Title: Sketches by Seymour — Complete

Author: Robert Seymour

Release date: July 13, 2004 [eBook #5650]

Most recently updated: December 29, 2020

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5650

Credits: Produced by David Widger

EBOOK EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION:

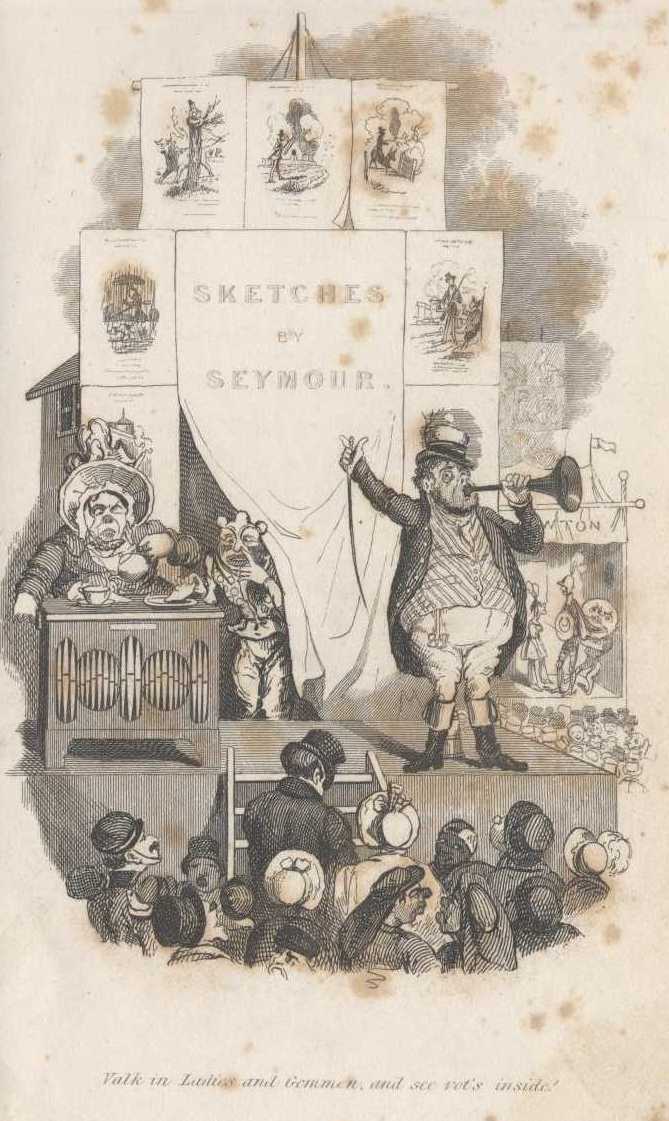

“Sketches by Seymour” was published in various versions about 1836. The copy used for this PG edition has no date and was published by Thomas Fry, London. Some of the 90 plates note only Seymour's name, many are inscribed “Engravings by H. Wallis from sketches by Seymour.” The printed book appears to be a compilation of five smaller volumes. From the confused chapter titles the reader may well suspect the printer mixed up the order of the chapters. The complete book in this digital edition is split into five smaller volumes—the individual volumes are of more manageable size than the 7mb complete version.

The importance of this collection is in the engravings. The text is often mundane, is full of conundrums and puns popular in the early 1800's—and is mercifully short. No author is given credit for the text though the section titled, “The Autobiography of Andrew Mullins” may give us at least his pen-name.

DW

SCENE I. Sleeping Fisherman.

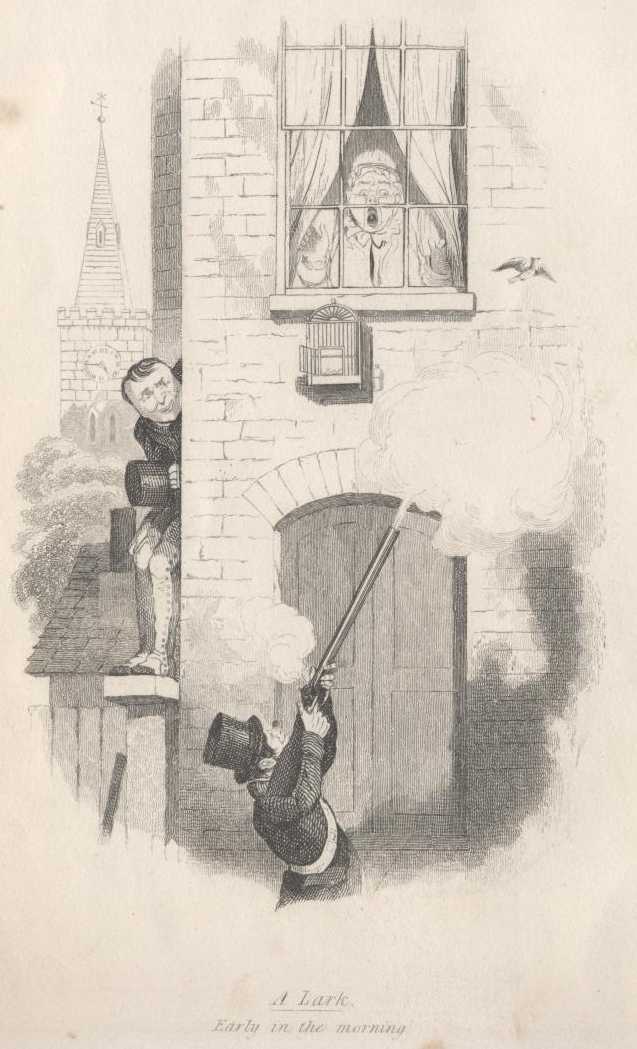

SCENE II. A lark—early in the morning.

SCENE III.

The rapid march of Intellect!

SCENE IV. Sally, I told my missus vot you said.

SCENE

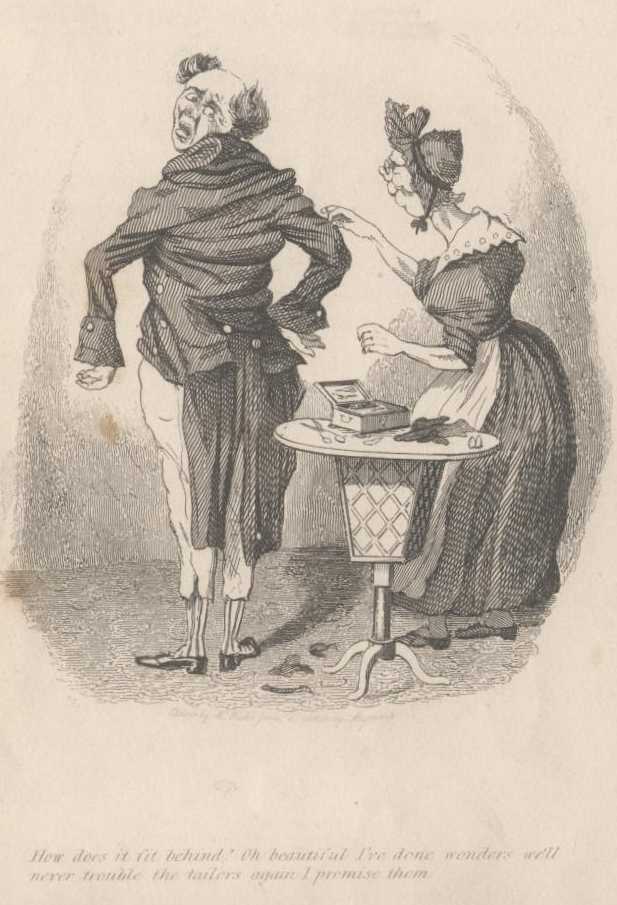

V. How does it fit behind?

SCENE VI. Catching-a cold.

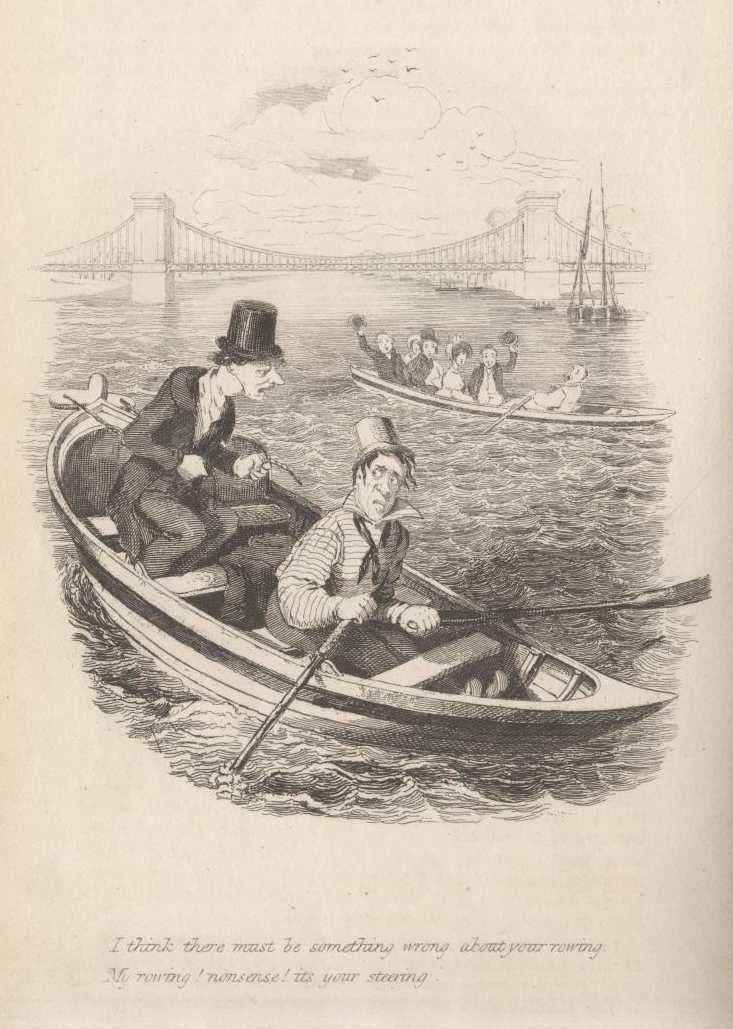

SCENE VII. This

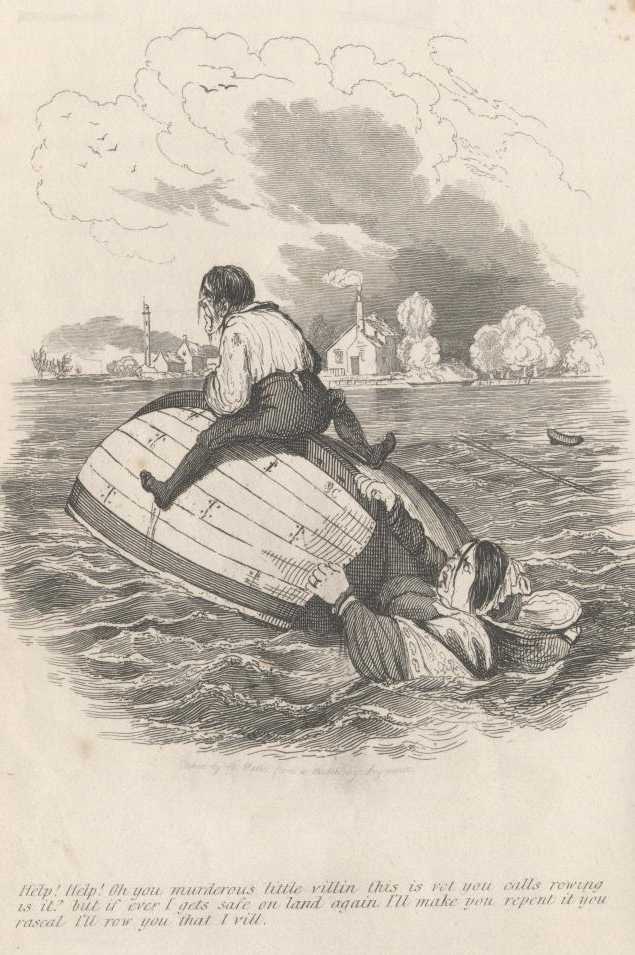

is vot you calls rowing, is it?

SCENE VIII.

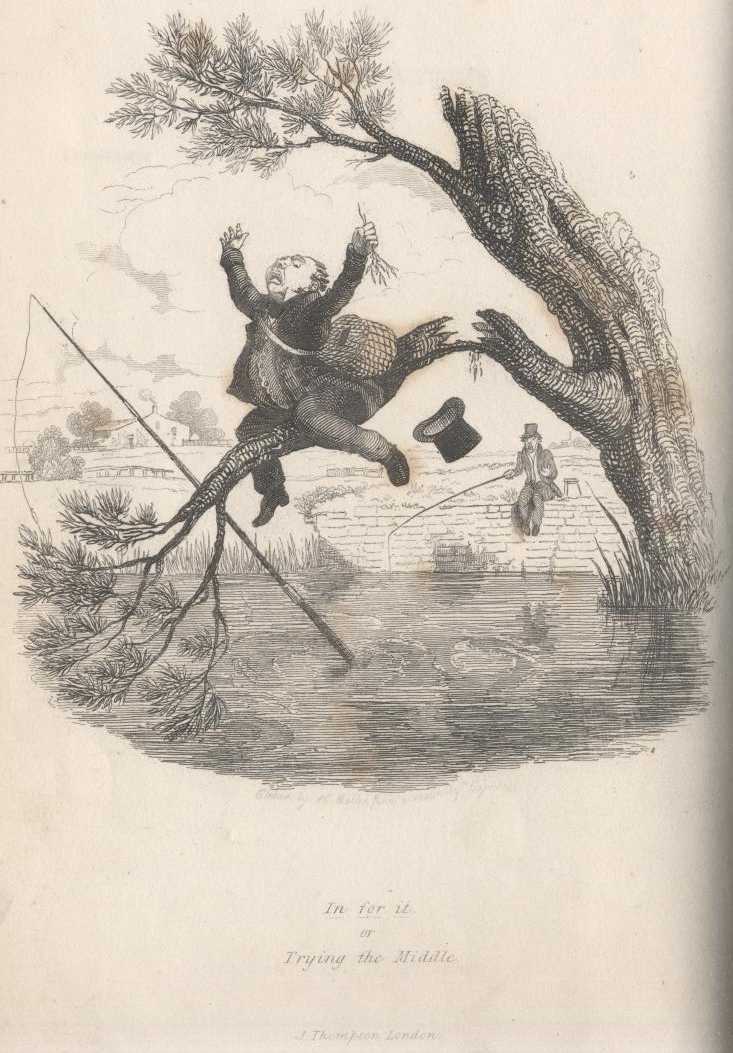

In for it, or Trying the middle.

CHAP. I. The Invitation, Outfit, and the sallying forth

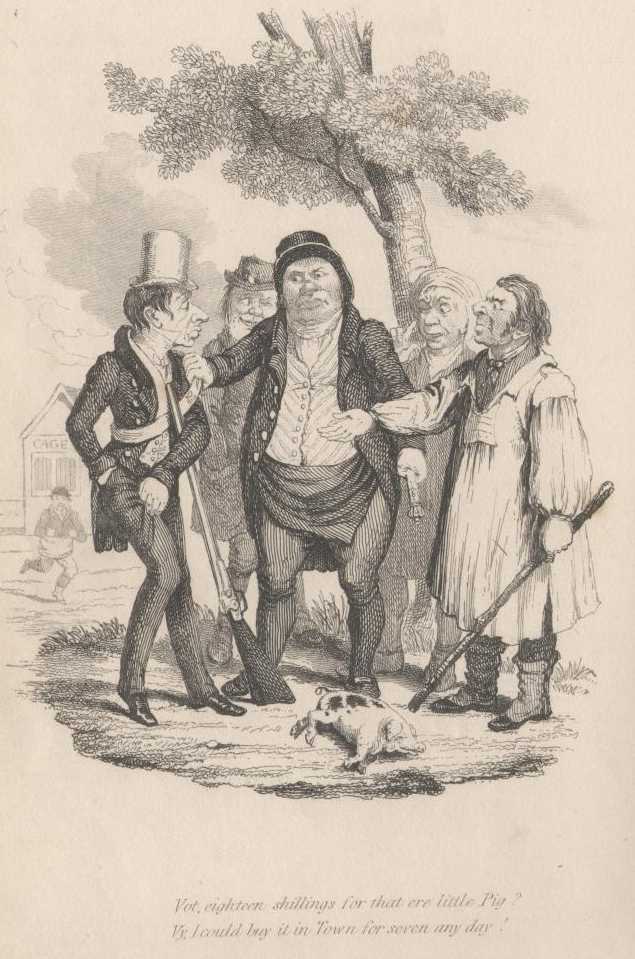

CHAP. II. The Death of a little Pig

CHAP.

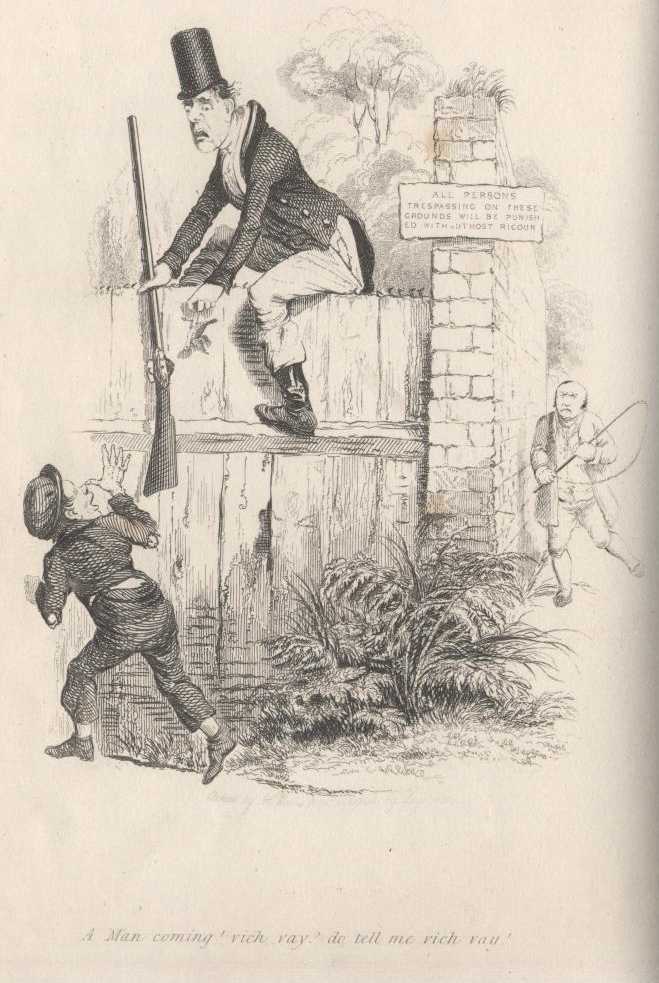

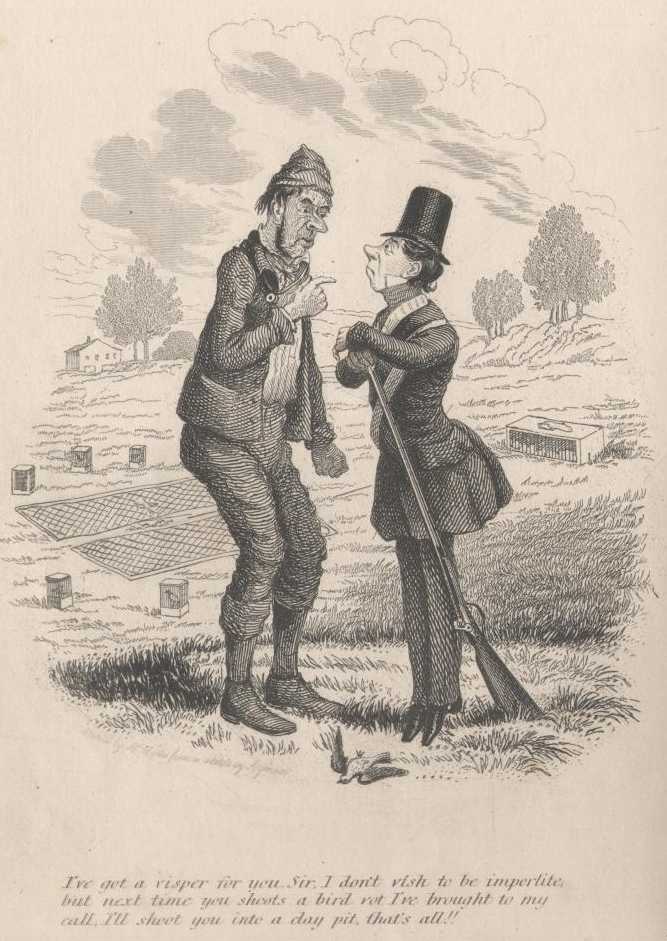

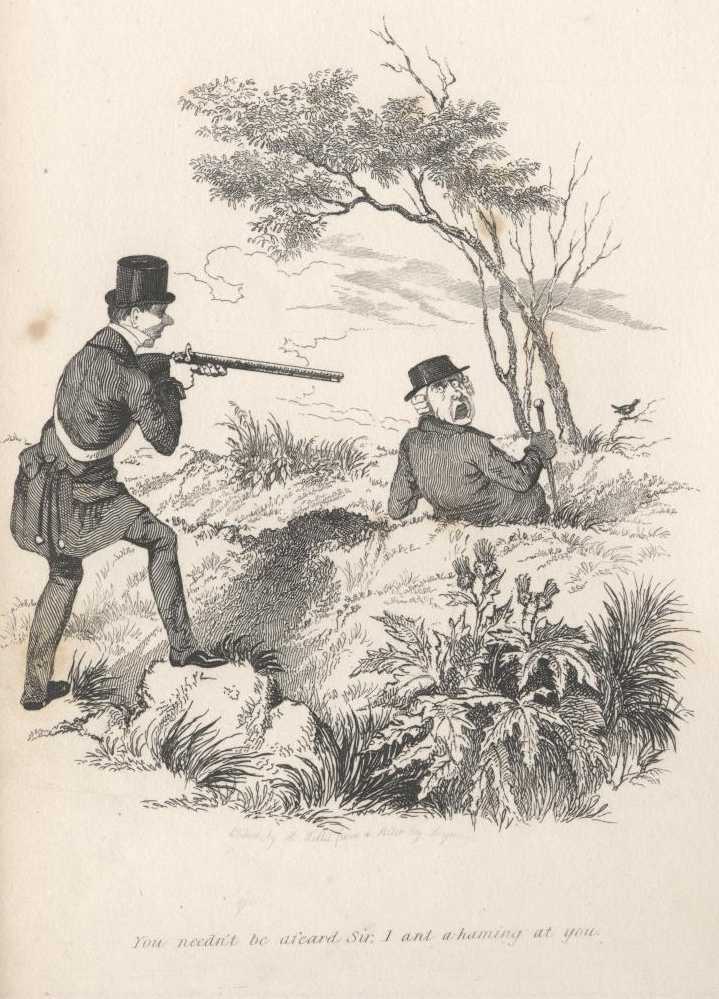

III. The Sportsmen trespass on an Enclosure

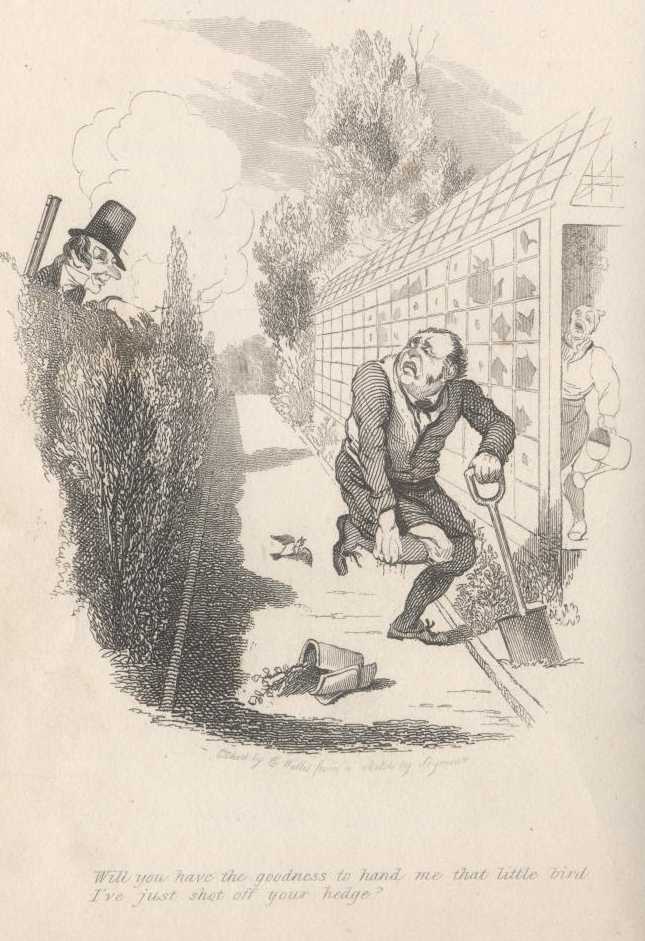

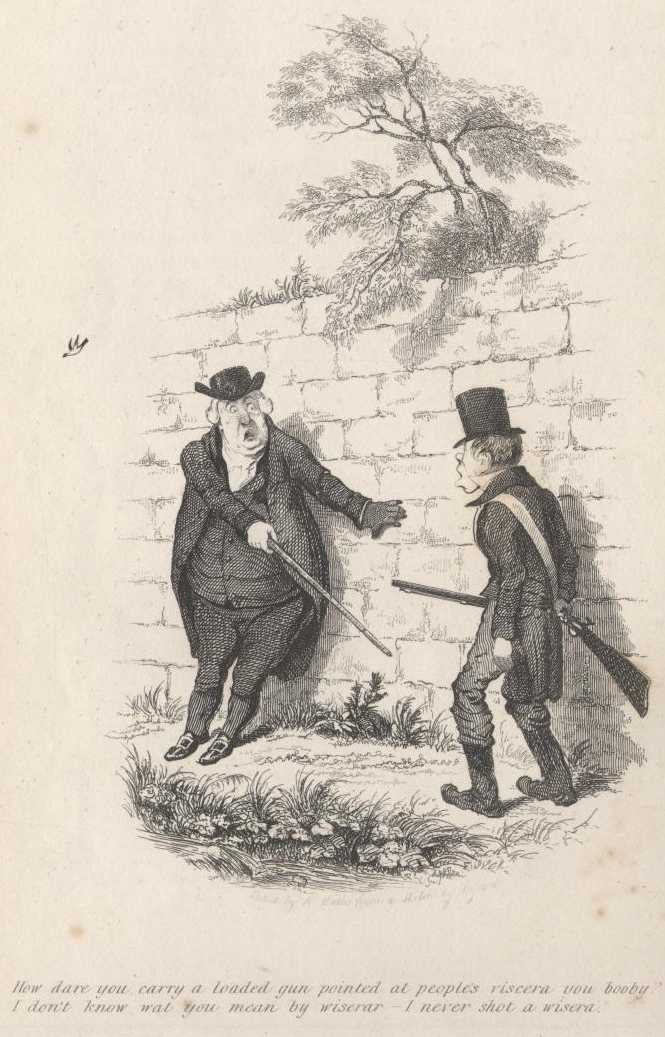

CHAP. IV. Shooting a Bird, and putting Shot into a Calf!

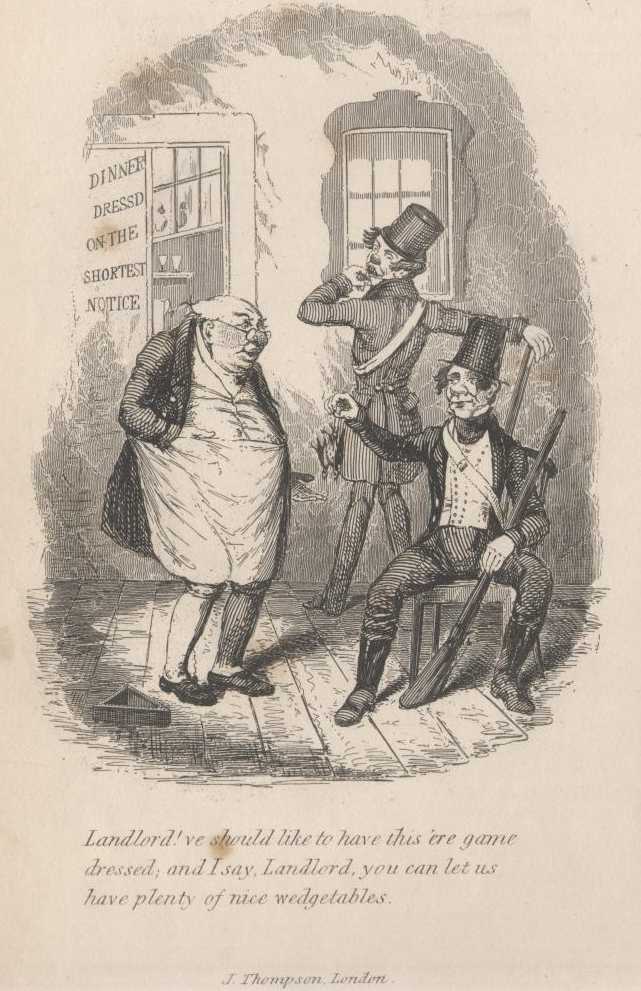

CHAP. V. A Publican taking Orders.

CHAP.

VI. The Reckoning.

CHAP. VII.

A sudden Explosion

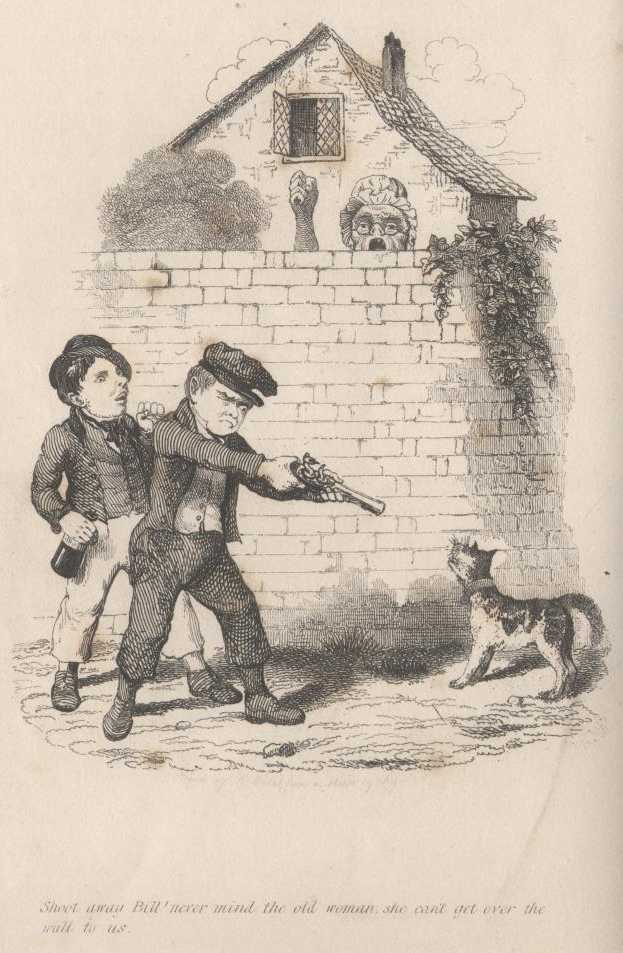

SCENE IX. Shoot away, Bill! never mind the old woman

SCENE X. I begin to think I may as well go back.

SCENE XI. Mother says fishes comes from hard roes

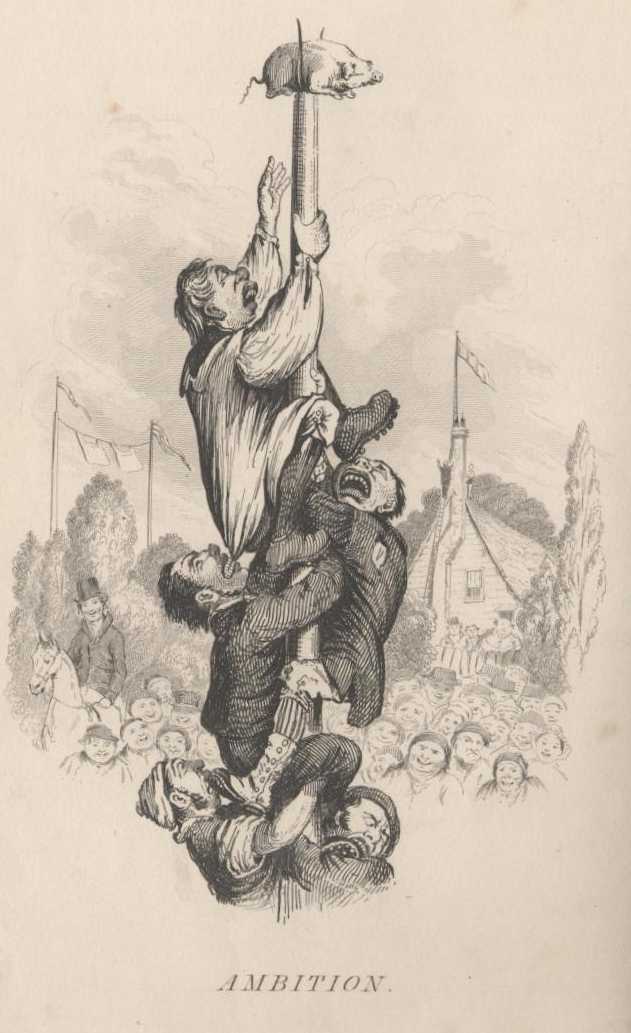

SCENE XII. Ambition.

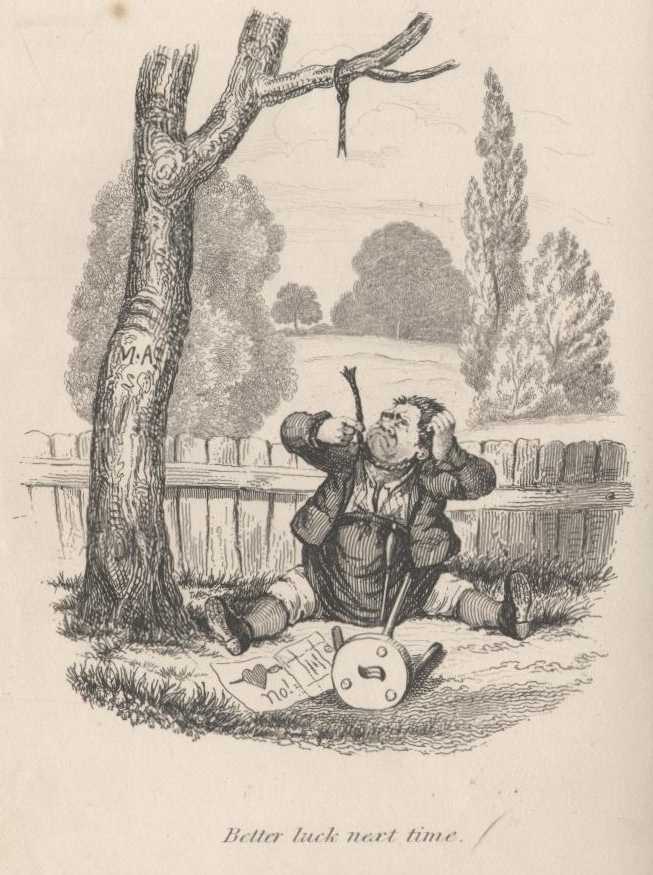

SCENE XIII. Better luck next time.

SCENE XIV. Don't you be saucy, Boys.

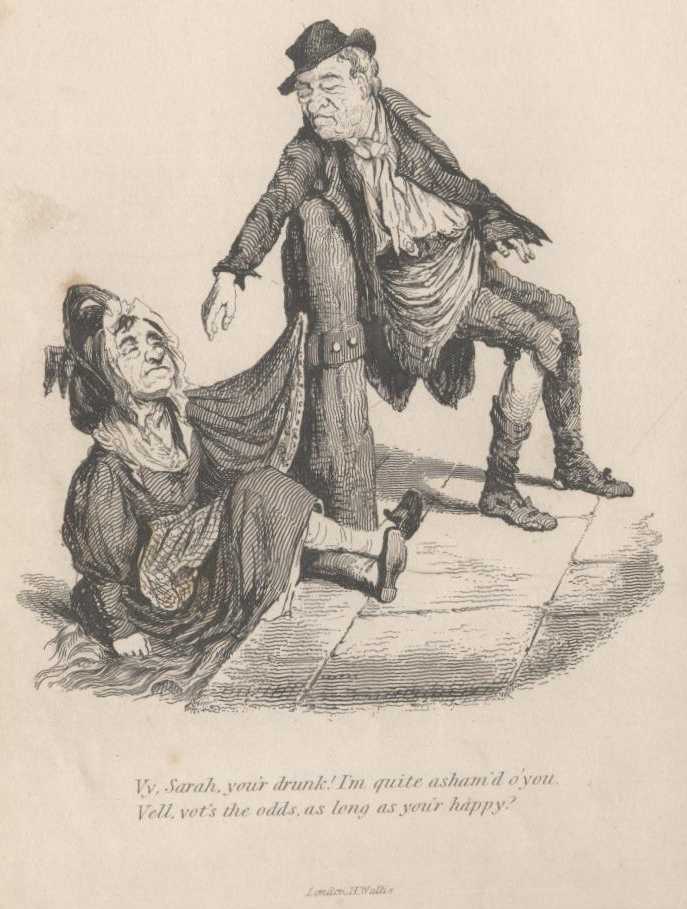

SCENE XV. Vy, Sarah, you're drunk!

SCENE XVI. Lawk a'-mercy! I'm going wrong!

SCENE XVII.

I'm dem'd if I can ever hit 'em.

SCENE

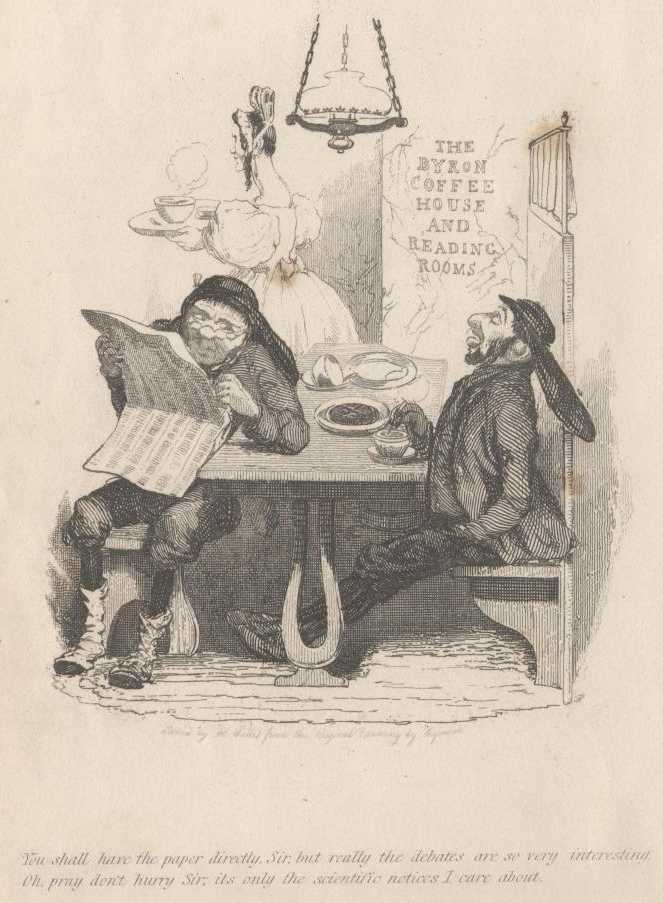

XVIII. Have you read the leader in this paper

SCENE XIX. An Epistle from Samuel Softly, Esq.

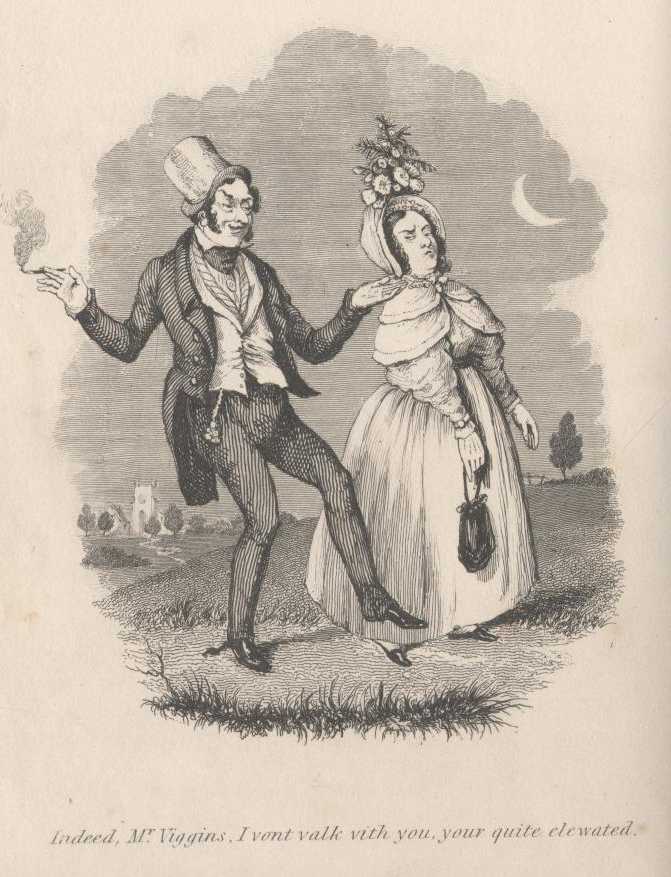

SCENE XX. The Courtship of Mr. Wiggins.

SCENE XXI. The Courtship of Mr. Wiggins.(Continued)

SCENE XXII. The Itinerant Musician.

SCENE

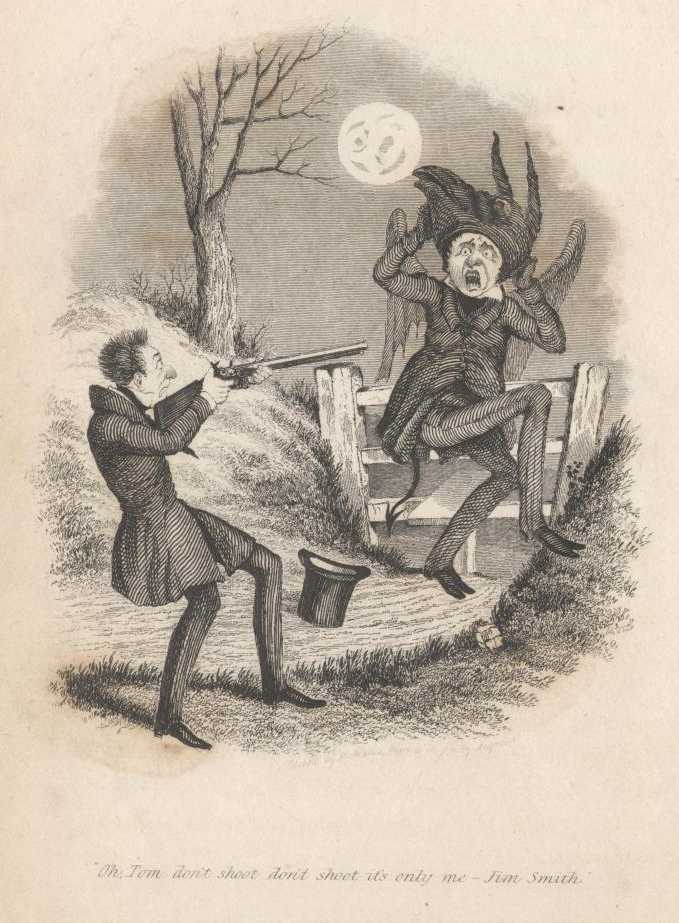

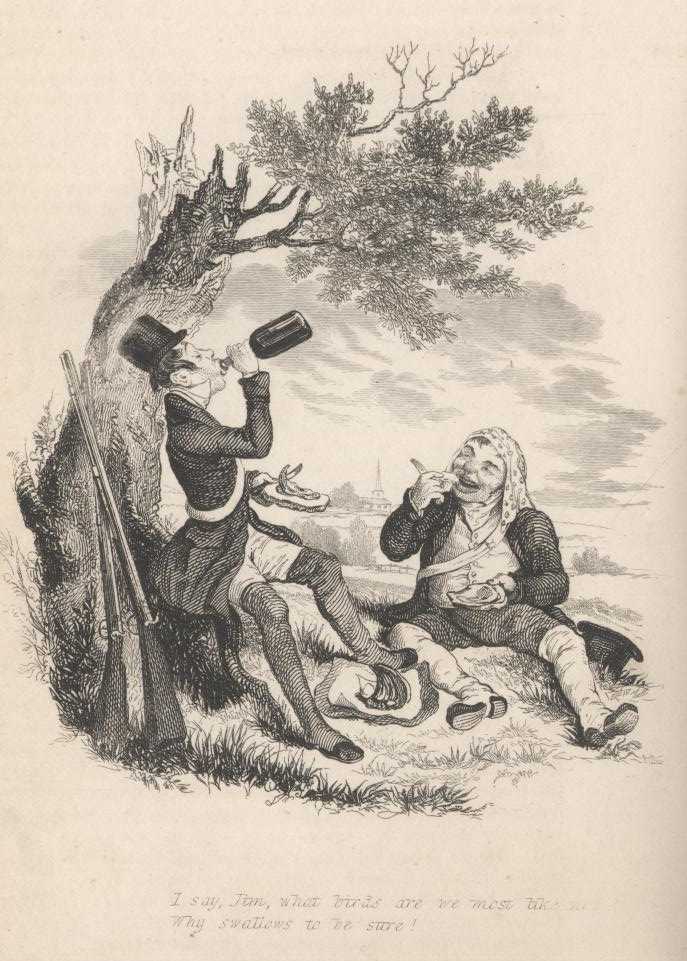

XXIII. The Confessions of a Sportsman.

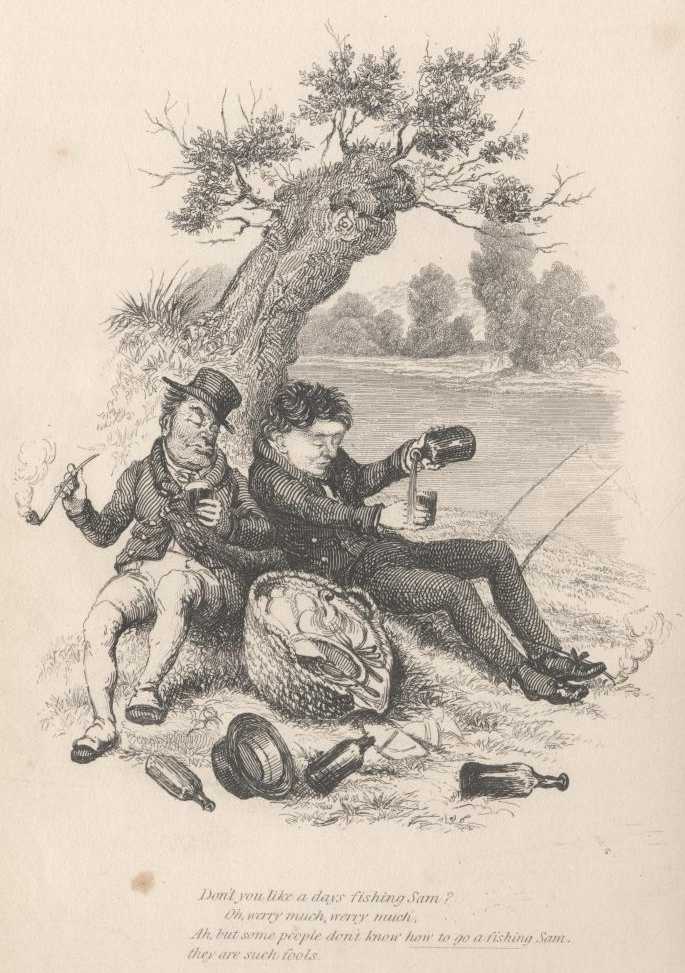

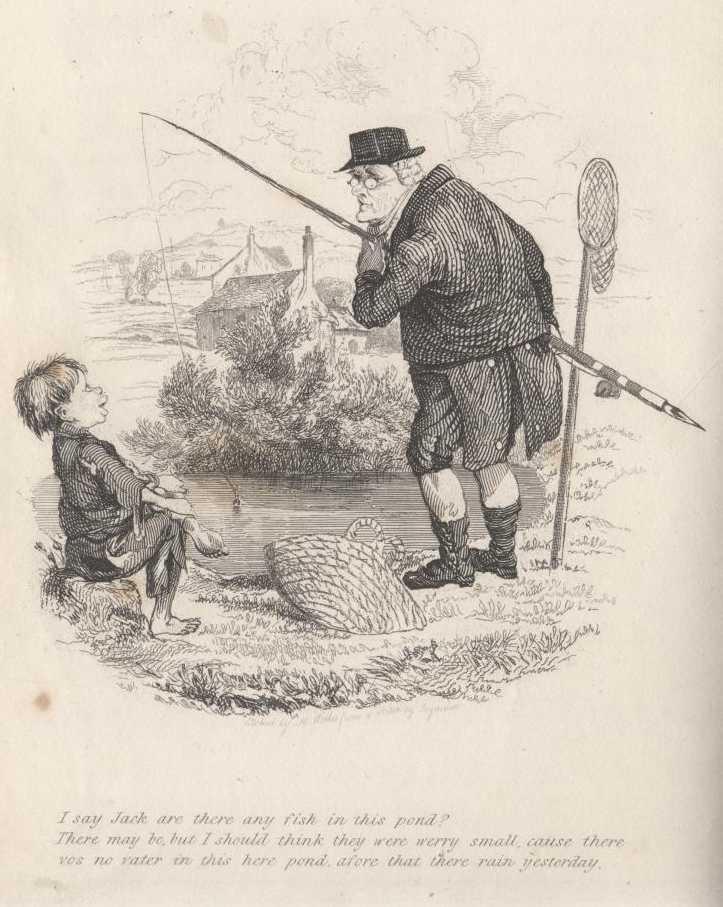

PLATE I. THE JOLLY ANGLERS.

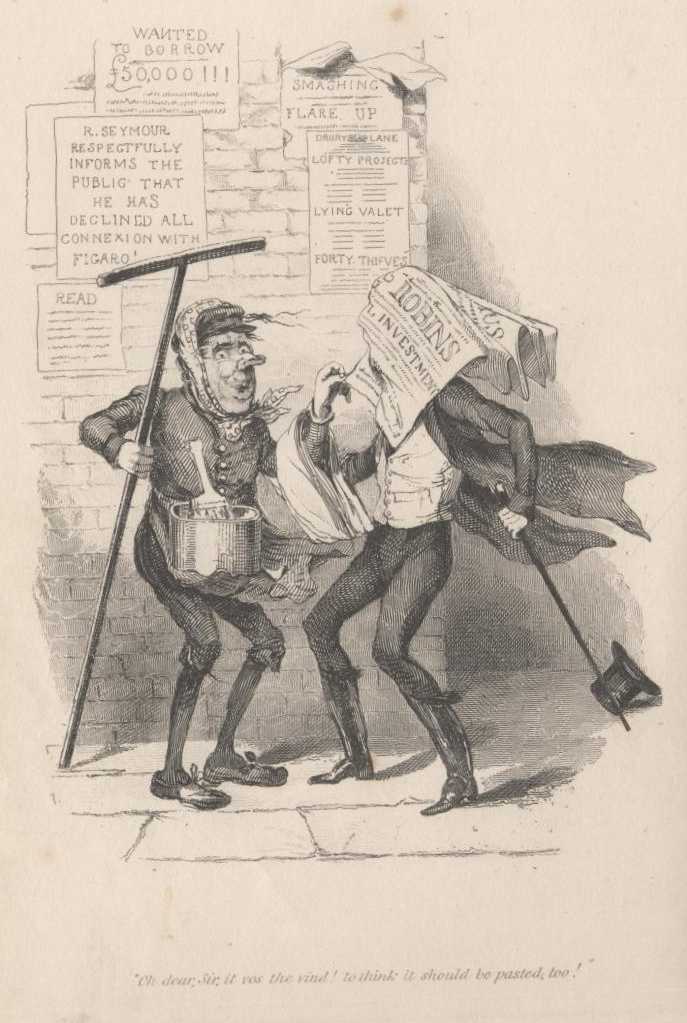

PLATE II. THE BILL-STICKER.

PLATE III. OLD FOOZLE.

PLATE IV.

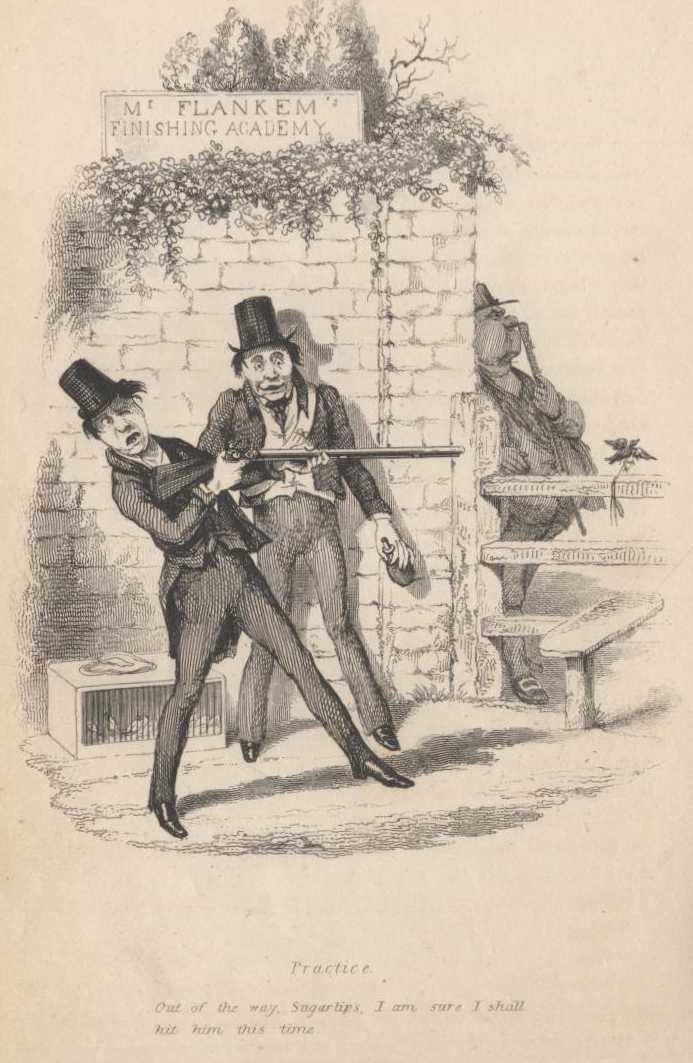

THE “CRACK-SHOTS.” No. I.

PLATE V. THE “CRACK-SHOTS.” No. II.

PLATE VI. THE “CRACK-SHOTS.” No. III.

PLATE VII. DOCTOR SPRAGGS.

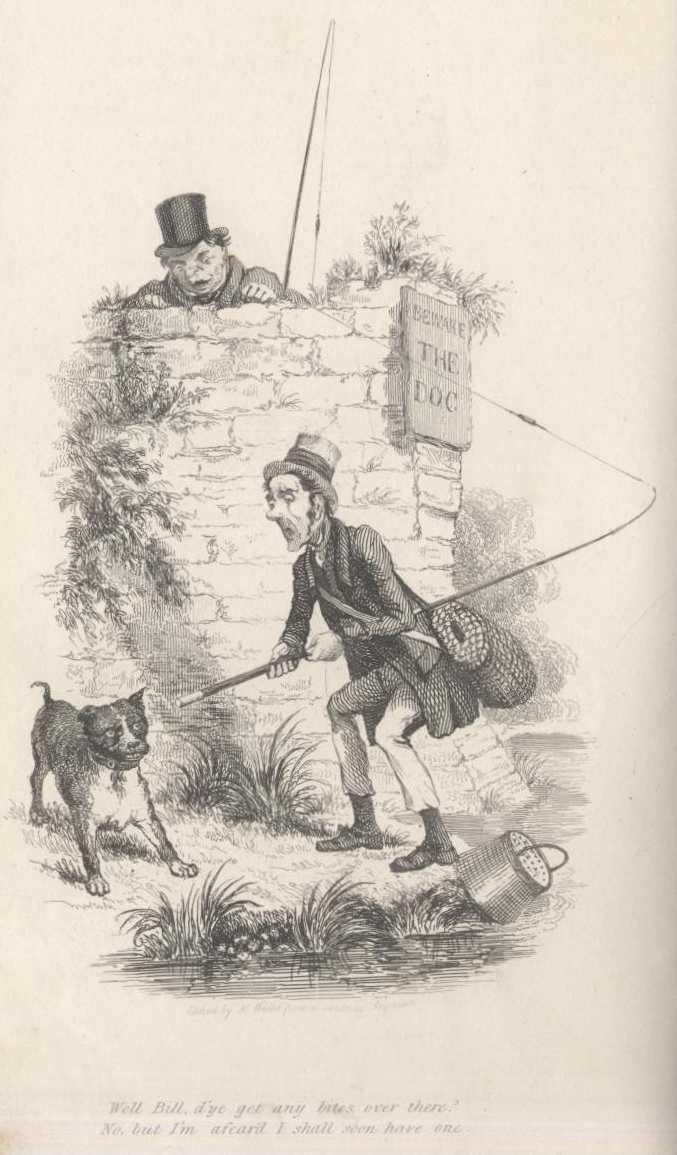

PLATE VIII. [SCENE IX.(b)] Well, Bill,

d'ye get any bites?

PLATE IX. THE

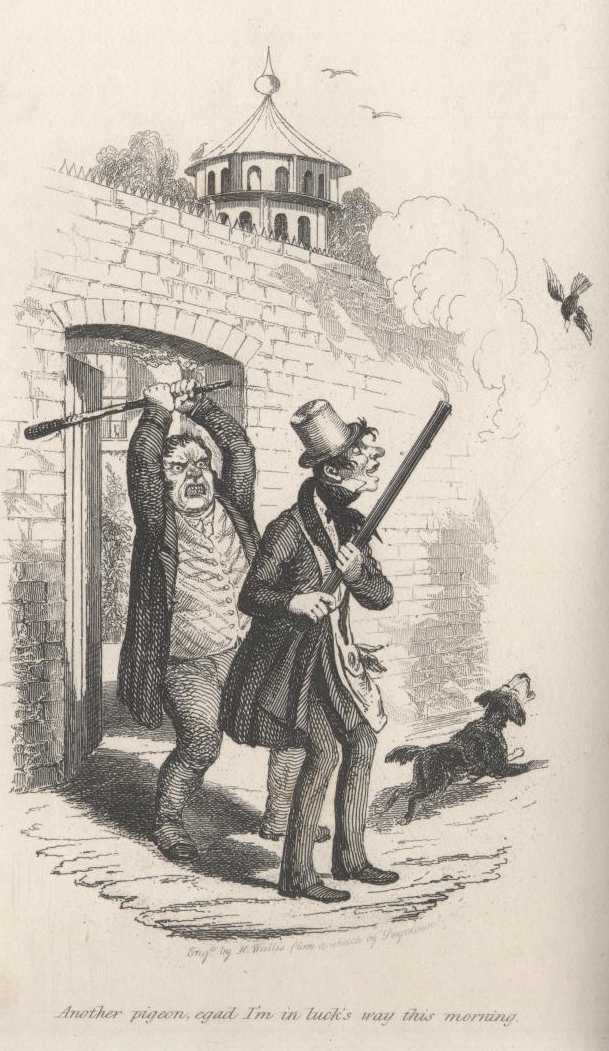

POUTER AND THE DRAGON.

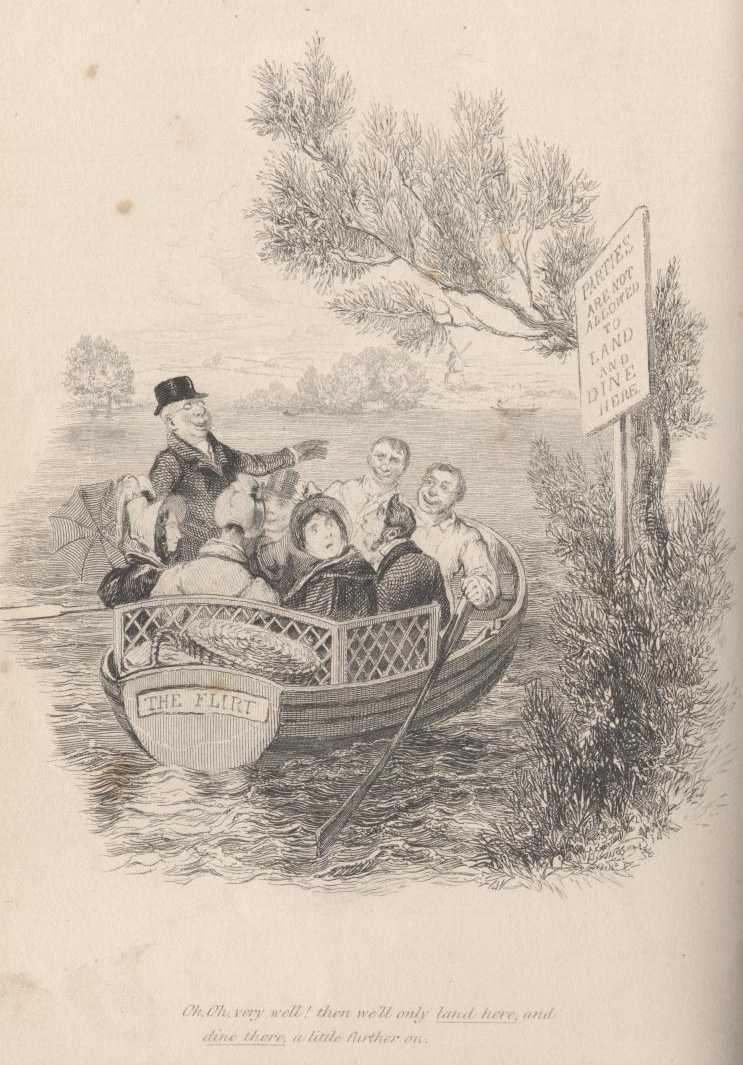

PLATE X. THE

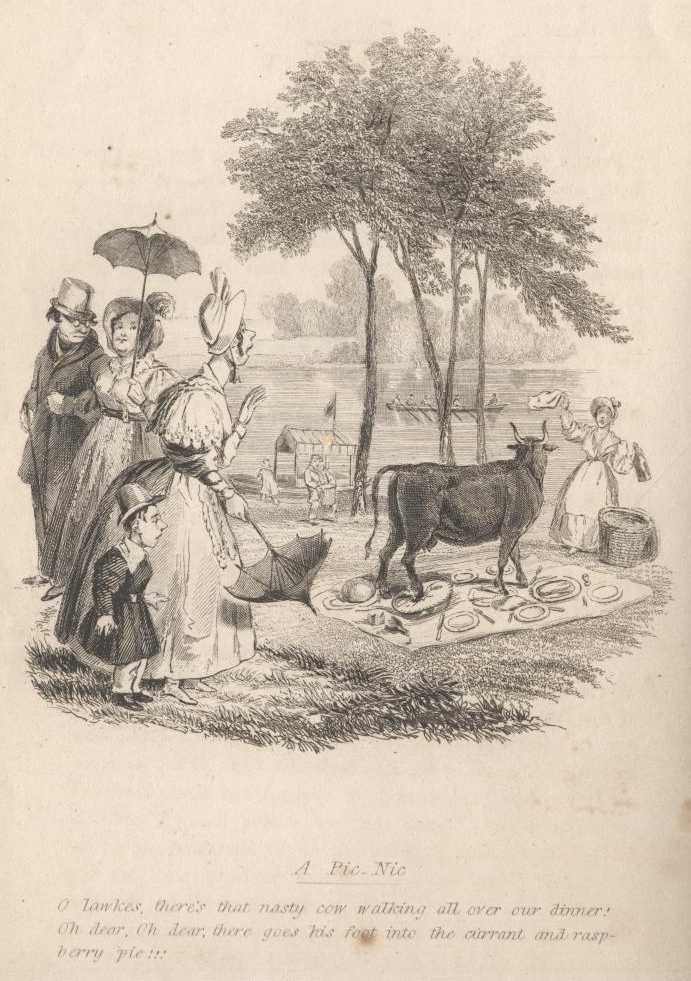

PIC-NIC. No. I.

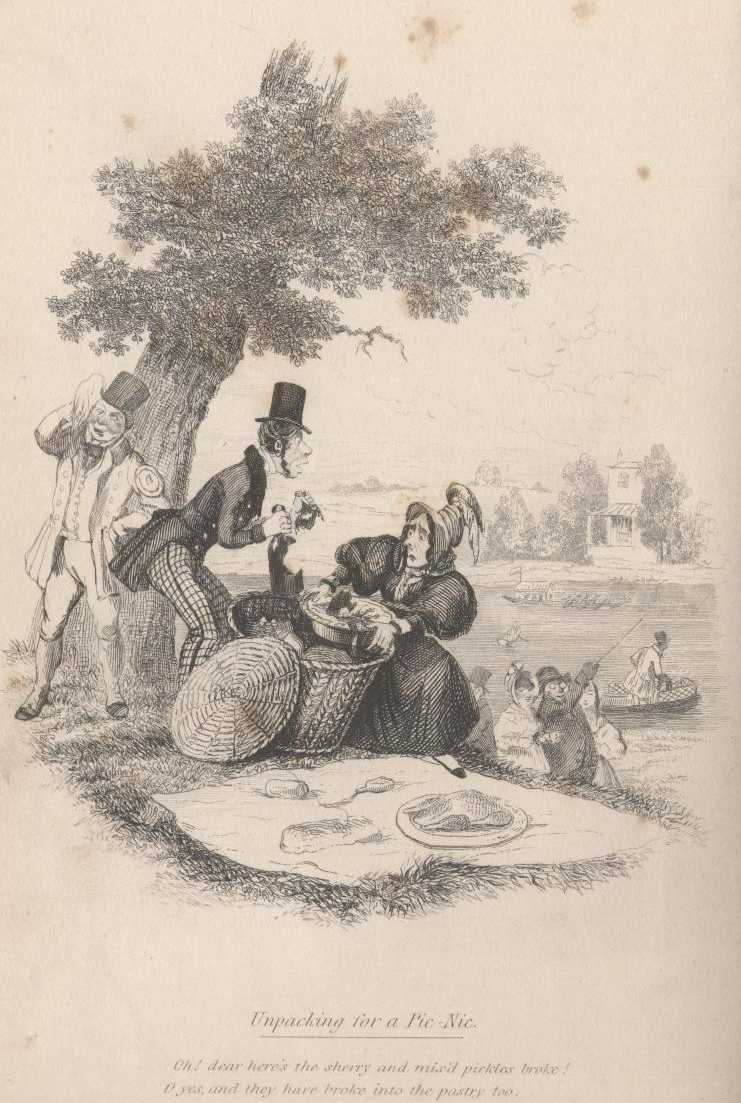

PLATE XI. THE

PIC-NIC. No. II.

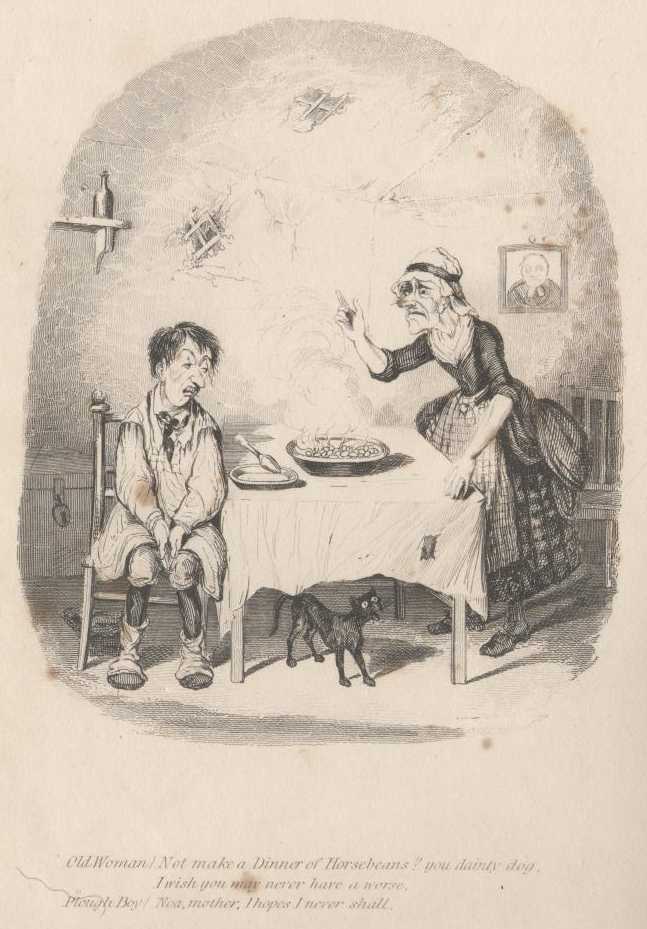

PLATE XII. THE

BUMPKIN.

TITLE PAGE II.

VOLUME II.

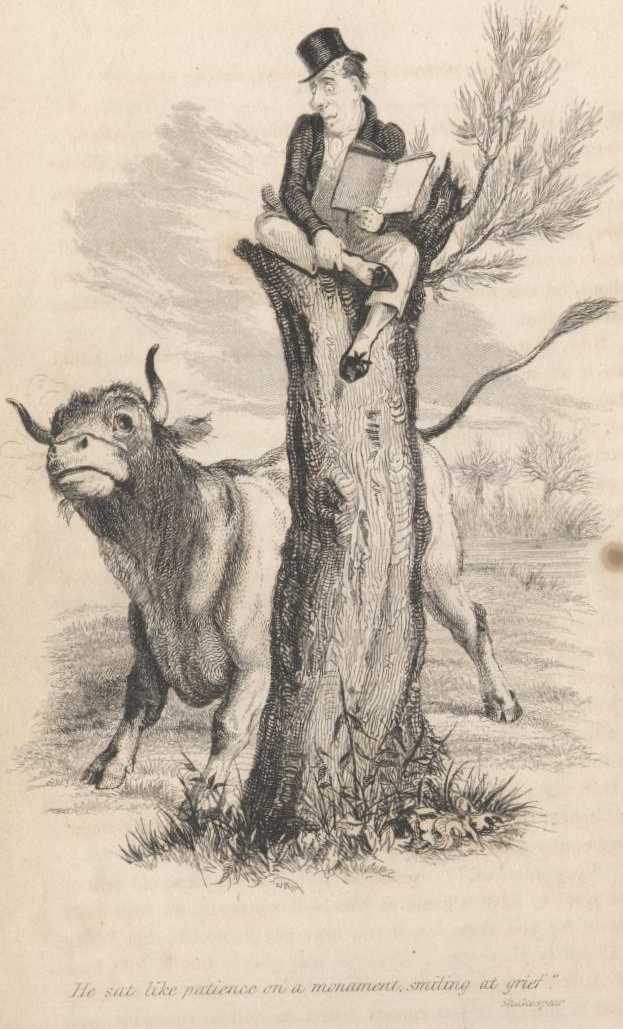

PLATE XIII. [WATTY WILLIAMS AND BULL]

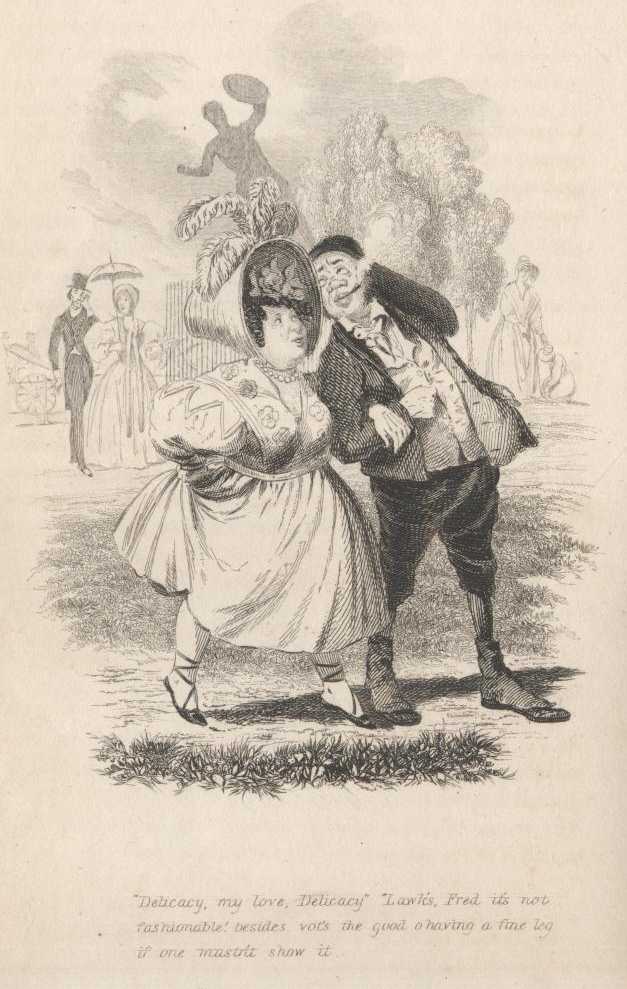

PLATE

XIV. DELICACY!

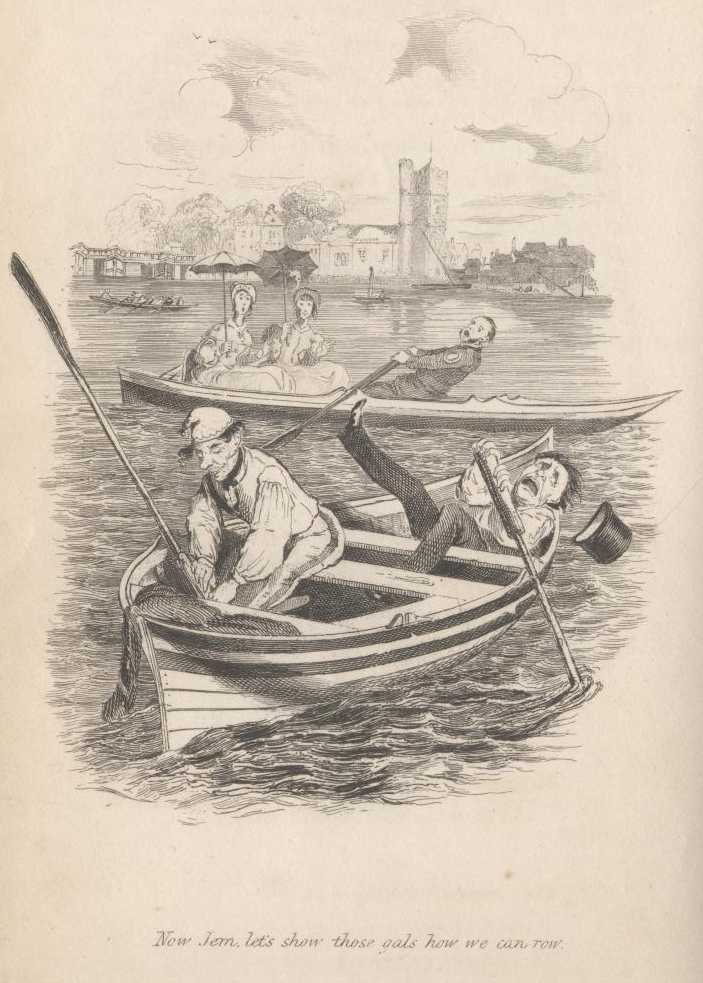

PLATE XV. Now, Jem, let's shew these gals how we can row

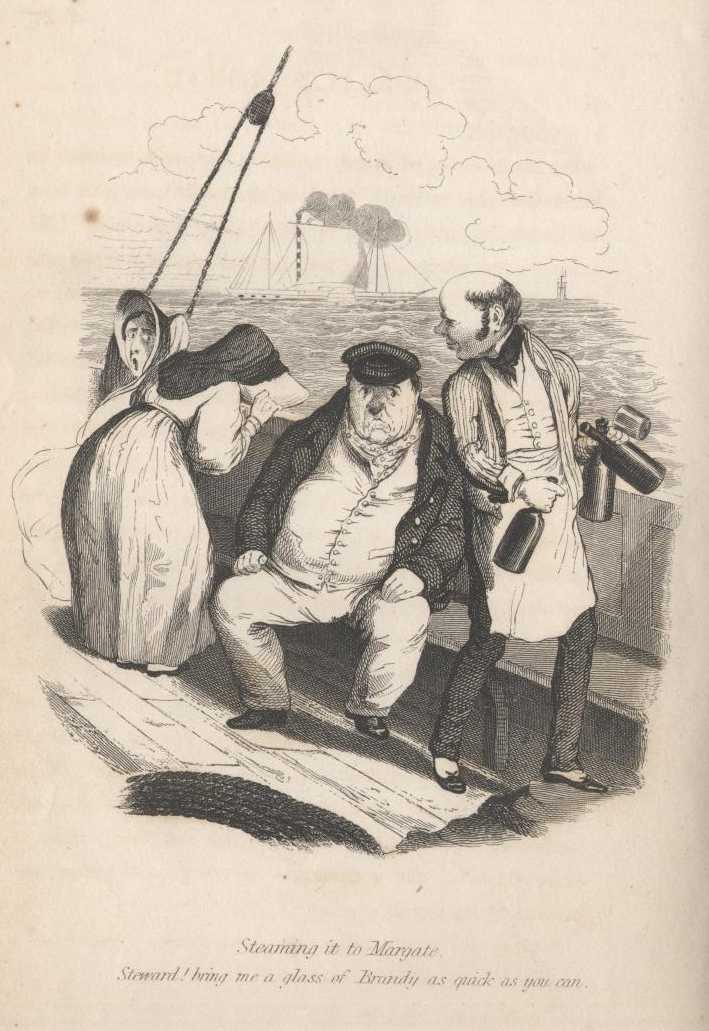

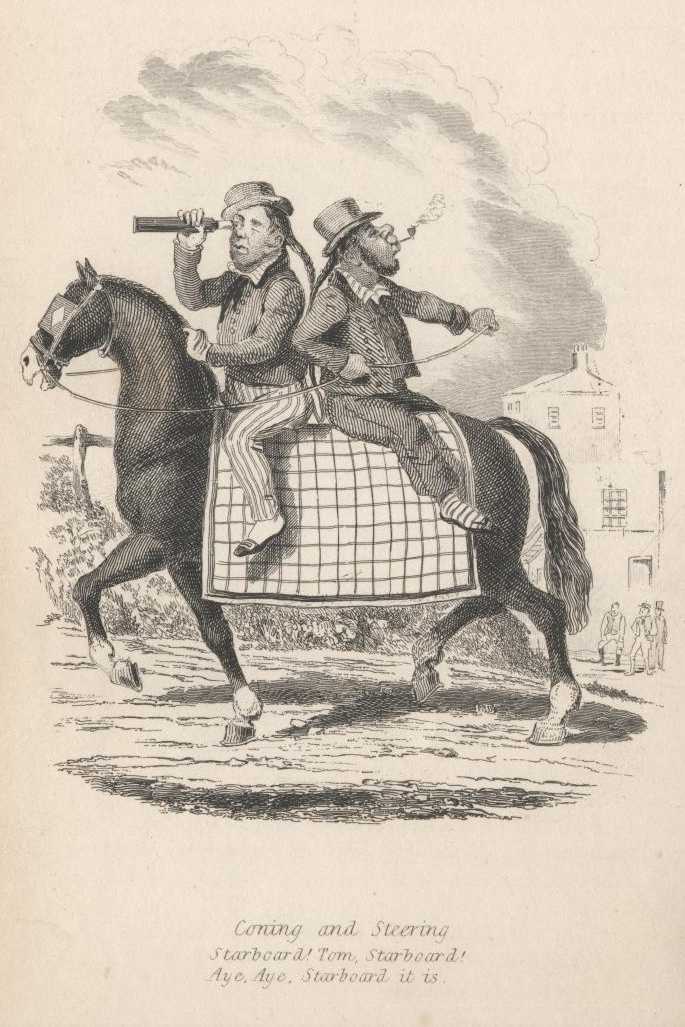

PLATE XVI. STEAMING IT TO MARGATE.

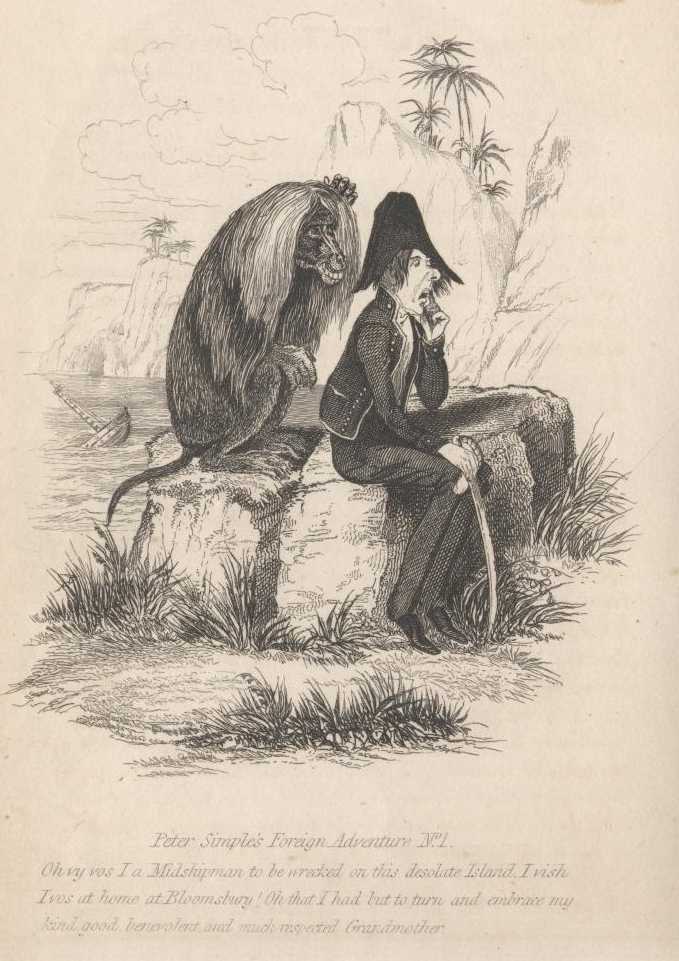

PLATE XVII. PETER SIMPLE'S FOREIGN ADVENTURE. No.

I.

PLATE XVIII. PETER SIMPLE'S

FOREIGN ADVENTURE. No. II.

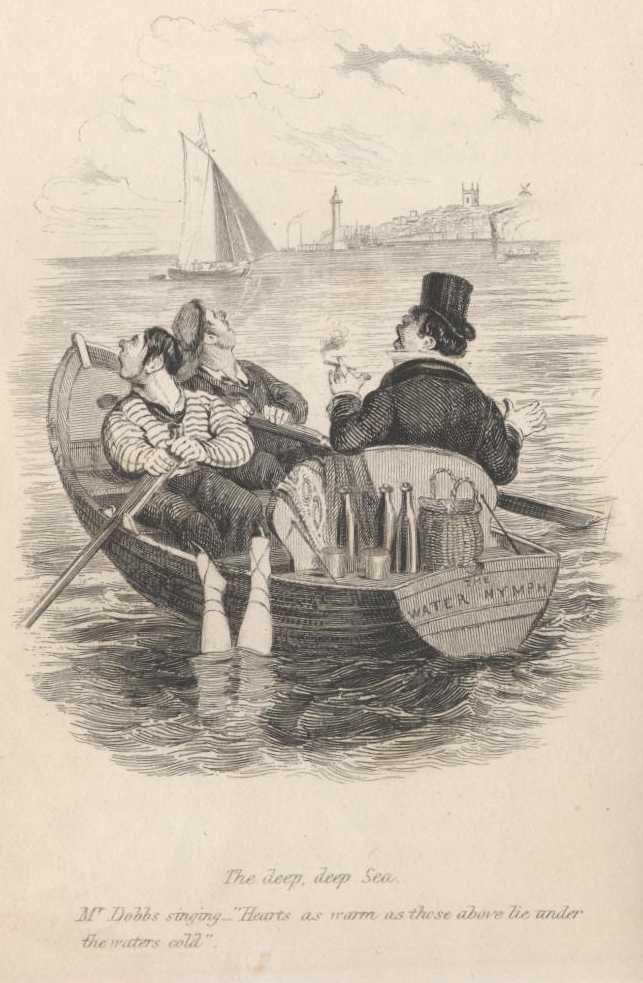

PLATE XIX. DOBBS'S

“DUCK.”—A LEGEND OF HORSELYDOWN.

PLATE XX. STRAWBERRIES AND CREAM.

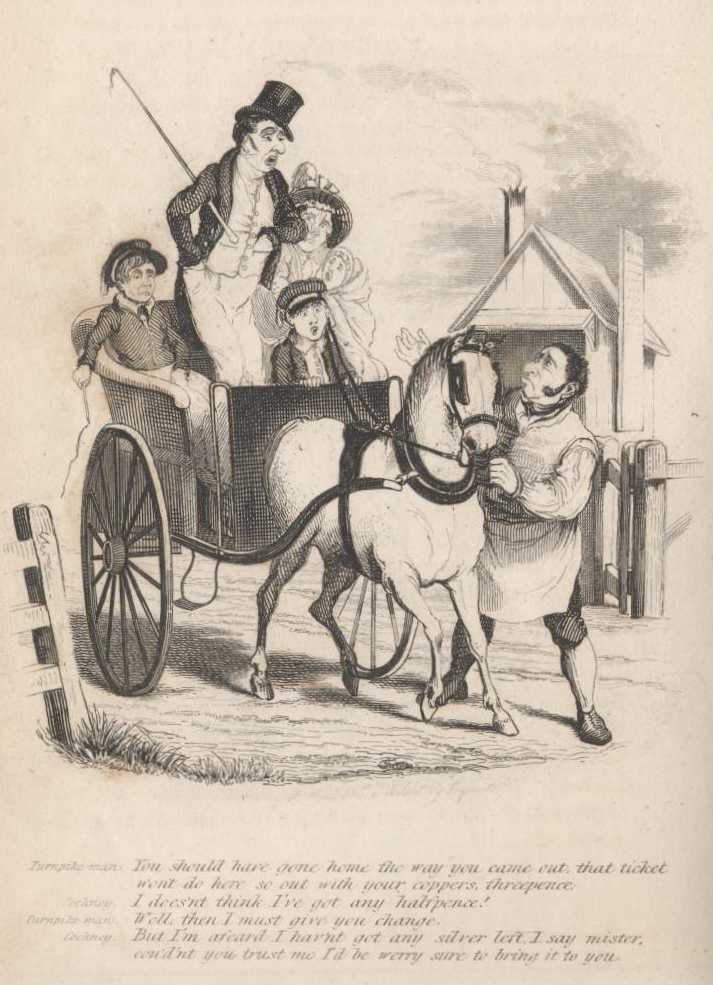

PLATE

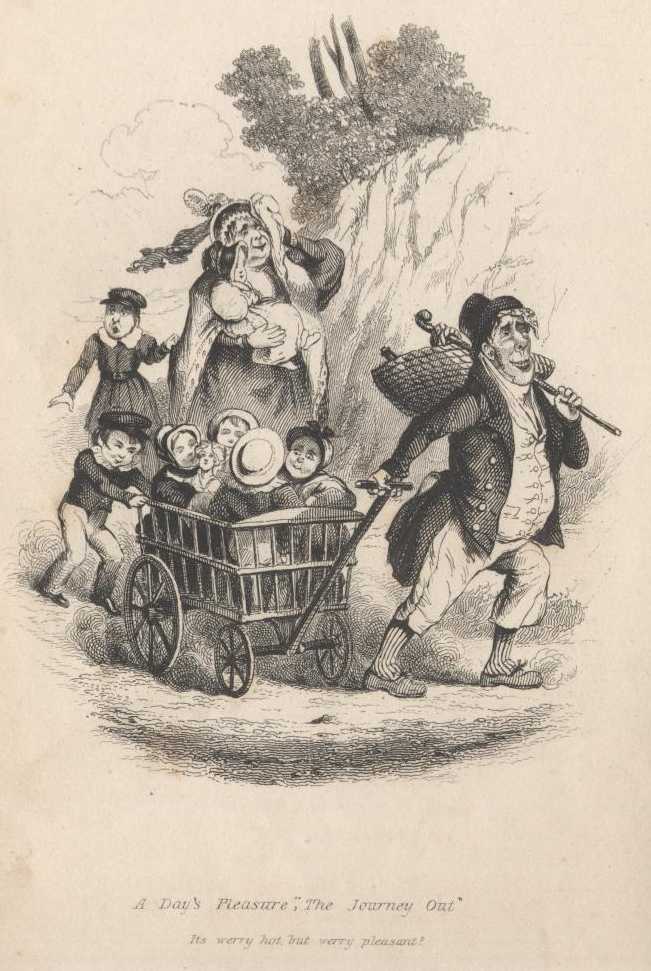

XXI. A DAY'S PLEASURE. No. I.—THE

JOURNEY OUT.

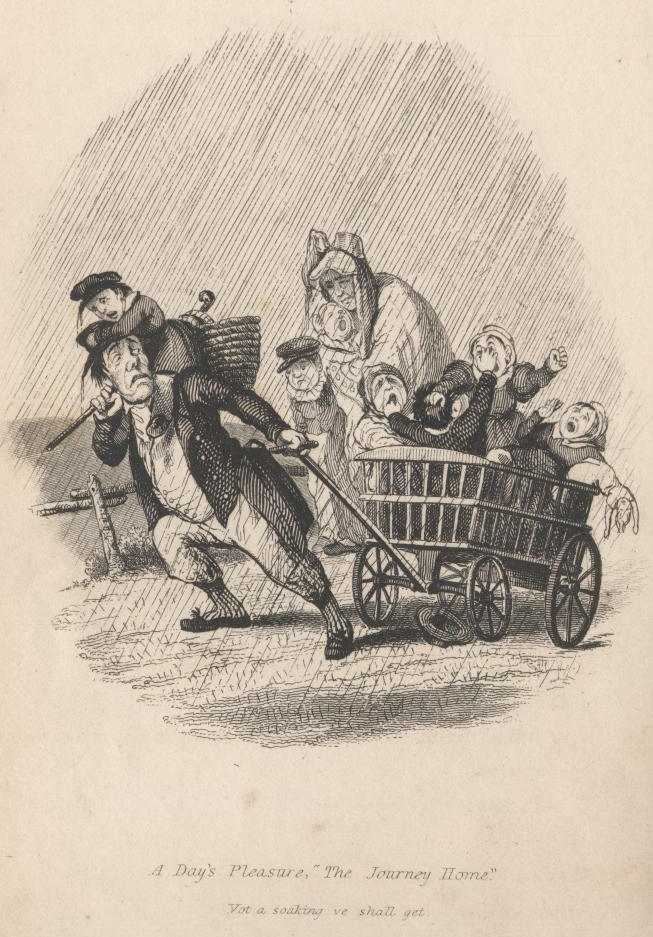

PLATE XXII. A DAY'S

PLEASURE. No. II.—THE JOURNEY HOME.

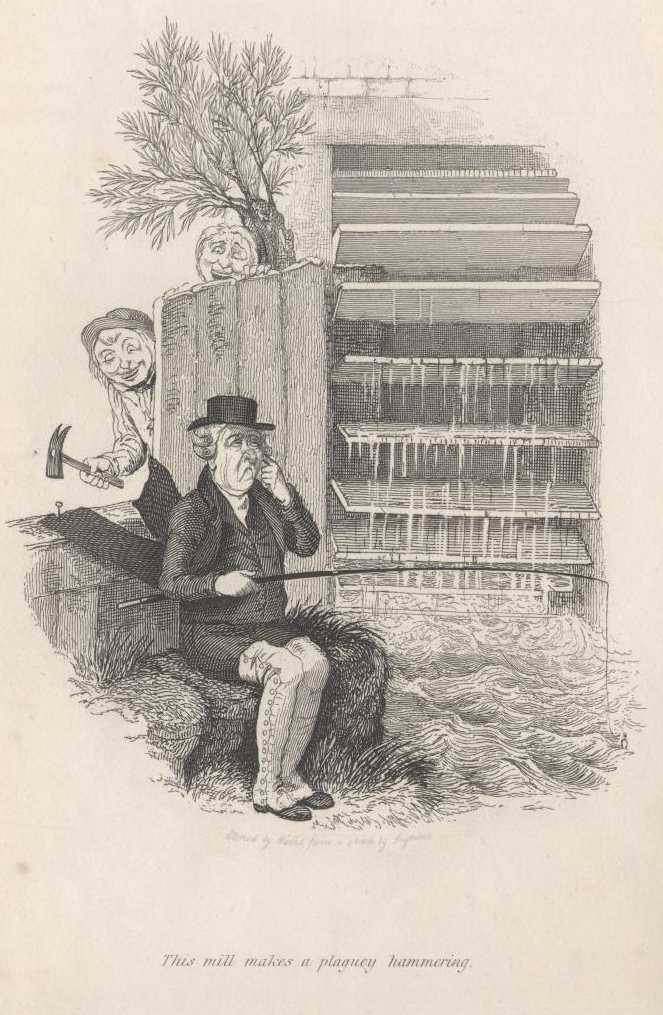

PLATE XXIII. [HAMMERING] Beside a meandering stream

PLATE XXIV. PRACTICE.

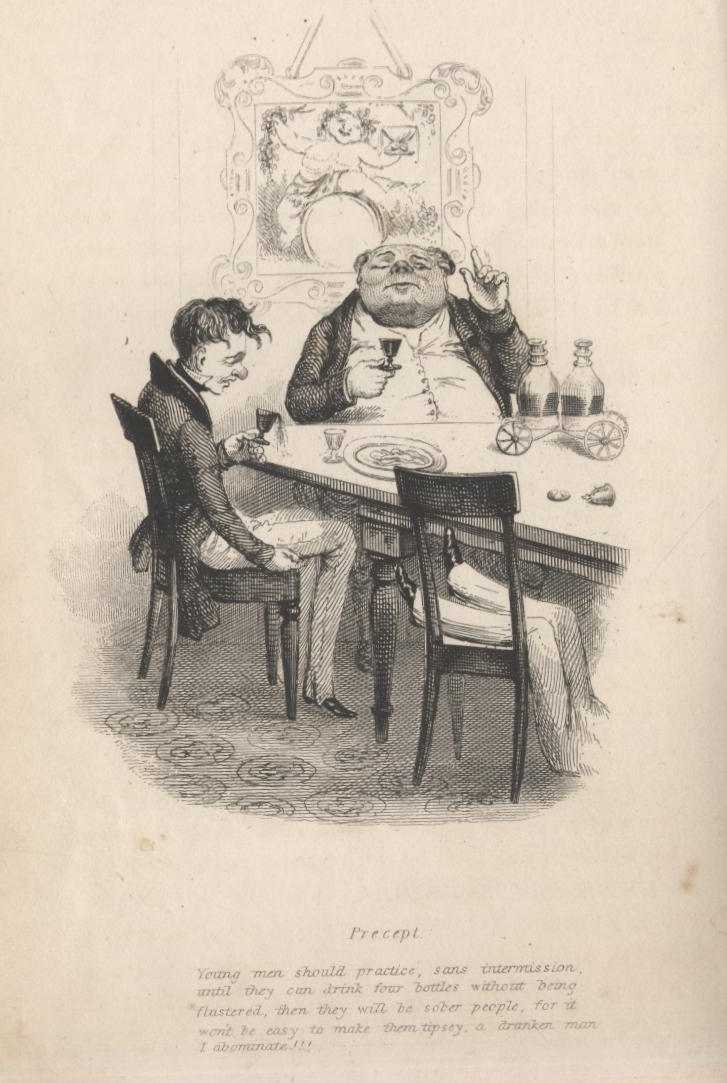

PLATE XXV.

PRECEPT.

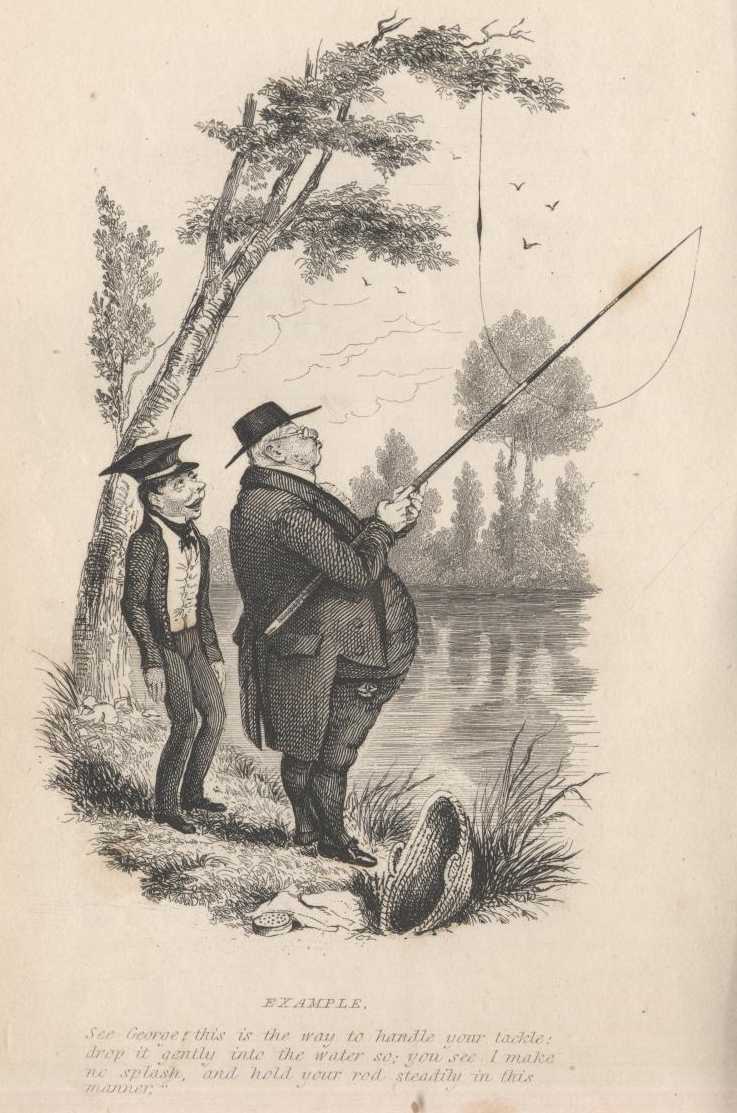

PLATE XXVI. EXAMPLE.

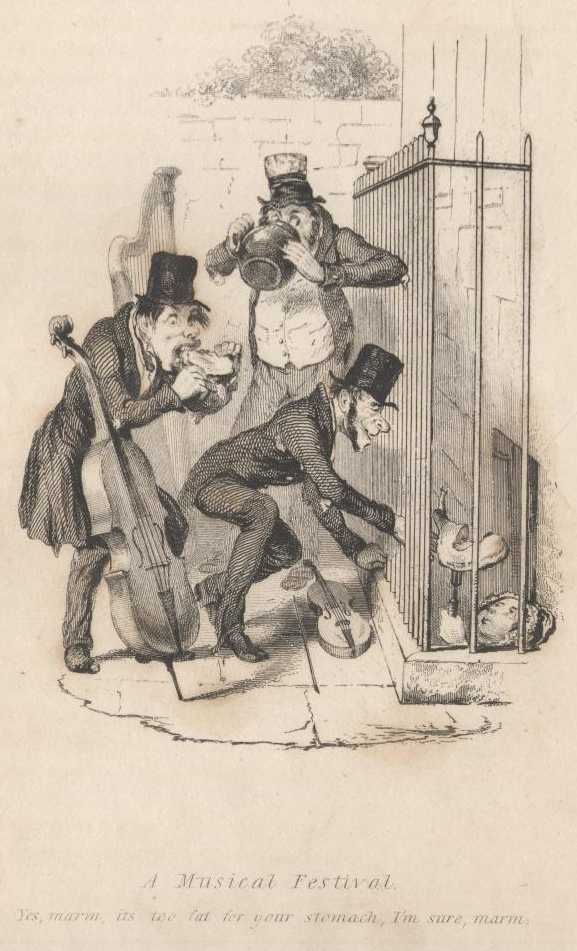

PLATE XXVII. A MUSICAL FESTIVAL.

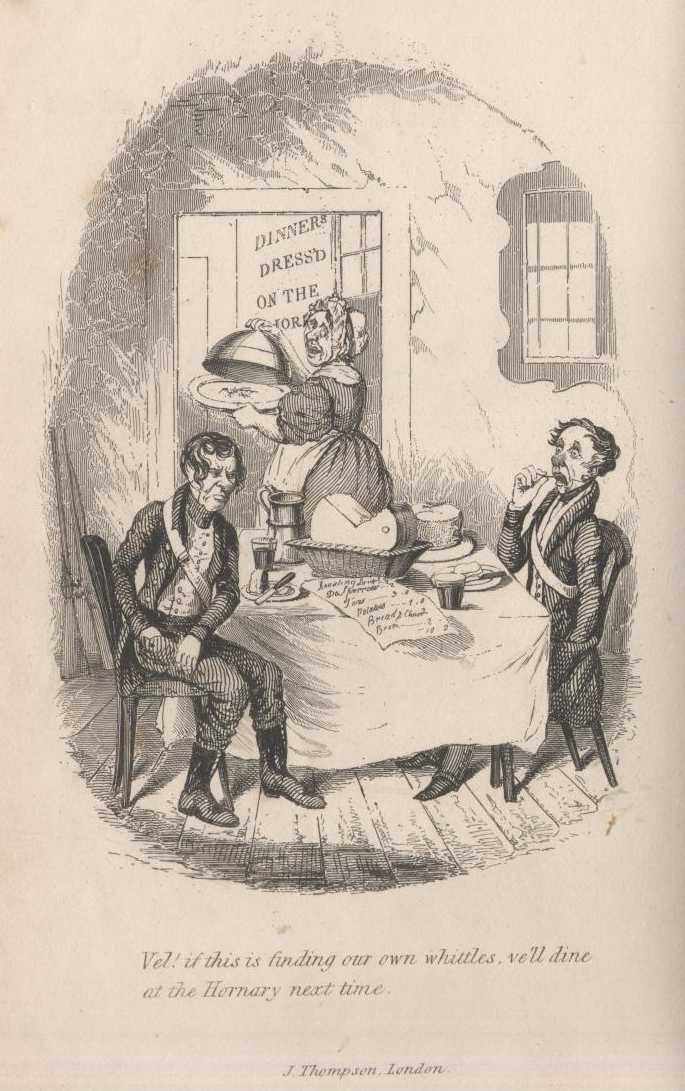

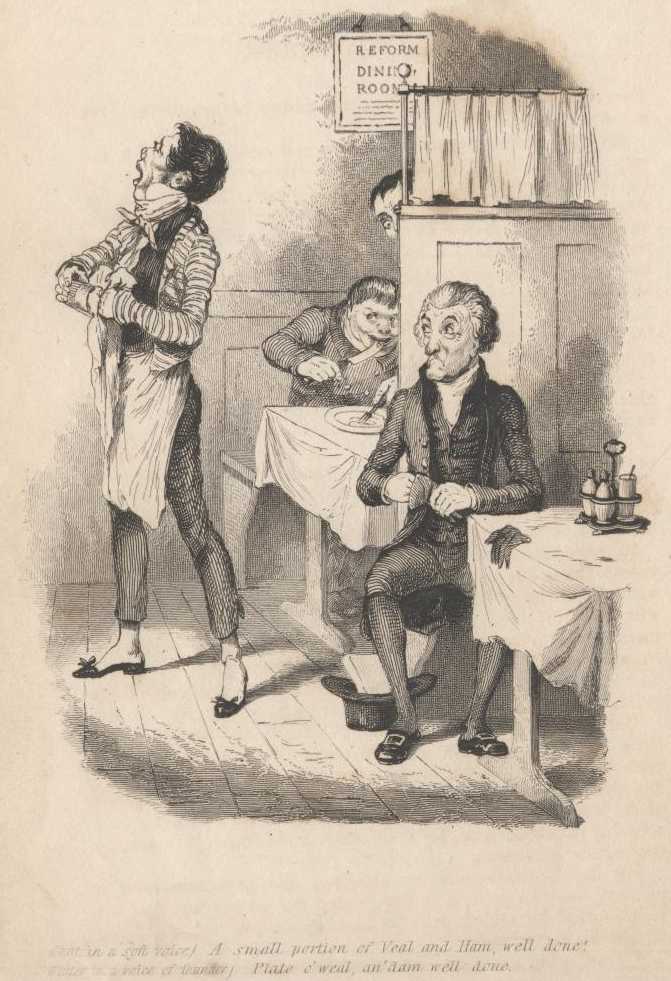

PLATE XXVIII. THE EATING HOUSE.

PLATE XXIX. [SCENE X.(b)] This is a werry lonely spot,

Sir

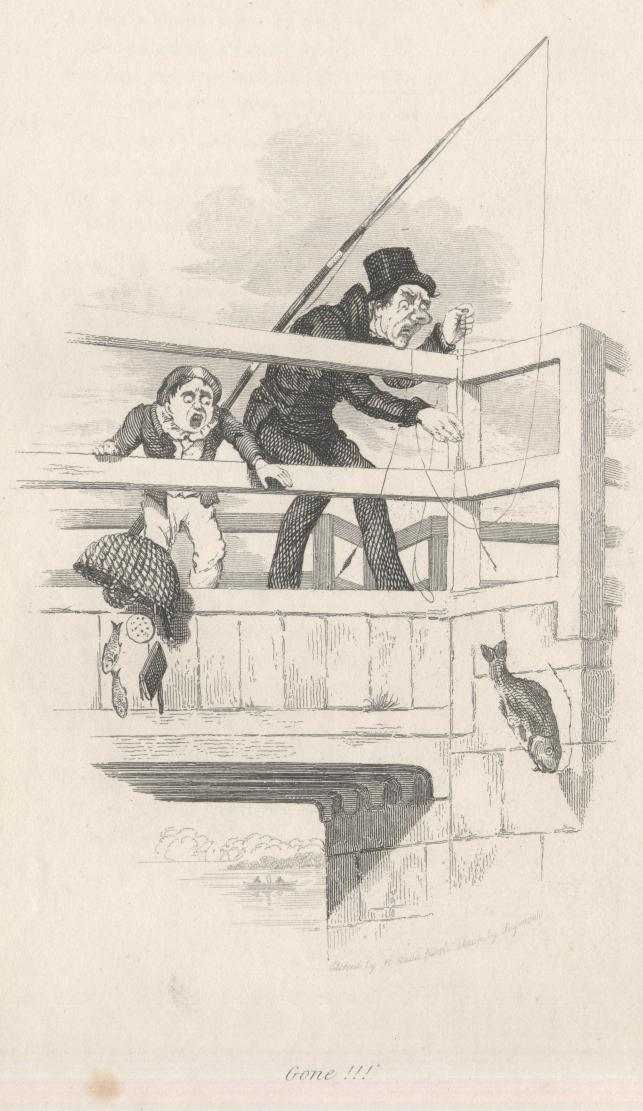

PLATE XXX. GONE!

PLATE XXXI. THE PRACTICAL JOKER. No. I.

PLATE XXXII. THE PRACTICAL JOKER. No. II.

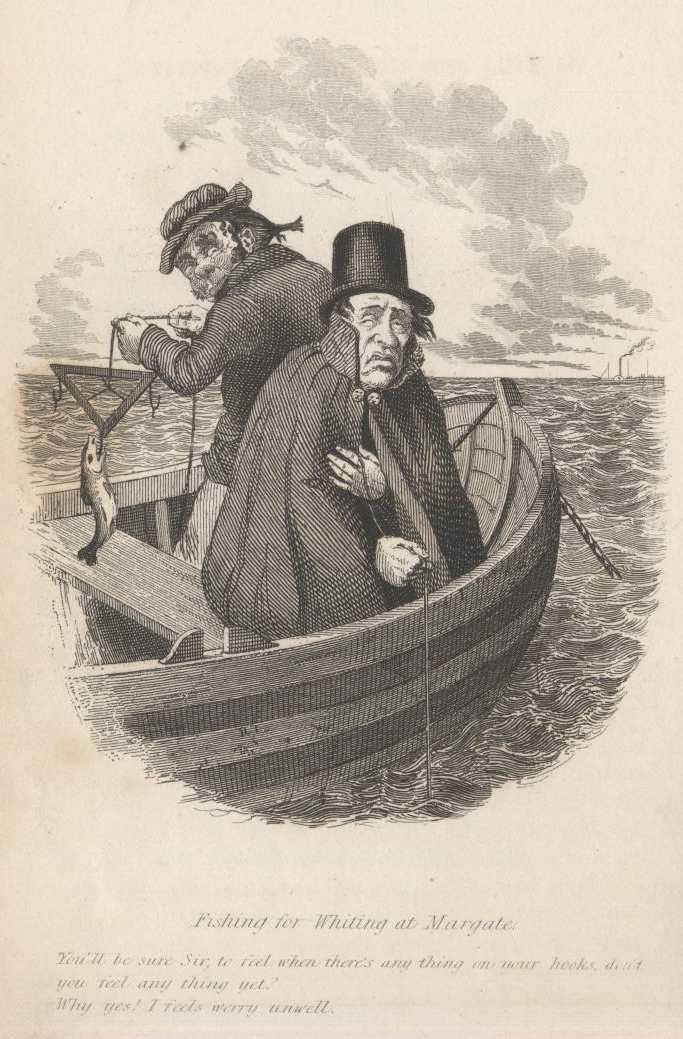

PLATE XXXIII. FISHING FOR WHITING AT MARGATE.

ANDREW MULLINS. —AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY. CHAP. I. Introductory

CHAP. II. Let the neighbors smell ve

has something

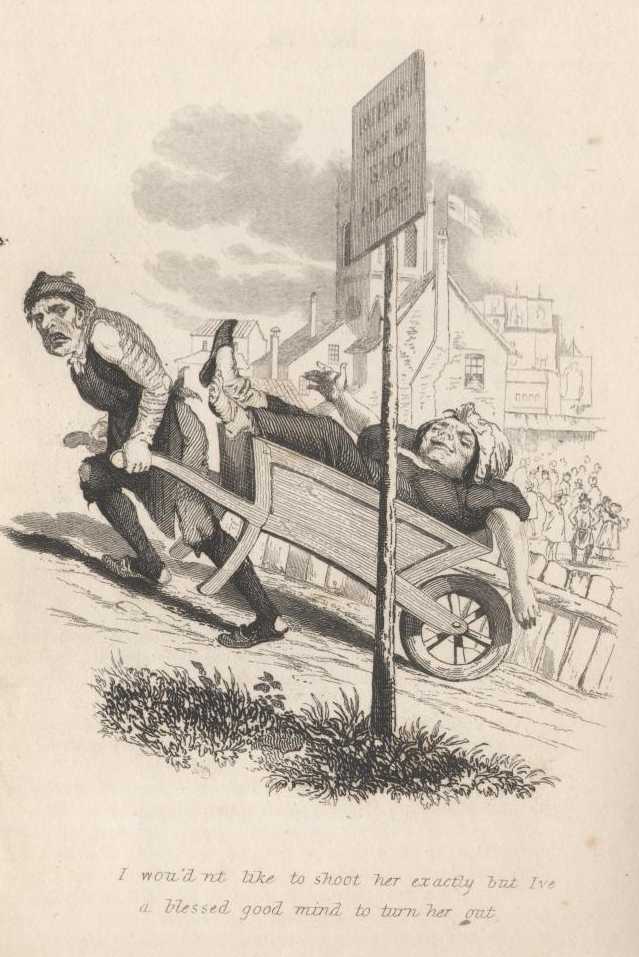

CHAP. III. I wou'dn't like

to shoot her exactly

CHAP. IV. A

Situation.

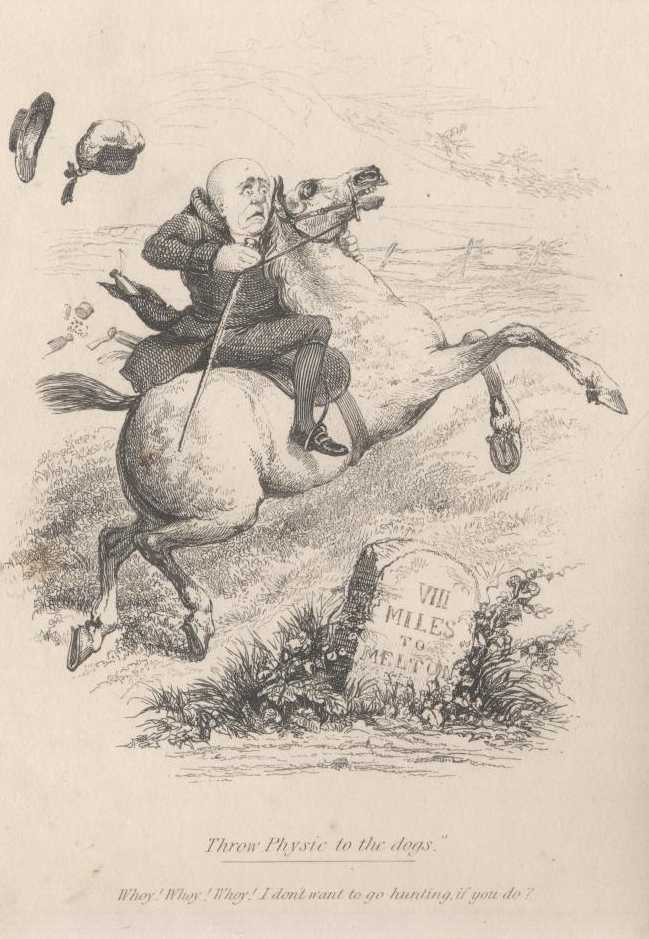

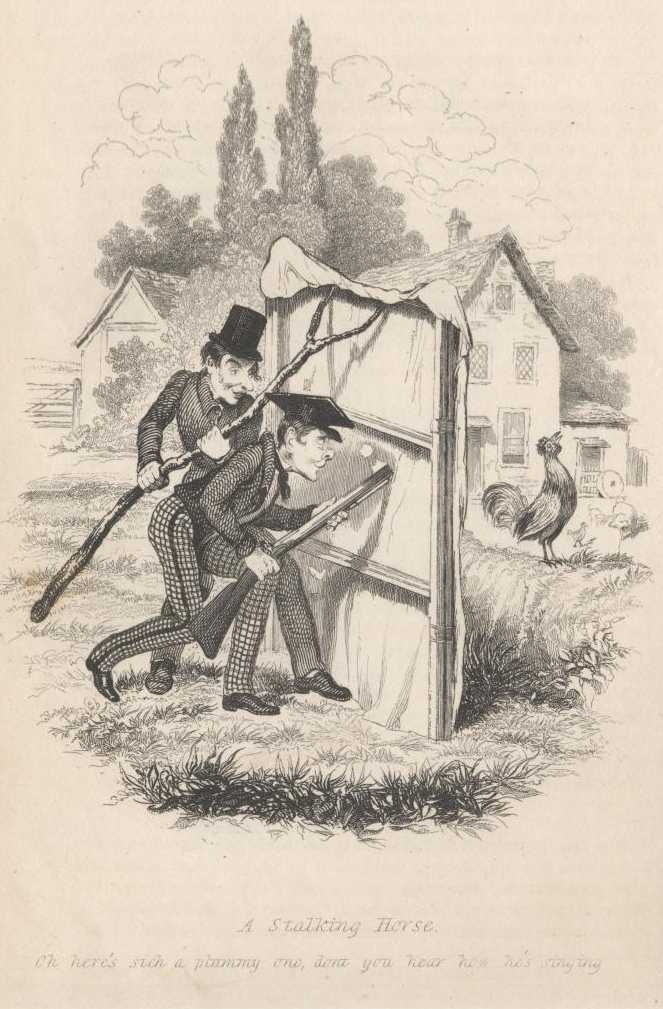

CHAP. V. The Stalking Horse.

CHAP. VI. A Commission.

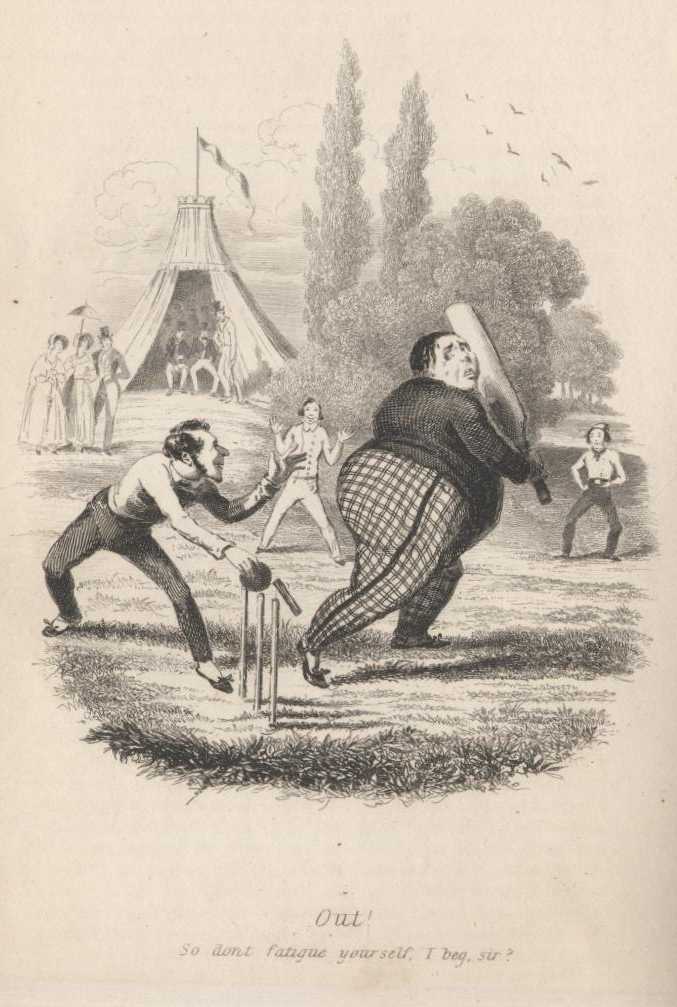

CHAP. VII. The Cricket Match

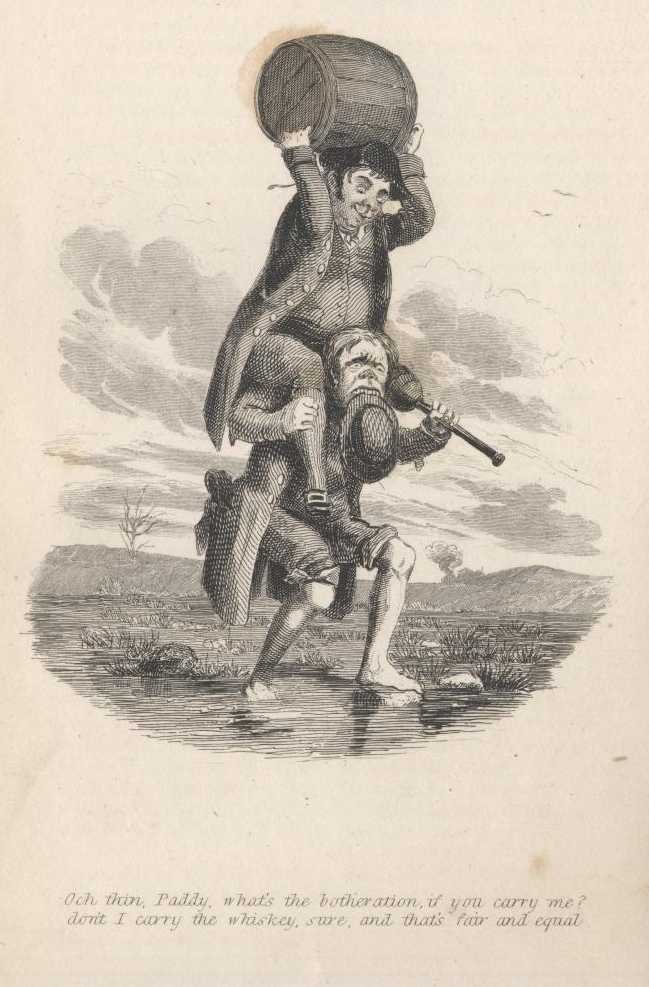

CHAP. VIII. The Hunter.

CHAP. IX. A

Row to Blackwall.

CHAP. X. The Pic-Nic.

CHAP. XI. The Journey Home.

CHAP. XII.

Monsieur Dubois.

CHAP. XIII. My Talent Called into Active Service.

CHAP. XIV. A Dilemma.

CHAP. XV. An Old Acquaintance.

CHAP. XVI. The Loss of a Friend.

CHAP. XVII. Promotion.

A RIGMAROLE. PART I. "De omnibus rebus."

PART II. "Acti labores Sunt jucundi"

PART III. "Oderunt hilarem tristes."

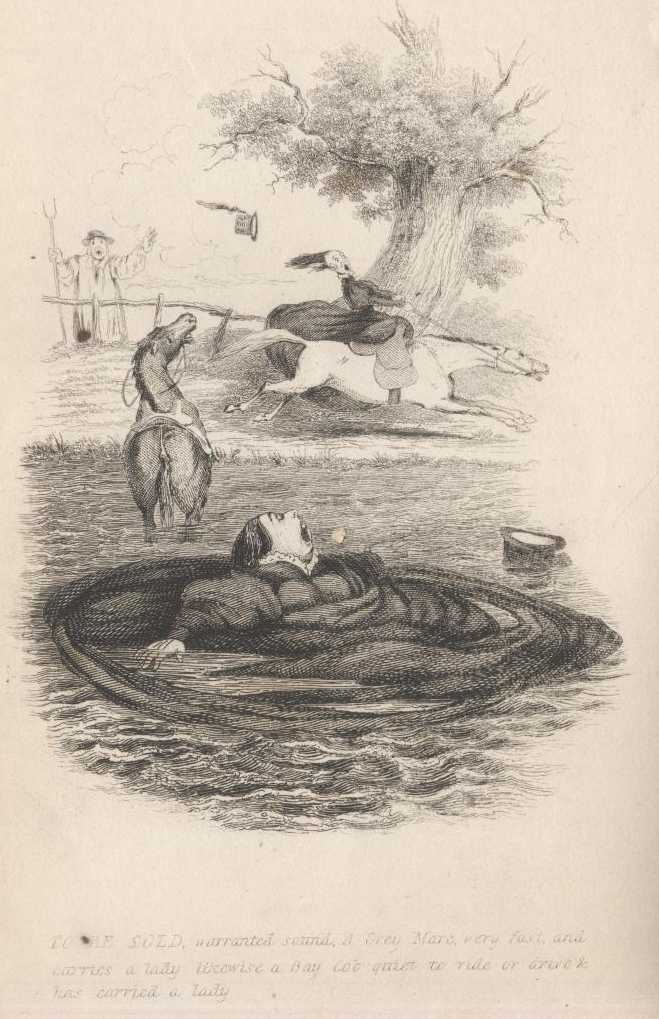

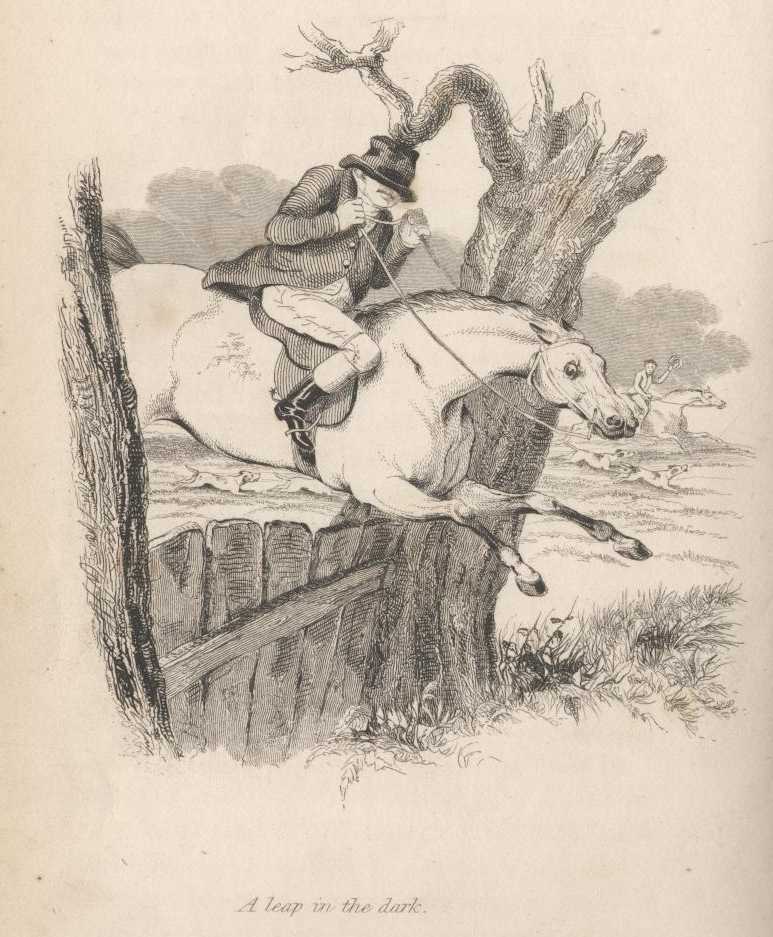

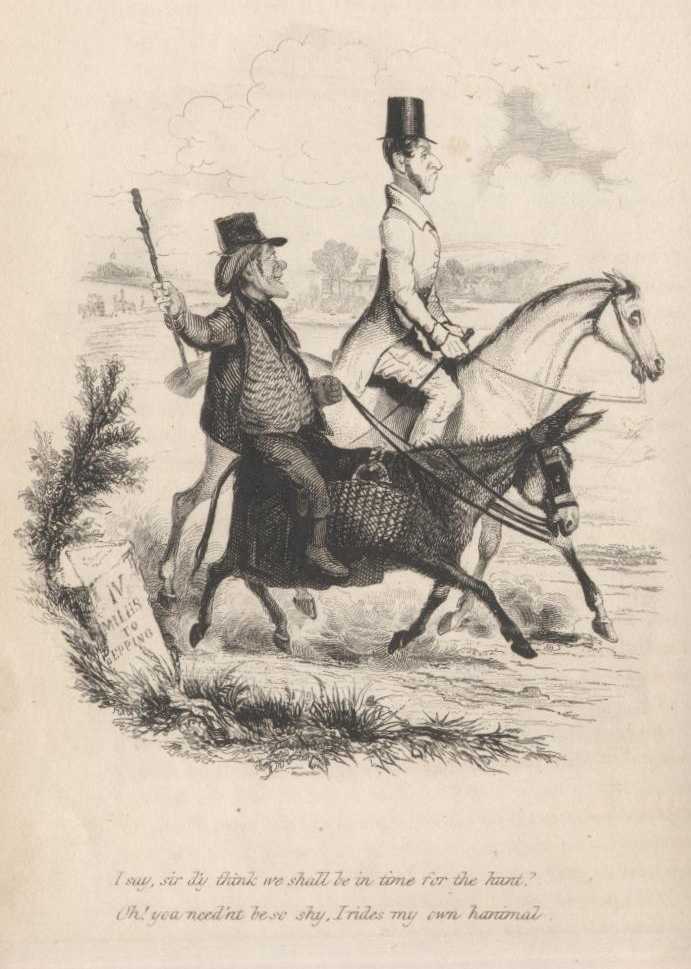

INTERCEPTED LETTER PLATE I. Dye think ve

shall be in time for the hunt?

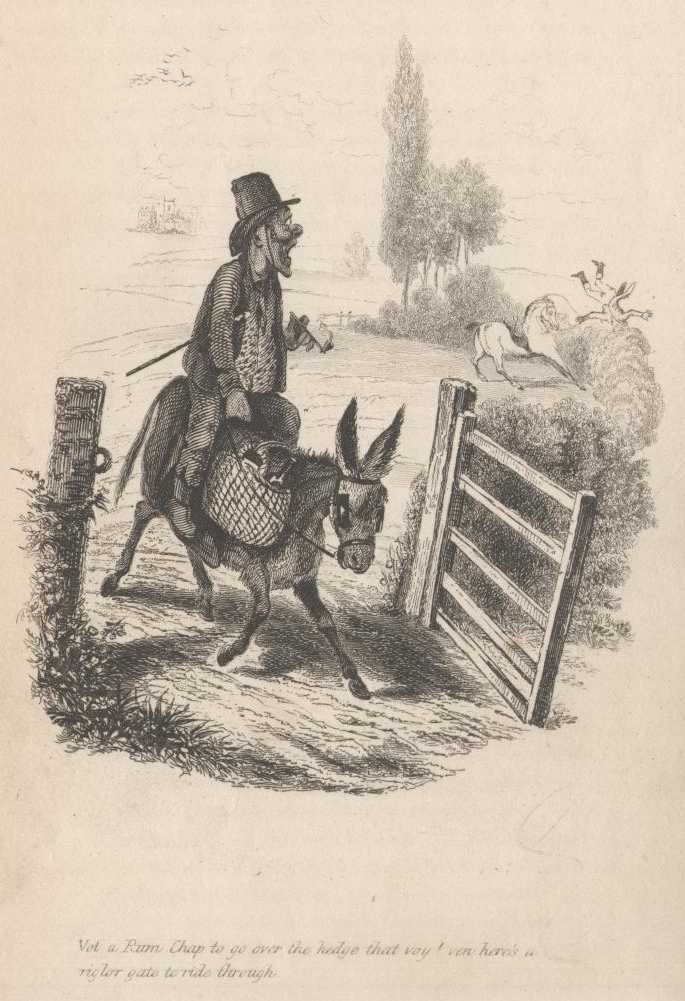

PLATE II. Vat a rum chap to go over the 'edge that vay!

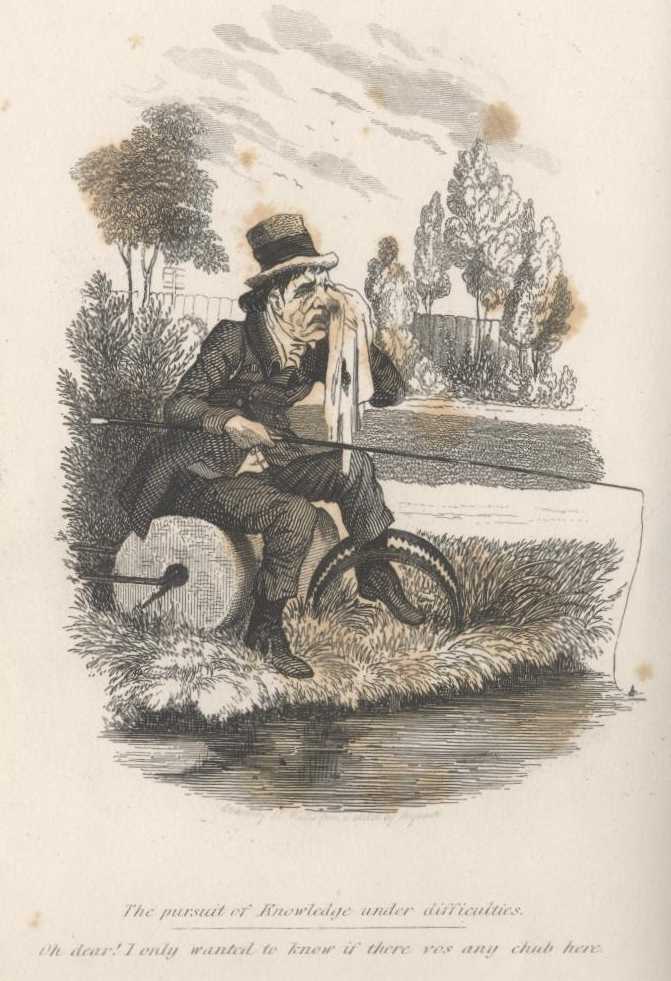

“Walked twenty miles over night: up before peep o' day again got a capital place; fell fast asleep; tide rose up to my knees; my hat was changed, my pockets picked, and a fish ran away with my hook; dreamt of being on a Polar expedition and having my toes frozen.”

O! IZAAK WALTON!—Izaak Walton!—you have truly got me into a precious line, and I certainly deserve the rod for having, like a gudgeon, so greedily devoured the delusive bait, which you, so temptingly, threw out to catch the eye of my piscatorial inclination! I have read of right angles and obtuse angles, and, verily, begin to believe that there are also right anglers and obtuse anglers—and that I am really one of the latter class. But never more will I plant myself, like a weeping willow, upon the sedgy bank of stream or river. No!—on no account will I draw upon these banks again, with the melancholy prospect of no effects! The most 'capital place' will never tempt me to 'fish' again!

My best hat is gone: not the 'way of all beavers'—into the water—but to cover the cranium of the owner of this wretched 'tile;' and in vain shall I seek it; for 'this' and 'that' are now certainly as far as the 'poles' asunder.

My pockets, too, are picked! Yes—some clever 'artist' has drawn me while asleep!

My boots are filled with water, and my soles and heels are anything but lively or delighted. Never more will I impale ye, Gentles! on the word of a gentleman!—Henceforth, O! Hooks! I will be as dead to your attractions as if I were 'off the hooks!' and, in opposition to the maxim of Solomon, I will 'spare the rod.'

Instead of a basket of fish, lo! here's a pretty kettle of fish for the entertainment of my expectant friends—and sha'n't I be baited? as the hook said to the anger: and won't the club get up a Ballad on the occasion, and I, who have caught nothing, shall probably be made the subject of a 'catch!'

Slush! slush!—Squash! squash!

O! for a clean pair of stockings!—But, alack, what a tantalizing

situation I am in!—There are osiers enough in the vicinity, but no

hose to be had for love or money!

A lark—early in the morning.

Two youths—and two guns appeared at early dawn in the suburbs. The youths were loaded with shooting paraphernalia and provisions, and their guns with the best Dartford gunpowder—they were also well primed for sport—and as polished as their gunbarrels, and both could boast a good 'stock' of impudence.

“Surely I heard the notes of a bird,” cried one, looking up and down the street; “there it is again, by jingo!”

“It's a lark, I declare,” asserted his brother sportsman.

“Lark or canary, it will be a lark if we can bring it down,” replied his companion.

“Yonder it is, in that ere cage agin the wall.”

“What a shame!” exclaimed the philanthropic youth,—“to imprison a warbler of the woodlands in a cage, is the very height of cruelty—liberty is the birthright of every Briton, and British bird! I would rather be shot than be confined all my life in such a narrow prison. What a mockery too is that piece of green turf, no bigger than a slop-basin. How it must aggravate the feelings of one accustomed to range the meadows.”

“Miserable! I was once in a cage myself,” said his chum.

“And what did they take you for?”

“Take me for?—for a 'lark.'”

“Pretty Dickey!”

“Yes, I assure you, it was all 'dickey' with me.”

“And did you sing?”

“Didn't I? yes, i' faith I sang pretty small the next morning when they fined me, and let me out. An idea strikes me Suppose you climb up that post, and let out this poor bird, ey?”

“Excellent.”

“And as you let him off, I'll let off my gun, and we'll see whether I can't 'bang' him in the race.”

No sooner said than done: the post was quickly climbed—the door of the cage was thrown open, and the poor bird in an attempt at 'death or liberty,' met with the former.

Bang went the piece, and as soon as the curling smoke was dissipated, they sought for their prize, but in vain; the piece was discharged so close to the lark, that it was blown to atoms, and the feathers strewed the pavement.

“Bolt!” cried the freedom-giving youth, “or we shall have to pay for the lark.”

“Very likely,” replied the other, who had just picked up a few feathers,

and a portion of the dissipated 'lark,'—“for look, if here ain't the—bill,

never trust me.”

“You shall have the paper directly, Sir, but really the debates are so very interesting.”

“Oh! pray don't hurry, Sir, it's only the scientific notices I care about.”

WHAT a thrill of pleasure pervades the philanthropic breast on beholding the rapid march of Intellect! The lamp-lighter, but an insignificant 'link' in the vast chain of society, has now a chance of shining at the Mechanics', and may probably be the means of illuminating a whole parish.

Literature has become the favourite pursuit of all classes, and the postman is probably the only man who leaves letters for the vulgar pursuit of lucre! Even the vanity of servant-maids has undergone a change—they now study 'Cocker' and neglect their 'figures.'

But the dustman may be said, 'par excellence,' to bear—the bell!

In the retired nook of an obscure coffee-shop may frequently be observed a pair of these interesting individuals sipping their mocha, newspaper in hand, as fixed upon a column—as the statue of Napoleon in the Place Vendome, and watching the progress of the parliamentary bills, with as much interest as the farmer does the crows in his corn-field!

They talk of 'Peel,' and 'Hume,' and 'Stanley,' and bandy about their names as familiarly as if they were their particular acquaintances.

“What a dust the Irish Member kicked up in the House last night,” remarks one.

“His speech was a heap o' rubbish,” replied the other.

“And I've no doubt was all contracted for! For my part I was once a Reformer—but Rads and Whigs is so low, that I've turned Conservative.”

“And so am I, for my Sal says as how it's so genteel!”

“Them other chaps after all on'y wants to throw dust in our eyes! But it's no go, they're no better than a parcel o' thimble riggers just making the pea come under what thimble they like,—and it's 'there it is,' and 'there it ain't,'—just as they please—making black white, and white black, just as suits 'em—but the liberty of the press—”

“What's the liberty of the press?”

“Why calling people what thinks different from 'em all sorts o' names—arn't that a liberty?”

“Ay, to be sure!—but it's time to cut—so down with the dust—and

let's bolt!”

“Oh! Sally, I told my missus vot you said your missus said about her.”—

“Oh! and so did I, Betty; I told my missus vot you said yourn said of her, and ve had sich a row!”

SALLY. OH! Betty, ve had sich a row!—there vas never nothink like it;— I'm quite a martyr. To missus's pranks; for, 'twixt you and me, she's a bit of a tartar. I told her vord for vord everythink as you said, And I thought the poor voman vould ha' gone clean out of her head!

BETTY. Talk o' your missus! she's nothink to mine,—I on'y hope they von't meet, Or I'm conwinced they vill go to pulling of caps in the street: Sich kicking and skrieking there vas, as you never seed, And she vos so historical, it made my wery heart bleed.

SALLY. Dear me! vell, its partic'lar strange people gives themselves sich airs, And troubles themselves so much 'bout other people's affairs; For my part, I can't guess, if I died this werry minute, Vot's the use o' this fuss—I can't see no reason in it.

BETTY. Missus says as how she's too orrystocratic to mind wulgar people's tattle, And looks upon some people as little better nor cattle.

SALLY. And my missus says no vonder, as yourn can sport sich a dress, For ven some people's husbands is vite-vashed, their purses ain't less; This I will say, thof she puts herself in wiolent rages, She's not at all stingy in respect of her sarvant's wages.

BETTY. Ah! you've got the luck of it—for my missus is as mean as she's proud; On'y eight pound a-year, and no tea and sugar allowed. And then there's seven children to do for—two is down with the measles, And t'others, poor things! is half starved, and as thin as weazles; And then missus sells all the kitchen stuff!—(you don't know my trials!) And takes all the money I get at the rag-shop for the vials!

SALLY. Vell! I could'nt stand that!—If I was you, I'd soon give her warning.

BETTY. She's saved me the trouble, by giving me notice this morning. But—hush!

I hear master bawling out for his shaving water— Jist tell your

missus from me, mine's everythink as she thought her!

“How does it fit behind? O! beautful; I've done wonders—we'll never trouble the tailors again, I promise them.”

IT is the proud boast of some men that they have 'got a wrinkle.' How elated then ought this individual to be who has got so many! and yet, judging from the fretful expression of his physiognomy, one would suppose that he is by no means in 'fit' of good humour.

His industrious rib, however, appears quite delighted with her handiwork, and in no humour to find the least fault with the loose habits of her husband. He certainly looks angry, as a man naturally will when his 'collar' is up.

She, on the other hand, preserves her equanimity in spite of his unexpected frowns, knowing from experience that those who sow do not always reap; and she has reason to be gratified, for every beholder will agree in her firm opinion, that even that inimitable ninth of ninths—Stulz, never made such a coat!

In point of economy, we must allow some objections may be made to the extravagant waist, while the cuffs she has bestowed on him may probably be a fair return (with interest) of buffets formerly received.

The tail (in two parts) is really as amusing as any 'tale' that ever emanated from a female hand. There is a moral melancholy about it that is inexpressibly interesting, like two lovers intended for each other, and that some untoward circumstance has separated; they are 'parted,' and yet are still 'attached,' and it is evident that one seems 'too long' for the other.

The 'goose' generally finishes the labours of the tailor. Now, some carping critics may be wicked enough to insinuate that this garb too was finished by a goose! The worst fate I can wish to such malignant scoffers is a complete dressing from this worthy dame; and if she does not make the wisest of them look ridiculous, then, and not till then, will I abjure my faith in her art of cutting!

And proud ought that man to be of such a wife; for never was mortal

'suited' so before!

“Catching—a cold.”

WHAT a type of true philosophy and courage is this Waltonian!

Cool and unmoved he receives the sharp blows of the blustering wind—as if he were playing dummy to an experienced pugilist.

Although he would undoubtedly prefer the blast with the chill off, he is so warm an enthusiast, in the pursuit of his sport, that he looks with contempt upon the rude and vulgar sport of the elements. He really angles for love—and love alone—and limbs and body are literally transformed to a series of angles!

Bent and sharp as his own hook, he watches his smooth float in the rough, but finds, alas! that it dances to no tune.

Time and bait are both lost in the vain attempt: patiently he rebaits,

until he finds the rebait brings his box of gentles to a discount; and

then, in no gentle humour, with a baitless hook, and abated ardor, he

winds up his line and his day's amusement(?)—and departs, with the

determination of trying fortune (who has tried him) on some, future and

more propitious day. Probably, on the next occasion, he may be gratified

with the sight of, at least, one gudgeon, should the surface of the river

prove glassy smooth and mirror-like. (We are sure his self-love will not

be offended at the reflection!) and even now he may, with truth, aver,

that although he caught nothing, he, at least, took the best perch in the

undulating stream!

“Help! help! Oh! you murderous little villin? this is vot you calls rowing, is it?—but if ever I gets safe on land again, I'll make you repent it, you rascal. I'll row you—that I will.”

“MISTER Vaterman, vot's your fare for taking me across?”

“Across, young 'ooman? vy, you looks so good-tempered, I'll pull you over for sixpence?”

“Are them seats clean?”

“O! ker-vite:—I've just swabb'd 'em down.”

“And werry comfortable that'll be! vy, it'll vet my best silk?”

“Vatered silks is all the go. Vel! vell! if you don't like; it, there's my jacket. There, sit down a-top of it, and let me put my arm round you.”

“Fellow!”

“The arm of my jacket I mean; there's no harm in that, you know.”

“Is it quite safe? How the wind blows!”

“Lord! how timorsome you be! vy, the vind never did nothin' else since I know'd it.”

“O! O! how it tumbles! dearee me!”

“Sit still! for ve are just now in the current, and if so be you go over here, it'll play old gooseberry with you, I tell you.”

“Is it werry deep?”

“Deep as a lawyer.”

“O! I really feel all over”—

“And, by Gog, you'll be all over presently—don't lay your hand on my scull!”

“You villin, I never so much as touched your scull. You put me up.”

“I must put you down. I tell you what it is, young 'ooman, if you vant to go on, you must sit still; if you keep moving, you'll stay where you are—that's all! There, by Gosh! we're in for it.” At this point of the interesting dialogue, the young 'ooman gave a sudden lurch to larboard, and turned the boat completely over. The boatman, blowing like a porpoise, soon strode across the upturned bark, and turning round, beheld the drenched “fare” clinging to the stern.

“O! you partic'lar fool!” exclaimed the waterman. “Ay, hold on a-stern,

and the devil take the hindmost, say I!”

In for it, or Trying the middle.

A little fat man

With rod, basket, and can,

And tackle complete,

Selected a seat

On the branch of a wide-spreading tree,

That stretch'd over a branch of the Lea:

There he silently sat,

Watching his float—like a tortoise-shell cat,

That hath scented a mouse,

In the nook of a room in a plentiful house.

But alack!

He hadn't sat long—when a crack

At his back

Made him turn round and pale—

And catch hold of his tail!

But oh! 'twas in vain

That he tried to regain

The trunk of the treacherous tree;

So he

With a shake of his head

Despairingly said—

“In for it,—ecod!”

And away went his rod,

And his best beaver hat,

Untiling his roof!

But he cared not for that,

For it happened to be a superb water proof,

Which not being himself,

The poor elf!

Felt a world of alarm

As the arm

Most gracefully bow'd to the stream,

As if a respect it would show it,

Tho' so much below it!

No presence of mind he dissembled,

But as the branch shook so he trembled,

And the case was no longer a riddle

Or joke;

For the branch snapp'd and broke;

And altho'

The angler cried “Its no go!”

He was presently—'trying the middle.'

The Invitation—the Outfit—and the sallying forth.

TO Mr. AUGUSTUS SPRIGGS,

AT Mr. WILLIAMS'S, GROCER, ADDLE STREET.

(Tower Street, 31st August, 18__)

My dear Chum,

Dobbs has give me a whole holiday, and it's my intention to take the field to-morrow—and if so be you can come over your governor, and cut the apron and sleeves for a day—why

“Together we will range the fields;”

and if we don't have some prime sport, my name's not Dick, that's all.

I've bought powder and shot, and my cousin which is Shopman to my Uncle at the corner, have lent me a couple of guns that has been 'popp'd.' Don't mind the expense, for I've shot enough for both. Let me know by Jim if you can cut your stick as early as nine, as I mean to have a lift by the Highgate what starts from the Bank.

Mind, I won't take no refusal—so pitch it strong to the old 'un, and carry your resolution nem. con.

And believe me to be, your old Crony,

RICHARD GRUBB.

P. S. The guns hasn't got them thingummy 'caps,' but that's no matter, for cousin says them cocks won't always fight: while them as he has lent is reg'lar good—and never misses fire nor fires amiss.

In reply to this elegant epistle, Mr. Richard Grubb was favoured with a line from Mr. Augustus Spriggs, expressive of his unbounded delight in having prevailed upon his governor to 'let him out;' and concluding with a promise of meeting the coach at Moorgate.

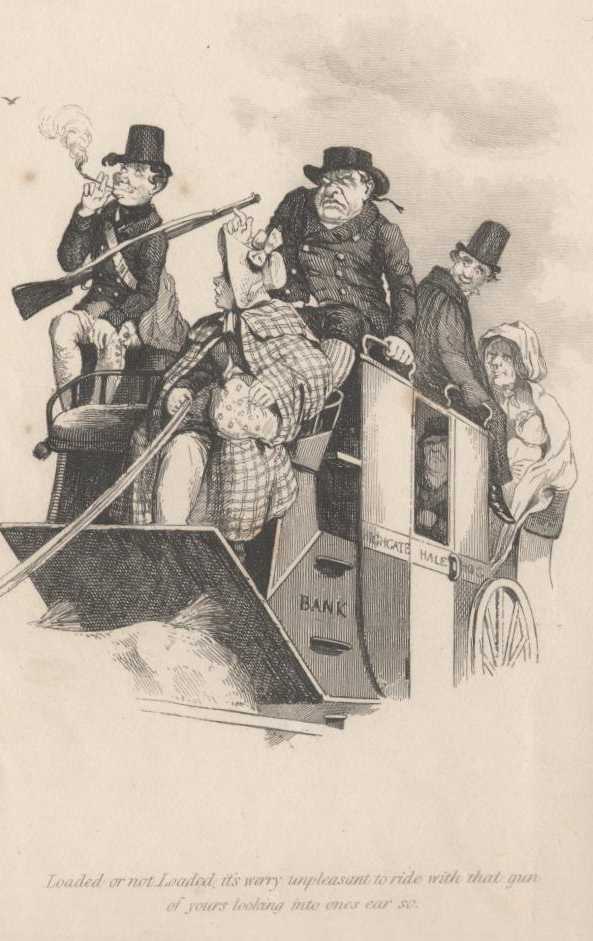

At the appointed hour, Mr. Richard Grubb, 'armed at all points,' mounted the stage—his hat cocked knowingly over his right eye—his gun half-cocked and slung over his shoulder, and a real penny Cuba in his mouth.

“A fine mornin' for sport,” remarked Mr. Richard Grubb to his fellow-passenger, a stout gentleman between fifty and sixty years of age, with a choleric physiognomy and a fierce-looking pigtail.

“I dessay—”

“Do you hang out at Highgate?” continued the sportsman.

“Hang out?”

“Ay, are you a hinhabitant?”

“To be sure I am.”

“Is there any birds thereabouts?”

“Plenty o' geese,” sharply replied the old gentleman.

“Ha! ha! werry good!—but I means game;—partridges and them sort o' birds.”

“I never see any except what I've brought down.”

“I on'y vish I may bring down all I see, that's all,” chuckled the joyous Mr. Grubb.

“What's the matter?”

“I don't at all like that 'ere gun.”

“Lor! bless you, how timorsome you are, 'tain't loaded.”

“Loaded or not loaded, it's werry unpleasant to ride with that gun o' yours looking into one's ear so.”

“Vell, don't be afeard, I'll twist it over t'other shoulder,—there! but a gun ain't a coach, you know, vich goes off whether it's loaded or not. Hollo! Spriggs! here you are, my boy, lord! how you are figg'd out—didn't know you—jump up!”

“Vere's my instrument o' destruction?” enquired the lively Augustus, when he had succeeded in mounting to his seat.

“Stow'd him in the boot!”

The coachman mounted and drove off; the sportsmen chatting and laughing as they passed through 'merry Islington.'

“Von't ve keep the game alive!” exclaimed Spriggs, slapping his friend upon the back.

“I dessay you will,” remarked the caustic old boy with the pigtail; “for it's little you'll kill, young gentlemen, and that's my belief!”

“On'y let's put 'em up, and see if we don't knock 'em down, as cleverly as Mister Robins does his lots,” replied Spriggs, laughing at his own wit.

Arrived at Highgate, the old gentleman, with a step-fatherly anxiety, bade them take care of the 'spring-guns' in their perambulations.

“Thankee, old boy,” said Spriggs, “but we ain't so green as not to know

that spring guns, like spring radishes, go off long afore Autumn, you

know!”

The Death of a little Pig, which proves a great Bore!

“Now let's load and prime—and make ready,” said Mr. Richard, when they had entered an extensive meadow, “and—I say—vot are you about? Don't put the shot in afore the powder, you gaby!”

Having charged, they shouldered their pieces and waded through the tall grass.

“O! crikey!—there's a heap o' birds,” exclaimed Spriggs, looking up at a flight of alarmed sparrows. “Shall I bring 'em down?”

“I vish you could! I'd have a shot at 'em,” replied Mr. Grubb, “but they're too high for us, as the alderman said ven they brought him a couple o' partridges vot had been kept overlong!”

“My eye! if there ain't a summat a moving in that 'ere grass yonder—cock your eye!” “Cock your gun—and be quiet,” said Mr. Grubb. The anxiety of the two sportsmen was immense. “It's an hare—depend on't—stoop down—pint your gun,—and when I say fire—fire! there it is—fire!”

Bang! bang! went the two guns, and a piercing squeak followed the report.

“Ve've tickled him,” exclaimed Spriggs, as they ran to pick up the spoil.

“Ve've pickled him, rayther,” cried Grubbs, “for by gosh it's a piggy!”

“Hallo! you chaps, vot are you arter?” inquired a man, popping his head over the intervening hedge. “Vy, I'm blessed if you ain't shot von o' Stubbs's pigs.” And leaping the hedge he took the 'pork' in his arms, while the sportsmen who had used their arms so destructively now took to their legs for security. But ignorance of the locality led them into the midst of a village, and the stentorian shouts of the pig-bearer soon bringing a multitude at their heels, Mr. Richard Grubb was arrested in his flight. Seized fast by the collar, in the grasp of the butcher and constable of the place, all escape was vain. Spriggs kept a respectful distance.

“Now my fine fellow,” cried he, brandishing his staff, “you 'ither pays for that 'ere pig, or ve'll fix you in the cage.”

Now the said cage not being a bird-cage, Mr. Richard Grubb could see no prospect of sport in it, and therefore fearfully demanded the price of the sucking innocent, declaring his readiness to 'shell out.'

Mr. Stubbs, the owner, stepped forward, and valued it at eighteen shillings.

“Vot! eighteen shillings for that 'ere little pig!” exclaimed the astounded sportsman. “Vy I could buy it in town for seven any day.”

But Mr. Stubbs was obdurate, and declared that he would not 'bate a farden,' and seeing no remedy, Mr. Richard Grubb was compelled to 'melt a sovereign,' complaining loudly of the difference between country-fed and town pork!

Shouldering his gun, he joined his companion in arms, amid the jibes and jeers of the grinning rustics.

“Vell, I'm blowed if that ain't a cooler!” said he.

“Never mind, ve've made a hit at any rate,” said the consoling Spriggs, “and ve've tried our metal.”

“Yes, it's tried my metal preciously—changed a suv'rin to two bob! by jingo!”

“Let's turn Jews,” said Spriggs, “and make a vow never to touch pork again!”

“Vot's the use o' that?”

“Vy, we shall save our bacon in future, to be sure,” replied Spriggs, laughing, and Grubb joining in his merriment, they began to look about them, not for fresh pork, but for fresh game.

“No more shooting in the grass, mind!” said Grubb, “or ve shall have the

blades upon us agin for another grunter p'r'aps. Our next haim must be at

birds on the ving! No more forking out. Shooting a pig ain't no lark—that's

poz!”

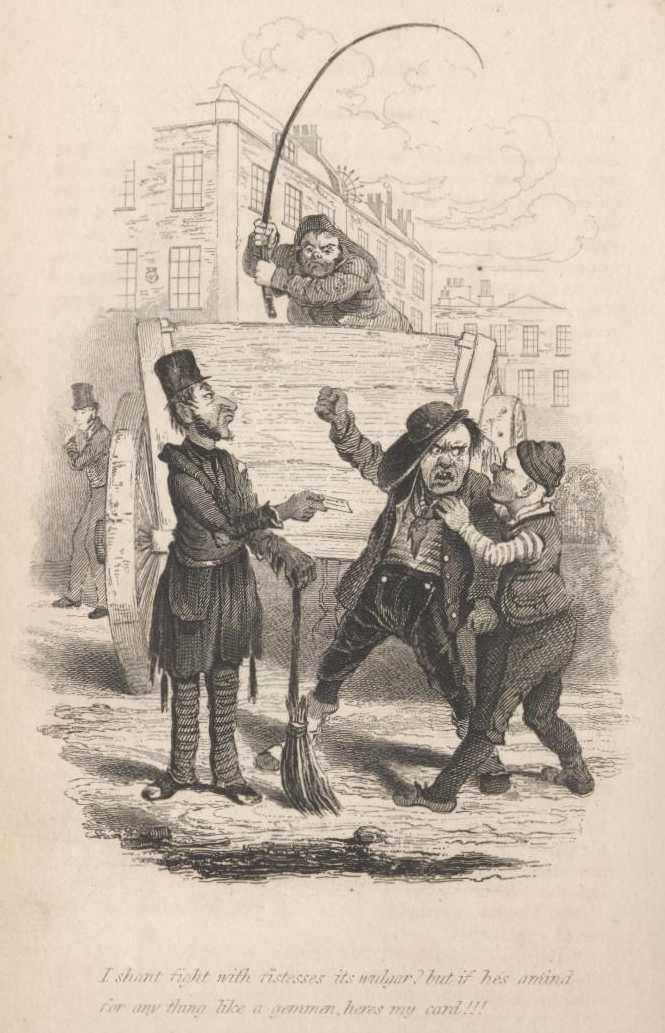

The Sportsmen trespass on an Enclosure—Grubb gets on a paling and runs a risk of being impaled.

“Twig them trees?”—said Grubb.

“Prime!” exclaimed Spriggs, “and vith their leaves ve'll have an hunt there.—Don't you hear the birds a crying 'sveet,' 'sveet?' Thof all birds belong to the Temperance Society by natur', everybody knows as they're partic'larly fond of a little s'rub!”

“Think ve could leap the ditch?” said Mr. Richard, regarding with a longing look the tall trees and the thick underwood.

“Lauk! I'll over it in a jiffy,” replied the elastic Mr. Spriggs there ain't no obelisk a sportsman can't overcome”—and no sooner had he uttered these encouraging words, than he made a spring, and came 'close-legged' upon the opposite bank; unfortunately, however, he lost his balance, and fell plump upon a huge stinging nettle, which would have been a treat to any donkey in the kingdom!

“Oh!—cuss the thing!” shrieked Mr. Spriggs, losing his equanimity with his equilibrium.

“Don't be in a passion, Spriggs,” said Grubb, laughing.

“Me in a passion?—I'm not in a passion—I'm on'y—on'y—nettled!” replied he, recovering his legs and his good humour. Mr. Grubb, taking warning by his friend's slip, cautiously looked out for a narrower part of the ditch, and executed the saltatory transit with all the agility of a poodle.

They soon penetrated the thicket, and a bird hopped so near them, that they could not avoid hitting it.—Grubb fired, and Sprigg's gun echoed the report.

“Ve've done him!” cried Spriggs.

“Ve!—me, if you please.”

“Vell—no matter,” replied his chum, “you shot a bird, and I shot too!—Vot's that?—my heye, I hear a voice a hollering like winkin; bolt!”

Away scampered Spriggs, and off ran Grubb, never stopping till he reached a high paling, which, hastily climbing, he found himself literally upon tenter-hooks.

“There's a man a coming, old fellow,” said an urchin, grinning.

“A man coming! vich vay? do tell me vich vay?” supplicated the sportsman. The little rogue, however, only stuck his thumb against his snub nose—winked, and ran off.

But Mr. Grubb was not long held in suspense; a volley of inelegant phrases saluted his ears, while the thong of a hunting-whip twisted playfully about his leg. Finding the play unequal, he wisely gave up the game—by dropping his bird on one side, and himself on the other; at the same time reluctantly leaving a portion of his nether garment behind him.

“Here you are!” cried his affectionate friend,—picking him up—“ain't you cotch'd it finely?”

“Ain't I, that's all?” said the almost breathless Mr. Grubb, “I'm almost dead.”

“Dead!—nonsense—to be sure, you may say as how you're off the hooks! and precious glad you ought to be.”

“Gracious me! Spriggs, don't joke; it might ha' bin werry serious,” said Mr. Grubb, with a most melancholy shake of the head:—“Do let's get out o' this wile place.”

“Vy, vat the dickins!” exclaimed Spriggs, “you ain't sewed up yet, are you?”

“No,” replied Grubb, forcing a smile in spite of himself, “I vish I vos, Spriggs; for I 've got a terrible rent here!” delicately indicating the position of the fracture.

And hereupon the two friends resolving to make no further attempt at

bush-ranging, made as precipitate a retreat as the tangled nature of the

preserve permitted.

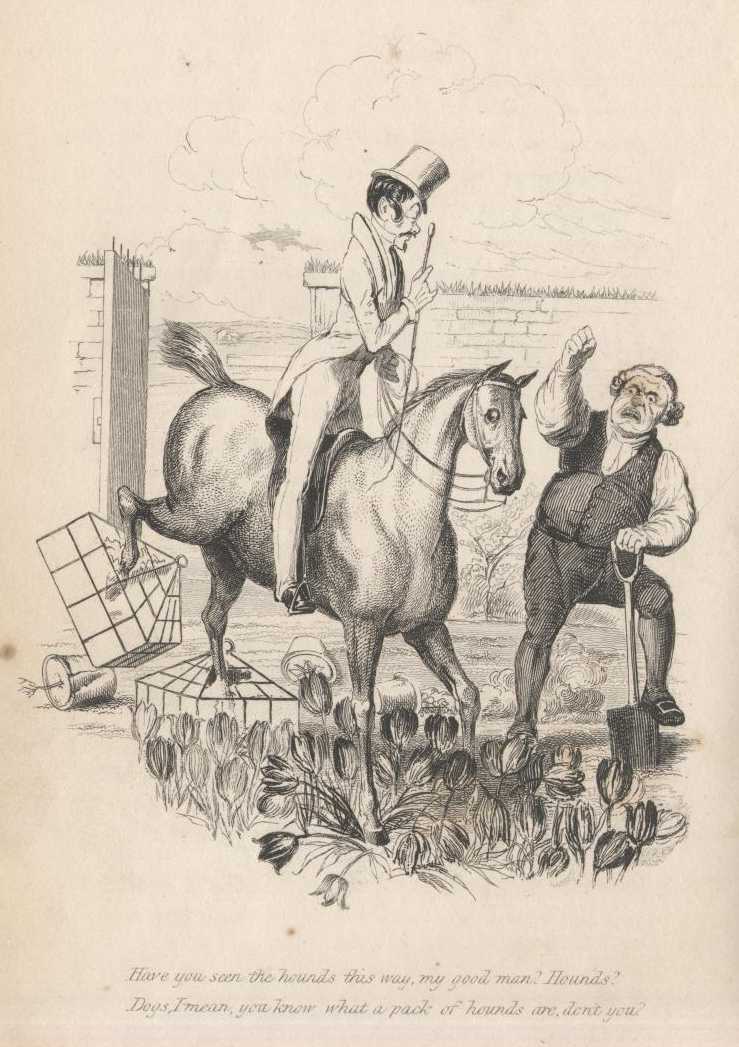

Shooting a Bird, and putting Shot into a Calf!

“ON'Y think ven ve thought o' getting into a preserve—that ve got into a pickle,” said Sprigg, still chuckling over their last adventure.

“Hush!” cried Grubb, laying his hand upon his arm—“see that bird hopping there?”

“Ve'll soon make him hop the twig, and no mistake,” remarked Spriggs.

“There he goes into the 'edge to get his dinner, I s'pose.”

“Looking for a 'edge-stake, I dare say,” said the facetious Spriggs.

“Now for it!” cried Grubb! “pitch into him!” and drawing his trigger he accidentally knocked off the bird, while Spriggs discharged the contents of his gun through the hedge.

“Hit summat at last!” exclaimed the delighted Grubb, scampering towards the thorny barrier, and clambering up, he peeped into an adjoining garden.

“Will you have the goodness to hand me that little bird I've just shot off your 'edge,” said he to a gardener, who was leaning on his spade and holding his right leg in his hand.

“You fool,” cried the horticulturist, “you've done a precious job— You've shot me right in the leg—O dear! O dear! how it pains!”

“I'm werry sorry—take the bird for your pains,” replied Grubb, and apprehending another pig in a poke, he bobbed down and retreated as fast as his legs could carry him.

“Vot's frightened you?” demanded Spriggs, trotting off beside his chum, “You ain't done nothing, have you?”

“On'y shot a man, that's all.”

“The devil!”

“It's true—and there'll be the devil to pay if ve're cotched, I can tell you—'Vy the gardener vill swear as it's a reg'lar plant!—and there von't be no damages at all, if so be he says he can't do no work, and is obleeged to keep his bed—so mizzle!” With the imaginary noises of a hot pursuit at their heels, they leaped hedge, ditch, and style without daring to cast a look behind them—and it was not until they had put two good miles of cultivated land between them and the spot of their unfortunate exploit that they ventured to wheel about and breathe again.

“Vell, if this 'ere ain't a rum go!”—said Spriggs—“in four shots—ve've killed a pig—knocked the life out o' one dicky-bird—and put a whole charge into a calf. Vy, if ve go on at this rate we shall certainly be taken up and get a setting down in the twinkling of a bed-post!”

“See if I haim at any think agin but vot's sitting on a rail or a post”—said Mr. Richard—“or s'pose Spriggs you goes on von side of an 'edge and me on t'other—and ve'll get the game between us—and then—”

“Thankye for me, Dick,” interrupted Spriggs, “but that'll be a sort o' cross-fire that I sha'n't relish no how.—Vy it'll be just for all the world like fighting a jewel—on'y ve shall exchange shots—p'r'aps vithout any manner o' satisfaction to 'ither on' us. No—no—let's shoot beside von another—for if ve're beside ourselves ve may commit suicide.”

“My vig!” cries Mr. Grubb, “there's a covey on 'em.”

“Vere?”

“There!”

“Charge 'em, my lad.”

“Stop! fust charge our pieces.”

Having performed this preliminary act, the sportsmen crouched in a dry ditch and crawled stealthily along in order to approach the tempting covey as near as possible.

Up flew the birds, and with trembling hands they simultaneously touched the triggers.

“Ve've nicked some on 'em.”

“Dead as nits,” said Spriggs.

“Don't be in an hurry now,” said the cautious Mr. Grubb, “ve don't know for certain yet, vot ve hav'n't hit.”

“It can't be nothin' but a balloon then,” replied Spriggs, “for ve on'y fired in the hair I'll take my 'davy.”

Turning to the right and the left and observing nothing, they boldly advanced in order to appropriate the spoil.

“Here's feathers at any rate,” said Spriggs, “ve've blown him to shivers, by jingo!”

“And here's a bird! hooray!” cried the delighted Grubb—“and look'ee, here's another—two whole 'uns—and all them remnants going for nothing as the linen-drapers has it!”

“Vot are they, Dick?” inquired Spriggs, whose ornithological knowledge was limited to domestic poultry; “sich voppers ain't robins or sparrers, I take it.”

“Vy!” said the dubious Mr. Richard-resting on his gun and throwing one leg negligently over the other—“I do think they're plovers, or larks, or summat of that kind.”

“Vot's in a name; the thing ve call a duck by any other name vould heat as vell!” declaimed Spriggs, parodying the immortal Shakspeare.

“Talking o' heating, Spriggs—I'm rayther peckish—my stomick's

bin a-crying cupboard for a hour past.—Let's look hout for a hinn!”

An extraordinary Occurrence—a Publican taking Orders.

TYING the legs of the birds together with a piece of string, Spriggs proudly carried them along, dangling at his fingers' ends.

After tramping for a long mile, the friends at length discovered, what they termed, an house of “hentertainment.”

Entering a parlour, with a clean, sanded floor, (prettily herring-boned, as the housemaids technically phrase it,) furnished with red curtains, half a dozen beech chairs, three cast-iron spittoons, and a beer-bleached mahogany table,—Spriggs tugged at the bell. The host, with a rotund, smiling face, his nose, like Bardolph's, blazing with fiery meteors, and a short, white apron, concealing his unmentionables, quickly answered the tintinabulary summons.

“Landlord,” said Spriggs, who had seated himself in a chair, while Mr. Richard was adjusting his starched collar at the window;—“Landlord! ve should like to have this 'ere game dressed.”

The Landlord eyed the 'game' through his spectacles, and smiled.

“Roasted, or biled, Sir?” demanded he.

“Biled?—no:—roasted, to be sure!” replied Spriggs, amazed at his pretended obtuseness: “and, I say, landlord, you can let us have plenty o' nice wedgetables.”

“Greens?” said the host;—but whether alluding to the verdant character of his guests, or merely making a polite inquiry as to the article they desired, it was impossible, from his tone and manner, to divine.

“Greens!” echoed Spriggs, indignantly; “no:—peas and 'taters.”

“Directly, Sir,” replied the landlord; and taking charge of the two leetle birds, he departed, to prepare them for the table.

“Vot a rum cove that 'ere is,” said Grubb.

“Double stout, eh?” said Spriggs, and then they both fell to a-laughing; “and certain it is, that, although the artist has only given us a draught of the landlord, he was a subject sufficient for a butt!

“Vell! I must, say,” said Grubb, stretching his weary legs under the mahogany, “I never did spend sich a pleasant day afore—never!”

“Nor I,” chimed in Spriggs, “and many a day ven I'm a chopping up the 'lump' shall I think on it. It's ralely bin a hout and houter! Lauk! how Suke vill open her heyes, to be sure, ven I inform her how ve've bin out with two real guns, and kill'd our own dinner. I'm bless'd if she'll swallow it!”

“I must say ve have seen a little life,” said Grubb.

“And death too,” added Spriggs. “Vitness the pig!”

“Now don't!” remonstrated Grubb, who was rather sore upon this part of the morning's adventures.

“And the gardener,”—persisted Spriggs.

“Hush for goodness sake!” said Mr. Richard, very seriously, “for if that 'ere affair gets vind, ve shall be blown, and—”

—In came the dinner. The display was admirable and very abundant, and the keen air, added to the unusual exercise of the morning, had given the young gentlemen a most voracious appetite.

The birds were particularly sweet, but afforded little more than a mouthful to each.

The 'wedgetables,' however, with a due proportion of fine old Cheshire, and bread at discretion, filled up the gaps. It was only marvellous where two such slender striplings could find room to stow away such an alarming quantity.

How calm and pleasant was the 'dozy feel' that followed upon mastication, as they opened their chests (and, if there ever was a necessity for such an action, it was upon this occasion,) and lolling back in their chairs, sipped the 'genuine malt and hops,' and picked their teeth!

The talkative Spriggs became taciturn. His gallantry, however, did prompt him, upon the production of a 'fresh pot,' to say,

“Vell, Grubbs, my boy, here's the gals!”

“The gals!” languidly echoed Mr. Richard, tossing off his tumbler, with a

most appropriate smack.

The Reckoning.

“PULL the bell, Spriggs,” said Mr. Richard, “and let's have the bill.”

Mr. Augustus Spriggs obeyed, and the landlord appeared.

“Vot's to pay?”

“Send you the bill directly, gentlemen,” replied the landlord, bowing, and trundling out of the room.

The cook presently entered, and laying the bill at Mr. Grubb's elbow, took off the remnants of the 'game,' and left the sportsmen to discuss the little account.

“My eye! if this ain't a rum un!” exclaimed Grubb, casting his dilating oculars over the slip.

“Vy, vot's the damage?” enquired Spriggs.

“Ten and fourpence.”

“Ten and fourpence!—never!” cried his incredulous companion. “Vot a himposition.”

“Vell!” said Mr. Grubb, with a bitter emphasis, “if this is finding our own wittles, we'll dine at the hor'nary next time”—

“Let's have a squint at it,” said Mr. Spriggs, reaching across the table; but all his squinting made the bill no less, and he laid it down with a sigh. “It is coming it rayther strong, to be sure,” continued he; “but I dare say it's all our happearance has as done it. He takes us for people o' consequence, and”—

“Vot consequence is that to us?” said Grubbs, doggedly.

“Vell, never mind, Dick, it's on'y vonce a-year, as the grotto-boys says—”

“It need'nt to be; or I'll be shot if he mightn't vistle for the brads. Howsomever, there's a hole in another suv'rin.”

“Ve shall get through it the sooner,” replied the consoling Spriggs. “I see, Grubb, there aint a bit of the Frenchman about you”—

“Vy, pray?”

“Cos, you know, they're fond o' changing their suv'rins, and—you aint!”

The pleasant humour of Spriggs soon infected Grubb, and he resolved to be jolly, and keep up the fun, in spite of the exorbitant charge for the vegetable addenda to their supply of game.

“Come, don't look at the bill no more,” advised Spriggs, “but treat it as old Villiams does his servants ven they displeases him.”

“How's that?”

“Vy, discharge it, to be sure,” replied he.

This sage advice being promptly followed, the sportsmen, shouldering their guns, departed in quest of amusement. They had not, however, proceeded far on their way, before a heavy shower compelled them to take shelter under a hedge.

“Werry pleasant!” remarked Spriggs.

“Keep your powder dry,” said Grubb.

“Leave me alone,” replied Spriggs; “and I think as we'd better pop our guns under our coat-tails too, for these ere cocks aint vater-cocks, you know! Vell, I never seed sich a rain. I'm bless'd if it vont drive all the dickey-birds to their nestes.”

“I vish I'd brought a numberella,” said Grubbs.

“Lank! vot a pretty fellow you are for a sportsman!” said Spriggs, “it don't damp my hardour in the least. All veathers comes alike to me, as the butcher said ven he vos a slaughtering the sheep!”

Mr. Richard Grubb, here joined in the laugh of his good-humoured friend, whose unwearied tongue kept him in spirits—rather mixed indeed than neat—for the rain now poured down in a perfect torrent.

“I say, Dick,” said Spriggs, “vy are ve two like razors?”

“Cos ve're good-tempered?”

“Werry good; but that aint it exactly—cos ve're two bright blades, vot has got a beautiful edge!”

“A hexcellent conundrum,” exclaimed Grubb. “Vere do you get 'em?'

“All made out of my own head,—as the boy said ven be showed the

wooden top-spoon to his father!”

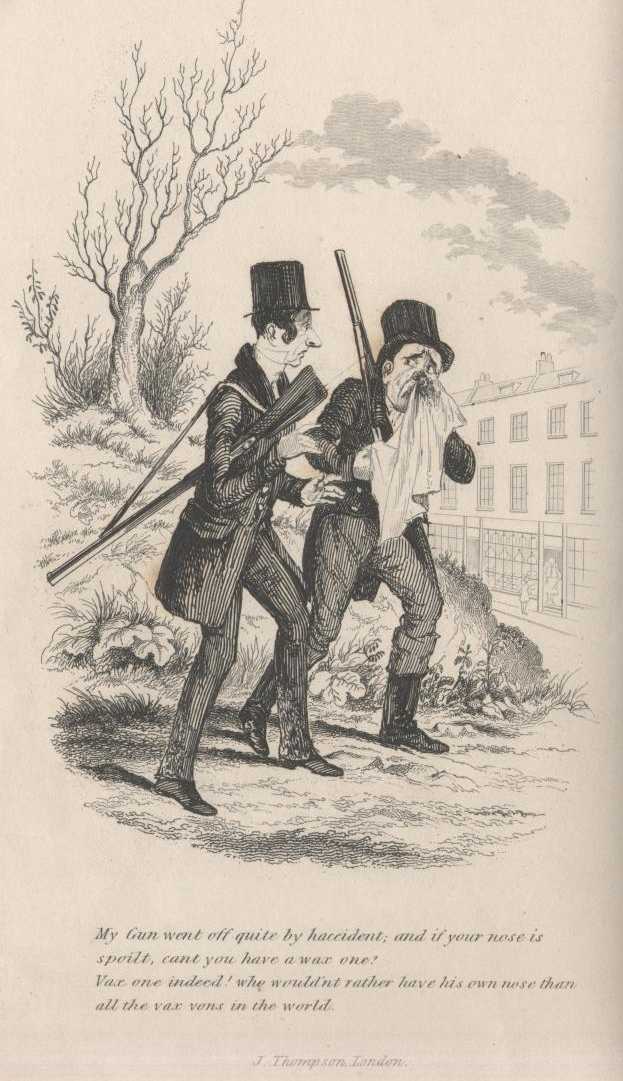

A sudden Explosion—a hit by one of the Sportsmen, which the other takes amiss.

A blustering wind arose, and like a burly coachman on mounting his box, took up the rain!

The two crouching friends taking advantage of the cessation in the storm, prepared to start. But in straightening the acute angles of their legs and arms, Mr. Sprigg's piece, by some entanglement in his protecting garb, went off, and the barrel striking Mr. Grubb upon the os nasi, stretched him bawling on the humid turf.

“O! Lord! I'm shot.”

“O! my heye!” exclaimed the trembling Spriggs.

“O! my nose!” roared Grubb.

“Here's a go!”

“It's no go!—I'm a dead man!” blubbered Mr. Richard. Mr. Augustus Spriggs now raised his chum upon his legs, and was certainly rather alarmed at the sanguinary effusion.

“Vere's your hankercher?—here!—take mine,—that's it—there!—let's look at it.”

“Can you see it?” said Grubb, mournfully twisting about his face most ludicrously, and trying at the same time to level his optics towards the damaged gnomon.

“Yes!”

“I can't feel it,” said Grubb; “it's numbed like dead.”

“My gun vent off quite by haccident, and if your nose is spoilt, can't you have a vax von?—Come, it ain't so bad!”

“A vax von, indeed!—who vouldn't rather have his own nose than all the vax vons in the vorld?” replied poor Richard. “I shall never be able to show my face.”

“Vy not?—your face ain't touched, it's on'y your nose!”

“See, if I come out agin in an hurry,” continued the wounded sportsman. “I've paid precious dear for a day's fun. The birds vill die a nat'ral death for me, I can tell you.”

“It vos a terrible blow—certainly,” said Spriggs; “but these things vill happen in the best riggle'ated families!”

“How can that be? there's no piece, in no quiet and respectable families as I ever seed!”

And with this very paradoxical dictum, Mr. Grubb trudged on, leading himself by the nose; Spriggs exerting all his eloquence to make him think lightly of what Grubb considered such a heavy affliction; for after all, although he had received a terrible contusion, there were no bones broken: of which Spriggs assured his friend and himself with a great deal of feeling!

Luckily the shades of evening concealed them from the too scrutinizing observation of the passengers they encountered on their return, for such accidents generally excite more ridicule than commiseration.

Spriggs having volunteered his services, saw Grubb safe home to his door in Tower Street, and placing the two guns in his hands, bade him a cordial farewell, promising to call and see after his nose on the morrow.

The following parody of a customary paragraph in the papers will be considered, we think, a most fitting conclusion to their day's sport.

“In consequence of a letter addressed to Mr. Augustus Spriggs, by Mr.

Richard Grubb, the parties met early yesterday morning, but after firing

several shots, we are sorry to state that they parted without coming to

any satisfactory conclusion.”

“Shoot away, Bill! never mind the old woman—she can't get over the wall to us.”

One day two urchins got

A pistol, powder, horn,

and shot,

And proudly forth they went

On sport intent.

"Oh,

Tom! if we should shoot a hare,”

Cried one,

The elder son,

"How

father, sure, would stare!”

"Look there! what's that?”

"Why, as

I live, a cat,”

Cried Bill, “'tis mother Tibbs' tabby;

Oh! what

a lark

She loves it like a babby!

And ain't a cat's eye, Tom, as

good a mark

As any bull's eyes?”

And straight “Puss! puss!” he

cries,

When, lo! as Puss approaches,

They hear a squall,

And

see a head and fist above the wall.

'Tis tabby's mistress

Who in

great distress

Loads both the urchins with her loud reproaches,

"You

little villains! will ye shoot my cat?

Here, Tink! Tink! Tink!

O!

lor' a' mercy! I shall surely sink,

Tink! Tink!”

Tink hears her

voice—and hearing that,

Trots nearer with a pit-a-pat!

"Now,

Bill, present and fire,

There's a bold 'un,

And send the tabby

to the old 'un.”

Bang! went the pistol, and in the mire

Rolled

Tink without a mew—

Flop! fell his mistress in a stew!

While

Bill and Tom both fled,

Leaving the accomplish'd Tink quite finish'd,

For Bill had actually diminish'd

The feline favorite by a head!

Leaving his undone mistress to bewail,

In deepest woe,

And

to her gossips to relate

Her tabby's fate.

This was her only

consolation—for altho'

She could not tell the head—she

could the tail!

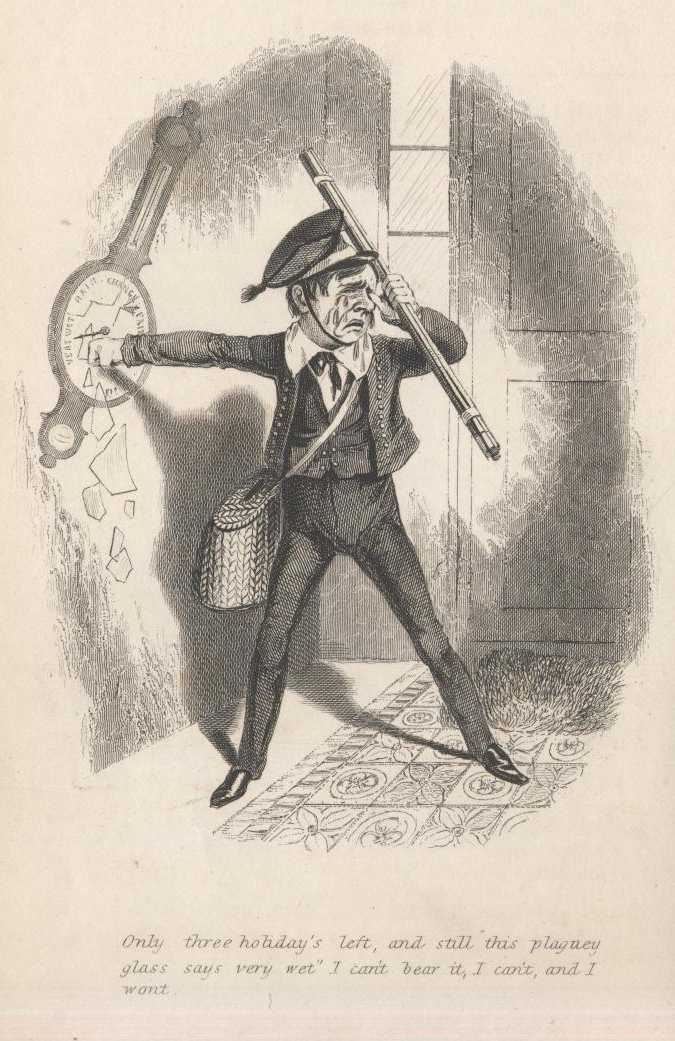

SEPTEMBER 1ST,—AN ONLY OPPORTUNITY.

“I begin to think I may as well go back.”

MY vig! vat a pelter this is—

Enough all

my hardour to tame;

In veather like this there's no sport,

It's

too much in earnest for game!

A ladle, I might as well be,

Chain'd fast to a hold parish pump,

For, by goles! it comes tumbling down,

Like vinking,—and

all of a lump.

The birds to their nestes is gone,

I can't see no woodcock, nor

snipe;

My dog he looks dogged and dull,

My leggins is flabby as

tripe!

The moors is all slipp'ry slush,

I'm up to the neck in the mire;

I don't see no chance of a shot,

And I long-how I long for a

fire!

For my clothes is all soak'd, and they stick

As close as a bailiff to

me

Oh! I wish I was out o' this here,

And at home with my mother

at tea!

This is the fust, as I've got

Permission from uncle to shoot;

He

hadn't no peace till he give

This piece, and the powder to boot!

And vat's it all come to at last?—

There isn't no chance of a

hit,

I feel the rain's all down my back,

In my mouth though I

hav'n't a bit!

O! it's werry wezaatious indeed!

For I shan't have another day soon;

But I'm blow'd, if I don't have a pop—

My eye! I've shot

Dash! vot a spoon!

O! here's a partic'lar mess,

Vot vill mother say to me now?

For

he vas her lap-dog and pet,

Oh! I've slaughtered her darling bow-wow!

“Mother says fishes comes from hard roes, so I chuck'd in the roe of a red-herring last week, but I doesn't catch any fish yet.”

How beautiful is the simplicity of unsophisticated youth! Behold with what patience this innocent awaits a bite, trusting with perfect faith in the truth of his affectionate mother's ichthyological knowledge. Wishing to behold a live fish dangling at the end of his line, he has, with admirable foresight, drawn up the bucket, that in the ascent the finny prey may not kick it! It must be a hard roe indeed, that is not softened by his attentions; but, alas! he is doomed never to draw up a vulgar herring, or a well-bred fish!

Folks who are a little deeper read than the boy—(or the herring!)—may smile at his fruitless attempt, but how many are there that act through life upon the same principle, casting their lines and fishing for—compliments, who never obtain even a nibble—for why? their attempts at applause, like his red-herring, are smoked. He does not know that herrings are salt-water fish—and, in fact, that the well-water is not the roes—water!

But after all, is not such ignorance bliss?—for he enjoys the

anticipated pleasure; and if anticipation be really greater than reality—what

an interminable length will that pleasure be to him! Ever and anon he

draws up his line, like a militia captain for a review;—puts fresh

bait on the crooked pin, and lets it slowly down, and peeps in, wondering

what the fish can be at!—and is quite as much in the dark as his

float. But he may at last, perhaps, discover that he is not so deep as a

well—and wisely resolve to let well—alone; two points which

may probably be of infinite importance to him through life, and enable him

to turn the laugh against those who now mock his ignorance and simplicity.

Ambition.

“He was ambitious, and I slew him.”

WHAT carried Captain Ross to the North Pole? “A ship to be sure!” exclaims some matter-of-fact gentleman. Reader! It was AMBITION!

What made barber Ross survey the poll, make wigs, and puff away even when powder was exploded? What caused him to seek the applause of the 'nobs' among the cockneys, and struggle to obtain the paradoxical triplicate dictum that he was a werry first-rate cutter!' What made him a practical Tory? (for he boasts of turning out the best wigs in the country!)

What induces men to turn theatrical managers when a beggarly account of empty boxes nightly proves the Drama is at a discount—all benefits visionary, and the price of admission is regarded as a tax, and the performers as ex-actors!—when they get scarcely enough to pay for lights, and yet burn their fingers?—AMBITION!

The candidate for the county cringes, and flatters the greasy unwashed ten-pounders, in order to get at the head of the poll—so likewise the bumpkin (in imitation of his superior) rubs his hand in the dirt to enable him to cling fast, and reach the top of the soap'd poll, whereon the tempting prize is displayed. And, what prompts them both to the contest?—AMBITION!

What is the 'primum mobile,' of the adventurous Aeronaut, Mr. Green, one of the most rising men of the day, who aspires even unto the very clouds, and in his elevation looks upon all men of woman born as far beneath him?—AMBITION!

What prompts the soldier who spends half-a-crown out of sixpence a-day to thrust his head into the cannon's mouth, to convince the world that he is desirous of obtaining a good report and that he is fearless of the charge?—AMBITION!

What makes the beardless school-boy leap ditches and over posts at the risk of his neck, and boast that he'll do another's dags'—or the sporting man turn good horses into filthy dog's meat, in riding so many miles in so many minutes?—AMBITION!

What magic influence operates upon the senses of the barrister (a scholar and a gentleman) to exert his winning eloquence and ingenuity in the cause of a client, who, in his conscience, he knows to be both morally and legally unworthy of the luminous defence put forth to prove the trembling culprit more sinned against than sinning?—AMBITION!

What urges the vulgar costermonger to bestride his long-ear'd Arabian, and

belabor his panting sides with merciless stick and iron-shod heels to

impel him to the goal in the mimic race—or the sleek and polish'd

courtier to lick the dust of his superiors' feet to obtain a paltry riband

or a star?—AMBITION!

Better luck next time.

The lamentation of Joe Grishin.

“O! Molly! Molly! ven I popp'd my chops through the arey railings, and seed you smile, I thought you vos mine for ever! I wentur'd all for you—all—. It war'n't no great stake p'r'aps, but it was a tender vun! I offer'd you a heart verbally, and you said 'No!' I writ this ere wollentine, and you returns it vith a big 'No!'

“O! Molly your 'No's,' is more piercinger and crueller than your heyes. Me! to be used so:—Me! as refused the vidder at the Coal Shed! (to be sure she wore a vig and I didn't vant a bald rib!) Me!—but it's o' no use talking; von may as vell make love to a lamp-post, and expect to feed von's flame vith lights! But adoo to life; this 'ere rope, fix'd round the 'best end o' the neck' will soon scrap me, and ven I'm as dead as mutton, p'r'aps you may be werry sorry.

“It'll be too late then, Molly, ven you've led me to the halter, to vish as you'd married me.”

After this bitter burst of wounded feeling, and, urged by the rejection of his addresses, the love-lorn Butcher mounted a joint-stool, and stepping on a fence, twisted the awful rope round the branch of a tree, and then, coiling it about his neck, determined that this day should be a killing day; vainly supposing, in the disordered state of his mind, that the flinty-hearted Molly would probably esteem her 'dear' (like venison) the better for being hung! Mystically muttering 'adoo!' three times, in the most pathetic tone, he swung off and in an instant came to his latter end—for the rope snapp'd in twain, and he found himself seated on the turf below, when he vainly imagined he was preparing himself for being placed below the turf!

“Nothin' but disappointments in this world;” exclaimed he, really feeling hurt by the unexpected fall, for he had grazed his calves in the meadow, and was wofully vexed at finding himself a lover 'turned off' and yet 'unhung.'

Cast down and melancholy, he retraced his steps, and seizing a cleaver

(dreadful weapon!) vented his suicidal humour in chopping, with malignant

fury, at his own block!

Don't you be saucy, Boys

“WHAT are you grinning at, boys?” angrily demanded an old gentleman seated beside a meandering stream, of two schoolboys, who were watching him from behind a high paling at his rear.—“Don't you know a little makes fools laugh.”

“Yes, sir! that's quite true, for we were laughing at what you've caught!”

“Umph! I tell you what, my lads, if I knew your master, I'd pull you up, and have you well dressed.”

“Tell that to the fishes,” replied the elder, “when you do get a bite!”

“You saucy jackanapes! how dare you speak to me in this manner?”

“Pray, sir, are you lord of the manor? I'm sure you spoke to us first,” said the younger.

“More than that,” continued his companion. “We are above speaking to you, for you are beneath us!”

The old gentleman, rather nettled at the glibness of the lads, stuck a hook vengefully into an inoffensive worm, and threw his line.

The boys still retained their post, and after many whispered remarks and tittering, the younger thrust his handkerchief into his mouth to smother a burst of irrepressible laughter, while the other, assuming a modest and penitent air, said:

“I beg your pardon, sir.”

“What?” demanded the old gentleman sharply.

“Hope you are not offended, sir?”

“Get along with you,” replied the unfortunate angler, irritated at his want of success.

“I can tell you something, sir,” continued the lad;—“there's no fish to be had where you are. I know the river well. Father's very fond o' fish; he always brings home plenty. If you like, sir, I can show you the place.”

Here his companion rolled upon the grass and kicked, perfectly convulsed with laughter, luckily hidden from the view of the now mollified old gentleman.

“Indeed!” cried the angler: “is it far from this?”

“Not a quarter of a mile,” replied the boy.

“That is nothing. I've walked eighteen this morning,” said the old gentleman, packing up his apparatus. “I'll go with you directly, and thank you too, for I'm a perfect stranger in these parts.”

When he had joined them, the laughing fits of the younger had subsided, although he chose to fall in the rear. “Now, to shew you how much more profitable it is to respect than to mock at your superiors in years, there's a (let me see)—there's a halfpenny for you to purchase cakes.”

“Thank ye, sir,” said he, and turning to his companion with a wink: “Here Bill, run to Cummins' and buy a ha'p'orth of eights—we'll make the most of it—and I'll come to you as soon as I've shown the gentleman the fish.”

“Show me the place, and I'll find the fish,” said the anticipating angler.

On they trudged.

“Must we go through the town?” asked his companion, as he marched with his long rod in one hand and his can in the other.

“Yes, sir, it ain't far;” and he walked on at a quicker pace, while all the crowd of rustics gazed at t e extraordinary appearance of the armed Waltonian, for it happened to be market-day. After parading him in this fashion nearly through the town, he presently twitched him by his coat-sleeve.

“Look there, sir!” cried he, pointing to a well-stocked fishmonger's.

“Beautiful!—what a quantity!” exclaimed the venerable piscator.

“I thought you'd like it, sir—that's the place for fish, sir,—good morning.”

“Eh! what—you young dog?”

“That's where father gets all his, I assure you, sir,—good morning,”

said the youth, and making a mock reverence, bounded off as fast as his

legs could carry him.

“Vy, Sarah, you're drunk! I am quite ashamed o' you.”

“Vell, vots the odds as long as you're happy!”

JACK was an itinerant vender of greens, and his spouse was a peripatetic distributor of the finny tribe, (sprats, herrings or mackerel, according to the season,) and both picked up a tolerable livelihood by their respective callings.

Like the lettuces he sold, Jack had a good heart, and his attention was first attracted to the subsequent object of his election by the wit of a passing boy, who asked the damsel how she sold her carrots? Jack's eyes were in an instant turned towards one whom he considered a competitor in the trade—when he beheld the physiognomy of his Sarah beaming with smiles beneath an abundant crop of sunny hair!

“You are a beauty and no mistake,” exclaimed the green grocer in admiration.

“Flummery!” replied the damsel—the deep blush of modesty mantling her cheeks. Jack rested his basket on a post beside her stall, and drank deep draughts of love, while Sarah's delicate fingers were skilfully employed in undressing a pound of wriggling eels for a customer.

“Them's rig'lar voppers!” remarked Jack.

“Three to a pound,” answered Sarah, and so they slipped naturally into discourse upon trade, its prospects and profits, and gradually a hint of partnership was thrown out.

Sarah laughed at his insinuating address, and displayed a set of teeth that rivalled crimped skate in their whiteness—a month afterwards they became man and wife. For some years they toiled on together—he, like a caterpillar, getting a living out of cabbages, and she, like an undertaker, out of departed soles! Latterly, however, Jack discovered that his spouse was rather addicted to 'summut short,' in fact, that she drank like a fish, although the beverage she affected was a leetle stronger than water. Their profit (unlike Mahomet) permitted them the same baneful indulgence—and kept them both in spirits!

Their trade, however, fell off for they were often unable to carry their baskets.

The last time we beheld them, Sarah was sitting in the cooling current of a gutter, with her heels upon the curb (alas! how much did she need a curb!) while Jack, having disposed of his basket, had obtained a post in a public situation, was holding forth on the impropriety of her conduct.

“How can you let yourself down so?” said he,—“You're drunk—drunk, Sarah, drunk!”

“On'y a little elevated, Jack.”

“Elevated!—floor'd you mean.”

“Vell; vot's the odds as long as you're happy?”

Jack finding all remonstrance was vain, brought himself up, and reeling

forward, went as straight home—as he could, leaving his spouse (like

many a deserted wife) soaking her clay, because he refused to support her!

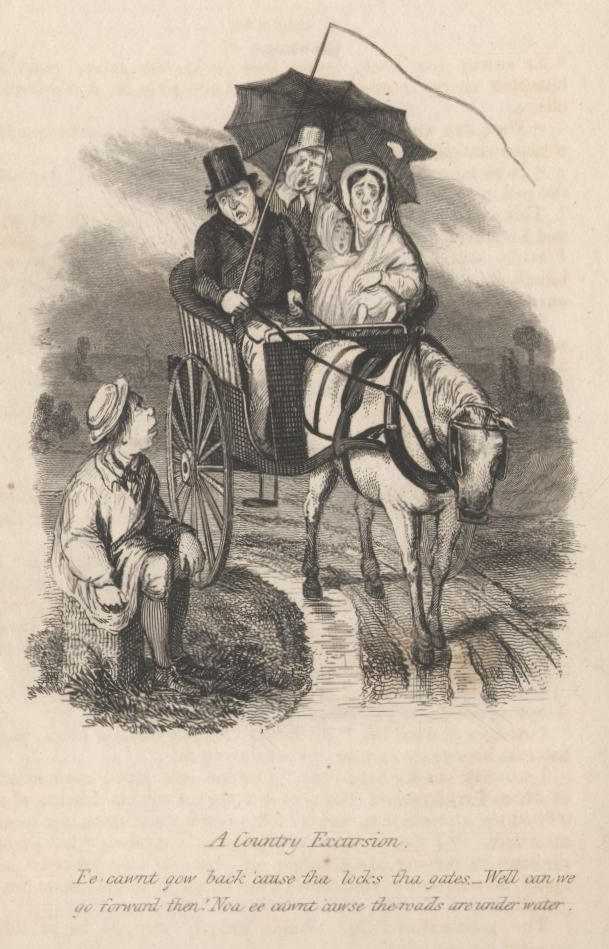

“Lawk a'-mercy! I'm going wrong! and got to walk all that way back again.”

A PEDESTRIAN may get robbed of his money on the highway, but a cross-road frequently robs him of time and patience; for when haply he considers himself at his journey's end, an impertinent finger-post, offering him the tardy and unpleasant information that he has wandered from his track, makes him turn about and wheel about, like Jim Crow, in anything but a pleasant humor.

It were well if every wayfarer were like the sailor, who when offered a quid from the 'bacoo box of a smoker, said, 'I never chews the short-cut!' and in the same spirit, we strongly advise him, before he takes the short-cut to think of the returns!

Should the weather prove rainy, the hungry traveller may certainly get a wet on the road, although he starves before he reaches the wished-for inn.

As there is likewise no more chance of meeting a good tempered guide on a cross-road, than of finding eggs and bacon, in an edible state, at least on a common—and as he can no more pull in the summer-rains than he can the reins of a runaway stallion; the result is, the inexperienced youth ludicrously represents so many pounds of 'dripping,' and although he may be thirsty, he will have no cause to complain that he is—dry! The best mode for an honest man to go round the country, is to take a straight-forward course, especially when the surcharged clouds do rule the horizon with sloping lines of rain! Besides, it is by no means a pleasant thing for a man with a scanty wardrobe, to find his clothes running away at a most unpleasant rate, while he can scarcely drag one clay-encumbered leg after the other.

It is a difficult trial, too, of a man's philosophy, after trudging over a long field, to be encountered by the mockery of a 'ha! ha!'—fence! He utters a few bitter expletives, perhaps, but nought avails his railing against such a fence as that!

The shower which makes all nature smile, only causes him to laugh—on the wrong side of his mouth, for he regards it as a temperance man does a regular soaker!

Reader! never attempt a bye-way on a wet day, with a stick and bundle at

your back—(if you have a waterproof trunk, you may indeed weather

it)—but go a-head on the turnpike road—the way of all mails—leaving

long and short commons to the goose and donkey—and the probability

is, that you may not only I make a sign before you die, but get a feed—and

a shelter.

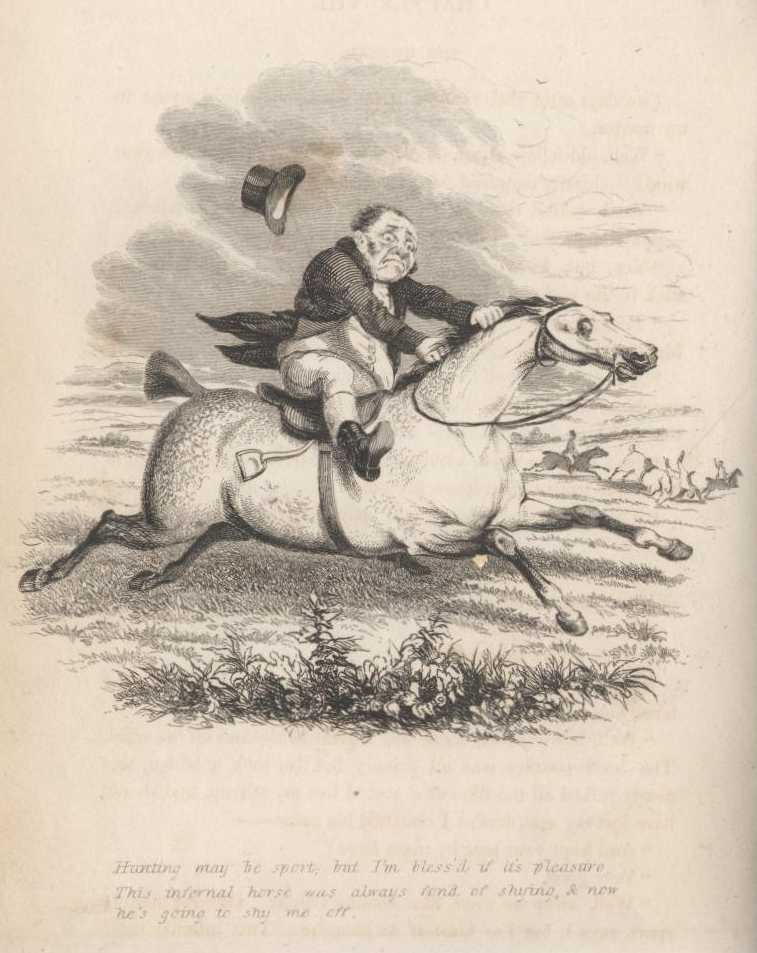

“I'm dem'd if I can ever hit 'em.”

IT is a most extraordinary thing, 'pon my veracity: I go out as regularly as the year, and yet I never bring down an individual bird.

I have one of the best Mantons going with such a bore! and then I use the best shot—but not being the best shot in the world myself—I suppose is the identical reason why I never hit any thing. I think it must arise from a natural defect in my sight; for when I suppose a covey as near—as my miser of an uncle—they are probably as distant—as my ninety-ninth cousin!

Such a rum go!—the other day I had a troop of fellows at my heels, laughing like mad; and what do you think?—when I doffed my shooting jacket, I found some wag had stuck the top of a printed placard on my back, with the horrid words, “A young Gentleman missing!”

It was only last week, a whole flight of sparrows rose at my very feet—I fired—bang!—no go!—but I heard a squall; and elevating my glass, lo! I beheld a cottage within a few yards of my muzzle—the vulgar peasant took the trouble to leap his fence, and inform me I had broken his windows—of course I was compelled to pay him for his panes.

To be sure he did rather indicate a disposition to take away my gun—which I certainly should never have relinquished without a struggle—and so I forked out the dibs, in order to keep the piece! I'm quite positive, however, that the vagabond over-charged me, and I kicked, as was quite natural, you know, under such circumstances!

I really have an imperfect notion of disposing of my shooting-tackle—but

I'm such an unfortunate devil, that I really believe when I post 'em up

for sale—my gun will not go off!—dem me!

“Have you read the leader in this paper, Mr. Brisket?”

“No! I never touch a newspaper; they are all so werry wenal, and Ovoid of sentiment!”

BOB.

O! here's a harticle agin the fools,

Vich our poor British

Nation so misrules:

And don't they show 'em up with all their tricks—

By gosh! I think they'd better cut their sticks;

They never can

surwive such cuts as these is!

BRISKET.

It's werry well; but me it never pleases;

I never reads

the news, and sees no merit

In anythink as breathes a party sperrit.

BOB.

Ain't you a hinglishman? and yet not feel

A hint'rest,

Brisket, in the common-weal?

BRISKET.

The common-weal be—anything for me,—

There

ain't no sentiment as I can see

In all the stuff these sons of—Britain

prate—

They talk too much and do too little for the state.

BOB.

O! Brisket, I'm afeard as you're a 'Rad?'

BRISKET.

No, honour bright! for sin' I was a lad

I've stuck

thro' thick and thin to Peel, or

Vellinton—for Tories is

genteeler;

But I'm no politician. No! I read

These 'Tales of

Love' vich tells of hearts as bleed,

And moonlight meetins in the

field and grove,

And cross-grain'd pa's and wictims of true love;

Wirgins in white a-leaping out o' winders—

Vot some old

codger cotches, and so hinders—

From j'ining her true-love to

tie the knot,

Who broken-hearted dies upon the spot!

BOB.

That's werry fine!—but give me politics—

There's

summat stirring even in the tricks

Of them vot's in to keep the

t'others out,—

How I Should like to hear the fellers spout!

For some on 'em have sich a lot o' cheek,

If they war'n't

stopp'd they'd go it for a week.

BRISKET.

But they're so wulgar, Bob, and call sich names

As

quite the tag-rag of St. Giles' shames

The press too is so wenal,

that they think

All party herrors for the sake o' chink.

BOB.

But ain't there no false lovers in them tales,

Vot hover

wirgin hinnocence perwails?

BRISKET.

Vy, yes, but in the end the right one's married,

And

after much to do the point is carried

So give me love sincere and

tender,

And all the rest's not worth a bender.

AN EPISTLE

FROM

SAMUEL SOFTLY, ESQ. TO HIS FRIEND, RICHARD GUBBINS, ESQ. OF TOOLEY STREET.

O! DICK!

Such a misfortin' has you never heard on as come upon your friend. I'll jist give you a breef houtline of the circumstantials as near as my flurry vill let me. T'other mornin' I vips up my gun for to go a-shootin', and packin' up my hammunition, and some sanwidges, I bids adoo to this wile smoky town, vith the intention of gettin' a little hair. Vell! on I goes a-visshin' and thinkin' on nothin', and happy as the bumblebees as vos a-numming around me. Vell! a'ter an hour or more's valking, not an house nor a brick vos wisible.

Natur', in all her werdur', vos smilin' like a fat babby in its maternal harms! But, as somebody has it—

“Man never ain't, but al'ays to be bless'd,”

and I'm bless'd if that ain't true too, as you shall see presently. Vell! I pops at von bird and then at another; but vether the poor creturs vos unaccustom'd to guns, and so vos frighten'd, I don't know, but somehow I couldn't hit 'em no-how.

Vell! and so I vos jist a-chargin' agin ven a great he-fellow, in a ruff coat and partic'lar large viskers, accostes me (ciwilly I must say, but rayther familler)—

“Birds shy?” says he.

“Werry;—ain't hit nothin',” says I.

“I'll tell you vot it is, young gentleman,” says he, “it's the unevenness o' the ground!”

“D've think so?” says I.

“Sure on it,” says he; “I'm a hold sojer! Know this 'ere place, and have picked up many a good dinner in it. Look at them fe'l'fares yonder,” says he, “on'y let me have a slap at 'em for you, and see if I don't finish some on 'em in the twinkling of a pig's visper.”

In course I felt obleeged by sich a hoffer, and hands him the gun. Vell! I vos a-follerin' him quite pleased, ven he visks round, and puttin' the muzzle o' the hinstrument fist agin my vescoat, says he, “Now you've lent us your gun, you may as vell lend us your votch. I can't shoot any think for you till I sees vot's o'clock!”

Here vas a go!—but I see vot vas a clock in a hinstant—and no mistake. So I cotch'd hold on the two butiful chased seals and tugs it out.

“That's the time o' day!” says he, a-cockin' his hugly heye at the dial; “and now,” says he, “as you seems frightened at the gun, I shall jist put it out o' harm's way.”

And with that he chucks it splash, into a duck-pond, and hoff marches my hold sojer in a jiffy! I vos putrified! and fell to a-blubberin' like a hinfant.

O! Dick, vot's to be done?

You know I ham, at any rate,

Yours truly,

S. SOFTLY.

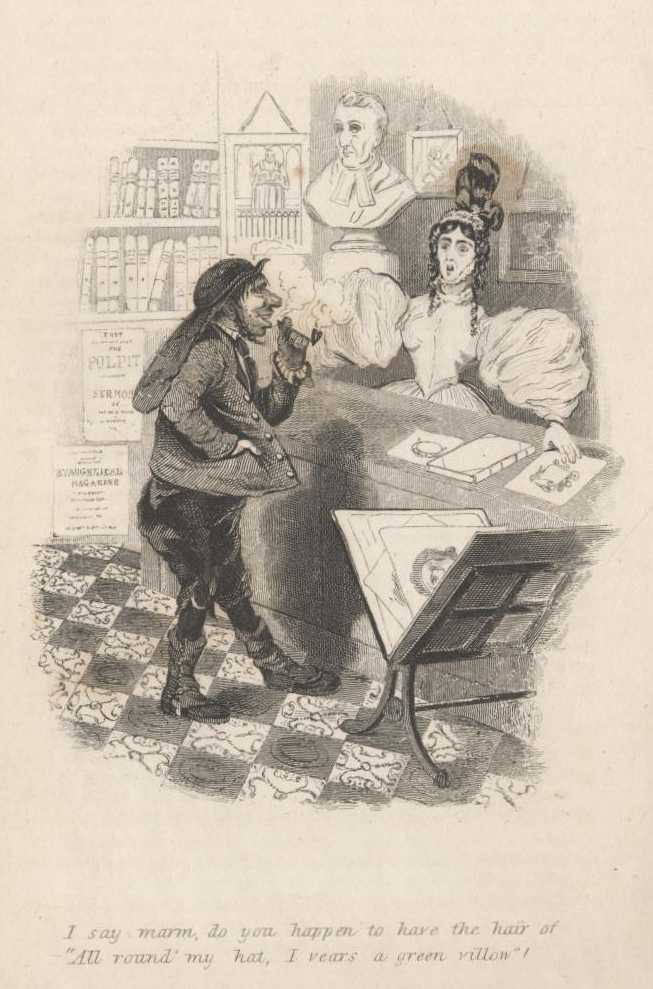

The Courtship of Mr. Wiggins.

AMONG the very few fashionable foibles to which Mr. Wiggins was addicted, was the smoking of cigars. Attracted by the appearance of a small box marked 'Marylands—one penny each,' very much resembling lettuce-leaves with the yellow jaundice, he walked into the chandler's shop where they were displayed.

“Let us look at them cigars,” said he, and then, for the first time, glancing at the smart, good-looking mistress of the emporium, he added, “if you please, ma'am—”

“Certain'y, sir.”

A pretty little fist that, howsomever! thought Wiggins, as she placed the box before him.

“Vill you have a light?”

“Thank'ye, ma'am,” said he, ramming the cigar into his mouth, as if he really intended to bolt it.

She twisted a slip of waste, and lighting it, presented it to her admiring customer, for it was evident, from the rapt manner in which he scanned her, that he was deeply smitten by her personal appearance.

She colored, coughed delicately, as the smoke tickled the tonsils of her throat, and looked full at the youth. Such a look! as Wiggins asserted. “I'm afeared as the smoke is disagreeable,” said he.

“Oh! dear no, not at all, I assure you; I likes it of all things. I can't abide a pipe no-how, but I've quite a prevalence (predilection?) for siggers.” So Wiggins puffed and chatted away; and at last, delighted with the sprightly conversation of the lady, seated himself on the small-beer barrel, and so far forgot his economy in the fascination of his entertainer, that he purchased a second. At this favourable juncture, Mrs. Warner, (for she was a widow acknowledging five-and-twenty) ordered the grinning shop-boy, who was chopping the 'lump,' to take home them 'ere dips to a customer who lived at some distance. Wiggins, not aware of the 'ruse,' felt pleased with the absence of one who was certainly 'de trop' in the engrossing 'tete-a-tete.' We will pass over this preliminary conversation; for a whole week the same scene was renewed, and at last Mrs. Warner and Mr. Wiggins used to shake hands at parting.

“Do you hever go out?” said Wiggns.

“Sildom-werry sildom,” replied the widow.

“Vos you never at the Vite Cundic, or the hEagle, or any of them places on a Sunday?”

“How can I go,” replied the widow, sighing, “vithout a purtector?”

Hereupon the enamoured Wiggins said, “How happy he should be,” etc., and

the widow said, “She was sure for her part,” etc. and so the affair was

settled. On the following Sunday the gallant Mr. Wiggins figged out, in

his best, escorted the delighted and delightful Mrs. Warner to that place

of fashionable resort, the White Conduit, and did the thing so handsomely,

that the lady was quite charmed. Seated in one of the snug arbors of that

suburban establishment, she poured out the hot tea, and the swain the most

burning vows of attachment. “Mr. Viggins, do you take sugar?” demanded the

fair widow. “Yes, my haingel,” answered he, emphatically. “I loves all

wot's sweet,” and then he gave her such a tender squeeze! “Done—do—you

naughty man!” cried she, tapping him on the knuckles with the plated

sugar-tongs, and then cast down her eyes with such a roguish modesty, that

he repeated the operation for the sake of that ravishing expression.

Pointing his knife at a pat of butter, he poetically exclaimed, “My heart

is jist like that—and you have made a himpression on it as time will

never put out!” “I did'nt think as you were quite so soft neither,” said

the widow. “I ham,” replied the suitor—“and there,” continued he,

cutting a hot roll, and introducing the pat, “I melts as easily afore the

glance of your beautiful heyes!” Resolved to carry on the campaign with

spirit, he called for two glasses of brandy and water, stiff, and three

cigars! And now, becoming sentimental and communicative, he declared, with

his hand upon his heart, that “hif there vos a single thing in life as

would make him completely happy, it vos a vife!”

The Courtship of Mr. Wiggins.

Mr. Wiggins was so intoxicated with love, brandy-and-water and cigars, that he scarcely knew how he reached home. He only remembered that he was very dizzy, and that his charming widow—his guide and friend—had remonstrated with him upon the elevation of his style, and the irregularity of his progression.

With his head in his hand, and a strong “dish of tea” without milk, before him, he was composing himself for business the following morning, when an unexpected visitor was announced.

“Please, sir, there's Mrs. Warner's 's boy as wants to speak vith you,” said his landlady.

“Show him up,” languidly replied our lover, throwing his aching head from his right to his left hand.

“Vell, Jim, vot's the matter!” demanded he—“How's your missus?”

“She ain't no missus o' mine no longer,” replied Jim.

“How?”

“I tell you vot it is, sir, she promised to give me a shillin'-aweek an' my feed; an' she ain't done vun thing nor t' other; for I'm bless'd if I ain't starved, and ain't seen the color of her money sin' I bin there. Father's goin' to summon her.”

“It's some mistake, sure?”

“It's no mistake tho',” persisted Jim, “an' I can tell you she ain't got a farden to bless herself vith!—an' she's over head-and-ears in debt too, I can tell you; an' she pays nobody—puttin' 'em all off, vith promises to pay wen she's married.”

“My heye!” exclaimed the excited Wiggins, thrown all a-back by this very agreeable intention upon his funds.

“More nor that, sir,” continued the revengeful Jim, “I know she thinks as she's hooked a preshus flat, an' means to marry you outright jist for vot she can get. An' von't she scatter the dibs?—that's all; she's the extravagantest 'ooman as hever I came anigh to.”

“But, (dear me! ) she has a good stock—?”

“Dummies, sir, all dummies.”

“Dummies?”

“Yes, sir; the sugars on the shelves is all dummies—wooden 'uns, done up in paper! The herrin' tub is on'y got a few at top—the rest's all shavins an' waste.—There's plenty o' salt to be sure—but the werry soap-box is all made up.”

“And so's my mind!” emphatically exclaimed the deluded Wiggins, slapping the breakfast-table with his clenched fist.

“Jim—Jim—you're a honest lad, and there's half-a-crown for you—

“Thank'ye for me, sir,” said the errand-boy, grinning with delight—” “and—and you'll cut the missus, Sir!”

“For ever!—”

“Hooray! I said as how I'd have my rewenge!” cried the lad, and pulling the front of his straight hair, as an apology for a bow, he retreated from the room.

“What an escape!” soliloquized Wiggins—“Should n't I ha' bin properly hampered? that's all. No more insinniwating widows for me!—”

And so ended the Courtship of Mr. Wiggins.

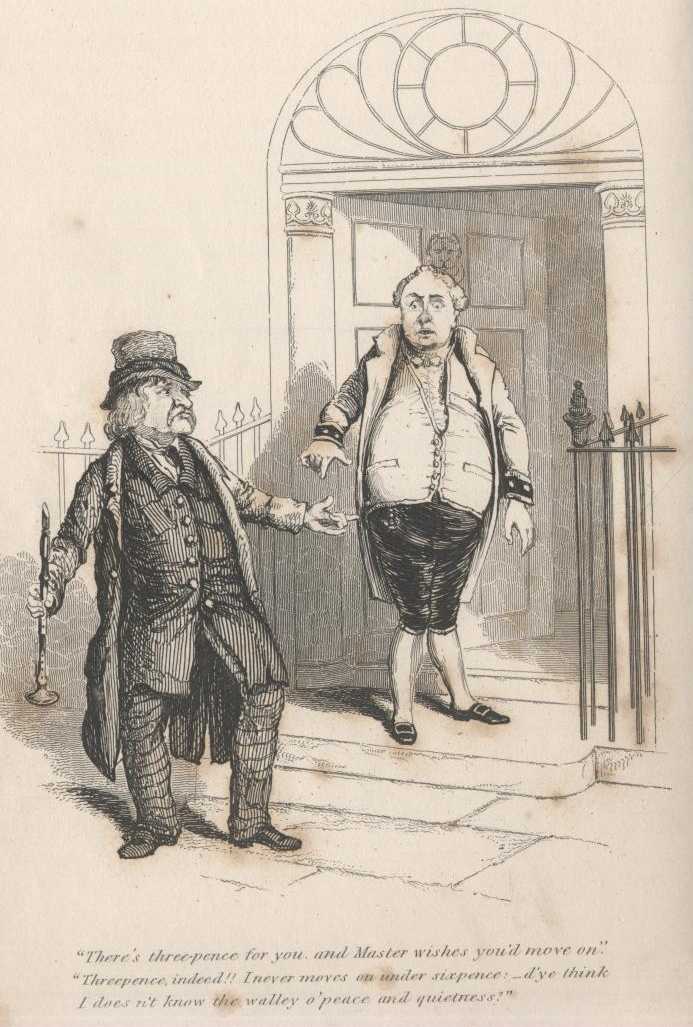

The Itinerant Musician.

A WANDERING son of Apollo, with a shocking bad hat, encircled by a melancholy piece of rusty crape, and arrayed in garments that had once shone with renovated splendour in that mart of second-hand habiliments 'ycleped Monmouth-street, was affrighting the echoes of a fashionable street by blowing upon an old clarionet, and doing the 'Follow, hark!' of Weber the most palpable injustice.