THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE

IN MEMORIAM

N. F. P. + E. L. P.

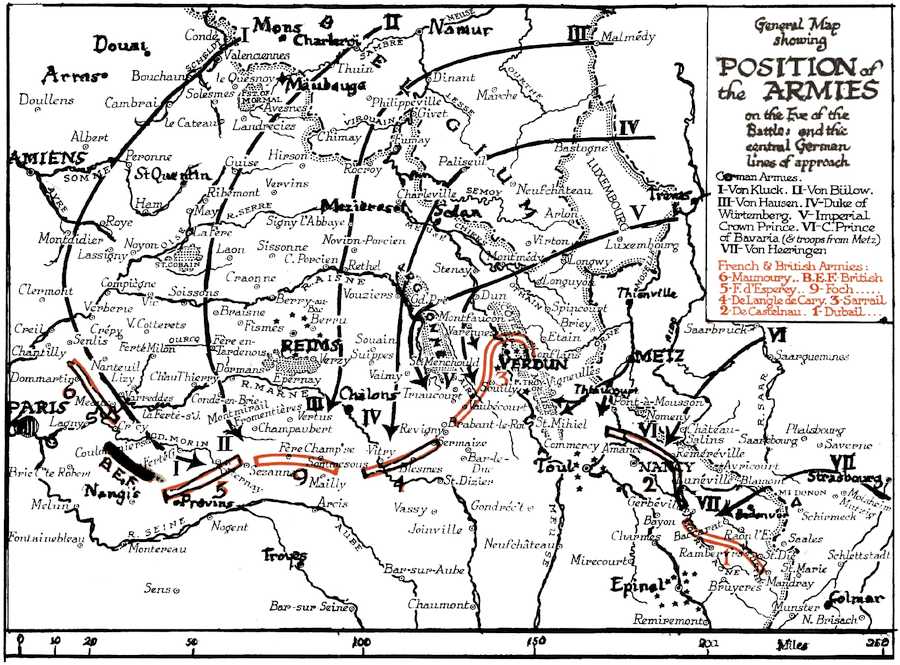

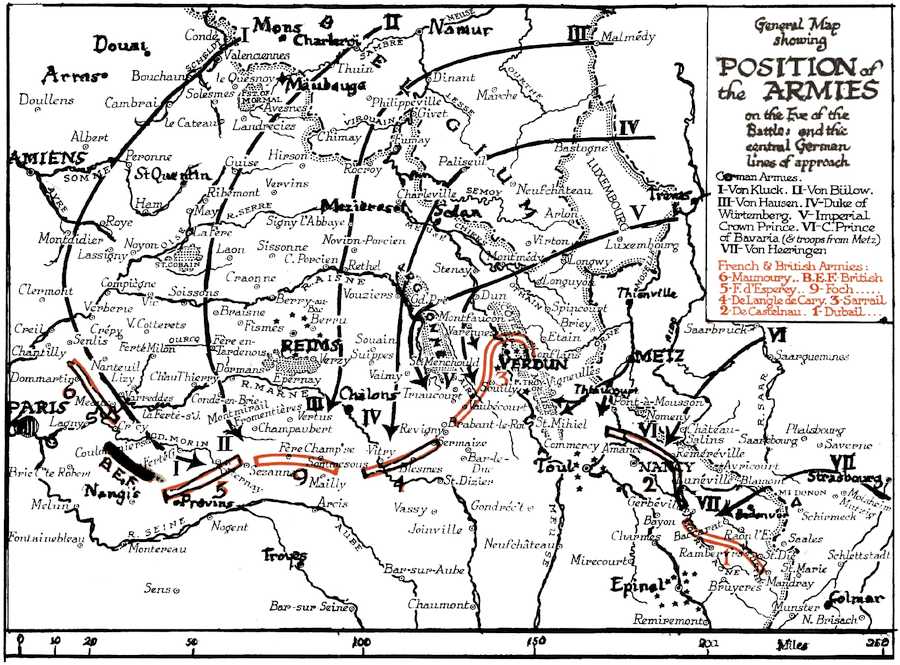

General Map showing

POSITION of the ARMIES

on the Eve of the Battle, and the central German lines of approach.

German Armies.

I–Von Kluck. II–Von Bülow.

III–Von Hausen. IV–Duke of Würtemberg.

V–Imperial Crown Prince.

VI–C. Prince of Bavaria (& troops from Metz).

VII–Von Heeringen.

French & British Armies:

6–Marmoury. B.E.F. British.

5–F. d’Espérey. 9–Foch.

4–DeLangle de Cary. 3–Sarrail.

2–DeCastelnau. 1–Dubail.

THE BATTLE OF

THE MARNE

BY

GEORGE HERBERT PERRIS

SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT OF “THE DAILY CHRONICLE”

WITH THE FRENCH ARMIES, 1914–18

WITH TWELVE MAPS

JOHN W. LUCE & CO.

BOSTON

MCMXX

v

The great war has entered into history. The

restraints, direct and indirect, which it imposed

being gone with it, we return to sounder tests

of what should be public knowledge—uncomfortable

truths may be told, secret places explored. At the

same time, the first squall of controversy in France

over the opening of the land campaign in the West

has subsided; this lull is the student’s opportunity.

No complete history of the events culminating in the

victory of the Marne is yet possible, or soon to be

expected. On the German side, evidence is scanty

and of low value; on that of the Allies, there is yet a

preliminary work of sifting and measuring to undertake

ere definitive judgments can be set down. Any narrative

conceived in a scientific, not an apologetic or

romantic, spirit may claim to further this end.

The difficulty lies less in following the actual movements

of that great encounter—the most important of

which, and their part in the result, can now be traced

pretty accurately—than in estimating the factors that

produced and moulded it. Yet, if we are right invi

holding the battle of the Marne to be essentially the

completion of a chapter, the resultant of certain designs

and certain misadventures, a vast strategical reversal

and correction, such an estimate is necessary to the

subject. How did the two chief antagonists envisage

the process of modern warfare? Why was the action

which was to close the first phase of the war, and

largely to shape its after-course, fought not near the

northern or eastern frontiers, but between Paris and

Verdun? Why and how were the original plans of

campaign modified to reach this result? What conditions

of victory existed on the Marne that had been

lacking on the Sambre? In a word, the key to the

meaning of the battle must be sought in the character

of the forces in play, their comparative numbers,

organisation, and training, armament and equipment,

leadership and inspiration.

No sooner is such an inquiry opened than a number

of derivative problems appear. Where exactly lay the

German superiority of force at the outset, and why

was it not maintained? Was the first French concentration

justifiable? If not, was it promptly and

soundly changed? Could the northern frontier have

been defended? Was Lanrezac responsible for Charleroi,

and, if so, why not Castelnau for Morhange? Was the

German plan of envelopment exaggerated? Could the

British have done more at Mons, and were they slow

and timorous when the hour arrived to turn about?

Was Paris ever in danger? And, coming to the battlevii

itself, how was it decided? What parts did Gallieni,

Von Kluck, Sir John French, and Foch play? Was

Joffre really master of the field? It may be too soon

to answer fully such questions as these; it is too

late to evade them.

Outside the mass of official and semi-official bulletins,

dispatches, and explanations, much of it now best left

to oblivion, a considerable literature has accumulated

in France, including personal narratives by combatants

of all arms, and critical essays from points of view the

most diverse. With the rather cruel sincerity of the

French intelligence, the whole military preparation of

the Republic has been challenged; and, in the consequent

discussion, many important facts have come

to light. Thus, we have the texts of the most decisive

orders, and many details of the dispositions of troops.

We have Marshal Von Bülow’s valuable diary of field

movements, and the critical reflections of distinguished

officers like Lt.-Col. de Thomasson, Generals Malleterre,

Berthaut, Verraux, Percin, Canonge, Bonnal, Palat,

Cherfils, and Col. Feyler. Fragmentary statements by

General Joffre himself, by Generals Foch, Lanrezac,

and Maunoury, the Ministers of War, MM. Messimy and

Millerand, by Generals von Freytag-Loringhoven, Von

Kluck, and other German officers and men, give useful

indications. We are also indebted to the more

systematic works of MM. Hanotaux, Reinach, Engerand,

and Babin; and, with regard to the British Force, the

volumes of Marshal French and Major-General Mauriceviii

are important. These and other sources are cited

in the pages of “Notes and References” at the end

of the volume, in which some questions of detail,

especially relating to the preparation of the battle,

are discussed.

Having been privileged to watch the war in France

from beginning to end, and to live with the French

armies (as Correspondent attached to General Headquarters)

for more than two years, the writer has also

had exceptional opportunities of studying the terrain,

and of discussing the drama as a whole and in detail

with officers and men from the highest to the most

humble. To name all those from whom he has received

aid would be impossible; to name any might

seem to associate them with conclusions for which he

is solely responsible; but he may record his deep

gratitude to the French Government, the Headquarters

Staff, and the various Army Staffs, for the rare experience

of which this volume is unworthy fruit.

February 1920.

German units are throughout numbered in Roman capitals (“the XX

Corps”), Allied in ordinary figures (“the 20th Corps”).

The small figures in the text refer to “Notes and References” at the end

of the volume.

ix

NOTES AND REFERENCES

The German Objective (p. 239); The Opposed Forces (p. 240); De Bloch’s

Prophecy and French’s Confession (p. 242); Criticisms and Defence of the

French Staff (p. 244); The Surprise in the North (p. 247); The Abandonment

of Lille (p. 252); M. Hanotaux and the B.E.F. (p. 252); The Fall

of Maubeuge (p. 256); Paris and the German Plan (p. 259); Some Books

on the Battle (p. 263); General Bonnal and the British Army (p. 265);

Scenes at Farthest South (p. 266); The Myth of the 42nd Division

(p. 268).

xi

| 1. |

Position of the Armies and Lines of Approach |

Frontispiece |

| |

FACING PAGE |

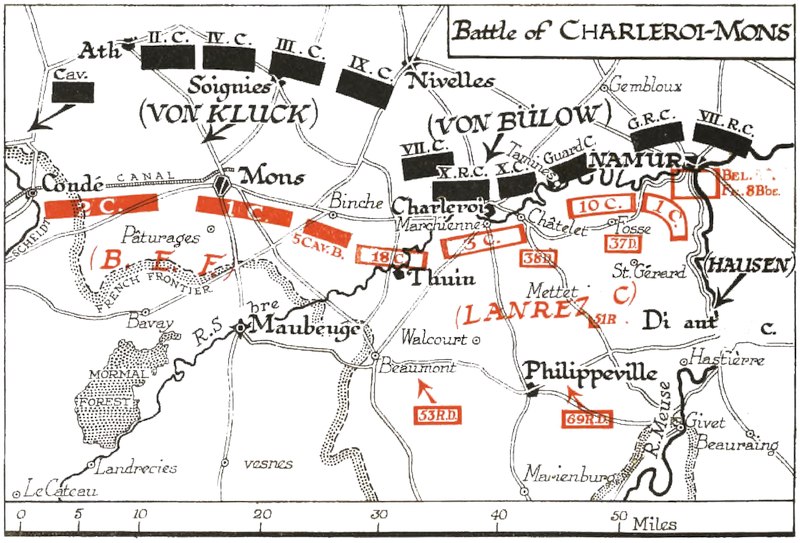

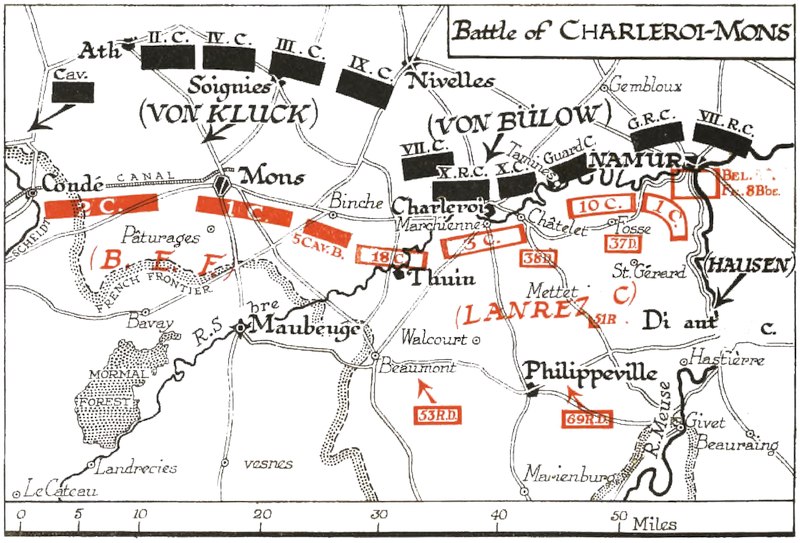

| 2. |

Battle of Charleroi–Mons |

38 |

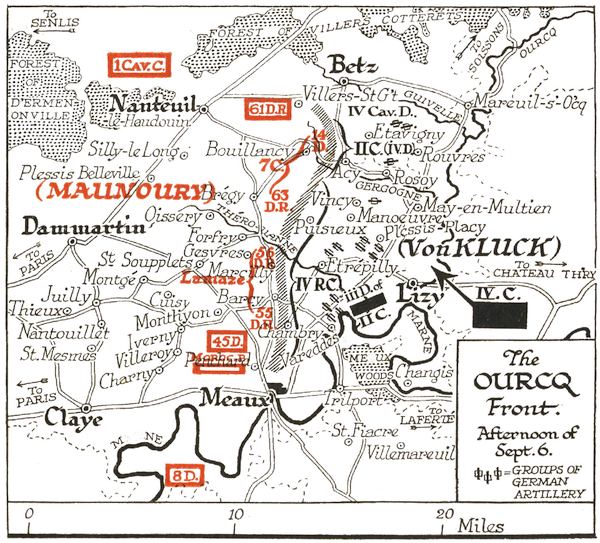

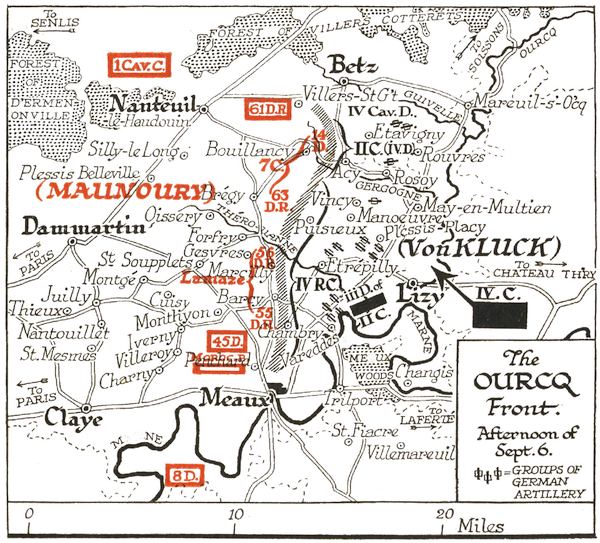

| 3. |

The Ourcq Front, Afternoon, Sept. 6 |

118 |

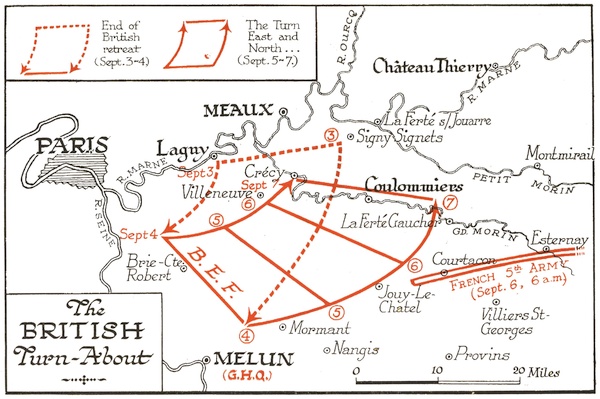

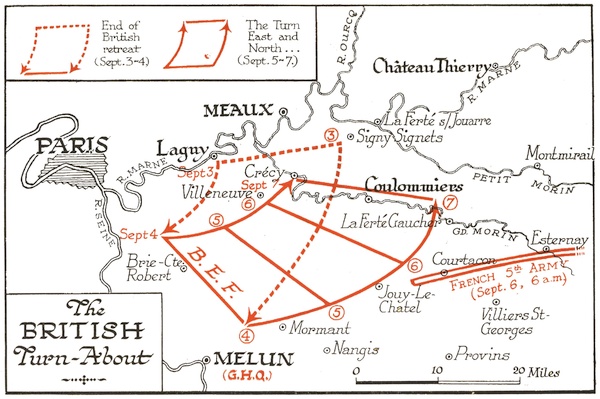

| 4. |

The British Turn-About |

122 |

| 5. |

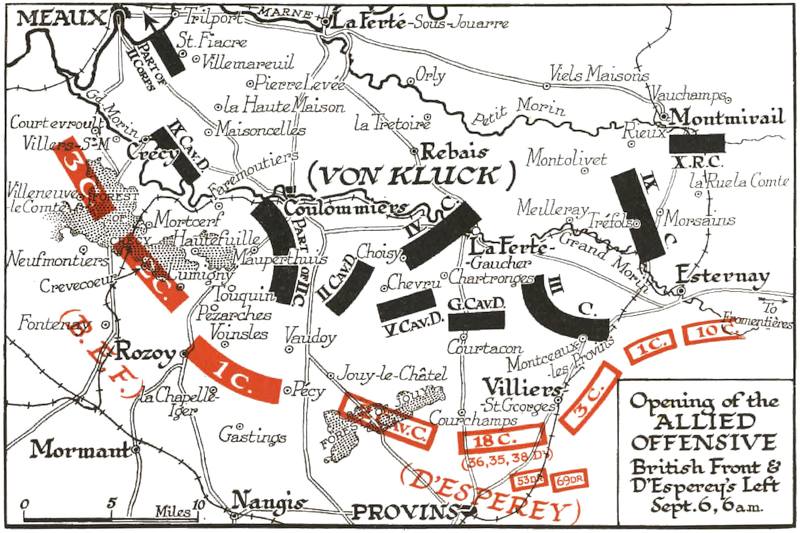

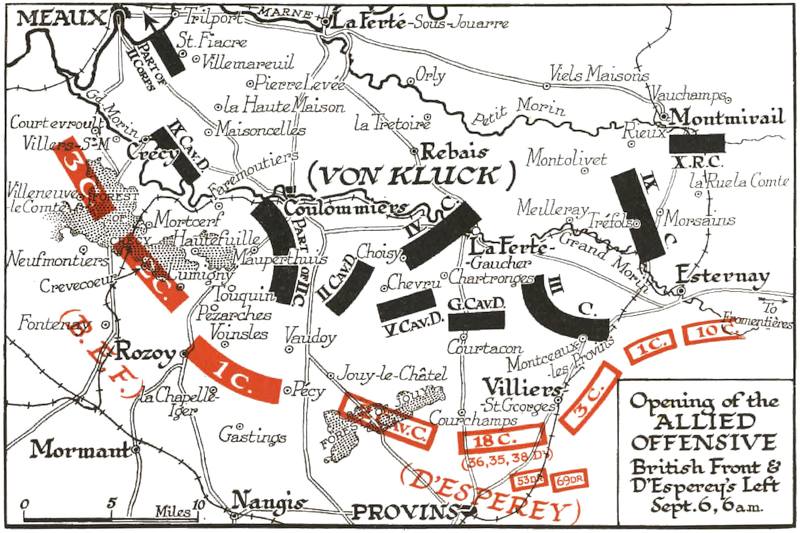

Opening of Allied Offensive, Sept. 6 |

136 |

| 6. |

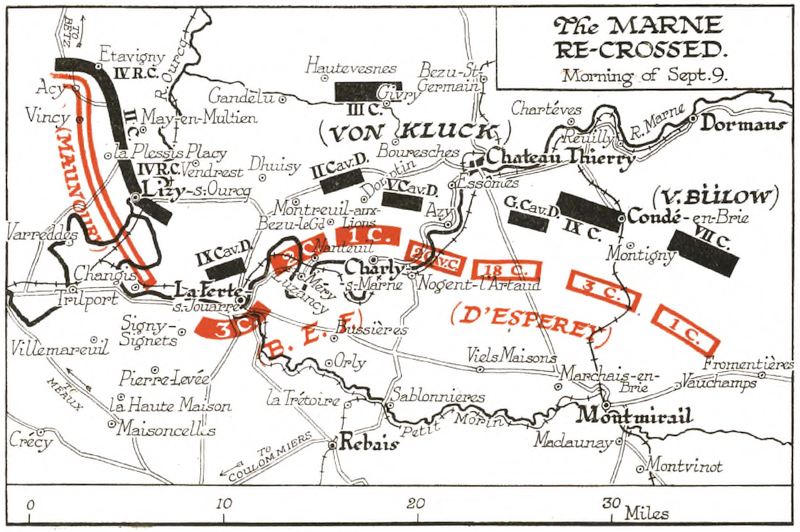

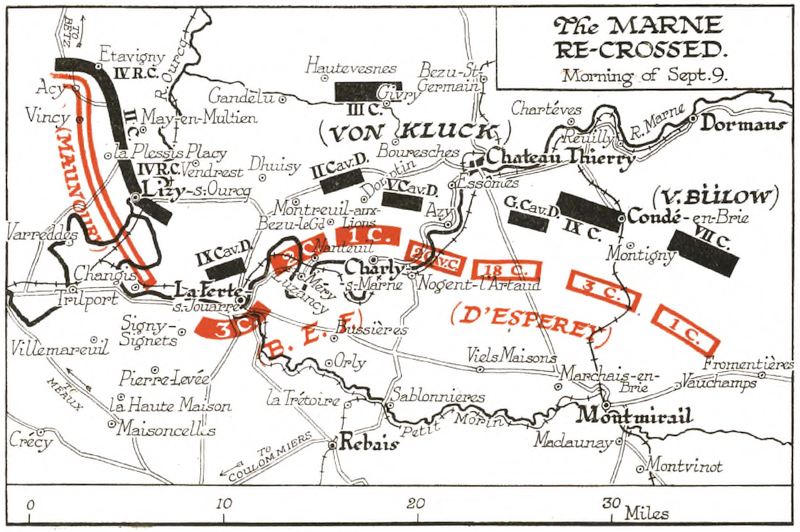

The Marne Re-crossed, Sept. 9, a.m. |

142 |

| 7. |

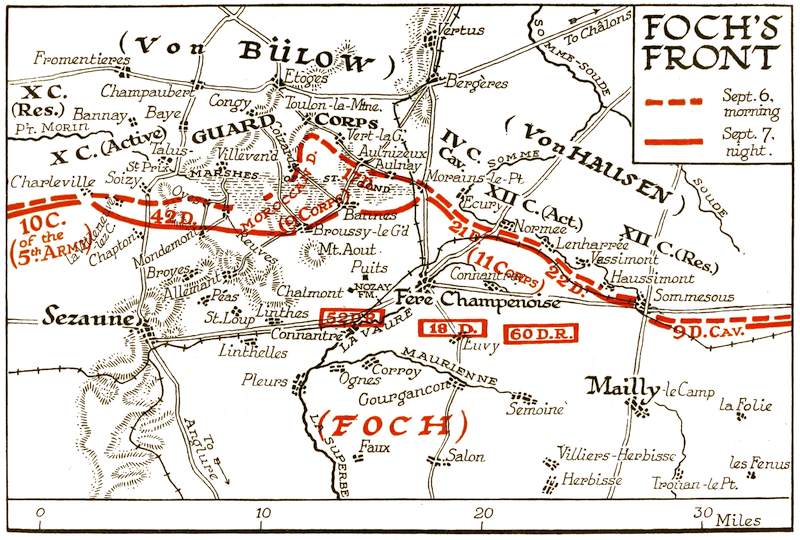

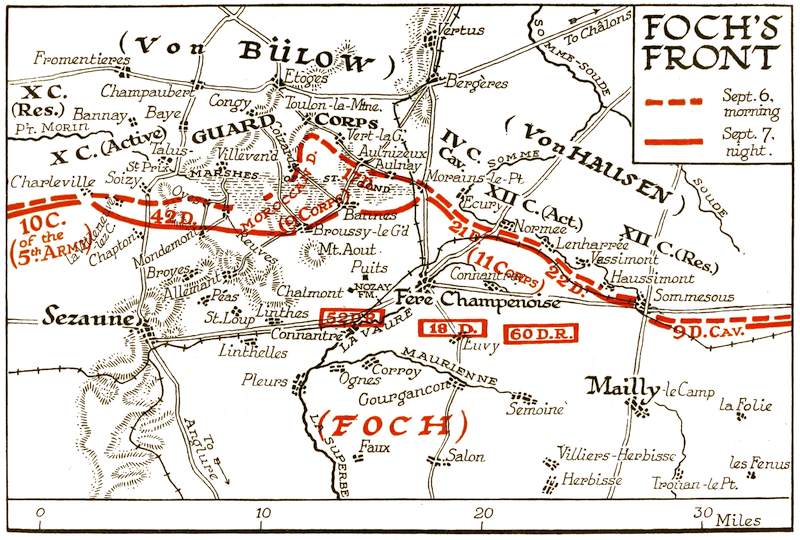

Foch’s Front, Sept. 6 and 7 |

146 |

| 8. |

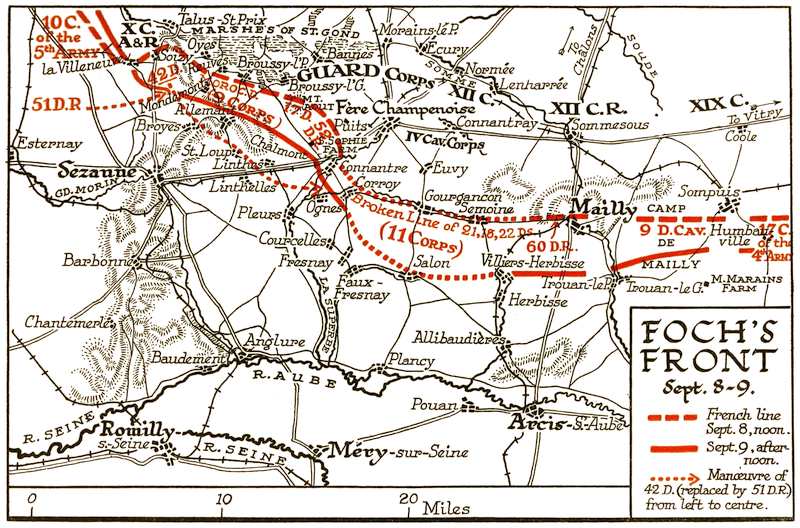

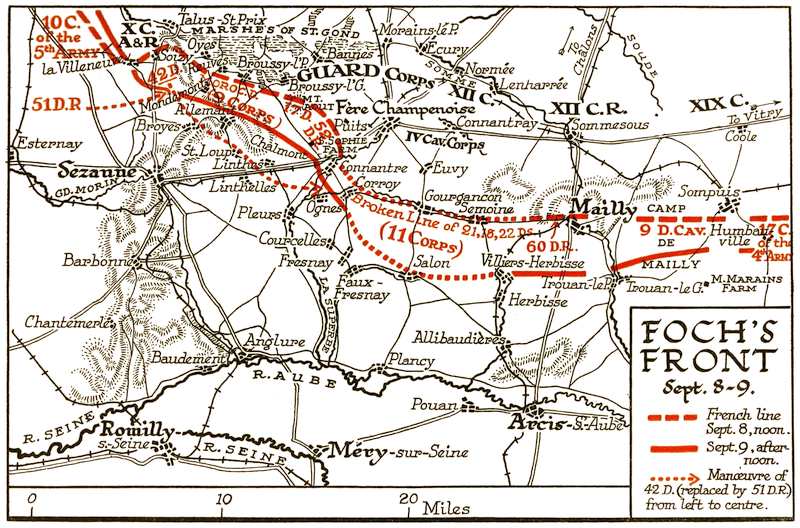

Foch’s Front, Sept. 8 and 9 |

156 |

| 9. |

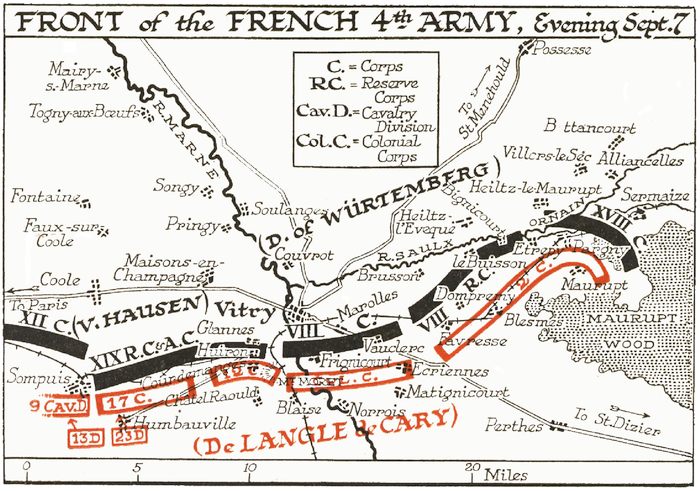

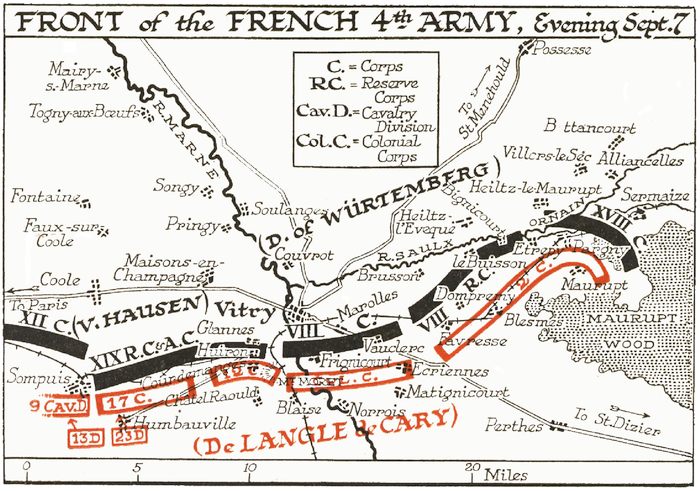

Front of French 4th Army |

172 |

| 10. |

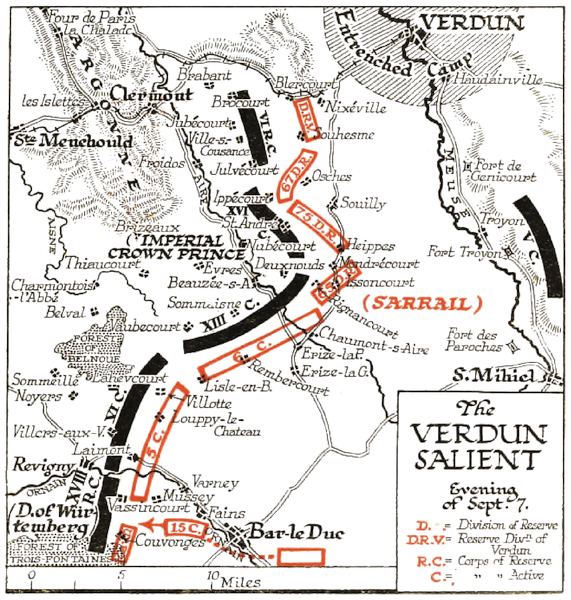

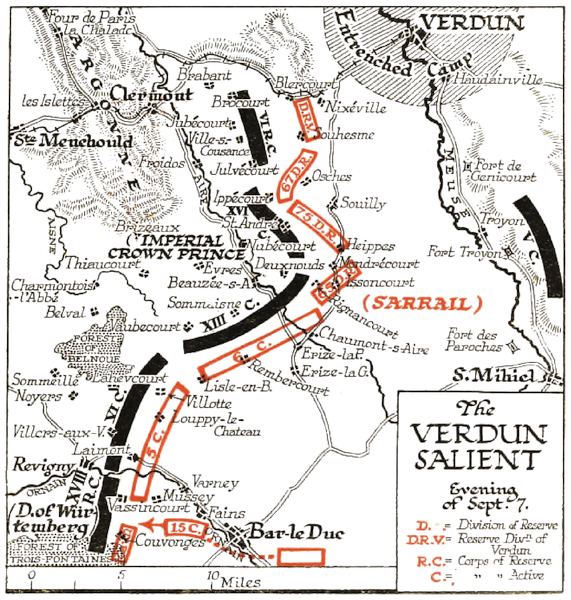

The Verdun Salient |

180 |

| 11. |

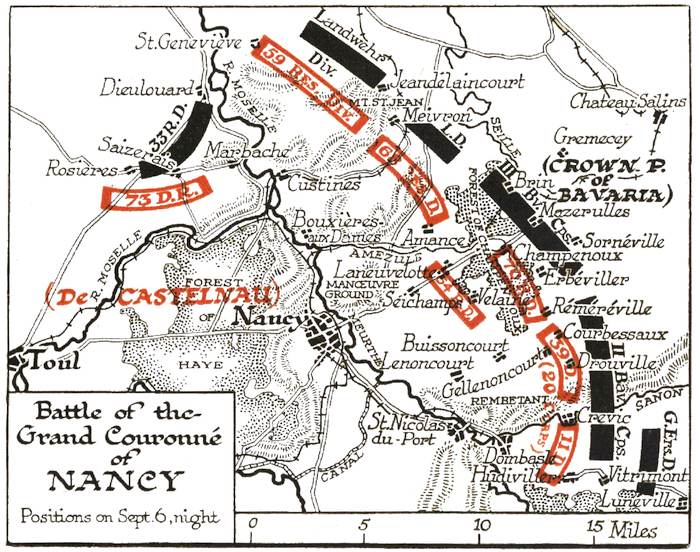

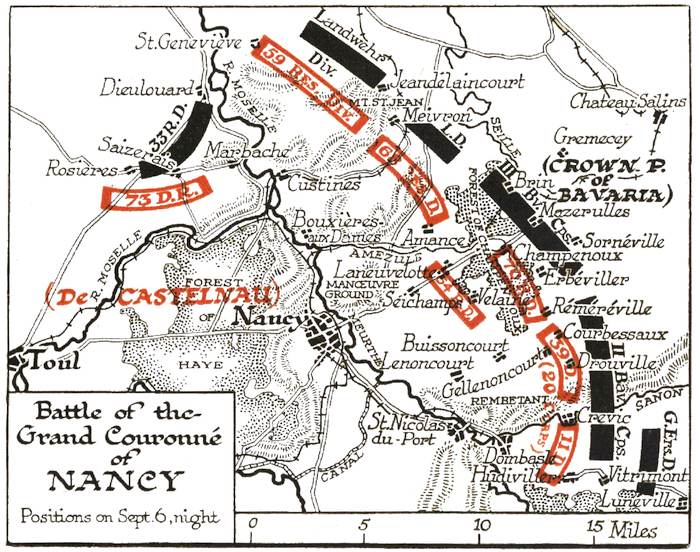

Battle of the Grand Couronné |

206 |

| 12. |

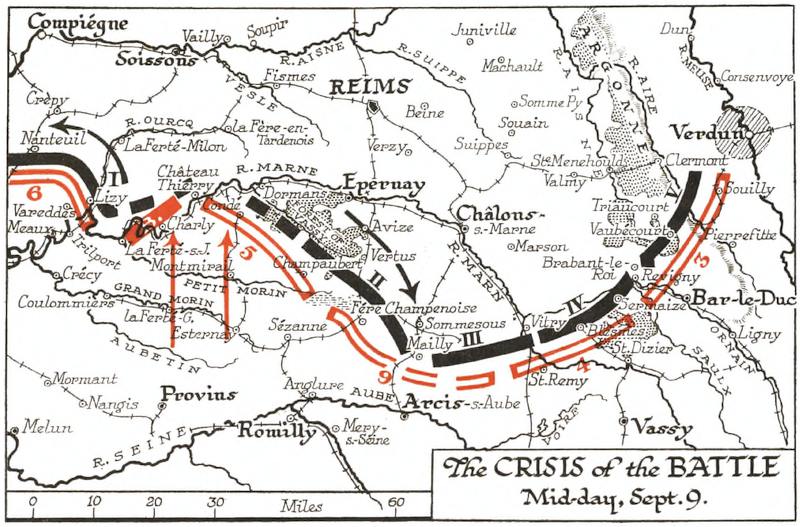

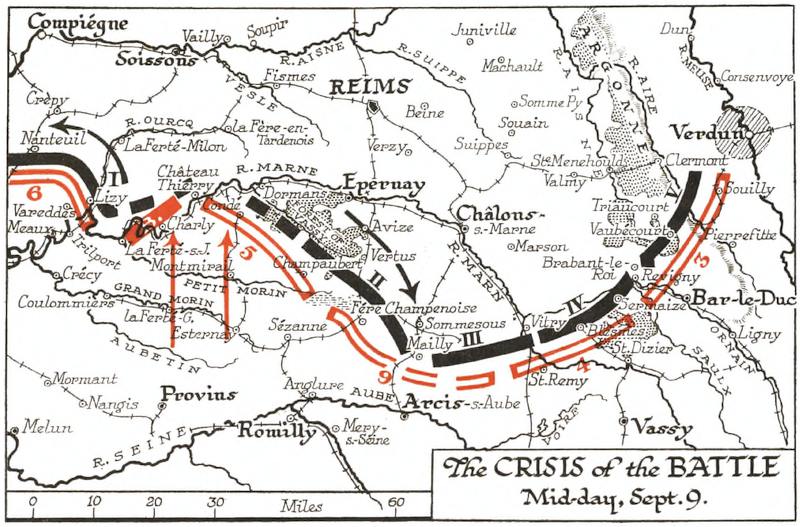

Crisis of the Battle of the Marne |

224 |

1

CHAPTER I

THE DELUGE

August 25, 1914: three weeks after Von

Emmich opened the war before Liège; five

days after the French Army of Lorraine was

trapped at Sarrebourg and Morhange; two days after

Namur fell, and Charleroi and Mons were abandoned.

On this black day, the 25th, while Louvain was

burning, the 80,000 men of the old British regular

Army made an average of 20 miles under a brazen

sun, pursued by the enormous mass of Von Kluck’s

marching wing. The 1st Corps under Haig came into

Landrecies at 10 p.m., and, after a stiff fight and two

or three hours’ sleep, trudged on to Guise; while the

2nd, Smith-Dorrien’s, at Le Cateau and towards

Cambrai, spent most of a showery night in preparing

for the battle of the morrow, which was to save the

western flank of the Allies. On the British right, the

French 5th Army, Lanrezac’s, surprised in the Charleroi–Namur–Dinant

triangle by the onset of Von

Bülow and the cleverly secreted approach of Von

Hausen, had struck a wild blow, and then reeled2

back; the two German commanders were now

driving it over the Belgian frontier from Avesnes

to Rocroi. The 4th Army, under de Langle de Cary,

no less heavily punished between Paliseul and Neufchateau

in the Belgian Ardennes, was just reaching the

French Meuse between Sedan and Stenay, there to

dispute the passages against the Duke of Würtemberg.

Eastward again, Ruffey, beaten back on a wide crescent

from Virton to Briey in the Woevre by the Imperial

Crown Prince, was standing better against a relaxed

pressure, from toward Montmédy, through Spincourt,

to Etain. Thus, Sarrail, in taking over the command

of the 3rd Army, was able to make ready, though with

inadequate means, for the three-sided defence of

Verdun. On the eastern border, Castelnau and

Dubail, withdrawing hardly from ill-starred adventures

in Lorraine and Alsace, were rallying the 2nd and 1st

Armies around the Nancy hills and on both sides of

the Gap of Charmes. Mulhouse, twice captured, was

finally abandoned by General Pau, with all save a corner

of Alsace and the southern passes of the Vosges.

“It is a cruel necessity,” said the official communiqué

of August 26, “which the Army of Alsace and its

chief have submitted to with pain, and only at the last

extremity.” They had discovered that “the decisive

attack” had to be met “in the north.” At that

moment, in fact, a hardly less “decisive” attack was

being met in the heart of Lorraine.

It was everywhere the same bitter story of defeat—defeat

by surprise, by locally superior numbers, by

superior armament, sometimes by superior generalship;

and everywhere the retreat was accompanied

and hampered by the flight of masses of peasantry3

and townsfolk whose flaming homes lit upon the

horizon behind a warning to hasten their feeble steps.

Before we seek the Staffs in their shifting quarters,

to explain this extraordinary situation, let us see what

it meant for the commonalty of the armies, without

whose strength and confidence the best plans must be

as chaff in the wind. Over a million strong, they had

left their homes, and gathered at their depots during

these three weeks, to be whirled off to the frontiers

and the first scarcely imaginable trial of modern

conscript systems. It was a new thing in the world’s

history, this sudden tremendous clash of the whole

manhood of highly developed nations, armed with

the most murderous machinery science could devise,

and supported by vast reserves of wealth. It had

fallen swiftly upon them, the doom that many learned

men had declared to be impossible in the twentieth

century; yet its essential nature was crude enough to

be immediately understood, and the intelligence of

France, though shocked, was not stunned. This

million of peasants and workmen, merchants, manufacturers,

priests, artists, idlers, and the nation behind

them, were unanimous as never before. They knew

the issue was not of their making; they knew equally

that it could not be refused, but must be fought out,

and that it would be a hard fight. The Napoleonic

wars were to be eclipsed; and there was now no

Little Corporal to flash his genius like a searchlight

across Europe. The enemy had no less advantage in

prestige than in effectives, preparation, initiative.

Few of the million guessed, as yet, that most of

them were marked down for sacrifice. The general

opinion was that it would be all over by Christmas,4

at latest. A four months’ war seemed tragic enough

in those first days. With the unwonted agreement,

an unwonted gravity spread across the sunny lands

from the Channel to the Alps where the crops were

ripening. If international idealism lay shattered,

national democracy rose well to the trial—never better.

No recrimination (even the murderer of Jaurès was

set aside), no conspiracy, no guillotine, marked the

great revival of the republican spirit. England would

at least guard the coasts, and keep the seaways open.

France went into the struggle without wavering or

doubt.

And so, “Aux armes, Citoyens!”—for these, mark

you, are, in very fact, citizen armies, independent, free-thinking,

high-spirited fellows, no Emperor’s “cannon-food.”

From the smallest hamlet to the boulevards

of the great city, every pulse of life is feverishly concentrated

upon their gathering and departure. At the

barracks the reservists, clad, armed, equipped, are

ready to entrain. Crowds of women, whose red eyes

belie their brave words, children at their skirts,

surround the gates, and run forward with bunches

of flowers and tricolor rosettes. The officers carry

bouquets at their saddle-bows, the men cap their rifles

with roses and ribbons. At the railway station, long

lines of goods-vans, with a few passenger carriages;

more flowers and little flags; allied colours in front of

the engine; a wag chalks up the direction: “Berlin,

aller et retour.” The horses and guns are aboard;

the men jostle in the open doorways, and exchange

cries with the crowd. A stanza of the “Marseillaise”

is broken by last adieux, shouts of “Vive la France!”

and the curtain falls upon the first memorable act.

5

Interminable journeys follow, by road and rail,

toward the frontiers, then from town to village, and

from farm to farm of countrysides more and more

deserted and desolate. In the passes of the Vosges,

the hills and flats of Lorraine, the woods of the French

Ardennes, the men accustom themselves uneasily to

the oppressive heat of day and the chill and damp of

night; to sore feet and chafed shoulders; to spells

of hunger due to late or lost convoys; to the deprivation

of accustomed comfort, and the thousand

minor ills which in all times have been the ground-stuff

of the showy tapestries of war. Superfluous

graces of civilised life vanish before the irreconcilable

need of economy in every effort. Officers begin to

be honoured not for rank or show, but for the solid

talents of leadership; pals are chosen, not from

effusion of heart, but for assurance of help in emergency.

The mantles of the chasseurs are still blue, the

breeches of the infantry red, the uniforms of the

artillery and engineers nearly black; but already

bright colours tend to disappear, and every other tone

to assimilate with the dust of the high roads. By

day and night there is but one traffic throughout these

northern and eastern departments—files of cavalry,

batteries of field-guns, columns of heavy-laden men,

convoys of Parisian autobuses and hooded carts, pass

incessantly through the silent forests out into the open

plains. The civilian population steadily diminishes,

even in the larger towns; the gendarmerie keep those

who remain under suspicion of espionage. The

frontier villagers welcome the marching troops hospitably,

until local food supplies are exhausted, and6

until news comes in from the front of reverses and of

foul cruelty to the peasants on the part of the enemy.

Only a fortnight has gone by when the national confidence

in a speedy victory receives this heavy blow.

Bad news gathers and reverberates. It is a little

difficult, after years of bloodshed, to recover the fresh

sense of these first calamities. Men were then not yet

broken to the pains, the abominable spectacles, of war.

That their self-offering to the fatherland should win

them an honoured grave might well be. But defeat

at the outset, the shame of retreat almost before a

blow could be struck, this was an incredible, monstrous,

intolerable thing.

The incredible, however, generalised itself over all

the highways of Lorraine and Belgium. Take any

typical scene on the march-routes of August 22 or the

following days.1 The roads are black with columns

of troops retreating west- and south-ward, more or

less broken, linesmen, chasseurs, artillerymen, supply

and special services, with their guns, munition wagons,

Red Cross detachments, convoys of heavy-laden carts

with wounded men sitting on top or clinging behind;

and, in the breaks, crowds of panic-stricken peasants,

in farm wagons or on foot, old men, women, and children,

with bedding, boxes, bird-cages, and other strange

belongings. Dismay broods like a palpable cloud

over these pitiful processions. There is an incessant

jostling. Drivers flog their horses cruelly. Wounded

men drop by the wayside and lie there untended,

their haggard faces stained with mire and powder,

blood oozing through their coats, trickling out into

the litter of torn knapsacks and broken arms. The

sun blazes inexorably, the air is poisoned with clouds7

of dust, or drenching showers of rain produce another

sort of misery; and ever the long stream of failure

and fear flows on, eddying here and there into acute

confusion as some half-mad woman sets up a cry:

“The Prussians!”

Night follows day: soldiers and country-folk, hungry

and exhausted, fall into the corners of any sheltered

place they can find—an empty barn, the nave of a

village church—for an unsatisfying sleep, or, too sick

to sleep, watch the fantastic shadows and fugitive

lights dancing upon the walls, mocking their anguished

thoughts of the morrow. The batteries and convoys

have gone on through the darkness, men rolling from

side to side with fatigue on their horses or gun-carriages,

as though drunk. With daybreak the greater

trek recommences. The enemy has not been idle: in

the distance behind rolls the thunder of heavy guns;

pillars of smoke and flame rise from burning villages.

And as, day after day, a new stage of retirement—increasingly

controlled, it is true—is ordered, the

question pierces deeper: What is to become of France?

Those who have lived at the centre as well as on

the skirts of armed hosts become habituated to one enveloping

condition: the rank and file, and even most

of the officers, know little or nothing of what is passing

outside their own particular spheres. It is in the

nature and necessity of military operations, especially

at the beginning and in a phase of rapid movement,

that it should be so. Perhaps it is also a necessity

of the psychology of endurance. Of these

republican armies, only a small minority of the men

were old soldiers; most of them had all they could do

to adapt themselves, day by day and hour by hour,8

to the new world of violence, squalor, and general

unreason in which they were now prisoned. They

had to learn to bear fatigue and pain such as they had

never known; to overcome the spasm of fear that grips

the stoutest heart in unaccustomed emergencies; to

thrust the bayonet not into a sandbag, but into soft,

quivering flesh, and draw it forth again; to obey men

who were incompetent and stupid, as well as born

leaders. The German heavy shells, aeroplanes, motor

transport, the formidable entrenchments and fields

of wire—gradually they recognised these and other

elements of the invader’s superiority. Weaklings

cried: “We are betrayed. It is 1870 over again.”

What could the bravest reply? Letters were few

and far between. Newspapers were never so barren.

What was Paris doing? What were Russia and

England doing? The retreating columns marched

with downcast eyes, wrapped in a moody silence.

By what revolt of the spirit did these apparently

broken men become, a fortnight later, the heroes of the

Marne? The answer must be that they were not

broken, but were passing through the sort of experience

which, in a virile race, wakens the dull-minded

to their utmost effort, blows away the last traces of

laxity and false idealism, and, by setting above

every other fear the fear of a ruined Fatherland,

rallies the whole mass on the elementary ground of

defence to the death. Voices, lying voices, had

whispered that France was diseased, body and soul,

that the Republic would surely die of its corruptions.

We have since discovered the immeasurable strength

of democratic communities. Then it was questioned

by the few, unsuspected by the many. England and9

America, even more than France, had outgrown any

sort of liking for war. To be driven back to that

gross test was a profound surprise. For the quick,

proud French mind to find itself suddenly in face of

defeat and the threat of conquest was a second and

severer shock. The long retreat gave it time to perceive

that this calamity arose largely from its own

errors, and to re-group its forces in a truer conception

of the character of modern warfare. Even Joffre

may not have clearly realised this need; great instincts

count in the crisis of leadership equally with powerful

reasoning. Amid the tramp-tramp of the weary,

dust-blinded columns, by the night bivouacs, under

the rain of shrapnel and the crash of high explosive,

men of the most diverse condition and character,

shedding old vanities and new alarms, came down

step by cruel step to the fundamental honesty, unity,

and resolution of our nature. The mirage of an easy

victory vanished; in its place a finer idea rose and

rose till the armies saw nothing else: France must

live! I may die, or be doomed to a travesty of life;

at any price, France must be saved.

So the steel was tempered for the supreme trial.

10

CHAPTER II

A TRAGEDY OF ERRORS

I. The German Plan of Campaign

“Errors,” “vanities”? These words must

be justified, however gently, however briefly.

To regard the battle of the Marne without

reference to the grievous beginnings that led to and

shaped it would be to belittle and falsify a subject

peculiarly demanding care for true perspective. The

battle may be classed as negatively decisive in that it

arrested the invasion long enough to enable the Allies

to gain an equality of forces, and so to prevent a final

German victory; it was only positively decisive in

the larger sense that it re-created on a sounder base

the military spirit and power of France, which alone

among the Western Allies seriously counted in that

emergency, and, by giving the army a new direction,

the nation a new inspiration, made it possible for them

to sustain the long struggle that was to follow. Perilous

illusions, military as well as pacifist, were buried

beside the Marne. A fashion of thought, a whole

school of teaching was quietly sunk in its waters.

The French mind rose to its full stature as the nature

of the surprise into which it had fallen broke upon it.

This surprise was threefold. In the first place,

the German plan of campaign was misconceived.11

That plan was grandiose in its simplicity. It rested

upon a sound sense of the separation of the Allies:

their geographical dispersion, which gave the aggressor

the advantages famous in the career of Frederick the

Great, as in that of Napoleon; the diversity of character,

power, and interest within the Entente, which

was, indeed, hardly more than an improvisation,

without any sort of common organ, so far; its lack of

unity not only in command but in military theory and

practice generally. The first of these data indicated

to the German Command the Frederician succession

of swift offensives; the second narrowed the choice

for the first effort, and suggested an after-work of

political intrigue; the third had fortified Prussian

pride and discipline with a daring strategy and an

armament superior, in most respects, to anything the

rest of the world had conceived to be possible. Which

of the three great States, then, should be first struck

down? The wildest Pan-Germanist could not reply

“England,” in face of her overwhelming sea-power.

So the British Empire, with the North Sea and Channel

coasts, were, for the moment, ignored. Its internal

problems, its peaceful, almost neutral, temper, its

slow-mindedness in European affairs, were more

regarded than the trivial military force which alone

England could at once offer its friends. For speed

was to be of the essence of the plan. Remained

France and Russia; and here political as well as

military calculations entered. The inchoate Empire

of the East would, it was thought, be the slower in

getting to its feet. Would a new Moscow expedition

break its will for self-defence? The author of the

“Willy-Nicky” letters imagined a better way. France12

would stand by her ally. The “Republic of the

Rochettes and Steinheils,” however, was not naturally

impregnable; when it was finished, would not “dear

Nicky” be glad to return to the Drei-Kaiserbund, the

old Bismarckian order, and to join in a friendly rearrangement

of the world? So the conclusion, with

all the neatness of a professorial thesis: Russia was

to be held up—actively, on the south, by the Austro-Hungarian

armies, passively on the north, by a screen

of German troops—while France, as the principal

enemy, was swiftly crushed. Thus far, there should

have been no surprise.

It was otherwise with the plan of campaign itself,

and there are details that will remain in question till

all the archives are opened. Yet this now appears

the only plan on which Germany could hope to bring

an aggressive war to a successful issue. A repetition

of the triumph of 1870 would not be enough, for, if

France resisted as long this time, everything would

be put in doubt. The blow must be still more swift

and overwhelming. To be overwhelming, it must at

once reach not portions, but the chief mass, of the

French armies. But nowhere in the world had

military art, working upon a favourable terrain, set

up so formidable a series of obstacles to grand-scale

manœuvre as along the line of the Meuse and Moselle

Heights and the Vosges. A piercing of this line at

the centre, between the fortified systems of Verdun–Toul

on the north and Epinal–Belfort on the south,

might be an important contributory operation; in

itself it could not give a speedy decision. A mere

diversion by Belgium, in aid of a main attack in

Lorraine, would not materially alter this calculation.13

The full effects of surprise, most important of all

factors in a short struggle, could only be expected

where the adversary was least prepared, which was

certainly across the north. These offensive considerations

would be confirmed by a defensive consideration:

German Lorraine, also, was so fortified

and garrisoned as to be beyond serious fear of invasion.

In neither direction could Alsace provide

favourable conditions for a great offensive.

The political objects of the war being granted, these

arguments would lead to the strategical conclusion:

the strongest possible force will be so deployed, on a

vast arc stretching from southern Lorraine to Flanders,

that its superiority may at once be brought fully into

play. The method was a variant drawn from

the teaching of Clausewitz and Schlieffen. The

“march on Paris” occupied in the plan no such

place as it long held in the popular imagination. The

analogy of closing pincers has been used to describe

the simultaneous onset of seven German armies ranged

in a crescent from the Vosges to Brussels; but it is

uncertain whether the southern wing was originally

intended to participate immediately in the destructive

stroke, or whether this purpose followed upon the

collapse of the first French offensives. The latter

supposition is the more probable; and we may,

therefore, rather picture a titanic bolas ending in five

loaded cords, of which the two outer ones are the

most heavily weighted. These two outer masses were

(a) Kluck’s and Bülow’s Armies on the west; (b) the

Crown Prince of Bavaria’s and Heeringen’s on the

east. Approximately equal, they had very different

functions, the road of the one being open, of the other14

closed; the one, therefore, being essentially offensive,

the other provisionally defensive. Between these

two masses, there were three lesser forces under

Hausen, the Duke of Würtemberg, and the Imperial

Crown Prince. While the eastern armies held the

French forces as originally concentrated, the western

mass, by an immense envelopment, was to converge,

and the three inner bodies were to strike direct,

toward the north-centre of France—perhaps toward

the upper Seine, but there could hardly be a precise

objective till the invasion developed2—destroying any

resistance in their path. The eastern thrust which

actually followed appears, on this hypothesis, as an

auxiliary operation rather than part of a double

envelopment: we shall see that, delivered at the

moment when the Allies in the west were being

driven in between Le Cateau and Givet, it failed

against a successful defence of the only open road of

the eastern frontier, the Gap of Charmes, and that

it again failed a fortnight later. The other German

armies went triumphantly forward. In every part

of the field is evident the intention to conceal, even

to hold back, the movements of approach, and so to

articulate and synchronise them that, when the hour

of the decisive general action had arrived, there should

be delivered a single, sudden, knock-out blow.

II. The Forces in Play

In every part the German war-machine was designed

and fitted to deliver such a blow. Its effective

force was the second great element of surprise for the

Entente.

15

It is now clear that, taking the field as a whole,

France was not overwhelmed by superior numbers.

True, as a French official report says, “the military

effort of Germany at the outset of the war surpassed

all anticipations”; but the element of surprise

lay not in numbers, but in fighting quality

and organisation. Of the whole mass mobilised in

August 1914, one quarter was sent to the East. The

remainder provided, in the last week of August, for

employment against Belgium and France, an effective

force of about 80 infantry divisions—45 active, 27

reserve, mixed Ersatz brigades presently grouped in

6 divisions, and 4 Landwehr divisions in course of

formation,3 with about 8 divisions of cavalry,—about

a million and a half of men, for the most part young,

highly trained and disciplined, including 115,000

re-engaged non-commissioned officers (double the

strength of the French company cadres). Of the

prodigious mass of this west-European force, about

a half was directed through Belgium, and—essential

fact—nearly a third passed to the west of the

Meuse.

The French, on the other hand, admirably served

by their railways,4 put at once into the field 86

divisions (47 active, 25 reserve, 12 Territorial, and

2 Moroccan), of which 66 were at the front, with 7

divisions of cavalry, on the eve of the critical battles

of the Sambre and the Gap of Charmes, in the third

week of August. Before the battle of the Marne, all

French active troops had been withdrawn from the

Italian frontier, only a few Territorials being left

there. An exact numerical comparison cannot yet

be made. It seems certain, however, that, including16

five British and six Belgian divisions, in the whole

field the Allies were not outnumbered. There was

no great difference in cavalry.

But there was a vital difference in the infantry

organisation, as to which the French Command had

been completely deceived. Not only had it failed to

foresee the creation of brigades of Ersatz troops (to

say nothing of the Landwehr divisions which appeared

in September): it had never contemplated the use of

reserve formations as troops of shock. In the

French Army, the reserve battalions, regiments, and

divisions were so many poor relations—inadequate in

younger officers and non-coms, insufficiently armed

(especially in artillery), insufficiently trained and

disciplined, and, accordingly, destined only for lesser

tasks. When, as occurred almost at once under

pressure of the successful example of the enemy,

reserve divisions and groups of divisions had to be

thrown into the front line, the homogeneity of the

armies and the confidence of their chiefs suffered.

Meanwhile, realising a plan initiated in 1913, the

German Staff had created 16 army corps of reserves,

of which 13 were used on the Western front, where

they proved as solid as the regulars, and were given

tasks as responsible in all parts of the field. The main

mass of attack, therefore, consisted not of 22, but 34,

army corps—a difference larger than the strength

of the two armies of Kluck and Bülow to which the

great enveloping movement was entrusted.5 Without

this supplementary force—the result not of

numbers available, but of superior training and

organisation—the invasion could hardly have been

attempted, or would assuredly have failed. On the17

other hand, as we shall see, had it been anticipated,

the French plan of campaign must have been profoundly

modified.

The balance in armament was not less uneven. The

French 3-inch field-gun from the first justified the

highest expectations of its rapidity and accuracy of

fire. But in pieces of heavier weight and longer

range the inferiority was flagrant. While Frenchmen

had been counting their “75” against heavier but

less handy German guns, while they were throwing

all the gravamen of the problem of national defence

on three-years’ service, the enemy was developing a

set of instruments which immensely reinforced his

man-power. Instead of resting content with light

guns, he set himself to make heavier types more

mobile. The peace establishment of a German active

corps included 160, a French only 120, guns. It was,

however, in weight, rather than numbers, that the

difference lay. Every German corps had 16 heavy

5·9-inch mortars. The French had no heavy artillery

save a few batteries of Rimailho 6·1-inch rapid-fire

pieces, and a few fortress cannon. In addition to 642

six-piece batteries of horse and field artillery (3·1-inch

field-gun and 4·1-inch light howitzer), the German

armies had, in all, before the mobilisation, 400 four-piece

batteries of 5·9-inch howitzers and 8·2-inch mortars.

The German artillery alone at the outset had aviators

to correct their fire. “Thus,” says General Malleterre,

speaking from experience in the long retreat6—“thus

is explained the terrible surprise that our troops

suffered when they found themselves overwhelmed at

the first contact by avalanches of projectiles, fired

from invisible positions that our artillery could not18

reach. For there was this of unexpected in the German

attack, that, before the infantry assault, the deployment

of units was preceded by showers of shells of all

calibres, storms of iron and fire arresting and upsetting

our shaken lines.”

In air services, in petrol transport, and in the art

of field defences, also, the French were outmatched.

Aviation was essentially their sport and science; but

the army had shown little interest in it, and had made

only a beginning in its two main functions—general

reconnaissance and the ranging of artillery fire.7

Thus ill-prepared for a modern large-scale offensive,

France had not acquired the material or the tactic

of a strategical defence. The light and rapid “75”

had been thought of almost exclusively as an arm of

attack, in which weight and range were now become

the master properties. Its remarkable qualities for

defence began to appear in the unfortunate actions

presently to be traced, and were only fully understood

many months later, when “barrage” fire had been

elaborated. The mitrailleuse was essentially a French

invention; but its greatest value—in defence—was

not yet appreciated. The numerical provision of

machine-guns was the same as that of the German

Army (though differently organised). It was owing

to a more considerable difference of tactical ideas

that a legend grew up of an actual German superiority

in this arm. In the French Army, all defensive

methods were prejudiced; in the German, they were

not. The deep trenches that might have saved

much of Belgium and northern France were

scouted, until it was too late, as incompatible with

the energy and pride of a great army. The lessons19

from recent wars drawn, among others, by the

Russian State Councillor, Jean de Bloch, fifteen years

before,8 went for nothing. “It is easy to be ‘wise

after the event,’” writes Field-Marshal French; “but

I cannot help wondering why none of us realised what

the most modern rifle, the machine-gun, motor traction,

the aeroplane, and wireless telegraphy would bring

about. It seems so simple when judged by actual

results.... I feel sure that, had we realised the true

effect of modern appliances of war in August 1914,

there would have been no retreat from Mons.”9

While the German armies were born and bred in the

old offensive spirit, their masters had seen the difficulties

created by the development of modern gunfire.

With a tireless and pitiless concentration of will,

the men had been organised, trained, and in every

essential way provided, to carry out an aggressive

plan of campaign. Yet their generals did not despise

scientific field-works, even in the days of their first

intoxication, as witness any French story of the battle

of Morhange, or this characteristic note on the fighting

in the region of Neufchateau and Palliseul: “The

enemy, whom our aeroplanes and cavalry had not been

able to discover, had a powerful defensive organisation:

fields of wire entanglement on the ground;

wide, deep holes concealing pikes and sword blades;

lines of wire 2 yards high, barbed with nails and hooks.

There were also, unfortunately, in certain of our corps,

insufficiencies of instruction and execution, imprudences

committed under fire, over-bold deployments leading

to precipitate retreats, a lack of co-ordination between

the infantry and the artillery. The enemy profited

by our inexperience of the sort of defence he had20

organised.”10 For the German soldiers at the outset

of the war, this was only a passing necessity. The

principle of the instant strategical offensive well expressed

the spirit of an authoritarian Government

bent on aggression, of its constituency, at once

jealous and servile, and its war-machine, sustained

by a feverishly developed industrialism. None of these

conditions obtained under the Third Republic. Of

the weaknesses of the French Army in tactical science,

one result is sufficiently tragic proof; in the first

month of the war, 33 army corps and divisional

generals were removed from their commands.11

III. The French War Doctrine

It was not the fault, but the glory, of France that

she lived upon a higher level, to worthier ends, than

her old enemy. But if we find reason to suspect that,

the nation having accepted the burden of taxation

and armed service, its arms and preparation were not

the best of their kind, that a superstitious fidelity to

conservative sentiments and ideas was allowed to

obscure the hard facts of the European situation and

the changing nature of modern warfare, the fact

that certain critics have plunged rashly into the

intricacies of a most difficult problem, or the risk

of being corrected when more abundant information

appears, must not prevent us from facing a conclusion

that is important for our subject. We do not

espouse any partisan thesis, or question any individual

reputation; we can do no more here than open a line

of inquiry, and no less than recall that the men whose

responsibility is in cause had suddenly to challenge21

fate on evidence at many points slighter than now

lies before any studious layman.

In every detail, Germany had the benefit of the

initiative. The French Staff could not be sure in

advance of British and Belgian aid or of Italian

neutrality, and it was bound to envisage the possibility

of attack by the Jura, as well as by Belgium. It

could not be sure that any smaller strength would

secure the Lorraine frontier; and it was possibly right

in regarding a defeat on the east as more dangerous

than a defeat in the north. The distrust of fortification,

whether of masonry and steel, or of field-works,

may have become exaggerated by a too lively sense

of the power of the newer artillery; but it had a certain

basis in the fear of immobilising and paralysing the

armies. To discover a happy mean between a

dangerous obstinacy in defending a frontier, and a

dangerous readiness to abandon precious territory and

its people in order to preserve freedom of movement,

was perhaps beyond any brain of that time. Nevertheless,

when all allowances have been made, it must

be said (1) that the importance of gaining time by

defensive action was never realised, and this chiefly

because of dogmatic prepossessions; (2) that the

actual concentration expressed a complete misjudgment

of the line of greatest danger; and (3) that these

two faults were aggravated by the kind of offensive

upon which all hopes were placed. The misapprehension

of the German system of reserves, referred to

above, and therefore of the total effective strength of

the enemy, had led the French Staff to conclude that

there was nothing to fear west of the Meuse, and at the

same time had confirmed a temperamental belief in22

the possibility of crippling the attack by a rapid and

unrestrained offensive. The whole conception was

erroneous.

For Belgium, there was no other hope than a provisional

defensive. In any war with Germany, the

principal object for France, it now seems evident, must

be to stave off the coup brusqué till Russia was fully

ready, and England could bring more aid. But the

traditional dogma was in possession; any doubt was

damned as a dangerous heresy. The chief lesson of

1870 was now thought to be the folly of passivity.

Looking back upon events, many French soldiers

recognise, with General Malleterre, that the French

strategy should have been “a waiting disposition

behind a powerfully-organised Meuse front, with a

mass of manœuvre ready to be directed against the

principal attack.” “But,” adds this writer, “our

minds had been trained in these latter years to the

offensive à outrance.”12 They had been trained in part

upon German discussions, the deceptive character of

which, and the very different facts behind, were not

realised. At its best, for instance in Foch’s lectures

at the Ecole Supérieure de Guerre (1895–1901), there

was in this teaching somewhat too much of emotion,

too little of cold analysis. The faith in sheer energy

and will is placed too high, the calculation of means to

ends too slightly insisted upon. It is true, it is, indeed,

a truism, that “the battle must not be purely defensive,”

that “every defensive battle must be terminated

by an offensive action, or it will lead to no

result.” Foch himself, before he had risen to the

supreme direction of the Allied armies, had learned

to recognise that, with millions of men in play, no23

effort of will can suddenly give a decision, that the

defensive may have to continue for months, even for

years, a new war-machine may have to be built up,

ere a victorious reaction becomes possible.

In the General Staff instructions of October 28,

1913, the doctrine had received its extremest expression.

The milder instructions of 1895 were condemned

as based upon the “most dangerous” idea

that a commander might prefer defence on a favourable,

to attack on an unfavourable, ground. “In

order to avoid all misunderstanding on so important a

point of doctrine, the new instructions admit only a

single justification for the defensive in combat, that

is, the necessity of economising troops on certain points

in order to devote more forces to attacks; so understood,

the defensive is, properly speaking, no more

than an auxiliary of the offensive.” “The offensive

alone leads to positive results”; this is the sole

permissible rule governing the conduct of operations.

Attacks must be pressed to the extremity without

arrière-pensée or fear of heavy losses: “every other

conception must be rejected as contrary to the very

nature of war” (art. 5). “A Commander-in-Chief

will never leave to his adversary the priority of action

on the pretext of waiting for more precise information;

he will, from the beginning of the war, stamp it with

such a character of violence and determination that

the enemy, struck in his morale and paralysed in

action, will perhaps find himself compelled to remain

on the defensive” (art. 6). “All the decisions of the

command must be inspired by the will to seize and

keep the initiative”; and they must be pursued

“even if the information collected up to then on the24

forces and dispositions of the enemy be obscure and

incomplete.” The plan should, indeed, be supple,

so that changes can be made according to new information;

but “success in war depends more on perseverance

and tenacity than on ability in the conception

of the manœuvre” (art. 15). “The French Army,”

added the Commission which elaborated these rules,

“returning to its traditions, now admits in the conduct

of operations no law other than that of the offensive.”

Fortunately, no code can do more than hamper the

natural elasticity of the French mind. But the direction

of the armies from top to bottom, and even the

traditional aim of keeping in hand a mass of manœuvre,

which had figured strongly in the teaching of Foch

and other military writers of ten or fifteen years

before, were affected by the current prescriptions

of the Staff. We cannot here attempt to trace the

growth of the perversion. The spirit of the French

command on the eve of the war is, however, sufficiently

evidenced in its actual dispositions; and we know

that it threw its only mass of manœuvre (the 4th Army)

into the Belgian Ardennes in the third week of August,

and had to fight the battle of the Marne without any

general reserve. In brief, along with every arm and

method of defence, the service of information, the

preparation of battle, and the art of manœuvre—which

is irreconcilable with a dogma of universal and

unconditional attack—were depreciated and prejudiced.13

In the strength and weakness of this

creed, France entered the war.

The results in the lesser commands were serious

enough. Speaking of the advance into the Ardennes,

M. Hanotaux, in general an apologist of the old school,25

says that it was conducted “in an extremely optimistic

mood,” that “mad bayonet charges were launched

at a mile distance from the enemy without artillery

preparation,” and that, “doubtless, the spirit of the

offensive, ill-regulated and ill-restrained, among officers

as well as men, was one of the causes of our reverse.”

Officers and men took only too literally the rules on

which they had been trained. Strengthened by the

general belief in a short war, and by an exaggerated idea

of the importance of first results, a like infatuation

governed the strategy and the tactics of the French

armies. A succession of surprises marks the light

regard for information of the enemy’s means and

movements, as a series of instant reverses measures

the scorn for well-pondered manœuvre. Was France

required by her Eastern ally to attack at once? The

attack need not have surpassed the proportions of

holding actions punctuating a stout defence. Was

Belgium closed to the French armies by the old treaty

of neutrality? That did not justify a plan of campaign

which left the north uncovered to a German

aggression. For all that followed from disunity of

the Allied commands, England and Belgium share the

responsibility. Had they, as well as Russia, been long

in alliance, and Italy’s neutrality assured in advance,

all might have gone otherwise; probably, indeed, there

would have been no war. These circumstances do

not afford excuse for a radically unsound conception

of the danger and the reply.

A German attack through Belgium had been much

and long discussed. If few would have said before the

event, as the German Chancellor and Foreign Secretary

pleaded immediately afterward, that it was “a question26

of life and death for the Empire,” “a step absolutely

required,” it was at least more than probable; and

we have Marshal Joffre’s word for it that the contingency

was contemplated by the French Staff.14

But two doubts remained, even in vigilant minds.

Would the invasion by the north be large or small, and

would it be more or less extensive, proceeding only

by Belgian Luxembourg and the Meuse valley, or also

by a more daring sweep across the Flanders plain into

the valley of the Oise? Moltke had advocated a

march to the North Sea coast, and a descent by the

Channel ports, through the trouée of the Oise, upon

Paris, turning not merely the principal line, but the

whole system, of the French fortresses. Bernhardi

had toyed with the idea of an even more extensive

movement, violating Dutch territory, but seemed

at last to favour the more limited project, “the army

of the right wing marching by the line Trêves–Stenay,

crossing Luxembourg and southern Belgium.” In

fact, neither of these ways was taken. The invasion

pursued a middle route, Holland being avoided, the

descent upon the coast deferred, and armies thrown

across both the Flanders plain and the difficult country

of the Belgian Ardennes.

Notwithstanding the advertisement of the Kaiser’s

chief Ministers in their famous pleas in justification,

on the first day of the war, the French Staff do not

seem to have anticipated anything more in the north

than an attack by Luxembourg and the Ardennes,

or to have altered their dispositions to meet it until

the middle of August. We do not yet fully know

what are the reasons for the arrest of the German

offensive after the effective reduction of Liège, until27

August 19. Instead of six days, with, perhaps, three

more for re-concentration, the German right wing took

sixteen days in crossing Belgium. As this week of

Belgium’s vicarious sacrifice saved France, it cannot

be supposed to have been a voluntary delay made

simply for the purpose of deceiving the Allies. It

had that effect, however. Thwarted at Liège, the

German command did everything it could to conceal

the true nature of the blow it was about to deliver—by

terrorising the population and occupying the mind

of the world with its atrocities, by the ubiquitous

activity of its cavalry screen, by avoiding Western

Flanders and the coast, and by holding up the advance

of its first three armies behind the line of the Gette

and the Meuse till everything was ready. The Allies

altogether failed to pierce the veil of mystery covering

the final concentration. They were deceived (1) as

to the main direction of the coming onslaught, (2) as

to its speed, (3) as to its power in men and armament.

General Sordet’s cavalry got little information during

their Belgian wanderings; the few French aviators

still less. No doubt, the Allies hoped for a longer

Belgian resistance, especially at Liège and Namur,

as the enemy expected a shorter. The French Staff

clung blindly to its belief that it need expect, at most,

only an attack by the Meuse valley and the Ardennes.15

The first French plan of campaign, then, envisaged

solely the eastern and north-eastern frontier. The

original concentration placed the two strongest armies,

the 1st and 2nd (Dubail and Castelnau—each five

corps) between Belfort and Toul; the 3rd and 5th

(Ruffey and Lanrezac—three and five corps respectively)

from Verdun to Givet, where the Meuse enters28

Belgium; the 4th (de Langle de Cary—three corps)

supporting the right, at its rear, between the Argonne

and the Meuse. Of 25 reserve divisions, three were

kept in the Alps till Italy declared her neutrality, three

garrisoned Verdun, and one Epinal. The remainder

were grouped, one group being sent to the region of

Hirson, one to the Woevre, and one before Nancy.

There was also a Territorial group (d’Amade) about

Lille. These dispositions are defended as being supple

and lending themselves to a redirection when the

enemy’s intentions were revealed.16 We shall see that,

within a fortnight, they had to be fundamentally

changed, Lanrezac being sent into the angle of the

Sambre and Meuse, de Langle bringing the sole reserve

army in on his right, and Ruffey marching north into

the Ardennes—a north-westerly movement involving

awkward lateral displacements, the crossing of columns,

and oblique marches. Some of the following failure

and confusion resulted from the dislocating effect of a

conversion so vast.

IV. The Three French Offensives

Instead of an initial defensive over most of the

front, with or without some carefully chosen and

strongly provided manœuvre of offence—as the major

conditions of the problem would seem to suggest—the

French campaign opened with a general offensive,

which for convenience we must divide into three parts,

three adventures, all abortive, into Southern Alsace,

German Lorraine, and the Belgian Ardennes. The

first two of these were predetermined, even before

General Joffre was designed for the chief command;29

the second and third were deliberately launched after

the invasion of Belgium was, or should have been,

understood. A fourth attack, across the Sambre, was

designed, but could not be attempted.

The first movement into Alsace was hardly more

than a raid, politically inspired, and its success might

have excited suspicions. Advancing from Belfort, the

1st Army under Dubail took Altkirch on August 7, and

Mulhouse the following day. Paris rejoiced; General

Joffre hailed Dubail’s men as “first labourers in the

great work of la revanche.” It was the last flicker of

the old Gallic cocksureness. On August 9, the Germans

recovered Mulhouse. Next day, an Army of

Alsace, consisting of the 7th Corps, the 44th Division,

four reserve divisions, five Alpine battalions, and a

cavalry division, was organised under General Pau. It

gained most of the Vosges passes and the northern

buttress of the range, the Donon (August 14). On the

19th, the enemy was defeated at Dornach, losing 3000

prisoners and 24 cannon; and on the following morning

Mulhouse was retaken—only to be abandoned a

second time on the 25th, with all but the southern

passes. The Army of Alsace was then dissolved to

free Pau’s troops for more urgent service, the defence

of Nancy and of Paris.

The Lorraine offensive was a more serious affair, and

it was embarked upon after the gravity of the northern

menace had been recognised.17 The main body of the

Eastern forces was engaged—nine active corps of the

2nd and 1st Armies, with nine reserve and three cavalry

divisions—considerably more than 400,000 men, under

some of the most distinguished French generals, including

de Castlenau, unsurpassed in repute and30

experience even by the Generalissimo himself; Dubail,

a younger man, full of energy and quick intelligence;

Foch, under whose iron will the famous 20th Corps of

Nancy did much to limit the general misfortune; Pau,

who had just missed the chief command; and de

Maud’huy, a sturdy leader of men. As soon as the

Vosges passes were secured, after ten days’ hard

fighting, on August 14, a concerted advance began,

Castelnau moving eastward over the frontier into the

valley of the Seille and the Gap of Morhange, a narrow

corridor flanked by marshes and forests, rising to formidable

cliffs; while Dubail, on his right, turned north-eastward

into the hardly less difficult country of the

Sarre valley. The French appear to have had a marked

superiority of numbers, perhaps as large as 100,000

men; but they were drawn on till they fell into a

powerful system, established since the mobilisation, of

shrewdly hidden defences, with a large provision of

heavy artillery, from Morville, through Morhange,

Bensdorf, and Fenetrange, to Phalsburg—the Bavarian

Army at the centre, a detachment from the Metz

garrison against the French left, the army of Von

Heeringen against the right. The French command

can hardly have been ignorant of these defences,

but must have supposed they would fall to an impetuous

assault. Dubail held his own successfully throughout

August 19 and 20 at Sarrebourg and along the Marne-Rhine

Canal, though his men were much exhausted.

Castelnau was immediately checked, before the natural

fortress of Morhange, on August 20. His centre—the

famous 20th Corps and a southern corps, the 15th—attacked

at 5 a.m.; at 6.30 the latter was in flight,

and the former, its impetuosity crushed by numbers31

and artillery fire, was ordered to desist. The German

commanders had concentrated their forces under

cover of field-works and heavy batteries. Under the

shock of this surprise, at 4 p.m., Castelnau ordered the

general retreat. Dubail had to follow suit.

Happily, the German infantry were in no condition

for an effective pursuit, and the French retirement was

not seriously impeded. The following German advance

being directed southward, with the evident intention

of forcing the Gap of Charmes, and so taking all the

French northern armies in reverse, the defence of

Nancy was left to Foch, Castelnau’s centre and right

were swung round south-westward behind the Meurthe,

while Dubail abandoned the Donon, and withdrew to

a line which, from near Rozelieures to Badonviller and

the northern Vosges, made a right-angle with the line

of the 2nd Army, the junction covering the mouth of the

threatened trouée. In turn, as we shall see (Chap. III.

sec. iii.), the German armies here suffered defeat, only

five days after their victory. But such failures and

losses do not “cancel out,” for France had begun at

a disadvantage. Ground was lost that might have

been held with smaller forces; forces were wasted that

were urgently needed in the chief field of battle. Evidently

it was hoped to draw back parts of the northern

armies of invasion, to interfere with their communications,

and to set up an alarm for Metz and Strasbourg.

These aims were not to any sensible extent accomplished.

Despite the improbability of gaining a rapid success

in a wild forest region, the French Staff seems to have

long cherished the idea of an offensive into the Belgian

Ardennes in case of a German invasion of Belgium,

the intention being to break the turning movement by32

a surprise blow at its flank. By August 19, the French

were in a measure prepared for action between Verdun

and the Belgian Meuse. Ruffey’s 3rd Army (including

a shortlived “Army of Lorraine” of six reserve

divisions under Maunoury), and Langle de Cary’s

4th Army, brought northwards into line after three or

four days’ delay, counted together six active corps

and reserve groups making them nearly equal in numbers

to the eleven corps of the Imperial Crown Prince

and the Duke of Würtemberg. But, behind the

latter, all unknown till it debouched on the Meuse, lay

hidden adroitly in Belgian Luxembourg another

army, the three corps of the Saxon War Minister,

Von Hausen. Farther west, the disparity of force

was greater, Lanrezac and Sir John French having only

about seven corps (with some help from the Belgians

and a few Territorial units) against eleven corps

left to Bülow and Kluck after two corps had been

detailed to mask the Belgian Army in Antwerp.

Neither the Ardennes nor the Sambre armies could be

further strengthened because of the engagements in

Lorraine and Alsace.

A tactical offensive into the Ardennes, a glorified

reconnaissance and raid, strictly limited and controlled,

might perhaps be justified. The advance

ordered on the evening of the defeat of Morhange,

and executed on the two following days, engaging

the only general reserve at the outset in a thickly-wooded

and most difficult country, was too large

for a diversion, and not large enough for the end

declared: it failed completely and immediately—in a

single day, August 22—with heavy losses, especially

in officers.18 Here, again, there was an approximate33

equality of numbers; again, the French were lured

on to unfavourable ground, and, before strong entrenchments,

crushed with a superiority of fire.

Separated and surprised—the left south-west of

Palliseul, the centre in the forests of Herbeumont and

Luchy, the Colonial Corps before Neufchateau and

Rossignol, where it fought literally to the death

against two German corps strongly entrenched, the

2nd Corps near Virton—the body of the 4th Army was

saved only by a prompt retreat; and the 3rd Army

had to follow this movement. True, the German IV

Army also was much exhausted; and an important

part of the enemy’s plan missed fire. It had been

soon discovered that the Meuse from Givet to Namur

was but lightly held; and the dispatch thither of the

Saxon Army, to cut in between the French 4th and 5th

Armies, was a shrewd stroke. Hausen was late in

reaching the critical point, about Dinant, and, by

slowness and timidity, missed the chance of doing

serious mischief.

Meanwhile, between the fields of the two French

adventures into German Lorraine and Belgian Luxembourg,

the enemy had been allowed without serious

resistance to occupy the Briey region, and so to carry

over from France to Germany an iron- and coal-field

of the utmost value. “Briey has saved our life,”

the ironmasters of the Rhineland declared later on,

with some exaggeration. Had it been modernised,

the small fortress of Longwy, situated above the

River Chiers three miles from the Luxembourg frontier,

might have been an important element in a defence of

this region. In fact, its works were out of date, and

were held at the mobilisation by only two battalions34

of infantry and a battery and a half of light guns.

The Germans summoned Colonel Darche and his

handful of men to surrender on August 10; but the

place was not invested till the 20th, the day on which

the 3rd Army was ordered to advance toward Virton

and Arlon, and to disengage Longwy. Next day,

Ruffey was north and east of the place, apparently

without suspecting that he had the Crown Prince’s

force besieging it at his mercy. On the 22nd, it was

too late; the 3rd and 4th Armies were in retreat;

Longwy was left to its fate.19

V. The Battle of Charleroi–Mons

The completest surprise naturally fell on the west

wing of the Allies; and, had not the small British

force been of the hardiest stuff, an irreparable disaster

might have occurred. Here, with the heaviest preponderance

of the enemy, there had been least preparation

for any hostilities before the crisis was

reached. On or about August 10, we war correspondents

received an official map of the “Present

Zone of the Armies,” which was shown to end, on the

north, at Orchies—16 miles S.E. of Lille, and 56 miles

inland from Dunkirk. The western half of the northern

frontier was practically uncovered. Lille had ceased

to be a fortress in 1913, though continuing to be a

garrison town; from Maubeuge to the sea, there was

no artificial obstacle, and no considerable body of

troops.20 The position to be taken by the British

Expeditionary Force—on the French left near Maubeuge—was

only decided, at a Franco-British Conference

in London, on August 10.21 On August 12, the British35

Press Bureau announced it as “evident” that “the

mass of German troops lie between Liège and Luxembourg.”

Three days later, a Saxon advance guard tried,

without success, to force the Meuse at Dinant. Thus

warned, the French command began to make the new

disposition of its forces which has been alluded to.

Lanrezac had always anticipated the northern attack,

and had made representations on the subject without

effect.22 At last, on August 16, General Joffre, from

his headquarters at Vitry-le-François, in southern

Champagne, agreed to his request that he should move

the 5th Army north-westward into the angle of the

Sambre and Meuse. At the same time, however, its

composition was radically upset, the 11th Corps and

two reserve divisions being sent to the 4th Army,

while the 18th Corps and the Algerian divisions were

received in compensation. On August 16, the British

Commander-in-Chief, after seeing President Poincaré

and the Ministers in Paris, visited the Generalissimo

at Vitry; and it was arranged that the Expeditionary

Force, which was then gathering south of Maubeuge,

should move north to the Sambre, and thence to the

region of Mons. On the same day, General d’Amade

was instructed to proceed from Lyons to Arras, there

to gather together three Territorial divisions of the

north which, reinforced by another on the 21st and

by two reserve divisions on the 25th, ultimately

became part of the Army of the Somme. Had there

been, on the French side, any proper appreciation of

the value of field-works, it might, perhaps, not have been

too late to defend the line of the Sambre and Meuse.

It was four or five days too late to attempt a Franco-British

offensive beyond the Sambre.

36

To do justice to the Allied commanders, it must

be kept clearly in mind that they had (albeit largely

by their own fault) but the vaguest notion of what

was impending. Would the mass of the enemy come

by the east or the west of the Meuse, by the Ardennes

or by Flanders, and in what strength? Still sceptical

as to a wide enveloping movement, Joffre was reluctant

to adventure too far north with his unready

left wing; but it seemed to him that, in either case,

the intended offensive of the French central armies

(the 3rd and 4th) across the Ardennes and Luxembourg

frontier might be supported by an attack by Lanrezac

and the British upon the flank of the German western

armies—the right flank, if they passed by the Ardennes

only; the left, if they attempted to cross the Flanders

plain toward the Channel. Thus, it was provisionally

arranged with the British Commander that, when the

concentration of the Expeditionary Force was complete,

which would not be before the evening of August 21, it

should advance north of the Sambre in the general

direction of Nivelles (20 miles north-east of Mons,

and half-way between Charleroi and Brussels). If the

common movement were directed due north, the British

would advance on the left of the 5th Army; if to the

north-east or east, they would be in echelon on its

left-rear. General Joffre recognised that the plan

was only provisional, it being impossible to define the

projected manœuvre more precisely till all was ready

on August 21, or till the enemy revealed his intentions.

It was only on the 20th that two corps of the French

5th Army reached the south bank of the Sambre—one

day before Bülow came up on the north, with his VII

Corps on his right (west), the X Reserve and X Active37

Corps as centre, the Guard Active Corps on his

left, and the VII Reserve (before Namur) and Guard

Reserve Corps in support. In this posture, on the

evening of August 20, Lanrezac received General

Joffre’s order to strike across the Sambre. Namur

was then garrisoned by the Belgian 4th Division,

to which was added, on the 22nd, part of the

French 8th Brigade under General Mangin. Lanrezac

had not even been able to get all his strength aligned on

the Sambre when the shock came.23 On the 21st, his

five corps were grouped as follows: The 1st Corps

(Franchet d’Espérey) was facing east toward the

Meuse north of Dinant, pending the arrival, on the

evening of the 22nd, of the Bouttegourd Reserve

Division; the 10th Corps (Defforges), with the 37th

(African) Division, on the heights of Fosse and Arsimont,

faced the Sambre crossings at Tamines and Auvelais;

the 3rd Corps (Sauret) stood before Charleroi, with

the 38th (African) Division in reserve; the 18th Corps

(de Mas-Latrie) was behind the left, south of Thuin.

Of General Valabrègue’s group of reserve divisions, one

was yet to come into line on the right and one on the

left.

Could Lanrezac have accomplished anything by

pressing forward into the unknown with tired troops?

The question might be debatable had the Allies had

only Bülow to deal with; but, as we shall see, this was

by no means the case. Meanwhile, the British made

a day’s march beyond the Sambre. On the 22nd

they continued the French line west-north-westward,

still without an enemy before them, and entrenched

themselves, the 5th Cavalry Brigade occupying the

right, the 1st Corps (Haig) from Binche to Mons, and38

the 2nd Corps (Smith-Dorrien) along the canal to Condé-on-Scheldt.

West and south-west of this point, there

was nothing but the aforesaid groups of French

Territorials. The I German Army not yet having

revealed itself, the general idea of the French

command, to attack across the Sambre with its centre,

and then, if successful, to swing round the Allied left

in a north-easterly direction against what was supposed

to be the German right flank, still seemed feasible.

But, in fact, Kluck’s Army lay beyond Bülow’s to the

north-west, on the line Brussels–Valenciennes; it is

quite possible, therefore, that a preliminary success by

Lanrezac would have aggravated the later defeat.

Battle of Charleroi–Mons

However that may be, the programme was at once

stultified by the unexpected speed and force of the

German approach. The bombardment of the nine

forts of Namur had begun on August 20. Bülow’s

Army reached the Sambre on the following day, and

held the passages at night. Lanrezac’s orders had

become plainly impossible, and he did not attempt to

fulfil them. Early on the afternoon of the 21st, while

Kluck approached on one hand and Hausen on the

other, Bülow’s X Corps and Guard Corps attacked

the 3rd and 10th Corps forming the apex of the French

triangle. These, not having entrenched themselves,

and having, against Lanrezac’s express orders, advanced

to the crossings between Charleroi and Namur,

there fell upon strong defences flanked by machine-guns,

and were driven back and separated. Despite repeated

counter-attacks, the town of Chatelet was lost. On

the 22nd, these two French corps, with a little help

from the 18th, had again to bear the full weight of

the enemy. Their artillery preparation was inadequate,39

and charges of a reckless bravery did not

improve their situation.24 Most desperate fighting took

place in and around Charleroi. The town was repeatedly

lost and won back by the French during

the day and the following morning; in course of these

assaults, the Turcos inflicted heavy losses on the

Prussian Guard. While the 10th Corps, cruelly

punished at Tamines and Arsimont, fell back on Mettet,

the 3rd found itself threatened with envelopment

on the west by Bülow’s X Reserve and VII Corps,

debouching from Chatelet and Charleroi.

That evening, the 22nd, Lanrezac thought there was

still a chance of recovery. “The enemy does not yet

show any numerical superiority,” he wrote, “and the

5th Army, though shaken, is intact.” The 1st Corps was

at length free, having been relieved in the river angle

south of Namur by the 51st Reserve Division; the

18th Corps had arrived and was in full action on the

left about Thuin; farther west, other reserves were

coming up, and the British Army had not been seriously

engaged. The French commander therefore asked his

British confrère to strike north-eastward at Bülow’s

flank. The Field-Marshal found this request “quite

impracticable” and scarcely comprehensible. He

had conceived, rightly or wrongly, a very unfavourable

idea of Lanrezac’s qualities; and the sight of infantry

and artillery columns of the 5th Army in retreat southward

that morning, before the two British corps had

reached their positions on either side of Mons, had

been a painful surprise. He was already in advance

of the shaken line of the 5th Army; and news was

arriving which indicated a grave threat of envelopment

by the north-west. French had come out from40

England with clear warning that, owing to the impossibility

of rapid or considerable reinforcement, he

must husband his forces, and that he would “in no

case come in any sense under the orders of any Allied

General.” He now, therefore, replied to Lanrezac that

all he could promise was to hold the Condé Canal

position for twenty-four hours; thereafter, retreat

might be necessary.