Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XXX, No. 2, February 1847

Author: Various

Editor: George R. Graham

Release date: February 10, 2018 [eBook #56537]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed

Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net from

page images generously made available by the Internet

Archive (https://archive.org)

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXX. January, 1847. No. 1.

Table of Contents

Fiction, Literature and Articles

Poetry, Music and Fashion

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

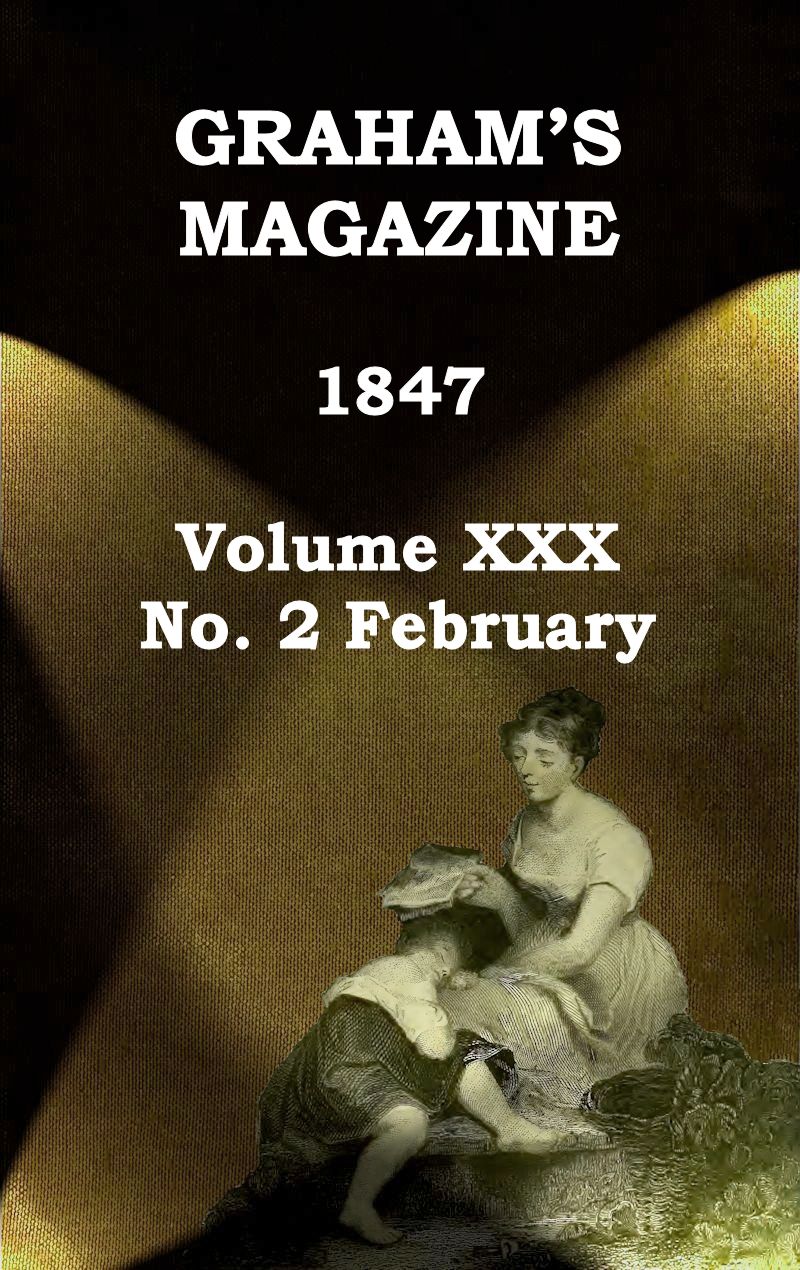

Ch. Bodmer pinx. ad. Nat. Engd by Rawdon, Wright & Hatch

ON THE UPPER MISSOURI.

LE FOLLET

Boulevart St. Martin, 61.

Robes et blousons de Mme. Thiery, boul. Montmartre, 65—Chapeaux de Mme. Baudry, r. Richlieu 87;

Bonnet et lingeries de Mlle. Malteste, r. de la Paix, 20—Mouchoirs de L. Chapron & Dubois, r. de la Paix, 7;

Essences et parfums de Guerlain, r. de la Paix, 11—Chaussures de Bobin, r. Richlieu, 29.

Graham’s Magazine.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXX. PHILADELPHIA, FEBRUARY, 1847. No. 2.

A MAN WITHOUT A HOPE.

(A PHRENOLOGICAL ILLUSTRATION.)

———

BY JOSEPH C. NEAL.

———

It is inconvenient to have to bear with personal deficiencies—troublesome and disheartening not to possess all the senses and the faculties which are demanded to enable man to compete with his fellows upon equal terms; and it requires philosophy that we do not repine when we find ourselves in any respect, either physical or mental, compelled to stand aside in the unpleasant attitude of being an exception to the general rule. It is true that the march of science is able, to a considerable extent, to obviate corporeal default. Eyes are constructed so well as to deceive the eye, although the constructed eye is not yet so perfect that we shall hope to see with it far into the opacity of mill-stones. Legs are manufactured more symmetrically beautiful than the majority of real legs; and the skillful artist will, if you are only tall enough, modulate you into a figure which might put an Apollo to the blush. But the steam leg, in its swiftness of locomotion, is as yet no more than a dream of the visionary; and we may pad ourselves into muscularity as much as we please, without gaining a particle of power.

We are aware that by the aid of spectacles he who would otherwise be always stumbling over the dog, and tripping in contact with other people’s feet, periling his precious countenance by rude collisions with every species of obstacle, may contrive to see his way through the world in comparative clearness. But science has not perhaps succeeded to the same extent in the work of metaphysical regeneration; nor do we know that any man’s geese have as yet been fully converted into swans, though he may think them progressive creatures in the scale of ornithology, and likely to reach a higher position than has been attained by former members of the race. It is theoretical, we learn, with the phrenologists, and probably practical also, to a greater extent than the world is willing to admit, that there are processes whereby the neglects of dame nature may at least be partially counteracted and repaired, so that “bumps” shall be raised, where depressions exist, and some degree of potency be secured in those “organs” which were originally faint and feeble; just as the muscular fibre is strengthened by exercise, and as our agile capabilities are increased by a judicious practice of the thews and sinews on which activity depends.

Now, while we hope for the sake of humanity in general, that these assumptions will fully bear the test of experiment, it must yet be conceded that education fails somewhat in this regard; and that in thinking, as in dancing, much depends upon the configuration of mind and of body with which we were endowed from the outset. The phrenologists are right in the belief that training has its advantages; but there must be a basis on which that training is to proceed, or the result will be such as cannot fail to lead to serious disappointment.

For example, and in the way of parenthesis, it would be a parlous difficulty to teach the innate craven to plunge valiantly onward at the desperate head of a forlorn hope, or to hurl himself recklessly upon the sharp and bristling array of a forest of hostile bayonets. You may debate the question if you are so inclined, insisting on it vehemently that, in honor’s view, there is no essential difference in a case like this, between a glorious death and the triumph of a victory, and that the most disastrous of the two is infinitely preferable to an age without a name, yet, our life on it, it will prove that your friend of the weak nerve, and of the nonchivalrous temperament, is not to be talked, by the most persuasive, into any relish for cold steel, or into any decided fancy for the reception into himself of certain intrusive pellets of hot lead. Nay, Ciceronian eloquence would be wasted in the endeavor to induce him to come to the conclusion that it is much better for him to be extended face upward on the ensanguined plain, after the fashion of the “grinning honor” of Sir Walter Blount, than to find himself sound in body, but without a single sprig of laurel to his name, snugly enfolded in the blankets awaiting a call to breakfast. Nature, you will observe, has denied to him the perception of the romantic and the poetical. He has no desire to be posthumous to his own reputation. To such a one, the hard knock is simply a hard knock, unmitigated by transcendental embellishment; and renown has no part in the plain arithmetic of his calculations. He values life by its admeasurements—according to the number and length of its days. So give it up at once—there is no sun—of Austerlitz or of any other place—that can ripen this man into a warrior, or tempt him to enter into fierce competition for the wreath of glory.

And thus—musically—we find that people “without an ear,” do not often take the lead in operatic performances; or, if they do participate, that the operatic performances are not particularly benefitted by their interference. The querulous and fretful—do they acquire the resources of patient fortitude? Not often, so far as our experience extends; and we do not know that the simpleton, school him ever so much, is likely to obtain distinction for himself as a philosopher—nay, he is often furthest from it at the very moment when he imagines himself a great deal wiser than his neighbors.

Such as these, as well as others who might be mentioned, have no foundation on which the deficient “bump” is to be elevated; and, as a general rule, it is just as well to abandon as a “bad job” all effort to render them distinguished in the display of those faculties which form no part of their primary constitution. The superstructure that may be raised on an insecure soil, must of necessity be weak and “shackling;” and all the military education that can be bestowed on the poltroon, will not avail to prevent an ill-timed manifestation of that species of plumage which obtains ignoble renown under the epithet of the “white feather.” It has been in him probably from his birth, that he must locomote in a direction contrary to that in which “the nettle danger” uprears its ugly front; and, under these circumstances, the impulse to retrograde travel will burst all the artificial and conventional bonds which have been devised to drive it into the teeth of the battery. It was the design of nature that our friend should run; and who will venture to stand antagonistical to nature?

It is a mere flight of fancy, no doubt, into the illimitable regions of hypothesis, but we should very much like to see the day when a Bumpological art shall be matured, and a practical science of Organology be brought into operation. Then there will be some use in the knocks about the sconce, which are now so wofully wasted; and when we shall be driven into frenzies, the manifestations of our wrath will become really beneficial to those on whom they may chance to be bestowed. Then we should find the rationale of corporal punishment—a thing not to be whirled about in random kicks and cuffings; but to be so applied as to develop that very bump, a deficiency of which, in the offending party, has so raised our vengeful ire. Such, perchance, is the latent reason why we are so anxious to maltreat those who are not disposed to obey our behests, as well as the true motive why it is an impulse of our nature to chastise the enemy. Education would thus be revolutionized, and the Art of War would be brought within the range of the directly useful sciences.

But to descend at once to the facts that are before us, it is a blessed thought to believe that by a wise system of tuition, the small uncertain spark of a virtue may be breathed into a steady flame; and if, infirm of purpose as so many are, they could be strengthened into a surer aim by due attention to the feebler parts of character, none, we are sure, could be found to regret it; and so we are, and we intend to be, full of respect to this phrenological idea, which might, we think, be somewhat more carefully engrafted upon systems of educational improvement, so that the mere appeal to the memory might leave room for the analysis and development of the moral being.

We should go to school upon a different principle then; and probably it may not be a useless waste of imagination to reflect a little upon the novel scenes that would then be presented in the halls of the academy.

“My son Bob, Mr. Professor—this is Bob, sir, trying to hide himself behind the door—stand up, Bob, and behave like a man—Bob, Mr. Professor, hasn’t got any pride, and has the smallest quantity of dignity. He’s always letting himself down, and never tries to hyst himself up—likes the raggedest boys the best, Mr. Professor, and prefers the company of the sweeps to going to the nicest of tea-parties. Bob always feels flat in genteel society, does Bob.”

“Ah—I comprehend—a very common case, indeed; but curable—take Bob, Mr. Simpkins, and touch him up in the region of self-esteem. Don’t be afraid—we’ll make Bob—you’ll have to call him Master Robert then—as proud as Lucifer, in a week or two. When we send him home, he will hardly speak to his own father, and he wont own any of his relations.”

“And here is Peter, sir, and Sam—nice boys as ever was, only they don’t care nothing for nobody, and will have it all their own way, which is apt to be the wrong way, if not a bad way.”

“Ho! ho! knock up a bump in the region of approbativeness, so that they may quit thinking for themselves, and always want somebody to think for them.”

“Please, Mr. Professor, our Tom appropriates and conveys—sugar, sir, or pennies convertible to sugar—he bones, sir, and he filches, sir, whatever he can lay his blessed little hands upon, the darling; every thing is fish that comes to Tom’s net.”

“Just so—Tom has not yet got beyond the first principle of human nature, which impels us to help ourselves to whatever we want—the application must be made to Tom, sharply, just where his conscience ought to be. Bump up a conscience for Tommy.”

The disrespectful, who, in some way or other, are disposed to make faces at their superiors, would require to be rapped rather soundly in and about “veneration;” and we are not now to be told that a smart blow on the eye is sure to awaken vociferous displays of the faculty of “language.” For him who comes too late, which is bad—or stays too late, which is worse—what could be better than a forcible appeal to “time?” And if a boy—your boy, or any other body’s boy—cannot be easily made to see the essential difference between his own selfish will and your authoritative behest, you have only to perform for him a tune upon his slumbering organ of “comparison,” and you shall have music, you may depend upon it. If the same rebellious individual is slow to discern why he should obey, lend him a smart fillip upon his “casualty,” educive of the why, and provocative of the wherefore; and if you yourself cannot discover the point of a joke, taking the fact for granted that it is a joke which comes to a point—some jokes, like some people, come to nothings—depend upon it that your “wit” is beginning to lose its edge, and is getting to be somewhat rusty in the method of its operation.

No one, we presume, will venture to deny that “cautiousness,” well rubbed and roused, has a tendency to keep our fingers out of the fire; or that an inflammation of our “combativeness” will give us joy in the facing of our foe. But what, let us ask, what is to be done, if, like the peculiar one who now comes under our special notice—what is to be done, if in all the qualities which go to make up our mentality, we have not one scintilla of self reliance and expectation, and are like

TRIBULATION TREPID,

A MAN WITHOUT A HOPE!

You see, the case is in every way a hopeless one—for Tribulation Trepid never had a hope. He has no more idea of what you mean by a hope than a blind man can understand what you are talking about when you speak of colors. Hope!—how do you go about it—how do you begin when you want to hope? The first principle of hopefulness is not resident within the confines of the craniology of Tribulation Trepid; and, therefore, from the very moment of his birth, up and down—but more down than up—poor Tribulation Trepid has been lost in despond and in despair. Who ever called him “Young Hopeful?” It would have been the very heartlessness of cold derision.

If in the adventurousness of youth—for the earlier stages of existence form a perpetual exploring expedition, and an unceasing voyage of discovery into all sorts of holes and corners, to the constant annoyance of those who do not appreciate the march of mind in its primary manifestations—if then, at this interesting period, Tribulation Trepid undertook to exercise his limbs, and to gratify his curiosity by climbing up the chair, or ascending the table, that in this way his knowledge of the laws of gravitation might be increased, and his power of self-reliance extended, and if, thwartingly, at such perilous moment, as too often happens to be the case, the usual maternal caution fell upon his ear,

“Tribby, Tribby, what are you at? That child will fall and break its good-for-nothing neck!”

Tribby, of course, did fall—he was sure to do it—only suggest the worst of the alternatives to his mind, and, lacking hope to sustain his trembling limbs, he dropped at once into the fell catastrophe. He took it for granted that it must be so; and so it was. The great secret of successful adventure is confidence—a fixed faith in the potency of your star; and he who is deficient in this belief, will find it much better to remain at home, or to “go ashore,” than to tempt the chances of the storm. He, in truth, seeketh a shipwreck, who is not assured of his own buoyancy; and that man marches to an overthrow, whose mind is always dwelling on the probabilities of being beaten. He alone triumphs, who disdains to entertain a doubt of his own invincibility, and thus compels fortune to perch, whether she will or no, upon his daring banner. But such was not our Tribulation.

“Here, Tribby, take this pitcher down to Susan, and be sure you don’t fall, or I’ll box your ears, you Tribby.”

Under the doctrine of pains and penalties, which until lately formed the basis of all education—sound whipping and sound teaching having heretofore been identical—one would have thought that, with such a threatening over his head, Tribulation Trepid would not have dared to treat himself to a luxury so expensive as the species of tumble now referred to. To slip down stairs by himself is wicked enough in any child, when we reflect upon the uproar which every child is apt to create under these circumstances. But to slip down stairs, including a best pitcher in the gymnastic operation, to the exceeding detriment of the crockery, is an offence not to be excused at the judgment-seat of the good housekeeper. It is a sin which cannot be pardoned or overlooked.

“Now mind—don’t you fall and break that pitcher, Tribby, as you always do,” was the pursuing admonition to our child of wo, as he entered upon the labyrinthine convolutions of the dark stairway—but just then—did you not expect it?—cr-a-a-sh!—bimble—bumble—rub-dub!—Tribby has achieved his descent by a short hand process, and lies vociferously prone upon his back at the landing-place, environed by the fragments of the ware. We are not satisfied that it mended the matter at all, and we are quite sure it did not mend the pitcher; but we presume it was a satisfaction, if not to both, at least to one of the parties involved; and a satisfaction is something in this unsatisfactory state of existence; and so Tribulation Trepid received his promised reward—“I’ll teach you,” and so forth—causing his auricular appendages to reverberate for an hour or two, and likewise to be comfortably warm for at least the same space of time, affording him both his music and his caloric at the lowest possible rate; though it can scarcely be said that his hope underwent any considerable degree of augmentation by the process.

“Tribby Trepid doesn’t know his lesson, I am tolerably well assured of that,” said the teacher, glancing significantly at his rattan—for Tribulation Trepid underwent his share of schooling when rattan was lord paramount in the academic groves, and served, as it made the schoolboy “smart” in more senses than one, to counteract, on the part of preceptors, the baneful influences of sedentary life, by affording wholesome exercise in the “dusting of jackets.”

Now Tribby’s hope not being strong in the faith that he would prove thoroughly conversant with his lesson, when brought up to the test of actual experiment, though he was acquainted with it passing well when he left home, the announcement of this foregone conclusion in the teacher’s mind, coupled with certain tingling remembrances connected with rattan, drove all other lessons from his desponding brain; and he was executed accordingly, to the infinite relief of Mr. Switchem’s dyspeptic symptoms, and to the marvelous increase of the aforesaid Switchem’s appetite for dinner. And so, reproof, condemnation and rattan being inevitable, why should Tribulation Trepid annoy himself by the previous pain of toilsome study? He did so no more.

“I shan’t know ’em if I do; and I shall be whipped whether I do or not,” said Tribby, and he forthwith bowed himself down to that which appeared to be the inevitable, allowing hope to be crushed beneath the lumbering wheels of a Juggernaut of fear.

Hope on—hope ever. There is nothing in this world so valuable as hope. The thing hoped for, precious though it be, is perhaps less of a blessing in itself than the state of mind which convinces us that by the proper effort we are able to obtain it. Better is it to be full of hope than to have triumphed in the pursuit of all that man regards as most desirable. Hope is richer than a diadem. Hopefulness is a perpetual banquet—a feast that never cloys; and he who has around him the glowing atmosphere which hope alone can bring, has no need to envy the successes that others have achieved. His dreams surpass reality.

But Tribulation Trepid has no hope. If there were a germ of it at the outset of his career, it was, as it were, trampled down and buried by a conviction steadfastly impressed, that, if others could succeed he was sure to fail; and therefore, he did fail.

Did he mount a horse—oh! Tribulation Trepid will be thrown from the saddle, as a matter of course—and he was thrown. Did he undertake to leap the brook—the discouraging idea seemed to arrest him midway that he could not do it; and Trepid emerged dripping from the wave. And so it was, and so it has been, throughout the life of Tribulation—such, it may be, is the secret why the lives of so many of our kind present an unbroken series of disastrous failure. They lack the inspiring voice of hope. They knew it would be so; and so it is.

It is a melancholy thing, moreover, to have to do with the family of the Trepids. In the endeavor to encourage them, your own hopefulness seems to fade away; and the more you labor to elevate them and to push them forward, the more heavily, and inertly, and listlessly do they fall back upon your hands. They are convinced that it is of “no use doing nothing,” and they tamely suffer every competitor to pass them in the race.

Just so it is with the lugubrious individual now before us, who invariably puts the worst possible face upon every matter, for the simple reason that, as in the reflection of a mirror, every matter wears the worst possible face to him; and as he looks at matters sadly, despondingly, just so do matters return the glance. He sighs over matters, and groans over matters. He walks through the streets with a longitude of visage and a mournful down-drawing of the corners of the mouth that would be neat and appropriate at the funeral of his best friend, but which are sadly out of time and place at every other moment; and he feels assured always that it is going to rain—if not to-day, certainly to-morrow—that is, in case a shower is not wanted. Otherwise, it will never rain again—it has forgotten how.

Beware, then, how your sympathizing nature induces you to accost Tribulation Trepid in the highway, unless you are proof against the contagious influences of sorrow, and are firmly fixed in the confidence of your own hope; for it seems to afford a mournful satisfaction to all the Trepids to bring others down to their own melancholy level.

“You may try,” say they—“no objection to any body’s trying—but it’s not often that trying comes to any thing. Whatever it may be, it will never answer—we never knew things to answer. Things never answer nowadays,” with various other assurances of a like enlivening nature. Beware, then, of the effect of contact with the Trepids, unless your nature is of that sanguine sort which bids defiance to the chill, and has hardihood to sport itself safely in December’s snow.

“How are you Trepid? How do you feel to-day, Mr. Trepid?”

“A great deal worse than I was, thank’ee—’most dead, I am obliged to you—I’m always worse than I was, and I don’t think I was ever any better. I’m very sure, any how, that I’m not going to be any better; and, for the future, you may always know I’m worse without asking any questions; for the questions make me worse, if nothing else does.”

“Why, Trepid, what’s the matter with you?”

“Nothing, I tell you, in particular; but a great deal is the matter with me in general; and that’s the danger, because we don’t know what it is. That’s what kills people—when they can’t tell what it is—that’s what’s killing me. My great grandfather died of it, he did, and so will I. The doctor’s don’t know—they can’t tell—they say I’m well enough, when I’m bad enough; and so there’s no help. I’m going off some of these days, right after my great grandfather, dying of nothing in particular, but of every thing in general. That’s what finishes our folks.”

But as Tribulation Trepid has now got under way in reference to his bodily health, it may be as well to suffer him to explain himself in the matter of his pecuniary relations, which are in quite as bad a condition.

“Well, but, Trepid, how do you come on otherwise? Why don’t you go into some sort of business and keep a shop.”

“Keep a shop!—what’s the use of my keeping a shop? If I keep a shop, nobody would ever come into it; and if they did come in, they wouldn’t buy any thing. Didn’t I try once, and nobody came, because they said I hadn’t enough of an assortment? Ketch me! Why did they not buy what I had, instead of trying to coax me to get things, which they would not have bought after all? Me keep a shop! Yes, to be sold out by the sheriff—I’m always sold out—don’t I know it beforehand?”

“Apply for a situation did you say? Nonsense! Aint they always very sorry—if I had only come sooner, or if they had only know’d of it before—isn’t that always the answer? Could I ever get anywhere soon enough, or before somebody else had been there, and had gathered up all the good things that were agoing? Don’t talk to me about applying for a situation. It’s almost as bad as trotting about to get an office. ‘Bring your recommendations,’ say they; and by the time you’ve got your recommendations, oh, how sorry they are, for such a nice man as you, only the place is filled already.

“I’ve a great mind never to try to go anywhere any more, after situations—somebody must sleep there all night; for, however bright and early I get up of a morning, there he is; and I might have had the place if I had been in time, as if that was any comfort.

“And as for trying to borry money of people, which is a nice easy way of getting a living as a gentleman could desire, if you’ve a pretty good run of business in that line, I never could do much at it, somehow or other. I never could take the moneyed people by surprise. They seemed to know what I wanted as soon as I looked at them, and they were always very sorry, too—everybody is very sorry to me—but they had no cash to spare just now, and just now is all the time when people don’t want to lend. No—nothing is to be done in that line unless you can take them by surprise, like a steel trap; and I’m not quick enough for that operation. There’s never any money when I’m coming.

“I’ll give up—yes, if nobody will leave me a fortune, and no rich widow will marry me, I’ve a great mind to give up, and see what will become of me then. I suppose something must become of me: though I hardly believe it will, for nothing ever become of me yet. But of this I’m sure, there’s no use of my trying to get along by myself; and I’ll just sit down by the side of life’s turnpike and wait till something goes traveling by to get me along. But I guess I’ll have to wait a good while; for the place will be occupied—they’ll be very sorry, to be sure, and they’ll wish they had know’d it in time; but there’s no room left.”

It will thus be seen that Tribulation Trepid adopts the expectant method of treatment, as the course of practice best adapted to the peculiarities of his case. He waits for something to “turn up” in his favor, because he lacks force, faith and hope to urge him onward to energetic effort—for, in the collapsed recesses of his trembling heart, he does not really believe that any thing favorable will “turn up” for him. Such turnings up never have occurred for his special benefit. All his turnings have been turnings down; as the turnings of this world generally prove to be, unless our own shoulder is so applied to the turning as to induce it to turn in the proper direction. And this brings us to the great query of all queries—the unsolved problem in our social theory—what is to be done to help him who, by nature or by education, proves to be unable to help himself—what measure of relief is to be passed for the benefit of the sinking family of the Trepids, as they stumble down the depths of disaster?—Gentle reader, and most sagacious friend, if you should think of any, pray announce it betimes; and in return receive a position among the most distinguished of the benefactors of the human race. Cheer, if thou canst,

THE MAN WITHOUT A HOPE.

———

BY FRANCES S. OSGOOD.

———

Kate Carol to Mary H——.

“I miss you, Mary mine, more than I can tell, with this cold pen and sluggish ink. I own I love Right Angledom. After the bustle and randomness of life in New York—its straight ways, its quiet and its monotony, are refreshing. I love the Quakers too, with their delicious repose of manner—their low, lulling, musical voices, and their simple truthfulness of character and conversation. Their ‘ways are ways of pleasantness, and all their paths are peace.’ But I must confess to, now and then, a feeling, I cannot say of home-sickness—for I, wanderer that I am, have no home, unless it be in your heart, and in some few others, a precious few, indeed—but a feeling of regret, a pining for the past; for the few true and pure spirits to whom I have dared reveal myself, who know me thoroughly, faults and all, and who love me the more for those faults; because love and pity come together on their divine mission from the gate of heaven, and walk hand-in-hand, twin children of God, ever tender, and beautiful, and sad, through this clouded vale of tears.

“ ‘Thee knows,’ Mary, as a lovely Quaker maiden said to me in a low lute-tone the other night, ‘Thee knows the gravel and the gold run together in all characters.’ Sweet Lizzie L——, thee does not know how much that simple Orphic saying consoled me. Well, there is some gold in my character, but it requires the sunbeams of love and sympathy to light it up, and so reveal it; and they might change even the gravel to gold in a heart so docile as mine, if they only knew it, and would only take the trouble.

“Thee knows, Mary dear, my invincible aversion to strangers. Gay, careless, confiding, frank, indeed to a fault, among those who seem to love me, I am shy, cold, dull—nay, worse, I am wretched, where I am not sure of pleasing. This is a most unfortunate weakness of mine, and has been the cause of many troubles to me. I recollect once in New York going to a party, which I afterwards heard was made for me—made expressly to introduce me to some distinguished authors—and just see, Mary, how badly I behaved; see what a wayward, naughty lion I was. Had I only known then, as I afterward did, the kind interest that my host took in me, I should have been so happy, so social, so delightful; but as it was, with my usual want of self-confidence, finding myself among strangers, I felt my heart, like the pimpernel on the approach of rain, coldly shrinking and shutting up, leaf by leaf, until I became a statue of lead; and on my introduction to those writers, whom I had all my life been eager to see, and whom, if I had only been sure that they would let me, I could have loved at once. I replied in monosyllables, so coldly, so drily, that they left me, surprised and repelled; and my dear, kind, disappointed host, afterward said, in reply to some encomiums by a friend—‘Yes, I suppose she is all that, but you must allow that she is very eccentric.’ Am I eccentric, Mary? Am I any thing but foolish and timid, and sensitive to a ridiculous degree?

“Now it was this shrinking of the heart that I felt, when I first took possession of a large, and at first, somewhat dreary room in a Philadelphia boarding-house. The sister of a dear friend, then in Washington, called upon me, and with a single magical sentence, like a gleam from the lamp of Aladdin, warmed, and furnished, and lighted up the chamber, till it seemed a home even to my lonely and sorrowing heart. She simply said, ‘Oh! this is the room that Sophy had!’ The following impromptu will show you how fervently I felt the change.

THE ROOM THAT SOPHY HAD.

Though strange and chill at first the room,

How soon it seemed with comfort clad,

When some one said—and blessed the gloom—

“It is the chamber Sophy had.”

With that sweet word the sunshine stole,

Around a spirit lone and sad,

A lingering ray from her true soul,

Still warmed “the room that Sophy had.”

And here has beat her happy heart;

And here have rung her accents glad;

And here the darling mused apart,—

Oh, precious “room that Sophy had.”

And here, perhaps, my image stole,

When care unwonted made her sad,

And whispered love through all her soul,

And cheered “the room that Sophy had.”

No palace-hall a queen may pace,

With splendor lit—with beauty clad,

Would seem so filled with light and grace,

As this dear “room that Sophy had.”

“You bid me send you all the verses I write. You little dream of the shower that would overwhelm you, were I to comply literally with your request ‘Nulla die sine linea,’ is my motto as well as that of the painter of old, and while I sew, or walk, or ride, or lounge, I am forever singing to myself impromptu love-songs, from imaginary damsels to imaginary youths, set to music by a score written in the air, and invisible to all eyes but mine, while a band of aerial musicians play the accompaniment, with my heart, for the leader, beating time. You shall have one of them, dear, and that, I think, will content you for the present—

Should all who throng, with gift and song,

And for my favor bend the knee,

Forsake the shrine, they deem divine,

I would not stoop my soul to thee!

The lips, that breathe the burning vow,

By falsehood base unstained must be;

The heart, to which mine own shall bow,

Must worship Honor more than me!

The monarch of a world wert thou,

And I a slave on bended knee,

Though tyrant chains my form might bow,

My soul should never stoop to thee!

Until its hour shall come, my heart

I will possess, serene and free;

Though snared to ruin by thine art,

’Twould sooner break than bend to thee!

“Ah, Mary! if only my dream-opera could play on through life, uninterrupted by the coarser or commoner cares of every-day existence—if the charm of that music, inaudible to others, to which, when I am let alone, my spirit moves, gliding or dancing as the measure chances to be swift or slow, might not be broken by the discord of reality, how light would float the fairy hours, led by that weird and wondrous melody, from ‘night to morn, from morn till dewy eve.’ But often, just in the midst of my heroine’s most impassioned reply to my hero—the bell rings for dinner—or our little Lily-belle wants her robe arranged—or rosy, roguish Mary insists upon playing that she is my mamma and that I am her youngest and naughtiest responsibility; and, after all, the glee that our three loving hearts play and sing together, with now and then a coo from the cradle from our little dove, our precious ‘Picciola,’ as an accompaniment—if less ethereal—less artistic—is quite as sweet and more spirited than the dream-music that Fancy plays in the air for me. To be sure, I have to be punished and put in the corner by my little tyrant, rather oftener than is convenient or agreeable, and to spell hard words, that I eschewed in my vagrant school-days some—forty years ago!—if we count time by ‘heart-throbs,’ as Festus bids us, I have lived longer than that—

“I broke that chain of thought, attracted by the peculiar grace of a compliment paid by a gentleman to a very lovely woman, who is sitting near me, bending a pair of superb Spanish eyes and a graceful Psyche-head over a suspender, on which, beneath her fairy hands a wreath of exquisitely delicate flowers is growing and glowing; all too daintily for the heart it is meant to chain—since that heart is man’s—

For still the fairest, frailest flowers

He soonest casts aside!

But the compliment. Some one remarked, that her head would be perfect, were it not that the organ of reverence was entirely wanting in it. ‘It has never been brought into play,’ was the reply, ‘for she has found no superior on earth.’

“Last night, as I watched her pensive look, I found myself chanting to myself a song to her lost child—the most divinely beautiful being that I ever beheld. I loved her as my own, and the tears still spring to my eyes whenever I think of her. Will you hear the song, Mary?

TO LITTLE ANNIE C——.

Thy dark eyes danced in light,

And on thy cheek the while,

Life’s morning, rosy bright, Annie,

Did softly glow and smile.

A rare and radiant grace,

A beauty not of earth,

Had ‘o’erinformed’ thy face, Annie!

God’s darling! from thy birth.

When last I pressed thy brow,

There dawned thy soul divine;

But Heaven has won thee now, Annie!

A lovelier morn is thine!

While paled life’s early rose,

Thy spirit plumed her wings,

And now—how soft they close, Annie!

While God’s new angel sings!

“Some time before her death, the dear little child had frequently looked up in her mother’s face, and exclaimed, without any apparent or immediate cause—‘Happy Annie!’ and ‘Happy Annie!’ was the only epitaph they traced upon the simple slab of white marble that marked her little grave.

“But I shall sing you to sleep, my own Marie, if I give you any more of my verses: so take a spirit-kiss, and believe me still

“Your fondly attached,

“Kate Carol.”

A STORY OF THE REVOLUTION.

———

BY CHARLES J. PETERSON.

———

(Continued from page 8.)

Here’s a good world!

——Knew ye of this fair work?—King Lear.

The news of so important an event as the capture of Mr. Mowbray was not long in traveling to Mrs. Blakeley’s. One morning, as she and her niece sat at work together, the butler rushed into the room, betraying considerable agitation. We have already alluded to his pomposity and affectation of high-sounding phrases; another foible, the desire to play an important part, sometimes got the better of his discretion, as in the present instance.

“I’ve just heard such news, Missus Blakeley,” he exclaimed, breathlessly, wiping the perspiration from his face. “It’s completely admonished me. I’se run all de way from de head of de abenue, where I heard it from Jim Benson, who listed wid de British, and is now going home on a furbelow; a berry respectable person he is for a Tory and a common white man. In his new uniform he looks almost like an officer, I insure you!”

Here the old man paused, overcome by the rapidity of his utterance. Both Mrs. Blakeley and her niece understood his peculiarities too well to interrupt him, but they looked up smiling.

“Such news!” he began again. “I hope young missus won’t faint. Be sure, such things must recur; but to think it should happen to Mr. Mowbray—Lor’ save us.”

Kate, at the mention of her father’s name, turned pale, and could no longer endure the speaker’s prolixity.

“What is the matter with my father?” she gasped, “Is he dead?”

“Oh, no, missus—only taken by de Tories. But dey say he is to be hung.”

The sight of Kate’s ghastly face stopped the officious announcement—but it was too late; with a shriek she fell to the floor. At this spectacle, the old slave, struck with sudden remorse, cried, wringing his hands,

“I have killed her. Oh, Lor’!—oh, Lor’!—will she ever survive again?”

“You have only made her swoon by your hasty announcement of this terrible news,” said Mrs. Blakeley, sternly. “Run and send her maid.”

It was long before Kate was restored to consciousness. Meantime, Mrs. Blakeley learned from old Jacob all he had to impart. Of her brother’s ultimate fate she could scarcely entertain a doubt. She well knew the character of that bitter warfare. The orders of Lord Rawdon, the then superior officer of the royal army in South Carolina, had just been repeated, that all who had once signed the protection, yet subsequently been captured in arms against the king, should be summarily executed. The sentence of Mr. Mowbray, according to old Jacob’s report, was already issued. Mrs. Blakeley was scarcely less shocked than her niece, but her fortitude was required to sustain Kate, and she struggled to appear composed.

“Let us go to Col. Watson at once,” were almost the first words of Kate, on recovering her senses. “Surely he will not refuse us. He was but lately your guest—how can he then deny your prayer.”

“Alas! my child,” replied her aunt, with tears in her eyes, “war converts men into fiends, and dries up all the kindlier feelings of the soul; but especially in a civil war like this, no such thing as friendship is acknowledged. Have you forgotten the fate of Gabriel Marion, the neighbour of the general—youthful, beautiful, unoffending, the pride of that old man’s heart? He was taken in a skirmish, and, as soon as recognized, told to make ready for death. His prayers for a respite—for paper to write to his uncle—for time to make his peace with God, were alike denied him.” She shuddered as she continued. “They made him kneel on the highway, and then basely murdered him.”

“But they will not, they cannot murder my father thus. The men who did that foul deed were Tory outcasts. Col. Watson has a kind heart; he will spare my father’s life.” And Kate, clasping her hands, addressed her aunt supplicatingly, as if on the words she might speak hung her parent’s existence.

Mrs. Blakeley could not reply for some time for weeping. Twice she essayed to speak: twice tears choaked her utterance. At last she shook her head mournfully.

“Say not so—you do not mean it,” cried Kate, eagerly.

“Alas! alas! my darling,” sobbed Mrs. Blakeley, clasping Kate in her arms, “I would as willingly hope as you; but there is no hope. Was not solicitation, influence, promises, every thing exerted to save Col. Hayne; but to no purpose? They are inexorable. Did not the general say, in refusing a pardon, that if it were his own brother, he could do no more?”

At these words the full truth of her father’s situation seemed for the first time to break on Kate, who hitherto had hoped that aid from some quarter, her own prayers, or other influence, might save his life. During the time Mrs. Blakeley was speaking, the unfortunate girl gazed with stony eyes upon her, every feature rigid, her arms motionless and set, hanging by her side, and her head slightly advanced, with half parted lips, listening eagerly. Even when the speaker ceased, only a vague sense of what she said seemed to rest on Kate, and she murmured vacantly,

“No hope!—none, did you say?”

Mrs. Blakeley shook her head, mournfully. Her own heart was swelled to bursting; that stony look, those rigid lips, made her tremble for the reason of her niece.

“No hope!” whispered Kate, in those thrillingly low tones that are more eloquent than all the accents of despair. “Oh, just Heaven!” she exclaimed, suddenly elevating her voice; and she raised her outstretched hands on high, “wilt thou see this foul injustice done?”

But here the pitch of horror to which the unfortunate girl had been wound up, proved too much for a frame already weakened by preceding agitation, and she suddenly fell back, rigid and paralyzed, in another fainting fit.

All that day, and part of the night, Mrs. Blakeley watched over her niece. Toward midnight the sufferer sank into a slumber. On awaking in the morning, wan and haggard, she seemed only the shadow of her former self; but she had gained composure; though in the quivering lip, and the eye that filled unconsciously with tears, might have been read the agony of a breaking heart.

But though Mrs. Blakeley did not allow herself to hope, and thought it her duty to bid her niece discard all expectation of the prisoner’s pardon, she nevertheless resolved to do every thing that could be done to induce Col. Watson to save Mr. Mowbray’s life, or at least to grant a respite until head-quarters could be heard from. Accordingly, she spent the hours of the night, after Kate, stupefied alike by exhaustion and by narcotics, had sunk into slumber, in writing to Col. Watson. She also penned a hasty epistle to Major Lindsay, beseeching his interposition; for though Mrs. Blakeley was well aware of his pretensions to the hand of her niece, she thought this no time for morbid delicacy. These epistles being indited, and confided to the hand of a trusty servant, with orders to spare neither whip nor spur until he reached Col. Watson’s quarters, Mrs. Blakeley, toward morning, sought her couch, almost as much exhausted, both physically and mentally, as her unfortunate niece.

The morning broke in that once happy mansion as on a house of death. The shutters were half closed, as if to exclude the light, and the servants stole noiselessly to and fro, speaking in whispers scarcely above their breath. The morning meal remained almost untouched. Kate could eat nothing; and often set down her teacup, while her eyes filled with tears. Mrs. Blakeley, spite of all her self-control, was nervous and trembling. The old butler, who remained in the room, often turned his back, and brushed the honest tears from his eyes; for though unwilling to betray his emotion, he was unable to prevent it. Even Mrs. Blakeley’s pet grey-hound seemed to know and participate in the grief; for, instead of rushing up to his mistress boisterously, when she came down stairs, as had been his wont, he walked slowly and sadly toward her, looking up appealingly into her face, as if assuring her of his sympathy. The same dull pantomime was gone through with when Kate entered, and made her lip quiver.

Mrs. Blakeley had informed her niece of what she had done, and said that nothing now remained but to wait an answer to her letters. Kate, however, begged that she might be allowed to go to Col. Watson’s head-quarters to see her father; and though Mrs. Blakeley strove to dissuade her from this purpose, believing that the interview would only harrow up unnecessarily the feelings of both, filial love prevailed, and Kate extorted a lingering consent that they should set forth as soon as the heavy, lumbering carriage could be prepared.

It was during this delay that the galloping of a horse arrested her ear, and Major Lindsay was seen to alight on the lawn. During the moment that elapsed before his announcement, Kate had time to indulge in a thousand wild speculations. Hope whispered to her that Major Lindsay had procured the pardon of her father, or else come to announce a reprieve. Breathless and trembling, she did not wait for his entrance, but hurried to the door of the parlor. Mrs. Blakeley was almost equally agitated. Her first supposition was that Major Lindsay had received her note, and hurried at once to their aid; but a moment’s reflection satisfied her that time enough for this had not elapsed. She concluded then that he had hastened, on his own suggestion, to comfort them; and she advanced to meet him as eagerly as Kate.

Major Lindsay met them at the door. He started back at the sight of Kate’s wan face, for never could he have believed it possible that human agony could be so forcibly depicted on the countenance; but, recovering himself he advanced eagerly, and clasping the hand of each lady in his own, looked from one to the other with a smile, not gay yet encouraging.

“You bring us good news, I know,” said Kate, turning deadly pale, and then flushing to the forehead.

“I hope so,” said he, with marked emphasis. “God grant it!”

“God grant it, indeed,” faltered Mrs. Blakeley, in reply, the blood going back coldly on her heart at these equivocal words.

Kate, however, did not notice this: hope blinded her eyes, willingly; and she eagerly answered,

“I knew you would bring us words of cheer. He is free—he is on his way hither; he will be here soon. Is it not so?” and she looked so beautifully earnest, as she lifted her eyes eagerly to Major Lindsay’s face, that he vowed inwardly no obstacle should prevent him from winning so charming a bride.

“Not exactly that,” he replied, with some hesitation. “Mr. Mowbray is not free yet—but I hope, nay, I may promise that he is in no danger—that is, provided,” he stopped, embarrassed.

Mrs. Blakeley looked searchingly at the speaker, yet her heart would not allow her to entertain the suspicion that had flashed across her, and she discarded it indignantly. Kate, hurled suddenly from her pinnacle of hope, trembled, and clung speechlessly to her aunt’s arm.

Major Lindsay’s embarrassment continued. He looked imploringly at Mrs. Blakeley, as if he half expected her to come to his aid. But Mrs. Blakeley was as agitated as Kate. She struggled to subdue her emotion, saying, eagerly,

“Do not torture us by suspense, I implore you, Major Lindsay. If any thing is expected of us, fear not to tell us at once; we will strip ourselves to the uttermost farthing, if a heavy fine can save my brother’s life.”

Major Lindsay, thus thrown on his own resources, hesitated and stammered, but found words at length to say,

“Do not be alarmed, ladies. I repeat it, there is nothing to fear. But I come rather as an ambassador than as the herald of joy. In other words, I have certain matters to mention, which are preliminary, I regret, to the pardon of Mr. Mowbray. My message, too, is exclusively to Miss Mowbray, and I fear can be delivered to her alone. But understand me, there is no doubt of all yet going well.”

“I will leave you with this dear girl at once,” said Mrs. Blakeley, imprinting a kiss on Kate’s brow. “I need scarcely say how deeply she has been agitated, and beg you to spare her as much as possible.”

“I will do it,” said Major Lindsay earnestly, his eyes compassionately bent on Kate; and Mrs. Blakeley, notwithstanding her suspicions, could not doubt his sincerity.

Kate trembled with a strange foreboding feeling, as she saw the door close on her aunt; and yet what was there of alarm in this approaching interview? Were not the words and looks of Major Lindsay kind and encouraging? Yet still Kate trembled to find herself alone with him.

——

“Where the greater malady is fixed,

The lesser is scarce felt.”—King Lear.

The apartment in which Major Lindsay found himself, was one with which he had been familiar on his preceding visit to the mansion; but, for a minute after Mrs. Blakeley’s exit, he gazed around him as if examining for the first time the architecture and furniture of the room. It was an apartment, too, well worth his scrutiny. Few even of the gentry of that proud state could boast a dwelling like that of Mrs. Blakeley. The walls of the parlor were wainscoted to the ceiling with richly carved cornices; and over the mantelpiece, encircled by a wreath of roses carved in the wood, were the arms of the family. The furniture was of mahogany, consisting of massive tables and chairs, with elaborately carved feet. A couple of fine portraits adorned the walls—one a picture of the deceased Mr. Blakeley, the other a likeness of Mr. Mowbray.

Major Lindsay cast his eyes from the cornice to the floor, and from the mantelpiece to the portraits, and at length stealthily turned them in the direction of Kate, who sat on the sofa, her color rapidly changing, equally constrained and embarrassed. That a young and almost inexperienced girl should want perfect self-possession was less singular, however, than that a practiced man of the world like Major Lindsay should be without it. But the truth was that he scarcely knew how to introduce his errand to Kate.

When his eyes, however, met those of the fair girl, there was an expression of surprise and inquiry at his silence, not to be misunderstood; and he thought it best to refer at once to the purpose of the interview.

“It pains me exceedingly—you cannot imagine how much—my dear Miss Mowbray,” he began, “to come here without the unconditional pardon of your father. But there are two circumstances which prevented me from succeeding to the extent of my wishes, and thus having the honor and pleasure of bringing you such welcome news. In the first place, Mr. Mowbray is not, as you suppose, a prisoner to Col. Watson, that officer being on his march to join Lord Rawdon at Camden; but, on the contrary, is in the hands of Lieut. Col. Campbell, who now holds the post of Georgetown, and who, besides being a gentleman of a more inexorable nature, is personally unacquainted with your father. Now, had it been Col. Watson to whom Mr. Mowbray had been surrendered, I indulge the hope that, difficult as the task would have been, his intimacy with yourself and Mrs. Blakeley, to say nothing of my own solicitations, would have procured the release of your parent. But with Col. Campbell the case is different. He is not only a stranger to you all, but he is nearly an entire stranger to myself. There does not exist between us those terms of intimacy that, in the case of Col. Watson, would have justified me in asking for the release of your father as a personal favor.”

Here Major Lindsay stopped, as if expecting Kate to answer; but she only bowed. It was evident also from her look of continued surprise that she could not yet make out the speaker’s purpose.

“In the second place,” continued Major Lindsay slowly, “there is nothing in this case to distinguish it from others—nothing, I mean, to justify Colonel Campbell in his own eyes for pardoning your parent, when so many others, also taken with arms in their hands, are executed. Lord Rawdon’s orders are explicit. Every man who, having once signed the protection, is afterward captured fighting against the king, is to be punished with death. This command hitherto has been rigidly enforced. Nor is there in Mr. Mowbray’s case, as I before said, any thing to take him out of the general rule. On the contrary, as Col. Campbell assured me, there is every reason why he should be proceeded against even more rigidly than others. Your father is rich and has great personal influence; and his pardon would lead the gentry generally to suppose that they could revolt with impunity. To suffer the leaders to escape—these were the words of my superior—yet punish their deluded followers, is neither justice nor good policy. These considerations induced Col. Campbell, to whom I hastened at once as an intercessor, being fortunately in Georgetown, to refuse my suit, though he kindly condescended to explain the reasons, as I have recapitulated to you.”

Kate clasped her hands at these words, and became pale as a corpse.

“Then he is to die!” she gasped. “It is thus you would break the news to me.”

“Nay, not so, as I hope in heaven!” cried Major Lindsay, earnestly, springing forward to support the fainting girl. “Your father’s life may yet be spared—Col. Campbell himself assured me how.”

Kate’s eyes were eagerly turned to the speaker at these words, though by a motion of her hand she waved off his assistance.

“The colonel said,” continued Major Lindsay, seeing she waited for him to speak, “that it was only necessary to give a proper pledge to the royal government for his future neutrality, and Mr. Mowbray might yet be saved. He himself hinted at the character of that pledge, or else I should have remained in doubt. ‘Go to Miss Mowbray,’ he said, ‘and tell her that with her it rests to preserve her father’s life. I have heard of your suit in that quarter; obtain her consent to a speedy marriage; and then to the father-in-law of one of his majesty’s most faithful subjects I can grant that life which I must deny to a rebel in arms.’ These were his words. And now, dear Miss Mowbray, think not I come to take advantage of you,” said Major Lindsay, speaking rapidly and eagerly, as he saw her avert her face, “God knows nothing is further from my thoughts. But it is the weakness of love to be selfish, and when the way by which I might win my suit was thus pointed out to me, I had not the strength to resist. Besides, I knew I should never forgive myself if I refused to come, and your father lost his life in consequence. My very love for you, by making me anxious for his life, would have forced me hither, even if I knew beforehand that you would spurn me.”

Surprise and indignation chased each other through Kate’s mind at hearing these words. The embarrassment of Major Lindsay was now explained, for well might he hesitate to avow his baseness in making her father’s life the price of her hand. Kate was firmly persuaded that he might have saved her parent if he would; and her bosom heaved with indignant feelings. But had she known all: had she known that Major Lindsay himself had planned her father’s capture, and instigated his superior to dictate the only terms of pardon—how would she have turned from him with horror and loathing inexpressible!

Kate’s first impulse was to rise and leave the room. But she remembered how completely she was in her auditor’s power, and her feelings suffered a revulsion. She burst into tears.

“I see I pain you,” said the major, in affected sorrow. “Nay! then I will leave your presence. Heaven bless you!” and he rose sadly and prepared to go.

Kate was staggered by these words. Could one who thus spoke have really acted as basely as she but now supposed? She could not believe it. Yet she still turned with repugnance from the idea of a union with Major Lindsay. Meantime that individual had advanced several steps toward the door, while Kate continued sobbing violently on the sofa. Her heart was torn with conflicting emotions. If she suffered her visiter to depart, her father’s blood would be on her hands. The major had already turned the lock: there was no longer room for delay. Springing wildly from her seat, she rushed forward and laid her hand on his arm.

“Stay!” she gasped. “Do with me as you will.”

A gleam of triumph shot across Major Lindsay’s face.

“You know not how you transport me,” he said rapidly. “If the devotion of a life can repay you for this promise, here I swear to bestow it in requital,” and taking those fair but listless fingers in his hand, he would have raised them to his lips.

But Kate instinctively drew them back, and with an almost haughty gesture. The next moment, however, she again burst into tears.

“Oh!” she exclaimed, “is there no other way? Be generous, Major Lindsay.”

She stood like an imploring Niobe, her eyes raised in supplication, her whole face beaming.

The countenance of her auditor, on that sudden withdrawal of her hand, had flushed with sudden anger; but he had now once more controlled his features to a look of pity, and he replied—

“Would I could do as you wish; would there was some other way.”

“There is—there is,” said Kate, eagerly. “You yourself will go again to Col. Campbell and intercede for us.”

“Alas! I have done that already.”

“To Lord Rawdon, then,” breathlessly interposed Kate.

“It would be useless. Nay, if he hears of this matter prematurely, before you are mine, neither Col. Campbell nor I can save your father.”

There was a tone of decision in him as he pronounced these words, that shut out all farther entreaty. Kate felt, moreover, that what he said was true; from Lord Rawdon no hope could be entertained. With a groan she buried her face against the sofa.

Major Lindsay stood at a respectful distance. During the interview he had more than once been smote to the heart by Kate’s agony. He was not a villain in the ordinary acceptation of the term. Impelled by his necessities, and stung by Kate’s persevering refusal, he had planned her father’s capture, intending to purchase her hand by his pardon, and little doubting that, in time, she would learn to love him. He had found little difficulty in persuading Col. Campbell to further his scheme, representing to that officer that Kate was not indifferent to him in secret, but was unwilling, on her father’s account, to marry a royal officer. But Major Lindsay, though engaged in this black plot, really loved Kate; and had he not gone too far to retreat, perhaps would have been moved from his purpose by the sight of her suffering. His commiseration was not, therefore, all affected; and even now, as he stood awaiting her final decision, which he no longer doubted would be in his favor, a pang of remorse shot through his heart on raising his eyes and beholding Mr. Mowbray’s picture—for the mute canvas seemed to rebuke him with its sad, earnest gaze.

Perhaps five minutes thus passed—the major leaned on his sword—Kate, her face buried from sight, continued to sob. At length she looked up, and holding out her hand with averted head, she said,

“My father shall be saved.” And then, as if almost choked by the words, she added, “Leave me now.”

“Thank you for those blessed words,” said Major Lindsay; and bowing over her hand, which he just touched with his lips, he left the room.

Kate waited till the door closed after him, then, with a cry of anguish, she gave way to fresh tears.

“Oh, miserable, unhappy me!” she groaned, “would nothing but this save my father!”

All at once she started up, and a wild gleam of joy irradiated her face. She dashed the tears from her eyes; for the first time it had occurred to her that Preston could avert her horrible destiny—in what way she knew not; but in childhood he had always been her protection, and she still felt the habit of looking up to him in peril.

But in an instant came the reflection of the terms on which they now stood to each other. They had parted in anger; and he either despised or hated her. Under such circumstances her womanly modesty revolted from appealing to him for aid. “No,” she mentally ejaculated, “I will die sooner.” And as she came to this resolution, she fell back again in hopeless misery on her seat.

Major Lindsay, meanwhile, had sought out Mrs. Blakeley, to whom he related the result of his interview with Kate. To her aunt, who knew little of our heroine’s feelings, the sacrifice appeared an inconsiderable one; and Mrs. Blakeley had always regarded Major Lindsay with favor. She informed her guest that they were soon to set forth for Georgetown, and invited him to accompany them. He declined, alledging the necessity of his returning as speedily as possible; but offered to leave a portion of his dragoons to escort the ladies.

“I shall be the first to meet you in Georgetown,” he said, as he bid Mrs. Blakeley farewell on the steps of her mansion; and plunging spurs into his steed, he was soon out of sight with his train.

——

“Who thundering comes on blackest steed.”—Byron.

While Major Lindsay was galloping from Blakeley Hall, Captain Preston, by the same road, was advancing toward it. He had been out on a scouting expedition, and hearing that Kate was still with her aunt, determined, in a moment of relenting, to visit her. He had not yet heard of her father’s capture—of course he was ignorant of her own peril; and Kate determined that he should still remain so.

The rapidity of Major Lindsay’s pace was in unison with the tumult of his thoughts. Now that all was settled, conscience was stilled; and he felt only the wild exultation of success. Exposure was the only thing he had to dread; but of that he felt no alarm, the unsettled state of the country affording secrecy as well as impunity.

He had no doubt Kate would soon love him. With other women he had generally been successful; he attributed his failure in her case to her remembrance of Preston as her old playmate. But once finding herself the husband of another, duty would soon teach her to forget the past. Occupied with these reflections, Major Lindsay’s spirits rose. Triumphant guilt is rarely given to remorse.

“But one thing only is wanting,” he said. “If I could meet this Preston—this braggadocia—I would at once have my revenge, and get rid of all possibility of future rivalry.”

As if in answer to this half expressed wish, there was at that moment seen, on the crest of a slight elevation in front, a single horseman, who, even at that distance, was recognized as wearing the uniform of Marion’s brigade.

“Wheel to the right,” said Major Lindsay sharply and suddenly to his dragoons, “into this old wood-road. Halt! We will lie in ambush here until we know something of the strength of the enemy. They do not yet see us.”

His orders were immediately executed. The troopers dashed into the pine barren, where they were easily concealed behind some high brush. Major Lindsay alighted and stealthily advanced to reconnoitre.

First he saw a trooper idly descending the hill; then another immediately cut the clear acclivity with his figure; and soon a third, fourth, and fifth appeared in rapid succession. The last comer was at a gallop, and dashed by the others until he reached their head. Even at that distance Major Lindsay thought there was something familiar in this person. He could not believe, however, that he had seen the whole of the enemy’s force, until the five horsemen had nearly descended the hill, when he concluded that they were merely a scouting party of the foe. He beckoned to him his orderly.

“Do you know those fellows?” he said.

The approaching horsemen were still at a considerable distance, so the man, shading his eyes with one hand, while with the other he held back the brushwood to get an opening for his face, peered long and eagerly. Then he drew back, nodding his head.

“I know ’em,” he said, “least ways one o’ ’em, who is that Capt. Preston that used to plague us so, up at the hall, yonder,” and he jerked his finger over his shoulder in the direction of Mrs. Blakeley’s, which they had left about an hour before.

“Are you sure?” said Major Lindsay, eagerly. “I would rather lose a dozen guineas than that you should be mistaken.”

“Then you’ll keep your guineas, sir,” said the orderly, “that’s Capt. Preston, and nobody else.”

“Is that fellow, Macdonald, with him? He is worth two men, and it would be a lucky hit to get both.”

“No, sir, I know his cut well—but he’s not along. And that’s odd too, for he and Capt. Preston always go together like dogs hunting in couples.”

“Then we have him!” said Major Lindsay, exultingly. “He cannot escape us.”

“Shall we blow trumpet and charge at once then?” said the orderly. “Our men will go at ’em like hungry wolves. They’ve a long score to settle.”

“Not yet,” said Major Lindsay, “we will wait till those fellows come up; then, boot and saddle, and upon them. I would not have them escape us for my life.”

The dragoons, informed who the enemy was, chafed impatiently to begin the attack—for they had a hundred insults to avenge on the bold partisan before them. Meanwhile, our hero, for the orderly had been right in saying Capt. Preston led the troop, approached on a trot, completely unconscious of the presence of his hidden enemy. He was engaged in a scouting expedition of some extent, and had no idea an armed royalist was within twenty miles. Suddenly, however, he drew in his rein, for he thought he heard a horse stamping in the forest; but it was too late; Major Lindsay saw they were discovered, and immediately gave the long wished for word.

“Charge!” he said, plunging his rowels into the sides of his horse, and clearing at one bound the space between him and the road.

With a loud huzza, the dragoons shouting, “no quarter,” followed his example, horse and man suddenly filling the road like apparitions. Preston saw he was surrounded. Their cries told him, moreover, that it was to be a life and death struggle. Five against fifteen was fearful odds, yet he cried,

“Marion for ever!” and drawing his sabre, he dashed at Lindsay, whom he recognized. “Ha! have we met!” he cried.

“Yes! and I have you,” was the reply hissed between his adversary’s teeth.

As Major Lindsay thus spoke, he raised himself in his stirrups, and throwing all his strength into one gigantic blow, he brought his heavy sabre down, right on the almost unprotected head of Preston. For a moment it seemed as if the trenchant blade would cut through cap and skull, even to the shoulder—and had it struck fair it would; but with a dexterous movement, our hero evaded the stroke, and in return dealt a side cut that, if Major Lindsay’s horse had not fortunately swerved, would have ended his life at once.

But though foiled in this first attempt, each was eager to return to the charge, and wheeling their horses, they rushed again upon each other. It was Preston’s turn now to deal the first blow. He rode with very short stirrups, of which he took advantage to throw himself backward, and then, projecting himself forward, and casting all his strength into the blow, he brought his sabre down on the helmet of Major Lindsay with a force that was irresistible. Cutting clean though the crest as if it had been a smoke wreath, the well-proved blade descended with full violence on the steel cap, through which it crashed like an egg-shell; but here it stopped, broken into fragments by the tremendous stroke and the resistance of the iron casque combined. Nothing but that well-tempered steel head-piece could have saved Major Lindsay’s life. As it was, stunned and bewildered, he reeled in his saddle.

“Hew him down!—Use the cold lead!—Have at him there, one and all!”

Such were the exclamations that met our hero’s ear, as he recovered himself from that blow, and found only the hilt and a fragment of his broken blade left in his hand. He looked around hastily. His four followers had already been put hors de combat, and the dragoons were now, like dogs around a wild boar, waiting a chance to rush in on him, encouraging each other by shouts; for such was the terror of Preston’s name, and so terrific was the blow they had just seen dealt their leader, that each man hung back an instant, preferring that his neighbor should go in first. Preston saw this advantage, and hastened to avail himself of it, for, as pistols were already drawn, he knew his chance would last scarcely a moment.

“Ho, Thunderer!” he said, addressing his steed—a powerful animal, jet black all over—and turning his head toward that part of the circle of his foes which seemed the thinnest, he added, “stand by me now, and we escape them yet.”

As he spoke, he dashed his spurs into the animal’s sides till the blood spurted beneath the sharp steel, and with a pistol in his right hand, sprang fiercely forward. Right and left the dragoons, panic-struck, gave way, as when a flock of sheep fly before the onset of an angry wolf—only one man attempting to stop his progress. But, without so much as being wounded, the trooper went down headlong, overthrown by the shock of Preston’s powerful charger; and our hero, yielding to an uncontrollable impulse, as he saw the way thus cleared before him, rose in his stirrups, and waving his arm on high, looked back, and gave utterance to a shout that long after he had vanished, like a bolt shot from some huge catapult, echoed and re-echoed in the startled woods.

“He is off, by God,” said the orderly. “Saw you ever the like?”

For a second the dragoons stood stupidly looking at each other; then, all at once, a dozen pistols were snapped at the fugitive, and a dozen steeds put to the pursuit. Moreover, Major Lindsay, though his head still swam from that tremendous blow, had recovered sufficiently to understand what was passing, and he now lent his voice to encourage the chase, and himself pressed forward among the first.

All this had occupied less time than it has taken us to relate it. The attack, the fight, the escape succeeded each other like flashes of summer lightning; and when Preston, adroitly turning his horse into the narrow and winding road where his foes had lain in ambush, passed momently out of sight, unharmed by the shots that whistled past, it seemed to him almost as if he were in a dream. But the shouts of pursuers, and the rapid tread of hoofs, speedily convinced him of the reality, and plying voice and spur, he went onward at a slashing pace, now and then looking behind to see if the dragoons gained on him.

There is something inexpressibly still and refreshing in an old, deserted road, winding through a cool pine-forest. The tall trees lapping overhead, the thick carpet of splintering leaves below, and the delicious fragrance all around, have always had a charm for us; and Preston felt it so, especially after the fierce excitement of that life and death struggle; so that when he came to a little dark stream, gliding softly across the road, he longed to stop and bathe his throbbing temples, and take one long, sweet draught, as he had often done upon a hot day in the forest when a boy. But the red foe was behind him, and he shot on like an arrow.

Presently he came to an old clearing, which had been long abandoned. Here, for about a quarter of a mile, was an open space, where ploughed fields had once been, but the furrows of which now were overgrown with a dry, stunted grass. He would have preferred the winding forest road, but there was no alternative, and on he dashed. He had nearly regained the shelter of the forest on the other side, when he heard a wild burst of cheering, and looking back, he saw the dragoons, with Major Lindsay and one other in advance, entering on the open space. They had caught sight of him for the first time since he entered the old road, and their shouts betokened renewed hope and determination on their part.

Breathlessly Preston kept on, but with less assurance than before, for his horse was already hard worked, and he soon saw with dismay that blood was flowing from his fore-shoulder freely from a wound. A half mile further on the poor animal began to flag sensibly; yet, cruel as it seemed, and much as it pained his own generous nature, Preston was forced to urge on the dying steed. He knew that at the distance of a mile and a half ahead was a swamp, into the recesses of which, if he could once plunge, he would be safe. But now he heard behind him a rapid hoof. It came nearer and nearer, though still out of sight. One, if not more, of his pursuers was gaining upon him. Again he spurred his steed, and encouraged him with words. The noble animal answered with a feeble cry, and staggered on. Scarcely half a mile now remained to gain the swamp. If he could only reach it, Preston knew all danger would be past. But this was impossible.

That rapid gallop came nearer and nearer, like the clock that ticks the hour of the criminal’s fate. He heard a shout behind him, and looking over his shoulder saw the trooper, whom he had last noticed side by side with Major Lindsay, come thundering on. He cheered his dying steed to a last effort—but it was in vain; the dragoon made two strides to his one. A few paces only now separated them; the swamp lay thrice the distance before. Already the trooper had risen in his stirrups, broadsword in hand. Preston had no such weapon. Suddenly he recollected the pistol in his other holster, and drawing it with the velocity of thought, he turned half around in his saddle and fired. With unerring aim the ball entered the brain of the dragoon, who fell dead to the earth.

It was the work of a moment to leap to the ground and catch the fallen soldier’s horse, on which Preston sprang. Poor Thunderer was already dead; he had sunk to the earth as his master fired the last shot.

Thus fate interposed to prevent an interview between Preston and our heroine, at a time when it would have been of incalculable advantage to both, and have circumvented a plot as base and cruel as it was now certain of success. At the very hour when Preston, after having ridden over thirty miles from the spot where he was attacked, threw himself wearied from his horse, in one of the most secret recesses of the forest, Kate and her aunt were setting forth for Georgetown, where they arrived on the succeeding day.

Never was human creature in a more isolated and mournful situation than Kate now found herself. Indulging in what she thought a hopeless passion, every motive of delicacy forbade her revealing it to those who alone could befriend her. She well knew that if her father became aware how much her marriage with Major Lindsay was against her inclinations, he would interpose even at the very altar, and ascend the scaffold to save her. Neither would it do to let her aunt guess her abhorrence at this union. Both her father and Mrs. Blakeley had, indeed, at one time hoped that a matrimonial connection would be formed between her and Preston, but the mutual coldness of the parties had long since dissipated this expectation. It was no time now to reveal her secret preference; such a confession would only have sealed her father’s fate without rendering her happy. Kate was forced therefore to wear a smiling face, when her heart was lacerated.

As Major Lindsay was compelled to be at Camden in six days, his leave of absence closing at that period, the marriage was fixed for the evening before his departure. This was an earlier day than Kate had looked for, but she could not object without exposing her secret. She submitted therefore in silence.

But who can tell the agony of her spirit, when in company with her aunt and parent she was forced to wear a smiling aspect! yet when alone she gave free vent to her sorrow. The image of Preston often intruded on those bitter moments. Alas! that one so young should be so miserable. She could have prayed for death but that it would have been impious.

Oh, the heart, the heart! what a mystery it is. There are blows worse than those on the wheel; it is when a gay heart is broken with anguish.

[Conclusion in our next.

WHAT THE OLD WOMAN SAID TO THE SCHOOL-GIRL.

———

BY THOMAS BUCHANAN READ.

———

Little maiden, you may laugh

That you see me wear a staff!

For your laughter’s but the chaff

From the melancholy grain!

Through the shadows long and cool

You are tripping down to school,

But your teacher’s cloudy rule

Only dulls the shining pool

With its loud and stormy rain!

There’s a higher lore to learn

Than his knowledge can discern;

There’s a valley deep and dern

In a desolate domain!

But for this he has no chart!

Shallow science—shallow art!

Thither—oh be still my heart—

One too many did depart

From the halls of Linden Lane!

I can teach you better things;

For I know the secret springs

Where the spirit wells and sings

Till it overflows the brain!

Come when eve is closing in,

When the spiders all begin,

Like philosophers, to spin

Gilded tissues vain and thin

Through the shades of Linden Lane.

While you sit as in a trance,

Where the moon-made shadows dance,

From the distaff of Romance

I will spin a silken skein!

Down the misty years gone by

I will turn your azure eye;

You shall see the changeful sky

Falling dark or hanging high

O’er the halls of Linden Lane!

Come, and sitting by the trees,

O’er the long and level leas,

Stretched between us and the seas,

I can point the battle-plain:

If the air comes from the shore

We may hear the billows roar;

But oh! never, nevermore

Shall the wind come as of yore

To the halls of Linden Lane!

Those were weary days of wo,

Ah! yes, many years ago,

When a cruel foreign foe

Sent his fleets across the main!

Though all this is in your books,

There are countless words and looks,

Which, like flowers in hidden nooks,

Or the melody of brooks,

There’s no volume can retain!

Come, and if the night be fair,

And the moon be in the air,

I can tell you when and where

Walked a tender loving twain:

Though it cannot be, alas!

Yet, as in a magic glass,

We will sit and see them pass

Through the long and rustling grass

At the foot of Linden Lane!