Title: The Book of the Ocean

Author: Ernest Ingersoll

Release date: January 5, 2018 [eBook #56311]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Brian Wilcox and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

THE BOOK OF THE OCEAN

Other books in similar style and binding.

THE CENTURY

WORLD’S FAIR BOOK

FOR BOYS & GIRLS.

BY TUDOR JENKS.

The standard young folks’ book of the Fair. The story of two boys who visited the great exhibition with their tutor. 250 pages, richly illustrated, from photographs, etc. $1.50.

BY ELBRIDGE S. BROOKS.

Issued under the auspices of the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution. Each with about 250 pages and as many illustrations, in handsome binding. $1.50.

THE CENTURY BOOK

FOR YOUNG AMERICANS.

Telling in attractive story form what every boy and girl ought to know about the government,—the President, Senate, etc. Introduction by General Horace Porter.

THE CENTURY BOOK OF

THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION.

The story of the pilgrimage of a party of young folks to the famous Revolutionary battle-fields from Lexington to Yorktown. Introduction by the Hon. Chauncey M. Depew.

THE CENTURY BOOK

OF FAMOUS AMERICANS.

Describing a trip to the historic homes of America—Washington’s, Lincoln’s, Grant’s, etc. With an introduction by the President-General of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

The Century Co.

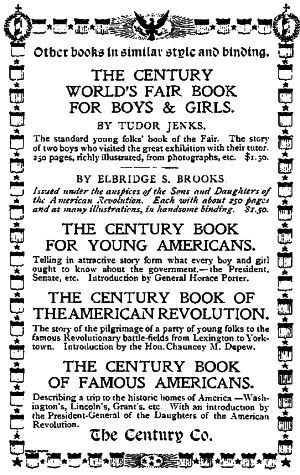

Original Image.

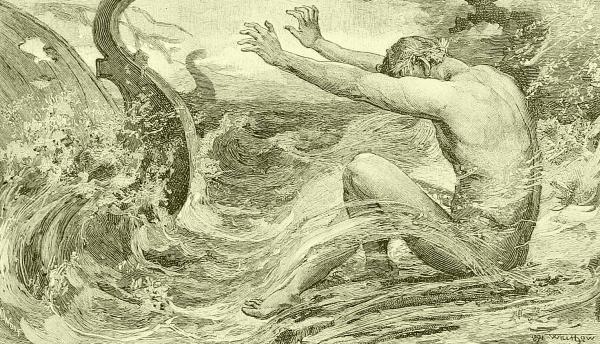

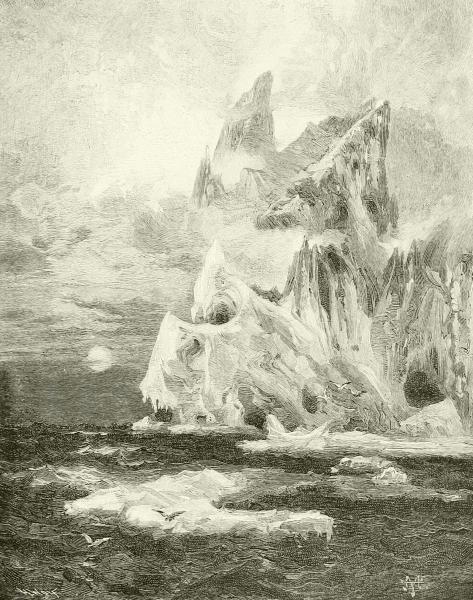

DRAWN BY LOUIS LOEB.ENGRAVED BY M. HAIDER.

THE MAJESTY OF THE SEA.

AUTHOR OF “KNOCKING ROUND THE ROCKIES,”

“THE OYSTER INDUSTRIES OF THE UNITED STATES,”

“FRIENDS WORTH KNOWING,”

“WILD NEIGHBORS,”

“THE CREST OF THE CONTINENT,” ETC.

Illustrated

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1898

Copyright, 1898,

By The Century Co.

THE DE VINNE PRESS.

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| I | The Ocean and its Origin | 1 |

| II | Waves, Tides, and Currents | 9 |

| III | The Building and Rigging of Ships | 27 |

| IV | Early Voyages and Explorations | 39 |

| Part I—Previous to the Discovery of America. | ||

| Part II—From Columbus to Cook. | ||

| V | Secrets Won from the Frozen North | 77 |

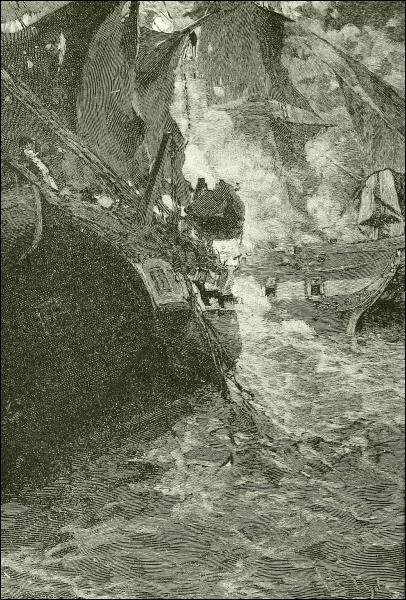

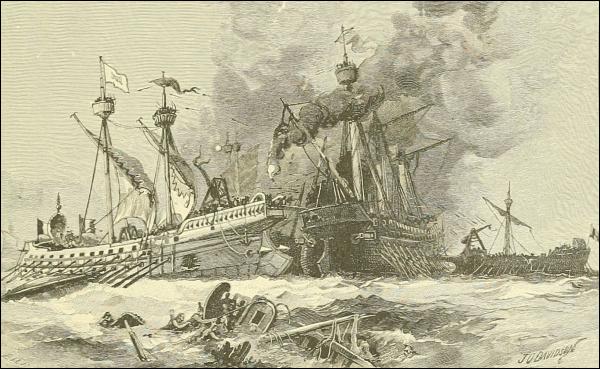

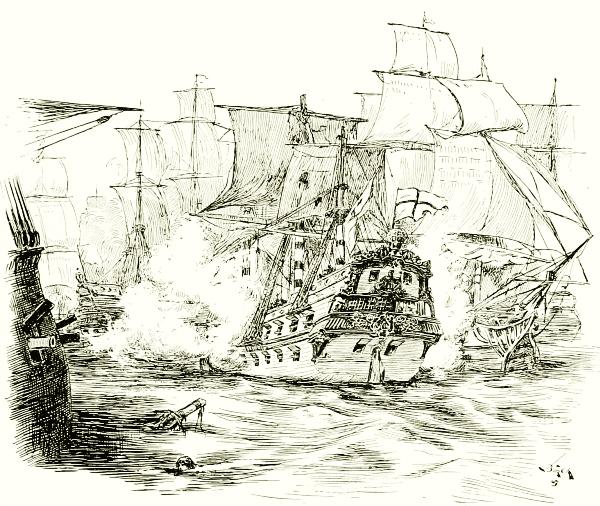

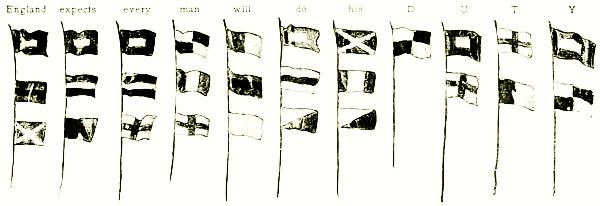

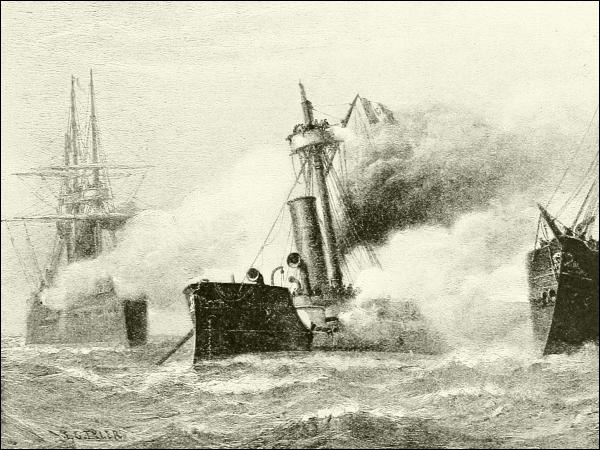

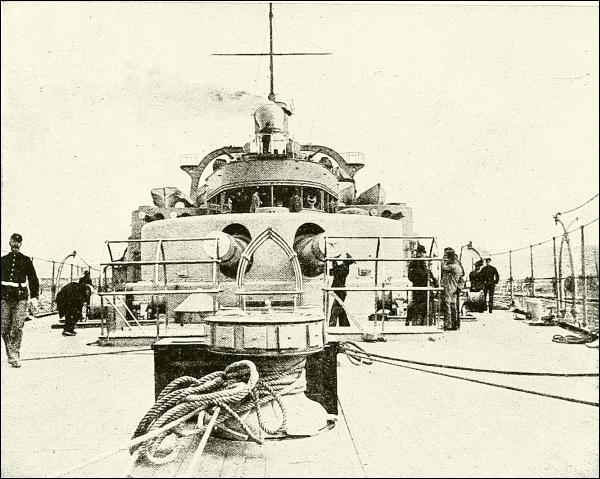

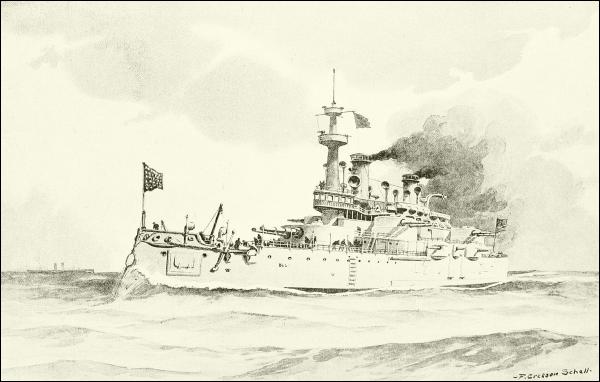

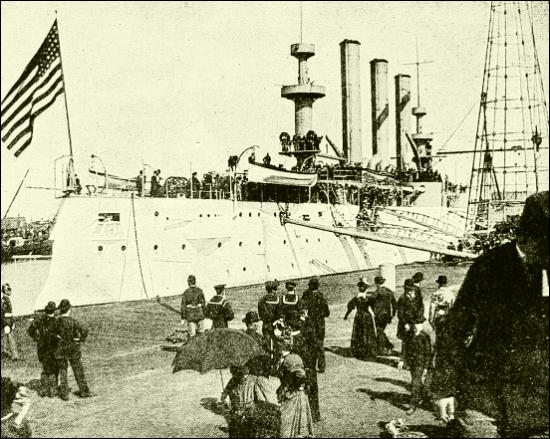

| VI | War-Ships and Naval Battles | 107 |

| Part I—Wooden Walls, from Salamis to Trafalgar. | ||

| Part II—The Present Era of Steam and Steel. | ||

| VII | The Merchants of the Sea | 155 |

| VIII | Robbers of the Seas | 171 |

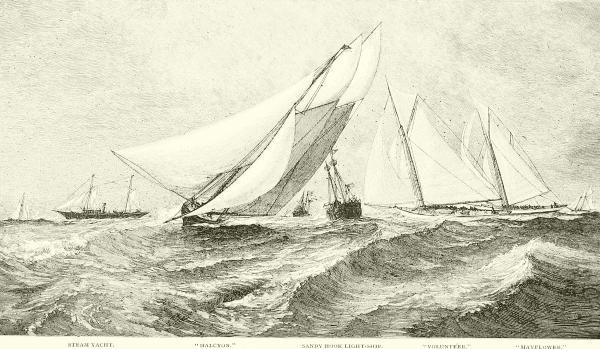

| IX | Yachting and Pleasure-Boating | 187 |

| X | Dangers of the Deep | 201x |

| XI | Fishing and other Marine Industries | 231 |

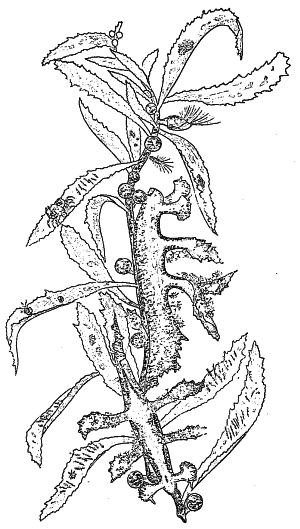

| XII | The Plants of the Sea and their Uses | 249 |

| XIII | Animal Life in the Sea | 259 |

| Index of Illustrations | 275 | |

| General Index | 277 | |

THE BOOK OF THE OCEAN

Looking at the land, we divide the surface of the earth into eastern and western hemispheres; but looking at the water, we make an opposite classification. Encircle the globe in your library with a rubber band, so that it cuts across South America from about Porto Alegre to Lima on one side, and through southern Siam and the northernmost of the Philippine Islands on the other, and you make hemispheres, the northern of which (with London at its center) contains almost all the land of the globe, while the southern (with New Zealand as its central point) is almost entirely water, Australia, and the narrow southern half of South America being the only lands of consequence in its whole area. Observing the map in this way, noticing that, besides nearly a complete half-world of water south of your rubber equator, much of the northern hemisphere also is afloat, you are willing to believe the assertion that there is almost three times as much of the outside of the earth hidden under the waves as appears above them. The estimate in round numbers is one hundred and fifty million square (statute) miles of ocean surface, as compared with about fifty million square miles of land on the globe.

To the people whose speculations in geography are the oldest that have come down to us, the earth seemed to be an island around which was perpetually flowing a river with no further shore visible. Beyond it, they thought, lay the abodes of the dead. This river, as the source of all other rivers and waters, was deified by the early Greeks and placed among their highest gods as Oceanus, whence our word “ocean.” Accompanying, or belonging to him, there grew up, in the fertile imagination of that poetic people, a large company of gods and goddesses, while men hid their absence of real knowledge by peopling the deep with quaint monsters.

“The word for ‘ocean’ (mare) in the Latin tongue means, by derivation, a desert, and the Greeks spoke of it as ‘the barren brine.’”

Over these old fables we need not linger. All the myths and guesswork that went before history represented the sea as older than the land, and told how creation began by lifting the earth above the universal waste of waters. The story in Genesis is only one of many such stories.

A QUIET SEA, AND THE SUN AT MIDNIGHT.

From a photograph.

Scientific men believe that when our planet first went circling swiftly in its orbit it was a glowing, globular mass of fiery vapors; but as time passed, the icy chill of space slowly cooled these vapors, and chemical changes steadily modified, sorted, and solidified the materials into the beginnings of the present form and character, until at last water came into existence. This must have been at first in the form of a thick envelop of heated vapors, impregnated with gases, that inwrapped the globe in a darkness lit only by its own fires.

After that, when further changes had come about,—let us picture it,—what deluges of rain were poured out of and down through those murky clouds where thunders bellowed and lightnings warred! At first all the rains that fell must have been turned to steam again; but by and by the3 steady downpour cooled the shaping globe so that all the water was not vaporized, but some stayed as a liquid where it fell, and this increased in amount more and more, until finally, between the hissing core of the half-hardened planet and the dense clouds which kept out all the sunlight, there rolled the heated waves of the first ocean—an ocean broken only by the earliest ridges, like chains of islands, marking the skeletons of the continents that were to follow—an ocean sending up ceaseless volumes of steam to form new clouds.

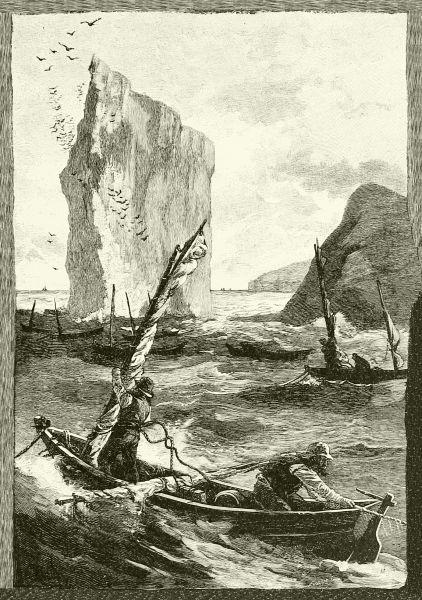

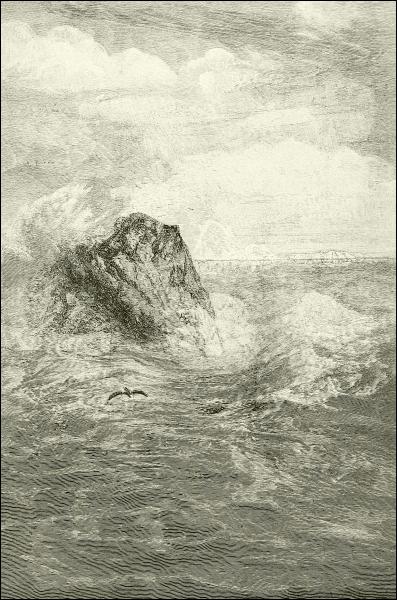

EATING AWAY THE COAST.

Yet all the while the cooling of the planet went on. Now, when any heated substance cools it contracts, and the globe as a whole is no exception to the rule; but a sphere formed of so incompressible a substance as rock can shrink only by some sort of folding or displacement of its surface. Therefore, as the cooling of our globe proceeded, explosions and swellings constantly occurred at weak points or lines on or near the surface, where the prodigious strain forced a break. That these upheavals were most prominent and extended in the northern hemisphere is shown by the fact that the great masses and heights of land are grouped there; and the trend of mountain-ranges seems to show that the range of breakage and upheaval was in general in north-and-south lines. Elsewhere, and mainly in the southern hemisphere, broad areas of perhaps stiffer crust sank downward, making the vast depressions into which poured the waters of the primeval sea, and where our oceans still sway and roll.

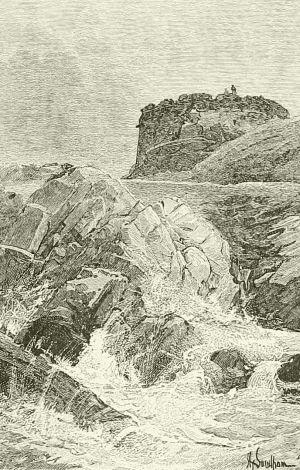

SURF AT FORT DUMPLING, R. I.

All these changes, however, have been in the direction of insuring more4 and more stability; and when the ocean water had thoroughly cooled, the very chill of its vast masses in the depths of the troughs assisted in the work, for the cold water, by more rapidly withdrawing their heat, caused the rocks beneath their basins to become denser, thicker, stronger, and consequently less liable to break or change, than were those rocks forming the foundations of the continents.

The moment it had shores to beat upon, that moment the ocean began to knock them to pieces under its pounding surf, and to grind the fragments so small that they could be drifted away, reassorted, and deposited wherever the water was sufficiently quiet to let them fall. The original rocks—chiefly granite—held the different forms of lime, magnesia, etc., to make the limestones; the silica to make the gritty sandstones; the alumina to make the clays; and so on. The sea not only was the agent to eat this old, rich crust to pieces and respread it into strata, but to sort out for us the materials to a considerable extent, laying down beds of limestone by themselves, and sandstone, shales, marl, etc., by themselves. It is probable, says Professor Shaler, that layers of rock twenty miles in thickness have thus been laid down on the gradually settling ocean floor, much of which has been raised again to form continental lands.

Hitherto we have spoken of the waters that surround the continents as if they formed one mass, as, practically, they do; but for convenience sake we may designate certain areas by separate names, which ought now to be defined. Thus the larger, more open spaces are known as oceans, and of these five are recognized, namely, Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Arctic, and Antarctic. Parts or branches of these, more or less inclosed by land and usually comparatively shallow, are termed seas.

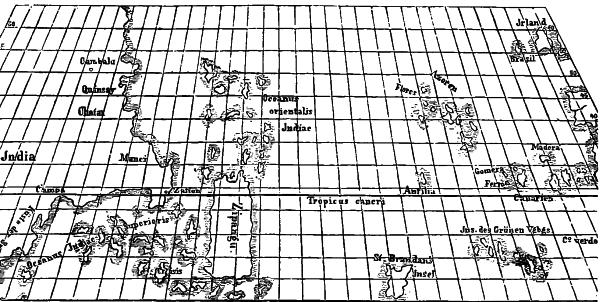

The Pacific Ocean is the largest, it alone covering more space than all the continents combined, having a breadth, east and west, of ten thousand miles (about the length of the Atlantic), and an area of seventy million square miles. The equator divides it into the North and South Pacific. The former is comparatively free from islands, and is inclosed northward by the approaching extremities of Alaska and Siberia; while the latter widens at the south into the boundless Antarctic Ocean. Its basin is a vast depression of fairly uniform depth, studded in the western part by island peaks,—the summits of submerged volcanic mountain-ranges. The name “Pacific,” or “Peaceful,” was given to it by Magalhaens (Magellan), its first navigator, in 1540 (see Chapter IV), in his joy at having escaped from the tempestuous experience he had long endured in the South Atlantic. On the whole the Pacific deserves its name as compared with the Atlantic—a fact chiefly due to its great size. The term “South Sea” was5 formerly much used for it, but English-speaking persons now usually mean by that phrase the island-studded district between Hawaii and Australia.

PERCÉ ROCK, IN THE GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE, SHOWING DESTRUCTION OF SHORE-ROCKS BY WATER.

The Atlantic commemorates in its name the myth of Atlas and his island. Atlas seems to have been originally, among the Greeks, the name of the Peak of Tenerife, of which they had vague information from the earlier6 Phenician sea-wanderers. Then this was forgotten, and in place of the fact arose a myth of a Titan who stood upon a vast island in or beyond the “Western Sea,” called Atlantis. Legends of wars with its people form a part of the nebulous hero-story of the beginnings of Athens; and it is said to have sunk out of sight long before records began. There have always been those who believed this story founded upon fact, and only a few years ago a book was printed in the United States arguing that the tale was the history of a real land; but not only is there no literary or historical evidence that Atlantis had any firmer foundation than vague memories of the Cape Verd or Canary Islands, but every evidence of the geological condition and history of the eastern shores and bed of the middle Atlantic Ocean shows that no such convulsion as the destruction of this island calls for ever took place there, or that there was ever such a land to be submerged. The Atlantic occupies a long, winding, comparatively narrow trough, that measures about ten thousand miles north and south, from the ice of the Antarctic to the ice of the Arctic ocean, and has only a few islets south of Iceland, the Faroes and the Shetlands, which rise from a plateau stretching from Labrador to Great Britain, the higher points of which were probably above the water within comparatively recent geological times, possibly since man appeared upon the globe. The average depth of the Atlantic south of this ridge is about thirteen thousand feet, but greater depths are found along the African and American coasts, on each side of a long submerged ridge from which rise the isolated islands of Cape Verd, St. Helena, and Tristan da Cunha. The width from Norway to Greenland is only about eight hundred miles, but between Montevideo and Cape Town it is thirty-six hundred miles, and the average width is about three thousand miles. The shape and situation of the Atlantic make it the most stormy of the three great oceans, and it is the one where the phenomena of tides, currents, etc., are most prominently manifested, as we shall see. It is also the most frequented and best known, because it has been necessary to study it for the benefit of commerce.

The Indian Ocean is simply the extension of the vast southern water-zone northward of parallel 40°, south latitude, where, from the Cape of Good Hope to Tasmania, it is six thousand miles in width. At this line the depth suddenly decreases, as though the edge of a submerged Antarctic plateau defined the southerly rim of its basin there. This ocean contains several large and some groups of small islands, but these are mostly near the shore, and connected with the neighboring continent by shallow waters, showing that they rise from a submerged plateau. The average depth of the Indian Ocean is about fourteen thousand feet; its surface-water is7 warmer and salter than that of any other; and its winds and weather are more regular and peaceful than in either the Atlantic or the North Pacific.

The Arctic Ocean is the well-defined body of water around and probably over the north pole. It is connected with the Pacific only by the narrow and very shallow Bering Strait, and with the Atlantic by comparatively narrow openings. It has been fairly well explored as far north as the parallel of 80°, and found to contain many islands; but it appears that there is great depth of water north of Spitzbergen and northeast of Greenland, making it probable that the trough of the Atlantic reaches to or beyond the pole itself. Most of its area is covered with drifting ice.

The Antarctic Ocean is regarded as the space of water within the Antarctic circle; but this is surrounded by a zone of deep ocean, unbroken almost half-way to the equator, except by the narrow southern part of South America and by New Zealand. It is an area, apparently rather shallow, of ice, fogs, and tempestuous gales, inclosing lands of unknown extent.

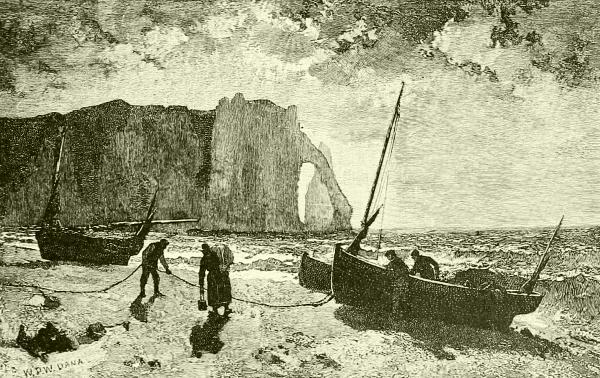

WAVE-WORN CLIFFS AND PEBBLE-BEACH AT ETRETAT, FRANCE.

(FROM A PAINTING BY WILLIAM P. W. DANA.)

But these geographical distinctions are merely convenient methods of speech. After all, there is only one ocean “poured round all,” and its particles are incessantly changed in place and remingled by means of a world-wide system of tides and currents, the effect of which is to keep sea-water everywhere uniform in character and perfectly pure and healthful.

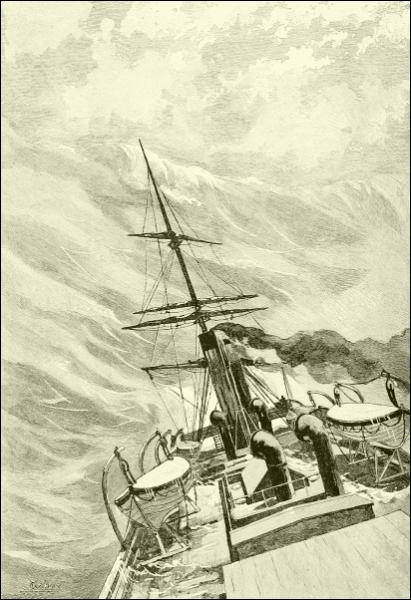

IN MID-OCEAN: A GREAT WAVE.

Now that we have studied the ancient ocean, it is time to study its present characteristics and understand the great and important part it plays in the world.

A very striking thing about the ocean is its flatness. Being water, it seeks always to find its level; and we commonly assume that it everywhere does so, and take the sea-level as the standard from which to calculate all heights above or depths below its surface; that is, we assume that every part of the surface of the ocean when calm and at mean tide is exactly the same distance from the center of the globe. This, however, is not wholly true. Careful observation has shown that the Pacific is several feet lower on the western shore of the Isthmus of Darien than is the Atlantic on its eastern shore—a fact due, no doubt, to the crowding of water by the Gulf Stream into the Caribbean Sea. The Mediterranean is known to be somewhat higher than the Atlantic, and other differences exist in similar places elsewhere.

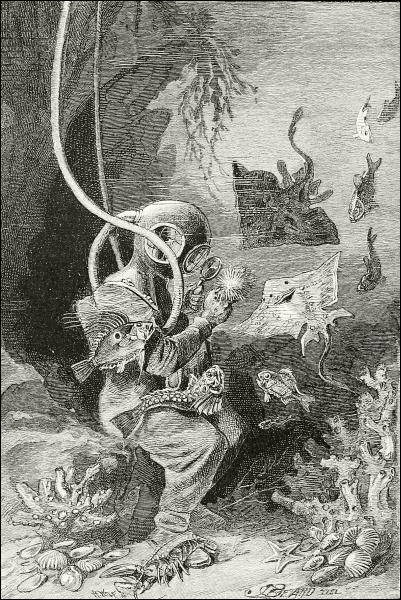

This introduces the subject of depth—a matter which we have learned accurately only within a very few years. In the early days ropes alone were used for sounding, and these had to be of considerable size to bear the strain; but a mile or so of rope became too heavy to handle, and depths below that length remained unmeasured. Then a little machine was tried consisting of a heavy weight having attached to it, by a trigger, a wooden float. This was thrown overboard. It sank, and when it touched bottom the shock released the float. From the time that elapsed before the float reappeared the depth was estimated. This, however, was little better than guesswork; and accurate soundings exceeding one thousand fathoms were not obtained until an American naval officer began to use wire instead of rope. From this hint was developed elaborate machinery, operated by steam, using steel piano-wire, having automatic registers of the amount reeled out, and carried down by weights that were released when the bottom10 was struck, making it easier to recover the wire. To these weights (or rather to the wire just above them) were attached devices for clutching and bringing to the surface specimens of the bottom, self-closing jars to fetch water from the lowest layer, self-registering thermometers that recorded the temperatures at the greatest or at various intermediate depths, and other means of learning the character of the water, bottom-material, and animal life several miles below the surface, including methods of photographing by aid of a submerged electric light. Such investigations, carried on in ships suitably equipped, have been prosecuted by several governments, most notably by the expedition of the Challenger, a British surveying-ship which circumnavigated the globe during the years from 1872 to 1876.

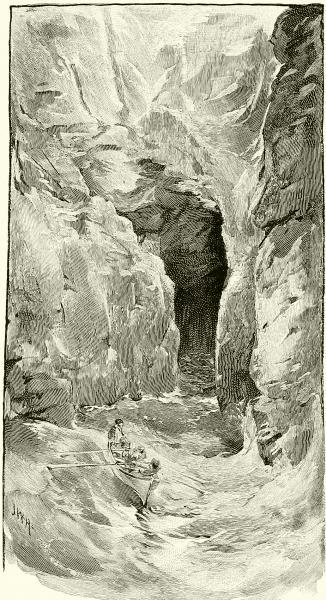

SEA-CAVE

NEAR GIANT’S CAUSEWAY,

NORTH OF IRELAND.

This and many other expeditions have sounded in all parts of the world, and explored large tracts where the water uniformly exceeded three miles in depth. The United States ship Enterprise, after passing the Chatham Islands in her run from New Zealand to the Strait of Magellan, found the water everywhere more than thirteen thousand11 feet deep. Throughout her run from Montevideo to New York the water varied from twelve to eighteen thousand feet deep, and Captain Nares and Admiral Belknap found like depths over equally vast breadths elsewhere.

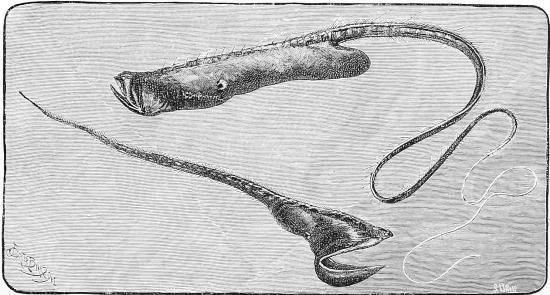

Yet even in these basins more profound pits and valleys exist. Several places are known near Japan and off Porto Rico exceeding five miles in depth; and an English officer sounded 29,400 feet in the southern Pacific Ocean, nineteen hundred miles east of Brisbane, without finding bottom.

The average depth of all the oceans is estimated at from twelve thousand to fifteen thousand feet. As, according to Humboldt, the average height of the lands of the globe is only about one thousand feet, it will be seen that all the land now above the water, and its foundations, could be shoveled into the ocean troughs and still leave water more than two miles in depth covering the whole planet.

The soundings and dredgings of which I have spoken enable us to make a tolerable map of the ocean beds and to describe their features. All the continents are bordered by a shelf reaching out under the shallow shore-water to a greater or less distance, and then dropping, usually with much abruptness, to the ocean trough. This shelf, perhaps originally a part of the primeval continent, bears most of the great islands near continents, such as Newfoundland, the West Indies, Great Britain and Ireland, Madagascar, the Aleutian, Japanese, and Philippine groups, the Malay Archipelago, and others. If you will look at a map that has marked upon it the line of one thousand fathoms’ depth along the shores of the various continents, you will find it reaching far out from the eastern shores of both Americas, the western and northern shores of Europe, the eastern shores of South Africa, prolonging India hundreds of miles, and embracing great spaces among the East Indies, while even the hundred-fathom line would connect many an island with the mainland or with some other island, as they actually have been connected in times gone by. The fact is, there is not a single proper mountain-peak rising out of deep water at any great distance from the margins of the continents. All the numerous islands of the wide oceans are either coral reefs or the summits of volcanic cones.

Upon this shelf, and for the most part within two hundred miles of the coast, are deposited all of the materials torn from the land by the sea or brought down by rivers or glaciers, excepting the very finest, which currents may float somewhat farther out, and also excepting the rocks that icebergs carry away and drop in mid-ocean; but this is not a great amount, for most icebergs strand on the shallows off Newfoundland or in Bering Sea.

Almost nothing from the shores, therefore, reaches the central depths of the open oceans, whose beds are in substantially the same condition that12 they were in at the beginning, except for two things—volcanic upheavals in some places, and the remains of animal life everywhere. The former exception is a very important one, since it is now known, according to Professor Shaler, that volcanoes, by their eruptions, send more dust and broken materials to the seas than the rivers and shores combined.

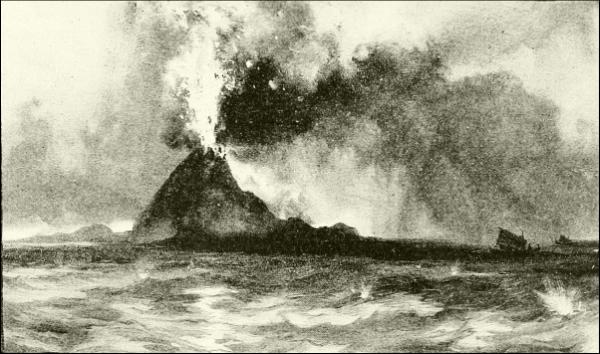

THE VOLCANO KRAKATOA (SUNDA STRAIT) IN ERUPTION IN 1883.

“Although the deeper sea-floors probably lack mountains,” says Professor Shaler, “they are not without striking reliefs, which, if they could be seen, would present all the dignity which their size gives to the Himalayas or Andes: the difference is that these elevations are not true mountains, but volcanic peaks, sometimes isolated, again accumulated in long, narrow ridges, but all made up of matter poured out from the craters or through great fissures in the crust. So numerous are these heaped masses of lava and other ejections from these vents that there is hardly any considerable area of the oceans where they do not rise above the surface. There are indeed thousands of these volcanic peaks distributed from pole to pole.... Thus on the floor of the North Atlantic there is evidently a long, irregular chain of these elevations extending from the Icelandic group of islands southward to the Azores. If an explorer could view this part of the sea-bottom, he would probably find that the line of craters was as continuous as that exhibited by the volcanoes of the Andes.

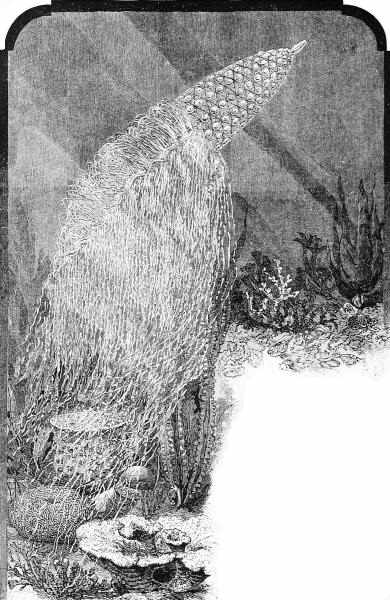

“Besides the volcanic peaks,” Professor Shaler continues, “the sea-bottom in certain parts of the tropics ... is beset with the singular elevations formed by coral reefs.” But of these I shall have more to say toward the end of the book, and I allude to them here only as a feature of the invisible landscape beneath the waves.

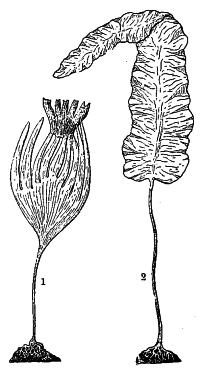

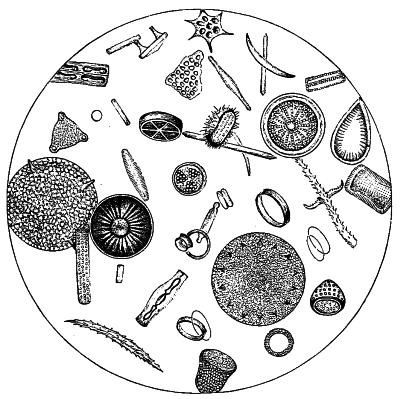

Over the vast, gently undulating spaces separating these submerged lines of volcanoes and the ridges of coral, lies a mat of mud of unknown thickness, which naturalists term “ooze.” It is principally composed of volcanic dust and of the microscopic “tests,” or flinty limy skeletons of minute animals, few of which are large enough to be seen by the unaided eye. “Dwelling in myriads in the superficial parts of the sea, these foraminifera, as they are termed, sink at death to the bottom, over which they accumulate a thick coating of minutely divided limestone powder, forming a layer of ooze as unsubstantial as the finest snow.”

In regions like the North Atlantic this ooze consists almost wholly of such animal matter; but in other regions, such as the South Pacific, where volcanoes prevail, it is constantly and largely increased by an enormous quantity of mineral matter hurled broadcast by volcanoes, all of which are on islands or near sea-coasts. A part of this is the merest dust, which slowly settles from the air, perhaps hundreds of miles from where it was ejected. A larger part consists of that spongy lava called pumice, which is so full of holes filled with air and gases that it may float half way around the globe before it sinks, as happened after the explosion of Krakatoa.

Into the oceanic ooze, too, sinks so much of all dead fishes and other mid-sea animals as is not dissolved or devoured before reaching it; and it forms the grave of thousands of men. It is often said that ships and other things would not sink far, but would float, suspended by dense water or some miraculous influence, only a few hundred or a few thousand feet below the surface, for no one knows how long. But this eerie notion has no foundation in fact. “No other fate,” we are assured by those who know, “awaits the drowned sailor or his ship than that which comes to the marine creatures who die on the bottom of the sea. In time their dust all passes into the great storehouse of the earth, even as those who receive burial on land.” Wooden wrecks probably last much longer than those of iron.

I have mentioned that a small part of what the sea tears away from the land, or receives from rivers, winds, and other sources, is dissolved in its waters, which now contain, no doubt, samples of every ingredient of the rocks and soils of the dry land, and very likely some elements not yet detected. This solvent power of the sea explains its saltness, and it must go on growing more and more bitter as long as its waves grind at the14 shores and the rivers run down. The salinity varies in degree, water at great depths being salter than that near the surface, and excelling in saltness where evaporation is rapid, as under the trade-winds, while fresher in the regions of equatorial calms, where an immense amount of rain falls; broadly, the lightest (freshest) water is found at the equator, and the heaviest in the temperate regions. Inclosed, or nearly inclosed, areas become very salt. Thus the Dead Sea is what chemists call a saturated solution, being nearly one third (28 per cent.) salt, and Great Salt Lake in Utah is not far behind. The Red Sea contains 4 per cent., and some parts of the Mediterranean nearly as much. Taking all the open oceans together, about 3½ in every 100 parts (3½ per cent.) is composed of various salts, more than three quarters of which is common salt (chloride of sodium), and the remainder mainly forms of magnesium. One of the Challenger authors has estimated that the oceans contain enough salt to make a layer 170 feet thick over their whole area, and another writer says that the amount, if heaped up, would be four times larger than the whole bulk of Europe above the level of high-water mark, mountains and all.

In early times, indeed, sea-water, which yields about a quarter of a pound of crystallized salt per gallon, was almost the only source of salt for food. Even yet it is the principal source of supply for the manufacture of commercial salt in France, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Austria, the West Indies, and Central and South America; and it is largely used in Holland, Belgium, and Great Britain. The early process, still extensively practised in some parts of Europe, was to admit the sea-water to large partitioned flats floored with clay, where it evaporated rapidly. The salt-crystals remaining were then collected, purified to a greater or less degree, and sold off-hand. It was by similar means that our great-grandfathers in New England and along the Southern coasts provided themselves with salt, only they used large vats arranged over fires instead of earthen basins exposed to the sun.

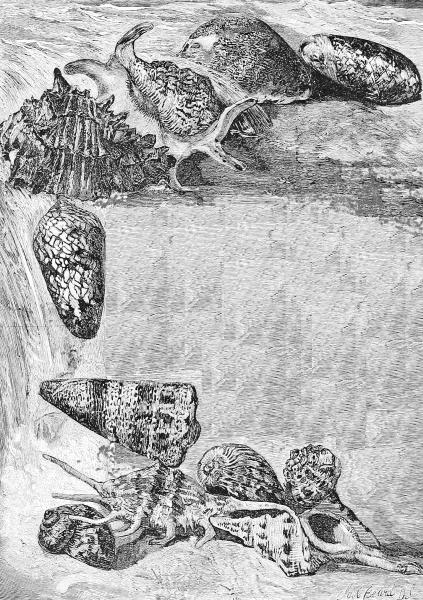

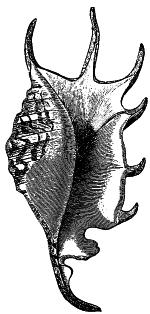

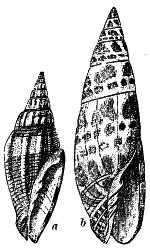

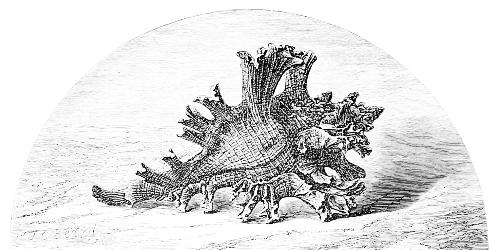

But analysis of sea-water discloses small quantities of many other recognizable minerals. Silica must be there to supply the needs of many foraminifers, sponges, and other animals; lime in various forms exists, or else such sea animals as mollusks could not compose their shells, nor polyps erect their enormous reefs; bromine is present, and to the iodine and other mineral dyes in the water we owe the lovely purples, crimsons, and scarlets painting corallines, seaweeds, echinoderms, and some molluscan shells, as that of the Sargasso-snail (Janthina).

As for gold and silver, both are present. I have seen it stated that a voyage of a year or two is sufficient to permit the formation of a film of15 silver all over the copper sheathing of a ship’s bottom, so that a frigate returning from a long cruise is really silver-plated; but I fancy this is more a matter of imagination than visible reality. Gold, in certain chemical combinations, certainly exists in sea-water, and may be extracted therefrom. Up to the present, however, the cost of the extraction has been more than the precious metal obtained was worth. Gold is often washed from sea-sand.

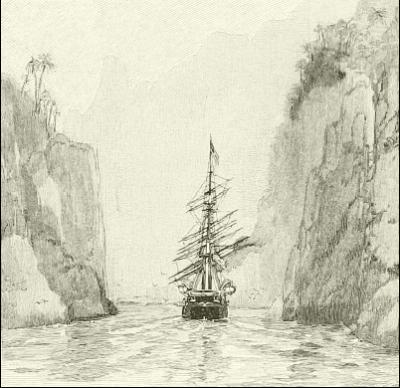

A FIORD, OR DEEP CREVICE WORN IN SEA-CLIFFS.

The ceaseless restlessness of the ocean forms another of the greatest contrasts between it and the immovable land—terra firma, as those like to call it who have been tossing too long on the “rolling deep”. This characteristic restlessness involves some of the most important and interesting facts in physical geography; for were the waters still,—that is, were the oceans simply huge, quiet ponds,—none of that action could take place along the shores which has been so important an agent in shaping the world and making it a suitable place for human habitation and social development.

On a planet with an atmosphere and changing seasons like ours, however, a stagnant ocean is as impossible as a motionless air; indeed, it is because the air is always in motion that large bodies of water are never at rest, for it is the changing density and temperature and movements (winds) of the air that produce waves and currents.

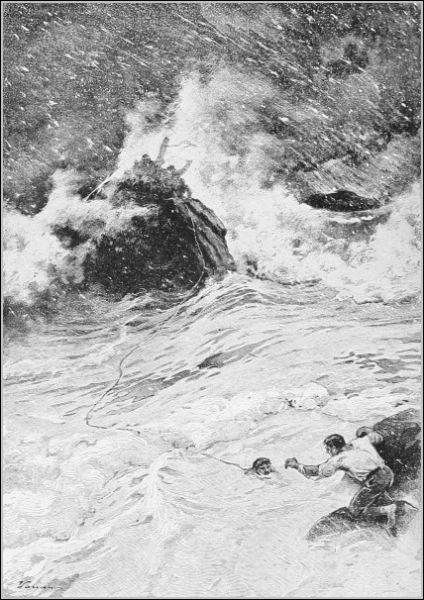

Waves are caused by the pressure and friction of the wind upon the surface of the water, as you may readily see at any pond; and the water in them simply rises and falls, driving forward a little at the very surface so as to cause a gentle current called wind-drift. When the waves approach the shallow, sloping border of the land they are checked at the bottom by the slope of the beach, while the freer upper part goes forward, and the waves speedily lose their rounded form and become more and more sharply16 ridged and steep on the front side as they sweep on until at last they pitch forward in the crash and thunder of surf.

In the open ocean the waves are usually doing little work except to cause the surface to rise and fall. The harder the wind blows, the higher the waves become, and the faster they travel. This speed has been calculated, and has been found to be proportionate to size.

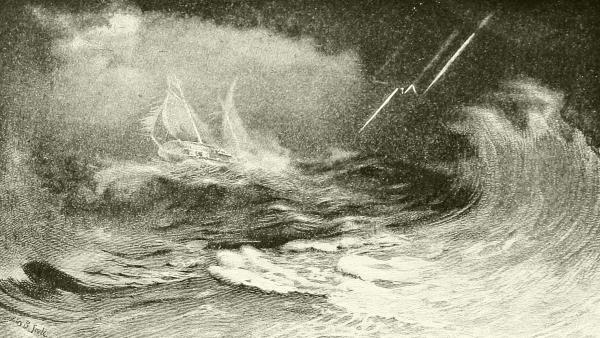

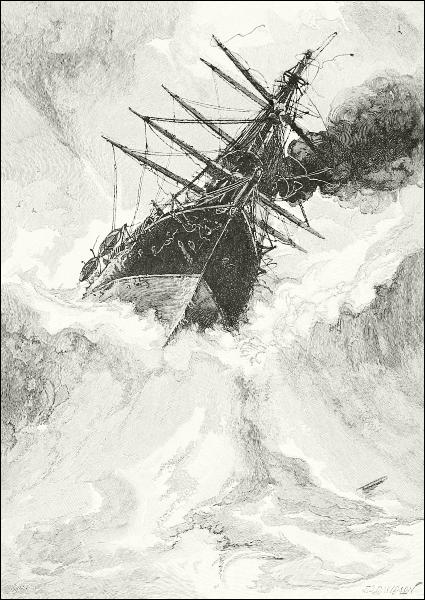

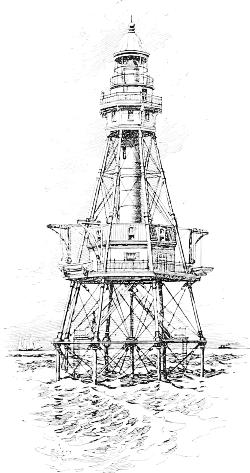

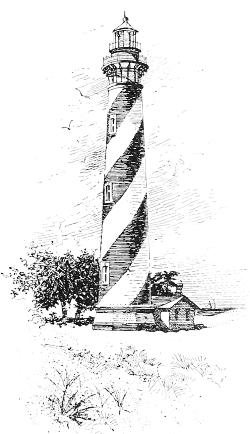

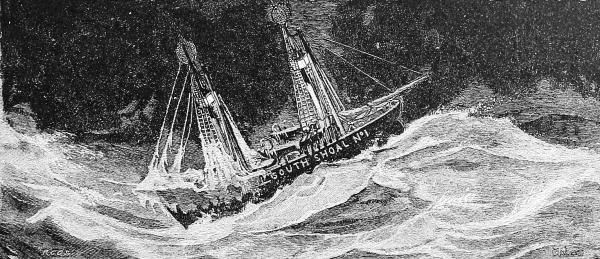

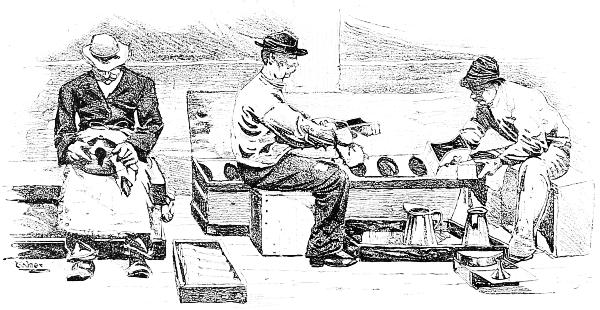

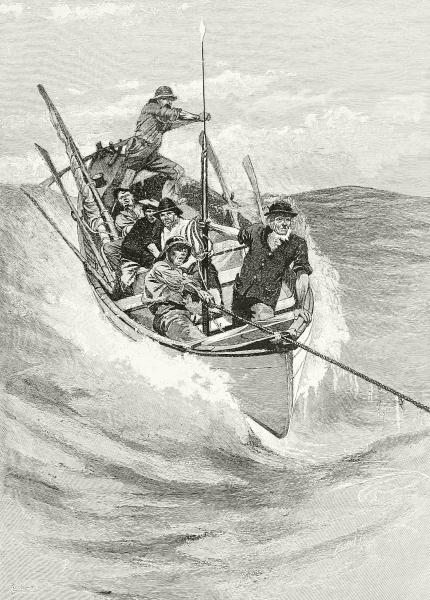

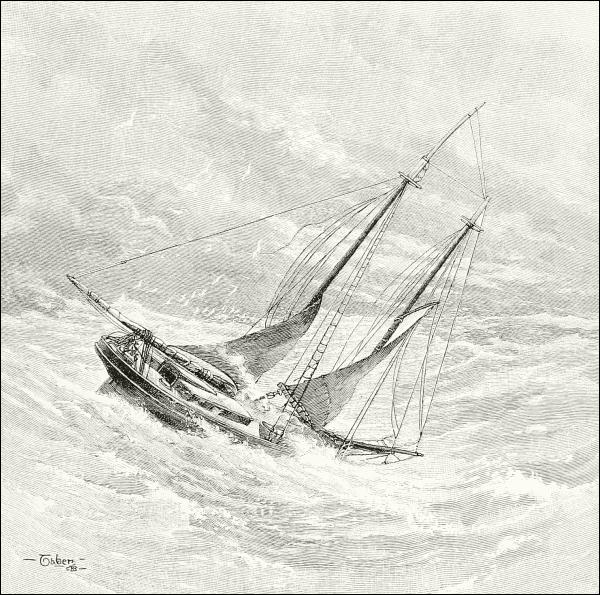

“Waves 200 feet long from hollow to hollow,” we are told, “travel about 19 knots per hour; those of 400 feet in length make 27 knots; and those of 600 feet rush forward irresistibly at 32 knots.” These, of course, are under the furious impulse of a gale, and it is marvelous that ships can be made to ride over them; nor is it any wonder that excited mariners clinging to the bulwarks of some small and heeling craft, should call them “mountain high,” and declare in all seriousness that they have seen their crests rising one hundred feet above their hollows. No such altitude, nor half of it, probably, is ever reached by a storm-wave in the heaviest cyclone. An excellent authority, Lieutenant Qualtrough, assures us that the highest trustworthy measurements are from forty-four to forty-eight feet. The height of a wave depends upon what mariners call its “fetch”—that is, its distance from the place where the waves began to form. This has been worked out mathematically by Thomas Stevenson (father of the late Robert Louis Stevenson, the novelist), an eminent engineer and designer of lighthouses, who gives the following formula: “The height of the wave in feet is equal to 1½ multiplied by the square root of the fetch in nautical miles.” If the waves began 100 miles away from your ship, the waves about you will be 15 feet high, because the square root of 100 is 10, and one and a half times 10 is 15 (feet). The highest waves are not formed in the greatest tempests, which beat down their crests, but when the gale is both very strong and long continued. The worst “seas,” as sailors call big waves, are those met with off the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn.

The depth to which wave disturbance extends depends on the violence of the wind, and near shore upon the slope of the bottom. Prestwich tells us that pebbles may sometimes be moved at the depth of one hundred feet, and sand much deeper, as is shown by the fact that the bottom is disturbed in heavy storms on the Banks of Newfoundland.

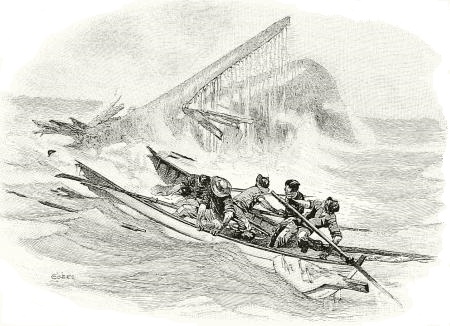

The weight and power of such on-rushing masses of water are tremendous, as appears from the effect on coasts where they strike; but this opens up a subject which is too large for treatment here, and I must refer readers to geological treatises, and to such special works as Professor N. S. Shaler’s excellent “Sea and Land,” where the work of the ocean in tearing down and building up its coasts is fully and entertainingly explained. I shall have17 something more to say on this point, also, when I come to the chapter “Dangers of the Deep,” and speak of the terrible destruction caused by earthquakes, and in certain other agitations of the sea not due to the wind, and often styled “tidal waves.” There is only one kind of “tidal wave,” properly speaking, however; and this is a theoretical rather than an actual one, perceptible usually only in that rising and falling of the water along coasts twice each twenty-four hours that we call the flow and ebb of the tides; and here we see the effect rather than the thing itself.

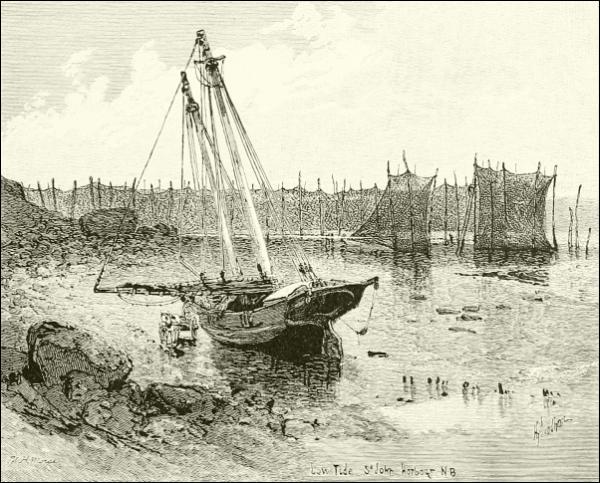

LOW TIDE, ST. JOHN’S HARBOR, N. B.

The tide has been an inevitable circumstance of the existence on the earth of the ocean, or any other great body of water, ever since its origin, yet it was not until Sir Isaac Newton made us comprehend the law of gravitation that its mystery was explained. We now know with certainty—if you want the mathematical formulæ and so forth, consult some good modern encyclopædia under the word tide—that this periodical rising and falling of the sea is due to the attraction of the sun and moon,—to the last three times as much as to the first, because it is so much nearer. This attraction is exerted toward the globe as a whole; and its visible effect upon the movable water is to lift it bodily on that side18 nearest the moon, and at the same time to pull away the earth from the water on the opposite side, which amounts to the same thing; and thus high tides are simultaneously produced at these antipodes, which accounts for the two a day. At the same time, however, the intermediate spaces have low tides caused by an attraction there toward the center of the earth. “There are thus always simultaneously and directly under the moon two high waters opposite each other, and two low waters at equal distances between them. Owing to the rotation of the earth, this permanent system of swells and troughs travels from east to west over every part of the ocean and of its coast, and explains the regular succession of rising and falling waters, at equal intervals of time, which we call the tides.”

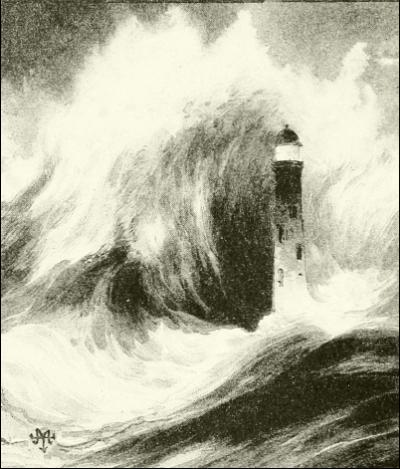

THE EARTHQUAKE WAVE PASSING OVER

THE LIGHTHOUSE ON POINT ANJER.

But the sun also exerts a similar but lesser influence, producing four daily solar tides, which most of the time are lost to view in the greater lunar tides. When, however, the moon gets into line with the earth and the sun, so that both the heavenly bodies pull together like a tandem team, as happens twice a month,—at new moon and full moon,—their combined action causes unusually high water, which is the sum of the lunar and solar tides, and is called the spring tide. High water is then highest, and low water lowest. On the other hand, in the midst of these fortnightly intervals, when the moon is at its first or third quarter, the sun is a full quarter of the heavens (90°) away from the moon. Its influence, therefore, acts at right angles to or practically against that of the moon, and the solar tides go to swell the low waters and diminish the high waters, forming what sailors call neap tides,—preserving an old English word meaning low.

Now remember that the globe is not standing still, even while we make these explanations, but is revolving at a tremendous speed, so that the water under the moon lifted by lunar attraction is changing place every instant at the rate of over one thousand miles an hour, and you have the conception of a low wave on each side of the earth, reaching north and south, highest and swiftest on the equator and diminishing toward the poles. These are the true tidal waves. Were the globe covered with an unbroken mantle of water, such waves, each about twenty inches (or twenty-nine inches at springtide) high on the average at the equator, would follow one another round and round the earth at the rate of one complete circuit in every twenty-four hours. That must have been the case in the primeval ocean before any continents existed; and something of it still exists in the belt of unobstructed water surrounding the Antarctic continent of ice. It would then be flood tide or ebb tide at the same hour along the whole length of any one meridian. But in the present condition of the globe, where the oceans are separated by continents and broken by islands, the progress of the tidal waves is obstructed, deflected, and wholly stopped in a great variety of ways and places, so that the hours, amount, and behavior of the tides are exceedingly varied in different regions, and are often very puzzling, forming one of the most difficult matters with which the practical navigator has to deal. Interference of tidal currents forms the Maelstrom, off the coast of Norway, whose revolution is reversed twice daily, the classic Scylla and Charybdis, in the Straits of Messina, so much dreaded by the navigators of old, and many other whirlpools of less celebrity. The tidal wave sweeping northward across the Atlantic has time to round the northern end of Scotland and flood the German Ocean with southward swelling currents before the rising water pouring into the southern end of the English Channel has time to push its way through that narrow and shallow passage; hence the two floods meet in the Straits of Dover, which accounts for the miserable chop-sea so sadly prevalent in that unfortunate bit of water.

The natural height of the tide seems to be from two to five feet, as shown in the midst of the broad Pacific. “But when dashing against the land, and forced into deep gulfs and estuaries,” to quote Professor Simon Newcomb, “the accumulating tide-waters sometimes reach a very great height. On the eastern coast of North America, which is directly in the path of the great Atlantic wave, the tide rises on an average from 9 to 12 feet. In the Bay of Fundy, which opens its bosom to receive the full wave, the tide, which at the entrance is 18 feet, rushes with great fury into that long and narrow channel, and swells to the enormous height of 60 feet, and even to20 70 feet in the highest spring tides. In the Bristol Channel, on the coast of England, the spring tides rise to 40 feet, and swell to 50 in the English Channel at St. Malo on the coast of France.”

To this cause is also due in some degree those great oceanic currents which form another striking fact in the history of the sea; but they are mainly due to temperature, wind, and the rotation of the earth.

The drops that make up a body of water are the most restless things in the world; they are always sliding down the least slope, sinking out of the way of lighter substances, rising to let a heavier object pass beneath them, or moving hither and thither in an ever hopeful search of that levelness and quiet that we call equilibrium. Furthermore, when water is heated it becomes lighter. Should, therefore, a portion of the sea grow warmer than the remainder, it must and will rise to the surface; and whenever a portion becomes cooled, it must and will sink.

Now, under the continuous blazing sun of the torrid zone the sea-water near the surface gets fairly warm,—having an average temperature of about 85° along the equator,—while in the polar regions the ocean is always chilled by permanent or floating ice until it is nearly cold enough to freeze; but these masses of warm and cold water cannot remain separate in the universal ocean. The hot tropical flood, continually rising, must flow away somewhere to find its level; and it can flow nowhere except toward the poles, for there the ever-sinking volume of chilled and therefore heavier water sucks it in to take its place, while it, in turn, creeps underneath toward the equator, there to fill the gap which the escaping warm water leaves behind. So we know there is constantly going on an interchange of water—a constant flowing away from the equator northward and southward on the surface, and a flowing in toward the equator along the bottom; an endless springing up in the torrid zone and a steady settling down in the polar seas. One out of many proofs of this fact is that the thalassal abysses below the depth of a mile or so are known to be ice-cold. This could not happen unless they were constantly filled and refilled with new water from the great coolers at the poles; for if the water at those depths should remain unchanged, it would soon become very warm from the heat of the interior of the earth, whence it does constantly extract some heat.

But while this invisible vertical circulation is going on, another more visible and interesting set of movements is in progress on the surface, forming what are known as ocean currents. These are vast rivers in the ocean flowing across its face in certain directions and to a certain depth, as rivers make their way along the land. They begin and are kept going mainly by a union of the two causes already explained—heat and wind.

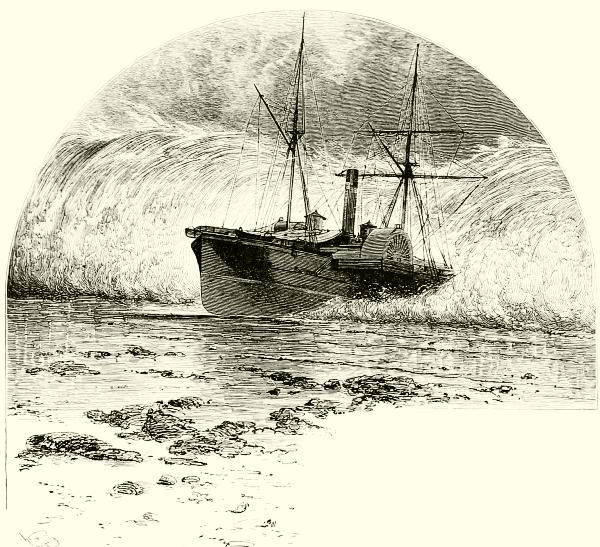

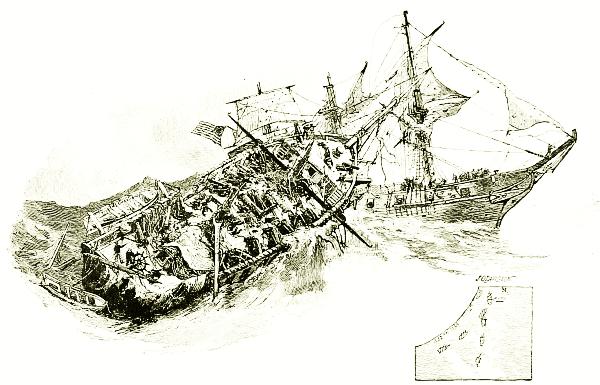

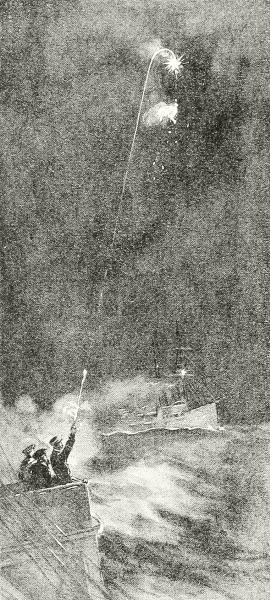

A STEAMER BORNE ASHORE BY AN EARTHQUAKE-WAVE.

The heat of the sun at the equator, warming, lightening, and evaporating the water, constantly tends to draw the colder water from the poles, most copiously from the South Pole; but the Antarctic water, hastening to the equator, is soon interrupted by the extremities of Australia, Africa, and South America, and so split into three great branches. That which passes into the South Atlantic goes on northward along the western coast of Africa, part of it becoming so warm under the hot sun there that it will not sink, but constantly comes more and more to the surface, until it strikes against the great shoulder of Guinea and is turned sharply westward. Now it is squarely under the trade-wind and headed the same way; constantly urged forward by this moderate but endless tugging of the wind upon its waves, the current can never swerve, but flows along the equator, and for half a dozen degrees each side of it, straight across the Atlantic. South America, however, stands in its path, and the wedge-like coast of Brazil, pointed with Cape St. Roque, splits this great river. Part of it now turns southward and swings back across toward Africa, making an eddy a couple of thousand miles wide in the South Atlantic, while another arm runs down the Patagonian coast. But by far the largest part of the divided current is sent northward, past22 the coast of upper Brazil into the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, where it is well heated, and thence poured into the North Atlantic, to become widely celebrated as the Gulf Stream.

Gathered in full force, the Gulf Stream flows northward close along the coast of our Southern States at the rate of eighty or ninety miles a day until Cape Hatteras gives it a swerve away, when it strikes out to sea and pushes straight across to Spain, where a branch leaves it and runs northward between Iceland and the British Islands, while the main body turns southward to mingle again with the equatorial current from Africa and repeat its journey all over again. It is in the heart of this great circle of currents in the middle of the Atlantic that navigators find that dreaded region of heat and calms which they call the Doldrums; and here, too, float round and round the wide, buoyant meadows of the Sargasso Sea.

Meanwhile another most important cold stream is making its way through the Atlantic, known as the Arctic current. It comes down out of Baffin’s Bay, joins a similar flood from the outer coast of Greenland, is thrown up to the surface by the Banks of Newfoundland (where meeting warm air, it produces those thick and prolonged fogs so common in that region), fills the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the bight between Nova Scotia and Cape Cod with chilly water, and finally dips under the Gulf Stream amid that commotion of winds and waters that makes the track of the steamships between New York and Europe the most tempestuous of ocean highways. It is the mingling of these warm and cold waters there which is chiefly responsible for the stormy condition of the North Atlantic.

The Pacific has a similar arrangement of circulation north and south of the equator. The Antarctic waters form a cold stream named the Humboldt current, which pours up the western side of South America, keeping the climate down to a far more wintry condition than it is entitled to by latitude, until it reaches the southern trade-winds, which sweep it westward straight across the Pacific, where much of it is lost among the archipelagoes of Oceanica, and the southern part flows onward into the Indian Ocean.

North of the Pacific equator a similar westward current moves steadily over the great waste of waters past the Sandwich Islands to the coast of China. From the Philippines and Japan northward, however, there is a far stronger flow, known to the Japanese as the Black Current (Kuroshiwo), which skirts the coast of Japan and the Kurile Islands, makes these and Kamchatka habitable, then turns sharply east along the front of the foggy Aleutian chain of islands, and broadening and cooling as it turns, swings down the temperate coast of Alaska and gradually disappears. These two23 great currents and their inclosed eddies are far broader and less distinct than those of the North and South Atlantic, but they follow the same laws.

In a similar but lesser way the Indian Ocean has a strong westerly stream flowing straight across from Australia to South Africa, which is of immense help to ships returning from the East around the Cape of Good Hope. From Mozambique the water turns northward to make the return round, but here it is complicated by the peculiar conditions made by the inflow and outflow of the Red Sea, Arabian Gulf, and so on, and by the disturbing influences of the monsoons, until it can hardly be defined.

Of all these currents none is as well marked as the Gulf Stream. Its blue water is in such contrast to the darker, greenish hue of the remainder of the ocean that sailors can often tell when they enter the edge of the current, half their vessel being in and half out of the stream. If you approach from the west you find that the water at first shows a warmth of only fifty or sixty degrees near the surface; but as you sail on, this increases until, opposite Sandy Hook, you may get as high a reading on the thermometer as eighty degrees, and opposite Florida above one hundred degrees. This difference in temperature between the eastern and western margins of the Gulf Stream is owing to the presence of the great river of Arctic water flowing in an opposite direction between the Gulf Stream and the shore. Off Florida the Gulf Stream is about sixty miles wide; off New York it is over one hundred miles in width, but is less sharply defined. Its depth is hard to determine, but certainly amounts to several hundred feet. It is worth remembering that, although some guesses had been made at it before, Dr. Benjamin Franklin was the first man to study the Gulf Stream and to tell us anything of its origin and course.

The way in which some of these ocean currents affect the weather of the lands upon which they border shows how great is the influence of the sea upon land-climates; indeed, it may be truthfully said that only the continents and such great islands as Australia or Madagascar have any climate essentially distinct from that of the ocean in their quarter of the globe. But the equability that would reign over an ocean of quiet water, determining the amount of cold and heat by regular gradation in latitude between the equator and the poles, is completely upset by the great current-movements I have outlined. Scotland, for example, lies as far north as Labrador, and the latitude of London is above that of Lake Superior, yet neither have those terrible frosts and heavy snows which prevail in Canada, and make Labrador a land of ice almost uninhabitable. This difference is due almost wholly to the fact that the Gulf Stream pours its warm flood against the coast of Great Britain, and even tempers the Norwegian coast, keeps24 Barentz’s Sea largely free from summer ice, and clothes Spitzbergen with vegetation, although within ten degrees of the pole. Hence in the forests of northern Scandinavia Laps can dwell in much comfort on a line with the frozen barren grounds north of Hudson Bay.

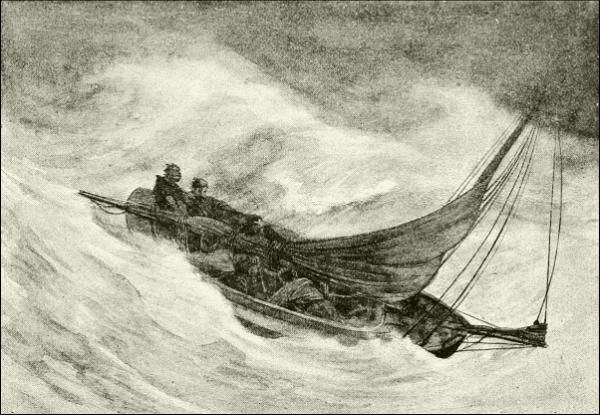

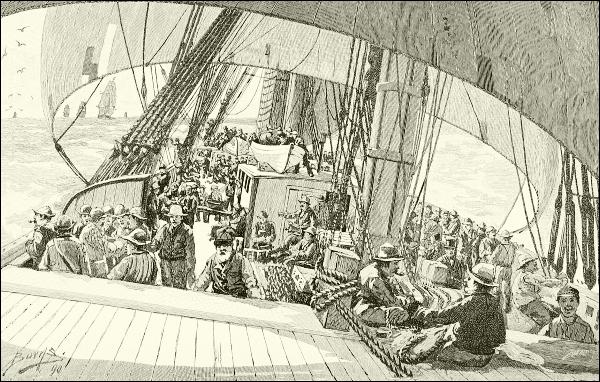

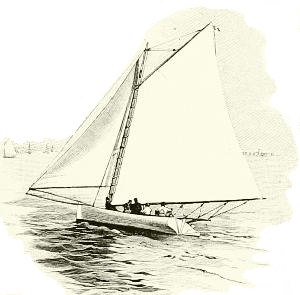

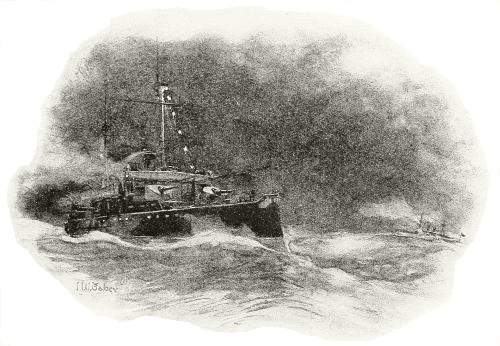

A ROUGH NIGHT IN THE GULF STREAM.

On the other hand, the unfortunate coasts of Greenland are bathed in water chilled by months of captivity near the pole, and loaded with ice that cools down all the winds that blow ashore. Greenland itself is covered with an unbroken sheet of ice, hundreds or thousands of feet thick, yet most of it is no farther north than Sweden. The whole northeastern coast of America, down to Labrador, is incrusted with ice; and the region south of the St. Lawrence has a similar climate to Finland; while even farther south, Boston, within the protecting arm of Cape Cod, is in winter a city of frost and snow and fog from November till April, when it really is little farther north than sunny Naples, where one laughs at winter.

Similarly, in the Pacific Ocean, the northward movement of the great Japanese current makes the coast of China habitable and pleasant clear to the Sea of Okhotsk, gives the Aleutian archipelago a pretty decent climate, and causes the islands and coasts of Alaska and British Columbia to nourish25 the most magnificent forests in America, and to have a climate resembling that of Great Britain. Glasgow and Sitka are, in fact, in the same latitude, and under very similar climatic conditions, except that in Scotland there are no such lofty and cold mountains to precipitate constant rains as is the case along the northwestern margin of America.

Similar examples and contrasts might be drawn in other parts of the world. The weather in the interior of continents is pretty much alike on similar latitudes the world round, varying with height; but the climate of all sea-coasts is good or bad as a place to live, in accordance with the temperature of the water which the currents bring to that part of the ocean.

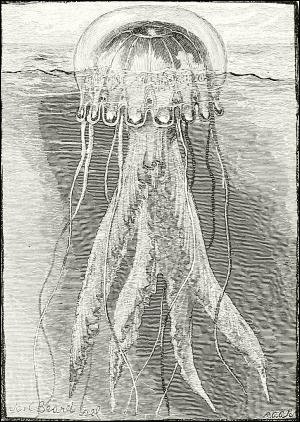

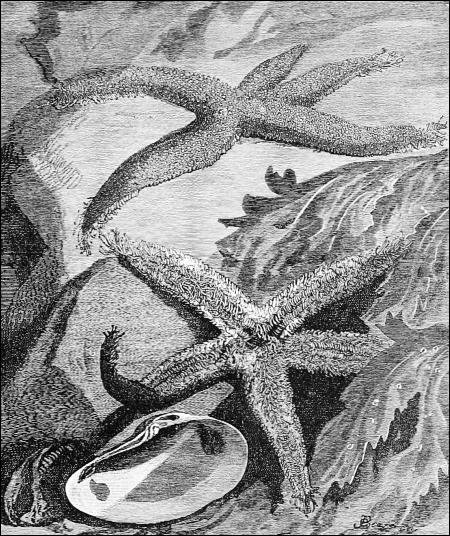

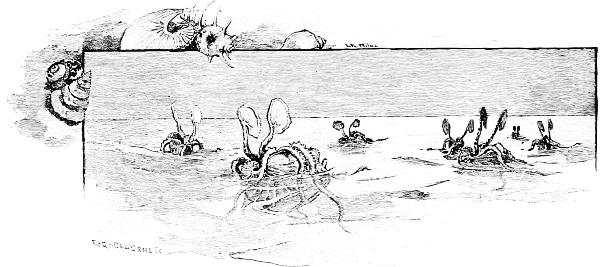

But the currents of the ocean influence something besides the weather. Upon them depends to a considerable extent whether a certain part of the coast shall have one or another kind of animals dwelling in the salt water. This is not so much true of fishes as it is of the mollusks or “shell-fish,” the worms that live in the mud of the tide-flats, the anemones, sea-urchins, starfish and little clinging people of the wet rocks, and of the jellyfishes, great and small, that swim about in the open sea.

Nothing would injure most of these “small fry” more than a change in the water making it a few degrees colder or warmer than they were accustomed to. Since the constant circulation of the currents keeps the ocean water in all its parts almost precisely of the same density, and food seems about as likely to abound in one district as another, naturalists have concluded that it is temperature which decides the extent of coast or of sea-area where any one kind of invertebrate animal will be found. It thus happens that the life of Cuban waters is different from that of our Carolina coast; and that, again, largely separate from what you will see off New York; while Cape Cod seems to run out as a partition between the shore life south of it and a very different set of shells, sand-worms, and so forth, characteristic of the colder waters to the northward.

Out in the ocean, however, the warm current of the Gulf Stream forms a genial pathway along which southern swimming animals, like the wondrously beautiful Portuguese-man-o’-war (Physalia), may wander northward for hundreds of miles beyond where they are found near shore; yet if by chance they stray outside the limits of the warm Gulf Stream, they will at once be chilled to death, as happened once to millions of tile-fish.

Ocean currents carry floating burdens long distances. They bring the icebergs to form those terrible fogs of Alaska and Newfoundland; and they often bear far away the logs that float out of tropical rivers.

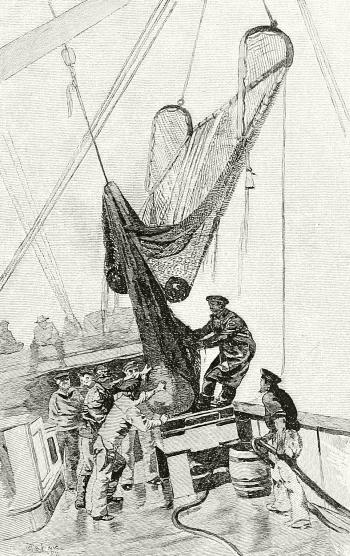

A YOUNG SHIP-RIGGER.

These drifting logs often have plants growing upon them or contain quantities of seeds which are not injured by their short voyages. When,26 therefore, the coral polyps build up one of their reef-islands until it appears above the waves, thither the currents bring roots and seeds from neighboring islands, and quickly plant them upon the new barren shores, so that in a few seasons the little islet becomes green and wooded and ready to hold its own against the winds and waves. Moreover, the same drifting stuff will carry land animals as passengers,—insects, snails of many kinds, reptiles, and even four-footed beasts,—and so not only give the island a vegetation, but populate it with various of the smaller animals. This seems to you, perhaps, a very accidental and haphazard way of fitting out a country so that presently it may support human beings, nor is it the only means by which barren islands become productive; but it is important as far as it goes, and when we study into the distribution of plants and animals in an archipelago, we are pretty sure to find those of the same sort upon islands that lie in the same current—even to the human inhabitants.

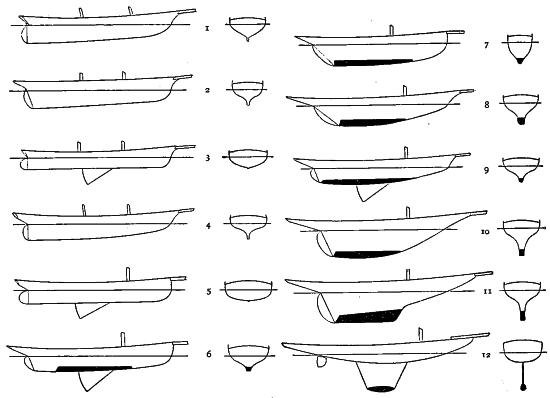

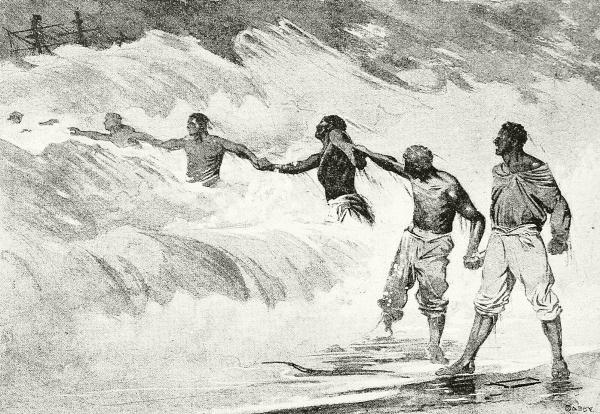

As late as 1861 an exploring ship was visited by natives of Western Australia, riding simple rough logs. To smooth and sharpen the log’s end and then to hollow it out has been thought to be the first step taken by primitive man in his progress toward a boat; but I think the dugout probably came later, or at any rate no earlier, than the folding of bark into a trough and tying up the ends, as some savages are still content to do. In North America, where materials were favorable, this germ developed into the very highest type of canoe—the Algonkin birch-bark. It may have been an attempt to imitate the bark canoe in a more durable form which led to the laborious hollowing of dugouts; but here again, in regions where suitable trees grew, the art developed so highly as to produce the great sea-boats of the Papuans and our Northwest Coast Indians, carved from a single log, yet able to carry sixty or more persons and their luggage. Such boats as these, when provided with sails, are practically “ships,” and satisfy every need of their owners.

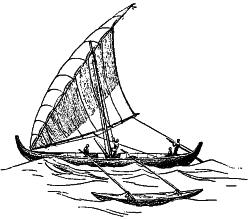

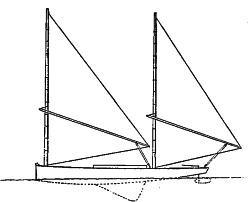

Another root of naval architecture lies in the raft, which long ago reached a high degree of usefulness in the sea-going balsa of western South America. It is probable that the South Sea catamaran is a clever outgrowth of experience with a raft. In Polynesia it took the form of two great canoes, exactly equal, fastened close together and covered by a single central deck; and such are the seaworthiness and speed of these double boats, that the Polynesians voyage hundreds of miles in them.

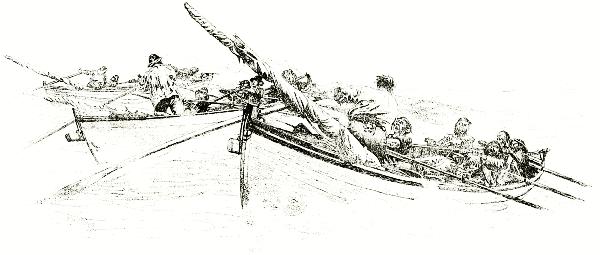

Similar in purpose—namely, to insure stability—are the various outriggers that at once characterize and distinguish among themselves the native craft of the South Seas. This device consists of a beam of the lightest obtainable wood, usually about half as long as the canoe, which rests upon the water parallel to and a few feet away from the side of the boat, and is connected with its gunwale by elastic rods or planks. Sometimes these are28 covered, or partly covered, by a light platform, and there are many variations in form; but the idea in all cases is to keep the boat from overturning.

In many parts of the world logs could be obtained large enough only for a narrow bottom or hollowed keel, and the remainder of the boat was built up of planks and pieces ingeniously pegged and knit together with treenails, ratan, and cords made of vegetable fibers that tightened when wet. The Madras surf-boats are a familiar example in civilized waters of boats made in this way which have great elasticity, and out of them have developed, without much change, the swift proas of the Malays, and the junks of China, Korea, and Japan. One device for stitching these boats firmly together was the leaving of ridges on the inner side of the planks or pieces, through holes in which they could be tied to each other and to the inner framework without making a hole reaching the outside. This system seems to have been earlier than the use of treenails.

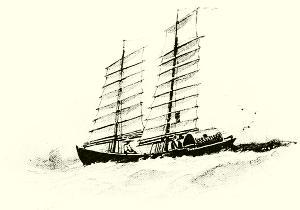

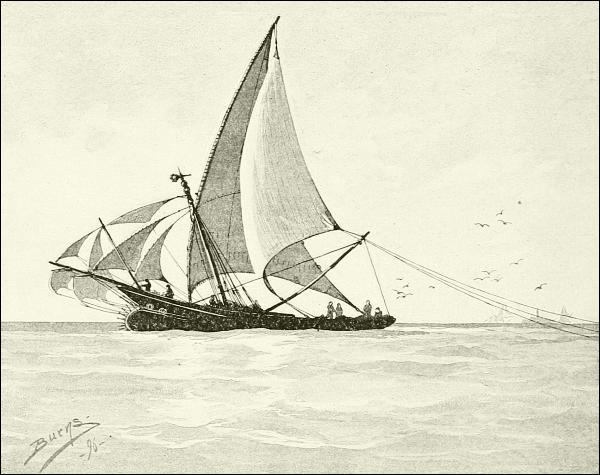

PROA, WITH OUTRIGGER.

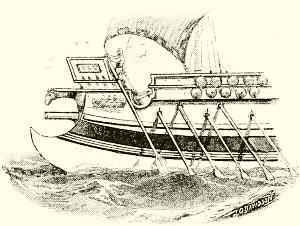

Of similar construction, apparently, were the boats of the Egyptians and other peoples about the eastern end of the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, which, as far back as three thousand years before Christ, at least, had reached the size and capabilities of true ships, making, as we shall presently see, extensive sea voyages. Pictures of them remain in the very ancient tombs, and show that the planking consisted of pieces about three feet square, which were laid on overlapping, like shingles on a roof, and fastened to the framework by wooden treenails. The Phenicians, and their pupils the Greeks and Romans, improved on these methods in various ways, at last substituting iron, copper, and bronze nails or bolts (which would not rust) for the wooden pegs of their ancestors.

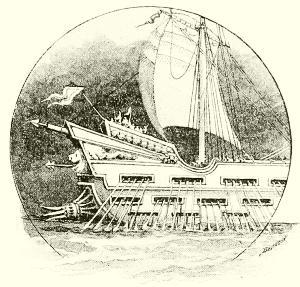

All of these boats and those of all western Europe (of which the best outside the Mediterranean were the vikings’ ships) differed in one essential point of construction from Oriental ships: instead of making the shell of the vessel, and fitting into it a framework of connected braces, as the Malays and Polynesians did (and yet do), they laid a keel, bending it up or setting into it stem- and stern-posts at the ends, and inserted along its sides curving upright timbers, well styled “ribs,” which swelled out amidships, and narrowed in forward and aft, making a skeleton of the shape the hull was intended to be. Finally, over and upon this well-braced framework were securely fastened the planks, which were narrow and ran lengthwise29 in every case except that of the ancient Nile boats. The Scandinavian vikings developed a craft of their own, one of the most interesting of the ancient ships; and to these northern craftsmen is traceable the principal influence that has shaped British (and consequently American) ship-building and seamanship. This early Scandinavian boat was always made of oak, sharp at both ends, and rather shallow, the general form being much like that of a modern whaleboat, with a great rounding keel—if, indeed, this wonderful sea-craft may not be a lineal descendant of the viking ship. The hewn planks were attached to the keel and to the ribs (usually single, naturally bent V-shaped prongs of oak) in a most ingenious and serviceable manner, and they were always overlapping or clinker (i. e., clencher) built. Several of these and other prehistoric boats have been found buried in peat-moss and in mounds in Germany, Denmark, and Scandinavia, and have been described by various writers.

The motive power of all the early boats was found in human arms, wielding paddles or oars. It is said that the oldest forms of paddles of which we have any record among the Egyptian or Assyrian hieroglyphs show them to have been shaped somewhat like the arm and hand, and that similar paddles were to be seen a few decades ago on the canals in Holland. This is natural, because undoubtedly the first paddle ever used was the naked hand. Short paddles were soon found less powerful than long ones; but in order to work the latter it was necessary to brace them against something in the middle. Notches were therefore cut in the edge of the boat, or thole-pins were inserted, the paddle became an oar, and by and by boatmen learned the art of feathering, and so forth.

Steering could be done of old, as now, with a turn of the rearmost paddle in a canoe, and as canoes enlarged, the steering-paddle was lengthened. As the sterns of the ancient boats were usually either sharp, like the prows, or else built up into an ornamental height, the most convenient place for the steering-oar was over the right side, where it was balanced in a loop of cable, or otherwise, as close to the after end of the boat as practicable, and then a cross-piece extended inboard from the handle, enabling the steersman to move it more easily by giving him the benefit of leverage. Such was the arrangement of steering-gear in all the ancient Mediterranean boats, and it is to a similar arrangement in the sea-going craft of our northern ancestors that we owe our words stern and starboard, which originally meant “steering-place” and “steering-side.” The modern rudder is substantially the same oar, set upright, tiller and all, and hinged to the stern-post; in fact, the word has descended from the old Teutonic name for “oar,” and all gradations between steering-oar and true rudder may still be found.

Though some romantic stories are told by the old mythologists as to its origin, the idea of rigging was as natural and practical in its development as that of hull or steering-gear. That a strong breeze moves a canoe, and that, if a man in a canoe holds his robe outstretched or a thick bush upright, the force will send him along without the labor of paddling, and lengthwise rather than sidewise, because that is the direction of least resistance, were facts quickly and gratefully seized upon by the earliest boatmen. To have a skin ready for the purpose, and to set up a pole and ropes to hold it in position, were easy matters; yet in this simple arrangement you have the first sail.

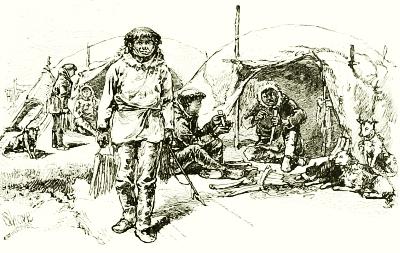

But skins were too heavy and valuable for such a purpose, except in such limited circumstances as those of the Arctic Eskimos.

Persons who spent much time on the water, therefore, like the most ancient Egyptians and the islanders of the Chinese and South seas, soon devised a way of weaving rushes or splints of bamboo into broad mats, and thus were able, on account of their lightness, to carry much larger and more effective sails, which were kept outstretched by one or more cross-poles or spars, and could be taken down quickly. Many such sails are in use to this day not only among Asiatic and African boatmen, but on the northwest coast of Canada. A fine example hangs above my desk as I write.

With the discovery of how to make cloth and cordage of woolen, silken, hempen, and cotton fibers (and in Egypt of papyrus), came a still better material for ropes and sails, since cloth was so much lighter that a far greater extent of it could be spread than before; its flexibility enabled it to be handled, changed, and rolled up snugly, and its cheapness encouraged its use and the practice of navigation generally. We read of silken sails on the royal barges of medieval times, but they could hardly have exceeded in strength or elegance those of the fine Phenician ships that carried the commerce of the world twenty-five centuries ago. “Fine linen with broidered work from Egypt was that which thou spreadest forth to be thy sail,” exclaims the sacred chronicler (Ezekiel xxvii. 7). Hempen cloth, indeed, was preferred for sails until the present century, as is expressed in our word canvas, which is derived from the Latin name of flax; but now cotton has mainly superseded it.

Anciently the sails were often colored, purple or vermilion being the badge of a monarch or an admiral. Black denoted mourning. “In some cases the topsail seems to have been colored, while the sail below was plain; and frequently a patchwork of colors was produced by using different stuffs.” Various inscriptions and devices were also woven or painted on the sails, sometimes in gold. The Venetians and Greeks do the same31 to this day, adding a gaudy feature to the lovely Levantine sea-scenery; and the sails of the North Sea fishermen are turned to a rich red and yellow by the tanning mixture in which they soak their canvas.

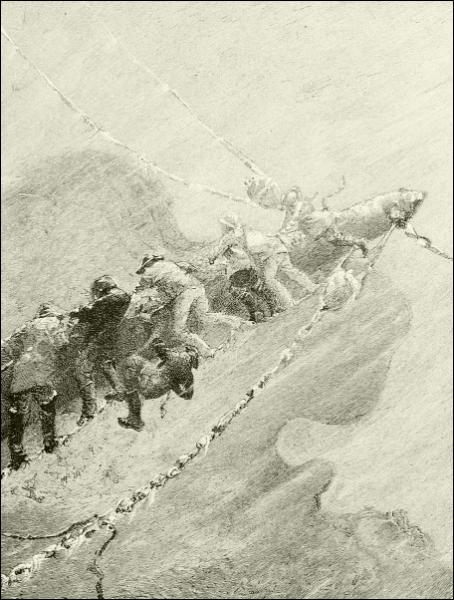

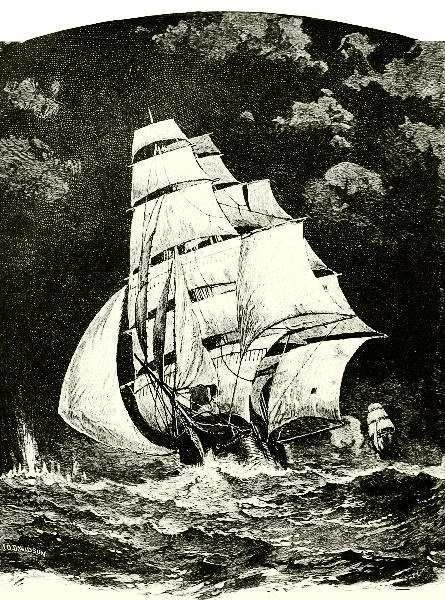

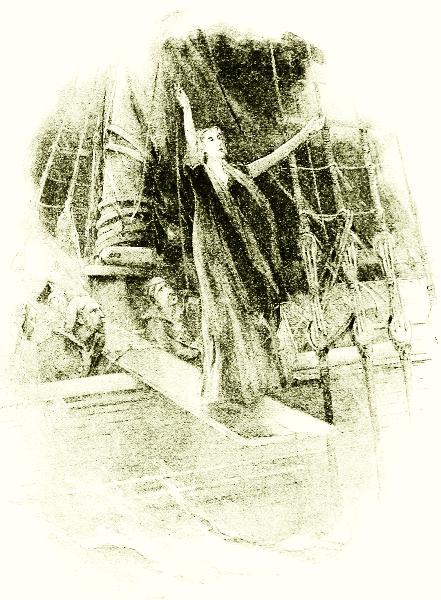

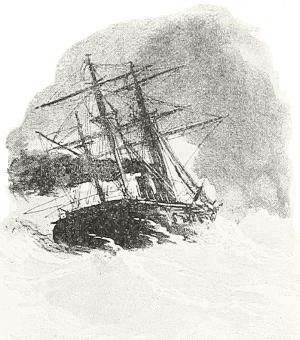

REEFING A TOPSAIL IN A STORM.

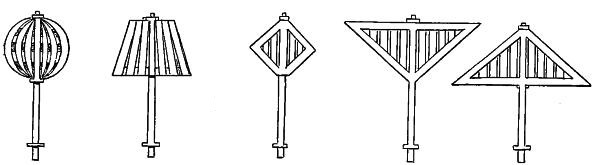

As for the shape, all rigs seem reducible to two types—the lateen and the square. The former is characteristic of the eastern half of the world,32 the latter of the western half, including primitive America, where, so far as I know, only plain, rectangular sails were ever made by the Indians.

A HONG-KONG “PULL-AWAY” BOAT.

Showing method of hoisting and reefing matting sails.

There must be some good reason for a broad division like this, and it is found in the different conditions which eastern and western seamen had to meet. The lateen seems to have originated in the Indian Ocean, is seen wherever Arabs are, and has been taken eastward by the Malays as far into the South Sea Islands as their influence extended. It is a huge, triangular canvas extended at a steep angle by a long, flexible yard balanced across the mast to which it is loosely hung, and controlled by a sheet attached to the free corner. It is thus very lofty, and therefore suitable to a region of steady and usually light winds. This is the characteristic rig of the Arab dhow—a model that has come down from remote antiquity and is capable of excellent service on the northern and eastern coasts of Africa, where it prevails. It was probably in a small vessel of this kind that the Apostle Paul suffered shipwreck; and an outgrowth and perfection of it is the dahabiyeh of the Nile, now become famous as a tourists’ pleasure-boat, whose immensely lofty sail is precisely adapted to catch every faint breath that comes across the river from the deserts. Such sails are spread like the great pointed wings of an albatross over the narrow decks of the Malayan “flying proas” and other swift South Sea craft, and urge upon their fleet errands the xebecs, saics, feluccas, and other light craft of the Levant and Barbary coasts, identified with former piracy and modern smuggling, as well as with fishing and freighting. Some of these boats have two or three masts, the xebec and felucca being notable because of the curious forward rake of the foremast; and in that extremely picturesque Portuguese fishing-boat called the muleta there are, in addition to the big lateen, a huge free second sail ballooning out to leeward from the tip of the yard, and a host of little flying jibs forward, which somebody has well likened to a flock of birds hovering about the prow. Good examples of lateen-rigged boats may be seen in Louisiana, built and manned by the Greek, Maltese, and Sicilian fishermen.

The difficulty of handling in rough or squally weather this long yard and expansive canvas makes it unsuitable for such weather as prevails in33 the western Mediterranean or on the Atlantic; and to meet these stormy and frequently changing conditions, and obtain a rig with which they could beat to windward, the earliest rough-water seamen devised square sails. What the rig of the ancient far-voyaging Phenician ships was we have no means of knowing, but the indications are that they carried lug sails, which appear to be the simplest and earliest of the “square” forms; that is, sails suspended from short cross-yards, and controlled by ropes (sheets) attached to their lower corners. Such at least were the sails of the Roman and Greek merchant and war vessels of the classical era, and they persist to-day in the local fishing-smacks of the stormy Adriatic.

The true home of the square-sailed craft, however, was northern Europe, where the Norwegian, Dutch, and Norman coasters and fishermen of to-day probably represent fairly well the rigs of the bold viking boats of twelve or fifteen centuries ago.

Of the slow development of ship-building during the middle ages we have little information, but in the fourteenth century we begin to hear of a revival in the art, as, indeed, was needful when the long voyages were to be undertaken which the discovery of the mariner’s compass had then rendered possible. In this revival the Venetians and Genoese took the lead, but the English were not far behind. There was a large variety of vessels in that day, rude though they were, and called by names we should hardly recognize.

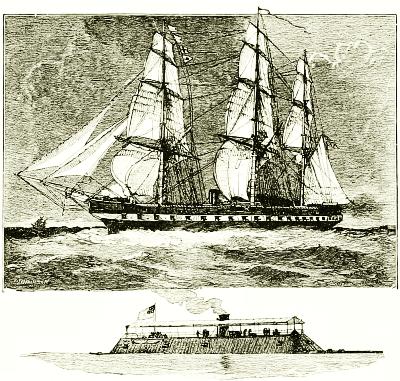

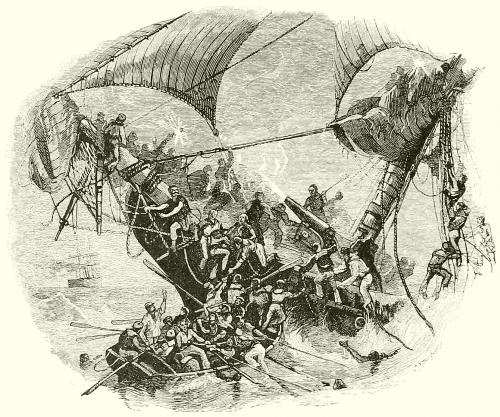

Though the hulls of these vessels were large and tight, their shape was poorly adapted for speed or for safety in bad weather. Their decks were built up into immensely high structures at the stern and bows, after the old galley model, and to form forts for soldiers. Our word “forecastle” reminds us of this old usage. Their masts were single sticks,—not divided into topmasts,—and hence, necessarily, were thick and heavy; and they bore upon their summits large “top-castles” where marines stood in battle to shoot down upon the enemy’s decks. This weight above, with the height of surface exposed to the wind and the clumsy rigging, made it impossible for them to sail safely except with a fair and gentle wind (they never attempted it otherwise), and they were required to carry an enormous quantity of ballast. There was so little room for anything except armament, sleeping-berths, and a cooking-room in the war-ships that every war fleet had to take with it small vessels carrying provisions; and the case was little better in respect to merchant vessels.

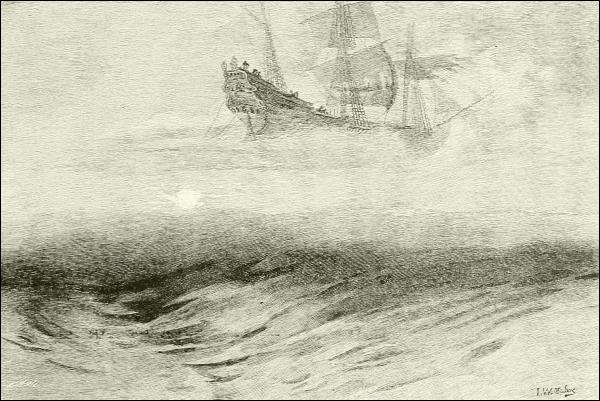

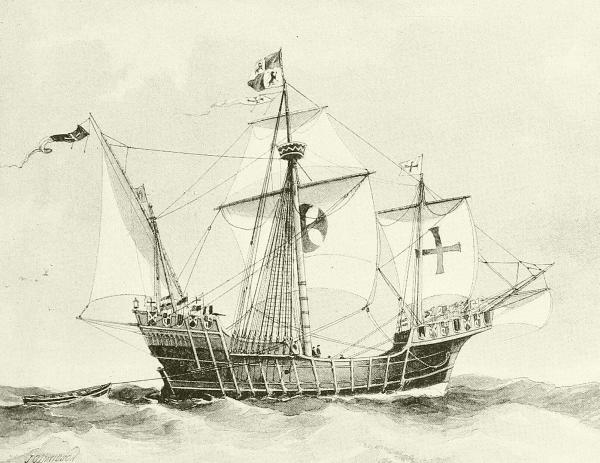

The ships in which Vasco da Gama, Columbus, the Cabots, and other explorers did their marvelous work were no better than this. Strangely inefficient they seem to us, and we wonder that some of the simplest contrivances in rigging were not adopted centuries before they came into use34 until we remember that it was not for long, speedy voyages that vessels were intended previous to the sixteenth century (with certain exceptions in northern seas), but simply as a means of carrying slowly from one coast-port to another a great number of men or huge cargoes.

However, as the known world widened and trade grew, inventions by private ship-owners continually improved the rigging, though it would be hard to find a class of men slower to change old ways for new than the seamen. Columbus’s “caravel” had four short masts, the forward one having a square lug-sail and the three after masts lateens. It was very gradually, indeed, that lateens were given up, and most curious combinations of sails were to be seen in this transition period of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The old-fashioned Mediterranean barca, for example, had as foremast the forward-raking “trinchetto” of the felucca, with a huge lateen, while the mainmast bore three square sails and the mizzen two lugs; and in addition to this two banks of oars were provided! In fact, it was not until 1800 that English frigates substituted a spanker for the lateen-rigged mizzen.

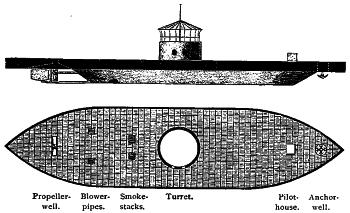

Another curiosity of rigging possessed by these solidly built, beautifully carved vessels (no such exterior decoration has been seen since as adorned the ships of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries) was the quaint little spritsail-topmast. By this time the single heavy pole-mast had been superseded by the three built-up masts and topmasts, braced by stays, made accessible by rope ladders (shrouds), and carrying several tiers of topsails instead of only one. A bowsprit had been added, also, and this became almost a fourth mast, so loaded were it and its stays with various small sails. Its outer end bore this miniature spritsail-mast, with topmast, shrouds, and tiny sails all complete, surmounted by a pole-head, or jack-staff, upon which was hoisted the flag since known as the jack, and always now carried at the prow of any national boat or ship, even such as the shapeless monitors.

But gradually, out of the experience of long voyages, the competition of merchants, and as an effect of improved gunnery and consequent changes in naval tactics, the lofty deck-structures, great tops, needless outworks, and odd sails, like this spritsail, were got rid of, and vessels were trimmed down and equalized until they became, as now, “ship-shape, Bristol-fashion.”

The rigging of modern sailing-vessels is divided into “standing” and “running”; the former includes the masts, their stays, now generally made of wire, and such other rope-work as is not adjustable.

The sails, also, may be assigned to two classes: first, those attached to a mast, with or without boom and gaff, or to a stay, which are called fore-and-aft sails because they may be ranged lengthwise of the ship; and, second, those suspended by their upper and lower edges to or between35 spars or “yards” swung across the mast, and known as “square” sails, the lowermost of which are really lugs. All the variations of shape seen in America, except the rare and local lateens, can be counted in one or the other of these classes.

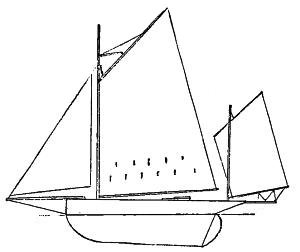

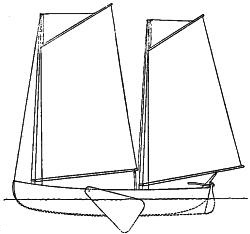

The styles of rig visible in American waters are not many, and are easily learned. Let us begin with the simplest—that having one mast.

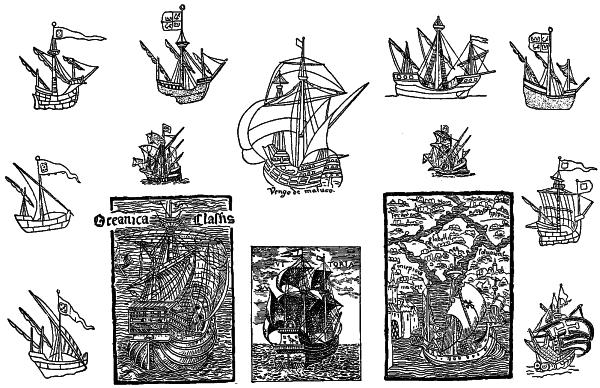

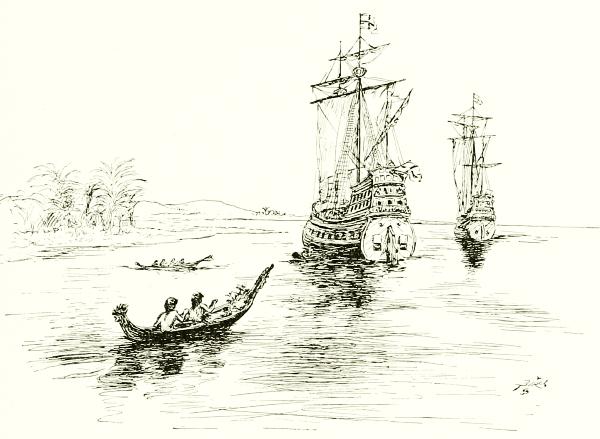

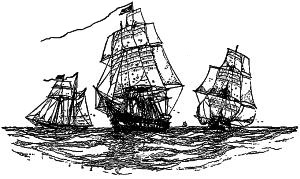

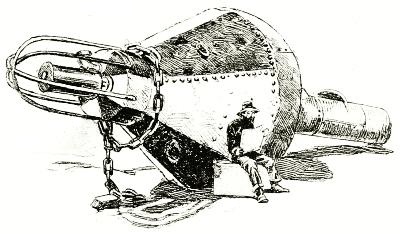

ANCIENT CARAVELS.

Copied from old manuscripts and tapestries.

The cat-boat (i. e., cat-rigged boat) is one having a simple pole-mast stepped very near the bow, and a fore-and-aft sail laced to a gaff and boom and managed by a sheet. This is the rig of the ordinary American sail-boat, which is noted for its ability in pointing up into the wind. In England it is known as a una-boat. Sometimes the peak of the sail is sustained by a little loose spar called a “sprit,” instead of a gaff. In the chapter on Yachting will be found further illustrations of these small rigs.

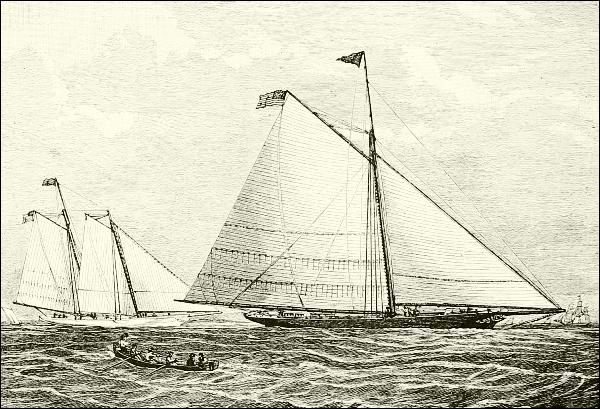

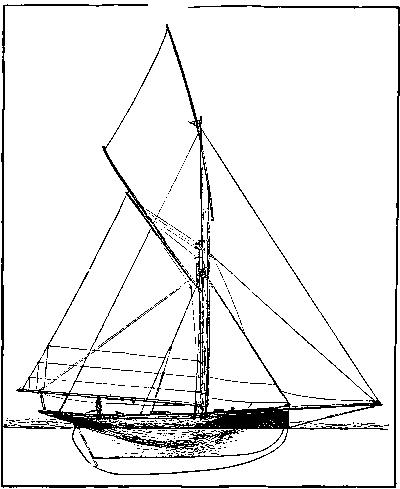

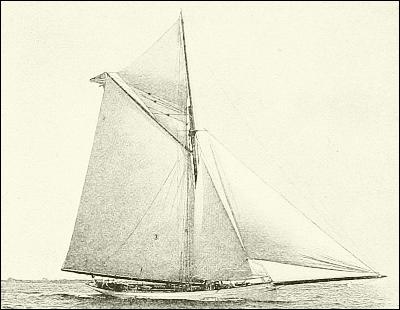

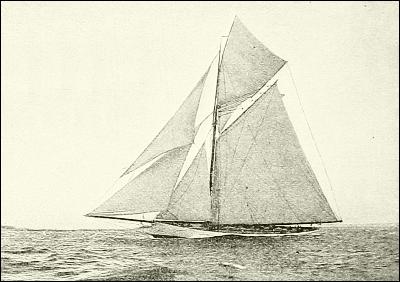

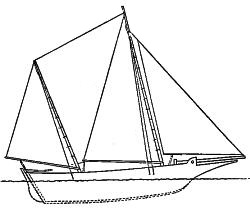

A sloop has one mast (with topmast) set well back from the stem, and a bowsprit. The sloop-rig consists of a fore-and-aft mainsail, spread by means of a boom and gaff, a gaff-topsail, a forestaysail, and one or more jibs. A cutter is now substantially the same thing, though formerly somewhat distinguished. Both are derived, probably, from the northern lugger, and old-time pictures show queer intermediate forms, often having a square topsail instead of a gaff. Thus the earlier of the Hudson River36 sloops, which were not only the freight-carriers but the packet-boats between New York and Albany from the time the Dutch introduced them until steamboats took their place, had the top of the mainsail supported, lug-fashion, by a short yard, and carried above that a square topsail; but this rig was steadily modified toward the modern type to make it faster and safer in the sudden squalls that beset this hill-girt river.

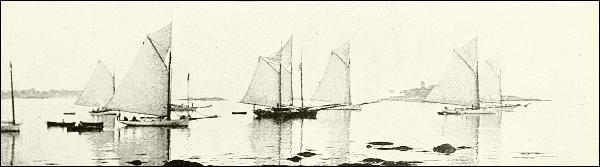

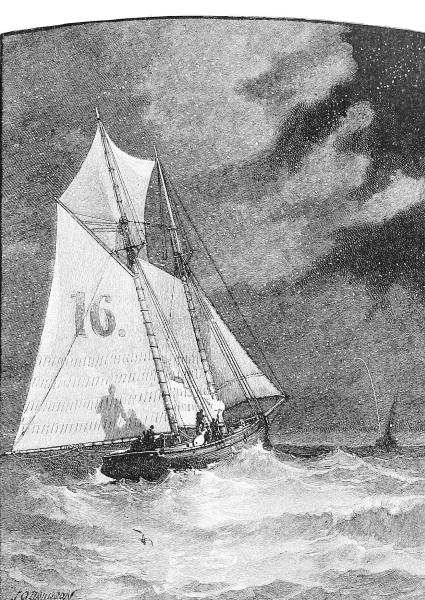

Of two-masted rigs, the oldest is the brig, which has square sails on both masts, just like the main and mizzen masts of a full-rigged ship. Then there is the brigantine, a slight modification of the brig, and the hermaphrodite brig, or brig-schooner, with fore-and-aft sails on the after mast. This kind of vessel has been greatly modified (one of its most extraordinary forms was the ketch), is less common now than formerly, and took its name, which is derived from the same source as “brigand,” from the fact that it was the most common rig of the pirates of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Its place was largely taken for small vessels by a purely American invention, and one of the greatest of Yankee notions—the schooner. The schooner was originally small, and had two masts; but now is often built of great size, with as many as five or six masts, each of which has a fore-and-aft rig—that is, a sloop’s mainsail and gaff-topsail on every mast, with forestaysail and several jibs in front, and staysails between. Sometimes a square sail is placed on the foretopmast, which makes the vessel a topsail schooner. The first one was built by a Gloucester sea-captain about 1817, and proved so satisfactory that all the fishing-fleet were soon rigged in that way, whence the idea has spread to all parts of the world.

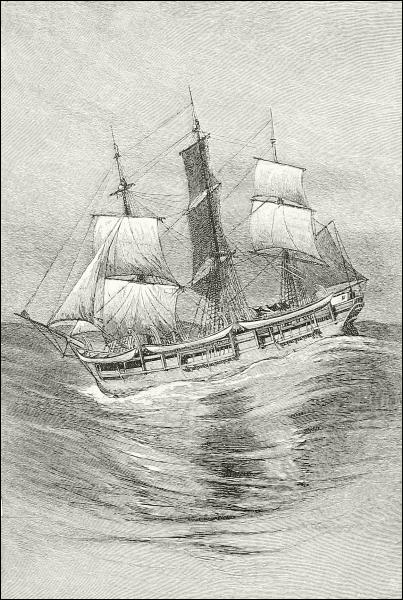

Until recently, however, vessels large enough to have three masts were always “square-rigged,” as barks, barkentines, or ships; for, although we have come to speak of any big vessel as a “ship,” yet in proper nautical language a ship is a vessel rigged in a particular way, and it is nothing else. In fact, in olden times they were sometimes very small—too small to be economical, as we now know. The “Naval Chronicle” for 1807 contained an account of a full-rigged ship of only thirty-six tons’ burden, which for one hundred and thirty years previous to that date had been cruising about the English coast, and may be doing so yet, for aught I know.

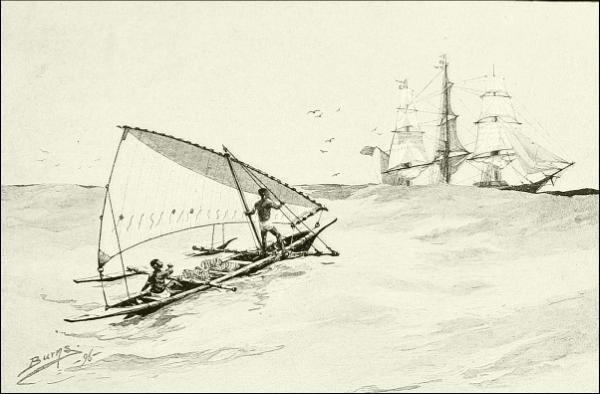

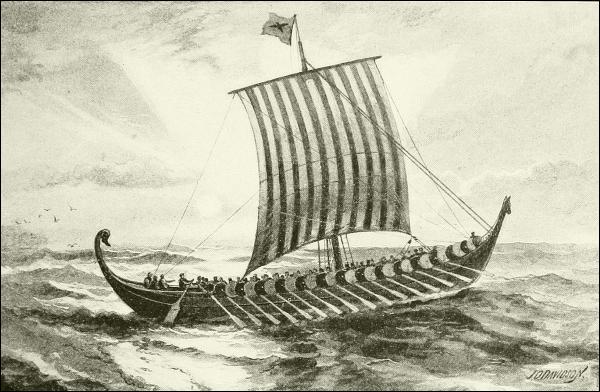

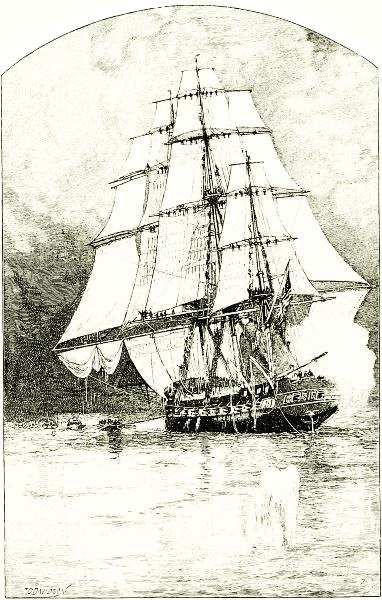

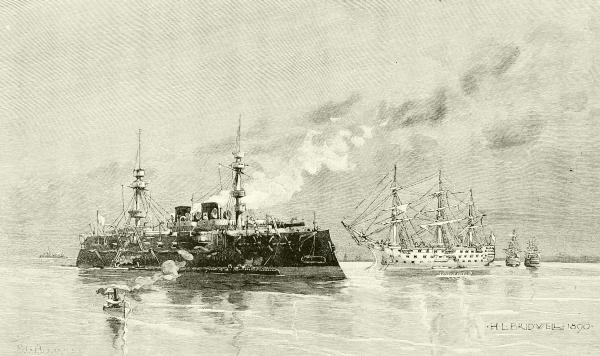

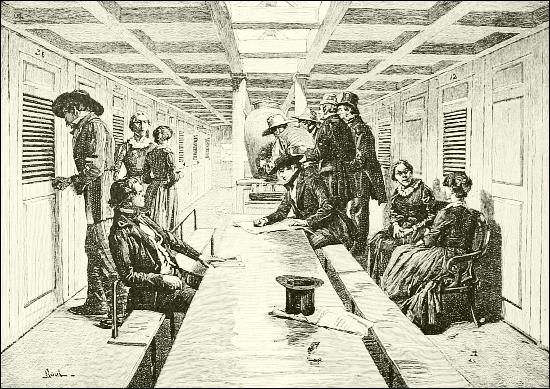

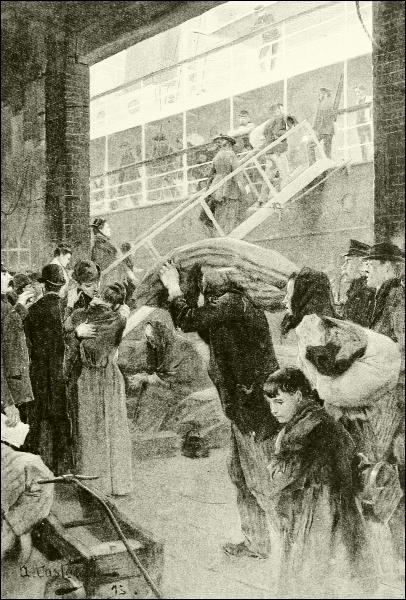

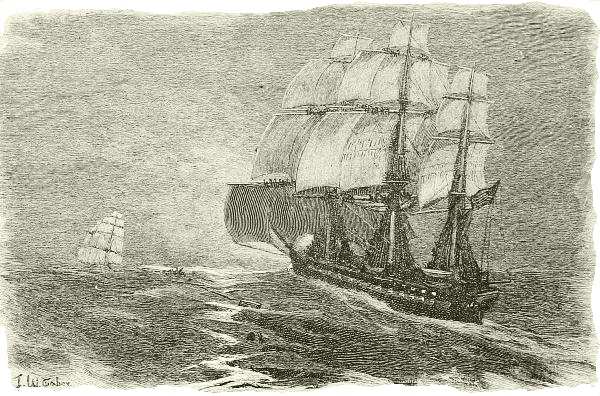

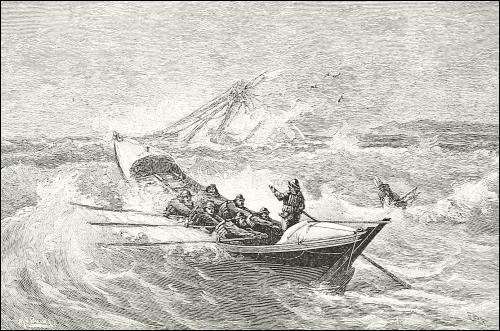

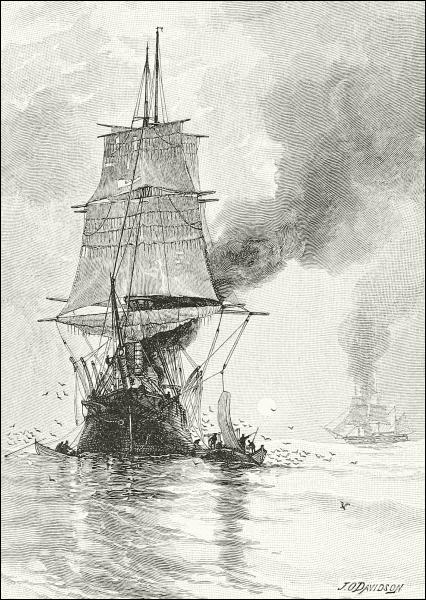

A FIJI ISLAND OUT-RIGGED CANOE, APPROACHING A FULL-RIGGED SHIP HOVE-TO.