Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XXXV, No. 1, July 1849

Author: Various

Editor: Joseph R. Chandler

George R. Graham

Bayard Taylor

Release date: August 15, 2017 [eBook #55362]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed

Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net from

page images generously made available by Google Books

JULY

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

1849.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXV. July, 1849. No. 1.

Table of Contents

Fiction, Literature and Articles

Poetry, Music, and Fashion

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

GRAHAM’S

AMERICAN MONTHLY

MAGAZINE

Of Literature and Art,

EMBELLISHED WITH

MEZZOTINT AND STEEL ENGRAVINGS, MUSIC, ETC.

WILLIAM C. BRYANT, J. FENIMORE COOPER, RICHARD H. DANA, JAMES K. PAULDING,

HENRY W. LONGFELLOW, N. P. WILLIS, J. R. LOWELL, HENRY B. HIRST.

MRS. LYDIA H. SIGOURNEY, MISS C. M. SEDGWICK, MRS. FRANCES S. OSGOOD,

MRS. EMMA C.EMBURY, MRS. ANN S. STEPHENS, MRS. AMELIA B. WELBY,

MRS. A. M. F. ANNAN, ETC.

PRINCIPAL CONTRIBUTORS.

G. R. GRAHAM, J. R. CHANDLER AND J. B. TAYLOR, EDITORS.

VOLUME XXXV

PHILADELPHIA:

SAMUEL D. PATTERSON & CO. 98 CHESTNUT STREET.

. . . . . .

1849.

CONTENTS

OF THE

THIRTY-FIFTH VOLUME.

JUNE, 1849, TO JANUARY, 1850.

POETRY.

| A Daughter’s Memory. By Mary L. Lawson, | 34 | |

| Alice. By Thomas Dunn English, | 200 | |

| A Parting Song. By Professor Campbell, | 214 | |

| A Thought. By Isaac Gray Blanchard, | 232 | |

| Alice Vernon. By E. Curtiss Hine, | 342 | |

| Bunker-Hill at Midnight. By E. Curtiss Hine, | 303 | |

| Communion of the Sea and Sky. By E. Jones, | 176 | |

| Dirge. By Richard Penn Smith, | 371 | |

| Elim. By Virginia, | 91 | |

| Ermengarde’s Awakening. By F. S. Osgood, | 112 | |

| From Amalthæus. By Richard Penn Smith, | 34 | |

| Faith’s Warning. By Henry T. Tuckerman, | 92 | |

| Fragments of an Unfinished Story. By Mrs. Frances S. Osgood, | 263 | |

| Flower Fancies. By H. Marion Stephens, | 306 | |

| Good-Night. By Walter Herries, Esq. | 139 | |

| I will be a Miner too. By Mrs. Juliet H. L. Campbell, | 6 | |

| I’m Thinking of Thee! By A. D. Williams, | 16 | |

| Kubleh. By Bayard Taylor, | 120 | |

| Lines. By Walter Herries, Esq. | 60 | |

| Lament of the Gold-Digger. By E. C. Hine, | 92 | |

| Little Willie. By Mrs. H. Marion Stephens, | 98 | |

| Lily Leslie. By Gretta, | 156 | |

| Lines. By Forlorn Hope, | 281 | |

| Lines. By Sarah Helen Whitman, | 303 | |

| Mary. By Mrs. O. M. P. Lord, | 15 | |

| My Spirit. By Henry Morford, | 125 | |

| New Year Meditation. By Enna Duval, | 40 | |

| Northampton. By Henry T. Tuckerman, | 232 | |

| Parting. By Miss Phœbe Carey, | 265 | |

| Pleasant Words. By Caroline May, | 370 | |

| Passing Away. By Annie Grey, | 371 | |

| Song. By Thomas Fitzgerald, | 228 | |

| Speak Out. By S. D. Anderson, | 238 | |

| Spiritual Presence. By Mary G. Horsford, | 306 | |

| Summer’s Night. By Sam. C. Reid, Jr. | 332 | |

| Song. By Agnes, | 342 | |

| The Emigrant’s Daughters. By Gretta, | 6 | |

| The Tulip-Tree. By Bayard Taylor, | 16 | |

| To My Wife. By S. D. Anderson, | 26 | |

| To ——. By Henry B. Hirst, | 35 | |

| The Omnipresence of God. By R. Coe, Jr. | 35 | |

| The Image. By A. J. Requier, | 46 | |

| The Pilgrim’s Fast. By Mary G. Horsford, | 54 | |

| To My Mother in Heaven. By T. Fitzgerald, | 54 | |

| The Fortieth Sonnet of Petrarca. By F. R. | 58 | |

| The Improvisatrice. By Mary G. Horsford, | 81 | |

| The Eighteenth Sonnet of Petrarca. By F. R. | 81 | |

| To Mary. By Lucy Cabell, | 98 | |

| Translation from Sappho. By G. Hill, | 109 | |

| This World of Ours. By S. D. Anderson, | 124 | |

| To the Lily of the Valley. By Prof. Campbell, | 139 | |

| The Spanish Maiden. By Agnes Coleman, | 150 | |

| The Angel’s Visit. By Mrs. S. Anna Lewis, | 154 | |

| To a Portrait. By Mrs. H. Marion Stephens, | 157 | |

| The Odalisque. By Bayard Taylor, | 163 | |

| To Inez. By S. D. Anderson, | 175 | |

| Time and Change. By Isaac Gray Blanchard, | 178 | |

| The Rain. By T. A. Swan, | 188 | |

| The Fountain in Winter. By Bayard Taylor, | 213 | |

| The Light of Life. By Mrs. O. M. P. Lord, | 214 | |

| The Bride of Broek-in-Waterland. By C. P. Shiras, | 220 | |

| The Willow by the Spring. By J. Hunt, Jr. | 247 | |

| The Broken Household. By Alice Carey, | 262 | |

| The Fear of Death. By Mary L. Lawson, | 274 | |

| The Seminoles’ Last Look. By Fayette Robinson, | 291 | |

| To My Sister E. By Adaliza Cutter, | 300 | |

| To My Steed. By S. Anderson, | 321 | |

| The Death of the Year. By Henry B. Hirst, | 333 | |

| The Cottage. By J. Hunt, Jr. | 333 | |

| The Misanthrope. By A New Contributor, | 340 | |

| The Broken Reed. By S. S. Hornor, | 318 | |

| The Old Wooden Church on the Green. By Henry Morford, | 359 | |

| The Death of Cleopatra. By W. G. Simms, | 363 | |

| The Fairies’ Song. By Heinrich, | 364 | |

| The Undivided Heart. By Myrrha, | 371 | |

| Watouska. By Kate St. Clair, | 79 | |

| Words of Waywardness. By Prof. Campbell, | 100 | |

| Woman’s Heart. By Rufus Henry Bacon, | 178 | |

| We are Changed. By Edith Blythe, | 247 |

REVIEWS.

| H. Kavanagh. A Tale. By H. W. Longfellow, | 71 | |

| My Uncle the Curate. By the Author of “The Bachelor of the Albany,” etc. | 71 | |

| The Personal History and Experience of David Copperfield the Younger. By Charles Dickens, | 71 | |

| Characteristics of Literature. By Henry T. Tuckerman, | 131 | |

| The Earth and Man. By Arnold Guyot, | 131 | |

| The History of the United States of America. By Richard Hildreth, | 191 | |

| Dante’s Divine Comedy: The Inferno. By John A. Carlyle, M. D. | 192 | |

| A Second Visit to the United States of North America. By Sir Charles Lyell, F. R. S. | 251 | |

| The Liberty of Rome. By Samuel Eliot, | 251 | |

| The Penance of Roland. By Henry B. Hirst, | 252 | |

| History of the National Constituent Assembly. By J. F. Corkran, | 252 | |

| Oliver Goldsmith: A Biography. By Washington Irving, | 311 | |

| Bulwer and Forbes on the Water Treatment, | 311 | |

| The Child’s First History of Rome. By E. M. Sewell, | 312 | |

| A Lift for the Lazy, | 312 | |

| Poems. By Robert Browning, | 378 | |

| Physician and Patient. By Worthington Hooker, | 379 | |

| History of England. By David Hume, | 379 | |

| Success in Life. By Mrs. L. C. Tuthill, | 379 | |

| Sketches of Life and Character. By T. S. Arthur, | 380 | |

| History of the French Revolution of 1848. By A. De Lamartine, | 380 | |

MUSIC.

| What’s a Tear? Composed by M. W. Balfe. | ||

| Yes, Let Me Like a Soldier Fall. Written and Adapted by E. R. Johnston. | ||

| Oh, Let Thy Locks Unbraided Fall. Words by John W. Watson, Esq. Music by John A. Janke, Jr. | ||

| I Love, When the Morning Beams. By D. W. Belisle. | ||

| Wake, Lady, Wake. Music Composed and Arranged for the Piano, by B. W. Helfenstein, M. D. | ||

| My Life is Like the Summer’s Rose. Words by Hon. Richard Henry Wilde. Music by An Amateur. | ||

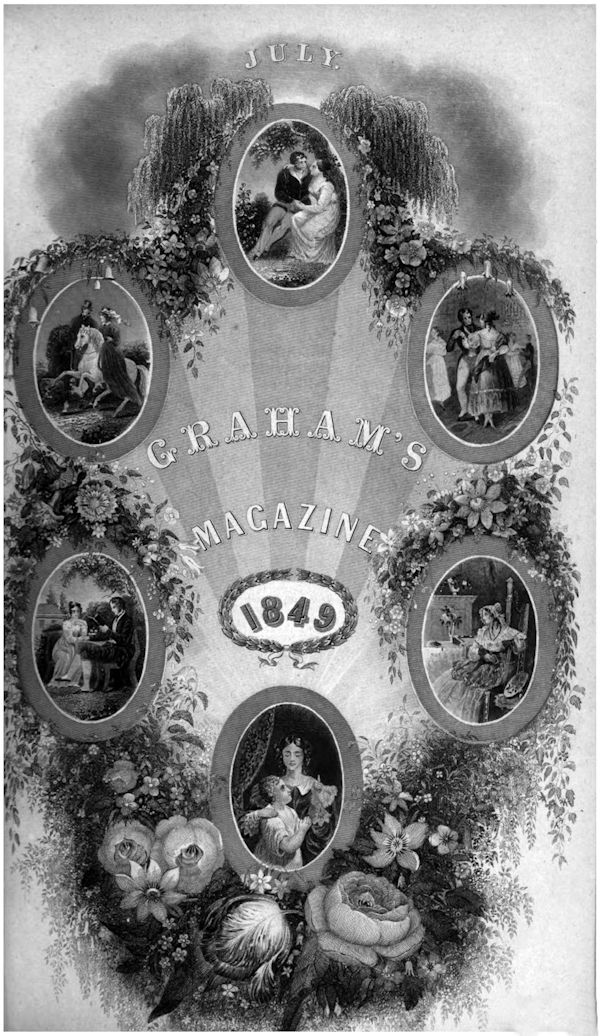

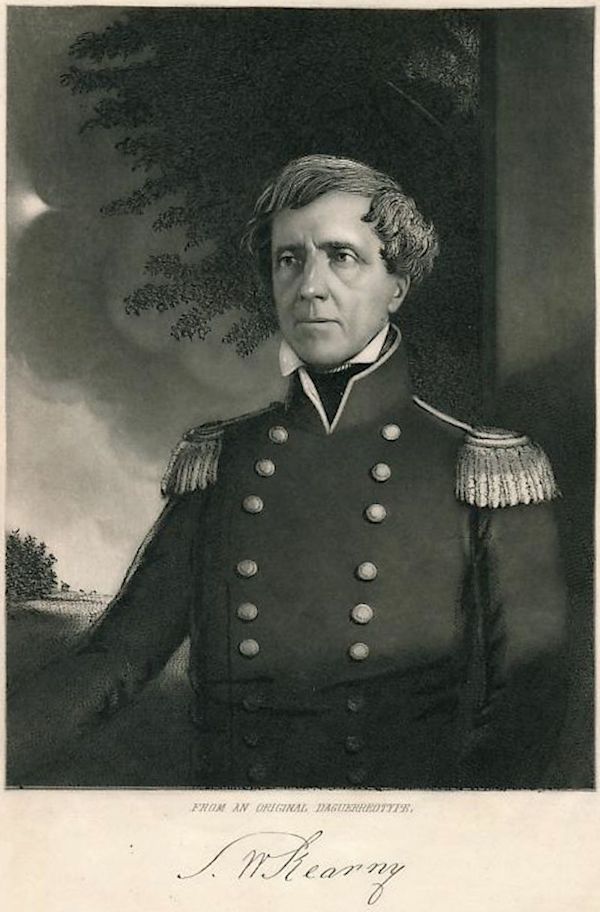

ENGRAVINGS.

| Cross Purposes, engraved by J. M. Butler. | ||

| General Kearny, engraved by T. B. Welch. | ||

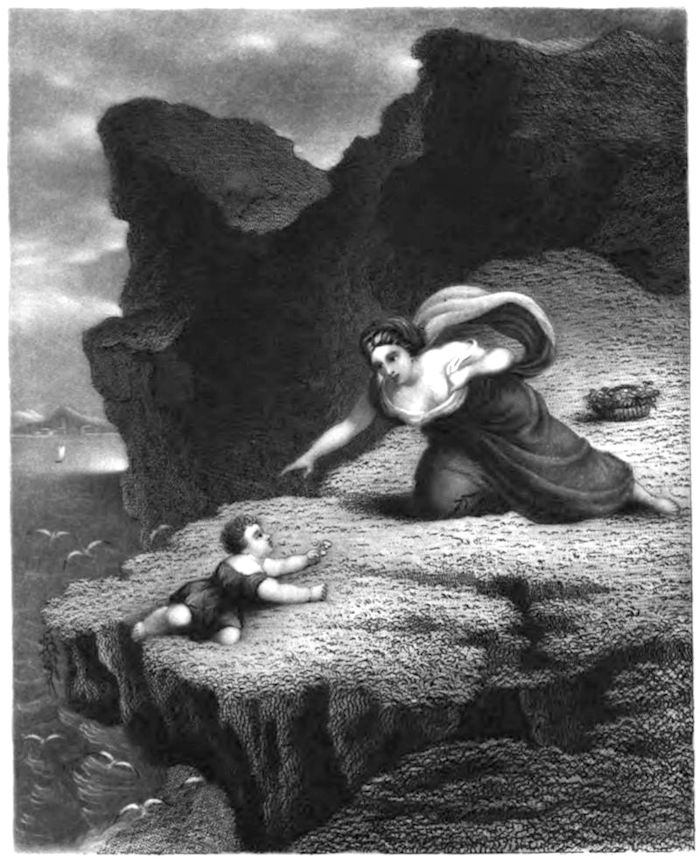

| Nature’s Triumph, engraved by F. Humphreys. | ||

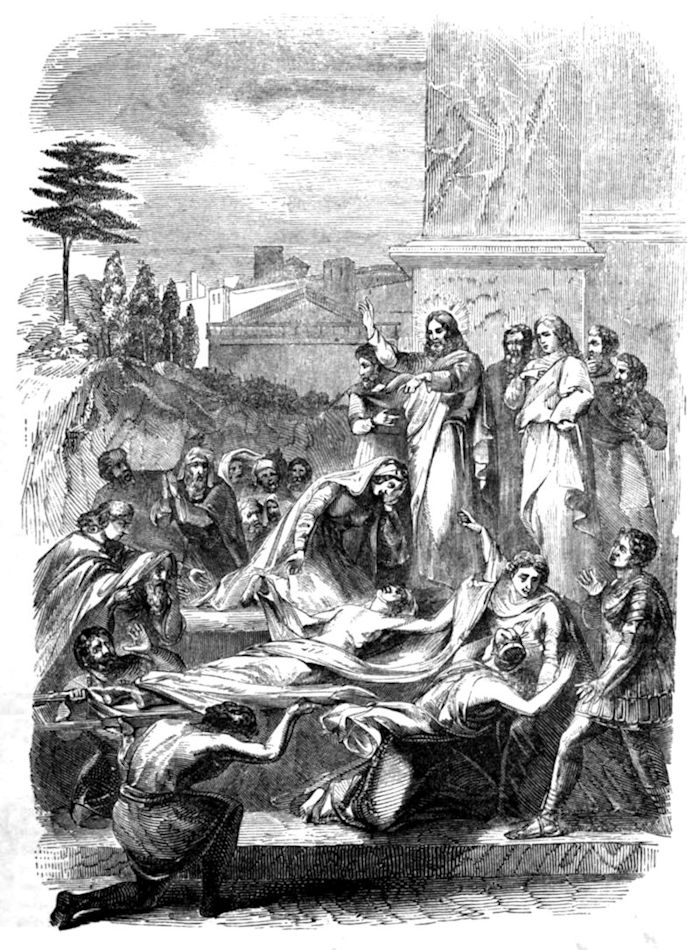

| The Widow of Nain. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| Title Page, engraved by W. E. Tucker. | ||

| The Golden Age, engraved by W. E. Tucker. | ||

| La Siesta, engraved by Geo. P. Ellis. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| Olden Times. | ||

| No Rose Without a Thorn, engraved by J. M. Butler. | ||

| The Bullfinch, engraved by F. Humphreys. | ||

| Love Tests of Hallowe’en, Nos. 1 and 2. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| Effie Deans, engraved by T. B. Welch. | ||

| Rose Carlton, engraved by W. H. Egleton. | ||

| The Baggage Wagon, engraved by A. L. Dick. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| The Engraver’s Daughter. | ||

| Happy as a King, engraved by J. M. Butler. | ||

| Head-Quarters of Gen. Knox, engraved by W. H. Ellis. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| The Balize. | ||

| The Death of the Year, engraved by Wm. E. Tucker. | ||

| Opera Extravagance. | ||

| The Conscript’s Departure and Return, engraved by John M. Butler. | ||

| A Case of Gold Fever. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. |

FROM AN ORIGINAL DAGUERREOTYPE.

S. W. KEARNY

Engraved by T. B. Welch expressly for Graham’s Magazine.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXV. PHILADELPHIA, JULY, 1849. No. 1.

OF MAJOR-GENERAL STEPHEN WATTS KEARNY, U. S. A.

[WITH AN ENGRAVING]

———

BY FAYETTE ROBINSON.

———

Few men who have ever been in the service of the United States have enjoyed a more enviable reputation than Stephen Watts Kearny, or have left behind them more admiring friends. The recent death of this excellent soldier, and above all his distinguished services, covering a space of more than forty years, make his career at this time peculiarly an object of interest to the country.

Stephen Watts Kearny was born in the year 1793, in the town of Newark, New Jersey, in a mansion yet the property of his family. Though not prone to admit that the adventitious circumstances of birth add any real dignity to individuals, either in America or elsewhere, it may not be improper to state that the family connections of the deceased general were of such a character as to have entitled him to a prominent social position any where, he being a relation of the well-known Lady Mary Watts, and a connection of the gallant and noble General Alexander (Lord Stirling) of the revolutionary army. The grandson of an emigrant, who settled in New Jersey, before the revolution, the family of Gen. Kearny had always occupied a prominent position in society, and exerted much influence in his native state.

At the commencement of the war of 1811, young Kearny, then about eighteen, was a student at Princeton College. Contrary, it is said, to the advice of his friends, he obtained a commission from Mr. Madison, and reported for duty as a lieutenant in the 13th regiment of infantry, in which he was attached to the company of which the present very distinguished General John E. Wool was the captain.

With two companies of his regiment he was present at the gallant affair of Queenstown, and with Colonel, since Gen. Scott, was surrendered a prisoner of war. This was on the 13th of October, 1812. In this affair the companies of the thirteenth had been long opposed to the greatly celebrated and highly disciplined forty-ninth British infantry, a regiment which had stood the ordeal of the Peninsula War, and had won laurels from the best troops of France. The forty-ninth had occupied, with heavy reinforcements of Canadian militia, a battery on a commanding position. The cannonade and musketry from this point was so severe that every commissioned officer was in the first assault either killed or wounded, and Col. Van Rensselaer who commanded, was carried from the field unable to stand. Before he left, however, he ordered every man who could move to storm the battery. Three more gallant officers than those who carried his order into execution probably never lived. They were Captain Wool, Lieutenant Kearny, and 2nd Lieutenant T. B. Randolph, late of the Virginia regiment. By orders of Capt. Wool the two companies of the 13th, which originally had numbered but one hundred, all told, were extended and ordered to close upon the guns. This perilous manœuvre was executed with brilliant success, the enemy were driven precipitately from his guns, which were the first trophies to the United States of the war with Great Britain. This field was young Kearny’s first arms, and was a brilliant promise of what was to be his future career. The battle was important to the United States, though, as is well known, Col. Scott and his gallant command of regulars were forced to surrender. To the English it was most disastrous, Major Gen. Sir Isaac Brock, the captor of Detroit, a man thought worthy to compete with Wellington for the command of the British army in Spain, having been picked off by an American marksman. Throughout this trying engagement young Kearny sustained himself with the firmness which he maintained through life. When driven to the hill selected by the present Col. Totten as the strongest point, his perseverance was as distinguished as his impetuosity had been during the charge.

After the surrender, Kearny, with the other prisoners, was marched to the Canadian village of Niagara, where, it is said, they were scarcely treated with the consideration due such gallant soldiers. There occurred a circumstance of thrilling character often told—the attempted murder of Col. Scott by the Indian chiefs “young Brandt and Captain Jacobs,” which, had it proved successful, would have made irreconcilable the war between Great Britain and the United States. It failed through the great personal courage of Col. Scott and the gallantry of Captain Coffin, an aide of Gen. Sheafe, but the would-be murderers were never punished by the British government. The recurrence of such scenes, and the probability of long confinement, exercised a most unhappy effect on the mind of Kearny, who saw as the consequence of his captivity (at that day there were no exchanges of prisoners) the ruin of his professional prospects. After a confinement of some weeks at Niagara, Kearny was with the other prisoners sent to Quebec. For a long time he continued moody and morose, until a circumstance occurred, which the present general-in-chief relates, that restored his wonted alertness. The prisoners were taken to Quebec in a vessel, and from the carelessness incident to this mode of travel, the idea of a possible escape occurred to Col. Scott. The plan was to overpower the guard, to march at once to the nearest division of the United States troops on the frontier, and take their conductors with them as captives. Col. Scott imparted this plan to Kearny, who at once entered into it with his whole soul. His energy returned, and he became again the wild subaltern who had led the first platoon of the thirteenth at Queenstown. Circumstances prevented this plot from being carried into execution, but it had gone far enough to show that the subject of this memoir had as much prudence as valor.

The prisoners at last arrived at Quebec, and their situation at once became most painful. They were confined in the old French castle, and were subjected to many indignities. This was before Niagara and Lundy’s Lane, and countless other fields had taught the British army that the American soldiers were worthy antagonists. At that time the British army was filled with the aristocracy of the country, which could not conceive or imagine the true position of a country without a nobility. Countless trivial insults were daily given, and which galled to the last degree the forbearance of the prisoners. The following anecdote may explain what they were.

On one occasion, when the American prisoners dined at the garrison mess, an officer of the British staff arose, and with a pointed pomposity gave the toast, “Mr. Madison, dead or alive.” The faces of the American officers flushed with indignation, which was not diminished when they saw a young American lieutenant rise from his chair, and in the blandest manner, and with a most insinuating smile, give thanks for the remembrance of the Chief Magistrate of the United States. All thought him drunk or mad, as he proceeded to say, “he felt the weightiness of the burden imposed on him by the silence of his seniors, that he would not give thanks for the toast last drunken, but would give another in return. He was sure the officers of both services present would understand him when he gave ‘the health of his royal highness, the Prince of Wales, DRUNK OR SOBER.’” If a shell had exploded under the table the surprise could not have been greater, and the danger of a collision became imminent, when the senior officer of the British army present, a man of tact and taste, interfered, and sent the person who had given the first toast from the table under arrest. This anecdote is variously told in the service, and sometimes is attributed to Gen. Kearny, and sometimes to the late Mann Page Lomax, major of artillery, who was at the time a prisoner in the castle of Quebec. It is perfectly characteristic of each of these officers, and whether Gen. Kearny be the hero or not, aptly enough illustrates this portion of his career. The American victories in the West, by which hosts of prisoners were acquired, soon placed the men of Queenstown in a different position, and they were exchanged.

Kearny was with Scott at the time the latter officer resisted the attempt to place in confinement the Irishmen surrendered at Queenstown, and ably sustained him in his energetic action in relation to this high-handed measure. He sailed in the cartel to Boston, and immediately on his arrival, proceeded to rejoin his regiment. He was subsequently stationed at Sacket’s Harbor, where he acquired the reputation for discipline and soldiership which never deserted him. While at this post the British commander, Sir James Yoe, and Commodore Chauncy, were manœuvring for possession of the lake. On one occasion, when in possession of a temporary superiority, Sir James appeared in front of the harbor and challenged the commodore to a fight. This the latter refused, because he had no marines. When the reason was told Capt. Kearny, (he had in the interim been promoted) a gallant officer of New York, a captain of artillery, named Romain, offered at once to go on board and serve as marine. The offer was not, however, accepted, much to the chagrin of Kearny and Romain.

Captain Kearny served through the war, and on the reductions of 1815 and 1821, was retained in the service with his old grade and rank. In 1823 he received the usual brevet for ten years faithful service, and was assigned to the command of the beautiful post of Bellefontaine, near St. Louis, and in that year accompanied Brigadier General Atkinson in his famous expedition to the Upper Missouri. This was before the introduction of steamboats into those waters, and the expedition was one of the most tedious imaginable. The boats were necessarily to be propelled by poles and oars against the rapid current of the Missouri, and not unfrequently by the tedious process of cordelling. This is done by extending from the capstan of the boat a cable, which is made fast to the shore, and thus the vessel must carefully be wound up until the rope is exhausted. Then a new rope is stretched, and the same tedious process undergone. Often, when in the midst of rapids, the cable would break, and before the vessel could be brought up, a greater distance than had been gained in a week would be passed over. In the course of two years they reached the Yellow Stone river, twenty-two hundred miles above St. Louis, and displayed the colors of the 1st and 6th infantry where the United States flag had never been seen before. The Sioux, the Pawnee, the Mandan, and Arickra, were made acquainted with the government, of which before they had but a vague knowledge, and the vast resources of that immense country for the first time revealed to the nation.

On his return Major Kearny received a full majority in the third infantry, and was removed to a new sphere, to the southern extremity of the Indian territory. While major of this regiment he established the post of Towson, on the banks of Red River. To reach this place, easy of access as it is at present, it was necessary to pass through what was then a wilderness of prairie, but which to the soldiers inured to the incessant storms of the Upper Missouri, seemed almost an Arcadia. After crossing the northern tributaries of the Arkansas, they were in the midst of the range of the buffalo, and the countless herds of wild horses which then abounded even there. The latter, not unfrequently, amazed at the novel sight of the marching troops, would dash up, as if to charge the columns, pause with as much unanimity as if they acted by command, encircle it, and tossing their long manes and forelocks, hurry out of view. New objects continually met his gaze, and the information then amassed was among the most valuable ever collected under the auspices of the government. On this march Major Kearny was accompanied by his accomplished wife, a step-daughter of Gen. M. Clark, of St. Louis, whom, about the time of his promotion, he had married. With the third infantry Major Kearny remained until the Black Hawk war, when almost all the troops of the country were concentrated in the country of the hostile Indians.

While a major of the third, an incident occurred, which, though often told, will bear repetition. On one occasion, while stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Major Kearny was drilling a brigade on one of the open fields near the post. The manœuvre was the simple exercise of marching in line to the front. An admirable horseman, he sat with his face toward the troops, while the horse he rode, perfectly trained, was backed in the same direction, along which the command was marched. At once the animal fell, fastening the rider to the ground by his whole weight. His brigade had been drilled to such a state of insensibility, that not one of them came to his assistance; nor was it necessary. The line advanced to within about ten feet of him, when, in a loud, distinct voice, calmly as if he had been in the saddle under no unusual circumstance, Major Kearny gave the command, “Fourth company—obstacle—march.” The fourth company, which was immediately in front of him, was flanked by its captain in the rear of the other half of the grand division. The line passed on, and when he was thus left in the rear of his men, he gave the command, “Fourth company into line—march.” He was not seriously injured—extricated himself from his horse, mounted again, passed to the front of the regiment, and executed the next manœuvre in the series he had marked out for the day’s drill.

We are now, however, to see Major Kearny in a new and more important sphere of action.

During the whole of the last war with Great Britain cavalry was not once employed as a battle-piece, and in spite of the great services of the horse which had been commanded, during the revolution, by Cols. Lee and Washington, and by Count Pulaski, this great arm had become most unpopular. Consequently, on the reduction, no skeleton even of a corps had been retained—the sabres were locked up, the saddles and horses sold, and the officers and men disbanded. The policy, however, of disposing the eastern tribes along the western frontier, and the rapid strides of emigration west ward, brought the army into contact with the mounted tribes of the prairie, who evidently could never be overtaken or punished for depredations they at that time used to commit, by foot-soldiers, armed with heavy muskets, and laden down with knapsacks and camp equipage. Of this evident proof had been obtained in the expedition of Gen. Atkinson, mentioned above, and other excursions which had brought the officers and men of the 6th, 3rd and 1st infantry into contact with the nomad tribes of the Camanch. If other demonstration were required, it was furnished by the events of the Black Hawk war, when it became necessary to raise a body of mounted gunmen for special service, which was done under the auspices of the present distinguished Senator from Wisconsin, Mr. Dodge. These troops, called Rangers, did good service enough to induce Congress to authorize the levy of a strict cavalry corps called Dragoons. The whole army, with very few exceptions, was impressed with the necessity of this corps, for which the most distinguished men in their several grades of the service applied. On its organization, Major Kearny was appointed lieutenant-colonel of the regiment, and on him depended almost exclusively the discipline, the colonel, Dodge, though a brave man, not having the military education or experience requisite to make him the active head of a new corps, in the details of which not only men but officers were to be instructed. Col. Kearny, during his long seclusion in the west, had been a patient student, and had made himself master of all the theory of his profession, and in a short time made his regiment one of the best in the world. Within less than a year after the first muster of the regiment, it was sent, under its colonel, as a part of the command with which the lamented Gen. Leavenworth marched to the Spanish Peaks. This disastrous march, in the course of which so many men and officers died, was most trying to a new corps, which had no guide to direct them. Here all the experience of the old world was at fault. Cavalry had there to march but from one hamlet to another, finding forage and grain everywhere. Here eight hundred miles of wilderness were to be overcome, and more than once the jaded horses were without even water. This proved the perfectness of the regiment, and the thoroughness of the discipline which induced the gallant and veteran Gen. Gaines to speak, in an official letter, of the first dragoons as “the best troops I ever saw;” and the officer who had defended Fort Erie, beaten back a victorious enemy at Chrysler’s Field, and received the keys of St. Augustine, certainly knew what a soldier was.

In 1835, Col. Kearny visited with one wing of his regiment, the Sioux, on the Upper Missouri, and had the satisfaction at a council to reconcile the long animosity between them and the Sauks and Foxes. He also made a long march to the head-waters of the Mississippi, visiting the village of Wabisha, and effecting a cessation of the trespassing of the British subjects, from the Earl of Selkirk’s settlement at Pembina, on the territories of the United States. In July, 1836, he was made colonel of the first dragoons; and from this period a sketch of his services would be almost a history of the West, not one trouble on the frontier occurred in the settlement of which he was not instrumental; and with six companies of his regiment he was able to protect a line of frontier eight hundred miles long. Stationed at Fort Leavenworth, be made himself the idol of the West, and devoting himself to his regiment, made its discipline perfect. He had now acquired a high rank, and the qualities he had always possessed became conspicuous. Bland in his manners, but of iron firmness, kind to his juniors, his equals, or those nearly so, requiring the strictest obedience, measuring his expectations by the rank of the officer, his conduct became proverbial. To his men he was most considerate, so that they looked on him as a protector. It is believed that during the whole time he commanded the first dragoons no soldier ever received a blow, except by the sentence of a general court martial for the infamous crime of desertion. The lash disappeared, and though probably the strictest disciplinarian in the service, there was less punishment in his corps than in any other. About this time the system of drill of the dragoons was changed, and he was long engrossed in the instruction of his regiment, having the troublesome task of unlearning them all he had taught of the old system, from which the new one differed entirely in mode and principle of combination.

In the year 1839, the two Ridges, father and son, and Elias Boudinot, chiefs of the Cherokees, were murdered by a hostile clique of their own tribe, and there seemed imminent danger that a war would originate. Immediately on the receipt of the news of a possible collision, Col. Kearny determined to proceed to the scene. The officer of the quarter-master’s department on duty with him being unable to furnish the requisite funds, the colonel provided them from his own resources, and after a very rapid march appeared with six companies of his regiment at Fort Wayne. Words can not express the difference between his companies and those in garrison at that post; the beautiful condition of the men and horses of the first, and the rough-coated nags and unclean condition of the men of the second. After the difficulty had gone by, he effected an exchange of garrisons, and with the neglected and abused left wing, proceeded to Fort Leavenworth, where, in a short time these companies became equal in discipline to the others of the corps. The companies of the Fort Wayne garrison which he took with him to Leavenworth, were those which, under the command of the gallant and lamented Capt. Burgwin, and the excellent soldier, Major Grier, did such good service, and so much distinguished themselves in the campaign in New Mexico against the revolters and the Pueblo and Navajo Indians.

In 1842, he was appointed to the command of the third military department, with head-quarters at St. Louis. There he remained until 1846, with the exception of his long march to the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains in 1845. There is no doubt that this is one of the most extraordinary marches on record, both from its distance, its rapidity, and the fact that he passed among semi-hostile tribes nearly two thousand miles; crossed deep and rapid streams by swimming, gave protection to the immense army of emigrants en route to California, and returned without losing a man or horse.

In 1846, the war with Mexico began, and he was assigned to the command of the army of the West with orders to occupy New Mexico and California. To reach Santa Fe an immense march was to be undertaken across a country but sparsely furnished with wood and water, and where no supplies were to be met with or obtained until the enemy’s country should be reached, and in all probability a battle fought and won. To accomplish this, precisely such a man as Col. Kearny was required. He was familiar with the service, and possessed the unbounded confidence of the people of Missouri, from which state the volunteers who were to compose the main body of his army were to be drawn. In a most unprecedented short time the men were enrolled, and all necessaries supplied, and before Armijo, the governor of New Mexico was aware of his approach, the army was in the capital of the province. Like Cæsar, Gen. Kearny might say, “I came, I saw, I conquered.”

Immediately before the capture of Santa Fe, Col. Kearny had received his promotion to the grade of Brigadier-General, and abandoned to his successor the standard of a regiment he had borne from the Gulf of Mexico to the head-waters of the Mississippi, and which was to be the first flag of the army which waved on the shores of the Pacific. After obeying his orders, and providing for the future peace of the country, he proceeded to California, across a country where an army had never marched before, and which was considered impassable. Cold, a wilderness, absolute barrenness, were all to be overcome. Scarcely, however, had he set out on this expedition than he was met by an express, informing him that California was conquered. Relying on this, he sent back all his troops except one hundred men, and proceeded to the valley of the Gila. Of the sufferings of his men, of the almost starvation which forced them to eat the flesh of the emaciated dragoon-horses which had borne them so far we will not speak. When he emerged into the fertile country, it was not until after severe contests against immense odds, and until he had lost many favorite officers and picked men, to all of whom he had become endeared by participation in the dangers of a march across the American continent.

On the 2d of December, 1846, Gen. Kearny arrived at Warner’s Rancho, one of the extreme eastward settlements of California. He there learned certainly what he had previously heard from a party of Californians, that the population had risen against the invaders and that Andreas Pico was near San Diego with a superior party, intending to give him battle. Though exhausted by a long march, and mounted on broken-down mules, Gen. Kearny hurried to attack him. On the night of December 5, he heard that Pico was at the village of San Pascual, and on the next morning met him. At once a charge was ordered, which broke Pico’s line and forced it to retreat. After a flight of half a mile, however, it was rallied and charged the head of the American force, and lanced many of the foremost men. A desperate hand to hand fight ensued, which resulted in the discomfiture of Pico, not, however, until Captains Moore and Johnston, and Lieutenant Hammond, and sixteen men had been killed, and fourteen persons wounded, including the general himself, and all the officers except Captain Turner, who, though he greatly distinguished himself, escaped untouched. The inequality of the contest was immense, when we remember that the Californians, the most superb horsemen in the world, were mounted on excellent chargers, while the dragoons were on mules which had marched from Santa Fe. The dead were buried; this sad duty, and the necessity of making further arrangements, detained the party all day. On the next day the march was resumed, but encumbered as they were, they were able to proceed but nine miles when the enemy charged them again. The needful preparations to receive them were made, when the enemy wheeled off, and attempted to occupy an eminence which commanded the route. From this, after a sharp skirmish, they were driven with some loss, and then Gen. Kearny encamped. As Pico evidently intended to dispute every pass, the general determined to remain where he was until reinforcements, for which he had sent to the naval commander at San Diego, should arrive. Four days afterward a force of marines, under Capt. Zelin, U. S. M. C. and of sailors, commanded by Lieutenant Gray, arrived, and with this force Gen. Kearny marched without molestation to San Diego, a distance of thirty miles. A difficulty about the command here arose between Commodore Stockton and Gen. Kearny, which could not be settled in California, where the naval commander had far the superior force. It did not prevent their undertaking a joint expedition against Puebla de los Angelos, which was in possession of a strong Mexican force under Flores.

On the 8th of January the Mexicans were met six hundred strong, with four guns, in the face of whom the American force of sailors, marines, and the remnant of the dragoons, forded the river, and after a short, sharp, and decisive affair, drove them from the field. On the next day the enemy again appeared, and, as usual, were beaten, and on the 10th Puebla de los Angelos was occupied. At these affairs both the naval and army commanders were present, and the question of who was commander added somewhat to the difficulty already existing between them. At this time Lieut. Col. J. C. Fremont, then of the mounted rifles, commanded a numerous body of volunteers in California. Gen. Kearny ordered this officer to join him. This Col. Fremont did not do, but on the contrary, considered Com. Stockton as his commander. Consequently, when on the arrival of land reinforcements from the United States, Gen. Kearny assumed and maintained his command, he ordered Col. Fremont to accompany him home. Col. Fremont was subsequently arrested and tried for this dereliction of duty, found guilty of mutinous conduct, and sentenced to be dismissed the service. A portion of the court which tried him having recommended the remission of the sentence, the President acquiesced, and he was ordered to duty, but immediately resigned his commission. The prosecution of the charges against Col. Fremont detained Gen. Kearny in Washington during a portion of the winter of ’47 and ’48, and was, doubtless, most painful to him, for no man in the army had previously borne a higher character for soldiership than Col. Fremont. The court martial fully sustained Gen. Kearny in every pretension, and but one person has been found in America to cavil at the sentence.

In the spring of 1848, Gen. Kearny was ordered to Mexico, whither he proceeded at once. All hostilities were, however, then over, and though he was in the discharge of his duty, his service there was uneventful. On the conclusion of the war he returned home, and was assigned to the command of the military division of which St. Louis is the head-quarters. He there had the proud satisfaction to receive the brevet of major-general for his services in New Mexico and California. He had, however, brought with him the seeds of an insidious disease which soon overcame his strength, enfeebled as it was by privations and trials of every kind. He died at St. Louis, October 31, 1848, leaving a wife and a family of young sons to regret him.

In the eventful career of Gen. Kearny he had always been distinguished as one of the best officers of his grade in the service. From a subaltern to the highest rank he rose, every step having been won by service. He was bland in his manners, dispassionate and calm. Quick and ready in forming his opinions, he yet did not act hastily, and when once he had decided, was immutable in his course. A great student and thinker, he never talked except when he had something to say, yet possessed a fund of anecdote and universal information rarely to be met with. In the West he was a popular idol, so that the whole population acquiesced in the apparently arbitrary steps he was often called on to take in the discharge of his duty. To his subalterns he was endeared by a thousand kindnesses, and to the whole army by respect and admiration. He left in all the army list no one superior to him in personal courage, science in his profession, or the minor qualities which contribute so much to make the soldier.

Immediately on the receipt of the news of his death, the Secretary of War, Mr. Marcy, published an order containing the following high tribute to his important services.

“War Department.

Washington, Nov. 6, 1848.

The President with feelings of deep regret announces to the Army the death of Brigadier-General Stephen W. Kearny, Major-General by brevet. The honorable and useful career of this gallant officer terminated on the 31st of October at St. Louis, in consequence of a disease contracted while in the discharge of his official duties in Mexico.

General Kearny entered the army in 1812 as lieutenant, and continued in it until his death—a period of more than thirty-six years. His character and bearing as an accomplished officer were unsurpassed, and challenge the admiration of his fellow citizens and the emulation of his professional brethren. His conquest of New Mexico and valuable services in California have inseparably connected his name with the future destiny of these territories, and it will be ever held in grateful remembrance by the successive generations which will inhabit these extensive regions of our confederacy.”

He was buried in St. Louis by the 7th and 8th regiments of infantry and a squadron of that regiment of dragoons which he had made so famous, commanded by one of his favorite captains, the present Col. E. V. Sumner, of the 1st dragoons. All the city of St. Louis accompanied the cortège to pay their last tribute of respect to the general and the MAN.

———

BY MRS. JULIET H. L. CAMPBELL.

———

All around me men are delving,

Deep within the troubled earth,

Searching for the darksome treasures

Hidden since creation’s birth.

Wearying toil and ceaseless effort

Bring the buried ore to view;—

Though I be but feeble woman,

I will be a miner too!

Heart of mine! thou art a cavern,

Sad and silent, dark and deep—

In thy fathomless recesses

Spirit gnomes their treasures keep.

Gems of love, and hope, and joyance,

Bury there their flashing beam—

Wilder passions fret their prison

With the fierceness of their gleam.

Though unburnished, prized and precious,

To the enraptured poet’s sight,

As the jewels, proudly flashing,

On the brow of beauty bright.

True, unto the sordid worldling

These are gems of little worth,

Yet, for thee, high-hearted poet!

I will strive to bring them forth!

Lamp of truth, my brow adorning,

Lighting up the weary way—

I, in pain, will probe my bosom,

Bare its treasures to the day.

Wearying toil and ceaseless effort

Bring the buried ore to view;—

Though I be but feeble woman,

I will be a miner too!

———

BY GRETTA.

———

I had but two; they were my only treasure,

Two lovely daughters of the imperial isle;

They gave my quiet hearth-stone every pleasure,

They gave my lone heart every sunny smile,

And to your land I brought them o’er the sea,

To hear the tones which tell of Liberty!

They were twin lasses; one was like the Rose,

With deep, dark crimson on its opening breast;

The other like the Daisy, when it glows

With evening’s pearls upon its snowy crest.

And when they nestled near me lovingly,

They were like morn and quiet eve to me.

But she, the golden haired, is with the stars!

She, the blue-eyed, the fondest of the twain,

For her was opened heaven’s glorious bars,

Just as the sun was sinking in the main,

And flowers less fair, each in its soft green nest,

On the far shore, had sunk like her to rest.

Upon the waves she died—the sounding waves—

The sands her pillow, and the weeds her pall;

And there the deepest, tideless water laves

The mortal part of half my little all;

And though I know her soul is bright above,

Still earth is desolate without her love.

She drooped from day to day—within my arms

I cradled her dear form, so slight, so fair,

And gazed with doating love upon her charms,

While my big tears were glistening in her hair,

Till o’er her upturned eyes the fringed-lid fell,

And soft she said—I know she said—“Farewell!”

She died without a moan, without a sigh;

A golden day had faded in the west,

And mother Night descending from on high,

Was hushing Nature to her dreamy rest;

And ere another day broke o’er the sea,

Deep rolled the waves between my child and me.

I chanted o’er her lays of her old home—

And she, the stricken mourner by my side,

Mingled her tears with ocean’s moonlit foam,

And sent her wail upon the shoreless tide.

Oh! it was sad to hear that heart-wrung moan

On the wild sea, so vast, so still, so lone!

On my own native Scotland’s hallowed ground,

In a low glen, from worldly din afar,

The stars look down upon the grassy mound

Where she is laid—my young life’s morning star—

And in the trackless deep, the bud she gave

From her fond bosom, fills a briny grave.

And with this one, all that my heart has left,

I raise my altar where your heaven glows;

Here the lone pair, of all they loved bereft,

Would find in you, Bethesda for their woes.

They’ll think of home, with memory’s burning tear,

But turn to meet Hope’s smiling welcome here!

OR THE COURSE OF PASSION.

———

BY HENRY WILLIAM HERBERT.

———

In the commencement of the seventeenth century, there stood among the woody hills and romantic gorges which sweep southwardly down from the bleak expanse of Dartmoor, one of those fine old English halls, which, dating from the reign of the last of the Tudors, united so much of modern comfort with so much of antique architectural beauty. Many specimens of this style of building are still to be found scattered throughout England, with their broad terraces, their quaintly sculptured porticoes, their tall projecting oriels, their many stacks of richly decorated chimneys, and their heraldic bearings adorning every salient point, grotesquely carved in the red freestone, which is their most usual, as indeed their most appropriate material. No one, however, existed, it is probable, at that day, more perfect in proportion to its size, or more admirably suited to its wild and romantic site, than the manor-house of Widecomb-Under-Moor, or, as it was more generally called in its somewhat sequestered neighborhood, the House in the Woods. Even at the present time, that is a very rural and little frequented district; its woods are more extensive, its moorlands wilder, its streams less often turned to purposes of manufacturing utility, than in any other tract of the southern counties; but at the time of which I write, when all England was comparatively speaking an agricultural country; when miles and miles of forest existed, where there now can scarcely be found acres; when the communications even between the neighboring country towns were difficult and tedious, and those between the country and metropolis almost impracticable; the region of Dartmoor and its surrounding woodlands was less known and less frequented, except by its own inhabitants, rude for the most part and uncultured as their native hills, than the prairies of the Far West, or the solitudes of the Rocky Mountains.

The few gentry, and lords of manors who owned estates, and had their castellated or Elizabethan dwellings, scattered here and there, at long intervals, among the sylvan scenery of that lonely region, were for the greater part little superior in habits, in refinement, and in mental culture, to the boors around them. Staunch hunters, and hard drinkers, up with the lark and abed before the curfew, loyal to their king, kind and liberal to their dependents, and devout before their God, they led obscure and blameless lives, careless of the great world, a rumor of which rarely wandered so far as to reach their ears, unknown to fame, yet neither useless nor unhonored within the sphere of their humble influence, marked by few faults and many unpretending virtues.

To this general rule, however, the lords of Widecomb Manor had long been an exception. Endowed with larger territorial possessions than most of their neighbors, connected with many of the noblest families of the realm, the St. Aubyns of Widecomb Manor had for several generations held themselves high above the squires of the vicinity, and the burghers of the circumjacent towns. Not confining themselves to the remote limits of their rural possessions, many of them had shone in the court and in the camp; several had held offices of trust and honor under Elizabeth and her successor; and when, in the reign of the unfortunate Charles, the troubles between the king and his Parliament broke out at length into open war, the St. Aubyn of that day, like many another gallant gentleman, emptied his patrimonial coffers to replenish the exhausted treasury; and melted his old plate and felled his older oaks, in order to support the king’s cause in the field, at the head of his own regiment of horse.

Thence, when the good cause succumbed for a time, and democratic license, hardly restrained by puritanic rigor, strode rampant over the prerogative of England’s crown, and the liberties of England’s people, fines, sequestrations, confiscations, fell heavily on the confirmed malignancy, as it was then termed, of the Lord of Widecomb; and he might well esteem himself fortunate, that he escaped beyond the seas with his head upon his shoulders, although he certainly had not where to lay it.

Returning at the restoration with the Second Charles, more fortunate than many of his friends, Sir Miles St. Aubyn recovered a considerable portion of his demesnes, which, though sequestrated, had not been sold, and with these the old mansion, now, alas! all too grand and stately for the diminished revenues of its owner, and the shrunken estates which it overlooked.

It would not perhaps have been too late, even then for prudence and economy, joined to a resolute will and energetic purpose, to retrieve the shaken fortunes of the house; but having recovered peace and a settled government, the people and the court of England appeared simultaneously to have lost their senses. The overstrained and somewhat hypocritical morality of the Protectorate was succeeded by the wildest license, the most extravagant debauchery; and in the orgies which followed their restoration to their patrimonial honors, too many of the gallant cavaliers discreditably squandered the last remnant of fortunes which had been half ruined in a cause so noble and so holy.

Such was the fate of Sir Miles St. Aubyn. The brave and generous soldier of the First Charles sank into the selfish, dissipated roysterer under his unworthy successor. He never visited again the beautiful oak-woods and sparkling waters of his native place, but frittered away a frivolous and useless life among the orgies of Alsatia and the revels of Whitehall; and died, unfriended, and almost alone, leaving an only son, who had scarce seen his father, the heir to his impoverished fortunes and little honored name.

His son, who was born before the commencement of the troubles, of a lady highly-bred, and endowed as highly, who died—as the highly endowed die but too often—in the first prime of womanhood, was already a man when the restoration brought his father back to his native land, though not to his patrimonial estates or his paternal duties.

Miles St. Aubyn, the younger, had been educated during the period of the civil war, and during the protracted absence of his father, by a distant maternal relative, whose neutrality and humble position alike protected him from persecution by either of the hostile parties. He grew up, like his race, strong, active, bold and gallant; and if he had not received much of that peculiar nurture which renders men graceful and courtly-mannered, almost from their cradles, he was at least educated under the influence of those traditional principles which make them at the bottom, even if they lack something of external polish, high-souled and honorable gentlemen.

After the restoration he was sent abroad, as was the habit of the day, to push his fortunes with his sword in the Netherlands, then, as in all ages of the world, the chosen battle-ground of nations. There he served many years, if not with high distinction, at least with credit to his name; and if he did not win high fortune with his sword—and indeed the day for such winnings had already passed in Europe—he at least enjoyed the advantage of mingling, during his adventurous career, with the great, the noble, and the famous of the age; and when, on his return to his native land after his father’s death, he turned his sword into a ploughshare, and sought repose among the old staghorned oaks at Widecomb, he was no longer the enthusiastic, wild and headstrong youth of twenty years before; but a grave, polished, calm, accomplished man, with something of Spanish dignity and sternness engrafted on the frankness of his English character, and with the self-possession of one used familiarly to courts and camps showing itself in every word and motion.

He was a man moreover of worth, energy and resolution, and sitting down peacefully under the shadow of his own woods, he applied himself quietly, but with an iron steadiness of purpose that ensured success, to retrieving in some degree the fortunes of his race.

Soon after he returned he had taken unto himself a wife, not perhaps very wisely chosen from a family of descent prouder and haughtier even than his own, and of fortunes if not as much impoverished, at least so greatly diminished, as to render the lady’s dower a matter merely nominal. But it was an old affection—a long promise, hallowed by love and constancy and honor.

She was, moreover, a beautiful and charming creature, and, so long as she lived, rendered the old soldier a very proud and very happy husband, and when she died—which, most unhappily for all concerned, was but a few months after giving birth to an only son—left him so comfortless, and at the same time so wedded to the memory of the dead, that he never so much as envisaged the idea of a second marriage.

This gentleman it was, who, many long years after the death of the gentle Lady Alice, dwelt in serene and dignified seclusion in the old Hall, which he had never quitted since he became a widower; devoting his whole abilities to nursing his dilapidated estates, and educating his only son, whom he regarded with affection bordering on idolatry.

With the last Miles St. Aubyn, however, we shall have little to do henceforth, for the soldier of the Netherlands had departed so far from the traditions of his family—the eldest son of which had for generations borne the same name of Miles—as to drop that patrimonial appellation in the person of his son, whom he had caused to be christened Jasper, after a beloved friend, a brother of the lady afterward his wife, who had fallen by his side on a well-fought field in the Luxembourg.

What was the cause which induced the veteran, in other respects so severe a stickler for ancient habitudes, to swerve from this time-honored custom, it would be difficult to state; some of those who knew him best, attributing it merely to the desire of perpetuating the memory of his best friend in the person of his only child; while others ascribed it to a sort of superstitious feeling, which, attaching the continued decline of the house to the continual recurrence of the patronymic, looked forward in some degree to a revival of its honors with a new name to its lord.

Whatever might have been the cause, the consequences of this deviation from old family usage, as prognosticated by the dependents of Widecomb, and the superstitious inhabitants of the neighboring woods and wolds, were any thing but likely to better the fortunes of the lords of the manor; for not a few of them asserted, with undoubting faith, that the last St. Aubyn had seen the light of day, and that in the same generation which had seen the extinction of the old name the old race should itself pass away. Nor did they lack some sage authority to which they might refer for confirmation of their dark forebodings; for there existed, living yet in the mouths of men, one of those ancient saws, which were so common a century or two ago in the rural districts of England, as connected with the fortunes of the old houses; and which were referred to some Mother Shipton, or other equally infallible soothsayer of the county, whose dicta to the vulgar minds of the feudal tenantry were confirmations strong as proofs of Holy Writ.

The prophecy in question was certainly exceeding old; and had been handed down through many generations, by direct oral tradition, among a race of men wholly illiterate and uneducated; to whom perhaps alone, owing to the long expatriation of the late and present lords of the manor, it was now familiar; although in past times it had doubtless been accredited by the family to which it related.

It ran as follows, and, not being deficient in a sort of wild harmony and rugged solemnity, produced, by no means unnaturally, a powerful effect on the minds of hearers, when recited in awe-stricken tones and with a bended brow beside some feebly glimmering hearth, in the lulls of the tempest haply raving without, among the leafless trees, under the starless night—It ran as follows, and, universally believed by the vassals of the house, it remains for us to see how far its predictions were confirmed by events, and how far it influenced or foretold the course of passion, or the course of fate—

While Miles sits master in Widecomb place,

The cradle shall rock on the oaken floor,

And St. Aubyn rule, where he ruled of yore.

But when Miles departs from the olden race,

The cradle shall rock by the hearth no more,

Nor St. Aubyn rule, where he ruled of yore.

Thus far it has been necessary for us to tread back the path of departed generations, and to retrace the fortunes of the Widecomb family, inasmuch as many of the events, which we shall have to narrate hereafter, and very much of the character of the principal personage, to whom our tale relates, have a direct relation to these precedents, and would have been to a certain degree incomprehensible but for this retrogression. If it obtain no other end, it will serve at least to explain how, amid scenes so rural and sequestered, and dwelling almost in solitude, among neighbors so rugged and uncivilized, there should have been found a family, deprived of all advantages of intercommunication with equals or superiors in intellect and demeanor, and even unassisted by the humanizing influence of familiar female society, which had yet maintained, as if traditionally, all the principles, all the ideas, and all the habitudes of the brightest schools of knightly courtesy and gentlemanly bearing, all the graces and easy dignity of courts, among the remote solitudes of the country.

At the time when our narrative commences, the soldier of the Netherlands, Sir Miles St. Aubyn—for though he cared not to bear a foreign title, he had been stricken a knight banneret on a bloody battle-field of Flanders—had fallen long into the sere, the yellow leaf; and though his cheek was still ruddy as a winter pippin, his eye bright and clear, and his foot firm as ever, his hair was as white as the drifted snow; his arm had lost its nervous power; and if his mind was still sane and his body sound, he was now more addicted to sit beside the glowing hearth in winter, or to bask in the summer sunshine, poring over some old chronicle or antique legend, than to wake the echoes of the oakwoods with his bugle-horn, or to rouse the heathcock from the heathy moorland with his blythe springers.

Not so, however, the child of his heart, Jasper. The boy on whom such anxious pains had been bestowed, on whom hopes so intense reposed, had reached his seventeenth summer. Like all his race, he was unusually tall, and admirably formed, both for agility and strength. Never, from his childhood upward, having mingled with any persons of vulgar station or unpolished demeanor, he was, as if by nature, graceful and easy. His manners although proud, and marked by something of that stern dignity which we have mentioned as a characteristic of the father, but which in one so youthful appeared strange and out of place, were ever those of a high and perfect gentleman. His features were marked with all the ancestral beauties, which may be traced in unmixed races through so many generations; and as it was a matter of notorious truth, that from the date of the conquest, no drop of Saxon or of Celtic blood had been infused into the pure Norman stream which flowed through the veins of the proud St. Aubyns, it was no marvel that after the lapse of so many ages the youthful Jasper should display, both in face and form, the characteristic lines and coloring peculiar to the noblest tribe of men that has ever issued from the great northern hive of nations. Accordingly, he had the rich dark chestnut hair, not curled, but waving in loose clusters; the clear gray eye; the aquiline nose; the keen and fiery look; the resolute mouth, and the iron jaw, which in all ages have belonged to the descendant of the Northman. While the spare yet sinewy frame, the deep, round chest, thin flanks, and limbs long and muscular and singularly agile, were not less perfect indications of his blood than the sharp, eagle-like expression of the bold countenance.

Trained in his early boyhood to all those exercises of activity and strength, which were in those days held essential to the gentleman, it needs not to say that Jasper St. Aubyn could ride, swim, fence, shoot, run, leap, pitch the bar, and go through every manœuvre of the salle d’armes, the tilt-yard, and the manège, with equal grace and power. Nor had his lighter accomplishments been neglected; for the age of his father and grandfather, if profligate and dissolute even to debauchery, was still refined and polished, and to dance gracefully, and touch the lute or sing tastefully, was as much expected from the cavalier as to have a firm foot in the stirrup, or a strong and supple wrist with the backsword and rapier.

His mind had been richly stored also, if not very sagely trained and regulated. For Sir Miles, in the course of his irregular and adventurous life, had read much more than he had meditated; had picked up much more of learning than he had of philosophy; and what philosophy he had belonged much more to the cold self-reliance of the camp than to the sounder tenets of the schools.

While filling his son’s mind, therefore, with much curious lore of all sorts; while making him a master of many tongues, and laying before him books of all kinds, the old banneret had taken little pains—perhaps he would not have succeeded had he taken more—to point the lessons which the books contained; to draw deductions from the facts which he inculcated; or to direct the course of the young man’s opinions.

Self-taught himself, or taught only in the hard school of experience, and having himself arrived at sound principles of conduct, he never seemed to recollect that the boy would run through no such ordeal, and reap no such lessons; nor did he ever reflect that the deductions which he had himself drawn from certain facts, acquired in one way, and under one set of circumstances, would probably be entirely different from those at which another would arrive, when his data were acquired in a very different manner, and under circumstances altogether diverse and dissimilar.

Thence it came that Jasper St. Aubyn, at the age of seventeen years, was in all qualities of body thoroughly trained and disciplined; and in all mental faculties perfectly educated, but entirely untrained, uncorrected and unchastened.

In manner, he was a perfect gentleman; in body, he was a perfect man; in mind, he was almost a perfect scholar. And what, our reader will perhaps inquire, what could he have been more; or what more could education have effected in his behalf?

Much—very much—good friend.

For as there is an education of the body, and an education of the brain, so is there also an education of the heart. And that is an education which men rarely have the faculty of imparting, and which few men ever have obtained, who have not enjoyed the inestimable advantage of female nurture during their youth, as well as their childhood; unless they have learned it in the course of painful years, from those severe and bitter teachers, those chasteners and purifiers of the heart—sorrow and suffering, which two are experience.

This, then, was the education in which Jasper St. Aubyn was altogether deficient; which Sir Miles had never so much as attempted to impart to him; and which, had he endeavored, he probably would have failed to bestow.

We do not mean to say that the boy was heartless—boys rarely are so, we might almost say never—nor that the impulses of his heart were toward evil rather than good; far from it. His heart, like all young and untainted hearts, was full of noble impulses—but they were impulses; full of fresh springing generous desires, of gracious sympathies and lofty aspirations—but he had not one principle—he never had been taught to question one impulse, before acting upon it—he never had learned to check one desire, to doubt the genuineness of one sympathy, to moderate the eagerness of one aspiration. He never had been brought to suspect that there were such virtues as self-control, or self-devotion; such vices as selfishness or self-abandonment—in a word, he never had so much as heard

That Right is right, and that to follow Right

Were wisdom, in the scorn of consequence—

and therefore he was, at the day of which we write, even what he was; and thereafter, what we propose to show you.

At the time when the youthful heir had attained his seventeenth year, the great object of his father’s life was accomplished; the fortunes of the family were so far at least retrieved, that if the St. Aubyns no longer aspired, as of old, to be the first or wealthiest family of the county, they were at least able to maintain the household on that footing of generous liberality and hospitable ease which has been at all times the pride and passion of the English country gentleman.

For many years Sir Miles had undergone the severest privations, and it was only by the endurance of actual poverty within doors, that he was enabled to maintain that footing abroad, without which he could scarcely have preserved his position in society.

For many years the park had been neglected, the gardens overrun with weeds and brambles, the courts grass-grown, and the house itself dilapidated, literally from the impossibility of supporting domestics sufficiently numerous to perform the necessary labors of the estate.

During much of this period it was to the beasts of the forest, the fowl of the moorland, and the fish of the streams, that the household of Widecomb had looked for their support; nor did the table of the banneret himself boast any liquor more generous than that afforded by the ale vats of March and October.

Throughout the whole of this dark and difficult time, however, the stout old soldier had never suffered one particle of that ceremonial, which he deemed essential as well to the formation as the preservation of the character of a true gentleman, to be relaxed or neglected by his diminished household.

Personally, he was at all times clad point device; nor did he ever fail in being mounted, himself and at least one attendant, as became a cavalier of honor. The hours of the early dinner, and of the more agreeable and social supper, were announced duly by the clang of trumpets, even when there were no guests to be summoned, save the old banneret and his motherless child, and perhaps the only visiter for years at Widecomb Manor, the gray-haired vicar of the village, who had served years before as chaplain of an English regiment in the Low Countries, with Sir Miles. Nor was the pewter tankard, containing at the best but toast and ale, stirred with a sprig of rosemary, handed around the board with less solemnity than had it been a golden hanap mantling with the first vintages of Burgundy or Xeres.

Thus it was that, as Jasper advanced gradually toward years of manhood, the fortunes of the house improving in proportion to his growth, seeing no alteration in the routine of the household, he scarcely was aware that any change had taken place in more essential points.

The eye and ear of the child had been taken by the banners, the trumpets, and the glittering board, and his fancy riveted by the solemnity and grave decorum which characterized the meals partaken in the great hall; and naturally enough he never knew that the pewter platters and tankards had been exchanged, since those days, for plate of silver, and the strong ale converted into claret or canary.

The consequence of this was simply that he found himself a youth of seventeen, surrounded by all the means and appliances of luxury, with servants, horses, hounds, and falcons at his command, the leading personage, beyond all comparison, of the neighborhood, highly born, handsome, well bred and accomplished. All this, by the way, was entirely uncorrected by any memory of past sufferings or sorrows, either on his own part or on that of his family, or by any knowledge of the privations and exertions on the part of Sir Miles, by which this present affluence had been purchased; and he became, naturally enough, somewhat over confident in his own qualities, somewhat over-bearing in his manner, and not a little intolerant and inconsiderate as to the opinions and feelings of others. He then presented, in a word, the not unusual picture of an arrogant, self-sufficient, proud and fiery youth, with many generous and noble points, and many high qualities, which, duly cultivated, might have rendered him a good, a happy, and perhaps even a great man; but which, untrained as they were, and suffered to run up into a rank and unpruned overgrowth, were but too likely to degenerate themselves into vices, and to render him at some future day a tormentor of himself, and an oppressor of others.

Now, however, he was a general favorite, for largely endowed with animal spirits, indulged in every wish that his fancy could form, never crossed in the least particular, it was rarely that his violent temper would display itself, or his innate selfishness rise conspicuous above the superficial face of good-nature and somewhat careless affability, which he presented to the general observer.

It was, perhaps, unfortunate for Jasper, no less than for those who were in after days connected with him, whether for good or evil, that, at this critical period of his adolescence, when the character of the man is developed from the accidents of boyhood, in proportion as his increasing years and altered habits and pursuits led him to be more abroad, and cast him in some degree into the world, the advancing years and growing infirmities of his father kept him closer to the library and the hall.

So that at the very time when his expanding mind and nascent passions most needed sage advice and moderate coercion, or at least wary guidance, he was abandoned almost entirely to his own direction. The first outbreaks, therefore, of evil principles, the germs of a masterful will, the seeds of fierce and fiery passions, and, above all, the growing recklessness with regard to the feelings and the rights of others, which could scarcely have escaped the notice of the shrewd old man had he accompanied his son abroad, and which, if noticed, would surely have been repressed, were allowed to increase hourly by self-indulgence and the want of restraint, unknown and unsuspected to the youth himself, for whom one day they were to be the cause of so many and so bitter trials.

But it is now time that, turning from this brief retrospect of previous events, and this short analysis of the early constitution of the mind of him whose singular career is to form the subject of this narrative, we should introduce our reader to the scene of action, and to the person whose adventures in after life will perhaps excuse the space which has necessarily been allotted to the antecedents of the first marked event which befel him, and from which all the rest took their rise in a train of connection, which, although difficult to trace by a casual observer, was in reality close and perfect.

The manor-house of Widecomb, such as it has been slightly sketched above, stood on a broad flat terrace, paved with slabs of red freestone, and adorned with a massive balustrade of the same material, interspersed with grotesque images at the points where it was reached from the esplanade below, by three or four flights of broad and easy steps.

The mansion itself was large, and singularly picturesque, but the beauties of the building were as nothing to those of the scenery which it overlooked.

It was built on the last and lowest slope of one of those romantic spurs which trend southerly from the wild and heathery heights of Dartmoor. And although the broad and beautifully kept lawn was embosomed in a very woody and sylvan chase, full of deep glens and tangled dingles, which was in turn framed on three sides by the deep oak-woods, which covered all the rounded hills in the rear of the estate and to the right and left hand, yet as the land continued to fall toward the south for many and many a mile, the sight could range from the oriel windows of the great hall, and of the fine old library, situated on either hand of the entrance and armory, over a wide expanse of richly cultivated country, with more than one navigable river winding among the woods and corn-fields, and many a village steeple glittering among the hedgerows, until in the far distance it was bounded by a blue hazy line, which seemed to melt into the sky, but which was in truth, though not to be distinguished as such unless by a practiced eye, the British Channel.

The Hall itself and even the southern verge of the chase, which bounded the estate in that direction, lay, however, at a very considerable distance from the cultivated country, and was divided from it by a vast broken chasm, with banks so precipitous and rocky that no road had ever been carried through it, while its great width had deterred men from the idea of bridging it. Through this strange and terrific gorge there rushed an impetuous and powerful torrent, broken by many falls and rapids, with many a deep and limpid pool between them, favorite haunts of the large salmon and sea trout which abounded in its waters. This brook, for it scarcely can be called a river, although after the rains of autumn or the melting snows of spring it sent down an immense volume of dark, rust colored water, with a roar that could be heard for miles, to the distant Tamar, swept down the hills in a series of cascades from the right hand side of the park, until it reached the brink of the chasm we have described, lying at right angles to its former course, down which it plunged in an impetuous shoot of nearly three hundred feet, and rushed thence easterly away, walled on each side by the precipitous rock, until some five miles thence it was crossed at a deep and somewhat dangerous ford, by the only great road which traversed that district, and by which alone strangers could reach the Hall and its beautiful demesnes.

To the westward or right hand side of the chase the country was entirely wild and savage, covered with thick woods, interspersed with lonely heaths, and intersected by hundreds of clear brawling rills. To the eastward, however, although much broken by forest ground, there was a wide range of rich pasture fields and meadows, divided by great overgrown hawthorn hedges, each hedge almost a thicket, and penetrated by numerous lanes and horse-roads buried between deep banks, and overcanopied by foliage, that, even at noonday, was almost impenetrable to the sunshine.

Here and there lay scattered among the fields and woods innumerable farm-houses and granges, the abodes of small freeholders, once tenants and vassals of the great St. Aubyns; and, at about six miles from the Hall, nestled in a green valley, through which ran a clear, bright trout-stream to join the turbulent torrent, stood the little market town of Widecomb-Under-Moor, from their unalienated property in which the family of St. Aubyn derived the most valuable portion of their incomes.

Over the whole of this pleasant and peaceful tract, whether it was still owned by themselves, or had passed into the hands of the free yeomanry, the Lords of Widecomb still held manorial rights, and the few feudal privileges which had survived the revolution; and, through the whole of it, Sir Miles St. Aubyn was regarded with unmixed love and veneration, while the boy Jasper was looked upon almost as a son in every family, though some old men would shake their heads doubtfully, and mutter sage but unregarded saws concerning his present disposition and future prospects; and some old grandames would prognosticate disasters, horrors, and even crimes as hanging over his career, in consequence, perhaps, of the inauspicious change in the patronymic of his race.

They were a happy and an unsophisticated race who inhabited those lonely glens. Sufficiently well provided to be above the want of necessaries, or the fear of poverty, they were not so far removed from the necessity of labor as to have incurred vicious ambitions—moderate, frugal, and industrious, they lived uncorrupted, and died happy in their unlearned innocence.

It was the boast of the district that bars and locks were appendages to doors entirely unusual and useless; that the cage of Widecomb had not held a tenant since the days of stiff old Oliver; and that no deed of violence or blood had ever tainted those calm vales with horror.

Alas! how soon was that boast to be annulled; how soon were the details of a dread domestic tragedy, full of dark horrors, and reproductive of guilt through generations, to render the very name of Widecomb a terror, and to invest the beauteous scenery with images of superstitious awe and hatred. But we must not anticipate, nor seek as yet to penetrate the secrets of that destiny, which even during the morn of promising young life, seemed to overhang the house,

And hushed in grim repose,

Expects its evening prey.

——

The Peril.

I say beware—

That way perdition lies, the very path

Of seeming safety leading to the abyss.

—MS.

It was as fair a morning of July as ever dawned in the blue summer sky; the sun as yet had risen but a little way above the waves of fresh green foliage which formed the horizon of the woodland scenery surrounding Widecomb Manor; and his heat, which promised ere midday to become excessive, was tempered now by the exhalations of the copious night-dews, and by the cool breath of the western breeze, which came down through the leafy gorges, in long, soft swells from the open moorlands.

All nature was alive and joyous; the air was vocal with the piping melody of the blackbirds and thrushes, caroling in every brake and bosky dingle; the smooth, green lawn, before the windows of the old Hall was peopled with whole tribes of fat, lazy hares, limping about among the dewy herbage, fearless, as it would seem, of man’s aggression; and to complete the picture, above a score of splendid peacocks were strutting to and fro on the paved terraces, or perched upon the carved stone balustrades, displaying their gorgeous plumage to the early sunshine.

The shadowy mists of the first morning twilight had not been long dispersed from the lower regions, and were suspended still in the middle air in broad fleecy masses, though melting rapidly away in the increasing warmth and brightness of the day.

And still a faint blue line hovered over the bed of the long rocky gorge, which divided the chase from the open country, floating about it like the steam of a seething caldron, and rising here and there into tall smoke-like columns, probably where some steeper cataract of the mountain-stream sent its foam skyward.

So early, indeed, was the hour, that had my tale been recited of these degenerate days, there would have been no gentle eyes awake to look upon the loveliness of new-awakened nature.