Title: The Boy Fortune Hunters in China

Author: L. Frank Baum

Illustrator: Emile A. Nelson

Release date: October 18, 2017 [eBook #55767]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mary Glenn Krause, MFR, Stephen Hutcheson,

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University

of South Florida and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By

FLOYD AKERS

Author of

“The Boy Fortune Hunters in Alaska,”

“The Boy Fortune Hunters in Panama,”

“The Boy Fortune Hunters in Egypt”

CHICAGO

THE REILLY & BRITTON CO.

PUBLISHERS

Cloth 12 mos. illustrated, 60 cents each.

COPYRIGHT 1909 BY

THE REILLY & BRITTON CO.

Those readers who have penetrated far into the Chinese Empire, as has the author, will be quick to discover that he has substituted for the name of the Thibetan Province one that will not be recognized.

The reasons for this are evident. Ancestor worship is still the prevailing creed of the most numerous class of Chinese, and a violation of the sanctity of any ancestral chih, or underground tomb, would naturally be resented if it disgraced a family so important as that of a royal prince of the realm.

The Chinese characters presented in the story are drawn from life. Prince Kai Lun Pu is a well-known type of the liberal-minded, educated young men who are the best guarantee of the future expansion of the Celestial Empire. The rule of the Chief Eunuch still dominates every palace in China, and even the efforts of the late Dowager Empress could not restrain the encroaching powers of these masterful creatures.

The manners and customs herein described will serve to acquaint those who have not visited China with some of the most curious traditions of that ancient race, while the adventures related, startling as they are, are fully within the bounds of possibility.

The sinking of the first-class passenger steamship Karamata Maru in the neighborhood of Hawaii on June 17, 1908, has been the subject of so much newspaper comment that doubtless the reader imagines he knows all the circumstances connected with the fatal affair. But I have carefully read these newspaper reports and am astonished to find them quite perverted and unreliable, the result of carelessness or ignorance on the part of correspondents, the desire of officials to shield themselves from blame and the tendency of editors to amplify scant material into three-column articles with numerous “scare heads.”

I may well speak with authority in this connection, because it was our ship, the Seagull, which first arrived at the scene of the disaster and rescued the passengers and crew of the ill-fated Karamata Maru from their imminent peril So I shall tell you the story in my own way, as it has an important bearing on the extraordinary events that afterward took place—events which have led me to write this book, and place on record a series of adventures so remarkable as to have been seldom if ever equalled.

To begin with, I beg to introduce myself as Sam Steele, of Chelsea, Massachusetts, eighteen, years of age and filling the responsible position of purser and assistant supercargo on the trim little merchantman yacht, the Seagull. Indeed, I am one of the three owners of our ship, the others being my father, Captain Richard Steele, and my uncle, Naboth Perkins. My father is a seasoned and experienced seaman, who has sailed in nearly every navigable part of the world. My uncle is an expert trader and an honest man—a combination that accounts for his great success in his profession.

Circumstances placed me on shipboard at an early age, and in the course of several long and eventful voyages I have encountered many adventures and queer happenings that have made me richer in experience than most young fellows.

One may remain modest and unassuming, I think, and still bear witness to the truth of adventures in which he has participated. It is not because I love to speak of myself that I am telling my own story, but because I have full knowledge of those events in which I bore a personal part, and so am qualified to relate them. And you will discover, when I have finished the tale, that I have not posed as a hero, but merely as a subordinate actor in the drama—what, I believe, is called a “walking gentleman” or “general utility man” in theatrical parlance. The theatre being, at its best, a reflection of real life, the illustration is permissible.

It will be necessary to tell you something about the company assembled aboard the Seagull when she began her voyage from San Francisco early in May to carry a cargo of mixed merchandise to Canton, China.

The Seagull has no regular itinerary, but sails a free lance in any sea and to any country where it may be profitable for her to go. Both my father and Uncle Naboth have adventurous natures, and prefer to let fate direct their future rather than attempt to plan a succession of tedious and uninteresting voyages which might mean surer gain but would afford less excitement. This has resulted, however, in a neat fortune for each of the Seagull’s three owners, and our success has encouraged us to persist in our eccentric methods. In the merchant service our beautiful ship is dubbed a “tramp,” and I and my chums are called “the Boy Fortune Hunters,” Uncle Naboth “the Yankee Trader” and Captain Steele “crazy old Peg-leg,”—because poor father has really a wooden leg, which in no way, however, renders him less able as a skipper. But we laugh at this harmless raillery and, well knowing that we are envied by many who thus banter us, pursue our own way with unconcern.

So it happened that after a prosperous voyage around the Horn, to deliver a valuable cargo of tin-plate to the great canning factories of Oregon and Washington, we had barely anchored in the bay at San Francisco before we received a commission to sail to Canton with a cargo of merchandise. This suited us all; but none better than me, for I had long desired to visit China, Japan and the Philippines. Also it suited Joe Herring, our cabin boy and my particular friend; and it suited Archie Ackley, a well-to-do young fellow who had sailed with us on a former voyage and passed as my chum. Archie was a reckless, adventurous sort of chap, and had made the trip around the Horn on the Seagull to give a broken leg time to knit perfectly, the said leg having been damaged in a foolish wrestling bout.

I am sure you would shake your head dubiously if I were to recount all of the characteristics of this youth which had endeared him to our little ship’s company. I should be obliged to say, for instance, that Archie was stubborn as a mule, conceited as a peacock, reckless of all conventionalities, and inclined to quarrel and fight on the slightest provocation. But I should hasten to add that he was brave as a lion and tender as a woman to those he loved. His loyalty had been fully proven on the occasion of that former voyage to which I have referred, when he accompanied us to Egypt and won our hearts completely.

Archie was about my age; but Joe, our cabin boy, was a little younger, and as staunch a friend and queer a character in his way as you will ever be able to find on this astonishing earth.

Joe is rich. He could purchase a mate to the Seagull and never feel the expenditure. He could sail on our craft, if he chose, as an honored guest; but he prefers to remain a cabin-boy. Yet, in truth, there is little caste among us, and if Joe prefers to have duties to occupy him during a voyage, and fulfils those duties admirably, no one admires him less for that reason. Captain Steele slaps him on the shoulder as fondly and familiarly as he does Archie or me, and fat little Uncle Naboth locks arms with Joe and promenades the deck with him for hours.

A slight, stooping lad, is Joe, with great dark eyes, steady and true, and a faint smile always curling his lips. His face is sensitive and expressive, and in his slender frame lurk strength and agility that are positively amazing when they are called into action. Yet he is a silent fellow, though by no means unsociable, and when he speaks you are inclined to pay attention, for you know that Joe has something to say. We three boys were inseparable comrades at the time of which I am writing, although perhaps Joe and I were a little closer to each other than we were to Archie.

The ship’s crew were staunch and able-bodied seamen, carefully selected by my father, and our engineers were picked men of proven ability. But I must not forget to introduce to you two important characters in the persons of our chef and steward. The former was a South Sea Islander named Bryonia, and the latter another South Sea Islander named Nux. I say “named” advisedly, for Uncle Naboth named them in this queer way when he rescued the poor natives from an open boat years ago and restored them to life by liberal doses of nux and bryonia—the only medicines that happened to be in his possession at the time. They were, of course, unable to speak English, at first; but they learned rapidly and were devoted to Uncle Naboth, and afterward to me. Indeed, I had come to regard both Nux and Bry as my own personal followers, and well had they proven their claim to this title. They were nearly as dark as Africans, but very intelligent and faithful in every emergency. In addition to these qualities Bry was a capital cook, while as a steward Nux was unsurpassed, and looked after our comforts in a way so solicitous that he really spoiled us.

We were about ten days out of the Golden Gate and had left Honolulu well on our starboard quarter, when one evening we ran into a dense fog that could almost be felt. It set the deck hands all coughing and wetted them to the skin; so we all shut ourselves up aft in the cabin and Captain Steele slowed the Seagull down to half speed and kept the fog-horn blowing every half-minute. We believed there was little danger in this part of the broad Pacific, although every sailor dreads a fog as he does a ghost and is uneasy until it lifts.

Uncle Naboth and Archie played checkers on one end of the cabin table while Joe and I had a quiet game of cribbage together. Father smoked his pipe and darned stockings under the light of the swinging lamp, for Ned Britton, the first mate, was in charge of the deck, and no better sailor than Ned, or one more careful, ever was born.

So we passed the evening of the 16th of June pleasantly enough, in spite of the drenching fog outside, and when the watch changed all of us save Captain Steele turned into our bunks and fell asleep without minding the weird wail of the fog-horn in the least. It is the kind of noise you forget to listen to when you get used to it.

I was roused from my slumbers by the agitated shuffling of feet on the deck overhead, the violent ringing of the engine bells for the ship to go astern and a medley of shouts and orders through which my father’s clarion voice could be distinctly heard.

Before I was fully awake I found myself standing on the floor and fumbling with my clothes, instinct guiding me rather than knowledge of what was impending. Danger there was, I realized, and I noticed that my cabin was dimly lighted, as though by the break of day. A moment later I rushed on deck, to find all crowding at the starboard bulwarks and peering out into the mist.

Suddenly—scarce a boat’s length away, it seemed—there came a terrific crash and a grinding of timbers, followed by shrieks and cries so heartrending that I found myself shuddering with horror. Yet not a man of us moved. We stood as if turned to stone. For it was not the Seagull that had struck; but behind the impenetrable curtain of the fog a tragedy of the sea was being enacted that was terrible enough to curdle the blood in our veins; for we realized that Death was claiming his victims from the men and women of some unknown vessel.

Then, by one of those marvelous transformations wrought by Nature, the fog instantly lifted and dissipated, and there before us was a sight that wrung moans, curses or shouts from our very hearts, so awful was it.

A big liner—the Karamata Maru, we afterward learned—had driven her bow straight into the broad side of a great freighter, a derelict known as the Admiral Swain, which had been abandoned in a storm a month earlier.

The Karamata Maru had crushed through the sides of the derelict and then her bow had lifted and slid high and dry across it, plunging the stern of the liner deep into the sea. In this terrible position the great liner trembled a moment and then broke in two. Her steel plates buckled and crumbled like tin, and the crash that followed as she splintered and tore asunder was greater than that when she struck. Again we heard the screams and terrified cries of the poor victims and as the sea rushed madly into the gaping compartments and the escaping steam hissed from the open seams, scores of men and women threw themselves into the water in an effort to escape what seemed a more horrible fate than drowning.

We saw and heard all this, for the Seagull had lost headway and floated gently a short distance from the scene of the tragedy. But the next moment we awoke to action. Every life preserver and rope’s end we could muster flew overboard and our boats were manned and lowered in a twinkling. Big Ned Britton, the mate, was the first to put off in the cutter, and was picking the struggling forms from the sea long before the whaler was on the scene and assisting in the work of rescue. I took the gig myself and at once found my task so arduous that I had little time to mark what the other boats were doing. I only know that we all accomplished wonders, and every man, woman and child that managed to float until we reached them was rescued. Fortunately the sea was calm, and the light breeze that had dissipated the fog merely rippled the waves.

At last, as I looked around for more survivors, someone hailed me from the wreck of the Karamata Maru and I bade my men row swiftly to her side. Already the great liner rode so low that the little group awaiting me was almost on a level with my head, and I realized that I was in a dangerous position in case she sank. The freighter also was filling rapidly.

First those on the Karamata Maru lowered an injured man into the gig, and two attendants—one the ship’s doctor, I afterward learned—came with him.

“Hurry, gentlemen,” I called to the others; but they shook their heads and retreated from the side.

“It’s no use, sir,” growled the doctor. “They’re ship’s officers and won’t leave their charge. Cast off, for God’s sake, or we’ll follow her to the bottom when she sinks!”

I obeyed, seized with a sudden panic at the warning words, and my men rowed lustily from the dangerous neighborhood of the wreck.

We reached the side of the Seagull just as Ned had assisted the last of his rescued passengers up the ladder, and I made haste to get my own aboard. The injured man had fainted. I noticed that he was a Chinaman, although dressed in European costume, and that he was an object of great solicitude on the part of his attendant and the doctor. We put him in a sling and hoisted him up the side, and after the others had followed and I was preparing to mount the ladder myself a mighty shout from our deck arrested my attention. I turned quickly, just in time to see the awful climax to this disaster. The derelict and the liner sank together, and the sea gave a great gasp and closed over them, whirling and seething about the spot as if a thousand sea-monsters were disporting themselves there. The suction was so great that had we not already caught the davit falls the gig would have assuredly been drawn into the whirlpool, while the ship to which I clung trembled in every beam, as if with horror at the sight she had witnessed.

When I gained the deck of the Seagull an affecting sight met my eyes. It was crowded thick with despairing and agitated men and women, for all had lost their possessions and many their friends and relatives within the preceding half hour. Bry had brewed huge pots of coffee, for the morning air was still chilly and the rescued ones had nearly all been pulled from the water; so, our hearts full of pity for the poor wretches, we tried to comfort and cheer them as well as lay within our power.

The collision happened at twenty minutes after five in the morning; by six o’clock all the rescued were on the deck of the Seagull. We found we picked up two hundred and eighteen out of the three hundred and twenty-seven who had constituted the passengers and crew of the ill-fated Karamata Maru. One hundred and nine, including the Japanese officers, who deliberately went down with their ship, had perished.

It was nine o’clock before the steamship Nagasaki Maru hove in sight, and eleven when she came alongside us. I make this positive statement despite the inaccurate newspaper reports to the effect that the Nagasaki Maru was at the scene of the collision and assisted the Seagull to rescue the survivors.

Of course the Nagasaki Maru, belonging to the same line as the lost Karamata Maru, promptly transferred all the rescued ones to her own decks; and that was just as well, because our ship was too small to carry them all in comfort, and we were really under no obligations to do more than we had already done. The Karamata Maru had been bound for Japan, so the Nagasaki Maru, being on her way to San Francisco, undertook to leave the passengers and crew of her sister ship at Honolulu until they could be picked up by some other west-bound ship.

As they steamed away from us the poor survivors who swarmed upon her decks saluted us with a hearty cheer of gratitude for our services, and this appreciation fully repaid us.

As I stood leaning over the rail and watching the fast receding Nagasaki Maru, Joe touched my elbow.

“Lunch is ready, Sam.”

Then I remembered that I had eaten nothing except a cup of Bryonia’s coffee since early morning, and I quickly went below. Already we had steamed away upon our course and the midday sun was shining brightly overhead.

I found all our ship’s officers assembled in the saloon except the second mate, old Eli Trent, who had the deck watch, and during the meal we naturally discoursed at length upon the exciting events of the morning.

I had nearly finished luncheon when our steward, Nux, whispered over my shoulder:

“Chinaman wants to see you, Marse Sam.”

“What Chinaman, Nux?” I asked in surprise.

“Hurt man, Marse Sam. He in front stateroom.”

I looked inquiringly at my father.

“We’ve took a passenger, Sam,” said the Captain, calmly buttering his toast. “The ‘Chink’ you took off’n the wreck is a high mandarin, a prince, or suthin’, and wanted to get home to China as soon as possible, fer he’s hurt bad.”

“We don’t usually accept passengers,” I remarked thoughtfully, “but if this poor fellow is injured and homesick, it’s our duty to do what we can for him.”

“And that isn’t much,” added a gruff voice behind me, and the ship’s doctor from the Karamata Maru dropped into a seat at the table and began to eat. We watched him a moment in silence. Then I asked:

“Is your patient very bad, Doctor——”

“Gaylord; my name’s Gaylord. I’m an Englishman, although I sailed on that blasted Jap ship. And my patient, Prince Kai, is dying. He’ll never see China again.”

“Oh!” I exclaimed, really distressed, and the others echoed my sympathy.

“He got jammed between the timbers,” explained Dr. Gaylord, as he continued his luncheon, “and although three of his attendants threw themselves around him and met their own death in trying to shield him, the Prince was badly smashed and can’t possibly live more than a day or two. It’s a shame,” he added, shaking his grizzled head, “for Kai Lun Pu has just been made one of the five Viceroys of the Empire, and he’s a fine young fellow who had a promising future. The redemption of China, gentlemen, must come through these young scions of the nobility who are being educated at the colleges of England and America. They’ll imbibe modern, progressive ideas, and in time upset the old prejudices of the Flowery Kingdom altogether.”

He turned and cast at me a scrutinizing gaze.

“You’re the young man who brought us off the wreck, I think?”

I nodded.

“The Prince has asked for you twice. Perhaps you’d better go to him now. I’ve given him a hypodermic and he feels easier.”

“Why does he wish to see me?” I asked curiously.

“Some fool notion of gratitude, I suppose. These educated Chinese are very courteous and punctilious fellows. It’s likely he wouldn’t die comfortably if he had neglected to thank you for your slight services.”

“Shall I go in alone?” I asked hesitatingly.

“Yes; walk right in. The Death’s-Head is with him,” added the doctor with a snort of contempt that I did not understand.

So I softly turned the handle of the stateroom door and walked in. It was not a pleasant errand to visit a dying man, and I wanted to get it over with as soon as possible.

The state cabin of the Seagull was a roomy—almost spacious—apartment, and we had fitted it up carefully for the use of any important guest we might have aboard. It had never been used but once before, and as I glanced around it I felt a pang that it was now to be the scene of a death, and that a miserable Chinaman should put this blemish upon it.

Seated upon a stool beside the curtained bunk was the Chinese attendant I had brought aboard with the Prince and the doctor. Immediately I understood Dr. Gaylord’s expression, “the Death’s-Head,” for this Chinaman typified that mythical horror in feature and expression. Perhaps I should say lack of expression, for his face was as immobile as Death itself, of a pallid gray-green color, and the skin was drawn tight as parchment over his high cheek-bones and across his thin lips. The eyes were dark and bright, but conveyed no more animation or intelligence than would glass eyes. He was dressed rather primly in a suit of black broadcloth, cut in London fashion.

As I entered, this attendant rose like an automaton and drew the curtains of the bunk, muttering a brief sentence in Chinese.

I advanced with a respectful bow and found myself looking squarely into the eyes of the injured man. Then I gave a start of surprise, for a young man—almost a boy, he seemed—was smiling at me from the pillows as cheerily as if greeting an old friend who had come to take part in a jubilation.

In my recollections of him I have never thought of Prince Kai Lun Pu as a Chinaman. His features bore certain characteristics of his race, assuredly; but he was so thoroughly Europeanized, so cultured, frank and agreeable in demeanor, that no one could possibly think of him otherwise than as a royal good fellow whom it was a privilege to know. With his poor maimed body covered by the counterpane, the pleasant—almost merry—expression of his boyish face made one doubt that he had been injured at all, and I thought he looked as little like a dying man as anyone could.

“You are young Mr. Steele,” said he in perfect English, “and I am well pleased to see you, sir; for you have rendered me a rare service and have earned my lasting gratitude.”

“It was a simple duty,” I responded, with an answering smile; “but I am glad I was able to serve so important a personage, Prince.”

“Important?” said he, arching his eyebrows; “ah, perhaps you might find me so, were we together in my own province of Kwang-Kai-Nong.” A shadow passed over his face, and he sighed; but next moment, with renewed cheerfulness, he added, “but we are not in China, Mr. Steele, and aboard your noble ship the humble passenger must defer to your own more powerful individuality.” He cast an amused glance at the Death’s-Head and said:

“Defer, Mai Lo, to the noble American; defer for us both, since I am helpless!”

The attendant, outwardly unmoved and unresponsive, prostrated himself before me, and then resumed his former position. I could not resist a light laugh at the ridiculousness of the performance, and the Prince joined in the merriment. Then, suddenly recollecting myself, I became grave and asked:

“Are you suffering, Prince? Do you think you are badly hurt?”

The bright eyes regarded me intently for an instant, after which he turned to the Death’s-Head.

“Leave me, Mai Lo; I would converse with my host,” said he.

The attendant again prostrated himself, this time to his Prince, and retired without a word of protest. But almost immediately the Doctor came hurrying in, and there was protest in both his words and demeanor.

“Look you, Prince Kai,” he said, “this is no time for reckless folly. I gave you morphine to quiet your pain and enable you to sleep, and you positively must not excite yourself and neutralize the effect of the medicine.”

The young man gave him a look half whimsical, half sympathetic.

“My dear Gaylord,” said he, “you have, in your wisdom, numbered the hours remaining to me, and I accept the decree as final. But why should I sleep during those brief hours, when rest eternal will soon be mine?”

The Doctor flushed and cast down his eyes. He was a good-hearted man, and not yet calloused in the presence of death. The Prince smiled upon him in kindly fashion and asked:

“Is there an ample supply of morphine?”

“There is ample, my Prince.”

“Then listen to my wish. I do not care to sleep, nor do I want to suffer in the brief time you have allotted me. Let me secure all the pleasure I am able to until the Earth Dragon completes his vengeance upon me. That will be kind, dear Doctor, and your reward shall be provided for.”

The old surgeon took the Chinaman’s hand and pressed it warmly.

“Never mind the reward, my Prince,” said he. “I’m out of a job just now, and am glad to experiment upon you, so I shan’t get rusty. Your wish shall be respected.”

“Then leave me with Mr. Steele awhile,” was the reply, “and see that Mai Lo doesn’t disturb us.”

The Doctor bowed with deference and withdrew.

“Prince,” said I, “they call me Sam aboard this ship, and I’ll be glad to have you do the same. I’m not much used to a handle to my name, and if we’re to be friends——”

“We’re to be friends, Sam,” he rejoined, quickly; “so just squat upon that stool and let us have a good chat together.”

I was really charmed with my new acquaintance, he was so animated, so frank in admitting me to his friendship and so evidently grateful to me for the slight service I had rendered him. His brightness made me forget the pitiful fact that he had but a short time to live, until he himself reminded me of it.

I can imagine no more delightful a companion than Prince Kai Lun Pu must have been before his terrible accident. He began by telling me much of his history, in a whimsical, half facetious way that deprived the relation of any affectation or egotism.

A prince of the royal blood and related to the reigning Manchu family, Kai had been early singled out for an important position in the empire and sent to England to be educated. He had graduated from Oxford a year before, and after a brief visit to his own country, where he held a long consultation with the Emperor and that terrible old woman, Tsi An, the Dowager Empress, he had toured Europe, Egypt and India, and afterward visited the principal cities of the United States. This had enabled him to study other nations and to note their manners and customs, and he was returning to China as a Viceroy and a member of the Imperial Cabinet, to which post he had already been appointed, when he met with the terrible accident which was to cut short his brilliant career.

So much this royal prince confided to me in our first interview; but he cared less to talk of himself than to be amused, and soon he began to question me as to my own history and adventures.

Being willing to amuse the poor fellow, and having no duties that required my attention, I passed the afternoon in relating the adventures of my brief life. These seemed to astonish him greatly, and he questioned me closely in regard to Alaska and Panama, where I had voyaged with my father and Uncle Naboth, but which he had never visited. I also told him some queer adventures of mine in Egypt, but he was more familiar with that country.

I feared to weary the young Prince with my long stories, but he would not let me go. Twice during the afternoon Dr. Gaylord came in and administered to his patient hypodermic injections of morphine, and these must have kept him free from pain, for he made no complaints and retained his bright cheerfulness until I finally insisted on leaving him.

Outside his door was the unemotional Mai Lo, standing as stiffly as a statue. The attendant saluted me with great respect and immediately entered his master’s room.

Dr. Gaylord was in the saloon smoking a cigar, and he nodded as I approached and said;

“Queer fellow, Prince Kai, isn’t he?”

“A very charming fellow, I think, Doctor.”

“Yes; and richer than Rothschild—or your Rockefeller,” he added. “You should have seen him arrayed in his native costume on board the Karamata Maru, and surrounded by his four devoted followers. He was a picture, I assure you, and dignified and gracious enough to warrant his royal blood. Everyone liked him, heathen though he is.”

“Heathen!” I echoed, surprised.

“Of course he’s a heathen. But I admit he makes you forget that, for in London and at Oxford he acquired the polish of an English gentleman. It was only when I noted the rascals surrounding him that I realized he was a Chinaman.”

“But they were faithful,” I suggested.

“To the death,” said he, with a slight shudder. “They even tried to oppose their frail bodies between him and the ship’s splintering timbers. Sir, it would have made you cringe to see their mangled remains——as I did. But the sacrifice did no good at all.”

“You are sure he will die?” I asked.

“I am positive. Surgical skill can do nothing to save him. If only old Death’s-Head had perished with him,” he added, with a glance toward the state cabin, “I should feel more reconciled. But Mai Lo happened to be in a safe place, and escaped.”

“Is he old?” I asked musingly.

“You never can tell a Chinaman’s age from his looks,” said the Doctor. “Yet I would wager that Mai Lo is sixty, if he’s a day. I’m told that at home he’s the governor of Prince Kai’s native province, and a person of consequence.”

“I don’t like him,” said I, frankly.

“No one likes him, not even his young master,” returned the Doctor. “By the way, how old should you judge Kai Lun Pu to be?”

“Perhaps the Prince is eighteen—or nineteen,” I hazarded.

“He is seven-and-twenty. These Chinese seem to age very slowly, unless they’re addicted to opium, like the coolies. Have a cigar, sir?”

I shook my head and went on deck, where Archie and Joe at once collared me with a demand to know what “His Royal Muchness, the Chink” had been talking about all the afternoon. I was quite full of the subject and told them as much as I knew about our injured passenger, adding that I was sincerely sorry the poor fellow must die.

Next morning after breakfast I was again summoned to attend Prince Kai Lun Pu. I may as well remark in this place that with the Chinese the surname comes first, and Kai was my new friend’s family name, as mine is Steele. “Pu” with him stood in the place of “Sam” with me, and Lun was his middle name. But as the Chinese name always means something, a free translation of Kai Lun Pu into English would be “blossom of the tree,” Kai being a tree, or in some connections the root of a tree. So the Prince’s name was a very pretty and appropriate one, although it sounds so queer to our uncomprehending ears.

My new friend greeted me as cheerily as on the previous day, although I noted the fact that dark circles had settled around his eyes and his cheeks were a bit more hollow. The doctor was with him when I came in, and I asked if his patient had slept.

“Not a wink,” he replied. “Our Prince does not intend to lose a moment of life, and so I sat up with him until after midnight myself. Then he talked to Mai Lo until daylight.”

“And that was time wasted,” added the Prince, with a queer glance at his attendant, “for Mai Lo has a limited vocabulary, although he is so wise and experienced. I think he spoke six words to me in return for all my chatter. So now I will excuse him from my presence until I require his services.”

Mai Lo heard and prostrated himself humbly before his Prince, retiring with the stealthy glide of a ghost. The doctor was preparing his hypodermic syringe, and the sick man watched him thoughtfully.

“Do you see much change in my condition?” he presently asked.

“A little,” answered the doctor. “Your vitality is wonderful. An ordinary man would have succumbed long ago.”

“Am I sure of today?” enquired the Prince.

The surgeon administered the hypodermic before replying. Then he said, slowly:

“While your heart retains its action you will live; but a clot may interfere with the action at any time. I cannot promise you even today, yet you may see the light tomorrow—or of several tomorrows.”

“But not many of them?”

“Not many, Prince.”

“Ah, the Earth Dragon is relentless. I cannot reach China?”

“No, indeed. To Shanghai or Hong Kong is two weeks. And there is another thing that I must speak to you about. I have no means of embalming or preserving your body.”

For a moment the Prince looked grave. Then he laughed again, lightly, but I thought with little or no mirth. In spite of his Occidental education Kai Lun Pu retained the prejudices of his forefathers and longed to have his body carried to China and laid to rest in his ancestral halls.

“What a fuss old Mai Lo will make when I am cast into the sea!” he remarked. “You’ll have to put him in irons, Sam, or he’ll run amuck among you and cause mischief.”

“If he does he shall go after you,” I promised. “That is, unless you wish him preserved to carry out your bequests at home and convey your messages to your friends.”

The Prince made a face so ridiculous that both Gaylord and I smiled at him.

“I will confide to you a secret,” said he; “my servant is fully as repulsive to me as he is to you. But he is a man of high birth, a mandarin and the hereditary governor of my own province; so I had to carry the fellow with me on my travels.”

“He looks like a dummy,” I suggested.

“And his looks are very deceptive,” retorted the Prince. “Mai Lo is remarkably subtle and observing, and as intelligent as he is proud and ambitious. Really, until my accident occurred, I feared the fellow, although I knew he would sacrifice his life for me if necessary. It will be his duty after my death to return to his home, propitiate the Earth Dragon, and then commit suicide; but the chances are Mai Lo will find a way to avoid that. There will be too much to feed his ambition.”

“Will he inherit your estates?” inquired the doctor.

“By no means. Mai Lo is noble, but not of the blood royal. My estates will go to the Emperor, because I have no heir; my ancestral halls will be sealed up and abandoned, and—I shall soon be forgotten.”

“Why so?” I asked.

“Because I shall never become an ancestor myself,” he responded, laughing genuinely this time. “An absurd statement, isn’t it, Sam? But my countrymen are devoted Shintoists, or ancestor worshippers, and while I have gained honor and respect in life through my powerful ancestry, in death I lose all and am speedily forgotten.”

While I thoughtfully pondered this statement the doctor withdrew and left us alone together.

“Do you believe in this queer religion of ancestor worship, Prince?” I inquired.

“Of course not, Sam. I’m a mighty poor Chinaman, as far as our orthodox traditions and religious observances are concerned. In fact my people are not really religious at all, for they vilify and even thrash their bronze and wooden gods if they do not behave properly, and the whole ceremonial worship of China is a farce. I do not mind telling you that even before I went to Europe my heart refused to acknowledge those decayed ancestors of mine as more important than the dust to which they have returned in the course of nature. But I kept the secret of my apostacy to myself, and in order to secure ample funds to enjoy the pleasures of Europe I even robbed my ancestral halls of a portion of their treasure.”

“Oh!” I said. “Is there treasure, then, in your ancestral halls?”

He smiled.

“More than half the wealth of China—the accumulated wealth of centuries—is tied up forever in this absurd manner,” he replied. “My family was old at the time of the Tartar invasion, and it has always been wealthy. In my ancestral halls, in my province of Kwang-Kai-Nong, lies a mass of treasure that would startle the world if it were to be unearthed and publicly displayed. Yet no one has ever seen it in my generation but myself.”

“I do not quite understand this system,” I said, much interested in these statements.

“It is our immemorial custom,” explained the Prince, “to bury with each head of a family one-half the wealth he possesses, to be used by him when his resurrection occurs at the end of the world. The remaining half is inherited by his eldest son, his successor. A daughter never inherits, you know. When the son dies, one-half his wealth is laid with his body in the tombs of the ancestral halls, and so this accumulation goes on from century to century, and half the wealth of the nation is continually abstracted from its resources.”

“But suppose there is no son,” said I. “What happens then?”

“Then the line ends. In the case of a noble family, such as ours, the confidential servant secretly seals up the ancestral halls and then commits suicide, so that no one may ever discover where they are located. If he hesitates to kill himself by the ninth day the other servants promptly kill him; so his fate is really sealed in case his lord dies without an heir.”

“And is Mai Lo your confidential servant in this case?” I asked curiously.

“You have guessed it,” replied the Prince, smiling. “If I were sure he would do his duty it would deprive death of half its sting; but I suspect, Sam, that Mai Lo has as little respect for ancestor worship as I myself, and it is my impression that he will rob the tombs of my forefathers very freely before he seals them up forever.”

“But won’t his fellow-servants kill him if he fails to commit suicide?” I asked.

“I could answer that question more positively if I knew the mind of Mai Lo better,” returned the Prince, more gravely than was his wont. Then he brightened and said:

“I am much interested in your friends Archie and Joe, who were so loyal and brave in your Egyptian adventures, which you related to me yesterday. Did you not say they were still your comrades?”

“Yes, indeed, Prince. Both are now aboard the Seagull.”

“May I see them? Will you bring them here to see me?” he asked, eagerly.

“They will be greatly pleased,” I replied. “When?”

“At once. You remember the doctor’s warning.”

“I’ll get them,” said I, rising.

“Send Mai Lo,” suggested the Prince. I did so, asking the attendant, who stood stiffly outside the door, to summon my friends to an audience with Kai Lun Pu.

In a few minutes Joe and Archie arrived, as eager as I knew they would be to make the acquaintance of our interesting passenger.

The Prince conversed with them upon various subjects for fully an hour, pressing them for details of our former adventures and shrewdly drawing out the characteristics of both the boys without their suspecting it in the least. I felt quite proud of my friends, for although each in his own way was odd to the verge of eccentricity, two more manly, truer hearted fellows did not exist—or at least that was my opinion of them.

The Prince seemed to approve of them, too, and with their quaint answers and ways they certainly amused him—Archie bluff and outspoken and Joe modest and retiring as a girl.

Presently, as he lay back upon his pillows, Kai Lun Pu began to laugh. He laughed again, seemingly much amused; and still again, with evident enjoyment of some thought that had occurred to him. Archie and Joe stared at him rather uneasily, and I own I had myself a fleeting suspicion that his maimed body was finally affecting his mind. But the next moment the Prince said, in his ordinary tones:

“By all the big and little gods, I’ll do it!”

“Do what, Prince?” I asked, curiously.

“Give you a new adventure to undertake,” he replied, almost gleefully. “You three boys are not tired of adventures, are you?”

“Not much,” returned Archie, stoutly.

“And although you’ve found some small treasure already, you wouldn’t object to finding more, would you?” he continued, eyeing us closely.

Our eager faces must have answered him; but I said, as calmly as I could:

“What is the proposition, your Highness?”

“The proposition is simply this, Sam; I’m going to show you how to rob my ancestral halls!”

I’m afraid we looked rather foolish at this suggestion. Archie was open-mouthed and wide-eyed; Joe’s sensitive face took on a frown, and I felt myself flushing red.

“You see, Prince,” I said at last, shifting uneasily in my seat, “we’ve been adventurers, but not buccaneers, and to rob——”

“Nonsense!” cried Kai, laughing at us again; “the word ‘rob’ does not mean to steal, even in your bungling English. And I used it figuratively. To rob my ancestral halls would not be a sin, for you would deprive no living person of what is his at present or might be his in the future. As for the dead, my opinion is that my ancestors are very dead; and, in case their bodies resurrect at the end of the world, they won’t mind whether they are wealthy or not. I tell you, Sam, I can imagine no more foolish idea than to bury treasure with the dead, and had I lived to return to China it was my firm intention to rob the ancestral halls myself. In that case no one would ever know it, and there would be no danger. Why, as I said before, I abstracted certain jewels from the tombs years ago, and spent the proceeds in high living. So, if I was willing to rob the ancestral halls myself, and approve of your robbing them in my place, now that I am prevented, you need have no scruples on the plea of morality. Listen, friends: I present to you three—to Sam and Joe and Archie—all of the treasure contained in my ancestral halls. It is yours—I give it freely—but you must go and secure it, and that will be a dangerous expedition.”

“Why so?” asked Archie.

“Because you won’t have me to assist you,” he replied. “Because you must oppose the ancestral devotion, amounting to a religion, of the entire Chinese nation. Because my own followers and servants would cut you down in an instant if your errand were discovered, and——”

He hesitated.

“Any more interesting reasons?” I asked.

“The strongest of all,” said he. “Because I am convinced that Mai Lo means to get the treasure himself.”

Joe gave a low whistle, and Archie looked especially thoughtful.

“Is it worth while, then, for us to undertake the adventure?” I questioned.

“For centuries past one-half of the wealth of one of the richest families in China has been placed in the vaults which I call my ancestral halls,” he returned. “This wealth consists of jade, precious stones—especially rubies—pearls and stores of gold and silver. There is enough to ransom a kingdom, and as I cannot use it myself I should like you to get it—if you can. Your task would be difficult in any event, for to rob any ancestral hall is a great crime in China. Even the graves of the poor, which are stone or mud vaults with roofs of bamboo and palm leaves, are respected by all. Yet your greatest danger is from Mai Lo. If he cannot rob my ancestral halls himself he will try to prevent anyone else from doing so.”

“Well, then,” said Archie; “let’s toss him overboard, while we have the chance. He’s only a Chinaman.” The next instant, seeing the amused smile on the Prince’s face, he realized what he had said and began to apologize. “It’s so hard, sir,” he added, “to think of you except as one of ourselves.”

Perhaps the naive compliment pleased the Prince, for he laughed and said:

“It might be a wise thing to cast Mai Lo into the sea. But I do not think you will undertake murder, even to secure my treasure. So I will do what I can to enable you to outwit the mandarin. Can you find me a piece of paper and a small brush?”

Joe got them from his cabin in a few moments, and while he was absent we all sat in silence.

I spread the piece of paper upon the coverlet in front of the Prince, and dipped the brush in ink for him. His left arm was broken and useless, but fortunately he could use his right arm and hand, though with difficulty. At once he began writing in Chinese characters upon the paper, and presently he finished and held out the brush for me to take.

“You cannot read my signature, Sam,” said he, “but it is there, and will be recognized. It is an order to all my dependents to recognize you and your companions as my guests for one year, and to serve you as faithfully as they would myself. I have added that my spirit will watch to see if I am obeyed and to take vengeance if I am not. That is, of course, nonsense to us; but it ought to be effective with my people. Take the paper, Sam, and guard it carefully. Stay! call in Mai Lo for a moment.”

I did so, and the Prince said to his attendant in an easy tone:

“Witness this order, Mai Lo.”

The mandarin glanced at the document, but though I watched him carefully I could detect no sign of emotion in his glassy eyes, or even surprise or interest upon his putty-like features. He took the brush from my hand and obediently added his signature to that of the Prince. Then, at his master’s command, he again retired.

I took the paper, folded it carefully, and placed it in my wallet.

“Then you are decided to undertake the adventure?” asked the Prince, in a pleased voice.

I looked at Archie and Joe, and they both nodded. So I answered:

“We will seek for the treasure, your Highness.”

“Good!” said he. “Now take the signet ring from my finger.”

I obeyed. It was a heavy gold band, curiously engraved and set with a huge ruby. The stone had an upper flat surface, on which were cut three strange characters.

“Do not display this ring except in case of necessity,” warned Kai Lun Pu. “When you do, it will command obedience of every man in my province. It will even be powerful with the Emperor. So keep it safely.”

I thanked him and stowed the ring in my pocket.

“And now,” said the Prince, “there is but one more thing I can do for you, but that ought to prove of great assistance in your venture. Listen carefully, all of you, for the secret I am about to confide to your ears may not be written down in any way, and the memory alone must guard it. Heretofore it has been handed down in my family from generation to generation by confiding the knowledge to the eldest son, who alone inherits. My ancestors would have died sooner than allow a stranger or an alien to know this family secret; but I—I am different. In me the shackles of tradition and foolish custom have been broken by a liberal education and a knowledge of the great world whose existence many of my countrymen do not even suspect.”

He paused a moment, as if in thought, and then continued as follows, speaking slowly and distinctly but in a lowered voice:

“It will be easy for you to locate the ancestral halls of the family of Kai. It is near to my own palace, and you will first see a quaint but beautiful house of polished bamboo, with an entrance on each of its four sides. Each entrance is guarded by a god, and it will be wise for you to pretend to propitiate these gods by offerings. Burn prayers for my spirit’s welfare before them. You must not enter this house, for it is sacred; but I will describe it to you.

“In the center is a stone walled pit, with steps leading downward. In the center of the pit is a bronze tablet, which, when lifted, discloses a passageway. This passage forms a long tunnel slanting into the earth, and if you could follow it, it would lead you to the underground vault, or chih, where my noble ancestors lie buried. This vault is cut from the solid rock, and is a big domed chamber ornamented with the best art of the ages that have elapsed since its construction. The tapestries are said to be the best and most valuable in the whole Empire. Around the sides of this chamber are the niches where repose the burial caskets of my respected ancestors, and beside each casket are placed the chests, urns and taborets containing one-half the wealth this ancestor died possessed of. Do you understand this description?”

“I can picture it perfectly,” said I.

“That is well. But now for the secret.” Again he lowered his voice, with an uneasy glance toward the door, behind which he knew Mai Lo was stationed. Then he continued:

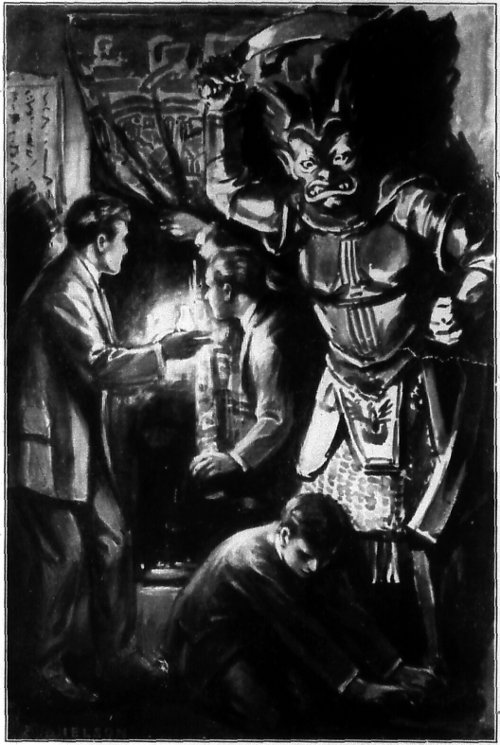

“There is a second, or secret, entrance to the burial chamber, which no one outside of the heir of our house has ever suspected. It was built seven centuries ago by Kai Tai, a pious man who wished to worship in secret at the tombs of his ancestors without the formal ceremony required when entering the ancestral hall publicly. This private entrance is also a tunnel, and leads from my palace itself. Now, my friends, pay strict attention. There is, in the palace, a set of rooms called the Suite of the Horned Fish, from its mode of decoration. These are the apartments always occupied by the royal prince of our line, and so they will be vacant when you arrive at the palace. The main doorway to the Suite of the Horned Fish will doubtless be guarded night and day, and it will not be wise for you to try to force an entrance therein. But in the bend of the passageway just beyond the entrance is a tapestry representing the Earth Dragon embracing a woman, and behind this tapestry you will find a small ball or knob of bronze. Pull this ball toward you, outward, and a private door will open leading directly into my sleeping chamber. Once there, you are not liable to interruption.

“In one corner of this chamber is a great statue of the first Kai in armor. It is a dreadful thing, and used to frighten me when a boy; but in its carving the statue shows great artistic skill. By pushing the left foot sideways—it will require a strong pressure—a panel in the wall back of the statue will be released. It is the entrance to the secret passage and once you have found it the rest is easy. It leads to one of the niches in the vault of my ancestors, the tapestries cleverly concealing the doorway. By means of this passage you may convey all or a part of the treasure to my chamber in the palace, and from there I must leave you to your own ingenious devices to transport it safely to Shanghai or aboard your ship. Have I made this quite plain to you, my friends?”

“Quite plain,” we all answered, pleased to have the adventure so easily arranged for us; and I added:

“How can we thank you, Prince Kai?”

He smiled.

“I am well repaid in believing you will outwit old Mai Lo, and secure the treasure he means to steal,” was his reply. “If I possess spirit I shall try to watch you and enjoy the fun.”

“Oh, don’t do that!” exclaimed Archie with a shudder.

“But you won’t know it, and I haven’t much faith in a spiritual existence,” he replied.

“What have you faith in?” I asked, shocked to hear him speak so lightly on his death-bed.

“We Shintoists believe in our ancestors,” said the Prince mockingly, I thought; “and that has always made us more sensible than our Buddhist neighbors. Also I have studied Christianity, Mohammedanism and Theosophy, and they have led me to admire Confucius more. So I get back to Shintoism in the end. I shall die in the faith of my ancestors, but not hampered by their narrow prejudices, I hope.”

He sighed with this, and I thought his cheeks looked more sunken and his skin more pallid than I had yet noticed them. So I said:

“This has been a trying interview, your Highness, and you need rest. Shall we retire?”

He hesitated, and then nodded with a return of his old brightness:

“Send in the doctor,” said he, “it’s time for more morphine.”

When we arrived on deck again the wind had freshened and the pleasant spell of weather we had lately experienced seemed likely to leave us. But our gallant Seagull headed the waves merrily, with scarcely any heaving of her swanlike body, and we knew her staunchness so well that we did not dread any weather that might overtake us.

Finding a sheltered position in the waist, we three boys eagerly discussed our important interview with the Prince and the chances of success in the adventure offered us.

“He’s made everything so blamed easy for us that it’s like taking candy from a babe,” said Archie, gleefully.

“He has certainly proved himself a generous friend,” I assented. “It’s a pity he must die. I’d rather have him alive and my friend, than to get the treasure. Eh, Joe?”

“Exactly,” answered Joe, in his quiet voice.

“I like the chap, too,” said Archie, “but our sentiment won’t alter the facts in the case, will it? Here’s a treasure—and a whopper, too, I imagine—calling to us to come and take it, and——”

“And here’s Mai Lo, who wants it himself,” added Joe.

“Oh, him!” cried Archie, scornfully.

“Joe’s right,” said I, thoughtfully; “Mai Lo is a power to be reckoned with. Even the Prince fears him.”

“I don’t,” declared Archie, “the man’s a dummy. Anyone that’ll kow-tow and get on his knees the way this fellow does, is a coward and a sneak.”

“The doctor,” said Joe, softly, “calls him ‘Old Death’s-Head.’”

“Well, what of it?”

“I’m afraid of Death.”

We both started at this; but Archie, recovering courage, asked:

“What can one miserable Chinaman do, opposed to three Americans?”

“Very little, in America,” replied Joe. “But we’re going to his own country, to China, where old Death’s-Head is a high mandarin, and the governor of a province. He won’t kow-tow there, for the Prince is his only superior, and the Prince will be deep under the ocean soon.”

We thought this over. There was usually something to think over when Joe made a long speech.

“Do you mean, then, that you’re scared out; that you won’t undertake this thing?” demanded Archie, finally.

“No,” said Joe, “I’m going to China. That is, if you fellows are game to go with me.”

“That’s the way to talk!”

“But we’re putting our heads in the jaws of a trap, and the least little thing is likely to spring it,” added Joe.

Archie looked puzzled.

“I can’t understand why you take that view of it,” he protested. “It seems to me the thing’s easy enough. We’ve got the Prince’s letter to his people, and the ring, and the secret of the private way into his ancestral hall. If we bungle such a job as that, we ought to be hanged.”

“And will be, or worse. So we mustn’t bungle it,” said Joe. “Where is this province of Kwang-Kai-Nong, Sam?”

“I forgot to ask,” I replied, wondering at my oversight.

“China’s a big country,” suggested Joe.

“I know. I’ll inquire about the location, and how to get to it, the next time I see the Prince.”

“Do,” said Archie, “that’ll help a lot.”

But I didn’t see the Prince again. At the lunch table we found the doctor, eating with apparent gusto but with an intent look on his face.

“How’s your patient, Doc?” Uncle Naboth was asking as I entered.

“Why, I’m out of a job again,” replied Doctor Gaylord, gravely.

“Great Goodness! The man ain’t dead, is he?” demanded my uncle.

“He is, sir.”

I do not know why I had such a sudden sinking of the heart as I heard this. Perhaps the noble young Chinaman had won from me more admiration and affection than I had suspected, during the brief time I had known him.

I glanced at Joe and Archie, and they were looking mighty solemn.

“Wasn’t it rather sudden, Doc?” inquired Uncle Naboth, after a pause, during which he stirred his tea energetically.

“Yes, he might have lived another four-and-twenty hours. But he wore out the morphine and began to suffer terribly. So I killed him.”

“What!”

“Gave him an overdose of morphine, at his own request, and he went to his long sleep with a smile of gratitude upon his face.”

There was another pause.

“Ahem!” said Capt. Steele, clearing his throat, “was that—er—er—strictly professional, Dr. Gaylord?”

“It was strictly humane, Captain. The man was crushed and mangled from the waist down, and according to all the laws of science and common-sense has been as good as dead ever since the accident. He couldn’t have lived until now without the morphine. When that failed to soothe him the end was bound to creep nearer by slow degrees, allowing him to suffer horrible torments. I couldn’t stand that, and he couldn’t. So he begged me to end it for him, and I did.”

“You’re a good man, Gaylord,” remarked Uncle Naboth, mopping his bald head with his red bandanna. “I’m glad you had the courage to do it.”

“This Prince of China,” said the doctor, leaning back in his chair and thrusting his hands in his pockets, “was a royal good fellow. I had observed him on shipboard, and was attracted by his cheerful, intelligent face. When the Karamata Maru broke up I left everyone else to attend to Kai Lun Pu, until I discovered he was fatally injured. Unfortunately all my surgical tools and requirements were out of reach, and in the pockets of the clothes which I grabbed up before I rushed on deck were only a small medicine case and my hypodermic outfit. I assisted Mai Lo, the only one of the Prince’s attendants who survived, to get Kai off the wreck and safe aboard this ship, and at his urgent request I remained with him, since the doctor of the Nagasaki Maru could look after the few survivors of the Karamata Maru who were injured. I am well paid for doing this, but I want to state that the money did not influence me in the least.”

To look at the doctor was evidence of the truth of this statement; so we merely nodded assent.

“As soon as I had him settled in your cabin yonder,” he continued, “I told him that he was dying. Kai accepted the decree like a philosopher and asked me how long I could keep him alive without suffering. It was then that we made our bargain, and I promised he should die comfortably. It seems he had certain family affairs to arrange with Mai Lo, who represents him in his province, and afterward he had several long talks with Sam and the other boys here.”

He paused to look from one to the other of us curiously, and the shrewd glance from beneath his prominent gray eyebrows was rather disconcerting.

“By good luck,” he went on, “the Prince finished his arrangements, whatever they were, before the effect of the morphine wore out. When I went to him a while ago I saw the time had come to fulfil my promise. I asked him if he was ready and he said he was. So, in the parlance of the Chinese, he sleeps with his ancestors.”

In the silence that followed we were all busy with our own thoughts. Finally my father asked:

“Where is Mai Lo?”

“Burning prayers before the body. He’s going to make trouble for us, pretty soon.”

“How’s that?” asked the Captain.

“These Chinese believe it’s a lasting disgrace to allow their bodies to be buried anywhere but at home. Mai Lo has already asked me when I would embalm the body; but I’ve been making inquiries and find there’s no material aboard the Seagull that will enable me to preserve the corpse of Kai Lun Pu until we can get him to China. He himself understood this, and was willing to be cast overboard; but old Death’s-Head has different ideas, and when he learns what we are going to do he will make trouble, as I said.”

“What can he do?” asked Uncle Naboth.

“These Chinese have a disagreeable way of running amuck and slicing a few people into mincemeat before they can be overcome. I won’t say Mai Lo will do that, but he will do something—anything in his power to prevent us lowering his master’s body into the sea.”

“He won’t run amuck,” said I, positively; “nor will he do anything that will endanger his own life.”

“Why not, Sam?” asked my father. “Mai Lo’s a queer chap. I can’t make him out at all. Seems to me he’s likely to do anything.”

“Except endanger himself,” I added. “The Prince knew Mai Lo better than anyone, and from what he told me I believe Mai’s more clever than you suppose, and too ambitious to sacrifice his life for a mere whim.”

“It isn’t a mere whim,” said the doctor. “The Shintoists are ancestor worshippers, and the sacredness of a dead body is part of their religion. Mai Lo, if he’s a good Shintoist, believes he himself will be condemned by the spirits of his own ancestors if he allows his master to be cast into the sea, whence it is impossible he can be resurrected when the end of the world comes.”

“But is Mai Lo a good Shintoist?” I asked.

“Mm—I don’t know. He claims to be; but the fellow puzzles me. Many of the Chinese wear a mask of expressionless reserve; but Mai Lo is the most incomprehensible being I have ever met. If he weren’t clever he wouldn’t be a high mandarin, so we can’t judge him by his terracotta face and beady eyes.”

“Oh, well,” remarked my father, “we can’t endanger our own health by keeping a decaying body on board, so whenever you’re ready for the ceremony, Doctor, we will give the Prince as decent a sea-burial as possible. And that in spite of the old mandarin. By the way, Sam, see if Mai Lo wants anything to eat.”

I arose and knocked softly upon the door of the state cabin. Presently it was opened a mere crack and I caught a glimpse of Mai Lo’s expressionless face behind it. But when he saw me he closed the door again quickly, before I had time to speak; and I heard the key click in the lock.

“Let the beast starve,” I growled, turning away to go on deck; and the others seemed to approve the sentiment, for they followed me without protest.

“You’ll find my first suggestion was good,” said Archie, as we stood in the shelter of the wheel-house, for the wind was half a gale by this time. “The proper thing to do is to chuck old Death’s-Head overboard.”

“It would certainly simplify matters,” I agreed; “but unfortunately it can’t be done.”

“Then we ought to cultivate his friendship,” said Joe.

“How can we?”

“I don’t know; but it’s a great mistake to allow him to think he’s our enemy.”

“Why so, Joe?”

“We’ve got to go into his province to get the treasure. He’s powerful there, and we need his good will. He might make it pretty hot for us otherwise.”

“True enough,” said Archie, gloomily. “But you can’t cultivate the friendship of a dummy. He won’t respond worth a cent.”

“He must have some sentiment,” suggested Joe; “his faithfulness to his Prince proves that. Let’s study him and try to discover how to reach his gratitude, or self-esteem, or——”

“Or what?”

“How to further his ambition.”

“If the Prince is buried at sea,” I said, reflectively, “Mai Lo will be disgraced at home. If we can save him from this disgrace he ought to be grateful, for it will give him a chance to carry out his ambitious plans.”

“I thought he was obliged to commit suicide,” said Archie.

“So he is; but not immediately. First he must settle his master’s affairs, and that business ought to provide pretty fair pickings for an unscrupulous man. Then he will be obliged to seal up the ancestral hall and destroy all traces of any entrance to it, or even its existence. All this takes time, and will give him a chance to complete his plans for running away with his plunder, most of which will be stolen from the tombs of the Prince’s ancestors.”

“Will he dare do that?” asked Archie.

“Mai Lo has seen a good deal of the world outside of China,” said I, “and such experience is bound to destroy many of the doctrines of his religious belief. Contact with our western civilization made the Prince an unbeliever in Shintoism, and perhaps did the same for Mai Lo.”

“Then why is he so set on lugging the body of the Prince to China? He must know that this ancestor worship is a humbug.”

“He does. Also he knows that his people at home are still firm believers in it. It is to save himself from disgrace that he will insist on taking the body home.”

“I see,” responded Archie. “But he can’t do that, you know. There’s no way to embalm the Prince properly, and Captain Steele has already decided to drop the body overboard.”

Looking aft I saw the doctor pacing the quarter-deck with his pipe in his mouth, and suddenly the sight inspired me with an idea.

“Boys,” I said, “we’ve got to have some help in this affair. We can’t carry out the adventure all alone. Suppose we ask the doctor to join us?”

“Old Gaylord?”

“Yes. He has good stuff in him, to my notion; and he says he’s out of a job.”

“A good idea,” said Joe.

“Won’t he ask for too big a slice of the pie?” inquired Archie.

“According to the Prince there’s more treasure in his ancestral halls than we could cart away in a year. If Dr. Gaylord will help us we won’t lose anything by giving him his share.”

“I don’t see how he can help us a bit,” declared Archie. “For my part I’d rather have Ned Britton or Mr. Perkins. They’re true blue and game to fight to the last.”

“This isn’t a matter that depends on fighting, Archie,” I reminded him. “Our whole ship’s crew wouldn’t make a showing against the thousands of Chinamen if it came to open warfare. It’s a question of ready wit, courage and audacity.”

“Then I can’t make out why you want the doctor,” returned Archie, with a puzzled look.

“I know,” said Joe, in his quiet voice. “I think I’ve caught Sam’s idea, and it’s a good one.”

“What is it, then?” asked Archie.

“With the doctor’s help we can fool Mai Lo and save him from disgrace. And that will win his gratitude. Eh, Sam?”

“Quite right, Joe. Shall I call the doctor over?”

They nodded, and at my summons Dr. Gaylord willingly joined our little group.

“Doctor,” said I, “there’s a conspiracy afloat. Do you want to join it?”

He gave me a shrewd glance.

“I knew there was something up,” he said, “and I’ve been trying to study out what secret Prince Kai confided to you. It has worried me almost as much as it has Mai Lo.”

“Oh!” said I, with a gasp. “Does he suspect anything?”

“Mai Lo is no fool, and you were closeted with Prince Kai a long time. Also, he witnessed an important paper, and I heard him ask the Prince what had become of his ring.”

“What was the reply?” I inquired.

“Prince Kai told him he had given it to Sam Steele for an important purpose, and that he had appointed you to carry out his secret wishes. Also he exacted a promise from Mai Lo to obey you and render you any assistance you might demand.”

“Good!” I exclaimed.

“Good as far as it goes,” said the doctor, drily; “but it won’t go far with Mai Lo. He’s likely to cut your throat some night if you leave your door unlocked.”

“Then you distrust him?” I asked, uneasily.

“More than that, Sam. I’m afraid of him. But let me have your story and your proposal, and I’ll tell you in a jiffy whether I’ll join your conspiracy or not.”

So I began by relating in full my various interviews with Prince Kai, in the last of which Archie and Joe had been participants. I added that I believed the Prince’s idea of our robbing his ancestors arose from my relation of our former adventures in search of a treasure, which I had told him with a view to amusing him. Once the mischievous notion had seized him, he began to plan ways to assist us, and I think he derived a certain pleasure during his last hours in imagining our difficulties and trying to overcome them. Another thing that doubtless influenced him was the desire to outwit Mai Lo, whom he suspected, probably with good reason, of a desire to rob the tombs himself.

Dr. Gaylord listened to all the story without interruption, and I could see that he was intensely interested. When I finished he smoked for a time in silence, while we watched him rather anxiously. Finally he knocked the ashes from his pipe and said, with decision:

“It looks too pretty to miss, my lads, and if you see where an old fellow like me can be of use to you, I’ll stand by to the last. But I want to warn you that we are taking big chances in this adventure, and if any one of us escapes with a whole skin he’ll be lucky. On the other hand, I know something of the enormous wealth of these ancestral halls, and if we succeed in our undertaking our fortunes will be made. That won’t mean much to you youngsters, of course; but it will enable me to buy a snug farm in England and settle down to end my days in peace. So I’m with you, lads, and you can count on my venturing as much as any of you.”

“Do you know in what part of China the province of Kwang-Kai-Nong is, doctor?” I inquired.

“Surely. It’s away up in the northwest, in the foothills of the Himalayas—a most retired and out-of-the-way place; and that’s what’s going to make our task doubly hard.”

“How can we get there?” asked Archie.

“By starting at Shanghai, traveling up the Yang-tse-Kiang a thousand miles or so to Ichang, and then cutting across country by elephant-train to the edge of the world, which is the province of Kwang-Kai-Nong. That’s not very definite, is it? But the road to Kai-Nong, the capital, is probably well known.”

“Mai Lo will show us the way,” I said.

The doctor looked at me blankly.

“We shall be obliged to take my father and Uncle Naboth into our confidence soon,” I continued, “for the Seagull must make straight for Woosung anchorage, so that we may escort the body of Prince Kai to Shanghai, and up the Yang-tse, while our ship goes to Canton to unload. Then they can pick us up when we return.”

“Look here,” said Dr. Gaylord, testily, “have you gone crazy?”

“I hope not, sir.”

“Then what’s this nonsense about escorting Prince Kai’s body——”

“To Kai-Nong, so he may rest with his ancestors,” I interrupted. “That will save Mai Lo from disgrace, and will enable him to return home in triumph. To do this, he will gladly show us the way.”

The doctor’s stare turned to a grin.

“I begin to understand,” said he. “So that is why you wanted me to join your party.”

“Exactly,” I replied. “We can’t get along without you.”

“And the spoils of war?”

“There shall be an equal division.”

“Very good!” said the doctor. “Very good indeed. The conspiracy is an established fact, and the conspirators are bound to win.”

With a smile I glanced over his shoulder to where a motionless form stood by the rail gazing steadfastly into the sea. The man was too far away to have overheard us, but the sight of him froze my smile in an instant.

It was Mai Lo.

“Come,” I said abruptly; “let’s go below and talk it over. It’s getting chilly here.”

The doctor and I had an important interview with Mai Lo that very evening. The man was evidently on guard before the door of his dead master’s room; for, the moment one of us approached the state cabin, there was Mai Lo confronting him, although the mandarin had been seen at quite another part of the ship a short time before. At such times the expressionless face and unfathomable beady eyes were turned toward us like those of a basilisk, and they impressed me with an uneasy sensation in spite of the fact that I felt that he alone was helpless to oppose us in anything we might decide to do.

But it was not our cue at present to antagonize Mai Lo, but to win his confidence. My father had already loudly declared in the Manchu’s hearing that the body of Prince Kai must be buried at sea, and considering Mai Lo’s prejudices it was not unreasonable to suppose that he looked upon us as his enemies.

Our first act in the comedy we were playing was to send Uncle Naboth to explain to the attendant that Captain Steele regretted the necessity of disposing of the body of his master at sea; but because the Seagull’s medicine chest contained no drugs or chemicals with which to embalm or preserve the body, there was no way to avoid this sea-burial if we wished to preserve the health of all on board.

Mai listened in apparent apathy to this explanation, which he had doubtless understood before, and the doctor and I waited a couple of hours to give him time to think it over before we sought him out and with mysterious gestures beckoned him to follow us to my own cabin. This he did, but would not close the door and sat in a position where he could keep an eye upon the locked door of the state cabin.

“Mai Lo,” said I, “you know that Prince Kai and I became friends before he died, and that he wished me to go to his palace at Kai-Nong and there perform for him certain services, the details of which are secret and must not be confided to anyone—even to you, his most faithful servant.”

He listened to me calmly, and then nodded his head.

“The Prince well knew his body would be lowered into the waters of the sea,” I continued, “and he was resigned to the necessity. We Americans do not care very much what becomes of our bodies when we are dead, but I know you Chinese feel differently about it, and it has made me unhappy to think I could not take the body of my friend Kai to China and place it in the burial-halls of his ancestors. Dr. Gaylord and I were conversing upon this subject, a short time ago, when he informed me that his science had taught him a way to preserve a body for a long period without the use of the usual drugs; but it is a method that requires great skill and labor, and constant watching, and is, moreover, very expensive.”

By this time Mai Lo was intensely interested; there was no doubt of that. His gaze was fixed steadfastly upon my face and I thought there was a faint gleam of curiosity in his eyes.

He was silent at first; but I intended he should speak, and after a long pause he did so.

“The expense,” said he, in a harsh, guttural voice, but fair English, “is not to be considered. The estates of Prince Kai are ample to meet any demand.”

“Just so,” I replied easily. “Were it not so, my own fortune would willingly be devoted to the honor of my friend. The question is not one of money, but whether we can prevail upon Doctor Gaylord to give us his time and services. He says the task is a difficult one; and, if he undertakes to preserve the body of my friend and your master, he must watch over it constantly and escort it in person to the halls of Prince Kai’s ancestors. I have promised to go with him and to take two of my own friends to assist him and guard him; but the doctor knows something of China and fears he will be molested and perhaps lose his life during the long journey to the province of Kwang-Kai-Nong and back again to Shanghai. It is this that makes him refuse the undertaking, so I have decided to ask you if you cannot help us, and relieve Doctor Gaylord of his fears.”

I spoke slowly, so that each word might be fully understood by the Chinaman, and it was not long before he answered me.

“China is a safe country at all times,” said Mai Lo, and I noticed that his raspy, guttural tones were as expressionless as his face. “But on this mission, when one is in the service of Mai Lo, and favoring the powerful family of Kai, the person of Doctor Gaylord would be sacred from harm.”

There were several things about this brief assertion that I did not like. The mandarin, so humble and subservient to his Prince that I had come to regard him as a mere valet, now assumed that we would be “in the service of Mai Lo” during our journey into the interior. Then, again, our return trip was not assured; it would only be of interest to Mai Lo to see that we arrived safely at the capital of Kai-Nong with the body.

This struck the doctor, too; for he said, in his positive way:

“If I go in safety I must return in safety. It won’t do, Mai Lo, to give me empty promises. Either you must show me, without the shadow of a doubt, how I am to return to Shanghai with my American escort, or I don’t stir a step and the body of Prince Kai goes overboard.”

Mai Lo took a silver box from inside his richly embroidered robe and abstracted some betel-nut and lime leaves, which he placed in his mouth.

“What assurance do you demand?” he asked.

“This,” said the doctor. “You will yourself remain on board the Seagull as an hostage, until we return from Kai-Nong.”

Mai Lo remained silent a long time, while we watched him anxiously. At last he spoke, as deliberately as before.

“You imperil your own safety by this request,” said he. “Without me to protect you, your party might be attacked and slain.”

“I thought you said China was perfectly safe!” I exclaimed, contemptuously.

“It is perfectly safe wherever I go,” he answered.

We were both greatly disappointed at this position of Mai Lo, for we had thought that by leaving him on board the ship we could carry out our plans safely. China might be a dangerous country to travel in, but we feared this incomprehensible mandarin more than anything else.

“Oh, well,” said the doctor, carelessly, “let us abandon the idea altogether. I don’t want the job, to be frank with you both, and I won’t run my head into danger if I can help it. So we’ll say no more about it.”

“There are other ways to assure your safety,” said Mai Lo, as the doctor rose as if to go.

Then he turned his face toward me and asked:

“Cannot the friend of Prince Kai trust the promises of his friend’s servant?”

“No,” I replied. “The Prince himself told me to trust no one.”

“You have his letter of authority and his ring.”

“He is dead,” I answered, with a shrug. “I am not sure the commands of the dead Prince are as powerful as those of his living servant. I am told you are all-powerful in Kai-Nong, Mai Lo.”

“We who worship our ancestors obey the commands of the dead without question, even if it costs us our lives,” said the mandarin.

This might be true, but I had little faith in Mai Lo being influenced by the traditions of his people. Prince Kai had distrusted the man and warned me to look out for any treachery from him. But it was not my purpose to antagonize the mandarin at this juncture.

“Satisfy the doctor, and you satisfy me,” I declared, with assumed indifference.