Title: Historical record of the Seventh Regiment, or the Royal Fusiliers

Author: Richard Cannon

Release date: December 21, 2017 [eBook #56220]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from images made available by the

HathiTrust Digital Library.)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Some minor changes are noted at the end of the book.

HORSE-GUARDS,

1st January, 1836.

His Majesty has been pleased to command that, with a view of doing the fullest justice to Regiments, as well as to Individuals who have distinguished themselves by their Bravery in Action with the Enemy, an Account of the Services of every Regiment in the British Army shall be published under the superintendence and direction of the Adjutant-General; and that this Account shall contain the following particulars, viz.:—

—— The Period and Circumstances of the Original Formation of the Regiment; The Stations at which it has been from time to time employed; The Battles, Sieges, and other Military Operations in which it has been engaged, particularly specifying any Achievement it may have performed, and the Colours, Trophies, &c., it may have captured from the Enemy.

—— The Names of the Officers and the number of Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates Killed or Wounded by the Enemy, specifying the Place and Date of the Action.

—— The Names of those Officers who, in consideration of their Gallant Services and Meritorious Conduct in Engagements with the Enemy, have been distinguished with Titles, Medals, or other Marks of His Majesty's gracious favour.

—— The Names of all such Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers, and Privates, as may have specially signalized themselves in Action.

And,

—— The Badges and Devices which the Regiment may have been permitted to bear, and the Causes on account of which such Badges or Devices, or any other Marks of Distinction, have been granted.

By Command of the Right Honourable

GENERAL LORD HILL,

Commanding-in-Chief.

John Macdonald,

Adjutant-General.

The character and credit of the British Army must chiefly depend upon the zeal and ardour by which all who enter into its service are animated, and consequently it is of the highest importance that any measure calculated to excite the spirit of emulation, by which alone great and gallant actions are achieved, should be adopted.

Nothing can more fully tend to the accomplishment of this desirable object than a full display of the noble deeds with which the Military History of our country abounds. To hold forth these bright examples to the imitation of the youthful soldier, and thus to incite him to emulate the meritorious conduct of those who have preceded him in their honourable career, are among the motives that have given rise to the present publication.

The operations of the British Troops are, indeed, announced in the "London Gazette," from whence they are transferred into the public prints: the achievements of our armies are thus made known at the time of their occurrence, and receive the tribute of praise and admiration to which they are entitled. On extraordinary occasions, the Houses of Parliament have been in the habit of conferring on the Commanders,[iv] and the Officers and Troops acting under their orders, expressions of approbation and of thanks for their skill and bravery; and these testimonials, confirmed by the high honour of their Sovereign's approbation, constitute the reward which the soldier most highly prizes.

It has not, however, until late years, been the practice (which appears to have long prevailed in some of the Continental armies) for British Regiments to keep regular records of their services and achievements. Hence some difficulty has been experienced in obtaining, particularly from the old Regiments, an authentic account of their origin and subsequent services.

This defect will now be remedied, in consequence of His Majesty having been pleased to command that every Regiment shall in future keep a full and ample record of its services at home and abroad.

From the materials thus collected, the country will henceforth derive information as to the difficulties and privations which chequer the career of those who embrace the military profession. In Great Britain, where so large a number of persons are devoted to the active concerns of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce, and where these pursuits have, for so long a period, been undisturbed by the presence of war, which few other countries have escaped, comparatively little is known of the vicissitudes of active service, and of the casualties of climate, to which, even during peace, the British Troops are exposed in every part of the globe, with little or no interval of repose.

In their tranquil enjoyment of the blessings which the country derives from the industry and the enterprise of the agriculturist and the trader, its happy inhabitants may be supposed not often to reflect on the perilous duties of the soldier and the sailor,—on their sufferings,—and on the sacrifice of valuable life, by which so many national benefits are obtained and preserved.

The conduct of the British Troops, their valour, and endurance, have shone conspicuously under great and trying difficulties; and their character has been established in Continental warfare by the irresistible spirit with which they have effected debarkations in spite of the most formidable opposition, and by the gallantry and steadiness with which they have maintained their advantages against superior numbers.

In the official Reports made by the respective Commanders, ample justice has generally been done to the gallant exertions of the Corps employed; but the details of their services, and of acts of individual bravery, can only be fully given in the Annals of the various Regiments.

These Records are now preparing for publication, under His Majesty's special authority, by Mr. Richard Cannon, Principal Clerk of the Adjutant-General's Office; and while the perusal of them cannot fail to be useful and interesting to military men of every rank, it is considered that they will also afford entertainment and information to the general reader, particularly to those who may have served in the Army, or who have relatives in the Service.

There exists in the breasts of most of those who have served, or are serving, in the Army, an Esprit de Corps—an attachment to everything belonging to their Regiment; to such persons a narrative of the services of their own Corps cannot fail to prove interesting. Authentic accounts of the actions of the great, the valiant, the loyal, have always been of paramount interest with a brave and civilized people. Great Britain has produced a race of heroes who, in moments of danger and terror, have stood "firm as the rocks of their native shore;" and when half the World has been arrayed against them, they have fought the battles of their Country with unshaken fortitude. It is presumed that a record of achievements in war,—victories so complete and surprising, gained by our countrymen, our brothers, our fellow-citizens in arms,—a record which revives the memory of the brave, and brings their gallant deeds before us, will certainly prove acceptable to the public.

Biographical memoirs of the Colonels and other distinguished Officers will be introduced in the Records of their respective Regiments, and the Honorary Distinctions which have, from time to time, been conferred upon each Regiment, as testifying the value and importance of its services, will be faithfully set forth.

As a convenient mode of Publication, the Record of each Regiment will be printed in a distinct number, so that when the whole shall be completed, the Parts may be bound up in numerical succession.

The natives of Britain have, at all periods, been celebrated for innate courage and unshaken firmness, and the national superiority of the British troops over those of other countries has been evinced in the midst of the most imminent perils. History contains so many proofs of extraordinary acts of bravery, that no doubts can be raised upon the facts which are recorded. It must therefore be admitted, that the distinguishing feature of the British soldier is Intrepidity. This quality was evinced by the inhabitants of England when their country was invaded by Julius Cæsar with a Roman army, on which occasion the undaunted Britons rushed into the sea to attack the Roman soldiers as they descended from their ships; and, although their discipline and arms were inferior to those of their adversaries, yet their fierce and dauntless bearing intimidated the flower of the Roman troops, including Cæsar's favourite tenth legion. Their arms consisted of spears, short swords, and other weapons of rude construction. They had chariots, to the[viii] axles of which were fastened sharp pieces of iron resembling scythe-blades, and infantry in long chariots resembling waggons, who alighted and fought on foot, and for change of ground, pursuit, or retreat, sprang into the chariot and drove off with the speed of cavalry. These inventions were, however, unavailing against Cæsar's legions: in the course of time a military system, with discipline and subordination, was introduced, and British courage, being thus regulated, was exerted to the greatest advantage; a full development of the national character followed, and it shone forth in all its native brilliancy.

The military force of the Anglo-Saxons consisted principally of infantry: Thanes, and other men of property, however, fought on horseback. The infantry were of two classes, heavy and light. The former carried large shields armed with spikes, long broad swords and spears; and the latter were armed with swords or spears only. They had also men armed with clubs, others with battle-axes and javelins.

The feudal troops established by William the Conqueror consisted (as already stated in the Introduction to the Cavalry) almost entirely of horse; but when the warlike barons and knights, with their trains of tenants and vassals, took the field, a proportion of men appeared on foot, and, although these were of inferior degree, they proved stout-hearted Britons of stanch fidelity. When stipendiary troops were employed, infantry always constituted a considerable portion of the military force;[ix] and this arme has since acquired, in every quarter of the globe, a celebrity never exceeded by the armies of any nation at any period.

The weapons carried by the infantry, during the several reigns succeeding the Conquest, were bows and arrows, half-pikes, lances, halberds, various kinds of battle-axes, swords, and daggers. Armour was worn on the head and body, and in course of time the practice became general for military men to be so completely cased in steel, that it was almost impossible to slay them.

The introduction of the use of gunpowder in the destructive purposes of war, in the early part of the fourteenth century, produced a change in the arms and equipment of the infantry-soldier. Bows and arrows gave place to various kinds of fire-arms, but British archers continued formidable adversaries; and owing to the inconvenient construction and imperfect bore of the fire-arms when first introduced, a body of men, well trained in the use of the bow from their youth, was considered a valuable acquisition to every army, even as late as the sixteenth century.

During a great part of the reign of Queen Elizabeth each company of infantry usually consisted of men armed five different ways; in every hundred men forty were "men-at-arms," and sixty "shot;" the "men-at-arms" were ten halberdiers, or battle-axe men, and thirty pikemen; and the "shot" were twenty archers, twenty musketeers, and twenty harquebusiers, and each man carried, besides his principal weapon, a sword and dagger.

Companies of infantry varied at this period in numbers from 150 to 300 men; each company had a colour or ensign, and the mode of formation recommended by an English military writer (Sir John Smithe) in 1590 was:—the colour in the centre of the company guarded by the halberdiers; the pikemen in equal proportions, on each flank of the halberdiers; half the musketeers on each flank of the pikes; half the archers on each flank of the musketeers; and the harquebusiers (whose arms were much lighter than the muskets then in use) in equal proportions on each flank of the company for skirmishing.[1] It was customary to unite a number of companies into one body, called a Regiment, which frequently amounted to three thousand men; but each company continued to carry a colour. Numerous improvements were eventually introduced in the construction of fire-arms, and, it having been found impossible to make armour proof against the muskets then in use (which carried a very heavy ball) without its being too weighty for the soldier, armour was gradually laid aside by the infantry in the seventeenth century: bows and arrows also fell into disuse, and the infantry were reduced to two classes, viz.: musketeers, armed with matchlock muskets,[xi] swords, and daggers; and pikemen, armed with pikes from fourteen to eighteen feet long, and swords.

In the early part of the seventeenth century Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, reduced the strength of regiments to 1000 men; he caused the gunpowder, which had heretofore been carried in flasks, or in small wooden bandoliers, each containing a charge, to be made up into cartridges, and carried in pouches; and he formed each regiment into two wings of musketeers, and a centre division of pikemen. He also adopted the practice of forming four regiments into a brigade; and the number of colours was afterwards reduced to three in each regiment. He formed his columns so compactly that his infantry could resist the charge of the celebrated Polish horsemen and Austrian cuirassiers; and his armies became the admiration of other nations. His mode of formation was copied by the English, French, and other European states; but so great was the prejudice in favour of ancient customs, that all his improvements were not adopted until near a century afterwards.

In 1664 King Charles II. raised a corps for sea-service, styled the Admiral's regiment. In 1678 each company of 100 men usually consisted of 30 pikemen, 60 musketeers, and 10 men armed with light firelocks. In this year the king added a company of men armed with hand-grenades to each of the old British regiments, which was designated the "grenadier company." Daggers were so contrived as to fit in the muzzles of the muskets, and bayonets[xii] similar to those at present in use were adopted about twenty years afterwards.

An Ordnance regiment was raised in 1685, by order of King James II., to guard the artillery, and was designated the Royal Fusiliers (now 7th Foot). This corps, and the companies of grenadiers, did not carry pikes.

King William III. incorporated the Admiral's regiment in the Second Foot Guards, and raised two Marine regiments for sea-service. During the war in this reign, each company of infantry (excepting the fusiliers and grenadiers) consisted of 14 pikemen and 46 musketeers; the captains carried pikes; lieutenants, partisans; ensigns, half-pikes; and serjeants, halberds. After the peace in 1697 the Marine regiments were disbanded, but were again formed on the breaking out of the war in 1702.[2]

During the reign of Queen Anne the pikes were laid aside, and every infantry soldier was armed with a musket, bayonet, and sword; the grenadiers ceased, about the same period, to carry hand-grenades; and the regiments were directed to lay aside their third colour: the corps of Royal Artillery was first added to the army in this reign.

About the year 1745, the men of the battalion companies of infantry ceased to carry swords;[xiii] during the reign of George II. light companies were added to infantry regiments; and in 1764 a Board of General Officers recommended that the grenadiers should lay aside their swords, as that weapon had never been used during the seven years' war. Since that period the arms of the infantry soldier have been limited to the musket and bayonet.

The arms and equipment of the British troops have seldom differed materially, since the Conquest, from those of other European states; and in some respects the arming has, at certain periods, been allowed to be inferior to that of the nations with whom they have had to contend; yet, under this disadvantage, the bravery and superiority of the British infantry have been evinced on very many and most trying occasions, and splendid victories have been gained over very superior numbers.

Great Britain has produced a race of lion-like champions who have dared to confront a host of foes, and have proved themselves valiant with any arms. At Crecy, King Edward III., at the head of about 30,000 men, defeated, on the 26th of August, 1346, Philip King of France, whose army is said to have amounted to 100,000 men; here British valour encountered veterans of renown:—the King of Bohemia, the King of Majorca, and many princes and nobles were slain, and the French army was routed and cut to pieces. Ten years afterwards, Edward Prince of Wales, who was designated the Black Prince, defeated, at Poictiers, with 14,000 men, a French army of 60,000 horse, besides infantry, and took John I., King of France, and his son[xiv] Philip, prisoners. On the 25th of October, 1415, King Henry V., with an army of about 13,000 men, although greatly exhausted by marches, privations, and sickness, defeated, at Agincourt, the Constable of France, at the head of the flower of the French nobility and an army said to amount to 60,000 men, and gained a complete victory.

During the seventy years' war between the United Provinces of the Netherlands and the Spanish monarch, which commenced in 1578 and terminated in 1648, the British infantry in the service of the States-General were celebrated for their unconquerable spirit and firmness;[3] and in the thirty years' war between the Protestant Princes and the Emperor of Germany, the British troops in the service of Sweden and other states were celebrated for deeds of heroism.[4] In the wars of Queen Anne, the fame of the British army under the great Marlborough was spread throughout the world; and if we glance at the achievements performed within the memory of persons now living, there is abundant proof that the Britons of the present age are not inferior to their ancestors in the qualities [xv]which constitute good soldiers. Witness the deeds of the brave men, of whom there are many now surviving, who fought in Egypt in 1801, under the brave Abercromby, and compelled the French army, which had been vainly styled Invincible, to evacuate that country; also the services of the gallant Troops during the arduous campaigns in the Peninsula, under the immortal Wellington; and the determined stand made by the British Army at Waterloo, where Napoleon Bonaparte, who had long been the inveterate enemy of Great Britain, and had sought and planned her destruction by every means he could devise, was compelled to leave his vanquished legions to their fate, and to place himself at the disposal of the British Government. These achievements, with others of recent dates in the distant climes of India, prove that the same valour and constancy which glowed in the breasts of the heroes of Crecy, Poictiers, Agincourt, Blenheim, and Ramilies, continue to animate the Britons of the nineteenth century.

The British Soldier is distinguished for a robust and muscular frame,—intrepidity which no danger can appal,—unconquerable spirit and resolution,—patience in fatigue and privation, and cheerful obedience to his superiors. These qualities, united with an excellent system of order and discipline to regulate and give a skilful direction to the energies and adventurous spirit of the hero, and a wise selection of officers of superior talent to command, whose presence inspires confidence,—have been the leading causes of the splendid victories gained by the[xvi] British arms.[5] The fame of the deeds of the past and present generations in the various battle-fields where the robust sons of Albion have fought and conquered, surrounds the British arms with an halo of glory; these achievements will live in the page of history to the end of time.

The records of the several regiments will be found to contain a detail of facts of an interesting character, connected with the hardships, sufferings, and gallant exploits of British soldiers in the various parts of the world where the calls of their Country and the commands of their Sovereign have required them to proceed in the execution of their[xvii] duty, whether in active continental operations, or in maintaining colonial territories in distant and unfavourable climes.

The superiority of the British infantry has been pre-eminently set forth in the wars of six centuries, and admitted by the greatest commanders which Europe has produced. The formations and movements of this arme, as at present practised, while they are adapted to every species of warfare, and to all probable situations and circumstances of service, are calculated to show forth the brilliancy of military tactics calculated upon mathematical and scientific principles. Although the movements and evolutions have been copied from the continental armies, yet various improvements have from time to time been introduced, to ensure that simplicity and celerity by which the superiority of the national military character is maintained. The rank and influence which Great Britain has attained among the nations of the world have in a great measure been purchased by the valour of the Army, and to persons who have the welfare of their country at heart, the records of the several regiments cannot fail to prove interesting.

[1] A company of 200 men would appear thus:—

| | |||||||||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Harquebuses. | Muskets. | Halberds. | Muskets. | Harquebuses. | |||||

| Archers. | Pikes. | Pikes. | Archers. | ||||||

The musket carried a ball which weighed 1/10 of a pound; and the harquebus a ball which weighed 1/25 of a pound.

[2] The 30th, 31st, and 32nd Regiments were formed as Marine corps in 1702, and were employed as such during the wars in the reign of Queen Anne. The Marine corps were embarked in the Fleet under Admiral Sir George Rooke, and were at the taking of Gibraltar, and in its subsequent defence in 1704; they were afterwards employed at the siege of Barcelona in 1705.

[3] The brave Sir Roger Williams, in his Discourse on War, printed in 1590, observes:—"I persuade myself ten thousand of our nation would beat thirty thousand of theirs (the Spaniards) out of the field, let them be chosen where they list." Yet at this time the Spanish infantry was allowed to be the best disciplined in Europe. For instances of valour displayed by the British Infantry during the Seventy Years' War, see the Historical Record of the Third Foot or Buffs.

[4] Vide the Historical Record of the First, or Royal Regiment of Foot.

[5] "Under the blessing of Divine Providence, His Majesty ascribes the successes which have attended the exertions of his troops in Egypt to that determined bravery which is inherent in Britons; but His Majesty desires it may be most solemnly and forcibly impressed on the consideration of every part of the army, that it has been a strict observance of order, discipline, and military system, which has given the full energy to the native valour of the troops, and has enabled them proudly to assert the superiority of the national military character, in situations uncommonly arduous, and under circumstances of peculiar difficulty."—General Orders in 1801.

In the General Orders issued by Lieut.-General Sir John Hope (afterwards Lord Hopetoun), congratulating the army upon the successful result of the Battle of Corunna, on the 16th of January, 1809, it is stated:—"On no occasion has the undaunted valour of British troops ever been more manifest. At the termination of a severe and harassing march, rendered necessary by the superiority which the enemy had acquired, and which had materially impaired the efficiency of the troops, many disadvantages were to be encountered. These have all been surmounted by the conduct of the troops themselves; and the enemy has been taught, that whatever advantages of position or of numbers he may possess, there is inherent in the British officers and soldiers a bravery that knows not how to yield,—that no circumstances can appal,—and that will ensure victory when it is to be obtained by the exertion of any human means."

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE FORMATION OF THE REGIMENT

IN 1685,

AND OF ITS SUBSEQUENT SERVICES

TO 1846.

COMPILED BY

RICHARD CANNON, Esq.,

ADJUTANT-GENERAL'S OFFICE, HORSE-GUARDS.

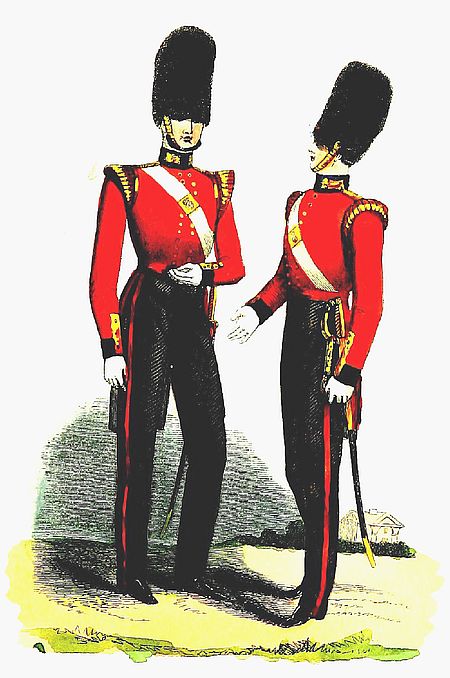

ILLUSTRATED WITH PLATES.

LONDON:

PARKER, FURNIVALL, & PARKER,

30 CHARING CROSS.

MDCCCXLVII.

London: Printed by W. Clowes and Sons, Duke Street, Stamford Street,

For Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

THE SEVENTH REGIMENT,

OR

THE ROYAL FUSILIERS,

BEARS IN THE CENTRE OF ITS REGIMENTAL COLOUR,

THE ROSE WITHIN THE GARTER AND THE CROWN OVER IT;

AND IN THE CORNER THE WHITE HORSE;

ALSO THE WORD

"MARTINIQUE,"

FOR ITS GALLANT CONDUCT AT THE CAPTURE OF THAT ISLAND IN 1809;

AND THE WORDS

"TALAVERA," "ALBUHERA," "BADAJOZ,"

"SALAMANCA," "VITTORIA," "PYRENEES," "ORTHES,"

"TOULOUSE," "PENINSULA,"

TO COMMEMORATE ITS DISTINGUISHED SERVICES IN THE

PENINSULA AND SOUTH OF FRANCE

FROM 1809 TO 1814.

| Year | Page | |

| 1685 | Formation of the Regiment | 1 |

| —— | Names of Officers | 3 |

| —— | Uniform of the Regiment | 4 |

| 1688 | Augmentation of the Establishment | 6 |

| 1689 | Proceeds to Holland | 8 |

| —— | Battle of Walcourt | – |

| 1690 | Returns to England | 9 |

| —— | Proceeds to Ireland, and is engaged in the Sieges of Cork and Kinsale | 10 |

| 1691 | Embarks for Flanders | — |

| —— | Serves the Campaign under King William III. | 11 |

| 1692 | Battle of Steenkirk | — |

| 1693 | Battle of Landen | 13 |

| 1694 | Reviewed by King William III. | 15 |

| 1695 | Siege of Namur | 16 |

| 1696 | Arrives at Gravesend, but returns to Flanders without landing in England | 18 |

| —— | Joins the Army of Flanders under the Prince of Vaudemont | — |

| 1697 | Returns to England | — |

| —— | Placed on a Peace Establishment | — |

| 1698 | Proceeds to Jersey and Guernsey | — |

| 1702 | Forms part of the force employed in the Expedition under the Duke of Ormond against Cadiz | 19 |

| 1702 | [xxiv] Capture of the Towns of Rota, Port St. Mary's, and Fort St. Catherine | 19 |

| —— | Sails for England, after having destroyed the Enemy's Shipping at Vigo | 20 |

| 1703 | Employed as Marines on board the Fleet | — |

| 1705 | Stationed at Plymouth | — |

| 1706 | Proceeds to Barcelona | 21 |

| 1707 | Stationed in Spain | — |

| —— | Capture of Lerida | 22 |

| 1708 | Returns to England | — |

| 1709 | Proceeds to Spain | 23 |

| 1710} | ||

| TO } | Stationed at Minorca | — |

| 1719} | ||

| —— | Returns to England | — |

| 1719} | ||

| TO } | Stationed in Ireland | — |

| 1727} | ||

| 1734 | Proceeds to Gibraltar | — |

| 1749 | Returns to Ireland | — |

| 1751 | Authorized by Royal Warrant to continue to bear certain Distinctions | 24 |

| 1755 | Arrives in England from Ireland | — |

| 1756 | Serves as Marines on board the Fleet under Admiral Byng | — |

| —— | Engaged with the French Fleet off Minorca | — |

| —— | Forms part of the Garrison of Gibraltar | — |

| 1763 | Embarks for England | — |

| 1765 | Proceeds to Scotland | — |

| 1770 | Returns to England | — |

| 1773 | Embarks for Canada | — |

| 1775 | Forms part of the Garrison of St. John's and Fort Chambly | 25 |

| —— | Siege of Quebec | 26 |

| 1776 | [xxv] Operations in Canada | 27 |

| —— | Proceeds to New York | — |

| 1777 | Action at Staten Island | — |

| —— | Capture of Forts Montgomery, Clinton, and Constitution | 29 |

| —— | Engaged with the Americans at Philadelphia | 30 |

| 1779 | Capture of Newhaven | — |

| —— | Expedition against Fairfield and Norwalk | 31 |

| 1780 | Capture of Charleston | 32 |

| 1781 | Engagement at Cow-Pens | 33 |

| 1782 | Stationed in South Carolina and New York | — |

| 1783 | Returns to England | 34 |

| —— | Reduction of Establishment | — |

| 1786 | Proceeds to Scotland | — |

| 1790 | Embarks for Gibraltar | — |

| 1791 | Proceeds to Canada | — |

| 1794 | Stationed in Nova Scotia | — |

| 1795 | Formed into two Battalions | 35 |

| 1796 | Incorporated into one Battalion | — |

| 1802 | Proceeds to Bermuda and the Bahamas | 36 |

| 1804 | A second Battalion added | — |

| 1806 | Returns to England | 37 |

| 1807 | The First Battalion proceeds to Ireland | — |

| —— | ———————– embarks for Denmark | — |

| —— | Siege of Copenhagen | — |

| —— | The First Battalion returns to England | — |

| 1808 | ———————– embarks for Nova Scotia | 38 |

| —— | The Second Battalion proceeds to Ireland | — |

| 1809 | Capture of Martinique | — |

| —— | Authorized to bear the word "Martinique" on its Colours | 41 |

| —— | Returns to Nova Scotia | — |

| —— | The Second Battalion proceeds to Portugal | 45 |

| —— | Expulsion of the French from Oporto | — |

| 1809 | [xxvi] Battle of Talavera | 46 |

| —— | Authorized to bear the word "Talavera" on its Colours | 48 |

| 1810 | Removal of the First Battalion from North America to the Peninsula | 49 |

| —— | Battle of Busaco | 50 |

| 1811 | Siege of Olivenza | 53 |

| —— | Blockade of Badajoz | — |

| —— | Battle of Albuhera | 54 |

| —— | Authorized to bear the word "Albuhera" on its Colours | 62 |

| —— | Blockade of Ciudad Rodrigo | 65 |

| —— | Action at Aldea de Pont | — |

| 1812 | Capture of Ciudad Rodrigo | 66 |

| —— | Siege of Badajoz | 67 |

| —— | Authorized to bear the word "Badajoz" on its Colours | 69 |

| —— | Battle of Salamanca | 71 |

| —— | Authorized to bear the word "Salamanca" on its Colours | 72 |

| 1813 | Attack on the village of Montevite | 74 |

| —— | Battle of Vittoria | 75 |

| —— | Authorized to bear the word "Vittoria" on its Colours | — |

| —— | Blockade of Pampeluna | 76 |

| —— | Battle of the Pyrenees | — |

| —— | Authorized to bear the word "Pyrenees" on its Colours | 79 |

| —— | Passage of the Bidassoa | — |

| 1814 | Battle of Orthes | 80 |

| —— | Authorized to bear the word "Orthes" on its Colours | — |

| —— | Battle of Toulouse | 81 |

| —— | Returns to England | 82 |

| 1814 | [xxvii] First Battalion proceeds to North America | 83 |

| 1815 | Operations against New Orleans | 84 |

| —— | Attack on Mobile and Capture of Fort Bowyer | 87 |

| —— | Embarks for England | — |

| —— | Proceeds to Flanders | — |

| —— | Advances to Paris | — |

| —— | Second Battalion disbanded | 88 |

| —— | A Recruiting Company added to the First Battalion | — |

| 1816 | Forms part of the Army of Occupation in France | — |

| 1817} | Reduction of Establishment | 89 |

| 1818} | ||

| 1818 | Returns to England | 90 |

| —— | Proceeds to Ireland | — |

| 1820 | Embarks for Scotland | — |

| 1821 | Marches to England | — |

| 1825 | Divided into Service and Depôt Companies | 91 |

| —— | Service Companies embark for the Ionian Islands | — |

| 1828 | Stationed at Malta | — |

| 1833 | Depôt Companies proceed to Ireland | — |

| 1836 | Service Companies return to England | — |

| —— | Presentation of a piece of plate by command of His Majesty King William IV. | — |

| 1837 | Service Companies proceed to Ireland | 92 |

| 1839 | Service Companies embark for Gibraltar | — |

| 1841 | Depôt Companies proceed to England | — |

| 1844 | Service Companies embark for the West Indies | — |

| 1845 | Depôt Companies return to Ireland | — |

| 1846 | The Conclusion | 93 |

| Year | Page | |

| 1685 | George Lord Dartmouth | 95 |

| 1689 | John Earl of Marlborough | 98 |

| 1692 | Lord George Hamilton | 103 |

| 1692 | Edward Fitzpatrick | 104 |

| —— | Sir Charles O'Hara | 105 |

| 1713 | The Honourable James O'Hara | 106 |

| 1739 | William Hargrave | 107 |

| 1751 | John Mostyn | —– |

| 1754 | Lord Robert Bertie | 108 |

| 1776 | Richard Prescott | —– |

| 1788 | The Honourable William Gordon | —– |

| 1789 | His Royal Highness The Duke of Kent | 109 |

| 1801 | Sir Alured Clarke | 113 |

| 1832 | Sir Edward Blakeney | —– |

OF

THE SEVENTH REGIMENT,

OR

THE ROYAL FUSILIERS.

The invention of gunpowder was speedily followed by the introduction of cannon; but many years elapsed before a corps of artillery was added to the army. The guns were fired by men hired for the purpose, under the direction of a master-gunner, and an officer styled the Master of the Ordnance, and the whole were under the orders of the Master-general of the Ordnance. Non-commissioned officers and private soldiers of infantry regiments were frequently employed as gunners; and the care and protection of the guns were confided to particular corps. On the augmentation of the army during the rebellion of James Duke of Monmouth, in the summer of 1685, King James II. resolved, that the first infantry corps raised on that occasion should be an Ordnance Regiment, for the care and protection of the cannon; of which corps His Majesty appointed George Lord Dartmouth, then Master-general of the Ordnance, colonel, by commission dated the 11th of June, 1685.

The regular regiments of foot were composed, at this period, of Musketeers,—men armed with muskets and swords; Pikemen,—armed with long pikes and swords; and Grenadiers,—armed with hand-grenades, muskets, bayonets, swords, and small hatchets; but in the Ordnance Regiment every man carried a long musket called a fusil, with a sword and bayonet, from which peculiarity in the arming, the regiment obtained the designation of "Fusiliers;" and the King being desirous of appearing publicly to patronize this new corps, conferred upon it the title of "Royal Fusiliers."[6]

Regiments of infantry had, originally, a colour to each company, which was called an ensign, and was carried by the junior subaltern officer of each company, who was styled "ancient," and afterwards "ensign," which term signified "colour-bearer." The regiments of fusiliers did not have colours or ensigns to each company, consequently the title of ensign or colour-bearer was not given to the junior subaltern officer of each company; but having, in consequence of the peculiar services they were called upon to perform, a care and responsibility equal to that of a lieutenant, both the subaltern officers of each company were styled lieutenants. They were both placed on the same rate of pay; but the terms first lieutenant and second lieutenant were used in their commissions for several years, and afterwards discontinued.

The regiment consisted of thirteen companies,—twelve[3] of fusiliers and one of miners; each company consisting of three officers, three serjeants, three corporals, two drummers, and one hundred private men. The two first companies were of very old date; having been independent companies in the Tower of London many years; the other ten companies were raised in London and its vicinity by George Lord Dartmouth,[7] Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Talmash or Tollemache, afterwards colonel of the fifth foot and second foot guards; Richard Fowler, Major Beckman, Henry Cornwall, Sir John Morgan, John Boyce, Thomas Whalley, Charles Fitzwilliams, and Henry Vaughan; and the company of[4] miners by Captain James Adams. Thomas Talmash was appointed to the lieutenant-colonelcy; and Robert St. Clair, who commanded one of the old independent companies, obtained the commission of major. The uniform was scarlet coats, lined with yellow; grey breeches and grey stockings; and the men wore yellow cloth caps, ornamented with military devices similar to those afterwards adopted for grenadiers; the other regiments of foot wore round hats with broad brims turned up on one side.

The regiment was speedily raised, and on the 4th of July the several companies were directed to proceed to the Tower of London, and perform the duties of that fortress. The rebellion being soon afterwards suppressed, and the Duke of Monmouth beheaded, the regiment was reduced to eleven companies of fusiliers, of three officers, three serjeants, three corporals, two drummers, and fifty private soldiers each; and one company of miners, of two officers, one serjeant, two corporals, one drummer, and forty miners.

After the suppression of the rebellion, King James formed a camp on Hounslow-heath; where the Scots brigade in the service of Holland, and a numerous body of English cavalry and infantry, were assembled, and the Royal Fusiliers proceeded to the camp in charge of the train of artillery. When the camp was broken up, the regiment returned with the guns to the Tower of London, from whence three companies were detached to Sheerness, where they were directed to remain in garrison.[8]

During the summer of 1686 the Royal Fusiliers were again encamped in charge of the train of artillery on Hounslow-heath. The corps assembled on the heath consisted of three troops of life guards, nine regiments of cuirassiers, three of dragoons, and thirteen battalions of foot. In a description of the camp, written at the time, and published in the Antiquarian Repertory, it is stated:—"The horse, foot, and dragoons are encamped in a straight line; the intervals between the foot is seventy paces, the intervals between each regiment of horse about fifty paces, and the interval between the horse on the left and the dragoons (because of the ground) is near half mile. The lieutenants' and ensigns' tents are in the rear of the respective companies in a direct line, seventeen paces from the soldiers' huts or tents; the captains' tents twelve paces behind the lieutenants'; the colonels' tents behind the captains', ten paces; the lieutenant-colonel on the right of the colonel, and the major on the left in a direct line. The brigadier-generals have their tents twenty paces behind the colonels'. The King's tent and chappel is in the rear of the left of the horse on the left, and the general officers' tents behind the[6] King's. The Fusiliers are encamped in the rear of the line, a good distance behind the interval between the Earl of Craven's regiment and the Scots guards; and in several parties about the horse carriages. The guns are planted about a hundred paces before the line, before the interval between the Scots guards and Prince George's regiment, guarded by a party of Fusiliers; each gun having two gunners and a matrosse to attend it. The suttling booths are about two hundred paces in the rear of the line."

In August the Royal Fusiliers struck their tents, and, returning to the Tower with the guns, were stationed at that fortress during the remainder of the year.

The establishment was again augmented to thirteen companies in the spring of 1687, as appears by the following warrant:—

"JAMES R.

"Whereas we have thought fit to add one company more to Our Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, and to apply the pay of one of the non-regimented companies mentioned in Our establishment to the entertainment of the said company of Fusiliers, with the addition of one shilling per diem to the youngest lieutenant, and one shilling and sixpence for the pay of one serjeant, and one shilling for one drummer more, Our will and pleasure is, that you include the pay of the said company, and additional allowances, within the certificates or debentures you shall from time to time make out for the pay of Our said Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, to commence from the 1st of January last; and for so doing this shall be your sufficient warrant.

"Given at Our Court at Whitehall this 12th day of March, 1686-7, in the third year of Our reign.

"By His Majesty's Command.

| (Signed) | "Sunderland P. | Shep. Fox. |

| "Bellasis. | J. Ernle. |

"To the Paymaster-General,

&c. &c. &c."

In the summer of 1687 and 1688, the Royal Fusiliers were again encamped on Hounslow-heath. On the 1st of September, 1688, an augmentation of ten men per company was made to the establishment, which consisted, at this period, of eleven companies of fusiliers, one of grenadiers, and one of miners.

The King having manifested a determination to establish papacy and arbitrary government, many noblemen and gentlemen solicited the aid of William Henry Prince of Orange to enable them to oppose the proceedings of the court. On the receipt of information of warlike preparations in Holland, a strong detachment of the Royal Fusiliers embarked on board of men-of-war, to serve as marines, and sailed to the Nore. The fleet was commanded by their colonel, Admiral Lord Dartmouth, whose loyalty to King James II. was not doubted; but the rear-admiral, Sir John Barry, and many of the captains, inferior officers, and seamen, entertained sentiments favourable to the Prince of Orange; no collision, however, took place. While the English fleet was wind-bound at the mouth of the Thames, the Dutch armament passed along the British Channel with little molestation; the wind becoming more favourable, the English navy put to sea; but the Prince of Orange was so far in advance, that he landed on the Devonshire coast, on the[8] 5th of November, without interruption; and the wind changed immediately afterwards, and blew with such violence, that the English fleet was driven into Portsmouth harbour in a damaged condition. The sentiments entertained in the navy were also prevalent in the army; the troops refused to fight in the cause of Papacy and arbitrary government, and King James fled to France. The Royal Fusiliers landed and were ordered by the Prince of Orange to occupy quarters at Barnet.

From this period the Royal Fusiliers ceased to be considered exclusively as an Ordnance Regiment, and took their turn of duty with the regular regiments of the line: the regiment was not, however, furnished with a division of pikemen; but every man continued to be armed with a fusil.

Six companies were removed from Barnet to Yarmouth, where they took part, in February, 1689, in the proclamation of the accession of King William III. and Queen Mary to the throne. Shortly afterwards the regiment embarked for Holland, forming part of the force under Lieutenant-General the Earl of Marlborough, sent to assist the Dutch in their war with France in the place of the troops which the Prince of Orange had brought with him to England.

The Royal Fusiliers joined the Dutch army at Tongres, and served the campaign of this year under Prince Waldeck. On the 25th of August a piquet under Colonel Hodges was attacked by the French forces under Marshal de Humières near Walcourt, and a sharp action ensued, in which the English infantry evinced firmness and intrepidity. The French were defeated with the loss of two thousand men killed and wounded; and King William, writing to the Earl of Marlborough[9] on this subject, observed,—"I am very happy that my troops behaved so well at Walcourt. It is to you that this advantage is principally owing."[9] In a few days after this event King William conferred the colonelcy of the Royal Fusiliers, which had been vacant some time, in consequence of the removal of Lord Dartmouth for adhering to the interests of King James, on the Earl of Marlborough, who held also the colonelcy of the third troop of life guards.

Before the following campaign the regiment returned to England, where it was stationed while King William was in Ireland, endeavouring to rescue that country from the power of King James, who had proceeded thither with a body of troops from France.

King William having defeated the Irish forces and their French allies at the Boyne, besieged Limerick. "During the time His Majesty was before the town, it was proposed by the Earl of Nottingham to My Lord Marlborough, and afterwards approved of in council, as very advantageous to their Majesties' affairs, to send a party from England, who, joining with a detachment from the King's army, might reduce the two important garrisons of Cork and Kinsale, and arrangements were made accordingly; but not being ready so soon as was designed, His Majesty, upon his return to England, sent the Earl of Marlborough, with his own regiment of Fusiliers, Brigadier Trelawny's (now fourth), Princess Anne's (eight), Colonel Hastings' (thirteenth), Colonel Hales', Sir David Collier's, Colonel Fitzpatrick's, one hundred of the Duke of Bolton's, two hundred of Monmouth's under Major Johnston, with Lord Torrington's[10] and Lord Pembroke's marine regiments, to undertake this service."[10] Arriving at Cork roads on the 21st of September, the fleet entered the harbour on the following day, and the co-operation of part of the army on shore having been secured, the Royal Fusiliers and other corps landed and commenced the siege. A breach having been made, the Royal Fusiliers and three other English regiments, commanded by Brigadier-General Churchill, and a body of Danes, passed the river wading up to the arm-pits to the east marsh, in order to storm the wall on that side. The grenadiers led the attack; but before they gained the breach, the Irish hung out a white flag, and agreed to surrender; the garrison, consisting of six regiments, became prisoners of war.

From Cork the Royal Fusiliers advanced towards Kinsale; the garrison vacated the town and retired to two strong forts. One of these forts was speedily reduced; the other held out until the middle of October, when the garrison surrendered on the condition of being permitted to proceed to Limerick.

The Royal Fusiliers were afterwards placed in garrison at Kinsale, where they remained three months.

The loss of the battle of Fleurus on the 21st of June, 1690, by the Dutch troops under Prince Waldeck, gave the French the ascendancy over the confederates in Flanders; and the Royal Fusiliers were selected to augment the forces in that country, where His Majesty resolved to command in person. The regiment embarked from Cork in January 1691, and sailing for Flanders experienced very severe weather at sea, and[11] two vessels, having on board part of the Fusiliers, were wrecked on the English coast, and many men perished. The remainder of the regiment landed at Ostend and went into quarters in West Flanders, where it was joined by a fine body of recruits and by a number of men who had been left sick at Kinsale.

When the army took the field, the Royal Fusiliers were formed in brigade with the regiments of Bath (tenth), Hodges (sixteenth), and Fitzpatrick (afterwards disbanded), commanded by Brigadier-General Churchill, and served the campaign of this year with the main army commanded by King William; but no general engagement occurred. The regiment passed the winter in cantonments among the Belgic peasantry.

The Earl of Marlborough, having fallen under the displeasure of King William, was removed from his commands, and was succeeded in the colonelcy of the Royal Fusiliers by Lord George Hamilton by commission dated the 23rd of January, 1692.

On the army taking the field, the regiment was again placed in the brigade commanded by Brigadier-General Churchill, and it served at the battle of Steenkirk on the 24th of July, 1692. On this occasion the leading column attacked the French forces commanded by Marshal Luxemburg with signal gallantry and success; but owing to the thick woods, with narrow and difficult defiles, which the army had to pass, together with the tardiness of Count Solms in obeying His Majesty's commands, some delay occurred. The Royal Fusiliers and a few other corps hastened through the defiles, and formed line at the skirts of the wood, where they were exposed to a heavy cannonade, and lost several men. In consequence of the delay which had occurred, the King ordered a[12] retreat, and the French did not venture to attack the army in its retrograde movement.

Sir Robert Douglas having been killed in the act of rescuing the colours of the first battalion of the Royals from the enemy, was succeeded in the colonelcy of that regiment by Lord George Hamilton; and the command of the Royal Fusiliers was conferred on Colonel Edward Fitzpatrick, from a newly-raised regiment, which had been disbanded.

On the 22nd of August the regiment was detached from the main army, with several other corps, under Lieutenant-General Talmash, to Furnes, where the troops encamped until the fortifications were put in a state of defence; the Royal Fusiliers afterwards proceeded to Dixmude, and were employed in repairing the works;[11] and after the completion of this service, they marched into quarters at Ghent, where they passed the winter.

Leaving Ghent in May, 1693, the regiment was in line at the celebrated position of Parck camp, where it was formed in brigade with the Royals (first), Queen Dowager's (second), Prince George of Denmark's (third), and the Queen's (fourth) regiments under Brigadier-General Churchill. After several movements the army was posted near the village of Landen, where it was attacked on the 19th of July by a French army of very superior numbers under Marshal Luxemburg.

The Royal Fusiliers were posted near the right of the confederate army, where a slight entrenchment had been made during the preceding night. As the first rays of morning light appeared in the horizon, waving masses of glittering arms, traversing the undulating grounds in front, gave indication of an approaching enemy, when the artillery opened a heavy fire, and the battle began. For some time the Fusiliers were spectators of the action, while much fighting took place at the villages of Laér, Neer-Winden, Neer-Landen, and the fortune of the day was everywhere in favour of the confederates; but eventually the position was forced at the village of Neer-Winden, and the Hanoverian Cavalry were broken. Heavy columns of pikemen and musketeers, consisting of the French brigades of Vermandois, Nice, Roussillon, and Sare, flanked by dragoons, and preceded by a cloud of grenadiers, approached the ground where the Royal Fusiliers were posted. Colonel Fitzpatrick was at the head of the regiment, and directed the men to reserve their fire until the near approach of their opponents. As the French soldiers sprang forward with their characteristic energy, and threw a shower of hand-grenades over the breast-work, a well-directed volley from the Fusiliers rent chasms in the French[14] ranks; but the survivors, being supported by an immense superiority of numbers, and urged forward by Marshal Villeroy, renewed the attack; while the marshal led a chosen body of men to the charge, and forced the right of the entrenchment. The Royal Fusiliers, and other corps at this part of the field, were attacked in front and flank, and a sanguinary conflict ensued. Colonel Fitzpatrick was carried from the field wounded, yet the Fusiliers stood their ground; ranks of opponents ascended the breast-work, and were speedily cut down or forced back. At length the British battalions were overpowered and driven from their ground. Stung with resentment at this disaster, they speedily rallied, and, rushing sword in hand upon their opponents, they once more regained the lost ground. A momentary pause ensued; but soon a fresh body of opponents renewed the fight, and the British regiments were again overpowered by superior numbers. The Fusiliers evinced the stern valour of British soldiers; their commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Whalley, fell mortally wounded; Major Wilson was removed bleeding to the rear; yet they disputed the ground with sanguinary tenacity until all chance of ultimate success had passed away, when they withdrew from the field, and joining a large body of infantry under Lieutenant-General Talmash, retired by the brook Beck upon Dormal, and thence to Lewe. The enemy attempted to interrupt the retreat; but the British battalions facing about to confront their pursuers, the French halted, and the retrograde movement of this body of men was performed with trifling loss; the remainder of the army had, however, to pass the river Gheet by a narrow bridge, and the defiles becoming choked with gun-carriages, the rear was severely[15] handled by the French, and the King narrowly escaped being taken prisoner.

The loss of the regiment on this occasion was very severe: among the killed were Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Whalley, an officer of distinguished merit, who raised one of the companies of the regiment at its formation in 1685, and Lieutenants Fairbrother, Cooper, and Blackmore; Captain Ruthwin died of his wounds: among the wounded were Colonel Edward Fitzpatrick, Major Wilson, Captains Harte, Betsworth, and Withers, and Lieutenant Fletcher; the loss in non-commissioned officers and private soldiers was very great; but the exact number has not been ascertained.

The regiment was employed in the movements of the main army until the end of the campaign, when it returned to Ghent, where it was stationed during the winter, together with three battalions of foot-guards, and the Queen Dowager's regiment of foot.

In the spring of 1694 a numerous body of recruits from England replaced the losses of the preceding campaign, and when the regiment took the field, it was reviewed by King William, and complimented on its martial appearance, and the steadiness with which it performed the simple manœuvres practised at that period. It served in the brigade under the orders of Brigadier-General Erle, and performed many long and toilsome marches in Flanders and Brabant; but no general engagement occurred, and it passed another winter in barracks at Ghent.

When the season for taking the field, in the spring of 1695, arrived, the British monarch appeared at the head of a splendid army of British, Spaniards, Dutch, and Germans; in the preceding years His Majesty had been[16] satisfied with arresting the progress of the French arms; but in 1695 he resolved to wrest the strong and important fortress of Namur from the power of Louis XIV. Colonel Fitzpatrick, having been eighteen months in England to recover of his wounds, rejoined the army on the 19th of June, and was placed at the head of a brigade, of which his own regiment of Fusiliers formed part. King William attacked Fort Kenoyne, and having drawn the French forces to the Flanders side of their line of entrenchments, he invested Namur. The Royal Fusiliers were detached from the army at Wonterghem to take part in the siege, and pitched their tents at Templeaux, a post about five miles from the town. On the 6th of July they were on duty in the trenches; on the 8th they marched into the lines of circumvallation, and in the evening of the same day a detachment was engaged in a successful attack on the covered way upon the hill of Bouge. The attack was made about seven in the evening; and such were the spirit and energy with which the British soldiers rushed upon their opponents, that the palisades were speedily broken down,—the covered way carried,—the French overpowered and chased among the works, many of them throwing themselves into stone pits to escape the fury of their assailants.

This success stimulated the soldiers to fresh exertions, and on the 17th of July, when the Royal Fusiliers were directed to take part in the storming of the counterscarp, they engaged in this service with a cheerful alacrity, which proved the ardour which glowed in every breast. The grenadiers led the assault, and, rushing to the glacis, cast their grenades over the palisades into the covered way. Following up this attack with spirit, the French were overpowered, the counterscarp was carried in gallant style,[17] and the Royal Fusiliers were thanked by King William for their distinguished bravery. They had Lieutenant Dancy killed and Captain Negus wounded; also a number of private men killed and wounded. The siege was prosecuted with vigour, and with such success that before the end of July the town was delivered up, Marshal Boufflers retiring with the garrison into the castle.

One hundred and thirty-six pieces of cannon and fifty mortars opened their fire on the castle of Namur on the 11th of August, and being continued without intermission, breaches were made in the Terra Nova and Cohorne, and on the night of the 20th of August, a detachment of the Royal Fusiliers was engaged under Lord Cutts in the attack of the counterscarp and breach of Terra Nova, and had several men killed and Captain Groves, Lieutenant Rainsford, and a number of men wounded. The fire of the artillery was continued, and preparations were made for another assault; but the further effusion of blood was prevented by the surrender of the place. After the repair of the works, the King, being satisfied with the capture of so important a place, dismissed the army to its winter quarters, and the Fusiliers returned to their usual station at Ghent.

During the following winter a conspiracy was formed in England for the assassination of King William: at the same time an insurrection was organised, and a French army was assembled near the coast to aid in the replacing of King James on the throne. A body of troops was immediately ordered to return from Flanders; and the Royal Fusiliers embarked at Sas van Ghent, sailed from thence to Flushing, where the transports were placed under the convoy of Dutch men-of-war, and, afterwards[18] resuming the voyage, arrived at Gravesend in March, 1696. The plot had, however, been discovered, the conspirators arrested, and the British fleet was manned and sent to sea; the French monarch's designs were thus frustrated, and the Fusiliers returned to Flanders without landing in England.

During the campaign of 1696 the regiment served with the Brabant army commanded by King William; but no fighting took place. In the beginning of September it joined the army of Flanders under the Prince of Vaudemont, and, encamping near the village of St. Michael, was employed in constructing works for the protection of Bruges. In October it marched to Ghent.

In November, 1696, Brigadier-General Sir Charles O'Hara was appointed colonel of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, in succession to Brigadier-General Fitzpatrick, drowned.

Leaving Ghent on the 13th of March, 1697, the regiment proceeded into village quarters between Brussels and Malines. Two companies were detached to form part of the garrison of Oudenarde, and the remainder subsequently encamped behind the forest of Soignies, where the men suffered much from wet weather and from the want of their clothing, which was due, but had not arrived from England.

The Royal Fusiliers took part in the operations of this campaign. In September a treaty of peace was signed at Ryswick, and during the winter the regiment returned to England; at the same time its numbers were reduced to a peace establishment.

In August, 1698, the regiment proceeded to Jersey and Guernsey, to relieve a corps of marines which was ordered to be disbanded.

The regiment remained in Jersey and Guernsey until 1702, when the accession of Philip Duke of Anjou (grandson of Louis XIV.) to the throne of Spain, to the prejudice of the House of Austria, had involved Europe in another war. This violation of existing treaties was followed by the Courts of France and Spain acknowledging the Pretender as King of Great Britain. Queen Anne declared war against France and Spain, and in the summer of 1702 three companies of the Royal Fusiliers were called from Jersey and Guernsey to take part in an expedition, under the Duke of Ormond, against the city of Cadiz; their colonel, Major-General Sir Charles O'Hara, was also employed in this enterprise. The fleet arrived off the coast of Andalusia in Spain, and a landing was effected in the middle of August, within a short distance from Cadiz. The wind being high, about thirty boats crowded with soldiers were overturned by the surge, and above twenty men of the Royal Fusiliers were drowned. The towns of Rota, and Port St. Mary's with Fort St. Catherine, were captured; but the fortress of Cadiz was found too strong, and the garrison too numerous to be reduced by the small expedition sent against it. The wealthy and flourishing town of Port St. Mary's was found deserted by the inhabitants, the houses well furnished, and much valuable merchandise in the warehouses. Strict discipline not being preserved, the town was plundered, and a great quantity of property was removed on board the fleet. Several officers were charged with participating in the plunder, and Sir Charles O'Hara was implicated and brought to trial, but was acquitted. The capture of Cadiz being found impracticable, the troops re-embarked, and sailed for England; but while at sea, information was received of the arrival of a valuable[20] Spanish fleet under a French convoy, at the harbour of Vigo, and the expedition immediately proceeded thither. A landing was effected on the south side of the river, above Vigo; a strong fort and a battery were captured; the British fleet forced an entrance, and the French and Spanish shipping were all captured or destroyed. The fleet afterwards returned to England; and the Duke of Ormond received the thanks of parliament for his success in this enterprize. The three companies of the Fusiliers were landed and placed in garrison at Tilbury, excepting fifty men, who were sent to the West Indies to complete Brigadier-General Gustavus Hamilton's regiment.

The war being continued, the Royal Fusiliers were employed during the summer of 1703 as marines on board the fleet: they afterwards landed, and were placed in garrison at Portsmouth, from whence a detachment was sent to the Isle of Wight in August, 1704. In 1705 the regiment was stationed at Plymouth.

In the meantime several regiments had been sent to Portugal; an armament under the Earl of Peterborough had captured Barcelona, and Catalonia and Valencia had declared in favour of Archduke Charles of Austria, who was acknowledged as sovereign of Spain by Great Britain, Holland, &c. The house of Bourbon assembled a well-appointed army and a powerful fleet to retake Barcelona, which was besieged by King Philip in April, 1706. King Charles remained in the city, that his presence might inspire confidence in the garrison, which was weak and ill provided with the means of defence. Succours were sent from England, and the Royal Fusiliers were embarked for this service. On the approach of the British squadron the French fleet retired. The Royal Fusiliers landed[21] at Barcelona on the 8th of May, and immediately marched to the breach to repel an expected attack by storm, which did not, however, take place. The arrival of the British fleet with reinforcements decided the fate of the town; and the army of King Philip raised the siege and retired, leaving its battering train and magazines behind.

From Barcelona the Royal Fusiliers marched a distance of forty-seven miles, to Gironne, a fortified town of Catalonia, situated at the base of a steep mountain, with the river Tar running through the town. Here the regiment passed in comfortable quarters among the Spaniards the remainder of the year 1706 and the early part of 1707. Provisions and wine were abundant, and the regiment was preserved in a state of efficiency.

While the Royal Fusiliers were at Gironne, the allied British, Portuguese, and Dutch army, was overpowered on the plains of Almanza on the 25th of April, 1707. Soon after this disaster the Royal Fusiliers traversed the country from Gironne to Lerida (anciently called Ilerda), a place celebrated in history for the beauty of its situation, the fertility of the adjacent country, and for having been the capital of the country of the Ilergetes long before the first invasion of Spain by the Romans. At this pleasant city, situated on the declivity of a hill on the west bank of the Segra, the Royal Fusiliers remained a short time, expecting the approach of the victorious French and Spanish forces. The officers and soldiers could view the ground where Scipio defeated Hanno, the Carthaginian general, and where Julius Cæsar conquered the lieutenants of Pompey; but no hope of victory could be entertained by the Royal Fusiliers in the approaching contest, the disparity of numbers being too great.

The garrison of Lerida consisted of the Royal Fusiliers, Wills's marines (now thirtieth regiment), with one Portuguese and two Dutch battalions, commanded by Prince Henry of Hesse d'Armstadt and Major-General Wills. A powerful French and Spanish army under His Royal Highness the Duke of Orleans and the Duke of Berwick invested the town on the 10th of September, and, having effected a breach, gave a general assault on the 12th of October. The garrison defended its post with admirable courage and resolution, and the firmness and steady valour of the Royal Fusiliers were conspicuous. The enemy having made a lodgment, the garrison vacated the town, and retired to the castle at the top of the hill, where a vigorous defence was continued until the water and provisions were expended, when the fortress was surrendered on honourable terms. The garrison marched, out on the 12th of November with colours flying, taking with them all their baggage and two pieces of cannon, and proceeded to join the army under the Earl of Galway.

The Royal Fusiliers, having sustained considerable loss in the defence of Lerida, returned to England in the spring of 1708 to recruit, and their colonel, Major-General Sir Charles O'Hara, was advanced to the peerage by the title of Baron Tyrawley.

During the winter of 1708 and spring of 1709 the regiment occupied extensive cantonments in Devonshire and Somersetshire, and its ranks were rapidly recruited.

This year Lieut.-General Stanhope formed the design of surprising Cadiz, and concerted measures with Admiral Sir George Byng, on board of whose squadron he embarked from Port Mahon with two regiments of foot, and sailed to Gibraltar to await the arrival of a body of troops from England. The Royal Fusiliers were selected to[23] take part in this enterprise, and they embarked at Portsmouth on board of the squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Baker; but the fleet was detained so long by contrary winds, that it did not reach Portugal until October, when the season was too far advanced for prosecuting this adventure, and the regiment sailed to Barcelona.

The island of Minorca having been captured in 1708, the Royal Fusiliers were selected to form part of the garrison of that important place during the remainder of the war, which was terminated in 1713 by the Treaty of Utrecht. By this treaty Minorca was ceded to Great Britain, and the regiment was one of the corps destined to remain on the island.

On the 29th of January, 1713, the colonelcy was conferred on the Honourable James O'Hara, in succession to his father, James Lord Tyrawley.

The Royal Fusiliers remained at Minorca until the spring of 1719, when they were relieved, and arrived at Plymouth in May of that year; in July they proceeded to Ireland, where they continued until 1727.

In 1727, when the Spaniards besieged Gibraltar, the regiment was ordered to return to England, and it was subsequently held in readiness to join the Dutch in their war with Austria; but no embarkation took place.

The regiment remained in Great Britain until 1734, when it proceeded to Gibraltar.

Lord Tyrawley having been removed to the fifth horse (now fourth dragoon guards) in August, 1739, his lordship was succeeded in the colonelcy by Major-General William Hargrave, from the ninth foot.

Leaving Gibraltar in 1749, the regiment proceeded to Ireland, where it was stationed six years.

In the royal warrant dated 1st July, 1751, the Royal Fusiliers are authorized to bear the following distinctions. "In the centre of their colours, the Rose within the Garter, and the Crown over it; the White Horse in the corners of the second colour. On the grenadier caps the Rose within the Garter, and Crown as in the colours. White Horse and motto over it, Nec aspera terrent. The same device of the Rose within the Garter, and Crown on their drums and bells of arms, with the rank of the regiment underneath."

On the decease of General Hargrave in January, 1751, the command of the Royal Fusiliers was conferred on Colonel John Mostyn, who was removed, in August, 1754, to the thirteenth dragoons, and was succeeded by Colonel Lord Robert Bertie.

In the spring of 1755 the regiment embarked from Dublin, and, having landed at Liverpool, occupied quarters in England until the breaking out of the Seven Years' War, when it was embarked on board the fleet commanded by Admiral Byng, in March, 1756, to serve as marines, and sent to the Mediterranean to endeavour to preserve Minorca from the power of the French. It served at the engagement with the French fleet off Minorca on the 20th of May; but the enemy had previously landed an army, and captured the whole island excepting Fort St. Philip, and the relief of this fort was not attempted. The admiral was afterwards brought to trial and shot.

The Royal Fusiliers landed at Gibraltar, and were stationed at that fortress during the remainder of the war. In 1763 they embarked for England; in 1765 they proceeded to Scotland; but returned to England in the spring of 1770, and in April, 1773, they embarked for Canada.

After performing garrison duty at Quebec several months, the regiment embarked for Montreal, and occupied several posts in Lower Canada.

While the Royal Fusiliers were in Lower Canada, the misunderstanding between Great Britain and her North American colonies, on the subject of taxes, attained a crisis; thirteen states united against the mother-country, and, hostilities having commenced, the Congress resolved to attempt the conquest of Canada. The only regular forces in Lower Canada, at this period, were the Seventh and twenty-sixth regiments, and their number being weak, they were unequal to the defence of this extensive province against the very superior numbers of the enemy: the eighth foot were in upper Canada.

In May, 1775, a body of Americans surprised and captured the posts of Ticonderoga and Crown-point; and this success was followed by the advance of two divisions of the American army at different points. The British governor, Lieut.-General Carlton, sent the Royal Fusiliers and twenty-sixth from Montreal to St. John's, where they were employed in constructing two redoubts.

In the autumn one division of the American army, under Colonel Montgomery (a native of Ireland, who had quitted the British service a short time before, and settled at New York), besieged St. John's. The garrison, consisting of five hundred and fifty men of the Seventh and twenty-sixth, and a few Canadian volunteers, commanded by Major Charles Preston of the twenty-sixth, had but a small supply of ammunition and provision, and the works were in an imperfect state, yet a most gallant resistance was made.

The American commander turned the siege into a blockade, and invested Fort Chambly, where Major the[26] Honourable Joseph Stopford of the Royal Fusiliers, and about eighty men, were in garrison. This post kept up the communication between St. John's and Montreal; but the works were not in a good condition; the place was not deemed capable of resisting artillery, and no effectual resistance could, consequently, be made against the very superior numbers of the enemy. The garrison surrendered on the 20th of October.

After this success Colonel Montgomery resumed the siege of St. John's, and the Seventh and twenty-sixth regiments made a determined resistance. The hardships they endured were borne with patience; they were often knee-deep in mire, and were reduced to half-allowance of provision; yet they held out with the most heroic bravery until their strength was exhausted, and no chance of being relieved remained, when they surrendered. Thus at the commencement of the war the Royal Fusiliers were nearly all made prisoners.

The enemy subsequently advanced upon Montreal, and Lieut.-General Carlton, being deserted by the Canadians, and without the means of defence, retired down the river St. Lawrence to Quebec, accompanied by a party of the Royal Fusiliers.

Quebec was besieged by two divisions of Americans under Colonels Montgomery and Arnold, and the garrison, of which sixty men of the Royal Fusiliers formed part, defended the place with firmness and intrepidity; the winter was particularly severe, and the soldiers of both sides served amidst ice and snow. About five o'clock on the morning of the 31st of December, during a storm of sleet and snow, the Americans made a general assault with the view of carrying the place by storm; but the garrison withstood the tempest of war with such determined[27] resolution, that the storming party was repulsed with the loss of between six and seven hundred men; Colonel Montgomery was killed, and Colonel Arnold wounded. The garrison only lost one officer and four private soldiers killed, and seven private soldiers wounded.

After this repulse the Americans turned the siege into a blockade, and placed their troops in village cantonments: in April, 1776, they resumed the siege, and the British defended the place with resolution. In the early part of May reinforcements arrived from England, and on the 6th of that month Lieut.-General Carlton marched out of the fortress at the head of the garrison to attack the American camp, when the besieging army made a precipitate retreat, leaving its artillery, stores, scaling ladders, &c., behind. The British followed their opponents up the country, recovered Montreal, and drove the Americans out of Canada.

In the meantime a detachment of the regiment had arrived at Boston from England, and on the evacuation of Boston, it proceeded to Halifax in Nova Scotia.

In October, 1776, Lord Robert Bertie was appointed to the command of the second troop (now second regiment) of life guards; and the colonelcy of the Royal Fusiliers was conferred on their lieut.-colonel, William Prescott, by commission dated the 12th of November, 1776.

In the autumn of this year the Royal Fusiliers transferred their services from Canada to New York; as the men taken prisoners were exchanged, the numbers of the regiment were increased; clothing and appointments arrived from England, and the regiment occupied quarters for the winter at Amboy in Middlesex county.

From Amboy the Royal Fusiliers were removed to Staten Island, which was attacked in August, 1777, by[28] the Americans under General Sullivan, who were repulsed with loss.

At this period a British force under Lieut.-General Burgoyne was advancing from Canada upon Albany; at the same time another British army under General Sir William Howe was proceeding against Philadelphia; and Lieut.-General Sir Henry Clinton, who commanded at New York, resolved to penetrate into Jersey for a diversion in favour of both armies. The Royal Fusiliers, with several other corps, were accordingly embarked for this service, and on the 12th of September effected a landing at four different places without meeting with serious opposition. The Seventh, twenty-sixth, and fifty-second regiments, with a body of German grenadiers and three hundred provincials under Brigadier-General Campbell, landed at Elizabeth-Town-Point, at about four in the morning, and advanced up the country: the enemy opposed the march, and a sharp firing was kept up throughout the day. The King's forces, however, had the advantage; they took Newark, and were advancing on Aquakinack, when they received orders to halt and wait the advance of the troops which had effected a landing at the other points. The enemy afterwards appeared in force, and several skirmishes occurred, but the British succeeded in capturing four hundred head of cattle, four hundred sheep, and a few horses. On the 16th of September the Royal Fusiliers marched to Bergen Point, where they re-embarked and returned to Staten Island, without the loss of one man in this expedition, and with only Lieutenant Haymer and one private soldier wounded.

In October of the same year the Royal Fusiliers were embarked to join an expedition against the enemy's forts up Hudson's River. About three thousand men were[29] collected for this service from New York and the lines at Kingsbridge; and having embarked on board of transports, were convoyed up the river by some frigates and other armed vessels under Commodore Hotham. The troops landed at day-break on the 6th of October at Stony-point, and arrangements were immediately made for the attack of Forts Montgomery and Clinton. The troops had to march a distance of twelve miles over mountains, and to overcome many obstructions; they, however, surmounted every difficulty, and attacked the forts by storm on the same day. As the Americans were prepared, and their works strong, they made an obstinate defence; but nothing could withstand the ardour of the royal troops, and every corps gained a share in the glory. Fort Constitution was also taken on the 7th of October. Not far from these forts was a new settlement called Continential Village, where there was a barrack for fifteen hundred men. The Royal Fusiliers, with two German corps and two three-pounders, were sent against this place, and having destroyed the settlement and burnt the barrack and stores, the troops returned.

Notwithstanding these successful diversions, Lieut.-General Burgoyne experienced great difficulties in his advance, and eventually, his troops being exhausted with fatigue and privation, his advance opposed by superior numbers, and his retreat cut off, he capitulated. The army under General Sir William Howe had better success, and captured Philadelphia. The enemy having despatched part of the force originally opposed to Lieut.-General Burgoyne, to join their army of the south under General Washington, the Royal Fusiliers were sent from the vicinity of New York to reinforce the army in Pennsylvania, and in the early part of December they[30] were engaged in a skirmish with the Americans in front of Philadelphia; but only lost one man.