Title: John Brown the Hero: Personal Reminiscences

Author: J. W. Winkley

Author of introduction, etc.: F. B. Sanborn

Release date: October 8, 2017 [eBook #55707]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David E. Brown and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTES:

The cover image has been created by the transcriber from the title page of the original.

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

Inconsistencies in spelling and hyphenation have been retained from the original.

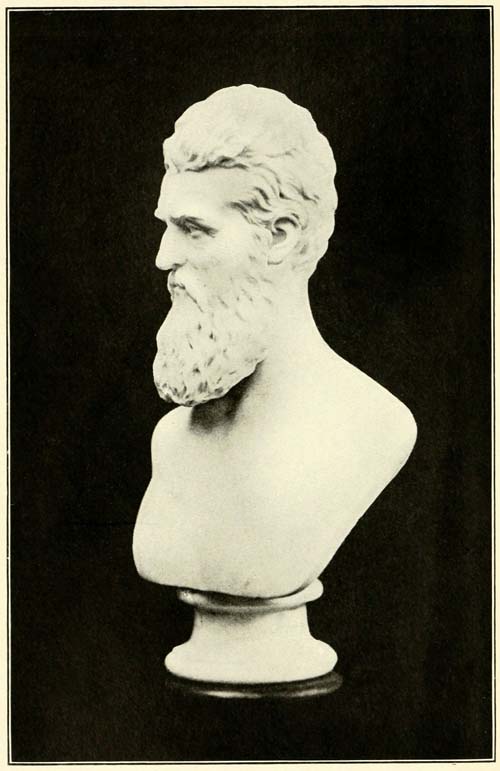

Bust of John Brown.

(See Note.)

Personal Reminiscences

BY

J. W. WINKLEY, M.D.,

Editor of Practical Ideals and Author of "First

Lessons in the New Thought."

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

FRANK B. SANBORN

ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON

JAMES H. WEST COMPANY

Copyright, 1905

By James H. West Company

THE sub-title, "Personal Reminiscences," is rightly appended to this volume. The old saying, "Much of which I saw, and part of which I was," the author can truthfully apply to himself in connection with the interesting and stirring occurrences here recorded. He relates the events because they were, in large measure, personal experiences. And the narrative is made up, for the most part, of historical matter which has not been presented heretofore by any writer. In other words, it is history at first hand.

Another and more particular reason[Pg 6] for the preparation of this little volume is because it is believed by the writer that these narrations will serve to throw some especially valuable side-lights upon the subject of them. John Brown was one of the most unique characters in all our American history, and an original factor in an important part of that history.

The volume will surely be welcome to all admirers of Brown, and it should be of considerable interest to the general public.

It hardly needs mentioning here that the standard work on John Brown, giving very fully his life and letters, is that of the Hon. Frank B. Sanborn, who kindly contributes the Introduction to the present volume.

Boston, January, 1905.

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | 9 | |

| I. | A Call for Aid | 19 |

| II. | The Prairie Wonder | 24 |

| III. | The Night March | 29 |

| IV. | A Siege and its Heroine | 35 |

| V. | The March Resumed | 43 |

| VI. | Seeking the Enemy | 50 |

| VII. | The Battle | 55 |

| VIII. | A Scene for a Painter | 59 |

| IX. | Brown's Night Appointment | 62 |

| X. | An Intrepid Charge | 68 |

| XI. | Brown to Our Prisoners | 76 |

| XII. | Hard Lines | 82 |

| XIII. | A Government Musket | 88 |

| XIV. | An Unfailing Guide | 94 |

| XV. | Hazardous Journeys | 102 |

| XVI. | The Osawatomie Battle | 111 |

| XVII. | Conclusion | 121 |

The frontispiece to this volume is a representation of a bust of Captain Brown, conveying in so far a correct idea of the exterior man.

This excellent bust, the best representation of him extant, was made from measurements taken by the sculptor in the Charlestown (Va.) prison, while Brown was awaiting trial there. The photograph was courteously furnished by the present owner of the bust, Mr. F. P. Stearns, of Medford, Massachusetts, whose father, Mr. Henry Stearns, a life-long friend of Brown, caused the bust to be made.

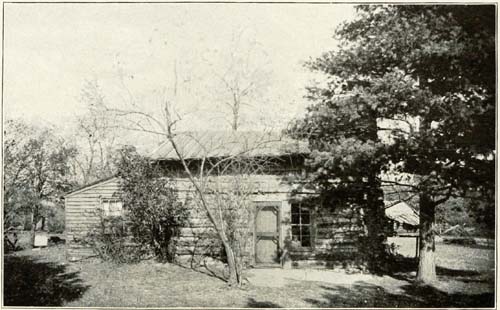

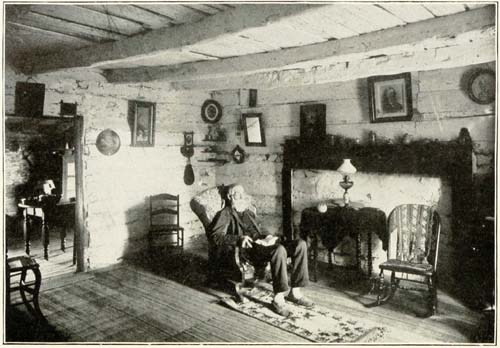

In other places in the volume are pictures of the log cabin of the Adair family, one an exterior view of it, the other an interior, for which we are indebted to Mr. F. B. Sanborn.

Under this modest roof Brown often sought and never failed to find welcome resting-place and hospitality. Mrs. Adair was his half-sister; her husband, a Methodist clergyman, ministered to the spiritual needs of a scattered flock in the territory.

The writer, on the occasion of a visit a few years since to Kansas to view the old familiar spots, found the cabin, almost the last of its race, not much changed outside or within from what it was in the former days. It is owned and occupied, as is the farm on which it stands, by a son of the pioneer minister.

THE interest attaching to this little book demands from me some notice of its author, and of my indebtedness to him while preparing, twenty years ago, a "Life and Letters of John Brown," which has since become the basis of several biographies of that hero. Dr. J. W. Winkley, long a citizen of Boston, was one of those who, in 1856, became a Free State colonist of Kansas Territory, then the skirmish-ground of the long conflict between free labor and Negro slavery. His residence there was brief (1856 and 1857), as was that of many who went out in the years 1855-'58 to take part on one side or the[Pg 10] other of the contest; but he had the good fortune, as a youth, in the perceptive and receptive period of life, to come under the influence of a hero; and this book portrays the incidents of that interesting acquaintance. Nearly thirty years later he communicated to me this story, and I succinctly mentioned it in my book. But it required a fuller statement; especially since it seems largely to have escaped the notice of the chroniclers of that disturbed and confused period of 1856. The partisan movements here described came in between two of Brown's famous fights,—that of Black Jack, in early June, when he captured the Virginian captain, Pate, and that in the end of August, when he repelled the formidable attack of the Missourians upon the small settlement of Osawatomie. The brothers Winkley and their comrades took up arms in the neighborhood of Osawatomie, after the engagements of the first two weeks in August, which culminated[Pg 11] in the capture of several camps or "forts" of the Southern invaders of eastern Kansas, August 14 and 16. Fort Saunders, not far from Lawrence was taken by a Free State force under General Lane, August 14. On the 16th, another Pro-slavery "fort," garrisoned by a Colonel Titus, was captured, near Lecompton. The reason for these attacks was thus given by John Brown, Jr., then a prisoner at Lecompton, guarded by Captain Sackett with a force of United States dragoons (August 16, 1856):

"During the past month the Ruffians have been actively at work, and have made not less than five intrenched camps, where they have, in different parts of the Territory, established themselves in armed bands, well provided with arms, provisions, and ammunition. From these camps they sally out, steal horses, and rob Free State settlers (in several cases murdering them), and then slip back into their camp with their plunder.[Pg 12] Last week, a body of our men made a descent upon Franklin (four miles south of Lawrence) and, after a skirmishing fight of about three hours, took their barracks and recovered some sixty guns and a cannon, of which our men had been robbed some months since, on the road from Westport. Yesterday our men invested another of their fortified camps, at Washington Creek.... Towards evening the enemy broke and fled, leaving behind, to fall into the hands of our men, a lot of provisions and 100 stand of arms.... This morning our men followed Colonel Titus closely, and fell upon his camp (near Lecompton), killed two of his men, liberated his prisoners, took him and ten other prisoners, and with a lot of arms, tents, provisions, etc., returned, having in the fight had only one of our men seriously wounded.... This series of victories has caused the greatest fear among the Pro-slavery men. Great numbers are leaving for Missouri.... I see by the Missouri papers that they regard John Brown as the most terrible foe they have to encounter. He stands very high with the Free State men[Pg 13] who will fight, and the great majority of these have made up their minds that nothing short of war to the death can save us from extermination."

Immediately following the date of this letter of young John Brown came the adventures which Dr. Winkley so well describes. They may have had no other chronicler; and it is well that the testimony of an eye-witness should at last be given, ending with the striking incident, just following the Osawatomie fight of August 30, when young Winkley, in the log-cabin of the missionary Adair, husband of Brown's half-sister, saw John Brown sternly mourning over the body of his son Frederick, killed on the morning of the fight, on the high prairie above Osawatomie. I visited Mr. Adair in this cabin, in 1882, and talked with him on the events of that year of contention, and the pictures here printed of his prairie home are true to the fact as I then saw it. Two weeks after the burial of Frederick Brown, as[Pg 14] mentioned by Dr. Winkley (September 14, 1856), Charles Robinson, who had commissioned John Brown as captain nine months earlier, wrote to him by that title from Lawrence, and said in his letter:

"Your course has been such as to merit the highest praise from every patriot, and I cheerfully accord to you my heartfelt thanks for your prompt, efficient, and timely action against the invaders of our rights and the murderers of our citizens. History will give your name a proud place on her pages, and posterity will pay homage to your heroism in the cause of God and humanity."

Robinson was at this time the nominal leader of the Free State settlers, being their duly chosen State Governor under the Topeka Constitution; and he became the first actual Free State Governor in 1861, when Kansas was admitted to the Union under another Constitution. Many years later, at the dedication of a monument[Pg 15] commemorating the Osawatomie fight (August 30, 1877), Charles Robinson said, among other things:

"The soul of John Brown was the inspiration of the Union armies in the emancipation war; and it will be the inspiration of all men in the present and the distant future who may revolt against tyranny and oppression; because he dared to be a traitor to the government that he might be loyal to humanity."

Dr. Winkley agrees in this statement of Robinson; and his portrayal of the man as he was in the midst of surprises and responsibilities, but ever the same intrepid and resourceful leader, will add a new picture to those we already had of John Brown in action. Active or in chains, in the battlefield or in his Virginia prison, he always commanded attention, and received the applause of those who knew him.

The verdict of the world has confirmed this praise; and of all the men[Pg 16] connected with the dark and bloody story of Kansas, from 1854 till the close of the Civil War, Brown's name is the most widely known. Blame has been mingled with praise; but the involuntary tribute paid, by the natural human heart, to invincible courage and unwearied self-sacrifice will insure the prevalence of praise over blame. Those who cannot approve all his acts, as Dr. Winkley cannot, are yet convinced generally of the high purpose and grand result of his arduous life. Richard Mendenhall, a Kansas Quaker, who knew him well but "could not sanction his mode of procedure," yet said, after Brown's death in Virginia:

"Men are not always to be judged so much by their actions as by their motives. I believe John Brown was a good man, and that he will be remembered for good in time long hence to come."

Quite recently an English author, William Stevens, writing a history of[Pg 17] slavery and emancipation, has occasion to name John Brown, and the warmth of his eulogy does not satisfy the cool judgment of that most reflective journal, the London Spectator, which says:

"Mr. Stevens asks if Brown did not see the forces moving towards abolition more clearly than did his friends who protested against the daring of his schemes: yet he emphasizes too much, surely, the forlorn recklessness of the man's methods. But a more fearless, resolute, and cooler-headed man never lived. His family life, the devotion of his own flesh and blood to him, and his tenderness were indications of a character intensely human, but also of a man who had counted the cost and knew that the individual must yield to the race. He lit, not a candle, but a powder-magazine; and his last words prove that he foresaw, as plainly as man ever saw sunrise follow dawn, that blood, and blood alone, would loosen the shackles of the slave."

Events, in fact, followed the track which Brown pointed out, and with a[Pg 18] swiftness that startled even such as accepted his clear insight of the national situation. There was something prophetic in his perception of the future; he could not see well what was directly before him, but of the consequences of his action, and of that of other men, he had the most piercing and sagacious view. Such men appear on earth but rarely; when they come, it is as martyrs and seers. Fatal are their perceptions, and to themselves as well as to the order of things they subvert. But it is more fatal to disregard the warning they give. Their remedy for existing ills, sharp as it must be, is for the healing of the nations and for the relief of man's estate.

F. B. Sanborn.

Concord, January, 1905.

IT was of an August morning in that eventful year of Kansas history, 1856, in the gray of the earliest dawn, that a horseman came riding at full speed up the creek, the south branch of the Pottawatomie, from the direction of the lower settlements,[Pg 20] and halted before our cabin door.

The animal he rode was all afoam, and gave other signs of having been urged hard and over a long distance. As the rider dismounted, his nervous and excited manner told us he was the bearer of ill tidings or that he was on some errand of unusual importance.

"What news below?" was asked the stranger.

"Bad news," he replied quickly. "The Ruffians are over the border upon us again, in strong force; and they are bent on 'cleaning us out' this time. If they keep on they won't leave a cornstalk standing to show where our crops grew."

There is every reason to conclude that our informant was no other than James Montgomery, then all unknown[Pg 21] to fame, but who was later to distinguish himself as a leader in the Kansas struggle for freedom.

As the writer remembers him as he appeared that morning, he gave evidence of being a man of intelligence and character. He was tall,—some six feet in height,—rather slender in build, and of dark complexion. This answers the description given of Montgomery by those who knew him well.

Montgomery afterward gained well-earned distinction by leading Free State settlers, banded together for self-defense, to fire upon United States troops, putting them to rout. He became, still later, a colonel in the Northern army at the outbreak of the Civil War.

The trooper's story was soon told, as it needed to be, for there was no[Pg 22] time to be lost. He was a messenger from the Middle River region, so-called, dispatched to us by his comrades in distress. He had come twenty-five miles through the night and darkness, in an almost incredibly short time, stopping by the way only to arouse the scattered Free State men to arms.

He had been sent to ask help. The need was pressing. The invaders were many, defiant, and reckless. They had encamped in the neighborhood, were burning haystacks, foraging their horses in the cornfields, hunting down Free State men, and sending terror to the hearts of women and children. Detachments of marauders were sent out here and there on these errands of mischief. They had even penetrated, not twelve hours before, to within ten[Pg 23] miles of the spot where we stood; had made prisoner and borne away a pronounced Free State man; and, in addition to that, had besieged other Northerners in their log cabins and destroyed their property by pillage or fire,—as we shall see further on in our story.

BY this recital of the messenger our sympathies were sufficiently enlisted; but if anything additional were needed, further to gain our attention, it was given then and there.

As the speaker drew his narration to a close, all present instinctively turned their eyes in the direction whence he had come: namely, toward the south-east. There a sight met our gaze that riveted us to the spot—a spectacle as marvelous as it was beautiful, and singularly confirmatory of our informer's words. To our utter[Pg 25] astonishment we looked directly, at that moment, into the enemy's camp twenty miles away, though seemingly less than a quarter of that distance. It was one of those peculiar phenomena, rarely seen on the water and less frequently on the land, and more wonderful in the latter case when it does thus appear, because more perfect and on a grander scale: the mirage.

The prairie mirage is of wondrous beauty. It is usually in the autumn, when all the atmospheric conditions are favorable, that these strange illusions take place on the prairie ocean. Along the eastern horizon, near sunrise, a narrow belt of silver light appears. As it grows broader the silvery gray of its lower side changes slightly golden. Fleecy clouds above the belt take on a yellow red. The grayish shadows of the dawn lift[Pg 26] slowly from the earth. Just before the red disk of the sun peers above the horizon-line, one sees in the sky the landscape of trees, of waving grasses or grain, of rocks and hills, held together as it were by threads of yellow and gray and azure. The earth stands inverted in the air.

The groundwork of this illusion is a grayish, semi-opaque mist; and the objects are seen standing or moving along in it. The feet of animals and of men, the trunks of trees, the rocks and hillocks, are set in this aqueous soil. When the conditions are perfect, objects far beyond the range of vision over the prairie are brought near and into plain view of the beholder.

That morning was such a time and afforded such a scene. There was the camp of the enemy,—miles away, as has been said,—mirrored[Pg 27] perfectly and beautifully on the sky, every feature of it traced with the minuteness of a line-engraving. By the aid of our military field-glass we could see the early risers moving through the camp-ground; the horses, standing patiently outside awaiting their morning meal; the positions of the pickets keeping guard; the tent-doors flapping in the slight breeze or swaying back and forth as the men made egress or entrance. Here and there were knots of soldiers,—of two or three or four men each,—apparently discussing the situation or lighting the early camp-fires for breakfast. Even the curling smoke of the newly kindled flame, as it ascended upward, curiously traced itself visibly to the eye.

But, what was of yet more interest and practical moment to us, we beheld the stacks of arms, the rifles and shot-guns,[Pg 28] of our foe, reflecting their burnished steel, and the army-wagons for bearing their luggage and provisions, stretched along the exposed sides of their position to serve as barricades for defense in case of attack. Moreover, there were the evidences on every side of wanton and cruel destruction,—whole cornfields stripped or trodden into the dust, and the blackened sites or yet smoking remains of burned houses, corn-bins, and wheat-stacks, the property of the Northern settlers.

Here we had, right before our eyes, direct demonstration of the truth that had just been told us. Deeply impressive was it indeed, and well calculated to fire us and to spur us to the rescue.

Surely that effect it had.

IT would perhaps suffice here, so far as the main point in our story is concerned, simply to say: We went to their relief. But I am tempted to give a brief account of that march, and of the incidents by the way, as affording the reader some idea of the difficulties and vicissitudes of that Western-border, Kansas warfare.

In the settlement of the South Pottawatomie river there were thirty-six men and boys, all told, capable of bearing arms. They had been organized into a company, and were officered and drilled ready for emergencies.[Pg 30] But, inasmuch as they were scattered up and down the creek over a distance of some miles, to inform all, and for each to make ready, and for all to get together occupied the swift hours of nearly the entire day.

Ammunition was to be collected; provisions were to be packed for the journey; horses were to be gathered up from the prairie and bridled and saddled. And, withal, preparations were to be made for home defense and for the care of the women and children to be left behind. These, though few, were all the more precious. The males who were sick or wounded, lame or otherwise disabled, constituted the "Home Guard."

Finally, the leave-taking of wives and little ones, though hastily made, also consumed time, so that the sun's rim already dipped the western horizon before we were well under way.

[Pg 31]The march thus taken up was one into a night of terror of which we little dreamed when we set out.

We had not gone far before darkness settled down upon us. The sky, cloudless through the day, became overcast, and one could hardly see his hand before him. Only with great difficulty could we keep our direction and follow the trail over the prairie.

But the possibility of losing our way was the least of our troubles. In marching at all that dark night we ran fearful risks. Of that fact we were perhaps only too unduly conscious. Fortunately, however, the perils we feared we did not encounter. Some of them we escaped by the merest and luckiest chance. And some of the dangers were wholly imaginary, though they were none the less harassing on that account. To[Pg 32] our excited minds, a foe lurked behind every bush; in every thicket and cluster of underbrush was the enemy in ambush.

Our apprehensions were augmented by the rumor which twice met us that the "Border Ruffians" had commenced their march up the creek at nightfall, as we began ours down. The terribly anxious, distracted state of mind we were in it is difficult to portray to the reader. It was mainly owing to the doubt and uncertainty as to everything.

This is the case, naturally, in all such warfare. It is otherwise where there are regularly organized military operations. In the latter case, by a proper system of spies and scouts, the general is of course kept informed of the whereabouts of the enemy, of their numbers, and of their movements.

[Pg 33]With us it was wholly different. The air was full of rumors,—all perhaps unreliable; yet it was not safe to let them go unheeded. If we gave no heed to the reports we might find ourselves attacked wholly unexpectedly.

We were not cowards, I will venture to assert, and as the sequel will abundantly show; but such uncertainty and suspense were terribly trying to the nerves, especially on such a night, and in such darkness;—ten times more so than real battle would have been. With open daylight and a fair field we would not have hesitated a moment to fight double our own number. But the thought of being mowed down in the darkness by an ambushed foe, without the chance of striking back in defense, was truly a harrowing situation.

On the way we had several lesser[Pg 34] or larger streams to ford; and, in that prairie country, all such were densely wooded. At any of these points, a dozen men well posted would have been equal to six times their number, and could have cut us off almost to a man.

Every unusual noise grated upon our senses. Twice we halted and prepared to repel an attack. But the alarms were needless: one was occasioned by a drove of cattle crossing the prairie, the other by a herd of wild deer startled from their lair.

Twice we took a vote whether we should continue our march, or intrench in a good position and await patiently the enemy or the daylight. Once the ballot was a tie, and only by the casting vote of our commander, Captain Anderson, was it decided to proceed.

THE population of the region, friends and foes, were now up in alarm. Reports met us of the outrages of the Ruffians upon Free State settlers the night previous.

Here is the story of one of the depredations, detailed to us at one of our halts.

It was upon a stanch old German and his family, settled near the junction of the North and South branches of the Pottawatomie. Old Kepler, as he was nicknamed, had not taken any leading or even active part in the[Pg 36] "troubles" (as they were termed), but his strong anti-slavery sentiments had cropped out and were known to the enemy.

They now made directly for his cabin, evidently resolved, as the opportunity might offer, to force him to declare himself for one side or the other. No man, in fact, in those days of the Kansas conflict,—partisan, bitter, bloody,—could long occupy anything like neutral ground. If one undertook to "sit on the fence," he soon became a target for both parties and was relentlessly dislodged.

It was not the nature of the old German to dissemble, when the trial came. On the approach of the Ruffians he prepared for the worst, as he expected no favor. He barricaded his cabin door and refused their demand for admittance. They burned[Pg 37] his wheat and hay stacks, and all his outbuildings, and then called upon the besieged to surrender.

It was believed, probably rightly, by the assailants, that the old man was possessed of considerable money, brought with him from the old country. This lent incitement to their attack; while, if true, the fact was undoubtedly an additional motive on his part for keeping the invaders at a distance.

Brave old Kepler was quite advanced in years. He was about three score and ten, but all the old valorous Teutonic blood in his veins was aroused, and he prepared to resist the spoilers even to the death, if need be. His wife, partner of his New World adventures and toils, had succumbed not long before to the frontier hardships and had passed on. He had one son, a chip of the old[Pg 38] block, brave, strong, and inured to the rough Western life, equally interested with the father in carving out their fortunes in this new country, and in the making of their Western prairie home.

And there was an only daughter, alike the support and solace of both father and brother;—the light, indeed, of the household and of the neighborhood.

I must interpolate a word here, in passing, descriptive of this daughter,—the worthy heroine of the event, as we shall see. She was a light-haired, blond-complexioned young girl, with all the proverbial German fairness,—bright and handsome as a prairie flower. And she had the German habit of taking a share in the work in the open field. Often was she seen by the passers up and down the creek, "chopping in corn"[Pg 39] (as they call it in the West),—keeping even step in the row with her robust brother; or now driving the cattle while he held the plough; then changing work with him, guiding the share while he drove the oxen.

Her household duties, however, were not neglected meanwhile. Doubtless the brother, in return, here gave her a helping hand. Nowhere else on the road (as the writer can testify from personal experience) did the weary and hungry traveler find such bread as when thrown upon the Keplers' hospitality,—bread of this young girl's manufacture.

Besides all this,—and appropriately to be said in this connection,—this fair maiden could handle a rifle on occasion, as we shall presently see. Such ability was often a quite useful accomplishment for the gentler sex on our wild Western border. It[Pg 40] proved eminently so in the case before us.

The yelling, hooting, and now drunken mob began at length to fire upon the cabin at its vulnerable points. The heroic inmates returned the shots through the holes between the logs in the loft, and not without effect. One of the assailants was seriously wounded and several others less so. The battle grew warm, the effusion of blood thus far serving only to increase the wild fury of the besiegers.

The father and son stood with their guns at the openings, while the young girl loaded the pieces for them as fast as they were emptied. At length the baffled and maddened crowd changed their tactics. They managed to pile wood, logs, and rubbish against the cabin, hoping to fire the building. There was danger that[Pg 41] the dastardly effort would prove only too successful. The flames began to crackle. All now seemed lost, when suddenly the brave daughter unbarred the cabin door and sprang forth with a bucket of water in her hand to dash out the newly kindled flames. This was done from the girl's own impulse at the moment. Had they divined her intention, the father and brother would not have allowed it. The feat, however, strange to say, was as successful as it was heroic and perilous.

The surprised besiegers were not actually cowardly and base enough to fire upon the unarmed, defenseless girl. However, one of them sprang from his covert behind a tree to seize her. But the old backwoodsman father, watching breathlessly the scene below from his post in the loft,—his hand and eye steadied to[Pg 42] perfect accuracy by the imminent danger,—sent a rifle-bullet straight to the heart of the venturesome wretch, and he fell forward dead at the maiden's feet.

The girl regained the door and, with the aid of her brother, who hastened to her assistance, rebarred it securely. All was now again safe for the time being,—and permanently, as it proved. The marauders, overawed by this episode and by the generally unexpected course of affairs,—one of their number being actually killed and several others more or less severely wounded,—hastily fell back to a safe distance and finally beat a retreat from the neighborhood.

IT did not require the narration of this stirring tale to nerve our forward movement, but it certainly increased our determination to proceed at all hazard.

Our next halt was made at the cabin, some miles further on, from which, as mentioned in the first chapter, the young man whom we all knew and counted as one of us had been borne off a prisoner. As soon as it was made known, by the usual signs, that we were friends, we were joyfully if tearfully greeted. The family, consisting of aged parents, sister,[Pg 44] brother's wife and little children, were in despair. Dreadful anxiety filled their minds. It was an illustration of the saying that "to know the worst is better than suspense." If in the great cause then firing their hearts this family had seen that son and brother shot down before their eyes, they would have borne the affliction silently and with submission. But the terrible uncertainty as to his fate wrought upon them. A price had previously been set upon the young man's head, and they had reason to fear the worst for him.

It must be added, in passing, that his beloved ones never saw him again alive. The good fortune fell to us to liberate him the next day from his captors, when we found him bound upon his horse, with his hands lashed behind him and his feet tied together under the animal; but, alas! his liberation[Pg 45] gave him only a short respite from death. He fell, only a few days after, heroically fighting at the battle of Osawatomie.

Some miles beyond we had to make that ford of the Pottawatomie river of unenviable fame, and which we looked upon as the danger-point of all others in our journey; for there our enemy, we thought, would most likely be in ambush. But we swam the swift, dark, muddy stream, swelled by recent rains to a flood, with the water up to our horses' backs, luckily without hindrance or serious mishap.

That ford was the notorious Dutch Henry's crossing, so-called,—surely a gloomy, gruesome, and dreaded spot at that dark midnight hour. There, close by, had been enacted, just two months prior, the rightly named Pottawatomie tragedy, which made that locality, on account of this[Pg 46] bloody event, verily for the time the "storm center" of the Kansas conflict. But, terrible as it was, it served a great purpose and was speedily followed by good.

The hero of our sketch was the central figure in this tragic act of the Kansas drama, as he was in most others at this trying period. Brown was the cyclonic force, the lightning's flash in the darkness, that cleared and lighted the way for the men of that day.

Despite all delays on the way, we made our forced night-march of twenty-two or more miles in remarkably good time, and arrived at our destination about two o'clock in the morning, as weary, exhausted, and hungry a set of troopers as ever drew rein and slipped stirrup to seek rest and refreshment.

The Adair Log Cabin.

[Pg 47]It will be of interest to our readers to learn here that, a couple of miles from the town,—our halting place,—we passed the log cabin of the Adair family, which has such historic interest gathered about it, and which we shall have occasion to mention again later.

It so happened, as we learned afterward, that the hero of our story lodged under that roof that night. He was aroused from his slumbers and watched us from the window as we marched past,—having been reliably assured, by our advanced guard, that we were no threatening foe, but his firmest and safest friends.

A photographic view of the cabin's exterior is given on the opposite page, as it appears to-day; and nearly the same as it existed at that early date, now almost fifty years ago.

The town referred to was Osawatomie, soon to be made famous by[Pg 48] the man who is the principal subject of these sketches.

We were challenged by friendly pickets on guard, who escorted us to the old "block-house" reared for town defense, where we were glad to find shelter, and especially to find food, for hungry we were indeed.

To what a sumptuous feast were we welcomed on that occasion! And yet, strange to relate, the recollection of it is not calculated to make one's mouth water. It so happened that a side of bacon and a barrel of hardtack were stored there, for just such emergencies as the present one, and these were now pressed into our service.

Their edible condition was such as naturally to suggest certain Scripture phrases as descriptive thereof;—of the bacon, "ancient of days"; and of the biscuit, "fullness of life." As we[Pg 49] crunched the latter between our teeth, the peculiar, fresh, sweet-and-bitter taste, commingling at every mouthful, told us too well of the "life" ensconced therein. No comments were made, however, except the ejaculation occasionally, by one and another, "Wormy!" " Wormy!"

However, nothing daunted, we paused not in our eating till our ravenous hunger was appeased. And then, on the bare floor of boards, rived roughly out of forest trees,—though it was a little difficult to fit our forms to their ridges and hollows,—we gained a few hours of as sweet and refreshing slumber as ever visited mortal eyes.

IT will be asked, perhaps, why we came to this particular place. In this little town were encamped, at this particular time, Captain John Brown and his daring and trusty band of men.

"Old Brown," as he was most often called, was a tower of strength in time of need. He had become by that time a veritable terror to the enemy. Tell a Border Ruffian: "John Brown is coming," and he would shake in his shoes, or would run away had he strength enough left[Pg 51] for locomotion. Missouri mothers frightened their babies to sleep or to quietude by the sound of his name.

If our information were correct, the foe we sought largely outnumbered us. What more natural than that we should, under the circumstances, desire the counsel of the stanch old man, and his help, if needed.

He had not looked for an invasion from the direction at present threatened, but was daily expecting one from another quarter. He detailed two small companies, Captain Shore's and Captain Cline's,—two-thirds of his own command,—to join our force; then bade us seek the enemy, with the direction, if we found them too strong for us, to send back word to him, whereupon he would come[Pg 52] to our aid. Meanwhile, he said, he would stay with the remainder of his men and guard the town.

We set out in the morning, early and hopefully. Scouts with fleet horses were dispatched in advance, and we rapidly followed after. Rumors of all wild and exaggerated sorts met us as we went. First, it was said, there were three hundred of the enemy, well armed and mounted; then there were five hundred men, strongly intrenched to receive our attack; later, there were a thousand, coming to meet us.

At last we began to be a little apprehensive, possibly a grain frightened. In the uncertainty, a messenger was sent back to Captain Brown to say that probably we should need his help.

But we resolutely pushed on, if[Pg 53] with somewhat slackened speed. Presently a scout returned bearing reliable tidings. The position and strength of the invaders had been quite accurately ascertained. They were about three hundred in number, quietly encamped, and as yet unaware of our approach.

Our officers decided not to wait for Captain Brown to come up, but to press forward to the attack and by celerity of movement gain what advantage was possible.

One point was, nevertheless, taken into consideration. We were but about sixty in number, all told. We were prepared and determined to do some hard fighting if necessary; but, it was argued, if we could take the enemy by surprise, victory would be more fully assured us, and much needless spilling of blood might be avoided.

[Pg 54]We therefore proceeded cautiously till we arrived within two miles of the hostile force, where our advanced scouts had taken up position and were actually looking down with spy-glasses into the enemy's camp and watching their every movement. The foe seemed wholly unconscious of any impending danger.

IN less time than it takes to relate it, the plan of battle was arranged.

Our men were divided into three companies. Two divisions were to make flank movements, one on the right and the other on the left of the foe, while the third was to assault directly in front. The plan of attack was well conceived and as successfully executed.

We had a circuit of some miles to make to gain the flank positions. It was quickly and silently traveled. In our division, detailed on the left flank, hardly a word was spoken during a[Pg 56] two hours' march. Each man was busy with his own thoughts. It is said that persons in critical situations will sometimes have their whole lives pass before them. I believe that most of us, during this march, recalled nearly all we had ever done or seen, known or felt.

We were suddenly awakened, at length, from such reveries, by the crack of rifles and the clash of musketry, and by bullets actually whizzing about our ears. So closely had we stolen the march on them that when we opened fire we were actually more in danger from the guns of our friends than from those of our foes.

The enemy were taken completely by surprise. As prisoners whom we took told us afterward, they thought that "Old Brown" was surely upon them; and their next and only thought was of escape. They left[Pg 57] all, and ran for dear life, some on foot, shoeless and hatless; others springing to their horses, and, even without bridle or saddle, desperately making the trial of flight. Perfectly bewildered, they ran this way and that; and naturally, as our forces were positioned, many ran directly into our hands.

The one thing they did not do well was to fight, except in the case of a few desperate ones and of the leaders, who called in vain upon their men to rally. Then they gave up all for lost, and each looked out for himself. Many discharged their pieces at the first onslaught, but so much at random that not a man of our number was fatally injured, though several were more or less severely wounded. We took many prisoners, and captured some thirty horses, all the enemy's wagons and luggage, and[Pg 58] much ammunition and arms. The victory was complete.

Not until all was over did Captain Brown and his reserve come up, though they had ridden hard to lend us a helping hand. He warmly congratulated us, however, upon our good success, saying that he could not have done it better himself, and that he was just as glad and proud of our victory as though he had won it.

THERE were incidents not a few, connected with the day and with the central figure of our sketch, which would add interest to our pages. One there was which especially impressed itself upon all witnesses of it.

This relates to one of the enemy who was fatally wounded in the battle. He desired very much, he said, to see "Old Brown" before he died.

Captain Brown was informed of the wish, whereupon he rode up to the wagon which served as ambulance,[Pg 60] and, with somewhat of sternness in his manner, said to the prisoner, "You wish to see me. Here I am. Take a good look at me, and tell your friends, when you get back to Missouri, what sort of man I am."

Then he added in a gentler tone, "We wish no harm to you or to your companions. Stay at home, let us alone, and we shall be friends. I wish you well."

The prisoner meanwhile had raised himself with great difficulty, and viewed the old man from head to foot as if feasting his eyes on a great curiosity. Then he sank back, pale and exhausted, as he answered, "I don't see as you are so bad. You don't talk like it."

The countenance of Brown as he viewed the sufferer had changed to a look of commiseration. The wounded man saw it, and, reaching out his[Pg 61] hand, said, "I thank you." Brown tenderly clasped it, and replied, "God bless you," while he turned with tears in his eyes and rode away.

The present writer was standing within a few feet of Brown at the time, and naturally drank in the scene with a boy's eager curiosity and susceptibility to impression.

It was a scene for a painter, and the artist could with appropriateness have called his work, "The Conqueror Conquered."

But it was perfectly illustrative of the man and of the hero. Brown was as brave as a lion. He seemed absolutely not to know fear. Yet withal he possessed a heart tender as a child's or as the tenderest woman's.

WE gathered together the spoils and took up our march on the backward track toward home, discussing the exciting events of the day and recounting to each other our individual experiences, adventures, and "hairbreadth escapes." When we had thus proceeded some three miles, it was nearing sundown, and we halted for supper and to determine our course for the night.

Meanwhile we had learned an important fact from our prisoners, namely: that we had not met all of our enemies. A part of them, quite[Pg 63] a large force, had gone north that morning, and might be at that very moment ravaging our own homes which we had left behind the evening before. Naturally, these unwelcome tidings cast a cloud across our rejoicings. They might after all be turned to mourning!

Having nearly finished our meal, and while we were yet speculating on the situation, Captain Brown hastily rose to his feet and called upon all those, who were ready to go with him, to mount their horses. Forty or more men instantly sprang into their saddles, and others were about to do the same, when the old man cried, "Enough—and too many." He thanked them for their readiness, and then selected thirty of the number, tried and trusted men who had followed him before, and without asking why or whither. In the present instance[Pg 64] also they ventured not a question.

Brown seldom disclosed his intention or plans to any one. He wished no man with him who was not absolutely reliable. He required the implicit confidence of his followers and unquestioning obedience to his commands. Whoever put himself under his leadership took his life in his hand and followed whithersoever he was led.

On this occasion some not acquainted with his habits plied him with queries as to where he was going and what he would do. He only answered, characteristically, that he "had an appointment with some Missourians and must not disappoint them." One ventured jocosely to ask further, concerning the appointed place of meeting. He replied, they had not been kind enough to fix upon[Pg 65] the precise spot, but he felt bound, out of courtesy, inasmuch as they came from a distance, to hold himself in readiness when wanted. This left us, of course, wholly in the dark as to his movements.

With some words of advice to those of us remaining,—that we would better seek our homes, be prepared to defend them, and ready for any action when needed,—he gave the command, "Ready! Forward!" and, with a wave of his hand, led his Knights Errant away.

After they had departed it was decided that it would be advisible for us to return to the camping-ground of the enemy and pitch our tents there for the night; because, it was argued, when the detached force gone north returned, they would naturally seek their friends in the camp where they left them.

[Pg 66]Accordingly, though weary near to exhaustion, we returned and camped there, threw out our pickets, and made every preparation to give the marauders a warm reception should they appear. We slept on our arms, ready for any emergency, but the night passed and we were undisturbed.

The next morning dawned on us clear and beautiful. All our apprehensions of danger had passed with the darkness. Our pickets were withdrawn. The scouts, who had been sent out to gather news of the scattered settlers, had come back with no tidings of the foe we had awaited. Consequently, relieved of all military restraint, we gave ourselves up for the time to the preparation and enjoyment of an early breakfast.

The wagons were unpacked of their provisions. The horses were[Pg 67] picketed, or were turned loose for grazing. The prisoners, disarmed, were allowed comparative freedom. Fires were lighted here and there for cooking. And thus we were spread out over a large area, forgetful of the enemy, without a thought of an attack, and bent only on making ready to satisfy the cravings of hunger.

THEN occurred the scene which gives us one of the glimpses of John Brown for the sake of which these reminiscences have been written.

Suddenly, over the hill or rising ground some half or third of a mile away, two horsemen came up at full speed.

"Look! look!" was whispered in suppressed voices from one to another of our party, and all eyes were upturned in that direction.

Observing us, the horsemen as[Pg 69] suddenly turned on their heels, and disappeared the way they came, leaving us stupefied with doubt and wonder.

In a moment more, however, the heads of a whole troop rose in sight, and the cry, "The Missourians! the Missourians!" rang through our camp in startling accents.

We were in dismay, for we were entirely unprepared for attack and there was no time to make ready. We were apparently caught just as our enemy had been surprised by ourselves. Men sprang, some for their arms, some for their horses. Whether to fight or to try to escape was uppermost in their minds,—each could settle that question only for himself. At any rate, every one felt that a daring and determined foe, apparently numbering a hundred, which was double our own number,[Pg 70] could, in the condition in which we were, utterly cut us to pieces and destroy us at a blow.

What grave emotions that thought aroused! It is difficult for one, never thrown into any such situation, to realize or in any degree even imagine the feelings that may surge through the bosom of men thus placed. Accounts have been given of what panic-stricken crowds or armies will sometimes do, but a description of what they feel on such occasions of disaster was never yet fully penned or painted by man.

Meanwhile, some of our number, who had been cool enough to observe the fiercely advancing cavaliers, perceived that they were friends, not foes. It was old Captain Brown himself and his trusty band. With joy, this news rang through our[Pg 71] ranks. All eyes were then directed toward them, enchained and enchanted. It was a splendid sight.

They at first, naturally, took us for enemies, not dreaming but that we were miles away, where they left us the evening before. They suspected us to be the force, encamped there, which they had been riding all night to overtake,—the same force we had awaited.

They came swiftly up over the brow of the hill, in full view, with Brown at their head, and, without halting or even slackening their speed, swung into line of battle. Only thirty men! yet they presented a truly formidable array. The line was formed two deep, and was stretched out to give the men full room for action. Brown sprang his horse in front of the ranks, waving his long broadsword, and on they[Pg 72] came, sweeping down upon us with irresistible fury.

It was indeed a splendid and fearful sight, never to be forgotten by the beholders. Only thirty men! yet they seemed a host. In their every action, in their entire movements, seemed emblazoned, as in their determined souls it was written, "Victory or death!"

Their leader looked the very impersonation of Battle. Many of us had seen John Brown before, some of us a number of times, and under trying circumstances. But now all felt that the real man we had never before beheld. The daring, the intrepidity, the large resources of the man, none of us had imagined till that moment.

Not a gun was discharged, their commander having given to his men the same strict orders that were[Pg 73] given at Bunker Hill of old, that they should "reserve their fire till they could see the whites of their enemy's eyes." But before they had quite gained that very dangerous proximity to us, we succeeded in making them understand that we were their friends.

Then such a glad shout as rent the air from both sides was seldom ever heard, we believe, on any field even of victory. They were as glad to find that we were their friends, as we, in our helpless condition, were glad to learn that they were not our enemies.

The full intrepidity of Brown and his men, though it appeared to us astounding, was not fully appreciable till we came to look at it somewhat from their own view-point.

We were actually about eighty men, prisoners and all. But, spread[Pg 74] out as we were, with the many horses grazing, the scattered and unpacked wagons, numerous camp-fires,—widely separated for convenience,—arms stacked in some places, and men gathered in groups in others, we presented altogether a formidable appearance. What was more, this was enhanced by our peculiar position, so that, to them, our numbers and strength were exaggerated, while our weakness and confusion were concealed. Brown admitted to us himself, afterward, that he thought he was undertaking to whip a force of two or three hundred, while his men declared that they believed they were actually charging upon not less than a thousand.

Brown's quick military eye took in, at the first, the supposed situation; and, as in a flash, he decided what to[Pg 75] do. All depended, he concluded, upon rapidity of action. His only hope lay in striking a sudden and crushing blow, for which we were unprepared, and from which we could not recover till he had made victory sure. From the time Brown's forces came in sight over the hill, till they were within gunshot of us, hardly thirty seconds elapsed,—a very short notice in which to prepare for action, even if an attack were expected.

AFTER mutual congratulations over the bloodless and happy conclusion of the adventure, we set our friends down with us to eat the interrupted breakfast, to which they were prepared to do ample justice. They had ridden all night, some forty or fifty miles, in pursuit of the enemy,—had ridden all night, without rest or food, from the time they left us, at dusk of evening, till they surprised us that morning with their dauntless charge.

Another incident in connection with the events described it seems fitting to mention, as affording a very[Pg 77] interesting side-glance at the character of our hero. After the meal, Captain Brown was asked by our officers to give a talk to the prisoners taken the day before, who were now drawn up in line for parole. He responded without an instant's hesitation or a moment to think what he should say.

He spoke to them in a plain, simple, unpretentious way, but with a directness, a force, and an eloquence withal, which doubtless wonderfully impressed those addressed, as certainly it held spell-bound all others who listened. Such vivid and indelible impression did this speech of Brown make on the mind of the present writer that, even after the lapse of these many years, he is able to reproduce it, not only in substance, but almost word for word; and he has no doubt of its exceptional[Pg 78] character. Perhaps it was second only to that immortal address which the hero made three years later to the court at his trial in Virginia, which Emerson pronounced one of the three most remarkable addresses in the world.

On the latter occasion, however, instead of a few plain, simple, rough and ready, but intensely admiring followers, he had almost the whole civilized world eagerly to hear and sacredly to preserve his utterance.

Brown's speech to the prisoners was probably not over five minutes long in its delivery, but it lasted those forty trembling men a lifetime. It was not known that one of them ever afterward ventured over the Missouri border into the Kansas territory.

The address was as follows:

[Pg 79]"Men of Missouri, one of your number has asked to see John Brown. Here he is. Look at him, and hereafter remember that he is the enemy of all evil-doers.

"And what of you yourselves, men! You are from a neighboring State. What are you here for? You are invaders of this territory,—and for evil purposes, you know as well as we know. You have been killing our men, terrorizing our women and children, and destroying our property,—houses, crops, and animals. So you stand here as criminals.

"You are fighting for slavery. You want to make or keep other people slaves. Do you not know that your wicked efforts will end in making slaves of yourselves? You come here to make this a slave State. You are fighting against liberty, which our Revolutionary fathers fought to establish[Pg 80] in this Republic, where all men should be free and equal, with the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Therefore, you are traitors to liberty and to your country, of the worst kind, and deserve to be hung to the nearest tree.

"But we shall not touch a hair of your heads. Have no fear. You are deluded men. You have been deceived by men who are your elders but not your betters. You have been misled into this wrong, by those your leaders; thus, they are the real criminals and worse than traitors, and, if we had them here instead of you, they would not find such mercy at our hands.

"You we forgive. For, as you yourselves have confessed, we believe it can be said of you that, as was said of them of old, you being without[Pg 81] knowledge, 'you know not what you do.' But hereafter you will be without excuse.

"Go in peace. Go home and tell your neighbors and friends of your mistake. We deprive you only of your arms, and do that only lest some of you are not yet converted to the right. We let you go free of punishment this time; but, do we catch you over the border again committing depredations, you must not expect, nor will you receive, any mercy.

"Go home, and become liberty-loving citizens of your State and country, and your mistakes and misdeeds, as also the injuries which you have inflicted upon us, will not have been in vain."

THE personal experiences here related are of interest and have a value mainly as they throw somewhat of fresh light upon the character of the subject of this work, Captain Brown, and upon the events and times in which he was the leading actor.

Those were troublous times,—times that indeed "tried the men's souls" who experienced them. The hardships were severe. Danger and disease, death by ruthless hands, and even death from starvation, often stared us in the face. At one time[Pg 83] we lived six weeks solely on Indian-meal mixed with water and dried before the fire, and that without even a condiment. This was our common fare in times of scarcity. Bacon and molasses, and tea without milk or sugar, were our luxuries in times of plenty.

For months, in the summer of '56, the men in our settlement never had their clothes off, day or night, unless torn or worn off. On a trip early in the summer mentioned, made by a companion and myself to Kansas City for provisions, we chanced to come across John Brown and his company encamped in the woods on a river-bank. After we made ourselves known as friends we were invited into their camp. A more ragged set of men than we found were rarely, we believe, ever seen,—Brown worst off of all, for he[Pg 84] would not fare better than his men. They had no shirts to their backs, and their outer clothing was worn or torn to tatters. While in camp, they were going barefoot to save the remnants of their worn-out shoes for emergencies. And withal, they were, they said, on short rations, having no bread, but only Indian-meal and water. They were glad of the opportunity to engage us to bring them provisions on our return, but they confessed they were as short of money as they were of provisions, which simply meant that we must share ours with them.

The men of our company worked hard by day to raise crops, with their rifles near at hand, and slept in the "bush" at night to avoid surprise and capture in their cabins. Only the women and children ran the risk of remaining in the houses, in their[Pg 85] defenselessness trusting to the mercy of the enemy. That border life invited sickness, especially the malaria of the low prairie. Our cabins were roughly made, and so open that when it rained it was about as wet inside of them as outside.

We had not time to dig wells, and in mid-summer the rivers were low and the water so stagnant that we had to brush the green scum from the surface when we dipped the water to drink or for other uses. Every man, woman, and child of the settlement was ill with the "fever and ague," so termed. There came near being an exception to the rule. One man kept so full of whiskey, continuously, that the ague didn't seem to have even a fighting chance; but at length the liquor fell short, and the ague then found its opportunity and even made up for lost time.

[Pg 86]As for fire-arms with which to defend ourselves, we were not well off. The famous Sharpe's rifles—"Beecher's Bibles," so-called, from the great preacher's contribution of them—won Kansas to freedom in large measure; but more by their terrible name than by virtue of any large number of the weapons themselves. The Free State men in Kansas actually had few of them.

When my older brother, with whom I went to the territory, and myself called on Theodore Parker in Boston,—for one thing to ask him if those going to Kansas would be helped to fire-arms,—he said he was sorry that his previous contributions had left him "nary red" which he could give for the purpose, and he referred us to the Aid Society. We concluded, however, to depend on our own means, though slender, and so[Pg 87] bought, to use between us, one Sharpe's rifle for twenty-five dollars. We thought it might be useful to bring down prairie hens and wild turkeys, if not needed for more serious use.

This was the only Sharpe's rifle owned in our settlement of thirty-six men and youth able to bear arms. The members of our company, in fact, at this early period in the Kansas troubles of which we write, were very slimly accoutered for warfare, and the writer actually went into the battle of Sugar Mound, described in previous pages, with an old, worn-out flint-lock rifle, being a boy put off with the poorest weapon, which, with the greatest care, he could not discharge more than once in a half-dozen times' trying. And it was the only weapon he had until he made prisoner a Missourian and possessed himself of better arms.

WHAT does the reader suppose these arms were? The one of interest was a United States army musket, altered over from a "flint-lock" to a modern "percussion-cap,"—a very effective fire-arm. It will be seen that we had to contend not only with the Border Ruffian, but with the greater ruffian at that time behind him, the United States Government itself, which was covertly lending its influence and even its arms on the side of slavery. Those Government guns were stored at Fort Scott, on the Missouri border, and the Pro-slavery[Pg 89] men were allowed to help themselves to them.

That Government musket I intended to keep as a souvenir of Kansas times; but later, on the occasion of coming down the Missouri river, when boarding the steamboat with this musket in a common gun-case, I thoughtlessly, on entering the main saloon, stood it in a conspicuous corner. It was soon afterward noticed,—"spotted," as the phrase went,—and I heard some one whisper, "Kansas." A rough-looking passenger approached the piece, removed its case in examining it, and inquired in a loud voice for its owner. Everybody was now all interest. It was a time when the Kansas excitement was at its height, and passions ran wild.

The cry, "Yankee! Yankee!" burst from the crowd. "Overboard[Pg 90] with him! Overboard! Overboard!" was howled, and "Yankee! Yankee!" again rang out in hot, angry tones.

The subject of these gentle remarks, it goes without saying, was surely one of the most interested spectators of the scene of all the members of the crowd, and, as was quite politic, joined in the outcries. The odds seemed to be decidedly against him, and dissent was surely unwise. Apparently there was not another Eastern man on board, and this one felt—as once a Western man said he did when expecting to be lynched by a howling mob—"a little lonesome." Very fortunately for him, no one observed that he was in any way connected with the interesting implement of warfare. Had it been discovered that he was the owner of that musket,—well! he would probably not be here now to[Pg 91] tell his story. If the possessor of it, on the contrary, had proved to be a "Pro-slavery" from the territory, he would immediately have been lionized as a hero.

"All's well that ends well." The only matter of regret to the owner was that he lost sight and possession forever, that troublous night, of his souvenir musket. It was secretly made away with by some one's hands, under cover of the darkness.

An incident in the story of the musket we may here relate, on account of its probable significance, not apparent at that time, but revealed at a later date.

As we were making our way leisurely from the battlefield at Sugar Mound, the opportunity was afforded me to show Captain Brown my share of the trophies of our recent victory. He seemed rather indifferent as he[Pg 92] looked at the revolvers, the fine powder-horn, the shot-bag, and the cartridge-pouch; but when he caught sight of the musket he grasped it eagerly and scrutinized it with intense interest. On the gun-stock was inscribed: "Made at the U. S. Armory, Harper's Ferry, Va.,"—or words to that effect.

When, three years later, occurred that startling episode in our history at Harper's Ferry, Brown's scrutiny of the musket was recalled by me and apparently found its explanation. It raises the question, How long had he contemplated carrying the war into Africa?

In Brown's view, slavery was war, aggressive and in actual operation. Therefore, any attack on the institution was virtually defensive warfare, legitimate and justifiable. He was a worshiper, heart and soul, at liberty's[Pg 93] shrine, and to his mind no sacrifice in its cause was too great or costly. In that light must be interpreted his hard saying: "It would be better that a whole generation of men, women, and children should be sacrificed than have liberty perish from the earth."

THE youngest male member of our Kansas party, hardly more than a boy, was possessor of a peculiar psychical faculty—very fortunately for us during all our troublous experiences in the territory. It was a modest gift, but an exceedingly useful one to us under the exceptional circumstances in which we often found ourselves, and this not alone to its owner, but to the whole company. It cannot be better designated, in brief, than as the faculty of "finding the way," the term usually employed in speaking of it.

[Pg 95]It probably will not lessen the interest of the reader in the matter if he is here told that the writer of this account himself was the happy possessor of this useful power. From a boy, a mere child, he may say, it was known among his playmates that he could lead them safely and surely to any place or object, when there was doubt about its locality, and could also discover the whereabouts of things lost. The shyness of the boy led him to keep his gift in the background.

In Kansas it was as suddenly as remarkably made prominent perforce. It came into use the first day after we set out on our journey over the prairie. We had not gone far from the borders of civilization,—only far enough for its objects to be out of view,—when our whole caravan of travelers, their teams, horses, oxen,[Pg 96] and wagons, came to a full stop. The trail over the prairie branched into two, and all were in doubt which was the right one to take. The clouds had shut in the sun, and the boundless prairie stretched out on all sides, with not an object, house or tree, hill, or even a rock, in view, as a landmark by which we could aim our course. One of the party, with a little experience in traveling on the prairie, warned us that an error made here might mislead us a whole day's journey.

The situation began to be a little distressing; whereupon the older brother of the psychic boy said: "Call up my brother. He will tell you which trail to take." Accordingly, the boy was summoned to the front; and to the older heads, waiting there with amused smiles on their faces for the decision, he pointed[Pg 97] out what, in his belief, was the right trail. Being wholly in doubt, they, with their smiles deepening to laughter, said they might as well follow the trail he indicated. It turned out to be the correct one.

During the following ten or a dozen days' journey, as many times at least the youth was summoned to the front, and his psychical faculty put to the test. Its possessor was made happy, and his companions were equally gratified, that his power in no instance failed him.

These trails, mere wagon-tracks across the country, ran in almost all directions, crosswise, parallel, and at all angles, and were enough to puzzle the very elect,—the elect being in this instance the psychic youth. The earnest wish to find the way in any case—and the stronger and more earnest the wish the better—seemed[Pg 98] to be a sort of mainspring to the action of the power to insure its success.

This gift was brought into play many times during the two years of Kansas events sketched here, and served us well; was often invaluable. The fact just mentioned, that the strong wish insured its effectiveness, was often clearly shown. For instance, on the occasion referred to in a previous chapter, of our happening upon Captain Brown's camp in an out-of-the-way spot on our trip for provisions, there was a strong desire on our part, excited, perhaps, much by curiosity, to see Brown and his men at that particular time in their temporary hiding-place; and seemingly by this intense desire inciting the psychic power, we were led to the spot,—for it had taken us, as we found afterward, quite a[Pg 99] number of miles out of our direct course.

In passing, we will here digress a little from our story to say that, at this time of our visit, Brown was being hunted down, like a criminal or a wild beast, by the Government military as well as by his other enemies, and was all the time liable to betrayal into their hands.

I remember well, in this connection, how we found him armed that day. He carried about his person not less than twenty shots with which to defend himself did it become necessary: a Remington repeater—six shots; a brace of revolvers—six-shooters; and a pair of pistols. He had also a long knife or dirk, and his usual trusty old broadsword. Most of these arms, he seemed to take pains to inform us, were presented to him by his[Pg 100] friends. Particularly did the old man impress me, while showing us the weapons, when he quietly remarked: "Our enemies would like much, no doubt, to get hold of me; but," he added with sternness, "I will never be taken alive, and I warn them I shall punish them to the extent of my power if they attempt my capture."

To return from this digression, it was a perilous thing in those days for one to venture out alone on the prairie. It was perilous to life, and perhaps still more dangerous to the property of him who ventured,—at least in some ways. For one thing, we did not dare to risk our horses. Horses were valuable, and the enemy considered them as legitimate contraband of war. The luckless horseman caught abroad by his foes was simply ordered to dismount. His[Pg 101] horse, saddled and bridled, was led off, and the owner was left to make his way on foot, no matter how far the distance. When a team without a load was overtaken by our opponents, the horses were appropriated and the wagon left standing on the prairie. Were the wagon loaded with valuables, both animals and wagon were confiscated, and their owner was told, very likely with rifles pointed at him, to run for life till out of sight. In such cases, were one found with money or other valuables on his person, he was summarily relieved of them. Sometimes we sewed our money within the lining of our clothes, for safety; but that device for concealment had its risks. One was liable to be stripped, and to have his clothing cut or torn to shreds in the hurried search for the money.

SUCH were some of the hazards of travel at that time, when the new territory was indeed "bleeding Kansas."

Journeys, nevertheless, had to be made, and long ones, and many of them from sheer necessity. We were obliged to buy in a distant market all the food we ate, with all other necessaries of life. Shipment of goods must be made by ox-teams—the use of horses being out of the question, for the reasons mentioned; and the ox-team was rather a slow means of transportation. Some[Pg 103] ten days were necessary to make the journey from our settlement to the nearest good market, Kansas City, and return.

There was another matter we had to consider. The journeys were hazardous to men as well as to horses. Men were valuable and scarce. Not more than two at most were ever allowed to go on these dangerous errands, and usually one only.

It is not strange, as will readily be understood, that the boy who could "find his way" was for that reason chosen to make these trips, and he generally went alone. Another reason for this choice was that the settlers would not run the risk of sacrificing their mature, strong male members in this service, could it be avoided. This youth—because a youth, with no one, wife or[Pg 104] children, dependent upon him—would not be so great a loss to the community if capture, imprisonment, or death befell him! He was, however, inspired by, and felt not a little pride because of, the confidence reposed in his ability to perform the difficult and dangerous task assigned him.

Quite a number of these trips I made alone, and in not one did I lose my way. On one occasion the guiding faculty was put to a severe test. At the end of a day's travel the oxen were freed as usual from the wagon for two or three hours, in order that they might graze. Meanwhile, strict watch of them was necessary, lest they should wander away. That night, through much exhaustion and lack of rest, it was my misfortune to fall asleep. When I awoke, long past midnight,[Pg 105] the cattle were gone. The full moon shone brightly overhead, lighting up the horizon far away on all sides; but, far and wide as the eye could reach, no sight or sign of the animals was visible on that prairie ocean.

A serious state of things this appeared to be, at first thought, and it awakened serious apprehensions. Far from home, I was left with my valuables on the prairie, bereft of all means of taking them to their destination. But upon second thought, often the better, I calmly fell back, for rescue, on my humble psychic faculty. Humble and inconsequential I had held it, but, if it served me true this time, it never again should be lightly valued.

It proved as true as the needle to the pole.

It seemed to me that the cattle[Pg 106] had gone in a certain direction; and in that direction I went, in a straight line over the prairie, three or four miles, directly to them. There they were, quietly feeding, close to a stream at which they had evidently quenched their thirst. They were led, doubtless, to find this water, in their need that night, by an instinct similar to, and equally as unerring as, that possessed by their owner which he had used to find them.

Whether the same instinct that "found the way" in the instances related served to secure successful avoidance of the enemy on these journeys will not be asserted; but this interesting fact can be affirmed, namely, that, happily for the lone teamster and for the settlers whose property, whether money or purchases, was intrusted to his care, not once were dangerous foes encountered[Pg 107] on these trips, and only in one instance was there a near approach to it.

One day three horsemen appeared on the horizon in the rear, bearing down upon me. When we have not strength sufficient, we are prone to resort to strategy for protection or to extricate ourselves from difficulty. On board my wagon, the usual large "prairie-schooner," covered with canvas, was a box of firearms which, with foolhardiness, I had undertaken to deliver in Osawatomie. For one to transport arms was to invite the services of the executioner.

I had reason that day, however, to thank my foolhardiness. At first sight of the approaching horsemen I sprang into the cart, forced off the box-cover, and stuck several of the gun-muzzles out under the sides of the wagon-canopy.

[Pg 108]And another reason I had for thankfulness that day. It had been my good fortune that summer, while lying ill of the ague, to learn a little of the ventriloquist's art from a half-breed Indian. The accomplishment served me well now. As the strange horsemen closely approached, I was busy carrying on a conversation, ventriloquist-wise, with my imaginary companions inside the covered wagon.

"Lie still and make up your sleep. Lie still. No danger."

"Who is it?" (from the wagon.)

"They are travelers," was answered; "friendly, no doubt. Lie still and get your sleep."

(From inside the wagon) "Whistle if you want us."

Answer: "O yes, I will. Lie still. No danger,—they're friends."

By this time the troopers were alongside. They looked hard at me,[Pg 109] but harder at the gun-muzzles, made the usual "good-day" greeting, asked a few questions, and rode on. My little artifice had worked like a charm. My visitors, I felt little doubt, had planned and meant mischief; had probably been in search of my team, possibly for days, incited by hope of rich plunder.

This record of personal experiences will serve the main purpose for which it is written if it lays bare to the reader in some degree the difficulties and dangers, the trials and sacrifices, of the Free State settlers whom John Brown led at last to victory in the Kansas struggle for freedom.

In closing this chapter, I will give my readers the only explanation I am able to proffer of the strange faculty of localization which has been mentioned. No voice is heard, nothing[Pg 110] like an impression is felt, there is no experience of any occult power of vision. Indeed, I have already stated all that I am conscious of, in the words, "it seems to me" that the object of quest, or the locality sought, lies in a certain direction or place, whenever this faculty is brought into play to find it.

THE engagement at Sugar Mound (also called Middle Creek) took place on Monday, the 25th of August. Five days later, on Saturday, August 30th, was fought the really famous battle of Osawatomie, the Bunker Hill of the Kansas struggle.

In the early dawn of that day some four hundred of the enemy, well mounted and equipped,—with their bayonets glistening in the morning sun,—bore down upon the devoted town and its stanch defenders. There, in that day's notable battle,[Pg 112] John Brown showed that he possessed real military talent. In this case he was acting on the defensive, and manifested coolness and caution equal in effectiveness to the dash and daring displayed on other occasions.

To our settlement on the South Pottawatomie, the same thing occurred on this memorable occasion as on the earlier one already described. A rider came up the creek twenty miles, asking for our aid.

This time the messenger was sent by Brown himself, and there was a similar ready and willing response to the call, even though we had so lately arrived home. There was the same eager hurrying to and fro to get our force together, the same quick preparations, hasty leave-taking, setting out at dusk, and the like night-march. We made all possible haste to the rescue.

[Pg 113]Before midnight, however, when we had covered only half the distance to our friends in distress, a scout met us with unwelcome news, which, to our dismay, ran: "Battle at Osawatomie, John Brown killed, Free State men defeated, and the town burned to ashes." Moreover, our informant thought it probable that the victors were on their way to lay waste our settlement.

The only thing now to be done was to return to our homes, and to make ready, if the need came, to defend them. One prior thing it was decided it would surely be well to do, namely: dispatch two scouts to our friends at the scene of disaster and get accurate information of their fate or fortune.

The choice fell upon the two brothers, the writer and his older brother, and for the reason (comforting[Pg 114] to them) that, being the youngest men, with none dependent upon them, their loss, were they killed, would be less to the community than the loss of older men. And besides, one of them was good at "finding the way" and the other had won a reputation for extra courage and trustiness in emergencies. We were assigned, to say the least, a rather delicate and hazardous duty, and probably there were few men in the company that night anxious or willing to undertake it.