Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XXX, No. 3, March 1847

Author: Various

Editor: George R. Graham

Release date: February 11, 2018 [eBook #56549]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed

Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net from

page images generously made available by the Internet

Archive (https://archive.org)

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXX. March, 1847. No. 3.

Table of Contents

Fiction, Literature and Articles

Poetry and Fashion

| Song | |

| The Midshipman’s Farewell | |

| A Prayer | |

| Heart Struggles | |

| Fanny | |

| Lines | |

| The Love Dial | |

| The Brickmaker | |

| To Mrs. A. T. | |

| Le Follet | |

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

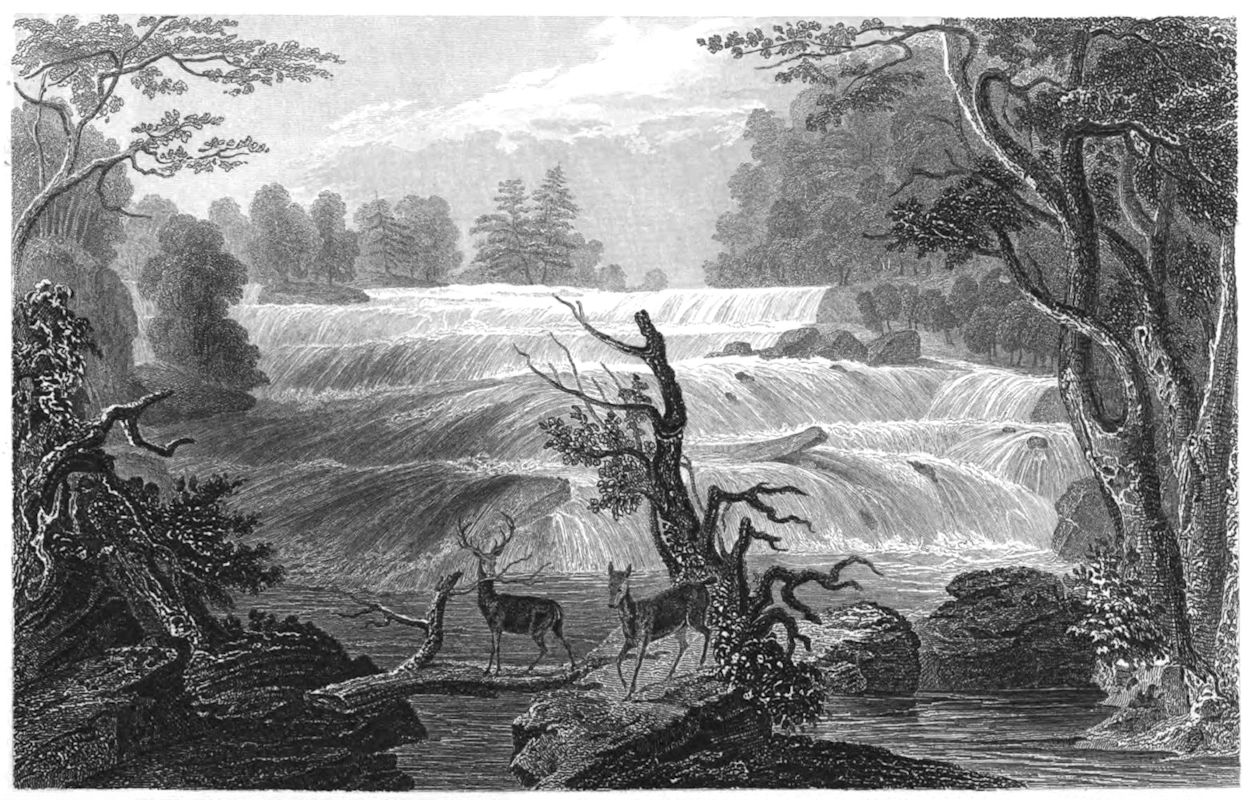

drawn by J. Smillie from a sketch by T. Addison Richards Graham's Magazine 1844. Engd by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch & Smillie

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXX. PHILADELPHIA, MARCH, 1847. No. 3.

———

BY HENRY D. THOREAU.

———

Thomas Carlyle is a Scotchman, born about fifty years ago, “at Ecclefechan, Annandale,” according to one authority. “His parents ‘good farmer people,’ his father an elder in the Secession church there, and a man of strong native sense, whose words were said to ‘nail a subject to the wall.’ ” We also hear of his “excellent mother,” still alive, and of “her fine old covenanting accents, concerting with his transcendental tones.” He seems to have gone to school at Annan, on the shore of the Solway Firth, and there, as he himself writes, “heard of famed professors, of high matters classical, mathematical, a whole Wonderland of Knowledge,” from Edward Irving, then a young man “fresh from Edinburgh, with college prizes, &c.”—“come to see our schoolmaster, who had also been his.” From this place, they say, you can look over into Wordsworth’s country. Here first he may have become acquainted with Nature, with woods, such as are there, and rivers and brooks, some of whose names we have heard, and the last lapses of Atlantic billows. He got some of his education, too, more or less liberal, out of the University of Edinburgh, where, according to the same authority, he had to “support himself,” partly by “private tuition, translations for the booksellers, &c.,” and afterward, as we are glad to hear, “taught an academy in Dysart, at the same time that Irving was teaching in Kirkaldy,” the usual middle passage of a literary life. He was destined for the church, but not by the powers that rule man’s life; made his literary début in Fraser’s Magazine, long ago; read here and there in English and French, with more or less profit, we may suppose, such of us at least as are not particularly informed, and at length found some words which spoke to his condition in the German language, and set himself earnestly to unravel that mystery—with what success many readers know.

After his marriage he “resided partly at Comely Bank, Edinburgh; and for a year or two at Craigenputtock, a wild and solitary farm-house in the upper part of Dumfriesshire,” at which last place, amid barren heather hills, he was visited by our countryman Emerson. With Emerson he still corresponds. He was early intimate with Edward Irving, and continued to be his friend until the latter’s death. Concerning this “freest, brotherliest, bravest human soul,” and Carlyle’s relation to him, those whom it concerns will do well to consult a notice of his death in Fraser’s Magazine for 1835, reprinted in the Miscellanies. He also corresponded with Goethe. Latterly, we hear, the poet Stirling was his only intimate acquaintance in England.

He has spent the last quarter of his life in London, writing books; has the fame, as all readers know, of having made England acquainted with Germany, in late years, and done much else that is novel and remarkable in literature. He especially is the literary man of those parts. You may imagine him living in altogether a retired and simple way, with small family, in a quiet part of London, called Chelsea, a little out of the din of commerce, in “Cheyne Row,” there, not far from the “Chelsea Hospital.” “A little past this, and an old ivy-clad church, with its buried generations lying around it,” writes one traveler, “you come to an antique street running at right angles with the Thames, and, a few steps from the river, you find Carlyle’s name on the door.”

“A Scotch lass ushers you into the second story front chamber, which is the spacious workshop of the world maker.” Here he sits a long time together, with many books and papers about him; many new books, we have been told, on the upper shelves, uncut, with the “author’s respects” in them; in late months, with many manuscripts in an old English hand, and innumerable pamphlets, from the public libraries, relating to the Cromwellian period; now, perhaps, looking out into the street on brick and pavement, for a change, and now upon some rod of grass ground in the rear; or, perchance, he steps over to the British Museum, and makes that his studio for the time. This is the fore part of the day; that is the way with literary men commonly; and then in the afternoon, we presume, he takes a short run of a mile or so through the suburbs out into the country; we think he would run that way, though so short a trip might not take him to very sylvan or rustic places. In the meanwhile, people are calling to see him, from various quarters, very few worthy of being seen by him, “distinguished travelers from America,” not a few, to all and sundry of whom he gives freely of his yet unwritten rich and flashing soliloquy, in exchange for whatever they may have to offer; speaking his English, as they say, with a “broad Scotch accent,” talking, to their astonishment and to ours, very much as he writes, a sort of Carlylese, his discourse “coming to its climaxes, ever and anon, in long, deep, chest-shaking bursts of laughter.”

He goes to Scotland sometimes to visit his native heath-clad hills, having some interest still in the earth there; such names as Craigenputtock and Ecclefechan, which we have already quoted, stand for habitable places there to him; or he rides to the seacoast of England in his vacations, upon his horse Yankee, bought by the sale of his books here, as we have been told.

How, after all, he gets his living; what proportion of his daily bread he earns by day-labor or job-work with his pen, what he inherits, what steals—questions whose answers are so significant, and not to be omitted in his biography—we, alas! are unable to answer here. It may be worth the while to state that he is not a Reformer, in our sense of the term, eats, drinks, and sleeps, thinks and believes, professes and practices, not according to the New England standard, nor to the Old English wholly. Nevertheless, we are told that he is a sort of lion in certain quarters there, “an amicable centre for men of the most opposite opinions,” and “listened to as an oracle,” “smoking his perpetual pipe.”

A rather tall, gaunt figure, with intent face, dark hair and complexion, and the air of a student; not altogether well in body, from sitting too long in his workhouse, he, born in the border country and descended from moss-troopers, it may be. We have seen several pictures of him here; one, a full length portrait, with hat and overall, if it did not tell us much, told the fewest lies; another, we remember, was well said to have “too combed a look;” one other also we have seen in which we discern some features of the man we are thinking of; but the only ones worth remembering, after all, are those which he has unconsciously drawn of himself.

When we remember how these volumes came over to us, with their encouragement and provocation from mouth to mouth, and what commotion they created in many private breasts, we wonder that the country did not ring, from shore to shore, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, with its greeting; and the Boons and Crockets of the West make haste to hail him, whose wide humanity embraces them too. Of all that the packets have brought over to us, has there been any richer cargo than this? What else has been English news for so long a season? What else, of late years, has been England to us—to us who read books, we mean? Unless we remembered it as the scene where the age of Wordsworth was spending itself, and a few younger muses were trying their wings, and from time to time, as the residence of Landon; Carlyle alone, since the death of Coleridge, has kept the promise of England. It is the best apology for all the bustle and the sin of commerce, that it has made us acquainted with the thoughts of this man. Commerce would not concern us much if it were not for such results as this. New England owes him a debt which she will be slow to recognize. His earlier essays reached us at a time when Coleridge’s were the only recent words which had made any notable impression so far, and they found a field unoccupied by him, before yet any words of moment had been uttered in our midst. He had this advantage, too, in a teacher, that he stood near to his pupils; and he has no doubt afforded reasonable encouragement and sympathy to many an independent but solitary thinker. Through him, as usher, we have been latterly, in a great measure, made acquainted with what philosophy and criticism the nineteenth century had to offer—admitted, so to speak, to the privileges of the century; and what he may yet have to say, is still expected here with more interest than any thing else from that quarter.

It is remarkable, but on the whole, perhaps, not to be lamented, that the world is so unkind to a new book. Any distinguished traveler who comes to our shores, is likely to get more dinners and speeches of welcome than he can well dispose of, but the best books, if noticed at all, meet with coldness and suspicion, or, what is worse, gratuitous, off-hand criticism. It is plain that the reviewers, both here and abroad, do not know how to dispose of this man. They approach him too easily, as if he were one of the men of letters about town, who grace Mr. Somebody’s administration, merely; but he already belongs to literature, and depends neither on the favor of reviewers, nor the honesty of book-sellers, nor the pleasure of readers for his success. He has more to impart than to receive from his generation. He is another such a strong and finished workman in his craft as Samuel Johnson was, and like him, makes the literary class respectable. As few are yet out of their apprenticeship, or even if they learn to be able writers, are at the same time able and valuable thinkers. The aged and critical eye, especially, is incapacitated to appreciate the works of this author. To such their meaning is impalpable and evanescent, and they seem to abound only in obstinate mannerisms, Germanisms, and whimsical ravings of all kinds, with now and then an unaccountably true and sensible remark. On the strength of this last, Carlyle is admitted to have what is called genius. We hardly know an old man to whom these volumes are not hopelessly sealed. The language, they say, is foolishness and a stumbling-block to them; but to many a clear-headed boy, they are plainest English, and despatched with such hasty relish as his bread and milk. The fathers wonder how it is that the children take to this diet so readily, and digest it with so little difficulty. They shake their heads with mistrust at their free and easy delight, and remark that “Mr. Carlyle is a very learned man;” for they, too, not to be out of fashion, have got grammar and dictionary, if the truth were known, and with the best faith cudgelled their brains to get a little way into the jungle, and they could not but confess, as often as they found the clue, that it was as intricate as Blackstone to follow, if you read it honestly. But merely reading, even with the best intentions, is not enough, you must almost have written these books yourself. Only he who has had the good fortune to read them in the nick of time, in the most perceptive and recipient season of life, can give any adequate account of them.

Many have tasted of this well with an odd suspicion, as if it were some fountain Arethuse which had flowed under the sea from Germany, as if the materials of his books had lain in some garret there, in danger of being appropriated for waste paper. Over what German ocean, from what Hercynian forest, he has been imported, piece-meal, into England, or whether he has now all arrived, we are not informed. This article is not invoiced in Hamburg, nor in London. Perhaps it was contraband. However, we suspect that this sort of goods cannot be imported in this way. No matter how skillful the stevedore, all things being got into sailing trim, wait for a Sunday, and aft wind, and then weigh anchor, and run up the main-sheet—straightway what of transcendant and permanent value is there resists the aft wind, and will doggedly stay behind that Sunday—it does not travel Sundays; while biscuit and pork make headway, and sailors cry heave-yo! it must part company, if it open a seam. It is not quite safe to send out a venture in this kind, unless yourself go supercargo. Where a man goes, there he is; but the slightest virtue is immovable—it is real estate, not personal; who would keep it, must consent to be bought and sold with it.

However, we need not dwell on this charge of a German extraction, it being generally admitted, by this time, that Carlyle is English, and an inhabitant of London. He has the English for his mother tongue, though with a Scotch accent, or never so many accents, and thoughts also, which are the legitimate growth of native soil, to utter therewith. His style is eminently colloquial—and no wonder it is strange to meet with in a book. It is not literary or classical; it has not the music of poetry, nor the pomp of philosophy, but the rhythms and cadences of conversation endlessly repeated. It resounds with emphatic, natural, lively, stirring tones, muttering, rattling, exploding, like shells and shot, and with like execution. So far as it is a merit in composition, that the written answer to the spoken word, and the spoken word to a fresh and pertinent thought in the mind, as well as to the half thoughts, the tumultuary misgivings and expectancies, this author is, perhaps, not to be matched in literature. In the streets men laugh and cry, but in books, never; they “whine, put finger i’ the eye, and sob” only. One would think that all books of late, had adopted the felling inflexion. “A mother, if she wishes to sing her child to sleep,” say the musical men, “will always adopt the falling inflexion.” Would they but choose the rising inflexion, and wake the child up for once.

He is no mystic either, more than Newton or Arkwright, or Davy—and tolerates none. Not one obscure line, or half line, did he ever write. His meaning lies plain as the daylight, and he who runs may read; indeed, only he who runs can read, and keep up with the meaning. It has the distinctness of picture to his mind, and he tells us only what he sees printed in largest English type upon the face of things. He utters substantial English thoughts in plainest English dialects; for it must be confessed, he speaks more than one of these. All the shires of England, and all the shires of Europe, are laid under contribution to his genius; for to be English does not mean to be exclusive and narrow, and adapt one’s self to the apprehension of his nearest neighbor only. And yet no writer is more thoroughly Saxon. In the translation of those fragments of Saxon poetry, we have met with the same rhythm that occurs so often in his poem on the French Revolution. And if you would know where many of those obnoxious Carlyleisms and Germanisms came from, read the best of Milton’s prose, read those speeches of Cromwell which he has brought to light, or go and listen once more to your mother’s tongue. So much for his German extraction.

Indeed, for fluency and skill in the use of the English tongue, he is a master unrivaled. His felicity and power of expression surpass even any of his special merits as a historian and critic. Therein his experience has not failed him, but furnished him with such a store of winged, aye, and legged words, as only a London life, perchance, could give account of; we had not understood the wealth of the language before. Nature is ransacked, and all the resorts and purlieus of humanity are taxed, to furnish the fittest symbol for his thought. He does not go to the dictionary, the word-book, but to the word-manufactory itself, and has made endless work for the lexicographers—yes, he has that same English for his mother-tongue, that you have, but with him it is no dumb, muttering, mumbling faculty, concealing the thoughts, but a keen, unwearied, resistless weapon. He has such command of it as neither you nor I have; and it would be well for any who have a lost horse to advertise, or a town-meeting warrant, or a sermon, or a letter to write, to study this universal letter-writer, for he knows more than the grammar or the dictionary.

The style is worth attending to, as one of the most important features of the man which we at this distance can discern. It is for once quite equal to the matter. It can carry all its load, and never breaks down nor staggers. His books are solid and workmanlike, as all that England does; and they are graceful and readable also. They tell of huge labor done, well done, and all the rubbish swept away, like the bright cutlery which glitters in shop-windows, while the coke and ashes, the turnings, filings, dust, and borings, lie far away at Birmingham, unheard of. He is a masterly clerk, scribe, reporter, and writer. He can reduce to writing most things—gestures, winks, nods, significant looks, patois, brogue, accent, pantomime, and how much that had passed for silence before, does he represent by written words. The countryman who puzzled the city lawyer, requiring him to write, among other things, his call to his horses, would hardly have puzzled him; he would have found a word for it, all right and classical, that would have started his team for him. Consider the ceaseless tide of speech forever flowing in countless cellars, garrets, parlors; that of the French, says Carlyle, “only ebbs toward the short hours of night,” and what a drop in the bucket is the printed word. Feeling, thought, speech, writing, and we might add, poetry, inspiration—for so the circle is completed; how they gradually dwindle at length, passing through successive colanders, into your history and classics, from the roar of the ocean, the murmur of the forest, to the squeak of a mouse; so much only parsed and spelt out, and punctuated, at last. The few who can talk like a book, they only get reported commonly. But this writer reports a new “Lieferung.”

One wonders how so much, after all, was expressed in the old way, so much here depends upon the emphasis, tone, pronunciation, style, and spirit of the reading. No writer uses so profusely all the aids to intelligibility which the printer’s art affords. You wonder how others had contrived to write so many pages without emphatic or italicised words, they are so expressive, so natural, so indispensable here, as if none had ever used the demonstrative pronouns demonstratively before. In another’s sentences the thought, though it may be immortal, is, as it were, embalmed, and does not strike you, but here it is so freshly living, even the body of it, not having passed through the ordeal of death, that it stirs in the very extremities, and the smallest particles and pronouns are all alive with it. It is not simple dictionary it, yours or mine, but IT. The words did not come at the command of grammar, but of a tyrannous, inexorable meaning; not like standing soldiers, by vote of parliament, but any able-bodied countryman pressed into the service, for “sire, it is not a revolt, it is a revolution.”

We have never heard him speak, but we should say that Carlyle was a rare talker. He has broken the ice, and streams freely forth like a spring torrent. He does not trace back the stream of his thought, silently adventurous, up to its fountain-head, but is borne away with it, as it rushes through his brain like a torrent to overwhelm and fertilize. He holds a talk with you. His audience is such a tumultuous mob of thirty thousand, as assembled at the University of Paris, before printing was invented. Philosophy, on the other hand, does not talk, but write, or, when it comes personally before an audience, lecture or read; and therefore it must be read to-morrow, or a thousand years hence. But the talker must naturally be attended to at once; he does not talk on without an audience; the winds do not long bear the sound of his voice. Think of Carlyle reading his French Revolution to any audience. One might say it was never written, but spoken; and thereafter reported and printed, that those not within sound of his voice might know something about it. Some men read to you something which they have written, in a dead language, of course, but it may be in a living letter, in a Syriac, or Roman, or Runic character. Men must speak English who can write Sanscrit; and they must speak a modern language who write, perchance, an ancient and universal one. We do not live in those days when the learned used a learned language. There is no writing of Latin with Carlyle, but as Chaucer, with all reverence to Homer, and Virgil, and Messieurs the Normans, sung his poetry in the homely Saxon tongue; and Locke has at least the merit of having done philosophy into English—so Carlyle has done a different philosophy still further into English, and thrown open the doors of literature and criticism to the populace.

Such a style—so diversified and variegated! It is like the face of a country; it is like a New England landscape, with farm-houses and villages, and cultivated spots, and belts of forests and blueberry-swamps round about it, with the fragrance of shad-blossoms and violets on certain winds. And as for the reading of it, it is novel enough to the reader who has used only the diligence, and old-line mail-coach. It is like traveling, sometimes on foot, sometimes in a gig tandem; sometimes in a full coach, over highways, mended and unmended, for which you will prosecute the town; on level roads, through French departments, by Simplon roads over the Alps, and now and then he hauls up for a relay, and yokes in an unbroken colt of a Pegasus for a leader, driving off by cart-paths, and across lots, by corduroy roads and gridiron bridges; and where the bridges are gone, not even a string-piece left, and the reader has to set his breast and swim. You have got an expert driver this time, who has driven ten thousand miles, and was never known to upset; can drive six in hand on the edge of a precipice, and touch the leaders anywhere with his snapper.

With wonderful art he grinds into paint for his picture all his moods and experiences, so that all his forces may be brought to the encounter. Apparently writing without a particular design or responsibility, setting down his soliloquies from time to time, taking advantage of all his humors, when at length the hour comes to declare himself, he puts down in plain English, without quotation marks, what he, Thomas Carlyle, is ready to defend in the face of the world, and fathers the rest, often quite as defensible, only more modest, or plain spoken, or insinuating, upon “Sauerteig,” or some other gentleman long employed on the subject. Rolling his subject how many ways in his mind, he meets it now face to face, wrestling with it at arm’s length, and striving to get it down, or throws it over his head; and if that will not do, or whether it will do or not, tries the back-stitch and side-hug with it, and downs it again—scalps it, draws and quarters it, hangs it in chains, and leaves it to the winds and dogs. With his brows knit, his mind made up, his will resolved and resistless, he advances, crashing his way through the host of weak, half-formed, dilettante opinions, honest and dishonest ways of thinking, with their standards raised, sentimentalities and conjectures, and tramples them all into dust. See how he prevails; you don’t even hear the groans of the wounded and dying. Certainly it is not so well worth the while to look through any man’s eyes at history, for the time, as through his; and his way of looking at things is fastest getting adopted by his generation.

It is not in man to determine what his style shall be. He might as well determine what his thoughts shall be. We would not have had him write always as in the chapter on Burns, and the Life of Schiller, and elsewhere. No; his thoughts were ever irregular and impetuous. Perhaps as he grows older and writes more he acquires a truer expression; it is in some respects manlier, freer, struggling up to a level with its fountain-head. We think it is the richest prose style we know of.

Who cares what a man’s style is, so it is intelligible—as intelligible as his thought. Literally and really, the style is no more than the stylus, the pen he writes with—and it is not worth scraping and polishing, and gilding, unless it will write his thoughts the better for it. It is something for use, and not to look at. The question for us is not whether Pope had a fine style, wrote with a peacock’s feather, but whether he uttered useful thoughts. Translate a book a dozen times from one language to another, and what becomes of its style? Most books would be worn out and disappear in this ordeal. The pen which wrote it is soon destroyed, but the poem survives. We believe that Carlyle has, after all, more readers, and is better known to-day for this very originality of style, and that posterity will have reason to thank him for emancipating the language, in some measure, from the fetters which a merely conservative, aimless, and pedantic literary class had imposed upon it, and setting an example of greater freedom and naturalness. No man’s thoughts are new, but the style of their expression is the never failing novelty which cheers and refreshes men. If we were to answer the question, whether the mass of men, as we know them, talk as the standard authors and reviewers write, or rather as this man writes, we should say that he alone begins to write their language at all, and that the former is, for the most part, the mere effigies of a language, not the best method of concealing one’s thoughts even, but frequently a method of doing without thoughts at all.

In his graphic description of Richter’s style, Carlyle describes his own pretty nearly; and no doubt he first got his own tongue loosened at that fountain, and was inspired by it to equal freedom and originality. “The language,” as he says of Richter, “groans with indescribable metaphors and allusions to all things, human and divine, flowing onward, not like a river, but like an inundation; circling in complex eddies, chafing and gurgling, now this way, now that;” but in Carlyle, “the proper current” never “sinks out of sight amid the boundless uproar.” Again: “His very language is Titanian—deep, strong, tumultuous, shining with a thousand hues, fused from a thousand elements, and winding in labyrinthic mazes.”

In short, if it is desirable that a man be eloquent, that he talk much, and address himself to his own age mainly, then this is not a bad style of doing it. But if it is desired rather that he pioneer into unexplored regions of thought, and speaks to silent centuries to come, then, indeed, we could wish that he had cultivated the style of Goethe more, that of Richter less; not that Goethe’s is the kind of utterance most to be prized by mankind, but it will serve for a model of the best that can be successfully cultivated.

But for style, and fine writing, and Augustan ages—that is but a poor style, and vulgar writing, and a degenerate age, which allows us to remember these things. This man has something to communicate. Carlyle’s are not, in the common sense, works of art in their origin and aim; and yet, perhaps, no living English writer evinces an equal literary talent. They are such works of art only as the plough, and corn-mill, and steam-engine—not as pictures and statues. Others speak with greater emphasis to scholars, as such, but none so earnestly and effectually to all who can read. Others give their advice, he gives his sympathy also. It is no small praise that he does not take upon himself the airs, has none of the whims, none of the pride, the nice vulgarities, the starched, impoverished isolation, and cold glitter of the spoiled children of genius. He does not need to husband his pearl, but excels by a greater humanity and sincerity.

He is singularly serious and untrivial. We are every where impressed by the rugged, unwearied, and rich sincerity of the man. We are sure that he never sacrificed one jot of his honest thought to art or whim, but to utter himself in the most direct and effectual way, that is the endeavor. These are merits which will wear well. When time has worn deeper into the substance of these books, this grain will appear. No such sermons have come to us here out of England, in late years, as those of this preacher; sermons to kings, and sermons to peasants, and sermons to all intermediate classes. It is in vain that John Bull, or any of his cousins, turns a deaf ear, and pretends not to hear them, nature will not soon be weary of repeating them. There are words less obviously true, more for the ages to hear, perhaps, but none so impossible for this age not to hear. What a cutting cimiter was that “past and present,” going through heaps of silken stuffs, and glibly through the necks of men, too, without their knowing it, leaving no trace. He has the earnestness of a prophet. In an age of pedantry and dilettantism, he has no grain of these in his composition. There is no where else, surely, in recent readable English, or other books, such direct and effectual teaching, reproving, encouraging, stimulating, earnestly, vehemently, almost like Mahomet, like Luther; not looking behind him to see how his Opera Omnia will look, but forward to other work to be done. His writings are a gospel to the young of this generation; they will hear his manly, brotherly speech with responsive joy, and press forward to older or newer gospels.

We should omit a main attraction in these books, if we said nothing of their humor. Of this indispensable pledge of sanity, without some leaven, of which the abstruse thinker may justly be suspected of mysticism, fanaticism, or insanity, there is a super-abundance in Carlyle. Especially the transcendental philosophy needs the leaven of humor to render it light and digestible. In his later and longer works it is an unfailing accompaniment, reverberating through pages and chapters, long sustained without effort. The very punctuation, the italics, the quotation marks, the blank spaces and dashes, and the capitals, each and all are pressed into its service.

Every man, of course, has his fane, from which even the most innocent conscious humor is excluded; but in proportion as the writer’s position is high above his fellows, the range of his humor is extended. To the thinker, all the institutions of men, as all imperfection, viewed from the point of equanimity, are legitimate subjects of humor. Whatever is not necessary, no matter how sad or personal, or universal a grievance, is, indeed, a jest more or less sublime.

Carlyle’s humor is vigorous and Titanic, and has more sense in it than the sober philosophy of many another. It is not to be disposed of by laughter and smiles merely; it gets to be too serious for that—only they may laugh who are not hit by it. For those who love a merry jest, this is a strange kind of fun—rather too practical joking, if they understand it. The pleasant humor which the public loves, is but the innocent pranks of the ball-room, harmless flow of animal spirits, the light plushy pressure of dandy pumps, in comparison. But when an elephant takes to treading on your corns, why then you are lucky if you sit high, or wear cowhide. His humor is always subordinate to a serious purpose, though often the real charm for the reader, is not so much in the essential progress and final upshot of the chapter, as in this indirect side-light illustration of every hue. He sketches first with strong, practical English pencil, the essential features in outline, black on white, more faithfully than Dryasdust would have done, telling us wisely whom and what to mark, to save time, and then with brush of camel’s hair, or sometimes with more expeditious swab, he lays on the bright and fast colors of his humor everywhere. One piece of solid work, be it known, we have determined to do, about which let there be no jesting, but all things else under the heavens, to the right and left of that, are for the time fair game. To us this humor is not wearisome, as almost every other is. Rabelais, for instance, is intolerable; one chapter is better than a volume—it may be sport to him, but it is death to us. A mere humorist, indeed, is a most unhappy man; and his readers are most unhappy also.

Humor is not so distinct a quality as for the purposes of criticism, it is commonly regarded, but allied to every, even the divinest faculty. The familiar and cheerful conversation about every hearth-side, if it be analyzed, will be found to be sweetened by this principle. There is not only a never-failing, pleasant, and earnest humor kept up there, embracing the domestic affairs, the dinner, and the scolding, but there is also a constant run upon the neighbors, and upon church and state, and to cherish and maintain this, in a great measure, the fire is kept burning, and the dinner provided. There will be neighbors, parties to a very genuine, even romantic friendship, whose whole audible salutation and intercourse, abstaining from the usual cordial expressions, grasping of hands, or affectionate farewells, consists in the mutual play and interchange of a genial and healthy humor, which excepts nothing, not even themselves, in its lawless range. The child plays continually, if you will let it, and all its life is a sort of practical humor of a very pure kind, often of so fine and ethereal a nature, that its parents, its uncles and cousins, can in no wise participate in it, but must stand aloof in silent admiration, and reverence even. The more quiet the more profound it is. Even nature is observed to have her playful moods or aspects, of which man seems sometimes to be the sport.

But, after all, we could sometimes dispense with the humor, though unquestionably incorporated in the blood, if it were replaced by this author’s gravity. We should not apply to himself, without qualification, his remarks on the humor of Richter. With more repose in his inmost being, his humor would become more thoroughly genial and placid. Humor is apt to imply but a half satisfaction at best. In his pleasantest and most genial hour, man smiles but as the globe smiles, and the works of nature. The fruits dry ripe, and much as we relish some of them, in their green and pulpy state, we lay up for our winter store, not out of these, but the rustling autumnal harvests. Though we never weary of this vivacious wit, while we are perusing its work, yet when we remember it from afar, we sometimes feel balked and disappointed, missing the security, the simplicity, and frankness, even the occasional magnanimity of acknowledged dullness and bungling. This never-failing success and brilliant talent become a reproach. To the most practical reader the humor is certainly too obvious and constant a quality. When we are to have dealings with a man, we prize the good faith and valor of soberness and gravity. There is always a more impressive statement than consists with these victorious comparisons. Besides, humor does not wear well. It is commonly enough said, that a joke will not bear repeating. The deepest humor will not keep. Humors do not circulate but stagnate, or circulate partially. In the oldest literature, in the Hebrew, the Hindoo, the Persian, the Chinese, it is rarely humor, even the most divine, which still survives, but the most sober and private, painful or joyous thoughts, maxims of duty, to which the life of all men may be referred. After time has sifted the literature of a people, there is left only their Scripture, for that is WRITING, par excellence. This is as true of the poets, as of the philosophers and moralists by profession; for what subsides in any of these is the moral only, to re-appear as dry land at some remote epoch.

We confess that Carlyle’s humor is rich, deep, and variegated, in direct communication with the back bone and risible muscles of the globe—and there is nothing like it; but much as we relish this jovial, this rapid and detergeous way of conveying one’s views and impressions, when we would not converse but meditate, we pray for a man’s diamond edition of his thought, without the colored illuminations in the margin—the fishes and dragons, and unicorns, the red or the blue ink, but its initial letter in distinct skeleton type, and the whole so clipped and condensed down to the very essence of it, that time will have little to do. We know not but we shall immigrate soon, and would fain take with us all the treasures of the east, and all kinds of dry, portable soups, in small tin canisters, which contain whole herds of English beeves, boiled down, will be acceptable.

The difference between this flashing, fitful writing and pure philosophy, is the difference between flame and light. The flame, indeed, yields light, but when we are so near as to observe the flame, we are apt to be incommoded by the heat and smoke. But the sun, that old Platonist, is set so far off in the heavens, that only a genial summer-heat and ineffable day-light can reach us. But many a time, we confess, in wintery weather, we have been glad to forsake the sun-light, and warm us by these Promethean flames.

Carlyle must undoubtedly plead guilty to the charge of mannerism. He not only has his vein, but his peculiar manner of working it. He has a style which can be imitated, and sometimes is an imitator of himself. Every man, though born and bred in the metropolis of the world, will still have some provincialism adhering to him; but in proportion as his aim is simple and earnest, he approaches at once the most ancient and the most modern men. There is no mannerism in the Scriptures. The style of proverbs, and indeed of all maxims, whether measured by sentences or by chapters, if they may be said to have any style, is one, and as the expression of one voice, merely an account of the matter by the latest witness. It is one advantage enjoyed by men of science, that they use only formulas which are universal. The common language and the common sense of mankind, it is most uncommon to meet with in the individual. Yet liberty of thought and speech is only liberty to think the universal thought, and speak the universal language of men, instead of being enslaved to a particular mode. Of this universal speech there is very little. It is equable and sure; from a depth within man which is beyond education and prejudice.

Certainly, no critic has anywhere said what is more to the purpose, than this which Carlyle’s own writings furnish, which we quote, as well for its intrinsic merit as for its pertinence here. “It is true,” says he, thinking of Richter, “the beaten paths of literature lead the safeliest to the goal; and the talent pleases us most, which submits to shine with new gracefulness through old forms. Nor is the noblest and most peculiar mind too noble or peculiar for working by prescribed laws; Sophocles, Shakspeare, Cervantes, and in Richter’s own age, Goethe, how little did they innovate on the given forms of composition, how much in the spirit they breathed into them! All this is true; and Richter must lose of our esteem in proportion.” And again, in the chapter on Goethe, “We read Goethe for years before we come to see wherein the distinguishing peculiarity of his understanding, of his disposition, even of his way of writing, consists! It seems quite a simple style, [that of his?] remarkable chiefly for its calmness, its perspicuity, in short, its commonness; and yet it is the most uncommon of all styles.” And this, too, translated for us by the same pen from Schiller, which we will apply not merely to the outward form of his works, but to their inner form and substance. He is speaking of the artist. “Let some beneficent divinity snatch him, when a suckling, from the breast of his mother, and nurse him with the milk of a better time, that he may ripen to his full stature beneath a distant Grecian sky. And having grown to manhood, let him return, a foreign shape, into his century; not, however, to delight it by his presence, but, dreadful, like the son of Agamemnon, to purify it. The matter of his works he will take from the present, but their form he will derive from a nobler time; nay, from beyond all time, from the absolute unchanging unity of his own nature.”

But enough of this. Our complaint is already out of all proportion to our discontent.

Carlyle’s works, it is true, have not the stereotyped success which we call classic. They are a rich but inexpensive entertainment, at which we are not concerned lest the host has strained or impoverished himself to feed his guests. It is not the most lasting word, nor the loftiest wisdom, but rather the word which comes last. For his genius it was reserved to give expression to the thoughts which were throbbing in a million breasts. He has plucked the ripest fruit in the public garden; but this fruit already least concerned the tree that bore it, which was rather perfecting the bud at the foot of the leaf stalk. His works are not to be studied, but read with a swift satisfaction. Their flavor and gust is like what poets tell of the froth of wine, which can only be tasted once and hastily. On a review we can never find the pages we had read. The first impression is the truest and the deepest, and there is no reprint, no double entendre, so to speak, for the alert reader. Yet they are in some degree true natural products in this respect. All things are but once, and never repeated. The first faint blushes of the morning, gilding the mountain tops, the pale phosphor and saffron-colored clouds do verily transport us to the morning of creation; but what avails it to travel eastward, or look again there an hour hence? We should be as far in the day ourselves, mounting toward our meridian. These works were designed for such complete success that they serve but for a single occasion. It is the luxury of art, when its own instrument is manufactured for each particular and present use. The knife which slices the bread of Jove ceases to be a knife when this service is rendered.

[Conclusion in our next.

———

BY WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT.

———

These prairies glow with flowers,

These groves are tall and fair;

The mocking-bird with music fills

The fragrant morning air.

And yet I pine to see

My native hill once more,

And hear the sparrow’s friendly chirp

Beside its cottage door.

And he for whom I left

My native hill and brook,

Alas! I sometimes think I trace

A coldness in his look.

If I have lost his love,

I know my heart will break;

And haply they I left for him

Will sorrow for my sake.

———

BY MRS. CORNELIA DA PONTE.

———

When slumber seals those heavenly eyes,

And dreams of rapture round thee glow,

When angels watch, for angels love

To guard the pure from ills below,

Mine in that hour must keep the watch

Alone upon the midnight sea,

As winds and waves with hated speed

Bear me away from home and thee.

Yes, mine shall fix their silent gaze,

Nor shrink if danger hover near;

This hand that trembles now in thine,

Must grasp the sword without a fear;

And for the music of thy voice,

The stormy wave with shout of men,

For whispers soft, words stern and cold

Must be the sounds that hail me then.

The hour has come, fresh blows the gale,

Our ship moves down yon tide afar,

Away, away beyond that tide

Thy image follows as a star;

Farewell to thee, farewell to all,

My native land and skies above;

O who will greet the wanderer now

With soothing words or smiles of love?

Remember me, ’tis all I ask,

When others gaze, when others sigh,

When others plead with bending knee,

And drink the beauty of thine eye,

Remember then, for e’en in dreams,

Though bright they come, this heart shall weep,

My thirsting spirit vainly seek

Thy image on the lonely deep.

OR GAINING A CASE.

———

BY ICHABOD JONES.

———

“So, Oliver, you have a case with which to commence your career at the bar?”

“Yes, thanks to Uncle Scott, I have.”

“And will you allow me to ask what it is?”

“Well, to tell you that, I must first know myself. I believe it to be in relation to a contested will, but as to the particulars you are as wise as I.”

“A will case, eh! I have heard old lawyers say they were the best of cases, as far as fee is concerned.”

“To-morrow I am to have an interview with my client. My uncle gave such a glowing description of her that he has quite raised my curiosity.”

“A lady for a client! why that’s better yet. By the bye, Oliver, you seem somewhat indifferent to the divine sex; and yet you have a warm heart.”

“For friendship, James, but how can I think of love, the owner of the six chairs, book-case and table you see, and nothing but my profession to rely on for the future. Love never flourishes in so stern a climate.”

“We have the best authority for knowing that it lives through the fiercest tempest, as well as under the beautiful skies of Italy. What do you think, Oliver, of a rich wife?”

“I think such advice comes very badly from you. Let me ask in turn why you are about to connect yourself with a penniless girl, when you might win the greatest fortune in town.”

This question came to the point, but it received no other answer than a light laugh as the young man turned on his heel to go.

“Well, Oliver, I wish you great success in the cause of this lovely client. Good day,” said he, in the gleeful tone of a heart free from care. And, indeed, if this could be the condition of any mortal in this care-worn world, it was that of James Ashly. Thus far in life his path had been strewn with flowers, and in the horizon of the future no clouds were visible. The son of an opulent merchant, endowed by nature with a good mind, and possessing in a rare degree that animation only to be acquired by intercourse with gay society, he was an unusual favorite with those in whose company he mingled, especially the fairer portion, whose gentle hearts are ever gracious, to that easy air and manner, too much neglected by their fancied lords and superiors. But he joined with these superficial graces of address, a cultivated intellect, stored with much useful information, which are so seldom united as to be deemed inconsistent, if not antagonistical. By the latter he retained all the good will and esteem which by the former he gained.

In his extensive acquaintance no friend was more valued than Oliver Barton, a young lawyer, in whose office the above conversation occurred, and whose fortune consisted of little more than a well-furnished mind and generous heart—a kind of wealth little appreciated in this matter-of-fact world. He had been educated by a maternal uncle, who rejoiced in the name of Scott, and having made choice of the legal profession, was fitted in due course for the bar. In the maiden speech he delivered, shortly after his admission, he gave promise of future eminence and distinction. Unlike his friend, he was reserved and somewhat diffident, but his intrinsic worth and handsome form won favor and respect by less striking, but equally certain means. It was only when well known that those nice shades of merit, which so permanently recommend their possessor, could be discovered in his character. His prominent forehead and rather heavy brow gave a slight shade of melancholy to his countenance, but their intellectual expression, increased by the steady light of a dark eye, commanded admiration. When he smiled a row of glistening teeth revealed themselves, and his features were lit up with a life and joy rendered more striking by their usual thoughtful repose.

——

The next day Oliver Barton proceeded to his office at an earlier hour than usual; so early indeed that most of those adjoining were still closed. Being of a meditative turn of mind, and even inclined to castle-building, this era of his life afforded much subject for thought. “If I succeed,” thought he, “it will be the commencement of an extensive practice.” Forthwith, upon this contingency, he proceeded to erect a magnificent superstructure in the air, which was finally blown away by it occurring to him that he might not succeed. Unwilling to contemplate this side of the picture, and remembering his client was a lady, he took from the table before him “Chesterfield’s Letters,” in hopes of finding something there both useful and entertaining.

Notwithstanding the agreeable wit and advice of his lordship, the hours passed heavily. At last in came Uncle Scott, a little, genteel-looking person, in tight pantaloons and well-brushed coat, carrying his ivory-headed cane under his arm. He looked the very personification of a precise old bachelor, who had lived in the great world and grown wise by experience.

“Here I am, according to appointment,” said he, pulling a showy watch from its fob, “just half past twelve, and we are to be at Miss Medford’s at one.”

“I’m ready, uncle,” returned Oliver, after having changed his coat and settled his hat before the glass with extra attention. Mr. Scott, like most old bachelors, was very punctual in fulfilling engagements.

“You told me, I believe, that Miss Medford was an orphan?” said Oliver, when they had reached the street.

“Yes, poor thing,” answered Mr. Scott, “she lost her mother while still an infant, and it has now been ten years since her father, Charles Medford, died. He was a generous, noble-hearted fellow, but too much given to fine company and expense. I recollect him well, for we were young men together, and dashed about in the same gay society. He married a beautiful woman for love,” and Uncle Scott sighed, “with her face for her fortune, and as his own amounted to little more, the match was any thing but happy. To be deprived of the only parent she had ever known nearly broke Clara’s heart, and she wept long and bitterly. So touching was her grief it affected the heart of her uncle, John Medford, who, as he was a bachelor, adopted her, and resolved to cherish her as his own. He was one of the most singular men I have ever known. Withered and forbidding in appearance, crabbed in temper, and particular about money matters even to parsimony, he was no attractive object to so tender a flower as Clara. But, by her childish love and attention, she insinuated herself into his unkindly heart, and soothed the many cares of the declining years of his life—so that even he blessed her. At his death the principal amount of his property was bequeathed to her, but with this singular provision, that if she marry within ten years it was to go to some distant relative. Among the many whims of the old man, he particularly hated a branch of his family, the children of a disobedient sister. These are now endeavoring to prove the illegality of the will in question, as they are entirely cut off by it from all share in his estate; but you shall hear more of the circumstances from her own lips.”

They were now at their destination, and in a few moments found themselves seated in a spacious and richly furnished parlor, containing many indications of female taste and attention. On the centre-table lay a small boquet of beautiful flowers, blushing with the freshness of the field, but which, on a closer inspection, were found to be artificial, doubtless moulded under the delicate fingers of the presiding fairy. A number of beautifully shaded landscape sketches next attracted Oliver’s attention, and as he turned from one to another he would have forgotten the dry subject on which he came, but for the promptings of Mr. Scott.

They had not waited long before Clara Medford entered. If Oliver had been affected by her story he was still more touched with her winning grace and beauty, enhanced rather than obscured by the deep mourning in which she was dressed. She was somewhat pale, but he would have found no difficulty in accounting for this in her late affliction, had not the sweet expression of her hazel eye more than atoned for it. Her mien was so easy and unaffected that Oliver, who had dreaded the awkward formality of so embarrassing an interview, felt at once perfectly self-possessed. There was something serene and even childlike in her countenance, which was extremely interesting, and she seemed polite, rather because it was natural to her, than in obedience to the requirements of custom.

We leave them to converse over the business of the suit, of which the reader already knows sufficient for the purposes of our narrative.

——

Some weeks after the scene of our last chapter, Clara Medford was sitting where the young attorney had first seen her. Jane Preston, an intimate friend, who had called to pay a morning visit, sat by her side on the sofa with bonnet and shawl still on.

“Well, Clara,” said she, changing their conversation, “you are now secured in the possession of this house and all your uncle’s property; my, what wealth! I’m sure I wish it may yield you all the happiness you desire.”

“Thank you, Jane, for your kind wishes,” answered Clara mildly, “but I have thought that wealth seldom confers as much real happiness as it brings additional care and anxiety.”

“But your care, unlike that of others, ends for the best.”

“True, I have no disappointment to complain of,” said Clara, “but my success is only a negative pleasure, after all.”

“I am sure I should think it a very positive one,” returned Miss Preston, as she rose to go. Clara pressed her to stay longer, but, pleading an engagement, she proceeded to the door.

“But, Clara,” said she, continuing their conversation on the steps, “do tell me who young Lawyer Barton is?”

“I know little more of him than that he is very talented in his profession,” replied Clara, slightly blushing, more at the manner in which it was asked than at the question itself.

“I have heard he was very retired, and went but little into company,” continued Jane, giving information when she found none was to be obtained. “But every one agrees that he has conducted your late suit with great ability, for which, I suppose, you are very grateful,” said she, with an arch side glance at her companion.

“I am, sincerely so,” returned Clara seriously, but with a rapid change of countenance she added, “Oh! Jane, I almost forgot to ask you whether you have yet appointed a day to gratify your sighing swain?”

“Oh!” exclaimed she, blushing crimson in turn, “I’ll tell you when we’ve more time, for it’s a long story. Good-by, Clara, don’t be too grateful to the handsome Mr. Barton,” and with a ringing, joyous laugh, she tripped lightly down the marble steps.

“Good-by,” returned Clara, gazing after her retiring form, and almost envying her the happy spirit with which she was animated.

At the time the above conversation occurred, Oliver Barton was meditating on his encouraging success in the late trial, alone in the office where twice before we have seen him. There was a more than usual melancholy in the expression of his countenance. His head rested on his hand, and at intervals he would heave an involuntary sigh, as though his thoughts were of no agreeable nature. One would have concluded that some great misfortune, rather than triumphant success, had befallen him. At length he was roused from his reverie by the sound of rapid footsteps in the entry, and in another moment James Ashly had entered.

“Well, Oliver,” said he, “so you exerted your eloquence to some purpose. I knew when I saw your eye that you intended carrying all before you. But,” continued he, observing the dejected mood of his friend, “what is the matter—have you heard of the death of any near relative?”

“No,” answered Oliver, “I ought, I know, to be very happy.”

“You have cause to be so, certainly; then what has made you look like a man contemplating suicide.”

“Sit down, James,” said Oliver, in a calm tone, and composing himself as with an effort, “and I will tell you the cause; I confide in your friendship, because I know its sincerity. The truth is, my sentiments toward Miss Medford are not those of mere admiration, they are warmer; I feel that I love her,” and starting from his chair, he strode rapidly across the room.

“And, Oliver,” urged James, when the first surprise of so unexpected an announcement was over, “is it cause of grief to love a girl so amiable and beautiful as Miss Medford? You are already esteemed by her, and time may incline her heart to a more tender sentiment. There is but one short step between friendship and love. This suit is now so happily terminated—”

“You have named the most embittering reflection of all,” said Oliver, stopping before him and speaking earnestly; “by that decision the validity of a will is established, which deprives her of the right to dispose of her hand. By its mandate she must resign all; and what could I offer to compensate her for the sacrifice? The homage of my heart, and the devotion of my life, are worthless trifles. I knew, while striving to establish her rights, that if successful I sealed my own unhappiness, and forever cut off all hope of calling her mine. I even debated with myself whether I might not lose the case by mismanagement, and then win the heart of the trusting, beautiful Clara. It was a great conflict for a single moment, but the temptation yielded to a sense of honor and justice. Her cause triumphed; and at least I have the melancholy satisfaction left of knowing that I served the one I love.”

Oliver spoke with the eloquence of despair, and his friend listened, engrossed in astonishment and admiration.

“I can appreciate the feelings which so trying a situation prompts, but,” added he, the naturally sanguine disposition of his mind prevailing over its first gloomy sensations, “trust to time for a happy termination; for although your way is now overhung with clouds, as you advance into the future, it will become brighter, and a glorious store of happiness will be opened to your view.”

“Your words bid me hope,” answered Oliver, “but I fear while you utter them your heart misgives you. No, no, James—I see no room for hope, nothing to brighten my path with a solitary ray of comfort. I must try to banish her image from my heart, and think of her only in connexion with every thing lovely and perfect, never as my first and only love. I can but make the effort, though I believe it will fail.”

James was sensible of all the deep despair and silently corroding influence of “hope deferred;” its dreams and disappointments; its moments of bright anticipation succeeded by still darker views of the stern reality; its overwhelming anguish, and its rush of mad gayety more dreadful than tears. He knew, too, the depth of passionate feeling of which Oliver’s heart was capable, and shuddered as he thought that the soul of one so generous and noble would be made the prey of that slow and deadly poison, hopeless love. But by an effort he suppressed the rising emotions of his breast, and continued to urge the possibility of the future removing the obstacles which now appeared so formidable.

“It is not to be expected,” said he, “nay, it is impossible, that one so young and beautiful should remain single, in mere obedience to the foolish whim of an uncle, no longer living. If her heart become engaged, she will soon resign the gold, which is but a useless burthen, and some one less scrupulous will possess the hand that might be your own. Besides, will she not appreciate the struggle you have endured, and the sacrifice of self in your conduct? And these aided by the gratitude she already feels, are sufficient to win the heart of any maiden.”

But the view thus presented, skillfully colored by the hand of friendship, could not change the determination he had expressed.

“It was I,” said Oliver, “who undertook the case, and succeeded in securing to her the full benefit of her uncle’s will; knowing, then, its provisions, would it not be inconsistent, even fraudulent, in me to attempt to defeat it now?”

To this James could oppose nothing, for he felt the delicacy of his friend’s situation; he knew how deep was the suffering excited by that absorbing passion of the soul when struggling with adversity or oppression, and his own heart swelled with a generous sympathy, as he grasped the hand of his friend on parting.

——

Again we take a leap over a period of time which, to those in the enjoyment of a life of pleasure and excitement, appears short, but to the sufferer on a bed of sickness, or the condemned felon, is an age. They, in whom we are more immediately interested, thought it either brief or tedious, as it brought good or ill fortune. James Ashly, though deeply concerned in the distress of his friend, was enabled by the elasticity of his spirits to preserve that sprightly air, which had in a manner become habitual. But he had much real cause for joy. The girl who had long reigned mistress of his heart, had consented to become a bride, and appointed a day for the wedding. As for Oliver Barton, a heavy cloud rested on his brow, denoting deep-seated grief. In vain his friend tried to entertain him, and draw his mind from the melancholy subject on which it continually brooded; in vain Oliver himself endeavored to carry out his resolution, and banish all thought of Clara Medford from his mind; the effort only proved the strength of his affection. But it was not weakness; he could have trusted himself in her society, conversed with, worshiped her, and yet kept the secret buried in his breast.

“Oliver,” said uncle Scott one day, bustling into his nephew’s office, with a huge book under his arm, which looked as though it might have been bound near the beginning of the seventeenth century, “here is an old relic of your family, which I think you have never seen—no less than the family Bible, containing a record of the births, marriages, and deaths, of the ancestors in whose connexion you have just reason to be proud.”

This was delivered with all the importance of one communicating a valuable secret, never doubting that Oliver would feel as lively an interest as himself.

“It is, in fact,” continued he, “a complete history of the house for several generations back. The character of the writer is shown in the chirography much better than in many a prosy biography.”

Oliver expressed much more interest in the “old relic” than he really felt, from a desire to please an indulgent uncle by humoring his whims.

“Your father,” continued Mr. Scott, spreading the old volume before him, and looking intently on it, “you will observe, was an only son, with two sisters, Mary and Catharine Blake. The former died early; here is the record in his own hand.” Oliver gazed on with awakened attention. “The latter married Charles Blake.”

“Her name, then, was Catharine Blake,” said Oliver, earnestly.

“Yes,” answered Mr. Scott, “it was; my recollection serves me to recall an incident in relation to her marriage. It was this; John Medford loved her devotedly, but she could never return his affection, and finally bestowed her hand on Charles Blake, who had nothing but spotless worth and intelligence to recommend him. She left no children, and is long since dead; but Medford, who always cherished an affection for her, could never be persuaded of the truth of the report.”

This account was heard by Oliver with breathless attention, and as he examined the venerable record, a glow of intense joy lit up his face. Observing this, Mr. Scott proceeded further back into the annals of the Bartons, and expiated on the events and eras with critical exactness. But the mind of his nephew was engrossed by what he had already learned, and he scarcely heard the list of marriages, and intermarriages, deaths, and births, which his uncle recounted with painful minuteness.

At length he was alone.

“A ray of hope,” exclaimed he, “has already dawned, destined probably to shed a propitious fight on my path. James was right; the future may yet have a store of happiness provided for me, too great even to contemplate.”

A goodly company was assembled in the lofty parlors of Miss Medford’s residence. The young, the gay, the serious, the frivolous, were there in indiscriminate profusion; some chatting familiarly on the luxurious sofas and lounges, others walking or standing beneath the chandelier, and not a few engaged in unseen, as they thought, flirtations in the corners. The young and the old of both sexes seemed to enjoy the scene with a peculiar relish. The flowers sparkled in their vases, under the rich light of the numerous lamps; the jewels glistened, their owners smiled, and all was gay, happy, and inspiring.

Among that numerous and fashionable company, James Ashly was the most joyful of the joyous, the happiest of the happy. His heart had secured the prize for which it had so long contended—its constant love had been crowned with success; and in the sweet being leaning on his arm, he felt he possessed such a treasure as the world could not equal. After a prolonged courtship, Jane Preston became his bride—and they were now the admired of all admirers. The small figure and benevolent countenance of Mr. Scott were not less conspicuous in the crowd of happy faces which thronged the apartments, whose walls had never witnessed so animated a scene.

But there was one individual who seemed to have no connexion with any one present. He sat by himself, and took no part in the conversation of either the young or old. His countenance bore deep traces of habitual care and discontent, which, with the wrinkles of age, gave it a sour and forbidding aspect. Dressed in a blue coat, which might have fitted him when it was made, but now hung loosely about his form; straight-collared vest, too long and too loose; and pantaloons of the greatest redundancy of cloth—he appeared to no advantage, nor did he seem to care. A nervous uneasiness pervaded his frame, as though contemplating something beyond the mere pleasure of being present. Sometimes his attention was attracted by a witty remark, or joyful laugh, but he would turn away his head, and smile dismally, as though he envied the happy heart from which it echoed. The name of this person was Sandford. He had been engaged in business with the deceased Mr. Medford, and was in every respect a congenial spirit. At his death, Sandford was left executor, and entrusted with the administration of the will.

The occasion which brought together this various company, and gave it so lively a tone, was no less than the marriage of the modest and charming Clara Medford to the handsome and talented Oliver Barton.

The hour approached when the knot was to be tied, and the grave minister, in his robes, was already present. A bustle was suddenly perceptible through the rooms as the youthful couple entered, the bride blushing to the borders of her dress, and the groom, it must be confessed, paler than usual. The ceremony began with that embarrassment always attending such occasions; and many a heart palpitated with mingled emotions of joy and terror under the solemn and impressive voice of the clergyman. The earnest appeal was made for those who knew of any impediment “to speak now, or ever after hold their peace.”

“This lady,” said Sandford, in the pause that followed, with the astonished eyes of every one fixed on him, “this lady, by the present act, forfeits, according to her uncle’s will, all title to his wealth, which is to go to one Catharine Blake, or her heirs, if she be not living. I thought it proper to make this declaration, as the legal executor of the deceased Mr. Medford. The ceremony may now proceed.”

“And, sir,” said Oliver Barton, “the only surviving heir of Catharine Blake you will recognize in me.”

A whisper of delight ran through the rooms at this unexpected dénouement; the service proceeded, and in a few moments, tears, kisses, and confusion announced the silken bands of matrimony had firmly united two as pure, confiding hearts as ever throbbed in human breast.

And thus the case was doubly gained.

———

BY C. P. CRANCH.

———

I have often wondered whether there ever was in our whole blessed United States, such a queer place as my Aunt Fabbins’s garret. In all my migrations from city to city, from house to house, from room to room, where I was the guest of people who were quite differently constituted by nature and education from my good aunt, I have thought to myself as I observed somewhat of the family economy in these various hospitable abodes, that there could not possibly be in a single one of them a room whose internal arrangement or disarrangement bore the faintest resemblance to that queer old garret at my Aunt Fabbins’s. Oh, it was the queerest of all queer places that the sun ever peeped into or did not peep into. Language utterly fails to tell how queer it was. I have sometimes thought I would seriously sit down and describe it at length; that I would take an inventory of all the queer things it contained, one by one, with scientific patience and accuracy, and give to the herein unenlightened world the results of my researches and labors, in the shape of an article for some antiquarian society, or, perhaps, some national academy of arts and sciences. Catacombs and tombs, and Egyptian pyramids, have been thrown open to the gaze of mankind, and the dim religious light of old cloisters and cathedrals has been invaded by the prying spirit of utilitarian curiosity and reform; and that which was hidden and mysterious, hath been everywhere brought into the atmosphere of vulgar daylight, and Penny Magazines, and Lyceum Lectures—and science every where is laying his cold clutch upon the shrinking form of poetic truth; then why should not the secrets of my Aunt Fabbins’s queer old musty fusty garret be disclosed, and the world be one little wrinkle the wiser?

Now I do not propose to treat this old garret and its contents scientifically or chronologically—perhaps I shall treat it hardly reverentially; and though there was many a monument therein of past years, and many a hieroglyphic of deep significance were the key only known, yet I shall modestly decline entering the lists with Champollion or Mr. Gliddon. Other spirits more peculiarly gifted with powers of investigation than myself, may, at some future time, visit my aunt’s house, and if they should be favored by chance, or by friendship, to enter that dim upper receptacle of the shadows of the past, they may more fully explore a field which I have scarcely had the courage or patience to do with completeness and accuracy.

But before I enlighten my readers upon the subject of this old garret and its arcana, it will be necessary for me to give a glance at one feature in the domestic economy of my Aunt and Uncle Fabbins.

A worthier and more warm-hearted old couple never lived. For forty years they had shared the joys and sorrows of life together; they had known many trials, but these had only bound them more closely to each other, and to Heaven. They had married early, and brought up a large family, like good parents and good Christians as they were. In the earlier period of their wedded state, they had both, through habit and necessity, managed all their domestic affairs with the strictest economy. They were perfect patterns of housekeeping and management to their neighbors. With the extravagant Southerners, among whom they lived (for my uncle and aunt emigrated from the land of steady habits, old Massachusetts, soon after their marriage, into a more southern latitude, for the same reasons, I suppose, which carry so many of our young couples, nowadays, off to the west); among these Southerners, I say, my Uncle and Aunt Fabbins were absolute wonders, so different were their habits from those about them. There was no end, no bound to the wonder of these people. They could not comprehend how, with their limited income, they contrived to live so snugly and genteelly. The richest families among them could not keep their household arrangements from going “out in the elbows.” In the winter time they never could keep their parlors warm, or their doors shut. Their windows would rattle; the wind would blow in, bringing influenza and consumption on its wings; they could not keep their closets supplied with medicines, or even always with the necessary eatables of life, but were somehow or other obliged to borrow of the Fabbins’s. And in summer, they would leave their windows open to every rain, or their chimneys would tumble down, or their garden-tools would get lost or broken, or their children catch the ague and fever, from running about in puddles, or eating green fruit; and then the whole family establishment and family counsel and assistance of the Fabbins’s were taxed for the ill-management of these extravagant and improvident neighbors. If a pump-handle were loose, or needed oiling, no one could put it to rights like Uncle Fabbins. If a wheelbarrow or rake were broken, they invariably borrowed of neighbor Fabbins. If a baby had the croup, the whole family came in a committee of the whole to wait on the Fabbins’s; Uncle Fabbins must prescribe the physic, and weigh it out, and Aunt Fabbins must leave her sewing, or her pickling, or her ironing, and run in to put the child into a warm bath. If a neighboring housewife wanted a quart of meal, or a loaf of bread, or a pound of butter, she would not scruple to send at all hours of the day, or night to draw upon Mrs. Fabbins’s exhaustless store-house. Everybody knew just where to go when any sudden want or emergency overtook them. I remember hearing of a man who sent out his servant to one of his neighbors’ houses, when a thunder storm was coming up, to give his master’s compliments, and “please wouldn’t he lend him his lightning-rod for a little while.” I have never heard that my uncle’s neighbors ever went quite so far in their neighborly feelings as this, but I do remember hearing my aunt relate one circumstance nearly as amusing as this. A storm was coming up, and all the windows and doors were closed—not a sign of any living creature was seen abroad, save a few lazy cows, who began to think it best to retire to their apartments in their respective cow-yards. The sky was growing darker and darker; the wind swept by over trees and dusty roads in fearful gusts; a few large rain-drops were beginning to fall, and one or two vivid flashes of lightning had cleft the dark clouds, followed by tremendous claps of thunder; when a small boy was seen running violently toward my uncle’s house—a loud knocking was heard—the summons was answered—and the embassy was not exactly to borrow a lightning-rod, for there were none in those days, I believe, but, “mother says, please lend her”—“What, child, is anybody dying?” “No, marm, but mother says, please lend her—a nutmeg!”

“Parturiunt Montes!” I said to myself, when I heard it, (it was in my college days, when I was fond of Latin quotations,) “et nascitur ridiculus mus.”

This is not altogether a digression from my subject. I will come to the garret presently, after I have patiently conducted my readers up the preliminary steps. We must always begin at the bottom of the stairs before we can get to the top; that old garret may be called the flower, run to seed, of all this beautiful economy in the household affairs of the Fabbins’s.

It was, indeed, a beautiful system of economy. The Fabbins’s homestead was a little world in itself of ways and means—a microcosm, where, for years, every thing that was needed stood at hand ready for use, and every thing had its place. You could not lay your hand upon the merest bit of broken crockery, or rusty nail, or weather-stained shingle, or fragment of tangled twine, but it came into service, sooner or later, in some part of the establishment—at least so my aunt always affirmed. Honor to these good old folks for their principles and their practice. If the world—if society at large—if government could but take a lesson from these humble lights of their little circle, how much poverty, and crime, and misery, would be avoided, which now runs riot over the world.

But, alas! there is an old adage which will come sneaking into the corner of my brain, as I continue to trace my way up toward the old garret—some cynic philosopher must have given it birth; “too much of a good thing is good for nothing.” Rather harsh, friend philosopher, but the rough shell may be found to contain a kernel of truth.

And here I am much disposed to fall into some deep reflections, and give utterance to some very profound remarks, and even go into some winding digressions about the philosophy of ultraism, and show how there is no one truth, or good principle, which, if emphasized too strongly and exclusively, may not result in a falsity and an evil. Virtue may become vice, truth error, if we persist in riding our favorite hobby forever in the same way, and on the same road. Let us not dwell forever in the parts and particles of good, but in the whole. Let us not breathe the gasses, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, or carbonic acid, but air.

Having taken my patient reader this long step upward, we come to a landing and a breathing place on the stairs. Let us have a little more patience yet, and we shall finally come to the garret. I already, in fancy, begin to inhale its musty fragrance.

Acting uniformly on this principle of throwing away or destroying nothing that might, at some future time, be turned to account in some of the departments of the household economy, my good uncle and aunt had gradually accumulated around them a little of every thing that was ever known or thought of in the memorandum-book of a housekeeper. It so happened that they had gone through several removals from one house to another, in their forty years of housekeeping, (they always had an aversion to boarding,) and all their effects from the greatest to the least, from looking-glasses and bedsteads down to broken saucers and barrel-hoops, were always taken along with them. Not a scrap of any kind, were it nothing more than an old newspaper, or a dozen of old broken corks, was ever suffered to be thrown away.