Title: An Enquiry into the Life and Legend of Michael Scot

Author: J. Wood Brown

Release date: August 6, 2017 [eBook #55280]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Edinburgh: Printed by T. and A. Constable

FOR

DAVID DOUGLAS

| LONDON | SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT AND CO., LTD. |

| CAMBRIDGE | MACMILLAN AND BOWES |

| GLASGOW | JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS |

An Enquiry into

The Life and Legend of

Michael Scot

By Rev. J. WOOD BROWN, M.A.

AUTHOR OF ‘AN ITALIAN CAMPAIGN,’ ‘THE COVENANTERS OF THE MERSE,’ ETC.

‘Michael next ordered that Eildon Hill, which was then a uniform cone, should be divided into three.’—Lay of Last Minstrel, note.

EDINBURGH: DAVID DOUGLAS

1897

[All rights reserved]

D. D. D.

ALMAE MATRI SUAE

EDINBURGENSI

HAUD IMMEMOR

AUCTOR

After some considerable time spent in making collections for the work which is now submitted to the public, I became aware that a biography of Michael Scot was in existence which had been composed as early as the close of the sixteenth century. This is the work of Bernardino Baldi of Urbino, who was born in 1553. He studied medicine at Padua, but soon turned his attention to mathematics, especially to the historical developments of that science. Taking holy orders, he became Abbot of Guastalla in 1586, and in the quiet of that cloister found time to produce his work ‘De le vite de Matematici’ of which the biography of Scot forms a part. He died in 1617.

This discovery led me at first to think that my original plan might with some advantage be modified. Baldi had evidently enjoyed great advantages in writing his life of Scot. His time lay nearer to that of Scot by three hundred years than our own does. He was a native of Italy, where so large a part of Scot’s life was passed. He had studied at Padua, the last of the great schools in which Averroës, whom Scot first introduced to the Latins, still held intellectual sway.[viii] All this seemed to indicate him as one who was exceptionally situated and suited for the work of collecting such accounts of Michael Scot as still survived in the south when he lived and wrote. The purpose he had in view was also such as promised a serious biography, not entirely, nor even chiefly, occupied with the recitation of traditional tales, but devoted to a solid account of the philosopher’s scientific fame in what was certainly one of the most considerable branches of science which he followed. It occurred to me therefore that an edition of Baldi’s life of Scot, which has never yet been printed, might give scope for annotations and digressions embodying all the additional material I had in hand or might still collect, and that a work on this plan would perhaps best answer the end in view.

A serious difficulty, however, here presented itself, and in the end proved insuperable, as I was quite unable to gain access to the work of Baldi. It seems to exist in no more than two manuscripts, both of them belonging to a private library in Rome, that of the late Prince Baldassare Boncompagni, who had acquired them from the Albani collection. The Boncompagni library has been now for some time under strict seal, pending certain legal proceedings, and all my endeavours to get even a sight of the manuscripts were in vain. In these circumstances I fell back upon a printed volume, the Cronica de Matematici overo Epitome dell’Istoria delle vite loro, which is an abbreviated[ix] form of Baldi’s work and was published at Urbino in 1707. The account of Michael Scot which it gives is not such as to increase my regret that I cannot present this biography to the reader in its most complete form. Thus it runs: ‘Michele Scoto, that is Michael the Scot, was a Judicial Astrologer, in which profession he served the Emperor Frederick II. He wrote a most learned treatise by way of questions upon the Sphere of John de Sacrobosco which is still in common use. Some say he was a Magician, and tell how he used to cause fetch on occasion, by magic art, from the kitchen of great Princes whatever he needed for his table. He died from the blow of a stone falling on his head, having already foreseen that such would be the manner of his end.’ Now Scot’s additions to the Sphere of Sacrobosco are among the more common of his printed works, while the tales of his feasts at Bologna, and of his sudden death, are repeated almost ad nauseam by almost every early writer who has undertaken to illustrate the text of Dante. So far as we can tell, therefore, Baldi would seem to have made no independent research on his own account regarding Scot’s life and literary labours, but to have depended entirely upon very obvious and commonplace printed authorities. To crown all, he assigns 1240 as the floruit of Michael Scot, a date at least five years posterior to that of his death! On the whole then there is little cause to regret that his work on this subject is not more fully accessible.

My study of the life and times of Scot thus resumed its natural tendency towards an independent form, there being no text known to me that could in any way supply the want of an original biography. It is for the reader to judge how far the boldness of such an attempt has been justified by its success. The difficulties of the task have certainly been increased by the want of any previous collections that could be called satisfactory. Boece, Dempster, and Naudé yield little in the way of precise and instructive detail; their accounts of Scot fall to be classed with that of Baldi as partly incorrect and partly commonplace. Schmuzer alone seems by the title of his work[1] to promise something more original. Unfortunately my attempts to obtain it have been defeated by the great rarity of the volume, which is not to be found in any of the libraries to which I have access.

This failure in the department of biography already formed has obliged me to a more exact and extensive study of original manuscript sources for the life of Scot than I might otherwise have thought necessary, and has proved thus perhaps rather of advantage. It is inevitable indeed that a work of this kind, undertaken several ages too late, should be comparatively barren in those dates and intimate details which are so satisfactory to our curiosity when we can fall upon them. In the absence of these, however, our attention is naturally fixed, and not, as it seems to me, unprofitably, on what[xi] is after all of higher or more enduring importance. The mind is free to take a wider range, and in place of losing itself in the lesser facts of an individual life, studies the intellectual movements and gauges the progress of what was certainly a remarkable epoch in philosophy, science, and literature. The almost exact reproduction in Spain during the thirteenth century of the Alexandrian school of thought and science and even superstition; the part played by the Arab race in this curious transference, and the close relation it holds to our modern intellectual life—if the volume now published be found to throw light on subjects so little understood, yet so worthy of study, I shall feel more than rewarded for the pains and care spent in its preparation.

In the course of researches among the libraries of Scotland and Italy, of England and France, of Spain and Germany, I have received much kindness from the learned men who direct these institutions. I therefore gladly avail myself of this opportunity to express my thanks in general to all those who have so kindly come to my help, and in particular to Signor Comm. G. Biagi, and Signor Prof. E. Rostagno of the Laurentian Library; to Signore L. Licini of the Riccardian Library; to the Rev. Padre Ehrle of the Vatican Library; to Signor Cav. Giorgi, and the Conte Passerini of the Casanatense; to Signor Prof. Menghini of the Vittorio Emanuele Library, Rome; and to Signor Comm. Cugnoni of the Chigi Library. I am also much[xii] indebted to the kindness of Professor R. Foerster of Breslau; of Mr. W. M. Lindsay, Fellow of Jesus College, Oxford, and the Rev. R. Langton Douglas of New College, who have furnished me with valuable notes from the libraries of that university, and, not least of all, to the interest taken in my work by Mr. Charles Godfrey Leland, who has been good enough to read it in manuscript, and to favour me with curious material and valuable suggestions.

If the result of my studies should prove somewhat disappointing to the reader, I can but plead the excuse with which Pliny furnishes me, it is one having peculiar application to such a task as is here attempted: ‘Res ardua,’ he says, ‘vetustis novitatem dare, novis auctoritatem, obsoletis nitorem, obscuris lucem, fastiditis gratiam, dubiis fidem, omnibus vero naturam, et naturae suae omnia.’

17 Via Montebello,

Florence, November 17th, 1896.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| State of Scotland in the twelfth century—Necessity of foreign travel to scholars bred there—Michael Scot: his Nation and Birthplace.—The account given by Boece, how far it is to be believed—The date of Scot’s birth and nature of his first studies—Scot at Paris: his growing fame, and the degrees he won in that school—Probability that further study at Bologna formed the introduction to his life in the south, | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The position held by Scot at the Court of Sicily—His service under the Clerk Register, who seems to have been the same as Philip of Tripoli—Scot appointed tutor to Frederick II.—Advantages of such a position—He teaches the Prince mathematics and acts as Court Astrologer—Publication of the Astronomia and Liber Introductorius—Frederick’s marriage—Scot produces the Physionomia and presents it on this occasion—Account of this the most popular of his books, and of the sources from which it was derived—Scot quits Sicily for Spain, | 18 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| An important moment—The history of the Arabs in their influence on the intellectual life of Europe—The school of Toledo—Scot fixes his residence in that city—The name and fame of Aristotle—Scot engages in translating Arabic versions of the works of Aristotle on Natural History—The De Animalibus and its connection with the Physionomia—The [xiv]Abbreviatio Avicennae and its relation to former versions of the Toledo school—The date when Scot finished this work.—Frederick’s interest in these books—The De partibus animalium—Did Scot know Greek?—How the Arabian Natural History contrasts with the modern—Toledo, | 42 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Alchemy: its history, both primitive and derivative—The Gnostics influence it, and it passes by way of the Syrians to the Arabs—Disputes divide their schools in the twelfth century regarding the reality of this art—Spain the scene of this activity and the place where alchemy began to become known among the Latins—The time when the work of translation commenced, and the course it followed—Scot’s position in the history of this art, and an examination of his chemical works: the spurious De natura solis et lunae, the Magisterium, the Liber Luminis Luminum, and the De Alchimia, | 65 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Connection between alchemy and astronomy—Scot’s interest in the latter science—Toledo a favourable place for such study—Progress made by the Moors in astronomy—Scot translates Alpetrongi—Relation of this author to those who had preceded him: to Albategni; to Al Khowaresmi and to Alfargan—The fresh contributions made by Alpetrongi to a theory of the heavenly motions—His solution of the problems of recession and solstitial change—The date of Scot’s version of the Sphere, and its possible coincidence with that of the great astronomical congress at Toledo, | 96 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Averroës of Cordova and the fame he enjoyed among the Latins—His works condemned by the Church—Frederick II. likely to have been attracted by this philosophy—Michael Scot at Cordova—Constitution of a new College at Toledo under imperial patronage for the purpose of translating the works of Averroës into Latin—Correspondence between [xv]this and the similar enterprise of a hundred years before—Andrew the Jew interprets for Scot—Defence of this literary method—Versions of the De Coelo et Mundo, the De anima, the Parva Naturalia and others—The Quaestiones Nicolai Peripatetici: with a summary of this important treatise—Works found in the Venice manuscript—The Nova Ethica—Michael Scot shines as a translator from the Greek—Comparison between him and Bacon in regard to this, | 106 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

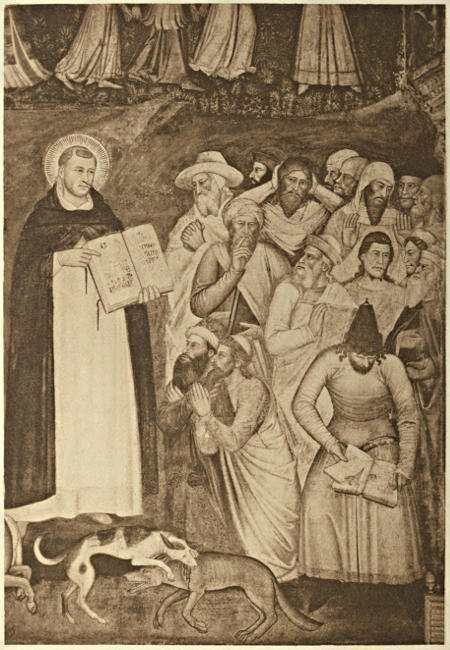

| Scot returns from Spain to the Imperial Court—Dante’s reference to this and to the costume worn by the philosopher—Probability that he is represented in the fresco at S. Maria Novella. The Latin Averroës suppressed and Scot resumes his post as Imperial Astrologer—He publishes on this subject—Remarks on Scot by Mirandola, Salimbene, and Bacon—He comments on the Sphere of Sacrobosco—A legend of Naples and its interpretation—Testimony of Leonardo Pisano—Scot’s medical studies and skill—He composes a treatise in that science—Two prescriptions, and some account of the plagues then prevalent, | 137 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Scot on the way to ecclesiastical preferment—Honorius III. exerts himself to obtain a benefice for the philosopher—He refuses the Archbishopric of Cashel—A similar case of conscience in the same age.—Gregory IX. applies again to Canterbury but without result—Effect of these disappointments on Scot.—His prophecies in verse and prose—The Cervilerium—His mental state at this time; and an attempt to estimate his real character—The publication of Scot’s version of Averroës now possible—Frederick II. indites a circular letter to the Universities—Scot travels through Italy, France, and England to the borders of Scotland—His death—The Emperor permits a copy of the Abbreviatio Avicennae to be made as a tribute to Scot’s memory, | 157 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The legendary fame of Scot—Nature of the magic then studied in [xvi]Spain—Reasons for thinking that Scot’s fame as a magician is mostly mythical—Origin of the story in his connection with the Emperor, and from the place and nature of his Spanish studies—Probability that he composed a work on algebra, which was afterwards mistaken for something magical—His association with the Arthurian legend in its southern development confirms his character as a magician, and may have suggested several details in the stories that are told concerning him, | 179 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| How Dante used the legend of Michael Scot—The nature of subjective magic or glamour—Stories told by those who commented on the Divine Comedy—Boccaccio’s reference to Scot, and sundry tales of court and camp—The fifteenth century produces spurious magical works under Scot’s name—Folengo introduces him into the Baldus.—Dempster and the Scottish tales.—The tasks of Scot’s familiar spirit.—His embassy to Paris—Story of the witch of Falsehope—The Book of Might—Two stories of Scot as told by an old woman of Florence in the present year of grace—Conclusion, | 206 |

| Appendix, | 231 |

| Index, | 277 |

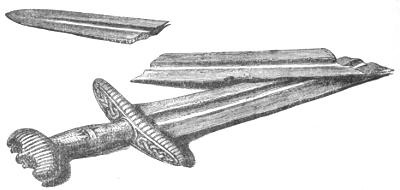

Frontispiece, A Magician, from the S. Maria Novella Fresco—Photogravure by Alinari, Florence

Vignette on Title—The Eildons, from an engraving kindly lent by Messrs. A. and C. Black, London

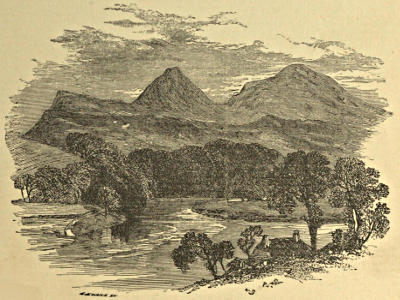

Facsimile of colophon to Scot’s Abbreviatio Avicennae (Fondo Vaticano 4428, p. 158 recto), to face page 55

In the Borders of Scotland it is well known that any piece of hill pasture, if it be fenced in but for a little from the constant cropping of the sheep, will soon show springing shoots of forest trees indigenous to the soil, whose roots remain wherever the plough has not passed too deeply. Centuries ago, when nature had her way and was unrestrained, the whole south-eastern part of the country was covered with dense forests and filled with forest-dwellers; the wild creatures that form the prey of the snare and the quarry of the chase. In the deep valleys, and by the streams of Tweed and Teviot, and many another river of that well-watered land, stood the great ranks and masses of the oak and beech as captains and patriarchs of the forest, mingled with the humbler whitethorn which made a dense undergrowth wherever the sun could reach. On the heights grew the sombre firs; their gnarled and ruddy branches crowned with masses of bluish-green foliage, while the alders followed the water-courses, and, aided by the shelter of these secret valleys, all but reached the last summits of the hills, which alone, in many a varied slope and peak and swelling breast, rose eminent and commanding over these dark and almost unbroken woodlands.

Such was south-eastern Scotland in the twelfth century: a country fitted to be the home of men of action rather than of thought; men whose joy should lie in the chase and the conflict with nature as yet unsubdued, who could track the savage creatures of the forest to their dens, and clear the land where it pleased them, and build, and dwell, and beget children in their own likeness, till by the labours of generations that country should become pastoral, peaceful, and fit for fertile tillage as we see it now.

Already, at the early time of which we speak, something of this work had been begun. There were gaps in the high forest where it lay well to the sun: little clearings marked by the ridge and furrow of a rude agriculture. Here and there a baron’s lonely tower raised its grey horn on high, sheltering a troop of men-at-arms who made it their business to guard the land in war, and in peace to rid it of the savage forest-creatures that hindered the hind and herd in their labour and their hope. In the main valleys more than one great monastery was rising, or already built, by the waters of Tweed and Teviot. The inmates of these religious houses took their share in the whole duty of peaceful Scottish men by following trades at home or superintending the labours of an army of hinds who broke in and made profitable the wide abbey lands scattered here and there over many a lowland county. All was energy, action, and progress: a form of life which left but little room for the enterprises of the mind, the conflicts and conquests which can alone be known and won in the world of thought within.

These conditions we know to have reared and trained generations of men well fitted to follow the pursuits of hardy and active life, yet they cannot have been so constraining as to hinder the birth of some at least who possessed an altogether different temper of mind and body. The lowland Scots were even then of a mixed race: the ancestry which tends more than any other to the production of life-eddies, where thought rather than activity naturally forms and dwells, while the current of the main stream sweeps past in its ordinary course. Grant the appearance of such natures here and there in these early times, and it is easy to see much in the only life then possible that was fit to foster their natural tendencies. The deep woodlands were not only scenes of labour where sturdy arms found constant employment, they were homes of mystery in which the young imagination loved to dwell; peopling them with half-human shapes more graceful than their stateliest trees, and half-brutal monsters more terrible than the fiercest wolf or bear. The distant sun and stars were more than a heavenly horologe set to mark the hours for labour or vigil, they were an unexplored scene of wonder which patient and brooding thought alone could reach and interpret. The trivial flight and annual return of birds, tracing like the wild geese a mysterious wedge against the sky of winter, gave more than a signal for the chase, which was all that ordinary men saw in it. To these finer natures it brought the awakening which those know who have learned to ask the mighty questions—Why? Whence? and Whither? demands which will not be denied till they have[4] touched the heights and fathomed the depths of human life itself. Our life is a bird, said one in these early ages, which flies by night, and, entering lighted hall at one end, swiftly passeth out at the other. So come we, who knoweth whence, and so pass we, who knoweth whither? From the darkness we come and to the darkness we go, and the brief light that is meanwhile ours cannot make the mystery plain.

But though the nature of this primitive life in early Scottish days could not hinder the appearance of men of thought, and even helped their development as soon as they began to show the movements of active intellect, yet on the other hand Scotland had not reached that culture which affords such natures their due and full opportunity. Centuries were yet to pass before the foundation of St. Andrews as the first Scottish university. The grammar-schools of the country[2] were but a step to the studies of some foreign seat of learning. The churchmen who filled considerable positions at home were either Italians, or had at least been trained abroad, so that everything in those days pointed to that path of foreign study which has since been trodden by so many generations of Scottish students. The bright example of Scotus Erigena, who had reached such a high place in France under Charles the Bald, was an incitement to the northern world of letters. Young men of parts and promise naturally sought their opportunity to go abroad in the hope of finding like[5] honourable employment, or, better still, of returning crowned with the honours of the schools to occupy some distinguished ecclesiastical position in their native country.

This then was the age, and these were the prevailing conditions, under which Michael Scot was born. To the necessary and common impulse of Scottish scholars we are to trace the disposition of the great lines on which his life ran its remarkable and distinguished course. He is certainly one of the most notable, as he is among the earliest, examples of the student Scot abroad.

There can be little doubt regarding the nation where he had his birth. Disregarding for a moment the varying accounts of those who lived centuries after the age of Scot himself, let us make a commencement with one whose testimony is of the very highest value, being that of a contemporary. Roger Bacon, the famous scientist of the thirteenth century, introduces the name of Michael Scot in the following manner: ‘Unde, cum per Gerardum Cremonensem, et Michaelem Scotum, et Aluredum Anglicum, et Heremannum (Alemannum), et Willielmum Flemingum, data sit nobis copia translationum de omni scientia.’[3] In this passage the distinctive appellation of each author is plainly derived from that of his native country. That Bacon believed Michael to be of Scottish descent is therefore certain, and his opinion is all the more valuable since he was an Englishman, and not likely therefore to have confused the two nations of Great Britain as a foreigner might haply have done. To[6] the same purpose is the testimony of Guido Bonatti, the astrologer, who also belonged to the age of Bacon and Scot. ‘Illi autem,’ he says,[4] ‘qui fuerunt in tempore meo, sicut fuit Hugo ab Alugant, Beneguardinus Davidbam, Joannes Papiensis, Dominicus Hispanus, Michael Scotus, Stephanus Francigena, Girardus de Sabloneta Cremonensis, et multi alii.’ Here also the significance of Scotus, as indicating nationality, is one that hardly admits of question. It was in all probability on these or similar authorities that Dempster relied when he said of Michael:[5] ‘The name Scot, however, is not a family one, but national,’ though he seems to have pressed the matter rather too far, it being plainly possible that Scotus might combine in itself both significations. In Scotland it might indicate that Michael belonged to the clan of Scott, as indeed has been generally supposed, while as employed by men of other nations, it might declare what they believed to have been this scholar’s native land.

At this point, however, a new difficulty suggests itself. It is well known that the lowland Scots were emigrants from the north of Ireland, and that in early times Scotus was used as a racial rather than a local designation. May not Michael have been an Irishman? Such is the question actually put by a recent writer,[6] and certainly it deserves a serious answer. We may commence by remarking that even on this understanding of it the name is an indefinite one as regards locality, and might therefore have been applied to one born in Scotland[7] just as well as if he had first seen the light in the sister isle. So certainly is this the case that when we recall the name of John Scotus we find it was customary to add the appellative Erigena to determine his birthplace. At that time the separation of race was much less marked than it had become in Michael’s day, and it seems certain therefore that if Michael Scotus was thought a sufficient designation of the man by Bacon and Bonatti, they must have used it in the sense of indicating that he came of that part of the common stock which had crossed the sea and made their home in Scotland. But to find a conclusive answer to this difficulty we need only anticipate a little the course of our narrative by mentioning here a highly curious fact which will occupy our attention in its proper place. When Michael Scot was offered high ecclesiastical preferment in Ireland he declined it on the ground that he was ignorant of the vernacular tongue of that country.[7] This seems to supply anything that may have been wanting in the other arguments we have advanced, and the effect of the whole should be to assure our conviction that there need be now no further attempt made to deny Scotland the honour of having been the native land of so distinguished a scholar.

Nor are we altogether without the means of coming to what seems at least a probable conclusion regarding the very district of the Scottish lowlands where Michael Scot was born. Leland the antiquary tells us that he was informed on good authority that Scot came from the territory of Durham.[8] Taken literally this statement would make him an[8] Englishman, but no one would think of quoting it as of sufficient value to disprove the testimony of Bacon and Bonatti who both believed Michael to have been born in Scotland. If, however, there should offer itself any way in which both these apparently contending opinions can be reconciled, we are surely bound to accept such an explanation of the difficulty, and in fact the solution we are about to propose not only meets the conditions of the problem, but will be found to narrow very considerably the limits of country within which the birthplace of Scot is to be looked for.

The See of Durham in that age, and for long afterwards, had a wide sphere of influence, extending over much of the south-eastern part of the Scottish Borders. Many deeds relating to this region of Scotland must be sought in the archives that belong to the English Cathedral. To be born in the territory of Durham then, as Leland says Scot had been, was not necessarily to be a native of England, and the anonymous Florentine commentator on Dante uses a remarkable expression which seems to confirm this solution as far as Scot is concerned. ‘This Michael,’ he says, ‘was of the Province of Scotland’;[9] and his words seem to point to that part of the Scottish lowlands adjacent to the See of Durham and in a sense its province, as subject to its influence, just as Provence, the analogous part of France, had its name from the similar relation it bore to Rome. The most likely opinion therefore that can now be formed on the subject leads us to believe that Scot was born somewhere in the[9] valley of the Tweed; if we understand that geographical expression in the wide sense which makes it equivalent to the whole of the south-eastern borders of Scotland.

Nor is this so contrary as might at first appear to the tradition which makes Scot a descendant of the family of Balwearie in Fife. Hector Boëce, Principal of Marischal College, Aberdeen, who first gave currency to the story,[10] could hardly have meant to imply that Michael was actually born at Balwearie. It is to be presumed that he understood Scotus to have been a family name; and the Scotts, who became of Balwearie by marriage with the heiress of that estate, did not enter into possession of it till long after the close of the twelfth century.[11] To call Michael a son of Balwearie in the genealogical sense, however, is in perfect agreement with the conclusion regarding his origin which we have just reached; for the original home of the Scotts who afterwards held that famous property as their chef lieu, lay by the upper streams of Tweed in the very district which every probability has already indicated to us as that of Michael’s birthplace. In 1265 we find an entry of money paid by the Crown ‘to Michael Scot and Richard Rufus who have occupied the waste lands at Stuth,’ near Peebles.[12] Identification is here out of the question, as Michael the scholar, of whom we write, was by this time long in his grave, but the entry we have quoted shows that a family of this surname, who still used the Christian name of Michael, was flourishing in[10] this part of Scotland during the second half of the thirteenth century.

It is to be remarked, too, that the Scottish tales of wonder relating to Michael Scot have a local colour that accords well with the other signs we have noticed. The hill which the sorcerer’s familiar spirit cleaves in sunder is the triple peak of Eildon; the water which he curbs is that of Tweed; from Oakwood he rides forth to try the witch of Falsehope, and in Oakwood tower may still be seen the Jingler’s room: a curious anachronism, for Oakwood is a building much more recent than the days of Michael Scot, yet one which fixes for us in a picturesque and memorable way the district of country where, according to the greatest number of converging probabilities, this remarkable man was born.

As to the date of his birth, it is difficult to be very precise. The probability that he died suddenly, and before he had completed the measure of an ordinary lifetime, prevents us from founding our calculations upon the date of his decease, which can be pretty accurately determined. A more certain argument may be derived from the fact that Scot had finished his youthful studies, made some figure in the world, and entered on the great occupation of his life as an author, as early as the year 1210.[13] Assuming then that thirty was the least age he could well have attained at the period in question, the year 1180 would be indicated as that of his birth, or rather as the latest date to which it can with probability be referred; 1175 being in every way a more likely approximation to the actual time of this event.

It is unfortunate that we find ourselves in the same position with regard to the interesting question of Scot’s early education, having only the suggestions derived from probable conjecture to offer on this subject also. Du Boulay indeed, in his account of the University of Paris,[14] pretends to supply a pretty complete account of the schools which Scot attended, but, as he adds that this was the usual course of study in those days, we find reason to think that he may have been guided in his assertions, rather by the probabilities of the case, than by any exact evidence. Nor is it likely that any more satisfactory assurance can now be had on this point: the time being too remote and the want of early material for Scot’s biography defeating in this respect all the care and attention that can now be given to the subject.

We know, however, that there was a somewhat famous grammar-school at Roxburgh in the twelfth century,[15] and considering the rarity of such an opportunity at so early a period, and the proximity of this place to the district in which Scot was born, we may venture to fancy that here he may have learned his rudiments, thus laying the foundation of those deeper studies, which he afterwards carried to such a height.

With regard to Durham, the matter may be considered to stand on firmer ground. The name of Michael Scot, as we have already seen, has for many ages been associated with this ancient Cathedral[12] city by the Wear. If the question of his birthplace be regarded as now determined in favour of Scotland, no reason remains for this association so convincing as that which would derive it from the fact that he pursued his education there. The Cathedral School of Durham was a famous one, which no doubt exerted a strong attraction upon studious youths throughout the whole of that province. In Scot’s case the advantages it offered may well have seemed a desirable step to further advances; his means, as one of a family already distinguished from the common people, allowing him to plan a complete course of study, and his ambition prompting him to follow it.

The common tradition asserts that when he left Durham, Scot proceeded to Oxford. This is not unlikely, considering the fame of that University, and the number of students drawn from all parts of the land who assembled there.[16] The only matters, however, which offer themselves in support of this bare conjecture are not, it must be said, very convincing. Roger Bacon shows great familiarity with Scot, and Bacon was an Oxford scholar, though his studies at that University were not begun till long after the time when Scot could possibly have been a student there. It is quite possible, however, that the interest shown by Bacon in Scot’s labours and high reputation—not by any means of a kindly sort—may have been awakened by traditions that were still current in the Schools of Oxford when the[13] younger student came there. Near the end of his life, Scot visited in a public capacity the chief Universities of Europe, and brought them philosophic treasures that were highly thought of by the learned. It seems most probable, from the terms in which Bacon speaks of this journey,[17] that it may have included a visit to Oxford. This might of course be matter of mere duty and policy, but one cannot help observing how well it agrees with the tradition that these schools were already familiar to Scot. As a recognised alumnus of Oxford, he would be highly acceptable there, being one whose European fame shed no small lustre upon the scene of his early studies.

As to Paris, the next stage in Scot’s educational progress, the historian of that University becomes much more convincing when he claims for Lutetia the honour of having contributed in a special sense to the formation of this scholar’s mind. For here tradition has preserved one of those sobriquets which are almost invariably authentic. Scot, it seems, gained here the name of Michael the Mathematician,[18] and this corresponds, not only with what is known concerning the character of his studies, but also with the nature of the course for which Paris was then famous. There is another circumstance which seems to point strongly in the same direction. Every one must have noticed how invariably the name of Scot is honoured by the prefix of Master. This is the case not only in his printed works, but also in popular tradition, as may be seen in the[14] well-known rhyme:—‘Maister Michael Scot’s man.’[19] A Florence manuscript, to which we shall presently refer more fully, throws some light upon the meaning of this title, by describing Scot as that scholar, ‘who among the rest is known as the chief Master.’[20] It is matter of common knowledge, that this degree had special reference to the studies of the Trivium and Quadrivium, being the scholastic crown reserved for those who had made satisfactory progress in the liberal arts. Scot then, according to the testimony of early times, was the supreme Master in this department of knowledge. But it is also certain that Paris was then recognised as the chief school of the Trivium and Quadrivium, just as Bologna had a like reputation for Law, and Salerno for Medicine.[21] We are therefore warranted to conclude that Michael Scot could never have been saluted in European schools as ‘Supreme Master,’ had he not studied long in the French capital, and carried off the highly esteemed honours of Paris.

Another branch of study which tradition says Scot followed with success at Paris was that of theology. Du Boulay declares, indeed, that he reached the dignity of doctor in that faculty, and there is some reason to think that this may actually have been the case. There can be no doubt that an ecclesiastical career then offered the surest road to wealth and fame in the case of all who aspired to literary honours. That Scot took holy orders[22] seems very probable. He may well have done so even before he came to Paris, for Bacon makes it one of[15] his reproaches against the corruption of the times, that men were ordained far too readily, and before they had reached the canonical age: from their tenth to their twentieth year, he says.[23] It is difficult to verify Dempster’s assertion that Scot’s renown as a theologian is referred to by Baconthorpe the famous Carmelite of the following century.[24] This author was commonly known as the Princeps Averroïstarum. If he really mentions Michael, and does not mean Duns Scotus, as there is some reason to suspect, his praise may have been given quite as much on the ground of profane as of religious philosophy. On the other hand we find abounding and unmistakable references to Scripture, the Liturgy, and ascetic counsels in the writings of Scot, from which it may safely be concluded that he had not merely embraced the ecclesiastical profession as a means of livelihood or of advancement, but had seriously devoted himself to sacred studies. It is true that we cannot point to any instance in which he receives the title of doctor, but this omission may be explained without seriously shaking our belief in the tradition that Scot gained this honour at Lutetia. During the twelfth century the Bishop of Paris forbade the doctors of theology to profess that faculty in any other University.[25] Scot may well, therefore, have been one of those philosophical divines who taught entre les deux ponts, as the same statute commanded they should, though in other lands and during his after-life, he came to be known simply[16] as the ‘Great Master’: the brightest of all those choice spirits of the schools on which Paris set her stamp.

At this point we may surely hazard a further conjecture. Bacon tells us that in those days it was the study of law, ecclesiastical and civil, rather than of theology, which opened the way to honour and preferment in the Church.[26] Now Paris was not more eminently and distinctly the seat of arts than Bologna was the school of laws.[27] May not Michael Scot have passed from the French to the Italian University? Such a conjecture would be worth little were it not for the support which it undoubtedly receives from credible tradition. Boccaccio in one of his tales[28] mentions Michael Scot, and tells how he used to live in Bologna. Many of the commentators on the Divine Comedy of Dante dwell on the theme, and enrich it with superstitious wonders.[29] It would be difficult to find a period in the scholar’s life which suits better with such a residence than that we are now considering. On all accounts it seems likely that he left Paris for Bologna, and found in the latter city a highly favourable opening, which led directly to the honours and successes of his after-life.

He was now to leave the schools and enter a wider sphere, not without the promise of high and enduring fame. A child of the mist and the hill, he had come from the deep woods and wild outland life of the Scottish Border to what was already no inconsiderable position. He knew Paris, not, need[17] it be said, the gay capital of modern days, but Paris of the closing years of the twelfth century, Lutetia Parisiorum: her low-browed houses of wood and mud; her winding streets, noisome even by day, and by night still darker and more perilous; her vast Latin Quarter, then far more preponderant than now—a true cosmopolis, where fur-clad barbarians from the home of the north wind sharpened wits with the Latin races haply trained in southern schools by some keen-browed Moor or Jew. And Paris knew him, watched his course, applauded his success, crowned his fame by that coveted title of Master, which he shared with many others, but which the world of letters made peculiarly his own by creating for him a singular and individual propriety in it. From Paris we may follow him in fancy to Bologna, yet it is not hard to believe he must have left half his heart behind, enchained in that remarkable devotion which Lutetia could so well inspire in her children.[30] Bologna might be, as we have represented it, the gate to a new Eden, that of Scot’s Italian and Spanish life, yet how could he enter it without casting many a longing glance behind to the Paradise he had quitted for ever when he left the banks of the Seine?

All tradition assures us that the chief occupation of Scot’s life was found at the Court of Frederick II., King of Sicily, and afterwards Emperor of Germany: a Prince deservedly famous, not only for his own talent, but for the protection and encouragement he afforded to men of learning. A manuscript in the Laurentian Library,[31] hitherto unnoticed in this connection, seems to throw some light upon the time and manner of this employment: points that have always been very obscure. The volume is a collection of Occulta, and at p. 256 we find the following title, ‘An Experiment of Michael Scot the magician.’ What follows is of no serious importance: such as it has we shall consider in speaking of the Master’s legendary fame. The concluding words, however, are of great interest, especially when we observe that this part of the manuscript, though written between 1450 and 1500, is said[32] to have been copied ‘from a very ancient book.’ The colophon runs thus: ‘Here endeth the necromantic experiment of the most illustrious doctor, Master[33] Michael Scot, who among other scholars is known as the supreme[19] Master; who was of Scotland, and servant to his most distinguished chief Don Philip,[34] the King of Sicily’s clerk;[35] which experiment he contrived[36] when he lay sick in the city of Cordova. Finis.’

Taking the persons here named in the order of their rank, we notice first the great Emperor Frederick II., the patron of Michael Scot. It is worth remark that he is styled simply ‘King of Sicily,’ a title which belongs to the time previous to 1215, when he obtained the Imperial crown. This is a touch which seems to give high originality and value to the colophon. We may feel sure that it was not composed by the fifteenth century scribe, who would certainly have described Frederick in the usual style as Emperor and Lord of the World. He must have copied it, and everything leads one to suppose that he was right in describing the source from which he drew as ‘very ancient.’

Next comes Don Philip, whom we have rightly described as the clerk of Sicily, for the word coronatus in its mediæval use is derived from corona in the sense of the priestly tonsure, so that Philippus coronatus is equivalent to Philippus clericus.[37] Of this distinguished man we find many traces in the historical documents of the period.[38] Two deeds passed the seals of Sicily in the year 1200 when the King, then a boy of five years old, was living under the care of his widowed mother the Queen Constantia. These are countersigned by the royal notary, who is described as ‘Philippus de Salerno, notarius et fidelis noster scriba.’ His name is found in the[20] same way, apparently for the last time, in 1213. This date, and the particular designation of Philip the Notary as ‘of Salerno,’ connect themselves very naturally with the title of a manuscript belonging to the De Rossi collection.[39] It is as follows: ‘The Book of the Inspections of Urine according to the opinion of the Masters, Peter of Berenico, Constantine Damascenus, and Julius of Salerno; which was composed by command of the Emperor Frederick, Anno Domini 1212, in the month of February, and was revised by Master Philip of Tripoli and Master Gerard of Cremona at the orders of the King of Spain,’ etc. The person designed as Philip of Salerno was very likely to be put in charge of the revision of a medical treatise, and as he disappears from his duties as notary for some time after 1213 we may suppose that it was then he passed into the service of the King of Spain. This conjecture agrees also with the mention of Cordova in the Florence manuscript, and with other peculiarities it displays, such as the spelling of the name Philippus like Felipe, and the way in which the title Dominus is repeated, just as Don might be in the style of a Spaniard. There is, in short, every reason to conclude that Philip of Salerno and Philip of Tripoli were one and the same person. We may add that Philip was the author of the first complete version in Latin of the book called Secreta Secretorum, the preface of which describes him as a clericus of the See of Tripoli. As will presently appear, Michael Scot drew largely from this work in composing one of his own;[40] another proof that in confronting with each other these three names—Philippus[21] coronatus or clericus; Philippus de Salerno, and Philippus Tripolitanus—and in concluding that they belong to one and the same person, we have a reasonable amount of evidence in our favour.

From what has just been said it is plain that three distinct periods must have composed the life of Philip so far as we know it: the first when he served as an ecclesiastic in Tripoli of Syria or its neighbourhood; the second when he came westward, and, not without a certain literary reputation, held the post of Clerk Register in Sicily; the last when Frederick sent him, in the height of his powers and the fulness of his fame, to that neighbouring country of Spain, then so full of attraction for every scholar. In which of these periods then was it that Michael Scot first came into those relations with Philip of which the Florentine manuscript speaks? The time of his residence in Spain, likely as it might seem on other accounts, would appear to be ruled out by the fact that it was too late for Philip to be then described as servant of the King of Sicily. Nor did he hold this office, so far as we can tell, until he had left Tripoli for the West. We must pronounce then for the Sicilian period, and precisely therefore for the years between 1200 and 1213. This conclusion, however, does not hinder us from supposing that the relation then first formally begun between Michael and Philip continued to bind them, in what may have been a friendly co-operation, during the time spent by both in Spain.

The period thus determined was that of the King’s boyhood, and this opens up another line of argument which may be trusted not only to confirm[22] the results we have reached, but to afford a more exact view of Scot’s occupation in Sicily. Several of his works are dedicated to Frederick, from which it is natural to conclude that his employment was one which brought him closely in contact with the person of the King. When we examine their contents we are struck by the tone which Scot permits himself to use in addressing his royal master. There is familiarity when we should expect flattery, and the desire to impart instruction instead of the wish to display obsequiousness. Scot appears in fact as one careless to recommend himself for a position at Court, certain rather of one which must have been already his own. What can this position have been?

A tradition preserved by one of the commentaries on Dante[41] informs us that Michael Scot was employed as the Emperor’s tutor, and this explanation is one which we need feel no hesitation in adopting, as it clears up in a very convincing way all the difficulties of the case. His talents, already proved and crowned in Paris and Bologna, may well have commended him for such a position. The dedication of his books to Frederick, and the familiar style in which he addresses the young prince, are precisely what might be expected from the pen of a court schoolmaster engaged in compiling manuals in usum Delphini.[42] Nay the very title of ‘Master’ which Scot had won at Paris probably owed its chief confirmation and continued employment to the nature of his new charge. Since the fifth century there had prevailed in Spain the habit[23] of committing children of position to the course of an ecclesiastical education.[43] They were trained by some discreet and grave person called the magister disciplinae, deputed by the Bishop to this office. Such would seem to have been the manner of Frederick’s studies. His guardian was the Pope; he lived at Palermo under charge of the Canons of that Cathedral,[44] and no doubt the ecclesiastical character of Michael Scot combined with his acknowledged talents to point him out as a suitable person to fill so important a charge. It was his first piece of preferment, and we may conceive that he drew salary for his services under some title given him in the royal registry. This would explain his connection with Philip, the chief notary, on which the Florentine manuscript insists. Such fictitious employments have always been a part of court fashion, and that they were common in Sicily at the time of which we write may be seen from the case of Werner and Philip de Bollanden, who, though in reality most trusted and confidential advisers of the Crown, were known at Court as the chief butler and baker, titles which they were proud to transmit to their descendants.[45]

It was at Palermo, then, that Michael Scot must have passed the opening years of the thirteenth century; now more than ever ‘Master,’ since he was engaged in a work which carried with it no light responsibility: the early education of a royal youth destined to play the first part on the European stage. The situation was one not without advantages[24] of an uncommon kind for a scholar like Scot, eager to acquire knowledge in every department. Sicily was still, especially in its more remote and mountainous parts about Entella, Giato, and Platani, the refuge of a considerable Moorish population, whose language was therefore familiar in the island, and was heard even at Court; being, we are assured, one of those in which Frederick received instruction.[46] There can be little doubt that Scot availed himself of this opportunity, and laid a good foundation for his later work on Arabic texts by acquiring, in the years of his residence at Palermo, at least the vernacular language of the Moors.

The same may be said regarding the Greek tongue: a branch of study much neglected even by the learned of those times. We shall presently produce evidence which goes to show that Michael Scot worked upon Greek as well as Arabic texts,[47] and it was in all probability to his situation in Sicily that he owed the acquisition of what was then a very rare accomplishment. Bacon, who deplores the ignorance of Greek which prevailed in his days, recommends those who would learn this important language to go to Italy, where, he says, especially in the south, both clergy and people are still in many places purely Greek.[48] The reference to Magna Grecia is obvious, and to Sicily, whose Greek colonies preserved, even to Frederick’s time and beyond it, their nationality and language. So much was this the case, that it was thought necessary to make the study of Greek as well as of Arabic part of Frederick’s education. We can hardly err[25] in supposing that Scot profited by this as well as by the other opportunity.

In point of general culture too a residence at Palermo offered many and varied advantages. Rare manuscripts abounded, some lately brought to the island, like that of the Secreta Secretorum, the prize of Philip the Clerk, which he carried with him when he came from Tripoli to Sicily, and treasured there, calling it his ‘precious pearl’;[49] others forming part of collections that had for some time been established in the capital. As early as the year 1143, George of Antioch, the Sicilian Admiral, had founded the Church of St. Maria della Martorana in Palermo, and had enriched it with a valuable library, no doubt brought in great part from the East.[50] A better opportunity for literary studies could hardly have been desired than that which the Prince’s Master now enjoyed.

The society and surroundings in which Michael Scot now found himself were such as must have communicated a powerful impulse to the mind. The Court was grave rather than gay, as had befitted the circumstances of a royal widow, and now of an orphan still under canonical protection and busied in serious study, but this allowed the wit and wisdom of learned men free scope, and thus invited and encouraged their residence. Already, probably, had begun that concourse and competition of talents, for which the Court of Frederick was afterwards so remarkable. Amid delicious gardens at evening, or by day in the cool shade of courtyards: those patios which the Moors had built so well and adorned with such fair arabesques, all that[26] was rarest in learning and brightest in wit, held daily disputation, while the delicate fountains played and Monte Pellegrino looked down on the curving beauties of the bay and shore. A strange contrast truly to the arcades of Bologna, now heaped with winter snow and now baked by summer sun; to the squalor of mediæval Paris, and much more to the green hillsides and moist forest-clad vales of southern Scotland. Here at last the spirit of Michael Scot underwent a powerful and determining influence which left its mark on all his subsequent life.

As royal tutor, his peculiar duty would seem to have been that of instructing the young Prince in the different branches of mathematics. This we should naturally have conjectured from the fact that Scot’s fame as yet rested entirely upon the honours he had gained at Paris, and precisely in this department of learning; for ‘Michael the Mathematician’ was not likely to have been called to Palermo with any other purpose. We have direct evidence of it however in an early work which came from the Master’s pen, and one which would seem to have been designed for the use of his illustrious pupil. This was the Astronomia, or Liber Particularis, and in the Oxford copy,[51] the colophon of that treatise runs thus: ‘Here endeth the book of Michael Scot, astrologer to the Lord[27] Frederick, Emperor of Rome, and ever August; which book he composed in simple style[52] at the desire of the aforesaid Emperor. And this he did, not so much considering his own reputation, as desiring to be serviceable and useful to young scholars, who, of their great love for wisdom, desire to learn in the Quadrivium the Art of Astronomy.’ The preface says that this was the second book which Scot composed for Frederick.

The science of Astronomy was so closely joined in those times with the art of Astrology, that it is difficult to draw a clear distinction between them as they were then understood. The one was but the practical application of the other, and in common use their names were often confused and used interchangeably. We are not surprised then to find the title of Imperial Astrologer given to Michael Scot in the colophon to his Astronomia; he was sure to be employed in this way, and the fact will help us to determine with probability what was the first book he wrote for the Emperor, that to which the Liber Particularis was a sequel. For there is actually extant under Scot’s name an astrological treatise bearing the significant name of the Liber Introductorius.[53] This title agrees exceedingly well with the position we are now inclined to give it, and an examination of the preface confirms our[28] conjecture in a high degree. It commences thus: ‘Here beginneth the preface of the Liber Introductorius which was put forth by Michael Scot, Astrologer to the ever August Frederick, Emperor of the Romans, at whose desire he composed it concerning astrology,[54] in a simple style[55] for the sake of young scholars and those of weaker capacity, and this in the days of our Lord Pope Innocent IV.’[56] One cannot help noticing the close correspondence between this and the colophon of the Astronomia. The two treatises were the complement each of the other. They must have been composed about the same time, and were doubtless meant to serve as text-books to guide the studies of Frederick’s youth. That this royal pupil should have been led through astrology to the higher and more enduring wonders of astronomy need cause no surprise, for such a course was quite in accordance with the intellectual habits of the age. It may be doubted indeed whether the men of those times would have shown such perseverance in the observations and discoveries proper to a pure science of the heavens, had it not been for the practicable and profitable interest which its application in astrology furnished. Astronomy, such as it then was, formed the last and highest study in the Quadrivium.[57] It was here that Scot had carried off honours at Paris, and now in his Liber Introductorius and Astronomia, we see[29] him imparting the ripe fruits of that diligence to his royal charge, whose education, so far as regarded formal study, was thereby brought to a close.

In the year 1209, when Frederick was but fourteen years of age, the quiet study and seclusion in which he still lived with those who taught him was brought to an abrupt and, one must think, premature conclusion. The boy was married, and to a lady ten years his senior, Constance, daughter of the King of Aragon, and already widow of the King of Hungary. It is not hard to see that such a union must have been purely a matter of arrangement. The Prince of Palermo, undergrown and delicate as he was,[58] promised to be, as King of Sicily and possibly Emperor, the noblest husband of his time. Pope Innocent III., his guardian, foresaw this, and chose a daughter of Spain as most fit to occupy the proud position of Frederick’s wife, queen, and perhaps empress. Had the wishes of Rome prevailed at the Court of Aragon from the first, this marriage would have taken place even earlier than it did. The delay seems to have been owing, not to any reluctance on the part of the bride’s parents, but solely to the doubt which of two sisters, elder or younger, widow or maid, should accept the coveted honour.

It was in spring, the loveliest season of the year in that climate, that the fleet of Spain, sent to bear the bride and her suite, rose slowly over the sea rim and dropped anchor in the Bay of Palermo. Constantia came with many in her company, the flower of Catalan and Provençal chivalry, led by her brother, Count Alfonso. The Bishop of Mazara,[30] too, was among them, bearing a commission to represent the Pope in these negotiations and festivities. And now the stately Moorish palace, with its courtyard, its fountains, and its gardens, became once more a scene of gaiety, as—in the great hall of forty pillars, beneath a roof such as Arabian artists alone could frame, carved like a snow cave, or stained with rich and lovely colour like a mass of jewels set in gold—the officers of the royal household passed solemnly on to offer homage before their Prince and his bride. In the six great apartments of state the frescoed forms of Christian art: Patriarchs in their histories, Moses and David in their exploits, and the last wild charge of Barbarossa’s Crusade,[59] looked down upon a moving throng of nobles and commons who came to present their congratulations, while the plaintive music of lute, of pipe, and tabor, sighed upon the air, and skilful dancers swam before the delighted guests in all the fascination of the voluptuous East.

What part could Michael Scot, the grave ecclesiastic, and now doubly the ‘Master’ as Frederick’s trusted tutor, play in the gay scene of his pupil’s marriage? For many ages it has been the custom among Italian scholars, the attached dependants of a noble house, to offer on such occasions their homage to bride and bridegroom in the form of a learned treatise; any bookseller’s list of Nozze is enough to show that the habit exists even at the present day. This then was what Scot did; for there is every reason to think that the Physionomia, which he composed and dedicated to Frederick, was produced and presented at the time of the royal marriage. No date suits this publication so well as 1209, and[31] nothing but the urgent desire of Court and people that the marriage should prove fruitful can explain, one might add excuse, some passages of almost fescennine licence which it contains.[60] We seem to find in the advice of the preface that Frederick should study man, encouraging the learned to dispute in his presence what may well have been the last word of a master who saw his pupil passing to scenes of larger and more active life at an unusually early age, and before he could be fully trusted to take his due place in the great world of European politics.

The Physionomia, however, is too important a work to be dismissed in a paragraph. Both the subject itself, and the sources from which Scot drew, deserve longer consideration. The science of physiognomy, as its name imports, was derived from the Greeks. Achinas, a contemporary of the Hippocratic school, and Philemon, who is mentioned in the introduction to Scot’s treatise, seem to have been the earliest writers in this department of philosophy. It was a spiritual medicine,[61] and formed part of the singular doctrine of signatures, teaching as it did that the inward dispositions of the soul might be read in visible characters upon the bodily frame. The Alexandrian school made a speciality of physiognomy. In Egypt it attained a further development, and various writings in Greek which expounded the system passed current during the early centuries of our era under the names of[32] Aristotle and Polemon. Through the common channel of the Syriac schools and language it reached the Arabs, and in the ninth century had the fortune to be taken up warmly by Rases and his followers, who made it a characteristic part of their medical system. From this source then Scot drew largely; chapters xxiv.-xxv. in Book II. of his Physionomia correspond closely with the De Medicina ad Regem Al Mansorem[62] of Rases.[63]

Among ancient texts on physiognomy, however, perhaps the most famous was the Sirr-el-asrar, or Secreta Secretorum, which was ascribed to Aristotle. Its origin, like that of other pseudo-Aristotelic writings, seems to have been Egyptian. When the conquests of Alexander the Great had opened the way for a new relation between East and West, Egypt, and especially its capital, Alexandria, became the focus of a new philosophic influence. The sect of the Essenes, transported hither, had given rise to the school of the Therapeutae, where Greek theories developed in a startling direction under the power of Oriental speculation. The Therapeutae were sun-worshippers, and eager students of ancient and occult writings, as Josephus[64] tells us the Essenes had been. We find in the Abraxas gems, of which so large a number has been preserved, an enduring memorial of these people and their system of thought.[65]

The preface to the Sirr-el-asrar affords several matters which agree admirably with what we know of the Therapeutae. The precious volume was the prize of a scholar on his travels, who found it in the possession of an aged recluse dwelling in the penetralia of a sun-temple built by Æsculapius.[66] All this is characteristic enough, and when we examine the substance of the treatise it appears distinctly Therapeutic. Much of it is devoted to bodily disease, to the regimen of the health, and to that science of physiognomy which professed to reveal, as in a spiritual diagnosis, the infirmities of the soul. The ascription of the work to Aristotle, Alexander’s tutor, seems quite in accordance with this theory; in short, there is no reason to doubt that it first appeared in Egypt, where it probably formed one of the most cherished texts of the Therapeutae.

The preface to the Sirr-el-asrar throws light not only upon the origin of the treatise but also upon its subsequent fortunes. It is said to have been rendered from the Greek into Chaldee or Syriac,[67] and thence into Arabic, the usual channel[34] by which the remains of ancient learning have reached the modern world. The translator’s name is given as Johannes filius Bitricii, but this can hardly have been the well-known Ibn-el-Bitriq, the freedman of Mamoun. To this latter author indeed, the Fihrist, composed in 987, ascribes the Arabic version of Aristotle’s De Cœlo et Mundo, and of Plato’s Timaeus, so that his literary faculty would seem to accord very well with the task of translating the Sirr-el-asrar. But Foerster has observed[68] that we find no trace of this book in Arabian literature before the eleventh century. Now the famous Ibn-el-Bitriq lived in the ninth, as appears from several considerations. His works were revised by Honain ibn Ishaq (873), and, if we believe in the authenticity of the El Hawi, where he is mentioned by name, then he must have belonged to an age at least as early as that of Rases who wrote it. In these perplexing circumstances, Foerster gives up the attempt to determine who may have been the translator of the Sirr-el-asrar, contenting himself with the conjecture that some unknown scholar had assumed the name of El Bitriq to give importance to the production of his pen. We may be excused, however, if we direct attention to two manuscripts of the British Museum[69] which do not seem to have been noticed by those who have devoted attention to this obscure subject. One of these, which is written in a hand of the thirteenth century, informs us that the man who transcribed[35] it was a certain Said Ibn Butrus ibn Mansur, a Maronite priest of Lebanon in the diocese of Tripolis, a prisoner for twelve years in the place where the royal standards were kept (? at Cairo), who was released from that confinement in the time of al Malik an Nazir. The other—a mere fragment—contains a notice of the priest Yahyā, or Yuhannā, ibn Butrus, who died in the year 1217 A.D. It is not unlikely that some confusion might arise between the names Patrick and Peter, often used interchangeably. ‘Filius Patricii’ then may have been no assumed designation, but the equivalent of Ibn Butrus, the real name of this priest of Tripoli, who was perhaps the translator of the Sirr-el-asrar at the close of the twelfth century.

Those chapters of the Sirr-el-asrar which relate to regimen were translated into Latin by Johannes Hispalensis. Jourdain identifies this author with John Avendeath, who worked for the Archbishop of Toledo between the years 1130 and 1150.[70] But Foerster shows that caution is needed here.[71] The Latin version was dedicated to Tarasia, Queen of Spain. A queen of this name certainly lived contemporaneously with John Avendeath, but she was Queen of Portugal. Another Tarasia, however, was Queen of Leon from 1176 to 1180. We may observe that this latter epoch agrees well enough with the lifetime of Ibn Butrus, who died in 1217, and we find trace of another Johannes Hispanus, who was a monk of Mount Tabor in 1175. Such a man, who from his situation in Syria could scarcely have been ignorant of Arabic, and whose nationality agrees so well with a dedication to[36] the Queen of Spain, and who was a contemporary of Tarasia of Leon, may well have translated the Sirr-el-asrar into Latin. That part of the book thus made public in the West appeared under the following title: ‘De conservatione corporis humani, ad Alexandrum.’ It is found in several manuscripts of the Laurentian Library in Florence.[72]

Soon afterwards, and probably in the opening years of the thirteenth century, the whole book was published in a Latin version by the same Philippus Clericus, with whom we have already become acquainted. We may recall the fact that he belonged to the diocese of Tripoli, as Ibn Butrus also did, and as Johannes Hispanus was also a monk of Syria, these three scholars are seen to be joined by a link of locality highly increasing the probability that they actually co-operated in the publication of this hitherto unknown text. In his preface, Philip speaks of the Arabic manuscript as a precious pearl, discovered while he was still in Syria. This leads us to think that his work in translating it was done after he had left the East, and possibly in the course of his voyage westward. We know that the Hebrew version of Aristotle’s Meteora was produced in similar circumstances. Samuel ben Juda ben Tibbun says he completed that translation in the year 1210, while the ship that bore him from Alexandria to Spain was passing between the isles of Lampadusa and Pantellaria.[73] However this may be, Philip of Tripoli dedicated his version of the Sirr-el-asrar, which he called the Secreta[37] Secretorum, to the Bishop under whom he had hitherto lived and laboured: ‘Guidoni vere de Valentia, civitatis Tripolis glorioso pontifici’: a name and title little understood by the copyists, who have subjected them to strange corruptions.[74]

It is highly in favour of our identifying, as we have already done, Philip of Tripoli, the translator of the Secreta, with Philip of Salerno, the Clerk Register of Sicily, that we find Michael Scot, who stood in an undoubtedly close relation to the Clerk Register, showing an intimate acquaintance with the Secreta Secretorum. Foerster has given us a careful and exact account of several passages in different parts of the Physionomia of Scot, which have their correspondences in the works of Philip, so that it is beyond question that the Latin version of the Secreta was one of the sources from which Scot drew. Before leaving this part of the subject, we may notice that translations of Philip’s version into the vernacular languages of Italy, France, and England were made at an early date, both in prose and verse.[75][38] The English version of the Secreta came from the hand of the poet Lydgate.

Another treatise of the same school, to which Scot was also indebted, is to be found in the Physionomia ascribed, like the Secreta, to Aristotle. The Latin version of this apocryphal work was made, it is said, directly from a Greek original, by Bartholomew of Messina. This author wrote for Manfred of Sicily, and at a time which excludes the notion that Scot could have seen or employed his work. Yet several passages in the preface to Book II. of Scot’s Physionomia have evidently been borrowed from that of the Pseudo-Aristotle. As no Arabic version of the treatise is known to exist, the fact of this correspondence is one of the proofs on which we may rely in support of the conclusion that Scot must have known and used the Greek language in his studies.

The last two chapters of Book I. in the Physionomia of Scot show plainly that he had the Arabic version of Aristotle’s History of Animals before him as he wrote. We shall recur to this matter when we come to deal with the versions which Scot made expressly from these books. Meanwhile let us guard against the impression naturally arising from our analysis of the Physionomia, that it was a mere compilation. Many parts of the work show no correspondence with any other treatise on the subject that is known to us, and these must be held as the results of the author’s[39] own observations. The arrangement of the whole is certainly original, nor can we better conclude our study of the Physionomia, than by giving a comprehensive view of its contents in their order. The work is divided into three books, each having its own introduction. The first expounds the mysteries of generation and birth, and reaches, as we have already remarked, even beyond humanity to a considerable part of the animal world so much studied by the Arabians. The second expounds the signs of the different complexions, as these become visible in any part of the body, or are discovered by dreams. The third examines the human frame member by member, explaining what signs of the inward nature may be read in each. The whole forms a very complete and interesting compendium of the art of physiognomy as then understood, and must have seemed not unworthy of the author, nor unsuitable as an offering to the young prince, who by marriage was about to enter on the great world of affairs, where knowledge of men would henceforth be all-important to his success and happiness. The book attained a wide popularity in manuscript, and the invention of printing contributed to increase its circulation in Europe:[76] no less than eighteen editions[40] are said to have been printed between 1477 and 1660.[77]

In the copy preserved at Milan, the Physionomia is placed immediately after the Astronomia, or Liber Particularis. A similar arrangement is found in the Oxford manuscript. This fact is certainly in favour of the view we have adopted, and would seem to fix very plainly the date and relation of these works. They stand beside the Liber Introductorius, and, together with it, form the only remains we have of Scot’s first literary activity, being publications that were called out in the course of his scholastic duty to the King of Sicily. The Liber Introductorius opens this series. It is closely related by the nature of its subject-matter to the Astronomia, or Liber Particularis, while the Physionomia forms a fitting close to the others with which it is thus associated. In this last treatise Michael Scot sought to fulfil his charge by sending forth his pupil to the great world, not wholly unprovided with a guide to what is far more abstruse and incalculable than any celestial theorem, the mystery of human character and action.

In presenting the Physionomia to Frederick, Scot took what proved a long farewell of the Court; for many years passed before he saw the Emperor again. The great concourse of the Queen’s train, together with the assembly of Frederick’s subjects at Palermo, bred a pestilence under the dangerous heats of spring. A sudden horror fell on the masques and revels of these bright days, with the death of the Queen’s brother, Count Alfonso of[41] Provence, and several others, so that soon the fair gardens and pleasant palace were emptied and deserted as a place where only the plague might dare to linger. The King and Queen, with five hundred Spanish knights and a great Sicilian following, passed eastward; to Cefalù first, and then on to Messina and Catania, as if they could not put too great a distance between themselves and the infected spot. Meanwhile Michael Scot, whose occupation in Palermo, and indeed about the King, was now gone, set sail in the opposite direction and sought the coast of Spain. Whether the idea of this voyage was his own, was the result of a royal commission, or had been suggested by some of the learned who came with Queen Constantia from her native land, it is now impossible to say. It was in any case a fortunate venture, which did much, not only for Scot’s personal fame, but for the general advantage in letters and in arts.

In following the course which Michael Scot held in his voyage to Spain, we approach what was beyond all doubt the most important epoch in the life of that scholar. Hitherto we have seen him as the student preparing at Paris or Bologna for a brilliant future, or as the tutor of a youthful monarch, essaying some literary ventures, which justified the position he held in Sicily, and recommended him for future employment. But the moment was now come which put him at last in possession of an opportunity suitable to his training and talents. We are to see how he won in Spain his greatest reputation in connection with the most important literary enterprise of the age, and one which is indeed not the least remarkable of all time.

The part which the Arabs took in the intellectual awakening of Europe is a familiar theme of early mediæval history. That wonderful people, drawn from what was then an unknown land of the East, and acted on by the mighty sense of religion and nationality which Mohammed was able to communicate, fell like a flood upon the weak remains of older civilisations, and made huge inroads upon the Christian Empire of the East. Having reached this point in their career of conquest they became[43] in their turn the conquered, not under force of arms indeed, but as subdued by the still vital intellectual power possessed by those whom they had in a material sense overcome. In their new seat by the streams of the Euphrates they learned from their Syrian subjects, now become their teachers, the treasures of Greek philosophy which had been translated into the Aramaic tongue. Led captive as by a spell, the Caliphs of the Abassid line, especially Al Mansour, Al Rachid, and Al Mamoun, encouraged with civil honours and rewards the labours of these learned men. Happy indeed was the Syrian who brought to life another relic of the mighty dead, or who gave to such works a new immortality by rendering them into the Arabic language.

Meanwhile the progress of the Ommiad arms, compelled to seek new conquests by the defeat they had sustained in the East from the victorious Abbassides, was carrying the Moors west and ever westward along the northern provinces of Africa. Egypt and Tripoli and Tunis successively fell before their victorious march; Algiers and Morocco shared the same fate, and at last, crossing the Straits of Gibraltar, the Moors overran Spain, making a new Arabia of that western peninsula, which in position and physical features bore so great a likeness to the ancient cradle of their race.

It is true indeed that long ere the period of which we write the Moorish power in the West had received a severe check, and had, for at least a century, entered on its period of decay. The battle of Tours, fought in 732, had driven the infidels from France. The Christian kingdoms of Spain[44] itself had rallied their courage and their forces, and, in a scene of chivalry, which inspired many a tale and song, had freed at least the northern provinces of that country from the alien power. But weapons of war, as we have already seen in the case of the Arabs themselves, are not the only means of conquest. The surest title of the Moors to glory lies in the prevailing intellectual influence they were able to exert over that Christendom which, in a political sense, they had failed to subdue and dispossess. The scene we have just witnessed in the East was now repeated in Spain, but was repeated in an exactly opposite sense. The mental impulse received from the remains of Greek literature at Bagdad now became in its turn the motive power which not only sufficed to carry these forgotten treasures westward in the course of Moorish conquest, but succeeded, through that nation, in rousing the Latin races to a sense of their excellence, and a generous ambition to become possessed of all the culture and discipline they were capable of yielding.