Title: The Faery Queen and Her Knights: Stories Retold from Edmund Spenser

Author: Alfred John Church

Edmund Spenser

Release date: October 17, 2017 [eBook #55765]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Stephen Hutcheson, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Faery Queen and Her Knights, by Alfred John Church

THE FAERY QUEEN

AND HER KNIGHTS

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

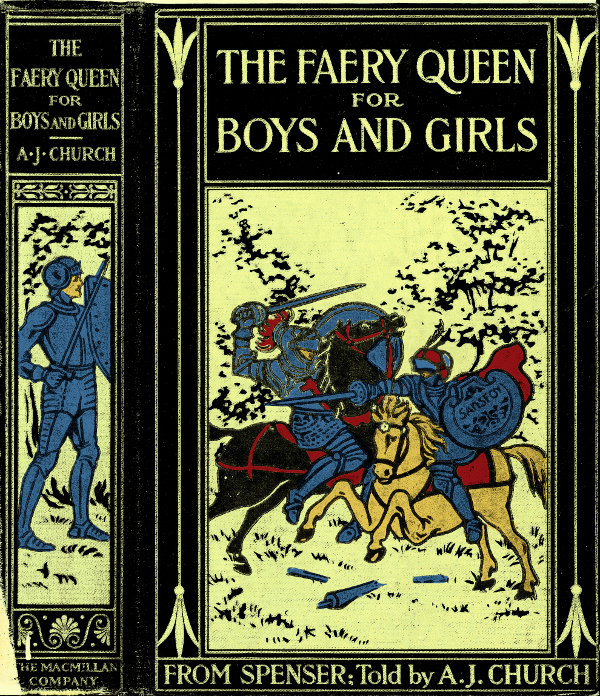

The Slaying of the Dragon.

STORIES

RETOLD FROM

EDMUND SPENSER

BY THE

Rev. ALFRED J. CHURCH, M.A.

Author of “Stories from Homer”

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR

NEW YORK

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1909

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1909,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published October, 1909.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

Once upon a time there might have been seen a gentle Knight, riding across the plain. He was clad in armour of proof, and on his arm he carried a silver shield. A shield it was that brave men had carried before him, for there were great dints upon it, which were as a witness of great fights that had been fought. Now the Knight himself had never yet been in battle; but he seemed as one who could bear himself bravely, so well did he sit upon his horse, and so stout of limb he was. On his breast he wore a cross, red as blood, in token that he was vowed to serve the Lord Christ, who had died for him; and on his shield was yet another cross, to be as it were a sign that this service should be a defence to him in all dangers. Somewhat sad of look he was, not as though he had fear in his heart, but rather as one upon whom had been laid the burden of a great task. And such, in truth, there was, for Queen Gloriana had sent him upon a great enterprise, and all his heart was full of the thought of how he should best accomplish it. And the task was this—to slay the Great Dragon.

Beside the Knight a lady was riding on an ass as white as snow. Very fair she was; but she hid her fairness under a veil, which was brought low over her face. She was clad also in a garment of black; and she, too, was somewhat sad of look, nor, indeed, without cause. She came of a royal stock, being descended from ancient kings and queens, who had held wide sway in their land until this same Dragon had driven out their ancient house and had cruelly wasted all their realm. The third of this company was a Dwarf, who lagged behind, wearied, it may be, with the weight of the bag in which he bore this fair lady’s gear.

While the three, to wit the Knight, and the Lady, and the Dwarf, passed on, the sky was suddenly covered with clouds, and there began to fall a great storm of rain, so that they were fain to seek some shelter. Gladly, then, did they espy a wood hard by that promised, so thickly grown it was, a shelter from the rain. Tall were the trees and spreading wide with shady branches, so that neither sun by day nor star by night could pierce through. And all about were paths and ways, worn as by the treading of many feet, which seemed to lead to the abodes of men—a fairer place of shelter, as it seemed, there scarce could be. So they passed along, the birds singing sweetly the while; overhead were trees of many kinds, trees of the forest and of the orchard, the cedar and the oak, and the elm with the vine clinging to its stem, the yew for bows, and the birch for arrows, and the fruitful olive. So fair was the place, and so full of delights, that the travellers took no heed of the way by which they went. So it came to pass that they strayed from the path by which they first entered the wood, nor could they win to it again when once they had left it, so many were the ways and so like the one to the other. After a time, when they had taken counsel together, it seemed best to choose the way which seemed most trodden by the feet of travellers, as being the likeliest to lead to a certain end. When they had followed this awhile, they came to a great cave, deep in the very thicket of the wood. Here the Knight sprang from his horse, and gave to the Dwarf his spear, thinking that he should not need it. But his sword he kept.

Then said the Lady Una, for that was her name: “Be not overbold, Sir Knight; there may be mischief here of which you know nothing, peril which gives no sign of itself, even as a fire which burns without smoke; hold back, I pray you, till you have made some trial of the place.”

The Knight made reply: “Fair lady, it were a shame to fall back for fear of a shadow. The cave, doubtless, is dark, but where there is courage there is not wanting a light for the feet.”

Then said the Lady again: “Nay, nay, Sir Knight; I know this place by repute, though I thought not of it before. This wood in which we are lost is the Wood of Wandering; this cave which you see before you is the Den of Error, a monster, hateful both to God and man. Beware, therefore, beware!” And the Dwarf cried out aloud in his fear: “Fly, Sir Knight, fly, this is no place for mortal man.”

But the Knight would not be persuaded. He stepped into the cave, and the light of day, shining from without on his armour, showed him dimly the monster that was within. Hideous it was to behold, half a serpent and half a woman, and all as foul as ever creature was, upon the earth or under it. All the length of the cave she lay, her tail wound in many coils; and in every coil there was a deadly sting. And all round her was a brood of young ones. Many different shapes they had, but hideous all. And as soon as the light from the Knight’s armour glimmered through the darkness, they fled for shelter to the mouth of their dam.

The monster, wakened from her sleep, curled her tail about her head, and rushed to the cavern’s mouth, but, seeing one armed from top to toe in shining mail, would have turned again. But the Knight leaped at her, fierce as a lion leaps upon his prey, and barred her backward way with his sword. First she darted at him her great tail, and threatened him with the deadly sting that lay in it; but he, not one whit dismayed, aimed at her head a mighty blow. Her head it wounded not, but glanced on to the neck with force so great that for a while the great beast was stunned. Then, coming to herself, she raised her body high from the ground, and leaped upon the Knight’s shield, and wrapped his body round with huge folds.

Then Una, seeing in how sore plight he was, cried out: “Now show, Sir Knight, what you are. Put out all your force, and, above all things, back your force with faith, and be not faint. Strangle this monster, or surely she will strangle you!”

Greatly was his heart stirred within him with grief and anger, and, knitting all his strength together, he gripped the creature by the throat so mightily that she was constrained to loosen the bonds which she had cast about him. And yet, it had well-nigh cost him dear to come so close to the monster, so foul she was. And of this foulness the worst was this, that she caused to come forth out of her mouth, as in a flood, the brood which had taken shelter therein at the first. Serpents they were, like to their dam, small indeed, but full of venom, and they swarmed over him, twining themselves about his arms and legs, so that he could not strike a blow nor even move. So, in some still eventide, a shepherd, sitting to watch his flock, is suddenly assailed by a cloud of gnats; feeble creatures they are, and slight their sting, but they suffer him not to rest. The Red-Cross Knight was in a strait more dire, for these evil creatures had power to do him a more grievous harm. But he thought to himself, “Shall I be vanquished in this fashion?” He was somewhat moved by the danger wherein he stood, but more ashamed that he should be overcome in so foul a fashion. So, resolved in his heart that he would put all his strength into a stroke, either to win or to lose, he gathered himself together, and struck the monster with a blow so fierce that he shore the head from the body, and she fell dead upon the ground.

Then said the Lady Una: “Well, indeed, have you carried yourself, Sir Knight. Surely you were born under a lucky star, seeing that you have overcome so terrible a foe. You are worthy of these arms wherewith you are clad. So is your first adventure brought to a good result. God grant that you have many such in the time to come, and that they may be brought to as happy an ending.”

Then the Knight sprang upon his horse, and the Lady Una mounted again her ass, and the Dwarf followed as before. And now they kept with steadfast purpose to the one way which they saw to be most trodden, turning neither to the right nor to the left, how fair soever the path might seem. So at last they came to the outskirts of the Wandering Wood, and journeyed once more across the plain.

So the two, the Knight and the Lady, rode on, the Dwarf following as before. After a while they chanced to meet an old man by the road. He was clothed in black and barefooted, and he had a long white beard, and a book was hanging from his belt. A very wise old man he seemed, sober and even somewhat sad, and as he went along he seemed to be praying; and now and again he would beat upon his breast, saying, “God be merciful to me a sinner!” He made a humble reverence to the Knight, and the Knight in his courtesy made his salute, and said: “Sir, do you know of any adventure that a Christian man may undertake?”

“My son,” said the old man, “how should one who lives in his cell and tells his beads and does penance for his sins know aught of wars and enterprises by which glory may be won? Nevertheless, I can tell of a very evil man who dwells in these forests and wastes all the country-side.”

“Ah!” cried the Knight, “it is for such an adventure, the setting right of wrong, that I seek. Bring me to this villain’s dwelling and I will reward you well.”

“Willingly,” said the old man, “will I guide you thither, but the way is long and painful.”

“And surely,” said the Lady Una, “you are wearied with your late encounter. I take it that he who lacks rest lacks strength, however stout of limb he be. Take your rest then with the sun, and begin your new work with the new day.”

“This is wise counsel, Sir Knight,” said the old man, “and wise counsel ever wins the day. The day is far spent; come, then, and take such poor entertainment as my home can give.”

With this the Knight was well content. So they followed the old man to his dwelling. It was a lowly hermitage, in a valley, close to the forest, with a chapel hard by, and by this chapel a brook crystal clear. Humble was their fare, but the rest after the day’s toil made it sweet enough, as also did the old man’s talk, for he discoursed of many things and many men, saints and popes, and the great deeds which they had done. Then, as the night drew on and sleep began to fall upon their eyes, he showed them the places where they should lodge for the night.

Now this old man, who seemed so pious and good, with his long white beard, and his prayers, and his beating of his breast, was really a wicked magician. So soon as he had taken his guests to their lodgings, he went to his study, where he kept his books of charms with other contrivances of his art, and taking one of these books from the shelf on which it stood, opened it, and began to mutter some dreadful words which it were a great sin for anyone to write or read. With these he brought up from their dwelling-place in the lower parts of the earth a very legion of evil spirits. To these he gave a part of his evil work to do, and some of this work he kept to himself; and the work was this: To cheat the hearts of those whom he wished to deceive with false dreams and visions. What these were, it is best not to tell: let it be enough to say that they wrought such doubts concerning the Lady Una in the heart of the Red-Cross Knight that, as soon as the morning dawned, he rose from his bed, and clothed himself with all haste, and crying for the Dwarf that he should bring him his horse, rode away as fast as the beast could carry him.

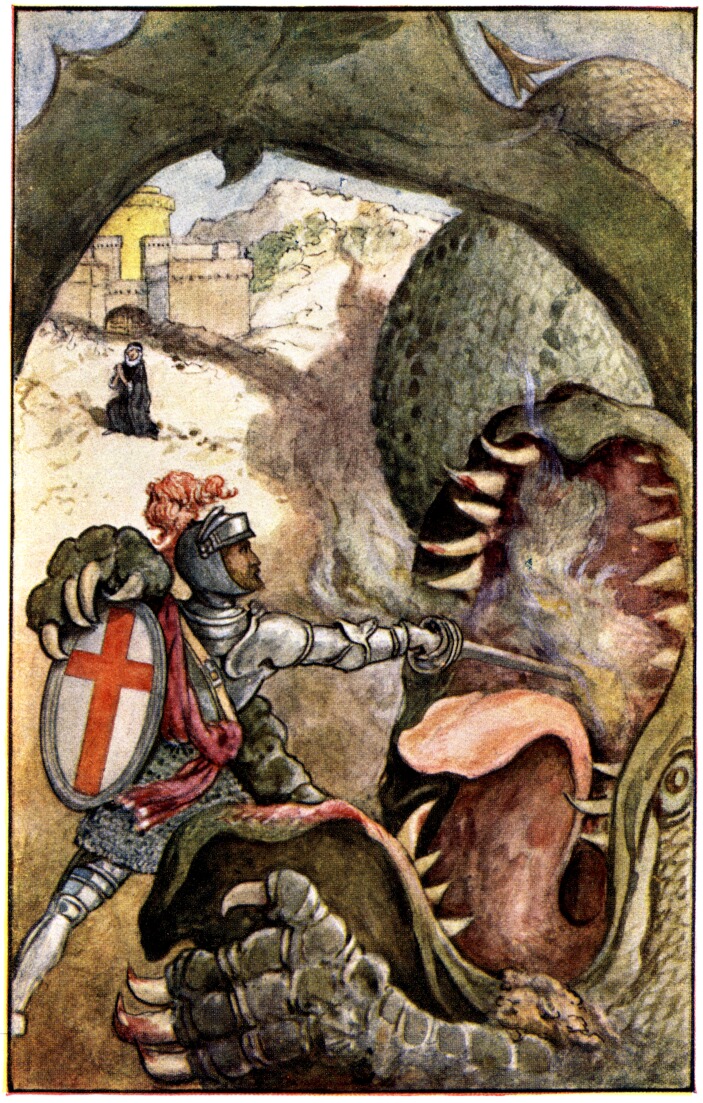

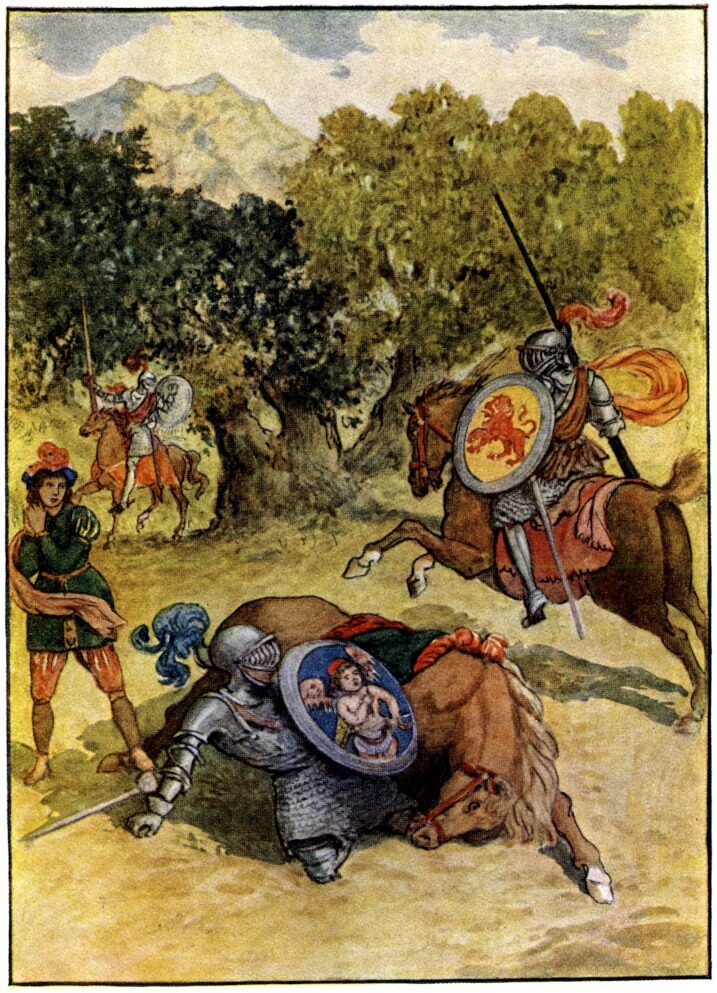

He had not ridden many miles before there met him a paynim knight. A tall warrior and a strong he was, armed from top to toe, and carrying a great shield on which were written in scarlet letters the words “Sans Foy,” which, being interpreted, mean “Without Faith.” With him there rode a fair lady, clad also in scarlet, with ornaments of gold and necklaces of coral, and on her head a Persian cap set round with crowns of gold. Her horse also had gay trappings, and her bridle was set with bells of gold, which tinkled bravely as she rode. So soon as she saw the Red-Cross Knight she said to her companion, “See now, here comes your enemy; make ready.”

No sooner had she spoken, but he stuck spurs in his horse, and rode at the Red-Cross Knight. Nor did the knight hold back from the fray, for he also put his spear in rest and charged. So the two met fully and fairly, with so fierce a shock that the two horses stood, as it were, struck to stone, and the riders were borne backwards in their saddles, holding each of them in his hand his broken spear. Then the Saracen drew his sword from the scabbard, and addressed himself again to the fray. So did the Christian also; blow for blow did they deal one to the other, till the sparks flew from their shields, and when they chanced to strike home, the blood flowed forth and dyed the earth under their feet. After a while cried the Saracen: “Now curse upon that Cross which keeps your body from harm! You had been dead long since but for that magic power. For all that, I bid you now beware, and keep safe your head if it may be.”

So saying, he dealt a blow so fierce that it shore away half the Christian’s crest, yet glancing down upon the shield harmed him no more. Yet was it not struck in vain, for it roused him of the Red Cross to such rage that he made a more than like reply. Full on the Saracen’s helmet he dealt his stroke. Right through the steel it passed, and cleft the head, so that the Saracen fell a dead man from his horse.

When the lady saw her champion fall, not a moment did she stay to see how it had fared with him, either to tend his wounds, or to weep for his death, but fled away as fast as her horse could carry her. Then the Red-Cross Knight, crying to the Dwarf that he should pick up the dead man’s shield to be a memorial of the fight, rode after her, and overtaking her, bade her halt: “You have no cause to fear, fair lady,” he said.

The Red Cross Knight and Sansfoy.

Then she, turning back, cried aloud: “Fair Sir, have mercy on an unhappy woman!”

Much was he moved to see her humbleness, for she was beautiful to look on, and richly clad, as one of noble birth might be. “Lady,” said he, “be of good heart. It pitieth me to see you in such distress; tell me now who you are, and whence you come, and who was this your champion?”

“Sir,” she answered, weeping the while, “I have suffered much from evil fortune. I was the only daughter of an emperor, who had wide dominion over the land of the West, setting his throne where flows the famous stream of Tiber. Being such, I was betrothed in my early youth to the only son and heir of a most wise and mighty king. Never surely was prince so fair and faithful as he, never one so gentle and debonair. But alas! ere the day appointed for our marriage came, my lord fell into the hands of cruel enemies, and was most foully slain. When this ill news came to me, I said to myself: ‘Now will I at least do due honour to the dear body of him whom I loved.’ So I set forth from my father’s house upon this quest. Long did I wander over the world, a virgin widow, nor did I find that for which I sought. At last I chanced to meet this Saracen, who now lies dead upon the plain. He constrained me to go with him, and would fain have won me for his wife, but I ever said him nay. And now he lies dead. An evil man he was, one of an evil brotherhood of three—Sansloy, the eldest; Sansjoy, the youngest; and this Sansfoy, of middle age between the two.”

“Be contented, fair lady,” answered the Knight; “you have done well. You have found a new friend and lost an old foe. Friend, be he ever so new, is better, I trow, than foe, new or old.”

So the two rode on, he making merry with gay talk, as became a courteous knight, and she, with much modest show of bashfulness. After a while they came in their journey to two fair trees, which spread their branches across the road. Lovely trees they seemed, and fair was the shade which they cast. Yet was the place held in ill-repute of all the country-side; never did shepherd sit beneath them to rest or play upon his oaten pipe, for all men held it to be unlucky ground. But of this the good Knight knew nothing, so, the sun being now high in heaven, and of so fierce a heat that a man might scarcely abide it, he dismounted and bade the lady do likewise, so that they might rest awhile, and anon, in the cool of the evening, might pursue their journey. So the two sat them down and talked.

Now the Knight, being in a merry mood, said to himself: “Surely, this is the fairest of women; it is meet that she should be crowned.” So saying, he plucked a branch which he would have shaped into a garland for the lady’s head. Then, lo! from the place where the branch had been plucked came trickling drops of blood, and there issued forth a lamentable voice which said: “Stranger! Tear not in this cruel fashion the tender human limbs which are covered by the bark of this tree. Fly also from the place, fly, lest haply the same fate should come upon you as came upon me in this place, both on me and on the dear lady also who was my love.”

Much was the Knight astonished to hear such words, and for a while he stood speechless. Then he said: “What ghost is this from the world below, what wandering spirit that talks in this strange fashion?”

Then there came this answer: “No ghost am I from the nether world, nor wandering spirit of the air. I was a man, Fradubio by name, as now I am a tree, being charmed by the arts of a wicked witch. But I am yet a man, for I feel the winter cold and the summer heat in these branches, even as a man might feel.”

Then said the Knight: “Tell me now, Fradubio, be you tree or man, how you came to suffer in this fashion. It is good for a man to tell his trouble; he who hides it in his heart makes his griefs to be twice as great.”

Then did Fradubio tell his tale, “Know, stranger, that I suffer this trouble through the arts of a false sorceress, Duessa by name; nor I only, for she has brought many knights into a like evil case. In my youth, which indeed is not long passed, I loved a fair lady, whom you may see, not indeed in the fashion of a lady, but as yonder tree which joins its branches with these. Once upon a time, when I was riding abroad with her, I chanced to meet a knight, who also had a fair lady for a companion. A fair lady I called her, and so she seemed, but she was in truth this same false witch Duessa. Said the strange Knight: ‘I do declare that this lady is the fairest dame in all the world, and this I will make good with my sword and spear against all the world.’ For the witch had cast her spells over him and deceived him. And when I put forth the same challenge for my own lady, we fell to fighting, and he fared so ill, that he fell by my hand.

“So now there were two fair ladies, for so it seemed, Fraelissa, who was fair in truth, and Duessa, who by her wicked arts had made herself so to seem. And I knew not to which I should give the prize of beauty, for it seemed the due of each. But while I doubted, this wicked witch raised by evil arts such a mist as made Fraelissa’s face to lose all its fairness. Which when she had accomplished, she cried: ‘See now how this false dame has lost her beauty, for indeed it was but borrowed. Many has she deceived in time past, even as now she has deceived you.’ When I heard this, I would fain have killed the fair lady that had been my true love. But this the false Duessa, feigning compassion, would not suffer. Only with her magic arts she changed her into that tree which you see yonder.

“Now you must know that for every witch, be she as crafty as she may, there is one day in every year when she is constrained to take her true shape. And on this day I chanced to see Duessa as she was in truth, old and foul of hue, fouler than one had thought woman could be. Nor did she fail to perceive that I had discovered the truth, though indeed I sought to bear myself as before, having it in my mind secretly to escape, and fly from her company. So she practised upon me the same wicked arts that she had used with my Fraelissa, changing me into the semblance of a tree. And here we stand, banished from the company of men, and wasting weary days and nights.”

“But,” said the Knight, “how long shall this endure? What is the appointed end of your sufferings?”

“We must here abide till we shall be bathed in a living well,” Fradubio made answer.

“Can I find this same well?” asked the Knight.

“That shall be as the Fates may decree,” said Fradubio.

All this Duessa—who called herself Fidessa—heard, and knew it for truth. She well-nigh fainted for fear; but the time for the discovering of her falseness was not yet.

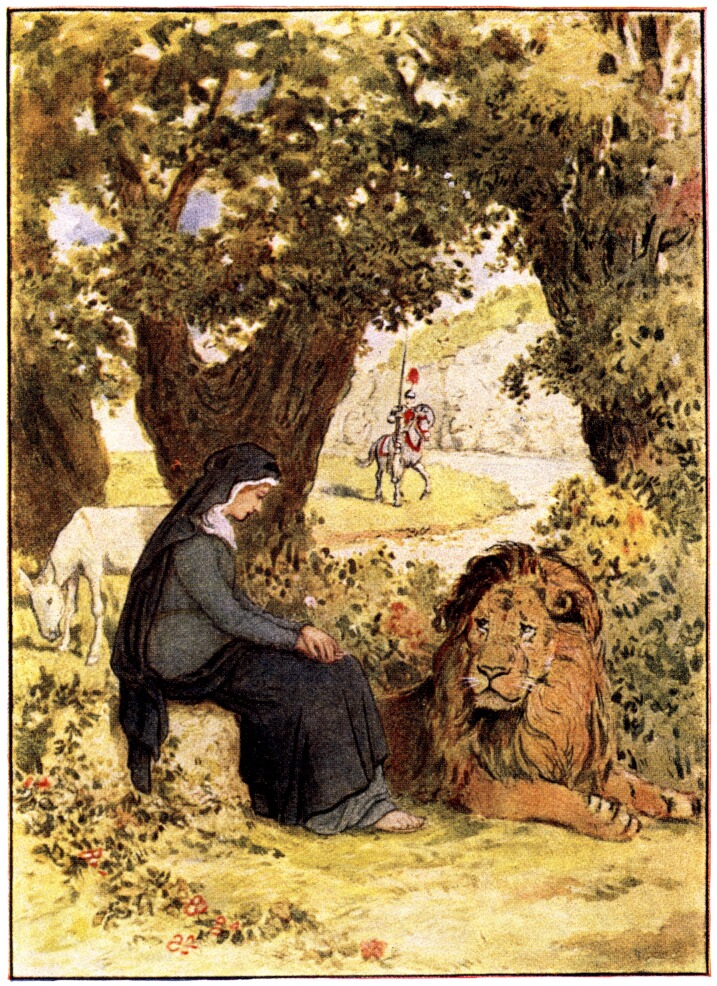

While the Red-Cross Knight was thus faring, the Lady Una was not a little troubled that she should have been so left by her champion. Never did she cease to search for him, wandering the while over plain, and forest, and mountain, and not one whit afraid, however desolate they were.

On a certain day she lighted off the ass, on which she was wont to ride, and laid herself down to rest in a solitary place, under the shadow of a tree; she took the covering from her head, and laid aside her black cloak; her faithful beast grazed hard by, for there was much grass in the place. As she lay, there rushed out of the wood with which the meadow was circled about a furious lion. Wild he was with hunger, and was hunting for prey. And when he saw the royal maid, he ran greedily at her with open mouth, as if he would have devoured her; but when he came near, and saw what manner of maid she was, all his rage departed from him. He kissed her weary feet, and licked with his tongue her lily hands, crouching down before her as if to show himself her servant. At the first sight of the beast the Lady Una was not a little afraid, but when she saw how gently he bore himself, she sighed and said: “See now, how this lion, who is the king of the forest, forgets his hunger and his rage in pity of my sad state, while he who was my champion leaves me to wander alone.” So she spake till she could speak no more for very tears, and the lion meanwhile stood looking upon her. Then—for the lady was of a brave spirit—she shut up her sorrows in her heart, and mounted on her steed again, and set out once more upon her quest. It was a long and weary way which she went, through divers places, where there were no inhabitants, and still the lion went with her, ready to guard her against all dangers. While she slept, he watched over her, and when she awaked he awaited her command, watching her eyes so that he might discern her pleasure.

After long journeying, in which they saw no sign of the presence of man, they came to a place which, from the wearing of the grass, seemed to be trodden by human feet. And in no long time the lady espied a woman, who was following the path with slow steps, and carrying on her head a pitcher of water. The lady cried to her, “Tell me now, my friend, whether there may be any dwelling near to hand, where I may rest awhile?” But the woman answered her never a word, seeming as if she could neither understand nor speak. But when, turning her eyes, she saw the lion by the lady’s side, she threw down her pitcher, and fled as fast as her feet could carry her. Not once did she look behind her, but fled as if for her life till she came to the house where she dwelt with her mother, a blind woman. Not a word did she say, but her fear was plain to see, and the old woman perceived that there was some great danger at hand, so when they two had shut the door they hid themselves in the darkest corner of the cottage.

In a short space of time came Una and her lion to the door. Thereat the lady knocked, but when no one answered, and the time was passing, the lion in his impatience rent the wicket-gate with his claws and let her in. No further hurt did he, and when Una had with much gentle speech allayed the women’s fear, they laid themselves down to sleep.

But when the night was far spent, there came one to the door demanding entrance, and when this was not speedily given him, using many oaths and curses. He was a sturdy thief, by name Kirkrapine, that is to say, Robber of Churches, and this indeed was his trade. He was wont to steal away the ornaments of churches, and to strip off from the images of the saints the vestments with which they were clad, and to purloin the robes of the priests, and to break open the boxes in which were put the alms for the poor. No small share of the plunder did he bring to the house where Una lay that night, for he was the lover of the old woman’s daughter, and he could never give her enough of gold and jewels and precious things. But whether the old woman knew of the matter none can tell, though it might have seemed that such doings were not to her mind, seeing that she told her beads and prayed both by day and by night; nine hundred Paternosters would she say daily, and of Ave Marias twice as many. Thrice in the week, also, did she sit in ashes; thrice three times she fasted from all food and drink, and she wore sackcloth nearest to her skin.

Now when this same Kirkrapine found that, for all his cursing, he could not win an entrance, for, indeed, though the women heard him, they were hindered from rising by fear of the lion, he let fly furiously at the door and brake it down, and would have entered. But as he was about to cross the threshold, the beast, thinking that his lady was in danger, sprang at him, and brought him to the ground, and so tore him that he died, which, having done, the lion came back to his place by the lady’s side, and watched her as before.

When the day broke, the Lady Una rose from her place, and went forth from the cottage, and journeyed onwards still seeking the Knight, and the lion went with her. The old woman also and her daughter, so soon as the house was clear of its guests, rose up. But when they found Kirkrapine lying dead before the door, great was their grief and greater still their anger.

“This,” they cried, “the savage beast has done,” and they followed with all the speed they might use, and so overtook her. Harm her they might not, for they feared the lion, and when they had cursed her loud and long they turned back to go to their own house.

As they went they met a knight, fully clad in armour. But yet he was no knight but only the wizard Archimage, who had taken upon himself, by help of his wicked arts, the semblance of the Red-Cross Knight. The false knight asked them whether they had seen a lady journeying alone.

“Yea,” the old woman answered, “such I have seen; an evil woman she is, and much harm hath she wrought.” And she told a piteous tale of the things which she had suffered. This done, she showed him the way by which he must go, if he would overtake the lady, and he, having thanked her with due courtesy, rode on. Nor was it long before he overtook the Lady Una, for she, having but an ass for her steed, travelled slowly. When she saw him, and noted the Red Cross on his shield and the like emblem on his breast, she said to herself: “Now God be thanked, I see my true champion again,” and she rode to meet him, and greeted him with friendly words, saying: “Where have you been these weary days, my lord? I have fared ill without your company,” and she told him of all the troubles and dangers through which she had passed.

On the other hand, the false knight spoke her fair: “For this cause I left you, dearest lady, that I might seek an adventure of which Archimage told me, and how I might deal with a felon who had done great harm to many gallant knights. And, indeed, I did deal with him, so that he shall hurt such knights no more. I pray you, fair lady, to pardon me that I left you awhile, even for such cause, and to take me once more as your faithful servant and champion.”

The Lady Una and the Lion.

So the two rode on together. They had not travelled many miles when they saw coming to them, riding at the full speed of his horse a knight fully armed. When he came near they saw that he was a man of very fierce aspect, and that he carried on his shield the name Sansloy. Fierce as he was of look, he grew fiercer yet when he perceived the false knight’s shield, how it had the badge of the Red Cross. Not a word did he speak, but he laid his spear in rest and rode fiercely forward.

Sorely dismayed was Archimage, and loath to meet the stranger in battle, for, indeed, he was not used to bearing arms. Yet could he not hold back for very shame. The Lady Una also looked at him that he should bear himself bravely. But it fared ill with him, and, indeed, it would have fared worse but that his steed, being no less timorous than himself, held back in the onset, so that the shock of their meeting was the less fierce. Nevertheless, he was thrown to the ground, where he lay helpless and without defence.

The strange knight leapt lightly from his horse, and made as though he would have slain his adversary. “Ha!” he cried, “so he that slew the brave knight Sansfoy, my brother, has come by his deserts. Sansfoy he slew, and by Sansloy he shall be slain!”

Then he began to unlace the man’s helmet as he lay upon the ground, but the Lady Una cried, “Oh, Sir Knight, hold your hand; is it not enough that you have vanquished him? He lies there at your mercy. Therefore have mercy upon him. Verily there is not in the whole world a truer knight than he.” But the stranger had no mind to hold his hand, for, indeed, he had no compassion within his heart. But when he had ended the unlacing of the helmet, and was now ready to strike, he saw the hoary head and wrinkled face of Archimage, and cried: “What is this that I see, Archimage, luckless sire? By what ill-fortune have you come across me in this fashion? Is the fault with me or with you, that I should have dealt with a friend as though he were an enemy?”

So he spake, but not a word did the wizard answer. He lay in a swoon, and the shadow of death was on his face. And now the Lady Una had come and was looking into the old man’s face. Sore dismayed she was and sore vexed; for he whom she had taken for her champion was a deceiver; nor could she divine how she might escape from the hand of this paynim knight. And now she had to bear yet another grief. For when Sansloy laid a rude hand upon her and bade her descend from her steed, and caught away her veil that he might look upon her face, the lion, not enduring to see his mistress so handled and treated, sprang at the knight, but alas! what was he to withstand a knight clad in armour of proof, with spear and sword? Soon did Sansloy thrust him through with the iron point, so that the faithful beast fell dead upon the ground, and the lady was left helpless and without defence.

The Red-Cross Knight rode on with the false Fidessa, not knowing that she was indeed the witch Duessa, who had changed the unhappy Fradubio into a tree. After a while they came to a road which was manifestly much frequented of men, and following this beheld before them a very stately palace. “Come,” said Duessa, “let us seek shelter here, for I am weary with my journeying and the day is far spent.”

It was, indeed, a very noble house, cunningly built of bricks laid artfully together without mortar. It had very lofty walls, but they were as slight as they were high, overlaid with shining gold, with many towers rising from them, and goodly galleries disposed among them, and spacious windows. No one could blame the skill of the architect that had planned it, or of the builders that had raised it up, so fair it was to look upon; yet it was passing strange that it had been built in a place so ill chosen, to wit, upon a sandy hill, so that the foundations were ever slipping away from it; and when the winds blew upon it it was shaken most perilously, and the lower parts, for all that they were painted so as to make a very brave show, were ruinous and old.

They passed by the porter, whose name was Malvenu, which being interpreted is “Ill come,” without challenge, and so came into the hall. This was right richly arrayed with arras and cloth-of-gold, and was filled from end to end with a great crowd of people of all sorts and degrees, waiting, all of them, for a sight of the lady of the house. These also they passed, as being guests to whom special honour was due, and so were brought into the presence of the lady, where she sat with as fair and richly-clad a company of knights and dames about her as ever was seen upon the earth. High on a throne, splendid in royal robes and ornaments of gold and jewels costly beyond all count, sat the lady. Fair she was, so fair that throne and robes and gold and gems were as nothing in comparison with her beauty. Under her feet was a great dragon, and in her hand she held a shining mirror of brass, and her name was Lucifera. She was, indeed, the Queen of Pride, and all her brave show was a false seeming, and her kingdom a kingdom of unrighteousness.

The Knight, not knowing what the lady truly was, and false Duessa, to whom all these things were well pleasing, being introduced by a certain usher of the court, Vanity by name, bowed themselves low before the throne. And the Knight said, “Lady, we are come to see your royal state, and to prove the report of your great majesty which has gone through all the world.” “I thank you,” said the lady, but in a disdainful way, for she did not so much as cast her eyes upon them, nor did she bid them rise. On the other hand, the knights and ladies set themselves with much heartiness to entertain the new-comers. The knights were right glad to welcome among them a companion so fair and so stalwart, and to the dames the false Duessa was well known. Nevertheless the Knight was but ill pleased that the Lady Lucifera should show such scant courtesy to a stranger. “She is overproud,” he thought to himself, “and there is too much of vain show in these her surroundings.”

While he was thus thinking, the lady rose suddenly from her place, and said that she would ride abroad, and bade call for her coach. A stately coach it was, like to that which, as it was said of old, Queen Juno rode with six peacocks, spreading out great starry tails, for horses. Six steeds had this Queen also, but they were but ill matched, and on each of them did ride one of the six counsellors who advised her in affairs of state, and the six were Idleness, and Gluttony, and Lust, and Avarice, and Envy, and Anger. The false Duessa followed close after the Lady Lucifera, for she was of a kindred spirit, but the Knight, though he knew not all the truth, yet held aloof from the rout, not liking their company. When they had tarried awhile in the fields, breathing the fresh air of the country-side, they turned back to the palace. There they found a Saracen knight newly come, who carried on his shield the name Sansjoy. He was ill-favoured and ill-conditioned, as one who bore a grudge against his fellows. But when he saw how the page of the Red-Cross Knight carried a shield on which was written the name of Sansfoy, then was he filled with fury, and sprang upon the lad and wrenched it from him, which the Red-Cross Knight perceiving, being ill content so to lose the trophy which he had won in fair fight, ran at the Saracen, and recovered that which was his own. Already had they drawn their swords to fight out their quarrel hand to hand, when the Queen Lucifera interposed her high command: “Sirs,” she said, “I command you on pain of my high displeasure to forbear. To-morrow, if you will, you shall prove in fair fight to whom this shield, for which I perceive you contend, in right belongs. Meanwhile I bid you be at peace.”

“I beg your pardon, noble Queen,” said the Saracen, “for that I have thus broken the peace of your court; in truth I could not refrain myself when I saw this false knight possessing the shield of the brave Sansfoy, whom he slew not in fair fight, but by magic arts, ay, and not possessing it only, but that he might do it dishonour, commanding that it should be publicly borne.” So spake Sansjoy, but the Red-Cross Knight said nothing; he was a man of deeds, not of words. Only he threw his gauntlet on the ground, to be a pledge that he would meet his adversary in the field.

Then, for evening was now come, all sat down to the banquet. Right royally did they feast, for Gluttony was steward that night, and ordered their meat and drink; and when they had feasted to the full, they betook themselves to their beds, and Sloth was their chamberlain. But before she slept Duessa made Sansjoy aware that she was no friend to the Red-Cross Knight.

It is ever the way with noble hearts, that they cannot rest till they have fully accomplished that which they purpose to do. So all night long the Red-Cross Knight considered with himself how he should most wisely bear himself in the morrow’s fight, and so considering he waited till the morning light should shine upon the earth. So soon therefore as the sun appeared in the sky he rose from his bed, and arrayed himself in his armour, making ready for his combat with the Saracen. This done, he descended into the castle hall, where there was already gathered a great crowd of men, who had come to see what the issue of the day should be. There were musicians making melody on harps and viols, and bards who were ready to celebrate in song the strength and valour of him who should win the victory. After him by no great space of time came the Saracen, clad in chain armour. Fierce was his look, as though he would strike fear into his adversary, but the Knight was of a temper which no looks could dismay. Then the pages brought in two cups of wine from Greece, and mingled therein spices from farthest India, for such was the custom of the place. It was to kindle the champions’ courage forsooth, but neither Christian nor Saracen, I take it, had need of such encouragement. And as they drank they sware a solemn oath that they would duly observe the laws of honourable war.

This done, the Queen Lucifera came with a great train of knights and ladies, and took her seat upon the throne which had been set for her with a great canopy over it. Before her was an open space, railed in on every side, that none should be near either to help or to hinder the champions. Over against the Queen was set another throne, of less account and dignity. On this was set false Duessa. And on a tree hard by was hung the shield of Sansfoy, and a laurel crown which should be the conqueror’s meed.

And now was heard the shrill note of a trumpet, and the two champions addressed themselves to the battle. Each man carried his shield on his left arm, and took his sword in his right hand, for such was the order of the fight, that for a speedier issue they should lay aside their spears and take at once their swords. Both knights were sturdy and brave, and long they fought without advantage gained. Stroke was answered with stroke, while the sparks flew from either shield, and each helmet showed the dints where the steel had been well-nigh broken through. Neither did this champion or that escape without harm, for the blood was seen to flow out and dye their coats of mail, but neither suffered such a wound as to hinder him from the fight, nor did the crowd that watched them know which would prevail. And now it chanced that the Saracen, as he shifted his place, caught the sight of his brother’s shield, where it hung upon the tree, to be the conqueror’s prize. The sight stirred him to a double rage: “Ah! brother,” he cried, “dost thou sit so long by that dark lake of death the while thy shield hangs here to be the prize of victory? Go, caitiff,” so he cried, as he turned him to the Red-Cross Knight, “go and tell him that I have redeemed his shield from shame.” And as he spoke, he smote upon the crest of the Knight a mightier stroke by far than he had ever dealt. Twice did the Knight reel as he stood; twice was he ready to fall; while all that watched were assured that the battle was indeed won and lost, and the false Duessa cried aloud: “Well done, Sansjoy; the shield is yours, and I and all.” But when the Knight heard the voice of the lady—for he knew not yet her true quality—he raised himself from his swoon, and his faith that had waxed weak grew strong again, and the chill departed from his limbs. Wrath and shame and love wrought such new strength within him, that he struck his foe with a stroke so mighty that it brought him to his knee. “Ah! thou miscreant,” he cried, “go now and take yourself your message to this dear brother, and tell him that the conqueror has his shield.” But when he would have dealt yet another blow, and so ended the fight beyond all doubt, lo! there was a dark cloud over all the place, and the Saracen was nowhere to be seen. He called him aloud, but there came no answer. The darkness had swallowed him up. Then the false Duessa came down from her seat and entreated him with many words: “O most valiant Knight that ever lady chose for her champion, abate now your rage; your adversary lies low; be content with your victory.” But not one whit was his wrath diminished; willingly would he have driven his sword-hilt deep into the body of his enemy, so finishing his work. But nowhere could he espy him. While he stood wondering, the trumpets sounded again, now with a note of victory, and heralds came and paid him homage, making low obeisance to him, and giving into his hands the shield. After this they took him to the Queen, where she sat upon her throne; and he, bending his knee before her, made proffer of his service, which she accepted with much courtesy of thanks. This done, she returned to the palace, having the Knight by her side, the people following with loud shouts and much rejoicing.

And now, because his wounds were many—for not without much cost of pain had he won this victory—they laid him in a bed and bound up his hurts, pouring in oil and wine, the while the musicians made sweet music to comfort him in his sickness. While he thus lay, Duessa resorted to a certain witch of whom she had knowledge, and told her of how the Christian Knight had slain Sansfoy, and now had stricken Sansjoy well-nigh to death, and prayed her help. So the two returned together to where the Saracen lay, still covered with the magic cloud. They bound up his wounds, and laid him in the witch’s car, and carried him to hell to the dwelling of Æsculapius. Now this Æsculapius was a great physician in the days of old, and because he had brought to life again a certain man who had been unjustly slain he had suffered grievous punishment. He could not die, for he was of immortal race, but he had been struck down to hell with a thunderbolt. There he had lain, age after age, striving, if it might be, to heal his own hurts. To him, therefore, the witch and Duessa brought Sansjoy, and prayed him that he would recover him of his deadly hurt. “Nay, nay,” said he, “you ask what may not be. You tempt me to do again the very thing for which I suffer all this pain. Shall I again, with a like deed, renew the wrath of him that so dealt with me?”

The witch made answer: “What more can you suffer than you have suffered already? You hope for nothing; what then should you fear? You are in this lowest deep; is there a lower to which you can fall? Deny not my prayer; rather show the power which has given you your great renown in heaven and on earth and in hell itself.”

“Be it so,” he said. So they brought the knight, and the great physician used all his arts, applying to the man’s wound all the healing powers that he knew. Then Duessa, having accomplished her purpose, so far as it might be done, journeyed back to the Palace of Pride, but when she came thither she found that the Red-Cross Knight had departed.

Now the cause of his going was this. He was not, indeed, fit for travel, nor had his wounds been duly healed, but he might not stay, having heard what his faithful Dwarf had told him; and the thing was this, that there were dungeons beneath this fair castle, with all its splendid furnishing, in which lay a crowd of prisoners in most miserable plight, men of the old times and of the new, such as were Nimrod the great hunter, and the lords of Babylon and Nineveh, and great chiefs of Rome, all who by wicked pride had sinned against God and man. This had the watchful Dwarf espied. And when the Knight heard the tale he would tarry no longer, but that very hour, while it was yet dark, for it would have gone ill with him had he been espied, he fled from the castle. By a bye-way he fled, and lo! it was so full of the corpses of men that he and the Dwarf could scarce make their way, for though the castle was fair in all its public parts, those that were secret were foul beyond all thinking.

Though the wizard Archimage was an ill companion for the Lady Una, yet was Sansloy, by whom he was overthrown, a worse. They had not travelled together far when he said, “Lady, deign, I pray you, to show me that fair face of yours. I would fain know for whom I have done battle. Yours, I ween, is such beauty as the old villain whom I overthrew was not worthy to take in charge.” And when she answered him not a word, he stretched forth a lawless hand, and would have torn the veil from her face. Then she cried aloud. “Ay,” said he, “cry if you will; there is none to help you here.” But even while he spoke there came running out of the wood, which was hard by, a great multitude of strange creatures, fauns and satyrs, half man and half beast. They were dancing and making merry in the forest, which is their natural dwelling-place, and when they heard the cry, one said to another: “This is the cry of some mortal in distress, and it has the note of a woman’s voice; let us see what is the cause.” So they made all haste to the place from which the cry came. And when the Saracen beheld them he was sore afraid. Such creatures he had never seen in all his life; so he sprang upon his horse, and fled as fast as he could. Nor, indeed, was the Lady Una wholly quit of her fears. So it may chance that when a wolf carries off a lamb, and drops it for fear of a lion, the lamb may be in no better case. But when the strange creatures saw by the lady’s face that she was sore afraid, they tried to show their goodwill towards her; they threw themselves upon the ground and kissed her feet, and sought to show her that they were her dutiful servants. So, gathering courage, she raised herself from the earth on which she had thrown herself in fear and distress, and made signs that she would go with them. So they led her through the wood, dancing and shouting and singing; and some strewed branches of trees on the ground before her, and one, who was a chief among them, put a crown of olive leaves about her head. So they led her to their chief Sylvanus, and he, waked from his sleep by their shouting, came forth to meet them, leaning on a staff of cypress wood, and having a rope of ivy knitted about his middle. When he saw her, much did he marvel who she could be. “This is not Venus,” he said to himself, “for Venus never was in so sober a mood; no, nor Diana, for I see not her bow and arrows and the buskins up to her knee.” And while he stood and wondered, the nymphs flocked in to see, nymphs of the fountains and the woods, and they whose lives are bound to a single tree, living while it lives and dying when it dies. Nor were they less astonished, but they were ill pleased that one so fair should come among them: “Who of the wood folk,” they said to themselves, “will think of us when this mortal maid is near?”

Many days Lady Una tarried with this strange folk, and not unwillingly, for it was as it were a breathing time, giving her rest from the long toil of her journey. And while she tarried she strove to the utmost to teach them something of the Christian faith: but ever she had much ado to keep them from the worshipping of herself. And when she had scarcely kept them from this, they turned to worship her ass.

After a while there came into these parts a certain knight, Satyrane by name, so called because he was the son of a prince among the satyrs, but his mother was of the race of men. He was brought up in the woods, far from all human company; nor did he learn letters or any craft whatsoever, but only to be ever of a good courage and to banish fear. So he would lay his hand on lions and bears, and tame the wild bulls of the forest, riding on them as one might ride upon a horse. And he grew to be so swift of foot that he would overtake the roebuck in his flight. ’Tis said that once when his mother came to see him, for she had gone back to dwell with her own kind, she saw him carrying in his arms the cubs of a lioness which he had carried away from their dam, while the creature, in its rage, followed him, roaring aloud, yet dared not spring, so well did all the beasts of the forest know and fear him. When he grew to years of manhood he was not content with the conquest over wild beasts, or with life in the wood far from man. He went therefore into distant lands seeking adventures, in which he acquitted him so well that no man could boast of having overthrown him. Yet it was his custom from time to time to return to his old dwelling-place to see his old father and to rest awhile from his labours. And so coming now, he chanced to find the Lady Una sitting with a company of the forest folk around her, teaching them holy things. Much he marvelled to see how fair she was, and more did he marvel at the wise and gracious words that came from her lips; for, indeed, by this time, being by nature of a lively wit, he had himself learnt many things. So he gladly sought her company, and would fain be her disciple and learn the ways of righteousness and peace from her lips.

After certain days the Lady Una, seeing that this Satyrane was an honourable knight and worthy of trust, said to him, “I would fain go on with journeyings, if haply I may find my champion.” “Lady,” he made answer, “I am bound to do your pleasure; it shall be as you say.” So having watched for a time when the forest folk were away, he took her through the forest till they came to the plain beyond. When the day was now far spent they spied a traveller on the road, and judging from his look and garb that he had come from far, hastened towards him, hoping that they might by chance hear something that would help them in their quest. He was an old man of low estate, as it seemed, his garments worn and soiled with much dust from the road, his sandals torn with much travelling, and his face bronzed by the sun, as if he had travelled long in Arabian or Indian land. A staff he carried in his hand, and on his shoulders hung a wallet in which he carried such things as were needed for his journey.

Satyrane said to him: “Friend, have you aught to tell me of wars and adventures in these or in foreign parts, for indeed you seem to have come a long way?” “Nay,” answered the stranger, “I am a simple man, and know nothing of such matters.” Then said the Lady Una: “Tell me now whether you have seen or heard aught of the champion whom I am seeking? He bears a red cross on his armour.” The old man answered: “Fair lady, truly I have seen such an one with these eyes, and a sorry sight it was, for he lay dead upon the ground.” When the Lady Una heard these words she fell to the earth in a swoon. When Satyrane with much care had brought her back to life, she said: “Friend, tell me all that you know; one who has borne the greater pain may well endure the less.”

The old traveller answered: “On a certain day—an evil day it was, and I am grieved that I ever lived to see it—as I chanced to be passing on my way, I saw two knights contending fiercely together; one was a Saracen, and the other bore a red cross on his shield, and he that carried this device was slain.” “Oh to think,” cried the Lady Una, “that he should be thus overcome, he that was so stout and brave. How could such an evil chance befall?” “That I know not, fair lady,” said the old man; “I can but relate the thing which I saw with mine eyes.” Then said Satyrane: “Tell me now, old man, where is the Saracen knight that did this deed? Is he far from hence or near at hand?” The old man made answer: “You may find him not far from here. I left him but a short time ago sitting by a fountain where he washed his wounds.”

The knight Satyrane, having further inquired by what way he should go, made all haste to find the Saracen, fearing lest haply he should have departed. And, indeed, he found him, sitting by the fountain side under the shade of a tree, for it was Sansloy, the same that had overthrown Archimage. And Satyrane cried aloud: “Rise from your place, accursed miscreant, you that by some unknightly craft and treachery have slain the Red-Cross Knight, for I know well that you could not have overcome him in fair fight. Rise up, and either maintain your cause in arms, or confess your guilt.” The Saracen, when he heard these words, rose quickly from his place and put his helmet on his head, and took his shield upon his arm, and drew near to his adversary. But first he said: “Truly you have been sent hither in an evil hour to fight a quarrel that is not yours. And, indeed, you blame me for a deed which I have not done. The Red-Cross Knight I slew not, nor indeed did I engage in fight with him. Someone who falsely bore his arms I overthrew. But come now, if you may not fight in his quarrel, fight in your own.”

Then the two men came together in fierce encounter. When they were at the hottest of the fray, the Lady Una came to the place, for Satyrane had left her behind in his haste. And when she saw the Saracen she said to herself: “Now what shall I do if this false villain should get the upper hand of Satyrane?” And the thought struck such terror into her heart that she straightway turned and fled from the place. And the old traveller, who had told the false tale of the slaying of the Red-Cross Knight, followed her, for, indeed, he was none other than Archimage.

When the false Duessa came back to the Palace of Pride from the journey which she had made in the matter of Sansjoy, she found that the Red-Cross Knight had departed. Thereupon she set out without delay, being altogether unwilling that he should escape out of reach of her nets. Nor, indeed, was it long before she found him, sitting by the side of a spring in the shade of a tree. He had put off his armour by reason of his weariness and of the heat of the day. “You did ill to leave me in that ill place Sir Knight,” she said, “for ill I found it to be, even as you did yourself.” Then he excused himself with courteous words, and so peace was made again between the two.

Now the spring by which the Knight was taking his rest was not as other springs, but there lay a curse upon it, because the nymph which dwelt therein had fallen out of favour with her mistress, Diana. And the cause of her so falling was this. On a certain day, as Diana and her train were following the chase, the nymph of this spring, being wearied with the heat and toil of the day, sat herself down to rest. With this her mistress, being very keen in her hunting, was ill pleased: “Maid,” she cried, “you are dull and slow; such, then, shall these waters be for ever, ay, and whosoever shall drink of them.” Of this the Knight knew nothing, but because the waters were crystal clear and cold, and his thirst was great, he drank a great draught. And as he drank, the powers of body and soul grew faint and feeble, but by slow degrees and unperceived. Ere long there came to his ears a loud bellowing sound which made the trees to tremble and the very earth to shake. The Knight leapt from the ground, and would have armed himself, but yet, such was the working of that magic spring, was strangely slow. Certain it is that ere he could don his armour or thrust his arm into the fitting of his shield, there came stalking along with mighty stride the most fearsome giant that ever was seen on the face of the earth. His stature was thrice that of man, and in his right hand he carried an oak tree which he had torn from the earth by its roots. It served him for a staff whereon to stay his steps, and for a mace with which to slay his foes. So soon as he spied the Knight he came against him with the oak tree lifted in his hand. On the other hand, the Knight made a vain show of battle, but the strength had departed from his arm, and the heart in him failed for fear. He lifted his sword, indeed, but he had no power to strike. Then the giant aimed at him a mighty blow, such as would have levelled to the ground a tower of stone. Verily, but for the grace and help of God, it had ground him to powder, but he leapt from under it, yet its very wind laid him prostrate on the ground. When the giant saw him lie helpless in this fashion, he lifted his hand again as if to slay him, but the false Duessa, who, for her own ends, would not have the Knight perish in this fashion, cried aloud: “O Orgoglio, greatest of all creatures under the sun, slay him not, but make him your thrall and slave.” The giant listened to this prayer. He took the Knight in his arms and carried him to his castle, and there threw him into a dungeon that had been dug deep into the earth. There he lay for a while, with such scant provision of meat and drink as sufficed to keep the life in him.

The faithful Dwarf had seen his master fall, for he had the Knight’s war-horse in charge, while the beast was grazing in the meadow hard by. And now, the giant having departed with his prisoner, he gathered together the arms and the armour, for these Orgoglio had left lying on the ground as taking no account of such things. There was the helmet and the cuirass, and the greaves and the shield with the cross upon it, and the spear—things sad to behold, now that there was none to wear or wield them. He laid them on the back of the war-horse, and so departed. He had not gone far before he met the Lady Una herself. When she saw him and the war-horse and the burden which it bore, there was no spirit left in her, so that she fell without sense to the ground. Willingly would the faithful Dwarf have died, knowing what ill tidings he bore, and seeing how ill they were taken. Nevertheless he did not lose heart, but with much pain and care sought to recover the lady from her swoon. Thrice did he bring her back to life, and thrice she fell as one dead to the ground. At last, when the spirit within her had somewhat recovered itself, she said with faltering tongue: “Tell me now, faithful friend, the whole story from the beginning, how it is that I see these relics of the bravest knight that ever was. Verily Fortune has spent all her spite upon him and me. Worse than that which I feel in my heart I cannot hear. Begin your tale and carry it to the very end. If haply it shall be in aught less dreadful than what I fear, so much I shall have gained.”

Then the Dwarf rehearsed from the beginning all that had befallen the Red-Cross Knight from the time of their parting, the deceits of Archimage and the wiles of the false Duessa, and the fate of the two lovers who had been changed to trees, and the Palace of Pride, and the combat with Sansjoy, and how the Knight had been taken unprepared by the giant Orgoglio.

To these things the lady listened with attentive ear, and when the Dwarf had ended his tale she said: “Verily I will seek him as long as I live. Lead on, and show me the way that I must go.” So they travelled both together.

They had not journeyed far before they met a knight riding on the way with his squire behind him. Never was there more gallant warrior or more gallantly arrayed. His armour shone like the sun, and across his breast he wore a baldrick richly adorned with precious stones. Costly were they all, but one among them shone most excellently, a great diamond like to the head of a fair lady, brighter than all the rest, even as the star of evening is brighter than all the hosts of heaven. His sword hung from his side in a sheath cunningly made of ivory; its hilt was of burnished gold, and its buckle also of gold. The crest of his helmet was a great dragon, with wings spread out on either side, and above the crest a horse-hair plume, which waved to and fro as an almond tree waves its blossoms in the breath of spring. But the great marvel of his equipment was his shield. It was not made of iron or of brass, as are the shields of common men, but of one great diamond. Only it was covered up from sight. When he would dismay some huge monster, or strike with fear some great array of the enemy, then he would show its brightness. No power of man, no enchantments, strong and subtle as they might be, could prevail against it, or diminish aught of its power, for indeed it was made by the greatest magician that ever lived upon the earth, even Merlin.

The gallant knight spake full courteously to the Lady Una, asking if he could help her or serve her in aught. “Oh, Sir,” she answered, “my sorrow is so great that it is past all remedy. What would it profit to tell the tale? ’Tis best to hide it in my heart nor stir the hidden grief.”

“Nay, lady,” answered the knight, “I doubt not that your grief is great, but I would counsel you to tell the tale for all it is so sad. Pain is ever lessened, be it ever so great, by wise counsel, and he who will not reveal his trouble may never find help.”

So they spake together, he persuading her to reveal her sorrow and she unwilling to bring it to the light, till at last, yielding to his words of wisdom, she told her tale.

“I am the daughter,” she said, “the only child of a king and queen whose kingdom lies far by the river Euphrates. Long did they reign in great prosperity, till a great dragon, bred in the lakes of Tartary, wasted their land till there was nothing left of all that belonged to them, save the one castle in which they dwelt, and to this the dragon has laid siege now for the space of four years. Many knights have taken in hand this enterprise, to subdue the dragon and to deliver those whom he oppresses. From every country under heaven have they come, brave men and famous for great deeds, but they have failed, one and all. For want of faith or for the hidden weakness of some secret sin they have fallen before him. At last there came to our land a report of certain famous knights that had been bred in this realm of Fairy Land. Thereupon I betook myself thither, even to the Court of Queen Gloriana, who dwells in the City of Renown, hoping that I might there find some faithful knight who should deliver my father and mother from the power of the tyrant. Nor did I go in vain. It was my good fortune to find a gallant knight who was fit and willing to undertake this task. Unproved indeed he was, but he was of a fair body and a noble soul. It was he who set forth upon this enterprise. Of his prowess I saw full many a proof. Yea, the sword and the spear which you see on the back of yonder steed might tell, if they could speak, of the great deeds which he has wrought. But by ill chance he encountered a most false magician, by whose arts he was betrayed. First this vile creature made division between my knight and me, so that he misdoubted of my faith. Next he delivered him to the wiles of a certain false woman, Duessa by name. And she has betrayed him into the hands of a great and terrible giant, Orgoglio by name. And in this giant’s dungeon he now lies pining to death. This is my grief, Sir Knight, and greater, surely, never woman bore.”

“Your grief is indeed great,” answered the stranger knight; “but be of good cheer. I will never leave you till I have set your champion free. Come now, let us bring this matter to an end.”

So they rode on together with the Dwarf for their guide. The name of the gallant knight who bore the shield of diamond was Arthur.

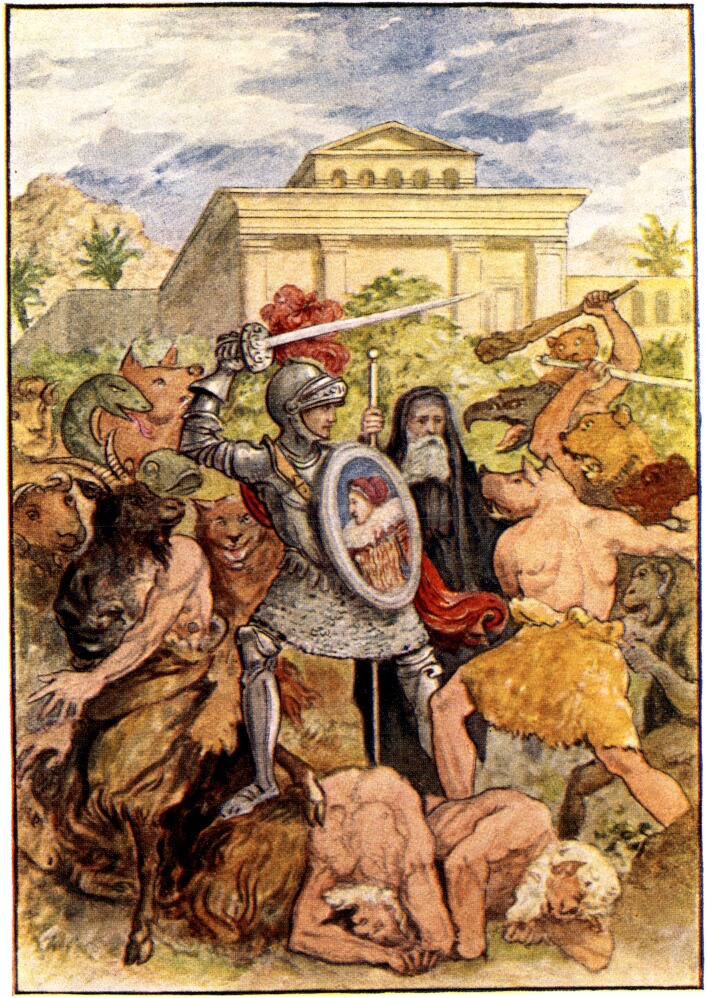

When they had travelled a score of miles or so, they came to a castle which was built very high and strong. Thereupon the Dwarf cried out, “This is the place in which my good lord lies a prisoner, the thrall of the giant Orgoglio.” Thereupon the Prince Arthur alighted from his steed, and said to the Lady Una, “Stay here, madam, and await the issue of this day’s combat.” Then, at his bidding, the squire came near to the wall of the castle. He found the gates fast shut, with no warder to guard them, nor was there any to answer when he called. Then the squire took in his hand a bugle that he bore, that hung by his side with a chain of gold decked with gay tassels. It was a bugle of wondrous power; for three miles it could be heard, and there came out of space three answers to its blast, nor could anyone in whose heart there was aught of falsehood endure to hear it without dismay, nor could any bolt or bar, however stout they might be, withstand its summons. This bugle, then, Prince Arthur’s squire sounded before the giant’s castle. And it was shaken straightway from the foundation to the topmost towers, and the doors flew open of their own accord. The giant himself was much troubled at the sound, and came with staggering steps, as one smitten with a sudden fear, to see what it might mean. And after came the false Duessa, riding on a many-headed beast, with fiery tongues, for such a monster the giant had given her for her own.

Prince Arthur without delay addressed himself to the fight. Nor did the giant draw back, being persuaded that no mortal man could stand up against him and prevail. He thought, indeed, to slay him with a single blow, and lifted up his mighty club. But the Prince was wise and wary, and, lightly leaping aside, he escaped the stroke unhurt, for he thought it no shame to use his craft against brute strength. As for the club, so missing its aim, it sank deep into the earth, making a furrow a yard deep and more. The giant pulled at it amain, seeking to lift it for another stroke, but could not prevail, so fast was it buried. The knight, therefore, had him at a disadvantage, and smote him with his sword so deadly a stroke that it shore off his arm. Loud did he bellow with fear and pain, and Duessa, seeing her champion in sore distress, made the great beast on which she sat advance against the Knight. But now Prince Arthur’s squire, a gallant warrior, worthy of such a lord, stood forth and, with his single sword, barred the way. In high disdain to be hindered by so weak a foe Duessa yet again urged on the beast, but still the squire stood firm; he would not give place a single step lest the enemy should so gain an advantage against his lord. Then Duessa had recourse to her magic arts, for she took of the magic juices which she ever carried with her, and sprinkled them upon the youth, and quenched his courage and robbed him of his strength, so that he could neither see nor stand. So he fell all his length upon the earth, and the beast laid his deadly claws upon his neck, and would have crushed the life out of him. But the Knight, perceiving his evil plight, turned quickly from his own adversary, and addressed himself to the beast, for, indeed, it grieved him much that his faithful squire should have come into such peril of his life. So, lifting high the sword with which he had smitten the giant, he smote the beast upon one of its heads, making the blood pour out amain. But when the beast, writhing to and fro in its pain, would have shaken Duessa from her seat upon its back, and she cried out in her fear, the giant came to her help. He was, indeed, of no common nature, nor was he disabled by the wound which would have bereft all other creatures of strength. In the one hand which was left to him there dwelt the strength of the two, and now being free to use again his club of oak, he lifted it up high and dealt such a blow at Prince Arthur’s shield that it brought him to the ground. But now by this very stroke the Knight’s deliverance was wrought, for the covering was torn from the shield by its violence, and all its brightness was revealed. With so great a splendour did it blaze into the giant’s eyes that he dropped his arm and let fall the club with which he was ready to slay his adversary. The beast also was blinded by that brightness, and fell reft of its senses on the ground. Nor when Duessa cried aloud to the giant in her fear could he render effectual help. With stroke after stroke the Prince lopped from him limb after limb, till he lay dead upon the ground. And then this marvel came to pass. This creature which had seemed so vast seemed to vanish away. As for Duessa, she sprang from off the beast, and would have fled away upon her feet. But this the squire would not suffer, for, pursuing her with speedy feet, he laid hold of her and brought her back to the Prince to await his judgment.

And now the Lady Una, who in fear and trembling had watched the combat from a distance, came near and thanked both Knight and squire for the good service which they had rendered. “I cannot repay you,” she said; “may Heaven give you your reward and with usury. Suffer me to say one thing. Let not this false woman depart, for, indeed, she is the cause of all the mischief that has been wrought.” Then Prince Arthur said to his squire: “Take this woman in charge; I will go seek the Red-Cross Knight.” So he departed on this errand, and, entering the castle, sought someone of whom he might inquire. No one did he find, and though he called aloud, there was none to answer. At last there came forth an old man leaning on a staff with which he guided his steps, for the sight of his eyes had failed him long since, and carrying a great bunch of keys, but all of them overgrown with rust. His name was Ignaro. A reverend sire he seemed, and the Knight asked him with all courtesy: “Who are they that dwell in this place, and where may they be found?” “I cannot tell,” he said. Then the Prince asked again: “Where, then, is the Knight whom the giant Orgoglio holds in thrall?” “I cannot tell,” said he again, nor did he say any other words. The Prince’s anger rose at this foolishness, but he checked it as should a courteous knight, and, taking the keys from the old man’s hand, essayed to open the doors, nor did they delay to yield. Great riches he found within—store of gold, and tapestry finely wrought, and much splendid furnishing; but the floor was foul with blood. Vainly did he search through all the chambers; the prisoner he could not find. At last he came to an iron door. It was fast locked, nor was there a key upon the bunch that would open it. But in the door there was a grating of iron bars. Through this he called aloud: “Dwells there anyone in this place, for I will set him free?” To this there came a low voice making this reply: “Who is that who comes? Three months have I lain in this foul dungeon, and if you bring me death itself I would choose it rather than to stay in this place.” When the Prince heard these words he was overcome with horror and pity; not the less, gathering up all his strength, he smote the door, and brake it from its hinges. But when the opening was made, lo! on the other side was no floor but only a deep pit, dark as night, from which there came up a loathsome smell. But neither the pit nor the darkness nor the vile stench abated the Prince’s courage. With much pains and toil he drew up the prisoner from the pit. Sadly wasted was he. He could not stand upon his feet, and his eyes, deep sunk in the sockets, could not bear to look upon the light, and his arms that had been so staunch and strong in the old time were wasted to the bone. So the Prince carried him to the castle door. And when the Lady Una saw him, she was filled with pity and ruth and would have comforted him: “Welcome, my lord,” she cried, “whom I have so long desired to see. Soon shall you have a recompense for all that you have suffered.” “Dear lady,” he made answer, “we will not speak of the evil that is past; only let us beware that we fall not into it again. For, indeed, there is engraven in my heart, as with a pen of iron, this true saying: ‘Happiness may not abide in the heart of mortal man.’”

As for the false Duessa, they were content to strip her of her robes and ornaments. And fouler creature to behold there never was. Then the knights and the squire and the Lady Una tarried awhile in the castle, where they found all things that they needed. So they took for sundry days a rest from their toil.

The time was now come when, having rested sufficiently, the Red-Cross Knight must set forth again, and Prince Arthur, being bound for another land, must bid his companions farewell. Then said the Lady Una: “Tell us now your name and nation, for it would be a great loss not to know to whom we owe so great a debt.” “Fair lady,” said he, “you ask me that which it passeth my wit to answer. This only do I know, that so soon as I was born I was taken by a knight of Fairyland to Timon, now the wisest, as he was once the most expert, in arms among living men, by him to be brought up in all virtuous lore and noble accomplishment. To his house the great Merlin would often come, for he had the chief charge of my upbringing, and he, when I asked him of my family, answered: ‘Be content; you are the son and heir of a king, as shall be made manifest in due time.’” “And how,” said the Lady Una, “came you here seeking adventure?” “You bid me renew an unspeakable grief,” he answered. “There was a time when I laughed at the name of Love, and thought scorn of all that suffered from its power. But there came a time when I myself confessed it. On a certain day, being wearied out with sport, I laid me down to sleep. And in my sleep I dreamt a dream. The Queen of Fairyland stood by my side and told me that she loved me and would show her love when the time should come. Such was my dream; whether it was false or true I know not—only that never in this world did man see so fair a sight or hear words so sweet. And when I woke I vowed in my heart that I would seek her, and never rest till I had found her. Nine months have I sought her, but in vain.” The Lady Una said: “Happy Queen of Fairies that has found so gallant a champion!” and the Red-Cross Knight said: “O sir, to whom I owe my life, if ever man was worthy of such love, you are surely he!”

And now the time was come when they must part. Prince Arthur gave to the Knight a box of diamonds set in gold, wherein were drops of a wondrous liquid of a virtue so excellent that it could heal the most grievous wounds. And the Knight gave to the Prince a book in which the Gospels were written in golden letters.

They had not journeyed far when they were aware of a knight, in complete armour, riding towards them as fast as his horse could gallop. He seemed to be flying from an enemy or from some dreadful thing, for, ever and anon, he cast a look behind him as though an enemy were close at his heels. When he came near they saw that his head was uncovered, and that his hair bristled with fear, while his face was as pale as death, and that round his neck was a rope of hemp, which, indeed, ill agreed with his shining armour. But he made no account, so overcome with fear was he, either of rope or of arms. The Red-Cross Knight rode as fast as he could so as to meet him as he fled, and said to him: “Tell me, Sir Knight, what has befallen you? From whom do you flee? Never have I seen knight in such evil plight.”

Not a word did the stranger speak, but stood staring widely out of stony eyes. But after a while he gathered strength to speak, but full low, and with faltering words: “For the love of God,” he said, “gentle Knight, hinder me not: he comes; see! he comes after me, as fast as he can ride.” But the Red-Cross Knight held him fast, and using now comfort and now reproach, at last put some little heart into him, so that he could tell his tale, and the tale was this—

“I chanced of late to be in company with a gentle knight, Sir Terwin by name. He was a man of good repute for courage and skill in arms, but he fared ill in one matter, in that he loved a fair lady who had but little love for him, but rather took pleasure in seeing him languish and lament. On a certain day as we were coming away from the lady’s dwelling—for he had been paying her court, and had been most disdainfully treated—we met a stranger who greeted us courteously, and, as we fared on together, told us many wonderful tales of great adventures. When he had in this way won our regard, he inquired with a show of friendship of our condition, and when he had heard the same, and knew that we suffered not a little distress in this matter of love, for I, too, was not less troubled in this respect than was my friend, he began to talk to us in the most gloomy fashion, taking from us all hope of relief, and in the end counselling us to end our troubles with death. And that we might do this the more easily, he gave to me this rope and to Sir Terwin a rusty knife. With this said knife Sir Terwin, unhappy man that he was, forthwith slew himself; but I, whether I was more faint of heart or more fortunate I know not, fled away with all speed.”

“I would see this fellow,” said the Red-Cross Knight, “and deal with him according to his deserts.”

“Nay,” said the other, whose name was Trevisan, “I counsel you not to go within hearing of his speech, so powerful is he to persuade.” And when the Red-Cross Knight was urgent to go, Sir Trevisan answered: “To do your pleasure, friend, I will show the place, but I myself would sooner die than enter.”