resolved to destroy the works and mole, and to withdraw the garrison.

At this period the attention of King Charles II. was directed to the improvement of his army; and, resolving to retain the Tangier Horse in his service, he commissioned Colonel John Churchill (afterwards the great Duke of Marlborough) to raise a troop of dragoons at St. Alban's and its vicinity; and Viscount Cornbury (son of the[9] Earl of Clarendon) to raise another troop of dragoons at Hertford; and His Majesty constituted these two troops, with the four troops of Tangier horse, a regiment, to which he gave the distinguished title of The King's Own Royal Regiment of Dragoons: the words "King's Own" were, however, discontinued soon afterwards, and the regiment was styled "The Royal Regiment of Dragoons."[15] The colonelcy was conferred on John Churchill, who was advanced to the peerage of Scotland by the title of Baron Churchill of Aymouth; and the lieutenant-colonelcy on Viscount Cornbury, by commission dated the 19th of November, 1683.

The establishment was fixed by a warrant bearing date the 1st of January, 1684, from which the following is an extract:—

"Charles R.

"Charles the Second, by the Grace of God, King of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, &c.

"Our will and pleasure is, that this establishment of our Guards, garrisons, and land forces within our Kingdom of England, Dominion of Wales, and Town of Berwick upon Tweed, and the Islands thereunto belonging, and of all other officers and charges therein expressed, do commence on the 1st day of January, 1683-4, in the Thirty-Fifth year of our Reign."

| HIS MAJESTY'S OWN ROYAL REGIMENT OF DRAGOONS. | |||

| Staff-Officers. | Per Diem. | ||

| £. | s. | d. | |

| Colonel, as Colonel, xiis, and iij horses iijs | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| Lieutenant-Colonel, as Lieut.-Colonel, vijs, and ij horses ijs | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Major, as Major vs, and j horse js | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Chaplaine | 0 | 6 | 8 |

| Chirurgeon ivs, and j horse to carry his chest, ijs | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Adjutant ivs, and for his horse js | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Quarter-Master and Marshal in one person ivs, his horse js | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Gunsmith ivs, and his servant is | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| —— | —— | —— | |

| 2 | 17 | 8 | |

| —— | —— | —— | |

| The Colonel's Troop. | |||

| The Colonel, as Captaine, viiis, and iij horses iijs. | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Lieutenant ivs, and ij horses ijs | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Cornett iijs, and ij horses ijs | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Quarter-Master, for himself and horse | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Two Serjeants each js vid, and ijs for horses | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Three Corporals each js, and iijs for horses | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Two Drummers each js, and ijs for horses | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Two Hautboys each is, and ijs for horses | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Fifty Soldiers each is vid for man and horse | 3 | 15 | 0 |

| —— | —— | —— | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| —— | —— | —— | |

| Five Troops more at the same rate | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| —— | —— | —— | |

| The Major to have no Troop, but instead thereof the pay of a Captain xis, in lieu of servants iiis | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| —— | —— | —— | |

| Total | 39 | 11 | 8 |

| —— | —— | —— | |

| Total Per Annum £14,447 18s. 4d. | |||

The four troops at Tangier arrived in England in February, 1684;[16] and, having returned their armour into store, the whole were equipped as dragoons with long muskets and bayonets.[17]

The uniform of the regiment was scarlet lined with blue. The men wore hats bound with silver lace, and ornamented with blue ribands, having a metal headpiece fastened inside the crown; also high boots: their horse furniture was made of scarlet cloth trimmed with blue, with the King's cipher embroidered in yellow characters on the housings and holster-caps. The drummers and hautboys were clothed in splendid liveries, which (according to the War-Office Records) cost upwards of 10l. per suit; and each troop was furnished [12]with a crimson standard or guidon, with the following devices embroidered thereon, namely:—

On the standard of the Colonel's Troop,—the King's cipher and crown.

The Lieutenant-Colonel's Troop,—the rays of the sun, proper, crowned, issuing out of a cloud, proper: a badge used by the Black Prince.

The First Troop,—the top of a beacon crowned, or, with flames of fire, proper: a badge of Henry V.

The Second Troop,—two ostrich feathers crowned, argent: a badge of Henry VI.

The Third Troop,—a rose and pomegranate impaled, leaves and stalk vert: a badge of Henry VII.

The Fourth Troop,—a phœnix in flames, proper: a badge of Queen Elizabeth's.[18]

The following officers were at this period holding commissions in the regiment:—

| Troops. | Captains. | Lieutenants. | Cornets. |

| Colonel's. | Lord Churchill | Thos. Hussey | Wm. Hussey |

| Lieut.-Col.'s | Visc. Cornbury | Charles Ward | Piercy Roche |

| 1st Troop. | Alex. Mackenzie | H. Wyndham[19] | John Cole |

| 2nd " | Chas. Nedby | John Williams | George Clifford |

| 3rd " | John Coy | Charles La Rue | Wm. Stamford |

| 4th " | Thos. Langston | F. Langston[20] | Thos. Pownel |

| Hugh Sutherland | Major | ||

| Thomas Crawley | Adjutant | ||

| Henry Hawker | Quarter-Master & Marshal | ||

| Theobald Churchill | Chaplain | ||

| Peregrine Yewel | Chirurgeon | ||

The Royal Regiment of Dragoons being [13]constituted, generally, of men of military experience and approved valour, appears to have advanced, at once, into royal favour; and as soon as it was regularly organized, it marched into quarters in the borough of Southwark. On the 1st of October it was reviewed, with several other corps, by King Charles II., accompanied by the Queen, the Duke of York, and many distinguished personages, on Putney Heath; and on the 13th of that month marched into quarters at Newbury, Abingdon, and Hungerford. Shortly afterwards the following order was issued relative to the regiment:—

'Charles R.

'For the preventing of all disputes that might arise concerning the rank of Our Royal Regiment of Dragoons, or of any other regiment of Dragoons that shall be employed in Our service, We have thought fit hereby to declare Our pleasure,

'That Our Royal Regiment of Dragoons, and all other regiments of Dragoons which may be employed in Our service, shall have precedency both as Horse and Foot, as well in garrison as in the field, and in all councils of war and other military occasions; and the Colonels and Officers of the said regiments of Dragoons shall command as officers of Horse and Foot, according to the nature of the place where they shall be: that is to say, that in the Field the said regiments shall take place as regiments of Horse, and the officers shall command and do duty as officers of Horse, according to the dates of their[14] commissions; and that in Garrison they shall command as Foot officers, and their regiment take place amongst the Foot according to their respective seniorities from the time they were raised.

'Given at Our Court at Whitehall the 30th day of October, in the thirty-sixth year of Our reign (1684).

'By His Majesty's Command,

'Sunderland.'

The decease of King Charles II. took place on the 6th of February, 1685; and on the evening of the same day, his successor (James II.) commanded the Royal Dragoons to march into quarters in the immediate vicinity of the metropolis. Previous to the coronation they were furnished with new standards, and the drummers and hautboys with new liveries.[21] The ceremonial of their Majesties' coronation was conducted with extraordinary magnificence: but the agitated state of the United Kingdom gave early indication of approaching contests; and, towards the end of April, two troops of the Royal Dragoons were despatched to Carlisle, and placed under the command of the governor, Sir Christopher Musgrave, for the purpose of assisting in the seizure of 'divers outlawed and seditious persons, who, for the avoiding of Justice, have fled from Scotland into the county of Cumberland and parts adjacent.'[22] These troops arrived at Carlisle on the 10th of May, and several persons were apprehended. In [15]the middle of that month an insurrection, headed by the Earl of Argyle, broke out in Scotland; and in June, James Duke of Monmouth raised the standard of rebellion in the west of England and proclaimed himself king. The establishment of the Royal Dragoons was immediately augmented to sixty men per troop: an independent troop of dragoons, raised by Colonel Strother in 1683, was incorporated in the regiment; and five troops of dragoons were raised in the vicinity of London by Richard Leveson, John Williams, Edward Lea, Francis Russel, and Thomas Hussey, and added to the Royal Dragoons: the numbers were thus increased to twelve troops, amounting to about nine hundred officers and men.

Two troops of the regiment, with some other forces, were despatched under Brigadier-General Lord Churchill against the rebels in the west; and on the 19th of June two other troops marched for the same destination under the orders of Lieutenant-General the Earl of Feversham, who was appointed to the chief command of the King's army. The royal forces having been united, the four troops of dragoons were placed under the orders of Viscount Cornbury; and the whole marched in pursuit of the rebels.

After several marches and skirmishes the Duke of Monmouth took post at Bridgewater; and the Earl of Feversham, having sent a troop of the Royal Dragoons, commanded by Captain Coy, to Lamport, to secure that pass, and to gain intelligence in the event of the rebels marching westward, advanced with the royal army to Weston[16] (about three miles from Bridgewater), where he arrived on Sunday, the 5th of July. Having quartered the cavalry in the village, and ordered the infantry to encamp on a plain fronting Sedgemoor, he sent a party of life guards to patrole in the direction of Bristol, and posted a piquet of fifty of the Royal Dragoons with a squadron of the blues supported by one hundred men of the royal regiment of foot, on the moor, in front of the camp. A guard of the Royal Dragoons was also posted over the artillery, which consisted of sixteen pieces, and was drawn up on the high road from Weston to Bridgewater.

During the night the Duke of Monmouth marched out of Bridgewater with the view of surprising the royal army; but the piquet in advance gave the alarm, and after exchanging a few shots with the rebels, retreated to the camp, and formed on the right of the infantry; at the same time the remainder of the Royal Dragoons, being aroused in their quarters in the village of Weston, turned out in the dark in good order, and formed on the left of the foot. The rebels commenced the attack with loud shouts,—the contest became general along the whole line,—and the moor sparkled with fire. The rebel horse soon gave way and fled in disorder; but their infantry stood firm and fought with great resolution. Day at length began to break; and the King's foot advancing to the charge, whilst the Royal Dragoons and other cavalry attacked the flanks of the rebels and put them in disorder, their whole line then gave way and fled in confusion, and were[17] pursued across the moor and adjoining corn-fields with great slaughter. Two troops of the Royal Dragoons continued the pursuit as far as Bridgewater, where they were ordered to halt by the Earl of Feversham.

In the mean time Captain Russel's troop of the Royal Dragoons had been attached to three Scots regiments of foot, which had recently arrived from Holland under the command of Major-General Mackay, and ordered to join the army in the west; but, on the news of Monmouth's defeat at Sedgemoor, these forces were directed to halt at Bagshot; the Royal Dragoons were subsequently dispersed in small parties into the adjoining counties to seize suspected persons; the Scots regiments returned to Hounslow, and, after encamping a short time on the heath, re-embarked for Holland.

One troop of the Royal Dragoons was ordered to Winchester to escort the Duke of Monmouth and other prisoners to London; on its arrival this troop was quartered in the Borough of Southwark, and it was under arms when the Duke was beheaded on Tower Hill on the 15th of July. Two other troops were ordered to Salisbury to mount guard over the prisoners there, and were subsequently directed to attend Judge Jeffries during the trial and execution of the captured rebels; in which painful service the troopers were spectators of numerous acts of barbarity perpetrated by the remorseless Judge, who sacrificed the lives of upwards of two hundred persons in these "bloody assizes," as historians have denominated them.

After the suppression of this rebellion the establishment of the Royal Regiment of Dragoons was reduced to eight troops, of forty private men per troop; and the supernumerary troops were embodied into a regiment of dragoons, which was commanded by the Duke of Somerset, and is now the third light dragoons.

On the 1st of August Lord Churchill was appointed colonel of the third troop of life guards, and the colonelcy of the Royal Dragoons was conferred on Lieutenant-Colonel Viscount Cornbury. The two troops of the regiment having returned from Carlisle, the whole were stationed in London in October, and subsequently marched into quarters in Devonshire.

King James II., being a Roman Catholic, adopted measures calculated to effect the subversion of the Protestant church; and, with the view of overawing his subjects, he doubled the numbers of the regular army, and had large bodies of troops encamped, from time to time, on Hounslow Heath, where he frequently attended in person and witnessed the exercise of the troops. The Royal Regiment of Dragoons formed part of the force at these encampments in the summer of 1686, again in 1687, and in 1688. At this period many noblemen and gentlemen, resolving to preserve the nation from papal domination, solicited the Prince of Orange to come to England with a Dutch force to assist them in opposing the proceedings of the King, and the Prince provided an armament for that purpose.

The colonel of the Royal Dragoons appears[19] to have been a zealous Protestant, and to have entered warmly into the measures taken to resist the proceedings of the Papists who surrounded the court. In November, 1688, when the Prince of Orange had landed, Viscount Cornbury, having marched with his regiment to Salisbury,[23] where the King's army was ordered to assemble, and where the blues and eighth horse had already arrived, resolved, in connexion with Lieut.-Colonel Langston, of the eighth horse, and several officers of the blues, to endeavour to take these three regiments over to the Prince, in the following manner:—

On the night of the 11th of November, directions were given for the adjutants and quarter-masters to await the arrival of the post, as orders to march were expected. At twelve o'clock the post arrived, when Colonel Langston opened the bag before the officers, and the orders, apparently from the Secretary-at-War, were produced, and carried to Viscount Cornbury, who gave directions for the regiments to proceed, at five o'clock, towards the enemy. The regiments were accordingly on the march before daylight on the 12th; continuing their progress throughout that day and the following night (excepting a few short halts to refresh the men and horses[24]), on the afternoon of the 13th, they arrived at Axminster, within six miles of the Prince of Orange's quarters, where they were joined by the Earl of Abingdon, Sir Walter Clerges, and about [20]thirty other gentlemen, who pretended to be volunteers. It was now asserted that a design of the Dutch to surprise the quarters of the King's forces had been discovered, and orders were issued for beating up the quarters of the enemy that night. Accordingly, after dark, the three regiments were again in motion, and the Prince of Orange, apprized of their approach by Lord Cornbury, sent a large body of cavalry to meet them. The greater part of the men, however, resolved not to join the Prince of Orange, and, when they observed what was taking place, they galloped back. Major Robert Clifford, of the Royal Dragoons, marched back that regiment, with the exception of a few officers and about fifty dragoons, who accompanied Viscount Cornbury. The blues also returned, excepting about twenty-seven. But the Duke of St. Alban's regiment (eighth horse) having mustered at a distance, the men, ignorant of the transaction, followed Colonel Langston to Honiton, where they were received as friends by the Dutch general.[25] Many of the men, however, returned to the King's service; and the Duke of Berwick, having collected the remains of the three regiments, marched them back to Salisbury.

The king arrived at Salisbury on the 20th of November, and his Majesty rewarded the loyalty of Major Clifford by promoting him to the colonelcy of the Royal Dragoons. The King, however, soon discovered that the defection among[21] the officers was general, and that the soldiers, although they were reluctant to desert his service, were not disposed to fight in the cause of Papacy. The superior officers of the army, with the nobility and gentry, continued to flock to the Prince's standard, and King James, alarmed for his personal safety, returned in haste to London; at the same time the Royal Dragoons marched into garrison at Portsmouth. The Prince of Orange advanced to the capital without experiencing serious opposition; King James fled to France; and the Prince, having assumed the reins of government, restored Viscount Cornbury to the colonelcy of the Royal Dragoons, and ordered them to occupy quarters at Farnham and Alton.[26]

After the flight of the King to France, the crown was conferred on William and Mary, Prince and Princess of Orange. Their Majesties' accession, however, met with opposition; and Viscount Dundee having induced several of the Highland clans to take arms in favour of King James, the Royal Dragoons were immediately ordered to the north.[27] At the same time, the Earl of Clarendon refusing to act with the new government, his son, Viscount Cornbury, was superseded in the command of the regiment by the lieutenant-colonel, Anthony Hayford, whose commission as colonel was dated the 1st of July, 1689.

On the 27th of July, six battalions of infantry [22]and two newly-raised troops of Scots horse, commanded by Lieut.-General Mackay, were defeated at Killicrankie by the Highlanders and a few Irish, under Viscount Dundee and Brigadier-General Cannon. Immediately after the action, the Royal Dragoons were directed to march to the assistance of Lieut.-General Mackay, and they arrived at Perth in the early part of August. The object of the Commander-in-Chief being the prevention of the descent of the mountaineers into the lowlands, the regiment was posted a short time at Forfar, under the command of Major-General Sir John Lanier, and subsequently proceeded by forced marches to Aberdeen. The Highlanders eventually retired over the mountains by paths inaccessible to cavalry, and separated to their homes.

In the mean time, the lord-lieutenant of Ireland (Earl Tyrconnel) had retained the greater part of that kingdom in the interest of King James. King William sent an army to that country under the veteran Duke Schomberg; and, immediately after the dispersion of the rebel Highlanders, the Royal Dragoons were ordered to proceed to Ireland. They embarked for this service in the early part of October, landed at Carlingford on the 9th of that month,[28] and were ordered to take post at Armagh and Clownish, from whence they were removed to the isle of Maghee.

Several skirmishes occurred during the winter; and in the spring of 1690 the Royal Dragoons were before Charlemont, which place was blockaded[23] by the King's forces. Charlemont was defended by a garrison of 500 men, commanded by Sir Teague O'Regan, a humorist, who returned the following laconic answer to the summons to surrender:—"Tell the General, from Teague O'Regan, that he's an old knave; and, by St. Patrick, he shall not have the town at all." He, however, surrendered on the 14th of May, and a detachment of the Royal Dragoons escorted the garrison towards Armagh.[29] Soon after the surrender of Charlemont Lieut.-Colonel Edward Matthews, from Leveson's (now third) dragoons, was appointed colonel of the regiment. In June it was encamped near Loughbritland, where it was joined by a remount from England. On the 22nd of June King William arrived at the camp, and "His Majesty was no sooner come than he was in amongst the throng of the troops, and observed every regiment very critically. This pleased the soldiers mightily, and every one was ready to give what demonstrations it was possible both of his courage and duty."[30]

The French and Irish, commanded by King James, took post on the banks of the Boyne, to dispute the passage of that river. King William marched to the opposite bank on the 30th of June, and, on the morning of the 1st of July, the army forded the river and drove the enemy from his position with great slaughter. The Royal Dragoons and other British troops engaged in forcing the passage of the Boyne are reported to have "acquitted themselves well." King James fled from the field and proceeded to France; and the British army advanced on Dublin. A few days after the battle King William reviewed the Royal Dragoons at Finglass, on which occasion they brought 406 private troopers into the field.

On the 21st of July Major-General Kirke proceeded with the Royal Dragoons and Queen Dowager's and Colonel Cambron's regiments of foot to Waterford, and summoned the place, and on the 25th the governor capitulated.

At the moment when success attended the operations of the army in Ireland, the English and Dutch fleets, commanded by Lord Torrington and Admiral Evertsen, were defeated by the French fleet under the Count de Tourville, and the enemy afterwards menaced the descent of a formidable force on the British coast. King William commanded a troop of life guards, with Count Schomberg's horse (now seventh dragoon guards), the Royal Dragoons, and Trelawny's and Hastings' (fourth and thirteenth) foot to be immediately embarked for England.

The Royal Dragoons landed at Highlake, in[25] Cheshire, in the early part of August. The alarm of invasion, however, soon subsided; and they were ordered to return to Ireland, in which country they again landed on the 20th of October, and proceeded into extended cantonments in the county of Cork. Many thousands of the Roman Catholic peasantry of Ireland were, at this period, in arms in behalf of King James: they were called rapparees, and being formed into bands they made frequent incursions into the cantonments of the English regiments. Several men of the Royal Dragoons were murdered in their quarters by these rapparees; and detachments of the regiment were frequently sent out to scour the country and chase these bands of marauders from the English cantonments.

Towards the end of December a detachment of the Royal Dragoons proceeded, with some other troops, on an expedition commanded by Major-General Tattea, and on the 1st of January, 1691, attacked an Irish fort near Scronclaird, which was taken in two hours, although the enemy had employed five hundred men during two months to build it.[31]

In the spring, when the army took the field, the Royal Dragoons were ordered to remain in the county of Cork to restrain the incursions of the rapparees, and to prevent the several forts and small garrisons from being attacked. In the early part of June Major Culliford, with a detachment of the Royal Dragoons and some militia,[26] penetrated that part of the country from whence the enemy received their supplies, defeated the Irish troops, and captured several droves of cattle. At length General St. Ruth, who commanded the French and Irish forces, detached two thousand horse and foot to cover this part of the country. Major Culliford, however, continued to make inroads, and having advanced with one hundred and twenty men of the Royal Dragoons, and fifty militia foot, he encountered two troops of Irish cavalry. The English dragoons advanced boldly to the charge, defeated their opponents, killed twenty men upon the spot, and pursued the remainder to Newmarket, where the Irish, being reinforced, made another stand. The Royal Dragoons, however, attacked them again with great bravery, and having sabred fifteen, the remainder fled in disorder, leaving a quantity of provision and some cattle behind. Major Culliford despatched eleven dragoons and twenty-four of the militia to the rear with the booty, and then pursued the fugitives four miles farther, when he encountered five hundred of the enemy's horse commanded by Sir James Cotter. Notwithstanding their disparity of numbers, the Royal Dragoons boldly confronted their opponents, and made a gallant resistance, but were eventually overpowered; and forty men having fallen, Major Culliford made good his retreat with the remainder. In retiring, the dragoons,—chafed in spirit and burning with revenge,—often turned round upon their pursuers; and at length Captain Bower and twenty men boldly faced about and killed about[27] twenty of the Irish horsemen, whose eagerness in the chase had caused them to advance in front of their main body. In the meantime the eleven dragoons and twenty-four of the militia, with the captured cattle and stores, arrived at Drumaugh, where they were attacked by a detachment of the enemy, but defended themselves with success until relieved by a body of troops under Colonels Hastings and Ogleby.

At the time the Royal Dragoons were making these diversions, the main army, commanded by Lieutenant-General De Ginkell, gained a decisive victory over the French and Irish at Aghrim; and on the 1st of August the regiment joined the army at Banagher-bridge. The enemy collected the remains of their defeated regiments at Limerick; and towards the end of August Lieutenant-General De Ginkell besieged that city, commencing his work on the right bank of the Shannon: the Irish army lay encamped at the same time on the opposite side of the river.

A pontoon bridge having been prepared, several regiments were ordered to cross the river at daybreak of the 16th of September. The Royal Dragoons took the lead; and Brigadier-General Clifford,[32] who commanded four regiments of King James's dragoons, being taken by surprise, made little opposition: some infantry, however, attempted to make a stand; but a squadron of the Royal Dragoons dashed forward[28] and routed them in an instant. Two or three French and Irish battalions retired to a bog and wood in their rear, from whence they were driven with the loss of several men killed, and a French lieut.-colonel, a captain, and a number of men made prisoners. The regiments which had passed the river advanced upon the enemy's camp, where a curious spectacle presented itself:—many of the Irish were running about in their shirts, some were pulling down tents, others driving away cattle, many were making their escape into the town, and others hurrying towards the mountains; a regiment of dragoons, whose horses were two miles distance at grass, dispersed in confusion: at the same time a party of horse buckled on their arms and made a show of fighting; but they fled on the advance of the English, who took possession of the camp, where they found a quantity of beef, brandy, and corn, with the saddles and appointments of three hundred dragoons. The Royal Dragoons were commended by Lieut.-General De Ginkell for their gallant conduct, and they returned to the other side of the river on the same day.[33]

On the 22nd of September the regiment, with several other corps, crossed the Shannon into the county of Clare; when the advance-guard, which consisted of eighteen men of the Royal Dragoons, was attacked by a squadron of the Irish cavalry: this small party sustained the first onset with admirable firmness, but were forced to retire; part[29] of the regiment, however, soon advanced to their assistance, when the enemy was defeated and chased under the range of their batteries, and three small pieces of brass ordnance were captured. Orders were then given for the infantry to attack the works which covered Thoumond bridge. These works were carried after a sharp struggle; when the troops which had defended them endeavoured to enter the town; but the drawbridge had been raised, and they were left to the mercy of the English, who slaughtered such numbers, that the dead bodies lay in heaps on the bridge higher than the parapet walls. Five colours were taken on this occasion, and so many men slain, drowned, and taken prisoners, that the enemy surrendered the place in a few days afterwards.

The conquest of Ireland having been effected, the Royal Dragoons returned to England, where they arrived in January, 1692, and marched into dispersed cantonments in Leicestershire; and during a part of the summer a detachment was stationed in garrison at Portsmouth. The regiment was subsequently stationed, on revenue duty, in the maritime towns on the southern coast of the kingdom; and in the autumn of 1693 it had the honour of furnishing a relay of escorts to attend King William from Margate to London, when His Majesty returned from Holland.

The war with France, which was commenced in 1689, had been continued with varied success; and in the spring of 1694 the Royal Dragoons were ordered to proceed on foreign service. They left England in May; joined the army encamped near[30] Tirlemont in South Brabant, on the 21st of June, and were reviewed by King William on the following day. On arriving at this camp they were ordered to take post in front of the village of Camtich, and this quarter being much exposed to attacks from the enemy, they were reinforced by two regiments of Dutch infantry. The army marched from Tirlemont on the 13th of July, and encamped at Mont St. André and Ramilies, where the regiment was formed in brigade with the royal Scots and Fairfax's (now second and third) dragoons, under the command of Brigadier-General Matthews, and this brigade was encamped on the left of the line. The French army encamped near Huy, with their left upon the Mehaine. On the 17th of July a foraging party of the allies crossed the river, and, meeting with several French squadrons, a skirmish ensued, when the Royal Dragoons lost eight horses and had three men wounded. On the 28th of the same month another foraging party encountered a detachment of the enemy, when the regiment had two men and several horses killed. The allied army was again in motion on the 8th of August: much manœuvring, and some skirmishing took place between the hostile squadrons, but no general engagement occurred. On the 29th of August the Royal Dragoons were stationed at Wacken—a post situate at the junction of the Mandel and the Scheldt; and in October they marched into cantonments in the villages between Ghent and Sans-van-Ghent.[34]

In the spring of 1695 the Royal Dragoons marched to Dixmude, forming part of a division of the army commanded by Major-General Ellenberg, and were brigaded with Lloyd's (now third) dragoons and a regiment of Danish cavalry. On the 7th of June the Duke of Wirtemberg took command of this division, and attacked the French forts at Kenoque as a diversion to conceal King William's design upon the strong and almost impregnable fortress of Namur, which he commanded to be invested shortly afterwards. The Royal Dragoons joined the covering army towards the end of June; but were detached to Bruges in July: they were subsequently recalled from thence and joined the camp between Genappe and Waterloo, from whence they proceeded to the vicinity of Namur, to protect the troops employed in the siege from a threatened attack of the French army. After the surrender of the important fortress of Namur, the regiment marched into cantonments behind Ghent.

The French menaced an attack upon the quarters of the allied army in Flanders in the spring of 1696, when the Royal Dragoons were suddenly called from their cantonments to encamp on the banks of the canal between Ghent and Bruges, where they were reviewed by King William on the 29th of May. They served the campaign of this year with the army of Flanders, commanded by the Prince of Vandemont, and were brigaded with the royal Scots and royal Irish (second and fifth) dragoons, commanded by Brigadier-General Matthews. The object of this army was the protection[32] of Ghent, Bruges, and the maritime towns of Flanders: no general action occurred; but a party of the Royal Dragoons, with a detachment of Langston's horse (now fourth dragoon guards), surprised one of the French out-guards on the night of the 20th of September and took thirty prisoners. This appears to be the only action in which the regiment took part during the campaign of this year; and on the 6th of October it marched into quarters in the villages behind the Bruges canal.

During the campaign of 1697 the regiment served under King William in the army of Brabant, and was brigaded with the royal Scots and Eppinger's dragoons.

On the 28th of May Brigadier-General Matthews died; and on the 30th His Majesty conferred the colonelcy of the Royal Dragoons on Thomas Lord Raby, afterwards Earl of Strafford.

The enemy, having great superiority of numbers, besieged and took Aeth, and afterwards menaced Brussels; but were frustrated in their designs by King William. The Royal Dragoons were encamped before Brussels in June; and subsequently at Wavre. Hostilities were terminated in September by the treaty of Ryswick, and after the conclusion of peace, the regiment embarked from the Netherlands,—landed at the Red House in Southwark on the 21st of November, and, at the end of the same month, marched into extensive quarters in Yorkshire, where the establishment, which during the war had been eight troops, amounting to five hundred and ninety officers and[33] men, was reduced to six troops of two hundred and ninety-four officers and men.

During the two succeeding years the Royal Dragoons occupied quarters in Lancashire and Leicestershire. In June, 1700, they assembled on Hounslow Heath and were reviewed by King William III., who was pleased to express his royal approbation of their appearance and discipline. Leaving the south of England in July, they proceeded into quarters in Yorkshire and Cumberland, with one troop stationed in garrison at Carlisle and another at Hull.

In 1701 the Royal Dragoons were stationed in Yorkshire, with three troops in garrison at Hull; at this period the ambitious Louis XIV. of France violated the treaties he had entered into, and procured the accession of his grandson, Philip, Duke of Anjou, to the throne of Spain. War was resolved upon, and the establishment of the regiment was augmented to eight troops amounting to five hundred and thirty-two officers and men; and it embarked for Holland in the beginning of March, 1702. Before the transports sailed, the death of King William occurred (8th March, 1702), when the regiment was disembarked and placed in cantonments in the villages in the immediate vicinity of the metropolis. In a few days afterwards, Her Majesty Queen Anne having resolved to pursue the foreign policy of her predecessor, the regiment re-embarked, and after landing at Williamstadt, went into quarters at Breda, where it was formed in brigade with the royal Scots and royal Irish (second and fifth) dragoons,[34] under the command of that excellent officer, Brigadier-General Ross, and was placed as a guard to the English train of artillery.[35]

A powerful French army was in the field menacing the frontiers of Holland. The Earl of Marlborough assembled the forces under his orders towards the end of June, and in July the Royal Dragoons joined the army with the train of artillery. By a daring advance the British commander disconcerted the designs of his opponents, who retired without venturing an engagement. The Royal Dragoons were employed in covering the sieges of Venloo, Ruremonde, and Stevenswaert; and took part in the capture of the city of Liege: they afterwards marched back to Holland, and were quartered at Arnheim, the capital of the province of Guelderland, where they were reviewed in April, 1703, by their colonel, Lord Raby, who was passing through Holland on his way to Prussia, as envoy extraordinary to that court.[36]

At the commencement of the campaign of 1703 the Royal Dragoons were employed in covering the siege of Bonn, and afterwards joined the army near Maestricht, with six battalions of infantry commanded by the Prince of Hesse, and were formed in brigade with the same regiments as in the preceding year.

On the advance of the allied army commanded by the Duke of Marlborough, the French retreated, and took post behind their fortified lines.

On the 27th of July the British commander proceeded, with four thousand horse and dragoons, towards the enemy's intrenchments, and Lieutenant Benson, with thirty men of the Royal Dragoons, who formed the advance-guard, charged and defeated a piquet of forty French horsemen, and chased them to the barriers of their intrenchments with signal gallantry, which gave his Grace an opportunity of advancing within musket-shot of the lines. He was desirous of attacking these formidable works, but was prevented by the timidity and pertinacity of the Dutch generals and field deputies. In August, when the siege of Huy was undertaken, the Royal Dragoons were encamped on the banks of the river Maese, to secure the bridge, and to keep up the communication. They were subsequently engaged in the siege of Limburg, a city situated on a pleasant eminence among the woods near the banks of the little river Wesdet. Spanish Guelderland having been delivered from the power of France, and the Dutch freed from the dread of an invasion, the Royal Dragoons quitted the vicinity of Limburg and marched back to Holland. In the mean time circumstances had occurred which occasioned their removal from the army commanded by the celebrated Duke of Marlborough, to another theatre of war.

During the summer the Emperor of Germany and Prince Joseph renounced their pretensions to the Spanish monarchy in behalf of Archduke Charles, who was acknowledged as King of Spain by several of the states of Europe; and a treaty of[36] alliance having been concluded with the King of Portugal, the Royal Dragoons were selected to accompany the Archduke to Lisbon, and to take part in the attempt to place him on the throne of Spain by force of arms.

The Portuguese monarch having engaged to provide horses for the English cavalry, the Royal Dragoons transferred their horses to the British regiments in Holland, and embarked, dismounted, in October; but were so long detained by contrary winds and severe weather, that they did not arrive at the capital of Portugal before March, 1704, when they landed with the remainder of the British and Dutch forces commanded by Duke Schomberg.

In consequence of the horses produced by the Portuguese authorities being of so inferior a description that the English officers rejected the greater part of them, only twenty men per troop of the Royal Dragoons were mounted; the dismounted men proceeded to Abrantes to await the arrival of horses, and the mounted men advanced to the frontiers of Portugal, and encamped on a pleasant plain near Estremos. Tardiness and inability were, however, manifested by the Portuguese authorities to such an extent, that the Duke of Berwick, having arrived from France with eighteen battalions of infantry and nineteen squadrons of cavalry, and taken the command of the French and Spanish forces, attacked the frontiers of Portugal before the allies were prepared to take the field. The court of Lisbon was alarmed, the provinces were in consternation; the Duke[37] Schomberg solicited to be recalled, and the Earl of Galway was sent with reinforcements to Portugal, and appointed to the command of the British forces in that country.

One hundred and twenty men of the Royal Dragoons formed part of a body of cavalry, which crossed the frontiers and made a successful incursion into the Spanish territory. Extraordinary measures were adopted to procure horses, and at the close of the summer the regiment had upwards of three hundred mounted men in the field. In the autumn the army was enabled to act on the offensive, and the Royal Dragoons were among the forces which penetrated Spain; but on arriving at the vicinity of Ciudad Rodrigo, the enemy was found so advantageously posted on the opposite side of the Agueda, that the Portuguese generals would not venture the passage of the river; and, after reconnoitring the hostile army several times, the allies returned to Portugal, and the Royal Dragoons went into village cantonments in the Alentejo.[37]

During the winter and the spring of 1705 the regiment procured an additional supply of horses, and when it again took the field it was much better mounted than in the preceding year. It joined the army in April, and, advancing into Spanish Estremadura, formed part of the force which invested Valencia de Alcantara, which fortress was captured in the early part of May.

Albuquerque was subsequently besieged and taken; and the capture of Badajoz was contemplated, but that undertaking was abandoned until the summer's heat was abated.

In the mean time an expedition had been fitted out in England, and a land force, commanded by Lieut.-General the Earl of Peterborough, embarked for the purpose of furthering the designs of the house of Austria. The fleet arrived at Lisbon in June, and, King Charles resolving to accompany the expedition, the Royal and Cunningham's (now eighth) dragoons, and four regiments of foot, were embarked to strengthen the land force. The fleet put to sea, and, after several consultations among the general and naval officers, an attack on Barcelona was resolved upon. The fleet arrived before that fortress on the 22nd of August (N.S.), and on the 24th the Royal Dragoons landed near a river called Bassoz, on the east side of the city, and encamped about a mile from the walls, in a place well fortified by nature, where the army was joined by many of the country people, who were formed into bands, and acted as a guerilla force: "they were" (as Bishop Burnet observes) "good at plundering, but could not submit to regular discipline, nor were they willing to expose themselves to dangerous services."