Sir Walter Scott

Title: The Country of Sir Walter Scott

Author: Charles S. Olcott

Release date: June 26, 2017 [eBook #54980]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

BY

CHARLES S. OLCOTT

Author of George Eliot: Scenes and People of Her Novels

ILLUSTRATED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

BY THE AUTHOR

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY CHARLES S. OLCOTT

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published September 1913

TO

MY WIFE

THE COMPANION OF MY TRAVELS

TO WHOSE SYMPATHETIC COOPERATION I AM

INDEBTED FOR MUCH OF THE MATERIAL

THIS BOOK

IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

CONTENTS

I. The 'Making' of Sir Walter

II. The Lay of the Last Minstrel

III. Marmion

IV. The Lady of the Lake

V. Rokeby

VI. The Bridal of Triermain

VII. The Lord of the Isles

VIII. Waverley

IX. Guy Mannering

X. The Antiquary

XI. The Black Dwarf

XII. Old Mortality

XIII. Rob Roy

XIV. The Heart of Midlothian

XV. The Bride of Lammermoor

XVI. A Legend of Montrose

XVII. Ivanhoe

XVIII. The Monastery

XIX. The Abbot

XX. Kenilworth

XXI. The Pirate

XXII. The Fortunes of Nigel

XXIII. Peveril of the Peak

XXIV. Quentin Durward

XXV. St. Ronan's Well

XXVI. Redgauntlet

XXVII. Tales of the Crusaders

XXVIII. Woodstock

XXIX. The Fair Maid of Perth

XXX. The Chronicles of the Canongate and Other Tales

The Highland Widow

The Two Drovers

The Surgeon's Daughter

Anne of Geierstein

Count Robert of Paris

Castle Dangerous

XXXI. A Successful Life

ILLUSTRATIONS

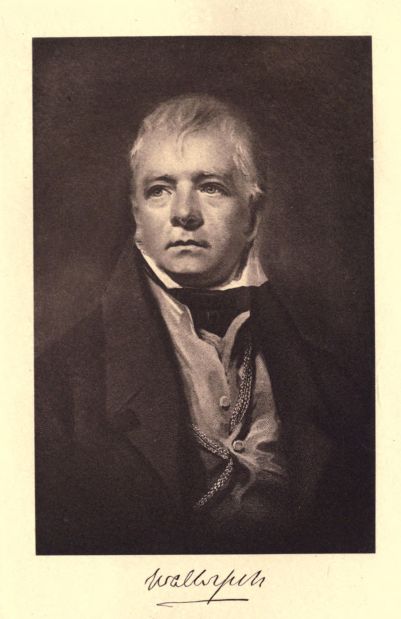

Portrait of Sir Walter Scott . . . Frontispiece

Photogravure from an engraving by William Walker of a painting

by Sir Henry Raeburn, R.A., 1822.

Map Of Scotland

Showing localities of Scott's writings

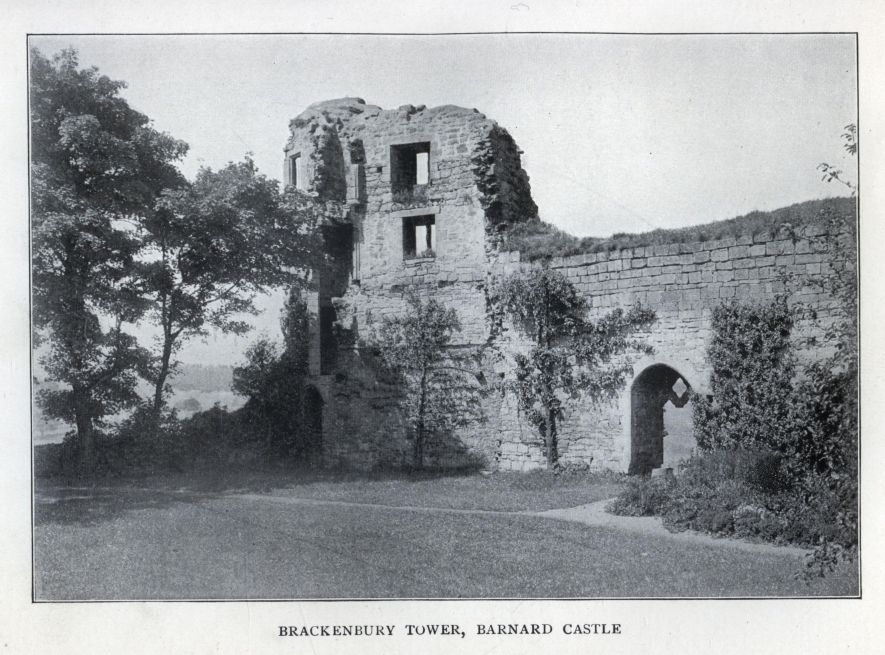

Brackenbury Tower, Barnard Castle

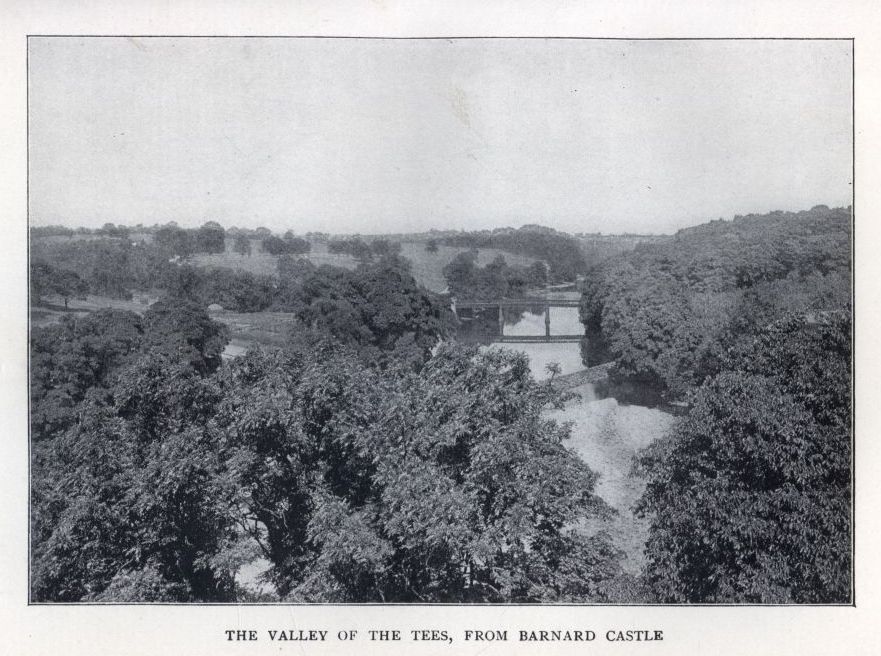

The Valley of the Tees

From Barnard Castle

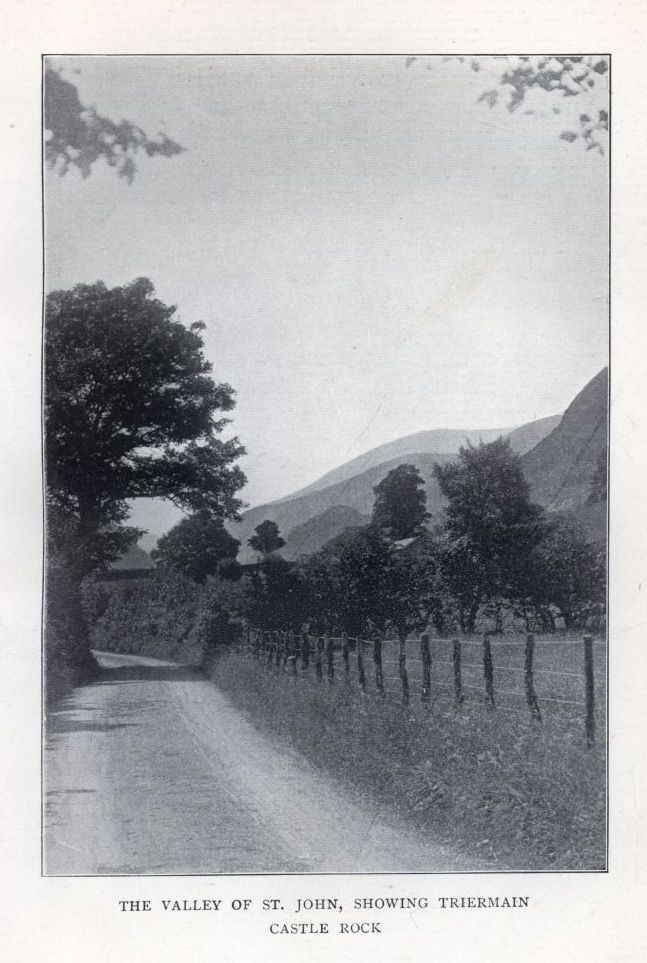

The Valley of St. John

Showing Triermain Castle Rock

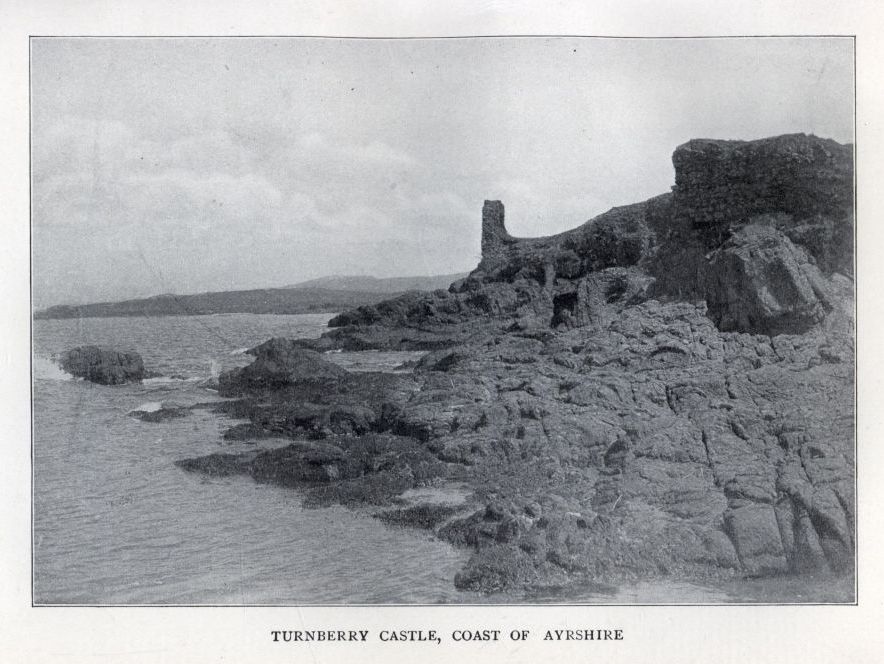

Turnberry Castle, Coast of Ayrshire

Doune Castle

From the Teith

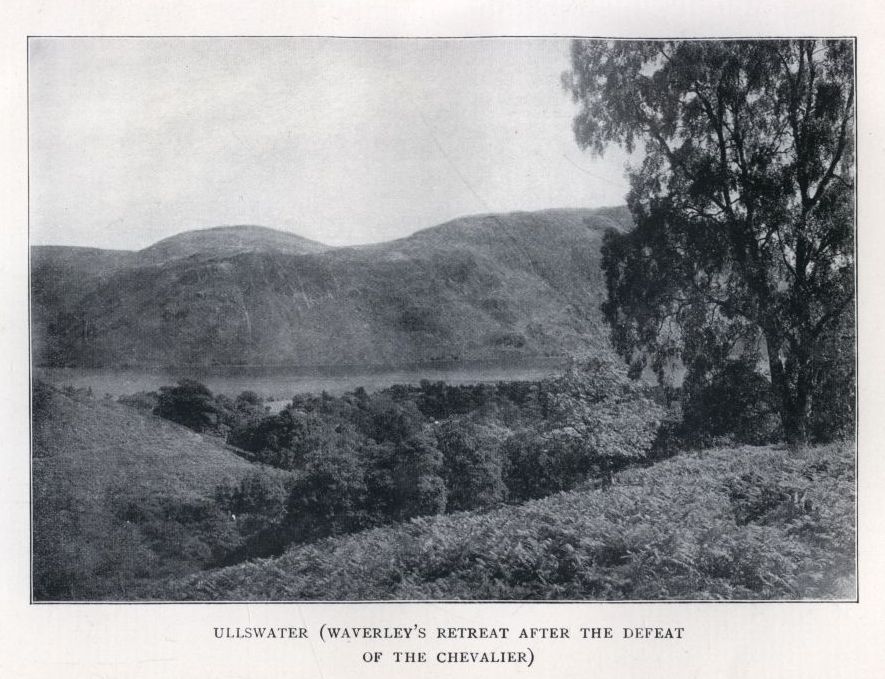

Ullswater

Waverley's retreat after the defeat of the Chevalier

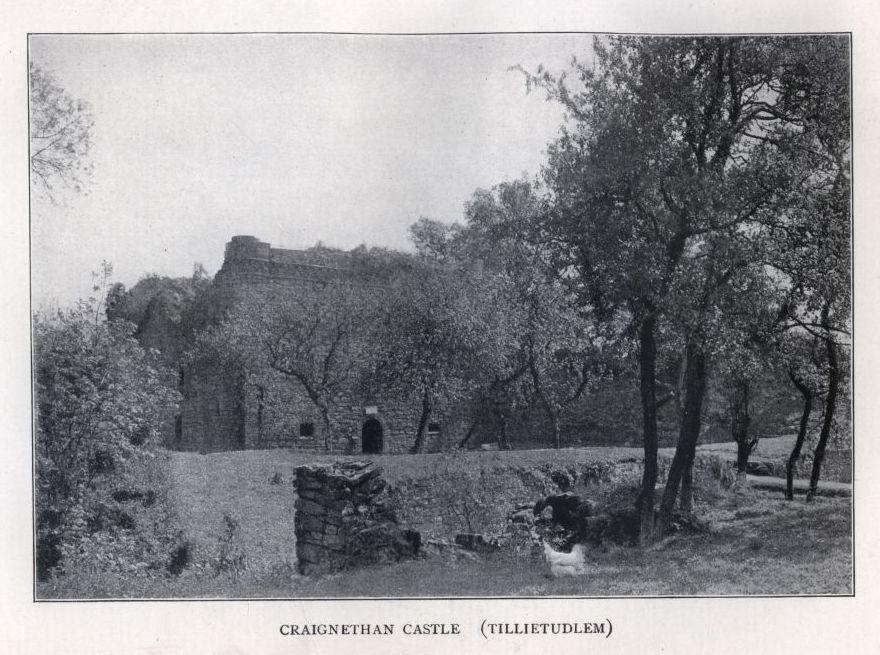

Craignethan Castle (Tillietudlem)

Map of England

Showing Localities of Scott's writings

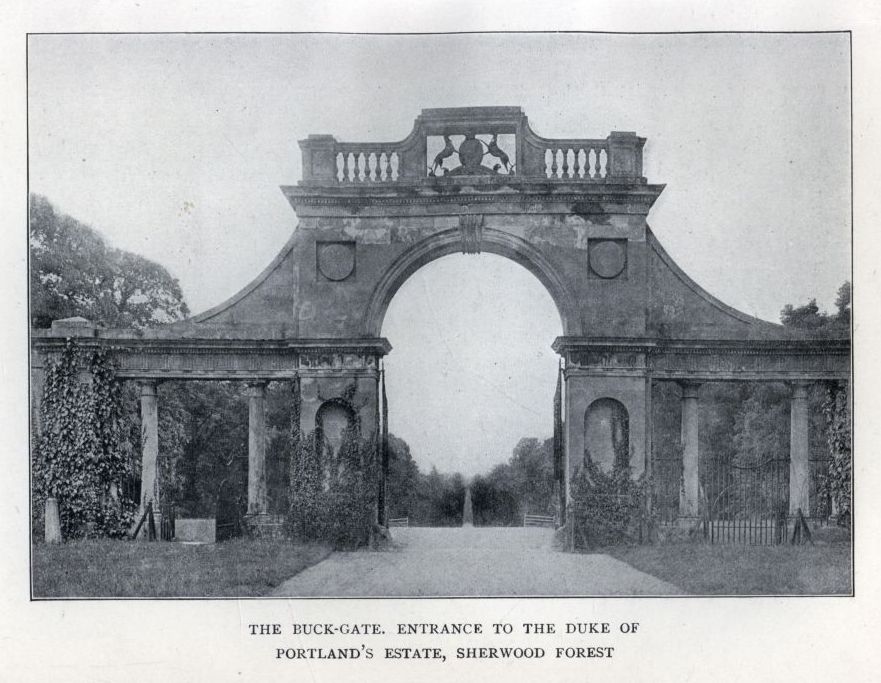

The Buck-Gate

Entrance to the Duke of Portland's estate, Sherwood Forest

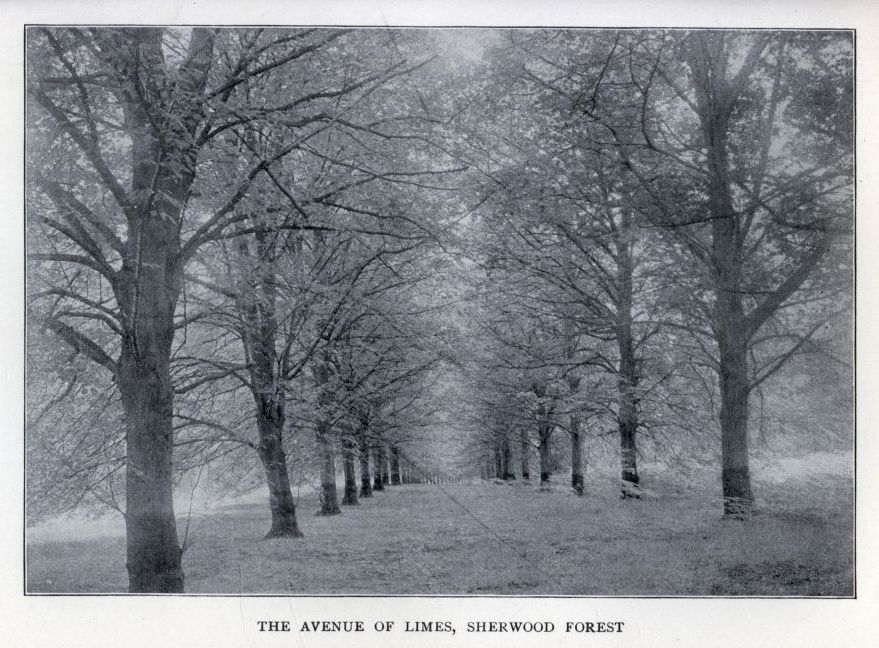

The Avenue of Limes, Sherwood Forest

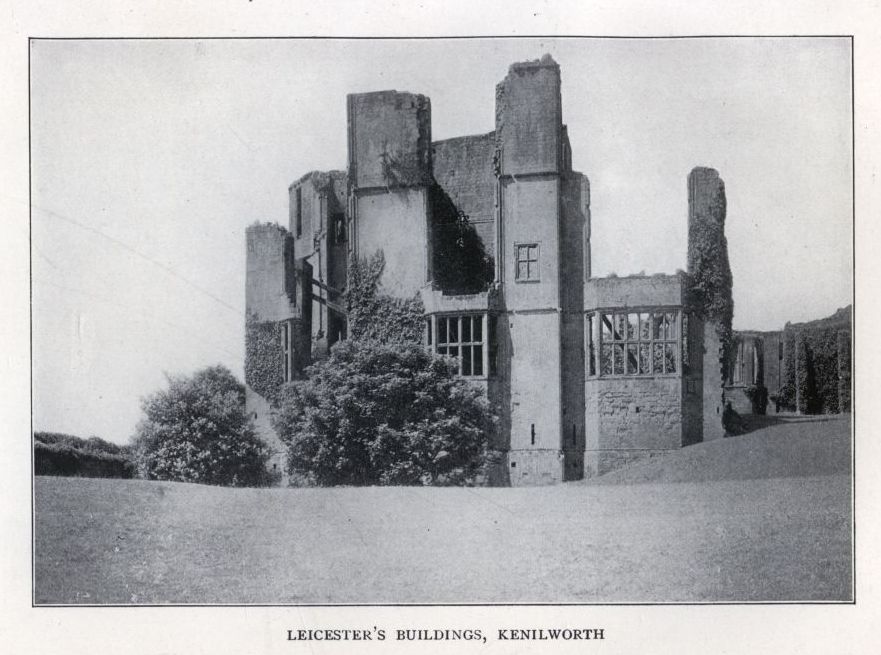

Leicester's Buildings, Kenilworth

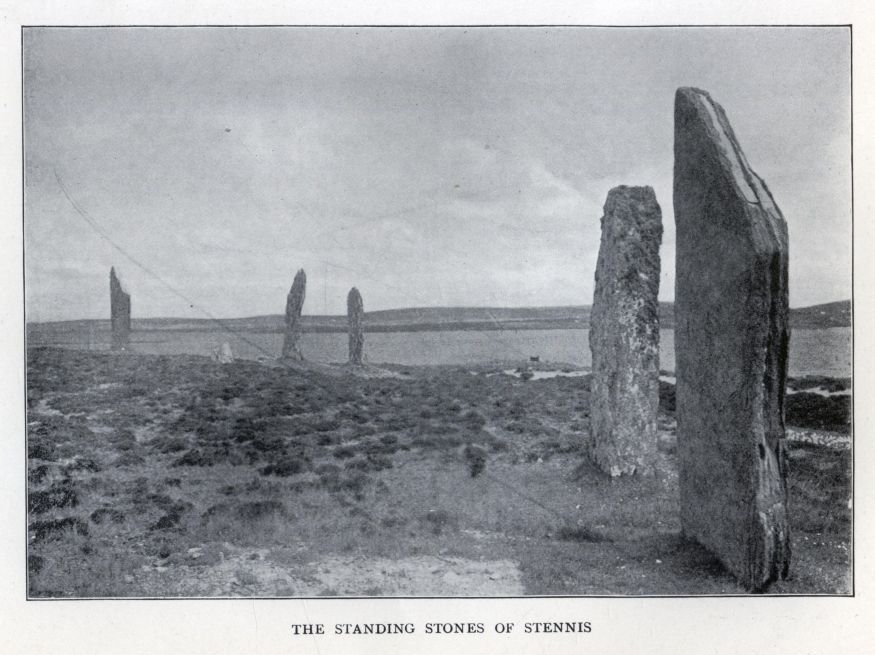

The Standing Stones of Stennis

Map of London

Showing localities of Scott's writings

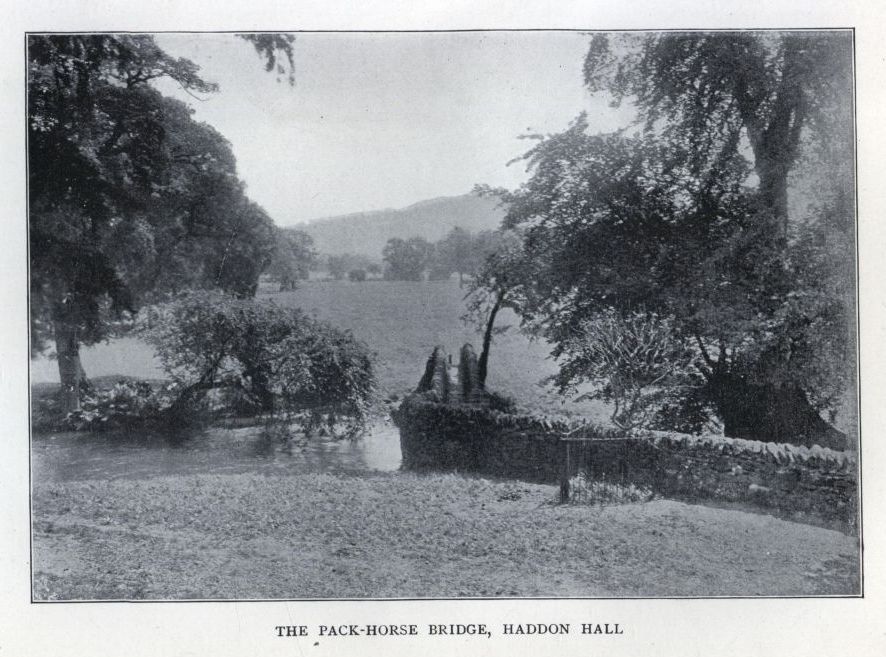

The Pack-Horse Bridge, Haddon Hall

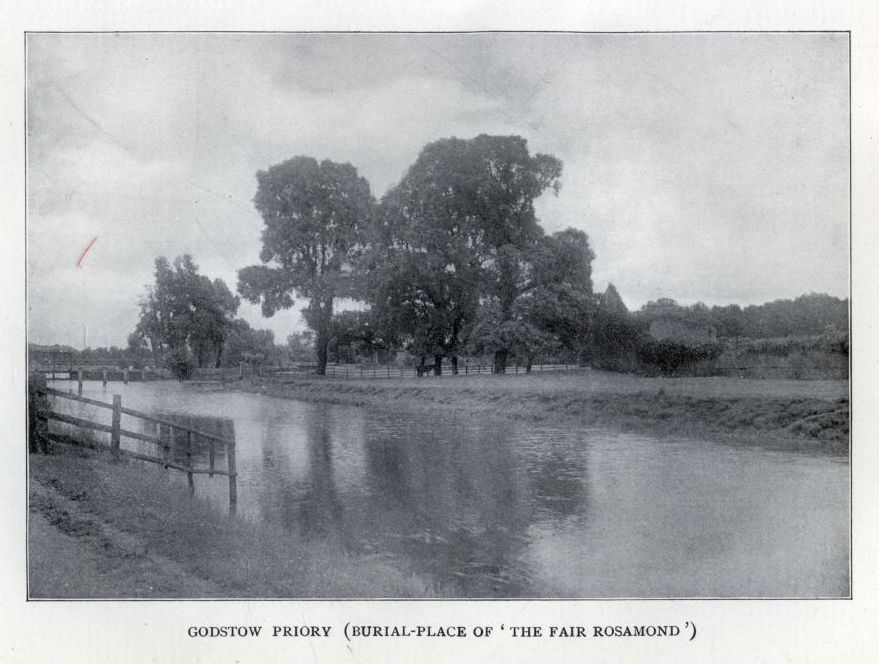

Godstow Priory

Burial-place of 'The Fair Rosamond'

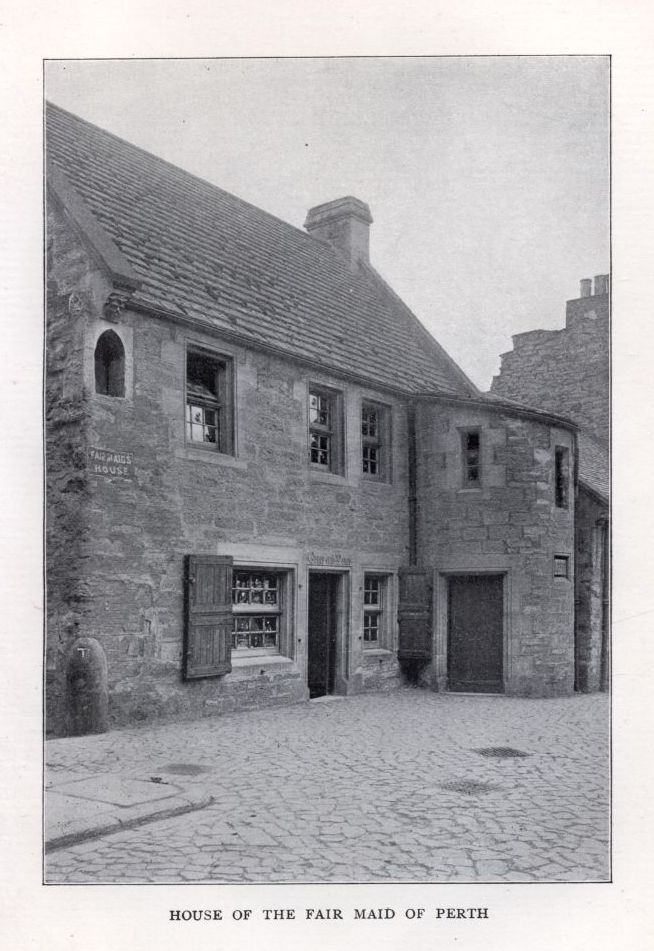

House of the Fair Maid of Perth

On the first day of May, 1911, we began our exploration of the 'Scott Country.' I say we, because I was accompanied by the companion of a much longer journey, of which that year was the twenty-fifth milestone. Whether from reasons of sentiment resulting from the near approach of our silver anniversary, or because of more prosaic geographical considerations, we began at the place where Walter Scott discovered that he would be likely to see more of the beauty of life if he were equipped with two pairs of eyes rather than one. This was at the village of Gilsland, in the north of England, where the poet first met the companion who was to share the joys and sorrows of the best years of his life. A pony and dogcart took us clattering up to the top of the hill, where, leaving our conveyance, we started down the glen to the banks of the river Irthing. Here the camera promptly responded to the call of a beautiful view and the first exposure was made:—a gently flowing stream of shallow water, scarcely covering the rocky bed of the river; a pleasant path along the bank, well shaded from the sun; and a slender little waterfall in the distance;—the same scene which so often met the eyes of Walter Scott and his future bride as they strolled along the stream in their 'courting' days.

This was the beginning of a tour which eventually led into nearly every county of Scotland, as far north as the Shetland Islands, and through a large part of England {xiv} and Wales. We went wherever we thought we might find a beautiful or an interesting picture, connected in some way with the life of Sir Walter, or mentioned by him in some novel or poem. Knowing that he had derived his inspiration from an intimate knowledge of the country, we sought to follow his footsteps so far as possible. Months of preparation had been devoted to the work before leaving home. Every novel and poem had to be read, besides many books of reference, including, of course, Lockhart's Life, for it would not have been safe to trust to the recollections of earlier reading. Notes were made of the places to be sought, and two large maps were prepared on which I marked circles with a red pencil around all points which I thought ought to be visited, until my maps began to look as though they were suffering from a severe attack of measles. Then the route was laid out by 'centres.' The first was Carlisle, then Dumfries, Melrose, Edinburgh, Berwick, Glasgow, Stirling, Callander, the Trossachs, Oban, and so on until the entire country had been covered. From each 'centre' as a convenient point of departure we explored the country in many directions, visiting so far as possible every scene of the novels and poems that could be identified.

It was surprising to find so many of these scenes exactly as Sir Walter had described them. The mountains and valleys, the rivers, lakes, and waterfalls, the wild ruggedness of the seaside cliffs, the quaint little old-fashioned villages, the ruined castles and abbeys, all brought back memories of the romances which he had so charmingly set amidst these scenes. It was like actually living the Waverley Novels to see them. And in seeing {xv} them, we came to know, on intimate terms, Sir Walter himself; to feel the genial influence of his presence as if he were a fellow traveller, and to love him as his companions had done a century ago.

But our constant purpose was to do more than this. With the help of the camera we sought to catch something of the spirit of the scenery and to bring it home with us, in the hope that those who have never seen the 'Scott Country' might at least have a few glimpses of it, and that those who have seen all or a part of it, might find in these views a pleasant reminder of what must have been a happy experience.

There is no occasion to add at the present time to the volume of literary criticism of such well-known novels and poems as those of Scott, nor is it possible to add any material facts to his biography. This book makes no such claim. It does not attempt to retell the romances, except in so far as may be necessary to explain their connexion with the scenery or to introduce the 'original' of some well-known character. If a glimpse of the novelist's genial face is seen now and then, it is because his spirit pervades every nook and corner of bonnie Scotland, and it would be impossible for appreciative eyes to view the scenery without seeing something of the man whose genius has added so greatly to its charm.

If this book shall add to the pleasure of any of the readers of Sir Walter Scott by bringing them into the atmosphere of his novels and poems, and so a little nearer to the kindly personality of the man, its purpose will have been fulfilled.

THE COUNTRY

OF SIR WALTER SCOTT

'He was makin' himsel' a' the time, but he didna ken maybe what he was about till years had passed; at first he thought o' little, I dare say, but the queerness and the fun.'

In these expressive words, Robert Shortreed, who guided Walter Scott on the celebrated 'raids' into the Liddesdale country, correctly summarized the youth and early manhood of the future poet and novelist. Scott was thirty-four years old when the 'Lay of the Last Minstrel' appeared, and had reached the mature age of forty-three before he published the first of the Waverley Novels. But from early childhood he was busily engaged, with more or less conscious purpose, in gathering the materials for his future work.

It is the purpose of this chapter to show, by a brief survey of these preparatory years, how he acquired that intimate knowledge of human nature that enabled him to record so truthfully and with such real sympathy the thoughts and feelings, the hopes and fears, the manners of life, the dress, the conversation, and the personal peculiarities of people of every degree, from Mary, Queen of Scots, to Meg Merrilies, the Queen of the {2} Gipsies; from the lordly Earl of Montrose down to the humblest of the Children of the Mist. It will also aim to suggest something of the method by which he learned to paint such charming pictures of ancient castles and ruined abbeys, of princes' palaces and fishermen's cottages, of rocky shores and wild paths through the woods, of rivers, lakes, and mountains, and all the other elements that make up the varied and beautiful scenery of Scotland and England.

In the hilly country south of Edinburgh, standing alone on a high rock, is an old feudal tower called Smailholm. Outlined against the western sky, in the glow of a summer sunset, it seemed to us like a proud and beautiful capital letter 'I,' saying with some emphasis on the personal pronoun, 'I am a thing of some importance.' We forgave the egotism, for the old tower really is important, marking the very beginning of Walter Scott's career, the spot where he received his first poetic impulse. Here at the age of three years, he rolled about on the rocks with the sheep and lambs as if he were one of them. He had been brought to Sandy Knowe, the home of his grandfather, in an effort to save his life, for he had been a sickly child, and six brothers and sisters had died in infancy, so that his parents were naturally more than anxious. The life out of doors soon brought a marked improvement, and except for the lameness, which never left him, the boy became healthy and vigorous. He was attended by an old shepherd, known as the 'cow-bailie,' who had a great fund of Border stories, to which the lad listened eagerly.

A devoted aunt, Miss Janet Scott, who lived at the farm, often read to him stories of Bible heroes and of the {3} great men of Scottish history. From a few volumes of miscellaneous poetry which the family chanced to own, she read some Scottish ballads which quickly seized upon his childish fancy. He was especially fond of historical tales, and under the shadow of the old tower he used to marshal the armies of Scotland and England, fighting their battles with mimic forces of pebbles and shells, and always ending the conflict with the complete rout of the English and the triumph of the Scottish arms. One day he was missed during a violent thunderstorm, and the household set out in search of him. He was found lying on his back on the rocks, kicking his heels in the air and clapping his hands with delight as he watched the vivid lightning; and as one flash followed another, each more brilliant than the one before, he would shout, 'Bonnie! Bonnie!! Dae it again! Dae it again!' I like to think of this scene as symbolic; as a prophecy of the time, soon to come, when the lad, grown to manhood, would be sending out flash after flash of his genius while the whole world looked on in delight, shouting, 'Bonnie! Bonnie!! Dae it again! Dae it again!'

How much the old tower of Smailholm really had to do with Scott's earliest poetic fancy he has himself told in a touching reference in the Introduction to the Third Canto of 'Marmion':—

And still I thought that shattered tower

The mightiest work of human power,

And marvelled as the aged hind

With some strange tale bewitched my mind.

He made it the setting of one of his earliest poems, 'The Eve of St. John,' and probably had it in mind, when {4} writing 'The Monastery' and 'The Abbot,' as the original of Avenel Castle. Smailholm was once surrounded by water, all of which has been drained off except a very small portion on the eastern side. With the addition of the original lake it would make a very good prototype of Avenel.

At the age of six, Scott was taken for a visit to Prestonpans, where he made the acquaintance of George Constable, the original of Monkbarns in 'The Antiquary.' This statement should be qualified, however, for Scott himself was the real 'Antiquary' in many ways. None but a genuine antiquarian could ever have written that keen bit of humorous characterization. This old gentleman, besides giving Scott his first knowledge of Shakespeare, told him many excellent stories of the 'affair of 1745' and of the battle of Prestonpans. Here he also made the acquaintance of an old man who had seen much service in the German wars and who was delighted to find a good listener to his tales of military feats. Under the guidance of this old soldier, whose name, Dalgetty, subsequently reappears in 'A Legend of Montrose,' he explored the battle-field, heard the story of Colonel Gardiner's death, and found the grave of 'Balmawhapple,' 'where the grass grew rank and green, distinguishing it from the rest of the field.' This was in 1777, when Scott was only six. Thirty-seven years later these early impressions found a place in 'Waverley.'

At about the same period young Walter was presented with a Shetland pony, an animal not so large as a full-grown Newfoundland dog. He soon learned to ride, and often frightened his Aunt Jenny by dashing recklessly {5} over the rocks about the tower. The importance of the event lies in the fact that it was the beginning of Scott's fondness for horseback riding, his proficiency in which played an important part in later years, enabling him to gather valuable material that would not otherwise have been accessible. Scott's father now thought best to bring him back to Edinburgh, where he lived the life of an average schoolboy, with this difference, that his lameness frequently confined him to the house, compelling him to seek his amusement in books instead of romping with his fellows in George's Square. At twelve years, and again a little later, he went for a vacation visit to his Aunt Jenny,—Miss Janet Scott,—who was then living at Kelso in a small house, pleasantly situated in a garden of seven or eight acres, 'full of long straight walks, between hedges of yew and hornbeam' and 'thickets of flowery shrubs.' The Grammar School of Kelso was attached to the old Abbey. Here he met the two men who, though lifelong friends, were destined to bring to Walter Scott the saddest experience of his career—James and John Ballantyne, the publishers, whose failure clouded the last years of the novelist's life, forcing upon him the payment of a debt of £117,000,—a task which he manfully assumed, and wore out his life in the execution of it. Another school fellow here was Robert Waldie, whose mother showed Scott many attentions. It was through his association with 'Lady Waldie,' who was a member of the Society of Friends, that Scott in subsequent years was enabled to paint the lovely picture of the home life at Mount Sharon of Joshua Geddes and his sister, which adds so much to the pleasure of 'Redgauntlet.'

An old vault in Kelso Abbey was used as the village prison—the kind of a jail which Edie Ochiltree thought 'wasna so dooms bad a place as it was ca'd.' No doubt the real Edie was often confined here. He was an old mendicant, well known in the neighbourhood, by the name of Andrew Gemmels. Scott met him often. Many curious stories are related of his eccentricities. He was once presented with a good suit of clothes which he thankfully accepted. The friendly donor chanced to meet him later in the day, dragging the clothes behind him along the road through the dirt and mud. Being asked why he treated the gift in that way he replied that he would have 'to trail the duds that way for twa days, to mak them fit for use.'

A few miles southeast of Kelso, in the village of Kirk Yetholm, Scott picked up another of his most famous characters—the picturesque Meg Merrilies. Kirk Yetholm was in Scott's boyhood, and even later in his life, the headquarters of a large gipsy tribe. Such a people could not fail to interest one of his temperament and he soon came to know them on familiar terms. The Queen of the Gipsies introduced herself by giving him an apple. She was a woman of extraordinary height, dressed in a long red cloak, who naturally inspired the boy with a feeling of awe. Her name was Madge Gordon, a granddaughter of Jean Gordon, the most famous of the Gipsies. Jean's history was well known. She was an ardent Jacobite, and met her death at Carlisle in 1746, in a most inhuman fashion, being drowned by a mob in the river Eden. She was a powerful woman and as the men struggled to keep her head under the water, she kept coming to the surface, each time screaming, {7} 'Charlie yet! Charlie yet!' Scott as a child often heard her story and cried piteously for old Jean Gordon. She was the real Meg Merrilies.

During his frequent visits to Kelso and subsequent residence at Rosebank, near by, Scott explored the country in every direction. He rode over the battlefield of Flodden, becoming convinced that 'never was an affair more completely bungled.' He explored the heights of Branxton Hill, and riding through the village of Coldstream, passed the old town of Lennel, where Marmion paused on the eve of the battle. Then recrossing the river, he came to Twisel Bridge, and following the course of the Tweed, reached the ruins of Norham Castle, where Marmion was entertained by Sir Hugh Heron. This was an old Border fortress which passed from Scottish to English hands and back again for several centuries. Thus, without conscious effort, Scott laid the foundation for 'Marmion' early in life, though the poem did not take final shape until nearly twenty years later.

When not spending his vacations in the country, Scott was attending the college in Edinburgh and later preparing himself for the practice of the law. During all these years the gathering of materials for his future writings continued. A favourite companion of the days in Edinburgh was John Irving. On Saturdays, or more frequently during vacations, the two used to borrow three or four books from the circulating library and walk to Salisbury Crags, climb high up to some sequestered nook and read the books together. After continuing this practice for two years, during which they devoured a prodigious number of volumes, Scott {8} proposed that they should make up adventures of their favourite knights-errant, and recite them to each other alternately—a pastime in which Scott greatly excelled his companion. At this time the former began to collect old ballads, and as Irving's mother knew a great many, he used to go to her and learn all she could repeat. Salisbury Crags and Arthur's Seat found their way into 'Waverley,' and later, with St. Leonard's Hill, in the same vicinity, became the background for the earlier chapters of the 'Heart of Midlothian.' The ruins of St. Anthony's Chapel, on the ascent to Arthur's Seat, must have been one of these favourite nooks. Blackford Hill, the third of these resorts, lies south of Edinburgh. Here Scott carried Marmion for that superb view of Edinburgh, 'mine own romantic town,' so well described in the poem:—.

Still on the spot Lord Marmion stayed,

For fairer scene he ne'er surveyed.

The scene is still a beautiful one, for though the plain that held the Scottish camp is now filled with well-built suburban homes, we still may see

Yon Empress of the North

Sit on her hilly throne,

Her palace's imperial bowers,

Her castle, proof to hostile powers,

Her stately halls and holy towers.

So great was Scott's love of the picturesque and especially of the old feudal castles that he yearned to become a painter. But it was of no use. His lessons came to naught and he could make no progress. Perhaps this was fortunate, for, as Lockhart points out, success with the pencil might have interfered with his future greatness {9} as a 'painter with the pen.' At fifteen, Scott entered upon an apprenticeship to his father as a writer's (lawyer's) clerk, during which period he formed an intimate companionship with a relative of his friend Irving, William Clerk, a young man of good intellect and many accomplishments. The experiences of these two young law students will be found in 'Redgauntlet.' William Clerk was the Darsie Latimer of that story, while Scott himself was Alan Fairford. Alan's precise and dignified father, Mr. Saunders Fairford, whose highest hope in life was to see his son attain 'the proudest of all distinctions—the rank and fame of a well-employed lawyer,' was a fairly good portrait of Scott's own father. The house in which the Fairfords lived was in Brown Square, then considered 'an extremely elegant improvement.' It is still standing, and is now used as a dental college. Old 'Peter Peebles,' whose interminable lawsuit was used for young lawyers to practise on, actually existed and haunted the law courts at this time. Scott himself admits that he took his turn as 'counsel' to the grotesque old litigant.

The Edinburgh of Scott's day was still chiefly confined to the Old Town. High Street in those days was considered the most magnificent street in the world. Again and again Scott refers to it. At one end is the great Castle, old enough to remember the time when even the Old Town did not exist. Lower down is St. Giles and the Parliament House. Next to St. Giles is the site of the Old Tolbooth, which, after serving the city as a prison for two hundred and fifty years, was pulled down in 1817. In Writer's Court in the same locality was the tavern where the lawyers held 'high {10} jinks' in 'Guy Mannering.' Greyfriars Church, where Colonel Mannering heard a sermon by Scott's old friend, the Rev. John Erskine, is not far off. Down the street, in the part called the Canongate, is the house of the Earl of Murray, the Regent of Scotland in Queen Mary's time, who figures prominently in 'The Abbot.' Street fighting was a common occurrence in Edinburgh in those days and there is a good description of such a broil in 'The Abbot.' 'My Lord Seton's Lodging,' where Roland Graeme took refuge after a scrimmage, is in the same street, and a little farther on is the 'White Horse Close,' where the officers of Prince Charles made their headquarters in 'Waverley.' Holyrood Palace is at the extreme end of the street, about a mile from the Castle. The great ball, which Scott describes in 'Waverley,' was given here by the young Chevalier, Charles Edward Stuart, on the evening of September 17, 1745.

While still in his fifteenth year, Scott made his first excursion into the Highlands of Perthshire through scenery unsurpassed in natural beauty by any other region in all Scotland. Approaching from the south, he rode over the mountains, through a pass no longer accessible, known as the Wicks of Baiglie. Here 'he beheld, stretching beneath him, the valley of the Tay, traversed by its ample and lordly stream; the town of Perth, with its two large meadows, or Inches, its steeples and its towers: the hills of Moncreiff and Kinnoul faintly rising into picturesque rocks, partly clothed with woods; the rich margin of the river, studded with elegant mansions; and the distant view of the huge Grampian Mountains, the northern screen of this exquisite landscape.' These words were written as part of the Introduction to the {11} 'Fair Maid of Perth' in 1828. The impression they record was made upon the mind of a boy of fifteen, forty-two years earlier. On this visit, no doubt, he saw the original house of Simon Glover in Curfew Street, and also the home of Hal o' the Wynd, not far away. Both houses still remain, and the stories connected with them were of course current in Scott's time.

During all the time that the scenes and the stories connected with this and other excursions were making their impress upon the mind of Walter Scott, it must be remembered that he was not thinking of any ultimate use of them in literature, but was only ambitious to make a success of his chosen profession of the law. It so happened that one of the earliest duties which fell to his lot as a writer's apprentice was to serve a writ upon a certain obstreperous family in the Braes of Balquhidder, the country made famous by the exploits of Rob Roy. Fearing that the execution of the summons would be resisted, an escort of a sergeant and six men was procured, and Scott, a young man of scarcely sixteen, marched into the Highlands, 'riding,' as he said, 'in all the dignity of danger, with a front and rear guard, and loaded arms.' The sergeant was full of good stories, principally about Rob Roy, and proved to be a very good companion. This expedition was Scott's first introduction to the scenery around Loch Katrine, which later owed most of its fame to his pen. It enabled him, by actual contact with the Highland clans, to learn for the first time some of the thrilling tales with which the region abounded and to become familiar with the habits, the speech, the dress, and all the other marked characteristics of a romantic people. The delightful {12} scenery of Loch Vennachar, Loch Achray, and Loch Katrine, the rugged slopes of Ben Venue and Ben An, the more distant peaks of Ben Lomond and Ben Ledi, the tangled masses of foliage in the 'deep Trossachs' wildest nook,'—all appealed at once to the artistic sense within him, to his poetic feeling, and to his love of nature. 'The Lady of the Lake' was not written until twenty-three years later, but the germ of that poem was planted in his bosom by this first youthful experience and its writing was only a labor of love.

On his subsequent excursions to the Highlands, Scott gathered some valuable material which later appeared in 'Waverley.' He found one old gentleman who had been obliged to make a journey to the cave of Rob Roy, where he dined on 'collops' or steaks, cut from his own cattle. This cavern is on Loch Lomond in the midst of most beautiful scenery. Scott makes it the retreat of Donald Bean Lean in 'Waverley,' but does not refer to it in his story of 'Rob Roy.' From another aged gentleman he heard the history of Doune Castle, a fine old ruin on the river Teith, near Stirling, and this he also introduced into 'Waverley.' The story of Waverley's saving the life of Colonel Talbot and the death at Carlisle of Fergus MacIvor are based upon incidents related to Scott at this time.

Among the many places visited was Craighall, in Perthshire, from which some of the features of Tully Veolan were copied. The situation of this country-seat was convenient for the story, and near by was a cave, similar to that in which the Baron of Bradwardine sought concealment. But there is another house, a little to the west, on the river Tay, which is said to correspond {13} even more closely with Scott's description. This is Grandtully Castle, the beautiful estate of the Stewart family. Another house which entered into this composite picture was the residence of the Earl of Traquair, a place on the Scottish Border well known to Scott and frequently visited by him during the time when he was writing 'Waverley.' It has a curious entrance gate, surmounted by some queer-looking bears, which doubtless suggested the Bears of Bradwardine.

These numerous excursions, however fruitful they may have proved in later years, were not by any means the chief business of Scott's life at this time. They were only vacation trips, except the first, which seems to have had a business purpose. He was for the most part hard at work in Edinburgh in the study of the law and in the duties of a writer's apprentice, which meant copying by hand page after page of legal documents, sometimes accomplishing as much as a hundred and twenty pages in one day. In 1792, at the age of twenty-one, he successfully passed the law examinations and was admitted to the Bar, very much to his father's delight. The real Alan Fairford and Darsie Latimer 'put on the gown' the same day, a solemn ceremony followed by a jolly dinner to their companions.

Scott was now a fine, handsome young fellow with a host of friends. The sickliness of childhood had given way to a robust and vigorous manhood. His lameness still remained, but in spite of this he had acquired the frame of a young athlete. He was tall, well formed, big-chested, and powerful. His complexion was fresh and even brilliant; his eyes were bright and twinkling with fun; there was a queer little look about his lips as though {14} they were about to break out into some funny remark—an expression that was the delight of all his friends and the despair of portrait painters. Perhaps the most striking feature of his face was the high forehead, bespeaking intellectual power and dignity, yet in perfect consonance with his good humour and affectionate kindliness. In every company of young people he was easily the life and soul of the group. They crowded around him to revel in his store of anecdotes and ballads à propos to every occasion, and his jokes usually kept them in a gale of merriment. He was fond of every kind of outdoor amusement, especially of fishing, hunting, and riding. Few could excel him in horsemanship, either in skill or endurance. From the days of his first Shetland pony he had loved horses, and but for his ability to make long journeys on horseback to remote regions at a time when there were no railways and few coach-roads, he would have been unable to acquire the knowledge of places and people which gave a peculiar charm to all his writings.

The day after his admission to the Bar, Scott 'escaped' to the country, going first to Rosebank and then to Jedburgh, where he met Robert Shortreed, a sheriff-substitute of Roxburghshire, who consented to become his guide on a visit to the wild and inaccessible district of Liddesdale. For seven successive years they made these 'raids' as Scott called them, 'exploring every rivulet to its source and every ruined peel from foundation to battlement.' 'There was no inn or public-house of any kind in the whole valley; the travellers passed from the shepherd's hut to the minister's manse, and again from the cheerful hospitality of the manse to the {15} rough and jolly welcome of the homestead; gathering, wherever they went, songs and tunes, and occasionally more tangible relics of antiquity.' To his friendly familiarity with these unsophisticated people and the intimate knowledge thus acquired of their manner of living, we are indebted for some of the most charming pages of 'Guy Mannering.' Whether the future poet had any plan in his mind for using the material so gathered is doubtful, though much of it went into the 'Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border' and perhaps these raids suggested that undertaking.

In the summer vacation of 1797, Scott set out for a visit to the English Lakes. He was accompanied by his brother John and Adam Ferguson, an intimate friend through whom he had been introduced to the highest literary circles of Edinburgh. Their first stop was at the country home of Dr. Ferguson, the distinguished philosopher and historian, and the father of Scott's friend. This was at Hallyards, in the vale of Manor Water, near Peebles. The venerable old gentleman, then in his seventy-third year, had become interested in one of the strangest men, physically and mentally, who ever lived,—a poor, ungainly, and hideous dwarf named David Ritchie. Dr. Ferguson conducted his young friend to the rude hut of this horrible being, and Scott, strong and fearless as he was, is said to have come away as pale as ashes and shaking in every limb. This singular meeting resulted, nineteen years later, in the story of 'The Black Dwarf,' where Scott skilfully combined some good traits, which Ritchie was known to possess, with the grotesque and terrifying external figure.

Proceeding to the English Lakes, Scott now saw for the {16} first time the wild and rugged beauty of Saddleback and Skiddaw and the desolate loneliness of Helvellyn, contrasting with the calm loveliness of Grasmere and Windermere and with the sweet homeliness of the dalesmen's cottages, their pastures and peaceful flocks. Like all other scenes of beauty, it made its impression upon his mind. He found a home here for Colonel Mannering; when Waverley was hard-pressed after the failure of the insurrection of 1745, he found it convenient to make a home for his hero with a farmer at Ullswater; and he marched his gallant Baron of Triermain into 'the narrow Valley of St. John' in search of the mysterious castle, as directed by the sage of Lyulph's tower. The tower of Lyulph may be seen near the shores of Ullswater, and on the side of a hill rising above St. John's Beck, a little stream flowing out of Lake Thirlmere, is a huge rock now called 'Triermain Castle,' which at a distance, under certain conditions of the atmosphere, bears a fancied resemblance to the phantom castle of the poem.

Scott frequently showed his profound admiration for the English Lake district, and if he did not love it with all the devotion of his friend Wordsworth, it was only because his own beloved Highlands had a prior claim upon his affections.

On a summer day soon after his return from the Lake District, in the same year, Scott and his friend Adam Ferguson were riding together along a country road near the pleasant little village of Gilsland, in the north of England. The former was then twenty-six years of age. He was a tall man of athletic frame, who rode as though incapable of fatigue. There was a peculiar grace and charm in both face and figure, which almost irresistibly {17} caused a passer-by to follow his first glance with a second and longer scrutiny.

As they rode along, the two companions chanced to pass a young lady, also on horseback, who immediately attracted their notice. Her form was like that of a fairy, light and full of grace. Her long silken tresses were jet black, her complexion a clear olive, and her eyes a lovely brown, large, deep-set, and brilliant. Young and vivacious, with a natural air of gaiety, she was both pleasant to meet and charming to look upon.

At the ball which took place in the evening there was much rivalry among the young men for the honour of dancing with this vision of loveliness, who had blotted out all other thoughts from their morning ride. To the tall young man fell the privilege of taking the fair stranger to supper, and this was the introduction of Walter Scott to Miss Charlotte Margaret Carpenter. The evening of September 30, immediately following the ball, was one of the happiest Scott ever knew. A friend records that he 'was sair beside himself about Miss Carpenter;—we toasted her twenty times over—and sat together, he raving about her until it was one in the morning.'

This was not Scott's first love affair, but it was equally genuine. Some four years previously he had chanced to meet at the Greyfriars Church in Edinburgh, a very charming young lady of seventeen. As the Sunday service closed, an unexpected shower came up. Scott had an umbrella and the lady had none—sufficient reason for escorting the fair one to her home. There was also sufficient reason for falling in love with her, for Miss Williamina Stuart was not only beautiful in face and {18} figure, but lovely in character. Highly educated, accomplished in music and painting, well versed in literature, and with the best family connections, she was still a sweet girl, of charming manners and no affectation. For three years Scott cherished the most ardent feelings of love, but in silence. He was then a young man of small worldly prospects. He had written nothing and was unknown outside the circle of friends in the law courts, where he was but a beginner. This, however, would not have been an insurmountable difficulty had the love been mutual. But the young lady had already given her heart unreservedly to an intimate friend of Scott's, William Forbes, a man of noble character. She gave Scott no encouragement, but frequently, wrote him in a friendly way, chiefly concerning literary topics. After many months of patient restraint, Scott finally wrote her a frank and unreserved declaration of his feelings, and received in reply a letter which filled him with many forebodings but with 'new admiration of her generosity and candour.' She urged upon him the continuation of their simple friendship as the 'prudent line of conduct.' Unfortunately, Scott read between the lines, as too hopeful persons sometimes do, sentiments which were not intended. The final disappointment came in the autumn of 1796, and in the following January Miss Stuart became the bride of Walter Scott's successful rival. It is pleasant to think that the success of the one and the disappointment of the other led to no bitterness. Both were men of noble and generous minds. And in the days of Scott's adversity, when he was wearing away his vitality in a desperate but honourable endeavour to pay his debts, Sir William Forbes, though {19} his own bank was one of the heavy losers in the disaster that overwhelmed Scott, came forward with offers of assistance, and even went so far as to pay secretly a large and pressing debt, that his friend Sir Walter might not be entirely crushed.

The poet never forgot the tender experiences of these years, and long afterward drew a lovely picture of Williamina in 'Rokeby':—

Wreathed in its dark brown rings, her hair

Half hid Matilda's forehead fair,

Half hid and half revealed to view

Her full dark eye of hazel hue.

The rose, with faint and feeble streak,

So lightly tinged the maiden's cheek,

That you had said her hue was pale:

But if she faced the summer gale,

Or spoke, or sung, or quicker moved,

Or heard the praise of those she loved,

The mantling blood in ready play

Rivalled the blush of rising day.

But Walter Scott was a young man, and in his great big heart there was still room for love. If he thought his heart was broken, he admitted that it was 'handsomely pieced' again. Fascinated with the vivacity and attractiveness of Miss Carpenter, Scott remained at Gilsland much longer than he had intended. The lovers strolled through many delightful paths—walks which left their impress upon the poet's mind and gave him many backgrounds for his future verses and tales.

Miss Carpenter had rooms at a large hotel, known as Shaw's, where the momentous ball was held, and Scott was at Wardrew House, a private residence with a picturesque walled-in garden on the slope of a hill not far away. We followed them in fancy as they descended {20} into the glen which separates these two houses, where they might drink of the mineral spring which gives a local fame to the place. Then like the faithful page of the Baron of Triermain, no doubt they 'crossed green Irthing's Mead' and wandering along the shady bank of this pleasant stream, reached

the favourite glade,

Paled in by copsewood, cliff and stone,

Where never harsher sounds invade

To break affection's whispering tone

Than the deep breeze that waves the shade,

Than the small brooklet's feeble moan.

Then, turning a bend in the stream, perchance he invited her to

Come! rest thee on thy wonted seat;

Mossed is the stone, the turf is green,

A place where lovers best may meet

Who would not that their love be seen.

Here is the so-called 'Popping Stone,' where, local tradition asserts, Scott asked the all-important question. Whether this is true or not makes no difference. The question was asked and the stone is there. Whatever virtue there may be in the stone, it is certain that thousands of young couples have found their way thither, and they have literally worn it away until now it is scarcely half its original size.

A little farther west we came to the beautiful old ruins of Lanercost, in which is the tomb of Thomas, Lord Dacre, to whom Marmion, with his last dying gasp on the field of Flodden, sent a message with his signet ring. Near by and entered through a beautiful park is the fine old feudal castle of Naworth, the stronghold of the {21} Dacres and later of the Howards, both of whom are mentioned in 'The Lay of the Last Minstrel.'

The place which seems to have interested Scott the most in these rambles was the old ruined wall of Triermain Castle. He saw more of it than can be seen to-day, for a great part of it remained standing until 1832. But it was a ruin in the time of Queen Elizabeth. Scott's imagination, however, soon rebuilt and repeopled it, and Sir Ronald de Vaux became immortalized in 'The Bridal of Triermain,' though forgotten in the pages of history. In almost the latest years of his life, the novelist came back to these scenes of his early manhood for another character whom he took from the same old castle of Triermain, the big and burly, but always faithful, Sir Thomas de Multon of 'The Talisman.'

During the autumn of 1797, Scott was a frequent visitor to the city of Carlisle, where Miss Carpenter was living in Castle Street. A few steps beyond the site of her house is Carlisle Cathedral, the most striking feature of which is the beautiful East Window, said to be the finest in England. The cathedral was founded by Henry I in 1101. During the Civil War it was occupied by soldiers, who pulled down ninety-six feet of the nave to build fortifications. The portion that remained, thirty-nine feet, was later enclosed and used as the parish Church of St. Mary. Here, standing between two great Norman pillars of red sandstone, on the day before Christmas, 1797, Walter Scott and Charlotte Carpenter were married.

They went to live in Edinburgh, but during the following summer took up their abode in a charming little cottage with a thatched roof and a delightful garden on {22} the banks of the river Esk at Lasswade. It was then a small house with only one room of fair size, though now very much enlarged. The thatched portion, however, is carefully preserved. Mrs. Scott's good taste and her husband's enthusiasm soon converted the house and grounds into a veritable bower of delight. Unfortunately, the rustic archway of ivy, which Scott took so much pleasure in fashioning, has disappeared. But the vale of the Esk still remains, to thrill the souls of the romantic. Not even in lovely Scotland is there a river or glen to surpass it. Deep down between precipitous cliffs and rocks, shaded by tall trees and overgrown by a bewildering profusion of creeping plants and overhanging vines, the little river flows merrily along, seeming to sparkle at every bend with some new recollection of the romantic legends or fantastic tales of the barons of old, who once peopled its ancient castles and drank their wine while they listened to the rhythmic stories of the minstrel bards. Here six happy summers were spent. Friends came down from Edinburgh and new friendships were formed with important personages living in the villas and castles of the vicinity. All found that Scott had formed a connection with one who had the 'sterling qualities of a good wife,' to quote Lockhart's phrase. The brothers of the Mountain—a group of boon companions who were closely associated and very fond of each other's society—welcomed Mrs. Scott with the greatest delight. A married life of perfect serenity was inaugurated, which lasted until the death of 'the ever faithful and true companion' in 1826.

In a confidential letter to Lady Abercorn, written in 1810, Scott refers to his attempt, in the 'Lady of the {23} Lake,' to make 'a knight of love who never broke a vow,' and mentions his own melancholy experience of early days. He adds: 'Mrs. Scott's match and mine was one of our own making, and proceeded from the most sincere affection on both sides, which has rather increased than diminished during twelve years' marriage. But it was something short of love in all its forms, which I suspect people only feel once in their lives; folks who have been nearly drowned in bathing rarely venturing a second time out of their depth.'

These words should not be misconstrued. Whatever the ardency of his first love, the second was no less sincere and true. If the first was the highly poetic type, the young dream of a peculiarly sensitive nature, the second was the kind that enables young couples to meet in peace and serenity all the varied problems of life, to establish their housekeeping in mutual helpfulness, to laugh away their cares, as Scott wrote to Miss Carpenter, or if the load is too heavy, to share it between them, 'until it becomes almost as light as pleasure itself.' It was in this spirit that the young people established their household gods in the cottage at Lasswade.

To a man of Scott's disposition, happy in his new home life, with every incentive to improve his opportunities, his mind steeped from infancy in the rude ballads of the border country and his heart bounding with delight at the beauties of nature, this new environment seemed all that was needed to turn his whole thought to poetry.

Sweet are the paths, O passing sweet!

By Esk's fair streams that run

O'er airy steep through copsewood deep

Impervious to the sun.

There the rapt poet's step may rove,

And yield the muse the day;

There Beauty, led by timid Love

May shun the telltale ray.

No afternoon stroll could be more delightful than one through the valley of the Esk as far as Roslin. Many go to Roslin by coach from Edinburgh, but they fail to see the glen. Guided by a Scottish friend, we found that the better way is to go to Hawthornden and walk through the gardens and grounds of the ancient castle where the poet Drummond lived and wrote to his heart's content of the beauties of the scene. Here we saw the caves, cut out of the solid rock beneath the castle, which sheltered Robert Bruce during the troublous times when Fortune seemed to frown. Here, too, we stood under the sycamore tree where Drummond welcomed Ben Jonson to his home. Descending the path to the river, we crossed by a little wooden bridge, with a gate in the middle, which can be opened only from the Hawthornden side. Then a walk, which was half scramble, brought us finally to Roslin Castle, on a rock peeping over the foliage, high above the river. Both Roslin and Hawthornden are mentioned in 'The Lay of the Last Minstrel' in the ballad of the lovely Rosabelle:—

O'er Roslin all that dreary night

A wondrous blaze was seen to gleam;

'T was broader than the watch-fire light,

And redder than the bright moonbeam.

It glared on Roslin's castled rock,

It ruddied all the copsewood glen;

'T was seen from Dreyden's groves of oak,

And seen from caverned Hawthornden.

The quiet of Lasswade gave Scott the opportunity for the compilation of the 'Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border,' and its romantic beauty furnished the inspiration for his first serious attempts to write new ballads in imitation of the old ones. 'It was amidst these delicious solitudes,' says Lockhart, 'that he produced the pieces which laid the imperishable foundations of all his fame. It was here that when his warm heart was beating with young and happy love, and his whole mind and spirit were nerved with new motives for exertion—it was here in the ripened glow of manhood he seems to have first felt something of his real strength, and found himself out in those splendid original ballads which were at once to fix his name.'

At this period Scott was a man of unusually robust health. In spite of the lameness with which he had been afflicted from infancy, his powers of endurance were very great. He could walk thirty miles a day or ride one hundred without resting. He was quartermaster of the Edinburgh Volunteers and had a great reputation as a skilful horseman. 'He had a remarkably firm seat on horseback,' said Mr. Skene, 'and in all situations a fearless one: no fatigue ever seemed too much for him, and his zeal and animation served to sustain the enthusiasm of the whole corps.' His companions called him 'Earl Walter,' and whenever there came, at drills, a moment of rest, all turned intuitively to the quartermaster, whose ever ready fun never failed to lighten the burdens of the day. It was really this remarkable gift of good companionship, coupled with his fondness for horses and unusual powers of endurance, that enabled Scott to gather the materials for his poems.

'Eh me,' said Shortreed, his companion and guide in the Liddesdale raids, 'sic an endless fund o' humour and drollery as he then had wi' him! Never ten yards but we were either laughing or roaring or singing. Wherever we stopped, how brawlie he suited himsel' to everybody! He aye did as the lave did; never made himsel' the great man, or took ony airs in the company.' It was literally true, as he said, that he 'had a home in every farmhouse.'

To his rare good fellowship and his powers of endurance, Scott added one other quality without which his vigorous search for literary material might have been of little use, namely, a most extraordinary memory, which enabled him to retain what he had heard and use it many years afterward. James Hogg, the eccentric Ettrick shepherd, gives a fine instance of this power. One night Scott, with his friends, Hogg and Skene, was out on a fishing expedition. 'While we three sat down on the brink of a river,' says Hogg, 'Scott desired me to sing them my ballad of Gilman's Cleugh. Now be it remembered that this ballad had never been printed: I had merely composed it by rote, and, on finishing it three years before, had sung it over once to Sir Walter. I began it, at his request, but at the eighth or ninth stanza I stuck in it and could not get on with another verse, on which he began it again and recited it every word from beginning to end. It being a very long ballad, consisting of eighty-eight stanzas, I testified my astonishment, knowing that he had never heard it but once, and even then did not appear to be paying particular attention. He said he had been out with a pleasure party as far as the opening of the Firth of Forth, and, {27} to amuse the company, he had recited both that ballad and one of Southey's ("The Abbot of Aberbrothock"), both of which ballads he had only heard once from their respective authors, and he believed he recited them both without misplacing a word.'

Living in a country where new beauty appears at every turn in the road and romance is echoed from every hillside, happy in his domestic relations, blessed with the faculty of making friends wherever he went, whether among farmers and shepherds or lords and ladies, active in travelling into every nook or corner where material could be found, keen to appreciate a good story or a pleasing ballad, and able to remember all he ever heard or read, Walter Scott became a poet as easily and naturally as the rippling waters of his beloved Tweed find their way to the sea.

The years at Lasswade were marked by one of the most momentous decisions of Scott's life. He had reached the parting of the ways; one leading to the practice of the law; the other—and the more alluring one—to literature as a profession. Had his father been alive, it is probable that a high sense of duty and loyalty would have determined him to continue in the law, for the old gentleman had set his heart upon that, and Scott would have submitted to almost any irksome requirement rather than wound the feelings of his parent. But the worthy barrister's death a year or two after his son's marriage had put an end to any scruples on his account. Although Scott had not made a failure, his success at the Bar was not remarkable. In the year preceding his marriage and the fifth year of his practice, his fee-book showed an income of only one hundred forty-four pounds, ten shillings. He never had any fondness for the law. As he afterwards expressed it: 'My profession and I came to stand nearly upon the footing which honest Slender consoled himself on having established with Mistress Anne Page: "There was no great love between us at the beginning and it pleased Heaven to decrease it on farther acquaintance."' He began to realize that 'the Scottish Themis was peculiarly jealous of any flirtation with the Muses,' and that a young lawyer could not expect to succeed unless he kept up the appearance of {29} being busy even when he had nothing to do. A barrister who spent his time 'running after ballads' was not to be trusted. To succeed in the law meant, therefore, a farewell to literature. It meant other sacrifices, too. His vigorous health at this period enabled him to indulge a natural fondness for country sports, horseback riding, hunting, fishing, and the like. His membership in the Edinburgh Volunteers gave him a most agreeable companionship with a fine class of men, among whom he was extremely popular and with whom he spent some of the happiest hours of his life. All this would have to be given up if he continued at the Bar, and instead he would feel obliged to tie himself down to a severe course of study in some musty old office in Edinburgh.

Two circumstances combined to make feasible the more attractive path. The first was Scott's appointment as Sheriff of Selkirk with an income of three hundred pounds a year, which gave him a certain degree of independence, while the duties were not onerous. The second was the success of the 'Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.' For several years Scott had travelled extensively through many remote nooks and corners in search of material for this compilation, and its publication had brought him into public notice as a man of no small literary skill. His gratification with its success may be judged from a letter to his brother-in-law, Charles Carpenter, in 1803:—

I have continued to turn a very slender portion of literary talents to some account by a publication of the poetical antiquities of the Border, where the old people had preserved many ballads descriptive of the manners of the country during the wars with England. This trifling collection was {30} so well received by a discerning public, that, after receiving about £100 profit for the first edition, which my vanity cannot omit informing you went off in six months, I have sold the copyright for £500 more.

This enterprise, paying as much as the entire proceeds of Scott's first five years of legal effort, gave assurance of a financial success in literature, which coupled with a certain income as Sheriff seemed to make the future fairly secure. Reasoning in this way, Scott finally reached his decision to abandon the law and devote his life to literature.

'The Lay of the Last Minstrel' was the immediate result. Scott felt the responsibility of his position. He was now the head of a family, having a wife and three children of whom he might well be proud, and he felt impelled to make a financial as well as literary success of his chosen profession. He had previously tried his hand at original composition. Inspired perhaps by his familiarity with the old Scottish ballads, he had essayed something of the same character. The first of these productions was 'Glenfinlas,' growing out of his early visits to the Highlands. Glenfinlas is a forest in Perthshire, north of the Trossachs and east of Loch Katrine. Next came 'The Eve of St. John,' in which Scott rebuilt and repeopled the old tower of Smailholm which had so fascinated his boyish fancy. In 'The Gray Brother,' an incomplete ballad of this period, the poet sang the praises of the vale of the Esk, then the scene of his almost daily walks. The fourth of these early poems was 'Cadyow Castle,' a ballad on the assassination of the Regent Murray. Cadyow Castle is a very dilapidated old ruin in a park of wondrous beauty near Hamilton, {31} southeast of Glasgow. There is a deep glen, through which runs a little river, the Avon, and on the banks are many tall and beautiful trees. The park was once a part of the old Caledonian forest, a few of the ancient oaks of which still remain standing. It was the habitation of the fierce wild cattle which furnished the liveliest and most dangerous sport whenever a hunt was arranged. Something of the spirit and fire of Scott's later work is seen in these lines:—

Mightiest of all the beasts of chase

That roam in woody Caledon,

Crashing the forest in his race,

The Mountain Bull comes thundering on.

Fierce on the hunter's quivered band

He rolls his eyes of swarthy glow,

Spurns, with black hoof and horn, the sand

And tosses high his mane of snow.

The man who could write such lines as these must have felt an instinct for poetry which no amount of reasoning could ever set aside. It was, therefore, well that Scott did not attempt to resist his natural inclinations.

We find him, then, deliberately turning to poetry, and carefully surveying the field to choose his first subject. Three influences, widely different in character, combined to solve this problem. The first was his interest in the stories of Border warfare aroused by the tales of his childhood and immensely stimulated by his thorough search for ballads to make up the 'Border Minstrelsy.' The second was his membership in the Edinburgh Volunteers which gave a military trend to his thoughts. The third was his desire to oblige a lady. The young Countess of Dalkeith, afterward Duchess of Buccleuch, {32} was an intellectual woman of extreme beauty and lovely character. She was, moreover, the wife of the chief of the clan of Scott, and therefore entitled, in the poet's view at least, to the fealty of her kinsmen. Having heard the legend of Gilpin Horner, a goblin dwarf in whom most of the people implicitly believed, the Countess, much delighted with the story, enjoined upon Scott the task of composing a ballad on the subject. The slightest wish of one so beloved was a command.

The poet soon realized that the goblin was likely to prove a veritable imp of mischief, threatening to ruin his ballad, and before the poem was finished, relegated him to the kitchen where he properly belonged. With the goblin story reduced to a mere incident, the poem expanded to a tale of Border warfare in which all of Scott's military spirit and knowledge of history and legend came to the front. He wrote it, as he declared in a letter to Wordsworth, to discharge his mind of the ideas which from infancy had rushed upon it. In a letter to George Ellis in 1802, he refers to it as a 'kind of romance of Border chivalry in a light-horseman sort of stanza.' In the autumn of that year, while on duty with his troop at Musselburgh, during a charge on Portobello sands, he received a kick from his horse which confined him to his rooms for three days. This accident gave an unexpected opportunity, and in these three days the actual writing of the poem was started and the whole of the first canto completed except the introductory framework. It is easy to recognize the 'light-horseman' stanza. Indeed, the clatter of horses' hoofs is heard distinctly as Sir William of Deloraine sets forth upon his night ride to Melrose:—

'O swiftly can speed my dapple-grey steed

Which drinks of the Teviot clear;

Ere break of day,' the warrior 'gan say,

'Again will I be here:

And safer by none may thy errand be done

Than, noble dame, by me!'

*****

Soon in his saddle sate he fast,

And soon the steep descent he passed,

Soon crossed the sounding barbican,

And soon the Teviot side he won.

*****

And soon he spurred his courser keen

Beneath the tower of Hazeldean.

The clattering hoofs the watchmen mark:

'Stand ho! thou courier of the dark!'

'For Branksome, ho!' the knight rejoined,

And left the friendly tower behind.

The spirited ride to Melrose; the opening of the wizard's grave; the delightful picture of the ruined abbey; the meeting of Lady Margaret and Lord Cranstoun; the telling encounter of the latter with the Knight of Deloraine; the manly spirit of the young heir of Branksome; the tales of Watt Tinlinn and the Scotts of Thirlstane, of Harden and of Eskdale, the coming of the Englishmen, Belted Will Howard and Lord Dacre, the duel resulting in the death of Richard of Musgrave, and the triumph of Cranstoun's love for the fair Margaret, all combine to produce a vivid impression of the stirring events, the conditions of life, and the ideals of the Border country in the days of chivalry.

The framework of this picture, from which it takes its name, is generally considered the most beautiful part of the poem. The old minstrel is supposed to relate the tale, with the accompaniment of his harp, to the noble {34} Duchess of Buccleuch. The minstrel, with his reverence and enthusiasm for the old ballad poetry, now in its decadence, is of course the poet himself and the Duchess is his patron, who first suggested the poem. In no more beautiful and delicate way could the poet have shown his devotion to the lord and lady who had so greatly inspired him. Moreover, it gave him the method of showing, as he said, that he had no intention of setting up a new school of poetry, but was only making 'a feeble attempt to imitate the old.' The historical basis of the poem is told in a letter to Lady Dalkeith:—

Dame Janet Beatoun, Lady Buccleuch, who flourished in Queen Mary's time, was a woman of high spirit and great talents. According to the superstition of the times, the vulgar imputed her extraordinary abilities to supernatural knowledge. If Lady Dalkeith will look into the Introduction to the 'Border Ballads,' pages xv and xxix, she will find some accounts of a deadly feud betwixt the clans of Scott and Kerr, which, among other outrages, occasioned the death of Sir Walter Scott of Buccleuch, the husband of Janet Beatoun, who was slain by the Kerrs in the streets of Edinburgh. The lady resented the death of her husband by many exploits against the Kerrs and their allies. In particular the Laird of Cranstoun fell under her displeasure, and she herself headed a party of three hundred horse with the intention of surprising and killing that baron in the chapel of St. Mary, beside St. Mary's Loch at the head of Yarrow. The Baron escaped, but the lady burned the chapel and slew many of the attendants.... The feud was finally ended by Cranstoun marrying the lady's daughter.

About this fragment of history Scott wove his stirring tale of the Scottish lowlands in the sixteenth century.

The last of all the bards was he

Who sung of Border chivalry,

The aged minstrel is introduced as he passes

where Newark's stately tower

Looks out from Yarrow's birchen bower.

The old ruin was a favourite resort for Scott, and many a happy holiday excursion was made to those 'rich groves of lofty stature' which Wordsworth celebrated in his 'Yarrow Visited.' The ancient tower stands on high ground above the Yarrow, on a road leading westward from Selkirk, over which Scott often walked or rode. About two miles away is Bowhill, a country-seat of the Duke of Buccleuch, where the poet was always a welcome guest. He refers to it affectionately in the closing stanza of the 'Lay':—

When summer smiled on sweet Bowhill.

Still farther south is Oakwood Tower, a stronghold of the celebrated Wat of Harden, one of the poet's ancestors.

Wide lay his lands round Oakwood Tower

And wide round haunted Castle-Ower.

This was 'Auld Wat,' who married the 'Flower of Yarrow,' one of the most beautiful women of the Border, who lived at Dryhope, near the foot of St. Mary's Loch.

High over Borthwick's mountain flood

His wood-embosomed mansion stood.

The Borthwick joins the Teviot just above the town of Hawick. The house of Harden stands high up above a deep and romantic glen where there was ample room to conceal 'the herds of plundered England.'

Marauding chief! his sole delight

The moonlight raid, the morning fight;

Not even the Flower of Yarrow's charms

In youth might tame his rage for arms.

{36} Auld Wat's son, afterwards Sir William Scott of Harden, a remarkably handsome man and an early favourite of King James VI, inherited some of his father's propensities for driving off his neighbour's cattle and other irregularities common to the time. In a raid upon the lands of Sir Gideon Murray of Elibank he was captured and carried in chains to the castle. Elibank is now a ruin on the banks of the Tweed not far from Ashestiel, whither Scott was fond of walking on Sunday mornings. The legend which Scott tells, about as it was told to him in his youth, and not, perhaps, in exact accordance with the facts, is as follows:—

When the young marauder was brought to the castle in chains, the Lady Murray asked her lord what he proposed to do with him. 'Why, hang the robber, assuredly,' was the answer. 'What,' answered the lady, 'hang the handsome young knight of Harden when I have three ill-favoured daughters unmarried! No, no, Sir Gideon, we'll force him to marry our Meg.' 'Meikle-mouthed Meg' was the ugliest woman in the country, and young Sir William promptly decided that he would rather hang. Three days were given him to think the matter over, after which he was led out beneath a convenient oak, with a rope tied around his neck and the other end was passed over a stout limb of the tree. Then he began to reconsider and decided that, as between nooses, he preferred the matrimonial one. There may be some advantages in ugly wives after all, and one of them, in this case at least, seemed to be an entire absence of jealousy. It was said, moreover, that 'Meg' had 'a curious hand at pickling the beef which Sir William stole.' They lived a very happy life. The marriage {37} contract was written on the head of a drum and the parchment is still preserved. Scott was so fond of the legend that he wanted to make it the subject of a comic ballad. He accordingly began, but never finished 'The Reiver's Wedding.' The grandson of this couple was Walter Scott, known as 'Beardie,' the great-grandfather of the poet.

About a mile above the junction of the Teviot with the Borthwick stands the castle of Branksome. Seen from the opposite side of the river standing on a terraced slope, partly hidden by the trees and shrubs, it makes a pretty picture.

All, all is peaceful, all is still,

and there is nothing to suggest the time when

Nine and twenty knights of fame—

Hung their shields in Branksome Hall.

It seemed to us more modern than it really is, for it was completed in its present form in the year 1576. The barony of Branxholme, or Branksome, came into the possession of Sir William Scott of Buccleuch in the early part of the fifteenth century and still remains in the family. The towers which formerly occupied the site were attacked by the English again and again, and the castle burned and pillaged. It will be remembered that after a preliminary survey of the castle and its attendant knights, the minstrel tells the story of how Lord Walter fell, of the widow's desire for vengeance, and of the Lady Margaret's love for Lord Cranstoun, her father's foe. Then for some purpose which is not clearly defined, the 'Ladye' calls to her side the boldest knight of her train, Sir William of Deloraine, and bids him ride with all {38} haste to Melrose Abbey, there to open the grave of the wizard, Michael Scott, and to take from it the 'Mighty Book.' Sir Michael Scott was a man of learning who flourished in the thirteenth century. He wrote several philosophical treatises and devoted much time to the study of alchemy, astrology, chiromancy, and other abstruse subjects, whence he gained the reputation of being a wizard. Many weird tales are told of his performances. Being sent as an ambassador to France to demand satisfaction for certain grievances, he opened his magic book and caused a fiend in the shape of a huge black horse to fly out. Mounting, he flew across the sea and presented himself to the king. His demands were about to be met with a curt refusal when Michael begged the king to defer his answer until the black horse had stamped three times. The first stamp set all the bells in Paris to ringing; the second tumbled over three towers of the palace; the horse raised his foot for the third stamp, but the king would not risk another and gave to Michael what he wanted. It was this same wizard who 'cleft the Eildon Hills in three,' the triple peaks which so picturesquely dominate the entire landscape in the vicinity of Melrose, having been formerly, so it is said, a single summit. It has always been understood that the 'magic book' was buried with the wizard, and that no one dared remove it because of the 'terrible spells' which it contained.

The knight arrived after a spirited gallop, and shortly after midnight rapped with the hilt of his dagger on the wicket gate. The porter hurried to admit him, and soon he greeted the aged monk of St. Mary's Aisle. Sighing heavily the monk conducted the man of arms through {39} the cloisters, which may still be seen looking very much as the poet described them in lines not only poetically beautiful but literally true:—

Spreading herbs and flowerets bright

Glistened with the dew of night;

Nor herb nor floweret glistened there

But was carved in the cloister arches as fair.

Seven graceful arches, forming stalls or seats once used by the dignitaries of the church, make a continuous line along the eastern wall. Above the arches, and joining one to another, are stone carvings of rare delicacy and beauty. Of the more than a hundred separate figures in this frieze no two are alike. There are roses, lilacs, thistles, ferns, oak leaves, and scores of other representations of the forms of nature, all exquisitely carved with inimitable accuracy. Scott admired these arches so greatly that he copied one of them for the fireplace of the entrance hall at Abbotsford.

The 'steel-clenched postern door,' through which the monk and the knight now entered the chancel, stands nearly intact. Its three arches rest on graceful pilasters surmounted by capitals, with carved foliage so delicate that a straw can be passed behind the stalks of the leaves. We found it interesting upon entering this door to note the accuracy of the poet's descriptions, which the guide quoted with great fluency. The pillars supporting the lofty roof spread out to form the great arches, seeming to be 'bundles of lances which garlands had bound.'

We stood beneath this arched roof for a long time to admire the beautiful East Window, and the guide quoted:—

The moon on the East oriel shone

Through slender shafts of shapely stone

By foliaged tracery combined.

It is almost impossible to realize that these long and slender shafts are really carved out of stone and that the work was done many centuries ago. Scott accounts for it poetically:—

Thou wouldst have thought some fairy's hand

Twixt poplars straight the osier wand

In many a freakish knot had twined,

Then framed a spell when the work was done,

And changed the willow wreaths to stone.

Beneath the window lies the heart of Robert Bruce. It had been the desire of the monarch that his heart be interred in the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. After his death the body was buried beneath the high altar of the church at Dunfermline, but the heart was taken out and committed to the keeping of James, Lord Douglas, who undertook to carry it to the Holy Land. But James was defeated and killed by the Saracens, and the heart of his royal master was taken to Melrose and buried there. This was as it should be, for the heart of Bruce, figuratively speaking, was always in Melrose. After the destruction of the abbey in 1322 by Edward II on his retreat from Scotland, Bruce made a grant of £2000 sterling, a sum equivalent to about £50,000 in the money of to-day. Because of this munificence the abbey was rebuilt in all the beauty and perfection which Gothic architecture could suggest, so that even in ruins it is still a structure of graceful magnificence. In 1384, the abbey was again destroyed, but later restored. In 1544, 1545, and finally a century later under the Reformation, {41} the abbey suffered serious damage from which it never recovered.

The grave of Michael Scott which Deloraine was sent to open was pointed out to us, as it is to all visitors, but in reality its exact position is not known. Johnny Bower, an old guide of whom Scott was very fond, discovered the position of the grave by noting the direction of the moonbeams through the oriel window. 'I pointed out the whole to the Shirra,' said he, 'and he couldna' gainsay but it was varra clear.' 'Scott,' says Washington Irving, who tells the story, 'used to amuse himself with the simplicity of the old man and his zeal in verifying every passage of the poem, as though it had been authentic history, and always acquiesced in his deductions.'

Like all other visitors we wanted to see the abbey properly, and that, according to the poet, could only be done by moonlight.

If thou wouldst view fair Melrose aright,

Go visit it by the pale moonlight.

The moon was full while we were there and seemed to offer a splendid opportunity. But an unexpected obstacle appeared. In Scotland, in the summer time, the evenings are very long, the twilight lasting until ten or eleven o'clock, while the moon makes very little impression until a late hour. And the custodian of the abbey goes to bed early! So it was impossible to see the moon shining through the east oriel, but fortunately we could see the outer walls from the windows of our hotel, which adjoins the ruin, and the moon kindly favoured us by making

Buttress and buttress alternately

Seem framed of ebon and ivory.

{42} The next day we were treated to a superb view from the private grounds of a gentleman whose estate adjoins the abbey. From this point the entire southern wall, which remains nearly intact, gives at first glance the impression of a complete and beautiful Gothic structure. The distant hills furnish a fine background and the well-kept lawns and graceful birches perform the double duty of shutting out the graveyard and making a charming foreground.

But to return to the story. While William of Deloraine, with the mystic book pressed close to his breast, was eagerly returning to Branksome, the fair Lady Margaret was early awake and seeking the greenwood at dawn of light to meet her lover, the Baron Henry.

A fairer pair were never seen

To meet beneath the hawthorn green.

He was stately and young and tall,

Dreaded in battle and loved in hall;

And she, when love, scarce told, scarce hid,

Lent to her cheek a livelier red,

When the half sigh her swelling breast

Against the silken ribbon pressed,

When her blue eyes their secret told,

Though shaded by her locks of gold—

Where would you find the peerless fair

With Margaret of Branksome might compare!

Lockhart finds in this passage 'the form and features of Scott's first love,' and also says that the choice of the hero was dictated by the poet's affection for the living descendants of the Baron of Cranstoun. One of these, George Cranstoun, afterward Lord Corehouse, was one of Scott's earliest friends. His sister, the Countess of Purgstall, was the confidante of Scott at the time of his early disappointment in love.

The meeting of the lovers was all too brief. The Baron's horse pricked up his ears, 'as if a distant noise he hears,' and the goblin dwarf signed to the lovers to part and fly. William of Deloraine, returning from his all-night ride, was seen coming down the hill into 'Branksome's hawthorn green.' No words were wasted.

Their very coursers seemed to know

That each was other's mortal foe.

Like the bursting of a thundercloud the two champions met, and in another moment William of Deloraine lay on the ground, with Cranstoun's lance, broken, in his bosom. The goblin page was directed to attend the wounded knight, and in doing so discovered the 'Mighty Book' from which he learned some mischievous 'spells.' The son of the Ladye of Branksome was lured into the woods and fell into the hands of an English yeoman who took him, a captive, to Lord Dacre. Scouts hurrying into the castle brought news of the approach of three thousand Englishmen led by 'Belted Will Howard' and 'Hot Lord Dacre.'

Naworth Castle, the home of the Dacres and later of the Howards, was one of the first places we visited. It is a fine old baronial castle in Cumberland County, about twelve miles from Carlisle. It was built in the fourteenth century by the Dacre family, who derived their name from the exploits of an ancestor who was conspicuous at the Siege of Acre in the Holy Land, under King Richard the Lion-Hearted. In the sixteenth century it passed into the possession of Lord William Howard, a famous 'warden of the marches,' who became known as 'Belted Will Howard.'

His Bilboa blade, by Marchmen felt,

Hung in a broad and studded belt;

Hence, in rude phrase, the Borderers still

Called noble Howard Belted Will.

One of the towers of Naworth, which this celebrity occupied, still remains much as he left it, even to the books that formed his library. Lanercost Priory, the burial-place of the Howards and Dacres, is an unusually picturesque and interesting ruin in the same vicinity.

The beacon fires soon summoned a goodly array of the best blood of Scotland to meet the English invaders, among whom were Archibald Douglas, seventh Earl of Angus, a descendant of James, Lord Douglas, who attempted to carry the heart of Bruce to the Holy Land. But the battle was averted, and instead a single combat arranged between Richard of Musgrave and William of Deloraine, the prize of the field to be the young Buccleuch, who had fallen into the hands of the English. The Lady of Branksome was escorted to the field of the tournament by Lord Howard, while Margaret had the stately Douglas by her side. The strife was desperate and long, and in the end Musgrave was slain. But not by the hand of William of Deloraine. Lord Cranstoun, by the aid of magic learned from the 'Mighty Book' and assisted by the goblin page, had contrived to array himself in the armour of Sir William and so had won the fight.

'And who art thou,' they cried,

'Who hast this battle fought and won?'

His pluméd helm was soon undone—

'Cranstoun of Teviot-side!

For this fair prize I've fought and won'—

And to the Ladye led her son.

Then and there the feud was ended. The Ladye of Branksome, declaring that 'pride is quelled and love is free,' gave the hand of Margaret to the Baron of Cranstoun, with all the noble lords assembled to grace the betrothal with their presence.