Title: The Art of Paper-Making

Author: Alexander Watt

Release date: October 15, 2017 [eBook #55757]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by MWS, John Campbell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Art of Paper-Making, by Alexander Watt

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/artofpapermaking00watt |

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes are noted at the end of the book.

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

Just ready. Fourth Edition, Revised and Enlarged. Crown 8vo,

7s. 6d. cloth.

THE ART OF SOAP-MAKING: A Practical Handbook of the Manufacture of Hard and Soft Soaps, Toilet Soaps, &c. Including many New Processes, and a Chapter on the Recovery of Glycerine from Waste Leys. With numerous Illustrations.

"Really an excellent example of a technical manual, entering as it does, thoroughly and exhaustively, both into the theory and practice of soap manufacture. The book is well and honestly done, and deserves the considerable circulation with which it will doubtless meet."—Knowledge.

Second Edition. Crown 8vo, 9s. cloth.

THE ART OF LEATHER MANUFACTURE: Being a Practical Handbook, in which the Operations of Tanning, Currying, and Leather Dressing are fully Described, and the Principles of Tanning Explained, and many Recent Processes Introduced. With numerous Illustrations.

"A sound, comprehensive treatise on tanning and its accessories.... The book is an eminently valuable production."—Chemical Review.

Just Published. Third Edition, revised and much enlarged. 600 pp.,

crown 8vo, 9s. cloth.

ELECTRO-DEPOSITION: A Practical Treatise on the Electrolysis of Gold, Silver, Copper, Nickel, and other Metals and Alloys. With descriptions of Voltaic Batteries, Magneto and Dynamo-Electric Machines, Thermopiles, and of the Materials and Processes used in every Department of the Art, and several Chapters on ELECTRO-METALLURGY. With numerous Illustrations.

"Eminently a book for the practical worker in electro-deposition. It contains minute and practical descriptions of methods, processes and materials, as actually pursued and used in the workshop. Mr. Watt's book recommends itself to all interested in its subjects."—Engineer.

Just Published. Ninth Edition, enlarged and revised, 12mo, 4s. cloth.

ELECTRO-METALLURGY: Practically Treated. Ninth Edition, Enlarged and Revised, with Additional Matter and Illustrations, including the most recent Processes.

"From this book both amateur and artisan may learn everything necessary for the successful prosecution of electro-plating."—Iron.

CROSBY LOCKWOOD & SON, 7, Stationers' Hall Court, London, E.C.

THE ART OF

PAPER-MAKING

A PRACTICAL HANDBOOK OF THE MANUFACTURE

OF PAPER FROM RAGS, ESPARTO, STRAW, AND

OTHER FIBROUS MATERIALS, INCLUDING

THE MANUFACTURE OF PULP FROM

WOOD FIBRE

With a Description of the Machinery and Appliances used

TO WHICH ARE ADDED

DETAILS OF PROCESSES FOR RECOVERING SODA FROM WASTE LIQUORS

By ALEXANDER WATT

AUTHOR OF "THE ART OF SOAP-MAKING," "LEATHER MANUFACTURE," "ELECTRO-METALLURGY," "ELECTRO-DEPOSITION," ETC., ETC.

LONDON

CROSBY LOCKWOOD AND SON

7, STATIONERS' HALL COURT, LUDGATE HILL

1890

[All rights reserved]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY J. S. VIRTUE AND CO., LIMITED.

CITY ROAD.

In the present volume, while describing the various operations involved in the manufacture of paper, the Author has endeavoured to render the work serviceable as a book of reference in respect to the processes and improvements which have from time to time been introduced, and many of which have been more or less practically applied either at home or abroad.

The recovery of soda from waste liquors has been fully dealt with, and the details of several applied processes explained.

Special attention has also been directed to some of the more important methods of producing pulp from wood fibre, since it is highly probable that from this inexhaustible source the paper-maker will ultimately derive much of the cellulose used in his manufacture. Indeed it may be deemed equally probable, when the processes for disintegrating wood fibre, so largely applied in America and on the Continent, become better understood in this country, that their adoption here will become more extensive than has hitherto been the case.

To render the work more readily understood alike by the practical operator and the student, care has been taken to avoid, as far as possible, the introduction of unexplained technicalities; at the same time it has been the writer's aim to furnish the reader with a variety of information which, it is hoped, will prove both useful and instructive.

It is with much pleasure that the Author tenders his sincere thanks to Mr. Sydney Spalding, of the Horton Kirby Mills, South Darenth, for his kind courtesy in conducting him through the various departments of the mill, and for explaining to him the operations performed therein. To Mr. Frank Lloyd he also acknowledges his indebtedness for the generous readiness with which he accompanied him over the Daily Chronicle Mill at Sittingbourne, and for the pains he took to supply information as to certain details at the Author's request. His best thanks are also due to those manufacturers of paper-making machinery who supplied him with many of the blocks which illustrate the pages of the book.

Balham, Surrey, January, 1890.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| CELLULOSE. | |

| PAGE | |

| Cellulose—Action of Acids on Cellulose—Physical Characteristics of Cellulose— Micrographic Examination of Vegetable Fibres—Determination of Cellulose—Recognition of Vegetable Fibres by the Microscope | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| MATERIALS USED IN PAPER-MAKING. | |

| Raw Materials—Rags—Disinfecting Machine—Straw—Esparto Grass— Wood—Bamboo—Paper Mulberry | 9 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| TREATMENT OF RAGS. | |

| Preliminary Operations—Sorting—Cutting—Bertrams' Rag-cutting Machine—Nuttall's Rag-cutter— Willowing—Bertrams' Willow and Duster—Dusting—Bryan Donkin's Duster or Willow—Donkin's Devil | 19 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| TREATMENT OF RAGS (continued). | |

| Boiling Rags—Bertrams' Rag-boiler—Donkin's Rag-boiler—Washing and Breaking—Bertrams' Rag-engine— Bentley and Jackson's Rag-engine—Draining—Terrance's Drainer | 29 |

| [viii] | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| TREATMENT OF ESPARTO. | |

| Preliminary Treatment—Picking—Willowing Esparto—Boiling Esparto—Sinclair's Esparto Boiler— Roeckner's Boiler—Mallary's Process—Carbonell's Process—Washing Boiled Esparto—Young's Process—Bleaching the Esparto | 40 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| TREATMENT OF WOOD. | |

| I. Chemical Processes—Watt and Burgess's Process—Sinclair's Process—Keegan's Process—American Wood-pulp System— Aussedat's Process—Acid Treatment of Wood—Pictet and Brélaz's Process—Barre and Blondel's Process—Poncharac's Process— Young and Pettigrew's Process—Fridet and Matussière's Process | 53 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| TREATMENT OF WOOD (continued). | |

| Sulphite Processes—Francke's Process—Ekman's Process—Dr. Mitscherlich's Process—Ritter and Kellner's Boiler— Partington's Process—Blitz's Process—M'Dougall's Boiler for Acid Processes—Graham's Process—Objections to the Acid or Sulphite Processes—Sulphite Fibre and Resin—Adamson's Process—Sulphide. Processes—II. Mechanical Processes— Voelter's Process for preparing Wood-pulp—Thune's Process | 68 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| TREATMENT OF VARIOUS FIBRES. | |

| Treatment of Straw—Bentley and Jackson's Boiler—Boiling the Straw—Bertrams' Edge-runner—M. A. C. Mellier's Process— Manilla, Jute, &c.—Waste Paper—Boiling Waste Paper—Ryan's Process for Treating Waste Paper | 80 |

| [ix] | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| BLEACHING. | |

| Bleaching Operations—Sour Bleaching—Bleaching with Chloride of Lime—Donkin's Bleach Mixer— Bleaching with Chlorine Gas (Glaser's Process)—Electrolytic Bleaching (C. Watt's Process)—Hermite's Process— Andreoli's Process—Thompson's Process—Lunge's Process—Zinc Bleach Liquor—Alum Bleach Liquor—New Method of Bleaching | 89 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| BEATING OR REFINING. | |

| Beating—Mr. Dunbar's Observations on Beating—Mr. Arnot on Beating Engines—Mr. Wyatt on American Refining Engines— The Beating Engine—Forbes' Beating Engine—Umpherston's Beating Engine—Operation of Beating—Test for Chlorine—Blending | 101 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| LOADING.—SIZING.—COLOURING. | |

| Loading—Sizing—French Method of preparing Engine Size—Zinc Soaps in Sizing—Colouring—Animal or Tub Sizing— Preparation of Animal Size—American Method of Sizing—Machine Sizing—Double-sized Paper—Mr. Wyatt's Remarks on Sizing | 114 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| MAKING PAPER BY HAND. | |

| The Vat and Mould—Making the Paper—Sizing and Finishing | 129 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| MAKING PAPER BY MACHINERY. | |

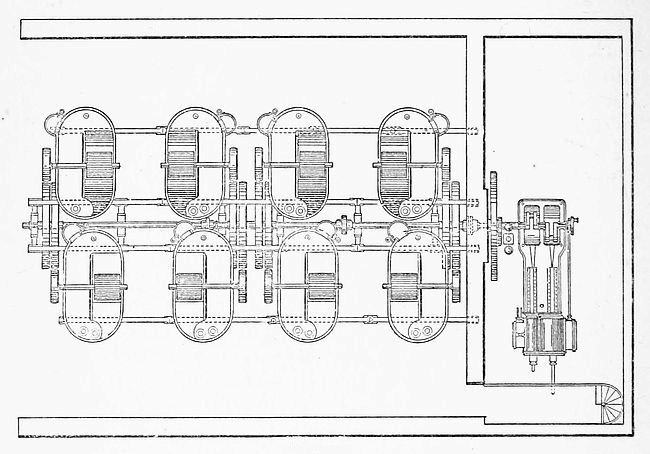

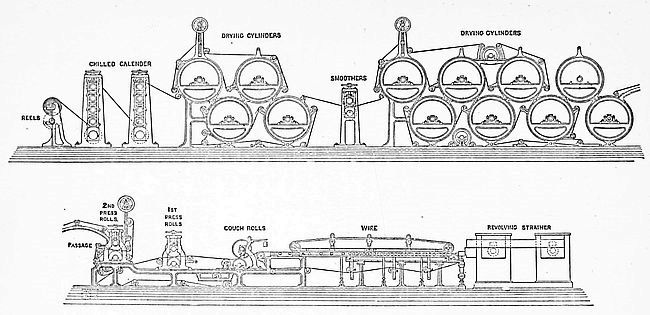

| The Fourdrinier Machine—Bertrams' Large Paper Machine—Stuff Chests—Strainers—Revolving Strainer and Knotter— [x] Self-cleansing Strainer—Roeckner's Pulp Strainers—The Machine Wire and its Accessories—Conical Pulp-Saver— The Dandy-Roll—Water-Marking—De la Rue's Improvements in Water-Marks—Suction Boxes—Couch Rolls—Press Rolls— Drying Cylinders—Smoothing Rolls—Single Cylinder Machines | 133 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| CALENDERING, CUTTING, AND FINISHING. | |

| Web-Glazing—Glazing Calender Damping Rolls—Finishing—Plate Glazing—Donkin's Glazing Press—Mr. Wyatt on American Super-Calendering—Mr. Arnot on Finishing—Cutting—Revolving Knife Cutter—Bertrams' Single-sheet Cutter— Packing the finished Paper—Sizes of Paper | 154 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| COLOURED PAPERS. | |

| Coloured Papers—Colouring Matters used in Paper-making—American Combinations for Colouring—Mixing Colouring Materials with Pulp— Colouring Paper for Artificial Flowers—Stains for Glazed Papers—Stains for Morocco Papers—Stains for Satin Papers | 165 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| MISCELLANEOUS PAPERS. | |

| Waterproof Paper—Scoffern and Tidcombe's Process—Dr. Wright's Process for preparing Cupro-Ammonium—Jouglet's Process— Waterproof Composition for Paper—Toughening Paper—Morfit's Process—Transparent Paper—Tracing Paper—Varnished Paper— Oiled Paper—Lithographic Paper—Cork Paper—New Japanese Paper—Blotting Paper—Parchment Paper—Mill and Cardboard— Making Paper or Cardboard with two Faces by ordinary Machine—Test Papers | 174 |

| [xi] | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| MACHINERY USED IN PAPER-MAKING. | |

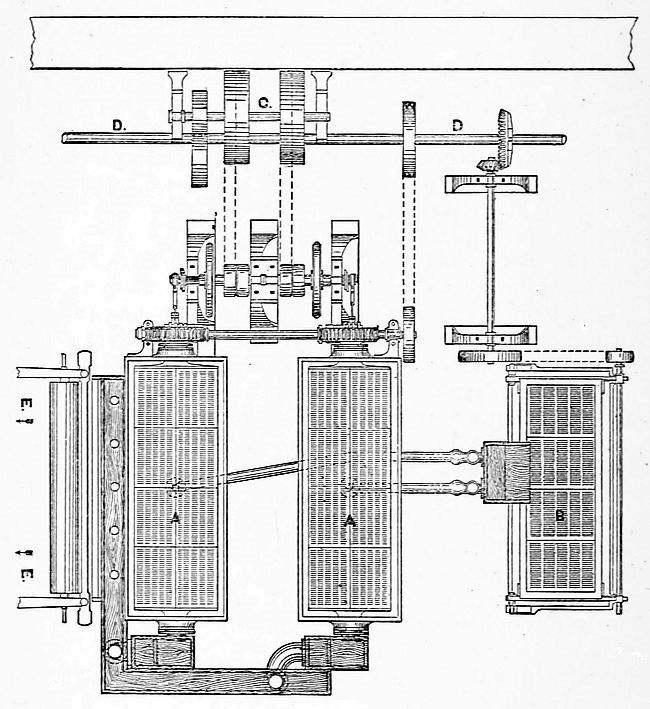

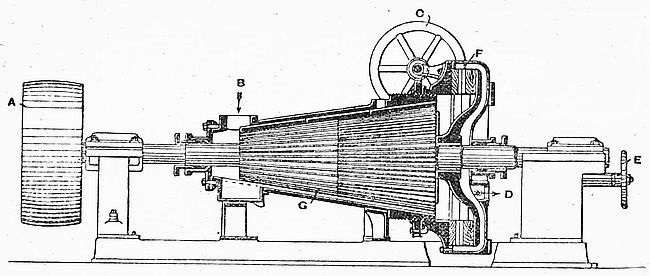

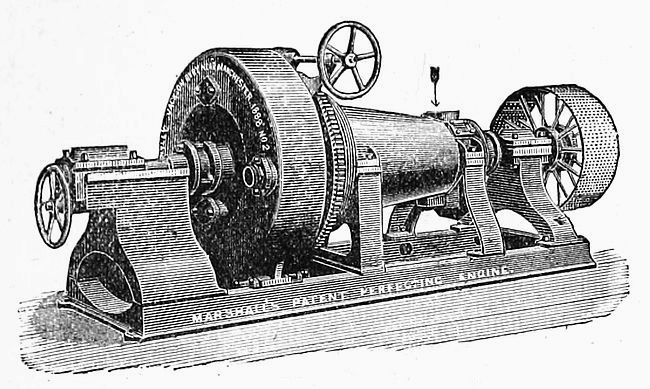

| Bentley and Jackson's Drum-Washer—Drying Cylinders—Self-acting Dry Felt Regulator—Paper Cutting Machine—Single-web Winding Machine— Cooling and Damping Rolls—Reversing or Plate-glazing Calender—Plate-planing Machine—Roll-bar Planing Machine—Washing Cylinder for Rag Engine— Bleach Pump—Three-roll Smoothing Presses—Back-water Pump—Web-glazing Calender—Reeling Machine—Web-ripping Machine— Roeckner's Clarifier—Marshall's Perfecting Engine | 184 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| RECOVERY OF SODA FROM SPENT LIQUORS. | |

| Recovery of Soda—Evaporating Apparatus—Roeckner's Evaporator—Porion's Evaporator—Yaryan's Evaporator—American System of Soda Recovery | 204 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| DETERMINING THE REAL VALUE OR PERCENTAGE OF COMMERCIAL SODAS, CHLORIDE OF LIME, ETC. | |

| Examination of Commercial Sodas—Mohr's Alkalimeter—Preparation of the Test Acid—Sampling Alkalies—The Assay—Estimation of Chlorine in Bleaching Powder—Fresenius' Method—Gay-Lussac's Method—The Test Liquor—Testing the Sample—Estimation of Alumina in Alum Cake, &c. | 221 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| USEFUL NOTES AND TABLES. | |

| Preparation of Lakes—Brazil-wood Lake—Cochineal Lake—Lac Lake—Madder Lake—Orange Lake—Yellow Lake—Artificial Ultramarine— Twaddell's Hydrometer—Imitation Manilla from Wood-pulp—Testing Ultramarines—Strength of Paper | 235 |

| [xii] | |

| Tables.—Dalton's Table showing the Proportion of Dry Soda in Leys of different Densities—Table of Strength of Caustic Soda Solutions at 59° F. = 150° C. (Tünnerman)—Table showing the Specific Gravity corresponding with the Degrees of Baumé's Hydrometer—Table of Boiling Points of Alkaline Leys— Table showing the Quantity of Caustic Soda in Leys of different Densities—Table showing the Quantity of Bleaching Liquid at 6° Twaddell (specific gravity 1·030) required to be added to Weaker Liquor to raise it to the given Strengths—Comparative French and English Thermometer Scales—Weights and Measures of the Metrical System—Table of French Weights and Measures | 241 |

| List of Works relating to Paper Manufacture | 246 |

THE ART

OF

PAPER-MAKING.

CELLULOSE.

Cellulose.—Action of Acids on Cellulose.—Physical Characteristics of Cellulose.—Micrographic Examination of Vegetable Fibres.—Determination of Cellulose.—Recognition of Vegetable Fibres by the Microscope.

Cellulose.—Vegetable fibre, when deprived of all incrusting or cementing matters of a resinous or gummy nature, presents to us the true fibre, or cellulose, which constitutes the essential basis of all manufactured paper. Fine linen and cotton are almost pure cellulose, from the fact that the associated vegetable substances have been removed by the treatment the fibres were subjected to in the process of their manufacture; pure white, unsized, and unloaded paper may also be considered as pure cellulose from the same cause. Viewed as a chemical substance, cellulose is white, translucent, and somewhat heavier than water. It is tasteless, inodorous, absolutely innutritious, and is insoluble in water, alcohol, and oils. Dilute acids and alkalies, even when hot, scarcely affect it. By prolonged boiling in dilute acids, however, cellulose undergoes a gradual change, being converted into hydro-cellulose. It is also affected by boiling water alone, especially under high pressure, if boiled for a lengthened period. Without going deeply into the chemical properties of cellulose,[2] which would be more interesting to the chemist than to the paper manufacturer, a few data respecting the action of certain chemical substances upon cellulose will, it is hoped, be found useful from a practical point of view, especially at the present day, when so many new methods of treating vegetable fibres are being introduced.

Action of Acids on Cellulose.—When concentrated sulphuric acid is added very gradually to about half its weight of linen rags cut into small shreds, or strips of unsized paper, and contained in a glass vessel, with constant stirring, the fibres gradually swell up and disappear, without the evolution of any gas, and a tenacious mucilage is formed which is entirely soluble in water. If, after a few hours, the mixture be diluted with water, the acid neutralised with chalk, and after filtration, any excess of lime thrown down by cautiously adding a solution of oxalic acid, the liquid yields, after a second filtration and the addition of alcohol in considerable excess, a gummy mass which possesses all the characters of dextrin. If instead of at once saturating the diluted acid with chalk, we boil it for four or five hours, the dextrin is entirely converted into grape sugar (glucose), which, by the addition of chalk and filtration, as before, and evaporation at a gentle heat to the consistence of a syrup, will, after repose for a few days, furnish a concrete mass of crystallised sugar. Cotton, linen, or unsized paper, thus treated, yield fully their own weight of gum and one-sixth of their weight of grape sugar. Pure cellulose is readily attacked by, and soon becomes dissolved in, a solution of oxide of copper in ammonia (cuprammonium), and may again be precipitated in colourless flakes by the addition of an excess of hydrochloric acid, and afterwards filtering and washing the precipitate. Concentrated boiling hydrochloric acid converts cellulose into a fine powder, without, however, altering its composition, while strong nitric acid forms nitro-substitution products of various degrees, according to the strength of the acid employed. "Chlorine gas passed into water in which cellulose is suspended rapidly oxidises[3] and destroys it, and the same effect takes place when hypochlorites, such as hypochlorite of calcium, or bleaching liquors, are gently treated with it. It is not, therefore, the cellulose itself which we want the bleaching liquor to operate upon, but only the colouring matters associated with it, and care must be taken to secure that the action intended for the extraneous substances alone does not extend to the fibre itself. Caustic potash affects but slightly cellulose in the form in which we have to do it, but in certain less compact conditions these agents decompose or destroy it."—Arnot.[1]

Physical Characteristics of Cellulose.—"The physical condition of cellulose," says Mr. Arnot, "after it has been freed from extraneous matters by boiling, bleaching, and washing, is of great importance to the manufacturer. Some fibres are short, hard, and of polished exterior, while others are long, flexible, and barbed, the former, it is scarcely necessary to say, yielding but indifferent papers, easily broken and torn, while the papers produced from the latter class of fibres are possessed of a great degree of strength and flexibility. Fibres from straw, and from many varieties of wood, may be taken as representatives of the former class, those from hemp and flax affording good illustrations of the latter. There are, of course, between these extremes all degrees and combinations of the various characteristics indicated. It will be readily understood that hard, acicular[2] fibres do not felt well, there being no intertwining or adhesion of the various particles, and the paper produced is friable. On the other hand, long, flexible, elastic fibres, even though comparatively smooth in their exterior, intertwine readily, and felt into a strong tough sheet.... Cotton fibre is long and tubular, and has this peculiarity, that when dry the tubes collapse and twist on their axes, this property greatly assisting the adhesion of the particles in the process of paper-making. In the process of dyeing cotton, [4]the colouring matter is absorbed into the tubes, and is, as will be readily appreciated, difficult of removal therefrom. Papers made exclusively of cotton fibre are strong and flexible, but have a certain sponginess about them which papers made from linen do not possess."

Linen—the cellulose of the flax-plant—before it reaches the hands of the paper-maker has been subjected to certain processes of steeping or retting, and also subsequent boilings and bleachings, by which the extraneous matters have been removed, and it therefore requires but little chemical treatment at his hands. "Linen fibre," Arnot further observes, "is like cotton, tubular, but the walls of the tubes are somewhat thicker, and are jointed or notched like a cane or rush; the notches assist greatly in the adhesion of the fibres one to another. This fibre possesses the other valuable properties of length, strength, and flexibility, and the latter property is increased when the walls of the tubes are crushed together under the action of the beating-engine." From this fibre a very strong, compactly felted paper is made; indeed, no better material than this can be had for the production of a first-class paper. Ropes, coarse bags, and suchlike are made from hemp, the cellulose or fibre of which is not unlike that of flax, only it is of a stronger, coarser nature. Manilla[3] yields the strongest of all fibres. Jute, which is the fibre or inside bark of an Indian plant (Corchorus capsularis), yields a strong fibre, but is very difficult to bleach white. Esparto fibre holds an intermediate place between the fibres just described and those of wood and straw.... The fibre of straw is short, pointed, and polished, and cannot of itself make a strong paper. The nature of wood fibre depends, as may readily be supposed, upon the nature of the wood itself. Yellow pine, for example, yields a fibre long, soft, and flexible, in fact very like cotton; while oak and many other woods yield short circular fibres which, unless perfectly free from extraneous matters, possess no flexibility, and in any case are not elastic.

Micrographic Examination of Vegetable Fibres.—The importance of the microscope in the examination of the various fibres that are employed in paper manufacture will be readily evident from the delicate nature of the cellulose to be obtained therefrom.[4] Amongst others M. Girard has determined, by this method of examination, the qualities which fibres ought to possess to suit the requirements of the manufacturer. He states that absolute length is not of much importance, but that the fibre should be slender and elastic, and possess the property of turning upon itself with facility. Tenacity is of but secondary importance, for when paper is torn the fibres scarcely ever break. The principal fibres employed in paper-making are divided into the following classes:—

1. Round, ribbed fibres, as hemp and flax.

2. Smooth, or feebly-ribbed fibres, as esparto, jute, phormium (New Zealand flax), dwarf palm, hop, and sugar-cane.

3. Fibro-cellular substances, as the pulp obtained from the straw of wheat and rye by the action of caustic ley.

4. Flat fibres, as cotton, and those obtained by the action of caustic ley upon wood.

5. Imperfect substances, as the pulp obtained from sawdust. In this class may also be included the fibre of the so-called "mechanical wood pulp."

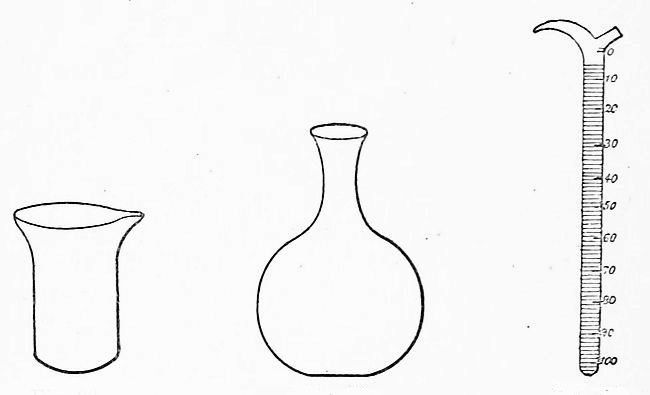

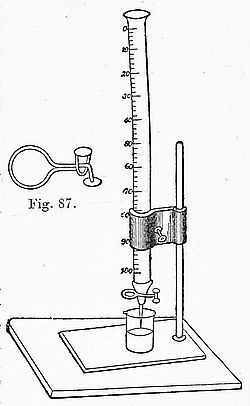

Determination of Cellulose. For the determination of cellulose in wood and other vegetable fibres to be used in paper-making Müller recommends the following processes:[5] 5 grammes weight of the finely-divided substance is boiled four or five times in water, using 100 cubic centimètres[6] each time. The residue is then dried at 100° C. (212° Fahr.), weighed, and exhausted with a mixture of equal measures of benzine and strong alcohol, to [6]remove fat, wax, resin, &c. The residue is again dried and boiled several times in water, to every 100 c.c. of which 1 c.c. of strong ammonia has been added. This treatment removes colouring matter and pectous[7] substances. The residue is further bruised in a mortar if necessary, and is then treated in a closed bottle with 250 c.c. of water, and 20 c.c. of bromine water containing 4 c.c. of bromine to the litre.[8] In the case of the purer bark-fibres, such as flax and hemp, the yellow colour of the liquid only slowly disappears, but with straw and woods decolorisation occurs in a few minutes, and when this takes place more bromine water is added, this being repeated until the yellow colour remains, and bromine can be detected in the liquid after twelve hours. The liquid is then filtered, and the residue washed with water and heated to boiling with a litre of water containing 5 c.c. of strong ammonia. The liquid and tissue are usually coloured brown by this treatment. The undissolved matter is filtered off, washed, and again treated with bromine water. When the action seems complete the residue is again heated with ammoniacal water. This second treatment is sufficient with the purer fibres, but the operation must be repeated as often as the residue imparts a brownish tint to the alkaline liquid. The cellulose is thus obtained as a pure white body; it is washed with water, and then with boiling alcohol, after which it may be dried at 100° C. (212° Fahr.) and weighed.

Recognition of Vegetable Fibres by the Microscope.—From Mr. Allen's admirable and useful work on "Commercial Organic Analysis"[9] we make the following extracts, but must refer the reader to the work named for fuller information upon this important consideration of the subject. In examining fibres under the microscope, [7]it is recommended that the tissues should be cut up with sharp scissors, placed on a glass slide, moistened with water, and covered with a piece of thin glass. Under these conditions:—

Filaments of Cotton appear as transparent tubes, flattened and twisted round their axes, and tapering off to a closed point at each end. A section of the filament somewhat resembles the figure 8, the tube, originally cylindrical, having collapsed most in the middle, forming semi-tubes on each side, which give the fibre, when viewed in certain lights, the appearance of a flat ribbon, with the hem of the border at each edge. The twisted, or corkscrew form of the dried filament of cotton distinguishes it from all other vegetable fibres, and is characteristic of the matured pod, M. Bauer having found that the fibres of the unripe seed are simply untwisted cylindrical tubes, which never twist afterwards if separated from the plant. The matured fibres always collapse in the middle as described, and undergo no change in this respect when passing through all the various operations to which cotton is subject, from spinning to its conversion into pulp for paper-making.

Linen, or Flax Fibre, under the microscope, appears as hollow tubes, open at both ends, the fibres being smooth, and the inner tube very narrow, and joints, or septa,[10] appear at intervals, but are not furnished with hairy appendages as is the case with hemp. When flax fibre is immersed in a boiling solution of equal parts of caustic potash and water for about a minute, then removed and pressed between folds of filter-paper, it assumes a dark yellow colour, whilst cotton under the same treatment remains white or becomes very bright yellow. When flax, or a tissue made from it, is immersed in oil, and then well pressed to remove excess of the liquid, it remains translucent, while cotton, under the same conditions, becomes opaque.

New Zealand Flax (Phormium tenax) may be distinguished from ordinary flax or hemp by a reddish colour produced on immersing it first in a strong chlorine water, and then in ammonia. In machine-dressed New Zealand flax the bundles are translucent and irregularly covered with tissue; spiral fibres can be detected in the bundles, but less numerous than in Sizal. In Maori-prepared phormium the bundles are almost wholly free from tissue, while there are no spiral fibres.

Hemp Fibre resembles flax, and exhibits small hairy appendages at the joints. In Manilla hemp the bundles are oval, nearly opaque, and surrounded by a considerable quantity of dried-up cellular tissue composed of rectangular cells. The bundles are smooth, very few detached ultimate fibres are seen, and no spiral tissue.

Sizal, or Sisal Hemp (Agave Americana), forms oval fibrous bundles surrounded by cellular tissue, a few smooth ultimate fibres projecting from the bundles; is more translucent than Manilla, and a large quantity of spiral fibres are mixed up in the bundles.

Jute Fibre appears under the microscope as bundles of tendrils, each being a cylinder, with irregular thickened walls. The bundles offer a smooth cylindrical surface, to which the silky lustre of jute is due, and which is much increased by bleaching. By the action of hypochlorite of soda the bundles of fibres can be disintegrated, so that the single fibres can be readily distinguished under the microscope. Jute is coloured a deeper yellow by sulphate of aniline than is any other fibre.

MATERIALS USED IN PAPER-MAKING.

Raw Materials.—Rags.—Disinfecting Machine.—Straw.—Esparto Grass.—Wood.—Bamboo.—Paper Mulberry.

In former days the only materials employed for the manufacture of paper were linen and cotton rags, flax and hemp waste, and some few other fibre-yielding materials. The reduction of the excise duty, however, from 3d. to 1½d. per lb., which took effect in the first year of Her Majesty's reign—namely, in 1837—created a greatly increased demand for paper, and caused much anxiety amongst manufacturers lest the supply of rags should prove inadequate to their requirements. Again, in the year 1861 the excise duty was totally abolished, from which period an enormously increased demand for paper, and consequently paper material, was created by the establishment of a vast number of daily and weekly papers and journals in all parts of the kingdom, besides reprints of standard and other works in a cheap form, the copyright of which had expired. It is not too much to say, that unless other materials than those employed before the repeal of the paper duty had been discovered, the abolition of the impost would have proved but of little service to the public at large. Beneficent Nature, however, has gradually, but surely and amply, supplied our needs through the instrumentality of man's restless activity and perseverance.

The following list comprises many of the substances from which cellulose, or vegetable fibre, can be separated for the purposes of paper-making with advantage; but the[10] vegetable kingdom furnishes in addition a vast number of plants and vegetables which may also be used with the same object. We have seen voluminous lists of fibre-yielding materials which have been suggested as suitable for paper-making, but since the greater portion of them are never likely to be applied to such a purpose, we consider the time wasted in proposing them. It is true that the stalks of the cabbage tribe, for example, would be available for the sake of their fibre, but we should imagine that no grower of ordinary intelligence would deprive his ground of the nourishment such waste is capable of returning to the soil, by its employment as manure, to furnish a material for paper-making. Again, we have seen blackberries, and even the pollen (!) of plants included in a list of paper materials, but fortunately the manufacturer is never likely to be reduced to such extremities as to be compelled to use materials of this nature.

Raw Materials.

Cotton rags.

Cotton wool.

Cotton waste.

Cotton-seed waste.

Linen rags.

Linen waste.

Hemp waste.

Manilla hemp.

Flax waste, etc.

Jute waste, etc.

China grass.

Bamboo cane.

Rattan cane.

Banana fibre.

Straw of wheat, etc.

Rushes of various kinds.

New Zealand flax.

Maize stems, husks, etc.

Esparto grass.

Reeds.

Woods of various kinds, especially white non-resinous woods, as poplar, willow, etc.

Wood shavings, sawdust, and chips.

Old netting.

Sailcloth.

Sea grass (Zostera marina).

Fibrous waste resulting from pharmaceutical preparations.

Potato stalks.

Stable manure.

Barks of various trees, especially of the paper mulberry.

Peat.

Twigs of common broom and heather.

Mustard stems after threshing.

Buckwheat straw.

Tobacco stalks.

Beetroot refuse from sugar works.

Megass, or "cane trash"—refuse of the sugar cane after the juice has been extracted.

Fern leaves.

Tan waste.

Dyers' wood waste.

Old bagging.

Old bast matting.

Hop-bines.

Bean stalks.

Old canvas.

Old rope.

Gunny bags.

Waste paper.

Binders' clippings, etc.

Silk cocoon waste.

Oakum.

Flax tow.

Rag bagging.

Leather waste.

Tarpaulin. Etc., etc.

Rags.—Linen and cotton rags are imported into Great Britain from almost all the countries of Europe, and even from the distant states of South America, British South Africa, and Australasia. The greater proportion, however, come from Germany. The rags collected in England chiefly pass through the hands of wholesale merchants established in London, Liverpool, Manchester, and Bristol, and these are sorted to a certain extent before they are sent to the paper-mills. By this rough sorting, which does not include either cleansing or disinfecting, certain kinds of rags which would be useless to the paper-maker are separated and sold as manure. Woollen rags are not usually mixed with cotton rags, but are generally kept apart to be converted into "shoddy." The importance of disinfecting rags before they pass through the hands of the workpeople employed at the paper-mills cannot be over-estimated, and it is the duty of every Government to see that this is effectually carried out, not only at such times when cholera and other epidemics are known to be rife in certain countries from which rags may be imported, but at all times, since there is no greater source of danger to the health of communities than in the diffusion of old linen and cotton garments, or pieces, which are largely contributed by the dwellers in the slums of crowded cities.

Respecting the disinfecting of rags, Davis[11] thus explains the precautions taken in the United States to guard against the dangers of infection from rags coming from foreign or other sources. "When cholera, or other infectious or contagious diseases exist in foreign countries, or in portions of the United States, the health officers in charge of the various quarantines in this country require[12] that rags from countries and districts in which such diseases are prevalent shall be thoroughly disinfected before they are allowed to pass their stations. Rags shipped to London, Hull, Liverpool, Italian, or other ports, and re-shipped from such ports to the United States, are usually subjected to the same rule as if shipped direct from the ports of the country in which such diseases prevail. It is usually requisite that the disinfection shall be made at the storehouse in the port of shipment, by boiling the rags several hours under a proper degree of pressure, or in a tightly-closed vessel, or disinfected with sulphurous acid, which is evolved by burning at least two pounds of roll sulphur to every ten cubic feet of room space, the apartment being kept closed for several hours after the rags are thus treated. Disinfection by boiling the rags is usually considered to be the best method. In the case of rags imported from India, Egypt, Spain, and other foreign countries where cholera is liable to become epidemic, it is especially desirable that some efficient, rapid, and thorough process of disinfecting should be devised. In order to meet the quarantine requirements, it must be thorough and certain in its action, and in order that the lives of the workmen and of others in the vicinity may not be endangered by the liberating of active disease-germs, or exposure of decaying and deleterious matters, and that the delay, trouble, and exposure of unbaling and rebaling may be avoided, it must be capable of use upon the rags while in the bale, and of doing its work rapidly when so used."

Disinfecting Machine.—To facilitate the disinfecting of rags while in the bale, Messrs. Parker and Blackman devised a machine, for which they obtained a patent in 1884, from which the following abstract is taken.

Formerly rags and other fibrous materials were disinfected by being subjected to germ-destroying gases or liquids in enclosed chambers, but in order to render the disinfecting process effectual, it was found necessary to treat the material in a loose or separated state, no successful[13] method having been adopted for disinfecting the materials while in the bale. "This unbaling and loosening or spreading of the undisinfected material is absolutely unsafe and dangerous to the workmen, or to those in the vicinity, because of the consequent setting free of the disease germs, and the exposing of any decaying or deleterious matters which may be held in the material while it is compressed in the bale. The unbaling and necessary rebaling of the material for transportation also involves much trouble and expense and loss of time. Large and cumbrous apparatus is also necessary to treat large quantities of material loosened or opened out as heretofore."

It is specially necessary that rags coming from Egypt and other foreign countries should be thoroughly disinfected by some rapid and effectual means, which, while not endangering the health of workmen employed in this somewhat hazardous task, will fully meet all quarantine requirements. The apparatus devised by Messrs. Parker and Blackman,[12] an abridged description of which is given below, will probably accomplish this much-desired object.

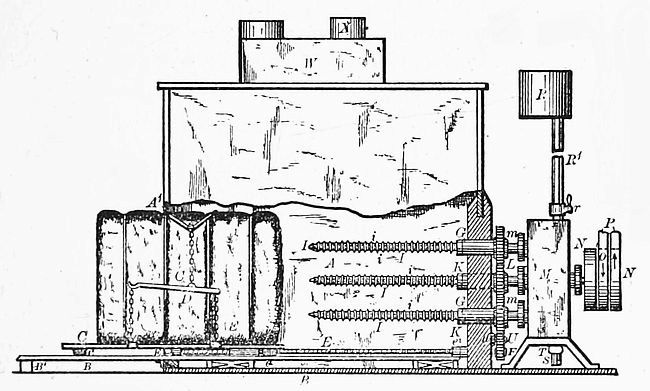

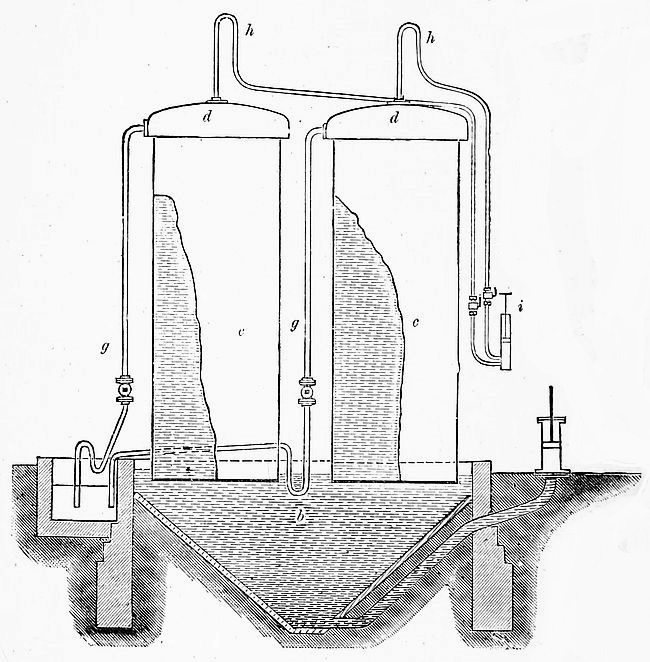

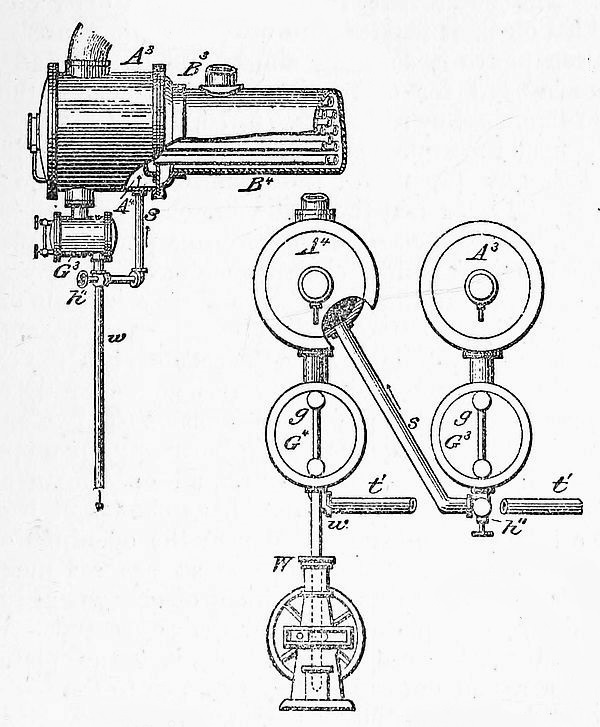

In the illustration, Fig. 1, A is the disinfecting chamber. At one end is an opening A1, and a door B, hinged at its lower edge and adapted to be swung up, so as to close the opening tightly. For supporting and carrying the bale C of material to be placed in the chamber is a carriage C1, consisting of a platform supported upon wheels or castors c c. While the carriage is wholly within the chamber A, as shown in Fig. 2, these wheels rest upon the false bottom B2; when the carriage is rolled back and out of the chamber, as shown in Fig. 1, they roll upon the upper face of door B swung down. The carriage is provided with a clamping device D to hold the bale firmly and immovably. To cause the carriage to move into and out of the chamber, the inventors provide upon the under side of the platform a fixed sleeve E, interiorly threaded to fit the screw E1, journalled at one end near the opening in the chamber end in a stationary block E2 fixed upon the false bottom B2. From this end the screw extends along under the carriage through the screw sleeve and to the other end of the chamber. A collar e2 on the screw bears against the inner end of this journal-bearing, and upon the end of the shank e bearing against the other end of the journal is fixed a pinion F, which is to be[15] driven in either direction as desired. Above this journal-bearing is a series of similar bearings (five being shown), G G, passing through the wall of the chamber. Of these the middle one is in a line with the centre of the bale, supported and held on the carriage. The others are arranged at the corners of a square. Journalled in these bearings are the hollow shanks H H of the hollow screws I I pointed at I1 I1. Each screw is perforated, i i, between the threads i1 i1 from the fixed collar K K. Upon the tubular shanks H H of the screws are fixed the gear-wheels L L. At a short distance from the end of the chamber, A is the hollow chamber or receptacle M, into which is to be forced the disinfectant liquid or gas. The tubular shanks H H of the screws project through the wall M, passing through stuffing-boxes m m, and their bores communicate with the interior of the chamber, the shank of the middle screw being continued through the opposite wall and a stuffing-box, its solid or projecting end being provided with two fixed pulleys, N N, and a loose pulley O. When a gaseous disinfectant is used, it can be forced by any desired means through the pipe S into the chamber. Where a liquid disinfectant is used, an elevated tank R containing the fluid may be used. As most fibrous materials, and especially rags, are baled so as to be in layers, it is preferable so to place the bale upon the carriage that the perforated screws may penetrate the material at right angles to the layers by which the gas or liquid issuing through the holes in the screws passes in all directions throughout the mass within the bale.

In the upper part of chamber A are perforated shelves V V, upon which, if desired, the material can be spread out and subjected to disinfecting gas or vapour. On the top of the chamber is a tank W nearly filled with disinfecting liquid. A passage W1 extends from upper part of the chamber up into the tank above the level of the liquid therein, and is then carried at its end down below the surface of the liquid. At its other end the tank is provided at its top with a discharge opening X and a suitable pipe[16] X1, forming a continuation of the opening; by this means all foul and deleterious vapours or gases passing out of the closed chamber A through the passage W must pass through the disinfecting liquid in the tank before escaping through the opening X and stack X1 into the air, and are thus rendered harmless.

When a sufficient amount of the disinfectant has been forced into and through the bale, the disinfectant is turned off, and cold dry air can be forced through chamber M, and out through the nozzles and bale, whereby the material within the bale becomes cooled and dried, and all the foul air from the chamber A driven out, so that it may be opened and entered with safety. Any suitable disinfectant may be used with this apparatus, as, for example, sulphurous acid, in gas or solution, superheated steam, carbolic acid, or any solution or vapour containing chlorine.

Straw.—Very large quantities of this material are used in the manufacture of paper, but more especially for newspapers, the straw from wheat and oats being mostly employed. Although the percentage of cellulose in straw is about equal to that of esparto, the severe treatment it requires to effectually remove the silicious coating by which the fibre is protected, and to render the knots amenable to the action of the bleach, greatly reduces the yield of finished pulp. Many processes have been introduced for the treatment of straw for paper-making, but the most successful of them appear to be modifications of a process introduced in 1853 by MM. Coupier and Mellier.

Esparto Grass.—This important fibrous material is largely imported from Algeria, Spain, and other countries, and constitutes one of the most valuable fibre-yielding materials with which the manufacturer has to deal. Some idea of the amount of esparto and other fibres which find their way to our shores may be gleaned from the fact that while the import of cotton and linen rags in the year 1884 was 36,233 tons, of the value of £487,866, that of esparto[17] and other fibres amounted to 184,005 tons, of the value of £1,125,553.

Wood.—As a paper-making material, the fibre obtained from various kinds of wood now holds an important position, since the sources of supply are practically inexhaustible. The first practical process for manufacturing pulp from wood fibre was perfected and introduced by the author's father, the late Mr. Charles Watt, who, in conjunction with Mr. H. Burgess, obtained a patent for the invention on August 19th, 1853. The process was afterwards publicly exhibited at a small works on the Regent's Canal, when the Earl of Derby (then Lord Stanley), many scientific men and representatives of the press, were present, and expressed themselves well satisfied with its success. Specimens of the wood paper, including a copy of the Weekly Times printed thereon, were exhibited, as also some water-colour drawings which had been produced upon paper made from wood pulp. Failing to get the process taken up in England, an American patent was applied for and obtained in 1854, which was subsequently purchased; but with the exception of an instalment, the purchase-money was never paid to the inventor! Thus the process "got" into other hands, the original inventor alone being unbenefited by it.

It has been repeatedly stated,[13] no doubt unwittingly, that a person named Houghton first introduced the wood paper process into this country; but considering that his patent was not obtained until 1857, or four years after the process above referred to was patented and publicly exhibited in England, it will be seen that the statement is absolutely without foundation. The first knowledge Mr. Houghton received concerning wood as a paper-making material was from the author's father, and he (Mr. Houghton), in conjunction with Mr. Burgess, introduced the Watt and Burgess process into America in the year 1854. These are the facts.

Bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris).—The leaves and fresh-cut stems of this plant are used for paper material, but require to pass through a preliminary process of crushing, which is effected by suitable rolls, the second series of crushing rolls being grooved or channelled to split or divide the material, after which the stems are cut to suitable lengths for boiling.

Paper Mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera).—The inner bark of this tree, and also some other basts, have long been used by the Japanese and Chinese in the manufacture of paper of great strength, but of extreme delicacy.

TREATMENT OF RAGS.

Preliminary Operations.—Sorting.—Cutting.—Bertrams' Rag-cutting Machine.—Nuttall's Rag-cutter.—Willowing.—Bertrams' Willow and Duster.—Dusting.—Bryan Donkin's Duster or Willow.—Donkin's "Devil."

Preliminary Operations.—Before the rags are submitted to the various processes which constitute the art of paper-making, they are subjected to certain preliminary operations to free them from dirty matters, dust, and even sand, which is sometimes fraudulently introduced into rags to increase their weight. This preliminary treatment may be classified under the following heads, namely:—Sorting; Cutting; Willowing; Dusting.

Sorting.—The rags being removed from the bags or bales in which they are packed, require first to be sorted according to the nature and quality of the fabrics of which they are composed; thus linen, cotton, hemp, wool, &c., must be carefully separated from each other; the thickness of the substance, its condition as to the wear it has undergone, and the colour of the material, all these considerations are taken into account by the women and girls who are employed in the operation of sorting. The finer qualities are set aside for writing-paper, inferior sorts being used separately, or mixed, according to the requirements of the manufacturer. Blue rags are generally separated from the rest and kept for the manufacture of blue paper, but most of the other coloured rags require bleaching. In sorting rags, a good deal of judgment and skill are required to avoid mixing the better qualities with those of an inferior class, which would occasion loss in the[20] manufacture. It is also important that those of inferior colour should not be mixed with the finer qualities, which would be liable to affect the colour and deteriorate the quality of the paper. Paper manufacturers generally classify the rags obtained from home sources, that is, from different parts of the United Kingdom, under the following heads:—

Home Rags.

New cuttings.

Linen pieces.

Cotton pieces.

Fines (whites).

Superfines (whites).

Outshots (whites).

Seconds (whites).

Thirds (whites).

Colours or prints.

Blues.

Gunny, clean.

Gunny, dirty.

Rope (white).

Rope (hard).

Rope, bagging, etc.

Foreign rags are distinguished as below:—

Belgian Rags.

White linens.

Mixed fines (linens and cottons).

Grey linens.

Strong linens.

Extra fine linens.

Blue linens.

Superfine white cottons.

Outshot cottons.

Seconds.

Half jute and linen.

Light prints.

Mixed prints.

Blue cottons.

Fustians.

Black calicoes.

White hemp, strings, and rope.

Tarred hemp, strings, and rope.

Jute spinners' waste.

Jute waste.

New.

White linens.

Grey linens.

Blue linens.

Unbleached cottons.

White linens and cottons.

Print cuttings (free from black).

Blacks.

Fustians.

French Rags.

French linens.

White cotton.

Knitted cotton.

Blue cotton.

Coloured cotton.

Black cotton.

Marseilles whites.

Light prints.

Mixed prints.

New white cuttings.

German Rags.

S. P. F. F. F.

S. P. F.

F. F.

F. G.

L. X. F.

L. F. R. blue.

C. S. P. F. F. F.

C. F. B. blue.

C. F. X. coloured.

Trieste.

P. P. white linen (first).

P. white linen (second).

S. fine greys.

X. coloured cottons.

Leghorn.

P. L. linens.

P. C. cottons.

S. C.

T. C.

Turkey and Beyrout.

Bright reds.

Alexandria.

Whites. Blues. Colours.

Baltic and Russian.

S. P. F. F.

S. P. F.

L. F. B.

F. G.

F. F.

B. G.

L. F. X.

Woollen rags are only used to a very moderate extent in blotting and filtering papers and also in coarse papers and wrappers. Many attempts have been made to bleach woollen rags, but the severity of the treatment required invariably ended in a destruction of the fibrous substances mingled with them. It is customary to dispose of such material for re-making into common cloths, and for shoddy. Rags collected in large cities, in consequence of the frequent bleachings they have been subjected to, are considerably weakened in fibre, tearing easily, and are therefore subject to loss in process of manufacture into pulp. Country rags, being coarser and greyer because less bleached, are stronger in fibre and give a better body to the paper. In sampling rags it is necessary to take precautions against the fraudulent "tricks of the trade," which are often resorted to to cheat the manufacturer. Samples should be taken from the interior of the bags[22] or bales, to ascertain if the material in the interior is equal in quality with that at the outside—that is to say, that the quality is fairly averaged throughout. It may also be found that the rags have been purposely wetted to increase their weight. If such is found to be the case, a few handfuls should be weighed, and then dried in a warm room, and afterwards re-weighed, when if the loss exceeds 5 to 7 per cent. it may be assumed that the rags have been fraudulently wetted. It is generally found, however, that the merchants in the principal towns transact their business honourably and are therefore reliable.

The sorting is generally performed by women, who not only separate the various qualities of the rags, which they place in separate receptacles, but also remove all buttons, hooks and eyes, india-rubber, pins and needles, &c., and loosen all seams, hems and knots. The rags are next carefully looked over by women called over-haulers, or over-lookers, whose duty it is to see that the previous operations have been fully carried out in all respects. Usually there is one over-hauler to every eight or ten cutters.

Cutting.—In some mills it is preferred to have the rags cut into pieces from 2 to 4 inches square, but the actual size is not considered of much importance. The chief object is to have them in such a condition that they may be thoroughly cleansed in subsequent operations, and able to float throughout the water in the rag-engine, without twisting round the roller. If the rag pieces are smaller than is required to effect this it tends to create a loss of fibre in the operations of willowing and dusting.

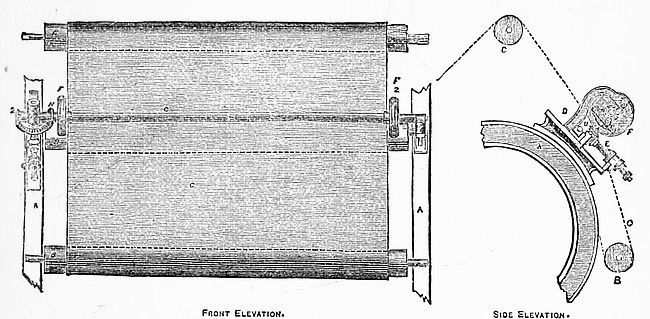

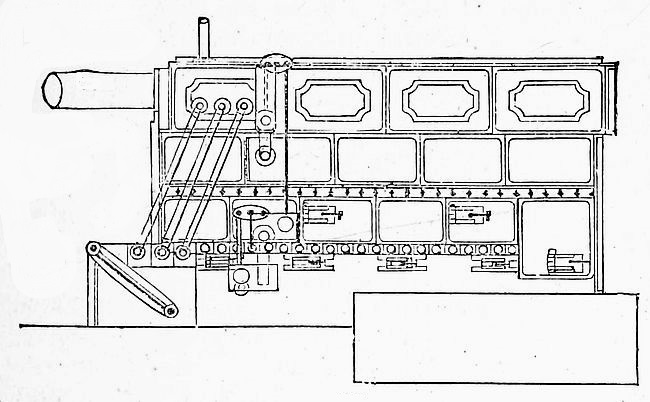

The process of cutting is performed by hand or by machinery. When the rags are cut by hand, the operation, which is accomplished by women, is conducted as follows:—The cutter takes her place in front of an oblong box, as in Fig. 3, covered with coarse wire netting, containing three threads per inch, through which dust, &c., passes to a receptacle beneath; in the centre is fixed,[23] in a slanting position, a large-bladed knife of peculiar form, with its back towards the operator, who is surrounded by a number of boxes, corresponding with the number of the different qualities of rags; these are lined at the bottom with coarse wire gauze. In the operation of cutting, if any foreign substances, such as buttons, hooks, &c., which may have escaped the sorters are found, these are at once removed. The rags as they are cut are put into baskets to be conveyed to the rag-engine room. In some mills rags are cut by machinery, but hand cutting is usually adopted for the better kinds of paper, as it is obvious that the machine would not be able to reject, as is the case in hand cutting, unpicked seams and other irregularities which may have escaped observation by the sorters and overhaulers. Machine cutting is, therefore, generally adopted for the materials which are to be used for the coarser papers. There are several rag-cutting machines in use, of which one or two examples are given below.

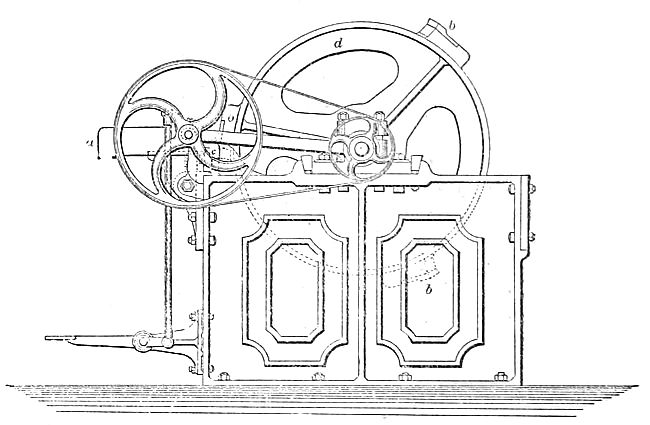

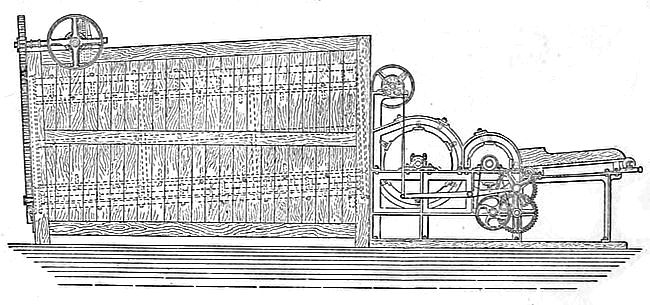

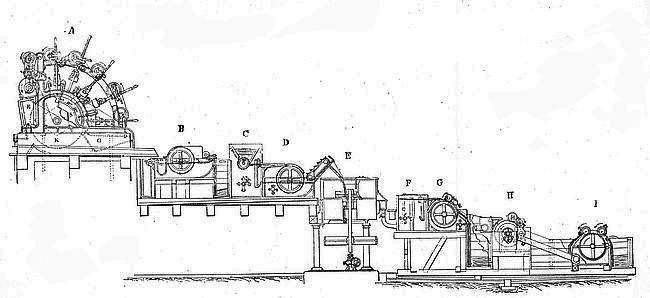

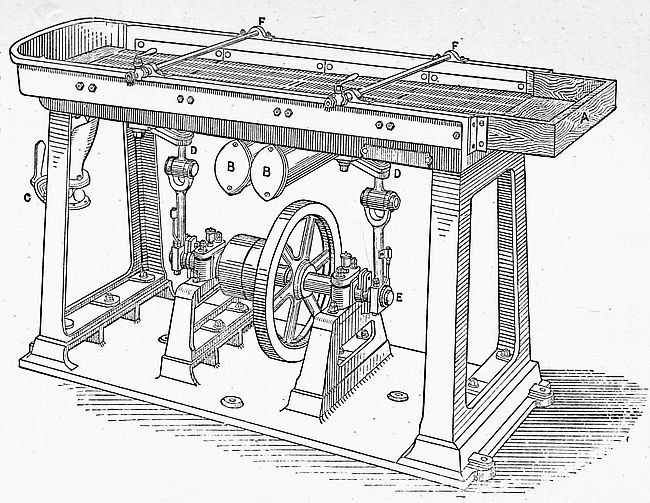

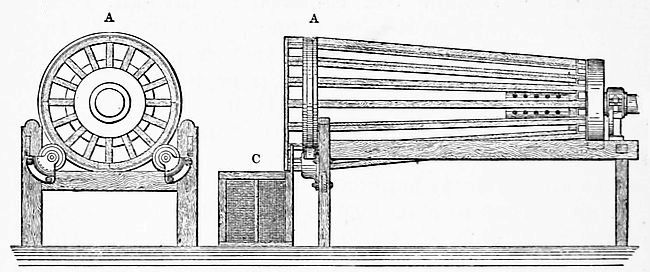

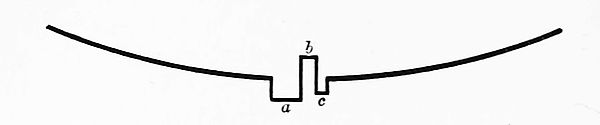

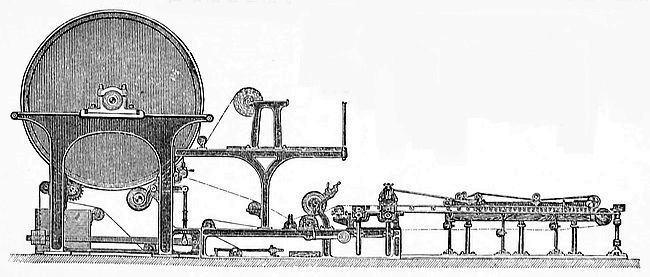

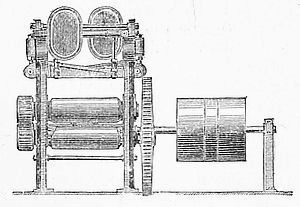

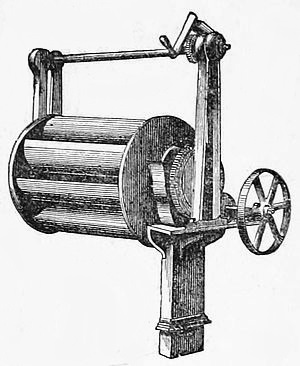

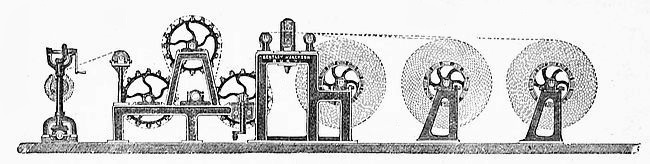

Bertrams' Rag-Cutting Machine.—The engraving, Fig. 4, represents a machine manufactured by Messrs. Bertrams, Limited, of St. Katherine's Works, Edinburgh, to whose courtesy we are indebted for this and other illustrations of their machinery, which have been reproduced in outline from their illustrated catalogue. The machine, which is suitable either for rags or ropes, has three revolving knives, and one dead knife, which is rendered reversible to four edges, and has self-acting feed gear, side frames, drum, and other connections of substantial construction; it is wood covered, and[24] furnished with sheet-iron delivery spout. The material passes into the machine along the table at a, where it passes between the dead knife c and the knives b fixed to the revolving drum d. The cut rags fall into a receptacle beneath the drum.

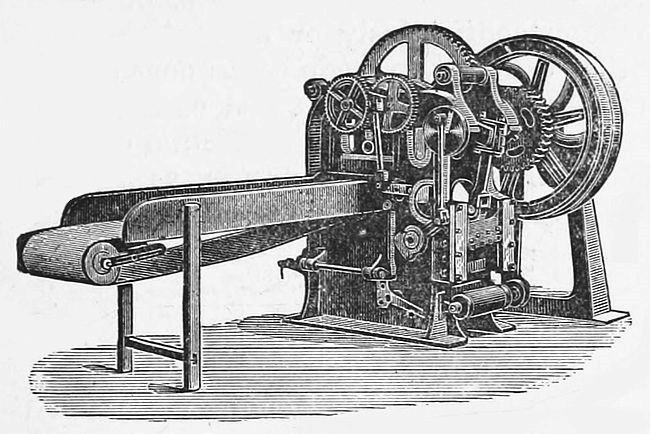

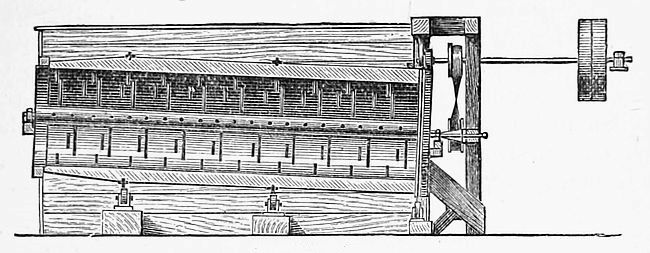

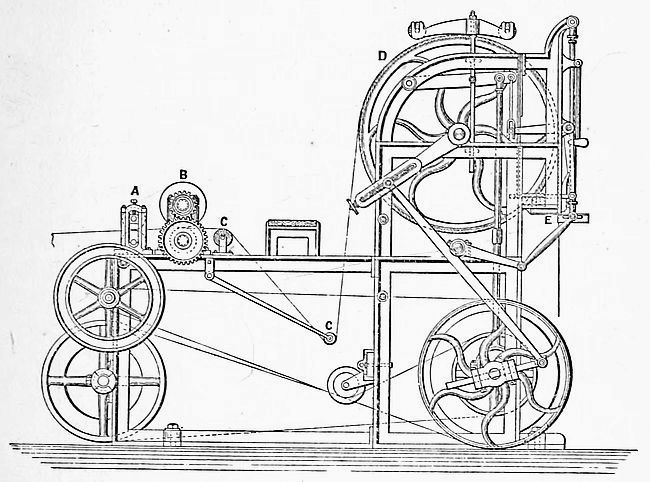

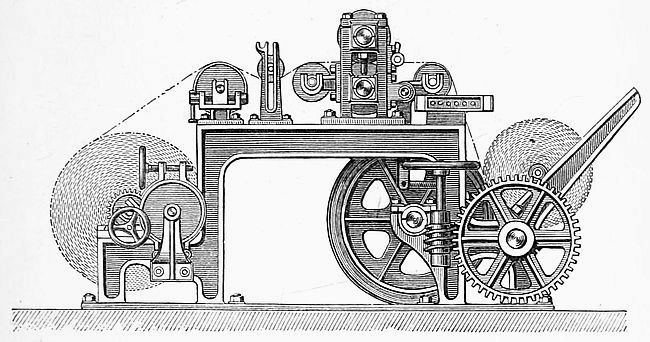

Nuttall's Rag Cutter.—Another type of rag cutter, and which is also suitable for cutting bagging, sailcloth, tarpaulin, Manilla and other fibres, is Nuttall's Rag Cutter, a drawing of which is shown in Fig. 5. This machine is manufactured by Messrs. Bentley and Jackson, of Bury, near Manchester, and is generally known as the "Guillotine Rag Cutter," from the principle of its action, which is that of chopping the material. The machine is adopted at many mills, and a large-sized machine has recently been put down at the Daily Telegraph mills, Dartford. A medium-sized machine will cut about one ton of rags in an hour.

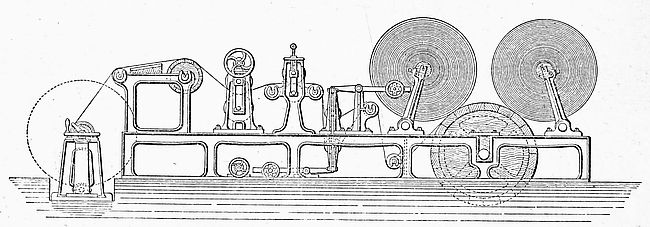

Willowing.—In some mills the cut rags are conveyed to a machine called the "willow," which in one form of machine consists of two cast-iron cylinders, 2½ feet in diameter[25] and 3½ feet wide, provided with numerous iron teeth, which project about 4 inches. These cylinders are placed one behind the other, and beneath them is a semi-circular screw, and above them a cover of the same form. This cover is also furnished with teeth, and is so adjusted that the teeth in the cylinders pass those in the cover at a distance of ½ to ¾ of an inch. In front are a pair of rollers and revolving apron, which carry the rags into the cylinders, which rotate rapidly; and the rags, which are thrown by the first into the second cylinder, are allowed to remain in them for about 20 seconds, when a sliding door, which rises three times per minute, allows the rags to be discharged into a duster. Each time the sliding door opens the revolving apron moves forward and recharges the willow with a fresh supply. The rags, after being beaten and teazed in the willow, are considerably loosened in texture, and a good deal of dust and gritty matters fall through the screen beneath.

Fig. 6 represents a combined willow and duster, specially useful for waste rags and jute, but may be used for all fibres, manufactured by Bertrams, Limited, the main features of which are thus described:—"There are two drums, which have malleable-iron cross-bars and teeth, and malleable-iron harp motion below for escape of dust.[26] The framework of the willow is of cast iron, and the sides are filled in with cast-iron panel doors, the top being covered in with sheet iron. The gear is arranged so that the willow will deliver to the duster or otherwise by self-acting motion continuously or intermittently. The feed to the willow can also be made continuous or intermittent. The drums, framework, panels, and casing being made of iron, the chance of fire from the friction of its working is reduced to a minimum. The duster, as a rule, is 12 feet long, about 5 feet in diameter, and has eight longitudinal bars of cast iron fitted between the front and end revolving rings. These bars are fitted with malleable-iron spikes, pitched and so arranged that the rags or fibres are delivered at the exit end automatically. The outside of the duster can be lined with wire-cloth, perforated zinc, iron, etc. It is driven by outside shafts and friction gear, so that there is no internal shaft to interfere with the delivery of the fibres."

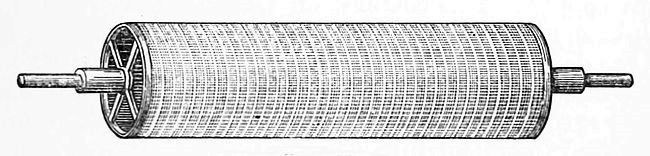

Dusting.—In Fig. 7 is shown a rag-dusting machine, manufactured by Messrs. Bryan Donkin and Co., of Bermondsey, London. The cylinder of this machine, which is conical in form, to enable the rags to travel from one end to the other, whence they are ejected, revolves, as also does a second cylinder of a skeleton form, but in the opposite direction. Each cylinder is fitted with knives, or spikes—those of the outer cylinder projecting[27] towards the centre; the knives of the centre cylinder being attached to its exterior surface: when the machine is in motion the two sets of blades pass each other so that when the rags come between them the action is that of scissors. When the rags are ejected at the end of the cylinder, they pass into another cylinder of wire, through which the dust falls and leaves them in a fairly clean condition, when they are lowered through a trap-door to the boiling room below.

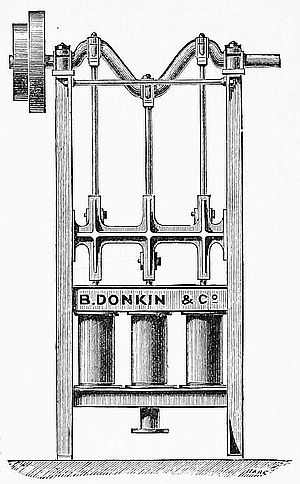

Donkin's "Devil."—For removing the dust and dirt from coarse and very dirty rags, oakum, rope, etc., the presence of which would seriously injure the quality of the paper, a still more powerful machine has been introduced,[28] called the "devil," which is constructed on the same principle as the willow, but revolves at a lower speed. The revolving axle of this machine is conical, and is provided with teeth, arranged in a spiral form. The case in which it rotates is fed continuously, instead of intermittently; and although it facilitates the subsequent treatment of the fibre, it is said to be wasteful, while also consuming a considerable amount of power. A machine, or "devil," for cleaning rags or half stuff is manufactured by Messrs. Donkin and Co., a representation of which is shown in Fig. 8.

TREATMENT OF RAGS (continued).

Boiling Rags.—Bertrams' Rag Boiler.—Donkin's Rag Boiler.—Washing and Breaking.—Bertrams' Rag Engine.—Bentley and Jackson's Rag Engine.—Draining.—Torrance's Drainer.

Boiling Rags.—To remove greasy matters, and also to dissolve out the cementing substances from the stems of flax and shell of the cotton, the rags are next boiled in a solution of caustic soda, caustic lime, or a mixture of carbonate of soda and lime. The boiling has also the effect of loosening the dirt contained in the rags, whereby the colour of the material is greatly improved, while at the same time it is rendered more susceptible to the action of the bleaching agent. Strong linen rags will sometimes lose from one-third to one-fifth of their weight by the process of boiling. The vessels for boiling rags are of various construction, and have been the subject of numerous ingenious patents. These boilers are either cylindrical or spherical, and are also stationary or rotary—the latter form being devised for the purpose of keeping the caustic alkali solution freely diffused throughout the mass of fibre during the boiling.

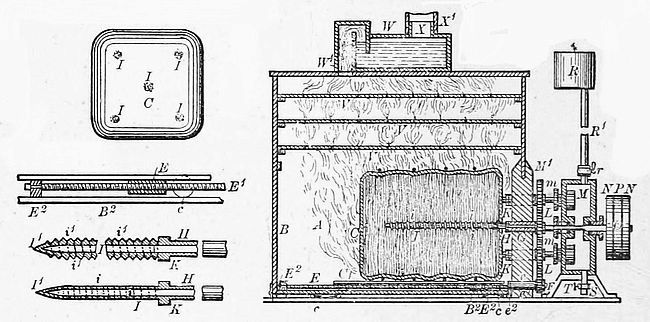

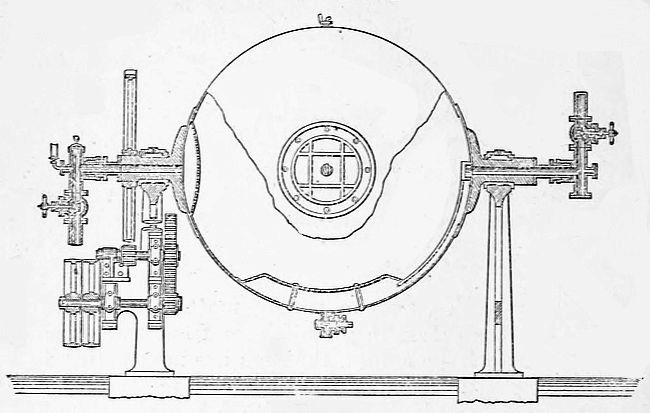

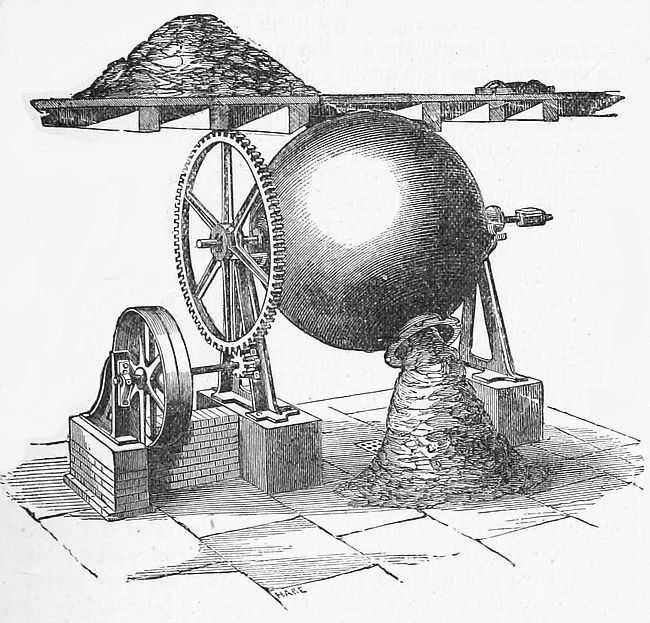

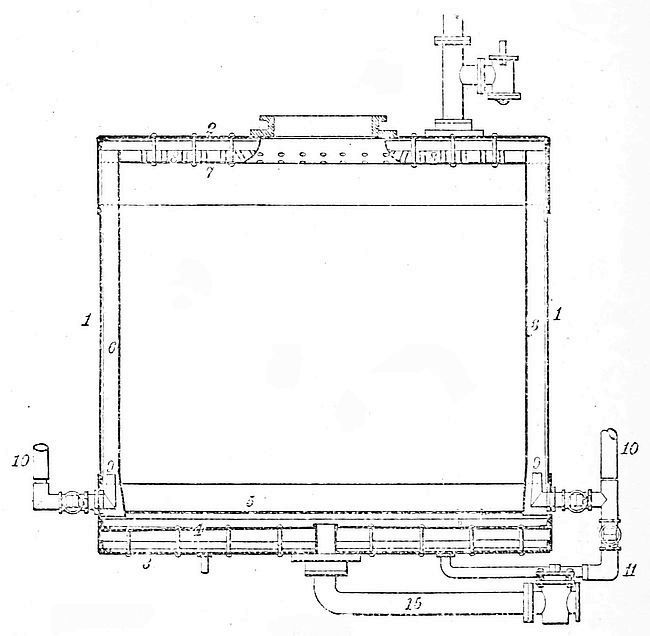

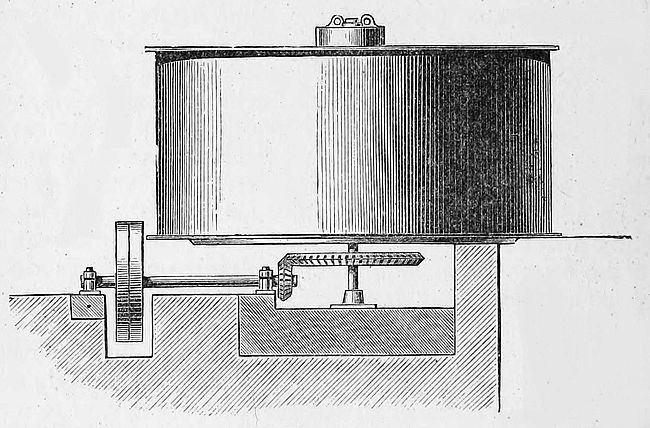

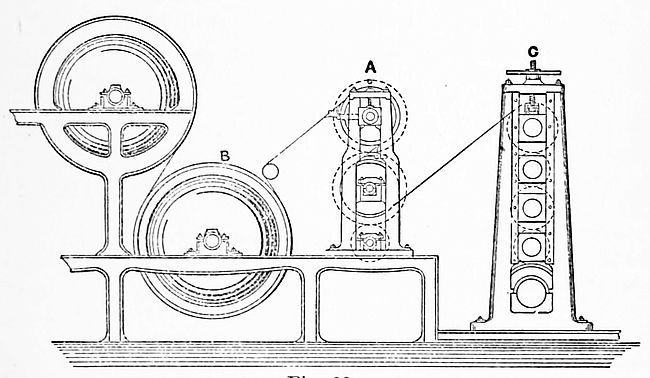

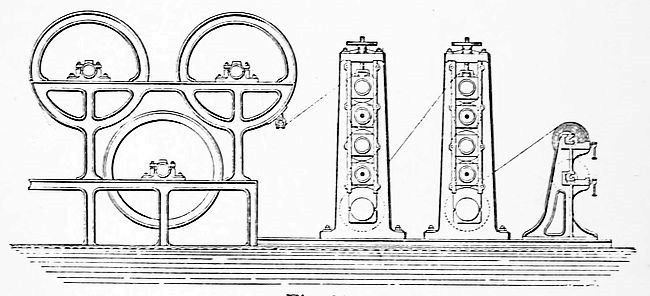

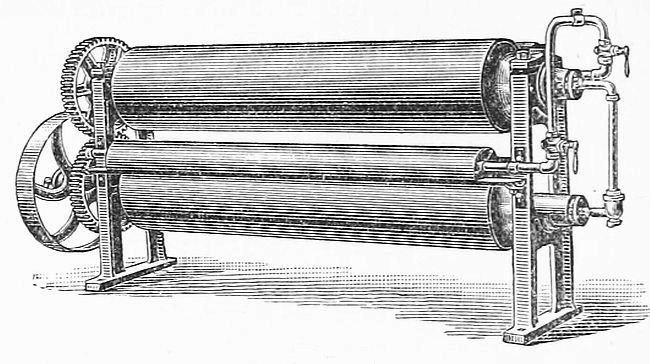

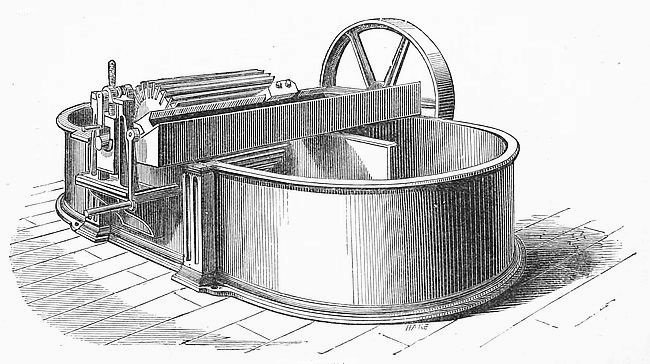

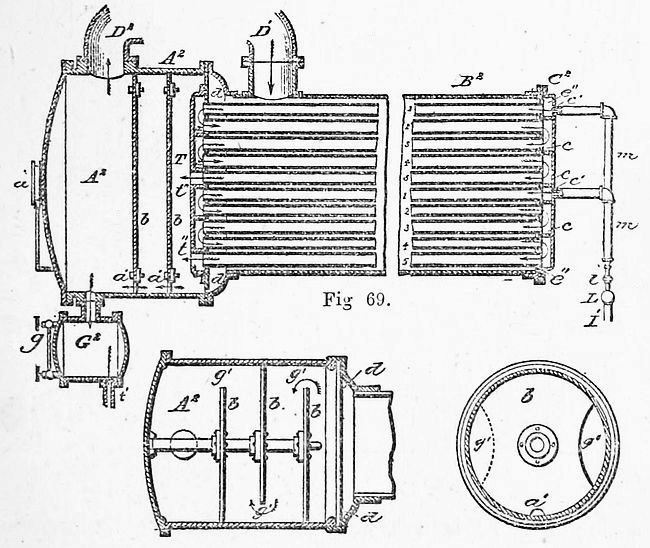

Bertrams' Rag Boiler.—An illustration of a spherical boiler, as manufactured by Bertrams, Limited, of Edinburgh, is given in Fig. 9. The shell of this boiler is made from malleable iron, is 8 feet in diameter and 9 feet deep. The boiler is constructed on what is termed the "vomiting" principle, by which a free circulation of the alkaline liquor is constantly maintained. These boilers are made to withstand any pressure of steam, but the size[30] given is usually worked at from 35 to 45 lbs. pressure, and carries about 30 cwt. of dry esparto.

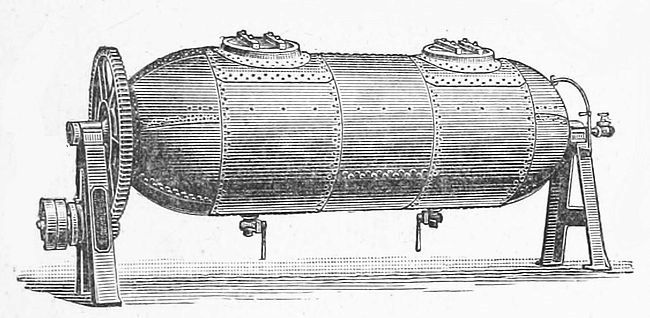

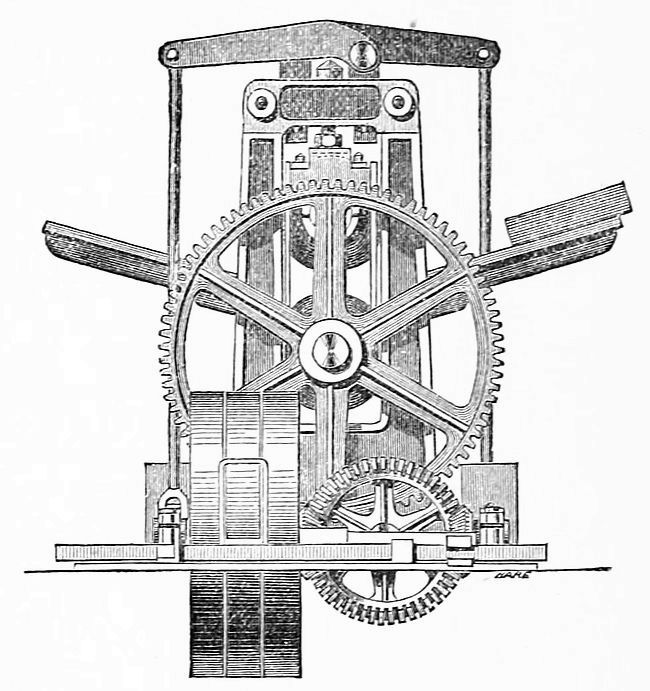

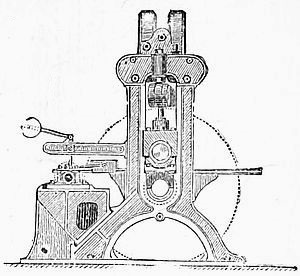

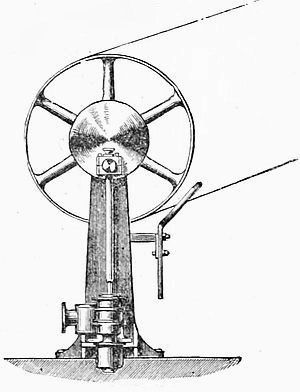

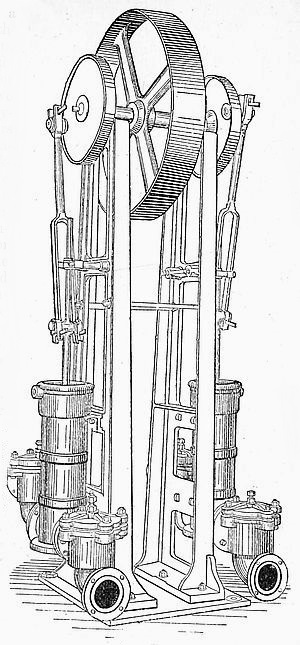

Donkin's Rag Boiler.—The spherical boiler of Messrs. Bryan Donkin and Co. is shown in Fig. 10. Being of a spherical form, it is twice as strong as a cylindrical boiler of the same diameter and thickness. The plates used are, notwithstanding, of the usual substance, thus rendering it perfectly safe, durable, and suitable for high-pressure steam. The spherical shape also allows the rags to fall out by themselves when the boiler is revolving with the cover off. Within the boiler are strainers to carry off the dirt, and lifters to agitate the rags during the process of either boiling or washing. To avoid cement, or even lead joints, the gudgeons and the boiler are turned true in the lathe to fit each other, the joints being simply made with red lead. These boilers are usually about 8 feet in diameter, and are capable of boiling from 20 cwt. to 25 cwt. of rags. The idea of giving motion to the boiler, so as to insure a perfect mixture of the rags and the caustic liquor, is of American origin, and was first introduced into this country by Messrs.[31] Bryan Donkin and Co. It is usual to fix the boiler so that it can be fed with rags through a trap in the floor above, while the boiler is in a vertical position and the lid removed. The trunnions are hollow, to admit the introduction of steam, alkaline ley, or water, and its rotary motion, which is about three times in two minutes, is given by the gearing on the left of the illustration.

The alkalies used for boiling rags are either caustic soda, soda ash, slaked lime, made into a cream and sifted, or a mixture of slaked lime and carbonate of soda. A description of the preparation of caustic soda ley will be[32] found in another chapter. It has been customary at most of the larger paper-mills to purchase their caustic soda direct from the alkali manufacturers, who supply it in a solid form enclosed in iron drums, hermetically closed, which are broken and the contents removed and dissolved when required for use. As to the strength of caustic soda liquor to be used for boiling rags, this is regulated according to the nature and condition of the material, and the quality of the paper it is intended for (see p. 34). For the finest papers the caustic soda should be perfectly pure, and as there are various grades of this chemical substance sold by the alkali makers, only the purer qualities are used for the better kinds of paper. The proportion of caustic soda per cwt. of rags varies to the extent of from 5 to 10 per cent. of the former to each cwt. of the latter, the coarser materials, of course, requiring more alkali than those of finer quality. In cases where rags are boiled in an open boiler—as was formerly the case—a much larger proportion of caustic soda would be required than when the boiling is conducted under high pressures, as is now very generally the custom. In boiling the finer qualities of rags, less pressure of steam is required than for the coarser qualities, and the heat being proportionately lower, there is less destruction of the fibre. Some paper-makers prefer to boil the rags with caustic lime only, in which case the lime, after being slaked in the usual way, is mixed with water until it attains a milky consistence, when it is passed through a sieve to separate any solid particles which may be present. About the same percentage of lime may be used as in the former case.

When a mixture of lime and carbonate of soda is used, a method much adopted on the Continent, the lime should be well screened from lumps before being mixed with the soda. The usual method of preparing this mixture is as follows:—A wooden tank, 15 feet long, 5 feet wide, and 4 feet deep is divided into three compartments, each of which has a false bottom perforated with ½-inch holes to keep[33] back lumps, stones, pieces of coal, etc., which frequently abound in the lime. The fresh lime is put into the first compartment, where it is slaked with water in the usual way; the resulting powder is then put into the next compartment together with sufficient water, where it is agitated until converted into what is technically termed "milk of lime." In the partition which separates the second from the third division is a movable sluice, through which the milk of lime flows into the third compartment; in this is fitted a revolving drum, similar to the drum-washer of the breaking-engine, through which the milk of lime which flows from the sluice becomes strained, and is lifted in the same way as water is lifted by the drum-washer of the breaking-engine, and is thence discharged through a pipe into the rag boilers; an additional straining can be effected by placing a fine wire strainer over the mouth of this pipe leading to the boiler, which will prevent objectionable particles from entering the boiler. Each compartment is provided with a large waste pipe, through which, by the aid of a sufficient supply of water, all impurities which have been rejected by the drum are carried away. The soda solution is prepared by dissolving the required proportion in water, and the resulting liquor, after careful straining, is introduced into the boiler to which the charge of rags has been given; the head of the boiler is then fixed in its position and steam turned on, until a pressure of about 20 to 30 lbs. to the square inch is attained, and the boiling kept up for two to six hours, according to the quality of the rags. By the Continental system of boiling rags, for No. 1 stuffs, 216 lbs. of lime and 114 lbs., of 48 per cent., soda ash are used for every 4,000 lbs. of rags; for Nos. 3 and 5 stuffs, 324 lbs. of lime and 152 lbs. of soda ash are used; and for No. 4 stuff 378 lbs. of lime and 190 lbs. of soda ash, and the boiling in each case is kept up for twelve hours, under a pressure of 30 lbs., the operation being conducted in boilers which revolve horizontally.

In boiling the finest qualities of rags, it is considered[34] preferable to boil with lime alone, which is believed to be less injurious to delicate fibres than caustic soda. Dunbar[14] gives the following proportions of 70 per cent. caustic soda per cwt. of rags:—

S. P. F. F. F. is boiled with lime alone, then washed in the boiler, and again boiled with 2 per cent. of soda ash.

| S. P. F. F. is | boiled | with | 12 | lbs. of | (70 per cent.) | caustic soda | per cwt. |

| S. P. F | " | " | 14 | " | " | " | " |

| Fines | " | " | 7 | " | " | " | " |

| Seconds | " | " | 6 | " | " | " | " |

| L. F. X. | " | " | 20 | " | " | " | " |

| C. L. F. X. | " | " | 27 | " | " | " | " |

| C. C. L. F. X. | " | " | 30 | " | " | " | " |

| F. F. | " | " | 15 | " | " | " | " |

These are all boiled at a pressure of from 20 to 25 lbs. for 10 hours, in stationary boilers without vomit, and also in boilers revolving horizontally. In some mills, where the best qualities of paper are made, iron boilers are objected to, as small particles of oxide of iron are apt to become dislodged from the interior of the boiler, and produce discolouration of the paper. In such cases wooden vats, with mechanical stirrers, are employed; sometimes a jacketed boiler is used.

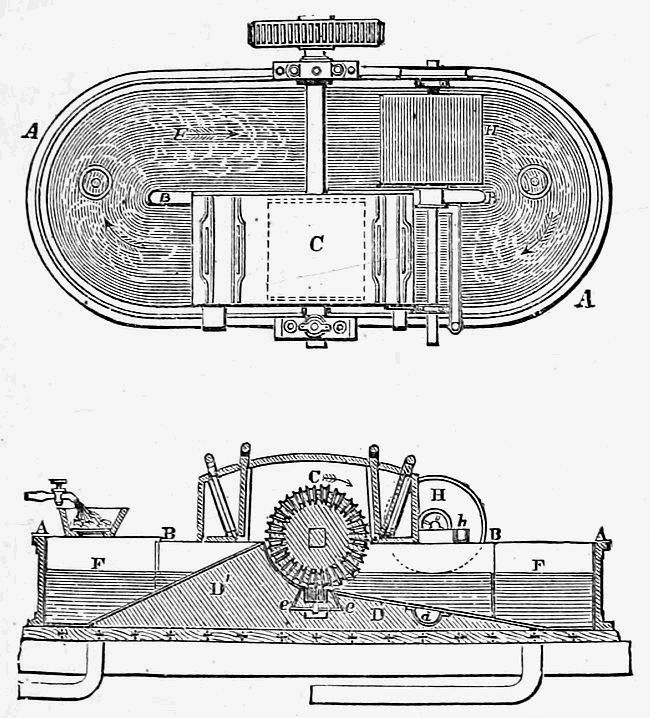

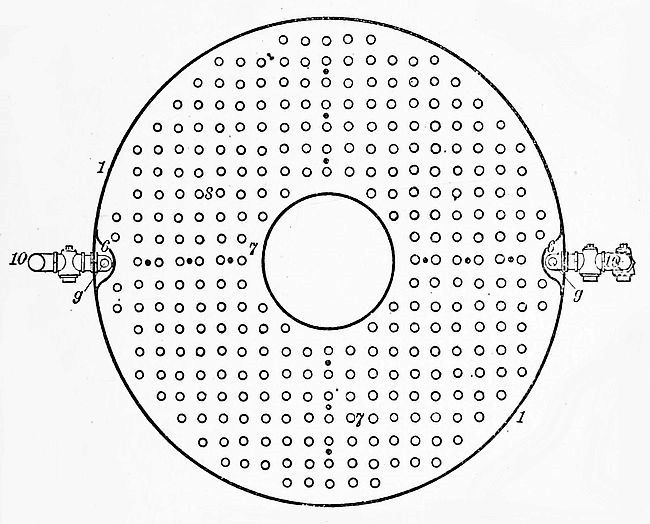

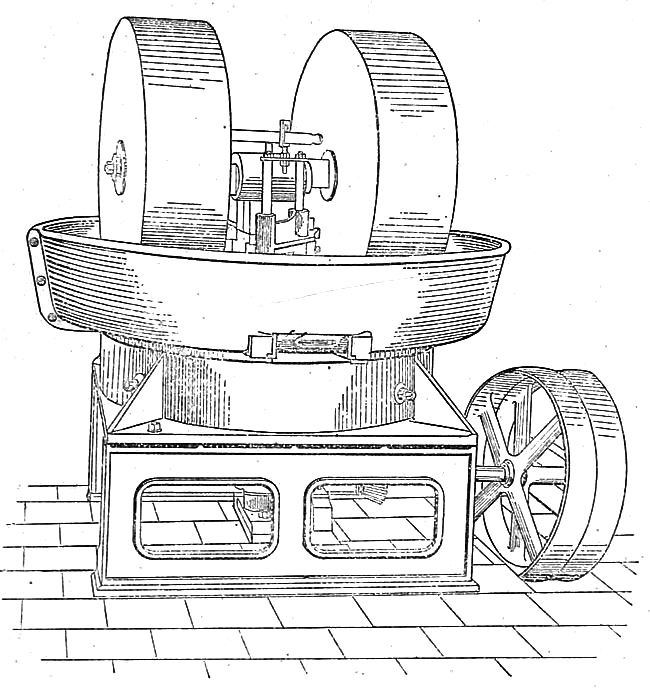

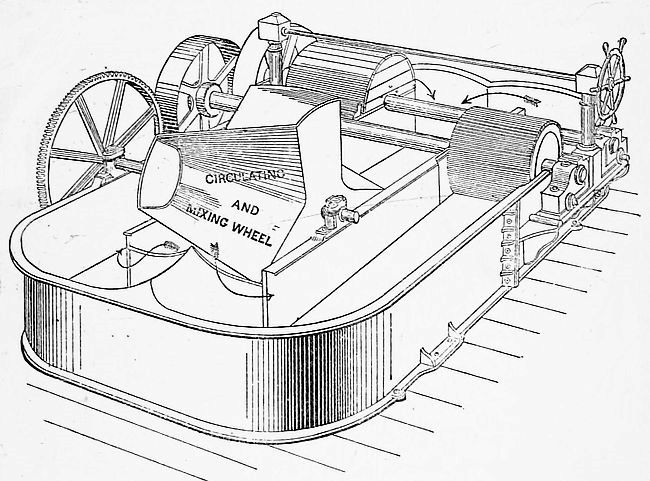

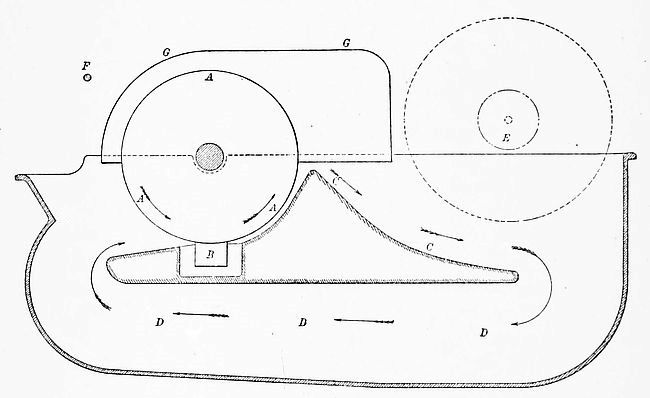

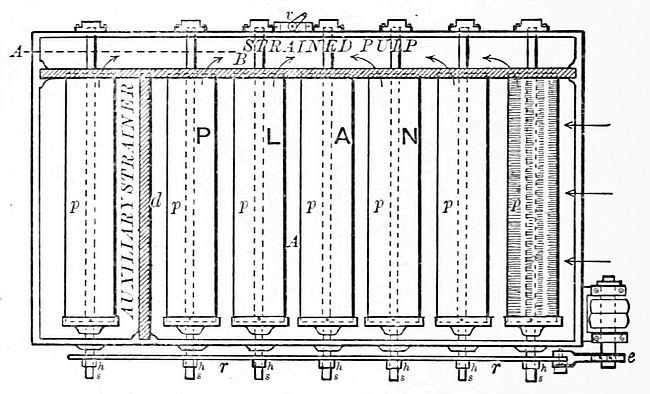

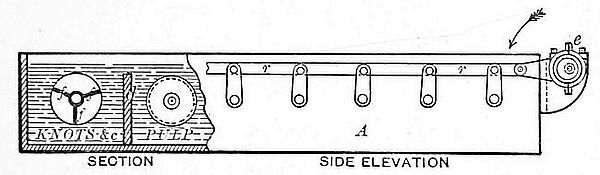

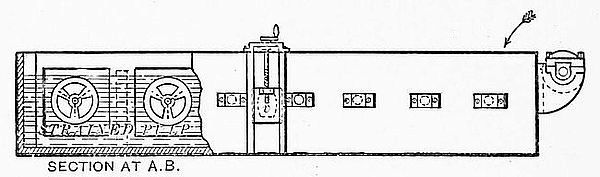

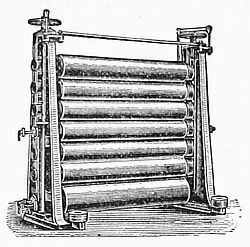

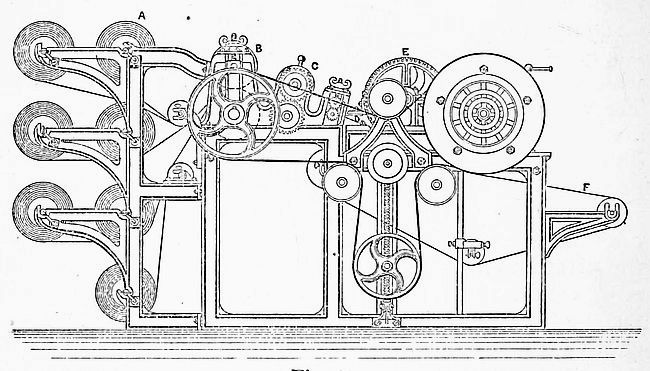

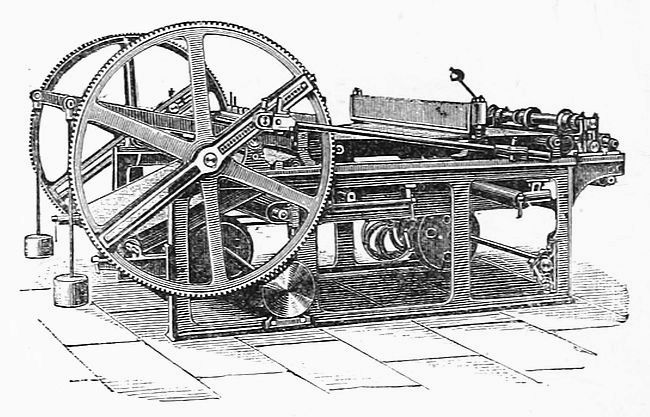

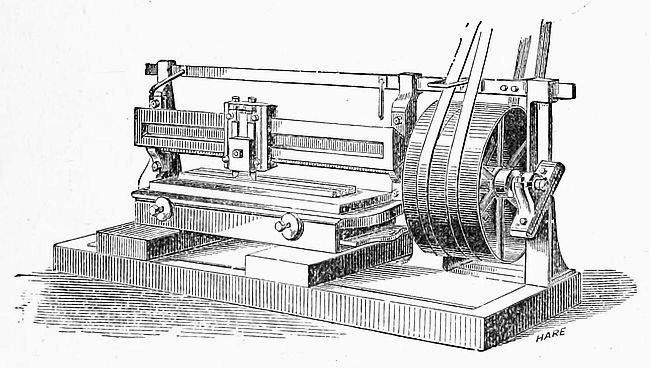

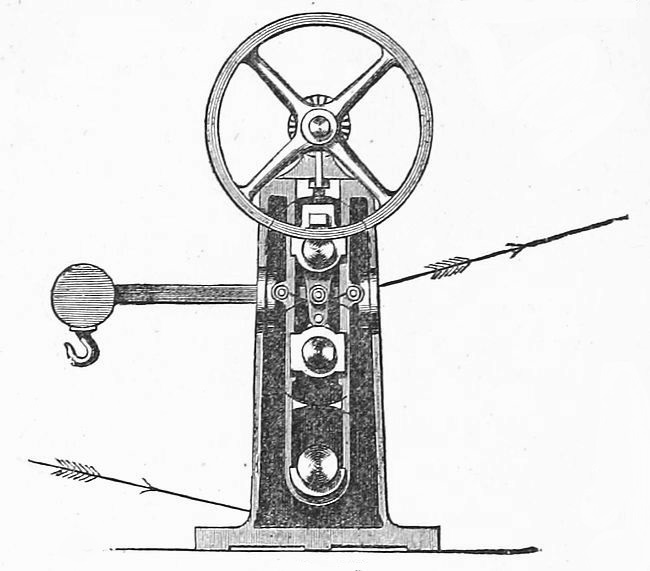

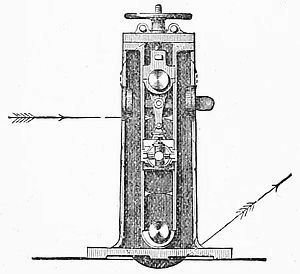

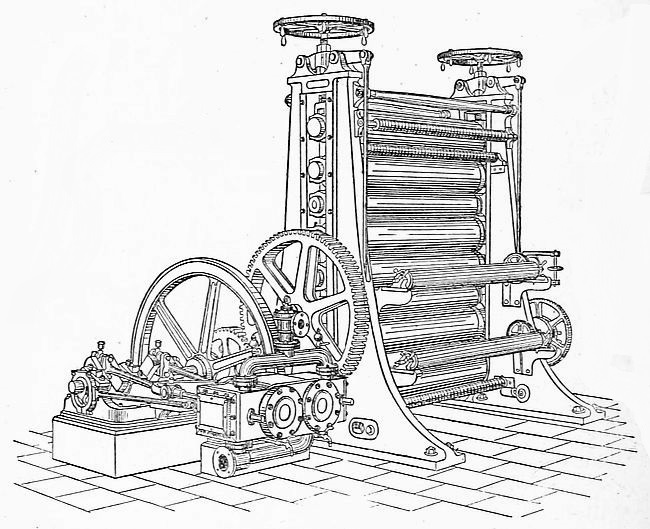

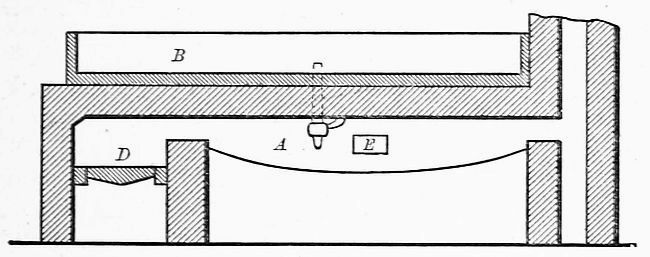

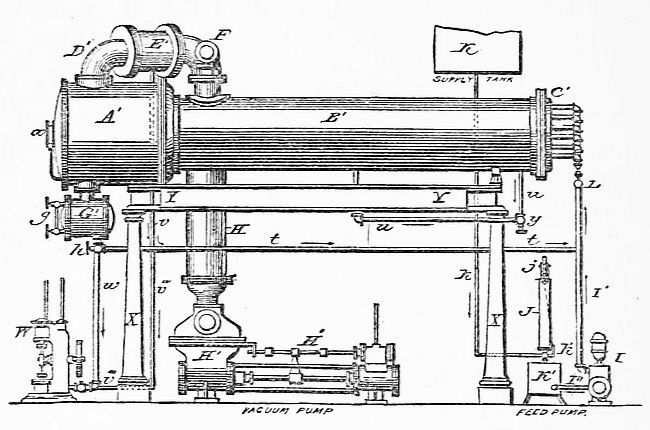

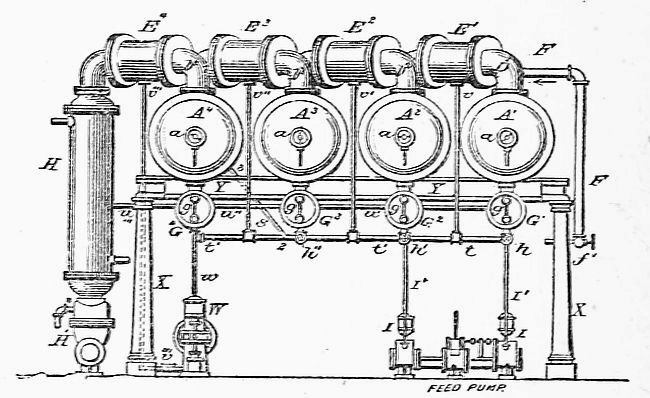

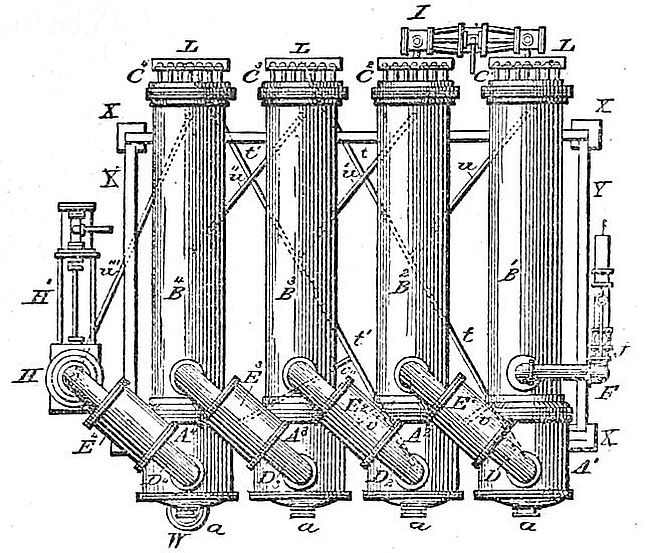

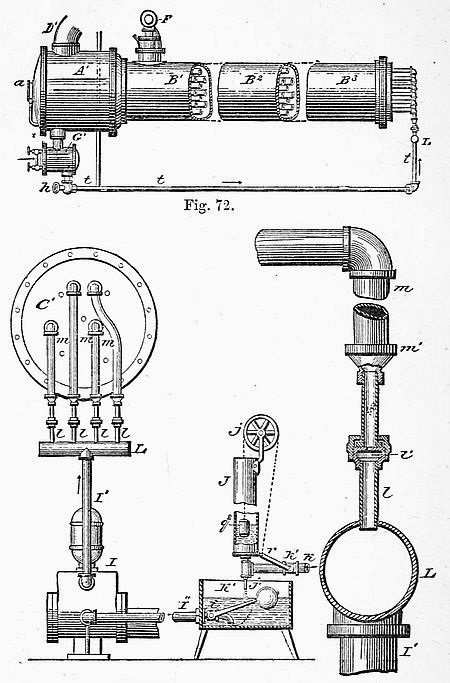

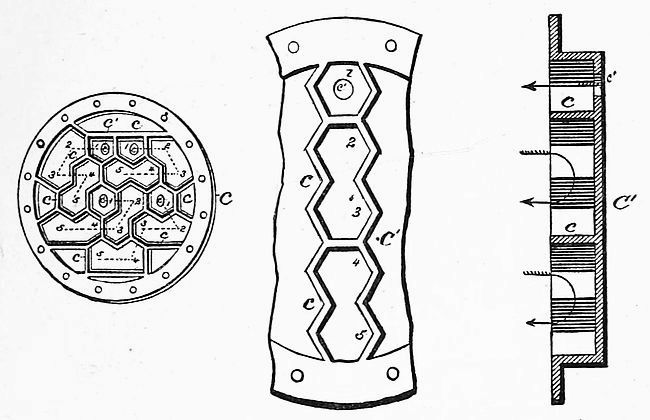

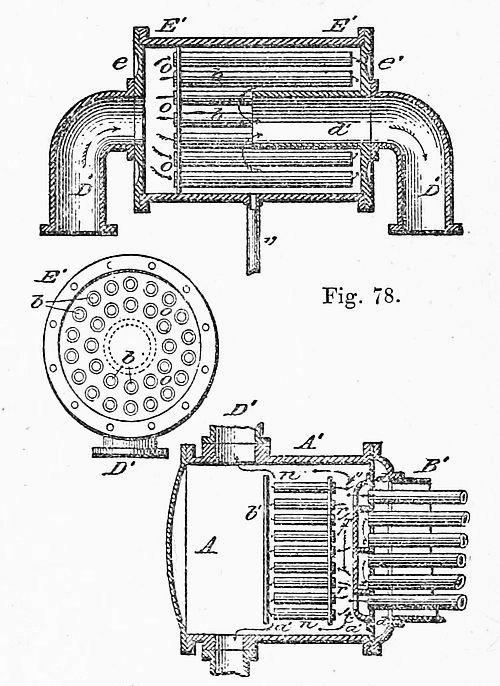

Washing and Breaking.—The removal of the dirty water resulting from the boiling is effected in the washing and breaking engine, or "rag engine," as it is commonly called, which is constructed on the same principle as the beating engine, but is provided with an extra drum, called the drum-washer, which, being covered with wire gauze, allows the washing waters to escape without permitting the fibrous stuff to pass through. The rag engine, having been invented by a Dutchman, acquired, and still retains, the name of the Hollander, and although it has been considerably improved upon, its principle is still retained in the modern engines, of which there are many different forms. The ordinary rag engine, Figs. 11 and 12, consists[35] of a cast-iron trough A, about 10 feet long, 4½ feet wide, and 2½ feet deep, and rounded at the ends, and is firmly bolted to a wooden foundation. It is provided with a partition termed the midfeather B, of such a length as to have the trough of uniform width round it. A cylinder, or roll, C, furnished with a series of steel knives, rotates in one of the divisions formed by the midfeather, and the floor of the trough in this division is inclined in such a manner as to cause the pulp, as it travels, to pass under the roll. Beneath the roll is the bed-plate, which is fitted with a series of steel knives c c similar to those on the exterior of the roll. The distance between the knives of the roll and the bed-plate is regulated by levelling screws, which are so adjusted that both ends of the roll are raised at the same time, which is a great improvement upon the older types of breaking engines in which only one end of the roll was raised, whereby the knives became unequally worn. By[36] the present method of regulating the distance between the respective sets of knives, any required degree of fineness can be given to the fibrous substances treated. The roll is generally caused to rotate at a speed of about 230 revolutions per minute, causing the water and rags to circulate in the engine and to be constantly under the action of the knives. In the other division F F of the trough is the drum-washer H, which, being covered with fine gauze wire, allows the water to enter, but keeps back the fibrous material. The ends of the drum are formed of two discs of wood, generally mahogany, upon which the coarse gauze is fastened as a backing, and this is covered with the fine wire gauze. The interior of the drum is sometimes furnished with a series of buckets, which conduct the water to a trough in the axis of the drum, by which it is led away. This is also accomplished by dividing the interior of the cylinder into compartments by means of a partition. The drum-washer is so arranged that it can be wholly raised out of the trough, which is necessary in certain parts of the operation, when the removal of the liquid is not required; or it can be partially raised, or otherwise, according to requirement. The floor of the compartment containing the roll C is inclined at D, so as to cause the pulp to pass directly under the roll, and at D′ is the backfall, over which the pulp travels to the opposite side of the midfeather.

In working the rag engine, it is first partly filled with water, and then set in motion; the boiled stuff is then gradually put in, and a constant supply of clean water is run in from a cistern provided with means of preventing sand or other impurities from finding their way into the engine. It is of the utmost importance that the water should be abundant and of good quality, more especially as the material (rags) is mostly required for making the finer qualities of paper. In this respect the county of Kent and a few other localities on the chalk formation are considered specially suitable for this particular manufacture.

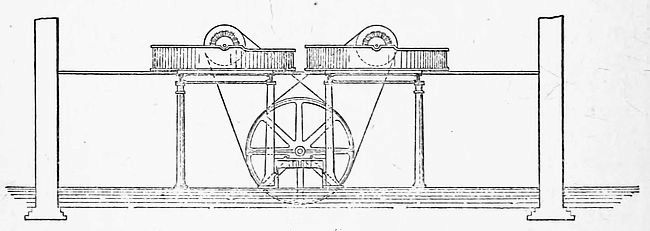

With respect to the driving of the engines, this was formerly effected by what is called toothed gearing, but cog-wheels were afterwards replaced by iron spur-wheel gearing, which enabled manufacturers to drive four or more engines from one source of power, by continuing the line of shafting and spur-wheels; but even with small rolls the wear and tear on this system was considerable, while it was quite inadequate to the driving of a number of large rolls of 30 inches in diameter, such as are now used. The introduction of belt-gearing, by Messrs. G. and W. Bertram, proved to be a great improvement on the older system, and it is found that the rags are broken not only more uniformly, but in less time, as the rolls work more steadily on the plates than with any system of wheel-gearing, while the various working parts of the engine last longer than when subjected to the vibrating action of wheel-gearing.

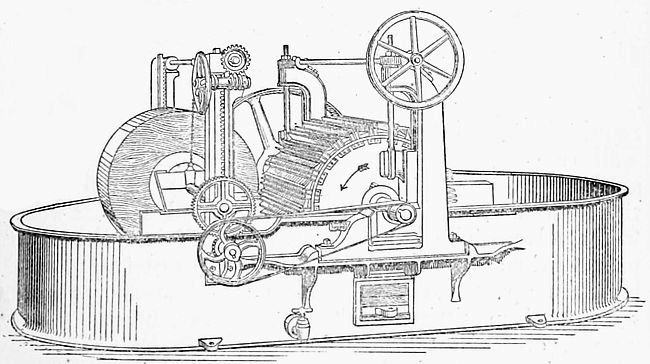

Bertrams' Rag Engine.—This engine, of which a drawing is shown in Fig. 13, may be used either as a washing and breaking engine, potcher, or beater. It is provided with double lifting gear, and has "all sweeps, curves, and angles" of the most improved design to save[38] lodgments and ensure steady and thorough travelling of the pulp. The drum-washer is shown lifted by rack and pinion and worm gear, and empties down the midfeather direct to mouthpiece. The emptying can be done by spout and pipe, or by a chamber cast on the engine, down back or front side, as well as through the midfeather; but it is not advisable that it should be emptied down the midfeather if the rag engine is to be used as a beater.

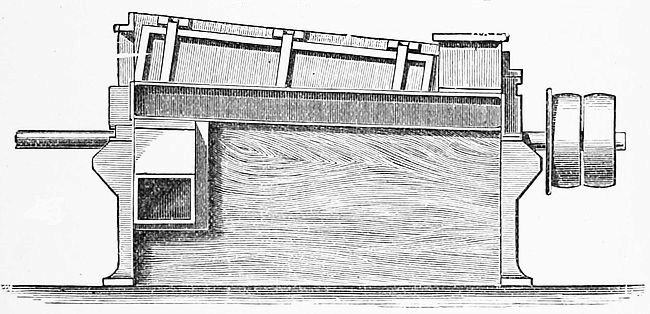

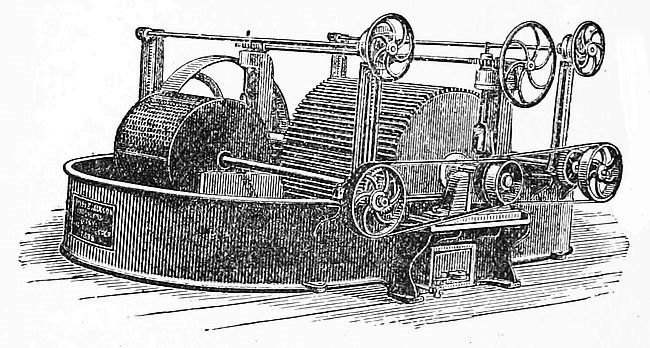

Bentley and Jackson's Rag Engine.—This form of engine is shown in Fig. 14. The trough is of cast-iron, and made whole, and the engine can be obtained of any required dimensions. The trough is provided with a sand-well, cast-iron grate, and cock in front of the roll, and a sand-well, cast-iron grate, and brass valve on the back of the midfeather, a brass let-off valve and a brass waste-water valve. The bottom of the trough is "dished," to prevent the stuff from lodging. There are two movable bridge trees, fitted with pedestals and brass steps, and wrought-iron lifting links and screws, worm-wheels, worms, cross-shaft and hand-wheel for simultaneously lifting the roll on both sides. The roll is covered by a polished pitch-pine cover. The drum-washer may have either iron or wooden ends, has strong copper brackets, and is covered with brass backing and covering wires, mounted on a wrought-iron shaft, and carried by cast-iron[39] stands, fitted with improved lifting gear, driving-wheels, and pulley.

When the engine is set in motion by the revolving shaft or spindle, the combined action of the knives of the roll and bed-plate causes the rags, which circulate in the water, to be gradually cut into small fragments, and the operation is kept up until the rags are converted into what is technically termed half-stuff. While this process is going on, fresh water is constantly supplied by a pipe at the end of the washing-engine; and when it is found that nothing but clear water escapes from the drum-washer, this is raised, and the spindle bearing the roll is lowered, so as to bring the respective knives closer together, to enable them to cut the reduced material still finer.

Draining.—When the material is sufficiently broken, as it is termed, the engine is then emptied by means of its valves, and the contents run into large vats or drainers, furnished with perforated zinc floors, in which it is allowed to drain thoroughly; and in order to remove the water more effectually, the pulp is afterwards pressed, either by an extractor or a centrifugal drainer, which dries it sufficiently for gas-bleaching, or for treatment in the potcher or poacher. This is a larger engine than the washer, and instead of the cylinder and bars, has a hollow drum which carries on its periphery a number of cast-iron paddles, which thoroughly agitate the pulp, and thus render it more susceptible of being freely and uniformly acted upon by the bleaching agent. The drum-washer of this engine should have a finer wire than is used for the breaker.

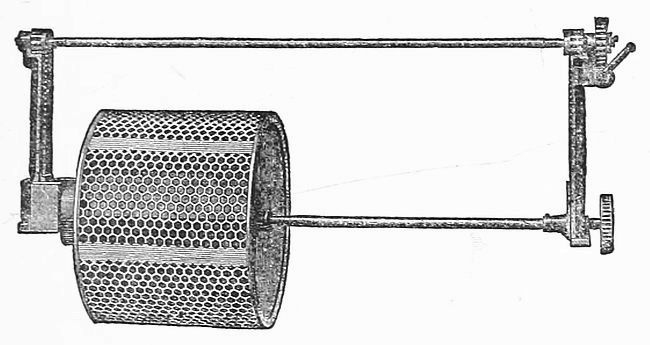

Torrance's Drainer.—This machine, which has been extensively used, is manufactured by Messrs. J. Bertram and Son, of Edinburgh. It consists of a perforated cylindrical box, enclosed in a fixed case, which revolves at about two hundred and fifty revolutions per minute. The machine is capable of treating about 4 cwt. of pulp per hour.

TREATMENT OF ESPARTO.

Preliminary Treatment.—Picking.—Willowing Esparto.—Boiling Esparto.—Sinclair's Esparto Boiler.—Roeckner's Boiler.—Mallary's Process.—Carbonell's Process.—Washing Boiled Esparto.—Young's Process.—Bleaching the Esparto.

Preliminary Treatment: Picking.—Esparto is imported in bales or trusses, tightly compressed by hydraulic presses, and bound with twisted bands of the same material, much in the same manner as hay, except that which comes from Tripoli, which is bound with iron bands. The bands being cut, the loosened material is then spread out upon tables, partly covered with iron, or galvanised-iron, netting, to allow earthy matter or sand to pass through to a receptacle beneath. Here it is carefully picked by women and girls, who remove all roots, other kinds of grass, weeds, and heather. The material thus cleansed from impurities is transferred to the boiling-room. This careful preliminary treatment has been found necessary, since pieces of root and other vegetable matters which may be present are liable to resist the action of the bleaching liquor to a greater extent than the grass itself, and therefore produce specks, or "sheave" as they are termed at the mill, in the manufactured paper.

At some mills, however, as at the Horton Kirby Mills of Messrs. Spalding and Hodge, at South Darenth, for example, the cleaning of esparto is admirably effected by means of a willow, or esparto-cleaner, constructed by Messrs. Masson, Scott, and Bertram, which entirely supersedes the system of hand-picking. Having recently visited the mill referred to, we were enabled, through the[41] courtesy of Mr. Sydney Spalding, to witness the action of this willow, which appeared to perform its functions with perfect uniformity, and to clean the grass most effectually. The rationale of the operation of willowing esparto may be thus described:—

Willowing Esparto.—A bale of the grass is unbound at a short distance from the machine, and the grass, which is in the form of small bundles or sheaves, tied with bands of the same material, is thrown by a woman on to a table or platform placed by the side of the willow, and a second woman, standing near the hopper of the machine, takes the bundles, a few at a time, and drops them into the hopper. The machine being in motion, in a few moments the grass, freed from its bands and dirty matters, appears in a perfectly loose condition at the wider end of the drum, and passes upward along a travelling-table to a room above, in the floor of which are the man-holes of a series of esparto boilers. During the passage of the loosened fibre, women standing on steps or platforms at the sides of the travelling-table are enabled to examine the material, and to remove any objectionable matters that may be present. Beneath the drum of the machine is a pipe, through which the dust and dirty matters are drawn away by means of a fan.