PERKINS, THE FAKEER

PERKINS, The FAKEER

A TRAVESTY ON REINCARNATION

His Wonderful Workings in the Cases of

"When Reginald Was Caroline"

"How Chopin Came to Remsen"

and "Clarissa's Troublesome Baby"

BY EDWARD S. VAN ZILE

Author of "With Sword and Crucifix," etc.

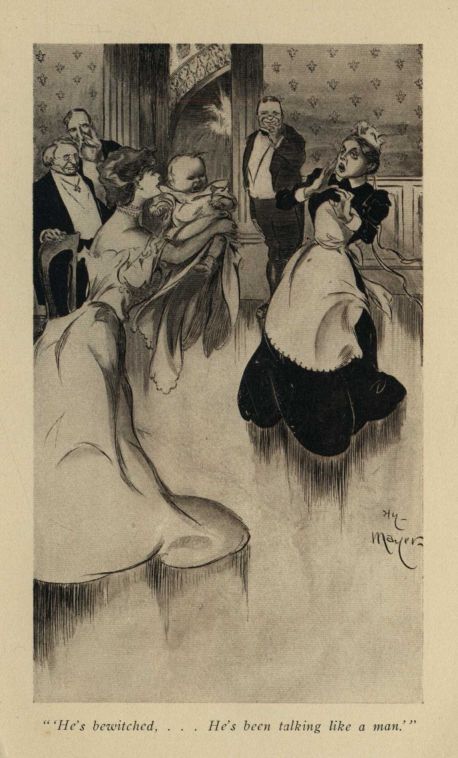

ILLUSTRATED BY HY MAYER

1903

The Smart Set

PUBLISHING CO.

NEW YORK LONDON

COPYRIGHTED

July, 1900, December,

1901, July, 1902

By ESS ESS

PUBLISHING CO.

COPYRIGHTED

1903, BY

THE SMART SET

PUBLISHING CO.

First Printing in April

PREFACE

In offering to the public in book form the following tales, from the pages of THE SMART SET, the opportunity is presented to the author of answering the questions that have frequently been asked of him and the publishers, since these stories first appeared in print, concerning their origin. He is not, and has not been, the deus ex machina.

One Perkins, a Yankee who lived for fifty years in India, and became an adept in mysteries rejected by the Occidental mind, is responsible for the curious psychical transpositions described in the following pages. I am not at liberty to say much about Perkins. He has control of a power that is so peculiar, and I may say erratic, that I dare not offend him. If, in this preface, I should tell the public too much about Perkins, he has both the ability and the inclination to work me harm of the disastrous sort herein described. I do not dare to defy him.

I have taken the liberty of telling these stories in the first person. My choice of this method will at once commend itself to the thoughtful reader; and, what is more important, I am sure that it will satisfy the amour propre of Perkins, the Fakeer--a consummation devoutly to be wished.

E. S. VAN Z.

Hartford, Conn., March, 1903.

CONTENTS.

WHEN REGINALD WAS CAROLINE.

CHAPTER

HOW CHOPIN CAME TO REMSEN.

CLARISSA'S TROUBLESOME BABY.

I.

When Reginald Was Caroline.

That night the wife of King Sûddhôdana,Maya the Queen, asleep beside her Lord,Dreamed a strange dream.THE LIGHT OF ASIA.

CHAPTER I.

TRANSPOSED.

But what a mystery this erring mind!It wakes within a frame of various powersA stranger in a new and wondrous world.--N. P. Willis.

To begin at the beginning: the tragedy or farce--whichever it may prove to be--opened just a week ago. I turned on my side, as I awoke last Wednesday morning, to look into my wife's face, and, lo, I beheld, as in a mirror, my own countenance. My first thought was that I was under the influence of the tag end of a quaint dream, but presently my eyes, or rather my wife's, opened slowly and an expression of mingled horror and amazement shone therein.

"What--what--" groaned Caroline, in my voice, plucking at my--or perhaps I should say our--beard. "Reginald, am I mad--you look--where are you? What is this on my chin--and what have you done to yourself?"

Whether to laugh or swear or weep I hardly knew. The bedroom looked natural, thank God, or I think that at the outset we should have lost our transposed minds even more completely than we had. The sun came in through the window as usual. I could see my trousers--if they were mine--lying across a chair at the further end of my dressing-room. It was all common-place, natural, homelike. But when I glanced again at my wife, there she lay, pale and trembling, with my face, beard, tousled hair and heavy features. I rubbed a slender white hand across my brow--or, to be accurate, the brow that had been my wife's. There could be no doubt that something uncanny, supernatural, theosophical or diabolical had happened. While we lay dead with sleep our respective identities had changed places, through some occult blunder that, I realized clearly enough, was certain to cause us no end of annoyance.

"Don't move," I whispered to Caroline, and there flashed before my mind a circus-poster that I had gazed at as a boy, marveling in my young impressionability at the hirsute miracle that had been labeled in red ink, "The Bearded Lady."

"Don't move," I continued, hoping against hope that by prompt measures I might repair the mysterious damage that had been done to us by this psychical transposition. "Shut your eyes, Caroline, and lie perfectly still. Don't worry, my dear. Make your mind perfectly blank--receptive to impressions. Now, we'll put forth an effort together. I'm lying with my eyes closed, and I am willing myself to return to my own body. Do likewise, Caroline. Don't tremble so! There's no danger. Things can't be worse, can they? There's comfort in that, is there not? Now! Are you ready? Use your will power, my dear, for all it's worth."

We lay motionless, blind, silent for a time. That I should gaze into my wife's own face when I opened my eyes again I fondly imagined, for I had always been proud of my force of will. Caroline, too--as I had good reason to know--possessed a stubborn determination that had great dynamic possibilities.

"Ready!" I exclaimed, presently. "Open your eyes, my dear!"

Horror! There was my wife gazing at me with my eyes and pulling nervously at my infernal beard. As she saw that I was still occupying her fair body, my eyes began to fill, and a man's hoarse sobs relieved my wife's overwrought feelings.

"Is it--oh, Reginald!--is it reincarnation, do you think?" she questioned in her misery.

"Ah, something of that nature, I fear, Caroline," I admitted, reluctantly. "It's a new one on me, anyway. But it can't last. Don't be impatient, my dear. It'll soon pass off."

But even as I spoke I knew that I was using my wife's sweet, soft voice for deception. Whatever it was, it had come to stay--for a time at least.

"I think, Reggie, dear, that, if you don't mind, I'll have breakfast in bed."

Like a flash, Caroline's remark revealed to me the frightful problems that would crop up constantly from our present plight. Number one presented itself instantly; I had an important engagement at my office at 9:30. If Caroline remained in bed I couldn't keep it. Then it came to me that if she rose and dressed I should be in no better case. Dressed? She would be obliged to put on my clothes, anyway! What other alternative was there?

"I think, Caroline, dear," I suggested, gently, "that we'd better wait awhile before we make our plans. It may go away suddenly. A change may take place at any moment."

"It came in our sleep, and it'll go in our sleep," said my wife, confidently, and I was struck by the gruffness that a firm conviction gave to my voice. I had never noticed it when I had been in full and free possession thereof.

"If we could only go to sleep," I sighed, glancing again at my trousers and suppressing a harsh expletive that arose to my beautiful lips.

"I couldn't sleep, Reginald. I'm sure of that. I feel a horror of sleep, but I need something. Perhaps--oh, Reggie, it can't be that!--but I can't help thinking that I want a--a--cocktail."

Caroline hid her borrowed face in my great, clumsy hands.

It required an effort of memory for me to put myself into sympathy with her present craving. I hadn't thought of a cocktail since I had awakened. It was only once in a very great while that I indulged in an eye-opener. But I had been out very late Tuesday night--in fact, it had been this morning before I had reached home from the club--and I was not, upon reflection, altogether astonished at the wish that my poor wife had expressed with such awkward coyness. But to grant her request demanded heroic action, and I hesitated before taking what might prove to be an irrevocable step. If I left the bed under existing conditions, a temporary psychical maladjustment might become permanent. Then, again, I realized that my little feet felt repelled by the chill that would come to them if exposed to a cold draught that blew through a window open in my--or, rather, Caroline's--dressing-room.

"Go into the bathroom and take a cold plunge," I suggested to Caroline, to gain time. "It's more bracing than a cocktail."

"You ought to know, Reginald," she remarked, in my most playful voice.

Her ill-timed jocosity struck me as ghastly.

"Caroline, dear," I began, "we must beware of recriminations. 'It is a condition, not a theory, that confronts us,'" I quoted, mournfully. "If we should fall out, you and I----"

"If we only could!" sighed Caroline.

"Could what?" I cried, in shrill falsetto.

"Fall out, Reginald," she answered, grimly. "Can't you think of something else to try? Really, it's too absurd! What is the matter with us, Reggie? Are we dreaming?"

I listened, intently. The servants were astir down-stairs, and through the windows came the clatter of early vehicles and the thin voice of a newsboy crying at eight o'clock the ten o'clock "extra" of a yellow journal. There was nothing in our environment to suggest the supernatural or to explain a mystery that deepened as the moments passed. The external world was unchanged, and--startling thought!--Caroline and I must confront it presently under conditions that were, so far as I knew, unprecedented in the history of the race.

"That's no dream!" I exclaimed, terror-stricken. My wife's maid had rapped, as usual at the outer door of our apartments. "Good God, Caroline, what shall we do?"

"Tell her I don't want her this morning, Reginald! Send her away, will you? She mustn't see me--yet."

"But my--your--this hair, Caroline? How'll I get it up without Suzanne's help?"

"I'll do it for you," answered Caroline, in a voice that sounded like a despairing moan.

"Look at those hands--my hands, Caroline! You can't dress hair with them. Take my word for that."

Suzanne rapped again, thinking, doubtless, that we were still asleep.

"I'll be there directly, Suzanne," cried Caroline, in my voice.

We turned cold with consternation. What would Suzanne think of this? My reputation in my own household had been jeopardized on the instant.

"Caroline! Caroline! You must pull yourself together!" I whispered. "Have courage, and do keep your wits about you! Act like a man, will you? Keep quiet, now. I'll speak to Suzanne."

With a courage begotten by desperation, I sat erect. Fear and hope had been at war within me as, for the first time since I had awakened, I changed my posture. I had dreaded the uncanny sensation that would spring from further proof that I was really imprisoned in my wife's body. But I had clung to a shred of hope. It might be that Caroline and I in motion would find the psychical readjustment that had been denied to us in repose. I was instantly undeceived. As I sat up in bed, Caroline's luxuriant dark tresses fell over my shoulders and I looked down at a lock of hair that lay black against my tapering white fingers. A wave of physical well-being swept over me, and, despite the horror of my situation, my heart beat with a great joy in life. The blood came into my well-rounded cheeks, as I recalled Caroline's recent request for a cocktail. What a shame it was that a big, healthy man should want a stimulant early in the day!

"Suzanne!" I cried. "Suzanne, are you still there?"

"Oui, madame," came the maid's voice, a note echoing through it that I did not like.

"I shall not want you for fifteen minutes, Suzanne," I said. "Come back in a quarter of an hour." I felt a cold chill creeping over me, and Caroline's sweet voice trembled slightly. "And may the devil fly away with you, Suzanne!" I muttered, as I fell back against the pillows.

"We've had our sentence suspended for fifteen minutes, Caroline," I said, presently. "But how the deuce am I going to get through my toilet? My French is not like yours, my dear, and you never speak English to Suzanne. It's actually immoral, Caroline, the way I get my genders mixed up in French."

"Oh, don't say that, Reginald!" exclaimed my wife, in a horrified basso.

"Say what, Caroline?" I asked, petulantly.

"That about mixing genders being immoral, Reggie," she fairly moaned. "I'm not immoral, even if--if--if I have got your gender, Reginald. I didn't want it," she added, sternly, "and I can't be held responsible if I am masculine or neuter or intransitive. My advice to you, Reginald, is not to say much to Suzanne in any language."

I could not refrain from a silvery chuckle, the sound of which changed my mood instantly.

"How often I've said that to you, Caroline!" I remarked, most unkindly.

"I don't gossip with Suzanne any more than you do with your man," growled Caroline, in a tone that hurt me deeply.

My man! Great Lucifer, I had almost forgotten his existence. He would be in my dressing-room presently to trim my beard and make of himself a nuisance in various ways. Jenkins had his good points as a valet, but he was too talkative at times and always inquisitive. I could have murdered Suzanne and Jenkins at that moment with good appetite.

"Caroline," I said, gloomily, "Fate has ordained that you and I, for some reason that is not apparent, must make immediate choice between two courses of action. We can commit suicide--there's a revolver in the room. Or we may face the ordeal bravely, helping each other, as the day passes, to conceal from the world our strange affliction. I have no doubt that while we sleep to-night the--ah--psychical mistake that has been made will be rectified."

My voice faltered as I uttered the last sentence. Neither my experience nor reading had furnished me with data upon which I could safely base so optimistic a conclusion.

"I--I don't want to die, Reggie," muttered Caroline, with a gesture of protest.

"The club was rather quiet last night," I remarked, musingly; but my wife did not catch the significance of the words. "Well, if we're to brace up and stand the racket, Caroline, we must begin at once. You must give me a few pointers about Suzanne. I'll reciprocate of course, and you'll have no trouble in bluffing Jenkins to a standstill. There he is now! Call out to him, my dear. Don't be afraid of using--ah--my voice. Tell him you are coming to him at once." Unbroken silence ensued.

"Now, Caroline, be a man--that's a good girl! Tell him you'll be out in five minutes."

My wife's stalwart figure was shaking with nervousness.

"Oh--ah--oh, Jenkins," she roared, presently. "Jenkins, go away. I don't want you this morning. Go away! go away! Do you hear me? Go away!"

"Yes, sir," came Jenkins's voice to us, amazement and flunkeyism mingled therein in equal parts. "Yes, sir. I'm going at once, sir."

"Now you have done it, Caroline!" I cried, in a high treble of anger. "Great Scott! how that man will talk down-stairs!"

For a moment the sun-lighted room whirled before my eyes like a golden merry-go-round, and I lay there, limp and helpless, awaiting in misery Suzanne's imminent return.

CHAPTER II.

A WEIRD TOILETTE.

My spirit wrestles in anguishWith fancies that will not depart;A ghost who borrowed my semblanceHas hid in the depth of my heart.--Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen.

"Madame seems to be in very low spirits this morning," Suzanne had the audacity to remark to me as she deftly manipulated my wife's dark, luxuriant hair, to my infinite annoyance. She spoke in French, a language that always rubs me the wrong way. I gazed restlessly at the dainty furnishings of Caroline's dressing-room, and remained silent.

Presently Suzanne spoke again. "I hope that madame has received no bad news."

"Great Scott, girl! what are you driving at?" I heard my wife's voice exclaim, and my recklessness appalled me. Suzanne was paralyzed for a moment. I could see her pretty face in the mirror, and it had turned pale on the instant.

"Pardon me, madame," she gasped, "but I--I thought----"

"Don't think!" I cried, crossly. "Tie up my--this--ah, hair, and let me do the thinking, will you?"

Repentance for my harsh words came to me at once. Suzanne stifled a gasp and a sob and continued her work as a coiffeuse. I realized that I must control my impulsiveness at once. I had never understood what my friends had meant when they had accused me of a lack of imagination. I had taken pride in the fact that I was a straightforward, two-plus-two-makes-four kind of a man, not given to foolish fancies nor errant day-dreams. I had attributed my success in business to this tendency toward the matter-of-fact, but now, for the first time in my life, I regretted my lack of imaginative power. I must, for my dear Caroline's sake--yes, in the name of common decency--preserve my psychical incognito in the presence of my wife's maid. Suddenly, I was startled by hearing my voice in the bathroom uttering something that sounded much like an exclamation of horror. In my consternation I sat erect, listening intently.

"What is the matter, madame?" whispered Suzanne, excitedly. "Monsieur, too, seems out of sorts this morning."

I realized that Caroline had found sufficient courage to set out in quest of the cold plunge that I had advised in lieu of a cocktail. There came the sound of running water from the bathroom.

"Go on, Suzanne," I said, gently. "Get through with this hair of mine, will you? There's nothing the matter. Caroline--Reginald--ah--Mr. Stevens didn't get quite enough sleep, that's all. He's made the spray too cold."

Suzanne's hands trembled perceptibly as she resumed her task.

"There's a note for madame this morning," she said, presently, lowering her voice again, and always speaking her detestable mother-tongue.

"Of course there is," I remarked, astonished at the maid's manner. "Her--ah--my mail is full of 'em. Who's the note from, Suzanne?"

"Madame is so remote to-day!" murmured Suzanne, helplessly. "Did I not tell madame that he would write to her?"

A chill ran through my veins, but I made neither sound nor movement. Apparently my wife's maid had become a discreet postmistress, whose good offices it might behoove me to look into.

"I'll read the note later in the day, Suzanne. Are you nearly done with this infernal hair?"

"Mon Dieu!" exclaimed the girl, but she went no further.

A splash, a groan, followed by a hoarse yell, echoed through the suite.

"Damn it!" I cried, desperately. "Why didn't Jenkins stay here? She--he'll never get dressed!"

"Where is Jenkins, madame?" asked Suzanne, nervously. "Monsieur seems to be excited. And madame--what is the matter with madame?"

The girl's consternation was not strange. Caroline, the grand dame, gentle, self-poised, unexcitable, sat before the wide-eyed Suzanne, swearing in a voice that had been fashioned by nature for nothing harsher than a drawing-room expletive.

"Caroline," came my wife's borrowed voice, faintly, as if she were talking to herself. It was some time before I realized that she was calling me.

"Yes--ah--Reginald!" I managed to cry, in a trembling falsetto.

"Monsieur seems to want you, madame," said Suzanne, wonderingly. "Where is Jenkins, madame?"

"God only knows!" I exclaimed, desperately. "Down-stairs, I suppose, talking through his hat. Send him to me at once, girl."

"Madame! Jenkins? Send Jenkins to you? Madame, I do not comprehend."

"To me? I didn't say to me, did I? Send him to Car--Reginald--Mr. Stevens! Wasn't that what I said? Go, Suzanne! And--wait a minute. If you mention my name to Jenkins--that is, if you gossip with him coming up-stairs, I'll dismiss you this morning. Tell Jenkins to hold his chattering tongue, or he'll get the grand--ah, manner nayst pah?"

Suzanne burst into tears, and, instead of obeying my behest, fell, with true French impetuosity, upon her knees at my feet, and, seizing my cold hands, buried her face in them, sobbing hysterically.

"Oh, madame! madame! What have I done to deserve this?" she moaned, in her diabolical French. "Why do you speak to me--treat me--this way? It is so cruelly cruel! Oh, madame, have I not been faithful, discreet, blind, deaf, dumb? Have I ever betrayed even a little, little secret of yours?"

"Caroline!" There was a note of mingled anger and dismay in my voice as it came to me, harsh and unwelcome, from my distant dressing-room, the door of which Caroline had closed.

"I must go to her!" I cried, springing to my feet, and tripping over my dressing-gown as I pushed by the kneeling, hysterical maid. Suzanne grasped what I now believe to have been the hem of my garment.

"Oh, madame, you must not go to him! Monsieur's voice is so wild! I am sure that he is not well. You must rest here, madame! See, I am going. I will send Jenkins to monsieur at once. Mon Dieu! Mon Dieu! I go, madame! I shall return to you very soon."

Suzanne had really gone, and, pulling myself together by a strong effort of will, I stumbled from the dressing-room, crossed our bed-chamber and knocked on the door, behind which I could hear Caroline uttering subdued exclamations in my raucous voice.

"Who's there? Go away! Who is it?" cried my wife, in a panic.

"Don't get rattled, my dear," I called out, in Caroline's sweetest tones. "Suzanne has gone to find Jenkins. Let me in, my dear. I may be able to give you a few tips."

The door flew open and I saw that Caroline had managed to don my underclothing. My heavy features displayed the joy that my wife felt at my arrival. I learned afterward that she had been having serious trouble with my linen shirt.

"Oh, Reggie," she exclaimed, making my voice tremble with emotion. "I've had such a horrible time!" She threw my great, muscular arms around her neck, and I felt my beard scratching my--her smooth, delicate cheeks.

"Sit down, Caroline, and calm yourself," I implored her. "This is no time for this kind of thing. We've got but a moment to ourselves. Suzanne has gone to bring Jenkins back."

Caroline shuddered, but said nothing.

"You gave me a terrible shock, my dear," I remarked, calmly. "I feared that some terrible accident had happened to you."

"The very worst has happened, Reggie," she mused, in something like a prolonged growl. "I don't think I'll ever be able to go through with it."

"We've made a bad beginning, Caroline. I'll admit that. But all is not yet lost. Jenkins and Suzanne doubtless imagine that you are merely suffering from a somewhat stubborn and persistent jag."

"How horribly vulgar!" groaned Caroline.

"Don't disabuse Jenkins's mind of the idea," I implored her. "It's hard on you, I'll admit, but it's better than the truth. We can't tell them that we've changed bodies for a time. They'd think us crazy, Caroline."

"We will be, Reginald," growled the dismayed giant, seemingly on the verge of tears. "If I were only dressed I wouldn't be so frightened. But you are such a clumsy creature, Reggie."

I sprang to my feet. I thought I heard voices in the lower hall.

"They're coming, Caroline. Don't say much to Jenkins, but, if you think of it, my dear, swear at him softly now and then. It'll quiet his suspicions, if he has any."

As I started to leave the room, I turned sharply, and eyed my own face searchingly. Imitating Suzanne's voice as well as I could, I said:

"There's a note for madame this morning. Did I not tell madame that he would write to her?"

Bitterly did I regret my untimely sarcasm. Caroline, white to the lips, tottered where she stood.

"Reginald!" she cried, in a deep, horror-stricken voice that could have been heard throughout the house and in the street outside.

Rushing back, I helped her towards a chair.

"It's all right, Caroline," I said, in dulcet, pleading tones. "Don't mind it, my dear. I am sure that you will be able to explain the--ah--little matter wholly to my satisfaction." Then a thought flashed through my mind that was like a cold douche, and I added: "And don't forget about Jenkins, my dear. Don't encourage him to talk. And, above all, don't believe anything that he may say. He's a most stupendous liar."

With that I hurried back to Caroline's dressing-room just in time to seat myself before Suzanne, panting from haste and excitement, rushed into the room.

"Jenkins, madame," she cried, wringing her hands, "Jenkins is a villain, a rascal, a scoundrel." The girl appeared to have a long list of opprobrious French epithets in her vocabulary.

"Calm yourself, Suzanne," I said, coolly. "You have sent Jenkins to monsieur?"

"Alas, madame, he refused to obey me unless I agreed to kiss him. The horrid, degenerate, unprincipled English beast! Mon Dieu! I could not kiss him, madame."

"Curse the man's devilish impudence!" I exclaimed, while Suzanne stared at me, her pretty mouth wide open in amazement.

"You say such queer things to-day, madame!" she murmured, presently, resuming her duties in a melancholy way. "What will madame wear for breakfast?"

Her question startled me. My mind endeavored, without much success, to recall Caroline's morning costumes.

"What's the matter with her--ah--my plum-colored--ah--tea-gown?" I asked, recklessly.

"Madame is jocose--facetious," remarked Suzanne, pretending to laugh. I reflected bitterly that I could not see the joke.

"You have such excellent taste, Suzanne," I said, proud of my cleverness. "Tog me out in any old thing. But it must be warm and snug, girl. I have had chills up my back until I feel like a small icicle in a cold wind." Suddenly an inspiration came to me. "Suzanne, you'll find a bottled cocktail in the bedroom closet. Never mind the cracked ice. Pour me out about four fingers and bring it to me at once. Don't stare at me like that, girl! Quick work, now. And--ah--don't let Caro--that is, Mr. Stevens hear you. Go!"

Suzanne, pale with amazement, hurried away to find the stimulant that had become suddenly the one thing on earth that I really desired. Presently, she returned, carrying a half-filled cocktail glass.

"Here's how, Suzanne!" I cried, joyously, forgetting caste distinctions in my delight at the opportunity of restoring my waning vitality. I swallowed the smooth concoction at a gulp, Suzanne watching me with a puzzled smile on her disturbed countenance.

"Jenkins is with monsieur," she remarked as she took the empty glass from my white, slender hand. Apprehension clutched at my heart again.

"Does--ah--Mr. Stevens--monsieur--seem to be--ah--quiet?" I asked, eagerly.

"I didn't hear his voice, madame," answered Suzanne, arranging a sky-blue morning-gown for my use. "But Jenkins is talking, talking, talking all the time, madame."

"Damn him for a confounded cockney gas-bag!" I murmured, despondently, but fortunately Suzanne was at that moment busy at the further end of the dressing-room. I stood erect, impatient of further delay.

"Look here, girl," I exclaimed, "will you quit this fussy nonsense and get me out of here? I've got an engagement at----"

My sweet, velvety voice failed me as I realized that I was again forgetting myself, or, rather, Caroline.

The long suffering Suzanne was at my side, instantly.

"Madame may go now," she said, giving a finishing touch here and there to my hair and costume. I made for the bedroom eagerly, but tripped over my dress, recovering my equilibrium and went on. Suzanne said something to herself in French, but the only words that came distinctly to my ears were:

"Le cocktail! Il est diabolique!"

CHAPTER III.

CAROLINE'S USURPATION.

In philosophic mood last night, as idly I was lying,That souls may transmigrate, methought, there could be no denying;So just to know to what I owe propensities so strong,I drew my soul into a chat--our gossip lasted long.--Béranger.

It was not wholly unpleasant to find myself facing Caroline across the breakfast-table. There she sat, attired in my most becoming gray business suit, in outward seeming a large, well-groomed man-of-the-world. The light in her--or my--eyes suggested the possibility that she had found compensations for her soul's change of base. If that was the case, Caroline was more to be envied than I was, for, despite the feminine beauty that had become mine for a time, I was wholly ill-at-ease and disgruntled. My hand trembled and I spilled the coffee that it had become my duty to serve. Jones, our phlegmatic butler, appeared to be politely astonished at my clumsiness and glanced at me furtively now and again.

"Two lumps, Caroline?" I asked, absently. Catching my wife's masculine eye, I felt the blood rush to my cheeks. "Reginald, I mean!"

"Three lumps, and plenty of cream, Caroline," said my wife, with ready wit. What a domineering note there was in my voice when used vicariously! I wondered if Caroline had noticed it.

"You may go, Jones," I said, presently. "I'll ring if we need you."

A gleam of surprise came into the butler's eyes, but he controlled it instantly, and strode from the breakfast-room like a liveried automaton.

"You are not eating, Reginald," said my wife, in a gruff whisper, glancing at the door through which Jones had made his exit. "You must not give way to your nervousness, dear boy. You'll need all your strength before the day is over."

"Gad, you're right--if I can judge by the last hour, Caroline," I remarked, endeavoring by force of will to beget an appetite for toast and eggs. "Just hand me my letters, will you? Here are yours, my dear."

I saw the masculine cheeks redden, but Caroline made no effort to act upon the suggestion that I had thrown out.

"Reggie! Reggie!" she moaned, hoarsely, "is there no help for us? Can't you think of something that will change us back again? It's simply unbearable. Sometimes it makes me laugh, but I almost died before I got out of the bath-room. And Jenkins was simply detestable! You must get us out of this, Reginald, or I warn you I shall read these letters, go down to your office and your club--and enjoy life in your way for a while, my dear."

There was something in all this that I did not altogether like, but I smiled as I said:

"Are you laboring under the delusion, Caroline, that my daily life, filled to overflowing with business cares that you know nothing about, is pleasanter than yours? You can do as you please all day long--see people or deny yourself to them, as you choose. I had noticed a tendency upon your part, my dear, before this--ah--accident occurred, to complain that your existence was dull, that a man had a happier lot than a woman. It's all bosh, that idea. From the moment when I leave this house in the morning, Caroline, I am a slave to duties that I cannot shirk. I am under a terrific strain all day long. As for you, my dear, you may go and come as you please, see the people you like, and dodge those you detest; take a nap if you're tired, a drive if you're suffocated, a walk if you feel energetic. And you have nothing but petty worries that don't amount to a row of beans. Great Scott! Caroline, what an easy job a woman in your position has!"

Caroline refused to meet my gaze, and I observed with annoyance that my eyes sometimes had a shifty way with them. She had placed one large relentless hand over my small pile of letters. Presently, she said, in a tone that indicated a stubborn spirit:

"You are off the track, Reginald. What I want to know is whether you think that we have exhausted every method for getting out of this queer scrape?"

"Drop that, will you, Caroline?" I exclaimed, petulantly. "I'm no theosophist nor faith-curist. I'm not going to fool with this thing at all. If we get to tampering with it--whatever it is--you may find yourself in Jenkins's shoes and I may be Suzanne or Jones for a change. I'm banking on a readjustment in our sleep to-night. Until then, we'll have to accept the situation as it stands."

"Then I'm going to boss things, Reggie," remarked my wife, firmly. "If I'm obliged to get about in your great, hulking figure, my dear, I'm going to enjoy all the perquisites for the next few hours. I don't believe--I never did believe--that you work half as hard as you say you do, nor that you have such horrible dragons to slay every day before dinner. Then, I want you to see for yourself how much leisure I really enjoy. You can stay at home and run my affairs, Reggie, dear. I'm going down-town to see 'the boys' at work!"

"Good heavens, Caroline, you are joking!" I cried, my delicate hand trembling as I endeavored to raise my coffee-cup to my white lips. "It would be utter madness--what you plan! I'll have to let things slide for to-day. I'll telephone to the office saying that I'm down with the grip. Grip? That's good," I went on, hysterically. "It's just what we've lost, Caroline. But never mind! It's a word that will serve my turn. And then, my dear, we'll pass the day together here. We might get a readjustment at any moment, don't you see, if we stick close to each other. If you're down-town--great Nebuchadnezzar! anything might happen to us, Caroline."

"But there's the telephone, Reginald," suggested my wife, coldly. "As soon as I reach your office I'll call you up. If you don't leave the house to-day you'll have me at the end of a 'phone most of the time. And let me tell you, Reggie, you'll need me. I am very much inclined to think, my dear, that you'll wonder, before the day is over, what has become of my sinecure. I am quite sure that you'll not find time for a great many naps."

"If you leave me, Caroline," I said, musingly, "I shouldn't dare to fall asleep. But I really can't believe, my dear, that you seriously contemplate the expedition you have mentioned. You'll have the devil's own time, let me tell you, Caroline. Let me glance at that memorandum-book in your inside coat-pocket. Thanks. Wednesday? To-day is Wednesday. Nine-thirty--Boggs and Scranton. We'll scratch that off. I'm late for that, as it is. Rogers!" To myself, I cried: "Lord, she mustn't meet Rogers! I shouldn't have given him my office address."

As I glanced through the day's appointments, item by item, my horror grew apace. Caroline, if she went to my office, was bound to derive a wholly false impression of the general tenor of my life. There would be so many things that would be open to misconstruction! Unimaginative I might be, but my memoranda enabled me to foretell just what kind of an experience awaited Caroline in my daily haunts. The methods by which a successful business is conducted in New York would puzzle her sorely, and place me in a most uncomfortable light.

"It can't be done, my dear," I said, presently; and Caroline's sweet voice annoyed me by its lack of an imperative note. It seemed to beat impotently against that stubborn-looking countenance across the breakfast-table. "You'd bungle matters most desperately if I allowed you to go down. As it is, I dread the outcome of my enforced absence. Playing lady to-day will cost me a cool ten thousand, at the very least."

I could see, plainly enough, that what I had said had made very little impression upon my wife. Perhaps she doubted my word or felt confidence in her own business ability. In desperation, I took a new tack.

"I think, Caroline, that, on the whole, it would be much better for you to remain here with me and tell me all about that note to which Suzanne referred. It may take some time, my dear, to get that--ah--little matter straightened out."

My eyes never wavered as I gazed into their depths.

"It's easily explained, Reggie, dear," said Caroline, coldly. "It will take me but a moment. As to your interpretation of what Jenkins has been saying to me--that, of course, is another matter. Your explanations may require considerable time, Reggie, darling."

I dropped my coffee-cup, which went to pieces with its saucer.

"Jenkins?" I cried; in a tone so high that it gave me a headache. "Didn't I warn you that he was a great liar, Caroline? You mustn't believe more than ten per cent. of what he says."

"H'm!" growled Caroline, while she glanced idly at the outside of the envelopes beside her coffee-cup.

"I tell you, Caroline," I went on, feverishly, wondering why I had grown to hate my wife's voice so quickly, "I tell you, Caroline, that Jenkins is a waif from the School for Scandal. He was valet to Lord Runabout before he came over here. Jenkins's standards, I must say, are low. You know what Runabout is, my dear. Well, Jenkins seems to think that to be a gentleman one must have Runabout's tastes. I was idly curious at first to hear what Jenkins had to say. Naturally, he got a wrong impression, and there you are! Sometimes, Caroline, you'd think, to hear Jenkins talk to me, that I was a wild blade, a dare-devil rake, of the latest English pattern. In certain moods, he amuses me; at other times, I don't listen to him. But I can readily understand, my dear, what a shock he must have given you. Of course, you couldn't know--I should have told you more about it in detail--that I'm really a hero to my valet. It's not a nice kind of hero, of course, but it's the kind that Jenkins admires. In short, Caroline, dear, while I'm Dr. Jekyll to the world, I'm Mr. Hyde to my man."

"H'm," came my gruff voice again, and there was a smile on my face that aroused my anger. During our five years of married life I had never lost my temper with Caroline. But her present manner, made doubly offensive by the use of my own body as its medium, filled me with rage.

"By the eternal horn spoon, Caroline, you must drop that!" I cried, in a shrill treble. "If you say 'h'm' to me again in that cheap actor's manner--I'll--I'll--"

"Get a divorce, perhaps," suggested Caroline, pleasantly. "Come, come, Reginald, you've gone far enough. You have no cause for anger--unless, indeed, your conscience goads you. But I've put up a flag of truce. Suppose we drop this unpleasant subject for the present." Here she calmly stuck my letters into a pocket of my coat. "I'll look these over riding down-town. Just ring for Jones, will you, and ask him if the coupé is at the door."

"Caroline! Caroline!" I moaned, falling back in my chair, limp and hopeless, "you must not--you dare not attempt this mad prank! I tell you, Caroline, that you will regret your foolhardiness to the last day of your life."

"Listen to me, Reginald," said my wife, standing erect and drawing herself up to my full height. "Jones will come to you up-stairs for his orders. Think of it, my dear! You can order whatever you like best for dinner. The Van Tromps and Edgertons dine with us to-night. Don't forget that."

I groaned aloud, and felt the tears rushing to Caroline's beautiful eyes.

"This morning," she went on, seemingly in high spirits, "my new ball dress should arrive. Mrs. Taunton--you never liked her, Reggie, but she's really charming--is to lunch with me. Professor Von Gratz will be here at eleven to hear me play Beethoven's Opus 22. He's apt to be severe, but don't mind him, my dear. His bark is worse than his bite." Caroline bent down and touched the bell in front of me.

"Is the coupé ready, Jones?" she asked, as the butler entered.

"Yes, sir."

"Ta-ta, Reggie," cried my wife, in my most playful voice. "I'll call you by 'phone the moment I reach the office. Hope you'll have a pleasant day. Ta-ta!"

A moment later, I sat alone in the breakfast-room, gazing down at my broken coffee-cup and saucer. I regretted their accidental destruction. It would have pleased me now to smash them by design.

CHAPTER IV.

THE STRENUOUS LIFE.

No longer memory whispers whence aroseThe doom that tore me from my place of pride.--Whittier.

I had had the telephone placed in the library for reasons that need not be given here, and it was to this room that I betook myself after I had recovered from Caroline's cruel exit. I realized, in a vague kind of way, that the library was not my wife's customary haunt after breakfast, but I lacked the courage to seek a clue to her usual morning habits. That Suzanne would discover me presently in my hiding-place, I had no doubt, but I was safe from intrusion for a time, at least, and might find in solitude a poultice for the blows that this deplorable day--always to be remembered as Black Wednesday--had already given to me.

As I seated myself beside a table covered with books and magazines, a feeling of rebellion, not unmingled with envy, came over me. It was a clear, bracing, sunny morning, and Caroline, in my outward seeming, was rolling down-town, rejoicing, doubtless, like a bird that has escaped unexpectedly from a narrow cage. A new life lay before her. She had gone forth to see the world, while I, beautiful but despondent, sat trembling, in momentary dread of discovery by Jones or Suzanne. Menaced by a ball-dress, a music teacher, Mrs. Taunton and various unknown household duties, my mind exaggerated the miseries of my situation. Unworthy passions agitated my throbbing bosom. A longing for vengeance, a mad desire to make Caroline regret her base desertion of the man whom she had vowed to love, honor and obey, swept through me. It would go hard with me, indeed, if some opportunity for punishing my errant spouse did not present itself during the long day that confronted me.

With great presence of mind, despite my agitation, I had brought Caroline's mail into the library with me. Should I open it? Why not? She had carried off my letters with a piratical nonchalance quite consistent with her present high-handed methods of procedure. It was only fair that I should dip into her correspondence at my leisure. But I feared, just now, any further shock to my nerves, and sat motionless, gazing listlessly at the little pile of notes addressed to Caroline. Suddenly, a thought came into my mind that sent the blood rushing through my veins. Was it not more than probable that my library contained a few volumes dealing with the occult sciences? At all events, I was sure that I owned several books relating to Oriental philosophy. Then there was Sir Edwin Arnold's "Light of Asia" at my disposal, and, if I became impatient of research, I could look up "Reincarnation," "Transmigration" and kindred topics in the encyclopædia.

But what had become of my courage? Great as was my curiosity regarding the strange psychical displacement that had made me practically a prisoner in my own home, I feared to take steps that, while they might increase my erudition, might also deprive me of all hope of the night's readjustment.

"I'd better leave it alone," I murmured to myself, despondently. "My very ignorance of this kind of thing may prove to be my salvation in the end. I'm up against it, there's no doubt of that. And the queer thing about it all is that I'm not more astonished at what has happened. It didn't hurt a bit! It was like taking gas. You wake up in a dentist's chair, and the only tooth you knew you possessed has gone. I wonder, by the way, if it would pay to consult a doctor--some specialist in nervous disorders? I could use an assumed name, and-- Bosh! I haven't the sand to do it. And it might lead to an investigation as to my sanity. Great guns, girl! You here again?" The last words I spoke aloud, gazing upward into Suzanne's pale, disturbed face.

"I am so worried about madame," said Suzanne in French, glancing nervously around the library, as if she sought in my environment an explanation of her mistress's eccentricity. "Would it not be well for madame to come up-stairs and try to get a nap?"

"A nap!" I cried, in a vibrant treble. "Not on your life, girl! I'm up for all day, you may bet on that. Get me the morning papers, Suzanne. And--wait! Where's Jenkins?"

Suzanne gazed at me in surprise.

"He's eating his breakfast, madame."

"Bring me the papers, and then tell Jenkins to take a day off. Tell him he may go as far away as Hoboken if he wants to. He needn't return until to-morrow."

Suzanne glided from my side with a quick, silent movement that reminded me of a black cat.

A wild, fleeting hope seized me that Jenkins would carry the girl away with him, but presently Suzanne entered the library again.

"Jenkins sends his thanks to madame, and will take a holiday, after reporting to monsieur at his office," said my pretty gadfly, glibly, placing the morning newspapers beside me.

"Confound his impudence!" I exclaimed, and I saw at once that Suzanne considered me "no better."

"And now, girl, what next? Jones, I suppose."

"Yes, madame. He is awaiting your pleasure outside the door."

At that moment Jones entered the library.

"You called me, madame," he said, pompously, magnificent as a liar. "Your orders, madame?"

"We have guests for dinner, Jones," I remarked, bravely.

"Yes, madame. How many?"

"Four, Jones. Six at the table, that is. Cocktails to start with, Jones, and serve my best wines--freely, do you understand? I want you to give us a dinner to-night, Jones, that'll--make a new man of me," I murmured under my breath.

"Yes, madame," said the butler, respectfully, but I certainly caught a gleam of delight in his heavy eyes. "You give me carte blanche, madame?"

"Throw everything wide open, and let 'er go, Jones," I cried, with enthusiasm. Caroline should see that I know how "to provide."

Jones bowed, more, I believe, to conceal his astonishment than for mere ceremony, and turned to leave the room.

"Jones," I called, before he had disappeared, "if you talk to Jenkins before he leaves the house I shall discharge you."

The butler turned, with a flush in his face, and gave me a haughty stare. Then he said, recovering his machine-made humility:

"Yes, madame. Your orders shall be obeyed." With that he was gone.

"Go to the 'phone, Suzanne," I said at once, "and call up 502, Rector. When you've got 'em, let me know."

Suzanne was too nervous to accomplish this task, and I was forced to go to her assistance.

"Hello!" I heard Caroline's voice crying presently, and it warned me to be careful.

Standing at a 'phone it was hard for me to remember that I was far from being quite myself.

"Who's this?" came to my ears from 502, Rector.

"Has--ah--Mr. Stevens reached the office yet?" I asked.

"We expect him every moment. He's late this morning," came the answer in a man's voice, (I had grown very sensitive to sex in voices.) "Who is this?"

"I am--ah--Mrs. Stevens." Suddenly, I realized that I was talking to Morse, my head-clerk. How he happened to be in my inner office puzzled me. "Anything new this morning, Morse?" I inquired, impulsively. There was a sound that can be described as an electric gurgle at his end of the line.

"Hello," he cried, above a buzzing of the wires that might have been caused by his astonishment. "Are you still there, Mrs. Stevens?"

"Well, rather," I said to myself. Then aloud: "Will you kindly call me up--ah--Mr. Morse, the moment Mr. Stevens arrives?"

"On the instant, Mrs. Stevens," said Morse, deferentially.

Curiosity overcame my discretion.

"How did the market open, Mr. Morse?" I asked, recklessly.

Again that electric gurgle escaped from my startled clerk.

"It seems to be very feverish, madame," answered Morse, evidently recovering his equanimity.

"Naturally!" I exclaimed, feelingly, but I doubt that Morse caught the word.

"Is that all, Mrs. Stevens?" he asked, presently.

"That'll do for the present--ah--Mr. Morse," I said, reluctantly. "Good-bye!"

I returned to my seat beside the reading-table and found Suzanne gazing at me with soft, sympathetic eyes.

"If I had but dared to tell him to unload," I mused aloud, but went no further, for the French girl's glance had become an interrogation-mark.

"Tell monsieur to unload?" murmured Suzanne, who sometimes spoke English when she especially craved my confidence. "But--mon Dieu!--monsieur is not--what you say, madame, loaded?"

I broke into a silvery, high-pitched laugh that annoyed me, exceedingly. But it was not unpleasant to realize that the girl knew that Mr. Stevens was a gentleman. I felt grateful to Suzanne for her good opinion. A moment later, the telephone rang, sharply.

"There's Caroline," I said to myself; but I was quickly undeceived when I had placed the receiver to my ear.

"Is that you, Caroline?" I heard a voice saying. "This is Louise. What have you decided to do about those lectures on Buddhism? Will you join the class, my dear?"

"Not in a thousand years!" I fairly shrieked through the 'phone. "Good-bye!"

"More trouble, madame?" asked Suzanne, as I tottered back to my chair. "I am so sorry. Really, I think madame should come up-stairs with me and lie down. I will bathe madame's head, and she may drop off for a time."

"Suzanne," I said, solemnly, making a strong effort of will and controlling my temper nicely--"Suzanne, if you suggest a sleep to me again to-day I shall be forced to send you to Hoboken to find Jenkins. What's that? The telephone again? Ah--Mr. Stevens must have reached his office."

I was right this time. If my memory is not at fault, our conversation across the wire ran as follows.

"Hello!"

"Hello!"

Silence for a time and a buzzing in my ear.

"Is that you, Caroline?" from my office.

"You know best--ah--Reginald," in the sweetest tones that I could beget in my wife's voice.

"Hello!"

"Hello!" I returned. "Pleasant ride down--ah--Reginald?"

"Do be serious, will you?" gruffly, from the office.

"Tell Morse to sell L stock and industrials at once. Do you get that?"

"I'll have to use my own judgment in that matter, Caroline." My voice came to me through the 'phone with its own stubborn note.

"Great Scott!" I cried, realizing that I was absolutely helpless. "Be careful what you do--ah--Reginald. It's a very treacherous market. For heaven's sake, sell out at once, will you?"

"I must get to work now, my dear," said my wife, gruffly. "There's a heavy mail this morning, and several men are waiting to see me. Mr. Rogers comes in to me at once."

A cold chill ran through me, and Caroline's voice trembled as I cried:

"Don't see Rogers--ah--Reginald! I haven't decided yet what answer to give the man. Bluff him off, if you've got a spark of sense left in you. Tell him to call at the office next week."

"Good-bye, Caroline," came my voice to me, remorselessly. "I'll call you up again later. How's your ball dress? Does it fit you nicely? Don't over-exert yourself, my dear. You weren't looking well at breakfast. Ta-ta! See you later."

I heard the uncompromising click of the receiver, and knew that my wife had returned to my affairs. As I turned my back to the telephone, I felt that ruin was staring me in the face. If Caroline played ducks and drakes with my various stocks I stood to lose half my fortune. What a fool I had been, engaged in a profitable business, to go into speculation! Had it not been for what may be considered a feeling of false pride I should have sent Suzanne for a cocktail at once. It seemed to me that my masculine individuality exhausted Caroline's nervous energy at a most deplorable rate.

CHAPTER V.

SUZANNE'S BUSY DAY.

Births have brought us richness and variety, and other births have brought us richness and variety.--Walt Whitman.

Buttons, the hall-boy was accustomed to sit where he could keep one ear on the 'phone in the library, the other on the bell in the main entrance, and both of them on the voice of Jones, the butler. The library stifled me, and the very sight of the telephone threatened me with nervous prostration.

"Tell Buttons," I said to Suzanne, "to listen to the 'phone, and if--ah--Mr. Stevens calls me up again, to let me know of it at once. Then come to me up-stairs. And, Suzanne, say to Buttons that if--what was her name?--ah, yes, Louise--rings me up again to tell her I've got an attack of neuralgia in my--ah--astral body, and that I'm writing to Buddha to ask for his advice in the matter. That'll shut her off for all day, I imagine."

"Oui, madame," murmured Suzanne, wearily. She was beginning to feel the effects of a great nervous strain. As I reached the door of the library, the effort to carry myself like a lady overcame my momentary infusion of energy.

"Suzanne," I said, "it might be well for you to bring some cracked ice with you. Ask Jones for it. Tell him I have a headache, if he glares at you."

As I mounted the stairs slowly, wondering how women manage to hold their skirts so that their limbs move freely, a feeling of relief came over me. It was pleasant to get away from the floor over which Jones, the phlegmatic and tyrannical, presided. I had lost all fear of Suzanne, but the butler chilled my blood. If Caroline and I failed to obtain a psychical exchange to-night Jones must leave the house to-morrow. Suddenly, I stood motionless in the upper hallway and laughed aloud, nervously. What would Jones think could he learn that he had become unwittingly a horror in livery to a lost soul? The absurdity of the reflection brought a ray of sunshine to my darkened spirit, and I entered Caroline's morning-room in a cheerful mood.

"Pardon me, Mrs. Stevens, but I was told to wait for you here."

A pretty girl confronted me, standing guard over a large pasteboard box that she had placed upon a chair.

"You--ah--have something for me?" I asked, coldly. I was beginning to wonder where Caroline's leisure came in.

"Your new ball-dress, Mrs. Stevens. You promised to try it on this morning, you remember."

"Very well! Leave it, then. I'll get into it later on. I've no doubt it'll fit me like a glove."

The girl stared at me for a moment, then recovered herself and said:

"Madame Bonari will be displeased with me, Mrs. Stevens, if I do not return to her with the report that you find the dress satisfactory. I may await your pleasure, may I not? Madame Bonari would discharge me if I went back to her now."

"Let me see the dress, girl," I muttered, reluctantly. To don a ball-dress in full daylight to save a poor maiden from losing her situation was for me to make a greater sacrifice than this dressmaker's apprentice could realize.

The girl opened the box, and I gazed, awestruck, at a garment that filled me with a strange kind of terror. There was not a great deal of it. It was not its size that frightened me; it was the shape of the thing that was startling.

"That'll do, girl," I exclaimed, somewhat hysterically. "Tell--ah--Madame Bonari that this--ah--polonaise is a howling success. I can see at a glance that it was made for me," and added, under my breath, "to pay for."

The girl stood rooted to the spot, gazing at me in mingled sorrow and amazement.

"But oh, Mrs. Stevens," she cried, the tears coming into her eyes, "you will not dismiss me this way? I will lose my place if you do!"

I sank into a chair, torn by conflicting emotions, as a novelist would say of his distraught heroine.

"Do you want me to climb into that thing, here and now?" I gasped.

"If madame will be so kind," murmured the girl, imploringly.

With joy, I now heard the tinkling of cracked ice against cut-glass. Suzanne, to my great relief, entered the room.

"Suzanne," I said, courageously, "I will trouble you to tog me out in this--ah--silk remnant. Have you got a kodak, girl?" I asked, playfully, turning toward the astonished young dressmaker. "You're not a yellow reporter?"

"Oh, Mrs. Stevens!" cried the girl, deprecatingly, glancing interrogatively at Suzanne. Perhaps the cracked ice and my eccentric manner had aroused suspicions in her mind.

A moment later, I found myself in Caroline's dressing-room alone with Suzanne, who had recovered her spirits in the delight that her present task engendered.

"Madame's neck and arms are so beautiful!" she murmured in French, pulling the skirt of the ball-dress, a dainty affair made of mauve silk, with a darker shade of velvet for trimmings, into position. "Ah, such a wonderful hang! It is worthy of Paris, madame."

"Don't stop to talk, Suzanne," I grumbled. "This is indecent exposure of mistaken identity, and I can't stand much of it; so keep moving, will you?"

"The corsage is a marvel, madame!" exclaimed Suzanne, ecstatically.

"It is, girl," I muttered, glancing at myself in a mirror. "It feels like a cross between a modern life-preserver and a mediæval breast-plate. Don't lace the thing so tight, Suzanne. I've got to talk now and then!"

Suzanne was too busy to listen to my somewhat delirious comments.

"It is a miracle!" she cried in French. "Madame is a purple dream, is she not?"

"Madame will be a black-and-blue what-is-it before you know it," I moaned. "Does that girl outside there expect to have a look at--ah--this ridiculous costume?" I asked, testily.

"Madame is so strange to-day," murmured Suzanne, wearily. "You are free to go now, madame."

"I clutched at the train that anchored me to my place of torture, and moved clumsily toward the room in which the young dressmaker awaited me.

"Ah!" cried the girl, as I broke upon her vision, a creature of beauty, but very far from graceful. "Madame Bonari will be overjoyed. The dress is perfection, is it not, Mrs. Stevens? I've never seen such a fit."

"It feels like a fit," I remarked, pantingly. "Suzanne," I called out, desperately, "slip a few cogs in front here, will you? This is only a rehearsal, you know. If I must suffocate at the ball I'll school myself for the occasion. But I refuse to be a pressed flower this morning. Thanks, that's better. It's like a quick recovery from pneumonia. You may go, girl. Give my compliments to Madame--ah--Bonari, and tell her I'm on the road to recovery. Good morning!"

Suzanne and I were alone.

"A cocktail, girl. Quick, now! Do you think I wanted that ice as a musical instrument? If I ever needed a stimulant, Suzanne, I need one now. Make the dose stiff, Suzanne, for I'm not as young as I was. Do you hear me? Hurry!"

A rap at the door checked Suzanne in full career. We heard the strident voice of Buttons in the hallway.

"Open the door, Suzanne," I cried, nervously, bracing myself for another buffet from fate.

"Mr. Stevens is asking for Mrs. Stevens on the 'phone," I heard Buttons say to Suzanne. "He seems to be in a hurry, too."

Suzanne hastened back to me.

"I know the worst, girl! Say nothing!" I exclaimed, petulantly. "I must go down-stairs in this infernal ball-dress," and the ordeal before me filled me with consternation. If Jones should find me skulking around his domain in a décolleté dress at this time of day the glance of his arrogant eyes would terrify me. But there wasn't time for reflection, nor, alas! for a cocktail. Caroline was calling vainly to me with my voice through an unresponsive telephone. I must go to her at once. Doubtless, she craved immediate advice regarding the manipulation of my margins. Why, oh! why, had I jeopardized my fortune for the sake of quick returns, when my legitimate business was sufficient for my needs?

"I fly, Suzanne!" I cried, as I stumbled toward the hall. "If anybody calls to ask if I'm engaged for the next dance, tell 'em my card is full." Suzanne smiled. "And I wish I was!" I muttered to myself, desperately, as I looked down the staircase and wondered if it would be well to use my mauve train as a toboggan.

How I managed to reach the telephone, I cannot say. In the lower hall, I caught a glimpse of Jones's self-made face, and just saved myself from coming a cropper. To acquire a firm seat in a ball-dress requires practice.

"Hello!" I shouted, desperately, through the 'phone. "Is that you--ah--Reginald?"

"Jenkins is here." I heard my voice saying at the other end of the line. "What'll I do with him?"

"Send him to--ah--Hoboken, will you?" I returned, in a shrill falsetto. "But you have the better of it, my dear. He's not a marker to Jones. What have you done with the specialties?"

"Buying! buying! buying!" cried Caroline, in a triumphant basso that froze my blood. "Rogers gave me an inside tip, as he calls it. It was awfully nice of him, wasn't it?"

"Damn Rogers!" I exclaimed.

"Good-bye!" cried Caroline, with righteous indignation, and my attempt to call her back was futile.

My heart was heavy as I made my way, slowly and clumsily, from the library. Buttons, as bad luck would have it, had just opened the front door to a black-eyed, long-haired little man, who carried a roll of music under his arm. As I hesitated, hoping to make good my retreat to the library, Professor Von Gratz--as he proved to be--hurried toward me. If he was amazed at my costume, he managed to control his mobile face and musical voice.

"Oh, madame, I am zo glad to zee you are eager for de lezzon!" he exclaimed, bowing almost down to his knees. "Ve vill haf grade muzic, nicht war? You vill blay de vonderful Opuz 22! Beethoven, de giant among de pygmies, vill open de gates of baradize to us. It vill be beautiful. You are ready, madame?"

My bosom rose and fell with a conflict of emotions. I felt an almost irresistible longing to throw this detestable little foreigner out of the house. The sudden realization that my biceps, etc., were at my office cooled my ardor for action, and I said, presently, marveling at my own ingenuity:

"I regret to say--ah--Professor, that my doctor has put me upon a very slim musical diet. He says that--ah--Beethoven is ruining my nerves. But if you want to sing 'Danny Deever,' come into the music-room. I think I could manage to knock out the accompaniment."

Von Gratz stared at me in most apparent agitation, pulling at his horrid little black goatee with his left hand.

"I vill pid you gute morgen, madame," he gasped, bowing again. "Ven you are much petter you vill zend for me, nicht war? Gute morgen!"

The gates of paradise were not to be opened to the professor this morning. On the contrary, Buttons, to my great relief, shut the front door behind the hurrying figure of the master-pianist, whose farewell glance of mingled astonishment and anger haunted me as I mounted the stairs.

"Suzanne!" I gasped, as I tottered into the room in which the girl awaited my return. "Suzanne, unbuckle this chain-armor, will you? It's breaking my heart. That's better, Suzanne. Oh, yes, I'm going to a ball, all right. Or, rather, you're going to bring me one at once."

CHAPTER VI.

VERSES AND VIOLETS.

Oh, my brothers blooming yonder, unto Him the ancient prayThat the hour of my transplanting He will not for long delay.--From the Persian.

Relieved of Caroline's new ball-dress and having swallowed a cocktail, I was horrified to find a feeling of almost irresistible drowsiness stealing over me.

"Suzanne," I cried, "it is imperative that you keep me awake--even if is becomes necessary for you to do the skirt-dance to drive sleep from my eyelids. Not that I approved of these Oriental vagaries. Far from it, Suzanne. Though I may at present come under that head myself--but n'importe! You might assert, plausibly enough, that all this is Occidental. In a certain sense, I suppose that it is. But--Great Scott!"

I sank back in an easy-chair, startled by my own flippancy. The uncanny, inexplicable change that had made me what I was must not be revealed to Suzanne! Was it not enough that I had already driven my maid to the very verge of hysteria? And here I sat, talking recklessly to keep awake, and wearing my secret on my sleeve. Should Suzanne learn the truth from my punning tongue, her mind might become unhinged. In that case, another sudden transposition of identities might take place! Frightful possibility! I must not yield to the inclination creeping over me to indulge in a short nap. Perhaps Caroline's mail would revive me!

And just here I found myself confronted by a difficult problem in ethics. Despite the fact that my wife, with a heartless disregard of my wishes in the matter, had seized my letters, captured my business office, and assumed the full possession of all my business affairs, great and small, I could not forget that I still remained a gentleman. That Caroline had taken advantage of a psychical mischance to lay bare my inner life before her prying gaze could not excuse my surrender to a not unfounded but, perhaps, unwholesome curiosity.

"Suzanne," I said presently, and the girl stole softly to my side. "You spoke of a letter that you had received for me. It is--ah--from--ah?"

"Yes, madame," answered Suzanne, eagerly, but somewhat irrelevantly. "Here it is, madame. It is from him, I feel sure."

I gazed at the envelope with Caroline's brilliant eyes, but I was not thankful for my temporary perfection of face and form. It came to me grimly that beauty may be a nuisance, or even a curse. I lacked the courage to open this note--an unconventional, perhaps lawless, tribute to my my wife's powers of fascination. There was an air of Spanish or Italian intrigue about the whole affair that shocked me. My imagination, which had developed wonderfully since early morning, likened myself and Suzanne to Juliet and her nurse.

"O, Romeo, Romeo! wherefore art thou, Romeo?" I exclaimed, somewhat wildly. Suzanne drew back from me nervously.

"Will you not read the note, madame?"

"Anon, good nurse! But if thou mean'st not well, I do beseech thee--"

"Mon Dieu!" gasped Suzanne, gazing at me, awe-struck. But I was pitiless.

"Suzanne," I said, firmly, glancing at the note in my hand, the chirography upon which seemed to be familiar, "Suzanne, I am very beautiful, am I not?"

"Oui, madame," assented Suzanne, enthusiastically.

"And I love my husband dearly, do I not?"

"Devotedly, madame."

"Then, surely, Suzanne, I should not receive this epistle. What did I do with his--ah--former notes?"

I had made a most egregious blunder. An expression of amazement came into the French maid's mobile face.

"But, madame, this is the first one, is it not? I know of no others, madame."

There was a gleam of suspicion in the girl's eyes. It was evident that, for a moment, she suspected my dear Caroline of a lack of straight-forwardness. Impulsively I tore Romeo's note into a dozen fragments.

"There, Suzanne." I cried, in a triumphant treble, "my alibi is perfect. Who wrote this note I do not know. What he had to say I do not care. If you can get word to him, girl, tell him that if he comes prowling around my balcony again I'll have--ah--Reginald pull his nose for him. A bas Romeo!"

"But, madame," murmured Suzanne, evidently pained by my flippant fickleness and fickle flippancy, "monsieur, the writer of the note, dines here to-night, you know."

"The deuce he does, girl!" I cried, impulsively, making as if to pull my beard, and bruising my spirit against new conditions. "Who are our guests? Edgerton and his wife. It can't be Edgerton. He's not a blooming idjit. Van Tromp? Dear little Van Tromp! It must be Van Tromp. Oh, Van Tromp, Van Tromp, wherefore art thou, Romeo? Van Tromp's the man, eh, Suzanne?"

Caroline's maid was red and tearful.

"Madame is so strange this morning," she complained. "It was Mr. Van Tromp's man who brought the note, madame."

My soul waxed gay in Caroline's bosom. I warbled a snatch of song from Gounod's "Faust."

"Suzanne," I cried, "gather up the fragments of Romeo's billet-doux. Possibly his note is not what I supposed it was. I'll read what the dear little boy has to say. Thank you, Suzanne. I think I can put these pieces together in a way to extract the full flavor of Van Romeo's sweet message. What saith the youth? Ha! I have it.

"'MY DEAR MRS. STEVENS: Is it presumption upon my part to believe that you meant what you said to me at the Cromptons' dance? At all events, I have had the audacity to cherish your words in my heart of hearts. I am sending you a few violets to-day. If you do me the honor of wearing them at dinner to-night, I shall know that there was a basis of earnestness underneath the words that were as honey to my soul.'

"Listen to that, Suzanne," I cried, hysterically. "Is it not worthy of a young poet? I wonder what the dev--what Caro--ah--I said to this--ah--Romeo? Here's richness, Suzanne! I'll wear his flowers--with a string to 'em, eh? We'll have a merry dinner, Suzanne! I told Jones to throw everything wide open. I'll include young Van Tromp in the order. He shall be my special care, Suzanne. Van Tromp's mine oyster! What think you, Suzanne? Should I not quaff a toast to the success of my little game?"

"Madame, I do not understand," murmured the girl, in French. "Madame is feverish. Let me bathe madame's head, and she may get a quieting nap. If you could lose yourself only for an instant, madame!"

"Great Jupiter, Suzanne, will you get that idea out of your head? I don't want to lose myself. On the contrary--but--n'importe, as we say when we're feverish. You'll find some cigarettes in the bedroom, girl. Bring 'em to me at once. Don't stare at me that way! If I don't smoke I'll drink another cocktail, and then what'll happen?"

Suzanne shuddered and hurried away. Presently I was blowing smoke into the air, much to my own satisfaction and to Suzanne's ill-disguised amazement.

"Tobacco is quieting, Suzanne; soothing, cheerful. It stimulates hope and calms the perturbed soul. Damn it! what's that? Somebody's knocking, Suzanne. See who it is. If it's anyone for me, tell them that I won't draw cards this morning, but may take a hand later on. Don't stand staring at me, girl! Put a stop to that rapping at once."

"Mon Dieu!" groaned Suzanne, as she crossed the room. How much longer she could stand the strain of my eccentricities was becoming problematical. Presently she returned to me, carrying a box of flowers.

"Romeo's violets," I murmured, rapturously. "Tell me, nurse, did Juliet mean what she said to Romeo? Well, rather! I'll wear thy flowers, little boy! What's this? Another note, smothered in violets. Listen, Suzanne! Romeo has dropped into poetry. Listen:

"'Go, purple blossoms, the glory of Spring,Gladden her eyes with thy velvety hue;What are the words of the song that I sing?They came to my heart as the dew came to you."'My love is a flower, my song is its scent;Let it speak to her soul in the violet's breath!And my spirit with thee, by a miracle blent,Shall drink deep of life, of love unto death.'

"Take these away, Suzanne! Take them away!" I cried, in a panic. "Haven't I had enough of this theosophical, transmigration idiocy for one day? Take them away! 'By a miracle blent!' Confound the boy! if I got into that little Van Tromp's body through these infernal flowers I could never hold up my head again. What's that, Suzanne? Yes, keep them fresh. Give them water. But don't let me get near them again until I've got my courage back. Perhaps I'll dare to wear them to-night. I can't say yet."

I needed rest. Reclining in my chair, I idly watched Suzanne as she moved restlessly about the room trying to quiet her excitement by action.

"Suzanne," I cried, softening toward the maid, "don't look so sad. All will come right in the end. Brace up, girl. 'While there's life there's hope.'"

"Do I look sad, madame? I am very sorry. I will try to be more cheerful, for madame's sake. But if madame could put herself into my place for a moment--"

"There you go again, Suzanne," I exclaimed, testily. "We'll change the subject, girl. What next?"

"I think it might be well for madame to dress for luncheon," suggested Suzanne, nervously. It was evident that she had begun to lose confidence in my intervals of calm.

"Let me think, Suzanne. Somebody lunches with me. Who is it? Oh, yes, Mrs. Taunton. And now I think of it, Suzanne, Mrs. Taunton is little Van Tromp's sister. That's the reason I never liked her, I suppose."

"But madame and Mrs. Taunton seem to be such good friends," remarked Suzanne, in French, moving about in a way that filled me with foreboding. It was evident that she contemplated changing my costume at once.

"Appearances are often deceptive, Suzanne," I remarked, feelingly, lighting a fresh cigarette, somewhat clumsily. "What are you up to now, girl?"

"Madame must look her best at luncheon," remarked Suzanne, professionally. "Mrs. Taunton has such exquisite taste."

I was not pleased at Suzanne's remark. Mrs. Taunton, an avowed admirer of Caroline, had never disguised the fact that she considered me a nonentity. But fate had vouchsafed to me a great opportunity for proving to Mrs. Taunton that I was not altogether insignificant. Disguised in Caroline's outward seeming I might readily avenge myself for Mrs. Taunton's persistent indifference to my good points. Little Van Tromp had placed a double-edged weapon in my hand.

"Suzanne," I said, gazing grimly at the dress that she had laid out for me, "before you go further with my toilet, I wish you would make a copy of these verses for me. You write English, do you not?"

Suzanne glanced at me, inquisitively.

"Madame knows well that I do," she remarked, mournfully. But the trembling of her slender hand as she grasped Van Tromp's screed to do my bidding augured ill for the copy that she would make of his verses.

CHAPTER VII.

IRRITATION AND CONSOLATION.

Waste not your hour, nor in the vain pursuitOf this and that endeavor and dispute;Better be merry with the fruitful grapeThan sadden after none, or bitter fruit.--Omar Kháyyám.

I must get on more rapidly with my narrative. It has been a great temptation to me to indulge in conjectures and surmises regarding the soul-displacement that may make my story a presentment worthy of attentive consideration from the Society for Psychical Research. But from the outset I have endeavored to resist this inclination and to give to the reader merely a bald statement of facts in their actual sequence. It must be apparent by this time, furthermore, that I am not fitted by education to discuss the uncanny problems begotten by the strange affliction that had befallen my wife and myself. That I have become perforce a sadder and wiser man may be true, but, despite my practical experience of what may be called instability of soul, I am not in any sense a psychologist. From various points of view; therefore, it seems best that I should eschew all philosophical or scientific comments on the curious phenomena with which I have been forced to deal, leaving, as it were, the circumference of my story to the care of the erudite, and confining my own endeavors strictly to its diameter.

Behold me, then, fresh from Suzanne's deft hands, confronting Caroline's bosom friend, Mrs. Taunton, across the luncheon-table. Our conversation, if my memory is not at fault, ran something as follows:

"You look flushed and excited, Caroline," said Mrs. Taunton, a large, blond, absurdly haughty woman, strangely unlike little Van Tromp, her poetical brother. "Something has happened to upset you, my dear?"

"Well, rather!" I could not refrain from exclaiming. What the deuce was Mrs. Taunton's given name? If I did not recall it soon she would begin to wonder at Caroline's peculiar bearing. It was not Mrs. Taunton, however, who was driving me toward hysteria. To find myself again in the realm over which the phlegmatic but terrifying Jones presided was to lose confidence in my ability to stem the tide of disaster. Jones was so conservative! Such a radical change as I had undergone would be even more incomprehensible to him than it had been to me. I realized vaguely that I had grown to be supersensitive, and that what I took to be suspicion in the butler's eyes must be a product of my own overwrought nerves. But, struggle as I might against the impression, I could not free myself from the feeling that Jones watched me furtively, questioningly, as if he had gained possession of a clue to a great mystery.

"Tell me all about it, Caroline," urged Mrs. Taunton, sweetly. "If you were not so beautiful, my dear, you would not have so much trouble."

The blood rushed into Caroline's cheeks, and I found myself glaring angrily at Jones, who was serving croquettes to Mrs. Taunton. The latter had displayed the most wretched taste in praising my, or rather Caroline's, appearance before the butler. But Mrs. Taunton evidently looked upon a servant as a mere automaton, not to be considered even in heart-to-heart talks with young women. My growing annoyance made itself manifest in Caroline's voice, as I stammered:

"My--ah--beauty, such as it is, don't you know, is only--ah--skin deep. But my troubles--ah-- Jones! Don't be so slow! Spend as much time outside as you can, will you?"

Mrs. Taunton stared at me in amazement, while Jones, showing no signs of emotion, made a most dignified exit.

"What is the matter with you, Caroline?" asked my vis-à-vis, anxiously. "I never heard you speak like that before."

An explanation seemed to be due to my guest.

"It's curious, don't you know," I began, lamely, trying to recall Mrs. Taunton's baptismal name, "it's curious--ah--my dear, what an intense repulsion I feel toward that man Jones. It came upon me suddenly. It's intermittent, not chronic, I think, but it's all there, and means business. Did you ever feel that way?"

"Caroline!" gasped Mrs. Taunton, pained surprise resting upon her patrician face.

"It's beneath me, I acknowledge," I went on, feverishly, making an effort to eat a croquette between sentences. "A butler's merely a necessary piece of movable furniture, and should--ah--not arouse a feeling of antagonism. But Jones has got an eye to--ah--induce intoxication."

"Caroline," queried Mrs. Taunton, solemnly, "have you--forgive me, my dear, for the question--have you been taking anything?"

"A fair exchange is no robbery," I remarked, impulsively, in my own defense, but Mrs. Taunton's face assured me that I had spoken irrelevantly.

"I should advise a cup of black coffee, Caroline," said my guest, in her iciest tone.

"We'll wait a bit, if you don't mind," I ventured to suggest. "No coffee without Jones. I'm not quite up to Jones at this moment--er--my dear."

Mrs. Taunton held my gaze to hers, and her light-gray eyes chilled me. It was evident that little Van Tromp's sister had no poetical nonsense in her make-up. Practical, obstinate, strong-willed she seemed to be, as she endeavored to solve from Caroline's beautiful eyes the mystery of my eccentric demeanor.

"Your sudden and inexplicable aversion to your butler, Caroline," remarked my guest, presently, apparently desirous of soothing my nerves by a poultice of gossip, "reminds me of the lecture upon Buddhism that I heard yesterday morning. An adept from India--Yamama, I think, is his name--talked to us, you know, about our Western blindness, as he called it, to the marvels of soul-sensitiveness."