The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Title: British Bees

Author: William Edward Shuckard

Release date: December 18, 2017 [eBook #56201]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Rachael Schultz, Barry Abrahamsen, Bryan Ness

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

A few words are necessary explanatory of the course pursued in the following work, as regards the citation of authorities.

All the facts recorded without reference to authorities, are the result either of personal observation or of diligent study, which, from the length of time that has intervened, have become so blended in my mind that I can no longer separate their sources. I may, however, state that observation has, certainly, as often anticipated the perusal of the discoveries of others, as their record has stimulated direct observation to confirm them.

The habits of animals, in which instinct is the sole prompter, are so uniform, that these, once well observed, may be considered as permanently established. The slight deviations that have been occasionally noticed, although temporarily infringing, do not abrogate the inflexibility of the law which regulates this faculty; and viiithe descendants inevitably resume the economy of the ancestor.

The merit that attaches to the discovery of such facts is due merely to patience and diligence, very common attributes; and the repeated mention of the supposed first observer must, necessarily, in a work of this kind, which is far from being of a strictly scientific character, diminish the interest of the narrative by interrupting its connection, and thus making it an incongruous mosaic. The omission to cite authorities may also take place without any wish to detract from the merit of the discoverer, which is patent to all by his own record in the archives of science.

Before concluding, I wish to express my best thanks to Thomas Desvignes, Esq., for the kindness and willingness with which he lent me, for the purposes of this work, my own selection from the Bees of his choice collection of British insects.

I now dismiss the book—truly a labour of love—with the hope that it will fall into the possession of many, who may be sufficiently interested in the subject to induce them to become ardent entomologists, by showing them within how small a compass much agreeable instruction lies.

June, 1866.

| PAGE | |

| PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS, COMPRISING GENERAL REMARKS UPON THE USES OF BEES IN THE ECONOMY OF NATURE, THEIR DIVISION INTO SOCIAL AND SOLITARY, AND A NOTICE OF THEIR FAVOURITE PLANTS | 1 |

| GENERAL HISTORY OF BEES | 17 |

| THE EGG | 18 |

| THE LARVA | 19 |

| THE PUPA | 22 |

| THE IMAGO | 23 |

| SKETCH OF THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE GENERA OF BRITISH BEES | 61 |

| NOTICE OF THE MORE CONSPICUOUS FOREIGN GENERA | 101 |

| PARASITES OF BEES AND THEIR ENEMIES | 109 |

| GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF SCIENTIFIC ARRANGEMENT | 118 |

| BRIEF NOTICE OF THE SCIENTIFIC CULTIVATION OF BRITISH BEES | 142 |

| A NEW ARRANGEMENT OF BRITISH BEES, WITH ITS RATIONALE, AND AN INTRODUCTION TO THE FAMILY, SUBFAMILIES, SECTIONS, AND SUBSECTIONS | 153 |

| A TABLE, EXHIBITING A METHOD OF DETERMINING THE GENERA OF BRITISH BEES WITH FACILITY | 170 |

| EASY DISTRIBUTION OF THE BEES | 176 |

| THE SCIENTIFIC ARRANGEMENT AND DESCRIPTION OF THE GENERA, WITH LISTS OF OUR NATIVE SPECIES, AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE HABITS AND ECONOMY OF THE INSECTS, WITH INCIDENTAL OBSERVATIONS SUGGESTED BY THE SUBJECT | 184 |

| ANDRENIDÆ (SUBNORMAL BEES) | 185 |

| GEN. 1. COLLETES | 185 |

| GEN. 2. PROSOPIS | 191 |

| GEN. 3. SPHECODES | 196 |

| GEN. 4. ANDRENA | 200 |

| GEN. 5. CILISSA | 211 |

| GEN. 6. HALICTUS | 214 |

| GEN. 7. MACROPIS | 220 |

| GEN. 8. DASYPODA | 224 |

| xiAPIDÆ (NORMAL BEES) | 227 |

| SCOPULIPEDES (BRUSH-LEGGED BEES) | 227 |

| GEN. 9. PANURGUS | 227 |

| GEN. 10. EUCERA | 231 |

| GEN. 11. ANTHOPHORA | 236 |

| GEN. 12. SAROPODA | 242 |

| GEN. 13. CERATINA | 245 |

| NUDIPEDES (CUCKOO-BEES) | 249 |

| GEN. 14. NOMADA | 249 |

| GEN. 15. MELECTA | 255 |

| GEN. 16. EPEOLUS | 258 |

| GEN 17. STELIS | 262 |

| GEN. 18. CŒLIOXYS | 265 |

| DASYGASTERS (ARTISAN BEES) | 269 |

| GEN. 19. MEGACHILE | 269 |

| GEN. 20. ANTHIDIUM | 279 |

| GEN. 21. CHELOSTOMA | 283 |

| GEN. 22. HERIADES | 288 |

| GEN. 23. ANTHOCOPA | 290 |

| GEN. 24. OSMIA | 294 |

| CENOBITES (SOCIAL BEES) | 302 |

| GEN. 25. APATHUS | 302 |

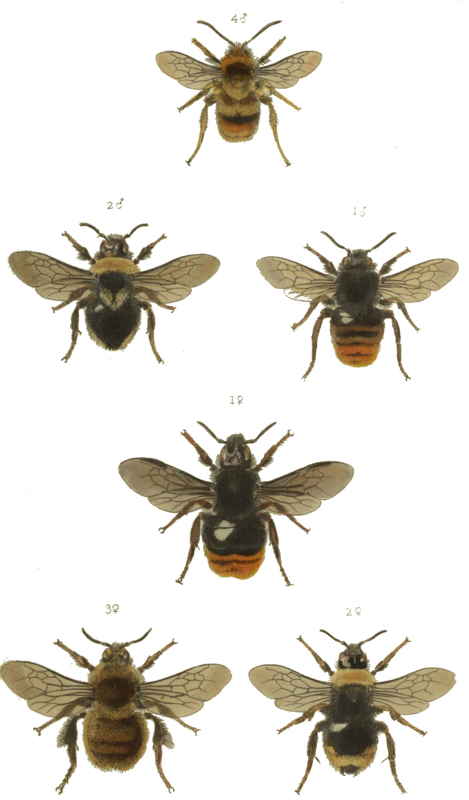

| GEN. 26. BOMBUS | 307 |

| GEN. 27. APIS | 318 |

| INDEX | 363 |

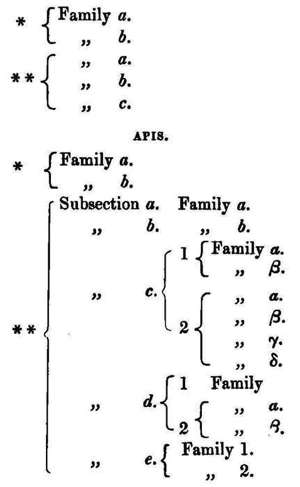

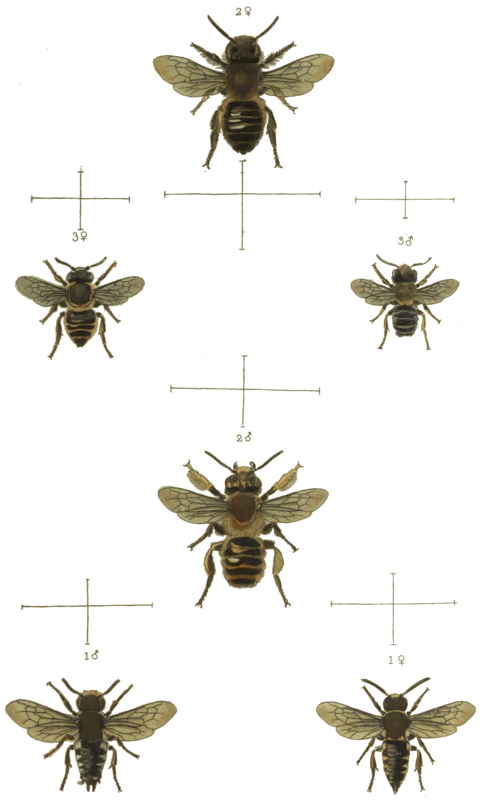

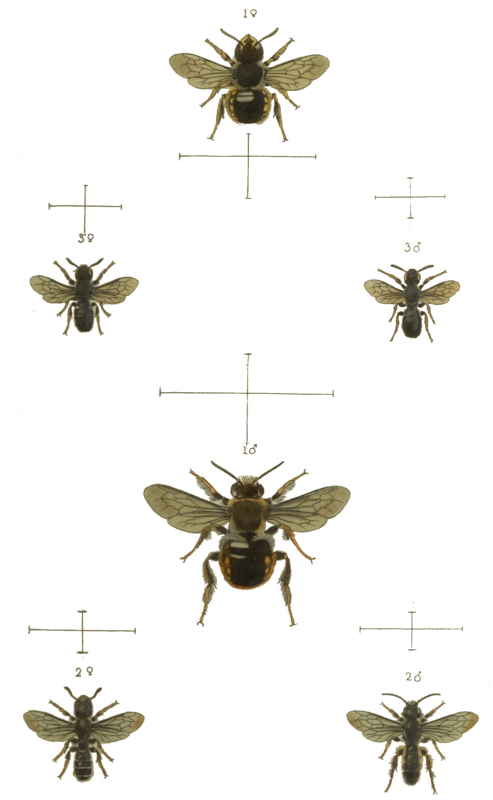

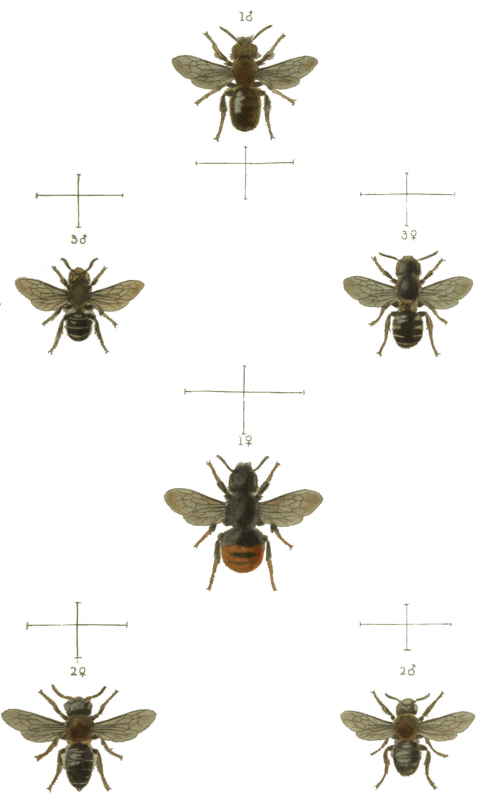

xivPlate IX.

It is very natural that the “Bee” should interest the majority of us, so many agreeable and attractive associations being connected with the name. It is immediately suggestive of spring, sunshine, and flowers,—meadows gaily enamelled, green lanes, thymy downs, and fragrant heaths. It speaks of industry, forethought, and competence,—of well-ordered government, and of due but not degrading subordination. The economy of the hive has been compared by our great poet to the polity of a populous kingdom under monarchical government. He says:—

Nothing escaped the wonderful vision of this “myriad-minded” man, and its pertinent application.

This description, although certainly not technically accurate, is a superb broad sketch, and shows how well he was acquainted with the natural history and habits of the domestic bee.

The curiosity bees have attracted from time immemorial, and the wonders of their economy elicited by the observation and study of modern investigators, is but a grateful return for the benefits derived to man from their persevering assiduity and skill. It is the just homage of reason to perfect instinct running closely parallel to its own wonderful attributes. Indeed, so complex are many of the operations of this instinct, as to have induced the surmise of a positive affinity to reason, instead of its being a mere analogy, working blindly and without reflection. The felicity of the adaptation 3of the hexagonal waxen cells, and the skill of the construction of the comb to their purposes, has occupied the abstruse calculations of profound mathematicians; and since human ingenuity has devised modes of investigating, unobserved, the various proceedings of the interior of the hive, wonder has grown still greater, and admiration has reached its climax.

The intimate connection of “Bees” with nature’s elegancies, the Flowers, is an association which links them agreeably to our regard, for each suggests the other; their vivacity and music giving animation and variety to what might otherwise pall by beautiful but inanimate attractions. When we combine with this the services bees perform in their eager pursuits, our admiration extends beyond them to their Great Originator, who, by such apparently small means, accomplishes so simply yet completely, a most important object of creation.

That bees were cultivated by man in the earliest conditions of his existence, possibly whilst his yet limited family was still occupying the primitive cradle of the race at Hindoo Koosh, or on the fertile slopes of the Himalayas, or upon the more distant table-land or plateau of Thibet, or in the delicious vales of Cashmere, or wherever it might have been, somewhere widely away to the east of the Caspian Sea,—is a very probable supposition. Accident, furthered by curiosity, would have early led to the discovery of the stores of honey which the assiduity of bees had hoarded;—its agreeable savour would have induced further search, which would have strengthened the possession by keener observation, and have led in due course to the fixing them in his immediate vicinity.

4To this remote period, possibly not so early as the discovery of the treasures of the bee, may be assigned also the first domestication of the animals useful to man, many of which are still found in those districts in all their primitive wildness. The discovery and cultivation of the cereal plants will also date from this early age. The domestication of animals has never been satisfactorily explained, but all inquiry seems to point to those regions as the native land, both of them, and of the gramineæ, which produce our grain; for Heinzelmann, Linnæus’s enthusiastic disciple, found there those grasses still growing wild, which have not been found elsewhere in a natural state.

Thus, long before the three great branches of the human race, the Aryan, Shemitic, and Turonian, took their divergent courses from the procreative nest which was to populate the earth, and which Max Müller proposes to call the Rhematic period, they were already endowed from their patrimony with the best gifts nature could present to them; and they were thus fitted, in their estrangement from their home, with the requirements, which the vicissitudes they might have to contend with in their migrations, most needed. They would eventually have settled into varying conditions, differently modified by time acting conjunctively with climate and position, until, in the lapse of years, and the changes the earth has since undergone, the stamp impressed by these causes, which would have been originally evanescent, became indelible. That but one language was originally theirs, the researches of philology distinctly prove, by finding a language still more ancient than its Aryan, Shemitic, and Turonian derivatives. From this elder language these all spring, their common origin 5being deduced from the analogies extant in each. These investigations are confirmed by the Scriptural account that “The whole earth was of one language and of one speech,” previous to the Flood, and it describes the first migration as coincident with the subsidence of the waters.

That violent cataclysms have since altered the face of the then existing earth, the records of geological science amply show; and that some of mankind, in every portion of the then inhabited world, survived these catastrophes, and subsequently perpetuated the varieties of race, may be inferred from those differences in moral and physical features which now exist, and which have sometimes suggested the impossibility of a collective derivation from one stock. The philological thread, although generally a mere filament of extreme tenuity, holds all firmly together.

That animals had been domesticated in a very early stage of man’s existence, we have distinct proof in many recent geological discoveries, and all these discoveries show the same animals to have been in every instance subjugated; thus pointing to a primitive and earlier domestication in the regions where both were originally produced. That pasture land was provided for the sustenance of these animals, they being chiefly herbivorous, is a necessary conclusion. Thence ensues the fair deduction that phanerogamous, or flower-bearing plants coexisted, and bees, consequently, necessarily too,—thus participating reciprocal advantages, they receiving from these plants sustenance, and giving them fertility.

These islands, under certain modifications, were, previous to the glacial period, one land with the continent of Europe; and it was when thus connected that those 6many tropical forms of animal life, whose fossil remains are found embedded in our soil, passed hither. By the comparatively rapid intervention of geological changes, some of the lower forms of life went no further than the first land they reached, and are, consequently, not even now to be found so far west as Ireland: the migration appears clearly to have come from the East. Thus, although we have no direct evidence of the presence of “bees,” yet as insects must have existed here, from the certainty that the remains of insect-feeding reptiles are found, as well as those of herbivorous animals, it may be concluded that “bees” also abounded.

Claiming thus this very high antiquity for man’s nutritive “bee,” which was of far earlier utility to him than the silkworm, whose labours demanded a very advanced condition of skill and civilization to be made available; it is perfectly consistent, and indeed needful, to claim the simultaneous existence of all the bee’s allies. The earliest Shemitic and Aryan records, the Book of Job, the Vedas, Egyptian sculptures and papyri, as well as the poems of Homer, confirm the early cultivation of bees by man for domestic uses; and their frequent representation in Egyptian hieroglyphics, wherein the bee occurs as the symbol of royalty, clearly shows that their economy, with a monarch at its head, was known; a hive, too, being figured, as Sir Gardner Wilkinson tells us, upon a very ancient tomb at Thebes, is early evidence of its domestication there, and how early, even historically, it was brought under the special dominion of mankind. To these particulars I shall have occasion to refer more fully when the course of my narrative brings me to treat of the geographical distribution of the “honey-bee;” I adduce it now merely to 7intimate how very early, even in the present condition of the earth, bees were beneficial to mankind, and that, therefore, the connection may have subsisted, as I have previously urged, in the remotest and very primitive ages of the existence of man; and that imperatively with them, the entire family of which they form a unit only, was also created.

In America, where Apis mellifica is of European introduction, swarms of this bee, escaping domestication, resume their natural condition, and have pressed forward far into the uncleared wild; and widely in advance of the conquering colonist, they have taken their abode in the primitive, unreclaimed forest. Nor do they remain stationary, but on, still on, with every successive year, spreading in every direction; and thus surely indicating to the aboriginal red-man the certain, if even slow, approach of civilization, and the consequent necessity of his own protective retreat:—a strong instance of the distributive processes of nature. It clearly shows how the wild bees may have similarly migrated in all directions from the centre of their origin. That they are now found at the very ultima Thule, so far away from their assumed incunabula, and with such apparent existing obstructions to their distributive progress, is a proof, had we no other, that the condition of the earth must have been geographically very different at the period of their beginning, and that vast geological changes have, since then, altered its physical features. Where islands now exist, these must then have formed portions of widely sweeping continents; and seas have been dry land, which have since swept over the same area, insulating irregular portions by the submergence of irregular intervals, and thus have left them in their present condition, with 8their then existing inhabitants restricted to the circuit they now occupy. That long periods of time must necessarily have elapsed to have effected this by the methods we still see in operation, is no proof that it has not been. Nature, in her large operations, has no regard for the duration of time. Her courses are so sure that they are ever eventually successful; for, as to her, whose permanency is not computable, it matters not what period the process takes; and she is as indifferent to the seconds of time whereby man’s brevity is spanned, as she is to the wastefulness of her own exuberant resources, knowing that neither is lost to the result at which she reaches. Consuming the one, and scattering broadcast the other, but in unnoticeable infinitesimals, she does it irrespective of the origin, the needs, or the duration of man, who can only watch her irrepressible advances by transmitting from generation to generation the record of his observations; marking thus by imaginary stations the course of the incessant stream which carries him upon its surface.

That other bees are found besides the social bees, may be new to some of my readers, who will perhaps now learn, for the first time, that collective similarities of organization and habits associate other insects with “the bee” as bees. Although the names “domestic bee,” “honey-bee,” or “social bee,” imply a contradistinction to some other “bee,” yet it must have been very long before even the most acute observers could have noticed the peculiarities of structure which constitute other insects “bees,” and ally the “wild bees” to the “domestic bee,” from the deficiency of artificial means to examine minutely the organization whereby the affinity is clearly proved. This is also further shown in 9the poverty of our language in vernacular terms to express them distinctively; for even the name of “wild bees,” in as far as it has been applied to any except the “honey-bee” in a wildered state, is a usage of modern introduction, and of date subsequent to their examination and appreciation. Our native tongue, in the words “bee,” “wasp,” “fly,” and “ant,” compasses all those thousands of different winged and unwinged insects, which modern science comprises in the two very extensive Orders in entomology of the Hymenoptera and the Diptera;—thus exhibiting how very poor common language is in words to note distinctive differences in creatures, even where the differences are so marked, and the habits so dissimilar, as in the several groups constituting these Orders. But progressively extending knowledge, and a more familiar intimacy with insects and their habits, will doubtless, in the course of time, supervene, as old aversions, prejudices, and superstitions wear out, when by the light of instruction we shall gradually arouse to perceive that “His breath has passed that way too;” and that, therefore, they all put forth strong claims to the notice and admiration of man.

It is highly improbable that ordinary language will ever find distinctive names to indicate genera, and far less species: and although we have some few words which combine large groups, such as “gnats,” “flesh-flies,” “gad-flies,” “gall-flies,” “dragon-flies,” “sand wasps,” “humble-bees,” etc. etc.; and, although the small group, it is my purpose in the following pages to show in all their attractive peculiarities, has had several vernacular denominations applied to them to indicate their most distinctive characteristics, such as “cuckoo-bees,” “carpenter bees,” “mason bees,” “carding bees,” 10etc., yet many which are not thus to be distinguished, will have to wait long for their special appellation.

The first breathings of spring bring forth the bees. Before the hedge-rows and the trees have burst their buds, and expanded their yet delicate green leaves to the strengthening influence of the air, and whilst only here and there the white blossoms of the blackthorn sparkle around, and patches of chickweed spread their bloom in attractive humility on waste bits of ground in corners of fields,—they are abroad. Their hum will be heard in some very favoured sunny nook, where the precocious primrose spreads forth its delicate pale blossom, in the modest confidence of conscious beauty, to catch the eye of the sun, as well as—

The yellow catkins of the sallow, too, are already swarmed around by bees, the latter being our northern representative of the palm which heralded “peace to earth and goodwill to man.” The bees thus announce that the business of the year has begun, and that the lethargy of winter is superseded by energetic activity.

The instinctive impulse of the cares of maternity prompt the wild bees to their early assiduity, urging them to their eager quest of these foremost indicators of the renewed year. The firstling bees are forthwith at their earnest work of collecting honey and pollen, which, kneaded into a paste, are to become both the cradle and the sustenance of their future progeny.

Wherever we investigate wonderful Nature, we observe the most beautiful adaptations and arrangements,—everywhere the correlations of structure with function; 11in confirmation of which I may here briefly notice in anticipation, that the bees are divided into two large groups,—the short-tongued and the long-tongued,—and it is the short-tongued,—some of the Andrenidæ,—which are the first abroad; the corollæ of the first flowers being shallow and the nectar depositories obvious, an arrangement which facilitates their obtaining with facility the honey already at hand. These bees are also amply furnished,—as will be afterwards explained,—in the clothing of their posterior legs, or otherwise, with the means to convey home the pollen which they vigorously collect, finding it already in superfluous abundance, and which, being borne from flower to flower, impregnates and makes fruitful those plants which require external agents to accomplish their fertility. Thus nature duly provides, by an interchange of offices, for the general good, and by simple, although sometimes obscure means, gives motion and persistency to the wheel within wheel which so exquisitely fulfil her designs, and roll forward, unremittingly, her stupendous fabric.

The way in which the bees execute this object and design of nature, and to which they, more evidently than any other insects, are called to the performance, is shown in the implanted instinct which prompts them to seek flowers, knowing, by means of that instinct, that flowers will furnish them with what is needful both for their own sustenance, and for that of their descendants. Flowers, to this end, are furnished with the requisite attractive qualifications to allure the bees. Whether their odour or their colour be the tempting vehicle, or both conjunctively, it is scarcely possible to say, but that they should hold out special invitation is requisite to the maintenance of their own perpetuity. This, it is 12supposed, the colour of flowers chiefly effects by being visible from a distance. Flowers, within themselves, indicate to the bees visiting them the presence of nectaria by spots coloured differently from their petals. This nectar, converted by bees into honey, is secreted by glands or glandulous surfaces, seated upon the organs of fructification; and nature has also furnished means to protect these depositories of honey for the bees, from the intrusive action of the rain, which might wash the sweet secretion away. To this end it has clothed the corollæ with a surface of minute hairs, which effectually secures them from its obtrusive action, and thus displays the importance it attaches to the co-operation of the bees. That bees should vary considerably in size, is a further accommodation of nature to promote the fertilization of flowers, which, in some cases, small insects could not accomplish. Many plants could not be perpetuated, but for the agency of insects, and especially of bees; and it is remarkable that it is chiefly those which require the aid of this intervention that have a nectarium, and secrete honey. By thus seeking the honey, and obtaining it in a variety of ways, bees accomplish this great object of nature. It often, also, happens that flowers which even contain within themselves the means of ready fructification cannot derive it from the pollen of their own anthers, but require that the pollen should be conveyed to them from the anthers of younger flowers; in some cases the reverse takes place, as for instance, in the Euphorbia Cyparissias, wherein it is the pollen of the older flower which, through the same agency, fertilizes the younger. Although many flowers are night-flowers, yet the very large majority expand during the day; but to meet the requirements of those 13which bloom merely at night, nature has provided means by the many moths which fly only at that time, and thus accomplish what the bees perform under the eye of the sun. Here insects are again subservient to the accomplishment of this great act; for the petals of even the flowers which open in the night only are usually highly coloured, or where this not the case, they then emit a powerful odour, both being means to attract the required co-operation. But of course our clients have nothing to do with these night-blooming flowers, as I am not aware of a single instance of a night-flying bee; nor are they on the wing very late in the evening, being before sunset, already in their nidus. In those occasional cases where the nectarium of the flower is not perceptible, if the spur of such a flower which usually becomes the depository of the nectar that has oozed from the capsules secreting it, be too narrow for the entrance of the bee, and even beyond the reach of its long tongue, it contrives to attain its object by biting a hole on the outside, through which it taps the store. The skill of bees in finding the honey, even when it is much withdrawn from notice, is a manifest indication of the prompting instinct which tells them where to seek it, and is a matter of extreme interest to the observer, for the honey-marks—the maculæ indicantes—surely guide them; and where these, as in some flowers, are placed in a circle upon its bosom, as the mark upon that of Imogen, who had—

they work their way around, lapping the nectar as 14they go. To facilitate this fecundation of plants, which is Nature’s prime object, bees are usually more or less hairy; so that if even they limit themselves to imbibing nectar, they involuntarily fulfil the greater design by conveying the pollen from flower to flower. To many insects, especially flies, some flowers are a fatal attraction, for their viscous secretions often make these insects prisoners, and thus destroy them. To the bees this rarely or never happens, either by reason of their superior strength, or possibly from the instinct which repels them from visiting flowers which exude so clammy a substance. It is probably only to the end of promoting fertilization by the attraction of insects that the structure of those flowers which secrete nectar is exclusively conducive, and which fully and satisfactorily explains the final cause of this organization.

To detect these things, it is requisite to observe nature out of doors,—an occupation which has its own rich reward in the health and cheerfulness it promotes,—and there to watch patiently and attentively. It is only by unremitting perseverance, diligence, and assiduity that we can hope to explore the interesting habits and peculiar industries of these, although small, yet very attractive insects.

Amongst the early blossoming flowers most in request with the bees, and which therefore seem to be great favourites, we find the chickweed (Alsine media), the primrose, and the catkins of the sallow; and these in succession are followed by all the flowers of the spring, summer, and autumn. Their greatest favourites would appear to be the Amentaceæ, or catkin-bearing shrubs and trees, the willow, hazel, osier, etc., from the male flowers of which they obtain the pollen, and from the female 15the honey; all the Rosaceæ, especially the dog-rose, and Primulaceæ, the Orchideæ, Caryophyllaceæ, Polygoneæ, and the balsamic lilies; clover is very attractive to them, as are also tares; and the spots on those leaves of the bean which appear before the flower, and exude a sweet secretion; also the flowers of all the cabbage tribe. Beneath the shade of the lime, when in flower, may be heard above one intense hum of thrifty industry. The blossoms of all the fruit-trees and shrubs, standard or wall, and all aromatic plants are highly agreeable to them, such as lavender, lemon-thyme, mignonette, indeed all the resedas; also sage, borage, etc. etc.; but the especial favourites of particular genera and species I shall have occasion subsequently to notice in their series; but to mention separately all the flowers they frequent would be to compile almost a complete flora. Bees are also endowed with an instinct that teaches them to avoid certain plants that might be dangerous to them. Thus, they neither frequent the oleander (Nerium Oleander) nor the crown imperial (Fritillaria imperialis), and they also avoid the Ranunculaceæ, on account of some poisonous property; and although the Melianthus major drops with honey, it is not sought. It is a native of the Cape of Good Hope, and may be attractive only to the bees indigenous to the country, which is also the case with other greenhouse plants equally rich in honey, but which not being natives, possibly from that cause the instincts of native insects have no affinity with them.

Bees may be further consorted with flowers by the analogy and parallelism of their stages of existence. Thus, the egg is the equivalent to the seed; the larva to the germination and growth; the pupa to the bud; and the imago to the flower. The flower dies as soon 16as the seed is fully formed, which is then disseminated by many wonderful contrivances to a propitious soil; and the wild bees die as soon as the store of eggs is as wonderfully deposited, according to their several instincts, in fitting receptacles, and provision furnished to sustain the development of the progeny. Thus, each secures perpetuity to its species, but individually ceases; whereas the unfecundated plant and the celibate insect may, severally, prolong for a short but indefinite period, a brief existence, to terminate in total extinction. Nature thus vindicates her rights, for nothing remains sterile with impunity.

Although the preceding pages have been written upon the assumption that the reader knows what a bee is, now that we are gradually approaching the more special and technical portion of the subject it will be desirable to conform a little to the ordinary usages of scientific treatment.

The bees constitute a family of the order Hymenoptera, viz. insects ordinarily, but in the case of bees always, with four transparent wings, which are variously but partially traversed longitudinally and transversely with threads, called nervures, supposed to be tubular, the relative position of which, together with the areas they enclose, called cells, help to give characters to the genera.

Most of the Hymenoptera further possess some kind of an ovipositor,—of course restricted to the females,—varying considerably in the different families. This is sometimes external, but is often seated within the apex of the abdomen, whence it can be protruded for the purpose of depositing the egg in its right nidus. In our insect this organ is converted into a weapon of defence 18and offence, and forms a sting, supplied by glands with a very virulent poison, which the bee can inject into the wound it inflicts. It is not certain that this organ is used by the bee as an ovipositor, although it is evident it is its analogue. This brief description of the essential peculiarities of the family will, for the present, suffice. In the notice of the imago, I shall enlarge upon the general structure, and then particularize those portions of it which may facilitate further progress.

The Egg.—Although the egg of the parent is the source of the origin of the bee, we cannot abruptly commence from this point, for the preliminary labours of the mother are indispensable to the evolution of its offspring. This egg has to be placed in a suitable depository, together with the requisite food for the sustenance of the vermicule that will be disclosed from it.

Instinct instructs the parent where and how to form the nidus for its egg. These depositories differ considerably in the several genera, but, as a general rule, they are tubes burrowed by the mother either in earth, sand, decaying or soft wood, branches of plants having a pith, the halm of grain, cavities already existing in many substances, and even within the shells of dead snails. These perforations are sometimes simple, and sometimes they have divergent and ramifying channels. Sometimes they are carefully lined with a silky membrane secreted by the insect, and sometimes they are hung with a tapestry of pieces of leaves, cut methodically from plants, but some leave their walls entirely bare. All these particulars I shall have ample opportunity to note in the special descriptions of the genera. I merely indicate them to show how various are the receptacles for the offspring of our bees.

Fig. 1. The Egg.

Before the egg is placed within its nidus, this is supplied with the requisite quantity of food needful for the support of the young to the full period of its maturity. The receptacle is then closed, and the same process is repeated again and again until the parent has laid her whole store of eggs. In other cases one tube, or its ramification, contains but one egg. These eggs are usually oblong, slightly curved, and tapering at one extremity; they vary in size according to the species, but are never, however, above a line in length, and sometimes they are very minute. When the stock of the mother bee is exhausted she leaves them to the careful nursing of nature, and the young is speedily evolved. She then wanders forth; time has brought senility; her occupation has gone; and she passes away; but her progeny survive to perpetuate the continual chain of existence.

The Larva.—The temperature of the perforated tube wherein the egg is deposited must necessarily be higher and more equal than that of the external atmosphere, being secluded from its vicissitudes. The egg is soon hatched, and the larva emerges from its shell to feed ravenously upon the sustenance stored up for its supply. This consists of an admixture of pollen and honey formed into a paste, the quantities varying according to the size of the species. By some species it is formed into little balls; by others, it is heaped irregularly at the bottom of the cell. In the case of Andrena the quantity stored is of about the size of a pea. That it must be exceeding nutritious may be inferred from its very nature, consisting, as it does, of the virile, energetic, and fertilizing powder of plants,—the concentration of their living principle. It is strictly analogous to the 20fecundating property of the semen in animals, and, like them, produces spermatozoa, a fact corroborated by the researches of Robert Brown, Mirbel, and other distinguished vegetable physiologists.[1]

1. Might not, by parity of inference, the milt of fishes, such as the herring, mackerel, etc., be a useful food in cases of consumption, both from the iodine necessarily existing in it, and also from its doubtless nutritive nature?

We are told that the cells of Hylæus, or Prosopis, and of Ceratina are supplied with a semifluid honey. It is very doubtful if Hylæus collects its own store, but that Ceratina does, I have the authority of an exact observer (Mr. Thwaites) to verify it, for he has caught this insect with pollen on its posterior legs, which the long hair covering the tibia is intended for. What may be the nature of this semifluid honey? It is questionable if the larva could be nurtured upon honey alone without the admixture of pollen, thus contradicting analogies presumable from ample verification in nature’s processes. How, too, does it become semifluid? It is the property of honey, at a certain temperature, to be very fluid, and this is doubtless the temperature that prevails within the receptacle of the larva during the time of the operations of the bees.

Its semifluid consistency could then apparently be produced only by some more solid admixture, which, if not of pollen, of what can it be? This, even in small quantities, might, upon the bursting of its vesicles, have the power of thickening the fluent honey to the necessary consistency.

But a bee without polliniferous organs cannot collect pollen, and the instance of the hive bee, which collects honey in superabundance, feeding its larva with the bee-bread, 21must inevitably lead to the conclusion that the larvæ of bees require more than honey for their sustenance. Nature is not usually wantonly wasteful of its resources, and if honey sufficed for the nurture of the grub, so much pollen would not be abstracted from its legitimate purpose, nor would bees have this double trouble given to them. By the admixture of pollen the honey has energetic power infused into it by the spermatozoa which that contains. But it must necessarily be collected, for I never observed, nor have I seen recorded, any instance of the pollen being eaten on the flower and regurgitated into the cell in combination with the imbibed honey.

Pollen is eaten by the domestic bee and humble-bee to form wax for the structure of their cells, but the solitary bees do not themselves consume it.

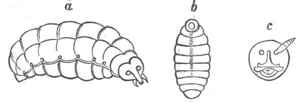

Fig. 2.—a, the Larva, when growing;

b, when preparing to change;

c, the head, viewed in front.

The larva, when excluded from the egg, is a fleshy grub, slightly curved, and a little pointed at each extremity. Its body is transversely constricted, the constrictions corresponding with its fifteen segments, each of which, excepting the head and four terminal ones, is supplied with a spiracle placed at the sides, whereby it breathes; and it has no feet. These segments have on each side a series of small tubercles, which facilitate the restricted motions of the grub, confined to the boundaries 22of its cell. Its small head, which is smooth above, has a little projecting horn on each side representing the future antennæ. The small lateral jaws articulate beneath a narrow labrum or lip, which folds down over them. To prove that the food provided requires still further comminution, these jaws are incessantly masticating it. The form of these jaws approximates to that of the insect which it will produce, being toothed and broad at the apex in the artisan and wood-boring bees, and simple in those which burrow in softer substances. On each side beneath these jaws there is an appendage, rather plump, having a setiform process at its extremity, and beneath these, in the centre, we observe a fleshy protuberance which, at its tip, has a smaller perforated process that emits the viscid liquid with which the grub spins its cocoon, and which immediately hardens to the consistency of silk.

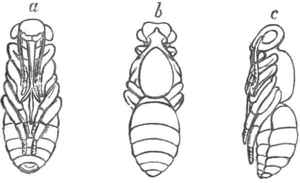

Fig. 3.—a, the pupa, seen beneath;

b, seen

above;

c, seen laterally.

Having constructed its cocoon, where the species does so,—for it is not incidental to all the genera,—and shrunk to its most compact dimensions, the larva becomes transformed into

The Pupa.—This is semi-transparent at first, and there may be seen through the thin pellicle, which invariably clothes every portion separately of the body, the ripening bee, which lies, like a mummy, with its wings and legs folded lengthwise along its breast. The parts gradually assume consistency, and the natural colours and 23clothing of the perfect insect display themselves through its pellucid envelope. When arrived at perfect maturity, and ready to commence the part it has to perform in the economy of nature, it bursts its cerements, making its way through the dorsal covering of its silken skin, and, leaving the exuviæ behind, it crawls forth from its dormitory, when, becoming invigorated by the bracing air and the genial sunshine, it stretches its legs and expands its wings, and flies forth jubilant, rejoicing in its awakened faculties.

The Imago.—The bee having attained its majority, loses no time in quitting the confined abode wherein it has been hitherto secluded. It comes forth prepared to undertake the cares, and meet the vicissitudes of existence. The new life that now opens to it is one apparently teeming exuberantly with every delight. It dwells in sunshine and amidst flowers; it revels in their sweets, attracted by their beautiful colours and their delightful odours; and the consummation of its bliss is to find a congenial partner. With him it enjoys a brief connubial transport, but which is speedily succeeded by life-long labour, for the cares of maternity immediately supervene.

I believe the wild bees are not polyandrous, and therefore many males, if there be any preponderating discrepancy in favour of that sex, must die celibate. But the fact of finding the males associated together in great numbers upon the same flowers or hedges, is certainly not conclusive of this being the case. To provide a fitting receptacle, furnished with suitable provision, for its future progeny, occupies all the subsequent solicitude of the female.

As frequent reference will hereafter be made to 24peculiarities of structure, it will be desirable to take a rapid survey of the external anatomy of the bee, for it will enable me to introduce in due order the requisite technicalities with their local explanations. This course will be found most subservient to preciseness and accuracy, and when mastered, which will be found to be a very simple affair, it will greatly facilitate exact comprehension. No circumlocution can convey what a few technicalities, thoroughly understood, will immediately explain, and no special scientific work can be read with any profit until they are acquired.

Diagrams are introduced to aid the imagination in its conception of what is meant to be conveyed.

This necessary detail I shall endeavour to make as entertaining as I possibly can, by introducing, with the description of the organ, the uses it serves in the economy of the insect. I hope thus to add an interest to it which a merely dry technical and scientific definition would not possess.

Structure is always expressive of the habits of the bees, and is as sure a line of separation, or means of combination, as instinct could be were it tangible. Hence the conclusion always follows with a certainty that such-and-such a form is identical with such-and-such habits, and that, in the broad and most distinguishing features of its economy, the genus is essentially the same in every climate. Climate does not act upon these lower forms of animal life, with the modifying influences it exercises upon the mammalia and man. A Megachile is as essentially a Megachile in all its characteristics in Arctic America, the Brazils, tropical Africa, Northern China, and Van Diemen’s Land, as in these islands, and Apis is, wherever it occurs, as truly an Apis. Therefore 25the habits, in whatever country the genus may be found, can thus be as surely affirmed of all its species, from the knowledge we have of those at home, as if observation had industriously tracked them. Therefore, the technicalities of structure once learnt, they become permanently and widely useful.

The body of the bee consists of a head, thorax, and abdomen, which, although to the casual observer, seemingly not separated from each other, are, upon closer inspection, more or less distinctly disconnected. The three parts are merely united by a very short and slight tubular cylinder. This is sometimes so much reduced as to be only a perforation of the parts combined by a ligament, and through which aperture a requisite channel is formed for the passage of the ganglion or nervous chord, which extends from one portion of the body to the other, giving off laterally, in its progress from the sensorium in the head onwards, the filaments required by the organs of sensation and motion, as well as all which control the other functions of the body of the insect.

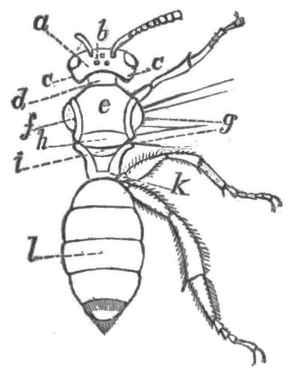

Fig. 4.—Body of the bee.

a, head and antennæ;

b, vertex and ocelli;

c, genæ, or cheeks;

d, prothorax;

e, mesothorax;

f, squamulæ;

g, insertion of the wings;

h, scutellum;

i, post-scutellum;

k, metathorax;

l, abdomen.

These apertures form also the necessary medium of connection between the several viscera, whereby the food and other sustaining juices are conveyed from the mouth through the œsophagus to the various parts of the body.

As this work will impinge but very incidentally upon the internal organization of the bee, it is unnecessary to be more explanatory. All that I shall have to notice 26here are those portions of the external structure which have any special bearing upon the economy and habits, or upon the generic and specific determination of the insects, and to which therefore I shall specially limit myself.

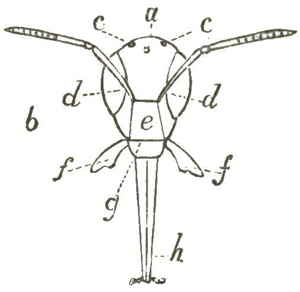

Fig. 5.—Front of the head of the bee.

a, vertex;

b, face;

c, ocelli or stemmata;

d, compound eyes;

e, clypeus;

f, mandibles;

g, labrum;

h, lingual apparatus folding for repose.

The head is the most important segment of the insect’s body, if we may elevate to such distinction any portion, when all conduce to the same end, and either would be imperfect without the other, yet we may perhaps thus distinguish it from the rest as it exclusively contains that higher class of organs, those of sense, which are most essential to the functions of the creature. The head consists of the vertex, or crown; the genæ, or cheeks; the face; the clypeus, or nose; the compound eyes; the stemmata, or simple eyes; the antennæ, or feelers, and the trophi, or organs of the mouth collectively.

The thorax, the second segment, carries all the organs of locomotion. It consists of the prothorax or collar, which carries beneath the anterior pair of legs; the mesothorax, or central division, with which articulate laterally above the four wings, the anterior of which have their base protected by the squamulæ, or epaulettes, or wing-scales, and beneath it carries the intermediate pair of legs; the metathorax, or hinder portion, which has in the centre above, behind the scutellum, the post-scutellum, and at the extremity of this division just above the articulation of the posterior legs is attached the last segment of the insect,—the Abdomen.

The vertex, or crown of the head, is that portion 27which lies between the upper extremities of the compound eyes. Upon the vertex are placed the stemmata, or ocelli (the simple eyes), in a curve or triangle; they are three in number, and are small, hyaline, circular protuberances, each containing within it a lens; sometimes they occur very far forward upon the face, especially when the compound lateral eyes meet above, as in the male domestic bee or drone. The uses of these simple eyes, from the experiments which have been made, seem to be for long and distant vision. To test their function, Réaumur covered them with a very adhesive varnish, which the bee could not remove, and he then let it escape. He found upon several repeated trials, that the insect always flew perpendicularly upwards, and was lost. Although this was anything but conclusive as to the uses of these eyes, it would seem that by losing the vision of this organ, the insect lost with it all sense of distance.

The compound eyes, seated on each side of the head, extend from the vertex generally to the articulation of the mandibles or jaws, their longitudinal axis being perpendicular to the station of the insect. They vary in external shape and convexity in the several species and genera, although not greatly, and consist of a congeries of minute, hexagonal, crystalline facets, each slightly convex externally, and their interstices are sometimes clothed with a short and delicate pubescence. Each separate hexagon has its own apparatus of lens and filament of optic nerve, each having its own distinct vision, but all converge to convey one object to the sensorium. The function of the compound eyes is concluded to be the microscopic sight of near objects.

The face, which sometimes has a longitudinal carina, 28or prominent ridge, down its centre, lies between these eyes, descending from the vertex to the base of the clypeus, or nose, but which is without the function of that organ. This clypeus is sometimes protuberant, and from shape or armature, characteristic. This part, however, is not always distinctly apparent, although a line or suture usually separates it above, from the face. At its lower extremity the labrum, or upper lip, articulates, over which it is sometimes produced; and it extends at each lateral apex to the base of the insertion of the mandibles. The genæ, or cheeks, descend from the vertex laterally, behind the compound eyes, to the cavity of the head which contains the lingual apparatus, when folded in repose. These cheeks, at their lower extremity, sometimes embrace the articulation of the mandibles.

Fig. 6.—1, Clavate antennæ;

2, filiform ditto;

a, scape;

b, flagellum.

The antennæ, or feelers, are two filamentary organs articulating on each side of the face and above the clypeus. They comprise the scape (a), or basal joint, and (b) the flagellum or terminal apparatus; the latter consists of closely attached conterminal joints, and usually forms an elbow with the scape; collectively these joints number twelve in the female and thirteen in the male. They are all of various relative lengths, which sometimes aid specific determination. The scape, however, is usually much longer than any of the rest, and in some males has a very robust and even angulated shape. A description of the antennæ always enters into the generic character; they usually differ very materially both in length and form in the sexes. They are often filiform (2), but more generally subclavate (1), and sometimes distinctly so, and where they have the latter structure it is found in both 29sexes. They constantly differ in the species of a long genus (Andrena, Normada, Halictus). In the male of the genus Eucera, they have a remarkable extension, being as long as the body, whereas folded back they are rarely so long, or not longer than the thorax in other males, speaking in reference only to our native kinds. In the females they are not often longer than the head. It is in the males of the genus Halictus that they take the greatest extension. In the male of the genus Eucera, we also find the remarkable peculiarity of the integument of some of the joints being distinctly of an hexagonal structure,—a peculiarity often observable in natural structures. In this case it may refer to the sensiferous function of the organ, and to which I shall have occasion to revert when I speak of the senses of our insects. We sometimes find the joints of the antennæ moniliform, something like a string of beads, or with each separate joint forming a curve, or with their terminal one, as in Megachile, greatly compressed.

The relative lengths of the joints often yield conclusive separative specific characters, and which may be very advantageously made available, especially where other distinctive differences are obscure, and in cases where the practised eye observes a distinction of habit, evidently specific, although it is difficult to seize tangible characteristics.

The trophi are the organs of the mouth of the bee collectively. When complete in all the parts, as exemplified in the genus Anthoptera, they consist of the labrum, or upper lip; the epipharynx, or valve, falling over and closing the aperture of the gullet; the pharynx, or gullet, which forms the true mouth and entrance to the œsophagus; the hypopharynx which lies immediately below 30the gullet and assists deglutition; the labium, or lower lip, and the true tongue. These parts are all single; the parts in pairs are the mandibles, the maxillæ, the maxillary palpi, the labial palpi, and the paraglossæ.

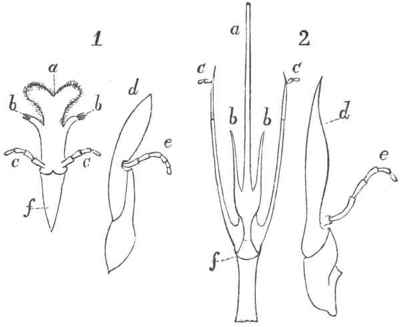

Fig. 7.—Trophi and their unfolding.

a, labrum;

b, epipharynx;

c, pharynx;

d, hypopharynx;

e, mandible;

f, maxillæ;

g, maxillary palpi;

h, mandible;

i, cardium;

k, labium;

l, labial palpi;

m, paraglossæ;

n, tongue.

The labrum, or upper lip, is attached by joint to the apex of the clypeus; it has a vertical motion, and falls over the organs beneath it, in repose, when it is itself covered by the mandibles. It is usually transverse in form, but is sometimes perpendicular, especially in the artisan bees. It takes many forms, sometimes semilunar or linear, emarginate or entire, convex, concave, or flat, and is occasionally armed with one or two processes, like minute teeth projecting from its surface, but of what use these may be we do not know. In the female of Halictus, it has a slightly longitudinal appendage in the centre. It is usually horny, but is sometimes coriaceous or leathery. This labrum often yields good specific characters.

The pharynx, or gullet, is a cavity immediately beneath the epipharynx, which articulates directly under the base of the labrum, and which closes the pharynx from above, and immediately beneath this cavity is another small appendage, almost triangular, which receives the food or honey from the canal conveying it 31from the tongue, or directly from the mandibles, when it is masticated, and helps it forward to the pharynx to be swallowed. The epipharynx closes this orifice from above, the labrum then laps over it and the articulation of the lingual apparatus, both which are further protected in repose by the mandibles closing over the labrum. This triple protection shows the importance nature attaches to these organs. The more direct portions of the lingual apparatus are the labium, or lower lip, which forms the main stem of the rest, and articulates beneath the hypopharynx, and is beneath of a horny texture; it forms a knee or articulating bend at about half its length, and has a second flexure at its apex, where the true tongue is inserted. This labium is extensible and retractile at the will of the insect, and lies inserted within the under cavity of the head when in complete repose, and the insect can withdraw or extend a portion or the whole at its pleasure. Attached on each side, at its first bend or elbow, lie the maxillæ, which, for want of a better term, are called the lower jaws, and perhaps properly so from the function they perform; for at the point of their downward flexure, which occurs at the apex of the labium, and where the true tongue commences, they each extend forward in a broad, longitudinal membrane, partly coriaceous throughout its whole length, and these, folded together and beneath, form the under sheath of the whole of the rest of the lingual apparatus in repose, and often lap over its immediate base when even it is extended. Externally continuous, the line of these maxillæ is broken at the point of flexure at the apex of the labium, by a deep sinus or curve, and within this is inserted the first joint of the maxillary palpi. The portion of the maxillæ 32extending forwards, hence takes several forms, usually tapering to an acute point, but sometimes rounded or hastate, according to the structure of the tongue, to which they form a protection.

The maxillary palpi are small, longitudinal joints, never exceeding six in number, and generally in the normal or true bees not so numerous. They vary in relative length to the organ to which they are attached, and usually progressively decrease in length and size from the basal ones to the apical, but each joint, excepting the terminal one, is generally more robust at its apex than at its own special base. The function of these maxillary palpi is unknown. They are always present in full number in the Andrenidæ, and in some few genera of the true bees, but they vary from their normal number of six to five, four, three, two, and one in the latter; and it is curious that they are most deficient in those bees having the most complicated economy, as in the artisan bees and the cenobite bees; they thus evidently show that it is not a very paramount function that they perform. On each side, at the apical summit of the labium, are inserted the labial palpi. These are invariably four in number, but vary considerably in length and substance. In the Andrenidæ they have always the form of subclavate, robust joints, and are usually as long as the tongue, but not always; they are only half the length of that organ in the subsection of the acute-tongued Andrenidæ. In the normal bees, even in the genus Panurgus, which is the most closely allied to the Andrenidæ, the labial palpi immediately take excessive development, especially in their two basal joints, and the structure of these two joints, excepting in this genus and in Nomada, partakes of a flattened form 33and membranous substance. All these four joints are either conterminal, or the two apical ones, or one of them is articulated laterally, towards the apex of the preceding joint. These two are always very short joints, and are comparatively robust.

The labial palpi are, in the majority of cases, about half or two-thirds the length of the tongue, but in Apathus and Apis they are of its full length. At the immediate base of the tongue, and attached to it laterally, rather than to the apex of the labium, are the paraglossæ, or lingual appendages, which are membranous and acute, except in the Andrenidæ, where, in some, their apex is lacerated and fringed with short hairs. These organs are always present in the Andrenidæ and generally in the Apidæ, where they usually obtain extensive relative development; but in the artisan bees they are all but obsolete, and in Ceratina, Cælioxys, Apathus, and Apis, they are not even apparent. Their use also has hitherto eluded discovery, but that they are not essential to the honey-gathering instinct of the bee is especially proved by the latter instance.

The true tongue is attached to the centre of the apex of the labium, having the paraglossæ, when extant, and the labial palpi at its sides. In the Andrenidæ it is a flat short organ of varying form, either lobated, emarginate, acute, or lanceolate; but in the Apidæ, with Panurgus it immediately becomes very much elongated, and with this genus the apparatus whereby the tongue folds beneath obtains its immediate development; but this development exhibits itself most fully in the genus Anthophora. The tongue is usually linear, tapering slightly to its extremity, and terminating in some genera with a small knob. It is clothed throughout with a very delicate 34pubescence, which enables the bee to gather up the nectar it laps. That it should be called the lip seems an absurdity, for it exercises all the functions of a tongue, and it would seem almost that the fine hairs, with which it is covered, are the papillæ of taste. Its structure in some genera seems to be a spiral thread twining closely round and round, but in others it appears throughout identical.

Fig. 8.—Extremes of structure of tongues:

1, in subnormal bees (Colletes);

2, in normal bees (Anthophora).

a, tongue;

b, paraglossæ;

c, labial palpi;

d, maxillæ;

e, maxillary palpi;

f, labium.

This tongue was formerly thought to be tubular, and that the bee sucked the honey through an aperture at its apex. The knowledge of the flat form of the tongues of other bees should have dissipated the illusion, for we could have been perfectly sure of the analogical structure and function of an organ in creatures so nearly alike. Réaumur’s patient observations have totally dissipated the mistake, and through him we exactly know how the bee conveys the honey into its stomach 35As it exhibits an agreeable instance of the persevering industry and unblenching patience with which he made his researches, I will give a summary of what he says, for his bulky volumes, although teeming with delightful instruction, pleasantly narrated, will necessarily not be in every entomologist’s hand, and where not, not even always readily accessible. His observations were made upon the honey-bee, but we may attribute the same mode of collecting to all the rest. He says:—When this tongue is not lapping the nectar of flowers but in a state of perfect repose it is flattened. It is then at least three times broader than thick, but its edges are rounded. It gradually narrows from its base to its extremity. It terminates in a slight inflation, almost cylindrical, at the end of which there is a little knob, which appears perforated in the centre. From the circumference of this knob tolerably long hairs radiate, and the upper side of the tongue is also entirely covered with hairs. The basal and widest portion above seems striated transversely with minute lines closely approaching each other.

The upper side of the anterior portion of the tongue seems of a cartilaginous substance, but the under side of the same part appears cartilaginous only over a portion of its width. The centre is throughout its whole course more transparent than the rest, and seems membranous and folded. It is only necessary to press the posterior portion of this trunk, whilst holding its anterior part closely to a light, towards which its upper surface must be turned, and then upon examining its inner surface with a lens of high power, a drop of liquid may be soon observed at its foremost portion. By continuing to press it this drop is urged forward, and as it passes every 36portion swells considerably, and the two edges separate more widely from each other. The under side of the tongue, which was before flat, rises and swells considerably, and all that thus rises up is evidently membranous. It looks like a long vessel of the most transparent material. But whilst this great increase of bulk is made upon the lower surface, the upper surface swells only a little, which seems to prove that its immediate envelope is not capable of much distension.

If a bee be observed whilst sipping any sweet liquor, the anterior portion of its trunk will be sometimes seen more swollen than when in action, and alternations will be observed in it of varying expansion.

The posterior portion of the trunk is a great deal larger than the anterior, and it is only in repose that the former nearly equals the latter in length. This posterior portion (this is the portion treated above as the labium, or under lip) is joined to the anterior by a very short ligature, wholly fleshy, and very flexible, which permits the folding of the trunk, and then its under side is quite scaly, very shiny, and rounded (the maxillæ). This portion is apparently more substantial than the rest. Its diameter gradually increases as it recedes from about the middle to about two-thirds of its length; there it is a little constricted, and the first of the two pieces of which it is composed there terminates. The first piece is rounded, for the purpose, it would appear, of fitting itself upon another, which serves as its base and pivot. This base is conical and of a scaly texture, and terminates in rather an acute point. It is this point which is articulated at the junction of the two small elongate portions of which we spoke at the commencement, and which carry the trunk forward.

37In repose, the posterior part of the trunk lies along the lower part of the mouth, and the anterior part is folded back upon it, when it is covered by the maxillæ, which then seem to form a portion of it. It has further another interior envelope; these are the two first joints of the labial palpi (in the Apidæ), which are entirely membranous, and these in repose cling closely to the tongue laterally.

The bee would certainly not collect its honey differently from a flower than it would from a glass wherein it might be placed to observe the process; and here it never appeared to obtain the honey by suction. The bee was never observed to place the end of its tongue in the drop of syrup, as it would necessarily do if it were requisite to imbibe it through what seems the small aperture at the extremity of the knob, at the end of the tongue, previously described. As soon as the bee finds itself near the spot spread with honey or syrup, it extends its tongue a line or so beyond the end of the palpi, which continue to envelope it throughout the rest of its length. If the honey be spread over the glass, the anterior portion of the tongue, which is exposed, is turned round that its superior surface may be applied to the glass. There this portion does precisely what the tongue of any animal would do in lapping a liquid. This tongue repeatedly rubs the glass, and, moving about with astonishing rapidity, it makes hundreds of different inflexions.

If the drop of syrup presented to the bee be thicker, or if it meet with a drop of honey, it then thrusts the anterior portion of its tongue into the liquid, but apparently only to use it as a dog might do its tongue in lapping milk or water. Even in the drop of honey the bee bends the 38end of its tongue about, and lengthens and shortens it successively, and, indeed, withdraws it from moment to moment. We then observe it not merely lengthen and shorten this end, but it is also seen to curve it about, causing from time to time the superior surface to become concave,—to give, as it were, to the liquid with which it is loaded a downward inclination towards the head. In fact, this portion of the trunk appears to act as a tongue, and not as a pump. Indeed its extremity, where the aperture for receiving the liquid is assumed to be, is repeatedly above the surface of the liquid which the insect is lapping.

By these continuous motions this anterior extremity of the tongue charges itself with the nectareous fluid, and conveys it to the mouth. It is along the upper surface of this pilose tongue that the liquid passes. The bee strives especially to load and cover it with honey. In shortening the tongue to the extent, sometimes, of withdrawing it entirely beneath its sheaths, it conveys and deposits the liquid with which it is charged within a sort of channel, formed by the upper surface of the tongue and the sheaths which fold over it. Thus, these sheaths are, perhaps, less for the purpose of covering the tongue than to form and cover the channel by which the liquid is conveyed to the mouth. I have previously remarked that the trunk can swell and contract; these swellings and constrictions are observed to succeed each other, and may be for the purpose of urging the liquid, already in transit beneath the sheaths, forward towards the true mouth. Further, I moved the sheaths aside from their position above the tongue of a bee which I held in my fingers, and I succeeded, by means of the point of a pin, in placing an extremely small drop of 39honey upon the tongue of this bee at a spot where it could be covered by the extremities of the external sheath. I then let these sheaths loose. Sometimes they spontaneously resumed their previous position, and sometimes I assisted them to resume it. The drop of honey which they then covered has in no instance returned to the extremity of the tongue; it has always passed towards the mouth, and doubtless entered that orifice itself. It is therefore very certain that the bee imbibes its honey by lapping, and that it never passes through the aperture which has been supposed to have been seen at the extreme apex of the tongue. Did this aperture really exist, it would be of extreme minuteness, and it did not appear to me possible that a large drop of honey, which I have seen imbibed in a very few instants, could in so short a time have passed by so minute an opening. A further confirmation of the non-existence of this orifice has been given me when, by pressing a tongue towards its origin to compel it to swell, I have detected the liquid which gave it its extension, but all my pressing would never make the liquid pass through the extremity, although the pressure has sometimes made it almost rend the membranes, to give it an opening to escape by. Having thus passed through the œsophagus into the stomach, it is then regurgitated into its requisite repository upon arriving at home.

Apidæ.

Fig. 9.—Mode of folding the tongue in repose.

1. In abnormal bee.

2. In normal bee.

a, point of articulation beneath the hypopharynx:

b, apex of the tongue.

The entire proboscis, with all its appendages attached, has in the Apidæ three distinct hinges or articulations, including that which attaches it by its extreme base to 40the under surface of the mouth and lower portion of the head, the cavity of which, when folded, it fills, and even then the apex of the tongue protrudes in some genera beyond the sheathing maxillæ. In the Andrenidæ it has but two articulations, and the maxillæ always cover them entirely in repose. The first articulation, forming the fulcrum of the whole, is always elbowed in the Apidæ, and consequently not capable, like the rest of the joints, of full linear extension. The attached diagram will give a clearer conception of the mode of folding: a is the labium, and b the tongue.

As we have no complete description of the mode by which the tongue of the bee is worked, and how it gathers up its honey, I thought it desirable to be fuller upon the subject than was originally my intention.

Fig. 10.—Mandibles: 1, of leaf-cutter bee (Megachile);

2, of burrower (Andrena);

3, of parasite (Nomada).

The last portion of the trophi, also double, are the mandibles; they articulate on each side with the cheeks; they act laterally, and are variously formed, according to the economy of the insect. In the females they are usually more or less toothed, and are especially broad, curved, and toothed in the artisan bees. In Apis and Bombus they are subdentate. In males they are frequently simply acute, but in some species, especially in Andrena, they have a long spine at the base, which points downwards when they are closed. To this sex they appear to be of no use beyond aiding them to stay the wayward caprice or flight of their mistresses; and, although they have an analogical structure in the males of those genera wherein they are much dilated and toothed, yet they do 41not seem to be at all used by that sex for any purpose but sexual. In the females they are used for the construction of their burrows and nests, and for the purpose of nipping the narrow spurs and tubes of flowers to get at the nectar; and they often nip, whilst seeking pollen, the anthers of the flowers which have not yet burst their receptacles of pollen.

These insects must necessarily nicely appreciate the quantity of pollen requisite to the full development of the young insect, and, although we often observe a remarkable difference of size in the individuals of a species, this may rather arise from some defect in the quality of the nutritive purveyance than in its quantity, for instinct would as efficiently provide for this purpose as it unquestionably guides to the collection and storing of the nutritive supplies.

Having thus completed the description of the head and of all its attachments, I proceed to—

The Thorax, which is divided by sutures into three parts already mentioned above, viz. the prothorax, the mesothorax, and the metathorax.

The collar, or upper part of the prothorax, is often very distinct, and even angulated laterally in front, and frequently presents, both in colouring and form, a specific character. At its under portion on each side the anterior legs are articulated.

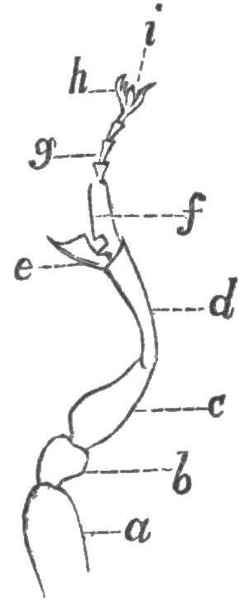

Fig. 11.—Anterior leg.

a, coxa;

b, trochanter;

c, femur, or thigh;

d, tibia, or shank;

e, spur and velum;

f, planta and strigilis;

g, digitus;

h, claw;

i, pulvillus, or cushion.

All the legs comprise the coxa, or hip-joint; the trochanter, which is a small joint forming the connection between this and the next joint the femur, or thigh; the tibia, or shank; and the tarsus, or foot. The latter consists of five joints, declining in length from the first, which is generally as long as all the rest united together; the first, in the anterior pair, being called the palmæ, 42or palms; and in the four posterior plantæ, or soles; the other joints are called the digiti, or fingers, or tarsus collectively; at the extremity of the terminal one are the two claws, which are sometimes simple hooks, but usually have a smaller hooklet within; they have both lateral and perpendicular motion, and between their insertion is affixed the pulvillus, or cushion. The coxæ in their occasional processes exhibit very useful specific characters, as do the markings and form of the remaining joints of the leg and foot, which in several genera furnish generic peculiarities. The four anterior tarsi have each a moveable spine, or spur, at their apex within, which can be expanded to the angle at which the insect wishes to place the limb, and to which it forms a collateral support; the posterior tibiæ have two each of these spurs, excepting in the genus Apis, which has none to this leg. Attached to this spur on the anterior tibiæ of all the bees, there is, within, a small velum, or sail, as it has been called; this is a small angular appendage affixed within the spur by its base. At the base of the palmæ of the same legs, and opposite the play of this velum, there is a deep sinus, or curved incision, the strigilis, called thus or the curry-comb, from the pecten, or comb of short stiff hair which fringes its edge. Upon this aperture the velum can act at the will of the insect, and combined they form a circular orifice. The object of this apparatus is to keep the antennæ clean, for the insect, when it wishes to cleanse one or the other of them, lays it within this sinus of the palma, and then, pressing the 43velum of the spur upon it, removes, by the combined action of the comb and the velum, all excrescences or soilure from it, and this process it repeats until satisfied with the cleanliness of the organ: and this it may be frequently seen doing. This arrangement proves how essential to the well-being of the insect is the condition of its antennæ, the sinus, or strigilis, or curry-comb, as it may be called, being always adapted in size to the thickness of the antennæ, for insects being always both right- and left-handed, they therefore use the limb on each side to brush the antenna of that side. The palmæ and other joints of the tarsus of the fore legs are greatly dilated in many males, or fringed externally with stiff setæ, which give it as efficient a dilatation as if it were the expansion of its corneous substance. The anterior tarsi of the females are likewise fringed with hair, to enable them to sweep off and collect the pollen, and to assist also in the construction and furnishing of their burrows. The intermediate tarsi are as well often very much extended in the males, being considerably longer than those of the other legs. The use of the claws at the apex of the tarsi is evidently to enable the insect to cling to surfaces.

The manner in which the bee conveys either the pollen, or other material it purposes carrying home, to the posterior legs, or venter, which is to bear it, is very curious. The rapidity of the motions of its legs is then very great; so great, indeed, as to make it very difficult to follow them; but it seems first to collect its material gradually with its mandibles, from which the anterior tarsi gather it, and that on each side passes successively the grains of which it consists to the intermediate legs by multiplicated scrapings and twistings of the limbs; this then passes it on by similar manœuvres, and deposits 44it, according to the nature of the bee, upon the posterior tibiæ and plantæ, or upon the venter. The evidence of this process is speedily manifested by the posterior legs gradually exhibiting an increasing pellet of pollen. Thus, for this purpose, all the legs of the bees are more or less covered with hair. It is the mandibles which are chiefly used in their boring or excavating operations, applying their hands, or anterior tarsi, only to clear their way; but by the constructive or artisan bees they are used both in their building and mining operations, and are worked like trowels to collect moist clay, and to apply it to the masonry of their habitations.

The mesothorax, or central division of the thorax, has inserted on each side near the centre the four wings, the anterior pair articulating beneath the squamulæ, or wing-scales, which cover their base like an epaulette, and this wing scale often yields a specific character. In repose the four wings lie, horizontally, along the body, over the abdomen, the superior above, the inferior beneath. The wings themselves are transparent membranes, intersected by threads darker than their own substance, called their nervures, which are supposed to be tubular. These nervures and the spaces they enclose, called cells, are used in the superior wing only, and only occasionally, as subsidiary generic characters, and their terminology it will be desirable to describe, as use will be made subsequently of it. At the same time, to facilitate the comprehension of the terms, an illustrative diagram is appended; but those parts only will be described which have positive generic application. I may, however, first observe that upon the expansion of the wings in flight, the insect has the voluntary power 45of making the inferior cling to the superior wing by a series of hooklets with which its anterior edge is furnished at about half the length of that wing, which gives to the thus consolidated combination of the two a greater force in beating the air to accelerate its progress. That the insect has a control over the operation of these hooklets is very evident, for, upon settling, it usually unlocks them, and the anterior are often seen separated and raised perpendicularly over the insect; but that this can be mechanically effected also is shown sometimes in pinning a bee for setting, when by a lucky accident the pin catches the muscles which act upon the wings, and they become distended, as in flight, closely linked together. Both the diagram and the description of this superior wing I borrow from an elaborate paper of my own in the first volume of the ‘Transactions of the Entomological Society of London,’ wherein I gave a tabulated view, in chronological order, of the nomenclature introduced by successive entomologists in the use they made of the anterior wing of the Hymenoptera for generic subdivision, and which I subsequently applied to my own work upon the ‘Fossorial Hymenoptera of Great Britain.’

Fig. 12.—Superior wing.

a, marginal cell;

b, first cubital or submarginal cell;

c, second ditto;

d, third ditto;

e and f, first and second recurrent nervures.

Attached to the mesothorax in the centre, above and behind, are the scutellum and post-scutellum, which in colouring or form often yield subsidiary generic or specific characters. On each side of the mesothorax in front, above the pectus, or breast, and just below and before the articulation of the anterior wings, there is a 46small tubercle, or boss, separated from the surrounding integument by a suture, the colouring of which frequently yields a specific character, but its uses are not known.

Fig. 13.—Posterior legs:

1, of abnormal bee (Andrena);

2, scopuliped normal bee (Eucera);

3, parasitic bee (Nomada).

a, coxa;

b, trochanter, with flocculus;

c, femur;

d, tibia;

e, planta;

f, spinulæ;

g, tarsus, with its claws.