Title: Social Life in the Reign of Queen Anne, Taken from Original Sources

Author: John Ashton

Release date: August 26, 2017 [eBook #55429]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

The Daily Courant.

Wednesday, March 11, 1702.

From the Harlem Courant, Dated March 18. N. S.

Naples, Feb. 22.

On Wednesday last, our New Viceroy, the Duke of Escalona, arriv'd here with a Squadron of the Galleys of Sicily. He made his Entrance drest in a French habit; and to give us the greater Hopes of the King's coming hither, went to Lodge in one of the little Palaces, leaving the Royal One for his Majesty. The Marquis of Grigni is also arriv'd here with a Regiment of French.

Rome, Feb. 25. In a Military Congregation of State that was held here, it was Resolv'd to draw a Line from Ascoli to the Borders of the Ecclesiastical State, thereby to hinder the Incursions of the Transalpine Troops. Orders are sent to Civita Vecchia to fit out the Galleys, and to strengthen the Garrison of that Place. Signior Casali is made Governor of Perugia. The Marquis del Vasto, and the Prince de Caserta continue still in the Imperial Embassador's Palace; where his Excellency has a Guard of 50 Men every Night in Arms. The King of Portugal has desir'd the Arch-Bishoprick of Lisbon, vacant by the Death of Cardinal Sousa, for the Infante his second Son, who is about 11 Years old.

Vienna, Mar. 4. Orders are sent to the 4 Regiments of Foot, the 2 of Cuirassiers, and to that of Dragoons, which are broke up from Hungary, and are on their way to Italy, and which consist of about 14 or 15000 Men, to hasten their March thither with all Expedition. The 6 new Regiments of Hussars that are now raising, are in so great a forwardness, that they will be compleat, and in a Condition to march by the middle of May. Prince Lewis of Baden has written to Court, to excuse himself from coming thither, his Presence being so very necessary, and so much desir'd on the Upper-Rhine.

Francfort; Mar. 12. The Marquiss d'Uxelles is come to Strasburg, and is to draw together a Body of some Regiments of Horse and Foot from the Garisons of Alsace; but will not lessen those of Strasburg and Landau, which are already very weak. On the other hand, the Troops of His Imperial Majesty, and his Allies, are going to form a Body near Germeshein in the Palatinate, of which Place, as well as of the Lines at Spires, Prince Lewis of Baden is expected to take a View, in three or four days. The English and Dutch Ministers, the Count of Frise, and the Baron Vander Meer; and likewise the Imperial Envoy Count Lowenstein, are gone to Nordlingen, and it is hop'd that in a short time we shall hear from thence of some favourable Resolutions for the Security of the Empire.

Liege, Mar. 14. The French have taken the Cannon de Longie, who was Secretary to the Dean de Mean, out of our Castle, where he has been for some time a Prisoner, and have deliver'd him to the Provost of Maubeuge, who has carry'd him from hence, but we do not know whither.

Paris, Mar. 13. Our Letter from Italy say, That most of our Reinforcements were Landed there; that the Imperial and Ecclesiastical Troops seem to live very peaceably with one another in the Country of Parma, and that the Duke of Vendome, as he was visiting several Ports, was within 100 Paces of falling into the Hands of the Germans. The Duke of Chartres, the Prince of Conti, and several other Princes of the Blood, are to make the Campaign in Flanders under the Duke of Burgundy; and the Duke of Maine is to Command upon the Rhine.

From the Amsterdam Courant, Dated Mar. 18.

Rome, Feb. 25. We are taking here all possible Precautions for the Security of the Ecclesiastical State in this present Conjuncture, and have desir'd to raise 3000 Men in the Cantons of Switzerland. The Pope has appointed the Duke of Berwick to be his Lieutenant-General, and he is to Command 6000 Men on the Frontiers of Naples: He has also settled upon him a Pension of 6000 Crowns a year during Life.

From the Paris Gazette, Dated Mar. 18. 1702.

Naples, Febr. 17. 600 French Soldiers are arrived here, and are expected to be follow'd by 3400 more. A Courier that came hither on the 14th. has brought Letters by which we are assur'd that the King of Spain designs to be here towards the end of March; and accordingly Orders are given to make the necessary Preparations against his Arrival. The two Troops of Horse that were Commanded to the Abruzzo are posted at Pescara with a Body of Spanish Foot, and others in the Fort of Montorio.

Paris, March. 18. We have Advice from Toulon of the 5th instant, that the Wind having long stood favourable, 22000 Men were already sail'd for Italy, that 2500 more were Embarking, and that by the 15th it was hoped they might all get thither. The Count d'Estrees arriv'd there on the Third instant, and set all hands at work to fit out the Squadron of 9 Men of War and some Fregats, that are appointed to carry the King of Spain to Naples. His Catholick Majesty will go on Board the Thunderer, of 110 Guns.

We have Advice by an Express from Rome of the 18th of February, That notwithstanding the pressing Instances of the Imperial Embassadour, the Pope had Condemn'd the Marquis del Vasto to lose his Head and his Estate to be confiscated, for not appearing to Answer the Charge against him of Publickly Scandalizing Cardinal Janson.

ADVERTISEMENT.

It will be found from the Foreign Prints, which from time to time, as Occasion offers, will be mention'd in this Paper, that the Author has taken Care to be duly furnish'd with all that comes from Abroad in any Language. And for an Assurance that He will not, under Pretence of having Private Intelligence, impose any Additions of feign'd Circumstances to an Action, but give his Extracts fairly and Impartially; at the beginning of each Article he will quote the Foreign Paper from whence 'tis taken, that the Publick, seeing from what Country a piece of News comes with the Allowance of that Government, may be better able to Judge of the Credibility and Fairness of the Relation: Nor will he take upon him to give any Comments or Conjectures of his own, but will relate only Matter of Fact; supposing other People to have Sense enough, to make Reflections for themselves.

This Courant (as the Title shews) will be Publish'd Daily; being design'd to give all the Material News as soon as every Post arrives: and is confin'd to half the Compass, to save the Publick at least half the Impertinences, of ordinary News-Papers.

LONDON. Sold by E. Mallet, next Door to the King's-Arms Tavern at Fleet-Bridge.

SOCIAL LIFE

IN THE

REIGN OF QUEEN ANNE

TAKEN FROM ORIGINAL SOURCES

BY

JOHN ASHTON

AUTHOR OF 'CHAP-BOOKS OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY' ETC.

A NEW IMPRESSION

WITH 84 ILLUSTRATIONS

FROM CONTEMPORARY PRINTS

LONDON

CHATTO & WINDUS

1919

From the time of Dean Swift downwards to our own days many Political Histories of the Reign of Queen Anne have been written, but its Social Life we have been left to gather mainly from the efforts of novelists, who have been more or less conscientious, according to their knowledge, in placing it before us.

No doubt the drudgery of the work, the wading through all the newspapers, and reading all the literature of the time, has deterred many from attempting what, in its execution, has proved a very pleasant task; for in doing it, one has got to be thoroughly identified with the age—its habits and customs—which, being taken from the very words of the people, then living, writing for living people, who could contradict their statements, if false or exaggerated, a charm was lent to the task, which fully compensated for its labour.

All history, unless it is contemporary, must necessarily, if honest, be a compilation, and my idea is, that it should honestly be avowed as such, and the authorities given for all facts; and this I have done, even at the risk of proving wearisome.

In compiling it, my task has been similar to one who, having a necklace of old beads, finds it broken, and the beads scattered hither and thither. His business, naturally, is to gather them (p. vi) together, and string them so as to satisfy criticism. He may not pick them all up, and he may not please everyone's taste in his arrangement, but his course is clear—he should not add new beads of his own to supply deficiencies, but should confine himself to putting together all he can find in the best manner he possibly can.

The almost total absence of domestic news in the newspapers has compelled me to draw largely on the essays and descriptive books of the time, and in one or two instances I have ventured to transcribe (as in the case of Misson) from works published, or written, two or three years before Anne actually reigned—but the facts were precisely the same as then obtained, so that much has been gained thereby.

The Illustrations might, undoubtedly, have been made more artistic and unreal—but I have carefully taken them from contemporary prints, and prefer to present them in all their uncouthness and reality.

John Ashton.

CHAPTER I.

CHILDHOOD AND EDUCATION (BOYS).

PAGE

The Duke of Gloucester — The Queen's refusal to marry again — Treatment of children after birth — Baptismal feasts — A christening — 'Daffy's Elixir' — Treatment of infantile diseases — The nursery — Toys — Children's books — Horn-books — Private tuition — Boarding and day schools — Free schools — Classical education — School-books — Penmanship — Runaway boys — College education — Charity schools 1

CHAPTER II.

CHILDHOOD AND EDUCATION (GIRLS).

Boarding schools — Town and country educations — Pastry schools — Dancing — Toasts — 'The Little Whig' — Madame Spanheim 17

CHAPTER III.

MARRIAGE.

Eloping with heiresses — Marriage between children — Tax on bachelors — Valentines — Marriage settlements — Pin money — Posies — Drummers — Private marriages — Irregular marriages — Fleet parsons — Marriage Act — Facility of marriage — Liability of husbands — Public marriages — Marriage customs — Bride's garters — Throwing the stocking — The Posset — Honeymoon 22

CHAPTER IV.

DEATH AND BURIAL.

Longevity — Undertakers' charges — Costliness of funerals — Mourning — Burial in woollen — Burial Societies — Burial by night — A cheat — Mourning rings — Funeral pomp — Monuments — Description of a funeral — A Roman Catholic funeral — Widows 35

(p. viii) CHAPTER V.

HOUSES, FURNITURE, ETC.

'Queen Anne' houses — Vanbrugh's house — Real 'Queen Anne' houses — Hangings and wall papers — Letting and rent — Prevention of fire — A fire — Insurance companies — Water supply — Thames Water Works — New River — Coals — Furniture — China — Bedsteads 46

CHAPTER VI.

SERVANTS.

Number of servants — Footmen — Wages — Liveries — 'How d'ye' — The Upper Gallery — Footmen's Parliament — Accomplishments — White slaves from Barbary — Negro slaves — Runaways — Apprentices 58

CHAPTER VII.

DAILY LIFE (MEN).

Out-of-door amusements — A holiday — Hatred of French fashions — Beaus' oaths — Kissing — Fops: their daily life 63

CHAPTER VIII.

DAILY LIFE (WOMEN).

Receiving in bed — A lady's life — A fine lady's diary — Walking — Visiting — Tea-table scandal — Shopping — Daily church — Pets — Dancing — Books on ditto — A dancing-master 68

CHAPTER IX.

GAMBLING AND SPECULATION.

Games at cards — Curious cards — Price — Tax on cards — Female passion for gambling — The Groom Porter's — Gaming houses — Gamesters — Noted gamesters — Debts of honour — Speculation — Life insurances — Marine and other insurances — Shopkeepers' lotteries — Government lotteries — Prizes and winners 78

CHAPTER X.

SUPERSTITION.

Astrologers — Their advertisements — Their tricks — Witchcraft — Cases of witchcraft 89

(p. ix) CHAPTER XI.

COSMETICS, ETC.

Habit of snuff-taking — Perfumes — Charles Lillie — List of Scents — Soaps — Wash-balls — 'Complections' — Tooth powder — Hair-dye — Spectacles 95

CHAPTER XII.

TRADE, ETC.

The penny post — Dockwra's vindication of himself — Abolition of penny post — Post days and rates — Halfpenny post — Method of doing business — The Exchange — Description of frequenters — Bankers — Curious advertisement of Sir Richard Hoare's 99

CHAPTER XIII.

MEN'S DRESS.

A beau — An inventory of him — Hats — Wigs: their price: varieties — Hair powder — Robbery of wigs — Natural hair — Neck-cloths — Shirts — Open waistcoats — Colonel Edgworth — Coats — Cheap clothiers — Stockings — Boots and shoes — Shoeblacks and blacking — Handkerchiefs — Muffs — Swords — Walking-sticks — Watches — Overcoats — Night-caps — Night-gowns 104

CHAPTER XIV.

WOMEN'S DRESS.

The Commode — Description of ladies' dress — The Petticoat — The Bodice — A costly wardrobe — Underlinen — Dressing like men — Scents — Patches — Patching Whig and Tory — Masks — The hood — High-crowned hats — Furs — Umbrellas — Pattens — The fan — Mobs — Shopping — Stuffs — List of Indian stuffs — Lace — Linens — Tallymen — Jewellery — Diamonds — Plate — Children's jewellery 123

CHAPTER XV.

FOOD (SOLID).

English fare — Time of dining — Pontack's — Other ordinaries — Books on cookery — Receipts — Pudding — Fish — Oysters — Poultry — Assize of bread — Markets — Vegetables — Lambeth gardeners — Fruit — Dried fruit 141

CHAPTER XVI.

FOOD (LIQUID).

Beer — Hard drinking — 'Whetters' — Wines — List of French and Spanish wines — Wines of other countries — Duties on wines — Spirits — Liqueurs — Homemade wines — Prices of tea — Adulteration — Price of coffee — Chocolate — Its price — Duty on 150

Habit of smoking — Women and children smoking — Prices of tobacco — Customs duty — Origin of snuff-taking — The Vigo expedition — Snuff-rasps — Ladies taking snuff — Proper use of the snuff-box — Use of a spoon — Prices of snuffs — List of ditto — Duty on snuff 156

CHAPTER XVIII.

COFFEE-HOUSES AND TAVERNS.

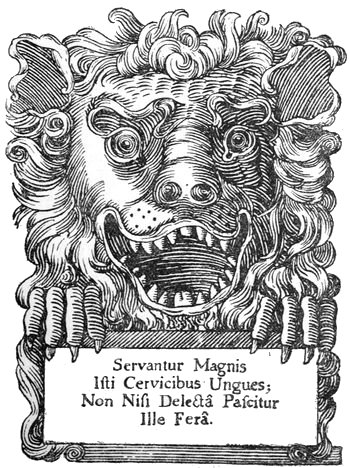

Universal use of coffee-houses — Their convenience — Company — First coffee-house — Number of them — Anecdote of Bishop Trelawney — Description of interior — The news — Advance in price — Chocolate-houses — Famous coffee-houses — Button's Lion — Lloyd's — Sales by candle — Jenny Man — Don Saltero's collection — Taverns — Noblemen frequenting them — Drinking own wine — Purl houses — List of old taverns 161

CHAPTER XIX.

CLUBS.

Origin — October Club — Calves' Head Club — Kit Cat Club — Other clubs — Suggested clubs 179

CHAPTER XX.

SIGHT-SEEING AND FAIRS.

Royal visits to the City — Lord Mayor's show — The lions at the Tower — The Armoury — Tombs at Westminster — Bartholomew Fair — Description — Shows — Tight-rope dancing — Natural curiosities — Theatrical performances, etc. — Abolition — May Fair — Lady Mary — Pinkethman — Shows — Visit to — Abolition — Southwark Fair — Its Shows 185

CHAPTER XXI.

OTHER SIGHTS.

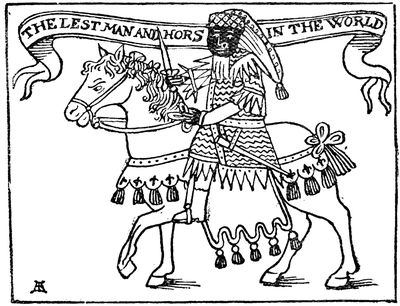

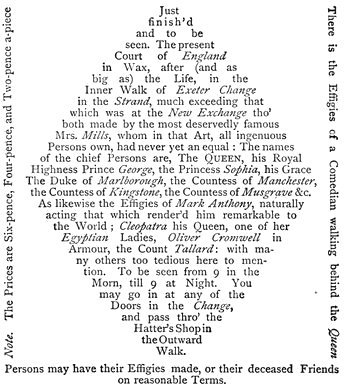

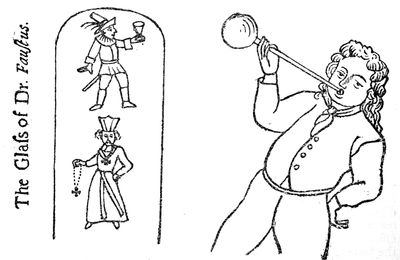

The Lincolnshire ox — The large hog — The whale — Monkeys and wild beasts — 'The Lest Man and Hors in the World' — Performing horse Dwarfs and giants — Human curiosities — Helen and Judith — Conjurers — Posture masters — Mr. Clinch — Waxwork — Mrs. Salmon, etc. — Westminster Abbey wax-figures — Powell's puppets — Moving pictures — Glass-blowing — Miraculous fountain — Winstanley — His waterworks — The four Indian chiefs 201

CHAPTER XXII.

ROUGH SPORTS.

Bear-baiting — Bear-gardens — Bull-baiting — Description — Extraordinary bull-bait — Cock-fighting — Cock-pits — Value of matches — Training 223

(p. xi) CHAPTER XXIII.

HORSE-RACING, HUNTING, SHOOTING, ETC.

The Queen's love of racing — Visit to Newmarket — Queen's plates — Value of matches — Race meetings — Tregonwell Frampton — His horse Dragon — The Queen's love of hunting — Sir Roger de Coverley — Fox-hunting — Stag-hunting — Hare-hunting — Coursing — Packs of hounds — Fishing — Hawking — Netting — The Game Act — Shooting sitting and flying — Match shooting — Archery 228

CHAPTER XXIV.

SWORD-PLAY AND OTHER SPORTS — GARDEN, ETC.

Challenges — The stakes — The combatants — Description of fights — General combativeness — Boxing — Cudgel-playing — Pedestrianism — Tennis — Cricket — Football — Skating — Billiards — Country wakes — Bowling — Bowling greens — Formal gardening — Clipping trees — Books on gardening — Trees and Flowers — Town and country life — Country labourers 237

CHAPTER XXV.

THE DRAMA.

The theatres — Dorset Gardens — Its demolition — Performances — Lincoln's Inn Fields — Theatre Royal, Drury Lane — Its company — Mrs. Tofts — The Queen's Theatre, Haymarket — Its foundation stone — Its operas — Pinkethman's theatre at Greenwich — The Queen and the stage — Her reforms — Strolling players — Behaviour at the theatre — Orange wenches — Stage properties — Actors — Betterton — Verbruggen — Cave Underhill — Estcourt — Dogget — Colley Cibber — Wilks — Booth — Pinkethman — Minor Actors — Actresses — Mrs. Barry — Mrs. Bracegirdle — Mrs. Oldfield — Mrs. Verbruggen — The ballet 243

CHAPTER XXVI.

OPERAS — CONCERTS — MUSIC.

Introduction of Italian opera — Its rapid popularity — Mixture of Languages — Handel — His operas, and visit here — Singers — Abel — Hughs — Leveridge — Lawrence — Ramondon — Mrs. Tofts — Her madness — Foreign singers — Margherita de l'Epine — Nicolino Grimaldi — Isabella Girardeau — Composers — Dr. Blow — Jeremiah Clarke — Dean Aldrich — Tom D'Urfey — Henry Carey — Britton, the small coal man — His concerts — His death — Concerts and concert rooms — Gasparini, the violinist — Musical instruments — Musical scores 268

CHAPTER XXVII.

PAINTERS AND ARCHITECTS.

Wollaston — Murray — Hugh Howard — Lewis Crosse — Luke Craddock — Charles Jervas — Richardson — Sir James Thornhill — Sir Godfrey (p. xii) Kneller — Closterman — Pelegrini — Sebastian Ricci — Vander Vaart — Laguerre — Dahl — Boit — Class of pictures in vogue — Water Colours — Drawings — Engravings — Sculpture — Grinling Gibbons — Architects: Sir C. Wren — Vanbrugh 279

CHAPTER XXVIII.

SCIENCE, ETC.

Its infancy — Virtuosi — Gresham College — Visit to the Royal Society's Museum — Their curiosities — Their new house — Geology — Experimental philosophy — Courses of chemistry — Mathematics — List of patents — Hydraulic machinery — Savery's steam-engine — Description 286

CHAPTER XXIX.

LITERATURE, THE PRESS, ETC.

Authors — Public libraries — Their condition — George Psalmanazar — Hack writers — Poverty of authors — Their punishment — The Press — Daily Courant — List of newspapers — London Gazette — Postboy — Postman — Dawk's News Letter — Dyer's — Evening papers — Dearth of domestic news — Amenities of the press — Roper and Redpath — Tutchin — His trial — Press remuneration — Mrs. Manley — 'The Essay Papers' — The half-penny stamp — Its effect — Advertising — Almanacs — List of them — Moore's — 'The Ladies' Diary' — 'Poor Robin's Almanack' — 'Merlinus Liberatus' — The Essayists and Partridge — His false death — His elegy and epitaph — An amateur magazine 293

CHAPTER XXX.

MEDICAL.

List of diseases — Quackery — Bleeding, etc. — Physicians — Surgeons — Apothecaries — Dissension between the physicians and apothecaries — The Dispensary — Pharmacopœias — Some nostrums — Prescriptions — Cupping — Treatment of lunatics — Physicians' carriages — Dr. Radcliffe — Sir Samuel Garth — Sir Hans Sloane — Dr. Mead — His duel with Woodward — Study of anatomy — Surgical instruments — Oculists — Sir William Read — Roger Grant — The Queen touching for the evil — Description of the ceremony — Quack remedies — Quacks' harangues 313

CHAPTER XXXI.

SPAS AND BATHING.

Bath — Manners of the company there — Description of Bath — Its gaieties — Sale of the water — Tunbridge — Epsom — Hampstead — Other spas — Turkish baths — Controversy on hot and cold bathing — The Hummums — Description of a Turkish bath — Other bagnios — Cold bathing and baths 329

(p. xiii) CHAPTER XXXII.

RELIGIONS.

Inactivity of the Church — Dulness of Sunday — Contempt of the clergy — Low estimation of a chaplain — Dress of the clergy — Church furniture — Traffic in benefices — Forged Orders — Dr. Sacheverell — 'The Modern Champions' — Queen Anne's Bounty — Its history — Fifty new churches — Protestant tone of Church feeling — The effigies on Queen Elizabeth's birthday — Oppression of Roman Catholics — Religious sects — Eminent Nonconformists — Daniel Burgess — Dislike to Quakers — Examples — William Penn 337

CHAPTER XXXIII.

LEGAL.

The different branches of the law — Briefless barristers — Green bags — Forensic wigs — Attorneys — Knights of the Post — Lord Somers — Lord Cowper — His abolition of New Year's gifts 353

CHAPTER XXXIV.

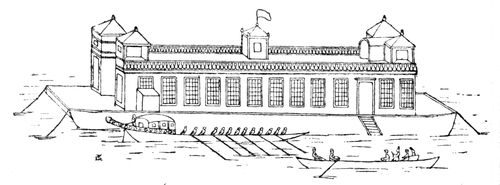

THE RIVER.

Use as a highway — River slang — Rates of watermen — Description of wherries — Pleasure parties and barges — The Folly — Its frequenters — Gravesend tilt boat — Fares at the Horse Ferry — The Fleet Ditch 356

CHAPTER XXXV.

THE STREETS.

Size of London — Pall Mall — London in wet weather — Early morning — Street cries — A list of them — Roguery in the streets — Orderly regulations — State of the roads — Rule of the road — Street signs — Description of the streets — Milkmaids on May Day — Hyde Park — Its regulations — Lighting the streets — The streets at night 362

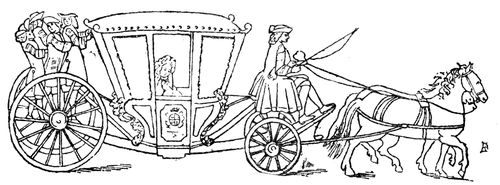

CHAPTER XXXVI.

CARRIAGES, ETC.

Smithfield — Horse coursers — Waggons — Stage coaches — Travelling in them described — Bad roads — Posting — Hackney coaches — Their fares — Hackney coachmen — State coaches — Other carriages — Suburban drives — Mechanical coach — Mourning coaches — Harness — Sedan chairs — Chairmen 372

(p. xiv) CHAPTER XXXVII.

THE MOHOCKS.

Scourers, etc. — Bully Dawson — Two outbreaks — That in 1712 — Hawkubites — Exploits of the Mohocks — Sir Roger de Coverley — Swift's fear of them — Emperor of the Mohocks — Gog and Magog — The Queen's proclamation — Decline of the scare — Constables and watchmen 382

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

DUELLING.

Its prevalence — Bullying — Fielding's duels — Favourite localities — Its illegality — Col. Thornhill and Sir Cholmley Dering — Their quarrel and duel — Duke of Hamilton and Lord Mohun — Story of their duel 390

CHAPTER XXXIX.

THE ARMY AND NAVY.

Sale of commissions — General practice — Its illegality — Arrears of pay — Descriptions of officers — Army chaplains — The rank and file — Description of them — Irregularity of pay — Rations — Recruiting — Bounty — Gaol birds — Vagrants — Desertions — Story of seditious drummers — Train bands — The navy — Its deeds — Unpopularity of the service — Pressing — Desertion — Rewards for capture — Pay — Description of Admiralty — Mercantile marine 396

CHAPTER XL.

CRIME.

Capital punishment — Its frequency — An execution described — Behaviour on the scaffold and way to execution — Revival after hanging — 'Peine forte et dure' — Hanging in chains — Highwaymen — Claude du Val lying in state — Ned Wicks and Lord Mohun — Their swearing match — A highwayman hanged — Highwaymen in society — Highway robberies — Footpads — Burglars — John Hall — Benefit of clergy — Coining — Pickpockets — Robbery from children — Perjury — Sharpers — Begging impostors — Gipsies — Constables — Private detectives — Commercial frauds — 'Society for the Reformation of Manners' — Statistics of their convictions — The pillory — Ducking stool 407

CHAPTER XLI.

PRISONS.

Dreadful condition of prisons — Bridewell — Description of — Flogging — Houses of Correction — Compters — Description of the Poultry Compter — 'Garnish' — Newgate — Description of — Marshalsea — Queen's Bench — Fleet and Ludgate — Poor Debtors — Kidnappers — Country prisons — Bankrupts 425

(p. xv) CHAPTER XLII.

WORKHOUSES, HOSPITALS, ETC.

The London Workhouse — Life therein — Bedlam — Its building — Regulations — Description of interior — Governors — Bartholomew Hospital — St. Thomas's — Almshouses 435

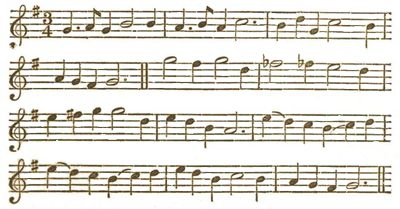

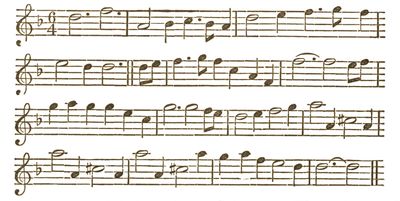

Lilli-Burlero 439

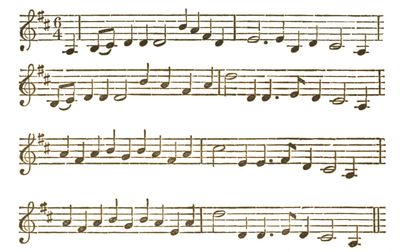

Hunt the Squirll 439

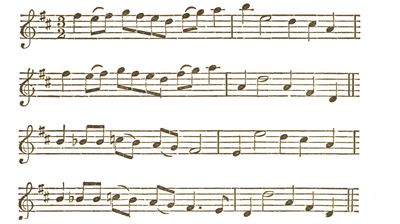

Moll Peatley 440

A List of all the Persons to whom Rings and Mourning were presented upon the occasion of Mr. Pepys's Death and Burial 441

Lord Mayor's Delight 444

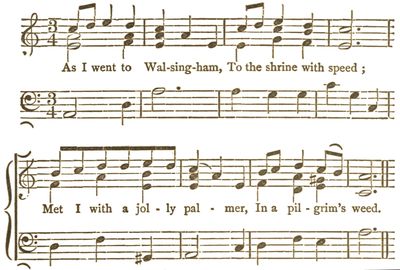

Walsingham 445

The Children in the Wood 445

A List of some of the Coffee-houses in London during Queen Anne's Reign, 1702-14 448

Chocolate-houses 453

Sir Roger de Coverley 453

Roger of Coverly 453

Christ Church Bells in Oxon 454

Cheshire Rounds 455

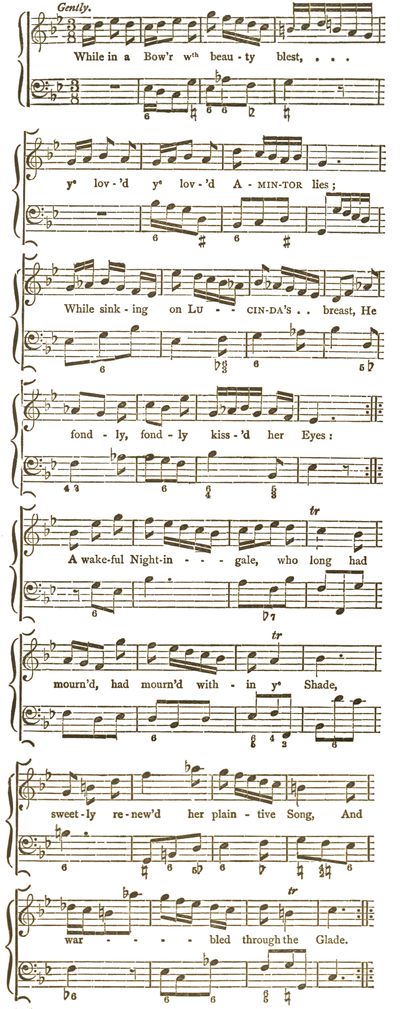

The Nightingale 455

INDEX 459

PAGE

The 'Daily Courant,' March 11, 1702 Frontispiece

The Nursery (Steele's 'Ladies' Library,' ed. 1714) 8

'Troope, every one' (Lauron's 'Habits and Cryes of the City of London,' ed. 1709) 9

A Raree Show ('Cris de Paris,' 1700. Print Room, B. M.) 10

'Oh, Raree Show!' (Lauron) 10

'Ripe Strawberryes!' (Lauron) 11

'Six Pence a Pound Fair Cherryes' (Lauron) 11

A Corpse (Undertaker's Bill, Harl. MSS. 5931, 129) 36

Invitation to a Funeral (Harl. MSS. 5931, 186) 37

Lying in State (Fletcher's 'The Tamer Tamed,' ed. 1711) 43

A Widow ('Ladies' Library') 45

A Fire ('Verses of John Hall, Bellman of Canterbury,' 1708) 51

'New River Water!' (Lauron) 52

'Small Coale!' (Lauron) 55

Fireplace and Utensils (Harl. MSS. 5961, 220) 56

A Bed (Harl. MSS. 5961, 180) 58

'The Merry Fidler' (Lauron) 65

Men Kissing (from a Contemporary View of Marlborough House—Guildhall) 67

A Tea Party (Satirical Prints, No. 1555. 1710? B. M.) 72

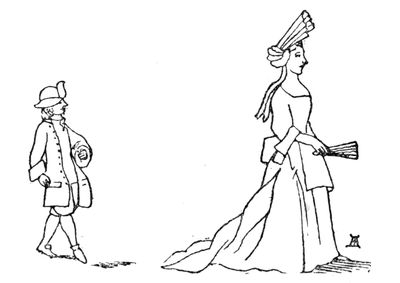

A Lady and Footman (View of Marlborough House—Guildhall) 74

Riding Pillion (From a View of Whitehall—1713—Guildhall) 76

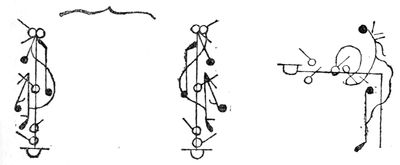

A Bourée and a Contretemps (Weaver's 'Orchesography') 77

A Sissone (Siris' translation of Feuillet's book on Dancing) 77

A Card Table (Mrs. Centlivre's 'Basset Table,' ed. 1706) 79

A Gambling Scene (Lucas's 'Memoirs, &c., of the most famous Gamesters, &c.,' ed. 1714) 81

A Lottery (Steele's 'A Good Husband for Five Shillings,' ed. 1710) 88

An Astrologer (Harl. MSS. 5931, 12) 92

'4 Paire for a Shilling, Holland Socks!' (Lauron) 115

A Jack-boot 117

(p. xviii) Shoe-black ('Cris de Paris') 118

A Watch Riband (Harl. MSS. 5961, 222) 121

'Old Cloaks, Suits, or Coats!' (Lauron) 122

'Old Satin, Old Taffety or Velvet!' (Lauron) 122

A Commode (Anna Sophia of Hanover—Playing Cards, 1707, B. M.) 124

Coiffure (Princess Royal of Prussia—Playing Cards, 1707, B. M.) 128

Patching (Lauron) 129

A Mask or Vizard (Harl. MSS. 5996, 3) 131

An Umbrella (Gay's 'Trivia,' 1st ed.) 132

Costume of a Lady 140

'Four for Sixpence, Mackerell!' (Lauron) 144

'Twelve Pence a Peck, Oysters!' (Lauron) 146

A Coffee House ('Vulgus Britannicus,' 1710) 162

The Lion at Button's (Ireland's 'Graphic Illustrations of Hogarth') 169

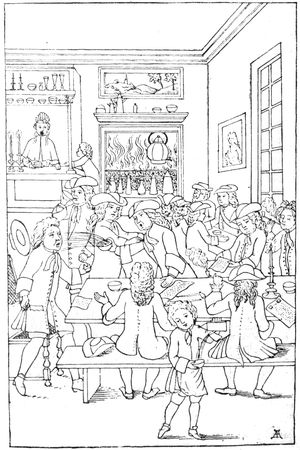

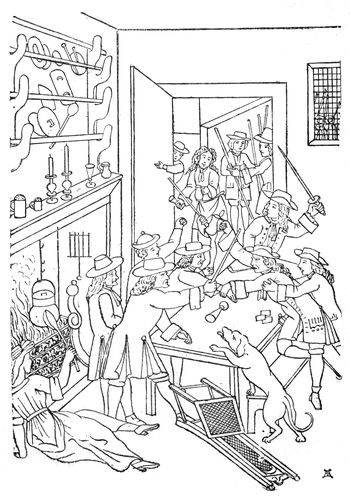

A Tavern Scene (Satirical Prints, No. 1582. B. M. 1712) 176

A Leopard (Harl. MSS. 5961, 327) 203

'The Lest Man and Hors in the World' (Harl. MSS. 5996, 1) 206

Hungarian Youth (Harl. MSS. 5931, 280) 209

A Posture Master (Harl. MSS. 5961, 5) 211

Portrait of Powell (from 'A Second Tale of a Tub,' ed. 1715) 215

Glass-blowing (Harl. MSS. 5961, 224) 218

Wonderful Fountain (Harl. MSS. 5961, 331) 220

The Four Indian Kings (Hand Bill, B. M. 816. m. 19/26) 222

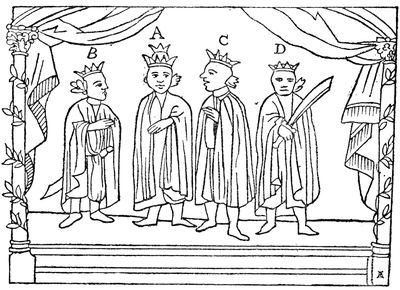

Billiards (Cotton's 'Compleat Gamester,' ed. 1709) 243

Savery's Steam Engine (from 'The Miner's Friend,' 1702) 291

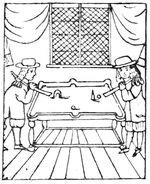

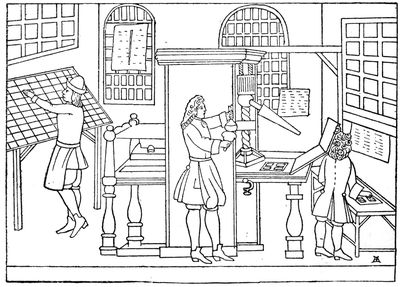

A Printing Press (Harl. MSS. 5915, 215) 296

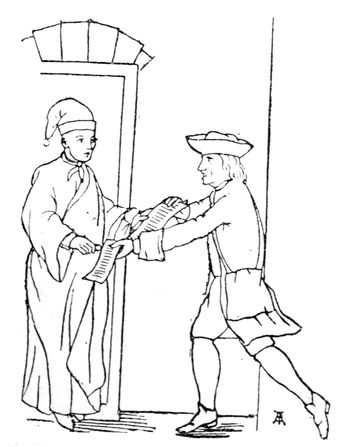

'London Gazettes here!' (Lauron) 298

A News Man ('Cris de Paris') 301

Newspaper Stamp (Newspapers of and after 1 Aug. 1712) 307

Partridge and Bickerstaff (Harl. MSS. 5931, 10) 310

Sir William Read operating (Handbill B. M. 778. K. 15/13) 324

A Quack (Harl. MSS. 5931, 147) 327

A Clergyman's Walking Costume (Satirical Prints, B. M. No. 1546—A.D. 1702) 341

A Bishop's Walking Costume (Satirical Prints, B. M. No. 1546—A.D. 1702) 342

A Prebend's Walking Costume (Satirical Prints, B. M. No. 1546—A.D. 1702) 342

'The Modern Champions' (Banks' Collection, B. M. 1890 e) 344

(p. xix) A Nonconformist Minister (Lauron) 350

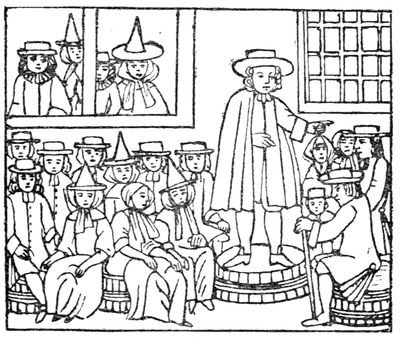

A Quakers' Meeting ('The Quaker's Art of Courtship,' 1710) 351

Ditto. (Satirical Prints, B. M. No. 1554, by Heemskirk, A.D. 1710) 352

'The Folly on the Thames' (View of White Hall—Guildhall) 360

A Street Scene (Gay's 'Trivia,' 1st ed.) 363

Milkmaid on May Day (Lauron) 369

Hackney Coach (View of Westminster Abbey—Guildhall) 375

A State Coach (Thanksgiving at St. Paul's for Peace, July 7, 1713—Guildhall) 377

Ditto (Thanksgiving at St. Paul's for Peace, July 7, 1713—Guildhall) 378

A Sedan Chair (Vue du Palais Royall de White Hall—Guildhall) 381

The Watch (Bell Man's Verses, 1708) 388

A Constable (Ward's 'Nuptial Dialogues') 389

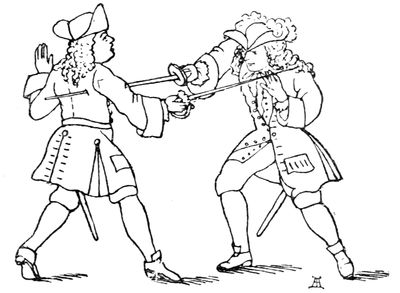

A Duel (Playing Cards, 1707, B. M.) 391

Duel between Duke of Hamilton and Lord Mohun (Historical Prints, B. M. 1712) 394

Soldiers (Historical Prints, B. M. 1709) 400

An Admiral 404

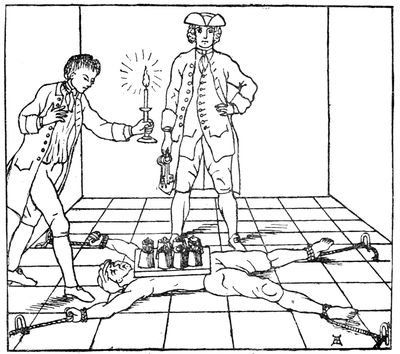

'Peine Forte et Dure' ('Newgate Chronicle'—Wm. Spigott, Pressed 1721) 411

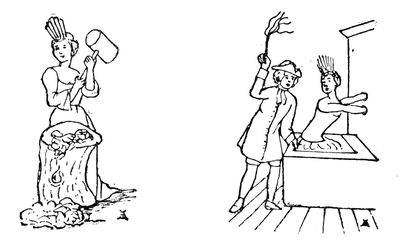

Beating Hemp (Bell Man's Verses, 1708) 428

Flogging a Woman (ibid) 428

'Remember the Poor Prisoners!' (Lauron) 433

(p. 1) SOCIAL LIFE

IN THE

REIGN OF QUEEN ANNE.

The Duke of Gloucester — The Queen's refusal to marry again — Treatment of children after birth — Baptismal feasts — A christening — 'Daffy's Elixir' — Treatment of infantile diseases — The nursery — Toys — Children's books — Horn books — Private tuition — Boarding and day schools — Free schools — Classical education — School books — Penmanship — Runaway boys — College education — Charity schools.

In all climes, and in all ages, since Man's creation, he has been subject to the same conditions, modified only by circumstances. He has been born—has had to receive some education (if only taught to fish and hunt for his subsistence), which was to fit him for the position he was to occupy in this life. This was absolutely necessary, for it is scarcely possible to imagine a more helpless being than an infant. In most cases he married, and so helped to preserve his species, and most certainly he died.

The scheme of existence in Queen Anne's time was no exception to the normal state of things—only, as the ways of people then were not exactly similar to ours, it will be interesting to note the differences attending childhood, education, marriage, and death. The Queen herself had more than once been a mother;[1] but only one child, the Duke of Gloucester, lived any length of time, and in his infancy he was indebted for his life to a young Quakeress, who acted as his wet nurse. Poor little fellow! his brief stay on earth was not a pleasant one. He suffered from hydrocephalus (water on the brain), and his head was so big that at five years of age his hat was large enough for an ordinary man. He could hardly toddle (p. 2) about, and felt himself unable to go upstairs without being led. His father and mother seemed to think that this assistance was not necessary; and, shutting themselves in a room with the poor little boy, Prince George gave him such a severe thrashing with a birch rod, that sheer pain made him move, and from that time he managed to get up and down stairs without help. Coddled by the women, and with somewhat rough playmates of his own sex, he amused himself by drilling his company of boy soldiers, even reviewing them on his eleventh birthday, the day before he sickened with scarlet fever, of which he speedily died. His mother grieved sorely for him, but never had another child to supply his place.

On her accession to the throne, the succession (failing her issue) was unsettled, and most anxious was the whole nation that she should yet be the mother of their future sovereign. In 'The form of prayer with thanksgiving to Almighty God to be used in all churches and chapels within this realm, every year upon the eighth day of March (being the day upon which Her Majesty began her happy reign),' in the prayer at the Communion service, immediately before the reading of the epistle, 'for the Queen as supreme Governor of this Church,' was the following petition: 'And that these Blessings may be continued to after Ages, make the Queen, we pray thee, an happy Mother of Children, who being Educated in Thy true Faith and Fear may happily succeed Her in the Government of these Kingdoms.' Her husband, Prince George, died October 28, 1708; and it was not until January 13 of the next year, that the Council struck out this portion of the service, some one evidently remembering that the 8th of March was approaching. On January 28, 1709, both Houses of Parliament petitioned Her Majesty to marry again; but her wounds were too recent and too sore. She replied that the provision she had made for the Protestant succession would always be a proof of her hearty concern for the happiness of the nation; but that the subject of their address was of such a nature that she was persuaded they did not expect a particular answer.[2]

Ignorantly as the little Duke of Gloucester was treated, what was the condition of ordinary babies? Let a contemporary tell the tale. Steele,[3] writing as if his familiar Pacolet was speaking, and giving an experience of his sensations, says: 'The first thing that ever struck my senses was a noise over my head of one shrieking; after which, methought I took a full jump, and found myself in the hands of a sorceress, who seemed as if she had been long waking, and employed in some incantation. I was thoroughly frightened, and cried out; but she immediately seemed to go on in some magical operation, and anointed me from head to foot. What they meant I could not imagine: for there gathered a great crowd about me, crying, "An heir! an heir!" upon which I grew a little still, (p. 3) and believed this was a ceremony only to be used to great persons, and such as made them what they called heirs.

'I lay very quiet, but the witch, for no manner of reason or provocation in the world, takes me, and binds my head as hard as possibly she could; then ties up both my legs, and makes me swallow down an horrid mixture. I thought it an harsh entrance into life, to begin with taking physic; but I was forced to it, or else must have taken down a great instrument in which she gave it to me. When I was thus dressed, I was carried to a bedside, where a fine young lady (my mother, I wot) had liked to have hugged me to death. From her they faced me about, and there was a thing with quite another look from the rest of the company, to whom they talked about my nose. He seemed wonderfully pleased to see me; but I know since, my nose belonged to another family.

'That into which I was born is one of the most numerous among you; therefore crowds of relations came every day to congratulate my arrival; amongst others, my cousin Betty, the greatest romp in nature; she whisks me such a height over her head, that I cried out for fear of falling. She pinched me and called me squealing chit, and threw me into a girl's arms that was taken in to tend me. The girl was very proud of the womanly employment of a nurse, and took upon her to strip and dress me anew, because I made a noise, to see what ailed me; she did so, and stuck a pin in every joint about me. I still cried; upon which she lays me on my face in her lap; and to quiet me, fell to a-nailing in all the pins, by clapping me on the back, and screaming a lullaby. But my pain made me exalt my voice above hers, which brought up the nurse, the witch I first saw, and my grandmother. The girl is turned downstairs, and I stripped again, as well to find what ailed me as to satisfy my granam's farther curiosity. This good woman's visit was the cause of all my troubles. You are to understand that I was hitherto bred by hand, and anybody that stood next me gave me pap if I did but open my lips; insomuch, that I was grown so cunning as to pretend myself asleep when I was not, to prevent my being crammed.

'But my grandmother began a loud lecture upon the idleness of this age, who, for fear of their shapes, forbear suckling their own offspring; and ten nurses were immediately sent for; one was whispered to have a wanton eye, and would soon spoil her milk; another was in a consumption; the third had an ill voice, and would frighten me instead of lulling me to sleep. Such exceptions were made against all but one country milch-wench, to whom I was committed and put to the breast. This careless jade was perpetually romping with the footman, and downright starved me; insomuch that I daily pined away, and should never have been relieved had it not been that on the thirtieth day of my life a Fellow of the Royal Society,[4] who had writ upon "Cold Baths," came to visit me, and (p. 4) solemnly protested I was utterly lost for want of that method; upon which he soused me head and ears into a pail of water, where I had the good fortune to be drowned.'

After its birth the babe was soon baptized, but there does not seem to have been a great social fuss made about the event. That most entertaining and observant traveller Henri Misson, who visited England at the very close of the seventeenth century, and whose book was translated into English in 1719,[5] says, 'The custom here is not to make great feasts at the birth of their children. They drink a glass of wine and eat a bit of a certain cake, which is seldom made but upon these occasions.'

Ward,[6] however, has left us a humorous description of a private christening. He was asked by a relation to stand Godfather to his newborn Child, and 'I, wanting ill-Nature enough to resist his Importunities, submitted to his Requests; and engag'd for once to stand as a Tom Doodle for an hour or two, to be banter'd by a Tittle-Tattle Assembly of Female Gossips. The time appointed for the Solemnisation of this Ancient piece of Formality being come, after I had put on a clean Band, and bestow'd Two Penniworth of Razorridge on the most Fertile part of my Face, whose Septuary Crop requir'd Mowing, away I Trotted towards the Joyful Habitation of my Friend and Kinsman, but with as aking a Heart as a Wise Man goes to be Married, or a Broken Merchant comes near the Counter.... As soon as we came into the Room, and had bow'd our Backs to the old Cluster of Harridans, and they in return had bent their knees to us, I sneak'd up to the Parson's Elbow, and my Partner after me ... whilst Old Mother Grope stood rocking of the Bantling in her Arms, wrap'd up in so Rich a Mantle as if both Indias had club'd their utmost Riches to furnish out a Noble covering for my little Kinsman, who came as callow into the world as a Bird out of an Eggshell.

'At last the Babe was put into my hands to deliver, tho' not as my Act and Deed, to the Parson, who having consecrated some New River water for his purpose, wash'd away Original Sin from my new Nephew, and brought him amongst us Christians into a state of Salvation. But when my froward Godson felt the Cold Water in his face, he threaten'd the Priest with such a parcel of Angry Looks, that if he had been strong enough I dare swear he would have serv'd him the same Sauce, and under the same Ignorance would have return'd him but little thanks for his Labour. After we had joined together in a Petition for the good of the infant Christian, the Religious part was concluded.... As soon as the Parson had refreshed his Spirits with a bumper of Canary, dedicated to the Mother; and the Clerk had said Amen to his Master's good Wishes, after the like manner, each of 'em accepted of a Paper of Sweetmeats for his Wife or his Children, and away they (p. 5) went, leaving the Company behind.' They then seem to have drunk a full quantity of wine, and the women having eaten, drank, and gossiped sufficiently, were each presented with 'a Service of Sweetmeats, which every Gossip carried away in her Handkerchief.... Having now struggled through every difficult part of these Accustomary Formalities, I had nothing to do but to Thank them for our Liberal Entertainment, Wish the Women well again, and both much Happiness in their Male Offspring, and so take my Leave, which I did accordingly; and was as greatly overjoyed when I got out of the House as ever Convict was that had broke Gaol or Detected Pick Pocket that had Escaped a Horse Pond.'

Having launched our baby thus far in life, we will see how he was treated when suffering from any of the numerous ailments which infancy is subject to. The marvel is that so many grew up. It was eminently 'the survival of the fittest.' Sanitary arrangements were extremely rudimentary; little care being taken either as to the purity of the water supply, or the efficiency of drainage. Fever was always in their midst, and, neither inoculation nor vaccination being known, or practised, smallpox was rampant, and spared no class, from the Queen (Mary) to the beggar. Was the child fretful, there was that cordial dear to old nurses of the Gamp school—Daffy's Elixir. This remedy, which has survived as a popular nostrum to our own time, was not new in Queen Anne's reign. It must even then have been a profitable property, for rivals could afford to quarrel over it, as the following advertisements show:—

'DAFFY'S FAMOUS ELIXIR SALUTIS,[7]

PREPARED BY KATHARINE DAFFY.

The Finest now expos'd to Sale, prepar'd from the best Druggs, according to Art, and the Original Receipt, which my Father Mr. Thomas Daffy, late Rector of Redmile, in the Valley of Belvoir, having experienc'd the Virtue of it, imparted to his Kinsman Mr. Anthony Daffy, who publish'd the same to the Benefit of the Community, and his own great Advantage. This Very Original Receipt is now in my possession, left to me by my Father aforesaid, under his own Hand. My own Brother Mr. Daniel Daffy, formerly Apothecary in Nottingham, made this ELIXIR from the same Receipt, and Sold it there during his Life. Those who know me will believe what I Declare; and those who do not may be convinc'd that I am no counterfeit, by the Colour, Tast, Smell, and just Operation of my ELIXIR. To be had at the Hand and Pen in Maiden Lane, Covent Garden, London; and many other Places in Town and Country.'

Primâ facie, the lady would seem to have made out her case; but there were other aspirants to fame—as the following notice[8] will show:—

'Forasmuch as Mrs. Elizabeth Daffy has lately Published an Advertisement containing Invidious Reflections upon me, in relation to my Elixir Salutis, I should be wanting to my Self if I should not obviate them in the like public manner, to let the World see they are Malicious, unreasonable, and false.

'In the first place she charges me with Clandestinely taking the House in Prugeon's Court; which, by her leave, is equally absurd and unjust; for the House was to be Lett a long time before I took it (nor had she any lease of the House, or any Power to Lett it), so consequently any one else might have taken the same. As for my pretending to have been her Husband's Assistant in preparing the Elixir, I will only say this is just as true as the former Story; and I challenge her to produce one single Evidence of Refutation to prove her Assertion: nor had I need of any such trifling pretence, having known the Secret some time before the Death of his Father Dr. Anthony Daffy; which I presume was before the said Elias Daffy was privy to the preparing of the said Elixir (he being then a Cambridge scholar), and the same was communicated to me in the year 1684, at the time I was going to travel beyond Sea, where, in divers Countries, considerable Quantities of my Elixir has been taken by Persons of the greatest Rank, Quality, and Note, to their great Satisfaction.

'And whereas the said Mrs. Daffy is pleased to call my Elixir Spurious, and Insinuates as if it were hazardous to the Lives of Men; the numerous Instances of Good it has done, both here and abroad, do manifestly evince the Contrary. And I appeal to all who have taken it in this City, or elsewhere, whether they have not found at least as much Benefit from This as from any Thing of the like Nature they have ever taken; insomuch that I am well assured that those who have tried mine will apply themselves to nobody else for Elixir Salutis.

'John Harrison.

'From my House in Prujean's Court in the Great Old Baly (The Original and famous Elixir Salutis) being wrote in Golden Characters over the Door fronting the Court Gate. March the 31st, 1709.'

One doctor at least (John Pechy) made the diseases of infants and children his study, and wrote upon the subject. I have been unable to get his book, but a few remedies from the medical works then in vogue will show how these diseases were then treated. Here is a recipe for a child's cough.[9]

Horehound, ℥ix; Liquorice, Maidenhair, Hyssop, Wild Thyme, Coltsfoot, Penny royal, ana ℥iij. Aniseeds and Fennel seeds ana ℥iss. Raisins of the Sun ℥vj. Figs, Jujubes ana ℥iv. Elecampane ℥ij, boil all in lb. vj. of water to 1/2. Strain, and add Honey, Sugar, (p. 7) ana lb. j. Boil to a Syrup; and when almost cold add Orrice, Woodlice, both in fine powder, ana ℥j.'

This mixture might not have been bad, but why add powdered woodlice?

Worms in children were to be treated with 'Prevotius's Oyl to kill Worms.[10] Take—Wormwood, Carduus, Scordium, Tobacco, ana Mj, Roots of Sow bread ℥fs, Coloquintida, ℥ij, Oyl, Vinegar, ana lb. j: boil to the consumption of the vinegar, then add Myrrh in powder ℥j; mix, and boil to the dissolution of the Myrrh. The Title shows the Virtues, anoint it upon the Stomach and Belly.' If this was not effective, the child might be given some lozenges made as follows—'Take Rhubarb, Citron seeds husked, Worm seeds, seeds of Purslain, of Coleworts, Broom finely powdered, ana ʒiij ☿ dulcis ʒij, White Sugar ʒxvj, all being in fine pouder; mix and incorporate with mucilage of Gum Tragacanth, made with Orange-flower water, of which Past make Lozenges each weighing ʒj. They kill all Worms in the Stomach and Bowels, and you may give one or two of the lozenges at a time to a Child in the Morning fasting, but some suppose that the best time is the last three days of the Moon.'

The Measles were simply treated—the patient only had a draught to soothe any cough, 'Let the sick keep their bed two days after the first coming forth of the spots.'[11]

In teething, a child should be soothed every four hours with a spoonful of black cherry water, in which two, three, or four drops of Spirits of Hartshorn have been mixed.[12]

There is[13] 'An experimented Remedy for the Rickets. Take roots of Smallage, Parsly, Fennel, and Angelica Roots, slice and boil them in distilled water of Angelica, unset Hyssop and Coltsfoot, of each one part, till they are tender, then strain it, and boil it up to a syrup, with white Honey. Then take a stick of Liquorice, scrape it, and bruise one end of it, and give the Child with it of the syrup one spoonful in the Morning, at four of the Afternoon, and at night.'

There was also advertised 'A necklace that cures all sorts of Fits in children occasioned by Teeth or any other Cause; as also all fits in Men and Women. To be had at Mr. Larance's in Somerset Court, near Northumberland House in the Strand; price 10s. for 8 days, though the cure will be performed immediately;' and there was a palatable medium for the little ones in 'the so-much approved Purging Sugar Plumbs.'

Of the Nursery we know very little; indeed children are very seldom mentioned. It is most likely that, in well-to-do families, they were relegated to the nursery, and the care of their mothers, until they were of fit age to go to school. The accompanying illustration, taken from 'The Ladies' Library,' ed. 1714, by Steele, gives us an excellent view of the nursery.

The very babies were amused much as now—for Addison, Spectator, No. 1, speaking of his natural gravity, says, 'I threw away my rattle before I was two Months old, and would not make use of my Coral till they had taken away all the Bells from it.' Some of these corals were very beautiful and costly, even being made of gold.

(p. 9) We know how, from the earliest ages, a doll has been the favourite toy with girls, and the reign of 'Good Queen Anne' was no exception to the general rule—but they were not then called Dolls, but 'Babies'; so, indeed, were Powel's Marionettes—as also the milliner's models. 'On Saturday last, being the 12th instant, there arrived at my House in King Street, Covent Garden, a French Baby for the year 1712' &c. Some were made of wax, but these were, of course, of the expensive sort, as must also have been those in Widow Smith's raffle—'large joynted dressed Babies.' Probably, dolls were the girls' only playthings. As to the boys, history records very little of their amusements. Give a boy in the nursery a whip, or a stick, to beat somebody, or something, he generally is content. How superlatively happy, however, must he have been in the possession of one of these wonderful horses?—warranted chargers—troop horses, every one! They also had card-board windmills on the end of sticks. We hear nothing of marbles, tops, or any other toys; but, doubtless, children's ingenuity supplied any defects that way, then as now, and made shift to play, and amuse themselves, until the time of enfranchisement came, and the boy could wander in the streets and see the marvels of the raree show, and buy 'hot baked wardens—hot,' or some of old 'Colly Molly Puffe's' pastry—or, should his tastes be simpler, there were 'Ripe Strawberryes,' or 'Sixpence a pound fair Cherryes.'

'TROOPE, EVERY ONE.'

These little folk, however, had their special literature. For there was compiled and printed 'A Play book for Children, to allure them to read as soon as they can speak plain; composed of small Pages so as not to tire children; printed with a fair and pleasing Letter, the Matter and Method plainer and easier than any yet extant.' The price of this was fourpence, and it must have been a favourite, for it is advertised as being in its second edition in 1703. Certainly, the little ones then lacked many advantages in this way that ours possess—but, on the other hand, so much was not required of them. There was no dreaded 'Exam.' to prepare for—no doing lessons all day long, and then working hard at night to get ready for the next day's toil. They were not taught half a dozen languages, and all the ologies, whilst still in the nursery; but, were the suggestions and advice given to 'the Mother' in Steele's 'Lady's Library' thoroughly carried out, they would grow up good men and women.

The boys, however, had strong meat provided for them in such tales as 'Jack and the Giants,' &c. Steele, in Tatler 95, says, speaking of a little boy of eight years old, 'I perceived him a very great historian in "Æsop's Fables," but he frankly declared to me his mind "that he did not delight in that learning, because he did not believe they were true," for which reason I found he had very much turned his studies for about a twelvemonth past unto the lives and adventures of Don Bellianis of Greece, Guy of Warwick, the Seven Champions, and other historians of that age.... He would tell you the mismanagements of John Hickerthrift, find fault with the passionate temper in Bevis of Southampton, and loved Saint George for being the champion of England.... I was extolling his accomplishments, when his mother told me that the little girl who led me in this morning was in her way a better scholar than he. "Betty," says she, "deals chiefly in Fairies and Sprights; and sometimes in a winter night will terrify the maids with her accounts, until they are afraid to go up to bed."'

'OH, RAREE SHOW.'

In all probability the child learned his letters in the first instance from a 'Hornbook,' such as were then commonly used and sold—as the following excerpt from an advertisement shows: 'Joseph Hazard at the Bible, in Stationers Court, near Ludgate, sells ... Spelling books, Primers, Hornbooks, &c.' Hornbooks are now very scarce indeed, and the man lucky enough to possess a genuine one must feel proud of his rarity. It consisted of a small sheet of paper, generally about 4 in. × 3 in. or (p. 11) so—sometimes smaller—on which was printed the alphabet, both in capitals and small text, the vowels, and a few simple combinations, such as ab, eb, ib, ob, ub,—ba, be, bi, bo, bu, &c., and the Lord's Prayer. This was laid on a flat piece of board with a roughly shaped handle, and covered with a thin plate of horn, fastened to the board by copper tacks driven through an edging of thin copper. It therefore would stand a vast amount of rough usage before it would be destroyed—a fact of great importance in elementary education.

'RIPE STRAWBERRYES!' 'SIX PENCE A POUND FAIR CHERRYES!'

Private tuition existed then as now. 'A Grave Gentlewoman of about 50 years of age desires to be Governess to any Gentleman's Children; she can give a very good account of herself,' and 'Whereas in this degenerate Age Youth are kept for so many Years in following the Latin Tongue, and many of them are quite discourag'd, Mr. Switterda (who was formerly recommended to the late King William, and well known by their Excellences my Lord Sparkein and my Lord Methuen) offers a very easy and delightful Method, by which any Person of tolerable Capacity, who can but spare time to be twice a Week with him, and an Hour at a Time, nay, Children of ten Years of Age, may in one Year learn to speak Latin and (p. 12) French fluently, according to the Grammar rules, and to understand a Classical Author; and if they are not compleat in that time, he will teach them without any farther Charge, provided they will be manag'd.' Another gentleman, living in Abchurch Lane, offered to do the same, and, moreover, 'he offereth to be bound to every one for the performance thereof, and to give a Month's trial.'

But a Day School was the normal institution for a boy, although there were Boarding Schools. Judging by the advertisements, these must have been but few in the beginning of the reign, as they gradually become more numerous towards its close. A record of one or two will suffice to show what kind of education they gave. 'At the upper end of Knights Bridge, near the Salutation, there is a Boarding School for young Gentlemen, where, besides French, are carefully taught, after the best English method, Latin, Greek, Writing, Arithmetic, Geography, &c.' And again, 'At Lady Day next will be open'd a Boarding School for young Gentlemen at Kensington Gravel Pits, by Richard Johnson, A.M., author of the Grammatical Commentaries.... There will be taught also French, Writing, Arithmetick, and Mathematicks;' whilst another takes a wider range: 'A boarding School will be open'd after Easter, at Chertsey ... for the Instruction of Youth in the English, French, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew Tongues, besides Geography, History, Mathematicks, Writing, and Accompts; to fit 'em either for the University, Study of the Law, or other Business.'

In London, too, were many free schools. There were Westminster, Merchant Taylors', Paul's, Greyfriars, Christ's Hospital, and St. Olave's, Southwark. There were three free schools in Westminster besides the Queen's School; these were, Palmer's in Tuttlefields, Almery School, and Hill's School. Besides which were Lady Owen's School, Islington, and Bunhill School—and there were free schools in Cherrytree Alley, Castle Street (Tennyson's), Great Queen Street, Parker's Lane, Church Entry, Old Jewry, Whitechapel, Ratcliffe, Foster Lane, Hoxton, St. Saviour's, Southwark, Plough Yard, Rotherhithe, and East Smithfield—and this probably is not an exhaustive list.

Although French, High Dutch, and Italian were taught, it was a Classical age, and every gentleman was bound to be a fair, if not a good, classical scholar; indeed, other branches of education were neglected for this, as Steele complains (Spectator, No. 147) that boys at school, 'When they are got into Latin, they are looked upon as above English, the reading of which is wholly neglected, or at least read to very little purpose.' We might look a long time now-a-days for an advertisement such as the following: 'At Hogarth's[14] Coffee House in St. John's Gate, the mid-way between Smithfield Bars and Clerkenwel, there will meet every day at 4 o'clock some Learned Gentlemen who speak Latin readily, where any Gentleman that is either skilled in that Language, or desirous (p. 13) to perfect himself in speaking thereof, will be welcome. The Master of the House, in the absence of others, being always ready to entertain gentlemen in the Latin Tongue.' It is much to be doubted if that literary society, the Urban Club, which till lately held its meetings at the same place, St. John's Gate, could do the same.

Let us glance at a few of the school books then in vogue. First of all is one of the immortal Cocker, 'according to' whom all correct calculations should be made. Although he had been long dead (since 1677), his works lived after him; and there were also other works on Algebra, Geometry, Trigonometry, and the use of the Globes. (By the way, a pair of 9-in. diam. globes only cost a guinea.) There were Latin Dictionaries, Lilly's Latin Grammar, and an abridgment of it for the use of Blackheath School. There was that English Grammar which 'Isaac Bickerstaff' (Steele) puffed up so: 'That as grammar in general is on all hands allow'd the foundation of all arts and sciences, so it appears to me that this grammar of the English tongue has done that justice to our language which, 'till now, it never obtained;' and there was 'A Guide to the English Tongue, by Thos. Dyche, schoolmaster in London,' the second edition of which was published in 1710, but which has been so popular that a revised edition of it was published as late as 1816; and there were any quantity of books on writing—notably the 'Paul's Scholar's Copy Book, by John Rayner,' immortalised in Tatler 138. The writing of the age was very good—and many are the specimens of elaborate caligraphy in the 'Bagford Collection': for unassuming and yet good writing, perhaps, however, the best are in Harl. MS. 5995, 211, &c.[15] In the eighteenth century penmanship was held in higher estimation than now, and in 1763 W. Massey published 'The Origin and Progress of Letters,' in which he gave the lives of the most famous writing masters during the preceding hundred years. He mentions some half-dozen or more, as living in Anne's reign, but Charles Snell seems to have been the most famous.

As may be supposed, when so much pains was taken in writing, there were many curiosities of caligraphic art. Here is one: 'A piece of close Knotting, viz. 2 Boys holding Circles in their Hands, either being less than a Silver Penny, in which are perspicuously wrote the Lords Prayer in Latin and English. Invented and perform'd by John Dundas (who will shortly publish a Copy book with about 50 new Fancies).... N.B. Any Gentleman or Lady that desires small Writing for a Ring, Locket, or other Curiosity, may be furnished by the Author.'

That pens other than quill were in use is evidenced by an advertisement re a lost pocket-book, which contained 'a Brass Pen.'

Stenography was practised somewhat extensively, to judge by (p. 14) the numerous advertisements; but William Mason, living at the Hand and Pen, in the Poultry, claimed to be 'the Author and Teacher of the shortest Shorthand extant.'

And yet, with all these scholastic advantages, some boys would not be happy; but, as boys have done ever since boarding schools have been invented, they sometimes ran away. Vide the following advertisements: 'A Gentleman's only Child is run from School; he is about 12 years of Age, with light Cloaths lin'd with red, a well favour'd brisk Boy, with a fair old Wig: speaks a little thro' the Scots, his Name Alex Mackdonald: he has been in Spain and Portugal, which makes his Parents fear that some Ship may entertain him.' Whoever captured this lad was to be 'sufficiently rewarded,' whilst the next runaway was only valued at 'half a guinea and charges,' although he was dressed so smartly: 'A little slim, fair hair'd handsome English Boy, who speaks French very well, between 11 and 12 Years of Age, with a sad colour, coarse Kersay Coat trim'd with flat new Gilded Brass Buttons, with a whitish Calla-manca Waistcoat with round Plate Silver Buttons, and a little Silver Edging to his Hat, with fine white Worsted rowl'd Stockings, and with Silver Plate Buttons to his sad colour Sagathy Stuff Britches: went away from School on Thursday, the 6th Inst. Supposed to be gone towards Wapping, Rotherif, Greenwich, or Gravesend, he having been seen near the Thames Side asking for a Master to go to sea.' Curious how, in every century since Elizabeth's time, the runaway English boy naturally flies to the water. Always the same tale: ran away and went to sea. Here were two well-nurtured lads, more than ordinarily accomplished, yet they were bitten by this same tarantula.

Let the Spectator describe the rising generation of that time after they had finished their academic career and had gone to the university. In No. 54, attributed to Steele, speaking of Cambridge, he says, 'Now for their manner of living: and here I shall have a large field to expatiate in; but I shall reserve particulars for my intended discourse, and now only mention one or two of their principal exercises. The elder proficients employ themselves in inspecting mores hominum multorum, in getting acquainted with all the signs and windows in the town. Some have arrived to so great knowledge, that they can tell every time a butcher kills a calf, every time any old woman's cat is in the straw; and a thousand matters as important. One ancient philosopher contemplates two or three hours every day over a sun-dial; and is true to the dial.

As the dial to the sun,

Although it be not shone upon.

Our younger students are content to carry their speculation as yet no further than bowling greens, billiard tables, and such like places.'

Of the reading men, he says, 'They were ever looked upon as (p. 15) a people that impaired themselves more by their strict application to the rules of their order than any other students whatever. Others seldom hurt themselves any further than to gain weak eyes, and sometimes headaches; but these philosophers are seized all over with a general inability, indolence, and weariness, and a certain impatience of the place they are in, with an heaviness in removing to another.

'The loungers are satisfied with being merely part of the number of mankind, without distinguishing themselves from amongst them. They may be said rather to suffer their time to pass than to spend it, without regard to the past or prospect of the future. All they know of life is only in the present instant, and do not taste even that. When one of this order happens to be a man of fortune, the expense of his time is transferred to his coach and horses, and his life is to be measured by their motion, not his own enjoyments or sufferings. The chief entertainment one of these philosophers can possibly propose to himself is to get a relish of dress. This, methinks, might diversify the person he is weary of, his own dear self, to himself. I have known these two amusements make one of these philosophers make a tolerable figure in the world; with variety of dresses in public assemblies in town, and quick motion of his horses out of it, now to Bath, now to Tunbridge, then to Newmarket, and then to London, he has, in process of time, brought it to pass, that his coach and his horses have been mentioned in all these places.' And this description, with a little alteration, would pass as a fair reflex of modern undergraduate existence at either Oxford or Cambridge.

Before closing the question of male education, we must not forget that in Queen Anne's time was inaugurated that system of charity schools which has played so prominent a part in our national system of education, and which has not yet been superseded by our Board Schools. Steele (Spectator, 380) notices this movement—

'St. Bride's, May 15, 1712.

'Sir,—'Tis a great deal of Pleasure to me, and I dare say will be no less Satisfaction to you, that I have an Opportunity of informing you that the Gentlemen and others of the Parish of St. Brides have raised a Charity School of fifty Girls as before of fifty Boys. You were so kind to recommend the Boys to the Charitable World, and the other Sex hope you will do them the same Favour in Fridays Spectator for Sunday next, when they are to appear with their humble Airs at the Parish Church of St. Brides. Sir, the Mention of this may possibly be serviceable to the Children: and sure no one will omit a good Action attended with no expence.

'I am, Sir,

'Your very humble Servant,

'The Sexton.'

(p. 16) At the public thanksgiving for peace in 1713,[16] the charity children were placed in rising rows of seats in the Strand to see the procession pass, and the Queen go to St. Paul's to return thanks—and bitter must have been the disappointment of the little ones at the Queen's absence, on account of illness.

A contemporary account of this festival says: 'Upon the Thanksgiving day for the Peace, about Four Thousand Charity Children (Boys and Girls), new Cloath'd, were placed upon a Machine in the Strand, which was in Length above 600 Foot, and had in Bredth Eight Ranges of seats one above another, whereby all the Children appear'd in full View of both Houses of Parliament, in the solemn Procession they made to St. Paul's upon that joyful Occasion, and who, by their singing Hymns of Prayer and Praise to God for her Majesty, as well as by their Appearance, contributed very much to adorn so welcome a Festival; and gave great Satisfaction to all the Spectators, not without some Surprize to Foreigners who never had beheld such a glorious Sight. The Trustees of the several Charity Schools in and about London and Westminster readily agreed upon Measures for placing the Children in the expected View of Her Majesty, as a Testimony of their great Duty and Humble Thankfulness to Her Majesty for the particular Countenance and Encouragement Her Majesty hath always vouchsafed to give to the Charity Schools,[17] whereby She may be truly stiled their Patron and Protector. Her Majesty not being present, the Hymns were both sung and repeated during the whole Procession, which lasted near Three Hours; and for the Satisfaction and Entertainment of the Publick they are printed as follows:—

'Hymns to be sung by the Charity Children upon the 7th of July, 1713, being the Thanksgiving Day for the PEACE.

'As Her MAJESTY goes to St. Paul's—

Lord give the QUEEN Thy saving Health,

Whose Hope on Thee depends:

Grant Her Increase of Fame and Wealth,

With Bliss that never ends!

Allelujah, Allelujah, Allelujah, Allelujah!

Allelujah, Allelujah, Allelujah, Allelujah, Allelujah!

(p. 17) For Her our fervent Vows aspire,

Our Praises are Address'd;

Thou hast fulfill'd Her Heart's Desire

And granted Her Request.

Allelujah, &c.

A Nursing Mother to Thy Fold,

Long, long may She remain,

And then with Joy Thy Face behold,

And with Thee ever Reign.

Allelujah, &c.

As Her MAJESTY returns from St. Paul's—

Glory to GOD who Reigns on High,

Whom Saints and Angels praise;

Who from His Throne above the Sky,

The Sons of Men surveys.

Allelujah, &c.

PEACE, His best Gift, to Earth's return'd,

Long may it here remain;

As we too long its Absence mourn'd,

Nor sigh'd to Heav'n in vain.

Allelujah, &c.

Good Will, Fair Friendship (Heavenly Guest!)

And Joy and Holy Love,

Make all Mankind completely bless'd,

Resembling Those above.

Allelujah, &c.

Boarding schools — Town and country educations — Pastry schools — Dancing — Toasts — 'The Little Whig' — Madame Spanheim.

Girls were not all educated at home—though, doubtless, the majority of them were, with the exception of their dancing lessons—but had boarding schools of their own; and the schoolmistresses seem always to have been harassed by malicious reports. For instance: 'Whereas it is reported that Mrs. Overing who keeps a Boarding School at Bethnal Green near Hackney, is leaving off; this is to give Notice that the said Report is false, if not Malicious. And that she continues to take sober young Gentlewomen to board, and teaches whatsoever is necessary to the Accomplishment of that Sex.' Take another: 'Mrs. Elizabeth Tutchin[18] continues to (p. 18) keep her School at Highgate, notwithstanding Reports to the contrary. Where young Gentlewomen may be soberly Educated, and taught all sorts of Learning fit for young Gentlewomen.' Observe the stress that was then laid on the sobriety inculcated in these establishments. Read the plays—read the essays of the time—and then, if they are to be taken at all as a just standard of feminine conduct, you will, undoubtedly, come to the conclusion that sobriety of conduct was just the very quality that required instilling into the heads of the maidenhood of the time. Pert little hoydens—ogling the men, flirting their fans, their thoughts always running on a husband—the schoolmistresses of that time must have had hard work to keep them serious, and need of most dragon-like guardianship. They were not taught much, these girls; 'the Needle, Dancing, and the French tongue,' says one—'a little Music, on the Harpsichord, or Spinet, to read, write, and cast accounts in a small way'—this was the sum of their education. Essentially were they to be housekeepers. Here is the description an exceptionally accomplished young lady gives of her own education:[19] 'You know my father was a tradesman, and lived very well by his traffick; and I, being beautiful, he thought nature had already given me part of my portion, and therefore he would add a liberal education, that I might be a complete gentlewoman; away he sent me to the boarding school; there I learned to dance and sing, to play on the bass viol, virginals, spinet, and guitar. I learned to make wax work, japan, paint upon glass, to raise paste, make sweetmeats, sauces, and everything that was genteel and fashionable.' Here we see the best obtainable education of the town-bred lady. What was a girl's education in the country like?[20]

Priscilla. Did she not bestow good breeding upon you there?

Eugenia. Breeding! what, to learn to feed Ducklings, and cram Chickens?

Clara. To see Cows milk'd, learn to Churn, and make Cheese?

Eugen. To make Clouted cream, and whipt Sillabubs?

Clara. To make a Caraway Cake and raise Py Crust?

Eugen. And to learn the top of your skill in Syrrup, Sweetmeats, Aqua mirabilis, and Snayl water.

Clara. Or your great Cunning in Cheese cakes, several Creams and Almond butter.

Prisc. Ay, ay, and 'twere better for all the Gentlemen in England that Wives had no other breeding, but you had Musick and Dancing.

Eugen. Yes, an ignorant, illiterate, hopping Puppy, that rides his Dancing Circuit thirty Miles about, lights off his tyred Steed, draws his Kit[21] at a poor Country Creature, and gives her a Hich in her Pace, that she shall never recover.

Clara. And for Musick an old hoarse singing man riding ten miles from his Cathedral to Quaver out the Glories of our Birth and State, or it may be a Scotch Song more hideous and barbarous than an Irish Cronan.

Eug. And another Musick Master from the next town to Teach one to (p. 19) twinkle out Lilly burlero[22] upon an old pair of Virginals, that sound worse than a Tinker's Kettle that he cries his work on.

We saw that even the accomplished town young lady was taught how to raise paste, &c.; indeed that was a regular branch of a girl's education, and all housewifely gifts were thoroughly appreciated.

Niece. Good madam, don't upbraid me with my Mother Bridget, and an excellent housewife.

Aunt. Yes, I say, she was, and spent her time in better Learning than ever you did. Not in reading of Fights and Battels of Dwarfs and Giants; but in writing out receipts for Broths, Possets, Caudles and Surfeit Waters, as became a good Country Gentlewoman.[23]

But, if girls could not learn pastry-making at home, or wanted a higher class of education therein, there were the forerunners of our 'Schools of Cookery' in the shape of 'Pastry Schools,' where the professor demonstrated. Here is one of them. 'To all Young Ladies at Edw. Kidder's Pastry School in little Lincoln's Inn Fields, are taught all Sorts of Pastry and Cookery, Dutch hollow works, and Butter Works, on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays in the Afternoon, and on the same days, in the Morning, at his School in Norris Street in St. James's Market, and at his School in St. Martin's Le Grand, on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday in the Afternoon. And at his School at St. Mary Overies Dock, Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesday mornings from 9 to 12.'

But one branch of a girl's education seems never to have been neglected—her dancing. Steele says,[24] 'When a girl is safely brought from her nurse, before she is capable of forming one simple notion of anything in life, she is delivered to the hands of her dancing master, and with a collar round her neck, the pretty wild thing is taught a fantastical gravity of behaviour, and forced to a particular way of holding her head, heaving her breast, and moving with her whole body; and all this under pain of never having a husband, if she steps, looks or moves awry.'

He gives a humorous description of the dancing master:[25] 'There was Colonel Jumper's Lady, a Colonel of the Train Bands, that has a great Interest in her Parish; she recommends Mr. Trott for the prettiest Master in Town, that no Man teaches a Jigg like him, that she has seen him rise Six or Seven Capers together with the greatest Ease imaginable, and that his Scholars twist themselves more ways than the Scholars of any Master in Town; besides there is Madam Prim, the Alderman's Lady, recommends a Master of her Own Name, but she declares he is not of their (p. 20) Family, yet a very extraordinary Man in his Way; for, besides a very soft Air he has in Dancing, he gives them a particular Behaviour at a Tea-Table, and in presenting their Snuff Box: to twirl, flip or flirt a Fan, and how to place Patches to the best advantage, either for Fat or Lean, Long or Oval Faces.

Indeed, dancing was much thought of as an accomplishment, and more will be said of it in its place among the social habits of the time. One book alone, 'The Dancing Master' for 1713, 15th ed., contains 358 different figures and tunes for country dances. It got to be a fine art, and books were written on 'Chorography' and 'Orchesography,' illustrated with wonderful and most perplexing diagrams. A contemporary sketch of a dancing academy is interesting. It is by Budgell.[26] 'I am a Man in Years, and by an honest Industry in the World have acquired enough to give my Children a liberal Education, tho' I was an utter Stranger to it myself. My eldest Daughter, a Girl of Sixteen, has for some time past been under the Tuition of Monsieur Rigadoon, a Dancing Master in the City; and I was prevailed upon by her and her Mother to go last Night to one of his Balls. I must own to you, Sir, that having never been at any such Place before, I was very much pleased and surprized with that Part of his Entertainment which he called French Dancing. There were several young Men and Women, whose limbs seemed to have no other Motion but purely what the Musick gave them. After this Part was over, they began a Diversion which they call Country Dancing, and wherein there were also some things not disagreeable, and divers Emblematical Figures, compos'd, as I guess, by Wise Men for the Instruction of Youth.

'Amongst the rest, I observed one, which I think they call[27] Hunt the Squirrel, in which while the Woman flies, the Man pursues her; but as soon as she turns, he runs away, and she is obliged to follow.

'The Moral of this Dance does, I think, very aptly recommend Modesty and Discretion to the Female Sex.

'But as the best Institutions are liable to Corruptions, so, Sir, I must acquaint you, that very great Abuses are crept into this Entertainment. I was Amazed to see my Girl handed by, and handing young Fellows with so much Familiarity; and I could not have thought it had been in the Child. They very often made use of a most impudent and lascivious Step called Setting, which I know not how to describe to you, but by telling you that it is the very reverse of Back to Back. At last an impudent young Dog bid the Fiddlers play a Dance called Mol Patley,[28] and after having made two or three Capers, ran to his Partner, locked his Arms in hers, and whisked her round Cleverly above Ground in such manner that I, who sat upon one of the lowest Benches, saw further above her Shoe than I can think fit to acquaint you with. I could no longer endure these Enormities; wherefore, just as my Girl was (p. 21) going to be made a Whirligig, I ran in, seized on the Child, and carried her home.'

Poor Budgell! what would have been his feelings could he have but seen a galop, or a valse à deux temps?

We may now consider the girl's education complete, and, as she may be 'sweet seventeen' or so, she naturally would be, if either pretty or witty, 'a TOAST' among her male friends. This peculiar institution has its rise in Queen Anne's time, and is aptly described[29] as 'a new name found out by the Wits, to make a lady have the same effect, as burridge in the glass when a man is drinking.' Pope, even, could hardly make it out.

Say why are beauties prais'd and honour'd most,

The wise man's passion, and the vain man's toast?

Why deck'd with all that land and sea afford,

Why angels call'd, and angel-like adored?