Approaching Marin's Shores.

Title: In Tamal Land

Author: Helen Bingham

Release date: November 27, 2017 [eBook #56061]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

In Tamal Land

BY

HELEN BINGHAM

THE CALKINS PUBLISHING HOUSE

San Francisco, U. S. A.

Copyrighted, 1906,

By Helen Bingham

All Rights Reserved

To the chum of my childhood,

The friend of my youth,

And my kindred soul—

My Mother—

This volume is lovingly dedicated.

A secret nook in a pleasant land,

Whose groves the frolic fairies planned,

Where arches green, the livelong day,

Echo the blackbird's roundelay,

And vulgar feet have never trod

Spots that are sacred to thought and God.

—Emerson.

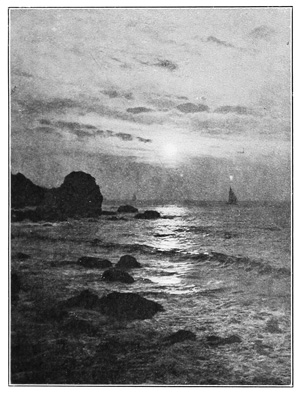

| Approaching Marin's Shores | Frontispiece |

| Title sketch | 1 |

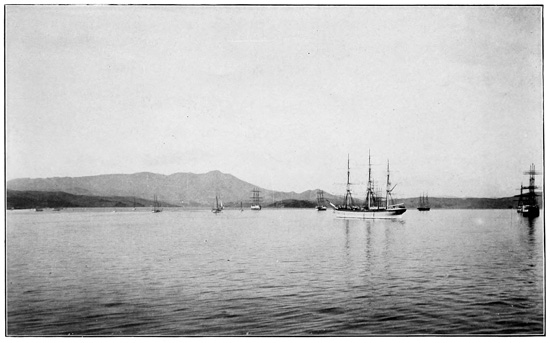

| One of the Commodious Ferry-boats | 1 |

| The Ferry Landing | 2 |

| Main Street, Sausalito | 3 |

| Sausalito Residences | 4 |

| The Club House, Sausalito | 5 |

| The Son of the Renowned Captain | 7 |

| A Typical Roadway | 8 |

| A Reminder of Rhineland | 9 |

| A Hillside Road | 10 |

| Hillside Gardening | 11 |

| O'Connell's Seat | 12 |

| Daniel O'Connell | 13 |

| A Windblown Tree | 14 |

| Fissures of the Cliffs | 15 |

| Nearing the Point | 16 |

| Fishing Boats | 17 |

| The Derrick Wharf | 19 |

| Point Bonita Lighthouse | 20 |

| Overlooking the Fog | 21 |

| The First Fog Signal | 22 |

| Angel Island | 23 |

| The Departing Day | 23 |

| Mt. Tamalpais from Mill Valley | 25 |

| The Powerhouse | 27 |

| An Electric Train | 27 |

| A Relic of the Past | 28 |

| Mill Valley Depot | 29 |

| The Three Wells | 30 |

| The Cascade | 30 |

| The Old Mill | 31 |

| Like the Mikado's Realm | 33 |

| A Reminder of the Toriis | 34 |

| Some of the Quaint Lamps | 35 |

| The Dining-room at Miyajima | 35 |

| A Creek in Summer | 36 |

| In the Hayfield | 36 |

| "The Outdoor-Art Club" | 37 |

| What the Club is Trying to Prevent | 38 |

| The Mountain Train | 39 |

| Through the Redwoods | 39 |

| Turning the Innumerable Curves | 40 |

| From the Crest of Mt. Tamalpais | 41 |

| The Marine Observatory | 43 |

| The Tavern | 43 |

| The Bow-Knot | 44 |

| A Wireless Telegraphy Station | 45 |

| The Bolinas Stage | 46 |

| Bolinas Bay | 46 |

| A Glimpse of Bolinas | 47 |

| Flag Staff Inn | 48 |

| Sand Dunes | 49 |

| The Breakers | 49 |

| The Oil Well | 50 |

| Where Don Gregorio Died | 50 |

| Thad Welch's Cabin | 51 |

| Duxbury Reef | 53 |

| The Lone Tree | 54 |

| Thad Welch at Work | 54 |

| Among the Redwoods | 55 |

| Primal Solitudes | 56 |

| In the Canyon | 57 |

| Angel Island from the Mainland | 58 |

| The Tiburon Depot | 59 |

| "The Tropic Bird" | 60 |

| In the Cove | 61 |

| Belvedere | 63 |

| An Artistic Church | 64 |

| Unloading Codfish | 65 |

| Drying Codfish | 66 |

| San Quentin | 67 |

| Point San Quentin as seen from Mt. Tamalpais | 68 |

| Lagunitas, San Rafael's Water Supply | 69 |

| Trolling on the Lake | 70 |

| A Marin Landscape. (From the original by Thad Welch) | 71 |

| Mt. Tamalpais from Ross Valley | 73 |

| A Home in Ross Valley | 74 |

| A Shaded Avenue | 75 |

| Dress Parade, Hitchcock Military Academy | 76 |

| Theological Seminary, San Anselmo | 77 |

| Dominican Convent | 77 |

| Court House, San Rafael | 78 |

| Escalle Vineyard and Winery | 79 |

| "Fairhills" | 81 |

| Fourth Street, San Rafael | 82 |

| Entrance to Hotel Rafael | 83 |

| Hotel Rafael | 83 |

| The Late Owner of the Olompali | 84 |

| The Last of the Race | 85 |

| A Wood Interior | 87 |

| Summer in the Redwoods | 87 |

| A Charming Drive | 88 |

| Browsing | 89 |

| A Characteristic Stream | 90 |

| Relics from a Shell Mound | 91 |

| Haying Time | 92 |

| Apple Picking in Marin | 93 |

| Cheese Industry | 95 |

| Young Heron | 96 |

| On the Marsh | 97 |

| R. H. Hotaling's Residence on "Sleepy Hollow Ranch" | 98 |

| The Taxidermist of Marin | 99 |

| A Quail's Nest | 100 |

| A Humming Bird's Nest | 101 |

| Little Songsters | 101 |

| A Sportsman | 102 |

| Near to Nature's Heart | 103 |

| A Bend in the Road | 105 |

| One of the Sparkling Lakes | 106 |

| Shafter Lake | 107 |

| On the Shore of Shafter Lake | 108 |

| Entering Bear Valley | 109 |

| The Country Club | 109 |

| Among the Ferns | 110 |

| At the Trough | 111 |

| Nearing Tomales Bay | 113 |

| Tomales Bay | 114 |

| Church of the Assumption, Tomales | 115 |

| Feeding Time | 116 |

| Chicken Ranches in Marin | 117 |

| Defacing Nature | 119 |

| Dairying on the Edge of the Pacific | 120 |

| In the Pasture | 121 |

| Going Home | 122 |

| A Marin Ranch | 123 |

| Sir Francis Drake | 125 |

| A Bay of Solitude | 126 |

| Drake's Bay | 127 |

| A Bit of Rocky Shore | 128 |

| Marin Cows | 129 |

| Drake's Cross | 131 |

| A Rugged Coast Line | 132 |

| Point Reyes | 133 |

| Point Reyes Life Saving Station | 134 |

| Plowing in October | 135 |

| "The Warrior Queen" | 137 |

| The Lighthouse | 138 |

| Cloud-Hosts | 138 |

| Where the Waves Break | 139 |

| The Glory of the Dying Day | 140 |

To the average tourist there are few states in the Union which offer more attractions than California.

Though its mild climate, fertile valleys, and scenic beauties are counted among its chief assets, still they are not its sole possessions, for, linked to the present great commercial activity of the Pacific Coast is a chain of picturesque events, clustered about its birth and infancy, which lends to the whole a peculiar charm, giving it a distinct individuality.

While the footsteps of the Spaniards grow fainter and fainter as they glide away into the corridors of time, and their traces become gradually assimilated by the progressive and oft-times aggressive Yankee, nevertheless the echoes from that former non-progressive splendor float back to us, and history re-animates the old adobes, breathing into a few secluded valleys the spirit of the past.

As the seat of historic interest, Monterey has received more homage than any other county on the Slope. Tourists flock to pay court to her old landmarks, writers eagerly pore over her time-worn archives, and the wielders of the brush have congregated in such numbers as to form an artists' colony. Though Monterey is undoubtedly justified in carrying off the palm for her many attractions, yet it is but fair that she should divide the honors of the past with her sister counties, being content to reign as Sovereign of the Coast.

Skirting the Northern end of San Francisco Bay is one of the smallest and most picturesque counties of California.

As a tiny gem in a coronet appears insignificant when contrasted with the other stones in point of size, but when viewed alone is admired for the diversity of its coloring and rare quality, so Marin, when measured by acres, appears insignificant, but when estimated by the beauty and diversity of its scenery stands unique, apart, alone.

As we approach Marin's shores, after a half hour's ride across the Bay on a commodious modern ferry-boat, our first thought on nearing the land is its remarkable similarity to an Italian settlement. For surely this town, situated on the steep hillside, is a counterpart of many an Italian hamlet, which, clinging to some abrupt cliff or bluff, seems to defy nature by its occupancy.

The clear blue of the California sky overhead but added to the illusion, although upon closer approach it was gradually dispelled by the modern American houses in place of quaint Italian structures.

Leaving the Depot we passed an attractive little park, well kept and gay with flowers, and a walk of a few moments brought us to the most historic part of Sausalito.

Though not in the section designated "old Sausalito," still it is the oldest in memories, for it was here that John Read, the first English-speaking settler in the County, came in 1826, erecting near the beach a crude board house. While waiting for a land grant from the Mexican Government, Read lived here.

Being of an ingenious turn of mind and having a practical nautical knowledge, Read set about constructing a sail boat, which he subsequently plied between Sausalito and San Francisco, carrying passengers. This was the first ferry boat on the Bay and when we contrast the little sailboat making its periodical trips across a solitary Bay with the present ferry craft, passing on their route ships from every quarter of the globe, a mere three score of years seems short for such a change, and proves what can be accomplished by Anglo-Saxon energy and enterprise.

Upon receiving his grant for the Rancho Corte Madera del Presidio, lying north of Sausalito, Mr. Read moved there in 1834.

A few hundred yards back from the beach, in what is now called "Wildwood Glen," was the first adobe house built in Sausalito. Only a few stones now mark the spot on which it stood, and a solitary pear-tree, gnarled and knotted with age stands a living witness of peace and plenty and decay. For it was in the bountiful days preceding the great influx into California by the Americans that Captain William Antonio Richardson, an Englishman but lately arrived on a whaling vessel from "the Downs," made application, and was given a grant to the Sausalito Rancho by the Mexican Government. He soon began building his adobe house and with the aid of the Indians it was rapidly completed. In the spring of 1836 he brought his beautiful young wife, formerly the Senorita Maria Antonia Martinez, to their new abode.

The Senora Maria Antonio was the daughter of Ygnacio Martinez, for whom the present town of that name in Contra Costa County was called.

Of all the dreams of happiness and love that filled the minds of the youthful pair on that fair spring morning, as in a small boat they were rowed across the Bay, by Indians, to their new home, we can not judge, but I am sure their dreams, however fond, were realized, for it is recorded somewhere that joy and peace reigned supreme in the little adobe.

However this may be, a young orchard was set out, cattle were bought and tended and the Senora's clever hands soon had the walls laden with the sweetest of Castilian roses. A stream flowed by the house on its way to the Bay, and on many a bright morning the Indian women of the household might be seen bending low over the stones washing the family linen. The stream has long since disappeared, as also the remnant of the race that washed in its waters—one through an unaccountable law of nature, the other through the rapacious greed and oppression of the Anglo-Saxon race.

Owing to the abundance of pure, fresh water found on the Sausalito Rancho it was shipped to Yerba Buena and the Presidio. The water was conducted by spouts to the beach, thence into a tank on a scow, which conveyed it across the Bay. This mode of supplying San Francisco with water lasted for some time, until with the increase of population this primitive means was abandoned.

A tule boat operated by Indians regularly crossed the Bay for the mail, many of the Indians evincing considerable skill in navigation under the tutelage of their able master.

Standing beside a heap of stones—historic stones because the sole remnant of this abode of the past—my glance wandered to the blue water of the Bay which laps the edge of the glen and stretches over to the distant hills which descend in gentle undulations to this beautiful shimmering sheet of blue. And this Bay, too, speaks of the second settler of Marin, for it bears his name.

As my glance now fell on the enchanting little glen with its tangled woodland and steep declivities, and then to the fair stretches of land that lay beyond, a sigh of sadness escaped from me unawares. I thought how all this lovely region, this Rancho Sausalito, comprising 19,500 acres, as varied and beautiful as ever nature put her seal to, this land, which rightfully belonged to Richardson and his descendants, had been appropriated by others through pretext of law and what not, until the heirs of the pioneer can call but a small building lot their own. Thus we ever find that "man's inhumanity to man makes countless thousands mourn."

But the son of the renowned Captain, a hale, hearty old gentleman, with a pleasant Spanish accent, speaks with calm equanimity of their loss of fortune, showing not a vestige of ill-will toward the transgressors, and practicing in full the true Christian spirit so often lauded but rarely seen.

"Sometimes, it is true, it makes me sad," he once replied, in answer to my queries, "to think of all the Rancho being gone. As a boy I used to ride, chasing the cattle, climbing the steep mountain sides followed by our vaqueros ... and how wild it was then and so beautiful—so beautiful!" Thus the heir to all these acres would extol their beauty without more reproach than that it sometimes made him sad.

Ascending the glen by a winding country road, shadowed by trees and shrubs, it was not long before we reached a small, low shingled cottage nestled deep in the shade of tall bays and buckeyes. A neat sign over the door bearing the inscription "O'Connell Glen," met our gaze, and then we knew that this little cottage, with its wealth of solitude and humble exterior, was the former home of the poet, Daniel O'Connell. For it was in this rural retreat that O'Connell, with his family, spent many busy, imaginative years.

A bohemian of the truest kind, he delighted in what Marin had to offer. With a stout stick, and accompanied by his daughters, he would often be seen sallying forth from his rustic lodge to tramp over hills and through canyons, exploring the apparently inaccessible, viewing and absorbing the wondrous beauty of woodland fastnesses, airy heights, and rugged cliffs. Feeling the very pulse of nature, his poems were the embodiment of all he had seen and felt, delighting the reader with their subtle charm and graceful imagery, which were peculiarly the author's own.

Leaving his favorite retreat and last abode, for it was here in 1899 that the poet breathed his last, a short walk around the bend of the hill brought us to another spot, sacred to the memory of the poet. This is the O'Connell monument which, as the inscription tells us, was erected by his sorrowing friends. The monument is in the form of a granite seat, some fifteen feet in length, fashioned in a graceful, curving crescent. Placed on the bank above the roadway, it is surrounded by great masses of bright-colored flowers, and approached by a few stone steps. The floor is of small, inlaid stones, in the center of which a three-leaf Shamrock proclaims the nationality of the poet.

Besides the name he made for himself, O'Connell came of illustrious ancestors, being the son of a distinguished lawyer, Charles O'Connell, and grand-nephew of the great Irish patriot, Daniel O'Connell.

On the back of the seat are inscribed these lines, written by the poet but ten days before his fatal illness, and prophetic of the long journey he was so soon to take, where, away from the cares and turmoil of this world, his soul could solve its remaining problems:

I have a Castle of Silence, flanked by a lofty keep,

And across the drawbridge lieth the lovely chamber of sleep;

Its walls are draped in legends woven in threads of gold.

Legends beloved in dreamland, in the tranquil days of old.

Here lies the Princess sleeping in the palace, solemn and still,

And knight and countess slumber; and even the noisy rill

That flowed by the ancient tower, has passed on its way to the sea,

And the deer are asleep in the forest, and the birds are asleep in the tree.

And I in my Castle of Silence, in my chamber of sleep, lie down.

Like the far-off murmur of forests come the turbulent echoes of town.

And the wrangling tongues about me have now no power to keep

My soul from the solace exceeding the blessed Nirvana of sleep.

Lower the portcullis softly, sentries, placed on the wall;

Let shadows of quiet and silence on all my palace fall;

Softly draw the curtains.... Let the world labor and weep—

My soul is safe environed by the walls of my chamber of sleep.

Turning from these verses to rest on the granite seat, we were confronted with a view of surpassing loveliness. Our attention had been so engrossed in examining this monument to genius that, until then, we had failed to perceive the commanding situation it held.

Below us stretched the peaceful waters of the Bay; on the left Angel Island and the Berkeley hills, with old Diablo dimly seen in the distance; in front, Alcatraz with its warlike aspect lay basking in the sun; while to the right the City, with its many hills and pall of smoke, could be plainly discerned. Truly a fitting spot for this memorial to genius.

Another attractive feature of Sausalito, besides its superb marine view, is its abundance of flowers. These not only grow in thick profusion in the quaint hillside gardens, but are planted beside the roadways, covering many an erstwhile bare and unsightly bank with trailing vines, gay nasturtiums and bright geraniums. There is something in the spirit of this hillside gardening, this planting of sweet blossoms for the public at large, that is very appealing in these days of monopolistic greed, when everything that is worth while has a fence around it. Thus it is refreshing to find a little spot in this dollar-mad America where the citizens disinterestedly beautify the public streets for the enjoyment of each passer-by.

Owing to the hilly surface of Sausalito, driving is rather a precarious enjoyment, but there is one drive which, with its superb marine vistas, amply compensates for the apparent lack of level roads. With the intention of taking this drive we procured a team and were soon driven rapidly along the boulevard skirting the water front, past the San Francisco Yacht Club, with its medley of white sailboats and smaller craft bobbing about in the water, and then through old Sausalito nestled in the gulch. Thence ascending the hill, the road wound around bend after bend with the Bay ever below us at a distance of a few hundred feet.

Arriving at a small, shingled lodge beside a gate through which we passed into the reservation, we soon came upon the Fort Baker Barracks in the hollow of the hills. It seems as if Nature, in anticipation of man's conflict with his brother man, had formed these hills on purpose for a fortification, so well adapted do they seem for their present use.

Beyond the Barracks, at the base of a cliff, we spied some small, white buildings clustered on the rocks extending out into the water. This proved to be Lime Point, and the buildings we were approaching belong to the Government, constituting a lighthouse- and fog-signal station. We found it to be one of the many smaller stations that are distributed along the Coast. There is a diminutive white light, and a steam fog whistle is kept ever ready to send out its note of warning at the slightest approach of the milky vapor which is a terror to the seamen.

Lime Point is directly opposite Fort Point, the distance being but seven-eighths of a mile, and forms the Northern point of Golden Gate Strait. While the view from these rocks is expansive, still it could not be called commanding, as the Point is too near the sea level to give the height and majesty requisite for an enchanting ocean vista.

As a pass is required before one can go through the reservation we retraced our steps to the Barracks and upon receiving the passport from the Sergeant Major, proceeded on our way up the steep, winding road which leads out of the Valley. Reaching the summit, the road continues its circuitous route; now in sight of the Bay and City, and again in among the bare, rolling hills.

While descending into a little valley we were stopped by a number of heavily laden teams, lined up in the middle of the road. Before we could question as to the delay, a volley of shots rang out, resounding again and again in the silent canyons, and a flapping red flag near by plainly denoted that the soldiers were engaged in target practice.

In reply to our query as to the length of time we should be required to halt, a soldier on the team in front informed us that sometimes one had to wait an hour or an hour and a half. Other teams having lined up behind, a retreat was impossible, and the prospect of a long wait in the hot sun was not very agreeable. We learned that a new barracks was in the course of construction below, in the valley at the head of the Rodeo Lagoon, and these teams were laden with provisions for the men stationed there.

Just as we had composed ourselves for the inevitable, a brisk waving of red flags was seen in the Valley, followed by the moving of the cavalcade in front; and, much to our satisfaction, we soon left our pessimistic informer far in the rear.

On the most southerly point of Marin a narrow rocky neck of land extends some distance into the Ocean. At the base are jagged rocks over which the sea surges ceaselessly, cutting arches and miniature caves in the fissures of the cliffs. From this rocky headland, which formerly was a menace and terror to navigators, now streams a steady light, and the point erstwhile spelling destruction now proves a blessing to vessels which are guided safely into port by the aid of its welcome light. This is Point Bonita and the Bonita Light, which, as we approached, stood out clear in the afternoon sun.

Stopping at the lighthouse keeper's dwelling, we proceeded on foot to the Point, accompanied by the keeper. Pausing in the narrow pathway, he drew our attention to a small derrick-wharf for the tender, at the base of the steep cliff on which we stood. This he explained was where the boat, which touches here three times a week, lands provisions, oil, and fuel.

"But, how," I asked in astonishment as I gazed down the dizzy depth, "do you get them up here?"

"Oh, that is very simply done," he responded; "we start up the engine and they are hauled up the bluff on a tram."

Owing to the perilous windings of the path around an almost perpendicular cliff a small tunnel has been cut through the solid rock. As we emerged from this tunnel the Lighthouse confronted us only a few yards away.

The tower containing the light is a square, brick structure twenty-one feet in height, situated at the edge of the Point at an elevation of one hundred and twenty-four feet. The Bonita Light, although of second-class rating, is so advantageously situated that its fixed, white rays are visible seventeen miles at sea.

The first lighthouse was established here in 1855, the light being placed in the picturesque old tower still standing higher up on an adjoining promontory and now serving as a day signal. The location was unsurpassed, they say, in clear weather; but when the fog rolled in it was quickly seen that a great mistake had been made in elevating the lamp, for often when the light was entirely obscured by a fog bank, the bluff below would be quite clear, so in 1877 the light was removed to its present location.

An old gun, now rusty, lying beside its gun-carriage on the bluff, was the first fog signal established on the Pacific Coast by the government. In foggy weather it was discharged every hour and a half during day and night.

When we contrast the present steam sirens, blowing five blasts every thirty-five seconds, with the former primitive means, we realize a little what scientists and inventors have been doing these fifty years.

The genial keeper, who is a second cousin of the late Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll, showed us every nook and cranny in the place, from the boilers, the lamp, and its appurtenances down to the neat store-rooms and paint lockers.

Though I have visited many fog-stations before, this one surpassed all others in its perfect order and scrupulous cleanliness, reminding one of a well regulated ship. So exactly was every corner and space utilized, that, as Dickens once remarked of a steam-packet, "everything was something else than what it pretended to be."

All the appliances of the Station are in duplicate. Thus, if one siren becomes disabled, another immediately takes its place; so with the boilers, etc.

Retracing our steps to the mainland, we noted on the edge of the cliff near the keeper's dwelling the life-saving station whose crew do much effective work about these jagged headlands. Bidding good-bye to the keeper, we turned our backs on Bonita and started homeward. We had been so engrossed with the Point and its environs as to be unconscious of the flight of time, and, noting with surprise the waning afternoon, we urged our horses to a brisk pace and sped rapidly along the elevated roadway.

The sun was slowly approaching the edge of the horizon, and Bonita, still visible in the West, stood out a silhouette against a brilliant sky. At its feet lay outstretched the gorgeously illumined sea; some fleecy golden cloudlets, floating over the Gate, seemed a soft shower of petals from the State's fair emblem; while the mellow light of the departing day still rested lovingly on the loftiest hilltops, and over on the city side occasional windows reflected his glory, as with a spot of glistening gold. To the southward the blue misty tones of the Santa Cruz Mountains began to merge into their robes of approaching night.

Suddenly out upon the still air rang a deep boom! boom! Angel Island was rendering her last tribute to the god of day.

Then there came to me those beautiful lines of our own poet, Lowell Otus Reese:

A touch of night on the hill-tops gray;

A dusky hush on the quivering Bay;

A calm moon mounting the silent East—

White slave the day-god has released;

Small, scattered clouds

That seemed to wait

Like sheets of fire

O'er the Golden Gate.

And under Bonita, growing dim,

With a seeming pause on the ocean's rim,

Like a weary lab'rer, sinks the sun

To the booming crash of the sunset gun.

All over the long slopes grown with green,

With the white tents scattering in between,

The flickering camp-fires start to glow

In the groves of the fair Presidio;

While the solemn chord

Of the evening hymn

Rolls over the Bay

Through the twilight dim

As the flag comes down to an anthem grand,

The brave, old song of our native land,

And Angel Isle, when the song is done,

Booms out "Amen!" with its sunset gun.

Although Marin County was first opened up by the advent of the North Pacific Coast Railroad in 1875, it was not until the transfer to the North Shore that the road was operated in its present modern system.

With the exception of the extreme North and East where the trains are run by steam, the County is traversed by well appointed electric trains which combine easy riding with quick transit.

This was the first electric line in California to be operated by the third rail system, and it has proved satisfactory in every detail. Owing to the danger of contact with the third rail, the road is fenced on both sides, and the rail is concealed at stations.

At the head of Richardson's Bay, and but a short distance from Mill Valley, is situated the North Shore Powerhouse. Here the power, which is transmitted from Colgate, over 150 miles away, is stored. Should there be any accident and stoppage to the power, electricity is generated at the Powerhouse by steam, which is always kept in readiness.

As I gazed at the three switches, each in its separate vault (in order to be kept fire-proof) it was difficult to realize that in the small wires I beheld were centered power to operate trains, illuminate and run machinery and countless other utilities.

As this, the greatest motive power in the world to-day, was long unknown except as an element of destruction, until the man came who harnessed the lightning and made it do man's work, so there are still undoubtedly other forces of nature which but await the master mind to discover their utility.

A short distance west of the Powerhouse, on a slightly elevated mound, is an old orchard whose gnarled trees have sheltered for a generation and more the yellow adobe walls of the first settler of Marin.

But the elements of nature with relentless fingers have played about this relic of the past, until but a small vestige is left to remind us of what has been.

When a grant to the Corte Madera del Presidio Rancho was given to John Read he began building his home, and in order to construct a large, commodious adobe, he erected a sawmill in the vicinity, and there the lumber for his home was whipsawed.

Thus, it is this mill, which is still standing in undisturbed repose these many years, which gave the surrounding valley its name.

Read had barely finished his adobe when he died, and the place subsequently passed into the hands of the boldest bandit of Marin.

The terror of the surrounding counties—whose very name sent a chill even to the bravest heart—was Barnardino Garcia, otherwise called "Three-fingered Jack." He possessed all the daring and bravery of a dauntless marauder, and the anecdotes of his bloody adventures form many a weird and ghostly tale when told by the flickering firelight of a winter's night, sending the listener to bed inwardly quaking, with eyes peering into dark corners.

The most widely known of his crimes was committed shortly after the raising of the Bear Flag at Sonoma, which proclaimed the Golden West to be the Republic of California.

The Bear Flag party being short of ammunition and a rumor gaining circulation to the effect that General Vallejo had a cache of powder stored on the Sotoyome Rancho near the present town of Healdsburg, it was decided to send men to procure some. Cowie and Fowler volunteered to go, although the journey was known to be a perilous one; but the need was great, and these pioneers considered it no risk.

They were warned, however, to avoid the way through Santa Rosa, and to confine their paths to the hills out of the ken of Garcia and his band.

Whether the Americans failed to heed the warning, or whether Garcia's men discovered them in the hills, will never be known. They were taken prisoners, under a pledge that their lives would be spared, but were finally murdered with great cruelty.

When Cowie and Fowler did not return to Sonoma within a reasonable time, great anxiety was felt in the little garrison.

Finally a searching party was sent out, but it soon returned with news of the murder.

The Bear Flag leaders swore revenge on the murderers, and eventually captured a number of Garcia's band, although he himself escaped. A fugitive from justice, he journeyed south, becoming lieutenant to the famous desperado, Joaquin Murietta, only to be subsequently shot in 1853 by Captain Harry Love's Rangers. His hand of three fingers was sent as a trophy to the commandant.

Thus ended the career of this bold adventurer.

Though there are many towns in Marin which command a more expansive vista, and offer by their marine situation greater diversity in out-door sports, still Mill Valley, nestling at the base of Tamalpais, has proved a delightful summer retreat and home center; for, dotted in the wooded canyons, beside the streams, or in some sunny exposure may be found many artistic dwellings which, while possessing the advantages of the country, are within easy access of the city.

The most notable among the attractive residences is the home of Mr. George T. Marsh.

Stepping within the odd wooden gate, which reminds one of the "Toriis," or sacred gates of Nikko, the stranger feels that he has indeed touched a fairy wand, and been transported to the heart of the Mikado's realm.

Liquid streams, spanned by fantastic miniature bridges on whose banks dwarf shrubs of various kind abound; fish ponds and islands; quaint metal lamps beside the roadway on their low posts, that are unique by daylight and when lit add all the witchery and charm of the floral isle; these and numerous other features of the Orient come unexpectedly upon the enchanted visitor, until he forgets the busy commercial activity of the outer world, and is in fancy again wandering in the grand old dreamy groves of Miyajima.

Another spot deserving the attention of the visitor is the quaint Club-House of the Out-Door Art Club. This Club has been organized by the ladies of Mill Valley for the purpose of preserving the natural beauties of the town and vicinity and staying, if possible, the hand of those primitive beings who, with ruthless vandalism, cut down and otherwise destroy the most prized of our rural possessions, our noble trees.

Much credit is due these energetic ladies in their worthy endeavor to teach those who have "eyes that see not" the wondrous beauties of Nature.

Besides its own unique features, the chief attraction which draws to this little burg tourists and travelers from all parts, as by a magnet, is the fact that it is the starting point of the Mill Valley and Mt. Tamalpais Scenic Railway.

Leaving the station, the mountain train winds through redwood groves, beside streams and pools, passing on its route the Hotel Blithedale, founded many years ago by Dr. Cushing as a sanitarium, so propitious to health is this sheltered, sunny exposure.

The train is operated by a steam-traction engine which combines the ordinary cog system with an additional contrivance appropriate for turning curves. As the train gradually climbs in its serpentine route, and chaparral takes the place of redwood, the country below begins to unfold; towns appear in miniature, and hills which on close approach have distinct characteristics now merge into one another, forming an unbroken mass which stretches west to the Pacific, on whose sapphire bosom may frequently be seen the dim outline of the Farallon Islands, while to the southward Point San Pedro and the City are visible, and San Francisco Bay with intricate windings can be seen to join San Pablo and Suisun bays on the east.

It requires many trips to fully appreciate and comprehend the marvelous diversity of views spread before one, while the variety of superb effects to be witnessed from this mountain cannot be found in a single visit.

To watch the wonderful radiance of sunrise when Apollo mounts in his chariot of fire above the Berkeley hills, or to see a billowy floor of fog, outspread before one, obscuring the lower world and leaving naught save this mountain peak unwrapped by the fog-mantle; and then to witness the pale light of the moon marking a silver pathway on the Bay, and casting grotesque shadows on the landscape; and these are but a few of the beauties garnered here.

The road which is known as "the crookedest in the world," turns innumerable sharp curves, finally twisting into a double bow-knot and, extricating itself, continues winding its way up, stopping a few moments at West Point, where passengers for Bolinas take the stage.

Arriving at the railroad's destination, the Tavern, the passengers alight to luncheon in its well-appointed dining-room, or lounge on the spacious veranda, enjoying at ease the superb views revealed below.

But if the traveller be something of a pedestrian he will take the zigzag, cleated steps which lead from the Tavern to the top.

Here the San Francisco Examiner's Marine Observatory is located, whose telescope is said to sight ships seventy miles at sea.

But this is not the only walk on the Mountain. Many trails wind about its sides disclosing shady nooks, a delightful cool spring and countless other surprises, which are easily reached owing to the guidance of artistic little signs which appear at short distances apart, while location rods are placed at intervals on the path circling the Mountain, enabling the visitor to find the various points of interest without any difficulty.

A few hundred feet from the Tavern is located a Government Weather Bureau, and in its proximity is to be placed the seismograph now being made in Strasburg, Germany, by order of the Weather Bureau Department in Washington. The instrument is said to be on a more elaborate plan than any in this country except the one in Washington, D. C., of which this will be a counterpart. Some time is required for its completion, so, presumably it will not be installed and ready to receive earthquakes until early next year.

Descending the mountain on the train to West Point, we alighted and after lunching at the Inn, mounted the stage which was bound for Bolinas.

The air on these mountain slopes is most exhilarating, and as we sped along down the gradually descending roadway, the breath of azaleas was wafted on the breeze from the canyons, while at each bend of the road the salt zephyrs from the Ocean became more perceptible.

Leaving the Monarch of Marin we soon came in sight of the white sand-spit with Dipsea, the new resort on the beach, and the glorious Pacific stretching thousands of miles beyond the horizon.

Alighting from the stage we embarked in a steam-launch which glided rapidly across the Bolinas Lagoon. Steep, massive hills encircle the Lagoon on the right, while on the left, becoming more apparent at each glide of the launch, lies Bolinas, the town, and our destination.

Owing to its small size and remote location we expected the usual hardships which accrue from a country hotel and its numerous incongruities; imagine our surprise therefore, when arriving at this little town, which is a stranger as yet to railroads, to find a cozy hostelry awaiting us.

Though unpretentious in appearance, the Flag Staff Inn proved as orderly and neat as any of its English prototypes. Whether it was due to the landlord's being a Briton or not, I can not say, but there was undoubtedly an English atmosphere about the place, and if honest Mrs. Lupin or Mark Tapley had issued from the porch to welcome us, I should not have been in the least surprised.

West of the little settlement of Bolinas a neck of land extends for a mile and a half out into the Ocean, the top forming a mesa. Owing to the fogs abounding in this region, it is green almost the entire year and makes splendid grazing, as in fact does all the land in the vicinity.

At the end of the mesa, some oil prospecting was being done, and at the time of our visit there was one shaft sunk. Although there are numerous deposits of oil to be found in and about these cliffs, the output thus far has not exceeded a barrel a day. Yet who can tell what rich veins may lie beneath this mesa.

On Duxbury Reef, a succession of small rocks extending farther out into the ocean, there is said to be found at low tide gas escaping from the rocks, which, being ignited occasionally by fishermen, does not become extinguished until the tide rises.

At the other extremity of the town is to me the most interesting section of Bolinas, for it was here that the first settlement was made. The name Bolinas—then spelled Baulinas—is believed by some to signify stormy and untamed, while others accredit it to be the name of an Indian girl.

Which is correct may never be ascertained. Either is probable; owing to its situation "stormy" may well apply, and as the Tamal Indians formerly inhabited this region, and in fact spread over the entire County, the last theory is equally feasible. To my mind they are both correct, for might it not have been named for an Indian maiden called Bolinas, whose nature was as stormy and untamed as the tempests which often surge about these headlands?

This Rancho Bolinas first belonged to Rafael Garcia, who disposed of the grant to his brother-in-law, Gregorio Briones, of whom tradition says there were few so honest, upright and brave as this dignified son of Spain, who died respected and beloved by all who knew him.

It was in the days before the "Gringo" came, when peace and plenty reigned throughout this land, and hospitality was proverbial to every household, that Gregorio Briones settled in Bolinas.

To be a skillful horseman and expert vaquero was all that was then required, for as cattle could live and thrive all the year round on the hills, there was no necessity for making hay for winter feed, or building stables for winter shelter; therefore, with little labor requisite, the natural consequence was the easy, careless life led by the Californians. Thus their spare energies were devoted to horse-racing, dancing, gambling, and kindred amusements.

Horses roamed the hills untethered and a caballero's first occupation in the morning was to catch a horse, saddle and bridle it, and either use or keep it tied up at his door during the day, ready for use at any moment, as both young and old rarely went from one house to another, no matter how short the distance, except on horseback.

As to the riders themselves, there were probably no better horsemen in the world than the native Californians.

On a fair spring morning in the month of May, 1850, a single horse, with two riders, might have been seen threading its way up the steep mountain trail leading from Bolinas to San Rafael. The bright, girlish face of the first rider peered wistfully from beneath the soft folds of her mantilla, while the young caballero, on the crupper behind, whispered to her in those sweet, melodious tones unheard save from a liquid Spanish tongue. Of the purport of their whispers we can but judge, for on arriving at the Mission they were greeted by a joyous peal of wedding bells.

The groom was Francisco Sebrean, the bride the beautiful Senorita Maria Briones, daughter of the pioneer. This was the first marriage in Bolinas and the celebration which followed their return to the Rancho was the most notable ever witnessed in that region. Dancing, feasting, music and gayety continued until the gray dawn appeared to touch the surrounding hilltops and proclaim the approach of another day.

Stopping at the home of the only remaining daughter of Don Briones, now a dignified, delightful, old lady, with the charming manners and graces of a true descendant of old Spain, we procured directions and soon found the oldest house in Bolinas. Although this was not the first built there, it is the oldest standing, and was occupied by the Briones family, Don Gregorio dying many years ago, while his wife, the Senora Briones, lived there until 1903, reaching her one hundred and seventh birthday—which goes to prove that it is the simple, natural life which begets old age.

If one is a good pedestrian and has a desire to get acquainted with nature untamed "without her hair combed" he should take the Lone Tree Trail leading from Bolinas over the hills, through the canyons and along the ridges back to the starting point, Mill Valley.

In a little "Steep Ravine" amid the high hills, and but a short distance from the Ocean and Bolinas, stands the solitary cabin of the man who by the magic of his brush first awoke the outer world to a realization of the beauties and possibilities of this region.

With the hand of a master, Thad Welch caught the rare effects abounding here, which have delighted and won the admiration of all nature-lovers, and linked his name inseparably with Marin. While at present residing in another portion of the County, the cabin which he formerly occupied here is in a state of neglect, but while his little abode may perish, his pictures will live and be cherished in the ages yet to come.

Some distance from the Steep Ravine the trail descends an abrupt, wooded hillside, at the foot of which lies the Redwood Canyon. For this forest of giant redwoods, comprising six hundred acres, negotiations were pending toward making it a national reserve, but the efforts proved unsuccessful. Though of smaller dimensions than the Calaveras Big Trees, these redwoods gain by beauty of situation what they lack in size.

The Canyon runs diagonally with the sea coast and has its rise in one of Tamalpais' western ribs, from which a railroad similar to the Mount Tamalpais Railway is under course of construction, connecting the Mountain with the Canyon.

Its present owners, Messrs. Kent & Cushing, intend to erect a hotel at the terminus of the new road, and the building, on which it is said will be expended some fifty or sixty thousand dollars, will be a fully equipped, sumptuous modern hostelry.

It is to be hoped that the march of civilization, which so often leaves nature's handiwork crushed, broken and even obliterated, will spare this grand, majestic forest in which beauty now reigns supreme.

Bending low over the little stream which winds through this canyon huge sprays of azaleas filled the air with their delicate perfume; on the banks lacy wood warriors and the hardy sword-ferns mingled in graceful profusion, while the flickering sunlight filtering aslant through the tree tops fell on the transparent hazel leaves lending a soft, green glint to a neighboring pool which rippled every now and then by the action of numerous trout catching flies on its surface.

Wandering beneath these perennial columns, these huge monoliths of whose birth there is no record, one feels as if treading the grandest of cathedral aisles, and that in truth "The groves were God's first temples" and "Solitude is the veritable audience chamber of the Creator."

No echo follows our footsteps on the soft needles and oxalis and save for the murmuring of the little stream and the occasional calling of a mourning dove in the tree tops above there is no sound. Here, alone in these solitudes, the higher self—the soul—strikes off its shackles, and expands to the very infinitude of things, through nature to the Infinite.

Near the southeastern shores of Marin lies the largest and most picturesque of the three islands which adorn San Francisco Bay. Though lawfully a portion of Marin County, Angel Island, separated from the mainland by Raccoon Straits, besides being set aside as a Government reserve, is therefore seldom classed with the County, and usually ranks with her sister islands, Alcatraz and Yerba Buena.

But a sketch of Marin, however cursory, would be incomplete without her southern isle, for besides the United States Barracks, situated on the western part of the Island, there is located in a northern cove the Federal quarantine station, that most necessary adjunct of San Francisco, which prevents contagion by quenching the pestilence often brought to our shores from the Orient and South American ports.

Besides its present significance the Island has another and far older claim on our attention.

In the summer of 1775, Juan de Ayala, a lieutenant of the Royal Spanish Navy, was given a commission from Junipero Serra and Bucareli, the Mexican Viceroy, to proceed to "the arm of the sea" lying north of Monterey, which had been twice viewed by the padres from the land, to ascertain if it were a canal or bay, and make a survey of it.

Pursuant to these instructions Ayala cautiously crept up the Coast and on the ninth day sighted the narrow passage which is now known the world over as the Golden Gate.

A crude launch was sent to explore the opening, which was found to be deep and without obstructions. By the time the launch returned it had grown dark, nevertheless Ayala headed for the Bay and on the night of August 5, 1775, the San Carlos sailed in through the Strait, the first ship that ever passed the pillared passage or entered what is now known as the Bay of San Francisco.

Having entered safely, Ayala moored his vessel just inside the Bay, and the next morning, looking around him, selected an island not far from the entrance as a convenient spot to make his headquarters.

Upon examination, he found a suitable place for mooring his vessel, also wood and water in abundance. This Island was then named Nuestra Senora de Los Angeles, the appellation which it still bears, though shortened to Angel Island.

On the mainland, directly across from the Island, lies Tiburon, the ferry and terminus of the California Northwestern Railroad. Besides the Company's shops, Tiburon consists mainly of stores—in short all that is included in the usual "Water Front."

The most interesting object in Tiburon is on the road between that place and Belvedere. This is none other than the remains of a remarkable old hulk, now beached and converted into a habitation. Besides its unique appearance, there is an interesting tale connected with the Tropic Bird which is something like the following:

"Early in the year 1850 the good ship, Tropic Bird, Captain Homans skipper, set sail from Gloucester, Mass., with a cargo of general produce bound for the Golden Gate. On board was a mixed crew, seafaring men and land lubbers, all having but one hope, one idea—the far-famed gold fields of California. A good true ship was the Tropic Bird and a good true man her skipper, who had with him his brother.

"One day is very much like another on a long ocean voyage,—when the wind holds good and the weather is fair; but there came a time when ominous murmurings, gathering force each day, the echo of a mutinous discontent, reached the quick ears of the young Captain and his brother.

"The cargo was a valuable one. They were on the high seas. If the crew stood together against the two men they were as nothing in their hands.

"One night the cloud burst, there was a loud cry from the first mate, and in a second every one was in the scrimmage.

"The Captain rushed on deck. Though light, he was strong and a famous wrestler. As soon as he appeared he was pounced upon by the leader of the mutiny, called Dutch Dick, a big, heavy, slouching fellow. With almost superhuman strength the gallant Captain disarmed and stunned his foe after a heavy tussle.

"Men were moaning, yelling, dying on all sides, when suddenly above this howling, cursing, blood-thirsty mob, there was a bright, piercing flash, the sharp battalion crack, crack of thunder.

"The storm was on them. No time now for murder and rapine. It was a battle against the elements. The Captain was up roaring orders to his men. Those who could, obeyed and worked with a will in the common danger.

"Battered, tempest-torn, thrown hither and thither, a mere cockle shell in the hands of God's elements, the staunch ship, skilfully handled by her skipper, just managed to reach the Golden Gate.

"Water-logged and mauled, the gallant Tropic Bird was then unfit to further cope with the elements, and, after being converted into a boarding house at the foot of Telegraph Hill by her courageous Captain, she was later sold and beached at Tiburon, where she now rests, her labors o'er, a worthy ship with a peaceful, useful old age."

Belvedere—beautiful Belvedere it is called, and with justice, too; for who could view this thickly wooded hillside with its charming villas without exclaiming Beautiful! These villas are interspersed with graceful irregularity amid their leafy setting; the sparkling water at their feet, gay in summer, with house-boats, launches, yachts and other craft is resonant of one theme, united in one chord—the care-free, happy, guileless merriment which does more to erase the worry lines begotten of cities than all the lotions ever prepared. And this, in truth, is the veritable home of the sportsman, for across the cove on the Tiburon side is situated the Corinthian Yacht Club, famous in yachting annals.

However gay this little cove may appear by day it is by the pale light of the moon that Belvedere, like Venice, is at her best; for the harsher lines of fact are mellowed, and imagination gives the floating habitations a fairy aspect, while the strains of the military band from the Island but lend to the fantasy.

On the opposite side of Belvedere is situated one of the most prosperous industries conducted in Marin County.

Nestling at the base of the cliffs on an extensive wharf built for the purpose are the buildings of the Union Fish Company. The Company has several fishing stations in Alaska, the most extensive of which are on the Shumagin and Popof Islands. A schooner plying between the stations and this port brings the fish direct to the fishery, where they are prepared for use.

At the time of our visit, the schooner, which had arrived but a few days previously, was unloading and we were thus fortunate enough to see the evolution of the codfish from the time it leaves the hold of the ship until it is packed in neat boxes ready for shipment.

There were four hundred tons, or one hundred and seventy thousand fish on the vessel. When one thinks that each fish is caught by hook and line, the amount of work represented seems enormous, but this is a mere bagatelle compared to the process following.

On leaving the hold they are first thrown into vats of brine for rinsing, then loaded on small cars operated on a track and run into the building; from thence they are laid on immense racks in the sun to dry. If not for immediate shipment they are stored in huge vats of brine.

In one large room there were many men at long tables, engaged in skinning and boning the fish, and the celerity and skill with which this was accomplished are marvelous to watch. The refuse, which formerly was discarded as being useless, is now utilized, the bones being made into a fertilizer, while the skins are used for glue.

There are seventy-five men employed in this establishment, and the order and cleanliness of the place testify to its able management.

Owing to the inclemency of the weather during the winter months, a steam-drying apparatus was in the course of construction by which the fish can be dried with safety in the rainy season.

Leaving Tiburon, a short ride on the California Northwestern Railway brought us to Greenbrae, a small station, uninteresting in itself and unimportant save as the place from which is reached that huge institution known as the state prison, San Quentin.

Situated on Point San Quentin, which extends into upper San Francisco Bay, with round guard towers perched on the hill overlooking it, and a twenty-foot wall enclosing its eight acres, the prison would seem impregnable and unpropitious for an outbreak.

The high somber buildings, which are of red brick, have been added to and remodeled at intervals without any given plan, and thus they form an irregular mass, interspersed with paved courts and narrow cells.

A large, square plot is devoted to grass and flowers and lends a cheering tone to the grim structures surrounding it. One of these, a tall edifice with a succession of iron doors opening on to small, long balconies, reached by narrow steps, is called the Tanks.

The average cell in this building is eight by twelve feet in dimensions. In each of these five men are stowed—one could not say accommodated for the narrow bunks placed in tiers, with a still narrower passageway between, vividly suggested the over-crowded lodging houses of Mulberry Bend, which Jacob Riis's perseverance eradicated.

In other buildings are cells, each of which is thirty by twenty-seven feet, which contain twenty-six men, and one cell, of thirty-six by twenty-one feet, lodges forty-eight convicts.

Though the system of ventilation is by means of flues attached to the ceiling and door, still these rooms, in which are herded individuals of all ages and classes, must become exceedingly foul and unhealthful; while the opportunity which this congregate system affords the prisoners for concocting plots and outbreaks is undeniably assured.

Of the prison industries the jute mill is of sole importance to the outer world; all other products being consumed there. Some eight hundred convicts labor at the mill, and five million sacks are annually sent from the prison.

There are paint and tin shops which supply all the tin-cups, hand basins, pails, etc., used in the institution; tailor shops in which are made all the clothes; carpenter shops for repairing and furniture, while sixty pairs of shoes are turned out each week from the boot shop. In the machine shops where are manufactured all the needles used in sewing the jute bags half a dozen excellent sewing machines were recently made.

The extensive laundry where numerous Chinese convicts are employed, is only one of the many evidences of cleanliness witnessed in this institution, where order and system are apparent to even the casual observer. But however orderly, systematic and cleanly a prison may be kept, that is only one means toward eliminating crime; for so long as we continue in our congregate system of indiscriminate herding together of all classes of offenders so long will our penitentiaries be hot-houses for fostering crime. Instead of eliminating, we confirm; instead of inciting decency and self-respect, we incite indecency and rebellion.

At the time of our visit there were in San Quentin about a dozen lads, the youngest but fourteen years of age, imprisoned on charges of murder, who, had it not been for the supervision of Warden Tompkins, would have been placed with the confirmed, hardened criminals.

The State makes no provision for these offenders, and, unless as in this instance they are separated by the individual action of the Warden, they would ere now be proficient in the lore of crime.

Crime is contagious, because thought is contagious.

By this it is not meant that you and I, if we mix with criminals, will become criminally inclined; because our ego—or soul—not having any prenatal defect or susceptibility to crime will be unresponsive to its influence.

But to a criminal, whether he be a first offender or not, the pernicious, indiscriminate companionship of fellow convicts who suggest crime in its various distorted shapes to his abnormal, defective mind, will plant seed-thoughts which thus sown thrive and grow until we have the confirmed criminal.

If a criminal is so receptive to suggestions of evil, and his criminal capacity is so strengthened and fixed by the ideas and emotions that he entertains, would not counter-suggestions have just as potent an effect on the individual?

If, through the channels of thought, he is susceptible to maleficent influences will he not be equally responsive, through the same medium, to the beneficial?

Granting this to be true, would it not be well to surround the convict with all that stands for advancement, and through intelligent education and suggestion awaken the latent good which is in each individual, no matter how dormant and perverted it may be?

By education is not meant the rudimentary school education, for many criminals are proficient in that, but the far more important study of self-respect, honesty, veracity, industry, unselfishness, and an appreciation and proper use of the things that are.

Methinks if with the contemplated enlargement to the prison an educative, segregative, industrial system similar to that adopted with such marked success in the Elmira Reformatory, New York, were inculcated in our state prison there would be less "recedivists"—fewer many-term offenders—and the fifteen thousand dollars which it costs the State monthly to conduct a prison would not be devoted to confirming criminals.

Although Marin County is sparsely populated, owing to its large tracts of hilly surface and consequent non-agricultural facilities, still the towns within its borders are of average population, the largest, San Rafael, comprising five thousand inhabitants.

Besides being the county seat, San Rafael has the distinction of having once been a mission settlement, and though the church has long since mingled with the dust, the memory of its bygone glory clings like the lichen of the remaining pear trees to the spot which knew it in its prime; when to the clanging of the mellow toned Spanish bells, the neofites, the children of the soil, would kneel in meek devotion before the sacred altar whose fires, like their lives, have long been quenched but appear again, let us hope, in their successive higher spheres.

Except in memories San Rafael is essentially modern.

The factory and the loom form no part of its existence, and with the exception of two brick kilns and a planing mill on the outskirts, the town is without industries.

Therefore, sheltered as it is by beautiful rolling hills on three sides, with a mild climate and not even a street-car, as yet, to disturb the stillness, San Rafael, like Ross Valley, is considered an ideal spot for homes.

Besides its handsome residences and long shaded avenues, which afford much enjoyment for driving, San Rafael is noted for its excellent schools.

These not only consist of the splendid public schools, but of private institutions, notably the Hitchcock and Mt. Tamalpais Military Academies for boys, and the excellent Dominican Convent for girls, besides the St. Vincent and Presbyterian orphan asylums in the vicinity procure for the town the name of an educational center.

A short time ago, Mr. Andrew Carnegie donated to Marin's county seat the sum of twenty-five thousand dollars for a public library, the plans of which are now under consideration.

That her residents are not less generous than the famous philanthropist was forcibly shown on April 29, 1905, when Mr. and Mrs. John F. Boyd transferred to the town some seventy acres for a memorial park. The occasion of its dedication was marked by able addresses from the "Wizard of the Plant World," Mr. Luther Burbank, United States Judge W. W. Morrow, and Judge Thomas J. Lennon.

Abounding in natural verdure, artistically embellished and converted into a perpetual pleasure ground, the Boyd Memorial Park seems a fitting testimonial to the memory of the sons of its donators.

While noted as an educational center, San Rafael also has the unique distinction of being the Gretna Green of the Coast; and the blushing brides and happy grooms united here exceed in numbers those from the erstwhile famous European village.

To this charming little northern settlement from all the surrounding counties and various parts of the state they come to plight their troth, averaging, it is said, five a day; "and the best and most remarkable part of it all is," Marin's genial Judge informed me, "they turn out all right," and, really, I suppose he ought to know.

Notable among the many charming residences in San Rafael is Fairhills, a summer home of Mr. A. W. Foster.

It is surrounded by a stately garden where the choicest plants abound in graceful profusion, blending one with another in a perfect harmony of colors, while the majestic trees, spreading a deep shade over the sloping velvety lawn, are reminiscent of a Warwickshire landscape.

To the westward, wooded hills—truly fair hills—with their ever changing, hazy tones, are visible from the spacious veranda, and the perpetual calmness and majesty of their lofty slopes would seem to impart some of themselves to the beholder, for, as Rousseau says, "Our meditations gain a character of sublimity and grandeur proportioned to the objects around us."

Although essentially a resident settlement, the tourist will find ample accommodations at Hotel Rafael, sometimes called the "Del Monte of the North." Though of smaller dimensions, and with less sumptuous appointments and surroundings than the southern hostelry, Hotel Rafael, within easy access of the City, is more convenient for those who enjoy the country, yet never leave their business for its sake.

While the Assyrians, Babylonians, Greeks and later Gauls and Romans were weaving the first few threads of our planet's history in the old world, the aborigines of America roamed our trackless, primeval forests, boundless save for two shimmering oceans and a blue canopy overhead.

Fearless, they plunged into the thickets, swam the streams, hunted game, caught the bear and bison, trapped the fowl, and dauntlessly lived on in fear of neither nature, beast nor man—primitive—just a savage, but possessing the fundamental requisites from which all civilizations, sects, isms, or communities have been evolved—a human being with a soul.

Therefore the red man is to America what the cave man is to Europe—the father of his country.

In the history of our State the aborigines played an all-important part, as the founding of the missions by the Friars was with the avowed intention of reclaiming these children of the wilderness, to teach them civilization.

The first mention made of the Indians in Marin County is found in an old legend which states that about the time of the erection of the Mission at San Francisco a party of Spaniards crossed the Straits at what is now known as Lime Point and traveled northward. It was late in the season, and they found no streams of running water until they arrived at Olompali, so named from a great and powerful tribe of Indians who dwelt at this place, the Olompalis. Here they were kindly received by the natives, and all their wants were supplied as far as it lay in their power. The party was so well entertained that the leaders decided to remain a fortnight and recruit their horses and become thoroughly rested, preparatory to proceeding on their arduous journey. In return for the kindness received, they taught the Indians how to make adobe brick and construct a house.

That history corroborates this legend is shown in an old chronicle by the biographer of Junipero Serra, Father Palou, which says that "in 1776, after the Presidio and before the Mission (in San Francisco) were established, an exploration of the interior was organized as usual by sea (the bay), and land."

Thus, in the northeast corner of the County, near Novato, was built the first adobe house north of San Francisco Bay, on the Olompali Rancho, owned by the late Dr. Burdell.

The first adobe has long since disappeared, the last mention found of it being a remark of General Vallejo's when, some thirty years ago, on passing the Olompali Rancho and pointing to a crumbling adobe he remarked to a companion, "That is over a hundred years old."

But the adobe that concerns us, the long, low, rambling adobe, is still standing in good condition and occupied by Dr. Burdell's family. This was supposedly the second built and is accredited to have been constructed by the last chief of the tribe, Camillo Ynitia.

Camillo, after obtaining three successive patents for the Rancho, first from Spain, then from Mexico, and lastly from the United States, sold it for five thousand dollars, which he was believed to have buried in the vicinity. Refusing to divide the proceeds of the Rancho, and furthermore to disclose the spot where the gold was buried, Camillo was subsequently murdered by his brother.

The Olompali Rancho is beautifully situated, lying as it does at the base of Mt. Olompali which is believed to be an extinct volcano.

Mortars found five feet under ground in the river bed, together with sand, mud, gravel, pebbles, and cement strata on the mountain side, testify to volcanic action.

From this mountain which formerly, in unknown ages emitted hot, sulphuric gases from its bosom, now runs a clear and limpid stream, a perpetual penance to nature for the havoc it once wrought.

When the Spaniards first visited the County, there were said to be thirty distinct tribes of Indians, each with its separate chief; while their language or dialect differed materially.

That they lived on mussels, sturgeon, and game from the marshes, is evidenced by the remains found in the huge shell mounds distributed throughout the County.

What these mounds are and how they became so, is merely a matter of conjecture, although the scientists of the University of California and Stanford are revealing additional clues from time to time as new deposits are discovered.

In the Marin mounds have been found mortars and pestles, queer old pipes, beads of wampum, oyster picks, skulls, and in many instances entire skeletons, while the arrow-points testify to certain warlike propensities, although on the whole they were said to be peaceful tribes.

The bows which they used with such celerity and skill were uniquely fashioned; the cord consisting of the nerves taken from a deer's back. The Marin Indians and in fact all the California tribes, dwelt in small huts built of willows with tules or rushes, and formed by taking a few poles, placing them in a circle, and finally weaving them together to a conical point, giving, when completed, the appearance of inverted baskets.

They were usually constructed on the banks of streams, and, being small, were easily warmed in winter.

The aborigines' knowledge of the proper treatment of disease was very limited. Roots and herbs were sometimes used as remedies but the "sweat-house" (temescal) was the principal reliance in desperate cases.

One of these sweat-houses was found on the Nicasio Rancheria, just over the Olompali Mountains.

It consisted of a large circular excavation, covered with a roof of boughs, plastered with mud, having a hole on one side for an entrance, another in the roof to serve as a chimney.

A fire having been lit in the center, the sick were placed there to undergo a sweat bath for many hours, to be succeeded by a plunge in the ice-cold waters of a neighboring stream.

This treatment was their cure-all, and whether it killed or relieved the patient depended upon the nature of his disease and his constitution.

It seems but fitting that this County, which formerly was a favorite rendezvous of the Indians, should derive its name from a famous chief of the Lacatuit Indians, who frequented the southern part of the Peninsula.

Between the years 1815 and 1824 Chief Marin, aided by his people, is said to have vanquished the Spaniards in several skirmishes for supremacy. Being finally captured by his enemies, and making his escape, Marin took shelter on a tiny island in upper San Francisco Bay. This island being subsequently called after him, communicated its name to the adjacent mainland.

Falling into the hands of his foes a second time, he barely escaped being put to death through the interference of the priests at the Mission San Rafael.

While surveying the County several years ago, Mr. Jacob Leese had with him as assistants the old Indian chief, Marin, and some of his followers. It became necessary for the surveyor to establish an initial point on the top of Mt. Tamalpais, and he wished Marin and some others to go up with him. To this they made strong objections, stating that the top of the Mountain was inhabited by evil spirits, and no one could go up there and come back alive. After vainly trying to persuade them to accompany him, Mr. Leese, finally decided to go up alone, which he did, the Indians prophesying that they never expected to see him again.

On reaching the top and accomplishing his purpose, he was puzzled to know how he could convince the redskins of having reached the summit. To do this he placed a large limb across an old dead tree, thus forming a cross which could be seen in the Valley below. He then descended and directed the attention of the Indians to the cross.

Prior to this, Marin had been considered by his followers as the bravest man in the world. He therefore found that it would never do for him to be afraid to attempt what a white man had accomplished.

Marin then determined, against the most earnest entreaties of his men, to go up where the white man had been. Tearing himself from his men he ascended the Mountain alone and when there had to study how he should convince his followers of the fact.

Unwinding his outer blanket he suspended it on the arm of Mr. Leese's cross, having done which, he descended the Mountain.

On seeing him without his garment, his followers concluded that he had been robbed by the Devil himself; but pointing out to them his blanket waving upon the cross, much joy was expressed over his restoration to them as the bravest of the brave.

The foregoing tale is only one of many which illustrate the profound superstitions prevailing among the Indians.

Certain rocks and mountains were regarded as sacred, while the grizzly was held in superstitious awe, nothing inducing them to eat its flesh.

The idea of a future state was universal among the California Indians, for as they expressed it, "as the moon died and came to life again so man came to life after death," and they believed that "the hearts of good chiefs went up to the sky and were changed into stars to keep watch over their tribes on earth."

A short distance from the Olompali Rancho is Novato, a small town which until a few years ago possessed the largest apple orchard in the world.

At the present time the New York and the Novato French cheese factories are its only noteworthy industries. The latter, which is representative of a thriving, modern cheese-factory, is conveniently located beside the California Northwestern Railway on whose cars the local shipments are made twice each day.

But this local trade is by no means the factory's sole outlet, for besides supplying the Coast and the East as far as Iowa (where another branch is located), cheese is exported to the Hawaiian Islands, Japan, China and other foreign countries.

In this unpretentious building, in which but twelve men are employed, fifty thousand five-pound cases of cheese are manufactured a year, or a little more than four thousand (cases) a month. In the spring from twelve hundred to fourteen hundred pounds of cheese are manufactured each day.

Besides its famous Circle Brand Breakfast Cheese, the Novato French Cheese Factory manufactures large quantities of Fromage de Brie, Neufch, Sierra, Fromage de Chanembert, Schlosskase and Kummelkase.

On a tiny island amid the marshes in this, the extreme northeastern corner of Marin, is located the Miramonte Club. A sportsman's club in every particular, it is very advantageously situated, for around these northern marshes the game is very plentiful and the sportsman is usually rewarded for his labor.

Besides the fowl for the larder, there are many other birds about the marshes. In summer redwinged blackbirds, each with its scarlet shoulder-patch, may frequently be seen, while the herons with their long, ungainly legs are often visible wading in the pools, or standing on some lonely reef, like solitary sentinels.

In the winter, great flocks of little sandpipers frequent this region; their white breasts gleaming in the sun in the course of their graceful evolutions. Then there are the slender beaked curlews which, like the heron, wade about the pools in search of food.

In the fall and winter the salt-water marshes have a peculiar charm not only for the sportsmen who delight in the abounding bird-life, but for the humble excursionists who, gunless, admire the marvelous diversity of coloring displayed in the grotesquely shaped marshland.

For no other weed, grass or vine assumes a greater variety of tints than the marsh vegetation, which from the dull russet of summer changes to a combination of olive, purple, magenta, copper, and violet, so harmoniously blended that, besides charming the observer, it lures many a local artist from his studio in town.

In Marin the feathered songsters hold a unique place, for, as the county is sparsely populated, possessing many wild, secluded valleys, and unnumbered rolling hills covered with virgin forests, it is but natural that the birds should congregate in great numbers, reveling in the solitude which man invariably destroys.

If the traveler is interested in these woodland tenants, and would learn something of their haunts and life, he should visit one who knows them as Thoreau knew all the wild and untamed things of nature.

A short distance from Fairfax the San Geronimo Valley, nestling among the hills, is a fitting location for this naturalist and bird-lover.

Though a taxidermist of much skill, Mr. Charles Allen is more widely known among ornithologists by that little fairy creature which makes its appearance in the early spring, known as Allen's Hummingbird.

Although similar in point of size, it is in its coloring that Allen's Hummer may be distinguished from other hummingbirds, for its green back, ruffus-tail, streaked with black, dark-wings and ruffus head, easily separate it from other varieties.

To a reflective mind there is no time of the year more joyous than spring. All nature seems gay and full of promise. Hope is vibrant in the air, and enters into the nature of the receptive man through more senses than science has yet named or discovered—an unnamed sense which is neither sight, nor sound, nor touch, nor intuition, a vibrant unseen force which is current throughout the universe, connecting man, unknowingly, to every tree, shrub, and atom. Thus, in the spring one feels that:

"There's a chorus in the valleys and an anthem on the hills

There's an echo from the music which our inner being thrills

Till we long to journey outward where no other foot has trod,

And join in the song of worship at the shrine of Nature's God."

Spring is synonymous with the return of the birds, and their blythe little songs are but another promise of hope and expectation.

Following close upon the return of Allen's Hummingbird is the little piliolated warbler with his green back, pale, sulphur yellow breast, and tiny "pee wit" call.

When the climbing roses are becoming gay with blossoms, our old friends, the linnets, returning from their winter's sojourn in lower California, begin to build their nests.

A walk in the woods in the early morning or evening will acquaint one with another spring bird, Vaux's Swift, invariably seen about the streams.