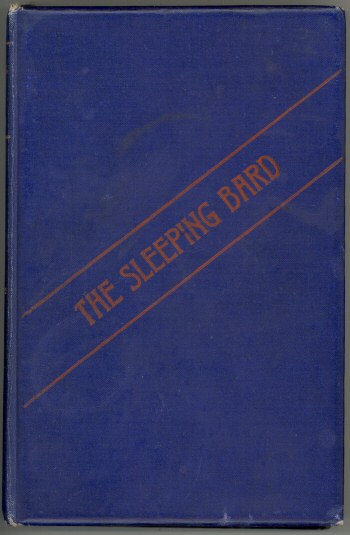

Title: The Visions of the Sleeping Bard

Author: Ellis Wynne

Translator: Robert Gwyneddon Davies

Release date: May 1, 2004 [eBook #5671]

Most recently updated: July 10, 2014

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5671

Credits: Transcribed from the 1897 Welsh National Press Company edition by David Price

Transcribed from the 1897 Welsh National Press Company edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

BEING

ELLIS WYNNE’S

“Gweledigaetheu y Bardd Cwsc”

TRANSLATED BY

ROBERT GWYNEDDON DAVIES

LONDON: SIMPKIN, MARHSALL & CO., LIMITED.

CARNARVON: THE WELSH NATIONAL PRESS COMPANY, LIMITED

MDCCCXCVII

TO

PROFESSOR JOHN RHŶS, M.A., LL.D.

PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE,

OXFORD

AND

VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY

COLLEGE

OF NORTH WALES,

IN TOKEN OF

His Distinguished Scholarship and

Unrivalled

Services

TO

CELTIC LITERATURE

This Translation

IS

Respectfully Dedicated

At the National Eisteddfod of 1893, a prize was offered by Mr. Lascelles Carr, of the Western Mail, for the best translation of Ellis Wynne’s Vision of Hell. The Adjudicators (Dean Howell and the Rev. G. Hartwell Jones, M.A.), awarded the prize for the translation which is comprised in the present volume. The remaining Visions were subsequently rendered into English, and the complete work is now published in the hope that it may prove useful to those readers, who, being unacquainted with the Welsh language, yet desire to obtain some knowledge of its literature.

My best thanks are due to the Rev. J. W. Wynne Jones, M.A., Vicar of Carnarvon, for much help and valuable criticism; to the Rev. R Jones, MA., Rector of Llanfair-juxta-Harlech, through whose courtesy I am enabled to produce (from a photograph by Owen, Barmouth) a page of the register of that parish, containing entries in Ellis Wynne’s handwriting; and to Mr. Isaac Foulkes, Liverpool, for the frontispiece, which appeared in his last edition of the Bardd Cwsc.

R. GWYNEDDON DAVIES.

Caernarvon,

1st July, 1897.

|

PAGE |

||

Frontispiece |

|

||

Genealogical Tables |

|||

Introduction:— |

|

||

|

I. |

The Author’s Life |

|

|

II. |

The Text |

|

|

III. |

The Summary |

|

Facsimile of Ellis Wynne’s Handwriting |

|

||

Vision of the World |

|||

Vision of Death |

|||

Vision of Hell |

|||

Notes |

|||

*** (I am indebted to E. H. Owen, Esqr., F.S.A., Tycoch, Carnarvon, for most of the information compiled in the following tables.)

Ellis Wynne was born in 1671 at Glasynys, near Harlech; his father, Edward Wynne, came of the family of Glyn Cywarch (mentioned in the second Vision), his mother, whose name is not known, was heiress of Glasynys. It will be seen from the accompanying table that he was descended from some of the best families in his native county, and through Osborn Wyddel, from the Desmonds of Ireland. His birth-place, which still stands, and is shown in the frontispiece hereto, is situate about a mile and a half from the town of Harlech, in the beautiful Vale of Ardudwy. The natural scenery amidst which he was brought up, cannot have failed to leave a deep impression upon his mind; and in the Visions we come across unmistakeable descriptions of scenes and places around his home. Mountain and sea furnished him with many a graphic picture; the precipitous heights and dark ravines of Hell, its caverns and its cliffs, are all evidently drawn from nature. The neighbourhood is also rich in romantic lore and historic associations; Harlech Castle, some twenty-five years before his birth, had been the scene of many a fray between Roundheads and Cavaliers, and of the last stand made by the Welsh for King Charles. These events were fresh in the memory of his elders, whom he had, no doubt, often heard speaking of those stirring times; members of his own family had, perhaps, fought in the ranks of the rival parties; his father’s grand-uncle, Col. John Jones, was one of those “who erstwhile drank of royal blood.”

It is not known where he received his early education, and it has been generally stated by his biographers that he was not known to p. xvihave entered either of the Universities; but, as the following notice proves, he at least matriculated at Oxford:—

Wynne, Ellis, s. Edw. of Lasypeys, co. Merioneth, pleb. Jesus Coll. matric. 1st March 1691–2, aged 21; rector of Llandanwg, 1705, & of Llanfair-juxta-Harlech (both) co. Merioneth, 1711. (Vide Foster’s Index Eccles.)

Probably his stay at the University was brief, and that he left without taking his degree, for I have been unable to find anything further recorded of his academic career. [0a] The Rev. Edmund Prys, Vicar of Clynnog-Fawr, in a prefatory englyn to Ellis Wynne’s translation of the “Holy Living” says that “in order to enrich his own, he had ventured upon the study of three other tongues.” This fact, together with much that appears in the Visions, justifies the conclusion that his scholarly attainments were of no mean order. But how and where he spent the first thirty years of his life, with the possible exception of a period at Oxford, is quite unknown, the most probable surmise being that they were spent in the enjoyment of a simple rural life, and in the pursuit of his studies, of whatever nature they may have been.

According to Rowlands’s Cambrian Bibliography his first venture into the fields of literature was a small volume entitled, Help i ddarllen yr Yscrythur Gyssegr-Lân (“Aids to reading Holy Writ”), being a translation of the Whole Duty of Man “by E. W., a clergyman of the Church of England,” published at Shrewsbury in 1700. But as Ellis Wynne was not ordained until 1704, this work must be ascribed to some other author who, both as to name and calling, answered to the description on the title-page quoted above. But in 1701 an accredited work of his appeared, namely, a translation into Welsh of Jeremy Taylor’s Rules and Exercises of Holy Living, a 12mo. volume published in London. It was dedicated to the Rev. Humphrey Humphreys, D.D., Bishop of Bangor, who was a native of the same district of Merionethshire as Ellis Wynne, and, as is shown in the genealogical table hereto, was connected by marriage with his family.

p. xviiIn 1702 [0b] he was married to Lowri Llwyd—anglicè, Laura Lloyd—of Hafod-lwyfog, Beddgelert, and had issue by her, two daughters and three sons; one of the daughters, Catherine, died young, and the second son, Ellis, predeceased his father by two years. [0c] His eldest son, Gwilym, became rector of Llanaber, near Barmouth, and inherited his ancestral home; his youngest son, Edward, also entered the Church and became rector of Dolbenmaen and Penmorfa, Carnarvonshire. Edward Wynne’s son was the rector of Llanferres, Denbighshire, and his son again was the Rev. John Wynne, of Llandrillo in Edeyrnion, who died only a few years ago.

The following year (1703), he published the present work—his magnum opus—which has secured him a place among the greatest names in Welsh Literature. It will be noticed that on the title-page to the first edition the words “Y Rhann Gyntaf” (“The First Part”) appear; the explanation given of this is that Ellis Wynne did actually write a second part, entitled, The Vision of Heaven, but that on hearing that he was charged with plagiarism in respect of his other Visions, he threw the manuscript into the fire, and so destroyed what, judging from the title, might have proved a greater success than the first part, as affording scope for lighter and more pleasing flights of the imagination.

It is said by his biographers that he was induced to abandon the pursuit of the law, to which he was educated, and to take holy orders, by Bishop Humphreys, who had recognised in his translation of the Holy Living marked ability and piety, and that he was ordained deacon and priest the same day by the Bishop, at Bangor, in 1701, and presented on the following day to the living of Llanfair-juxta-Harlech and subsequently to Llandanwg.

All these statements appear to be incorrect. To deal with them categorically: I find no record at the Diocesan Registry of his having been ordained at Bangor at all; the following entry in the parish register of Llanfair shows that he was not in holy orders in p. xviiiJuly, 1704: “Gulielmus filius Elizaei Wynne generosi de Lâs ynys et uxoris suis baptizatus fuit quindecimo die Julii, 1704.—W. Wynne Rr., O. Edwards, Rector.” His first living was Llandanwg, and not Llanfair, to which he was collated on January 1st, 1705. Moreover, the above-named Owen Edwards was the rector of Llanfair until his death which took place in 1711. [0d] From that date on to 1734, the entries in the register at Llanfair church are all in Ellis Wynne’s handwriting; these facts prove conclusively that it was in 1711 he became rector of the latter parish.

In 1710 he edited a new and revised edition of the Book of Common Prayer, at the request of his patron, the Bishop of Hereford (Dr. Humphreys) and the four Welsh bishops,—a clear proof of the confidence reposed in him by the dignitaries of his church as a man of learning and undoubted piety. He himself published nothing more, but A Short Commentary on the Catechism and a few hymns and carols were written by him and published posthumously by his son, Edward, being included in a volume of his own, entitled Prif Addysc y Cristion, issued in 1755.

The latter part of his life is as completely obscure as the earlier; he lapsed again into the silence from which he had only just emerged with such signal success, and confined his efforts as a Christian worker within the narrow limits of his own native parts, exercising, doubtlessly, an influence for good upon his immediate neighbourhood through force of character and noble personality, as upon his fellow-countrymen at large by means of his published works. His wife died in 1720, and his son, Ellis, in 1732; two years later he himself died and was buried under the communion table in Llanfair church, on the 17th day of July, 1734. [0e] There is no marble or “perennial brass” to mark the last resting-place of the Bard, nor was there, until recent years, any memorial of him in either of his parish churches, when the late Rev. John Wynne set up a fine stained-glass window at Llanfair church in memory of his illustrious ancestor.

p. xixEllis Wynne appeared at a time when his country had sore need of him, when the appointed teachers of the nation were steeped in apathy and corruption, when ignorance and immorality overspread the land—the darkest hour before the dawn. He was one of the early precursors of the Methodist revival in Wales, a voice crying in the wilderness, calling upon his countrymen to repent. He neither feared nor favored any man or class, but delivered his message in unfaltering tone, and performed his alloted task honestly and faithfully. How deeply our country is indebted to him who did her such eminent service in the days of adversity and gloom will never be known. And now, in the time of prosperity, Wales still remembers her benefactor, and will always keep honored the name of Ellis Wynne, the Sleeping Bard.

The Bardd Cwsc was first published in London in 1703, a small 24mo. volume of some 150 pages, with the following title-page

“Gweledigaetheu y Bardd Cwsc. Y Rhann Gyntaf. Argraphwyd yn Llundain gan E. Powell i’r Awdwr, 1703.” [0f]

A second edition was not called for until about 1742, when it was issued at Shrewsbury; but in the thirty years following, as many as five editions were published, and in the present century, at least twelve editions (including two or three by the Rev. Canon Silvan Evans) have appeared. The text followed in this volume is that of Mr. Isaac Foulkes’ edition, but recourse has also been had to the original edition for the purpose of comparison. The only translation into English hitherto has been that of George Borrow, published in London in 1860, and written in that charming and racy style which characterises his other and better known works. He has, however, fallen into many errors, which were only natural, seeing that the Visions abound in colloquial words and phrases, and in idiomatic forms of expression which it would be most difficult for one foreign to our tongue to render correctly.

The author’s name is not given in the original nor in any subsequent edition previous to the one published at Merthyr Tydfil in 1806, where the Gweledigaetheu are said to be by “Ellis Wynne.” But it was well known, even before his death, that he was the author; the fact being probably deduced from the similarity in style between the Visions and an acknowledged work, namely, his translation of the Holy Living. The most likely reason for his preferring anonymity is not far to seek; his scathing denunciation of the sins of certain classes and, possibly, even of certain individuals, would be almost sure to draw upon the author their most bitter attacks. Many of the characters he depicts would be identified, rightly or wrongly, with certain of his contemporaries, and many more, whom he never had in his mind at all, would imagine themselves the objects of his satire; he had nothing to gain by imperilling himself p. xxiat the hands of such persons, or by coming into open conflict with them; he had his message to deliver to his fellow-countrymen, his Visions a purpose to fulfil, the successful issue of which could not but be frustrated by the introduction of personal hatred and ill-will. Ellis Wynne was only too ready to forego the honor of being the acknowledged author of the Visions if thereby he could the better serve his country.

The Bardd Cwsc is not only the most popular of Welsh prose works, but it has also retained its place among the best of our classics. No better model exists of the pure idiomatic Welsh of the last century, before writers became influenced by English style and method. Vigorous, fluent, crisp, and clear, it shows how well our language is adapted to description and narration. It is written for the people, and in the picturesque and poetic strain which is always certain to fascinate the Celtic mind. The introduction to each Vision is evidently written with elaborate care, and exquisitely polished—“ne quid possit per leve morari,” and scene follows scene, painted in words which present them most vividly before one’s eyes, whilst the force and liveliness of his diction sustain unflagging interest throughout. The reader is carried onward as much by the rhythmic flow of language and the perfect balance of sentences, as by the vivacity of the narrative and by the reality with which Ellis Wynne invests his adventures and the characters he depicts. The terrible situations in which we find the Bard, as the drama unfolds, betoken not only a powerful imagination, but also an intensity of feeling which enabled him to realise the conceptions of such imagination. We follow the Bard and his heavenly guide through all their perils with breathless attention; the demons and the damned he so clothes with flesh and blood that our hatred or our sympathy is instantly stirred; his World is palpitating with life, his Hell, with its gloom and glare, is an awful, haunting dream. But besides being the possessor of a vivid imagination, Ellis Wynne was endowed with a capacity for transmitting his own experience in a picturesque and life-like manner. The various descriptions of scenes, such as Shrewsbury fair, the parson’s revelry and the deserted mansions; of natural scenery, as in the beginning of the first and last Visions; of personages, such as the portly alderman, and the young lord and his retinue, all are evidently drawn from the Author’s own experience. p. xxiiHe was also gifted with a lively sense of humor, which here and there relieves the pervading gloom so naturally associated with the subject of his Visions. The humorous and the severe, the grotesque and the sublime, the tender and the terrible, are alike portrayed by a master hand.

The leading feature of the Visions, namely the personal element which the Author infuses into the recital of his distant travels, brings the reader into a closer contact with the tale and gives continuity to the whole work, some parts of which would otherwise appear disconnected. This telling of the tale in propria persona with a guide of shadowy or celestial nature who points out what the Bard is to see, and explains to him the mystery of the things around him, is a method frequently adopted by poets of all times. Dante is the best known instance, perhaps; but we find the method employed in Welsh, as in “The Dream of Paul, the Apostle,” where Paul is led by Michael to view the punishments of Hell (vide Iolo MSS.). Ellis Wynne was probably acquainted with Vergil and Dante, and adopted the idea of supernatural guidance from them; in fact, apart from this, we meet with several passages which are eminently reminiscent of both these great poets.

But now, casting aside mere speculation, we come face to face with the indisputable fact that Ellis Wynne is to a considerable degree indebted to the Dreams of Gomez de Quevedo y Villegas, a voluminous Spanish author who flourished in the early part of the 17th century. In 1668, Sir Roger L’Estrange published his translation into English of the Dreams, which immediately became very popular. Quevedo has his Visions of the World, of Death and her (sic) Empire, and of Hell; the same characters are delineated in both, the same classes satirized, the same punishments meted out. We read in both works of the catchpoles and wranglers, the pompous knights and lying knaves—in fine, we cannot possibly come to any other conclusion than that Ellis Wynne has “read, marked and inwardly digested” L’Estrange’s translation of Quevedo’s Dreams. But admitting so much, the Bardd Cwsc still remains a purely Welsh classic; whatever in name and incident Ellis Wynne has borrowed from the Spaniard he has dressed up in Welsh home-spun, leaving little or nothing indicative of foreign influence. The sins he preached against, the sinners he condemned, were, he knew too p. xxiiiwell, indigenous to Welsh and Spanish soil. George Borrow sums up his comments upon the two authors in the following words: “Upon the whole, the Cymric work is superior to the Spanish; there is more unity of purpose in it, and it is far less encumbered with useless matter.”

The implication contained in the foregoing remarks of Borrow—that the Bardd Cwsc is encumbered to a certain degree with useless matter, is no doubt well founded. There is a tendency to dwell inordinately upon the horrible, more particularly in the Vision of Hell; a tiring sameness in the descriptive passages, an occasional lapse from the tragic to the ludicrous, and an intrusion of the common-place in the midst of a speech or a scene, marring the dignity of the one and the beauty of the other.

The most patent blemish, however, is the unwarranted coarseness of expression to which the Author sometimes stoops. It is true that he must be judged according to the times he lived in; his chief object was to reach the ignorant masses of his countrymen, and to attain this object it was necessary for him to adopt their blunt and unveneered speech. For all that, one cannot help feeling that he has, in several instances, descended to a lower level than was demanded of him, with the inevitable result that both the literary merit and the good influence of his work in some measure suffer. Many passages which might be considered coarse and indecorous according to modern canons of taste, have been omitted from this translation.

From the literary point of view The Visions of the Sleeping Bard has from the first been regarded as a masterpiece, but from the religious, two very different opinions have been held concerning it. One, probably the earlier, was, that it was a book with a good purpose, and fit to stand side by side with Vicar Pritchard’s Canwyll y Cymry and Llyfr yr Homiliau; the other, that it was a pernicious book, “llyfr codi cythreuliaid”—a devil-raising book. A work which in any shape or form bore even a distant relationship to fiction, instantly fell under the ban of the Puritanism of former days. To-day neither opinion is held, the Bardd Cwsc is simply a classic and nothing more.

The Visions derive considerable value from the light they throw upon the moral and social condition of our country two centuries p. xxivago. Wales, at the time Ellis Wynne wrote was in a state of transition: its old-world romance was passing away, and ceasing to be the potent influence which, in times gone by, had aroused our nation to chivalrous enthusiasm, and led it to ennobling aspirations. Its place and power, it is true, were shortly to be taken by religion, simple, puritanic, and intensely spiritual; but so far, the country was in a condition of utter disorder, morally and socially. Its national life was at its lowest ebb, its religious life was as yet undeveloped and gave little promise of the great things to come. The nation as a whole—people, patrician, and priest—had sunk to depths of moral degradation; the people, through ignorance and superstition; the patrician, through contact with the corruptions of the England of the Restoration; while the priesthood were

“Blind mouths, that scarce themselves knew how to hold

A sheep-hook, or had learnt aught else the least

That to the faithful herdman’s art belongs.”

All the sterner and darker aspects of the period are chronicled with a grim fidelity in the Visions, the wrongs and vices of the age are exposed with scathing earnestness. Ellis Wynne set himself the task of endeavouring to arouse his fellow-countrymen and bring them to realize the sad condition into which the nation had fallen. He entered upon the work endowed with keen powers of perception, a wide knowledge of life, and a strong sense of justice. He was no respecter of person; all orders of society, types of every rank and class, in turn, came under castigation; no sin, whether in high places or among those of low degree, escaped the lash of his biting satire. On the other hand, it must be said that he lacked sympathy with erring nature, and failed to recognize in his administration of justice that “to err is human, to forgive, divine.” His denunciation of wrong and wrong-doer is equally stern and pitiless; mercy and love are rarely, if ever, brought on the stage. In this mood, as in the gloomy pessimism which pervades the whole work, he reflects the religious doctrines and beliefs of his times. In fine, when all has been said, favourably and adversely, the Visions, it will readily be admitted, present a very faithful picture of Welsh life, manners, and ways of thought, in the 17th century, and are, in every sense, a true product of the country and the age in which they were written.

One summer’s day, the Bard ascends one of the mountains of Wales, and gazing a long while at the beautiful scene, falls asleep. He dreams and finds himself among the fairies, whom he approaches and requests permission to join. They snatch him up forthwith and fly off with him over cities and realms, lands and seas, until he begins to fear for his life. They come to a huge castle—Castle Delusive, where an Angel of light appears and rescues him from their hands. The Angel, after questioning him as to himself, who he was and where he came from, bids him go with him, and resting in the empyrean, he beholds the earth far away beneath them. He sees an immense City made up of three streets; at the end of which are three gates and upon each gate a tower and in each tower a fair woman. This is the City of Destruction and its streets are named after the daughters of Belial—Pride, Lucre and Pleasure. The Angel tells him of the might and craftiness of Belial and the alluring witchery of his daughters, and also of another city on higher ground—the City of Emmanuel—whereto all may fly from Destruction. They descend and alight in the Street of Pride amidst the ruined and desolate mansions of absentee landlords. They see there kings, princes, and noblemen, coquettes and fops; there is a city, too, on seven hills, and another opposite, with a crescent on a golden banner above it, and near the gate stands the Court of Lewis XIV. Much traffic is going on between these courts, for the Pope, the Sultan and the King of France are rivals for the Princesses’ hands.

They next come to the Street of Lucre, full of Spaniards, Dutchmen and Jews, and here too, are conquerors and their soldiers, justices and their bribers, doctors, misers, merchants and userers, shopmen, clippers, taverners, drovers, and the like. An election of Treasurer to the Princess is going on—stewards, money-lenders, lawyers and merchants being candidates, and whoso was proved the richest should obtain the post. The Bard then comes to the Street of Pleasure, where all manner of seductive joys abound. He passes p. xxvithrough scenes of debauchery and drunken riot, and comes to a veritable Bedlam, where seven good fellows—a tinker, a dyer, a smith and a miner, a chimney-sweep, a bard and a parson—are enjoying a carousal. He beholds the Court of Belial’s second daughter, Hypocrisy, and sees a funeral go by where all the mourners are false. A noble lord appears, with his lady at his side, and has a talk with old Money-bags who has lent him money on his lands—all three being apt pupils of Hypocrisy.

The Angel then takes him to the churches of the City; and first they come to a pagan temple where the human form, the sun and moon, and various other objects are worshipped. Thence they come to a barn where Dissenters imitate preaching, and to an English church where many practise all manner of hypocrisy. The Bard then leaves the City of Destruction and makes for the celestial City. He beholds one man part from his friends and, refusing to be persuaded by them, hasten towards Emmanuel’s City. The gateway is narrow and mean, while on the walls are watchmen urging on those that are fleeing from Destruction. Groups from the various streets arrive and claim admittance, but, being unable to leave their sins, have to return. The Bard and his Guide enter, and passing by the Well of Repentance come in view of the Catholic Church, the transept of which is the Church of England, with Queen Anne enthroned above, holding the Sword of Justice in the left hand, and the Sword of the Spirit in the right. Suddenly there is a call to arms, the sky darkens, and Belial himself advances against the Church, with his earthly princes and their armies. The Pope and Lewis of France, the Turks and Muscovites fall upon England and her German allies, but, the angels assisting, they are vanquished; the infernal hosts, too, give way and are hurled headlong from the sky; whereupon the Bard awakes.

It is a cold, winter’s night and the Bard lies abed meditating upon the brevity of life, when Sleep and his sister Nightmare pay him a visit, and after a long parley, constrain him to accompany them to the Court of their brother Death. Hieing away through forests and dales, and over rivers and rocks, they alight at one of the rear portals of the City of Destruction which opens upon a p. xxviimurky region—the chambers of Death. On all hands are myriads of doors leading into the Land of Oblivion, each guarded by the particular death-imp, whose name was inscribed above it. The Bard passes by the portals of Hunger, where misers, idlers and gossips enter, of Cold, where scholars and travellers go through, of Fear, Love, Envy and Ambition.

Suddenly he finds himself transported into a bleak and barren land where the shades flit to and fro. He is straightway surrounded by them, and, on giving his name as the “Sleeping Bard,” a shadowy claimant to that name sets upon him and belabours him most unmercifully until Merlin bid him desist. Taliesin then interviews him, and an ancient manikin, “Someone” by name, tells him his tale of woe. After that he is taken into the presence of the King of Terrors himself, who, seated on a throne with Fate and Time on either hand, deals out their doom to the prisoners as they come before him. Four fiddlers, a King from the neighbourhood of Rome with a papal dispensation to pass right through to Paradise, a drunkard and a harlot, and lastly seven corrupt recorders, are condemned to the land of Despair.

Another group of seven prisoners have just been brought to the bar, when a letter comes from Lucifer concerning them; he requests that Death should let these seven return to the world or else keep them within his own realm—they were far too dangerous to be allowed to enter Hell. Death hesitates, but, urged by Fate, he indites his answer, refusing to comply with Lucifer’s request. The seven are then called and Death bids his hosts hasten to convey them beyond his limits. The Bard sees them hurled over the verge beneath the Court of Justice and his spirit so strives within him at the sight that the bonds of Sleep are sundered and his soul returns to its wonted functions.

The Bard is sauntering, one April morning, on the banks of the Severn, when his previous visions recur to his mind and he resolves to write them as a warning to others, and while at this work he falls asleep, and the Angel once more appears and bears him aloft into space. They reach the confines of Eternity and descend through p. xxviiiChaos for myriads of miles. A troop of lost beings are swept past them towards the shores of a death-like river—the river of the Evil One. After passing through its waters, the Bard witnesses the tortures the damned suffer at the hands of the devils, and visits their various prisons and cells. Here is the prison of Woe-that-I-had-not, of Too-late-a-repentance and of the Procrastinators. There the Slanderers, Backbiters, and other envious cowards are tormented in a deep and dark dungeon. He hears much laughter among the devils and turning round finds that the cause of their merriment are two noblemen who have just arrived and are claiming the respect due to their rank. Further on is a crowd of harlots calling down imprecations upon those that ruined them; and in a huge cavern are lawyers, doctors, stewards and other such rogues. The Princesses of the City of Destruction bring batches of their subjects as gifts to their sire.

A parliament is summoned and Lucifer addresses his princes, calling upon them to do their utmost to destroy the rest of mankind. Moloch makes his reply, reciting all that he has done, when Lucifer in rage starts off to do the work himself, but is drawn back by an invisible hand. He speaks again, exhorting them to greater activity and cruelty. Justice brings three prisoners to Hell and returning causes such a rush of fiery whirlwinds that all the infernal lords are swept away into the Uttermost Hell.

The Bard hears the din of arms and news comes that the Turks, Papists, and Roundheads are advancing in three armies. Lucifer and his hosts immediately set out to meet them and after a stubborn contest succeed in quelling the rebellion. More prisoners are brought before the King—Catholics, who had missed the way to Paradise, an innkeeper, five kings, assize-men and lawyers, gipsies, laborers and scholars. Scarcely is judgment passed on these than war again breaks out—soldiers and doctors, lawyers and userers, misers and their own offspring, are fighting each other. The leaders of this revolt having been taken, another parliament is called and more prisoners yet brought to trial.

Lucifer asks the advice of his peers as to whom he should appoint his viceroy in Britain. Cerberus, first of all, offers the service of Tobacco; then Mammon speaks in praise of Gold and Apolyon tells what Pride can do; Asmodai, the demon of Lust, p. xxixBelphegor, the demon of Sloth, and Satan, devil of Delusion, each pleads for his own pet sin; and after Beelzebub has spoken in favour of Thoughtlessness, Lucifer sums up, weighs their arguments, and finally announces that it is another he has chosen as his vicegerent in Britain. This other is Prosperity, and her he bids them follow and obey. Then the lost Archangel and his counsellors are hurled into the Bottomless Pit, and the Angel takes the Bard up to the vault of Hell where he has full view of a three-faced ogress, Sin, who would make of heaven, a hell, and thence departing, a heaven of hell. The Angel then leaves him, bidding him, as he went, to write down what he had seen for the benefit of others.

Let whoso reads, consider;

Considering, remember,

And from remembering, do,

And doing, so continue.

Whoso abides in Virtue’s paths,

And ever strives until the end

From sinful bondage to be free,

Ne’er shall possess wherewith to feed

The direful flame, nor weight of sin

To sink him in th’ infernal mire;

Nor will he come to that dread realm

Where Wrong and Retribution meet.

But, woe to that poor, worthless wight

Who lives a bitter, stagnant life,

Who follows after every ill

And knows not either Faith or Love,

(For Faith in deeds alone doth live).

Eternal woe shall be his doom—

More torments he shall then behold

Yea, in the twinkling of an eye

Than any age can e’er conceive.

On [1a] the fine evening of a warm and mellow summer I betook me up one of the mountains of Wales, [1b] spy-glass in hand, to enable my feeble sight to see the distant near, and to make the little to loom large. Through the clear, tenuous air and the calm, shimmering heat, I beheld far, far away over the Irish Sea many a fair scene. At last, when mine eyes had taken their fill of all the beauty around me, and the sun well nigh had reached his western ramparts, I lay down on the sward, musing how fair and lovely compared with mine own land were the distant lands of whose delightful plains I had just obtained a glimpse; how fine it would be to have full view thereof, and how happy withal are they, besides me and my sort, who have seen the world’s course. So, from the long journeying of mine eye, and afterwards of my mind, came weariness, and beneath the cloak of weariness came my good Master Sleep [1c] stealthily to bind me, and with his leaden keys safe and sound he locked the windows of mine eyes and all mine other senses. But it was in vain he tried to lock up the soul which can exist and travel without the body; for upon the wings of fancy my spirit soared free from out the straitened corpse, and the first thing I perceived close by was a dancing-knoll and such a fantastic rout [4a] in blue petticoats and red caps, briskly footing a sprightly dance. I stood awhile hesitating whether I should approach them or not, for in my confusion I feared they were a pack of hungry gipsies and that the least they would do, would be to kill me for their supper, and devour me saltless. But gazing steadfastly upon them I perceived that they were of better and fairer complexion than that lying, tawny crew; so I plucked up courage and drew near them, slowly, like a hen treading on hot coals, in order to find out what they might be; and at last I addressed them over my shoulder, thus, “Pray you, good friends, I understand that ye come from afar, would ye take into your midst a bard who wishes to travel?” Whereupon the din instantly ceased, every eye was turned upon me, and in shrill tones “a bard” quoth one, “to travel,” said another, “into our midst,” a third exclaimed. By then I had recognised those who were looking at me most fiercely, and they commenced whispering one to another some secret charms, still keeping their gaze upon me; the hubbub then broke out again and everyone laying hands upon me, lifted me shoulder-high, like a knight of the shire, and off like the wind we go, over houses and lands, cities and realms, seas and mountains, unable to notice aught so swiftly were they flying. And to make matters worse, I began to have doubts of my companions from the way they frowned and scowled when I refused to lampoon my king [4b] at their bidding.

“Well, now,” said I to myself, “farewell to life; these accursed, arrant sorcerers will bear me to some nobleman’s larder or cellar and leave me there to pay penalty by my neck for their robbery, or peradventure they will leave me stark-naked and benumbed on Chester Marsh or some other bleak and remote place.” But on considering that those whose faces I knew had long been buried, and that some were thrusting me forward, and others upholding me above every ravine, it dawned upon me that they were not witches but what are called the Fairies. Without delay I found myself close to a huge castle, the finest I had ever seen, with a deep moat surrounding it, and here they began discussing my doom. “Let us take him as a gift to the castle,” suggested one. “Nay, let us throw the obstinate gallows-bird into the moat, he is not worth showing to our great prince,” said another. “Will he say his prayers before sleeping,” asked a third. At the mention of prayer, I breathed a groaning sigh heavenwards asking pardon and aid; and no sooner had I thought the prayer than I saw a light, Oh! so beautiful, breaking forth in the distance. As this light approached, my companions grew dark and vanished, and in a trice the Shining One made for us straight over the castle: whereupon they let go their hold of me and departing, turned upon me a hellish scowl, and had not the Angel supported me I should have been ground fine enough to make a pie long before reaching the earth.

“What is thy errand here?” asked the Angel. “In sooth, my lord,” cried I, “I wot not what place here is, nor what mine errand, nor what I myself am, nor what has made off with mine other part; I had a head and limbs and body, but whether I left ’em at home or whether the Fairies, if fair their deed, have cast me into some deep pit (for I mind my passing over many a rugged gorge) an’ I be hanged, Sir, I know not.” “Fairly, indeed,” said he, “they would have dealt with thee, had I not come in time to save thee from the toasting-forks of the brood of hell. Since thou hast such a great desire to see the course of this little world, I am commanded to give thee the opportunity to realize thy wish, so that thou mayest see the folly of thy discontent with thine own lot and country. Come now!” he bade, and at the word, with the dawn just breaking, he snatched me up far away above the castle; and upon a white cloudledge we rested in the empyrean to see the sun rising, and to look at my heavenly companion, who was far brighter than the sun, save that his radiance only shone upwards, being hidden from all beneath by a veil. When the sun waxed strong, I beheld in the refulgence of the two our great, encircled earth as a tiny ball in the distance below. “Look again,” said the Angel, and he gave me a better spy-glass than the one I had on the mountain-side. When I looked through this I saw things in a different light and clearer than ever before.

I could see one city of enormous magnitude, with thousands of cities and kingdoms within it, the wide ocean like a whirlpool around it, and other seas, like rivers, dividing it into parts. After gazing a longwhile, I observed that it was made up of three tremendously long streets, with a large and splendid gateway at the lower end of each street; on each gateway, a magnificent tower, and on each tower, in sight of all the street, a woman of exceeding beauty; and the three towers at the back of the ramparts reached to the foot of that great castle. Of the same length as these immense streets, but running in a contrary direction, I saw another street which was but narrow and mean compared with them, though it was clean and upon higher ground than they, and leading upwards to the east, whilst the other three led downwards northerly to the great towers. I could no longer withhold from asking my friend’s permission to speak. “What then,” said the Angel, “if thou wilt speak, listen carefully, so that there be no need of telling thee a thing twice.” “I will, my lord, and prithee,” asked I, “what castle is that, away yonder to the north?” “That castle aloft in the sky,” said he, “belongs to Belial, prince of the power of the air, and ruler of all that vast city below; it is called Castle Delusive: for an arch-deluder is Belial, and it is through delusion that he is able to keep under his sway all that thou see’st with the exception of that little bye-street yonder. He is a powerful prince, with thousands of princes under him. What was Cæsar or Alexander the Great compared with him? What are the Turk and old Lewis of France [7] but his servants? Great, aye, exceedingly great is the might, craftiness and diligence of Prince Belial and of the countless hosts he hath in the lower region.” “Why do those women stand there?” I asked, “and who are they?” “Slowly,” cried the Angel, “one question at a time; they stand there in order to be loved and worshipped.” “No wonder, in sooth,” said I, “so lovely are they that were I the possessor of hands and feet as once I was, I too would go and love or worship them.” “Hush! hush!” cried he, “if that is what thou wouldst do with thy members ’tis well thou’rt wanting them: know, foolish spirit, that these three princesses are no other than three destroying enchantresses, daughters of Prince Belial; and that all the beauty and gentleness which dazzles the streets, is nought else but a gloss over ugliness and cruelty; the three within are like their sire, full of deadly venom.” “Woe’s me, is’t possible,” cried I sorrowfully, “that their love wounds?” “’Tis true, the more the pity,” said he, “thou art delighted with the way the three beam on their adorers: well, there is in that ray of light many a wondrous charm, it blindens them so that they cannot see the hook; it stupifies them so that they pay no heed to their danger, and consumes them with an insatiate lust for more, even though it be a deadly poison, breeding diseases which no physician, yea, not death itself can ever heal, nor aught at all unless a heavenly medicine called Repentance be had to purge the evil in good time ere it become too deeply rooted, through gazing upon them too long.” “Wherefore will not Belial have this adoration to himself?” asked I. “It is the same thing,” said he, “for so long as a man adheres to these or to one of them, that man is sure to bear the mark of Belial and wear his livery.”

“By what names are these three enchantresses called?” “The furthest away is called Pride, the eldest daughter of Belial; the second is Pleasure, and the nearest to us is Lucre; these three are the trinity the world adores.” “I would fain know the name of this vast, madding city,” said I, “hath it a better name than great Bedlam?” “Yea, ’tis called the City of Destruction.” “Alas!” I cried, “are all that dwell therein ruined and lost?” “All,” said he, “save a few that flee from it into yon upper city which is King Emmanuel’s.” “Woe is me and mine! how shall they escape while ever staring at what makes them more and more blind, and preys upon them in their blindness?” “It would be utterly impossible for any man to escape hence were it not that Emmanuel sends his ministers from on high, night and morn, to persuade them to leave the rebels and turn to Him, their true Sovereign, and sends to some a gift of precious ointment called Faith to anoint their eyes, and whoso obtains that genuine ointment (for there is an imitation of this as of everything else in the City of Destruction) and anoints himself therewith, at once becomes aware of his own wounds and madness, and will not tarry here a moment longer, even though Belial gave him his three daughters, yea, or his fourth who is greatest of all, for staying.”

“What are the names of these immense streets?” I enquired. “They are called, each according to the name of the princess who rules therein; furthest is the Street of Pride, the middle, the Street of Pleasure, and next, the Street of Lucre.” “Who, prithee, dwell in these streets? What tongue is spoken there? Wherefrom and of what nations are their inhabitants?” “Many people,” answered he, “of every language, religion, and nation under the sun dwell there; many a one lives in each of the three streets at different seasons, and everyone as near the gateway as he can; and very often do they change about, being unable to stay long in the one because they so greatly love the princess of the other street. And the old renard, slyly looking on, lets everyone love whichever he prefers, or the three if he will—all the more certain is he of him.”

“Come nearer to them,” said the Angel, snatching me downwards in the veil through the noxious vapours rising from the city. We alighted in the Street of Pride, on the top of a great, roofless mansion with its eyes picked out by the dogs and crows, and its owners gone to England or France, there to seek what might be gotten with far less trouble at home; thus in place of the good old country-family of days gone by, so full of charity and benevolence, none keep possession now but the stupid owl, the greedy crows, or the proud-pied magpies or the like, to proclaim the deeds of the present owners. There were thousands of such deserted palaces, which but for pride might still be the resort of noblemen, a refuge for the weak, a school of peace and all goodness, and a blessing to the thousands of cottages surrounding them. From the top of these ruins we had plenty of room and quietness to see the whole street on both sides. The houses were very fine, and of wonderful height and grandeur, and good reason why, for emperors and kings lived there, princes in hundreds, noblemen and gentlemen in thousands, and a great many women of all grades. I could see many a horned coquette, like a full-rigged ship, strutting as if set in a frame with a fair store of pedlery about her, and pearls in her ears to the value of a good-sized farm: some were singing so as to be praised for their voices, some dancing, to show their figures; others coloring, to improve their complexion, others having been a good three hours before a mirror trimming themselves, learning to smile, pinning and unpinning, making grimaces and striking attitudes. Many a coy wench was there who knew not how to open her lips to speak, much less to eat, or from very ceremony, how to look under foot; and many a ragged shrew who would contend that she was equal to the best lady in the street, and many an ambling fop who might winnow beans by the wind of his train.

Whilst I was looking from afar at these and a hundred similar things, lo! there came by us a gaudy, strapping quean of arrogant mien, and after whom a hundred eyes were turned; some made obeisance, as if in worship of her, a few put something in her hand. I could not make out what she was, and so I enquired. “Oh,” said my friend, “she is one whose entire dowry is on show, and yet thou see’st how many fools there are who seek her, and the meanest is received notwithstanding all the demand there is for her; whom she will, she cannot have, and whom she can, she will not; she will only speak to her betters because her mother told her that a young woman can make no greater mistake than to be humble in courtship.” Thereupon a burly Falstaff, who had been alderman and in many offices, came out from beneath us, spreading out his wings as if to fly, when he could scarcely limp along like a pack-horse, on account of his huge paunch, and the gout, and many other gentlemanly complaints; but for all that you could not get a single glance from him except as a great favour, remembering the while to address him by all his title and offices. From him I turned my eyes to the other side of the street, and saw a bluff young nobleman with a numerous following, smiling graciously and bowing low to everyone he met. “It is strange,” said I, “that these two should belong to the same street.” “It is the same princess—Pride, who governs them both,” answered he, “this one’s errand is but to speak fair; he is now making a bid for fame with the intent thereby to attain the highest office in the State; he is most ready to weep with the people, and tell them how greatly they are wronged through the oppression of wicked ministers; yet it is his own exaltation, and not the common weal that is the main object of his pursuit.”

After looking for a longwhile I saw close by the Porch of Pride a fair city on seven hills, and over its magnificent court the triple crown, the swords and cross-keys. “Well, here is Rome,” quoth I, “here lives the Pope, is it not?” “Yes, most often,” said the Angel, “but he hath a court in each of the other streets.” Over against Rome I could see a city with a very fine court, whereon was raised on high a crescent on a golden banner, by which I knew the Turk was there. After these came the court of Lewis XIV. of France, as I perceived by his arms—the three fleur-de-lys on a silver banner reared high. Whilst admiring the loftiness and magnificence of these palaces, I observed that there was much traversing from one court to another, and asked the reason. “Oh, there is many a dark reason,” said the Angel, “existing between these three potent and crafty monarchs, but though they deem themselves fitting peers to the three princesses up yonder, their power and guile is nought compared with theirs. Yea more, great Belial deems the whole city, notwithstanding the number of its kings, unsuitable for his daughters. Although he offers them in marriage to everybody, he has never actually given them to anyone. Keen rivalry has existed between these three for their hands; the Turk, who calls himself the god of earth, would have the eldest, Pride, to wife. “Nay,” said the king of France, “she is mine, for I keep all my subjects in her street, and bring her many from England and many other realms.” Spain would have the Princess of Lucre, spite of Holland and all the Jews, and England, the Princess of Pleasure in spite of the Pagans. But the Pope claimed the three, and for better reasons than all the others; and Belial admits him next to them in each street.” “Is that the cause of this commerce?” said I. “No,” said he, “Belial has made peace between them upon that matter long ago. But now he has bid the three put their heads together to consider how they can the soonest destroy yon bye-street; that is the City of Emmanuel, and especially one great mansion therein, out of mere jealousy, perceiving it to be a finer edifice than any in all the City of Destruction. And Belial promises half his kingdom during his life, and the whole on his decease, to him who succeeds in doing so. But notwithstanding the magnitude of his power, the depth of his wiles, and the number of emperors, kings and crafty rulers that are beneath his sceptre in that huge City of Destruction, notwithstanding the courage of his countless hosts beyond the gates in the lower region, that task will prove too difficult for them; however great, powerful and untiring his majesty may be, in yon small street is a greater than he.”

I was not able to give very close attention to his angelic reasons, being occupied in watching the frequent falls people were having on the slippery street. Some I could see with ladders scaling the tower, and having reached the highest rung, falling headlong to the bottom. “Where do those fools try to get to?” I asked. “To a place that is high enough—they are endeavouring to break into the treasury of the princess.” “I warrant it be full,” quoth I. “Yes,” answered he, “of everything that belongs to this street, to be distributed among its denizens: all kinds of weapons for invading and extending territories; all kinds of coats-of-arms, banners, escutcheons, books of genealogy, sayings of the ancients, and poems, all sorts of gorgeous raiments, boastful tales and flattering mirrors; every pigment and lotion to beautify the face; every high office and title—in short, everything is there which makes a man think better of himself and worse of others than he ought. The chief officers of this treasury are masters of the ceremonies, roysters, heralds, bards, orators, flatterers, dancers, tailors, gamblers, seamstresses and the like.”

From this street we went to the next where the Princess of Lucre rules supreme; this street was crowded and enormously wealthy; yet not half so magnificent and clean as the Street of Pride, nor its people so foolishly haughty, for here they were for the most part skulking and sly. Thousands of Spaniards, Dutchmen, Venetians, and Jews were here, and also a great many aged people. “Prithee, sir,” said I, “what manner of men might these be?” “They are pinchfists one and all. In the lower end thou shalt see the Pope once more together with conquerors of kingdoms and their soldiery, oppressors, foresters, obstructors of public paths, justices and their bribers, and all their progeny from the barrister to the constable; on the other side, physicians, apothecaries, leeches, misers, merchants, extortioners, money lenders, withholders of tithes, wages, rents or doles left to schools, almhouses and the like; drovers, dealers who regulate the market for their own benefit; shopmen (or rather, sharpers) who profit on the need or ignorance of their customers; stewards of all grades; clippers [14] and innkeepers who despoil the idlers’ family of their goods and the country of its barley, which would otherwise be made into bread for the poor. All these are arrant robbers, the others in the upper end of the street are mostly small fry, such as highwaymen, tailors, weavers, millers, grocers and so on.”

In the midst of this I could hear a terrible commotion towards the far end of the street, and a great crowd of people thronging the gate, and such pushing and quarelling as made me think that there was a general riot afoot, until I asked my friend what was the matter. “There is very valuable treasure in that tower,” said the Angel, “and the reason for this tumult is that they are about to choose a treasurer for the Princess, instead of the Pope, who has been driven from office.” So we went to see the election.

The candidates for the post were the stewards, the money-lenders, the lawyers, and the merchants, and it was the wealthiest of these that was to have it (for the more thou hast, the more wilt thou have and seek for—an insatiate complaint pertaining to this street). The stewards were rejected at the outset, lest they might impoverish the whole street and, just as they had erected their mansions upon their masters’ ruins, in the end dispossess the princess herself. The contest then lay between the other three. The merchants had more silk, the lawyers more mortgages on land, and the money-lenders more bills and bonds and fuller purses. “Ho, they won’t agree this night,” said the Angel, “come away; the lawyers are richer than the merchants, the money-lenders than the lawyers, the stewards than the money-lenders, and Belial richer than all; for they and all that belongs to them are his.” “Why does the princess keep these robbers about her?” “What more befitting, seeing that she herself is arch-robber?” I was amazed to hear him call the princess by such name, and the proudest gentry in the land arrant robbers. “Why, pray my lord,” said I, “do you consider these great noblemen worse thieves than highwaymen?” “Thou art a simpleton—think on that knave who roves the wide world over, sword in hand, and with his ravagers at his back, slaying and burning, and depriving the true possessors of their states, and afterwards expecting to be worshipped as conqueror; is he not worse than the petty thief who takes a purse on the highway? What is a tailor who filches a piece of cloth compared to a squire who steals from the mountain-side half a parish? Ought the latter not be called a worse robber than the former, who only takes a shred from him, while he deprives the poor of pasture for his beast, and consequently of the means of livelihood for himself, and those depending upon him? What is the stealing a handful of flour in the mill compared with the storing up of a hundred bushels to rot, in order to obtain later on for one bushel the price of four? What is a threadbare soldier who robs thee of thy clothes at the swords’ point when compared with the lawyer who despoils thee of thy whole estate with the stroke of a quill, and against whom thou canst claim no recompense or remedy? What is a pickpocket who steals a five-pound in comparison to a dice-sharper who robs thee of a hundred pounds in the third part of a night? And what the swindler that deceives thee in a worthless old hack compared with the apothecary who swindles thee of thy money and life too, for some effete, medicinal stuff? And moreover, what are all these robbers compared with that great arch-robber who deprives them all of everything, yea, of their hearts and souls after the fair is over?”

From this foul and disorderly street we proceeded to the street of the Princess of Pleasure wherein I saw many English, French, Italians and Paynims. The Princess is very fair to behold, with mixed wine in one hand, and a fiddle and a harp in the other; and in her treasury, innumerable pleasures and toys to gain the custom of everybody, and retain them in her father’s service. Yea, many were wont to escape to this pleasant street to drown their grief for losses and debts they had incurred in the others. It was exceedingly crowded, especially with young people; whilst the Princess is careful to please everyone, and to have an arrow ready for every mark. If thou art thirsty, here thou will find thy favorite beverage; if thou lovest song and dance, here thou shalt have thy fill. If the beauty of the Princess has kindled thy lust, thou need’st but beckon one of her sire’s officers (who, although invisible, always surround her) and they will immediately attend thy behest. There are here fair mansions, fine gardens, full orchards, shady groves fit for every secret intrigue, or to trap birds or a white rabbit or twain; clear streams, most pleasant to fish in; rich, boundless plains, whereon to hunt the hare and fox. Along the street we could see them playing interludes, juggling and conjuring, singing lewd songs to the sound of the harp and ballads, and all manner of jesting. Men and women of handsome appearance danced and sang, and many came hither from the Street of Pride in order to be praised and worshipped. Within the houses we perceived some on silken beds wallowing in debauchery; some at the gaming-table, cursing and swearing, others tossing dice and shuffling cards. Some from the Street of Lucre, having a room here, ran hither to count their money, but stayed not long lest aught of the countless geegaws that are here should entice them to part with their money without interest. Others I saw at tables feasting with somewhat of every created thing before them; and when everyone, mess after mess, had guzzled as much of the dainties as would afford a moderate man a feast for a whole week, grace followed in the form of blasphemous howling; then the king’s health was called for, and that of every boon companion, and so on to quench the taste of the viands, and drown their cares. Then came tobacco, and then each one began to talk scandal of his neighbour—whether true or false it mattered not as long as it was humorous or fresh, or, best of all, degrading. At last, what with a round of blasphemy, and the whole crowd with clay pistols belching smoke and fire and slander of their neighbours, and the floor already befouled with dregs and spittle, I feared lest viler deeds should happen, and craved to depart.

Thence we went where we heard a loud noise, beating and clamouring, crying and laughing, shouting and singing. “Well, here’s Bedlam and no mistake,” quoth I. By the time we got in, the turmoil had ceased; one man lay like a log on the ground, another was vomiting, another nodding his head over a hearth full of battered flagons, and broken pipes and mugs. On enquiring, what should it be but a carousal of seven thirsty neighbours—a tinker, a dyer, a blacksmith, a miner, a chimney-sweep, a bard, and a parson who had come to preach sobriety, and to show in his own person how repulsive drunkenness is; and the beginning of the recent altercation was a discussion and dispute they had as to which of the seven callings loved best the pot and pipe; the bard had beaten all but the parson and, due regard being observed for the cloth, he was adjudged victor and worthy to be leader of his good comrades, and so the bard wound up the discussion thus:

“Where can ye find such thirsty seven,

Search every clime and land?

And quaffing off the ruddy ale,

Bard and parson lead the band.”

Thoroughly tired of these drunken swine, we drew nearer the gate in order to spy out the blemishes in the magnificent court of Love, the purblind king, wherein it is easy to enter, but difficult to get out again, and where are chambers innumerable. In the hall opposite the door stood giddy Cupid, with two arrows in his bow, darting a languishing venom called lust. Along the floor I saw many fair and comely women walking with measured steps, and following them, wretched youths gazing upon their beauty, and each one begging a glance from his mistress, fearing a frown even more than death; now and then one, bowing to the ground, would place a letter in his goddess’ hand, and another a sonnet, the while in fear expectant, like schoolboys showing their task to the master. They in return would favour their adorers with a simpering smile or two, just to keep their desires on edge, but granting nought more lest their lust be sated and they depart healed of the disease. Going on into the parlour I saw them having lessons in dancing and singing, with voice and hand, in order to make their lovers sevenfold madder than before; on again into the dining hall where they were taught coy smartness in eating; into the cellar, where potent love philtres were being mixed of nail parings and the like; in the upper rooms we could see one in a secret chamber twisting himself into all shapes, practising gentlemanly behaviour when in his mistress’ presence; another before a mirror learning how to smile correctly without showing his teeth too prominently to his ladylove; another preparing his tale to tell her, repeating the same thing an hundred times. Wearied with this insipid babbling we came to another cell: here a nobleman had sent for a poet from the Street of Pride to indite him a sonnet of praise to his angel, and an eulogy of himself; the bard was discoursing of his art: “I can,” said he, “liken her to everything red and everything white under the sun, and her tresses to an hundred things more yellow than gold, and as for your poem, I can trace your lineage through many knights and princes, and through the water of the deluge right up to Adam.” “Well, here’s a poet,” quoth I, “who is a better genealogist than I.” “Come, come,” said the Angel, “their intention is to deceive the woman, but, once in her presence, you may be sure they will have to meet trick with trick.”

Upon leaving these we had a glimpse of cells where fouler deeds were being done than modesty permits to mention, and which caused my companion to snatch me away in anger from this fatuous court into the princess’ treasury (for we went where we list notwithstanding doors and locks). There we saw myriads of fair women, all kinds of beverages, fruits and dainties, stringed instruments and books of songs,—harps, pipes, odes and carols, all sorts of games,—backgammon, dice [20] and cards; pictures of various lands, towns and persons, inventions and amusing tricks; all kinds of waters, perfumes, pigments and spots to make the ugly fair, and the old look young, and the leman’s malodorous bones smell sweet for the nonce. In short, the shadow of pleasure and the guise of happiness in every conceivable form was to be found there; and sooth to say, I almost think I too had been enticed by the place had not my friend instantly hurried me away far from the three alluring towers to the top end of the streets, and set me down near an immense palatial castle, the front view of which seemed fair, but the further side was mean and terribly ugly, though it was scarcely to be seen at all. It had a myriad portals—all splendid without but rotten within. “An’t please you, my lord,” asked I, “what is this wondrous place?” “This is the court of Belials’ second daughter whose name is Hypocrisy; here she keeps her school, and there is no man or woman throughout the whole city who has not been a pupil of hers, and most of them have imbibed their learning remarkably well; so that her lessons are discernible as a second nature intertwined with all their thoughts, words, and deeds from very childhood almost.” I had been looking awhile on the falsity of every part of the edifice when a funeral came by with many weeping and sighing, and many men and horses in mourning trappings; and shortly the poor widow, veiled so as not to see this cruel world any more, came along with piping voice and weary sighs, and fainting fits at intervals. In truth, I could not help but weep a little out of pity for her. “Nay, nay,” said the Angel, “keep thy tears for a more worthy occasion; these voices are only what Hypocrisy has taught, and these mourning weeds were fashioned in her great school. Not one of these weep sincerely; the widow, even before the body had left the house, let in another husband to her heart; were she rid of the expenses connected with the corpse she would not care a straw if his soul were at the bottom of hell; nor do his own kindred care any more than she: for when it went hardest with him, instead of giving him good counsel and earnestly praying for mercy upon him, they were talking of his property, his will or his pedigree; or what a handsome robust man he was, and such talk; and now this wailing [21] on the part of some is for mere ceremony and custom, on the part of others for company’s sake or for pay.”

Scarcely had these gone by than another throng came in sight: a most gallant lord with his lady at his side, slowly advancing in state, to whom many men of position doffed, and many were on tiptoe with eagerness to show him obeisance and reverence. “Here is a noble lord,” said I, “who is worthy such respect from all these!” “Wert thou to take everything to consideration thou wouldst speak differently. This lord comes from the Street of Pleasure, she is of the Street of Pride, and yon old man who is conversing with him comes from the Street of Lucre, and has a mortgage on almost every acre of my lord’s, and is come to-day to complete the loan.” We drew nigh to hear the conversation. “In sooth, sir,” Old Money-bags was saying, “I would not for all that I possess that you should lack anything which lies in my power to enable you to appear your own true self this day, especially seeing that you have met so beautiful and lovely a lady as madam here” (the wily dog knowing full well what she was). “By the — by the —,” said the lord, “next to gazing at her beauty, my greatest pleasure was to hearken to your fair reasons; I had liefer pay you interest than get money elsewhere free.” “Indeed, my lord,” said one of his chief friends called Flatterer, “nuncle pays you not a whit less respect than is due to you, but an it please you, he has bestowed upon her ladyship scarce the half her mead of praise. I defy any man,” quoth he, “to show a lovelier woman in all the Street of Pride, or a nobler than you in all the Street of Pleasure, or a kinder than you, good mine uncle, in all the Street of Lucre.” “Ah, that is your good opinion,” said my lord, “but I cannot believe that any couple were ever more united in the bonds of love than we twain.” As they went on the crowd increased, and everyone had a pleasant smile and low bow for the other, and hastened to salute each other with their noses to the ground, like a pair of gamecocks on the point of striking. “Know then,” said the Angel, “that thou hast seen naught of civility nor heard one word which Hypocrisy has not taught. There is no one here, after all this gentleness, who has a hap’orth of love one to another, yea, many of them are sworn foes. This lord is the butt [23] of everybody, and all have their dig at him. The lady looks only to his greatness and high degree, so that she may thereby ascend a step above many of her neighbours. Old Money-bags has his eye on my lord’s lands for his own son, and all the others on the money he received as dowry; for they are all his dependants, his merchants, tailors, cobblers and other craftsmen, who have decked him out and maintained him in this splendor, and have never had a brass farthing for it, nor are likely to get aught save smooth words and sometimes threats perhaps. How many layers, how many folds had Hypocrisy laid over the face of Truth! He, promising greatness to his love, while his lands were on the point of being sold; she, promising him dower and beauty, while her beauty is but artificial, and cancer is consuming both her dowry and her body.” “Well, this teaches us,” said I, “never to judge by appearances.” “Yes verily,” said he, “but come on and I will show thee more.”

At the word he transported me up to where the churches of the City of Destruction were; for everyone therein, even the unbelieving, has a semblance of religion. And it was to the temple of the unbelievers that we first came, and there I saw some worshipping a human form, others the sun, the moon and a countless other like gods down to onions and garlic; and a great goddess called Deceit was universally worshipped. However, there were some traces of the influence of Christianity to be found in most of these religions. Thence we came to a congregation of mutes, [24] where there was nothing but sighing and quaking and beating the breast. “Here,” said the Angel, “is the appearance of great repentance and humility, but which in reality is perversity, stubbornness, pride and utter darkness; although they talk much about the light within, they have not even the spectacles of nature which the heathen thou erstwhile saw, possess.”

From these dumb dogs we chanced to turn into an immense, roofless church, with thousands of shoes lying at the porch, whereby I learnt it was a Turkish mosque. These had but very dark and misty spectacles called the Koran; yet through these they gazed intently from the summit of their church for their prophet, who falsely promised to return and visit them long ago, but has left his promise unfulfilled.

From thence we entered the Jewish synagogue—these too were unable to flee from the City of Destruction, although they had grey-tinted spectacles, for when they look a film comes over their eyes from want of anointing them with that precious ointment—faith.

Next we came to the Papists. “Here is the church that beguiles the nations,” exclaimed the Angel, “it was Hypocrisy that built this church at her own cost. For the Papists encourage, yea, command men to break an oath with a heretic even though sworn on the sacraments.” From the chancel we went through the keyholes, up to the top of a certain cell which was full of candles, though it was broad daylight, and where we could see a tonsured priest walking about as if expecting someone to come to him; and ere long there comes a buxom matron, with a fair maid in her wake, bending their knees before him to confess their sins. “My spiritual father,” said the good wife, “I have a burthen too heavy to bear unless I obtain your mercy to lighten it: I married a member of the Church of England!” “What!” cried the shorn-pate, “married a heretic! wedded to an enemy? forgiveness can never be obtained!” At these words she fainted, while he kept calling down imprecations upon her head. “Woe’s me, and what is worse,” cried she when come to herself, “I killed him!” “Oh ho! thou hast killed him? Well, that’s something towards gaining the reconciliation of the Church; I tell thee now, hadst thou not slain him, thou wouldst never have obtained absolution nor purgatory, but a straight gate and a leaden weight to the devil. But where’s your offering, you jade?” he demanded with a snarl. “Here,” said she, handing him a considerable bag of money. “Well,” said he, “now I’ll make your reconciliation: your penance is to remain always a widow lest you should make another bad bargain.” When she was gone, the maiden also came forward to make her confession. “Your pardon, father confessor,” cried she, “I conceived a child and slew it.” “A fair deed, i’faith,” said the confessor, “and who might the father be?” “Indeed ’twas one of your monks.” “Hush, hush,” he cried, “speak no ill of churchmen. [25] What satisfaction have you for the Church?” “Here it is,” said she and handed him a gold trinket. “You must repent, and your penance will be to watch at my bedside to-night,” he said with a leer. Hereupon four other shavelings entered, dragging before the confessor a poor wretch, who came about as willingly as he would to the gallows. “Here’s for you a rogue,” cried one of the four, “who must do penance for disclosing the secrets of the Catholic Church.” “What!” exclaimed the confessor, looking towards a dark cell near at hand: “but come, villain, confess what thou hast said?” “Indeed,” began the poor fellow, “a neighbour asked me whether I had seen the souls that were groaning underneath the altar on All-souls’ day; and I said I had heard the voice, but had seen nothing.” “So, sirrah, come now, tell everything.” “I said moreover,” he continued, “that I had heard that you were playing tricks on us unlettered hinds, that, instead of souls, there was nothing but crabs making a row under the carpet.” “Oh, thou hell-hound! cursed knave!” cried the confessor, “but, proceed, mastiff.” “And that it was a wire that turned the image of St. Peter, and that it was along a wire the Holy Ghost descended from the roodloft upon the priest.” “Thou heir of hell!” cried the shriver, “Ho there, torturers, take him and cast him into that smoky chimney for tale-bearing.” “Well, this is the church Hypocrisy insists upon calling the Catholic Church, and she avers that these only are saved,” said the Angel; “they once had the proper spectacles, but they cut the glass into a thousand forms; they once had true faith, but they mixed that salve with substances of their own, so that they see no better than the unbelieving.”

Leaving the cell we came to a barn [26] where someone was delivering a mock sermon extempore, sometimes repeating the same thing thrice in succession. “These,” said the Angel, “have the right sort of spectacles to see ‘the things which belong unto their peace,’ but there is wanting in their ointment one of the most necessary ingredients, namely, perfect love. People come hither for various reasons; some out of respect to their elders, some from ignorance, and many for worldly gain. One would think, looking at their faces, that they are on the point of choking, but they will swallow frogs sooner than starve; for so does Princess Hypocrisy teach those meeting in barns.

“Pray tell,” said I, “where may the Church of England be?” “Oh, it is yonder in the upper city, forming a large part of the Catholic Church, but there are in this city a few probationary churches belonging to the Church of England, where the Welsh and English stay for a time on probation, so that they may become fit to have their names enrolled as members of the Catholic Church, and ever blessed be he who shall have his name so enrolled. Yet, more’s the pity, there are but few who befit themselves for its citizenship. For too many, instead of looking thitherwards, allow themselves to be blinded by the three princesses down below; Hypocrisy too, keeps many with one eye on the upper city and the other on the lower; yea, Hypocrisy is clever enough to beguile many who have withstood the other enchantresses. Enter here, and thou shalt see more,” he said, and snatched me up into the roodloft in one of the Welsh churches, when the people were at service; there we saw some busily whispering, some laughing, some staring at pretty women, others prying their neighbour’s dress from top to toe; others, in eagerness for the position due to their rank, keep shoving forward and showing their teeth at one another, others dozing, others assiduous at their devotions, and many of these too, dissimulating. “Thou hast not yet seen, nay, not even among infidels shamelessness so barefaced and public as this,” said the Angel, “but so it is, I am sorry to say, there is no worse corruption than the corruption of the best.” [28a] Then they went to communion, and everybody appeared fairly reverent before the altar; yet through my friend’s glass I could see one taking unto himself with the bread the form of a mastiff, another, that of a mole, another, that of an eagle, a pig or a winged serpent, and a few, ah, how few, received a ray of bright light with the bread and wine. “There,” he pointed out, “is a Roundhead, who is going to be sheriff, and because the law calls upon a man to receive the sacrament in the Church before taking office he has come here rather than lose it, and although there are some here who rejoice on seeing him, we have felt no joy at his conversion, because he has only become converted for the occasion. Thus thou perceivest that Hypocrisy, with exceeding boldness, approaches the altar in the presence of the God that cannot be deceived. But though she wields great power in the City of Destruction, she is of no avail in the City of Emmanuel beyond those ramparts.”