Title: American Indian Ways of Life: An Interpretation of the Archaeology of Illinois and Adjoining Areas

Author: Thorne Deuel

Release date: January 4, 2018 [eBook #56304]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

M. M. Leighton, Ph. D., Chairman

Illinois Geological Survey, Urbana

Everett P. Coleman, M. D.

Coleman Clinic

Canton

Percival Robertson, Ph. D.

The Principia College

Elsah

N. W. McGee, Ph. D.

North Central College

Naperville

Sol Tax, Ph. D.

University of Chicago

Chicago

Copyright by

ILLINOIS STATE MUSEUM

1958

STATE OF ILLINOIS

William G. Stratton, Governor

DEPT. OF REGISTRATION & EDUCATION—ILLINOIS STATE MUSEUM

Vera M. Binks, Director Thorne Deuel, Museum Director

STORY OF ILLINOIS SERIES, No. 9

An Interpretation of the Archaeology of Illinois and Adjoining Areas

by

Thorne Deuel

Springfield, Illinois

1958

[Printed by authority of the State of Illinois]

Site of the ancient Middle Mississippi religious city on the Kincaid farm near Metropolis, Illinois, as it is today. Four mounds can be seen; the village area is in the foreground and the plaza at the right (south) of the largest mound with house on it.

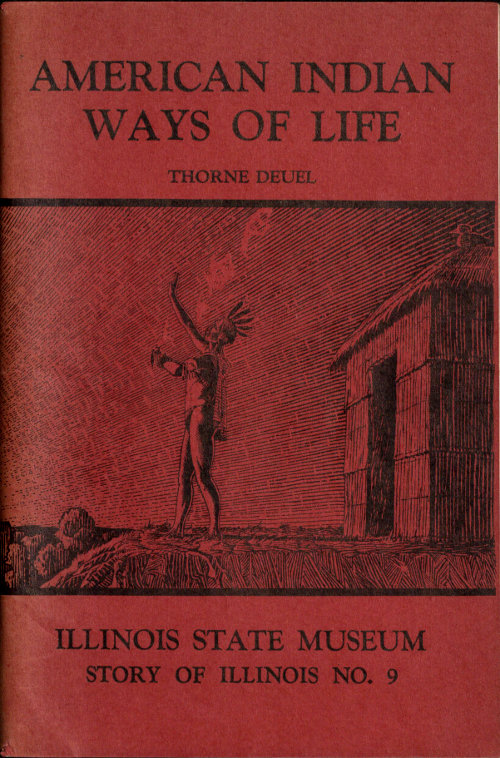

TABLE I. STAGES AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL UNITS

This paper is primarily planned for the layman, the beginning student of prehistory and others interested in acquiring a general understanding of how primitive man lived during his successive occupations of Illinois and neighboring areas in the more important archaeological periods. Most of the archaeological data for the chief cultures or ways of life are given in references in the accompanying bibliography of technical publications selected as those from which (in the opinion of the writer) the information can be most easily gleaned.

The reconstructions given of the cultural features, where not those ordinarily inferred from archaeological findings, are based on a study of the practices commonly found among primitive people now, or until recently, living in the same stage or substage. These are tentative conclusions resulting from a study of fifty tribes in the Self-Domestication (pre-farming) stage and forty in the Plant-Raising substage. Because primitive tribes which are under pressure from people with advanced food-draft-animal agriculture or with machine industry or which are in a transitional condition between two adjacent stages are disorganized or drastically changing a formerly stabilized mode of life, great care has been exercised in drawing general conclusions from their cultural features.

The reconstructions of the perishable objects shown in the drawings are generally in keeping with the culture in which they are exhibited but cannot be vouched for as to their detailed form. The handle of an adze, the shape of a cabin roof, the headdress of a tribal chief each served the purpose for which they were made and their exact form was and is of no more consequence in the culture than the fashions in women’s hats or the fins on an automobile are in our own. The details in cultures serve to set them apart from each other; it is the basic and significant features and subfeatures that determine relationships and permit the most useful classification.

The study mentioned above is still incomplete, but results so far obtained indicate:

1. That man in the same stage (and substage) of cultural development tends to invent and employ the same broad social and spiritual features, regardless of surroundings.

2. That where significant differences arise between substages of the same stage, they are (at least sometimes) linked with peculiarities of climate and/or natural resources which the people have seized upon and exploited to the improvement of their economic situation.

3. That many details within these broad types of economic, social and spiritual features appear to vary unpredictably within the range of available possibilities.

The stage and criterion for each were proposed in an earlier issue (No. 6) of this series, Man’s Venture In Culture, (Deuel 1950, pp. 5-12) as:

1. Natural Man (Protocultural), when “man” presumably employed sticks and stones as implements and weapons.

2. Self-Domestication, following the discovery of the principle of the conchoidal fracturing of flint and its control, and the invention of tool and weapon types.

3. Farming or Food-Raising, due to the discovery that grains (grasses) and food-draft animals could be bred and raised in captivity.

4. Inanimate Power Machine (Machine Age), after the discovery of the availability of water and wind as sources for energy and the adaptation of animal-driven machines to utilize them.

Man in the wild or Protocultural stage is thought not to have reached the Americas. The oxlike mammals were not domesticated in America for drawing ploughs and vehicles, turning grain mills or to serve as a continuous food supply source. Consequently, we are concerned in the following discussion only with peoples in the Self-Domestication stage and the Plant-Raising substage of Farming.

In ordinary language, the word “culture” is used in a diversity of senses. In these pages it is used in one of two ways, the one employed being readily understood from the context. In a general sense, culture means the significant beliefs, customary activities and social prohibitions that are peculiar to man (together with the man-made tools, weapons and other material objects that he finds or has found necessary) that modify, limit or enhance in some manner, most of his discernible natural activities due to and arising from his physical animal inheritance and organization. Culture in a specific sense refers to the significant cultural features of a group or period under consideration.

For convenience, any cultural activity according to its dominant purpose may be spoken of as belonging to one of three aspects of culture, (a) economic (technological and intellectual); (b) social (and political); and (c) spiritual (religious, artistic and recreational). To lesser degrees, most cultural activities have relationships with the two aspects other than the dominant.

Certain prevalent archaeological designations have been changed to remove time implications (e.g. “early” and “late” Woodland to Initial [beginning] and Final [end of an archaeological series]), or to shorten (e.g. “Tennessee-Cumberland” or “Gordon-Fewkes” to Cumberland).

Technical terms have generally been avoided; but where it has seemed necessary to retain them or to use words in a special sense, they are explained in the text or can be found in the glossary. The terms pattern and phase are those generally employed in the McKern system of classification, for the larger groupings into which it is customary to 7 place the “cultures” as determined from the typology of the artifacts, their association in the assemblage and pertinent data recovered at a site (or local community) with due regard to circumstances of time and location of other sites nearby and over a larger area. The largest unit is the pattern which is made up of a number of phases. Cultural divisions smaller than these units are spoken of here as subcultures.

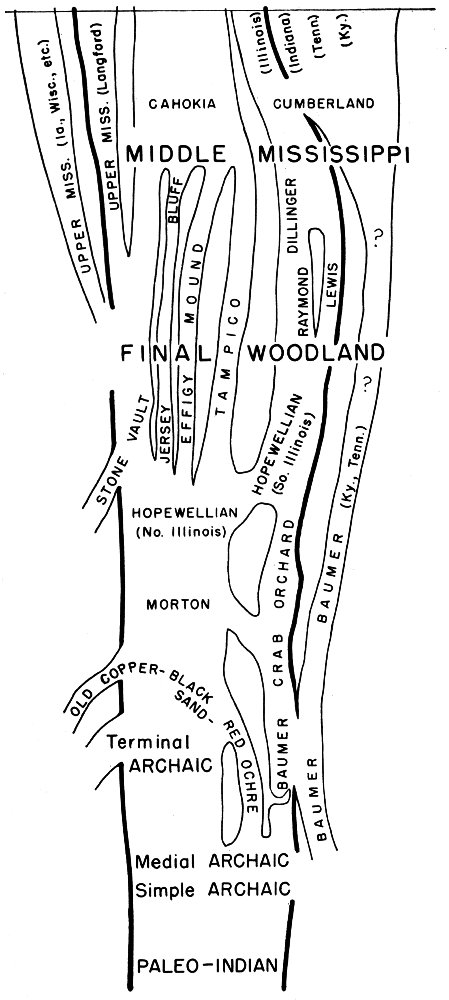

The approximate relationships of the archaeological units to the broader cultural stages and substages are given in Table I, page 4. The succession and coexistence of the archaeological units is indicated in the diagram “The Stream of Culture”, p. 57. The summary of “Characteristics of the Archaeological-Cultural Units” occurs on pages 70-76.

This is a story mainly of Illinois when occupied by American Indians but it would not give a reasonably true picture without showing the known extensions of some of the cultures into surrounding areas and the probable intrusions from outside the state.

Of necessity in attempting a summary of the archaeology of Illinois and adjacent areas, the writer has had to lean heavily on the field work and reports of the many anthropologists who have contributed so much to the present understanding of the American Indian in the United States. To this invaluable source material and to these able scientists the indebtedness of the writer is acknowledged to be very great indeed. In the compass of a work of this type it is impossible to name them or give them credit for original or similar views, nor is it practicable to include in the bibliography all the publications used.

Acknowledgment of assistance is made especially to Georg K. Neumann, Joseph R. Caldwell and Melvin L. Fowler, Milton D. Thompson, Ruth Kerr, Nora Deuel and Orvetta Robinson for reading and discussing the manuscript from various viewpoints, to Dr. James B. Griffin for helpful information on the dates of sites and of archaeological data, to Irvin Peithmann, Southern Illinois University, for photographs furnished, for information on sites he had discovered and the privilege of visiting them in his company, to George Langford for photographs and data regarding the Fisher site, to Charles Hodge for all photographs reproduced not otherwise credited, and to Jerry Connolly, Bettye Broyles, Barbara Parmalee and Jeanne McCarty for their excellent drawings. Without all this considerable and valuable aid the publication could not have been completed.

| CULTURAL UNIT | C14 DATE | SITE | STATE | COUNTY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIDDLE MISSISSIPPI | A.D. 1420±200 | Crable Village | Illinois | Fulton |

| MIDDLE MISSISSIPPI | 1326±250 | Nodena Village | Arkansas | Arkansas |

| MIDDLE MISSISSIPPI | 1156±200 | Cahokia | Illinois | Madison |

| EFFIGY MOUND[2] | 1041±212 | Effigy Mounds National Park | Iowa | Allamakee |

| HOPEWELLIAN | 508±60 | Twenhafel (Weber) Md. | Illinois | Jackson |

| HOPEWELLIAN | 432±200 | Rutherford Mound | Illinois | Hardin |

| HOPEWELLIAN | 256±200 | Knight Mound | Illinois | Calhoun |

| HOPEWELLIAN | 214±250 | Baehr Mound | Illinois | Brown |

| HOPEWELLIAN[2] | B.C. 48±160 | Hopewellian Group Mound #25 | Ohio | Ross |

| HOPEWELLIAN[3] | 57±108 | Wilson Mound | Illinois | White |

| HOPEWELLIAN | 315±164 | Havana Mound | Illinois | Mason |

| ADENA | 423±150 | Toepfner Mound #I | Ohio | Franklin |

| ADENA | 697±170 | Dover Mound | Kentucky | Mason |

| ARCHAIC | 704±80 | Poverty Point | Louisiana (N.E.) | W. Carroll Parish |

| ADENA | 826±410 | Toepfner Mound #II | Ohio | Franklin |

| ARCHAIC | 904±90 | Poverty Point | Louisiana (N.E.) | W. Carroll Parish |

| ARCHAIC | 1624±300 | Kays Landing | Tennessee | Humphrey |

| ARCHAIC[2] | 2170±215 | Indian Knoll | Kentucky | Ohio |

| ARCHAIC[2] | 2360±270 | Annis Mound | Kentucky | Butler |

| ARCHAIC | 2765±300 | Modoc Rock Shelter | Illinois | Randolph |

| ARCHAIC | 2812±250 | Perry Site | Alabama (N.W.) | Lauderdale |

| ARCHAIC | 2950±250 | Annis Shell Mound | Kentucky | Butler |

| ARCHAIC | 3325±300 | Modoc Rock Shelter | Illinois | Randolph |

| ARCHAIC | 3352±300 | Indian Knoll | Kentucky | Ohio |

| ARCHAIC | 3646±400 | Oconto Old Copper Site | Wisconsin (E.) | Oconto |

| ARCHAIC[2] | 3657±164 | Modoc Rock Shelter | Illinois | Randolph |

| ARCHAIC | 5194±500 | Eva Site | Tennessee | Benton |

| ARCHAIC | 5556±400 | Oconto Old Copper Site | Wisconsin (E.) | Oconto |

| ARCHAIC | 5945±500 | Graham Cave | Missouri | Montgomery |

| ARCHAIC | 6204±300 | Russell Cave | Alabama | Jackson |

| ARCHAIC[2] | 6219±388 | Modoc Rock Shelter | Illinois | Randolph |

| ARCHAIC | 7310±352 | Graham Cave | Missouri | Montgomery |

| ARCHAIC | 7922±392 | Modoc Rock Shelter | Illinois | Randolph |

| PALEO-INDIAN (Folsom)[2] | 7934±350 | Lubbock Site | Texas (N.W.) | Lubbock |

| PALEO-INDIAN (Sandia) | 18,000 | Sandia Cave | New Mexico (Center) | Bernalillo |

| PALEO-INDIAN (?) | 22,000 | Tule Spring Site | Nevada (S.E.) | Clark |

| PALEO-INDIAN (Clovis?)[4] | 35,000 | Lewisville Site | Texas | Denton |

Man probably discovered America as early as 50,000 years ago and gradually occupied the two continents in the succeeding millenia. The first discoverers of the New World were of Mongolian racial stock as are the American Indians. They crossed from Siberia to Alaska over an existing land bridge, over ice, or possibly by wading or by boat over the shallow sea in the wake of mammoth, mastodon or musk ox herds on whose flesh they lived. Following in the path of the huge animals, they made their way possibly up the Yukon from its mouth to the divide, thence down into the Mackenzie Basin, and along a great river where now exist a chain of lakes and so into the Mississippi Valley.

The migrants trailing each herd doubtless traveled in their several ways in family groups, uniting from time to time to trap and kill one of the great shaggy beasts. When the animals stopped, the families bedded down nearby in the most sheltered spots available taking care not to lose touch with the herd. These were wanderers, not explorers, nor were they seeking new homes; they were hunters that traveled where the herd led.

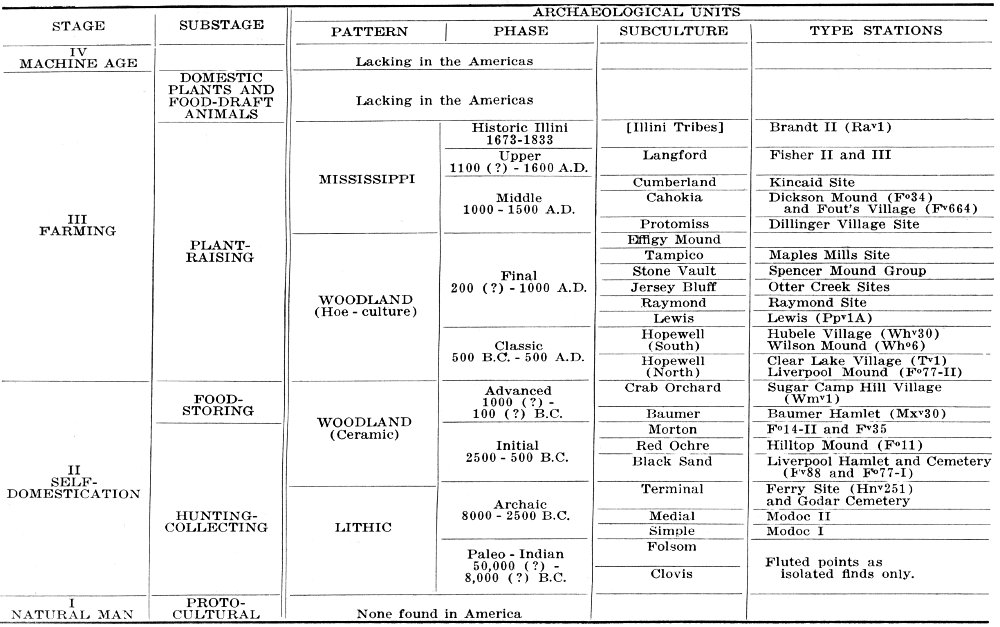

Fig. 1. Archaic flint drill, stone hammer, and flint scraper as used in Archaic period and their modern steel counterparts. (B.B.)

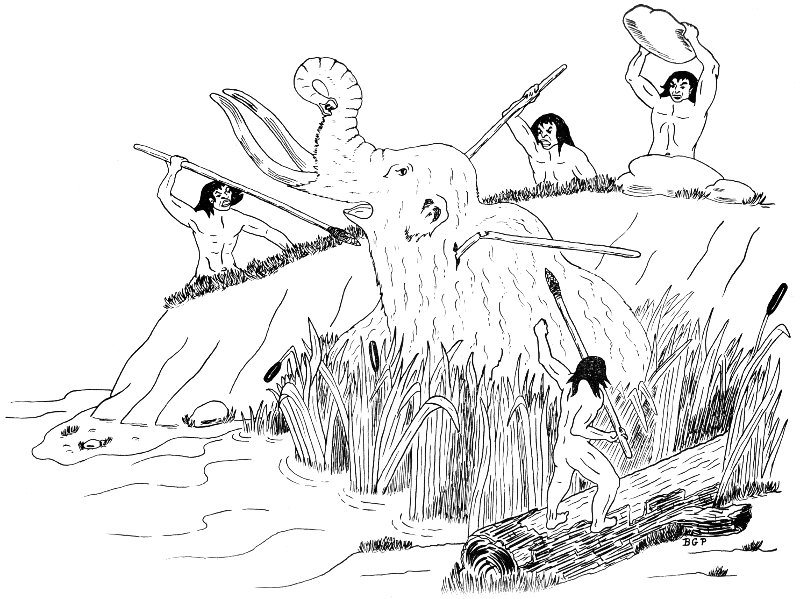

Fig. 2. Paleo-Indians attack a mired-down mammoth. (B.G.P.)

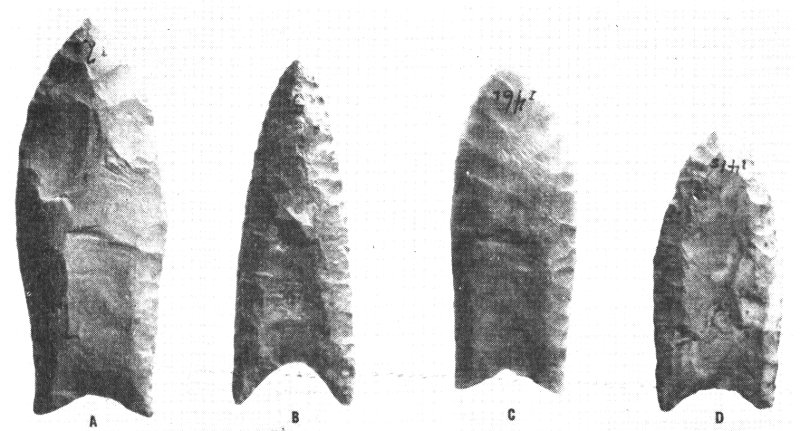

Fig. 3. Paleo-Indian spearheads from the William Small collection. A, B, and C are Clovis points; D, a Folsom point. All are from Illinois.

Their belongings, by our standards, were pitifully few, their way of life laborious, full of hardship and danger, but their needs were simple and their means of meeting them doubtless seemed ample to these hardy hunters. The chief weapon was a thrusting spear with a chipped flint head and a long shaft to keep the hunter as far from harm’s way as possible when attacking the dangerous animal. The narrow width of the spearpoint made it easy to withdraw from a wound and attack again. Our evidence that the Paleo-Indians (as the Big Game Hunters are commonly called) lived in Illinois are these same spearheads (Clovis and Folsom types), usually grooved or fluted lengthwise of the blade, which are scattered over much of the Illinois prairie as isolated finds. No campsites of this people have yet been discovered in Illinois, as they have been in Pennsylvania, Alabama and several southwestern states. We can only surmise that in Illinois the hunters also had stone hammers and chipped flint scrapers as they had elsewhere.

Having arrived in the great central valley between the Rocky Mountains and the eastern ranges, the herds probably moved slowly from one browsing ground to another in the open corridor between glaciers. It may have taken them many years to reach what is now the United States. Eventually the herds wandered back and forth across the Mississippi Valley, and some favorable spots came to be used as camping grounds again and again by the same or different families. Such places would appeal immediately to the campers because of their protection from rain and the piercing glacial winds, the presence of a plentiful supply of wood and water. The possibility of our gaining a better knowledge of Paleo-Indian life in Illinois rests on the discovery of such a site, difficult now to recognize because it may no longer provide wood, water, or shelter of any sort.

There are in southern Illinois a number of simple linear stone piles known locally as “stone forts,” all in the same type of land structure. Each forms an obstruction five to fifteen feet in height across a narrow neck or ridge leading to the plateau top of a near-vertical-sided “promontory” projecting out into a stream valley, making an excellent corral, with no fence necessary except across the entrance. They may have been used in late Paleo-Indian times and on into the Archaic period for impounding large game and/or driving them over the cliff.

We have reason to believe that the Big Game Hunters wandered over Illinois and the adjoining states during the last advance of the glaciers. Around 12,000 B.C. the climate in the Midwest became milder, the glaciers “retreated,” and the mighty torrents—the Mississippi, the Ohio and the Illinois that had torn irresistibly down their valleys—shrank into smaller, less turbulent rivers that occupied but a fraction of their former beds. The great shaggy mammoths, musk oxen, the ground sloths and the giant beavers moved westward toward the mountains or to the north.

Some of the Big Game Hunters with their families may have followed the retreating glacier and the herds; others stayed behind in country to which they had grown attached. With the great herds gone, the human families remaining in Illinois had to hunt the game animals that now frequented the area—deer, elk (wapiti), bear and smaller mammals. The large hunting party was no longer practicable. The game roamed over the country singly or by twos or threes and had to be stalked by one or two hunters. Families were compelled to live widely separated one from another in order to secure ample food throughout the year. Thus developed a new way of life which we call the Archaic phase or culture.

The hunter, as time passed, learned the secret habits of the deer, bear and raccoon and the more sluggish fishes. His wife and daughters learned the haunts and ways of the smaller animals, the rodents, turtles and lizards, discovered where edible greens, wild tubers, nuts and fruits grew and where mussels and snails abounded in creeks and rivers. With increasing knowledge Archaic man made better and fuller use of his changed and changing surroundings, food became more plentifully available, life easier and less hazardous though still very difficult from our standpoint.

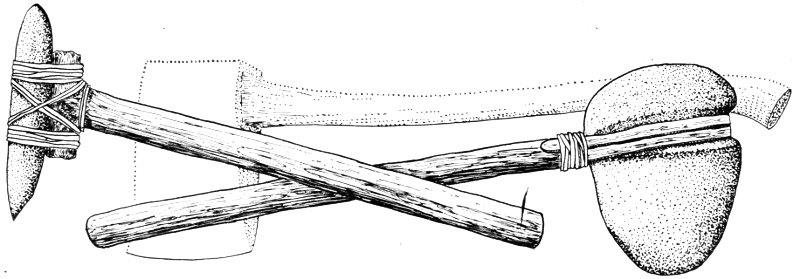

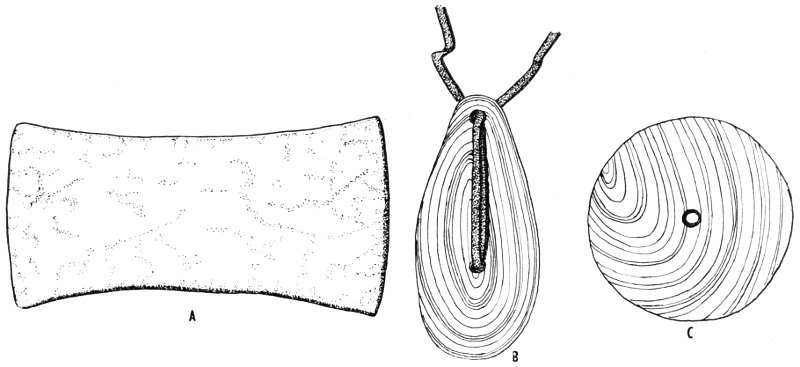

Fig. 4. Hafted primitive stone adze and grooved ax, with modern steel-bitted ax in the background. (B.B.)

With new needs and some leisure from the labor of providing food, Archaic man invented specialized devices, new methods of making tools and weapons, the more skillful among them shaping the objects carefully into symmetrical forms pleasing to the eye of others and strangely satisfying to the maker.[7] He pecked a hollow in both sides of his cobblestone hammer so he could grip it securely and use it more skillfully. He pecked and ground diorite and granite into adzes, hatchets (celts), and axes with a groove for hafting. These were a decided improvement over flaked choppers. He ground and polished banded and highly-colored shale (“slate”) into prismatic and cylindrical spearthrower weights and bored them with a tube, sand and water. His own person he decked out with necklaces and oval pendants (made by boring a hole in smooth flat waterworn pebbles) and with bone ornaments cut to shape, ground, engraved and polished. These he and his wife wore as had their forefathers but not the skin robes of glacial times.

As life grew easier, the family or local group increased in size. Sons brought their wives to the family dwelling place and built windbreaks near those of their parents. With food abundant the little settlement became a small cluster of households or a hamlet consisting possibly of sixty to seventy persons.

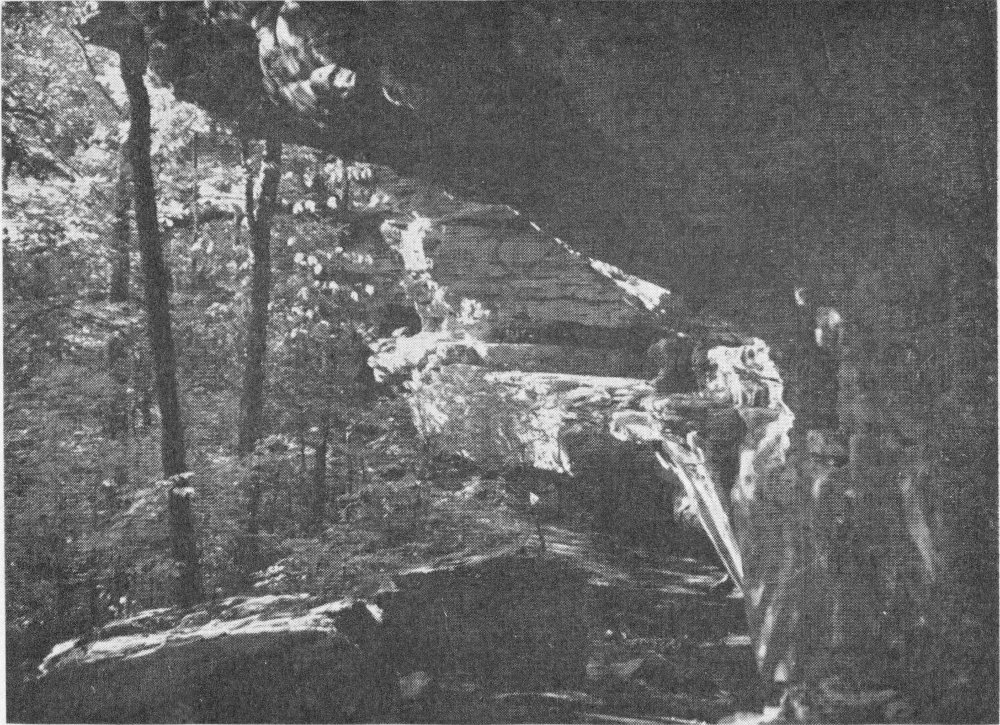

Fig. 5. Rock shelter near Cobden. Such shelters were used by Archaic and succeeding peoples. (Photograph by Irvin Peithmann)

If Archaic man in Illinois lived as do present-day Archaic peoples, the family or local group, though they restricted themselves during most of the year to their hunting grounds which they guarded jealously from trespassers, did not camp continuously in one spot. At appropriate seasons of the year they rotated from one hamlet site to another to take advantage of the food resources of that locality. In winter perhaps they moved to a rock shelter, like that of Modoc in Randolph County, Illinois, near the wooded valleys of streams emptying into the river where deer and elk sought protection from the rigors of winter; in spring to upland lakes for duck and other waterfowl; and in autumn to wooded 15 parklands to harvest acorns, hickory nuts, and berries. The spot chosen for each hamlet location was generally one that had been so used at that same season from time out of mind by the family and its forebears.

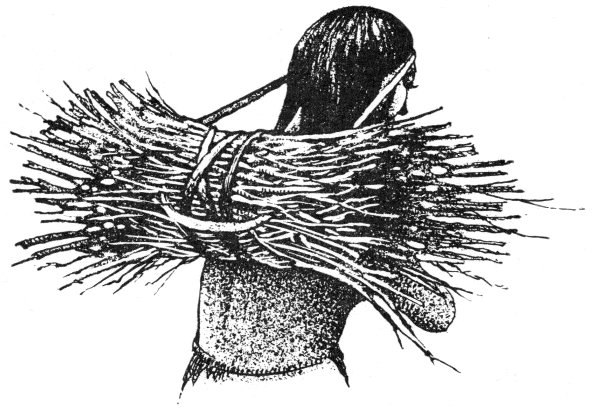

Fig. 6. Primitive woman carrying a load with the aid of a tumpline. (J.C.)

It is probable, as among most primitive peoples, that men did only work thought suitable to men, and women that appropriate for women. Men made the weapons and tools they used, did the hunting and fishing, and the fighting (when quarrels developed into feuds or wars between local groups of the same tribe). The rest of the labor fell to the women—caring for the children, collecting edible plants, clams and small animals, preparing the food, and carrying burdens. All work was done by hand; loads were carried on the back. It is possible that boats, perhaps of dugout type, were used as among present-day Archaic peoples living on waterways. There was no other specialization and each “household” provided for the needs of all its members to the best of its ability. No food was grown and no domestic animal except the dog was known.

Once or twice a year when food was easily and bountifully available, local groups from nearby hunting territories met together for religious rites. These local groups spoke the same dialect, had the same way of life, and considered themselves a unit or tribe. They had no political form of government but were kept in order through habits formed by early training and by extension of the kinship system to the whole tribe. Thus the tribal elders were considered fathers and mothers, and to them were due obedience and respect, just as children they had been taught to regard their own blood fathers, uncles, and other older relatives. The elders knew the tribal customs; and to be accepted as a tribal member, boys must respect, learn and conform to these customs.

The object of these annual gatherings was to teach the young the tribal customs and to perform solemn ceremonies, the purpose of which was to insure the security and well-being of the tribe, a continuing abundance of the favorite foods, and to express gratitude and thanksgiving to unseen Spirits who watched over the game animals (and possibly the edible plants) for the blessings received during the past year. These gatherings and cooperative undertakings served, on the one hand, as a welcome change from the usual daily grind and afforded opportunities for the young to get acquainted and choose mates and, on the other, to unify the language and customs of the constituent local groups, to enhance the influence of the tribal elders and keep fresh in the minds of all the history of the tribe, the importance of its activities, and its sacred tradition, all essential to the way of life of dynamic Archaic peoples of recent times.

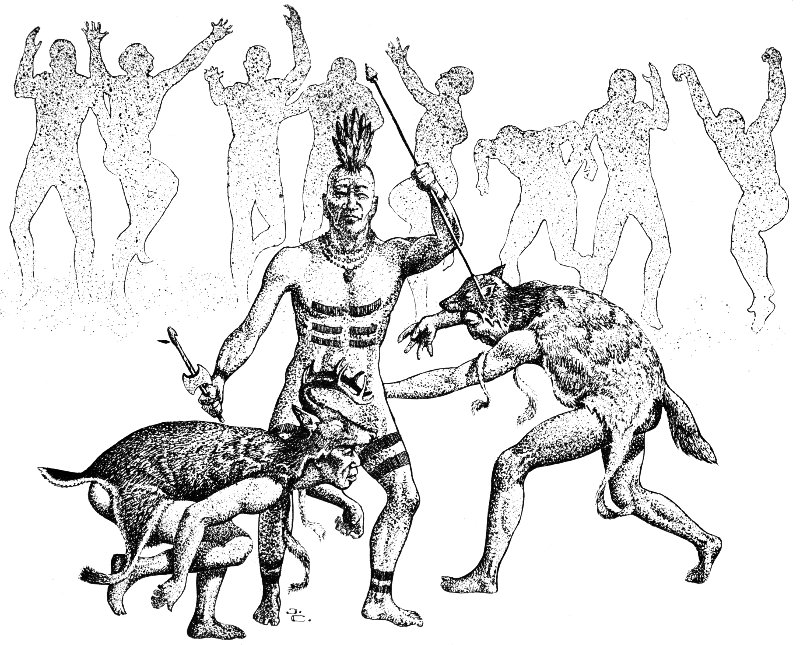

Fig. 7. Fertility rites were probably performed by Archaic peoples to ensure the abundance of game animals for the next year. (J.C.)

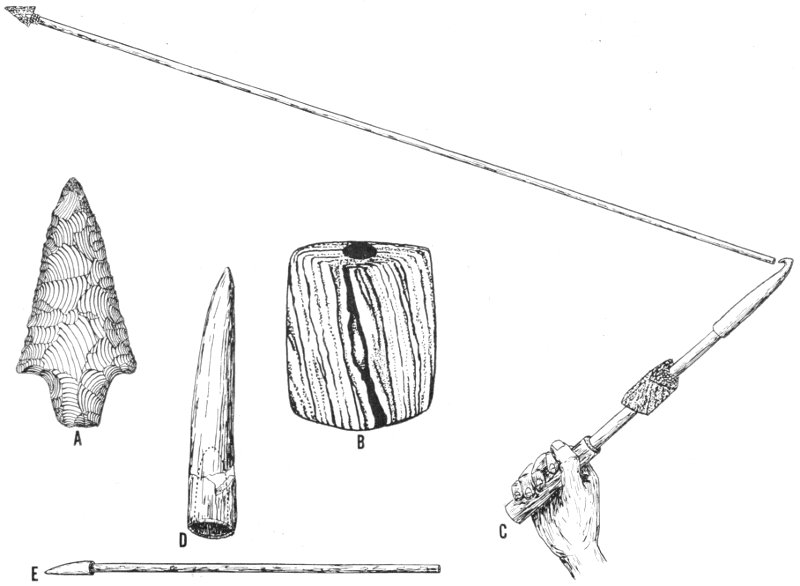

Fig. 8. Archaic weapons: A, Hidden Valley type spearhead; B, prismatic atlatl weight of polished red shale; C, throwing a spear with an atlatl; D, socketed antler spearhead; E, short thrusting spear or javelin. A, B, and D are from Modoc Shelter in Randolph County, Illinois.

In the later (Medial) Archaic period at Modoc, the dead were buried in the floor of the rock shelter. Burial probably indicates a belief in life after death. Care in preparing the body for burial, in the funeral rites and burying, and in the customary mourning thereafter was highly important so the dead man could go promptly to the spirit world in peace and not remain in the neighborhood to disturb his kinsmen. Immediately after the burial, it is probable that the little settlement removed to a distant location as is customary with peoples in this stage of culture.

The rites for important dead in the Terminal period probably began with the conventional mourning of relatives, with painting the body with red ochre and grease and adorning it with the dead man’s jewelry, followed at the appropriate time by the conveyance of the body to the grave side, where the corpse was deposited in a pit together with personal insigne and weapons. The grooved stone axe, large spearheads, 18 daggers, bannerstones, spearthrower with weight and more rarely copper articles were placed alongside or on the corpse. In some instances large stones were laid upon the grave probably for one or more of the following reasons: (a) to mark the grave of an important tribesman; (b) to keep the body from being disturbed by animals; and (c) to hold the dead man’s ghost until he departed for the spirit world.

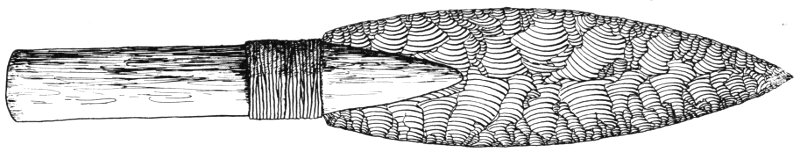

Fig. 9. Grooved stone axes are frequently found in Archaic graves but were not buried with the dead after this period. (J.C.)

It is very probable that, on occasions of social and religious import, Modoc man and other Archaic tribes in Illinois bedecked themselves in their best paint and jewelry. Possibly the colorful and intriguing bannerstones, which were undoubtedly developed from the spearthrower weight, were carried or worn by the local group headmen who had won that right because they were skillful hunters, courageous fighters, or learned in the tribal customs and beliefs and thus recognized by the tribe as leaders for the time being.

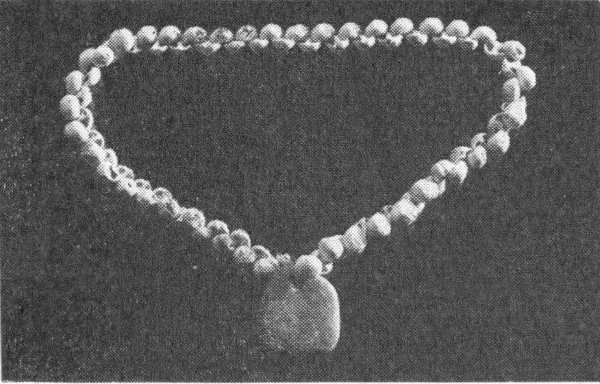

Fig. 10. Anculosa shell necklace with flat pendant of water-worn stone from the Archaic period. Anculosa necklaces were worn by many Illinois peoples probably up to the European contact period.

Man can live virtually anywhere on the earth’s surface where he can obtain food, water and fuel, and do so without any fundamental change in his physical structure. This is largely because he is easily able to modify his customary ways of filling his basic needs under new or changing conditions of his surroundings. For primitive man to “live better” required an increasing knowledge of the resources in his locality and ingenuity in devising effective means and contrivances for exploiting them.

Because of this ability, the Paleo-Indian wanderers (Big Game Hunters) in Illinois around 12,000 to 10,000 B.C., when confronted with rising temperatures and other regional changes, could choose whether they would follow the mammoth and musk ox herds and familiar subglacial conditions elsewhere or adopt new and strange methods of securing food and other requirements.

As Big Game Hunters they probably lived as a number of families attached to a herd and relatively independent of each other except at hunting times. They had no homes, only temporary camps, and were bound to a moving herd, not to any particular region. The Paleo-Indian culture consisted of methods of trapping and slaying the great beasts and of filling other simple physical needs; a simple code of social behavior which enabled men and wives to live together with their children and, for brief periods, in gatherings of the families in relative peace and contentment; with religious beliefs and rites suitable to their cultural level that they believed assured them of a continuance of their satisfactory existence.

When the climate changed, those families that chose to remain in Illinois had to develop, perhaps slowly and painfully, a new way of life. The habits and haunts of deer, elk, bear and raccoon had to be learned. Other methods of hunting and of making tools and devices to fit new conditions were invented as a result of the new fund of knowledge assembled. Each family eventually acquired a more or less definite piece of land or hunting territory in which it selected certain favorable places to build the temporary hamlet at suitable seasons. As the man and his family became better adapted to the land and its resources, he hunted more successfully, and the family or local group grew larger in number.

Probably a number of neighboring families, when food was especially abundant, gathered together for social and religious purposes as peoples living today in the same status still do. Religious beliefs and other customs had all this time doubtless been shifting gradually in meeting the needs and dangers of changing conditions to a new way of life we call the Archaic culture.

Every way of life is built on an older, often simpler, culture from which it has changed more or less rapidly. Due to important inventions, the group may modify its economy (ways of securing and processing 20 food, etc.) and produce a substantially improved manner of living which, from archaeological evidence alone, may be difficult to recognize as a development from its earlier phase.

On occasion, people from another region may invade an area, drive out the inhabitants and bring in a differing way of life. Usually this merely extends, to a desirable region less effectively exploited by others, the range of a vigorous cultural group whose territory has become too densely populated.

Sometimes newcomers essay to live peaceably with the natives and a new cultural blend is developed. If fundamental changes are made in the economy by internal development or by imitating another culture, social and religious customs are very likely to change too, though usually at a slower pace.

As time went on, the Archaic way of life slowly changed and finally disappeared, but probably not so suddenly as might at first appear; for many Archaic customs, tools, and weapons continued to be made and used in the “new” culture by the descendants of rugged earlier people or were adopted by newcomers to the region. Other changes were added through new inventions and incoming people from other regions producing a new culture now generally known as Woodland.

After 5000 B.C. the temperatures continued to rise producing a climatic interval known as the Thermal Maximum when it was warmer and drier than at the present time. After reaching its high point, the temperature gradually declined and probably ended in southern Illinois about 2100 B.C. or later in a climate much like that of today.

By projecting the rate of deposit from the eight- to the eleven-foot level of the Modoc Rock Shelter up to the five-foot level where the Archaic remains appear to end, we secure a date for its upper limit of about 2100 B.C. (Deuel 1957, p. 2). The remains between the five- and eight-foot depths are scantier and less varied than in the earlier (lower) layers and may indicate a cultural group in a losing struggle to maintain itself under changing conditions.

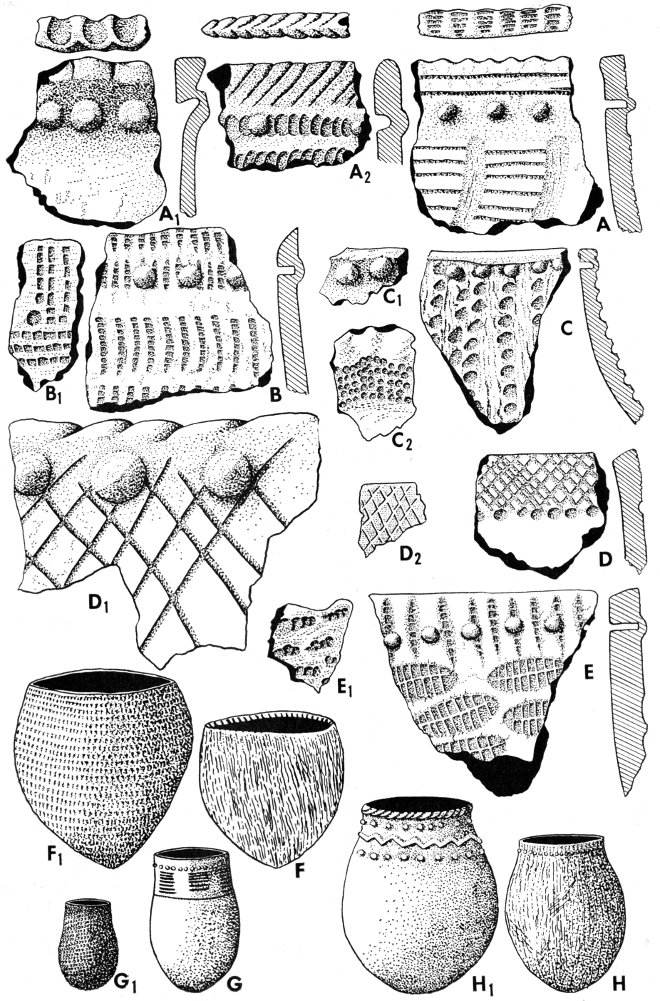

Fig. 11. Potsherds from the Lake Baikal in southern Siberia resemble those of Initial and Classic Woodland (Hopewellian) in Illinois. The letters with subscripts refer to Siberian pottery. A-E, reduced to ½ actual size; F-H, reduced to ¹/₁₆ actual size. (Siberian pottery from Richthofen in ANTHROPOS, 1932: 128, 129, 130; Illinois pottery from Illinois State Museum collections.)

In northern Illinois, similar climatic conditions were developing. There, possibly as early as 2500 B.C., a new culture, the Initial (early) Woodland, was coming into existence. At any rate, groups living there some time prior to 1000 B.C. made pottery, placed their dead in cemeteries and in low burial mounds in a flexed or “doubled-up” position, occasionally with food, personal ornaments and other funeral offerings.

Fig. 12. A flint dagger or hunting knife from “Red Ochre subculture” of Initial Woodland. (B.B.)

The pottery of one Woodland group (Morton) in the Illinois valley resembled, in shape, surface treatment, design and area decorated, pots made in the Lake Baikal region in Asia some 7000 miles distant. The appearance of such striking similarities has long been a puzzle to anthropologists. In the first place the detailed likenesses suggest both were made by one and the same people. It seems fairly obvious that the several resemblances did not travel from tribe to tribe from Asia to central North America. The preservation of a pottery tradition during a migration of 7000 miles, probably lasting for several generations, seems equally incredible. Perhaps the most plausible explanation is that two widely separated divisions of a people originating in central Asia with the same cultural background and similar surroundings arrived independently at a remarkably similar but very simple pottery type.

Fig. 13. A copper gorget, A, (possibly patterned after the double-bitted ax-shaped bannerstone) and shell gorgets, B and C, from “Red Ochre subculture” of Initial Woodland. All from Mound 11, Fulton County, Illinois.

These late migrants probably found groups like the Black Sand (and Red Ochre) peoples in Illinois who were just emerging from the Archaic phase into Initial Woodland. The settlements of all early 23 Woodland peoples were small in extent and poor in cultural remains. The population of these hamlets probably seldom exceeded fifty. No traces of house structures have yet been discerned. Temporary huts, probably built of small poles and brush, may have been conical or hemispherical in shape. The artifacts or cultural objects, except for a small amount of jewelry (shell and copper beads and pendants) and the few offerings placed in graves, show little evidence of any urge to fine workmanship or much feeling for beauty of line or form. Life was probably too hard and the effort in securing food and other requirements too exacting to leave much leisure for artistic workmanship in durable materials.[10]

It has been seen that in southern Illinois the Archaic way of life may have persisted until 2100 B.C. or perhaps even later. Across the state on the Ohio River a Woodland people succeeded the earlier Archaic residents. Their culture is known as Baumer and their nearest cultural relatives lived south of the Ohio in Kentucky (Round Grave or Upper Valley People). The Baumer artifacts do not resemble those of the Archaic period very closely, giving one the impression that the Baumer people developed their way of life elsewhere and moved into Illinois, possibly while Archaic groups were still in the region.

The Baumer culture differs in several ways from the northern Initial Woodland; actually it appears to be more advanced although it has been termed early Woodland by some archaeologists. In the first place, the area of settlement was more extensive which seems to indicate a larger population than do early northern Woodland campsites. Their artifacts are numerous and varied, suggesting they were well adapted to their surroundings. Flat forms of polished stone (resembling in outline certain Archaic bannerstones from which they may have derived) served presumably as breast ornaments or gorgets (as similar pieces did in the Hopewellian period). Tear-shaped stone objects (plummets) were made as they had been in Medial and Terminal Archaic. House structures were semi-permanent, large, square, made of poles or logs set in holes in the ground. Huts with circular floors seem to have been in use also. Most important of the cultural habits noted were numerous pits apparently for the storage of food. In these the remains of acorns 24 and hickory nuts were found. These people, like the acorn gatherers of California and the Eskimo, knew how to preserve food over long periods. Acorns were probably abundant enough for a Baumer family to lay up several months’ supply in a short time. This permitted them to live in larger settlements and gave them sufficient leisure to build rather substantial houses and shape symmetrical ornaments from stone. These facts seem to substantiate the hypothesis that they were a sedentary people by virtue of their knowledge of how to store food.

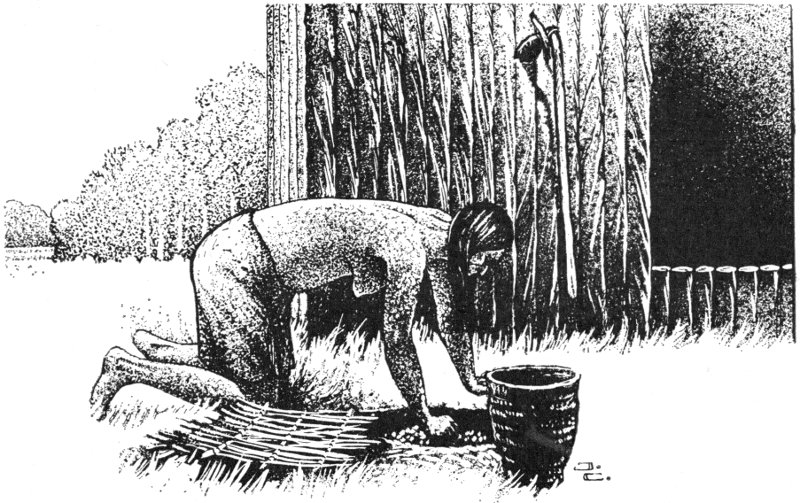

Fig. 14. Housewife storing roasted acorns in a pit near door of her square log cabin dwelling. Characteristic clay vessel (“flower-pot” type) with “mat-impressed exterior.” Baumer period. (J.C.)

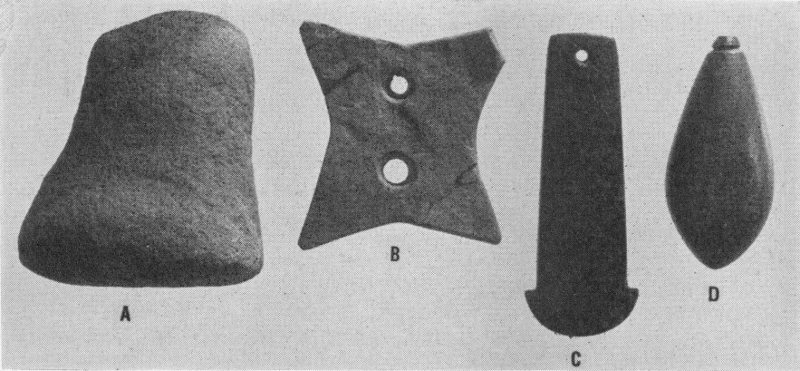

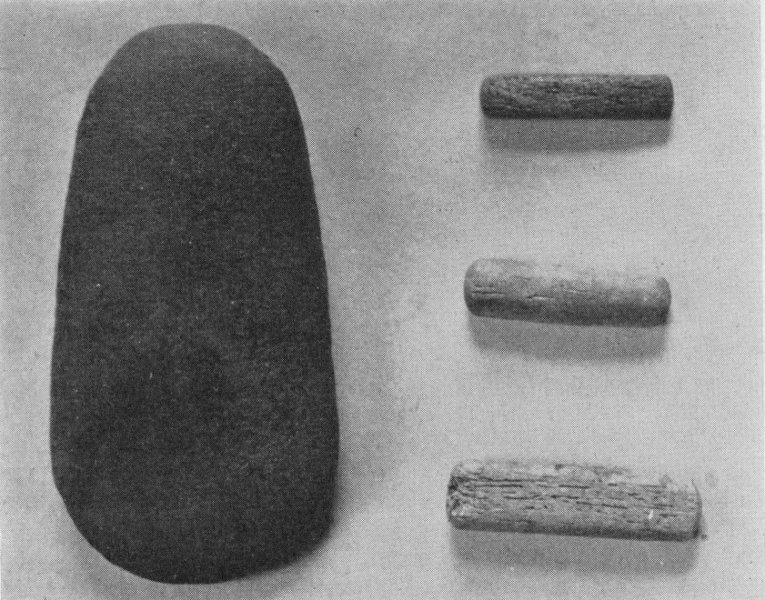

Fig. 15. A, stone pestle; B, reel-shaped stone gorget; C, “spud-shaped” stone gorget or pendant; D, grooved plummet. From the Baumer subculture and site.

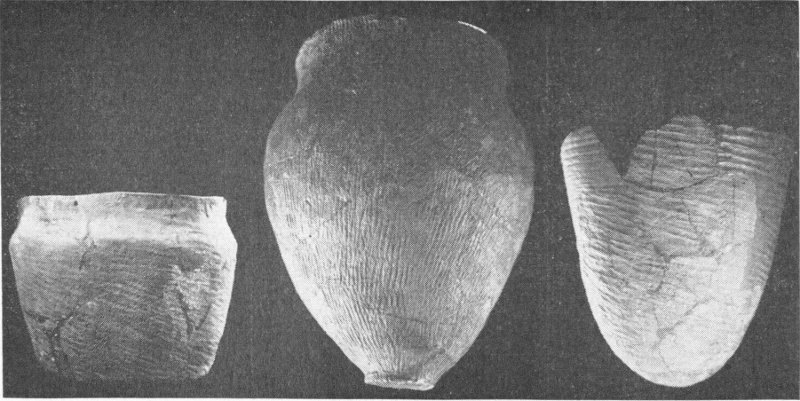

Fig. 16. Pots from the Crab Orchard period of Baumer subculture recovered from the Sugar Camp Hill Site by Moreau Maxwell for Southern Illinois University. Vessel in center is roughly 16″ tall. (Photographs furnished through courtesy of Dr. James B. Griffin, Univ. of Michigan.)

The size of the Baumer settlement, the semi-permanent houses, the presence of chipped spades, stone pestles and pottery might lead one to think that these people were plant-growers rather than simple food storers. Comparing them with the acorn-gathering tribes of California, who were storers and not food growers, it is seen that these, too, had permanent settlements with well over one hundred inhabitants, rather substantial houses, stone pestles, and some tribes, at least, had pottery vessels. The Californians doubtless had digging tools since the rooms of some houses were dug four feet down into the soil.

Traces of Hopewellian influence, possibly indicating inter-marriage with Hopewellians, have been noted at the Sugar Camp Hill site (date undetermined) in Jackson County, which is presumably later than Baumer. However, the Baumerians like the native Californians were conservative, for four centuries intervened between the oldest Hopewellian village in the north and the earliest known station of that culture in southern Illinois.[11]

Toward the end of the Initial Woodland period maize or corn, as we call it today, was introduced into northern Illinois, presumably from Mexico and Middle America through the agency of intervening tribes. In an apparently short time, its production seems to have been greatly intensified and exploited. Other food crops and tobacco may have accompanied maize.

About the same time, a formalized religion arose, probably concerned with the worship of deities who personified natural forces like the sun, rain and thunder, which were important to a plant-growing people. From the evidence of burial places, there seem to have been two or possibly three social classes. Doubtless the first comprised the families who introduced and grew the new food plants and who were inspired to invent the complex religion. The burial of the dead, especially those socially important and of the highest class, was accompanied by elaborate and colorful ceremonies closely bound to the religion. This seems to be a continuation in grander form of the earlier Red Ochre funeral and burial. It is unfortunate that we do not have tangible evidence of their other religious and political ceremonies which may have been even more impressive and significant. The official dress and insignia of the officials, which we can barely glimpse in the rich and varied remains in the tombs, signify a political system of social control and an established priesthood for the spiritual guidance of the community. Shamans or medicine men probably had only the duty of treating disease. Reverence for and possibly worship of ancestors is suggested by the impressive tomb chambers and mounds and the care obviously bestowed on certain of their socially prominent dead.

Social and political prestige, religious pomp and ceremonial, all seem to have combined to stimulate a demand for rare materials, beautiful jewels and impressive regalia. This initiated the search for pearls at home, the development of skillful and artistic workmanship in flint, bone, shell, copper and mica, travel abroad and trade in materials obtainable only in distant regions.

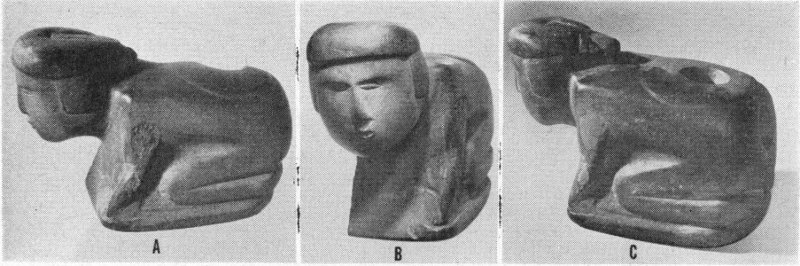

Aside from those technologies connected with the growing of plant foods, probably few new crafts appeared in the culture; rather those 27 already, existing in the Initial Woodland were raised to a high degree of excellence. Art in several forms flourished—carving in the round and in relief, the making of fine symmetrical polished, decorated and painted pottery commonly called typical Hopewellian, hammered copper jewelry, the setting of pearls and highly-colored native stones as eyes in sculptured animals and in bear-tooth pendants and ear ornaments, etching of delicate designs, naturalistic and conventional, on bone and the modeling and firing of exquisite statuettes in clay. We admire and wonder at the excellence of execution in the best of their small sculpture because they are skillfully fashioned and finished and because they so accurately portray the characteristics and habits of animals with which we are familiar. The artist had the crudest of tools to aid him—rough stone hammers and an anvil for pecking stone to the general form; sandstone files or abraders; clay and water to polish pieces; flint and tubular drills for boring; and flint knives to cut and engrave pottery and bone—in spite of which the best craftsmen well knew how to bring out the beauty of the piece.

Fig. 17. Artist’s idea of a Hopewellian chief or high priest in full ceremonial regalia. (J.C.) Evidence for dress (except for calumet) has been found in Illinois.

For the first time in Amerindian history in Illinois we become aware of an accumulation of wealth, a surplus of handmade goods over and above those needed for survival; many of these were neither well-suited nor intended for immediate physical needs, but rather were aimed at social display or spiritual enhancement. Wealth reflects a relatively constant and abundant supply of food and other necessities and the resulting accompaniment of considerable leisure time for a sizable portion of the community. It may also mark the beginning of craft specialization.[13]

It is hardly necessary to add that, if such a profusion of grave offerings as indicated by Hopewellian tombs—feather cloth robes, pearl necklaces, copper hatchets, and beautifully fashioned art objects—were left with the dead, that the high political and religious officers were correspondingly bedecked in gorgeous apparel for civil and religious ceremonies.

Nor should sight be lost of the fact that these creations and materials, so commonplace and inexpensive today, were to the Hopewellians as valuable and highly desirable as gold, silk, and precious stones are to us in Western civilization. For a better perspective these tomb offerings should be compared with objects usually found in camp and grave sites of the Initial and Final Woodland peoples.

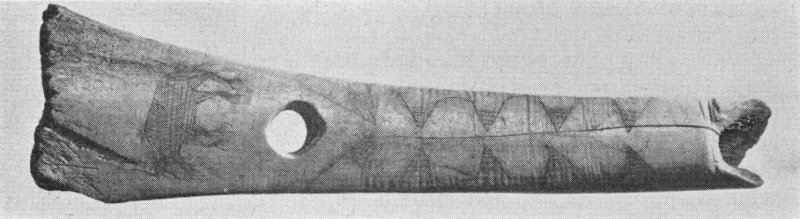

Traders may have gone to distant regions to select and barter for raw materials, to the Lake Superior region for copper, to Ohio for pipestone, to the south Atlantic and Gulf Coasts for the small Marginella and Oliva shells, for the larger Cassis and Busycon shells, and to the Yellowstone or Mexico for obsidian (of which little is found in Illinois graves). Trade, to some degree, removes the limitations imposed by the immediate surroundings. Pearls were secured in quantity from the clams of the native streams. Bone, antler, tortoise and clam shell, bears’ teeth, bear, wildcat and wolverine jaws from their hunting and collecting pursuits were utilized more fully than ever before. Even human jaws, possibly of enemies, were cut, polished and bored for use as pendants.

Though the Hopewellians may not have been the pacifists they are sometimes painted, there must have been long periods of peaceful relationships with distant and nearer neighbors with whom they traded or through whose territories their traders had to pass. Whether or not a condition of peace was maintained within the borders of their culture area by the force of arms is an interesting question that cannot now be answered.

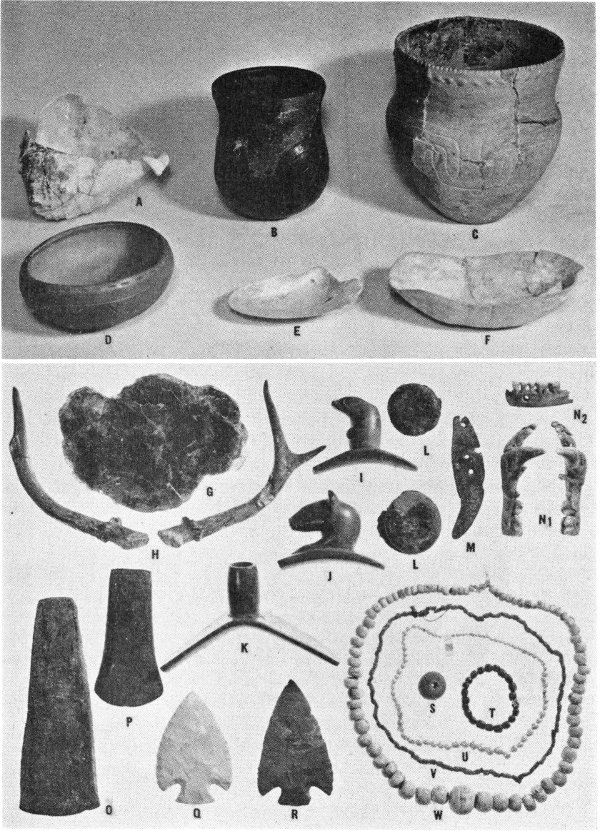

Fig. 18. The Hopewellian assemblage of artifacts that collectively identify the Hopewellian (Classic Woodland) period and, except for shell spoon, turtle shell dish, and some bead types, distinguish it from the other Woodland assemblages. A, drinking cup of marine shell (Cassis madagascarensis); B, C, D, Hopewellian pottery (restored); E, mussel shell spoon with “handle”; F, turtle shell dish; G, sheet mica (mirror?); H, antler headdress; I, J, platform pipes with effigy mammal bowls, polished stone (Otter and bear’s head, eyes set with copper pellets); K, platform pipe (plain bowl), curved base, polished stone; L, copper earspools or ornaments, pair; M, imitation bear tooth, copper; N, (Below) N₁, Bear jaw, cut in half, ground and drilled to be worn as a double pendant; (Above) N₂, Fragment of a human jaw that has been similarly treated; O, copper hatchet that carries imprint of textile on its surface; P, copper adze; Q, R, Hopewellian spearheads; S, massive bead of copper; T, bracelet of copper beads; U, necklace of pearls; V, necklace of copper beads; W, necklace of graduated ground shell beads from columella (central column) of marine shell.

In southern Illinois the advance of Hopewellian culture was slower. The infiltration of new pottery styles noted at Crab Orchard very possibly represents intermarriage with Hopewellian women. Possibly through ties of relationship and the acceptance of the new food plants, the old Baumer way of life was submerged by the Hopewellian customs though here and there former habits still are recognizable. Some customs of Baumer and Crab Orchard were adopted by the northern Hopewellians—the reel-shaped gorget, the plummet and the chipped stone hoe.

In the north of Illinois, Hopewellian lasted until 250 A.D. (Poole site) and in the west and south to about 450 or 500 A.D. Though the culture died out in Illinois by 500 A.D., it still flourished in Mississippi (Bynum site) around 800 A.D. and at Marksville, Louisiana, as late as 850 A.D.

As was stated earlier, emerging cultures grow out of earlier ones. Although it may not yet be generally recognized, the Hopewellian civilization probably exerted tremendous influence on the Mississippi cultures and on tribes that followed them in the great central valley of the United States and beyond, down to historic times. It must be borne in mind that in spite of their splendid achievements, the Hopewellians had no domestic animals but the dog, no herds for meat and great wealth, no draft animals to drag the plough and turn the mill. All labor was “by hand,” all transport on the back or in a boat driven by human power.

The Hopewellian civilization apparently disappeared as suddenly as it seems to have arisen. This impression is probably due to the fact that the people continued to live in the old villages long after the characteristic colorful Hopewell customs were no longer practiced. Actually the culture may have declined for a century or more before it finally broke down completely. Many of the simpler folk traditions probably persisted in the area for some centuries afterward.

Possibly long continued abuses of power and privilege by religious and political officials, especially those from the highest social caste, weakened the confidence of the lower classes in their leaders and the culture. Newcomers from Iowa, Missouri and Kentucky may have further disorganized certain settlements and separated areas of the larger community from each other. Generally, however, the writer gets the impression that the decay began within the civilization although its final downfall may have been accelerated by external pressures.

With failing confidence and a rising uneasiness, trade would naturally decrease and the incentive to fine workmanship decline. The larger cultural community split apart into a number of small tribes, who were isolationists and individualists. All the separate little tribal units were Woodland culturally with some small evidence of their Hopewellian heritage, but each differed in certain respects from its 31 neighbors. Villages dwindled to the mere hamlets, widely separated one from another. The elaborate ceremonial dress, insignia, and jewelry, and the artistic creations (at least in durable materials) became a part of the past; the people found themselves reduced to the rude cultural level of their early Woodland ancestors. Huts were flimsy and left no discernible remains. Tools, weapons, and ornaments were, in general, carelessly made and poorly finished. Although tobacco was smoked and small patches of maize and beans may have been grown, the chief economic dependence undoubtedly was on hunting, fishing and collecting.

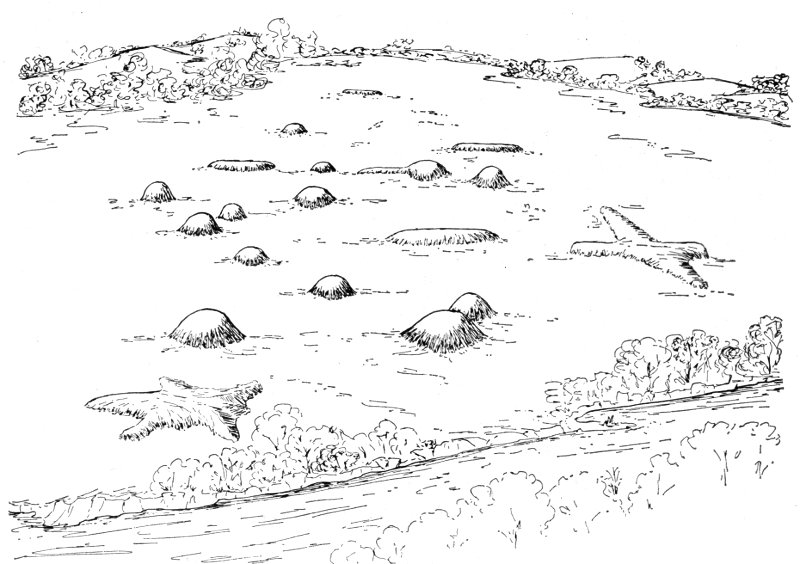

Fig. 19. Group of mounds exhibiting bird, mammal, linear and conical mounds as they occur characteristically in Effigy Mound subculture of Final Woodland. (B.B.)

The religious beliefs, too, were probably simplified and mixed with magic and superstition, surviving relics of the religion of the past age. In a word, the social and religious customs of the little tribes were broadly similar but in minor details differed from each other much as do their artifactual remains.

A study of the Final Woodland and other phases of Illinois history reveals certain relationships among some distinguishable differences of detail:

1. The almost complete lack of evidence of Hopewellian art, trade and religion in the late Woodland period gives little apparent indication that the people were the direct descendants and heirs of that civilization. 32 On the other hand, the general resemblance of Final Woodland assemblages to those of the Initial phase seems marked. Let us examine further.

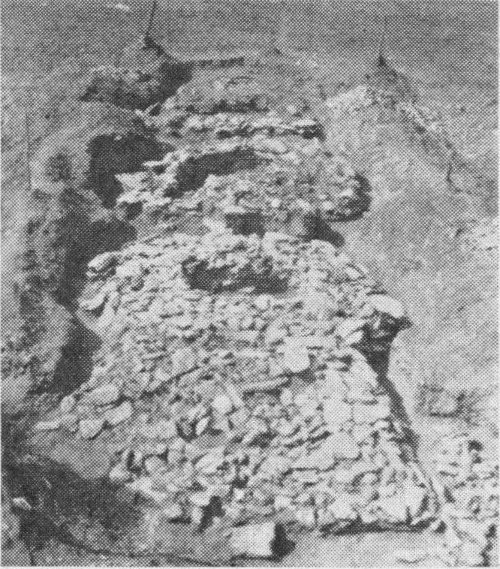

Fig. 20. Graves near Quincy, Illinois, Stone Vault period. (Photographs through courtesy of O. D. Thurber.)

Four excavated “vaults”, the third of which shows a “corridor” entrance with stone steps.

The tobacco pipe of the late phase with the stem projecting beyond the bowl is found in most aspects. Likewise, the vertically elongated pot is common but not the only form. Burials are often in mounds, frequently in a central chamber or grave, with skeletons in the flexed and/or extended positions, occasionally accompanied by grave offerings. All these are broadly reminiscent of Hopewellian customs and, in the writer’s opinion, indicate a continuing thread of tradition from Initial Woodland through Hopewellian into the Final phase.

2. The relationship to the Middle Mississippi seems more evident and has been attributed by some authors to the “impact” of a high culture on that of cruder or “under-developed” neighbors. What are the grounds for these conclusions?

New pottery forms were being attempted, the flattened globular pot, the shallow bowl (occasionally found in Hopewellian sites), the cup or beaker and the plate. In southern counties, a new method of making pits is indicated by a tendency of sherds, even grit-tempered ones, to split or laminate (see Maxwell, Woodland Cultures of Southern Illinois, Beloit, 1951, p. 204). Secondary features previously lacking begin to appear as “raised points” or knobs on rims, some roughly resembling animal heads with ears and a snout. Triangular arrowheads and others reflecting larger spearhead types are all made from curved, not flat flakes as the Mississippian points are. The stone discoidal that seems to be the game piece of the historically known chunkey game, which was possibly initiated in late Hopewellian times (see Fowler, The Rutherford Mound, Springfield, 1957, pp. 31-33) occurs in the Bluff subculture and probably in the Tampico also.

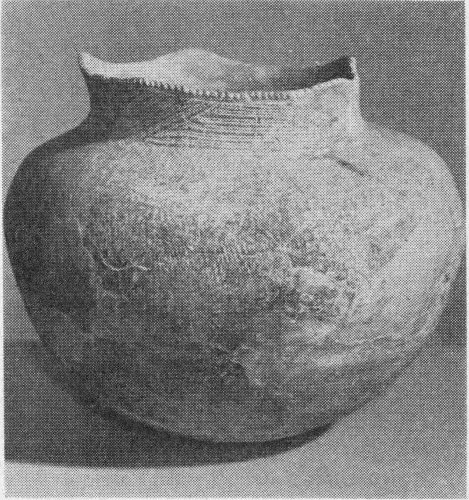

Fig. 21. Canton ware pot (Tampico subculture) from Clear Lake village site in Tazewell County. Designs are formed with cord impressions. (From Schoenbeck collection in Illinois State Museum. Max. diam. at shoulder 18″.

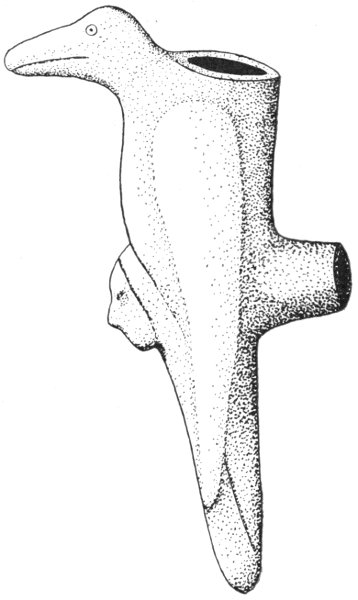

Fig. 22. “Handled” pipe in form of raven with head projecting from rim, from Jersey Bluff subculture. After Titterington. Reduced about ½.

All these bespeak Middle Mississippian tendencies. A common conclusion, as mentioned previously, is that these features were borrowed from non-Woodland groups. The writer, however, gets the impression from his studies that the Middle Mississippi phase developed through the interplay of invention and adoption of improvements, modification and re-invention, between the Final Woodland subcultures in Illinois and adjacent territory. This does not mean that Illinois communities alone were responsible for the emergence of this phase but rather that they played an important dynamic role in its development. The Cahokia subculture of western and central Illinois probably constituted the native local tribe or nation.

Archaeologically these peoples are in the Final Woodland phase of culture. The Final Phase yields tobacco pipes and crude flint arrowheads, its chief artifactual differences with the Initial phase. The clay of their pottery was generally mixed with grit or sand to prevent firing cracks in the vessel walls. The customary vertically-elongated pot with a conical or pointed bottom was accompanied by new forms—the globular or flattened globular with “round” (spherical) bases, the “coconut shell” cup or larger vessel, and shallow bowls. The flattened globular pots and the bowls were occasionally decorated with two or 34 four knobs or with “raised points” on the rim, sometimes giving a squarish appearance to the mouth. In some instances these decorative projections were crudely modeled ears and snout which give the effect of animals’ heads facing out and foreshadowing the Middle Mississippi effigy shallow bowls. An important invention, the bow and arrow, appears in Illinois for the first time in this period. Judging by the crudity of the chipped flint arrowheads, these people were poor archers and preferred the spear and spearthrower in hunting and fighting. Pipes, like most artifacts except weapon heads, are rare. The “elbow” or L-shaped pipe is generally representative of the culture.

The six recognized Final Woodland subcultures with their diagnostic (though not very significant) traits are (1) Effigy Mound named for its distinguishing characteristic; (2) Tampico with pottery decorated with designs formed by cord-impressions, in northern Illinois; (3) Stone Vault with stone mounds containing walled tomb chambers; (4) Jersey Bluff with its unique “handled” tobacco pipes, in the west; (5) Raymond, best characterized by the generalized Woodland nature of its artifacts; and (6) Lewis with incised spiral designs on pottery, in southern Illinois.

The Middle Mississippi culture seems to have arisen, as previously suggested, in the area where several important highways of aboriginal travel converged—the region surrounding the Ohio and Mississippi rivers from the mouth of the Wabash to the mouth of the Illinois. Whether or not its development was stimulated by the contracts of Muskhogeans and Algonkians or whether it was due to interplay between the cultures of the Final Woodland petty tribes is unknown.

Two slightly differing subcultures of the Middle phase appeared in the state. One, known archaeologically as the Cumberland (Tennessee-Cumberland), may have embraced at one time all the southern Illinois counties between the mouths of the Kaskaskia and the Wabash. [The Angel Site near Evansville, Indiana, may belong to the Cumberland subculture.] The other subculture, which may be termed Cahokia, flourished in counties bordering on the Mississippi from Union County to Wisconsin. As the two periods show few significant cultural differences, they will, except as noted hereafter, be treated as a single unit.

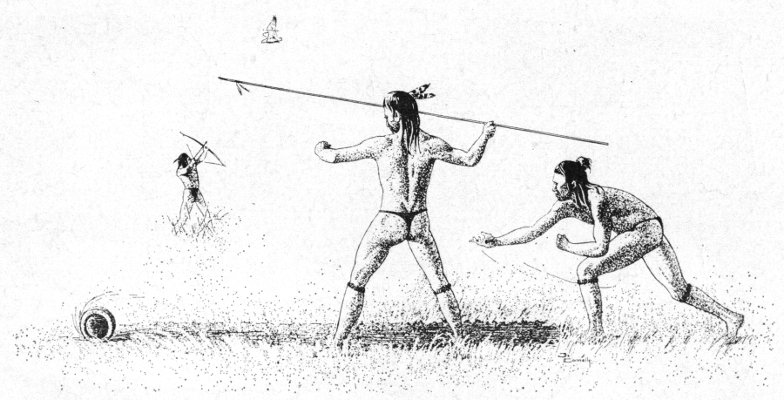

The bow and arrow invented in the Final Woodland phase, was developed early in the Middle Mississippi period into an effective weapon although spear and perhaps spearthrower continued in use. The chunkey game was probably played as a part of a religious ceremony though it may quite possibly have served as a popular pastime as well.

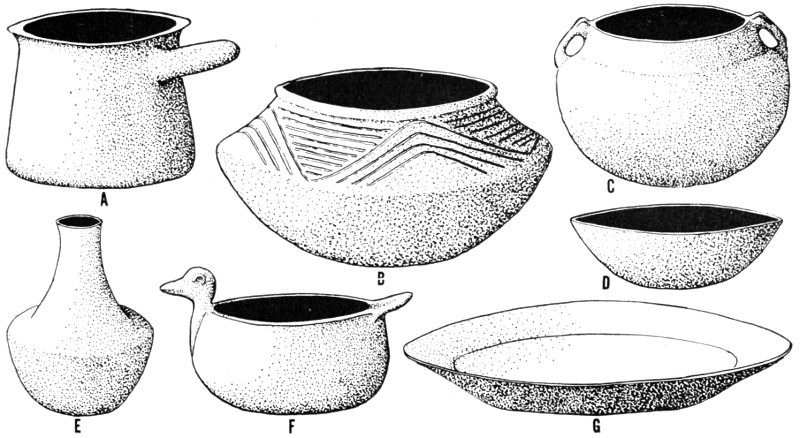

Pottery was slow at first to change from its more obvious Woodland characteristics but new shapes foreshadowing most of those of the fully 35 developed (Old Village) cultural phase practically replaced the conical-based elongated pot early in the period. Cord-roughening and grit-tempering disappeared in the classic Cahokia period, and a fine polished blackware and a painted pottery were added to the smooth utilitarian ware. An excellent “dull gray” ware with smooth gray to brown surfaces was of more common occurrence. It appears to differ from the fine ware only in its partially oxidized surfaces probably due to poorly controlled firing methods.[14]

Fig. 23. The chunkey game in foreground. Man hunting with bow and arrow in background. Middle Mississippi period. (J.C.)

There were probably two or more social classes among the Middle phase people as there were among Hopewellians, Natchez and Polynesians.[15] The fine polished black and painted wares may have been 36 marks of distinction between the highest and lower classes since it is much less common. In Hopewellian times, it is probable that both the fine ware and the specialized forms (which were usually of the highest quality) were reserved for the highest caste. In the Mississippi period, the shallow bowl, the cup or beaker, and the plate of dull gray ware seem to have been wide-spread in the village and may indicate a general improvement of living conditions among the lower social classes since Hopewellian times.

Fig. 24. Pottery shapes, Middle Mississippi period. A, “bean pot”; B, angular-shouldered pot or olla; C, common pot or olla; D, shallow bowl; E, water bottle; F, effigy bowl; G, plate.

Advances in the economy were obviously present in the fully developed Middle phase. The Union County flint “mines” and workshops were intensively worked. Trade with the Lake Superior, lower Atlantic and Gulf Coast regions was resumed. Chief imports of raw materials were copper and marine shells, Busycon, Marginella, Oliva and Olivella. Art, while possibly as highly developed as Hopewellian, resulted in a far smaller number of art objects in fewer durable media. Intaglio rock carvings (chiefly in southern Illinois) of geometric designs, human hands, ceremonial paraphernalia, animal outlines, and, in a few instances, painted hollowed-out animal silhouettes can probably be ascribed to this period on the basis of the symbols employed. Dwellings or cabins were relatively substantial structures and the extent of village remains indicate a large general population as compared to earlier times in the state. Trade and art suggest leisure and wealth or surplus available for exchange or to support officials and others in non-food productive 37 pursuits. This prosperity was possibly due to newly discovered methods of intensive cultivation of maize and possibly to a greater diversity of crops than ever before.

Fig. 25. Carved stone pipe (fragmentary) from Kingston Lake Site (Cahokia subculture, Middle Mississippi period). Owned by Donald Wray. Right-hand figure shows the pipe reconstructed.

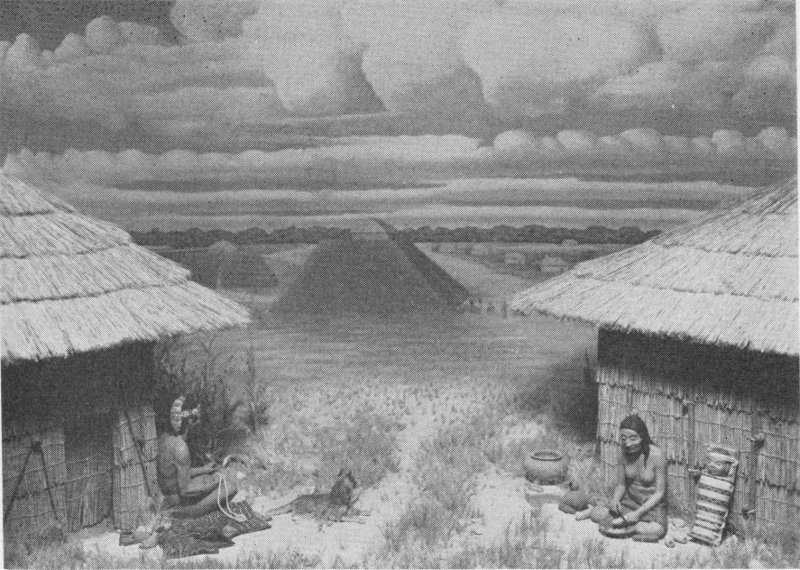

Territorially the tribe probably consisted of a number of villages and the surrounding country. Each tribe may have had a chief village or capital that was also a religious center with tribal (public) buildings and a temple. Archaeological and historical evidence shows that these buildings, presumably temples and the dwellings of tribal chiefs and the high priests, were erected on the flat tops of rectangular earthen mounds or pyramids, which were grouped around a plaza of ceremonial square. Here the tribe gathered for religious and political ceremonies and for important funerals. Intertribal negotiations and chunkey games were probably also staged on or near the plaza.

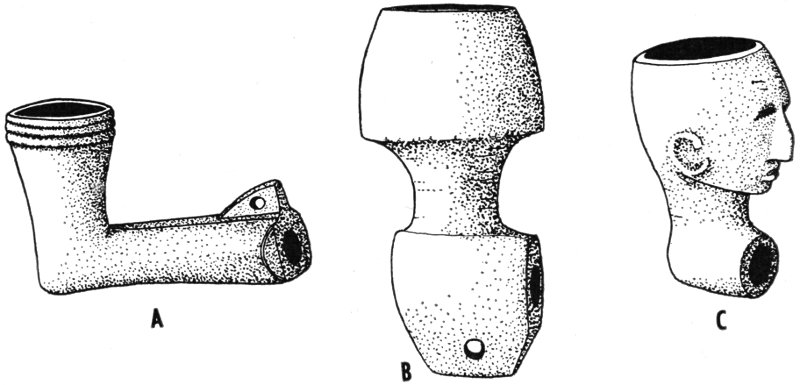

Pipes, either of stone or pottery, were generally of the “equal-armed” type (where stem length is about equal to bowl height). In numerous instances, a short projection resembling the stem in shape but shorter, extends beyond the bowl away from the smoker. Massive effigy pipes of stone were widespread but not numerous. Some were excellently carved. From their construction, it is obvious that they were made to be smoked through a reed or hollow wooden stem called in later times the calumet. These together probably constituted a form of ceremonial pipe that served as a safe conduct between tribes, as a bond and signature at peace- and treaty-making ceremonies, and to present tobacco smoke as incense to the gods in religious rituals.

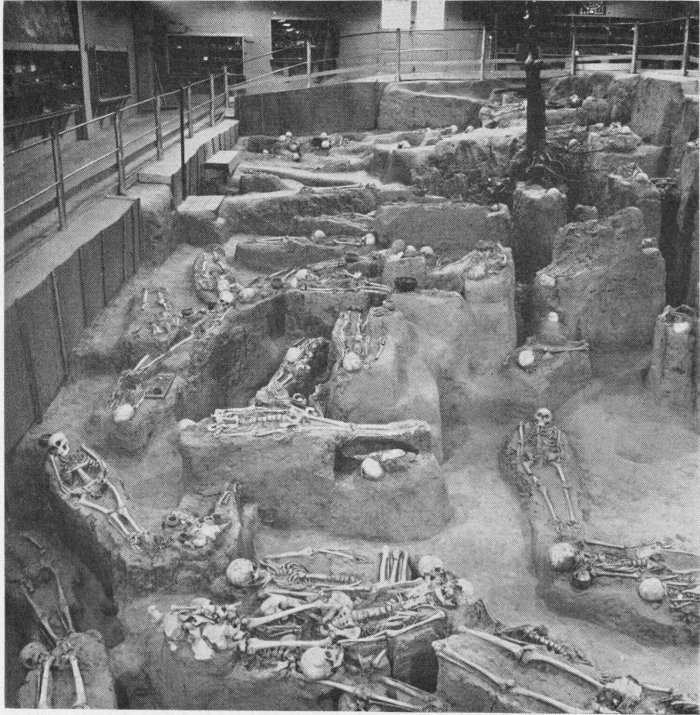

Priests and possibly tribal chiefs were interred in the flat tops of mounds (e.g. the Powell Mound) near temple or cabin. Generally, however, the dead were buried in cemeteries. In some instances, bodies were laid on the surface above a “full” cemetery and covered with earth brought from outside. Continuing this practice eventually produced a mound (e.g. Dickson Mound near Lewistown). Possibly the burial mounds at Cahokia were reserved for the socially prominent while the 38 lower classes were interred in the cemeteries nearby. The dead, especially important personages were attired in their finest apparel, insignia and personal ornaments. Beside them in the grave were placed their weapons, favorite chunkey stones, food and water in pottery vessels with shell spoons or a dipper.

Fig. 26. Interior view of Dickson Mound (in Dickson Mounds State Park near Lewistown, Illinois), showing pottery and other artifacts as originally placed with the dead. Cahokia subculture, Middle Mississippi phase.

Chief villages were large religious centers often protected by an encircling palisade or clay wall reinforced with vertical posts or logs. Remains of defensive walls can still be readily traced by a trained eye at the Kincaid (Massac County) and Lynn (Union County) villages. Exploration of the Aztalan village (Wisconsin) yielded remains of a reinforced clay wall surmounted at regular intervals with towers of like construction. The Cahokia village seems to have been without fortifications.

Fig. 27. Reconstruction of Kincaid Village (Cumberland subculture, Middle Mississippi period) near Metropolis, Illinois. (Diorama by Arthur Sieving.)

Smaller villages occasionally had one or two small flat-topped mounds which doubtless served as bases for the cabins of the Village Chief and possibly War Chief. Other Middle phase villages had no mounds or fortifications.

Cabins were of three or more types. In Illinois, two kinds had rectangular floor outlines and may have developed from the earlier Baumer square dwelling and the Lewis house. One of these types prevalent at Kincaid, as determined from charred remains, had a thatched gable roof supported on four corner posts with their lower ends sunk in the ground. Walls were made of clay daubed on a latticework of cane (with foliage) interlacing vertical wall posts, the interior covered with split cane mats. The rafters, corner and wall posts, and wall plates were of poles or small logs lashed together and held in place by braided ropes. Floors do not appear to have been depressed below surrounding ground level. A larger more substantial structure, presumably a temple, on a Kincaid mound (Mxo9) had thick walls of clay mixed with grass, but otherwise resembled the dwelling just described. The clay floor and wall surfaces were smooth. Fire basins of puddled clay within the building may have been the remains of altars.

Cabins in Fulton County (Fout’s Village) and at Cahokia were rectangular in floor plan but wall posts were probably bent over to be joined with corresponding opposite members to form an arched or vaulted roof, the precursor perhaps of the “barrel-shaped” Illini cabins 40 reported by French explorers. Floors were sunk somewhat below the ground level. Remains of cabins with circular floors occur also at Cahokia and in Fulton County.

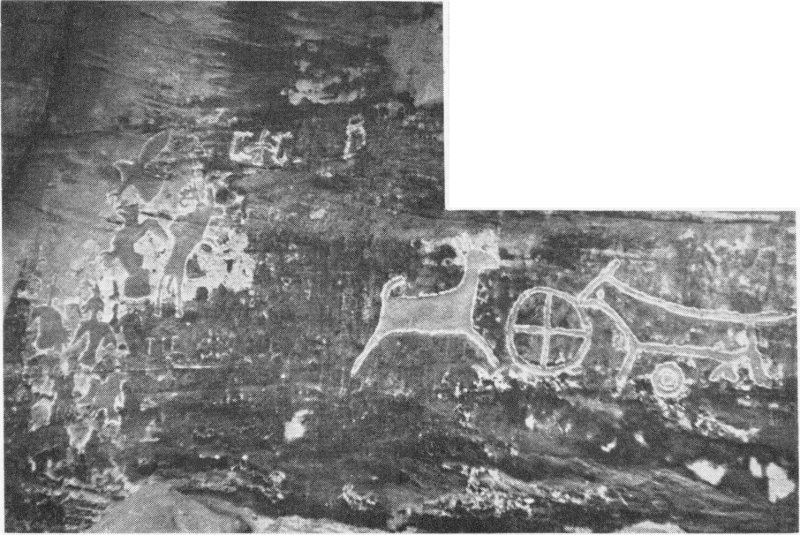

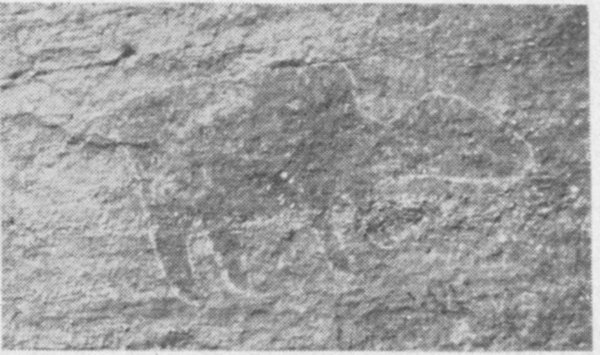

Fig. 28. Petroglyphs from southern Illinois sites probably made by Middle Mississippian peoples. All figures are hollowed out or intaglio. (Photographs by Irvin Peithmann.)

Back wall of rock shelter near Gorham, Illinois.

Figure of buffalo calf painted yellow over entire depressed area. The outlines were chalked in for the purpose of photographing.

Walls and wall posts of the Fulton County cabins appear in some instances to be formed of bundles of small branches or cane set in trenches possibly a foot deep. There is no evidence of the wattle-and-daub structure. Walls may have been covered with mats, or with rectangles of bark. Roofs were probably thatched.

Possibly the Cahokia subculture peoples constituted a single tribe, a small nation, or a confederation of tribes. At its most powerful period, the Cahokia settlement was perhaps the capital and religious center. The region south of a line joining the mouths of the Kaskaskia and Wabash rivers at one time probably belonged to another tribe or subtribe whose chief village was the Kincaid community in Pope and Massac counties and who, linguistically and culturally, were closely related to peoples in Tennessee and Kentucky and at the Angel site in Indiana.

Archaeologically speaking, the Middle Mississippi contrasts sharply with the Hopewellian culture. Certain artifacts are readily distinguishable and easily identified with the craftsman’s cultures. Actually the Mississippians differ from the Hopewellians chiefly in having substantial cabins, athletic games and the bow and arrow.

Remains of Hopewellian dwellings are rare, but the three or four found up to now are characterized by round or oval floor plans outlined with post holes of three to four inches in diameter. These seem to indicate hemispherical wigwams. No further evidence of wall or roof structure has been recovered. The rarity of these dwellings certainly suggests a less permanent dwelling than the Mississippi cabin. However, it will be remembered that some peoples pattern their tombs upon their dwellings. The upper caste Hopewellians built rectangular burial chambers which were walled up with logs laid one on another and roofed over with half-logs or bark. Similar log house surface structures would seldom leave discernible remains on decay. It is possible, though by no means certain, that the Hopewellians of highest caste, and perhaps of the other castes, built log cabins for dwellings.

The evidence for playing of athletic games in Hopewellian is very late and scanty. The only tangible indication are the rings, “pulleys” and a stone discoidal found with a skeleton in the Rutherford Mound. (See M. L. Fowler, The Rutherford Mound, Scientific Papers Series, Vol. VII, No. 1, Springfield, Ill. 1957, pp. 31-33). The rings of pottery and of cannel coal (or jet) seem too fragile for actual playing pieces and may rather be trophies or prizes, replicas of similar pieces made of wood. Such wooden pieces may have been used in games throughout middle and late Hopewellian times.

Fig. 29. (Photographs by Irvin Peithmann.)

View of a stream-side flint mine and workshop (in field alongside) near Cobden, Illinois.

Close-up showing spherical or “ball-flint” nodules from stream banks similar to those worked up by Middle Mississippians and others in adjacent workshop.

The bow and arrow, at least, seems to be a decided improvement over the spear. It constituted a repeating weapon. Ammunition could be carried in the belt or on the back in a quiver without unduly hampering the bowman. On the other hand, it was useless in hand-to-hand fighting and a spear or dagger was needed to supplement it. Moreover, the spear with a thrower was a more accurate weapon than the bow, unless the arrows were carefully made and balanced. The bow never 42 seems to have wholly replaced the spear which continued to be a favorite weapon down into the European contact period.

The improvements that distinguish the Mississippians above the Hopewellians may be more apparent than real in the first two instances and, in the third, may represent a significant rather than a fundamental advance. Looking at the two periods from the broader cultural viewpoint, they appear to have many cultural features in common. The Middle Mississippians probably added new food and fibre plants to those of earlier periods, and perhaps increased production by improved, more intensive methods of cultivation. Their staple crops like those of the Hopewellians were corn, beans and tobacco.

The technologies or methods of making the necessary tools in the two cultures varied but little. Art was revived or rather re-developed in the Mississippian period but fewer media are employed. In artistic skill, imagination and productiveness perhaps the Hopewellians had an edge on the later people.

Trade and travel, though resumed to distant sections of the continent, does not appear so widespread or general as in the Hopewellian period. A formalized religion with colorful ceremonies seems to have revitalized the life of the people but possibly no more effectively than in the earlier period.

There was no significant improvement in labor, power or transportation; all were still accomplished wholly by human effort without the aid of draft animals. Traveling by boat was known and probably used by both cultures.

Comparing the two peoples with other plant growers having no domestic food-draft animals, it seems apparent that each had an effective political organization, a formalized vital religion with true priests (not “self-appointed” shamans) and a system of moral values and tenets that “church” and “state” were organized to maintain. All in all, from the broader cultural standpoint, they were amazingly alike.

Less advanced Mississippi tribes with customs showing some admixture of Woodland cultural elements living contemporaneously in Missouri, Iowa, Wisconsin, Indiana and Ohio, encircled the Middle phase peoples on the east, north and west. Known generally now as the Upper phase peoples their sole representative in Illinois was the people of the Langford subculture, who dwelt around the southern end of Lake Michigan as well as in adjacent parts of Indiana and Michigan. The type station is the Fisher Village and Mounds near Joliet which were ably investigated by Mr. George Langford, Sr. some years ago.[16]

They built no flat-topped pyramids and left little, if any, evidence of their religious practices. Their art, as exhibited by pottery, personal ornaments or weapons was not of a high order. There is no evidence that they played the chunkey game. Some copper hatchets and ornaments were in use, but these appear to be of Middle Mississippi workmanship and may have been trade articles.

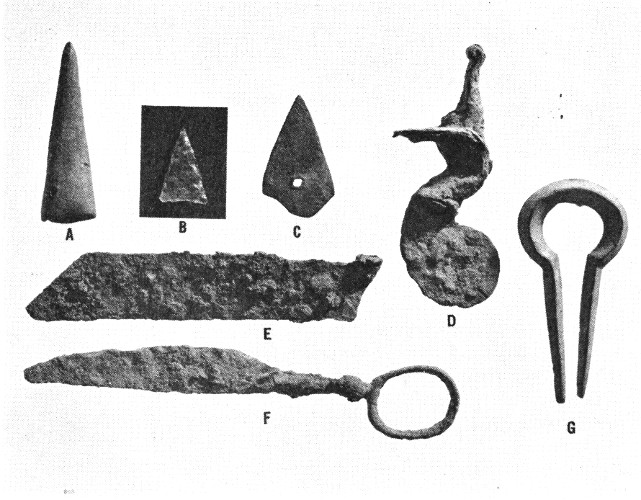

On the positive side, they buried their dead in dome-shaped earthen mounds, usually in the extended position, frequently with food (in clay pots with shell spoons), weapons (arrows and tomahawks or hafted celts), personal ornaments and various utilitarian implements. Dwellings had subsurface circular floors and were doubtless dome-shaped (hemispherical). The bow and arrow were in common use with arrowheads primarily of slender simple triangular shape, very rarely with side notches. Implements, weapons and ornaments were chiefly of chipped flint, ground or polished stone, river clam shells, bone and animal teeth. Copper was rarely employed.

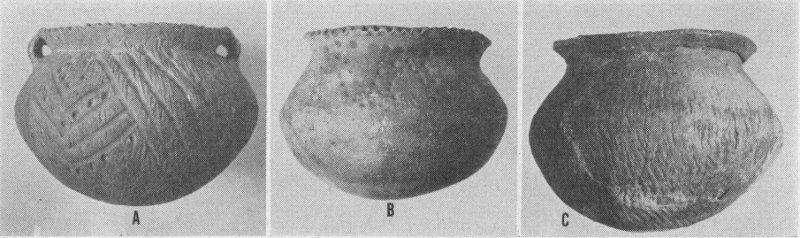

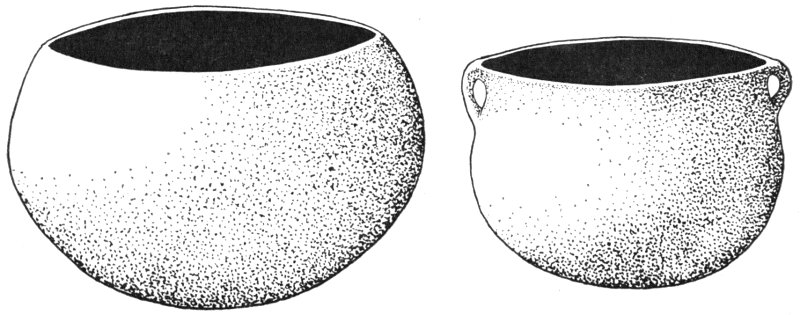

Fig. 30. Characteristic pottery from the Langford subculture, Upper Mississippi phase, (Fisher Site near Channahon, Illinois). (Photograph by George Langford, Chicago Natural History Museum.)

Pots were generally of the globular or flattened globular shape (olla or jar), tempered with grit (early) and shell (later), and decorated with geometric designs in broad lines and dots, drawn (“trailed”) or impressed on the shoulder region with a blunt tool (such as an antler tine). Lips of vessels were usually pressure-notched and surfaces cord-roughened. Loop handles on the jars were common.

Numerous examples of flat stone tablets associated with a number of short solid antler cylinders lead one to suspect that a game of chance of some sort was played and that gambling was probably indulged in.

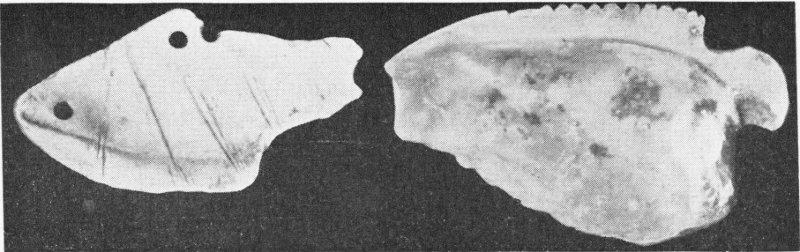

Other than pottery and personal adornment, the only art practiced was the cutting of mussel shell into handled spoons and outlines of fish and other objects. Apparently there was no urge for fine workmanship.

It is highly probable that these Upper Mississippians were plant growers who hunted to secure their meat. The extent of village remains and the evidence of semi-permanent dwellings point to this type of economy even though no grain or seeds of any kind were found in 44 the site. Shell hoes of the common type were used. The dog was the only domesticated animal.

Fig. 31. Effigy fish and a decorated spoon (fragmentary) made of mussel shells. Langford subculture, Upper Mississippi phase (Fisher site). (Photograph by George Langford, Chicago Natural History Museum.)

Fig. 32. Stone tablet and gaming pieces from the Langford subcultural period, Upper Mississippi phase (Fisher site). (Photograph by George Langford, Chicago Natural History Museum.)

Apparently most of their needs were supplied by their own efforts and from local sources. There is no evidence of any trade, except possibly of a very limited kind with near neighbors to the west.

The evidence for the residence around the southern lake shores is based chiefly on the occurrence of the Fisher pottery type. This area after 1760 was occupied by the Miami tribe who may possibly have been the builders of the Fisher Mounds.

The Illinois or Illini Indians are, so far as is now known, the next group to occupy the state following the Middle Mississippians. At the time of Marquette and Jolliet’s voyage in 1673, six tribes comprised the Illinois Confederacy, Kaskaskia, Cahokia, Michigamea, Peoria, Moingwena, and Tamaroa[18]. The tribes spoke the same or mutually intelligible dialects of the Algonkian language.

Some time before 1650, possibly a century or more, the Illinois Confederacy seems to have been a powerful nation but in the latter half of the 17th century this was a tradition rather than fact. The Confederacy appears to have engaged in no united action after 1650.

The Illini at that time were in the plant-raising stage of culture and possessed only the dog as a domesticated animal. Like many other plant-raisers, the families deserted the village for the hunt after the corn was hilled and again after the harvest.

Men went naked in summer except for mocassins. At times a breech cloth was worn; in winter buffalo skin robes were added and belts, leg bands and leggings on occasion.

Women when working apparently wore only a girdle (breech cloth), at other times a wrap-around skirt of skin with a belt passing over one shoulder and under the opposite arm. The skirt dates back to Hopewellian times and was used during the Mississippi period in Indiana and probably in Illinois. The bosom was covered with a deerskin wrap. Hair was worn long and fastened behind the head.

Labor was divided between the men and the women (and children). Men did the hunting, fighting and made the weapons. The women (and children) did the other work—the housework, planting and harvesting the crops, dressing deer and buffalo skins, making twine from bast, weaving cloth and, on the hunt, carrying the house parts and setting up the camp.

Buffalo meat was preserved by drying and smoking it over a fire in the hunting camp. Vegetable foods, corn, beans and squash were dried or parched and buried in containers or in lined pits in the ground and covered over. Watermelons, muskmelons (?), gourds and tobacco were also grown. Wild strawberries, paw paws, pecans, lotus roots, wild tubers, grapes and plums formed part of their diet.

The winter buffalo hunt usually took place a long way from the village. The hunting units each consisted of several families under a rigid police system and regulation to prevent the herd from being stampeded by an over-eager family before all were amply provided with meat. Violations of hunting regulations were punished by destruction of the offender’s property to which no resistance was ever attempted. The group surrounded the herd, at times encircling it with fires made at intervals near which the hunters stood and killed the stampeding animals. At times as many as 120 buffalo were killed in a day. The women cut out the tongues, skinned the animals, and, peeling off the sides of meat, dried and smoked them on wooden grates over a slow fire. The smoked sides were carried back to the village on the back, or when practicable in dugout boats. Carcasses and bones were left on the hunting grounds. Other animals were stalked by one or two hunters. Dog meat was considered a great delicacy.

Fish were caught in nets, by hook and line, speared or shot with bow and arrow. They were dried for preservation. Maple trees were tapped late in the winter, the sap caught in bark containers and made into a maple drink or reduced by boiling to syrup and sugar. Corn was ground into meal and baked into bread, or prepared as hominy.

Vessels and utensils were made of wood or clay, ladles from a section of the buffalo skull. Fire was produced by the hand drill in the usual manner.

The cabin type seems to have varied at different periods or in different tribes. In early times, cabins had rectangular floors and vaulted (barrel-shaped) roofs. They were roofed and floored with “double-mats” of flat rushes and were impervious to wind or rain. Occasionally they were erected on low mounds (two feet high) to keep the floors dry. Large cabins of the vaulted type had four fires, with one or two families at a fire.

Bark-covered hemispherical huts or wigwams may have been used on hunting trips. They were apparently common in some villages in 1723.

Overland travel was on foot. On streams the dugout boat was propelled by pole and possibly by paddle. Large boats were 40 to 50 feet long, capable of carrying 40 to 50 men. While dugouts were admirably suited for travel and trade between the Illini tribes along the Illinois and Mississippi rivers, they were, on account of their weight and unwieldiness in portaging, generally useless in raids against enemies.

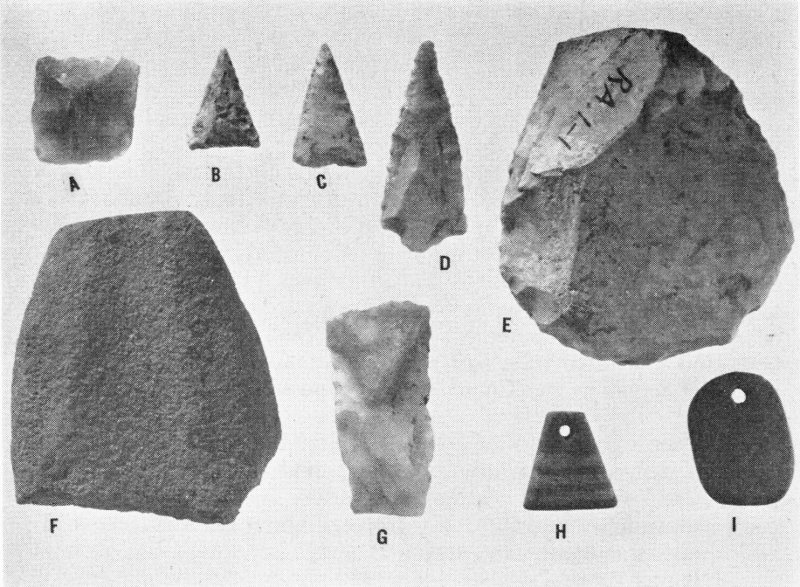

Fig. 33. Native Illini artifacts. A, Indian-made gun flint; B, C, D, chipped flint arrowheads; E, flint scraper; F, grooved abrader of sandstone; G, expanded base drill (grip only, point broken off); H, I, polished stone pendants. From Illini village site near mouth of Kaskaskia River, Randolph County.

An Illini man, desiring to get married, sent presents to the girl’s parents. If the suitor was acceptable, the parents kept the gift and took the bride to the man’s hut the following evening. Apparently there was no wedding ceremony.

Women had somewhat lower social status than their husbands. Wives did not eat with their husbands. A man was permitted two or more wives and often married two sisters. Children were well-treated. Infants were bound to a cradle board that the mother carried around. The cradle was pointed at the lower end and was stuck in the ground when the woman wanted to rest. Divorce was accomplished by a simple agreement to separate.

The explorers and writers to whom we are indebted for our knowledge of Illini social and religious organization were, unfortunately, casual and untrained observers who, on the whole, held the Indian and his customs in contempt. Important activities were often dismissed with meaningless generalizations, or omitted entirely, as if generally known. Consequently great gaps are left in the information that has come down to us.