Title: Humours of '37, Grave, Gay and Grim: Rebellion Times in the Canadas

Author: Robina Lizars

Kathleen Macfarlane Lizars

Release date: August 4, 2017 [eBook #55260]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Books project.)

The correction listed in the Erratum has been incorporated into the original.

| C. W. COATES, Montreal. | S. F. HUESTIS, Halifax. |

| 1897. | |

1

Entered, according to Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year one thousand eight hundred and ninety-seven, by Kathleen MacFarlane Lizars, at the Department of Agriculture. 2

The title of this book is built upon the assumption that humour is a sense of incongruity, not that there was anything specially humorous in the affairs of ’37 beyond that which arose from the crudeness of the times.

A medium between the sacrifice of detail attendant on compilation, and the loss of effect in a whole picture through too close application of the historic microscope, has been attempted. True proportion is difficult to compass at short range, yet the motives, ideas and occurrences which produced the animosities leading to the Rebellion were the inheritance, the special property, of the men who lived then; and of them few remain. To those who do and who have so kindly given their reminiscences special thanks are due. The works of the documentary and the philosophic historian lie on the shelves ready to one’s hand; but those who were “Loyalist” and “Rebel” are quickly dropping into that silence where suffering and injustice, defeat and victory, meet in common oblivion.

Like lichens on rocks, myths have grown about that time; but the myth is worth preserving for the sake of the germ of truth which gave it birth. Historians sometimes tell the truth, not always the whole truth, certainly never anything but the truth, and nothing is to be despised which gives a peep at the life as it really was. For complexion of the times, the local colour of its action, there can be nothing like the tale of the veteran, of the white-haired, dim-eyed survivor, whose quaking voice tells out the story of that eventful day. A page from Pepys or Bellasys lifts a curtain upon what really took place when the historic essence fails; then some morsels of secret 3 history come to light, and motives and actions hitherto puzzling stand revealed.

Were all contributed sentences herein to have their rights in inverted commas the publisher’s stock would be exhausted. The prejudice in favour of Italics has not been observed in certain cases. “A bas les prejudices;” in Canada French is not a foreign language.

It is also assumed that every Canadian is familiar with Canadian history, and that some one or other of its masters is well fixed in school memories. To those masters, and to many others, an apology is tendered for wholesale appropriation of their matter. If every statement made herein were substantiated by the customary foot-note many unsightly pages would be the result; therefore, as no statement has been made without due authority, we commend our readers to the writings of Parkman, Garneau, Dent, McMullen, McCarthy, Macaulay, Michelet, DeGaspé, LeMoine, David, Morgan, Carrier, Bonnycastle, F. B. Head, George Head, Macgregor, Bender, Lindsay, Rattray, Scadding, Thompson and others; to the writings and biographies of the statesmen and governors quoted; to Governmental Journals and House of Commons Debates; for the record of events as they daily took place to innumerable manuscripts, pamphlets and newspapers, written or published between Sarnia and Quebec and in many American cities, covering in particular the years ’36, ’37, ’38, ’39, ’40; and to various sources where Canada is treated as a side issue and not as a main point. Theller and McLeod have been used where the corroborative testimony of others warrants a transcription of their humours.

“Whether an eagle or ant in the intellectual world seems to me not to matter much,” says Joubert. The work of the humble ant is to gather fragments, and, as the humblest in the tribe, the collectors of the data from which this mélange has risen offer it to the public, and as humbly hope they have come within the same writer’s further observation: “A small talent, if it keeps within its limits and rightly fulfils its task, may reach the goal just as well as a great one.”

Stratford, October, 1897. 4

Several score of authorities, known or comparatively unknown, have been drawn on in the compilation of Gallows Hill. Bill Johnston and Colonel Prince, as they appear here, are derived from twenty-one and twenty-six authorities respectively. Therefore when the hundredth, and the twenty-second, and the twenty-seventh, shall arise to contradict, or disagree with, each and every word herein, the authors beg to be allowed to see nothing but a humour in the situation. 5

[We are indebted to Miss FitzGibbon for a copy of the Cobourg Star of February 7th, 1838, in which appears, under the above title, an epitome, from one point of view, of Rebellion events. Its humours make it a fitting introduction for the papers which follow.]

11

| PAGE | |

| Baneful Domination | 13 |

| More Baneful Domination | 44 |

| The Canadas at Westminster | 63 |

| A Call to Umbrellas | 91 |

| Le Grand Brule | 132 |

| Gallows Hill | 161 |

| Autocrats All | 202 |

| Huron’s Age Heroic | 272 |

| Deborahs of ’37 | 308 |

12

13

“Every reform was once a private opinion, and when it shall be a private opinion again it will solve the problem of the age.”

The vivacious Pompadour enlivens the twenty years of her boudoir conspiracies playing les graces with her lord’s colonies. She throws the ring; Pitt, at the other end of the game, catches Canada.

The mills of the gods in their slow grind have reversed the conditions of the contestants; the Norman conquest of England becomes a British conquest of New France. The descendants of the twenty thousand barbarians who landed at Hastings have but come to claim their own.

Life is “moving music.” The third movement in this historic sonata comes back to the original subject, even if the return to the tonic opens in a minor mode.

“Gentlemen, I commend to your keeping the honour of France,” says the dying Montcalm.

“Now, God be praised, I die in peace!” and Wolfe expires.

The fiercest of the conflict ever rages round a bit of bunting on the end of a stick. The lilies of France come down; up goes the Union Jack to usher in the birthday of 14 the Greater Britain, and Horace Walpole says, “We are forced to ask every morning what victory there is, for fear of missing one.”

Voltaire gives a fête at Fernay to celebrate the deliverance from fifteen hundred leagues of frozen country; the Pompadour tells her Louis that now he may sleep in peace; and outsiders ask of Pitt that which a celebrated novelist, a century later, asks of his hero—“What will he do with it?” “The more a man is versed in business,” said the experienced Pitt, “the more he finds the hand of Providence everywhere.”

But Providence would need to have broad shoulders if generals, kings and statesmen are to place all their doings there.

By 1837 Canada was no longer a giant in its cradle. Colonial boyhood had arrived; a most obstreperous and well-nigh unmanageable youth, with many of the usual mistakes of alternate harshness and indulgence from the parent. For it was not all wisdom that came from Downing Street, either in despatches or in the gubernatorial flesh. It is easy now to see that much emanating therefrom came from those whose vision was confined to the limits of a small island.

The great lubberly youth was given to measuring himself from time to time; for Canadian epochs are much like the marks made by ambitious children on the door jamb, marks to show increase in height and a nearer approach to the stature of the parent.

Canadians’ privileges, like children’s, existed only during the good pleasure of those who governed them. Some meant well and did foolishly; others were “somewhat whimsical, fond of military pomp, accustomed to address 15 deputations, parliamentary or others, as if they had been so many recruits liable to the quickening influence of the cat-o’-nine-tails.” One peer in the House of Lords, during a debate on the vexed Canadian question, demurred at the members of Colonial Assemblies being treated like froward children, forever tied to the Executive leading-strings. Canada was, in fact, bound to the Mother Country by bonds of red tape and nothing else. “Who made you?” catechized Great Britain. In the words of Mr. Henry Labouchere’s precocious young catechumen: “Let bygones be bygones; I intend to make myself,” replied the colony.

The problem of assimilation created by the influx of all nations, and the fact of two divisions, a conquering and a conquered, with languages, customs and creeds as diverse as the peoples, made up an enigma the solution of which still occupies French and English wits alike.

The English and the French temperaments, each the antipodes of the other, called for mutual patience and forbearance. But historic truth compels many admissions: first, that British rule with British freedom left out made a dark period from the Conquest to the Rebellion; second, that the national, religious and intellectual ideas of the French-Canadians, their whole mental attitude, were dominated by the Quebec Act; and the motto given them by Etienne Parent, “Nos institutions, notre langue et nos lois,” had become a kind of fetich. They looked upon themselves as the agents of their mother country and the Church in the New World; and they argued did they give up these laws, institutions and language, and become Anglicized, their nationality would be forever lost.

The toast among officers en route to the Conquest had been, “British colours on every fort, port and garrison in America.” For many years after the British flag had first 16 waved on the citadel the habitant on the plain lifted his eyes to where he had seen the lilies of France, and with heavy heart said to himself that which has become an historic saying, “Still we shall see the old folks back again”—words as pathetic in their hope as the Highlanders’ despairing “We return no more, no more.”

It is doubtful if at this period the old folks bothered themselves much about their late colony. Like their own proverb, “In love there is always one who kisses and one who holds the cheek,” French Canada was expending a good deal of sentiment upon people who had forgotten that tucked away in a remote corner of the new world was “a relic preserved in ice,” a relic of France before the Revolution, its capital the farthermost point of manner and civilization, a town with an Indian sounding name, which yet bore upon its front the impress of nobility. For Quebec is and should be the central point of interest for all Canadians; the history of the old rock city for many a day was in effect the history of Canada. History speaks from every stone in its ruined walls—walls that have sustained five sieges.

The Revolution did not create the same excited interest in Canada that might have been looked for, yet there were those who “wept bitterly” when they heard of the execution of the King. The patois, ignorance, superstition, devotion of its inhabitants, were identical with a time prior to the Revolution; and with them were the same social ideas and the same piety.

But the power divided in France among king, nobles, and priest, in Canada was confined to priest alone; and when the dream of a republic was dreamt it was the priest and not the British soldier who made the awakening. The British soldier and those who sent him seem to have been 17 not a whit better informed about the colony gained than France was about the colony lost. Some London journalists were not sure whether Canada formed part of the Cape of Good Hope or of the Argentine Republic. For a long time the English Government annually sent a flagpole for the citadel, probably grown in a Canadian forest. Nor did time improve their knowledge, for as late as the Trent affair one statesman in the House of Commons informed his more ignorant brethren that Canada was separated from the United States by the Straits of Panama.

The acts of Regicide France inspired horror in Canada, yet were not without their fruits. Despite his title of the “Corsican ogre” and their horror of revolution, the submission of all Europe to Napoleon did not make the French of Canadian birth more submissive. Nor did the nation of shop-keepers, whom he despised and who were to cut his ambition and send him to his island prison, become more plausible, courteous or conciliatory, through their sense of victory. Many a thing, had the positions been reversed, which would have been passed unnoticed by a phlegmatic Briton, was to the Gallican a national insult.

And LeMoine, that past grand master of the Franco-Anglo-Canadian complexion, says all too truthfully that conciliation was not a vice-regal virtue; and one of the singers of the day, a Briton of the Britons, confirms the opinion:

18

But, under its fossil simplicity, Quebec, the “relic preserved in ice,” untrue to its formation, burned with a fearsome heat and glow in the years ’37-’38, and those prior to them. The thoughtless words of such birds of passage as commandants and governors were not calculated to put out the fire. The very origin of the name Jean Baptiste, applied generically, arose from a Jean Baptiste answering to every second name or so of a roll called in 1812, when he turned out in force to defend the British flag. Getting tired of the monotony of them, said the officer in his cheerful English way: “D—— them, they are all Jean Baptistes.” And so the name stuck. General Murray, outraged at any gold and scarlet apart from his own soldiers, lost all patience at the sight of French officers in the streets of Quebec. “One cannot tell the conquering from the conquered when one sees these —— Frenchmen walking about with their uniforms and their swords.”1

But the French-Canadians did not struggle against individuals except as they represented a system considered vicious. With the British Constitution Jean Baptiste was a veritable Oliver Twist. He was not satisfied with the morsels doled out, but ever asked for more.

True, there were many—at any rate, some—of the higher class French whose horizon was not bounded by petty feelings regarding race and religion. These men accepted 19 British rule as one of the fortunes of war and enjoyed its benefits. An old seigneur, when dying, counselled his grandson, “Serve your English sovereign with as much zeal and devotion and loyalty as I have served the French monarch, and receive my last blessing.” And that king in whose reign insurrection was on the eve of breaking—irreverently called “Hooked-Nose Old Glorious Billy”—strangely enough had great sympathy with French-Canadian feeling, a sympathy which did much to hearten the minority who counselled abiding by the fortunes of war. But “Old Glorious” was also called the “People’s Friend,” and the Quebecers had lively and pleasant memories of him.

In the nine years preceding the fateful one of ’37 there had been eight colonial ministers, the policy of each differing from that of his predecessor, and all of them with at best but an elementary knowledge of colonial affairs and the complexities arising from dual language, despite the object-lesson daily under their eyes in the Channel Islands. A little learning is a dangerous thing. Each Colonial Secretary had that little, and it proved the proverbial pistol which no one knew was loaded. By them Canadians were spoken of as “aliens to our nation and constitution,” and it was not thought possible that Lower Canada, any more than Hindostan or the Cape, could ever become other than foreign. It was popular and fashionable in some quarters to underrate the historic recollections which were bound up in religion and language; and as for Canadian independence, that was an orchid not yet in vogue. By 1837 he who sat in state in the Château St. Louis (says LeMoine) in the name of majesty had very decided views on that subject. H. M. William IV.’s Attorney-General, Charles Ogden, by virtue 20 of his office “the King’s own Devil,” who was an uncompromising foe to all evil-doers, held it to mean a hempen collar.

The question of British or French rule grew steadily for a half century, until Melbourne’s cabinet and Sir John Colborne made effort to settle it in one way and forever. “Les sacres Anglais” was, in consequence, the name applied to the followers of the latter; and as to the former, probably the illiterate habitant, who could not read the papers but who had an instinct wherewith to reach conclusions, had his own patois rendering of an English colonial’s opinion that the politicians comprising the cabinet might “talk summat less and do summat more.” All classes, indeed, of all sections, were not backward in giving opinion as to the quality of ministerial despatches; for a titled lady, writing from a far-off land where she did much work for the Home Government, dipped her pen in good strong ink and wrote, “My Lord, if your diplomatic despatches are as obscure as the one which lies before me, it is no wonder that England should cease to have that proud preponderance in her foreign relations which she once could boast of.”

A humorous naturalist had said that the three blessings conferred upon England by the Hanoverian succession were the suppression of popery, the national debt, and the importation of the brown or Hanoverian rat.

Strange to say, one of the complexities of the Canadian situation was the position taken by that very popery which in England was still looked upon with distrust and suspicion. In 1794, not a decade’s remove from when the streets of London ran alike with rum and Catholic blood, through Protestant intolerance and the efforts of a mad nobleman, Bishop Plessis had thanked 21 God in his Canadian Catholic Cathedral that the colony was English and free from the horrors enacted in the French colonies of the day. “Thank your stars,” cried another from the pulpit, “that you live here under the British flag.”

“The Revolution, so deplorable in itself,” wrote Bishop Hubert of Quebec, “ensures at this moment three great advantages to Canada: that of sheltering illustrious exiles; that of procuring for it new colonists; and that of an increase of its orthodox clergy.” “The French emigrants have experienced most consolingly the nature of British generosity. Those of them who shall come to Canada are not likely to expect that great pecuniary aid will be extended; but the two provinces offer them resources on all sides.”

Many of the French officers whom the fear of the guillotine sent over in numbers to England found their way to that country which the Catholic Canadian priesthood so appreciated. Uncleared land and these fragments of French noblesse came together in this unforeseen way. But there was another view of their position when Burke referred to them as having “taken refuge in the frozen regions and under the despotism of Britain.” Truly has Britain shouldered many sins, made while you wait in the factory of rhetoric; nor is it less true that glorious sunny Canada has suffered equally unjustly as a lesser Siberia from a long line of writers, beginning with Voltaire, ending—let us hope—with Kipling.

The French Revolution over, and a mimic one threatening in the colony, the clergy did not hesitate to remind one another of the fate of their orders in France, to congratulate themselves they were under a different régime, nor fail to remember that the War Fund to sustain British action 22 against the Republicans of France in 1799 had been subscribed to heavily by many of their brethren and themselves. Le Seminaire stands in that list, in the midst of many historic names, against the sum of fifty pounds “per annum during the war.” One point of great difference between new and old was that the habitants, who were more enlightened and more religious than their brother peasants left behind in France, had, with the noblesse, a common calamity in any prospect which threatened subjugation. The variance ’twixt priest and people could only end in one way where the people were devout; and the Lower Canadian has ever been devout and true to Mother Church. But the “patriot,” who was more apt in diatribe against Tories than in prayers, spared not the priests in their historical leanings. “Who was the first Tory?” cries a patriot from his palpitating pages. “The first Tory was Cain, and the last will be the State-paid priest.”

But if the British Government had in some things acted so kindly and justly to those of French extraction as to merit such words, in other matters there had been much of harshness increased by ignorance and indifference, and the time had come when all had to suffer for such inconsistencies, and, unfortunately, those most severely who already were the victims of them.

“C’est la force et le droit qui reglent toutes choses dans le monde.” Said one of their own writers, “la force en attendant le droit.” In both Canadas “la force” was local supremacy. The painful development as to when it should be superseded proved “le droit” and British supremacy identical.

It was a political struggle prolonged beyond endurance,

more than a real wish to shake free from Britain; a

23

political struggle, where the combatants were often greedy

and abusive partisans who appealed to the vilest passions

of the populace and who were unscrupulous in choosing

their instruments of attack. Capital was made out of

sentiment most likely to appeal to the suffering:

“Hereditary bondsmen, know ye not

Who would be free themselves must strike the blow ——”

and Papineau, by speech, manifesto and admission, looked

toward the seat of vice-royalty and made plain the homely

sentiment, “Ote toi de là que moi je m’y mette.” He did

not agree with the humble habitant saying, “C’est le bon

Dieu qui nous envoya ça, il faut l’endurer.” His opinion

leaned more to that of O’Connell, who said the French

were the only rightful inhabitants of the country. How

much baneful domination had it taken to so change the

Papineau of 1820, when on the occasion of the death of

George III. he says, “... a great national calamity—the

decease of that beloved sovereign who had reigned

over the inhabitants of this country since the day they

became British subjects; it is impossible not to express

the feeling of gratitude for the many benefits received

from him, and those of sorrow for his loss so deeply felt in

this, as in every other portion of his extensive dominions.

And how could it be otherwise, when each year of his long

reign has been marked by new favours bestowed upon the

country?... Suffice it then at a glance to compare

our present happy situation with that of our fathers on the

eve of the day when George III. became their legitimate

monarch ... from that day the reign of the law

succeeded to that of violence.... All these advantages

have become our birthright, and shall, I hope, be the

lasting inheritance of our posterity. To secure them let

us only act as British subjects and freemen.”

24

About ’31 the Lower Canadian Assembly received a lot of new blood; and very hot, adventurous and zealous blood it was. Young men like Bleury, Lafontaine, and their confreres, were not backward in naming what they considered their rights; and they had somewhat unlimited ideas. The most ardent of the group centred round Papineau and excited him still further. They scouted Lord Goderich (Robinson) and his concessions so long as his countrymen formed a majority in their government. This was a “demarcation insultante” between victor and vanquished. Lord Dalhousie, “glowing with scarlet and gold,” and followed by a numerous staff, had brought a session to a close in a peremptory manner, with words which might have furnished a cue to himself and others. “Many years of continued discussion ... have proved unavailing to clear up and set at rest a dispute which moderation and reason might have speedily terminated.”

To the Loyalist Papineau was the root of all evil. A French loyal ditty attributed every calamity of the era to him, cholera morbus, earthquakes and potato-rot included, each stanza finishing with the refrain, “C’est la faute de Papineau.” “It is certain,” said the latter, “that before long the whole of America will be republicanized.... In the days of the Stuarts those who maintained that the monarchic principle was paramount in Britain lost their heads on the scaffold.” This, surely, was the proverbial word to the wise.

Naturally, such sentiments made him receive cool treatment in Downing Street, even when his Ninety-Two Resolutions embodied much truth and called for affirmative answers. Nothing but the most absolute democratic rule would satisfy the irreconcilables. Their act in the House had led to Lord Aylmer being forced to advance the 25 supplies from the Military Chest, and to embody his disapproval in a resolution of censure. They in turn voted his censures should be expunged from the journals of the House. Then Papineau, from the Speaker’s chair, inveighed against the Mother Country. After the presentation of the Resolutions, Lord Aylmer, alluding to them, imprudently said that dissatisfaction was mostly confined to within the walls of the Assembly rooms, that outside of them the country was at peace and contented. The men who framed them lost no time in giving him a practical denial. Resolutions from many parishes approved of the acts of the Assembly, and the newspaper columns teemed with accounts of popular demonstrations. Lord Aylmer, however, supposed himself within his rights. After his recall, at his interview with the King, and supported by Palmerston and Minto on either side, the monarch declared he entirely approved of Aylmer’s official conduct, that he had acted like a true and loyal subject towards a set of traitors and conspirators, and as became a British officer under the circumstances.

Lord Glenelg sent to the rescue that commission of enquiry, the prelude to the later Durham one, whereof Lord Gosford was chief. This nobleman, who became governor of the province, was Irish, and a Protestant, an opponent of Orangeism, a man of liberal opinions and decisive in speech and action. He tried every means to make friends in the French quarter; visited schools and colleges, enchanted all by his charming politeness of manner, gave a grand ball on the festival day of a favourite saint, and by his marked attentions at it to Madame Bedard showed at once his taste and his ability to play a part. He made a long address to the Chambers, breathing naught but patriotism and justice; so some still had 26 hope. “To the Canadians, both of French and British origin, I would say, consider the blessings you might enjoy but for your dissensions. Offsprings as you are of the two foremost nations of the earth, you hold a vast and beautiful country, having a fertile soil with a healthful climate, whilst the noblest river in the world makes sea-ports of your most remote towns.” He replied to the Assembly first in French, then in English. There is a possibility of doing too much, and the Montreal Gazette censured this little bit of courteous precedence so far as to deny the right of a governor to speak publicly in any language but his own, and construed this innovation by the amiable Earl into one that would lead to the Mother-Country’s degradation. Then what of the Channel Islands, where loyalty was and is above suspicion; where the Legislature declared that members had not the right to use English in debate, and “that only in the event of Jersey having to choose between giving up the French language, or the protection of England, would they consent to accept the first alternative.”

Matters progressed till rulers were burned in effigy, and bands of armed men, prowling about the most disaffected parts, confirmed M. Lafontaine’s saying, “Every one in the colony is malcontent.” “We have demanded reforms,” said he, “and not obtained them. It is time to be up and doing.” “We are despised!” cried M. Morin, “oppression is in store for us, and even annihilation.... But this state of things need endure no longer than while we are unable to redress it.”

“It is a second conquest that is wanted in that colony,” said Mr. Willmot in the House of Commons, when he heard the Canadian news via the Montreal Gazette.

So Lord Gosford asked for his recall, got it, stepped 27 into a canoe after a progress through streets lined with guards of honour composed of regular and irregular troops, amid “some perfunctory cheering,” and was paddled to his ship, the band of the 66th playing “Rule Britannia.” She might rule the waves, but many of those who listened were more than ever determined that she should not rule Canadians.

The Gosford report was vehemently protested against by Lord Brougham and Mr. Roebuck, who did not mince matters, but predicted the rebellion and outlined a probable war with the neighbouring republic.

But Lord John Russell, like Sir Francis Bond Head, did not anticipate a rebellion.

Lord Gosford had found his task more difficult than he expected. His predecessor, Sir James Kempt, had done his best and failed, through no fault of his own but because there was a determination in the majority of his subjects not to be satisfied. Lord Gosford tried the effect of a proclamation as an antidote for revolutions. But the habitants tore it to shreds, crying, “A bas le proclamation! Vive Papineau, vive la liberté, point de despotisme,” and made their enthusiasm sacred by holding their meetings at parish church doors. Papineau was omnipotent; one would imagine ubiquitous, for he seems everywhere. He made the tour of the northern bank of the St. Lawrence, while his supporters, Girouard and Lafontaine, took the southern, making the excited people still more discontented. In after years, as a refugee in Paris, Papineau disclaimed any practical treason at this time: “None of us had prepared, desired, or foreseen armed resistance.” Yet the pikes were further sharpened, and the firelocks looked to; and at St. Thomas (Que.) alone sixty men on horseback, carrying flags and maple boughs, preceded him, 28 and following him were several pieces of artillery and the remainder of the two thousand people who formed his procession. Bishop Lartigue, a relative of Papineau, warned his people to beware of revolt, declaring himself impelled by no external influence, only actuated by motives of conscience. Addressing one hundred and forty priests, he used unmistakable terms as to how they were to resist rebellion in the people; no Roman Catholic was permitted to transgress the laws of the land, nor to set himself up against lawful authority. He even speaks of “the Government under which we have the happiness to live,” while his relative was contending that the yoke on the necks of the Canadians was made in a fashion then obsolete—the Stuart pattern. But he spoke too late; his people were beyond his control, and they in turn condemned clerical interference in politics, and the curé in charge at the combustible Two Mountains had his barns burned in answer to his exhortation. On the first Monday of every month these sons of Liberty, organized by Storrow Brown, met—“Son projet réuissoit à merveille, chaque jours le corps augmentoit en nombre et déjà de pareilles sociétés se formaient dans la campagne.”

The chronic state of eruption in unhappy Lower Canada had intervals of quiet only when some governor, with manners of oil and policy of peace, made an interregnum. All time was not like that of the little Reign of Terror, full of fear and arbitrary measures, after the suppression of Le Canadien and the arrest of the judges; but the country felt itself to be a plaything of not much more weight than the cushion dandled by Melbourne or the feather blown about by that minister of deceptive manner. The famous Ninety-two Resolutions embodied the Canadian view of what was wrong, and the remedy for it. Papineau, 29 their author, owed much in their construction to his colleague, M. Morin, a gentle, polite man of letters, with the suave manners of a divine, who neither looked nor acted the conspirator, despite his many fiery words—as fervid as those of the idol of the people, the eloquent leader in Canadian debate, who was nightly carried home to his hotel on the shoulders of the enthusiastic crowd.

“Since the origin and language of the French-Canadians have become a pretext for vituperation, for exclusions, for their meriting the stigma of political inferiority, for deprivation of our rights and ignoring public interests, the Chamber hereby enters its protest against such arrogant assumptions, and appeals against them to the justice of the King and Parliament of Great Britain, likewise to the honourable feeling of the whole British people. The numerical though not dominant majority of this colony are not themselves disposed to esteem lightly the consideration which they inherit from being allied in blood to a nation equal, at least, to Britain in civilization and excelling her in knowledge of the arts and sciences—a nation, too, now the worthy rival of Britain for its institutions.”

Certain it is, the policy of the British Clique, so called, was moulded more upon old than new country needs and ideas, and was suited to the times of George I. and Louis XIV. more than to the dawn of the Victorian era. But ’tis always darkest the hour before day, and the torch lighted by Papineau was unfortunately to make conflagration as well as illumination. It was the old, old story of theorists and political agitators exciting popular discontent and alarm more than the occasion warranted, by exaggerations retarding instead of speeding a cause, with another story of procrastination and cross-purposes from the 30 Mother Country. Further, history was corroborated in that a demagogue ends as a tyrant. A super-loyal newspaper did not hesitate to say that the only way to calm Canada was to purge the Colonial Office from King Stephen down to Glenelg, and to do so by one huge petition to Majesty signed by every Canadian from Quebec to Amherstburg. For Lord Glenelg, with the best intentions in the world, had a positive genius for doing the wrong thing.

But even such evidences of ignorance as did arrive by despatches and otherwise did not warrant, in the minds of many Liberals, the overthrow of a monarchy. They made allowance for good disposition in the abstract, and spoke of “want of knowledge and characteristic apathy.” The influence of these men cannot now be overestimated. They were then looked upon with suspicion by either side, for they recognized that gigantic obstacles and class exclusions were to be met; a recognition which lessened the credit of their heartfelt “Je suis loyal.” On the other hand, a good many French Canadians were made to join the rebel side by intimidation.

If the assurance of “Je suis loyal” did not come quickly enough some inoffensive Frenchman would find himself popped into the guardhouse, and the results of jealousy and over-zeal have left us many absurd stories. A county M.P., at the Château one sultry evening, seeing the rest all busy at ice-cream, asked for some. The Canadian Solon took a huge spoonful, his first taste of such a delicacy. With a feeling of rage at what he thought an insult, or at least neglect, he cried out what is translated into, “You abominable rascal, had this been for an Englishman you would have taken the chill off.”

No more condemnatory record exists of the British 31 Clique than that left of it in its earliest days by Governor Murray, a man not likely, to judge by the personal anecdotes we have of his reign, to be accused of French proclivities. For a time everything was given a French turn, and “Don’t moushify me,” in the words of an eminent literary man, showed the essence of British feeling of the day.

Although Murray said the ignorance of the French-Canadian and his devotion to his priest ran together, and that the veneration was in proportion to the ignorance, he has to say also that, with the exception of nineteen Protestant families and a few half-pay officers, most of the British population were traders, followers of the army, men of mean education. All had their fortunes to make: “I fear few are solicitous about the means when the end can be obtained.... The most immoral collection of men I ever knew, of course little calculated to make the new subjects enamoured with our laws, religion and customs, and far less adapted to enforce these laws which are to govern.”

Canadians were then a frugal, industrious, moral set of men, noblesse and peasantry alike, knit to each other by ties made in the time of common danger; the former as much contemned by Murray’s compatriots for their superior birth and behaviour as the latter were by him for their ignorance. In his despatch to the king’s advisers he is particularly hard on the judge and attorney-general, neither of whom knew the French language,—nor, indeed, did any of the men to whom offices of greatest trust were bestowed by the sub-letting of posts whose property they became through favour. In a word, a more worthless set of officials could not be gathered together than that which carried out the beginning of British rule in Lower Canada. 32 Haphazard circumstance placed them where they were, and they scrupled not to make themselves paramount.

This oligarchy, made up “of the driftwood of the army and manned by buccaneers of the law, knew how to seize occasion and circumstance;” and the governors, “fascinated by these official anacondas, fell into their folds and became their prey, were their puppets and servants, and made ministers of them instead of ministering to them.”

Papineau contended that when all the people in any country unanimously repudiate a bad law it is thereby abrogated. To which sentiment Mr. Stuart responded, “This is rebellion.” Unfortunately, with many high in office, some governors included, any measure of opposition meant rebellion, and, like Mr. Stuart, they did not hesitate to say so.

Papineau, and those whom he represented, looked upon the British Government as a mélange of old usages, old charters, old fictions, and prejudices old and new, new and old corruptions, the right of the privileged few to govern the mass. The boasted “image and transcript” in Canada was called by them a veritable Jack-’o-lantern, a chameleon that assumed colour as required.

In Papineau’s interview with Lord Bathurst some years before rebellion, that nobleman, after allowing that difficulties existed, blaming remoteness from England and nearness to the United States as aggravating circumstances, asked for only twenty-five years of patriotic resignation to what he considered a hard but, under the circumstances, natural state of things. But Papineau’s Utopia differed from Lord Bathurst’s; and he told him so.

It was now that it came to be acknowledged there was something more powerful than Parliament, governor, or priest. That was opinion after it had spoken in print. 33 On being asked how much treason a man might write and not be in danger of criminal prosecution, Horne Tooke replied: “I don’t know, but I am trying to find out.” Where anything belonging to Majesty, even so remotely as an article in the military stores, was irreverently treated, the article in question became of importance through the importance of its royal owner, and treason could lurk in a misused garment.

“For grosser wickedness and sin,

As robbery, murder, drinking gin,”

the penalties were then heavy indeed; but the nature of

treason, according to the Common Law of England, is

vague, and judges were sometimes put to rare shifts to find

it. Evidently it did not always dwell in the heart alone,

but on occasion could be found by a diligent judge considerably

below that organ. A tailor, tried for the murder

of a soldier, had the following peroration tacked on to his

death sentence by a judge who was loyal enough to have

been a Canadian:

“And not only did you murder him, but you did thrust, or push, or pierce, or project, or propel the lethal weapon through the belly-band of his breeches, which were His Majesty’s!”

“To slay a judge under specified circumstances” was also a count in treason, and this knight of the bodkin doubtless longed to thrust his tool into his wordy antagonist. But as a phrenologist has told us, the judge could best illustrate his bump of veneration by the feeling with which Tories of the old school regarded their sovereign. In Canada a man had not to show sedition in order to be suspended; for there was a law to banish him if he were “about to endeavour to alienate the minds of His 34 Majesty’s subjects ... from his person or Government.” She foreshadowed the methods of the Mikado; when it was desired to punish a man “a crime was invented to suit his case”—an inversion of the punishment fitting the crime. Sir James Mackintosh succeeded in passing two bills lessening the list of crimes punished by hanging; but Lord Eldon demurred at the noose being done away with in case of five shillings worth of shoplifting, as the small tradesmen would be ruined. Then, why not quartering and other horrors for treason?

They certainly left no stone unturned in Canada to find out details in matters of treason or libel. The John Bull and other English papers handled some cases without gloves; but it was reserved for Canada to show what could be done with printers’ ink. The type fairly flew into place under the willing fingers of compositors who were also politicians. Minerva in the printing office is oftentimes undignified. She seems to have been particularly so in the case of Le Canadien, a paper founded in 1806. Its wood-cut frontispiece had the arms and emblems of Canada, with two beavers hard at work biting the slender tie which attached the scroll to the insignia of Great Britain, and, of course, a suitable motto. Two reporters of that stormy time added to the excitement of the Assembly by throwing assafœtida on the stoves. The odour was insupportable, and the too enthusiastic scribes were taken in charge by the sergeant-at-arms. Like many others whose freedom that functionary sought to curtail, they could not be found when wanted. When the type, paper and presses of Le Canadien office, under a warrant from Judge Sewell, were seized in 1810, the magistrate, attended by a file of soldiers, removed all to the vaults of the Courthouse. This act, with the long imprisonment without trial which followed, 35 was considered one of the most arbitrary committed since Hanoverian rule began. The printers were arrested, as were also the leading members of the Assembly, Messrs. Pierre Bedard, Tachereau and Blanchet. When some of these members had been admitted to the bar, M. Perrault, one of those discreet men who were the saving of their country, patriotic but prudent, made the caustic remark: “So many men forced to steal in order to make a living! I shall certainly yet see some of you hanged.” It was quite easy to hang a man in days when the death penalty covered an incredible number of offences, when a boy could receive that sentence for killing a cow or a child for stealing sweets from a pastry cook’s window. So M. Perrault had a margin for his prediction. This half-jocular condemnation of the legal profession was prevalent to a degree which made many believe that in a corner of the Protestant hell, which was separate from and hotter than the Roman Catholic one, was a place reserved for lawyers. “There they will have a little hell of their own, and even well lighted for them to see each other the better; and there, after having deceived their poor clients on earth, they will tear each other to pieces without the devil having the bother of helping them.”

In ’37, when three of the members had become judges, Perrault made his pun by saying, “I have often predicted that I should see some of you hanged (pendu); there are now three of you suspended (suspendu), which is nearly the same thing.” Those who were partners in guilt in the writings of this “seditious paper” were sent to gaol, and we learn that the article which gave chief offence was one entitled “Take hold of your nose by the tip.” Maladministration was evidently malodorous. Such proceedings naturally caused excitement, and the fears of 36 those in power made them redouble the city guards and patrols.

But if Le Canadien had been conducted with animosity, it was also marked by much ability. Nor had it a monopoly of the former. The Anglo-Canadian papers, too, knew how to be bitter and violent. The press of those times indulged in wonderful prophecies. But the future is in the lap of the gods, so said the more knowing ancients; and if any of those ’37 prophecies had the flavour of truth it is to be found in those of the contemned Reformers.

Early in the century Judge Sewell had got into trouble. He was accused of usurping parliamentary authority, by undue influence persuading the Governor (Craig) to dissolve the House and also to address the members in an insulting manner; and later there were the Bedards’ affairs. Judge Monk was also accused. Judge Sewell went to London to defend himself, which he did to such good purpose, backed by the influence of Prince Edward, that he gained the ear and confidence of Lord Bathurst. His explanations were accepted, and fresh favours were in store for him from the incoming Governor Sherbrooke.

Although “each new muddler” blamed his predecessor for his own misgovernment, the tasks falling to the Governors were not easy. Under Kempt came up the question of giving legal status to Jews and Methodists, the question regarding the former going back some twenty years, when, under the administration of “little king Craig,” there was endless trouble over Mr. Ezekiel Hart’s presence in the House. Expelled and returned alternately, Hart was doubly obnoxious as a Jew and an Englishman. 37 Methodism had an equally hard time since the First Gentleman in Europe had said that that faith was not the faith of a gentleman. The characteristics of the personnel of the House of Assembly in the years of the century prior to the Rebellion could doubtless fill volumes of humours. Most of the members from the Lower St. Lawrence arrived in schooners, sometimes remaining in them as boarders; or they put up at some Lower Town hostelry, content with their cowpacks and scorning Day & Martin. The members from down the Gulf were sure to be of the right political stripe, from a clerical point of view, or their constituents stood a chance of being “locked out of heaven.” One head of a house who dared to be a Liberal in those illiberal times, an educated man, and likely to have possessed weight in character as well as by his appointments in his native village, so locked himself out. His child of seven came home from school in tears one day, and after much coaxing to disburden his woe confided to his mother that in seven years his father, a parent much-beloved, would be a loup-garou. The end of this persecution was a removal over the border.

But there were not many who had the courage of their convictions in the face of the Church’s No—they were all too good Catholics then. Stories of their religious life provide material for a picture whose beauty cannot be surpassed. A niche was hollowed in a wall of most Canadian homes to hold a figure of the “Blessed Lord,” or His equally dear Mother; and it is recorded of one of the first of Canadian gentlemen of his time that he never passed a wayside cross without baring his head, saying once in explanation, “One should always bare the head before the sign of our redemption and perform an act of 38 penitence.” The humbler sort began no dangerous work, such as roofing, without a prayer. With heads uncovered, the workers knelt down, while some one of the oldest of the company recited the prayer to which all made response and Amen. Nor was thanksgiving omitted when the harvest firstfruits were sold at the door of the parish church. Close by the housewife’s bedhead hung her chaplet, black temperance cross and bottle of holy water; from the last the floor was sprinkled before every thunderstorm. And nothing was done by natural agency. Even the old, worn-out curé, who met death by the bursting of the powder-magazine on board the ship in which he was returning to France, was “blown into heaven.”

But once the primitive ones left their village they were much at sea, and we have a member for Berthier, whom we shall credit as being both pious and Tory, arriving in Quebec with his wife one winter’s evening in his traineau. They drew up at the parliamentary buildings and surveyed the four-and-twenty windows above them, wondering which one would fall to their lot for the season. They descended, boxes and bundles after them, rapped at the door and presented their compliments to the grinning messenger. “He was the member for Berthier, and this was Madame his wife;” they had brought their winter’s provisions with them, and all in life needed to allow him to pursue his work of serving his country as a statesman was a cooking stove, which he looked to a paternal government to supply. When told that not one of the four-and-twenty windows belonged to him, and that family accommodation did not enter into the estimates, the member from Berthier stowed his wife and bundles back in the traineau, gave his steed a smart cut, and indignantly and forever turned his back upon the Legislative walls of his province. 39

What did he not miss? Within them Papineau was making rounded periods, holding men entranced by his eloquence; Andrew Stuart was defending British rights; yet another Stuart thundered against the tyranny of the oligarchy, the privileged few; and Nielson and other discreet Liberals sought to steer a middle course of justice without rebellion. No wonder that from this concert discords met the ears of the audiences without.

Peculiarities and eccentricities were not confined to the rural populace and members of Parliament. “Go on board, my men, go on board without fear,” was a magistrate’s dismissal to two evil-faced tars who had deserted their ship at sailing time because they thought her unseaworthy; “I tell you you are born to be hanged, so therefore you cannot be drowned.”

“If anyone has a cause,” said one dignified prothonotary, “let him appear, for the Court is about to close.” “But,” said the judge above him, “the law states we must sit to-morrow.” Turning to the public the prothonotary made further announcement: “The judge says he will sit to-morrow, but the prothonotary will not be here.” And in his Louis XIV. costume, cut-away coat with stiff and embroidered collar, knee-breeches of black cloth, black silk stockings, frills on shirt-bosom and cuffs, the silver-buckled shoes of the prothonotary bore their somewhat stubborn wearer away.

At the beginning of the century it was only occasionally that foreign news reached Canada. With time postal matters improved; but news was still only occasional. At the advent of a vessel at Father Point the primitive telegraph of the yard and balls was used, and at night fires were lighted to carry the tidings from cape to 40 cape. The means of intercommunication depended upon the size of the post-bag, the fidelity of the carrier, and on the state of the storm-strewn paths or trackless wastes which had to be crossed. The bag for Gaspé and Baie des Chaleurs was made up once in a winter and sent to Quebec, dark leather with heavy clasps and strapped on an Indian’s back. The man travelled on snowshoes, and when tired would transfer his load to the sled drawn by his faithful Indian dog. There were others whose mode of transit was much the same, but whose beats were shorter and trips more frequent. “Do not forget,” would say a certain old Seigneur, “to have Seguin’s supper prepared for him.” Seguin was postman for that large country-side, and generally arrived during the night at the manor house. The doors, under early Canadian habit, were unlatched; Seguin would quietly enter, sit down, take his supper, and produce from his pockets the letters and papers which made the Seigneur’s mail, leave them on the table, then as quietly let himself out into the night again, to pursue his journey to the next point. Such latitude in trust was possible in a country where law in its beginning was a matter of personal administration aided by keep, and four-post gibbet whose iron collar might bear the family arms.

Nor was other travel in a very advanced state. The palm of beauty was then, as now, accorded the St. Lawrence, but one traveller from abroad wrote, “’Tis a sad waste of life to ascend the St. Lawrence in a bateau.” By 1818 “a first-class steamer” made its exhausted way from Quebec to Montreal; aided by a strong wind it covered seven leagues in nine hours. This exhilarating motion caused the historian Christie, one of the pleased passengers, to open his window and hail his friends, “We are going famously!” By the third day’s voyage they were at the foot of the current below Montreal, and with the 41 united aid of forty-two oxen they reached the haven for which they were bound.

With news so transmitted and the bulk of the population unable to read or write, and with only the comparatively wealthy and the adventurous able or willing to travel, it is not surprising that “the focus of sedition, that asylum for all the demagogic turbulence of the province,” the Assembly rooms at Quebec, had not succeeded in disseminating their beliefs and hopes among the most rural of the population. One thing which made remote villages loath to be disturbed was that they had more than once seen noisy demagogues and blatant liberators side with the alien powers when opportunity for self-aggrandizement came. Also, in many cases their isolated lot precluded feeling governmental pressure. But in the county of Two Mountains, at St. Denis, St. Charles, and also at Berthier, they were alert enough, and the most stirring pages in the coming revolt were to be written in blood in these localities. There secret associations flourished; open resistance only waited opportunity. There the Sons of Liberty drilled and wrote themselves into fervour, with pikes made by local blacksmiths and manifestoes founded on French and Irish models for outward tokens of the inward faith: “The diabolical policy of England towards her Canadian subjects, like to her policy towards Ireland, forever staining her bloody escutcheon.” The history of “my own, my native land,” inspires all words written from this point of view; one patriot, “plethoric with rhethoric,” had many fine lines, such as “the torch, the sword, and the savage,” and pages devoted to the “tyrannical government of palace pets.”

Away back in 1807 many militia officers of fluctuating loyalty had been dismissed, and the precedent established by Governor Craig was continued. Papineau was one of 42 these officers; he had made an insolent reply—“The pretension of the Governor to interrogate me respecting my conduct at St. Laurent is an impertinence which I repel with contempt and silence”—to the Governor’s secretary, and had to suffer for it. The political compact called the Confederation of the Six Counties was governed by some of those so dismissed, and they all grew still more enthusiastic from the sight of such banner legends as “Papineau and the Elective System,” “Our Friends of Upper Canada,” “Independence.” The Legislative Council was pictorially represented by a skull and cross bones, and the declaration of the rights of man was voiced.

In addition to present troubles there was a perpetual harking back at these meetings to old scores, impelling “the people to wrestle with the serried hordes of their oppressors in the bloody struggles which must intervene” before “the injured, oppressed, and enslaved Canadian” could escape from “the diabolical policy of England.” There was a liberty pole, and Papineau, burning, energetic, flowery of speech, promised all things as crown to laudable effort “in the sacred cause of freedom.” It was a Canada “regenerated, disenthralled, and blessed with a liberal government” which the prophetic speech of Papineau had foreshadowed; and the “lives, fortunes, and sacred honour” of his hearers were there and then pledged with his own to aid in that regeneration. That “Frenchified Englishman,” Dr. Wolfred Nelson, also spoke; and Girod,—a Swiss, who taught agriculture in a Quebec school for boys, got up by that true patriot Perrault,—destined shortly for a tragic fate, was there. At this meeting Papineau thought he had set a ball rolling which would not easily be stopped. Already it was careering in an unpleasantly rapid manner. He deprecated the use of arms, and advised as punishment to 43 England that nothing should be bought from her. This reprisal on the nation of shopkeepers Nelson thought a peddling policy; that the time was come for armed action, not pocket inaction. Papineau’s opinion was disappointing to the fiery wing of the Confederation. Again did Bishop Lartigue warn generally against evil counsels, reminding his flock that a cardinal rule of the Church was obedience to the powers that be; and every one of his clergy echoed him.

“Il n’y a que le premier pas qui coûte” was once oddly applied by a lady who heard a canon of the Church say that St. Piat, after his head was cut off, walked two leagues with it in his hand. She could not gainsay such an authority, so said, “I can quite believe it. On such occasions the first step is the only difficulty.”

Alas, many at these meetings were to exhibit the price of a first step; heads were to come off and necks to be broken, and every step in that blood-stained via doloroso which led to the Union, to the righting of Englishmen’s and Frenchmen’s wrongs, to establishing Canadian rights to be French or British, was to cost bitterly,—cost how bitterly only one can know who reads the story in its human aspect, not politically alone. It is a strange thing that privileges so purely British as those asked for, the abolition of the death sentence except in case of murder, “that chimera called Responsible Government,” the unquestioned use of a national language in public affairs, freedom of the press, should have been asked for by Frenchmen, denied by Englishmen, and fought for to the death by many of each nationality.

All time from the Conquest to the Rebellion seems to belong to the latter event. For the causes of it reach back by perspective into Misrule, making a vanishing point in Mistake. 44

Treason always labours under disadvantage when it makes preliminary arrangements; and it is often obliged to found combinations on defective data, not reckoning upon disturbing forces and the sudden appearance of the unforeseen. But if so in ordinary cases, what must it have been when, in Upper Canada, sympathy with the French and dissatisfaction with existing Upper Canadian institutions ended in a determination to combine forces and make a common cause.

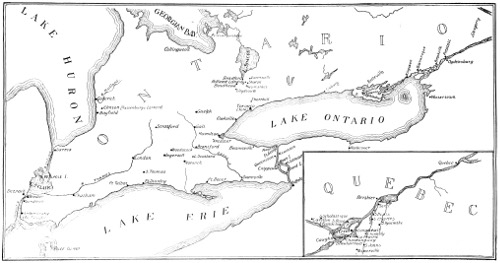

Each province had its distinct enemies; but distance was one common to both. They were divided from the metropolis and arsenal of the Empire by ocean, storm, and wooden ships; and tracts of native roadless wilderness, long stretches of roads of mud and corduroy, and the intercepting reserve, helped to keep man from man. A huge place; and the badness of its affairs was in proportion to its size. With no hint of the future iron belt from Atlantic to Pacific, all travel was by stage, a painful mode, and costing some $24.00 from Montreal to Toronto; or if by water, in long flat-bottomed bateaux rowed by four men, Durham boat, barge, or the new ventures, steamboats, where as yet passenger quarters were in the hold.

The element of Upper Canada was crude, and the homesick letters of the new-come emigrants sighed over the rude 45 surroundings. But perhaps the rudest thing which the settlers of ’37 found was the apology for a form of government then offered to them. An idea had prevailed in the home countries that Canada was the best of the colonies. But this idea was dispelled by Mackenzie; those of his earlier writings which reached Britain rendered such a sorry account of Canadian happiness that people who had confidence in his book thought twice before they risked fortune in what evidently had become his country through necessity.

Some time previous to the publication of his book (“Sketches of Canada and the United States”), he had been good enough to write Lord Dalhousie, “So far, your Lordship’s administration is just and reasonable.” To him Canadian affairs were like a falling barometer, soon to end in storm, and there was every ground for the statement of a United States editor that Mackenzie constituted himself the patron or the censor of the race.

There was no iron hand in a silken glove about the oligarchy; the hand was always in evidence to Mackenzie and his kind, and Canada was not a whit better than Kingsley’s apostrophized land.

It is easy at this time of day to cast reflections upon the ruling class of that period, a class chiefly composed of sons of officers in the army and navy, for the most part gentlemen in the conventional sense of the term—a crime laid to their charge by some who could not forgive it. They naturally came to centre in themselves all offices of honour and emolument; and the governors, all gentle if some foolish, looked to them for counsel and support, before 46 time was allowed for reflection, the governors so cleverly governed that they knew it not. Gifts of the Crown naturally followed, and the great Pact grew richer, alongside of that older Compact of the sister province. It is a case for “put yourself in his place.” The burden and heat of the day had fallen on these men; they but followed the instinct to reap where one has strawed, and carried out to the letter the axiom that unlimited power is more than mortal is framed to bear.

“The tyrannical government of palace pets” furnishes pages of misgovernment. It took a clear head, a steady will and a true heart to cling to British connection and the Union Jack, when desperation made some determined to be rid of the Toronto rule, which was to them odious, unjust, intolerable. And yet, when we review that epoch of dissolution and transformation, the errors and shortcomings of either party, the two sides of the dispute stand out so clearly that we wonder anyone could then think he was altogether right. “Flayed with whips and scorped with scorpions,” one side said, “there is no alternative but a tame, unmanly submission or a bold and vigorous assertion of our rights as freemen;” while the other, by the mouth of its governor, likened Canada, standing in “the flourishing continent of North America,” to a “girdled tree with drooping branches.” Certainly, the simile was good; and with all justice to the side of Tory or Reformer, Royalist, Rebel, Loyalist and Loyalist, a retrospective glance discloses a knife on either side busy at the process of girdling. “What is the best government on earth?” asks a school-book in use in Duncombe’s District and printed in Boston for Canadian schools; “A Republican Government like the United States,” is the unqualified next line. “What is the worst government on earth?”—“A Monarchical 47 Government like that of England and Canada.” “Can the King of England order any man’s head cut off and confiscate his property?”—“Yes.” “Will you, if the occasion arrives, rise up and rebel against such a government as yours, and join the States?”—“Yes, with all my power and influence.” The Yankee school-master, a chief agent of this propaganda, was one of the first prisoners.

The Family Compact believed the chief beauty of government to be simplicity, the foremost tenet loyalty to one another. But men outside the Pact, every whit as much gentlemen and each in turn bearing his part of that heat and burden, awoke to a sense of individualism, each to realize that he was a unit in the commonweal.

The forerunner of the new dispensation was Robert Gourlay. And what and if his sorrows had so overwhelmed his wits, he yet was the founder of public opinion in Upper Canada; nor is it less true that the first outcome of his martyrdom was that life was made harder for those who dared to follow where he had failed.

“Whaur ye gaun, Sawndie?” “E’en to the club just to conthradick a bit;” and Mackenzie, right as he was in many points, leaves us in no doubt as to his descent and his ability to “conthradick” for pure love of so doing. Also his club covered a wide area, and his influence over a tract as wide as his ability to contradict was phenomenal.

Passing the line between the Canadas, Glengarry showed the change from French to British ways. Not only were the features and tongues of the inhabitants different, but there was an entire absence of that thrifty, snug cottage comfort which distinguished the half-brother below. With outsides unfinished, no taut lines about them, both houses and original huts proclaimed a people undaunted 48 by obstacles and surmounting them by indifference to detail. Here all were loyal. Stories of the famous Glengarry Fencibles of 1812 took up the leisure hours, and the spirit of the Loyalist fighting bishop was paramount. That prelate would not tell his people how to vote, but he talked of “these radicals who aim at the destruction of our Holy Religion;” and this word to those already wise was sufficient.

Next came Prescott, once La Galette, well built on a rocky prominence, the site of a former entrenchment, a place mentioned in old French diaries from the time of La Salle, the white of its tall, massive tower, roofed with a tin dome and built out on a rounding point covered with evergreen, making an abrupt feature in the river bank. Enormous sails flapping in the breeze proclaimed its functions, and a fort in process of erection, not having a moiety of its aggressive strength of appearance, lay near it. Here the people were of two minds, many ready to be sympathisers in a movement though lacking the force to be leaders; prominent men, some of them, and wishing for a lead, while others, living in the remote shadow of the dominant party, were so securely attached to crown and flag that they were ready to defend that party for the sake of the flag whose exclusive property it seemed to be.

Farther on, as the river broadened towards the chain of lakes, came Kingston, its “agreeable, genteel society accommodated in houses of stone and wood,” also much divided by party. In the harbour ships of war stood close to the shore, where blockhouse and fort commanded the entrance. Fort Henry, begun in ’32, had by February, ’36, cost England more than £50,000; its area did not exceed an acre, the walls, massive 49 outworks and aspect evidently conveniently designed for the success of the enemy. A few more years were required for its completion and to level the glacis; but although unfinished it was to be the theatre of a tragedy. In its finished state it has been described as a colossal monument to military stupidity. From the top of the inner fort lie in view the famous “cow pasture,” Dead Man’s Bay where some fourteen men were drowned during construction of the fort on Cedar Island, and Shoal Tower, all points of arrest to the eye in that ever-beautiful scene. Several old war-ships left from 1812 were in 1831 kept at the dockyards, shingled over and protected, some fated later to be sunk as useless, one to be burnt to the water’s edge. Hard by there was a dockyard, furnished with every article of naval stores required for the equipment of ships of war. Two seventy-fours, a frigate, a sloop of war and eleven gunboats reposed under cover on stocks. They were not planked, but men employed for the purpose replaced decaying bits of timber, and it was estimated that in little more than a month they could be got ready for sea. Immense sums had been expended during that war upon unnecessary things, unaccountable ignorance having sent the woodwork of the frigate Psyche to a country where it could have been provided on the spot at one-hundredth of the expense and in one-tenth of the time necessary to convey it there. Even wedges had been sent, and the Admiralty, full of salt-water notions, was paternal enough to include a full supply of water casks for use on Lake Ontario, where a bucket overboard could draw up water undreamed of by Jack tars, from a reservoir through which flowed nearly half the fresh water supply of the globe. Clearly, details of geography were not included in the lists for those bright youths who were 50 preparing for the Admiralty, and nowhere in Canada was the foolish touch of a prodigal-handed parent seen to more advantage than in Kingston.

Across the lake at Sackett’s Harbour was a ship of 102 guns, apparently put together in a substantial manner in forty days from the day the first tree used in her construction was cut down. Peace declared, she was never launched; and, agreeably to the terms of the treaty, which called for the abolition of an armed force on the lakes, six or seven more American vessels were sunk in the harbour and, in the parlance of their owners, were “progressing to dissolution.” Green timber might have proved as good a vehicle for the squandering of money as imported wedges and water-casks.

But although there was then this show of vessels in Kingston, a practical military man of ’37 records that the dockyard was a grazing ground, that the Royal Engineers’ department did naught but patch up barracks in much the same state as the ships, not a ship, boat, sail or oar was available, and that sad havoc had been made by the twenty-two years of profound peace and disuse in harness, waggons, carriages, limbers, wheels, drag-ropes and other munitions of war. The powder would not light, and moths had destroyed blankets and bedding. Artillery with no horses to the guns, and part of the 66th regiment, represented the military force at the half-finished fort.

At Kingston Her Majesty’s accession was proclaimed on a certain Monday in August of ’37 by Mr. Sheriff Bullock and the other authorities, but “the procession was meagre and pitiful in the extreme.” And this state of affairs was because of the dislike “manifested by many to petticoat government.”

Farther on, the peninsula of Prince Edward should have 51 been the very paradise of loyalty if any inference were to be made from its nomenclature: Adolphusburg, Maryburg, Sophiasburg, a transatlantic inventory of major and minor royalties. But, although it had sent forth a Hagerman, the Bidwells were there too, all champions in the coming struggle for what each loyally believed to be the right. Every town and hamlet along that immense waterway had heard the call of Mackenzie from either lips or pen, and some dwellers in each had responded.

With York is reached the centre of grievance, the house of hate, where the principals in the coming struggle dwelt in a succession of patched-up peace, revolts, domineering unfairness, harsh punishments and secret reprisals, a panoramic play in which the first act was tyranny and the last revolution. Some of the by-play reads childishly enough. Mackenzie’s stationery shop in King Street contained window decorations of the most soul-harrowing kind, and all belonging to the era of belief in eternal punishment. The asperities of Mackenzie’s truly Presbyterian enjoyment had not yet been softened by a Farrar or a Macdonnell. The prints there displayed depicted Sir Francis Bond Head, Hagerman, Robinson, Draper and Judge Jones as squirming in all the torments of a realistic hell, relieved by sketches of a personal devil whose barbed tail was used as a transfixing hook for one or other of these Tories, the more conveniently to spit and cook him. The Canadian ejaculations of former times, “May an Iroquois broil me,” or “Tors mon âme au bout d’un piquet” (Twist my soul on the end of a fence rail), were forever routed. Like Pope and an interrogation point, Mackenzie was a little thing who would ask questions, any crookedness about him being the peculiar twists and turns made possible by nature to his rapier-like tongue. His paper heralded the day of 52 Carlyle and Doré, anticipating the former’s “gloomy procession of the nations going to perdition, America the advance guard.” When he thus bearded these lions in their dens they promptly called—through the government organ—for the suppression of the first issue of this obnoxious paper; further, that the editor should be banished, and the entire edition confiscated. Vituperative, he had a command of uncomfortable words fitted to every circumstance, his ability to scent out abuses phenomenal. But he was not banished, nor his pen and pencil confiscated, nor yet did his influence stop at this point in the long journey from Glengarry to Windsor. And why should such a pen be confiscated? While the Family Compact were expelling Mackenzie, imprisoning Collins, and hunting to death any poor stray printer who dared put his want of admiration of them in type, no less great a person than their King was feign to be out of his wits because he was not only libelled but had no redress. He laments the existence of “such a curse ... as a licentious and uncontrolled press,” and of a state of things which renders the law with respect to libellers and agitators a dead letter. Poor King, happy Family Compact; Canada had no dead laws if the people who administered them wished them quick. “The Irish agitators, the reviews and, above all, the press, continue to annoy the King exceedingly;” but Earl Grey said the only way with newspaper attacks was the Irish way, “to keep never minding.” Also Lord Goderich writes to Sir John Colborne in ’32: “I must entirely decline, as perfectly irrelevant to any practical question, the inquiry whether at a comparatively remote period prosecutions against the editors of newspapers were improperly instituted or not.” It is needless to look beyond Mr. Mackenzie’s journal to be convinced that there is no 53 latitude which the most ardent lover of free discussion ever claimed for such writers which is not enjoyed in Upper Canada. Had he looked beyond Mr. Mackenzie’s journal he would have found the Reformers called “juggling, illiterate boobies—a tippling band—mountebank riffraff—a saintly clan—Mackenzie a politico-religious juggler.” The Reform Parliament was “the league of knave and fool—a ribald conclave;” and Mr. Ryerson, when under a temporary cloud, was called “a man of profound hypocrisy and unblushing effrontery, who sits blinking on his perch like Satan when he perched on the tree of life in the shape of a cormorant, to meditate the ruin of our first parents in the Garden of Eden!”

Following the frontier line, Niagara, looking like a “dilapidated hennery,” had not much in the aspect of its feeble fort to awe the rebellious spirits. They remembered the cruel sufferings of Gourlay, the demolition of Forsyth’s property, and could not be awed back into what had technically come to be known as loyalty by any associations of “Stamford,” or by the leavening power of the U. E. Loyalism which abounded in that district. Thence on to the hamlets of Dunnville and Port Dover, past the Dutch settlement called the Sugar Loaves—six conical hills rising from the low ground near the lake—to where that old lion, Colonel Talbot, perched midway between Niagara and Detroit, on Lake Erie, dared any among his many settlers to name a grievance. Thence to Amherstburg and Windsor, and on to Goderich, youngest of them all, and beyond which was primeval wilderness, a matted and mighty forest on which clouds and thick darkness still rested—known only to the savage, the wild beast, or perhaps to some stoic of the woods who was hustled out of his dream of quiet by the hunt after that ever-receding 54 point of the compass, the West. Over such an area did the influence of this small, almost childish figure of a man extend. And up and down the land within this water-bound border, in outlying interior townships, did his message penetrate until, as the seasons advanced and the times grew ripe, he seemed to hold within the hollow of his small palm—a palm never crossed with gold—the power for which Governor and Council schemed without tiring or maintained by the right of might.

As early as ’34 the Canadian Alliance had been formed, not local in aim, but “entering into close alliance with any similar association that may be found in Lower Canada or other colonies.” The democratic tendency of its resolutions caused it to be called revolutionary by the governmental party; but then anything outside of that party was “rebel.” When matters focused between Sir Francis and that which he called his “low-bred antagonist, democracy,” evenly balanced persons became “notorious republicans;” Postmaster Howard, who came of ultra-loyal stock, was deposed from office chiefly because his son, a lad of ten, read a radical newspaper; and we find an “old dyed-in-the-wool Tory, a writer of some note,” afterwards saying: “When I look back over events which were thought all right by the Loyalists of those times, I only wonder there were not thousands of Mackenzies and Papineaus.” Might with the Loyalists made right; Mr. Hagerman would not “stoop to enquire whether this act was right or wrong, it was sufficient for him the House had done it.” It was clear, too, that the Chief-Justice himself was no student of George III. in the meaning of the word “mob,” and it was exasperating to the last to hear themselves spoken of as “a few individuals,” their serious conclaves as “casual meetings,” their petitions as “got up by somebody or other.” 55

The Alliance was pledged to disseminate its principles and educate the people by gratuitous issues of political pamphlets and sheets. The series of meetings organized to bring the people together showed sympathy with Papineau throughout. Lloyd was the trusted messenger sent to convey that sympathy; but at first it was not a sympathy backed up by physical force. “Much may be done without blood” was the keynote of its temperate tone. Yet, as where Papineau’s own disclaimers of physical force were heard, in Upper Canada the meeting ended in drill; Brown Besses were furbished up, and the clink of the blacksmith’s hammer might be heard in any forest forge busy fashioning into shape the pikes which were made in such shape as to be equally happy in ripping or stabbing.