The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Title: Lloyd's Treatise on Hats, with Twenty-Four Engravings

Author: Robert Lloyd

Release date: December 2, 2017 [eBook #56103]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by ellinora, Barry Abrahamsen and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

NOVEL DELINEATIONS OF HIS VARIOUS SHAPES, SHEWING THE MANNER IN WHICH THEY SHOULD BE WORN, THE SORT OF FACE AND PERSON BEST SUITED TO EACH PARTICULAR HAT, AND RULES FOR THEIR PRESERVATION; TO WHICH IS ADDED, THE WHOLE PROCESS OF HAT-MAKING; TOGETHER WITH THE CUSTOMS AND REGULATIONS OF JOURNEYMEN HATTERS, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION.

To what trifles do some men owe a perpetuation of their "famous memory." There is Nimrod, for instance, not but what he may have had other and greater merits, yet he is best known as a "mighty hunter," and one who "wore boots;" now, allowing the relation to be true, and that he did hunt, and he did wear boots, is there anything extraordinary attaching to either, unless indeed, it could be proved that he had wooden legs, or that he was capable of sitting on the backs of two or more animals at one time; and if such were not the case, the simple fact of itself was never worth recording; as well may it be said, a thousand years hence, that LLOYD was a great Hatmaker, and lived in a great City.

But possibly the hunting system of this old gentleman differed materially from the pastime of our modern Tally-ho's, and instead of running after hares, snipes, and conies, Nimrod's sport was on the field of battle; in whose days the most rational idea is, that all was game which caused pursuits, and all pursuits hunting: If it were not so, and his majesty's capability only extended to the riding upon a horse's back, there is not a butcher's boy, in any country village between Berwick and St. Ives, that would not have ridden Nimrod's rump off. But it may be asked by those whose inclinations and patience shall lead them to hunt through the following pages, whether this is what it professes to be, a Preface, which is supposed to explain, or prepare the mind for something to come; the answer to which is as follows: A horse that will not go without another being led before him, is not worth riding, and if what is herein written requires a Preface to render it intelligible, it is not worth the reading.

May, 1819.

The greatest difficulty a painter has professionally to encounter is to produce a striking resemblance of a countenance where there are no striking features: just so with the Hat called "John Bull." It has no marked style of peculiarity in the formation; but, independent of the fine texture, there is in it a combination of rare qualities not often met with: for instance-it has in appearance strong marks of becoming gravity-a bold but manly dignity-a pleasing diffidence, with a conscious, yet unassuming importance-and is recommended to persons somewhat robust in form, features full and round, with a complexion not too dark. In wearing, it should neither be placed aside, thrown too far back, nor brought particularly forward over the face, for the following reasons-the first position would bespeak an air of non challance-the second a sort of slovenly neglect in the person-and the third an incommunicative sullenness of disposition.

So called from the great Hero; not for the popularity of the name alone, but for the reason that such a Hat was actually worn by him; and, in fact, it is a shape uncommonly well suited both to his face and person; the former being a sort of long oval, and the latter without the least appearance of bulk: indeed a ponderous body, tall or short, with a round, or what is vulgarly termed a pudding face, cannot judiciously shelter itself under a Wellington. This Hat is not only particularly becoming the person of his Grace, but there is that in its appearance which is strongly characteristic of his great mind; for, to an excellently formed crown of about seven inches deep, overspreading an inch at top, there is united a fine arched brim of small dimensions, taking a smartish sweep of the fourth part of a circle, and when placed on the head somewhat a la Francais, carries with it an uncommon degree of brilliancy and fire: and the fore and hind parts terminating in a close point, clearly shows that, whether advancing or retreating, this modern Cæsar is always sure to carry his point.

This is a Hat wherein is displayed a good deal of what may be termed character; for which reason, its becoming wearers, comparatively speaking, will be few in number; but notwithstanding this marked peculiarity, there is a sort of style in its general feature which is uncommonly striking; nor is there any form whatever, where so much of that airy lightness is to be seen, as in the Tandem. Few persons over thirty become this Hat, and none under twenty, and even between those ages, if the head be more than twenty-two inches, or less than twenty-one and a half in circumference, the whole effect is destroyed. Shape of the face immaterial, provided the complexion is not too dingy; but, above all things, neither overgrown or little fat gentlemen should wear the Tandem. To have the best effect when on the head, it should be placed rather forward, inclining a little to one side.

A very comfortable and convenient hunting Hat, partaking in some degree the natural formation of the head: has many advantages over the old fashioned cap; is light, though strong-porous, which allows the heat of the head, arising from exertion, to fly off-and elastic, the effect of which is to sit close without pressure; but, above all, it has a most gentlemanly appearance, which it never fails to communicate to the wearer, particularly if he be a true sportsman.

A Hat more admired for the ease and simplicity of style than for any peculiar character in its general appearance; being low in the crown, it is worn to most advantage by tall thin gentlemen with very large heads; and as the fore and hind part of the brim is set nearly horizontal from the base of the crown, it has two great advantages; the first of which is, that it may be conveniently worn over a wig; and, secondly, if worn without, the shirt collar is kept clean much longer than usual. This Hat, to have its proper effect, should be placed on the head with a strict formality of set, which in many persons will beget an air of importance. N. B. The late Justice Addington generally wore a shallow.

For style and form has strong claims to favour; but, being rather small in appearance, the wearer, to show to most advantage, should be somewhat slender in his make, features not too prominent, and in stature about five feet five to five feet ten, but neither above nor below. One great advantage attending this Hat is, that the shape of the wearer's nose is not at all material, provided it be not of that class known by the term "bottled." It may be worn a little aside, but by no means placed too far on the head, a failing very general among country gentlemen.

A well-proportioned Hat in every respect, and may, not inaptly, be termed the Universal, as it becomes most persons who wear it; in point of form, there is nothing of what may be called character or singularity in its appearance, and has the rare property of giving to the wearer a sort of dignified affability, a courteous condescension, together with an agreeable modesty, at least in appearance. It is named after a certain nobleman, who has all the above qualities united, although in the prime of life. To show to advantage on the head, this Hat should not go lower than the tip of the ears, both of which it may barely touch, unless the wearer has a short neck, in that case it must be worn somewhat aside, touching one ear only, but by no means to be thrown back.

Unique in its way, strongly embodying the name in its form. This Hat is particularly recommended to gentlemen (and many are to be found) who hold their understandings libelled by acting, thinking, speaking, or dressing like other men; but, it must be observed, that slender persons with dark countenances, and about the middle size, best become these Hats: for, however eccentric a man would wish to appear, by adopting any peculiar mode of dress, he never can hope to succeed unless nature has done a little for him; it follows then of course, that a tall or short man, if he be stout and well grown, with a fine open florid countenance, cannot cleverly become an Eccentric; but an agreeable contorsion of the eye, a trifling disagreement in the symmetry of the shoulders, or a slight bias of the body right or left, are indescribable advantages in giving full effect to this Hat, which may be worn a little on one side, with a gentle inclination over the eyes, unless they are playing at cross purposes, in the event of which it must be thrown quite back, to give effect to their playful humour.

A finely-formed and most decidedly elegant Hat: is somewhat upon a large scale, the crown being upwards of seven inches high, much yeoman, with an excellently turned and corresponding brim, producing together a happy union of the nicest proportions: It is worn to most advantage by persons whose height and bulk are above the common stature; not that it is meant to be understood, that every athletic or robust form would become a Regent; on the contrary, there is not a shape in the whole catalogue that demands in the wearer a greater share of external requisites than this; even the very gait is concerned, which, to strike, should be stately and firm, though easy, each step measuring exactly half the length of the whole body-more would become an absolute stride-and less a mere strut; than which nothing can be farther removed from graceful carriage: Be it understood, also, that the Regent is most becoming when placed a little on the right side, but by no means to come within half an inch of the ear-unless the latter should exceed its fair dimensions-in that case it were best hid altogether; but then, to do this, the Hat is forced beyond the proper position, and what was intended as ornament, becomes the very reverse: So circumstanced, the Noble Lord, the Shallow, or the John Bull, might be worn to most advantage; but when Nature has been a little attentive to the minuter parts, as well as the greater proportions of manly exterior, the Regent cannot fail to give additional dignity to the wearer; creating thereby a combination of elegancies that must render his appearance absolutely IRRESISTIBLE.

A very gentlemanly Hat, and although there is not the dignity of the Regent about it, there is, notwithstanding, much to admire: Indeed, the scale of proportions are very similar in both; the only real difference existing in the crown, which is about one-half of an inch lower than the latter; and, in the nautical phraseology, may not inaptly be termed a Regent cut down. It is very singular, and worth remarking, that trifling as the Kent differs from the Regent in actual measurement, the contrariety of effect, when on the head, is great and striking; which unquestionably proves, that a very slight deviation from a given rule will produce results more opposed to each other than the deviation is to the rule itself. The style in which this Hat should be worn is as follows:-if the head be of an oval form, place it thereon, as near as possible, in an horizontal position; but if a round head (which of all descriptions is most dreaded by a castermonger) let the Hat be thrown a little back, with a slight inclination on the side most agreeable, which will tend to prevent its assuming that trencher-like appearance too common from such causes. The personal requisites suitable to the Kent, may be found on referring to the Cobourg; with this difference, that, as the brim is of larger dimensions, the wearer, if he pleases, may be six feet high.

This Hat, in outline and symmetry, is highly prepossessing, and will always have a number of admirers. The formation, dimensions, and style of the brim, are similar to the Regent and the Kent; but the crown is taper and much shallower than either. It should be worn as nearly horizontal as possible; and, if the wearer be of the middle stature, or above, his bulk or countenance is immaterial.

A remarkably STYLISH HAT, possessing great and peculiar advantages over most others, on which account its claims to patronage are of the highest order. The brim, before as well as behind, being brought down quite square, and almost in a perpendicular line with the crown itself, gives the wearer an opportunity of observing things en passant, by a sort of side-glance, without being seen so to do; thus, it is well adapted for gentlemen who would fain indulge in the most exquisite admiration of the beauteous fair: but by reason of their extreme modesty, shrink from the trial: There is, also, another and a very important consideration, which cannot be allowed to pass unnoticed-it is a well-known truth, that there are certain situations in life where the falling into is not at all times to be avoided; the result of which is, to create in the imagination, a perpetual apprehension lest some villainous intruder should, in defiance of eloquence or inclination, compel the acceptance of his official or rather officious attendance: to counteract so dirty a custom, as well as to nip the system in the very bud, this Hat is most admirably contrived-for by a simple elevation of the hinder part, the front may be brought so far over the face, as to form a complete shade for the countenance. Here then is the attainment of two great ends-modesty encouraged, and impertinence restrained. Lastly, and not the least of its useful purposes is, that should the introduction of the Vis-a-Vis become general, those novel and graceful evolutions of the body, denominated the bend, the flutter, and the poke, may be performed in a much smaller space than usual, and without the least danger to the eyes, which is greatly to be feared, when the distinguished votaries, in the eager performance of these newly-imported civilities, are brought too abruptly face to face.

Although there is much of the dash in this Hat, it has, notwithstanding, a sort of sombre appearance, which calls on the wearer for a figure and countenance to correspond; it is therefore, if ornamentally considered, recommended to such only, whose complexion is of a darkish hue, visage long, not over bulky in person, and above the middle size; but, if usefully considered, all the nicer distinctions must yield to imperious necessity.

A connoisseur examining a fine painting, was asked by a bye-stander, which part he most admired; his answer was, "no part." "What!" observed the other, "is it possible that so highly talented a production as this is acknowledged to be, can have no merits in your estimation?" To which the connoisseur replied-"Sir, a work so masterly in execution-so striking in effect-so perfect in all its parts, cannot be truly estimated but as a whole." Here, then, the picture is the Petersham-the selection of beauties therein, the difficulty: To get rid of which, be it sufficient to state, that the prominent feature in this Hat is elegance of style, strongly visible in all its parts, and each part in unison with the whole; which for tonish and exquisite dash has no competitor. It will be seen, from what is here stated, that, much as this Hat is capable of transfusing its graces to the wearer (and who can doubt it), some little attention to personal requisites is necessary-which, in stature, should be over five feet seven, and not too lusty; countenance or complexion is of little consequence; but the visage should be oval, such corresponding uncommonly well with the fine arched brim, which forms nearly two-fifths of a circle; and, when tastefully placed on the head, with a slight inclination over the face, so as to bring the fore point on a line with the tip of the nose, such will be the result, that, whatever difficulty may attend a just description of its astonishing effects, the advantages to a wearer will most assuredly be FELT.

This Hat is bold in appearance, but full of character: Indeed, there is so much of the whip in its general outline, that it can never, with propriety, be worn but as a driving Hat.

What a pleasing reflection it is, all things considered, that near as the human form may approach to perfection, still that form is capable of being improved by ingenuity; but then, the difficulty is to decide on what really are improvements: for instance, some will admire a fine slope in the coat skirts, tapering off like the tail of a goose; some (whether or no to catch the manners of a hoyden) will put on the frock; others, again, admire the pantaloon; and many give a decided preference to inexpressibles. But the Bang-up, as a Hat, is the very master-piece of inventive taste, wherein all admiration must of necessity centre, having not only in its general appearance a bold and manly front, but a pleasing harmony of parts, all tending to produce an agreeable union of taste and utility; who then would mount the "box" without being decorated with its chiefest ornament?

A very contemplative, sedate, pious-looking Hat, much worn by Police-Officers, Quack-Doctors, and Clergymen; this, it may be said, is a strange assemblage of characters to bring under one head, and some may hold the association to be a reflection on the latter, when in truth the very opposite is intended; in proof of which it is only necessary to observe that, where the attainment of an object depends on outward show, such contrivances will be resorted to as are best calculated to secure the object in view; and the very assumption of the habit here spoken of by the "traps" and "quacks" of the day, is evidence of the habit itself being in the highest possible estimation. If taken in an ornamental point of view, it would be no easy task to decide on its merits; but if usefully considered, the conclusion is plain and easy. It is an admitted fact, that an idea of dignity cannot embody itself with little things, hence the custom of wearing large wigs, for such doubtless these Hats were originally intended, and for this reason, the hinder part being drawn up with loops in two places, no peruke, however large its dimensions, can receive the least injury; in short, it may be worn under this Hat with as little discomfiture to the intricate friz as though it were absolutely on the very block itself: here then is produced what may be termed a happy union of wisdom and piety, inasmuch as it is allowed, when speaking of high legal characters, that the wisdom is in the wig, and by the same rule (when Clericus is worn by a Divine) the piety must be in the Hat. The style of putting on will greatly depend on the size of the peruke, without which it should never be worn, particularly if the hair be lank and black.

In point of form and fine proportions, this Hat cannot fail to rank high in general estimation. Its appearance very much resembles the Wellington, or rather it is between the Wellington and the Marquis; and, like the latter, there is that becoming style, which not only harmonizes, but gives a peculiar grace to the majority of its wearers.

This is a Hat highly respectable in appearance, and well suited to gentlemen in the decline of life; but as that is a state to which few will acknowledge while there is a capability of hobbling without a crutch, something definite had better be stated by giving the precise age;-take it then at fifty, which will put all doubts at rest. The reason for fixing on the Baronet, as suitable to those in declining years, is its grave, reflecting, methodical cast, such as would seem to say of the wearer-"Here is one that possesses a serenity of mind, an easy indifference of disposition, a tranquillity of thought, which would quietly disentangle itself from the vain, shadowy, fleeting desires of this life, and leave no regret behind." There are many other recommendatory properties in this Hat, but those already particularized are the most valuable; yes, valuable,-for it is a well-known fact, that mankind are often made up of contrivance, that is, they frequently give to appearance the shape of reality;-and however strange the doctrine may at first appear, it is nevertheless true, that the custom is often attended with very beneficial results, inasmuch as by endeavouring to maintain an apparent consistency between habit and action, the propriety of doing right becomes so strongly impressed on the mind, that the villainy of a bad practice is seen in its worst deformity, and conscience, the unerring monitor of the mind, rides triumphant over all. These are recommendations of no ordinary nature, and such that will no doubt cause much inquiry after the Baronet. As to growth or countenance, there is an old saying, that "beggars should not be choosers;" and the wearer, if he becomes so from necessity, will feel the propriety of leaving choice out of the question.

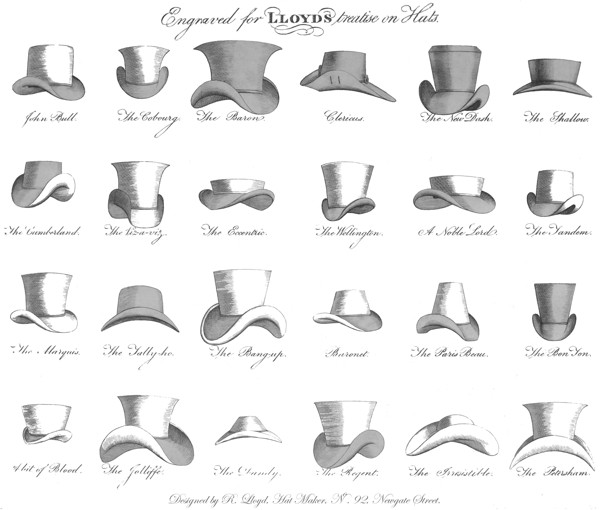

Engraved for Lloyd's treatise on Hats.

John

Bull. The Cobourg. The Baron. Clericus. The New Dash. The Shallow.

The

Cumberland. The Viz-a-viz. The Eccentric. The Wellington. A Noble

Lord. The Tandem.

The Marquis. The Tally-ho. The Bang-up.

Baronet. The Paris Beau. The Bon Ton.

A bit of Blood. The

Jolliffe. The Dandy. The Regent. The Irresistible. The Petersham.

Designed

by R. Lloyd, Hat Maker, No. 92, Newgate-Street.

A mind which is struck, through the medium of sight, with impressions of sublimity, will have those impressions strengthened in proportion as the magnitude of the object viewed is the greater, and as all things are but great or small comparatively, it follows, of course, that bodies of the same class, description, or affinity, which are less than the largest, must suffer, when brought into the scale of comparison with their superiors: agreeably to these rules, the Jolliffe, whose dimensions exceed all others, comes forward with strong claims to patronage, for besides the importance with which it never fails to strike every beholder, it is sure to convey a corresponding importance to the WEARER. Here then are considerations which should not be trifled with, particularly as the assumption of a thing is often taken for the thing itself-nay, are there not situations in life where appearances become so vitally important that it would be little short of criminality not to put them on? and where the attainment of great ends may be insured by nothing more than a simple attention to the formation of a Hat, it would be worse than folly to neglect the means. Rightly taken, what a multiplicity of persons might be benefitted by the above hints; Princes, Peers, and Plenipotentiaries; Senators, State-ministers, or Trading Politicians;-all-all may find their interest in the adoption of the Jolliffe; and that these great personages may not plead ignorance as to the manner in which it should be worn with the best effect, here follow the proper instructions.

If a Prince, let it be lightly placed on the head, and a little aside, which bespeaks a sort of cheerful approving confidence in one's own actions.-If a Peer, it should be worn in a firm horizontal position, just covering half the forehead; which gives the appearance of a wise and steady determination where great questions are agitated, particularly when they become self interesting.-If an Ambassador, it may be thrown a little back, inclining somewhat aside; such position indicating a bold and careless indifference to all around, which will be taken for granted that such could not arise from any other cause than a total disregard for the result of his mission; a practice, although not often hit on, may have many advantages. As to the three latter characters, their pursuits having all the same end-POPULARITY-let them consult the style of the Prince, and remember that, in whomsoever confidence has credit, popularity is sure to follow.

? As the Jolliffe is not likely to be worn unless for special purposes, to give an idea who would best become it is unnecessary.

The term itself naturally implies a something upon a small scale, which is the fact, and although there is nothing of that imposing dignity of style in the above Hat, which characterizes the Regent, the Petersham, &c. there is a lively, animated, and vigorous fire in all its features, that will not allow of any falling off in the general comparison. To give a complete catalogue of the many VIRTUES belonging to a bit of blood, would exceed the allotted limits; but it cannot be amiss to detail a few of the more prominent, that all, whose necessities may bear to the point, should be benefitted by the wearing: First then, it is admirably calculated for those who are about to ask favors, such being more readily granted when they seem the less wanted, and no one could suppose that the saucy animation which would be so strongly visible under this Hat could make the application from NECESSITY. Secondly, it will be of singular advantage to elderly gentlemen in pursuit of young wives, who nine times in ten decide on the choice of a man from the cock-of his Hat. Thirdly, (not that there is much need of it for such a purpose now-a-days) its advantages for those that are tormented with dunns are incalculable, for, by being placed pretty firm on the head, inclining rather to one side, at the same time assuming a sharp erect position of the body, a stern direction of the eye, and arms a-kimbo, the devil himself, in the shape of a creditor, would hardly hazard the REPETITION OF A VISIT.

N. B. No service to gentlemen of the learned profession.

Turks are said to assign as a reason for not wearing Hats, that they are put together by witchcraft. There is certainly a great deal of ingenuity in the practice, and some effects produced whose causes are as yet unexplained: but, with all due deference to these turban gentlemen, it is presumed that they have objections beyond what is above stated, some of which are as follows:-First, their country is destitute of the most essential material-FUR. Second, the climate being extremely sultry, stoves, irons, and scalding water are not likely to become favourites. Thirdly, being compelled by their religion to keep their heads close shaved, a Hat, above all human inventions, would be the most ridiculous covering they could adopt.

There are many opinions as to the time Hats were first invented, and, very probably, all equally erroneous. Some carry the date as far back as the foundation of Christianity, attributing the merit to St. Luke, of whom it is said, that he, having tender feet, put a layer of hair or fur between them and his sandals, in which situation friction and moisture caused such an interweaving of particles, that the whole became strongly united, or (technically called) FELTED. Whether the story, as applied to Luke, be true or false, is immaterial; but that such did happen with some one, is very likely; nor is it at all unlikely, but that an occurrence of this kind did really give the first idea of Hat-making. Having remarked thus much, I shall next proceed to state, what is not the less true than surprising, which is, that of the various branches of manufacture which this country is so highly distinguished for, none are less understood than Hat-making; nay, there is not one person in fifty who, if he were asked the question, could tell whether a Hat was or was not a woven substance; nor is there one in 500 but what suppose that the skin of a hare or rabbit is worked with the fur attached to it, as in the natural state; and, to form a correct judgment of the external material, when manufactured, whether it be hair, wool, or beaver, although many pretend, none are really competent but those experienced in the trade.

To show the absurd notions some entertain on this matter, I state as a fact, that I do not know a manufacturer or seller in the trade but what has been applied to, by some one or other, to have a Beaver Hat made from a hare's skin. Nay, I remember once offending a very good customer, and a man not wanting for sense either, by an involuntary burst of laughter, on his presenting the skin of a French lap-dog for the very same purpose.

It is no uncommon thing for persons who are on pretty good terms with their capabilities to give opinions as to the merits or demerits of a Hat; which opinions are as opposite to the true state of the case as the sun's rays to a state of darkness. I shall give an instance, although a trifling one, of a very common error among persons who suppose themselves to have a knowledge of the subject, which is this, if the picker has not a very good eye, some of the larger hairs will be left in the Hat, and consequently the most visible; these are directly termed "grey hairs," when the truth is, that they are the blackest in the whole composition; but being thicker than the general mass, they receive a greater portion of light, which is mistaken for a grey colour: an easy method of proving the fact is to pull one of these grey hairs from the Hat, and place it on a piece of white paper, the contrast will decide the question.

Again, whatever produces a glutinization of the NAP, is said to be the effect of the stiffening; this is not true in every case, for it is frequently owing to improper management in placing the Hat, when wet, before a large fire, which should never be done; the better way is, if very wet, to hang it up without brushing or wiping, and when dry it is easily put to rights, by gently passing over a clothes brush: if only slightly wet, wipe it with a handkerchief, and, when dry, it will brush clean. But the great fault with most persons is to put on their Hats, day after day, in the same dirty state as when taken off at night; from which it is natural to infer, that there must be a vast accumulation of dirt; it is this dirt, when exposed to the rain, that forms a sort of cement, or paste, having all the appearance of what is commonly called "gum."

Another proof of erroneous judgment-Profuse perspiration of the head is what many are subject to; by reason of which, from the frequency of wearing, and the porosity of the Hat, there is a continual absorption of moisture going on until it becomes completely saturated, particularly in front, the consequence is, that the nap lies buried in a greasy matter, which matter is also, but very inappropriately termed gum or stiffening, when in point of fact it is neither, for the very same effect would, under the like circumstances, be produced, and in much less time, if the Hat were not stiffened at all. The best remedy for this is a piece of thin flannel under the leather, and that frequently changed.

There is nothing so detrimental to a Hat as a severe exposure to rain on the first, second, or even third time of wearing; for this reason, the materials wherewith it is composed are in a manner quite green, and require seasoning; to effect which it should be frequently put on in dry weather. I have always found that a Hat, constantly worn for five or six weeks without being wet, underwent every sort of hardship afterwards with little or no injury, retaining at the same time its beauty-form-and wearing three times longer than it otherwise would have done. It may be asked, why not, to prevent accidents, render the Hat water-proof? that is, impervious to the action of either atmosphere or rain. The thing is easy enough, I admit; but where there is a choice of only two evils, it is always best to select the least. We all know (or should know) that if a man were to enclose himself, arms, legs, and body, in what is called an oil-skin dress, and that drawn close round the neck, the whole tightly fitted to every part of his person as a Hat is to the head, the most unpleasant consequences would ensue; the cause why is obviously this, the exhalations of the body, particularly in a state of exertion, would when so enclosed, be either prevented from flying off, as nature requires, or otherwise checked altogether; precisely so with the head if the porosity of the Hat was destroyed, which it must be to resist effectually the action of water. This deduction must be so clear and self-evident that further reasoning is unnecessary. Another great objection against water-proof Hats is, that the ingredients made use of for such purposes, when exposed to the sun's heat, are so acted upon as to cause a decomposition of the colour, and nine times in ten, the Hat, before it is half worn out, becomes any thing but what it was meant to be.

It is astonishing to hear the number of qualifications a Hat is said to have, and each as opposite to the other as it is possible for any two things to be; some, for instance, maintain that it cannot be good unless it is light, others again will decidedly condemn it for being so, insisting that the chief recommendation is its being firm and stout. All that is requisite to be observed on this, is that weight has no more to do with the quality of a Hat, than the situation of prime minister has to do with the cramming of turkies. A very inferior Hat may be made equally light with the most superior, and in both cases the cost of manufacture will be less than if they were made stout.

The length of the beaver too is another point on which the difference of opinion is often experienced; many are for very short naps, declaring all others to be outrageously vulgar; but the majority of wearers seem best pleased with long naps, which always take and retain the best black, while, on the contrary those that are very short never do. A medium between the two is the most preferable.

Having stated thus much, I shall next proceed to explain in what way a fine Hat is made, describing as accurately as possible the various processes it undergoes, as also the materials with which it is composed, the proportions of each as well as the quantity of work a man is capable of doing, whether maker or finisher, in a week, the amount of wages, together with some of the curious regulations, by-laws, &c. &c. &c.

In the first place, as I shall have occasion to mention a few of the implements by name, a short description of them may not be amiss.

There is the BOW, which in form is not unlike what is used for playing on a double bass, but in length and thickness is equal to a constable's staff; there is a bridge at each end, from one to the other of which is tightly strung a stout line of catgut.

The HURDLE is situate in what is called the bow garret, and is a sort of table, on which the fur is bowed, or mixed, having the farther end and sides enclosed to prevent the material from being blown away.

The BATTERY is somewhat like the hopper of a mill, in this is contained the hot liquor, and is mostly constructed for eight men, round which they stand when making; the lower part is lead, the upper or working part mahogany. All batteries are formed into divisions called PLANKS, one of which is allotted to each man. There are many other little things used by makers, but these three are all that deserve particular notice.

The first thing a maker looks for in the morning is the FUR, or raw material, which is furnished to him by weight; the quantity being more or less, according to the substance of the Hat required, and is in two parcels, one of which contains the BEAVER, or napping; the other the BODY (a proportionate scale of both will be seen hereafter). Thus provided he takes it to the BOW GARRET; the materials for the body are first placed on the hurdle, and the bow being hung at the centre for support, is held in the left hand horizontally, so that the catgut may come in contact with the fur; in the right hand is placed a small piece of stick, with a nut at the end, and in this position the work begins after the following manner. The catgut of the bow (being first placed in the midst of the fur) is pulled or struck with the knotted stick, which produces, from a quick repetition of the stroke, a continued vibration, this vibration it is that causes a separation or flitting of the fur, at the same time mixing and cleansing it. This operation is continued until such ends are fully attained. It is next divided into halves, one of which is laid aside, and the other again bowed over. In this second operation the workman contrives, partly by bowing, and partly by a slight wicker frame, to bring the material into an oblong form, and equal in size to a large sheet of cartridge paper; this is called a BAT, and when done it is gently pressed down by the wicker, after which a damp linen cloth is laid all over, and on this again is placed a thick piece of dry HORSE HIDE; the workman now begins to press hard on the hide for about five minutes; in the doing this the fur adheres close to the damp cloth, into which it is doubled up, and once more undergoes the pressure of the hand. Under this operation (which is called BASONING) the bat becomes consolidated, and may be thrown, when taken out of the cloth, from one end of the garret to the other without injury. The second half is next bowed, formed into a bat, and basoned as the first. This half remains on the hurdle, and a piece of paper, somewhat conical, is placed on it, over which, and agreeable to the shape, the sides of the bat are doubled. Here then is formed one half of the body, this is laid aside, and the first bat is then put flat on the hurdle on which the one previously doubled is placed with its open part downwards; the lower bat being transversely doubled over the top hat, forms a sort of conical, or harlequin's cap; in this state it is once more put into the damp cloth, where it receives another hardening for the purpose of uniting or knitting both bats together; after this it is folded into the compass of two hands, ready for the plank. The next thing is the beaver, or covering, which is bowed in form to correspond with the body, but has nothing to do with it in this stage.

Matters being completed thus far, this is called the first process of Hat-making. The second commences as follows:-The workman having gone from the bow garret to the making shop, takes his stand at the battery, under which is a FIRE, for the purpose of heating the liquor;[1] into this hot liquor the body is quickly immersed, where it remains till soaked through; it is afterwards laid on the plank to drain and cool; this done, it is unfolded, gently rolled, turned at short intervals in every direction, to prevent the sides uniting together; and as the liquor becomes cold and rolled out, it is continually supplied with hot and fresh, by the sprinkling of a brush, which is dipped in the kettle for that purpose; under this operation, assisted by the astringency of the vitriol, the body shrinks, and begins to assume a tough substance. When it has shrunk to a certain size (say three-fifths, if to be double covered), it is laid flat on the plank, and the first coat of beaver, as it comes from the bow, is laid quite over it; the brush is now dipped into the hot liquor, the contents of which is sprinkled all over the beaver, directly afterwards it is gently patted down with the hot brush; here the body is put into a hair-cloth, rolled in hot liquor, turned inside out, rolled again until the beaver, is completely worked into the body; when this is effected, it is in a fit state to receive the second covering, which is put on as the first, the working, turning, patting, and rolling still continuing until it is reduced to a fit dimension, the beaver quite clean, and all together assuming a closely felted, fine, solid piece of workmanship; after which it is immediately blocked in this same liquor, to the size wanted, and put into a stove to dry, from whence it is taken, and with a small fine card the beaver is gently raised; without this, one half would lie buried, and the beauty lost.-Here then is the complete PROCESS OF HAT-MAKING.

1. The liquor, which is always kept up to scalding heat, is nothing more than clean soft water, with a wine glass of vitriol, and a small quantity of beer dregs thrown in. The first is to shrink the body of the Hat in working; the other to destroy the pernicious effect of the vitriol.

It is next sent to the DYER from whom it passes to the FINISHER, who, after stiffening, blocking, and half finishing, sends it to be picked, which is performed by a woman, whose place it is to pull out the kemps or thick hairs, without injuring the beaver,[2] although that is not always accomplished. From the picker it returns to the finisher who, by the IRON and velvet cushion, gives it those highly brilliant and admired beauties that an English Hat is so pre-eminently distinguished for. The shaper next takes it in hand, who is guided in his operations by the fancy of the wearer, if bespoke, which is sometimes a little whimsical. After shaping, it goes to the trimmer, from whom it is returned to the TIPPER OFF; he gets it ready for wearing; it is then sent to its destination, when the master, if he is fortunate, puts the amount into his pocket.[3]

2. It has frequently been asked, why not make a Hat with beaver only, the answer is, there is not sufficient stamina or strength in it to become a sound felted substance. It would be worse than building a brick house without mortar or some sort of cement, to bind the whole together.

3. Some have payment before-hand, which brings out the following old, but very foolish saying, "there are but two bad paymasters, he who pays beforehand, and he who never pays." How the latter can be a paymaster requires some little ingenuity to determine.

To enter fully into the various regulations and forms that the "trade" have, from time to time, instituted and acted upon, would of itself fill a volume; all that can be done then in this small work will be to give the best possible outline of such matters as are most likely to interest those who may wish for information on the subject. The most important laws of this trade are these:-

First-No man shall work as a maker or finisher, unless he has served an apprenticeship of seven years to what is called a "fair master."

Second-To be a fair master, and entitled, according to the rules of the trade, to take an apprentice, he must have manufactured his own Hats, seven years prior to the taking, or otherwise have served a fair seven years' apprenticeship himself to the trade.

Third-Whether there be one, two, or more in a manufacturing firm, that firm are not to have more than two apprentices at one time.

Fourth-There are a number of masters who do not manufacture their own "stuff," but are employed by "Great Houses," who, although they have a right, by law, to take apprentices, yet those apprentices, by reason of their masters not working their own materials, are never admitted to stand by the side of fair men, on which account they must ever continue foul, and debarred of the usual privileges, or submit to a second apprenticeship. This is a case that frequently occurs; indeed it is no uncommon thing to see a man with a wife and half a dozen children, himself near thirty years old, serving a second apprenticeship for a fair time; the hardship of this must be admitted, inasmuch as it is punishing a man for a fault he never committed.

Fifth-A foul man is one that has not served his apprenticeship agreeably to the rule of the trade, or has been guilty of some act detrimental to the supposed interests of the journeymen in general. These are called "KNOBSTICKS."

Sixth-A fair man has the privilege of what is called "turns upon tramp," that is, if he cannot obtain work in the town where he resides, or has an inclination to travel, he may journey or tramp to the next; should any of the fraternity be there, and he wishes to get "shopped" he is "asked for" by one in that factory, (no man being allowed to ask for himself), if unsuccessful, there are two night's lodging for him, two pots of strong beer, bread and cheese, and a shilling or two to forward him to the next town. The money turn in London is five shillings, but no man is entitled to a second turn in one place, until after the expiration of six months from his receiving the first.

Seventh-If a journeyman has, by his own act, become foul, nothing can absolve him but submitting to a fine, and this is measured according to the offence, which, in some heinous cases, such as "creeping" into favour with the master, or going to work when all the rest have struck for wages, is as high as ten guineas.

There are three distinct courts for the examination and punishment of offenders. The first, or High Court of Congress, is a sort of general assembly, composed of either Makers or Finishers, just as their separate interests may be concerned; but on all joint questions these parties form a junction. In this court matters of importance only are discussed; as, for instance, the advance of prices, the abrogation of old laws, and the making of new ones, under the operation of which, it sometimes happens that both men and masters, as well as the law of the land, are alike the victims. The fines levied in this court are appropriated to special and "STRIKING" purposes, often tending to produce a "COMBINATION" of interesting effects. The masters too are not wholly exempt from these pretty little combinations, which, however, do not always realize or carry their intended point; this is owing (it is thought) to the vast affection journeymen bear towards their employers; indeed so much so, that they cannot bear the latter should "LOWER" themselves.

There is a court below this, which is formed by taking one or two men from the seven nearest shops. Their sitting, if not public, is sure to be in a public-house, president, Sir John Barleycorn. The matters chiefly brought here are those that relate to the misconduct of journeymen towards each other in the same factory, and which cannot be settled where they originated. This is called "DOZENING," and their power of FINE extends to two guineas, which is drank in good old stout by the whole seven shops; but as all dry subjects are prohibited in this tribune, the extent of fine greatly depends on the state of the weather; so that if it be a sultry summer's day, the punishment of an offender is in proportion to the sun's heat.

The third and lowest court is an assembly of shop-mates only, this meeting is called a "GARRET MATCH," and may be demanded for the punishment of an aggressor, by any aggrieved man in a factory. Power of fine from two to ten shillings.

I have before stated that there are in this trade foul men; in point of number they constitute about one-sixth part of the whole; but their earnings, or price of labour is the same as the fair trade.

A journeyman finisher in full work will earn, on an average, from three to four pounds a-week; while, on the contrary, a maker cannot get more than fifty shillings. This is a subject of much jealousy and discontent; nor is it likely to be otherwise, unless the latter can raise himself to an equality with the former; against this there are many obstacles, one of which is, the increasing foul trade, who would continue working, even though the fair men had "struck." Another is, that they could never obtain the co-operation of the finishers, who, being amply paid themselves, think it best to leave well alone.

These are the principal regulations which govern journeymen hatters, whether they have a good or a bad tendency is questionable; there are many in the trade who decidedly condemn them, giving as their reasons, that they encourage idleness, tippling, and endless squabbles. Idleness-inasmuch as when men are summoned to discuss the most trifling matters, even though the meeting be at five o'clock in the morning, they seldom feel disposed to return to their work that day. Tippling-for the reason that, as fines are mostly spent in drink, the conviction of a supposed offender is generally thirsted after; but as the quantum levied seldom suffices, all further supplies for the remainder of the day are met by individual subscription. In these cases there is no show of niggardliness, as every succeeding gallon of the "sparkling entire," is but an internal messenger, bearing the glad tidings of another to come. Squabbles, because it is natural, when the desire for a thing is once created, and the gratification of that desire (where nothing of criminality attaches) can be indulged, by having recourse to a little contrivance, that the opportunity of so doing should be more frequently made, than suffered to approach accidentally; which will account for the trifling magnitudes that are allowed to agitate shops and factories in general. The arguments in favour of these laws are, that without them, apprentices would be careless in serving out their time, the trade over-run with bad workmen, hats greatly deteriorated in the manufacture, the excellence of which is their chief recommendation in a foreign market, and the surest guarantee of the master's profits at home.

Having given the contending opinions, in reference to the laws of this trade, I shall say a word or two concerning the shape, and manner of placing a hat on the head.

There is no part of a man's dress that makes or mars his appearance so much as his hat; not that it is its striking beauty when new, or a want of it when old, that is most materially concerned in producing either of the above effects; the grand point is the form, and the position which it is made to assume on the head; yet how few there are who give the least attention to either, except indeed military men, and they in general are uncommonly tasty, affording the best example of the precise style in which a hat should be worn. It is no less singular than true, that the same hat, by being placed on the head in different positions, will give, in appearance, as many distinct characters to the same person as the number of those positions amount to. The most striking are as follows:-sullenness-indolence-gravity, and good humoured impudence. To give the first, draw the brim of the hat so far over the eyes that they shall be quite concealed. The second is produced by the hat being thrown quite back. The third by a prim horizontal set, covering equally all parts of the head; and the fourth will not be easily mistaken wherever an extravagant cock on either side is brought full into view. These are undoubtedly all extreme habits, and seldom pushed to the extent here described; yet a slight inclination to either position may, under circumstances, have a very good effect.

There is another bad custom that ought to be noticed, which I shall do by first observing, that a hat was intended solely to keep the head dry-ON which it should be worn; but many seem to differ from this opinion, using it as a sort of NIGHT-CAP wherein is thrust head, ears, and all. This is a most slovenly practice, as well as a dangerous one, inasmuch as it tends to keep the head in a continual and forced state of perspiration, rendering a liability to "take cold," every time the hat is removed. Yet even this habit is not so bad as sticking the hat on the back of the head, which, of all others, is the most general, and carries with it the greatest impropriety, because such a position not only destroys the shape, but by lodging on the coat collar, the hind part, from friction, becomes greasy, and the binding is always in a state of raggedness; added to these disadvantages, a most ridiculous effect is produced by the practice, that is, the head in appearance is converted into a sort of peg, AGAINST which the hat seems to hang, instead of being placed upon. A man who indulges in so bad a custom, should at least preserve a consistency in his dress by walking "slip shoed," breeches knees open, and without braces, stockings down, waistcoat unbuttoned, cravat half tied, one arm only in his coat sleeve, and at least a six months' uncombed crop of hair about his pericranium; here he would be of a piece; and grotesque as such a figure must appear, by a general adoption of these "captivating negligencies," there is no greater inconsistency in the whole catalogue than that of wearing a hat on the back part of the head.

As to the form of a hat, and what is best for this face or that person, there is more in it than what is generally supposed, and a great deal might be said on the subject; but to talk of a standard fashion is absurd in the extreme, in proof of which it need only be observed, that if very large hats were adopted, a thin man of five feet high, would, by the wearing, become as complete a caricature, as a twenty stone man of six feet would by wearing a very small one. The best fashion a man can follow in a hat is that which best becomes him, and various as heads, faces, and persons may be, all things are now accomplished (so far as a hat is concerned) that can either fit the one or ornament the other,

By the Head's sincere friend,

and well-wisher,

R. L.

Furs used in a Hat of fine quality, according to the present improved system of making, their proportions, value, cost of manufacture, &c. &c.

| s. d. | per oz. | s. d. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 oz. of seasoned coney wool, | 1 0 | .. | 4 0 |

| ½ oz. red wool | 2 4 | .. | 1 2 |

| ¼ oz. of silk | 0 9 | .. | 0 4½ |

| s. d. | per oz. | s. d. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 oz. of prime seasoned beaver | 8 6[4] | .. | 8 6 |

| Journeyman's wages for making[5] | 3 6 | ||

| Dyeing | 0 8 | ||

| Stiffening, finishing, and picking | 1 8 | ||

| Cost of lining, finding, band, and box | 2 6 | ||

| Sewing in of ditto | 0 6 | ||

| ----- | |||

| £1 2 10½ |

4. No hat can be good, or well covered, with less than one ounce of prime beaver; and, small as the quantity is, there was a time when journeymen makers (catching the custom of their betters, and by way of tythe) thought it no sin to appropriate a part of this material to their own use; but, for the credit of the trade be it said, the practice is long since abolished, and a man attempting it at the present day would be scouted from the factory where he worked, by every honest journeyman therein.

5. The average week's work of a maker is about ten hats; that of a finisher, from five to six dozen.

Such is the cost of materials and labour at the present period; it is true that the above scale is drawn from "credit prices;" but let every part of a manufacturing concern be carried on for money only, which is rarely the case, still the deduction from the whole cannot be more than 7½ per cent. All substitutes for the above materials are decidedly condemned; nor can their quantities, as here stated, be lessened, without injury to the remainder. Here then is sufficient evidence that a fine hat must, under the most favourable circumstances, stand the manufacturer in upwards of twenty-one shillings, yet many assume a capability of retailing such an article at less even than the charge of manufacture.

A General List of Lloyd's Fashionable Hats, invented, manufactured, and sold by him, at his Warehouse, 92, Newgate-Street, London.

| The John Bull | The Bang-up |

| The Wellington | The Jolliffe |

| The Tandem | Clericus |

| The Tally-Ho | The Bon-Ton |

| The Shallow | The Baronet |

| The Coburg | The Four-in-Hand |

| The Marquis | A Bit of Blood |

| The Eccentric | The Baron |

| The Regent | A Noble Lord |

| The Kent | The New Dash |

| The Cumberland | A Paris Beau |

| The Esquire | The Brutus |

| The Vis-a-Vis | The Exquisite |

| The Petersham | The Irresistible |

| The Tilbury | The Pic Nic |

| The Count | The Viscount |

| The Medium | And the Dandy. |

If the foregoing treatise to be judged by the letter and not the spirit-have mercy reader.

Rules for measuring a hat.-Take the circumference on the outside, where the band is fixed, in inches. The breadth of brim and depth of crown as wanted.