Title: Tudor school-boy life: the dialogues of Juan Luis Vives

Author: Juan Luis Vives

Translator: Foster Watson

Release date: January 2, 2018 [eBook #56286]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Clarity, Turgut Dincer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

TUDOR SCHOOL-BOY LIFE

All rights reserved.

THE DIALOGUES

OF

JUAN LUIS VIVES

TRANSLATED FOR THE FIRST TIME INTO ENGLISH

TOGETHER WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

FOSTER WATSON, M.A.

Professor of Education in the University College

of Wales, Aberystwyth

LONDON

J. M. DENT & COMPANY

MCMVIII

| Introduction— | PAGE | |

J. L. Vives: A Scholar of the Renascence | vii | |

The Significance of the Dialogues of J. L. Vives | xviii | |

The Dedication of the School-Dialogues of Vives | xxi | |

| Contents of the Dialogues | xxii | |

| Home and School Life | xxiii | |

| Subject-matter and Style | xxxii | |

| Popularity | xxxiv | |

| The Greek Words in Vives’ Dialogues | xxxv | |

| Euphrosynus Lapinus | xxxvi | |

| Style | xxxvi | |

Characteristics of Vives as a Writer of Dialogues | xxxvii | |

| Vives as a Precursor of the Drama | xxxvii | |

| Some Educational Aspects of Vives’ Dialogues | xxxix | |

| Vives’ Idea of the School | xxxix | |

| Games | xli | |

| Nature Study | xliv | |

| Wine-drinking and Water-drinking | xlv | |

| The Vernacular | xlvi | |

| The Educational Ideal of Vives | xlviii | |

Vives’ Last Dialogue: The Precepts of Education | l | |

| Dialogues | ||

| I. | Surrectio Matutina—Getting up in the Morning | 1 |

| II. | Prima Salutatio—Morning Greetings | 6 |

| III. | Deductio ad Ludum—Escorting to School | 9 |

| vi IV. | Euntes ad Ludum Literarium—Going to School | 11 |

| V. | Lectio—Reading | 18 |

| VI. | Reditus Domum et Lusus Puerilis—The Return Home and Children’s Play | 21 |

| VII. | Refectio Scholastica—School Meals | 26 |

| VIII. | Garrientes—Students’ Chatter | 39 |

| IX. | Iter et Equus—Journey on Horseback | 55 |

| X. | Scriptio—Writing | 65 |

| XI. | Vestitus et Deambulatio Matutina—Getting Dressed and the Morning Constitutional | 80 |

| XII. | Domus—The New House | 93 |

| XIII. | Schola—The School | 101 |

| XIV. | Cubiculum et Lucubratio—The Sleeping-room and Studies by Night | 109 |

| XV. | Culina—The Kitchen | 117 |

| XVI. | Triclinium—The Dining-room | 125 |

| XVII. | Convivium—The Banquet | 132 |

| XVIII. | Ebrietas—Drunkenness | 150 |

| XIX. | Regia—The King’s Palace | 163 |

| XX. | Princeps Puer—The Young Prince | 172 |

| XXI. | Ludus Chartarum seu Foliorum—Card-playing or Paper-games | 185 |

| XXII. | Leges Ludi—Laws of Playing | 198 |

| XXIII. | Corpus Hominis Exterius—The Exterior of Man’s Body | 210 |

| XXIV. | Educatio—Education | 219 |

| XXV. | Praecepta Educationis—The Precepts of Education | 234 |

| Index | 243 | |

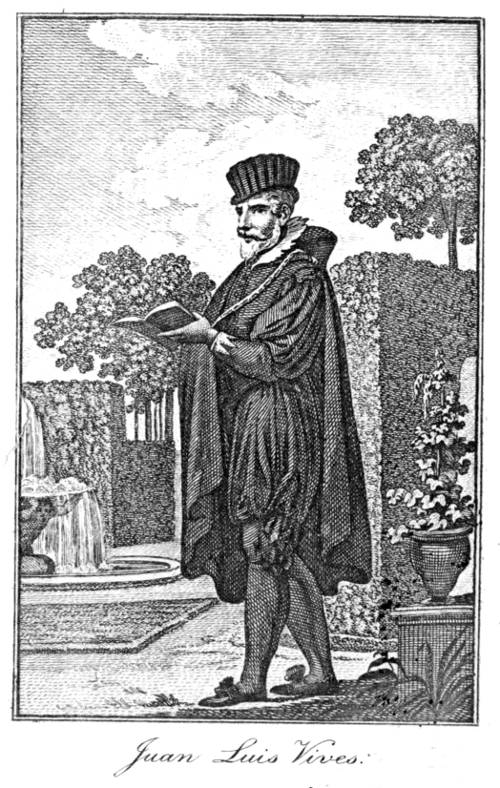

Erasmus was born in 1466, Budé (Budaeus) in 1468, and Vives in 1492. These great men were regarded by their contemporaries as a triumvirate of leaders of the Renascence movement, at any rate outside of Italy. The name of Erasmus is now the most generally known of the three, but in one of his letters Erasmus stated his fear that he would be eclipsed by Vives. No doubt Erasmus was the greatest propagandist of Renascence ideas and the Renascence spirit. No doubt Budé, by his Commentarii Linguae Graecae (1529), established himself as the greatest Greek scholar of the age. Equally, without doubt, it would appear to those who have studied the educational writings of Erasmus, Budé, and Vives, the claim might reasonably be entered for J. L. Vives that his De Tradendis Disciplinis placed him first of the three as a writer on educational theory and practice. In 1539 Vives published at Paris the Linguae Latinae Exercitatio, i.e., the School Dialogues which are for the first time, in the present volume, presented to the English reader.

Juan Luis Vives was born, March 6, 1492 (the year of Columbus’s discovery of America), at Valencia, in Spain. His father was Luis Vives, of high-born ancestry, whose device was Siempre vivas. Similarly his mother, Blanca March, was of a good family, which had produced several poets. Vives himself has described his parents, their relation to each otherviii and to himself, in two passages in his De Institutione Feminae Christianae (1523). This work was translated into English (c. 1540) by Richard Hyrde. As the two passages contain all that is known of the parents, and give a short but picturesque idea of the household relations, I transcribe them from Hyrde’s translation: “My mother Blanca, when she had been fifteen years married unto my father, I could never see her strive with my father. There were two sayings that she had ever in her mouth as proverbs. When she would say she believed well anything, then she used to say, ‘It is even as though Luis Vives had spoken it.’ When she would say she would anything, she used to say, ‘It is even as though Luis Vives would it.’ I have heard my father say many times, but especially once, when one told him of a saying of Scipio African the younger, or else of Pomponius Atticus (I ween it were the saying of them both), that they never made agreement with their mothers. ‘Nor I with my wife,’ said he, ‘which is a greater thing.’ When others that heard this saying wondered upon it, and the concord of Vives and Blanca was taken up and used in a manner for a proverb, he was wont to answer like as Scipio was, who said he never made agreement with his mother, because he never made debate with her. But it is not to be much talked in a book (made for another purpose) of my most holy mother, whom I doubt not now to have in heaven the fruit and reward of her holy and pure living.”

Vives states that he had the intention of writing a “book of her acts and her life,” and no one who reads the foregoing passage will be otherwise than regretful that he failed to carry out this purpose. As it is, we must content ourselves with another passage.1

“No mother loved her child better than mine did; nor any child did ever less perceive himself loved of his mother than I. She never lightly laughed upon me, she never cockered me; and yet when I had been three or four days out of her house, she wist not where, she was almost sore sick; and when I was come home, I could not perceive that ever she longed for me. Therefore there was nobody that I did more flee, or was more loath to come nigh, than my mother, when I was a child; but after I came to man’s estate, there was nobody whom I delighted more to have in sight; whose memory now I have in reverence, and as oft as she cometh to my remembrance I embrace her within my mind and thought, when I cannot with my body.”

Vives went to the town school of Valencia. The outlines of the history of this school have been sketched by Dr. Rudolf Heine.2 The foundation of the school dates back to the time of James I. of Aragon, when Pope Innocent IV. gave privileges to the newly founded school in 1245. The school, Dr. Heine says, was first a schola, then a studium, then a gymnasium, and in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was known as an academy, the name by which Vives describes schools in the Colloquies. In 1499 new statutes were drawn up for the Valencia Academy, ordaining the teaching of grammar, logic, natural and moral philosophy, metaphysics, canon and civil law, poetry, and “other subjects such as the city desires and requires.”

The spirit of scholasticism reigned supreme in the Valencian Academy when Vives was a pupil. The dominant subject of study was dialectic, and the all-controlling method of education was the disputation. Vives thus received a thorough drilling in dialectic and disputation. When Vives became a convert to the Renascence interest of literature and grammar, xhe was thus well prepared by his experience in the Valencian Academy for an effective onslaught on the old disputational methods. How deeply interwoven these methods were in the school instruction may be seen in Vives’ own words:—

“Even the youngest scholars (tyrones) are accustomed never to keep silence; they are always asserting vigorously whatever comes uppermost in their minds, lest they should seem to be giving up the dispute. Nor does one disputation or even two each day prove sufficient, as for instance at dinner. They wrangle at breakfast; they wrangle after breakfast; before supper they wrangle, and they wrangle after supper.... At home they dispute, out of doors they dispute. They wrangle over their food, in the bath, in the sweating-room, in the church, in the town, in the country, in public, in private; at all times they are wrangling.”

The names of two of Vives’ schoolmasters are preserved, Jerome Amiguetus and Daniel Siso. Amiguetus was a thorough-going scholastic, teaching by the old mediæval methods, and a stalwart opponent of the Renascence. Spain generally resisted the Revival of Learning, and wished to have a ban placed even on the works of Erasmus. But in the person of Antonio Calà Harana Del Ojo, better known as Antonio de Lebrijà (or Antonius Nebrissensis), a doughty champion of classicism appeared and raised a Spanish storm. In 1492, the year of Vives’ birth, Antonio published a grammar and a dictionary, and had the hardihood to present his learning in the Spanish language. About 1506 it was proposed to introduce Antonio’s Introductiones Latinae into the Valencian Academy. This suggestion was strenuously opposed by Amiguetus. With the enthusiasm of a school-boy of fourteen years of age, Vives espoused the side of his teacher, and by declamation and by pen supported the old methods.xi But when he published his De Tradendis Disciplinis (1531) more than a quarter of a century afterwards, he paid Lebrijà the praise which as a school-boy he had withheld, recognising his varied and broad reading, his intimate knowledge of classical writers, his glorious scholarship, and his modesty in only claiming to be a grammarian.

Of Vives’ school-life little more can be gathered, except indeed what in his writings may be surmised to be the reminiscences of his own boy-life. We find glimpses of this kind in the Dialogues. For example, in the twenty-second Dialogue—which expounds the laws of school games—he describes his native town and early environment.

In 1509 Vives went to Paris to continue his studies. Amongst the teachers under whom he studied here was the Spanish John Dullard. Vives tells us that Dullard used to say: Quanto eris melior grammaticus, tanto pejus dialecticus et theologus!3 Nevertheless, Paris had awakened Vives to the unsatisfactory nature of a one-sided training in dialectic. In 1512 he proceeded to Bruges. He became tutor in a Spanish family, by name Valdaura. One of the daughters, Margaret, whom he taught, he afterwards (in 1524) married. He speaks of the mother of the family, Clara Cervant, in the highest terms, and regarded her—next to his own mother—as the highest example of womanly devotion to duty he had ever known, for she had nursed her husband, it is said, from their marriage day for many years through a severe and obstinate illness. Whilst at Bruges his thoughts gathered strength in the direction of the Renascence. In 1514 he suggests that Ferdinand of Spain would do well to get Erasmus as tutor in his family, for he says Erasmus is known to him personally, and is all that is dear and worthy. It is thus certain xiithat Vives was confirmed by Erasmus in the study of classical literature as transcending all the old mediæval educational disciplines.

From 1512 onwards, with breaks, Vives’ main quarters were in Flanders, at Bruges or Louvain, at the former of which was the residence of many of his Spanish compatriots. One of these breaks of residence was in 1514 at Paris, another at Lyons in 1516. In 1518 Vives was at Lyons, where he was entrusted with the education of William de Croy, Cardinal designate and Archbishop of Toledo. The course of instruction which he gave was founded on a thorough reading of the ancient authors and instruction in rhetoric and philosophy. At Lyons, too, Vives met Erasmus. “Here we have with us,” writes Erasmus in one of his letters, “Luis Vives, who has not passed his twenty-sixth year of age. Young as he is, there is no part of philosophy in which he does not possess a knowledge which far outstrips the mass of students. His power of expression in speech and writing is such as I do not know any one who can be declared his equal at the present time.” In 1519 Vives was at Paris, where he became personally acquainted with the great William Budé. Of him Vives, in one of his letters to Erasmus, writes, “What a man! One is astounded at him whether we consider his knowledge, his character, or his good fortune.” But more interesting to English readers, is a letter about this time (1519) of Sir Thomas More on seeing some of the published work of Vives himself. He says: “Certainly, my dear Erasmus, I am ashamed of myself and my friends, who take credit to ourselves for a few brochures of a quite insignificant kind, when I see a young man like Vives producing so many well-digested works, in a good style, giving proof of an exquisite erudition. How great is his knowledge of Greek and Latin; greater still is the way in which he is versed in branches of knowledgexiii of the first rank. Who in this respect is there who surpasses Vives in the quantity and depth of his knowledge? But what is most admirable of all is that he should have acquired all this knowledge so as to be able to communicate it to others by instruction. For who instructs more clearly, more agreeably, or more successfully than Vives?”

At this point may be stated the chief works which Vives so far had written:—

1507. The boyish Declamationes in Antonium Nebrissensem (not extant).

1509. Veritas Fucata, in which he designates the contents of the classics as “food for demons.”

1514. Jesu Christi Triumphus.

1518. De Initiis, Sectis et Laudibus Philosophiae, perhaps the first modern work on the history of philosophy.

1519. In Pseudo-dialecticos. This famous treatise pours its invective and indignation against the formalistic disputational dialectic of the schools of Paris, and marks Vives’ complete break with scholastic mediævalism, and his acceptance of the Renascence material of knowledge and methods of inquiry.

1519. Pompeius Fugiens.

1519. Praelectio in Quartum Rhetoricorum in Herennium.

1519. The Dialogue called Sapiens.

1519. Praelectio in Convivia Philelphi.

1519. Censura de Aristotelis Operibus.

1519. Edited Somnium Scipionis, the introduction to which was afterwards known as Somnium Vivis. Vives here regards Plato as the herald of Christianity.

1520. Sex Declamationes.

1520. Aedes Legum. In this book Vives made important suggestions founded on Roman law for the improvement of law in his own times.

At the beginning of 1521 Vives’ old pupil and patron, Cardinal de Croy, died. It was at this time he took in hand his great work, the commentary on St. Augustine’s Civitas Dei. Erasmus suggested the work to him, so that Vives might do for St. Augustine what Erasmus himself had done for the works of St. Jerome. Vives’ edition of St. Augustine’s Civitas Dei was dedicated to King Henry VIII. of England.xiv The writing of this commentary was a huge labour, and it marks two crises in Vives’ life—firstly, he fell ill with a tertian fever, and, secondly, he gave up his teaching of youths, work which he had hitherto strenuously pursued along with his literary labours. In 1522 he wrote a pleading letter to Erasmus, begging him forgive his slowness in despatching the Civitas Dei. In it he confesses that “school-keeping has become in the highest degree repulsive,” and that he would rather do anything else than any longer continue “inter has sordes et pueros.” It appears that at the time Vives was giving three lectures daily in the University of Louvain as well as teaching boys.

In the autumn of 1522 Vives came to England for a short visit, and in the following year he was offered the Readership in Humanity in the University of Oxford. Whilst at Oxford he lived in Corpus Christi College. He had for patron Queen Catharine of Aragon, to whom he dedicated his De Institutione Feminae Christianae, which was published in 1523. Vives was entrusted with the direction of the Princess Mary (afterwards Queen Mary I.), for whose use was written De Ratione Studii Puerilis ad Catharinam Reginam Angliae, 1523. In the same year Vives also wrote De Ratione Studii Puerilis ad Carolum Montjoium Guilielmi Filium. These two tractates present an excellent account of the best Renascence views on education, in Tudor times, of a girl and a boy respectively.

The De Institutione Feminae Christianae already mentioned is one of the earliest and most important Tudor documents on women’s education. It marks the transition from the old mediæval tradition of the cloistral life as the highest womanly ideal to that of training for domestic life, in which the mother should be distinguished by the deepest culture of piety and all the intellectual education conducive to religious developxvment. It may be described as typical of Catholic Puritanism in the education of women in the Tudor times.

From 1522 onwards, till after the divorce of Catharine of Aragon, Vives appears to have spent a portion of the year in England, and to have earned enough money to keep him for the rest of the year in Flanders or elsewhere, where he continued his literary career. Although he sometimes lectured in Oxford his time seems principally to have been spent at the court of Henry VIII. and his wife, Catharine. He had times of great weariness in England. He writes in one of his letters of his London life: “I have as sleeping place a narrow den, in which there is no chair, no table. Around it are the quarters of others, in which so constant and great noise prevails that it is impossible to settle one’s mind to anything, however much one may have the will or need. In addition, I live a distance from the royal palace, and in order not to lose the whole day by often going and coming back, from early morning till late evening I have no time at home. When I have taken my mid-day meal I cannot once turn round in my narrow and low room, but must waltz round and round as on a cheese. Study is out of the question in such circumstances. I have to take great care of my health, for if I became ill they would cast me like a mangy dog on a dung-hill. Whilst eating I read, but I eat little, for with so much sitting I cannot digest, as I should do if I walked about. For the rest, life here is such that I cannot hide my ennui. About the only thing I can do, is to do nothing.”

Vives enjoyed allowances both from the king and from the queen, and he had other sources of earnings. In 1524 he was back in Flanders to marry his pupil Margaret Valdaura. Soon after his marriage, which appears to have been a very happy one—though with Vives’ frequent travellingxvi the two were often separated—he wrote one of his widest circulated works, the Introductio ad Sapientiam, which presents the grounds of the Christian religion and the right fashioning of life by intelligence and temperance.

Vives next turned his attention to great European military contests, and was a warm advocate of international peace between Christian powers together with combined warfare against the Turks. These views he elaborated in 1526 in his De Europae Dissidiis et Bello Turico. More remarkable still, in the same year, was his treatise, De Subventione Pauperum, in which he is the first advocate of national state provision for the poor. He would require those who are poor by their own fault to submit to compulsory labour, and even to help in the provision for other poor people.

In 1528 Vives wrote his De Officio Mariti, a companion volume to the De Institutione Feminae Christianae. In this year he had to leave England for good, since Henry VIII. was determined to divorce Catharine of Aragon. Vives was a strong supporter of Catharine. It is said that the queen wished to have Vives as her counsel before the judges on the case, but Henry cast Vives in prison for six weeks, and only freed him on the condition that he left the court and England. Vives retreated to Belgium.

In 1529 Vives wrote the De Concordia et Discordia in Humano Genero, another large-hearted discourse on the value of peace. In 1531 appeared his great pædagogical work, the De Disciplinis.4 In 1539 he wrote the De Anima et Vita, one of the first modern works on psychology, and the De Veritate Fidei Christianae. And in the same year appeared the Linguae Latinae Exercitatio or the School Dialogues. Vives died May 6, 1540.

The De Disciplinis, with the two divisions De Causis Corruptarum Artium and the De Tradendis Disciplinis, and the Exercitatio are the great pædagogical works of Vives, the first a most comprehensive theoretical work of education, probably the greatest Renascence book on education. The Exercitatio is perhaps the most interesting school-text-book of the age.

The Poverty of the Vernacular Literature before the Tudor Period

It is difficult to realise the position of the student of literature in England in the first half of the sixteenth century. The whole wealth of the Elizabethan writers, and all their successors in the Ages of Milton, of Dryden and Pope, of Samuel Johnson, of Charles Lamb, of Shelley, Byron, and Wordsworth, and the large range of Victorian literature, all this had to come. The modern man, therefore, must confess that it was not to English literature that the Tudor student could look for the material of education. Even if it be justifiable to claim that modern literature is a more fruitful study than ancient literature, for the ordinary man, the question remains: How was the ordinary educated man to be trained in the earlier Tudor Age, when the time of great modern literature was “not yet”?

Before we can understand the function served by a Latin text-book of boys’ dialogues like the work of Vives translated in this volume, we must, therefore, first realise the poverty of the vernacular literature of periods anterior to the sixteenth century, and the consequent delight of scholars in finding Latin and Greek literature ready to hand.

“There is every reason to believe that the English language, before the invention of printing, was held by learned or literary men in very little esteem. In the library of Glastonbury Abbey, which bids fair to have been one of thexix most extensive in the kingdom in 1248, there were but four books in English, and those upon religious subjects, all beside vetusta et inutilia. We have not a single historian in English prose before the reign of Richard II., when John Trevisa translated the Polychronicon of Randulph Higden. Boston of Bury, who seems to have consulted all the monasteries in England, does not mention one author who had written in English; and Bale, at a later period, has comparatively but an insignificant number; nor was Leland so fortunate as to find above two or three English books in the monastic and other libraries which he rummaged and explored under the King’s Commission.”5

The classical writers of Greece and Rome, however, have always drawn towards them a large proportion of the well-trained scholarly men of each generation. Before the vernacular literature existed, necessarily it was to the ancient classical languages that the literary scholar turned. In Greek, Plato and Aristotle had written; so, too, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, as dramatists, and the historians Thucydides, Herodotus, Xenophon, and the “divine poet” Homer. Amongst the Latin prose writers were Cicero, Terence, Livy; and amongst the poets, Horace and Vergil. On any showing, such classical writers hold their own high place even if brought into comparison with the greatest of the moderns. The intellectual discipline received by reading their works in the original Greek and Latin had its value. Hence the sixteenth-century English student was trained on those ancient Greek and Latin authors, all unconscious of the great awakening that was to be of modern English literature, into which the twentieth-century reader so lightly enters.

The whole of the well-educated, scholarly, learned men of the sixteenth century, in England and on the continent of xxEurope, all entered into the same classical heritage. They all honoured the same great names of Greek and Latin authors. Latin was the learned language, as the language of Latin literature, as well as the starting-point for the study of Greek. Latin, too, was spoken in every country amongst the learned, and even amongst many who were not regarded as learned. Latin was, it is to be clearly understood, not only a dead language, but a current, live language. It is said that beggars begged in Latin; shopkeepers and innkeepers, and indeed all who had to deal with the general public of travellers, are credited with a knowledge of some colloquial Latin. Church services, of course, were all in Latin, and youths were taught for the most part in the chantries of the churches, and even elementary education provided sufficient knowledge of Latin to enable the pupil to help the priest to say mass, i.e., a minimum of Latin and of music.

Latin, therefore, at least occupied the place in the Mediæval Ages which French holds to-day as an international language. When Laurentius Valla, about 1440, wrote his epoch-making Elegantiae Latinae Linguae, his aim was not to induce people to speak Latin—all well-conducted persons, of course, did so—but to give them the facilities for speaking correct and well-chosen Latin phrases, such as Cicero or Terence would have used. The complaint of the writers of the Renascence times was not that students and the ordinary educated people did not speak Latin, but that they spoke it so inaccurately that the Latin was spoken differently, not only in pronunciation but also in construction, in different countries, and even in different parts of the same country. Text-book after text-book was written to expose and correct the barbarisms in Latin which had become current. For this reason, in our own country, Dean Colet enjoined the reading of good literature in Latin and Greek. Colet requires “that filthiness andxxi all such abusion which the later blind world brought in, which much rather may be called blotterature than literature,” shall be absent from the famous school of St. Paul’s, which he founded.

The Renascence influence, then, attempted on the educational side to bring the pupils of the schools away from the jargon and barbarism of current Latin to the classical Latin of Terence and Cicero. The Renascence leaders had the courage to hope to bring this reform even into the ordinary conversation of educated men and women in their speaking of Latin.

Into this aim Vives entered with the keenest enthusiasm. This will become evident by reference to the Dedication of the Dialogues which I give in full.

“Vives to Philip, son and heir to the august Emperor Charles, with all good will.

“Very great are the uses of the Latin language both for speaking and thinking rightly. For that language is as it were the treasure-house of all erudition, since men of great and outstanding minds have written on every branch of knowledge in the Latin speech. Nor can any one attain to the knowledge of these subjects except by first learning Latin. For which reason I shall not grudge, though engaged in the pursuit of higher researches, to set myself to help forward to some degree the elementary studies of youth. I have, in these Dialogues, written a first book of practice in speaking the Latin language as suitable as possible, I trust, to boys. It has seemed well to dedicate it to thee, Boy-Prince, both because of thy father’s goodwill to me, in the highest degree,xxii and also because I shall deserve well of my country, that is, Spain, if I should help in the forming of sound morals in thy mind. For our country’s health is centred in thy soundness and wisdom. But thou wilt hear more fully and often enough on these matters from John Martinius Siliceus, thy teacher.”

It will be noted that the expressed aim of Vives is to help boys who are learning to speak the Latin language. For this purpose, Vives realised that the method must be conversational, that the style of speech must be clear, correct, and as far as possible based on classical models, and that the subject-matter must consist of topics interesting to children and connected with their daily life. The Prince Philip, to whom the Dialogues are dedicated, it should be noted, was afterwards Philip II., the consort of the English Queen Mary I., daughter of Catharine of Aragon.

The German historian of Latin School-Dialogues, Dr. Bömer, speaks of the characteristic power of Vives in introducing, in relatively short space, the ordinary daily life of boys, and tracking it into the smallest corners. “If a boy is putting on his clothes, we learn every single article of clothing, and all the topics of toilettes and the names of each object (Dialogues I. and XI.). When two school-boys pay a visit to a stranger’s house, we have shown to us its whole inner arrangement by an expert guide (XII.). Interesting observations are made on the different parts of the human body by a painter, Albert Dürer (XXIII.). With a banquet as the occasion, we are introduced to the equipment of a dining-room (XVI.), with ordinary kinds of foods and drinks (XVII.), and if we like we can betake ourselves to the cook in the kitchen and watch the direction of operations (XV.).xxiii We are told in another Dialogue (XVIII.) of a man’s fear to go home to his wife after too liberal a banquet, and how she would entertain him with longer homilies than those of St. Chrysostom. When a company of scholars wish to make a distant excursion, all kinds of horses and carriages, with their trappings, are presented to the notice of the reader (IX.).”6 Then, to show us life under the most favourable of circumstances, Vives gives a dialogue on the King’s Palace (XIX.).

Whilst the general environments of boys’ lives are thus pourtrayed in considerable detail, Vives is particularly careful to show boys the general features and significance of home and school life, and regards it as part of his duty to expound, in the last two dialogues, some general guiding principles of education for the boys, their teachers, and readers of the book to ponder over.

The first dialogue treats of getting up in the morning. The girl Beatrice tries to rouse the two boys Emanuel and Eusebius, the latter of whom makes the excuse, “I seem to have my eyes full of sand,” to which Beatrice replies, “That is always your morning song.” Then the boys dress. Beatrice enjoins them, “Kneel down before this image of our Saviour and say the Lord’s Prayer, etc. Take care, my Emanuel, that you think of nothing else while you are praying.” The interchange of wit between the boys and the maid is an interesting picture of child-life. In the second dialogue, after family morning greetings, which include playing with the little dog Ruscio, the father teaches his xxivlittle boy the difference between the little dog and a little boy. “What have you,” he asks his child, “in you why you should become a man and not he?” He suggests to him that the difference really is contained in the magic word “school.” The boy says: “I will go, father, with all the pleasure in the world.” Whereupon the boy’s elder sister gets him his little satchel and puts him up his breakfast (i.e., lunch) in it. The father takes the boy to the school, and (in III.) discusses with a neighbour the comparative merits of the schoolmasters Varro and Philoponus. The father is told that Philoponus has the smaller number of boys, and at once decides: “I should prefer him!” Then as Philoponus comes into view, he turns to his boy, saying: “Son, this is as it were the laboratory for the formation of men, and Philoponus is the artist-educator. Christ be with you, Master! Uncover your head, my boy, and bow your right knee.... Now stand up!”

Philoponus. May your coming to us be a blessing to all! What may be your business?

Father. I bring you this boy of mine for you to make of him a man from the beast.

Philoponus. This shall be my earnest endeavour. He shall become a man from the beast, a fruitful and good creature out of a useless one. Of that have no doubt.

Father. What is the charge for the instruction you give?

Philoponus. If the boy makes good progress it will be little; if not, a good deal.

Father. That is acutely and wisely said, as is all you say. We share the responsibility then; you to instruct zealously, I to recompense your labour richly.

It will thus be seen that the idea of co-operation and consultation of parents and teachers is no new one.7 But the enthusiasm of the parent, depicted by Vives, to recompense xxvthe teacher “richly” can hardly be said to have continued, if it existed in the Tudor age, outside of Vives’ generous heart.

The next dialogue (IV.) shows how boys loitered on the way to school, their difference in powers, and in the practice of observations and the self-training of the senses and wits in the streets, such as made R. L. Stevenson wonder if the truant from school did not gain more by his self-chosen though casual wanderings than if he had gone orderly to school.

An account of actual school-work in the subjects of reading (V.) and writing (X.) is given, and the raison d’être of school instruction in these subjects suggested. The boys go home (VI.) and a most pleasing picture is given of home-life, with the mother, the boys, the girls, and the serving maiden, introducing children’s games and the interference of meals with games.

Dialogue VII. deals with school-meals, and we plunge at once right into the heart of school interests and life. The sort of foods and drinks, the different kinds of banquets and feastings, mentioned in older writers, the preparation of the table, moderation in eating and drinking, the necessity of cleanliness in all the stages of a meal, including washing up, become topics of the dialogue as it proceeds. Then comes the fitting device of introducing a guest to the boys’ table, of another boy, a Fleming from Bruges. He is asked if he has brought his knife. He has not. “This is a wonder!” exclaims an interlocutor. “A Fleming without a knife, and he too a Brugensian, where the best knives are made!” The conversation proceeds in Latin, since boys were required to speak in and out of school in Latin, at least in all self-respecting establishments.

The Brugensian boy has been under John Theodore Nervius, and this becomes the occasion for a compliment to that schoolmaster. Bruges, too, we have seen, was thexxvi town in which Vives himself spent a considerable portion of his adult life. He does not hesitate to introduce himself, humorously, into this dialogue on school-boys’ meals.

Master. But what is our Vives doing?

Nepotulus. They say he is in training as an athlete, but not by athletics.

Master. What is the meaning of that?

Nepotulus. He is always wrestling, but not bravely enough.

Master. With whom?

Nepotulus. With his gout.

Master. O mournful wrestler, which first of all attacks the feet.

Usher. Nay, rather cruel victor, which fetters the whole body!

In this dialogue of school-boy meals, Vives has given samples of conversational topics, and their due treatment, in the presence of masters and in regular daily routine. In the next dialogue (VIII.), called “Pupils’ Chatter,” boys are out of doors, and a series of nineteen “stories” or topics of conversation get started. The subjects are of interest in showing the type of incidents which boys were supposed to introduce into conversation, and though didactic in tendency, certainly do not favour the supposition that school-boys were supposed to be absorbed in the study of recondite classical subtleties, or even in purely Ciceronian subjects.

Dialogue IX., “Journey on Horseback,” contains the record of what modern educationalists call “the school journey.” The idea of studying geography and history by taking journeys, in which instruction shall arise naturally out of the places of interest seen in the course of the journey, is not a new one, as is often supposed. Vittorino da Feltre, for instance, used to take his school in the summer months for excursions from Mantua to Goito. Vives represents his Parisian pupil as journeying from Paris to Boulogne. The occasion of holiday for the pupils is that Pandulphus, their teacher, has “incepted” in the university, and having thus become a “Master of Arts” (with the right to teach schoolxxvii on his own account), according to university custom he is performing his duty of giving a great feast to the other masters in honour of his laurels, and as a matter of fact, as these boys recognise, is making them drunk. This dialogue of the “Journey on Horseback” contains a full account of different kinds of locomotion. It is especially distinguished by the love that is shown for natural objects of the country, the river, the sweet scent of the fields, the nightingale, and the goldfinch.

In Dialogue XIII. the school is described. Each type and grade of scholar is discussed. Vives’ conception of a school was afterwards followed by Milton. It was an academy, in which the pupil remained from early years up to and including the university stage. In this dialogue is the account of a disputation, with description of the propugnator of a thesis, and several types of oppugnators.

Dialogue XIV. describes a scholar burning the midnight oil. Vives describes the extensive preparations of the scholar for his work of reading authors. The account is almost a supplement to Erasmus’s famous picture of the Ciceronian scholar setting himself to his composition. The dialogue ends with the scholar going to bed whilst one of his attendants sings to the accompaniment of the lyre the lines of Ovid beginning: Somne, quies rerum, placidissime somne deorum.

It has already been stated that Vives devoted a dialogue to an account of the King’s Palace. Similarly, in speaking now of Vives’ treatment of school life, careful notice should be taken of the fact that one dialogue (XX.) is concerned with the education of the boy-prince. This dialogue is of especial interest, since the boy-prince is Philip himself, the son of the Emperor Charles V., the child to whom Vives dedicates the Dialogues. Philip was born at Valladolid, May 21, 1527,xxviii and was therefore eleven years of age when Vives completed the writing of the Dialogues and was twelve years old when they appeared. It will be remembered that in 1554 Philip came to England to claim as his bride the English Queen Mary I., the “bloody” Mary, daughter of Catharine of Aragon, the first queen-consort of Henry VIII., whose coming to England was probably to some degree the ground of its attraction to Vives when he paid his first visit to England, in the autumn of 1522. It is interesting to note that Vives wrote, in 1523, a short treatise on the education of the Princess Mary, probably at the request of Queen Catharine of Aragon, and at any rate dedicated to that ill-fated queen. Vives, thus, is in the remarkable position of having prescribed, as consultant-educationalist, for the Spanish Philip in one of his dialogues (in 1538) and for the English Mary in 1523.8

In this dialogue, “The Boy Prince,” are the interlocutors, Prince Philip and the two counsellor-teachers, Morobulus and Sophobulus. Morobulus is a fawning sycophant, who advises Philip to “ride about, chat with the daughters of your august mother, dance, learn the art of bearing arms, play cards or ball, leap and run.” But as for the study of literature, why, that is for men of “holy” affairs, priests or artisans, who want technical knowledge. Get plenty of fresh air. Philip replies that he cannot follow all this advice without opposing his tutors, Stunica and Siliceus. Morobulus points out that these tutors are subjects of Philip, or at any rate of Philip’s father. Philip observes that his father has placed them over him. Morobulus advises resistance to them. Sophobulus urges, on the contrary, that if Philip does not obey them, he will become a “slave of the worst xxixorder, worse than those who are bought and sold from Ethiopia or Africa and employed by us here.”9

Sophobulus then shows, by three similitudes, that safety in actions and in the events of life depends upon knowledge and study. First, he proposes a game in which one is elected king. “The rest are to obey according to the rules of the game.” Let Philip be king. But Philip inquires as to the nature of the game. If he does not know the game, he inquires, how can he take the part of king in it?

Secondly, Philip is invited to ride the ferocious Neapolitan steed, well known for its kicking proclivities. Eleven-year-old Philip declines, because he has not as yet learned the art of managing a refractory horse, and has not got the strength to master such a horse.

Thirdly, Philip is offered, and declines, the rôle of pilot of a boat, which has lately been overturned by an unskilled helmsman.

The young prince is thus led to recognise that for playing games rightly, for riding properly, for directing a boat safely, in all these cases adequate knowledge and skill is necessary. He himself is led to suggest (in true pedagogical method) that for governing his kingdom it will be necessary for him to acquire the knowledge of the art and skill of sound government, and that this knowledge can only be gained by assiduous study and learning. Sophobulus leads the young prince, further, to the recognition that helpful wisdom can be learned from “monitors” like Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Seneca, Livy, Plutarch. Philip asks: “How can we learn from the dead? Can the dead speak?” “Yes,” is the reply. “These very men and others like them, departed from this earth, will talk to you as often and as much as you like.”

Surely Vives has chosen an attractive and reasonable way of presenting the significance of literature to the child. He uses a further illustration in urging the study of the words and writings of wise men. “Imagine that over the river yonder there was a narrow plank as bridge, and that every one told you that as many as rode on horseback and attempted thus to cross it had fallen into the water, and were in danger of their lives, and, moreover, with difficulty they had been dragged out half dead.... Would not, in such a case, a man seem to you to be demented, who, taking that journey, did not get off from his horse and escape from the danger in which the others had fallen?”

Philip. To be sure he would.

Sophobulus. And rightly. Seek now from old men, as to what chiefly they have felt unfortunate in this life, what negligence in themselves they most bitterly regret. All will answer with one voice, so far as they have learned anything, their regret is “not to have learned more.”

In two points the young Prince Philip seems to have risen to meet Vives’ hopes. When Philip came to England in 1554 and married Queen Mary, he is reported to have announced that he wished to live like an Englishman. He asked for beer at a public dinner, and “gravely commended it as the wine of the country.” He evidently had acquired courteous bearing. Still more clearly, in accordance with the wishes expressed in the Dedication, is the statement of the fact that Philip addressed in Latin a deputation of the council which he received at Southampton, on landing, and further that it was decided that reports of proceedings of the council should be made in Latin or Spanish. Whether Philip had learned to speak Latin from Vives’ School Dialogues is not recorded, but it is not unlikely.

The Dedication of the Dialogues shows how earnestly Vives had sought to influence Prince Philip. The last twoxxxi dialogues (XXIV. and XXV.) endeavour to lay down sound principles of education. The boys (and Prince Philip amongst them) who had read through the preceding dialogues were not to be dismissed until Vives had declared to them the whole gospel of education, as he conceived it. Learning Latin, even to speak it eloquently and to write it accurately, is not of itself education; even to read the sayings and writings of the wise and experienced dead, and to listen to the exhortations and suggestions of the noblest and most learned of living men, is not necessarily the essence of education. The underlying impulse of the student, the roots of his will, must be taken into account. Education is not the adornment of mental distinctions for the sake of popularity or reputation. It is not the acquisition of an additional charm to a particular grade of nobility. It is no artificial appanage. It is not a class distinction. The real argument for education is that it makes a man a better man. If you use the word better it implies the good. Vives shows “the good” does not consist in riches, honours, position, or in learning merely, but in a keen intellect, wise mature judgment, religion, piety towards God, and in performance of duties towards one’s country, one’s dependants, one’s parents, and in the cultivation of justice, temperance, liberality, magnanimity, equability of mind in calamity and brave bearing in adversity. It is in the acquisition of these qualities (for which learning is of high service) that we get “real, solid, noble education.” Such training to the man of court-life will bring “true urbanity,” and make him “pleasing and dear to all. But even this thou wilt not set at high value, but wilt have as sole care—to become acceptable to the Eternal God.”

In studying a work like the School-boy Dialogues of Juan Luis Vives the modern reader is likely to be attracted much more by the subject-matter than by the literary style of the author. Were the chief interest in Vives’ style, it would be difficult to plead any justification for presenting an English translation. But the fact is that these School Dialogues, in the course of time, have become, as it were, historical documents, serving a purpose which was certainly far from being present in the mind of the author. Vives, no doubt, wished his book to be regarded as good and pure Latinity, and would have been hurt to the quick if he had been charged with the barbarisms and inaccuracies which it was the very object of the book to supplant. But as for the subject-matter, he wanted it to contain the Latin expressions for all sorts of common things which entered into the notice of, and required mention from, the young student of Latin. Vives is thus the forerunner of Comenius, and when he treats of subjects such as clothes, the kitchen, the bed-chamber, dining-room, papers and books, the exterior of the body of man, and supplies the Latin for all the terms used in connection with these subjects, he is exactly on Comenius’s ground in the Janua Linguarum and the Orbis Pictus. But Vives is to be distinguished in two ways from Comenius:—(1) he is constantly in touch with the real interests of boys; (2) he is greatly concerned as to his methods of expression.

It is partly because Vives’ Dialogues are intrinsically attractive that we are content to believe they are a true picture of boys’ manners, habits, and life in the Tudor period. By their realistic sincerity the dialogues bring with them their own evidence of unconscious reality. But furtherxxxiii evidence is to be found in the great success and popularity of the dialogues. For had the details been inaccurate and invraisemblables, and had there been a wrong emphasis of educational spirit, it is not likely that the book would have had its extensive vogue. It must be remembered that there were many competing collections of dialogues. Vives’ Dialogues may therefore be regarded as being amongst the survivals of the fittest. Probably the Latin dialogues for schools which have actually had the widest circulation are those of Erasmus, Maturinus Corderius, and Sébastien Castellion. Of these undoubtedly the dialogues of Vives (1538) and of Corderius (whose dialogues were first published in 1564) throw the most light upon the school-life of boys and the conditions of the schools.

An amiable feature of the School Dialogues of Vives is the introduction, not uncommon in school dialogue-books, of well-known persons, ancient and contemporary, amongst the interlocutors. In this way Vives brings before the boys people like Prince Philip, Vitruvius, Joannes Jocundus Veronensis, and Baptista Albertus Leo, all famous architects (Vitruvius being an author of antiquity, the other two nearer Vives’ time), Pliny, Epictetus, Celsus, Dydimus, Aristippus, Scopas, Polaemon, and personal friends like Valdaura (one of the Bruges family into which Vives married), Honoratus Joannius, Gonzalus Tamayus; the painter Albert Dürer, the scholar Simon Grynaeus, and the poet Caspar Velius, and the great Greek scholar and educationalist Budaeus. Vives delights in devoting one of the dialogues to describe his native town Valencia, and in introducing local references of persons and places there. He also (in Dialogue X.) refers to Antonius Nebrissensis, the first to use Spanish vernacular in connection with Latin text-books. His references to schoolmasters are very numerous, and include manyxxxiv types. They are probably founded upon teachers known to him.

One point further should be mentioned. Vives wishes to supply details in the richest profusion in his various subjects, if for no other reason at least so as to increase the vocabulary of the pupils. Accordingly for his subject-matter he quotes and borrows from many of the old writers. J. T. Freigius, in his Nürnberg edition of 1582, not only names the various ancient authors on technical subjects whom Vives has consulted, but also suggests further reading of authors, whom he might with advantage have also quoted. Looking on the Dialogues as a whole, it is remarkable that so many interests were conciliated, as if by instinct—e.g., the schoolboy, the schoolmaster, the general reader, even in some cases the readers desirous of technical instruction. But the unifying factor was the desire of all those and others to learn to speak Latin, and to know the Latin terms for all useful objects.

J. T. Freigius, in the preface to his edition of 1582, tells us that the dialogues of Vives were read in his time “in well-nigh every school.” Bömer quotes orders for the government of ten grammar schools in Germany, between 1564 and 1661, in which the dialogues of Vives were prescribed. In England they were required to be read at Eton College in 1561, at Westminster School about 1621, at Shrewsbury School 1562–1562, at Rivington Grammar School 1564, and Hertford Grammar School 1614. These ascertained and official instances are probably typical of very many others, both in England and abroad, of which the traces are lost.

One of the criticisms frequently urged against Vives is that he used Latinised Graecisms very frequently. It is not improbable that this very fact helped to secure the success of the book, for though there was by 1538 considerable enthusiasm in the aspiration of learning Greek, there was little knowledge of that language as yet even amongst the learned. To know even a small vocabulary of Greek words was a distinction, and to have such knowledge whilst learning to speak Latin was the basis for acquiring at least a smattering of Greek knowledge later on. Sir Thomas Elyot in his Gouvernour (1531) wishes the child “to learn Greek and Latin authors at the same time, or else to begin with Greek. If a child do begin therein at seven years of age, he may continually learn Greek authors three years, and in the meantime use the Latin as a familiar language.” It was, no doubt, the desire of Vives, as of Sir Thomas Elyot, that children should learn as much as possible of Greek at the same time as Latin, and although the introduction of Greek words into the dialogues would not help the systematic study of Greek, it helped to create the atmosphere into which the study of Greek would find its place naturally enough in time.

The introduction of Greek words and phrases by Vives into his School Dialogues did not at any rate prevent the book from being in great demand, whilst the acknowledged difficulty of school teachers in translating the Greek terms brought about a series of expositions and commentaries on the School Dialogues that almost raised the book to the dignity of an ancient classical work. Issued first in 1538, in 1548 an edition was produced at Lyons with a commentary by Peter Motta and a Latin-Spanish index by Joannes Ramirus. In 1552, at Antwerp, Peter Motta’s interpretaxxxvition of Greek words, together with the old and somewhat obscure points in Vives, was supplemented by an alphabetical index of the more difficult words rendered into Spanish, French, and German. In 1553 Aegidius de Housteville published at Paris an edition, especially prepared for French boys, which gave the French for all difficult Latin words and included the commentary of Peter Motta.

In 1568 was published by Euphrosynus Lapinius at the Junta Press in Florence, an edition of Vives’ School Dialogues. This also included the commentary of Peter Motta and, in addition, an index of certain words in Vives’ Dialogues, with a translation of them into Etruscan.10

Vives’ School Dialogues, we have seen, had a circulation, with vernacular vocabulary, in Spain, France, Germany, Italy (there does not seem to have been any edition with an English vocabulary). The inclusion of the Greek words, it is not unreasonable to suppose, met a need amongst learned schoolmasters, and since sufficient translations of the hard words, both Greek and Latin, were forthcoming, the book was made available even in those cases where schoolmasters had not sufficient knowledge to translate all the passages in which the pupils might stick.

Erasmus in his Ciceronianus thus describes the style of Vives: “I find lacking in Vives neither innate power, nor erudition, nor power of memory. He is well provided with luxuriance of expression even when, in the beginning of a xxxviiwork, he is a little hard; day by day his eloquence matures more and more as he proceeds.... Daily he overcomes himself, and his genius is versatile enough for anything. Yet sometimes he has not achieved some portion of the Ciceronian virtues, especially in the direction of charm and mildness of expression.” (Quoted by Namèche, Mémoire sur la vie et les écrits de J. L. Vives.)

Vives’ characteristics have been well described by Bömer, who says: “In the dialogues of Vives we constantly have the pleasure of listening to conversations rich in thought, made spicy at the right moments with pointed wit, so that we are obliged to make an effort to understand the separate words.” It may be added that Vives is always desirous to help forward the cause of learning, yet, on occasion, he can detach himself from his learning and become a boy among boys. He has a strong sense of humour. He can tell a joke against himself, as for instance about his gout,11 or again about his singing.12

It might, with some ground, be urged that Vives and other writers of school dialogues are the precursors of the drama. For not only are there touches of wit and humour in the conversations, but there is a considerable amount of characterisation in the interlocutors. The right person says and does the right thing, and situations are sometimes hit off exquisitely with an epithet. It is clear that a training in following the school dialogues in the generation preceding the xxxviiiElizabethan dramatists may have had a distinctly preparative place in rendering the dialogue of the drama more familiar and attractive as a literary method. For a preparation in the power of audiences following the dialogues of the Elizabethan drama may be regarded as requiring an explanation, when we remember that the interest in and concentration on the dialogue was more urgent than now, owing to the absence of scenery and the other visual effects to which we are accustomed. The element in the drama which is conspicuous by its absence in the school dialogues is the plot. Yet in the school dialogue there is a definite method of construction observed. In the old methods of Latin composition, wherever there is a thesis, the writer must have regard to the sequence of the introduction, the narration, the confirmation, confutation, and the conclusion.

With regard to the school training towards the appreciation of the drama in the Tudor age, it must be remembered that the school-play was a recognised institution, especially the acting of the old plays of Terence, Plautus, and eventually of Greek tragedies. The school dialogue, it should be noted, was one of the earliest of school text-books, and its object, as already stated, was to train the child in readiness of expression in the speaking of Latin. The study of rhetoric followed, and this included not only the study of apt figures of speech in Latin conversation, but also the accompaniment of right gestures of the face, hands, and body. Hence it will be seen that the grammar schools of the early part of the sixteenth century paved the way for an intelligent appreciation of the Elizabethan drama. For the drama not only requires writers; to some extent an intelligent response is necessary in the spectators, at any rate when the plays involve the intellectual elements characteristic of the later part of the sixteenth-century drama in England.

It is remarkable that an elementary text-book for teaching boys to speak Latin should raise so many fundamental questions in the theory of education. But any presentation of the Dialogues of Vives would seem to be incomplete which left unconsidered such points as Vives’ idea of the school, of the school-games, of nature study, of the use of the vernacular in the school, and Vives’ view of the relation of religion and education.

We learn from another book of Vives, the De Tradendis Disciplinis (1531), that the “true academy,” as he calls his ideal school, is “the association together and fellow sympathy of men equally good and learned, who have come together themselves for the sake of learning, and to render the same blessing to others.” Vives suggests that to such a “school” not only should boys go, but also men. He suggests that “even old men, driven hither and thither in a great tempest of ignorance and vice, should betake themselves to the academy as it were to a haven. In short, let all be attracted by a certain majesty and authority.” Further, Vives informs us that in this academy it would certainly be best to place boys there from their infancy, “where they may from the first imbibe the best morals, and evil behaviour will be to them new and detestable.” We thus see that “the academy” combines our so-called elementary, secondary, and university education. The idea of the continuity of education is thus firmly conceived by Vives, and, in addition, the action and reaction of different ages of the individual scholars of the academy on one another. Nowadays, we realise that the association togetherxl of those with the same limitations, e.g., orphans, the blind, the deaf, may be a necessary evil, but that every progressive educational effort should be made to help all those who suffer from such limitations to become capable of taking their places amongst the normal pupils. But Vives goes much further; with him, it is a defect in education to isolate the young from the old, the old from the young. If all be bent on learning and scholarship, the differences of age disappear as clearly as the differences of rank and wealth.

It is necessary to bear in mind this conception of the academy in reading the school dialogues, for we have in them little children learning their alphabet13 and the elements of reading14 and writing,15 and we have also the youths (at our undergraduate stage) going on their academic journey on horseback from Paris to Boulogne. This reminds us of Milton’s sallying forth of students “at the vernal seasons of the year, when the air is calm and pleasant, and it were an injury and sullenness against nature not to go out and see her riches and partake in her rejoicing with heaven and earth.”

And we have the student of mature age, in his dressing-gown, at midnight, pursuing his classical meditations. Thus infancy, youth, manhood, all stages, come into the conception of education. Education is a continuous process lasting throughout life, and for Vives the educational institution of “schools” should embody and make facilities for the achievement of that idea. In passing, it should be remarked that John Milton, in his Tractate of Education (1644), and John Dury (1650), in his Reformed School, advocate what we may call the Vives-Academy view of school!16 It must occur xlito every reader of Vives’ De Tradendis Disciplinis as highly probable that Milton’s hurriedly dashed-off and eloquent tractate was written after a fairly recent perusal of Vives’ book.

The treatises on education in Tudor times have scarcely been surpassed by any later works in their treatment of physical education and advocacy of games. Particularly is this so in England, for in that period were published Sir Thomas Elyot’s Gouvernour (1531), Roger Ascham’s Toxophilus (1545), and Richard Mulcaster’s Positions (1581). But outstanding in their importance as these works were, Vives in his School Dialogues makes an interesting supplementary contribution.

Vives shows the value of “play” as an underlying spirit of school work, for the school is a form of “ludus” or play.17 The little child, Corneliola, learns the alphabet “playing,” as indeed children had done at any rate from the days of Quintilian. Indeed, one of the most charming pictures of children provided by Vives is in Dialogue VI., which describes the mother, the boys Tulliolus, Lentulus, Scipio, and the little girl Corneliola, on the return from school of the boys, as they engage in children’s play and discussion of it. The games named in that dialogue are the games of “nuts,” “odd and even,” dice-play, draughts, and playing cards. Vives passes over the question of the moral obliquity of dice-playing and card-playing, though much was said in the Tudor period with regard to them.18

Vives represents the school-boys playing dice and cards for counters, and in the case of the cards for money. But substantially he gives the picture of the play without combining a sermon. In passing, perhaps it is permissible to call attention to the pun in Dialogue XXI., where the Latin word charta is taken up ambiguously in the meaning of “map” as well as of “card.” The discovery of America in 1492 was comparatively recent in 1539, and much interest was felt in geographical questions. It is a great mistake to suppose that the classical scholars like Vives were so wrapt up in meditations on antiquity that they did not realise the significance of contemporary events, and that educationalists were not eager to turn current incidents to use in the class-room.19 An interesting example of the fascination of Vives in geographical discoveries is to be found in the dedication of the De Tradendis Disciplinis to the renowned King John III., King of Portugal, in which he relates the splendid deeds of the Portuguese in travel and discovery, which bring glory to descendants and the obligation to live up to their standard of achievement. In Dialogue XII., in the description of the entrance-hall of a house, a map is referred to in which “you have the world newly discovered by the Spanish navigations.”20

But educationally more important than any description of the games of the period described by Vives is the statexliiiment made by him of the laws which should regulate all play. The account is given in Dialogue XXII. Vives describes his native city of Valencia by sending three characters, Borgia, Scintilla, Cabanillius, on a promenade through the streets. They come to a public tennis-court, where the game of tennis is described. They proceed to the Town Court of Justice, whereupon one of the characters, Scintilla, is requested to state the laws of play which he has previously mentioned a teacher, by name Anneus, had written on a tablet which he had hung in his bed-chamber.

The six laws of play according to Anneus are:—

1. Quando Ludendum? The Time of Playing.—This should be when the mind or body has become wearied. Games are to refresh the mind and body, not for frivolity.

2. Cum Quibus Ludendum? Our Companions in Play.—These should be those who bring to the game no other purpose than your own, viz., that of thorough rest from labour and freedom from mental strain.

3. Quo Ludo? The Sort of Game.—It must be known well by all the players. It must serve for both bodily and mental recreation. It must not be merely a game of hazard.

4. Qua Sponsione? As to Stakes.—Small stakes are justifiable if they increase interest in exercise without producing excitement or anxiety of mind. Big stakes do not make a game; they introduce the rack.

5. Quemadmodum? The Manner of Play.—Win and lose with absolute equanimity. No game should serve to rouse anger. No oaths, swearing, deceit, sordidness.

6. Quamdiu Ludendum? Length of Play.—Until one is refreshed and the hour of serious business calls.

It has already been mentioned that Vives supplies a dialogue describing an academic journey.21 Two of the characters thus discourse:—

Misippus. Look how softly the river flows by! What a delightful murmur there is of the full crystal water amongst the golden rocks! Do you hear the nightingale and the goldfinch? Of a truth, the country round Paris is most delightful!

Philippus. How placidly the Seine flows in its current.... Oh, how the meadow is clothed with a magic art.

Missippus. And by what a marvellous Artist!

Philippus. What a sweet scent is exhaled.... Please sing some verses as you are wont to do.

Then Vives introduces some lines by Angelus Politian praising the joy of peaceful, silent days which pass by without the agitation of ambition and the allurement of luxury, with blamelessness, though we work as with the labour of the poor man. Again22:—

Bambalio. Listen, there is the nightingale!

Graculus. Where is she?

Bambalio. Don’t you see her there, sitting on that branch? Listen how ardently she sings, nor does she leave off.

Nugo. (As Martial says) Flet philomela nefas. (The nightingale bemoans any injustice.)

Graculus. What a wonder she carols so sweetly when she is away from Attica where the very waves of the sea dash upon the shore, not without their rhythm.

Then Nugo tells the story of the nightingale and cuckoo.23 One more instance. Several boys are out for a morning walk:—

Malvenda. Don’t let us take our walk as if in a rush, but slowly and gently....

Joannius [after contemplating the view]. There is no sense which has not a lordly enjoyment! First, the eyes! what varied colours, what clothing of the earth and trees, what tapestry! What paintings are comparable with this view?... Not without truth has the Spanish poet, Juan de Mena, called May the painter of the earth. Then the ear. How delightful to hear the singing of birds, and especially the nightingale. Listen to her (as she sings in the thicket) from whom, as Pliny says, issues the modulated sound of the completed science of music.... In very fact, you have, as it were, the whole study and school of music in the nightingale. Her little ones ponder and listen to the notes which they imitate. The tiny disciple listens with keen intentness (would that our teachers received like attention!) and gives back the sound.... Add to this there is a sweet scent breathing in from every side, from the meadows, from the crops, from the trees, even from the fallow-land and neglected fields.

There can be little doubt even from the descriptions of feasts in the School Dialogues of Vives, as well as of Mosellanus and Erasmus, that drunkenness was not uncommon even amongst teachers in the Tudor period.24 Vives distinguished himself by boldly advocating the claims of water against those of wines and beer. In Dialogue XI., “Getting dressed and a Morning Constitutional,” we read [speaking of the food for breakfast, after the walk]:—

Malvenda. Shall we have wine to drink?

Bellinus. By no means,—but beer, and that of the weakest, of yellow Lyons, or else pure and liquid water drawn from the Latin or Greek well.

Malvenda. Which do you call the Latin well and the Greek well?

Bellinus. Vives is accustomed to call the well close to the gate the Greek well; that one further off he calls the Latin well. He will give you his reasons for the names when you meet him.

J. T. Freigius, who is always ready to supply what Vives omits, gives in his commentary the reasons for Vives. The Greek well is the well close to the gate, because the Greek xlvilanguage is closer to the sources of language; the “Latin” well, for similar reasons, is further off from the gate.

In Dialogue XVII., called “The Banquet,” we read:—

Scopas. Don’t give one too much water (i.e. in his wine). Don’t you know the old proverb, “You spoil wine, when you pour water into it”?

Democritus. Yes, then you spoil both the water and the wine.

Polaemon. I would rather spoil them both than be spoiled by one of them.

But it is in Dialogue XVIII, on “Drunkenness,” that Vives specially launches his thunderbolts against excessive drinking. With the institution of lessons on temperance in schools under some Local Education Authorities in England, we have a return to the methods of Vives. For in the school dialogue referred to we have the matter put very strongly, and probably Vives’ statements would not prove unacceptable to modern teachers of this recently re-introduced subject. After describing the moral effects of drunkenness, one of the characters says: “Who would not prefer to be shut up at home with a dog or a cat than with a drunkard? For those animals have more intellect in them than the drunkard.” Another character remarks: “When you drink, you treat wine as you like. When you have drunk, it will treat you as it likes.”

It is surprising to find that though Vives, in 1538, produced his School Dialogues for the purpose of teaching children to speak Latin, and though he regarded early and thorough acquaintance with Latin, both for purposes of speaking and writing, as the very mark and seal of a well-educated man, there was no learned man of his age who went so far in advocacy of the importance of the teaching inxlvii the vernacular of the pupil at a still younger age. As this constitutes one of the grounds upon which the pre-eminence of Vives as an educationalist would be rested, as for instance in comparison with Erasmus, it may not be altogether irrelevant to quote here the translation of a passage from the De Tradendis Disciplinis explaining Vives’ views on this subject.

“The scholars should first speak in their homes their mother tongue, which is born with them, and the teacher should correct their mistakes. Then they should, little by little, learn Latin. Next let them intermingle with the vernacular what they have heard in Latin from their teacher, or what they themselves have learned. Thus, at first, their language should be a mixture of the mother-tongue and Latin. But outside the school they should speak the mother-tongue so that they should not become accustomed to a hotch-potch of languages.... Gradually the development advances and the scholars become Latinists in the narrower sense. Now must they seek to express their thoughts in Latin, for nothing serves so much to the learning of a language as continuous practice in it. He who is ashamed to speak a language has no talent for it. He who refuses to speak Latin after he has been learning it for a year must be punished according to his age and circumstances.”25

So much for the pupil’s knowledge of the vernacular. Still more emphatically Vives speaks with regard to the necessity of a thorough knowledge of the vernacular by the teacher.

“Let the teacher know the mother-tongue of his boys, so that by this means, with the more ease and readiness, he may teach the learned languages. For unless he makes use of the right and proper expressions in the mother-tongue, he will certainly mislead the boys, and the error thus imbibed will accompany them persistently as they grow up and xlviiibecome men. How can boys understand anything sufficiently well in their own language unless the words are said with the utmost clearness. Let the teacher preserve in his memory all the old forms of vernacular words, and let him develop the knowledge not only of modern forms, but also of the old words and those which have gone out of use, and let him be as it were the guardian of the treasury of his language.”26

It has been usual to enter to the credit of the Protestantism of John Sturm and Maturinus Corderius the educational ideal of pietas literata. No doubt the seventeenth-century Huguenots of France and the Puritans of England were distinguished by this double educational aim of piety and culture. But it was characteristic also of the earlier Catholic world of Erasmus and of Vives. Rising above the ordinary level of the scholars of the Italian Renascence, Erasmus and Vives had higher sympathy and delight in children. Erasmus dedicated his Colloquia or Dialogues (in 1524) to the little child John Erasmius Froben, the son of the renowned publisher Froben of Basle. “You have arrived,” he says, “at an age than which none happier occurs in the course of life for imbibing the seeds of literature and of piety.... The Lord Jesus keep the present season of your life pure from all pollutions, and ever lead you on to better things.”

So, too, in 1538, Juan Luis Vives dedicated his School Dialogues to a child, the eleven-years-old boy—Prince Philip.

Both Erasmus and Vives believed in early training in religious instruction. Vives writes as follows on religious education: “Who is there who has considered the power and loftiness of the mind, its understanding of the most xlixremarkable things, and through understanding love of them, and from love the desire to unite himself with them, who does not perceive clearly that man was formed, not for food, clothing, and habitation, not for difficult, secret, and vexatious knowledge, but to develop the desire to know God more truly, to participate in His Divine Nature and His Eternity?... Since piety is the only way of perfecting man, and accomplishing the end for which he was formed, therefore piety is of all things the one thing necessary. Without the others man can be perfected and complete; without this, he cannot but be most miserable.”27

In one passage Vives remarks that the strength of religion is developed by its exercise rather than by any theoretical knowledge. For this reason, when meals are described in the School Dialogues, we find some form of grace, before and after the meal, duly said. The tone of the Dialogues is reverential. A. J. Namèche says28 that in the Dialogues “Vives brings a sense of decency, respect for morals, the fear so laudable of doing any violence to the innocence of young people. We know well enough that Erasmus is far from being irreproachable in this respect, and that his language is free sometimes even to the extent of cynicism.” Without wishing to follow Namèche in the comparison of the moral aspects of Erasmus and Vives in their dialogues, a claim may be made for both that they were eager advocates in the joining of piety with culture, and that both Erasmus and Vives, each in his own way, did valiant work in endeavouring to raise the standard of manners and morals as well as to promote piety in young and old.

There can, however, be no doubt that Vives deserved the high reputation which he received of reverence for the morals lof youth. Peter Motta is full of enthusiasm for Vives in this respect. In the Preface to his Commentary on Vives’ School Dialogues, Motta says: “By reading other books such as those of Terence and Plautus, you can undoubtedly get extracts which show the fruit of eloquence. But who can avoid seeing that in them you will find incitements to vices, and stumbling blocks to morals? Now, in our author Vives, you will find little flowers of Latin elegance which he has brought together from various most renowned authors, whilst there is nothing in his work which does not seem to suggest even the Christ, or at least the highest morality and sound education.” This may be regarded as the exaggerated language of an admirer, but the reverential tone of Vives is clear enough, reminding one of Vittorino da Feltre, of whom it was said that he went to his teacher’s desk each day as if to an altar.

Vives lays down twenty-four Precepts of Education. Some critics have thought such precepts out of place in a book written for boys. But Vives has done all he could to interest boys on their own level. He has always retained the boy in himself, and has spoken from the fulness of his heart, as a boy, in the dialogues. And as he parts company with boys in these dialogues, he wishes, as all true, older human beings must wish, for once at least to give of his best to the young. He will give back to the boys who have followed him through the Dialogues (as a teacher who is a “good sort”) a full reward for their trouble. He will pay them the compliment of treating them seriously.

This seems a right instinct. It is not priggish (as some seem to think) to give of a man’s best to a boy or to boys atli the right moment. When once a boy is sure there is “the boy” in any man he knows, there is no camaraderie he delights in such as that which allows him to see a little of the man,—to jump, so to say, on the man’s mental shoulders to catch a better glimpse of the far distance.